Catégorie : Comprendre

Articles, analyses et conférences pédagogiques.

Articles, analyses et conférences pédagogiques.

L’histoire de l’art avec le regard d’un amoureux de toutes les renaissances.

FR/EN/NE/GE/IT/ES

Erasmus’ dream: the Leuven Three Language College

In autumn 2017, a major exhibit organized at the University library of Leuven and later in Arlon, also in Belgium, attracted many people. Showing many historical documents, the primary intent of the event was to honor the activities of the famous Three Language College (Collegium Trilingue), founded in 1517 by the efforts of the Christian Humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (1467-1536) and his allies. Though modest in size and scope, Erasmus’ initiative stands out as one of the cradles of European civilization, as you will discover here.

Revolutionary political figures, such as William the Silent (1533-1584), organizer of the Revolt of the Netherlands against the Habsburg tyranny, humanist poets and writers such as Thomas More, François Rabelais, Miguel Cervantes and William Shakespeare, all of them, recognized their intellectual debt to the great Erasmus of Rotterdam, his exemplary fight, his humor and his great pedagogical project.

For the occasion, the Leuven publishing house Peeters has taken through its presses several nice catalogues and essays, published in Flemish, French as well as English, bringing together the contributions of many specialists under the wise (and passionate) guidance of Pr Jan Papy, a professor of Latin literature of the Renaissance at the Leuven University, with the assistance of a “three language team” of Latinists which took a fresh look at close to all the relevant and inclusively some new documents scattered over various archives.

“The Leuven Collegium Trilingue: an appealing story of courageous vision and an unseen international success. Thanks to the legacy of Hieronymus Busleyden, counselor at the Great Council in Mechelen, Erasmus launched the foundation of a new college where international experts would teach Latin, Greek and Hebrew for free, and where bursaries would live together with their professors”, reads the back cover of one of the books.

For the researchers, the issue was not necessarily to track down every detail of this institution but rather to answer the key question: “What was the ‘magical recipe’ which attracted rapidly to Leuven between three and six hundred students from all over Europe?”

Erasmus’ initiative was unprecedented. Having an institution, teaching publicly Latin and, on top, for free, Greek and Hebrew, two languages considered “heretic” by the Vatican, was already tantamount to starting a revolution.

Was it that entirely new? Not really. As early as the beginning of the XIVth century, for the Italian humanists in contact with Greek erudites in exile in Venice, the rigorous study of Greek, Hebraic and Latin sources as well as the Fathers and the New Testament, was the method chosen by the humanists to free mankind from the Aristotelian worldview suffocating Christianity and returning to the ideals, beauty and spirit of the “Primitive Church”.

For Erasmus, as for his inspirer, the Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla (1403-1457), the « Philosophy of Christ » (agapic love), has to come first and opens the road to end the internal divisions of Christianity and to uproot the evil practices of greed (indulgences, simony) and religious superstition (cult of relics) infecting the Church from the top to the bottom, and especially the mendicant orders.

To succeed, Erasmus sets out to clarify the meaning of the Holy Writings by comparing the originals written in Greek, Hebrew and Latin, often polluted following a thousand years of clumsy translations, incompetent copying and scholastic commentaries.

Brothers of the Common Life

My own research allows me to recall that Erasmus was a true disciple of the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life of Deventer in the Netherlands, a hotbed of humanism in Northern Europe. The towering figures that founded this lay teaching order are Geert Groote (1340-1384), Florent Radewijns (1350-1400) and Wessel Gansfort (1420-1489), all three said to be fluent in precisely these three languages.

The religious faith of this current, also known as the “Modern Devotion”, centered on interiority, as beautifully expressed in the little book of Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), the Imitation of Christ. This most read book after the Bible, underlines the importance for the believer to conform one owns life to that of Christ who gave his life for mankind.

Rudolph Agricola

Hence, in 1475, Erasmus father, fluent in Greek and influenced by famous Italian humanists, sends his son to the chapter of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, at that time under the direction of Alexander Hegius (1433-1499), himself a pupil of the famous Rudolph Agricola (1442-1485) which Erasmus had the chance to listen to and which he calls a “divine intellect”.

Follower of the cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464), enthusiastic advocate of the Italian Renaissance and the Good Letters, Agricola would tease his students by saying:

“Be cautious in respect to all that you learned so far. Reject everything! Start from the standpoint you will have to un-learn everything, except that what is based on your sovereign authority, or on the basis of decrees by superior authors, you have been capable of re-appropriating yourself”.

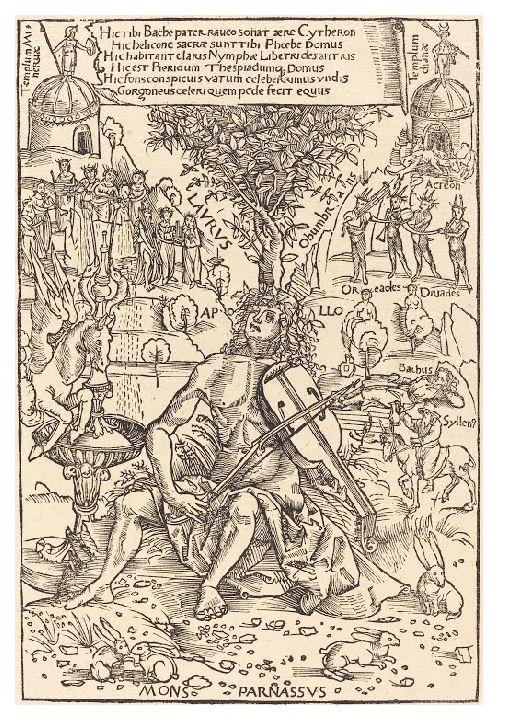

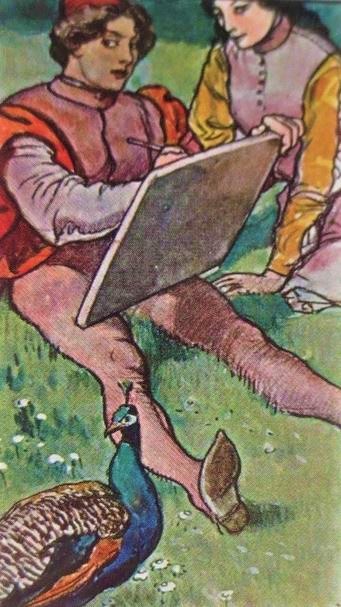

Erasmus, with the foundation of the Collegium Trilingue will carry this ambition at a level unreached before. To do so, Erasmus and his friend apply a new pedagogy. Hence, instead of learning by heart medieval commentaries, pupils are called to formulate their proper judgment and take inspiration of the great thinkers of the Classical period, especially “Saint Socrates”. Latin, a language that degenerated during the Roman Empire, will be purified from barbarisms.

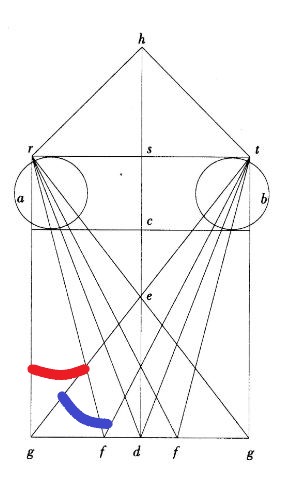

With this approach, for pupils, reading a major text in its original language is only the start. An explorative work is required: one has to know the history and the motivations of the author, his epoch, the history of the laws of his country, its geography, cosmography, all considered to be indispensable instruments to put each text in its specific literary and historical context and allowing reading, beyond the words, the intention of their author.

This “modern” approach (questioning, critical study of sources, etc.) of the Collegium Trilingue, after having demonstrated its efficiency by clarifying the message of the Gospel, will rapidly travel over Europe and reach many other domains of knowledge, notably scientific issues! By uplifting young talents, out of the small and sleepy world of scholastic certitudes, this institution rapidly grew into a hotbed for creative minds.

For the ignorant reader who often considers Erasmus as some kind of comical writer praising madness which lost it after an endless theological dispute with Martin Luther, such a statement might come as a surprise.

Scientific Renaissance

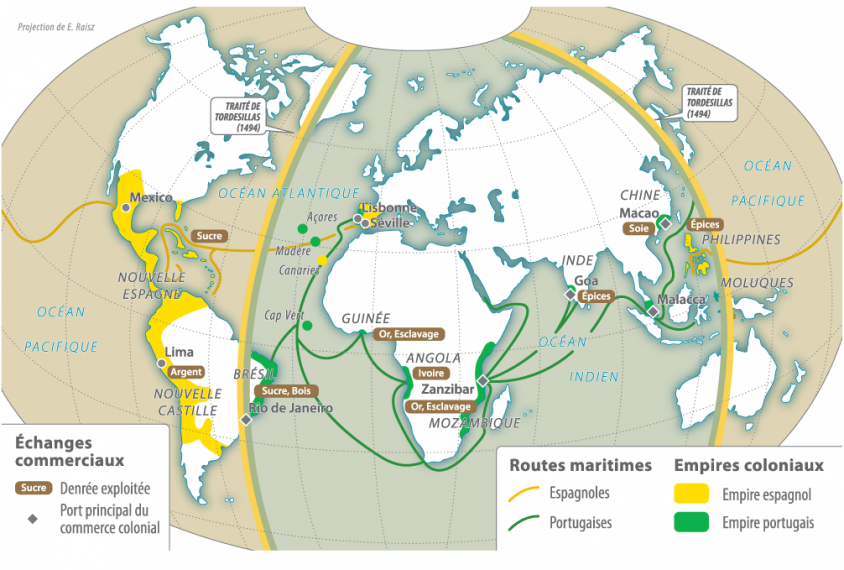

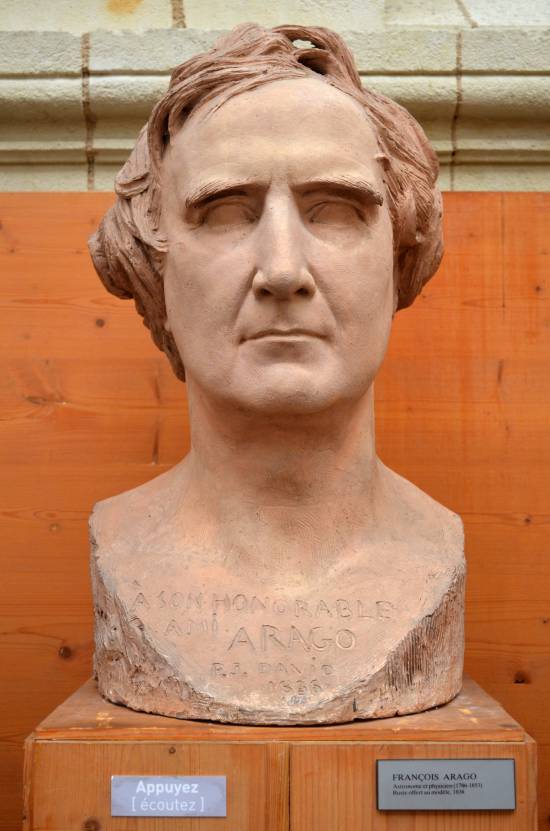

While Belgium’s contributions to science, under Emperor Charles Vth, are broadly recognized and respected, few are those understanding the connection uniting Erasmus with a mathematician as Gemma Frisius and his pupil and friend Gerard Mercator, an anatomist such as Andreas Vesalius or a botanist such as Rembert Dodonaeus.

Hence, as already thoroughly documented in 2011 by Professor Jan Papy in a remarkable article, the scientific renaissance which bloomed in the Netherlands and Belgium in the early XVIth century, could not have taken place if it were for the “linguistic revolution” provoked by the Collegium Trilingue.

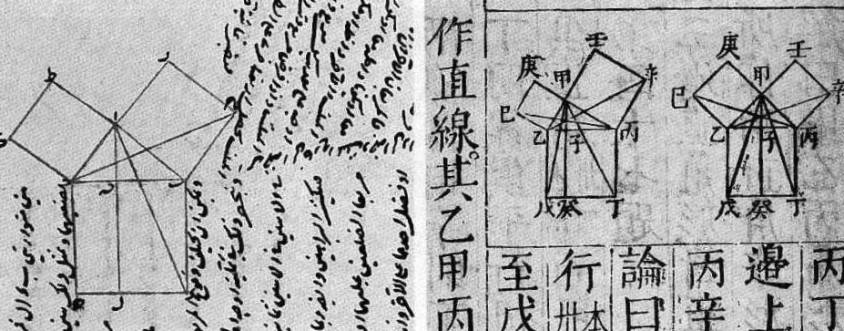

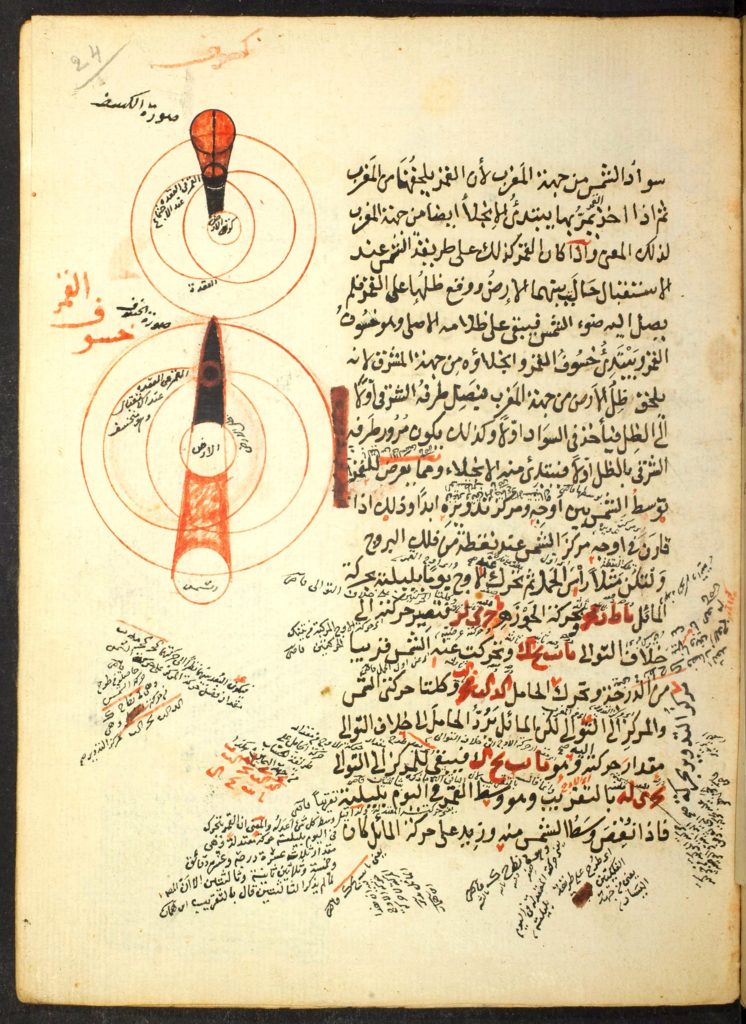

Because, beyond the mastery of their vernacular languages (French and Dutch), hundreds of youth, by studying Greek, Latin and Hebrew, suddenly got access to all the scientific treasures of Greek Philosophy and the best authors in those newly discovered languages.

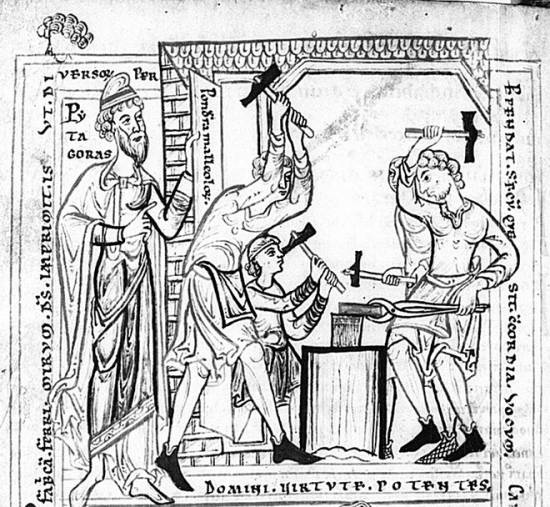

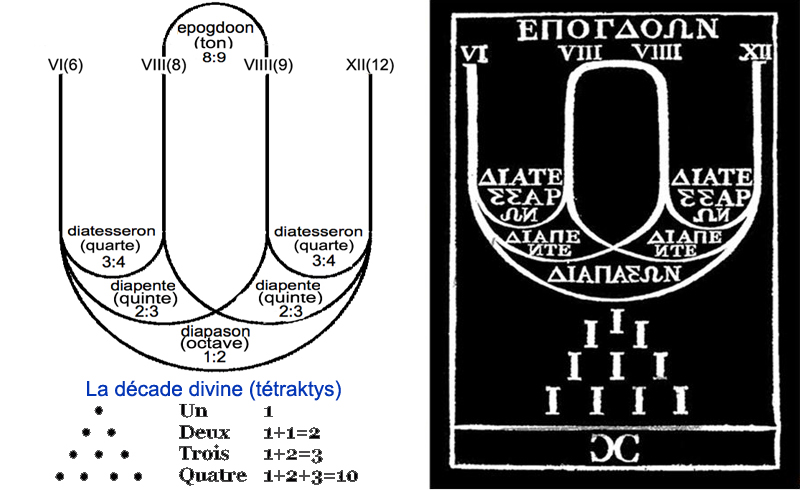

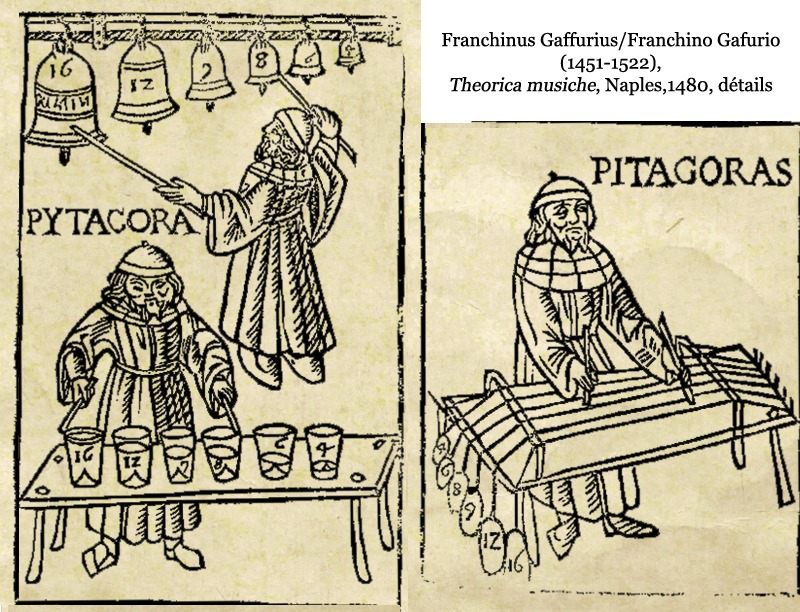

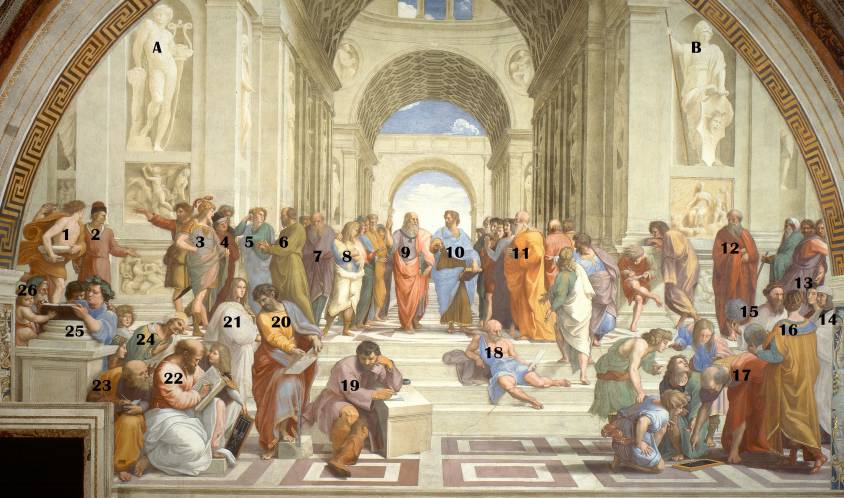

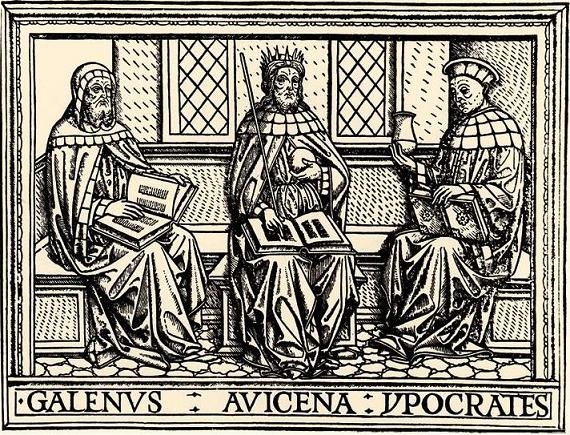

At last, they could read Plato in the text, but also Anaxagoras, Heraclites, Thales of Millet, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Pythagoras, Eratosthenes, Archimedes, Galen, Vitruvius, Pliny the elder, Euclid and Ptolemy whose work they will master and eventually correct.

As the books published by Peeters account in great detail, during the first century of its existence, the Collegium Trilingue had a rough time confronting political uproar and religious strife. Heavy critique came especially form the “traditionalists”, a handful of theologians for which the Greeks were nothing but schismatics and the Jews the assassins of Christ and esoterics.

The opposition was such that Erasmus himself never could teach at the Collegium and, while keeping in close contact, decided to settle in Basel, Switzerland, in 1521.

Despite all of this, the Erasmian revolution conquered Europe overnight and a major part of the humanists of that period were trained or influenced by this institution. From abroad, hundreds of pupils arrived to follow classes given by professors of international reputation.

27 European universities integrated pupils of the Collegium in their teaching staff: among them stood Jena, Wittenberg, Cologne, Douai, Bologna, Avignon, Franeker, Ingolstadt, Marburg, etc.

Teachers at the Collegium were secured a decent income so that they weren’t obliged to give private lectures to secure a living and could offer public classes for free. As was the common practice of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, a system of bursa allowed talented though poor students, including many orphans, to have access to higher learning. “Something not necessarily unusual those days, says Pr Jan Papy, and done for the sake of the soul of the founder (of the Collegium, reference to Busleyden)”.

While visiting Leuven and contemplating the worn-out steps of the spiral staircase (wentelsteen), one of the last remains of the building that had a hard time resisting the assaults of time and ignorance, one can easily imagine those young minds jumping down the stairs with enthusiasm going from the dormitory to the classroom. Looking at the old shopping list of the school’s kitchen one can conclude the food was excellent with lots of meat, poultry but also vegetables and fruits, and sometimes wine from Beaune in Burgundy, especially when Erasmus came for a visit! While over the years, of course, the quality of the learning transmitted, would vary in accordance with the excellence of its teachers, the Collegium Trilingue, whose activity would last till the French revolution, gave its imprint in history by giving birth to what some have called the “Little Renaissance” of the first half of the XVIth century.

In France, the Sorbonne University reacted with fear and in 1523, the study of Greek was outlawed in France.

François Rabelais, at that time a monk in Vendée, saw his books confiscated by the prior of his monastery and deserts his order. Later, as a doctor, he translated the medical writings of the Greek scientist Galen from Greek into French. Rabelais’s letter to Erasmus shows the highest possible respect and intellectual debt to Erasmus.

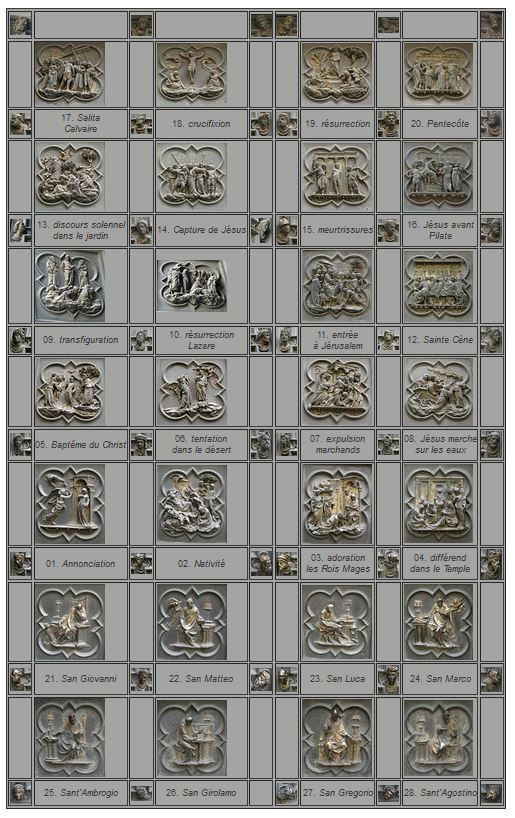

In 1530, Marguerite de Navarre, sister of King Francis, and reader and admirer of Erasmus, at war with the Sorbonne, convinced her brother to allow Guillaume Budé, a friend of Erasmus, to create the “Collège des Lecteurs Royaux” (ancestor of the Collège de France) on the model of the Collegium Trilingue. And to protect its teachers, many coming directly from Leuven, they got the title of “advisors” of the King. The Collège taught Latin, Hebrew and Greek, and rapidly added Arab, Syriac, medicine, botany and philosophy to its curriculum.

Dirk Martens

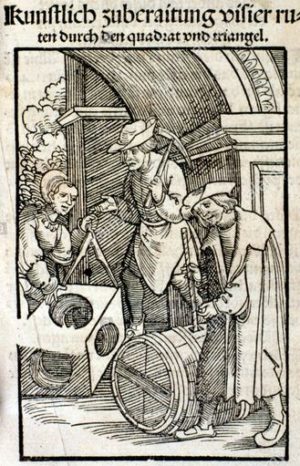

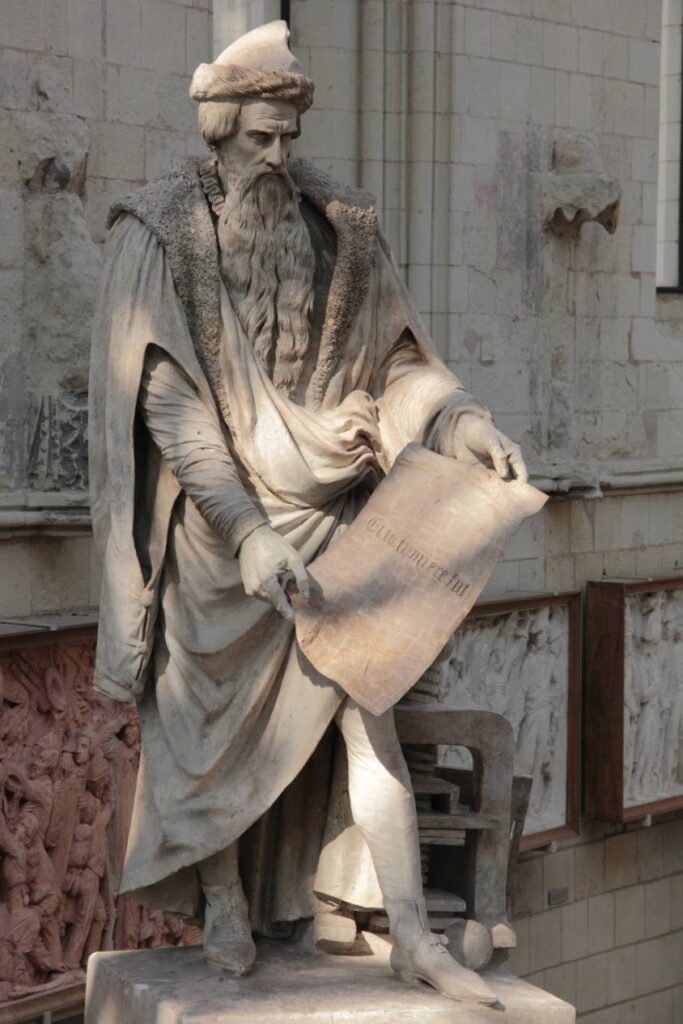

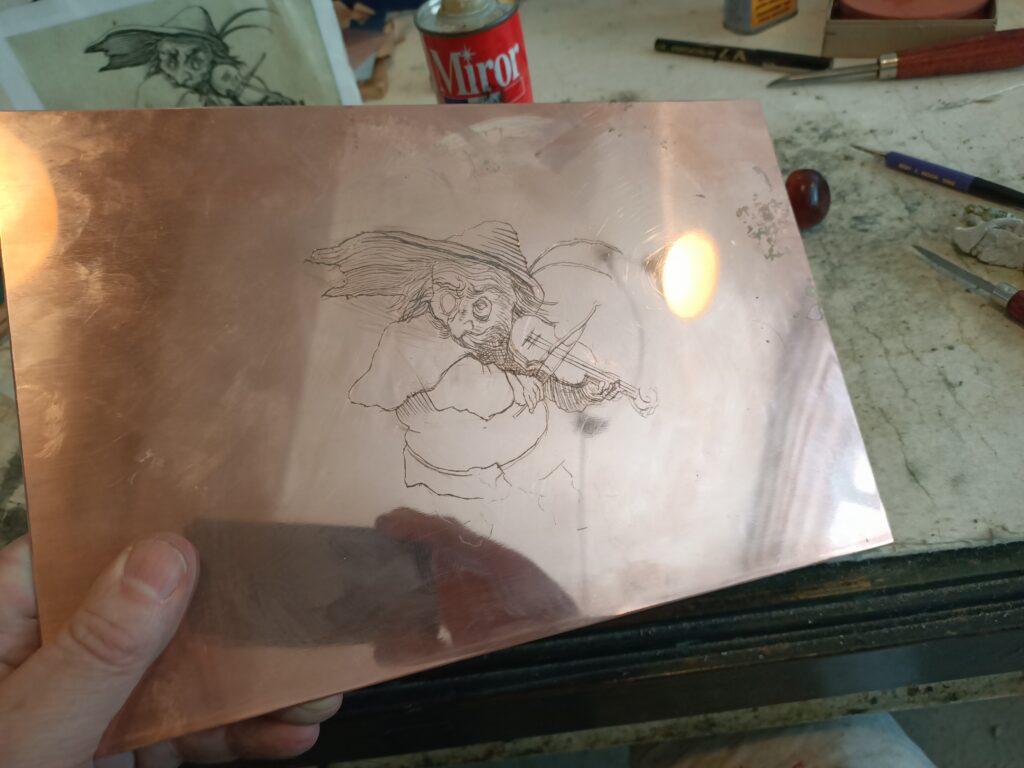

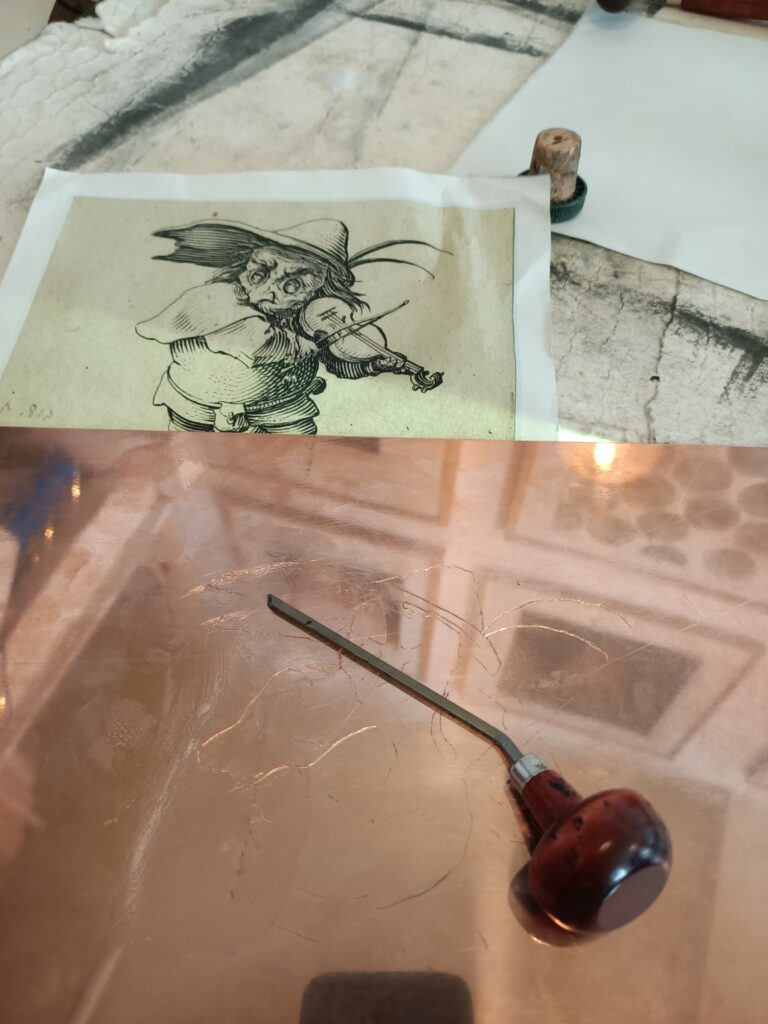

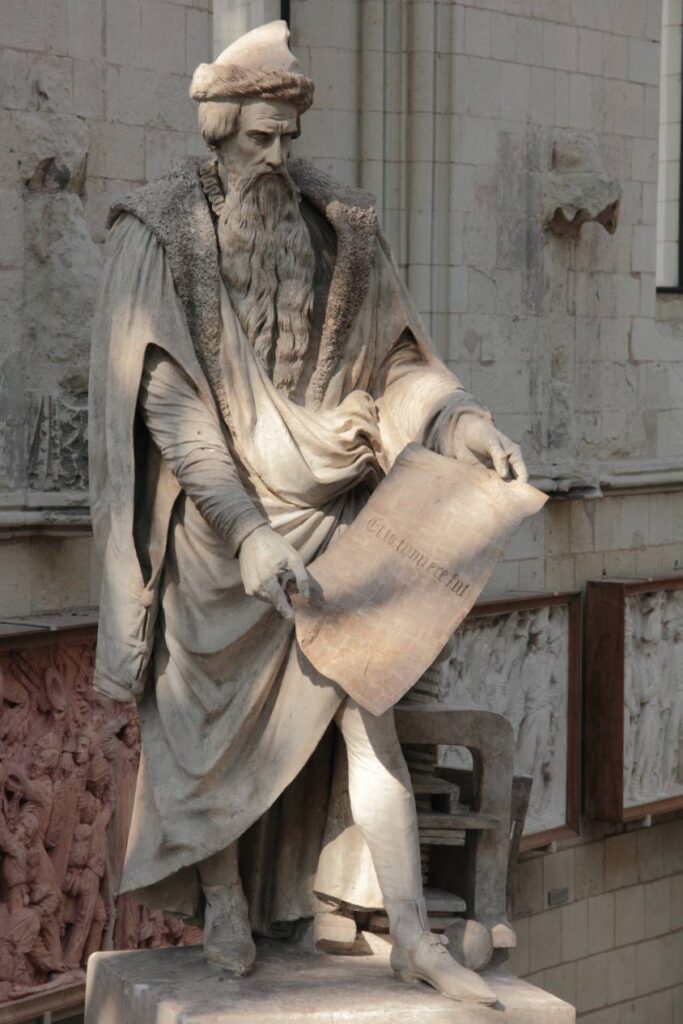

Also celebrated for the occasion, Dirk Martens (1446-1534), rightly considered as one of the first humanists to introduce printing in the Southern Netherlands.

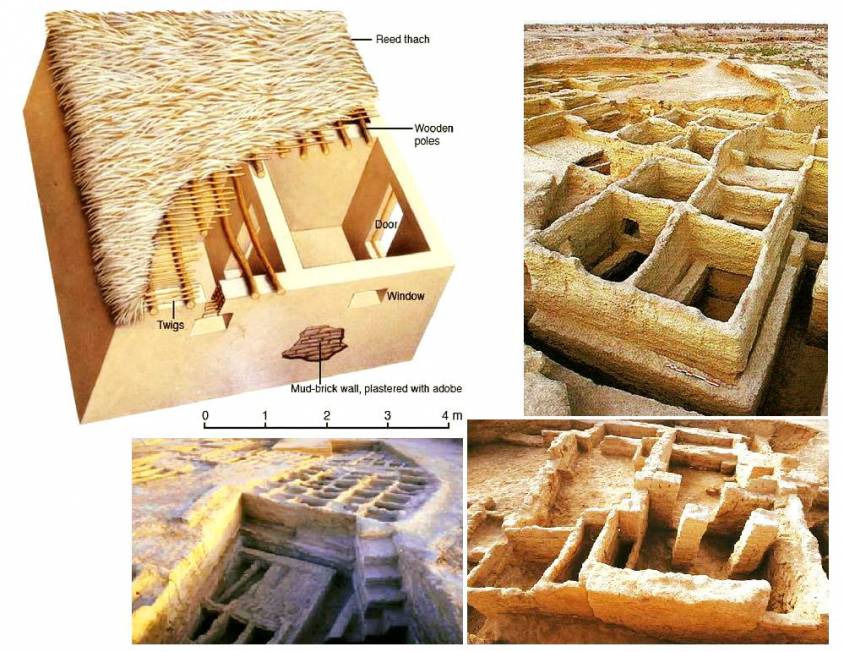

Born in Aalst in a respected family, the young Dirk got his training at the local convent of the Hermits of Saint William. Eager to know the world and to study, Dirk went abroad. In Venice, at that time a cosmopolite center harboring many Greek erudite in exile, Dirk made his first steps into the art of printing at the workshop of Gerardus de Lisa, a Flemish musician who set up a small printing shop in Treviso, close to Venice.

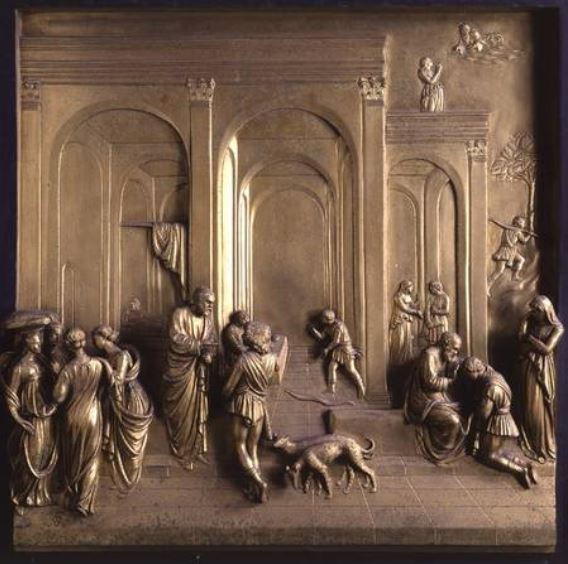

Back in Aalst, together with his partner John of Westphalia, Martens printed in 1473 the first book in the country with a movable type printing press, a treatise of Dionysius the Carthusian (1401-1471), a friend and collaborator of cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa, as well as the spiritual advisor of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy and thought to be the occasional « theological » advisor of the latter’s court painter, Jan Van Eyck.

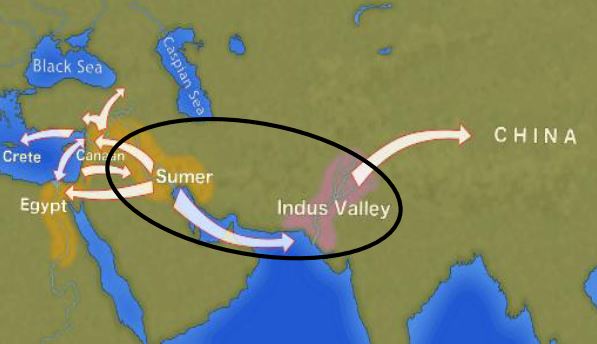

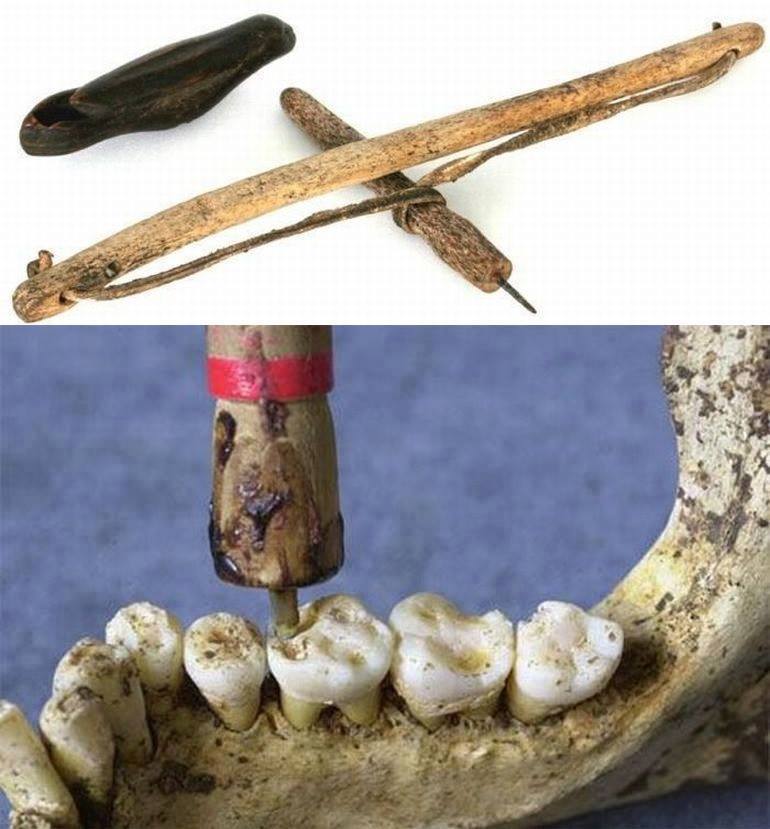

If the oldest printed book known to us is a Chinese Buddhist writing dating from 868, the first movable printing types, made first out of wood and then out of hardened porcelain and metal, came from China and Korea in 1234.

The history of two lovers, a poem written by Aeneas Piccolomini before he became the humanist Pope Pius II, was another early production of Marten’s print shop in Aalst.

Proud to have introduced this new technique allowing a vast increase in the spreading of good and virtuous ideas, Martens wrote in one of the prefaces: “This book was printed by me, Dirk Martens of Aalst, the one who offered the Flemish people all the know-how of Venice”.

After some years in Spain, Martens returned to Aalst and started producing breviaries, psalm books and other liturgical texts. While technically elaborate, the business never reached significant commercial success.

Martens then moved to Antwerp, at that time one of the main ports and cross-roads of trade and culture. Several other Flemish humanists born in Aalst played eminent roles in that city and animate its intellectual and cultural life. Among these:

—Cornelis De Schrijver (1482-1558), the secretary of the City of Aalst, better known under his latin name Scribonius and later as Cornelius Grapheus. Writer, translator, poet, musician and friend of Erasmus, he was accused of heresy and hardly escaped from being burned at the stake.

—Pieter Gillis (1486-1533), known as Petrus Aegidius. Pupil of Martens, he worked as a corrector in his company before becoming Antwerp’s chief town clerk. Friend of Erasmus and Thomas More, he appears with Erasmus in the double portrait painted by another friend of both, Quinten Metsys (1466-1530).

—Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), editor, painter and scenographer. After a trip to Italy, he set up a workshop in Antwerp. Pieter will produce patrons for tapestries, translated with the help of his wife the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius into Dutch and trained the young Flemish painter Bruegel the Elder who will marry his daughter.

Invention of pocket books

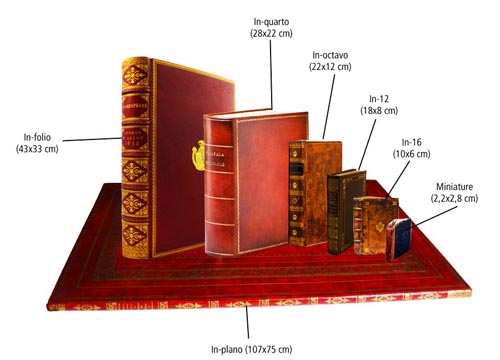

In Antwerp, Martens became part of this milieu and his workshop became a meeting place for painters, musicians, scientists, poets and writers. With the Collegium Trilingue, Martens opens a second shop, this time in Leuven to work with Erasmus. In order to provide adequate books to the Collegium, Martens proudly became, in the footsteps of the Venetian Printer Aldo Manuce, one of the first printers to concentrate on in-octavo 8° (22 x 12 cm), i.e. “pocket” size books affordable by all and which students could take home !

For the specialists of the Erasmus house of Anderlecht, close to Brussels,

“Martens innovated in nearly all domains. As well as in terms of printing types as lay-out. He was the first to introduce Italics, Greek and Hebrew letter types. He also generalized the use of ‘New Roman’ letter type so familiar today. During the first thirty years of the XVIth century, he also operated the revolution in lay-out (chapters and paragraphs) that gave birth to the modern book as we know it today. All this progress, he achieved in close cooperation with Erasmus”.

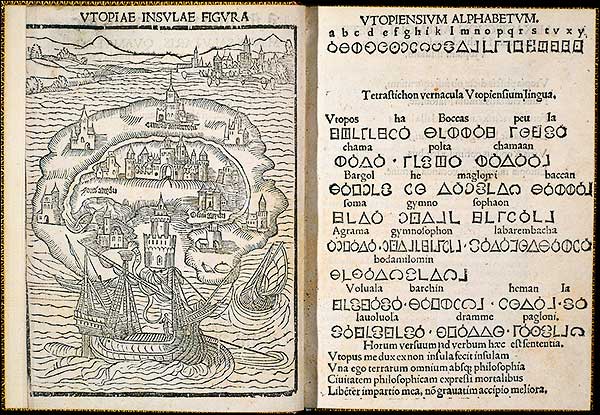

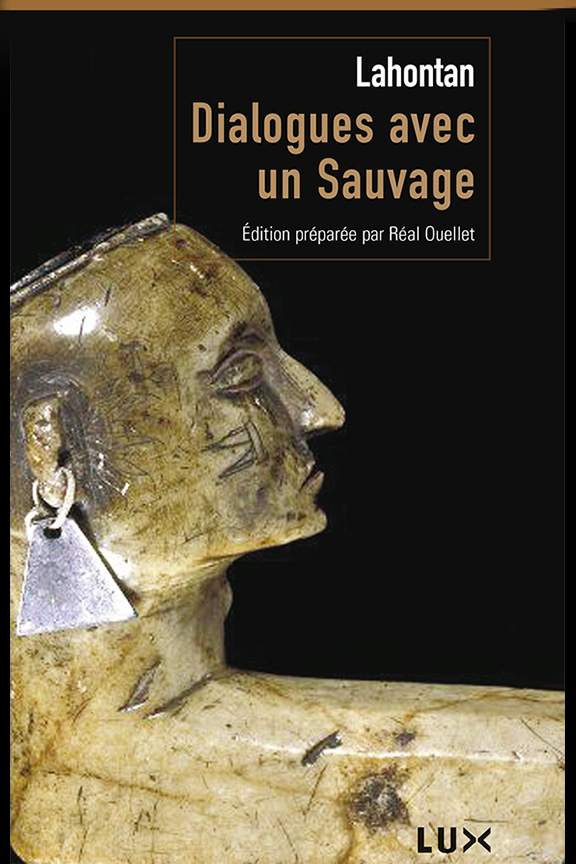

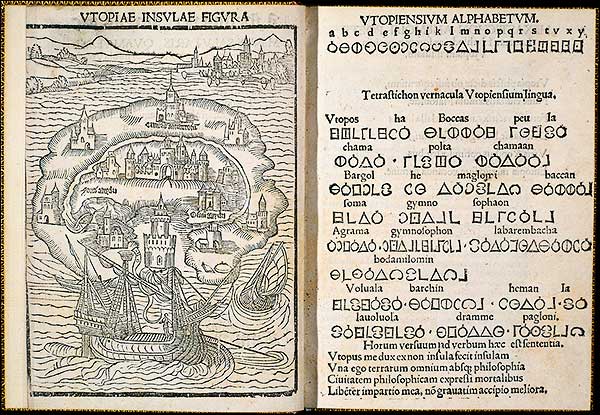

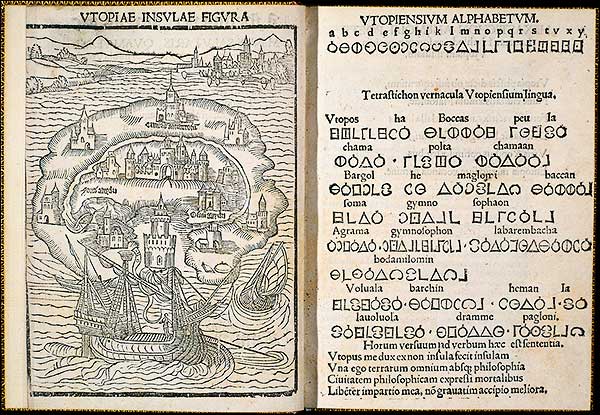

Thomas More’s Utopia

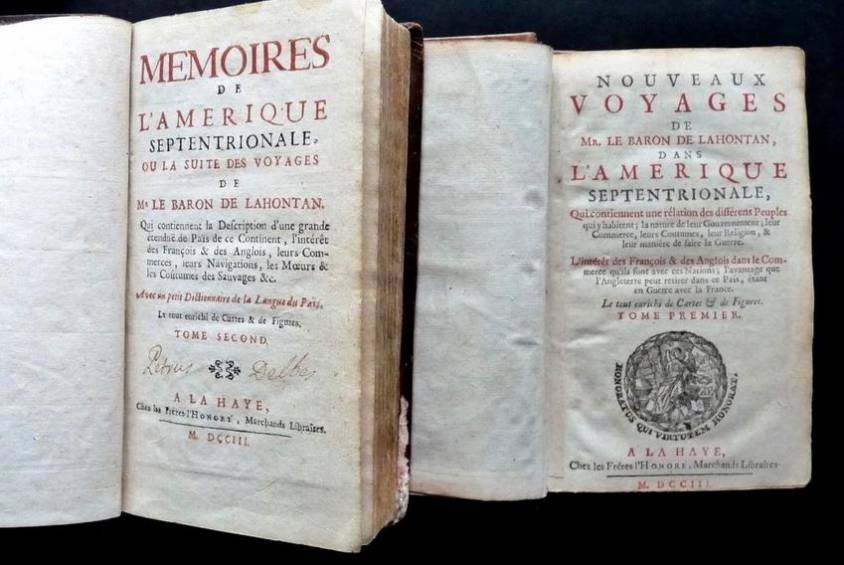

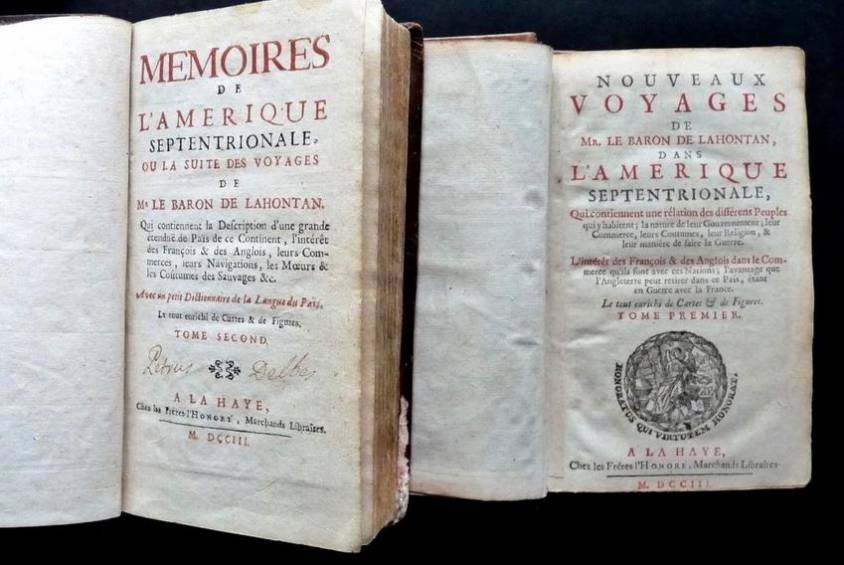

In 1516, it was Dirk Martens who printed the first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia. Among the hundreds of editions he printed mostly alone, 61 books and writings of Erasmus, notably In Praise of Folly. He also produced More’s edition of the roman satirist Lucian and Columbus’ account of the discovery of the new world. In 1423, Martens printed the complete works of Homer, quite a challenge!

In 1520, a papal bull of Leo X condemned the errors of Martin Luther and ordered the confiscation of his writings to be burned in public in front of the clergy and the people.

For Erasmus, burning books didn’t automatically erased their their content from the minds of the people. “One starts by burning books, one finishes by burning people” Erasmus warned years before Heinrich Heine said that “There, were one burns books, one ends up burning people”.

Printers and friends of Erasmus, especially in France, died on the stake opening the doors for the religious wars that will ravage Europe for the century to come.

What Erasmus feared above all, is that with the Vatican’s brutal war against Luther, it is the entire cultural renaissance and the learning of languages that got threatened with extinction.

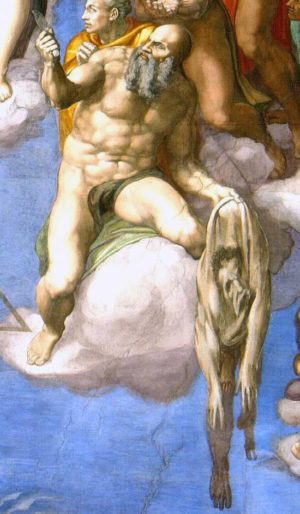

In July 1521, confronted with the book burning, the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer, who made his living with bible illustrations, left Antwerp with his wife to return to his native Nuremberg.

Thirty years later, in 1552, the great cartographer Gerardus Mercator, a brilliant pupil of the Collegium Trilingue, for having called into question the views of Aristotle, went into exile and settled in Duisbourg, Germany.

In 1521, at the request of his friends who feared for his life, Erasmus left Leuven for Basel and settled in the workshop of another humanist, the Swiss printer Johann Froben.

In 1530, with a foreword of Erasmus, Froben published Georgius Agricola’s inventory of mining techniques, De Re Metallica, a key book that vastly contributed to the industrial revolution of Saxen, Switzerland, Germany and the whole of Europe.

Conclusion

If certain Catholic historians try to downplay the hostility of their Church towards Erasmus, the fact remains that between 1559 and 1900, the full works of Erasmus were on the “Index Vaticanus” and therefore “forbidden readings” for Catholics.

If Thomas More, whom Erasmus considered as his twin brother, was canonized by Pius XI in 1935 and recognized as the patron saint of the political leaders, Erasmus himself was never rehabilitated.

Interrogated by this author in a letter, the Pope Francis returned a polite but evasive answer.

Let’s rebuild the Collegium Trilingue !

With the exception of the staircase, only a few stones remain of the historical building housing the Collegium Trilingue. In 1909, the University of Louvain planned to buy up and rebuild the site but the First World War changed priorities. Before becoming social housing, part of the building was used as a factory. As a result, today, there is no overwhelming charm. However, seeing the historical value of the site, we cannot but fully support a full reconstruction plan of the building and its immediate environment.

It would make the historical center of Leuven so much nicer, so much more attractive and very much more loyal to its own history. On top, such a reconstruction wouldn’t cost much and might interest private investors. The images in 3 dimensions produced for the Leuven exhibit show a nice Flemish Renaissance building, much in the style of the marvels constructed by architect Rombout II Keldermans.

Every period has the right to honestly “re-write” its own history, without falsifications, according to its own vision of the future.

It has to be noted here that the world famous “Rubenshuis” in Antwerp, is not at all the original building, but a scrupulous reconstruction of the late 1930s.

The hidden lesson of Sugata Mitra’s “Hole-in-the-Wall” experience

There are over a billion Indians. Unfortunately, around half of them are illiterate. Only one in four has access to proper sanitation. Some 350 million Indians live on less than one euro a day. And yet, in a strange paradox, India is also home to some of the world’s most advanced high-tech companies. New Delhi is, in a way, India’s Silicon Valley. And very recently, Indian genius has succeeded in landing a rover on the Moon.

Scandalized by the lack of access to education for his country’s children living far from urban centers, Dr. Sugata Mitra, an Indian physicist turned educational technology researcher, has been conducting a series of experiments since 1999, dubbed « The Hole-in-the-Wall », whose astonishing results are calling into question the foundations of conventional pedagogy.

“In early 1999”, writes Mitra, “colleagues and I sunk a computer into the opening of a wall near our office in Kalkaji, New Delhi. The area was located in an expansive slum, with desperately poor people struggling to survive.”

The screen was visible from the street, and the PC was available to anyone who passed by and all the people living “on the other side of the wall”. The computer had online access and a number of programs that could be used, but no instructions were given for its use. In principle, the children in this neighborhood could neither read nor write, and spoke a Tamil dialect. So, objectively speaking, the chances of them being able to cope with the computer were almost nil.

Fortunately, in the real world, things are different. Barely eight minutes after the computer had been installed, a young boy who had never seen a television screen in his life came up to sniff it out and explore the strange intruding object.

Asked if he could touch the screen, Mitra replied, « It’s on your side of the wall. » The rule was that everything on their side of the wall could be touched. The child soon realized that by moving the mouse in a certain direction, something moved on the screen in a similar way. Excited by what he had discovered, he immediately called his friends and showed them what he could do.

Typically, in the « Hole in the Wall » experiment, only one child operates the computer. He is surrounded by a first group of three others who give him advice. A second group of around sixteen children completes the team, who also interact with the child handling the equipment. Their advice is often less sound, or even wrong, but they learn too.

In hardly a few months, these kids were able to learn up to 200 English words. Although they couldn’t always pronounce them correctly, they understood their meaning and were able to interact with the computer. « You left us these machines that only speak English, so we had to learn it, » they said. Most of them succeeded in learning to navigate, play games and to draw pictures with a given application. What’s more, they have no trouble exchanging emails, and much more besides.

By repeating the experiment in several poor Indian towns, with boys as well as girls, Mitra, suspected of charlatanism by those who felt challenged by what his experience revealed, managed to dispel initial doubts that « someone » had secretly offered training to the children in advance.

What to conclude?

If the results are astonishing, they are often misinterpreted, with everyone, including Mitra himself, trying to demonstrate his or her own pre-established theory. You be the judge.

For Europeans, the experiment itself is considered borderline acceptable. Using children as “guinea pigs” without their parents’ permission is unethical by European standards. And isn’t bringing technology to the poor and thinking that everything will take care of itself one of those practices tinged with neo-colonialism that the World Bank ranks among the worst approaches to educational technology?

For their part, the gurus of Silicon Valley and GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft) were jubilant! They’ve been telling us for years: just give every child a computer (which they manufacture and control) and they’ll educate themselves! Really?

Remember the « One Laptop per Child » project launched a decade ago, to provide inexpensive solar-powered laptops and tablets to children in the poor countries? Without wishing to criticize the good will of its promoters, let’s just say that simply making computers available has not proved a promising approach. A recent evaluation of the project in Peru confirms this.

For his part, Mitra, whose goodwill cannot be questioned, came to the conclusion that experience shows that primary education can, at least in part, pretty much “take care of itself,” if the pupils are offered a « non-invasive education » environment.

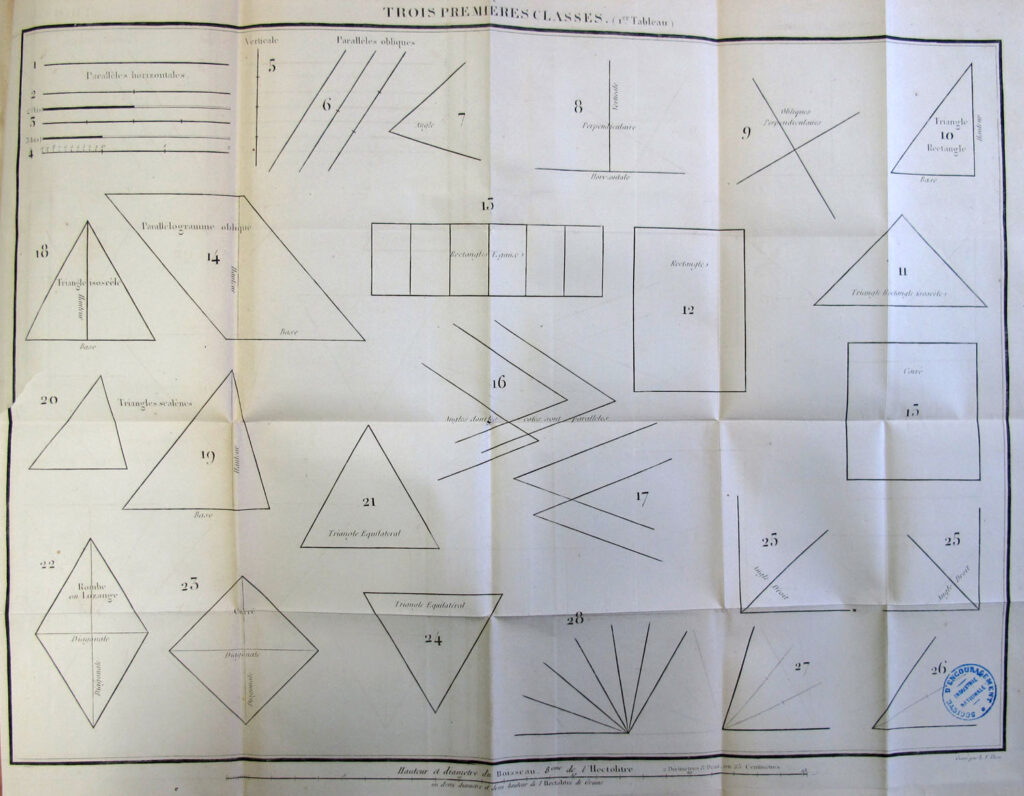

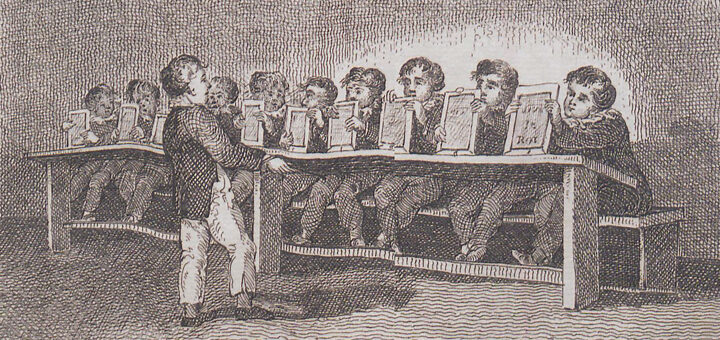

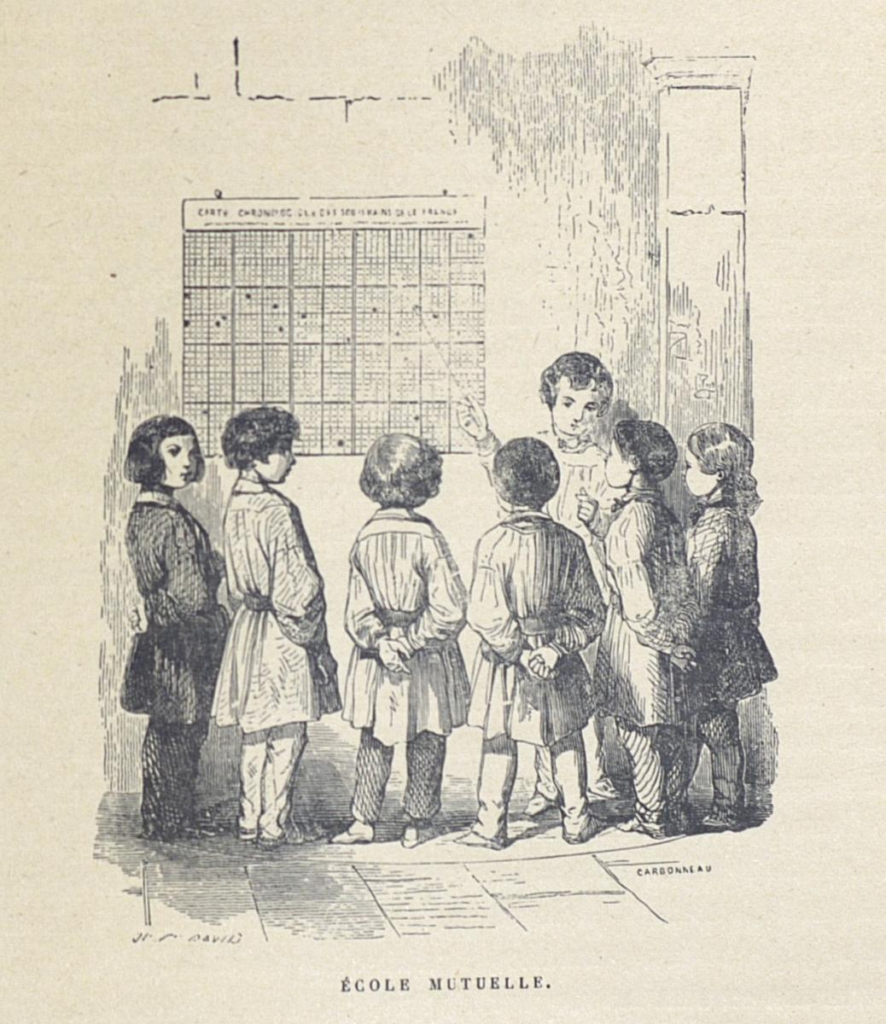

Mutual Education

Dr. Mitra, unfortunately, seems to be missing the major point of what his experience brilliantly demonstrates.

I explain:

In France, after having been an enthusiastic proponent of computers for all, author and high school teacher Vincent Faillet has also come to believe that giving every child a tablet is not the right approach. With good reason, he points out that it’s not the computer, tablet, or screen that teaches children, but the human interaction among students:

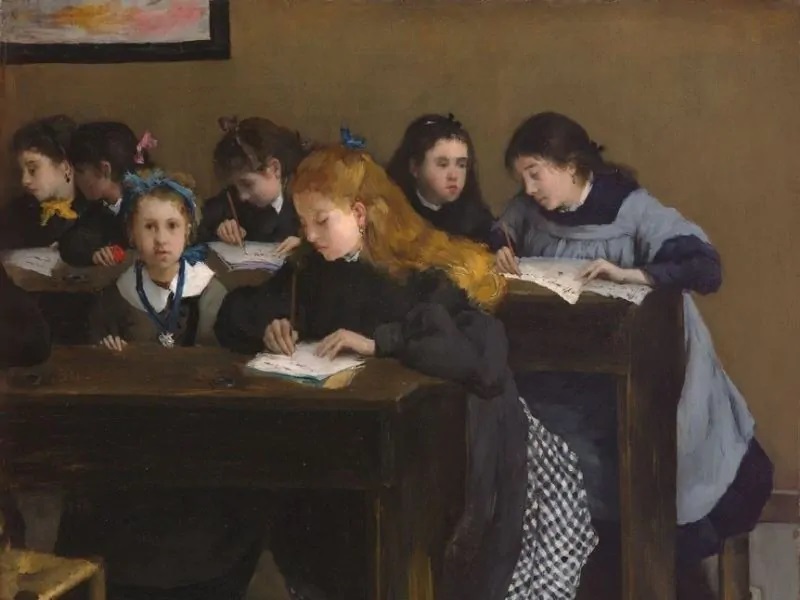

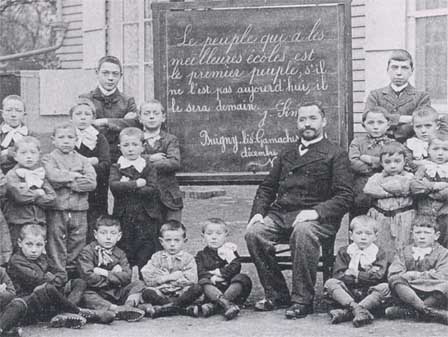

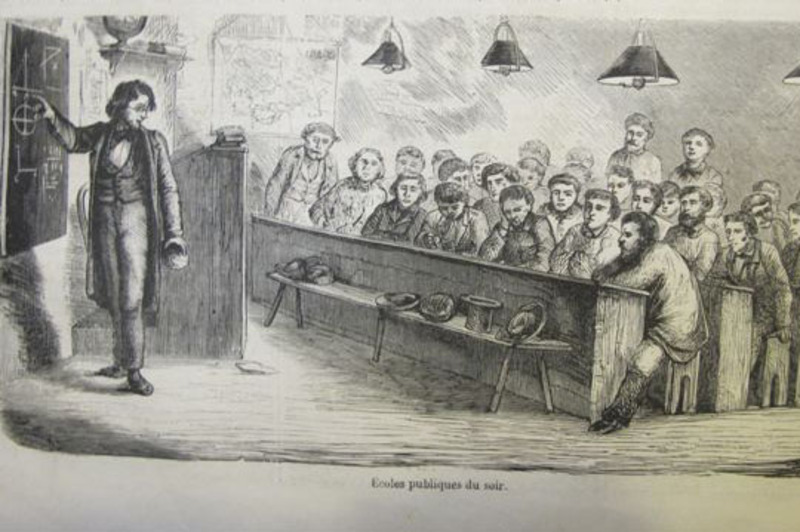

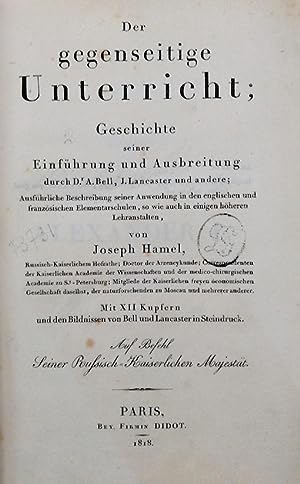

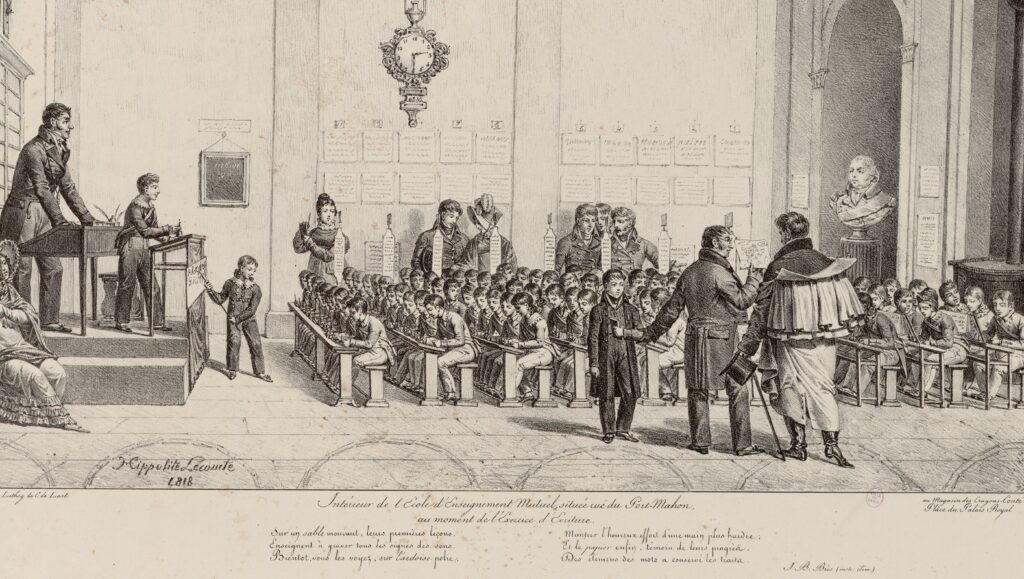

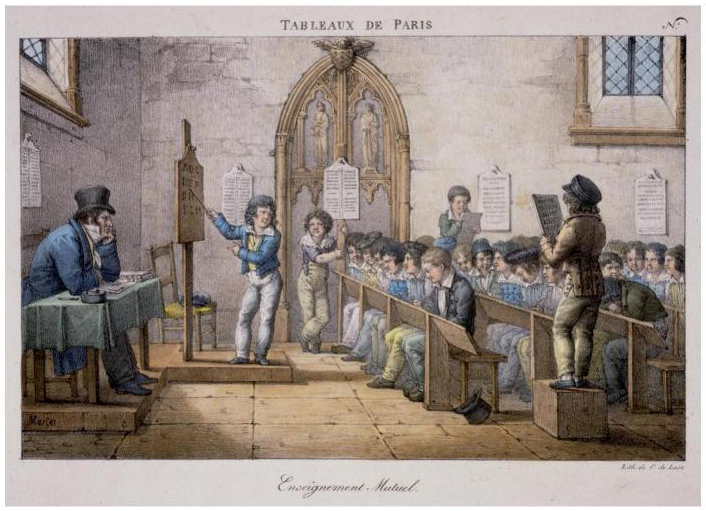

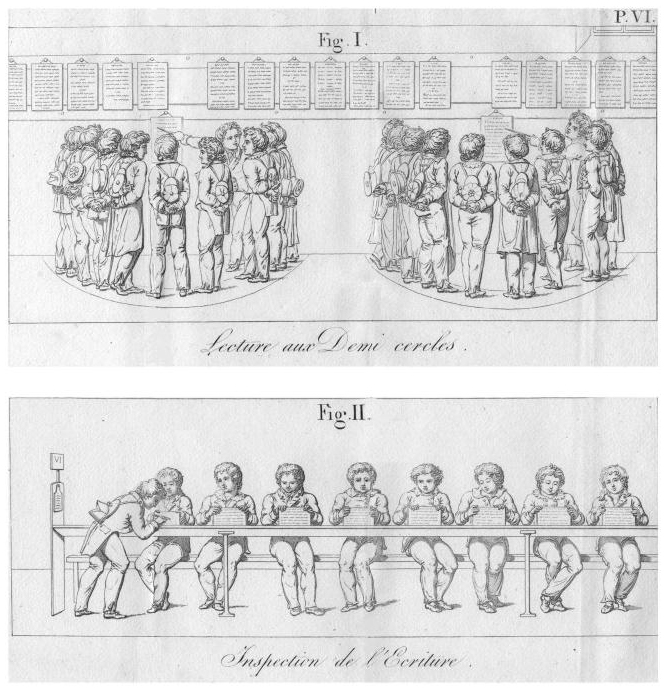

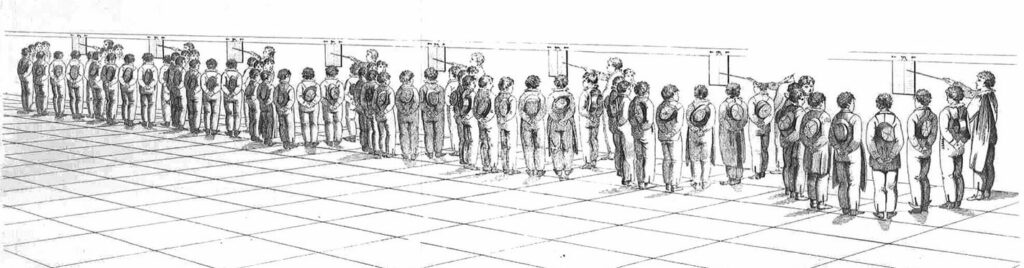

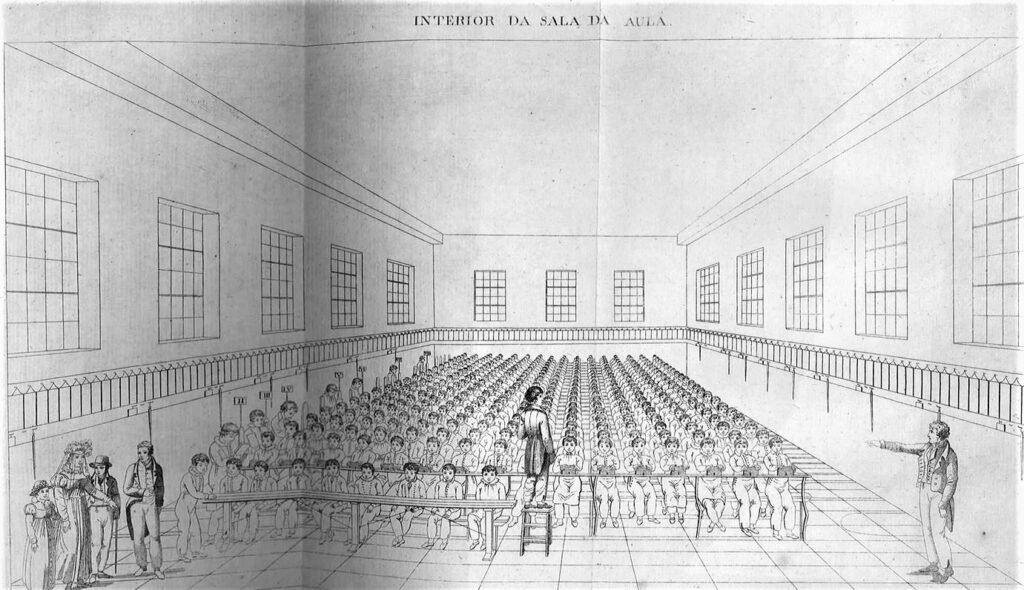

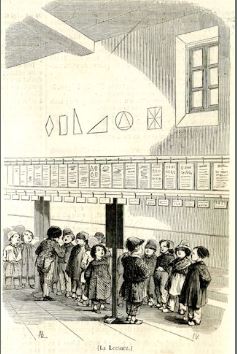

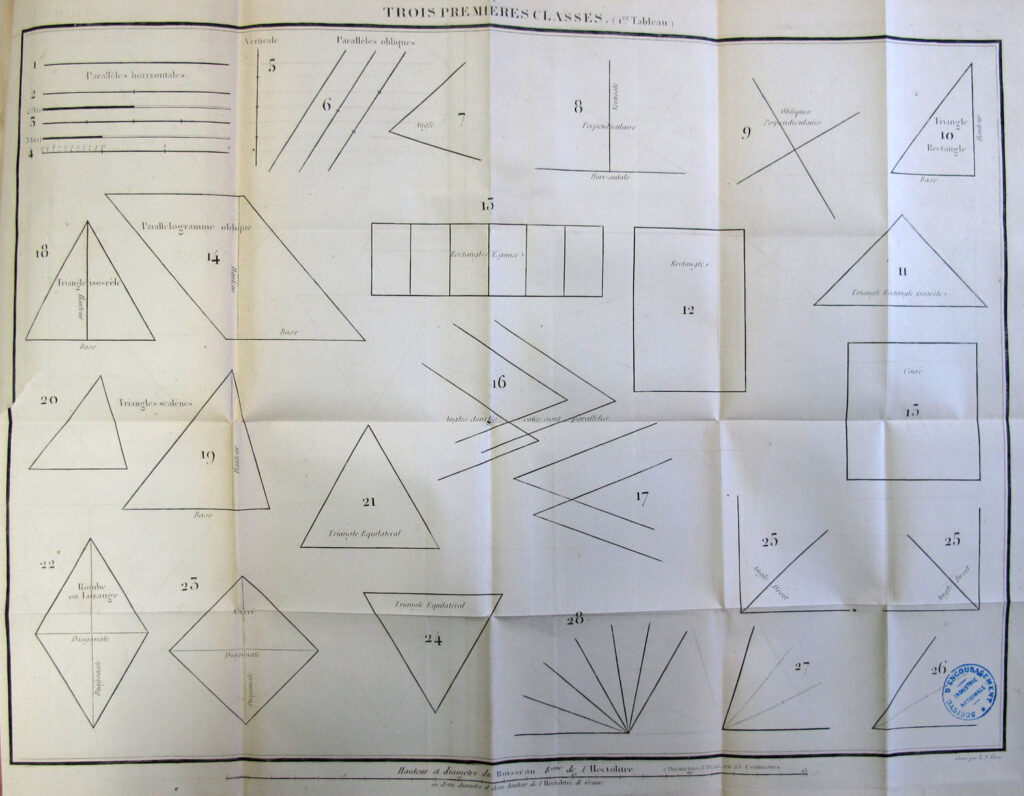

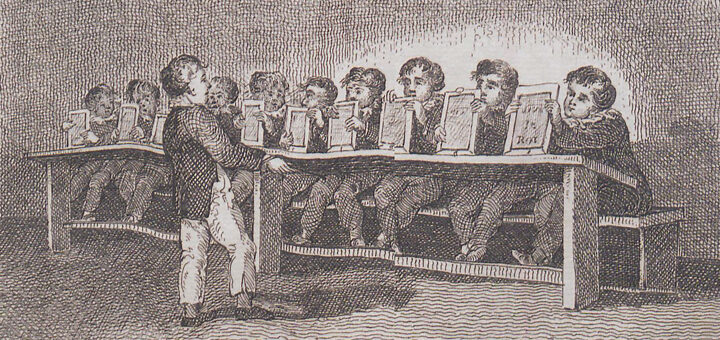

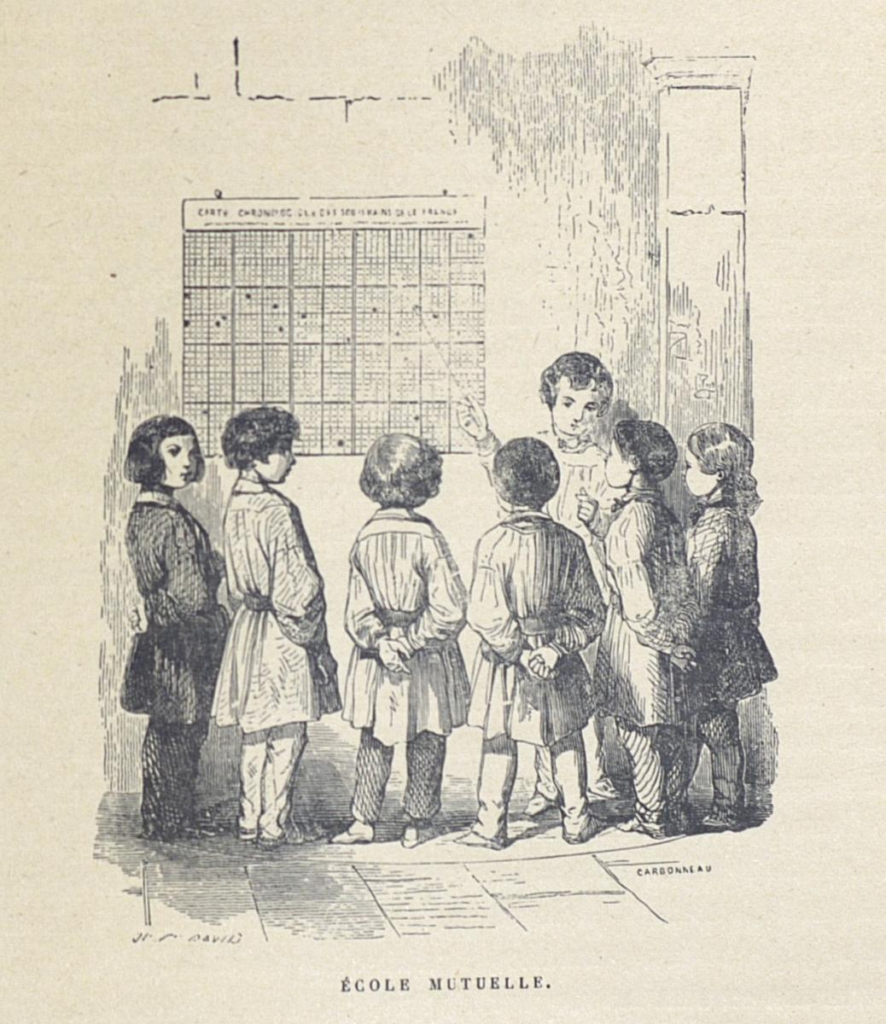

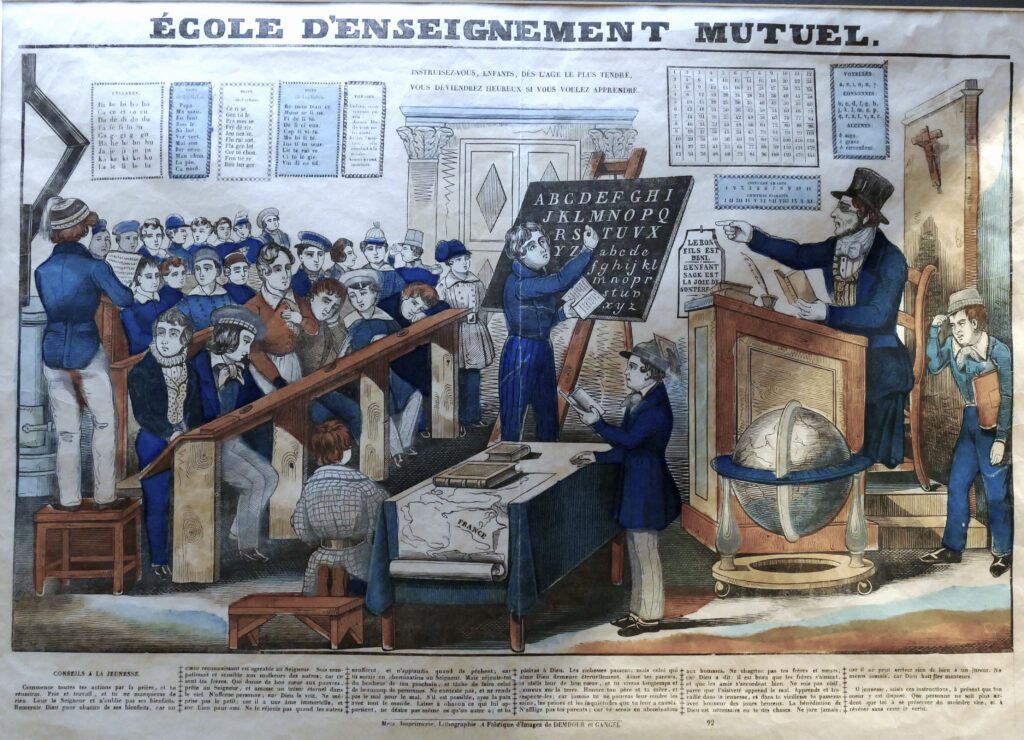

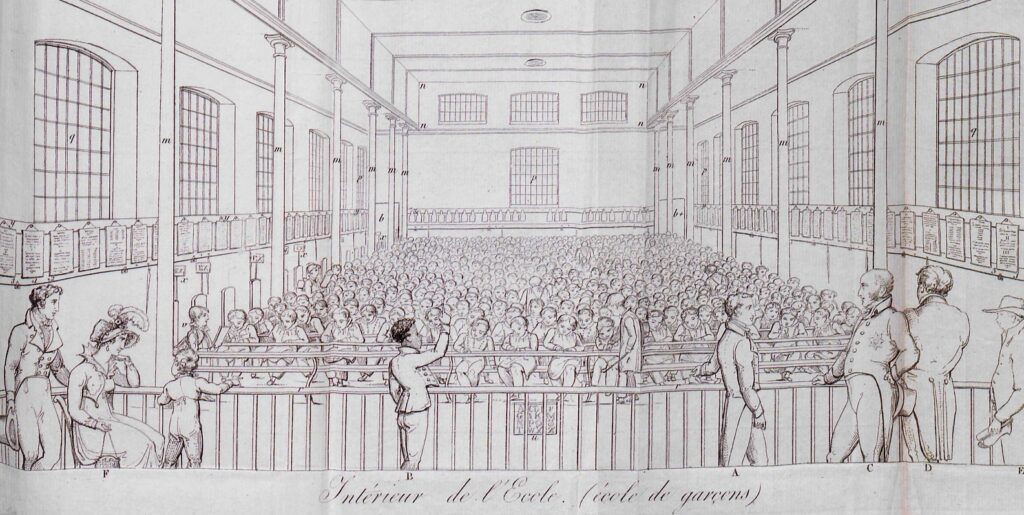

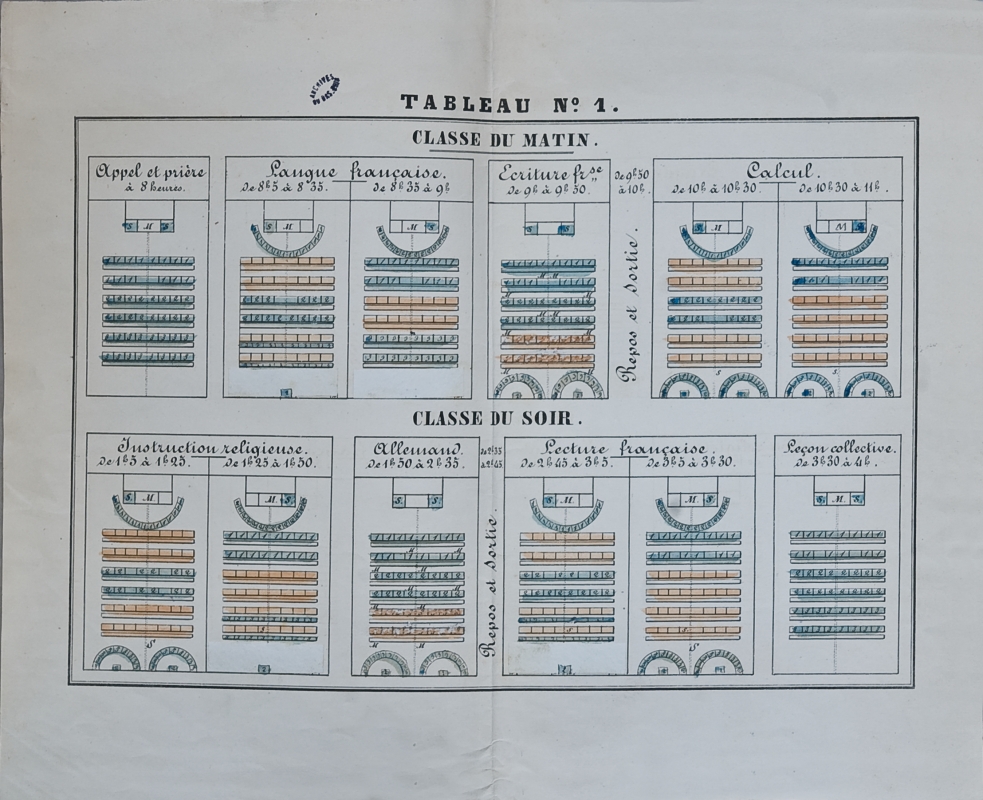

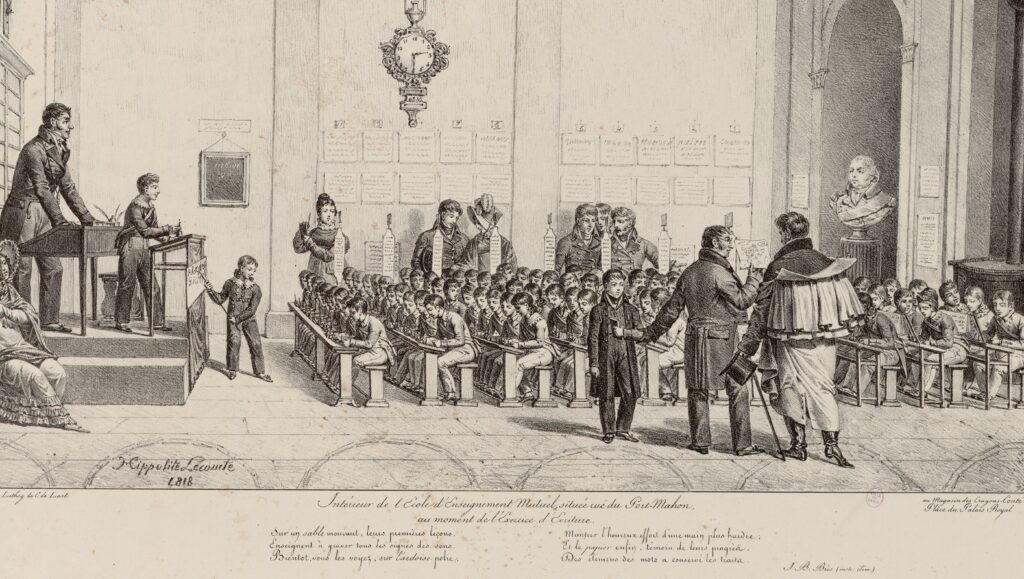

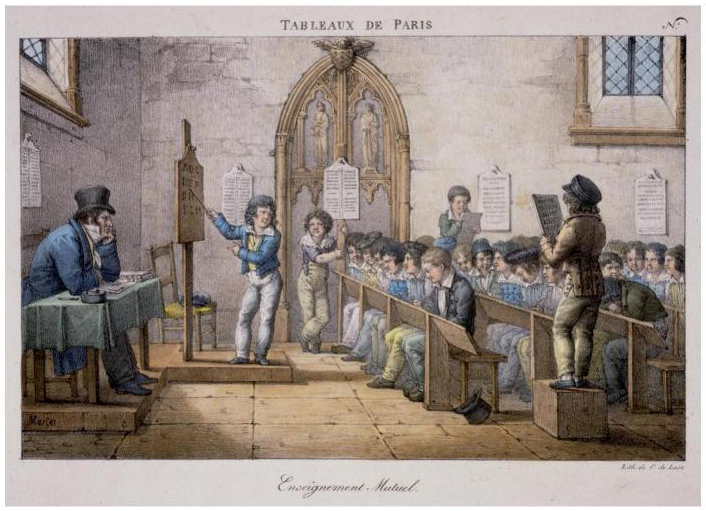

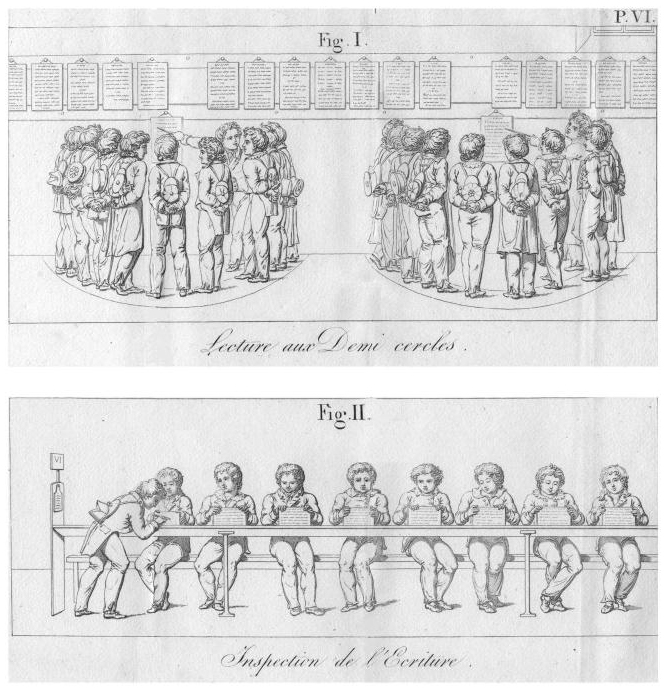

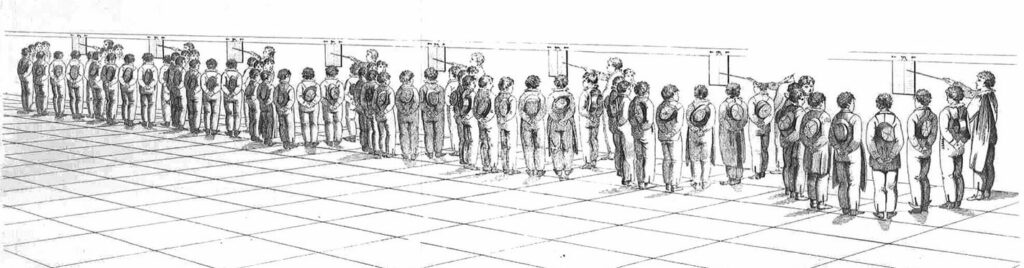

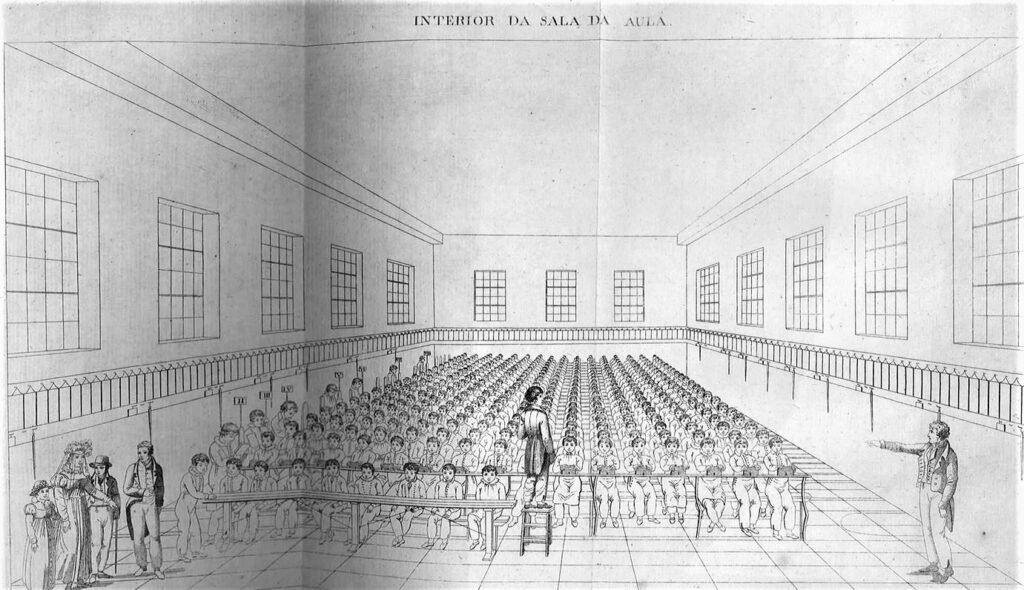

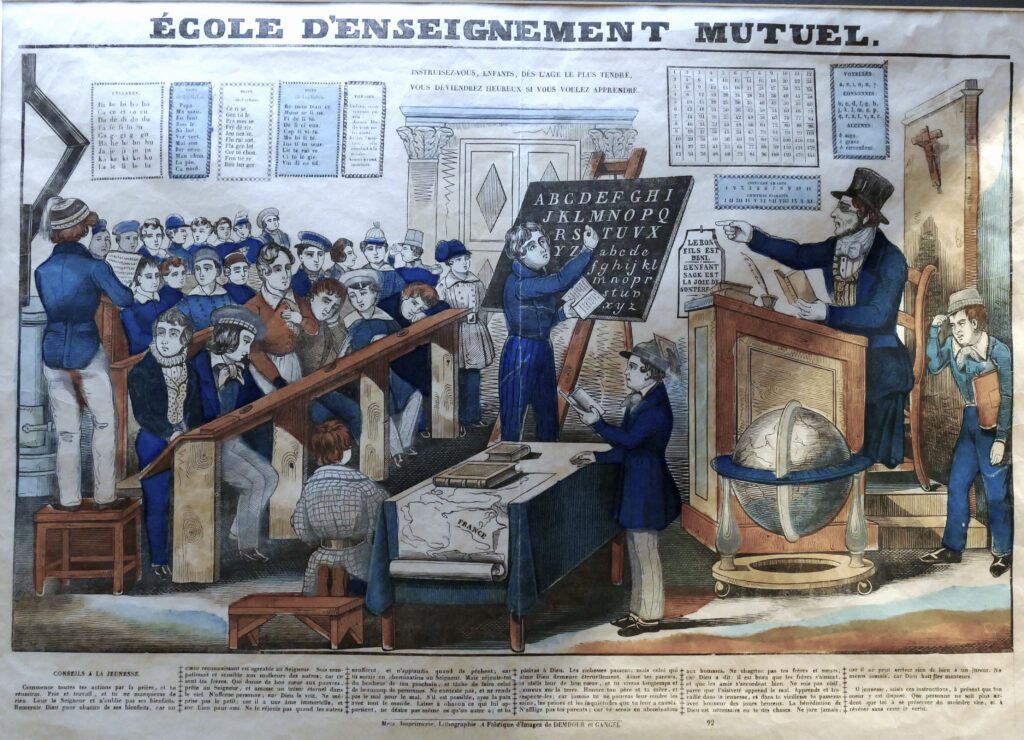

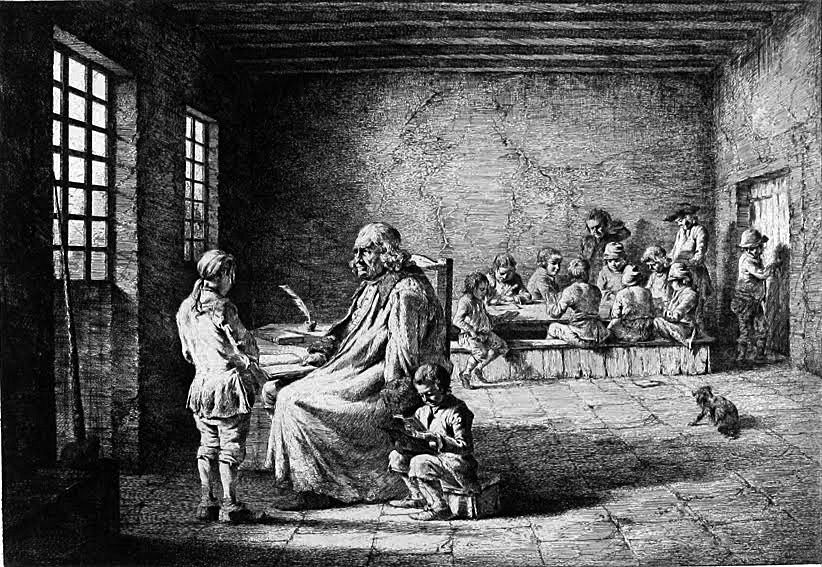

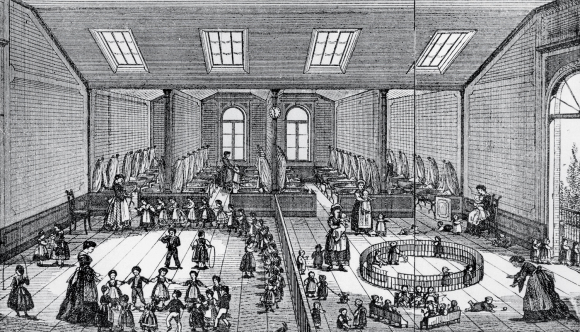

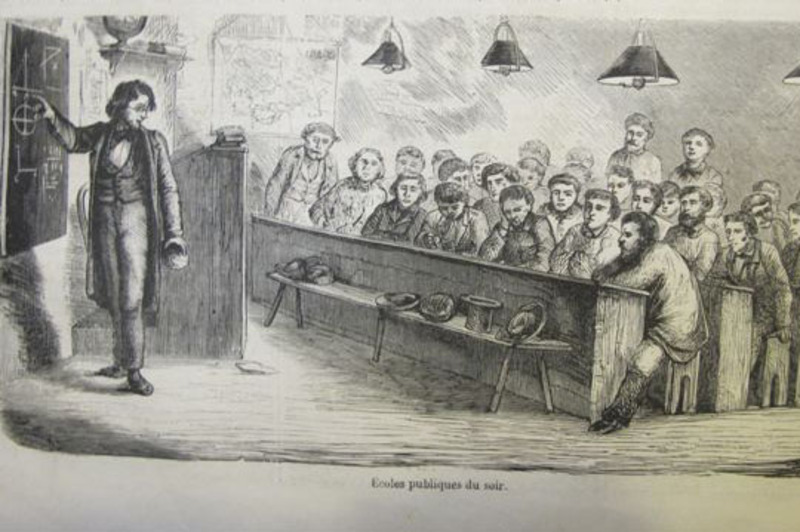

« Peer-to-peer learning, as defined by Sugata Mitra and which has amazed many pedagogues, » writes Faillet, « is in reality nothing more and nothing less than a modern, spontaneous form of ‘mutual education’. It’s striking to note that, despite the centuries that separate these observations, we find a constant pattern: children in a learning situation, grouped around a common screen for interaction, be it a box of sand, a blackboard or a computer screen. The idea of interaction is essential. As Sugata Mitra himself says, students don’t get the same results if there were to be one computer per child. You always require several children for ONE computer, in the same way that several children in mutual schools gather around the same blackboard. » (La Métamorphose de l’Ecole, Vincent Faillet, 2017)

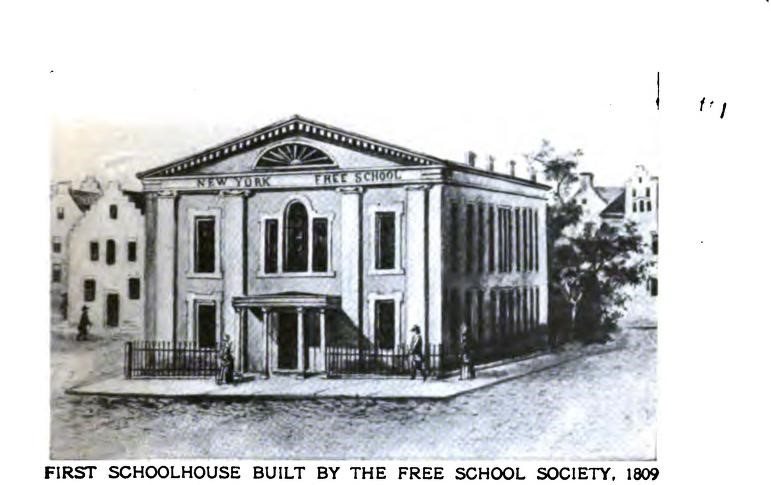

(For more on the “Mutual Tuition” methods of Carnot, Bell and Lancaster, see the author’s article on artkarel.com website)

The experiment is obviously promising for remote and poor regions, provided we understand what has just been said. What is certain is that the experience reminds the inhabitants of the North of the ineffectiveness of their pedagogical practices, and the high level of passivity engendered by our educational systems.

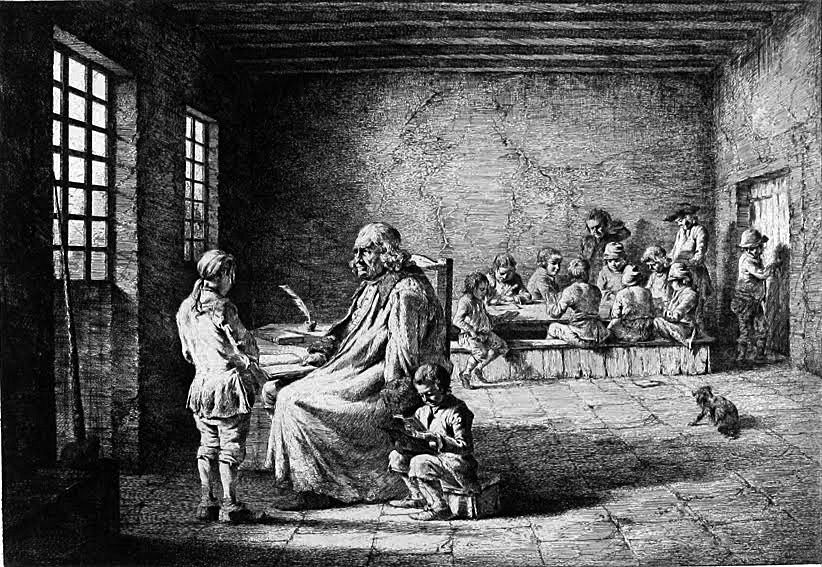

After the eradication of Lazare Carnot’s cherished « mutual teaching » methods in 1815, Jean-Baptiste de La Salle’s « simultaneous » method triumphed. The master teaches. His authority is unquestionable. As if at mass, the pupils stand still, remain religiously silent and obey.

In 2004, Hole-in-the-Wall Education Ltd., was founded, exporting Mitra’s idea to Cambodia and Africa. Mitra has also applied his method in England. Also there, the spectacular results caused quite a stir: students who teach each other, he claims, are 7 years ahead of their academic peers. As long as they are part of a mutual teaching process, the Internet, tablets and smartphones will find their rightful place as mere tools at the service of the teacher, and not destined to replace him or her.

Pupils as young as 8 or 9 who are allowed to search the internet to prepare for the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), not only pass the test, but still remember what they have learned when tested again three months later. We’ve even seen 14-year-olds pass baccalaureate-level tests at Newcastle University. Will they find jobs commensurate with their skills in the Global West ?

In the following excerpt,

Dr Mitra describes his findings:

“Certain common observations from our experiments emerged, suggesting the following learning process occurs when children self-instruct in computer usage:

1. Discoveries tend to happen in one of two ways: When one child in a group already knows something about computers, he or she shows off those skills to the others. Or, while the others watch, one child explores randomly in the GUI (Graphical User Interface) environment until an accidental discovery is made. For example, the child may discover that the cursor changes to a hand shape at certain places on the scre

2. Several children repeat the discovery for themselves by asking the first child to let them try it.

3. While in Step 2, one or more children make more accidental or incidental discoveries.

4. All the children repeat all the discoveries made and, in the process, make more discoveries. They soon start to create a vocabulary to describe their experiences.

5. The vocabulary encourages them to perceive generalizations, such as, « When you click on a hand-shaped cursor, it changes to the hourglass shape for a while and a new page comes up. »

6. They memorize entire procedures for doing something, such as how to open a painting program and retrieve a saved picture. Whenever a child finds a shorter procedure, he or she teaches it to the others. They discuss, hold small conferences, make their own timetables and research plans. It is important not to underestimate them.

7. The group divides itself into the « knows » and the « know-nots, » much as they might divide themselves into « haves » and « have-nots » with regard to their possessions. However, a child that knows will share that knowledge in return for friendship and reciprocity of information, unlike with the ownership of physical things, where they can use force to get what they do not have. When you « take » information, the donor doesn’t « lose » it!

8. A stage is reached when no further discoveries are being made and the children occupy themselves with practicing what they have already learned. At this point, intervention is required to plant a new seed for discovery (…) Usually, a spiral of discoveries follows and another self-instructional cycle begins.”

Source: edutopia.org

Ce que nous apprend l’expérience du « trou-dans-le-mur » de Sugata Mitra

On dénombre plus d’un milliard d’Indiens. Environ la moitié d’entre eux est malheureusement illettrée. Seulement un sur quatre a accès à des sanitaires dignes de ce nom. Quelque 350 millions d’Indiens vivent avec moins d’un euro par jour. Et pourtant, comme un étrange paradoxe, l’Inde est aussi l’un des terreaux qui voit fleurir des entreprises de haute technologie parmi les plus avancées au monde. New Delhi, c’est un peu la Silicon Valley à l’indienne. Et depuis peu, le génie indien a su poser un astromobile sur la Lune.

Scandalisé par le manque d’accès à l’éducation dont souffrent les enfants de son pays vivant loin des centres urbains, le Dr Sugata Mitra, un physicien indien devenu chercheur en technologie éducationnelle, a conduit, à partir de 1999, une série d’expériences baptisée « The Hole in the Wall » (le trou dans le mur), dont les résultats étonnants bousculent les fondements de la pédagogie conventionnelle.

Mitra, dont le bureau est accolé à un mur séparant un quartier résidentiel de New Delhi du bidonville de Kalkaji, décide alors de faire un trou dans ce mur. Il y installe son ordinateur et rend accessible son écran et la souris aux enfants vivant « de l’autre côté du mur ».

En principe, les enfants de ce quartier ne savent ni lire ni écrire et parlent un dialecte tamoul. La possibilité qu’ils puissent se débrouiller avec l’ordinateur est donc objectivement presque nulle.

Or, dans le monde réel, les choses se passent différemment. A peine huit minutes après l’installation de l’ordinateur, un gosse qui n’a jamais vu une télévision de sa vie vient renifler l’objet.

Lorsqu’il demande s’il peut toucher l’écran, Mitra lui répond : « C’est de votre côté du mur. » La règle veut, en effet, qu’ils aient le droit de toucher tout ce qui est de leur côté du mur.

Rapidement l’enfant se rend compte qu’en bougeant la souris dans un certain sens, quelque chose se déplace sur l’écran de façon similaire. Excité par ce qu’il a découvert, il appelle sans tarder ses copains et leur montre ce qu’il est capable de faire. En règle générale, dans l’expérimentation « Le trou dans le mur », un seul enfant manipule l’ordinateur. Il est entouré d’un premier groupe de trois autres qui lui donnent des conseils. Un second groupe d’environ seize enfants complète l’équipe, qui interagissent aussi avec l’enfant qui manipule le matériel. Leurs conseils sont souvent moins avisés, voire faux, mais ils apprennent aussi.

En quelques mois, les enfants sont capables d’apprendre jusqu’à deux cents mots d’anglais. S’ils ne les prononcent pas toujours correctement, ils en comprennent le sens et parviennent à interagir avec l’ordinateur. « Vous nous avez laissé ces machines qui ne parlent que l’anglais, alors nous avons dû l’apprendre ! » lui disent-ils. La plupart savent naviguer, jouer à des jeux ou faire des dessins avec Paint. Mieux encore, ils s’échangent sans problème des courriels, et bien d’autres choses encore.

En répétant l’expérience dans plusieurs villes pauvres d’Inde, avec des garçons aussi bien qu’avec des filles, Mitra, soupçonné de charlatanisme, parvient à dissiper les doutes initiaux insinuant qu’il y avait forcément « quelqu’un » qui avait formé les enfants à l’avance.

Les leçons à en tirer

Si les résultats étonnent, ils sont souvent mal interprétés, chacun, y compris Mitra, cherchant à démontrer sa propre théorie établie d’avance. Je vous laisse juge.

Pour les Européens, l’expérience elle-même est considérée comme à la limite de l’acceptable. Faire des enfants des cobayes sans l’autorisation de leurs parents n’est pas très éthique d’après les normes européennes. Et apporter de la technologie chez les pauvres et penser que tout s’arrangera tout seul, n’est-ce pas une de ces pratiques teintées de néo-colonialisme que la Banque mondiale classe parmi les pires approches en matière de technologie éducationnelle ?

De leur côté, les gourous de la Silicon Valley et du GAFAM jubilent ! Ils nous le disent depuis des années : il suffit de donner un ordinateur (qu’ils fabriquent et contrôlent) à chaque enfant et il s’éduque tout seul ! Vraiment ?

Rappelons-nous le projet « One Laptop per Child » lancé il y a une décennie, consistant à fournir des ordinateurs portables et des tablettes à énergie solaire, peu chères, aux enfants du tiers-monde. Sans vouloir critiquer la bonne volonté de ses promoteurs, disons que le fait de mettre simplement des ordinateurs à disposition ne s’est pas avéré une approche prometteuse. Une récente évaluation du projet faite au Pérou le confirme.

Pour sa part, Mitra, dont la bonne volonté est incontestable, conclut que l’expérience montre que l’éducation primaire peut se faire, du moins en partie, à peu près toute seule, une démarche qu’il a baptisée « éducation non invasive ».

A notre avis, le Dr Mitra semble malheureusement rater l’essentiel de ce que son expérience met brillamment en lumière.

En France, après en avoir été partisan, l’enseignant Vincent Faillet en est venu à penser, lui aussi, qu’offrir une tablette à chaque enfant n’est pas la bonne approche. Avec raison, il souligne que ce n’est pas l’ordinateur, la tablette ou l’écran qui enseigne aux enfants, mais bien l’interaction entre élèves :

« L’apprentissage entre pairs tel qu’il est défini par Sugata Mitra et qui a émerveillé nombre de pédagogues est, en réalité, ni plus ni moins qu’une forme moderne et spontanée d’enseignement mutuel. Il est frappant de constater qu’en dépit des siècles qui séparent ces observations, on retrouve un schéma constant : des enfants en situation d’apprentissage, regroupés autour d’une surface d’interaction commune, qu’il s’agisse de sable, d’un tableau ou d’un écran d’ordinateur. L’idée d’interaction est essentielle. Sugata Mitra le dit lui-même, les élèves n’obtiennent pas les mêmes résultats s’il devait y avoir un ordinateur par enfant. Il faut toujours plusieurs enfants pour un ordinateur, de la même façon que plusieurs enfants des écoles mutuelles se regroupent autour d’un même tableau. »

(La métamorphose de l’école, Vincent Faillet, 2017)

L’expérience est évidemment prometteuse pour les régions éloignées et pauvres, à condition que l’on comprenne bien ce qui vient d’être dit.

Ce qui est certain, c’est que l’expérience rappelle aux habitants du Nord l’inefficacité de leurs pratiques pédagogiques, avec la forte passivité qu’engendrent nos systèmes éducationnels. Après l’éradication des méthodes d’« enseignement mutuel » chères à Lazare Carnot en 1815, c’est la méthode « simultanée » de Jean-Baptiste de La Salle qui triomphe. Le maître enseigne. Son autorité est incontestable. Comme à la messe, les élèves ne bougent pas, se taisent et obéissent.

(Voir sur ce site notre article sur l’enseignement mutuel)

En 2004 est créée Hole-in-the-Wall Education Ltd., une entreprise qui exporte l’idée de Mitra au Cambodge et en Afrique. Ce dernier a également mis sa méthode en application en Angleterre.

Là aussi, ses résultats spectaculaires ont fait grand bruit : les élèves qui enseignent les uns aux autres, assure-t-il, ont sept ans d’avance sur leur niveau académique. Pourvu qu’ils s’inscrivent dans un processus d’enseignement mutuel, internet, tablettes et smartphones retrouvent effectivement toute leur place, celle d’outils au service de celui qui enseigne, et non pas voués à le remplacer.

Des élèves de seulement 8 ou 9 ans auxquels on permet de chercher sur internet pour se préparer au General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), non seulement réussissent l’épreuve, mais se souviennent encore de ce qu’ils ont appris lorsqu’on les teste à nouveau trois mois plus tard. On voit même des enfants de 14 ans passer avec succès des épreuves du niveau du baccalauréat à l’Université de Newcastle. Trouveront-ils des emplois à la hauteur de leurs compétences ?

Le Dr Mitra décrit ses résultats:

Extrait :

« Certaines observations communes ont émergé de nos expériences, suggérant que le processus d’apprentissage suivant se produit lorsque les enfants s’auto-instruisent dans l’utilisation de l’ordinateur :

« 1. Les découvertes ont tendance à se produire de deux manières : lorsqu’un enfant d’un groupe a déjà des connaissances en informatique, il montre ses compétences aux autres. Ou bien, pendant que les autres observent, un enfant explore au hasard l’environnement graphique jusqu’à ce qu’il fasse une découverte accidentelle. Par exemple, l’enfant peut découvrir que le curseur prend la forme d’une main à certains endroits de l’écran.

« 2. Plusieurs enfants répètent la découverte en demandant au premier enfant de les laisser essayer.

« 3. Au cours de l’étape 2, un ou plusieurs enfants font d’autres découvertes accidentelles ou fortuites.

« 4. Tous les enfants répètent toutes les découvertes faites et, ce faisant, en font d’autres. Ils commencent bientôt à créer un vocabulaire pour décrire leurs expériences.

« 5. Ce vocabulaire les encourage à percevoir des généralisations, telles que « lorsque vous cliquez sur un curseur en forme de main, il prend la forme d’un sablier pendant un certain temps et une nouvelle page s’affiche ».

« 6. Ils mémorisent des procédures entières pour faire quelque chose, par exemple pour ouvrir un programme de peinture et récupérer une image sauvegardée. Chaque fois qu’un enfant trouve une procédure plus courte, il l’enseigne aux autres. Ils discutent, organisent de petites conférences, établissent leurs propres calendriers et plans de recherche. Il est important de ne pas les sous-estimer.

« 7. Le groupe se divise entre « ceux qui savent » et « ceux qui ne savent pas », de la même manière qu’il se divise entre « ceux qui ont » et « ceux qui n’ont pas » en ce qui concerne leurs possessions. Cependant, un enfant qui sait partagera ses connaissances en échange d’une amitié et d’une réciprocité de l’information, contrairement à ce qui se passe avec la propriété des choses physiques, où ils peuvent utiliser la force pour obtenir ce qu’ils n’ont pas. Lorsque vous lui « prenez » une information, le donneur ne la « perd » pas !

« 8. Un stade est atteint lorsque les enfants ne font plus de découvertes et qu’ils s’emploient à mettre en pratique ce qu’ils ont déjà appris. À ce stade, il est nécessaire d’intervenir pour planter une nouvelle graine de découverte (…). Généralement, une spirale de découvertes s’ensuit et un autre cycle d’auto-apprentissage commence. »

Source : Sugata Mitra, 2012

Hippolyte Carnot, père de l’éducation républicaine moderne

Sommaire

- Introduction

- Dans la tempête

- De la charité à la scolarisation universelle

- Malebranche et les Oratoriens

- La Révolution des esprits

- Le Comité d’Instruction publique

- Condorcet et le « Parti américain »

- Le plan Condorcet

- La bataille sous la Convention

- Lazare Carnot sous les Cent-Jours

- Hippolyte reprend le flambeau de son père Lazare

- L’exil de Lazare Carnot

- Hippolyte avec l’Abbé Grégoire

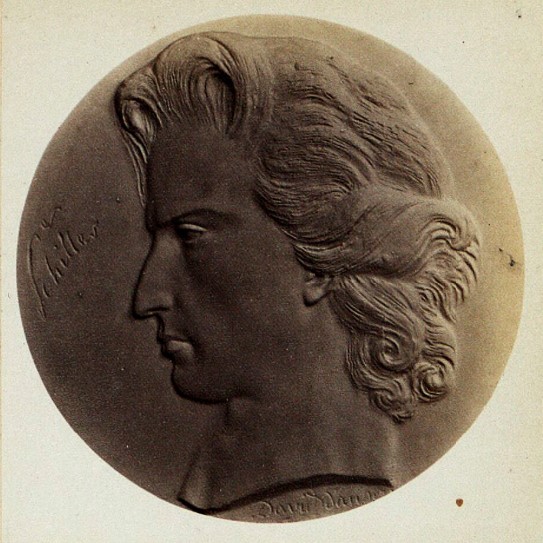

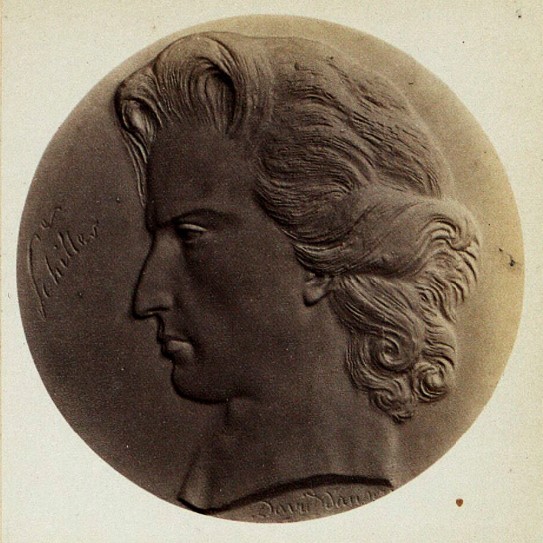

- Comme Friedrich Schiller, patriote et citoyen du monde

- La Révolution de juillet 1830

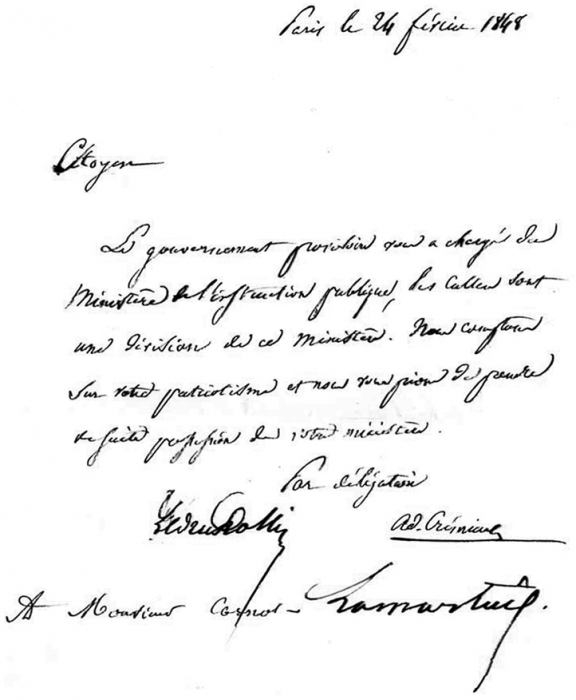

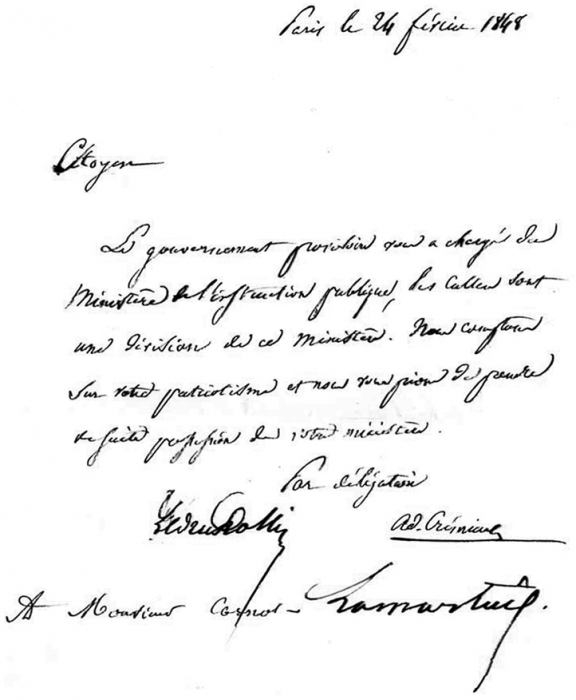

- Ministre de l’Instruction publique sous la IIe République

A. Ecole Maternelle

B. Ecole Primaire

C. Exposé des motifs de la loi de juin 1848 sur l’Ecole

D. Des instituteurs pour éclairer le monde rural

E. Enseignement secondaire

F. Haute Commission des études scientifiques et littéraires

G. Une Ecole d’Administration

H. Education pour tous tout au long de la vie

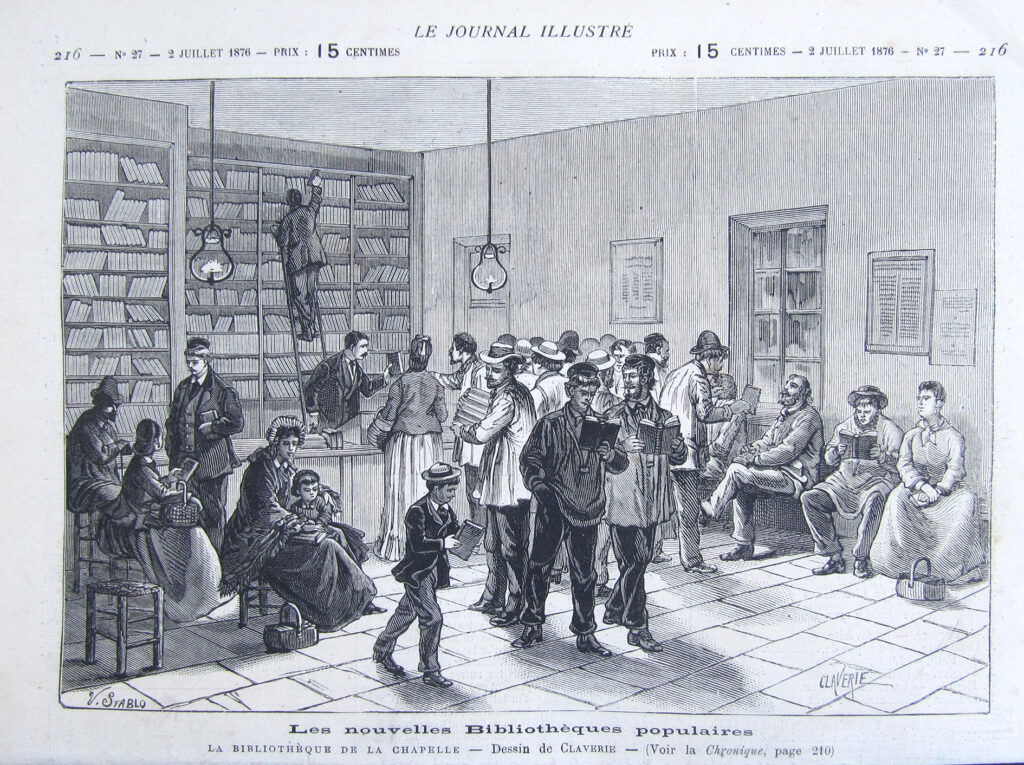

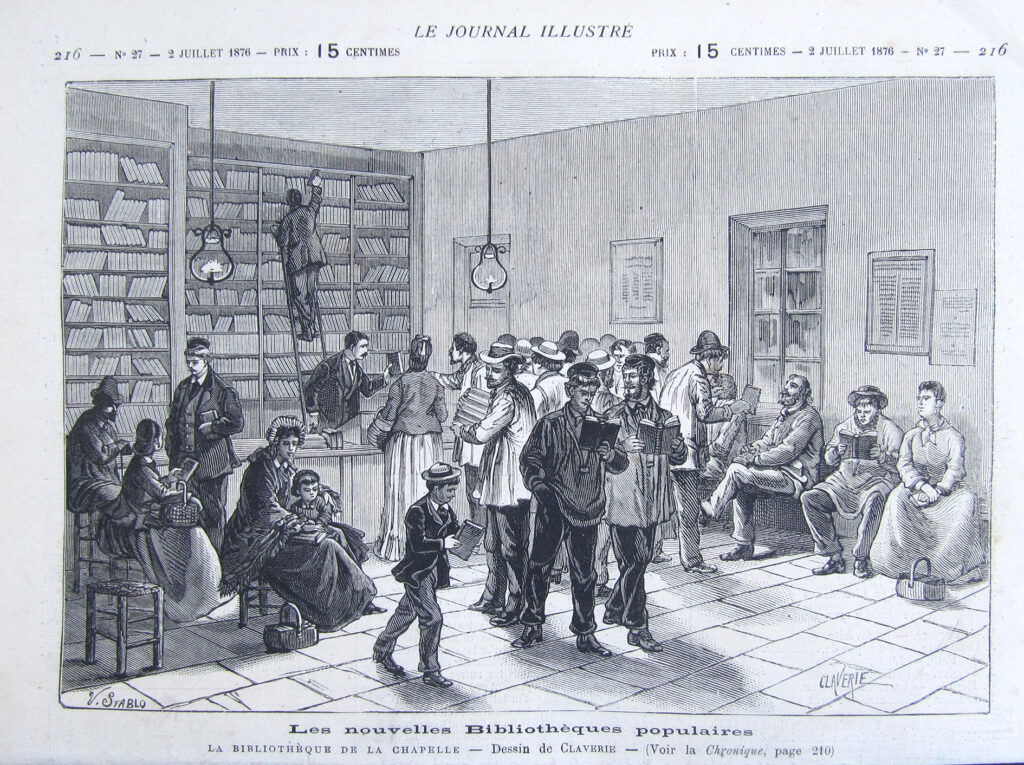

I. Bibliothèques circulantes

J. Beaux-Arts, hygiène et gymnastique au programme

K. Concorde citoyenne

- Conclusion

- Annexe : œuvres d’Hippolyte Carnot

- Quelque ouvrages et articles consultés

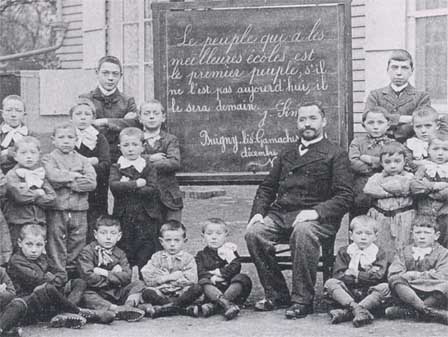

« L’arbre que vous plantez est jeune comme la République elle-même

(…) Il étendra sur vous ses rameaux, de même que la République étendra sur la France

les bienfaits de l’Instruction populaire. »

Hippolyte Carnot, Memorial, dossier 13, 1848.

1. Introduction

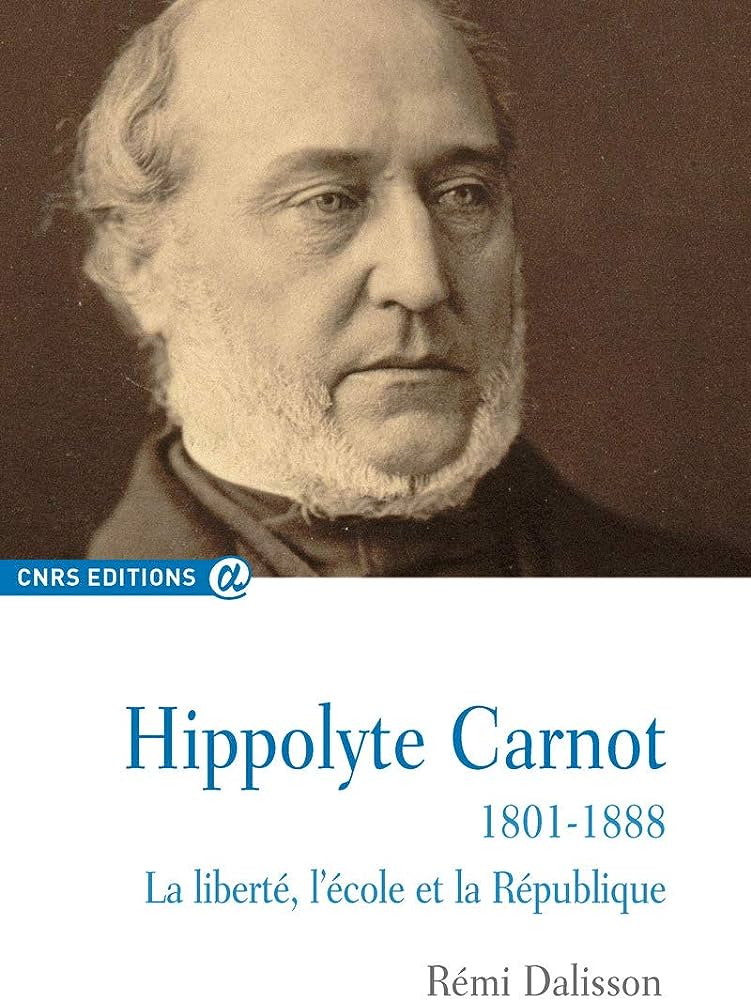

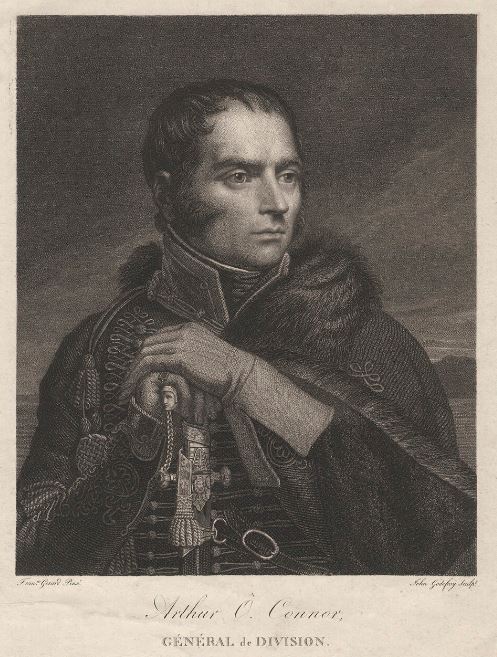

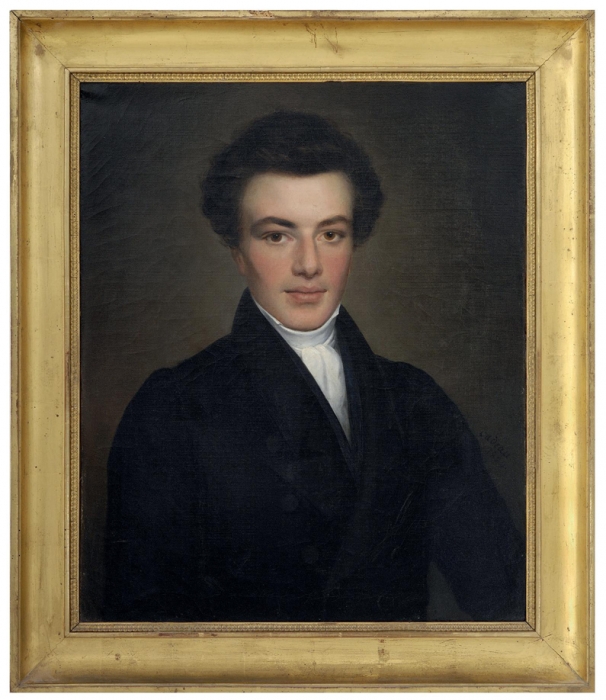

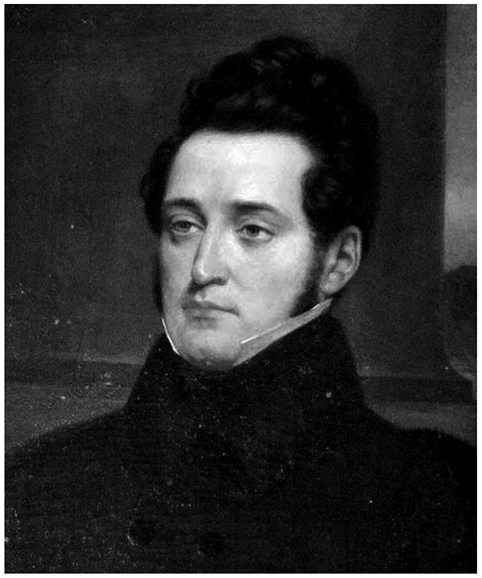

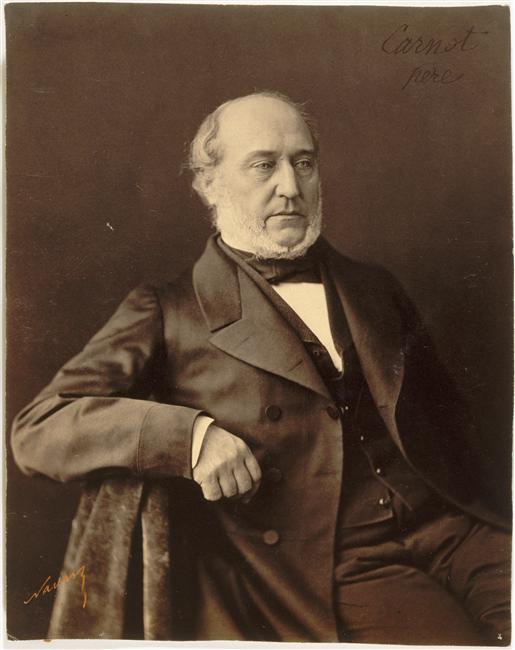

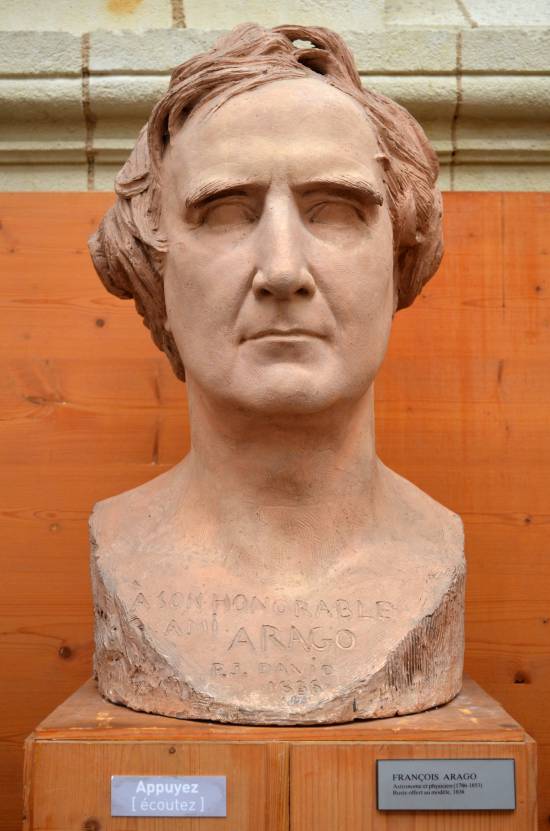

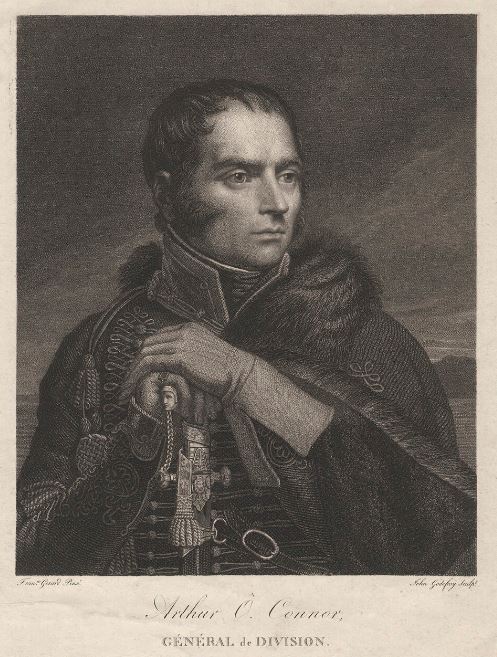

Hippolyte Carnot (1801-1888) n’a ni la gloire de son père Lazare Carnot (1753-1823), « l’organisateur de la victoire » de l’An II, ni le renom de son frère, l’inventeur de la thermodynamique Léonard Sadi Carnot (1796-1832), ni le destin tragique de son fils, François Sadi Carnot (1837-1887), président de la République assassiné par un anarchiste à Lyon.

L’histoire retient presqu’ exclusivement ses magnifiques « Mémoires sur Lazare Carnot par son fils », où il relate l’action, les idées et la vie de son père, le « grand Carnot », esprit scientifique, poète, fervent républicain et ministre de la Guerre.

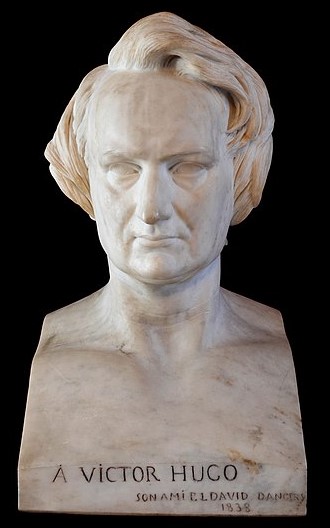

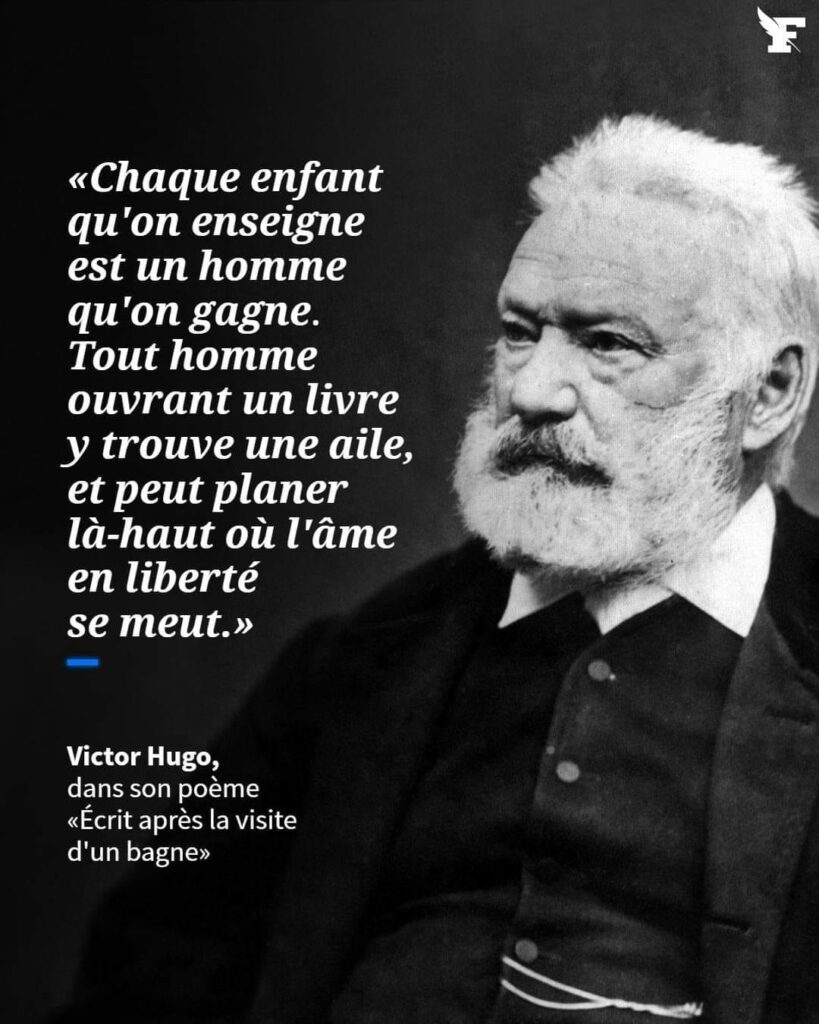

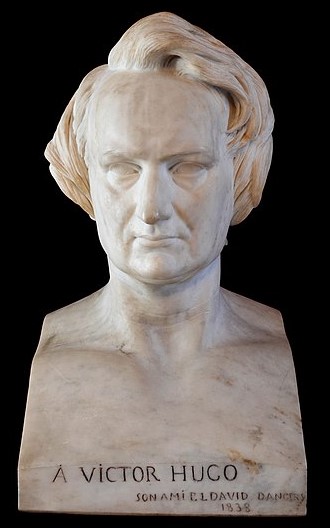

Hippolyte reste méconnu alors que sa longue vie (87 ans), un peu plus longue que celle de Victor Hugo (83 ans) couvre presque tout un siècle (1801-1888) et que son œuvre et son influence sont considérables.

Comme le démontre amplement la lecture de « Hippolyte Carnot et le ministère de l’Instruction publique de la IIe République » (PUF, 1948), écrit par son fils, le médecin Paul Carnot (1867-1957), il était bien plus qu’un simple observateur ou commentateur des événements.

Dans la tempête

Le XIXe siècle est une période de profonds changements. La flamme de l’espérance allumée par les Révolutions américaine et française, l’idéal de la liberté, de la fraternité et de l’émancipation, aussi bien des individus, des peuples que des Etats souverains, s’avère in-éteignable, s’affirme et se prolonge tout au long du XIXe siècle. La longue marche vers un nouveau paradigme est semée d’embûches. Les mutations s’opèrent lentement sur fond de crises brutales et de ruptures violentes.

Durant sa longue vie, Hippolyte Carnot connaîtra indirectement ou directement :

- Deux empires :

1803-1814 : Premier Empire sous Napoléon Bonaparte

1852-1870 : Second Empire sous Napoléon III - Trois monarchies :

1814-1815 : Première restauration sous Louis XVIII

1815-1830 : Seconde restauration sous Charles X

1830-1848 : Monarchie de juillet sous Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans. - Deux républiques :

1848-1852 : IIe République

1870 : IIIe République - Trois révolutions exprimant la ferveur républicaine :

1830 (Trois glorieuses) ;

1848 (soulèvements) ;

1871 (Commune).

Ainsi, dans un environnement toujours en transformation, traversant révolutions, coups d’État, monarchies, empires ou républiques, guerres et procès, celui qui sera (trop) brièvement ministre de l’Instruction publique en 1848, ami de Victor Hugo, Hippolyte Carnot sera un bâtisseur et un inspirateur.

Philosophe et journaliste, mémorialiste et ministre, franc-maçon et croyant, exilé politique et député, sénateur et membre de l’Académie, il participe à tous les combats pour les libertés publiques et privées, jette les bases de la formation des professeurs et de l’école gratuite et obligatoire, y compris maternelle, crée l’ancêtre de l’ENA et défend les causes les plus avancées (scolarisation des filles, suffrage universel, lutte contre l’esclavage et abolition de la peine de mort).

Rémi Dalisson, dans une biographie passionnante et richement documentée « Hippolyte Carnot 1801-1888. La liberté, l’école et la République », publié aux éditions du CNRS en 2011, preuves à l’appui, souligne que « la vulgate d’un Jules Ferry inventant l’école républicaine et laïque est largement battue en brèche ».

Etant donné que le nom et encore moins l’action d’Hippolyte Carnot ne figurent nulle part sur le site du ministère, l’auteur se désole que « rares sont ceux, y compris au ministère de l’Éducation nationale, qui rendent hommage au rôle et la personnalité d’Hippolyte Carnot ».

Les anthologies de textes et discours fondateurs de l’école républicaine, qui se sont multipliées ces dernières années, l’oublient systématiquement.

« C’est donc la réparation d’une injustice et d’un oubli que nous effectuerons en retraçant la vie et l’œuvre d’Hippolyte Carnot qui vont bien au-delà de ses projets et réalisations éducatives. Par sa stature, sa formation, son parcours, ses idées, ses écrits et combats, cet homme aux multiples talents nous permettra de retracer l’histoire de la construction de l’école et donc de la société au XIXe siècle (…) Et comme cette question renvoie à la question politique, sociale voire économique et culturelle de la nation, et comme le ministre fut de tous les combats philosophiques de son siècle (…) c’est en grande partie l’histoire d’un siècle qui sera évoquée (…) ».

Le texte intégral de cette magnifique biographie est en accès gratuit sur internet et nous nous en sommes largement inspiré pour écrire ce texte.

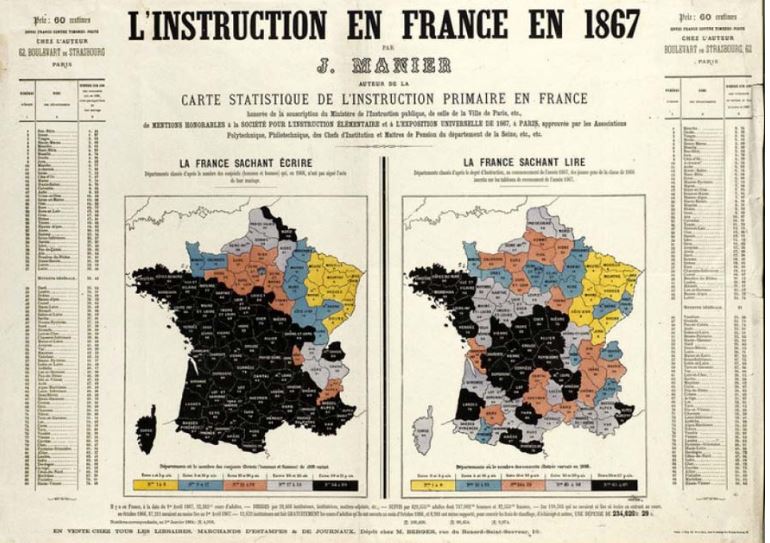

3. De la charité à la scolarisation universelle

Afin de pouvoir pleinement appréhender l’apport fondamental des conceptions de Lazare Carnot et du début de leur mise en œuvre par son fils Hippolyte, un bref historique de la scolarisation de notre pays s’impose.

Éduquer une poignée d’enfants plus ou moins talentueux ? On a su faire, surtout depuis les conseils savoureux des grands pédagogues de la Renaissance (Vittorino da Feltre, Alexandre Hegius, Erasme de Rotterdam, Juan Luis Vivès, Comenius, etc.). Mais organiser l’enseignement obligatoire, laïque et gratuit pour toute une nation, garçons et filles, restait un énorme défi à relever.

Et comme le montre la chronologie qui suit, la route vers la scolarisation universelle a été semée de nombreuses embûches.

En France, dès le XVIe siècle, l’Etat royal confie à l’église catholique (Jésuites, Oratoriens) le soin de former les enfants de la noblesse : seules les familles aisées arrivent à payer un précepteur pour les leurs, les autres, souvent qualifiés de personnes « n’étant pas faites pour des études », restent essentiellement analphabètes.

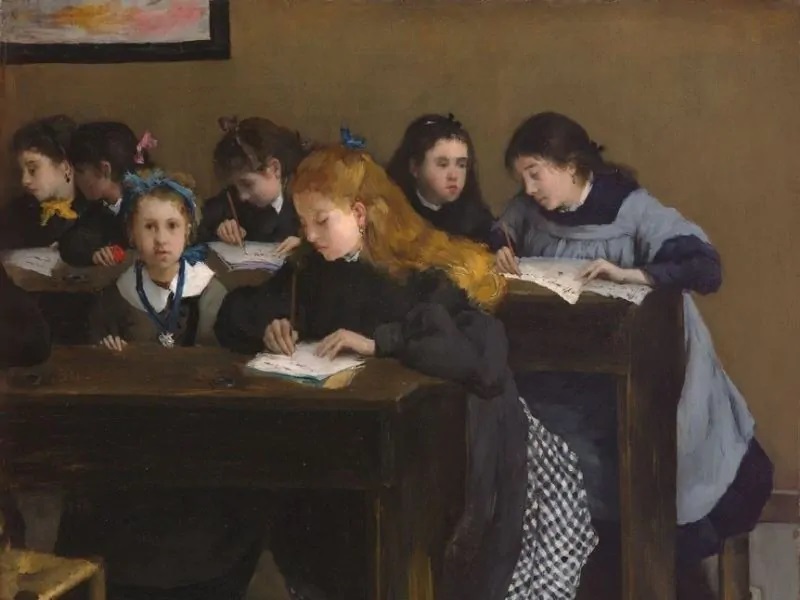

Au XVIIe siècle, de saints hommes, émus de la grande misère des enfants du peuple fondèrent des ordres enseignants qui prirent en charge gratuitement les orphelins et les enfants abandonnés. Un enseignement avant tout religieux, mais leur fournissant de quoi manger, des rudiments d’éducation et des bases d’écriture et de calcul. Au XVIIIe siècle, des congrégations féminines prirent en charge de la même façon les filles pauvres.

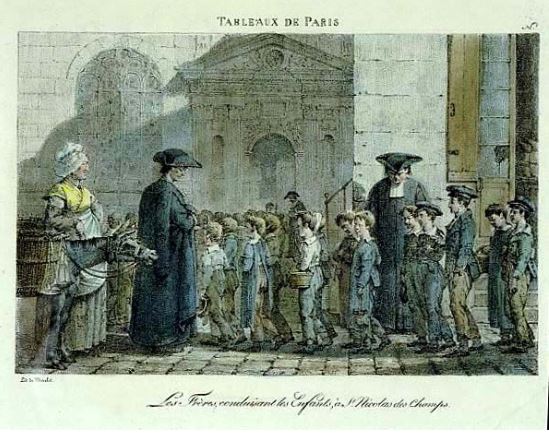

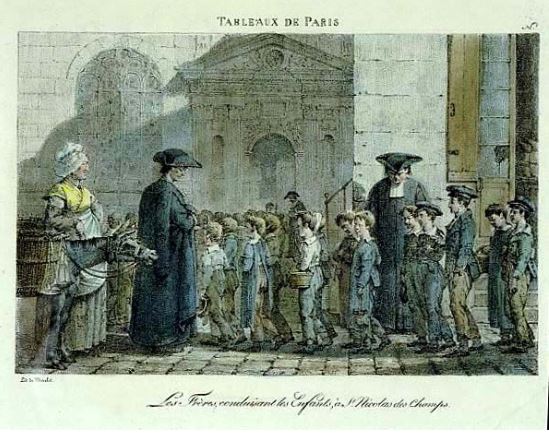

Peu importe ses motivations réelles, Louis XIV, après la révocation de l’édit de Nantes en 1685, ordonne en 1698 à chaque communauté villageoise ou paroisse d’ouvrir une école dont le maître doit être un prêtre catholique. C’est la première fois que l’Etat envisage de donner de l’instruction à des enfants des régions rurales. En charge d’y arriver, les Frères des Ecoles chrétiennes (« Lassalliens ») avec les méthodes qui seront les leurs.

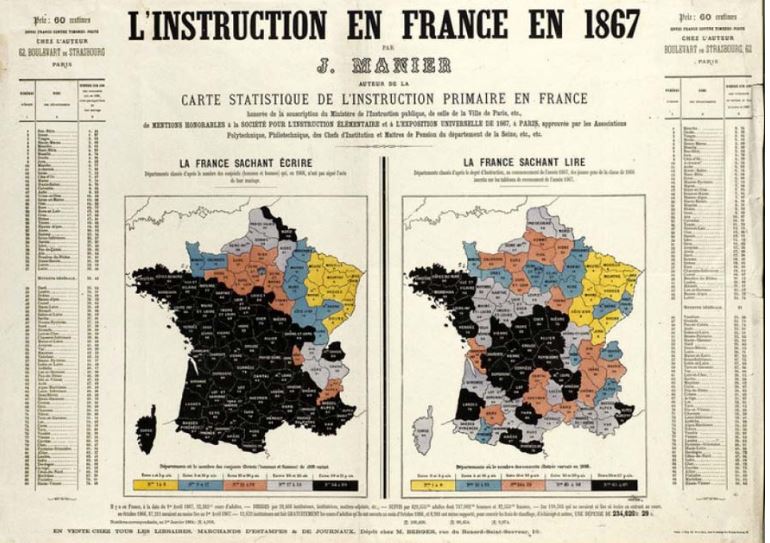

Les chiffres de l’alphabétisation à la fin de l’Ancien Régime montrent l’ampleur et les limites de l’œuvre accomplie. On estime à cette époque à 37 % la proportion des Français assez instruits pour signer leur acte de mariage au lieu de 21 % un siècle plus tôt. L’instruction féminine progressait lentement et environ un quart des femmes étaient alphabétisées, très sommairement pour nombre d’entre elles. Les disparités étaient importantes entre les villes et les campagnes.

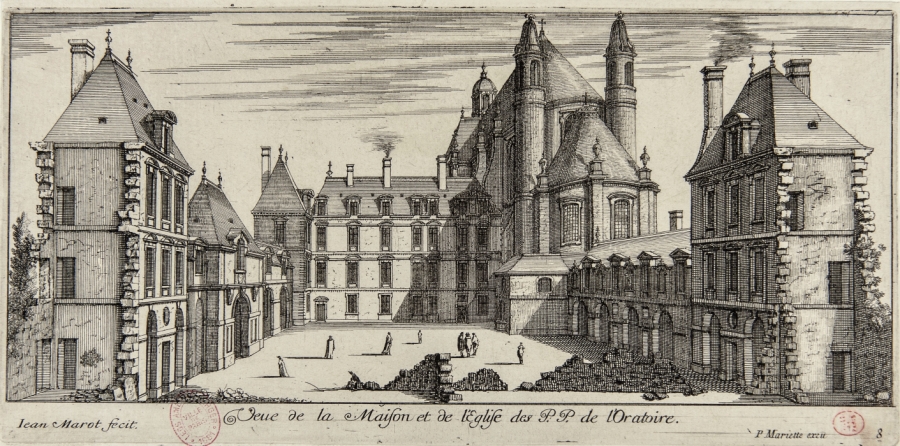

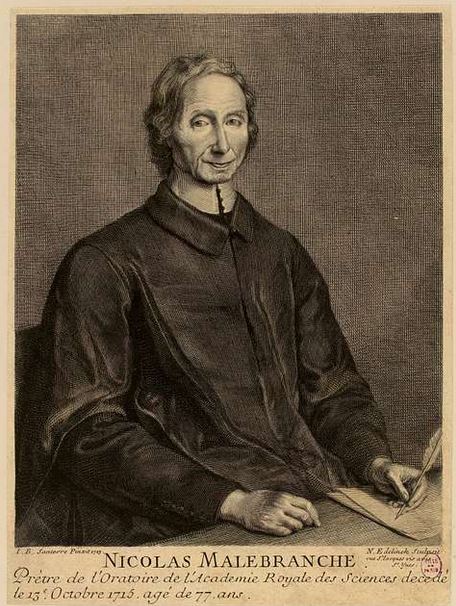

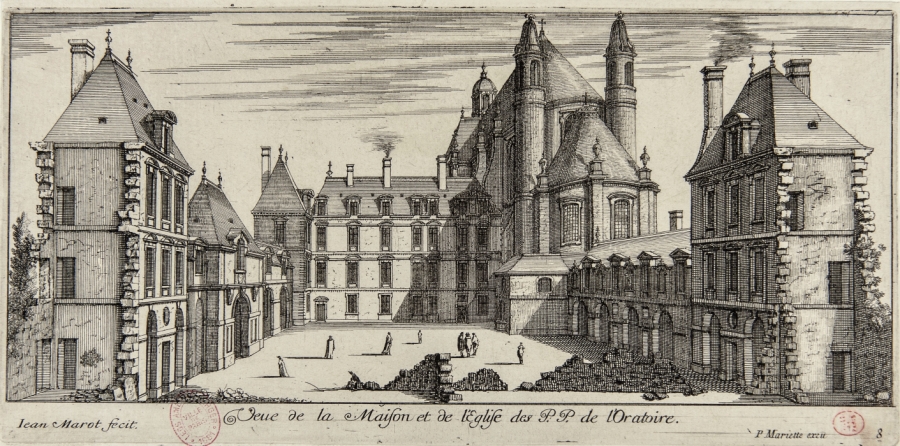

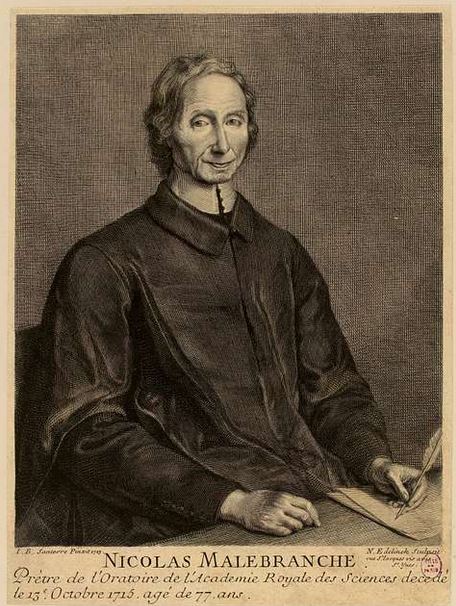

4. Malebranche et les Oratoriens

Parmi les congrégations, les Oratoriens, depuis 1660 sous l’influence du philosophe et théologien Nicolas Malebranche (1638-1715) qui en prend la direction, font exception. En rupture avec l’aristotélisme des Jésuites et le dualisme prôné par René Descartes, Malebranche, devenu membre honoraire de l’Académie des Sciences, par des échanges épistolaires soutenus, va se laisser gagner par la vision optimiste du grand scientifique allemand Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716). Réconciliant sciences et foi, sur le plan métaphysique, son dieu est un Dieu sage et raisonnable respectant toujours son essence et les lois de l’ordre qu’il engendre. Sa perfection réside avant tout dans sa fonction de législateur, identifiée à la sagesse ou à la raison, plutôt que dans un pouvoir arbitraire.

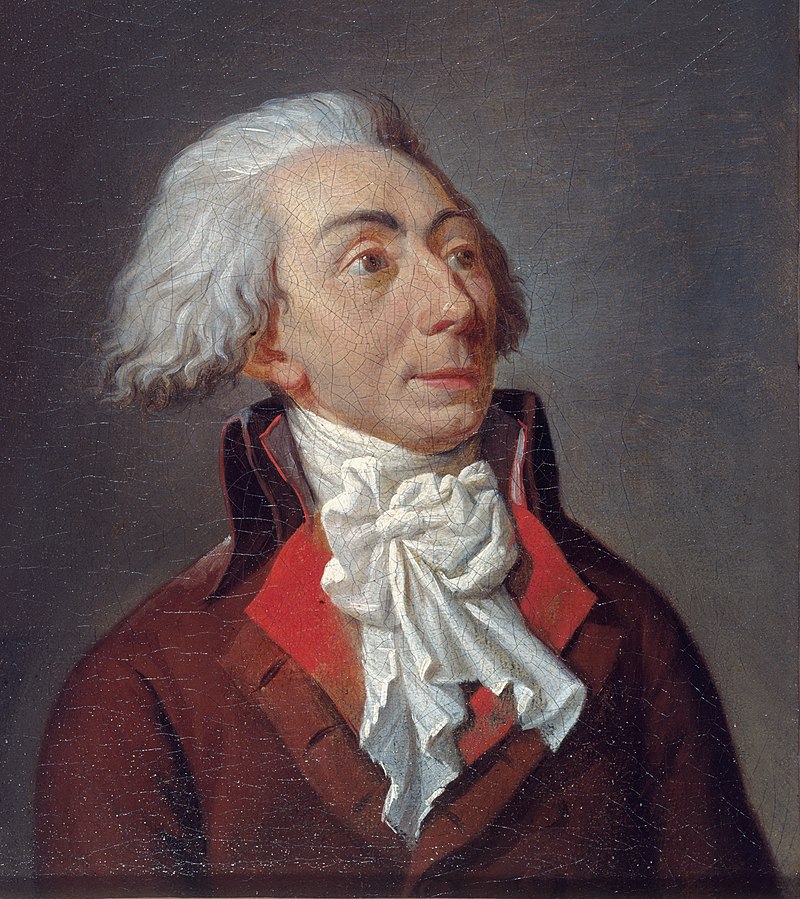

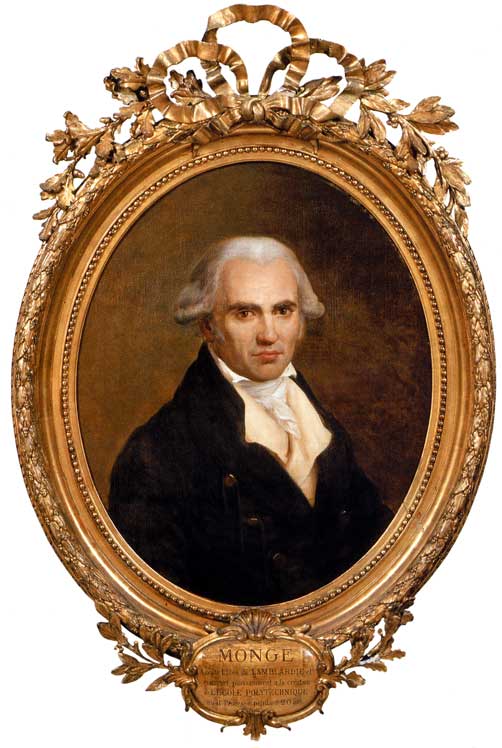

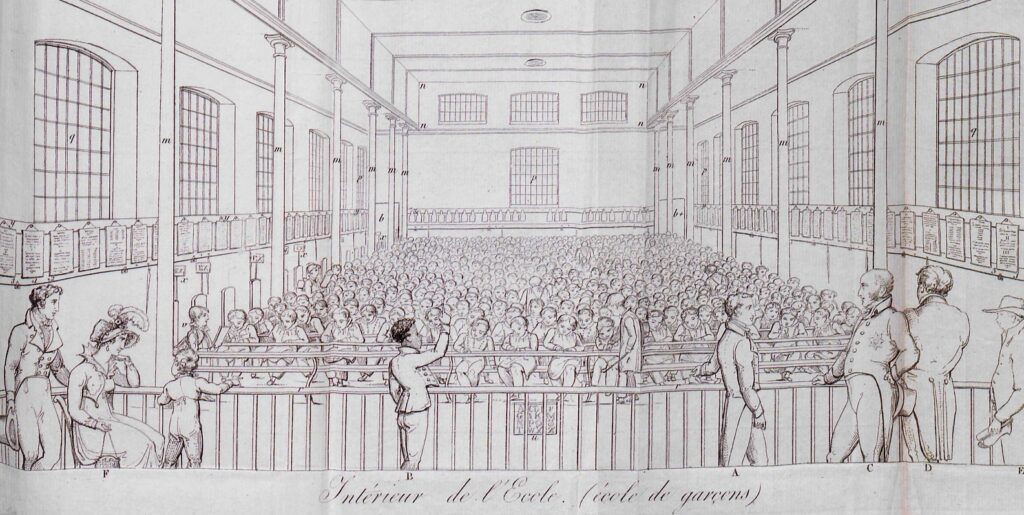

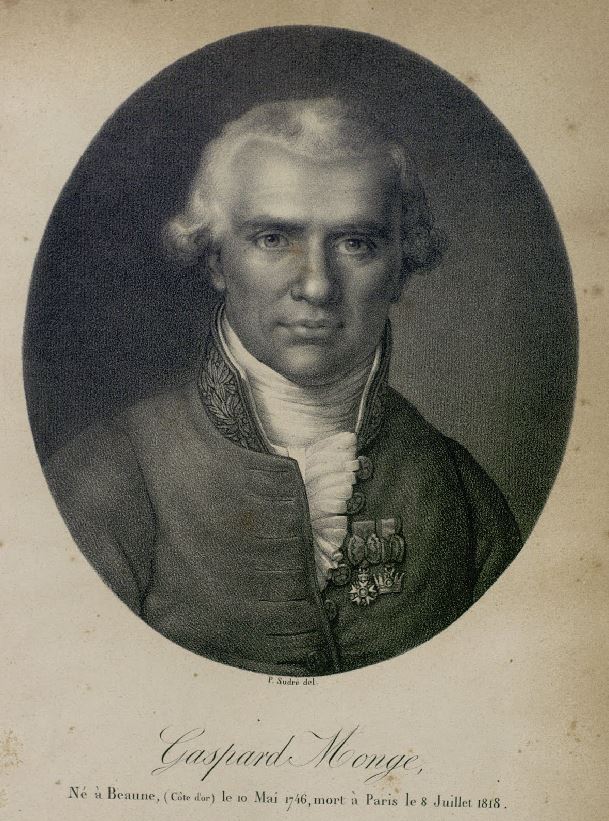

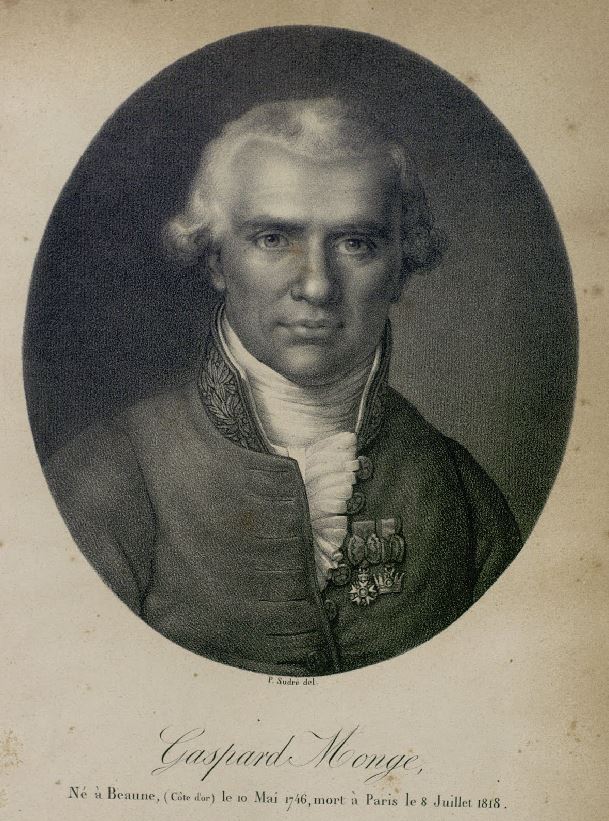

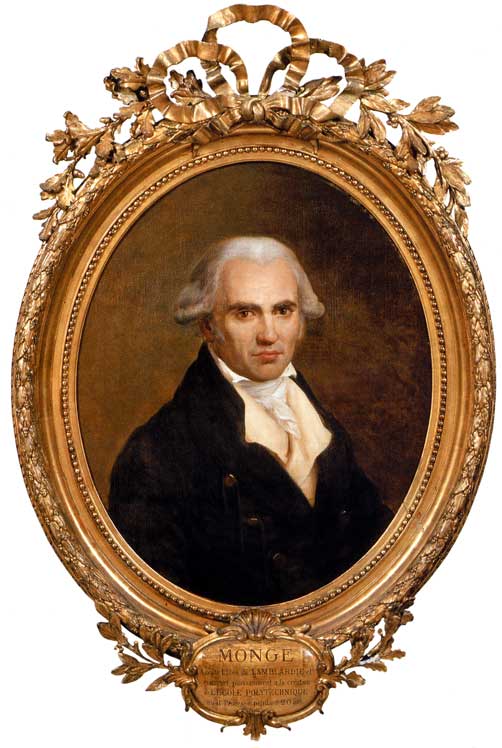

Deux exemples démontrent l’excellence de l’ enseignement des Oratoriens : Gaspard Monge et Lazare Carnot, deux grands esprits scientifiques et futurs cofondateurs de l’Ecole polytechnique. Convaincus que l’avenir politique, économique et industriel de la République en dépendait, ils mèneront le combat pour que la meilleure éducation possible soit accessible à tous et pas seulement aux privilégiés dont ils faisaient partie.

Fils d’un marchand savoyard, Gaspard Monge (1746-1818), suit des études au collège des Oratoriens de Beaune, sa ville natale. Dès 17 ans, il enseigne les mathématiques chez les Oratoriens de Lyon, puis en 1771, les mathématiques et la physique à l’École du Génie établie à Mézières. La même année, il entre en contact avec le physicien Jean Le Rond d’Alembert (1717-1783) et correspond avec le mathématicien Nicolas de Condorcet (1743-1794) qui le pousse à présenter quatre mémoires, un dans chacun des domaines des mathématiques qu’il étudie alors. Ses talents de géomètre ne tardent pas à s’exprimer : à l’Ecole du Génie de Mézières, il invente « la Géométrie descriptive » qui sera intégrée dans le programme d’études de l’école et qui fut essentielle à la révolution industrielle qui s’annonçait…

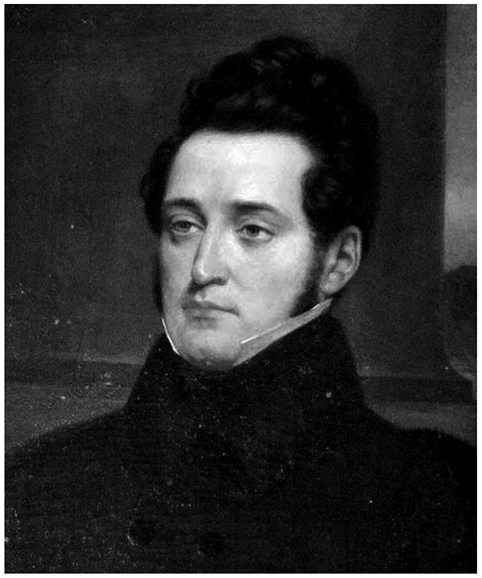

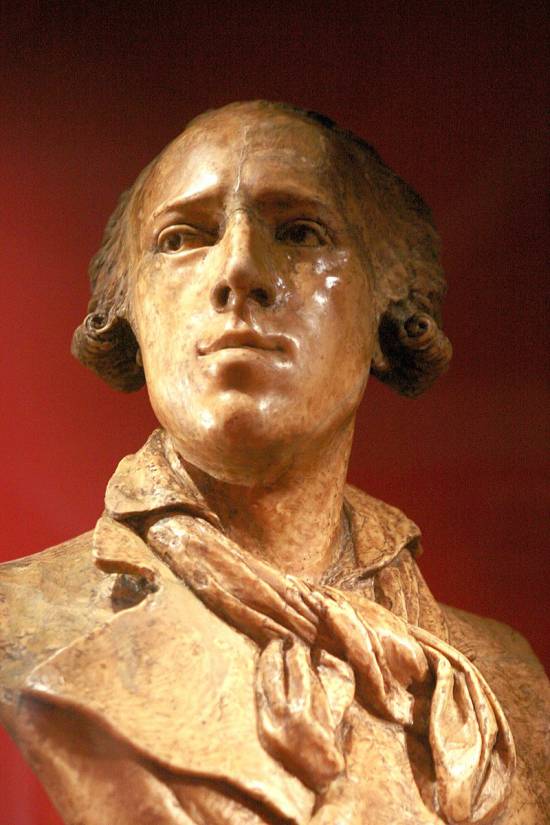

Quant au futur général Lazare Carnot (1753-1823), fils d’un notaire bourguignon, après des études chez les Oratoriens d’Autun (1762), il intègre lui aussi l’École du Génie de Mézières (1771) où il reçoit l’enseignement de Gaspard Monge.

5. La Révolution des esprits (1789)

En 1789, la Révolution chamboulera la situation. Dès le 13 février 1790, toutes les corporations et congrégations religieuses sont supprimées par décret et les religieux reçoivent l’injonction de prêter serment à la Révolution. C’est une remise en cause totale d’une Église toute puissante mais également l’effondrement du peu d’instruction qui existait.

En rupture avec l’Ancien Régime, la Constitution de 1791 affirme qu’il sera

« créé et organisé une instruction publique commune à tous les citoyens. »

Un rapport et un projet de loi, sont présentés par Talleyrand (1754-1838), le 10 septembre 1791. Rédigé grâce à la contribution des plus grands savants de l’époque (Condorcet, Lagrange, Monge, Lavoisier, La Harpe), le Rapport sur l’Instruction publique de Talleyrand, constitue une véritable rupture par rapport à la façon dont l’instruction était conçue pendant l’Ancien régime. Il pose la question de l’instruction publique dans des termes nouveaux, aussi bien au niveau des principes (l’instruction publique est présentée comme une nécessité à la fois politique, sociale et morale, et donc comme quelque chose que l’Etat doit garantir aux citoyens) qu’au niveau formel. Ce plan embrasse l’ensemble de l’éducation nationale, qui est organisée sur quatre niveaux et dont les établissements sont distribués sur le territoire national en fonction des découpages administratifs. Il met sur le papier les bases d’un enseignement gratuit pour tous y compris les filles (écoles et programmes séparés) et précise qu’« on y apprendra les premiers éléments de la langue française, soit parlée, soit écrite ».

En 1794, le juriste Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (1755-1841) précisera :

« Nous enseignerons le français aux populations qui parlent le bas-breton, l’allemand, l’italien ou le basque, afin de les mettre en état de comprendre les lois républicaines, et de les rattacher à la cause de la Révolution. »

Faute de temps, il n’est pas voté.

Dans son projet de loi, Talleyrand propose la création d’une école primaire dans chaque commune. L’Assemblée constituante venait de fixer l’organisation territoriale encore en place aujourd’hui. Le décret du 14 décembre 1789 venait de créer 44 000 municipalités (sur le territoire des anciennes « paroisses ») baptisées « communes » en 1793. La loi du 22 décembre 1789 créa les départements, le décret du 26 février 1790 en fixa le nombre à 83.

6. Le Comité d’Instruction publique (1791)

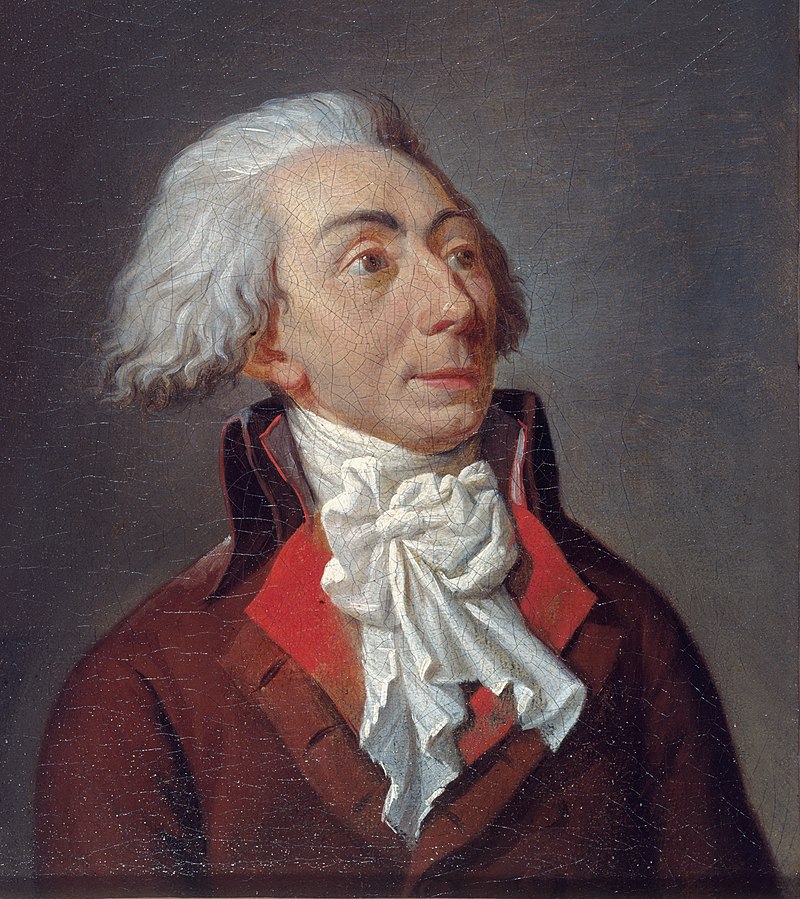

Un mois après le rapport de Talleyrand, le 14 octobre 1791, à l’Assemblée nationale législative, est créé un premier « Comité d’Instruction publique » dont Condorcet est élu président et l’avocat Emmanuel de Pastoret vice-président, les autres membres étant le futur général Lazare Carnot, le député Jean Debry, le mathématicien Louis Arbogast et l’homme politique Gilbert Romme.

Condorcet préside, en outre, l’une des trois sections, celle relative à l’organisation générale de l’Instruction publique. Le 5 mars 1792 il est nommé rapporteur du projet de décret sur l’organisation générale de l’instruction publique que le comité doit présenter à l’Assemblée.

Formé à 11 ans au collège des Jésuites de Reims, il est envoyé à 15 ans au collège de Navarre à Paris. De cette éducation-là, avant tout religieuse, il conservera toute sa vie des souvenirs douloureux et lui reprochera notamment ses brutalités et ses méthodes humiliantes. Son indignation le conduit à imaginer une approche totalement différente. Dans La Bibliothèque de l’homme public, il publie en 1791 « Cinq mémoires sur l’Instruction publique » constituant un véritable plan.

Ils seront la base du projet qu’il rédige à la Législative et seront approuvés par le comité d’instruction publique le 18 avril et présentés à l’Assemblée nationale les 20 et 21 avril 1792.

7. Condorcet et le parti américain

Hagiographe du physiocrate Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727-1781), tout en critiquant le sectarisme des « économistes », Condorcet adhère à certaines thèses physiocrates, notamment l’établissement de l’impôt sur le seul revenu agricole, considéré comme l’unique source de richesse de la nation, l’industrie étant considérée comme une catégorie « stérile » de l’économie nationale (voir mon article « La face cachée de la planète Marx »).

Pour les physiocrates, grands défenseurs de la rente terrienne qui les engraissait, l’ennemi à combattre était bien cet Etat centralisé, dirigiste et mercantile que Colbert, marchant dans les pas de Sully, avait commencé à mettre en place.

Ce qui n’empêche pas Condorcet, plus courageux que bien des gens de sa génération, de monter sur le devant de la scène pour soutenir ouvertement la Révolution américaine dans sa lutte contre les horreurs de l’Empire britannique : esclavage, peine de mort, droits de l’homme et de la femme.

Bien qu’ami de Voltaire, Condorcet écrit un éloge vibrant de Benjamin Franklin. Ami du pamphlétaire anglais influent Thomas Paine (1737-1809), il publie en 1786 « De l’influence de la Révolution d’Amérique sur l’Europe », dédié à La Fayette. Dans ce vibrant plaidoyer pour la démocratie et la liberté de la presse, Condorcet considère que l’Indépendance américaine pourrait servir de modèle à un nouveau monde politique.

Avec Paine et du Chastellet, Condorcet collabore de façon anonyme à une publication intermittente, Le Républicain, qui promeut les idées républicaines. À cette époque, il existe dans le monde seulement quelques états appelés républiques (les cantons suisses, Venise, les Provinces-Unies, notamment).

Par la suite, Condorcet se disputera violemment avec le deuxième président des Etats-Unis, John Adams, dont les encyclopédistes rejettent avec mépris le projet d’un parlement bicaméral.

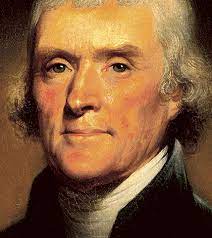

Condorcet se lie également avec le président américain Thomas Jefferson qui promeut et fait publier les écrits de Condorcet en faveur du physiocrate Turgot pour les faire connaître en Amérique. Le 31 juillet 1788, Jefferson écrit à James Madison : « Je vous envoie aussi deux petits pamphlets du marquis de Condorcet, dans lesquels se trouve le jugement le plus judicieux que j’aie jamais vu sur les grandes questions qui agitent cette nation en ce moment ». Il s’agissait des « Lettres d’un Citoyen des États-Unis à un Français et des Sentiments d’un Républicain ».

Pendant son séjour à Paris, Jefferson fréquente le salon cosmopolite de Mme de Condorcet. Avant de retourner en Amérique, il reçoit ses amis les plus proches une dernière fois chez lui, à l’hôtel de Langeac : Condorcet, La Rochefoucauld, Lafayette et le gouverneur Morris.

Après le retour de Jefferson en Amérique, Condorcet continua son dialogue avec le secrétaire d’État américain de Washington. Le 3 mai 1791, il lui envoya une copie du rapport sur le choix d’une unité de mesure, présenté par Borda, Lagrange, Laplace, Monge et lui-même, à l’Académie des sciences le 19 mars, et soumis ensuite à l’Assemblée nationale le 26. Il s’agissait en effet d’un centre d’intérêt commun : le 4 juillet 1790, Jefferson avait présenté au Congrès américain son rapport sur les poids et les mesures, dont il avait envoyé un exemplaire à Condorcet. C’était la même foi dans le progrès qui encourageait les deux hommes à soutenir l’idée d’un système de mesure décimal et universel.

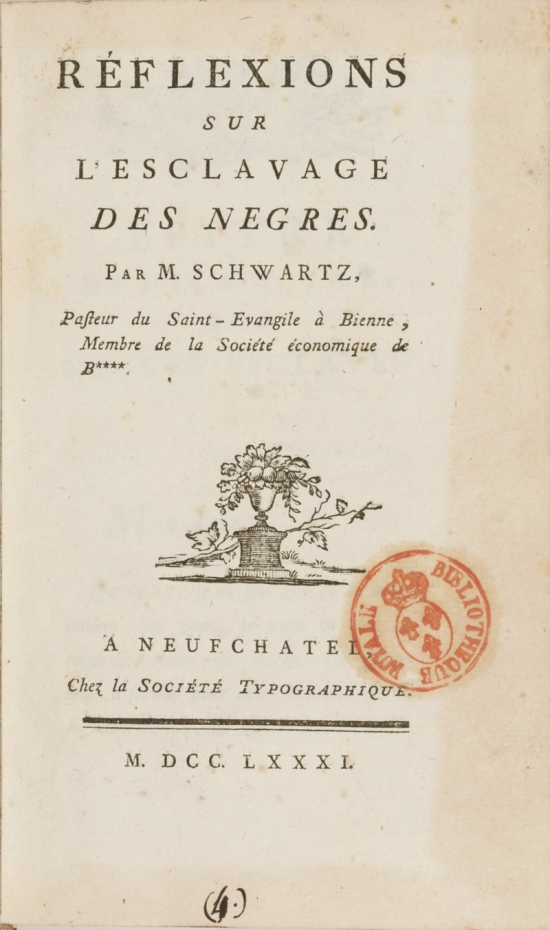

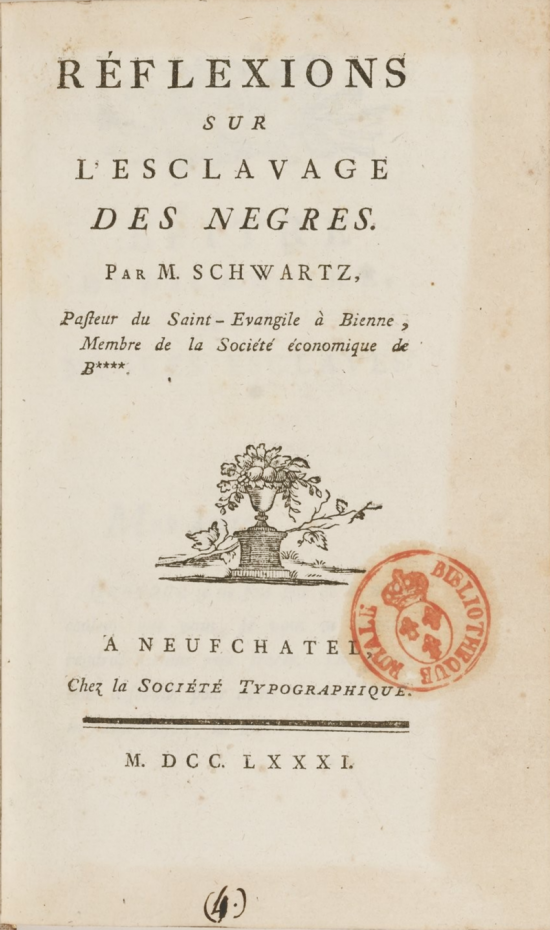

Dans une lettre, Jefferson informe Condorcet des travaux d’un mathématicien et astronome américain noir, Benjamin Banneker, auteur d’un almanach, dont il lui envoie un exemplaire. Dans les « Réflexions sur l’esclavage des nègres », bien que partisan convaincu de la liberté des noirs, Condorcet s’était exprimé en faveur d’une abolition graduelle de l’esclavage de la même manière que Jefferson dans ses « Notes on the State of Virginia ».

Jefferson oscilla dans ses positions, attribuant l’infériorité des Noirs tantôt à des causes naturelles, tantôt aux effets de l’esclavage, tandis que Condorcet – en accord avec Franklin – était convaincu depuis toujours de l’égalité naturelle de tous les hommes.

Dans les faits, celui qui fut le troisième président des Etats-Unis, posséda plus de 600 esclaves au cours de sa vie adulte. Il a libéré deux esclaves de son vivant, et cinq autres ont été libérés après sa mort, dont deux de ses enfants issus de sa relation avec son esclave Sally Hemings. Après sa mort, les autres esclaves ont été vendus pour rembourser les dettes de sa succession.

Jefferson s’oppose avec force aux « Fédéralistes » comme Alexander Hamilton qui promeuvent un Etat fédéral fort, le dirigisme économique à la Colbert et le mercantilisme. Condorcet va encourager Jefferson dans son projet de « démocratie agraire », la vision physiocratique des grands propriétaires terriens qui deviendra, jusqu’à l’arrivée de Lincoln et son conseiller Henry Carey, l’idéologie du Parti Républicain américain.

8. Le Plan Condorcet

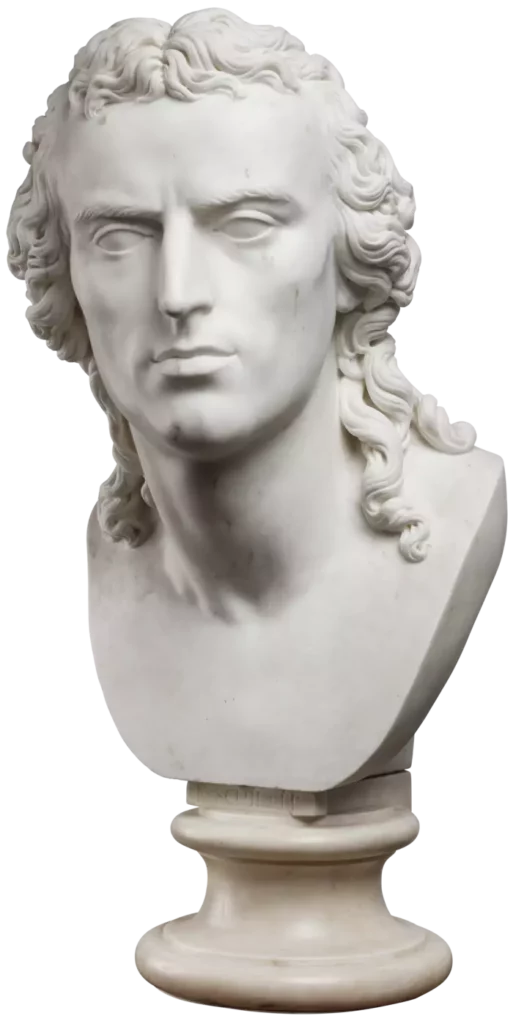

Les progrès de la science et de la raison mèneront au bonheur des sociétés et des individus, estime Condorcet. Dans l’Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain, il écrit :

« Nos espérances, sur l’état à venir de l’espèce humaine, peuvent se réduire à ces trois points importants : la destruction de l’inégalité entre les nations, les progrès de l’égalité dans un même peuple ; enfin, le perfectionnement réel de l’homme. »

Préférant « L’Instruction publique » à l’éducation nationale, il rêve d’une instruction totalement indépendante de l’État et libre de tout dogmatisme :

« La puissance publique ne peut même sur aucun objet, avoir le droit de faire enseigner des opinions comme des vérités ; elle ne doit imposer aucune croyance. » (Sur l’instruction publique, premier mémoire, 1791).

Esquissant des principes laïques, pour Condorcet, « les principes de la morale enseignée dans les écoles et dans les instituts seront ceux qui, fondés sur nos sentiments naturels et sur la raison, appartiennent également à tous les hommes. »

A l’Assemblée nationale, il est massivement applaudi lorsqu’il déclare que « dans ces écoles les vérités premières de la science sociale précéderont leurs applications. Ni la Constitution française ni même la Déclaration des droits ne seront présentées à aucune classe de citoyens, comme des tables descendues du ciel, qu’il faut adorer et croire. Leur enthousiasme ne sera point fondé sur les préjugés, sur les habitudes de l’enfance ; et on pourra leur dire : ‘Cette Déclaration des droits qui vous apprend à la fois ce que vous devez à la société et ce que vous êtes en droit d’exiger d’elle, cette Constitution que vous devez maintenir aux dépens de votre vie ne sont que le développement de ces principes simples, dictés par la nature et par la raison dont vous avez appris, dans vos premières années, à reconnaître l’éternelle vérité. Tant qu’il y aura des hommes qui n’obéiront pas à leur raison seule, qui recevront leurs opinions d’une opinion étrangère, en vain toutes les chaînes auront été brisées, en vain ces opinions de commande seraient d’utiles vérités ; le genre humain n’en resterait pas moins partagé en deux classes, celle des hommes qui raisonnent et celle des hommes qui croient, celle des maîtres et celle des esclaves.’»

Pour Condorcet, il s’agit d’assurer le développement des capacités de chacun et de tendre au perfectionnement de l’humanité. Son projet propose d’instituer cinq catégories d’établissements :

- les écoles primaires visant à la formation civique et pratique ;

- les écoles secondaires dans lesquelles sont surtout enseignées les mathématiques et les sciences ;

- les instituts, assurant dans chaque département la formation des maîtres d’écoles primaires et secondaires et, aux élèves, un enseignement général ;

- les lycées, lieu de formation des professeurs et de ceux qui « se destinent à des professions où l’on ne peut obtenir de grands succès que par une étude approfondie d’une ou plusieurs sciences. » ;

- la Société nationale des sciences et des arts ayant pour mission la direction des établissements scolaires, l’enrichissement du patrimoine culturel et la diffusion des découvertes.

Son plan se caractérise également par l’égalité des âges et des sexes devant l’instruction, l’universalité et la gratuité de l’enseignement élémentaire et la liberté d’ouverture des écoles. Enfin la religion ne doit relever que de la sphère privée.

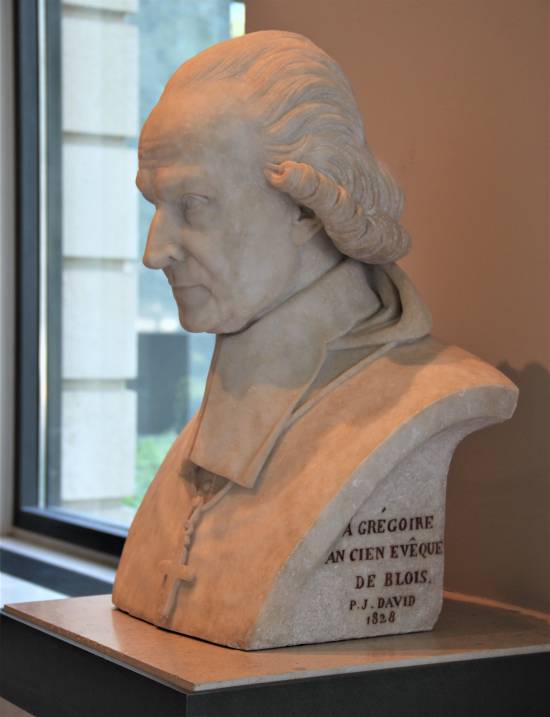

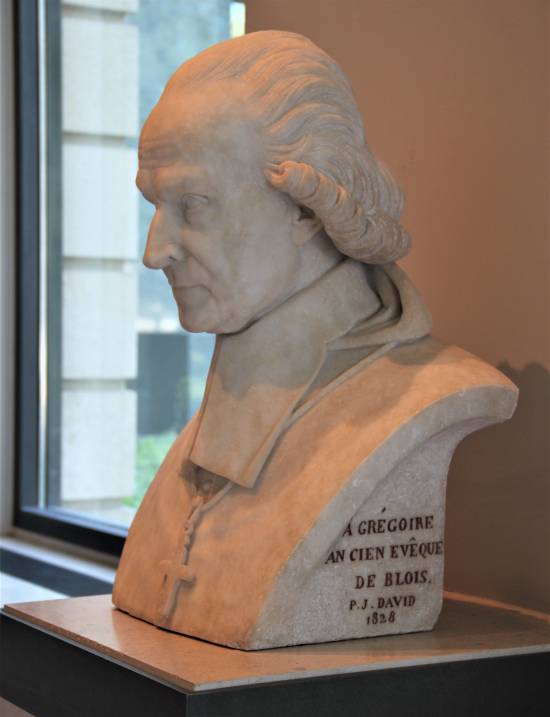

Le projet n’oublie nullement « le peuple », car des conférences hebdomadaires et mensuelles destinées aux adultes doivent permettre de « continuer l’instruction pendant toute la durée de la vie », une ambition que reprendront à leur compte l’abbé Grégoire (1750-1831) et Hippolyte Carnot.

Comme le relate Paul Carnot :

« L’Assemblée Constituante, dans sa courte existence, n’avait pu que transmettre le fameux rapport de Talleyrand à la Convention. Celle-ci, après les rapports, non moins fameux – de Condorcet et de Lakanal, après les discussions de son Comité d’Enseignement (presque aussi actif que le Comité de Salut public), avait proclamé des principes qui sont toujours les nôtres ceux de l’École primaire, obligatoire, gratuite et laïque. La Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme (art. XXII) proclamait, avec Robespierre ‘L’Instruction est le besoin de tous ; la société doit favoriser, de tout son pouvoir, les progrès de la raison publique et mettre l’Instruction à la portée de tous les citoyens’. »

Tous les partis, chose rare, étaient d’accord sur ces points. Les Girondins (Condorcet, Ducos) disaient, avec François Xavier Lanthenas (1754-1799), que:

« L’instruction est la première dette de l’État envers les citoyens. »

A propos de la gratuité, Georges Danton dira

« Nul n’est maître de ne pas donner l’instruction à ses enfants. Il n’y a pas de dépense réelle là où est le bon emploi pour l’intérêt public. Après le pain, l’instruction est le premier besoin du peuple.»

Mais le programme d’instruction publique menant à la perfectibilité de l’humanité, grâce à la raison, n’est pas une priorité, car le roi Louis XVI, sur proposition du général Dumouriez, vient de décider de se rendre à l’Assemblée nationale pour lui proposer de déclarer la guerre contre l’Autriche… A cela s’ajoute que l’argent pour l’éducation manque.

Condorcet doit interrompre la lecture de son projet. A la fin de l’après-midi de ce 20 avril 1792, l’Assemblée adopte la déclaration de guerre au roi de Bohême et de Hongrie, à l’unanimité moins sept voix. Le lendemain Condorcet termine la lecture de son projet. L’Assemblée décrète l’impression du rapport mais en diffère la discussion. C’est en vain que Romme, au nom du comité d’Instruction publique, demandera le 24 mai l’inscription à l’ordre du jour de la discussion du rapport. Le projet de Condorcet n’aura pas, tout comme le rapport de Talleyrand, le temps d’être débattu et ne sera pas adopté.

9. La bataille sous la Convention (1792-1795)

Les protagonistes de l’an I (sous la Convention) ne furent guère plus décisionnaires. Un nouveau Comité d’instruction publique est constitué. L’abbé Grégoire, abolitionniste et ami intime de Lazare Carnot et plus tard de son fils Hippolyte, et Joseph Lakanal (1762-1845) en font partie.

Le 12 décembre 1792, Marie-Joseph de Chénier (1764-1811) lit les propositions de Lanthénas qui reprend les idées de Talleyrand et Condorcet. Les discussions sont stériles et le projet est balayé par Marat. Ce dernier s’exclame ce jour-là :

« Quelque brillants, dit il, que soient les discours que l’on nous débite ici sur cette matière, ils doivent céder place à des intérêts plus urgents. Vous ressemblez à un général qui s’amuserait à planter et déplanter des arbres pour nourrir de leurs fruits des soldats qui mouraient de faim. Je demande que l’assemblée ordonne l’impression de ces discours, pour s’occuper d’objets plus importants. »

L’année d’après, Robespierre opte pour un plan d’éducation nationale imaginé par Lepeltier de Saint-Fargeau (1760-1793).

Selon ce plan, présenté par Robespierre en personne, le 13 juillet 1793, l’instruction sans une bonne dose d’idéologie républicaine ne saurait suffire à la régénération de l’espèce humaine. C’est donc l’État qui doit se charger d’inculquer une morale républicaine, en prenant en charge l’éducation en commun des enfants entre 5 et 12 ans.

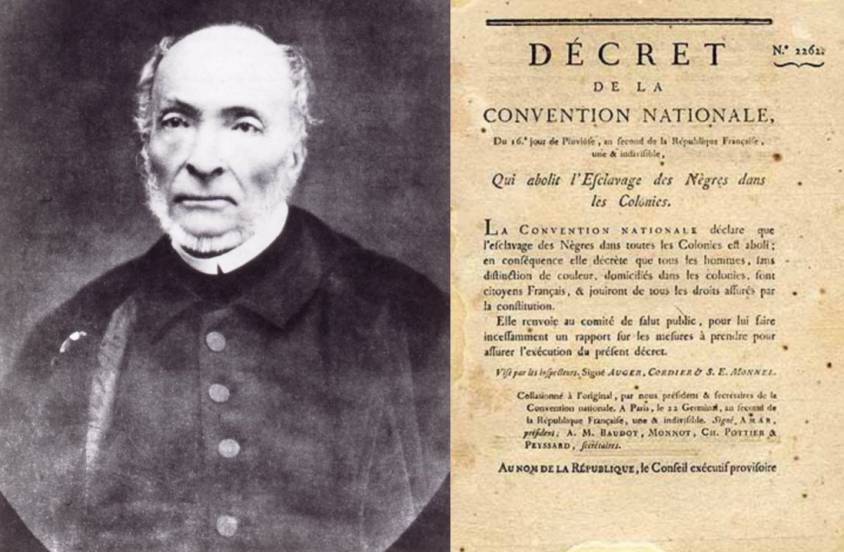

Le 21 Janvier 1793, le Roi est décapité. Alors que pour Carnot, il s’agit de ne plus jamais permettre le retour de la lignée des Bourbons, Condorcet, adversaire par principe à la peine de mort, s’y oppose. Les débats sur l’instruction publique sont ajournés. Ce n’est qu’en fin d’année qu’une législation de compromis sur l’organisation des écoles primaires voit le jour ; elle rend l’instruction obligatoire et gratuite pour tous les enfants de six à huit ans et fixe la liberté d’ouvrir des écoles. Le décret du 19 décembre 1793 précise que les études primaires forment le premier degré de l’instruction : on y enseignera les connaissances rigoureusement nécessaires à tous les citoyens et les personnes chargées de l’enseignement dans ces écoles s’appelleront désormais « instituteurs ». Ce décret ne sera que partiellement appliqué.

1794 vit rédiger une profusion de textes législatifs sur le sujet :

- le décret du 27 janvier 1794 impose enfin l’instruction en langue française.

- Le 21 octobre 1794 une autre décision organise la distribution des premières écoles dans les communes.

- Le 30 octobre est créée, pour former des enseignants, la première « école normale » sur l’impulsion de Dominique Joseph Garat, de Joseph Lakanal et du Comité d’instruction publique. La loi précise qu’« Il sera établi à Paris une École normale, où seront appelés, de toutes les parties de la République, des citoyens déjà instruits dans les sciences utiles, pour apprendre, sous les professeurs les plus habiles dans tous les genres, l’art d’enseigner ». L’école, prévue pour près de 1 500 élèves, s’installe dans un amphithéâtre du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, trop petit pour accueillir toute la promotion. Rapidement fermée, elle réunit néanmoins des professeurs brillants, tels que les scientifiques Monge, Vandermonde, Daubenton et Berthollet.

- Le 17 novembre, Lakanal fait adopter une loi rendant l’instruction gratuite, la République assurant un traitement et un logement aux instituteurs et autorisant la création d’écoles privées.

Également en 1794, Jacques-Élie Lamblardie, Gaspard Monge et Lazare Carnot, pères fondateurs de l’institution, se voient confier la mission d’organiser une « Ecole centrale des travaux publics », renommée « École polytechnique » en 1795 par Claude Prieur de la Côte d’Or, pour pallier la pénurie d’ingénieurs dans la France d’après la Révolution.

Malheureusement, sur le plan d’une scolarisation universelle, le bilan de 1795 est désastreux : aucun des décrets de 1794 n’a été appliqué!

Pire encore, le 25 octobre 1795, une nouvelle loi élaborée par Pierre Daunou marque même un recul : faute de budget, l’instruction n’est plus gratuite, les instituteurs doivent être salariés par les élèves (et leurs riches parents) et le programme scolaire devient indigent. Cette loi est restée en vigueur jusqu’aux textes napoléoniens sur l’enseignement secondaire et supérieur en 1802. Si elle prévoit l’abandon de l’obligation scolaire et de la gratuité, cette loi préconise la création d’une école primaire par canton et « d’école centrales » secondaires dans chaque département.

Les nouvelles autorités fixent aux communes des délais pour l’organisation des écoles. Elles mandatent des envoyés spéciaux pour voir si les communes prennent les mesures nécessaires pour rechercher et installer un instituteur.

Dans les villes, l’administration parvient à recueillir un certain nombre de candidats instituteurs, mais à la campagne, bien souvent la liste demeure vierge. Les administrations locales, en plus du problème de recrutements, se heurtent au problème du local, du mobilier, du chauffage de l’école et des ouvrages à utiliser. Les instituteurs en exercice se plaignent de la pénurie d’élèves car l’école républicaine suscite de la méfiance. Quand l’instituteur se risque à remplacer le catéchisme et les Évangiles par la Constitution et les Droits de l’Homme, les parents, incités en cela par des prêtres réfractaires, préfèrent garder leurs enfants chez eux. Le Comité d’instruction publique est submergé de questions, accablé de suggestions et de demandes.

Le 17 novembre 1795, Lakanal fait adopter par la Convention une nouvelle loi. L’instruction reste gratuite mais non obligatoire. Elle assure un traitement fixe et une retraite aux instituteurs et institutrices et leur fournit un local et un logement. Elle autorise tout citoyen à fonder des écoles particulières (privées).

10. Lazare Carnot sous les Cent-Jours (mars-juin 1815)

Le 9 novembre 1799, Bonaparte fomente un coup d’État et établit le régime du Consulat. Premier Consul, il signe avec le pape Pie VII le Concordat le 16 juillet 1801 qui abolit la loi de 1795 séparant l’Église de l’État.

Saisissant l’occasion du moment, et avant tout cherchant à répondre aux besoins immédiats, le ministre de l’Intérieur, le chimiste et industriel républicain Jean-Antoine Chaptal (1756-1832) soumet alors à Bonaparte un projet d’organisation de l’enseignement secondaire, confié, en particulier aux Oratoriens de Tournon. En 1800 il présente son « Rapport et projet de loi sur l’instruction publique. »

Rappelé par le Premier consul, Lazare Carnot reçoit le portefeuille de la Guerre qu’il conservera jusqu’à la conclusion de la paix d’Amiens en 1802, après les batailles de Marengo et d’Hohenlinden.

Révolutionnaire de la première heure, mais aussi modéré et républicain, il vote contre le Consulat à vie, puis est le seul Tribun à voter contre l’Empire le 1er mai 1804. Dès lors, privé de toute influence politique, il se recentre sur l’Académie des sciences. En 1814, la défense d’Anvers, ville dont il sera maire, lui est confiée : il s’y maintient longtemps et ne consent à remettre la place que sur l’ordre de Louis XVIII.

Mais quelques mois plus tard, l’Empereur revient au pouvoir pour les Cent-Jours, du 20 mars au 7 juillet 1815 (3 mois et 17 jours). C’est à ce moment que Lazare Carnot, menacé d’arrestation au point de se cacher rue du Parc-Royal, est nommé ministre de l’Intérieur le 22 mars 1815. Et comme ce ministère comporte dans ses attributions l’Instruction publique, il peut alors lancer le projet éducatif qui lui tient à cœur.

Trois jours après son installation au ministère, Lazare Carnot commande une étude sur l’enseignement.

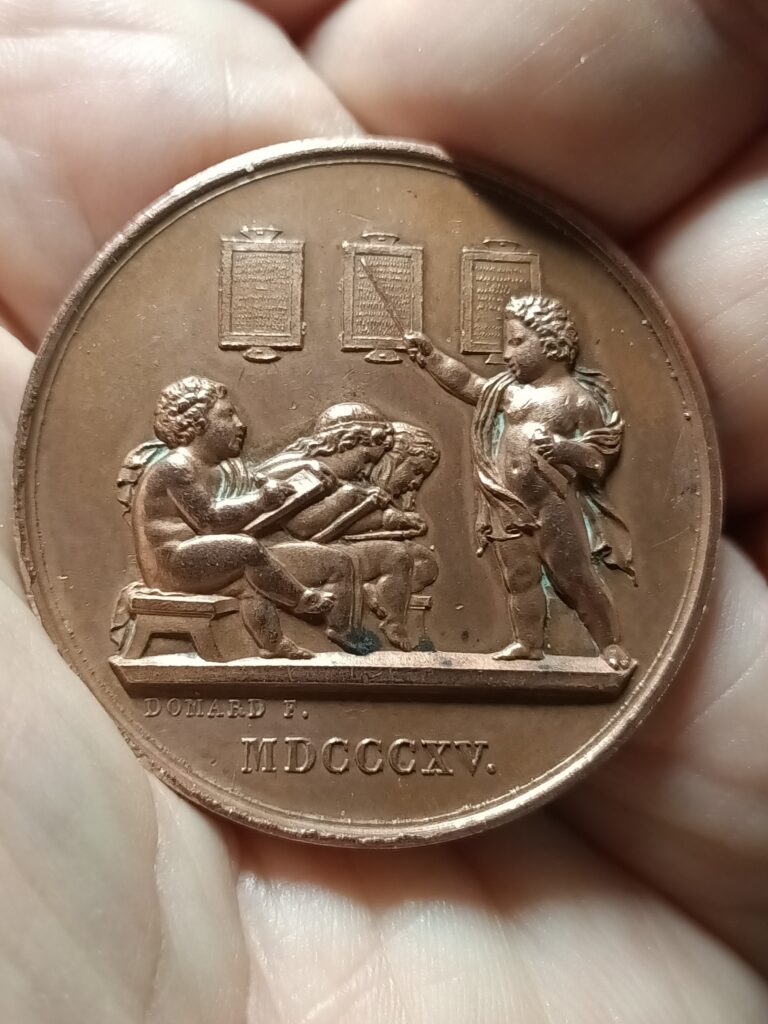

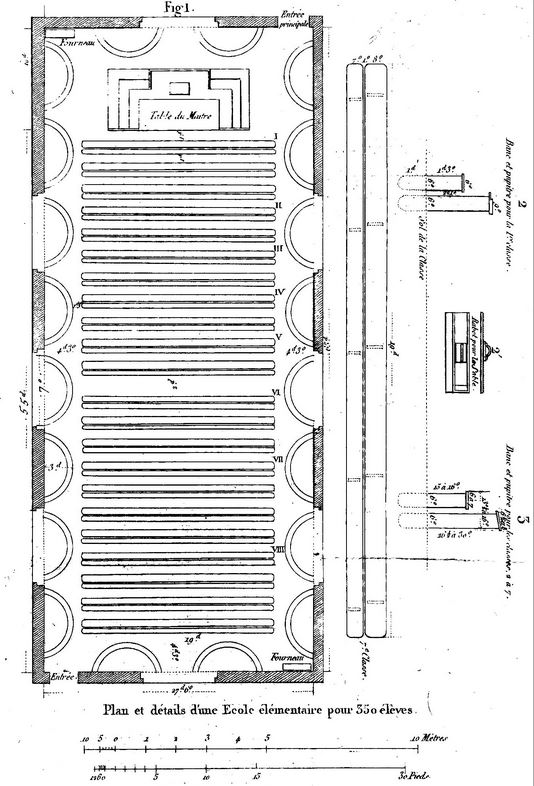

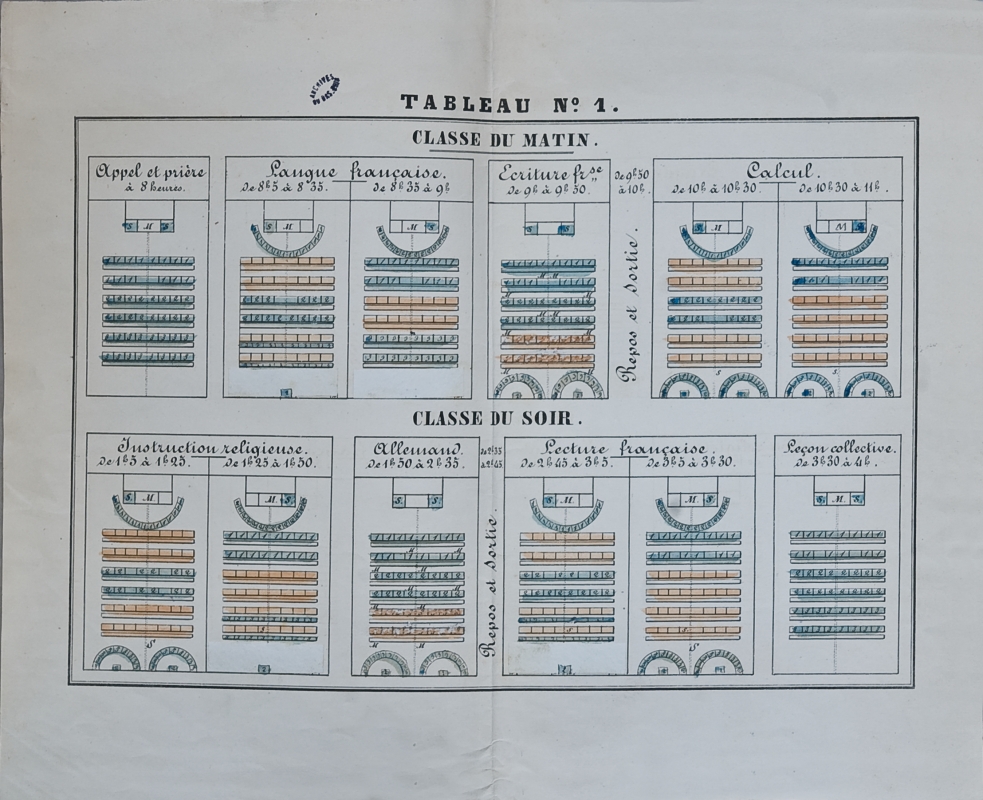

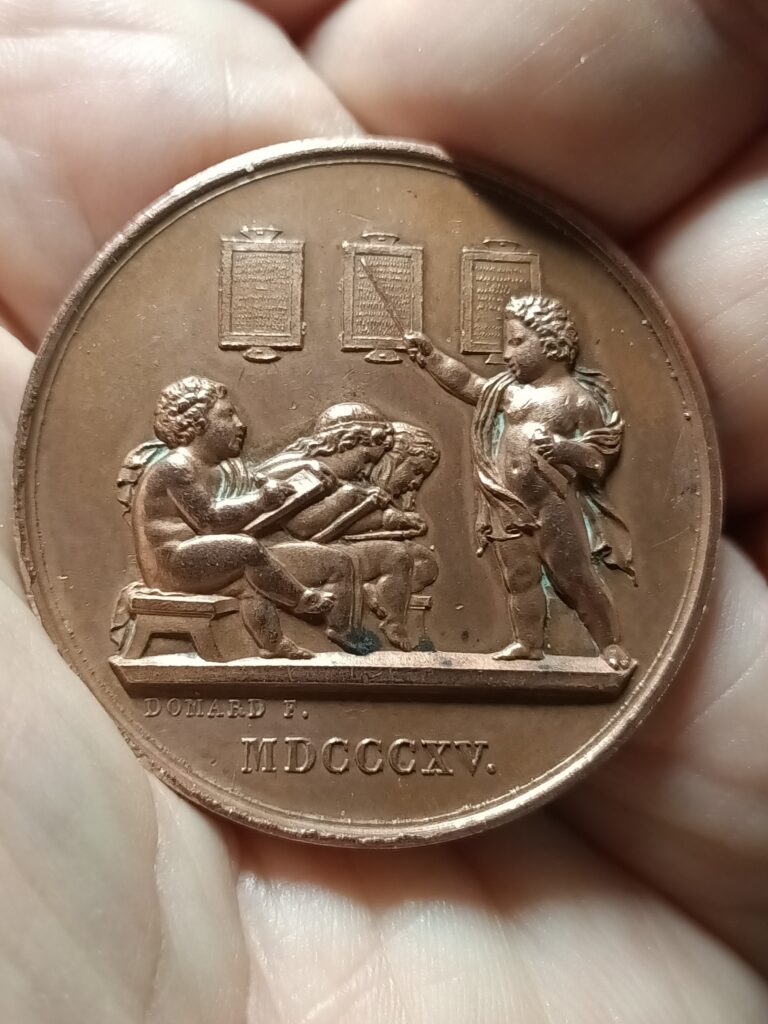

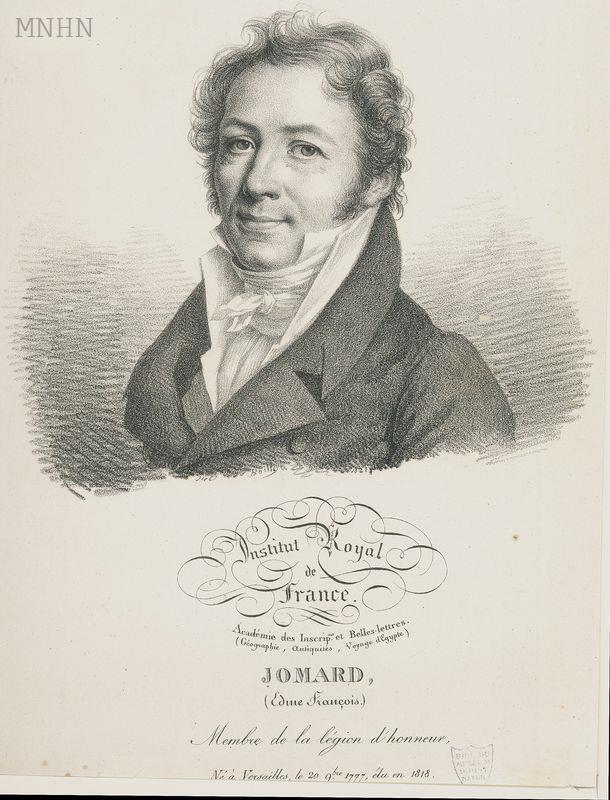

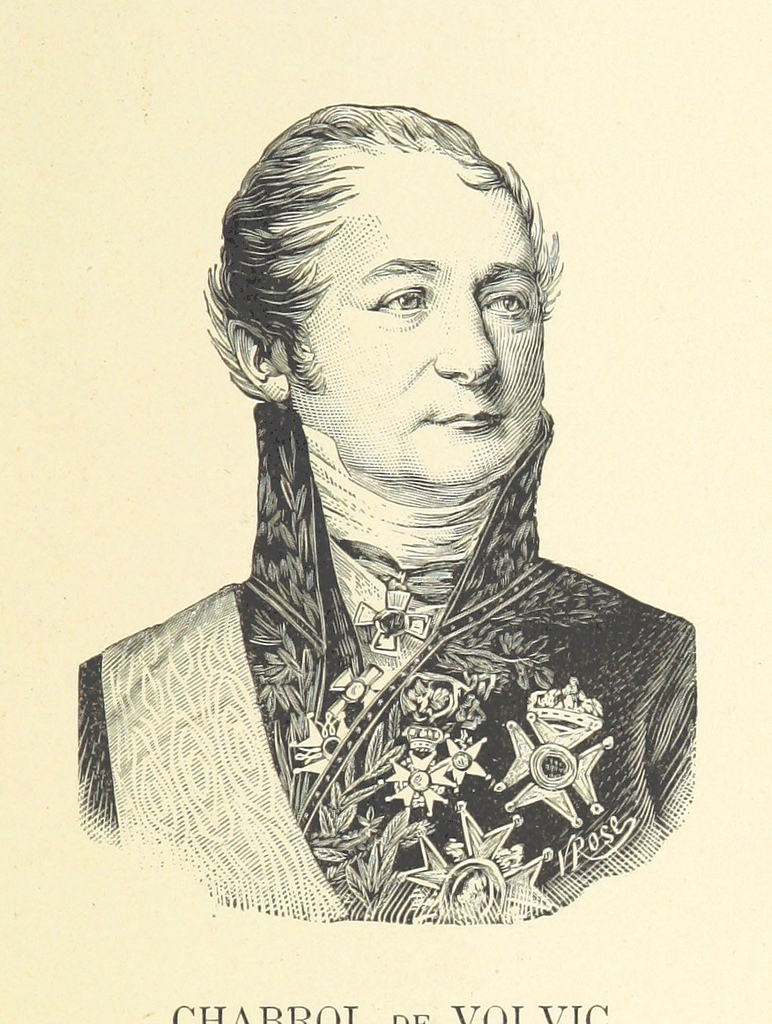

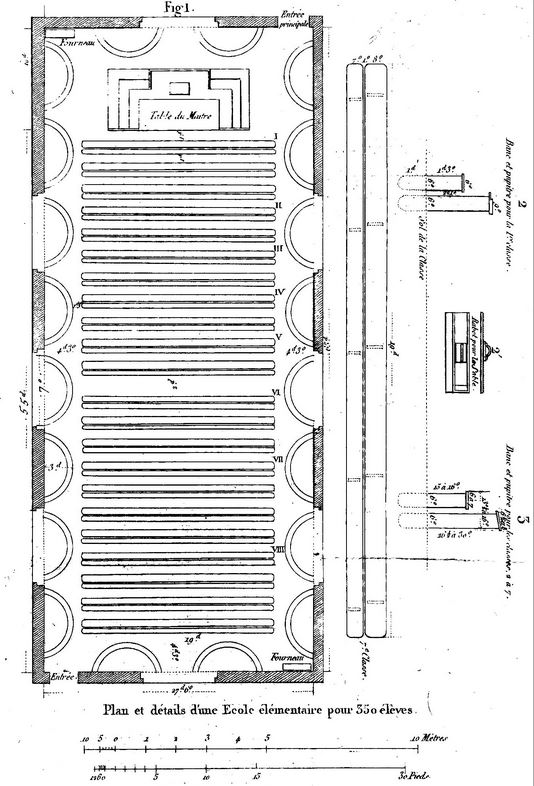

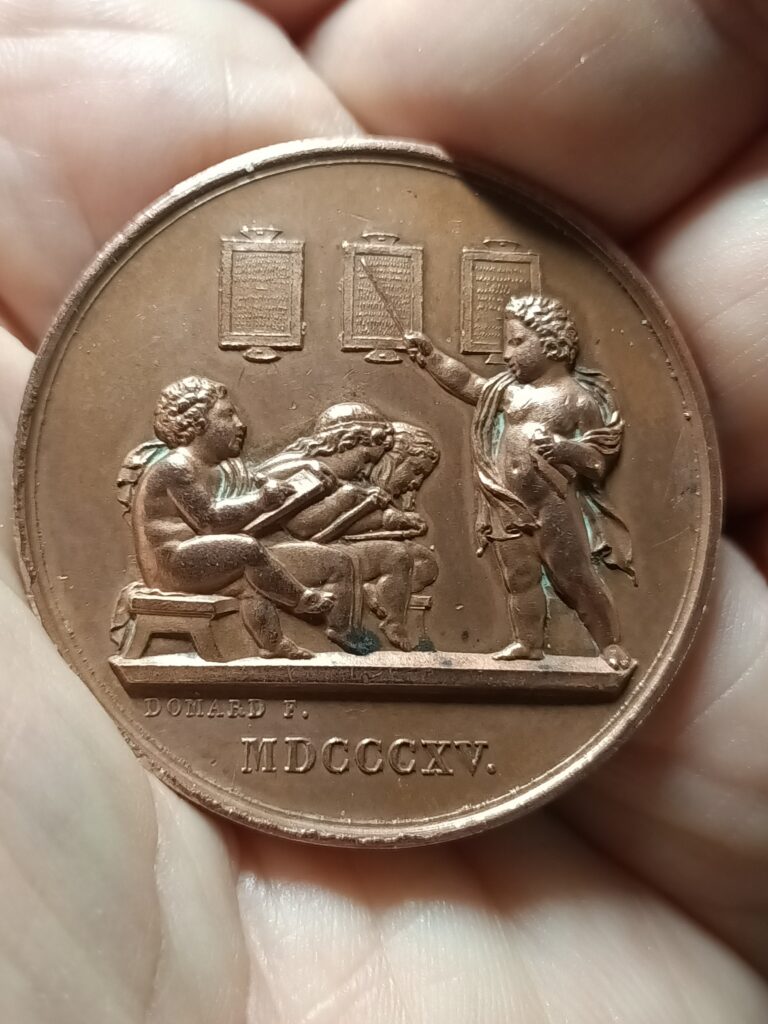

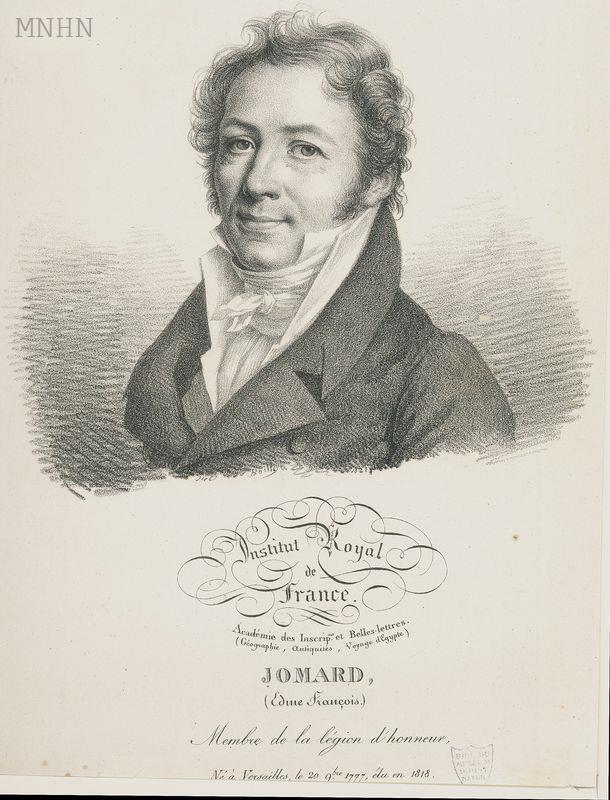

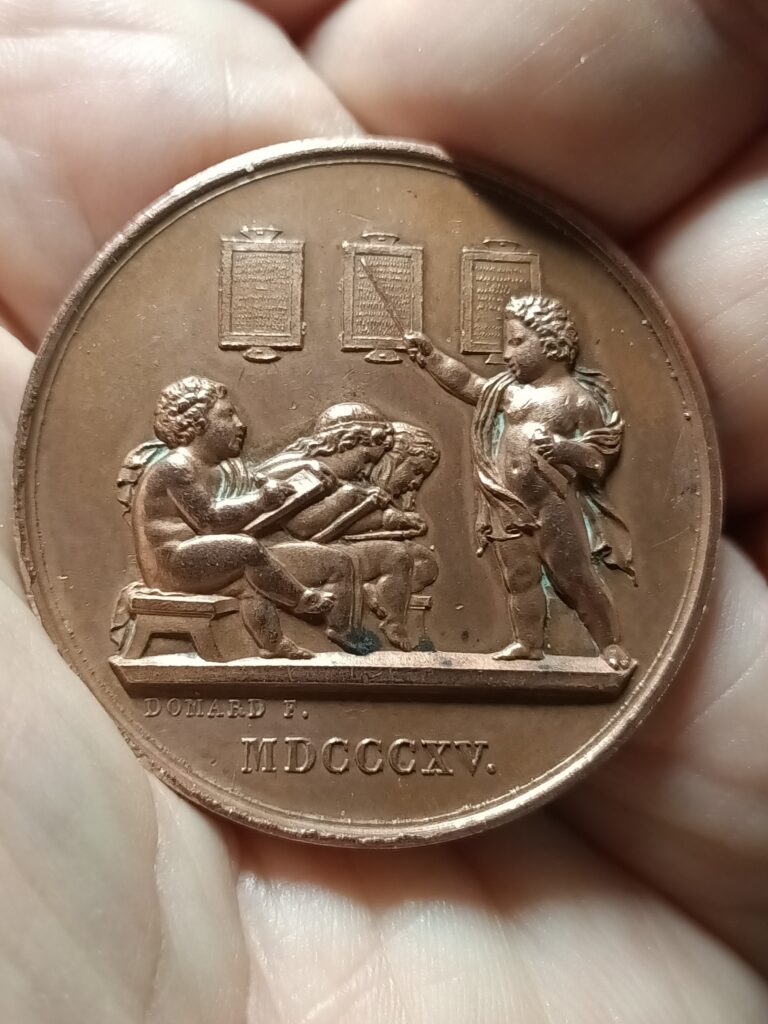

Elle s’inspire des travaux de la « Société d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale », fondée par Chaptal et dirigée par le philanthrope Joseph Marie de Gérando, lui aussi éduqué par les Oratoriens à Lyon et, avec Laborde, Lasteyrie et Jomard, partisan de la nouvelle méthode d’enseignement mutuel. (voir notre article sur ce site).

Carnot impulsera également la fondation de « Société pour l’instruction élémentaire (SIE) » afin de promouvoir ce type d’éducation.

Pour Carnot et Grégoire, l’éducation et l’instruction doivent « élever à la dignité d’Homme tous les individus de l’espèce humaine », éduquer autant que moraliser, et répandre l’amour entre les hommes.

Pendant les Cent-Jours, Carnot a juste eu le temps de préparer, en avril 1815, un « plan d’ensemble pour l’éducation populaire » suivi d’un décret et de la création d’une Commission spéciale pour l’enseignement élémentaire chargée de tracer des perspectives en la matière en s’inspirant des modèles anglais et hollandais.

Familiarisé avec les « brigades » inventées par Gaspard Monge à l’école du Génie de Mézières et ensuite à Polytechnique, où les meilleurs élèves encadrent les autres, Carnot est plus que favorable au système de l’enseignement mutuel dans les écoles populaires. Répandu en Angleterre et en Suisse, Carnot va l’établir en France.

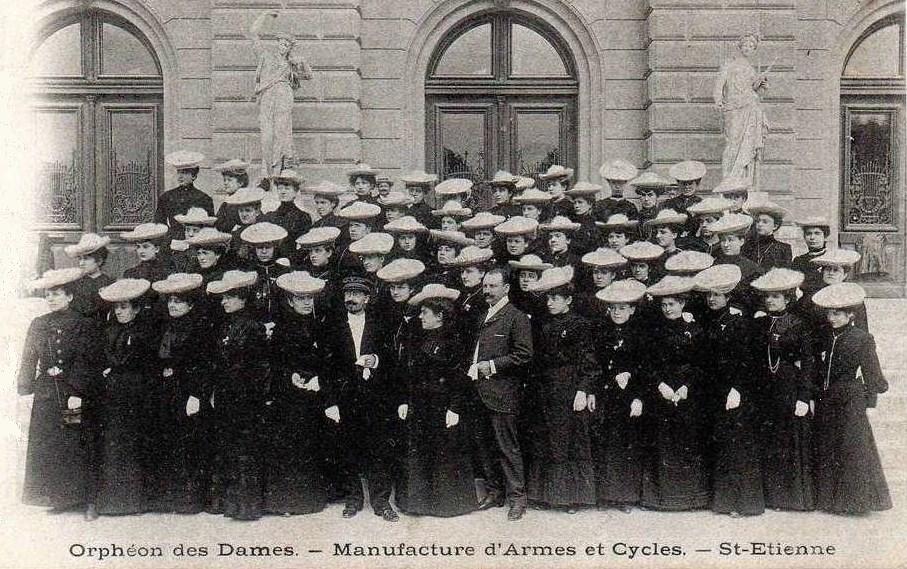

Convaincu de l’importance de la musique, il souhaite l’enseignement de celle-ci aux élèves. Dans cette intention, il rencontre plusieurs fois Alexandre-Étienne Choron (1771-1834), lui aussi passé par les Oratoriens, qui réunit un certain nombre d’enfants et leur fit exécuter en sa présence plusieurs morceaux appris en fort peu de leçons. Par ailleurs, Carnot connaissait le pédagogue Louis Bocquillon, dit Wilhem (1781-1832) depuis dix ans. Il entrevit aussi la possibilité d’introduire, par lui, le chant dans les écoles, et tous deux visitèrent ensemble celle de la rue Jean-de-Beauvais, ouverte à Paris à trois cents enfants. De son côté, Wilhem créa le mouvement musical de masse des « orphéons ».

11. Hippolyte Carnot reprend le flambeau de son père Lazare

Lazare, un esprit scientifique de haut vol, a des idées bien arrêtées sur l’éducation qui forgeront la personnalité de ses fils, notamment celle d’Hippolyte, le futur ministre de l’Instruction publique de la seconde République. Pour les deux Carnot,

« toutes les institutions sociales doivent avoir pour but l’amélioration sous le rapport physique, intellectuel et moral de la classe la plus nombreuse et la plus pauvre. »

Plus que des « têtes bien pleines », il aspirait à faire de ses fils des « têtes bien faites », et de « nous faire connaître la saveur des bonnes choses plutôt que nous rendre infaillibles sur le sens des mots », selon les mots de son cadet. Pour Lazare, il s’agit de mettre à l’épreuve en famille les principes éducatifs qu’il prône pour la nation.

Bien que peu féru de langues mortes et plus attiré par les langues vivantes, Lazare initie ses enfants au latin, redevenu langue obligatoire dans les lycées impériaux créés en mai 1802. Pour le reste, si la riche bibliothèque paternelle permet à Sadi Carnot et à son frère Hippolyte de se familiariser avec les classiques indispensables à la culture humaniste qui fonde l’enseignement secondaire, elle les initie à d’autres penseurs plus contemporains et novateurs.

Parmi eux, Hippolyte s’intéresse à ceux qui se penchent sur les questions éducatives comme Rousseau, mais aussi à des philosophes plus originaux comme Saint-Simon dont son père disait :

« Voilà un homme que l’on traite d’extravagant, or il a dit plus de choses sensées dans toute sa vie que les sages qui le raillent […]. Mais c’est un esprit très original, très hardi dont les idées méritent de fixer l’attention des philosophes et des hommes d’État. »

Évoquant son père, Hippolyte dira plus tard :

« Les leçons que nous recevions avaient toutes pour objet de nous rendre, comme le maître qui les donnait, vertueux sans effort, sages sans système. »

Lazare Carnot fait entrer Hippolyte à l’institution polytechnique, 8 avenue de Neuilly. D’après Dalisson,

« le jeune Carnot y reçoit une éducation spartiate où, si la discipline n’exclut pas les châtiments corporels sous la férule ‘d’Inspecteurs généraux’, la pédagogie est novatrice. Les élèves sont répartis dans des classes selon leur âge et l’enseignement allie éducation intellectuelle et physique à travers des programmes qui complètent l’éducation paternelle. Hippolyte se perfectionne ainsi en lecture, en langues, anciennes et vivantes, en littérature, en mathématiques, en physique et géométrie, goûte à la chronologie, à l’histoire, au dessin, à la musique, à l’escrime et à la danse, se révélant en tout point un excellent élève ».

12. Exil de Lazare Carnot (1816)

Après la seconde abdication de Napoléon, Lazare Carnot fait partie du gouvernement provisoire. Exilé au moment de la Restauration, il est banni comme régicide en 1816 et se retire à Varsovie, puis à Magdebourg, où il consacrera le reste de ses jours à l’étude et surtout à l’éducation de ses enfants.