Étiquette : Antwerp

Erasmus’ dream: the Leuven Three Language College

In autumn 2017, a major exhibit organized at the University library of Leuven and later in Arlon, also in Belgium, attracted many people. Showing many historical documents, the primary intent of the event was to honor the activities of the famous Three Language College (Collegium Trilingue), founded in 1517 by the efforts of the Christian Humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (1467-1536) and his allies. Though modest in size and scope, Erasmus’ initiative stands out as one of the cradles of European civilization, as you will discover here.

Revolutionary political figures, such as William the Silent (1533-1584), organizer of the Revolt of the Netherlands against the Habsburg tyranny, humanist poets and writers such as Thomas More, François Rabelais, Miguel Cervantes and William Shakespeare, all of them, recognized their intellectual debt to the great Erasmus of Rotterdam, his exemplary fight, his humor and his great pedagogical project.

For the occasion, the Leuven publishing house Peeters has taken through its presses several nice catalogues and essays, published in Flemish, French as well as English, bringing together the contributions of many specialists under the wise (and passionate) guidance of Pr Jan Papy, a professor of Latin literature of the Renaissance at the Leuven University, with the assistance of a “three language team” of Latinists which took a fresh look at close to all the relevant and inclusively some new documents scattered over various archives.

“The Leuven Collegium Trilingue: an appealing story of courageous vision and an unseen international success. Thanks to the legacy of Hieronymus Busleyden, counselor at the Great Council in Mechelen, Erasmus launched the foundation of a new college where international experts would teach Latin, Greek and Hebrew for free, and where bursaries would live together with their professors”, reads the back cover of one of the books.

For the researchers, the issue was not necessarily to track down every detail of this institution but rather to answer the key question: “What was the ‘magical recipe’ which attracted rapidly to Leuven between three and six hundred students from all over Europe?”

Erasmus’ initiative was unprecedented. Having an institution, teaching publicly Latin and, on top, for free, Greek and Hebrew, two languages considered “heretic” by the Vatican, was already tantamount to starting a revolution.

Was it that entirely new? Not really. As early as the beginning of the XIVth century, for the Italian humanists in contact with Greek erudites in exile in Venice, the rigorous study of Greek, Hebraic and Latin sources as well as the Fathers and the New Testament, was the method chosen by the humanists to free mankind from the Aristotelian worldview suffocating Christianity and returning to the ideals, beauty and spirit of the “Primitive Church”.

For Erasmus, as for his inspirer, the Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla (1403-1457), the « Philosophy of Christ » (agapic love), has to come first and opens the road to end the internal divisions of Christianity and to uproot the evil practices of greed (indulgences, simony) and religious superstition (cult of relics) infecting the Church from the top to the bottom, and especially the mendicant orders.

To succeed, Erasmus sets out to clarify the meaning of the Holy Writings by comparing the originals written in Greek, Hebrew and Latin, often polluted following a thousand years of clumsy translations, incompetent copying and scholastic commentaries.

Brothers of the Common Life

My own research allows me to recall that Erasmus was a true disciple of the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life of Deventer in the Netherlands, a hotbed of humanism in Northern Europe. The towering figures that founded this lay teaching order are Geert Groote (1340-1384), Florent Radewijns (1350-1400) and Wessel Gansfort (1420-1489), all three said to be fluent in precisely these three languages.

The religious faith of this current, also known as the “Modern Devotion”, centered on interiority, as beautifully expressed in the little book of Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), the Imitation of Christ. This most read book after the Bible, underlines the importance for the believer to conform one owns life to that of Christ who gave his life for mankind.

Rudolph Agricola

Hence, in 1475, Erasmus father, fluent in Greek and influenced by famous Italian humanists, sends his son to the chapter of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, at that time under the direction of Alexander Hegius (1433-1499), himself a pupil of the famous Rudolph Agricola (1442-1485) which Erasmus had the chance to listen to and which he calls a “divine intellect”.

Follower of the cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464), enthusiastic advocate of the Italian Renaissance and the Good Letters, Agricola would tease his students by saying:

“Be cautious in respect to all that you learned so far. Reject everything! Start from the standpoint you will have to un-learn everything, except that what is based on your sovereign authority, or on the basis of decrees by superior authors, you have been capable of re-appropriating yourself”.

Erasmus, with the foundation of the Collegium Trilingue will carry this ambition at a level unreached before. To do so, Erasmus and his friend apply a new pedagogy. Hence, instead of learning by heart medieval commentaries, pupils are called to formulate their proper judgment and take inspiration of the great thinkers of the Classical period, especially “Saint Socrates”. Latin, a language that degenerated during the Roman Empire, will be purified from barbarisms.

With this approach, for pupils, reading a major text in its original language is only the start. An explorative work is required: one has to know the history and the motivations of the author, his epoch, the history of the laws of his country, its geography, cosmography, all considered to be indispensable instruments to put each text in its specific literary and historical context and allowing reading, beyond the words, the intention of their author.

This “modern” approach (questioning, critical study of sources, etc.) of the Collegium Trilingue, after having demonstrated its efficiency by clarifying the message of the Gospel, will rapidly travel over Europe and reach many other domains of knowledge, notably scientific issues! By uplifting young talents, out of the small and sleepy world of scholastic certitudes, this institution rapidly grew into a hotbed for creative minds.

For the ignorant reader who often considers Erasmus as some kind of comical writer praising madness which lost it after an endless theological dispute with Martin Luther, such a statement might come as a surprise.

Scientific Renaissance

While Belgium’s contributions to science, under Emperor Charles Vth, are broadly recognized and respected, few are those understanding the connection uniting Erasmus with a mathematician as Gemma Frisius and his pupil and friend Gerard Mercator, an anatomist such as Andreas Vesalius or a botanist such as Rembert Dodonaeus.

Hence, as already thoroughly documented in 2011 by Professor Jan Papy in a remarkable article, the scientific renaissance which bloomed in the Netherlands and Belgium in the early XVIth century, could not have taken place if it were for the “linguistic revolution” provoked by the Collegium Trilingue.

Because, beyond the mastery of their vernacular languages (French and Dutch), hundreds of youth, by studying Greek, Latin and Hebrew, suddenly got access to all the scientific treasures of Greek Philosophy and the best authors in those newly discovered languages.

At last, they could read Plato in the text, but also Anaxagoras, Heraclites, Thales of Millet, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Pythagoras, Eratosthenes, Archimedes, Galen, Vitruvius, Pliny the elder, Euclid and Ptolemy whose work they will master and eventually correct.

As the books published by Peeters account in great detail, during the first century of its existence, the Collegium Trilingue had a rough time confronting political uproar and religious strife. Heavy critique came especially form the “traditionalists”, a handful of theologians for which the Greeks were nothing but schismatics and the Jews the assassins of Christ and esoterics.

The opposition was such that Erasmus himself never could teach at the Collegium and, while keeping in close contact, decided to settle in Basel, Switzerland, in 1521.

Despite all of this, the Erasmian revolution conquered Europe overnight and a major part of the humanists of that period were trained or influenced by this institution. From abroad, hundreds of pupils arrived to follow classes given by professors of international reputation.

27 European universities integrated pupils of the Collegium in their teaching staff: among them stood Jena, Wittenberg, Cologne, Douai, Bologna, Avignon, Franeker, Ingolstadt, Marburg, etc.

Teachers at the Collegium were secured a decent income so that they weren’t obliged to give private lectures to secure a living and could offer public classes for free. As was the common practice of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, a system of bursa allowed talented though poor students, including many orphans, to have access to higher learning. “Something not necessarily unusual those days, says Pr Jan Papy, and done for the sake of the soul of the founder (of the Collegium, reference to Busleyden)”.

While visiting Leuven and contemplating the worn-out steps of the spiral staircase (wentelsteen), one of the last remains of the building that had a hard time resisting the assaults of time and ignorance, one can easily imagine those young minds jumping down the stairs with enthusiasm going from the dormitory to the classroom. Looking at the old shopping list of the school’s kitchen one can conclude the food was excellent with lots of meat, poultry but also vegetables and fruits, and sometimes wine from Beaune in Burgundy, especially when Erasmus came for a visit! While over the years, of course, the quality of the learning transmitted, would vary in accordance with the excellence of its teachers, the Collegium Trilingue, whose activity would last till the French revolution, gave its imprint in history by giving birth to what some have called the “Little Renaissance” of the first half of the XVIth century.

In France, the Sorbonne University reacted with fear and in 1523, the study of Greek was outlawed in France.

François Rabelais, at that time a monk in Vendée, saw his books confiscated by the prior of his monastery and deserts his order. Later, as a doctor, he translated the medical writings of the Greek scientist Galen from Greek into French. Rabelais’s letter to Erasmus shows the highest possible respect and intellectual debt to Erasmus.

In 1530, Marguerite de Navarre, sister of King Francis, and reader and admirer of Erasmus, at war with the Sorbonne, convinced her brother to allow Guillaume Budé, a friend of Erasmus, to create the “Collège des Lecteurs Royaux” (ancestor of the Collège de France) on the model of the Collegium Trilingue. And to protect its teachers, many coming directly from Leuven, they got the title of “advisors” of the King. The Collège taught Latin, Hebrew and Greek, and rapidly added Arab, Syriac, medicine, botany and philosophy to its curriculum.

Dirk Martens

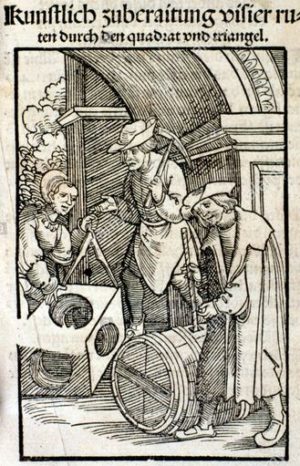

Also celebrated for the occasion, Dirk Martens (1446-1534), rightly considered as one of the first humanists to introduce printing in the Southern Netherlands.

Born in Aalst in a respected family, the young Dirk got his training at the local convent of the Hermits of Saint William. Eager to know the world and to study, Dirk went abroad. In Venice, at that time a cosmopolite center harboring many Greek erudite in exile, Dirk made his first steps into the art of printing at the workshop of Gerardus de Lisa, a Flemish musician who set up a small printing shop in Treviso, close to Venice.

Back in Aalst, together with his partner John of Westphalia, Martens printed in 1473 the first book in the country with a movable type printing press, a treatise of Dionysius the Carthusian (1401-1471), a friend and collaborator of cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa, as well as the spiritual advisor of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy and thought to be the occasional « theological » advisor of the latter’s court painter, Jan Van Eyck.

If the oldest printed book known to us is a Chinese Buddhist writing dating from 868, the first movable printing types, made first out of wood and then out of hardened porcelain and metal, came from China and Korea in 1234.

The history of two lovers, a poem written by Aeneas Piccolomini before he became the humanist Pope Pius II, was another early production of Marten’s print shop in Aalst.

Proud to have introduced this new technique allowing a vast increase in the spreading of good and virtuous ideas, Martens wrote in one of the prefaces: “This book was printed by me, Dirk Martens of Aalst, the one who offered the Flemish people all the know-how of Venice”.

After some years in Spain, Martens returned to Aalst and started producing breviaries, psalm books and other liturgical texts. While technically elaborate, the business never reached significant commercial success.

Martens then moved to Antwerp, at that time one of the main ports and cross-roads of trade and culture. Several other Flemish humanists born in Aalst played eminent roles in that city and animate its intellectual and cultural life. Among these:

—Cornelis De Schrijver (1482-1558), the secretary of the City of Aalst, better known under his latin name Scribonius and later as Cornelius Grapheus. Writer, translator, poet, musician and friend of Erasmus, he was accused of heresy and hardly escaped from being burned at the stake.

—Pieter Gillis (1486-1533), known as Petrus Aegidius. Pupil of Martens, he worked as a corrector in his company before becoming Antwerp’s chief town clerk. Friend of Erasmus and Thomas More, he appears with Erasmus in the double portrait painted by another friend of both, Quinten Metsys (1466-1530).

—Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), editor, painter and scenographer. After a trip to Italy, he set up a workshop in Antwerp. Pieter will produce patrons for tapestries, translated with the help of his wife the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius into Dutch and trained the young Flemish painter Bruegel the Elder who will marry his daughter.

Invention of pocket books

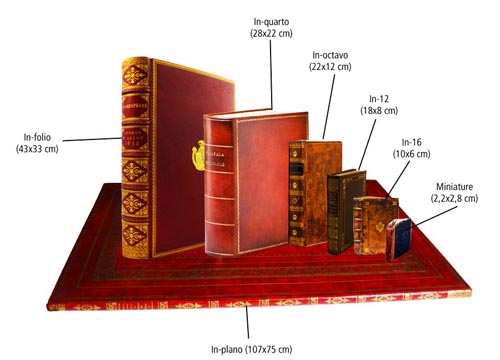

In Antwerp, Martens became part of this milieu and his workshop became a meeting place for painters, musicians, scientists, poets and writers. With the Collegium Trilingue, Martens opens a second shop, this time in Leuven to work with Erasmus. In order to provide adequate books to the Collegium, Martens proudly became, in the footsteps of the Venetian Printer Aldo Manuce, one of the first printers to concentrate on in-octavo 8° (22 x 12 cm), i.e. “pocket” size books affordable by all and which students could take home !

For the specialists of the Erasmus house of Anderlecht, close to Brussels,

“Martens innovated in nearly all domains. As well as in terms of printing types as lay-out. He was the first to introduce Italics, Greek and Hebrew letter types. He also generalized the use of ‘New Roman’ letter type so familiar today. During the first thirty years of the XVIth century, he also operated the revolution in lay-out (chapters and paragraphs) that gave birth to the modern book as we know it today. All this progress, he achieved in close cooperation with Erasmus”.

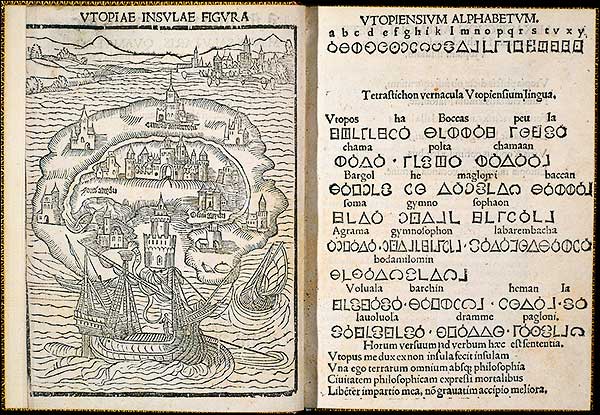

Thomas More’s Utopia

In 1516, it was Dirk Martens who printed the first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia. Among the hundreds of editions he printed mostly alone, 61 books and writings of Erasmus, notably In Praise of Folly. He also produced More’s edition of the roman satirist Lucian and Columbus’ account of the discovery of the new world. In 1423, Martens printed the complete works of Homer, quite a challenge!

In 1520, a papal bull of Leo X condemned the errors of Martin Luther and ordered the confiscation of his writings to be burned in public in front of the clergy and the people.

For Erasmus, burning books didn’t automatically erased their their content from the minds of the people. “One starts by burning books, one finishes by burning people” Erasmus warned years before Heinrich Heine said that “There, were one burns books, one ends up burning people”.

Printers and friends of Erasmus, especially in France, died on the stake opening the doors for the religious wars that will ravage Europe for the century to come.

What Erasmus feared above all, is that with the Vatican’s brutal war against Luther, it is the entire cultural renaissance and the learning of languages that got threatened with extinction.

In July 1521, confronted with the book burning, the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer, who made his living with bible illustrations, left Antwerp with his wife to return to his native Nuremberg.

Thirty years later, in 1552, the great cartographer Gerardus Mercator, a brilliant pupil of the Collegium Trilingue, for having called into question the views of Aristotle, went into exile and settled in Duisbourg, Germany.

In 1521, at the request of his friends who feared for his life, Erasmus left Leuven for Basel and settled in the workshop of another humanist, the Swiss printer Johann Froben.

In 1530, with a foreword of Erasmus, Froben published Georgius Agricola’s inventory of mining techniques, De Re Metallica, a key book that vastly contributed to the industrial revolution of Saxen, Switzerland, Germany and the whole of Europe.

Conclusion

If certain Catholic historians try to downplay the hostility of their Church towards Erasmus, the fact remains that between 1559 and 1900, the full works of Erasmus were on the “Index Vaticanus” and therefore “forbidden readings” for Catholics.

If Thomas More, whom Erasmus considered as his twin brother, was canonized by Pius XI in 1935 and recognized as the patron saint of the political leaders, Erasmus himself was never rehabilitated.

Interrogated by this author in a letter, the Pope Francis returned a polite but evasive answer.

Let’s rebuild the Collegium Trilingue !

With the exception of the staircase, only a few stones remain of the historical building housing the Collegium Trilingue. In 1909, the University of Louvain planned to buy up and rebuild the site but the First World War changed priorities. Before becoming social housing, part of the building was used as a factory. As a result, today, there is no overwhelming charm. However, seeing the historical value of the site, we cannot but fully support a full reconstruction plan of the building and its immediate environment.

It would make the historical center of Leuven so much nicer, so much more attractive and very much more loyal to its own history. On top, such a reconstruction wouldn’t cost much and might interest private investors. The images in 3 dimensions produced for the Leuven exhibit show a nice Flemish Renaissance building, much in the style of the marvels constructed by architect Rombout II Keldermans.

Every period has the right to honestly “re-write” its own history, without falsifications, according to its own vision of the future.

It has to be noted here that the world famous “Rubenshuis” in Antwerp, is not at all the original building, but a scrupulous reconstruction of the late 1930s.

Bruegel, Petrarca and the « Triumph of Death »

By Karel Vereycken, april 2020.

The Triumph of Death? The simple fact that the heir to the throne of England, Prince Charles, and even the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, have tested positive to the terrifying coronavirus currently sweeping the planet, tells something to the public.

As some commentators pointed out (no irony) it “gave a face to the virus”. Until then, when an elderly person or a dedicated nurse died of the same, it “wasn’t real”.

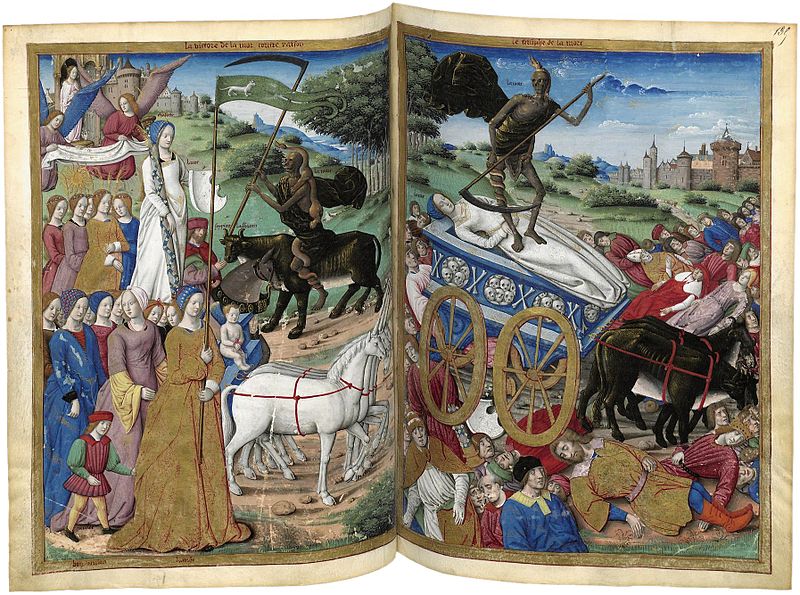

Realizing that these “higher-ups” are not part of the immortal Gods of Olympus but are mortals as all of us, brings to my mind “The Triumph of Death”, a large oil painting on panel (117 x 162 cm, Prado, Madrid), generally misunderstood, painted by the Flemish painter Peter Bruegel’s the elder (1525-1569), and thought to be executed between 1562 and his premature demise.

In order to discover, beyond the painting, the intention of the painter’s mind, it is always useful, before rushing into hazardous conclusions, to briefly describe what one sees.

What do we see in Bruegel’s « Triumph of Death« ? On the left, a skeleton, symbolizing death itself, holding a sand-glass in its hand, carries away a dead King. Next to him, another skeleton grabs the vast amounts of money no one can take with him into the grave. Death is driving a chariot. Below the charriot some people are crawling on their knees, hoping to remain unnoticed.

On the right, at the forefront, people are gambling and amusing themselves. A skeleton playing a musical instruments joins a prosperous young couple engaged in a musical dialogue and clearly unaware that Death is taking over the planet.

The message is simple and clear. No one can escape death, poor or rich, young or old, king or peasant, sick or healthy. When the hour comes, or at the end of all times, all mortals return to the creator since “physical” death triumphs over all of them.

Immortality

American thinker Lyndon LaRouche (1922-2019), in his speeches and writings, used to remind us, with his typical loving impatience: all human wisdom starts by a personal decision to acknowledge a fact proven without contest: we are all born and each of us, sooner or later, will die. So far, our bodies have all been proven mortal.

The duration of our mortal existence on the clock of the universe, he reminded, is less than a nanosecond.

Therefore, knowing this boundary condition of our mortal existence, we, each of us, have to make a personal sovereign decision: how will I spend the talent of my life ? Will I spend that talent chasing the earthly pleasures of the flesh, or dedicate my life to defending the truth, the beautiful and the good, to the great benefit of humanity as a whole, living in past, present and future ?

In 2011, in a discussion, LaRouche explained what he meant by saying that humanity has the potential to become an “immortal” species:

I live; as long as I live, I may generate ideas.

These conceptions give mankind a chance to move forward.

But then the time will come when I will die.

Now, two things happen: First of all, if these creative principles,

which have been developed by earlier generations,

are realized in the future, that means that mankind is an immortal species. We are not personally immortal;

but to the extent that we’re creative, we’re an immortal species.

And the ideas that we contribute to society

are permanent contributions to the human society.

We are therefore an immortal species,

based on mortal beings. And the key thing in life is to grasp that connection.

To say that we’re creative and die,

doesn’t tell us the story. If we, in our own lives, who are about to die,

can contribute something that is permanent, which will outlive our death, and be a benefit to mankind in future times, we have achieved the purpose of immortality.

And that is the crucial thing.

If people can actually face, with open minds, the fact that we’re each going to die—but look at it in the right way,

then we are impassioned to make the contributions,

to discover the principles, to do the work that is immortal.

Those discoveries of principle which are immortal, which pass on from one generation to the other. And thus, the dead live in the living;

because what the dead do, if they have done that in their lifetime, they are alive, not as in the flesh, but they’re alive in principle.

They’re part, an active part, of human society.

Christian humanism

LaRouche’s outlook, the “moral” obligation to live a “creative” existence on Earth in the image of the Creator, was deeply rooted in the philosophical outlook of both the Platonic and the Judeo-Christian tradition, whose happy marriage gave us the beautiful Christian humanism which, in the early XVth Century, ignited an unprecedented explosion, on a mass-scale and of unseen density of economic, scientific, artistic and cultural achievements, later qualified as a “Renaissance”.

In Plato’s Phaedon, Socrates develops the idea that our mortal body is a constant impediment to philosophers in their search for truth: “It fills us with wants, desires, fears, all sorts of illusions and much nonsense, so that, as it is said, in truth and in fact no thought of any kind ever comes to us from the body” (66c). To have pure knowledge, therefore, philosophers must escape from the influence of the body as much as is possible in this life. Philosophy (Literally “The love of wisdom”) itself is, in fact, a kind of “preparation for dying” (67e), a purification of the philosopher’s soul from its bodily attachment.

Also the Vulgate’s Latin rendering of Ecclesiastics 7:40 stresses: « in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin”. This passage finds expression in the christian ritual of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshippers’ heads with the words: “Remember Man that You are Dust and unto Dust You Shall Return.”

Is this a morbid ritual? No, it is a philosophy lesson. Christianity itself, as a religion, cherishes God’s own son made man, Jesus, for having renounced to his mortal life for the sake of mankind. It put Jesus’ death at the center. And in the XIVth century, Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), one of the leading intellectuals and founders of the Brothers of the Common Life, wrote that every Christian should shape his life in the “Imitation of Christ”. Both Nicolaus of Cusa (1401-1464) and Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) were powerfully influenced and trained by this intellectual current.

Concedo Nulli

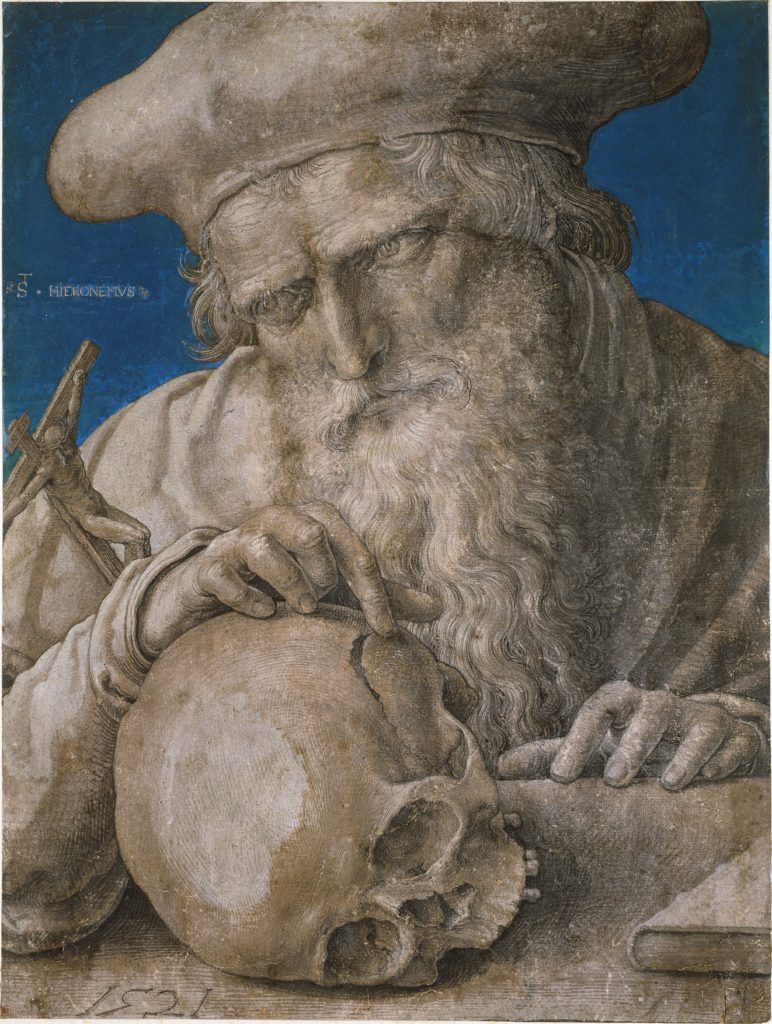

Erasmus’ personal armory was the juxtaposition of a skull and a sand-glass, referring to death and time as the boundary conditions of human existence.

In 1519, his friend, the Flemish painter and goldsmith Quentin Matsys (1466-1530) forged a bronze medal to the honor of the great humanist.

On one side of the medal there is an efigee of Erasmus and a Latin inscription informs us that this is “an image taken from life”. At the same time we are told in Greek, « his writings will make him better. known »

The reverse side of the medal shows solemn inscriptions surrounding an unusual image. At the top of a pillar that stands in rough, uneven ground, emerges the head of a young man with a stubbly chin and wild, flowing hair. Like Erasmus on the other side of the medal, he seems to have a faint smile upon his face. On either side of the head are the words “Concedo Nulli”– “I yield to no one.” On the pillar is inscribed Terminus, the name of a Roman god who presided over boundaries. Again bilingual quotations surround a profile. On the left, in Greek, is the instruction, « Keep in mind the end of a long life. » On the right, in Latin, is the stark reminder, « Death is the ultimate boundary of things. »

Adapting as his own motto “I yield to no one”, Erasmus took the great risk of using such a daring metaphor. Accused of intolerable arrogance by his sycophants, he underlined that “Concedo Nulli” had to be understood as death’s own statement, not his own. And who could argue with the assertion that death is the terminus that yields to no one?

Mozart, Brahms and Gandhi

Centuries later, the great humanist composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was the exact opposite of a morbid cynic. Revealing his inner mindset, Mozart once said that the secret of all genius, was love for humanity: “neither a lofty degree of intelligence nor imagination nor both together go to the making of genius. Love, love, love, that is the soul of genius”.

But on April 4, 1787, Mozart wrote to his father, Leopold, as he lay dying :

I need hardly tell you how greatly I am longing

to receive some reassuring news from yourself.

And I still expect it ; although I have now made a habit of being prepared in all affairs of life for the worst.

As death, when we come to consider it closely,

is the true goal of our existence,

I have formed during the last few years such close relations with this best and truest friend of mankind,

that his image is not only no longer terrifying to me,

but is indeed very soothing and consoling !

And I thank God for graciously granting me

the opportunity (you know what I mean)

of learning that death is the key

which unlocks the door to our true happiness.

I never lie down at night

without reflecting that –young as I am– I may not live to see another day.

Johannes Brahms 1865 German Requiem, quotes Peter 1:24-25 reminding us that

“For all flesh is as grass,

and all the glory of man as the flower of grass.

The grass withereth, and the flower thereof falleth away.

But the word of the Lord endureth for ever.”

Also Mahatma Gandhi, expressed, in his own way, somthing similar, about how one has to live simultaneously with mortality and immortality:

« Live as if you were to die tomorrow.

Learn as if you were to live forever. »

Memento Mori and Vanitas

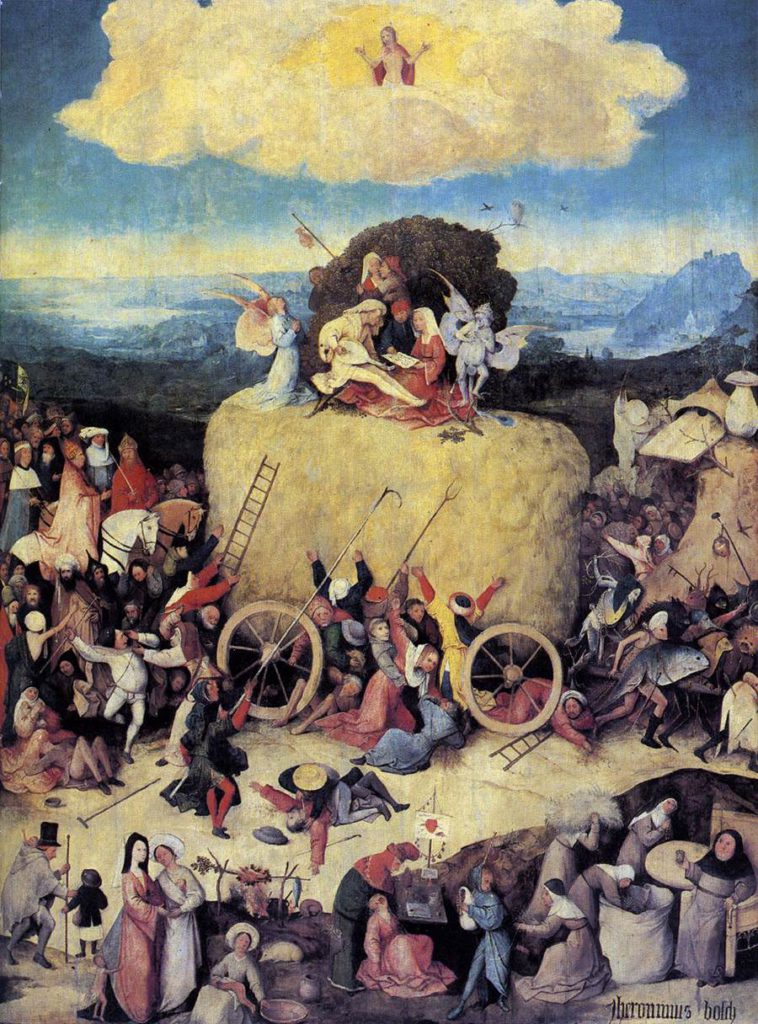

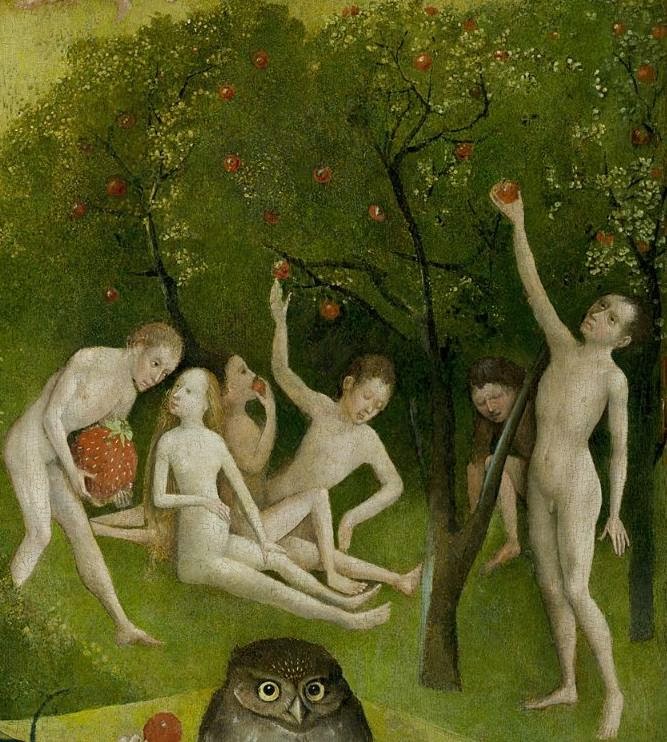

Just as Hieronymus Bosch’s (1450-1516) painting of the “Garden of Earthly Delights” (Prado, Madrid), where the great Dutch master uses the metaphor of naked humans incessantly chasing delicious fruits, calls on the viewer to become aware of his close-to-ridiculous, animal-like attachment to earthly pleasures and calls on his free will and his sens of humor to free himself, Bruegel’s “Triumph of Death” painting, on a first level, is fundamentally nothing else than a complex Memento Mori (Latin “remember that you must die”).

With this painting, Bruegel pays tribute to his intellectual godfather’s motto Concedo Nulli, that is, as Erasmus did in his writings, Bruegel paints the ineluctability of death, not by praising its horror, but with the aim of inspiring his fellow citizens to walk into immortality. In the same way Erasmus’ « In praise of folly » was in fact an inversion of his praise of reason, Brueghel’s « Triumph of Death » was conceived as a triumph of (immortal) life.

For the Catholic faith, the aim of a Memento Mori was to remind (and eventually terrorize) the believer that after death, he or she might end up in Purgatory or worse in Hell if they did not respect the Church and her rites. With the invention of oil painting in the early XVth century, panel paintings of this genre for private homes and small chapels were considered aesthetic objects crafted for the sake of religious and philosophical contemplation.

Hence, starting with the Renaissance, the Memento Mori painting became a much demanded artifact, re-branded in the following centuries as “Vanitas”, Latin for « emptiness » or « vanity ». Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, Vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies and hourglasses.

Iconography

A first source is of course, the famous designs and woodcuts executed by Erasmus intimate friend and illustrator of his “In Praise of Folly”, Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), for his satirical “Dance of Death” (1523), which –breaking with the way the “Dance macabre” was used before by the Flagellants and other madmen to desensitize the population in order to push them into a fatalistic retreat of the outer world– introduces the new philosophical dimension that Bruegel will develop.

The close-to-embarassing anamorphosic representation of a giant skull in Holbein’s work « The Ambassadors » (1533), demonstrates his profound understanding of the Memento Mori metaphor.

Erasmus’ friend Albrecht Dürer‘s engraving « Knight, Death and the Devil » (1513), or his « Saint Jerome in his study » (1514) (with skull and hourglass) are two other examples.

Bruegel and Italy

Ironically, Peter Bruegel the elder has always been presented as a painter of the Northern School who was completely closed to the “Italian” Renaissance.

The reality is that while rejected the transformation of the Renaissance into a form of mannerism in the XVIth century, he took most of his inspiration directly from two Italian Renaissance sources.

First, of course, the image of Death riding a horse, and even a group of persons such as the young couple engaged in their musical embrace, appear incontestably as taken from the Triumph of Deat”, a vast fresco from 1446 which decorated the walls of the Palazzo Sclafani in Palermo, Sicily. Bruegel’s trip to Southern Italy is a well documented fact.

The second source, which undoubtedly also inspired the painter of the fresco, is a series of allegorical poems known as “I Trionfi” (“The Triumphs”: Triomph of Love, of Chastity, of Death, of Fame, of Time and of Eternity), composed by the great Italian poet Francesco Petrarca, most likely following the “Black Death”, a pandemic outbreak which, starting with the 1345 banking crash, decimated a vast portion of the population of Europe.

Petrarca’s genius was precisely to offer to those terrified with the very idea of having to face their physical mortality, a philosophical answer to their anxiety.

As a result, his Trionfi became rapidly popular, not only in Italy but all over Europe. And for most painters, working on Petrarca’s themes became part of their common repertoire.

To conclude, here is an excerpt (English) of the poem, where Petrarca blasts the mad lust of Kings and Popes for wealth, pleasure and earthly power. In the face of death, he stresses, they are worthless. Petrarca’s wording fits to the detail the images used by Bruegel in his painting The Triumph of Death :

(…) afar we might perceive

Millions of dead heap’d on th’ adjacent plain;

No verse nor prose may comprehend the slain

Did on Death’s triumph wait, from India,

From Spain, and from Morocco, from Cathay,

And all the skirts of th’ earth they gather’d were;

Who had most happy lived, attended there:

Popes, Emperors, nor Kings, no ensigns wore

Of their past height, but naked show’d and poor.

Where be their riches, where their precious gems,

Their mitres, sceptres, robes, and diadems?

O miserable men, whose hopes arise

From worldly joys, yet be there few so wise

As in those trifling follies not to trust;

And if they be deceived, in end ’tis just:

Ah! more than blind, what gain you by your toil?

You must return once to your mother’s soil,

And after-times your names shall hardly know,

Nor any profit from your labour grow;

All those strange countries by your warlike stroke

Submitted to a tributary yoke;

The fuel erst of your ambitious fire,

What help they now? The vast and bad desire

Of wealth and power at a bloody rate

Is wicked,–better bread and water eat

With peace; a wooden dish doth seldom hold

A poison’d draught; glass is more safe than gold;

Whether Bruegel, who saw undoubtedly the fresco in Palermo during his trip in the 1550s, had read Petrarca’s poem remains an open question. It can be said that many of his direct friends were familiar with the Italian poet.

In Antwerp, the painter was a frequent guest of the Scola Caritatis, a humanist circle animated by one Hendrick Nicolaes, where Brueghel met poets, translaters, painters, engravers (Cock, Golzius) mapmakers (Mercator), cosmographers (Ortelius) and bookmakers such as the Antwerp printer Christophe Plantijn, who’se renowned printing shop would print Petrarca’s poetry.

Also in Antwerp, indicating how popular Petrarca’s poetry had become in the Low Countries and France, the franco-flemish Orlandus Lassus (1532-1594) published his first musical compositions, including his madrigals on each of the six Trionfi of Petrarca, among which the « Triumph of Death ».

Conclusion

All evil, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) hoped, can give birth to something good, far bigger and superior to the evil that provoked it. Therefore, we can hope that the current pandemic breakdown crisis will lead some of the leading decision-makers, with our help, to reflect on the sens and purpose of their lives. The worst would be to return to yesterday’s “normalcy” since that kind of “normal” is exactly what drove the planet currently to the verge of extinction.

At last, it should be stressed that in the same way Lyndon LaRouche, by his ruthless (Concedi Nulli) commitment to defend the sacred creative nature of every human individual, contributed to the enduring immortality of Plato, Petrarca, Erasmus and Bruegel, it is up to each of us to carry even further that battle.