Étiquette : Ghirlandaio

Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio and the art of military command

Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio and the art of military command. An inquiry into the key events and artistic achievements that created the Renaissance. By Karel Vereycken, Paris.

Prologue

If there is still a lot to say, write and learn about the great geniuses of the European Renaissance, it is also time to take an interest in those whom the historian Georgio Vasari condescendingly called « transitional figures ».

How can one measure the contributions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder without knowing Pieter Coecke van Aelst? How can we value Rembrandt’s work without knowing Pieter Lastman? How did Raphaelo Sanzio innovate in relation to his master Perugino?

In 2019, an exceptional exhibition on Andrea Del Verrocchio (1435-1488), at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., highlighted his great achievements, truly inspiring outbursts of great beauty that his pupil Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) would theorize and put to his greatest advantage.

The sfumato of Leonardo ? Verrochio is the pioneer, especially in the blurred features of portraits of women made with mixed techniques (pencil, chalk and gouache).

The joy of discovery

Leafing through the catalog of this exhibition, my joy got immense when I discovered (and to my knowledgne nobody else seems to have made this observation before me) that the enigmatic angel the viewer’s eye meets in Leonardo’s painting titled The Virgin on the Rocks (1483-1486) (Louvre, Paris), besides the movement of the body, is grosso modo a visual “quote” of the image of a terra cotta high relief (Louvre, Paris) attributed to Verrochio and “one of his assistants”, possibly even Leonardo himself, since the latter was training with the master as early as age seventeen ! The finesse of its execution and drapery also reminds us of the only known statue of Da Vinci, The Virgin with the laughing Child.

Many others made their beginnings in Verrocchio’s workshop, notably Lorenzo de Credi, Sandro Botticelli, Piero Perugino (Raphael’s teacher) and Domenico Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s teacher).

Coming out of the tradition of the great building sites launched in Florence by the great patron of the Renaissance, Cosimo de Medici for the realization of the doors of the Baptistery and the completion of the dome of Florence by Philippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), Verrocchio conceived his studio as a true “polytechnic” school.

In Florence, for the artists, the orders flowed in. In order to be able to respond to all requests, Verrocchio, initially trained as a goldsmith, trained his students as craftsman-engineer-artists: drawing, calculation, interior decoration, sculpture, geology, anatomy, metal and woodworking, perspective, architecture, poetry, music and painting. A level of freedom and a demand for creativity that has unfortunately long since disappeared.

The Ghiberti legacy

In painting, Verrocchio is said to have begun with the painter Fra Filippo Lippi (1406-1469). As for the bronze casting trade, he would have been, like Donatello, Masolino, Michelozzo, Uccello and Pollaiuolo, one of the apprentices recruited by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455) whose workshop, starting from 1401, over forty years, will be in charge of casting the bronze bas-reliefs of two of the huge doors of the Baptistery of Florence.

Others suggest that Verrocchio was most likely trained by Michelozzo, the former companion of Ghiberti who said up shop with Donatello. As a teenager, Donatello had accompanied Brunelleschi on their joint expeditions to Rome to investigate the legacy of Greek and Roman art, and not only the architectural legacy.

In reality, Verrocchio only perpetuated and developed the model of Ghiberti’s « polytechnic » studio, where he learned the art. An excellent craftsman, Ghiberti was also goldsmith, art collector, musician and humanist scolar and historian.

His genius is to have understood the importance of multidisciplinarity for artists. According to him « sculpture and painting are sciences of several disciplines nourished by different teachings ».

The ten disciplines that he considered important to train artists are grammar, philosophy, history, followed by perspective, geometry, drawing, astronomy, arithmetic, medicine and anatomy.

You can discover, says Ghiberti, only when you managed to isolate the object of your research from interfering factors, and you can discover by detaching oneself from a dogmatic system;

as the nature of things want it, the sciences hidden under artifices are not constituted so that the men with narrow chests can judge them.

Anticipating the type of biomimicry that will characterize Leonardo thereafter, Ghiberti affirms that he sought:

to discover how nature functioned and how he could approach it to know how the objects come to the eye, how the sight functions and in which way one has to practice sculpture and painting.

Ghiberti, who was familiar with some of the leading members of the circle of humanists led by Salutati and Traversari, based his own reflexions on optics on the authority of ancient texts, especially Arabic. He wrote:

But in order not to repeat in a superficial and superfluous way the principles that found all opinions, I will treat the composition of the eye particularly according to the opinions of three authors, namely Avicenna [Ibn Sina], in his books, Alhazen [Ibn al Haytam], in the first book of his perspective, and Constantine [Qusta ibn Luqa] in the first book on the eye; for these authors are sufficient and treat with more certainty the things that interest us.

Deliberately ignored (but copied) by Vasari, Ghiberti’s Commentaries are a real manuel for artists, written by an artist. Most interestingly, it is by reading Ghiberti’s Commentaries that Leonardo da Vinci became familiar with important Arab contributions to science, in particular the outstanding work of Ibn al Haytam (Alhazen) whose treatise on optics had just been translated from Latin into Italian under the title De li Aspecti, and is quoted at length by Ghiberti in his Commentario Terzio. Author A. Mark Smith suggests that, through Ghiberti, Alhazen’s Book of Optics

may well have played a central role in the development of artificial perspective in early Renaissance Italian painting.

Ghiberti’s comments are not extensive. However, for the pupils of his pupil Verrocchio, such as Leonardo, who didn’t command any foreign language, Ghiberti’s book did make available in italian a series of original quotes from the roman architect Vitruvius, arab scientists such as Alhazen), Avicenna, Averroes and those european scientists having studied arab optics, notably the Oxford fransciscans Roger Bacon, John Pecham and the Polish monk working in Padua, Witelo.

Finally, in 1412, Ghiberti, while busy coordinating all the works on the Gates of the Baptistry, was also the first Renaissance sculptor to cast a life-size statue in bronze, his Saint John the Baptist, to decorate Orsanmichele, the house of the Corporations in Florence.

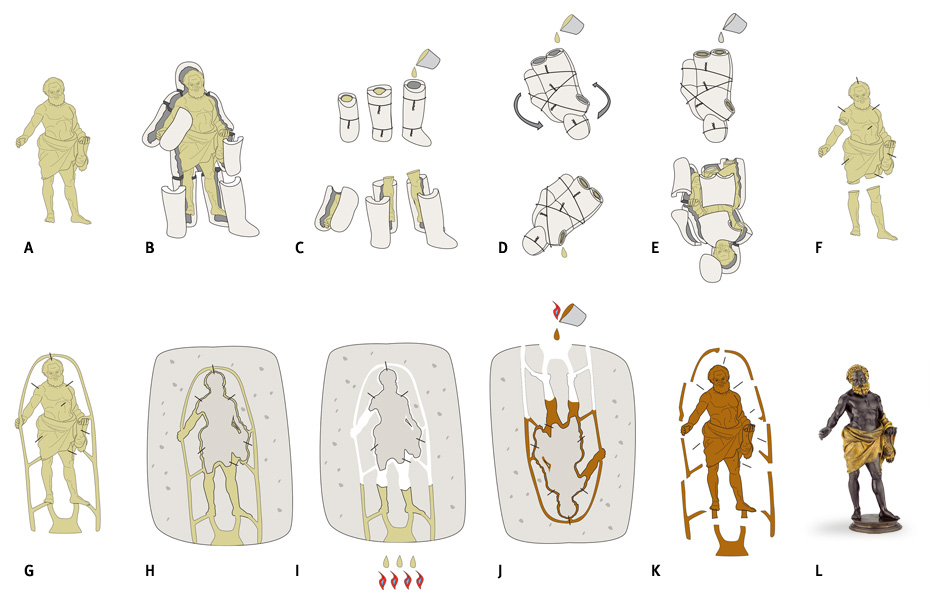

Lost wax casting

However, in order to cast bronzes of such a size, the artists, considering the price of metal, would use the technique known as “lost wax casting”.

This technique consists of first making a model in refractory clay (A), covered with a thickness of wax corresponding to the thickness of the bronze thought necessary.

The model is then covered with a thick layer of wet plaster (B) which, as it solidifies, forms an outer mold. Finally, the very hot molten bronze, pored into the mold it penetrates by rods (J) provided for this purpose, will replace the wax.

Finally, once the metal has solidified, the coating is broken. The details of the bronze (K) are then adjusted and polished (L) according to the artist’s choice.

This technique would become crucial for the manufacture of bells and cannons. While it was commonly used in Ifé in Africa in the 12th century for statuary, in Europe it was only during the Renaissance, with the orders received by Ghiberti and Donatello, that it was entirely reinvented.

In 1466, after the death of Donatello, it was Verrocchio’s turn to become the Medici’s sculptor in title for whom he produced a whole series of works, notably, after Donatello, his own David in bronze (Bargello National Museum, Florence).

If with this promotion his social ascendancy is certain, Verrocchio found himself facing the greatest challenge that any artist of the Renaissance could have imagined: how to equal or even surpass Donatello, an artist whose genius has never been praised enough?

Equestrian art

This being said, let us now approach the subject of the art of military command by comparing four equestrian monuments:

- Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius on the Capitoline square in Rome (175 AD) ;

- Paolo Uccello’s fresco of John Hawkwood in the church of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (1436);

- Erasmo da Narni, known as “Gattamelata” (1446-1450), casted by Donatello in Padua.

- Bartolomeo Colleoni by Andrea del Verrocchio in Venice (1480-1488).

Equestrian statues appeared in Greece in the middle of the 6th century B.C. to honor the victorious riders in a race. From the Hellenistic period onward, they were reserved for the highest state figures, sovereigns, victorious generals and magistrates. In Rome, on the forum, they constituted a supreme honor, subject to the approval of the Senate. Apart from being bronze equestrian statues, each one is placed in a place where their troops fought.

While each statue is a reminder of the importance of military and political command, the way in which this responsibility is exercised is quite different.

Marcus Aurelius in Rome

Marcus Aurelius was born in Rome in 121 A.D., into a noble family of Spanish origin. He was the nephew of the emperor Hadrian. After the death of Marcus Aurelius’ father, Hadrian entrusted him to his successor Antonin. The latter adopts and gives him an excellent education. He was initiated early in philosophy by his master Diognetus.

Interested in the stoics, he adopted for a while their lifestyle, sleeping on the ground, wearing a rough tunic, before he was dissuaded by his mother.

He went to Athens in 175 A.D. and became a promotor of philosophy. He helps financially the philosophers and the rhetoricians by granting them a fixed salary. Concerned with pluralism, he supported the Platonic Academy, the Lyceum of Aristotle, the Garden of Epicurus and the Stoic Portico.

On the other hand, during his reign, persecutions against Christians were numerous. He saw them as troublemakers – since they refused to recognize the Roman gods, and as fanatics.

Erected in 175 A.D., the statue was entirely gilded. Its location in antiquity is unknown, but in the Middle Ages it stood in front of the Basilica of St. John Lateran, founded by Constantine, and the Lateran Palace, then the papal residence.

In 1538, Pope Paul III had the monument of Marcus Aurelius transferred to the Capitol, the seat of the city’s government. Michelangelo restored the statue and redesigned the square around it, one of the fanciest in Rome. It is undoubtedly the most famous equestrian statue, and above all the only one dating back to ancient Rome that has survived, the others having been melted down into coins or weapons…

If the statue survived, it is thanks to a misunderstanding: it was thought that it represented Constantine, the first Roman emperor to have converted to Christianity at the beginning of the 4th century, and it was out of the question to destroy the image of a Christian ruler.

Neither the date nor the circumstances of the commission are known.

But the presence of a defeated enemy under the right foreleg of the horse (attested by medieval testimonies and since lost), the emperor’s gesture and the shape of the saddle cloth, unusual in the Roman world, make us to belief that the statue commemorated Marcus Aurelius’ victories, perhaps on the occasion of his triumph in Rome in 176, or even after his death. Indeed, his reign (161-180) was marked by incessant wars to counter the incursions of Germanic or Eastern peoples on the borders of an Empire that was now threatened and on the defensive.

The horse, while not that large, but looking powerful, has been sculpted with great care and represented with realism. Its nostrils are strongly dilated, its lips pulled by the bit reveal its teeth and tongue.

One leg raised, he has just been stopped by his rider, who holds the reins with his left hand. Like him, the horse turns his head slightly to the right, a sign that the statue was made to be seen from that side. Part of his harness is preserved, but the reins have disappeared.

The size of the athletic rider nevertheless dominates that of a powerful horse that he rides without stirrups (accessories unknown to the Romans). He is dressed in a short tunic belted at the waist and a ceremonial cloak stapled on the right shoulder. It is a civil and not a military garment, adapted to a peaceful context. He is wearing leather shoes held together by intertwined straps.

The statue is striking for its size (424 cm high) and for the majesty it exudes. Without armor or weapons, eyes wide open and without emotion, the emperor raises his right arm. His authority derives above all from the function he embodies: he is the Emperor who protects his Empire and his people by punishing their enemies without mercy.

The fresco by Paolo Uccello

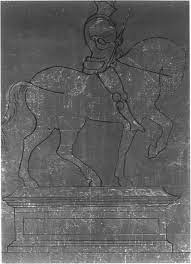

In 1436, at the request of Cosimo de’ Medici, the young Paolo Uccello was commissioned to paint a fresco depicting John Hawkwood (1323-1394), the son of an English tanner who had become a warlord during the Hundred Years’ War in France and whose name would be Italicized into Giovanno Acuto.

Serving the highest bidder, especially rival Italian cities, Hawkwood’s company of mercenaries was no slouch.

In Florence, although it may seem paradoxical, it was the humanist chancellor Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406) who put Hawkwood at the head of a regular army in the service of the Signoria.

This approach is not unlike that of Louis XI in France, who, in order to control the skinners and other cutthroats who were ravaging the nation, did not hesitate to discipline them by incorporating them into a standing army, the new royal army.

The humanists of the Renaissance, notably Leonardo Bruni (1370-1440) in his De Militia (1420), became aware of the curse of using mercenaries in conflicts and of the fact that only standing army, i.e. a permanent army formed of professionals and even better by citizens and maintained by a state or a city could guarantee a lasting peace.

Although Hawkwood faithfully protected the city for 18 years, his ugly “professionalism” as a mercenary was not unanimously accepted, to the point of inspiring the proverb “Inglese italianato è un diavolo Incarnato” (« An Italianized Englishman is a devil incarnate »).

Petrarch denounced him, Boccaccio tried in vain to mount a diplomatic offensive against him, St. Catherine of Sienna begged him to leave Italy, Chaucer met him and, no doubt, used him as a model for The Knight’s Tale (The Canterbury Tales).

All this will not prevent Cosimo, a member of the humanist conspiracy and a great patron of the arts, returning from exile, from wanting to honor him. But in the absence of the bronze equestrian statue (which had been promised to him…), Florence, will only offer him a fresco in the nave of Santa Maria del Fiore, that is to say under right under the cupola of the Duomo.

From the very beginning, Paolo Uccello’s fresco seems to have stirred quite a controversy. A preparatory drawing in the collections of Florence’s Uffizi Museum indicates the commander, more armed, taller, and, with his horse in a more military position. Uccello had originally depicted Hawkwood as « more threatening », with his baton raised and horse « at the ready ».

A recent ultraviolet study confirms the fact that the painter had originally depicted the condottiere armed from head to toe. In the final version, he wears a sleeveless jacket, the giornea, and a coat; only his legs and feet are protected by a piece of armor. The final version presents a less imposing rider, less warlike, more human and more individualized

In the dispute, it was not Uccello who was considered faulty, but his sponsors. Moreover, the painter was quickly given the task of redoing the fresco in a way deemed “more appropriate”.

Unfortunately, there is no record of the debates that must have raged among the officials of the church fabric (Opera Del Domo). What is certain is the fact that in the final version, visible today, the condottiere has been transformed from a warlord running a gang of mercenaries, into the image of philosopher-king whose only weapon is his commanding staff. At the bottom of the fresco, we can read in Latin: “Giovanno Acuto, British knight, who was in his time held as a very prudent general and very expert in military affairs.”

The position of the horse and the perspective of the sarcophagus have been changed from a simple profile to a di sotto in su view.

If this perspective is somewhat surrealistic and the pose of the horse, raising both legs on the same side, simply impossible, it remains a fact that Uccello’s fresco will set “the standards” of the ideal and impassive image of virtue and command that must embody the hero of the Renaissance: his goal is no longer to “win” a war (the objective of the mercenary), but to preserve the peace by preventing it (the objective of a philosopher-king or simply a wise head of state).

Paradigm shift

As such, one might say that Uccello’s fresco announces the “paradigm shift” marking the end of the age of perpetual feudal wars, to that of the Renaissance, that is to say to that of a necessary concord between sovereign nation-states whose security is indivisible, the security of one being the guarantee of the security of the other, a paradigm even more rigorously defined in 1648 at the Peace of Westphalia, when it made the agapic notion of the “advantage of the other” the basis of its success.

One historian suggests that the recommissioning of Uccello’s fresco was part of the « refurbishing » of the cathedral associated with its rededication as Santa Maria del Fiore by the humanist Pope Eugene IV in March 1436, determined to convince the Eastern and Western Churches to peacefully overcome their divisions and réunite as was attempted at the Council of Florence of 1437-1438 and for which the Duomo was central.

Interesting is the fact that Uccello’s fresco appeared at around the same time that Yolande d’Aragon and Jacques Coeur, who had his Italian connections, persuaded the French king Charles VII to put an end to the Hundred Years’ War by setting up a permanent, standing army.

In 1445, an ordinance was passed to discipline and rationalize the army in the form of cavalry units grouped into Compagnies d’Ordonnances, the first permanent army at the disposal, not of warlords or aristocrats, but of the King of France.

Donatello’s “Gattamelata” (1447-1453)

It was only some years later, in Padua, between 1447 and 1453, that Donatello would work on the statue of Erasmo da Narni (1370-1443), a Renaissance condottiere, i.e. the leader of a professional army in the service of the Republic of Venice, which at the time ruled the city of Padua. An important detail is that Erasmo was nicknamed “il Gattamelata”.

In French, « faire la chattemite » means to affect a false air of sweetness to deceive or seduce… Others explain that his nickname of “honeyed cat” comes from the fact that his mother was called Melania Gattelli or that he wore a crest (a helmet) in the shape of a honey-colored cat in battle…

The man was of humble origin, the son of a baker, born in Umbria around 1370. He learned to handle weapons from Ceccolo Broglio, lord of Assisi, and then, when he was in his thirties, from the captains of Braccio da Montone, who was known for recruiting the best fighters.

In 1427, Erasmo, who had the confidence of Cosimo de’ Medici, signed a seven-year contract with the humanist Pope Martin V, who wished to strengthen an army corps loyal to his cause with the aim of bringing to heel the lords of Emilia, Romagna and Umbria who were rebellious against papal authority.

He bought a huge suit of armor to reinforce his high stature. He was not an impetuous fighter, but a master of siege warfare, which forced him to take slow, thoughtful and progressive action. He spied on his prey for a long time before trapping it.

In 1432, he captured the fortress of Villafranca near Imola by cunning alone and without fighting. The following year he did the same to capture the fortified town of Castelfranco, thus sparing his soldiers and his treasure.

Those who were unable to grasp his tactics, accused him of being a coward for “running away” from the front-line, not realizing, that on a given moment, this was part of the tactics of his winning strategy.

He was a prudent captain, with a very well-mannered troop, and he was careful to maintain good relations with the magistrates of the towns that employed him. He obtained the rank of captain-general of the army of the Republic of Venice during the fourth war against the Duke of Milan in 1438 and died in Padua in 1443. Following his death, the Venetian Republic gave him full honors and Giacoma della Leonessa, his widow, commissioned a sculpture in honor of her late husband for 1650 ducats.

The statue, which represents the life-size condottiere, in antique-style armor and bareheaded, holding his commanding staff in his raised right hand, on his horse, was made by the lost-wax method. As early as 1447, Donatello made the models for the casting of the horse and the condottiere. The work progresses at full speed and the work is completed in 1453 and placed on its pedestal in the cemetery that adjoins the Basilica of Padua.

Brilliant for his cunning and guile, Gattamelata was a thoughtful and effective fighter in action, the type of leader recommended by Machiavelli in The Prince, and which appears in the sixteenth century by François Rabelais in his account of the “Picrocholine wars”.

Not the brute power of weapons, but the cunning and the intelligence will be the major qualities that Donatello will make appear powerfully in his work.

Contrary to Marcus Aurelius, it is not his social status that gives the commander his authority, but his intelligence and his creativity in the government of the city and the art of war. Donatello had an eye for detail. Looking at the horse, we see that it is a massive animal but far from static. It has a slow and determined gait, without any hesitation.

But that’s not all. A rigorous analysis shows that the proportions of the horse are of a “higher order” than those of the condottiere. Did Donatello make a mistake and make Erasmo too small and the horse too large? No, the sculptor made this choice to emphasize the value of Gattamelata who, thanks to his skills, is able to tame even wild and gigantic animals. In addition, the horse’s eyes show him as wild and untameable. Looking at him, one could say that it is impossible to ride him, but Gattamelata manages it with ease and without effort.

Because if you look at the reins in the hands of the protagonist, you will notice that he holds them in complete tranquility. This is another detail that highlights Erasmus’ powerful cunning and ingenuity.

Next, did you notice that one of the horse’s legs rests on a sphere? If this sphere (which could also be a cannonball, since Erasmus was a warrior) serves to give stability to Donatello’s composition as a whole, it also indicates how this animal of gigantic strength (symbolizing here warlike violence), once tamed and well used, allows the globe (the earthly kingdom) to be kept in balance.

Having told you about the horse, it is time to know more about the condottiere.

He has a proud and determined expression. The baton of command, which he holds in his hand, delicately touches the horse’s mane. The baton is not just a symbolic object; he may have received it in 1438 from the Republic of Venice.

Unlike Uccello’s fresco, Gattamelata is not dressed as a contemporary prince of commander, but as a figure beyond time embodying both the past, the present and the future. To capture this, Donatello, who takes care of every detail, has taken an ancient model and modernized it with incredible results. The details of the protagonist’s armor include purely classical motifs such as the head of Medusa, taken from Marcus Aurelius, in Greek mythology one of the three gorgons whose eyes had the power to petrify any mortal who crossed her gaze.

Although the helmet of Gattamelata would have allowed to identify him at eyesight, Donatello has discarded this option. With a helmet on his head, he would have been the symbol of a bloodthirsty warrior, rather than a cunning man. Even better, the absence of a helmet allows the artist to show us a fearless commander whose fixed gaze shows his determination. With the figure slightly bowed and legs extended, the sword in its scabbard placed at an angle, Donatello gives the illusion of an “imbalance” that reinforces in the viewer’s mind the idea that the horse is advancing with full strength.

Art historian John Pope-Hennessy is emphatic:

The fundamental differences between the Gattamelata and Marcus Aurelius are obvious. The (roman) emperor sits passively on his horse, legs dangling. In the fifteenth century, on the other hand, the art of riding implies the use of spurs. The impression of authority that emanates from the monument designed by Donatello comes from the total domination of the condottiere over his horse. (…) The soles of the feet are exactly parallel to the surface of the pedestal, as are the large six-pointed spurs, stretched to the middle of the animal’s flank.

As a result, Gattamelata is not a remake of the “classical Greek or Roman sculpture” of a hero with a sculpted physique, but a kind of new man who succeeds through reason. The fact that the statue has such a high pedestal also has its reason. Placed at such a height, the Gattamelata does not “share” our own space. It is in another dimension, eternal and out of time.

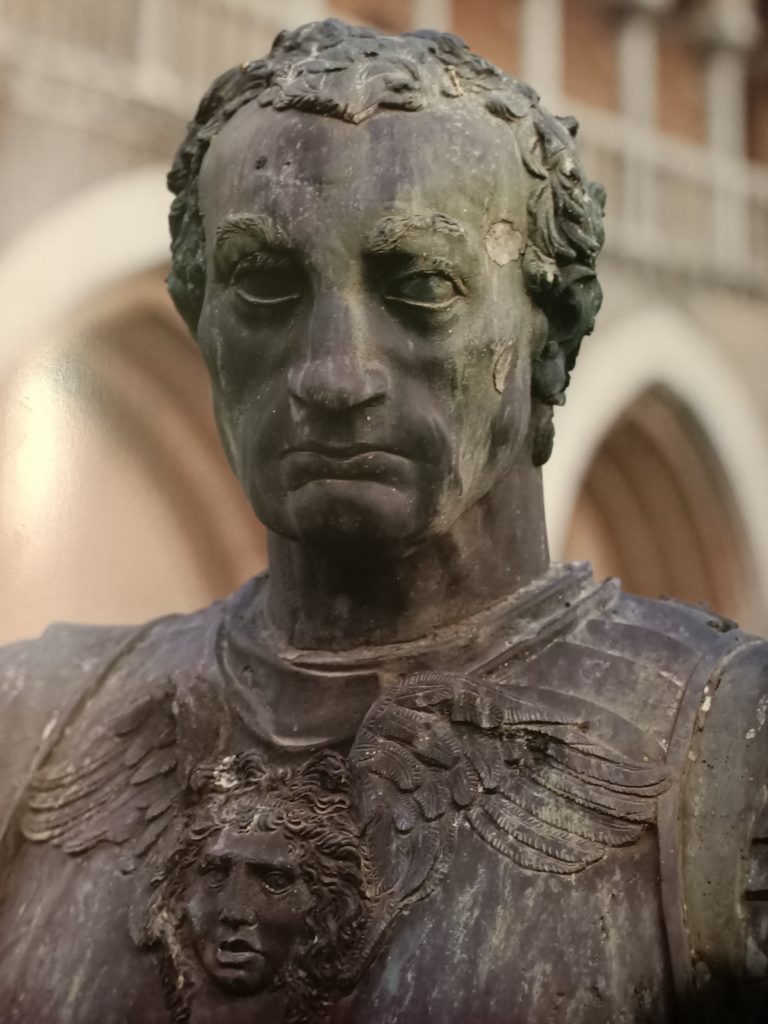

Verrocchio’s Colleoni

Some thirty years later, between 1480 and 1488, Andrea del Verrocchio, after a contest, was selected to make a large bronze equestrian statue of another Italian condottiere named Bartolomeo Colleoni (1400-1475).

A ruthless mercenary, working for a patron one day and his rival the next day, he served from 1454 the Republic of Venice with the title of general-in-chief (capitano generale). He died in 1475 leaving a will in which he bequeathed part of his fortune to Venice in exchange for the commitment to erect a bronze statue to his honor in St. Mark’s Square.

The Venetian Senate agreed to erect an equestrian monument to his memory, while charging the costs to the widow of the deceased…

In addition, the Senate refused to erect it in St. Mark’s Square, which was, along with St. Mark’s Basilica, at the heart of the city’s life. The Senate therefore decided to interpret the conditions set by Colleoni in his last will and testament without contradicting them, choosing to erect his statue in 1479, not in St. Mark’s Square, but in an area further from the city center in front of the Scuola San Marco, on the campo dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Although Verrocchio had started working on the project since 1482, it remained unfinished at his death in 1488. And it is, not as Verrocchio wished, his heir Lorenzo di Credi who will cast the statue, but the Venetian Alessandro Leopardi (who lost the contest to Verrocchio), who will not hesitate to sign it!

If the horse is in conformity with the typology of the magnificent horses composing the quadriga overseeing the Basilica of Saint Mark of Venice (Greek statuary of the IVth century BC brought back by the crusaders from Constantinople to Venice in 1204) and of the horse of Marcus Aurelius, its musculature is more nervously underlined and traced. Objectively, this statue is ideally more proportionate. There is also more fine detail, a result of new pre-sculpture techniques, making the work captivating and realistic to look at.

The sculpture overflows its pedestal. According to André Suarès quoted in The Majesty of Centaurs:

Colleone on horseback walks in the air, he will not fall. He cannot fall. He leads his earth with him. His base follows him […] He has all the strength and all the calm. Marcus Aurelius, in Rome, is too peaceful. He does not speak and does not command. Colleone is the order of the force, on horseback. The force is right, the man is accomplished. He goes a magnificent amble. His strong beast, with the fine head, is a battle horse; he does not run, but neither slow nor hasty, this nervous step ignores the fatigue. The condottiere is one with the glorious animal: he is the hero in arms.

His baton of command is even metamorphosed into a bludgeon! But since it is not Verrocchio who finished this work, let us not blame the latter for the warlike fury that emanates from this statue.

Venice, a vicious slave-trading financial and maritime Empire fronting as a “Republic”, clearly took its revenge here on the beautiful conception developed during the Renaissance of a philosopher-king defending the nation-state.

On the aesthetic level, this mercenary smells like an animal. As a good observer, Leonardo warned us: when an artist represents a man entirely imprisoned by a single emotion (joy, rage, sadness, etc.), he ends up painting something that takes us away from the truly human soul. This is what we see in this equestrian statue.

If, on the contrary, the artist shows several emotions running through the figure represented, the human aspect will be emphasized. This is the case, as we have seen, with Donatello’s Gattamelata, uniting cunning, determination and prudence to overcome fear the face of threat.

Leonardo’s own, gigantic project to erect a gigantic bronze horse, on which he worked for years and developed new bronze casting techniques, unfortunately was never build, seen the hectic circumstances.

Finally, beyond all the interpretations, let us admire the admirable know-how of these artists. In terms of craft and skill, it generally took an entire life to become able to realize such great works, not even mentioning the patience and boundless passion required.

Up to us to bring it back to life !

Bibliography:

- Verrocchio, Sculptor and Painter of Renaissance Florence, Andrew Butterfield, National Gallery, Princeton University Press, 2020;

- Donatello, John Pope-Hennessy, Abbeville Press, 1993;

- Uccello, Franco and Stefano Borsi, Hazan, 2004;

- Les Commentaires de Lorenzo Ghiberti dans la culture florentine du Quattrocento, Pascal Dubourg-Glatigny, Histoire de l’Art, N° 23, 1993, Varia, pp. 15-26;

- Monumento Equestre al Gattamelata di Donatello: la Statua del Guerriero Astuto, blog de Dario Mastromattei, mars 2020;

- La sculpture florentine de la Renaissance, Charles Avery, Livre de poche, 1996 ;

- La sculpture de la Renaissance au XXe siècle, Taschen, 1999;

- Ateliers de la Renaissance, Zodiaque-Desclée de Brouwer, 1998;

- Rabelais et l’art de la guerre, Christine Bierre, 2007.

- The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance, Karel Vereycken, jan. 2021.

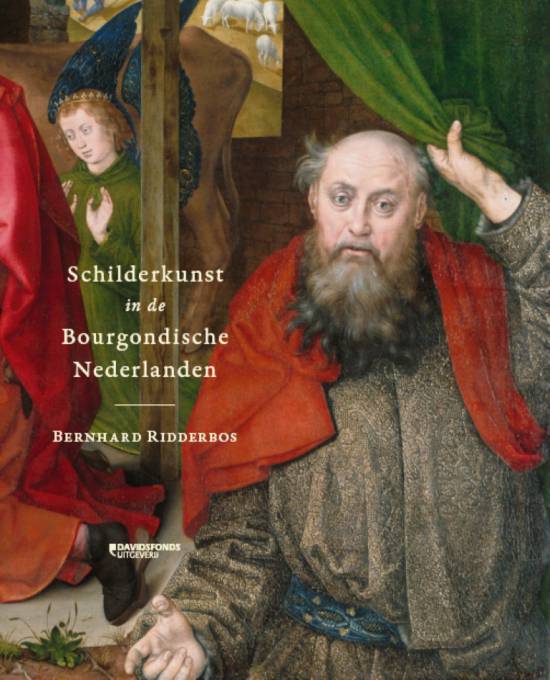

Hugo van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne

Le beau livre de l’historien néerlandais Bernhard Ridderbos, Schilderkunst in de Bourgondische Nederlanden (La peinture aux Pays-Bas bourguignon, Davidsfonds, Leuven 2015) est un régal pour les yeux et l’esprit.

Ridderbos, déjà irrité par l’habile campagne de propagande menée depuis des siècles par des banquiers italiens pour qui « la » Renaissance n’était qu’italienne et pour qui les fiammingo n’étaient que des « Primitifs », démarre son ouvrage en incendiant (non sans raison) une œuvre qui reste une référence, L’automne du Moyen Age (1919), de Johan Huizinga (1872-1945).

Pour cet historien néerlandais influant, recteur de l’Université de Leyden :

L’art de Van Eyck, dans sa capacité de figurer les choses saintes, a su atteindre un haut degré de détail et de naturalisme, marquant sans doute un point de départ sur le plan strict de l’histoire de l’art, mais signifiant en réalité une fin sur le plan historico-culturel. La tension extrême de l’imagination terrestre du divin fut atteint ici ; cependant, le contenu mystique de son imagination s’apprêtait à quitter ces images et à ne laisser les réjouissances qu’à la forme

Niant l’esprit clairement pré-renaissant des peintres flamands du début du XVe siècle, pour Huizinga, leur naturalisme n’était rien d’autre que « le déploiement ultime de l’esprit moyenâgeux tardif. »

Or, comme j’ai cherché à démontrer, en avril 2006, lors de mon exposé au Colloque international à la Sorbonne sur le thème de « La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique », Robert Campin, Jan van Eyck et d’autres peintres flamands, qu’on présente assez souvent comme récalcitrant à utiliser les modèles perspectivistes développés par l’italien Leon Battista Alberti et comme en témoigne la présence assez imposante de miroirs convexes dans leurs œuvres (Volets Werl, Epoux Arnolfini), se sont inspirés des travaux mathématiques et géométriques complexes du grand scientifique arabe Ibn Al-Haytam.

Mieux connu en Occident sous son nom latin Alhazen, ses travaux d’optique, notamment sur la lumière et les miroirs convexes, se retrouvent dans les carnets de Léonard de Vinci, lecteur assidu des Commentaires de Ghiberti. *

Libéré de cette chape de plomb de l’autocensure, Ridderbos approfondit l’iconographie, les contextes économiques, sociaux et culturels. Sans égarer le lecteur dans un marécage de détails et d’hypothèses stériles, il nous offre des éclairages très intéressants sur le comment et le pourquoi des créations artistiques de cette époque.

Ceux parmi vous qui n’ont jamais pris le temps de lire ni l’œuvre monumentale d’Erwin Panofsky, ni les imposantes monographies publiées en Belgique par le Fonds Mercator d’Anvers relatant in extenso la vie des grands peintres flamands tels que Robert Campin, Rogier Van der Weyden, Jan Van Eyck, Hans Memling, Thierry Bouts, Hugo Van der Goes et Gérard David, remercieront Ridderbos pour non seulement en avoir extrait la quintessence, mais pour les avoir mis en relation les unes avec les autres.

Les commanditaires

En premier lieu, il montre à quel point les artistes étaient soumis à des « carnets de charges » très stricts. Un tel monastère, une telle guilde, un tel seigneur passait commande. Ils fixaient la taille de l’œuvre, le sujet et les personnes à représenter. Plusieurs théologiens, spécialistes du thème à traiter, furent parfois nommés pour conseiller et accompagner le peintre dans sa représentation de sujets religieux. L’artiste exécuta d’abord, sur son panneau, un dessin. Et ce n’est qu’une fois validé par le commanditaire, souvent après de nombreuses modifications, qu’il appliqua les couleurs. Gérard David, par exemple, a du changer l’ensemble des portraits des échevins sur son œuvre, suite à l’élection d’une nouvelle équipe…

Rivalités

Ensuite, Ridderbos indique comment les rivalités des uns et des autres, princes, églises, mais aussi Cités-Etats, souvent en quête de prestige (le fameux « soft power » de nos jours), ont profité à la vie artistique flamande. Princes, ducs, rois et banquiers étrangers se disputaient les peintres flamands pour fanfaronner et se mettre en avant.

Pour monter en grade, un banquier des Médicis (Angelo Tani) commande un triptyque à Hans Memling, un Jugement dernier (1466-1473), largement inspiré de l’œuvre éponyme de Van Der Weyden pour l’Hospice de Beaune.

Lorsque son confrère (Tommaso Portinari, le fondé de pouvoir des Médicis à Bruges) l’apprend, il passe commande d’un autre triptyque, une Nativité (1475), bien plus grand et plus splendide encore chez Hugo Van der Goes. Ce « triptyque Portinari » sera dévoilé à Florence en 1483 et inspirera toute une série d’œuvres italiens, notamment celles du peintre italien Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Rogier Van der Weyden, après avoir travaillé pour la ville de Louvain, se voit offrir un bien meilleur salaire par la ville de Bruxelles, les deux villes cherchant à devenir la capitale de la région.

Lorsqu’il y peint pour l’Hôtel de Ville un grand retable sur la Justice (La Justice de Trajan et Herkenbald, ca. 1450), la ville de Louvain, pour ne pas être en reste, commandera plusieurs années après une œuvre semblable (La justice d’Otton III, 1473) à Thierry Bouts, provoquant à son tour une autre ville, celle de Bruges d’en commander un du même type (Le jugement de Cambyses, 1498) chez Gérard David, un disciple et proche de l’atelier de Van der Goes.

Ridderbos bien sûr ne se limite pas à tracer cette dynamique sociologique. Il analyse comment ces peintres vont dialoguer entre eux en reprenant à leur compte les apports techniques et iconographiques de leurs confrères. Tout en mobilisant le meilleur d’eux-mêmes, ils apportèrent des choses entièrement nouvelles. C’est un processus assez similaire à l’apport compositionnel d’un Ludwig van Beethoven montant lui-même « sur les épaules des géants » que furent avant lui Bach, Haydn et Mozart.

Van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne

Dans le chapitre VII, page 179, l’auteur fait un effort particulier pour mettre en valeur l’œuvre d’Hugo Van Der Goes, un peintre remarquable qu’on a rangé un peu vite dans l’ombre de Van Eyck, Van der Weyden et Memling.

Probablement né vers 1440 à Gand, Van der Goes est reçu maître de la guilde des peintres de cette ville en 1467 et en devient le doyen en 1474. Trois ans plus tard, il est à l’apogée de la reconnaissance professionnelle et de la réussite sociale.

C’est alors qu’il abandonne la vie bourgeoise pour s’associer au grand mouvement de réforme appelé la Dévotion moderne. Pour ce faire, Van Der Goes devient frère lai auprès des Soeurs et Frères de la Vie commune, plus précisément ceux de l’abbaye du Rouge-Cloître (Rooklooster) dans la Forêt de Soignes près de Bruxelles. Il y jouit de certains privilèges, comme d’être autorisé à continuer à peindre.

Deventer

La Dévotion moderne sera avant tout un mouvement éducateur. Elle fonda notamment à Deventer une école renommée ouverte aux pauvres et aux orphelins. Rudolf Agricola et son successeur Alexandre Hegius y enseignent le grec et le latin à toute une génération d’humanistes dont le plus connu s’appelle Erasme de Rotterdam.

Le fameux cardinal-philosophe, mathématicien et juriste allemand, Nicolas de Cues (1401-1464) tenait en haute estime les efforts des enseignants de Deventer. En 1469, cinq ans après sa mort, sans doute en accord avec ses derniers vœux, une partie de son héritage ira abonder (de 1470 à 1682) un fond dédié, la Bursa Cusana, permettant à une vingtaine d’élèves, dont la moitié originaire de la ville natale de Cues, d’y parfaire leur instruction.

Le piétisme de la Devotion moderne, centré sur l’intériorité, s’articule le mieux dans le petit livre de Thomas van Kempen (a Kempis) (1380-1471), L’imitation de Jésus Christ. Celui-ci souligne l’exemple à suivre de la passion du Christ tel que nous l’enseigne l’Évangile, message repris par Erasme.

Van Der Goes, animé à titre personnel par l’esprit de cette démarche, apparaît ainsi, sans l’avoir connu, avec le peintre anversois Quinten Matsys, comme « le plus erasmien » des peintres flamands. Et à ce titre, il sera capable de faire transparaître dans ses œuvres une tension dramatique plus aiguë, traduite par l’animation et l’expressivité des personnages.

Les bergers

On pense immédiatement aux magnifiques bergers du Triptyque Portinari. Cette œuvre est commanditée par un des banquiers les plus riches de l’époque et pourtant, ce ne sont pas les trois Rois mages qui se trouvent au premier plan, mais d’humbles bergers arrivés bien avant eux et les premiers à reconnaître l’enfant pour ce qu’il est.

Se démarquant nettement de la façon dont le peintre italien Andrea Mantegna les avait dépeint vingt ans plus tôt, c’est-à-dire comme des pauvres hères en haillons, hirsutes, sales et édentés, Van der Goes souligne leur dignité et met en avant leurs transformations.

D’ailleurs, les expressions des bergers incarneraient les trois étapes spirituelles définies par un autre inspirateur de la Devotion moderne, le mystique flamand Jan Van Ruysbroeck (1293-1381) : la vie active, la vie intérieure et la vie contemplative où l’Homme entre en communion spirituelle avec Dieu. **

Le chapeau de Nicodème

Autre exemple, son tableau La lamentation du Christ (après 1479) actuellement au Musée de Vienne. De prime abord rien de bien révolutionnaire dans cette représentation. On y voit la mère du Christ retenue par Jean lorsqu’elle s’effondre sur la dépouille mortelle de son fils.

C’est sur l’avant plan que deux figures méritent notre attention. S’appuyant sur les Geestelijke Opklimmingen (Des ascensions spirituelles) écrit par Gerard Zerbold de Zutphen (1367-1398), un auteur de la Dévotion moderne proche de Groote, Ridderbos identifie leur rôle dans cette œuvre.

A droite, d’abord, on voit Nicodème coiffé d’une capuche rouge. Selon l’Evangile selon Saint-Jean, Nicodème a été un des premiers pharisiens devenus secrètement disciples de Jésus. Ici, on le voit en pleine crise, pour ne pas dire agonie existentielle, portant un regard effrayé sur son riche chapeau posé par terre.

Or, lorsque l’on examine de plus près ce couvre-chef, on découvre qu’il est surmonté d’une couronne d’épines !

La métaphore est donc à l’image de la Dévotion moderne qui exigeait de chacun, non seulement de suivre fidèlement les rites, mais de « vivre à l’imitation du Christ », c’est-à-dire de s’élever à un tel niveau d’amour pour le Christ et l’humanité qu’on puisse offrir librement ses possessions, son patrimoine et même sa vie au vrai, au juste et au beau.

Enfin, pour compléter le tableau, à gauche, toujours au premier plan, la figure de Marie Madeleine, une autre disciple de Jésus qui le suit jusqu’à ses derniers jours.

Prostituée repentie, Marie Madeleine complète à merveille la métaphore en s’érigeant ici comme l’exemple même du travail d’introspection et d’auto-perfectionnement personnel qu’exigeaient les Sœurs et Frères de la Vie Commune.

Le message est fort : vous ne pouvez pas vous contenter d’adorer ou d’admirer le Christ ! Vous devez changer vos vies ! Un message qui n’a pas perdu de son actualité…

Notes:

* Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) écrivit quelques 200 ouvrages sur les mathématiques, l’astronomie, la physique, la médecine et la philosophie. Né à Bassora, et après avoir travaillé sur l’aménagement des cours du Nil en Égypte, il se serait rendu en Espagne. Il aurait mené une série d’expériences très précises sur l’optique théorique et expérimentale, y compris sur la camera obscura (chambre noire), travaux qu’on retrouve ultérieurement dans les études de Léonard de Vinci. Ce dernier a pu lire les longs passages d’Alhazen qui figurent dans les Commentari du sculpteur florentin Ghiberti. Après que l’évêque de Reims Gerbert d’Aurillac (le futur pape Sylvestre II en 999) ramena d’Espagne le système décimal avec son zéro et un astrolabe, c’est grâce à Gérard de Crémone (1114-vers 1187) que l’Europe va accéder à la science grecque, juive et arabe. Ce savant se rendra 1175 à Tolède pour y apprendre l’arabe et effectuera la traduction de quelques 80 ouvrages scientifiques de l’arabe en latin, notamment l’Almageste de Ptolémée, les Coniques d’Apollonius, plusieurs traités d’Aristote, le Canon d’Avicenne, les œuvres d’Ibn Al-Haytam, d’Al-Kindi, de Thabit ibn Qurra et d’Al-Razi. Dans le monde arabe, ces recherches furent reprises un siècle plus tard par le physicien persan Al-Farisi (1267-1319). Ce dernier a rédigé un important commentaire du Traité d’optique d’Alhazen. En prenant pour modèle une goutte d’eau et en s’appuyant sur la théorie d’Alhazen sur la double réfraction dans une sphère, il a donné la première explication correcte de l’arc-en-ciel. Il a même suggéré la propriété ondulatoire de la lumière, alors qu’Alhazen avait étudié la lumière à l’aide de balles solides dans ses expériences de réflexion et de réfraction. Désormais la question se posait ainsi : la lumière se propage-t-elle par ondulation ou par transport de particules ?

** Voir à ce propos : Nadeije Laneyrie-dagen, L’invention du corps : La représentation de l’homme du Moyen Âge à la fin du XIXe siècle, Paris 1997, 52. ; Delphine Rabier, Les trois degrés de la vision selon Ruysbroeck l’Admirable et les Bergers du triptyque Portinari de Hugo van der Goes, in Studies in Spirituality, 27, p. 163-179, 2017.

A la découverte d’un tableau

Jean-Luc, un jeune instituteur récemment titularisé, voulait faire découvrir la peinture à un petit groupe d’élèves. Il en choisit donc six parmi eux, qui étaient en âge de s’ouvrir à ce genre d’aventure, et les accompagna au musée du Louvre.

Lorsque l’instituteur parvint devant le tableau qu’il avait choisi d’expliquer aux enfants, les guides accrédités jetèrent un oeil noir sur ce groupe improvisé et y virent une concurrence déloyale.

L’un d’entre eux, une dame assez âgée munie de lunettes à montures étonnantes, les bouscula légèrement et déclama d’une voix nasillarde pour la douzième fois de la journée :

Domenico Ghirlandaio, né en 1449 et mort de la peste en 1494, à l’âge de 45 ans, fut l’un des peintres les plus importants de son époque. C’était le fils d’un orfèvre, Tommaso Corradi, surnommé Ghirlandaio parce qu’il fabriquait des parures en forme de guirlande très prisées des jeunes Florentines. A l’instar de Léonard de Vinci, Domenico fut formé par le peintre et sculpteur Andrea del Verrocchio ; il mit tout son talent au service des ordres religieux et des familles les plus riches du moment, les Medicis, les Malatestas. Le pape Sixte IV fit appel à lui pour la décoration de la chapelle Sixtine de Rome. Parmi les élèves de Ghirlandaio, l’un d’eux deviendra Michel-Ange, le plus grand sculpteur de tous les temps. De Ghirlandaio, voici le Portrait d’un vieillard et d’un jeune garçon réalisé vers 1485, peint sur bois avec une technique de tempera, astucieux mélange de jaune d’oeuf et d’huile.

Son allocution terminée, la guide se remit en route, suivie comme une mère poule par une quarantaine de touristes, dont certains avaient pris des photographies dans l’espoir de mieux comprendre… plus tard.

Jean-Luc, qui avait auparavant rêvé d’une carrière dans la bande dessinée, n’en revenait pas : vouloir tout voir sans rien comprendre lui semblait la meilleure façon de vous dégoûter pour toujours de l’art. Il avait, lui, une tout autre méthode : choisir une seule oeuvre, mais prendre le temps de l’approfondir.

Nous allons jouer aux devinettes, dit Jean-Luc à ses élèves. Moi, je prétends que le véritable nom de ce tableau n’est pas Portrait d’un vieillard et d’un jeune garçon. Ce n’est que le nom donné par le collectionneur qui a vendu le tableau. Alors, essayons de découvrir son véritable nom…

— Pourquoi a-t-il un nez grand et affreux qui semble tout gonflé par des piqûres de guêpes ? demanda Myriam en rougissant, sûre d’avoir dit ce qui lui passait par la tête, c’est-à-dire n’importe quoi.

— C’est vrai, tu as raison, il n’est pas très beau, mais bizarrement, le tableau, lui, est beau. Alors pourquoi ? interrogea Jean-Luc.

— L’enfant aussi est beau ; et en vieillissant, on attrapera tous des crevasses sur le pif ! remarqua malicieusement Pierre, l’éternel premier de la classe.

— Que voit-on d’autre sur ce tableau ? demanda le maître.

— Il y a une grosse montagne dans le fond, répondit Momo.

— Et un chemin qui y mène, ajouta Sarah.

— N’oublions pas le petit arbre tout près, qui lui aussi est jeune ! observa Pierre.

— Et tu n’as pas remarqué la petite église entourée de vieux arbres, sur la colline, note Myriam.

— Très bien, dit Jean-Luc, on avance dans la bonne direction. D’abord, on peut être laid à l’extérieur et posséder la beauté intérieure. Apprenez à ne pas juger vos camarades sur leur apparence. Notre enveloppe terrestre n’est pas si importante, parce qu’elle est de toute façon éphémère. Nous naissons tous et, dans le meilleur des cas, nous mourrons très vieux. Mais nul n’échappera à la mort.

— Mais ce n’est quand même pas le portrait de la mort, ce serait affreux ! s’exclama Florette.

— Le peintre a peut-être voulu dire que la vie est comme un chemin qui mène à la montagne. Ayant pris de la hauteur, on peut voir au-delà, revoir d’où le voyage a commencé. A cet instant, on peut réfléchir à ce qu’on a donné aux autres et à ceux qui survivront, proposa Jean-Luc…

— Mais c’est « l’amour » alors ! s’exclama Louise, pensant avoir trouvé le titre du tableau.

— Oui, concéda Jean-Luc, ces deux-là ont l’air de s’aimer, mais comment sont leurs visages ?

— Ils sont tristes, dit Sarah, comme s’ils allaient se séparer pour toujours. Peut-être que le vieux sait qu’il a une grave maladie et qu’il est au bout du voyage. C’est peut-être pour ça que son nez est si bizarre. En plus, il a le front tout fissuré !

— Les rayures qui apparaissent sur son front proviennent de la détérioration du tableau, expliqua Jean-Luc. La peinture à l’oeuf est un peu comme les illustrations des vieux manuscrits qui s’abîment quand ils sont exposés à la lumière et à l’air ambiant. Pour protéger les peintures, on eut plus tard l’idée de les vernir, puis d’utiliser le vernis lui-même comme moyen d’apposer les couleurs sur la surface à peindre.

Les Flamands furent parmi les premiers à pratiquer cette technique. Dès l’âge de huit ans, les apprentis-peintres apprenaient à broyer les couleurs et à encoller les panneaux de bois avec une colle à base de peau de lapin. Ces derniers étaient ensuite enduits d’une préparation composée de plâtre fin mêlé à une substance adhésive et de peinture blanche. Ils effectuaient ces tâches durant une douzaine d’années et leur maître leur confiait parfois la réalisation d’un dessin ou le détail d’un tableau.

Ainsi, le peintre Verrocchio demanda un jour à Léonard de Vinci, qui était alors son élève, de réaliser le détail d’un ange dans l’un de ses tableaux. Le résultat fut tellement beau que Verrocchio abandonna avec joie sa carrière de peintre pour celle de sculpteur, parce qu’il avait vu que son élève pouvait certainement le surpasser.

— Donc, si nous trouvons le titre du tableau, vous n’allez plus nous emmener dans les musées ? demanda Boris avec malice.

— Je crois qu’il est temps de rentrer, les enfants. Si nous voulons être à l’heure à la cantine, il faut partir maintenant, dit Jean-Luc en regardant sa montre.

— Mais le vrai nom du tableau ? demandèrent les enfants en choeur.

— Nous reviendrons, conclut Jean-Luc.

(fable écrite en 1994 par Karel Vereycken)