Rembrandt’s Anslo, the science of painting the « invisible »

Cet article en FR

this article in RU see bottom of this page

Lecture of Karel Vereycken, painter-engraver and historian, at the Nov. 8-9 International Paris joint conference organized by Solidarité & Progrès and the Schiller Institute.

I want this presentation to be more like a kind of « workshop ». Therefore I ask people who “know” not to immediately jump in with their answers to my questions but allow people not yet familiar with this domain to have the opportunity to express themselves and bring up their hypothesis.

In commercial contemporary art, the only science involved is to give up any form of rationality and to flap out any emotion which takes over the artist, often more “down-lifting” than “up-lifting”. But in well composed works of art, based on metaphorical paradoxes, there is a “science of composition”, elevating ideas and emotions, by a combination of invention and the skills of representation.

Very few artists allowed us to enter the back stage of their creative mind. One of them was the great American poet Edgar Allan Poe who, in 1846, in his “Philosophy of Composition” explained the genesis of his famous poem The Raven composed one year earlier.

Humanity is very lucky to have Rembrandt’s “Cornelis Anslo and his wife”, a the large oil painting on canvas done by Rembrandt in 1641, currently in the Gemäldegalerie of Berlin.

By examining the preparatory drawings and how they were changed during the creation process, we can in part read the footsteps of the creative process and lift a bit the curtain on Rembrandt’s creative genius.

Anslo and the Mennonites

On the painting, we see the Mennonite preacher Cornelis Anslo sitting at a table with some large books on his right and seemingly uttering words of consolation to a woman, most probably his wife.1

The composition is highly asymmetrical, quite unusual at that time. The low viewpoint from which the table with the books is seen, determines to a great extent the effect the painting makes. It is as if Anslo delivers a sermon from a pulpit.

The painting is quite large: 1m73 high and 207 cm large. The man with the black hat is Cornelis Claesz Anslo (1592-1646), a rich shipowner and cloth merchant. He was born in Amsterdam as the fourth son of the Norwegian-born Dutch cloth merchant Claes Claesz. « Anslo » (meaning “from Oslo”). Some pretend he has a fur coat because the painting was executed in winter, but the fur here is nothing but a sign of wealth, success and status. Anslo’s brothers were big names of the drapers guild that ran Amsterdam’s cloth industry. They made big money by selling the sort of carpets here on the table.

But Cornelis was also a deeply religious person for which religion means action rather than words alone. After getting married he created an almshouse for destitute old women. Well educated, he became then a preacher at the Grote Spijker, the church of the Waterlanders, the Mennonites of Amsterdam.

The Mennonites were a Dutch religious grouping originally founded by Simon Menno (1496-1561), a priest who left the Catholic faith and added his own branch to the protestant reformation. Some of the Amish people in the US are descendants of the Dutch and Flemish Mennonites.

It would be too long here to go into their history. In short they saw themselves as a gathering of Christians willing to live in the image of God. They didn’t want an official church. They just got together, read the Bible and tried to transform its message in concrete deeds. For example, the Mennonites took the scripture seriously when it said that Jesus told us to“Love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us”. As a result, the Mennonites decided they never would participate in war or go to war. So they were not exactly appreciated by the other religious faiths of that time, most of them engaged in battles. While many of his acquaintances were, Rembrandt never was a formal member of the Mennonites but he clearly identified with some aspects of their peace-loving worldview.2

Getting to work

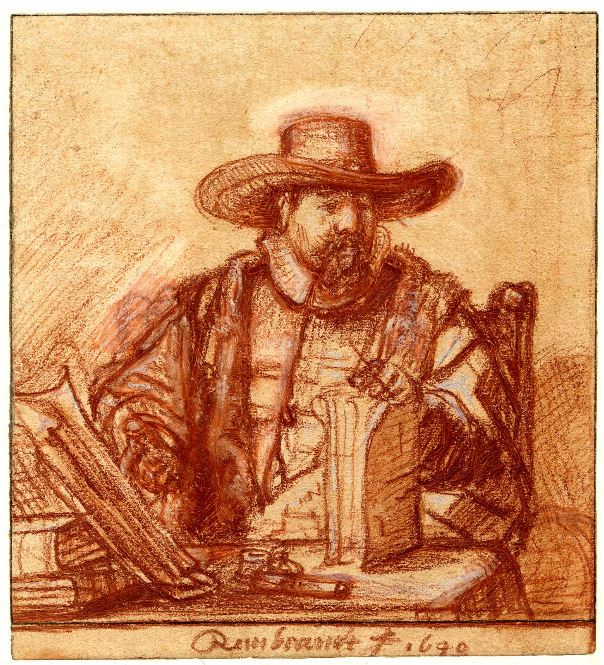

So in 1640-41, Anslo turned to Rembrandt to have his portrait done. The preacher probably asked the painter to do a sketch to get an idea of how the final portrait would look like. In the first drawing with red chalk in the British Museum, one sees the preacher.

QUESTION: What is special about this drawing ?

AUDIENCE: ….

KAREL: he holds his pen in his left hand, because the drawing is done to prepare for an etching. If you copy the image on a copper or zinc plate and then print it, you get a mirror image, which means that in the printed etching, Anslo appears as having a pen in his right hand, since the mirror image inverses the directionality. You have to plan that from the start.

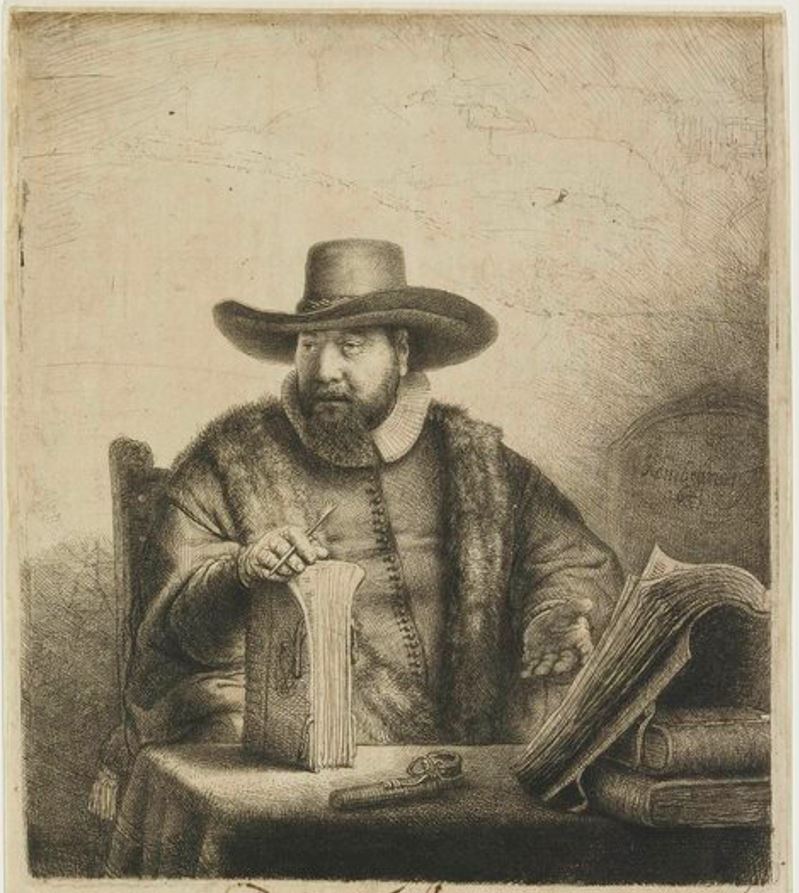

Then we have the etching of 1641 in the Met.

QUESTION: What is special about the etching as compared to the drawing?

AUDIENCE: ….

KAREL: He added empty space. Why?

AUDIENCE: …

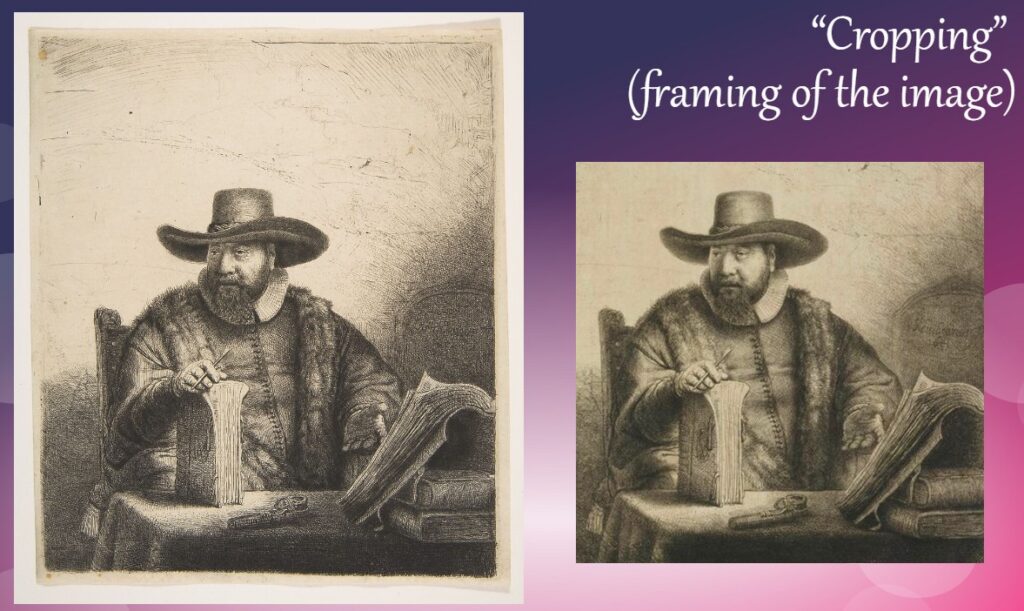

KAREL: In a good art school, you learn how to do “cropping” (re-framing) the image

KAREL: But, wait a minute, was the added space really empty?

AUDIENCE: …

KAREL: In fact, he added two things:

–one, a nail in the wall behind him (very aesthetic!);

–two: a painting put down on the floor with the image turned towards the wall (also very esthetic).

Vondel and Poetry

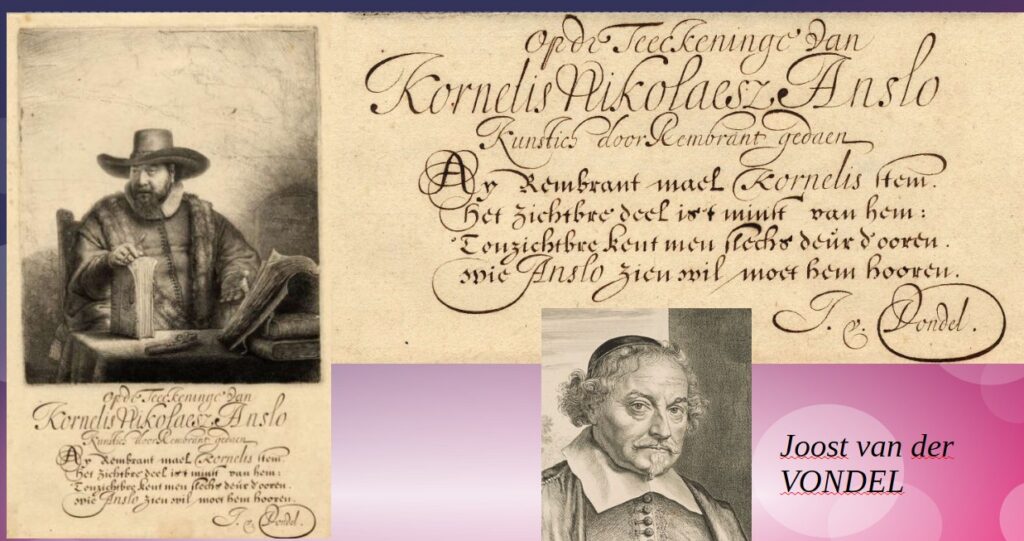

Strange? Not really. To come to an answer we need to go around it. What is hardly known, is that underneath the printed etching one finds a short poem of Joost van der Vondel, considered the greatest poet of the Dutch language:

It reads in Flemish:

« Op de Teekeninge van / Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo /

Kunstich door Rembrandt gedaen /

Ay Rembrandt mael Kornelis stem /

het zichtbare deel is’t minst van hem /

‘t onzichtbare kent men slecht deur d’ooren /

wie Anslo zien wil, moet hem hooren. /

J. v. Vondel »

Translated to English:

« On the drawing of Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo/

Artfully done by Rembrandt

“O, Rembrandt, paint Cornelis’s voice.

The visible part is the least of him;

the invisible we know only through our ears;

he who would like to see Anslo, must hear him”.

J. v. Vondel »

Now, till 1641, Vondel was the dean of the Waterlanders, the Mennonite grouping of Amsterdam of which Anslo was a leading preacher.

In fact the poem mentions a “tekening” (drawing), and the poem can be found already on the back of the initial sketch. It is fair to think that Anslo showed Rembrandt’s preparatory sketch to Vondel, the dean of the congregation. Reacting with his poem, Vondel accomplishes three things:

- He restates the “party line”, i.e. the core belief of the Mennonites, namely that the WORD (and even more the VOICE, that is the spoken word) was superior to the image to evangelize humanity. Transforming others with your voice had a higher value then just learning.3

- Vondel gently makes it clear that his own art, poetry, is superior to that of Rembrandt, painting…

- Vondel says Rembrandt might even do better.

It is clear that Rembrandt felt challenged by the poet remarks. The etching might be a first answer of the painter since it tries to state that point with the nail showing the image taken down and placed with its front side against the wall.

But to prepare the painting, Rembrandt, did a new sketch, now in the Louvre.

The image of the etching with the nail was certainly understood by the Mennonites of the Grote Spijker (meaning in Dutch both the « big storehouse », the nickname given to their temple, and the « big nail »…), but insufficient to reach out to a larger public like over time.

Painting the invisible

Something else had to be invented visually to present on a higher level the same argument and overcome the challenge of “painting the invisible”.

Already in the Louvre drawing, Anslo’s hand is moving to the left, or rather his head is moving to the right, leaning towards the person to which he is speaking. But in the drawing if he is not yet speaking, but “at the point” of speaking, that is a position of mid-motion-change as discussed by Lyndon LaRouche. The speaking will be absolutely manifest in the final painting. Anslo’s mouth is open and his eyebrows are raised.

Going beyond the portrait of Anslo per se, Rembrandt invents something totally new: he adds a person listening with great attention. So, in order to paint the “voice” (sound), he paints another invisible phenomenon, this one being the opposite of sound, namely silence. A voice resonating without somebody listening is as dead as the word in a book.

With this, Rembrandt overcomes the Vondel paradox and states the superiority of his own art, painting, and the fact that through, and by the image, the apparent opposites of sound and silence, can be overcome and make visible the word of God, acting through the voice of Anslo and the listening of his wife.

Now, the heavenly light of God arrives in the room, and extinguishes the earthly light of the candles to make place for the heavenly.

To conclude, if you want to continue this type of discussion, I invite all of you all join the international working group on art among practicing artists, initiated by Dr Ned Rosinsky. So far, it mainly includes Debbie Sonnenblick, Ilko Dimov, Dean Clark, eventually Sébastien Drochon, Agnès Farkas and Remi Lebrun, Philip Ulanowsky, Christine Bierre and myself. You see some works here (shows folder). Please get in touch with me for that.

Thanks,

SUMMARY BIOGRAPHY:

- Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, database

https://rembrandtdatabase.org/literature/corpus.html - Filippi, Elena, Weisheit zwischen Bild und Word in Fall Rembrandt, Coincidentia, Band 2/1, 2011;

- Haak, Bob, Rembrandt, Rembrandt: his life, work and times, Thames & Hudson, 1969;

- Kauffman, Ivan J. , Seeing the Light, Essays on Rembrandt’s religious images, Academia.edu, 2015;

- Schama, Simon, Rembrandt’s Eyes, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999;

- Schwartz, Gary, Rembrandt, Flammarion, Mercatorfonds, 2006;

- Tümpel, Christian, Rembrandt, Albin Michel, Mercatorfonds, 1986;

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt the nationbuilder, Nouvelle Solidarité, 1985;

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt and the Light of Agapè, Artkarel.com, 2001;

- Wright, Christopher, Rembrandt, Citadelles & Mazenot, 2000.

- Experts have often disagreed about the identity of the woman. Is it his mother, his wife, or a servant of the almshouse founded by Anslo. In 1767, Camelis van der Vliet, the governor of the almshouse, reported about a passage of the archives showing that Anslo preached the gospel not only in public but also “to’zijn vrouw en kinderen; gelijk hij ook dus wonderbaarlijk fraai verbeeld word in voorgemelde schilderij, sprekende tegen zijn vrouw over den bijbel, welke op een tafel bij zig open legt, en waama zijn vrouw, op eene onnavolgelijke wijze konstig verbeeld word aandagtig en ingespannen te horen’” (He preached “to his wife and children; just as he is most wonderfully portrayed in the aforementioned painting, speaking to his wife about the bible which lies open before him, to which his wife, depicted in an inimitably artful fashion, listens with devout attention”). Furthermore this woman is not dressed like a destitute inhabitant of an almshouse, but wholly inline with her position as the wife of a wealthy merchant. The painting, done for Anslo’s private house, only became property of the almshouse many years after his lifetime. ↩︎

- In 1686, the Italian art critic Filippo Baldinucci stated that “The artist professed in those days the religion of the Menists (Mennonites).” Recent research proves that Rembrandt had close ties with Amsterdam’s Waterlander Mennonite Community, particularly through Hendrick Uylenburgh, a Mennonite art dealer who ran an artists’ studio in which Rembrandt worked from 1631 to 1635. Rembrandt became chief painter of the studio and in 1634 married Van Uylenburgh’s first cousin Saskia van Uylenburgh, who wasn’t a Mennonite. ↩︎

- The conflict between VOICE, WORD and IMAGE, had sparked in 1625 had a violent dispute among the Amsterdam Waterlanders with a one faction saying that the written word “was dead” and that what was important, was the living word, that is Jesus, who was alive as the “inner word” of Christians. Anslo intervened by publishing an anonymous pamphlet aimed to prevent a schism. ↩︎

Comments are Closed