The « Miracle of Gandhara » : When Buddha turned himself into man

It was during my trip to Afghanistan in November 2023 that I realized how little I knew about this part of the world. Although Islam prevails in Afghanistan and Pakistan today, we often forget that a region shared by these two countries, historically known as Gandhara, played a major role in the epic of Buddhism from the 1st to the 3rd century AD, a spirituality which, by rejecting any idea of caste, was to shake up the world order.

A crossroads on the Silk Roads linking Europe to India and China, Gandhara was the site of a genuine dialogue between Eurasian, Persian, Turkish, Greek, Chinese and Indian cultures.

Buddhism. It was through the voluntarism of two Central Asian kings (Ashoka and the Kuchan ruler Kanishka) that Buddhism, born in Nepal, found the energy and determination to win over the minds and hearts of the world.

Finally, it was in Gandhara that Buddhist art, breaking with the master’s instructions, appropriated the most beautiful forms of various Greek, Indian, Persian and other artistic cultures, to present Buddha in human form to the faithful, an enlightened man, full of wisdom and animated by compassion.

By offering freshness, poetry and a spectacularly modern sense of movement, the early Buddhist artists of Gandhara invite us to identify within ourselves a leap towards self-perfection. In this respect, they are the precursors of classical humanism and of many a Renaissance.

Isn’t it time we recognize the just place that merits their contribution to universal civilization?

Finally, seen the current situation, I’d like to quote Indian Prime Minister Nehru, who on October 3, 1960, addressed the United Nations General Assembly with words that have become ever more relevant: « In the distant past, a great son of India, the Buddha, said that the only true victory was one in which all were equally victorious and no one was defeated. In today’s world, this is the only concrete victory; any other path leads to disaster. »

SUMMARY

- Introduction

- The life of the Buddha

- The Four Truths and the Eightfold Path

- Reincarnation

- Aryans and Vedism

- Brahmins and the caste system

- India before Buddhism

- The great Buddhist councils

- The arrival of the Greeks

- The Maurya Empire

- The reign of Ashoka the Great

- Edicts of Ashoka

- Content of the edicts

- The Kushan Empire

- The miracle of Gandhara

a) Poetry

b) Literature

c) Urbanisation

d) Architecture, the invention of the stupa

e) Sculpture

— Aniconism

— End of aniconism

— Difference in form, difference in content

1) Gandhara Greco-Buddhist school

2) Mathura school

3) Andrah Pradesh school

4) School of the Gupta period. - When Asia meets Greece

a) Kushan coins

b) Bimaran reliquary

c) Harra Triad

d) Taking the earth as witness

e) All Bodhisattvas? - Buddhism today

- Science and religion, Albert Einstein and Buddha.

Introduction

The 5th and 4th centuries BC were a period of global intellectual ferment. It was a time of great thinkers, such as Socrates, Plato, and Confucius, but also Panini and Buddha.

In northern India, it was the age of Buddha, after whose death a « non-theistic » faith (Buddha was only a man…) emerged and spread far beyond its region of origin.

With between 500 million and 1 billion believers today, Buddhism has established itself as one of the world’s leading religious and philosophical beliefs.

The life of the Buddha

The Buddha » (the enlightened one) is the name given to a man called Siddhartha Gautama Shakyamuni (the wise man of the Shakya clan). He reached the age of eighty.

Traditions differ on the exact dates of his life, which modern research tends to place increasingly later: around 623-543 BC according to Theravada tradition, around 563-483 BC according to most specialists of the early 20th century, while others today place him between 420 and 380 BC (his life would not have exceeded 40 years).

According to tradition, Siddhartha Gautama was born in Lumbini (in present-day Nepal) as a Prince of the royal family of Kapilavastu, a small kingdom in the foothills of the Himalayas in present-day Nepal.

An astrologer is said to have warned the boy’s father, King Suddhodana, that when growing up, the child would either become a brilliant ruler or an influential monk, depending on how he viewed the world.

Fiercely determined to make him his successor, Siddhartha’s father never let him see anything outside the palace walls.

While offering him every distraction and pleasure, he made him a virtual prisoner until the age of 29.

When the young man finally escapes his gilded cage, he discovers the existence of people affected by old age, illness, and death.

Moved by the suffering of the ordinary people he met, Siddhartha abandoned the ephemeral pleasures of the palace to seek a higher purpose.

He first tried ultra-severe asceticism, which he abandoned six years later, realizing it was an exercise in futility.

He then sat down to meditate under a large bodhi (fig tree), where he experienced nirvana (« liberation » or, in Sanskrit, « extinction » of the ego). He became known as « The Buddha » (“the enlightened one”).

The « Four Truths » and the « Eight-fold Path »

Buddha taught his young disciples the « Middle Path », between the two extremes of mortification and lavishness. He enunciates the « Four Noble Truths »:

- The noble truth of suffering;

- The noble truth of the origin of suffering;

- The noble truth of the cessation of suffering;

- The noble truth of the path leading to the cessation of suffering, that of the “Noble Eightfold Path”.

Somewhat similar to what Augustine and even more so the Brothers of the Common Life argued in the Christian world, Buddhism insists on the fact that our attachment to earthly existence (both the good and the evil) inflicts suffering. Among Christians, it is said that attachment to “Earthly Paradise” leads us inexorably to “sin”, a concept non-existent in Buddhism for which all errors come from ignorance of the right path.

For Buddha, it is necessary to combat, even extinguish, any sense of the excessive “I” (Today we could say “ego”). It is possible to end our suffering by transcending this strong sense of “I” to enter into greater harmony with things in general.

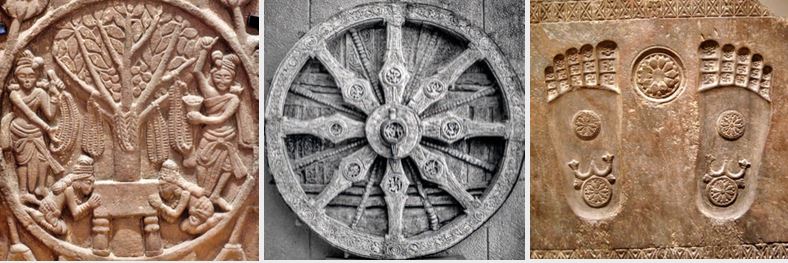

The means to achieve this are summarized in the « Noble Eightfold Path », sometimes represented by the eight spokes of a « Wheel of the Law » that Buddha will set in motion, the Dharma, a word one cannot translate with one word of western languages, but akin to “the law, or rather a set of moral and philosophical precepts to work on.

These eight points of the “Noble Eightfold Path” are:

- Right view.

- Right thought.

- Right speech.

- Right action.

- Right livelihood.

- Right effort.

- Mindfulness.

- Right concentration.

- Right view is important right from the start because if we can’t see the truth of the four noble truths, we can’t begin.

- Right thinking follows naturally from this. The term « right » here means « in accordance with the facts », i.e. with the way things are – which may be different from the way I would like them to be.

- Right thinking, right speech, right action, and right livelihood imply moral restraint – refraining from lying, stealing, committing violent acts, and earning a living in a way that is not detrimental to others. Moral restraint not only contributes to general social harmony but also helps us to control and diminish the inordinate sense of « self ». Like a spoiled child, the « I » grows wide and unruly the longer we let it have its way.

- Finally, right effort is important, because the « I » thrives on idleness and wrong effort; some of the greatest criminals are the most energetic people, so effort must be appropriate to the diminution of the « I » (today we’d say ego), and in any case, if we’re not prepared to make an effort, we can’t hope to achieve anything, either in the spiritual sense, or in life. The last two stages of the path, mindfulness and concentration or enthralment , represent the first step towards liberation from suffering.

The ascetics who had listened to the Buddha’s first discourse became the nucleus of a « sangha » (a community, a movement) of men (women were to join later) who followed the path described by the Buddha in his Fourth Noble Truth, the one specifying the “Noble Eightfold Path”.

To make Buddhist nirvana completely accessible to ordinary people during their individual lifetime, the Buddhist imagination invented the intriguing concept of « Bodhisattva », a word whose meaning varies according to context. It can refer to the state Buddha himself was in before his « awakening », or to an ordinary person who has resolved to become a Buddha in the future and has received confirmation or prediction from a living Buddha that this will be so.

In Theravada (“old school”) Buddhism, only a select few can become Bodhisattva, such as Maitreya, presented as the « Buddha of the future ». But in Mahayana Buddhism (“Great Vehicle”), a Bodhisattva refers to anyone who has generated “bodhicitta”, a spontaneous wish and compassionate spirit aimed at attaining Buddhahood for the benefit of “all sentient beings”, including humans and animals. Given that a person may, in a future life, be reincarnated as a mere animal, respect for animals is essential.

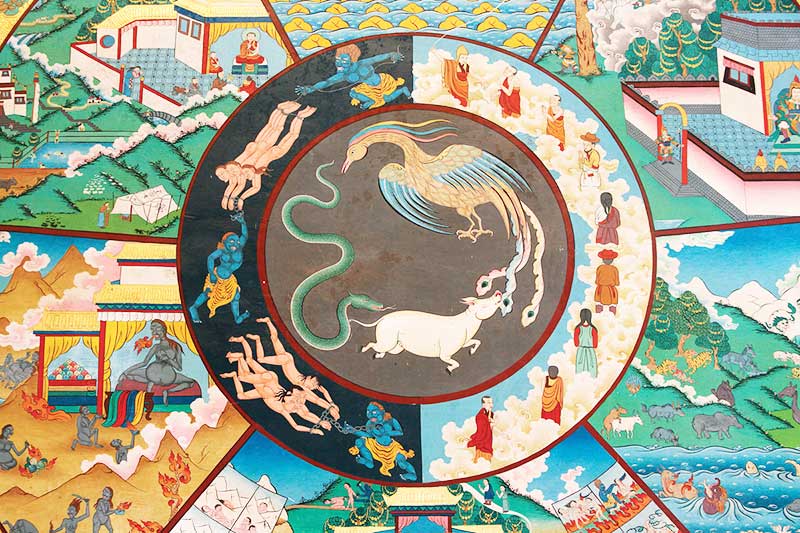

Reincarnation

If Siddhartha would build his own vision on certain foundations of Hinduism, one of the world’s oldest religions, he would introduce revolutionary changes with large political implications.

In most beliefs involving reincarnation (Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism), the soul of a human being is immortal and does not disperse after the physical body disappears. After death, the soul simply transmigrates (metempsychosis) into a newborn baby or animal to continue its immortality. The belief in the rebirth of the soul was expressed by ancient Greek thinkers, beginning with Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato.

Buddhism aims to bring lasting, unconditional happiness. Hinduism aims to free oneself from the cycle of births and rebirths and, ultimately, to attain moksha or liberation from births and rebirths.

Buddhism and Hinduism agree on karma, dharma, moksha, and samsara (reincarnation). But they strongly differ politically in that Buddhism sees personal commitment as more important than formal rituals and refuses the caste system. Buddhism therefore advocates a more egalitarian society.

Whereas Hinduism holds that the attainment of nirvana is only possible in future lives, the more voluntarist and optimistic Buddhism holds that once you’ve realized that life is suffering, you can put an end to that suffering in your present life.

Buddhists describe their rebirth as a flickering candle lighting another candle, rather than an « immortal » soul or « self » passing from one body to another, as Hindus do. For Buddhists, it’s a rebirth without a « self », and they regard the realization of non-self or emptiness as nirvana (extinction), whereas for Hindus, the soul, once freed from the cycle of rebirths, doesn’t become extinct, but unites with the Supreme Being and enters an eternal state of divine bliss.

Aryans and Vedism

One of the great traditions that shaped Hinduism was the Vedic religion (« Vedism »), which flourished among the Indo-Aryan peoples of the north-western Indian subcontinent (Punjab and the western Gangetic plain) during the Vedic period (1500-500 BC).

During this period, nomadic peoples from the Caucasus, calling themselves « Aryans » (« noble », « civilized » and « honorable »), entered India via the northwest frontier.

The term “Aryan” has a very bad historical connotation, especially in the 19th Century, once several virulent anti-Semites, such as Arthur de Gobineau, Richard Wagner, and Houston Chamberlain started promoting the obsolete historical “Aryan race” concept supporting the white supremacist ideology of Aryanism that portrayed the Aryan race as a “master race”, with non-Aryans regarded as racially inferior (Untermensch) and an existential threat to be exterminated.

From a purely scientific standpoint, in his book The Arctic Home (1903), the Indian teacher Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920), based on his analysis of astronomical observations contained in the Vedic hymns, formulates the hypothesis that the North Pole was the original home of the Aryans during the pre-glacial period. They supposedly left this region due to climatic changes around 8000 BC, migrating to the northern parts of Europe and Asia. Mahatma Gandhi called Tilak, who led the country’s early independence movement,« the architect of modern India ».

The Aryans arriving from the North were probably less barbaric than has been so far suggested. Thanks to their military superiority and cultural sophistication, they took over the entire Gangetic plain, eventually extending to the Deccan plateau in the South. This conquest has left its mark to the present day, as the regions occupied by these invaders speak Indo-Aryan languages derived from Sanskrit. (*1)

The Sanskrit philologist, grammarian, and scholar Panini, believed to be a contemporary of Buddha, is best known for his treatise on Sanskrit grammar, which has attracted much comment from scholars of other Indian religions, notably Buddhism.

In fact, according to the best archaeological research available today, Vedic culture has deep roots in the Eurasian culture of the Sintashta steppes (2200-1800 BC) south of the Urals, in the Andronovo culture of Central Asia (2000-900 BC) stretching from the southern Urals to the headwaters of the Yenisei in Central Siberia, and ultimately in the Indus Valley (Harappan) civilization (7000-1900 BC).

At the heart of this Vedic culture are the famous “Vedas” (knowledge), four religious texts recording the liturgy of rituals and sacrifices, and the oldest scriptures in Hinduism. The oldest part of the Rigveda was composed orally in north-western India (Punjab) between around 1500 and 1200 BC, i.e. 700 years before Plato but shortly after the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Scholars trace the origin of “Brahmanism” to Vedic times. The concept of “Brahman” was that of a pure essence that not only diffused itself everywhere but constituted everything. Men, gods, and the visible world were merely its manifestations. Such was the fundamental doctrine of Brahmanism, another name for Hinduism.

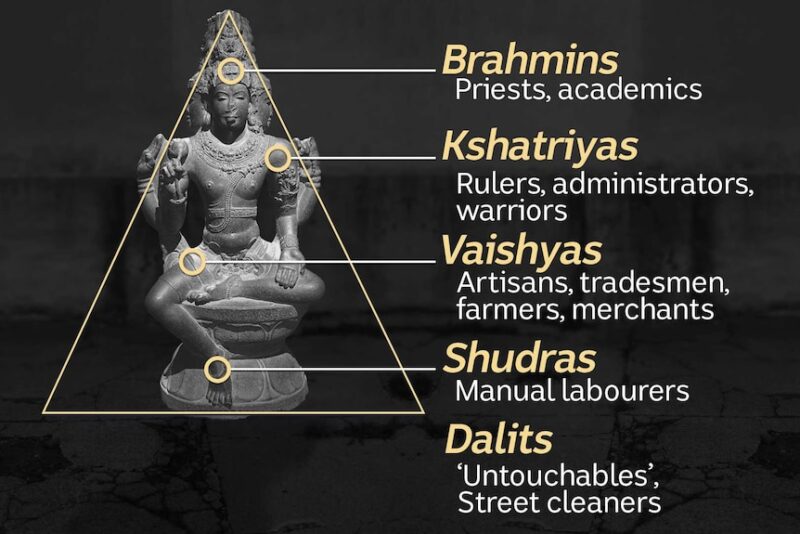

Brahmins and the caste system

To teach that to all of humanity, an all-powerful cast of high priests was created, the Brahmins whose social rank would rise to the top of a caste system. This makes it all a little bit complicated because while “Brahmâ” designates a God in Indian religions, “Brahman” designates Ultimate Reality and “Brahmin” the priest.

However, with the emergence of this Aryan culture came what is known as « Brahmanism », i.e. the birth of an all-powerful caste of high priests.

According to Gajendran Ayyathurai, an Indian anthropologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany:

« Numerous linguistic and historical studies point to socio-cultural disturbances resulting from this migration and the penetration of Brahman culture in various regions, from western South Asia to North India, South India, and South-East Asia ».

Although the term « Brahmin », literally a « superior » member of the highest priestly caste, does appear in the Vedas, modern scholars temper this fact and point out that « there is no evidence in the Rigveda of an elaborate, highly subdivided and very important caste system ».

But with the emergence of a ruling class of Brahmins, who became bankers and landowners, particularly during the, initially very promising, Gupta period (319 to 515 A.D.), a dehumanizing caste system was established. The feudal ruling class, as well as the priests, emphasized local gods, which they gradually integrated with Brahmanism to appeal to the masses. Even among the rulers, the choice of deities indicated divergent positions: part of the Gupta dynasty traditionally supported the god Vishnu, while its rivals supported the god Shiva.

The destructive caste system was then amplified and used to the full by the British East India Company, a private enterprise steering the British Empire, to impose its aristocratic and colonial power over India – a policy that still persists, especially in people’s minds.

The Hindu caste system revolves around two key concepts that categorize members of society: varna and jati. The varna (colors) divide first the Hindus and then the entire Indian society into a hierarchy of four major social classes:

- Brahmins (priestly class);

- Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers);

- Vaishyas (merchants);

- Shudras (manual workers).

In addition, jati refers to at least 3,000 hierarchical classifications, within the four varnas, between social groups according to profession, social status, common ancestry, and locality.

The justification for this “social stratification” is intimately linked to the Hindu vision of karma. Each person’s birth is directly linked to karma, the balance sheet of his or her previous life. Thus, mechanically, birth into the Brahmin varna is the result of good karma.

“Those whose conduct here has been good will quickly have a good birth – birth as a Brahmin, birth as a Kshatriya, or birth as a Vaishya. But those whose conduct here has been bad will quickly get a bad birth – birth as a dog, pig or chandala (bandit)”

(Chandogya Upanishad 5.10.7).

According to this theory, karma determines birth into a class, which in turn defines a person’s social and religious status, which in turn describes a person’s duties and obligations towards that specific status.

In 2021, a survey revealed that three out of ten Indians (30%) identify themselves as members of the four varnas. Only 4.3% of today’s 60.5 million Indians identify themselves as Brahmins. Only some members are priests, while others exercise professions such as educators, legislators, scholars, doctors, writers, poets, landowners, and politicians. As the caste system evolved, Brahmins became an influential varna in India, discriminating against other lower castes.

The vast remainder of Indians (70 percent), including Hindus, declare themselves as being « Dalits« , also known as « Untouchables », who are individuals considered, from the point of view of the caste system, to be out of the castes and assigned to functions or occupations deemed ‘impure’.

Present in India, but also throughout South Asia, the Dalits are victims of numerous forms of discrimination. In India, the overwhelming majority of Buddhists declare themselves as being Dalits.

As early as the 1st century, the Indian Buddhist philosopher, playwright, poet, musician, and orator Asvaghosa (c. 80 – c. 150 a. DC), vocally condemned this caste system with two kinds of argument. Some are borrowed from the most revered texts of the Brahmins themselves; others are based on the principle of the natural equality of all men.

The author underscores that

« the quality of Brahmin is inherent neither in the principle that lives within us, nor in the body in which this principle resides, and it results neither from birth, nor from science, nor from religious practices, nor from the observance of moral duties, nor from knowledge of the Vedas. Since this quality is neither inherent, nor acquired, it does not exist, or rather all men can possess it ».

A Buddhist allegory clearly rejects and mocks the very idea of the caste system:

« Just as sand doesn’t become food just because a child says so, when young children playing on a main road build sand blocks and give them names, saying ‘This one is milk, this one meat and this one curdled milk’, so it is with the four varnas, as you Brahmins describe them. »

India before Buddhism

The time of the Buddha was that of India’s second urbanization and great social protest. The rise of the sramanas, wandering philosophers who had rejected the authority of the Vedas and Brahmins, was new. Buddha was not alone in exploring ways of achieving liberation (moksha) from the eternal cycle of rebirths (punarjanman).

The realization that Vedic rituals did not lead to eternal liberation led to the search for other means. Primitive Buddhism and yoga but also Jainism, Ajivika, Ajnana, and Carvaka were the most important sramanas. Despite their success in disseminating ideas and concepts that were soon to be accepted by all the religions of India, the orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy (astika) opposed the sramanic schools of thought and refuted their doctrines as « heterodox » (nastika), because they refused to accept the epistemic authority of the Vedas.

For over forty years, the Buddha crisscrossed India on foot to spread his Dharma, a set of precepts and laws governing the behavior of his disciples.

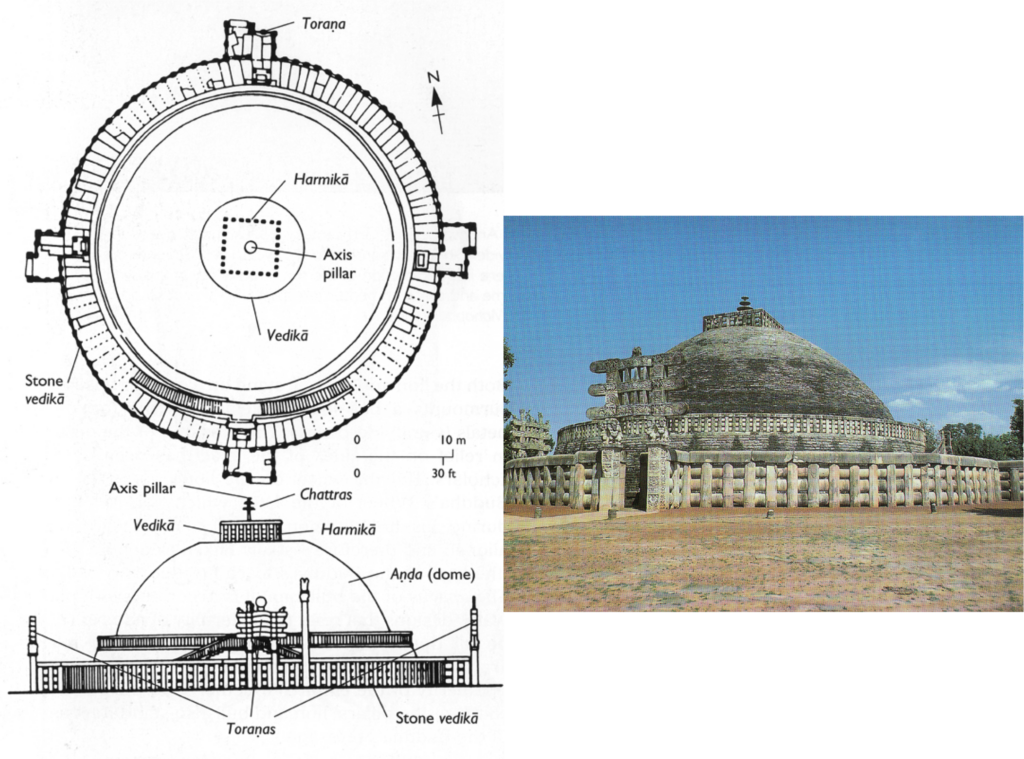

When he died, his body was cremated, as was the custom in India. The Buddha’s ashes were divided, and several reliquaries were buried in large hemispherical mounds known as stupas (dome-shaped funeral temples). By the time of his death, his religion was already widespread throughout central India and in major Indian cities such as Vaishali, Shravasti, and Rajagriha.

The Great Buddhist Councils

Four great Buddhist councils were organized, at the instigation of various kings seeking to escape the clutches of the Brahmin caste.

In 483 BC, just after the Buddha’s death, the first council was held under the patronage of King Ajatasatru (492-460 BC) of the Haryanka dynasty to preserve the Buddha’s teachings and reach a consensus on how his teachings could be disseminated.

The second Buddhist Council took place in 383 BC, one hundred years after the Buddha’s death, under the reign of King Kalasoka of the Sisunaga dynasty. Differences of interpretation arose on points of discipline as followers drifted further apart. A schism threatened to divide those who wished to preserve the original spirit and those who defended a broader interpretation.

The first group, called Thera (meaning « ancient » in Pâli), is at the origin of Theravada Buddhism. They aimed to preserve the Buddha’s teachings in their original spirit.

The other group was called Mahasanghika (Great Community). They interpreted the Buddha’s teachings more liberally and gave us Mahayana Buddhism.

The participants in the council tried to iron out their differences, with little unity but no animosity either. One of the main difficulties stemmed from the fact that the Buddha’s teachings, before being recorded in texts, had been transmitted only orally for three to four centuries. (*2)

The Arrival of the Greeks

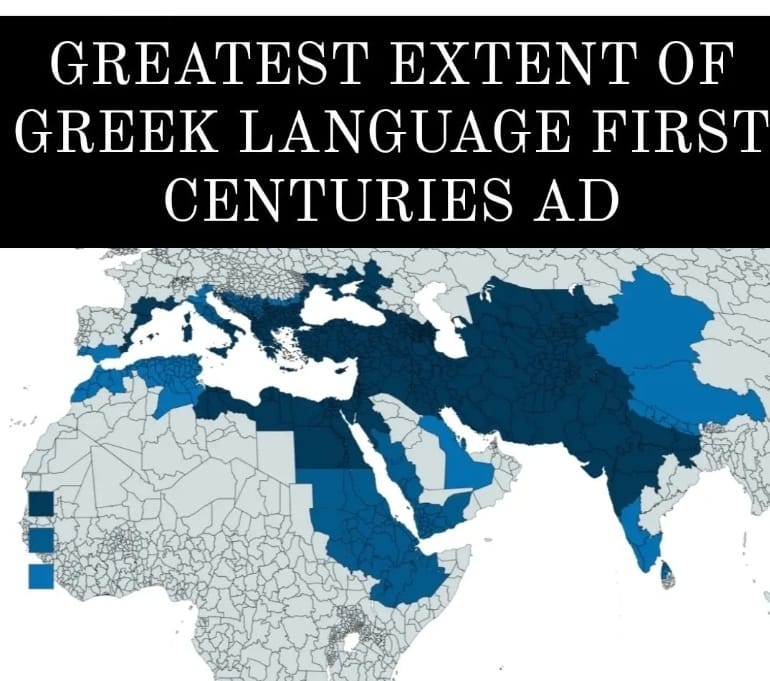

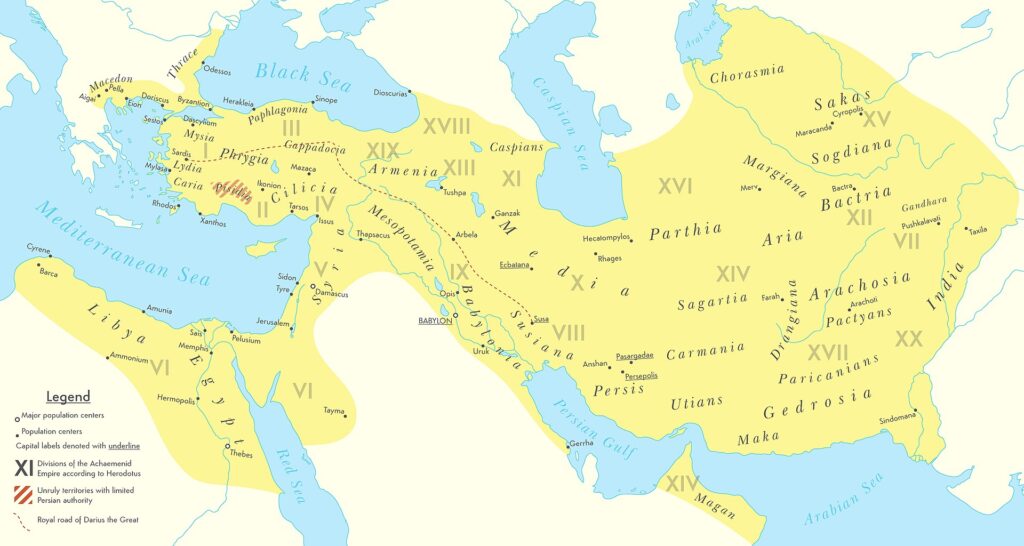

The Greeks began to settle in the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent during the time of the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

Darius the Great (550 – 486 BC) conquered the region, but he and his successors also conquered much of the Greek world, which at the time included the entire peninsula of western Anatolia.

When Greek villages rebelled under the Persian yoke, they were sometimes ethnically cleansed. Their populations were forcibly deported to the other side of the empire.

As a result, numerous Greek communities sprang up in the remotest Indian regions of the Persian Empire.

In the 4th century BC, Alexander the Great defeated and conquered the Persian Empire.

By 326 BC, this empire encompassed the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent as far as the River Beas (which the Greeks called the Hyphasis). Alexander established satrapies and established several colonies. He turned south when his troops, aware of the immensity of India, refused to advance further east.

From 180 BC to around 10 AD, more than thirty Hellenistic kings succeeded one another, often in conflict with one another. This period is known in history as the « Indo-Greek Kingdoms ». One of these kingdoms was founded when the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded India in 180 BC, creating an entity that seceded from the powerful Greco-Bactrian kingdom, Bactria (including northern Afghanistan, part of Uzbekistan, etc.).

During the two centuries of their reign, these Indo-Greek kings integrated Greek and Indian languages and symbols into a single culture, as evidenced by their coins, and blended ancient Greek, Hindu, and Buddhist religious practices, as evidenced by the archaeological remains of their cities and signs of their support for Buddhism.

The Maurya Empire and Ashoka the Great

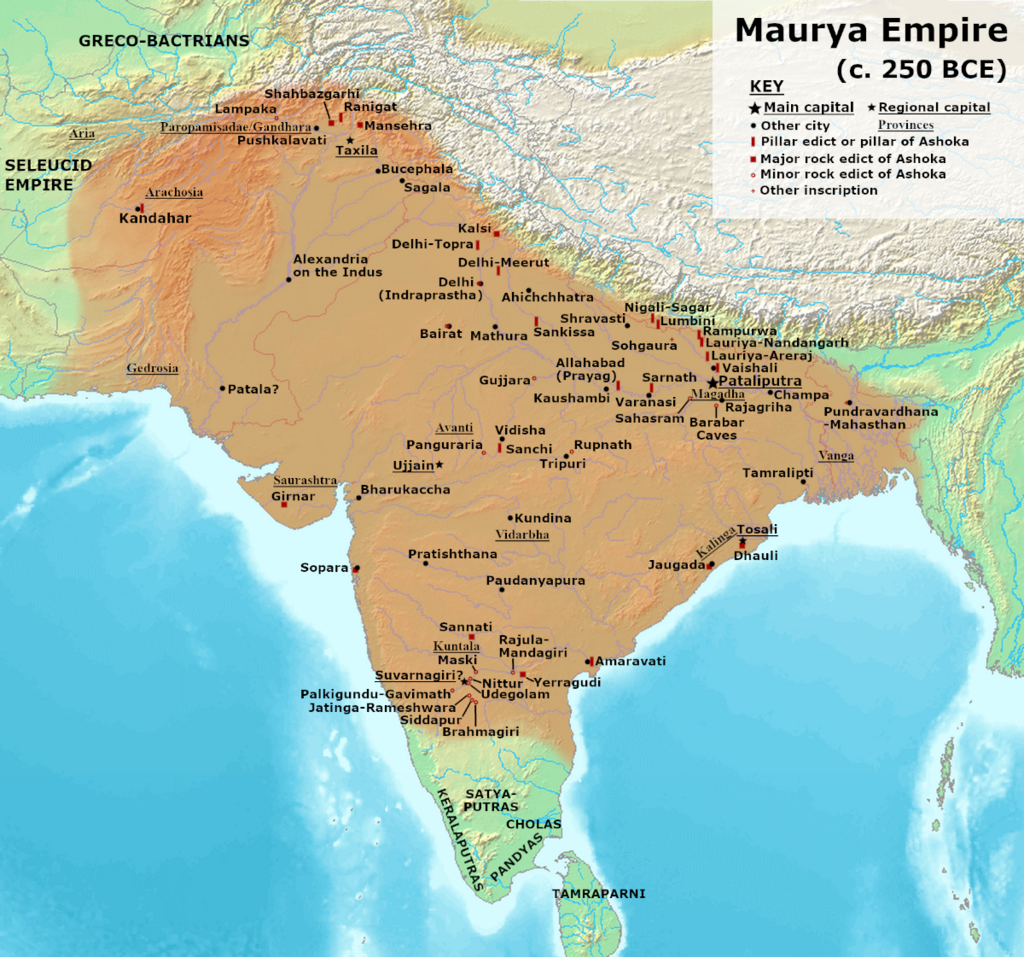

Around 322 BC, Greeks called Yona (Ionians) or Yavana in Indian sources, took part, along with other populations, in the uprising of Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire.

Chandragupta’s reign ushered in an era of economic prosperity, reform, infrastructure expansion, and tolerance. Many religions flourished in his kingdom and the empire of his descendants. Buddhism, Jainism, and Ajivika grew in importance alongside the Vedic and Brahmanic traditions, and minority religions such as Zoroastrianism and the Greek pantheon were respected.

Ashoka the Great

The Maurya Empire reached its apogee under the reign of Chandragupta’s grandson, Ashoka the Great, from 268 to 231 BC. Eight years after taking power, Ashoka led a military campaign to conquer Kalinga, a vast coastal kingdom in east-central India. His victory enabled him to conquer a larger territory than any of his predecessors.

Thanks to Ashoka‘s conquests, the Maurya Empire became a centralized power covering a large part of the Indian subcontinent, stretching from present-day Afghanistan in the west to present-day Bangladesh in the east, with its capital at Pataliputra (present-day Patna in India).

Before this, the Maurya Empire had existed in some disarray until 185 BC. It was Ashoka who transformed the kingdom with the extreme violence that characterized the early part of his reign. Between 100,000 and 300,000 people were killed in the Kalinga conquest alone!

But the weight of such destruction plunged the king into a serious personal crisis. Ashoka was deeply shocked by the number of people slaughtered by his armies.

Ashoka‘s Edict No. 13 reflects the great remorse felt by the king after observing the destruction of Kalinga:

« His Majesty felt remorse because of the conquest of Kalinga, for in the subjugation of a country not previously conquered, there are necessarily massacres, deaths, and captives, and His Majesty feels deep sorrow and regret. »

Ashoka subsequently renounced military displays of force and other forms of violence, including cruelty to animals. Deeply convinced by Buddhism, he devoted himself to spreading his vision of dharma, just and moral conduct. He encouraged the spread of Buddhism throughout India.

According to French archaeologist and scholar François Foucher, even if cases of animal abuse did not disappear overnight, belief in the brotherhood of all living beings still flourished in India more than anywhere else.

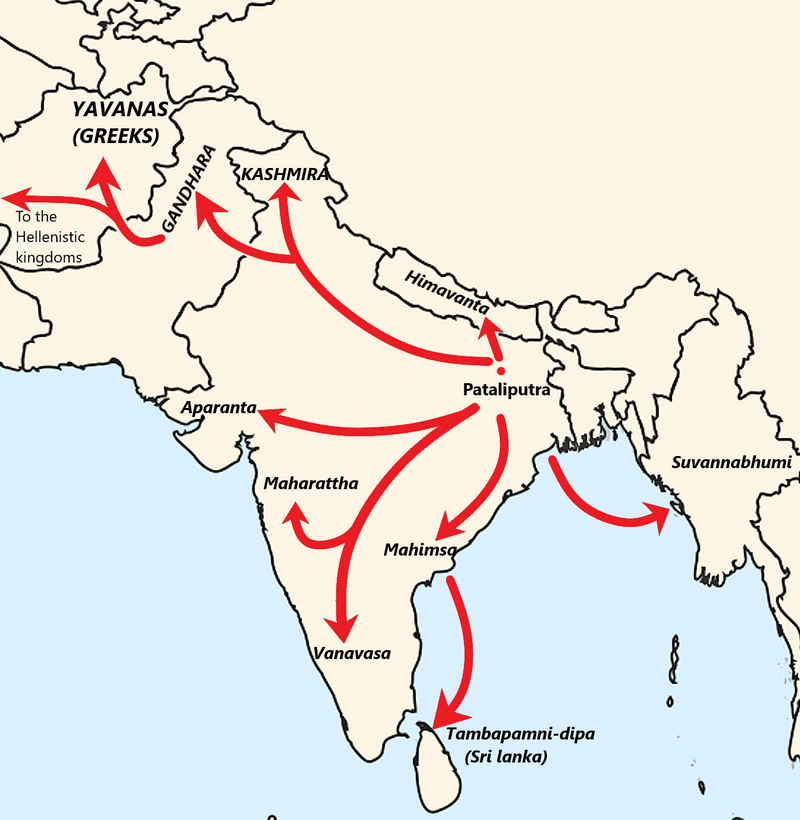

In 250 BC, Ashoka convened the third Buddhist council. Theravada sources mention that, in addition to settling internal disputes, the council’s main function was to plan the dispatch of Buddhist missionaries to various countries to spread Buddhism.

These reached as far as the Hellenistic kingdoms to the west, starting with neighboring Bactria. Missionaries were also sent to South India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia (possibly Burma). The fact that these missions were deeply involved in the flourishing of Buddhism in Asia during Ashoka‘s time is well supported by archaeological evidence. Buddhism was not spread by pure chance but as part of a creative, stimulating, and well-planned political operation along the Silk Roads.

According to the « Mahavamsa » (“Great Chronicle” XII, 1st paragraph), relating the history of the Sinhalese and Tamil kings of Ceylon (today Sri Lanka), the Council and Ashoka sent the following Buddhist missionaries:

- Elder Majjhantika led the mission to Kashmir and Gandhara (today’s northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan);

- Elder Mahadeva led the mission in southwest India (Mysore, Karnataka);

Rakkhita led the mission in southeast India (Tamil Nadu); - Elder Yona (Ionian, Greek) Dharmaraksita led the mission in Aparantaka (« the western frontier ») comprising northern Gujarat, Kathiawar, Kutch, and Sindh, which were all parts of India at the time);

- The elder Mahadharmaraksita led the mission to Maharattha (the western peninsular region of India);

- Maharakkhita (Maharaksita Thera) led the mission to the land of the Yona (Ionians), which probably refers to Bactria and possibly to the Seleucid kingdom;

- Majjhima Thera conducted the mission to the Himavat region (northern Nepal, Himalayan foothills);

- Sona Thera and Uttara Thera led missions to Suvarnabhumi (somewhere in Southeast Asia, perhaps Myanmar or Thailand); and

- Mahinda, Ashoka‘s eldest son and therefore Prince of his kingdom, accompanied by his disciples, went to Lankadeepa (Sri Lanka).

Some of these missions were successful, such as those that established Buddhism in Afghanistan, Gandhara, and Sri Lanka.

Gandharan Buddhism, Greco-Buddhism, and Sinhalese Buddhism have for generations been a powerful inspiration for the development of Buddhism in the rest of Asia, particularly China.

While missions to the Hellenistic Mediterranean kingdoms seem to have been less successful, it is possible that Buddhist communities were established for a limited period in Egyptian Alexandria, which may have been the origin of the so-called Therapeutae sect mentioned in some ancient sources such as Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BC – 50 AD).

The Jewish Essenes and the Therapeutae of Alexandria are said to be communities founded on the model of Buddhist monasticism.

According to French historian André Dupont-Sommer (1900-1983), « India is believed to have been the source of this vast monastic movement, which shone brightly within Judaism itself for around three centuries ». According to him, this influence contributed to the emergence of Christianity.

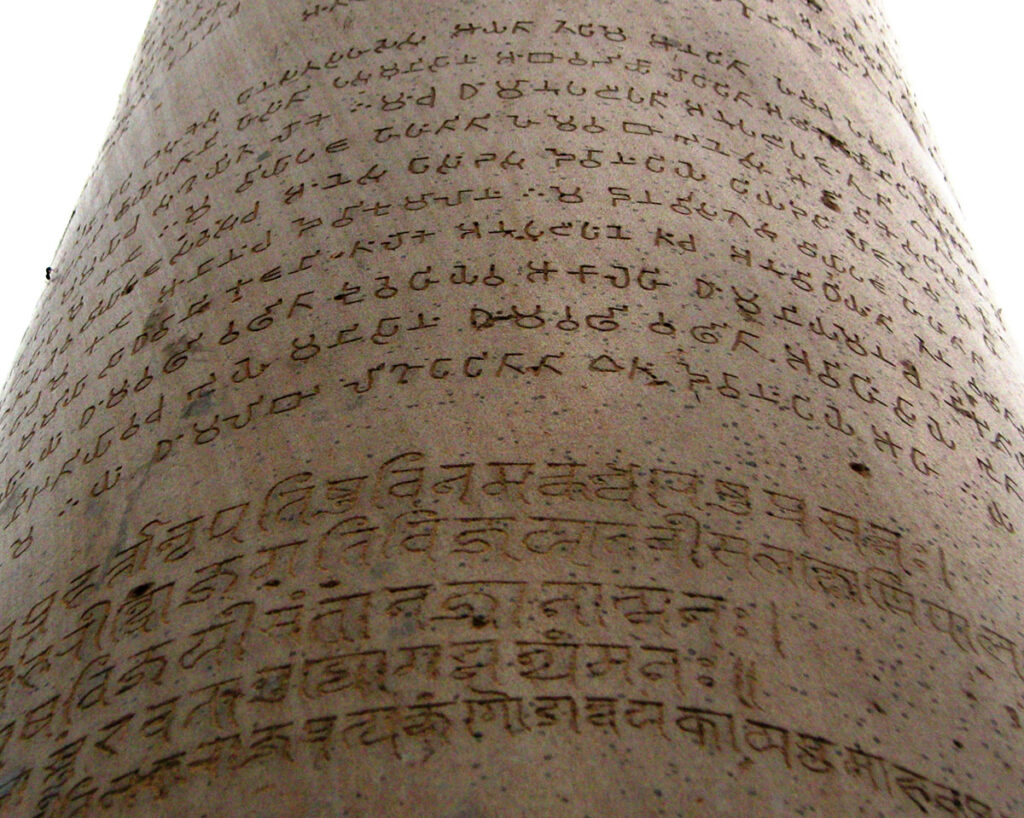

Ashoka’s Edicts

King Ashoka presented his messages through edicts engraved on pillars and rocks in various parts of the kingdom, close to stupas on pilgrimage sites and along busy trade routes.

Some thirty of them have been preserved. They were not written in Sanskrit, but:

- in Greek (the language of the neighboring Greco-Bactrian kingdom and the Greek communities of Ashoka‘s kingdom),

- in Aramaic (the official language of the ancient Achaemenid Empire); and

in various dialects of Prâkrit (*3), including ancient Gândhârî, the language spoken in Gandhara. The edicts were engraved in the language relevant to the region. For example, in Bactria, where the Greeks dominated, an edict near present-day Kandahar was written solely in Greek and Aramaic.

Content of Edicts

Some edicts reflect Ashoka‘s deep adherence to the precepts of Buddhism and his close relationship with the sangha, the Buddhist monastic order. He also uses the specifically Buddhist term dharma to designate the qualities of the heart that underpin moral action.

In the Minor Rock Edict N° 1, the King declares himself « a lay follower of the Buddha’s teaching for more than two and a half years », but admits that so far, he has « not made much progress ». He adds that « for a little over a year now, I’ve been getting closer to the Order ».

In the Minor Rock Edict N° 3 from Calcutta-Bairat, Ashoka emphasized that « what has been said by the Buddha has been said well » and described the Buddha’s teachings as the true dharma.

Ashoka recognized the close links between the individual, society, the king, and the state. His dharma can be understood as morality, goodness, or virtue, and the imperative to pursue it gave him a sense of duty. The inscriptions explain that dharma includes self-control, purity of thought, liberality, gratitude, firm devotion, truthfulness, protection of speech, and moderation in spending and possessions. Dharma also has a social aspect. It includes obedience to parents, respect for elders, courtesy and liberality towards Brahma worshipers, courtesy towards slaves and servants, and liberality towards friends, acquaintances, and relatives.

Non-violence, which means refraining from harming or killing any living being, was an important aspect of Ashoka‘s dharma. Not killing living beings is described as part of the good (Minor Rock Edict N° 11), as is gentleness towards them (Minor Rock Edict N° 9). The emphasis on non-violence is accompanied by the promotion of a positive attitude of care, gentleness, and compassion.

Ashoka adopts and advocates a policy based on respect and tolerance of other religions. One of his edicts reads as follows:

« All men are my children. To my children, I wish prosperity and happiness in this world and the next; my wishes are the same for all men ».

Far from being sectarian, Ashoka, based on the conviction that all religions share a common, positive essence, encourages tolerance and understanding of other religions:

« The beloved of the gods, King Piyadassi (name Ashoka gave himself after converting to Buddhism), wishes that all sects may dwell in all places, for all seek self-mastery and purity of spirit. (Major Rock Edict N° 7)

And he adds:

« For whoever praises his own sect or blames other sects, – all out of pure devotion to his own sect, i.e. intending to glorify his own sect, – if he does so, he is rather seriously harming his own sect. But concord is meritorious, (i.e.) they must both listen to and obey each other’s morals. » (Major Rock Edict N° 12)

Ashoka had the idea of a political empire and a moral empire, the latter encompassing the former. His conception of his constituency extended beyond his political subjects to include all living beings, human and animal, living within and outside his political domain.

His inscriptions express his fatherlike conception of kingship and describe his welfare measures, including the provision of medical treatment, the planting of herbs, trees, and roots for people and animals, and the digging of wells along roads (Major Rock Edict N° 2).

The emperor had become a sage. He ran a centralized government from the capital of the Maurya empire: Pataliputra.

Guided by the Arthashastra, the Mauryan state became the central land clearing agency with the objective of extending settled agriculture and breaking up the disintegrating remnants of the frontier hill tribes. Members of such tribes cultivated on these newly cleared forest lands. Agriculture developed thanks to irrigation, and good roads were built to link strategic points and political centers. Centuries before our great Duke de Sully in France, Ashoka demanded that these roads be lined with shade trees, wells, and inns. His administration collected taxes. He made his inspectors accountable to him. The king’s dhamma-propagating activities were not limited to his own political domain but extended to the kingdoms of other rulers.

Hence, Ashoka‘s very existence as a historical figure was close to being forgotten! But since the deciphering of sources in Brahmi script in the 19th century, Ashoka has come to be regarded as one of India’s greatest emperors. Today, Ashoka‘s Buddhist wheel is featured on the Indian flag.

As already mentioned, Ashoka and his descendants used their power to build monasteries and spread Buddhist influence in Afghanistan, large parts of Central Asia, Sri Lanka, and beyond to Thailand, Burma, Indonesia, China, Korea, and Japan.

Bronze statues from his time have been unearthed in the jungles of Annam, Borneo, and Sulawesi. Buddhist culture was superimposed on the whole of Southeast Asia, although each region, happily enough, kept some of its own personality, touch and character.

The Kushan Empire

The Maurya Empire, which ruled Bactria and other ancient Greek satrapies, collapsed in 185 BC, hardly five decades after the death of Ashoka, accused of spending too much on infrastructure and Buddhist missions and not enough on national defense. Some academics argue that Pushyamitra Sunga, who assassinated the last Mauryan monarch, Brihadratha, signalled a strong Brahmanical response against Ashoka’s pro-Buddhist policies and Dhamma. Others argue that Ashoka’s ahimsa (non-violence) philosophy was a contributing factor to the decline of the Mauryan Empire. The king’s non-violence also meant that he stopped exercising control over officials, particularly those in the provinces, who had become tyrannical and required control.

These were turbulent times. In the first century AD, the Kushans, one of the five branches of the Chinese Yuezhi confederation, emigrated from northwest China (Xinjiang and Gansu) and, following in the footsteps of the Iranian Saka nomads, seized control of ancient Bactria. They formed the Kushan empire in the Bactrian territories at the beginning of the 1st century. This empire soon extended to include much of what is now Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India, at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath, near Varanasi (Benares).

The founder of the Kushan dynasty, Kujula Kadphises, followed Greek cultural ideas and iconography after the Greco-Bactrian tradition and was a follower of the Shivaite sect of Hinduism. Two later Kushan kings, Vima Kadphises and Vasudeva II, were also patrons of Hinduism and Buddhism.

The homeland of their empire was in Bactria, where Greek was initially the administrative language before being replaced by « Bactrian » a language written in Greek characters until the 8th century, when Islam replaced it with Arabic.

The Kushans also became great patrons of Buddhism, particularly Emperor Kanishka the Great, who played an important role in its spread via the Silk Roads to Central Asia and China, ushering in a 200-year period of relative peace, rightly described as the « Pax Kushana ».

It also seems that, from the very beginning, Buddhism flourished among the merchant class, whose birth barred access to the religious orders of India and the Himalayas.

Buddhist thought and art developed along trade routes between India, the Himalayas, Central Asia, China, Persia, Southeast Asia, and the West. Travelers sought the protection of Buddhist images and made offerings to shrines along the way, collecting portable objects and shrines for personal use.

The term 4th Buddhist Council refers to two different events, one in the Theravada and the other in the Mahayana schools.

- According to Theravada tradition: to prevent the Buddha’s teachings, which had hitherto been transmitted orally, from being lost, five hundred monks led by the Venerable Maharakkhita gathered at Tambapanni, Sri Lanka in 72 AD, under the patronage of King Vattagamani (r. 103 — 77 BC) to write down the “Pâli Canon” on palm leaves. (*4) The work, which is said to have lasted three years, took place in the Aloka Lena cave near present-day Matale;

- However, according to Mahayana tradition, it was 400 years after the Buddha’s extinction that five hundred Sarvastivadin monks gathered in Kashmir in 72 AD to compile and clarify their doctrines under the direction of Vasumitra and the patronage of Emperor Kanishka. They produced the Mahavibhasa (Great Exegesis) in Sanskrit.

According to several sources, the Indian Buddhist monk Asvaghosa considered the first classical Sanskrit playwright whose attacks on the caste system we have presented, served as King Kanishka‘s spiritual adviser during the last years of his life.

Note that the oldest Buddhist manuscripts discovered to date, such as the 27 birch-bark scrolls acquired by the British Library in 1994 and dating from the 1st century, were found not in « India », but buried in the ancient monasteries of Gandhara, the central region of the Maurya and Kushan empire, which includes the Peshawar and Swat valleys (Pakistan), and extends westwards to the Kabul valley in Afghanistan and northwards to the Karakorum range.

Thus, after a first great impetus given by King Ashoka the Great, Gandhara culture was given a second wind under the reign of the Kushan king Kanishka. The cities of Begram, Taxila, Purushapura (now Peshawar), and Surkh Kotal reached new heights of development and prosperity.

The Miracle of Gandhara

It cannot be overemphasized that Gandhara, especially in the Kushan period, was at the heart of a veritable renaissance of civilization, with an enormous concentration of artistic production and unparalleled inventiveness. While Buddhist art was mainly focused on temples and monasteries, objects for personal devotion were very common.

Thanks to Gandhara’s art, Buddhism became an immense force for beauty, harmony, and peace, and has conquered the world.

Buddhism favored the creation of numerous artistic works that elevate thought and morality by using metaphorical paradoxes. The prevailing mediums and supports were silk paintings, frescoes, illustrated books and engravings, embroidery and other textile arts, sculpture (wood, metal, ivory, stone, jade), and architecture.

Here are a few examples:

A. Poetry

For most Westerners, Buddhism is a « typical » emanation of Asian culture, generally associated with India, Tibet, and Nepal, but also with China and Indonesia. Few of them know that the oldest Buddhist manuscripts known to date (1st century AD) were discovered, not in Asia, but rather in Central Asia, in ancient Buddhist monasteries of Gandhara.

Originally, before their transcription into Sanskrit (for long years the language of the elite), they were written in Gândhârî, an Indo-Aryan language of the Prâkrit group, transcribed with the “kharosthi alphabet” (an ancient Indo-Iranian script).

Gandhârî was the lingua franca of early Buddhist thought. Proof of this is the Buddhist manuscripts written in Gândhârî that traveled as far away as eastern China, where they can be found in the Luoyang and An-yang inscriptions.

To preserve their writings, the Buddhists were at the forefront of adopting Chinese book-making technologies, notably paper and xylography (single-sheet woodcut). This printing technique consists of reproducing the text to be printed on a transparent sheet of paper, which is turned over and engraved on a soft wooden board. The inking of the protruding parts then allows multiple print runs. This explains why the first fully printed book is the Buddhist Diamond Sutra (circa 868), produced using this process.

The Khaggavisana Suttra, literally « The Horn of the Rhinoceros », is a wonderful example of authentic Buddhist religious poetry. Known as the « Rhinoceros Sutra », this poetic work is part of the Pali collection of short texts known as the Kuddhhaka Nikava, the fifth part of the Pitaka Sutta, written in the 1st century CE.

Since tradition grants the Asian rhinoceros a solitary life in the forest – the animal dislikes herds – this sutra (teaching) bears the apt title « On the value of the solitary and wandering life ». The allegory of the rhinoceros helps communicate to devotees the keen sense of individual sovereignty required by the moral commitments prescribed by the Buddha to end suffering by disconnecting from earthly pleasures and pains. Excerpt:

Shunning violence towards all beings,

never harming a single one of them,

compassionately helping with a loving heart,

wander alone like a rhinoceros.

One keeping company nurtures affection,

and from affection suffering arises.

Realizing the danger arising from affection,

wander alone like a rhinoceros.

In sympathizing with friends and companions,

the mind gets fixed on them and loses its way.

Perceiving this danger is familiarity,

wander alone like a rhinoceros.

Concerns that one has for one’s sons and wives,

are like a thick and tangled bamboo tree.

Remaining untangled like a young bamboo,

wander alone like a rhinoceros.

Just like a deer, wandering free in the forest,

goes wherever he wishes as he grazes,

so a wise man, treasuring his freedom,

wanders alone like the rhinoceros.

Leave behind your sons and wives and money,

all your possessions, relatives, and friends.

Abandoning all desires whatsoever,

wander alone like the rhinoceros (…)

B. Literature

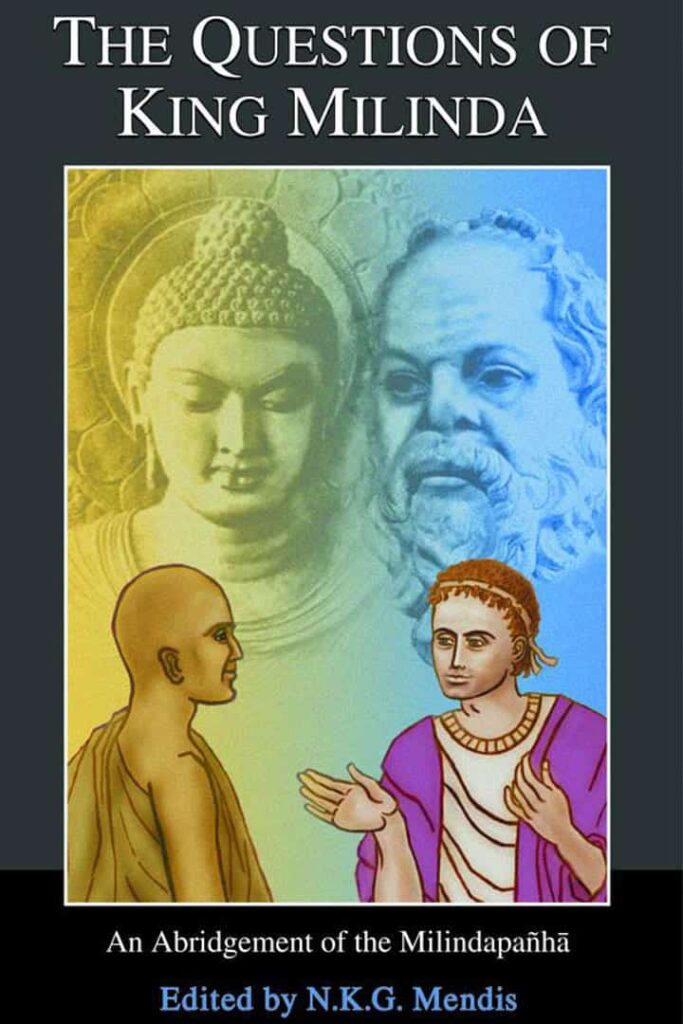

Two other masterpieces from the same oeuvre are the famous Jataka, or « Birth stories of the Buddha’s previous lives », and the Milindapanha, or « King Milinda’s questions”.

The Jataka, which features numerous animals, shows how, before the last human incarnation in which he attained nirvana, the Buddha himself was reincarnated countless times as an animal – as various kinds of fish, as a crab, a rooster, a woodpecker, a partridge, a francolin, a quail, a goose, a pigeon, a crow, a zebra, a buffalo, several times as a monkey or an elephant, an antelope, a deer and a horse. One story describes how the Bodhisattva was born as a Great Monkey who dwelled in a beautiful Himalayan forest among a large troop of monkeys. And since it’s Buddha who’s incarnated in the animal, the monkey suddenly speaks words of great wisdom.

But on other occasions, the characters are animals, while our Bodhisattva appears in human form. These tales are often peppered with piquant humor. They are known to have inspired La Fontaine, who must have heard them from Dr. François Bernier, who learned them from him while working as a physician in India for eight years.

The Questions of King Milinda is an imaginative account, a veritable Platonic dialogue between the Greek king of Bactria Milinda (the Greek, Menander), who ruled the Punjab, and the Buddhist sage Bhante Nagasena.

Their lively dialogue, dramatic and witty, eloquent, and inspired, explores the various problems of Buddhist thought and practice from the point of view of a perceptive Greek intellectual, both perplexed and fascinated by the strangely rational religion he discovers on the Indian subcontinent.

Through a series of paradoxes, Nagasena leads the Greek « rationalist » to ascend to the spiritual and therefore transcendental dimension, beyond logic and simple rationality, of nirvana, which, like space, has « no formal cause » and can therefore occur, but « cannot be caused ». So how do we get there?

And to one of his disciples, who once asked him whether the universe was finite or infinite, eternal or not, whether the soul was distinct from the body, what became of man after death, the Buddha replied with a parable:

« Suppose a man is seriously wounded by an arrow, and is taken to a doctor, and the man says: « I will not let this arrow be removed, until I know who wounded me, what caste he is, what village he was born in, what bow he used, what material the arrow was made of, from what direction it was shot. .. » Then this man would surely die before he got the answers. »

C. Urban Planning

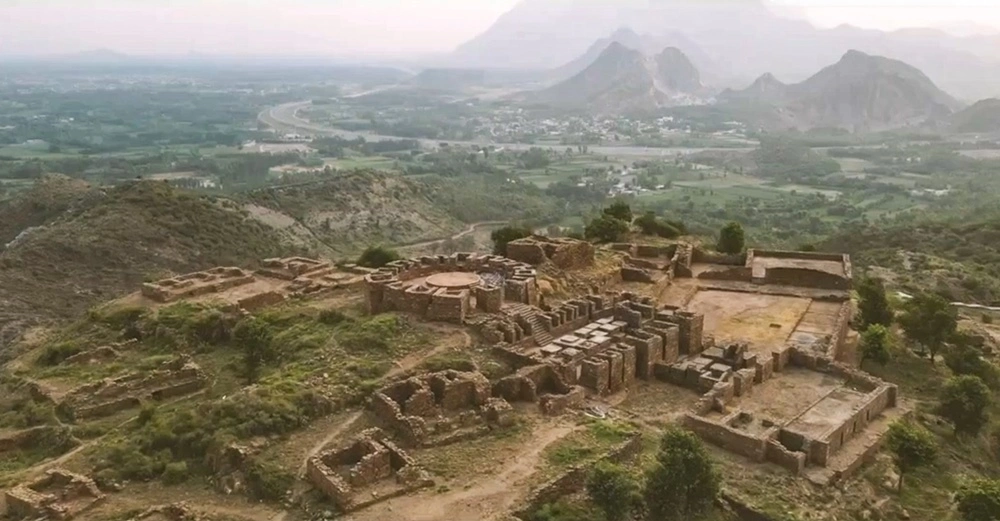

One of the great urban and cultural centers and, for a time, the capital of Gandhara, was Taxila or Takshashila (present-day Punjab), founded around 1000 BC on the ruins of a city dating from the Harappan period and located on the eastern bank of the Indus, the junction points between the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia.

Some ruins of Taxila date to the time of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, followed successively by the Mauryan Empire, the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the Indo-Scythians, and the Kushan Empire.

According to some accounts, the University of Ancient Taxila (centuries before the residential bouddhist University of Nalanda founded in 427 AD) can be considered one of the earliest centers of learning in South Asia.

As early as 300 BC, Taxila functioned largely as a “University” offering higher education. Students had to complete their primary and secondary education elsewhere before being admitted to Taxila.

The minimum age requirement was sixteen. Not only Indians but also students from neighboring countries like China, Greece, and Arabia flocked to this city of learning.

Around 321 BC, it was the great philosopher, teacher, and economist of Gandhara, Chanakya, who helped the first Mauryan emperor, Chandragupta, to seize power.

Under the tutelage of Chanakya, Chandragupta received a comprehensive education at Taxila, encompassing the various arts of the time, including the art of war, for a duration of 7–8 years.

In 303 BC, Taxila fell into their hands, and under Ashoka the Great, the grandson of Chandragupta, the city became a great center of Buddhist learning and art.

Chanakya, whose writings were only rediscovered in the early 20th century and who served as the principal advisor to both emperors Chandragupta and his son Bindusara, is widely considered to have played an important role in establishing the Mauryan Empire.

Also known as Kauṭilya and Vishnugupta, Chanakya is the author of The Arthashastra, a Sanskrit political treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy, and military strategy. The Arthashastra also addresses the question of collective ethics which ensures the cohesion of a society. He advised the king to launch major public works projects, such as the creation of irrigation routes and the construction of forts around the main production centers and strategic towns in regions devastated by famine, epidemics, and other natural disasters, or by war, and to exempt from taxes those affected by these disasters.

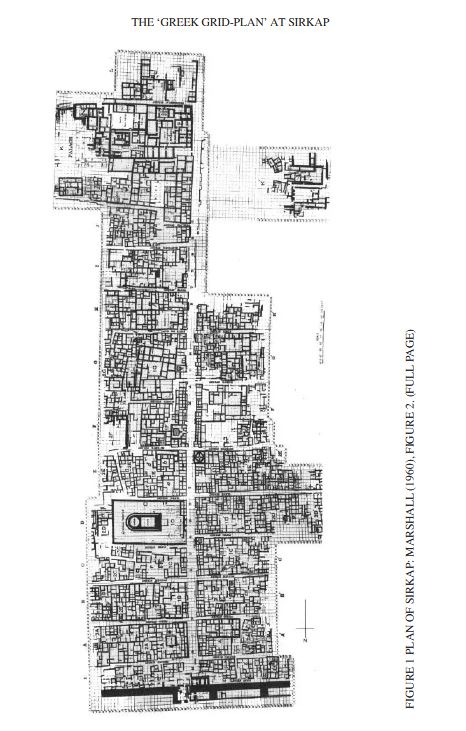

In the 2nd century BC, Taxila was annexed by the Indo-Greek kingdom of Bactria which built a new capital there named Sirkap, where Buddhist temples were contiguous with Hindu and Greek temples, a sign of religious tolerance and syncretism.

Sirkap was built according to the “Hippodamian” grid plan characteristic of Greek cities. (*5)

It is organized around a main avenue and fifteen perpendicular streets, covering an area of approximately 1,200 meters by 400, with a surrounding wall 5 to 7 meters wide and 4.8 kilometers long.

After its construction by the Greeks, the city was rebuilt during the incursions of the Indo-Scythians, then by the Indo-Parthians after an earthquake in the year 30 AD. Gondophares, the first king of the Indo-Parthian kingdom, built parts of the city, including the Buddhist stupa (funerary monument) of the double-headed eagle and the temple of the Sun god. Finally, inscriptions dating from 76 AD demonstrate that the city had already come under Kushan domination. The Kushan ruler Kanishka erected Sirsukh, about 1.5 km northeast of ancient Taxila.

Buddhist sutras from the Gandhara region were studied in China when the Kushan monk Lokaksema (born 147) began translating some of the earliest Buddhist sutras into Chinese. The oldest of these translations show that they were translated from the Gândhârî language.

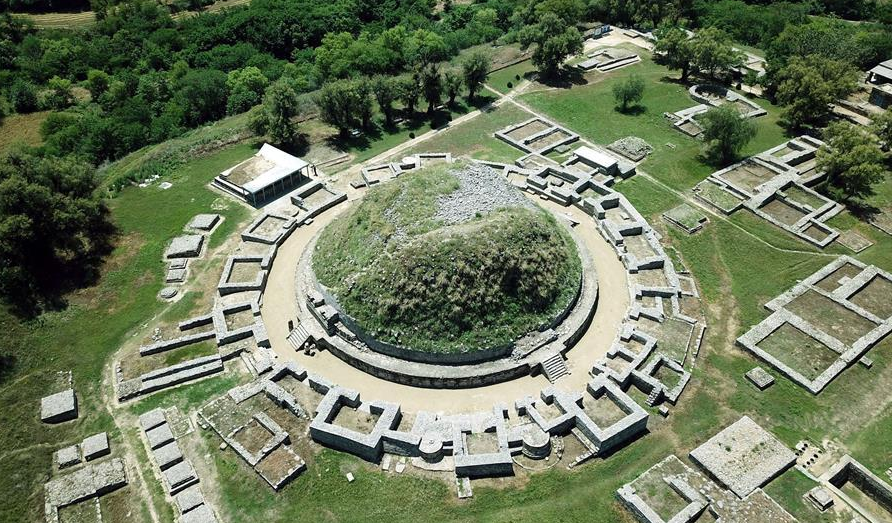

D. Architecture, the invention of Stupas

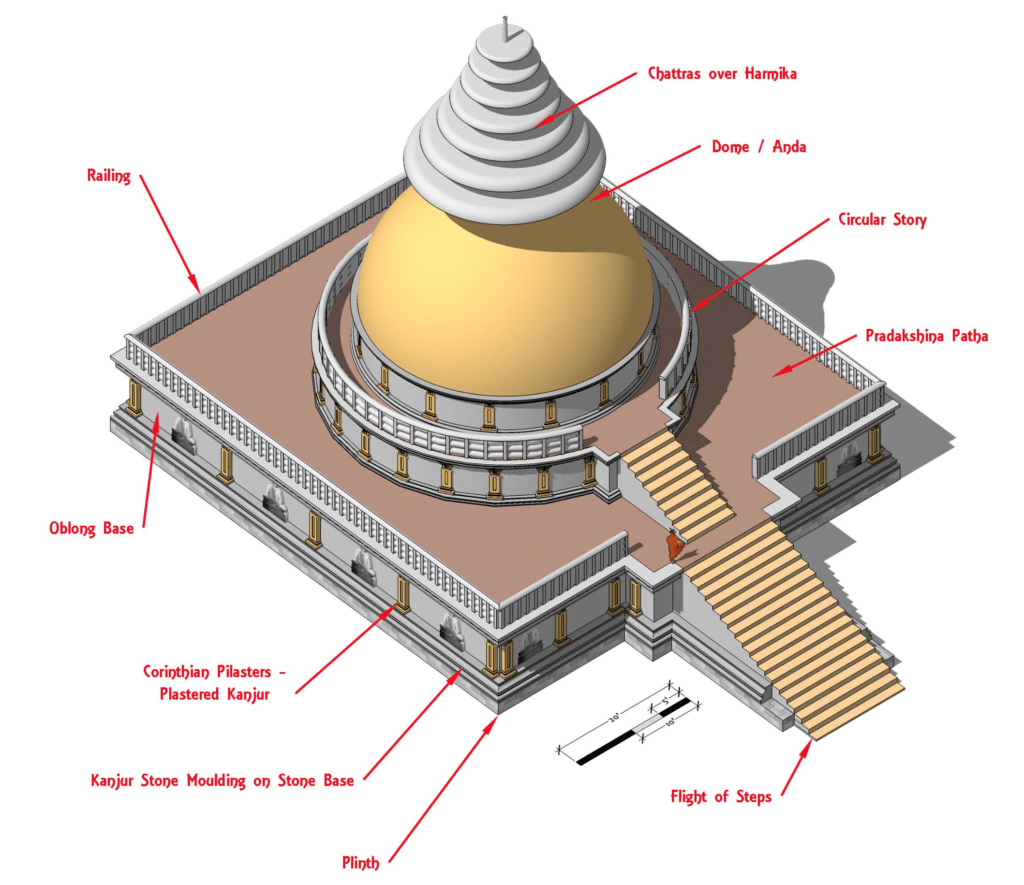

The construction of religious buildings in the form of a Buddhist stupa (reliquary) – a domed monument – began in India as memorials associated with the preservation of the sacred relics of the Buddha.

The stupas are surrounded by a balustrade which serves as a ramp for ritual circumambulation. The sacred area is accessed through doors located at the four cardinal points. Stupas were often built near much older prehistoric burial sites, notably those associated with the Indus Valley Civilization.

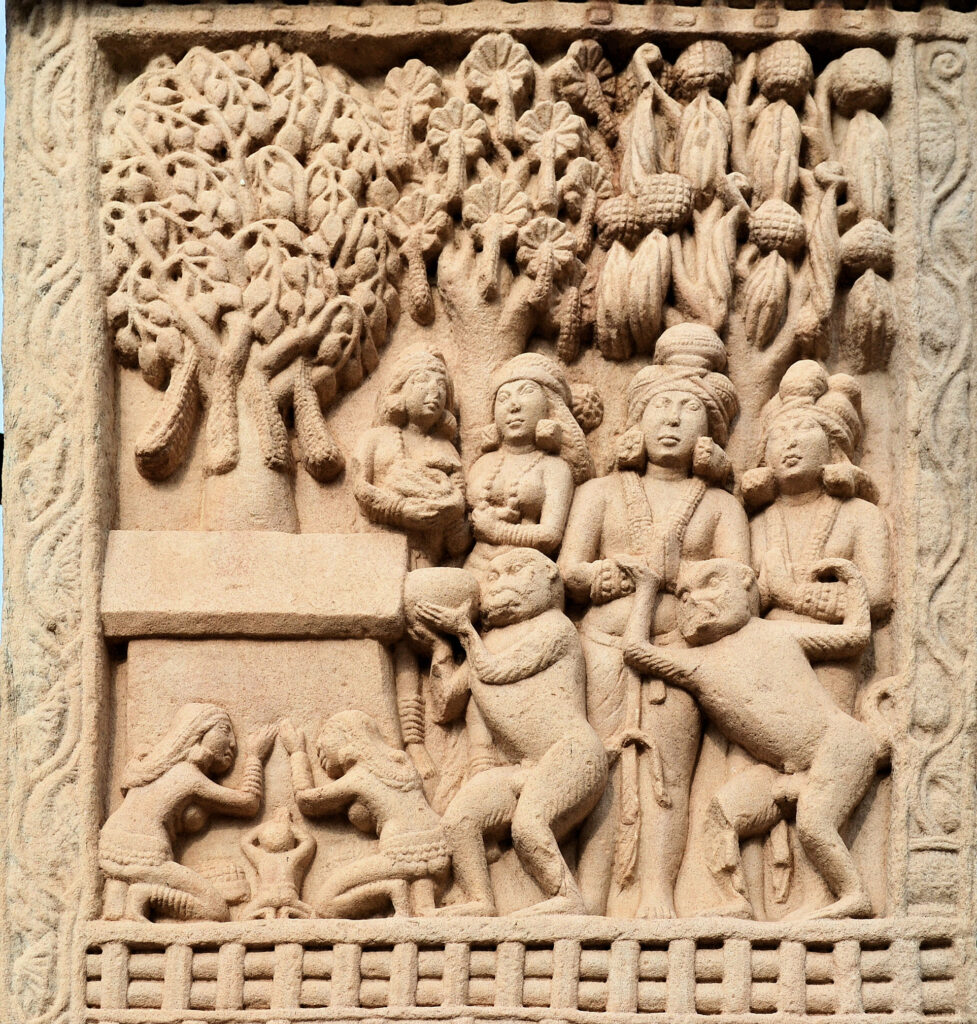

Stone gates and gates covered with sculptures were added to the stupas. The favorite themes are the events of the historical life of the Buddha, as well as his previous lives numbering 550 and described with much irony in the Jatakas. (See B)

The bas-reliefs of the stupas are like comic strips that tell us about the daily and religious life of Gandhara: wine amphorae, wine goblets (kantaros), bacchanalia, musical instruments, Greek or Indian clothing, ornaments, hairstyles arranged in style. Greek, artisans, their tools, etc. On a vase found inside a stupa, is the inscription of a Greek, Theodore, civil governor of a province in the 1st century BC, explaining in Kharosthi script how the relics were deposited in the stupa.

Many stupas are believed to date from Ashoka‘s time, such as that of Sanchi (Central India) or Kesariya (East India), where he also erected pillars with his edicts and perhaps the stupa of Bharhut (Central India), Amaravati (South-East India) or Dharmarajika (Taxila) in Gandhara (Pakistan). According to Buddhist tradition, Emperor Ashoka recovered the relics of the Buddha in older stupas and erected 84,000 stupas to distribute all these relics throughout Indian territory.

Following in the footsteps of Ashoka, Kanishka ordered the construction of the 400-foot grand stupa at Purushapura (Peshawar), which is among the tallest buildings of the ancient world.

Archaeologists who rediscovered its base in 1908-1909 estimated that this stupa had a diameter of 87 meters. Reports from Chinese pilgrims such as Xuanzang indicate that its height was around 200 meters and that it was covered in precious stones. Also, under the Kushans, huge statues of the Buddha were erected in monasteries and carved into hillsides.

Sculpture: when Buddha became man

ANICONIC PERIOD

It is important to know that in early times Buddha was never depicted in human form. For more than four centuries, his presence is simply indicated by symbolic elements such as a pair of footprints, a lotus (indicating the purity of his birth), an empty throne, an unoccupied space under a parasol, a horse without a rider or the Bodhi fig tree under which he reached nirvana. Scholars do not agree on whether these symbols represent the Buddha himself or whether they simply allude to anecdotes from his life.

END OF ANICONISM

What led Buddhists to abandon aniconic representations remains a vast mystery. Such a development is quite unique in the history of religions. Imagine Muslims suddenly promoting statues of the prophet Mohammed!

The explanations put forward so far leave us wanting more.

For some, the Buddhists wanted to appeal to a Greek clientele, but both the Greek population and Buddhism were in Gandhara long before the iconographic revolution in question. The timing doesn’t fit.

For others, practitioners, in the absence of Buddha himself, would have been desperate to find a visual focal point, be it a statue, a painting or even a few hairs… But for that purpose, the symbols they adopted (wheel, fig tree, empty chair, footprint, etc.), were sufficient.

“The Jataka of Kalingabodhi (a key script on the multiple lives of Buddha) relates the frustration of the inhabitants of Sravasti who, one day, discover that they have no one to worship when they go to the Jetavana and find the Buddha gone away on a trip. To remedy this situation, upon his return, the Buddha allowed (his disciple) Ananda to plant a bodhi fig tree in front of the (monastery of) Jetavana […] which serves as a substitute center for people’s devotions, each time that the Buddha is not in residence,”

(John Strong, Relics of the Buddha.)

Buddha, it is reported, refused to be represented in any way, fearing that idolatry would flourish.

But over time, Buddhism evolved. In Gandhara, Mahayana Buddhism flourished.

While for the old school, Siddhartha Gautama was only an enlightened man setting an example, for the new school of Mahayana Buddhism, Buddha was a (successful) attempt to personify (the omnipresent spiritual force, the ultimate and supreme principle of life) in the conception of the first Buddha of all. In short, a kind of Jesus. Consequently, just like Christ from the 5th century on, Buddha could be represented in human form and express elevated states of the soul, such as tenderness and compassion. Added to this is the fact that for Mahayana Buddhism, the objective of helping all living beings to attain nirvana and liberate them from suffering has priority over reaching nirvana on a purely personal level.

Unlike many Christian artists in the West, who, following the doxa, represented Christ suffering on the Cross (the founding event of the Christian faith and Church), the artists of Gandhara present the Buddha as a being totally detached from human pain, looking with compassion to all of humanity.

More importantly, the goal is the elimination of suffering in all humans, compassion is not a passive notion for Buddhists. It is not just empathy but rather an empathetic altruism that actively strives to free others from suffering, an act of kindness imbued with both wisdom and love.

DIFFERENCES IN FORM, DIFFERENCES IN CONTENT

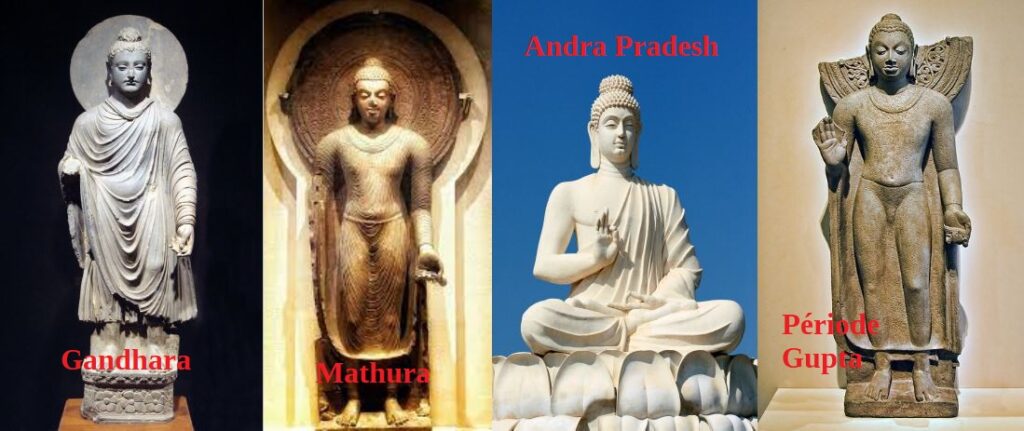

Before discussing their differences, let’s simply distinguish four types of Buddha representations, among many others:

- The « Greco-Buddhist » Gandhara school, produced in the region between Hadda (Afghanistan) and Taxila (Punjab), via Peshawar (Pakistan);

- The « Indo-Buddhist » school of Mathura;

- The Andra Pradesh school in southern India;

- The school of the Gupta period (3rd to 5th centuries).

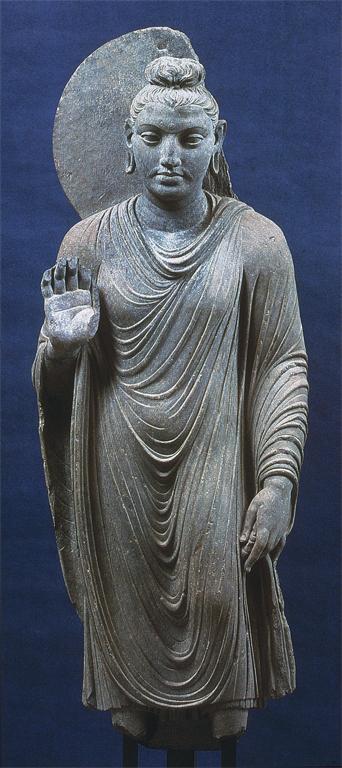

1. Greco-Buddhist in Gandhara

The term « Greco-Buddhist » refers to archaeologist Alfred Foucher’s (1865-1952) 1905 Sorbonne thesis on Gandhara art.

As André Malraux (1901-1976) wrote in Les Voix du silence in 1951, Greco-Buddhist art is the encounter between Hellenism and Buddhism. Instead of saying that art from Greece had metamorphosed into Buddhist art, as Malraux put it, I think that in Gandhara, it was Buddhist art that appropriated the best of Indian, Greek and steppe aesthetics.

However, Foucher was right to insist, against his English friends, that the influence was Hellenic and not Roman. For their part, with India emancipating itself from the British Empire, Indian scholars tried to validate the thesis of an indigenous creation of the Buddha image, contrasting the Gandhara style, which Foucher wanted to be Greco-Buddhist, with the style of Mathura, in the Delhi region, also part of the Kushan empire, and seen by some as contemporary, even if it is far less prolix than Gandhara art.

Gandhara art really took off during the Kushan period, particularly under the reign of King Kanishka.

Thousands of images were produced and spread throughout the region, from portable Buddhas to monumental statues in sacred places of worship.

In Gandhara, Buddha is depicted very realistically as a beautiful person, often a young man or even a woman. The spiritual charge is such that gender is no longer essential. We don’t know whether these are beautiful portraits taken from life, or pure figments of the artist’s imagination.

Buddha is often shown in meditative posture to evoke the moment when he reaches nirvana.

Crowned with a halo, his face serious or smiling, his eyes half-closed, he radiates light. Full of serenity, he embodies detachment, concentration, wisdom and benevolence.

His hair in a bun (the ushnisha) at the top of his head indicates that he is gifted with supramundane knowledge. The black dot between his eyes symbolizes the third eye, the eye of enlightenment.

In some sculptures, this cavity contains a crystal pearl, symbolizing radiant light. The earlobes are elongated to accommodate the heavy jewelry once worn by the young prince Siddhartha during his princely youth.

The positioning of the hands, as in the rest of Indian art, responds to codes. These include the « abhayamudra », the gesture of reassurance, with the palm facing outwards; the « varamudra », symbolizing giving, with the hand hanging open and the arm half-bent; or the « vitarkamudra », symbolizing argumentation, with the hand raised to chest height, half-closed, palm forward, index finger curved towards the thumb.

At Gandhara, Buddha is dressed in a monastic cloak covering both shoulders. The fabric is neither cut nor sewn, but simply draped in a Greek style around the body. The barely stylized folds follow natural volumes.

2. The School of Mathura

King Kanishka, while supporting all religions he found worthy, did not hide his preference for Buddhism. In practice, he encouraged both the Gandhara school of Greco-Buddhist art (in Taxila and Hadda) and the Indo-Buddhist school (in Mathura, closer to South Asia).

As one can see, in Mathura, local artists produced a very different type of Buddha. His body is dilated by the sacred breath (prana) and his monastic robe is draped in the Indian style in a way that bares the right shoulder.

Mathura artists used the image of statues of the pre-Buddhist yaksha cults of nature as models for their productions. The body position is often more static and without contrapposto. Clothing can be so thin that the lower parts of the anatomy make a showing and detract the viewers’ concentration on Buddha’s spiritual nature.

3. School of Andhra Pradesh

A third type of influential Buddha type developed in Andhra Pradesh in southern India, where images of large proportions, with serious, unsmiling faces, are dressed in robes that also reveal the left shoulder. These southern sites served as artistic inspiration for the Buddhist land of Sri Lanka, at the southern tip of India, and Sri Lankan monks visited them regularly. Many statues in this style spread from there throughout Southeast Asia.

4. The Gupta period

The Gupta period, from the 4th to 6th centuries AD, in northern India, often referred to as the Golden Age, is believed to have synthesized the three schools. In seeking an “ideal” image for mass production, mannerism took over.

The Gupta Buddhas have their hair arranged in small individual curls, and the robes have a network of strings to suggest the folds of the draperies (as at Mathura).

With their downward gaze and spiritual aura, the Gupta Buddhas became the model for future generations of artists, whether in post-Gupta and Pala India or Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia.

Metal Gupta statues of the Buddha were also carried by pilgrims along the Silk Road to China and Korea where Confucius literati sometimes felt threatened by the rise of Buddhism.

But the Buddhas of Gandhara are very special and truly unique. They are distinct examples escaping any codification and standards. They were made by artists with a high spirituality, exploring new frontiers of beauty, movement, and freedom, and not objects produced to satisfy an emerging market.

As early as the first century BC, local artists, who had worked with perishable materials such as brick, wood, thatch, and bamboo, adopted stone on a very large scale. The new material used was mainly a light to dark colour gray shale stone (in the Kabul River valley and Peshawar region). Later periods are characterized by the use of stucco and clay (a specialty of Hadda).

The origin of Buddha’s beautiful image is a subject Pakistanis, Indians, Afghans, and Europeans like to wrangle about today. All claim to have been the main sponsors and authors of the « Miracle of Gandhara », but few ask how it came about. The techniques used for the sculptures and coins of Gandhara are very close to those of Greece. Questions about whether they were created by traveling Greek sculptors or by the local artists they trained are up for discussion. Who did what and when remains an open question, but does it really matter?

When Asia meets Greece

Let’s take a look at some of the artistic expressions that testify to the beautiful encounter between Hellenic culture and Central Asian and Indian local cultures.

A. Kushan Coins

A gold coin dating from 120 AD shows the king dressed in a heavy Kushan cloak and long boots, with flames emanating from the shoulders, holding a standard in his left hand and making a sacrifice on an altar with the legend in Greek characters: “King of kings, Kanishka the Kushan”.

The reverse of the same coin represents a standing Buddha, in Greek costume, making the “fear nothing” (abhaya mudra) gesture with his right hand and holding a fold of his robe in his left hand. The legend in Greek characters now reads ΒΟΔΔΟ (Boddo), for the Buddha.

B. Bimaran Reliquary

A truly classical theme in the repertoire of any artist of the time consists of showing Buddha surrounded, welcomed, and protected by the deities of other beliefs and more ancient religions.

The oldest such representation known to date appears on a reliquary found in the Bimaran stupa in northwestern Gandhara. On this small gold urn, known as the Bimaran casket, generally dated 50-60 AD, there appears, inside vaulted niches of Greco-Roman architecture, a “Hellenistic” representation of the Buddha (hairstyle, contrapposto, prestigeous wrap, etc.), surrounded by the Indian deities Brahma and Shakra.

Just like Ashoka, the almost secular Kanishka, did not intend to reign against but with all and “above” all religions.

Thus, on occasion, the Greek deities, represented on coins (Zeus, Apollo, Heracles, Athena…), rub shoulders with the deities of Vedism, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism.

Another example of this form of inclusiveness, is the cave and the temple carved into the rock in Ellora, in central India, with representatives of the three religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism) rubbing shoulders in the center.

C. The Hadda Triad

Another exquisite example of this Gandharan art is a sculptural group known as the Triad of Hadda, excavated at Tapa Shotor, a large Sarvastivadin monastery near Hadda in Afghanistan, dating from the 2nd century AD.

To give an idea of its vast artistic production, it is worthy of note that some 23,000 Greco-Buddhist sculptures, in clay and plaster, were unearthed in Hadda alone between the 1930s and 1970s.

The site, heavily damaged during recent wars, had beautiful statues, including a seated Buddha (image above), dressed in a Greek chlamys (white coat), with curly hair, accompanied by Heracles and Tyche (Greek goddess of fortune and of prosperity), dressed in a chiton (Greek dress), holding a cornucopia.

Here, the only adaptation to local traditions of Greek iconography is the fact that Heracles no longer holds in his hand his usual club but the thunderbolt of Vajrapani (from the Sanskrit word which means “thunderbolt” (vajra) and « in the hand » (pani), one of the first three protective deities surrounding the Buddha.

Another statue recalls the portrait of Alexander the Great. Unfortunately, only photographs remain of this sculptural ensemble, .

According to Afghan archaeologist Zemaryalai Tarzi, the Tapa Shotor Monastery, with its clay sculptures dating back to the 2nd century AD, represents the « missing link » between the Hellenistic art of Bactria and the later stucco sculptures found at Hadda, generally dating back to between the 3rd – 4th century AD. Traditionally, the influx of master artists of Hellenistic art has been attributed to the migration of Greek populations from the Greco-Bactrian cities of Ai-Khanoum and Takht-I-Sangin (Northern Afghanistan).

Tarzi suggests that Greek populations settled in the plains of Jalalabad, which included Hadda, around the Hellenistic city of Dionysopolis (Nagara), and were responsible for the Buddhist creations of Tapa Shotor in the 2nd century AD.

The Greek colonists who remained in Gandhara (the “Yavanas” or Ionians) after the departure of Alexander, either by choice or as populations condemned to exile by Athens, greatly embellished the artistic expressions of their new spirituality.

Offering freshness, poetry, and a spectacularly modern sense of movement, the first Buddhist artists of Gandhara, capturing instants of « motion-change » allowing the human mind to apprehend a potential leap towards perfection, are an invaluable contribution to all human culture. Isn’t it high time that this magnificent work be recognized?

D. Take the Earth as your Witness

A magnificent sculpture, now on exhibition at the Cleveland Museum, depicts one of the narratives of the Buddha’s struggle to achieve nirvana. The bodhi fig tree under which the Buddha achieved enlightenment is at the center of the composition. It has been revered since ancient times by local villagers, as it is known to be the residence of a deity of nature. The altar itself is covered with kusha grass used as part of sacrificial offerings.

After sitting in meditation for seven days under his tree, approximately 2,500 years ago, the Buddha was challenged by nightmarish demons (Maras) who questioned the authenticity of his accomplishment.

Mara, who stands on the right in an arrogant swaying position among his beautiful daughters, tries everything to prevent Buddha from succeeding. He threatens him and encourages his daughters to seduce him. Innocently, he asks Buddha if he is sure he can find someone to testify that he has truly reached nirvana. In response to the challenge launched by Mara, the Buddha then touches the earth and calls it to witness.

According to mythology, when he touched the ground, the young Earth Goddess rose out of the ground and started to wring the cool waters of detachment out of her hair to drown Mara. On the sculpture, one can see the Earth goddess, very small, at the base of the altar, kneeling before Buddha in reverence. She also took a human form when rising from the ground. The old religions intervened here to defend and protect the new one, that of Buddha.

The Indians who converted to Buddhism also seem to have missed the old gods and goddesses of their pantheon; hence, they too include their deities above the head of Buddha or next to it, such as the Vedic god Indra, for example.

E. All Bodhisattvas?

Finally, to conclude this section on sculpture, a few words about the bodhisattva, a very interesting figure that has emerged from the Buddhist imagination to make Buddhist spirituality accessible to ordinary people.

Animated by altruism and obeying the disciplines intended for bodhisattvas, a bodhisattva must compassionately first help all other sentient beings to awaken, even by delaying his own nirwana!

Bodhisattvas are distinguished by great spiritual qualities such as the « four divine abodes »:

- loving-kindness (Maitri);

- compassion (karuna);

- empathic joy (mudita);

- equanimity (upekṣa).

The other various perfections (paramitas) of the Bodhisattva include prajnaparamita (« transcendent knowledge » or the « perfection of wisdom ») and skillful means (upaya).

Spiritually advanced Bodhisattva such as Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya, and Manjushri were widely revered in the Mahayana Buddhist world and are believed to possess great power which they use to help all living beings.

A wonderful example of the Bodhisattva concept can be seen at the Dallas Museum of Art (above). This terracotta sculpture represents a “thinking Bodhisattva” from the Hadda region in Afghanistan and is a typical production from Gandhara.

With very few visual elements, the artist produces here a huge effect.

The pillars of his large Bodhisattva chair are lions with slightly outlandish eyes, an allegorical representation of those passions that make us suffer and which are kept under sagacious control by the highly reflective effort of the heroic Bodhisattva on the chair at the center of the piece.

Buddhism today

Paradoxically, since the 12th century AD Buddhism, as a religion, has almost ceased to exist in its own birthplace of India.

A fine example of the incessant struggle of the best Indian minds for emancipation was in 1956 when nearly half a million « untouchables » converted to Buddhism under the leadership of the political leader who headed the committee responsible for drafting the Constitution of India, the social reformer B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956), and the Indian Prime Minister and leader of the Congress Party Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), himself from a Brahmin family.

In June of the same year, the UNESCO Courier dedicated its edition to “25 centuries of Buddhist art and culture”.

In India, the two statesmen orchestrated a year-long celebration honoring “2,500 years of Buddhism« , not to resurrect an ancient faith per se, but to claim status as the birthplace of Buddhism: this ancient religion that restores to the world an image advocating non-violence and pacifism.

Later, on November 9, 1961, during his state visit to the White House, Indian Prime Minister Nehru presented a Buddhist sculpture to President John F. Kennedy.

The West’s gaping ignorance about the real nature of Buddhism and Nehru’s “non-alignment” would eventually turn decolonization into bloody conflicts, such as in Vietnam, where close to 80 percent of the population was Buddhist, but where 80 percent of the land was owned by Catholic interests considered more robust to resist communist expansionism.

Mahatma Gandhi, like many Hindus, listened to Buddha’s message. For Hindus, Buddhism was just “another form of Hinduism”, and its justified social criticism, therefore, came “from within Hinduism”.

A point of view that Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru did not share. Deeply troubled by certain intrinsic features of Hinduism, such as ritualism and the caste system, Nehru could not place Buddhism, which abhorred these institutions, in the same category. Nehru was profoundly influenced by Buddhism. He even named his daughter Indira Priyadashini (the future Prime Minister Indira Gandhi), because « Priyadarshi » was the name adopted by the great emperor Ashoka after he became a Buddhist prince of peace!

Nehru was instrumental in making the Ashoka Chakra (the Buddhist wheel incorporated into the national flag) the symbol of India. Every time he visited Sri Lanka, he visited the Buddha statue at Anuradhapura.

Nehru, who continually urged superstitious and ritualistic Indians to cultivate a « scientific temperament » and bring India into the era of the atomic age, was naturally attracted to the rationalism advocated by the Buddha.

Nehru argued:

“Buddha did not ask anyone to believe in anything other than what could be proven by experience and test. All he wanted was for men to seek the truth and not accept anything on the faith of another man, even if it was the Buddha himself. It seems to me that this is the essence of his message” … adding, “Buddha dared to accept the truth and not to accept anything on the faith of another (…) Buddha had the courage to condemn popular religion, from superstition, ritual and priesthood, to all interests connected with them. He also condemned metaphysical and theological perspectives, miracles, revelations, and relationships with the supernatural. It appeals to logic, reason, and experience; he emphasizes ethics (…) His whole approach is like the breath of fresh mountain air after the stale air of metaphysical speculation (…) Buddha did not condemn castes directly, but in his own order, he did not recognize them, and there is no doubt that his whole attitude and activity weakened the caste system.”

The influence of the Buddha was manifested in Nehru’s foreign policy. This policy was motivated by a desire for peace, international harmony, and mutual respect. It aimed to resolve conflicts by peaceful methods.

On November 28, 1956, Nehru stated:

“It is mainly because of the Buddha’s message that we can view our problems in the right perspective and move away from conflicts and competition in the field of strife, violence and hatred « .

Visibly inspired by Buddhist precepts, the concepts of « non-alignment » and Nehru’s « Treaty of Panchsheel », commonly referred to as the « Treaty of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence », were formally enunciated for the first time in the agreement on trade and relations between the Tibetan region of China and India, signed on 29th April 1954.

This agreement stipulated, in its preamble, that the two governments,

“…have decided to conclude this Agreement based on the following principles: Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, Mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence”.

Nehru, at the International Buddhist Cultural Conference held on 29th November 1952, in Sanchi, the very city where Kanishka had started building the highest stupa of antiquity, specified:

“The message that Buddha conveyed 2,500 years ago enlightened not only India and Asia but the whole world. The question that inevitably arises is: To what extent can the Buddha’s great message be applied to today’s world? Maybe yes, maybe no, but I know that if we follow the principles set forth by the Buddha, we will gain peace and tranquility for the world.”

On 3rd October 1960, Nehru addressed the United Nations General Assembly when he said,

“In the distant past, a great son of India, the Buddha, said that the only true victory was when all were equally victorious, and no one was defeated. In today’s world, this is the only concrete victory; any other path leads to disaster.”

Nehru tried his best to apply the teachings of the Buddha in managing India’s internal affairs. His belief is that social change can only be achieved through the broadest social consensus that stems from the influence of the Buddha, Ashoka, and Gandhi.

In his speech of 15th August 15, 1956, on the occasion of Independence Day, Nehru sets out the challenges to be met: “We are proud that the soil on which we were born has produced great souls like Gautama Buddha and Gandhi. Let us refresh our memory once again and pay homage to Gautama Buddha and Gandhi, and to the great souls who, like them, shaped this country. Let us follow the path they showed us with strength, determination, and cooperation.”

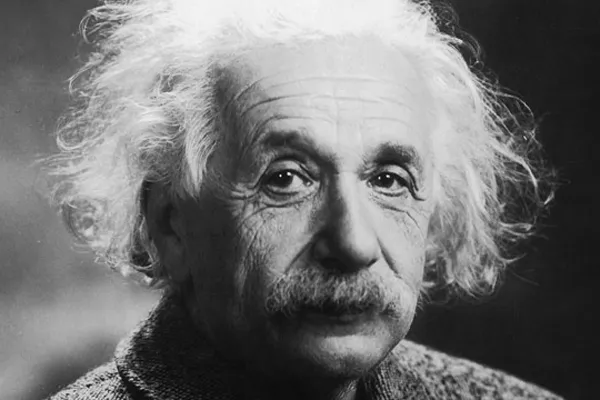

Science and religion, Albert Einstein and Buddha

To conclude, here are some quotes of Albert Einstein discussing the relation between science and religion where he underlines the importance of Buddha:

Cosmic religious feeling

« There is a third state of religious experience…which I will call cosmic religious feeling. It is very difficult to elucidate this feeling to anyone who is entirely without it, especially as there is no anthropomorphic conception of God corresponding to it. The individual feels the nothingness of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvellous order which reveal themselves both in nature and in the world of thought. He looks upon individual existence as a sort of prison and wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole.

The beginnings of cosmic religious feeling already appear at an early stage of development—e.g., in many of the Psalms of David and in some of the Prophets.