Catégorie : Etudes Renaissance

- Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa: Le défi que nous lance la modernité de la Civilisation de l’Indus (FR en ligne);

- Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa : The challenging modernity of the Indus Valley Civilization (EN online);

- La Route de la soie maritime, une histoire de 1001 coopérations (FR en ligne);

- The Maritime Silk Road, a History of 1001 cooperations (EN online);

- Afghanistan: le pays des 1000 cités d’or et Aï Khanoum (FR en ligne)

- Afghanistan: the Land of a 1000 Golden Cities and Aï-Khanoum (EN online);

- Le « miracle » du Gandhara, lorsque Bouddha s’est fait homme (FR en ligne);

- The « miracle » of Gandhara, when Buddha turned himself into man (EN online);

- Derrière les chevaux célestes chinois, la science terrestre (FR en ligne);

- The Earthly Science behind China’s Heavenly Horsepower (EN online)

- Et l’Homme créa l’acier… (FR en ligne);

- Portraits du Fayoum: un regard de l’au-delà (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio);

- La pratique ancestrale d’annulation des dettes (FR en ligne).

- The Ancient Practice of Debt Cancelation (EN online)

- Bagdad, Damas, Cordoue, creuset d’une civilisation universelle (FR online).

- Mutazilisme et astronomie arabe, deux étoiles brillantes au firmament de la civilisation (FR en ligne). (EN online version).

- Qanâts perses et Civilisation des eaux cachées (FR en ligne). (EN online version).

- Renaissance africaine: la splendeurs des royaumes d’Ifè et du Bénin (FR en ligne) + (EN online)

- Sur la peinture chinoise et son influence en Occident (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- L’invention de la perspective FR pdf (Fusion) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- La révolution du grec ancien, Platon et la Renaissance (FR en ligne)

- The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance (EN online).

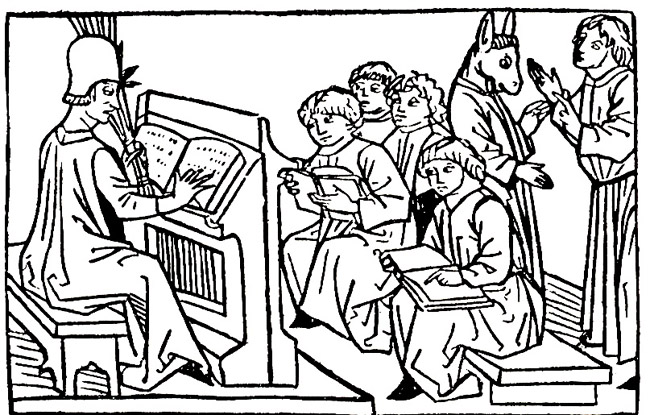

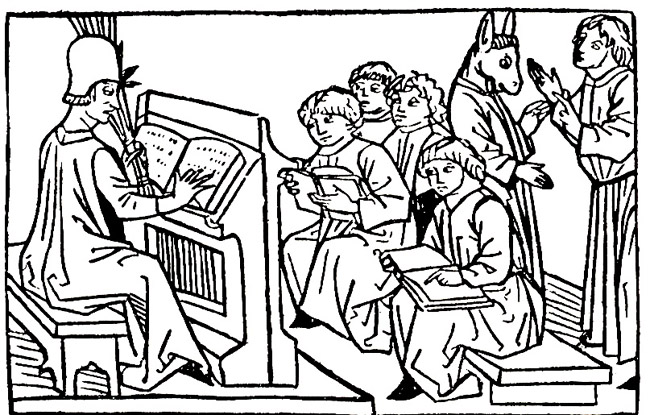

- Les Frères de la vie commune et la Renaissance du nord (FR en ligne)

- Moderne Devotie en Broeders van het Gemene Leven, bakermat van het humanisme (NL online)

- Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life, the cradle of humanism in the North (EN online)

- 1405: l’amiral Zheng et les expéditions maritimes chinoises (FR en ligne)

- Zhang He and the Chinese Maritime Expeditions (EN online)

- Jan van Eyck, la beauté comme prégustation de la sagesse divine (FR en ligne) + EN on line.

- Jan Van Eyck, un peintre flamand dans l’optique arabe (FR en ligne)

- Jan Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics (EN online)

- Rogier Van der Weyden, maître de la compassion (FR pdf)

- Comment Jacques Cœur a mis fin à la Guerre de Cent Ans (FR en ligne)

- How Jacques Coeur put an end to the Hundred Years War (EN online);

- Hugo van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne (FR en ligne)

- A la découverte d’un tableau (FR en ligne)

- Avicenne, Ghiberti, leur rôle dans l’invention de la perspective à la Renaissance (FR en ligne) et EN online.

- ENTRETIEN Omar Merzoug: Avicenne ou l’islam des lumières (FR en ligne). (EN pdf file).

- Les secrets du dôme de Florence (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Schiller Institute archive website) + DE pdf (Neue Solidarität).

- Le Dome de Brunelleschi, un défi, un scandale, un exploit (Hors Série Beaux Arts Magazine, 2013)

- L’œuf sans ombre de Piero della Francesca (FR en ligne)

- The Egg Without a Shadow of Piero della Francesca (EN online pdf)

- Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio et l’art du commandement militaire (FR en ligne) et EN online.

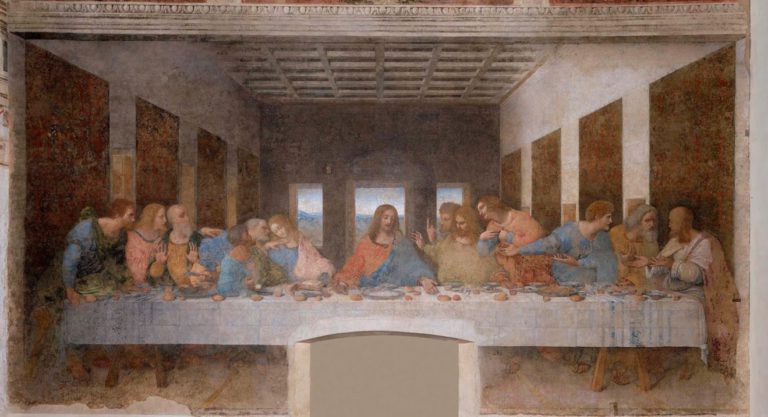

- La Cène de Léonard, une leçon de métaphysique (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- Léonard de Vinci : peintre de mouvement (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- La Vierge aux rochers, l’erreur fantastique de Léonard (FR en ligne).

- Romorantin et Léonard ou l’invention de la ville moderne (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Executive Intelligence Review) + DE pdf (Neue Solidarität) + IT pdf (Movisol website).

- L’Homme de Vitruve de Léonard de Vinci (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- Léonard en résonance avec la peinture traditionnelle chinoise — entretien avec Le Quotidien du Peuple. (en ligne: texte chinois suivi des traductions FR + EN).

- Raphaël, entre mythe et réalité (FR pdf + EN pdf)

- Raphaël 1520-2020 : ce que nous apprend « L’Ecole d’Athènes » (FR en ligne).

- Raphael 1520-2020: What Humanity can learn from The School of Athens (EN online);

- Jacob Fugger « The Rich », father of financial fascism (EN online);

- Jacob Fugger « Le Riche », père du fascisme financier (FR en ligne);

- Comment la folie d’Erasme sauva notre civilisation (FR en ligne) + NL pdf (Agora Erasmus) + EN pdf (Schiller Institute Archive Website) + DE pdf (Neue Solidarität).

- Hoe Erasmus zotheid onze beschaving redde (NL pdf online);

- Le rêve d’Erasme: le Collège des Trois Langues de Louvain (FR en ligne)

- Erasmus‘ dream: the Leuven Three Language College (EN online)

- ENTRETIEN: Jan Papy: Erasme, le grec et la Renaissance des sciences (FR en ligne)

- Dirk Martens, l’imprimeur d’Erasme qui diffusa le livre de poche (FR en ligne).

- 1512-2012 : Mercator et Frisius, des cosmographes aux cosmonautes + NL pdf (Agora Erasmus) + EN pdf (Schiller Institute Archive Website).

- La nef des fous de Sébastian Brant (FR en ligne), un livre d’une grande actualité !

- Avec Jérôme Bosch sur la trace du Sublime (FR en ligne);

- With Hieronymus Bosch, On the Track of the Sublime (EN, pdf online);

- Quinten Matsys en Da Vinci: dageraad van louterend gelach en creativiteit (NL online);

- Quinten Matsys et Léonard — L’aube d’une ère de rire et de créativité (FR en ligne);

- Quinten Matsys and Leonardo — The Dawn of the Age of Laugher and Creativity, (EN online);

- Квентин Массейс и Леонардо: на заре смехотворчества (RU pdf)

- Joachim Patinir et l’invention du paysage en peinture (FR en ligne).

- Joachim Patinir and the invention of landscape painting (EN online)

- Le Landjuweel d’Anvers de 1561 — Faire de l’art une arme pour la paix (FR en ligne)

- The 1561 Landjuweel of Antwerp that made art a weapon for Peace (EN online)

- Exposition de Lille : ce que nous apprennent les fabuleux paysages flamands (FR en ligne).

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel‘s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel‘s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- Pieter Bruegel l’ancien, commentateur politique et pacifiste (FR en ligne).

- Albrecht Dürer contre la mélancolie néo-platonicienne + EN pdf.

- How neo-Platonism gave Plato a bad name (EN pdf).

- La leçon d’économie de Shakespeare (FR en ligne);

- Shakespeare‘s lesson in Economics (EN online) ;

- Le combat inspirant d’Henri IV et de Sully + EN pdf (Schiller Institute Archives Website).

- La paix de Westphalie, une réorganisation financière mondiale (FR en ligne + EN online)

- Rembrandt, un bâtisseur de nations FR pdf (Nouvelle Solidarité).

- Rembrandt et la lumière d’Agapè (FR en ligne) : Rembrandt et Comenius pendant la guerre de trente ans.

- Rembrandt and the Light of Agapè (EN online)

- Rembrandt : 400 ans et toujours jeune ! (FR en ligne).

- Rembrandt: 400 years old and still young ! (EN online).

- Rembrandt et la figure du Christ (FR en ligne) + EN pdf + DE pdf.

- Le portrait d’Anslo de Rembrandt, la science de « peindre l’invisible » (FR en ligne);

- Rembrandt’s Anslo, the science of « painting the invisible » EN online;

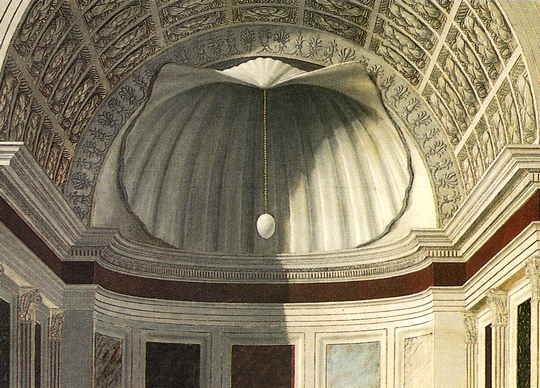

- Vermeer, Metsu, Ter Borch, Hals, l’éloge du quotidien. FR pdf (Nouvelle Solidarité)

- Entre l’Europe et la Chine: le rôle du jésuite flamand Ferdinand Verbiest. (FR en ligne).

- Avec Leibniz et Kondiaronk, re-créer un monde sans oligarchie (FR en ligne)

- With Leibniz and Kondiaronk, re-inventing a world without oligarchy (EN online);

- Francisco Goya et la révolution américaine (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio) + ES pdf.

- Karel Vereycken et Karl Lestar : El Degüello de Goya (livre ES)

- Beethoven et le Meeresstille: initiation à une culture de la découverte (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Schiller Institute Archive Website) + DE pdf (Neue Solidarität).

- Enseignement mutuel: curiosité historique ou piste d’avenir? (FR en ligne);

- Mutual Tuition: an historical curiosity or a promise of a better future? (EN online)

- Le combat républicain de David d’Angers, la statue de Gutenberg à Strasbourg (FR en ligne)

- The Republican struggle of David d’Angers and the Gutenberg statue in Strasbourg (EN online)

- Hippolyte Carnot, père de l’éducation républicaine moderne (FR en ligne)

- Hippolyte Carnot, father of modern republican education (EN online)

- Enquête sur les origines de l’art contemporain (FR en ligne) + EN pdf.

- On the Origins of Modern Art, the Question of Symbolism (EN online)

- Victor Hugo et le colosse (FR en ligne);

- Victor Hugo and the awakening of the colossus (EN online);

- Avec le peintre James Ensor, arrachons le masque à l’oligarchie (FR en ligne);

- How James Ensor ripped off the mask of the Oligarchy (EN online)

- Les racines symbolistes des killer games (FR en ligne).

- Neo-Platonism and Huxley’s Doors of Perception (EN online);

- L’art moderne de la CIA pour combattre le communisme (FR en ligne).

- The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) – How the CIA « weaponized » Moder Art (EN online).

- M. Hockney, le génie artistique n’est pas une illusion optique ! FR pdf (Fusion) + DE pdf + EN pdf (21st Science & Technology).

- Gérard Garouste et La Source (FR en ligne).

- Rembrandt’s oil painting is back… in China ! (EN online).

- Ce que nous apprend l’expérience Trou-dans-le-Mur de Sugata Mitra (FR en ligne)

- The hidden lesson behing Sugata Mitra‘s Hole-in-the-Wall experience (EN online)

- La défense du patrimoine culturel de l’Humanité, clé de la paix mondiale (FR en ligne)

- Empathy, Sympathy, Compassion — World Heritage Key to World Peace (EN online)

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Beethovens Meeresstille: Reise in eine Kultur des Entdeckens

Tags: artkarel, Beethoven, entdeckung, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Meeresstille, Musik, Reise, renaissance, Schubert, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Beethoven’s Meeresstille: voyage to a Culture of Discovery

Tags: artkarel, Beethoven, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Meeresstille Schubert, music, renaissance, Tranquility, Vereycken, water

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Dürer’s Fight Against Neo-Platonic Melancholy

Tags: acedia, Aristotle, artkarel, Ficino, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Melancholy, Mirandola, Pirckheimer, Plato, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Bookreview: Bruegel’s Mill and Way to Calvary

Tags: artkarel, Bruegel, cross, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Michael Gibson, mill, peinture, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Goya and the American Revolution

Tags: American Revolution, Amigos del Pais, artkarel, Benjamin Franklin, Cabarrus, Colbert, goya, Jovellanos, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Moratin, national bank, painting, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Rembrandt und das Gesicht Jesu

Tags: amsterdam, artkarel, Gesicht, gravure, Jesu, Jüden, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Rembrandt, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus

Tags: amsterdam, artkarel, dessin, Face of Jesus, Jesus, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Netherlands, Rembrandt, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur INTERVIEW — Michael Gibson: ‘For Bruegel, his world is vast’

Tags: artkarel, Bosch, Bruegel, Erasmus, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Landjuweel, painting, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Leonardo da Vinci, painter of movement

Tags: artkarel, Daniel Arrasse, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Leonardo, Movement, Painter of movement, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Rembrandt’s Anslo, the science of « painting the invisible » (Russian)

Tags: Anslo, artkarel, Karel, Karel Vereycken, nail, Rembrandt, renaissance, Vereycken, voice, Vondel

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Matsys and Leonardo — The Age of Laughter and Creativity (Russian)

Tags: antwerpen, artkarel, Cranach, Dürer, Erasmus, humanism, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Landjuweel, Quinten Matsys, renaissance, Satire, Thomas More, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur The Egg without a Shadow of Piero della Francesca (Russian)

Tags: artkarel, cusanus, egg, Egg without a shadow, geometry, Karel, Karel Vereycken, perspective, Piero della Francesca, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur 1512-2012: From Cosmography to the Cosmonauts, Mercator and Frisius

Tags: artkarel, cartography, Erasmus, Frisius, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Leuven, Mercator, projective geometry, renaissance, stars, Vereycken