Étiquette : agriculture

Horse-power, the Earthly Science behind China’s “Heavenly Horses”

Indicating the major role horses have played in the history of mankind, the fact that still today, when people talk about the engine of their cars, they use the term “horsepower” (hp) to indicate how much “work” the engine is capable of.

In a lecture on hydro-infrastructure in Kabul, Afghanistan, I recently used the domestication of the horse as an example of what one should understand when we talk about moving from a “lower” to a “higher infrastructure platform”.

The history of mankind completely changed with the domestication of the horse. Things considered “impossible” before the domestication of the horse became the “new normal”. How and when horses became domesticated has been disputed. Although horses appear in Paleolithic cave art as early as 36,000 BC (Chauvet cave, France), these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

Zoologists define « domestication » as human control over breeding, which can be detected in ancient skeletal samples by changes in the size and variability of ancient horse populations. Other researchers look at the broader evidence, including skeletal and dental evidence of working activity; weapons, art, and spiritual artifacts; and lifestyle patterns of human cultures. There is evidence that horses were kept as a source of meat and milk before they were trained as working animals.

In India, close to Bopal, the “Bhimbetka rock shelters”, which are the oldest known rock art of the country, figures dance and hunting scenes from the Stone Age as well as of warriors on horseback from a later time (10 000 BC).

Horses were a late addition to the barnyard. Dogs were domesticated 15,000 years ago; sheep, pigs and cattle, about 8,000 to 11,000 years ago. But clear evidence of horse domestication doesn’t appear in the archaeological record until about 5,500 years ago.

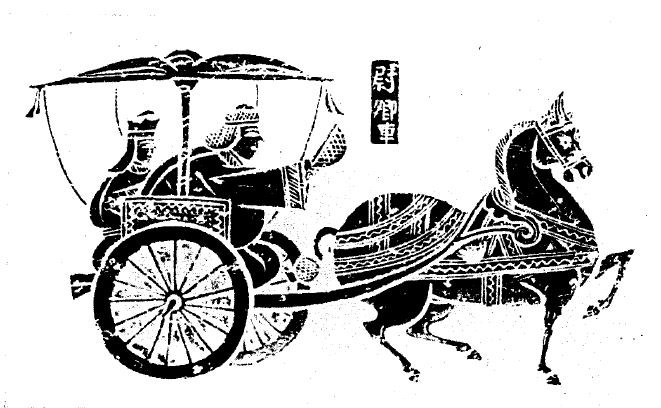

The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials. The earliest true chariots known are from around 2,000 BC, in burials of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in modern Russia in a cluster along the upper Tobol river, southeast of Magnitogorsk.

They contain spoke-wheeled chariots drawn by teams of two horses.

Kazakhstan and Ukraine

Up till recently, it was thought that the most common horse used today was a descendant of the horses domesticated by the Botai culture living in the steppes of the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan, around 3500 BC.

Recent genetic research points to the fact that the Botai horses were the forefathers of the Przewalski horse, a species that nearly disappeared.

Our common horse, the Equus ferus caballus, genetic research says, has been domesticated 4,200 years ago in Ukraine, in an area known as the Volga-Don, in the Pontic-Caspian steppe region of Western Eurasia, around 2,200 BC.

As these horses were domesticated, they were regularly interbred with wild horses.

Interesting in this respect, is the fact that according to the “Kurgan” or “steppe hypothesis”, most Indo-European languages spread from the same region throughout Europe and parts of Asia.

It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of what some call the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan, meaning tumulus or burial mound.

Tea Road, Horse Road or Silk Road?

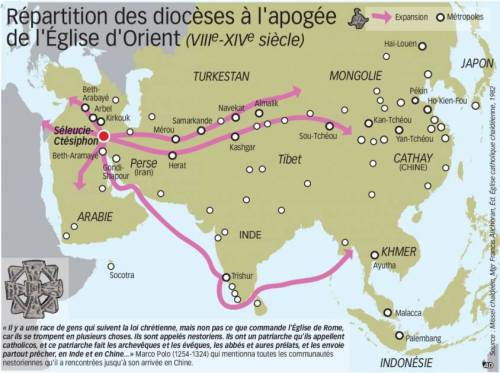

As a matter of fact, the main commodities traded on the “Silk Road” (a term only coined in 1877 by the German geographer Ferdinand Von Richthofen), were… horses, mules, camels, donkeys and onagers.

Silk and tea were of course traded, but appeared mainly as a means… to pay for horses. People “paid” with silk, gold, porcelain and tea, the animals they needed to secure the survival of their society!

What was known as the « Tea-Horse Road » (Southern Silk Road) extended from the city of Chengdu in Sichuan Province, China, south through Yunnan into India and the Indochina Peninsula, and extended westwards into Tibet. It was an important route for the tea trade throughout South China and Southeast Asia and contributed to the spread of religions like Taoism and Buddhism across the region.

Eurasian Steppe

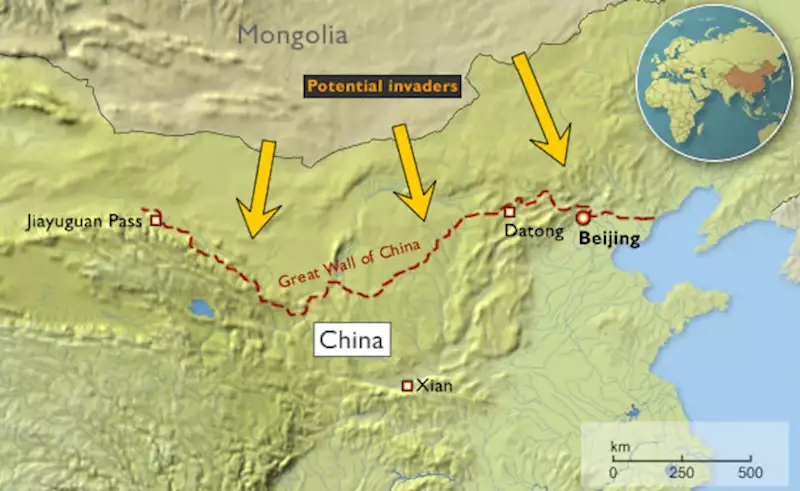

China, feeling itself under constant threat from the nomadic steppe people from the North, started building the first parts of its “Great Wall” as early as the VIIth Century BC, with selective stretches joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China and completed under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to become one of the most impressive feats in history.

The Eurasian nomads were groups of nomadic peoples living throughout the Eurasian Steppe. The generic title encompasses the varied ethnic groups who have at times inhabited the steppes of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, Russia, and Ukraine.

By the domestication of the horse around 2,200 BC (i.e. 4,200 years ago), they vastly increased the possibilities of nomadic life and subsequently their economy and culture emphasized horse breeding, horse riding, and nomadic pastoralism, usually engaging in trade with settled peoples around the steppe edges, be it in Europe, Asia or Central Asia.

Nomads, by definition, don’t create empires. It is thought they operated often as confederations. But it was them who developed the chariot, wagon, cavalry, and horseback archery and introduced innovations such as the bridle, bit, stirrup, and saddle and the very rapid rate at which innovations crossed the steppe-lands spread these widely, to be copied by settled peoples bordering the steppes.

During the Iron Age, Scythian (Persian) culture emerged among the Eurasian nomads, which was characterized by a distinct Scythian art.

China and the Horse

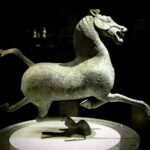

Throughout China’s long and storied past, no animal has impacted its history as greatly as the horse. Its significance was such that as early as the Shang dynasty (ca.1600-1100 BC), military might was measured by the number of the war chariots available to a particular kingdom.

The mounted cavalery, which emerged in the IIIrd century BC grew rapidly during the IInd century BC to meet the challenge of horse-riding peoples threatening China along the northern frontier.

Their large, powerful, horses were very new to China. As said before, traded for luxurious silk, they were the first major import to China from the “Silk Road.”

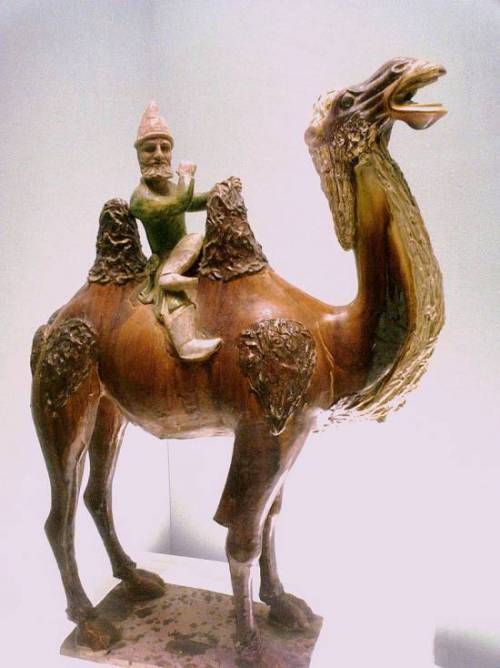

Chinese grave goods provide extraordinary amounts of information about how the ancient Chinese lived. Archaeological evidence shows that within a few years, the marvelous Arabian steeds had become immensely popular with military and aristocracy alike and upper-class tombs began to be filled with images of these great horses for use in the afterlife. But horses were hard to find in China.

Chinese diplomats and the Kingdom of Dayuan (Ferghana)

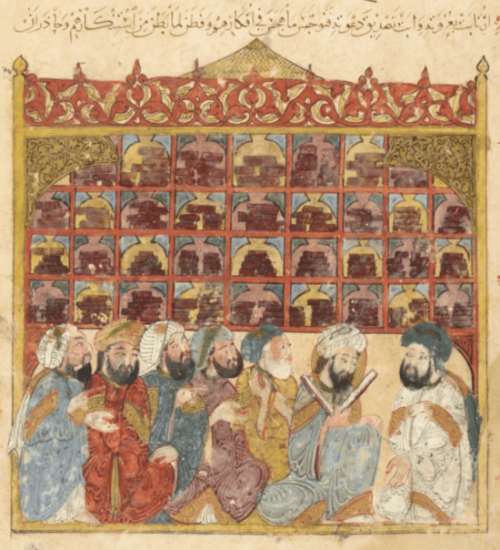

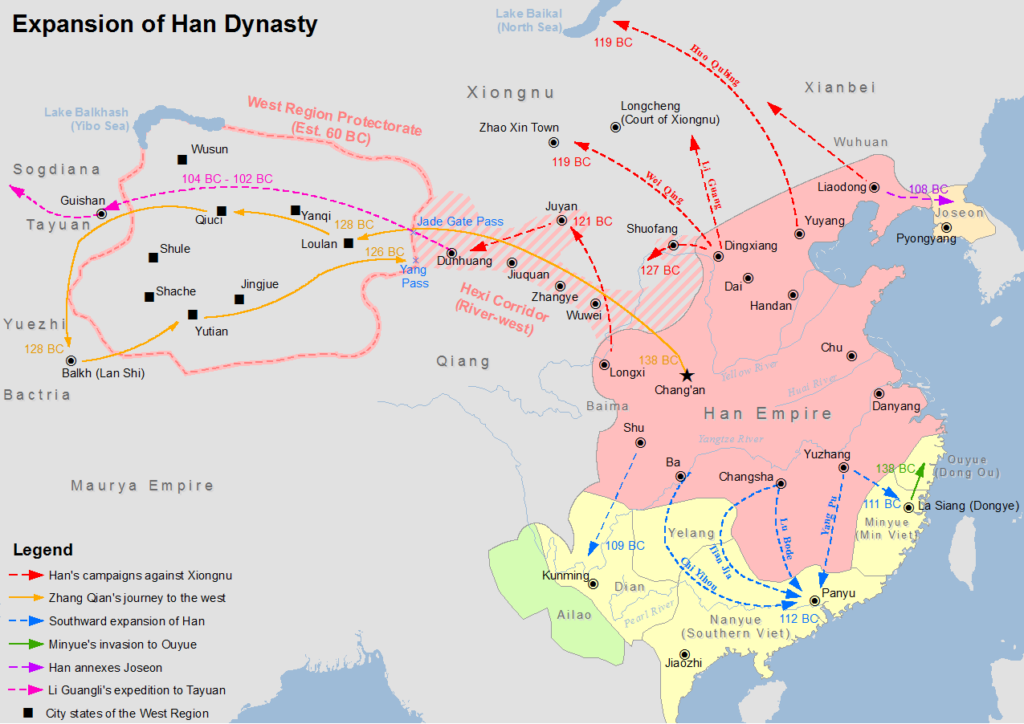

Something had to be done. In the late IInd Century BC, Zhang Qian, a Han dynasty diplomat and explorer, travels to Central Asia and discovers three sophisticated urban civilizations created by Greek settlers he named « Ionians ». The account of his visit to Bactria, including his recollection of his amazement at finding Chinese goods in the markets (acquired via India), as well as his travels to Parthia and Ferghana, are preserved in the works of the early Han historian Sima Qian.

Upon returning to China, his account prompts the Emperor to dispatch Chinese envoys across Central Asia to negotiate and encourage trade with China. Some historians say that this dicision gave « birth of the Silk Road.«

Besides Parthia and Bactria, where Chinese goods were being traded via Indian imports, Zhang Qian visited, in the fertile Ferghana valley (today essentially in Tajikistan), a State the Chinese called the “Kingdom of Dayuan” (“Da” meaning “great”, and “Yuan” being the transliteration of Sanskrit Yavana or Pali Yona, used throughout antiquity in Asia to designate « Ionians », i.e. Greek settlers).

The Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han describe the Dayuan as numbering several hundred thousand people living in 70 walled cities of varying size. They grew rice and wheat, and made wine from grapes. They had Caucasian features and “customs identical to those of Bactria” (the most Hellenistic state of the region since Alexander the Great) which is today’s northern Afghanistan.

The Chinese diplomat reported something of great strategic interest: unbelievable, fast and powerful horses raised by these Ionians in the Ferghana Valley!

Now, as said before, China felt under permanent threat by the nomadic people from the steppes and was in the process of building the “Great Wall”. China also was acutely aware that the nomadic steppe people derived their military superiority from something dramatically lacking at home: powerful horses !

Added to that, the fact that in terms of China’s scale of values, horses where nearly of the same mythological nature as dragons: they could fly and represented the divine, creative spirit of the universe itself, something essential for any Chinese emperor eager to acquire both military security for his Empire and for his personal immortality.

In short, having good horses became an issue of national security. So much, that in 100 BC, the Han dynasty started what is known as the “War of the Heavenly Horses” with Dayuan, when its ruler refused to provide high quality horses to China !

The War of the Heavenly Horses

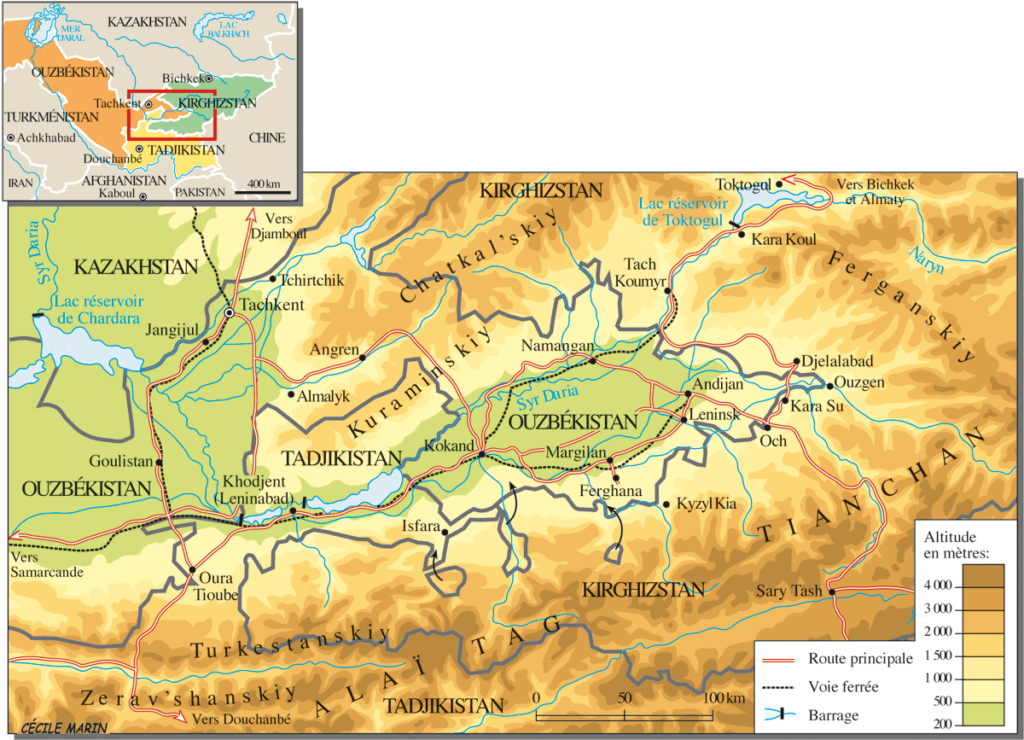

The War of the Heavenly Horses was a military conflict fought in 104 BC and 102 BC between China and a part of the Saka-ruled (Scythian) Greco-Bactrian kingdom known to the Chinese as Dayuan, in the Ferghana Valley (between modern-day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan).

First, Emperor Wu decided to defeat the nomadic steppe Xiongnu, who had harassed the Han dynasty for decades.

As said earlier, in 139 BC, the emperor sent diplomat Zhang Qian to survey the west and forge a military alliance with the Yuezhi nomads against another group of nomads, the Xiongnu. On the way to Central Asia through the Gobi desert, Zhang was captured twice. On his return, he impressed the emperor with his description of the « Heavenly Horses » of Dayuan, that could greatly improve the quality of Han cavalry mounts when fighting the Xiongnu.

The Han court sent at least five or six, and perhaps as many as ten diplomatic groups annually to Central Asia during this period to get a hold on these “Heavenly Horses”.

A trade mission arrived in Dayuan with 1000 pieces of gold and a golden horse to purchase these precious animals.

Dayuan, who was one of the furthest western states to send envoys to the Han court at that point, had already been trading with the Han for quite some time and benefited greatly from it. Not only were they overflowed by eastern goods, they also learned from Han soldiers how to cast metal into coins and weapons. However unlike the other envoys to the Han court, the ones from Dayuan did not conform to the proper Han rituals and behaved with great arrogance and self-assurance, believing they were too far away to be in any danger of invasion.

Hence, in a stroke of folly and taken by pure arrogance, the Dayuan king not only refused the deal, but confiscated the payment in gold. The Han envoys cursed the men of Dayuan and smashed the golden horse they had brought. Enraged by this act of contempt, the nobles of Dayuan ordered Yucheng, which lay on their eastern borders, to attack and kill the envoys and seize their goods.

Upon receiving word of the trade mission’s demise, humiliated and enraged, the Han court sent an army led by General Li Guangli to subdue Dayuan, but their first incursion was poorly organized and under-supplied.

A second, larger and much better provisioned expedition was sent two years later and successfully laid siege to the Dayuan capital at Alexandria Eschate, and forced Dayuan to surrender unconditionally.

The Han expeditionary forces installed a pro-Han regime in Dayuan and left with 3,000 horses, although only 1,000 remained by the time they reached China in 101 BCE.

The Ferghana also agreed to send two Heavenly horses each year to the Emperor, and lucerne seed was brought back to China providing superior pasture for raising fine horses in China, to provide cavalry which could cope with the Xiongnu who threatened China.

The horses have since captured the popular imagination of China, leading to horse carvings, breeding grounds in Gansu, and up to 430,000 such horses in the cavalry during the Tang dynasty.

China and the agricultural revolution

After imposing its role in military strategy for the next centuries, horsepower, together with water management, became a crucial factor to raise the productivity of the world’s food production.

First, contrary to the Romans, who preferred to use “human cattle” (slaves) rather than animals (which they raised for race contests), the Chinese greatly contributed to the survival of mankind with two crucial innovations respecting a more efficient use of horse power.

As can be seen in murals and paintings, through the ancient world, be it in Egypt or Greece, plows and carts were pulled using animal harnesses that had flat straps across the neck of the horse, with the load attached at the top of the collar, above the neck, in a manner similar to a yoke used for oxen.

In reality, this greatly limited a horse’s ability to exert itself as it was constantly choked at the neck. The harder the horse pulled, the harder it became to breathe.

Due to this physical limitation, oxen remained the preferred animal to do heavy work such as plowing. Yet oxen are hard to maneuver, are slow, and lack the quality of horses, whose power is equivalent but whose endurance is twice that of oxen.

China reportedly first invented the “breast strap” which was the first step in the right direction.

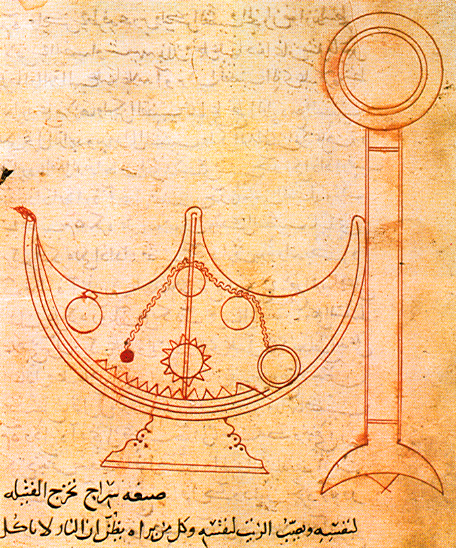

Then, in the Vth Century, China also invented what is called the “rigid horse collar”, designed as an oval that fits around the neck and shoulders of the horse.

It has the following advantages:

–First, it relieved the pressure of the horse’s windpipes. It left the airway of the horse free from constriction improving massively the animal’s energy through-put.

–Second, the traces could be attached to the sides of the collar. This allowed the horse to push forward with its more powerful hind-legs rather than pulling with the weaker front legs.

Now you can argue that this is anecdotal. It is NOT, because what appears as only a slight change had absolutely monumental consequences.

European Renaissance

In a strategic alliance and cooperation with the humanist Baghdad Abbasid caliphate, Charlemagne and his successors introduced the “rigid horse collar” in Europe.

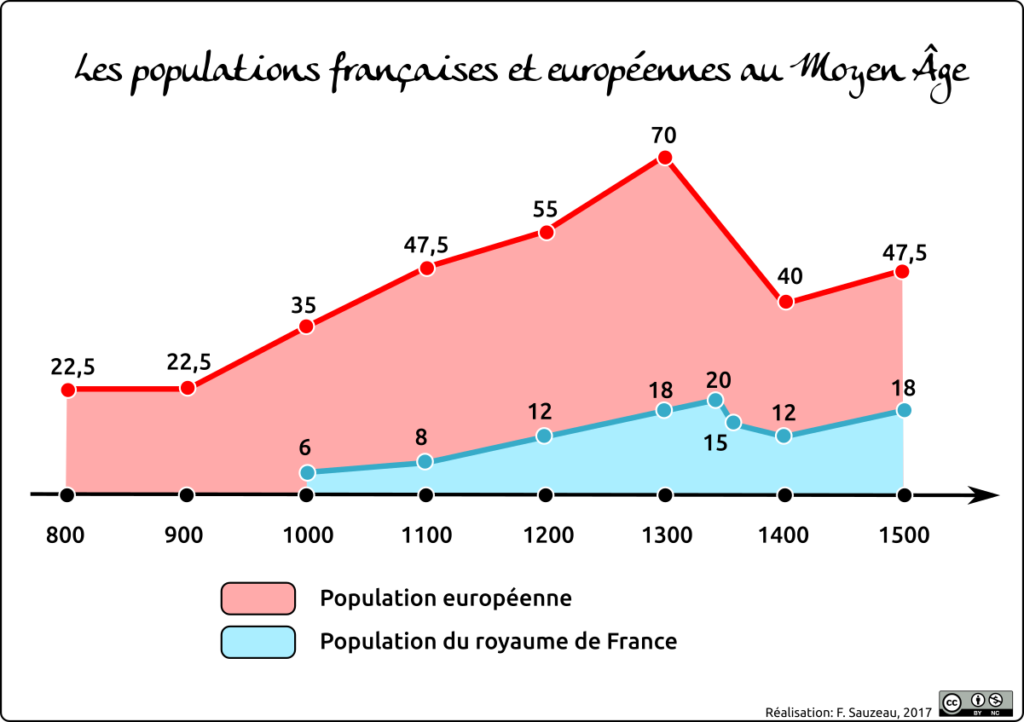

With that new, far more efficient tool, European farmers finally could take full advantage of a horse’s strength. The horse was able to pull another recent innovation, the heavy plow. This became particularly important in areas where the soil was hard and clay-like. This opened up new plots of lands to agriculture. The rigid horse collar, the heavy plow, and horseshoes helped usher in a period of increased agricultural production.

As a result, between 1000 CE and 1300 CE, it is estimated that in Europe, crop yields increased by threefold, allowing to feed a rising number of citizens in the urban cities appearing in the XVth century and kick starting the global “Golden” European Renaissance. Thank you, China!

Some numbers are nevertheless disturbing:

–it took humanity thousands of years to finally domesticate the horse (long after the cow), in 3200 BC.

–it took humanity another 3700 years to learn how to find out, in the Vth century AD, the most efficient way to use horse-power…

Shifting from a “lower” infrastructure platform to a “higher” infrastructure platform might take some time. Today’s new “higher” platforms are called “space data” and “fusion power.” Let’s not wait another century to find out how to use them correctly!

The ancient practice of debt cancellation

While anyone with a modicum of rationality knows that a huge proportion of the world’s debts are absolutely unpayable, it’s a fact that today any debt cancellation, however odious or illegitimate, remains taboo.

By Karel Vereycken, December 2020.

Debt repayment is presented by heads of state and government, central banks, the IMF and the mainstream press as imperative, inevitable, indisputable, compulsory. Citizens have elected their governments, so they must resign themselves to paying the debt. For not to pay is more than violating a symbol: it is to exclude oneself from civilization, and to renounce in advance any new credit that is granted only to « good payers ». What counts is not the effectiveness of the act, but the expression of one’s « good faith », i.e. one’s willingness to submit to the strongest. The only possible discussion is how to modulate the distribution of the necessary sacrifices.

It seems that the ultra-liberal, monetarist model that has been surreptitiously imposed on us is that of the Roman Empire: zero debt for states and cities, and no debt forgiveness for citizens!

In his treatise on Duties (De officiis), written in 44-43, Cicero, who had just quelled a revolt by people demanding a debt remission, justifies the radical nature of his policy towards indebtedness:

« What does the establishment of new debt accounts [i.e., remission] mean, if not that you buy land with my money, that you have this land, and that I don’t have my money? That’s why we have to make sure there are no debts, which can harm the state. There are many ways of avoiding it, but if there are debts, not in such a way that the rich lose their property and the debtors acquire the property of others. Indeed, nothing maintains the State more strongly than good faith (fides), which cannot exist if there is no need to pay one’s debts. Never has anyone acted more forcefully to avoid paying their debts than under my Consulate. It was attempted by men of all kinds and ranks, with weapons in hand, and by setting up camps. But I resisted them in such a way that this entire evil was eliminated from the State. »

What has been carefully concealed is that another human practice has also existed: moratoria, partial and even generalized debt cancellations have taken place repeatedly throughout history and were carried out according to different contexts.

Often, proclamations of generalized debt cancellation were the initiative of self-preservation-minded rulers, aware that the only way to avoid complete social breakdown was to declare a « washing of the shelves » – those on which consumer debts were inscribed – cancelling them to start afresh.

The American anthropologist David Graeber, in Debt, the first 5000 years (2011), pointed out that the first word we have for « freedom » in any human language is Sumerian amargi, meaning freed from debt and, by extension, freedom in general, the literal meaning being « return to the mother » insofar as, once debts were cancelled, all debt slaves could return home.

Debt cancellations were sometimes the result of bitter social struggles, wars and crises. What is certain is that debt has never been a detail of history.

David Graeber sums it up:

« For millennia, the struggle between rich and poor has largely taken the form of conflicts between creditors and debtors – disputes over the justice or injustice of interest payments, peonage, amnesty, property seizure, restitution to the creditor, confiscation of sheep, seizure of vineyards and the sale of the debtor’s children as slaves. And over the last 5,000 years, with remarkable regularity, popular insurrections have begun in the same way: with the ritual destruction of debt registers – tablets, papyri, ledgers or other media specific to a particular time and place. (After which, the rebels generally attacked cadastres and tax registers.) »

And as the great ancient scholar Moses Finley was fond of saying,

« All revolutionary movements have had the same program: cancellation of debts and redistribution of land. »

Let us now examine some historical precedents for voluntary debt forgiveness.

Debt cancellation in Mesopotamia

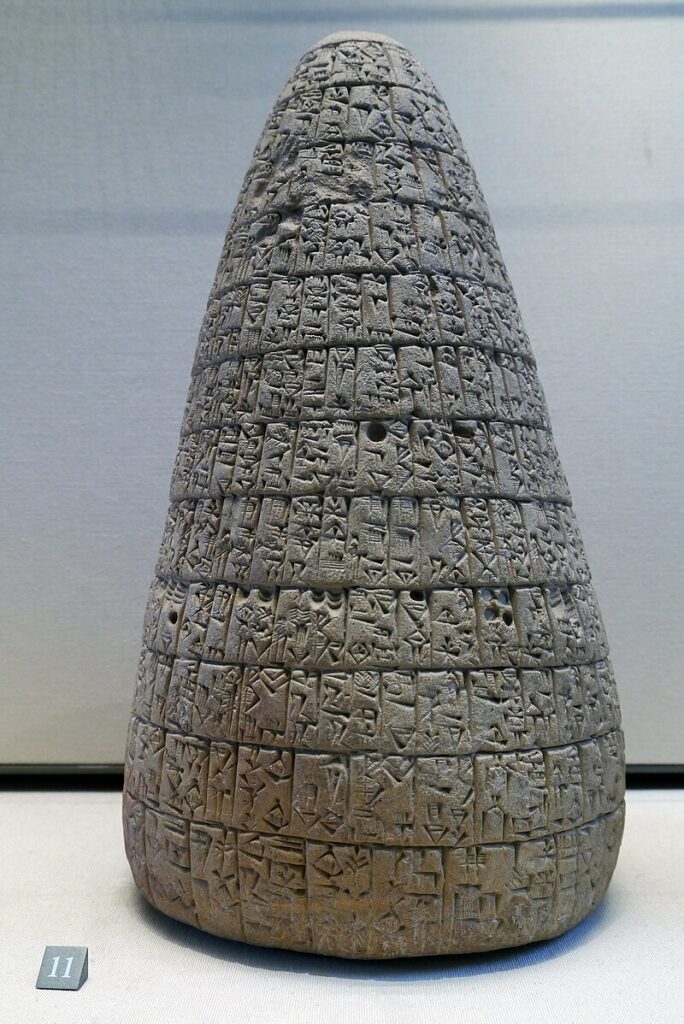

The earliest known debt cancellation was proclaimed in Mesopotemia by Entemena of Lagash c. 2400 BCE.

One of his successors, Urukagina, who was the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash, is known for his code of rules that includes debt cancelation.

Urukagina’s code is the first recorded example of government reform, seeking to achieve a higher level of freedom and equality by limiting the power of priesthood and a usurous land-owner oligarchy. Usury and seizure of property for debt payment were outlawed. « The widow and the orphan were no longer at the mercy of the powerful man ».

Similar measures were enacted by later Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian rulers of Mesopotamia, where they were known as « freedom decrees » (ama-gi in Sumerian).

This same theme exists in an ancient bilingual Hittite–Hurrian text entitled « The Song of Debt Release ».

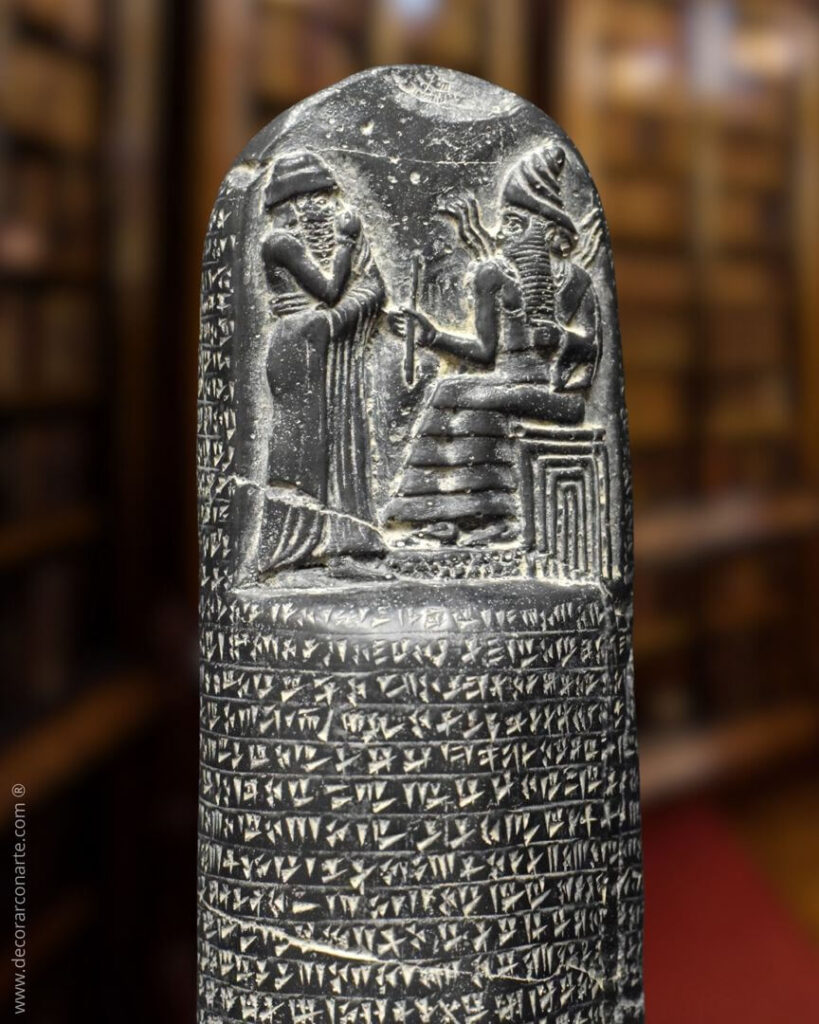

The reign of Hammurabi, King of Babylon (located in present-day Iraq), began in 1792 BC and lasted 42 years.

The inscriptions preserved on a 2-meter-high stele in the Louvre are known as the « Hammurabi Code ». It was placed in a public square in Babylon. If it is a long, very severe code of justice, prescribing the application of the law of retaliation (« an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth »), its epilogue nevertheless proclaims that « the powerful cannot oppress the weak, justice must protect the widow and the orphan (…) in order to render justice to the oppressed ».

Hammurabi, like the other rulers of the Mesopotamian city-states, repeatedly proclaimed a general cancellation of citizens’ debts to public authorities, their high officials and dignitaries.

Thanks to the deciphering of numerous documents written in cuneiform, historians have found indisputable evidence of four general debt cancellations during Hammurabi’s reign (at the beginning of his reign in 1792, in 1780, in 1771 and in 1762 BC).

Babylonian society was predominantly agricultural. The temple and palace, and the scribes and craftsmen they employed, depended for their sustenance on a vast peasantry from whom land, tools and livestock were rented.

In exchange, each farmer had to offer part of his production as rent. However, when climatic hazards or epidemics made normal production impossible, producers went into debt.

The inability of peasants to repay debts could also lead to their enslavement (family members could also be enslaved for debt).

The Hammurabi Code obviously wanted to change this. Article 48 of the Code of Laws states:

« Whoever owes a loan, and a storm buries the grain, or the harvest fails, or the grain does not grow for lack of water, need not give any grain to the creditor that year, he wipes the tablet of the debt in the water and pays no interest for that year. »

This ideal of justice is notably supported by the terms kittum, « justice as the guarantor of public order », and « justice as the restoration of equity. » It was asserted in particular during the « edicts of grace » (designated by the term mîsharum), a general remission of public and private debts in the kingdom (including the release of people working for another person to repay a debt).

Thus, to preserve the social order, Hammurabi and the ruling power, acting in their own interests and in the interests of society’s future, periodically agreed to cancel all debts and restore the rights of peasants, in order to save the threatened old order in times of crisis, or as a kind of reset at the beginning of a sovereign’s reign.

Proclamations of general debt cancellation are not confined to the reign of Hammurabi; they began long before him and continued afterwards. There is evidence of debt cancellations as far back as 2400 BC, six centuries before Hammurabi’s reign, in the city of Lagash (Sumer); the most recent date back to 1400 BC in Nuzi.

In all, historians have accurately identified some thirty general debt cancellations in Mesopotamia between 2400 and 1400 BC.

These proclamations of debt cancellation were the occasion for great festivities, usually during the annual spring festival. Under the Hammurabi dynasty, the tradition of destroying the tablets on which debts were written was established.

In fact, the public authorities kept precise accounts of debts on tablets kept in the temple. Hammurabi died in 1749 BC after a 42-year reign. His successor, Samsuiluna, cancelled all debts to the state and decreed the destruction of all debt tablets except those relating to commercial debts.

When Ammisaduqa, the last ruler of the Hammurabi dynasty, acceded to the throne in 1646 BC, the general cancellation of debts he proclaimed was very detailed. The aim was clearly to prevent certain creditors from taking advantage of certain families. The annulment decree stipulates that official creditors and tax collectors who have expelled peasants must compensate them and return their property, on pain of execution.

After 1400 BC, no deeds of debt cancellation have been found, as the tradition has been lost. Land was taken over by large private landowners, and debt slavery returned.

In Egypt

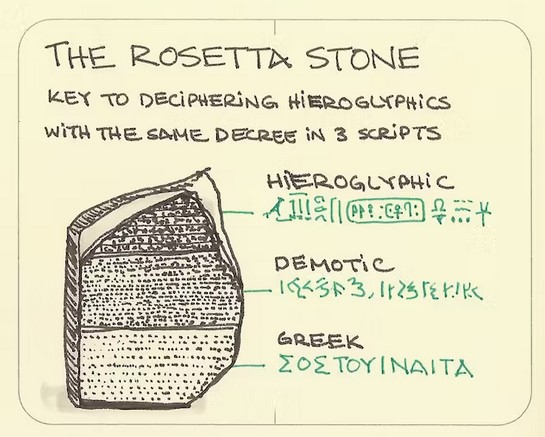

In Ancient Egypt interest-bearing debt did not exist for most of its history. When it started spreading in the Late Period, the rulers of Egypt regulated it and a number of debt remissions are known to have occurred during the Ptolemaic era, including the one whose proclamation was inscribed on the Rosetta Stone.

Now on display at the British Museum in London, the « Rosetta Stone » was discovered on July 15, 1799 at el-Rashid (Rosetta) by one of Napoleon’s soldiers during the Egyptian campaign. It contains the same text written in hieroglyphs, demotic (Egyptian cursive script) and Greek, giving Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) the key to the passage from one language to another.

This was a decree issued by Pharaoh Ptolemy V on March 27, 196 BC, announcing an amnesty for debtors and prisoners. The Greek Ptolemy dynasty that ruled Egypt institutionalized the regular cancellation of debts.

It was perpetuating known practices, since Greek texts mention that Pharaoh Bakenranef, who ruled Lower Egypt from c. 725 to 720 BC, had promulgated a decree abolishing debt slavery and condemning debt imprisonment.

TRANSCRIPTION OF THE PHARAOH’S DECREE

ON THE ROSETTA STONE:

Assembled the Chief Priests and Prophets there and those who enter the inner temple to worship the gods, and the Fanbearers and Sacred Scribes and all the other priests of the temples of the earth who have come to meet the king at Memphis, for the feast of the Assumption of PTOLEMEE, THE LIVING FOREVER, THE BELOVED OF PTAH, THE GOD EPIPHANES EUCHARISTOS, the successor of his father, All assembled in the temple of Memphis on this day when it was declared:

“that King PTOLEMEE, THE LIVING FOREVER, THE BELOVED OF PTAH, THE GOD EPIPHANES EUCHARISTOS, the son of King Ptolemy and Queen Arsinoe, the Philopator Gods, both benefactors of the temple and those who dwell therein, as well as their subjects, being a god from a god and the goddess loves Horus the son of Isis and Osiris who avenged his father Osiris by being favorably disposed towards the gods, delivered to the revenues of the temples silver and corn and undertook much expenditure for the prosperity of Egypt, and the maintenance of the temples, and was generous to all out of his own resources ;

“and exempted them from some of the revenues and taxes levied in Egypt and alleviated others so that his people and all others could be in prosperity during his reign ;

“and that he cleared the debts to the crown for many Egyptians and for the rest of the kingdom; ”

The existence of this decree therefore confirms that the practice had existed for many centuries.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (Ist Century BC) provides the following rationale for abolishing the debt bondage by Pharaoh Bakenranef:

« For it would be absurd… that a soldier, at the moment perhaps when he was setting forth to fight for his fatherland, should be haled to prison by his creditor for an unpaid loan, and that the greed of private citizens should in this way endanger the safety of all »

As one can see here, one of the very pragmatic reasons for debt cancellation was that the Pharaoh wanted to have a peasantry capable of producing enough food and, if need be, able to take part in military campaigns. For both of these reasons, it was important to ensure that peasants were not expelled from their lands under the thumb of creditors.

In another part of the region, the Assyrian emperors of the 1st millennium BC also adopted the tradition of debt cancellation.

In Greece: Solon of Athens

In Greece, the Athenian lawmaker Solon (c. 638 BC–558 BC), in order to rectify the widespread serfdom and slavery that had run rampant by the 6th century BCE, introduced a set of laws nown as the Seisachtheia introducing debt relief.

Before Solon, according to the account of the Constitution of the Athenians attributed to Aristotle, debtors unable to repay their creditors would surrender their land to them, then becoming hektemoroi, i.e. serfs who cultivated what used to be their own land and gave one sixth of produce to their creditors. However, should the debt exceed the perceived value of debtor’s total assets, then the debtor and his family would become the creditor’s slaves as well. The same would result if a man defaulted on a debt whose collateral was the debtor’s personal freedom. The fight for debt relief and the fight to abolish slavery were in practice identical.

Solon’s seisachtheia laws immediately cancelled all outstanding debts, retroactively emancipated all previously enslaved debtors, reinstated all confiscated serf property to the hektemoroi, and forbade the use of personal freedom as collateral in all future debts. The laws instituted a ceiling to maximum property size – regardless of the legality of its acquisition (i.e. by marriage), meant to prevent excessive accumulation of land by powerful families.

In the Torah and Old Testament

Social justice, particularly in the form of forgiving debts that shackle the poor to the rich, is a leitmotif in the history of Judaism. It was practiced in Jerusalem in the 5th century BC.

The writing of the Torah was completed at this time. Deuteronomy, 15 states:

The Year for Canceling Debts

15 At the end of every seven years you must cancel debts.

2 This is how it is to be done: Every creditor shall cancel any loan they have made to a fellow Israelite. They shall not require payment from anyone among their own people, because the Lord’s time for canceling debts has been proclaimed.

3 You may require payment from a foreigner, but you must cancel any debt your fellow Israelite owes you.

4 However, there need be no poor people among you, for in the land the Lord your God is giving you to possess as your inheritance, he will richly bless you,

5 if only you fully obey the Lord your God and are careful to follow all these commands I am giving you today.

6 For the Lord your God will bless you as he has promised, and you will lend to many nations but will borrow from none. You will rule over many nations but none will rule over you.

7 If anyone is poor among your fellow Israelites in any of the towns of the land the Lord your God is giving you, do not be hardhearted or tightfisted toward them.

8 Rather, be openhanded and freely lend them whatever they need.

9 Be careful not to harbor this wicked thought: “The seventh year, the year for canceling debts, is near,” so that you do not show ill will toward the needy among your fellow Israelites and give them nothing. They may then appeal to the Lord against you, and you will be found guilty of sin.

10 Give generously to them and do so without a grudging heart; then because of this the Lord your God will bless you in all your work and in everything you put your hand to.

11 There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore I command you to be openhanded toward your fellow Israelites who are poor and needy in your land.

Thus, the Israelites were obliged to free Hebrew slaves who had sold themselves to them for debt, and to offer them some of the produce of their small livestock, their fields and their wine presses, so that they would not return home empty-handed.

As the law is too rarely applied, Leviticus reaffirms it by modulating it:

The Year of Jubilee

8 “‘Count off seven sabbath years—seven times seven years—so that the seven sabbath years amount to a period of forty-nine years.

9 Then have the trumpet sounded everywhere on the tenth day of the seventh month; on the Day of Atonement sound the trumpet throughout your land.

10 Consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you; each of you is to return to your family property and to your own clan.

11 The fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you; do not sow and do not reap what grows of itself or harvest the untended vines.

12 For it is a jubilee and is to be holy for you; eat only what is taken directly from the fields.

13 “‘In this Year of Jubilee everyone is to return to their own property.

14 “‘If you sell land to any of your own people or buy land from them, do not take advantage of each other.

15 You are to buy from your own people on the basis of the number of years since the Jubilee. And they are to sell to you on the basis of the number of years left for harvesting crops.

16 When the years are many, you are to increase the price, and when the years are few, you are to decrease the price, because what is really being sold to you is the number of crops.

17 Do not take advantage of each other, but fear your God. I am the Lord your God.

Today, some will tell you that under these conditions, a year before the jubilee date, credit would necessarily be scarce and expensive, and that debt would thus find its limit!

This is a mistake, because to ensure that the law is followed, the codes describe in detail how purchases and sales of goods between private individuals must be carried out according to the number of years elapsed since the previous jubilee (i.e., the number of years remaining before the goods must be returned to their previous owner).

Another passage, this time from the prophet Jeremiah, vividly illustrates the scope of the law on the remission of debts.

Faced with the advance of enemy armies towards Jerusalem in 587 B.C., Jeremiah supports, in God’s name, the undertaking of King Zedekiah (then ruler of the Kingdom of Judea), who demands the immediate release of all those enslaved for debt from the powerful forces of his kingdom (Jer. 34:8-17).

Jeremiah forcefully recalls the ancient demand for the freeing of slaves… which the king, in fact, needs to patriotically reunite the social classes before the battle, and give himself sufficient troops free of all servile obligations!

A passage in the Book of (the prophet) Nehemiah (447 BC), the governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC), influenced by the ancient Mesopotamian tradition, also proclaims the cancellation of debts owed by indebted Jews to their rich compatriots.

The social situation Nehemiah discovered in Judea was appalling. To remedy the problem, Nehemiah placed the law of debt relief within a religious framework, the Covenant with Yahweh. From then on, it was God himself who commanded the forgiveness of debts and the liberation of slaves and their land, for the land belonged to God alone.

Nehemiah Helps the Poor

« Now the men and their wives raised a great outcry against their fellow Jews.

2 Some were saying, “We and our sons and daughters are numerous; in order for us to eat and stay alive, we must get grain.”

3 Others were saying, “We are mortgaging our fields, our vineyards and our homes to get grain during the famine.”

4 Still others were saying, “We have had to borrow money to pay the king’s tax on our fields and vineyards.

5 Although we are of the same flesh and blood as our fellow Jews and though our children are as good as theirs, yet we have to subject our sons and daughters to slavery. Some of our daughters have already been enslaved, but we are powerless, because our fields and our vineyards belong to others.”

6 When I heard their outcry and these charges, I was very angry.

7 I pondered them in my mind and then accused the nobles and officials. I told them, “You are charging your own people interest!” So I called together a large meeting to deal with them

8 and said: “As far as possible, we have bought back our fellow Jews who were sold to the Gentiles. Now you are selling your own people, only for them to be sold back to us!” They kept quiet, because they could find nothing to say.

9 So I continued, “What you are doing is not right. Shouldn’t you walk in the fear of our God to avoid the reproach of our Gentile enemies?

10 I and my brothers and my men are also lending the people money and grain. But let us stop charging interest!

11 Give back to them immediately their fields, vineyards, olive groves and houses, and also the money you are charging them—one percent of the money, grain, new wine and olive oil.”

12 “We will give it back,” they said. “And we will not demand anything more from them. We will do as you say.”

If we add to these passages the countless verses forbidding the lending of interest to fellow human beings and the taking of property as collateral, we get an idea of what the Israelites in the land of Canaan had put in place to try and maintain a certain social equilibrium.

Alas, in the first century AD, debt forgiveness and the freeing of slaves from debt were swept away from all Near Eastern cultures, including Judea.

The social situation there had deteriorated to such an extent that Rabbi Hillel was able to issue a decree requiring debtors to sign away their right to debt forgiveness.

In the Bible and New Testament

What happened to debt forgiveness in the New Testament?

While the Acts of the Apostles and the writings of the Fathers of the Church sometimes express a great docility, Jesus’ position on the forgiveness of debts, as reported repeatedly and most forcefully in Luke’s Gospel, chapter 4:16-21, appears to be marked by a revolutionary prophetic breath.

Luke places the passage at the beginning of Jesus’ public life. He makes it a key to everything that follows.

16 Jesus went to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, and on the Sabbath day he went into the synagogue, as was his custom. He stood up to read,

17 and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. Unrolling it, he found the place where it is written:

18 “The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

19 to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

20 Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him.

21 He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.”

Let’s not forget that the « year of the Lord’s favor (Jubilee Year) » to which he called, demanded at once rest for the land, forgiveness of debts and the liberation of slaves.

In the midst of the slave-owning Roman Empire, which fiercely rejected the concept of debt forgiveness, Jesus’ declaration could only be seen as a declaration of war on the ruling system.

Before he was arrested, Jesus made a highly symbolic material gesture: he forcefully overturned the tables of the money-changers in the Jerusalem temple. For the Jewish high priests and the Roman authorities, this was too much.

Peace of Westphalia of 1648

In 1648, after five years of negotiations, led by the French diplomat Abel Servien on the instructions of Cardinal Mazarin, the “Peace of Westphalia” was signed, putting an end to the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

Long before the UN Charter, 1648 made national sovereignty, mutual respect and the principle of non-interference the foundations of international law.

But there was more. As we have documented, the peace deal also included the cancelation of debts that had become the very reason for continuing the war.

Unpayable, unsustainable and illegitimate debts, interests, bonds, annuities and financial claims, explicitly identified as fueling a dynamic of perpetual war, were examined, sorted out and reorganized, most often through the cancellation of debts (articles 13 and 35, 37, 38 and 39), through moratoria or debt rescheduling according to specific timetables (article 69).

Article 40 concludes that debt cancellations will apply in most cases, “and yet the Sums of Money, which during the War have been exacted bona fide, and with a good intent, by way of Contributions, to prevent greater Evils by the Contributors, are not comprehended herein. » (Implying that these debts would have to be honored.)

Finally, looking to the future, for Commerce to be “reestablished”, the treaty abolished many tolls and customs established by “private” authorities for they were obstacles to the exchange of physical goods and know-how and hence to mutual development. (Art. 69 and 70).

TREATY OF WESTPHALIA (1648)

Art. 13:

“Reciprocally, the Elector of Bavaria renounces entirely for himself and his Heirs and Successors the Debt of Thirteen Millions, as also all his Pretensions in Upper Austria; and shall deliver to his Imperial Majesty immediately after the Publication of the Peace, all Acts and Arrests obtain’d for that end, in order to be made void and null.”

Art. 35:

“That the Annual Pension of the Lower Marquisate, payable to the Upper Marquisate, according to former Custom, shall by virtue of the present Treaty be entirely taken away and annihilated; and that for the future nothing shall be pretended or demanded on that account, either for the time past or to come.”

During the Cold War

In the United States, Eisenhower was elected in November 1952.

His Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, otherwise an evil man, noted that, despite the Marshall Plan, Europe, still burdened by a mountain of debt dating from before the First World War and the Treaty of Versailles, was unable to regain momentum.

So much so that it is in danger of turning to the USSR!

Action was called for. In 1953, under the leadership of German banker Hermann Abs, a former Deutsche Bank executive, a major conference was organized in London.

It was decided to write off 66% of Germany’s 30 billion marks in debt.

It was wisely agreed that annual repayments of German debt should never exceed 5% of export earnings. Those wishing to have their debts repaid by Germany should instead buy its exports, enabling it to honor its debts.

In other words, nothing like the madness recently imposed on Greece to « save » the euro!

Although this was done in the name of geopolitical principles, i.e. « in favor of some » but « against others », once again, it was in the name of a better future, i.e. a Europe capable of being the showcase of capitalism in the face of Moscow, that we were able to shed the weight of the past.

Christian Lévêque : l’écologie malade du « fixisme » ?

Karel Vereycken s’est entretenu fin mars 2021 avec l’écologue et hydrobiologiste Christian Lévêque, directeur de recherche émérite à l’Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD) et spécialiste des écosystèmes aquatiques. Il est également président honoraire de l’Académie d’agriculture de France et membre de l’Académie des sciences d’Outre-mer.

Parmi ses derniers écrits, nous recommandons :

- La biodiversité avec ou sans l’homme ? (Quae, 2017) ;

- La mémoire des fleuves et des rivières (Ulmer, 2019) ;

- La gestion écologique des rivières françaises – Regards de scientifiques sur une controverse (L’Harmattan, 2020, avec JP. Bravard) ;

- Reconquérir la biodiversité, mais laquelle ? (Fondapol, 2021).

Karel Vereycken : Dans vos écrits, vous soulignez que le discours qu’on entend dans les médias sur l’écologie est plus idéologique que scientifique. Que voulez-vous dire et en quoi est-ce préoccupant ?

Christian Lévêque : La première chose qui me préoccupe dans le discours écologique, c’est qu’il s’agit d’un discours à sens unique : « L’Homme détruit la nature. » C’est un discours de mise en accusation de l’homme dans son rapport à la nature. Or, ce que je vois autour de moi, ce n’est pas tout à fait ça. Prenons le cas du parc naturel de la Camargue, qu’on présente parfois comme un pur produit de la nature. En réalité, il s’agit d’un système aménagé par l’homme pour la production de sel et la riziculture. C’est un système géré artificiellement qui est néanmoins labellisé « parc naturel ». On voit bien, avec cet exemple, que l’action de l’homme n’est pas forcément négative.

Prenons maintenant le cas du bocage normand. Une fois de plus, ce n’est pas un système naturel, mais aménagé par l’homme et l’agriculture. Il est amusant de constater que le bocage figure dans tous les livres traitant de la biodiversité comme un bel exemple de nature qu’il faut préserver. On pourrait multiplier les exemples. Je prends souvent le cas du lac du Der (lac du Der-Chantecoq, en Champagne) qui est un barrage-réservoir (de 48 km²) sur la Marne, construit il y a une trentaine d’années pour protéger Paris des crues de la Seine. Or, tout comme la Camargue, ce site a été consacré « site Ramsar » (Note 1) en matière de préservation de la nature, en particulier pour l’habitat qu’il offre aux oiseaux.

On voit donc que le « vécu des gens » (la réalité) ne correspond en rien à celle dont parlent un certain nombre de mouvements militants qui ne font qu’accuser l’homme de ravager la nature. Pour moi, il y a quelque chose de totalement incohérent dans cette démarche. Ce qui ne veut pas dire pour autant que tout va pour le mieux, et il y a bien entendu des contre-exemples. Mais il faut revenir à des regards plus réalistes et moins dogmatiques sur nos rapports à la nature.

Ce qui me préoccupe le plus dans leur approche, c’est cette « vision fixiste » de la nature, sous-jacente dans la plupart des discours en matière de conservation de la nature. On a l’impression qu’en créant des aires protégées, on va protéger la nature. On oublie que la nature n’arrête pas de changer et qu’une aire protégée ne protège rien dans la durée. La flore et la faune vont évoluer sous l’influence du climat par exemple. Ou sous l’influence d’espèces qui vont se naturaliser sur le site. Et les espèces que l’on cherche à protéger peuvent disparaître car les conditions écologiques ne leur seront plus favorables. Ce sont des mesures d‘urgence qui peuvent être utiles comme telles, mais ce n’est pas une assurance à long terme.

Beaucoup de projets de restauration ou d’aménagement qui cherchent à reconstituer un état écologique historique (c’était mieux avant…) oublient que l’avenir ne peut pas être le passé. Les systèmes écologiques évoluent et se modifient en permanence sur la flèche du temps.

J’avais demandé, il y a quelques années, de faire une simulation sur la remontée du niveau de la mer, dans l’estuaire de la Seine dont je m’occupais. Si la mer monte d’un mètre – ce qui est possible et probable, d’ici à la fin du siècle – vous avez la moitié de la réserve de l’estuaire de la Seine qui est sous l’eau. Et si ça monte de deux mètres, il n’y a plus de réserve du tout. Est-ce qu’on pourrait repositionner la réserve plus haut ? Comme il y a beaucoup d’urbanisation, cela posera de grandes difficultés. C’était une parenthèse pour dire que les réserves naturelles sont un peu limitées en tant que perspective historique…

Si je vous comprends bien, ces écologistes font en quelque sorte un instantané de l’évolution, qu’ils veulent geler artificiellement pour toujours ?

Lorsqu’on regarde dans le passé, comme le font les paléo-écologues, on voit bien que la nature était différente de celle d’aujourd’hui. L’Europe a connu à diverses reprises des périodes de glaciation qui ont profondément modifié la flore et la faune.

Je dis souvent : réfléchissez. Il y a 10 à 20 000 ans, le nord de l’Europe était sous les glaces ainsi que le massif alpin, et l’on était en zone de permafrost là où nous sommes aujourd’hui. Cela a beaucoup changé depuis, non ? On est passé des toundras de Sibérie à des forêts luxuriantes et la biodiversité a également beaucoup changé. Et cela, en relativement peu de temps. La flore et la faune se sont reconstituées par des migrations ou des introductions d’espèces depuis environ 10 000 ans, ce qui est récent. A l’échelle géologique ou à celle de l’évolution, c’est une goutte d’eau.

Il faut bien intégrer que la nature est dynamique. Il est illusoire de penser que l’on pourra figer cette dynamique en établissant des normes et des lois pour la protéger. J’ai conscience que c’est difficile à intégrer car nous n’aimons pas beaucoup le changement, qui est porteur d’incertitudes et donc de dangers… Pour les scientifiques, la biodiversité est le produit du changement et donc de l’adaptation permanente des espèces aux fluctuations de leurs conditions d’existence.

Les mouvements environnementalistes nous alertent sur une forte érosion de la biodiversité et certains évoquent même la menace d’une « sixième extinction de masse » provoquée par l’action humaine. Qu’en est-il ?

Tout cela est compliqué et relève pour partie de la communication de grandes ONG environnementales. Il est vrai que les hommes ont un impact, mais il faut l’évaluer raisonnablement et ne pas tomber dans des discours inflationnistes.

A ceux qui tiennent ces discours, répliquez : « Apportez-moi les données ! » Or, on a beaucoup de mal à trouver les données sur lesquelles sont basées ces assertions.

J’ai vu récemment une communication de l’International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN, l’une des plus grandes associations environnementalistes) et de l’Office français de la biodiversité (OFB) sur le nombre d’espèces menacées de disparition en France, évalué à 2400 espèces. Quand vous regardez le détail, c’est une liste à la Prévert d’espèces dont certaines sont sans aucun doute en régression, il n’est pas question de le nier, et d’autres dont la présence sur la liste sert à faire du chiffre.

Deux exemples pour l’illustrer. Parmi les quelques rares espèces supposées éteintes en France, il y a trois espèces de poissons d’eau douce appartenant au groupe des corégones qui peuplent les lacs alpins. Ce groupe est connu chez les taxinomistes pour être très variable. Selon les auteurs, on distingue des dizaines d’espèces de corégones, ou seulement deux en Europe… Les trois « espèces » en question sont-elles de vraies espèces ou des écotypes ? Ce qui souligne la difficulté rarement abordée de la définition de l’espèce !

Autre exemple, on comptabilise parmi les espèces disparues ou pratiquement disparues en France, des espèces qui vivent dans des pays voisins et qui, pour des raisons diverses, font de temps à autre une incursion chez nous. Il existe ainsi sur cette liste deux espèces de poissons qui sont endémiques en Espagne, où elles sont très abondantes, mais qu’on a pu apercevoir à certains moments dans des régions frontalières en France. Ce sont des espèces qui peuvent être importées accidentellement par des oiseaux, des mammifères ou des hommes, et qui s’installent temporairement chez nous, avant de disparaître. Comptabiliser ce type d’espèces parmi les espèces en danger, c’est quand même un peu fort ! C’est ce que j’appelle faire du chiffre. On aimerait que les données qui sont diffusées par les médias fassent preuve d’une plus grande rigueur !

D’autre part, on mélange systématiquement dans ces analyses les espèces métropolitaines et les espèces ultra-marines.

C’est donc intellectuellement malhonnête…

C’est un problème de manipulation sémantique, oui. On sait que l’essentiel des disparitions d’espèces a lieu dans les îles. C’est clair, c’est net : 95 % des espèces recensées disparues sont des espèces insulaires, des îles indo-pacifiques notamment. Sur les continents, on a très, très peu d’espèces disparues à l’époque historique. Donc pratiquer l’amalgame et laisser croire que la situation est la même partout n’est pas honnête. Les problèmes sont très différents concernant l’érosion de la biodiversité sur l’île de la Réunion, à Mayotte ou en métropole.

Pour la plupart des métropolitains, la France, c’est la métropole ; il faudrait donc préciser en « France métropolitaine et ultra-marine », et distinguer ce qui concerne les îles et ce qui concerne les continents.

Le problème des îles porte sur les « espèces endémiques » (à distribution réduite, liées à un territoire). Dans ce sens, il y a des îles océaniques, mais également des îles continentales. Un lac peut être une « île continentale ». Le lac Tanganyika, en Afrique, est une île continentale dans la mesure où il n’a aucune connexion avec d’autres lacs. Dans une île, vous avez des populations (végétales et animales) qui vont évoluer de manière isolée et qui vont donner au bout d’un certain temps des espèces biologiquement différentes de celles qui existent sur les continents. En général, ces îles ont été peuplées d’espèces qui vivent sur le continent, et l’évolution a fait son œuvre.

En Corse, en Sardaigne, etc., vous avez des espèces endémiques. Si certaines sont de « vraies » espèces biologiques, il s’agit souvent de sous-espèces dont l’évolution n’est peut-être pas complètement terminée.

La faune endémique des îles a beaucoup souffert de l’introduction d’espèces domestiques (chats, chiens) et d’espèces commensales (rats), c’est incontestable. Mais ce n’est pas le cas en milieu continental. Il ne faut donc pas tout amalgamer, à moins de vouloir manipuler les chiffres pour donner l’impression qu’en métropole, il y a de nombreuses espèces qui ont disparu.

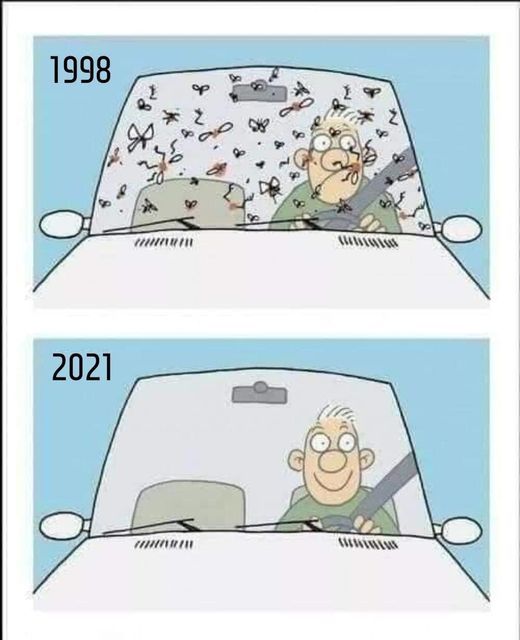

On évoque souvent le cas des insectes. Dans les années 1960, pour désigner le liquide lave-glace, on utilisait le terme « démoustiqueur », tellement on ramassait d’insectes sur le pare-brise lors des déplacements en voiture…

C’est vrai qu’il y a moins d’insectes, je ne le conteste pas. L’homme a forcément un impact sur son environnement. Ou alors il faut exclure l’homme comme le proposent certains, pour qui une belle nature est une nature sans l’homme. Veut-on suivre cette logique ? Ce n’est pas la mienne. Tous les animaux ont un impact sur la nature. Lorsque vous regardez les films animaliers à la télévision, il y a toujours cette pauvre lionne ou cette pauvre louve qui cherche désespérément de quoi nourrir ses petits… On voit avec plaisir et même avec soulagement la pauvre lionne tuer une antilope ou la louve tuer un chamois. C’est cruel, la nature. Ce n’est pas un monde paradisiaque. C’est un monde de rapports de force.

Pour revenir aux insectes, il faut, là encore, essayer de comprendre pourquoi, au cas par cas, certaines populations (pas toutes) sont en régression. Et si les pesticides sont au banc des accusés, ils ne sont pas les seuls coupables. Il y a les pratiques agricoles et la modification des paysages, mais aussi toutes les conséquences de l’artificialisation et des pollutions résultant de l’urbanisation.

Ce qui sous-tend vos propos, et je crois l’avoir vu dans vos écrits, c’est la notion de « co-construction » entre la civilisation humaine et la nature ?

C’est en effet ce que je dis – avec d’autres, car je ne suis pas seul dans ce domaine. La « nature » européenne est une co-construction entre les processus spontanés, c’est-à-dire la dynamique des espèces elles-mêmes, et les activités humaines. Le paysage européen, c’est le produit de l’agriculture, au sens large. Il n’y a plus rien d’originel. Mais c’est aussi de nos jours le produit de l’urbanisation. On voit bien que l’urbanisation artificialise le paysage. On n’a plus de grands espaces sans artifices.

En milieu urbain, notre « nature » est une hyper co-construction. On aménage des coins de nature en ville, des parcs, des jardins. C’est artificiel mais ces milieux hébergent également des espèces de plus en plus nombreuses qui s’adaptent à la ville. On y trouve même beaucoup d’espèces protégées.

Une vision romantique prétend que si l’homme disparaissait définitivement, la nature « reprendrait ses droits », mais on peut également craindre que cela ne soit pas forcément le cas. On peut même redouter que des formes plus primitives du vivant, du type virus « malveillants » ou autres, viennent ravager ce qui resterait.

On peut tout imaginer. Je ne suis pas hostile à ce qu’on réfléchisse à ces questions, loin de là. Je dirais que globalement, l’homme a besoin de la nature, c’est évident. Sans les ressources de la nature, il ne peut pas vivre, comme d’ailleurs beaucoup d’autres espèces. Le principe de la nature, c’est qu’il y a des mangeurs et des mangés, ne l’oublions pas. Néanmoins, la nature a existé pendant très longtemps sans l’homme. L’homme est un tout petit épisode dans l’histoire de la Terre et de la nature, en tout cas l’homme actuel. Et il y a fort à parier que si l’homme disparaît, la nature poursuivra son chemin…

Maintenant, ce qui est vrai, c’est que si l’on abandonne un certain nombre d’activités – notamment agricoles – de co-construction de la nature, les paysages vont changer. La déprise agricole (abandon et sous-utilisation à long terme des sols) entraîne ce qu’on appelle la « fermeture » des paysages. Ça veut dire que les systèmes forestiers vont prendre la place des systèmes prairiaux ouverts, ce qui provoquera un changement assez important dans les peuplements qui leur sont associés. Et l’une des raisons probables de l’érosion des populations d’oiseaux des champs en France et en Europe, dont on discute pas mal, est en partie liée à cette déprise agricole. Cela veut dire que beaucoup d’endroits qui étaient des milieux « ouverts » sont maintenant abandonnés à une forêt qui gagne du terrain en France.

Et puis il ne faut jamais oublier que l’artificialisation des sols (extension des zones habitables) progresse beaucoup. Lorsque l’on aborde le problème de la disparition des insectes (sans exclure le rôle des insecticides), il faut considérer le rôle de l’éclairage, celui des lampadaires qui tuent des quantités d’insectes. L’urbanisation détruit évidemment un certain nombre de milieux favorables aux insectes. Les pratiques agricoles, surtout avec les cultures extensives, éliminent les bosquets, etc. Je ne nie pas du tout le rôle des insecticides, mais je refuse d’en faire le seul facteur ou le bouc-émissaire de la disparition des espèces.

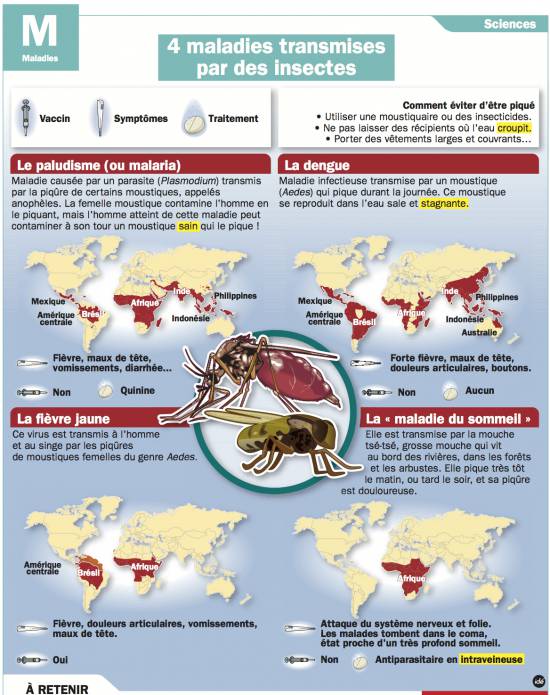

Derrière tout cela, je pose la question de savoir s’il est légitime ou pas que l’homme se protège des nuisances de la nature. N’a-t-on pas le droit de se protéger contre toutes ces nuisances que sont les insectes ravageurs des cultures, que sont les moustiques, que sont tous ces vecteurs de maladies, etc. ? Il y a une vraie question qui est posée… et jusqu’où aller ? Pouvons-nous imaginer des compromis et sur quelles bases ?

En plus, cette question ne se pose pas de la même façon dans les pays en voie de développement que dans les pays avancés. Lorsqu’on regarde le rôle des insectes dans la transmission des grandes maladies parasitaires, bactériennes et virales, on a un autre regard.

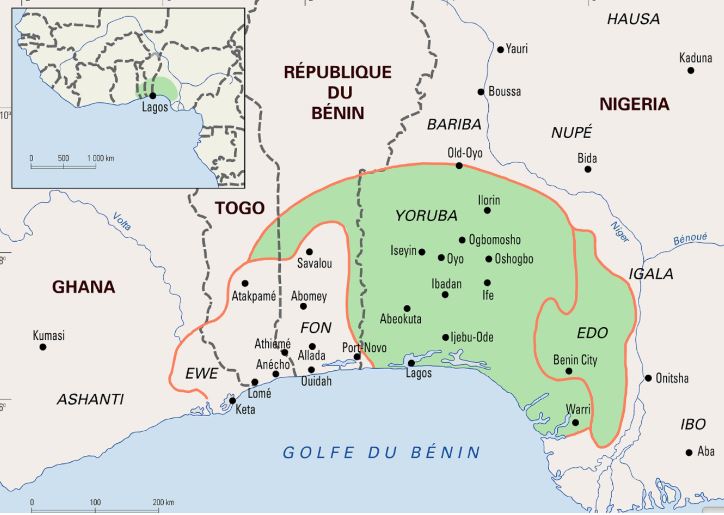

Moi, j’ai travaillé dans les pays en voie de développement. J’ai passé dix ans en Afrique et j’étais sur le terrain, pas derrière les écrans d’ordinateur d’un laboratoire français. Le discours actuel sur la biodiversité est complètement aberrant par rapport aux besoins et à la situation des pays en voie de développement.

Leur problème, ce n’est pas la conservation de la nature dans des réserves. Leur problème, c’est aussi de se protéger de la nature et de ses nuisances. Je dis bien aussi… car évidemment, ils ont aussi besoin de protéger leurs ressources.

Cette question des deux visages de la nature m’est particulièrement chère car dans le monde vécu des citoyens, la nature est une source inépuisable de nuisances (maladies, ravageurs de cultures, aléas climatiques, etc.). Mais les conservationnistes refusent d’en parler pour ne pas écorner cette image d’Epinal d’une nature bucolique assiégée par l’homme, qui est leur fonds de commerce !

Conservation de l’homme !

Ce n’est pas une guerre de tranchées, mais tout de même, ce n’est pas du tout la vision bucolique et idyllique que les « bobos » ont actuellement de la nature. Ça c’est vraiment un regard de pays riche.

Ce que vous avancez me semble très important. Pourtant, votre discours, sans être marginal, n’est pas médiatisé et reste très éloigné du discours dominant. Pourquoi y a-t-il tant de scientifiques qui s’adonnent à ce catastrophisme ?

C’est aussi une question que je me pose. Je me suis plusieurs fois étonné que mes collègues puissent avaliser des informations du type « 1 million d’espèces menacées de disparition », sans disposer des données permettant d’étoffer une telle affirmation ni savoir comment on l’a calculé. En principe, il existe une déontologie scientifique. Les scientifiques doivent parler de choses qui sont vérifiées, ou mettre des informations sur la table pour qu’on puisse en discuter. Or, on ne trouve nulle part de quelle manière ces chiffres ont été obtenus. Les affirmations de ce type qui tournent en boucle sur internet et sur les réseaux sociaux ne sont pas sourcées.

J’étais interrogé par l’hebdomadaire Le Point (20 février 2021) sur la question du WWF qui annonce, dans son rapport Planète vivante (Edition 2020) que 68 % des vertébrés ont disparu entre 1970 et 2016.

Manque de chance, il y a deux articles scientifiques qui, en s’appuyant sur les mêmes bases de données que le WWF, sortent des chiffres totalement différents. En gros, oui, il y a des espèces dont les populations sont en forte régression, c’est incontestable, on parle des lions, on parle des girafes, etc. Mais il y a également des populations qui sont en expansion et ça, on n’en parle jamais, de même qu’on ne parle jamais de l’évolution qui est en cours. On parle toujours de la disparition des espèces, mais quand on fait des analyses génétiques des populations, on s’aperçoit que l’évolution est toujours en cours. Vous avez des différences génétiques dans un même bassin fluvial, entre populations de poissons d’une même espèce à quelques dizaines de kilomètres de distance. L’évolution, c’est de l’adaptation, Les espèces sont en permanence en train de s’adapter. Quand vous introduisez une espèce américaine dans un lac européen, au bout de quelques décennies, elle se différencie de l’espèce d’origine et peut devenir une nouvelle espèce biologique.

Lors de conférences visant à populariser l’idée de la « grande réinitialisation » (Great Reset), c’est-à-dire le verdissement de la finance mondiale pour « sauver le climat », on a pu voir, à la fin de la grande session réunissant la fine fleur des financiers à Londres, le 11 novembre 2020, Greenpeace présenter la bande annonce de son film « Our Planet, Too Big too fail »…

Je sais…

On peut donc croire qu’il existe un lobby de la finance verte qui a bien besoin de ce genre de propagande…

Il y a « une machine à cash », pour dire les choses simplement. Si vous présentez un programme de recherche dans lequel vous dites « je veux montrer tout l’intérêt de la préservation du bocage et de sa transformation historique, soulignant le rôle positif de l’homme », alors vous ne trouverez absolument aucun financement. En revanche, si vous jouez le chercheur pyromane et que vous criez au feu : « Ah, les espèces invasives, ah, le changement climatique ! ça va tout transformer, ça va tout détruire ! »

Ça marche très bien au niveau des médias, ça marche très bien, hélas, au niveau d’un bon nombre de nos concitoyens, et là, vous allez obtenir des crédits, car vous allez dire « donnez-moi de l’argent, je vais vous apporter la solution ». Cela ressemble fort à ce qu’on appelait au Moyen-Âge le régime des indulgences (Note 2), lorsque l’Eglise disait « donnez-nous de l’argent, et votre âme sera sauvée ! »

C’est ce que dit le WWF : « Donnez-nous de l’argent et on va sauver la planète ! » Ça dure depuis des décennies sans que la question de l’érosion de la biodiversité soit réglée pour autant.

C’est pas mal, les indulgences vertes !

Tout cela crée une sorte de doxa. On se renvoie la balle, on fait de la surenchère. On a une « érosion sans précédent » mais qui n’est pas documentée. On se monte le bourrichon d’une certaine manière, mais ça rapporte – de la notoriété, parce qu’on passe dans les médias, et de l’argent parce que vous allez sauver le monde. Qui va dire le contraire ? On est dans un grand jeu de rôle.

Cela me conduit à la dernière question à laquelle vous avez déjà répondu en partie. Aux politiques, vous dites « regardez les chiffres et ne répondez pas aux images et aux émotions ». Existe-t-il des domaines de recherche prometteurs permettant de clarifier ce débat ?

Pour clarifier ce débat, il faudra d’abord que les politiques soient à l’écoute, ce qui n’est pas forcément le cas. C’est une question pour laquelle je n’ai pas de réponse définitive. Je ne suis pas un gourou. Je ne dis pas « il n’y a qu’à… » ou « il faut qu’on… ».

Lorsque je parle de préserver la diversité biologique, je souligne qu’il faut le faire dans un contexte qui dépasse la seule vision naturaliste. Il y a la nature « objet » et la nature vécue… et on ne peut pas parler de la préserver sans tenir compte des paramètres sociaux en matière d’usages et de santé.

Revenons au lac du Der, qui est devenu une zone de protection pour les oiseaux. Une zone humide, un peu marécageuse, ce n’est pas compliqué à faire. Vous creusez un trou, vous y mettez de l’eau, et au bout d’un an ou deux, vous aurez une belle zone humide. La nature fait très bien les choses et il y a naturellement des échanges importants d’espèces d’un endroit à un autre par le biais des oiseaux, des mammifères, du vent, etc. Si vous avez la chance d’avoir un jardin, faites un trou et mettez de l’eau. Après quelques semaines vous verrez que la vie s’y est bien installée.

Oui, le vivant est conquérant !

Il y a eu des expériences intéressantes de création de marais au nord de Paris, dans le Parc départemental du Sausset (93), par un collègue qui est urbaniste. Au début, des paysagistes y ont mis des plantes. Quelques années après, tout cela avait disparu et l’endroit était envahi par une végétation spontanée de zones humides. A tel point que cette zone est devenue un centre d’attraction pour de nombreuses espèces d’oiseaux. Le public appréciait ce coin de nature sauvage… en milieu urbain.

C’est une chose qui a été déterminante dans ma réflexion, pour dire qu’effectivement l’action de l’homme n’est pas systématiquement négative. Mais ce qui était fait initialement pour distraire le public est devenu une réserve ornithologique fermée au public !

Comme je l’ai développé dans certains articles, on n’est pas obligé d’avoir une vision monolithique des choses. J’aborde souvent ces questions du point de vue des rapports nature-société. Si les hommes ont envie, quelque part, de coins de nature protégée, parce que ça leur fait plaisir, et parce qu’ils y trouvent un intérêt, pourquoi pas ? On n’est pas pour autant obligé de faire de la France tout entière une réserve naturelle ! On doit réfléchir sur la base d’un compromis entre différentes attentes des citoyens et des usages de la biodiversité.

Entre 100 % parking et 100 % réserve naturelle, il y a de la marge…

On parle actuellement de 30 % d’aires protégées (terrestres et maritimes), et certains conservationnistes disent que ce n’est pas assez, qu’il faudrait passer à 50 %. Mais où va-t-on mettre les hommes, là-dedans ? On va les mettre dans des réserves indiennes ? Ça, on ne le dit pas… C’est bien le problème, et c’est irresponsable.

Si l’on revient aux pays en voie de développement, lorsqu’on parle de 30 ou 50 % d’aires protégées alors que leur population est en forte augmentation, va-t-on y faire des zones hyper-peuplées et d’autres hyper-dépeuplées ? Tout ça pour qu’on puisse admirer une belle nature dans les zones protégées alors que les hommes crèvent de faim à côté ? Vous avez lu le livre Le colonialisme vert de Guillaume Blanc ? Lisez-le.

J’ai vécu ça en partie. J’ai connu les zones protégées en Afrique de l’Ouest, elles n’ont pas résisté longtemps lorsqu’il y a eu des révoltes sociales. C’étaient des réserves de viande de brousse. C’est un peu différent en Afrique de l’Est, où c’est devenu en réalité du grand business. Pourquoi pas !

Pour protéger les animaux, certains sont près à abattre les hommes dans ces réserves…

Abattre est peut-être un peu fort (mais c’est vrai au sujet des braconniers…), mais les expulser sans aucun doute. C’est ce que fait le WWF. C’est ce que dit Blanc également et ce comportement a été dénoncé dans des articles parus dans Le Monde diplomatique.

Oui, la télévision néerlandaise y a également consacré un reportage extrêmement documenté.

On peut accepter que dans certains pays comme la France, on crée des réserves dans des endroits où il n’y a personne. C’est le cas du parc du Mercantour. Mais il est vrai aussi que nous avons des parcs régionaux qui essaient d’associer protection et activités humaines, avec un certain succès.

Ou le retour des haies ?

On peut replanter des haies, et c’est ce que l’on fait à petite échelle, mais c’est encore assez anecdotique. Une haie, ce n’est pas que de l’aubépine, c’est aussi des arbres, et il faut du temps. Il y a en théorie des choses simples à faire pour recréer l’hétérogénéité des habitats. Au lieu d’avoir d’immenses étendues de champs labourés, on peut reconstituer quelques bosquets, ce qui serait certainement très positif pour la biodiversité.

Cela offre un plus pour les oiseaux…

Ce sont les arbres qui sont importants pour beaucoup d’oiseaux. Il est également clair qu’il faut réduire les pollutions, mais celles de toute nature, et pas seulement les pesticides. Les pollutions lumineuses, ça existe, et l’on pense que pour les insectes et les oiseaux, cela joue un rôle actuellement. Il y a des scientifiques qui semblent disposer de données pour le prouver. On voit bien qu’il y a des choses à faire, mais ce n’est pas forcément la révolution.

C’est en « co-construisant » avec la nature et en se posant la question : qu’est-ce qu’on veut comme nature ? Ce qui nous amène à prendre en compte non seulement des facteurs écologiques, mais également des facteurs économiques et sanitaires. Je ne suis pas sûr que les citoyens soient prêts à accepter le retour des moustiques, par exemple. Mais je respecte aussi les choix de nature éthique. Encore faut-il qu’ils ne deviennent pas exclusifs.

Aujourd’hui, dès qu’il y a un coq qui chante ou des grenouilles qui croassent, on appelle la police et on exige que le maire du village soit fusillé !

Ce qui compte, c’est de rechercher des solutions au cas par cas, qui ne seront pas les mêmes partout. En évitant les excès et les attitudes trop dogmatiques. Mais à certains moments, il faut aussi savoir trancher. Ça c’est de la politique, pas de la science.

C’est pour cela que le concept de co-construction est vraiment la chose à faire connaître.

Il faut tenir compte, selon les endroits, du contexte écologique, économique, sociologique, etc. Il faut tenir également compte des changements dans la société. Au XIXe siècle, la préoccupation majeure était de survivre. L’agriculture ne produisait pas assez, les gens crevaient de faim dans certains endroits. Il fallait donc produire. On ne se posait pas la question de la protection de la nature. Aujourd’hui, c’est la même chose dans les pays en voie de développement.

Je ne sais pas si vous avez vu le cri d’alarme lancé par Jean-Christophe Debar, de la FARM (Fondation pour l’agriculture et la ruralité dans le monde). Car il y a toute une offensive européenne en cours, au nom du Green New Deal, contre la viande, accusée d’être en grande partie responsable des émissions de gaz à effet de serre.

C’est ce que l’on dit… encore faut-il faire des évaluations honnêtes de ces émissions.

On a vu alors des gens sortir leur calculette pour évaluer comment réduire de moitié l’élevage. Face à cela, M. Debar met en garde qu’imposer des baisses de rendement risque d’obliger à doubler les surfaces à cultiver. En gros, cela équivaut à raser les forêts pour faire du bio… Ils se trouvent pris dans leurs propres paradoxes.

Pour produire la même chose en bio, cela demande 30 à 50 % plus de terres qu’en traditionnel. Je ne défends pas forcément le traditionnel, mais c’est un fait. A partir de là, on peut discuter. On peut certainement faire du bio dans certains endroits, mais dans l’état actuel, le bio est plus consommateur d’espaces. Moi je développe une autre idée. Je vis dans un pays où il y a encore du bocage (zone d’élevage). Eh bien, si l’on supprime la viande, qu’est-ce qu’il va devenir, ce bocage ? Ça va s’emboiser : friche, bois… ou ça va faire de belles zones industrielles pour centres commerciaux, ou des centres de loisirs. Donc, si on mange moins de viande, on va modifier nos paysages et sa biodiversité, ce qui montre la complexité des phénomènes et la limite des raisonnements « y’a qu’à, faut qu’on ».

On veut faire de nos agriculteurs de simples « capteurs de carbone ». Ils ne seront plus rémunérés pour les aliments qu’ils produisent, mais pour leur gestion de champs considérés comme des puits de carbone… La question est de savoir ce qui capte le plus de CO2 : une friche, une forêt ou un champ cultivé ?

Cela dépend des cultures et de ce qu’on intègre comme éléments de calcul. Vous parlez des émissions de gaz à effet de serre. On accuse les vaches.

Cependant, un des grands émetteurs de méthane, ce sont les zones humides… Les « feux follets », vous connaissez ? C’est du méthane. Avec la décomposition de la matière organique, il y a émission de méthane.

Pourtant on protège les zones humides, c’est un grand enjeu de conservation, n’est-ce pas ? Mais personne ne veut parler de la production de méthane par les zones humides… Les ONG montent au créneau quand on leur dit ça.

Ségolène Royal serait mécontente de vous entendre !

C’est pourtant évident. J’ai assisté à une séance de l’Académie de l’agriculture où on a parlé de l’émission de méthane par le rot des vaches. J’ai demandé à quoi ça correspond par rapport aux émissions des zones humides ? Silence… Il existe aussi des données démontrant que le permafrost qui se dégèle émet des quantités considérables de méthane. Il faut dire ces choses. On s’amuse avec le rot des vaches, mais est-ce le fond du problème ? On amuse la galerie, en réalité…

Ne pensez-vous pas qu’il est temps de former à nouveau des écologues et des biologistes prêts à aller sur le terrain pour y faire des relevés, plutôt que de tout miser sur des modélisations informatiques ?

C’est un des grands problèmes de l’écologie actuellement. Récolter des données, aller sur le terrain, ça coûte cher, ce n’est pas valorisant au niveau des publications, et c’est parfois sportif ! Pour ces différentes raisons, l’écologie est en partie devenue une science spéculative. Dans son bureau, on fait de l’écologie théorique sur ordinateur avec des « modèles » et on sort ensuite de grandes théories qui ne sont pas validées par les données de terrain.

Pour moi, l’écologie est avant tout une science d’observation ! le modèle est un outil qui aide à traiter ses informations. Ce n’est pas une fin, et encore moins un moyen de se substituer au terrain. Ou alors on en reste à la vision fixiste de l’écologie et on croit que le vivant se conforme aux théories que l’on a imaginées. Comment prendre en compte la variabilité et les aléas dans des modèles déterministes ? Le modèle auquel on accorde un crédit prédictif est l’antithèse de la démarche adaptative.

Un mot pour conclure ?

A mon sens, il est urgent que « l’écologie » (et pas l’écologisme) fasse sa révolution copernicienne. L’écologie est née autour de l’objectif d’identifier les lois qui régulent la nature.

C’était le but recherché au début du XXe siècle : découvrir les lois de la nature. Avec l’arrière-pensée que si l’on connaissait les lois, on pourrait agir sur la nature. Tout comme on avait trouvé les lois des orbites planétaires et de la gravité avec Copernic et Newton, on espérait trouver des lois définissant le fonctionnement général de la nature. Avec le temps, on s’est aperçu qu’il n’y avait pas (ou très peu) de lois pouvant expliquer le fonctionnement général de la nature, mais beaucoup de situations particulières (la contingence). La seule grande loi est celle qui montre que la distribution des espèces à la surface du globe dépend du climat et de la géomorphologie. A part cela, chaque système écologique est relativement différent et fonctionne d’une manière différente. Il faut donc éviter les généralisations et les globalisations, comme le font les mouvements militants et les ONG lorsqu’ils parlent d’érosion de la biodiversité. On l’a vu à propos de la différence entre les espèces continentales et les espèces insulaires.

Et surtout, il faut se mettre dans la perspective que la nature, ça bouge, ce n’est pas en équilibre, ce n’est pas stable, et que penser la préserver dans des réserves ou à travers des lois normatives, c’est un peu de la fiction.

Ils font la même erreur sur le climat en évoquant une température globale de la planète…

Oui, ils appellent cela la « température moyenne » pour l’ensemble du globe. J’ai dit une fois, par boutade, « qu’est-ce que c’est, cette connerie ? » Ça signifie quoi, une moyenne globale ? On voit bien que ce n’est pas si simple au niveau de la planète. Il y a à la fois des réchauffements et des refroidissements, des canicules et des vagues de froid, etc. Il en est de même pour la biodiversité, elle n’est pas la même partout.