Étiquette : France

Thanks to WEST’s new record, world’s nuclear fusion community moving forward

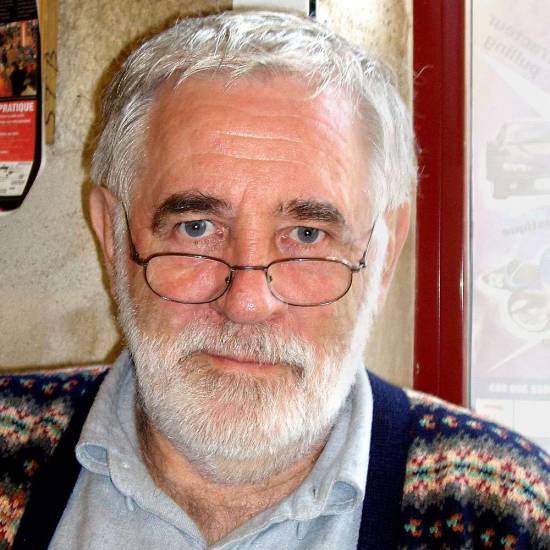

On Monday May 27, 2024, Karel Vereycken talked to physicist and nuclear fusion specialist Alain Bécoulet for Nouvelle Solidarité. He has been in charge of the ITER project’s engineering department since February 2020.

ITER is a large-scale scientific experiment intended to prove the viability of fusion as an energy source. ITER is currently under construction in the south of France. In an unprecedented international effort, seven partners—China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the United States—have pooled their financial and scientific resources to build the biggest fusion reactor in history.

Alain Bécoulet is a former research director at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), and in particular director of the IRFM, the Institut de recherche sur la fusion par confinement magnétique (Institute for Research on Fusion by Magnetic Confinement).

Karel Vereycken: Mr. Bécoulet, good morning, it’s great to have you on the phone.

Alain Bécoulet: Hello Mr. Vereycken, if I’ve understood correctly, you’re interested in what happened at WEST, in connection with the press releases that went out just about everywhere around May 15. (more below)

That’s right; I’ll give you my impressions and you can correct me. I understand that the Tore SUPRA Tokamak (in southern France)1, who with six minutes held a world record in duration till 2021, was a bit like your baby.

To tell the truth, I was director of the IRFM2, in charge of Tore SUPRA. If it can be considered “my baby”, it’s because under my governance it was radically modified and upgraded, and renamed “WEST”. Before me, it was Robert Aymar‘s baby3.

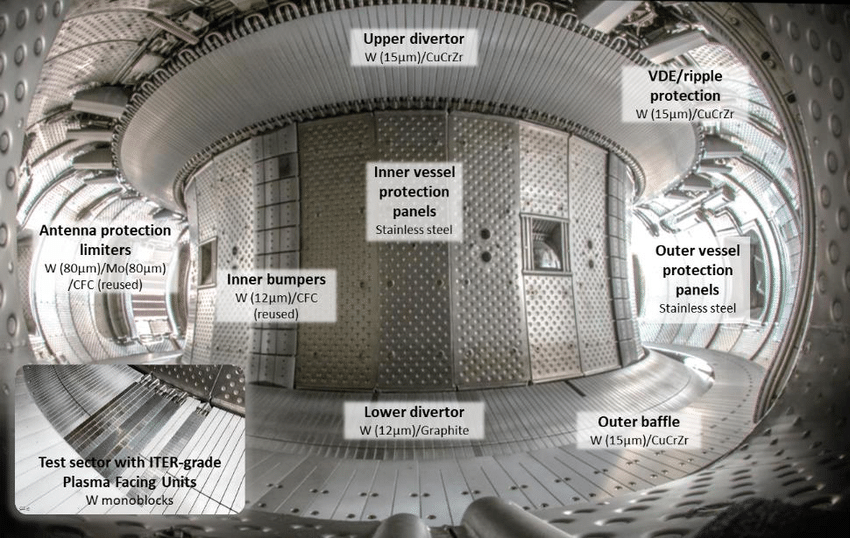

Right! But in WEST, it’s the W that does it all. And it’s a W for tungsten, a very heat resisting material that absorbs less than graphite and makes the machine more efficient?

Yes, it does. The major change we made with WEST, is that we went from a circular-limiter machine 4 to a “divertor” machine.5

On Tore SUPRA, the vertical plasma action was a circle resting on a graphite limiter and the plasma simply touched it.

For some years now, we’ve discovered that making a plasma in the shape of a D, or in the shape of a fish with an X point — called a “divertor” — produces much better results in terms of confining heat and impurities, particles, etc. So it was time for Tore SUPRA to go there.

At the same time, Tore SUPRA itself made it clear for us, that for ITER, it was not possible to continue with carbon – which was ITER’s original intention – and so ITER switched and was reconfigured to tungsten.

That’s when we took the opportunity to install a cooled tungsten divertor in Tore SUPRA. What’s more, Tore SUPRA’s mission has always been, even before ITER – we’ve been talking about it for a very long time now – the development and integration of technological solutions, and not so much performance-fusion.

If you put tritium in Tore SUPRA, you’re not going to get much in the way of power: it’s too small and not powerful enough in any ways to make fusion reactions of any note; but on the other hand, it’s perfectly relevant for all technological developments – it was on Tore SUPRA, it has to be recalled, that the first successful full-scale test of the superconducting coils now used in ITER took place!

I’m fully aware of that.

It was also Tore SUPRA that supplied all the rules for actively cooling all the components in front of the plasma, including diagnostics [i.e. measuring instruments], etc.; not forgetting solutions for continuous additional heating, in short a huge amount of technology.

So the idea, in the transition from Tore SUPRA to WEST, was to continue along the path of the “actively cooled tungsten divertor”.

I think the Koreans, too, with KSTAR, had already.…

There are several superconducting machines that have made equivalent advances –more successive than simultaneous– and that have inspired others; in this case, before talking about KSTAR, the machine that is closest to WEST, its little sister – you’re going to smile, but I didn’t call it WEST for nothing — is a machine that started up when Tore SUPRA was already operating, in Hefei, China, called EAST — with which we have cooperated enormously, both on coils and on plasma components, etc.

So the two laboratories have cooperated enormously; I chose the name WEST because we wanted to change the name of Tore SUPRA, to rejuvenate it and mark the fact that we were making this technology; so we called it WEST, a sort of sister machine to EAST, and the two machines really work together (EAST has now installed a tungsten divertor, etc.). ); even some of the modifications we made to WEST were made in cooperation, in partnership with the EAST machine, with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which supplied us with components, in particular the power supplies for the divertor coils, the new ICRH antennas, etc.; we had all this done by the Chinese.6

It’s extraordinary that this kind of cooperation can still take place in this world of conflict…

It really is! As for KSTAR, it’s quite a similar machine too, but I’d call it less pioneering. It’s only now arriving in this kind of world; it’s a long way behind –not that I’m blaming them, because since the teams are smaller, it’s more difficult– but that doesn’t stop us from cooperating a lot with KSTAR.

The only real difference with WEST lies in the coils, which are all inside a single cryostat (refrigeration system) – as with ITER, whereas in Tore SUPRA, when we built it, the coils were each in a separate cryostat.

To sum up: today, the large superconducting machines accompanying the ITER project are WEST, EAST, KSTAR and now the new JT60SA tokamak which has just gone into operation in Japan. It’s the size of the JET (at Culham in the UK) in superconductor, but doesn’t yet have a tungsten environment, and won’t for several years yet; so it’s not yet fully in a world as relevant, but it’s coming! And because it’s larger, it’ll probably outperform those EAST, WEST, etc. machines.

The press, and the official press release, reports a 15% gain in energy produced – which is still less than the energy spent on the reaction – and at the same time, they talk of a doubling of plasma density.

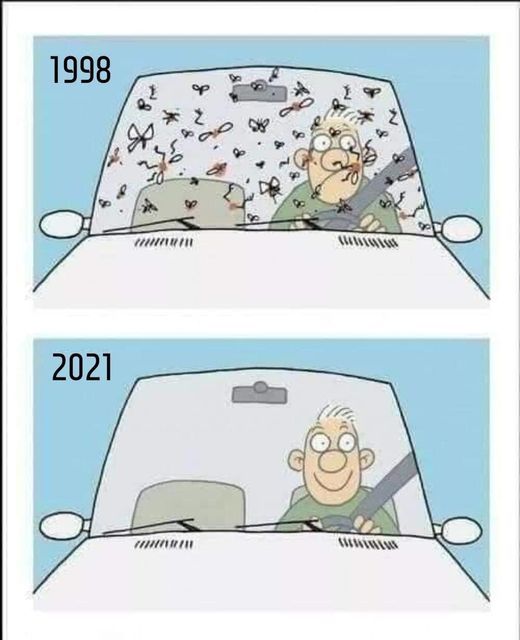

Please note: machines like WEST, EAST and KSTAR will never produce power fusion, for at least two good reasons:

- they’re too small;

- they’re not designed to hold tritium.

So there’s no fusion in these machines. Also, beware of energy gains and the like: these are gains in energy stored inside the machine, but not at all in energy supplied, in energy produced by fusion energy.

It’s not yet “break-even” (when the energy produced exceeds that of the reaction).

In fact, we improve confinement and increase confinement time. This improves the possibility of fusion, but we don’t enjoy fusion in these machines, which are too small and not powerful enough for that, particularly in terms of core plasma.

On the other hand, they are used because their edge plasma, i.e. the plasma inside the plasma interacting with structures such as tungsten, etc., is very similar to ITER’s. That’s why they’re so interesting, and as they can produce very long-lasting plasmas, the tests carried out in these machines are perfectly relevant to ITER.

So I’d like to come back to one of your questions, namely how this advances the promises of ITER. ITER is being built, and things are being manufactured, but ITER is a kind of big eater, constantly asking: “Can you continue the research?”

Obviously, we’re into things we’ve never tested, so anything we can test, anything that can debug things for us, is very welcome. So these machines, in particular WEST, EAST, etc., are helping us to consolidate our position, both in terms of design and in terms of manufacturing solutions –a divertor like the tungsten divertor currently cooled, it works!

And what WEST has just demonstrated– compared with the last time, when it achieved very high performance, particularly in terms of duration, with the Tore SUPRA configuration, on a carbon limiter, etc. — it did so in even more relevant conditions, thanks to a tungsten divertor.

The result of WEST was 364 seconds, or 6 minutes and 4 seconds, with an injected energy of 1.15 GJ, a stationary temperature of 50 million°C (4 keV) and an electron density twice that of the discharges obtained in the previous tokamak configuration, that of Tore SUPRA.

However, what’s really new and very important for ITER is that when these machines do this, it’s with components facing the plasma that are the same as ITER’s. We’ve taken great care to ensure that the WEST divertor has exactly the same technology as the ITER divertor. That’s how we test this technology, over timescales and with power flows arriving on these components that are highly relevant, as they are representative of the conditions in which they will live in ITER.

So ITER has become a globalized scientific experiment, decentralized and centralized at the same time.

ITER is the place where all the world’s fusion knowledge is being synthesized; but this process didn’t stop the day we signed the treaty, it’s being synthesized every day!

We continue to feed ITER with scientific and technical results. For example, if a machine says to us “wait a minute, you’ve done that, but we’ve found results that are different now that we’ve done more work”, we look at that very carefully, to find out whether or not there are any impacts. We’re in constant contact with all these people, to find out what’s coming out of the labs, experiments and simulations, and to find out whether or not there’s an impact on ITER, in which case we’re able to rectify the situation according to the scale of things

This sharing of cooperative data takes place in conditions of great trust?

It’s a scientific community that works like a scientific community, with no preconceptions, no ulterior motives, nothing at all.

A bit like the astronauts on the international space station?

Absolutely. We used to say “in the old days, it was taken for granted”, but now it’s true that it’s become almost surprising. If there’s a result in a Russian or Chinese machine, we have access to it and then we understand, we work, we discuss with them, it’s really very open.

That’s very promising.

We have to fight against the journalists who love to wonder whether there’s competition, whether someone has won or whatever…. That’s not what we’re about at all; we’re about cooperative scientific development. Everyone works in their own corner, of course, but for everyone! There’s no such thing as “I know, I know”, no, none of that exists in the world of fusion.

In the article I’m preparing, I’ll conclude by saying that the big problem with ITER is that there’s only one problem!

In a way, it’s almost true, it’s not the “big problem”, but it’s something that doesn’t encourage acceleration; competition encourages acceleration, we agree on that.

After all, the Chinese have 6 fusion reactors…

Be careful, they’re not “reactors”, beware of the vocabulary. They’re experiments, Tokamaks, plasma experiments, all much smaller. The biggest one I mentioned, in Japan, is ten times smaller than ITER!

Now there are start-ups and others, which we’re hosting here (at the CEA center in Cadarache, France) for three days; 50 start-ups are here, downstairs in the amphitheater, chatting with us; they’re all convinced they’re making reactors, but no! They’re just doing experiments, manips, experimental prototypes. Yes, even ITER isn’t a reactor. Mind you, the meaning of the word “reactor” is to produce electricity or energy, and we’re not there yet!

If someone tells you he is selling you a reactor, you can laugh in his face, because it’s not true, and it will remain so for a long time, unfortunately or fortunately, I don’t know. As far as the reactor phase is concerned, we’ve only just begun, with ITER, the transition to industry. That’s what we’re also doing these days, looking at how to transfer knowledge from laboratories – and ITER is THE world laboratory, in the true sense of the word, in the sense of a public research laboratory. How do we begin to transfer this to the industrialists who will have to build the reactors? But the time scale here isn’t next week!

Wouldn’t your real competitor be the National Ignition Facility (NIF)?7

Not even close! Because with the Americans, it’s in a way even worse, because they’re even less developed in their public research, it’s a long way from maturity. They once did a demonstration in a machine that wasn’t designed for it, and so on.

So if we wanted to go from the NIF to the reactor, we’d already have to make up all the ground we’ve accumulated since the state of magnetic fusion with the big JET experiments in 1997. So we’re almost 30 years away from reaching the levels of technological maturity, integration and overall maturity needed to move towards a reactor. And we, too, are still a long way from moving towards the reactor.

As far as competitors are concerned, to be honest, no one feels like a competitor today, and this is no joke: may the best man win! The problem is so complicated, and the stakes so high, that whoever comes up with the solution will have us all on our feet! There’s no such thing as competition.

We’re starting to see, with these new start-ups, people saying “yes, but we’re moving towards industrial solutions, etc., so we may develop patents that we obviously don’t want to reveal or sell”. Fair enough!

But hey, if they know how to make one of the “technological bricks” and it has a patent, good for them. But that’s not even going to stop us talking. A patent, once you’ve registered it, isn’t a secret, it’s simply something that belongs to you and that you can put on the public square; whoever uses it is just going to have to pay for it, that’s all. So it’s not a war or anything.

The problem is really extremely complicated, and we’re now entering the pre-industrial world of the thing, which is very exciting, isn’t it! I started my career as a theoretician 35 years ago, and I can tell you that we were really on the calculator and not even on the computer yet. Now we’re in: 1/ a complete demonstration of the feasibility of the whole system with ITER, which is in a way the end (the objective) of fundamental public research; 2/ the moment when we’ll say “here’s the great recipe, now it’s up to you to industrialize it, improve it, make it economically viable, etc.”. But ITER still has to show that we can do it, and I believe we can, even though we’re still building the machine and haven’t yet made plasma! But then again, on paper it’s always beautiful…

What do you see as the final hurdles? What more can the public authorities in the various countries do?

I’d encourage you to keep an eye on things until October-November, when the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) will issue a strategic document, prepared by all of us –and I’m one of its key authors. It’s a global strategy document on the development of fusion energy, i.e. the production of energy through fusion.

It’s a very interesting document which, in around twenty pages, covers all the regulatory, technological, scientific and industrial aspects – everything you could possibly dream of: it’s got it all!

And it gives a great deal of information on the challenges facing this community – which is in the process of moving from a purely public research community to a mixed public-private community, moving towards industry, etc. – and on what remains to be done by this community, in terms of nuclear regulations, industrialization, work on the overall efficiency of all sub-systems, and availability (a reactor can’t just run for three minutes every day, it has to work 24 hours a day for 40 years).

This strategic document, which will be issued by the International Agency, should enable all players – I’d almost say “outsiders”: investors, the press, politicians, etc. – to understand where the merger stands and what remains to be done. So it’s a fairly ambitious document, with such a lofty goal, but one that has been made simple and readable for once; we’ve put a lot of effort into it, and I think we’ve succeeded.

It’s really condensed: each paragraph covers 40 or 50 years of research (!), but I think it’s understandable; at the moment it’s being edited by the IAEA, and will be published in early autumn.

Ok, we’ll watch that.

And finally, here are my thoughts on what remains to be done for fusion:

- New technological building blocks. There are things that even ITER won’t be able to do, such as fully demonstrating the closure of the tritium cycle – how to make tritium, and how to really burn it in situ; we’re going to do a few demonstrations, but we don’t yet have the complete cycle, and we won’t have it just with ITER.

- Materials. Since magnetic fusion generates very energetic neutrons, and lots of them – a machine like ITER is designed to live for a certain time with a certain plasma rhythm, so it has no problem surviving these neutrons. But if we built the same ITER and ran it for 40 years, 24 hours a day, it wouldn’t last; its materials wouldn’t stand up to the shock. So we need other materials, and materials research and development.

- This brings us to maintenance: how can we learn to intervene in these kinds of objects without disturbing them too much, working with robotics and appropriate intelligence to understand these extremely complex systems? So we also need to model them; some elements are very difficult to manufacture, so we need to think about how to work on the design so that manufacturers have less difficulty in doing what they’re asked to do, etc.

- There are also nuclear regulations.

Is this new measuring device just demonstrated on WEST really a breakthrough?

The first to communicate this WEST result were the Americans, which surprised me, but hey, why not?

Yes, it surprised me too.

Because of an unfortunate sentence at the beginning of their article, we got the impression that WEST was a machine from the Princeton laboratory!

Yes, that’s right!

International Cooperation

I spoke to you about the collaboration with China; when I created WEST, we set up a collaborative, partnership-based process that is almost even more ambitious than ITER. We partnered some thirty laboratories around the world to help us build WEST. It thus became a kind of international machine, operated by the CEA without any problems, but an international machine, and we played the same role as ITER: we tried to do what we call supply in kind –I mentioned the Chinese, who gave us power supplies, heating antennas, etc., but there are many countries like that: the Indians have manufactured and supplied us with things, and in this case the Princeton laboratory has designed, manufactured and installed a diagnostic: what you call a measuring instrument is in fact an advance that we test on the machine, and the Americans, or the Princeton people now, can now say “there, we know how to do that, and the proof: we tested it there and there, etc.”. You can think of these major research instruments (like WEST, EAST, etc.), particularly in the field of fusion, as test benches for all kinds of things.

Do we have a machine that actually makes plasma? It’s a bit like CERN (Geneva based particle accellerator), where you’ve got a device that accelerates particles, and then you’ve got lots of people who come to watch, put particles together, make them collide like this, put them in this detector, make them do something, and exploit the science that goes with it.

A Tokamak is also a test bench somewhere, for testing components with plasma, diagnostics, heating systems and so on. So it lends itself well to partnership, because you’ve got a central unit, a central operator who’s going to do the bulk of the machine, who’s going to rectify the coils or the enclosures, etc.; and then afterwards, you can have a huge number of people who are going to come and contribute to a brick that we’re going to put into this machine.

And WEST works with China, with Korea, with many French laboratories –CNRS laboratories and universities that simply bring us diagnostics or simulations – with the United States, with India and with many other countries. And we have a steering committee; for this machine, it’s not just the CEA that decides on its experimental plan: once a year, people from all these labs get together to examine what we’ve done and what we want to do with this machine. Remember that these are always integrated contributions, mixing technology and physics.

It’s wonderful! Thank you for your answers, which have shown us the global, shared process towards a more peaceful world.

We’re trying… We believe in scientific diplomacy here. It’s not easy, it’s no easier than normal diplomacy, but scientific diplomacy does exist, it’s an aspect we believe in and demonstrate every day, we show that it exists and that it also contributes, effectively, to the planet’s progress, even if sometimes it’s more difficult… I’m used to comparing it to sports or artistic diplomacy; the Olympic Games shouldn’t turn as sour as it’s turning, it doesn’t make sense.

Thank you, congratulations, we’re proud of you and your teams, keep up the good work!

Thank you very much. See you soon.

- With a major radius of 2.25m (machine centre to plasma centre) and a minor radius of 0,70m, Tore Supra (before it was reconfigured as WEST) was one of the largest tokamaks in the world. Its main feature was the superconducting toroidal magnets which enabled generation of a permanent toroidal magnetic field. Tore Supra was also the only tokamak with plasma facing components actively cooled. Theses two features allow the study of plasma with long pulse duration. ↩︎

- Institut de recherche sur la fusion par confinement magnétique (Institute for Research on Fusion by Magnetic Confinement. ↩︎

- Robert Aymar was the Director General of CERN (2004–2008), serving a five-year term in that role. In 1977, Robert Aymar was appointed Head of the Tore Supra Project, to be constructed at Cadarache (France). In 1990, he was appointed Director of the Direction des Sciences de la Matière of the CEA, where he directed a wide range of basic research programmes, both experimental and theoretical. ↩︎

- The “Limiter” of the Tore SUPRA tokamak (made of graphite), was the element that extracted most of the energy contained in the plasma (in the shape of a flat circular ring located in the lower part of the donut shaped machine).

↩︎ - In WEST, the actively cooled 456-component divertor at the bottom of the vacuum vessel extracts the heat and ash produced by the fusion reaction, minimizes plasma contamination and protects the surrounding walls from thermal and neutron loads. ↩︎

- Most of this industrial production (i.e. 16,000 blocks of tungsten), was carried out by AT&M (China), with the support of the Chinese laboratory ASIPP as part of the joint CEA-China collaboration (SIFFER, SIno French Fusion Energy centeR). Already, in 2016, the Institute of Plasma Physics (ASIPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), had supplied ICRH (Ion Cyclotron Resonant Heating) antennas for Tore SUPRA. ↩︎

- In December 2022, an NIF experiment used 2.05 megajoules of laser energy to produce 3.15 megajoules of fusion energy.

↩︎

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: short note before starting your visit

Listen:

- To the audio on this website

Read:

- Index of articles dealing with art history and Renaissance studies on this website.

——————————

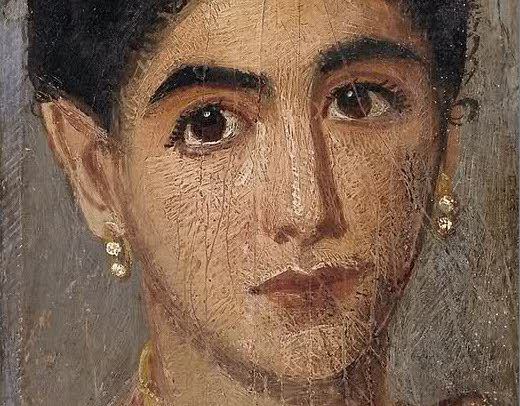

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: The Greek tradition behind the Fayum Mummy Portraits

Karel Vereycken comments the Louvre’s Fayum Mummy Portraits.

Listen:

To the audio on this website

Read:

Paris Schiller Institute stages Afghan civil society protest against UNESCO

Paris, Feb. 2024 – On Thursday February 22, between 10:00 am and 1:00 pm CET, members and supporters of the International Schiller Institute, founded and presided by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, gathered peacefully in front of one of the main buildings of the headquarters of UNESCO in Paris (1, rue Miollis, Paris 75015). An appeal (see below), endorsed by both Afghans and respected personalities of four continents, was presented to the Secretary General and other officials of UNESCO.

How it started

Following a highly successful conference in Kabul last November by the Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, a group of senior archaeologists of the Afghan Academy of Sciences (ASA), in discussion with the organizers and the invited experts of the Schiller Institute, suggested to launch a common appeal to UNESCO and Western governments to “lift the sanctions against cultural heritage cooperation.”

The Call

“We regret profoundly, says the call, that the Collective West, while weeping crocodile tears over destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, has imposed a selective ban of scientific cooperation on nations mistakenly considered as “opposed to its rules and values.” The complete freeze of all cooperation in the field of archaeology between France and both Syria and Afghanistan, is just one example of this tragedy.”

“The dramatic neglect of international cultural institutions and donors to Afghanistan, the lack of sufficient funds in the field of cultural heritage protection, and the political treatment of international cultural heritage institutions have seriously endangered Afghanistan,” underscores the petition.

Specifically, “UNESCO, which should raise its voice against any new form of ‘cultural and scientific apartheid,’ has repeatedly worsened the situation by politicizing issues beyond its prerogatives.”

To conclude, the signers call

“on the international community to immediately end this form of ‘collective punishment,’ which creates suffering and injustice, promotes ignorance, and endangers humanity’s capacity for mutual respect and understanding.”

Living Spirit of Afghanistan

To date, over 550 signatures have been collected, mainly from both Afghan male (370) and female (140) citizens, whose socio-professional profiles indicates they truly represent the « living spirit of the nation ».

Among the signatories: 62 university lecturers, 27 doctors, 25 teachers, 25 members of the Afghan Academy of Sciences, 23 merchants, 16 civil and women’s rights activists, 16 engineers, 10 directors and deans of private and public universities, 7 political analysts, 6 journalists, 5 prosecutors, several business leaders and dozens of qualified professionals from various sectors.

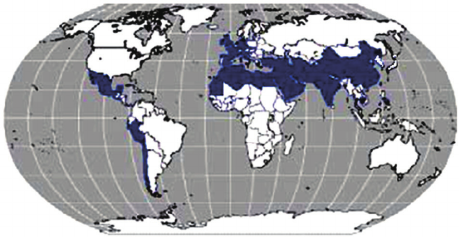

International support

On four continents (Europe, Asia, America, Africa), senior archaeologists, scientists, researchers, members of the Academy of Sciences, historians and musicians from over 20 countries have welcomed and signed this appeal.

Italian Professor Pino Arlacchi, a former member of the European Parliament and the former head of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) was the first to sign. Award-winning American filmmaker Oliver Stone, is a more recent signer.

In France, Syria, Italy, the UK and Russia, among the signers one finds senior researchers suffering the consequences of what some have identified as a « New Cultural Cold War. » Superseding the very different opinions they have on many questions, the signatories stand united on the core issue of this appeal: for science to progress, all players, beyond ideological, political and religious differences, and far from the geopolitical logic of ‘blocs’, must be able to exchange freely and cooperate, in particular to protect mankind’s historical and cultural heritage.

Testifying to the firm commitment of the Afghan authorities, the petition has also been endorsed by the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of Culture and Arts, and the Minister of Agriculture, as well as senior officials from the Ministries of Higher Education, Water and Energy, Mines, Finance, and others.

“The 46th session of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, to be held in New Delhi in July this year, offers UNESCO the opportunity to announce Afghanistan’s full return into world heritage cooperation, if we can have our voice heard,” says Karel Vereycken of the Paris Schiller Institute. “We certainly will not miss transmitting this appeal to HE Vishal V Sharma, India’s permanent representative to UNESCO, recently nominated to make the Delhi 46th session a success.”

For all information, interview requests in EN, FR and NL:

Karel Vereycken, Schiller Institute Paris

00 33 (0)6 19 26 69 38

Full text of the appeal

International Call to Lift Sanctions Against Cultural Heritage Cooperation

Following the international conference, organized by the Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center’s in Kabul in early November 2023, on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, a group of researchers launched the following petition:

We, the undersigned, researchers and experts in the domains of the history of civilizations, cultural heritage, archaeology, anthropology, sociology, and many other fields, and other enlightened citizens of the world, in Afghanistan, Syria, Russia, China, and many other countries, launch the following call.

1) We regret profoundly that the “Collective West”, while weeping crocodile tears over destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, has imposed a selective ban of scientific cooperation on nations mistakenly considered as “opposed to its rules and values.” The complete freeze of all cooperation in the field of archaeology between France and both Syria and Afghanistan, is just one example of this tragedy.

2) We request particular attention to the case of Afghanistan. Its neighboring countries, national and international institutions, and countries involved in international conventions for the protection of cultural and natural heritage are committed to cooperation in the field of guarding cultural heritage sites and artifacts and preventing their smuggling and destruction. Therefore, it is expected that in the current situation, they will fully play their role in the protection of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage in accordance with international laws and conventions. However, the dramatic neglect of international cultural institutions and donors to Afghanistan, the lack of sufficient funds in the field of cultural heritage protection, and the political treatment of international cultural heritage institutions have seriously endangered Afghanistan. Undoubtedly, the non-recognition of the Afghan government has dimmed the attention of cultural institutions. Considering the above, we expect these international institutions to renew their full support to protect both the tangible and the intangible cultural heritage of Afghanistan.

3) We regret that UNESCO, which should raise its voice against any new form of “cultural and scientific apartheid,” has repeatedly worsened the situation by politicizing issues beyond its prerogatives.

4) Therefore, we call on the international community to immediately end this form of “collective punishment,” which creates suffering and injustice, promotes ignorance, and endangers humanity’s capacity for mutual respect and understanding.

The progress of scientific knowledge, in a positive climate permitting all to share it, is by its very nature beneficial to each and to all and to the very foundation of a true peace.

SIGNERS:

A. FROM AFGHAN CIVIL SOCIETY:

– Hussain Burhani, Archaeologist, Numismatist, Afghanistan ;

– Ketab Khan Faizi, Archaeologist, Director of the Academy of Sciences at the International Centre for Kushan Studies in Kabul, Afghanistan;

– Stora Ishams Mayar, Archaeologist, member of the Academy of Sciences at the International Centre for Kushan Studies in Kabul, editor in chief of the journal of this mentioned center, Afghanistan;

– Mahmood Jan Drost, Senior Architect, head of protection of old cities of Afghanistan, Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, Afghanistan;

– Ghulam Haidar Kushkaky, Archaeologist, associate professor, Archaeology Investigation Center, Afghanistan ;

— Laieq Ahmadi, Archeologist, Former head, Archeology department of Bamiyan University, Afghanistan;

– Shawkatullah Abed, Chief of staff, Afghan Science Academy, Afghanistan;

– Sardar Ghulam Ali Balouch, Head of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan;

– Daud Azimi Shinwari, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Germany;

– Abdul Fatah Raufi, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Kabul, Afghanistan;

– Mirwais Popal, Dip, Master, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Germany;

B. FROM ABROAD:

(Russia, China, USA, Indonesia, France, Angola, Germany, Turkiye, Italy, UK, Mexico, Sweden, Iran, Belgium, Argentina, Czech Republic, Syria, Congo Brazzaville, Yemen, Venezuela, Pakistan, Spain, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo.)

– H.E. Mr Mohammad Homayoon Azizi, Afghanistan’s Ambassador to Paris, UNESCO and ICESCO, France;

— Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento, Researcher at the National Scientific Research Centre (CNRS), Archaeologist specializing in Central Asia; Former director of the Delegation of French Archaeologists in Afghanistan (DAFA) (2014-2018), France;

– Inès Safi, CNRS, Researcher in Theoretical Nanophysics, France;

– Pierre Leriche, Archeologist, Director of Research Emeritus at CNRS-AOROC, Scientific Director of the Urban Archaeology of the Hellenized Orient research program, France;

– Nadezhda A. Dubova, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Dr. in Biology, Prof. in History. Head of the Russian-Turkmen Margiana archaeological expedition, Russian Academy of Science (RAS), Russia;

— Alexandra Vanleene, Archaeologist, specialist in Gandhara Buddhist Art, Researcher, Independant Academic Advisor Harvard FAS CAMLab, France;

– Raffaele Biscione, retired, associate Researcher, Consiglio Nazionale delle Recerche (CNR); former first researcher of CNR, former director of the CNR archaeological mission in Eastern Iran (2009-2022), Italy;

— Sandra Jaeggi-Richoz, Professor, Historian and archaeologist of the Antiquity, France;

– Dr. Razia Sultanova, Professor, Cambridge University, UK;

– Dr. Houmam Saad, Archaeologist, Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums, Syria;

– Estelle Ottenwelter, Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Natural Sciences and Archaeometry, Post-Doc, Czech Republic;

– Didier Destremau, author, diplomat, former French Ambassador, President of the Franco-Syrian Friendship Association (AFS), France ;

– Wang Feng, Professor, South-West Asia Department of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), China;

– Dr. Engin Beksaç, Professor, Trakya University, Department of Art History, Turkiye;

– Bruno Drweski, Professor, National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO), France;

– Maurizio Abbate, National President of National Agency of Cultural Activities (ENAC), Italy;

– Patricia Lalonde, Former Member of the European Parliament, vice-president of Geopragma, author of several books on Afghanistan, France;

– Pino Arlacchi, Professor of sociology, Former Member of the European Parliament, former head of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Italy;

– Oliver Stone, Academy Award-winning Film director, Producer, and Screenwriter;

– Graham E. Fuller, Author, former Station chief for the CIA in Kabul until 1978, former Vice-Chair of the National Intelligence Council (1986), USA;

– Prof. H.C. Fouad Al Ghaffari, Advisor to Prime Minister of Yemen for BRICS Countries affairs, Yemen;

– Farhat Asif, President of Institute of Peace and Diplomatic Studies (IPDS), Pakistan;

— Dursun Yildiz, Director, Hydropolitics Association, Türkiye;

– Irène Neto, president, Fundacao Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto (FAAN), Angola;

– Luc Reychler, Professor international politics, University of Leuven, Belgium;

– Pierre-Emmanuel Dupont, Expert and Consultant in public International Law, Senior Lecturer at the Institut Catholique de Vendée, France;

— Irene Rodríguez, Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina;

– Dr. Ririn Tri Ratnasari, Professor, Head of Center for Halal Industry and Digitalization, Advisory Board at Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia;

– Dr. Clifford A. Kiracofe, Author, retired Professor of International Relations, USA;

– Bernard Bourdin, Dominican priest, Philosophy and Theology teacher, Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP), France;

– Dr. jur. Wolfgang Bittner, Author, Göttingen, Germany;

– Annie Lacroix-Riz, Professor Emeritus of Contemporary History, Université Paris-Cité, France;

– Mohammad Abdo Al-Ibrahim, Ph.D in Philology and Literature, University Lecturer and former editor in chief of the Syria Times, Syria;

– Jean Bricmont, Author, retired Physics Professor, Belgium;

– Syed Mohsin Abbas, Journalist, Broadcaster, Political Analyst and Political Justice activist, Pakistan;

– Eduardo D. Greaves PhD, Professor of Physics, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas, Venezuela;

– Dora Muanda, Scientific Director, Kinshasa Science and Technology Week, Democratic Republic of Congo;

– Dr. Christian Parenti, Professor of Political Economy, John Jay College CUNY, New York, USA;

– Diogène Senny, President of the Panafrican Ligue UMOJA, Congo Brazzaville;

– Waheed Seyed Hasan, Journalist based in Qatar, former Special correspondent of IRNA in New Delhi, former collaborator of Tehran Times, Iran;

– Alain Corvez, Colonel (retired), Consultant International Strategy consultant, France;

– Stefano Citati, Journalist, Italy;

– Gaston Pardo, Journalist, graduate of the National University of Mexico. Co-founder of the daily Liberacion, Mexico;

– Jan Oberg, PhD, Peace and Future Research, Art Photographer, Lund, Sweden.

– Julie Péréa, City Councilor for the town of Poussan (Hérault), delegate for gender equality and the fight against domestic violence, member of the Sète Agglopole Méditerranée gender equality committee, France;

– Helga Zepp-LaRouche, Founder and International President of the Schiller Institute, Germany;

– Abid Hussein, independent journalist, Pakistan;

– Anne Lettrée, Founder and President of the Garden of Titans, Cultural Relations Ambassador between France and China for the Greater Paris region, France;

– Karel Vereycken, Painter-engraver, amateur Art Historian, Schiller Institute, France;

– Carlo Levi Minzi, Pianist, Musician, Italy;

– Leena Malkki Brobjerg, Opera singer, Sweden;

– Georges Bériachvili, Pianist, Musicologist, France;

– Jacques Pauwels, Historian, Canada;

C. FROM AFGHAN AUTHORITIES

– Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, Deputy Foreign Minister, Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA);

– Mawlawi Muhibullah Wasiq, Head of Foreign Minister’s Office, IEA;

– Waliwullah Shahin, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Sayedull Afghani, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Hekmatullah Zaland, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Shafi Azam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Atiqullah Azizi, Deputy Minister of Culture and Art, Ministry of Information and Culture, IEA;

– Ghorzang Farhand, Ministry of Information and Culture, IEA;

– Ghulam Dastgir Khawari, Advisor of Ministry of Higher Education, IEA;

– Mawlawi Rahmat Kaka Zadah, Member of ministry of Interior Affairs, IEA;

– Mawlawi Arefullah, Member of Interior Affairs, IEA;

– Ataullah Omari, Acting Agriculture Minister, IEA;

– Mawlawi Hussain Ahmad, Head of office in Ministry of Agriculture, IEA:

– Musa Noorzai, Member of Ministry of Agriculture, IEA;

– Mawlawi Hussain Ahmad, Head of office, Ministry of Agriculture, IEA;

– Mawlawi Shar Aqa, Head of Kunar Agriculture Administration, IEA;

– Matiulah Mujadidi, Head of Communication of Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Zabiullah Noori, Executive Manager, Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Akbar Wazizi, Member of Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Nasrullah Ebrahimi, Auditor, Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Mir M. Haroon Noori, Representative, Ministry of Economy, IEA;

– Abdul Qahar Mahmodi, Ministry of Commerce, IEA;

– Dr. Ghulam Farooq Azam, Adviser, Ministry of Water & Energy (MoWE), IEA;

– Faisal Mahmoodi, Investment Facilitation Expert, Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, IEA;

– Rustam Hafiz Yar, Ministry of Transportation, IEA;

– Qudratullah Abu Hamza, Governor of Kunar, IEA;

– Mansor Faryabi, Member of Kabul Municipality, IEA;

– Mohammad Sediq Patman, Former Deputy Minister of Education for Academic Affairs, IEA;

COMPLEMENTARY LIST

A. FROM AFGHANS

- Jawad Nikzad, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Akram Azimi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Najibullah Totakhel, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Germany

- Ghulam Farooq Ansari, Professor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Imran Zakeria, Researcher at Regional Studies Center, Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan, Ibn Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Subhanullah Obaidi, Doctor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Germany ;

- Ali Shabeez, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Germany ;

- Mawlawi Wahid Ameen, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Shar M. Amir Zadah, Ibne-eSina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Rafiullah Halim, Professor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul Afghanistan ;

- Nazar Mohmmad Ragheb, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Faisal Mahmoodi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Basir, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Muneera Aman, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Shakoor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Waris Ebad, Employee of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Afghanistan ;

- Waisullah Sediqi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Hakim Aria, Employee of Ministry of Information and Culture, Afghanistan ;

- Nayebuddin Ekrami, Employee of Ministry of information and Culture, Afghanistan ;

- Latifa Azimi, Former Employee of Ministry of Education, Afghanistan ;

- Latifa Noori, Former Employee of Ministry of Education, Afghanistan ;

- Habibullah Haqani, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Shafiqullah Baburzai, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Abdullah Kamawal, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rashid Lodin, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Asef Nang, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Awal Khan Shekib, Member of Afghanistan Regional Studies Center, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Anwar Fayaz, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Farhad Ahmadi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Fayqa Lahza Faizi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hakim Haidar, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Rahimullah Harifal, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Sharifullah Dost, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Eshaq Momand, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Khalil Rahman Barekzal, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Haidar Kushkaki, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Nabi Hanifi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Marina Bahar, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Muhaidin Hashimi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Majid Nadim, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Elaha Maqsoodi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Khadim Ahmad Haqiqi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Shahidullah Safi, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Wahab Hamdard, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Burhanullah Niazi, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- M. Alam Eshaq Zai, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Hasan Farmand, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Zalmai Hewad Mal, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rahman Atash, Head of Afghanistan National Development Company (NDC), Afghanistan ;

- Obaidullah, Head of Public Library, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Abdul Maqdam, Head of Khawar construction company, Afghanistan ;

- Zaki Zarifi, Head of Zarifi company, Afghanistan ;

- Jamshid Faizi, Head of Faizi company, Afghanistan ;

- M. Yasin Farahman, Head of Agriculture Center, Afghanistan ;

- Mawlawi Nik M. Nikmal, Head of Planning in Technical Administration, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Wahid Rahimi, Member of Bashtani Bank, Afghanistan ;

- M. Daud Mangal, Head of Ariana Afghan Airlines, Afghanistan ;

- Mostafa Yari, entrepreneur, Afghanistan;

- Gharwal Roshan, Head of Kabul International Airfield, Afghanistan ;

- Eqbal Mirzad, Head of New Kabul City Project, Afghanistan ;

- Najibullah Sadiq, Vice-president of Afghan Chamber of Commerce and Indunstry (ACCI), Afghanistan;

- M. Yunis Mohmand, Vice-president of ACCI, Afghanistan;

- Khanjan Alikozai, Member of ACCI, Afghanistan;

- Mawlawi Abdul Rashid, Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Atiqullah Safi, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Jalil Safi, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Hujat Fazli, Head of Harakat, Afghanistan Investment Climate Facility Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mehrab Hamidi, Member of Economical Commission, Afghanistan;

- Hamid Pazhwak, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Awaz Ali Alizai, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- Shamshad Omar, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- Helai Fahang, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Alikozai, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Dunya Farooz, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Soman Khamoosh, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Drs. Shokoria Yousofi, Bachelor of Economy, Afghanistan;

- Sharifa Wardak, Specialist of Agriculture, Afghanistan;

- M. Asef Dawlat Shahi, Specialist of Chemistry, Afghanistan;

- Pashtana Hamami, Specialist of Statistics, Afghanistan;

- Asma Karimi, Master of Management, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Ahmad Zaki Afghanyar, Vice-President of Herat Health committee, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hashem Mudaber, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hekmatullah Arian, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Wahab Rahmani, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Karima Rahimyar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Sayeeda Basiri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Emran Sayeedi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Hadi Dawlatzai, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ghani Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Nafisa Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Ghani Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mohammad Younis Shouaib, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Halima Akbari, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Manizha Emaq, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Shafiq Shinwari, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Akbar Jan Foolad, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Haidar Omar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ehsanuddin Ehsan, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Wakil Matin, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Matalib, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Azizi Amer, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Nasr Sajar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Humayon Hemat, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Humaira Fayaq, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Sadruddin Tajik, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Baqi Ahmad Zai, Surgery Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Beqis Kohistani, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Nafisa Nasiri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Aziza Yousuf, Head of Malalai Hospital, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Yasamin Hashimi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Zuhal Najimi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Ahmad Salem Sedeqi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Fazel Raman, veterinary, Afghanistan;

- Khatera Anwary, Health, Afghanistan;

- Rajina Noori, Member of Afghanistan Journalists Union, Afghanistan ;

- Sajad Nikzad, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Suhaib Hasrat, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Shar Aqa Karimi, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Mohammad Suhrabi , Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Nasir Kuhzad, Journalist and Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Fazel Menallah, Political Analyst, Afghanistan;

- M. Wahid Benish, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Mahmood Jan Shafizada, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Fazel Rahman Orya, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Zarghon Shah Shinwari, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Ghafor Shinwari, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ahmad Yousufi, Dean, Kateb University, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Yayia Balaghat, Scientific Vice-President, Kateb University, Afghanistan ;

- Chaman Shah Etemadi, Head of Gharjistan University, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mesbah, Head of Salam University, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Pirzad Ahmad Fawad, Kabul University;

- Dr. Nasir Nawidi, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Zabiullah Fazli, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Ramish Adib, Vice of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- M. Taloot Muahid, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Ebrahim Ansari, School Manager, Afghanistan;

- Abas Ali Zimozai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Arshad Rahimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Fasihuddin Fasihi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Waisuddin Jawad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Murtaza Sharzoi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Matin Monis, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Wahid Benish, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Hussian Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Muhsin Reshad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Sadiq Baqori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Zahir Halimi, Univ. Lecturer , Afghanistan ;

- Rohla Qurbani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Murtaza Rezaee, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Rasoul Qarluq, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Najim Wahidi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Rashid Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rahman Matin, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Mujtaba Amin, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Amanullah Faqiri, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Abuzar Khpelwak Zazai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Belal Tayab, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Adel Hakimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Wasiqullah Ghyas, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Faridduin Atar, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Safiullah Jawhar, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Amir Jan Saqib, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Shekib Rahmani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Gulzar Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Taj Mohammad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Hekmatullah Mirzad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Haq Atid, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Fahim Momand, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Fawad Ehsas, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Naqibullah Sediqi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Maiwand Wahidi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- M. Nazir Hayati, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Najiba Rahmani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Abeda Baba Karkhil, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. M. Qayoum Karim, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Sayed Sharif Shabir, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Walid Howaida, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Zalmai Rahib, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Sadiq Baqori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mir Zafaruddin Ansari, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Atta Mohammad Alwak, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Zabiullah Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Hasan Fazaili, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- M. Jawad Jalili, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mukhtar Ali Nasto, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Namatullah Nabawi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ghulam Abas Noori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mustafa Anwari, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Fakhria Popal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Shiba Sharzai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Marya Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nilofar Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Munisa Hasan, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nazifa Azimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Sweeta Sharify, Lecturer; Afghanistan;

- Fayaz Gul, Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Zakia Ahmad Zai, Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nigani Barati, Education Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Azeeta Nazhand, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sughra, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Nadia Sharif, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Maryam Omari, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Masoud, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Zubair Ahmad, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Khalil Ahmad, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Khadija Omid, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Haida Rasouli, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Hemat Hamad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Wazir Safi, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Qasim, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Zamin Shah, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Qayas, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mehrabuddin, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Zahidullah Zahid, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Akmal Mahros, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sadia Mohammadi, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Mina Amiri, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- M. Sajad Nikzad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mursal Nikzad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Qadir Shahab, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- M. Hasan Sahi, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mirwais Haqmal, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Leeda Khurasai, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Karishma Hashimi, Instructor, Afghanistan;

- Majeed Shams, Architect, Afghanistan;

- Azimullah Esmati, Master of Civil Engineering, Afghanistan;

- Najibullah Hussaini, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Burhanuddin Nezami, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Hafiz Hafizi, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Bahir, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Wali Bayan, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Khaliq Najir, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Diana Niazi, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Imam Jan, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Khalil Ahmad Nadem, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Sayeed Aqa, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Edris Rasouli, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Raz Mohammad, Engineer of Mines, Afghanistan ;

- Nasrullah Rahimi, Technical Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Ehsanullah, Helmand, Construction Engineer, Netherlands;

- Ahmad Hamad, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Akmal Ahmadi, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Ershad Hurmati, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Akram Shafim, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Akbar Ehsan, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Raziullah, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Zaki Khorrami, IT Officer, Afghanistan ;

- Osman Nikzad, Graphic Designer, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Ayani, Carpet Weaver, Afghanistan ;

- Be be sima Hashimi, Tailor, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Masoumi, Tailor, Afghanistan ;

- Roya Mohammadi, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Nadia Sayes, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Nazdana Ebad, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Sima Ahmadi , Bachelor of Biology, Afghanistan;

- Sima Rasouli, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Khatera Nawabi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Haji Noor Agha Haqyar, Merchant, Afghanstan;

- Husna Anwari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Nargis Hashimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Shakira Barish, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Nasima Darwish, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Wajiha Haidari, Merchant of Jawzjan, Afghanistan ;

- Shagul, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Nik Rasoul, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Haji Farid Alikozai, Merchant, Afghanistan;

- Nigina Nawabi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Masouda Nazimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Najla Kohistani, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Kerisma Jawhari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Hasina Hashimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Husna Anwari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Maaz Baburzai, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Freshta Safari, Merchant, Afghanistan;

- Yalda Azimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Azim Jan Baba Karkhil, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Akhtar Mohammad, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- M. Haroon Ahmadzai, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Azizullah Faizi, Former head of Afghanistan Cricket Board, Afghanistan ;

- Wakil Akhar, Prosecutor, Afghanistan ;

- Akhtar M. Azimi, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Shabnam Noori, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Be be Abeda Wayar, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Madina Ahmad Zai, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Shakila Joya, Former Employee of Attorney General, Afghanistan;

- Sardar M. Akbar Bashash, Member, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Eng. Abdul Dayan Balouch, Spokesperson of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Shah Mahmood Lahoti, Member of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Khaliq Barekzai, Advisor, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Salahuddin Ayoubi Balouch, Advisor, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Faizuddin Lashkari Balouch, Member, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Ishaq Gilani, head of the National Solidarity Movement of Afghanistan, IEA;

- Haji Zalmai Latifi, Representative, Qizilbash tribes, Afghanistan ;

- Gul Nabi Ahmad Zai, Former Commander of Kabul Garrison, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Hussain Rezaee, Member, Habitat Organization, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Amani Adiba, Doctor of Liberal Arts in Architecture and Urban Planning, Afghanistan;

- Ismael Paienda, Afghan Peace Activist, France;

- Mohammad Belal Rahimi, Head of Peace institution, Afghanistan ;

- M. Mushtaq Hanafi, Head of Sayadan council, Afghanistan ;

- Sabira Waizi, Founder of T.W.P.S., Afghanistan ;

- Majabin Sharifi, Member of Women Network Organization, Afghanistan;

- Shekiba Saadat, Former head of women affairs, Afghanistan ;

- Atya Salik, Women rights activist, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Mahmoodi, Women rights activist, Afghanistan;

- Diana Rohin, Women rights activist , Afghanistan;

- Amena Hashimi, Head of Women Organization, Afghanistan;

- Fatanh Sharif, Former employee of Gender equality, Afghanistan;

- Sediq Mansour Ansari, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Sebghatullah Najibi, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Naemullah Nasiri, Civil Activist, Afghanistan;

- Reha Ramazani, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Lia Jawad, Civil Activist, Afghanistan;

- Arezo Khurasani, Social Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Beheshta Bairn, Social Activist, Afghanistan;

- Samsama Haidari, Social Activist, Afghanistan;

- Shabnam Nikzad, Humans Rights Activist, Afghanistan;

- Mliha Sadiqi, Head of Young Development Organization, Afghanistan;

- Mehria, Sharify, University Student;

- Shiba Azimi, Member of IPSO Organization, Afghanistan;

- Nadira Rashidi, Master of Management, Afghanistan;

- Sefatullah Atayee, Banking, Afghanistan;

- Khatira Yousufi, Employee of RTA, Afghanistan;

- Yalda Mirzad , Employee of Breshna Company, Afghanistan;

- Izzatullah Sherzad, Employee, Afghanistan;

- Erfanullah Salamzai , Afghanistan;

- Naser Abdul Rahim Khil, Afghanistan;

- Ghulam Rasoul Faizi, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mir Agha Hasan Khil, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Ghafor Muradi, Afghanistan;

- Gul M. Azhir, Afghanistan;

- Gul Ahmad Zahiryan, Afghanistan;

- Shamsul Rahman Shams, Afghanistan;

- Khaliq Stanekzai, Afghanistan;

- M. Daud Haidari, Afghanistan;

- Marhaba Subhani, Afghanistan;

- Maazullah Nasim, Afghanistan;

- Haji Mohammad Tayeb, Afghanistan;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Afghanistan ;

- Sweeta Sadiqi Hotak, Afghanistan ;

- Khatira Anwari, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Sharzad, Afghanistan ; Momen Shah Kakar, Afghanistan ;

- Shah Rukh Raufi, Afghanistan ;

- Hanifa Rasouli, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Qudsia Ebrahimi, Afghanistan ;

- Mahmood Haqiqat, Afghanistan ;

- Nasir Abdul Rahim Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Hamid Ahmadzai, Afghanistan ;

- Sardar Khan Sirat, Afghanistan ;

- Zurmatullah Ahmadi, Afghanistan ;

- Yasar Khogyani, Afghanistan ;

- Shar Sha Lodi, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Shah Omar, Afghanistan ;

- M. Azam Khan Ahmad Zai, Afghanistan;

- Nadia Farooq Sharzoi, Afghanistan;

- Shar Ali Tazari, Afghanistan ;

- Mayel Aqa Hakim, Afghanistan ;

- Khatira Hesar, Afghanistan ;

- Tamim Mehraban, Afghanistan ;

- Lina Noori, Afghanistan ;

- Khubaib Ghufran, Afghanistan ;

- M. Yasin Farahmand, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mir M. Ayoubi, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Namatullah Nabawi, Afghanistan ;

- Abozar Zazai, Afghanistan ;

- Atiqullah Rahimi, Afghanistan ;

- Fahim Ahmad Sultan, Afghanistan ;

- Humaira Farhangyar, Afghanistan ;

- Imam M. Wrimaj, Afghanistan ;

- Masoud Ashna, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Yahia Baiza, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Besmila, Afghanistan ;

- Ehsan Shorish, Germany;

- Irshad, Omer, Afghanistan;

- Musa Noorzai, Afghanistan;

- Lida Noori Nazhand, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Abdul Masood Panah, Afghanistan;

- Gholam Sachi Hassanzadah, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Sayed Ali Eqbal, Afghanistan;

- Hashmatullah Atmar, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Matin Safi, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Helmand, Afghanistan;

- Ehsanullah Helmand, Afghanistan;

- Izazatullah Sherzad, Afghanistan;

- Hafizullah Omarzai, Afghanistan;

- Hedayatullah Hilal, Afghanistan;

- Edris Ramez, student, Afghanistan;

- Amina Saadaty, Afghanistan;

- Muska Hamidi, Afghanistan;

- Raihana Ahmadi, Afghanistan;

- Zuhal Sherzad, Afghanistan;

- Meelad Ahmad, Afghanistan;

- Devah Kubra Falcone, Germany;

- Maryam Baburi, Germany;

- Suraya Paikan, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Fatah Ahmadzai, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mohammad Zalmai, Afghanistan ;

- Hashmatullah Parwarni, Afghanistan ;

- Asadullah, Afghanistan;

- Hedayat ullah Hillal, Afghanistan;

- Najibullah Zazai, Afghanistan;

- M. Yousuf Ahmadi, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Reshad Reka, Afghanistan;

- Sayed Ahmad Arghandiwal, Afghanistan;

- Nooria Noozai, Afghanistan;

- Eng. Fahim Osmani, Afghanistan;

- Wafiullah Maaraj, Afghanistan;

- Roya Shujaee, Afghanistan;

- Shakira Shujaee, Afghanistan ;

- Adina Ranjbar, Afghanistan;

- Ayesha Shafiq, Afghanistan;

- Hajira Mujadidi, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Zahir Shekib, Afghanistan;

- Zuhra Mohammad Zai, Afghanistan;

- Razia Ghaws, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Sabor Mubariz, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Khaliq Ferdows, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Shakoor Salangi, Afghanistan;

- Nasir Ahmad Basharyar, Afghanistan;

- Mohammad Mukhtar Sharifi, Afghanistan;

- Mukhtar Ahmad Haqtash, Afghanistan;

- Yousuf Amin Zazai, Afghanistan;

- Zakiri Sahib, Afghanistan;

- Mirwais Ghafori, Afghanistan;

- Nesar Rahmani, Afghanistan;

- Shar M. Amir Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Yasin Farahmand, Afghanistan;

- Faizul Haq Faizan, Afghanistan;

- Khaibar Sarwary, Afghanistan;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Afghanistan;

- Hamidullah Akhund Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Benish, Afghanistan;

- Hayatullah Fazel, Afghanistan;

- Faizullah Habibi, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Hamid Lyan, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Qayoum Qayoum Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Qazi Qudratullah Safi, Afghanistan;

- Noor Agha Haqyar, Afghanistan;

- Maryan Aiany, Afghanistan;

B. FROM ABROAD

- Odile Mojon, Schiller Institute, Paris, France ;

- Johanna Clerc, Choir Conductor, Schiller Institute Chorus, France ;

- Sébastien Perimony, Africa Department, Schiller Institute, France ;

- Christine Bierre, Journalist, Chief Editor of Nouvelle Solidarité, monthly, France ;

- Marcia Merry Baker, agriculture expert, EIR, Co-Editor, USA ;

- Bob Van Hee,Redwood County Minnesota Commissioner, USA ;

- Dr. Tarik Vardag, Doctor in Natural Sciences (RER), Business Owner, Germany;

- Richard Freeman, Department of Physical Economy, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Liliana Gorini, chairwoman of Movisol and singer, Italy;

- Ulrike Lillge,Editor Ibykus Magazine, Berlin, Germany ;

- Michelle Rasmussen, Vice President, Schiller Institute in Denmark, amateur musician;

- Feride Istogu Gillesberg, Vice President, Schiller Institute in Denmark;

- Jason Ross, Science Department, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Dennis Small, Director of the Economic Department, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Robert “Bob” Baker, Agriculture Commission, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Dr. Wolfgang Lillge, Medical Doctor, Editor, Fusion Magazine, Berlin, Germany ;

- Ulf Sandmark, Vice-Chairman of the Belt and Road Institute, Sweden ;

- Mary Jane Freeman, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Hussein Askary, South West Asia Coordinator, Schiller Institute, Sweden ;

- David Dobrodt, EIR News, USA ;

- Klaus Fimmen, 2nd Vice-Chairman of the Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität (Büso) party, Germany;

- Christophe Lamotte, Consulting Engineer, France ;

- Richard Burden, EIR production staff, USA ;

- Rolf Gerdes, Electronic Engineer, Germany;

- Marcella Skinner, USA ;

- Delaveau Mathieu, Farm Worker, France ;

- Shekeba Jentsch, StayIN, Board, Germany;

- Bernard Carail, retired Postal Worker, France ;

- Etienne Dreyfus, Social Activist, France ;

- Harrison Elfrink, Social Activist, USA ;

- Jason Seidmann,USA ;

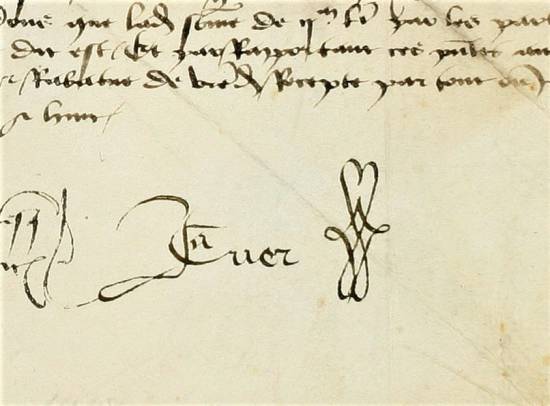

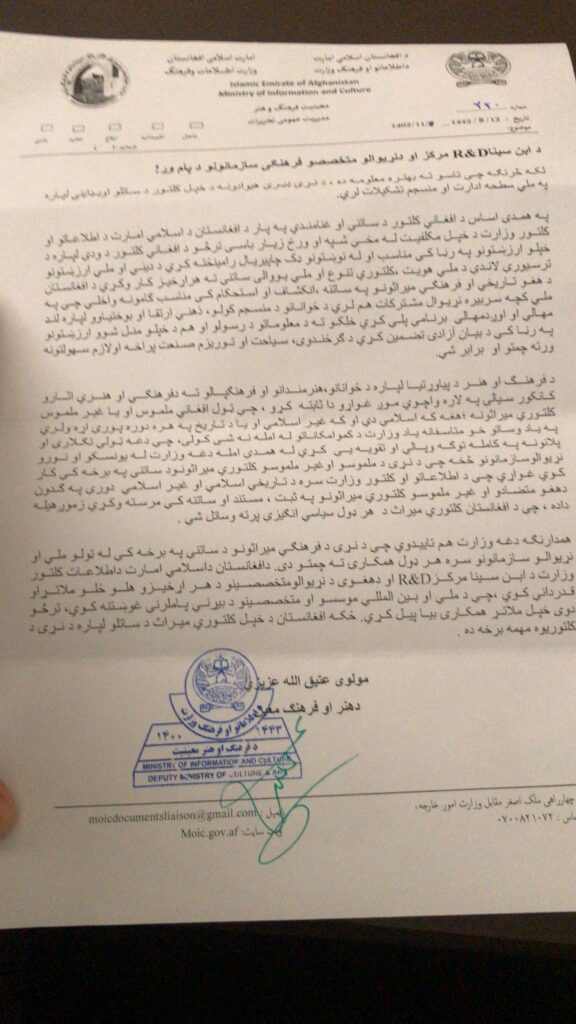

Letter of the minister of Information and Culture

Since Western researchers, based on what happened in the past, wondered about the current Afghan government’s actual policy on the issue of preservation of cultural and historical heritage, the Ibn-e-Sina Research and Development Center questioned the relevant authorities in Kabul.

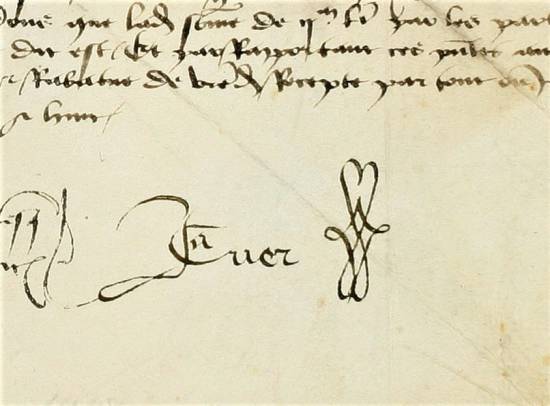

At the end of January 2024, the Minister of Arts and Culture, in an hand-signed letter, provided them (and the world) with the following response, which completely clarifies the matter.

Transcript below, bold as in the original.

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

Ministry of Information and Culture

Letter N° 220, Jan. 31, 2024

To the attention of Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, International experts and cultural organizations and to those it concerns:

The ministry of Information and culture of the Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) has, among others, the following tasks in its portfolio:

–To establish a suitable environment for the growth of genuine Afghan culture;

–To protect national identity, cultural diversity, and national unity;

–To preserve tangible and intangible cultural heritage;

–To support the development of creativities, initiatives and activities of various segments of the society in general and of the Afghan youth in particular;

–To support the freedom of speech;

–Development of tourism industry;

–Introduction and presentation of Afghan culture regionally and internationally, to transform Afghanistan into an important cultural hub and crossroads in the near future.

We would like to confirm that with preservation of tangible and intangible cultural heritage we mean all Afghan cultural heritage belonging to all periods of history, whether it belongs to Islamic or non/pre-Islamic periods of history.

This ministry expresses its concerns that due to insufficient means it is not able to preserve the Afghan cultural heritage sufficiently.

Therefore this ministry asks UNESCO and other international organizations, working on preservation of the world’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage, to support Afghanistan in preservation of its tangible and intangible cultural heritage, including the ones belonging to Islamic and non/pre-Islamic periods of its history. The cultural heritage of Afghanistan does deserve to be preserved without any political motivations.

Besides, this ministry also confirms it is ready for all kind of cooperation with all national and international organizations, working on preservation of world cultural heritage.

The ministry of Information and culture of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) supports and appreciates all efforts of the Ibn-e-Sina R&D centre and their international experts in appealing for urgent attention of national and international organizations and experts to resume their support and cooperation with Afghanistan to preserve its cultural heritage, an important part of world cultural and historical heritage.

Sincerely,

Mowlavi Atiqullah Azizi

Deputy Minister of Culture and Art

moicdocymentsliaison@gmail.com

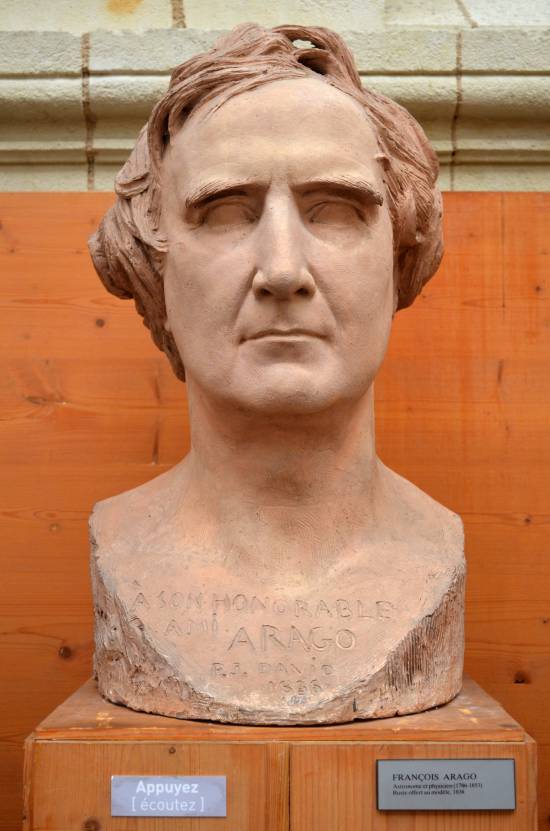

Afghanistan : « Le pays des 1000 cités d’or » et l’histoire d’Aï Khanoum

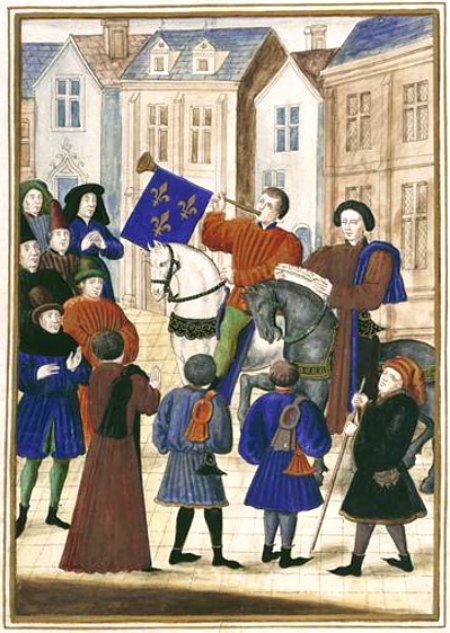

Invité par le Centre de recherche et de développement Ibn-e-Sina en tant que représentant de l’Institut Schiller, Karel Vereycken est intervenu le 7 novembre à la conférence sur la reconstruction du pays.

Son propos introductif, devant un groupe de travail composé d’historiens, d’archéologues et de membres de l’Académie des sciences d’Afghanistan, a donné lieu à une longue après-midi d’échanges sur le rôle de l’art, la méthodologie scientifique et les combats à mener pour sortir l’Afghanistan de son isolement et préserver un héritage culturel qui certes est afghan, mais appartient à toute l’humanité.

Parler de la culture d’un pays étranger est toujours une chose difficile, surtout si l’on n’en connaît pas la langue et si l’on n’a pas pu séjourner et voyager dans le pays pendant de longues périodes. Par conséquent, je ne peux que vous offrir mes impressions de l’extérieur et commenter ce que j’ai découvert dans des livres. Vous allez donc m’aider en me corrigeant et en me signalant ce qui a échappé à mon attention.

L’Afghanistan est un pays fascinant. Sa réputation de « tombeau des Empires » a capté mon imagination. Récemment, votre pays s’est émancipé de l’occupation américaine et de l’OTAN. Une poignée de combattants déterminés a mis en déroute un immense empire déjà en train de s’autodétruire. 34 ans plus tôt, le pays avait chassé l’occupant russe, après avoir résisté à l’Empire britannique au cours des trois guerres anglo-afghanes du XIXe siècle (1839-42, 1878-80 et 1919), alors que Londres, engagé dans le « Grand Jeu » (Great Game), tentait d’empêcher la Russie d’accéder aux mers chaudes.

Pour éviter d’être colonisé à la fois par la Russie et la Grande-Bretagne, l’Afghanistan a même courageusement refusé d’avoir des chemins de fer, ce qui explique qu’il n’existe aujourd’hui que 300 km de voies ferrées, une situation bien sûr inacceptable aujourd’hui.

Cette capacité de résistance et ce sentiment de dignité découlent, j’en suis convaincu, du fait que votre pays a su faire siennes les diverses influences qui s’y sont rencontrées. Voilà ce qui est devenu au fil des siècles le socle d’une forte identité afghane, totalement à l’opposé de l’étiquette tribale que les colonisateurs cherchent à lui coller.

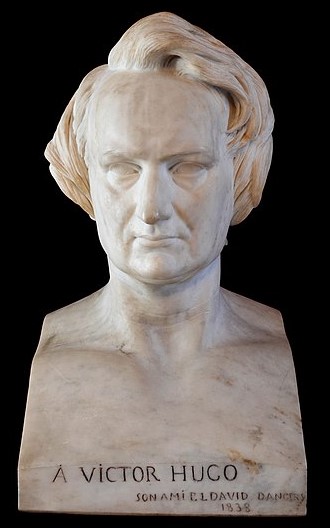

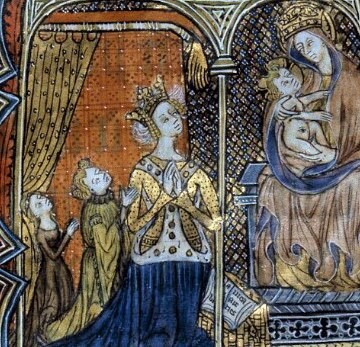

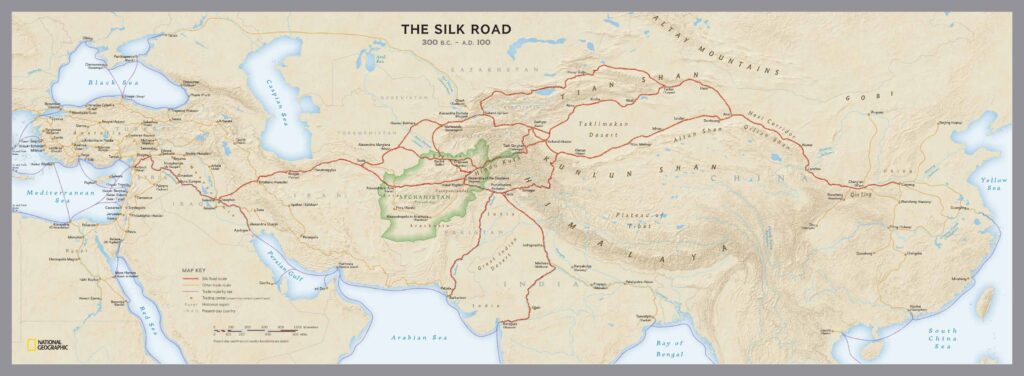

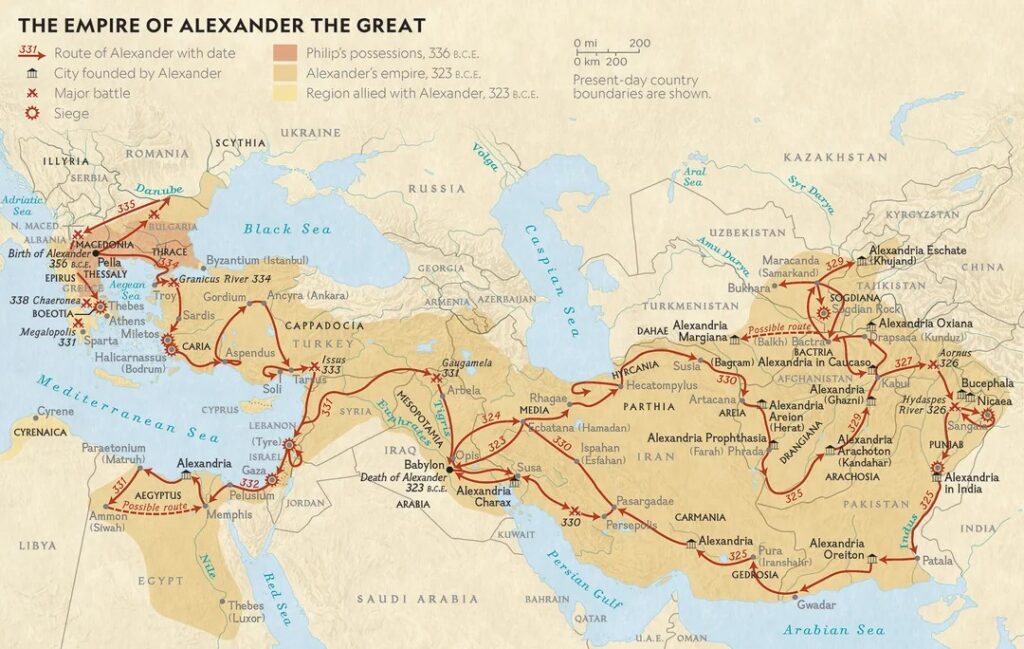

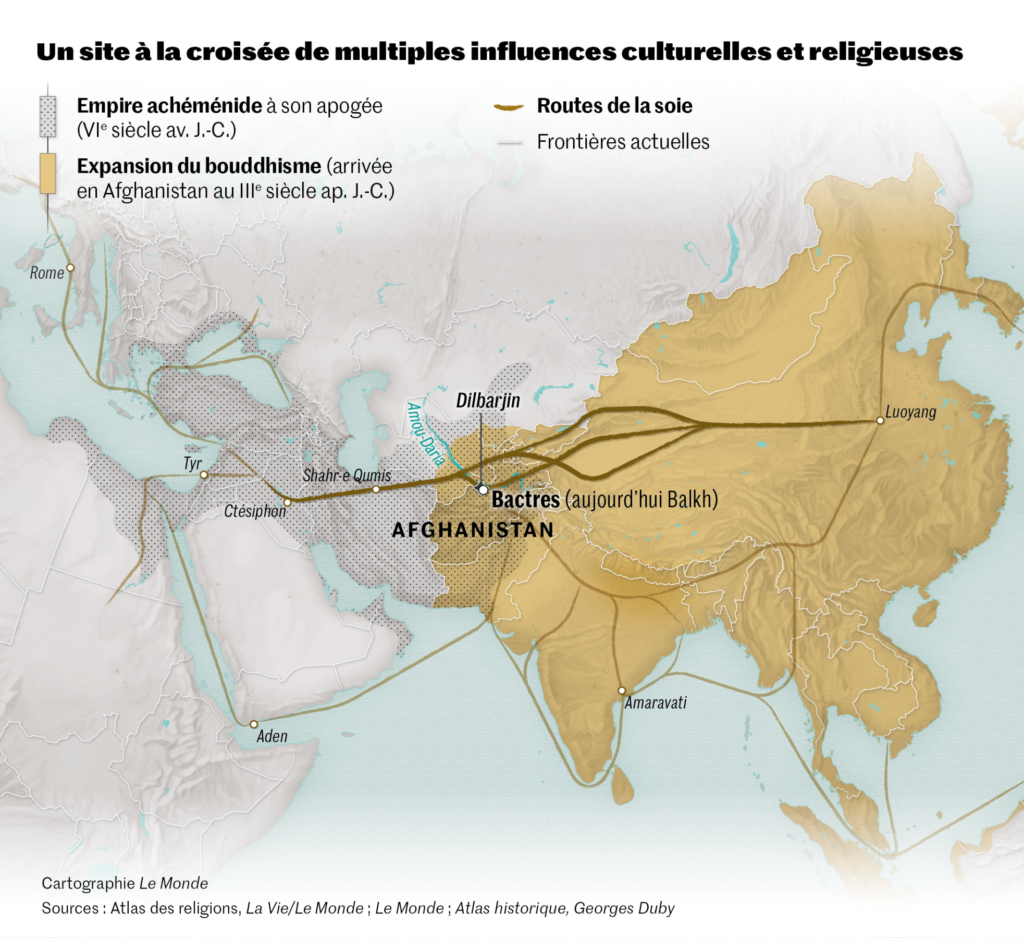

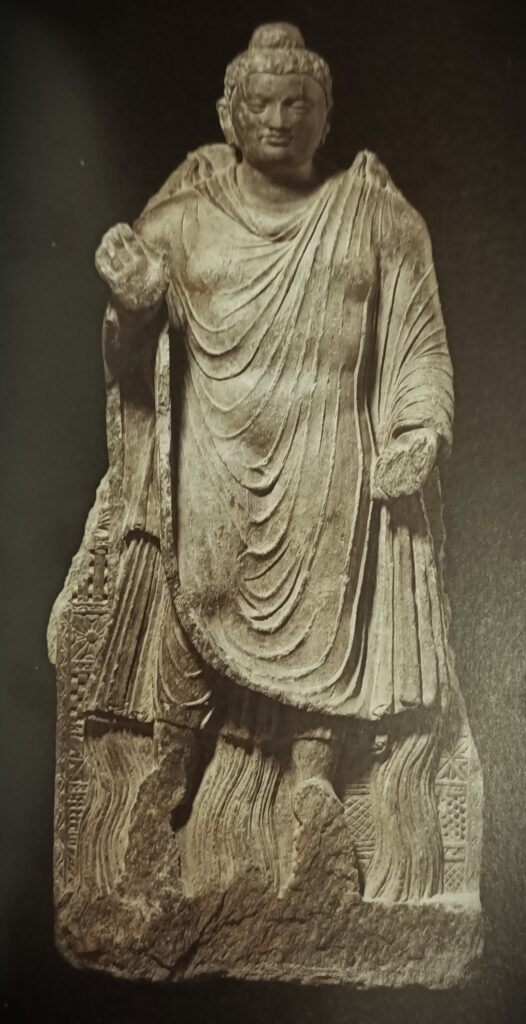

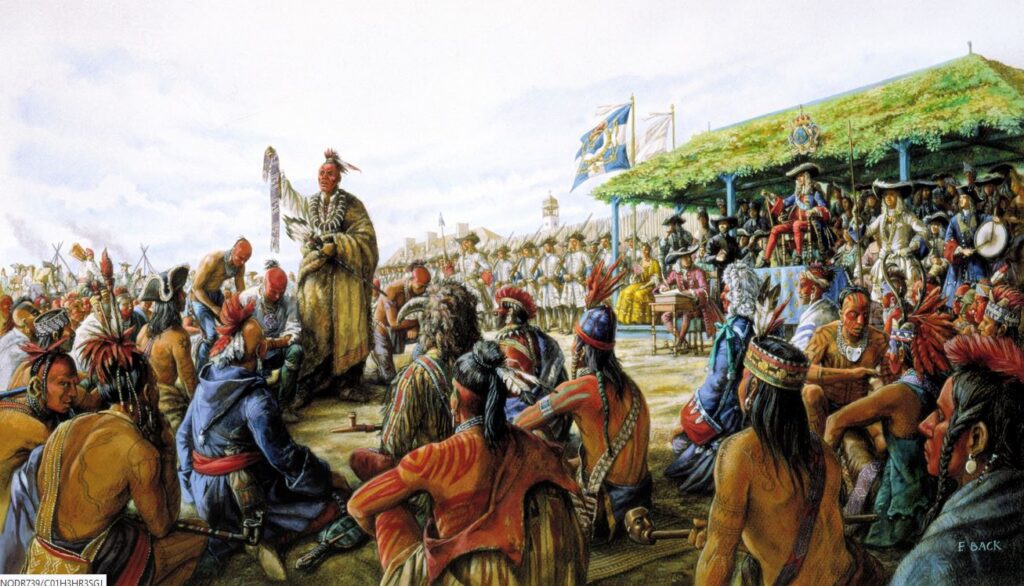

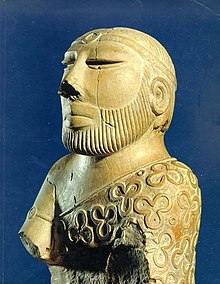

J’aborderai uniquement, aujourd’hui, l’influence grecque, qui s’est avérée majeure à partir du moment où Alexandre le Grand traverse le Hindou Kouch, en 329 av. JC.

Dès lors, des dizaines de milliers de colons grecs, appelés Ioniens, s’installent en Asie centrale.

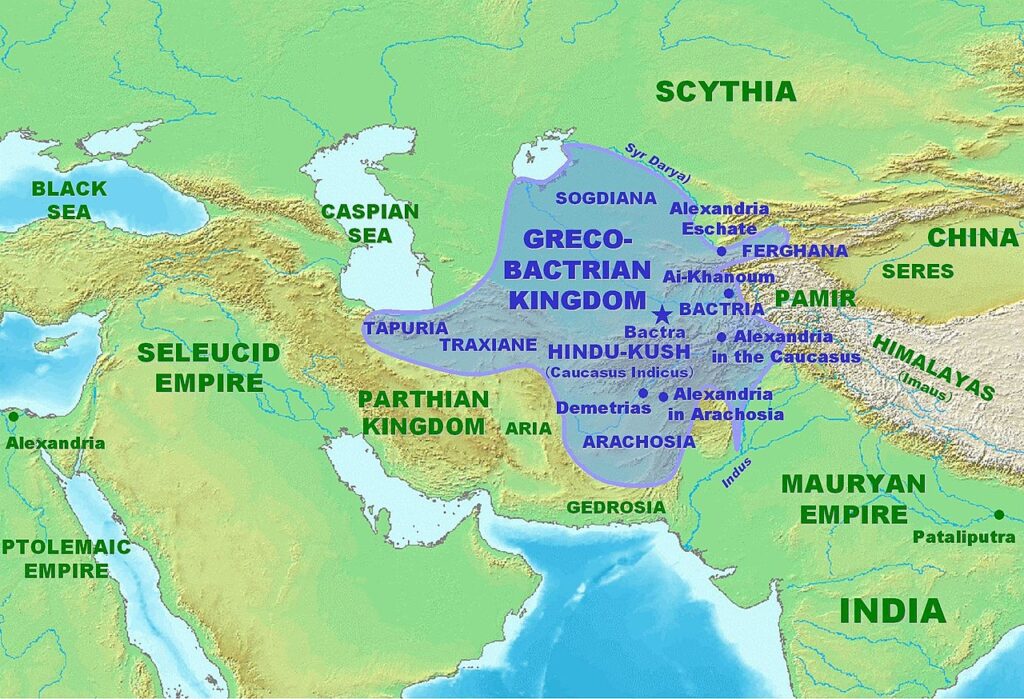

Sous le règne de ses successeurs concurrents, l’immense empire d’Alexandre le Grand se décompose en plusieurs entités et royaumes.

En 256 av. JC, Diodote Ier Soter fonde en Afghanistan le royaume gréco-bactrien, connu sous le nom de « Bactriane », dont le territoire englobe une grande partie de l’Afghanistan, de l’Ouzbékistan, du Tadjikistan et du Turkménistan actuels, ainsi que certaines parties de l’Iran et du Pakistan. L’influence grecque y perdure au moins jusqu’à l’arrivée de l’Islam au VIIIe siècle.

La Bactriane

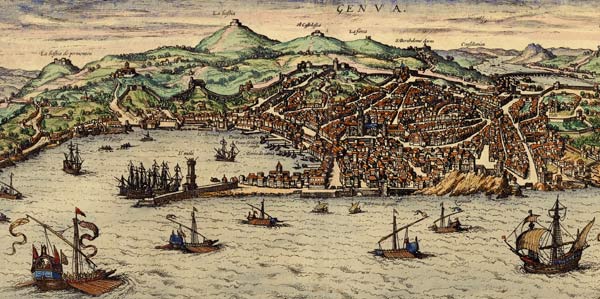

De nombreuses fouilles archéologiques confirment un développement urbain, économique, social et culturel remarquable.

Strabon (64 av. JC – 24 après JC), comme d’autres historiens grecs, qualifiait déjà la Bactriane de « Terre des mille cités », une terre que tous les écrivains, anciens et modernes, louaient pour la douceur de son climat et sa fertilité, car « la Bactriane produit tout, sauf de l’huile d’olive. »

Pour le naturaliste romain Pline l’Ancien (23 – 79 après JC), en Bactriane,

« les grains de blé poussent si gros qu’un seul grain est aussi gros que nos épis. »

Sa capitale Bactres (aujourd’hui Balkh, proche de Mazâr-e Charîf au nord de l’Afghanistan), « Mère des cités », figure parmi les villes les plus riches de l’Antiquité.

C’est là qu’Alexandre le Grand épouse Roxana (« Petite étoile ») et adopte l’habit perse pour pacifier son Empire. C’est également là que naîtra le père du grand médecin et philosophe Ibn Sina (Avicenne), avant de s’installer à Boukhara (Ouzbékistan).

Au fil du temps, la Bactriane sera le creuset de cultures et de civilisations où se mêlent, sur le plan artistique, architectural et religieux, traditions grecques et cultures locales.

Si le grec y est la langue de l’administration, les langues locales y foisonnent. Rien que les noms des villes démontrent la prédominance de la culture hellénique.

Ainsi, Ghazni s’appelle « Alexandrie en Opiana », Bagram « Alexandrie au Caucase », Kandahar « Alexandrie Arachosia », Hérat « Alexandria Ariana », etc., et la liste ne s’arrête pas là.

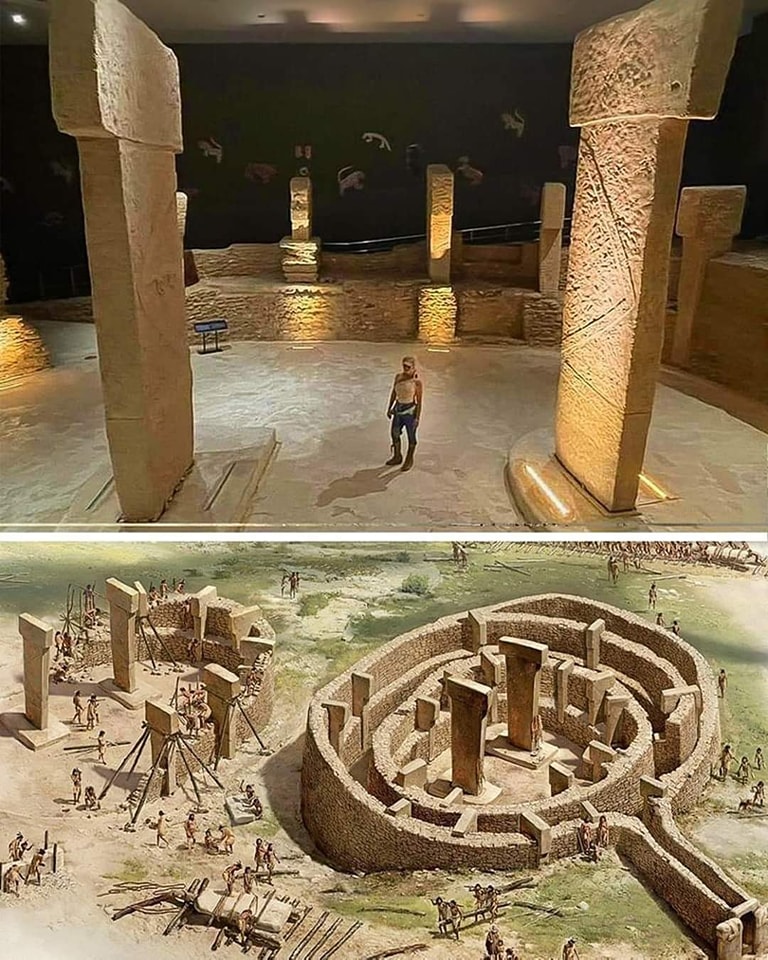

La ville de Gonur Depe (actuellement au Turkménistan, au nord de Mary, l’ancienne Merv), capitale du Royaume de Margiane, est un autre exemple de ce qu’on s’accorde maintenant à appeler la « Culture de l’Oxus »)

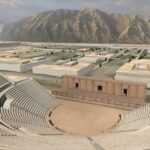

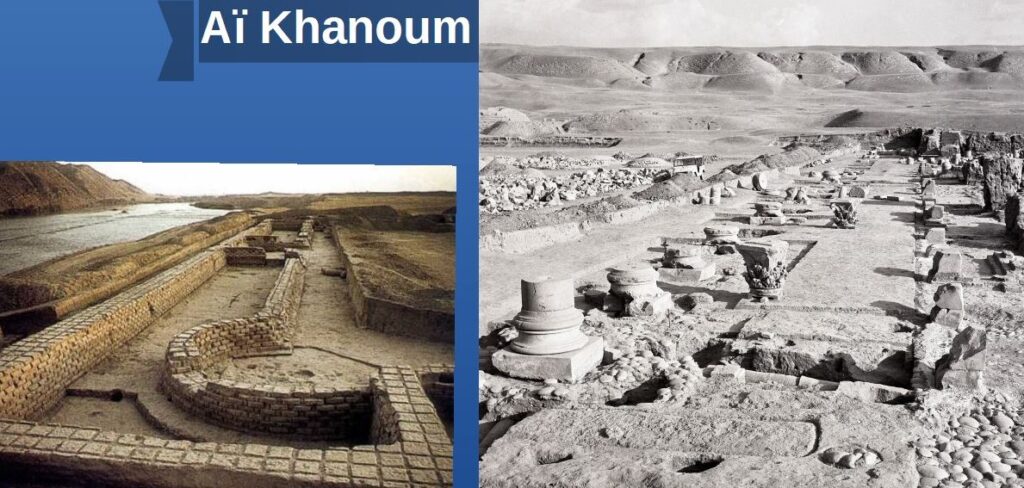

Aï Khanoum, la grecque

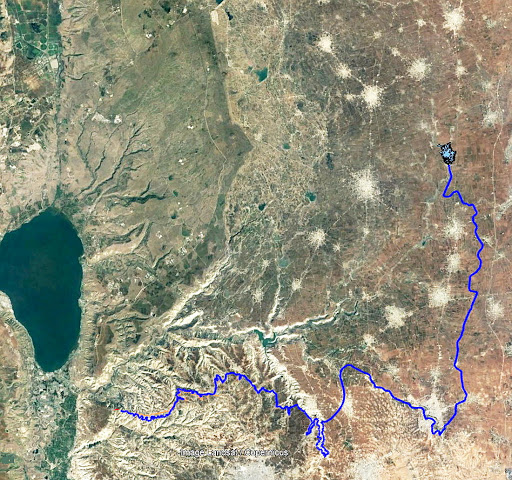

Si certaines villes ne font que changer de nom, d’autres sont construites ex nihilo. C’est le cas d’Aï Khanoum (« Dame Lune » en ouzbek), cité érigée au confluent du grand fleuve Amou Daria (l’Oxus des Grecs) et de la rivière Kokcha.

En 1961, le roi d’Afghanistan (Mohammed Zahir Shah), voulant marquer son indépendance vis-à-vis des Soviétiques et des Américains, invite la France à participer aux fouilles.

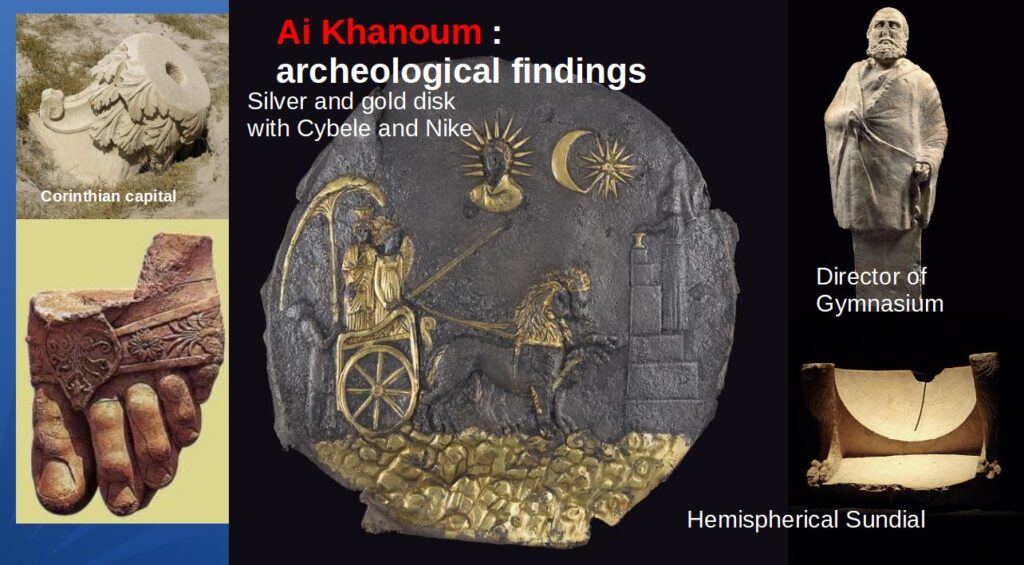

C’est le Département des archéologues français en Afghanistan (DAFA) qui met au jour les vestiges d’un immense palais dans la ville basse, ainsi qu’un grand gymnase, un théâtre pouvant accueillir 6000 spectateurs, un arsenal et deux sanctuaires.

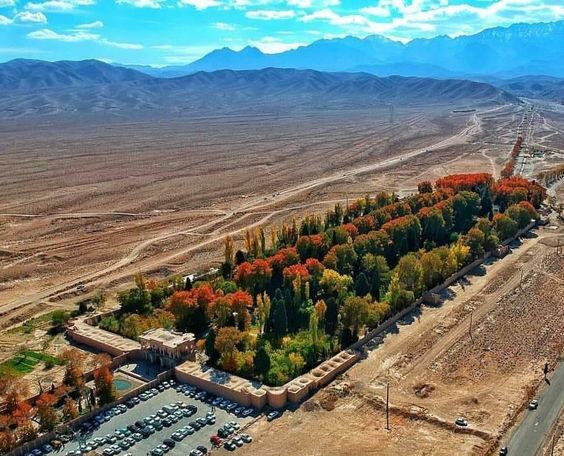

Entourée de terres agricoles bien irriguées, la ville elle-même était divisée entre une ville basse et une acropole de 60 mètres de haut.

Bien qu’elle n’est pas située sur une route commerciale majeure, Aï Khanoum commande l’accès aux mines du Hindou Koush. De vastes fortifications, continuellement entretenues et améliorées, entourent la ville.

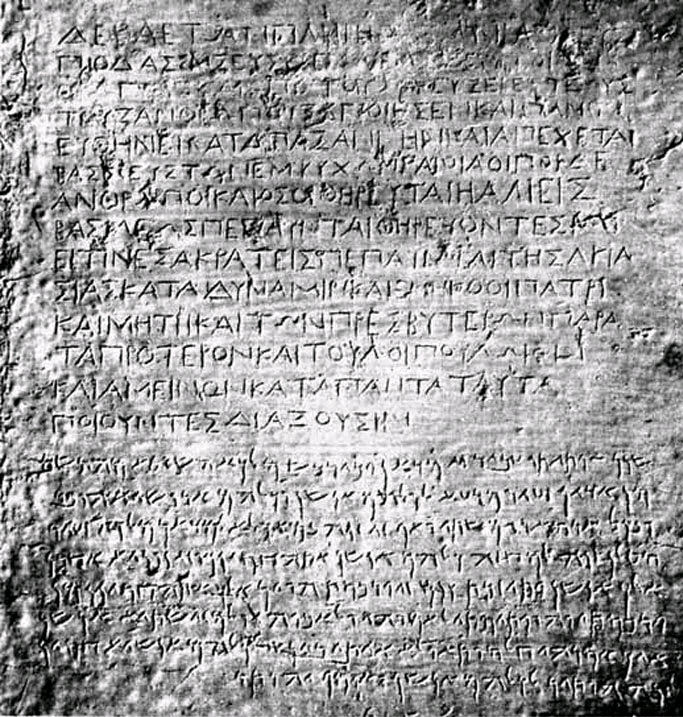

Un monument au cœur de la ville y présente une stèle inscrite en grec avec une longue liste de maximes incarnant les idéaux de la vie grecque. Celles-ci sont copiées de Delphes et se terminent par :

« Dès l’enfance, apprends les bonnes manières ;

dans la jeunesse, maîtrise tes passions ;

dans la vieillesse, sois de bon conseil ;

dans la mort, n’aie aucun regret. »

L’architecture du site indique que les colons grecques y vivent en bonne entente avec les populations locales. Elle est très grecque mais intègre en même temps diverses influences artistiques et éléments culturels que les Ioniens ont pu observer au cours de leur voyage du bassin méditerranéen à l’Asie centrale. Par exemple, ils utilisent les styles néo-babylonien et achéménide pour la construction de leurs cours.

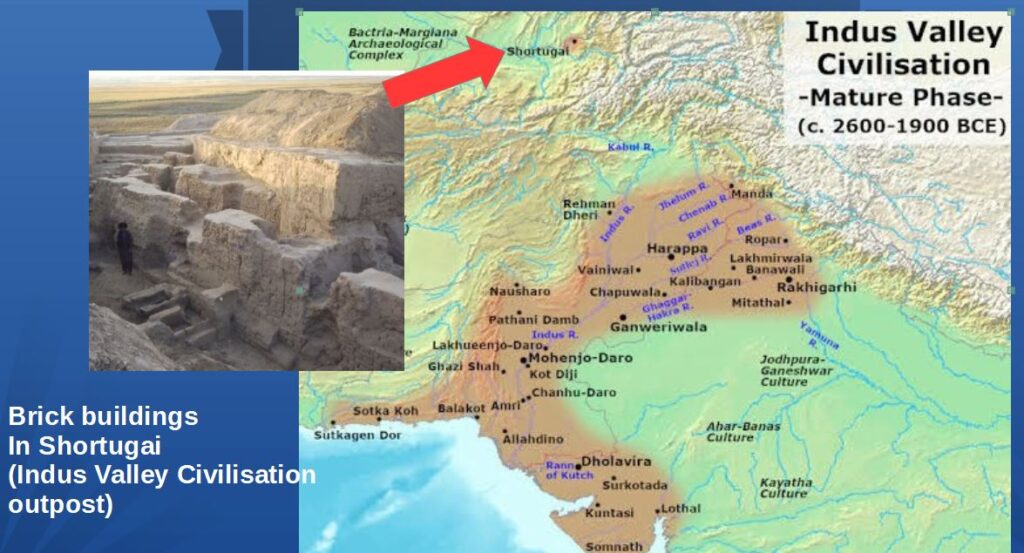

Shortugai et la Civilisation de la vallée de l’Indus

La date précise des premières fondations d’Aï Khanoum reste inconnue.

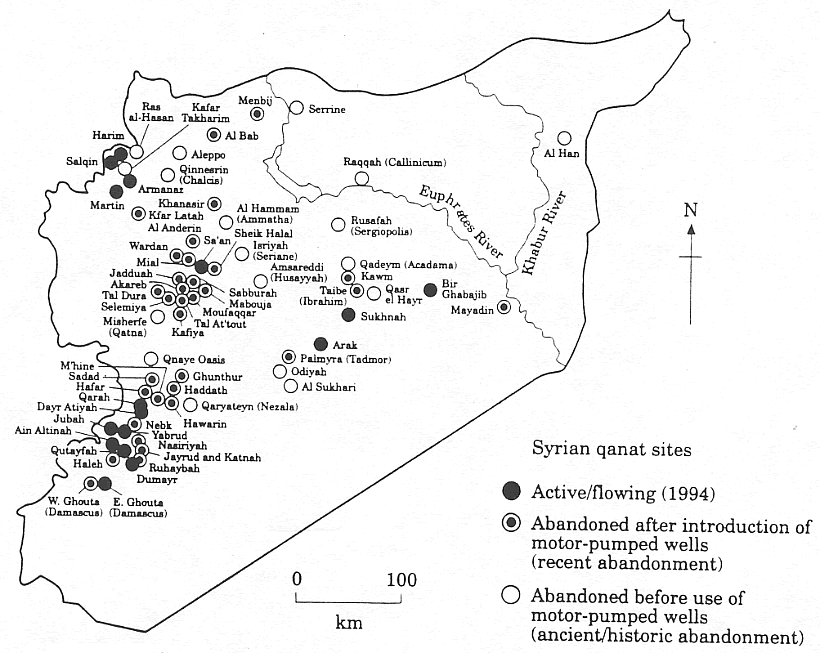

A une jetée de là, Shortugai, avant-poste commercial et minier de la fameuse civilisation de l’Indus (dite « harappéenne ») qui, au IIIe millénaire avant notre ère, était à l’avant-garde sur le plan de l’irrigation et de la maîtrise de l’eau. (voir notre article)

Des scientifiques de l’Institut indien de technologie de Kharagpur et du Service archéologique d’Inde ont publié le 25 mai 2016, dans la revue Nature, les fruits d’une recherche qui permettrait de dater la civilisation harappéenne d’au moins 8000 ans avant JC et non 5500 ans, comme on le croyait jusqu’à présent. Cette découverte majeure signifierait qu’elle serait encore plus ancienne que les civilisations mésopotamienne et égyptienne.

Shortugai est construite avec des briques standardisées typiques de la vallée de l’Indus. Des sceaux de la civilisation de la vallée de l’Indus ont également été trouvés sur d’autres sites archéologiques d’Afghanistan.

Pendant plusieurs siècles, Shortugai a fonctionné comme un site minier exceptionnel pour l’extraction de l’étain (un minerai indispensable pour la fabrication du bronze), de l’or et du fameux lapis-lazuli, cette pierre précieuse bleue qui, avec l’or, habille de sa splendeur la tombe du pharaon égyptien Toutankhamon et d’autres tombes religieuses majeures en Mésopotamie (Irak).

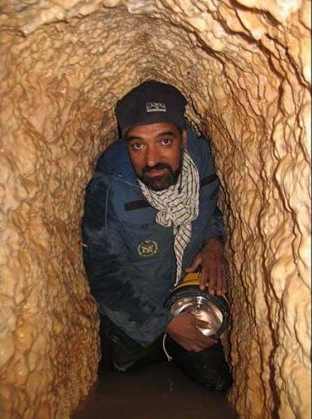

Les données archéologiques démontrent que Shortugai commerçait avec ses voisins d’Aï Khanoum et construisit les premiers systèmes d’irrigation de la région, une spécialité de la civilisation de la vallée de l’Indus.

Bien des sites restent inexplorés en Afghanistan, pays où les guerres, les occupations étrangères et les pillages ont perturbé ou rendu impossible les recherches archéologiques.

Voici quelques-unes des découvertes de la DAFA, dont certaines restent exposées au Musée national de Kaboul.