Étiquette : education

The hidden lesson of Sugata Mitra’s “Hole-in-the-Wall” experience

There are over a billion Indians. Unfortunately, around half of them are illiterate. Only one in four has access to proper sanitation. Some 350 million Indians live on less than one euro a day. And yet, in a strange paradox, India is also home to some of the world’s most advanced high-tech companies. New Delhi is, in a way, India’s Silicon Valley. And very recently, Indian genius has succeeded in landing a rover on the Moon.

Scandalized by the lack of access to education for his country’s children living far from urban centers, Dr. Sugata Mitra, an Indian physicist turned educational technology researcher, has been conducting a series of experiments since 1999, dubbed « The Hole-in-the-Wall », whose astonishing results are calling into question the foundations of conventional pedagogy.

“In early 1999”, writes Mitra, “colleagues and I sunk a computer into the opening of a wall near our office in Kalkaji, New Delhi. The area was located in an expansive slum, with desperately poor people struggling to survive.”

The screen was visible from the street, and the PC was available to anyone who passed by and all the people living “on the other side of the wall”. The computer had online access and a number of programs that could be used, but no instructions were given for its use. In principle, the children in this neighborhood could neither read nor write, and spoke a Tamil dialect. So, objectively speaking, the chances of them being able to cope with the computer were almost nil.

Fortunately, in the real world, things are different. Barely eight minutes after the computer had been installed, a young boy who had never seen a television screen in his life came up to sniff it out and explore the strange intruding object.

Asked if he could touch the screen, Mitra replied, « It’s on your side of the wall. » The rule was that everything on their side of the wall could be touched. The child soon realized that by moving the mouse in a certain direction, something moved on the screen in a similar way. Excited by what he had discovered, he immediately called his friends and showed them what he could do.

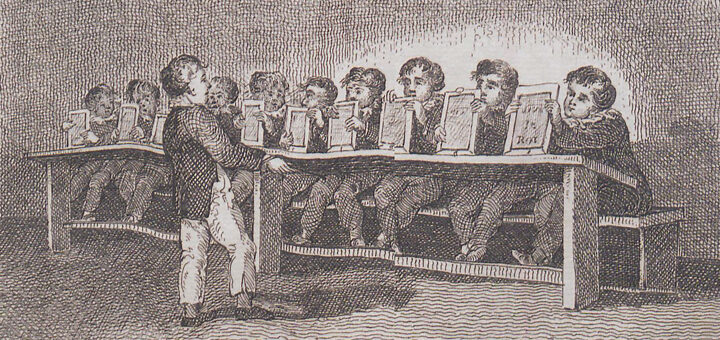

Typically, in the « Hole in the Wall » experiment, only one child operates the computer. He is surrounded by a first group of three others who give him advice. A second group of around sixteen children completes the team, who also interact with the child handling the equipment. Their advice is often less sound, or even wrong, but they learn too.

In hardly a few months, these kids were able to learn up to 200 English words. Although they couldn’t always pronounce them correctly, they understood their meaning and were able to interact with the computer. « You left us these machines that only speak English, so we had to learn it, » they said. Most of them succeeded in learning to navigate, play games and to draw pictures with a given application. What’s more, they have no trouble exchanging emails, and much more besides.

By repeating the experiment in several poor Indian towns, with boys as well as girls, Mitra, suspected of charlatanism by those who felt challenged by what his experience revealed, managed to dispel initial doubts that « someone » had secretly offered training to the children in advance.

What to conclude?

If the results are astonishing, they are often misinterpreted, with everyone, including Mitra himself, trying to demonstrate his or her own pre-established theory. You be the judge.

For Europeans, the experiment itself is considered borderline acceptable. Using children as “guinea pigs” without their parents’ permission is unethical by European standards. And isn’t bringing technology to the poor and thinking that everything will take care of itself one of those practices tinged with neo-colonialism that the World Bank ranks among the worst approaches to educational technology?

For their part, the gurus of Silicon Valley and GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft) were jubilant! They’ve been telling us for years: just give every child a computer (which they manufacture and control) and they’ll educate themselves! Really?

Remember the « One Laptop per Child » project launched a decade ago, to provide inexpensive solar-powered laptops and tablets to children in the poor countries? Without wishing to criticize the good will of its promoters, let’s just say that simply making computers available has not proved a promising approach. A recent evaluation of the project in Peru confirms this.

For his part, Mitra, whose goodwill cannot be questioned, came to the conclusion that experience shows that primary education can, at least in part, pretty much “take care of itself,” if the pupils are offered a « non-invasive education » environment.

Mutual Education

Dr. Mitra, unfortunately, seems to be missing the major point of what his experience brilliantly demonstrates.

I explain:

In France, after having been an enthusiastic proponent of computers for all, author and high school teacher Vincent Faillet has also come to believe that giving every child a tablet is not the right approach. With good reason, he points out that it’s not the computer, tablet, or screen that teaches children, but the human interaction among students:

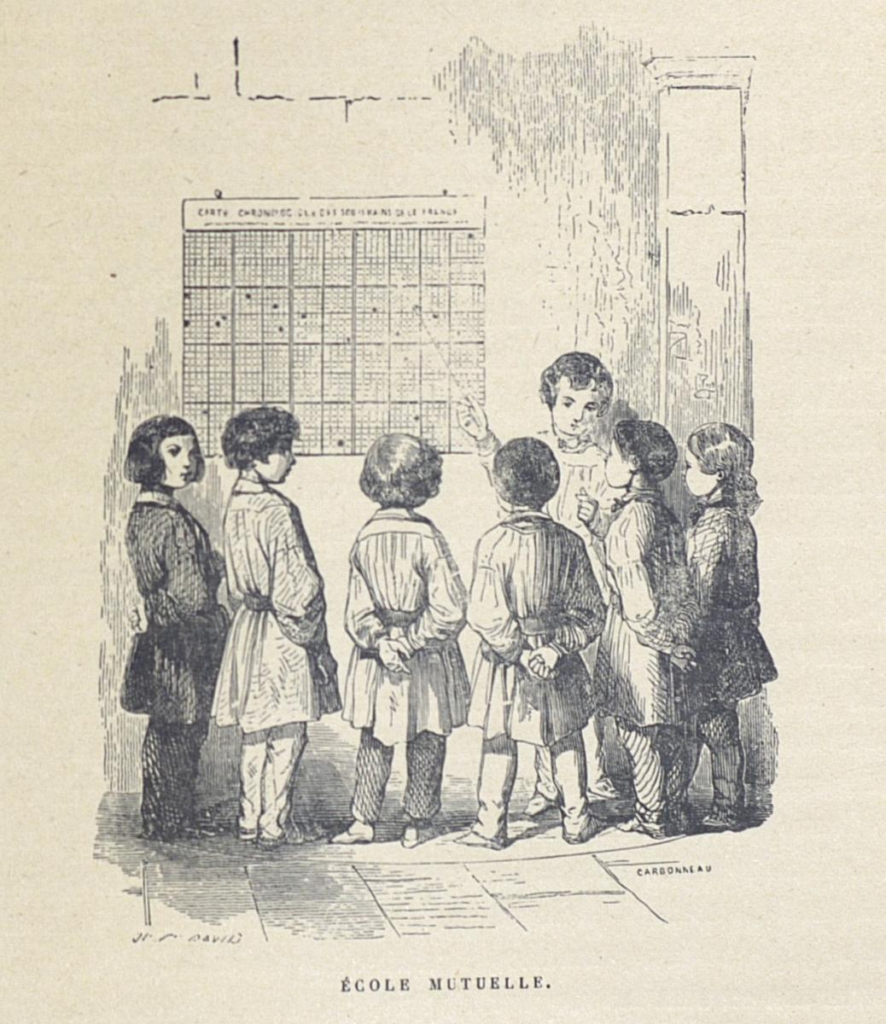

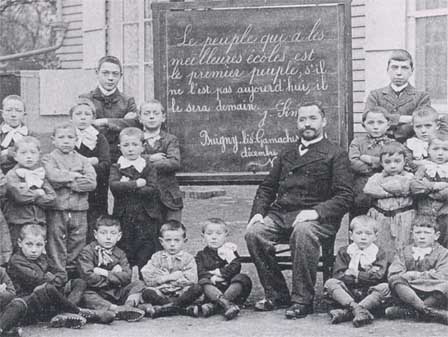

« Peer-to-peer learning, as defined by Sugata Mitra and which has amazed many pedagogues, » writes Faillet, « is in reality nothing more and nothing less than a modern, spontaneous form of ‘mutual education’. It’s striking to note that, despite the centuries that separate these observations, we find a constant pattern: children in a learning situation, grouped around a common screen for interaction, be it a box of sand, a blackboard or a computer screen. The idea of interaction is essential. As Sugata Mitra himself says, students don’t get the same results if there were to be one computer per child. You always require several children for ONE computer, in the same way that several children in mutual schools gather around the same blackboard. » (La Métamorphose de l’Ecole, Vincent Faillet, 2017)

(For more on the “Mutual Tuition” methods of Carnot, Bell and Lancaster, see the author’s article on artkarel.com website)

The experiment is obviously promising for remote and poor regions, provided we understand what has just been said. What is certain is that the experience reminds the inhabitants of the North of the ineffectiveness of their pedagogical practices, and the high level of passivity engendered by our educational systems.

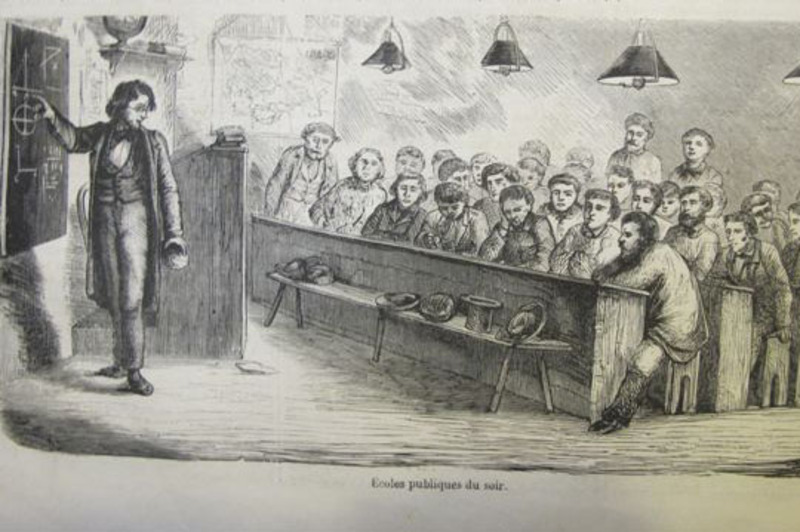

After the eradication of Lazare Carnot’s cherished « mutual teaching » methods in 1815, Jean-Baptiste de La Salle’s « simultaneous » method triumphed. The master teaches. His authority is unquestionable. As if at mass, the pupils stand still, remain religiously silent and obey.

In 2004, Hole-in-the-Wall Education Ltd., was founded, exporting Mitra’s idea to Cambodia and Africa. Mitra has also applied his method in England. Also there, the spectacular results caused quite a stir: students who teach each other, he claims, are 7 years ahead of their academic peers. As long as they are part of a mutual teaching process, the Internet, tablets and smartphones will find their rightful place as mere tools at the service of the teacher, and not destined to replace him or her.

Pupils as young as 8 or 9 who are allowed to search the internet to prepare for the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), not only pass the test, but still remember what they have learned when tested again three months later. We’ve even seen 14-year-olds pass baccalaureate-level tests at Newcastle University. Will they find jobs commensurate with their skills in the Global West ?

In the following excerpt,

Dr Mitra describes his findings:

“Certain common observations from our experiments emerged, suggesting the following learning process occurs when children self-instruct in computer usage:

1. Discoveries tend to happen in one of two ways: When one child in a group already knows something about computers, he or she shows off those skills to the others. Or, while the others watch, one child explores randomly in the GUI (Graphical User Interface) environment until an accidental discovery is made. For example, the child may discover that the cursor changes to a hand shape at certain places on the scre

2. Several children repeat the discovery for themselves by asking the first child to let them try it.

3. While in Step 2, one or more children make more accidental or incidental discoveries.

4. All the children repeat all the discoveries made and, in the process, make more discoveries. They soon start to create a vocabulary to describe their experiences.

5. The vocabulary encourages them to perceive generalizations, such as, « When you click on a hand-shaped cursor, it changes to the hourglass shape for a while and a new page comes up. »

6. They memorize entire procedures for doing something, such as how to open a painting program and retrieve a saved picture. Whenever a child finds a shorter procedure, he or she teaches it to the others. They discuss, hold small conferences, make their own timetables and research plans. It is important not to underestimate them.

7. The group divides itself into the « knows » and the « know-nots, » much as they might divide themselves into « haves » and « have-nots » with regard to their possessions. However, a child that knows will share that knowledge in return for friendship and reciprocity of information, unlike with the ownership of physical things, where they can use force to get what they do not have. When you « take » information, the donor doesn’t « lose » it!

8. A stage is reached when no further discoveries are being made and the children occupy themselves with practicing what they have already learned. At this point, intervention is required to plant a new seed for discovery (…) Usually, a spiral of discoveries follows and another self-instructional cycle begins.”

Source: edutopia.org

« Mutual tuition »: historical curiosity or promise of a better future?

By Karel Vereycken, July 2023, PARIS.

1. Introduction

2. Learning and teaching at the same time, a precious joy

3. Precedents:

A. In India

B. In France

4. Gaspard Monge’s brigades

5. Andrew Bell

6. Joseph Lancaster

7. Mutual Tuition, how it works

A. The class room

B. Teachers and monitors

C. A day at a mutual school

D. Progress according to each pupil’s knowledge

E. Tools

F. Command

8. Bellists vs. Lancasterians

9. France adopting Mutual Tuition

10. Lazare Carnot takes the helm

11. Mutual tuition and choral music

12. The rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais pilot project

13. Jomard, Choron, Francœur and elementary knowledge

14. Going Nationwide

15. Critique

16. Mechanistic drift?

17. Death of mutual tuition in France

18. Conclusion

19. Short list of books and texts consulted

« Answer, my friends: it must be sweet for you

To have as your only mentors children like yourselves;

Their age, their mood, their pleasures are your own;

And these victors of one day, tomorrow vanquished by others,

Are, in turn, adorned with modest ribbons,

Your equals in your games, your masters on the benches.

Mute, eyes fixed on your happy emulators,

You are not distracted by the fear of ferulas;

Never an avenging whip, frightening your spirits,

Makes you forget what they taught you;

I listen badly to a fool who wants me to fear him,

And I know much better what a friend teaches me. »

Victor Hugo, Discours sur les avantages de l’Enseignement mutuel, 1817.

1. Introduction

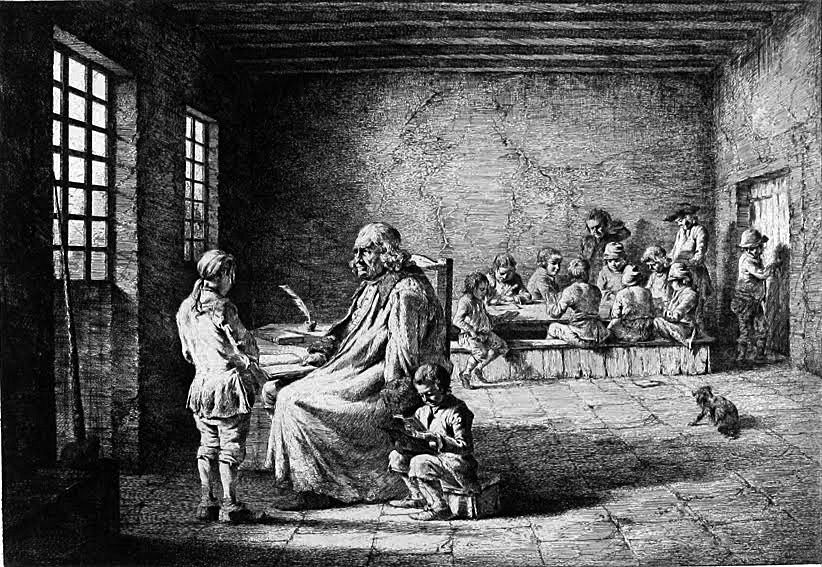

Teaching reading and writing to 1,000 children in the same room, without a teacher, without school books, without paper and ink, is clearly impossible. And yet, it has been imagined and put into practice with great success!

Shh! we mustn’t talk about it, because it could give some people ideas, and not just in emerging countries!

That such a challenge could be taken up could only worry the oligarchy and its servants, who since the dawn of time have been mandated to train an « elite » (the high priests of knowledge, « experts » and other know-it-alls) who reproduce in a vacuum at the top, while ensuring that the great mass of people below are educated just enough to be able to deliver parcels, pay their taxes, abide by the rules defined by the top, and above all, not make (too) much of a mess.

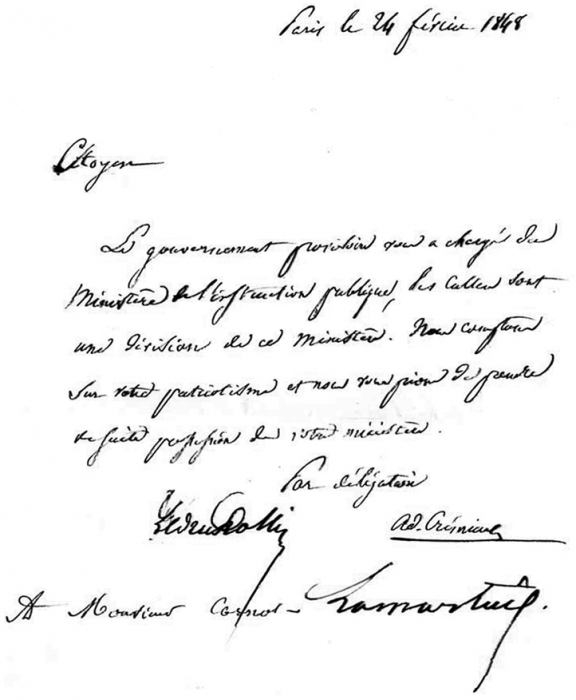

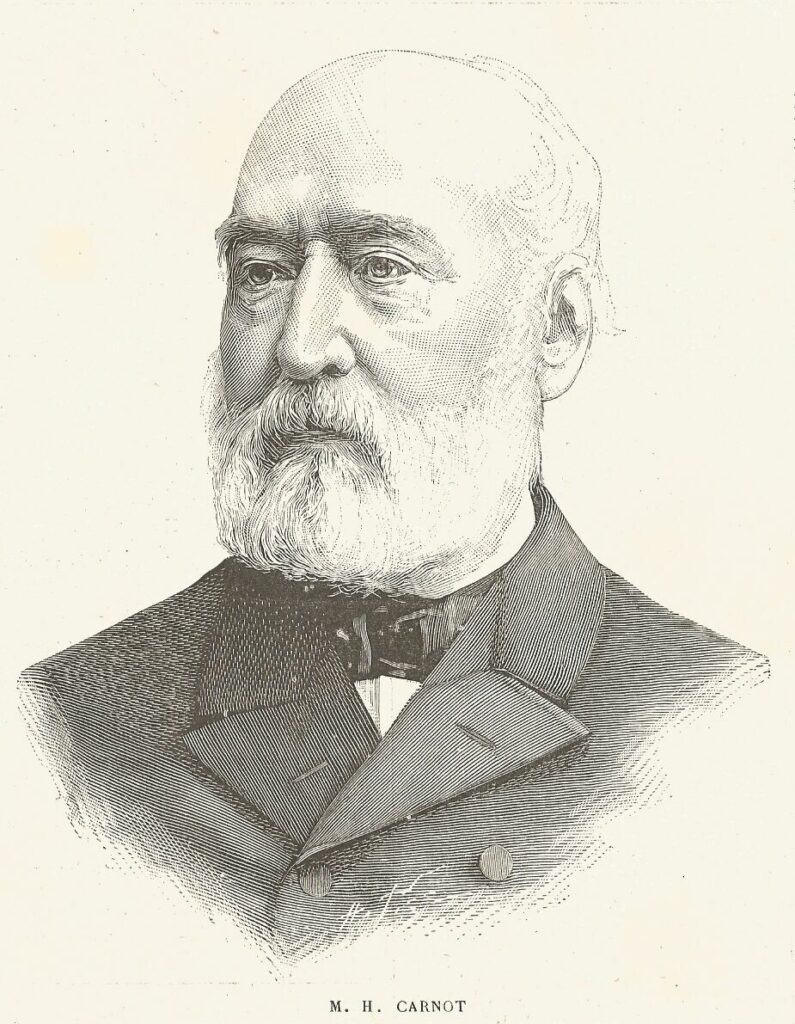

And yet, as Hippolyte Carnot, Minister of Public Instruction in the Second Republic, understood long before us, without a republican education – in other words, without genuine citizen training from kindergarten onwards – universal suffrage often becomes a tragic farce capable of producing monsters.

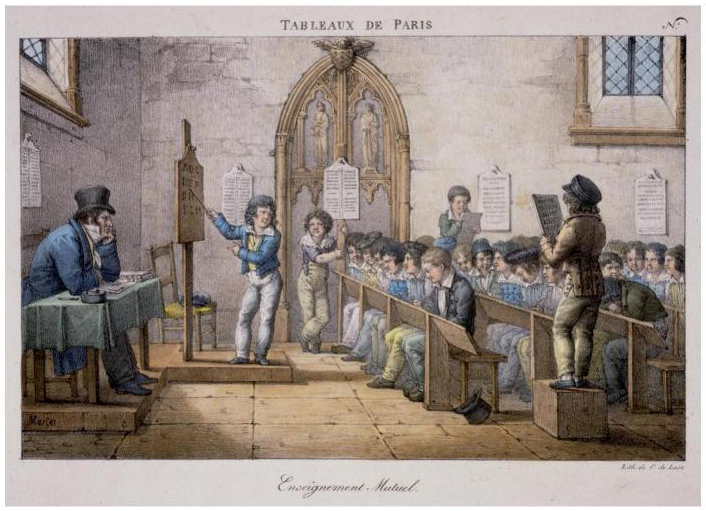

In the early 19th century, « mutual tuition », (sometimes referred to as the English Monitorial System, also known as Madras System or Lancasterian System), spread like wildfire across Europe and then the rest of the world including the United States of America.

If the teacher addresses a single pupil, it’s the individual mode (as in the case of the preceptor); if he addresses an entire class, it’s the simultaneous mode; if he instructs some children to teach others, it’s the mutual mode. The combination of simultaneous and mutual modes is called mixed mode.

Mutual tuition quickly fell victim to personal quarrels and ideological, political and religious issues. In France, it was seen as an aggression by religious congregations who practiced « simultaneous teaching », codified as early as 1684 by Jean-Baptiste de La Salle : classes by age, division by level, fixed and individual places, strict discipline, repetitive and simultaneous work supervised by an inflexible master.

With the formation of small groups where pupils teach each other and move around the classroom, mutual teaching immediately gave rise, rather foolishly, to the fear of an ass-over-head world straight out of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. What kind of world are we in if the pupil teaches the teacher? the child the parent? the faithful the priest? the citizen the government ! Without a clear leader, aren’t we lost ?

In 1824, Pope Leo XII (not to be confused with the benevolent Leo XIII), the « Pope of the Holy Alliance », a fierce supporter of order and suspect of a vast Protestant plot against the Vatican, forbade such teaching, believing it to « weaken the authority » of both teachers and political and religious authorities.

In France, where in the years following the 1830 revolution over 2,000 mutual schools existed, mainly in towns, in competition with denominational schools, François Guizot, Louis-Philippe’s minister and initially a promoter of broad public education, had them closed down.

2. Learning and teaching at the same time,

a precious joy

Today, « tutoring » is enjoying a revival in the context of school and vocational training. It is a process of « assistance by more experienced subjects to less experienced subjects, likely to enrich the latter’s acquisitions ».

Tutoring between children, in particular between children of different ages, is encouraged from nursery school right through to university, with the institutionalization of methodological tutoring at undergraduate level. Since the 1980s, elementary and secondary schools in France and abroad have seen the development of numerous tutoring experiments.

In reality, tutoring is no more than the pale heir to the mutual tuition system developed in England and then France in the 19th century.

Hence, the future of humanity depends on an exclusively human faculty: the discovery of new universal physical principles, often totally beyond the limits of our sensory apparatus, enabling Man to increase his capacity to transform the universe to qualitatively improve his lot and that of his environment. A discovery is never the result of the sum or average of opinions, but of an individual, perfectly sovereign act. Are we able to organize our society so that this « sacred » creative principle is cherished, respected and cultivated in any newborn child?

Because, without the socialization of this discovery, it will be useless. The history of mankind is therefore, by its very nature, the history of « mutual tuition ».

Is not the greatest pleasure of those who have just made a discovery – and this is natural for children – to share, with a view to a shared future, not only what he or she has just discovered, but the joy and beauty that every scientific breakthrough represents? And when those who discover teach and those that teach, discover, the pleasure is immense. So let’s give our professional teachers the time they need to make discoveries, for the quality of their teaching will be enhanced!

Precedents:

A. In India

In 1623, the Italian explorer Pietro Della Valle (1586-1652), after a trip to « Industan » (India), in a letter dispatched from Ikkeri (a town in south-west India), reports having seen boys teaching each other how to read and write using singing :

« In order to inculcate it perfectly in their memory, to repeat the previous lessons that had been prescribed to them, lest they forget them, one of them would sing in a certain musical tone a line from the lesson, such as two and two make four. After all, it’s easy to learn a song.

« While he sang this part of the lesson to learn it better, he wrote it down at the same time, not with a pen, nor on paper. But to spare him and not spoil it unnecessarily, they marked the characters with their fingers on the same floor where they were sitting in a circle, which they had covered for this purpose with very loose sand. After the first of these children had written in this way while singing, the others sang and wrote the same thing all together

« (…) When I asked them who (…) corrected them when they missed, given that they were all schoolboys, they answered me very reasonably, that it was impossible that a single difficulty should stop them all, four at the same time, without being able to overcome it and that for the subject they always practiced together so that if one missed, the others would be his teachers.«

In Della Valla‘s report, we can already identify some of the basic principles of mutual tuition, notably the simultaneous learning of reading and writing, the use of sand for writing exercises to avoid wasting paper, which is scarce and very expensive, a group lesson given by a teacher, followed by work in sub-groups in which pupils learn to self-regulate, and finally, an integration of knowledge which, thanks to the use of song, will facilitate memorization.

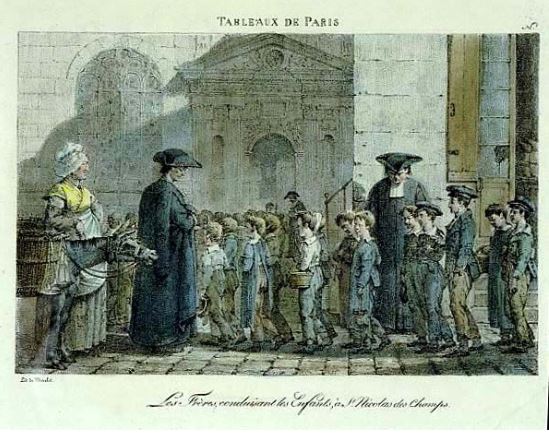

B. In France

In Lyon, the priest Charles Démia, was one of the precursors of mutual tuition, which he put into practice in the « petites écoles » for poor children he founded and theorized as early as 1688. According to the Nouveau dictionnaire de pédagogie et de l’instruction primaire:

« Démia introduced what later came to be known as mutual tuition into the classroom: he recommended that a certain number of officers be chosen from among the most capable and studious pupils, some of whom, under the name of intendants and decurions, would be responsible for supervision, while the others would have to have the master’s lessons repeated, correct pupils when they made mistakes, guide the hesitant hand of ‘young writers’, etc. » In order to make simultaneous teaching possible, Démia’s idea of ‘mutual teaching’ was based on the principle of ‘teaching to one another’. To make simultaneous teaching possible, the author of the regulations divides the school into eight classes, to be taught in turn by the master; each of these classes can be subdivided into bands ».

In Paris, as early as 1747, mutual education was practiced with great success in a school of over 300 pupils, established by M. Herbault, at the Hospice de la Pitié, in favor of the children of the poor. Unfortunately, the experiment did not survive its founder.

In 1772, the ingenious charity of Chevalier Paulet conceived and carried out the project of applying a similar method to the education of a large number of children, left without support in society by the death of their parents.

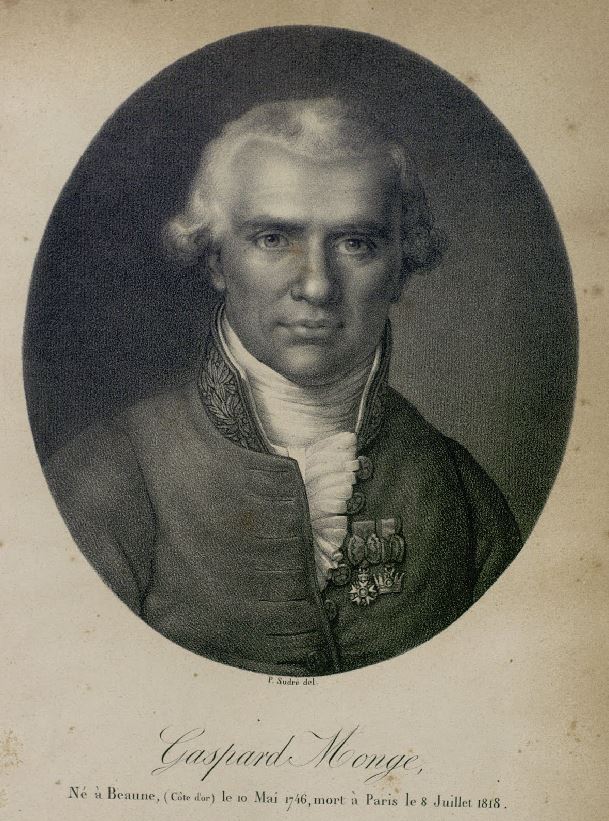

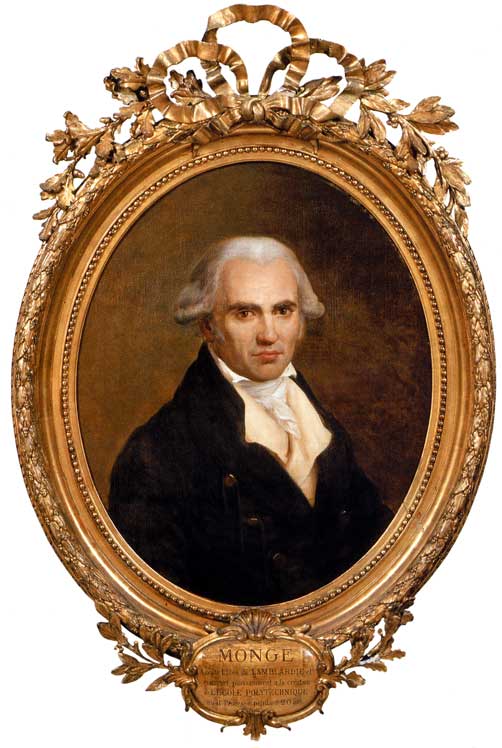

4. Gaspard Monge’s « brigades »

Finally, as recounted in his biography of Gaspard Monge by his most brilliant pupil, the astronomer François Arago (1786-1853), himself a close friend of Alexander von Humboldt, it was at the École Polytechnique that Monge perfected his own system of mutual tuition and tutoring.

Finding it unacceptable to have to wait three years for the first engineers to graduate from the Ecole Polytechnique, Monge decided to speed up student training by organizing « revolutionary courses », an accelerated training program lasting three months for those in charge of teaching to the others. To achieve this, he perfected the concept of « chefs de brigades », a technique he had already successfully tested at the Mézières engineering school.

François Arago:

« The brigade leaders, always working with small groups of students in separate rooms, were to have the extremely important task of ironing out difficulties as they arose. Never had a more skilful combination been devised to remove any excuse for mediocrity or laziness.

« This creation belonged to Monge. At Mézières, where the engineering students were divided into two groups of ten, and where, in fact, our colleague acted for some time as permanent brigade leader for both divisions, the presence in the classrooms of a person who was always in a position to overcome objections had produced results that were too fortunate for this former repetiteur, in drafting the developments attached to Fourcroy’s report, not to try to endow the new school with the same advantages.

« Monge did more; he wanted the 23 sections of 16 students each, of which the three divisions were to be composed, to have their brigade leader, as in ordinary times, following the revolutionary lessons, and at the opening of the courses of the three degrees. In a word, he wanted the School, at its beginning, to function as if it had already been in existence for three years.

« Here’s how our colleague achieved this seemingly unattainable goal. It was decided that 25 students, chosen by competitive examination from among the 50 candidates who had received the best marks from the admission examiners, would become brigade leaders of three divisions of the school, after receiving special instruction separately. In the mornings, the 50 young people, like all their classmates, attended revolutionary classes; in the evenings, they were brought together at the Hôtel Pommeuse, near the Palais-Bourbon, and various teachers prepared them for the functions they were destined to perform. Monge presided over this scientific initiation with infinite kindness, ardor and zeal. The memory of his lessons remains indelible in the minds of all those who benefited from them.

Arago then quotes Edme Augustin Sylvain Brissot (1786-1819), son of the famous abolitionist, , one of the 50 students, who reported : « It was there that we began to get to know Monge, this man so kind to youth, so devoted to the propagation of science. Almost always in our midst, he followed lessons in geometry, analysis and physics with private discussions where we found even more to gain. He became a friend to each and every one of the students at the Ecole provisoire, joining in the efforts he was constantly provoking, and applauding, with all the vivacity of his character, the successes of our young minds ».

While mutual teaching is fully practiced, the total dedication of a master as devoted as Monge completes what otherwise becomes nothing more than a « system ».

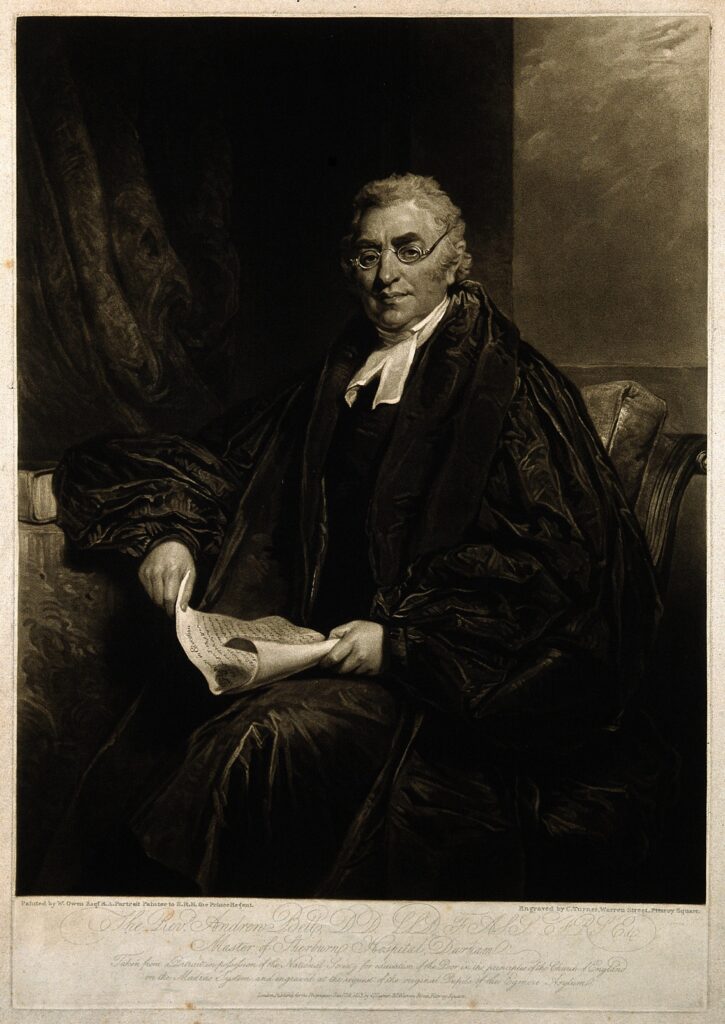

5. Andrew Bell

It was a Scotsman, the Anglican clergyman Andrew Bell (1753-1832), who claimed the paternity of mutual tuition, which he theorized and practiced in India, at the head of the Egmore Military Asylum for Orphans (Eastern India), an institution created in 1789 to educate and instruct the orphans and destitute sons of the European officers and soldiers of the Madras army.

After 7 years there, Bell returned to London and, in 1797, wrote a report to the East India Company (his employer in Madras) on the incredible benefits of his invention.

Russian physician, naturalist and inventor Iosif Khristianovich (Joseph) Hamel (1788-1862), a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, was commissioned by Alexander I, Emperor of Russia, to write a full report on this new type of education, which was then being discussed throughout Europe.

In Der Gegenseitige Unterricht (1818), he reports what Bell wrote in one of his writings: « It happened at this time, that one morning as I was taking my usual walk, I passed a school of young Malabar children, and saw them busy writing on the ground. The idea immediately occurred to me that perhaps the children at my school could be taught the letters of the alphabet by tracing on the sand. I immediately went home and ordered the teacher of the last class to carry out what I had just arranged. Fortunately, the order was very poorly received; for if the master had complied to my satisfaction, it is possible that all further development would have been stopped, and with it the very principle of mutual education… »

Mutual education was coldly received in England, but eventually won over Samuel Nichols, one of the school leaders at St. Botolph’s Aldgate, London’s oldest Anglican Protestant parish. Bell’s precepts were implemented with great success, and his method was taken up by Dr. Briggs when he opened an industrial school in Liverpool.

6. Joseph Lancaster

In England, it was Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), a twenty-year-old London schoolteacher, who seized upon the new way of teaching, perfected it and generalized it on a large scale. (See text of his 1810 booklet)

In 1798, he opened an elementary school for poor children in Borough Road, one of London’s poorest suburbs. Education was not yet totally free, but it was 40% cheaper than other schools in the capital. Lacking money, Lancaster did everything in his power to drive down the costs of what was becoming a veritable « system »: use of sand and slate instead of ink and paper (Erasmus of Rotterdam reported in 1528 that in his day, people wrote with a kind of awl on tables covered in fine dust); boards reproducing the pages of school books hung on the walls to avoid having to buy books; auxiliary teachers replaced by pupils to avoid paying salaries; increase in the number of pupils per class.

By 1804, his school had 700 pupils, and twelve months later, a thousand. Lancaster, getting deeper and deeper into debt, opened a school for 200 girls. To escape his creditors, Lancaster left London in 1806, and on his return was jailed for debt. Two of his friends, dentist Joseph Foxe and straw hat maker William Corston, repaid his debt and founded with him « The Society for the Promotion of the Lancasterian System for the Education of the Poor ».

Other Quakers stepped in with support, notably abolitionist William Wilberforce (1759-1833), whom the french sculptor David d’Angers depicted alongside Condorcet and Abbé Grégoire on his famous monument commemorating Gutenberg in Strasbourg.

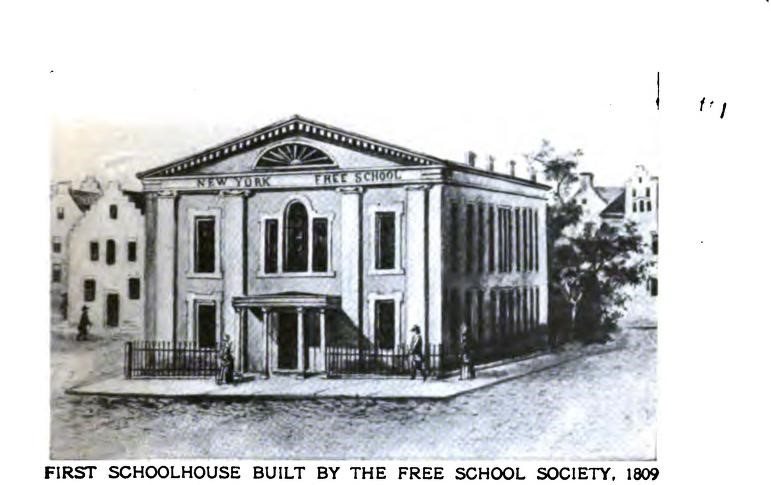

From there, as Joseph Hamel recounts in his 1818 report, the new approach spread to the four corners of the world: England, Scotland, France, Prussia, Russia, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Poland and Switzerland, not forgetting Senegal and several South American nations such as Brazil and Argentina and of course, the United States of America. Mutual Tuition was adopted as the official pedagogy in New York City (1805), Albany (1810), Georgetown (1811), Washington D.C. (1812), Philadelphia (1817), Boston (1824) and Baltimore (1829), and the Pennsylvania legislature considered statewide adoption.

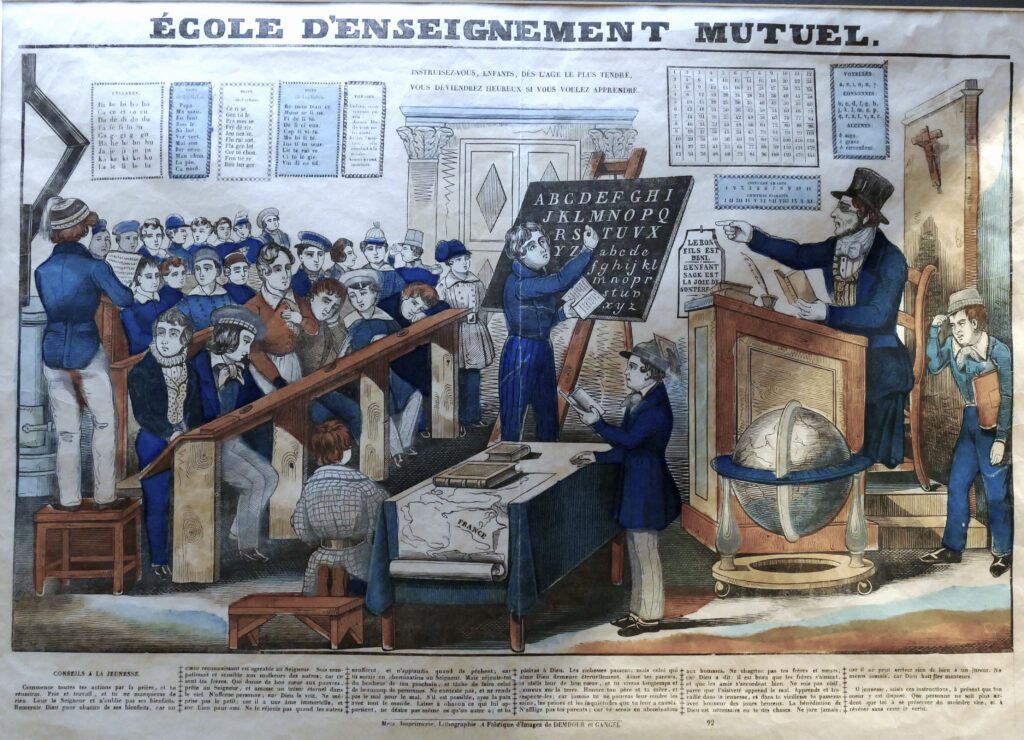

7. Mutual tuition, how does that works ?

The fundamental principle of « mutual tuition », particularly relevant to elementary school, is reciprocity of instruction between pupils, with the more able serving as teacher to the less able. From the outset, everyone progresses gradually, regardless of the number of pupils.

Bell and Lancaster, and their French disciples, postulated: the diversity of faculties, the inequality of progress, the rhythms of comprehension and acquisition. This led them to divide the school into different classes according to subjects and children’s level of knowledge, with age playing no part in this classification. Schoolchildren thus brought together take part in the same exercises. Their study program is identical in content and methods.

If the number of pupils in a division is too high in a particular subject – reading or arithmetic, for example – sub-groups are formed, which progress in parallel, while the teaching methods and materials remain identical.

So what does a school under the new system look like?

A. The classroom

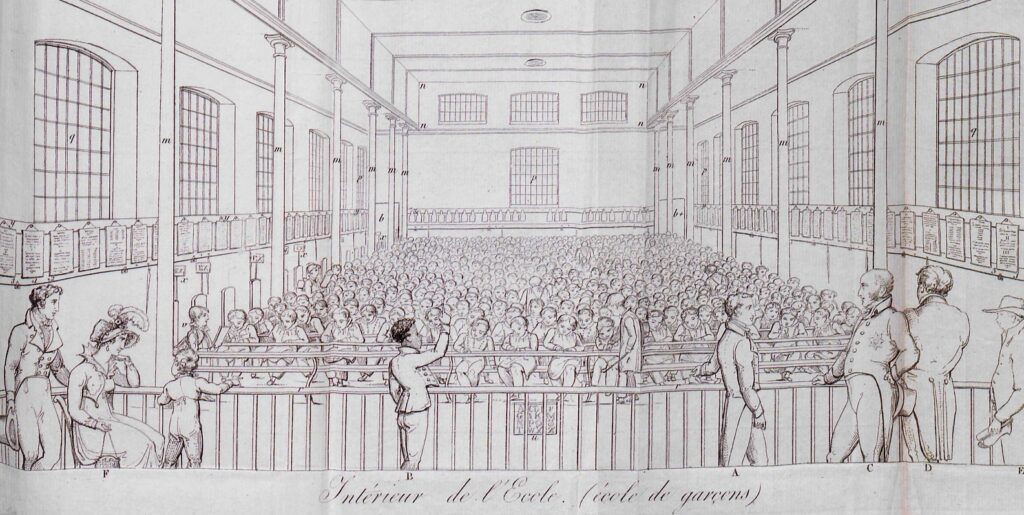

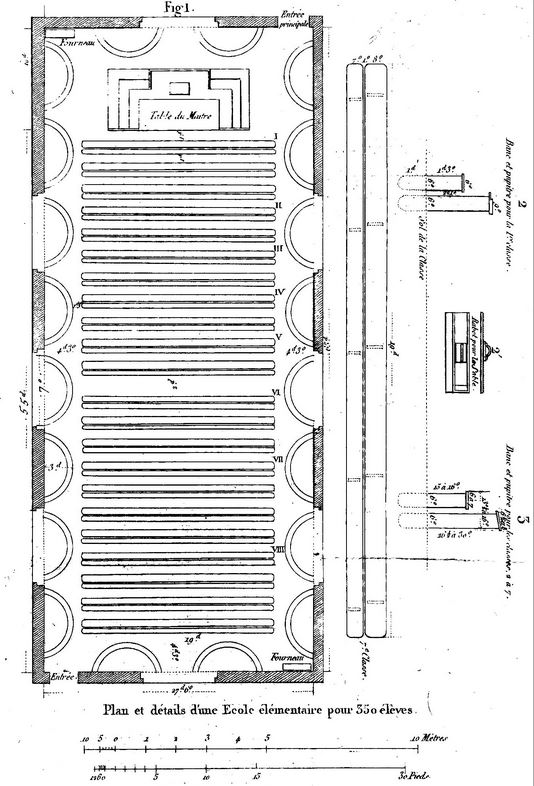

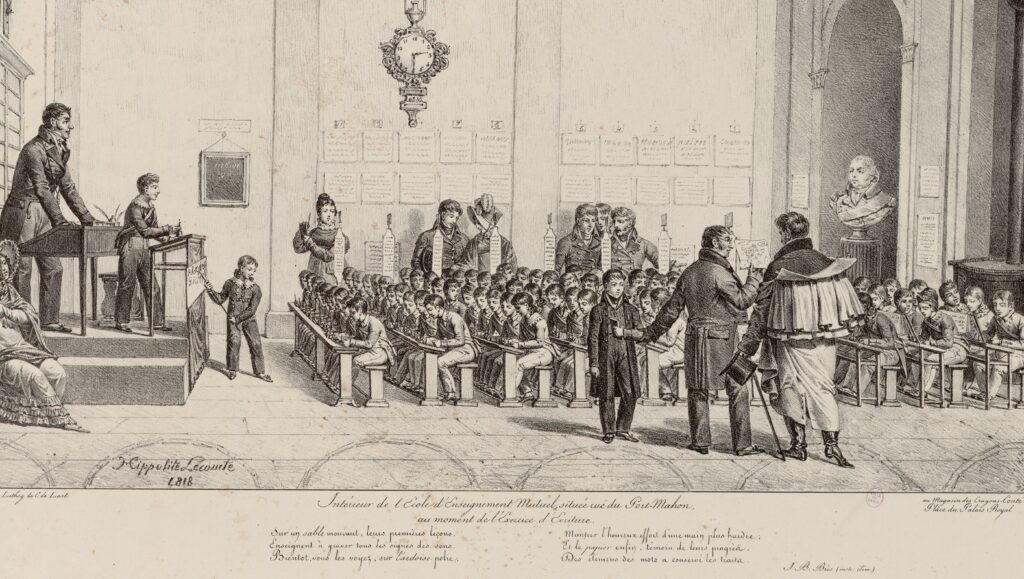

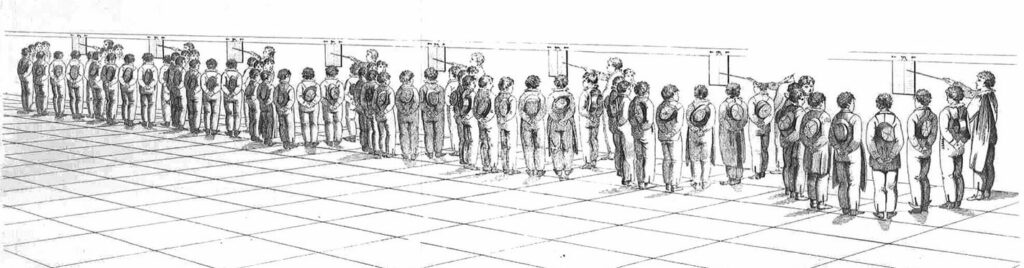

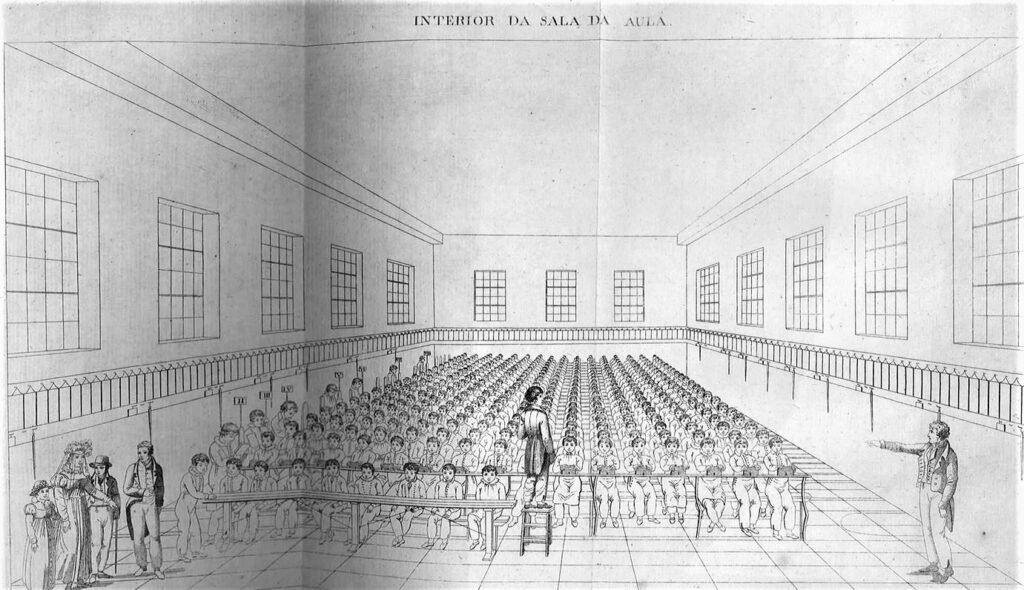

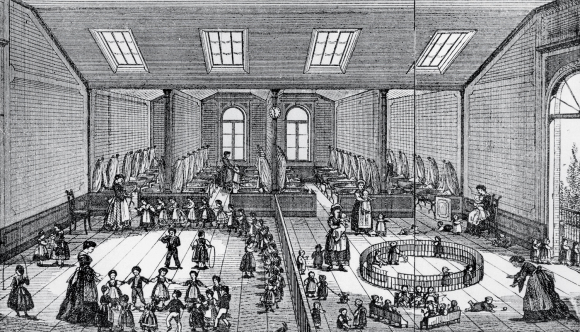

Whatever the number of pupils – around a 100 in French villages, close to a 1000 in the Lancaster school in London, 200 in Parisian schools – they are grouped together in one single rectangular room with no partitions.

Jomard, who was extraordinarily active and prolific in the early years of the mutual education system, set desirable standards for class sizes ranging from 70 to 1,000 pupils.

For 350 pupils, for example, he indicated the need for a room 18 m long by 9 m wide (graphic).

In England and the French countryside, a barn was often used for the new school. In France, a large number of religious buildings have been disused since the revolutionary period, and meet the required standards perfectly. Many mutual schools were built in these buildings.

B. « Masters » and « monitors »

The mutual method divided responsibility for teaching between the « master » and students designated as « monitors », considered « the linchpin of the method ».

As Bally reminded us as early as 1819: « The basis of mutual teaching rests on the instruction communicated by the strongest pupils to those who are weaker. This principle, which is the merit of this method, required a very special organization to create a reasonable hierarchy, which could contribute in the most effective way to the success of all. »

Each day, in a dedicated « classroom » reserved for instructors, the master imparts knowledge and provides his assistants with technical advice on the proper application of the method. During the course of the day, he remains in charge of the 8th class, and as such is responsible for conducting their exercises. He conducts periodic, monthly or occasional examinations in the classes, and may decide to change classes. Finally, it is he who, at the final stage, distributes punishments and rewards.

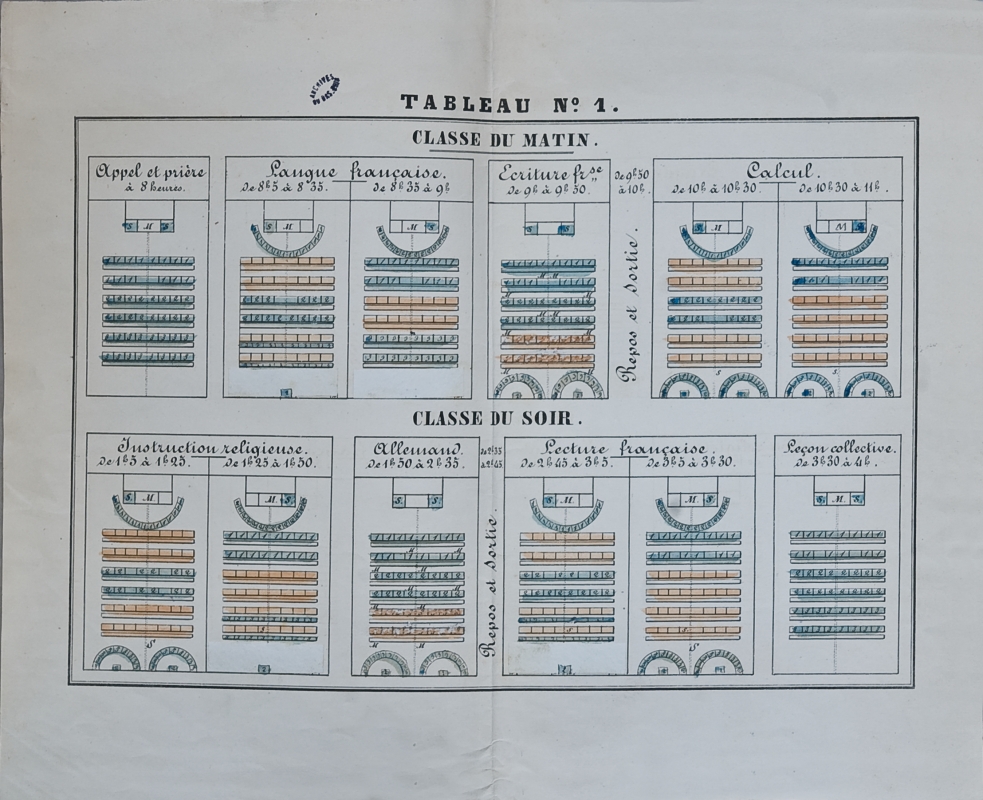

C. A day at a mutual school

Thus, on a platform, the teacher’s desk with a large drawer where money, reward tickets, registers, writing templates, whistles and children’s notebooks are kept.

Behind the teacher, next to the clock – an essential instrument for organizing teaching life – is a blackboard on which are written sentences and writing models.

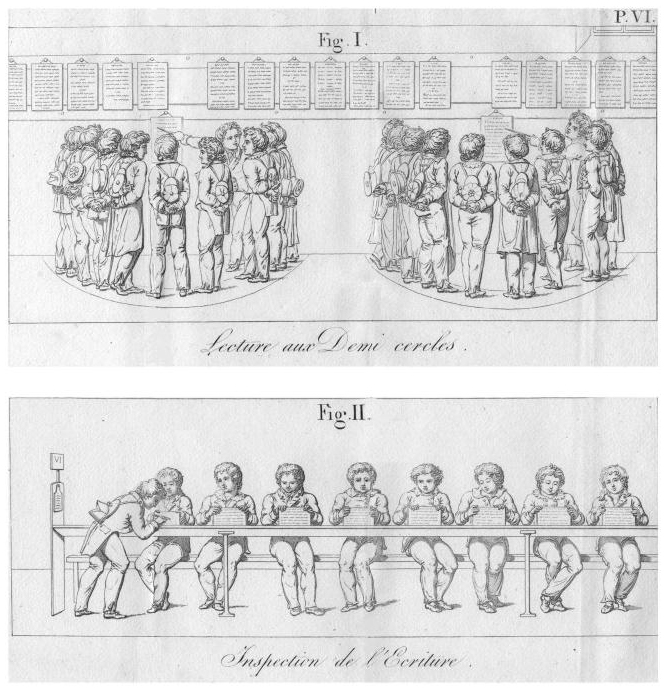

At the foot of the platform, benches are attached across the desks, of different sizes, in the middle of the room. The first tables, which are not inclined, have sand on which small children trace signs, while the other tables have slates; on the last of these there are lead inkwells and paper, and chopsticks to indicate words or letters to be read.

At the end of each table are « dictation tables » and telegraphic signals indicating the lesson’s moments, such as « COR » for « correction » or « EX » for « examination of work ». Semicircular table models were then proposed to facilitate the work of the instructors.

D. Progress according to each person’s knowledge

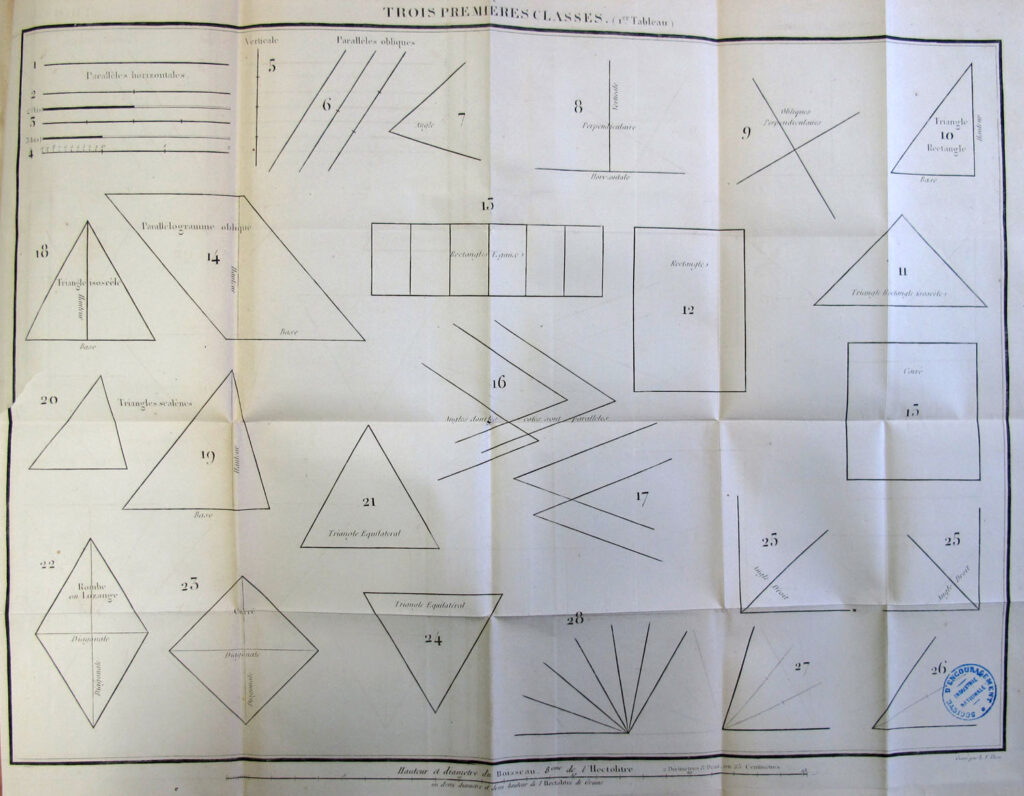

Initially, the mutual school program was limited to the 3 fundamental disciplines of reading, writing and arithmetic, and to the teaching of religion. Geography, grammar, writing, singing and linear drawing were soon added. The instrumental disciplines (music) are taught together, rather than in succession, as is customary in other schools. Pupil groupings are flexible, mobile and differentiated, depending on the nature of the subjects studied and the activities practised in the discipline.

Each subject matter taught in mutual schools is based on a precise, codified curriculum. This program is divided into 8 hierarchical levels, which must be covered in succession. Each degree is called a « class », and this is how we speak of the 8 classes of writing or arithmetic.

The term « class » refers only to acquisitions and knowledge, the 1st class being that of beginners and the 8th that of the completion of the school curriculum. The pace of learning and acquisition varies from student to student and from subject to subject.

Thus, after six months’ attendance, pupil « X » may find himself in 4th class reading, 5th class writing and 2nd class arithmetic. As we said, class assignment is decided on the basis of knowledge level, not age.

But this initial allocation is accompanied, within each class and in each subject, by the constitution of restricted groups established according to the activities to be practiced. In arithmetic, for example, written work is done on the slate. This takes place seated on benches reserved for this purpose, with a maximum of 16 to 18 students per bench, according to the standards established by Jomard.

Oral exercises, in reading or arithmetic, or with the aid of a blackboard, arithmetic or linear drawing, are done standing up, in groups of no more than 9, with pupils standing side by side, forming a semi-circle. Hence the name given to this kind of activity: « circle work ».

So, in a mutual school with 36 students in 3rd arithmetic class, bench work will be done in two groups with two monitors, and blackboard exercises with 4 groups and 4 monitors. Class sizes can therefore vary from school to school and throughout the year, the only limitation being the size of the premises.

D. Tools

Low costs are one of the preoccupations of the new teaching method. Furniture was therefore very basic.

- Benches and desks are made of ordinary planks, fastened with heavy nails. The benches have no backrests: a superfluous luxury!

- The platform is clearly elevated: about 0.65 m. Several steps lead up to the teacher’s desk. The master reigns over the children’s community as much by his material position as by his personal ascendancy.

- The clock is noted as « indispensable », as teaching and maneuvers are strictly timed.

- Half-circles, also known as reading circles, give mutual schools a typical and original appearance. These are usually semi-circular iron hangers that can be raised or lowered at will. Sometimes, the materialization is simply applied to the floor: grooves, large nails or arched strips.

- Blackboards were systematically used for linear drawing and arithmetic. They are 1 m long and 0.70 m wide, with a movable meter at the top. They are placed inside each semicircle.

- Telegraphs. When work takes place at the tables, such as writing, signals are used to link and communicate between the general monitor and the individual monitors: these are the telegraphs. A planchette, attached to the upper end of a round stick 1.70 m high, is installed at the first table of each class, thanks to two holes drilled at the top and bottom of the desk. On one side is the class number (1 to 8); on the other, EX (examen), replaced around 1830 by COR (correction). These telegraphs are portable. They could be moved if the number of students increased or decreased. In this way, the master and the general monitor have the exact composition of each class and the number of tables occupied by each. As soon as an exercise is completed, the class monitor turns the telegraph and presents the EX side to the desk. All monitors do the same. The general monitor gives the order to proceed with inspection and any corrections. Once these have been completed, the class number is presented again. And the exercises resume. Next to the telegraphs are the occasional board stands.

- Monitor rods. These are used to indicate on tables the letters or words to be read, the details of operations to be carried out, and the lines to be reproduced. In rural schools, these are generally only available thanks to the good will and ingenuity of the teachers, who obtain them from nearby woods.

- Sand (for writing) and then slates are constantly used in all subjects. This was an essential innovation in the mutual mode, as other schools did not use them.

- Boards instead of books. The first reason is financial, as a single board is sufficient for up to nine pupils. But the pedagogical reasons are no less important. The format makes them easy to read and store. The concern for presentation and highlighting certain characters is accompanied by a different layout from that of the textbooks.

- Books are reserved for the eighth grade, as are nibs, ink and paper.

- Registers, currently in use, ensure sound management of the schools. One in particular deserves special mention: « Le grand livre de l’école » (the school’s ledger), which is first and foremost a registration book. It records the child’s surname, first name and age, as well as the parents’ occupation and address. The teacher enters the precise date of entry and exit of each child, in each class, including music and linear drawing.

E. Communication

To ensure that dozens or hundreds of pupils are led and developed correctly, and to avoid wasting time, those in charge of mutual education have planned precise, rapid, immediately comprehensible orders:

- The voice is rarely used. Injunctions transmitted in this way are generally addressed to the instructors, sometimes to a specific class;

- The bell attracts attention. It precedes information or a movement to be executed;

- The whistle has a dual function. It is used to intervene in the general order of the school, « to impose silence », for example, and to signal the start or end of certain exercises during the lesson, « to have the pupils say by heart, to spell, to stop reading ». Only the teacher is authorized to use them.

- As for hand signals, they have been used extensively. Intended to evoke the act or movement to be accomplished, they attract the eye and should bring calm to the community.

« Bellists » versus « Lancasterians »

While the two schools, Bell’s and Lancaster’s, were very close to each other in terms of content, methods and organization, they clashed violently over the role and place of religious education. All other program-related differences are a matter of taste, habit or local circumstance.

As Sylvian Tinembert and Edward Pahud point out in « Une innovation pédagogique, le cas de l’enseignement mutuel au XIXe siècle » (Editions Livreo-Alphil, 2019), Lancaster, as a follower of the dissident Quaker movement,

« recognized Christianity but professed that belief belonged to the professional sphere and that each person was free in his or her convictions. He also advocates egalitarianism, tolerance and the idea that, in this country, there is such a variety of religions and sects that it is impossible to teach all doctrines. Consequently, it is necessary to remain neutral, to limit teaching to the reading of the Bible, avoiding any interpretation, and to leave fundamental religious instruction to the various churches, ensuring that pupils follow the services and teachings of the denomination to which they belong ».

Nevertheless, Bellists and Lancasterians had their differences. For the Lancasterians, Bell had invented nothing and was merely describing what he had seen in India. For the Bellists, furious that Lancaster found a positive response from certain members of the Royal family, Lancaster was portrayed as the devil, an « enemy » of the official Anglican religion, who admitted children of all origins and denominations to his schools !

9. France adopting mutuel tuition

In London, the Lancaster association was joined by a number of high-ranking personalities, both English and foreign. These included Geneva physicist Marc Auguste Pictet de Rochemont (1752-1825), French paleontologist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) and his compatriots, agronomist Charles Philibert de Lasteyrie (1759-1849) and Lancaster’s future translator into French, archaeologist Alexandre de Laborde (1773-1842).

After the peace of 1814, many countries – notably England, Prussia, France and Russia – bled dry by the Napoleonic wars, which had resulted in the loss of thousands of young teachers and qualified executives on the battlefields, made education their top priority, not least to keep up with the industrial revolution that was coming to shake them to their foundations.

Added to this is the fact that the number of orphans in Europe has become a major problem for all states, especially as the coffers are empty. To keep street children occupied, schools were needed, many of them to be built with very little money and many teachers… nonexistent. Learning of the resounding success of mutual education, several Frenchmen travelled to England to discover the new method.

Laborde brought back his « Plan d’éducation pour les enfants pauvres, d’après les deux méthodes (du docteur Bell et de M. Lancaster) », and Lasteyrie his « Nouveau système d’éducation pour les écoles primaires ». In 1815, the Duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt (1747-1827) published his book on Joseph Lancaster’s « Système anglais d’instruction ».

Since 1802, Paris had been home to the « Société d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale », whose Secretary General was linguist Joseph-Marie de Gérando (1772-1842), and of whom Laborde was a founder together with Jean-Antoine Chaptal (1752-1832). Unsurprisingly, Gérando had been raised by the Oratorians and was initially destined for the Church.

On March 1, 1815, Lasteyrie, Laborde and Gérando proposed to the Société d’Encouragement the creation of a new association whose purpose would be « to gather and spread enlightenment likely to provide the lower classes of the people with the kind of intellectual and moral education most suited to their needs ».

In his report presented to the Société d’Encouragement on March 20, 1815, Gérando proposed that the newly-appointed Minister of the Interior, Lazare Carnot (During les Cents-Jour, i.e. between March 20-June 22, 1815), be asked to promote « the adoption of procedures likely to regenerate primary education in France », i.e. the system of mutual tuition.

Political and social interests were not the only ones at stake. The French economy, too, was much to benefit from the development of education. « What can we expect, » said Carnot in 1815, « if the man who drives the plough is as stupid as the horses that pull it?«

Gérando also proposed the creation of an association dedicated specifically to its propagation, underlining the advantages of the new approach: economic advantage first, since it involves « employing the children themselves, in relation to each other, as teaching aids », and that a single teacher is sufficient for 1,000 pupils; educational advantage second, since it is possible « to teach, in two years, everything that children of inferior conditions need to know, and much more than they learn today by much longer processes »; a moral and social advantage, insofar as children « are imbued from an early age with a sense of duty, a feeling that will one day guarantee their obedience to the law and their respect for the social order ».

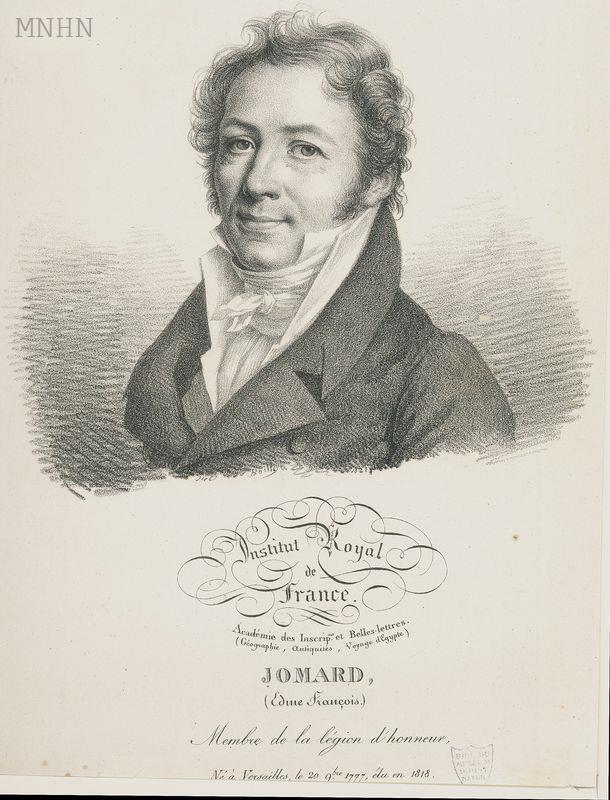

The engineer-geographer and polytechnician Edeme-François Jomard (1777-1862), for whom the education of the people is an obligation of society towards itself, said nothing else: « How can we demand that unfortunate people, devoid of all enlightenment, know the social pact and submit to it? Or how can we, without being foolish, count on their invariable and blind submission?«

The Société d’Encouragement then validated the conclusions of its report by subscribing the sum of 500 francs in favor of the new association, and by deciding that, in addition to its moral influence, it would place at the latter’s disposal the various means of execution that might belong to it.

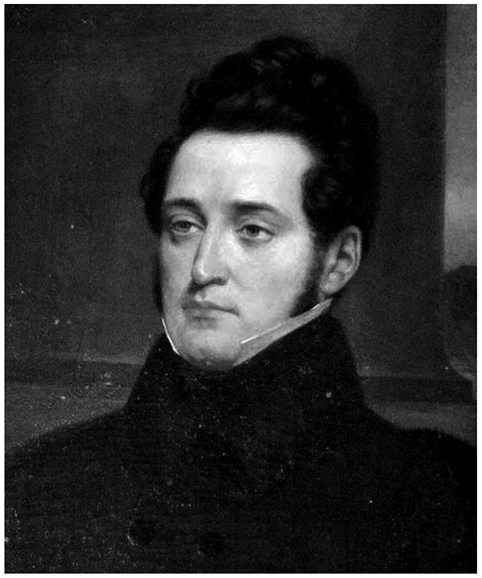

10. Lazare Carnot at the helm

Following the Concordat between Napoleon and the Vatican, the Emperor issued a decree on education on August 15, 1808, requiring schools to follow the « principles of the Catholic Church ».

The Frères des Ecoles Chrétiennes (Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools), unconditional advocates of the « simultaneous education » theorized by their founder Jean-Baptiste de La Salle (1651-1719), were to take charge of all primary education and train teachers.

Disbanded during the Revolution, the Brothers resumed their functions in 1810. Encouraged to develop to counter the influence of the Jesuits, authorized in 1816 to return to France, they rapidly expanded throughout France.

But the educational situation was pitiful. This is what senior French officials constantly say when they visit the territories annexed by the Empire, notably North Germany and Holland. The comparison with France makes them blush with shame.

In 1810, the naturalist Georges Cuvier wrote in his report:

« We would be hard pressed to convey the effect produced on us by the first elementary school we entered in Holland. Children, teachers, premises, methods, teaching, everything is in perfect order (…) Several prefects have assured us that we would not find a single young boy in their department today who did not know how to read and write. »

Faced with such a contrast, which was not to the conqueror’s advantage, the Imperial University, like ancient Rome, set out to teach the conquered country. In his decree of November 15, 1811, the Emperor decided:

« The council of our Imperial University will present us with a report on the part of the system established in Holland for primary instruction that would be applicable to the other departments of our Empire. »

The Emperor abdicated on April 4, 1814, before any decision had been taken to regenerate the French « petites écoles ». At least the Imperial University’s reports had exposed their misery and drawn public attention to them.

Appointed Minister of the Interior, and therefore in charge of Education during the Cents-Jours, Lazare Carnot, a co-founder of the Ecole Polytechnique, was completely convinced of the potential excellence of « mutual education ».

On April 10, 1815, he set up a Council for Industry and Charity, at whose first meeting he himself presented Gérando‘s report;

On April 27, 1815, he submitted a report to the Emperor in which he stated:

« There are 2 million children in France clamoring for primary education, and of these 2 million, some receive a very imperfect education, while others are completely deprived« .

He then recommended mutual education, whose « purpose is to give primary education the greatest degree of simplicity, rapidity and economy, while also giving it the degree of perfection suitable for the lower classes of society, and also by bringing into it everything that can give rise to and maintain in the hearts of children a sense of duty, justice, honor and respect for the established order ».

Minutes later, Lazare Carnot had the French Emperor sign the following decree:

« Article 1. – Our Minister of the Interior will call upon those persons who deserve to be consulted on the best methods of primary education. He will examine these methods, and decide on and direct the testing of those he deems to be preferable.

« Art. 2 – A primary education test school will be opened in Paris, organized in such a way as to be able to serve as a model and to become a normal school for training primary school teachers.

« Art. 3 – Once satisfactory results have been obtained from the trial school, our Minister of the Interior will propose the appropriate measures to ensure that all departments can rapidly benefit from the new methods that will have been adopted.«

For Carnot, contrary to those in the business of Philanthropy, there were not any longer poor or rich children. All citizens of the Republic required and had to be offered the best education available on Earth.

The advisory board set up by Carnot included his friends Laborde, Jomard, Abbé Gaultier, then Lasteyrie and Gérando, i.e. the very promoters or first founders of the Société en formation.

Thus, on June 17, 1815 (the eve of the defeat at Waterloo), the Société pour l’instruction élémentaire (SIE) was born, still under the impetus of Carnot, determined to win the war for education. The SIE’s first general meeting was held on the premises of the Société d’Encouragement. At its head were several protagonists of the ministerial commission: Jomard became one of the secretaries of the new society, alongside Gérando (president), Lasteyrie (vice-president) and Laborde (general secretary).

for whom Mutual Tuition was the core of their commitment to primary education.

Before the ordinance of 1816, the number of children attending « petites écoles » was 165,000 throughout France, and by the end of 1820 it had risen to 1,123,000. Almost a factor of 10!

Lazare Carnot clearly wanted to perpetuate the offensive he had launched during the Hundred Days to propagate mutual education throughout the country and, in so doing, to rapidly develop the education of all the children of the Patrie.

After its creation, subscriptions for the SIE poured in, and before long 150 names were added to those of the founders to promote and organize mutual education in France. One of these subscribers was Lazare Carnot.

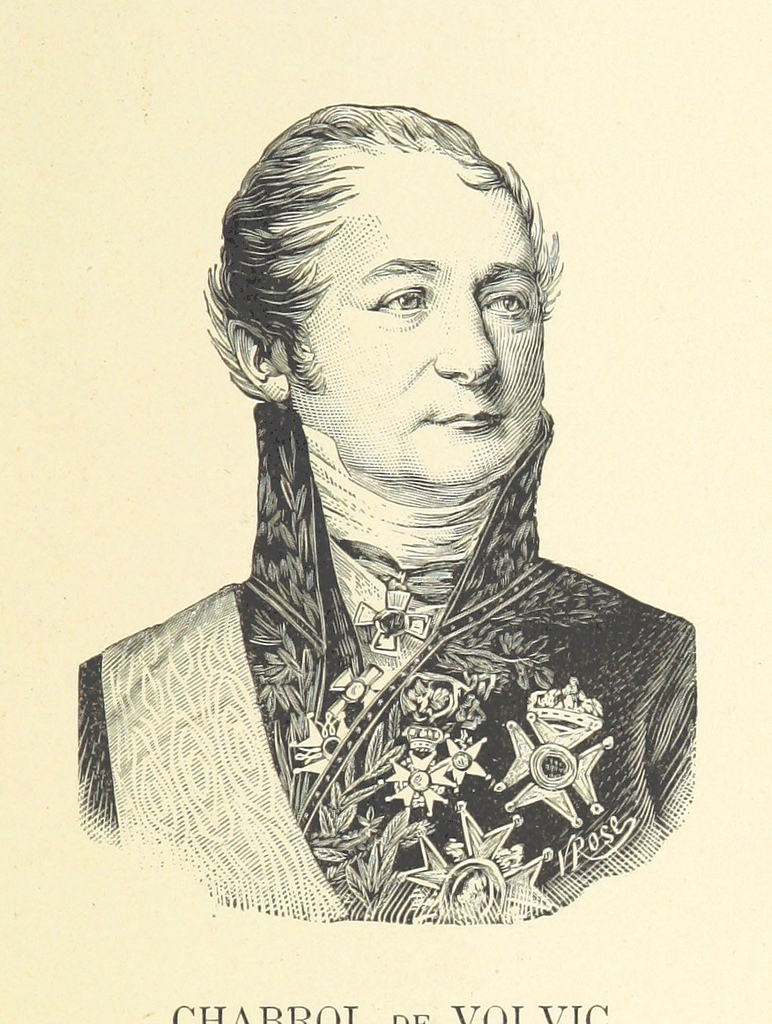

In its first year of existence, the SIE attracted almost 700 members, initially teachers from the École Polytechnique (Ampère, Berthollet, Chaptal, Guyton de Morveau, Hachette, Mérimée, Thénard), and then some 30 alumni, around half of them from the first graduating class (1794) of the École Polytechnique. Among the latter were a fellow student of Jomard‘s at the geographers’ school, Louis-Benjamin Francœur, professor of higher algebra at the Paris Faculty of Science, comrades from the Egyptian campaign, and Chabrol de Volvic, prefect of the Seine since 1812.

All had but one hope: that Monge’s genial methods of brigades and mutual tuition, which had been diminished and banned once Napoleon turned Polytechnique into a mere military school under the direction of mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827), could benefit the greatest number and organize a national recovery.

Based in Paris, the SIE extended its operations to the provinces, where it encouraged the founding of subsidiary companies, to which it offered « to send them teachers, to provide them with any information they might need, to give them paintings and books at cost price… ».

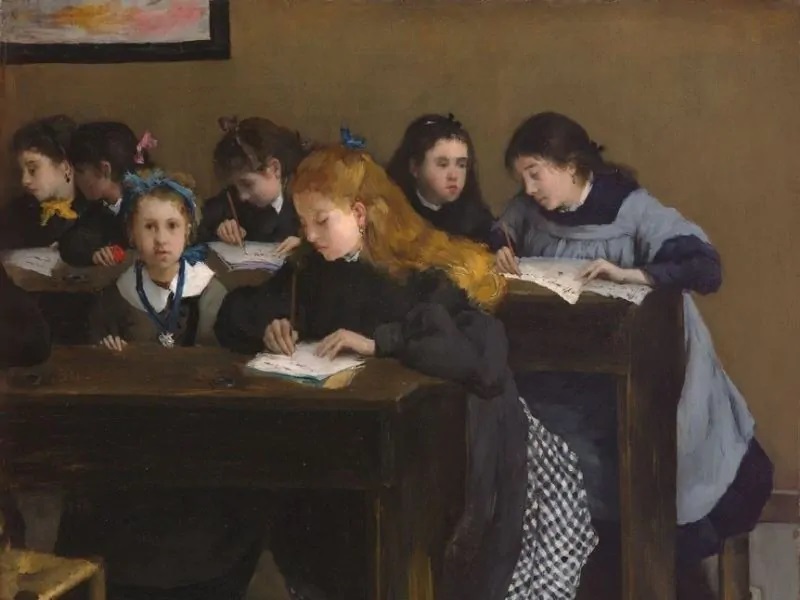

The SIE was also interested in education girls (art. 10). It set up a committee of ladies to look after them: president, Baroness de Gérando; vice-president, Countess de Laborde.

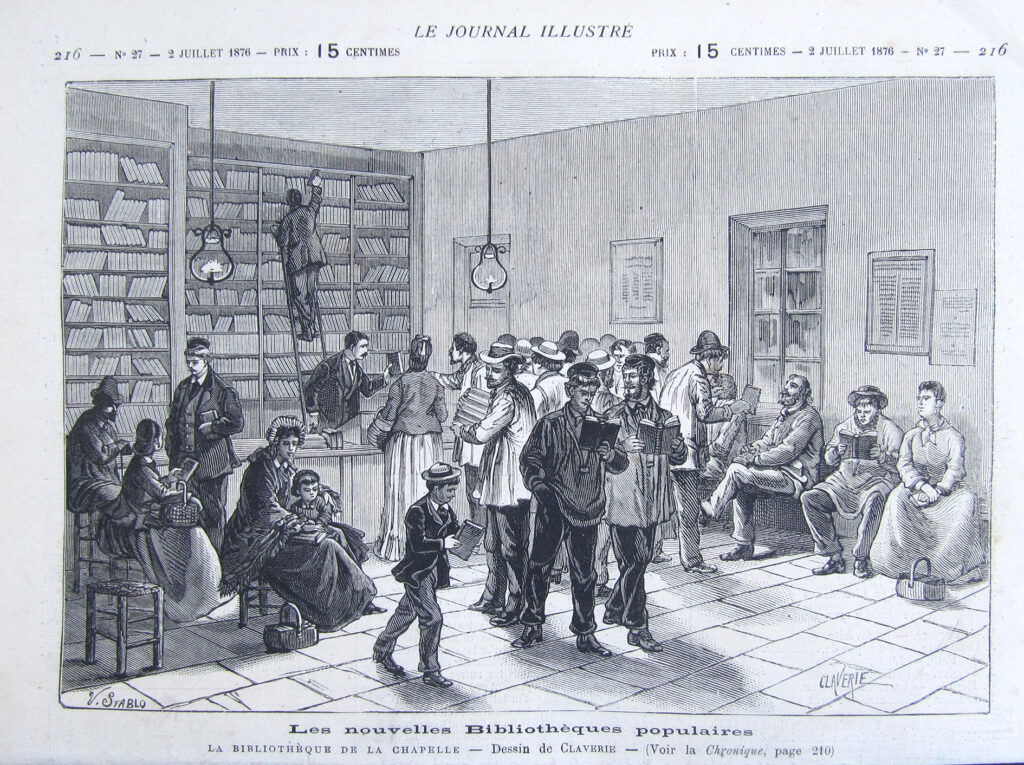

Beyond women, the movement spread to uneducated adults, so numerous at the time. On May 1, 1816, the Society set up a commission for the establishment of adult schools. It was also concerned with barracks, which were to be turned into military schools; prisons, especially children’s prisons; and the colored inhabitants of the colonies, who were to be regenerated by the development of education.

Finally, the members of the Society, attributing a human and general value to their mission, dreamed of founding branches abroad. In November 1818, Laborde called for the creation of a special committee to do so.

Last but not least, the Society did not limit its activities to simply creating schools, but also organized inspections and examinations. It published works (on the mutual tuition method, elementary books on reading, grammar and arithmetic). It distributed awards to the best teachers and instructors.

Following the promulgation of the ordinance of July 29, 1818 authorizing Caisse d’Epargne societies (Saving Banks associations), it asked teachers to entrust part of their salaries to these funds to ensure their retirement; setting an example, it deposited funds with the Caisse for the teachers of the schools it had set up.

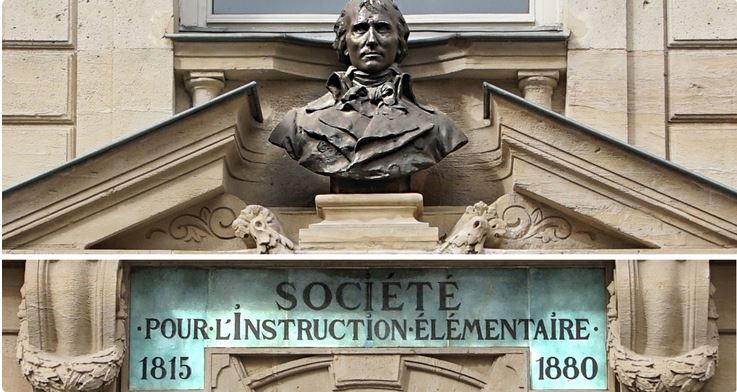

Today, the SIE, whose head office is a specially-built building at 6, rue du Fouarre in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, remains the oldest and largest secular primary education association in France.

11. The rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais pilot program

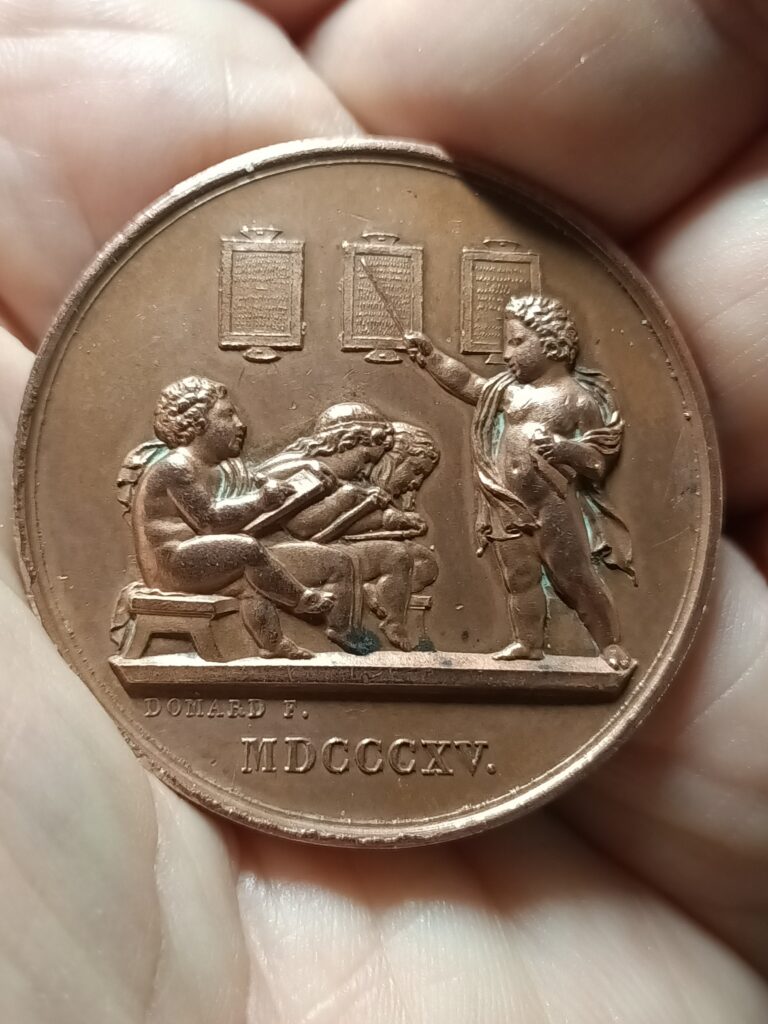

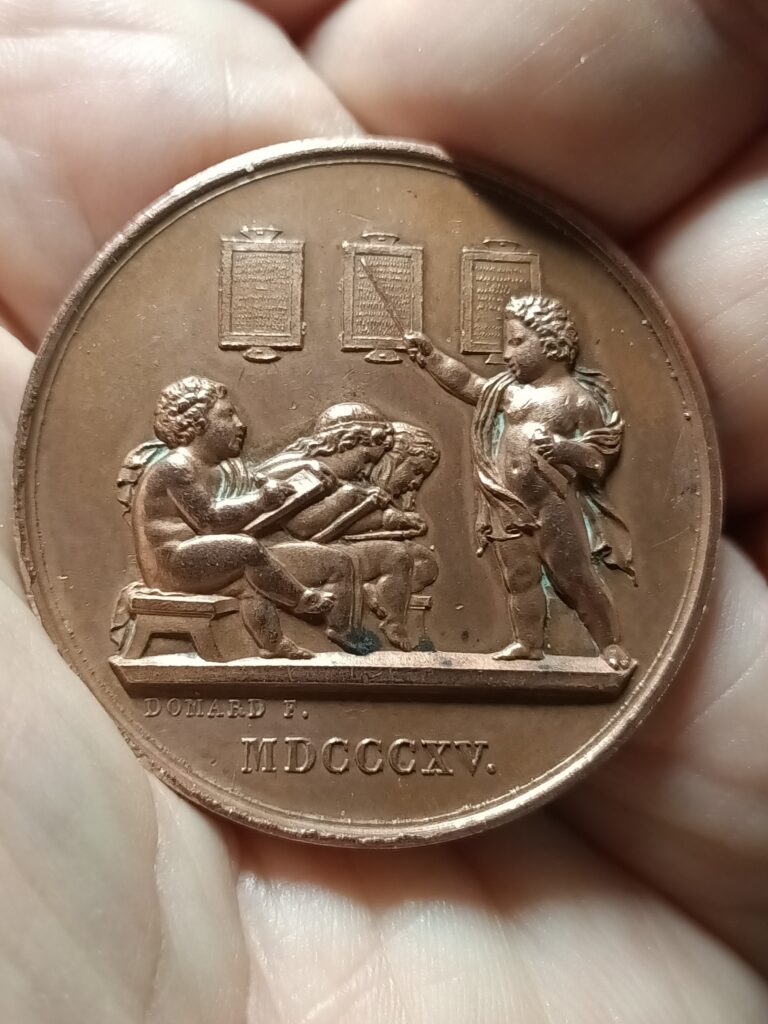

As said before, after his trip to England, Jomard, whose portrait appears in a medaillon on the façade of the SIE, also embraced the new system.

In his « reflections on the state of English industry », he wrote, after expressing his enthusiasm for various inventions observed across the Channel: « There is, however, something even more extraordinary: these are schools without teachers: nothing, however, is more real. We now know that there are thousands of children taught without a teacher, and at no cost to their families or the State: an admirable method that will soon spread to France.«

A graduate of the Ecole Polytechnique, and an exceptionnal scientist who went with Monge to Egypt, Jomard was the ideal man to oversee the material organization of the test school, in particular by arranging for furniture to be made and teaching aids to be printed in accordance with English principles. Jomard also supervised the training of a small nucleus of students – around 20 – as « monitors » before the opening of the school proper in September 1815, planned for 350 students: a modality reminiscent of the « chefs de brigade » of the first graduating class of the École polytechnique.

However, the members of the SIE soon realized that they needed to train trainers. The English therefore welcomed several Frenchmen to train them in mutual teaching. A pastor from the Cévennes, François Martin (1793-1837), after training as a « monitor » in England, was called in by Lasteyrie to run the first mutual school, which opened its doors on June 13, 1815, on rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais in Paris, close to Place Maubert. This was the model school that would enable other mutual schools to be opened, thanks to the training of competent « monitors ». The school was soon unable to keep up with demand from hundreds of communes, which were considering sending one of their own to be trained in the new method.

Pastor Paul-Emile Frossard, also trained by the English, took charge of a Parisian school on rue Popincourt, while Bellot ran another. In July, Martin submitted his report. The model class takes in some 15 students destined to become monitors and principals of elementary schools with up to 350 children. Martin reports that in six weeks, they read, write, calculate and « know how to execute the movements that form the gymnastic part of the new education system ».

12. Mutual tuition and music

As Christine Bierre amply documents in her article « La musique et formation du citoyen à l’ère de la Révolution française » (1990):

« It was at this school on rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais, under the direction of a Commission comprising Gérando, Jomard, Lasteyrie, Laborde and Abbé Gaultier, that the application of mutual teaching to the learning of solfeggio and singing was tested for the first time. Alexandre Choron (1771-1834), who since 1814 had opened two music schools for boys and girls, was also a member of the Commission. Not surprisingly, it was on the initiative of Baron de Gérando that the idea of introducing singing into primary education was adopted. When Monsieur le baron de Gérando proposed the introduction of elementary singing in primary schools’, says Jomard in a report presented to the Board of Directors of the Société pour l’Enseignement mutuel, ‘you were all struck by the correctness of the views developed by our colleague (…) It showed the happy influence that such a practice could have, and the real connection that exists between the proper use of song and the perfecting of morals, the ultimate goal of instruction and of all our efforts. Not only was the application of mutual instruction to music revolutionary in itself, but what was equally revolutionary was the fact that children were learning to read and write, almost as intensively. Children studied singing, for four to five hours a week! »

In fact, it was Lazare Carnot himself who wanted to introduce music into the mutual education schools. To this end, he met several times with musician Alexandre Choron (1771-1834), who brought together a number of children and had them perform in his presence several pieces learned in very few lessons. Carnot also was acquinted with Guillaume-Louis Bocquillon, known as Wilhem (1781-1842) for ten years. He saw the possibility of using him to introduce singing into schools, and together they visited the one on rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais, a free pilot school for mutual education in Paris open to three hundred children.

Michael Werner‘s recent article, « Musique et pacification sociale, missions fondatrices de l’éducation musicale (1795-1860) », echoes and confirms the groundbreaking research initiated by Christine Bierre in 1990.

Excerpt:

« One of the fields in which the results of mutualist pedagogy are clearly visible is musical education. Several players played a decisive role here, and deserve a brief mention.

The first is Guillaume-Louis Bocquillon, known as Wilhem (1781-1842). The son of an officer and himself from a military background, he then devoted himself to musical composition and teaching, particularly at the Lycée Napoléon (later Collège Henri-IV). His friend Pierre Jean de Béranger put him in touch with Joseph-Marie de Gérando and François Jomard, the leading lights of the SIE. Through them, he learned about mutual teaching and immediately understood the benefits of this method for musical education. In 1818, the Paris municipality allowed him to set up a first experiment at the elementary school on rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais. Wilhem developed a method, the necessary teaching materials (in the form of charts) and instructed the chosen student monitors. The results were, according to Jomard, spectacular. At the end of a few months’ instruction, the pupils had not only acquired the basic notions of solfeggio and musical notation, chromatic scales, intervals and measures, but were also performing collective songs in several voices (Jomard 1842: 228 ff)

This success led the SIE to propose to the Prefect and Minister of the Interior that music be introduced into the teaching of elementary schools in the city of Paris, a move officially endorsed in 1820. Wilhem himself was appointed full professor of music teaching in Paris, and music classes were introduced in many of the city’s schools, before spreading to the départements and regions. At the same time, the municipality opened two teacher-training colleges to train future singing teachers.

The second early player in the debate was the composer Alexandre Choron (1771-1834). A member, like Jomard and Francœur, of the first graduating class of the École polytechnique (1795), composer and friend of André Grétry, he had been concerned since 1805 about the decline of choral singing following the abolition of the master classes. An opponent of the Conservatoire, whose academicism and lack of interest in the teaching of choral singing he criticized, in 1812 he was entrusted by the Ministry with a mission to « reorganize the choir and the choirmasters of the churches of France ». He developed a teaching method known as the « concertante method », but also remained committed to the social vocation of choral music. Choron was also one of the founding members of the SIE in 1815, a sign of his commitment to educational issues. During the Restoration, he turned more to religious songs, which he considered to be the historical heart of choral practice. (…) Finally, with the king’s support, he founded the Institution royale de musique classique et religieuse, successfully competing with the Conservatoire in the teaching of vocal art.

For the general public, he arranged for oratorios, requiems and cantatas to be performed by singers from his school in a number of spacious churches, thus ensuring a new presence for sacred music on the Parisian stage. For some of these concerts, he sometimes mobilized student singers from elementary and poor schools, whom he never ceased to follow throughout his career. »

« (…) What fostered this expansion of music education for young people and the working classes from 1820 onwards was a political will shared by a broad spectrum of leaders and stakeholders. The liberals who formed the core of the SIE continued to adhere to the emancipatory mission of education set out by the Convention. By focusing on both the inner formation of the soul and the blossoming of a collective conscience, music – and singing in particular – became a prime field for popular education. Liberals therefore emphasized the moral benefits of music. Thus, in his proposal to introduce singing into elementary school, Gérando remarks:

‘Those of us who have visited Germany have been surprised to see how much simple music plays a part in popular entertainment and family pleasures, even in the poorest conditions, and have observed how salutary its influence is on morals. And Joseph d’Ortigue states lapidary: ‘A people that sings is a happy people, and therefore a moral people. This emphasis on the social benefits of musical activity fits in well with the idea of ‘universal education’, inherited from the Enlightenment and the foundation of the pedagogies of Lancaster in England or Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi in Switzerland.' »

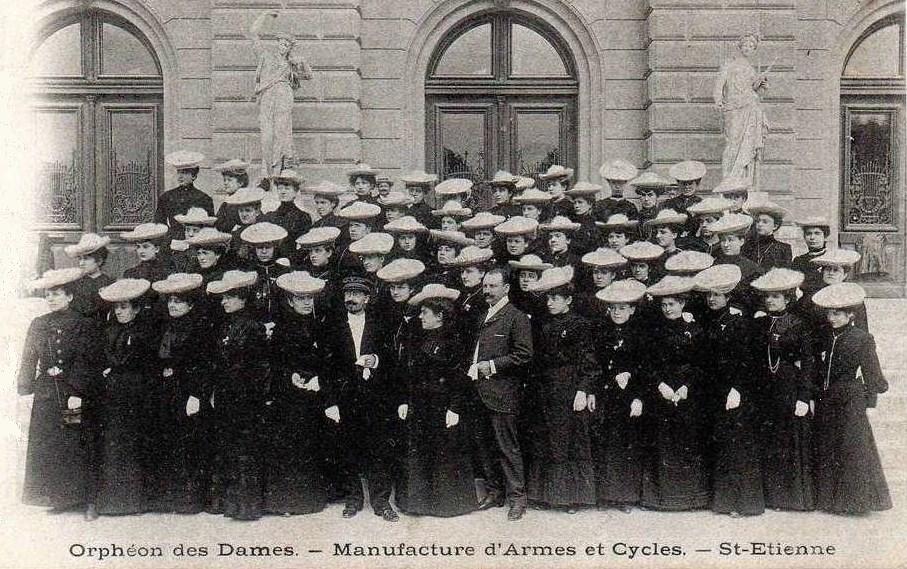

After a trial run at the St-Jean-de-Beauvais school in 1819, singing quickly spread to all the mutual schools. Wilhem was both the creator and the architect of the development of this teaching method, which soon spread to adult and apprentice classes. Periodic meetings of children initiated into vocal music were organized. Thus was born the first French post-school organization: the Orphéon, which, after Wilhem, counted Charles Gounod and Jules Pasdeloup among its directors.

In an 1842 speech to the SIE, Hippolyte Carnot asserted that Wilhem had « elevated music to the rank of a civic institution », and that the « ennoblement » of the individual soul was to be achieved in the new collective order of the reunited nation.

13. Jomard, Choron, Francoeur and « elementary » knowledge

Renaud d’Enfert‘s comprehensive article, published on the website of the Société de la bibliothèque et de l’histoire de l’Ecole polytechique (SABIX), completes the picture with a close-up on the work of Jomard and Francoeur, whose portraits are featured in a medallion on the façade of the SIE headquarters on rue du Fouarre in Paris.

Right from the start of the Second Restoration, the SEI received the backing and support of the Prefect of the Seine, Gaspard de Chabrol de Volvic (1773-1843). In the summer of 1815, the latter appointed Jomard, a linguist in contact with the Humboldt brothers who had been part of the short-lived commission under Carnot and who had protected him during the Hundred Days, « head of the office of public instruction and arts », a position he held until 1823.

In a decree dated November 3, 1815, Volvic, in order to take « the necessary measures to extend the benefits of instruction to all poor families domiciled within the prefecture » and to develop « the new system of elementary instruction » throughout the Seine department, created an eleven-person committee « to extend the benefits of free education to the Seine department », and included all the influential members of the SIE (Jomard, Gérando, Laborde, Doudeauville, Lasteyrie, Gaultier, etc.). ).

In this role, Jomard was responsible for finding sites for new schools. These rapidly multiplied in and around the capital: in 1818, he counted 18 free and 32 fee-paying mutual schools covering all of the capital’s arrondissements, as well as 13 schools in the arrondissements of Sceaux and Saint-Denis. From this work, he drew up his « Abrégé des écoles élémentaires » (1816), a sort of practical guide in which he compiled everything a cityen decided to set up a mutual school needed to know about material organization.

On the pedagogical front, Jomard was the author, in 1816, of a reading method produced in collaboration with the composer and musician Alexandre Choron, who had published a method for learning to read and write as early as 1802, and Abbé Gaultier, a pedagogue who had developed a teaching method under the name of « jeux instructifs » and had traveled to London to study English methods.

Designed for the new elementary school on rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais, where Choron was appointed music teacher, it breaks with the traditional spelling method.

Instead of saying « b-o-n = bon », she uses the musical sounds of the language to say « b-on = bon ». In 1821-1822, Jomard also published « Arithmétique élémentaire » (Elementary Arithmetic), designed to remedy the weaknesses of Lancaster’s arithmetic method, which he accused of « making children contract a simple, routine and mechanical habit » instead of serving « to fortify their attention and train them in reasoning ». In the meantime, he and Francœur and Lasteyrie had set up a « calligraphy commission » at the SIE, to develop the principles that would guide the teaching of writing in mutual schools, a writing style intended to be « national », to replace the English models.

For his part, Louis-Benjamin Francoeur (1773-1849) provides, according to Jomard, « a long series of luminous reports on treatises on arithmetic, weights and measures, singing and musical art, drawing and geometry, which it would take far too long to relate or quote ». Filling a gap, in 1819 Francœur published « Le dessin linéaire » (Linear Drawing), a drawing method based on freehand drawing of geometric figures, which broke with traditional, academically inspired ways of teaching and learning drawing.

For Jomard and Francoeur, the idea behind « mutuel tuition » was to broaden the range of subjects taught in primary schools beyond the traditional « reading, writing and arithmetic »: in addition to drawing, also singing, gymnastics, geography and grammar now made their appearance in elementary school.

Linear drawing was nonetheless seen as an elementary skill in its own right, on a par with reading, writing and arithmetic.

Presenting Francœur‘s method to the Société d’Encouragement, Jomard declared:

« The usefulness that industry may one day derive from it is so great and so visible, that it would be superfluous to insist on it. It is not without reason that this result has been considered as precious for the people, as the knowledge of reading and writing ».

Finally, for Jomard, the widespread teaching of reading, writing, arithmetic, linear drawing and singing is the prerequisite for the scientific education of the people:

« In recent times, we have rightly insisted on the usefulness of teaching the elements of the physical and mathematical sciences to the working class. On this depends the advancement of industry and agriculture, which, despite all their progress, are still backward in many respects. It is only through the possession of these elementary notions that workers will perfect their processes, their means, their instruments and their products, and will be able to become skilful foremen and good workshop managers. But how can this be achieved when the mass of the population is still so ignorant?

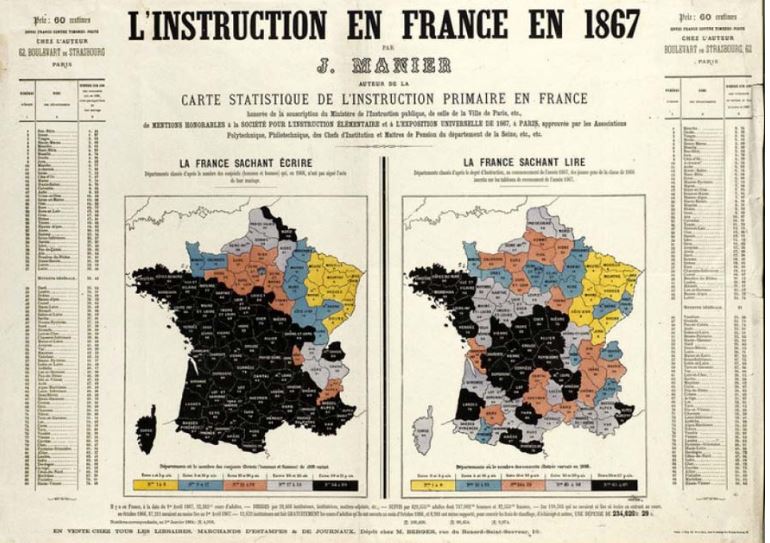

How, without the art of reading and writing, could they not understand a single word of the chemical and mechanical arts, but only feel their advantage and consent to engage in arduous studies? What’s this! Fifteen million Frenchmen and more perhaps, do not know how to do the first two rules of arithmetic, and we would flatter ourselves to propagate among them the first principles of mechanics and geometry! The basis of this improvement is obviously primary education made more general or even universal ».

14. Nationwide

The results of mutual education are spectacular and rapid, both in terms of learning time and the quality of skills acquired. Whereas in the Lasalle Brothers’ schools it took 4 years to learn to read, this time was reduced to a year and a half in the mutuel establishments!

The enthusiastic French of 1815, with their vivid imagination, saw in this teaching system a veritable panacea. It had undeniable advantages. First of all, it was economical, requiring few teachers and enabling a considerable number of children to be taught at low cost. It is estimated that 4,000 to 5,000 fr. a year were sufficient to maintain a school of 1,000 children: 4 fr. per pupil! Education would never have been so cheap. It also ensured rapid development of primary education, since the shortage of teachers was no longer a limiting factor. With figures to back it up, it was calculated that it would only take a dozen years to extend the benefits of primary education to the whole of France!

To these indisputable advantages, the travelers of 1815 added qualitative arguments. They considered the teaching of instructors superior to that of masters: « He does not know his lesson better than the master, » wrote Laborde, « but he knows it differently ». The child instructor (monitor) takes pleasure in communicating his newly acquired knowledge to his classmates, doing his job « with as much charm as a preceptor finds it disgusting » (Laborde).

On the other hand, being a child himself, he knows better than the teacher the difficulties of the task, the pitfalls of the lesson, over which he has just stumbled. He will therefore lead his classmates more slowly, more surely, and be a better guide for them.

But teaching won’t be the only thing to benefit from the mutual system; school discipline and morals will also benefit. The child, submissive to his classmate, will obey him more readily than the teacher, since the young instructor owes his superiority solely to his own merit. Finally, the child, with his classmate who knows him well because he lives with him, will not have, as with the teacher, the resource of lying to hide his intimate thoughts or faults: and dissimulation, the social scourge that was learned from the school benches, will thus disappear from mutual establishments.

And Laborde concluded his apology for the method : in the new schools, « work is for them a game, science a struggle, authority a reward ».

The benefits of this teaching were not to be confined to the school: children returning home would in turn exert a happy influence on their parents, becoming « missionaries » of both morality and truth in their families.

Gontard wrote in 1956:

« And let no evil spirits say that these are the daydreams and utopias of idealists! There is irrefutable proof of the value of this method. Look at Scotland. At the end of the 17th century, it was a land of beggary and misery, living without law, without religion, without morals, men drinking, women blaspheming, all fighting. In 1815, thanks to the magic wand of the mutual school, Scotland became a paradise. « It is not uncommon in Scotland to find a shepherd reading Virgil… but it is almost unheard of to meet a malefactor there, »

Laborde agrees.

« Let’s develop the method in France and, by 1850, it will be a land of prosperity and happiness, from which immorality, fanaticism, revolutions and social unrest, all sons and daughters of ignorance, will be banished. »

In 1818, Joseph Hamel, in his report to the Emperor of Russia, notes:

« The method of mutual education has been introduced throughout France with a rapidity and success far greater than could reasonably be expected, and in less than three years more than 400 schools have already been founded. There is every reason to hope that, in the not-too-distant future, more than 2 million children who were still in complete ignorance will be able to receive the benefits of a free education, sufficient for their future vocation.«

Right from the start, with Carnot and a generation of brilliant scientist coming out of Polytechnique, France was giving leadership !

Amiens and the Somme department

Interesting in that regard, the following account of the adoption of mutual tuition methods in Amiens and the Somme department.

« On May 15, 1817, after much mistrust and hesitation, the Amiens town council founded a society to encourage elementary education in the department. More than ennobling the pupils’ souls, for the rector, it was a question of ‘giving the children of these workers an elementary education, [to prepare them] not only for the habit of order and subordination that is acquired in the mutual education schools and which they carry over to the workshops, but also to put them in a position to serve more usefully inside the factories, how to study the industrial processes whose preservation and improvement are so essential to national prosperity' ».

For the Rector, speed of acquisition was a guarantee of success for the new method compared to the « simultaneous method »:

« That a primary education which takes children away for whole years from work necessary for the family’s subsistence becomes for the poor a very onerous burden; but that experience teaches the father of a family that a few months will suffice to procure for his children an advantage which he has regretted so many times in the course of life not to have been able to enjoy himself, we must hope that he will not sway to make a slight sacrifice in order to obtain an important result ».

These are mainly boys’ schools. There are a few girls’ schools and evening classes for adults. They mainly catered for the children of small craftsmen: dyers, octroi clerks, innkeepers, foremen, tailors, millers, dressmakers, coopers, dressmakers, locksmiths, butchers, spinners, ironers, laborers, car loaders, carpenters, booksellers, lamplighters, cutlers, bookbinders and so on.

At its peak, in 1821, mutual education in the Somme department included not one but 25 schools, 4 of them for girls (for a fee): 4 out of 10 were located in towns. In 1833, there were 16 more. The network shrank considerably thereafter, but did not disappear altogether. The last two schools in Amiens closed their doors involuntarily in 1879, and the one in Abbeville in 1880: until then, it played an important role in preparing candidates for examinations.

The Amiens Model School – the first provincial model school – prepares future teachers for the practice of mutual education. It was founded on May 26, 1817. It welcomed over 200 pupils. By 1818, 6 teachers from the Somme had graduated. Most of the teachers from the Aisne, Oise and Pas-de-Calais departments spent some time there before taking up their duties.

In 1831, when the Prefect created the Ecole normale de garçons, it was called the « Ecole normale primaire d’enseignement mutuel ». At first, it served as a training school: student teachers were required to visit the school once a week to observe and practice the mutual teaching method.

After the government reshuffles of 1817-1818, several SIE members were appointed to important ministries: Mathieu Molé (1778-1838) to the Navy, Laurent Gouvion-Saint-Cyr (1764-1830) to the War, Elie Decazes (1780-1860) above all to the Interior, the ministry on which primary education depended. Government support became systematic.

The Minister of the Interior supported the SIE de Paris and its subsidiaries with grants for school foundations and maintenance. He invited the prefects to contribute in any way they could to the development of the method. Prefects took the initiative in setting up local companies, and lobbied local assemblies for subsidies.

A growing number of General and Municipal Councils voted to set up mutual schools. Once a school had been founded, the local authorities (prefect and mayor) visited it and presided over the prize-giving ceremony. For its part, on July 22, 1817, the Commission d’Instruction Publique, which since 1815 had replaced the Grand Master of the University, decided to establish a model mutual-education school in the chief towns of France’s twelve Academies, as a breeding ground for future teachers. Other ministers, each in their own sphere, supported the method.

Molé, in charge of the colonies, founded mutual tuition schools in Senegal.

In 1818, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr established a full-fledged « Ecole normale militaire d’enseignement mutuel » in the caserne Babylone of Paris. Each regiment in Paris and the provinces was required to send one officer and one non-commissioned officer, who would return after a few months’ training to teach the troops the benefits of primary education.

In 1817-1818, mutual tuition triumphed. An irresistible enthusiasm carried France towards it. The network of schools continued to expand. From term to term, more and more reports arrived in Paris from the provinces, counting schools and their pupils.

It was a song of victory that Jomard could sing at the SIE meeting in January 1819. Of the 81 départements in France, only 5 had no mutual school; the other 76 had 687 schools, attended by over 40,000 pupils. There were also 105 regimental schools, 5 adult schools, 4 prison schools and 2 or 3 schools in Senegal.

Exemplifying what was becoming a new Promethean paradigm of scientific optimism, on December 15, 1821, at a meeting at Paris City Hall, the Geographical Society was founded by 217 leading figures, including some of the greatest scientists of the day, such as Jomard, Champollion, Cuvier, Chaptal, Denon, Fourier, Gay Lussac, Berthollet, von Humboldt and Chateaubriand. Other illustrious members include Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Dumont d’Urville, Élisée Reclus and Jules Verne.

The collection and study of geographical data from many continents enabled certain members, such as Gustave Eiffel and Ferdinand de Lesseps, to propose major infrastructure projects, notably the Suez and Panama Canals.

15. Criticism

The first criticisms of mutual education came not from its failure, but from its success. The first « risk » was that the children, having learned too effectively and too quickly (2 to 3 times faster !), would return « to the streets » too soon, not yet being old enough to go to work!

Children weren’t « locked up » at school long enough, and so mutual education disturbed the existing social order. In 1818, the General Council of Calvados heard: