Étiquette : LaRouche

Israel-Palestine: Time to Make Water a Weapon for Peace

« If we solve all the problems in the Middle East,

but not the problem of sharing water, our region will explode.

Peace will not be possible »

(Yitzhak Rabin, former Israeli Prime Minister, 1992).

« You only make peace with your enemies. »

(Yitzhak Rabin.)

Contents:

Introduction

1. Geography of the Middle East

2. Rainfall and Water resources

3. Hydrography of the Jordan basin

A. Source

B. Tributaries

C. Lake of Tiberias

D. Yarmouk river

4. Water sources for Israel-Palestine

A. Surface water

B. Groundwater

C. Desalination

D. Reuse of Waste water

5. Water Infrastructure Projects

A. National Water Carrier (NWC)

B. Johnston Plan

C. Ghor Canal

D. Med – Dead Sea aqueduct

E. Red Sea – Dead Sea Water Conveyance

F. Turkish projects

G. Hidden defects and non-application of the Oslo agreements

H. Ben-Gurion Canal

I. Oasis Plan

J. Alvin Weinberg, Yitzhak Rabin and Lyndon LaRouche

Introduction

This article provides readers with the keys. To understand the history of the water wars that continue to ravage the Middle East, it is essential to understand the geological, hydrographical, geographical and political issues at stake. In the second part, we examine the various options for developing water resources as part of a strategy to overcome the crisis. We will deal with the gas issue, another subject of potential conflict or cooperation, in a later article.

1. Geography

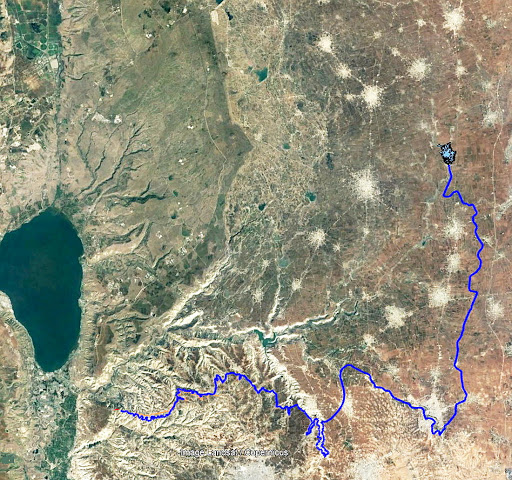

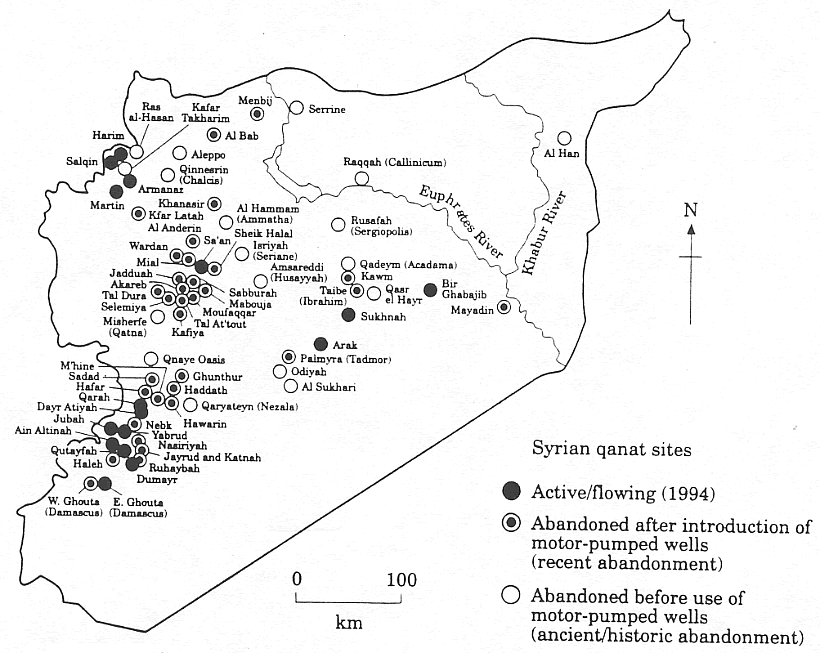

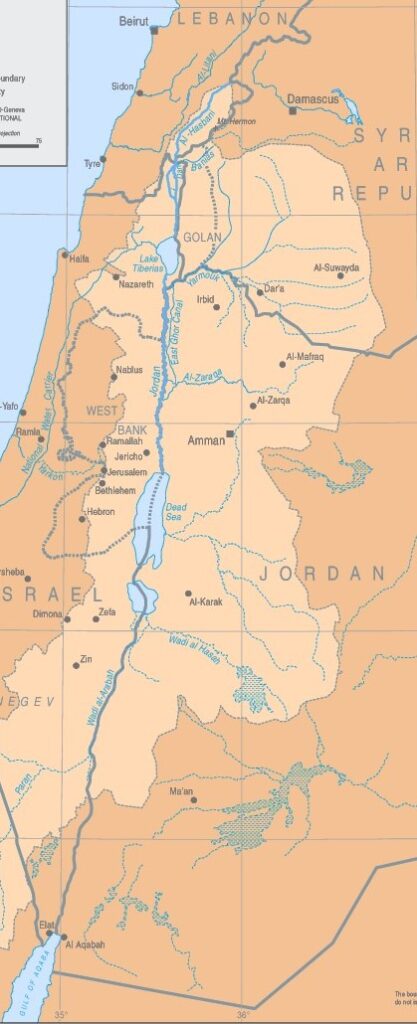

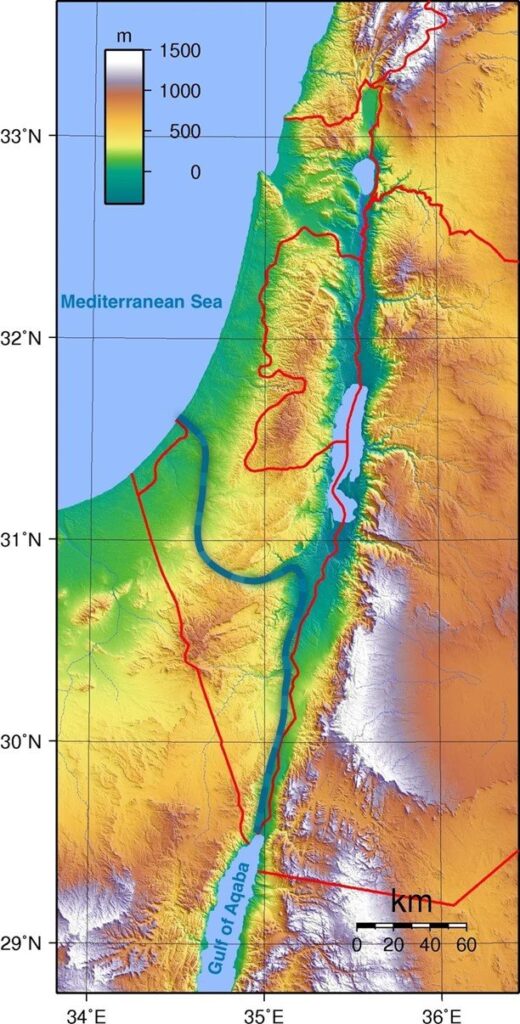

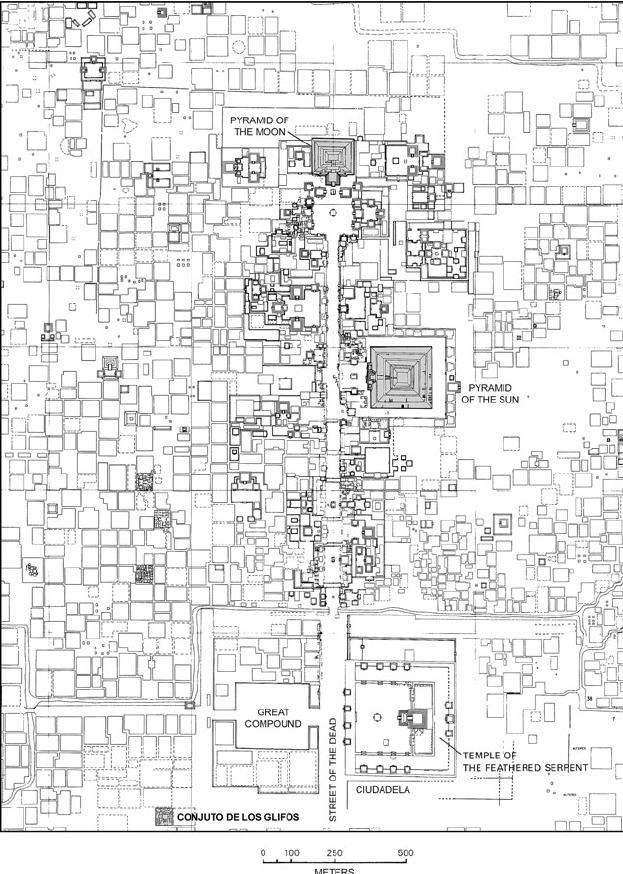

The Jordan River basin is shared by four countries: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel, plus the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza.

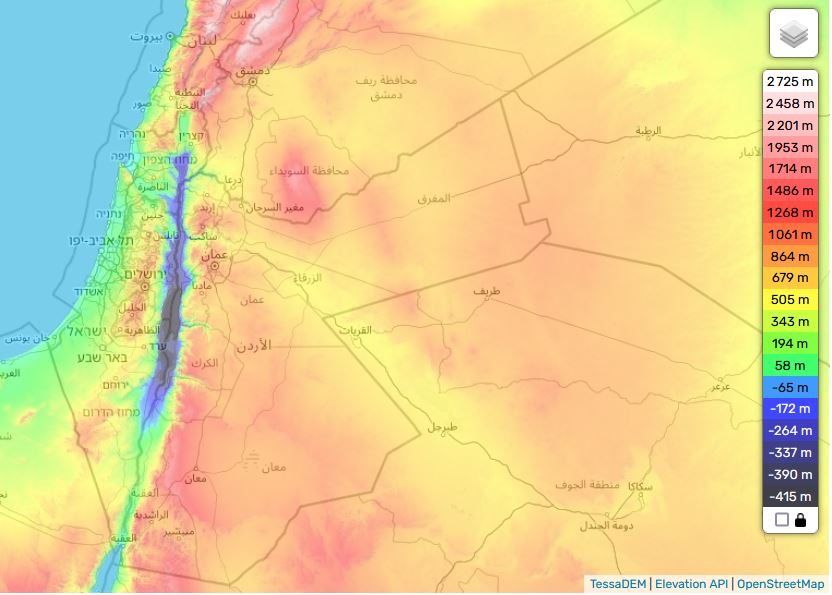

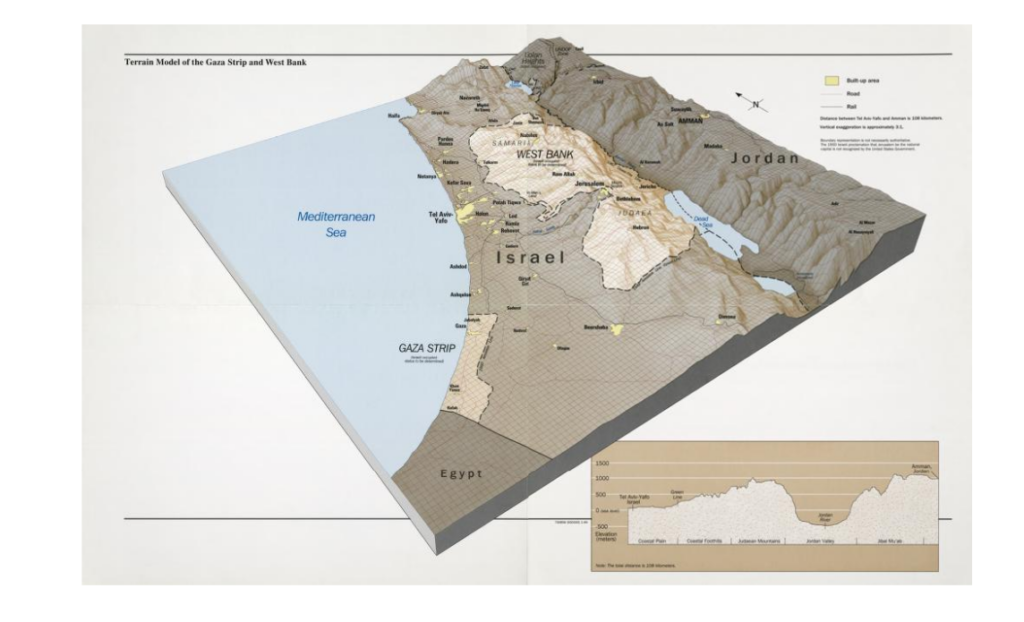

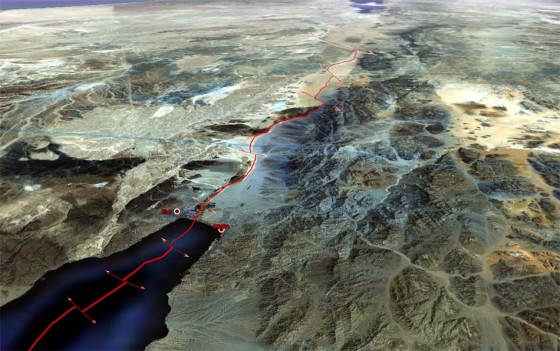

Situated in the hollow of a tectonic depression on the great fault that runs from Aqaba to Turkey, the Jordan Valley is one of the lowest-lying basins in the world, flowing into the Dead Sea at an altitude of 421 meters below sea level.

See interactive topographic map.

Added to this is the fact that this is an endorheic basin, i.e. a river that flows neither into the sea nor the ocean. As in the Aral Sea basin in Central Asia, this means that any water drawn or diverted upstream reduces the level of its ultimate receptacle, the Dead Sea (see below), and can even potentially make it disappear.

While remaining a fundamental artery for the entire region, the Jordan River has a number of drawbacks: its course is not navigable, its flow remains low and its waters, which are highly saline, are polluted.

As one of the key factors in the « Water, Energy, Food nexus » – three factors whose interdependence is such that we can’t deal with one without dealing with the other two – water resource management remains a key issue, and holds a primordial place for any future shared between Israel and its Arab neighbors. To grow food, one needs water. But to desalinate sea water, Israel spends 10 % of its electricity generated by consuming gas and oil.

2. Rainfall and water resources

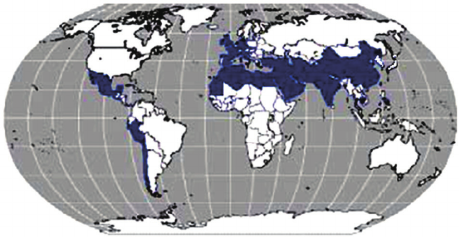

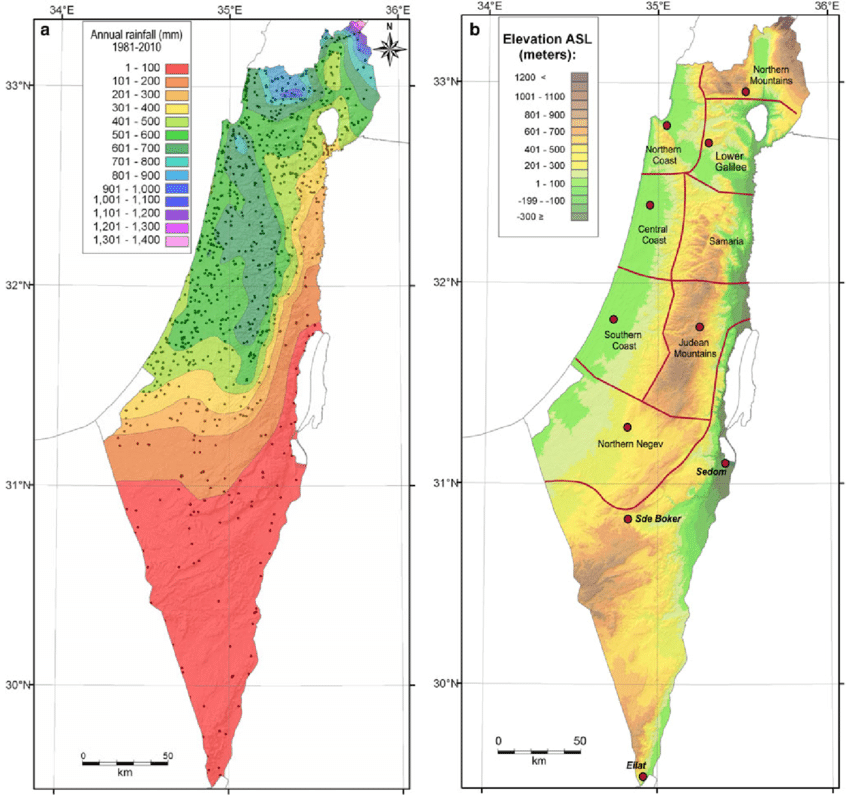

The Middle East forms a long, arid strip, only accidentally interrupted by areas of abundant rainfall (around 500-700 mm/year), such as the mountains of Lebanon, Palestine and Yemen.

Geographically, much of the Middle East lies south of the isohyet (imaginary line connecting points of equal rainfall) indicating 300 mm/year.

However, precipitation has only a limited effect due to its seasonality (October-February).

As a result, river flow and flooding are irregular throughout the year, as well as between years. The same applies to groundwater recharge.

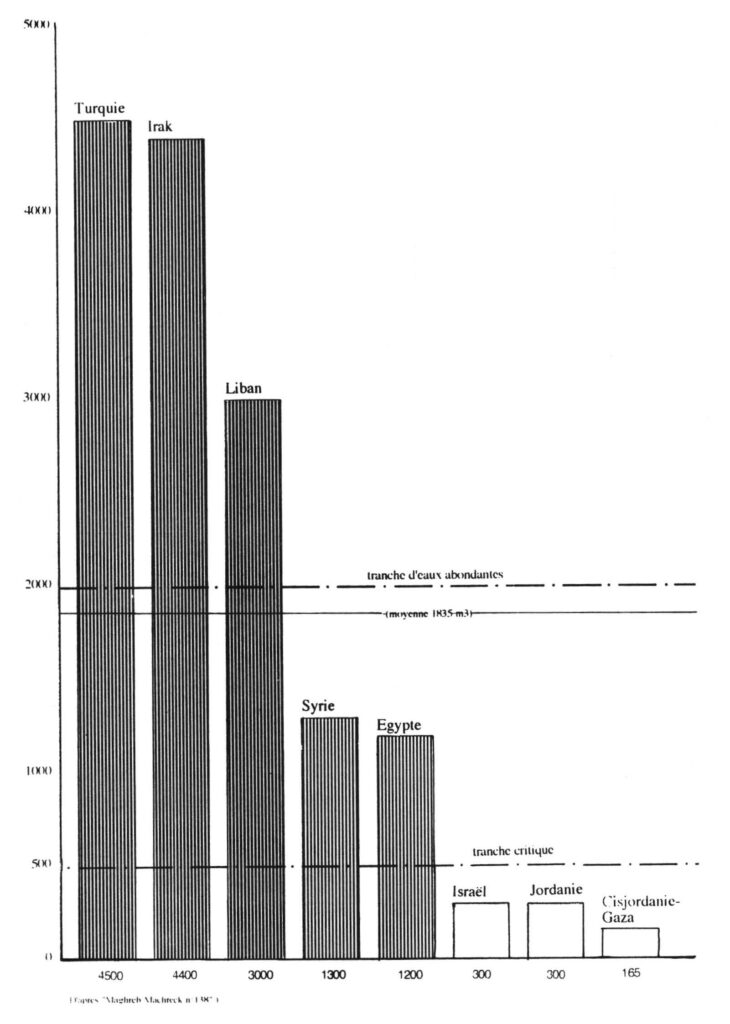

On a state-by-state basis, total water resources are very unevenly distributed in the region:

—Turkey and Iraq have over 4,000 cubic meters per person per year, and Lebanon around 3000 m³/person/year, which is above the regional average (1,800 m³/person/year).

—Syria and Egypt have around 1200 m³/person/year, one third lower.

On the other hand, some countries are below the critical 500 m³/year/capita bracket:

—Israel and Jordan have 300 m³/year/capita, and the Palestinian Territories (West Bank-Gaza) less than 200 m³/year/capita. They are in what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls a situation of « water stress ».

The Middle East enjoys plenty of water on a regional scale, but has many areas in chronic shortage, on a local scale.

3. Hydrography of the Jordan basin

A. Source

360 km long, the Jordan River rises from water flowing down the slopes of Jabal el-Sheikh (Mount Hermon) in southern Lebanon on the border with Syria.

B. Tributaries

Once over the Israeli border, three tributaries join the Jordan about 6 kilometers upstream from the former Lake Hula (now reclaimed):

1. The Hasbani, with a flow of 140 million cubic meters (MCM) per year, rises in Lebanon, a country it crosses over 21 kilometers. The upper reaches of the Hasbani vary greatly with the seasons, while the lower reaches are more regular.

2. The Banias, currently under Israeli control and 30 kilometers long, has an annual flow close to that of the Hasbani (140 MCM). It rises in Syria in the Golan Heights, and flows into Israel for around 12 kilometers before emptying into the Upper Jordan.

3. The Nahr Leddan (or Dan) forms in Israel when the waters of the Golan Heights come together. Although restricted, its course remains stable and its annual flow is greater than that of the other two tributaries of the Upper Jordan, exceeding 250 MCM per year.

C. Lake Tiberias or Kinneret (aka Sea of Galilee)

The Jordan then flows through 17 km of narrow gorges to reach Lake Tiberias, where the salinity is high, especially as the freshwater streams flowing into it have been diverted. Lake Tiberias, however, receives water from the many small streams running through the Golan Heights.

D. Yarmouk River

Next, the Jordan meets the Yarmouk River (bringing in water from Syria), then meanders for 320 km (109 km as the crow flies) to reach the Dead Sea. These 320 km are occupied by a humid plain (the humid zor), with subtropical vegetation, dominated on both sides (West Bank and Jordanian) by dry, gullied terraces.

4. Water sources for Israel

The Hebrew state has four main sources of water supply:

A. Surface Water

Israel benefits first and foremost from the freshwater reserves of Lake Tiberias in Galilee, in the north of the country. Crossed by the Jordan River, this small inland sea accounts for 25% of Israel’s water needs. The annexation of the Golan Heights and the occupation of southern Lebanon have made this source of water a sanctuary.

B. Groundwater

In addition to surface water (lakes and rivers), the country can rely on its coastal aquifers, from Haifa to Ashkelon.

Located between Israel and the occupied West Bank, the main aquifer, the Yarkon-Taninim mountain aquifer, has a capacity of 350 MCM per year. In the northeast and east of the West Bank are two other aquifers with capacities of 140 and 120 MCM per year respectively.

C. Seawater desalination

Five desalination plants built along the country’s coastline — in Ashkelon (2005), Palmachin (2007), Hadera (2010), Sorek (2013) and Ashdod (2015) — currently operate and two more are under construction. Collectively, these plants are projected to account for 85-90 per cent of Israel’s annual water consumption, marking a remarkable turnaround.

The Sorek desalination plant, located about 15 km south of Tel Aviv, became operational in October 2013 with a seawater treatment capacity of 624,000m³/day, which makes it world’s biggest seawater desalination plant. The desalination facility uses seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) process providing water to Israel’s National Water Carrier system (NWC, see below). A dozen more units of this type are considered for construction.

Israel, which has been facing severe droughts since 2013, even began pumping desalinated seawater from the Mediterranean into Lake Tiberias, a unique performance worldwide. While Israel faced water scarcity two decades ago, it now exports water to its neighbors (not too much to Palestine). Israel currently supplies Jordan with 100 MCM and fulfills 20 % of Jordan’s water needs.

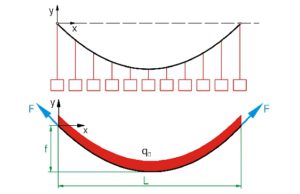

From 100 liters of seawater, 52 liters of drinking water and 48 liters of brine (brackish water) can be obtained. Although highly efficient and useful, desalination technology has still to be perfected, as it currently discharges brine into the sea, disrupting the marine ecosystem. To reduce this pollution and transform it into solid waste, we need to increase treatment and therefore energy consumption.

D. Wastewater

The country prides itself on reusing between 80% and 90% of its wastewater for agriculture. Treated wastewater used for irrigation is known as effluent. Israel’s effluent utilization rate is one of the highest in the world. Reclamation is carried out by 87 large wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) that supply over 660 MCM per year. This represents around 50% of total water demand for agriculture and around 25% of the country’s total water demand. Israel aims to more than double the amount of effluent produced for the agricultural sector by 2050.

5. Water infrastructure projects

For Israel, acquiring water resources in a desert region, through technology, military conquest and/or diplomacy, was from the outset an imperative to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population and, in the eyes of the rest of the world, a demonstration of its sovereign power and its superiority.

This symbolism is particularly evident in the figure of the father of the Hebrew state, David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), whose aim was to make the Negev desert in the south of the country « blossom ».

In his book Southwards (1956), Ben Gourion described his ambition:

« It is absolutely vital for the State of Israel, both for economic and security reasons, to go south: we must direct the water and rain to there, send the young pioneers there […] as well as the bulk of our budget resources to development. »

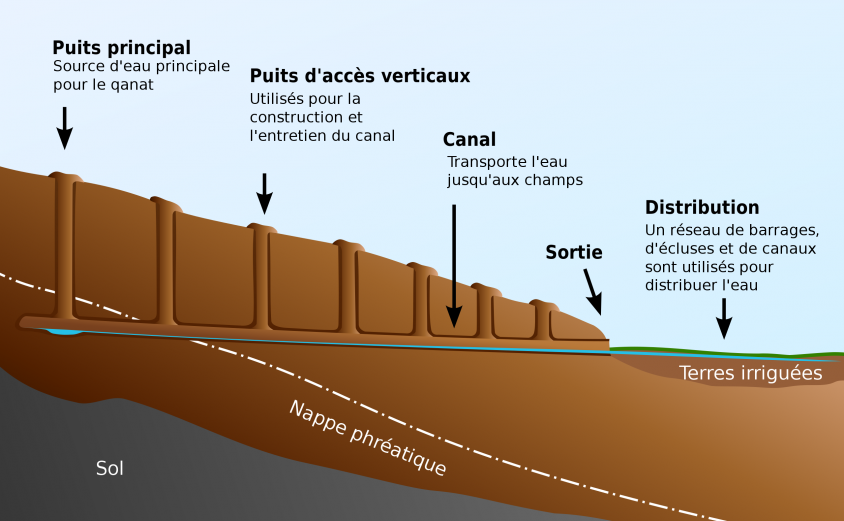

A. National Water Carrier of Israel (NWC)

OBJECTIVE: provide fresh water for Israel’s agriculture and growing population.

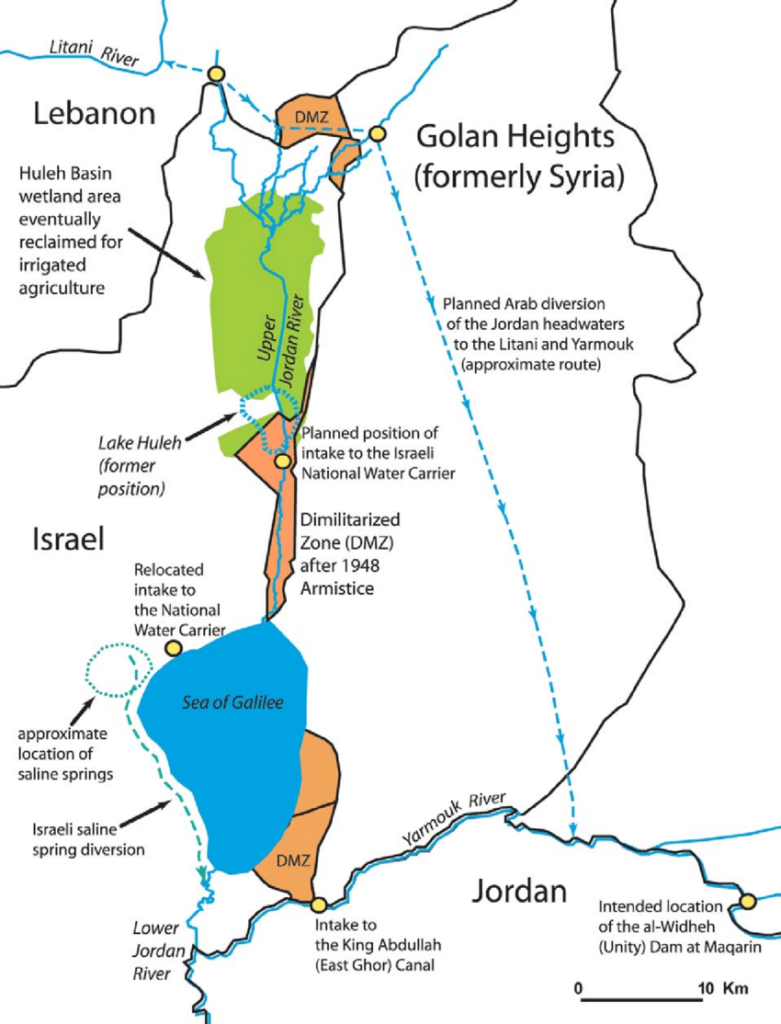

From 1959 to 1964, the Israelis built the National Water Carrier of Israel (NWC), the largest water project in Israel to date.

The first ideas appeared in Theodor Herzl‘s book Altneuland (1902), in which he spoke of using the springs of the Jordan for irrigation purposes and channeling seawater to generate electricity from the Mediterranean Sea near Haifa through the Beit She’an and Jordan valleys to a canal running parallel to the Jordan and Dead Sea.

In 1919, Chaïm Waizmann, leader of the World Zionist Organization, declared: « The whole economic future of Palestine depends on its water supply ».

However, he advocated incorporating the Litani Valley (in today’s southern Lebanon) into the Palestinian state.

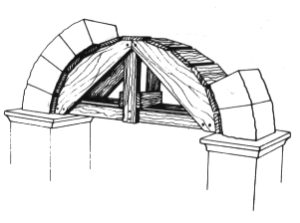

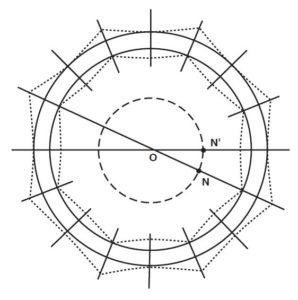

The NWC project was conceived as early as 1937, although detailed planning began after the recognition of Israel in 1948. In practice, the natural flow of the Jordan River is prevented by the construction of a dam, built south of Lake Tiberias. From there, water is diverted to the NWC, a 130 km-long system combining giant pipes, open channels, tunnels, reservoirs and large-scale pumping stations. The aim is to transfer water from Lake Tiberias to the densely populated center and the arid south, including the Negev desert.

When it was inaugurated in 1964, 80% of its water was allocated to agriculture and 20% to drinking water. By 1990, the NWC supplied half of Israel’s drinking water. With the addition of water from seawater desalination plants, it now supplies Tel Aviv, a city of 3.5 million inhabitants, Jerusalem (1 million inhabitants) and (outside wartime) Gaza and the occupied territories of the West Bank.

Since 1948, the area of irrigated farmland has increased from 30,000 to 186,000 hectares. Thanks to micro-irrigation (drip irrigation, including subsurface irrigation), Israeli agricultural production increased by 26% between 1999 and 2009, although the number of farmers fell from 23,500 to 17,000.

The Water War

In launching its NWC, Israel went it alone, while for the rest of the world, it was clear that diverting the waters of the Jordan River would give rise to sharp tensions with neighboring countries, particularly with Jordan and Syria, not to mention the Palestinians who have been largely excluded from the project’s economic benefits.

As early as 1953, Israel began the unilateral draining of Lake Hula (or Huleh), north of Lake Tiberias, leading to skirmishes with Syria.

In 1959, Israel kickstarted the NWC. The project was initially interrupted by a halt in American funding, as the Americans did not want to see violence escalate in the context of the Cold War.

It should be noted that, following the Suez crisis of 1956, the Soviet Union established itself in Syria as the protecting power of Arab countries against the « Israeli threat ». As part of the deployment of its naval presence in the Mediterranean, it obtained facilities for its fleet at Latakia in Syria.

However, Israel managed to quietly resume and continue the work on the NWC. Filling the system by pumping of Lake Tiberias began in June 1964 in utmost secrecy. When the Arab countries learned of this, their anger was great. In November 1964, the Syrian army fired on Israeli patrols around the NWC pumping station, provoking Israeli counter-attacks. In January 1965, the NWC was the target of the first attack by the Fatah (organization fighting for the liberation of Palestine) led by Yasser Arafat.

The Arab states finally recognized that they would never be able to stop the project through direct military action.

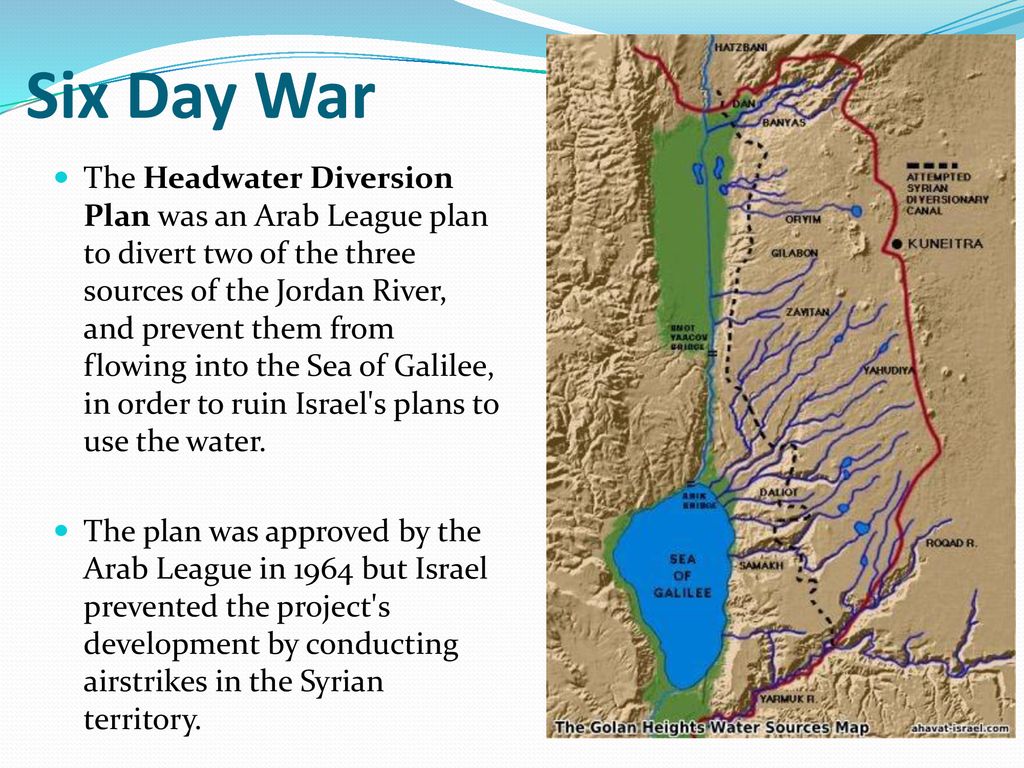

They therefore adopted a plan, the Headwater Diversion Plan immediately implemented in 1965, to divert water upstream from the tributaries of the Jordan River into the Yarmouk River (in Syria). The project was technically complicated and costly, but if successful would have diverted 35% of the water Israel intended to withdraw from the upper Jordan…

Israel declared that it considered this deviation of the water as an infringement of its sovereign rights. Relations degenerated completely and border clashes followed, with Syrian forces firing on Israeli army farmers and patrols. In July 1966, the Israeli air force bombed a concentration of earth-moving equipment and shot down a Syrian MiG-21. The Arab states abandoned their counter plan, but the conflict continued along the Israel-Syria border, including an Israeli air attack on Syrian territory in April 1967.

For many analysts, this was a prelude to the Six-Day War in 1967, when Israel occupied the Golan Heights to protect its water supply. The Six-Day War profoundly altered the geopolitical situation in the basin, with Israel now occupying not only the Gaza Strip and Sinai, but also the West Bank and the Golan Heights.

As French researcher Hervé Amiot explains:

« Israel went from being a downstream country to an upstream one, enabling it to gain control of vast resources. Israel now controlled 20% of the northern bank of the Yarmouk and occupied the Golan Heights, controlling all the small rivers flowing into Lake Tiberias. What’s more, total occupation of the West Bank gives them control over the important water tables ».

In fact, as early as 1955, between a quarter and a third of the water came from the groundwater in the south-western part of the West Bank. Today, the West Bank aquifers supply Israel with 475 million m³ of water, i.e. 25-30% of the country’s water consumption (and 50% of its drinking water).

Two months after the seizure of the occupied territories, Israel issued “Military Decree 92”, transferring authority over all water resources in the occupied territories to the Israeli army and conferring « absolute power to control all water-related matters to the Water Resources Officer, appointed by the Israeli courts ». This decree revoked all drilling licenses issued by the Jordanian government and designated the Jordan region a military zone, thus depriving Palestinians of all access to water while granting Israel total control over water resources, including those used to support its settlement projects.

Today, returning the Golan to Syria and recognizing the sovereignty of the Palestinian Authority over the West Bank seems impossible for Israel, given the Hebrew state’s increasing dependence on the water resources of these occupied territories. The exploitation of these resources will therefore continue, despite Article 55 of the Regulations of the IVth Hague Convention, which stipulates that an occupying power does not become the owner of water resources and cannot exploit them for the needs of its civilians…

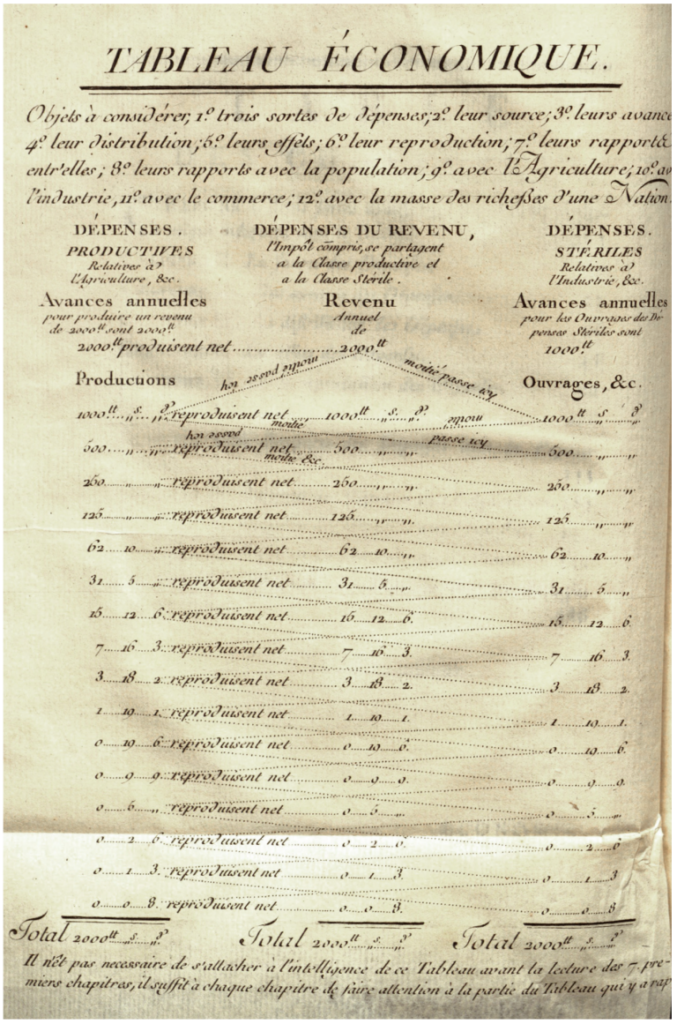

B. Johnston Plan

OBJECTIVE: In the context of the Cold War, counter Nasser’s growing influence in the region. Offer regional stability by building dams and canals allowing a just sharing of water resources and providing water and energy for both Israel and Arab states welcoming « unfortunate » Palestinian refugees.

One might think that the United States tried very early on to prevent the situation from degenerating in such a predictable way. They tried to take into account Israel’s legitimate interest in securing access to water, the absolute key to its survival and development, while at the same time offering neighboring countries (Jordan, Syria and Lebanon) sufficient resources to accommodate the millions of Palestinians exiled from their homes following the Nakba.

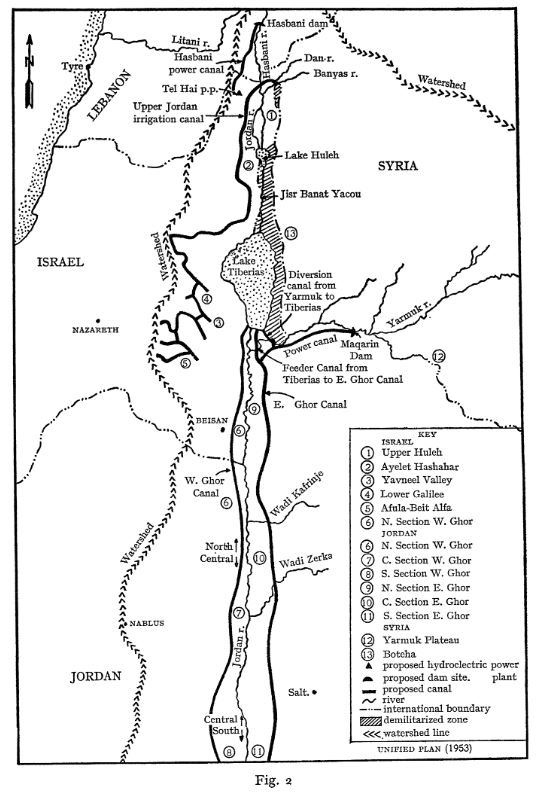

Faced with the risk of conflict, as early as 1953 – years before Israel launched its NWC plan – the American government proposed its mediation to resolve disputes over the Jordan basin. The result was the « Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan » (known as the « Johnston Plan »), named after Eric Allen Johnston, president of the United States Chamber of Commerce and US President Dwight Eisenhower‘s water envoy.

More concretely, “The Unified Development of the Water Resources of the Jordan Valley Region,” was prepared at the request of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees under the direction of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

On Oct. 13, 1953, Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, in a top secret letter instructed Johnston what his mission was all about and on Oct. 16, in a public statement Eisenhower explained:

« One of the major causes of disquiet in the Near East is the fact that some hundreds of thousands of Arab refugees are living without adequate means of support in the Arab states. The material wants of these people have been cared for through the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) … It has been evident from the start, however, that every effort must be made by the countries concerned, with the help of the international community, to find a means of giving these unfortunate people an opportunity to regain personal self-sufficiency.

« One of the major purposes of Mr. Johnston’s mission will be to undertake discussions with certain of the Arab states and Israel, looking to the mutual development of the water resources of the Jordan River Valley on a regional basis for the benefit of all the people of the area. …

« Such a regional approach holds a promise of extensive economic improvement in the countries concerned through the development of much needed irrigation and hydroelectric power and through the creation of an economic base on the land for a substantial proportion of the Arab refugees. It is my conviction that acceptance of a comprehensive plan for the development of the Jordan Valley would contribute greatly to stability in the Near East and to general economic progress of the region.«

This plan established the transboundary nature of the Jordan basin and proposed an equitable sharing of the resource, giving 52% of the water to Jordan, 31% to Israel, 10% to Syria and 3% to Lebanon.

The plan, just as the Tennessee Valley Authority during FDR’s New Deal, was essentially based on building dams for irrigation and hydropower. The water was there and correctly managed, sufficient for the needs of the population at that time. Its main features were:

- a dam on the Hasbani River to provide power and irrigate the Galilee area;

- dams on the Dan and Banias Rivers to irrigate Galilee;

- drainage of the Huleh swamps;

- a dam at Maqarin on the Yarmouk River for water storage (capacity of 175 million m³) and power generation;

- a small dam at Addassiyah on the Yarmouk to divert its water toward both the Lake Tiberias and south along the eastern Ghor;

- a small dam at the outlet of Lake Tiberias to increase its storage capacity;

- gravity-flow canals along the east and west sides of the Jordan valley to irrigate the area between the Yarmouk’s confluence with the Jordan and the Dead Sea;

- control works and canals to utilize perennial flows from the wadis that the canals cross.

See details of the Johnston plan in this comprehensive article.

The project was validated by the technical committees of Israel and the Arab League, and did not require Israel to abandon its ambition to green the Negev desert. Unfortunately, however, the presentation of the plan to the Knesset in July 1955 did not result in a vote.

The Arab Committee approved the plan in September 1955 and forwarded it to the Council of the Arab League for final approval. Tragically, this institution also chose not to ratify it on October 11, because of its opposition to an act implying an implicit act of recognition of Israel that would prevent the return of the Palestinian refugees to their home… The mistake here was to isolate the water issue from a broader agreement on peace and justice as the foundation of mutual development.

Then, after the Suez Canal crisis in 1956, the Arab countries, with the exception of Jordan, hardened their stance towards Israel considerably, and henceforth opposed the Johnston plan head-on, arguing that it would amplify the threat posed by that country by enabling it to strengthen its economy. They also claim that increasing Israel’s water resources could only increase Jewish migration to the Hebrew state, thereby reducing the possibility of the return of Palestinian refugees from the 1948 war…

History cannot be rewritten, but the adoption of the Johnston Plan could well have prevented conflicts, such as that of 1967, which cost the lives of 15,000 Egyptians, 6,000 Jordanians, 2,500 Syrians and at least 1,000 Israelis.

C. Jordan’s response: the Ghor irrigation Canal

OBJECTIVE: construct the Jordanian section of the Johnston Plan to have water for irrigation and the capital of Jordan.

At almost the same time as Israel was completing its NWC, Jordan was digging the East Ghor irrigation canal between 1955 and 1964, starting at the confluence of the Yarmouk and Jordan rivers and running parallel to the latter all the way to the Dead Sea on Jordanian territory.

Originally, this was part of a larger project – the « Greater Yarmouk » project – which included two storage dams on the Yarmouk and a future “Western Ghor Canal” on the west bank of the Jordan. The latter was never built, as Israel took the West Bank from Jordan in the 1967 Six-Day War.

In effect, by diverting the waters of the Yarmouk to fill up its own canal, Jordan secured water for its capital Amman and its agriculture, but of course, contributed reducing the waters of the Jordan River.

In Jordan, the Jordan’s river watershed is a region of vital importance to the country. It is home to 83% of the population, the main industries and 80% of irrigated agriculture. It is also home to 80% of the country’s total water resources.

Overall, the Hashemite kingdom is one of the world’s most water-poor countries, with 92% of its territory desert. While Israel has 276 m³ of natural freshwater available per capita per year, Jordan has just 179 m³, more than half of which comes from groundwater.

The UN considers that a country with less than 500 m³ of freshwater per capita per year suffers from « absolute water stress ». Added to this is the fact that since the start of the Syrian civil war, Jordan has welcomed nearly 1.4 million refugees onto its soil, in addition to its 10 million inhabitants.

The East Ghor Canal was designed in 1957 and built between 1959 and 1961 competing with Israel’s NWC. In 1966, the upstream section as far as Wadi Zarqa was completed. The canal was then 70 km long and was extended three times between 1969 and 1987.

The United States, through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), financed the initial phase of the project, after obtaining explicit assurances from the Jordanian government that Jordan would not withdraw more water from the Yarmouk than had been allocated to it under the Johnston Plan. They were also involved in the subsequent phases.

Waterworks in the region are often named after great political figures. The East Ghor Canal was named « King Abdallah Canal (KAC) » by Abdalla II after his great-grandfather, the founder of Jordan. At the time of the peace treaty with Israel in 1994, the two countries shared the flow of the Jordan, and Jordan agreed to sell its water from Lake Tiberias.

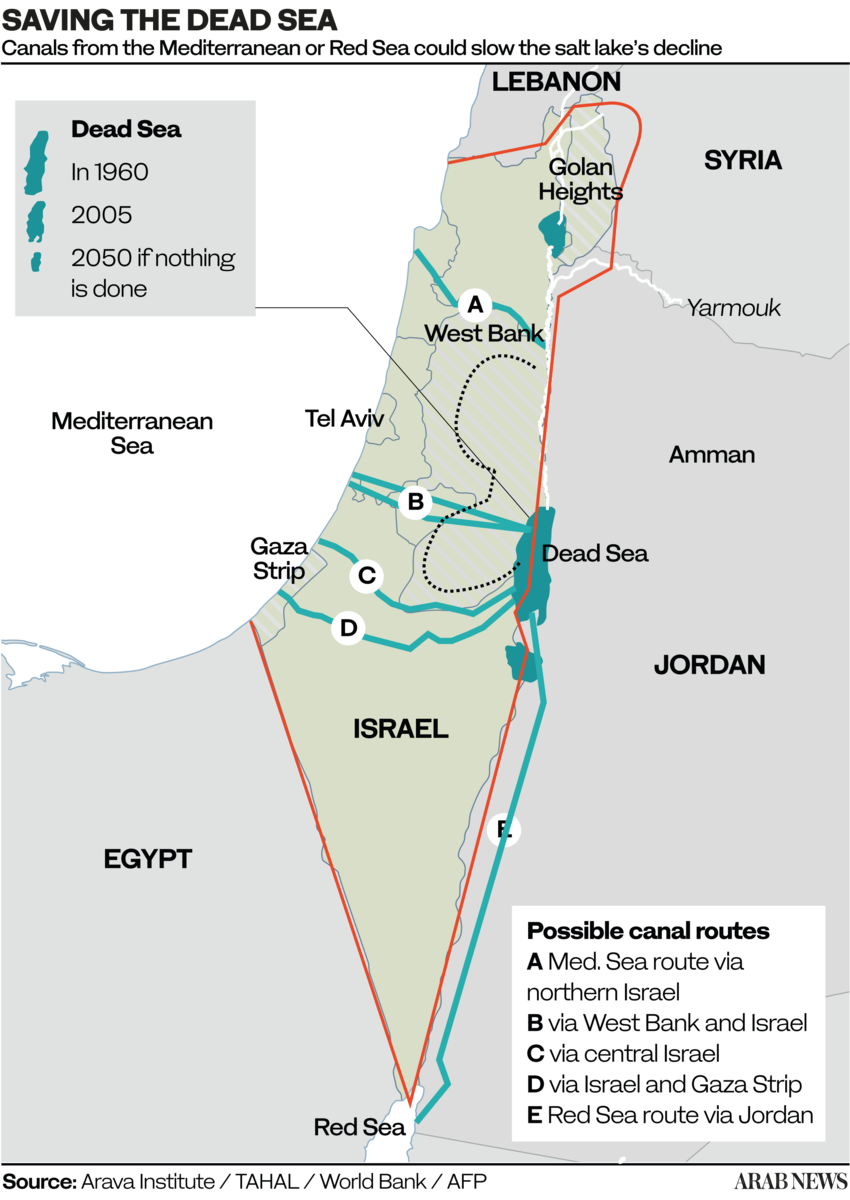

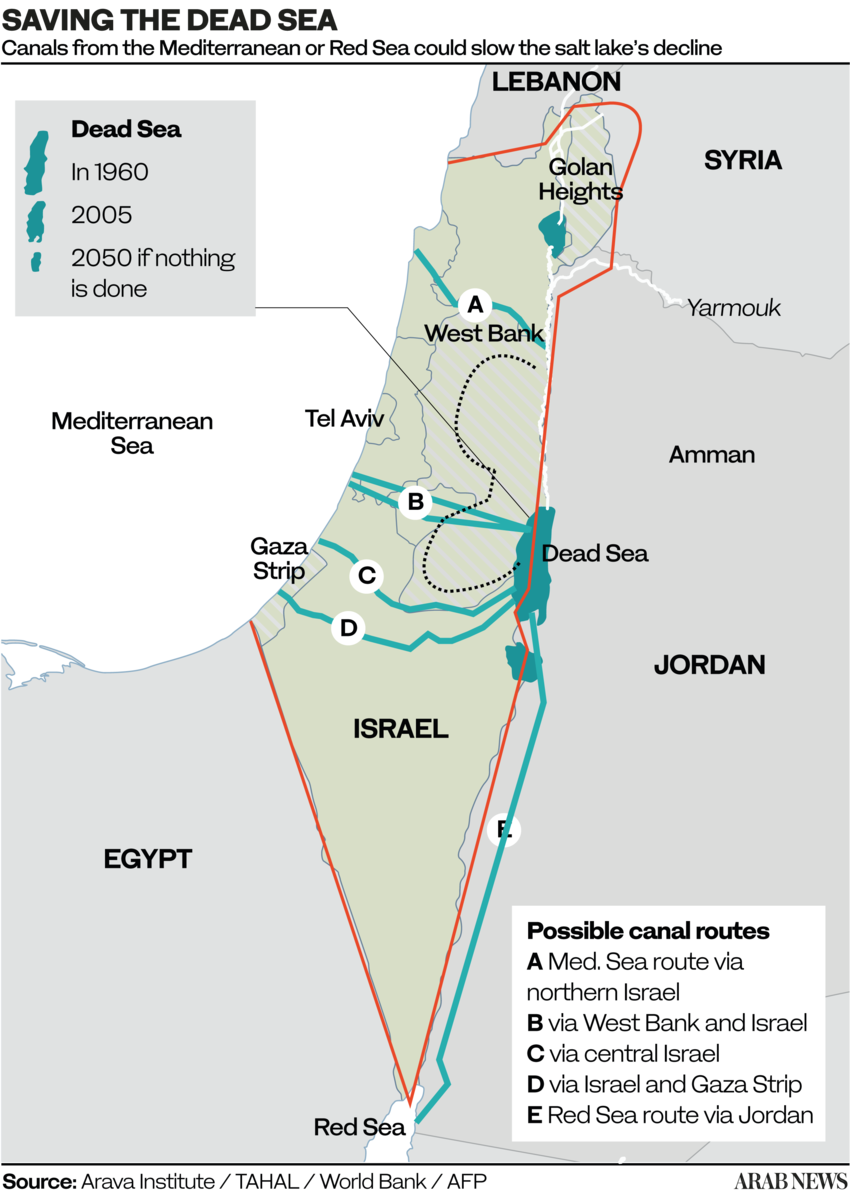

D. Mediterranean – Dead Sea Aqueduct

OBJECTIVE: generate hydro-electricity and make Israel independant from Arab oil and gas supplies.

A: Crossing solely Israelian territory;

B and C: Crossing Israel and West Bank (shortest, 70 km);

D. Crossing Gaza and Israel;

E. Crossing only Jordan (longest, 200 km).

The idea of a Dead Sea-Mediterranean Canal was first proposed by William Allen in 1855 in a book entitled The Dead Sea – A new route to India. At the time, it was not known that the level of the Dead Sea was far below that of the Mediterranean, and Allen proposed the canal as an alternative to the Suez navigation Canal.

Later, several engineers and politicians took up the idea, including Theodor Herzl in his 1902 short story Altneuland. Most early projects were based on the left bank of the Jordan, but a modified form, using the right bank (West bank), was proposed after 1967.

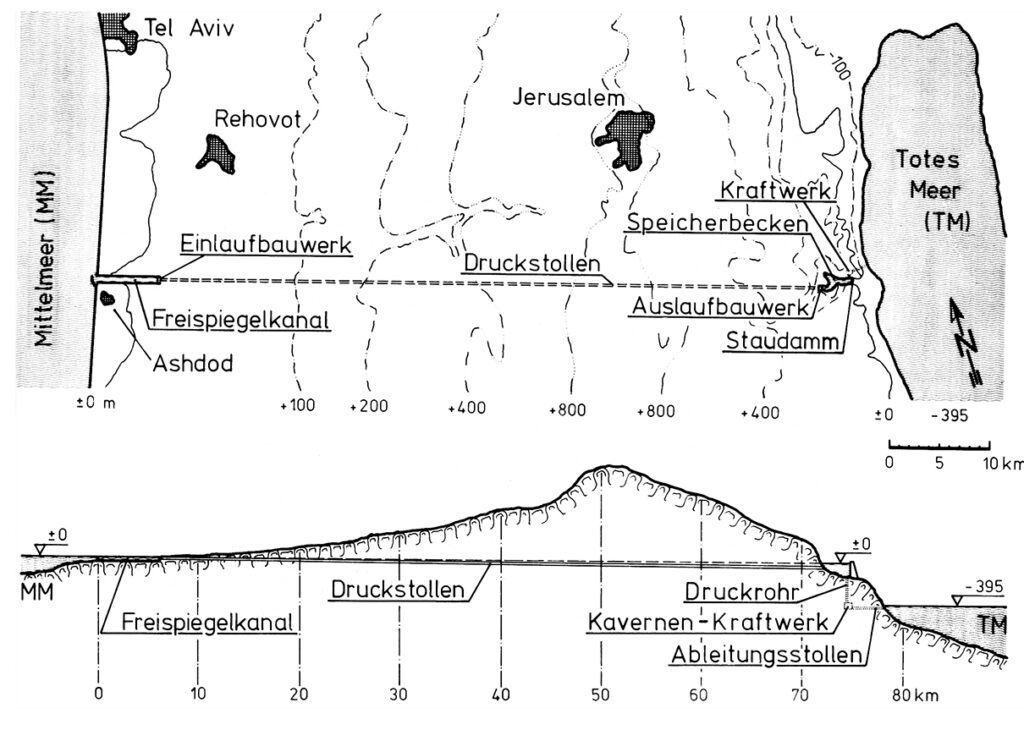

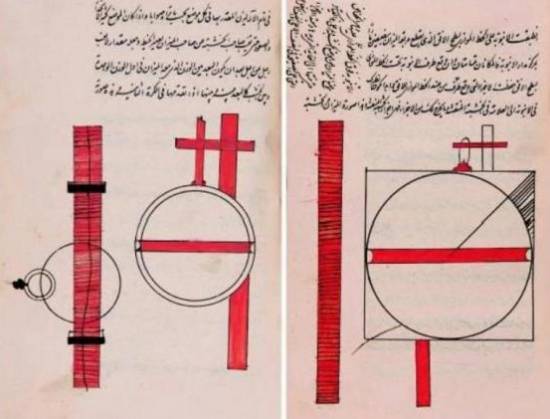

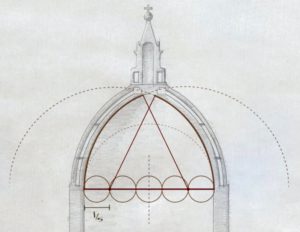

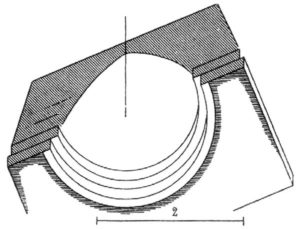

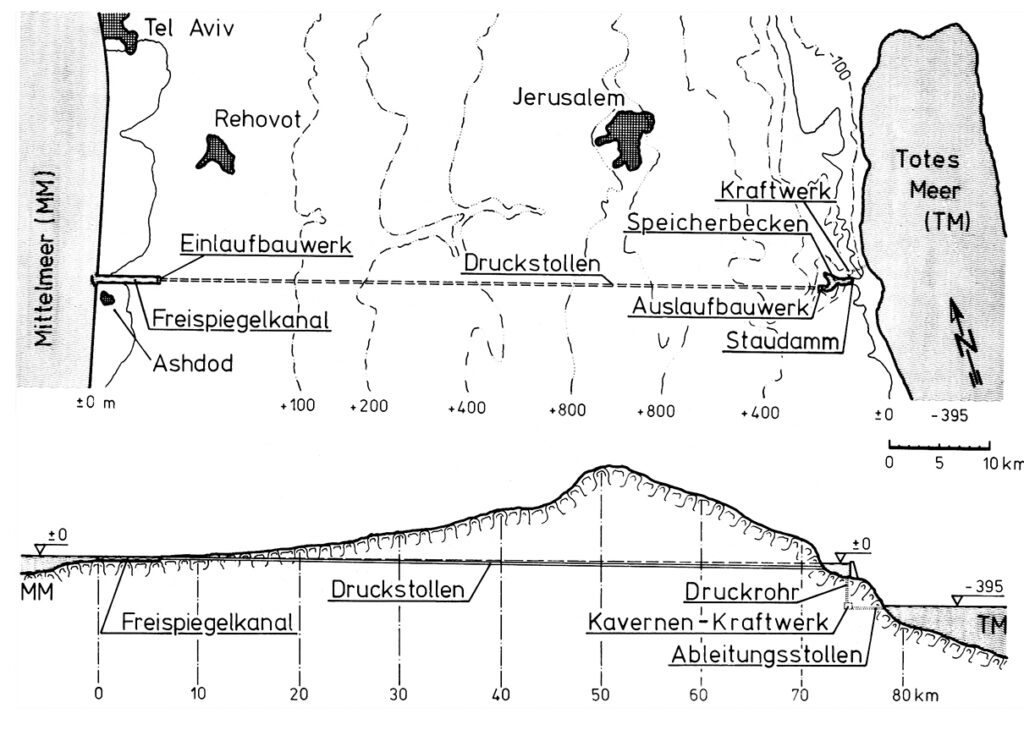

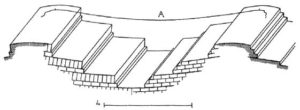

After extensive research, German engineers Herbert Wendt and Wieland Kelm proposed not a navigable canal, but an aqueduct consisting essentially of an overhead gallery running West-East, linking the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea.

Their 1975 detailed project study Depressionskraftwerk am Toten Meer – Eine Projektstudie, on how to use the difference of water levels between the Mediterranean sea (level 0) and the Dead Sea (- 400 m) for power generation was the subject of a first publication in the German journal Wasserwirtschaft (1975,3).

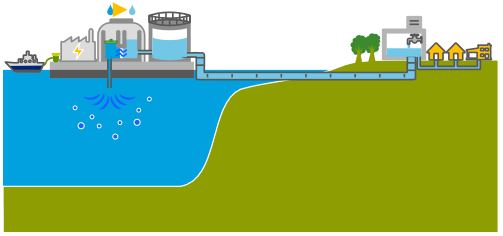

The diagram indicates the system operates as follows:

- The seawater intake is at Ashdod.

- An open channel allows the water to flow by gravity for 7 km.

- From there, the pressurized water travels through a 65 km-long hydraulic gallery;

- The water arrives in a 3km-long reservoir created by a dam on the edge of the steep descent to the Dead Sea. At that point, the water can be used to cool a thermal or nuclear power plant, the heat from which can be used for industrial or agricultural purposes.

- Through a shaft running from the bottom of the reservoir, the water descends a steep 400 metres.

- There, it powers three turbines, each producing 100 MWe.

- Finally, via an evacuation gallery, the seawater reaches the Dead Sea.

However, since the project was elaborated exclusively by Israel and without any consultation with its Jordanian, Egyptian and Palestinian neighbors, the project ran against a wall of political opposition.

Of course, as with any large scale infrastructure projects, many things needed to be adapted, including tourist equipment, roads, hotels, Jordanian potash exploitation, Palestinian farmland, etc.

Questions were also raised about (very infrequent) potential earthquakes and the difference of salinity of water from the Mediterranean and the Dead Sea.

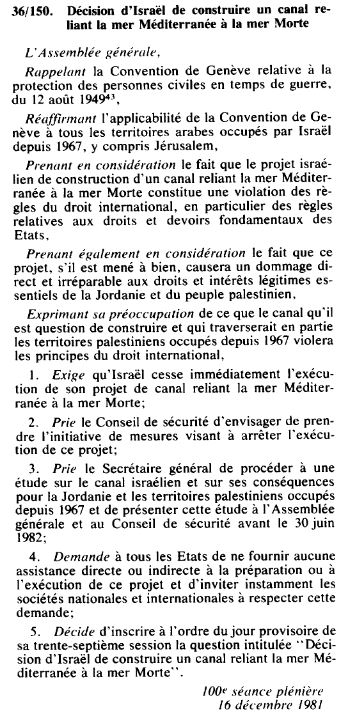

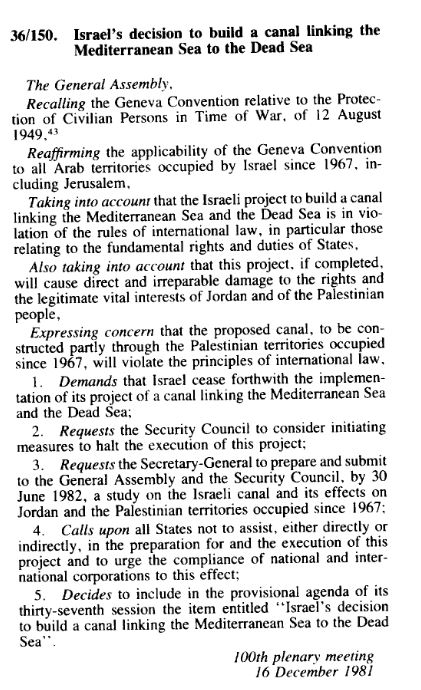

On Dec. 16, 1981, the UN General Assembly, arguing the canal project « will violate the principle of international law » adopted Resolution 36-150.

That resolution requested the UN Security Council « to consider initiating measures to halt the execution of this project » and calling « upon all States not to assist, either directly or indirectly, in the preparation for and the execution of this project. »

The request, in article 3, to submit a study was fulfilled. The report, not really convincing, details various objections but doesn’t call into question the technical feasability of the project.

E. Red Sea – Dead Sea Water Conveyance

OBJECTIVES: Build a desalination plant close to the Dead Sea to provide fresh water to Jordan, Israel and Palestine by desalinating seawater arriving via a pipeline from the Red Sea. Use the brine to refill the Dead Sea. Use the watersharing as a model for peaceful mutual beneficial cooperation. Make the project the heart of a development corridor.

In the framework of the peace treaty between Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan the integrated development Master Plan for the Jordan Rift Valley (JRV) was studied in the mid 1990’s.

The Red Sea – Dead Sea Canal (RSDSC) was considered to be one of the most important potential elements for implementing this Master Plan. The principal development objective of the RSDSC was to provide desalinated drinking water for the people of the area.

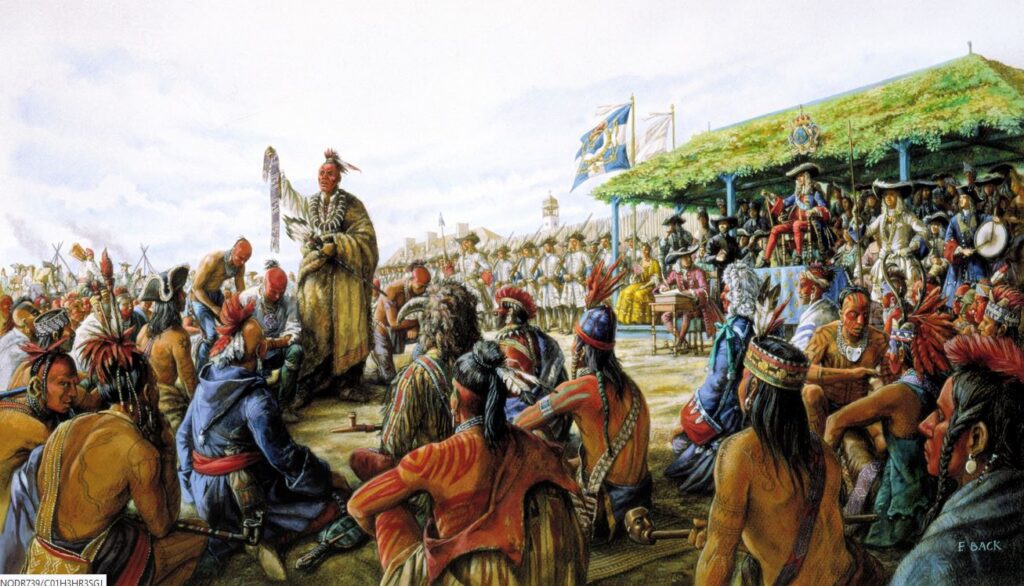

On October 17, 1994, then Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and King Hussein of Jordan validated the draft peace treaty between their two countries in Amman, after reaching agreement on the last two points in dispute – the water issue and border demarcation.

On November 26, the Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty was signed with great fanfare in the Arava Valley, between the Red Sea and the Dead Sea, by the prime ministers of the two countries, in the presence of US President Bill Clinton, whose country had helped bring the negotiations between Jerusalem and Amman to a successful conclusion.

This created the condition where the old idea of linking the Red Sea with the Dead Sea, a project renamed and supported by Shimon Peres as the « Peace Canal », could come back on the table.

Former Israeli water commissioner Professor Dan Zaslavsky, who opposed the project on cost grounds, wrote in the Jerusalem Post in 2006 about Peres’ obstinacy. To listen to the scientists, Peres summoned five of them. Each had to present his objections in a few minutes.

« At one point, Peres got up and said, ‘Excuse me. Don’t you remember that I built the nuclear reactor in Dimona? Do you remember that everyone was against it? Well I was right in the end. And this will prove to be the same thing! » And with that, Zaslavsky said with a flourish, « he left! »

The Dead Sea

For millennia, the Dead Sea was filled with fresh water from the Jordan River, via Lake Tiberias. Over the last fifty years, however, it has lost 28% of its depth and a third of its surface area. Its water level is falling inexorably, at an average rate of 1.45 meters per year. Its high salinity – over 27%, compared with the average for oceans and seas of 2-4% – and a level 430 meters below sea level, has always fascinated visitors and provided therapeutic benefits. Stretching 51 kilometers long and 18 kilometers wide, it is shared by Israel, Jordan and the West Bank.

The over-exploitation of upstream water resources (the National Aqueduct in Israel, the Ghor Canal in Jordan), together with potassium mining, is the cause of the sand desert which, if nothing is done, will continue to replace the Dead Sea.

If the Dead Sea needs the Jordan River, the Jordan River needs Lake Tiberias, from which it takes its source. However, the lake too has been affected by drastic drops in its water level in recent years, triggering a vicious circle between the three systems (Lake Tiberias, Jordan River and Dead Sea).

Aqueduct

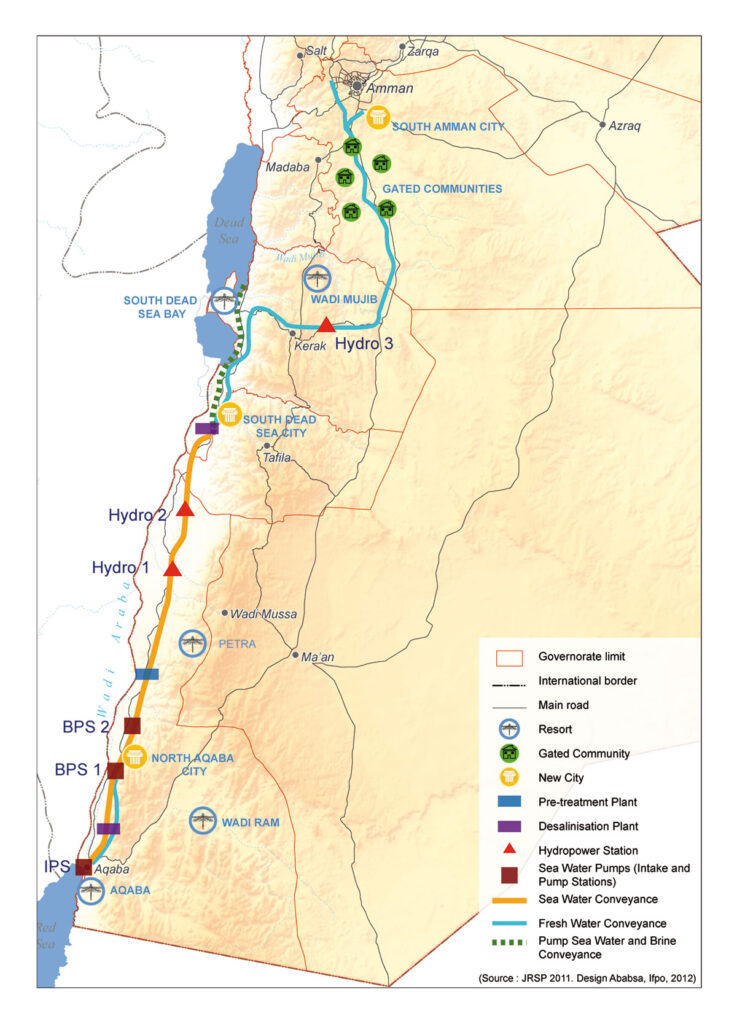

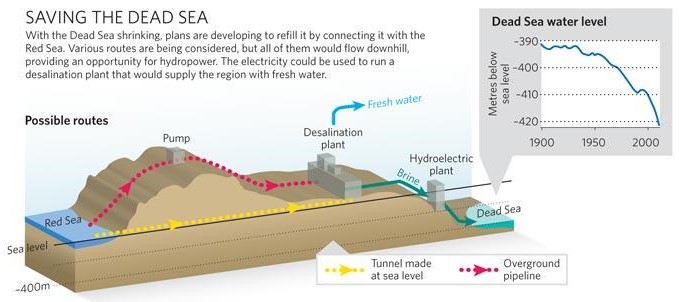

In response, at the end of 2006, the World Bank and Agence Française de Développement (AFD) assisted Israel and Jordan in the design of a colossal project to link the Dead Sea to the Red Sea via a 180-kilometer mainly underground pipeline.

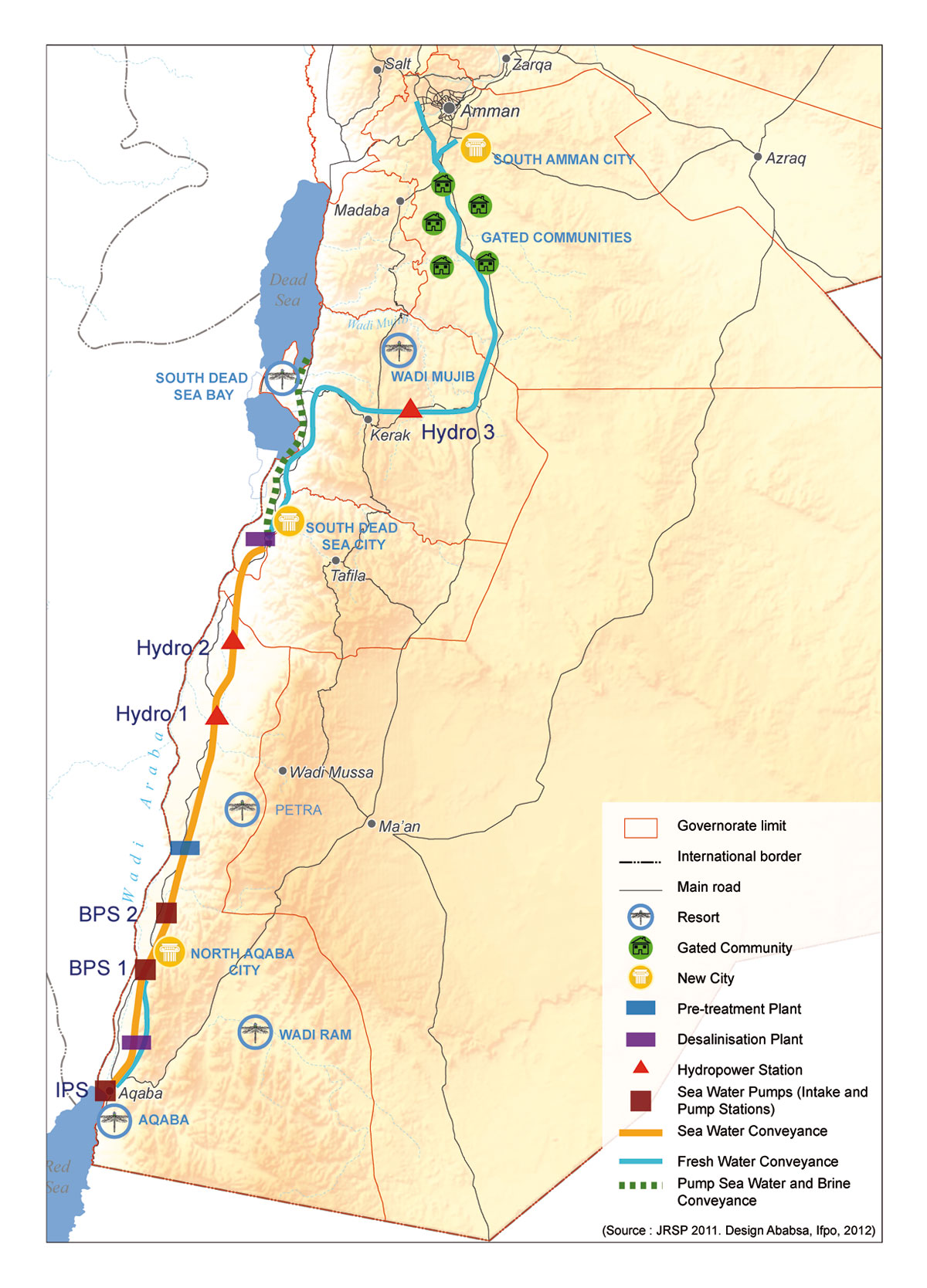

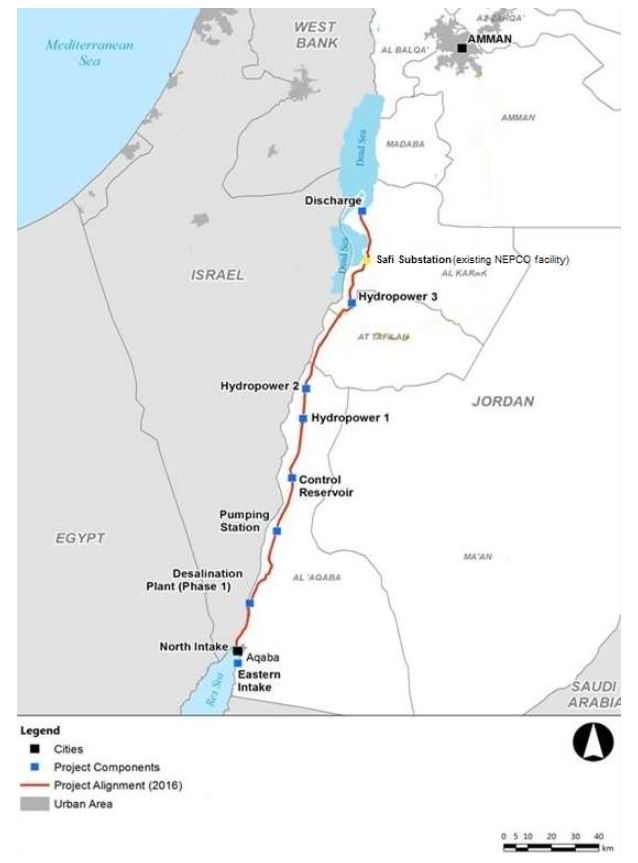

In the end, the project for an aqueduct starting from the Red Sea and built entirely on Jordanian territory was chosen, with the signing of a tripartite agreement between Israelis, Jordanians and Palestinians in December 2013.

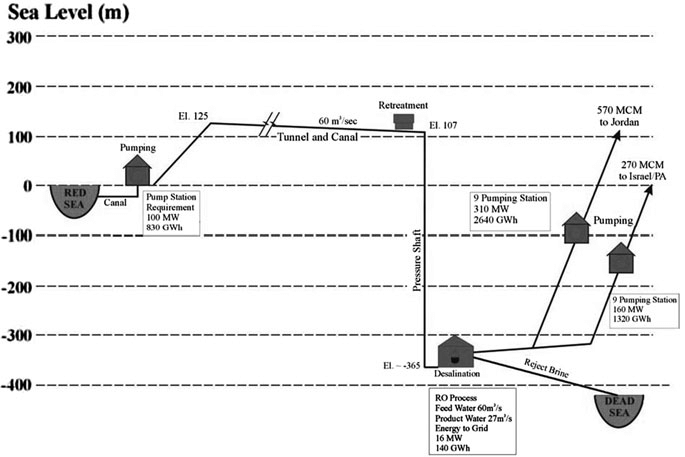

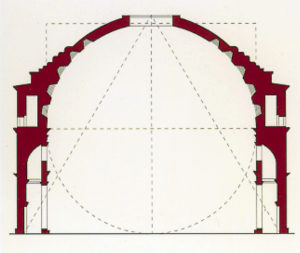

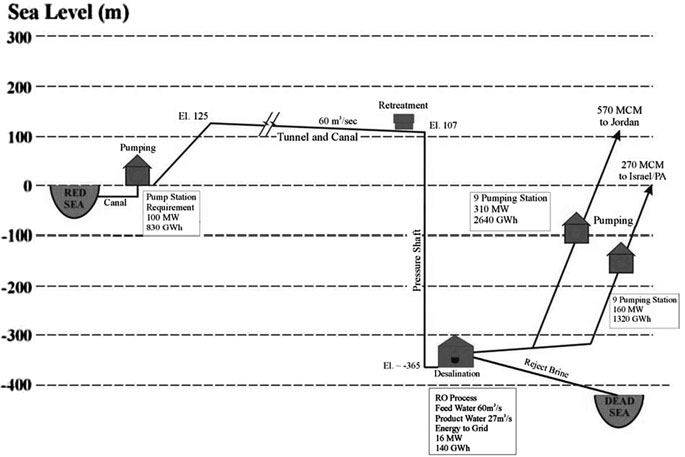

- Sea intake and pumping station

The seawater is pumped to +125 m above sea level at the Red Sea. - Pressure pipeline

The first part of the conveyance system transmits the seawater to the planned elevation. The length is 5 km from Aqaba (3% of the whole alignment). - A tunnel and canal conveyance system

Seawater is transmitted to the regulating and pretreatment reservoirs with a design flow of 60 m3 /s. A 121 km tunnel with 7 m diameter and 39 km canal were designed. - Regulating and pre-treatment reservoirs

Several reservoirs were designed at +107 m at Wadi G’mal at the southeastern margin of the Dead Sea. - Desalination plants

The 2 desalination plants are designed to operate by using the process of hydrostatically supported reverse osmosis to provide desalinated seawater. The main plant will be located at Safi at 365 m below the sea level with a water column of 475 m. - Fresh water

The project will produce around 850 MMC of fresh water per year, to be shared between Jordan, Israel and Palestine, the three countries that manage the Dead Sea. For the transmission of the water to Amman a double pipeline of 200 km with 2.75 m diameter was designed with nine pumping stations for the uplift of 1,500 m. For the transmission to Hebron a double pipeline of 125 km with an elevation difference of 1,415 m was designed. - The brine

The brine reject water will be conveyed from the desalination plant via a 7 km canal to the Dead Sea. 1,100 MMC per year of brine reject water will enter the Dead Sea. - Electricity generation

As the brine runs through the tunnel and canal, the turbines of one or more hydroelectric power plants will generate around 800 megawatts of electricity to partially offset the electricity consumed by pumping; - Three new cities will be built: North Aqaba city in northern Aqaba, South Dead Sea City, close to the desalination plant south of the Dead Sea, and South Amman City (see map at the beginning of this section).

In terms of environmental impact, scientists have expressed concern that mixing the brine (rich in sulfate) from the desalination plants with the Dead Sea water (rich in calcium) could cause the latter to turn white. It would therefore be necessary to proceed with a gradual water transfer to observe the effects of water transfer in this particular ecosystem.

Not enough to stabilize the level of the Dead Sea, but a first step to start slowing down its drying up, emphasized Frédéric Maurel, in charge of this project for AFD, in 2018. « We also need to use water more sparingly, both in agriculture and in the potash industry, » he stressed.

Political will?

In 2015, as a supplement to the program, agreements had been reached on reciprocal water sales: Jordan would supply drinking water to Israel in the south, which in return would increase its sales of water from Lake Tiberias to supply northern Jordan. And the Palestinians would also receive additional water supplies from Israel. By the end of 2016, five consortia of companies had been shortlisted.

In 2017, the European Investment Bank produced a 264 page detailed study to support the plan.

On the Israeli side, saving the Dead Sea is a necessity to maintain seaside tourism and thermalism. It is also a lever to guarantee its hydraulic control over the West Bank, as Israel does not trust the Palestinian Authority to manage water. Honest elements of the Hebrew state are aware of the peacemaking potential of this project, and need a stable partner in the region. Jordan, for its part, was by far the most interested in this project, given its critical situation.

In 2021, Jordan decided to put an end to the joint water pipeline project, believing that there was « no real desire on the part of the Israelis » for the plan, which had stagnated for several years, to go ahead.

To face its growing needs, Jordan has decided to build its own desalination plant directly on the Red Sea. The Aqaba-Amman Water Desalination and Conveyance Project will take water from the Red Sea at the Gulf of Aqaba in the south, desalinate it, and channel it 450 kilometres north to the capital Amman and its surrounding area, supplying a desperately needed 300 million cubic metres of water a year. Studies are complete and construction will start on July 2024. The plant will be powered with solar energy.

In 2022, Jordan, the UAE and Israel signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to continue feasibility studies for two interconnected projects: establishing the water desalination station at the Red Sea (Prosperity Blue) and establishing a solar power plant in Jordan (Prosperity Green). However, due to the ongoing war against Gaza and the rejection of the Jordanian public regarding the agreement’s signing, the Jordan government announced the suspension of the agreement.

The Dead Sea might slowly reappear

With huge desalinization capacities in hand, Israel adopted in 2023 the National Carrier Flow Reversal Project to return water to its natural resources, in particular to Lake Tiberias, the very source of freshwater for its entire national water system.

Lake Tiberias, as we have seen, is therefore a national treasure, a centerpiece of tourism, agriculture and, as we have seen, geopolitics.

According to Dodi Belser, Director of Innovation at water state giant Mekorot, if Israel wants to increase the water it sends to its Jordanian neighbors and to protect its reservoir, it’s vital to retain the lake’s water level. Currently Israel taps 100 million cubic meters of water from Lake Tiberias to send to Jordan, and did so even during the drought years of 2013 to 2018.

Increase resilience to climate chaos and preparing eventual futur water sharing, gave birth to the idea to pump desalinated water into the Lake Tiberias, up to 120 million cubic meters a year until 2026. That is happening right now.

It can partly increase the level of the Jordan river and therefore the water arriving into the Dead Sea. But the salt in the Dead Sea comes from the waters of the Jordan River. Every year, the famous river brings it some 850,000 tonnes of salt.

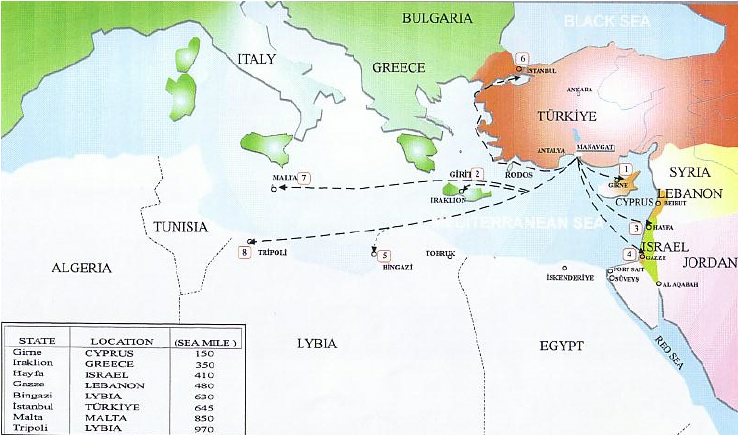

F. Turkish water sales

Turkye, a veritable « water tower » in the region, has long dreamed of exporting its water to Israel, Palestine, Cyprus and other Middle Eastern countries at a premium.

The most ambitious of these projects was President Turgut Ozal‘s « Peace Water Pipeline » in 1986, a $21 billion project to pipe water from the Seyhan and Ceyhan rivers to cities in Syria, Jordan and the Arab states of the Gulf.

In 2000, Israel was strongly considering purchasing 50 million m3 per year for 20 years from the Manavgat river near Antalya, but since November 2006, the deal has been put on hold.

The Manavgat project, technically completed in mid-March 2000, was a pilot project.

The complex on the Manavgat river – which rises in the Taurus mountains and flows into the Mediterranean between Antalya and Alanya – includes a pumping station, a refining center and a ten-kilometer-long canal. The aim was then to transport this fresh water by 250,000-ton tankers to the Israeli port of Ashkelon for injection into the Israeli NWC.

Eventually, Jordan was also interested in Turkey’s aquatic manna. A second customer downstream of its network would enable Israel to share costs. Another possibility would be to transport the water via a water pipeline linking Turkey to Syria and Jordan, and ultimately to Israel and Palestine if the latter could reach an agreement with its partners. The Palestinians, for their part, have been looking for a donor country to subsidize freshwater imports by tanker to Gaza.

The Manavgat project is not the only one through which Ankara hopes to sell its water. In 1992, Suleyman Demirel, then Prime Minister, expressed a credo that went viral: « Turkey can use the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers as it sees fit: Turkey’s water resources belong to Turkey, just as oil belongs to Arab countries.”

The countries downstream of the two rivers – Iraq and above all Syria – immediately protested. For them, the multiple dams that Ankara plans to build on the region’s main freshwater sources for irrigation or power generation are simply a way for the heir to the Ottoman Empire to assert its authority over the region.

Whatever Ankara’s real ambitions, the country has a real treasure trove at its disposal, especially given the dwindling resources of neighboring countries.

In the end, since November 2006, Israeli supporters of desalination have objected to the price of Turkish water and questioned the wisdom of relying on Ankara, whose government is critical of Israeli policies. Desalination or importation? The choice is a Cornelian one for Israel. And an eminently political one, since it comes down to knowing whether to stick to positions based on self-sufficiency or whether to play the regional cooperation card, which amounts to betting on trust…

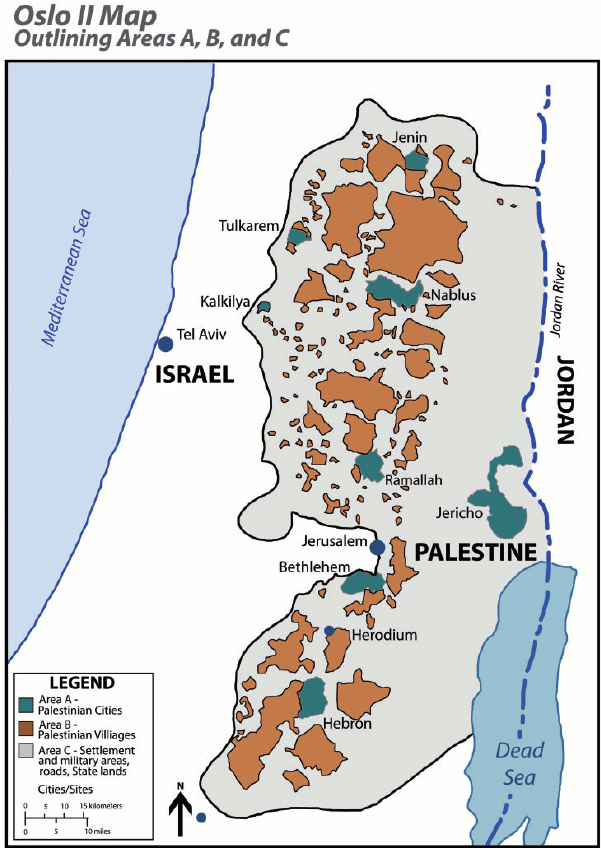

G. Hidden defects and non-implementation of Oslo

The recognition of Israel by Yasser Arafat – leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation –, and the election of Yitzhak Rabin as Israel’s Prime minister in 1992 opened new opportunities for peace and cooperation. The Oslo accords they signed established the Palestinian Authority and determined temporary groundwater allocations from the West Bank to Israel and Palestine. In the declaration, both parties agreed on the principle of “equitable utilisation” between Palestinians and Israelis.

The collapse of mutual trust following the assassination of Rabin in November 1995 and the subsequent election of Benjamin Netanyahu, who had been highly critical of Oslo, negatively affected cooperation on water.

In 2000, during the first six months of the second Intifada, there was hardly any contact between both sides regarding water issues. But with reason coming back, despite the conflict, Israeli and Palestinian leaders committed themselves to separating the water issue from violence and reactivated cooperation over water.

In 2004, Israel reportedly proposed a plan to build a desalination plant in order to increase the quantity of freshwater available and to channel desalinated water to the West Bank. Fearing that this might in effect imply a renunciation to Palestinian water claims on the Mountain aquifer (75% of which is allocated to Israel even though the Aquifer is on Palestinian land), the Palestinians rejected this solution.

The Oslo Accords, signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1993, although stipulating that « Israel recognizes the water rights of Palestine », in reality allowed Israel to continue controlling the region’s water sources… while awaiting a resolution to the conflict. Oslo II provided for the postponement of negotiations on water rights until those on permanent status, as well as on the status of Jerusalem, refugees’ right of return, illegal settlements, security arrangements and other issues.

But final status talks, scheduled to take place five years after the implementation of the Oslo Accords (in 1999, as planned), have not yet taken place.

The Oslo Accords also provided for the creation of a water management authority, and their « Declaration of Principles » stressed the need to ensure « the equitable use of common water resources, for application during the interim period [of the Oslo Accords] and thereafter ».

Hence, for decades, Israel has perpetuated a principle of water distribution that existed before the Oslo Accords were signed, allowing Israelis to consume water at will while limiting Palestinians to a predetermined 15% share.

The Oslo agreements did not take into account the division of the West Bank into zones A, B and C when it came to organizing water distribution between Israel and the Palestinians.

Israel was finally granted the right to control water sources, even in PA-controlled areas A and B.

Most water sources were already located in Area C, which is entirely controlled by Israel and comprises almost 61% of the West Bank.

On the ground, Israel has connected all the settlements built in the West Bank, with the exception of the Jordan Valley, to the Israeli water network. The water supply to Israeli communities on both sides of the Green Line is managed as a single system, under the responsibility of Israel’s national water company, Mekorot.

While the Oslo Accords allowed Israel to pump water from areas under its control to supply settlements in the occupied West Bank, they also prevent the PA from transferring water from one area to another in those it administers in the West Bank. Israel has disavowed most of the provisions of the Oslo Accords, but remains committed to those relating to water.

A member of the Palestinian delegation that signed the Oslo Accords, wishing to remain anonymous, tells Middle East Eye magazine that the delegation’s lack of expertise at the time resulted in the signing of an agreement that

« placed the fate of Palestinian access to water in Israel’s hands (…) Most Palestinian water experts withdrew from the negotiations at the outset of the Oslo process, as they were not satisfied with the way the negotiations were being conducted », he stressed. « As for the political leaders, their main objective was to reach an agreement. »

In practice, this means that Palestinians in the occupied West Bank are at the mercy of the Israeli occupation when it comes to their water supply.

Inequalities in terms of access to water in the West Bank are glaring, as shown by the Israeli NGO B’Tselem in a report entitled Parched, published in May 2023.

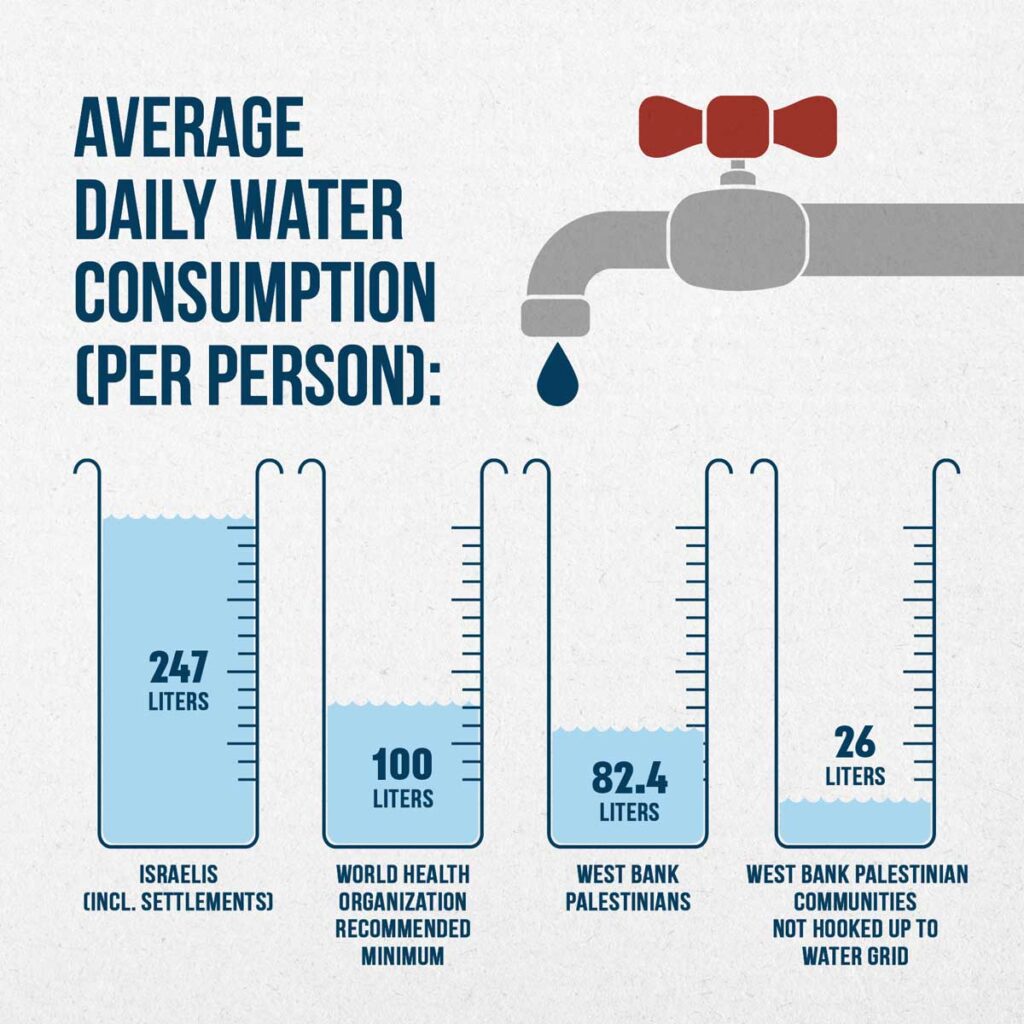

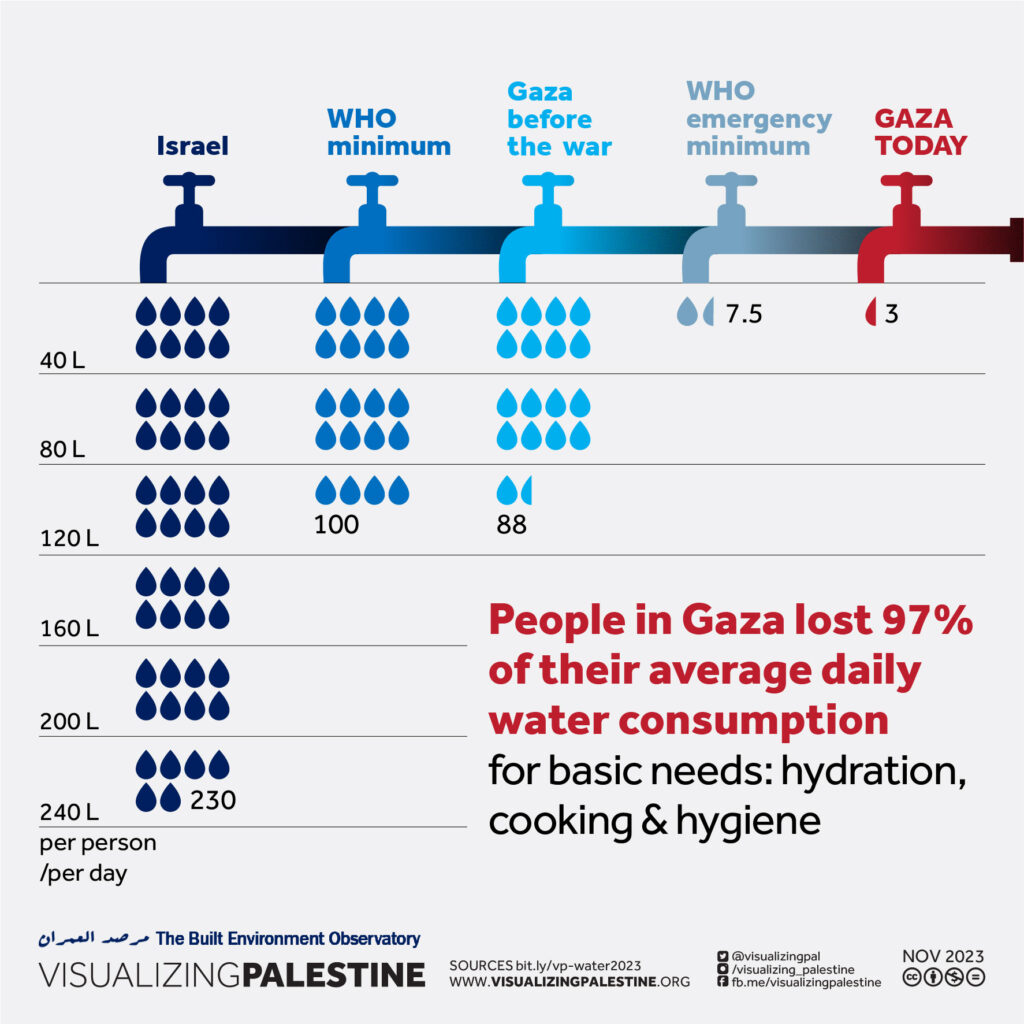

In 2020, each Palestinian in the West Bank consumed an average of 82.4 liters of water per day, compared with 247 liters per person in Israel and the settlements.

This figure drops to 26 liters per day for Palestinian communities in the West Bank that are not connected to the water distribution network. 36% of West Bank Palestinians have year-round access to running water, compared with 100% of Israelis, including settlers.

The Palestinian Authority, which claims more water, points out that Palestinian agriculture plays a major role in the economy of the Occupied Territories (15% of GDP, 14% of the working population in 2000). In comparison, Israeli agriculture, while far more productive, employs 2.5% of the working population and produces 3% of GDP.

Added to this the fact that the arable land recognized by Israel under the Oslo Accords as totally or partially autonomous to the Palestinians is located in the limestone uplands, where access to water is difficult, since it is necessary to dig deep to reach the water table.

What’s more, in Israel and the settlements, 47% of land is irrigated, compared with only 6% of Palestinian land. The Palestinian Authority is currently demanding rights to 80% of the mountain aquifer, which Israel cannot conceive of.

Myth of Thirsty Palestinian

Israeli spokespeople, such as Akiva Bigman in his article titled « The Myth of the Thirsty Palestinian » have three answers ready to pull out when they are confronted with the water shortages in West Bank Palestinian towns:

1) “Because the PA does not properly maintain its water system, it suffers from a 33 percent rate of water loss, mostly due to leakage; in contrast to an 11 percent loss from the Israeli system.”

Answer: leakage varies from 20 to 50% in the USA, far above the rate of poor Palestine.

2) “40 potential drilling sites in the Hebron area were identified and approved by the Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee; but in the two decades since then, drilling has taken place in only three places, and this is in spite of substantial funding provided to the PA by donor nations.”

One can ask where the money went. And yes, in reality, at the end of the day, for various technical reasons and unexpected drilling failures in the eastern basin of the aquifer (the only place the agreement allows the Palestinians to drill), the Palestinians ended up producing less water than the agreements set.

3) Israel has in its great generosity “doubled the amount of water it supplies to the Palestinians, compared to what was called for in the Oslo Accords.”

True. However, Oslo didn’t set a limit to the amount of water Israel can take, but limited the Palestinians to 118 MCM from the wells that existed prior to the accords, and another 70-80 MCM from new drilling. According to the Israeli NGO B’Tselem, as of 2014 the Palestinians are only getting 14 percent of the aquifer’s water. That is why the Israeli state company Mekorot (obeying to government directives) is selling the Palestinians the double of water stipulated in the Oslo Agreement – 64 MCM, as opposed to 31 MCM. 64 + 31 = 95 MCM in total, to be compated with current consumption by Palestinians in the West Bank: 239 MCM of water in 2020 of which 77.1 of them purchased from Israel.

A final detail that speaks volumes: Palestinians are charged the price of drinking water for their agricultural water while Jewish settlers benefit from agricultural tariffs and subsidies. The justification being that the Jewish settlers have invested in expensive irrigation techniques such as desalination

H. Ben Gurion Navigation Canal

At the end of 2023, the idea of the Ben-Gurion navigation Canal project was revived in the media. The canal would link the Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat) in the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, passing through Israel to terminate in or near the Gaza Strip (Ashkelon). This is an Israeli alternative to the Suez Canal, which became topical in the 1960s following Nasser’s nationalization of Suez.

The first ideas for a connection between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean appeared in the mid-19th century, on the initiative of the British, who wanted to link the three seas: the Red, the Dead and the Mediterranean. As the Dead Sea lies 430.5 meters below sea level, such an idea was not feasible, but it could be realized in another direction. Frightened by Nasser’s nationalization of Suez, the Americans considered the option of the Israeli canal, their loyal ally in the Middle East.

In July 1963, H. D. Maccabee of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, under contract to the U.S. Department of Energy, wrote a memorandum exploring the possibility of using 520 underground nuclear explosions to help dig some 250 kilometers of canals across the Negev desert. The document was classified until 1993. « Such a canal would constitute a strategically valuable alternative to the present Suez Canal and would probably contribute greatly to the economic development of the surrounding region, » says the declassified document.

The idea of the Ben Gurion Canal resurfaced at the same time as the signing of the so-called « Abraham Agreements » between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan.

On October 20, 2020, the unthinkable happened: Israel’s state-owned Europe Asia Pipeline Company (EAPC) and the UAE’s MED-RED Land Bridge signed an agreement to use the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline to transport oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, avoiding de facto the Suez Canal.

On April 2, 2021, Israel announced that work on the Ben Gurion Canal was due to start in June of the same year. But this has not been the case. Some analysts interpret the current Israeli reoccupation of the Gaza Strip as an event that many Israeli politicians were waiting for to revive an old project.

A closer look at the planned route shows that the canal starts at the southern edge of the Gulf of Aqaba, from the port city of Eilat, close to the Israeli-Palestinian border, and continues through the Arabah valley for around 100 km, between the Negev mountains and the Jordanian highlands. It then turns west before the Dead Sea, continues through a valley in the Negev mountain range, then turns north again to bypass the Gaza Strip and reach the Mediterranean Sea in the Ashkelon region.

The project’s promoters argue that their canal would be more efficient than the Suez Canal because, in addition to being able to accommodate a greater number of ships, it would allow the simultaneous two-way navigation of large vessels thanks to the design of two canal arms.

Unlike the Suez Canal, which runs along sandy banks, the Israeli canal would have hard walls that require almost no maintenance. Israel plans to build small towns, hotels, restaurants and cafés along the canal.

Each proposed branch of the canal would be 50 meters deep and around 200 meters wide. It would be 10 meters deeper than the Suez Canal. Ships 300 meters long and 110 meters wide could pass through the canal, corresponding to the size of the world’s largest ships.

If completed, the Ben-Gurion Canal would be almost a third longer than the Suez Canal, which measures 193.3 km, or 292.9 km. Construction of the canal would take 5 years and involve 300,000 engineers and technicians from all over the world. Construction costs are estimated at between $16 and $55 billion. Israel stands to gain $6 billion a year.

Whoever controls the canal, and apparently it can only be Israel and its allies (mainly the USA and Great Britain), will have enormous influence over international supply chains for oil, gas and grain, as well as world trade in general.

Israel argues that such a project would undermine the power of Egypt, a country strongly allied with Russia, China and the BRICS and therefore « a threat » to the West! With the depopulation of Gaza and the prospect of total Israeli control over this tiny territory, some Israeli politicians, including Netanyahu, are once again salivating over the prospect of such a project.

As Croatian analyst Matia Seric pointed out in Asia Review in November 2023:

« If realized, the Ben Gurion Canal would bring about a tectonic change as it would overshadow the Suez Canal. The project would launch Israel into the center of world shipping and world trade. Egypt would lose its monopoly on the shortest route between Africa, Asia and Europe. The emergence of an alternative Israeli channel would have a devastating impact on the Egyptian economy. President el-Sisi may regret putting his trust in Israel and Western governments above the well-being of the two million Palestinians in Gaza. Egypt, apart from formally condemning the mass crimes committed by Israeli forces against the civilian Palestinian population, has done little to prevent Israeli wrongdoing, which some call genocide. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has repeatedly expressed support for the idea of the canal along with the idea of building a high-speed railway from Eilat to Beersheba. Realizing, or at least starting, this project could redeem Netanyahu from his many mistakes during his long reign, including the intelligence and military failures that facilitated the October 7 attack by Hamas. »

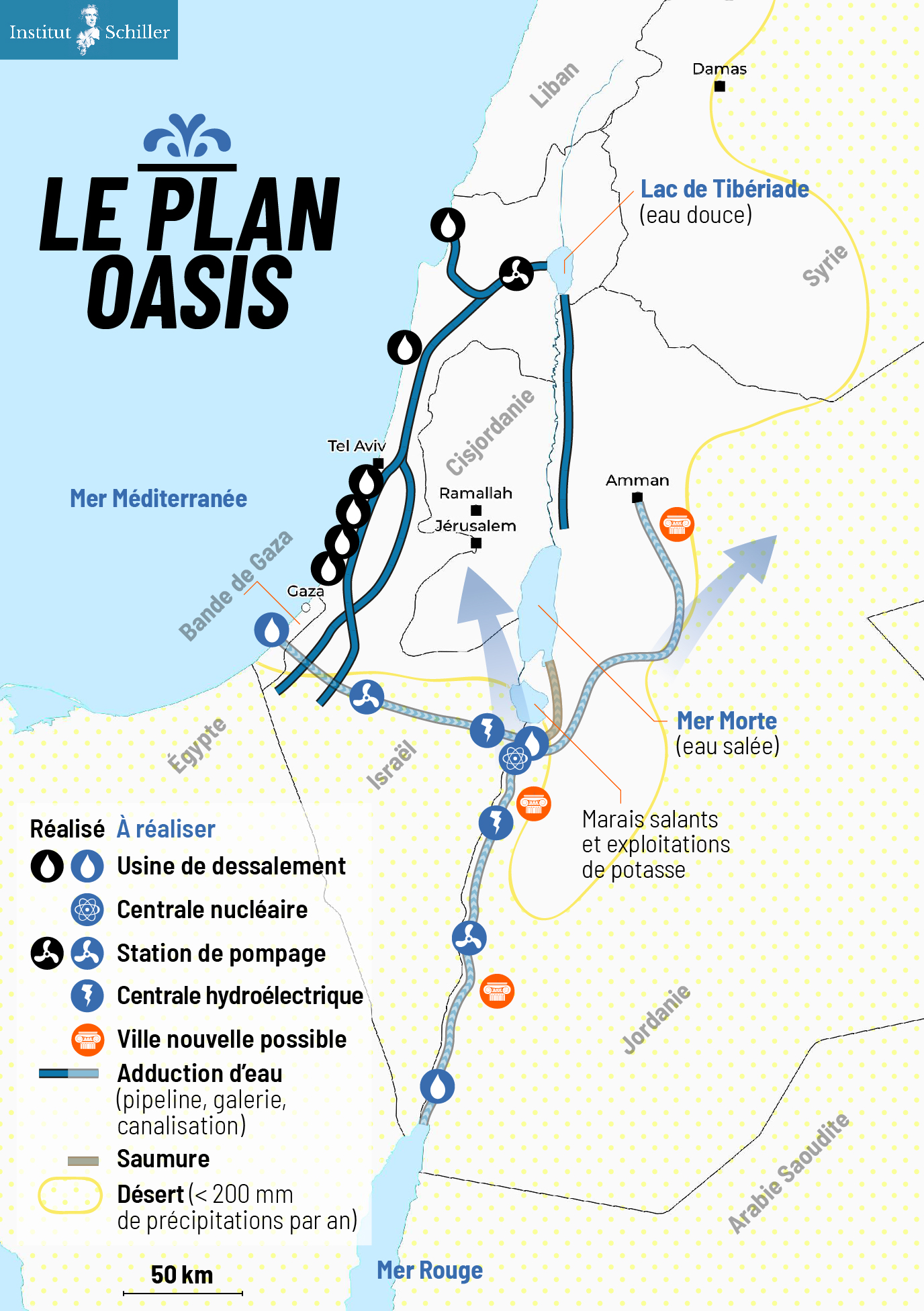

I. Oasis Plan

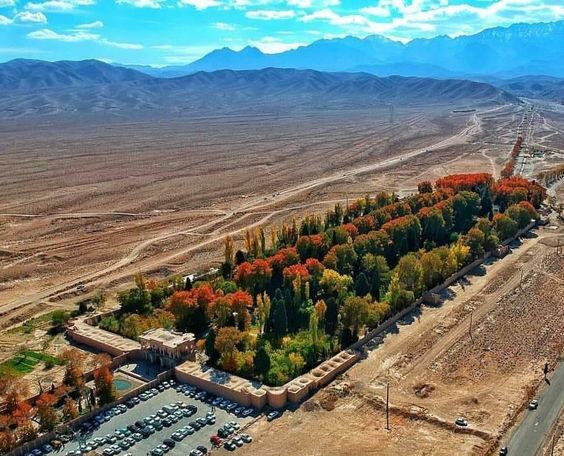

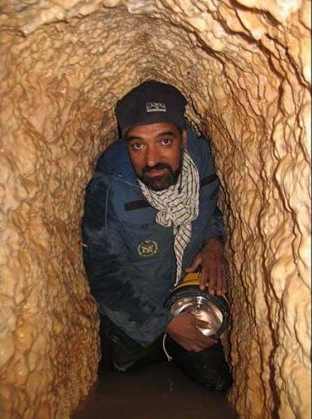

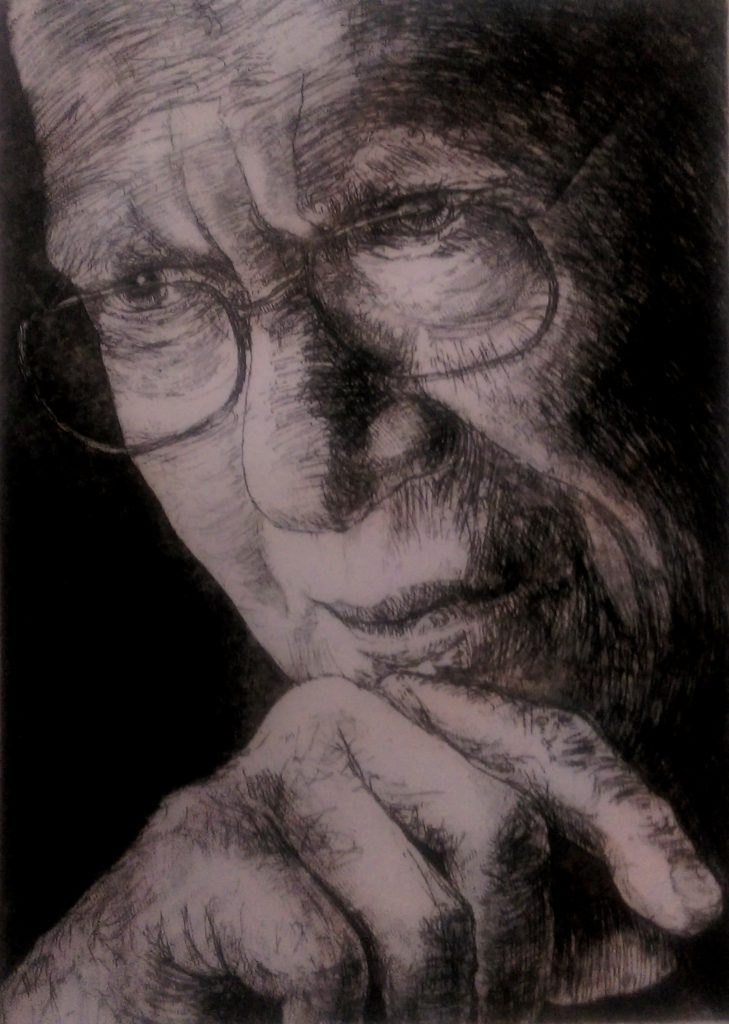

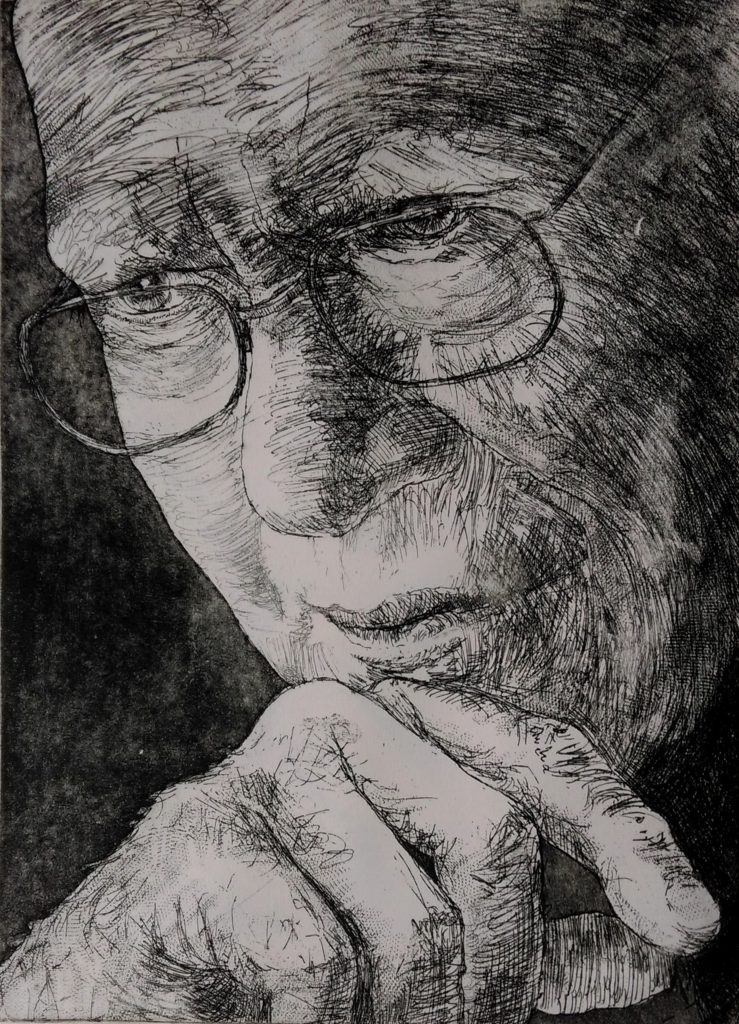

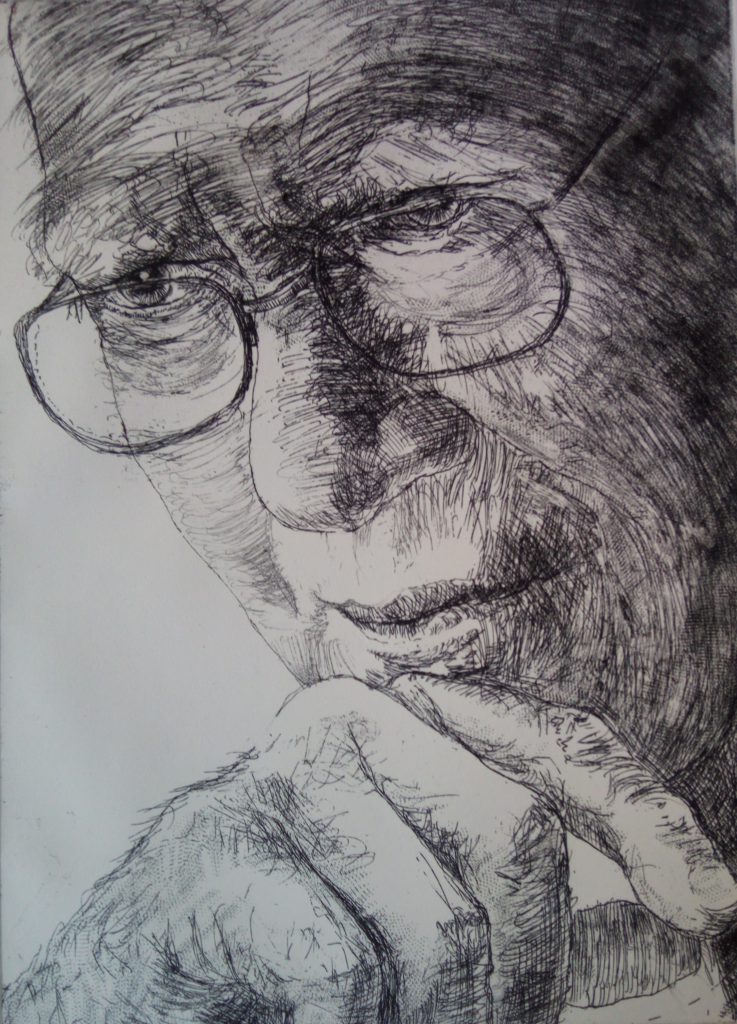

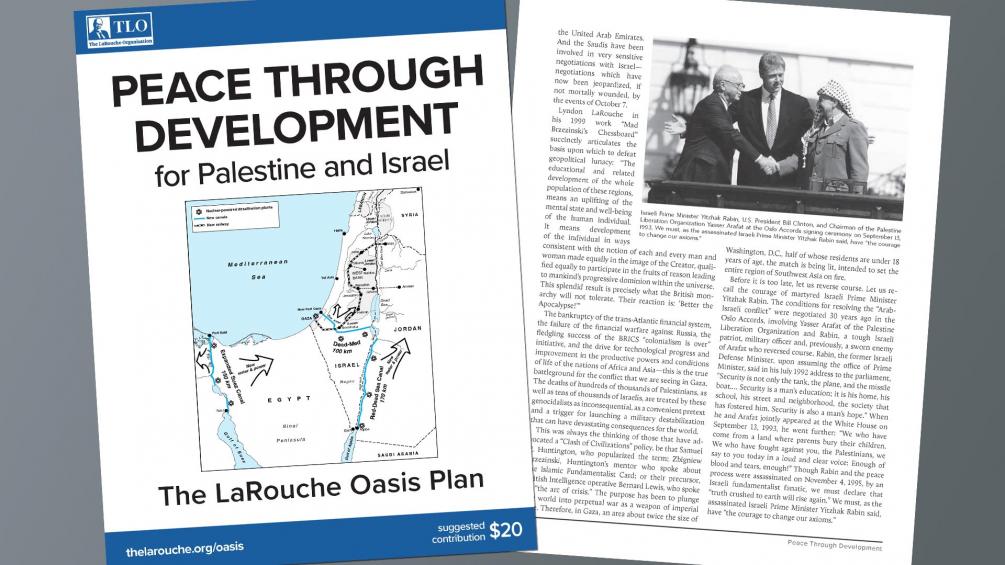

It is in the light of all these failures that the fundamental contribution of the « Oasis Plan » proposed by the American economist Lyndon LaRouche (1922-2019) becomes apparent.

In 1975, following talks with the leaders of the Iraqi Baath Party and sane elements of the Israeli Labor Party, the American economist LaRouche saw his Oasis Plan as the basis for mutual development to the benefit of the entire region.

Instead of waiting for « stability » and « lasting peace » to arrive magically, LaRouche proposed and even launched projects in the interests of all, and « recruited » all partners to participate fully, first and foremost in their own interests, but in reality in the interests of all.

LaRouche’s « Blue Peace » Oasis plan, to be put on the table of diplomatic negotiations as the « spine » of a durable peace agreement », includes:

- Israel’s relinquishment of exclusive control over water resources in favor of a fair resource-sharing agreement between all the countries in the region;

- The reconstruction and economic development of the Gaza Strip, including the Yasser Arafat International Airport (inaugurated in 1998 and bulldozered by Israeli in 2002), a major seaport backed up by a hinterland equipped with industrial and agricultural infrastructure.

- A floating, underwater or off-shore desalination plant will be stationed in front of Gaza.

- The construction of a fast rail network reconnecting Palestine (including Gaza) and Israel to its neighbors;

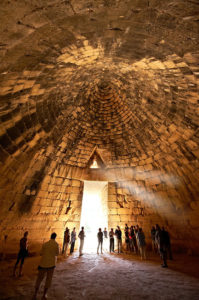

- The construction, for less than 20 billion US dollars of both the Red-Dead and the Med-Dead water conveyance system composed of tunnels, pipelines, water galeries, pumping stations, hydro-power units and nuclear powered desalination plants.

- Salted sea water, arriving at the Dead Sea, before desalination, will « fall » through a 400 meter deep shaft and generate hydro-electricity.

- Following desalination, the fresh water will go to Jordan, Palestine and Israel; the brine will refill and save the Dead Sea.

- The nuclear powered desalination plant will produce heat and electricity with « hybrid desalination » combining evaporation and Reverse Osmosis (RO) ;

- The industrial heat of the Molten Salt (MSR) high temperature reactors (HTR), will also be tapped for industrial and agricultural purposes;

- The reservoirs of the water conveyance systems will also function as a Pumped Storage Power Plant (PSPP), essential for regulating the region’s power grids;

- Part of the seawater going through the Med-Dead Water conveyance system will be desalinated in Beersheba, the « capital of the Negev » whose population, with new fresh water supplies, can be doubled.

- New cities and « development corridors » will grow around the new water conveyance systems.

- Israel’s Dimona nuclear center and power plant (currently a military reactor and medical nuclear waste treatment center) can form the basis to create a civilian nuclear program and contribute to the construction of nuclear desalination plants. Jordan can supply the uranium.

- US and Israeli plans to prepare the housing of 500,000/1 million people in the Negev exist but should be entirely reconfigured in terms of both scope and intent. They cannot be a mere extension of exclusively Jewish settlements, but should offer the opportunity to all Israeli citizens, in peaceful cooperation with the Bedouins who live there, the Palestinians and others, to roll back a common enemy: the desert.

- The policy of illegal settlements in the West Bank shall be halted. Settlers will be encouraged (through taxation, etc.) to relocate to the Negev, where they, in a shared effort with the Bedouins, Palestinians and others, can take up productive jobs and make the desert bloom (62% of Israeli territory).

PS: The Oasis Plan plan aims to bring peace to all through mutual development. It has nothing to do with Netanyahu’s Ben-Gurion canal project, a megalomaniac plan for a navigation canal connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean aimed to compete with the Suez Canal.

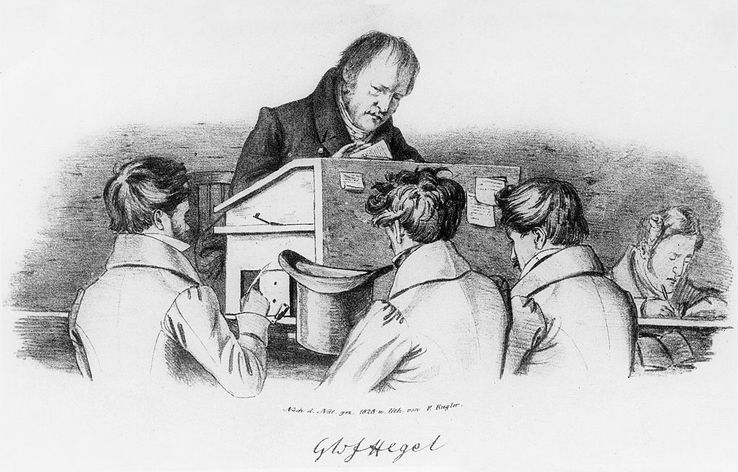

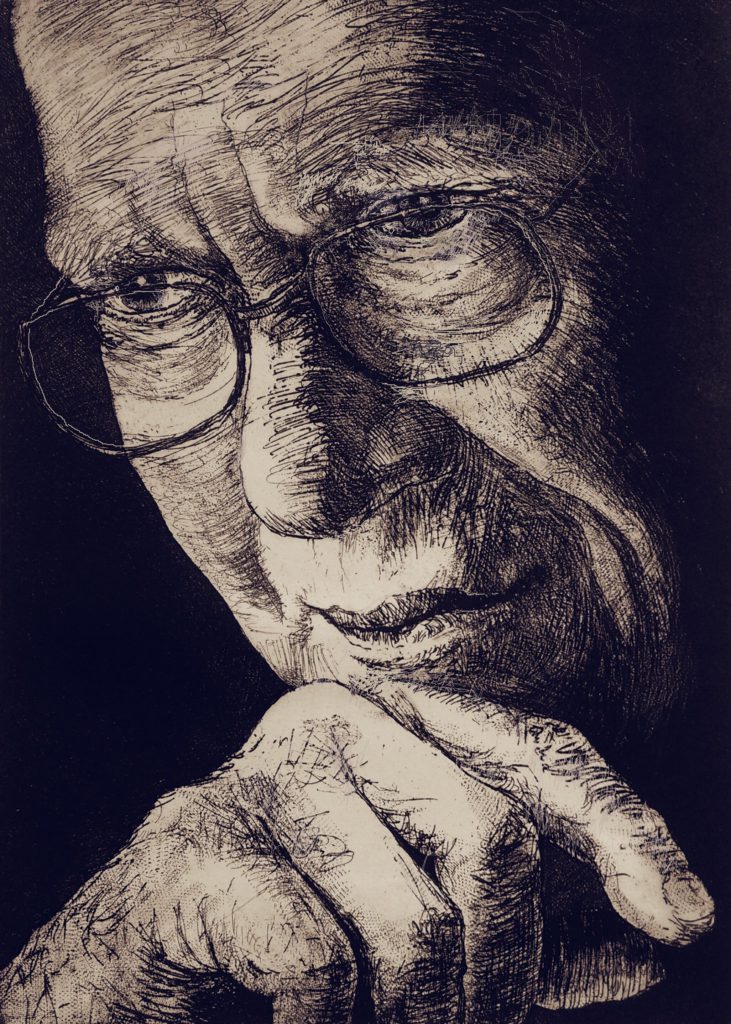

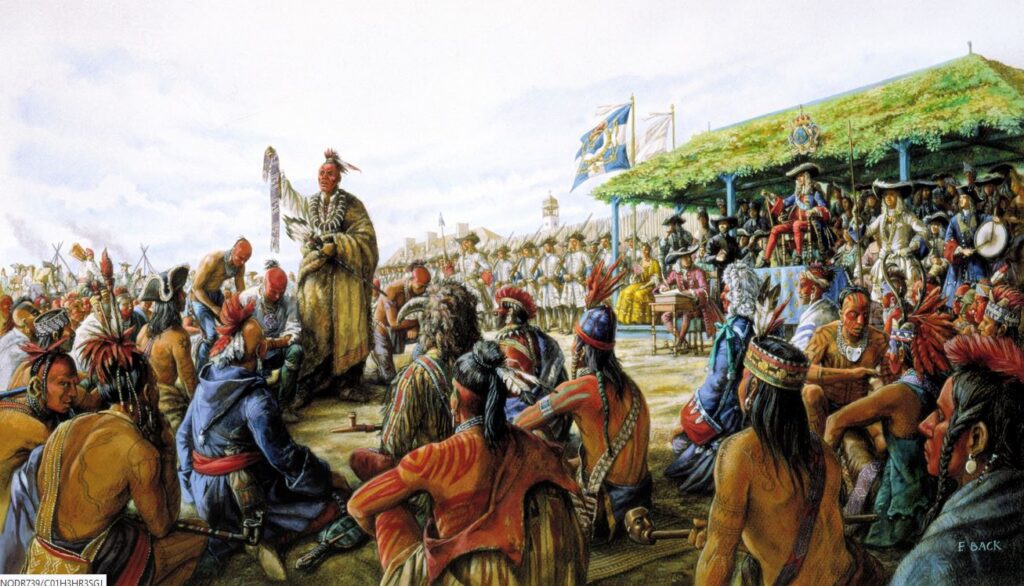

Alvin Weinberg, Yitzhak Rabin and Lyndon LaRouche

LaRouche proposed coupling hydrological, energy, agricultural and industrial infrastructures. These agro-industrial complexes, built around small high-temperature nuclear reactors, were called « nuplexes », a concept put forward in the post-war period by the American scientist Alvin Weinberg, head of the Oak Ridge Laboratories in Tennessee (ORNL) and co-inventor of several types of nuclear reactor, notably the molten-salt line using thorium as fuel (and therefore without the production of weapons-grade plutonium).

In chapter 8 of his autobiography, Weinberg recounts how ORNL, « embarked on a great enterprise: desalinating the sea with cheap nuclear power », with « multi-purpose » plants, « producing water, electricity and process heat at the same time ». The assertion that this was possible, Weinberg reports, « caused a stir within the Atomic Energy Commission ».

In the end, it was President John F. Kennedy who reacted most enthusiastically, speaking on September 25, 1963:

“We are now examining in the United States today the mixed economic-technical question of whether the very large scale nuclear reactors can produce unexpected savings in the simultaneous desalination of water and the generation of electricity? We will have before this decade is out or sooner a tremendous nuclear reactor which makes electricity and at the same time gets fresh water from salt water at a competitive price. What a difference this can make to the United States. And indeed, not only the US but all around the globe where there are so many deserts on the ocean’s edge.”

The idea reached later the ear of AEC’s patron Lewis Strauss.

“The time was 1967, just after the Six-Day War, and the Middle East was much on our minds. The ultimate problem of the Middle East is water – a point that is now perhaps more fully recognized than it was in 1967. Why not build dual-purpose nuclear and electric desalting plants in Egypt, Israel and Jordan – literally make the deserts bloom– and thereby create a major new possibility for a settlement in the Israeli-Arab conflict?”

Lewis conveyed this idea to Eisenhower and Ike published in Life magazine an outline of what became known as the Eisenhower plan, based “on what Lewis and I had discussed”, writes Weinberg.

ORNL then sent a team to visit Egypt, Israel and Lebanon where they were warmly received. The visit brought to Tennessee Israeli and Egyptian engineers who were integrated in the Middle East Study Project,

“which studied what we called ‘nuclear-powered agro-industrial complexes,’ something already studied in 1966. Such complexes would use nuclear reactors to produce electricity and water; the electricity would be used for both domestic and industrial purposes; the water would be used to grow high-value crops.”

“The Middle East project adapted these earlier results to the Israeli-Egyptian situation. A multi-volume report of the Middle East project was issued in which we examined the feasibility of nuclear agro-industrial complexes to be built as national projects in the El-Hamman area near Alexandria in Egypt, and the western Negev area of Israel, and as an international project near the Gaza strip. The implication was that the complexes would be subsidized by the United States.”

“I met with then-ambassador Yitzhak Rabin of Israel for about an hour at the Knoxville airport to tell him about our results. Rabin, who became prime minister of Israel, was skeptical – both as to the political feasibility of a project conducted jointly by Israelis and Arabs, and the economic feasibility of such a huge undertaking. But most of all he suggested that we had extraordinary chutzpah, sitting in Tennessee and figuring out a scheme to resolve a bitter ethnic dispute some six thousand miles away! Of course Rabin had a point on both scores; but I couldn’t refrain from saying, ‘But Mr. Ambassador, is our drawing up plans in Tennessee for agro-industrial complexes for the Middle East is any sillier than Theodore Herzl’s drawing up plans for Israel, in a Vienna café in 1896?’”

Weinberg, clearly unaware of the Dulles brothers‘ operations sabotaging anything good Ike wanted to accomplish regretted: “The Eisenhower-Baker plan was never implemented: the political will needed to support building large reactors in the strife-riven Middle East was lacking…”

The LaRouche Oasis plan, like any other proposal along the same lines, has so far been blocked by the Israeli, American and British sides, and we know only too well what happened to Yitzhak Rabin, assassinated after signing the Oslo Accords, to Shimon Peres, ousted, and to a demonized Yasser Arafat. In addition, LaRouche has been slandered and called an anti-Semite.

On April 13, 2034, LaRouche’s Oasis Plan and its relevance for today was discussed and debated during an international zoom conference and endorsed by several high level ambassadors and diplomats from Palestine, South Africa, Russia and Guyana.

Similar events are being prepared to continue the discussion and turn this dream into reality.

« Mutual tuition »: historical curiosity or promise of a better future?

By Karel Vereycken, July 2023, PARIS.

1. Introduction

2. Learning and teaching at the same time, a precious joy

3. Precedents:

A. In India

B. In France

4. Gaspard Monge’s brigades

5. Andrew Bell

6. Joseph Lancaster

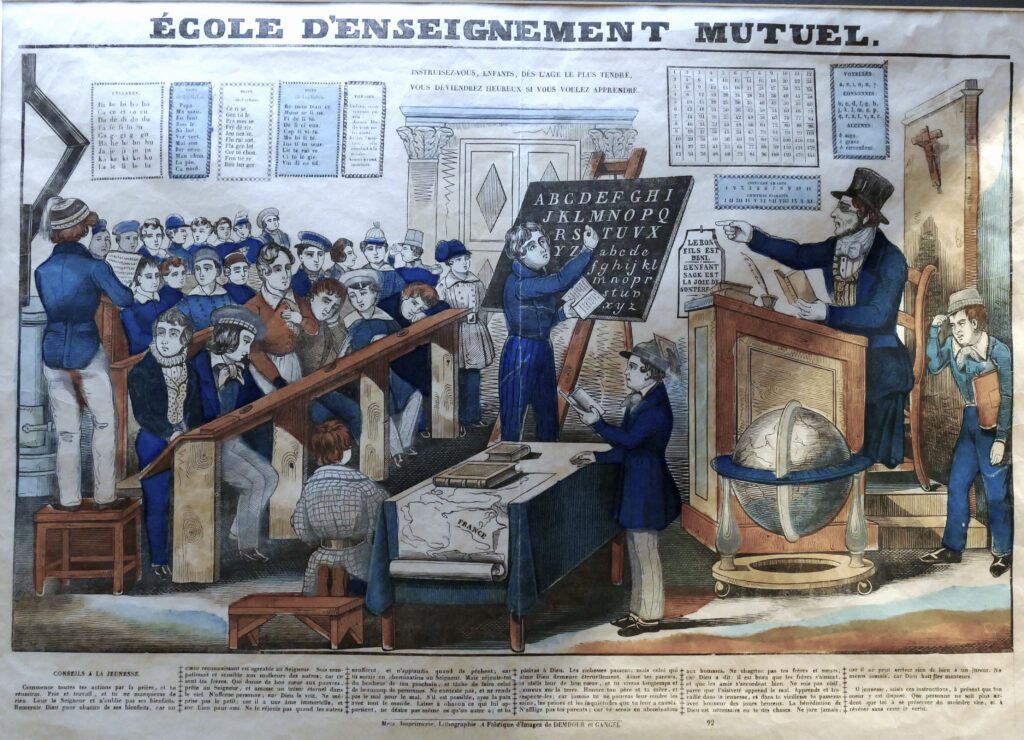

7. Mutual Tuition, how it works

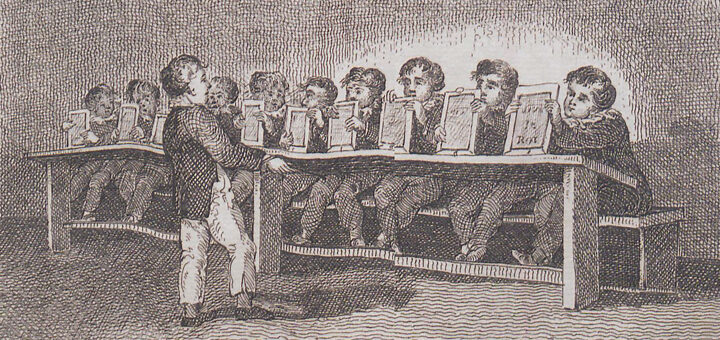

A. The class room

B. Teachers and monitors

C. A day at a mutual school

D. Progress according to each pupil’s knowledge

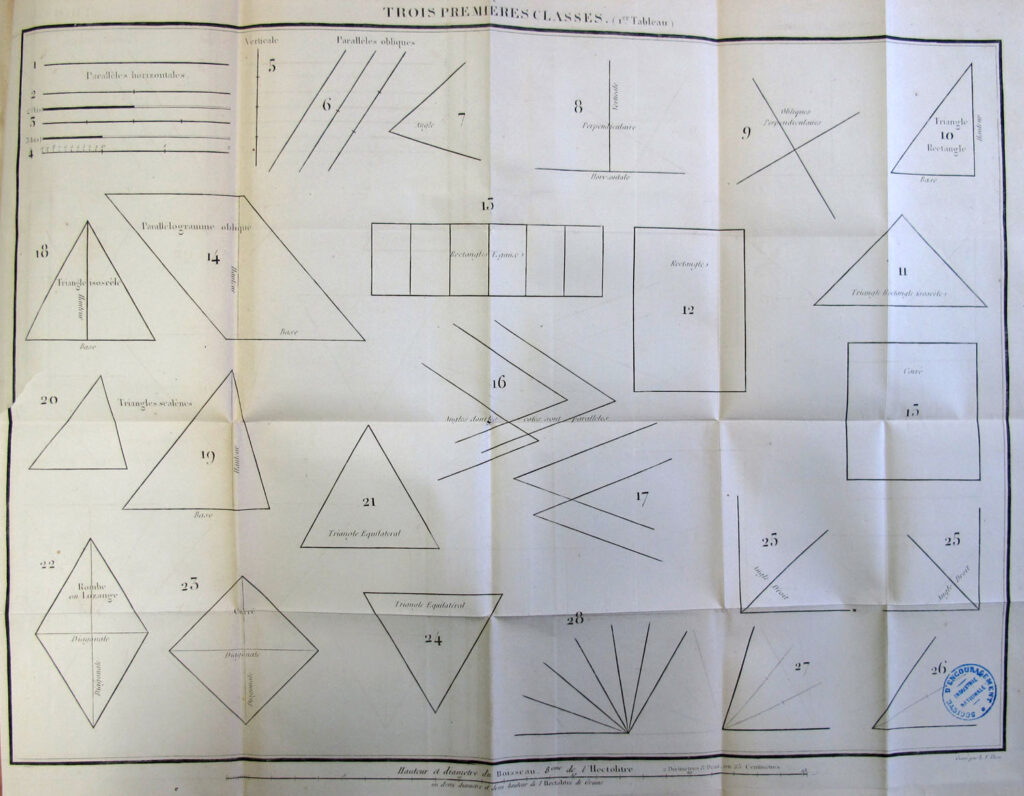

E. Tools

F. Command

8. Bellists vs. Lancasterians

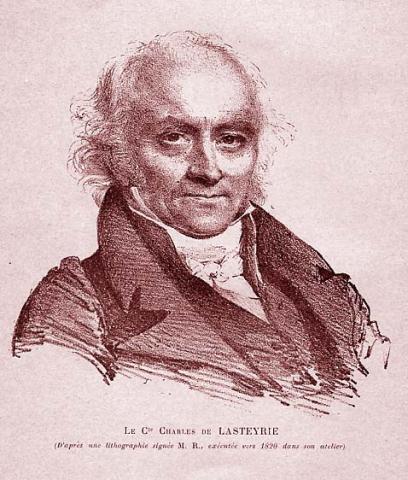

9. France adopting Mutual Tuition

10. Lazare Carnot takes the helm

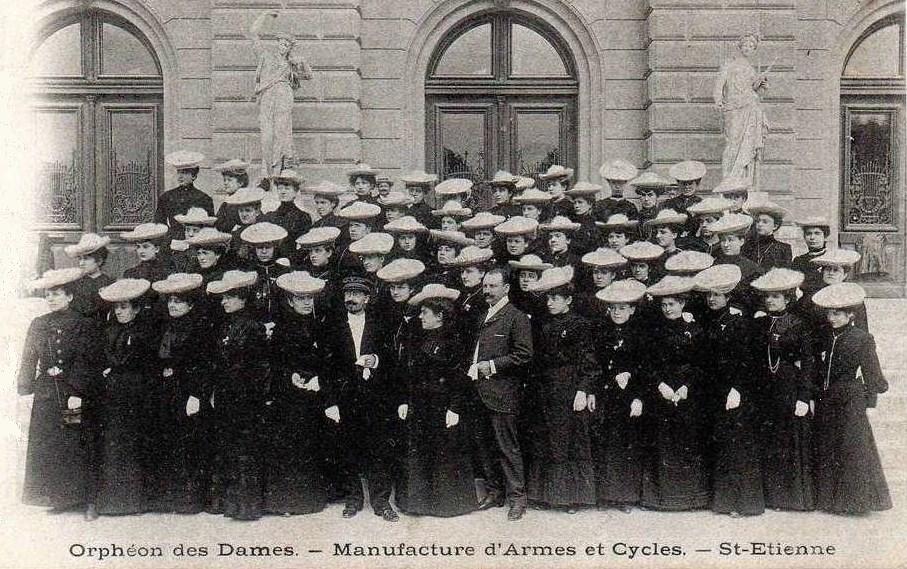

11. Mutual tuition and choral music

12. The rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais pilot project

13. Jomard, Choron, Francœur and elementary knowledge

14. Going Nationwide

15. Critique

16. Mechanistic drift?

17. Death of mutual tuition in France

18. Conclusion

19. Short list of books and texts consulted

« Answer, my friends: it must be sweet for you

To have as your only mentors children like yourselves;

Their age, their mood, their pleasures are your own;

And these victors of one day, tomorrow vanquished by others,

Are, in turn, adorned with modest ribbons,

Your equals in your games, your masters on the benches.

Mute, eyes fixed on your happy emulators,

You are not distracted by the fear of ferulas;

Never an avenging whip, frightening your spirits,

Makes you forget what they taught you;

I listen badly to a fool who wants me to fear him,

And I know much better what a friend teaches me. »

Victor Hugo, Discours sur les avantages de l’Enseignement mutuel, 1817.

1. Introduction

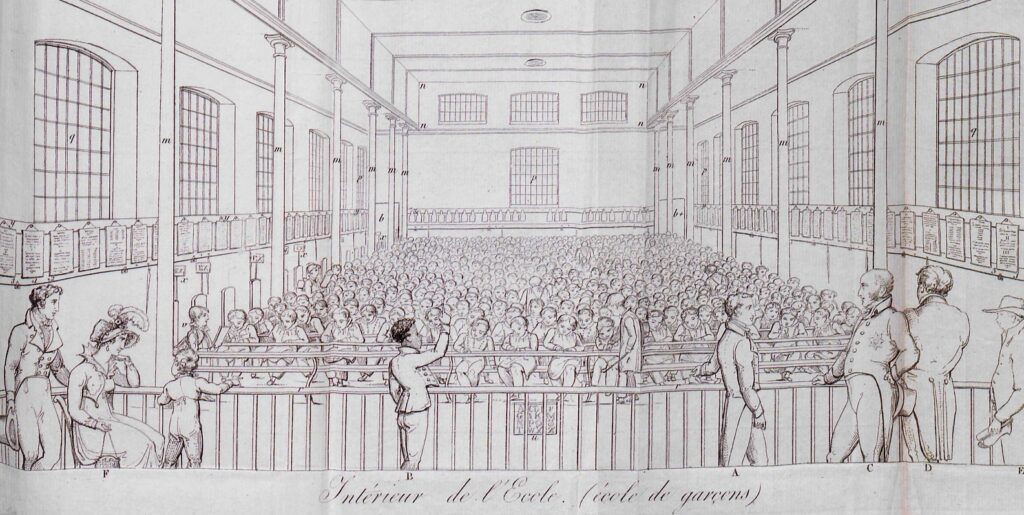

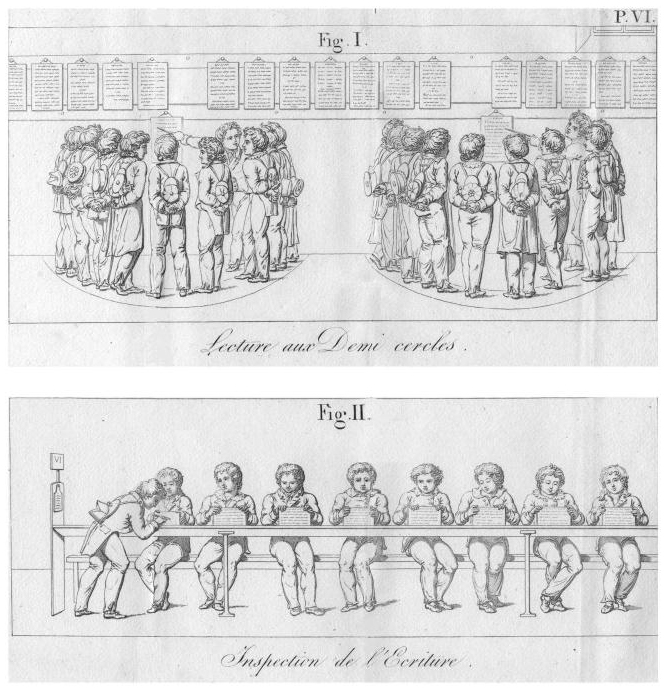

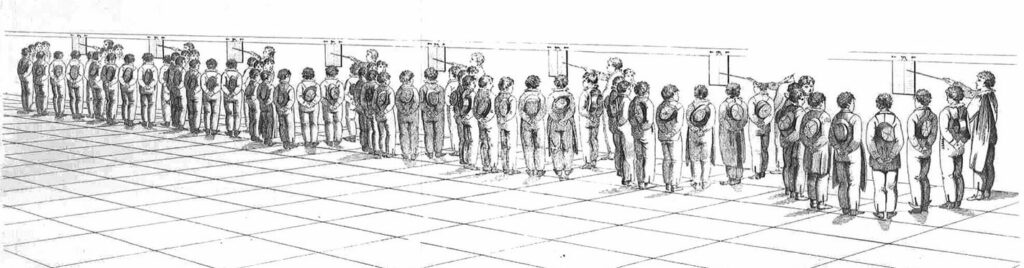

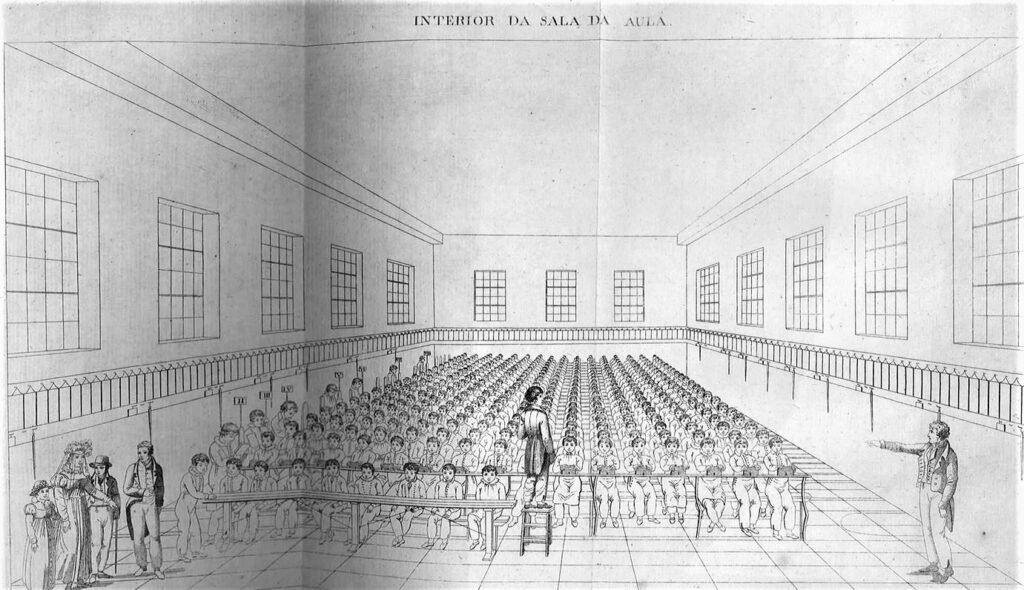

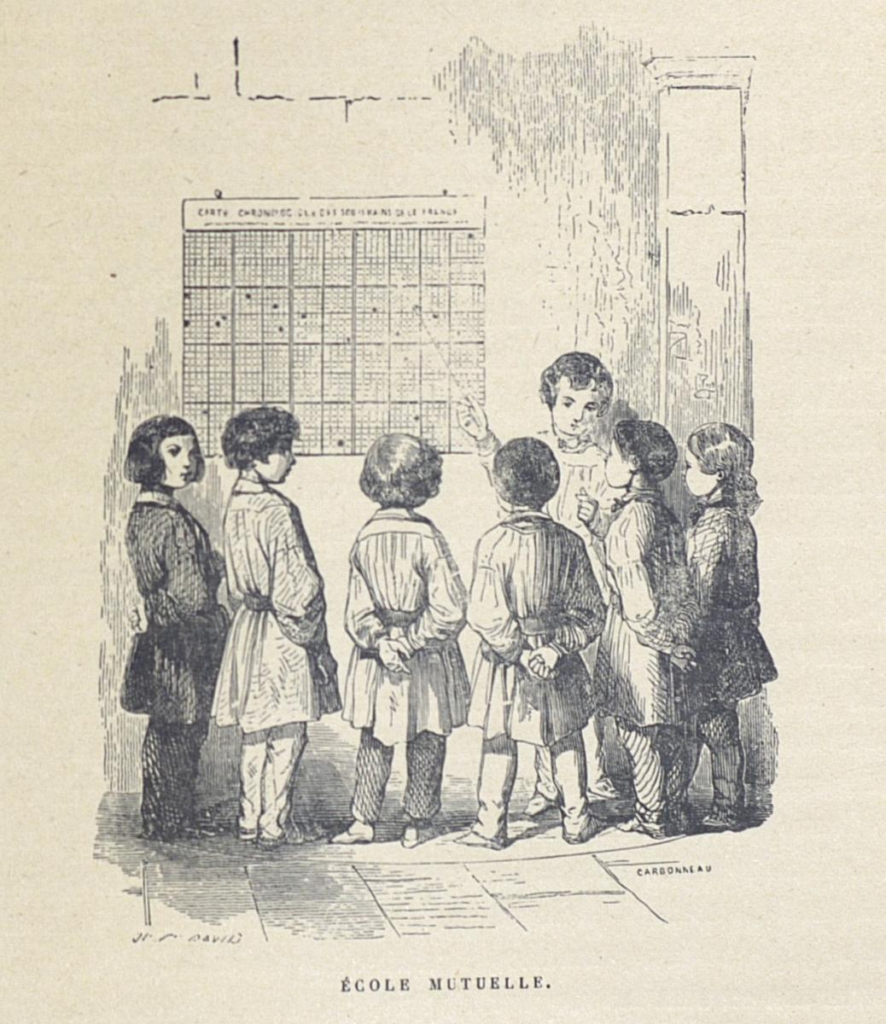

Teaching reading and writing to 1,000 children in the same room, without a teacher, without school books, without paper and ink, is clearly impossible. And yet, it has been imagined and put into practice with great success!

Shh! we mustn’t talk about it, because it could give some people ideas, and not just in emerging countries!

That such a challenge could be taken up could only worry the oligarchy and its servants, who since the dawn of time have been mandated to train an « elite » (the high priests of knowledge, « experts » and other know-it-alls) who reproduce in a vacuum at the top, while ensuring that the great mass of people below are educated just enough to be able to deliver parcels, pay their taxes, abide by the rules defined by the top, and above all, not make (too) much of a mess.

And yet, as Hippolyte Carnot, Minister of Public Instruction in the Second Republic, understood long before us, without a republican education – in other words, without genuine citizen training from kindergarten onwards – universal suffrage often becomes a tragic farce capable of producing monsters.

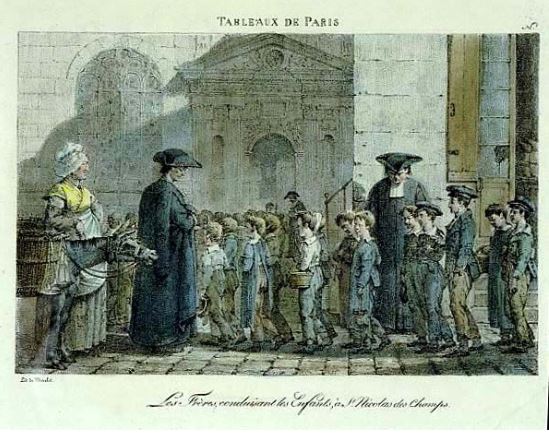

In the early 19th century, « mutual tuition », (sometimes referred to as the English Monitorial System, also known as Madras System or Lancasterian System), spread like wildfire across Europe and then the rest of the world including the United States of America.

If the teacher addresses a single pupil, it’s the individual mode (as in the case of the preceptor); if he addresses an entire class, it’s the simultaneous mode; if he instructs some children to teach others, it’s the mutual mode. The combination of simultaneous and mutual modes is called mixed mode.

Mutual tuition quickly fell victim to personal quarrels and ideological, political and religious issues. In France, it was seen as an aggression by religious congregations who practiced « simultaneous teaching », codified as early as 1684 by Jean-Baptiste de La Salle : classes by age, division by level, fixed and individual places, strict discipline, repetitive and simultaneous work supervised by an inflexible master.

With the formation of small groups where pupils teach each other and move around the classroom, mutual teaching immediately gave rise, rather foolishly, to the fear of an ass-over-head world straight out of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. What kind of world are we in if the pupil teaches the teacher? the child the parent? the faithful the priest? the citizen the government ! Without a clear leader, aren’t we lost ?

In 1824, Pope Leo XII (not to be confused with the benevolent Leo XIII), the « Pope of the Holy Alliance », a fierce supporter of order and suspect of a vast Protestant plot against the Vatican, forbade such teaching, believing it to « weaken the authority » of both teachers and political and religious authorities.

In France, where in the years following the 1830 revolution over 2,000 mutual schools existed, mainly in towns, in competition with denominational schools, François Guizot, Louis-Philippe’s minister and initially a promoter of broad public education, had them closed down.

2. Learning and teaching at the same time,

a precious joy

Today, « tutoring » is enjoying a revival in the context of school and vocational training. It is a process of « assistance by more experienced subjects to less experienced subjects, likely to enrich the latter’s acquisitions ».

Tutoring between children, in particular between children of different ages, is encouraged from nursery school right through to university, with the institutionalization of methodological tutoring at undergraduate level. Since the 1980s, elementary and secondary schools in France and abroad have seen the development of numerous tutoring experiments.

In reality, tutoring is no more than the pale heir to the mutual tuition system developed in England and then France in the 19th century.

Hence, the future of humanity depends on an exclusively human faculty: the discovery of new universal physical principles, often totally beyond the limits of our sensory apparatus, enabling Man to increase his capacity to transform the universe to qualitatively improve his lot and that of his environment. A discovery is never the result of the sum or average of opinions, but of an individual, perfectly sovereign act. Are we able to organize our society so that this « sacred » creative principle is cherished, respected and cultivated in any newborn child?

Because, without the socialization of this discovery, it will be useless. The history of mankind is therefore, by its very nature, the history of « mutual tuition ».

Is not the greatest pleasure of those who have just made a discovery – and this is natural for children – to share, with a view to a shared future, not only what he or she has just discovered, but the joy and beauty that every scientific breakthrough represents? And when those who discover teach and those that teach, discover, the pleasure is immense. So let’s give our professional teachers the time they need to make discoveries, for the quality of their teaching will be enhanced!

Precedents:

A. In India

In 1623, the Italian explorer Pietro Della Valle (1586-1652), after a trip to « Industan » (India), in a letter dispatched from Ikkeri (a town in south-west India), reports having seen boys teaching each other how to read and write using singing :

« In order to inculcate it perfectly in their memory, to repeat the previous lessons that had been prescribed to them, lest they forget them, one of them would sing in a certain musical tone a line from the lesson, such as two and two make four. After all, it’s easy to learn a song.

« While he sang this part of the lesson to learn it better, he wrote it down at the same time, not with a pen, nor on paper. But to spare him and not spoil it unnecessarily, they marked the characters with their fingers on the same floor where they were sitting in a circle, which they had covered for this purpose with very loose sand. After the first of these children had written in this way while singing, the others sang and wrote the same thing all together

« (…) When I asked them who (…) corrected them when they missed, given that they were all schoolboys, they answered me very reasonably, that it was impossible that a single difficulty should stop them all, four at the same time, without being able to overcome it and that for the subject they always practiced together so that if one missed, the others would be his teachers.«

In Della Valla‘s report, we can already identify some of the basic principles of mutual tuition, notably the simultaneous learning of reading and writing, the use of sand for writing exercises to avoid wasting paper, which is scarce and very expensive, a group lesson given by a teacher, followed by work in sub-groups in which pupils learn to self-regulate, and finally, an integration of knowledge which, thanks to the use of song, will facilitate memorization.

B. In France

In Lyon, the priest Charles Démia, was one of the precursors of mutual tuition, which he put into practice in the « petites écoles » for poor children he founded and theorized as early as 1688. According to the Nouveau dictionnaire de pédagogie et de l’instruction primaire:

« Démia introduced what later came to be known as mutual tuition into the classroom: he recommended that a certain number of officers be chosen from among the most capable and studious pupils, some of whom, under the name of intendants and decurions, would be responsible for supervision, while the others would have to have the master’s lessons repeated, correct pupils when they made mistakes, guide the hesitant hand of ‘young writers’, etc. » In order to make simultaneous teaching possible, Démia’s idea of ‘mutual teaching’ was based on the principle of ‘teaching to one another’. To make simultaneous teaching possible, the author of the regulations divides the school into eight classes, to be taught in turn by the master; each of these classes can be subdivided into bands ».

In Paris, as early as 1747, mutual education was practiced with great success in a school of over 300 pupils, established by M. Herbault, at the Hospice de la Pitié, in favor of the children of the poor. Unfortunately, the experiment did not survive its founder.

In 1772, the ingenious charity of Chevalier Paulet conceived and carried out the project of applying a similar method to the education of a large number of children, left without support in society by the death of their parents.

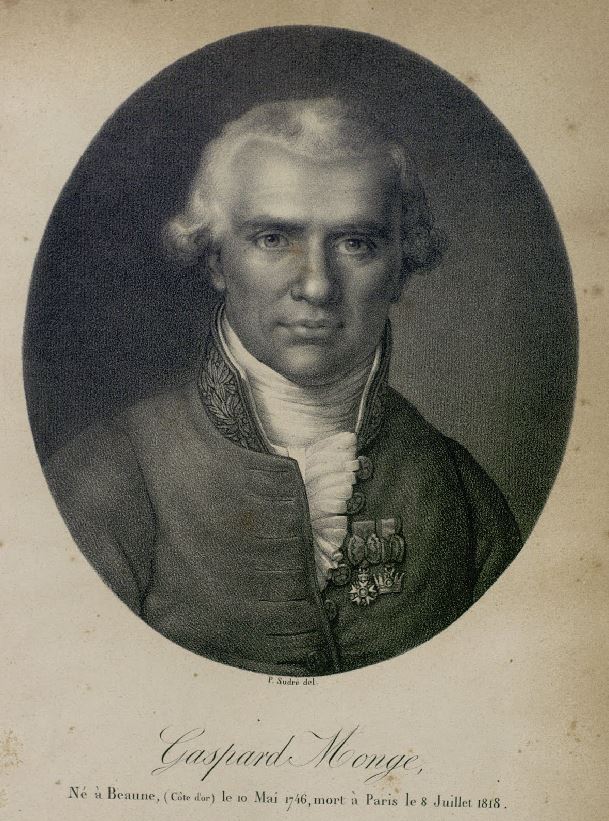

4. Gaspard Monge’s « brigades »

Finally, as recounted in his biography of Gaspard Monge by his most brilliant pupil, the astronomer François Arago (1786-1853), himself a close friend of Alexander von Humboldt, it was at the École Polytechnique that Monge perfected his own system of mutual tuition and tutoring.

Finding it unacceptable to have to wait three years for the first engineers to graduate from the Ecole Polytechnique, Monge decided to speed up student training by organizing « revolutionary courses », an accelerated training program lasting three months for those in charge of teaching to the others. To achieve this, he perfected the concept of « chefs de brigades », a technique he had already successfully tested at the Mézières engineering school.

François Arago:

« The brigade leaders, always working with small groups of students in separate rooms, were to have the extremely important task of ironing out difficulties as they arose. Never had a more skilful combination been devised to remove any excuse for mediocrity or laziness.

« This creation belonged to Monge. At Mézières, where the engineering students were divided into two groups of ten, and where, in fact, our colleague acted for some time as permanent brigade leader for both divisions, the presence in the classrooms of a person who was always in a position to overcome objections had produced results that were too fortunate for this former repetiteur, in drafting the developments attached to Fourcroy’s report, not to try to endow the new school with the same advantages.

« Monge did more; he wanted the 23 sections of 16 students each, of which the three divisions were to be composed, to have their brigade leader, as in ordinary times, following the revolutionary lessons, and at the opening of the courses of the three degrees. In a word, he wanted the School, at its beginning, to function as if it had already been in existence for three years.

« Here’s how our colleague achieved this seemingly unattainable goal. It was decided that 25 students, chosen by competitive examination from among the 50 candidates who had received the best marks from the admission examiners, would become brigade leaders of three divisions of the school, after receiving special instruction separately. In the mornings, the 50 young people, like all their classmates, attended revolutionary classes; in the evenings, they were brought together at the Hôtel Pommeuse, near the Palais-Bourbon, and various teachers prepared them for the functions they were destined to perform. Monge presided over this scientific initiation with infinite kindness, ardor and zeal. The memory of his lessons remains indelible in the minds of all those who benefited from them.

Arago then quotes Edme Augustin Sylvain Brissot (1786-1819), son of the famous abolitionist, , one of the 50 students, who reported : « It was there that we began to get to know Monge, this man so kind to youth, so devoted to the propagation of science. Almost always in our midst, he followed lessons in geometry, analysis and physics with private discussions where we found even more to gain. He became a friend to each and every one of the students at the Ecole provisoire, joining in the efforts he was constantly provoking, and applauding, with all the vivacity of his character, the successes of our young minds ».

While mutual teaching is fully practiced, the total dedication of a master as devoted as Monge completes what otherwise becomes nothing more than a « system ».

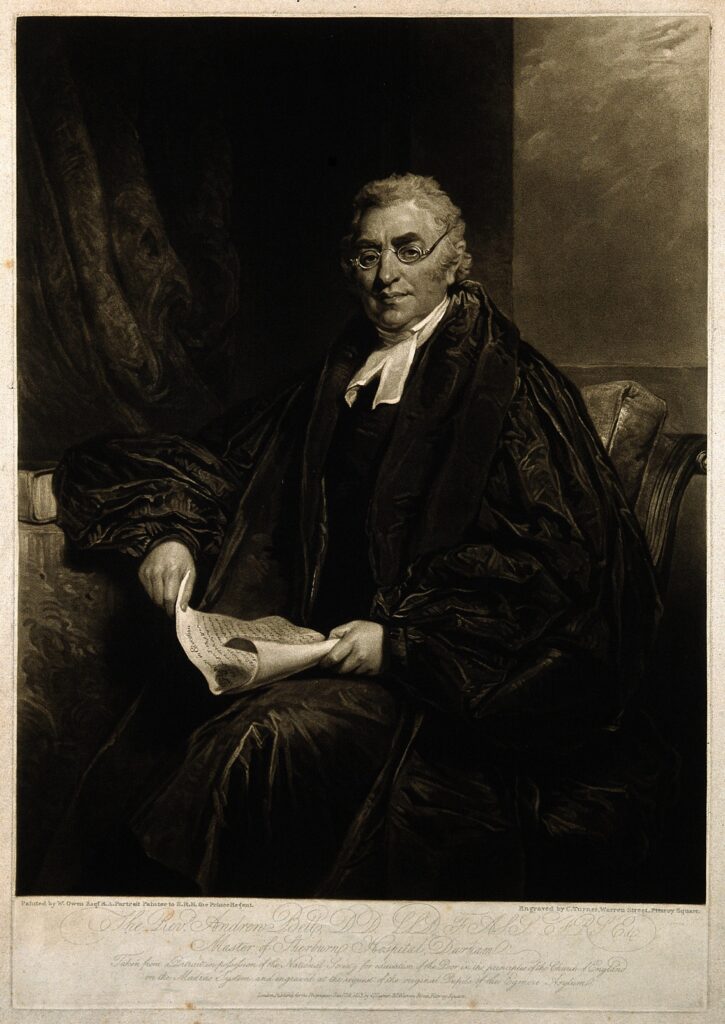

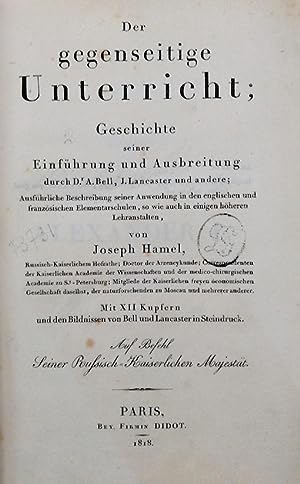

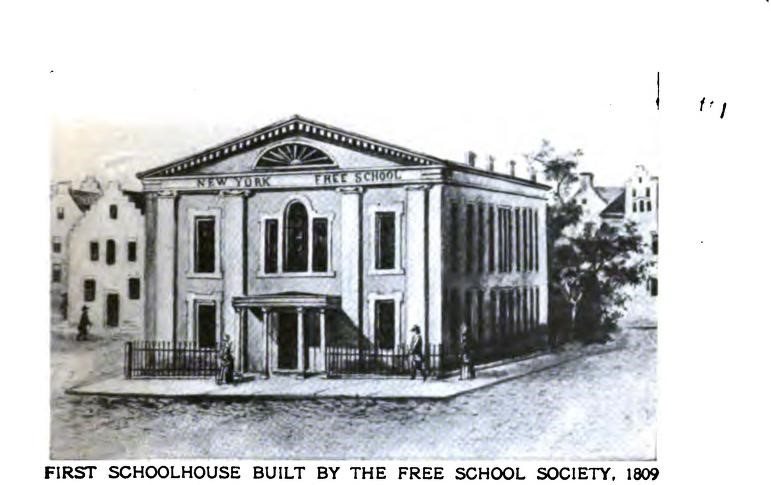

5. Andrew Bell