Étiquette : God

Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics?

What follows is an edited transcript of a lecture by Karel Vereycken on the subject of “Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting”.

It was delivered at the international colloquium “La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique” (The quest for the divine through geometrical space) at the Paris Sorbonne University on April 26-28, 2006, under the direction of Luc Bergmans, Department of Dutch Studies (Paris IV Sorbonne University).

Introduction

« Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting ». At first glance, this title may seem surprising. While the genius of fifteenth-century Flemish painters is universally attributed to their mastery of drying oil and their intricate sense of detail, their spatial geometry as such is usually identified as the very counter-example of the “right perspective”.

Disdained by Michelangelo and his faithful friend Vasari, the Flemish « primitives » would never have overcome the medieval, archaic and empirical model. For the classical “narritive”, still in force today, stipulates that only « Renaissance » perspective, obeying the canon of « linear », “mathematical” perspective, is the only « right », and the “scientific” one.

According to the same narrative, it was the research carried out around 1415-20 by the Duomo architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), superficially mentioned by Antonio Tuccio di Manetti some 60 years later, which supposedly enabled Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), proclaiming himself Brunelleschi’s intellectual heir, to invent « perspective ».

In 1435, in De Pictura, a book entirely devoid of graphic illustration, Alberti is said to have formulated the premises of a perspectivist canon capable of representing, or at least conforming to, our modern notions of Cartesian space-time (NOTE 1), a space-time characterized as « entirely rational, i.e. infinite, continuous and homogeneous », « in one word, a purely mathematical space [dixit Panofsky] » (NOTE 2)

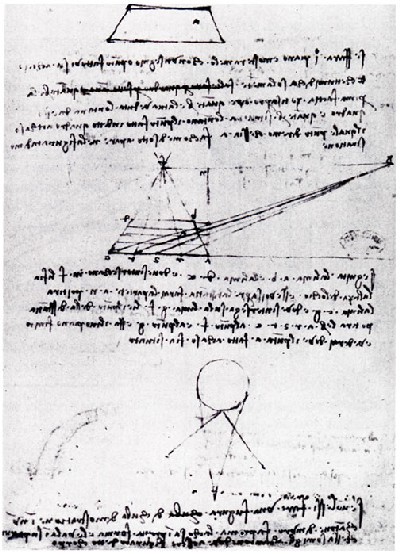

Long afterwards, in a drawing from the Codex Madrid, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) attempted to unravel the workings of this model.

But in the same manuscript, he rigorously demonstrated the inherent limitations of the Albertian Renaissance perspectivist canon.

The drawing on f°15, v° clearly shows that the simple projection of visual pyramid cross-sections on a plane paradoxically causes their size to increase the further they are from the point of vision, whereas reality would require exactly the opposite. (NOTE 3)

With this in mind, Leonardo began to question the mobility of the eye and the curvilinear nature of the retina. Refusing to immobilize the viewer on an exclusive point of vision (NOTE 4), Leonardo used curvilinear constructions to correct these lateral deformations. (NOTE 5) In France, Jean Fouquet and others worked along the same lines.

But Leonardo’s powerful arguments were ignored, and he was unable to prevent this rewriting of history.

Despite this official version of art history, it should be noted that at the time, Flemish painters were elevated to pinnacles by Italy’s greatest patrons and art connoisseurs, specifically for their ability to represent space.

Bartolomeo Fazio, around the middle of the 15th century, observed that the paintings of Jan van Eyck, an artist billed as the « principal painter of our time », showed « tiny figures of men, mountains, groves, villages and castles rendered with such skill that one would think them fifty thousand paces apart. » (NOTE 6)

Such was their reputation that some of the great names in Italian painting had no qualms about reproducing Flemish works identically. I’m thinking, for example, of the copy of Hans Memlinc‘s Christ Crowned with Thorns at the Genoa Museum, copied by Domenico Ghirlandajo (Philadelphia Museum).

But post-Michelangelo classicism deemed the non-conformity of Flemish spatial geometry with Descartes’ « extended substance » to be an unforgivable crime, and any deviation from, or insubordination to, the « Renaissance » perspectivist canon relegated them to the category of « primitives », i.e. « empiricists », clearly devoid of any scientific culture.

Today, ironically, it is almost exclusively those artists who explicitly renounce all forms of perspectivist construction in favor of pseudo-naïveté, who earn the label of modernity…

In any case, current prejudices mean that 15th-century Flemish painting is still accused of having ignored perspective.

It’s true, however, that at the end of the XIVth century, certain paintings by Melchior Broederlam (c. 1355-1411) and others by Robert Campin (1375-1444) (Master of Flémalle) show the viewer interiors where plates and cutlery on tables threaten to suddenly slide to the floor.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that whenever the artist « ignores » or disregards the linear perspective scheme, he seems to do so more by choice than by incapacity. To achieve a limpid composition, the painter prioritizes his didactic mission to the detriment of all other considerations.

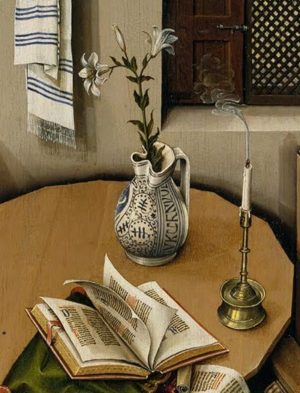

For example, in Campin’s Mérode Altarpiece, the exaggerated perspective of the table clearly shows that the vase is behind the candlestick and book.

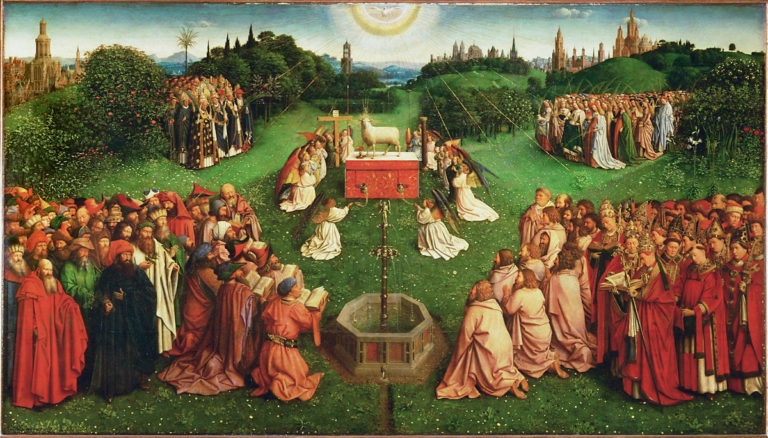

Jan van Eyck’s Lam Gods (Mystic Lamb) in Ghent is another example.

Never could so many figures, with so much detail and presence, be shown with a linear perspective where the figures in the foreground would hide those behind. (NOTE 7)

But the intention to approximate a credible sense of space and depth remains.

If this perspective seems flawed by its linear geometry, Campin imposes an extraordinary sense of space through his revolutionary treatment of shadows. As every painter knows, light is painted by painting shadow.

In Campin’s work, every object and figure is exposed to several sources of light, generating a darker central shadow as the fruit of crossed shadows.

Van Eyck influenced by Arab Optics?

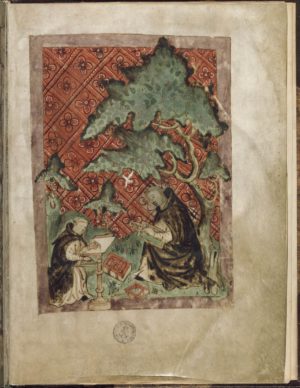

Roger Bacon, statue in Oxord.

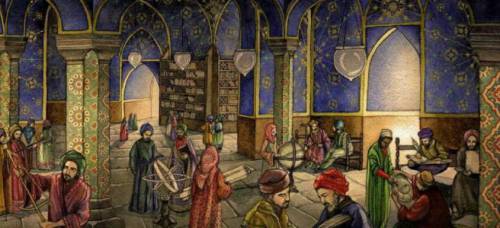

This new treatment of light-space has been largely ignored. However, there are several indications that this new conception was partly the result of the influence of « Arab » science, in particular its work on optics.

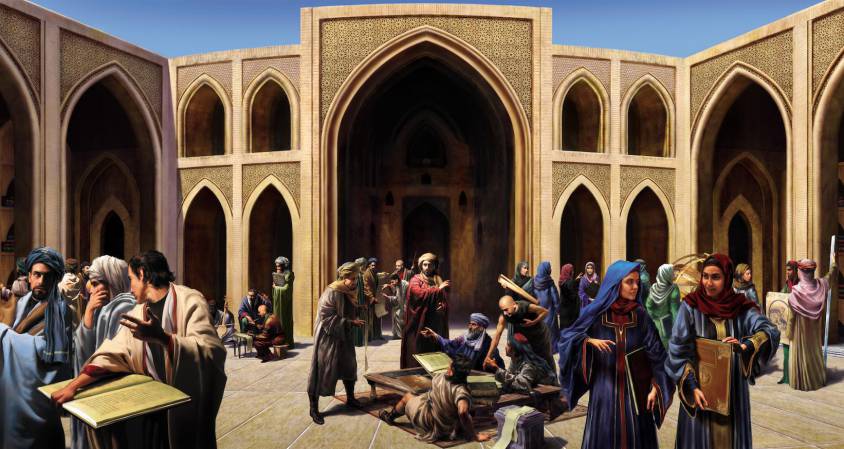

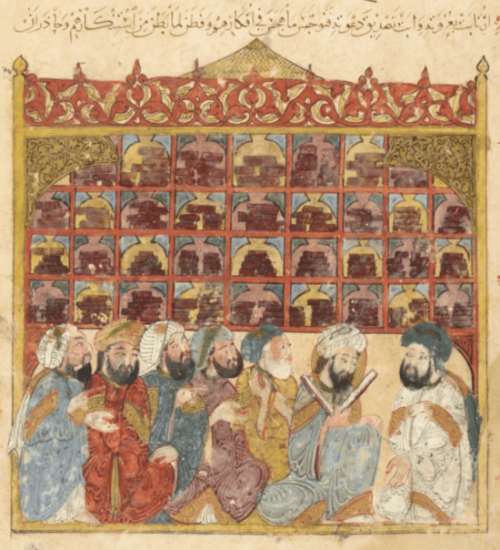

Translated into Latin and studied from the XIIth century onwards, their work was developed in particular by a network of Franciscans whose epicenter was in Oxford (Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) and whose influence spread to Chartres, Paris, Cologne and the rest of Europe.

It should be noted that Jan van Eyck (1395-1441), an emblematic figure of Flemish painting, was ambassador to Paris, Prague, Portugal and England.

I’ll briefly mention three elements that support this hypothesis of the influence of Arab science.

Curved mirrors

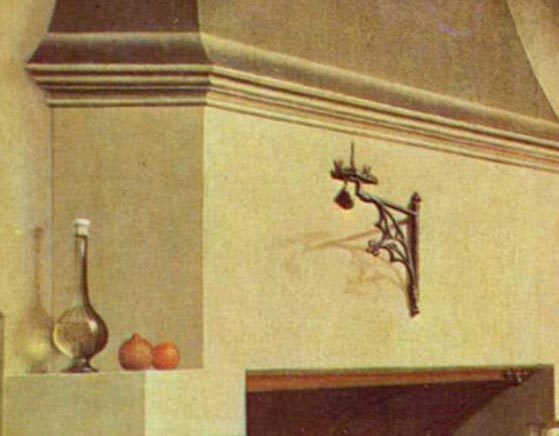

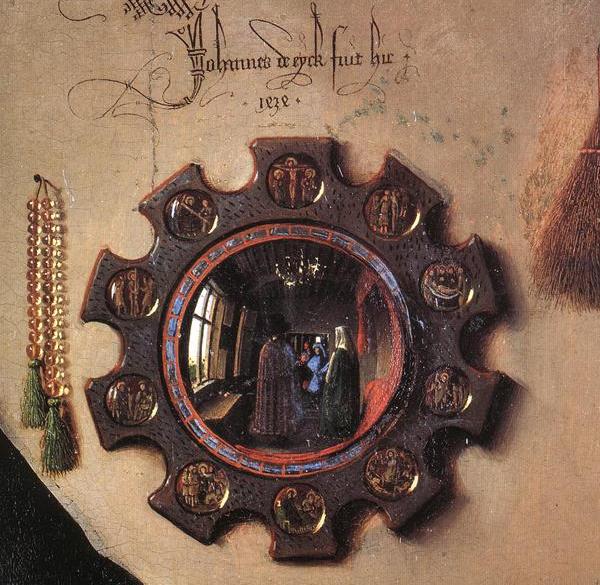

Robert Campin (master of Flémalle) in the Werl Triptych (1438) and Jan van Eyck in the Arnolfini portrait (1434), each feature convex mirrors of considerable size.

It is now certain that glaziers and mirror-makers were full members of the Saint Luc guild, the painters’ guild. (NOTE 8)

But it is relevant to know that Campin, now recognized as having run the workshop in Tournai where the painters Van der Weyden and Jacques Daret were trained, produced paintings for the Franciscans in this city. Heinrich Werl, who commissioned the altarpiece featuring the convex mirror, was an eminent Franciscan theologian who taught at the University of Cologne.

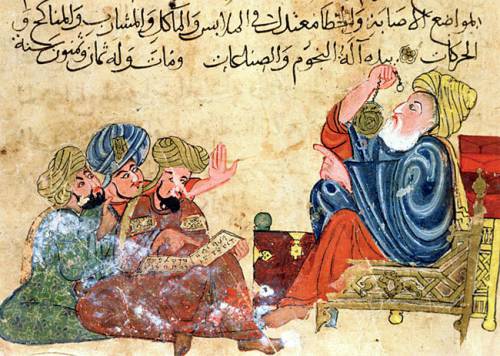

Artistic representation of Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen)

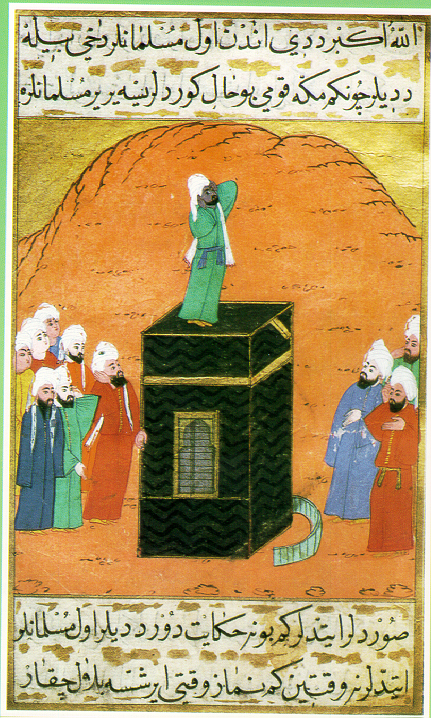

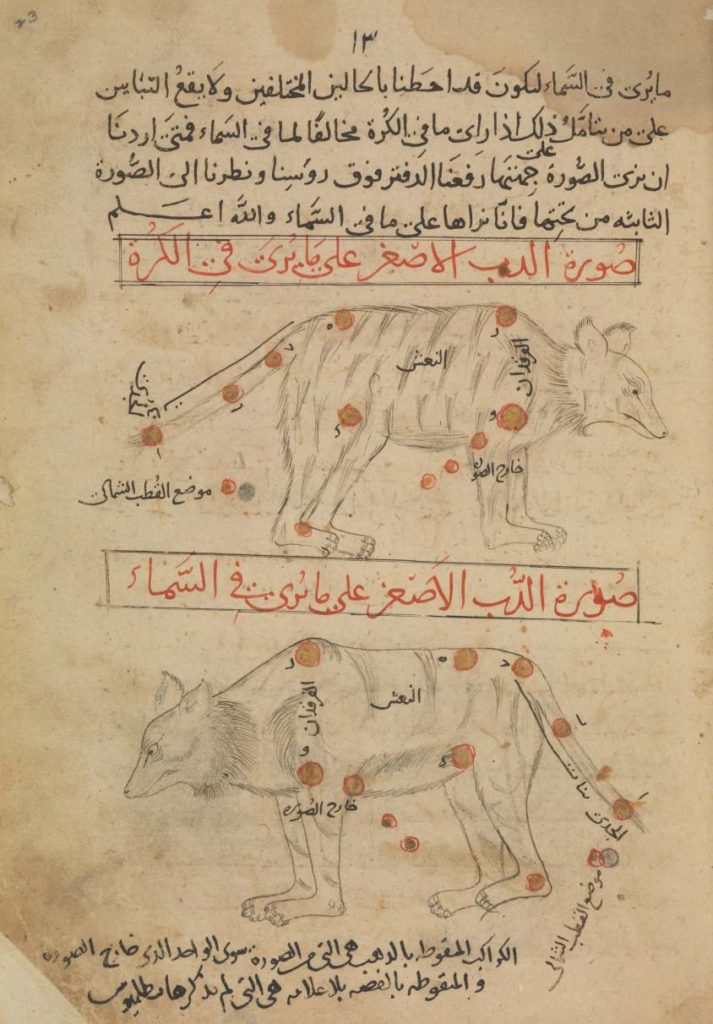

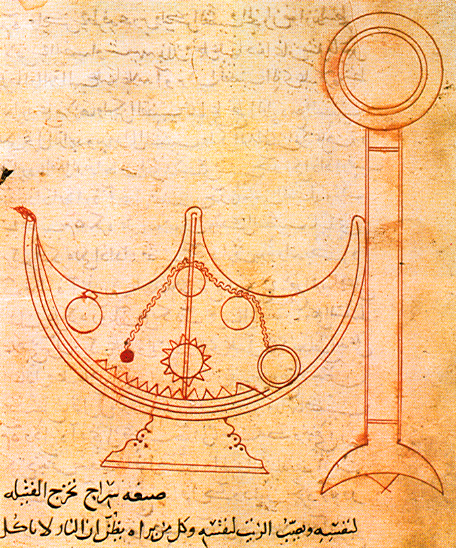

These convex and concave (or ardent) mirrors were much studied during the Arab renaissance of the IXth to XIth centuries, in particular by the Arab philosopher Al-Kindi (801-873) in Baghdad at the time of Charlemagne.

Arab scientists were not only in possession of the main body of Hellenic work on optics (Euclid‘s Optics, Ptolemy‘s Optics, the works of Heron of Alexandria, Anthemius of Tralles, etc.), but it was sometimes the rigorous refutation of this heritage that was to give science its wings.

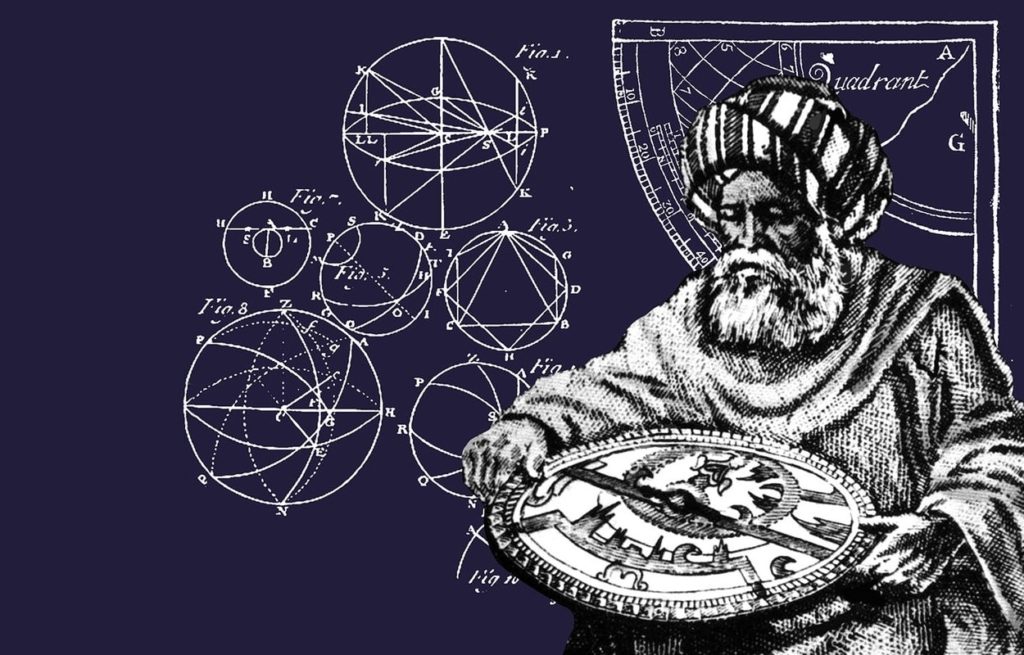

After the decisive work of Ibn Sahl (Xth century), it was that of Ibn Al-Haytam (Latin name : Alhazen) (NOTE 9) on the nature of light, lenses and spherical mirrors that was to have a major influence. (NOTE 10)

As mentioned above, these studies were taken up by the Oxford Franciscans, starting with the English bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste (1168-1253).

In De Natura Locorum, for example, Grosseteste shows a diagram of the refraction of light in a spherical glass filled with water. And in his De Iride he marvels at this science which he connexts to perspective :

« This part of optics, so well understood, shows us how to make very distant things appear as if they were situated very near, and how we can make small things situated at a distance appear to the size we desire, so that it becomes possible for us to read the smallest letters from incredible distances, or to count sand, or grains, or any small object.«

Grosseteste’s pupil Roger Bacon (1212-1292) wrote De Speculis Comburentibus, a specific treatise on « Ardent Mirrors » which elaborates on Ibn Al-Haytam‘s work.

Flemish painters Campin, Van Eyck and Van der Weyden proudly display their knowledge of this new scientific and technological revolution metamorphosed into Christian symbolisms.

Their paintings feature not only curved mirrors but also glass bottles, which they use as a metaphor for the immaculate conception.

A Nativity hymn of that period says:

« As through glass the ray passed without breaking it, so of the Virgin Mother, Virgin she was and virgin she remained… » (NOTE 11)

The Treatment of Light

In his Discourse on Light, Ibn Al-Haytam develops his theory of light propagation in extremely poetic language, setting out requirements that remind us of the « Eyckian revolution ». Indeed, Flemish « realism » and perspective are the result of a new treatment of light and color.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« The light emitted by a luminous body by itself -substantial light- and the light emitted by an illuminated body -accidental light- propagate on the bodies surrounding them. Opaque bodies can be illuminated and then in turn emit light. »

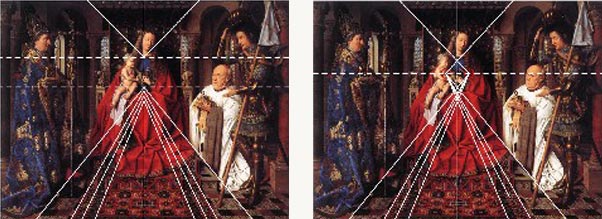

This physical principle, theorized by Leonardo da Vinci, is omnipresent in Flemish painting. Just look at the images reflected in the helmet of St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele (NOTE 12).

In each curved surface of Saint George’s helmet, we can identify the reflection of the Virgin and even a window through which light enters the painting.

The shining shield on St. George’s back reflects the base of the adjacent column, and the painter’s portrait appears as a signature. Only a knowledge of the optics of curved surfaces can explain this rendering.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« Light can penetrate transparent bodies: water, air, crystal and their counterparts. »

And :

« Transparent bodies have, like opaque bodies, a ‘receiving power’ for light, but transparent bodies also have a ‘transmitting power’ for light.«

Isn’t the development of oil mediums and glazes by the Flemish an echo of this research? Alternating opaque and translucent layers on very smooth panels, the specificity of the oil medium alters the angle of light refraction.

In 1559, the painter-poet Lucas d’Heere referred to van Eyck‘s paintings as « mirrors, not painted scenes.«

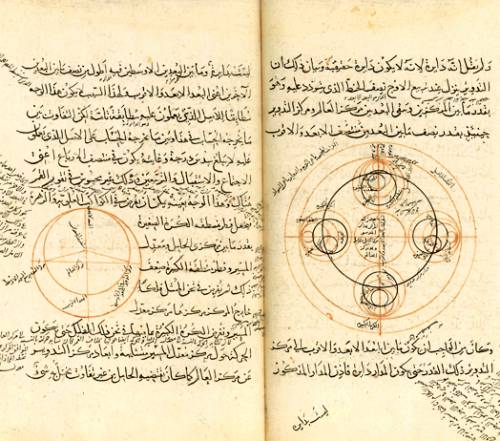

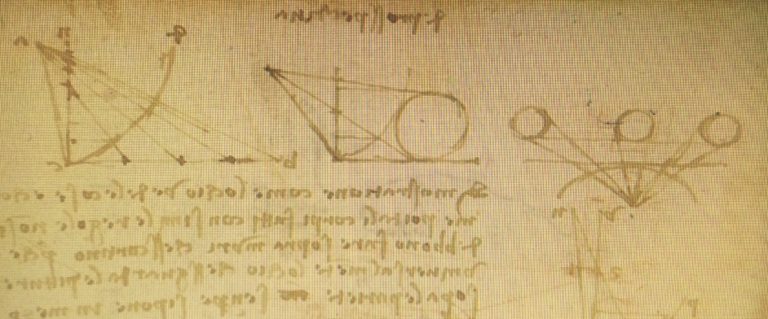

Binocular perspective

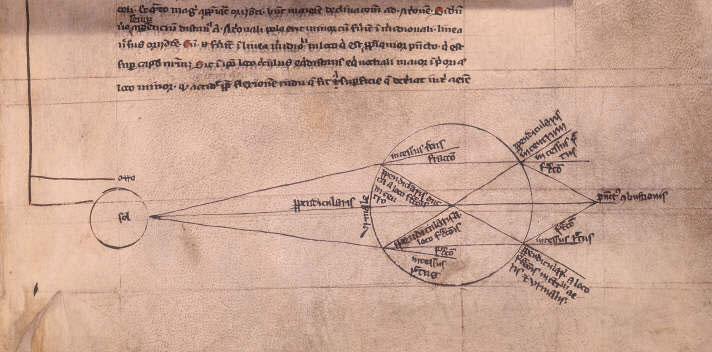

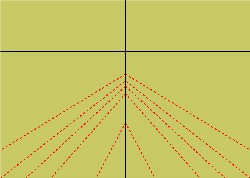

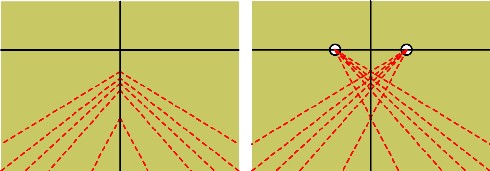

Before the advent of « right » central linear perspective, art historians sought a coherent explanation for its birth in the presence of several seemingly disparate vanishing points by theorizing a so-called central « fishbone » perspective.

In this model, a number of vanishing lines, instead of coinciding in a single central vanishing point on the horizon, either end up in a « vanishing region » (NOTE 13), or align with what some call a vertical « vanishing axis », forming a kind of « fishbone ».

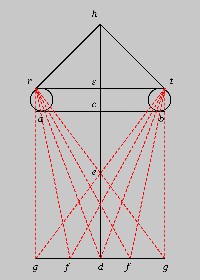

French Professor Dominique Raynaud, who worked for years on this issue, underscores that « all medieval treatises on perspective address the question of binocular vision », notably the Polish scholar Witelo (1230-1280) (NOTE 15) in his Perspectiva (I,27), an insight he also got from the works of Ibn Al-Haytam.

Witelo presents a figure to defend the idea that

« the two forms, which penetrate two homologous points of the surface of the two eyes, arrive at the same point of the concavity of the common nerve, and are superimposed at this point to become one » (Perspectiva, III, 37).

A similar line of reasoning can be found in Roger Bacon‘s Perspectiva Communis, written by John Pecham, Archbishop of Canterbury (1240-1290) for whom:

« the duality of the eyes must be reduced to unity »

So, as Professor Raynaud proposed, if we extend the famous vanishing lines (i.e., in our case, the « fish bones ») until they intersect, the « vanishing axis » problem disappears, as the vanishing lines meet. Interestingly, the result is a perspective with two vanishing points in the central region!

Suddenly, the diagrams drawn up to demonstrate the « empiricism » of the Flemish painters, if viewed from this point of view, reveal a legitimate construction probably based on optics as transmitted by Arab science and rediscovered by Franciscan networks and others.

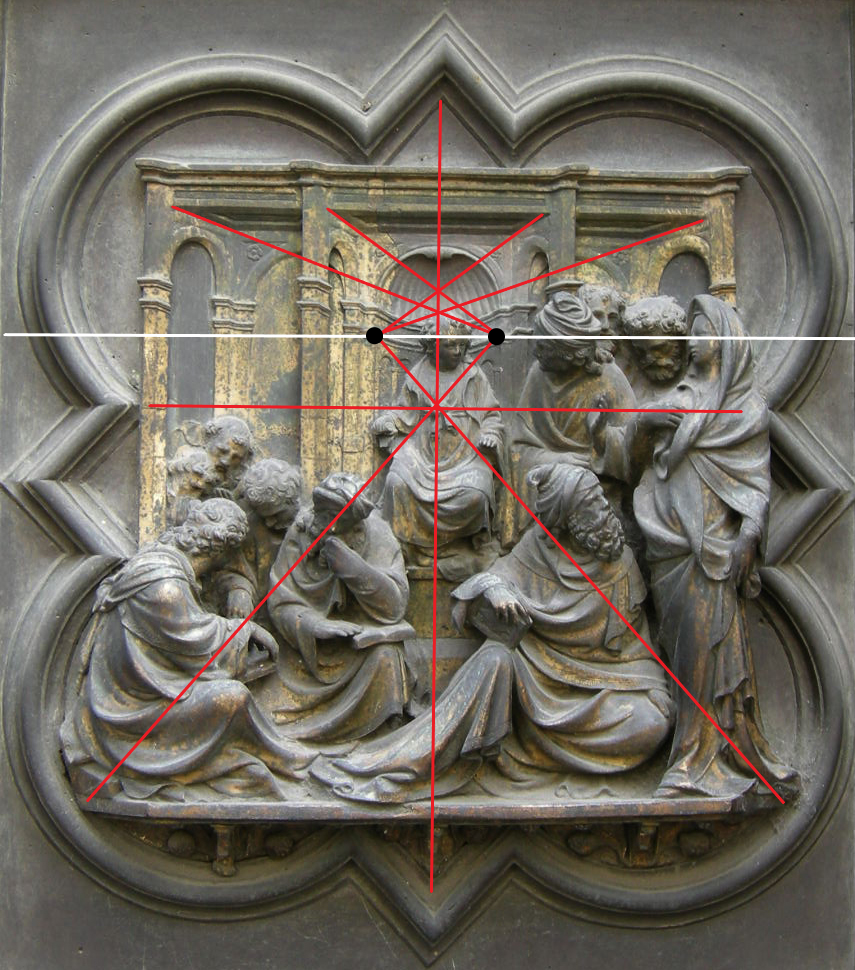

Two paintings by Jan van Eyck clearly demonstrate that he followed this approach: The Madonna with Canon van der Paele of 1436 and the Dresden Tryptic of 1437.

What seemed a clumsy, empirical approach in the form of a « fishbone » perspective (left) turns out to be a binocular perspective construction.

Was this type of perspective specifically Flemish?

A close examination of works by Ghiberti, Donatello and Paolo Uccello, generally dating from the first half of the XVth Century, reveals a mastery of the same principle.

Cusanus

But this whole demonstration is merely a look into the past through the eyes of modern scientific rationality. It would be a grave error not to take into account the immense influence of the Rhenish (Master Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso) and Flemish (Hadewijch of Antwerp, Jan van Ruusbroec, etc.) « mystics ».

This trend began to flourish again with the rediscovery of the Christianized neo-Platonism of Dionysius the Areopagite (Vth-VIth century), made accessible… by the new translations of the Franciscan Grosseteste in Oxford.

The spiritual vision of the Aeropagite, expressed in a powerful imagery language, is directly reminiscent of the metaphorical approach of the Flemish painters, for whom a certain type of light is simply the revelation of divine grace.

In On the Heavenly Hierarchy, Dionysius immediately presents light as a manifestation of divine goodness. It ennobles us and enables us to enlighten others:

« Let those who are illuminated be filled with divine clarity, and the eyes of their understanding trained to the work of chaste contemplation; finally, let those who are perfected, once their primitive imperfection has been abolished, share in the sanctifying science of the marvelous teachings that have already been manifested to them; similarly, let the purifier excel in the purity he communicates to others; let the illuminator, gifted with a greater penetration of spirit, equally fit to receive and transmit light, happily flooded with sacred splendor, pour it out in pressing streams on those who are worthy… » [Chap. III, 3]

Let’s think again of the St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele, which indeed pours forth the multiple images of the Virgin who enlightens him.

This theo-philosophical trend reached full maturity in the work of Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) (1401-1464) (NOTE 16), embodying the extremely fruitful encounter of this « negative theology » with Greek science, Socratic knowledge and Christian Humanism.

In contrast to both a science « without a hypothesis of God » and a metaphysics with an esoteric drift, an agapic love leads it to the education of the greatest number, to the defense of the weak and the humiliated.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, educating Erasmus of Rotterdam and inspiring Cusanus, are the best example of this.

But let’s sketch out some of Cusanus’ key ideas on painting.

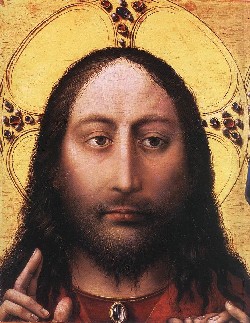

In De Icona (The Vision of God) (1453), which he sent to the Benedictine monks of the Tegernsee, Cusanus condenses his fundamental work On Learned Ignorance (1440), in which he develops the concept of the coincidence of opposites. His starting point was a self-portrait of his friend « Roger », the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden, which he sent together with his sermon to the monks.

This self-portrait, like the multiple faces of Christ painted in the XVth century, uses an « optical illusion » to create the effect of a gaze that fixes the viewer, regardless of his or her position in front of the altarpiece.

In De Icona, written as a sermon, Cusanus asks monks to stand in a semicircle around the painting and watch this gaze pursue them as they move along the segment of the curve. In fact, he elaborates a pedagogical paradox based on the fact that the Greek name for God, Theos, has its etymological origin in the verb theastai (to see, to look at).

As you can see, he says, God looks at you personally, and his gaze follows you everywhere. He is therefore one and many. And even when you turn away from him, his gaze falls on you. So, miraculously, although he looks at everyone at the same time, he nevertheless establishes a personal relationship with each one. If « seeing » for God is « loving », God’s point of vision is infinite, omniscient and omnipotent love.

A parallel can be drawn here with the spherical mirror at the center of Jan van Eyck’s painting The Arnolfini portrait, painted in 1434, nineteen years before this sermon.

Firstly, this circular mirror is surrounded by the ten stations of Christ’s Passion, juxtaposed by a rosary, an explicit reference to God.

Secondly, it reveals a view of the entire room, an image that completely escapes the linear perspective of the foreground. A view comparable to the allcompassing « Vision of God » developed by Cusanus.

Finally, we see two figures in the mirror, but not the image of the painter behind his easel. These are undoubtedly the two witnesses to the wedding. Instead of signing his painting with « Van Eyck invent. », the painter signed his painting above the mirror with « Van Eyck was here » (NOTE 17), identifying himself as a witness.

As Dionysius the Aeropagite asserted:

« [the celestial hierarchy] transforms its adepts into so many images of God: pure and splendid mirrors where the eternal and ineffable light can shine, and which, according to the desired order, reflect liberally on inferior things this borrowed brightness with which they shine. » [Chap. III, 2]

The Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381) evokes a very similar image in his Spiegel der eeuwigher salicheit (Mirror of eternal salvation) when he says:

« Ende Hi heeft ieghewelcs mensche ziele gescapen alse eenen levenden spieghel, daer Hi dat Beelde sijnre natueren in gedruct heeft. » (And he created each human soul as a living mirror, in which he imprinted the image of his nature).

And so, like a polished mirror, Van Eyck’s soul, illuminated and living in God’s truth, acts as an illuminating witness to this union. (NOTE 18)

So, although the Flemish painters of the XVth century clearly had a solid scientific foundation, they choose such or such perspective depending on the idea they wanted to convey.

In essence, their paintings remain objects of theo-philosophical speculation or as you like « intellectual prayer », capable of praising the goodness, beauty and magnificence of a Creator who created them in His own image. By the very nature of their approach, their interest lay above all in the geometry of a kind of « paradoxical space-light » capable, through enigma, of opening us up to a participatory transcendence, rather than simply seeking to « represent » a dead space existing outside metaphysical reality.

The only geometry worthy of interest was that which showed itself capable of articulating this non-linearity, a « divine » or « mystical » perspective capable of linking the infinite beauty of our commensurable microcosm with the immeasurable goodness of the macrocosm.

Thank you,

NOTES:

- Recently, Italian scholars have pointed to the role of Biagio Pelacani Da Parma (d. 1416), a professor at the University of Padua near Venice, in imposing such a perspective, which privileged only the « geometrical laws of the act of vision and the rules of mathematical calculation ».

- Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, p.41-42, Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris, 1975.

- Institut de France, Manuscrit E, 16 v° « the eye [h] perceives on the plane wall the images of distant objects greater than that of the nearer object. »

- Leonardo understands that Albertian perspective, like anamorphosis, condemns the viewer to a single, immobile point of vision.

- See, for example, the slight enlargement of the apostles at the ends of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in the Milan refectory.

- Baxandall, Bartholomaeus Facius on painting, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 27, (1964). Fazio is also enthusiastic about a world map (now lost) by Jan van Eyck, in which all the places and regions of the earth are depicted recognizably and at measurable distances.

- To escape this fate, Pieter Bruegel the Elder used a cavalier perspective, placing his horizon line high up.

- Lionel Simonot, Etude expérimentale et modélisation de la diffusion de la lumière dans une couche de peinture colorée et translucide. Application à l’effet visuel des glacis et des vernis, p.9 (PhD thesis, Nov. 2002).

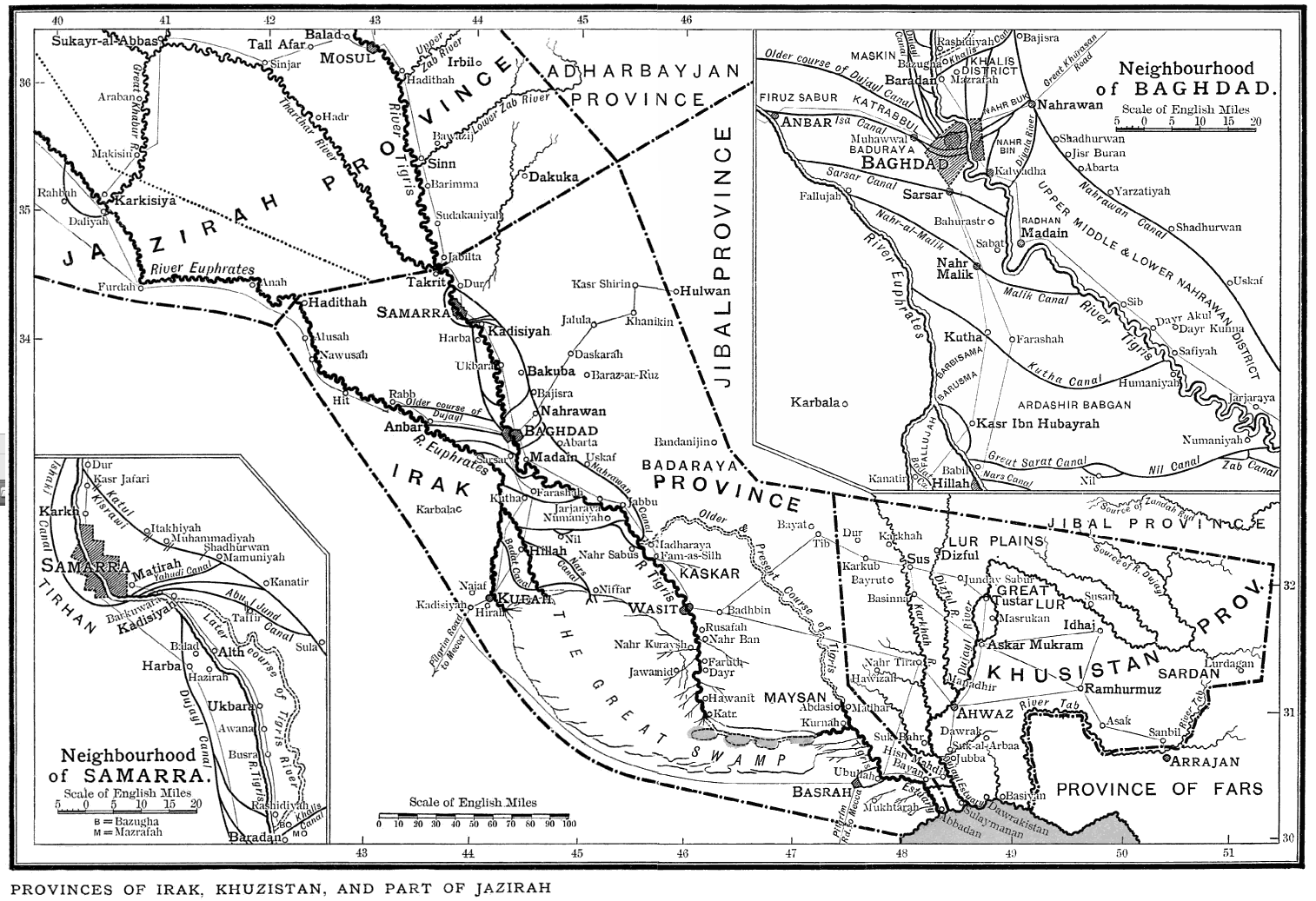

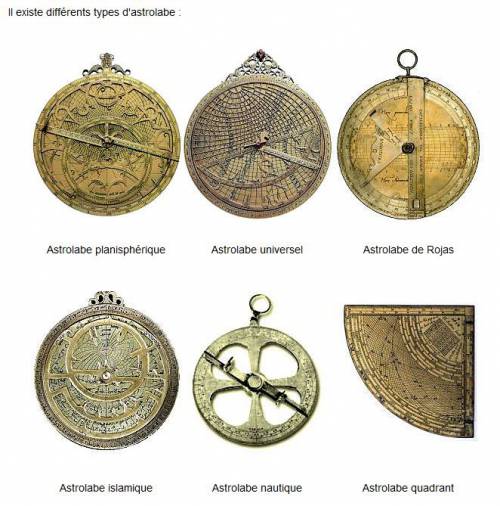

- Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) wrote some 200 works on mathematics, astronomy, physics, medicine and philosophy. Born in Basra, after working on the development of the Nile in Egypt, he travelled to Spain. He is said to have carried out a series of highly detailed experiments on theoretical and experimental optics, including the camera obscura (darkroom), work that was later to feature in Leonardo da Vinci’s studies. Da Vinci may well have read the lengthy passages by Alhazen that appear in the Commentari of the Florentine sculptor Ghiberti. According to Gerbert d’Aurillac (the future Pope Sylvester II in 999), Bishop of Rheims, brought back from Spain the decimal system with its zero and an astrolabe, it was thanks to Gerard of Cremona (1114-c. 1187) that Europe gained access to Greek, Jewish and Arabic science. This scholar went to Toledo in 1175 to learn Arabic, and translated some 80 scientific works from Arabic into Latin, including Ptolemy’s Almagest, Apollonius’ Conics, several treatises by Aristotle, Avicenna‘s Canon, and the works of Ibn Al-Haytam, Al-Kindi, Thabit ibn Qurra and Al-Razi.

- In the Arab world, this research was taken up a century later by the Persian physicist Al-Farisi (1267-1319). He wrote an important commentary on Alhazen’s Treatise on Optics. Using a drop of water as a model, and based on Alhazen’s theory of double refraction in a sphere, he gave the first correct explanation of the rainbow. He even suggested the wave-like property of light, whereas Alhazen had studied light using solid balls in his reflection and refraction experiments. The question was now: does light propagate by undulation or by particle transport?

- Meiss, M., Light as form and symbol in some fifteenth century paintings, Art Bulletin, XVIII, 1936, p. 434.

- Note also the fact that the canon shows a pair of glasses…

- Brion-Guerry in Jean Pèlerin Viator, sa place dans l’histoire de la perspective, Belles Lettres, 1962, p. 94-96, states in obscure language that « the object of representation behaves most often in Van Eyck as a cubic volume seen from the front and from the inside. Perspectival foreshortening is achieved by constructing a rectangle whose sides form the base of four trapezoids. The orthogonals thus tend towards four distinct points of convergence, forming a ‘vanishing region' ».

- Dominique Raynaud, L’Hypothèse d’Oxford, essai sur les origines de la perpective, PUF, Paris 1998.

- Witelo was a friend of the Flemish Dominican scholar Willem van Moerbeke, a translator of Archimedes in contact with Saint Thomas Aquinas. Moerbeke was also in contact with the mathematician Jean Campanus and the Flemish neo-Platonic astronomer Hendrik Bate van Mechelen. Johannes Kepler‘s own work on human vision builds on that of Witelo.

- Cusanus was above all a man of science and theology. But he was also a political organizer. The painter Jan van Eyck fought for the same goals, as evidenced by the ecumenical theme of the Ghent polyptych. It shows the Mystic Lamb, symbolizing the sacrifice of the Son of God for the redemption of mankind, capable of reuniting a church torn apart by internal differences. Hence the presence of the three popes in the central panel, here united before the lamb. Van Eyck also painted a portrait of Cardinal Niccolo Albergati, one of the instigators of the great Ecumenical Council organized by Cusanus in Ferrara and then moved to Florence. If Cusanus called Van der Weyden « his friend Roger », it is also thought that Robert Campin may have met him, since he would have attended the Council of Basel, as did one of his commissioners, the Franciscan theologian Heinrich Werl.

- Jan Van Eyck was one of the first painters in the history of art to date and sign his paintings with his own name.

- Myriam Greilsammer’s book L’Envers du tableau, Mariage et Maternité en Flandre Médiévale (Editions Armand Colin, 1990) documents Arnolfini’s sexual escapades. Arnolfini was taken to court by one of his victims, a female servant. Van Eyck seems to have understood that the knightly Arnoult Fin, Lucchese financier and commercial representative of the House of Medici in Bruges, required the somewhat peculiar presence of the eye of the lord.

The ancient practice of debt cancellation

While anyone with a modicum of rationality knows that a huge proportion of the world’s debts are absolutely unpayable, it’s a fact that today any debt cancellation, however odious or illegitimate, remains taboo.

By Karel Vereycken, December 2020.

Debt repayment is presented by heads of state and government, central banks, the IMF and the mainstream press as imperative, inevitable, indisputable, compulsory. Citizens have elected their governments, so they must resign themselves to paying the debt. For not to pay is more than violating a symbol: it is to exclude oneself from civilization, and to renounce in advance any new credit that is granted only to « good payers ». What counts is not the effectiveness of the act, but the expression of one’s « good faith », i.e. one’s willingness to submit to the strongest. The only possible discussion is how to modulate the distribution of the necessary sacrifices.

It seems that the ultra-liberal, monetarist model that has been surreptitiously imposed on us is that of the Roman Empire: zero debt for states and cities, and no debt forgiveness for citizens!

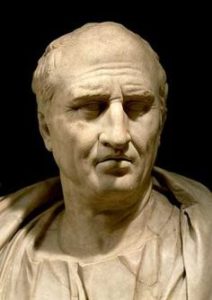

In his treatise on Duties (De officiis), written in 44-43, Cicero, who had just quelled a revolt by people demanding a debt remission, justifies the radical nature of his policy towards indebtedness:

« What does the establishment of new debt accounts [i.e., remission] mean, if not that you buy land with my money, that you have this land, and that I don’t have my money? That’s why we have to make sure there are no debts, which can harm the state. There are many ways of avoiding it, but if there are debts, not in such a way that the rich lose their property and the debtors acquire the property of others. Indeed, nothing maintains the State more strongly than good faith (fides), which cannot exist if there is no need to pay one’s debts. Never has anyone acted more forcefully to avoid paying their debts than under my Consulate. It was attempted by men of all kinds and ranks, with weapons in hand, and by setting up camps. But I resisted them in such a way that this entire evil was eliminated from the State. »

What has been carefully concealed is that another human practice has also existed: moratoria, partial and even generalized debt cancellations have taken place repeatedly throughout history and were carried out according to different contexts.

Often, proclamations of generalized debt cancellation were the initiative of self-preservation-minded rulers, aware that the only way to avoid complete social breakdown was to declare a « washing of the shelves » – those on which consumer debts were inscribed – cancelling them to start afresh.

The American anthropologist David Graeber, in Debt, the first 5000 years (2011), pointed out that the first word we have for « freedom » in any human language is Sumerian amargi, meaning freed from debt and, by extension, freedom in general, the literal meaning being « return to the mother » insofar as, once debts were cancelled, all debt slaves could return home.

Debt cancellations were sometimes the result of bitter social struggles, wars and crises. What is certain is that debt has never been a detail of history.

David Graeber sums it up:

« For millennia, the struggle between rich and poor has largely taken the form of conflicts between creditors and debtors – disputes over the justice or injustice of interest payments, peonage, amnesty, property seizure, restitution to the creditor, confiscation of sheep, seizure of vineyards and the sale of the debtor’s children as slaves. And over the last 5,000 years, with remarkable regularity, popular insurrections have begun in the same way: with the ritual destruction of debt registers – tablets, papyri, ledgers or other media specific to a particular time and place. (After which, the rebels generally attacked cadastres and tax registers.) »

And as the great ancient scholar Moses Finley was fond of saying,

« All revolutionary movements have had the same program: cancellation of debts and redistribution of land. »

Let us now examine some historical precedents for voluntary debt forgiveness.

Debt cancellation in Mesopotamia

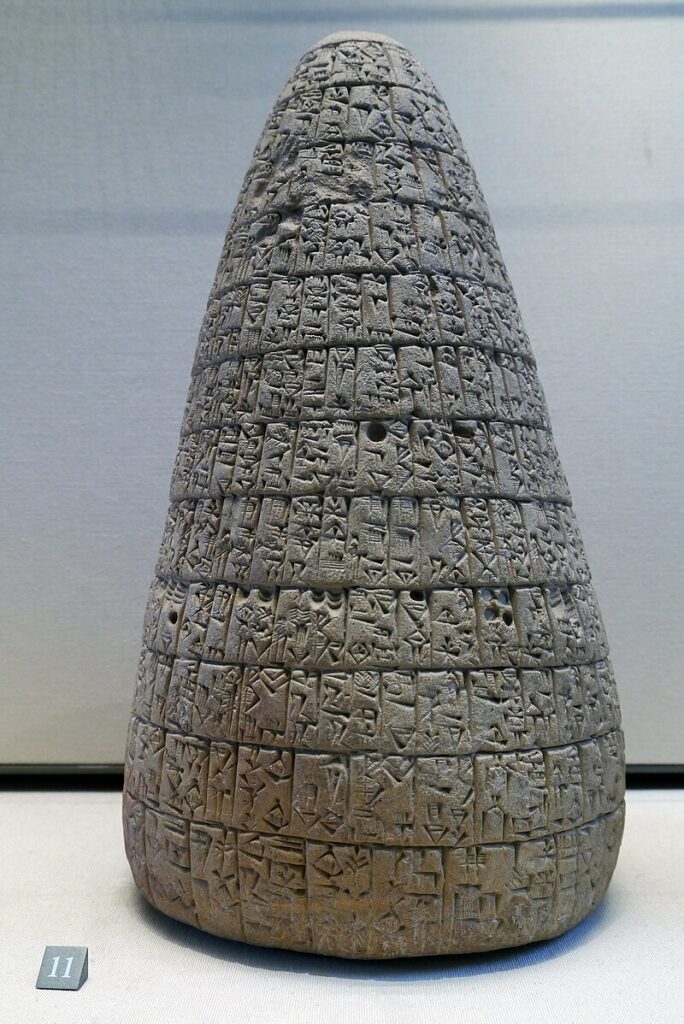

The earliest known debt cancellation was proclaimed in Mesopotemia by Entemena of Lagash c. 2400 BCE.

One of his successors, Urukagina, who was the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash, is known for his code of rules that includes debt cancelation.

Urukagina’s code is the first recorded example of government reform, seeking to achieve a higher level of freedom and equality by limiting the power of priesthood and a usurous land-owner oligarchy. Usury and seizure of property for debt payment were outlawed. « The widow and the orphan were no longer at the mercy of the powerful man ».

Similar measures were enacted by later Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian rulers of Mesopotamia, where they were known as « freedom decrees » (ama-gi in Sumerian).

This same theme exists in an ancient bilingual Hittite–Hurrian text entitled « The Song of Debt Release ».

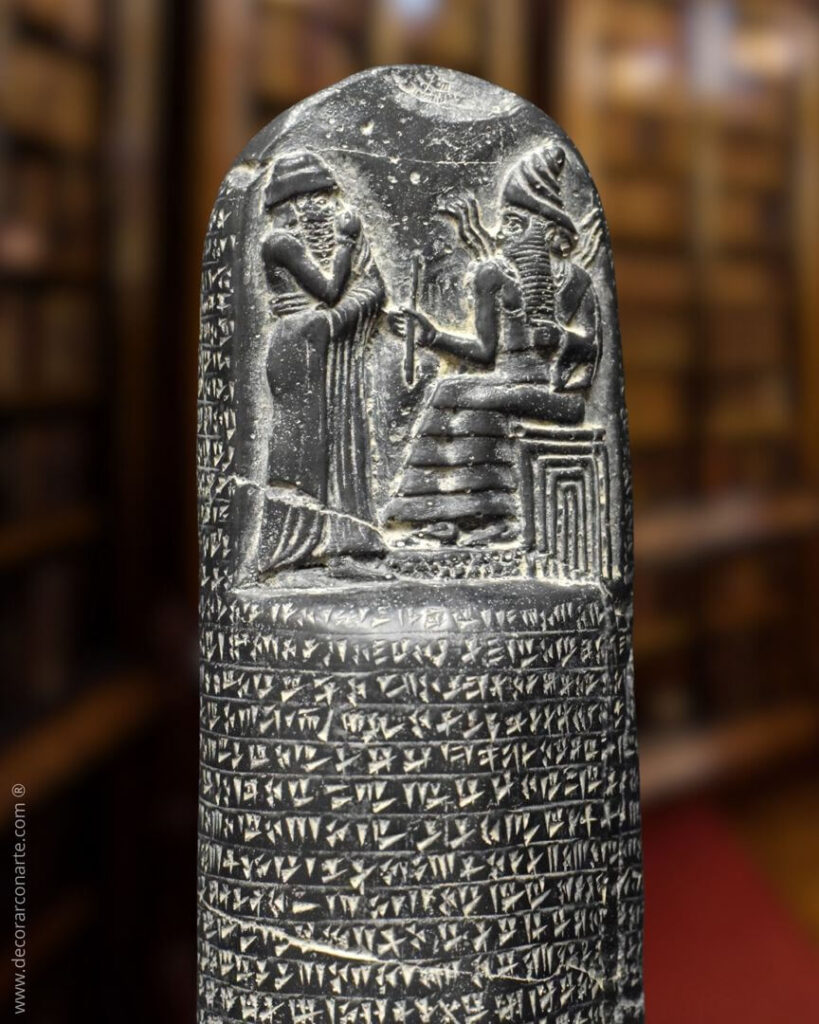

The reign of Hammurabi, King of Babylon (located in present-day Iraq), began in 1792 BC and lasted 42 years.

The inscriptions preserved on a 2-meter-high stele in the Louvre are known as the « Hammurabi Code ». It was placed in a public square in Babylon. If it is a long, very severe code of justice, prescribing the application of the law of retaliation (« an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth »), its epilogue nevertheless proclaims that « the powerful cannot oppress the weak, justice must protect the widow and the orphan (…) in order to render justice to the oppressed ».

Hammurabi, like the other rulers of the Mesopotamian city-states, repeatedly proclaimed a general cancellation of citizens’ debts to public authorities, their high officials and dignitaries.

Thanks to the deciphering of numerous documents written in cuneiform, historians have found indisputable evidence of four general debt cancellations during Hammurabi’s reign (at the beginning of his reign in 1792, in 1780, in 1771 and in 1762 BC).

Babylonian society was predominantly agricultural. The temple and palace, and the scribes and craftsmen they employed, depended for their sustenance on a vast peasantry from whom land, tools and livestock were rented.

In exchange, each farmer had to offer part of his production as rent. However, when climatic hazards or epidemics made normal production impossible, producers went into debt.

The inability of peasants to repay debts could also lead to their enslavement (family members could also be enslaved for debt).

The Hammurabi Code obviously wanted to change this. Article 48 of the Code of Laws states:

« Whoever owes a loan, and a storm buries the grain, or the harvest fails, or the grain does not grow for lack of water, need not give any grain to the creditor that year, he wipes the tablet of the debt in the water and pays no interest for that year. »

This ideal of justice is notably supported by the terms kittum, « justice as the guarantor of public order », and « justice as the restoration of equity. » It was asserted in particular during the « edicts of grace » (designated by the term mîsharum), a general remission of public and private debts in the kingdom (including the release of people working for another person to repay a debt).

Thus, to preserve the social order, Hammurabi and the ruling power, acting in their own interests and in the interests of society’s future, periodically agreed to cancel all debts and restore the rights of peasants, in order to save the threatened old order in times of crisis, or as a kind of reset at the beginning of a sovereign’s reign.

Proclamations of general debt cancellation are not confined to the reign of Hammurabi; they began long before him and continued afterwards. There is evidence of debt cancellations as far back as 2400 BC, six centuries before Hammurabi’s reign, in the city of Lagash (Sumer); the most recent date back to 1400 BC in Nuzi.

In all, historians have accurately identified some thirty general debt cancellations in Mesopotamia between 2400 and 1400 BC.

These proclamations of debt cancellation were the occasion for great festivities, usually during the annual spring festival. Under the Hammurabi dynasty, the tradition of destroying the tablets on which debts were written was established.

In fact, the public authorities kept precise accounts of debts on tablets kept in the temple. Hammurabi died in 1749 BC after a 42-year reign. His successor, Samsuiluna, cancelled all debts to the state and decreed the destruction of all debt tablets except those relating to commercial debts.

When Ammisaduqa, the last ruler of the Hammurabi dynasty, acceded to the throne in 1646 BC, the general cancellation of debts he proclaimed was very detailed. The aim was clearly to prevent certain creditors from taking advantage of certain families. The annulment decree stipulates that official creditors and tax collectors who have expelled peasants must compensate them and return their property, on pain of execution.

After 1400 BC, no deeds of debt cancellation have been found, as the tradition has been lost. Land was taken over by large private landowners, and debt slavery returned.

In Egypt

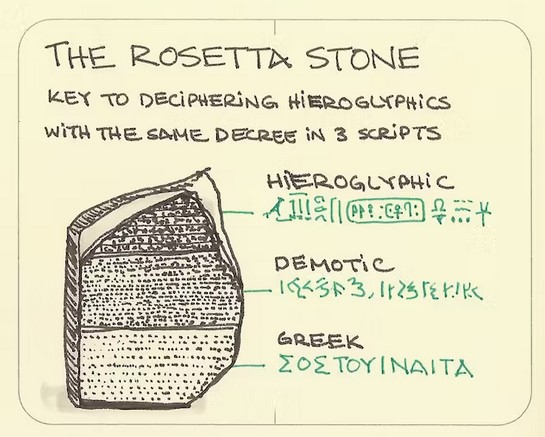

In Ancient Egypt interest-bearing debt did not exist for most of its history. When it started spreading in the Late Period, the rulers of Egypt regulated it and a number of debt remissions are known to have occurred during the Ptolemaic era, including the one whose proclamation was inscribed on the Rosetta Stone.

Now on display at the British Museum in London, the « Rosetta Stone » was discovered on July 15, 1799 at el-Rashid (Rosetta) by one of Napoleon’s soldiers during the Egyptian campaign. It contains the same text written in hieroglyphs, demotic (Egyptian cursive script) and Greek, giving Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) the key to the passage from one language to another.

This was a decree issued by Pharaoh Ptolemy V on March 27, 196 BC, announcing an amnesty for debtors and prisoners. The Greek Ptolemy dynasty that ruled Egypt institutionalized the regular cancellation of debts.

It was perpetuating known practices, since Greek texts mention that Pharaoh Bakenranef, who ruled Lower Egypt from c. 725 to 720 BC, had promulgated a decree abolishing debt slavery and condemning debt imprisonment.

TRANSCRIPTION OF THE PHARAOH’S DECREE

ON THE ROSETTA STONE:

Assembled the Chief Priests and Prophets there and those who enter the inner temple to worship the gods, and the Fanbearers and Sacred Scribes and all the other priests of the temples of the earth who have come to meet the king at Memphis, for the feast of the Assumption of PTOLEMEE, THE LIVING FOREVER, THE BELOVED OF PTAH, THE GOD EPIPHANES EUCHARISTOS, the successor of his father, All assembled in the temple of Memphis on this day when it was declared:

“that King PTOLEMEE, THE LIVING FOREVER, THE BELOVED OF PTAH, THE GOD EPIPHANES EUCHARISTOS, the son of King Ptolemy and Queen Arsinoe, the Philopator Gods, both benefactors of the temple and those who dwell therein, as well as their subjects, being a god from a god and the goddess loves Horus the son of Isis and Osiris who avenged his father Osiris by being favorably disposed towards the gods, delivered to the revenues of the temples silver and corn and undertook much expenditure for the prosperity of Egypt, and the maintenance of the temples, and was generous to all out of his own resources ;

“and exempted them from some of the revenues and taxes levied in Egypt and alleviated others so that his people and all others could be in prosperity during his reign ;

“and that he cleared the debts to the crown for many Egyptians and for the rest of the kingdom; ”

The existence of this decree therefore confirms that the practice had existed for many centuries.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (Ist Century BC) provides the following rationale for abolishing the debt bondage by Pharaoh Bakenranef:

« For it would be absurd… that a soldier, at the moment perhaps when he was setting forth to fight for his fatherland, should be haled to prison by his creditor for an unpaid loan, and that the greed of private citizens should in this way endanger the safety of all »

As one can see here, one of the very pragmatic reasons for debt cancellation was that the Pharaoh wanted to have a peasantry capable of producing enough food and, if need be, able to take part in military campaigns. For both of these reasons, it was important to ensure that peasants were not expelled from their lands under the thumb of creditors.

In another part of the region, the Assyrian emperors of the 1st millennium BC also adopted the tradition of debt cancellation.

In Greece: Solon of Athens

In Greece, the Athenian lawmaker Solon (c. 638 BC–558 BC), in order to rectify the widespread serfdom and slavery that had run rampant by the 6th century BCE, introduced a set of laws nown as the Seisachtheia introducing debt relief.

Before Solon, according to the account of the Constitution of the Athenians attributed to Aristotle, debtors unable to repay their creditors would surrender their land to them, then becoming hektemoroi, i.e. serfs who cultivated what used to be their own land and gave one sixth of produce to their creditors. However, should the debt exceed the perceived value of debtor’s total assets, then the debtor and his family would become the creditor’s slaves as well. The same would result if a man defaulted on a debt whose collateral was the debtor’s personal freedom. The fight for debt relief and the fight to abolish slavery were in practice identical.

Solon’s seisachtheia laws immediately cancelled all outstanding debts, retroactively emancipated all previously enslaved debtors, reinstated all confiscated serf property to the hektemoroi, and forbade the use of personal freedom as collateral in all future debts. The laws instituted a ceiling to maximum property size – regardless of the legality of its acquisition (i.e. by marriage), meant to prevent excessive accumulation of land by powerful families.

In the Torah and Old Testament

Social justice, particularly in the form of forgiving debts that shackle the poor to the rich, is a leitmotif in the history of Judaism. It was practiced in Jerusalem in the 5th century BC.

The writing of the Torah was completed at this time. Deuteronomy, 15 states:

The Year for Canceling Debts

15 At the end of every seven years you must cancel debts.

2 This is how it is to be done: Every creditor shall cancel any loan they have made to a fellow Israelite. They shall not require payment from anyone among their own people, because the Lord’s time for canceling debts has been proclaimed.

3 You may require payment from a foreigner, but you must cancel any debt your fellow Israelite owes you.

4 However, there need be no poor people among you, for in the land the Lord your God is giving you to possess as your inheritance, he will richly bless you,

5 if only you fully obey the Lord your God and are careful to follow all these commands I am giving you today.

6 For the Lord your God will bless you as he has promised, and you will lend to many nations but will borrow from none. You will rule over many nations but none will rule over you.

7 If anyone is poor among your fellow Israelites in any of the towns of the land the Lord your God is giving you, do not be hardhearted or tightfisted toward them.

8 Rather, be openhanded and freely lend them whatever they need.

9 Be careful not to harbor this wicked thought: “The seventh year, the year for canceling debts, is near,” so that you do not show ill will toward the needy among your fellow Israelites and give them nothing. They may then appeal to the Lord against you, and you will be found guilty of sin.

10 Give generously to them and do so without a grudging heart; then because of this the Lord your God will bless you in all your work and in everything you put your hand to.

11 There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore I command you to be openhanded toward your fellow Israelites who are poor and needy in your land.

Thus, the Israelites were obliged to free Hebrew slaves who had sold themselves to them for debt, and to offer them some of the produce of their small livestock, their fields and their wine presses, so that they would not return home empty-handed.

As the law is too rarely applied, Leviticus reaffirms it by modulating it:

The Year of Jubilee

8 “‘Count off seven sabbath years—seven times seven years—so that the seven sabbath years amount to a period of forty-nine years.

9 Then have the trumpet sounded everywhere on the tenth day of the seventh month; on the Day of Atonement sound the trumpet throughout your land.

10 Consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you; each of you is to return to your family property and to your own clan.

11 The fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you; do not sow and do not reap what grows of itself or harvest the untended vines.

12 For it is a jubilee and is to be holy for you; eat only what is taken directly from the fields.

13 “‘In this Year of Jubilee everyone is to return to their own property.

14 “‘If you sell land to any of your own people or buy land from them, do not take advantage of each other.

15 You are to buy from your own people on the basis of the number of years since the Jubilee. And they are to sell to you on the basis of the number of years left for harvesting crops.

16 When the years are many, you are to increase the price, and when the years are few, you are to decrease the price, because what is really being sold to you is the number of crops.

17 Do not take advantage of each other, but fear your God. I am the Lord your God.

Today, some will tell you that under these conditions, a year before the jubilee date, credit would necessarily be scarce and expensive, and that debt would thus find its limit!

This is a mistake, because to ensure that the law is followed, the codes describe in detail how purchases and sales of goods between private individuals must be carried out according to the number of years elapsed since the previous jubilee (i.e., the number of years remaining before the goods must be returned to their previous owner).

Another passage, this time from the prophet Jeremiah, vividly illustrates the scope of the law on the remission of debts.

Faced with the advance of enemy armies towards Jerusalem in 587 B.C., Jeremiah supports, in God’s name, the undertaking of King Zedekiah (then ruler of the Kingdom of Judea), who demands the immediate release of all those enslaved for debt from the powerful forces of his kingdom (Jer. 34:8-17).

Jeremiah forcefully recalls the ancient demand for the freeing of slaves… which the king, in fact, needs to patriotically reunite the social classes before the battle, and give himself sufficient troops free of all servile obligations!

A passage in the Book of (the prophet) Nehemiah (447 BC), the governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC), influenced by the ancient Mesopotamian tradition, also proclaims the cancellation of debts owed by indebted Jews to their rich compatriots.

The social situation Nehemiah discovered in Judea was appalling. To remedy the problem, Nehemiah placed the law of debt relief within a religious framework, the Covenant with Yahweh. From then on, it was God himself who commanded the forgiveness of debts and the liberation of slaves and their land, for the land belonged to God alone.

Nehemiah Helps the Poor

« Now the men and their wives raised a great outcry against their fellow Jews.

2 Some were saying, “We and our sons and daughters are numerous; in order for us to eat and stay alive, we must get grain.”

3 Others were saying, “We are mortgaging our fields, our vineyards and our homes to get grain during the famine.”

4 Still others were saying, “We have had to borrow money to pay the king’s tax on our fields and vineyards.

5 Although we are of the same flesh and blood as our fellow Jews and though our children are as good as theirs, yet we have to subject our sons and daughters to slavery. Some of our daughters have already been enslaved, but we are powerless, because our fields and our vineyards belong to others.”

6 When I heard their outcry and these charges, I was very angry.

7 I pondered them in my mind and then accused the nobles and officials. I told them, “You are charging your own people interest!” So I called together a large meeting to deal with them

8 and said: “As far as possible, we have bought back our fellow Jews who were sold to the Gentiles. Now you are selling your own people, only for them to be sold back to us!” They kept quiet, because they could find nothing to say.

9 So I continued, “What you are doing is not right. Shouldn’t you walk in the fear of our God to avoid the reproach of our Gentile enemies?

10 I and my brothers and my men are also lending the people money and grain. But let us stop charging interest!

11 Give back to them immediately their fields, vineyards, olive groves and houses, and also the money you are charging them—one percent of the money, grain, new wine and olive oil.”

12 “We will give it back,” they said. “And we will not demand anything more from them. We will do as you say.”

If we add to these passages the countless verses forbidding the lending of interest to fellow human beings and the taking of property as collateral, we get an idea of what the Israelites in the land of Canaan had put in place to try and maintain a certain social equilibrium.

Alas, in the first century AD, debt forgiveness and the freeing of slaves from debt were swept away from all Near Eastern cultures, including Judea.

The social situation there had deteriorated to such an extent that Rabbi Hillel was able to issue a decree requiring debtors to sign away their right to debt forgiveness.

In the Bible and New Testament

What happened to debt forgiveness in the New Testament?

While the Acts of the Apostles and the writings of the Fathers of the Church sometimes express a great docility, Jesus’ position on the forgiveness of debts, as reported repeatedly and most forcefully in Luke’s Gospel, chapter 4:16-21, appears to be marked by a revolutionary prophetic breath.

Luke places the passage at the beginning of Jesus’ public life. He makes it a key to everything that follows.

16 Jesus went to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, and on the Sabbath day he went into the synagogue, as was his custom. He stood up to read,

17 and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. Unrolling it, he found the place where it is written:

18 “The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

19 to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

20 Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him.

21 He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.”

Let’s not forget that the « year of the Lord’s favor (Jubilee Year) » to which he called, demanded at once rest for the land, forgiveness of debts and the liberation of slaves.

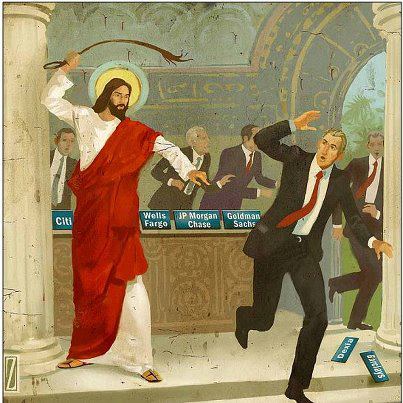

In the midst of the slave-owning Roman Empire, which fiercely rejected the concept of debt forgiveness, Jesus’ declaration could only be seen as a declaration of war on the ruling system.

Before he was arrested, Jesus made a highly symbolic material gesture: he forcefully overturned the tables of the money-changers in the Jerusalem temple. For the Jewish high priests and the Roman authorities, this was too much.

Peace of Westphalia of 1648

In 1648, after five years of negotiations, led by the French diplomat Abel Servien on the instructions of Cardinal Mazarin, the “Peace of Westphalia” was signed, putting an end to the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

Long before the UN Charter, 1648 made national sovereignty, mutual respect and the principle of non-interference the foundations of international law.

But there was more. As we have documented, the peace deal also included the cancelation of debts that had become the very reason for continuing the war.

Unpayable, unsustainable and illegitimate debts, interests, bonds, annuities and financial claims, explicitly identified as fueling a dynamic of perpetual war, were examined, sorted out and reorganized, most often through the cancellation of debts (articles 13 and 35, 37, 38 and 39), through moratoria or debt rescheduling according to specific timetables (article 69).

Article 40 concludes that debt cancellations will apply in most cases, “and yet the Sums of Money, which during the War have been exacted bona fide, and with a good intent, by way of Contributions, to prevent greater Evils by the Contributors, are not comprehended herein. » (Implying that these debts would have to be honored.)

Finally, looking to the future, for Commerce to be “reestablished”, the treaty abolished many tolls and customs established by “private” authorities for they were obstacles to the exchange of physical goods and know-how and hence to mutual development. (Art. 69 and 70).

TREATY OF WESTPHALIA (1648)

Art. 13:

“Reciprocally, the Elector of Bavaria renounces entirely for himself and his Heirs and Successors the Debt of Thirteen Millions, as also all his Pretensions in Upper Austria; and shall deliver to his Imperial Majesty immediately after the Publication of the Peace, all Acts and Arrests obtain’d for that end, in order to be made void and null.”

Art. 35:

“That the Annual Pension of the Lower Marquisate, payable to the Upper Marquisate, according to former Custom, shall by virtue of the present Treaty be entirely taken away and annihilated; and that for the future nothing shall be pretended or demanded on that account, either for the time past or to come.”

During the Cold War

In the United States, Eisenhower was elected in November 1952.

His Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, otherwise an evil man, noted that, despite the Marshall Plan, Europe, still burdened by a mountain of debt dating from before the First World War and the Treaty of Versailles, was unable to regain momentum.

So much so that it is in danger of turning to the USSR!

Action was called for. In 1953, under the leadership of German banker Hermann Abs, a former Deutsche Bank executive, a major conference was organized in London.

It was decided to write off 66% of Germany’s 30 billion marks in debt.

It was wisely agreed that annual repayments of German debt should never exceed 5% of export earnings. Those wishing to have their debts repaid by Germany should instead buy its exports, enabling it to honor its debts.

In other words, nothing like the madness recently imposed on Greece to « save » the euro!

Although this was done in the name of geopolitical principles, i.e. « in favor of some » but « against others », once again, it was in the name of a better future, i.e. a Europe capable of being the showcase of capitalism in the face of Moscow, that we were able to shed the weight of the past.

With Kondiaronk and Leibniz, re-inventing a society without oligarchy

By Karel Vereycken, May 2023.

Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the founder of the Schiller Institute, in her keynote address to the Schiller Institute’s Nov. 22, 2022 videoconference, “For World Peace—Stop the Danger of Nuclear War: Third Seminar of Political and Social Leaders of the World,” called on world leaders to eradicate the evil principle of oligarchy.

Oligarchy is defined as a power structure in which power rests with a small number of people having certain characteristics (nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, religious, political, or military control) and who impose their own power over that of their people.

To be precise, Zepp-LaRouche said :

“For 600 years, there has been a continuous battle between two forms of government, between the sovereign nation state and the oligarchical form of society, vacillating back and forth with sometimes a greater emphasis in this or that direction.

All empires based on the oligarchical model have been oriented towards protecting the privileges of the ruling elite, while trying to keep the masses of the population as backward as possible,

because as sheep they are easier to control (…)”

Now, unfortunately, most of the citizens of the transatlantic world and elsewhere will tell you that abolishing the oligarchical principle is “a good idea”, a “beautiful dream”, but that reality tells us “it can’t happen” for the very simple reason that “it never happened before”.

Societies, by definition, they argue, are in-egalitarian. Kings and Presidents of Republics, they argue, eventually might have “pretended” they ruled over the masses for their “common good”, but in reality, our fellow-citizens think, it was always the rule of a handful favoring their own interest over the majority.

The BRICS

Interesting for all of us, is that some leading thinkers involved in the BRICS movement, are trying to imagine new ways of collective rule excluding oligarchical principles.

For example, going in that direction, economist Pedro Paez, former advisor to Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, in his intervention at the April 15-16 Schiller Institute’s video conference, defended

“a new concept of currency based on monetary arrangements of clearing houses for regional payments, that can be joined into a world clearing house system, which could also prevent another type of unilateral, unipolar hegemony from arising, such as the one that was established with Bretton Woods, and that would instead open the doors to multipolar management”.

Also Belgian philosopher and theologian Marc Luyckx, a former member of the Jacques Delors famous taskforce « Cellule de Prospective » of the European Commission, in a video interview on the de-dollarization of the world economy, underlined that the BRICS countries are creating a world order whose nature makes it so that not a single member of their own group can become the dominant power.

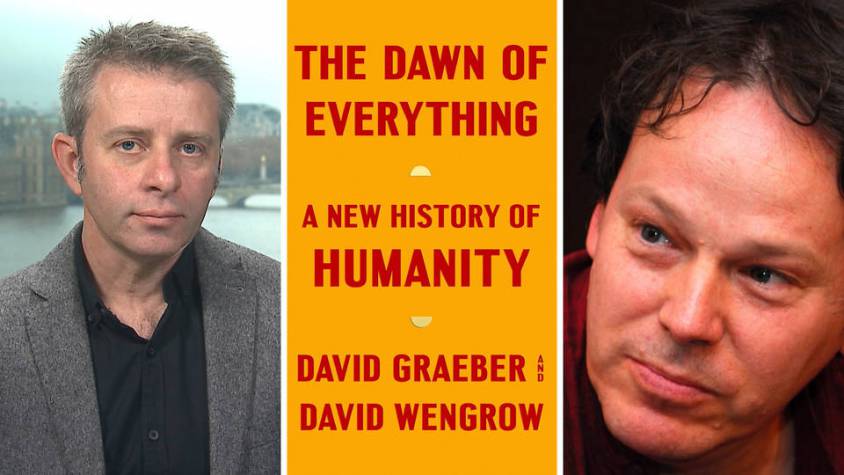

The Dawn of Everything

The good news is that a mind-provoking, 700-page book, titled “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity”, written and published in 2021 by the American anthropologist David Graeber and the British archaeologist David Wengrow, destroys the conventional notions of ancient human cultures making linear progress toward the neo-liberal economic model and therefore, by implication, high levels of inequality.

Even better, based on hard facts, the book largely debunks the “narrative” that oligarchical rule is somehow “natural”. Of course, the oligarchical principle ruled often and often for a long time. But, surprisingly, the book offers overwhelming indications and “hard facts” proving that in ancient times, some societies, though not all, which eventually prospered over centuries, through political choices, consciously adopted modes of governance preventing minority groups from permanently keeping a hegemonic grip over societies.

Zepp-LaRouche’s 10th point

The subject matter of this issue is intimately linked to the 10th point raised by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, which, in order to demonstrate that all sources of evil can be eradicated by education and political decision, that man’s natural inclination, is intrinsically to do the good. The very existence of historical precedents of societies surviving without oligarchy over hundreds of years, is of course, the “practical” proof of man’s axiomatic inclination to do the good.

Unsurprisingly, some argue that the issue of “good” and “evil” is nothing but a “theological debate”, since the concepts of “good” and “evil” are concepts made up by humans in order to compare themselves with one another. They argue it would never occur to anyone to argue about whether a fish, or a tree, were good or evil, since they lack any form of self-conscience enabling them to measure if their deeds and actions fulfill their own inclination or that of their creator.

Now, part of the “Biblical answer” to this question, if man is bad or evil, claims that people “once lived in a state of innocence”, yet were tainted by original sin. We desired to be godlike and have been punished for it; now we live in a fallen state while hoping for future redemption.

Overturning the evil Rousseau and Hobbes

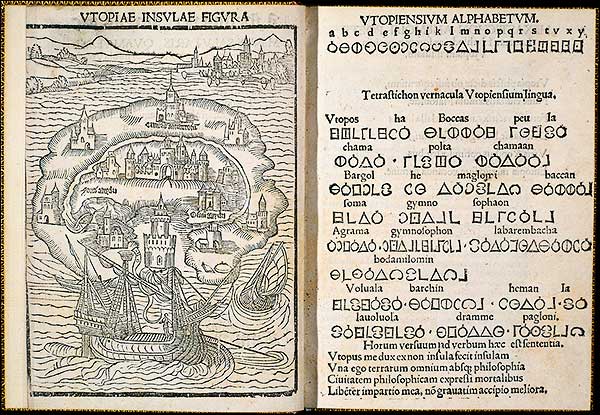

Graeber and Wengrow, establishing the core argument of their entire book, demonstrate in a very provocative way how we got brainwashed by the pessimistic and destructive oligarchical ideology, especially that promoted by both Rousseau and Hobbes, for whom inequality is the natural state of man, a humanity which might have eventually been good as “a noble savage”, before becoming “civilized” and a society only surviving thanks to a “social contract” (voluntary bottom-up submission) or a “Leviathan” (top down dictatorship) :

“Today, the popular version of this [biblical] story [of man thrown out of the Garden of Eden] is typically some updated variation on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind, which he wrote in 1754. Once upon a time, the story goes, we were hunter-gatherers, living in a prolonged state of childlike innocence, in tiny bands. These bands were egalitarian; they could be for the very reason that they were so small. It was only after the “Agricultural Revolution,” and then still more the rise of cities, that this happy condition came to an end, ushering in ‘civilization’ and ‘the state’—which also meant the appearance of written literature, science and philosophy, but at the same time, almost everything bad in human life: patriarchy, standing armies, mass executions and annoying bureaucrats demanding that we spend much of our lives filling in forms.

“Of course, this is a very crude simplification, but it really does seem to be the foundational story that rises to the surface whenever anyone, from industrial psychologists to revolutionary theorists, says something like ‘but of course human beings spent most of their evolutionary history living in groups of ten or twenty people,’ or ‘agriculture was perhaps humanity’s worst mistake.’ And as we’ll see, many popular writers make the argument quite explicitly. The problem is that anyone seeking an alternative to this rather depressing view of history will quickly find that the only one on offer is actually even worse: if not Rousseau, then Thomas Hobbes.

“Hobbes’s Leviathan, published in 1651, is in many ways the founding text of modern political theory. It held that, humans being the selfish creatures they are, life in an original State of Nature was in no sense innocent; it must instead have been ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’—basically, a state of war, with everybody fighting against everybody else. Insofar as there has been any progress from this benighted state of affairs, a Hobbesian would argue, it has been largely due to exactly those repressive mechanisms that Rousseau was complaining about: governments, courts, bureaucracies, police. This view of things has been around for a very long time as well. There’s a reason why, in English, the words ‘politics’ ‘polite’ and ‘police’ all sound the same—they’re all derived from the Greek word polis, or city, the Latin equivalent of which is civitas, which also gives us ‘civility,’ ‘civic’ and a certain modern understanding of ‘civilization.

“Human society, in this view, is founded on the collective repression of our baser instincts, which becomes all the more necessary when humans are living in large numbers in the same place. The modern-day Hobbesian, then, would argue that, yes, we did live most of our evolutionary history in tiny bands, who could get along mainly because they shared a common interest in the survival of their offspring (‘parental investment,’ as evolutionary biologists call it). But even these were in no sense founded on equality. There was always, in this version, some ‘alpha-male’ leader. Hierarchy and domination, and cynical self-interest, have always been the basis of human society. It’s just that, collectively, we have learned it’s to our advantage to prioritize our long-term interests over our short-term instincts; or, better, to create laws that force us to confine our worst impulses to socially useful areas like the economy, while forbidding them everywhere else

“As the reader can probably detect from our tone, we don’t much like the choice between these two alternatives. Our objections can be classified into three broad categories. As accounts of the general course of human history, they:

1) simply aren’t true;

2) have dire political implications and

3) make the past needlessly dull.”

As a consequence of the victory of imperial models of political power, the only accepted “narrative” of man’s “evolution”, automatically validating an oligarchical grip over society, is that which allows “confirming” the pre-agreed-upon dogma erected as immortal “truth”. And any historical findings or artifacts contradicting or invalidating the Rousseau-Hobbes narrative will be, at best, declared anomalies.

Open our eyes

Graeber and Wengrow’s book is an attempt

“to tell another, more hopeful and more interesting story; one which, at the same time, takes better account of what the last few decades of research have taught us. Partly, this is a matter of bringing together evidence that has accumulated in archaeology, anthropology and kindred disciplines; evidence that points towards a completely new account of how human societies developed over roughly the last 30,000 years. Almost all of this research goes against the familiar narrative, but too often the most remarkable discoveries remain confined to the work of specialists, or have to be teased out by reading between the lines of scientific publications.”

To give just a sense of how different the emerging picture is:

“[I]t is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory. Agriculture, in turn, did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies. And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers,

ambitious warrior-politicians, or even bossy administrators.”

Kondiaronk, Leibniz and the Enlightenment

In fact, Rousseau’s story, argue the authors, was in part a response to critiques of European civilization, which began in the early decades of the 18th century. “The origins of that critique, however, lie not with the philosophers of the Enlightenment (much though they initially admired and imitated it), but with indigenous commentators and observers of European society, such as the Native American (Huron-Wendat) statesman Kondiaronk,” and many others.

And when prominent thinkers, such as Leibniz, “urged his patriots to adopt Chinese models of statecraft, there is a tendency for contemporary historians to insist they weren’t really serious”.

However, many influential Enlightenment thinkers did in fact claim that some of their ideas on the subject of inequality were directly taken from Chinese or Native American sources!

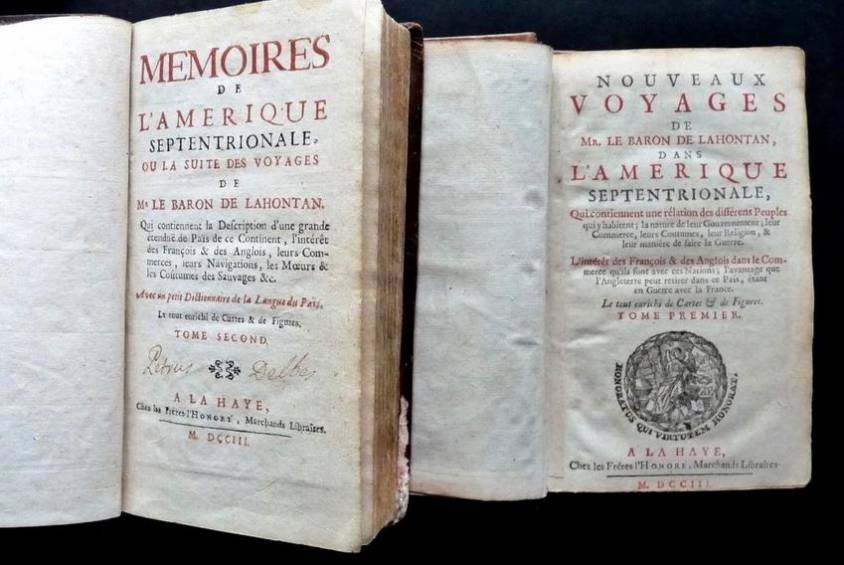

Just as Leibniz became familiar with Chinese civilization through his contact with the Jesuit missions, the ideas from Native Americans reached Europe by way of books such as the widely read seventy-one-volume report The Jesuit Relations, published between 1633 and 1673.

While today, we would think personal freedom is a good thing, this was not the case for the Jesuits complaining about the Native Americans. The Jesuits were opposed to freedom in principle:

“This, without doubt, is a disposition quite contrary to the spirit of the Faith, which requires us to submit not only our wills, but our minds, our judgments, and all the sentiments of man

to a power unknown to the laws and sentiments of corrupt nature.”

Jesuit father Jérôme Lallemant, whose correspondence provided an initial model for The Jesuit Relations, noted of the Wendat Indians in 1644: “I do not believe that there is a people on earth freer than they, and less able to allow to the subjection of their wills to any power whatever”.

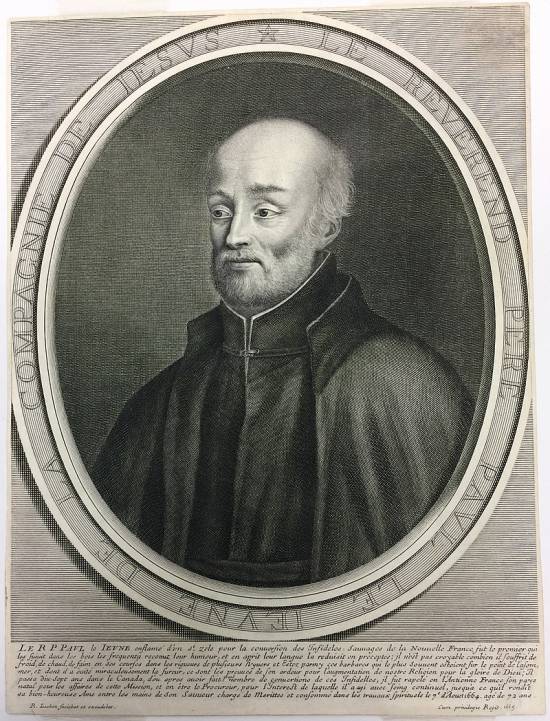

Even more worrisome, their high level of intelligence. Father Paul Le Jeune, Superior of the Jesuits in Canada in the 1630:

“There are almost none of them incapable of conversing or reasoning very well, and in good terms, on matters within their knowledge. The councils, held almost every day in the Villages, and on almost all matters, improve their capacity for talking”.

Or in Lallemant’s words:

“I can say in truth that, as regards intelligence, they are in no ways inferior to Europeans and to those who dwell in France. I would never have believed that, without instruction, nature could have supplied a most ready and vigorous eloquence, which I have admired in many Hurons (American Natives); or more clear-nearsightedness in public affairs, or a more discreet management in things to which they are accustomed”.

(The Jesuit Relations, vol. XXVIII, p. 62.)

Some Jesuits went much further, noting – not without a trace of frustration – that New World “savages” seemed rather cleverer overall than the people they were used to dealing with at home.

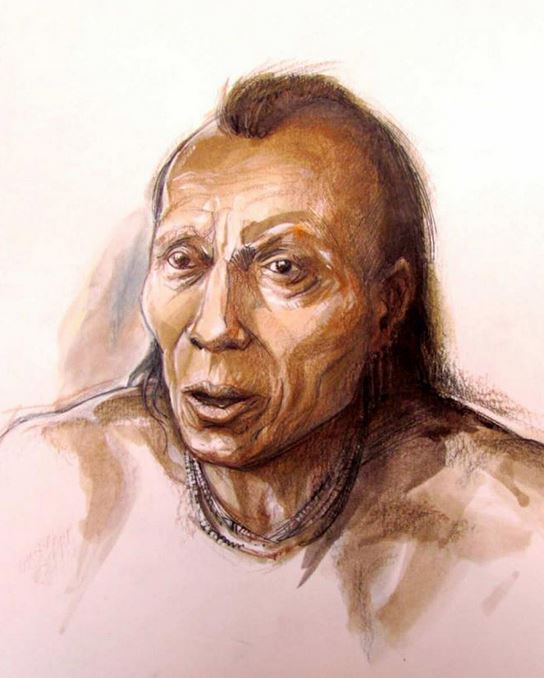

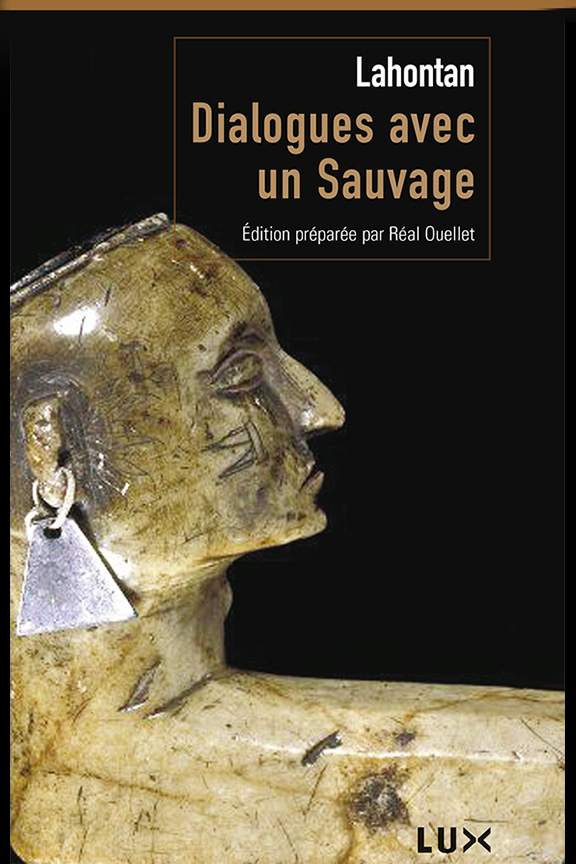

The ideas of Native Indian statesman Kondiaronk (c. 1649–1701), known as “The Rat” and the Chief of the Native American Wendat people at Michilimackinac in New France, reached Leibniz via an impoverished French aristocrat named Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de la Hontan, better known as Lahontan.

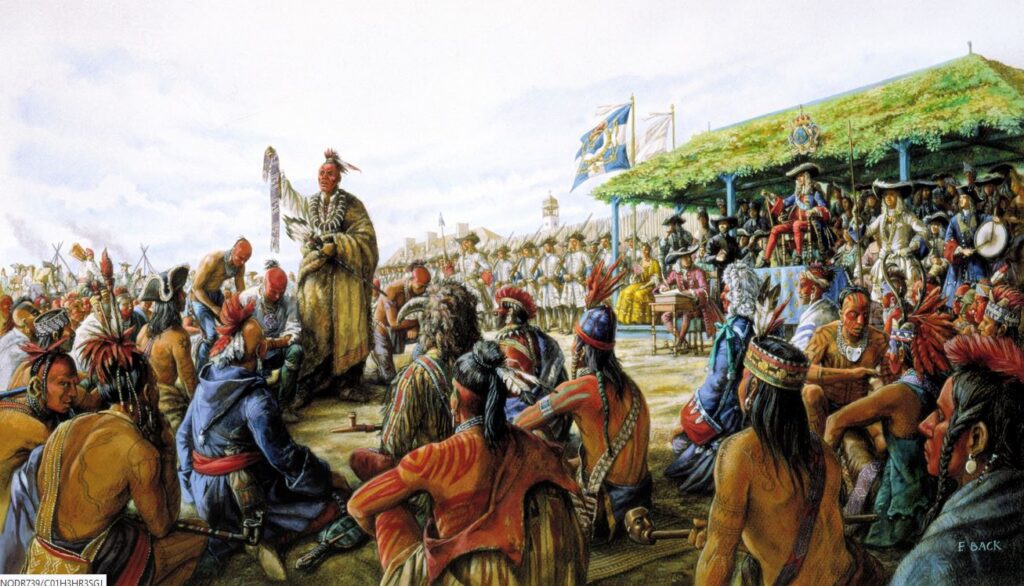

In 1683, Lahontan, age 17, joined the French army and was posted in Canada. In his various missions, he became fluent in both Algonkian and Wendat and good friends with a number of indigenous political figures, including the brilliant Wendat statesman Kondiaronk. The latter impressed many French observers with his eloquence and brilliance and frequently met with the royal governor, Count Louis de Buade de Frontenac. Kondiaronk himself, as Speaker of the Council (their governing body) of the Wendat Confederation, is thought to have been sent as an ambassador to the Court of the French King, Louis XIV, in 1691.

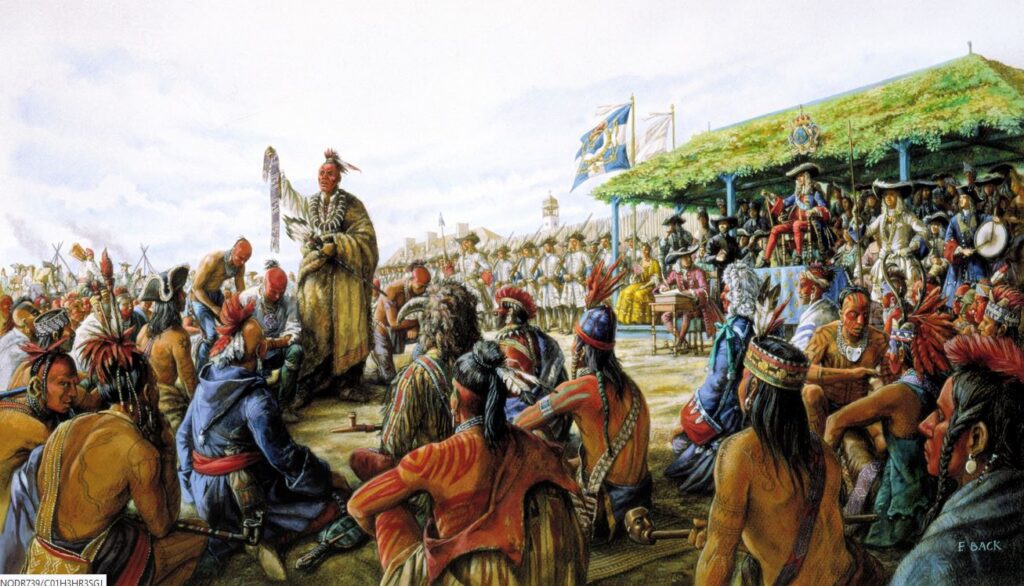

The Great Peace of Montreal

Even after being betrayed by the French, and obliged to conduct his own wars to secure his fellow men, Kondiaronk, played a key role in what is remembered as the “Great Peace of Montreal” of August 1, 1701, which ended the bloody Beaver Wars, in reality proxy wars between the British and the French, each of them using the native Indians as “cannon fodder” for their own geopolitical schemes

France was increasingly cornered by the British. Therefore, at the request of the French, in the summer of 1701, more than 1,300 Indians, from forty different nations, gathered near Montreal, dispite the fact that the city was ravaged by influenza. They came from the Mississippi Valley, the Great Lakes, and Acadia. Many were lifelong enemies, but all had responded to an invitation from the French governor. Their future and the fate of the colony were at stake. Their goal was to negotiate a comprehensive peace, among themselves and with the French. The negotiations dragged on for days, and peace was far from being guaranteed. The chiefs were wary. The main stumbling block to peace was the return of prisoners who had been captured during previous campaigns and enslaved or adopted.

Without Kondiaronk’s support, peace was unattainable. On August 1, seriously ill, he spoke for two hours in favor of a peace treaty that would be guaranteed by the French. Many were moved by his speech. The following night, Kondiaronk died, struck down by influenza at the age of 52.

But the next day, the peace treaty was signed. From now on there would be no more wars between the French and the Indians. Thirty-eight nations signed the treaty, including the Iroquois. The Iroquois promised to remain neutral in any future conflict between the French and the Iroquois’ former allies, the English colonists of New England.

Kondiaronk was praised by the French and presented as a “model” of peace-loving natives. The Jesuits immediately put out the lie that, just before dying, he had “converted” to the Catholic faith in the hope other natives would follow his model.

Lahontan from Amsterdam to Hanover

Now, following various events, Lahontan ended up in Amsterdam. In order to make a living he wrote a series of books about his adventures in Canada, the third one entitled Curious Dialogues with a Savage of Good Sense Who Has Travelled (1703), comprising four dialogues with a fictional figure, “Adario” (in reality Kondiaronk), which were rapidly translated into German, Dutch, English, and Italian. Lahontan, himself, gaining some sort of celebrity, settled in Hannover, where he befriended the great philosopher and scientist Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz.

On the lookout for everything that was being discussed in Europe, the philosopher, then 64 years old, seems to have been put on the track of Lahontan by Dutch and German journalists, but also by the text of an obscure theologian from Helmstedt, Conrad Schramm, whose introductory lecture, the « The Stammering Philosophy of the Canadians », had been published in Latin in 1707. Referring first to Plato and Aristotle (which he abandoned almost immediately), Schramm used the Dialogues and the Memoirs of Lahontan to show how the « Canadian barbarians knock on the door of philosophy but do not enter because they lack the means or are locked into their customs”.

Far less narrow-minded, Leibniz saw in Lahontan a confirmation of his own political optimism, which allowed him to affirm that the birth of society does not come from the need to get out of a terrible state of war, as Thomas Hobbes believed, but from a natural aspiration to concord.

But what captured his main interest, was not so much whether the “American savages” were capable, or not, of philosophizing, but whether they really lived in concord without government.

To his correspondent Wilhelm Bierling, who asked him how the Indians of Canada could live “in peace although they have neither laws nor public magistracies [tribunals]”, Leibniz replied:

“It is quite true […] that the Americans of these regions live together without any government but in peace; they know neither fights, nor hatreds, nor battles, or very few, except against men of different nations and languages.

I would almost say that this is a political miracle,

unknown to Aristotle and ignored by Hobbes.”

Leibniz, who claimed to know Lahontan well, underlined that Adario, “who came in France a few years ago and who, even if he belongs to the Huron nation, judged its institutions superior to ours.”

This conviction of Leibniz will be expressed again in his Judgment on the works of M. le Comte Shaftesbury, published in London in 1711 under the title of Charactersticks:

« The Iroquois and the Hurons, savages neighboring New France and New England, have overturned the too universal political maxims of Aristotle and Hobbes. They have shown, by their super-prominent conduct, that entire peoples can be without magistrates and without quarrels, and that consequently men are neither sufficiently motivated by their good nature, nor sufficiently forced by their wickedness to provide themselves with a government and to renounce their liberty. But these savages shows that it is not so much the necessity, as the inclination to go to the best and to approach felicity, by mutual assistance, which makes the foundation of societies and states; and it must be admitted that security is the most essential point”.

While these dialogues are often downplayed as fictional and therefore merely invented for the sake of literature, Leibniz, in a letter to Bierling dated November 10, 1719, responded: « The Lahontan’s Dialogues, although not entirely true, are not completely invented either.”

As a matter of fact, Lahontan himself, in the preface to the dialogues, wrote:

“When I was in the village of this [Native] American, I took on the agreeable task of carefully noting all his arguments. No sooner had I returned from my trip to the Canadian lakes than I showed my manuscript to Count Frontenac, who was so pleased to read it that he made the effort to help me put these Dialogues into their present state.”

People today tend to forget that tape-recorders weren’t around in those days.

For Leibniz, of course, political institutions were born of a natural aspiration to happiness and harmony. In this perspective, Lahontan’s work does not contribute to the construction of a new knowledge; it only confirms a thesis Leibniz had already constituted.

A critical view on the Europeans and the French in particular

Hence, Lahontan, in his memoirs, says that Native Americans, such as Kondiaronk, who had been in France,

“were continually teasing us with the faults and disorders they observed in our towns, as being occasioned by money. There’s no point in trying to remonstrate with them about how useful the distinction of property is for the support of society: they make a joke of everything you say on that account. In short, they neither quarrel nor fight, nor slander one another; they scoff at arts and sciences, and laugh at the difference of ranks which is observed with us. They brand us for slaves, and call us miserable souls, whose life is not worth having, alleging that we degrade ourselves in subjecting ourselves to one man [the king] who possesses all power, and is bound by no law but his own will.”

Lahontan continues:

“They think it unaccountable that one man should have more than another,

and that the rich should have more respect than the poor.

In short, they say, the name of savages, which we bestow upon them, would fit ourselves better,

since there is nothing in our actions that bears an appearance of wisdom.”

In his dialogue with Kondiaronk, Lahontan tells him that if the wicked remained unpunished, we would become the most miserable people of the earth. Kondiaronk responds:

“For my part, I find it hard to see how you could be much more miserable than you already are. What kind of human, what species or creature, most Europeans be, that they have to be forced to do the good, and only refrain from evil because of fear of punishment?… You have observed we lack judges. What is the reason for that? Well, we never bring lawsuits against one another. And why do we never bring lawsuits? Well because we made a decision neither to accept or make use of money. And why do we refuse to allow money in our communities? The reason is this: we are determined not to have laws – because, since the world was a world, our ancestors have been able to live contentedly without them.”

Brother Gabriel Sagard, a French Recollect Friar, reported that the Wendat people were particularly offended by the French lack of generosity to one another:

“They reciprocate hospitality and give such assistance to one another that the necessities of all are provided for without there being any indigent beggar in their towns and villages;

and they considered it a very bad thing when they heard it said

that there were in France a great many of these needy beggars,

and thought that this was for lack of charity in us, and blamed us for it severely”.

Money, thinks Kondiaronk, creates an environment that encourages people to behave badly: