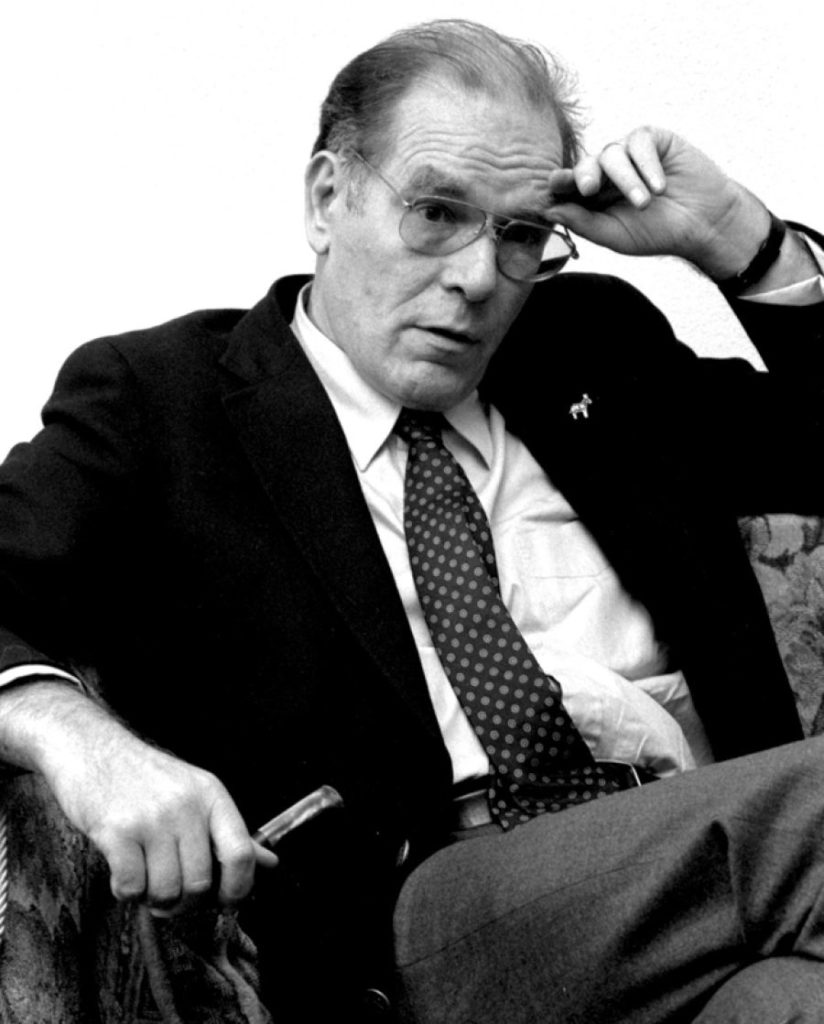

Étiquette : Erasmus

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Why Vermeer was hiding his convictions

Listen:

To the audio on this website

Read:

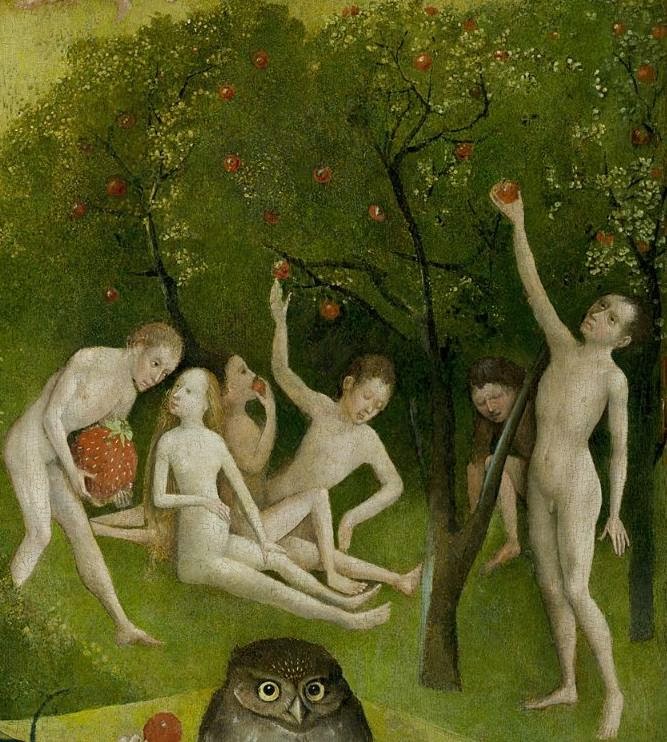

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: How Bosch’s Ship of Fools drove the Jester out of business

Liste:

To the audio on this website;

Read:

- With Hieronymous Bosh on the track of the Sublime;

- Comment la folie d’Erasme sauva notre civilisation (FR en ligne) + NL pdf (Agora Erasmus) + EN pdf (Schiller Institute Archive Website) + DE pdf (Neue Solidarität).

- Le rêve d’Erasme: le Collège des Trois Langues de Louvain (FR en ligne)

- Erasmus‘ dream: the Leuven Three Language College (EN online)

- ENTRETIEN: Jan Papy: Erasme, le grec et la Renaissance des sciences (FR en ligne)

- Dirk Martens, l’imprimeur d’Erasme qui diffusa le livre de poche (FR en ligne).

- 1512-2012 : Mercator et Frisius, des cosmographes aux cosmonautes + NL pdf (Agora Erasmus) + EN pdf (Schiller Institute Archive Website).

- La nef des fous de Sébastian Brant (FR en ligne), un livre d’une grande actualité !

- Avec Jérôme Bosch sur la trace du Sublime (FR en ligne) + EN pdf.

- Joachim Patinir et l’invention du paysage en peinture (FR en ligne).

- Joachim Patinir and the invention of landscape painting (EN online)

- Exposition de Lille : ce que nous apprennent les fabuleux paysages flamands (FR en ligne).

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

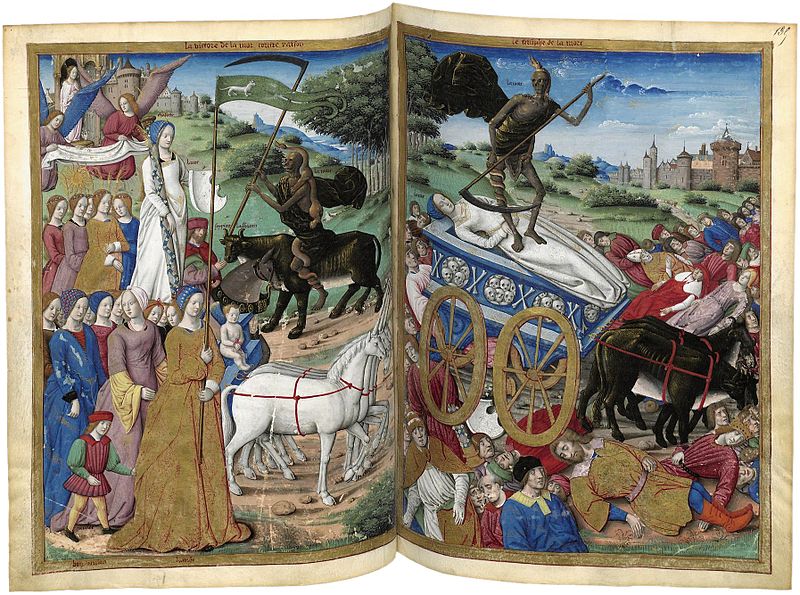

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

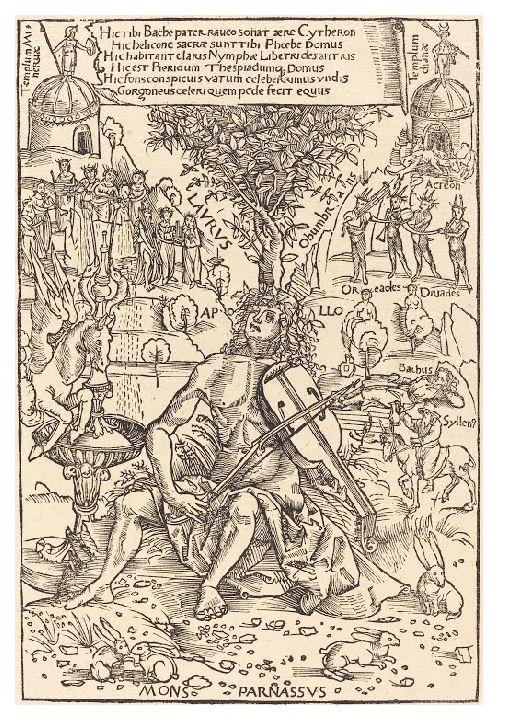

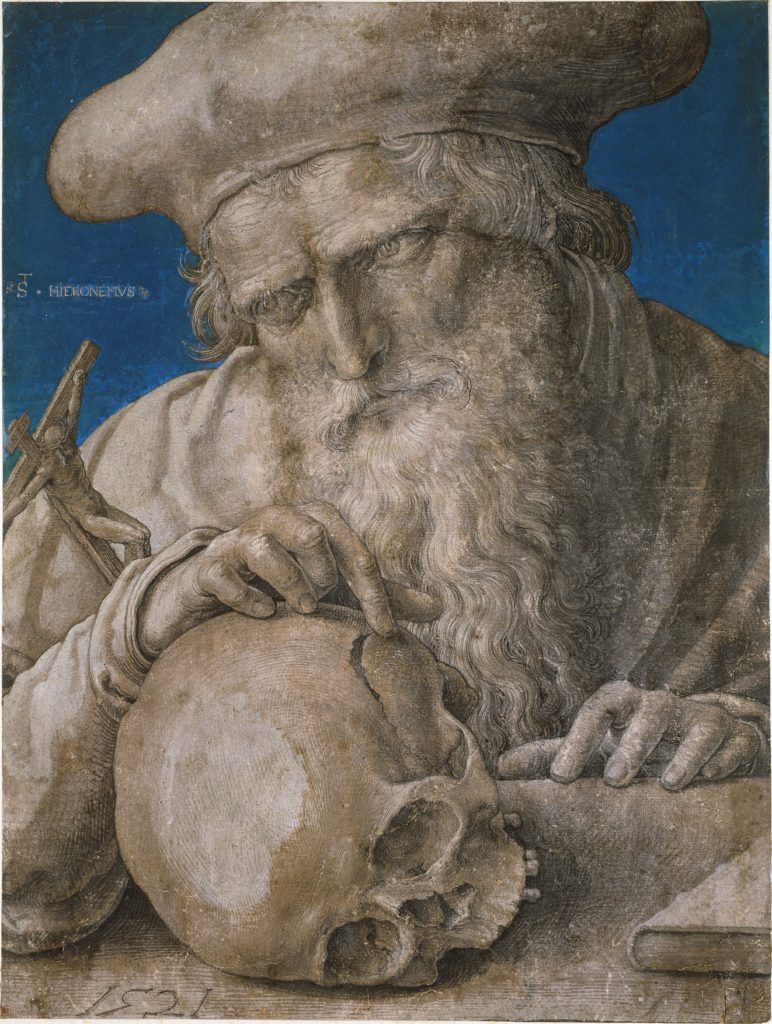

- Albrecht Dürer contre la mélancolie néo-platonicienne + EN pdf.

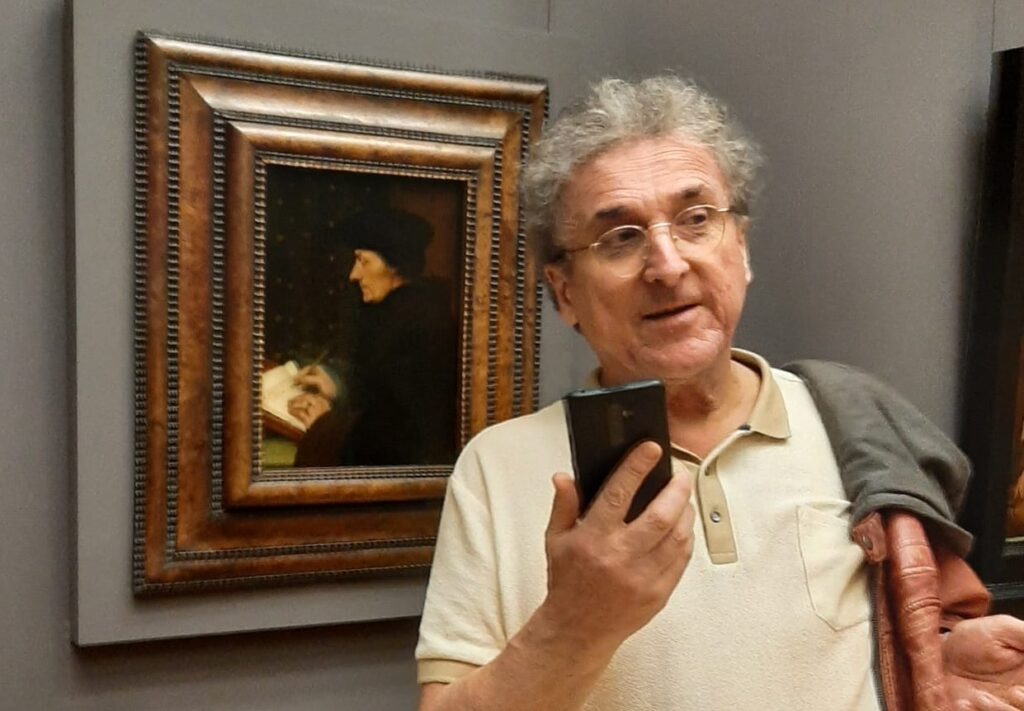

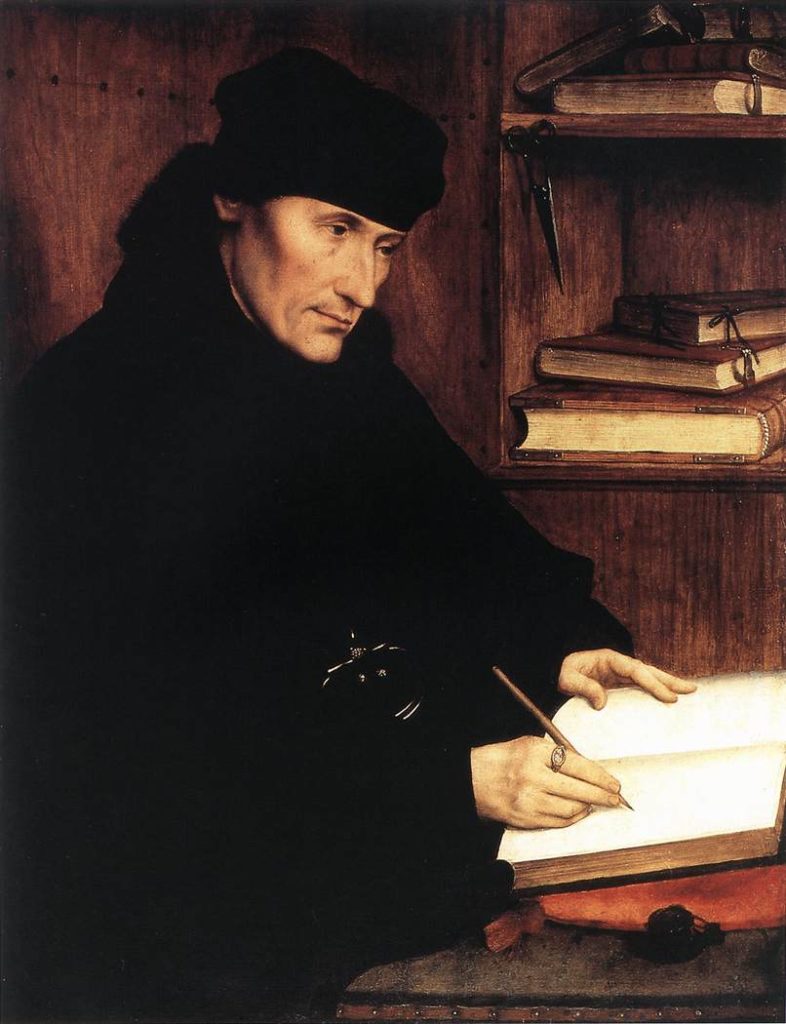

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Why Erasmus had no time to pause for portraits

Rembrandt: 400 years old and still young!

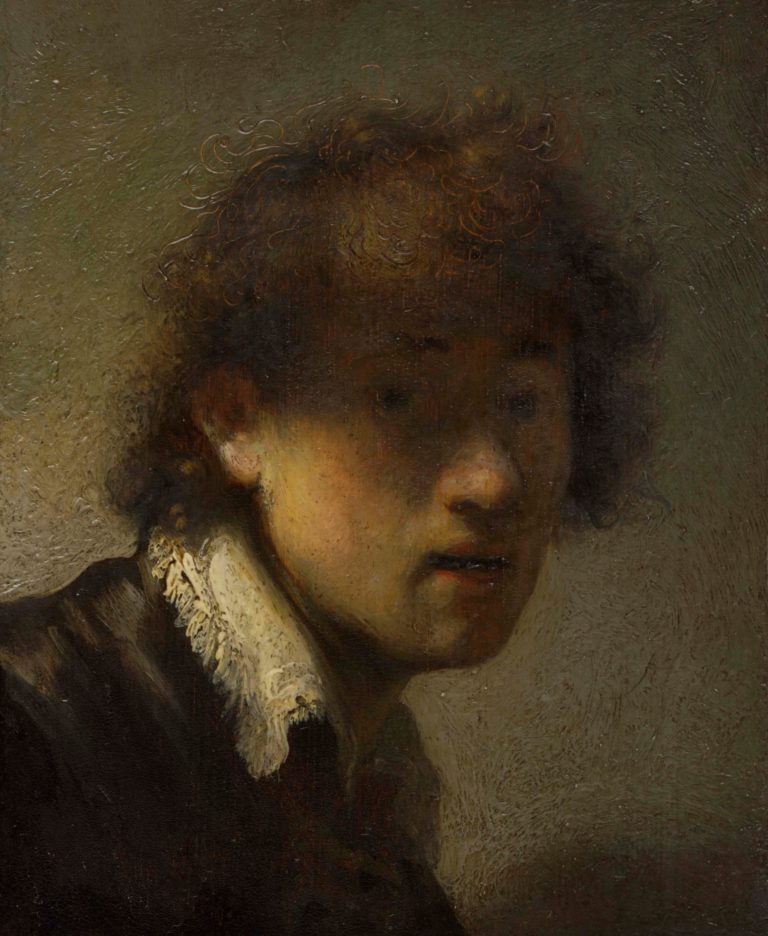

Rembrandt H. van Ryn, was born on July 15, 1606, as the son of a not so poor miller living in the revolutionary city of Leyden in the Netherlands.

Today (2006), four hundred years later, even without any knowledge of the specific historical context, few are those that remain indifferent to his artistic message and skill. Why Rembrandt? What particular quality of his paintings, engravings and drawings gave him the power to reach over centuries of time?

As we will document here, Rembrandt, a precocious intellectual, became already quite « universal » as a young adult. But let’s try to find out what « universal » means.

The Revolt of the Netherlands

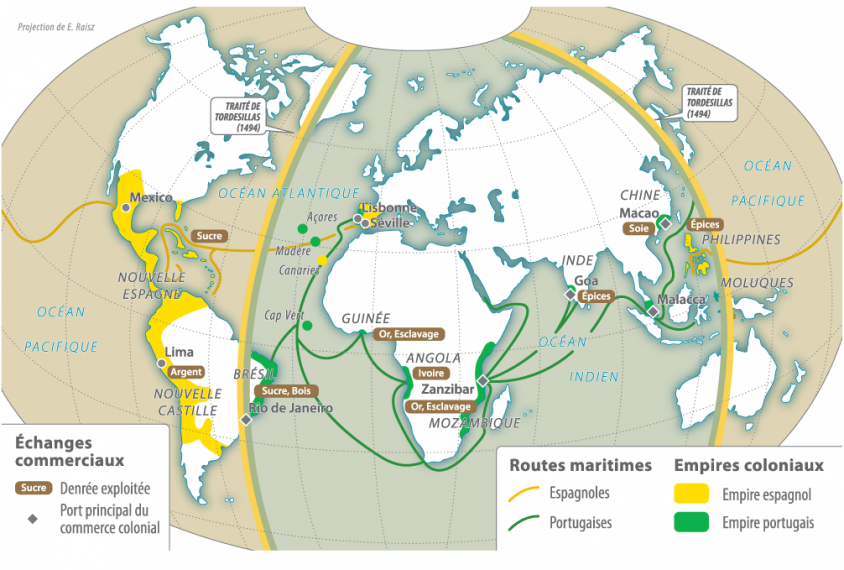

The revolt of the Burgundian Netherlands (Note 1) against the tyranny the Fuggers, bankers at the helm of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburg empire, resulted in the tragic break-up of this « nation-state in the making » between the north (today’s Netherlands) and the south (the territory that today includes Belgium and part of northern France).

The Habsburg empire, while brutally sticking to the rich southern part (Flanders), cynically offered the « insurgents » that, if they wished to have a country, they could settle in the malaria-infested swamps of the North, where 75% of the territory lies below sea level, but nevertheless an area slowly domesticated by generations of hardworking farmers thanks to a vast system of canals, dikes and locks, patiently erected since the end of the thirteenth century.

But Charles V, and even worse, his son Philip II of Spain, didn’t believe in the power of mind or that of work. Instead, they believed in the power of the sword and the terror of the Inquisition. After a long war and much unnecessary bloodshed, their policies had reached an impasse, and on April 9, 1609, the semi-bankrupt Habsburgs were forced to sign a twelve-year truce with the new Republic of the Netherlands.

Education

That same year, Rembrandt, hardly 3 years old, entered basic school, where girls and boys learn to read, to write and to calculate. School opens at 6 a.m. in the summer, at 7 a.m. in winter, and finishes only at 7 p.m. Classes start with prayer, the reading and discussion of passages of the Bible and the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt develops an elegant handwriting and more than rudiments of the Bible.

The Netherlands want to survive. Its leaders wisely used the 12 year truce (1609-1621) to fulfill their commitment to the general welfare. This way, early XVIIth century Holland became maybe the first country of the world where everybody got the chance to learn how to read, write and calculate.

That universal school system, whatever its inadequacies, offered to both poor and rich alike, was the secret of the Dutch « Golden Century ». It’s schooling will also create the generations of Dutch immigrants that will participate a hundred years afterwards in the American Revolution

Others would enter the secondary school at the age of 12, but Rembrandt precociously enters Leyden’s Latin School at the age of 7. There, pupils generally, besides rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn, not only Greek and Latin, but English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, since no age limit in the Netherlands bridled young talents, Rembrandt inscribed at the Leyden University. His choice is not Theology, Law, Science, nor Medicine, but Literature.

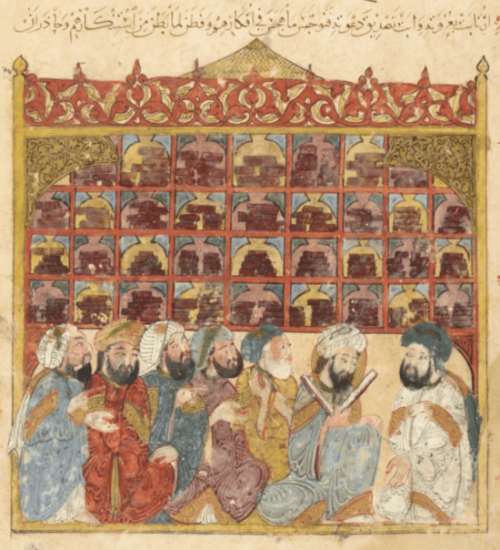

Did Rembrandt want to add to his knowledge of Latin, the mastery of Greek and Hebrew philology and perhaps Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Leyden was already publishing Arabic-Latin dictionaries, while the Netherlands were increasingly growing to become the book printing centre of the world.

From its foundation in 1585, after a historic battle for the city’s freedom, Leyden University became a rallying point for humanists worldwide and a center for new discoveries in optics, physics, anatomy and cartography, offering the world such famous scientists as Christian Huygens (1629-1695) and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), both correspondents of Leibniz.

People flocked in from Flanders, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, England and even Hungary. By 1621, over fifty Frenchmen were teaching in Leyden. In a desperate effort to pollute this source of creativity, in 1630, René Descartes registered as a « mathematician » at the University of Leyden. (Note 2)

But the big trouble had already started way before. A disastrous theological « debate » degenerated into a conflict akin to civil war. On the one side, Jacob Arminius, founder of the « Remonstrant » current upholding the Erasmian-Rabelaisian concept of man endowed with a free will although that free will remained to be fine-tuned with the grace of God. This view was also held by the elder general and capable national leader, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547-1619).

On the opposing side, one Franciscus Gomarus, defender of the fatalist Calvinist doctrine of « predestination », a doctrine adhered to by Prince Maurits, the young incoming son of the founder of the nation, William the Silent. While leaders were strongly divided, the 1619 « Dordrecht Synod » installed the radical Calvinist doctrine as the law.

But Leyden was mostly « Arminian » and so was Rembrandt. Rembrandt’s 1633 and 1635 portraits of Johannes Uytenbogaert, the main reverend leading the Arminians who was obliged to spent several years of his life in exile to escape from persecution, show how closely Rembrandt was connected to this movement.

So, when Rembrandt entered University, the situation was very hot. Arminian-minded teachers are on the leave and often forced to do so. So was Rembrandt, and after two months, at age 14, he quitted University and went full time into painting and set up his own workshop.

By 1621, the truce had come to an end, and the Spanish army was once again conducting an all-out war against the Netherlands, which was accused, not without reason, of supporting the Bohemian revolt and harboring the leaders of its resistance. (Note 3)

As a young intellectual confronted with injustice and political and religious madness, Rembrandt entered the studio of Jacob Isaaczoon van Swanenburg, a learned Dutch painter who lived in Venice and Naples, where he worked from 1600 to 1617 before running into trouble with the Inquisition, which accused him of « painting on Sundays ».

Few works have survived from this master, renowned for his city views and portraits. But his subjects and style resemble those of the great humanist Hieronymus Bosch. For three long years, Rembrandt learned how to grind pigments, master essences, varnishes, brushes, canvases and panels.

But above all, Swanenburgh made his pupil a master in the art of engraving and etching.

Pelgrims of Emmaus

Rembrandt’s interest in the power of ideas clearly appears in the « Pilgrims at Emmaus », where an atmosphere of astonishment and horror break out when Christ reveals himself to the disbelievers.

Then, before setting up his studio, Rembrandt will spend six months in the workshop of Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam. With Lastman, Rembrandt finally finds a master that departs from the traditional Dutch landscapes, still-lives and boring group portraits.

Building on the theatrical settings of Caravaggio, Lastman paints biblical, Greek and Roman mythology. He paints history! And Rembrandt always desired to become a historieschilder. Now, Rembrandt finally found in painting the literature he was looking for when inscribing in the University.

Also, in Lastman’s workshop, he meets the talented Jan Lievens, with whom he will work for a while.

Knowing how to know thyself

Rembrandts reputation is largely the fruit of the near to one hundred multiform self-portraits, including about twenty engravings, covering the walls of numerous museums around the world. Some pragmatists tell us Rembrandt did that many self-portraits because he just was the cheapest model in town, and probably the most patient one. Others claim he was simply noting down his unending grimaces, the famous tronies, to prepare future dramatic historical paintings.

We think there is more to it and we approve Simon Schama who wrote that, « The reason for the multiplication of his self-image was not a relentless, almost monomaniacal assertion of the artistic ego but something like the exact opposite. »

The self-portrait, an art expression that has nearly disappeared from today’s practice, always throws an extremely daring challenge to the painter looking into the mirror. Is this me? I didn’t realize I look that way. I’ve changed again! What is wrong? The a priori ideas in the mind of the perceiver or the sense perceptions he’s confronted with? Real thinking, in essence, comes down to confronting not just those burning paradoxes, but the joy of overcoming them with self reflexive irony, and a truthful commitment to the permanent discovery and communication of that increasing irony through a Socratic dialogue.

Rembrandt, at the age of 22 starts training his first pupil, Gerrit Dou, only fifteen years old. Samuel van Hoogstraten, who was another young pupil, reported Rembrandt advising him:

« Try to learn introducing in your work what you know already. Then, very soon, you will discover what escapes you and want to discover. »

Hoogstraten’s self-portrait at age 17 demonstrates what a contagious genius Rembrandt became rapidly as a teacher.

But Rembrandt’s main problem was to show movement. Anima means soul and for Rembrandt animating the mind of the viewer was the art of making that viewer conscious of his own quality of moving the soul, i.e. moving the mover. Through this process of teaching and self-teaching Rembrandt works out various ways to tell his-stories.

One funny way to put faces into motion is to wrap them into clothing, put on jewelry, and choose a specific light setting that generates interesting eye-attracting shadows bringing into light the plastic volumes. Explore facial expressions evoking anger, fear, happiness, self-doubt, laughter, etc.

The real subject is not Rembrandt, but the discovery of human consciousness through self-consciousness. The mirror image permits oneself to look over one’s shoulder down on oneself. Leonardo and others advised artists to view their own work in a mirror, since the « fresh » mirror image offered the artist another « viewpoint », revealing those remaining imperfections that had escaped from his attention.

Also, the compassion and self esteem one is forced to develop in that process becomes a basic ingredient for promethean and agapic character formation. Then, Rembrandt’s joyful process of self-discovery spills naturally over into the portraits done of others.

Look how funny Saskia smiles, when she dresses up « as Rembrandt » with a feathered reddish hat, carrying a golden chain and with her little hand lost in Rembrandt’s large glove.

Then, there are also the self-portraits in assistenza, where the painter’s face pops up uninvited in a larger painting, such as in Velazquez‘ « Las Meninas ».

The Stoning of Saint-Stephen

One of Rembrandt’s grimacing faces appears behind the martyr in the first known painting by the young Rembrandt, The Stoning of Saint-Stephen. Executed at the age of 19, the work powerfully expresses the basis of Rembrandt’s ideas. Loaded with some twenty figures, the subject had previously been treated by Lastman and Adam Elsheimer, a young German Mannerist living in Rome, whose works Rembrandt had admired while contemplating reproductions in Swanenburgh’s studio.

But why Saint-Stephen? Rembrandt’s choice stems directly from the subject. This Greek-speaking Jewish convert, the first Christian martyr, was tried by a court of law for blasphemy. He unabashedly told the Sanhedrin judges that they were « stiff-necked and uncircumcised in heart and ears » and that they were people who had « received the law by the disposition of angels, and have not kept it… »

Stephen also told them that God could not be kept « locked up in a temple ». At one point, Stephen,

« being full of the Holy Spirit, and having his eyes fixed on heaven, saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God, and he said: ‘Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God’.

« And crying aloud, they stopped their ears, and with one accord rushed upon him; and having pushed him out of the city, they stoned him; and the witnesses laid their garments at the feet of a young man called Saul. And they stoned Stephen, who prayed and said: Lord Jesus, receive my spirit. And kneeling down, he cried aloud: Lord, do not impute this sin to them. »

The painting leaves the left side entirely in shadow, in a partially failed attempt to evoke the idea of Stephen seeing the « open heavens. » Saul is in the shadows because he is the one encouraging the execution. Later, on the road to Damascus, he would have his own vision of the « heavens opening » and in turn convert to Christianity, since Saul is none other than the future St. Paul.

In short, as we have said, at the age of 19, Rembrandt powerfully asserts the principles for which he wants to live and for which he is prepared to die, ideas that he must have discovered at the age of fourteen during the great Sophist event, the great « theological debate » that was the beginning of the end of the Republic.

Ideas

Historians might scream there is no space here for political manifestos. They are right. Rembrandt’s ideas go far beyond simple minded militantism, and their political impact is much more profound.

In 1641, an artist, Philips Angel, adressing the painting guild, honored Rembrandt and underscored the artist’s « elevated and profound reflection ». What were these « elevated and profound » ideas all about?

- Truth. Somebody must mobilize the courage to stand up and tell the truth in front of established authorities or misleading public opinion. That theme comes regularly back, notably with « Suzanna and the Elders ». Daniel, a witness of injustice will speak up and saves Suzanna from the death sentence.

- Reason. Faith and religion do not always coincide with religious rites. Look to the angry angel preventing Abraham from killing his own son in « The sacrifice of Isaac ». Think before acting! Reason, love of God and love for mankind must guide any religious practice and on the basis of reason, a dialogue of cultures can enrich humanity.

- Self-perfection. Change, yes. People can find in themselves the means to identify their errors and change for the better. The example of Saint-Paul will stand as a permanent reference for Rembrandt, who painted him several times and even represented himself as the Church father.

- Love, Repentance, Pardon. In a period of permanent danger of « religious wars », Rembrandt strongly identifies with Saint Stephen’s demand « Lord, lay not this sin to their charge. » Rembrandt will paint several times « The return of the prodigal son ». The father gives a great feast for the returning son because he « who was dead came back to life ». The notion of pardon, and acting in the advantage of the other, will become the key concept for the success of the world Peace of Westphalia concluded in 1648 ending the thirty years war, including the recognition of the Netherlands as a sovereign state.

The Night Watch

Misrepresented as a nocturnal scene, the Night Watch is probably one of the greatest intellectual provocations against cold Aristotelian classicism.

The Netherlands was at war. Amsterdam, like most major cities, maintained a considerable militia of archers, crossbowmen and harquebusiers. These small citizen armies had a firing range and a meeting hall, the Kloveniersdoelen, where soldiers could rest after training.

Obviously, such glorious gatherings deserved to be immortalized in vast group portraits, where all the members of the company was presented in such a way that, as van Hoogstraten put it, « you could, as it were, behead them all with a single cannon shot. »

Rembrandt completely overturned this traditional representation. Firstly, apart from the 2 captains and their 16 companions (who each paid for their presence on the canvas), Rembrandt added another third of figures to the original number.

Secondly, the revolutionary concept implemented is the idea of depicting the whole group as « on the march », not just advancing, but raising flags and weapons after passing under a circular arch seen just behind them.

Thirdly, a spectacular sense of movement emanates from the rapid oscillation of a chiaro-oscura, illuminating one part, casting another into shadow.

Finally, the show seems formally a confused, chaotic scene. People enter from all sides. In infinite heteronomy, one loads his rifle, another beats the drum, another raises his spear while another stares at his rifle.

Beyond this apparent hectic confusion, what remains is the spirit of a republican citizenry called to arms and moving from chaos to unity, a subject Rembrandt represented the same year in an allegorical oil sketch, Concord of the State.

Against narrow academic rigor, the spirit of inclusion of the multitude so common to Flemish painters like Bruegel was once again manifesting itself.

Van Hoogstraten, defending Rembrandt against these critics (as usual, those who were jealous of his brilliant performance) commented:

« Rembrandt observed this requirement [of unity] very well… and although in the opinion of many he went too far, making the painting more according to his personal taste than according to the individual portraits he had been commissioned to paint.

Nevertheless, the painting, no matter how harsh the critics, will stand, in my judgment, against all these rivals because it is so picturesque in its conception and because it is so powerful that, according to some, all the other doelen works look like playing cards in comparison. »

Immortality

We took here just a few examples to demonstrate that Rembrandts universal character derives directly from his ruthless commitment, directed to make us conscious of the creative potential given to all human beings, men and women, old and young, Christians, Jews, Muslims or others, a creative and creating human nature called the soul.

This commitment is once again available in today’s new generation and can therefore be mobilized for great achievements.

From this point of view, Rembrandt is in a good position to become a reference individual capable of leading us out of the current cultural « dark age », where video games teach our children to take perverse pleasure in gratuitous violence and push them to become « naturally born killers ».

In contrast, a Rembrandt who catches life and loves mankind will trace the divine in the slightest spark of light. As some sort of 5th apostel, without ever painting God directly, Rembrandt reveals the harmony of his creation.

Those who took time studying his paintings can tell themselves: « God exists, I just met Rembrandt », since through Rembrandt’s art God’s tender love and blessing power are revealed to us in our human reality.

That « immortal » nature of Rembrandt’s soul will doubtlessly nourish the « immortality » of the creative geniuses he will inspire. Let us not wait another four hundred years to celebrate such a genius, for what he brings us is living and not to be buried in the history of art

Notes:

- Friedrich Schiller, The revolt of the Netherlands; Karel Vereycken, How Erasmus Folly saved our Civilization; Karel Vereycken, « Rembrandt, bâtisseur de nations » in Nouvelle Solidarité, June 10 and 17, 1985.

- Years earlier, René Descartes, using his own funds, made a trip to Bohemia and in 1620 took part in the battle of Montagne Blanche, leading to the massacre of Prague, the capital of Bohemia. One biographer reports that Descartes, entering Prague, immediately appropriated Kepler’s Brahe scientific instruments.

- For a detailed report on the links between Rembrandt and Comenius and the Bohemian revolt, see Karel Vereycken, The light of Agapê, Rembrandt and Comenius versus Rubens, Ibykus N°85, 2003.

- Ernst van Wetering, director of the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP), on the basis of scientific examinations of Rembrandt’s works, estimates that the master required his models to pose for three hours a day for at least three months.

- Karel Vereycken, Leonardo, painter of movement, Fusion N°108, 2006.

Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life: the cradle of humanism in the North

Presentation of Karel Vereycken, founder of Agora Erasmus, at a meeting with friends in the Netherlands on September 10, 2011.

The current financial system is bankrupt and will collapse in the coming days, weeks, months or years if nothing is done to end the paradigm of financial globalization, monetarism and free trade.

To exit this crisis implies organizing a break-up of the banks according to principles of the Glass-Steagall Act, an indispensable lever to recreate a true credit system in opposition to the current monetarist system. The objective is to guarantee real investments generating physical and human wealth, thanks to large infrastructure projects and highly qualified and well-paid jobs.

Can this be done? Yes, we can! However, the true challenge is neither economic, nor political, but cultural and educational: how to lay the foundations of a new Renaissance, how to effect a civilizational shift away from green and Malthusian pessimism towards a culture that sets itself the sacred mission of fully developing the creative powers of each individual, whether here, in Africa, or elsewhere.

Is there a historical precedent? Yes, and especially here, from where I am speaking to you this morning (Naarden, Netherlands) with a certain emotion. It probably overwhelms me because I have a rather well informed and precise sense of the role that several key individuals from the region where we are gathered this morning have played and how, in the fourteenth century, they made Deventer, Zwolle and Windesheim an intellectual hotbed and the cradle of the Renaissance of the North which inspired so many worldwide.

Let me summarize for you the history of this movement of lay clerics and teachers: the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, a movement that nurished our beloved Erasmus of Rotterdam, the humanist giant from whom we borrowed the name to create our political movement in Belgium.

As very often, it all begins with an individual decision of someone to overcome his shortcomings and give up those « little compromises » that end up making most of us slaves. In doing so, this individual quickly appears as a « natural » leader. Do you want to become a leader? Start by cleaning up your own mess before giving lessons to others!

Geert Groote, the founder

The spiritual father of the Brothers is Geert Groote, born in 1340 and son of a wealthy textile merchant in Deventer, which at that time, like Zwolle, Kampen and Roermond, were prosperous cities of the Hanseatic League.

In 1345, as a result of the international financial crash, the Black Death spread throughout Europe and arrived in the Netherlands around 1449-50. Between a third and a half of the population died and, according to some sources, Groote lost both parents. He abhorred the hypocrisy of the hordes of flagellants who invaded the streets and later advocated a less conspicuous, more interior spirituality.

Groote had talent for intellectual matters and was soon sent to study in Paris. In 1358, at the age of eighteen, he obtained the title of Master of Arts, even though the statutes of the University stipulated that the minimum age required was twenty-one.

He stayed eight years in Paris where he taught, while making a few excursions to Cologne and Prague. During this time, he assimilated all that could be known about philosophy, theology, medicine, canon law and astronomy. He also learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and was considered one of the greatest scholars of the time.

Around 1362 he became canon of Aachen Cathedral and in 1371 of that of Utrecht. At the age of 27, he was sent as a diplomat to Cologne and to the Court of Avignon to settle the dispute between the city of Deventer and the bishop of Utrecht with Pope Urban V. In principle, he could have met the Italian humanist Petrarch who was there at that time.

Full of knowledge and success, Groote got a big head. His best friends, conscious of his talents, kindly suggested him to detach himself from his obsession with « Earthly Paradise ». The first one was his friend Guillaume de Salvarvilla, the choirmaster of Notre-Dame of Paris. The second was Henri Eger of Kalkar (1328-1408) with whom Groote shared the benches of the Sorbonne.

In 1374, Groote got seriously ill. However, the priest of Deventer refused to administer the last sacraments to him as long as he refused to burn some of the books in his possession. Fearing for his life (after death), he decided to burn his collection of books on black magic. Finally, he felt better and healed. He also gave up living in comfort and lucre through fictitious jobs that allowed him to get rich without working too hard.

After this radical conversion, Groote decides to selfperfect. In his Conclusions and Resolutions he wrote:

« It is to the glory, honor and service of God that I propose to order my life and the salvation of my soul. (…) In the first place, not to desire any other benefit and not to put my hope and expectation from now on in any temporal profit. The more goods I have, the more I will probably want more. For according to the primitive Church, you cannot have several benefits. Of all the sciences of the Gentiles, the moral sciences are the least detestable: many of them are often useful and profitable both for oneself and for teaching others. The wisest, like Socrates and Plato, brought all philosophy back to ethics. And if they spoke of high things, they transmitted them (according to St. Augustine and my own experience) by moralizing them lightly and figuratively, so that morality always shines through in knowledge… ».

Groote then undertakes a spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen near Arnhem where he devotes himself to prayer and study.

However, after a three-year stay in isolation, the prior, his Parisian friend Eger of Kalkar, told him to go out and teach :

« Instead of remaining cloistered here, you will be able to do greater good by going out into the world to preach, an activity for which God has given you a great talent. »

Ruusbroec, the inspirer

Groote accepted the challenge. However, before taking action, he decided to make a last trip to Paris in 1378 to obtain the books he needed.

According to Pomerius, prior of Groenendael between 1431 and 1432, he undertook this trip with his friend from Zwolle, the teacher Joan Cele (around 1350-1417), the historical founder of the excellent Dutch public education system, the Latin School.

On their way to Paris, they visit Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), a Flemish “mystic” who lived in the Groenendael Priory on the edge of the Soignes Forest near Brussels.

Groote, still living in fear of God and the authorities, initially tries to make « more acceptable » some of the old sage’s writings while recognizing Ruusbroec as closer to the Lord than he is. In a letter to the community of Groenendael, he requested the prayer of the prior:

« I would like to recommend myself to the prayer of your provost and prior. For the time of eternity, I would like to be ‘the prior’s stepladder’, as long as my soul is united to him in love and respect.” (Note 1)

Back in Deventer, Groote concentrated on study and preaching. First he presented himself to the bishop to be ordained a deacon. In this function, he obtained the right to preach in the entire bishopric of Utrecht (basically the whole part of today’s Netherlands north of the great rivers, except for the area around Groningen).

First he preached in Deventer, then in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen and later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda and Delft. His success is so great that jealousy is felt in the church. Moreover, with the chaos caused by the great schism (1378 to 1417) installing two popes at the head of the church, the believers are looking for a new generation of leaders.

As early as 1374, Groote offered part of his parents’ house to accommodate a group of pious women. Endowed with a by-law, the first house of sisters was born in Deventer. He named them « Sisters of the Common Life », a concept developed in several works of Ruusbroec, notably in the final paragraph Of the Shining Stone (Van den blinckende Steen)

« The man who is sent from this height to the world below, is full of truth, and rich in all virtues. And he does not seek his own, but the honor of the one who sent him. And that is why he is upright and truthful in all things. And he has a rich and benevolent foundation grounded in the riches of God. And so he must always convey the spirit of God to those who need it; for the living fountain of the Holy Spirit is not a wealth that can be wasted. And he is a willing instrument of God with whom the Lord works as He wills, and how He wills. And it is not for sale, but leaves the honor to God. And for this reason he remains ready to do whatever God commands; and to do and tolerate with strength whatever God entrusts to him. And so he has a common life; for to him seeing [via contemplativa] and working [via activa] are equal, for in both things he is perfect.”

Radewijns, the organizer

Following one of his first sermons, Groote recruited Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Born in Utrecht, the latter received his training in Prague where, also at the early age of 18, he was awarded the title of Magister Artium.

Groote then sent him to the German city of Worms to be consecrated priest there. In 1380 Groote moved with about ten pupils to the house of Radewijns in Deventer; it would later be known as the « Sir Florens House” (Heer Florenshuis), the first house of the Brothers and above all its base of operation?

When Groote died of the plague in 1384, Radewijns decided to expand the movement which became the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Soon it will be branded the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion).

Books and beguinages

A number of parallels can be drawn with the phenomenon of the Beguines which flourished from the 13th century onward. (Note 2)

The first beguines were independent women, living alone (without a man or a rule), animated by a deep spirituality and daring to venture into the enormous adventure of a personal relationship with God. (Note 3)

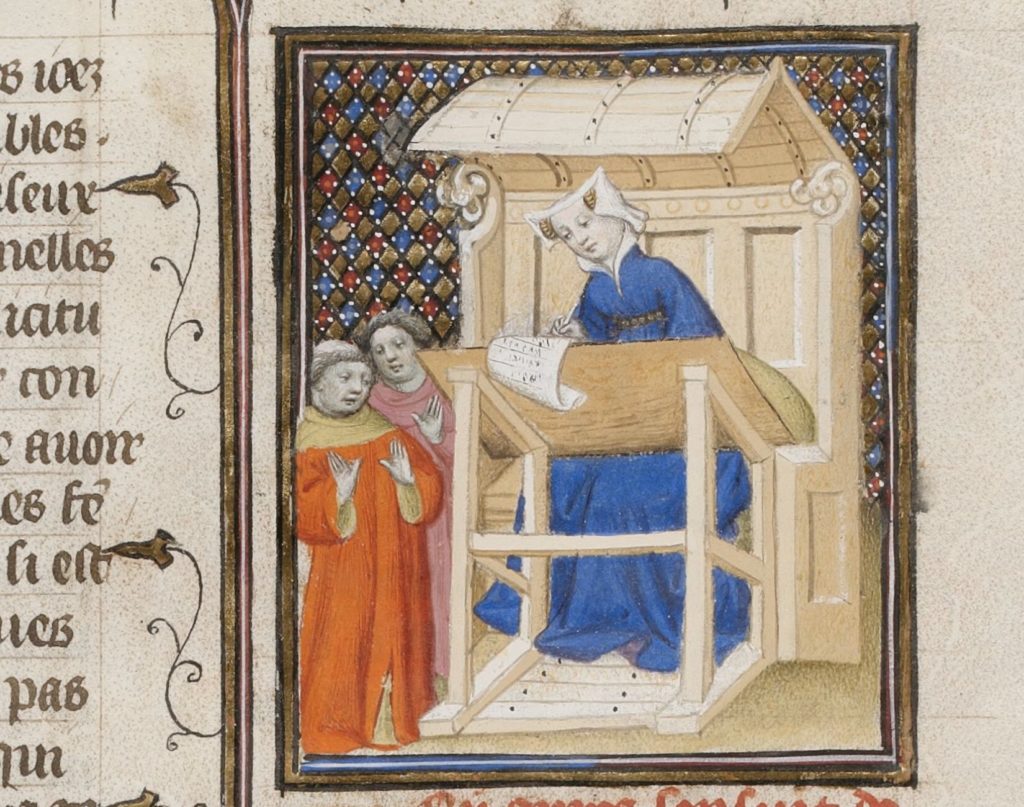

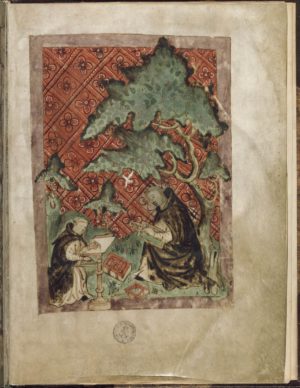

Operating outside the official religious hierarchy, they didn’t beg but worked various jobs to earn their daily bread. The same goes for the Brothers of the Common Life, except that for them, books were at the center of all activities. Thus, apart from teaching, the copying and production of books represented a major source of income while allowing spreading the word to the many.

Lay Brothers and Sisters focused on education and their priests on preaching. Thanks to the scriptorium and printing houses, their literature and music will spread everywhere.

Windesheim

To protect the movement from unfair attacks and criticism, Radewijns founded a congregation of canons regular obeying the Augustinian rule.

In Windesheim, between Zwolle and Deventer, on land belonging to Berthold ten Hove, one of the members, a first cloister is erected. A second one, for women this time, is built in Diepenveen near Arnhem. The construction of Windesheim took several years and a group of brothers lived temporarily on the building site, in huts.

In 1399 Johannes van Kempen, who had stayed at Groote’s house in Deventer, became the first prior of the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and gave the movement new momentum. From Zwolle, Deventer and Windesheim, the new recruits spread all over the Netherlands and Northern Europe to found new branches of the movement.

In 1412, the congregation had 16 cloisters and their number reached 97 in 1500: 84 priories for men and 13 for women. To this must be added a large number of cloisters for canonesses which, although not formally associated with the Windesheim Congregation, were run by rectors trained by them.

Windesheim was not recognized by the Bishop of Utrecht until 1423 and in Belgium, Groenendael, associated with the Red Cloister and Korsendonc, wanted to be part of it as early as 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cusanus and Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was the brother of the famous Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). The latter, trained in Windesheim, animated the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and was one of the towering figures of the movement for seventy years. In addition to a biography he wrote of Groote and his account of the movement, his Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) became the most widely read work in history after the Bible.

Both Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) and Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), two of Erasmus’ tutors during his training in Deventer, were direct pupils of Thomas a Kempis. The Latin School of Deventer, of which Hegius was rector, was the first school in Northern Europe to teach the ancient Greek language to children.

While no formal prove exists, it is tempting to believe that Cusanus (1401-1464), who protected Agricola and, in his last will, via his Bursa Cusanus, offered a scholarship for the training of orphans and poor students of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, was also trained by this humanist network.

What is known is that when Cusanus came in 1451 to the Netherlands to put the affairs of the Church in order, he traveled with his friend Denis the Carthusian (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), a disciple of Ruusbroec, whom he commissioned to carry on this task.

A native of Limburg, trained at the famous Cele school in Zwolle, Dionysius the Carthusian also became the confessor of the Duke of Burgundy and is thought to be the “theological advisor” of the Duke’s ambassador and court painter, Jan Van Eyck. (Note 4)

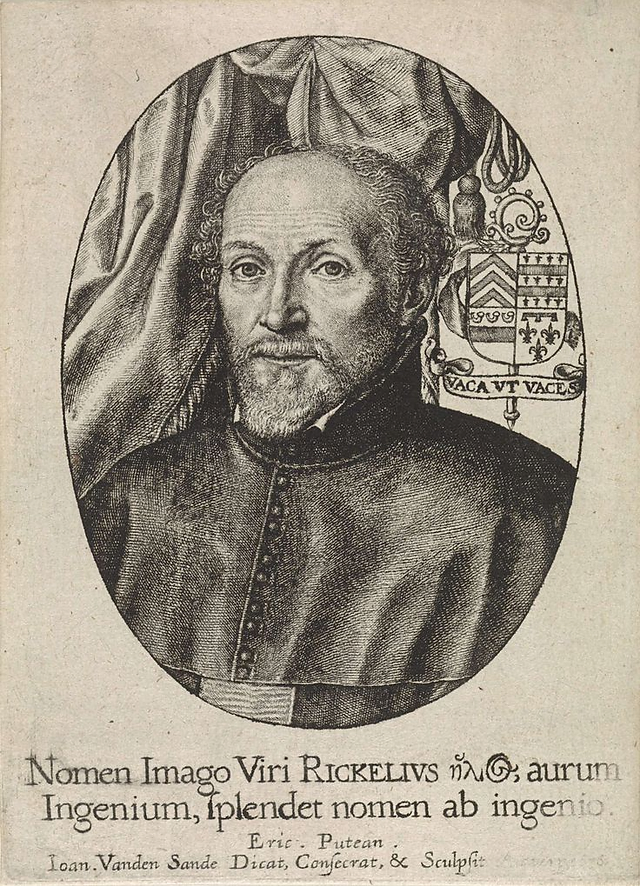

Gansfort

Wessel Gansfort (1419-1489), another exceptional figure of this movement was at the service of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion, the main collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) at the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1437. Gansfort, after attending the Brothers’ school in Groningen, was also trained by Joan Cele‘s Latin school in Zwolle.

The same goes for the first and only Dutch pope, Adrianus VI, who was trained in the same school before completing his training with Hegius in Deventer. This pope was very open to Erasmus’ reformist ideas… before arriving in Rome.

Hegius, in a letter to Gansfort, which he calls Lux Mundi (Light of the World), wrote:

« I send you, most honorable lord, the homilies of John Chrysostom. I hope that you will enjoy reading them, since the golden words have always been more pleasing to you than the pieces of this metal. As you know, I went to the library of Cusanus. There I found some books that I didn’t know existed (…) Farewell, and if I can do you a favor, let me know and consider it done.”

Rembrandt

A quick look on Rembrandt’s intellectual training indicates that he too was a late product of this educational epic. In 1609, Rembrandt, barely three years old, entered elementary school where, like other boys and girls of his generation, he learned to read, write and… draw.

The school opened at 6 in the morning, at 7 in the winter, and closes at 7 in the evening. Classes begin with prayer, reading and discussion of a passage from the Bible followed by the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt acquired an elegant writing style and much more than a rudimentary knowledge of the Gospels.

The Netherlands wanted to survive. Its leaders take advantage of the twelve-year truce (1608-1618) to fulfill their commitment to the public interest.

In doing so, the Netherlands at the beginning of the XVIIth century became the first country in the world where everyone had the chance to learn to read, write, calculate, sing and draw.

This universal educational system, no matter what its shortcomings, available to both rich and poor, boys and girls alike, stands as the secret behind the Dutch « Golden Century ». This high level of education also created those generations of active Dutch emigrants a century later in the American Revolution.

While others started secondary school at the age of twelve, Rembrandt entered the Leyden Latin School at the age of 7. There, the students, apart from rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn not only Greek and Latin, but also foreign languages such as English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, with no laws restricting young talents, Rembrandt enrolled in University. The subject he chose was not Theology, Law, Science or Medicine, but… Literature.

Did he want to add to his knowledge of Latin the mastery of Greek or Hebrew philology, or possibly Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Arabic/Latin dictionaries were already being published in Leiden at a time the city was becoming a major printing center in the world.

Thus, one realizes that the Netherlands and Belgium, first with Ruusbroec and Groote and later with Erasmus and Rembrandt, made an essential contribution in the not so distant past to the kind of humanism that can raise today humanity to its true dignity.

Hence, failing to extend our influence here, clearly seems to me something in the realm of the impossible.

Footnotes:

- Geert Groote, who discovered Ruusbroec’s work during his spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen, near Arnhem, has translated at least three of his works into Latin. He sent The Book of the Spiritual Tabernacle to the Cistercian Cloister of Altencamp and his friends in Amsterdam. The Spiritual Marriage of Ruusbroec being under attack, Groote personally defends it. Thus, thanks to his authority, Ruusbroec’s works are copied in number and carefully preserved. Ruusbroec’s teaching became popularized by the writings of the Modern Devotion and especially by the Imitation of Christ.

- At the beginning of the 13th century the Beguines were accused of heresy and persecuted, except… in the Burgundian Netherlands. In Flanders, they are cleared and obtain official status. In reality, they benefit from the protection of two important women: Jeanne and Margaret of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders. They organized the foundation of the Beguinages of Louvain (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerp (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ypres (1240), Lille (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Bruges (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Diest (1253), Mechelen (1258) and in 1271 it was Jan I, Count of Flanders, in person, who deposited the statutes of the great Beguinage of Brussels. In 1321, the Pope estimated the number of Beguines at 200,000.

- The platonic poetry of the Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (XIIIth Century) has a decisive influence on Jan van Ruusbroec.

- It is significant that the first book printed in Flanders in 1473, by Erasmus’ friend and printer Dirk Martens, is precisely a work of Denis the Carthusian.

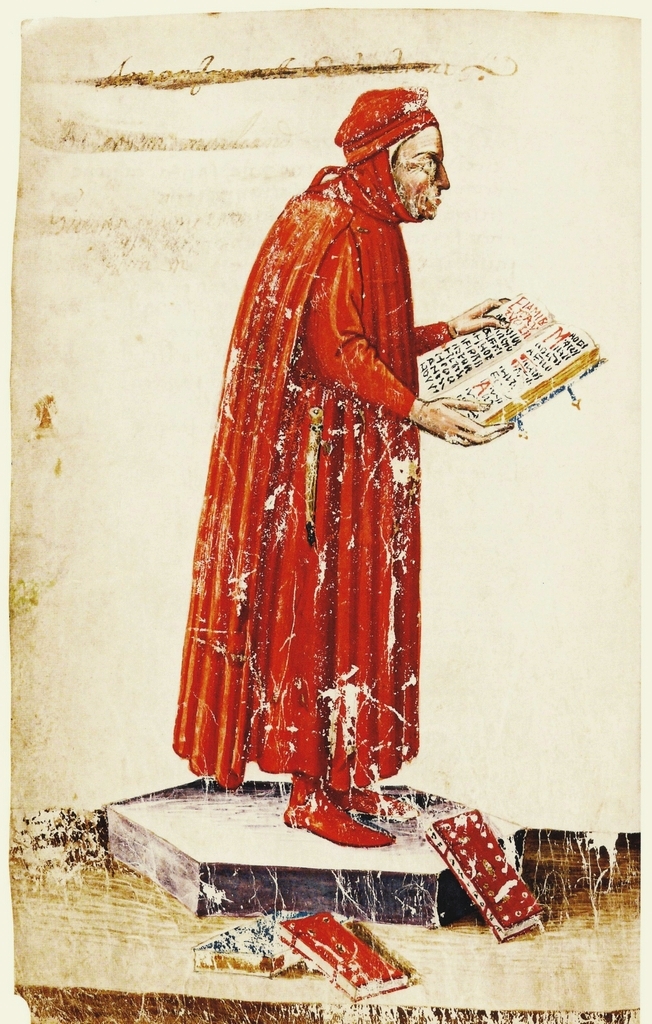

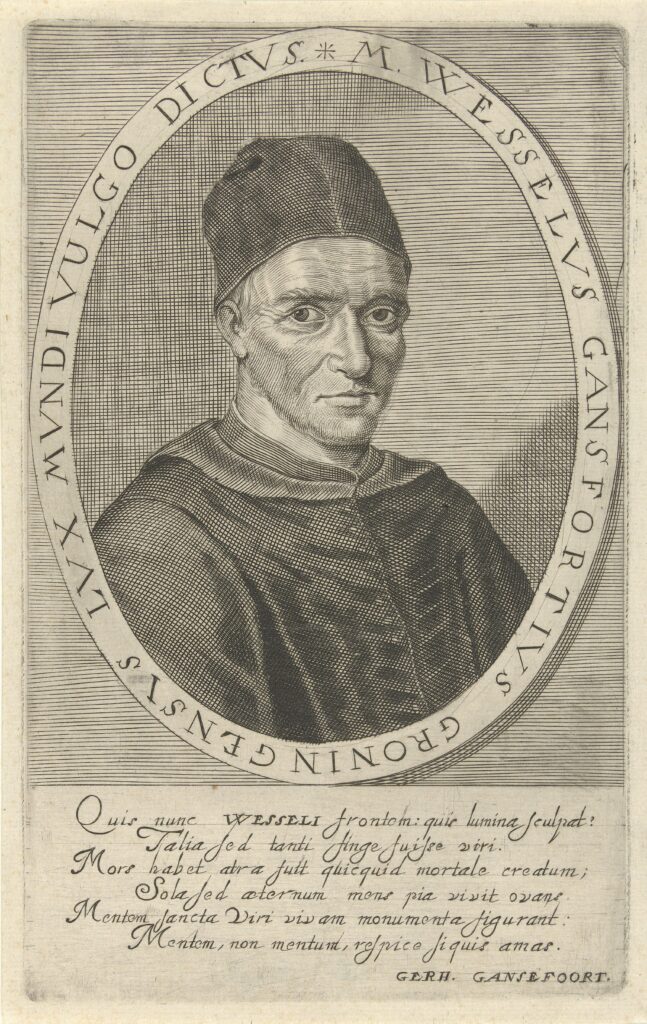

Erasmus’ dream: the Leuven Three Language College

In autumn 2017, a major exhibit organized at the University library of Leuven and later in Arlon, also in Belgium, attracted many people. Showing many historical documents, the primary intent of the event was to honor the activities of the famous Three Language College (Collegium Trilingue), founded in 1517 by the efforts of the Christian Humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (1467-1536) and his allies. Though modest in size and scope, Erasmus’ initiative stands out as one of the cradles of European civilization, as you will discover here.

Revolutionary political figures, such as William the Silent (1533-1584), organizer of the Revolt of the Netherlands against the Habsburg tyranny, humanist poets and writers such as Thomas More, François Rabelais, Miguel Cervantes and William Shakespeare, all of them, recognized their intellectual debt to the great Erasmus of Rotterdam, his exemplary fight, his humor and his great pedagogical project.

For the occasion, the Leuven publishing house Peeters has taken through its presses several nice catalogues and essays, published in Flemish, French as well as English, bringing together the contributions of many specialists under the wise (and passionate) guidance of Pr Jan Papy, a professor of Latin literature of the Renaissance at the Leuven University, with the assistance of a “three language team” of Latinists which took a fresh look at close to all the relevant and inclusively some new documents scattered over various archives.

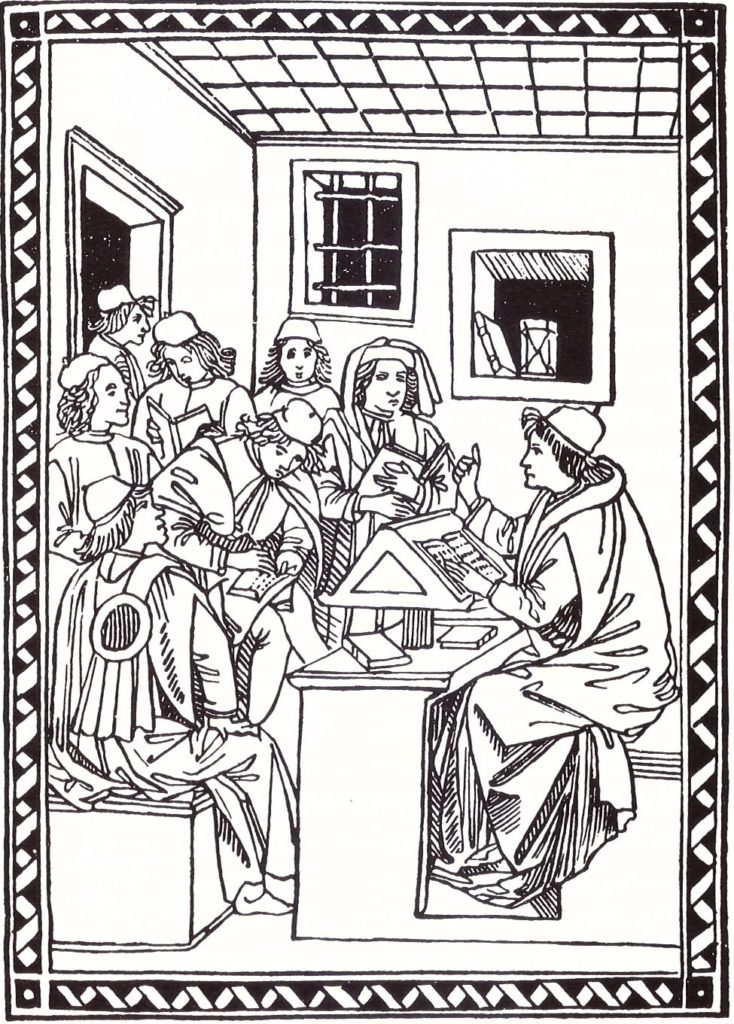

“The Leuven Collegium Trilingue: an appealing story of courageous vision and an unseen international success. Thanks to the legacy of Hieronymus Busleyden, counselor at the Great Council in Mechelen, Erasmus launched the foundation of a new college where international experts would teach Latin, Greek and Hebrew for free, and where bursaries would live together with their professors”, reads the back cover of one of the books.

For the researchers, the issue was not necessarily to track down every detail of this institution but rather to answer the key question: “What was the ‘magical recipe’ which attracted rapidly to Leuven between three and six hundred students from all over Europe?”

Erasmus’ initiative was unprecedented. Having an institution, teaching publicly Latin and, on top, for free, Greek and Hebrew, two languages considered “heretic” by the Vatican, was already tantamount to starting a revolution.

Was it that entirely new? Not really. As early as the beginning of the XIVth century, for the Italian humanists in contact with Greek erudites in exile in Venice, the rigorous study of Greek, Hebraic and Latin sources as well as the Fathers and the New Testament, was the method chosen by the humanists to free mankind from the Aristotelian worldview suffocating Christianity and returning to the ideals, beauty and spirit of the “Primitive Church”.

For Erasmus, as for his inspirer, the Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla (1403-1457), the « Philosophy of Christ » (agapic love), has to come first and opens the road to end the internal divisions of Christianity and to uproot the evil practices of greed (indulgences, simony) and religious superstition (cult of relics) infecting the Church from the top to the bottom, and especially the mendicant orders.

To succeed, Erasmus sets out to clarify the meaning of the Holy Writings by comparing the originals written in Greek, Hebrew and Latin, often polluted following a thousand years of clumsy translations, incompetent copying and scholastic commentaries.

Brothers of the Common Life

My own research allows me to recall that Erasmus was a true disciple of the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life of Deventer in the Netherlands, a hotbed of humanism in Northern Europe. The towering figures that founded this lay teaching order are Geert Groote (1340-1384), Florent Radewijns (1350-1400) and Wessel Gansfort (1420-1489), all three said to be fluent in precisely these three languages.

The religious faith of this current, also known as the “Modern Devotion”, centered on interiority, as beautifully expressed in the little book of Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), the Imitation of Christ. This most read book after the Bible, underlines the importance for the believer to conform one owns life to that of Christ who gave his life for mankind.

Rudolph Agricola

Hence, in 1475, Erasmus father, fluent in Greek and influenced by famous Italian humanists, sends his son to the chapter of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, at that time under the direction of Alexander Hegius (1433-1499), himself a pupil of the famous Rudolph Agricola (1442-1485) which Erasmus had the chance to listen to and which he calls a “divine intellect”.

Follower of the cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464), enthusiastic advocate of the Italian Renaissance and the Good Letters, Agricola would tease his students by saying:

“Be cautious in respect to all that you learned so far. Reject everything! Start from the standpoint you will have to un-learn everything, except that what is based on your sovereign authority, or on the basis of decrees by superior authors, you have been capable of re-appropriating yourself”.

Erasmus, with the foundation of the Collegium Trilingue will carry this ambition at a level unreached before. To do so, Erasmus and his friend apply a new pedagogy. Hence, instead of learning by heart medieval commentaries, pupils are called to formulate their proper judgment and take inspiration of the great thinkers of the Classical period, especially “Saint Socrates”. Latin, a language that degenerated during the Roman Empire, will be purified from barbarisms.

With this approach, for pupils, reading a major text in its original language is only the start. An explorative work is required: one has to know the history and the motivations of the author, his epoch, the history of the laws of his country, its geography, cosmography, all considered to be indispensable instruments to put each text in its specific literary and historical context and allowing reading, beyond the words, the intention of their author.

This “modern” approach (questioning, critical study of sources, etc.) of the Collegium Trilingue, after having demonstrated its efficiency by clarifying the message of the Gospel, will rapidly travel over Europe and reach many other domains of knowledge, notably scientific issues! By uplifting young talents, out of the small and sleepy world of scholastic certitudes, this institution rapidly grew into a hotbed for creative minds.

For the ignorant reader who often considers Erasmus as some kind of comical writer praising madness which lost it after an endless theological dispute with Martin Luther, such a statement might come as a surprise.

Scientific Renaissance

While Belgium’s contributions to science, under Emperor Charles Vth, are broadly recognized and respected, few are those understanding the connection uniting Erasmus with a mathematician as Gemma Frisius and his pupil and friend Gerard Mercator, an anatomist such as Andreas Vesalius or a botanist such as Rembert Dodonaeus.

Hence, as already thoroughly documented in 2011 by Professor Jan Papy in a remarkable article, the scientific renaissance which bloomed in the Netherlands and Belgium in the early XVIth century, could not have taken place if it were for the “linguistic revolution” provoked by the Collegium Trilingue.

Because, beyond the mastery of their vernacular languages (French and Dutch), hundreds of youth, by studying Greek, Latin and Hebrew, suddenly got access to all the scientific treasures of Greek Philosophy and the best authors in those newly discovered languages.

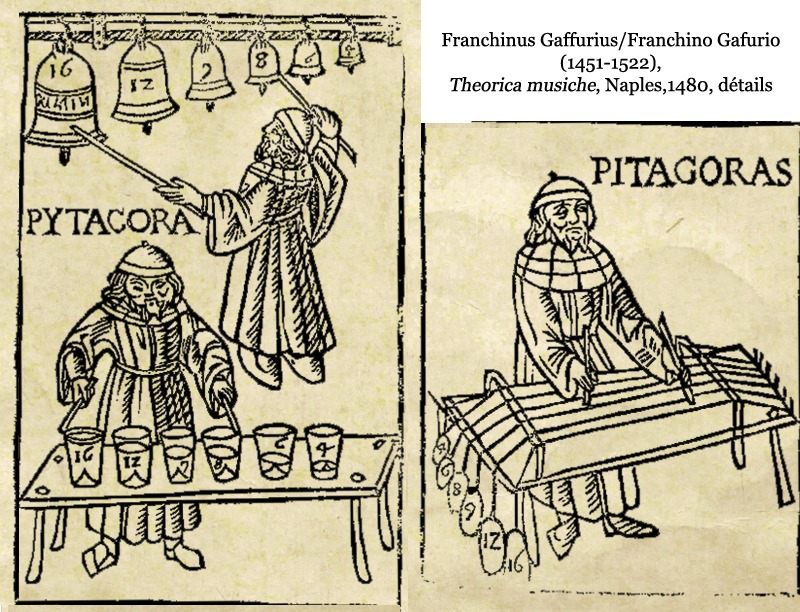

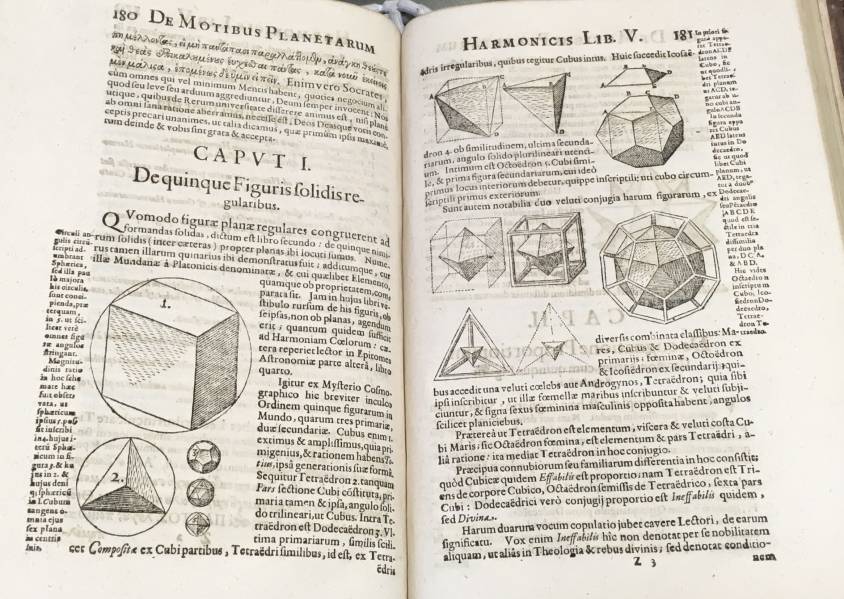

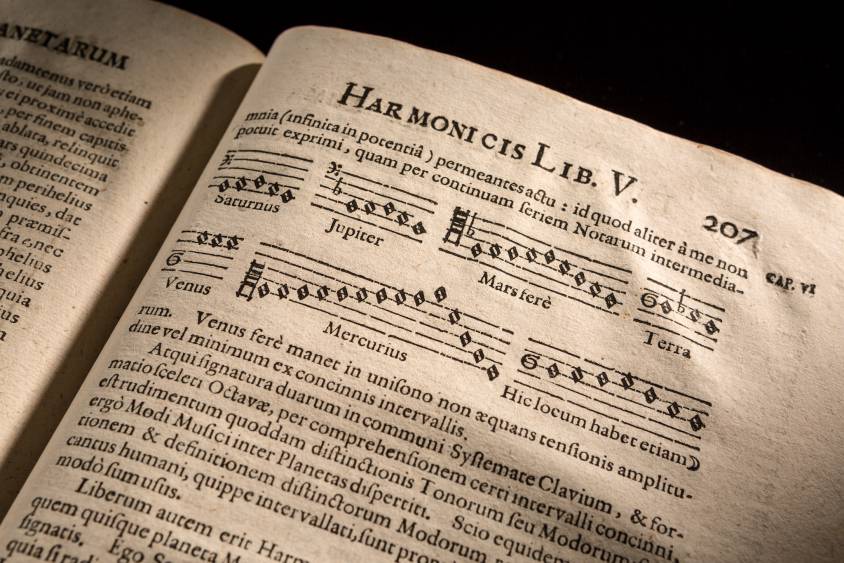

At last, they could read Plato in the text, but also Anaxagoras, Heraclites, Thales of Millet, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Pythagoras, Eratosthenes, Archimedes, Galen, Vitruvius, Pliny the elder, Euclid and Ptolemy whose work they will master and eventually correct.

As the books published by Peeters account in great detail, during the first century of its existence, the Collegium Trilingue had a rough time confronting political uproar and religious strife. Heavy critique came especially form the “traditionalists”, a handful of theologians for which the Greeks were nothing but schismatics and the Jews the assassins of Christ and esoterics.

The opposition was such that Erasmus himself never could teach at the Collegium and, while keeping in close contact, decided to settle in Basel, Switzerland, in 1521.

Despite all of this, the Erasmian revolution conquered Europe overnight and a major part of the humanists of that period were trained or influenced by this institution. From abroad, hundreds of pupils arrived to follow classes given by professors of international reputation.

27 European universities integrated pupils of the Collegium in their teaching staff: among them stood Jena, Wittenberg, Cologne, Douai, Bologna, Avignon, Franeker, Ingolstadt, Marburg, etc.

Teachers at the Collegium were secured a decent income so that they weren’t obliged to give private lectures to secure a living and could offer public classes for free. As was the common practice of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, a system of bursa allowed talented though poor students, including many orphans, to have access to higher learning. “Something not necessarily unusual those days, says Pr Jan Papy, and done for the sake of the soul of the founder (of the Collegium, reference to Busleyden)”.

While visiting Leuven and contemplating the worn-out steps of the spiral staircase (wentelsteen), one of the last remains of the building that had a hard time resisting the assaults of time and ignorance, one can easily imagine those young minds jumping down the stairs with enthusiasm going from the dormitory to the classroom. Looking at the old shopping list of the school’s kitchen one can conclude the food was excellent with lots of meat, poultry but also vegetables and fruits, and sometimes wine from Beaune in Burgundy, especially when Erasmus came for a visit! While over the years, of course, the quality of the learning transmitted, would vary in accordance with the excellence of its teachers, the Collegium Trilingue, whose activity would last till the French revolution, gave its imprint in history by giving birth to what some have called the “Little Renaissance” of the first half of the XVIth century.

In France, the Sorbonne University reacted with fear and in 1523, the study of Greek was outlawed in France.

François Rabelais, at that time a monk in Vendée, saw his books confiscated by the prior of his monastery and deserts his order. Later, as a doctor, he translated the medical writings of the Greek scientist Galen from Greek into French. Rabelais’s letter to Erasmus shows the highest possible respect and intellectual debt to Erasmus.

In 1530, Marguerite de Navarre, sister of King Francis, and reader and admirer of Erasmus, at war with the Sorbonne, convinced her brother to allow Guillaume Budé, a friend of Erasmus, to create the “Collège des Lecteurs Royaux” (ancestor of the Collège de France) on the model of the Collegium Trilingue. And to protect its teachers, many coming directly from Leuven, they got the title of “advisors” of the King. The Collège taught Latin, Hebrew and Greek, and rapidly added Arab, Syriac, medicine, botany and philosophy to its curriculum.

Dirk Martens

Also celebrated for the occasion, Dirk Martens (1446-1534), rightly considered as one of the first humanists to introduce printing in the Southern Netherlands.

Born in Aalst in a respected family, the young Dirk got his training at the local convent of the Hermits of Saint William. Eager to know the world and to study, Dirk went abroad. In Venice, at that time a cosmopolite center harboring many Greek erudite in exile, Dirk made his first steps into the art of printing at the workshop of Gerardus de Lisa, a Flemish musician who set up a small printing shop in Treviso, close to Venice.

Back in Aalst, together with his partner John of Westphalia, Martens printed in 1473 the first book in the country with a movable type printing press, a treatise of Dionysius the Carthusian (1401-1471), a friend and collaborator of cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa, as well as the spiritual advisor of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy and thought to be the occasional « theological » advisor of the latter’s court painter, Jan Van Eyck.

If the oldest printed book known to us is a Chinese Buddhist writing dating from 868, the first movable printing types, made first out of wood and then out of hardened porcelain and metal, came from China and Korea in 1234.

The history of two lovers, a poem written by Aeneas Piccolomini before he became the humanist Pope Pius II, was another early production of Marten’s print shop in Aalst.

Proud to have introduced this new technique allowing a vast increase in the spreading of good and virtuous ideas, Martens wrote in one of the prefaces: “This book was printed by me, Dirk Martens of Aalst, the one who offered the Flemish people all the know-how of Venice”.

After some years in Spain, Martens returned to Aalst and started producing breviaries, psalm books and other liturgical texts. While technically elaborate, the business never reached significant commercial success.

Martens then moved to Antwerp, at that time one of the main ports and cross-roads of trade and culture. Several other Flemish humanists born in Aalst played eminent roles in that city and animate its intellectual and cultural life. Among these:

—Cornelis De Schrijver (1482-1558), the secretary of the City of Aalst, better known under his latin name Scribonius and later as Cornelius Grapheus. Writer, translator, poet, musician and friend of Erasmus, he was accused of heresy and hardly escaped from being burned at the stake.

—Pieter Gillis (1486-1533), known as Petrus Aegidius. Pupil of Martens, he worked as a corrector in his company before becoming Antwerp’s chief town clerk. Friend of Erasmus and Thomas More, he appears with Erasmus in the double portrait painted by another friend of both, Quinten Metsys (1466-1530).

—Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), editor, painter and scenographer. After a trip to Italy, he set up a workshop in Antwerp. Pieter will produce patrons for tapestries, translated with the help of his wife the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius into Dutch and trained the young Flemish painter Bruegel the Elder who will marry his daughter.

Invention of pocket books

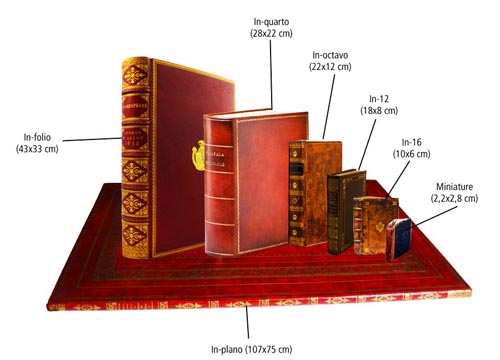

In Antwerp, Martens became part of this milieu and his workshop became a meeting place for painters, musicians, scientists, poets and writers. With the Collegium Trilingue, Martens opens a second shop, this time in Leuven to work with Erasmus. In order to provide adequate books to the Collegium, Martens proudly became, in the footsteps of the Venetian Printer Aldo Manuce, one of the first printers to concentrate on in-octavo 8° (22 x 12 cm), i.e. “pocket” size books affordable by all and which students could take home !

For the specialists of the Erasmus house of Anderlecht, close to Brussels,

“Martens innovated in nearly all domains. As well as in terms of printing types as lay-out. He was the first to introduce Italics, Greek and Hebrew letter types. He also generalized the use of ‘New Roman’ letter type so familiar today. During the first thirty years of the XVIth century, he also operated the revolution in lay-out (chapters and paragraphs) that gave birth to the modern book as we know it today. All this progress, he achieved in close cooperation with Erasmus”.

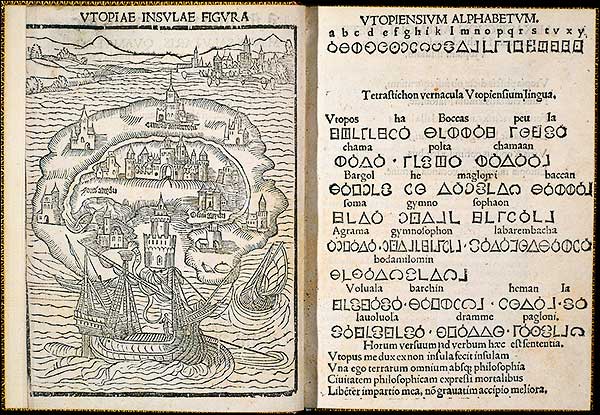

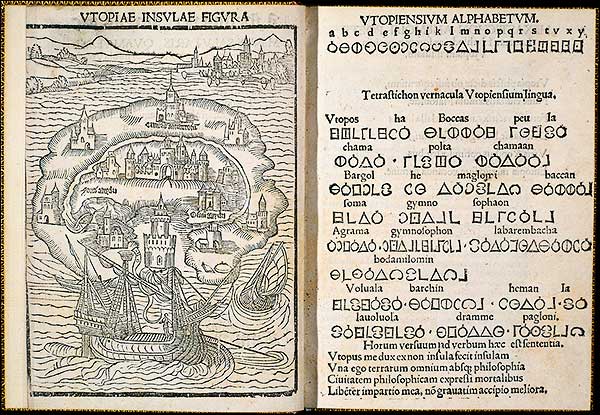

Thomas More’s Utopia

In 1516, it was Dirk Martens who printed the first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia. Among the hundreds of editions he printed mostly alone, 61 books and writings of Erasmus, notably In Praise of Folly. He also produced More’s edition of the roman satirist Lucian and Columbus’ account of the discovery of the new world. In 1423, Martens printed the complete works of Homer, quite a challenge!

In 1520, a papal bull of Leo X condemned the errors of Martin Luther and ordered the confiscation of his writings to be burned in public in front of the clergy and the people.

For Erasmus, burning books didn’t automatically erased their their content from the minds of the people. “One starts by burning books, one finishes by burning people” Erasmus warned years before Heinrich Heine said that “There, were one burns books, one ends up burning people”.

Printers and friends of Erasmus, especially in France, died on the stake opening the doors for the religious wars that will ravage Europe for the century to come.

What Erasmus feared above all, is that with the Vatican’s brutal war against Luther, it is the entire cultural renaissance and the learning of languages that got threatened with extinction.

In July 1521, confronted with the book burning, the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer, who made his living with bible illustrations, left Antwerp with his wife to return to his native Nuremberg.

Thirty years later, in 1552, the great cartographer Gerardus Mercator, a brilliant pupil of the Collegium Trilingue, for having called into question the views of Aristotle, went into exile and settled in Duisbourg, Germany.

In 1521, at the request of his friends who feared for his life, Erasmus left Leuven for Basel and settled in the workshop of another humanist, the Swiss printer Johann Froben.

In 1530, with a foreword of Erasmus, Froben published Georgius Agricola’s inventory of mining techniques, De Re Metallica, a key book that vastly contributed to the industrial revolution of Saxen, Switzerland, Germany and the whole of Europe.

Conclusion

If certain Catholic historians try to downplay the hostility of their Church towards Erasmus, the fact remains that between 1559 and 1900, the full works of Erasmus were on the “Index Vaticanus” and therefore “forbidden readings” for Catholics.

If Thomas More, whom Erasmus considered as his twin brother, was canonized by Pius XI in 1935 and recognized as the patron saint of the political leaders, Erasmus himself was never rehabilitated.

Interrogated by this author in a letter, the Pope Francis returned a polite but evasive answer.

Let’s rebuild the Collegium Trilingue !

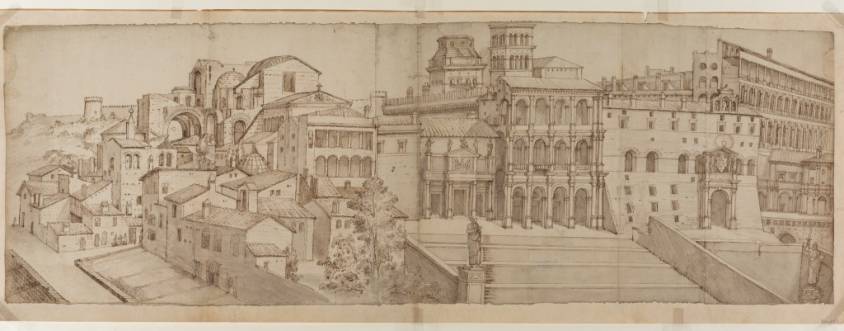

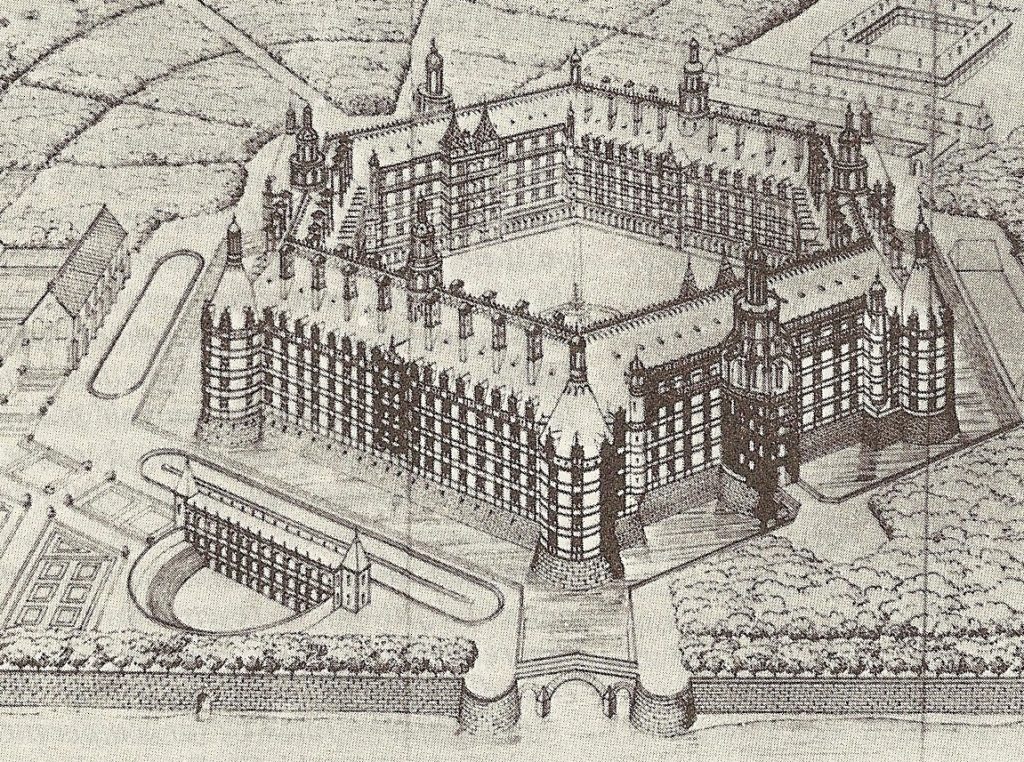

With the exception of the staircase, only a few stones remain of the historical building housing the Collegium Trilingue. In 1909, the University of Louvain planned to buy up and rebuild the site but the First World War changed priorities. Before becoming social housing, part of the building was used as a factory. As a result, today, there is no overwhelming charm. However, seeing the historical value of the site, we cannot but fully support a full reconstruction plan of the building and its immediate environment.

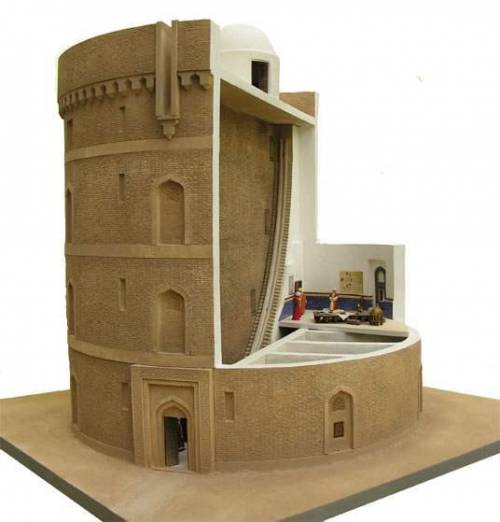

It would make the historical center of Leuven so much nicer, so much more attractive and very much more loyal to its own history. On top, such a reconstruction wouldn’t cost much and might interest private investors. The images in 3 dimensions produced for the Leuven exhibit show a nice Flemish Renaissance building, much in the style of the marvels constructed by architect Rombout II Keldermans.

Every period has the right to honestly “re-write” its own history, without falsifications, according to its own vision of the future.

It has to be noted here that the world famous “Rubenshuis” in Antwerp, is not at all the original building, but a scrupulous reconstruction of the late 1930s.

With Kondiaronk and Leibniz, re-inventing a society without oligarchy

By Karel Vereycken, May 2023.

Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the founder of the Schiller Institute, in her keynote address to the Schiller Institute’s Nov. 22, 2022 videoconference, “For World Peace—Stop the Danger of Nuclear War: Third Seminar of Political and Social Leaders of the World,” called on world leaders to eradicate the evil principle of oligarchy.

Oligarchy is defined as a power structure in which power rests with a small number of people having certain characteristics (nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, religious, political, or military control) and who impose their own power over that of their people.

To be precise, Zepp-LaRouche said :

“For 600 years, there has been a continuous battle between two forms of government, between the sovereign nation state and the oligarchical form of society, vacillating back and forth with sometimes a greater emphasis in this or that direction.

All empires based on the oligarchical model have been oriented towards protecting the privileges of the ruling elite, while trying to keep the masses of the population as backward as possible,

because as sheep they are easier to control (…)”

Now, unfortunately, most of the citizens of the transatlantic world and elsewhere will tell you that abolishing the oligarchical principle is “a good idea”, a “beautiful dream”, but that reality tells us “it can’t happen” for the very simple reason that “it never happened before”.

Societies, by definition, they argue, are in-egalitarian. Kings and Presidents of Republics, they argue, eventually might have “pretended” they ruled over the masses for their “common good”, but in reality, our fellow-citizens think, it was always the rule of a handful favoring their own interest over the majority.

The BRICS

Interesting for all of us, is that some leading thinkers involved in the BRICS movement, are trying to imagine new ways of collective rule excluding oligarchical principles.

For example, going in that direction, economist Pedro Paez, former advisor to Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, in his intervention at the April 15-16 Schiller Institute’s video conference, defended

“a new concept of currency based on monetary arrangements of clearing houses for regional payments, that can be joined into a world clearing house system, which could also prevent another type of unilateral, unipolar hegemony from arising, such as the one that was established with Bretton Woods, and that would instead open the doors to multipolar management”.

Also Belgian philosopher and theologian Marc Luyckx, a former member of the Jacques Delors famous taskforce « Cellule de Prospective » of the European Commission, in a video interview on the de-dollarization of the world economy, underlined that the BRICS countries are creating a world order whose nature makes it so that not a single member of their own group can become the dominant power.

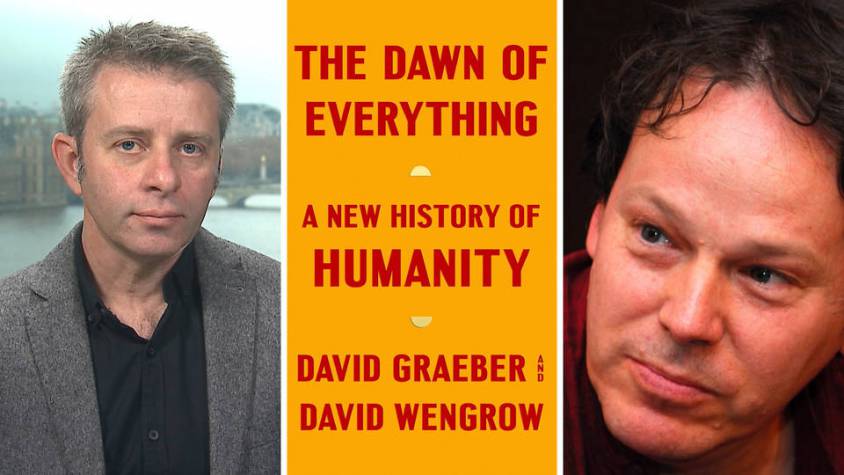

The Dawn of Everything

The good news is that a mind-provoking, 700-page book, titled “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity”, written and published in 2021 by the American anthropologist David Graeber and the British archaeologist David Wengrow, destroys the conventional notions of ancient human cultures making linear progress toward the neo-liberal economic model and therefore, by implication, high levels of inequality.

Even better, based on hard facts, the book largely debunks the “narrative” that oligarchical rule is somehow “natural”. Of course, the oligarchical principle ruled often and often for a long time. But, surprisingly, the book offers overwhelming indications and “hard facts” proving that in ancient times, some societies, though not all, which eventually prospered over centuries, through political choices, consciously adopted modes of governance preventing minority groups from permanently keeping a hegemonic grip over societies.

Zepp-LaRouche’s 10th point

The subject matter of this issue is intimately linked to the 10th point raised by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, which, in order to demonstrate that all sources of evil can be eradicated by education and political decision, that man’s natural inclination, is intrinsically to do the good. The very existence of historical precedents of societies surviving without oligarchy over hundreds of years, is of course, the “practical” proof of man’s axiomatic inclination to do the good.

Unsurprisingly, some argue that the issue of “good” and “evil” is nothing but a “theological debate”, since the concepts of “good” and “evil” are concepts made up by humans in order to compare themselves with one another. They argue it would never occur to anyone to argue about whether a fish, or a tree, were good or evil, since they lack any form of self-conscience enabling them to measure if their deeds and actions fulfill their own inclination or that of their creator.

Now, part of the “Biblical answer” to this question, if man is bad or evil, claims that people “once lived in a state of innocence”, yet were tainted by original sin. We desired to be godlike and have been punished for it; now we live in a fallen state while hoping for future redemption.

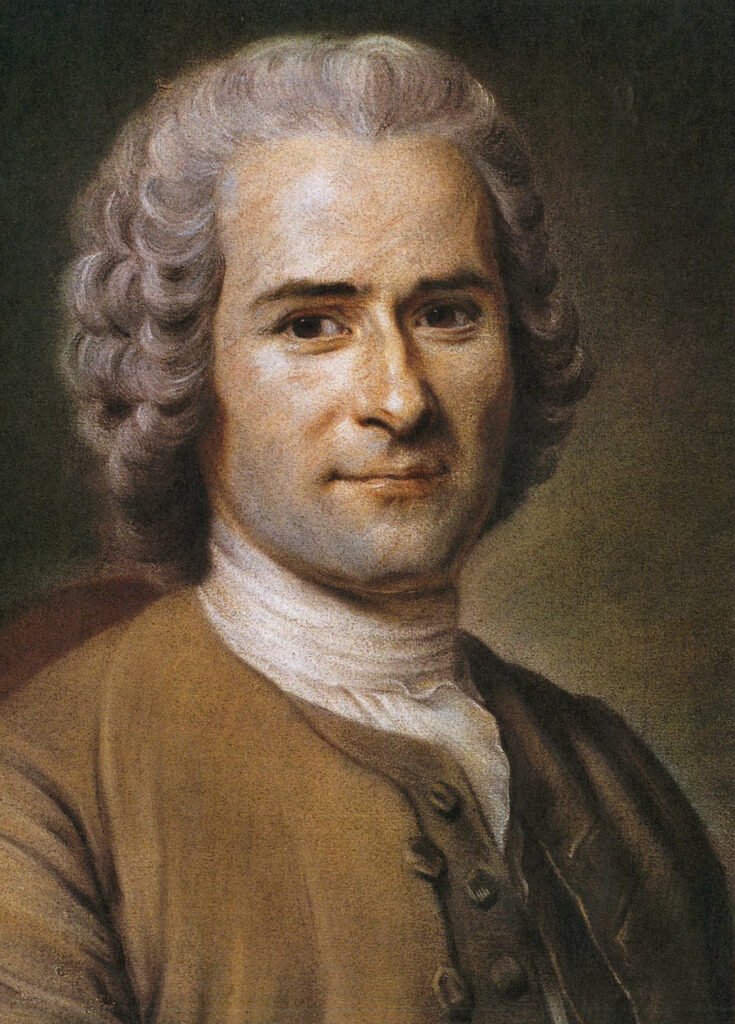

Overturning the evil Rousseau and Hobbes

Graeber and Wengrow, establishing the core argument of their entire book, demonstrate in a very provocative way how we got brainwashed by the pessimistic and destructive oligarchical ideology, especially that promoted by both Rousseau and Hobbes, for whom inequality is the natural state of man, a humanity which might have eventually been good as “a noble savage”, before becoming “civilized” and a society only surviving thanks to a “social contract” (voluntary bottom-up submission) or a “Leviathan” (top down dictatorship) :

“Today, the popular version of this [biblical] story [of man thrown out of the Garden of Eden] is typically some updated variation on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind, which he wrote in 1754. Once upon a time, the story goes, we were hunter-gatherers, living in a prolonged state of childlike innocence, in tiny bands. These bands were egalitarian; they could be for the very reason that they were so small. It was only after the “Agricultural Revolution,” and then still more the rise of cities, that this happy condition came to an end, ushering in ‘civilization’ and ‘the state’—which also meant the appearance of written literature, science and philosophy, but at the same time, almost everything bad in human life: patriarchy, standing armies, mass executions and annoying bureaucrats demanding that we spend much of our lives filling in forms.

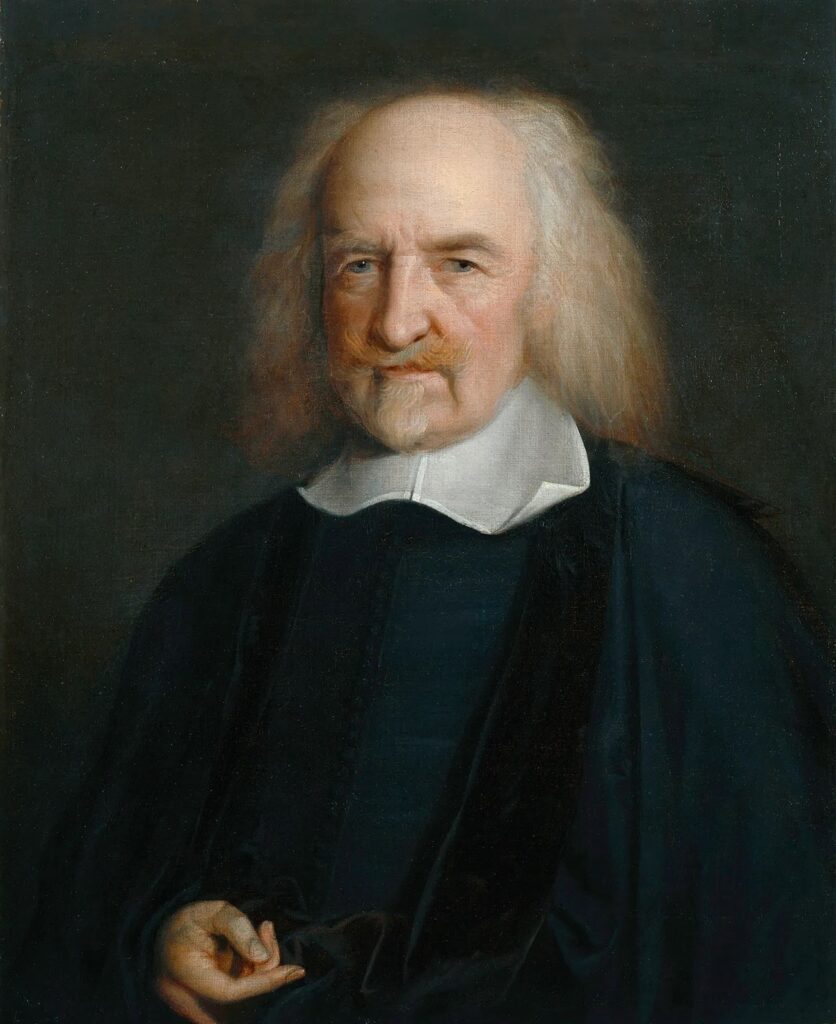

“Of course, this is a very crude simplification, but it really does seem to be the foundational story that rises to the surface whenever anyone, from industrial psychologists to revolutionary theorists, says something like ‘but of course human beings spent most of their evolutionary history living in groups of ten or twenty people,’ or ‘agriculture was perhaps humanity’s worst mistake.’ And as we’ll see, many popular writers make the argument quite explicitly. The problem is that anyone seeking an alternative to this rather depressing view of history will quickly find that the only one on offer is actually even worse: if not Rousseau, then Thomas Hobbes.

“Hobbes’s Leviathan, published in 1651, is in many ways the founding text of modern political theory. It held that, humans being the selfish creatures they are, life in an original State of Nature was in no sense innocent; it must instead have been ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’—basically, a state of war, with everybody fighting against everybody else. Insofar as there has been any progress from this benighted state of affairs, a Hobbesian would argue, it has been largely due to exactly those repressive mechanisms that Rousseau was complaining about: governments, courts, bureaucracies, police. This view of things has been around for a very long time as well. There’s a reason why, in English, the words ‘politics’ ‘polite’ and ‘police’ all sound the same—they’re all derived from the Greek word polis, or city, the Latin equivalent of which is civitas, which also gives us ‘civility,’ ‘civic’ and a certain modern understanding of ‘civilization.

“Human society, in this view, is founded on the collective repression of our baser instincts, which becomes all the more necessary when humans are living in large numbers in the same place. The modern-day Hobbesian, then, would argue that, yes, we did live most of our evolutionary history in tiny bands, who could get along mainly because they shared a common interest in the survival of their offspring (‘parental investment,’ as evolutionary biologists call it). But even these were in no sense founded on equality. There was always, in this version, some ‘alpha-male’ leader. Hierarchy and domination, and cynical self-interest, have always been the basis of human society. It’s just that, collectively, we have learned it’s to our advantage to prioritize our long-term interests over our short-term instincts; or, better, to create laws that force us to confine our worst impulses to socially useful areas like the economy, while forbidding them everywhere else

“As the reader can probably detect from our tone, we don’t much like the choice between these two alternatives. Our objections can be classified into three broad categories. As accounts of the general course of human history, they:

1) simply aren’t true;

2) have dire political implications and

3) make the past needlessly dull.”

As a consequence of the victory of imperial models of political power, the only accepted “narrative” of man’s “evolution”, automatically validating an oligarchical grip over society, is that which allows “confirming” the pre-agreed-upon dogma erected as immortal “truth”. And any historical findings or artifacts contradicting or invalidating the Rousseau-Hobbes narrative will be, at best, declared anomalies.

Open our eyes

Graeber and Wengrow’s book is an attempt

“to tell another, more hopeful and more interesting story; one which, at the same time, takes better account of what the last few decades of research have taught us. Partly, this is a matter of bringing together evidence that has accumulated in archaeology, anthropology and kindred disciplines; evidence that points towards a completely new account of how human societies developed over roughly the last 30,000 years. Almost all of this research goes against the familiar narrative, but too often the most remarkable discoveries remain confined to the work of specialists, or have to be teased out by reading between the lines of scientific publications.”

To give just a sense of how different the emerging picture is:

“[I]t is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory. Agriculture, in turn, did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies. And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers,

ambitious warrior-politicians, or even bossy administrators.”

Kondiaronk, Leibniz and the Enlightenment

In fact, Rousseau’s story, argue the authors, was in part a response to critiques of European civilization, which began in the early decades of the 18th century. “The origins of that critique, however, lie not with the philosophers of the Enlightenment (much though they initially admired and imitated it), but with indigenous commentators and observers of European society, such as the Native American (Huron-Wendat) statesman Kondiaronk,” and many others.

And when prominent thinkers, such as Leibniz, “urged his patriots to adopt Chinese models of statecraft, there is a tendency for contemporary historians to insist they weren’t really serious”.

However, many influential Enlightenment thinkers did in fact claim that some of their ideas on the subject of inequality were directly taken from Chinese or Native American sources!

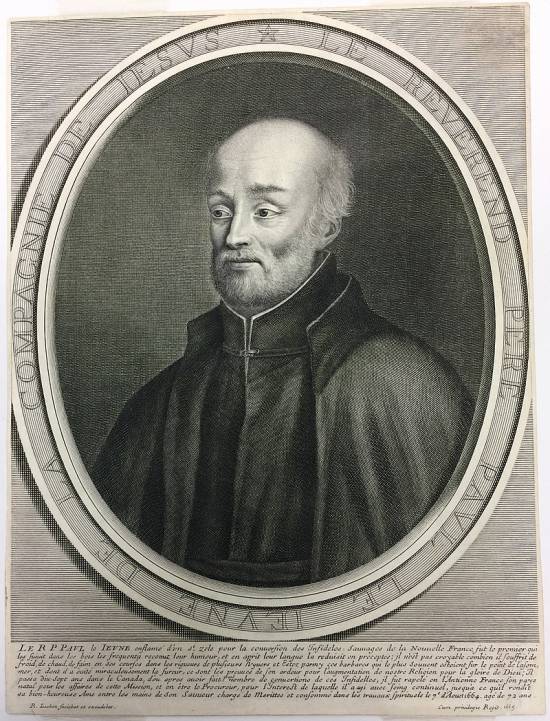

Just as Leibniz became familiar with Chinese civilization through his contact with the Jesuit missions, the ideas from Native Americans reached Europe by way of books such as the widely read seventy-one-volume report The Jesuit Relations, published between 1633 and 1673.

While today, we would think personal freedom is a good thing, this was not the case for the Jesuits complaining about the Native Americans. The Jesuits were opposed to freedom in principle:

“This, without doubt, is a disposition quite contrary to the spirit of the Faith, which requires us to submit not only our wills, but our minds, our judgments, and all the sentiments of man

to a power unknown to the laws and sentiments of corrupt nature.”

Jesuit father Jérôme Lallemant, whose correspondence provided an initial model for The Jesuit Relations, noted of the Wendat Indians in 1644: “I do not believe that there is a people on earth freer than they, and less able to allow to the subjection of their wills to any power whatever”.

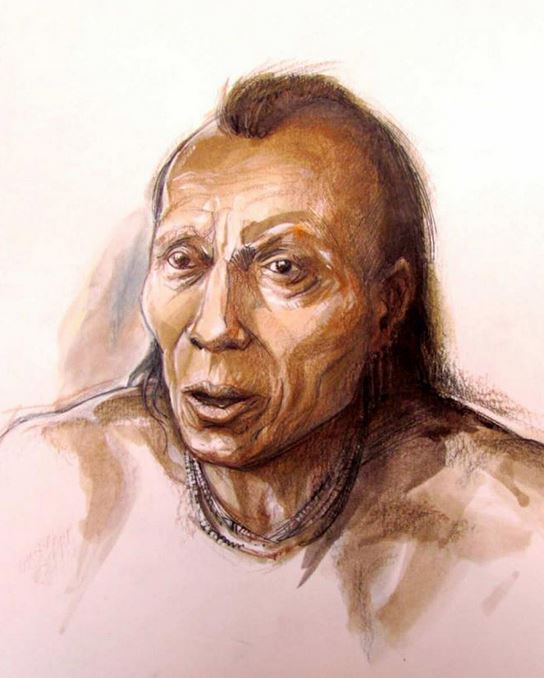

Even more worrisome, their high level of intelligence. Father Paul Le Jeune, Superior of the Jesuits in Canada in the 1630:

“There are almost none of them incapable of conversing or reasoning very well, and in good terms, on matters within their knowledge. The councils, held almost every day in the Villages, and on almost all matters, improve their capacity for talking”.

Or in Lallemant’s words:

“I can say in truth that, as regards intelligence, they are in no ways inferior to Europeans and to those who dwell in France. I would never have believed that, without instruction, nature could have supplied a most ready and vigorous eloquence, which I have admired in many Hurons (American Natives); or more clear-nearsightedness in public affairs, or a more discreet management in things to which they are accustomed”.

(The Jesuit Relations, vol. XXVIII, p. 62.)

Some Jesuits went much further, noting – not without a trace of frustration – that New World “savages” seemed rather cleverer overall than the people they were used to dealing with at home.

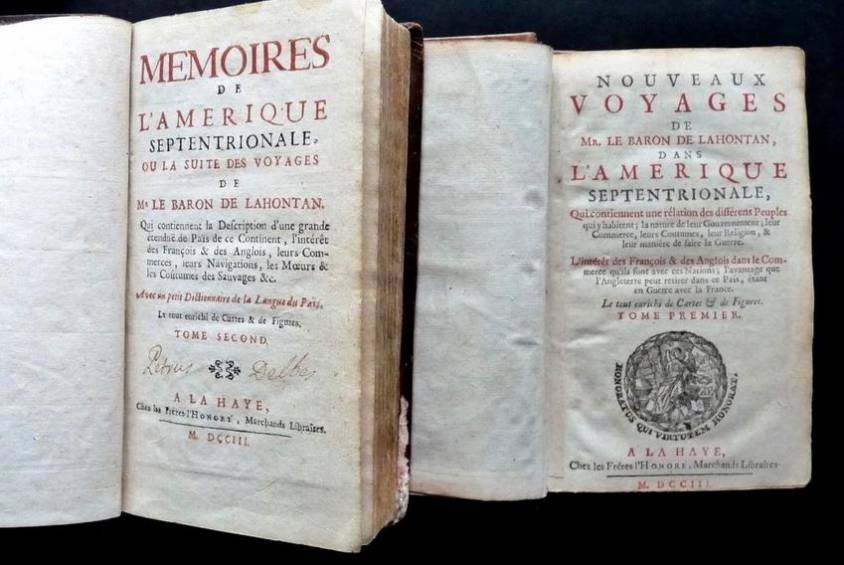

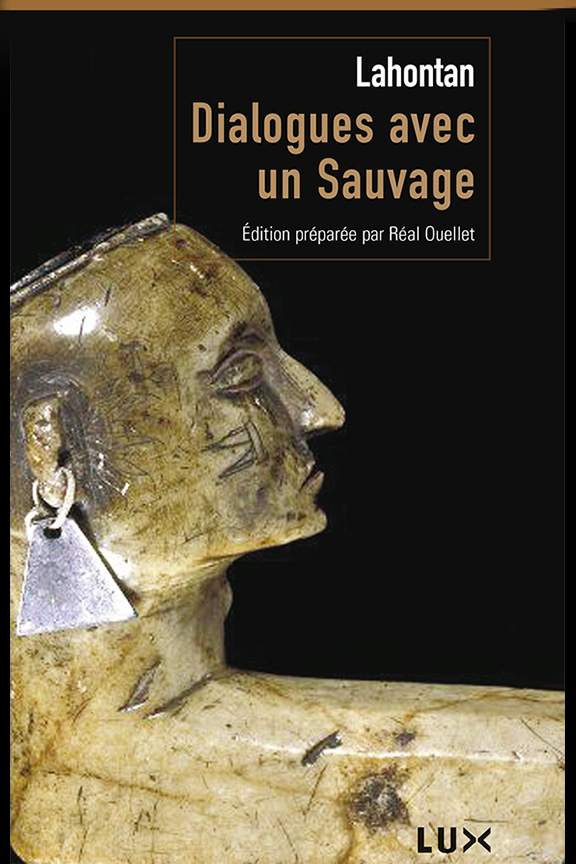

The ideas of Native Indian statesman Kondiaronk (c. 1649–1701), known as “The Rat” and the Chief of the Native American Wendat people at Michilimackinac in New France, reached Leibniz via an impoverished French aristocrat named Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de la Hontan, better known as Lahontan.

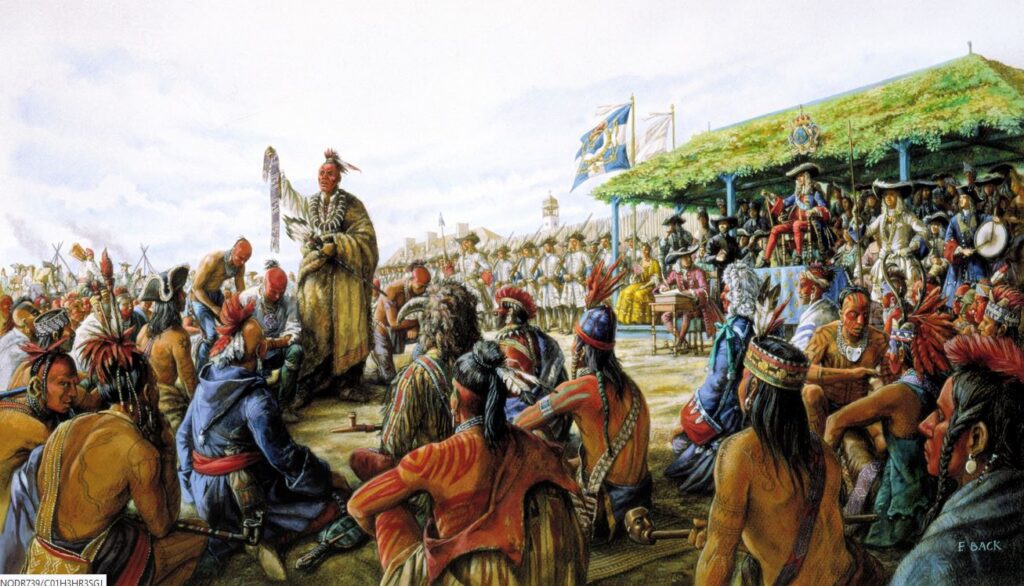

In 1683, Lahontan, age 17, joined the French army and was posted in Canada. In his various missions, he became fluent in both Algonkian and Wendat and good friends with a number of indigenous political figures, including the brilliant Wendat statesman Kondiaronk. The latter impressed many French observers with his eloquence and brilliance and frequently met with the royal governor, Count Louis de Buade de Frontenac. Kondiaronk himself, as Speaker of the Council (their governing body) of the Wendat Confederation, is thought to have been sent as an ambassador to the Court of the French King, Louis XIV, in 1691.

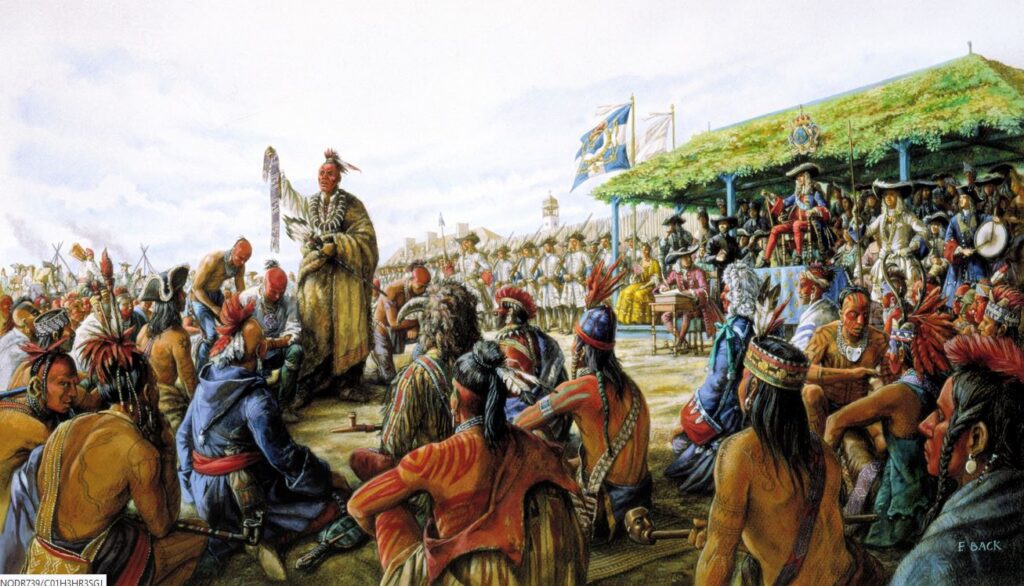

The Great Peace of Montreal

Even after being betrayed by the French, and obliged to conduct his own wars to secure his fellow men, Kondiaronk, played a key role in what is remembered as the “Great Peace of Montreal” of August 1, 1701, which ended the bloody Beaver Wars, in reality proxy wars between the British and the French, each of them using the native Indians as “cannon fodder” for their own geopolitical schemes

France was increasingly cornered by the British. Therefore, at the request of the French, in the summer of 1701, more than 1,300 Indians, from forty different nations, gathered near Montreal, dispite the fact that the city was ravaged by influenza. They came from the Mississippi Valley, the Great Lakes, and Acadia. Many were lifelong enemies, but all had responded to an invitation from the French governor. Their future and the fate of the colony were at stake. Their goal was to negotiate a comprehensive peace, among themselves and with the French. The negotiations dragged on for days, and peace was far from being guaranteed. The chiefs were wary. The main stumbling block to peace was the return of prisoners who had been captured during previous campaigns and enslaved or adopted.

Without Kondiaronk’s support, peace was unattainable. On August 1, seriously ill, he spoke for two hours in favor of a peace treaty that would be guaranteed by the French. Many were moved by his speech. The following night, Kondiaronk died, struck down by influenza at the age of 52.

But the next day, the peace treaty was signed. From now on there would be no more wars between the French and the Indians. Thirty-eight nations signed the treaty, including the Iroquois. The Iroquois promised to remain neutral in any future conflict between the French and the Iroquois’ former allies, the English colonists of New England.

Kondiaronk was praised by the French and presented as a “model” of peace-loving natives. The Jesuits immediately put out the lie that, just before dying, he had “converted” to the Catholic faith in the hope other natives would follow his model.

Lahontan from Amsterdam to Hanover