Statue du père Ferdinand Verbiest devant l’église de son village natal Pittem en Flandres (Belgique).

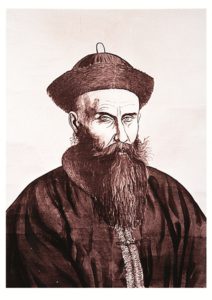

Le jésuite flamand Ferdinand Verbiest (1623 – 1688), né à Pittem en Belgique, a passé 20 ans à Beijing comme astronome en chef à la Cour de l’Empereur de Chine pour qui il élabora des calendriers, des tables d’éphémérides, des montres solaires, des clepsydres, un thermomètre, une camera obscura et même un petit charriot tracté par un machine à vapeur élémentaire, ancêtre lointain de la première automobile.

Verbiest, dont la volumineuse correspondance en néerlandais, en français, en latin, en espagnol, en portugais, en chinois et en russe reste à étudier, dessina également des cartes et publia des traités en chinois sur l’astronomie, les mathématiques, la géographie et la théologie.

Parmi ses œuvres en chinois :

- Yixiang zhi (1673), un manuel pratique (en chinois) pour la construction de toutes sortes d’instruments de précision, ornée d’une centaine de schémas techniques ;

- Kangxi yongnian lifa (1678) sur le calendrier de l’empereur Kangxi et

- Jiaoyao xulun, une explication des rudiments de la foi.

En latin, Verbiest publia l’Astronomie européenne (1687) qui résume pour les Européens les sciences et technologies européennes qu’il a promu en Chine.

Bien que les jésuites d’Ingolstadt en Bavière travaillaient avec Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), Verbiest, pour éviter des ennuis avec sa hiérarchie, s’en tient aux modèle de Tycho Brahé.

Son professeur, le professeur de mathématiques André Taquet, qui correspondait avec le collaborateur de Leibniz Christian Huyghens, affirmait qu’il refusait le modèle copernicien comme l’église l’exigeait, mais uniquement par fidélité à l’église et non pas sur des bases scientifiques.

Jusqu’en 1691, l’Université de Louvain refusait d’enseigner l’héliocentrisme.

Dans son traité, à part l’astronomie, Verbiest aborde la balistique, l’hydrologie (construction des canaux), la mécanique (transport de pièces lourdes pour les infrastructures), l’optique, la catoptrique, l’art de la perspective, la statique, l’hydrostatique et l’hydraulique. Dans le chapitre sur « la pneumatique » il discute ses expériences avec une turbine à vapeur. En dirigeant la vapeur produite par une bouilloire placé sur un petit charriot vers une roue à aubes, il rapporte d’avoir réussi à créer une auto-mobile rudimentaire. « Avec ce principe de propulsion, on peut imaginer pas mal d’autres belles applications », conclut Verbiest.

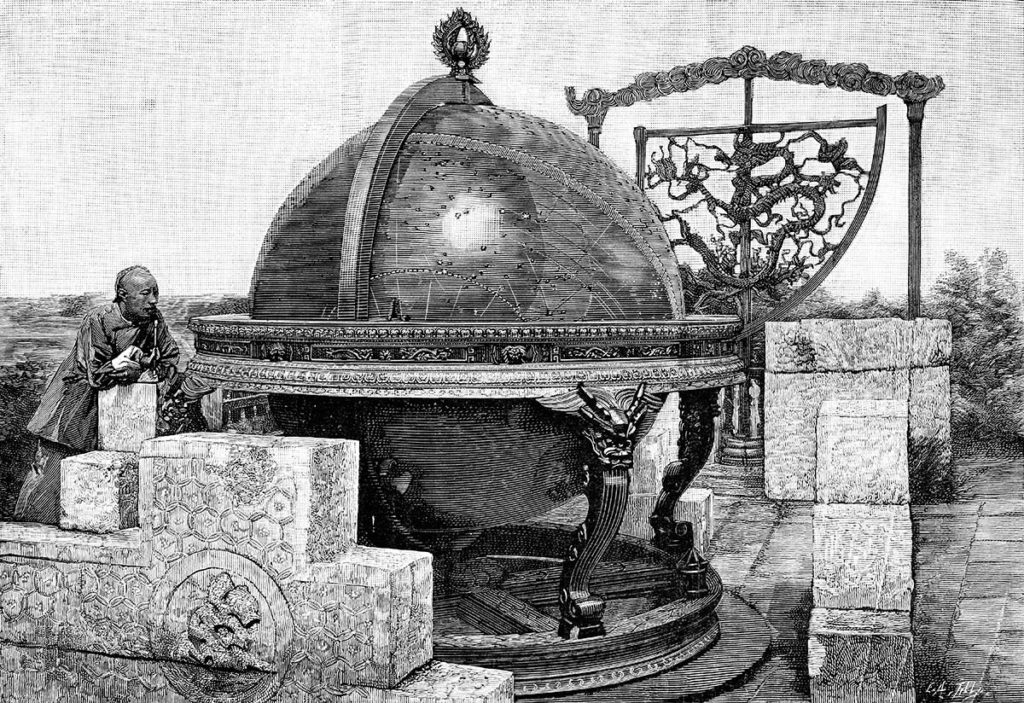

L’observatoire d’astronomie de Beijing, rééquipé par Verbiest avec des instruments dont il décrit le fonctionnement et les méthodes de fabrication, fut sauvé en 1969 par l’intervention personnelle de Zhou Enlai. Depuis 1983, cet observatoire qu’on nomme en Chine « le lieu où l’Orient et l’Occident se rencontrent », est ouvert à tous.

Évangélisation et/ou dialogue des cultures ?

Lorsqu’à partir du XIVe siècle la religion catholique cherchait à s’imposer comme la seule « vraie religion » dans les pays qu’on découvrait, il suffisait en général de quelques armes à feu et le prestige occidental pour convertir rapidement les habitants des pays nouvellement conquis.

Convertir les Chinois était un défi d’une toute autre nature. Pour s’y rendre, les missionnaires y arrivaient au mieux comme les humbles accompagnateurs de missions diplomatiques. Ils y faisaient aucune impression et se faisaient généralement renvoyer dans les plus brefs délais. L’estime pour la civilisation chinoise en Orient était telle que lorsque le jésuite espagnol Franciscus Xaverius se rend au Japon en 1550, les habitants de ce pays lui suggéraient : « Convertissez d’abord les Chinois. Une fois gagnés les Chinois au christianisme, les Japonais suivront leur exemple ».

Parmi plusieurs générations de missionnaires, trois jésuites ont joué le temps d’un siècle un rôle décisif pour obtenir en 1692 la liberté religieuse pour les chrétiens en Chine : l’Italien Mattéo Ricci (1552-1610), l’Allemand Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591 – 1666) et enfin le Belge Ferdinand Verbiest (1623 – 1688).

Pour conduire les Chinois vers le catholicisme, ils décidèrent de gagner leur confiance en les épatant avec les connaissances astronomiques, scientifiques et techniques occidentales les plus avancées de leur époque, domaine où l’Occident l’emportait sur l’Orient. Par ce « détour scientifique » qui consistait à faire reconnaitre la supériorité de la science occidentale, on espérait amener les Chinois à adhérer à la religion occidentale elle aussi jugé supérieure. Comme le formulait Verbiest :

Comme la connaissance des étoiles avait jadis guidés les mages d’Orient vers Bethléem et les jeta en adoration devant l’enfant divin, ainsi l’astronomie guidera les peuples de Chine pour les conduire devant l’autel du vrai Dieu !

Bien que Leibniz montrait un grand intérêt pour les missions des pères en Chine avec lesquelles il était en contact, il ne partagea pas la finalité de leur démarche (voir article de Christine Bierre sur L’Eurasie de Leibniz, un vaste projet de civilisation).

Ce qui est délicieusement paradoxale, c’est qu’en offrant le meilleur de la civilisation occidentale « à des païens », les pères jésuites, peu importe leurs intentions, ont de facto convaincu leurs intermédiaires qu’Orient et Occident pouvaient accéder à quelque chose d’universel dépassant de loin les religions des uns et des autres. Leur courage et leurs actions ont jeté une première passerelle entre l’Orient et l’Occident. A nous aujourd’hui d’en faire un « pont terrestre eurasiatique ».

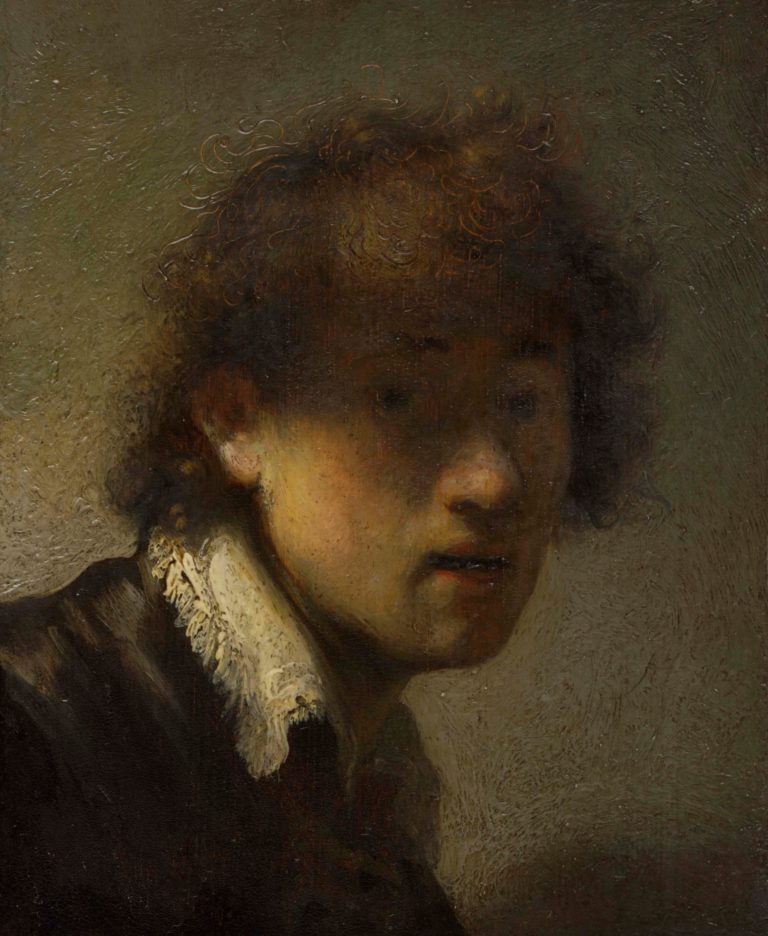

Matteo Ricci

Après avoir été obligé de rebrousser chemin dans plusieurs villes chinoises où il tentait d’engager l’évangélisation chrétienne, le père italien Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) se rendait à l’évidence que sans la coopération et la protection des plus hautes instances du pays, sa démarché était condamné à l’échec. Il se rend alors à Beijing pour tenter d’y rencontrer l’Empereur Wanli à qui il offre une épinette (petit clavecin) et deux horloges à sonnerie. Hélas, ou faut il dire heureusement, à peine quelques jours plus tard les horloges cessent de battre et l’Empereur appelle d’urgence Ricci à son Palais pour les remettre en état de marche. C’est seulement ainsi que ce dernier devient le premier Européen à pénétrer dans la Cité interdite. Pour exprimer sa gratitude l’Empereur autorise alors Ricci avec d’autres envoyés de lui rendre honneur. Mais à la grande déception du jésuite, il est seulement autorisé à s’agenouiller devant le trône vide de l’Empereur. Pour capter l’attention de l’Empereur, Ricci comprend alors que seule la clé de l’astronomie permettra d’ouvrir la porte de la muraille culturelle chinoise.

L’étude des étoiles et l’astrologie occupe à l’époque une place importante dans la société chinoise. L’Empereur y était le lien entre le ciel et la terre (comparable à la position du Pape, représentant de Dieu sur terre) et responsable de l’harmonie entre les deux. Les phénomènes célestes n’influent pas seulement les actes du gouvernement mais le sort de toute la société. A cela s’ajoute que l’histoire de la Chine est parsemée de révoltes paysannes et qu’une bonne connaissance des saisons reste la clé d’une récolte réussie. En pratique, l’Empereur était en charge de fournir chaque année le calendrier le plus précis possible. Sa crédibilité personnelle dépendait entièrement de la précision du calendrier, mesure de sa capacité de médier l’harmonie entre ciel et terre. Ricci, avec l’aide des Portugais, se concentre alors sur la production de calendriers et sur la prévision des éclipses solaires et lunaires et finit par se faire apprécier par l’Empereur. Le Pei-t’ang, l’église du nord, était la résidence de la Mission catholique à Beijing et deviendra également le nom de la bibliothèque de 5 500 volumes européens créé par Ricci.

Lorsque le 15 décembre 1610, quelques mois après le décès de Ricci, une éclipse solaire dépasse de 30 minutes le temps anticipé par les astronomes de la Cour, l’Empereur se fâche. Les astronomes chinois, qui avaient eu vent des travaux sur l’astronomie des Jésuites, demandent alors qu’on traduise d’urgence dans leur langue leurs œuvres sur la question. Un chinois converti par Ricci est alors chargé de cette tâche et ce dernier engage quelques pères comme ses assistants. De façon maladroite certains Jésuites font savoir alors leur opposition à des rites chinois ancestraux qu’ils jugent imprégnés de paganisme. Suite à une révolte de la population et des mandarins, en 1617 les Jésuites se voient estampillés ennemis du pays et doivent de se réfugier à Canton et Macao.

Adam Schall von Bell

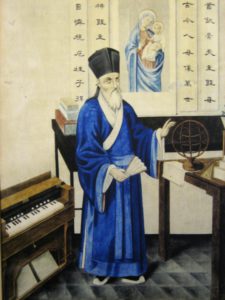

C’est seulement cinq ans plus tard, en 1622, que le père Adam Schall von Bell (1591 – 1666), un jésuite de Cologne qui arrive à Macao en 1619, arrive à s’installer dans la maison de Ricci à Beijing.

Attaqué au nord par les Mandchous, les Chinois, non dépourvus d’un fort sens de pragmatisme, feront appel aux Portugais de Macao pour leur fournir des armes et des instructeurs militaires. Du coup, les pères Jésuites se retrouvent protégés par le ministère de la défense comme intermédiaires potentiels avec les Portugais et c’est à ce titre qu’ils obtiennent des droits de résidence. Lorsqu’en 1628, les calculs pour l’éclipse lunaire s’avèrent une fois de plus erronés, Schall est nommé à la tête de l’Institut impérial d’astronomie.

Tant de succès ne pouvait que provoquer la fureur et la jalousie des astronomes chinois et musulmans qui furent éloigné de la Cour et dont les travaux étaient discrédités. Ils feront pendant des années campagne contre Schall et les jésuites. Au même temps Schall se faisait tancer par ses supérieurs à Rome et les théologiens du Vatican pour qui un prêtre catholique n’avait pas à participer dans l’élaboration de calendriers servant l’astrologie chinoise.

Vu le faible nombre d’individus – à peine quelques milliers par an – que les pères jésuites réussissaient à convertir au christianisme, Schall se résout à tenter de convertir l’Empereur en personne. Ce dernier, qui découvre que Schall a des bonnes notions de balistique, le charge en 1636 de produire des canons pour la guerre contre les Mandchous, une tache que Schall accompli uniquement pour préserver la confiance de l’Empereur. Les Chinois perdent cependant la bataille et le dernier Empereur des Ming met fin à sa vie par pendaison en 1644 afin de ne pas tomber aux mains de l’ennemi.

Les Mandchous

Les Mandchous reprennent sans sourciller les meilleures traditions chinoises et en 1645 Schall est nommé à la tête du bureau des mathématiques. L’Empereur le nomme également comme mandarin. En 1646 Schall reçoit et commence à utiliser les « Tables rudolphines », des observations astronomiques envoyés par Johannes Kepler à la demande du jésuite suisse missionnaire Johannes Schreck (Terrentius) lui aussi installé en Chine. Avec l’aide d’un élève chinois, ce dernier fut le premier à tenter de présenter au peuple chinois les merveilles de la technologie européenne dans un texte intitulé « Collection de diagrammes et d’explications des machines merveilleuses de l’extrême ouest ».

En 1655 un décret impérial ordonne que seules les méthodes européennes soient employées pour fixer le calendrier.

En Europe, les dominicains et les franciscains se plaignent alors amèrement des Jésuites qui non seulement pratiquent « le détour scientifique » pour évangéliser mais se sont livrés selon eux à des pratiques païens. Suite à leurs plaintes, par un décret du 12 septembre 1645, le pape Innocent X menace alors d’excommunication tout chrétien se livrant aux Rites chinois (culte des anciens, honneurs à Confucius). Après le contre-argumentaire du Père jésuite Martinus Martini, un nouveau décret, émis par le Pape Alexandre VII le 23 mars 1656, réconforte de nouveau la démarche des missionnaires jésuites en Chine.

Ferdinand Verbiest

Ce n’est en 1658, qu’après un voyage rocambolesque que le Père Ferdinand Verbiest arrive à son tour à Macao. En 1660, Schall, déjà âgé de 70 ans, fait venir Verbiest – dont il connait les aptitudes en mathématiques et en astronomie — à Beijing pour le succéder. Les controverses alors se déchainent. L’Empereur Chun-chih était décédé en 1661 et en attendant que son successeur Kangxi atteigne la majorité, quatre régents gèrent le pays.

Ces derniers n’étaient pas très favorables aux étrangers. Les envieux chinois attaquent alors Schall, non pas pour son travail en astronomie, mais pour le « non-respect » des traditions chinoises, notamment la polygamie. Un des détracteurs dépose plainte au département des rites, et alors que Schall, ayant perdu la voix suite à une attaque vasculaire cérébrale, a bien du mal à se défendre, Schall, Verbiest et les autres pères se font condamner pour des « crimes religieux et culturels ». Schall est condamné à mort.

La « providence divine » fait alors en sorte que plusieurs phénomènes naturels jouent en leur faveur. Etant donné qu’une éclipse solaire s’annonçait pour le 16 janvier 1665, les régents mettent aussi bien les accusateurs de Schall que Schall lui-même au défi de la calculer. Schall et Verbiest emportent la bataille haut la main ce qui fait naître le doute chez les régents. Le procès fut rouvert et renvoyé devant la cour suprême. Cette dernière confirma hélas le verdict du tribunal. Nouvelle intervention de dame nature : une comète, un tremblement de terre et un incendie du Palais impériale inspirent les pires craintes chez les Chinois qui finissent par relâcher les pères de prison sans pour autant les innocenter.

A l’exception des « quatre de Beijing » (Schall, Verbiest, de Magelhaens, Buglio) qui restent en résidence surveillé, tous sont forcés à l’exil. Schall meurt en 1666 et Verbiest travaille sur des nouveaux instruments astronomiques.

L’Empereur Kangxi

C’est en 1667 que le jeune Empereur Kangxi prend enfin les commandes. Dynamique, il laisse immédiatement vérifier les calendriers des astronomes chinois par Verbiest et oblige Chinois et étrangers de surmonter leurs oppositions en travaillant ensemble. En 1668 Verbiest est nommé directeur du bureau de l’Astronomie et en 1671 il devient le tuteur privé de l’Empereur ce qui fait naitre chez lui l’espoir de pouvoir un jour convertir l’Empereur au Christianisme.

Comme Schall, Verbiest sera en permanence sous attaque des « marins restés à quai » à Rome. Pour se défendre, Verbiest envoi son coreligionnaire, Philippe Couplet (1623-1693) en 1682 en Europe. Ce dernier s’y rend accompagné d’un jeune mandarin converti, Shen Fuzong qui parlait couramment le latin, l’italien et le portugais. C’est un des premiers Chinois à visiter l’Europe. Il suscite la curiosité à Oxford, où on lui pose de nombreuses questions sur la culture et les langues chinoises.

L’audience à Versailles est particulièrement fructueuse. A la suite de l’entrevue qu’il a avec Couplet et son ami chinois, Louis XIV décide d’établir une présence française en Chine et en 1685, six jésuites*, en tant que mathématiciens du roi et membres de l’Académie des Sciences, seront envoyés en Chine par Louis XIV.

C’est avec eux que Leibniz, lui-même à l’Académie des Sciences de Colbert, entrera en correspondance.

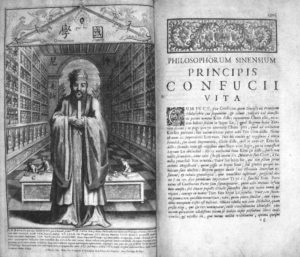

Dans son Confucius Sinarum philosophus, le collaborateur de Verbiest Couplet se montre enthousiaste : « On pourrait dire que le système éthique du philosophe Confucius est sublime. Il est en même temps simple, sensible et issu des meilleures sources de la raison naturelle. Jamais la raison humaine, ici sans appui de la Révélation divine, n’a atteint un tel niveau et une telle vigueur. »

A Paris, Couplet publie en 1687 le livre (dédié à Louis XIV) qui le fait connaître partout en Europe : le Confucius Sinarum philosophus. Couplet est enthousiaste :

On pourrait dire que le système éthique du philosophe Confucius est sublime. Il est en même temps simple, sensible et issu des meilleures sources de la raison naturelle. Jamais la raison humaine, ici sans appui de la Révélation divine, n’a atteint un tel niveau et une telle vigueur.

Verbiest diplomate

A la demande de l’Empereur, Verbiest apprend la langue Mandchou pour lequel il élabore une grammaire. En 1674 il dessine une mappemonde et, comme Schall, s’applique à produire avec les artisans chinois des canons légers pour la défense de l’Empire.

Verbiest sert également de diplomate au service l’Empereur. Par leur connaissance du latin, les Jésuites serviront d’interprètes avec les délégations portugaises, hollandaises et russes lorsqu’elles se rendent en Chine dès 1676. Ayant appris le chinois, le jésuite français Jean-Pierre Gerbillon est envoyé en compagnie du jésuite portugais Thomas Pereira, comme conseillers et interprète à Nertchinsk avec les diplomates chargés de négocier avec les Russes le tracé de la frontière extrême-orientale entre les deux empires. Ce tracé est confirmé par le traité de Nertchinsk du 6 septembre 1689 (un an après la mort de Verbiest), un important traité de paix établi en latin, en mandchou, en mongole, en chinois et en russe, conclu entre la Russie et l’Empire Qing qui a mis fin à un conflit militaire dont l’enjeu était la région du fleuve Amour.

C’est lors de son séjour en Italie, de mars 1689 à mars 1690, que Leibniz s’entretient longuement avec le jésuite Claudio-Philippo Grimaldi (1639-1712) qui résidait en Chine mais était de passage à Rome. C’est lors de leurs entretiens qu’ils apprennent la mort de Verbiest. Ce dernier était tombé de son cheval en 1687 avant de mourir en 1688 faisant de Grimaldi son successeur à la tête de l’Institut impérial d’astronomie.

Comme Schall avant lui, la Chine offre à Verbiest des funérailles d’Etat et sa dépouille mortelle reposera aux cotés de Ricci et Schall à Beijing et en 1692, L’Empereur Kanxi, sans doute en partie pour honorer pour Verbiest, décrète la tolérance religieuse pour les chrétiens.

La querelle des Rites

La réponse du Vatican fut parmi les plus stupides et le mandement de 1693 de Monseigneur Maigrot fait exploser une fois de plus la « Querelle des Rites ». Il propose d’utiliser le mot « Tian-zhu »** pour désigner l’idée occidentale d’un Dieu personnifié, concept totalement étranger à la culture chinoise, d’interdire la tablette impériale*** dans les églises, interdire les rites à Confucius, et condamne le culte des Ancêtres. Et tout cela au moment même où Kangxi décrète l’Édit de tolérance.

Parmi les Jésuites et les autres ordres de missionnaires, les avis sont partagés. Ceux qui admirent Ricci et sont en contacts avec les élites sont plutôt favorables au respect des rites chinois. Les autres, qui essayent de combattre toutes sortes de superstitions locales, sont plutôt favorables au mandement.

Ce qui est certain, c’est que les Chinois n’apprécient guère que des missionnaires s’opposent à leurs rites et traditions. Un décret de Clément XI en 1704 condamnera définitivement les rites chinois. Il reprend les points du Mandement. C’est à ce moment qu’est instauré par l’empereur le système du piao : pour enseigner en Chine, les missionnaires doivent avoir une autorisation (le piao) qui leur est accordée s’ils acceptent de ne pas s’opposer aux rites traditionnels. Mgr Maigrot, envoyé du pape en Chine, refuse de prendre le piao, et est donc chassé hors du pays.

L’empereur Kangxi, qui s’implique dans le débat, convoque l’accompagnateur de Mgr Maigrot et le soumet à une épreuve de culture. Ce dernier ne réussit pas à lire des caractères chinois et ne peut discuter des Classiques. L’empereur déclare que c’est son ignorance qui lui fait dire des bêtises sur les rites. De plus, il lui prête plus l’intention de brouiller les esprits que de répandre la foi chrétienne. Et lorsque l’Empereur Yongzheng succède à Kangxi, il fait interdire le christianisme en 1724. Seuls les Jésuites, scientifiques et savants à la cour de Pékin, peuvent rester en Chine.

C’est contre la querelle des rites que Leibniz dirigea une grande partie de ces efforts. Cette fragilité d’une entente globale entre les peuples du continent eurasiatique à de quoi nous faire réfléchir aujourd’hui. Est-ce que la nouvelle querelle des Rites provoqué par Obama et les anglo-américains contre la Russie et la Chine servira une fois de plus au parti de la guerre de semer la discorde ?

-

Les tombes des jésuites venus en Chine sont localisées au Collège Administratif de Pékin (qui forme les cadres du Parti communiste de la ville). Les tombes de 63 missionnaires ont été réhabilitées, 14 portugais, 11 italiens, 9 français, 7 allemands, 3 tchèques, 2 belges, 1 suisse, 1 autrichien, 1 slovène et 14 chinois. Les trois premières sont celles de Matteo Ricci, Adam Schall von Bell et Ferdinand Verbiest.