Étiquette : gravure

Avec le peintre James Ensor, arrachons le masque à l’oligarchie !

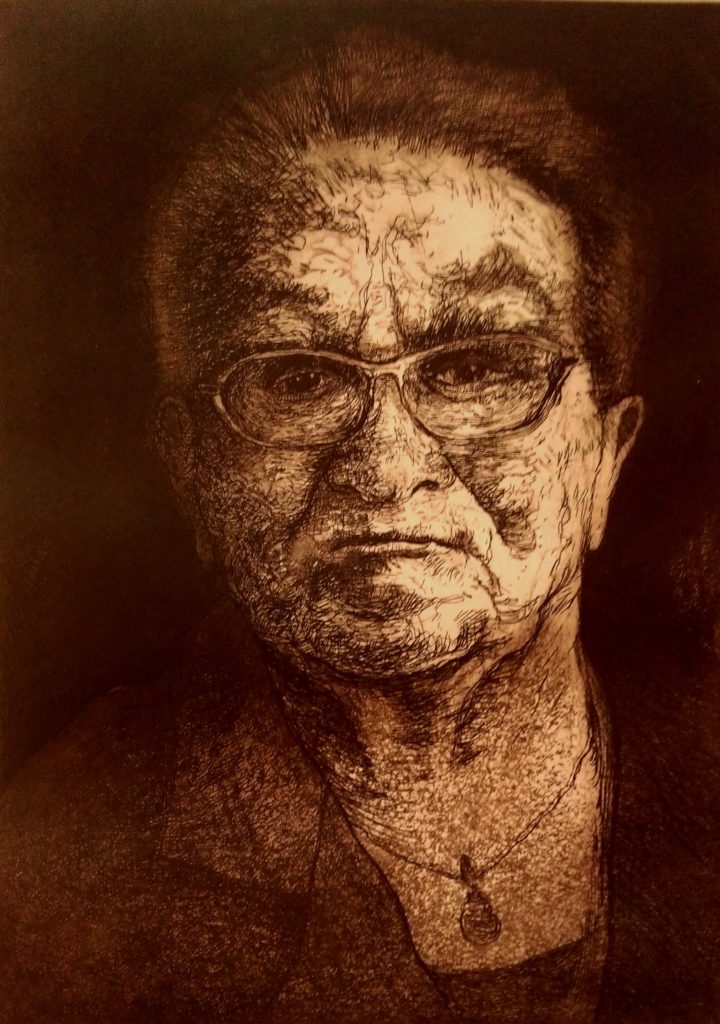

James Ensor est né le 13 avril 1860 dans une famille de la petite-bourgeoisie d’Ostende en Belgique. Son père, James Frederic Ensor, un ingénieur raté anglais anti-conformiste, sombre dans l’alcoolisme et l’héroïne.

Sa mère, Maria Catherina Haegheman, belge flamande, qui n’encourage guère sa vocation artistique, tient un magasin de souvenirs, coquillages, chinoiseries, verroteries, animaux empaillés et masques de carnaval, des artefacts qui peupleront l’imagination du peintre.

Esprit pétillant, James se passionne pour la politique, la littérature et la poésie. Un jour, commentant sa naissance lors d’un banquet offert en son honneur, il dira :

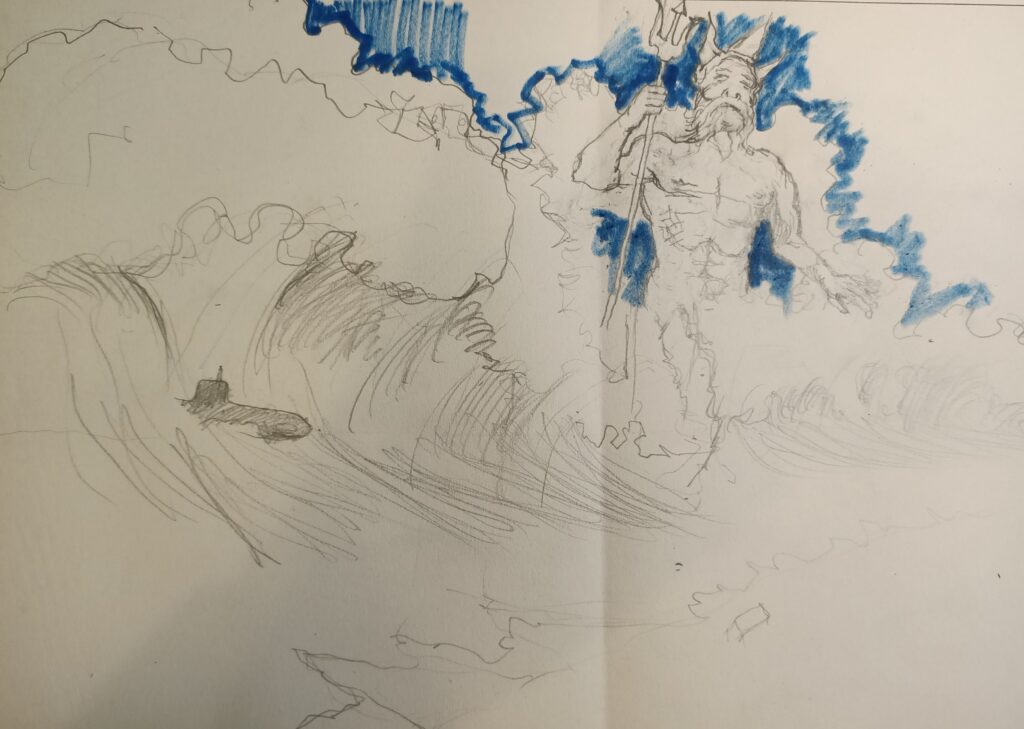

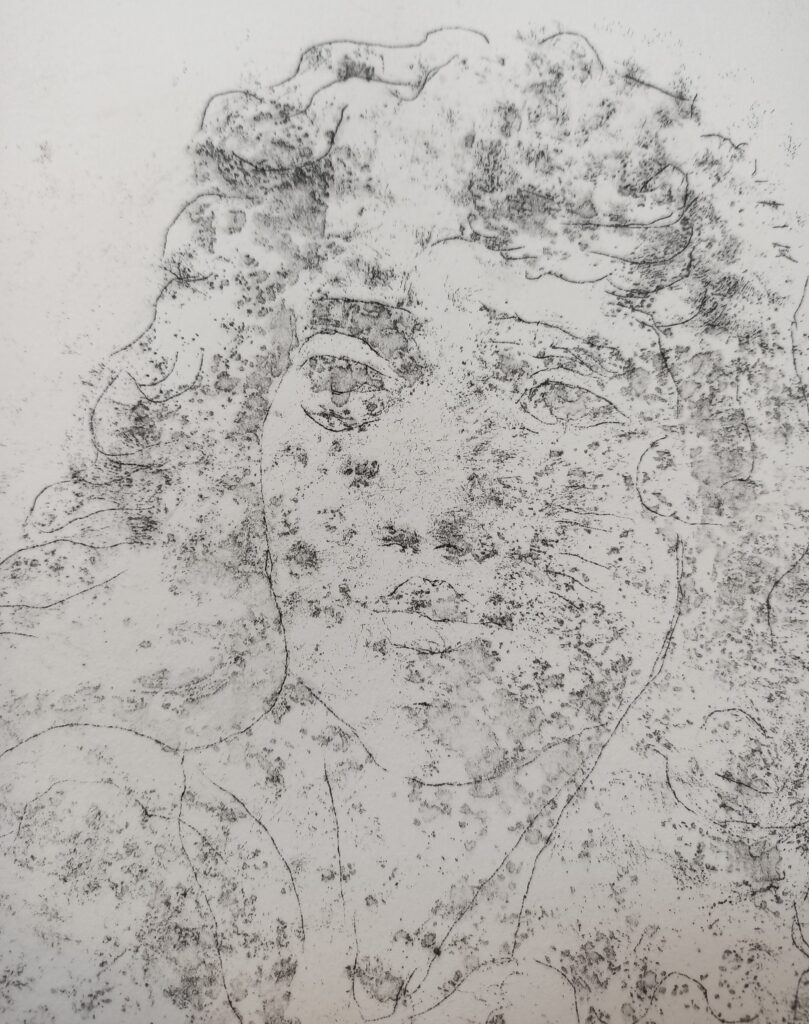

« Je suis né à Ostende un vendredi, jour de Vénus [déesse de la Paix]. Eh bien ! chers amis, Vénus, dès l’aube de ma naissance, vint à moi souriante et nous nous regardâmes longuement dans les yeux. Ah ! les beaux yeux pers et verts, les longs cheveux couleur de sable. Vénus était blonde et belle, toute barbouillée d’écume, elle fleurait bon la mer salée. Bien vite je la peignis, car elle mordait mes pinceaux, bouffait mes couleurs, convoitait mes coquilles peintes, elle courait sur mes nacres, s’oubliait dans mes conques, salivait sur mes brosses.«

Après une première initiation aux techniques artistiques à l’Académie d’Ostende, il débarque à Bruxelles chez son demi-frère Théo Hannon pour y poursuivre ses études à l’Académie des Beaux Arts. En compagnie de Théo, il est introduit dans les cercles bourgeois de libéraux de gauche qui fleurissent en périphérie de l’Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB).

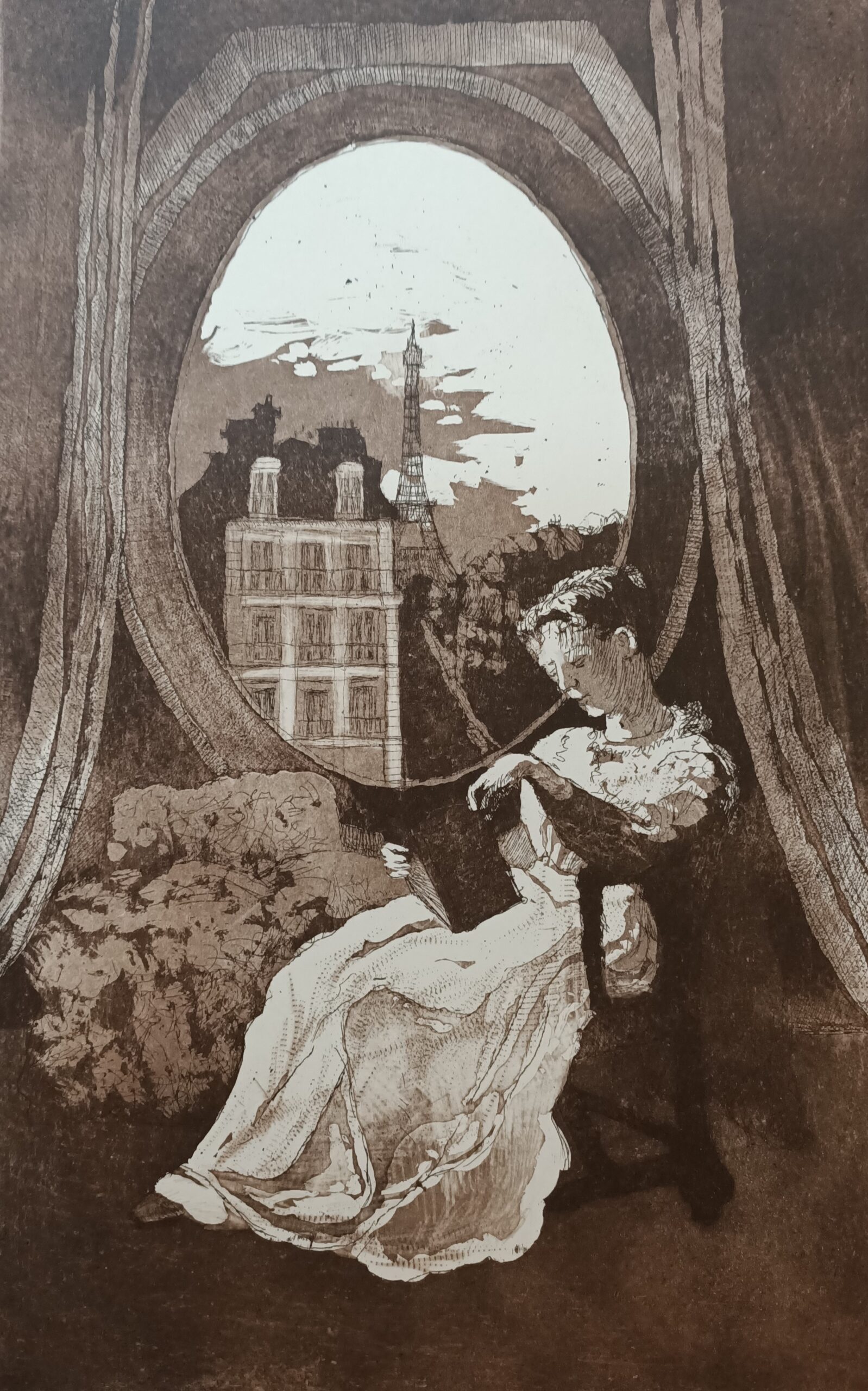

Chez Ernest Rousseau, professeur à l’Université libre de Bruxelles, dont il deviendra recteur, Ensor découvre les enjeux de la lutte politique. Madame Rousseau est microbiologiste, passionnée d’insectes, de champignons et… d’art. Les Rousseau tiennent salon, rue Vautier à Bruxelles, près de l’atelier d’Antoine Wiertz et de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique. Rendez-vous privilégié pour les artistes, les libres penseurs et autres esprits influents. Ensor y rencontre Félicien Rops et son beau-fils Eugène Demolder, mais aussi peut-être l’écrivain et critique d’art Joris-Karel Huysmans ainsi que l’anarchiste communard et géographe français Elisée Reclus.

De retour à Ostende, Ensor installe son atelier dans la maison familiale où il réalise ses premiers chefs-d’œuvre, portraits empreints de réalisme et paysages inspirés par l’impressionnisme.

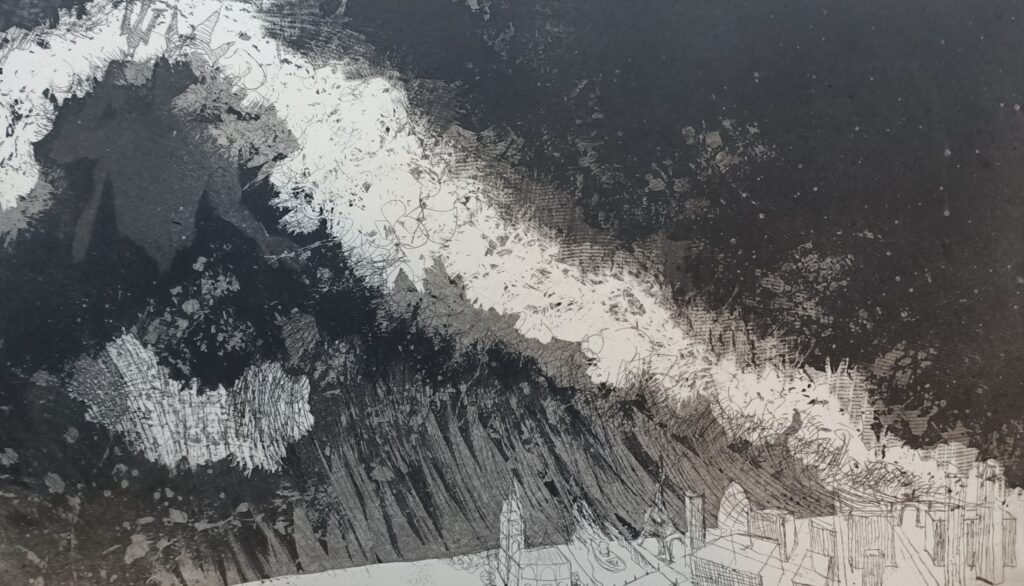

Aux pays des couleurs

« La vie n’est qu’une palpitation ! », s’écrie Ensor. Ses nuages sont des masses grises, or et azur au-dessus d’une ligne de toits. Sa Dame au brise-lames (1880) est prise dans un glacis de gris et de nacre, au bout de la jetée.

Ensor est un chef d’orchestre se servant de couteaux et de pinceaux pour étaler la peinture en couches fines ou épaisses et ajouter par-ci par-là des accents pâteux.

Son génie prend tout son envol dans son tableau La Mangeuse d’huîtres (1882). Même si l’ensemble a l’air de dégager une certaine tranquillité, il peint en réalité une gigantesque nature morte qui semble avoir avalé sa sœur cadette Mitche.

L’artiste baptise d’abord le tableau Au pays des couleurs, plus abstrait que La Mangeuse d’huîtres, puisque ce sont bien les couleurs qui jouent le rôle principal dans la composition.

Nacres des coquillages, blanc bleuâtre de la nappe, reflets des verres et bouteilles, tout est dans la variation, tant dans l’élaboration que dans les tonalités de couleur. Ensor conserve l’approche classique : il utilise toujours des sous-couches tandis que les impressionnistes appliquent la peinture directement sur la toile blanche. Les pigments dont il se sert sont également très traditionnels : rouge vermillon, blanc de plomb, terre brune, bleu de cobalt, bleu de Prusse et outremer synthétique. Le jaune chrome de La Mangeuse d’huîtres fait exception. L’intensité de ce pigment est bien plus élevée que celle du jaune de Naples plus pâle qu’il utilisait auparavant. Mais ses couleurs, qu’il utilise souvent de manière pure au lieu de les mélanger, sont bien plus claires que celles des anciens.

L’écrivain Emile Verhaeren, qui écrira plus tard la première monographie du peintre, contemple La Mangeuse d’huîtres et s’exclame : « C’est la première toile réellement lumineuse ».

Epoustouflé, il souhaite mettre en avant Ensor comme le grand innovateur de l’art belge. Mais les avis ne sont pas unanimes. La critique n’est pas tendre : les couleurs sont trop criardes et l’œuvre est peinte de manière négligée.

De plus, il est immoral de peindre « un sujet de second rang » (En monarchie, il n’existe pas de citoyens, seulement des « sujets », une femme ne faisant pas partie de l’aristocratie) dans de telles dimensions – 207 cm sur 150 cm. Par la vue plongeante, librement appliquée, on a l’impression que tout dans le tableau va déborder de son cadre.

Le Salon d’Anvers, qui expose le meilleur de l’art actuel, refuse l’œuvre en 1882. Même les anciens compères bruxellois de L’Essor refusent La Mangeuse d’huîtres un an plus tard.

Le groupe des XX

C’est ainsi qu’en Belgique, la révolution artistique de 1884 démarrera par une phrase lancée par un membre du jury officiel : « Qu’ils exposent chez eux ! » avait-il clamé, refusant les toiles de deux ou trois peintres ; c’est donc ce qu’ils firent, en exposant chez eux, dans des « salons citoyens », ou en créant leur propres associations culturelles.

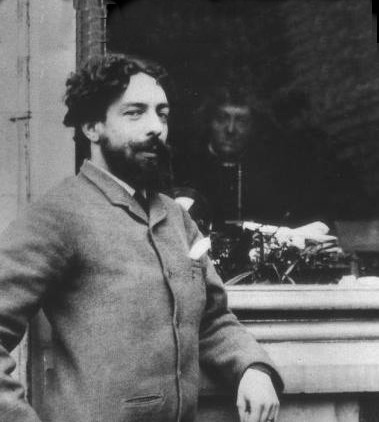

C’est dans ce contexte que Octave Maus et Ensor créeront à Bruxelles le « groupe des XX », cercle artistique d’avant-garde.

Parmi les « vingtistes » du début, outre Ensor, on trouve Fernand Khnopff, Jef Lambeaux, Paul Signac, George Minne et Théo Van Rysselberghe.

Parmi les artistes invités à venir exposer leurs œuvres à Bruxelles, de grands noms tels que Ferdinand Rops, Auguste Rodin, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, Gustave Caillebotte, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, etc.

C’est donc seulement en 1886 qu’Ensor peut exposer son œuvre novatrice La Mangeuse d’huîtres pour la première fois au groupe des XX.

Pour autant, ce n’est pas la fin de son calvaire. En 1907, le conseil communal de Liège décide de ne pas acheter l’œuvre pour le musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville.

Heureusement, Emma Lambotte, amie d’Ensor, ne laisse pas tomber le peintre. Elle achète le tableau et l’expose chez elle, dans son salon citoyen.

Engagement social et politique

Les troubles sociaux contemporains de son ascension en tant que peintre, qui virent à la tragédie lors des affrontements meurtriers de 1886 entre ouvriers et garde civique, l’incitent à trouver dans les masses en tant qu’acteur collectif un puissant compagnon d’infortune.

A la fin du XIXe siècle, la capitale belge, est une marmite bouillonnante d’idées révolutionnaires, créatrices et innovantes. Karl Marx, Victor Hugo et bien d’autres, y trouvent exil, parfois brièvement.

Le symbolisme, l’impressionnisme, le pointillisme et l’art nouveau s’y disputent leurs titres de gloire. Pour sa part, Ensor, il faut bien le reconnaître, puisant dans tous les courants, restera un inclassable s’élevant au-dessus des modes, des tendances du moment et des goûts éphémères, et de très loin.

Si Marx s’est trompé sur bien des points, il comprenait bien qu’à une époque où la finance tirait sa richesse de la production, la modernisation des moyens de production portait en germe la transformation des rapports sociaux. Tôt ou tard, et à tous les niveaux, ceux qui produisent la richesse clameront leur juste place dans le processus décisionnel.

Le combat d’Ensor pour un art plus libre reflète et coïncide avec le changement d’époque qui s’opère alors.

Partie de Vienne en Autriche, la crise bancaire de mai 1873 provoque un krach boursier qui marque le début d’une crise appelée la Grande Dépression, et qui court sur le dernier quart du XIXe siècle. Le 18 septembre 1873, Wall Street est pris de panique et ferme pendant 10 jours.

En Belgique, après une période marquée par une vertigineuse industrialisation, la loi Le Chapelier, une loi appliquée en 1791, soit quarante ans avant la naissance de la Belgique, qui interdisait la moindre forme d’organisation d’ouvriers, est abrogée en 1867, mais la grève est toujours un crime sanctionné par l’État.

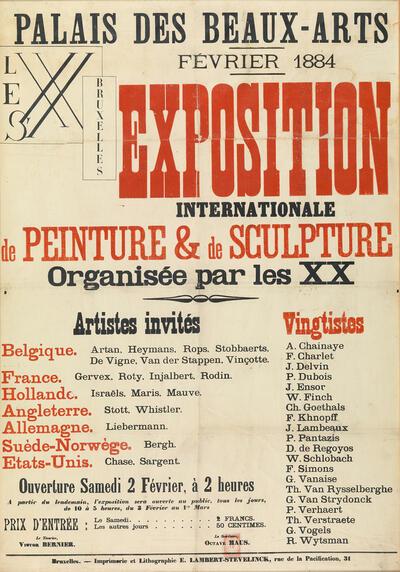

C’est dans ce contexte qu’une centaine de délégués de représentants de syndicats belges fondèrent en 1885 le Parti ouvrier belge (POB). Réformistes et prudents, ils réclament en 1894, non pas la « dictature du prolétariat », mais une forte « socialisation des moyens de production ».

La même année, le POB obtient 20 % des suffrages exprimés aux élections législatives et compte 28 députés. Il participe à plusieurs gouvernements jusqu’à sa dissolution lors de l’invasion allemande en mai 1940.

Horta, Jaurès et la Maison du Peuple de Bruxelles

L’architecte Victor Horta, grand innovateur de l’Art Nouveau et dont les premières demeures symbolisent un nouvel art de vivre, sera chargé par le POB de construire la magnifique « Maison du Peuple » à Bruxelles, un bâtiment remarquable, fait principalement d’acier, abritant un maximum de fonctionnalités : bureaux, salle de réunion, magasins, café, salle de spectacle…

Le bâtiment fut inauguré en 1899 en présence de Jean Jaurès. En 1903, Lénine y participa au congrès du Parti ouvrier social-démocrate de Russie.

Jean Jaurès prononça d’ailleurs son dernier discours, le 29 juillet 1914, au Cirque Royal de Bruxelles, lors d’une grande réunion de l’Internationale socialiste pour sauver la paix.

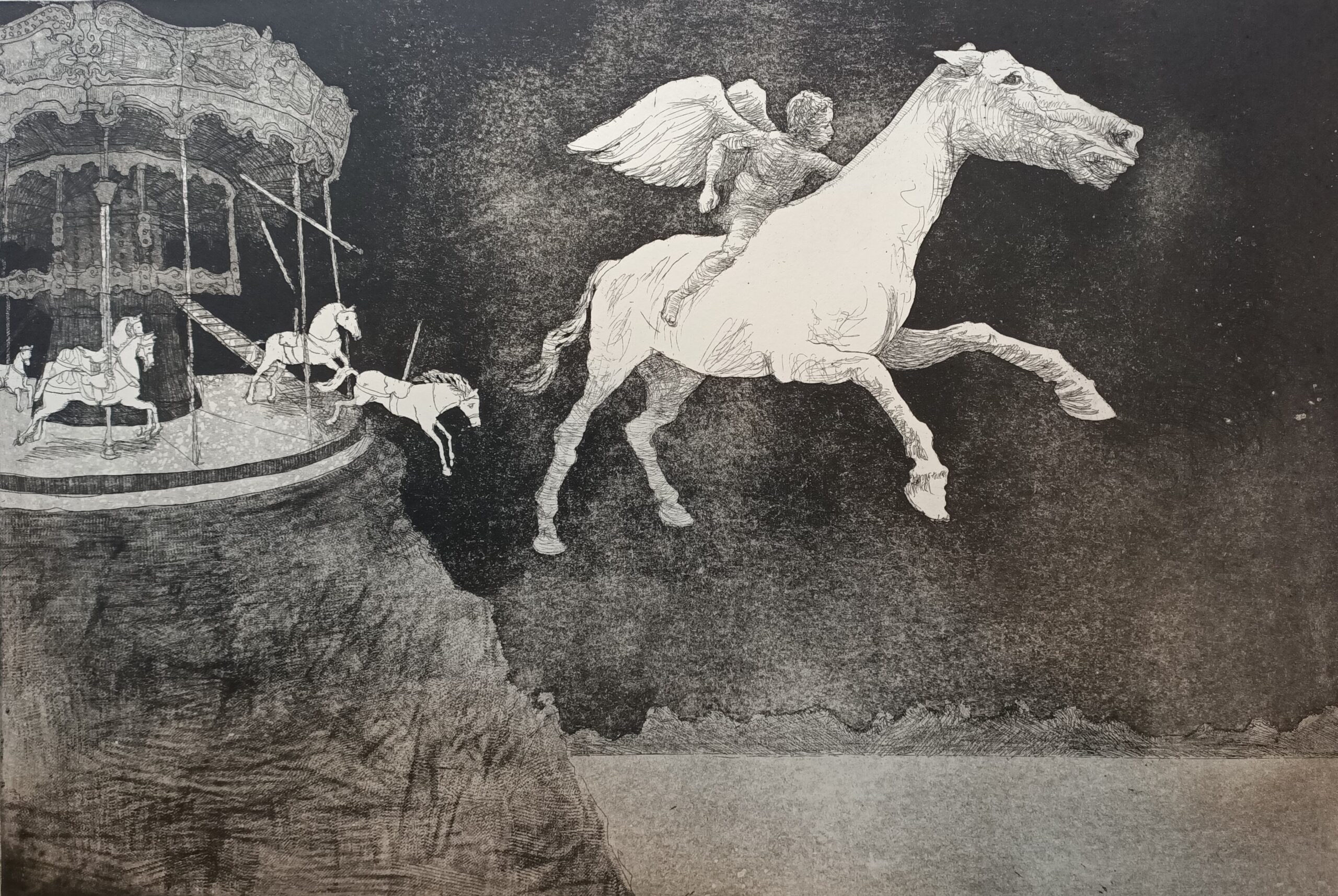

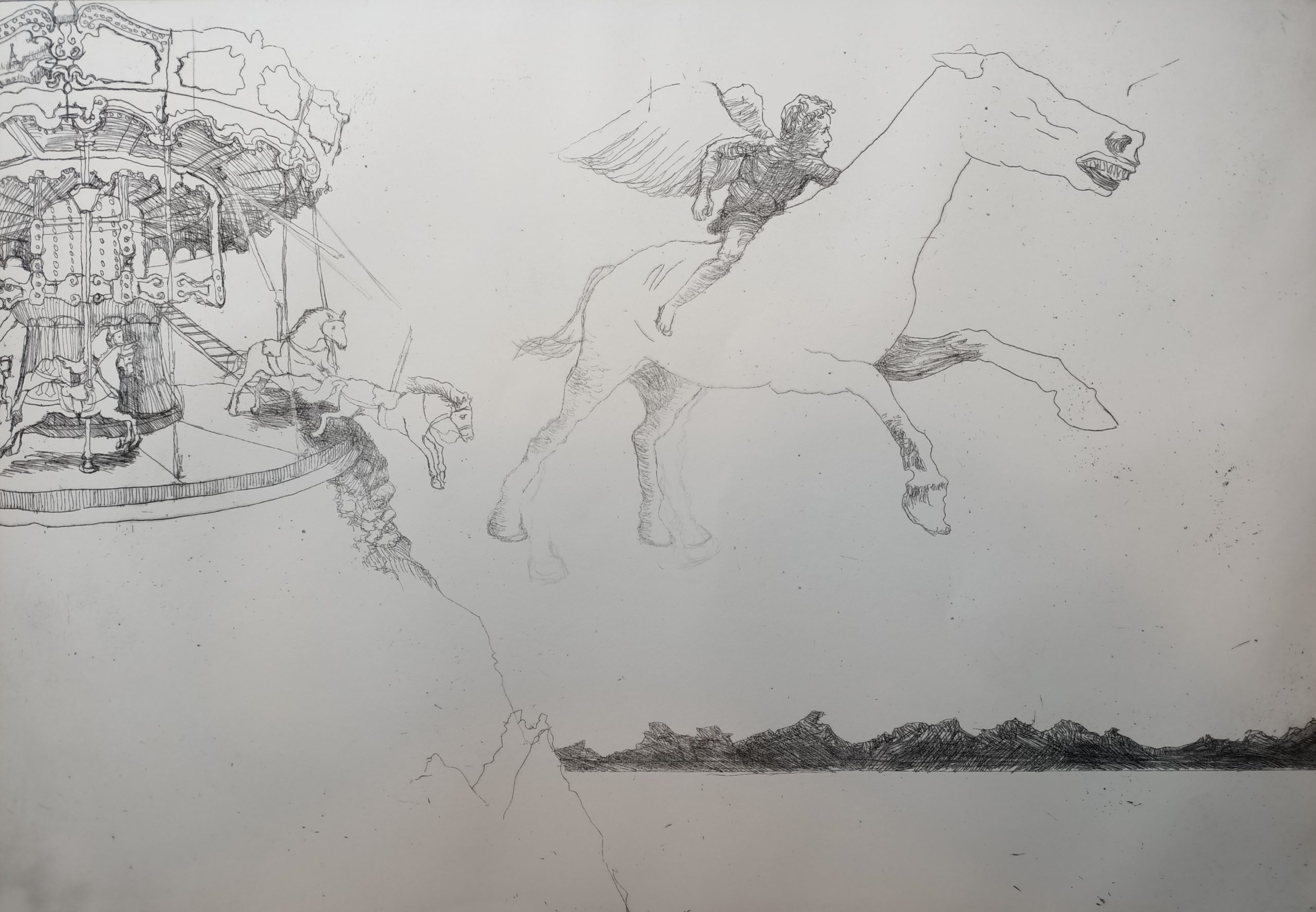

En parlant des menaces de la guerre, Jaurès dit :

« Attila est au bord de l’abîme, mais son cheval trébuche et hésite encore ». S’opposant, comme il le fit toute sa vie, à ce que la France se soumît à un rôle subalterne, il dit textuellement : « Si l’on fait appel à un traité secret avec la Russie, nous en appellerons au traité public avec l’Humanité ».

Et il termina son discours, le meilleur de sa vie, par des paroles prophétiques dont voici le texte quasi littéral : « Au début de la guerre, tout le monde sera entraîné. Mais lorsque les conséquences et les désastres se développeront, les peuples diront aux responsables : ’Allez-vous en et que Dieu vous pardonne’ ».

Selon les témoins, à Bruxelles, le discours de Jaurès souleva l’auditoire, composé de milliers de personnes appartenant à toutes les classes de la société. Deux jours plus tard, le 31 juillet 1914, Jaurès, de retour à Paris, est assassiné.

Quant à la Maison du Peuple de Bruxelles, elle fut détruite en 1965 et remplacé par un remarquable chef-d’œuvre de la laideur.

Alimentation doctrinaire

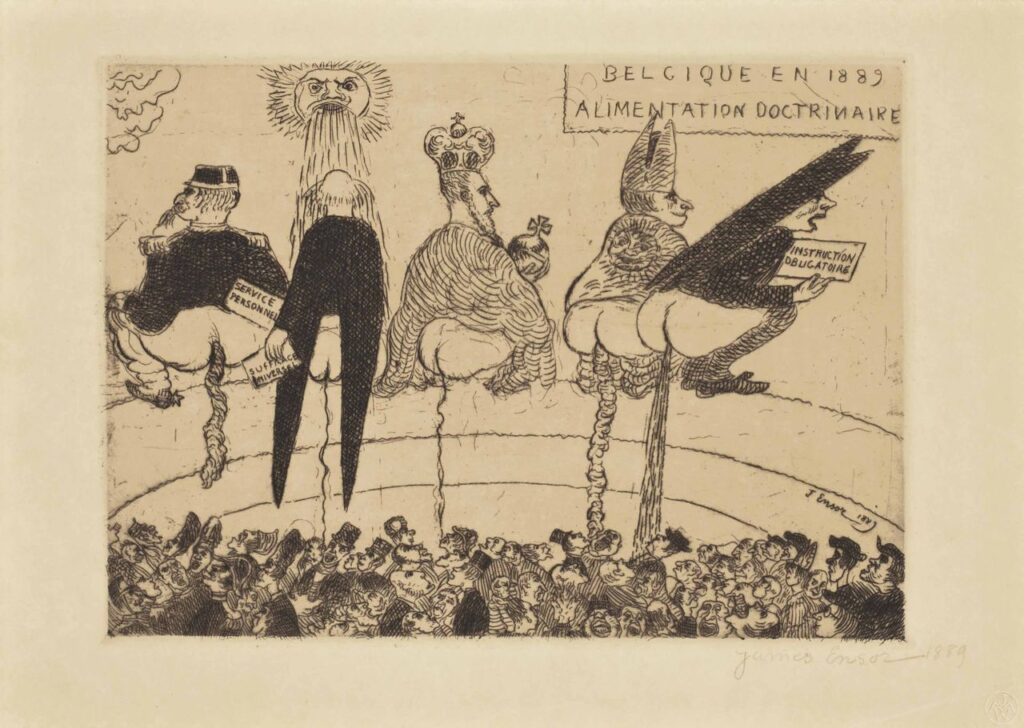

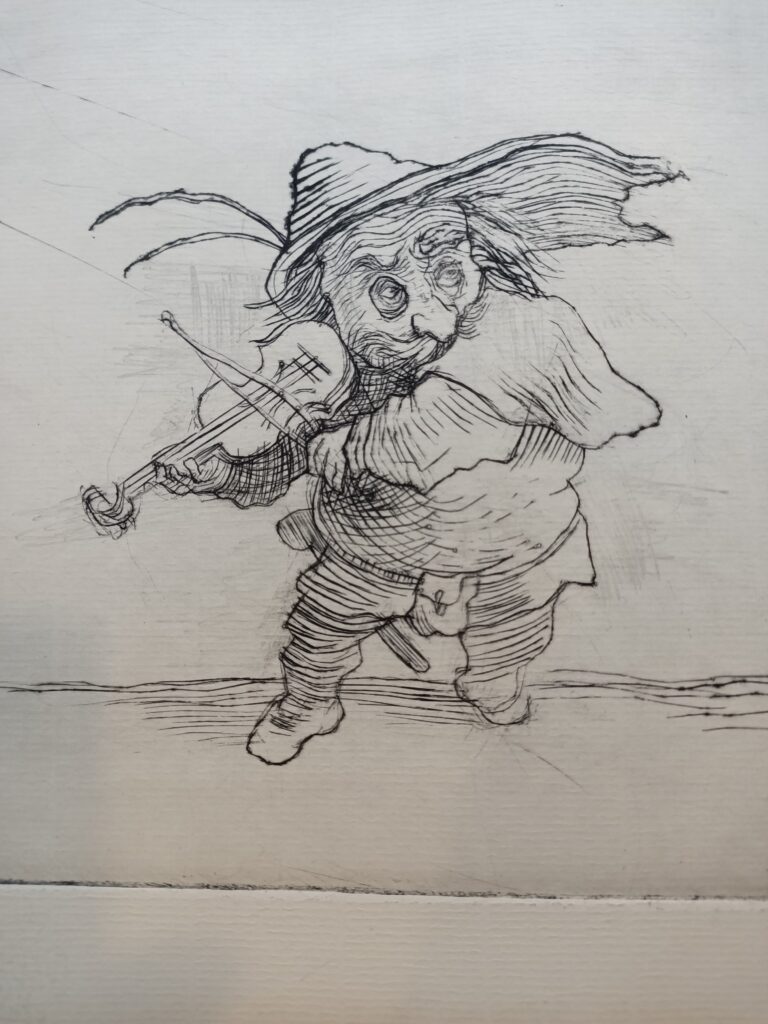

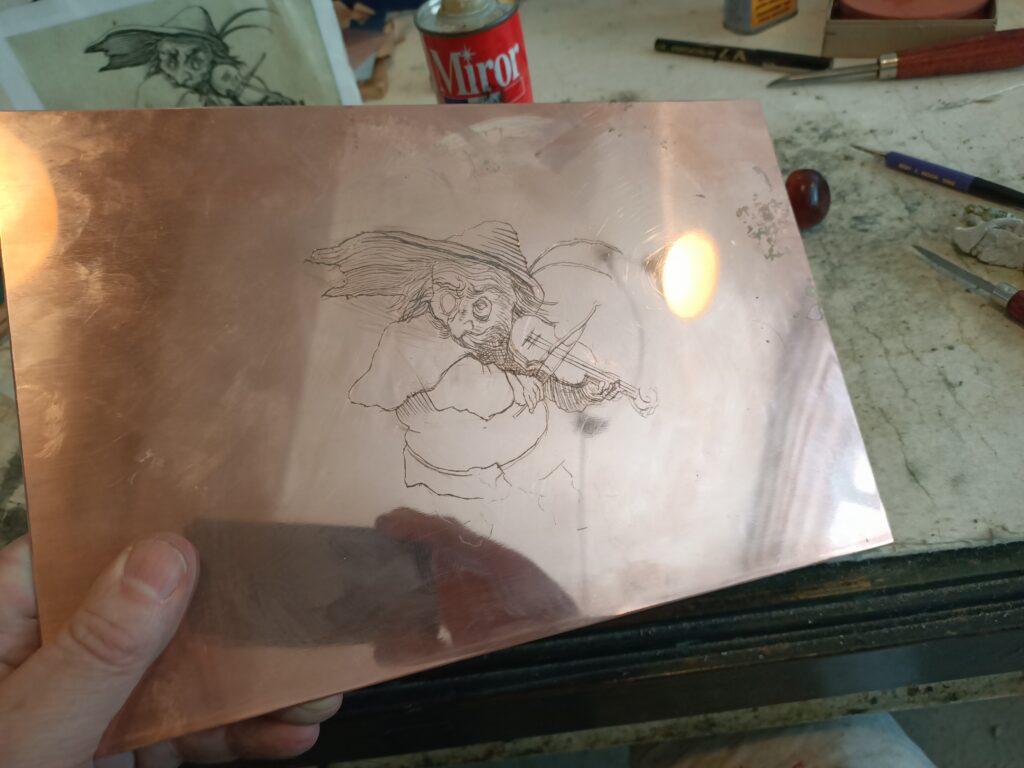

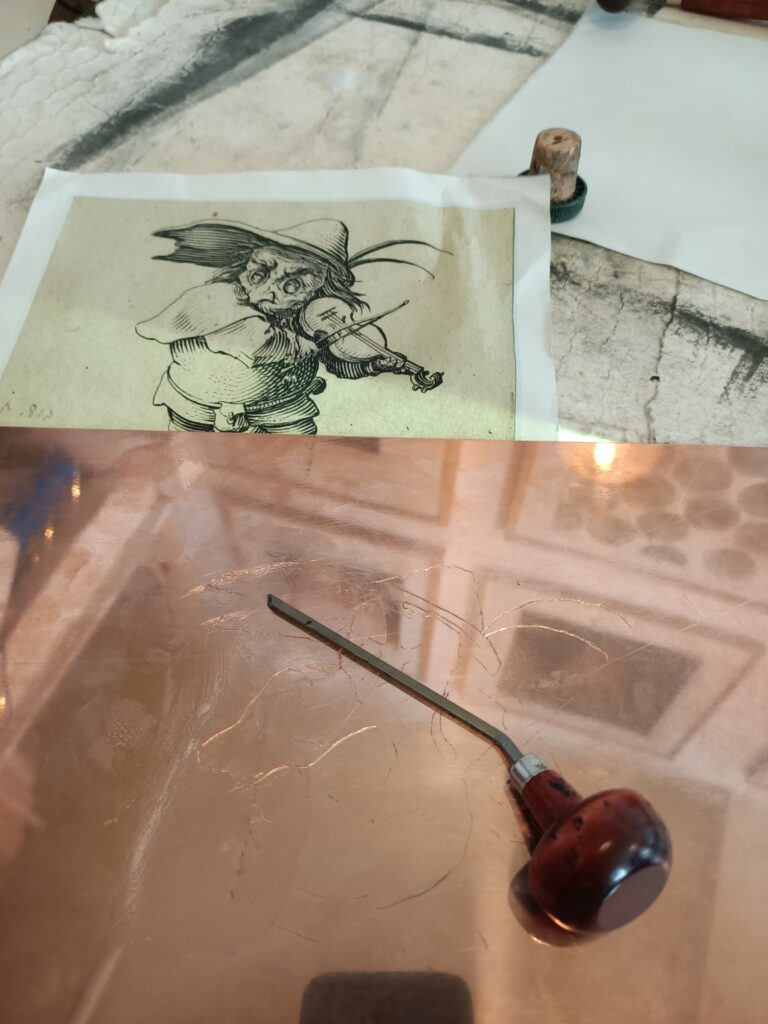

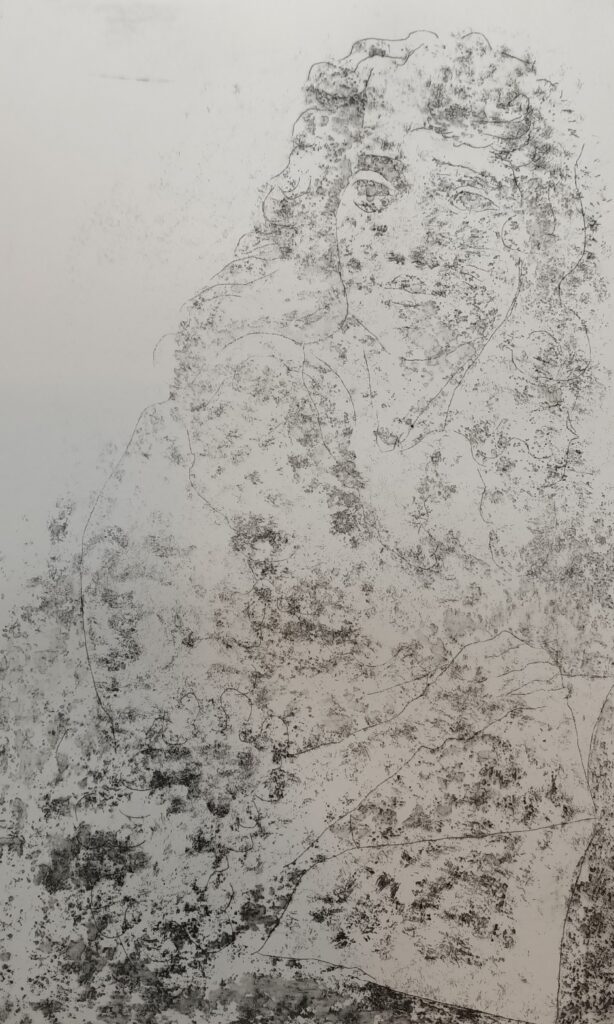

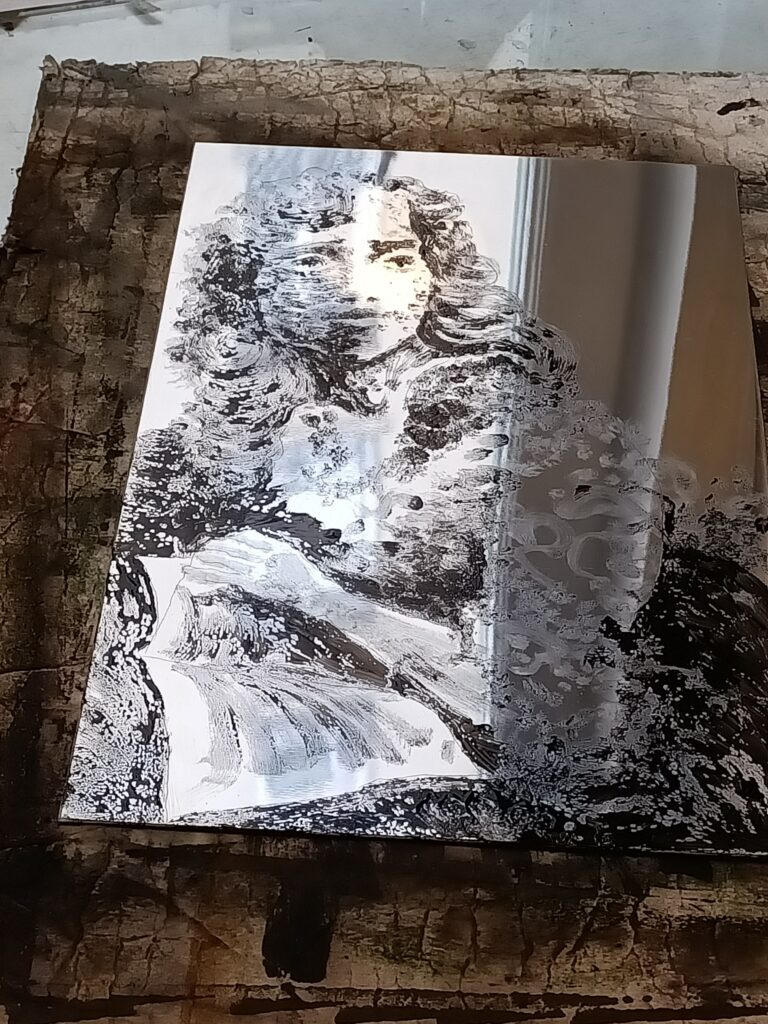

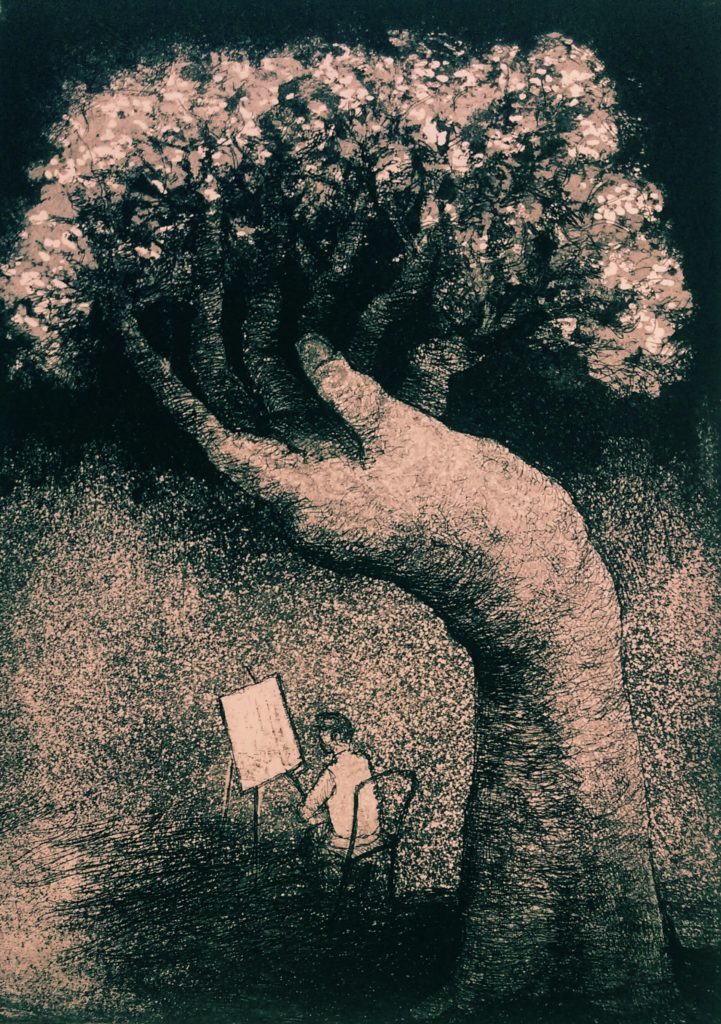

L’art d’Ensor, surtout dans ses gravures, sera l’écho de ce grand chamboulement. Sa critique sociale et politique serpente à travers ses meilleures œuvres, dont aucune n’est peut-être aussi virulente que sa gravure Alimentation doctrinaire (1889/1895) montrant des figures incarnant les pouvoirs en place (Le roi des Belges, le clergé, etc.) littéralement déféquant sur les masses, une sale habitude qui reste bien enracinée chez nos « élites », si l’on revoit le traitement qu’on a infligé, sans la moindre discrimination, à nos « gilets jaunes ».

Ensor, dans ces gravures, présente les grandes revendications du POB : le suffrage universel (voté en 1893, de façon imparfaite, du moins pour les hommes), le service militaire « personnel » (c’est-à-dire pour tous, voté en 1913) et l’instruction universelle obligatoire (votée en 1914).

La revanche

Face à l’injustice et à l’incompréhension, Ensor ne peut plus réprimer sa juste colère. Pour s’amuser, et reconnaissons-le, se venger, il compte bien « se payer » ceux qui l’ignorent, le méprisent et le sabotent, avant tout cette aristocratie belge qui s’accroche à ses privilèges comme les moules aux roches.

Déconstruisant le carcan des règles académiques, s’inspirant de Goya, Ensor se forge alors un langage puissant de métaphores et de symboles.

Dans un premier temps, il veut renvoyer cette élite oligarchique belge, se prétendant hypocritement « catholique », aux fondements mêmes des principes humanistes qu’elle piétine.

Entre 1888 et 1892, Ensor a commencé à traiter des thèmes religieux. Comme le firent aussi Gauguin et Van Gogh, le peintre s’identifie au Christ persécuté.

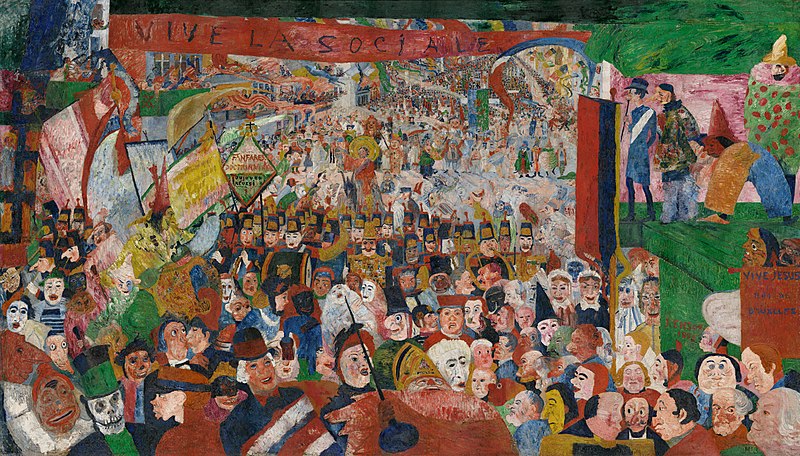

En 1889, à 28 ans, il peint L’Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, une vaste toile satirique qui fit sa renommée. Même ses proches, désireux de à se faire reconnaître pour exister, n’en veulent pas. La toile est refusée au Salon des XX où il est question de l’exclure du Cercle dont il est pourtant l’un des membres fondateurs ! Contre le souhait d’Ensor, les « vingtistes », courant vers le succès, se séparent quatre ans après pour se recréer sous le nom de La Libre Esthétique.

Dans cette œuvre, une large banderole rouge renseigne « Vive la sociale » et non « Vive le Christ ». Seul un petit panneau sur le côté applaudit un Jésus, roi de Bruxelles. Mais que diable le prophète, qui a les traits du peintre et presque perdu dans la foule, vient-il faire à Bruxelles ? Le socialisme a-t-il remplacé le christianisme au point que si Jésus revenait aujourd’hui, il le ferait sous la banderole « Vive la sociale », référence à la « République sociale » dont les partisans mettaient en avant le droit au travail, le rôle de l’État dans la lutte contre les inégalités, le chômage et la maladie ?

Pour les amis d’Ensor, il avait perdu la raison. En effet, il fallait « être fou » pour prendre de face, aussi bien l’oligarchie dominante que le peuple dont il espérait obtenir respect et reconnaissance.

L’avocat et critique d’art belge Octave Maus, co-fondateur avec Ensor des XX, a résumé de manière célèbre la réaction des critiques d’art contemporains au « coup de gueule pictural » d’Ensor :

« Ensor est le chef d’un clan. Ensor est sous les feux de la rampe. Ensor résume et concentre certains principes qui sont considérés comme anarchistes. En bref, Ensor est une personne dangereuse qui a initié de grands changements (…) Il est par conséquent marqué pour les coups. C’est sur lui que sont dirigées toutes les arquebuses. C’est sur sa tête que sont déversés les récipients les plus aromatiques des soi-disant critiques sérieux.«

En 1894, invité à exposer à Paris, son œuvre, plus objet intellectif qu’esthétique, suscite peu d’intérêt. Désespéré de ne pas rencontrer le succès, Ensor, persistera avec une peinture survoltée, sauvage, saturée et violemment bariolée.

Squelettes et masques

Très tôt, des têtes de mort, des squelettes et des masques font irruption dans son œuvre. Il ne s’agit pas là de l’imagination morbide d’un esprit malade comme le prétendent ses calomniateurs.

Radical ? Insolent ? Certes ; sarcastique, souvent ; pessimiste ? Jamais ! ; anarchiste ? disons plutôt « esprit gilet jaune », c’est-à-dire fortement contestataire d’un ordre établi ayant perdu toute légitimité et, absorbé par d’immenses manœuvres géopolitiques, marchant comme une horde de somnambules vers la « Grande Guerre » et la Deuxième Guerre mondiale qui vient derrière !

Têtes de morts, symboles de la vérité

Poétiquement, Ensor va ressusciter la métaphore ultra-classique des « Vanités » de la Renaissance, thème en somme très chrétien qui figure déjà dans « Le Triomphe de la Mort », ce poème de Pétrarque qui inspira le peintre flamand Pieter Bruegel l’Ancien ou encore la série de gravures sur bois d’Holbein, « La danse macabre ».

Un crâne juxtaposé à un sablier étaient les éléments de base permettant de visualiser le caractère éphémère de l’existence humaine sur terre. En tant qu’humains, nous rappelle cette métaphore, nous essayons en permanence de ne pas y penser, mais fatalement, nous finissons tous par mourir, du moins sur le plan corporel.

Notre « vanité », c’est cette envie permanente de nous croire éternels.

Ensor, n’hésitait pas à faire appel aux symboles. Pour pénétrer son œuvre, il faut donc savoir lire le sens qu’ils « cachent ». Visuellement, face au triomphe du mensonge et de l’hypocrisie, Ensor, en bon chrétien, érige donc la mort en seule vérité capable de donner du sens à notre existence. C’est elle qui triomphe sur notre existence physique.

Les masques, symbole du mensonge.

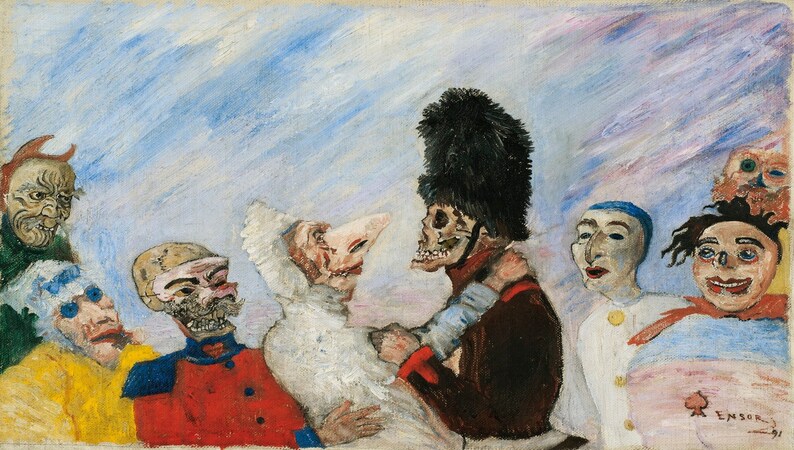

Petit à petit, comme dans La Mort et les masques (1897) (image en tête d’article), l’artiste va dramatiser encore un peu plus cette thématique en opposant la mort à des masques grotesques, symbole du mensonge et de l’hypocrisie des hommes. 1

Souvent dans ses œuvres, dans une inversion sublime des rôles, c’est la mort qui rit et ce sont les masques qui hurlent et pleurent, jamais l’inverse.

On dira que c’est grotesque et effroyable, mais en réalité, ce n’est que normal : la vérité rit lorsqu’elle triomphe et le mensonge pleure lorsqu’il voit sa fin arriver ! A cela s’ajoute, que lorsque la mort revient parmi les vivants et montre la flamme tremblante du chandelier, ces derniers hurlent, alors que la première a un gros avantage : elle est déjà morte et donc apparaît vit sans crainte !

Pensant sans doute à cette aristocratie bruxelloise qui accourut à Ostende pour y faire trempette, Ensor écrit :

« Ah ! Il faut les voir les masques, sous nos grands ciels d’opale et quand barbouillés de couleurs cruelles, ils évoluent, misérables, l’échine ployée, piteux sous les pluies, quelle déroute lamentable. Personnages terrifiés, à la fois insolents et timides, grognant et glapissant, voix grêles de fausset ou de clairons déchaînés.«

Ce même Ensor fustigea également les mauvais médecins tirant un immense ver solitaire du ventre d’un patient, les rois et les prêtres qu’il peignit « chiant » littéralement sur le peuple. Il pourfend les poissardes des bars, les critiques d’art qui n’ont pas vu son génie et qu’il peint sous la forme de crânes se disputant un hareng saur (jeu de mot sur « Art Ensor »).

Les Carnets du Roi

En 1903, un scandale d’une ampleur inédite éclate et secoue la Belgique, la France, et les pays voisins. Les Carnets du Roi, un ouvrage publié anonymement à Paris, et rapidement interdit à Bruxelles, dresse le portrait d’un autocrate à barbe blanche.

Sans le nommer, on y voit aisément Léopold II, le roi des Belges. Arrogant, prétentieux et roublard, il se révèle plus soucieux de s’enrichir et de collectionner les maîtresses que de veiller au bien commun des citoyens et au respect des lois d’un état démocratique. L’ouvrage, publié par un éditeur belge installé à Paris, avait jailli sous la plume d’un écrivain belge de la région liégeoise, Paul Gérardy (1870-1933), par hasard, un ami d’Ensor.

L’histoire des Carnets du Roi est avant tout celle d’un monarque dont on ne manque pas de se gausser par l’écrit et le dessin durant tout son règne, mais dont on critique également de façon extrêmement virulente, les méthodes utilisées pour gouverner son domaine personnel du Congo.

Divisé en une trentaine de courts chapitres, l’ouvrage se présente comme une suite de lettres et de conseils que le roi vieillissant adresse à celui qui devrait bientôt lui succéder sur le trône, son neveu Albert, par la suite protecteur d’Ensor et très impliqué avec son ami Albert Einstein qu’il accueillit en Belgique, à prévenir l’avènement de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale.

Dans Les Carnets, véritable satire, le monarque explique combien l’hypocrisie, le mensonge, la trahison et le double langage sont nécessaires à l’exercice du pouvoir : non pas pour assurer le bien des « gens du peuple » ou la stabilité de l’État monarchique, mais tout simplement pour s’enrichir sans vergogne. Les pages consacrées à l’exploitation des populations du Congo et au « rétablissement de l’esclavage » (sic) par un roi qui passait, via l’explorateur Stanley, pour en avoir été l’un des éradicateurs, sont d’une impitoyable lucidité.

Elles rejoignent les dénonciations les plus autorisées du monarque à la barbe blanche, à qui Gérardy prête ces mots :

« J’ai eu soin de faire publier que je n’étais soucieux que de civiliser les nègres, et comme cette sottise était affirmée avec sincérité par quelques convaincus, on y a cru rapidement et cela m’évita quelques ennuis.«

Rencontre avec Albert Einstein

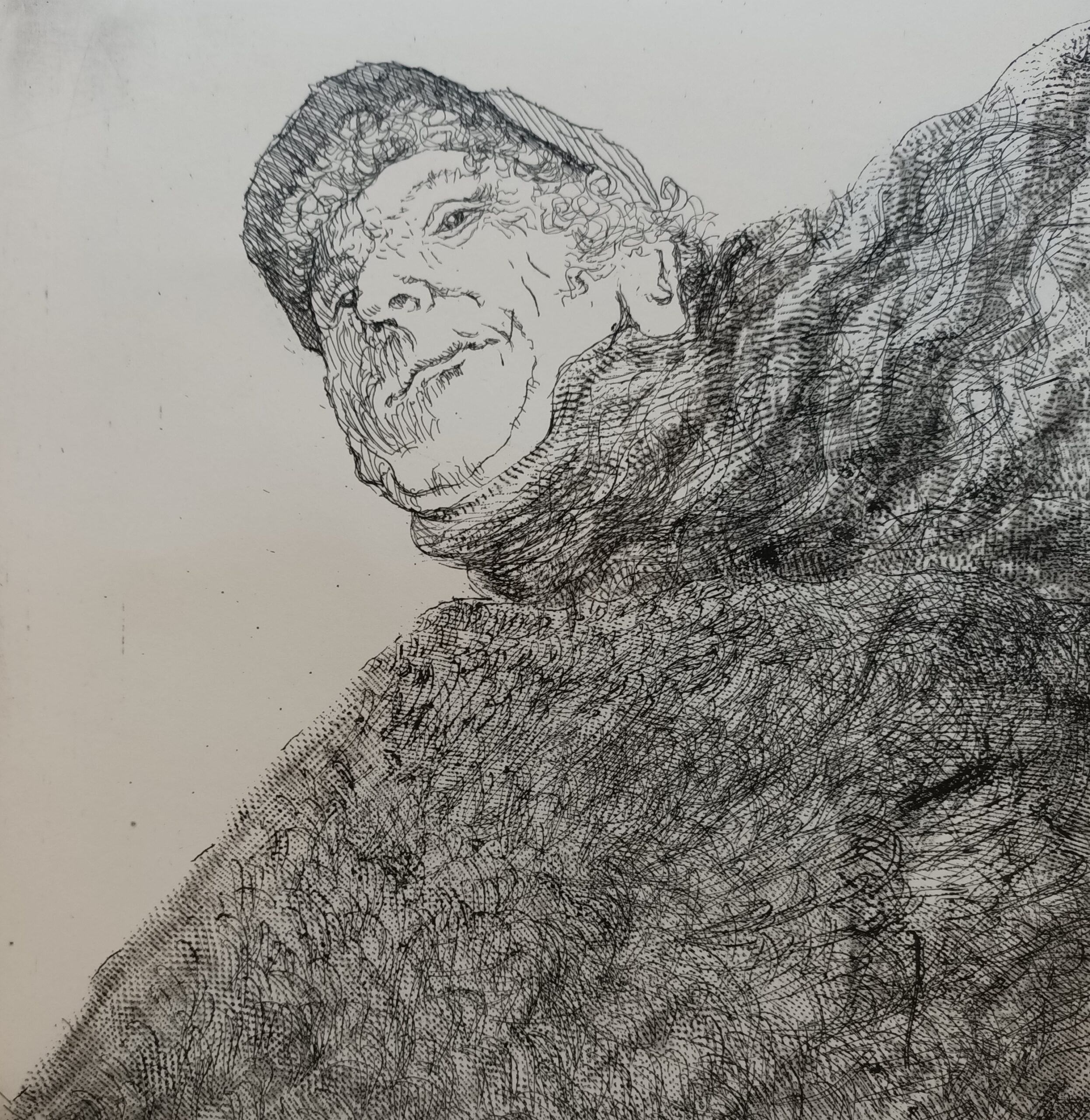

Après 1900, des premières expos lui sont consacrées. Verhaeren écrit sa première monographie. Mais, curieusement, ce succès a désamorcé sa force de peintre. Il se contente de répéter ses thèmes favoris ou de s’autoportraiturer, y compris en squelette. Il reçoit en 1903 l’Ordre de Léopold. Enfin reconnu !

Le monde entier défile à Ostende pour le voir. Au début de l’année 1933, Ensor y rencontre Albert Einstein, de passage en Belgique après avoir fui l’Allemagne. Einstein, qui a résidé pendant quelques mois à Den Haan, non loin d’Ostende, fut protégé par le roi des Belges, Albert Ier, avec qui il se coordonne pour tenter d’empêcher une nouvelle guerre mondiale.

Si l’on prétend qu’Ensor et Einstein ne se comprenaient guère, la citation suivante indique plutôt le contraire. Ensor, toujours lyrique, aurait dit :

« Louons tous promptement le grand Einstein et ses ordres relatifs, mais condamnons l’algébrisme et ses racines carrées, les géomètres et leurs raisons cubiques. Je dis que le monde est rond….«

En 1929, le roi Albert Ier accorde le titre de baron à James Ensor.

En 1934, à l’écoute de tout ce qu’apporte Franklin Roosevelt et voyant la Belgique prise dans le tumulte du krach de 1929, le roi des Belges missionne son Premier ministre De Broqueville pour réorganiser le crédit et le système bancaire à l’instar du modèle du Glass-Steagall Act adopté aux Etats-Unis en 1933.

Le 17 février 1934, lors d’une escalade à Marche-les-Dames, Albert I décède dans des conditions jamais élucidées. Le 6 mars, De Broqueville fait un discours au Sénat belge sur la nécessité de faire son deuil du Traité de Versailles et d’arriver à une entente des Alliés de 1914-1918 avec l’Allemagne sur le désarmement, faute de quoi on irait vers une nouvelle guerre…

De Broqueville entame ensuite avec énergie la réforme bancaire. Ainsi, le 22 août 1934 sont promulgués plusieurs Arrêtés Royaux notamment l’Arrêté n°2 du 22 août 1934, relatif à la protection de l’épargne et de l’activité bancaire, imposant une scission en sociétés distinctes, entre banques de dépôt et banques d’affaire et de marché.

Bombes picturales

A partir de 1929, Ensor est surnommé le « prince des peintres ». L’artiste a une réaction inattendue face à cette reconnaissance trop longtemps attendue et trop tard venue à son goût : il abandonne la peinture et consacre les dernières années de sa vie exclusivement à la musique contemporaine avant de mourir en 1949, couvert d’honneurs.

En 2016, une toile d’Ensor de 1891, surnommée « Squelette arrêtant masques », restée dans la même famille depuis près d’un siècle et inconnue des historiens, s’est vendu à 7,4 millions d’euros, record mondial pour cet artiste.

Au centre, la mort (ici un crâne coiffé du bonnet en peau d’ours typique du 1er régiment de grenadiers) prise à la gorge par d’étranges masques qui pourraient représenter les souverains de pays préparant les prochains conflits. Les masques (le mensonge) s’apprêtent à étrangler sans succès la vérité (la tête de mort) ? Ainsi, plus de cent ans plus tard, les bombes picturales d’Ensor explosent encore joyeusement à la tête des esprits étroits et frileux, des bourgeois enfarinés et des pisse-vinaigre, comme il l’aurait dit lui-même.

- En 1819, un autre artiste, le poète anglais Percy Bysshe Shelley avait composé son poème politique Le Masque de l’Anarchie en réaction au massacre de Peterloo (18 morts, 700 blessés) lorsque la cavalerie chargea une manifestation pacifique de 60 000 à 80 000 personnes rassemblées pour demander une réforme de la représentation parlementaire. Dans cet appel à la liberté, il dénonce une oligarchie tuant à sa guise (l’anarchie). Loin d’un appel à la contre-violence anarchique, il s’agit peut-être de la première déclaration moderne du principe de résistance non violente. ↩︎

Le Bac (d’après Pierre Billet)

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Mona Lisa made in China?

Listen?

Audio on this website

Read?

- La Cène de Léonard, une leçon de métaphysique (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- Léonard de Vinci : peintre de mouvement (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- La Vierge aux rochers, l’erreur fantastique de Léonard (FR en ligne).

- Romorantin et Léonard ou l’invention de la ville moderne (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Executive Intelligence Review) + DE pdf (Neue Solidarität) + IT pdf (Movisol website).

- L’Homme de Vitruve de Léonard de Vinci (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- Léonard en résonance avec la peinture traditionnelle chinoise — entretien avec Le Quotidien du Peuple. (en ligne: texte chinois suivi des traductions FR + EN).

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: short note before starting your visit

Listen:

- To the audio on this website

Read:

- Index of articles dealing with art history and Renaissance studies on this website.

——————————

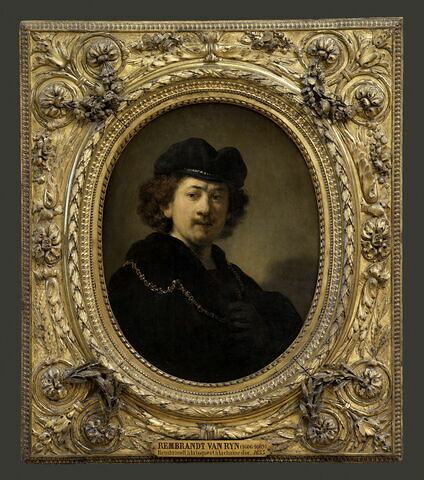

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Rembrandt, sculptor of light

Listen:

To the audio on this website.

Read:

- Rembrandt, un bâtisseur de nations FR pdf (Nouvelle Solidarité).

- Rembrandt et la lumière d’Agapè (FR en ligne) : Rembrandt et Comenius pendant la guerre de trente ans.

- Rembrandt and the Light of Agapè (EN online)

- Rembrandt : 400 ans et toujours jeune ! (FR en ligne).

- Rembrandt: 400 years old and still young ! (EN online).

- Rembrandt et la figure du Christ (FR en ligne) + EN pdf + DE pdf.

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Why Vermeer was hiding his convictions

Listen:

To the audio on this website

Read:

Rembrandt and the Light of Agapè

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. Don’t count on me here to tell his story in a few lines! (*1) In any case, since the romantics, all, and nearly to much has been said and written about the rediscovered Dutch master of light inelegantly thrown into darkness by the barbarians of neo-classicism.

By Karel Vereycken, June 2001.

The uneasy task that imparts me here is like that of Apelles of Cos, the Greek painter who, when challenged, painted a line evermore thinner than the abysmal line painted by his rival. In order to draw that line, tracing the horizons of the political and philosophical battles who raged that epoch will unveil new and surprising angles throwing unusual light on the genius of our painter-philosopher.

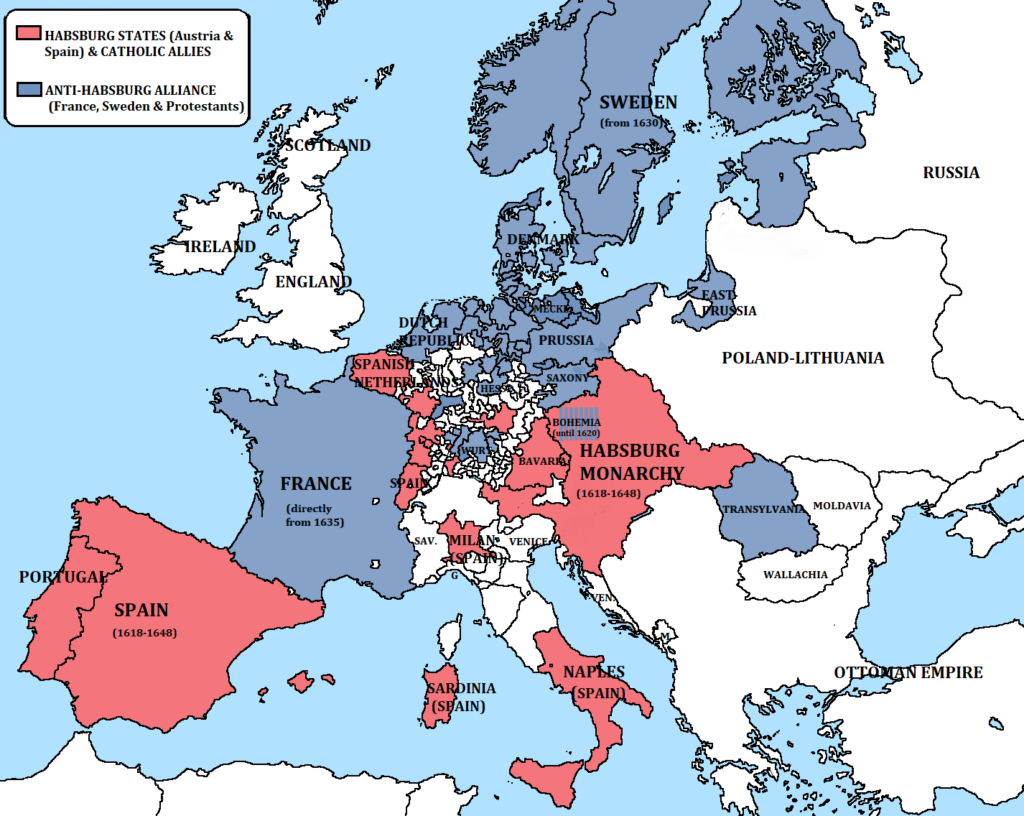

First, we will show that Rembrandt (1606-1669) was « the painter of the Thirty years War » (1618-1648), a terrible continental conflict unfolding during a major part of his life, challenging his philosophical, religious and political commitment in favor of peace and unity of mankind.

Secondly, we will inquire into the origin of that commitment and worldview. Did Rembrandt met the person and ideas of the Czech humanist Jan Amos Komensky (« Comenius ») (1592-1670), one of the organizers of the revolt of Bohemia? This militant for peace, predecessor of Leibniz in the domain of pansophia (universal wisdom), traveled regularly to the Netherlands where he settled definitively in 1656. A strong communion of ideas seems to unite the painter with the great Moravian pedagogue.

Also, isn’t it astonishing that the treaties of Westphalia, who put an end to the atrocious war, are precisely based on the notions of repentance and pardon so dear to Comenius and sublimely evoked in Rembrandt’s art?

Finally, we will dramatize the subject matter by sketching the stark contrast opposing Rembrandt’s oeuvre with that of one of the major war propagandist: (Sir) Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640).

Rembrandt, who finished rejecting any quest for earthly glory could not but paint his work away from that of the fashion-styled Flemish courtier painter. Moreover, Rubens was in high gear mobilizing all his virtuoso energy in support of the oligarchy whose Counter Reformation crusades and Jesuitical fanaticism were engulfing the continent with gallows, fire and innocent blood.

What Rembrandt advises us for his painting also applies to his life: if you stick your head to close to the canvass, the toxic odors will sharply irritate your nose and eyes. But taking some distance will permit you to discover sublime and unforgettable beauty.

What Art?

Since the triumph of Immanuel Kant‘s modernist thesis, the Critique of the Faculty of Judgment, it has not been « politically correct » to assert that art has a political dimension. And with good reason! If art can influence the course of history and shape it through its power, it is because it is a vector of ideas! An impossibility, according to the Kantian thesis, because art is a gratuitous act, free of everything, including meaning. The ultimate freedom! You either like it or you don’t, it’s all a matter of taste.

Following in the footsteps of the German poet Friedrich Schiller, we’re here to convince you otherwise, and abolish the tyranny of taste. For us, art is an eminently political act, although the work of art has nothing in common with a mere political manifesto, and the artist can in no way be reduced to an ordinary « activist ».

His domain, that of the poet, the musician or the visual artist, is to be a guide for mankind. To enable people to identify within themselves what makes them human, i.e. to strengthen that part of their soul, of their divine creativity, which places them entirely at the zenith of their responsibility for the whole of creation.

To achieve this, and we’ll develop this here, what counts in art is the type of conception of love it communicates. By making this « universal » sensitive, sublime art makes the most elevated conception of love accessible.

Such art, which forces us think, employs enigmas, ambiguities, metaphores and ironies to give us access to the idea beyond the visible. For art that limits itself to theatricality and the beauty of form fatally sinks into erotic, romantic love, depriving man of his humanity and therefore of his revolutionary power.

Rubens will be the ambassador of the great un-powers of his time: the glory of the empire and the magnificent financial strength of those days « new economy », the « tulip bubble ». In short, the oligarchy.

Rembrandt, in turn, will be the ambassador of the have-nots: the weak, the sick, the humiliated, the refugees; he will live in the image of the living Christ as the ambassador of humanity. It might seem strange to you to call such a man the « the painter of the thirty years war. »

Paradoxically, his historical period underscores the fact that very often mankind only wakes up and mobilizes its best resources for genius when confronted with the terrible menace of extinction. Today, when the Cheney’s, the Rumsfeld’s and the Kissinger’s want to plunge the world into a « post-Westphalian epoch », in reality a new dark age of « perpetual war », Rembrandt will be one of our powerful weapons of mass education.

Historical context and the origins of the war

Before entering Rembrandt, it is indispensable to know what was at stake those days. The academic name « Thirty Years War » indicates only the last period of a far longer period of « religious » conflict which was taking place around the globe during the sixteenth century, mainly centered in central Europe, on the territory of today’s Germany.

While 1618 refers to the revolt of Bohemia, the 1648 peace of Westphalia defines a reality far beyond the apparent religious pretext: the utter ruin of the utopian imperial dream of Habsburg and the birth of modern Europe composed of nation-states (*2)

On the reasons for « religious » warfare, let us look at the first half of the sixteenth century. At the eighteen years long Council of Trent (1545-1563), the Roman Catholic Church discarded stubbornly all the wise advise given earlier to avoid all conflict by one of its most ardent, but most critical supporters: Erasmus of Rotterdam.

As Erasmus forewarned, by choosing as main adversary the radical anti-semite demagogue Martin Luther, the church degraded itself to sterile and intolerant dogmatism, opening each day new highways for « the Reformation ».

The religious power-sharing of the « Peace of Augsburg » of 1555, between Rome and the protestant princes, temporarily calmed down the situation, but the ambiguous terms of that treaty incorporated all the germs of the new conflicts to come. Note that « freedom of religion » meant above all « freedom of possession ». The « peace » solely applied to Catholics and Lutherans, authorizing both to possess churches and territories, while ostracizing all the others, very often abusively labeled « Calvinists ».

Playing diabolically on internal divisions, some evil Jesuits of those days set up Calvinists and Lutherans to combat each other bitterly, by claiming, for example in Germany, that Calvinism was illegal since not explicitly mentioned in the treaty. Furthermore, the citizen obtained no real freedom of religion; he was simply authorized to leave the country or adopt the confessions of his respective lord or prince, which in turn could freely choose.

As a result of a general climate of suspicion, the protestant princes created in 1608 the « Evangelical Union » under the direction of the palatine elector Frederic V. Their eyes and hopes were turned on King Henri IV‘s France, where the Edit of Nantes and other treaties had ended a far long era of religious wars. After Henry IV‘s assassination in 1610, the Evangelical Union forged an alliance with Sweden and England.

The answer of the Catholic side, was the formation in 1609 of a « Holy League » allied with Habsburg’s Spain by Maximilian of Bavaria. Beyond all the religious and political labels, a real war party is created on both sides and the heavy clouds carrying the coming tempest threw their menacing shadows on a sharply divided Europe.

1618: The Revolt of Bohemia

Hence, after the never-ending revolt of the Netherlands, the very idea of an insurrection of Bohemia drove the Habsburgs (and the slave trading Fugger and Welser banking empires controlling them) into total hysteria, since they felt the heath on their plans. If Bohemia would become « a new, but larger Holland », then many other nations, such as Poland, could join the Reformation camp and destabilize the imperial geopolitical power balance forever.

As from 1576, the crown of Bohemia was in the hands of the Catholic Rudolphe II, Holy Roman Emperor. Despite a far-fetched passion for esotericism, Rudolphe II will be the protector of astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler in Prague.

In 1609, the Protestants of Bohemia obtain from him a « Letter of Majesty » offering them certain rights in terms of religion. After his death in 1612, his brother Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor, became his successor and left the direction of the country to cardinal Melchior Klesl, a radical Counter Reformation militant refusing any application of the « letter of majesty ».

This set the conditions for the famous « defenestration of Prague », when two representatives of the imperial power were thrown out of the window and fall on a manure heap, at the end of hot diplomatic negotiations. That highly symbolical act was in reality the first signal for a general uprising, and following the early death of Matthias, the rebels made Frederic V their sovereign instead of accepting Habsburg’s choice.

Charles Zerotina, a protestant nobleman and Comenius, (see box below), a Moravian reverend and respected community leader, masterminded that revolt. Frederic V, for example was crowned in 1619 by Jan Cyrill, who was Zerotina’s confessor, and whose daughter will become Comenius wife.

The insurgents were defeated at the battle of White Mountain, close to Prague, in 1620 by a Catholic coalition, composed of Spanish troops pulled out of Flanders together with Maximilian’s Bavarians. On the scene: French philosopher René Descartes, who paid his own trip and who was part of the war coalition and joined in entering defeated Prague in search for Kepler’s astronomical instruments… (*3)

An arrest warrant immediately targeted Comenius, who escaped with Zerotina from bloody repression. Protestantism was forbidden and the Czech language replaced by German.

Most resistance leaders were arrested and 27 beheaded in public. Their heads were put up on pins and shown on the roof of Prague’s Saint-Charles bridge.

One of them was the famous Jan Jessenius, head of the University of Prague who performed one of Europe’s early public anatomical dissections in 1600 and was a close friend of Tycho Brahe. To warn those who used their speech to encourage « heresy », his tongue was pulled out before he was beheaded, quartered and impaled.

Thirty thousand people went into exile while Frederic V and his court took refuge in Den Haag in the Netherlands. There, but years before, Comenius had a personal encouter with the future « Winterkönig » and his wife Elisabeth Stuart, on their way back from their wedding in England for which Shakespeare had arranged a representation of « The Tempest ».

A World War

1618 marked the outbreak of an all-out war across Europe, provoked by the imperial drive of Habsburg to reunify all of the continent behind one unique emperor and one single religion.

As of 1625, aided by French and English financial facilities, Christian IV of Denmark and Gustave Adolphus of Sweden intervened on the northern flank against Habsburg descending from the north as far as up till Munich.

Then, France opened another flank on the western front in 1635. Catholic cardinal Richelieu, who defeated the Huguenots at LaRochelle in 1628 (since he « fought their political rights but not their religious ones », will heavily aid the Protestant camp. His fears were that,

« if the protestant party is completely in shambles, the offensive of the house of Austria will come down on France ».

The famous etchings of the Lorraine engraver Jacques Callot, « Misery and calamities of war » of 1633, give an idea how this savage war swept Europe with its cortège of misery, famine, epidemics and desolation.

The estimated population loss on the territory of present day Germany indicates a downturn from 15 to less than 10 million. Hundreds of cities were turned back into simple villages and thousands of communities simply disappeared from the map.

War affected all the colonies of those powers involved in the conflict. Dutch and English pirates would sink any Spanish or Portuguese ships encountered at the other edge of the Earth’s curve. For Spain, loyal pillar of Habsburg, 250 million ducats were spent for the war effort (between 1568 and 1654), despite the state bankruptcy of 1575. That amount represents more than the double of the revenue from the loot of the new world (gold, spices, slaves, etc.) which scarcely amounted only to 121 million ducats…

Rembrandt and Comenius

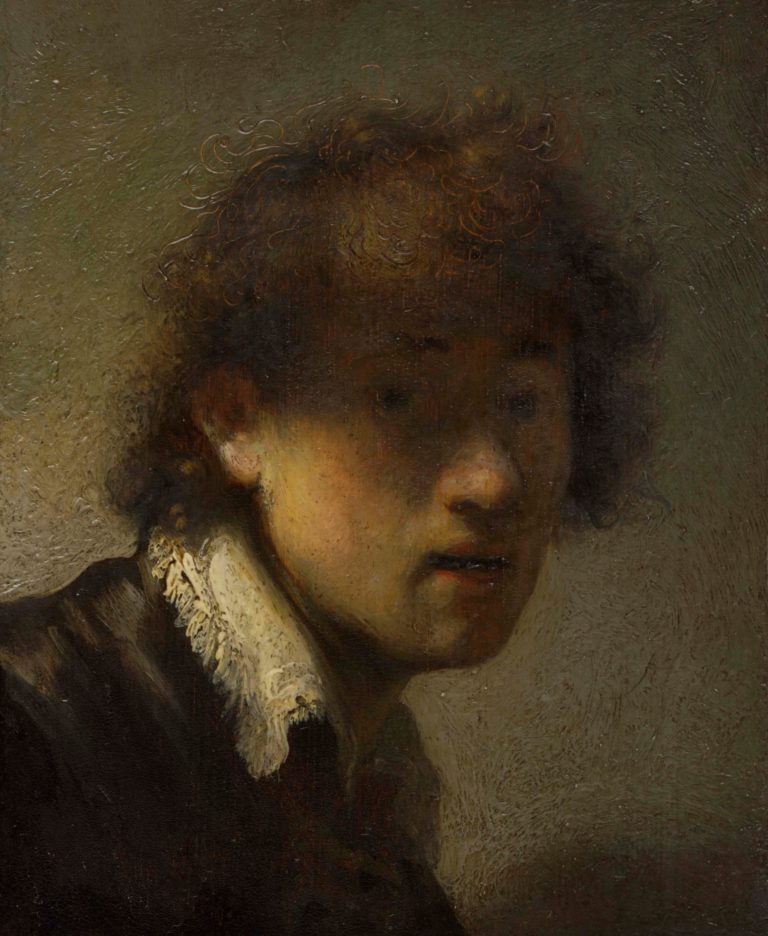

That the young Rembrandt was totally heckled by the situation of general war which was shaking up Europe is easily visible in the early self-portrait of Nuremberg.

Here he portrays himself divided between two choices. One shoulder reveals the gorget, a piece of armor that invokes the patriotic call for serving the nation calling on every young Dutchman of his generation in age of serving the military, especially after the surprise attack of the Spanish troops on Amersfoort of august 1629.

The other shoulder is nonchalantly caressed by a « liefdelok », the French « cadenette » or lovelock exhibited by amorous adolescents. What to choose? Love the nation, or the beloved?

More and more irritated by the ambitions of Constantijn Huygens, the powerful secretary of the stadholder which got him well-paid orders for the government and made him move from Leiden to Amsterdam, Rembrandt’s thinking and activity gets ever more concentrated and powerful.

Ten years later, the dying away of his wife Saskia in 1642, year of the « Night watch », plunges the painter into a deep personnal existential crisis. Gone, the self-portraits where he paints himself as an Italian courtier, with a glove in one hand carrying a heavy golden chain around his neck fronting for his social status and competing with the court. Suddenly he seems to realize that the totality of the world’s gold will never buy back the lost lives of those once loved.

When interrogated on the matter, Rembrandt would bluntly state he didn’t need to go to Italy, as the tradition used to be, since everything Italy ever produced came to him anyway as it was available in one form or another on the Amsterdam art market. But traveler he was, as drawings of the gates of London indicate, done in the early forties, maybe the year Comenius crossed the channel?

In 1644, the neo-Platonist rabbi and teacher of Spinoza, Menasseh Ben Israel, for which Rembrandt illustrated books, received a letter from Comenius agent John Dury, chaplain of Mary Princess of Orange, starting a discussion on the reintegration of the Jews in England, and Menasseh finally went for negotiations to meet Cromwell in 1655.

The Nightly Conspiracy

Although some timid hypothesis’ exists concerning Comenius‘ influence on Rembrandt, a rigorous historian’s research could certainly bring more light on this matter.

Although Rembrandt’s worldview evolved in an environment of the Mennonite community, peace-loving Anabaptists miles away from any political commitment, Rembrandt’s passion for the « cause of Bohemia » seems particularly striking in « The nightly conspiracy of Claudius Civilus at the Schakerbos ».

The large painting figured as one in a series planned to decorate the new Amsterdam city hall to celebrate the revolt of the Batavians against the Romans. Starting from historical elements of Tacitus, the story had been cooked up to warm up Dutch patriotism since the reference to Spanish tyranny was clear to all. For reasons unknown today, Rembrandt’s painting was taken down after a couple of months. To mock the cowardice of the ruling elites, Rembrandt seems to have transposed the historical scene into his present timeframe.

One Swedish historian thinks that the leader of the conspiracy here is not Claudius Civilis (the Batavian general who lost an eye in battle), but another general who equally lost an eye in battle and which was non-other than the Hussite general Jan Zizka! (*4).

Remember that Comenius and the revolt of Bohemia strongly identified with John Huss. Looking closely makes you discover that Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis is indeed dressed up in central European costume. From left to right one sees first a Dutch patrician. Is this a portrait of the then rising republican Jan De Wit?

Next, one sees a monk, without weapons, who poses his hand on Civilus’ arm in a conspiratorial gesture. Is this Comenius resistance movement, the Unity of the Brethren?

According to the historians, the two chalices, one wide, the other narrow, could signify the « Eucharist under the two species », namely that bread and wine be shared with all, which happened to be one of the demands of the Jan Hus tradition.

One also can identify a Jew or rabbi taking place in the conspiracy. Looks pretty weird for a simple Batavian conspiracy! That the establishment was unhappy to see their hero painted as an ugly Cyclops seems probable.

But to be challenged in their flight forward into pompous fantasy in stead of taking up the urgent tasks of their time was another one.

King of Swedish Steel, Louis De Geer

Comenius arrives in Amsterdam on invitation of the de Geer family in 1656, the year of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy (*5).

Louis de Geer, alias « the Steel King » and his son Laurent were the life-long protectors of Comenius for whom they paid the funeral and even build a chapel in the city of Naarden, some miles outside Amsterdam.

Originally from Luik (Liège) in today’s Belgium, that uncompromising Calvinist family settled in Amsterdam. It was the de Geer family who led the foundations of Sweden’s industrial flowering of iron, steel and copper . To do this, de Geer brought three hundred families of Walloon steelworkers to Sweden, and for whom he build hospitals, schools, housing projects and commercial facilities.

De Geer also financed the scottish preacher John Dury and the « intelligencer » Samuel Hartlib, two active friends of Comenius in England. At war with the Royal Society and Francis Bacon, they wanted to render scientific knowledge available to all of the population.

John Milton’s treatise On Education was dedicated to the same Samuel Hartlib. Louis de Geer and Sweden’s prime Minister Johan Skytte, realized Comenius education projects were the best of all possible investment to foster the physical economy. His educational reforms created a labor force of such an exceptional quality and astonishing productivity, that they warmly invited him to Sweden and asked him to reform the nation’s educational system.

That relationship of Comenius with the de Geer family leads us to Rembrandt, since Louis de Geer’s sister, Marghareta, and her husband Jacob Trip, one of the major shareholders of the Swedish copper mines, had their portrait done by Rembrandt, offering him a well paid order during very difficult years.

The City of Amsterdam allotted Comenius a yearly pension, encouraged him to publish his complete works on pedagogy and offered him the keys of the city library. Comenius brought over his family and assistants and installed a library and a printing shop behind the Westerkerk where Rembrandt will be buried.

Comenius, when going every day from his house to his printing shop crossed the street where Rembrandt lived his last days. Since early this century, Czech curators got convinced that Rembrandt’s Portrait of an old man at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, is in reality a portrait of Comenius (*6).

True or not, one has to realize that Rembrandt demanded to each of his models to sit each day for four hours over a period of three months to paint their portrait, a thing maybe not so evident for the aging Comenius.

But what is known with certainty is the fact that one of Rembrandt’s pupils, Juriaen Ovens, painted Comenius portrait during that period.

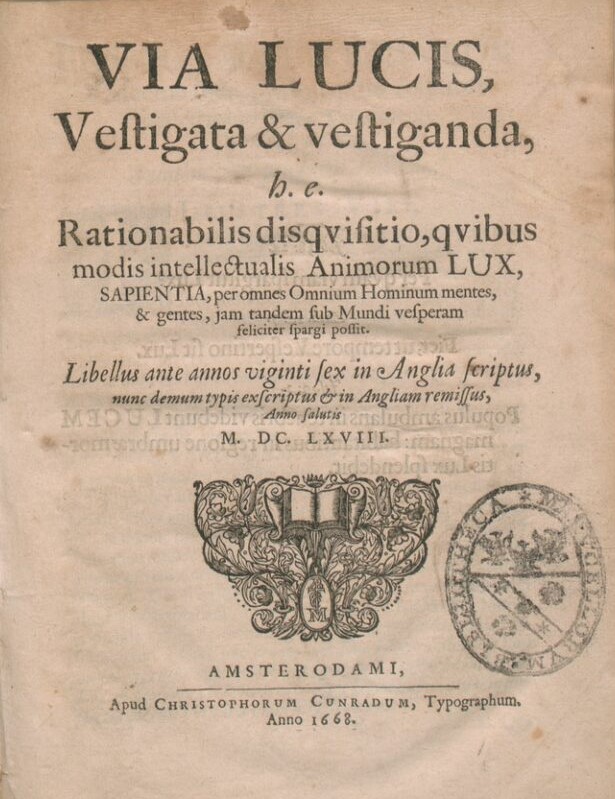

The Peace of Westphalia and the « Via Lucis »

Although Bohemia did not gain its long-desired independence at the peace of Westphalia, one cannot underestimate Comenius influence on the negotiations leading to the establishment of the peace-treaty. His work, Cesta Pokoje (Road to peace) of 1630, written in Czech is described as,

« an ethical-religious writing in which love, faith and mutual comprehension are established as the single ethical foundations of a possible peace ».

From 1641 to 1642, right before the start of the first peace negotiations, Comenius wrote the Via Lucis (The path of light), which could have been used as a guiding memorandum for the negotiators.

At the question if this Via Lucis was a millenarist mystical vision, as has been often pretended, we can consider the following.

Asked what could be hoped for and when a major change could take place, Comenius answered that the hope would come with the arrival of a time where the Gospel of the Kingdom would be preached all over the world and universal peace established.

That change could arise as the result of the emergence of a light to which will turn not only the Christian, but all the people of the world.

That light will come, « from the combination of the lanterns of human conscience, of a rational consideration of the works of God or of nature, and from the law or divine will ».

For him, « human enterprise can, through prayer and considerations of pious men imagine the possible ways to unite these rays of light, to irradiate them on the entirety of the human species and to spill similar thoughts in the minds of others » (*7).

One identifies exactly that concept in an etching of Rembrandt that Goethe awkwardly used by having it copied as frontispiece for his Faust in 1790 (*8).

The subject here is not at all a man going along to get along with the devil, but light (mirror of Christ) enlightening the life and the mind of the mortals. Way before Voltaire and opposed to the Venetian illuminati, Comenius and Rembrandt made own the metaphor of light.

To get an even more precise idea of Comenius demands for peace, one can read another memorandum called Angelus Pacis (The peace-angel),

« send to the English and Dutch peace Ambassadors at Breda, a writing designated to be sent afterwards to all the Christians of Europe and then to all the nations of the world in order to stop them, that they cease fighting each other ».

Comenius first remarks laconically that England and Holland are morally so degraded that they even don’t need some spiritual difference as a pretext, but fight each other for purely material possessions! As a way out, he proposes a new friendship:

« But how do you conceive that new friendship (or rather reestablishment of your friendship)? Will it be not by the general pardon that you will allow each other? The wise men have always seen the oblivion of received injuries as the surest road leading to peace. Touching too rudely the wounds, is to revivify the pains and to furnish the wounds an occasion for irritation.

« When this is true, it would be to be wished that the river Aa, whose tranquil waters irrigate Breda, would turn for this hour into the river Lethe of which the poets tell us that whoever drinks their water forgets everything of the past.

« The one who is guilty of trouble, God will find him, even when men, for love of peace, spare him. That the just one starts accusing himself; that means that the one whose conscience accuses him of having broken the friendship and witnessed enmity, should, according to justice, be the first one and the most ardent to reestablish friendship. If the offended party neglects that duty of justice, it will be the honor of the offended party to assume that honorable role, according to the word of the philosopher. » (*9)

COMENIUS: TEACH EVERYTHING TO ALL AND EVERYONE

Jan Amos Komensky (« Comenius ») (1592-1670) was above all a militant teacher, practicing « the universal art of teaching everything to everybody » (pan-sophia) and reckless source of inspiring enthusiasm.

One year after his death in 1670, Leibniz wrote of him: « time will come, Comenius, that honors will be offered to your works, to your hopes and even to the objects of your desires ».

In some domains, indeed, Comenius was Leibniz‘s precursor. First, he fought the fossilization of thought resulting from the dominant Aristotelianism: « Little time after that unification between Christ and Aristotle, the church fell into a pitiable state and became filled with the uproar of theological dispute ».

Strong defender of the free will that he didn’t see entirely in contradiction with an Augustinianconcept of predestination, he felt closer to John Huss than to Calvin, while generally labeled a « Calvinist » by historians.

In 1608, Comenius enters the Latin School of Prérov (Moravia), a school reorganized at the demand of Charles Zerotina on the model of the Calvinist school of Sankt-Gall in Switzerland. Zerotina was one of the key figures of the Bohemian nobility, promoter of the Church of Unity of Brethren, organizer of popular education and key leader of the international anti-Habsburg resistance. For example, in 1589 he lends a considerable amount of money to the French King Henri IV, which he meets in Rouen, France, in 1593 in support of ending the religious wars with the the Spanish.

Henri IV’s conversion to Catholicism (« Paris is worth a mass ») ruined Zerotina’s hope to reproach the Unity of Brethren with the French Huguenots. Befriended with Theodore de Bèze, which he met regularly when studying in Basel and Geneva, Zerotina sent Comenius to study at the Herborn University in Nassau. That University was founded in 1584 by Louis of Nassau, brother of William the Silent, the leader of the revolt of the Netherlands against Habsburg’s Spain. Louis of Nassau, a key international coordinator of the revolt was in permanent contact with the humanist Huguenot leader Gaspard de Coligny in France and with Walsingham, the chancellor of England’s Queen Elisabeth Ist.

Together with Zerotina, Comenius unleashed the revolt of Bohemia of 1618. After spending some time with the guerrilla forces for which he drew a map of Moravia, Comenius went into exile, as bishop of his church, the « Unity Brethren of Bohemia ».

Till his death, he was the soul of the Bohemian resistance, the gray eminence of the Diaspora and the guardian that prevented the Czech language from disappearing, since it was replaced by German in Bohemia. Since wars are only possible if large parts of the population remain uneducated, for Comenius education became the leading edge to fight for Peace.

Opposed to the Jesuit educators who consolidated their own power by education the elites only, Comenius, starting from his conviction that every individual is made in the living image of God, elaborated with great passion a very high level curriculum, which he wanted accessible to all, as he develops this in his « The Great Didactic » (1638).

Following the advice of Erasmus and Vivès, Comenius abolishes corporal punishment and decides to bring boys and girls in the same class. With him, a school needs to be available in every village, free of cost and open to everybody.

Breaking the division between intellectual and manual work, the schools were part-time technical workshops, anticipating France’s Ecole Polytechnique and the Arts et Metiers (technical school to perfect working people), completely oriented towards the joy of discovery. Leibniz idea of academies originated in Comenius’ schools and societies of friends.

For him, as for Leibniz, the body of physics couldn’t walk without the legs of metaphysics. Integrating that transcendence, he strongly rejected the very idea that nature was reducible to a mere aggregate defined by formal laws, and he adamantly lambasted Bacon, Galileo and Descartes for doing so. In stead, nature has to be looked to as a dynamic process defined by the becoming. That becoming is not repetitive, but permanent progression and potentialization: nature has a quality of development, tending towards self-accomplishment and harmony.

He was severely attacked by Descartes’ « Judgment of the Pansophical works » and mocked by Voltaire, who made him appear as Candide‘s naive philosophy teacher « Pangloss ».

Founder of modern pedagogy, he realized children are beings of affection, before becoming beings of reason. Up till those days, ignorant children were often seen as possessed by the devil, a devil which had to be beaten out of them. The French cardinal Pierre de Bérulle, founder of the Oratorians, reflected that mindset when he wrote that « infancy is the most vile and abject state of man’s nature after that of death ».

To make knowledge accessible to all, Comenius revolutionized the dogmas of that educational approach. In well-ordered classrooms, beautifully decorated with maps, classes would last only one hour covering all the domains one fiends in an engraving of Comenius: theology, manual works, music, astronomy, geometry, botany, printing, construction, painting and sculpture.

Comenius taught Latin, but was strongly convinced that every pupil had to master first his mother tongue. That was a total revolution, since up till then, Latin was taught in Latin, and to bad for those who didn’t understand already !

He also will also re-introduce illustrated textbooks (« The sensible world in images »)(1653), which had been stupidly banned from schools to « not invite the senses to disturb the intellect ». For Comenius, images have the same role as a telescope, displacing the field of perception beyond immediate limits.

His ideas, and especially the rapid successes of schools adopting his pedagogy attracted all of Europe and beyond. In 1642, Comenius was hired by Johan Skytte, the influential chancellor of the University of Uppsala, to reorganize the Swedish education system according to his principles. Skytte, an erudite Platonist inspired by Erasmus, will be Gustaphe Adolph’s preceptor and his son Bengt Skytte will be an influential teacher of Leibniz.

Before that job, Comenius discarded a similar offer originating from Richelieu of France and the offer that came from John Winthrop Junior from the United States who offered Comenius to preside Harvard University, newly founded in the Massachussetts Bay Colony of America.

Rembrandt and Forgiveness

To express in art that precise moment where love gives birth to pardon and repentance will be precisely one of Rembrandt’s favorite subjects. The fact that he choose the name Titus for his son, after the roman emperor who supposedly had showed great clemency toward the early Christians, demonstrates that point. But Titus was also the name of a bishop of Creta who was a close collaborator of Apostle Paul.

Rembrandt was fascinated by the figure of Saint-Paul, who used to be after all a roman officer who, through his conversion, showed the possible transformation of each individual for the better, capable of becoming a militant for the good.

Rembrandt’s self-portrait of the Rijksmuseum, with the famous « ghost-image » of a badly lit dagger nearly planted his breast supposedly represent him as Saint-Paul, traditionally represented defending Christian faith with the scripture in one hand and the sword in the other.

The bible in the armored hand do appear in that painting, but the sword here seems more as a dagger, suggesting an eventual reference to the name given by Erasmus to his Christian’s manual, the « Enchiridion » after the Greek word egkheiridion (dagger).

The Prodigal Son

In one of Rembrandt’s late works, the « Return of the prodigal son », despite the fact that the work was completed by a pupil, we see how profoundly he dealt with precisely that subject. The expressiveness of the figures is amplified by the nearly life-size representation on the wide canvas (262 x 205 cm).

The father’s eyes, plunged in interior vision, look yonder the small passage by which the son hasarrived, as doubting of the happiness that overwhelms him, since his son « who was dead », « came back to life ».

The son, who installs his convicts head on the father’s abdomen, engages in the act of total repentance. The naked foot who leaves behind the rotten shoe, communicates in a metaphorical way that sinners deed of repentance, offering what he has inside. The father embraces his son by putting his pardoning hands on his shoulders, while the jealous brothers stand by wondering and enraged why so much love is given to the son « who had spoiled the fathers good with prostitutes ».

Three observations indicate Comenius person and thought might have inspired this work.

First, according to all available portraits, the face of the father shows heavy resemblance with the treats of Comenius himself, a well known militant for peace based on repentance and pardon which Rembrandt probably met frequently during that period.

Second, and after a second look, the son doesn’t look European at all, but actually Negroid, which would add to the painting some critical thoughts on the widely practiced slavery of the European powers of those days.

To conclude, one could interpret the parable of the prodigal son in a much larger sense: is this not man itself, son of God, who returns to his father after having wandered on the roads of sin? Comenius, after a moment of nearly total desperation uses that same image in his book The labyrinth of the world and the paradise of the hearth (1623).

Similar to the image employed by the Dutch painter Hieronymous Bosch, in his « ambulant salesman », man gets lost in the multiplicity of the world that leads him to self-destruction, but after a crisis decides to regain divine unity.

In order to add still another dimension to the discussion on the quality of love involved in art, it is useful to contrast our master with the works of the most talented belonging to the tradition of his detractors: Peter-Paul Rubens.

Rembrandt, Rubens and other Philistines

But before investigating Rubens, it is appropriate to consider the following. Despite the fact that Rembrandt came out of the immense intellectual ferment of the late sixteenth century University of Leiden, one of the cradle’s of humanism, one cannot escape the fact that his lashing career would have infatuated many.

Remember, Constantijn Huygens « discovered Rembrandt » in 1629, while still a young millers son running a small boutique with Jan Lievens, asking them to come to Amsterdam and work for the government. (*10).

Rembrandt’s « patron » nevertheless would write without blushing in his diary Mijn Jeugd (my youth) that Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish baroque painter was « one of the seven marvels of the world ».

Rubens was, before everything else, the talented standard bearer of the « enemy » Counterreformation and its Jesuits army, whose admiration made Rembrandt totally uncomfortable. How could this virtuoso painter be seen as the brightest star on the firmament of painting? According to some, Huygens was looking for « a Dutch Rubens », capable of making shine the « elites » of the nation.

Rembrandt at one point got so irritated with Huygens’ shortsightedness that he

offered him a large painting called Samson blinded by the Philistines. The work, a pastiche of the violent style, painted « à la Rubens », shows roman soldiers gouging out Samson’s eye with a dagger. Did Rembrandt suggest that his Republic (the strong giant) and its representatives were blinded by their own philistinism?

When a little Page becomes a great Leporello

Rembrandt perfectly translates the feeling of revulsion any honest Dutch patriot would have felt in front of Rubens. Had the Dutch elites already forgotten that Peter Paul’s father, Jan Rubens, once a Calvinist city councilor of Antwerp close to the leadership of the revolt of the Netherlands, had severely damaged the integrity of the father of the fatherland by engaging in an extra-conjugal relationship with Anna of Saxen, the unstable spouse of William the Silent?

Humiliated, but with courage and determination, Rubens mother fought as a lioness to free her husband from an uncertain jail. Her son Peter Paul, could not but become the calculated instrument of vengeance against the protestants and an indispensable tool to do away the blame hanging over the family. Hence, at the age of twelve, Peter Paul was sent to the special college of Romualdus Verdonck, a private school specifically designed to train the shock troops of the Counterreformation.

From there on, Rubens becomes a pageboy at the little court of Marguerite de Ligne, countess de Lalaing at Oudenaarde, whose descendants still form the Royal blood of today’s Belgium. As a kid, Rubens copied the biblical images of the woodprints of Holbein and the Swiss engraver Tobias Stimmer. After two waves of iconoclasm (1566 and 1581), the Counterreformation was very eager to recruit image-makers of all kinds, but under strict regulations specified by the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563. (*12).

After a short training by Abraham van Noort, Rubens career was boosted by his entering of the workshop of Otto van Veen. Born in Leiden in 1556 and trained by the Jesuits, « Venius » was the pupil of the master-courtier Federico Zuccari in Rome. Zuccari was the court painter of Habsburg’s Philippe II of Spain and the founder of the « Accademia di San Luca ». Traveling from court to court, Venius succeeded in getting the favors of Alexander Farnèse, the malign Spanish governor in charge of occupying Flanders.

Farnèse, who actually organized the successful assassination of the father of the Netherlands, the erasmian humanist William the Silent in 1584, nominated Venius as his court painter and as engineer of the Royal armies.

Furthermore, Venius will be the man who opened Rubens mind on Antiquity and together they will read and comment classical authors in Latin. Especially, he will show Rubens that an artist, if he wants to attain glory during his lifetime, must appeal a little bit to his talent and a very much to the powerful.

In Italia

In may 1600, Rubens rides his horse to Venice. In June, during Carnival he encounters the Duke of Mantua, Vincent of Gonzague, who is the cousin of archduke Albert who is ruling then Flanders with Isabella since 1598.

The duke of Mantua, the oligarchic type Mozart portrays in his « Don Giovanni » and Verdi explicitly in « Rigoletto », was very fond at the idea to add a « fiamminghi » to his stable.

The court of Mantua, in a competition of magnificence with other courts, notably those of Milan, Florence or Ferrare, employed once the painter Mantegna, the architect Leon Battista Alberti and the codifier of courtly manners Baldassare Castiglione. At the times of Rubens, the court paid the living of poet Torquato Tasso and the composer Monteverdi which wrote in Mantua his « Orpheus » and « Ariane » in 1601.

Galileo was also one of the guests for a short period in 1606. But especially, the Duke had in his possession one of the largest collections of works of art of that period, and his agents in Italy and all over the world were in charge of identifying new works worth becoming part of the collection.

An inventory of 1629 lists three Titian’s, two Raphael’s, one Veronese, one Tintoretto, eleven Giulio Romano’s, three Mantegna’s, two Corregia’s and one Andrea del Sarto amidst others. Similar to Giulio Romano who became the mere instrument of the « scourge of the princes » Pietro Aretino, our Flemish painter became just another Leporello, an obligingly « valet » enslaved by the Duke.

When we look to his self-portrait with his Circle of friends in Mantua, we see a fearful man, who « became somebody » because surrounded by « people who made it » and recognized by the powerful.

In Espagna

Immediately the Duke gave Rubens a truly Herculean task: transport a quite sophisticated present to Philippe III and his prime minister the Duke of Lerma from Mantua to Madrid. On top of a little chariot specially designed for hunting and several boxes of perfume, the core of the present consisted of not less then forty copies of the best paintings of the Duke’s private collection, notably some Raphael‘s and Titians. On top, Rubens’ mission was « to paint the fanciest women of Spain » during his trip. While his patron in Mantua whines for his return, Rubens will deploy his seductive capabilities at the Spanish court which looked far more promising to his career.

Back in Italy, his immediate going to Rome seems an opportune move, since in these days Barocci was held for to old, Guido Reni for to young. Also, Annibale Carracci appeared out of order since suffering from melancholic apoplexies while Caravagio, accused of murder, was hiding on the properties of his patrons, the Colonna’s.

But essentially, Rubens goes to the holy city because he’s enthusiastically promoted there by the Genovese cardinal Giacoma Serra, very impressed by the « splendid portraits » of women Rubens painted for the Spinola-Doria dynasty in Genoa.

Nevertheless, hearing about the imminent death of his mother, Rubens rushes to Antwerp, and after much a hesitation settles his workshop there, far at a distance from the centers of power, but close to the fabulous privileges he obtains from the Spanish regents over the Netherlands, Albrecht and Isabella.

In Antwerpia

These advantages were such that conspiracy-theorist see them as sufficient proof that there was a blueprint to kill the soul of the Erasmian spirit in Christian painting in the region.

First, Rubens will receive 500 guilders per year without any obligation concerning his artistic output except the double portrait of the rulers, any supplementary order necessitating separate payment.

Next, Rubens obtains a status permitting him to bypass the regulations and obligations of the Saint-Luc painters guild, particularly the rule that limits the number of pupils and the amount of their salary. And since a lot is never enough, Rubens obtains a tax-exemption status in Antwerp! As a real patrician he orders the building of his palace.

Broken down long time ago, and for whatever reasons, one has to observe that it was during the times of Flemish collaboration with Hitler’s Germany (from 1938 to 1946) that his Genovese modeled resort, temporarily recreated in 1910 for the Universal Exposition in Brussels, will be entirely rebuild after the engravings of Jacobus Harrewijn of 1692, decorated as the original and the interior filled with fitting old furniture (*14).

It is true that his enthusiasm for opulent blondes and violent action was interpreted by Nazi historians as the expression of profound sympathy for the Nordic races, while his visual energy was seen as the antithesis of « degenerated » art. The Rubens cult in Antwerp might tell us something interesting about the recurrent rise of rightwing extremism in that city.

Propaganda Genius

Rubens feat was to « merchandize » the ruling taste of the oligarchy of his time. Similar to the German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl under Hitler, Rubens became the genial producer of their propaganda. Precocious child and brilliant draughtsman, he had spent hours and hours working after Italian collections and bas-reliefs in the ruins of Rome.

Since the « Warrior-pope » Julius II and Leo X took over the Vatican, art had to submit to the dictatorship of the degenerated taste of imperial Rome. Eight years of work, from 1600 to 1608, in Genoa, Mantua, Florence, Rome, without forgetting Madrid, with free access to nearly all the great collections of antiquities and paintings of the old families, enabled Rubens to constitute a « data-base », whose fructification will generate the bulk of his fortune.

Specialists do point easily to the unending stream of visual quotes identified in his works. A group of Michelangelo in « The Baptism of Christ » (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp); a pose of Raphael’s Aristotle in the School of Athens in his « St-Gregory with St-Domitilla, St-Maurus and Papianus » (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) or one of his Madonna’s in « The fall of man » (Rubenshuis, Antwerp), without forgetting a head of the Laocone in the « Elevation of the Cross » (Cathedral, Antwerp) or the « contraposto » of a Venus coming straight away from a roman statuary in « The union of Earth and Water » (Hermitage, Saint-Petersburg). (*11).

The Tulip, Seneca plus Ultra

The desire to be accepted by the ruling oligarchs becomes even clearer when we discover his admiration for Seneca.

Through his education and under the influence of his brother Philippe, Peter Paul Rubens will become a fanatical follower of the Roman neo-stoic Seneca (4 BC – 65 AC). In his painting The four philosophers, Rubens paints himself standing, once again « on the map » with those who got a chair at the table.

With a view on the palatine hill in the background, site of the Apollo cult considered the authentic Rome, we see his brother Philippe, a renowned jurist, sitting across the leading stoic ideologue of those days, Justus Lipsius and his pupil Wowerius, all situated beneath a niche filled with a bust of Seneca honored by a vase with four tulips, two of them closed, and the other two opened.

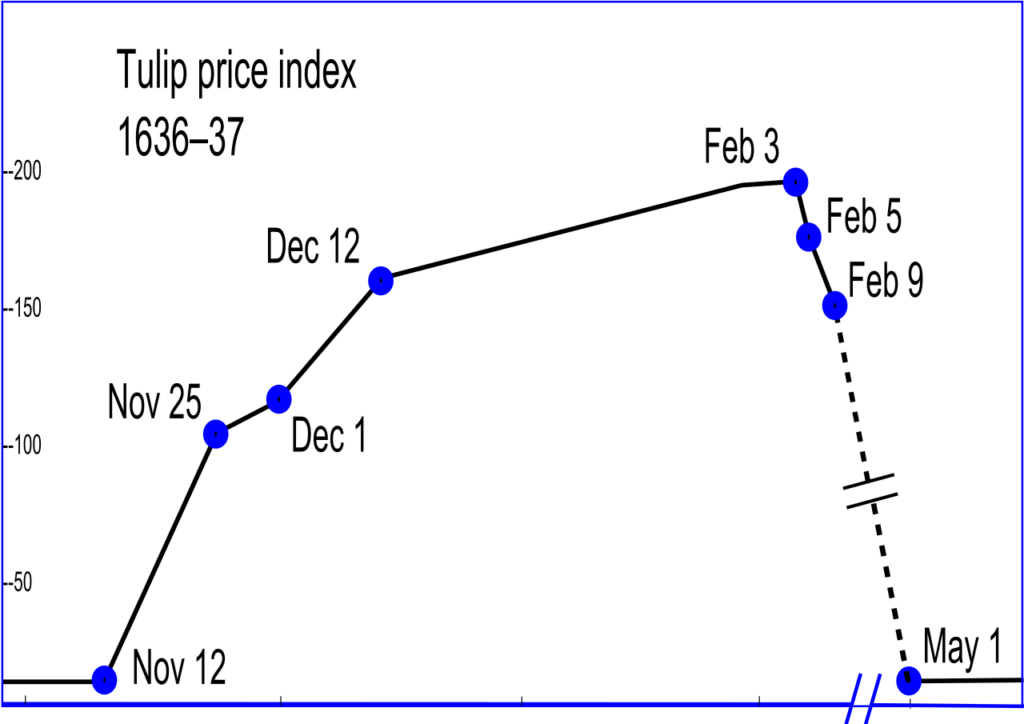

Originally from Persia, the tulip bulb was brought from Turkey to Europe by an Antwerp diplomat in 1560. Its culture degenerated rapidly from a hobby for gentleman-botanist into the immense collective folly known as the Tulip Mania and « tulip-bubble » or « Windhandel » (wind-trade).

That gigantic speculative bubble bursted in Haarlem on February 2, 1637, while some days earlier, a tulip with the name of « vice-roy » went for 2500 guilders, paid in real goods being two units of wheat and four of rye, four fat calves, eight pigs, a dozen of sheep, two barrels of wine, four tons of butter, a thousand pounds of cheese, a bed and a silver kettle drum (*14).

As can be seen in his painting Rubens in his garden with Helena Fourment, Rubens was not indifferent to that highly profitable business. Behind the master and his spouse, appears discretely behind a tree in Rubens garden a rich field of tulips!

But in the « Four philosophers », the tulip is nothing else than a metaphor of the « Brevity of life », an essay of Seneca.

The latter, tutor of Nero, preached a Roman form of sharp cynicism known under the label of fatum (fatality): to rise to (Roman) grandeur, man must cultivate absolute resignation. By an active retreat of oneself on oneself and by a obstinate denegation of a threatening and absurd world, man discovers his over-powerful self. That power even increases, if the self decides that death means nothing.

At the opposite of Socrates, who accepted to die for giving birth to the truth, Seneca makes his suicide his main existential deed. Waiting for his hour, his job is to steer his boredom by managing alternating pleasures and pains in a world where good and bad have no more sense.

As all cases of radical Aristotelianism, that philosophy, or « art of life » steers us in the hell of dualism, separating « reason », cleaned from any emotion, from the unbridled horses driving our senses. These two ways of being unfree makes us a double fool. Rubens fronts for that philosophy in his work Drunk Silenus.

The excess of alcohol evacuates all reason and brings man back to his bestial state, a state which Rubens considers natural. Instead of being a polemic, the painting reveals all the complacency of the painter-courtier with the concept of man being enslaved by blind passion. Instead of fighting it, as Friedrich Schiller outlines the case repeatedly and most explicitly in his « On the Esthetical Education of Mankind », Rubens cultivates that dualism and takes pleasure in it. And sincerely tries to recruit the viewer to that obscene and degrading worldview.

Peace IS war

As an example of « allegories », let us look for a moment at Rubens canvas Peace and War.

Above all, that painting is nothing but a glittering « business-card » as one understands knowing the history of the painting. At one point, Rubens, who had become a diplomat thanks to his international relations, organized successfully the conclusion of a peace-treaty between Spain and England (which collapsed fairly soon).

Repeating that for him « peace » was based on the unilateral capitulation of the Netherlands (reunification of the Catholic south with the North ordered to abandon Protestantism), he succeeded entering the Spanish diplomatic servicesomething pretty unusual for a Flemish subject, in particular during the revolt of the Netherlands.

Following this diplomatic success, the painter is threefold knighted: by the Court of Madrid to which he presents a demand to obtain Spanish nationality; by the Court of Brussels and also by the King of England!

Before leaving that country, he offers his painting « Peace and War » to King Charles. The canvas goes as follows: Mars is repelled by wisdom, represented as Minerva, the goddess protecting Rome. Peace is symbolized by a woman directing the flow of milk spouting out of her breast towards the mouth of a little Pluto. In the mean time a satyr with goat hooves displays the corn of abundance…

On the far left, a blue sky enters on stage while on the right the clouds glide away as carton accessories of a theatre. Rubens main argument here for peace is not a desire for justice, but the increase of pleasures and gratifications resulting from the material objects which men could accumulate under peace arrangements! Ironically, seen the cupidity of the ruling Dutch elites, which Rembrandt would lambaste uncompromisingly, it seems that Rubens might have succeeded in convincing these elites to sell the Republic for a handful of tulips. If only his art would have been something else then self-glorification! Here, his style is purely didactical, copied from the Italian mannerism Leonardo despised so much.

Instead of using metaphors capable to make people think and discover ideas, the art of Rubens is to illustrate symbolized allegories. The beauty of an invisible idea has never, and can not be brought to light by this insane iconographical approach. His « style » will be so impersonal that dozens of assistants, real slave laborers, will be generously used for the expansion of his enterprise.

King Christian IV’s physician, Otto Sperling, who visits Rubens in 1621 reported:

« While still painting he was hearing Tacitus read aloud to him and at the same time was dictating a letter. When we kept silent so as not to disturb him with our talk, he himself began to talk to us while still continuing to work, to listen to the reading and to dictate his letter, answering our questions and then displaying his astonishing power. »

« Then he charged a servant to lead us through his magnificent palace and to show us his antiquities and Greek and Roman statues which he possessed in considerable number. We then saw a broad studio without windows, but which captured the light of the day through an aperture in the ceiling. There, were united a considerable amount of young painters occupied each with a different work of which M. Rubens had produced the design by his pencil, heightened with colors at certain points. These models had to be executed completely in paint by the young people till finally, M. Rubens administered with his own hand the final touch.

« All these works came along as painted by Rubens himself, and the man, not satisfied to merely accumulate an immense fortune by operating in this manner, has been overwhelmed with honors and presents by kings and princes ». (*15).

We know, for example, that between 1609 and 1620, not less than sixty three altars were fabricated by « Rubens, Inc. ». In 1635, in a letter to his friend Pereisc, when the thirty years war is ravaging Europe, Rubens states cynically « let us leave the charge of public affairs to those who’s job it is ».

The painter asks and obtains a total discharge of his public responsibilities the same year while retiring to enjoy a private life with his new young partner.

Painter of Agapè, versus painter of Eros