Étiquette : Descartes

Rembrandt and the Light of Agapè

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. Don’t count on me here to tell his story in a few lines! (*1) In any case, since the romantics, all, and nearly to much has been said and written about the rediscovered Dutch master of light inelegantly thrown into darkness by the barbarians of neo-classicism.

By Karel Vereycken, June 2001.

The uneasy task that imparts me here is like that of Apelles of Cos, the Greek painter who, when challenged, painted a line evermore thinner than the abysmal line painted by his rival. In order to draw that line, tracing the horizons of the political and philosophical battles who raged that epoch will unveil new and surprising angles throwing unusual light on the genius of our painter-philosopher.

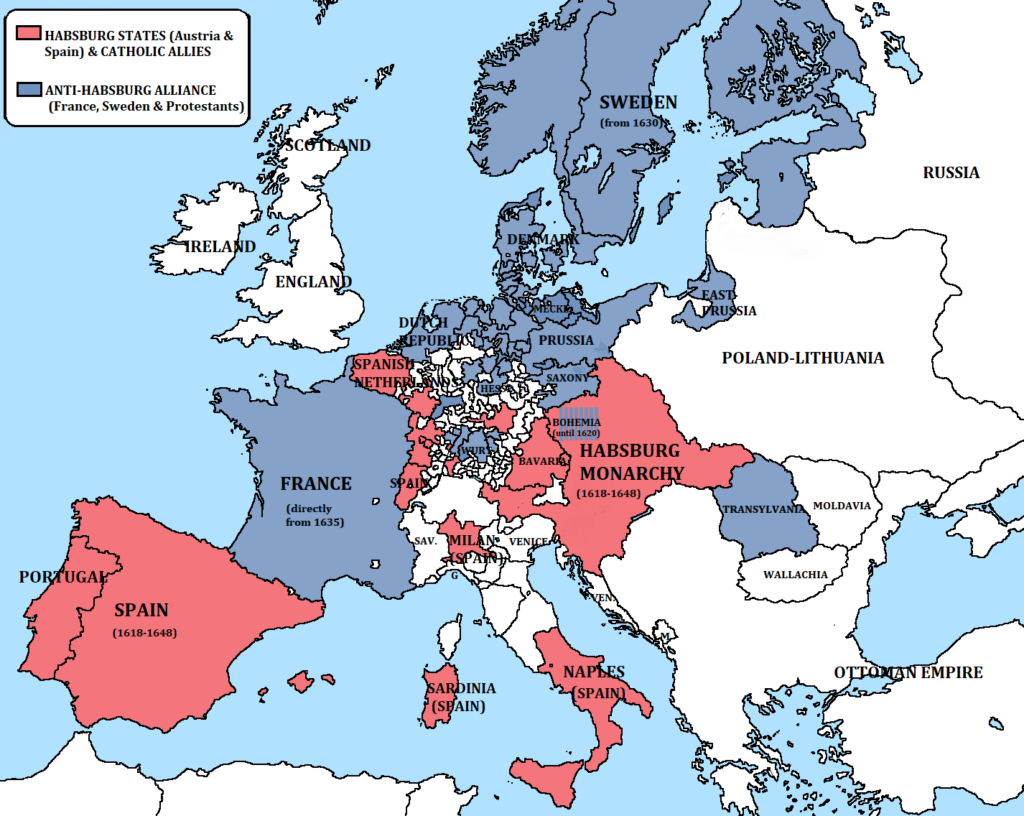

First, we will show that Rembrandt (1606-1669) was « the painter of the Thirty years War » (1618-1648), a terrible continental conflict unfolding during a major part of his life, challenging his philosophical, religious and political commitment in favor of peace and unity of mankind.

Secondly, we will inquire into the origin of that commitment and worldview. Did Rembrandt met the person and ideas of the Czech humanist Jan Amos Komensky (« Comenius ») (1592-1670), one of the organizers of the revolt of Bohemia? This militant for peace, predecessor of Leibniz in the domain of pansophia (universal wisdom), traveled regularly to the Netherlands where he settled definitively in 1656. A strong communion of ideas seems to unite the painter with the great Moravian pedagogue.

Also, isn’t it astonishing that the treaties of Westphalia, who put an end to the atrocious war, are precisely based on the notions of repentance and pardon so dear to Comenius and sublimely evoked in Rembrandt’s art?

Finally, we will dramatize the subject matter by sketching the stark contrast opposing Rembrandt’s oeuvre with that of one of the major war propagandist: (Sir) Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640).

Rembrandt, who finished rejecting any quest for earthly glory could not but paint his work away from that of the fashion-styled Flemish courtier painter. Moreover, Rubens was in high gear mobilizing all his virtuoso energy in support of the oligarchy whose Counter Reformation crusades and Jesuitical fanaticism were engulfing the continent with gallows, fire and innocent blood.

What Rembrandt advises us for his painting also applies to his life: if you stick your head to close to the canvass, the toxic odors will sharply irritate your nose and eyes. But taking some distance will permit you to discover sublime and unforgettable beauty.

What Art?

Since the triumph of Immanuel Kant‘s modernist thesis, the Critique of the Faculty of Judgment, it has not been « politically correct » to assert that art has a political dimension. And with good reason! If art can influence the course of history and shape it through its power, it is because it is a vector of ideas! An impossibility, according to the Kantian thesis, because art is a gratuitous act, free of everything, including meaning. The ultimate freedom! You either like it or you don’t, it’s all a matter of taste.

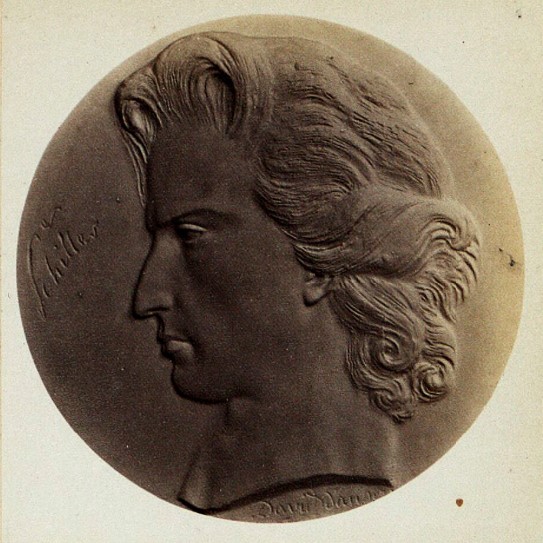

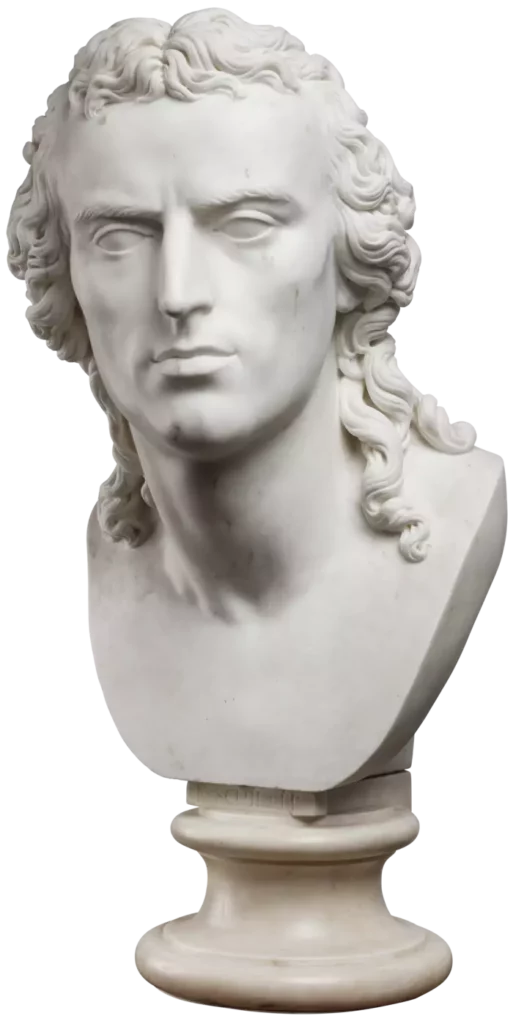

Following in the footsteps of the German poet Friedrich Schiller, we’re here to convince you otherwise, and abolish the tyranny of taste. For us, art is an eminently political act, although the work of art has nothing in common with a mere political manifesto, and the artist can in no way be reduced to an ordinary « activist ».

His domain, that of the poet, the musician or the visual artist, is to be a guide for mankind. To enable people to identify within themselves what makes them human, i.e. to strengthen that part of their soul, of their divine creativity, which places them entirely at the zenith of their responsibility for the whole of creation.

To achieve this, and we’ll develop this here, what counts in art is the type of conception of love it communicates. By making this « universal » sensitive, sublime art makes the most elevated conception of love accessible.

Such art, which forces us think, employs enigmas, ambiguities, metaphores and ironies to give us access to the idea beyond the visible. For art that limits itself to theatricality and the beauty of form fatally sinks into erotic, romantic love, depriving man of his humanity and therefore of his revolutionary power.

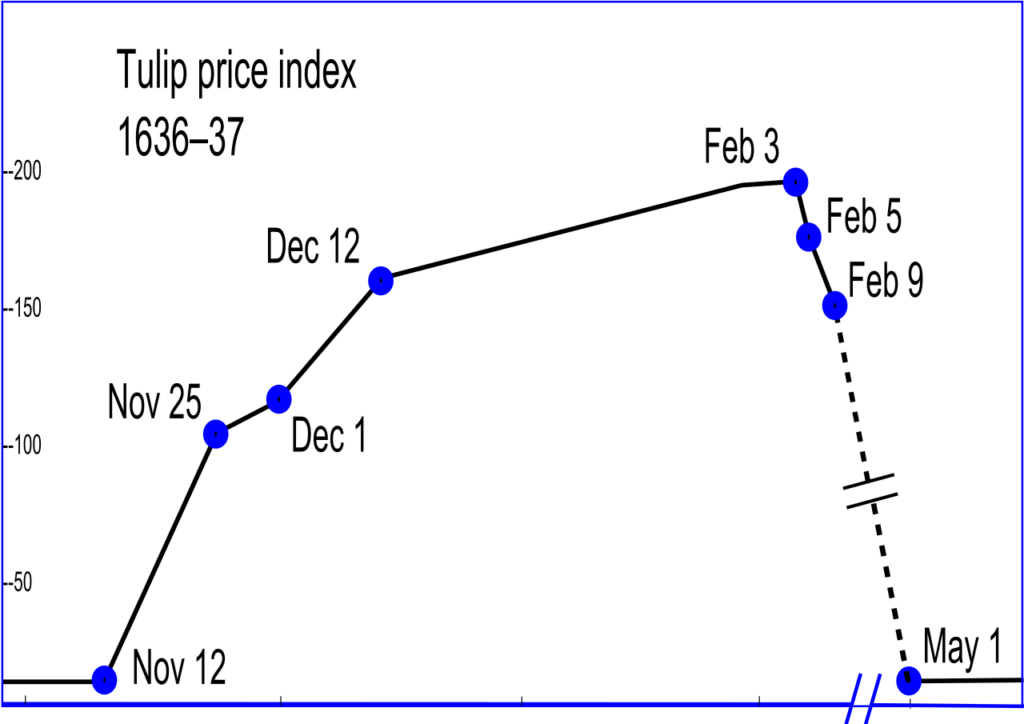

Rubens will be the ambassador of the great un-powers of his time: the glory of the empire and the magnificent financial strength of those days « new economy », the « tulip bubble ». In short, the oligarchy.

Rembrandt, in turn, will be the ambassador of the have-nots: the weak, the sick, the humiliated, the refugees; he will live in the image of the living Christ as the ambassador of humanity. It might seem strange to you to call such a man the « the painter of the thirty years war. »

Paradoxically, his historical period underscores the fact that very often mankind only wakes up and mobilizes its best resources for genius when confronted with the terrible menace of extinction. Today, when the Cheney’s, the Rumsfeld’s and the Kissinger’s want to plunge the world into a « post-Westphalian epoch », in reality a new dark age of « perpetual war », Rembrandt will be one of our powerful weapons of mass education.

Historical context and the origins of the war

Before entering Rembrandt, it is indispensable to know what was at stake those days. The academic name « Thirty Years War » indicates only the last period of a far longer period of « religious » conflict which was taking place around the globe during the sixteenth century, mainly centered in central Europe, on the territory of today’s Germany.

While 1618 refers to the revolt of Bohemia, the 1648 peace of Westphalia defines a reality far beyond the apparent religious pretext: the utter ruin of the utopian imperial dream of Habsburg and the birth of modern Europe composed of nation-states (*2)

On the reasons for « religious » warfare, let us look at the first half of the sixteenth century. At the eighteen years long Council of Trent (1545-1563), the Roman Catholic Church discarded stubbornly all the wise advise given earlier to avoid all conflict by one of its most ardent, but most critical supporters: Erasmus of Rotterdam.

As Erasmus forewarned, by choosing as main adversary the radical anti-semite demagogue Martin Luther, the church degraded itself to sterile and intolerant dogmatism, opening each day new highways for « the Reformation ».

The religious power-sharing of the « Peace of Augsburg » of 1555, between Rome and the protestant princes, temporarily calmed down the situation, but the ambiguous terms of that treaty incorporated all the germs of the new conflicts to come. Note that « freedom of religion » meant above all « freedom of possession ». The « peace » solely applied to Catholics and Lutherans, authorizing both to possess churches and territories, while ostracizing all the others, very often abusively labeled « Calvinists ».

Playing diabolically on internal divisions, some evil Jesuits of those days set up Calvinists and Lutherans to combat each other bitterly, by claiming, for example in Germany, that Calvinism was illegal since not explicitly mentioned in the treaty. Furthermore, the citizen obtained no real freedom of religion; he was simply authorized to leave the country or adopt the confessions of his respective lord or prince, which in turn could freely choose.

As a result of a general climate of suspicion, the protestant princes created in 1608 the « Evangelical Union » under the direction of the palatine elector Frederic V. Their eyes and hopes were turned on King Henri IV‘s France, where the Edit of Nantes and other treaties had ended a far long era of religious wars. After Henry IV‘s assassination in 1610, the Evangelical Union forged an alliance with Sweden and England.

The answer of the Catholic side, was the formation in 1609 of a « Holy League » allied with Habsburg’s Spain by Maximilian of Bavaria. Beyond all the religious and political labels, a real war party is created on both sides and the heavy clouds carrying the coming tempest threw their menacing shadows on a sharply divided Europe.

1618: The Revolt of Bohemia

Hence, after the never-ending revolt of the Netherlands, the very idea of an insurrection of Bohemia drove the Habsburgs (and the slave trading Fugger and Welser banking empires controlling them) into total hysteria, since they felt the heath on their plans. If Bohemia would become « a new, but larger Holland », then many other nations, such as Poland, could join the Reformation camp and destabilize the imperial geopolitical power balance forever.

As from 1576, the crown of Bohemia was in the hands of the Catholic Rudolphe II, Holy Roman Emperor. Despite a far-fetched passion for esotericism, Rudolphe II will be the protector of astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler in Prague.

In 1609, the Protestants of Bohemia obtain from him a « Letter of Majesty » offering them certain rights in terms of religion. After his death in 1612, his brother Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor, became his successor and left the direction of the country to cardinal Melchior Klesl, a radical Counter Reformation militant refusing any application of the « letter of majesty ».

This set the conditions for the famous « defenestration of Prague », when two representatives of the imperial power were thrown out of the window and fall on a manure heap, at the end of hot diplomatic negotiations. That highly symbolical act was in reality the first signal for a general uprising, and following the early death of Matthias, the rebels made Frederic V their sovereign instead of accepting Habsburg’s choice.

Charles Zerotina, a protestant nobleman and Comenius, (see box below), a Moravian reverend and respected community leader, masterminded that revolt. Frederic V, for example was crowned in 1619 by Jan Cyrill, who was Zerotina’s confessor, and whose daughter will become Comenius wife.

The insurgents were defeated at the battle of White Mountain, close to Prague, in 1620 by a Catholic coalition, composed of Spanish troops pulled out of Flanders together with Maximilian’s Bavarians. On the scene: French philosopher René Descartes, who paid his own trip and who was part of the war coalition and joined in entering defeated Prague in search for Kepler’s astronomical instruments… (*3)

An arrest warrant immediately targeted Comenius, who escaped with Zerotina from bloody repression. Protestantism was forbidden and the Czech language replaced by German.

Most resistance leaders were arrested and 27 beheaded in public. Their heads were put up on pins and shown on the roof of Prague’s Saint-Charles bridge.

One of them was the famous Jan Jessenius, head of the University of Prague who performed one of Europe’s early public anatomical dissections in 1600 and was a close friend of Tycho Brahe. To warn those who used their speech to encourage « heresy », his tongue was pulled out before he was beheaded, quartered and impaled.

Thirty thousand people went into exile while Frederic V and his court took refuge in Den Haag in the Netherlands. There, but years before, Comenius had a personal encouter with the future « Winterkönig » and his wife Elisabeth Stuart, on their way back from their wedding in England for which Shakespeare had arranged a representation of « The Tempest ».

A World War

1618 marked the outbreak of an all-out war across Europe, provoked by the imperial drive of Habsburg to reunify all of the continent behind one unique emperor and one single religion.

As of 1625, aided by French and English financial facilities, Christian IV of Denmark and Gustave Adolphus of Sweden intervened on the northern flank against Habsburg descending from the north as far as up till Munich.

Then, France opened another flank on the western front in 1635. Catholic cardinal Richelieu, who defeated the Huguenots at LaRochelle in 1628 (since he « fought their political rights but not their religious ones », will heavily aid the Protestant camp. His fears were that,

« if the protestant party is completely in shambles, the offensive of the house of Austria will come down on France ».

The famous etchings of the Lorraine engraver Jacques Callot, « Misery and calamities of war » of 1633, give an idea how this savage war swept Europe with its cortège of misery, famine, epidemics and desolation.

The estimated population loss on the territory of present day Germany indicates a downturn from 15 to less than 10 million. Hundreds of cities were turned back into simple villages and thousands of communities simply disappeared from the map.

War affected all the colonies of those powers involved in the conflict. Dutch and English pirates would sink any Spanish or Portuguese ships encountered at the other edge of the Earth’s curve. For Spain, loyal pillar of Habsburg, 250 million ducats were spent for the war effort (between 1568 and 1654), despite the state bankruptcy of 1575. That amount represents more than the double of the revenue from the loot of the new world (gold, spices, slaves, etc.) which scarcely amounted only to 121 million ducats…

Rembrandt and Comenius

That the young Rembrandt was totally heckled by the situation of general war which was shaking up Europe is easily visible in the early self-portrait of Nuremberg.

Here he portrays himself divided between two choices. One shoulder reveals the gorget, a piece of armor that invokes the patriotic call for serving the nation calling on every young Dutchman of his generation in age of serving the military, especially after the surprise attack of the Spanish troops on Amersfoort of august 1629.

The other shoulder is nonchalantly caressed by a « liefdelok », the French « cadenette » or lovelock exhibited by amorous adolescents. What to choose? Love the nation, or the beloved?

More and more irritated by the ambitions of Constantijn Huygens, the powerful secretary of the stadholder which got him well-paid orders for the government and made him move from Leiden to Amsterdam, Rembrandt’s thinking and activity gets ever more concentrated and powerful.

Ten years later, the dying away of his wife Saskia in 1642, year of the « Night watch », plunges the painter into a deep personnal existential crisis. Gone, the self-portraits where he paints himself as an Italian courtier, with a glove in one hand carrying a heavy golden chain around his neck fronting for his social status and competing with the court. Suddenly he seems to realize that the totality of the world’s gold will never buy back the lost lives of those once loved.

When interrogated on the matter, Rembrandt would bluntly state he didn’t need to go to Italy, as the tradition used to be, since everything Italy ever produced came to him anyway as it was available in one form or another on the Amsterdam art market. But traveler he was, as drawings of the gates of London indicate, done in the early forties, maybe the year Comenius crossed the channel?

In 1644, the neo-Platonist rabbi and teacher of Spinoza, Menasseh Ben Israel, for which Rembrandt illustrated books, received a letter from Comenius agent John Dury, chaplain of Mary Princess of Orange, starting a discussion on the reintegration of the Jews in England, and Menasseh finally went for negotiations to meet Cromwell in 1655.

The Nightly Conspiracy

Although some timid hypothesis’ exists concerning Comenius‘ influence on Rembrandt, a rigorous historian’s research could certainly bring more light on this matter.

Although Rembrandt’s worldview evolved in an environment of the Mennonite community, peace-loving Anabaptists miles away from any political commitment, Rembrandt’s passion for the « cause of Bohemia » seems particularly striking in « The nightly conspiracy of Claudius Civilus at the Schakerbos ».

The large painting figured as one in a series planned to decorate the new Amsterdam city hall to celebrate the revolt of the Batavians against the Romans. Starting from historical elements of Tacitus, the story had been cooked up to warm up Dutch patriotism since the reference to Spanish tyranny was clear to all. For reasons unknown today, Rembrandt’s painting was taken down after a couple of months. To mock the cowardice of the ruling elites, Rembrandt seems to have transposed the historical scene into his present timeframe.

One Swedish historian thinks that the leader of the conspiracy here is not Claudius Civilis (the Batavian general who lost an eye in battle), but another general who equally lost an eye in battle and which was non-other than the Hussite general Jan Zizka! (*4).

Remember that Comenius and the revolt of Bohemia strongly identified with John Huss. Looking closely makes you discover that Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis is indeed dressed up in central European costume. From left to right one sees first a Dutch patrician. Is this a portrait of the then rising republican Jan De Wit?

Next, one sees a monk, without weapons, who poses his hand on Civilus’ arm in a conspiratorial gesture. Is this Comenius resistance movement, the Unity of the Brethren?

According to the historians, the two chalices, one wide, the other narrow, could signify the « Eucharist under the two species », namely that bread and wine be shared with all, which happened to be one of the demands of the Jan Hus tradition.

One also can identify a Jew or rabbi taking place in the conspiracy. Looks pretty weird for a simple Batavian conspiracy! That the establishment was unhappy to see their hero painted as an ugly Cyclops seems probable.

But to be challenged in their flight forward into pompous fantasy in stead of taking up the urgent tasks of their time was another one.

King of Swedish Steel, Louis De Geer

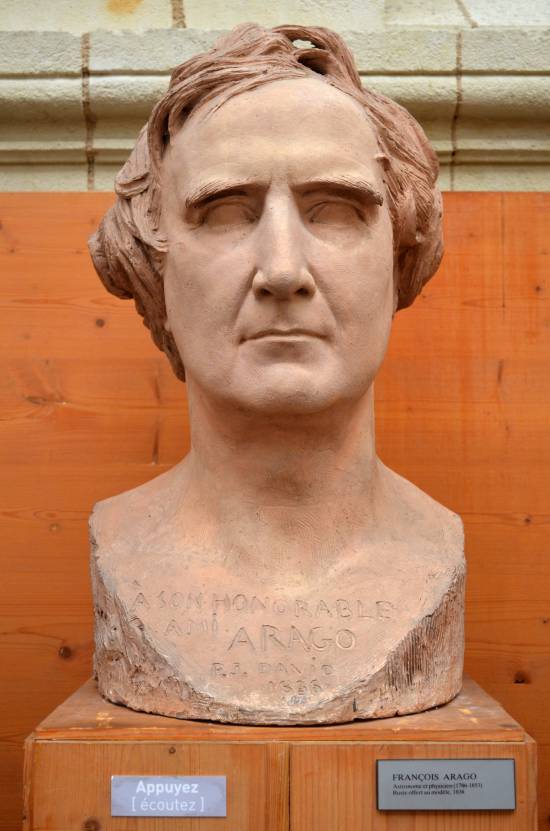

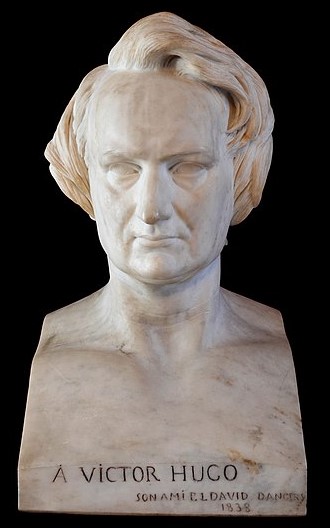

Comenius arrives in Amsterdam on invitation of the de Geer family in 1656, the year of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy (*5).

Louis de Geer, alias « the Steel King » and his son Laurent were the life-long protectors of Comenius for whom they paid the funeral and even build a chapel in the city of Naarden, some miles outside Amsterdam.

Originally from Luik (Liège) in today’s Belgium, that uncompromising Calvinist family settled in Amsterdam. It was the de Geer family who led the foundations of Sweden’s industrial flowering of iron, steel and copper . To do this, de Geer brought three hundred families of Walloon steelworkers to Sweden, and for whom he build hospitals, schools, housing projects and commercial facilities.

De Geer also financed the scottish preacher John Dury and the « intelligencer » Samuel Hartlib, two active friends of Comenius in England. At war with the Royal Society and Francis Bacon, they wanted to render scientific knowledge available to all of the population.

John Milton’s treatise On Education was dedicated to the same Samuel Hartlib. Louis de Geer and Sweden’s prime Minister Johan Skytte, realized Comenius education projects were the best of all possible investment to foster the physical economy. His educational reforms created a labor force of such an exceptional quality and astonishing productivity, that they warmly invited him to Sweden and asked him to reform the nation’s educational system.

That relationship of Comenius with the de Geer family leads us to Rembrandt, since Louis de Geer’s sister, Marghareta, and her husband Jacob Trip, one of the major shareholders of the Swedish copper mines, had their portrait done by Rembrandt, offering him a well paid order during very difficult years.

The City of Amsterdam allotted Comenius a yearly pension, encouraged him to publish his complete works on pedagogy and offered him the keys of the city library. Comenius brought over his family and assistants and installed a library and a printing shop behind the Westerkerk where Rembrandt will be buried.

Comenius, when going every day from his house to his printing shop crossed the street where Rembrandt lived his last days. Since early this century, Czech curators got convinced that Rembrandt’s Portrait of an old man at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, is in reality a portrait of Comenius (*6).

True or not, one has to realize that Rembrandt demanded to each of his models to sit each day for four hours over a period of three months to paint their portrait, a thing maybe not so evident for the aging Comenius.

But what is known with certainty is the fact that one of Rembrandt’s pupils, Juriaen Ovens, painted Comenius portrait during that period.

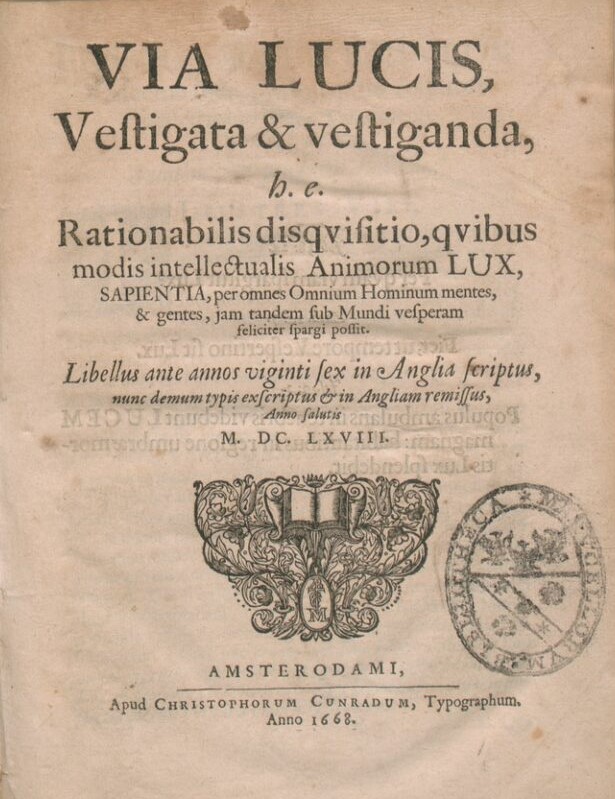

The Peace of Westphalia and the « Via Lucis »

Although Bohemia did not gain its long-desired independence at the peace of Westphalia, one cannot underestimate Comenius influence on the negotiations leading to the establishment of the peace-treaty. His work, Cesta Pokoje (Road to peace) of 1630, written in Czech is described as,

« an ethical-religious writing in which love, faith and mutual comprehension are established as the single ethical foundations of a possible peace ».

From 1641 to 1642, right before the start of the first peace negotiations, Comenius wrote the Via Lucis (The path of light), which could have been used as a guiding memorandum for the negotiators.

At the question if this Via Lucis was a millenarist mystical vision, as has been often pretended, we can consider the following.

Asked what could be hoped for and when a major change could take place, Comenius answered that the hope would come with the arrival of a time where the Gospel of the Kingdom would be preached all over the world and universal peace established.

That change could arise as the result of the emergence of a light to which will turn not only the Christian, but all the people of the world.

That light will come, « from the combination of the lanterns of human conscience, of a rational consideration of the works of God or of nature, and from the law or divine will ».

For him, « human enterprise can, through prayer and considerations of pious men imagine the possible ways to unite these rays of light, to irradiate them on the entirety of the human species and to spill similar thoughts in the minds of others » (*7).

One identifies exactly that concept in an etching of Rembrandt that Goethe awkwardly used by having it copied as frontispiece for his Faust in 1790 (*8).

The subject here is not at all a man going along to get along with the devil, but light (mirror of Christ) enlightening the life and the mind of the mortals. Way before Voltaire and opposed to the Venetian illuminati, Comenius and Rembrandt made own the metaphor of light.

To get an even more precise idea of Comenius demands for peace, one can read another memorandum called Angelus Pacis (The peace-angel),

« send to the English and Dutch peace Ambassadors at Breda, a writing designated to be sent afterwards to all the Christians of Europe and then to all the nations of the world in order to stop them, that they cease fighting each other ».

Comenius first remarks laconically that England and Holland are morally so degraded that they even don’t need some spiritual difference as a pretext, but fight each other for purely material possessions! As a way out, he proposes a new friendship:

« But how do you conceive that new friendship (or rather reestablishment of your friendship)? Will it be not by the general pardon that you will allow each other? The wise men have always seen the oblivion of received injuries as the surest road leading to peace. Touching too rudely the wounds, is to revivify the pains and to furnish the wounds an occasion for irritation.

« When this is true, it would be to be wished that the river Aa, whose tranquil waters irrigate Breda, would turn for this hour into the river Lethe of which the poets tell us that whoever drinks their water forgets everything of the past.

« The one who is guilty of trouble, God will find him, even when men, for love of peace, spare him. That the just one starts accusing himself; that means that the one whose conscience accuses him of having broken the friendship and witnessed enmity, should, according to justice, be the first one and the most ardent to reestablish friendship. If the offended party neglects that duty of justice, it will be the honor of the offended party to assume that honorable role, according to the word of the philosopher. » (*9)

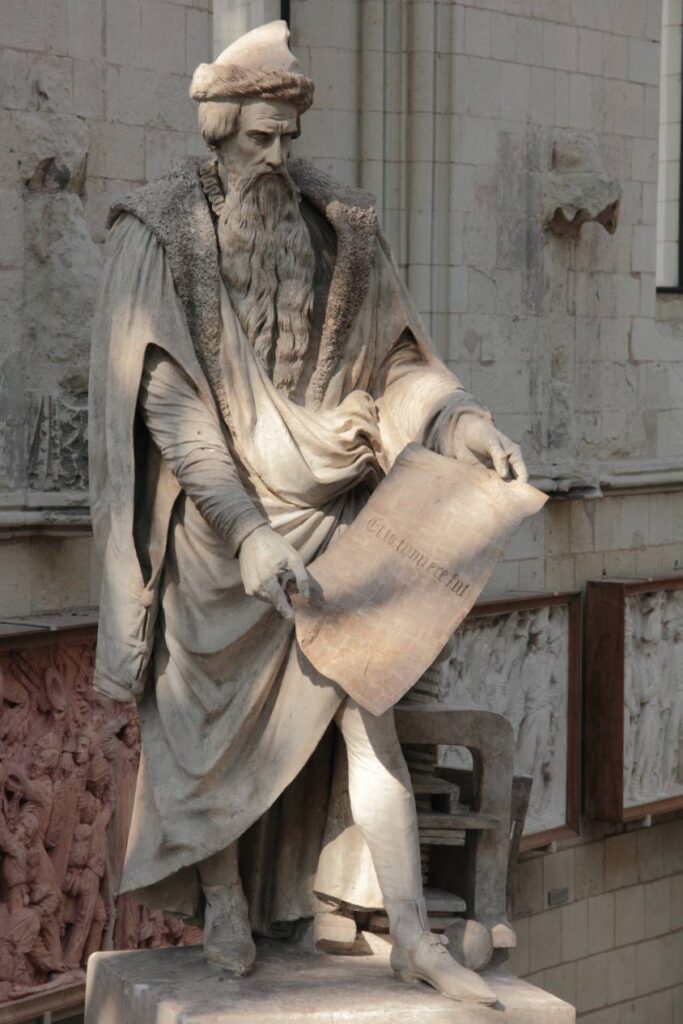

COMENIUS: TEACH EVERYTHING TO ALL AND EVERYONE

Jan Amos Komensky (« Comenius ») (1592-1670) was above all a militant teacher, practicing « the universal art of teaching everything to everybody » (pan-sophia) and reckless source of inspiring enthusiasm.

One year after his death in 1670, Leibniz wrote of him: « time will come, Comenius, that honors will be offered to your works, to your hopes and even to the objects of your desires ».

In some domains, indeed, Comenius was Leibniz‘s precursor. First, he fought the fossilization of thought resulting from the dominant Aristotelianism: « Little time after that unification between Christ and Aristotle, the church fell into a pitiable state and became filled with the uproar of theological dispute ».

Strong defender of the free will that he didn’t see entirely in contradiction with an Augustinianconcept of predestination, he felt closer to John Huss than to Calvin, while generally labeled a « Calvinist » by historians.

In 1608, Comenius enters the Latin School of Prérov (Moravia), a school reorganized at the demand of Charles Zerotina on the model of the Calvinist school of Sankt-Gall in Switzerland. Zerotina was one of the key figures of the Bohemian nobility, promoter of the Church of Unity of Brethren, organizer of popular education and key leader of the international anti-Habsburg resistance. For example, in 1589 he lends a considerable amount of money to the French King Henri IV, which he meets in Rouen, France, in 1593 in support of ending the religious wars with the the Spanish.

Henri IV’s conversion to Catholicism (« Paris is worth a mass ») ruined Zerotina’s hope to reproach the Unity of Brethren with the French Huguenots. Befriended with Theodore de Bèze, which he met regularly when studying in Basel and Geneva, Zerotina sent Comenius to study at the Herborn University in Nassau. That University was founded in 1584 by Louis of Nassau, brother of William the Silent, the leader of the revolt of the Netherlands against Habsburg’s Spain. Louis of Nassau, a key international coordinator of the revolt was in permanent contact with the humanist Huguenot leader Gaspard de Coligny in France and with Walsingham, the chancellor of England’s Queen Elisabeth Ist.

Together with Zerotina, Comenius unleashed the revolt of Bohemia of 1618. After spending some time with the guerrilla forces for which he drew a map of Moravia, Comenius went into exile, as bishop of his church, the « Unity Brethren of Bohemia ».

Till his death, he was the soul of the Bohemian resistance, the gray eminence of the Diaspora and the guardian that prevented the Czech language from disappearing, since it was replaced by German in Bohemia. Since wars are only possible if large parts of the population remain uneducated, for Comenius education became the leading edge to fight for Peace.

Opposed to the Jesuit educators who consolidated their own power by education the elites only, Comenius, starting from his conviction that every individual is made in the living image of God, elaborated with great passion a very high level curriculum, which he wanted accessible to all, as he develops this in his « The Great Didactic » (1638).

Following the advice of Erasmus and Vivès, Comenius abolishes corporal punishment and decides to bring boys and girls in the same class. With him, a school needs to be available in every village, free of cost and open to everybody.

Breaking the division between intellectual and manual work, the schools were part-time technical workshops, anticipating France’s Ecole Polytechnique and the Arts et Metiers (technical school to perfect working people), completely oriented towards the joy of discovery. Leibniz idea of academies originated in Comenius’ schools and societies of friends.

For him, as for Leibniz, the body of physics couldn’t walk without the legs of metaphysics. Integrating that transcendence, he strongly rejected the very idea that nature was reducible to a mere aggregate defined by formal laws, and he adamantly lambasted Bacon, Galileo and Descartes for doing so. In stead, nature has to be looked to as a dynamic process defined by the becoming. That becoming is not repetitive, but permanent progression and potentialization: nature has a quality of development, tending towards self-accomplishment and harmony.

He was severely attacked by Descartes’ « Judgment of the Pansophical works » and mocked by Voltaire, who made him appear as Candide‘s naive philosophy teacher « Pangloss ».

Founder of modern pedagogy, he realized children are beings of affection, before becoming beings of reason. Up till those days, ignorant children were often seen as possessed by the devil, a devil which had to be beaten out of them. The French cardinal Pierre de Bérulle, founder of the Oratorians, reflected that mindset when he wrote that « infancy is the most vile and abject state of man’s nature after that of death ».

To make knowledge accessible to all, Comenius revolutionized the dogmas of that educational approach. In well-ordered classrooms, beautifully decorated with maps, classes would last only one hour covering all the domains one fiends in an engraving of Comenius: theology, manual works, music, astronomy, geometry, botany, printing, construction, painting and sculpture.

Comenius taught Latin, but was strongly convinced that every pupil had to master first his mother tongue. That was a total revolution, since up till then, Latin was taught in Latin, and to bad for those who didn’t understand already !

He also will also re-introduce illustrated textbooks (« The sensible world in images »)(1653), which had been stupidly banned from schools to « not invite the senses to disturb the intellect ». For Comenius, images have the same role as a telescope, displacing the field of perception beyond immediate limits.

His ideas, and especially the rapid successes of schools adopting his pedagogy attracted all of Europe and beyond. In 1642, Comenius was hired by Johan Skytte, the influential chancellor of the University of Uppsala, to reorganize the Swedish education system according to his principles. Skytte, an erudite Platonist inspired by Erasmus, will be Gustaphe Adolph’s preceptor and his son Bengt Skytte will be an influential teacher of Leibniz.

Before that job, Comenius discarded a similar offer originating from Richelieu of France and the offer that came from John Winthrop Junior from the United States who offered Comenius to preside Harvard University, newly founded in the Massachussetts Bay Colony of America.

Rembrandt and Forgiveness

To express in art that precise moment where love gives birth to pardon and repentance will be precisely one of Rembrandt’s favorite subjects. The fact that he choose the name Titus for his son, after the roman emperor who supposedly had showed great clemency toward the early Christians, demonstrates that point. But Titus was also the name of a bishop of Creta who was a close collaborator of Apostle Paul.

Rembrandt was fascinated by the figure of Saint-Paul, who used to be after all a roman officer who, through his conversion, showed the possible transformation of each individual for the better, capable of becoming a militant for the good.

Rembrandt’s self-portrait of the Rijksmuseum, with the famous « ghost-image » of a badly lit dagger nearly planted his breast supposedly represent him as Saint-Paul, traditionally represented defending Christian faith with the scripture in one hand and the sword in the other.

The bible in the armored hand do appear in that painting, but the sword here seems more as a dagger, suggesting an eventual reference to the name given by Erasmus to his Christian’s manual, the « Enchiridion » after the Greek word egkheiridion (dagger).

The Prodigal Son

In one of Rembrandt’s late works, the « Return of the prodigal son », despite the fact that the work was completed by a pupil, we see how profoundly he dealt with precisely that subject. The expressiveness of the figures is amplified by the nearly life-size representation on the wide canvas (262 x 205 cm).

The father’s eyes, plunged in interior vision, look yonder the small passage by which the son hasarrived, as doubting of the happiness that overwhelms him, since his son « who was dead », « came back to life ».

The son, who installs his convicts head on the father’s abdomen, engages in the act of total repentance. The naked foot who leaves behind the rotten shoe, communicates in a metaphorical way that sinners deed of repentance, offering what he has inside. The father embraces his son by putting his pardoning hands on his shoulders, while the jealous brothers stand by wondering and enraged why so much love is given to the son « who had spoiled the fathers good with prostitutes ».

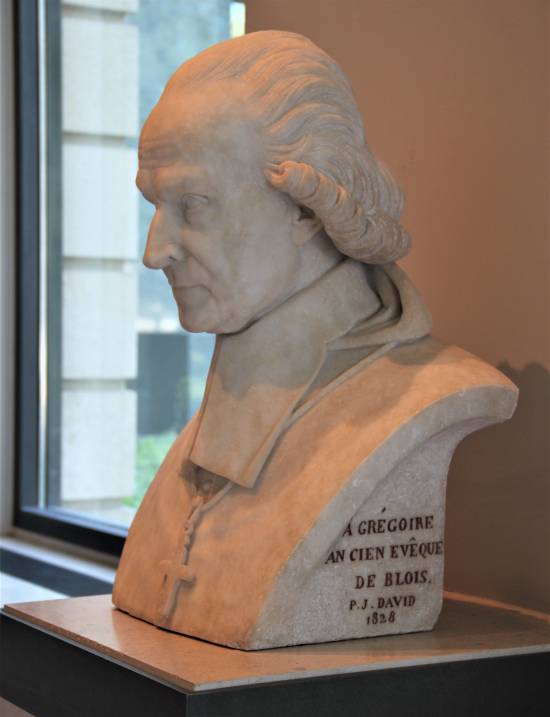

Three observations indicate Comenius person and thought might have inspired this work.

First, according to all available portraits, the face of the father shows heavy resemblance with the treats of Comenius himself, a well known militant for peace based on repentance and pardon which Rembrandt probably met frequently during that period.

Second, and after a second look, the son doesn’t look European at all, but actually Negroid, which would add to the painting some critical thoughts on the widely practiced slavery of the European powers of those days.

To conclude, one could interpret the parable of the prodigal son in a much larger sense: is this not man itself, son of God, who returns to his father after having wandered on the roads of sin? Comenius, after a moment of nearly total desperation uses that same image in his book The labyrinth of the world and the paradise of the hearth (1623).

Similar to the image employed by the Dutch painter Hieronymous Bosch, in his « ambulant salesman », man gets lost in the multiplicity of the world that leads him to self-destruction, but after a crisis decides to regain divine unity.

In order to add still another dimension to the discussion on the quality of love involved in art, it is useful to contrast our master with the works of the most talented belonging to the tradition of his detractors: Peter-Paul Rubens.

Rembrandt, Rubens and other Philistines

But before investigating Rubens, it is appropriate to consider the following. Despite the fact that Rembrandt came out of the immense intellectual ferment of the late sixteenth century University of Leiden, one of the cradle’s of humanism, one cannot escape the fact that his lashing career would have infatuated many.

Remember, Constantijn Huygens « discovered Rembrandt » in 1629, while still a young millers son running a small boutique with Jan Lievens, asking them to come to Amsterdam and work for the government. (*10).

Rembrandt’s « patron » nevertheless would write without blushing in his diary Mijn Jeugd (my youth) that Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish baroque painter was « one of the seven marvels of the world ».

Rubens was, before everything else, the talented standard bearer of the « enemy » Counterreformation and its Jesuits army, whose admiration made Rembrandt totally uncomfortable. How could this virtuoso painter be seen as the brightest star on the firmament of painting? According to some, Huygens was looking for « a Dutch Rubens », capable of making shine the « elites » of the nation.

Rembrandt at one point got so irritated with Huygens’ shortsightedness that he

offered him a large painting called Samson blinded by the Philistines. The work, a pastiche of the violent style, painted « à la Rubens », shows roman soldiers gouging out Samson’s eye with a dagger. Did Rembrandt suggest that his Republic (the strong giant) and its representatives were blinded by their own philistinism?

When a little Page becomes a great Leporello

Rembrandt perfectly translates the feeling of revulsion any honest Dutch patriot would have felt in front of Rubens. Had the Dutch elites already forgotten that Peter Paul’s father, Jan Rubens, once a Calvinist city councilor of Antwerp close to the leadership of the revolt of the Netherlands, had severely damaged the integrity of the father of the fatherland by engaging in an extra-conjugal relationship with Anna of Saxen, the unstable spouse of William the Silent?

Humiliated, but with courage and determination, Rubens mother fought as a lioness to free her husband from an uncertain jail. Her son Peter Paul, could not but become the calculated instrument of vengeance against the protestants and an indispensable tool to do away the blame hanging over the family. Hence, at the age of twelve, Peter Paul was sent to the special college of Romualdus Verdonck, a private school specifically designed to train the shock troops of the Counterreformation.

From there on, Rubens becomes a pageboy at the little court of Marguerite de Ligne, countess de Lalaing at Oudenaarde, whose descendants still form the Royal blood of today’s Belgium. As a kid, Rubens copied the biblical images of the woodprints of Holbein and the Swiss engraver Tobias Stimmer. After two waves of iconoclasm (1566 and 1581), the Counterreformation was very eager to recruit image-makers of all kinds, but under strict regulations specified by the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563. (*12).

After a short training by Abraham van Noort, Rubens career was boosted by his entering of the workshop of Otto van Veen. Born in Leiden in 1556 and trained by the Jesuits, « Venius » was the pupil of the master-courtier Federico Zuccari in Rome. Zuccari was the court painter of Habsburg’s Philippe II of Spain and the founder of the « Accademia di San Luca ». Traveling from court to court, Venius succeeded in getting the favors of Alexander Farnèse, the malign Spanish governor in charge of occupying Flanders.

Farnèse, who actually organized the successful assassination of the father of the Netherlands, the erasmian humanist William the Silent in 1584, nominated Venius as his court painter and as engineer of the Royal armies.

Furthermore, Venius will be the man who opened Rubens mind on Antiquity and together they will read and comment classical authors in Latin. Especially, he will show Rubens that an artist, if he wants to attain glory during his lifetime, must appeal a little bit to his talent and a very much to the powerful.

In Italia

In may 1600, Rubens rides his horse to Venice. In June, during Carnival he encounters the Duke of Mantua, Vincent of Gonzague, who is the cousin of archduke Albert who is ruling then Flanders with Isabella since 1598.

The duke of Mantua, the oligarchic type Mozart portrays in his « Don Giovanni » and Verdi explicitly in « Rigoletto », was very fond at the idea to add a « fiamminghi » to his stable.

The court of Mantua, in a competition of magnificence with other courts, notably those of Milan, Florence or Ferrare, employed once the painter Mantegna, the architect Leon Battista Alberti and the codifier of courtly manners Baldassare Castiglione. At the times of Rubens, the court paid the living of poet Torquato Tasso and the composer Monteverdi which wrote in Mantua his « Orpheus » and « Ariane » in 1601.

Galileo was also one of the guests for a short period in 1606. But especially, the Duke had in his possession one of the largest collections of works of art of that period, and his agents in Italy and all over the world were in charge of identifying new works worth becoming part of the collection.

An inventory of 1629 lists three Titian’s, two Raphael’s, one Veronese, one Tintoretto, eleven Giulio Romano’s, three Mantegna’s, two Corregia’s and one Andrea del Sarto amidst others. Similar to Giulio Romano who became the mere instrument of the « scourge of the princes » Pietro Aretino, our Flemish painter became just another Leporello, an obligingly « valet » enslaved by the Duke.

When we look to his self-portrait with his Circle of friends in Mantua, we see a fearful man, who « became somebody » because surrounded by « people who made it » and recognized by the powerful.

In Espagna

Immediately the Duke gave Rubens a truly Herculean task: transport a quite sophisticated present to Philippe III and his prime minister the Duke of Lerma from Mantua to Madrid. On top of a little chariot specially designed for hunting and several boxes of perfume, the core of the present consisted of not less then forty copies of the best paintings of the Duke’s private collection, notably some Raphael‘s and Titians. On top, Rubens’ mission was « to paint the fanciest women of Spain » during his trip. While his patron in Mantua whines for his return, Rubens will deploy his seductive capabilities at the Spanish court which looked far more promising to his career.

Back in Italy, his immediate going to Rome seems an opportune move, since in these days Barocci was held for to old, Guido Reni for to young. Also, Annibale Carracci appeared out of order since suffering from melancholic apoplexies while Caravagio, accused of murder, was hiding on the properties of his patrons, the Colonna’s.

But essentially, Rubens goes to the holy city because he’s enthusiastically promoted there by the Genovese cardinal Giacoma Serra, very impressed by the « splendid portraits » of women Rubens painted for the Spinola-Doria dynasty in Genoa.

Nevertheless, hearing about the imminent death of his mother, Rubens rushes to Antwerp, and after much a hesitation settles his workshop there, far at a distance from the centers of power, but close to the fabulous privileges he obtains from the Spanish regents over the Netherlands, Albrecht and Isabella.

In Antwerpia

These advantages were such that conspiracy-theorist see them as sufficient proof that there was a blueprint to kill the soul of the Erasmian spirit in Christian painting in the region.

First, Rubens will receive 500 guilders per year without any obligation concerning his artistic output except the double portrait of the rulers, any supplementary order necessitating separate payment.

Next, Rubens obtains a status permitting him to bypass the regulations and obligations of the Saint-Luc painters guild, particularly the rule that limits the number of pupils and the amount of their salary. And since a lot is never enough, Rubens obtains a tax-exemption status in Antwerp! As a real patrician he orders the building of his palace.

Broken down long time ago, and for whatever reasons, one has to observe that it was during the times of Flemish collaboration with Hitler’s Germany (from 1938 to 1946) that his Genovese modeled resort, temporarily recreated in 1910 for the Universal Exposition in Brussels, will be entirely rebuild after the engravings of Jacobus Harrewijn of 1692, decorated as the original and the interior filled with fitting old furniture (*14).

It is true that his enthusiasm for opulent blondes and violent action was interpreted by Nazi historians as the expression of profound sympathy for the Nordic races, while his visual energy was seen as the antithesis of « degenerated » art. The Rubens cult in Antwerp might tell us something interesting about the recurrent rise of rightwing extremism in that city.

Propaganda Genius

Rubens feat was to « merchandize » the ruling taste of the oligarchy of his time. Similar to the German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl under Hitler, Rubens became the genial producer of their propaganda. Precocious child and brilliant draughtsman, he had spent hours and hours working after Italian collections and bas-reliefs in the ruins of Rome.

Since the « Warrior-pope » Julius II and Leo X took over the Vatican, art had to submit to the dictatorship of the degenerated taste of imperial Rome. Eight years of work, from 1600 to 1608, in Genoa, Mantua, Florence, Rome, without forgetting Madrid, with free access to nearly all the great collections of antiquities and paintings of the old families, enabled Rubens to constitute a « data-base », whose fructification will generate the bulk of his fortune.

Specialists do point easily to the unending stream of visual quotes identified in his works. A group of Michelangelo in « The Baptism of Christ » (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp); a pose of Raphael’s Aristotle in the School of Athens in his « St-Gregory with St-Domitilla, St-Maurus and Papianus » (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) or one of his Madonna’s in « The fall of man » (Rubenshuis, Antwerp), without forgetting a head of the Laocone in the « Elevation of the Cross » (Cathedral, Antwerp) or the « contraposto » of a Venus coming straight away from a roman statuary in « The union of Earth and Water » (Hermitage, Saint-Petersburg). (*11).

The Tulip, Seneca plus Ultra

The desire to be accepted by the ruling oligarchs becomes even clearer when we discover his admiration for Seneca.

Through his education and under the influence of his brother Philippe, Peter Paul Rubens will become a fanatical follower of the Roman neo-stoic Seneca (4 BC – 65 AC). In his painting The four philosophers, Rubens paints himself standing, once again « on the map » with those who got a chair at the table.

With a view on the palatine hill in the background, site of the Apollo cult considered the authentic Rome, we see his brother Philippe, a renowned jurist, sitting across the leading stoic ideologue of those days, Justus Lipsius and his pupil Wowerius, all situated beneath a niche filled with a bust of Seneca honored by a vase with four tulips, two of them closed, and the other two opened.

Originally from Persia, the tulip bulb was brought from Turkey to Europe by an Antwerp diplomat in 1560. Its culture degenerated rapidly from a hobby for gentleman-botanist into the immense collective folly known as the Tulip Mania and « tulip-bubble » or « Windhandel » (wind-trade).

That gigantic speculative bubble bursted in Haarlem on February 2, 1637, while some days earlier, a tulip with the name of « vice-roy » went for 2500 guilders, paid in real goods being two units of wheat and four of rye, four fat calves, eight pigs, a dozen of sheep, two barrels of wine, four tons of butter, a thousand pounds of cheese, a bed and a silver kettle drum (*14).

As can be seen in his painting Rubens in his garden with Helena Fourment, Rubens was not indifferent to that highly profitable business. Behind the master and his spouse, appears discretely behind a tree in Rubens garden a rich field of tulips!

But in the « Four philosophers », the tulip is nothing else than a metaphor of the « Brevity of life », an essay of Seneca.

The latter, tutor of Nero, preached a Roman form of sharp cynicism known under the label of fatum (fatality): to rise to (Roman) grandeur, man must cultivate absolute resignation. By an active retreat of oneself on oneself and by a obstinate denegation of a threatening and absurd world, man discovers his over-powerful self. That power even increases, if the self decides that death means nothing.

At the opposite of Socrates, who accepted to die for giving birth to the truth, Seneca makes his suicide his main existential deed. Waiting for his hour, his job is to steer his boredom by managing alternating pleasures and pains in a world where good and bad have no more sense.

As all cases of radical Aristotelianism, that philosophy, or « art of life » steers us in the hell of dualism, separating « reason », cleaned from any emotion, from the unbridled horses driving our senses. These two ways of being unfree makes us a double fool. Rubens fronts for that philosophy in his work Drunk Silenus.

The excess of alcohol evacuates all reason and brings man back to his bestial state, a state which Rubens considers natural. Instead of being a polemic, the painting reveals all the complacency of the painter-courtier with the concept of man being enslaved by blind passion. Instead of fighting it, as Friedrich Schiller outlines the case repeatedly and most explicitly in his « On the Esthetical Education of Mankind », Rubens cultivates that dualism and takes pleasure in it. And sincerely tries to recruit the viewer to that obscene and degrading worldview.

Peace IS war

As an example of « allegories », let us look for a moment at Rubens canvas Peace and War.

Above all, that painting is nothing but a glittering « business-card » as one understands knowing the history of the painting. At one point, Rubens, who had become a diplomat thanks to his international relations, organized successfully the conclusion of a peace-treaty between Spain and England (which collapsed fairly soon).

Repeating that for him « peace » was based on the unilateral capitulation of the Netherlands (reunification of the Catholic south with the North ordered to abandon Protestantism), he succeeded entering the Spanish diplomatic servicesomething pretty unusual for a Flemish subject, in particular during the revolt of the Netherlands.

Following this diplomatic success, the painter is threefold knighted: by the Court of Madrid to which he presents a demand to obtain Spanish nationality; by the Court of Brussels and also by the King of England!

Before leaving that country, he offers his painting « Peace and War » to King Charles. The canvas goes as follows: Mars is repelled by wisdom, represented as Minerva, the goddess protecting Rome. Peace is symbolized by a woman directing the flow of milk spouting out of her breast towards the mouth of a little Pluto. In the mean time a satyr with goat hooves displays the corn of abundance…

On the far left, a blue sky enters on stage while on the right the clouds glide away as carton accessories of a theatre. Rubens main argument here for peace is not a desire for justice, but the increase of pleasures and gratifications resulting from the material objects which men could accumulate under peace arrangements! Ironically, seen the cupidity of the ruling Dutch elites, which Rembrandt would lambaste uncompromisingly, it seems that Rubens might have succeeded in convincing these elites to sell the Republic for a handful of tulips. If only his art would have been something else then self-glorification! Here, his style is purely didactical, copied from the Italian mannerism Leonardo despised so much.

Instead of using metaphors capable to make people think and discover ideas, the art of Rubens is to illustrate symbolized allegories. The beauty of an invisible idea has never, and can not be brought to light by this insane iconographical approach. His « style » will be so impersonal that dozens of assistants, real slave laborers, will be generously used for the expansion of his enterprise.

King Christian IV’s physician, Otto Sperling, who visits Rubens in 1621 reported:

« While still painting he was hearing Tacitus read aloud to him and at the same time was dictating a letter. When we kept silent so as not to disturb him with our talk, he himself began to talk to us while still continuing to work, to listen to the reading and to dictate his letter, answering our questions and then displaying his astonishing power. »

« Then he charged a servant to lead us through his magnificent palace and to show us his antiquities and Greek and Roman statues which he possessed in considerable number. We then saw a broad studio without windows, but which captured the light of the day through an aperture in the ceiling. There, were united a considerable amount of young painters occupied each with a different work of which M. Rubens had produced the design by his pencil, heightened with colors at certain points. These models had to be executed completely in paint by the young people till finally, M. Rubens administered with his own hand the final touch.

« All these works came along as painted by Rubens himself, and the man, not satisfied to merely accumulate an immense fortune by operating in this manner, has been overwhelmed with honors and presents by kings and princes ». (*15).

We know, for example, that between 1609 and 1620, not less than sixty three altars were fabricated by « Rubens, Inc. ». In 1635, in a letter to his friend Pereisc, when the thirty years war is ravaging Europe, Rubens states cynically « let us leave the charge of public affairs to those who’s job it is ».

The painter asks and obtains a total discharge of his public responsibilities the same year while retiring to enjoy a private life with his new young partner.

Painter of Agapè, versus painter of Eros

Being a human, Rembrandt correctly had thousand reasons to be allergic to Rubens. The latter was not simply « on the wrong side » politically, but produced an art inspiring nothing but lowness: portraits designated to flatter the pride of the mighty by making shine and glitter some shabby gentry; history scenes being permanent apologies of Roman fascism where, under the varnish of pseudo-Catholicism, the alliance of the violent forces of nature and iron-cold reason dominated. Behind the « art of living » of Seneca, there stood the brutal methods of manipulation of the perfect courtier described by Baldassare Castiglione in his « Courtier ». For courtly ethics, everything stands with balance (sprezzatura) and appearance, and behind the mask of nice epithets operates the savage passions of seduction, possession, rape and power-games.

On the opposite, Rembrandt is the pioneer of interiority, of the creative sovereignty of each individual. To show the beauty of that interiority, why not underline paradoxically exterior ugliness?

In the « Old man and young boy » of Domenico Ghirlandajo, an imperfect appearance unveils a splendid beauty. The old man has a terribly looking nose, but the visual exchange between him and the boy shows a quality of love which transcends both of them. At the opposite of Seneca, they don’t contemplate the « brevity of life », but the longevity or « immortality of the soul ».

Martin Luther King, in a sermon tries equally to define these different species of love. After defining Eros (carnal love), and Philia (brotherly love), he says:

« And then the Greek language comes out with another word. It’s the word agape. Agape is more than Eros; it’s more than an aesthetic or romantic love; it is more than friendship. Agape is understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill for all men. It is an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return. Theologians would say that it is the love of God operating in the human heart. And so when one rises to love on this level, he loves every man, not because he likes him, not because his ways appeal to him, but he loves every man because God loves him, and he rises to the level of loving the person who does an evil deed, while hating the deed that the person does. » (*17)

Then, King shows how that love intervenes into the political domain:

« If I hit you and you hit me and I hit you back and you hit me back and go on, you see, that goes on ad infinitum. It just never ends. Somewhere somebody must have a little sense, and that’s the strong person.

The strongperson is the person who can cut off the chain of hate, the chain of evil. And that is the tragedy of hate, that it doesn’t cut it off. It only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. Somebody must have religion enough and morality enough to cut it off and inject within the very structure of the universe that strong and powerful element of love. »

You probably understood our point here. Martin Luther King, in his battle for justice, was living in the same « temporal eternity » as Rembrandt and Comenius opposing the thirty years war. Isn’t that a most astonishing truth: that the most powerful political weapon at man’s disposal is nothing but transforming universal love, over more available to everyone on simple demand? But to become a political weapon, that universal love cannot remain a vague sentiment or fancy romantic concept. Strengthened by reason, Agapè can only reach height with the wings of philosophy.

Rembrandt and Comenius knew that « secret », which will remain a secret for the oligarchs, if they remain what they are. »

The Little Fur

Another comparison between two paintings will make the difference even more clearer between Eros and Agapè: Het pelsken (the little fur) of Rubens (left) and Hendrickje bathing in a river of Rembrandt (right).

That comparison has a particular significance since the two paintings show the young wives of both painters. At the age of fifty-three Rubens remarried the sixteen year old Helena Fourment, while Rembrandt settled at the age of forty-three with the twenty-two year old Hendrickje Stoffels.

The naked Helena Fourment, with staring eyes, and while effecting an hopeless gesture of pseudo-chastity, pulls a black fur coat over her shoulders. The stark color contrast between the pale body skin and the deep dark fur, a typical baroque dramatic touch of Rubens, unavoidably evokes basic instincts. No wonder that this canvas was baptized the « little fur » by those who composed the catalogues.

However, paradoxically, Hendrickje is lifting her skirt to walk in the water, but entirely free from any erotic innuendo! Her hesitating, tender steps in the refreshing water seem dominated by her confident smile. Here, the viewer is not some « Peeping Tom » intruding into somebody’s private life, but another human being invited to share a moment of beauty and happiness.

Suzanne and the Elderly

Another excellent example is the way the two painters paint the story of Suzanne and the elderly. Comenius, was so impassioned by this story that in 1643 he called his daughter Zuzanna in 1646 his son Daniel. This Biblical parable (Daniel 13) deals with a strong notion of justice, quite similar to the one already developed in Greece by Sophocles Antigone. In both cases, in the name of a higher law, a young woman defies the laws of the city.

In her private garden, far from intruding viewers, the beautiful Suzanne gets watched on by two judges which will try to blackmail her: or you submit to our sexual requests, or we will accuse you of adultery with a young man which just escaped from here! Suzanne starts shouting and refuses to submit to their demands. The next day, Suzanne gets accused publicly by the judges (the strongest) in front of her family, but Daniel, a young man convinced of her innocence, takes her defense and unmasks the false proofs forged by the judges. At the end, the judges receive the sentence initially slated for Suzanne.

In the Rubens painting, a voluptuous Suzanne lifts her desperate eyes imploring divine help from heaven. The image incarnates the dominant but

insane ideology of both Counterreformation Catholicism and radical Protestantism: the denial of the free will, and thus of the incapacity to obtain divine grace through one’s acting for the good. For the Calvinist/protestant ideologues, the soul was predestinated for good or evil. Reacting by a simple inversion to the crazy indulgences, it was « logical » that no earthly action could « buy » divine grace. So whatever one did, whatever our commitment for doing the good on earth, nothing could derail God’s original design. The Counterreformation Catholics thought pretty much the same, except that one could claim God’s indulgence in the context of the rites of the Roman Catholic Church, especially by paying the indulgences: « No salvation outside the church ».

In a spectacular way, Rembrandt’s Suzanne and the elderly reinstates the real evangelical Christian humanist standpoint: a chaste Suzanne looks straight in the eyes of the viewer which is witnessing the terrible injustice happening right under his nos. So, will you be the new Daniel? Will you find the courage to intervene against the laws of the State to defend a « Divine » justice? Hence, agapè is that infinite love for justice and truth, that leads you to courageous action and makes you a sublime personality capable of changing history, in the same way Antigone, Jeanne d’Arc, or Suzanne did before.

Plato versus Aristotle

The fact that Rembrandt was a philosopher is regularly put into question, even denied. The inventory of his goods, established when his enemies forced him into bankruptcy in 1654, doesn’t mention any book outside a huge bible, supposedly establishing a legitimate suspicion of him being near to illiteracy. While romanticized biographies portray him as an accursed poet, a narcissistic genius or the simple-minded mystical visionary son of a miller, a comment in 1641 from the artist Philips Angel underscores, not his painting, but Rembrandt’s « elevated and profound reflection ».

It is Aristotle contemplating Homer’s bust, which demonstrates once and for ever how stupid the Romantics can be. Ordered by an Italian nobleman, the painting shows Aristotle as a Venetian aristocrat, as a perfect courtier: with a wide white shirt, a large black hat and especially carrying a heavy golden chain.

In short, clothed as Castiglione, Aretino, Titian and Rubens… Rembrandt shows here his intimate knowledge of the species nature of Plato’s enemies of the Republic, that oligarchy to whom Aristotelianism became a quasi-religion.

With great irony, the canvas completely mocks knowledge derived from the « blind » submittal to sense perception. Here Rembrandt seems to join Erasmus of Rotterdam saying « experience is the school of fools! ».

Equipped with empty eyes, incapable of perception, Aristotle is groping with an uncertain hand Homer’s head of which he was supposedly a knowledgeable commentator. Homer, the Greek poet who turned blind, stares worriedly to Aristotle with the open eyes of mind.

That inversion of the respective roles of Aristotle and Homer is dramatized by situating the source enlightening the scene as a tangent behind the bust of the poet.

Light reflections illuminating Aristotle’s hat underneath make appear the ironical « ghost image » of donkey ears, the conventional attribute widely used since the Renaissance to designate the stubbornness of scholastic Aristotelianism.

To this Aristotelian blindness, Rembrandt, whose own father became blind, opposes the other clear-sightedness of Simeon, as seen in his last painting, found on Rembrandt’s easel after his death.

All during his life, Simeon had wished to see the Christ with his own eyes. But, growing old, that hope quitted him with along with his sight. As he did every day, Simeon went one day to the temple. There, Maria asked him to keep her child in his arms. Suddenly, an infinite joy

overwhelmed Simeon, who, without seeing Christ with his mortal eyes, saw him much more clearly with his mind than all the healthy seers. Rembrandt wanted us to reflect on that conviction: don’t believe what you see, but act coherently with God’s design and you might see him. On Simeon’s hands, a series of dashes of paint suggest some kind of crystal ball, an image which only « appears » when our minds dares to see it, underlining Simeon’s prophetic nature.

Jesus Christ healing the sick

Rembrandt’s anti-Aristotelian philosophy is also explicitly manifest in an engraving known as Christ healing the sick, an exceptionally large etching on which he worked passionately over a six year period. In order to « sculpt » the ambiguous image of the Christ, son of both God and mankind, Rembrandt executed six oil portraits featuring young rabbi’s of Amsterdam. But it was Leonardo’s fresco, the Last Supper, which Rembrandt extensively studied as shown by drawings done after reproductions, that seems to have been his starting point.

Scientific analysis of his still existing copperplate indicate that the Christ’s hands were originally drawn as an exact imitation of Leonardo’s « Last Supper » fresco.

Completely different from the kind of « spotlight theatrics » that go from Caravagio to Hitchcock, the work reminds the description of the myth of the cavern in Plato’s Republic. But here stands the Christ blessing the sick.

Transfigured, and akin to the prisoners in Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, the sick people walk from right to left towards Christ. Encountering the light transforms them into philosophers!

One generally identifies easily, amidst others, Homer and Aristotle (who’s turning his head away from Christ), but also Erasmus and Saint-Peter, which according to some possesses here the traits of Socrates.

The etching brings together in a single instant eternal several sequences of Chapter XIX of Saint Mathew:

“Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.”

In a powerful gesture, Christ brushes aside even the best of all wise wisdom to make his love the priority, where Peter desperately tries to prevent the children from being presented to Jesus.

Sitting close to him we observe the image of an undecided young wealthy man plunged in profound doubts, since he desired eternal life but hesitated to sell his possessions and give it all to the poor.

When he left, Jesus commented that it was certainly easier for a camel to get through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter the his kingdom.

Above simple earthly space situated in clock-ticking time, the action takes place in « the time of all times », an instantaneous eternity where human minds are measured with universality, some kind of « last judgment » of divine and philosophical consciousness.

The healing of the sick souls and bodies is the central breaking point which articulates the two universes, the one of sin and suffering, with the one of the good and happiness. Christ’s love, metaphorized as light, heals the « sick » and makes philosopher-kings out of them. They appear nearly as apostles and figure exactly on the same level as the apostles of Leonardo‘s milan fresco The last Supper. Brought out of darkness into the light, they become themselves sources of light capable of illuminating many others.

That « light of Agapè » is the single philosophical basis of Rembrandt’s revolution in the techniques of oil-painting: in stead of starting drawing and paint on a white gesso underground or lightly colored under-paint (the so-called priming, eventually adding imprimatura), all the later works are painted on a dark, even black under-paint!

The « modern » thick impasto, possible through the use of Venetian turpentine and the integration of bee wax, are revived by Rembrandt from the ancient « encaustic » techniques described by Pliny the Elder. They were employed by the School of Sycione three hundred years before Christ and gave us Alexander the Great‘s court painter Apelles, and the Fayoum mommy paintings in Alexandria, Egypt (*17).

Building the color-scale inversely permitted Rembrandt to reduce his late palette to only six colors and made him into a « sculptor of light ». His indirect pupil, Johannes Vermeer, systemized Rembrandt’s revolutionary discovery (*18).

Deprived of much earthly glory during their lives, Rembrandt and Comenius were immediately scrapped from official history by the oligarchic monsters that survived them. But their lives represent important victories for humanity. Their political, philosophical, esthetical and pedagogical battles against the oligarchy and its « valets » as Rubens, makes them eternal.

They are and will remain inexhaustible sources of inspiration for today’s and tomorrows combat.

NOTES:

- Karel Vereycken, « Rembrandt, bâtisseur de nation« , Nouvelle Solidarité, June 1985.

- The treatises of Westphalia (Munster and Osnabruck) of 1648, and the ensuing separate peace accords between France and the Netherlands with Spain, finally shred into pieces every political, philosophical and juridical argument serving as basis of the notion of empire, and by doing so put an end to Habsburg’s imperial fantasy, the « Thirty years war ». As some had outlined before, notably French King Henry IV’s great advisor Sully in his concept of « Grand Design », making the sovereign nation-state the highest authority for international law was, and remains today, the only safe road to guaranty durable peace. Empires, by definition, mean nothing but perpetual wars. If you want perpetual war, create an empire! Hence, through this revolution, small countries obtained the same rights as those held by large ones and the notions of big= strong, and small=weak, went out of the window. The Hobbesian idea that « might makes right » was abolished and replaced by mutual cooperation as the sole basis of international relations between sovereign nation-states. Hence, tiny Republics, as Switzerland or the Netherlands,the latter at war with Spain for nearly eighty years, finally obtained peace and international recognition. Second, and that’s undoubtedly the most revolutionary part of the agreements, mutual pardon became the core of the peace accords. For example paragraph II stipulated explicitly « that there shall be on the one side and the other a perpetual Oblivion, Amnesty or Pardon of all that has been committed since the beginning of these Troubles, in what place, or what manner soever the Hostilitys have been practis’d, in such a manner, that no body, under any pretext whatsoever, shall practice any Acts of Hostility, entertain any Enmity, or cause any Trouble to each other; » (translation: Foreign Office, London). Moreover, several paragraphs (XIII, XXXV, XXXVII, etc.) stipulate (with some exceptions) that there will be a general debt forgiveness concerning financial obligations susceptible of maintaining a dynamic of perpetual vengeance. In reality, the Peace of Westphalia was the birth of new political order, based on the creation of a new international economic and monetary system necessary to build peace on the ruins of the bankrupt imperial order.

- Footnote, p. 77 in Comenius by Olivier Cauly, Editions du Félin, Paris, 1995.

- Brochure dealing with that painting published by the Nationalmuseum of Stockholm.

- To put to an end to the politically motivated financial harassment which was organized by the family of his deceased wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, Rembrandt submits on July 14, 1656 to the Dutch High Court a cessio bonorum (Cessation of goods to the profit of the creditors), accepting the sale of his goods. In 1660, Rembrandt abandons the official management of his art trading society to his wife Hendrickje Stoffels and his son Titus.

- p. 105, Henriette L.T.de Beaufort, in Rembrandt, HDT Willinck & Zoon, Harlem, 1957.

- p. 358, Samuel Hartlib and Universal Reformation, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- p. 12-13, Bob van den Bogaert, in « Goethe & Rembrandt », Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1999.

- p. 25, Marcelle Denis in Comenius, pédagogies & pédagogues, Presse Universitaire de France, 1994.

- Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687), was an exceptional precocious erudite. Politician, scientist, moralist, music composer, he played the violin at the age of six, wrote poems in Dutch, Latin, French, Spanish, English and Greek. His satire, « ‘t Kostelick Mal » (expensive folly), opposed to the « Profijtelijk Vermaak » (profitable amusement) makes great fun of courtly manners and the then rampant beaumondism. His son, Christiaan Huygens was a brilliant scientist and collaborator of Leibniz at the Paris Academy of sciences.

- One has to outline shortly here that contrary to the rule of the Greek canon of proportions (height of man = seven heads and a half), the Romans, as Leonardo seems to observe sourly in his drawing reworking Vitrivius, increase the body size up to eight and sometimes many more heads. It was the Greek canon established after the « Doryphore » of Polycletius, which settled the matter much earlier after many Egyptian inquiries on these matters. Leonardo, who wasn’t a fool, realized Vitruvius proportions (8 heads) are wrong, as can be seen by the two belly-buttons appearing in the famous man bounded by square and circle. Hence, the proportional « reduction » of the head was an easy trick to create the illusion of a stronger, more powerful musculature. That image of a biological man displaying « small head, big muscles » supposedly stood as the ultimate expression of Roman heroism. Foreknowledge of this arrangement permits the viewer to identify accurately what philosophy the painter is adhering to: Greek humanist or Roman oligarch? That Rubens chose Rome rather than Athens, leaves no doubt, as proven by his love for Seneca.

- « The holy Council states that it isn’t permitted to anybody, in any place or church, to install or let be installed an unusual image, unless it has been approved so by the bishop »; « finally any indecency shall be avoided, of that sort that the images will not be painted or possess ornaments of provoking beauty… » P. 1575-77, t. II-2, in G. Alberigo, « The ecumenical Councils », quoted by Alain Taton (p. 132) in « The Council of Trent », editions du CERF, Paris, 2000.

- p. 172, Simon Schama, in his magnificent Rembrandt’s eyes, Knopf, New York, 1999.

- For a more elaborate description of the tulip-bubble, Simon Schama, p. 471, « L’embarras de richesses, La culture hollandaise au Siècle d’Or », Gallimard, Paris, 1991.

- p. 117, Otto Sperling, Christian IV’s doctor, quoted by Marie-Anne Lescouret in her biography Pierre-Paul Rubens, J.C. Lattès, Paris, 1990.

- « Love your enemies », sermon of Martin Luther King, November 17, 1957, Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Montgomery, Alabama. Quoted in Martin Luther King, Minuit, quelqu’un frappe à la porte, p.63, Bayard, Paris 1990.

- p. 87-88, Karel Vereycken, in The gaze from beyond, Fidelio, Vol. VIII, n°2, summer 1999.

- Johannes Vermeer of Delft was a close friend of Karel Fabritius, the most outstanding pupil of Rembrandt, who died at the age of thirty-four when the powderkeg of Delft exploded. Vermeer became the executor of his last will, a role generally reserved for the closest friend or relative. Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek, the inventor of the microscope and Leibniz correspondent, will become in turn the executor of Vermeer’s last will. That filiation does nothing more than prove the constant cross-fertilization of the artistic and scientific milieu. The Dutch « intimist » school, of which Vermeer is the most accomplished representative, is the most explicit expression of a « metaphysical » transcendence, transposed for political reasons, from the domain of religion, into the beauty of daily life scenes.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Baudiquey, Paul, Le retour du prodigue, Editions Mame, 1995, Paris.

- Bély, Lucien, L’Europe des Traités de Westphalie, esprit de la diplomatie et diplomatie de l’esprit, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 2000.

- Callot, Jacques, etchings, Dover, New York, 1974.

- Castiglione, Baldassare, Le Livre du Courtisan, GF-Flammarion, 1991.

- Cauly, Olvier, Comenius, Editions du Félin, Paris, 1995.

- Clark, Kenneth, An introduction to Rembrandt, Readers Union, Devon, 1978.

- Comenius, La Grande Didactique, Editions Klincksieck, Paris, 1992.

- Denis, Marcelle, Comenius, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1994.

- Descargues, Pierre, Rembrandt, JC Lattès, 1990.

- Goethe Rembrandt, Tekeningen uit Weimar, Amsterdam University Press, 1999.

- Grimberg, Carl, Histoire Universelle, Marabout Université, Verviers, 1964.

- Haak, B., Rembrandt, zijn leven, zijn werk, zijn tijd, De Centaur, Amsterdam.

- Hobbes, Thomas, Le Citoyen ou les fondements de la politique, Garnier Flammarion, Paris, 1982.

- Jerlerup, Törbjorn, Sweden und der Westphalische Friede, Neue Solidarität, mai 2000.

- King, Martin Luther, Minuit, quelqu’un frappe à la porte, Bayard, Paris, 2000.

- Komensky, Jan Amos, Le labyrinthe du monde et le paradis du cœur, Desclée, Paris, 1991.

- Lescourret, Marie Anne, Pierre-Paul Rubens, JC Lattès, Paris, 1990.

- Marienfeld Barbara, Johann Amos Comenius : Die Kunst, alle Menschen alles zu lehren. Neue Solidarität.

- Rembrandt and his pupils, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, 1993.

- Sénèque, Entretiens, Editions Bouquins, Paris, 1993.

- Schama Simon, Rembrandt’s Eyes, Knopf, New York 1999.

- Schama, Simon, L’embarras de richesses, La culture hollandaise au Siècle d’Or, Gallimard, 1991.

- Schiller, Friedrich, traduction de Regnier, Vol. 6, Histoire de la Guerre de Trente ans, Paris, 1860.

- Sutton, Peter C., Le Siècle de Rubens, Mercatorfonds, Albin Michel, Paris, 1994.

- Tallon, Alain, Le Concile de Trente, CERF, Paris, 2000.

- Tümpel, Christian, Rembrandt, Fonds Mercator-Albin Michel, 1986.

- Van Lil, Kira, La peinture du XVIIème siècle aux Pays-Bas, en Allemagne et en Angleterre, dans l’art du Baroque, Editions Köneman, 1998, Cologne.

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on avril 10, 2022

Avicenne et Ghiberti, leur rôle dans l’invention de la perspective à la Renaissance

This article, in EN

Tout visiteur du centre historique de Florence pose fatalement, à un moment donné, son regard sur les portes richement décorées du Baptistère, cet édifice roman faisant face à la cathédrale Santa Maria del Fiore, coiffée par Filippo Brunelleschi de sa magnifique coupole.

Dans cet article, Karel Vereycken apporte un éclairage nouveau sur les apports arabes à la science et le rôle crucial de Lorenzo Ghiberti dans l’invention de la perspective à la Renaissance.

Le Baptistère, que la plupart des Florentins pensaient être construit sur l’emplacement d’un temple romain dédié à Mars, le dieu tutélaire de l’ancienne Florence, est l’un des plus anciens bâtiments de la ville, construit entre 1059 et 1128 dans le style roman local.

Le poète italien Dante Alighieri et de nombreuses autres personnalités de la Renaissance, dont des membres de la famille Médicis, y furent baptisés.

A la Renaissance, à Florence, les corporations et les guildes se disputaient le premier rôle à coup de réalisations artistiques toutes aussi prestigieuses les unes que les autres.

Alors que l’Arte dei Lana (Corporation des producteurs de laine) finançait les Œuvres (Opera) du Duomo et donc la construction de sa coupole géante, l’Arte dei Mercatanti o di Calimala (Guilde des marchands d’étoffes étrangères) s’occupait du Baptistère et finançait l’embellissement des portes.

Les portes du Paradis