Étiquette : Bonaparte

Enseignement mutuel : curiosité historique ou piste d’avenir ?

Par Karel Vereycken, Paris, France

- Introduction

- Apprendre et enseigner, une même joie

- Précédents

A. En Inde

B. En France - Les brigades de Gaspard Monge

- Andrew Bell

- Joseph Lancaster

- Enseignement mutuel, comment ça marche ?

A. Le local

B. Maîtres et moniteurs

C. Fonctionnement

D. Progresser selon sa connaissance

E. Les outils

F. Commandement - Bellistes contre lancastériens

- Lorsque ça intéresse les Français

- Lazare Carnot à la manœuvre

- Enseignement mutuel et chant choral

- Le projet pilote de la rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais

- Jomard, Choron, Francœur et savoirs élémentaires

- Rayonnement national

- Critiques

- Dérive mécaniste ?

- Mort de l’enseignement mutuel en France

- Conclusion

- Quelques ouvrages et textes consultés, en accès libre

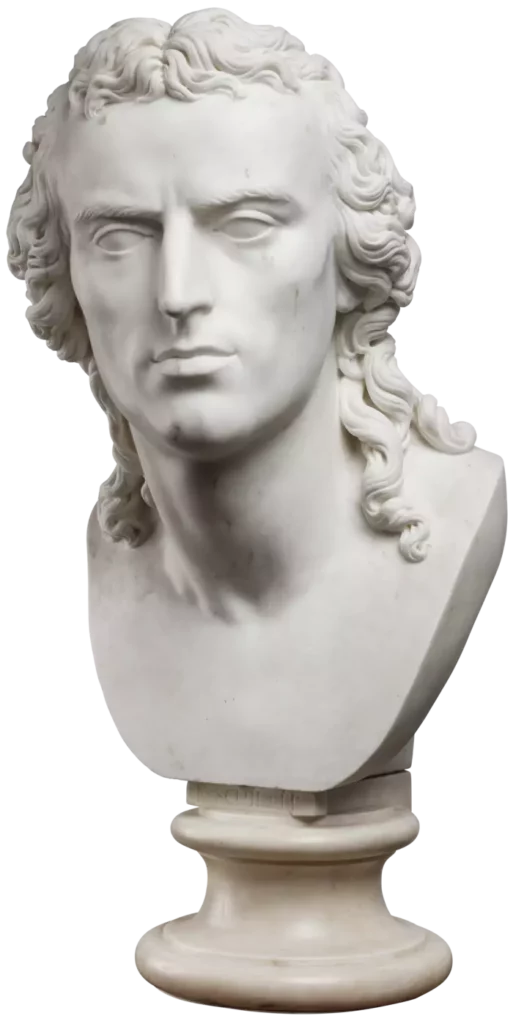

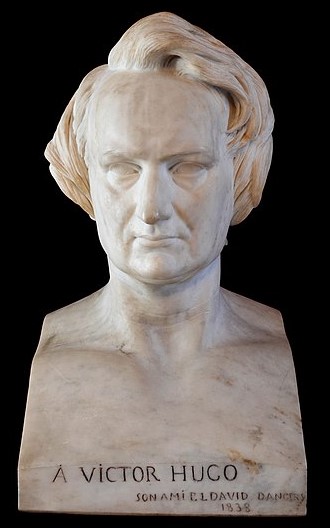

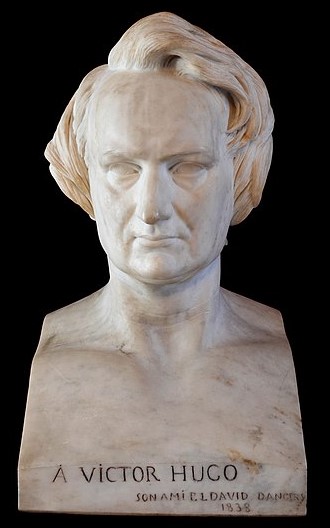

« Répondez, mes amis : il doit vous être doux

D’avoir pour seuls mentors des enfants comme vous ;

Leur âge, leur humeur, leurs plaisirs sont les vôtres ;

Et ces vainqueurs d’un jour, demain vaincus par d’autres,

Sont, tour à tour parés de modestes rubans,

Vos égaux dans vos jeux, vos maîtres sur les bancs.

Muets, les yeux fixés sur vos heureux émules,

Vous n’êtes point distraits par la peur des férules ;

Jamais un fouet vengeur, effrayant vos esprits,

Ne vous fait oublier ce qu’ils vous ont appris ;

J’écoute mal un sot qui veut que je le craigne,

Et je sais beaucoup mieux ce qu’un ami m’enseigne. »

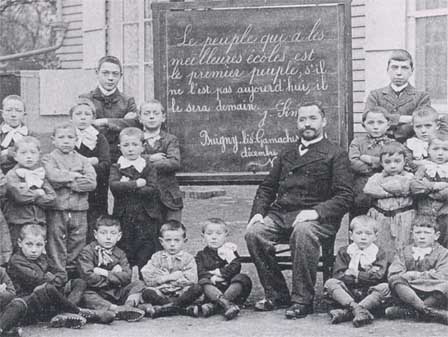

Victor Hugo, Discours sur les avantages de l’Enseignement mutuel, 1817.

1. Introduction

Enseigner la lecture et l’écriture à 1000 enfants présents dans une même salle, sans instituteur, sans livres scolaires, sans papier et sans encre, c’est clairement impossible. Et pourtant, cela a été imaginé et mis en pratique avec grand succès ! Chut ! Il ne faut pas en parler, car cela pourrait donner des idées à certains, et pas seulement dans les pays émergents !

Qu’un tel défi puisse être relevé ne pouvait qu’inquiéter l’oligarchie et ses serviteurs. Depuis la nuit des temps ils formatent une « élite » (les grands prêtres de la connaissance, les « experts » et autres sachants) se reproduisant en vase clos au sommet, tout en veillant à ce que la grande masse du peuple d’en bas s’instruise juste assez pour pouvoir livrer des colis, payer ses impôts, se plier aux règles définies par le sommet, et surtout, ne fasse pas (trop) désordre.

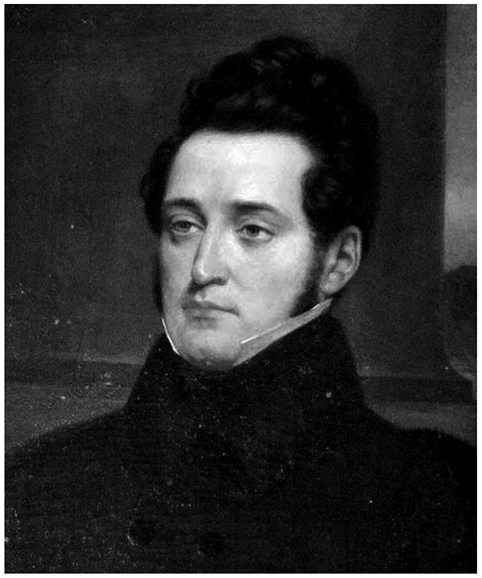

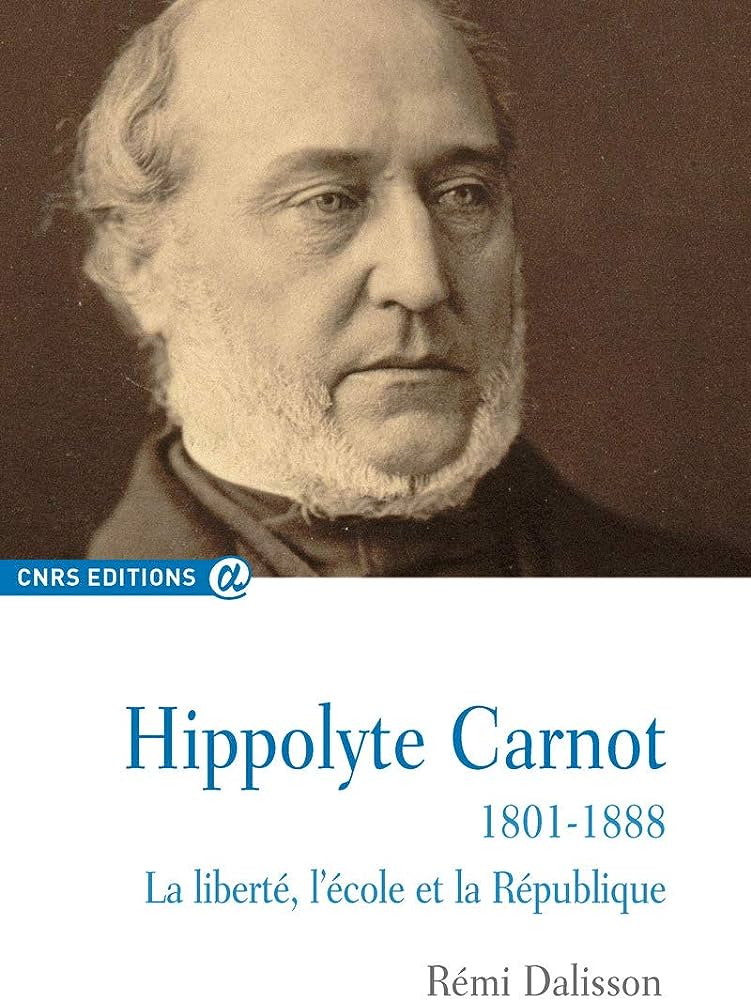

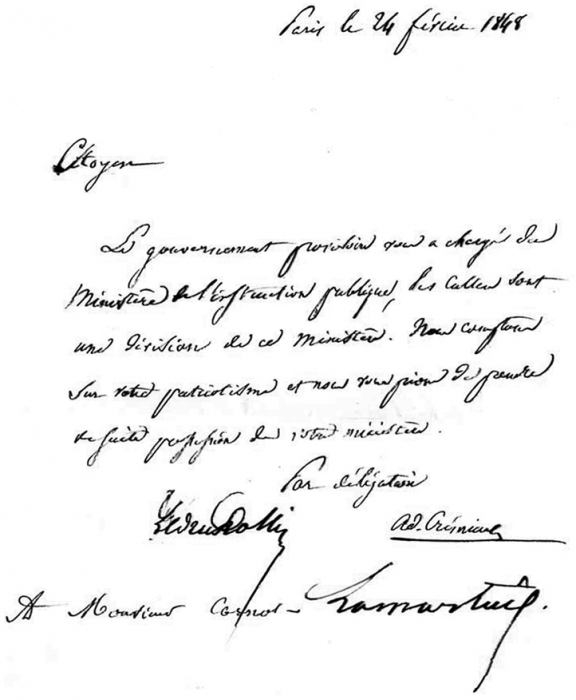

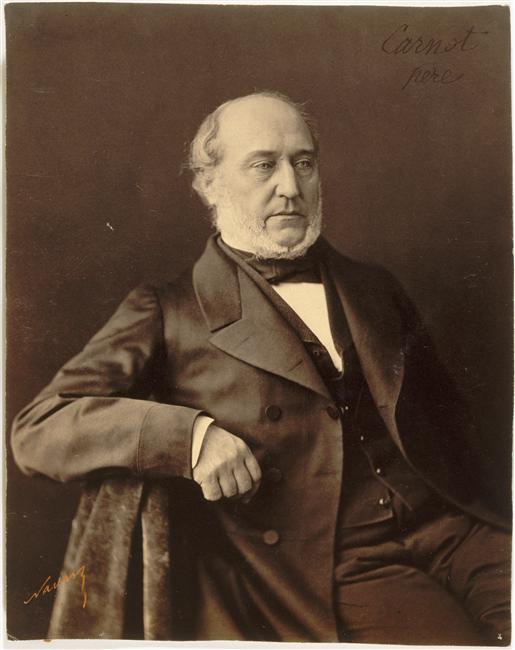

Pourtant, comme l’avait compris bien avant nous Hippolyte Carnot, ministre de l’Instruction publique de la IIe République, sans éducation républicaine, c’est-à-dire sans une véritable formation de citoyen dès la maternelle, le suffrage universel devient, assez souvent, une farce tragique capable d’engendrer des monstres.

Au début du XIXe siècle, « l’enseignement mutuel » (parfois appelé système « monitorial » anglais, « système de Madras » ou « système de Lancaster »), se répand comme un feu de brousse en Europe puis à travers le monde.

Si le maître s’adresse à un seul élève, c’est le mode individuel (cas du précepteur) ; s’il s’adresse à toute une classe, c’est le mode simultané ; s’il charge des enfants d’instruire les autres, c’est le mode mutuel. L’alliance des procédés simultané et mutuel est appelée mode mixte.

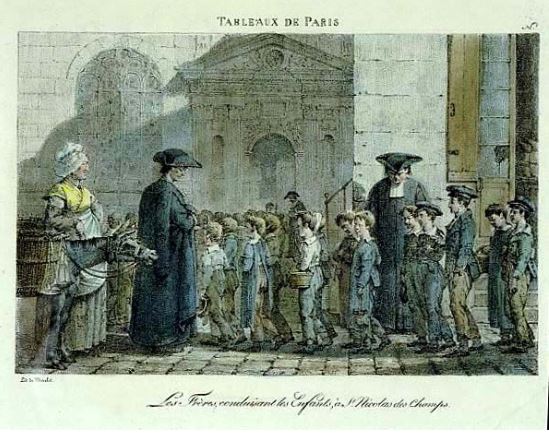

L’enseignement mutuel est rapidement victime de querelles de personnes et d’enjeux idéologiques, politiques et religieux. Il est vécu comme une agression par les congrégations religieuses qui pratiquent, elles, « l’enseignement simultané », édicté dès 1684 par Jean-Baptiste de la Salle pour les « Frères des écoles chrétiennes » : classes par âge, division par niveau, place fixe et individuelle, discipline stricte, travail répétitif et simultané surveillé par un maître inflexible.

Avec la constitution de petits groupes où les élèves enseignent les uns aux autres, se déplacent dans la salle de classe, l’enseignement mutuel a immédiatement fait naître, assez bêtement, la crainte d’un monde cul par-dessus tête, sortant d’un tableau de Jérôme Bosch. Dans quel monde sommes-nous si l’élève enseigne au maître, l’enfant au parent, le fidèle au prêtre, le citoyen au gouvernement ! Sans chef, que faire, chef ?

Estimant qu’un tel enseignement « affaiblit l’autorité » aussi bien des maîtres que des autorités politiques et religieuses, en 1824, le pape Léon XII (à ne pas confondre avec le bienveillant Léon XIII), le « pape de la Sainte-Alliance », farouche partisan de l’ordre et soupçonnant un vaste complot protestant contre le Vatican, l’interdit.

En France, où dans les années qui suivent la Révolution de 1830, près de 2 000 écoles mutuelles existent, principalement dans les villes, en concurrence avec les écoles confessionnelles, François Guizot, ministre de Louis-Philippe, les fera disparaître.

2. Apprendre et enseigner, une même joie

Le tutorat connaît aujourd’hui un regain d’intérêt dans le cadre des apprentissages scolaires et formations professionnelles. Il s’agit d’un processus « d’assistance de sujets plus expérimentés à l’égard de sujets moins expérimentés, susceptible d’enrichir les acquisitions de ces derniers ». C’est ainsi que le tutorat entre enfants, en particulier entre enfants d‘âges différents, est encouragé dès l’école maternelle, jusqu’à l’université avec l’institutionnalisation au niveau du premier cycle du tutorat méthodologique, en passant par l’école élémentaire et le secondaire qui ont vu se développer depuis les années 1980, tant en France qu’à l’étranger, de nombreuses expériences tutorales.

Or, le tutorat n’est que le pâle héritier de l’enseignement mutuel développé en Angleterre puis en France au XIXe siècle.

Il existe une vérité immuable : l’avenir de l’humanité dépend d’une faculté exclusivement humaine : la découverte de principes physiques universels nouveaux, parfois dépassant de loin les bornes de notre appareil sensoriel, permettant à l’Homme d’accroître sa capacité de transformation de l’univers afin d’améliorer de façon qualitative son sort et celui de son environnement. Or, une découverte n’est jamais le fruit d’une somme ou d’une moyenne d’opinions multiples mais bien celui d’un acte unique parfaitement souverain.

Cependant, sans la socialisation de cette découverte, elle ne servira à rien. L’histoire de l’humanité est donc, par sa propre nature, pourrait-on dire, l’histoire d’un « enseignement mutuel ».

Le plus grand plaisir de celui qui vient d’effectuer une découverte, et cela est naturel chez les enfants, n’est-il pas de partager, non seulement ce qu’il ou elle vient de découvrir, mais la joie et la beauté que représente toute percée scientifique ? Et lorsque ceux qui découvrent, enseignent, le plaisir est au rendez-vous. Laissons-donc à nos enseignants professionnels le temps de faire des découvertes, leur enseignement y gagnera en qualité !

3. Précédents

A. En Inde

En 1623, l’explorateur italien Pietro Della Valle (1586-1652), après un voyage en « Indoustan » (Inde), dans une lettre expédiée d’Ikkeri (ville du sud-ouest de l’Inde), rapporte avoir vu :

« certains jeunes enfants qui y apprenaient à lire d’une façon extraordinaire (…) Ils étaient quatre et avaient pris du maître une même leçon ; afin de l’inculquer parfaitement dans leur mémoire, de répéter les précédentes qui leur avaient été prescrites, de peur de les oublier, l’un d’eux chantait d’un certain ton musical une ligne de la leçon, comme par exemple deux et deux font quatre. En effet, on apprend facilement une chanson. Pendant qu’il chantait cette partie de leçon pour l’apprendre mieux, il l’écrivait en même temps, non pas avec une plume, ni sur du papier. Mais pour l’épargner et n’en pas gâter inutilement, ils en marquaient les caractères avec le doigt sur le même plancher où ils étaient assis en rond, qu’ils avaient couvert pour ce sujet d’un sable très délié. Après que le premier de ces enfants avait écrit de la sorte en chantant, les autres chantaient et écrivaient la même chose tous ensemble (…) Sur ce que je leur demandais qui (…) les corrigeait lorsqu’ils manquaient, vu qu’ils étaient tous écoliers, ils me répondirent fort raisonnablement, qu’il était impossible qu’une seule difficulté les arrêtât tous quatre en même temps, sans pouvoir la surmonter et que pour le sujet ils s’exerçaient toujours ensemble afin que si l’un manquait les autres fussent ses maîtres. »

Dans ce texte apparaissent déjà les grands principes de l’enseignement mutuel, notamment l’apprentissage simultané de la lecture et de l’écriture, l’utilisation du sable pour les exercices d’écriture afin de ne pas gaspiller le papier qui est rare et fort cher, un cours en collectif donné par un maître, puis un travail en sous-groupes dans lequel les élèves apprennent à s’autoréguler, et enfin, une intégration du savoir qui, grâce à l’utilisation du chant, va faciliter la mémorisation.

B. En France

A Lyon, le prêtre lyonnais Charles Démia figure comme l’un des précurseurs de l’enseignement mutuel qu’il a théorisé dès 1688, et qu’il mettait en pratique dans les « petites écoles » pour enfants pauvres qu’il a fondées. D’après le Nouveau dictionnaire de pédagogie et de l’instruction primaire,

« Démia introduisit dans les classes ce qu’on appela plus tard l’enseignement mutuel : il recommande de choisir, parmi les écoliers les plus capables et les plus studieux, un certain nombre d’officiers, dont les uns, sous le nom d’intendants et de décurions, seront chargés de la surveillance, tandis que les autres devront faire répéter les leçons du maître, reprendre les écoliers quand ils se trompent, guider la main hésitante des ‘jeunes écrivains’, etc. Pour rendre possible la simultanéité de l’enseignement, l’auteur des règlements divise l’école en huit classes, dont le maître devra s’occuper tour à tour ; chacune de ces classes peut se subdiviser en bandes. »

A Paris, dès 1747, l’enseignement mutuel est pratiqué avec un grand succès dans une école de plus de 300 élèves, établie par M. Herbault à l’hospice de la Pitié, en faveur des enfants des pauvres. L’expérience, hélas, ne survécut pas à son fondateur.

En 1772, la charité ingénieuse du chevalier Paulet conçut et exécuta le projet d’appliquer une semblable méthode à l’éducation d’un grand nombre d’enfants, que la mort de leurs parents laissaient sans appui dans la société.

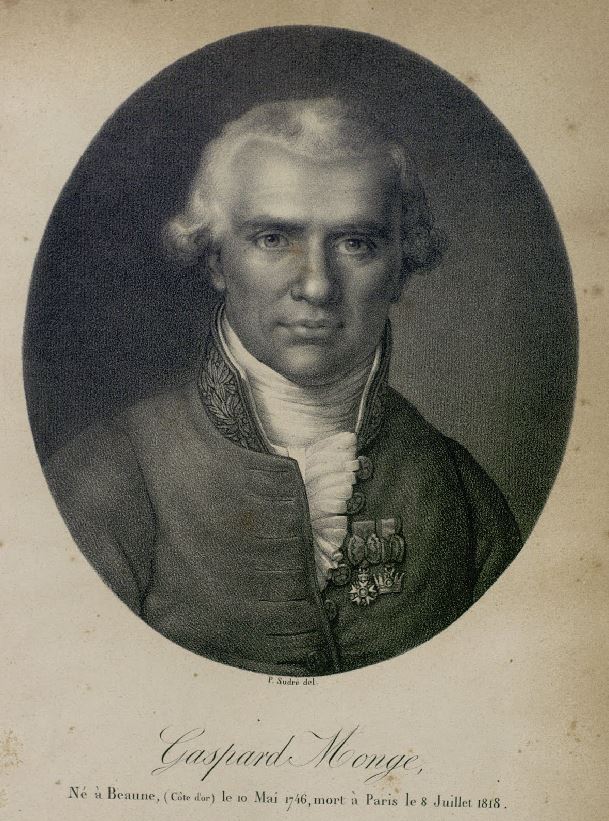

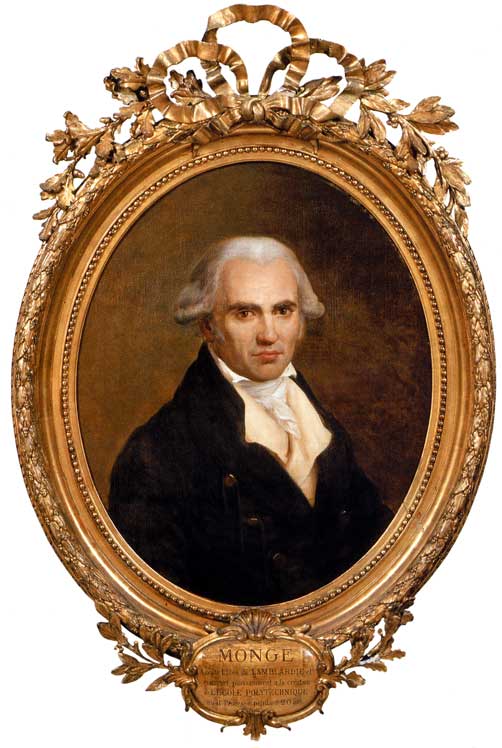

4. Les brigades de Gaspard Monge

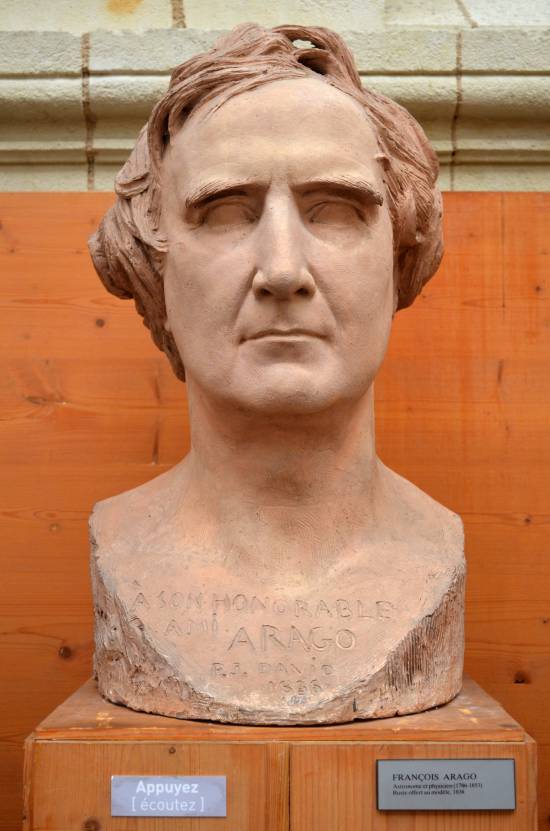

Enfin, comme le raconte, dans sa biographie de Gaspard Monge, son élève le plus brillant, l’astronome François Arago (1786-1853), lui-même un ami proche d’Alexandre de Humboldt, c’est à l’École polytechnique que Monge va peaufiner son propre système d’enseignement mutuel et de tutorat.

Jugeant qu’il était inacceptable de devoir attendre trois ans pour voir sortir les premiers ingénieurs de l’École polytechnique, Monge décida, afin d’accélérer la formation des élèves, d’organiser des « cours révolutionnaires », une formation accélérée pendant trois mois. Pour cela, il perfectionna le concept de « chefs de brigades », une technique qu’il avait déjà pu tester avec succès à l’école du Génie de Mézières.

François Arago :

« Les chefs de brigade, toujours réunis à de petits groupes d’élèves dans des salles séparées, devaient avoir des fonctions d’une importance extrême, celles d’aplanir les difficultés à l’instant même où elles surgiraient. Jamais combinaison plus habile n’avait été imaginée pour ôter toute excuse à la médiocrité ou à la paresse.

« Cette création appartenait à Monge. A Mézières, où les élèves du génie étaient partagés en deux groupes de dix, à Mézières, où, en réalité, notre confrère fit quelque temps, pour les deux divisions, les fonctions de chef de brigade permanent, la présence, dans les salles, d’une personne toujours en mesure de lever les objections avait donné de trop heureux résultats pour qu’en rédigeant les développements joints au rapport de Fourcroy, cet ancien répétiteur n’essayât pas de doter la nouvelle école des mêmes avantages.

« Monge fit plus ; il voulut qu’à la suite des leçons révolutionnaires, qu’à l’ouverture des cours des trois degrés, les 23 sections de 16 élèves chacune, dont l’ensemble des trois divisions devait être composé, eussent leur chef de brigade, comme dans les temps ordinaires ; il voulut, en un mot que l’École, à son début, marchât comme si elle avait déjà trois ans d’existence.

« Voici comment notre confrère atteignit ce but en apparence inaccessible. Il fut décidé que 25 élèves, choisis par voie de concours parmi les 50 candidats que les examinateurs d’admission avaient le mieux notés, deviendraient les chefs de brigade de trois divisions de l’école, après avoir reçu à part une instruction spéciale. Le matin, les 50 jeunes suivaient, comme tous leurs camarades, les cours révolutionnaires ; le soir, on les réunissait à l’hôtel Pommeuse, près du Palais-Bourbon, et divers professeurs les préparaient aux fonctions qui leur étaient destinées. Monge présidait à cette initiation scientifique avec une bonté, une ardeur, un zèle infinis. Le souvenir de ses leçons est resté en traits ineffaçables dans la mémoire de tous ceux qui en profitèrent. »

Arago cite alors le témoignage d’Edme Augustin Sylvain Brissot (1786-1819), fils du célèbre girondin et abolitionniste, un des 50 élèves :

« C’est là, que nous commençâmes à connaître Monge, cet homme si bon attaché à la jeunesse, si dévoué à la propagation des sciences. Presque toujours au milieu de nous, il faisait succéder aux leçons de géométrie, d’analyse, de physique, des entretiens particuliers où nous trouvions plus à gagner encore. Il devint l’ami de chacun des élèves de l’Ecole provisoire ; il s’associait aux efforts qu’il provoquait sans cesse, et applaudissait, avec toute la vivacité de son caractère, aux succès de nos jeunes intelligences ».

Si une forme d’enseignement mutuel y est pleinement pratiquée, le dévouement total d’un maître aussi fervent que Monge, vient compléter ce qui ne serait autrement qu’un « système ».

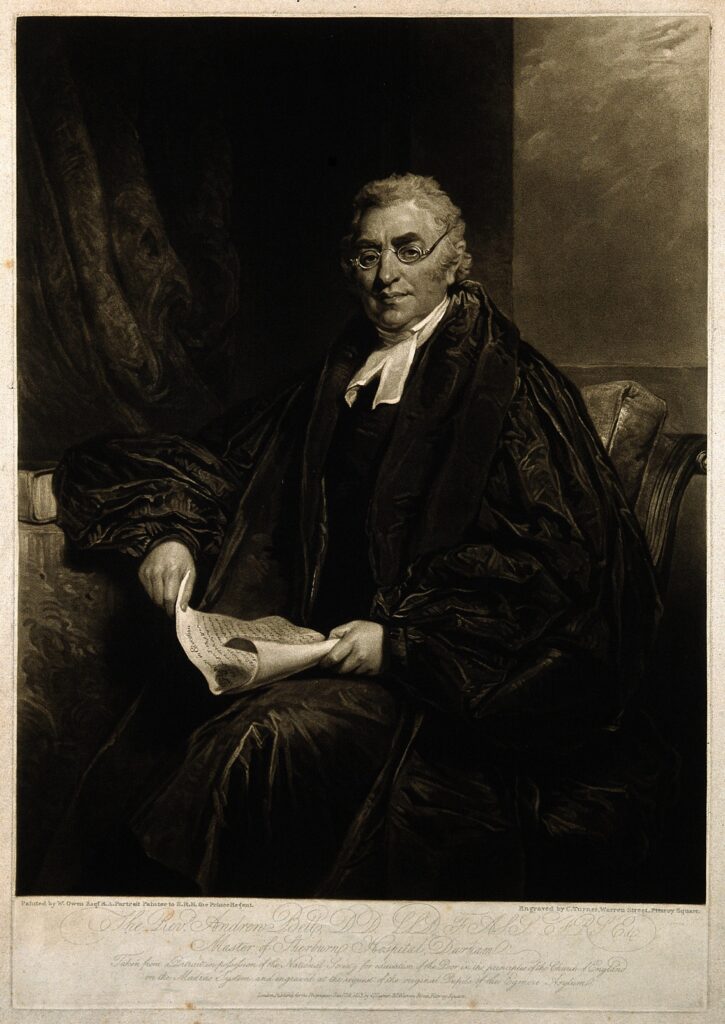

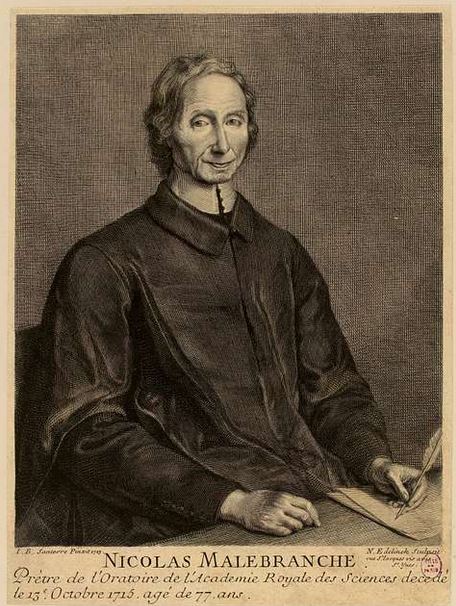

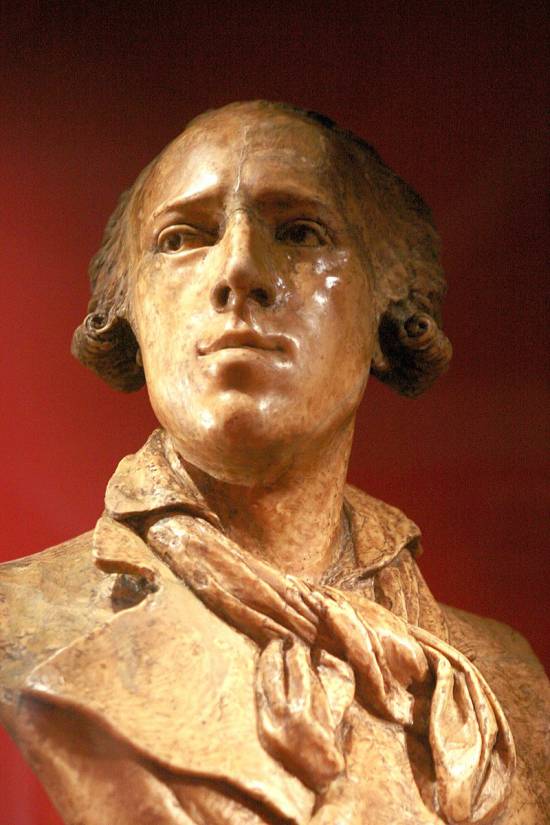

5. Andrew Bell

C’est un Écossais, le pasteur anglican Andrew Bell (1753-1832), qui revendique la paternité de l’enseignement mutuel qu’il a pratiqué et théorisé en Inde, à la tête de l’Asile militaire pour orphelins d’Egmore (Inde orientale). Cette institution, créée en 1789, est chargée d’éduquer et d’instruire les orphelins et les fils indigents des officiers et des soldats européens de l’armée de Madras.

Après sept ans sur place, Bell rentre à Londres et en 1797, il rédige un rapport destiné à la Compagnie des Indes (son employeur à Madras) sur les incroyables avantages de son invention.

Le médecin, naturaliste et inventeur russe Iosif Kristianovich (Joseph Christian) Hamel (1788-1862), membre de l’Académie des Sciences, est chargé par le Tsar de Russie Alexandre Ier, de faire un rapport complet sur ce nouveau type d’enseignement dont toute l’Europe discutait alors.

Il relate, dans Der Gegenseitige Unterricht (1818), ce qu’écrivait Bell dans un de ses écrits :

« Il arriva dans ce temps, qu’en faisant un matin ma promenade ordinaire, je passai devant une école de jeunes enfants Malabares, et je les vis occupés à écrire sur la terre. L’idée me vint aussitôt qu’il y aurait peut-être moyen d’apprendre aux enfants de mon école, à connaître les lettres de l’alphabet, en leur faisant tracer sur le sable. Je rentrai sur-le-champ chez moi, et je donnai ordre au maître de la dernière classe, de faire exécuter ce que je venais d’arranger dans mon chemin. Heureusement, l’ordre fût très mal accueilli ; car si le maître s’y fut conformé à ma satisfaction, il est possible que tout développement ultérieur eût été arrêté, et par là, le principe même de l’enseignement mutuel… »

Accueilli avec froideur en Angleterre, l’enseignement mutuel finit par séduire Samuel Nichols, un des dirigeants de l’école de St-Botolph’s Aldgate, la plus vieille paroisse protestante anglicane de Londres. La mise en œuvre des préceptes de Bell est réalisée avec grand succès et sa méthode est reprise par le docteur Briggs lorsqu’il ouvre une école industrielle à Liverpool.

6. Joseph Lancaster

En Angleterre, c’est Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), un instituteur londonien âgé de vingt ans, qui s’empare de la nouvelle manière d’enseigner, la perfectionne et la généralise à grande échelle.

En 1798, il ouvre une école élémentaire pour les enfants pauvres à Borough Road, un des faubourgs les plus miséreux de Londres. L’enseignement n’y est pas encore totalement gratuit mais 40 % moins cher que dans les autres écoles de la capitale.

Faute d’argent, Lancaster fait tout pour faire baisser encore les coûts de ce qui devient un véritable « système » : emploi de sable et d’ardoises plutôt que d’encre et de papier (Erasme de Rotterdam rapporte en 1528 qu’en son temps il y avait des gens qui écrivaient avec une sorte de poinçon sur des tables recouvertes d’une fine poussière) ; tableaux reproduisant les pages d’ouvrages scolaires suspendus aux murs pour éviter l’achat de livres ; maîtres auxiliaires remplacés par des élèves pour éviter de payer des salaires ; augmentation du nombre d’élèves par classe.

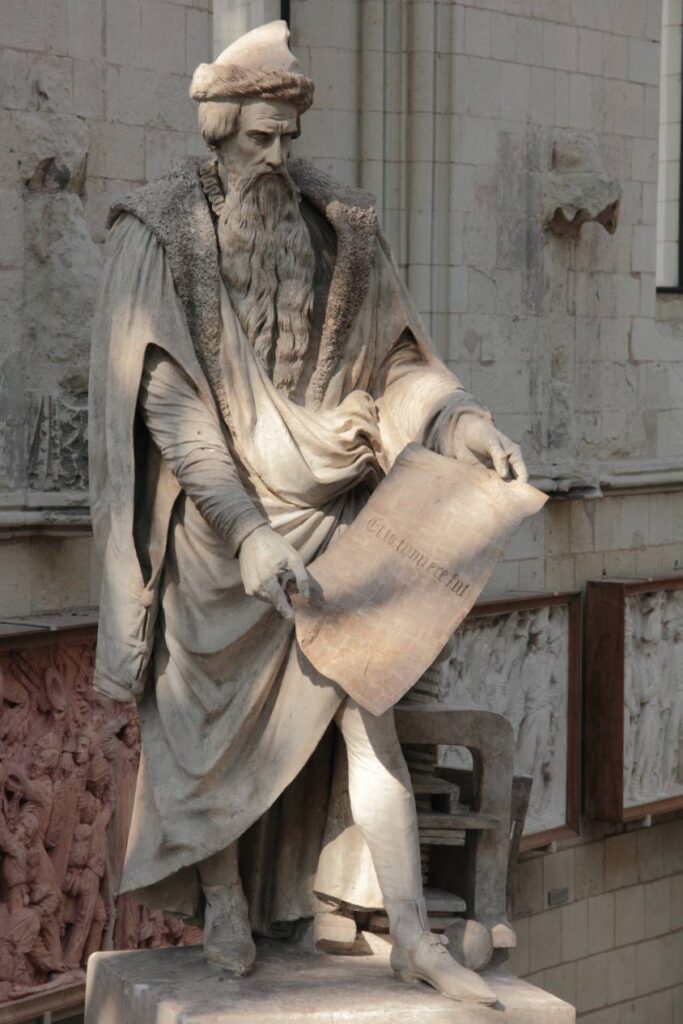

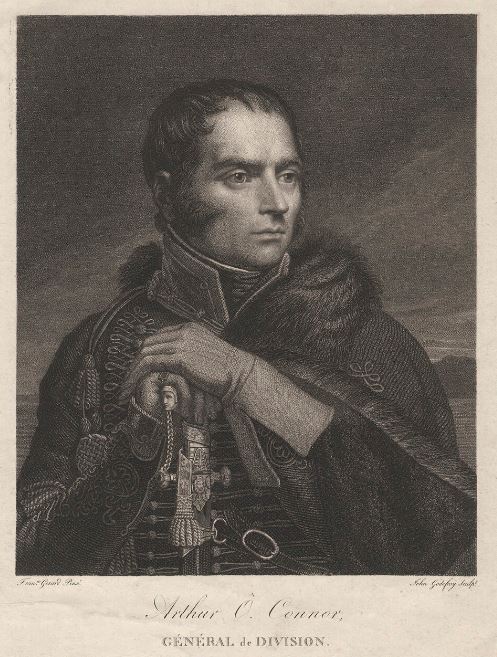

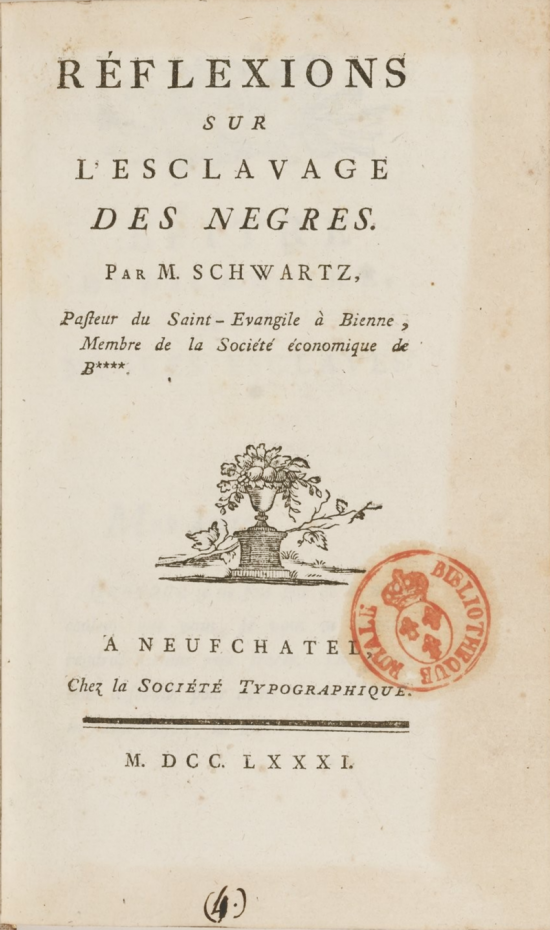

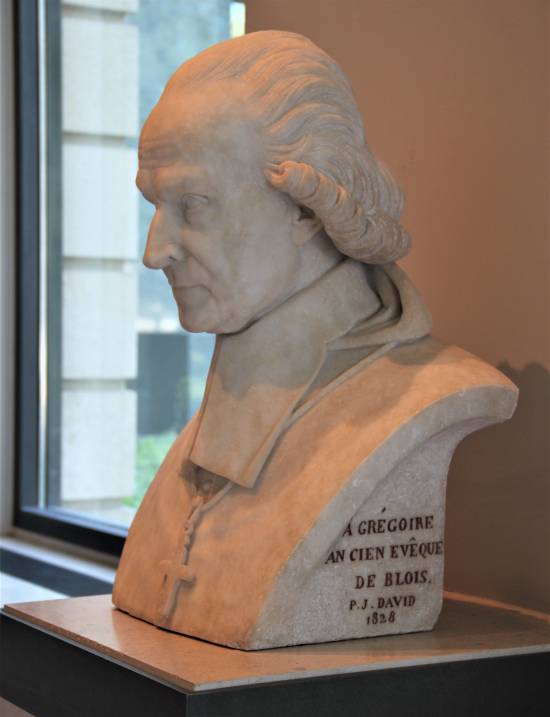

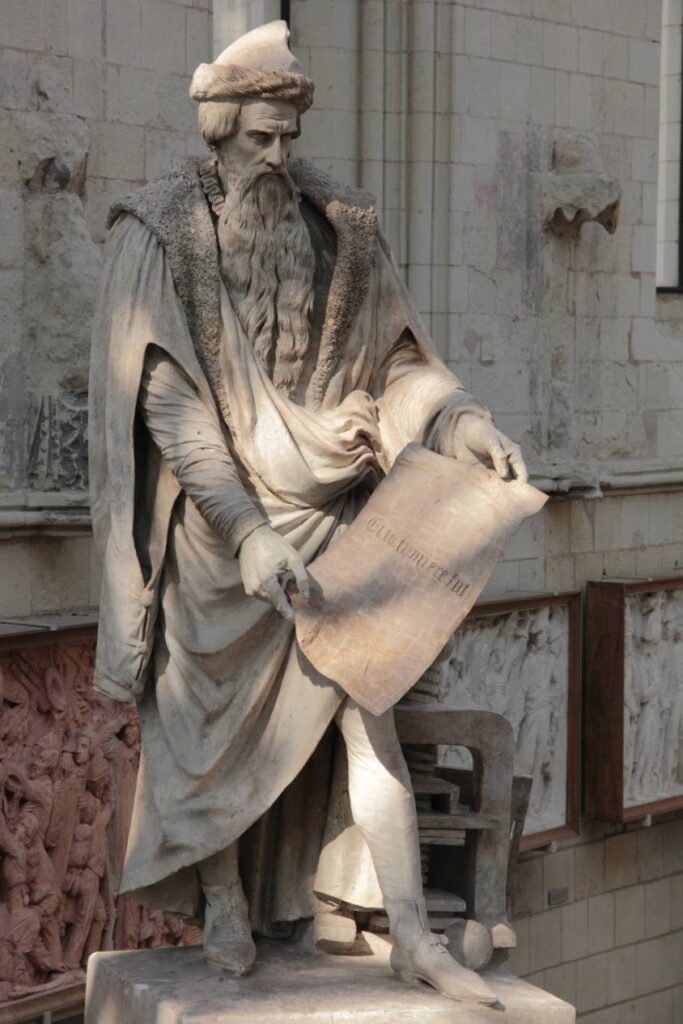

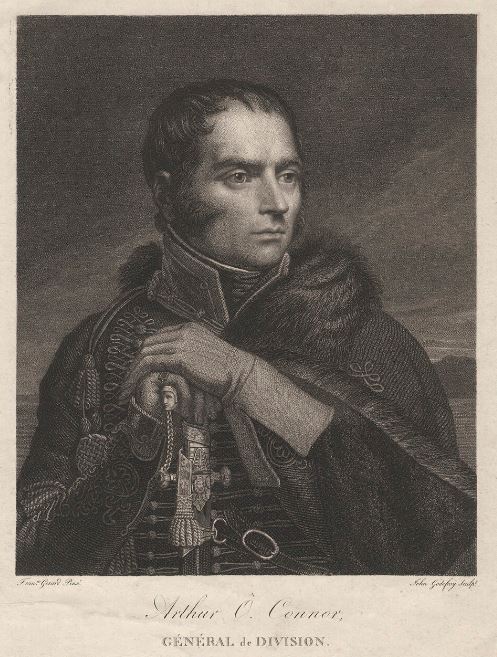

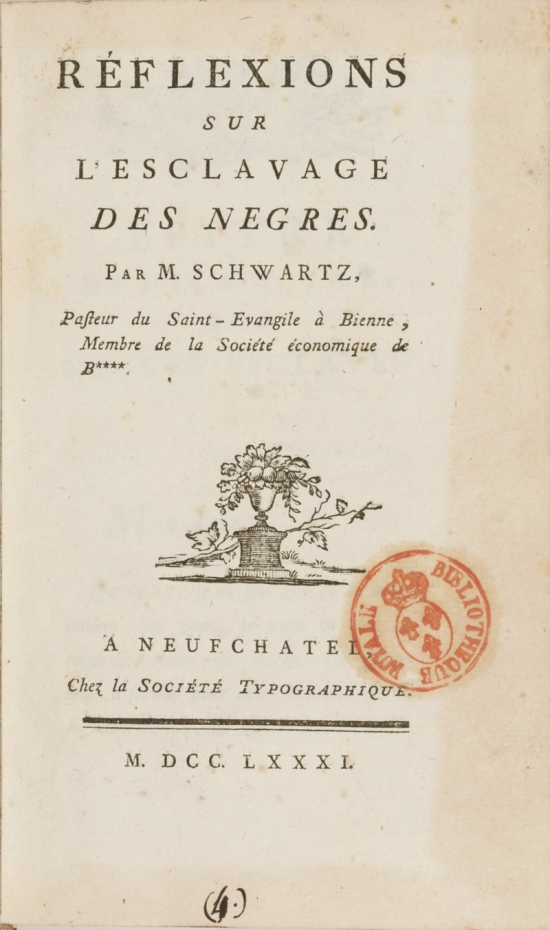

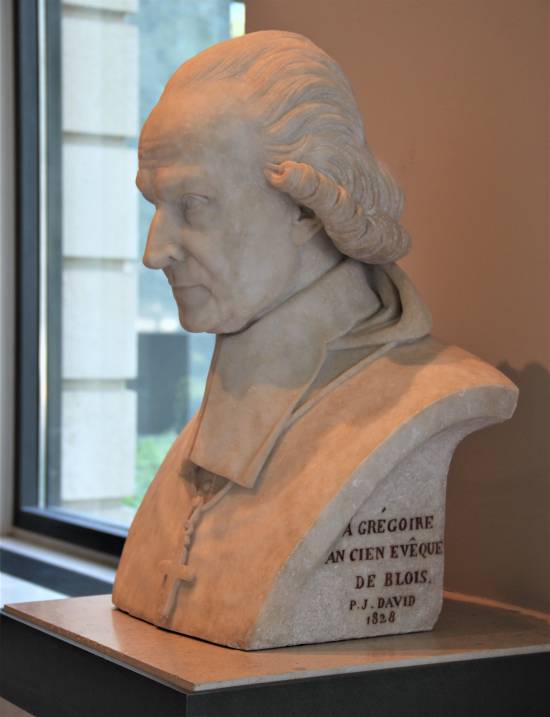

En 1804, son école compte 700 élèves, et douze mois plus tard, un millier. Lancaster, en s’endettant de plus en plus, ouvre une école pour 200 filles. Pour échapper à ses créanciers, il quitte Londres en 1806 et lors de son retour il est enprisonné pour dette. Deux de ses amis, le dentiste Joseph Foxe et le fabricant de chapeaux de paille William Corston, remboursent sa dette et fondent avec lui « La société pour la promotion du système lancastérien pour l’éducation des pauvres ». D’autres quakers viendront alors les soutenir, notamment l’abolitionniste William Wilberforce (1759-1833) que David d’Angers, sur le socle de son célèbre monument commémorant Gutenberg à Strasbourg, fait figurer aux côtés de Condorcet et de l’abbé Grégoire.

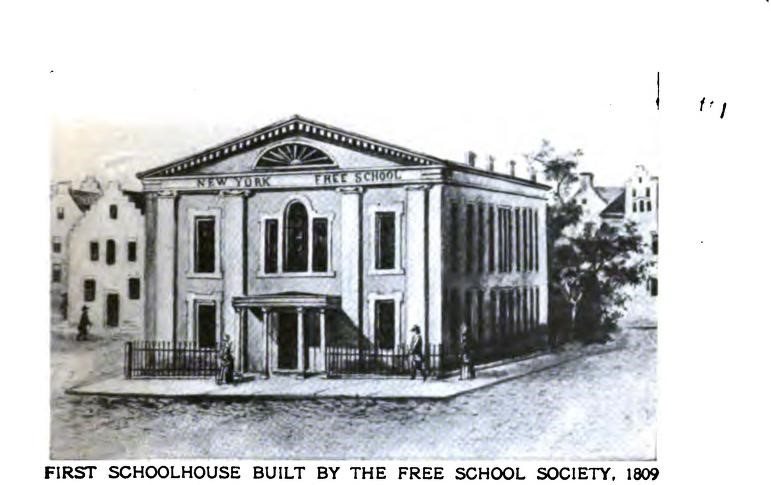

A partir de là, comme le relate Joseph Hamel dans son rapport de 1818, la nouvelle approche s’est répandue aux quatre coins du monde : Angleterre, Écosse, Irlande, France, Prusse, Russie, Italie, Espagne, Danemark, Suède, Pologne et Suisse, sans oublier le Sénégal et plusieurs pays d’Amérique du Sud comme le Brésil et l’Argentine et, bien sûr, les États-Unis d’Amérique. L’enseignement mutuel a été adopté comme pédagogie officielle à New York (1805), Albany (1810), Georgetown (1811), Washington D.C. (1812), Philadelphie (1817), Boston (1824) et Baltimore (1829), et la législature de Pennsylvanie a envisagé de l’adopter à l’échelle de l’État.

7. Enseignement mutuel, comment ça marche ?

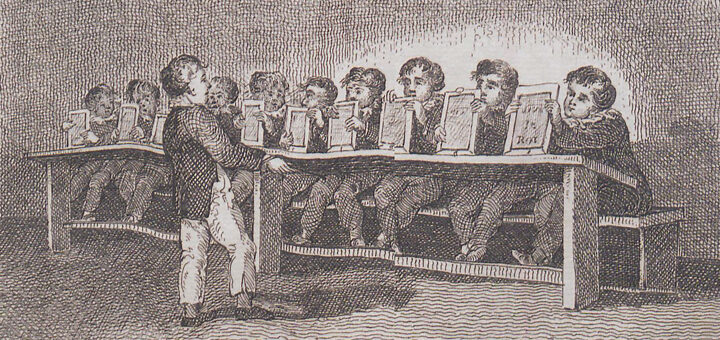

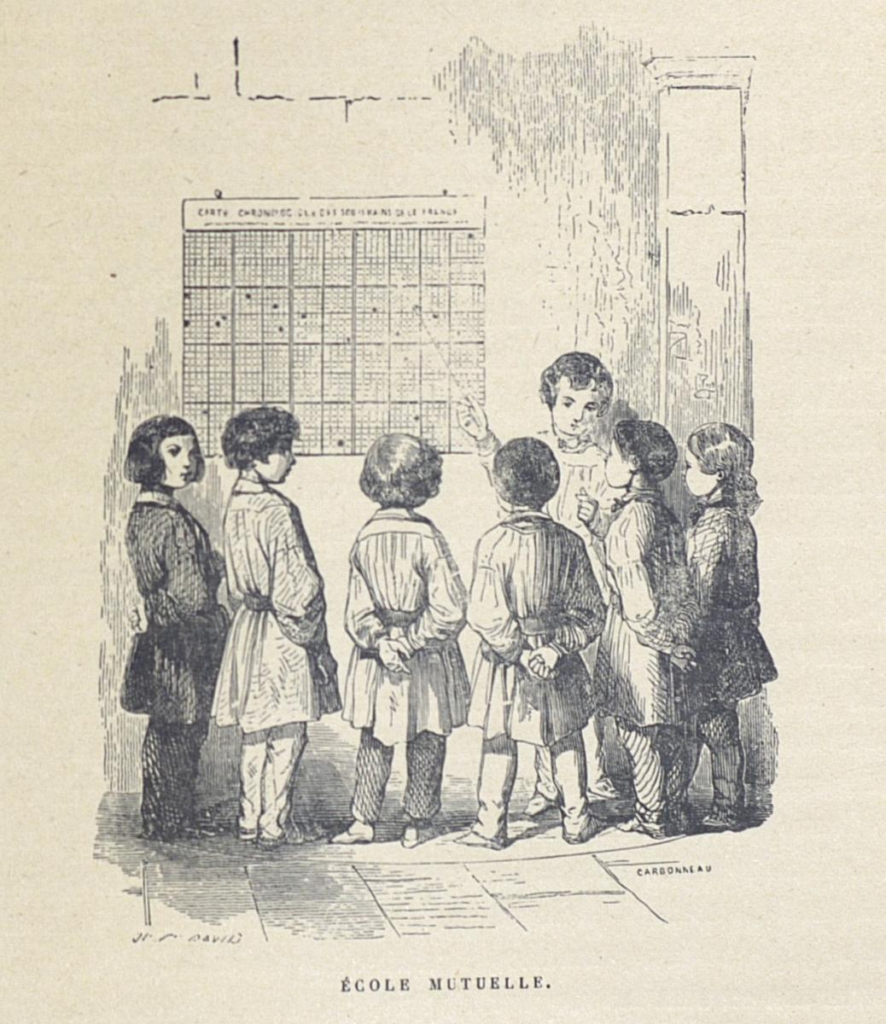

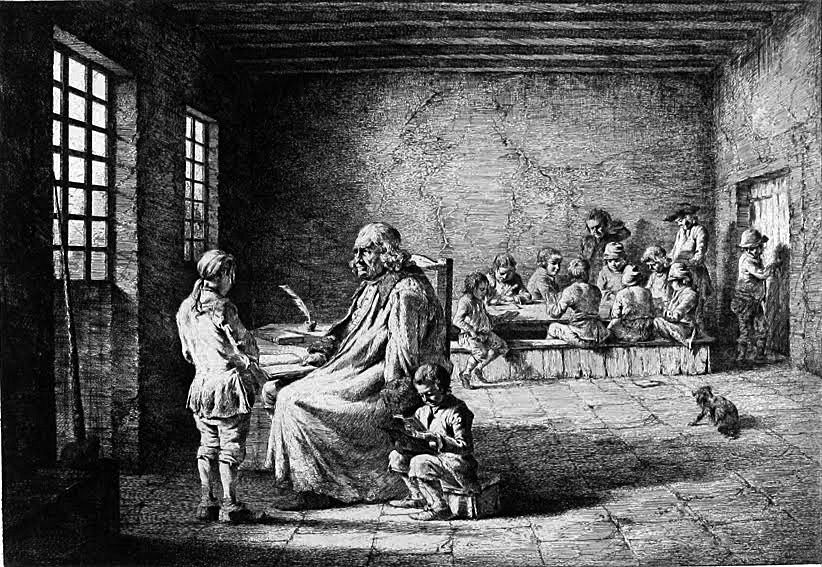

Le principe fondamental de « l’enseignement mutuel », particulièrement pertinent pour l’école primaire, consiste dans la réciprocité de l’instruction entre les écoliers, le plus capable servant de maître à celui qui l’est moins. Dès le début, tous avancent graduellement, quel que soit le nombre d’élèves. Bell et Lancaster, et leurs disciples français, posent en postulat la diversité des facultés, l’inégalité des progrès, des rythmes de compréhension et d’acquisition. Ils sont donc conduits à repartir les élèves en classes différentes suivant les disciplines et suivant le niveau de connaissances des enfants, l’âge n’intervenant aucunement dans cette classification. Les écoliers ainsi réunis prennent part aux mêmes exercices. Leur programme d’étude est identique dans son contenu et dans ses méthodes.

Si l’effectif d’une division est trop élevé dans une discipline, la lecture ou l’arithmétique, par exemple, on constitue des sous-groupes qui évoluent parallèlement, les méthodes et supports de l’enseignement restant identiques.

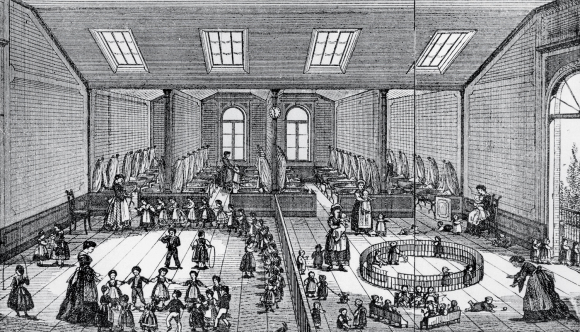

Comment se présente alors une école du nouveau système ?

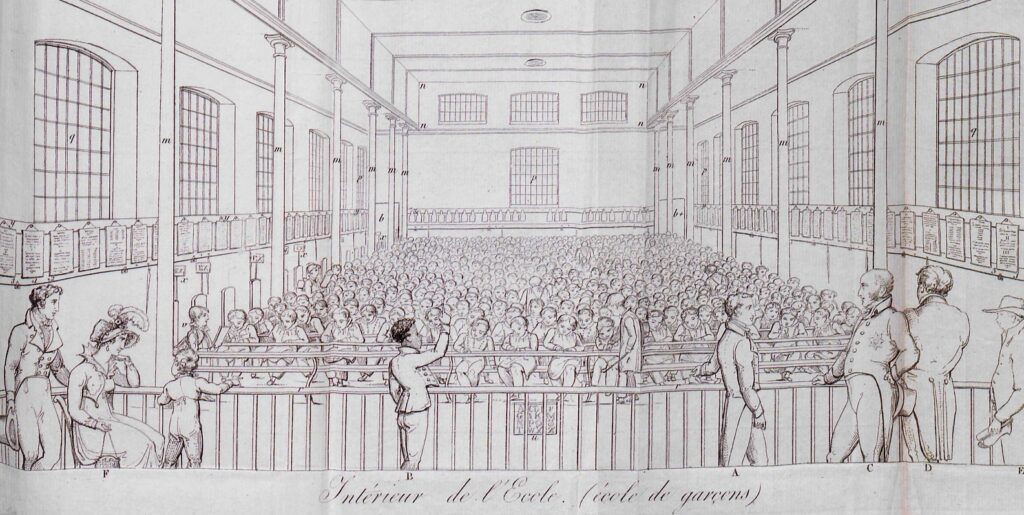

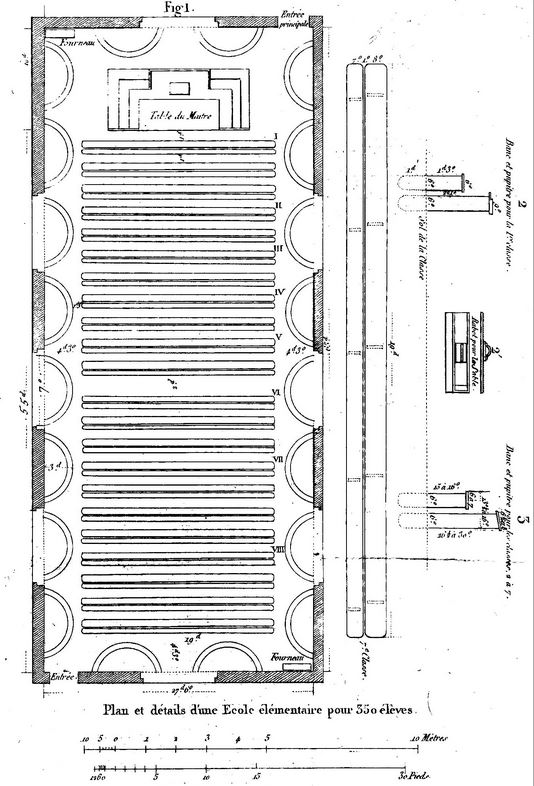

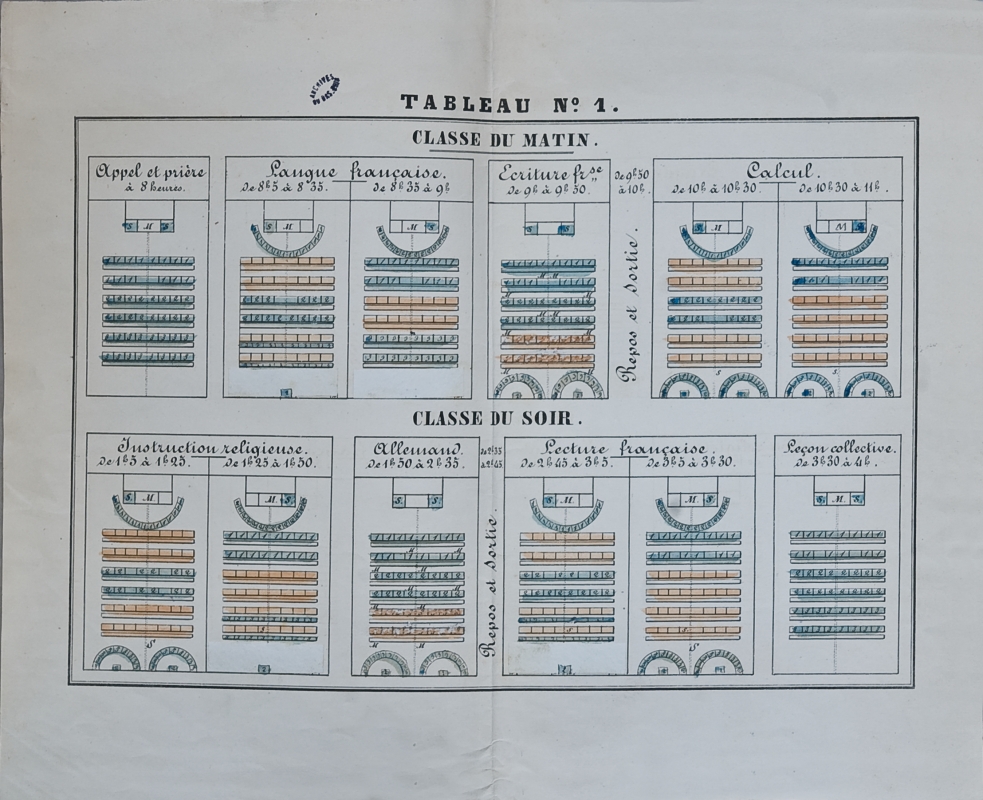

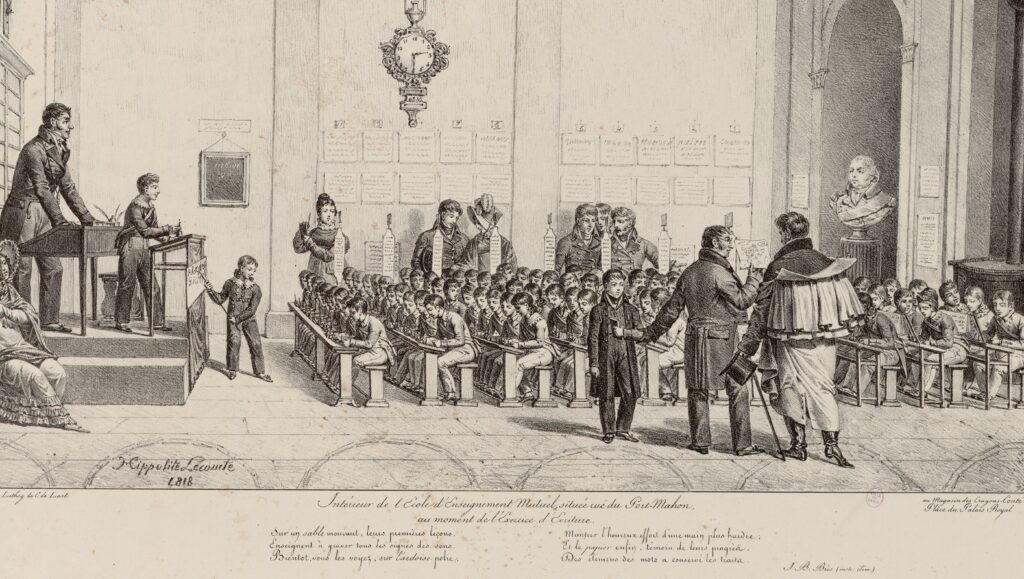

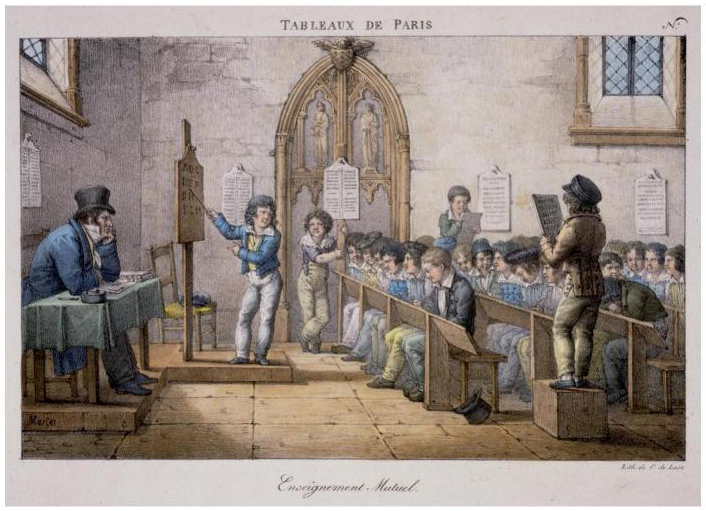

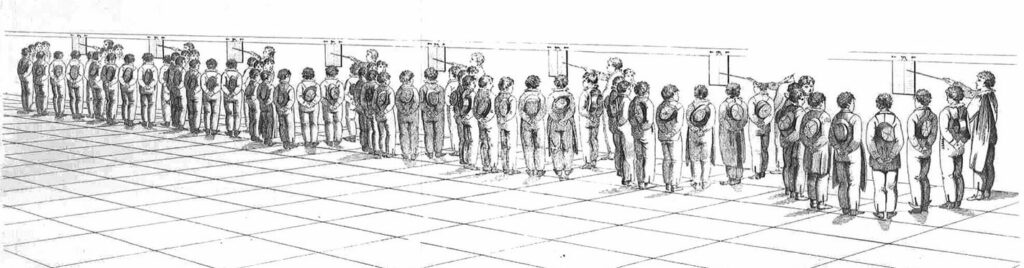

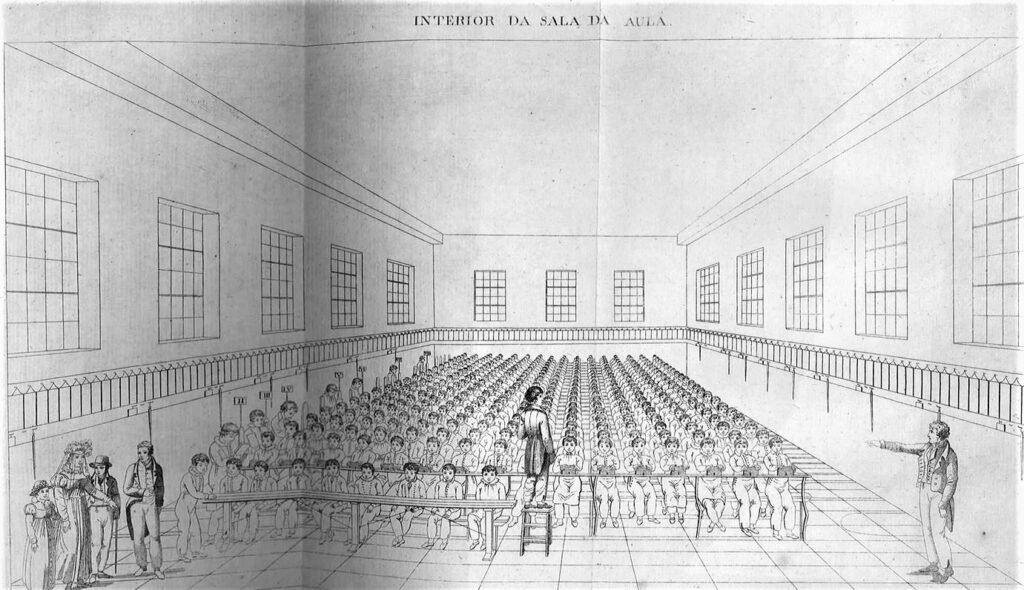

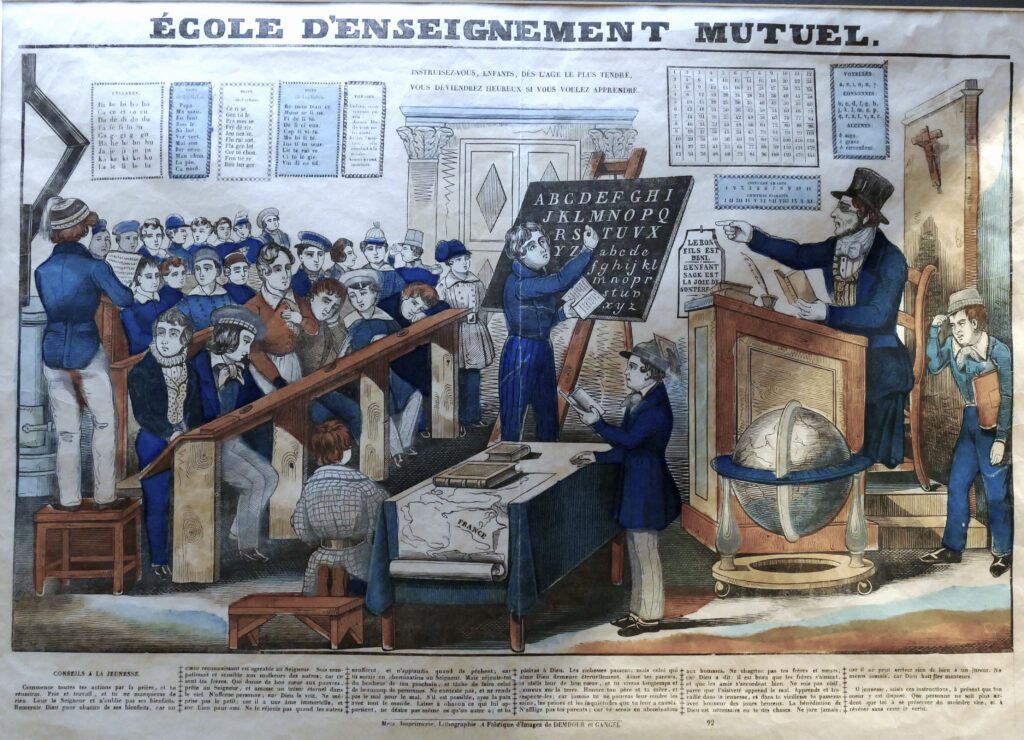

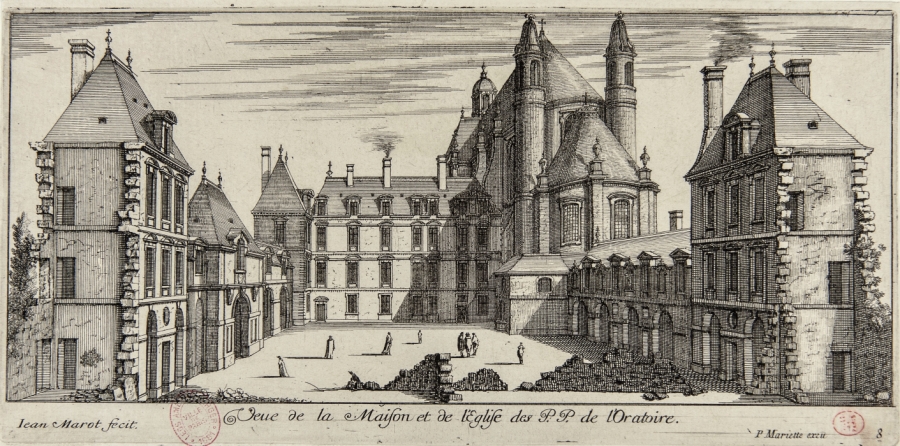

A. La salle de classe

Quel que soit le nombre d’élèves — une centaine dans les bourgades françaises, mille dans l’école de Lancaster à Londres, deux cents dans les écoles parisiennes – ceux-ci sont groupés dans une salle unique, rectangulaire, sans cloisons. Jomard qui déploya dans les premières années de l’installation du mode d’enseignement mutuel une extraordinaire et féconde activité, a fixé les normes souhaitables pour des effectifs variant de 70 à 1 000 élèves. Il indique, par exemple, pour 350 élèves la nécessité d’une salle de 18 m de long sur 9 m de large. En Angleterre et dans les campagnes françaises, on utilise souvent une grange pour la nouvelle école. En France, les édifices religieux désaffectés depuis la période révolutionnaire sont nombreux et répondent parfaitement aux normes souhaitées. Ils accueilleront beaucoup d’écoles mutuelles.

B. Maîtres et « moniteurs »

Le mode mutuel répartit la responsabilité de l’enseignement entre le « maître » et des élèves désignés comme « moniteurs » et considérés comme « la cheville ouvrière de la méthode ». Le moniteur (ou admoniteur) est un élève un peu plus grand et plus avancé dans la discipline. Il de doit point enseigner mais s’assurer que les élèves s’enseignent entre eux. Comme le rappelle Bally, dès 1819 :

« La base de l’enseignement mutuel repose sur l’instruction communiquée par les élèves les plus forts à ceux qui sont les plus faibles. Ce principe qui fait le mérite de cette méthode, a nécessité une organisation toute particulière pour créer une hiérarchie raisonnable, qui pût concourir de la manière la plus efficace, au succès de tous. »

Chaque jour, dans une « classe » réservée aux moniteurs, le maître transmet des connaissances et dispense à ses adjoints les conseils techniques pour la bonne application de la méthode. Au cours de la journée, il reste responsable de la 8e classe (celle de l’achèvement du cursus scolaire), et, à ce titre, se charge de la conduite de leurs exercices. Il procède aux examens périodiques, mensuels ou occasionnels, dans les classes et décide, éventuellement, des changements de classe. C’est lui, enfin, qui, au stade ultime, distribue punitions et récompenses.

C. Fonctionnement

Ainsi, sur une estrade, le bureau du maître avec un large tiroir où sont rangés argent, billets de récompense, registres, modèles d’écriture, sifflets, cahiers des enfants.

Derrière le maître, à côté de l’horloge – instrument essentiel pour organiser la vie de l’enseignement – un tableau noir sur lequel sont écrits sentences et modèles d’écriture.

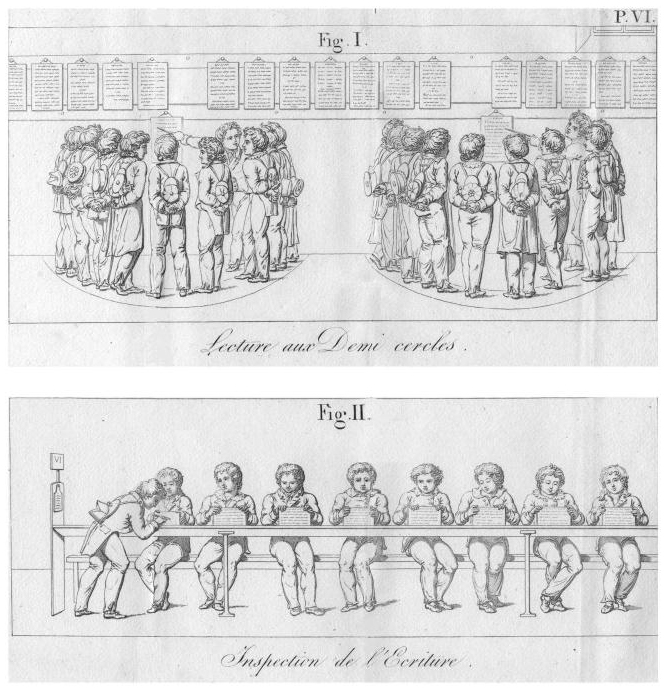

Au pied de l’estrade, des bancs sont fixés transversalement aux pupitres, de tailles différentes, au milieu de la pièce. Les premières tables, non inclinées, comportent du sable sur lesquelles les petits enfants tracent des signes, les autres tables reçoivent des ardoises ; on trouve également, sur les dernières d’entre elles, des encriers de plomb et du papier, des baguettes pour indiquer les mots ou les lettres à lire.

À l’extrémité de chaque table sont fixés les « tableaux de dictées » ainsi que des signaux télégraphiques indiquant les moments de la leçon, tel par exemple « COR » pour « correction » ou « EX » pour « examen du travail ». Des modèles de table demi-circulaire ont été ensuite proposés afin de faciliter le travail des moniteurs.

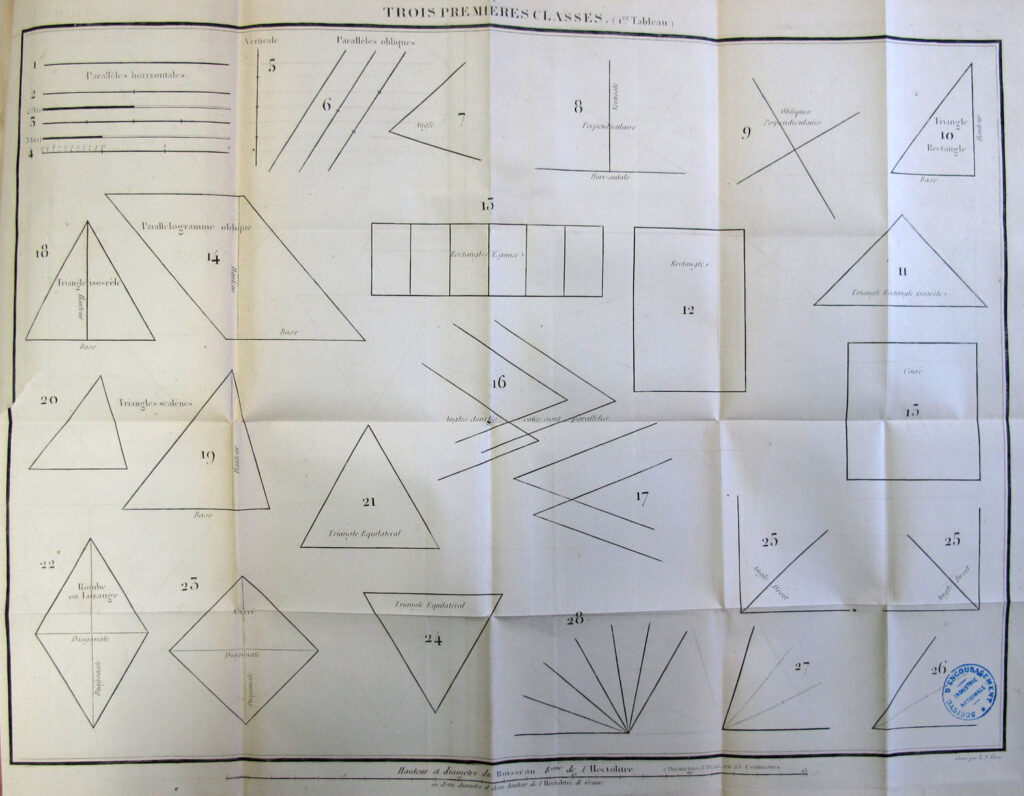

D. Progresser en fonction de sa connaissance

A l’origine, le programme de l’école mutuelle est limité aux trois disciplines fondamentales : lecture, écriture, arithmétique, et à l’enseignement de la religion. S’y ajouteront rapidement, la géographie, la grammaire, la rédaction, le chant et le dessin. Les groupements d’élèves, souples, mobiles, différenciés, sont fonction de la nature des matières d’étude et des activités pratiquées dans la discipline.

Chaque matière enseignée dans les écoles mutuelles repose sur un programme précis et codifié. Ce programme est découpé en 8 degrés hiérarchisés, qui doivent être parcourus successivement. Chaque degré s’appelle « classe » et c’est ainsi que l’on parle de 8 classes d’écriture ou d’arithmétique. Ce terme de « classe » est totalement exclusif de la notion d’architecture ou de local. Il ne s’entend que par rapport aux acquisitions et aux connaissances, la 1ere classe étant celle des débutants et la 8e celle de l’achèvement du cursus scolaire. Les rythmes d’apprentissages et les acquisitions varient suivant les élèves et suivant la discipline.

Ainsi, au bout de six mois de présence, tel élève pourra se trouver en 4e classe de lecture, en 5e classe d’écriture et en deuxième classe d’arithmétique. Comme nous l’avons dit, l’affectation dans la classe se décide en fonction du niveau de connaissance et non pas en fonction de l’âge.

Mais cette première répartition s’assortit, au sein de chaque classe et dans chaque discipline, de la constitution de groupes restreints établis selon les activités qui doivent y être pratiquées. En arithmétique, par exemple, des travaux écrits se font sur l’ardoise. Ils ont lieu, assis, sur les bancs réservés à cet usage, avec 16 à 18 élèves au maximum par banc, selon les normes établies par Jomard.

Les exercices oraux, en lecture, en arithmétique ou en dessin linéaire, à l’aide d’un tableau noir, se font debout, par groupes de 9 au maximum, les élèves se tenant côte à côte et formant un demi-cercle. De là, d’ailleurs, l’appellation donnée à ce genre d’activité : « travail au cercle ».

Ainsi, dans une école mutuelle ayant 36 élèves en 3e classe d’arithmétique, le travail aux bancs se fera en deux groupes avec deux moniteurs et les exercices au tableau noir avec 4 groupes et 4 moniteurs. Les effectifs des classes pourront donc varier suivant les écoles et tout au cours de l’année, la seule limitation étant imposée par l’étendue du local.

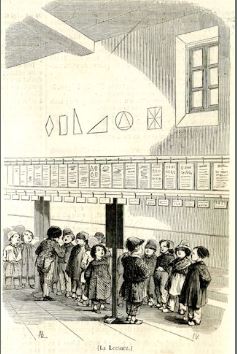

D. Les outils

Le souci d’économie est l’une des caractéristiques fondamentales du nouvel enseignement. Le mobilier reste donc très sommaire.

- Les bancs et pupitres sont faits de planches très ordinaires, fixées avec de gros clous. Les bancs n’ont pas de dossier : c’est un luxe superflu !

- L’estrade est nettement surélevée : 0,65 m environ. On accède par plusieurs marches au bureau du maître. Celui-ci règne sur la collectivité enfantine autant par sa position matérielle que par son ascendant personnel.

- La pendule est notée comme « indispensable », l’enseignement et les manœuvres étant strictement minutés.

- Les demi-cercles, encore appelés cercles de lecture, donnent aux écoles mutuelles un aspect typique et original. Ce sont, généralement, des cintres de fer, demi-circulaires, qui peuvent se lever ou s’abaisser à volonté. Parfois, la matérialisation est simplement portée sur le plancher : rainures, gros clous ou bandes tracées en forme d’arc.

- Les tableaux noirs ont été systématiquement utilisés pour le dessin linéaire et l’arithmétique. Ils mesurent 1 m de long sur 0,70 m de large et portent à leur partie supérieure un mètre mobile. On les place à l’intérieur de chaque demi-cercle.

- Les télégraphes. Lorsque le travail a lieu aux tables, l’écriture par exemple, on se sert de signaux permettant la liaison et la communication entre le moniteur général et les moniteurs particuliers : ce sont les télégraphes. Une planchette, fixée à l’extrémité supérieure d’un bâton rond de 1,70 m de haut, est installée à la première table de chaque classe, grâce à deux trous percés en haut et en bas du pupitre. Sur l’une des faces est inscrit le numéro de la classe (de 1 à 8) ; sur l’autre, la mention EX (examen) remplacée vers 1830 par COR (correction). Ces télégraphes sont transportables. On les déplace en cas d’augmentation ou de diminution du nombre d’élèves. Le maître et le moniteur général ont ainsi la composition exacte de chaque classe et le nombre de tables occupées par chacune d’elles. Dès qu’un exercice est terminé, le moniteur de classe fait tourner le télégraphe et présente vers le bureau la face EX. Tous les moniteurs font de même. Le moniteur général donne l’ordre de procéder à l’inspection et de faire des corrections éventuelles. Celles-ci achevées, on présente de nouveau le numéro de la classe. Et les exercices reprennent. Près des télégraphes se trouvent aussi, à l’occasion, les porte-tableaux.

- Les baguettes des moniteurs. Elles servent à indiquer sur les tables les lettres ou mots à lire, le détail des opérations à effectuer, les tracés à reproduire. Elles n’existent généralement dans les écoles rurales que grâce à la bonne volonté et à l’ingéniosité des moniteurs qui se les procurent dans les bois avoisinants.

- Le sable (pour l’écriture) puis les ardoises sont constamment utilisés dans toutes les disciplines. C’est là une innovation essentielle du mode mutuel, les autres écoles n’en faisant pas usage.

- Tableaux à la place de livres. La première raison est d’ordre pécuniaire, un seul tableau suffisant jusqu’à neuf élèves. Mais les motifs pédagogiques ne sont pas moindres. Le format permet une lecture aisée et un rangement facile. Le souci de présentation et de valorisation de certains caractères s’accompagne d’un souci de mise en page différent de ceux des manuels.

- Les livres sont réservés à la huitième classe, de même que les plumes, l’encre et le papier.

- Des registres, couramment en service, garantissent une saine gestion des établissements. L’un d’eux mérite une mention particulière : c’est « Le grand livre de l’école », avant tout un cahier- matricule. On y inscrit le nom, le prénom et l’âge de l’enfant, la profession et l’adresse des parents. Le maître y porte la date précise de l’entrée et de la sortie de chaque enfant, dans chaque classe, y compris pour les cours de musique et le dessin linéaire.

E. Le commandement

Pour conduire et faire évoluer correctement des dizaines ou centaines d’élèves et éviter toute perte de temps, les responsables de l’enseignement mutuel ont prévu des ordres précis, rapides, immédiatement compréhensibles :

- La voix intervient peu. Les injonctions transmises de cette manière s’adressent généralement aux moniteurs, parfois à une classe tout spécialement.

- La sonnette attire l’attention. Elle précède une information ou un mouvement à exécuter.

- Le sifflet est à double usage. Il permet des interventions dans l’ordre général de l’école, « imposer le silence », par exemple, et il commande le début ou la fin de certains exercices au cours de la leçon, «faire dire par cœur, épeler, cesser la lecture ». Le maître est seul habilité à s’en servir.

- Quant aux signaux manuels, ils ont été beaucoup utilisés. Destinés à évoquer l’acte ou le mouvement à accomplir, ils attirent le regard et doivent apporter le calme dans la collectivité.

Bellistes contre lancastériens

Alors que les deux écoles, celle de Bell et celle de Lancaster sont très proches l’une de l’autre, tant sur le plan des contenus d’enseignement que des méthodes et de l’organisation, elles s’opposeront violemment sur le rôle et la place de l’enseignement religieux. Toutes les autres divergences liées au programme sont affaires de goût, d’habitude ou de circonstances locales.

Comme le précisent Sylvian Tinembert et Edward Pahud dans Une innovation pédagogique, le cas de l’enseignement mutuel au XIXe siècle (Editions Livreo-Alphil, 2019), Lancaster, en tant qu’adepte du mouvement dissident quaker,

« reconnaît le christianisme mais professe que la croyance appartient à la sphère personnelle et que chacun est libre de ses convictions. Il prône également l’égalitarisme, la tolérance et défend l’idée que, dans le pays, il y a une telle variété de religions et de sectes qu’il est impossible d’enseigner toutes les doctrines. Par conséquent, il faut rester neutre, limiter cet enseignement à la lecture de la Bible, en évitant toute interprétation, et laisser l’instruction religieuse fondamentale aux diverses Églises en s’assurant que les élèves suivent les offices et les enseignements de la confession à laquelle ils appartiennent ».

N’empêche que Bellistes et Lancastériens vont s’écharper. Pour les Lancastériens, Bell n’a rien inventé et ne fait que décrire ce qu’il a vu en Inde. Pour les Bellistes, furieux que Lancaster trouve un répondant positif de la part de certains membres de la famille royale, il est dépeint comme le diable, un « ennemi » de la religion anglicane officielle, lui qui admet dans ses écoles des enfants de toutes les confessions !

9. Lorsque la méthode intéresse les Français

A Londres, l’association de Lancaster sera rejointe par de nombreuses personnalités de haut rang, aussi bien anglaises qu’étrangères. On y retrouve notamment le physicien genevois Marc Auguste Pictet de Rochemont (1752-1825), l’anatomiste et paléontologue français Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) et ses compatriotes, l’agronome Charles Philibert de Lasteyrie et le futur traducteur de Lancaster, l’archéologue Alexandre de Laborde (1773-1842).

Après la paix de 1814, de nombreux pays, notamment l’Angleterre, la Prusse, la France tout comme la Russie, rendus exsangues par les guerres napoléoniennes qui provoquèrent la perte de milliers de jeunes enseignants et cadres qualifiés sur les champs de bataille, font de l’éducation leur priorité notamment pour être à la hauteur de la révolution industrielle qui vient les bousculer.

A cela il faut ajouter que le nombre d’orphelins en Europe est devenu un problème majeur pour tous les États, d’autant plus que les coffres sont vides. Pour occuper les enfants de la rue, il faut des écoles, beaucoup d’écoles à construire avec très peu d’argent et beaucoup de professeurs… inexistants. Apprenant le succès retentissant de l’enseignement mutuel, plusieurs Français se rendent alors outre-Manche pour y découvrir la nouvelle méthode.

De Laborde en rapporte un « Plan d’éducation pour les enfants pauvres, d’après les deux méthodes (du docteur Bell et de M. Lancaster) », et Lasteyrie son « Nouveau système d’éducation pour les écoles primaires ». En 1815, le duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt (1747-1827), publie son livre sur le « Système anglais d’instruction de Joseph Lancaster ».

Depuis 1802, il existait à Paris la « Société d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale », dont le secrétaire général était le linguiste Joseph-Marie de Gérando (1772-1842) et dont Laborde était un des fondateurs. Sans surprise, Gérando avait été élevé par les Oratoriens et se destinait initialement à l’Église.

Le 1er mars 1815, Lasteyrie, Laborde et Gérando proposent à la Société d’encouragement la création d’une association qui aurait pour objet

« de rassembler et de répandre les lumières propres à procurer à la classe inférieure du peuple le genre d’éducation intellectuelle et morale le plus approprié à ses besoins ».

Dans son rapport présenté le 20 mars 1815 devant la Société d’encouragement, Gérando propose de solliciter le tout nouveau ministre de l’Intérieur Lazare Carnot (du 20 mars au 22 juin 1815) pour qu’il favorise « l’adoption des procédés propres à régénérer l’instruction primaire en France », c’est-à-dire le système d’enseignement mutuel.

L’intérêt politique et social ne sont pas seuls en jeu. L’économie française aussi doit tirer profit du développement de l’instruction. Qu’espérer, dit Carnot en 1815,

« si l’homme qui conduit la charrue est aussi stupide que les chevaux qui la tirent ? »

Gérando propose également la création d’une société dédiée spécifiquement à sa propagation en soulignant les avantages de la nouvelle approche : avantage économique d’abord, puisqu’il s’agit d’« employer les enfants eux-mêmes, les uns vis-à-vis des autres, comme auxiliaires de l’enseignement » et qu’un seul maître suffit pour 1000 élèves ; avantage éducatif ensuite, puisqu’il est possible « d’enseigner, en deux ans, tout ce que les enfants des conditions inférieures ont besoin de savoir et beaucoup plus qu’ils n’apprennent aujourd’hui par des procédés bien plus longs » ; avantage moral et social enfin, dans la mesure où les enfants « se pénètrent de bonne heure du sentiment du devoir, sentiment qui garantira un jour leur obéissance aux lois et leur respect pour l’ordre social ».

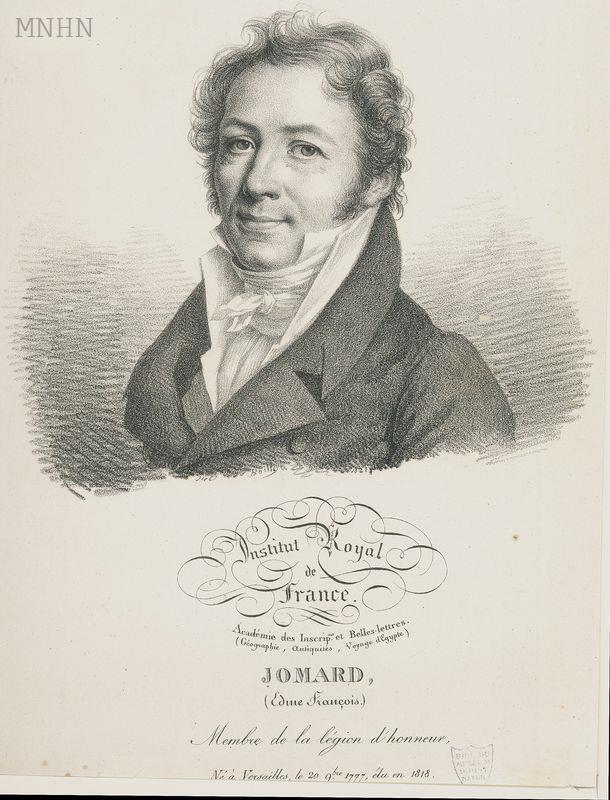

L’ingénieur-géographe et polytechnicien Edme-François Jomard (1777-1862), pour qui l’instruction du peuple est une obligation de la société vis-à-vis d’elle-même, ne disait rien d’autre: « Comment exiger d’infortunés, dénués de toutes lumières, qu’ils connaissent le pacte social et s’y soumettent ? ou comment pourrait-on, sans être insensé, compter sur leur invariable et aveugle soumission ? »

La Société d’encouragement valida alors les conclusions de son rapport en souscrivant pour une somme de 500 francs en faveur de l’association nouvelle et en décidant qu’elle mettrait à la disposition de celle-ci, outre son influence morale, les divers moyens d’exécution qui pouvaient lui appartenir.

10. Lazare Carnot à la manœuvre

Suite au Concordat entre Napoléon et le Vatican, l’Empereur, par son décret du 15 août 1808 sur l’éducation, décide que les écoles doivent désormais suivre les « principes de l’Église catholique ».

Les « Frères des écoles chrétiennes » (ou Lasalliens), partisans inconditionnels de « l’enseignement simultané », théorisé par leur fondateur Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, s’occuperont désormais de l’enseignement primaire et formeront les instituteurs.

Dispersés lors de la Révolution, ils reprennent leurs fonctions en 1810. Encouragés à se développer pour contrer l’influence des jésuites, autorisés en 1816 à revenir en France, ils se développent rapidement dans toute la France.

Mais la situation de l’éducation est pitoyable. C’est ce que constatent des hauts fonctionnaires français lorsqu’ils se rendent dans les territoires annexés par l’Empire, notamment l’Allemagne du Nord et la Hollande. La comparaison avec la France les fait rougir de honte.

« Nous aurions peine, écrit en 1810 le naturaliste Georges Cuvier dans son rapport, à rendre l’effet qu’a produit sur nous la première école primaire où nous sommes entrés en Hollande. »

Enfants, maîtres, local, méthodes, enseignement, tout est d’une tenue parfaite : « Plusieurs préfets ont assuré qu’on ne trouverait pas aujourd’hui dans leur département un seul jeune garçon qui ne sût lire et écrire. » Devant un tel contraste, qui ne tournait pas à l’avantage du conquérant, l’Université impériale, comme la Rome antique, se mit à l’école du pays conquis. Dans son décret du 15 novembre 1811 l’Empereur décide : « Le conseil de notre Université Impériale nous présentera un rapport sur la partie du système établi en Hollande pour l’instruction primaire qui serait applicable aux autres départements de notre Empire. »

L’Empereur abdique le 4 avril 1814 avant qu’une décision ait été prise pour régénérer les « petites écoles » françaises. Du moins l’Université Impériale avait-elle, par ses rapports, étalé au grand jour leur misère, attirant sur elles l’attention de l’opinion.

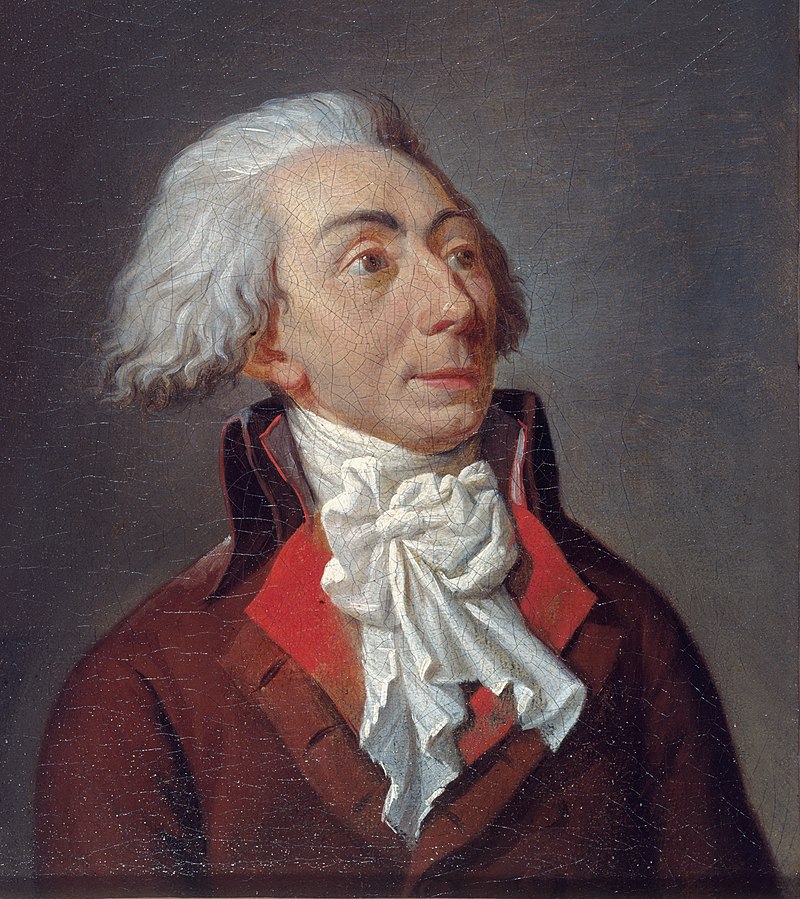

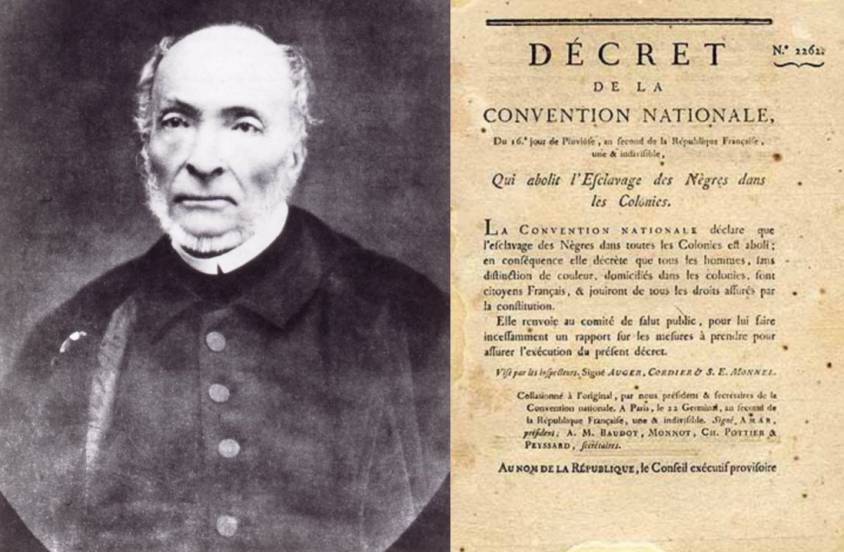

Nommé ministre de l’Intérieur, et donc en charge de l’Education lors des Cent-Jours, Lazare Carnot est persuadé du potentiel d’excellence de « l’enseignement mutuel ».

Il crée, le 10 avril 1815, un Conseil d’industrie et de bienfaisance, à la première séance duquel il donne lui-même communication du rapport de Gérando ;

Le 27 avril 1815, Lazare Carnot fait un rapport à l’Empereur où il dit :

« Il y a en France, 2 millions d’enfants qui réclament l’éducation primaire, et, sur ces 2 millions, les uns en reçoivent une très imparfaite, tandis que les autres en sont complètement privés. »

Il recommande alors l’enseignement mutuel :

« Elle a pour objet de donner à l’éducation primaire le plus grand degré de simplicité, de rapidité et d’économie, en lui donnant également le degré de perfectionnement convenable pour les classes inférieures de la société et aussi en y portant tout ce qui peut faire naître et entretenir dans le cœur des enfants le sentiment du devoir, de la justice, de l’honneur et le respect pour l’ordre établi ».

Il fait signer le même jour à l’empereur le décret suivant :

« Article 1er. – Notre ministre de l’Intérieur appellera près de lui les personnes qui méritent d’être consultées sur les meilleures méthodes d’éducation primaire. Il examinera ces méthodes, décidera et dirigera l’essai de celles qu’il jugera devoir être préférées.

« Art. 2. – Il sera ouvert, à Paris, une École d’essai d’éducation primaire, organisée de manière à pouvoir servir de modèle et à devenir école normale, pour former des instituteurs primaires.

« Art. 3. – Après qu’il aura été obtenu des résultats satisfaisants de l’École d’essai, notre ministre de l’Intérieur nous proposera les mesures propres à faire promptement jouir tous les départements des nouvelles méthodes qui auront été adoptées ».

Pour Carnot, en rupture avec ceux qui ne pensaient qu’en termes de philanthropie, il n’y avait plus d’enfants riches ou pauvres. En tant que citoyens, tous devraient désormais pouvoir disposer de la meilleure éducation possible.

Le conseil consultatif constitué par Carnot comprend ses amis Laborde, Jomard, l’abbé Gaultier, puis Lasteyrie et Gérando, c’est-à-dire les promoteurs mêmes ou les premiers fondateurs de la Société en formation.

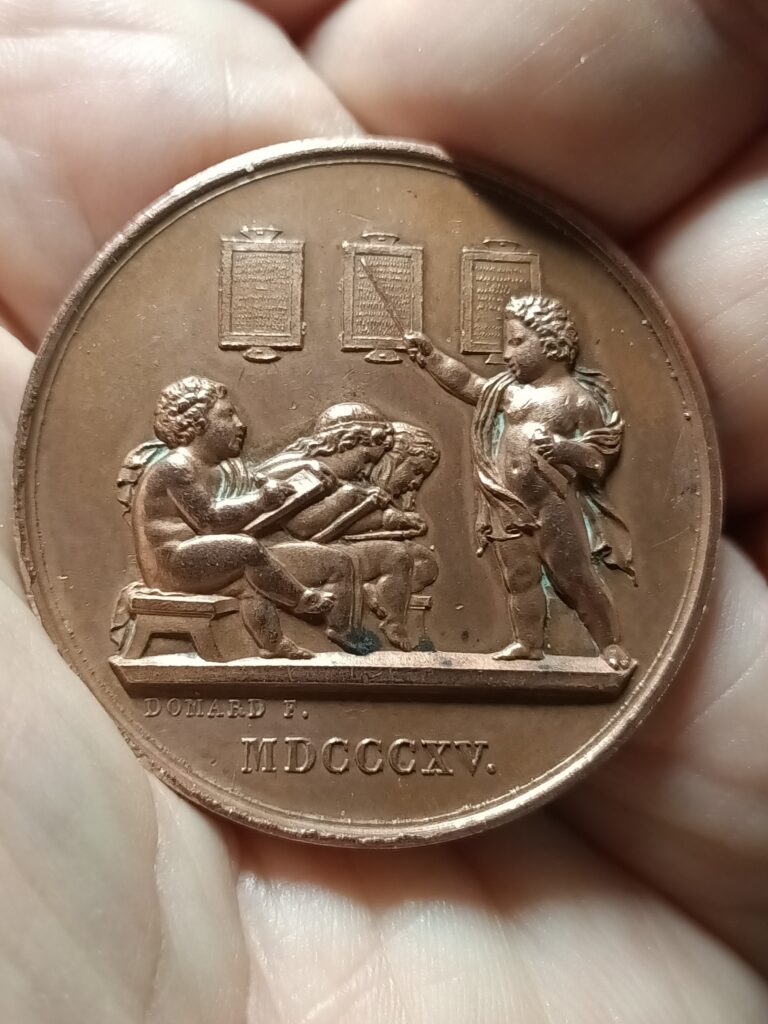

Ainsi naîtra, le 17 juin 1815 (c’est-à-dire la veille de la défaite de Waterloo) la Société pour l’instruction élémentaire (SIE), toujours sous l’impulsion de Carnot bien décidé à gagner la guerre pour l’instruction. La première assemblée générale de la SIE se tient dans les locaux de la Société d’encouragement. À sa tête, on retrouve plusieurs protagonistes de la commission ministérielle : Jomard devient l’un des secrétaires de la nouvelle société, aux côtés de Gérando (président), Lasteyrie (vice-président) et Laborde (secrétaire général).

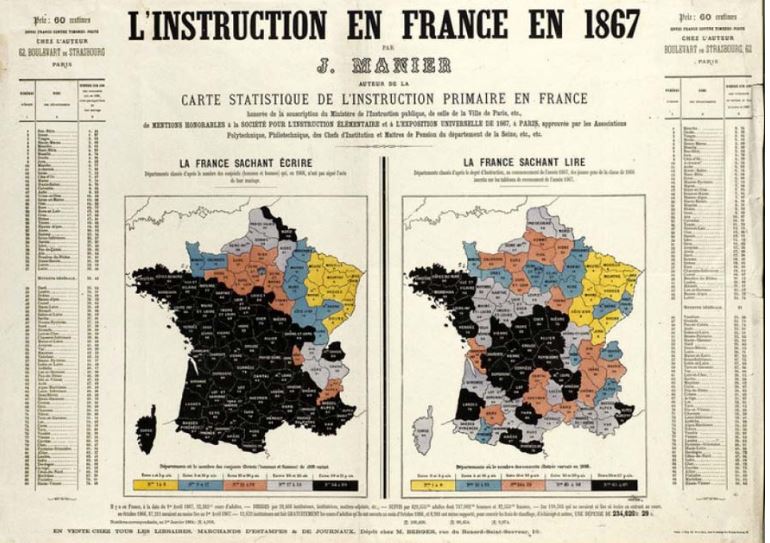

Avant l’ordonnance de 1816, le nombre d’enfants qui suivaient les petites écoles était de 165 000 dans toute la France, et il se trouve porté à 1 123 000 à la fin de 1820.

Lazare Carnot a clairement voulu pérenniser son offensive lancée durant les Cent-Jours en faveur de la propagation de l’enseignement mutuel à travers le pays et, ce faisant, en participant au développement rapide de l’instruction de tous les enfants de la Patrie.

Après sa création, les souscriptions pour la SIE affluent, et en peu de temps 150 noms s’ajoutent à ceux des fondateurs pour promouvoir et organiser l’enseignement mutuel en France. L’un de ces souscripteurs est forcément Lazare Carnot.

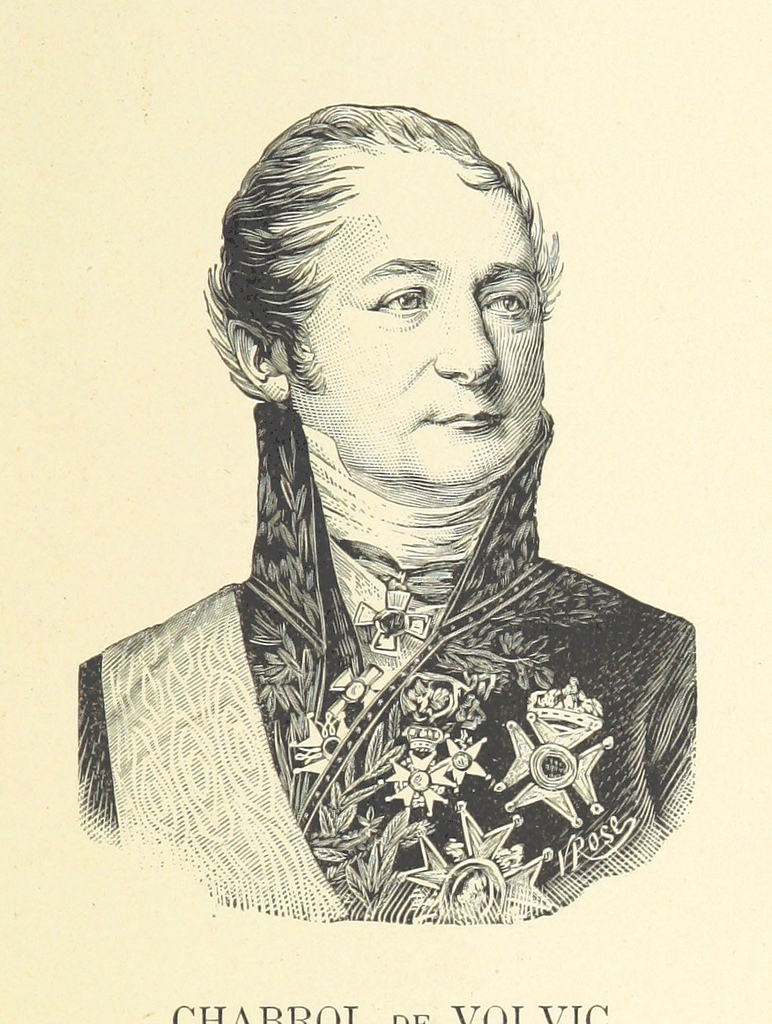

Au cours de sa première année d’existence, la SIE recueille l’adhésion de près de 700 membres, dans un premier temps des enseignants de l’École polytechnique (Ampère, Berthollet, Chaptal, Guyton de Morveau, Hachette, Mérimée, Thénard), et ensuite une trentaine d’anciens élèves, dont environ la moitié est issue de la première promotion (1794) de l’École polytechnique. Parmi ces derniers, un camarade de Jomard à l’Ecole des géographes, Louis-Benjamin Francœur, professeur d’algèbre supérieure à la Faculté des sciences de Paris, des camarades de la campagne d’Egypte ou encore Chabrol de Volvic, préfet de la Seine depuis 1812.

Tous n’ont qu’un seul espoir : que les méthodes géniales de Monge, brigades et enseignement mutuel, diminuées et interdites depuis que Napoléon a transformé Polytechnique en une simple école militaire sous la direction du mathématicien Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827), puissent profiter au plus grand nombre et organiser un redressement national.

De Paris, la sollicitude de la SIE s’étend à la province ; elle y encourage la fondation de sociétés filiales, à qui elle offre « de leur envoyer des maîtres, de leur communiquer les renseignements dont elles pourraient avoir besoin, de leur donner au prix coûtant les tableaux et les livres… ».

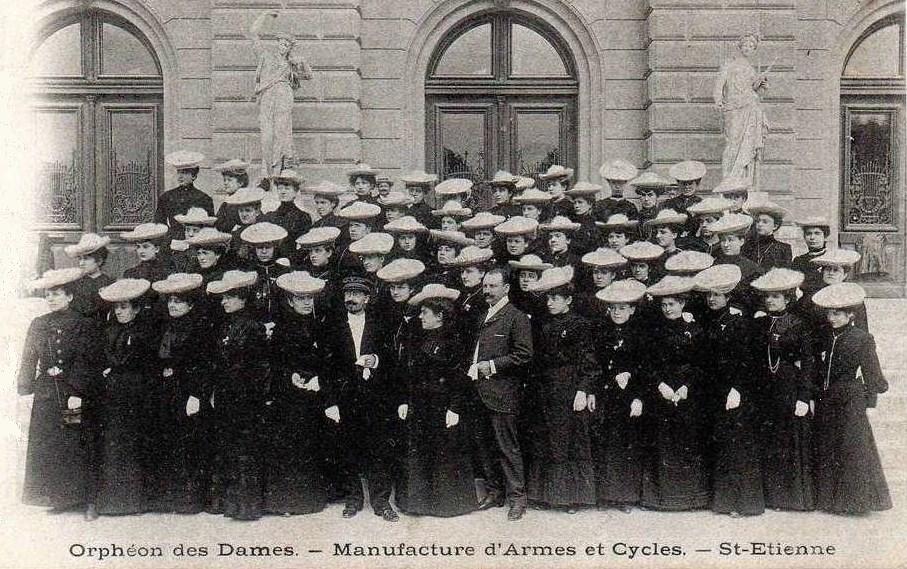

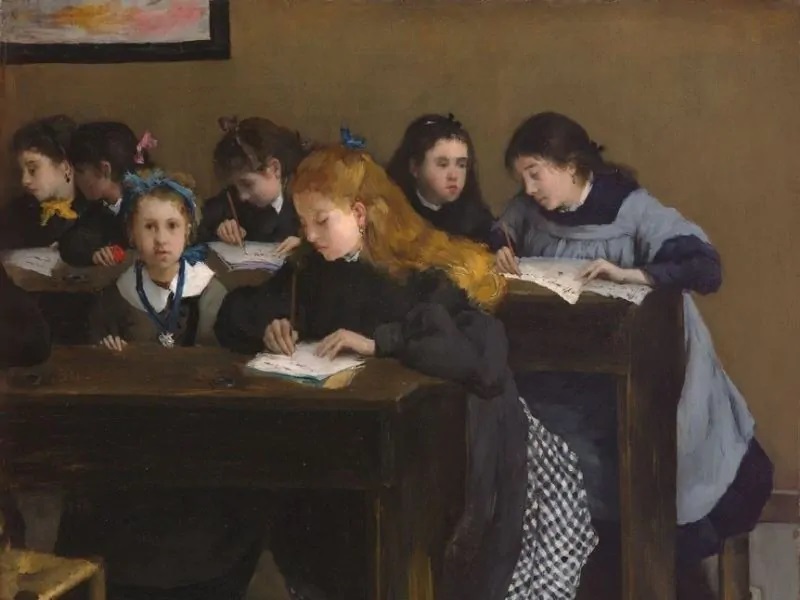

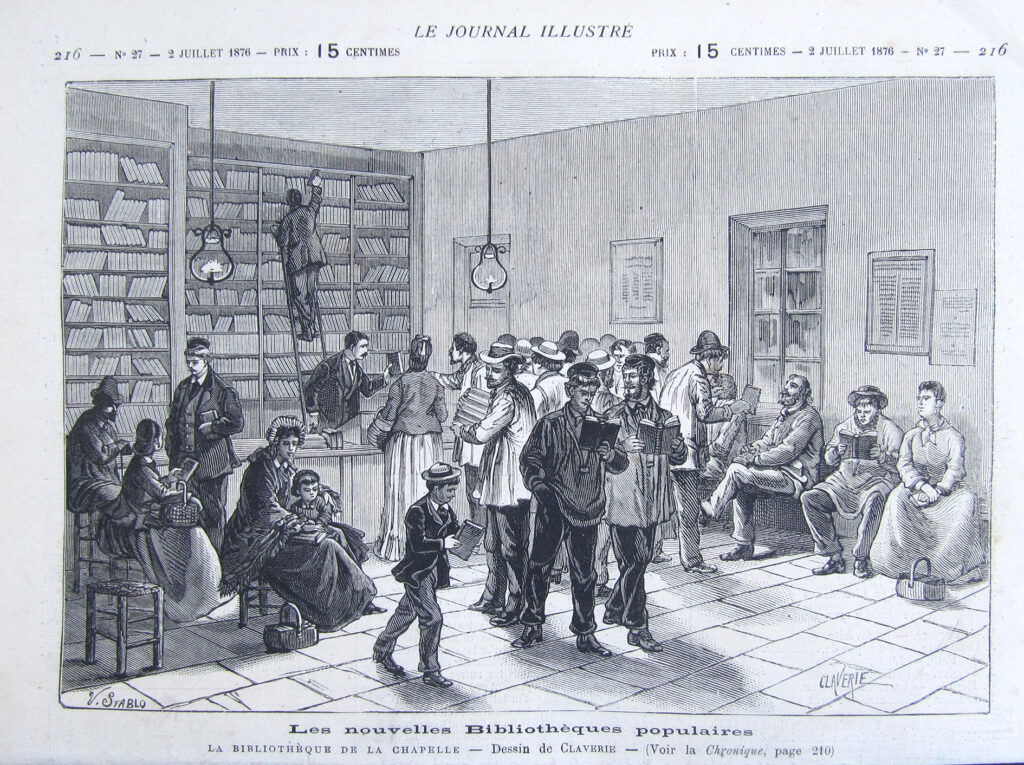

La SIE se mobilise également pour l’éducation publique des filles (art. 10). Elle met sur pied, pour s’occuper d’elles, un comité de dames : présidente, la baronne de Gérando ; vice-présidente, la comtesse de Laborde. Des filles, le mouvement gagne les adultes sans instruction, si nombreux alors.

Le 1er mai 1816 la Société créait une commission pour l’établissement d’écoles d’adultes. Elle s’occupe aussi des casernes, dont on veut faire des écoles pour militaires ; des prisons, prisons d’enfants surtout; des habitants des colonies, que l’on pense élever par le développement de l’instruction.

Enfin les membres de la Société, attribuant une valeur humaine et générale à leur mission, rêvent de fonder des filiales à l’étranger. En novembre 1818, Laborde demande la création d’un comité spécial pour les écoles étrangères.

La Société enfin, ne bornant pas son activité à la simple création d’écoles, organisait des inspections, des examens. Elle assurait la publication d’ouvrages (ouvrages relatifs à la méthode mutuelle, livres élémentaires de lecture, de grammaire et d’arithmétique). Elle distribuait des récompenses aux meilleurs maîtres et moniteurs. Elle demandait aux maîtres, après promulgation de l’ordonnance du 29 juillet 1818 autorisant les sociétés de Caisse d’Epargne, de confier à ces Caisses une partie de leurs gages pour assurer leurs vieux jours. Donnant l’exemple, elle déposait à la Caisse des fonds pour les maîtres des écoles créées par elle.

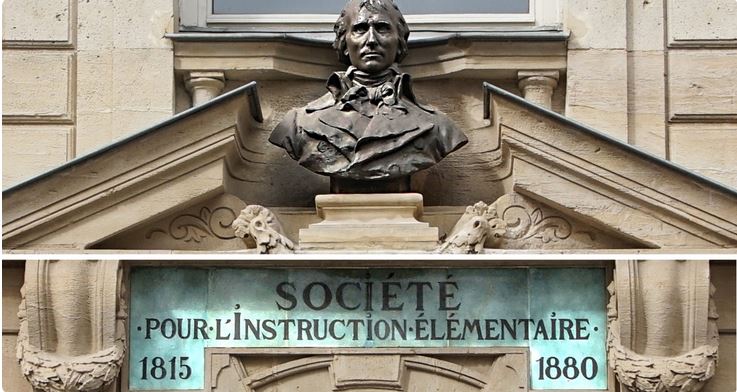

La SIE, dont le siège est un local spécialement construit pour elle, situé au 6, rue du Fouarre à Paris 5e, reste aujourd’hui la plus ancienne et la plus grande association laïque d’enseignement primaire que nous possédons en France.

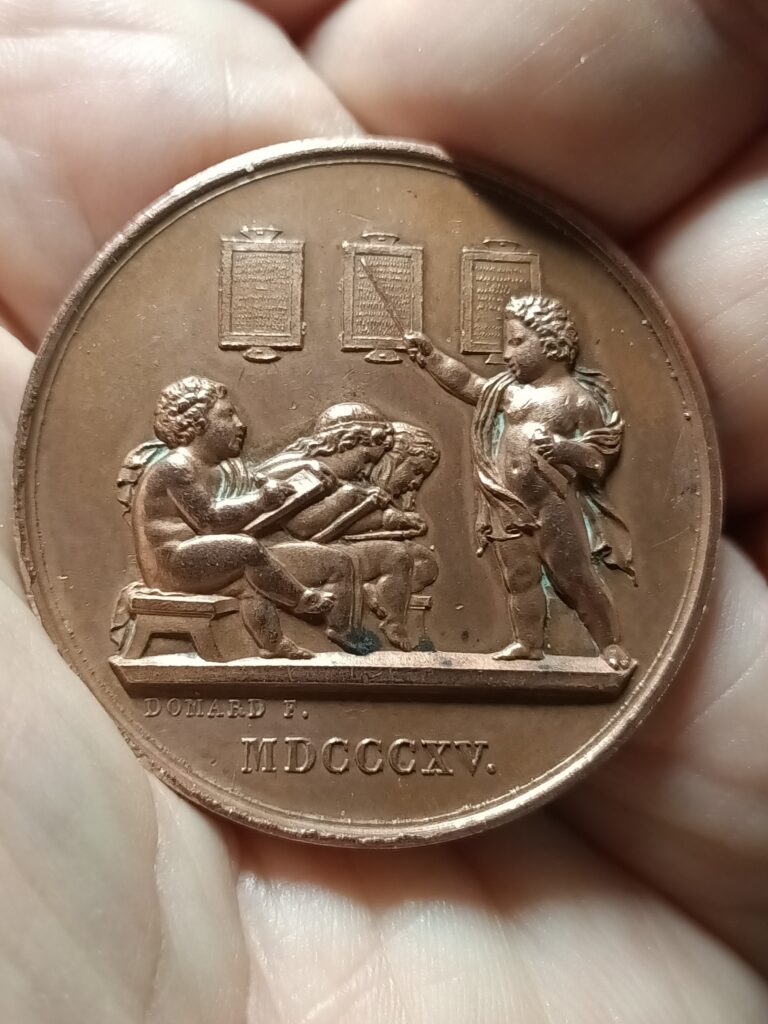

11. Le projet pilote de la rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais

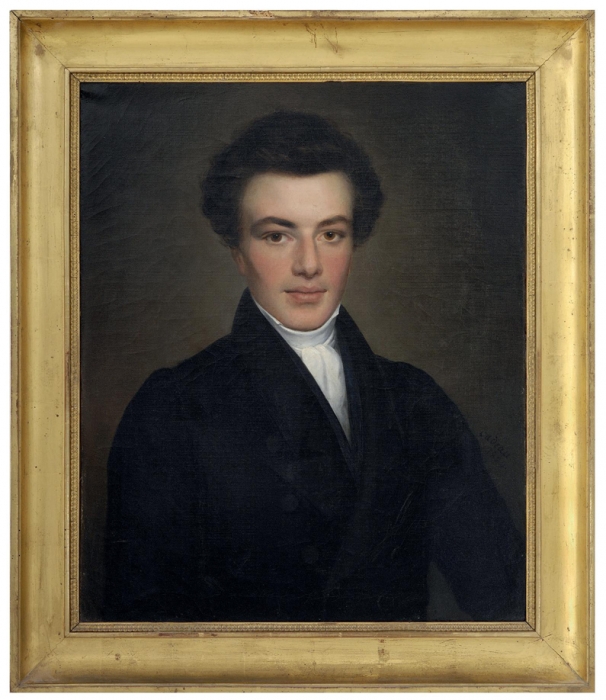

Après son voyage en Angleterre, Jomard, dont le portrait figure en médaillon sur la façade de la SIE est lui aussi acquis au nouveau système. Faisant part de ses « réflexions sur l’état de l’industrie anglaise », il écrit, après s’être enthousiasmé pour diverses inventions observées outre-Manche :

« Il y a cependant quelque chose de plus extraordinaire encore : ce sont des écoles sans maîtres : rien, pourtant, n’est plus réel. On sait à présent qu’il existe des milliers d’enfants enseignés sans maître proprement dit, et sans qu’il n’en coûte rien à leur famille, ni à l’État : admirable méthode qui ne peut tarder à se propager en France. »

Polytechnicien, Jomard est l’homme idéal pour piloter l’organisation matérielle de l’école d’essai, s’attachant notamment à faire réaliser le mobilier et imprimer les supports pédagogiques conformément aux principes anglais. Il supervise également la formation au rôle de « moniteur » d’un petit noyau d’élèves – ils sont une vingtaine – avant l’ouverture en septembre 1815 de l’école proprement dite, prévue pour 350 élèves : une modalité qui n’est pas sans rappeler les « chefs de brigade » de la première promotion de l’École polytechnique.

Cependant, très rapidement, les membres de la SIE se rendent à l’évidence qu’il faut former des formateurs. Les Anglais accueillent alors plusieurs Français pour les former à l’enseignement mutuel. Un pasteur cévenol, François Martin (1793-1837), après sa formation comme « moniteur » en Angleterre, est appelé par Lasteyrie pour diriger la première école mutuelle, qui ouvre ses portes le 13 juin 1815, rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais à Paris. Il s’agit de l’école modèle qui doit permettre l’ouverture d’autres écoles mutuelles grâce à la formation de « moniteurs » compétents. Rapidement, elle ne peut plus faire face à la demande de centaines de communes qui envisagent d’y envoyer l’un des leurs pour se former à la nouvelle méthode.

Le pasteur Paul-Emile Frossard, lui aussi formé par les Anglais, prend la tête d’une école parisienne rue Popincourt, Bellot en dirige une autre. En juillet, Martin rend son rapport. La classe modèle accueille une quinzaine d’élèves destinés à devenir moniteurs et directeurs d’écoles élémentaires qui comptent jusqu’à 350 enfants. Martin rapporte qu’en six semaines, ils lisent, écrivent, calculent et « savent exécuter les mouvements qui forment la partie gymnastique du nouveau système d’éducation ».

12. Enseignement mutuel et chant choral

Or, comme le documente amplement Christine Bierre dans son article « La musique et formation du citoyen à l’ère de la Révolution française » (1990),

« C’est à cette école de la rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais, sous la direction d’une Commission comprenant Gérando, Jomard, Lasteyrie, Laborde et l’abbé Gaultier, que fut testée pour la première fois, l’application de l’enseignement mutuel à l’apprentissage du solfège et du chant.

Alexandre Choron, qui depuis 1814 avait ouvert deux écoles de musique de garçons et de filles, faisait également partie de la Commission.

Il n’est donc pas étonnant de découvrir que ce fut à l’initiative du baron de Gérando, que l’idée d’introduire le chant dans l’instruction primaire a été adoptée. ‘Quant Monsieur le baron de Gérando vous a fait la proposition d’introduire le chant élémentaire dans les écoles de premier degré’, dit Jomard dans un rapport présenté au Conseil d’administration de la Société pour l’Enseignement mutuel, ‘vous avez tous été frappés de la justesse des vues développées par notre collègue (…) Il a fait voir l’influence heureuse que pourrait avoir une pareille pratique, et la connexion réelle qui existe entre un bon emploi du chant et le perfectionnement de la morale, but final de l’instruction et de tous nos efforts. Non seulement, l’application de l’enseignement mutuel à la musique était révolutionnaire en elle-même, mais ce qui l’était tout autant, c’est le fait que les enfants apprenaient à lire et à écrire, de façon presque aussi intensive. Les enfants étudiaient le chant, à raison de quatre à cinq heures par semaine ! »

En réalité, c’est Lazare Carnot lui-même qui a voulu introduire la musique dans les écoles d’enseignement mutuel. Dans cette intention, il rencontre plusieurs fois Alexandre Choron, qui réunit un certain nombre d’enfants et leur fait exécuter en sa présence plusieurs morceaux appris en fort peu de leçons. Carnot connaît Wilhem depuis dix ans. Il entrevoit donc la possibilité d’introduire, par lui, le chant dans les écoles, et tous deux visitent ensemble celle de la rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais, école pilote gratuite d’enseignement mutuel ouverte à Paris à trois cents enfants.

L’article récent de Michael Werner, « Musique et pacification sociale, missions fondatrices de l’éducation musicale (1795-1860) » dans la revue Gradhiva (N° 31/2020), vient en écho confirmer les recherches initiées par Christine Bierre en 1990.

Extrait :

« L’un des domaines où les résultats de la pédagogie mutualiste sont bien visibles est précisément l’éducation musicale. Plusieurs acteurs y ont joué un rôle décisif et méritent qu’on s’y attarde un moment. Le premier est Guillaume-Louis Bocquillon, dit Wilhem. Fils d’officier et lui-même issu d’une formation militaire, il s’est ensuite consacré à la composition et à l’enseignement musicaux, en particulier au lycée Napoléon (ultérieurement collège Henri-IV). Son ami Pierre Jean de Béranger le met en contact avec Joseph-Marie de Gérando et François Jomard, grands animateurs de la SIE. Par leur intermédiaire, il prend connaissance de l’enseignement mutuel et comprend immédiatement les apports de cette méthode à l’éducation musicale. En 1818, la municipalité de Paris lui permet de monter une première expérience à l’école élémentaire de la rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais.

Wilhem élabore une méthode, le matériel pédagogique nécessaire (sous forme de tableaux) et instruit les élèves moniteurs choisis. Les résultats sont, aux dires de Jomard, spectaculaires. Au terme d’un enseignement de quelques mois, les élèves ont non seulement acquis les notions de base du solfège et de la notation musicale, les gammes chromatiques, les intervalles et mesures, mais exécutent aussi des chants collectifs à plusieurs voix (Jomard 1842 : 228 sq.).

La réussite conduit la SIE à proposer au préfet et au ministre de l’Intérieur d’introduire la musique dans l’enseignement des écoles élémentaires de la ville de Paris, ce qui sera officiellement entériné en 1820. Wilhem lui-même est nommé professeur titulaire d’enseignement musical à Paris et les cours de musique se généralisent dans un grand nombre d’écoles de la ville avant de se répandre dans les départements et en région. En même temps, la municipalité ouvre deux écoles normales chargées de former les futurs professeurs de chant.

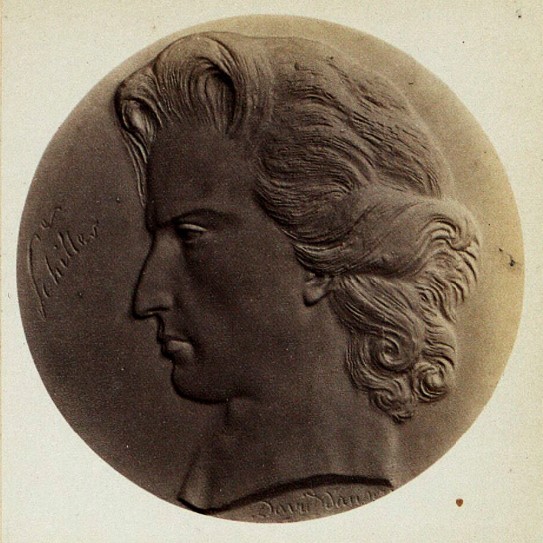

Le deuxième acteur à intervenir très tôt dans le débat est le compositeur Alexandre Choron. Membre, comme Jomard et Francœur, de la première promotion de l’École polytechnique (1795), compositeur et ami d’André Grétry, il s’est dès 1805 préoccupé du dépérissement du chant choral consécutif à la suppression des maîtrises. Adversaire du Conservatoire dont il critique l’académisme et le désintérêt pour l’enseignement du chant choral, il est chargé par le ministère en 1812 d’une mission de « réorganisation du chœur et des maîtrises de musiques des églises de France ». Il élabore une méthode d’enseignement appelée « méthode concertante », mais reste également attaché à la vocation sociale de la musique chorale. Choron fait par ailleurs partie des membres fondateurs de la SIE en 1815, signe de son engagement dans les questions éducatives. Pendant la Restauration, il se tourne davantage vers les chants religieux qu’il considère comme le cœur historique de la pratique de la chorale.

(…) Enfin, il fonde, avec l’appui du roi l’Institution royale de musique classique et religieuse, concurrençant avec succès le Conservatoire dans l’enseignement de l’art vocal. Pour le grand public, il fait exécuter, à grand renfort de chanteurs issus de son école, des oratorios, requiem et cantates dans quelques églises spacieuses, assurant ainsi à la musique sacrée une nouvelle présence sur la scène parisienne. Pour certains de ces concerts, il lui arrive de mobiliser des élèves chanteurs des écoles élémentaires et des écoles des pauvres qu’il n’a jamais cessé de suivre tout au long de sa carrière.

« (…) Ce qui a favorisé cette expansion de l’enseignement de la musique à destination des jeunes et des couches populaires à partir de 1820 était bien une volonté politique partagée par un large spectre de responsables et d’intervenants. Du côté des libéraux qui constituaient le noyau de la SIE, on continuait de s’inscrire dans la mission émancipatrice de l’éducation, fixée par la Convention. En pointant à la fois la formation intérieure de l’âme et l’épanouissement d’une conscience collective, la musique, et en particulier le chant, devient un terrain de choix pour l’éducation populaire. Les libéraux insistent donc sur les bienfaits moraux de la musique. Ainsi, dans sa proposition d’introduire le chant dans les écoles primaires, Gérando remarque-t-il : ‘Ceux d’entre nous qui ont visité l’Allemagne ont été surpris de voir toute la part qu’a une musique simple aux divertissements populaires et aux plaisirs de famille, dans les conditions les plus pauvres, et ont observé combien son influence est salutaire sur les mœurs.’

« Et Joseph d’Ortigue constate de façon lapidaire : ‘Un peuple qui chante est un peuple content, et par conséquent un peuple moral.’ Cette mise en avant des bienfaits sociaux de l’activité musicale correspond bien à l’idée d’une ‘éducation universelle’, héritée des Lumières et au fondement des pédagogies de Lancaster en Angleterre ou de Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi en Suisse.

« Le chant, après l’essai fait à l’école St-Jean-de-Beauvais en 1819, pénètre très rapidement dans toutes les écoles mutuelles. Wilhem est à la fois le créateur et l’artisan du développement de cet enseignement qui gagne bientôt les cours d’adultes et d’apprentis. Des réunions périodiques d’enfants initiés à la musique vocale furent organisées. Ainsi naquit la première œuvre post-scolaire française : l‘Orphéon qui, après Wilhem, compte parmi ses directeurs Charles Gounod et Jules Pasdeloup. »

Dans un discours de 1842 devant la SIE, Hippolyte Carnot (fils de Lazare Carnot) affirme que Wilhem « a élevé la musique au rang d’une institution civique » et que « l’ennoblissement » de l’âme individuelle doit s’accomplir dans le nouvel ordre collectif de la nation réunie.

13. Jomard, Choron, Francoeur et savoirs « élémentaires »

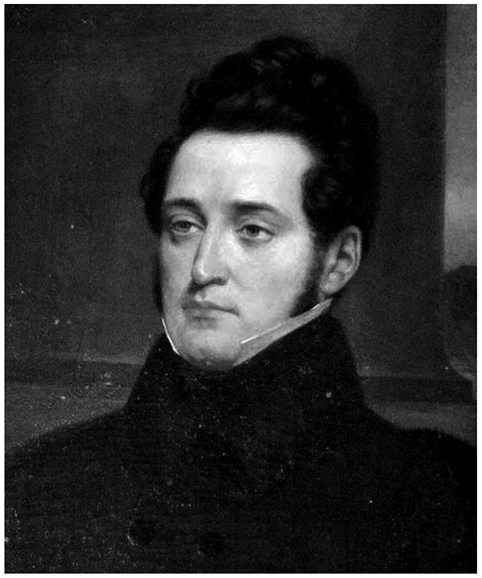

L’article très complet de Renaud d’Enfert, publié sur le site de la Société de la bibliothèque et de l’histoire de l’Ecole polytechnique (SABIX), permet de compléter le tableau en faisant un gros plan sur l’action de Jomard et Francoeur dont les portraits figurent d’ailleurs en médaillon sur la façade du siège de la SIE rue du Fouarre à Paris.

Dès le début de la Seconde Restauration, la SIE reçut l’adhésion et l’appui du préfet de la Seine, Gaspard Chabrol de Volvic (1773-1843). Ce dernier va nommer dès l’été 1815 Jomard, le linguiste en contact avec les frères Humboldt qui a fait partie de l’éphémère commission sous Carnot et qui l’a protégé pendant les Cent-Jours, « chef de bureau d’instruction publique et arts », poste qu’il occupe jusqu’en 1823.

Par un arrêté du 3 novembre 1815, Volvic, afin d’arrêter « les mesures nécessaires pour étendre le bienfait de l’instruction à toutes les familles pauvres domiciliées dans l’étendue de la préfecture » et de développer « le nouveau système d’instruction élémentaire » dans l’ensemble du département de la Seine, crée, « pour étendre les bienfaits de l’instruction gratuite au département de la Seine » un comité de onze personnes, et y fait entrer tous les membres influents de la SIE (Jomard, Gérando, Laborde, Doudeauville, Lasteyrie, Gaultier, etc.).

Dans ces fonctions, Jomard est chargé de trouver des sites pour établir de nouvelles écoles. Celles-ci se multiplient rapidement dans la capitale et ses environs : en 1818, il comptabilise 18 écoles mutuelles gratuites et 32 payantes couvrant l’ensemble des arrondissements de la capitale, ainsi que 13 écoles dans les arrondissements de Sceaux et de Saint-Denis. De ce travail, il tire son « Abrégé des écoles élémentaires » (1816), sorte de guide pratique dans lequel il réunit tout ce que doit savoir, du point de vue de l’organisation matérielle, tout citoyen décidé à fonder une école mutuelle.

Sur le plan pédagogique, Jomard est l’auteur, en 1816, d’une méthode de lecture réalisée en collaboration avec le compositeur et musicien Alexandre Choron qui avait publié dès 1802 une méthode pour apprendre à lire et à écrire, et l’abbé Gaultier, un pédagogue qui avait développé une méthode d’enseignement sous le nom de « jeux instructifs » et s’était rendu à Londres pour étudier les méthodes anglaises.

Conçue pour la nouvelle école normale élémentaire de la rue Saint-Jean-de-Beauvais, où Choron a été nommé comme enseignant de musique, elle rompt avec la méthode traditionnelle d’épellation. Au lieu de dire « b-o-n = bon », elle part des sonorités musicales de la langue pour dire « b-on = bon ».

Jomard fait également paraître, en 1821-1822, une « Arithmétique élémentaire », destinée à pallier les faiblesses constatées de la méthode d’arithmétique de Lancaster : celle-ci est en effet accusée de « faire contracter aux enfants une simple habitude routinière et mécanique » au lieu de servir « à fortifier leur attention et à les former au raisonnement ». Dans l’intervalle, il a mis au point avec Francœur et Lasteyrie, au sein d’une « Commission de calligraphie » de la SIE, les principes qui doivent guider l’apprentissage de l’écriture dans les écoles mutuelles, une écriture voulue « nationale », afin de remplacer les modèles anglais.

Pour sa part, Louis-Benjamin Francoeur (1773-1849) fournit, selon Jomard, « une longue suite de rapports lumineux sur les traités d’arithmétique, de poids et mesures, de chant et d’art musical, de dessin et de géométrie, qu’il serait bien trop long de rapporter ou de citer ».

Comblant un manque, Francœur publie en 1819 « Le dessin linéaire », une méthode de dessin basée sur le dessin à main levée des figures géométriques qui rompt avec les modalités traditionnelles d’enseignement et d’apprentissage du dessin, inspirées de pratiques académiques.

Pour Jomard et Francoeur, il s’agit, avec l’enseignement mutuel, d’élargir le nombre des matières de l’instruction primaire au-delà du traditionnel « lire, écrire, compter » : outre le dessin, des matières comme le chant, la gymnastique, la géographie ou la grammaire font ainsi leur apparition dans les écoles primaires via l’enseignement mutuel. Le dessin linéaire n’en apparaît pas moins comme un savoir élémentaire à part entière, au même titre que la lecture, l’écriture et l’arithmétique.

Présentant la méthode de Francœur à la Société d’encouragement, Jomard déclare ainsi :

« L’utilité que l’industrie en peut retirer un jour est si grande et si visible, qu’il serait superflu d’y insister. Ce n’est pas sans raison qu’on a regardé ce résultat comme aussi précieux pour le peuple, que la connaissance de la lecture et de l’écriture. »

Enfin, pour Jomard, l’apprentissage généralisé de la lecture, de l’écriture, du calcul, du dessin linéaire et du chant, est le préalable obligé à l’éducation scientifique du peuple :

« On a dans ces derniers temps, avec grande raison, insisté sur l’utilité de l’enseignement des éléments des sciences physiques et mathématiques à la classe ouvrière. C’est de là que dépend l’avancement de l’industrie et de l’agriculture, qui, malgré tous leurs progrès, sont encore arriérées chez nous sous plusieurs rapports. Ce n’est que par la possession de ces notions élémentaires que les ouvriers perfectionneront leurs procédés, leurs moyens, leurs instruments, leurs produits, et pourront devenir d’habiles contremaîtres et de bons chefs d’ateliers. Mais comment arriver à ce résultat, quand la masse de la population est encore si ignorante.

« Comment, sans l’art de lire et d’écrire, pourrait-elle, non pas comprendre un seul mot des arts chimiques et mécaniques, mais seulement en sentir l’avantage et consentir à se livrer à des études pénibles ? Quoi ! 15 millions de Français et plus peut-être, ne savent pas faire les deux premières règles de l’arithmétique, et l’on se flatterait de propager parmi eux les premiers principes de la mécanique et de la géométrie ! La base de cette amélioration est évidemment l’instruction primaire rendue plus générale ou même universelle. »

14. Rayonnement au niveau national

Les résultats de l’enseignement mutuel sont spectaculaires et rapides, qu’il s’agisse de la durée des apprentissages ou de la qualité des acquis. Alors que dans les écoles des Frères il fallait 4 années pour apprendre à lire, ce temps est réduit à une année et demie dans les établissements mutuels !

Les Français de 1815, à l’enthousiasme si prompt, et à l’imagination si vive, virent dans ce système d’enseignement, une véritable panacée. Il présentait certes d’incontestables avantages. D’abord il est économique puisqu’il exige peu de maîtres, et permet d’instruire à peu de frais un nombre considérable d’enfants. On estime qu’il suffisait de 4000 à 5000 fr. par an pour entretenir une école de 1000 enfants : 4 francs par élève ! Jamais l’instruction n’aura été donnée à si bas prix. Il permettait aussi d’assurer un développement rapide de l’enseignement primaire puisque l’on n’était plus arrêté désormais par la pénurie de maîtres. Chiffres à l’appui, on calculait qu’il suffirait d’une douzaine d’années pour étendre à la France entière les bienfaits de l’instruction primaire !

A ces avantages indiscutables, ceux qui avaient visité l’Angleterre en 1815 ajoutaient des arguments qualitatifs. Ils estimaient l’enseignement des instructeurs supérieur à celui des maîtres :

« Il ne sait pas sa leçon mieux que le maître, écrivait Laborde, mais il la sait autrement ».

L’enfant instructeur (moniteur) a plaisir à communiquer à ses camarades ses connaissances nouvellement acquises, il fait son travail

« avec autant de charme qu’un précepteur y trouve de dégoût » (Laborde).

D’autre part, étant enfant lui-même, il connaît mieux que le maître les difficultés de la tâche, les embûches de la leçon, sur lesquelles il vient juste de trébucher. Il conduira donc ses camarades plus lentement, plus sûrement, sera pour eux un meilleur guide.

Mais l’enseignement ne sera pas seul à profiter du système mutuel ; la discipline de l’école et la morale y trouveront aussi leur compte. L’enfant, soumis à son camarade, lui obéira plus volontiers qu’au maître, puisque le jeune instructeur ne doit sa supériorité qu’à son mérite. Enfin l’enfant, avec son camarade qui le connaît bien puisqu’il vit avec lui, n’aura pas, comme avec le maître, la ressource de mentir pour cacher ses pensées intimes ou ses fautes ; et la dissimulation, fléau social que l’on apprenait dès les bancs de l’école, disparaîtra ainsi des établissements mutuels. Et Laborde concluait son apologie de la méthode par ce chant de triomphe : dans les nouvelles écoles,

« le travail est pour eux un jeu, la science une lutte, l’autorité une récompense ».

Les bienfaits de cet enseignement ne devaient d’ailleurs pas se limiter au cadre de l’école : les enfants rentrés chez eux exerçaient à leur tour sur leurs parents une heureuse influence ; ils devenaient des « missionnaires », à la fois de la morale et de la vérité dans leur famille.

« Et que de mauvais esprits n’aillent pas dire qu’il s’agit là de rêveries et d’utopies d’idéalistes ! » écrit Gontard en 1956. Des preuves existent, et irréfutables, de la valeur de la méthode. Regardez l’Ecosse. C’était à la fin du XVIIe siècle une terre de mendicité et de misère, vivant sans loi, sans religion, sans morale, les hommes buvant, les femmes blasphémant, tous se battant. En 1815, grâce à la baguette magique de l’école mutuelle, l’Ecosse est devenue un paradis.

«Il n’est pas rare de trouver en Ecosse un berger lisant Virgile… mais il est presque inconnu d’y rencontrer un malfaiteur », renchérit Laborde. Que l’on développe la méthode en France et celle-ci, en 1850, sera une terre de prospérité et de bonheur, d’où seront bannis l’immoralité, le fanatisme, les révolutions, les troubles sociaux, tous fils et filles de l’ignorance.

En 1818 Joseph Hamel, dans son rapport à l’Empereur de Russie, constate que

« la méthode d’enseignement mutuel s’est introduite dans toute la France avec une rapidité et un succès fort supérieur à ce qu’on pouvait raisonnablement en attendre, et, en moins de trois années, on a déjà fondé plus de 400 écoles. Tout porte donc à espérer que, dans un temps peu éloigné, plus de 2 millions d’enfants qui restaient dans l’ignorance la plus complète, pourront recevoir chaque année les bienfaits d’un enseignement gratuit, suffisant pour leur vocation ultérieure ».

D’emblée, toute la France s’y met ! A titre d’exemple, le récit de l’arrivée à Amiens et dans le département de la Somme.

A Amiens et dans la Somme

Après beaucoup de méfiance et bien des hésitations, la mairie d’Amiens fonde, le 15 mai 1817, une société d’encouragement de l’instruction élémentaire dans le département. Plus que l’ennoblissement de l’âme des élèves, pour le recteur, il s’agit,

« en donnant aux enfants de ces ouvriers l’instruction élémentaire, [de les préparer] non seulement à l’habitude de l’ordre et de la subordination que l’on puise dans les écoles d’enseignement mutuel et qu’ils reportent dans les ateliers, mais encore que cela les mette en état de servir plus utilement dans l’intérieur des fabriques comment pouvoir étudier les procédés industriels dont la conservation et le perfectionnement sont si essentiels à la prospérité nationale ».

Pour le recteur, la rapidité d’acquisition est un gage de succès de la nouvelle méthode par rapport à la « méthode simultanée » :

« Qu’une instruction primaire qui enlève pendant des années entières les enfants à un travail nécessaire à la subsistance de la famille devienne pour les pauvres une charge très onéreuse ; mais que l’expérience apprenne au père de famille que quelques mois suffiront pour procurer à ses enfants un avantage dont il a regretté tant de fois dans le cours de la vie de n’avoir pas pu jouir lui-même, on doit espérer qu’il ne balancera pas pour faire un léger sacrifice pour obtenir un résultat important ».

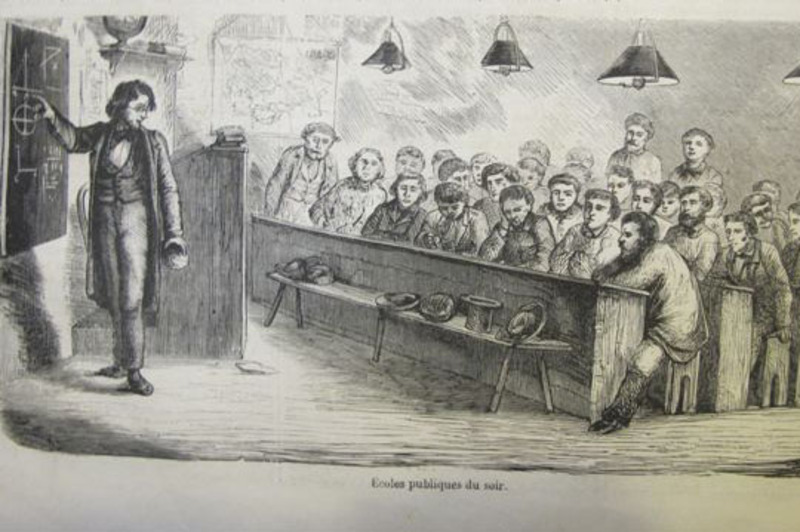

Ce sont principalement des écoles de garçons. Il existe quelques écoles de filles et des cours du soir pour adultes. Elles accueillent surtout des enfants de petits artisans : teinturier, employé d’octroi, cabaretier, contremaître, tailleur, garçon meunier, apprêteur, tonnelier, couturier, serrurier, boucher, fileur, repasseur, ouvrier, chargeur de voiture, menuisier, bouquiniste, allumeur de réverbère, coutelier, relieur, etc.

À son apogée, en 1821, l’enseignement mutuel comporte dans le département de la Somme non pas une école mais 25 dont 4 (payantes) pour des filles : près de la moitié sont situées en ville. Il en comportera encore 16 en 1833. Le réseau se réduira considérablement ensuite, toutefois, il ne disparaîtra pas complètement. Les deux dernières écoles d’Amiens fermeront involontairement leurs portes en 1879 et celle d’Abbeville en 1880 : jusqu’à cette date, elle jouera un rôle important dans la préparation des candidats aux examens.

L’école modèle d’Amiens – la première école modèle d’enseignement mutuel de province – prépare les futurs instituteurs à la pratique de l’enseignement mutuel. Elle est fondée le 26 mai 1817. Elle accueille plus de 200 élèves. Dès 1818, 6 instituteurs de la Somme en sortaient. La plupart des maîtres de l’Aisne, de l’Oise et du Pas-de-Calais y font un séjour avant de prendre leur fonction. C’est dire son importance, au point d’ailleurs que lorsque le préfet a créé l’école normale de garçons en 1831, elle s’appelle « école normale primaire d’enseignement mutuel ». Elle servit d’abord d’école d’application : les élèves maîtres devaient se rendre une fois par semaine dans ses locaux afin d’observer et de pratiquer, en s’exerçant, la méthode mutuelle.

Après les remaniements de 1817-1818, plusieurs membres de la SIE accèdent à des ministères importants : Mathieu Molé (1778-1838) à la Marine, Laurent Gouvion-Saint-Cyr (1764-1830) à la Guerre, Elie Decazes (1780-1860) surtout, à l’Intérieur, ministère dont dépend l’enseignement primaire. Le soutien gouvernemental devient alors systématique.

Le ministre de l’Intérieur soutient la SIE de Paris et ses filiales par des subventions pour fondation ou entretien d’écoles. Il invite les préfets à concourir par tous moyens au développement de la méthode. Les préfets prennent l’initiative de constituer des sociétés locales, ils interviennent auprès des assemblées pour solliciter des subventions.

Des conseils généraux et municipaux, en nombre croissant, votent des crédits pour l’établissement d’écoles mutuelles. L’école fondée, les autorités locales, préfet, maire, la visitent, et président sa distribution des prix. De son côté, la commission d’instruction publique, qui depuis 1815 remplace le Grand Maître de l’Université, décide le 22 juillet 1817 d’établir dans les chefs-lieux des douze Académies de France une école modèle pour l’enseignement mutuel, pépinière des futurs maîtres. Les autres ministres, chacun dans leur sphère, soutiennent la méthode.

Mathieu Molé, chargé de colonies, fonde des écoles d’enseignement mutuel au Sénégal.

En 1818, Laurent Gouvion-Saint-Cyr établit à Paris, dans la caserne Babylone, une véritable école normale militaire d’enseignement mutuel. Chaque régiment de Paris et de province doit y envoyer un officier et un sous-officier qui, de retour après quelques mois de stage, dispenseront à la troupe les bienfaits de l’instruction primaire.

En 1817-1818, l’enseignement mutuel triomphe. Un enthousiasme irrésistible porte la France vers lui. Le réseau des écoles ne cesse de s’étendre. De trimestre en trimestre, toujours plus nombreux, arrivent à Paris les comptes-rendus de la province, dénombrant les écoles et leurs élèves.

C’est un chant de victoire que peut entonner Jomard à la séance de la SIE de janvier 1819. Sur les 81 départements que compte la France, 5 seulement sont dépourvus d’école mutuelle ; les 76 autres groupent 687 écoles, fréquentées par plus de 40 000 élèves. On compte en outre 105 écoles régimentaires, 5 écoles d’adultes, 4 écoles de prisons, 2 ou 3 écoles au Sénégal.

Exemplaire de ce qui devient alors un nouveau paradigme prométhéen d’optimisme scientifique, le 15 décembre 1821, lors d’une réunion à l’hôtel de ville de Paris, est fondée la Société de géographie par 217 personnalités dont les plus grands savants de l’époque, notamment Jomard, Champollion, Cuvier, Chaptal, Denon, Fourier, Gay Lussac, Berthollet, von Humboldt, Chateaubriand. Parmi ses membres illustres, on peut citer également Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Dumont d’Urville, Élisée Reclus et Jules Verne.

La collecte et l’étude des données géographiques de nombreux continents vont permettre à certains membres, comme Gustave Eiffel et Ferdinand de Lesseps, de proposer de grands projets d’infrastructure, notamment le canal de Suez et le canal de Panama.

15. Critiques

Les premières critiques contre l’éducation mutuelle ne proviennent pas de son échec mais de son succès. Le premier « risque » venait du fait que les enfants, ayant appris trop efficacement et trop vite (de 2 à 3 fois plus rapidement), allaient retourner dans la rue trop tôt, n’ayant pas encore l’âge d’aller travailler !

Les enfants n’étaient pas « enfermés » à l’école assez longtemps, et donc l’enseignement mutuel troublait l’ordre social existant. Ainsi entendit-on au sein du Conseil général du Calvados en 1818 :

« Le plus grand service à rendre à la société serait peut-être d’imaginer une méthode qui rendît l’instruction destinée à la classe inférieure et indigente de la société plus difficile et plus longue »…

Le deuxième « risque » était qu’en continuant à utiliser l’enseignement mutuel, ces nouvelles personnes instruites, pour la plupart issues des classes les plus pauvres, deviennent trop intelligentes, trop « éveillées », et commencent à exprimer des revendications politiques ou sociales, et notamment que chacun ait les mêmes droits que les classes sociales les plus aisées.

Imaginez le chaos si l’ordre social est remis en question ! L’urbaniste et sociologue Anne Querrien remarque qu’en effet, une majorité des organisateurs du mouvement ouvrier à l’époque sont issus de l’école mutuelle au sein de laquelle ils avaient bien sûr appris à lire, à écrire, à compter, mais aussi à se faire confiance et à faire confiance à leurs camarades. L’école mutuelle pousse ses élèves à réfléchir, et notamment à réfléchir à l’organisation de la société, société qui leur assignait alors un destin de soumission et d’obéissance.

Pour l’influent théologien et homme politique breton, Félicité Robert de Lamennais (1782-1854),

« Les écoles à la Lancaster sont la folie du jour. Toutes les autorités de ce pays, et surtout le Préfet, en sont engouées au-delà de toute expression. La haine pour les prêtres entre pour beaucoup dans cette manie. Le fait est que tout ce qu’il y a de bon dans cette méthode, était pratiqué depuis plus d’un siècle par les Frères des Écoles chrétiennes ; le reste est pur charlatanisme. On parle d’apprendre à lire et à écrire en quatre mois aux enfants : d’abord ce serait un grand malheur, car que faire de ces enfants si bien instruits, et à qui leur âge ne permettrait pas encore de travailler ? En second lieu, rien n’est plus faux que ces résultats merveilleux ».

S’il faut « se prononcer entre l’instruction de l’abbé de La Salle et celle de Lancaster, la question est bien simple ; il s’agit de choisir entre la société et l’anarchie ».

Son frère, le vicaire Jean-Marie de la Mennais (1780-1860) prendra alors la tête de ce qu’il faut bien qualifier de chasse aux sorcières. Il dit :

« L’enseignement mutuel fut introduit en France par des protestants, dans les funestes cent jours. M. Carnot était alors ministre de l’Intérieur ; sous ses auspices, la société d’encouragement, établie pour propager cette méthode, tint sa première séance le 16 mai 1815 ».

Il se démène pour prouver que « la méthode lancastérienne est défectueuse dans ses procédés, dangereuse pour la religion et les mœurs dans ses résultats » et dans une brochure, De l’Enseignement mutuel, publiée en 1819 à Saint-Brieuc, il attaque vigoureusement ce mode d’enseignement.

Il n’est pas faux que la remise en question de l’autorité et de l’ordre établi est en soi inhérente à l’enseignement mutuel. L’école « simultanée » se base sur le postulat que pour transmettre un savoir il faut être diplômé (être le professeur). À l’inverse, au sein de l’école mutuelle, le professeur n’est plus le dépositaire du savoir, chaque élève pouvant expliquer à ses camarades.

Un autre souci pour les élites était lié au fait qu’avec cette méthode, les enfants ne sont plus qu’instruits et non pas « éduqués », qu’aucune éducation morale chrétienne ne leur est transmise.

Enfin, l’enseignement mutuel s’appuyait sur un nombre d’encadrants plus faible, du fait du rôle des élèves comme créateurs, transmetteurs et porteurs de savoirs. Certains ont peut-être eu peur pour leur poste…

Joseph Hamel, en 1818, dans son rapport à l’Empereur de Russie, répond aux principaux adversaires des mutualistes, les « Frères des écoles chrétiennes », qu’ils ignorent presque entièrement ce qu’ils dénoncent. Hamel rappelle également qu’il y a 40 000 communes à prévoir des écoles primaires et que le nombre d’écoles des Frères ne « s’élève pas à plus de 100 dans le royaume… »

Du côté négatif, ce qui frappe, lorsqu’on examine les incriminations, c’est qu’on dise une chose le matin et son contraire l’après-midi. Le matin on dit que l’enseignement mutuel brouille les esprits en diluant l’autorité des maîtres, l’après-midi on affirme qu’il « militarise » à outrance l’éducation par une structure de commandement totalement hiérarchisée ! Allez comprendre…

Sur la question de la moralité, jamais Lazare Carnot n’aurait cautionné une éducation ruinant l’esprit chrétien et encore moins la notion d’autorité légitime, tout en combattant avec vigueur celle qui en manquait, comme par exemple celle de la Monarchie de droit divin ou du Consulat à vie imposé par Napoléon. De la même façon, le matin on accuse le système mutualiste de ne pas transmettre « la morale » chrétienne, l’après-midi on y voit un complot protestant…

Or, l’élan national en faveur de « la patrie » et des générations futures, a justement réussi à unir, dans un même effort, des personnalités de tout bord politique et religieux. Cuvier (protestant) et Gérando (catholique), tous deux fervents républicains et promoteurs du mode mutuel, ainsi que l’inspecteur général de l’Université, Ambroise Rendu (1778–1860, catholique), participent même à la rédaction de l’ordonnance du 29 février 1816 promulguée par Louis XVIII et le ministre de l’Intérieur, de Vaublanc (1756–1845).

Suite aux pressions massives des congrégations, les enseignants mutualistes Martin, Frossard et Bellot, tous trois protestants, se voient contraints de quitter leur direction d’école. Martin se rendra fort utile dans d’autres pays européens, notamment à Bruxelles où il organise, en 1820, une école mutuelle aux Minimes.

16. Dérive mécaniste ?