Étiquette : sculpture

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Who whispered in the Ear of Joan of Arc?

Listen:

To the audio on this website.

Read :

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Leonardo and Verrochio’s workshop

Listen:

to the audio on this website

Read:

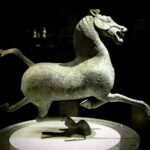

Derrière les « chevaux célestes » chinois, la science terrestre

Le fait qu’aujourd’hui encore, en parlant d’une voiture, on utilise l’unité « cheval » (CV) pour indiquer la puissance et donc le « travail » que le moteur peut fournir, en dit long sur le rôle majeur que les chevaux ont joué dans l’histoire de l’humanité.

Récemment invité à une conférence à Kaboul, en Afghanistan, j’ai évoqué à propos du besoin d’investissement en infrastructures hydrauliques, la domestication du cheval comme un bel exemple du passage d’une « plateforme infrastructurelle donnée » à une « plateforme supérieure », le terme plateforme faisant référence ici non pas à l’impact direct de l’infrastructure en question, mais à l’effet beaucoup plus large induit dans l’ensemble de l’économie d’un pays.

Nul besoin d’être anthropologue pour comprendre que l’histoire de l’humanité a radicalement changé avec la domestication du cheval, certaines choses considérées comme impossibles auparavant devenant, du jour au lendemain, la normalité.

La question de savoir quand et comment l’animal a été domestiqué reste sujet à controverse. Bien que des chevaux apparaissent dans l’art rupestre du paléolithique dès 36 000 ans avant notre ère (grotte Chauvet, France), il s’agissait alors de chevaux sauvages sans doute chassés pour leur viande.

Pour les zoologistes, la domestication se définit comme la maîtrise de l’élevage, pratique confirmée par des restes de squelettes anciens indiquant des changements dans la taille et la variabilité des populations de chevaux anciens.

D’autres chercheurs s’intéressent à des éléments plus généraux de la relation homme-cheval, notamment les preuves squelettiques et dentaires de l’activité professionnelle, les armes, l’art et les artefacts spirituels, ainsi que les modes de vie. Il est prouvé que les chevaux furent une source de viande et de lait avant d’être dressés comme animaux de travail.

En Inde, près de Bhopal, les abris-sous-roche du Bhimbetka, qui constituent le plus ancien art rupestre connu du pays (100 000 av. JC)), représentent des scènes de danse et de chasse de l’âge de pierre ainsi que des guerriers à cheval d’une époque plus tardive (10 000 av. JC).

Les preuves les plus évidentes de l’utilisation précoce du cheval comme moyen de transport sont les sépultures présentant des chevaux avec leurs chars. Les plus anciens vrais chars, datant d’environ 2000 av. JC, ont été retrouvés dans des tombeaux de la culture de Sintachta, dans des sites archéologiques situés le long du cours supérieur de la rivière Tobol, au sud-est de Magnitogorsk en Russie. Il s’agit de chars à roues à rayons tirés par deux chevaux.

Kazakhstan et Ukraine

Jusqu’à récemment, on pensait que le cheval le plus communément utilisé aujourd’hui était un descendant des chevaux domestiqués par la culture de Botaï, vivant dans les steppes de la province d’Akmola au Kazakhstan.

Cependant, des recherches génétiques récentes (2021) indiquent que les chevaux de Botaï ne sont que les ancêtres du cheval de Przewalski, une espèce qui a failli disparaître.

Selon les chercheurs, notre cheval commun, Equus ferus caballus, aurait été domestiqué il y a 4200 ans en Ukraine, dans la région du Don-Volga, c’est-à-dire la steppe pontique-caspienne de l’Eurasie occidentale, vers 2200 av. JC. Au fur et à mesure de leur domestication, ces chevaux ont été régulièrement croisés avec des chevaux sauvages.

Il est intéressant de noter à cet égard que, selon « l’hypothèse kourgane » formulée par Marija Gimbutas en 1956, c’est depuis cette région que la plupart des langues indo-européennes se sont répandues dans toute l’Europe et certaines parties de l’Asie.

Le nom vient du terme russe d’origine turque, « kourgane », qui désigne les tumuli caractéristiques de ces peuples et qui marquent leur expansion en Europe.

La Route du thé, du cheval ou de la soie?

La description des échanges commerciaux, culturels et humains tout au long des « Routes de la soie » a fait couler beaucoup d’encre. Or, ce terme est récent. Ce n’est qu’en 1877 que le géographe allemand Ferdinand von Richthofen l’utilise pour la première fois afin de désigner ces axes Est-Ouest structurant les échanges mondiaux.

En réalité, il s’avère que l’une des principales marchandises échangées sur ladite Route de la soie était… les chevaux et autres animaux de labour (mules, chameaux, ânes et onagres).

Si l’on y échangeait effectivement la soie et le thé, ces produits constituaient, comme la porcelaine et l’or, un moyen pour régler d’autres achats, notamment les chevaux que les Chinois cherchaient à acquérir.

Ce que l’on appelait la « Route du thé et du cheval » (route de la soie du sud) partait de la ville de Chengdu, dans la province du Sichuan, en Chine, traversait le Yunnan vers le sud, jusqu’en Inde et dans la péninsule indochinoise, et s’étendait vers l’ouest jusqu’au Tibet.

C’était une route importante pour le commerce du thé en Chine du Sud et en Asie du Sud-Est, et elle a contribué à la diffusion de religions comme le taoïsme et le bouddhisme dans la région. Il est vrai que « Route de la soie » est plus poétique que « route du crottin » !

La Steppe et ses nomades

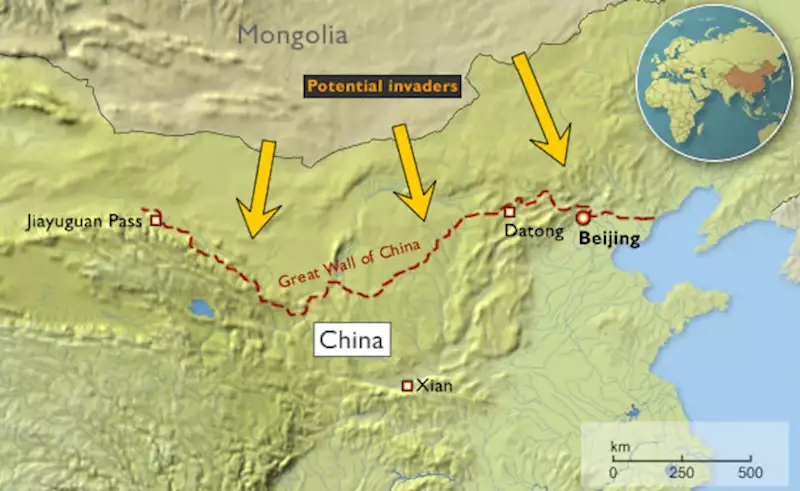

Constamment harcelée par les peuples nomades des steppes du Nord, la Chine entreprit la construction de sa Grande Muraille dès le VIIe siècle av. JC.

La liaison entre les premiers éléments fut réalisée par Qin Shi Huang (220-206 avant JC.), le premier empereur de Chine, et l’ensemble du mur, achevé sous la dynastie des Ming (1368-1644), est devenu l’un des exploits les plus remarquables de l’histoire humaine.

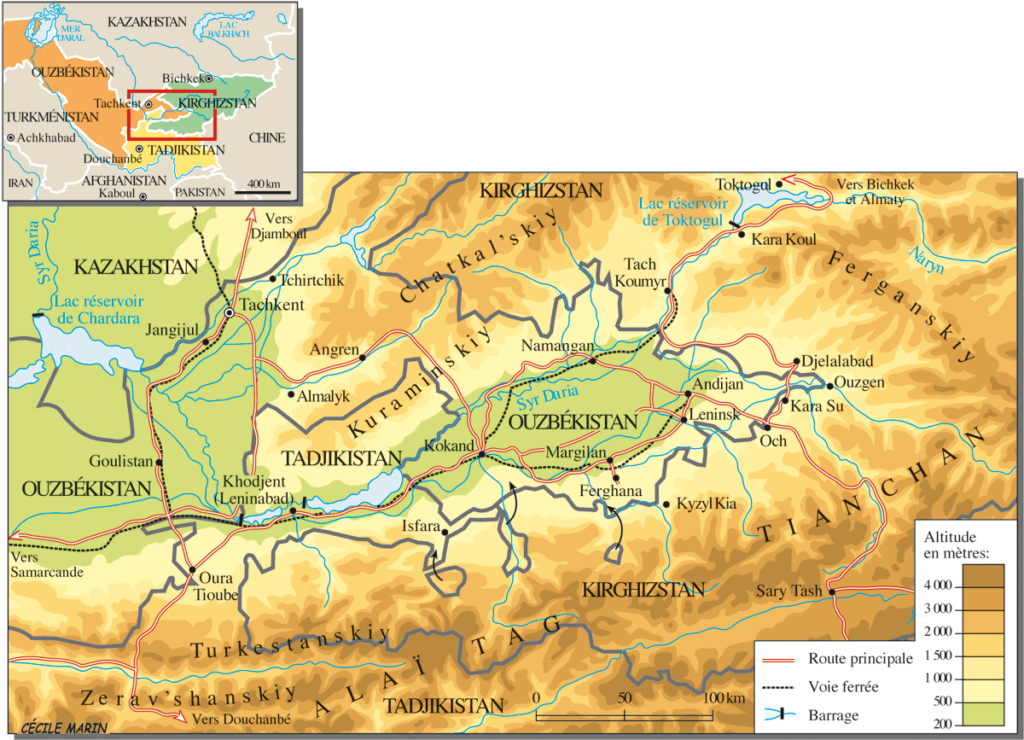

Le terme générique de « nomades eurasiens » englobe les divers groupes ethniques peuplant la steppe eurasienne, se déplaçant à travers les steppes du Kazakhstan, du Kirghizistan, du Tadjikistan, du Turkménistan, d’Ouzbékistan, de Mongolie, de Russie et d’Ukraine.

En domestiquant le cheval vers 2200 av. JC., ces peuples augmentèrent considérablement les possibilités de vie nomade.

Par la suite, leur économie et leur culture se concentrèrent sur l’élevage de chevaux, l’équitation et le pastoralisme nomade, permettant de riches échanges commerciaux avec les peuples sédentaires vivant en bordure de la steppe, que ce soit en Europe, en Asie ou en Asie centrale.

On pense qu’ils opéraient souvent sous forme de confédérations. Par définition, les nomades ne créent pas d’empires. Sans forcément les occuper, en contrôlant les points névralgiques, ils règnent en maître sur d’immenses territoires.

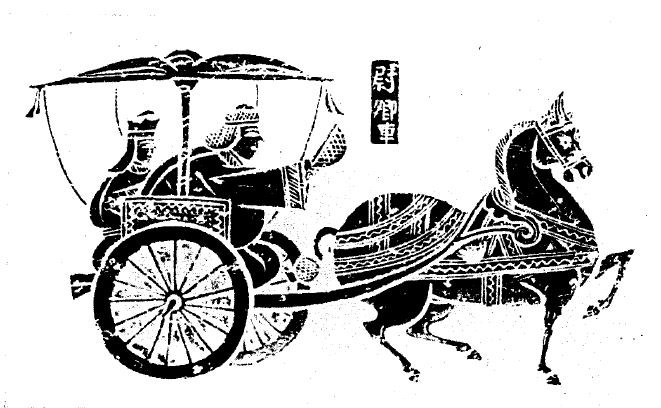

Ce sont eux qui développèrent le char, le chariot, la cavalerie et le tir à l’arc à cheval, introduisant des innovations telles que la bride, le mors, l’étrier et la selle, qui traversèrent rapidement toute l’Eurasie et furent copiées par leurs voisins sédentaires.

Durant l’âge du fer, des cultures scythes (iraniennes) apparurent parmi les nomades eurasiens, caractérisées par un art distinct, dont la joaillerie en or force l’admiration.

Le cheval en Chine

Les objets funéraires chinois fournissent une quantité extraordinaire d’informations sur le mode de vie des Chinois de l’Antiquité. La cavalerie militaire, mise sur pied dès le IIIe siècle avant J.C., s’y développe afin de faire face aux guerriers nomades et archers à cheval qui menacent la Chine le long de sa frontière septentrionale. Leurs grands et puissants chevaux étaient nouveaux pour les Chinois.

Échangés contre de la soie de luxe, comme nous l’avons dit, ils sont la première importation majeure en Chine depuis la Route de la soie. Des vestiges archéologiques montrent qu’en l’espace de quelques années, les merveilleux destriers arabes deviennent extrêmement populaires auprès des militaires et des aristocrates chinois, et les tombes des classes supérieures sont remplies de représentations de ces grands chevaux destinés à être utilisés dans l’au-delà. Ils restent cependant difficiles à trouver sur place…

Les diplomates chinois et le royaume de Dayuan (Ferghana)

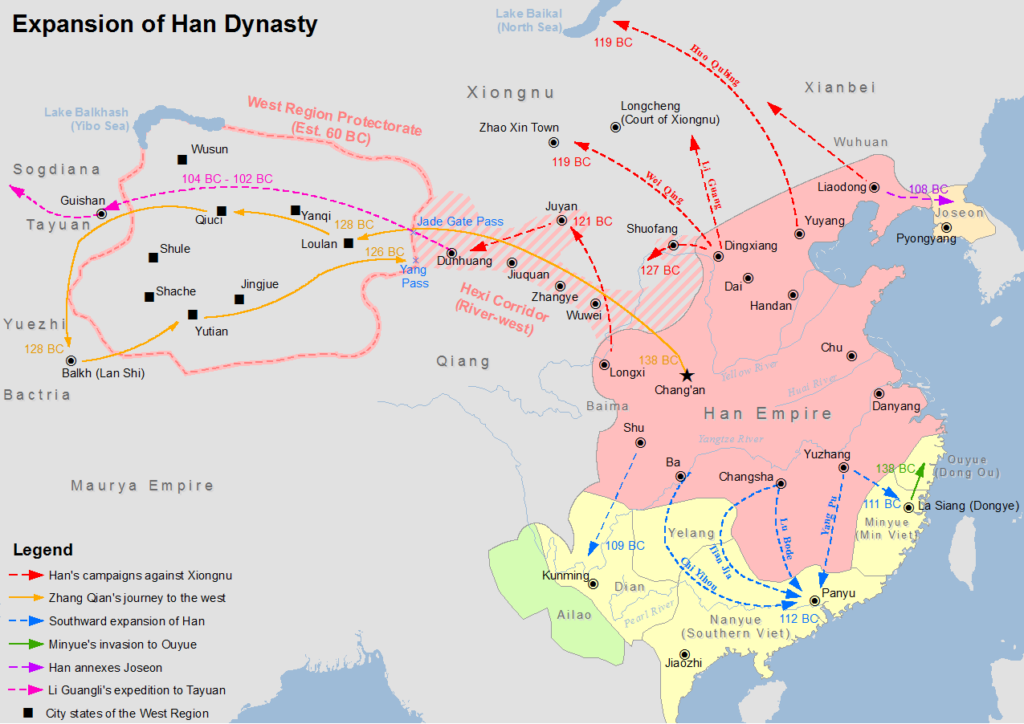

À la fin du IIe siècle av. JC., Zhang Qian, diplomate et explorateur de la dynastie Han, se rend en Asie centrale et découvre trois civilisations urbaines sophistiquées créées par des colons grecs appelés Ioniens.

Le récit de sa visite en Bactriane, et son étonnement d’y trouver des marchandises chinoises sur les marchés (acquises via l’Inde), ainsi que ses voyages en Parthie et au Ferghana, sont conservés dans les œuvres de Sima Qian, l’historien des premiers Han.

À son retour, son récit incite l’empereur chinois à envoyer des émissaires à travers l’Asie centrale pour négocier et encourager le commerce avec son pays. « Et c’est ainsi que naquit la route de la soie », affirment certains historiens.

Outre la Parthie et la Bactriane, Zhang Qian visite, dans la fertile vallée de Ferghana (aujourd’hui essentiellement au Tadjikistan), un État que les Chinois baptisèrent le royaume de Dayuan (« Da » signifiant « grand » et « Yuan » étant la translittération du sanskrit Yavana ou du pali Yona, utilisé dans toute l’Antiquité en Asie pour désigner les Ioniens, ou colons grecs).

Les Actes du grand historien et le Livre des Han décrivent Dayuan comme un pays de plusieurs centaines de milliers d’habitants, vivant dans 70 villes fortifiées de taille variable.

Ils cultivent le riz et le blé et produisent du vin à partir de leurs vignes. Ils avaient des traits caucasiens et des « coutumes identiques à celles de la Bactriane » (l’État le plus hellénistique de la région depuis Alexandre le Grand), dont l’épicentre se trouve alors au nord de l’Afghanistan. (voir notre article)

En outre, le diplomate chinois rapporte un fait d’un grand intérêt stratégique : la présence, dans la vallée de la Ferghana, de chevaux incroyables, rapides et puissants, élevés par ces Ioniens !

Or, comme nous l’avons déjà dit, la Chine, se sentant menacée en permanence par les peuples nomades des steppes, était en train de construire sa Grande Muraille. Elle avait également conscience de son infériorité militaire par rapport aux nomades des steppes et déplorait son manque cruel de puissants chevaux.

Sans oublier que, dans l’échelle des valeurs chinoises, le cheval possédait une valeur spirituelle et symbolique presque aussi forte que le dragon : il pouvait voler et représentait l’esprit divin et créatif de l’univers lui-même, chose essentielle pour tout empereur désireux d’acquérir aussi bien la sécurité militaire pour son empire que son immortalité personnelle.

Bref, posséder de bons chevaux est alors une question allant au-delà de la sécurité nationale, tout en l’incluant. À tel point qu’en 100 av. JC., lorsque le souverain de la vallée de Ferghana refuse de lui fournir des chevaux de qualité, la dynastie Han déclenche contre Dayuan la « guerre des chevaux célestes ».

Guerre des chevaux célestes

C’est un conflit militaire qui se déroule entre 104 et 102 av. JC. entre la Chine et Dayuan, Etat peuplé d’Ioniens (entre l’Ouzbékistan, le Kirghizstan et le Tadjikistan actuels

Tout d’abord, l’empereur Wu décide d’infliger une défaite décisive aux nomades des steppes, les Xiongnu, qui harcèlent la dynastie Han depuis des décennies.

Pour les faire plier, en 139 av. JC, il envoie le diplomate Zhang Qian avec pour mission d’arpenter l’ouest et d’y forger une alliance militaire avec les nomades chinois Yuezhi contre les Xiongnu.

Zhang Qian, comme nous l’avons dit, se rend en Parthie, en Bactriane et à Dayuan. À son retour, il impressionne l’empereur en lui décrivant les « chevaux célestes » de la vallée de Ferghana, qui pourraient grandement améliorer la qualité des montures de la cavalerie Han lors des combats contre les Xiongnu.

La cour des Han envoie alors jusqu’à dix groupes de diplomates pour acquérir ces « chevaux célestes ».

Une mission commerciale et diplomatique arrive donc à Dayuan avec 1000 pièces d’or et un cheval d’or pour acheter les précieux animaux. Dayuan, qui était à cette époque l’un des États les plus occidentaux à avoir des émissaires à la cour des Han, commerce déjà avec eux depuis un certain temps à son grand avantage. Non seulement sa population accède aux marchandises orientales, mais apprend des soldats Han la fonte des métaux pour fabriquer des pièces et des armes. Cependant, contrairement aux autres envoyés à la cour des Han, ceux de Dayuan ne se conforment pas aux rituels des Han et se montrent arrogants, pensant que leur pays est trop éloigné pour avoir à craindre une invasion.

Dès lors, dans un élan de folie et par pure arrogance, le roi du Dayuan non seulement refuse le marché, mais confisque l’or. Les envoyés des Han maudissent les hommes de Dayuan et brisent le cheval d’or qu’ils avaient amené. Furieux de cet acte de mépris, les nobles de Dayuan ordonnent aux militaires de Yucheng, qui se trouvent à leur frontière orientale, d’attaquer les envoyés, de les tuer et de s’emparer de leurs marchandises.

Humiliée et furieuse, la cour des Han envoie alors une armée dirigée par le général Li Guangli pour soumettre Dayuan, mais leur première incursion s’avère mal organisée et insuffisamment approvisionnée.

Deux ans plus tard, une seconde expédition, plus importante et mieux approvisionnée, parvient à assiéger la capitale des Dayuan, « Alexandria Eschate » (aujourd’hui proche de Khodjent, au Tadjikistan), forçant les Dayuan à se rendre sans condition.

Les forces expéditionnaires y installent alors un régime pro-Han et repartent avec 3000 chevaux. Il n’en restera que 1000 à leur arrivée en Chine, en 101 av. JC.

Le Dayuan accepte également d’envoyer chaque année deux chevaux célestes à l’empereur et des semences de luzerne sont ramenées en Chine, fournissant des pâturages de qualité supérieure pour élever de beaux chevaux afin de fournir une cavalerie capable de faire face aux Xiongnu qui menacent le pays.

Les chevaux ont depuis lors captivé l’imagination populaire en Chine, inspirant des sculptures, faisant l’objet d’élevage dans le Gansu et dotant la cavalerie de 430 000 chevaux de ce type sous la dynastie des Tang.

La Chine et la Révolution agricole

Après avoir imposé son rôle dans la stratégie militaire pour les siècles à venir, le cheval devient, avec la maîtrise de l’eau, le facteur clé permettant d’accroître la productivité agricole.

Contrairement aux Romains, qui préféraient utiliser du « bétail humain » (esclaves) plutôt que des animaux (qu’ils élevaient pour les courses), les Chinois ont contribué de façon décisive à la survie de l’humanité avec deux innovations cruciales concernant l’attelage des chevaux.

Rappelons que pendant toute l’Antiquité, que ce soit en Égypte ou en Grèce, charrues et chariots sont tirés à l’aide d’une bande de cuir encerclant le cou de l’animal.

Cet attelage s’apparente au joug utilisé pour les bœufs, la charge étant attachée au sommet du collier, au-dessus du cou. Le cheval se trouvant ainsi constamment étranglé, ce système réduit considérablement sa capacité à travailler, et plus il tire, plus il a du mal à respirer.

En raison de cette contrainte physique, le bœuf restera l’animal préféré pour les travaux lourds tels que le labourage. Cependant, il est lent, difficile à manœuvrer et n’a pas l’endurance du cheval, qui est deux fois supérieure pour une puissance équivalente.

La Chine aurait d’abord inventé la « bricole », large courroie de cuir enserrant le poitrail du cheval, ce qui était un premier pas dans la bonne direction.

Au Ve siècle, la Chine invente « le collier d’épaule », conçu comme un ovale rigide qui s’adapte au cou et aux épaules du cheval sans lui couper le souffle.

Il présente les avantages suivants :

— Il soulage la pression exercée sur la gorge du cheval, libérant les voies respiratoires de toute constriction, ce qui améliore considérablement le débit d’énergie de l’animal.

— Les traits peuvent être attachés de chaque côté du collier, ce qui permet au cheval de pousser sur ses pattes postérieures, plus puissantes, au lieu de tirer avec celles de devant, plus faibles.

Vous me direz qu’il s’agit là d’une simple anecdote. Vous avez tort, car ce qui semble n’être qu’un changement mineur aura des conséquences gigantesques.

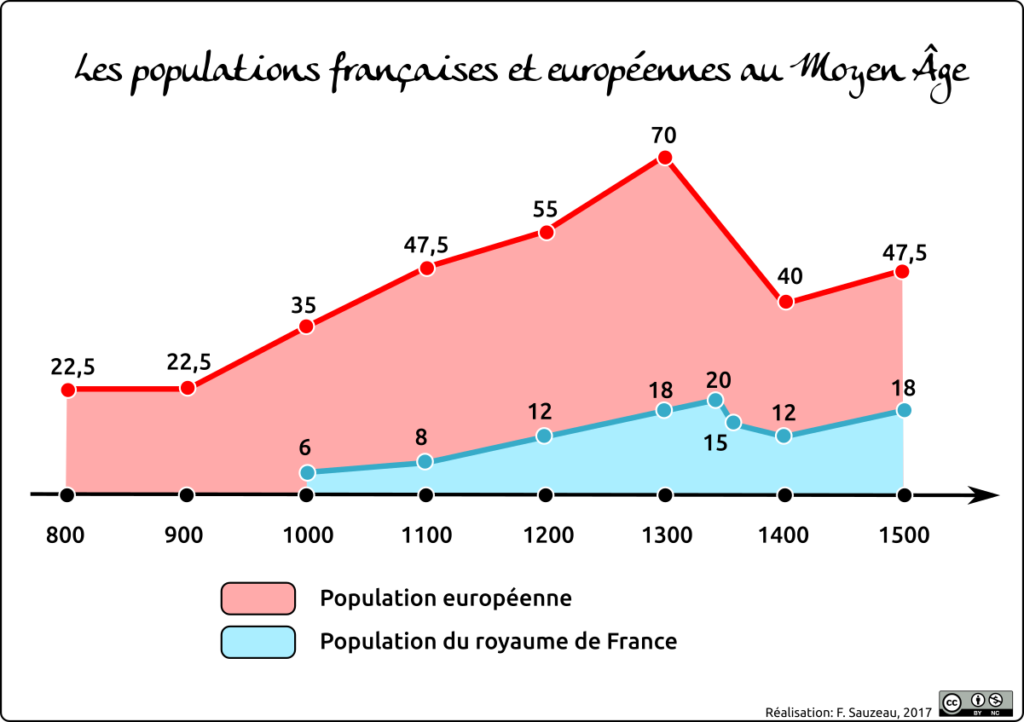

La Renaissance européenne

Dans le cadre d’une alliance stratégique et d’une coopération avec le califat humaniste des Abbassides de Bagdad (voir notre article), Charlemagne et ses successeurs ont défriché de vastes terrains pour l’agriculture, amélioré l’usage de l’eau et généralisé le collier d’épaule pour les chevaux de trait.

Grâce à ce nouvel outil beaucoup plus efficace, les agriculteurs européens ont pu tirer pleinement parti de la force du cheval, qui sera alors capable de tirer une autre innovation récente, la lourde charrue. Cela s’est avéré particulièrement appréciable pour les sols durs et argileux, ouvrant de nouvelles terres à l’agriculture.

Le collier, la charrue lourde et le fer à cheval ont contribué à l’essor de la production agricole.

Ainsi, entre l’an 1000 et l’an 1300, on estime qu’en Europe, les rendements agricoles ont triplé, permettant de nourrir un nombre croissant de citoyens dans les villes urbaines apparues au XVe siècle et de donner le coup d’envoi à la Renaissance européenne. Merci la Chine !

Certains chiffres laissent néanmoins perplexes :

–Il aura fallu des milliers d’années à l’humanité pour domestiquer le cheval, en 2200 av. JC. (bien après la vache).

— Il faudra encore 2700 ans à l’humanité pour trouver, au Ve siècle de notre ère, la façon la plus efficace d’utiliser sa force motrice…

Le passage d’une plateforme d’infrastructure inférieure à une plate-forme d’infrastructure supérieure peut certes prendre un certain temps. Les nouvelles plateformes supérieures d’aujourd’hui s’appellent l’espace et l’énergie de fusion.

N’attendons pas encore un millénaire pour savoir comment les utiliser correctement !

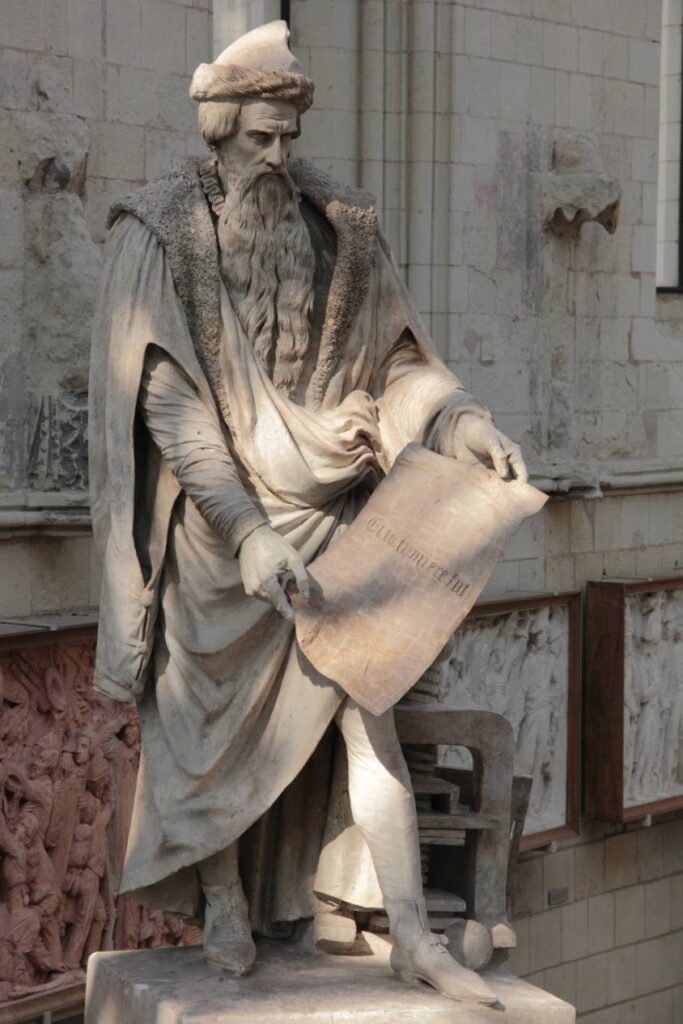

The republican struggle of David d’Angers and the statue of Gutenberg in Strasbourg

In the heart of downtown Strasbourg, a stone’s throw from the cathedral and with its back to the 1585 Chamber of Commerce, stands the beautiful bronze statue of the German printer Johannes Gutenberg, holding a barely-printed page from his Bible, which reads: « And there was light » (NOTE 1).

Evoking the emancipation of peoples thanks to the spread of knowledge through the development of printing, the statue, erected in 1840, came at a time when supporters of the Republic were up in arms against the press censorship imposed by Louis-Philippe under the July Monarchy.

Strasbourg, Mainz and China

Born around 1400 in Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg, with money lent to him by the merchant and banker Johann Fust, carried out his first experiments with movable metal type in Strasbourg between 1434 and 1445, before perfecting his process in Mainz, notably by printing his famous 42-line Bible from 1452.

On his death (in Mainz) in 1468, Gutenberg bequeathed his process to humanity, enabling printing to take off in Europe. Chroniclers also mention the work of Laurens Janszoon Coster in Harlem, and the Italian printer Panfilo Castaldi, who is said to have brought Chinese know-how to Europe. It should be noted that the « civilized » world of the time refused to acknowledge that printing had originated in Asia with the famous « movable type » (made of porcelain and metal) developed several centuries earlier in China and Korea (NOTE 2).

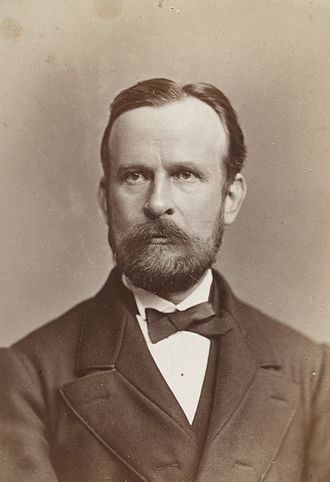

In Europe, Mainz and Strasbourg vie for pride of place. On August 14, 1837, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the « invention » of printing, Mainz inaugurated its statue of Gutenberg, erected by sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsenalors, while in Strasbourg, a local committee had already commissioned sculptor David d’Angers to create a similar monument in 1835.

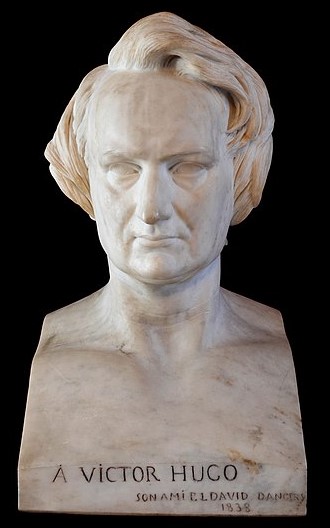

This little-known sculptor was both a great sculptor and close friend of Victor Hugo, and a fervent republican in personal contact with the finest humanist elite of his time in France, Germany and the United States. He was also a tireless campaigner for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery.

The sculptor’s life

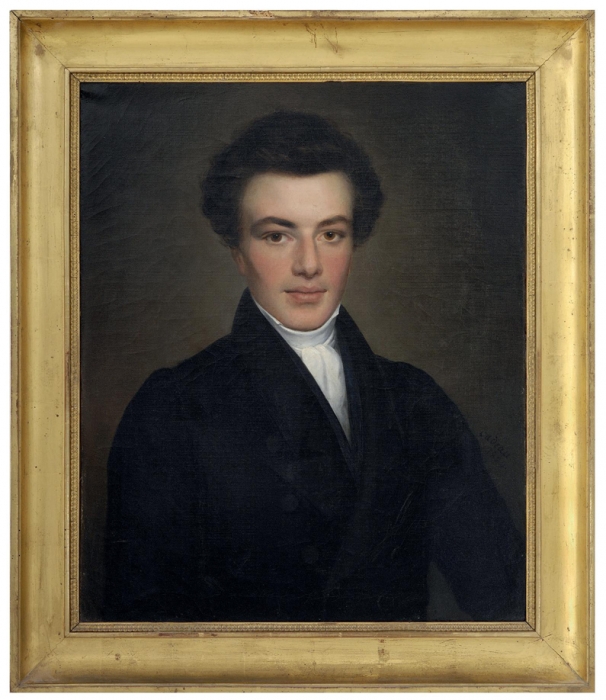

French sculptor Pierre-Jean David, known as « David d’Angers » (1788-1856) was the son of master sculptor Pierre Louis David. Pierre-Jean was influenced by the republican spirit of his father, who trained him in sculpture from an early age. At the age of twelve, his father enrolled him in the drawing class at the École Centrale de Nantes. In Paris, he was commissioned to create the ornamentation for the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and the south facade of the Louvre Palace. Finally, he entered the Beaux-arts.

David d’Angers possessed a keen sense of interpretation of the human figure and an ability to penetrate the secrets of his models. He excelled in portraiture, whether in bust or medallion form. He is the author of at least sixty-eight statues and statuettes, some fifty bas-reliefs, a hundred busts and over five hundred medallions. Victor Hugo told his friend David: « This is the bronze coin by which you pay your toll to posterity. »

He traveled all over Europe, painting busts in Berlin, London, Dresden and Munich.

Around 1825, when he was commissioned to paint the funeral monument that the Nation was raising by public subscription in honor of General Foy, a tribune of the parliamentary opposition, he underwent an ideological and artistic transformation. He frequented the progressive intellectual circles of the « 1820 generation » and joined the international republican movement. He then turned his attention to the political and social problems of France and Europe. In later years, he remained faithful to his convictions, refusing, for example, the prestigious commission to design Napoleon’s tomb.

Artistic production

David’s art was thus influenced by a naturalism whose iconography and expression are in stark contrast to that of his academic colleagues and the dissident sculptors known as « romantics » at the time. For David, no mythological sensualism, obscure allegories or historical picturesqueness. On the contrary, sculpture, according to David, must generalize and transpose what the artist observes, so as to ensure the survival of ideas and destinies in a timeless posterity.

David adhered to this particular, limited conception of sculpture, adopting the Enlightenment view that the art of sculpture is « the lasting repository of the virtues of men », perpetuating the memory of the exploits of exceptional beings.

The somewhat austere image of « great men » prevailed, best known thanks to some 600 medallions depicting famous men and women from several countries, most of them contemporaries. Added to this are some one hundred busts, mostly of his friends, poets, writers, musicians, songwriters, scientists and politicians with whom he shared the republican ideal.

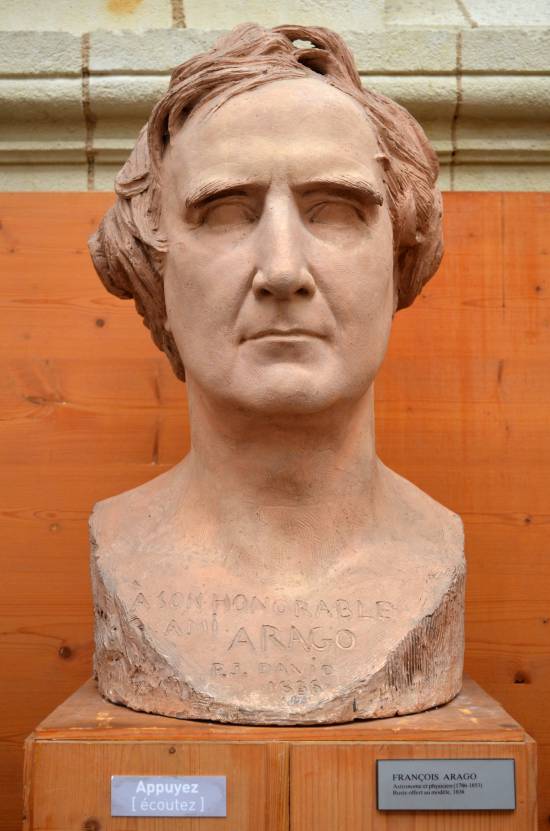

Among the most enlightened of his time were: Victor Hugo, Marquis de Lafayette, Wolfgang Goethe, Alfred de Vigny, Alphonse Lamartine, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Alfred de Musset, François Arago, Alexander von Humboldt, Honoré de Balzac, Lady Morgan, James Fenimore Cooper, Armand Carrel, François Chateaubriand, Ennius Quirinus Visconti and Niccolo Paganini.

To magnify his models and visually render the qualities of each one’s genius, David d’Angers invented a mode of idealization no longer based on antique-style classicism, but on a grammar of forms derived from a new science, the phrenology of Doctor Gall, who believed that the cranial « humps » of an individual reflected his intellectual aptitudes and passions. For the sculptor, it was a matter of transcending the model’s physiognomy, so that the greatness of the soul radiated from his forehead.

In 1826, he was elected member of the Institut de France and, the same year, professor at the Beaux-Arts. In 1828, David d’Angers was the victim of his first unsolved assassination attempt. Wounded in the head, he was confined to bed for three months. However, in 1830, still loyal to republican ideas, he took part in the revolutionary days and fought on the barricades.

In 1830, David d’Angers found himself ideally placed to carry out the most significant political sculpture commission of the July monarchy and perhaps of 19th century France: the new decoration of the pediment of the church of Sainte-Geneviève, which had been converted into the Pantheon in July.

As a historiographer, he wanted to depict the civilians and men of war who built Republican France. In 1837, the execution of the figures he had chosen and arranged in a sketch that was first approved, then suspended, was bound to lead to conflict with the high clergy and the government. On the left, we see Bichat, Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David, Cuvier, Lafayette, Manuel, Carnot, Berthollet, Laplace, Malesherbes, Mirabeau, Monge and Fénelon. While the government tried to have Lafayette’s effigy removed, which David d’Angers stubbornly refused, with the support of the liberal press, the pediment was unveiled without official ceremony in September 1837, without the presence of the artist, who had not been invited.

Entering politics

During the 1848 Revolution, he was appointed mayor of the 11th arrondissement of Paris, entered the National Constituent Assembly and then the National Legislative Assembly, where he voted with the Montagne (revolutionary left). He defended the existence of the Ecole des Beaux-arts and the Académie de France in Rome. He opposed the destruction of the Chapelle Expiatoire and the removal of two statues from the Arc de Triomphe (Resistance and Peace by sculptor Antoine Etex).

He also voted against the prosecution of Louis Blanc (1811-1882) (another republican statesman and intellectual condemned to exile), against the credits for Napoleon III’s Roman expedition, for the abolition of the death penalty, for the right to work, and for a general amnesty.

Exile

He was not re-elected deputy in 1849 and withdrew from political life. In 1851, with the advent of Napoleon III, David d’Angers was arrested and also sentenced to exile. He chose Belgium, then traveled to Greece (his old project). He wanted to revisit his Greek Maiden on the tomb of the Greek republican patriot Markos Botzaris (1788-1823), which he found mutilated and abandoned (he had it repatriated to France and restored).

Disappointed by Greece, he returned to France in 1852. With the help of his friend de Béranger, he was allowed to stay in Paris, where he resumed his work. In September 1855, he suffered a stroke which forced him to cease his activities. He died in January 1856.

Friendships with Lafayette, Abbé Grégoire and Pierre-Jean de Béranger

David d’Angers was a real link between 18th and 19th century republicans, and a living bridge between those of Europe and America.

Born in 1788, he had the good fortune to associate at an early age with some of the great revolutionary figures of the time, before becoming personally involved in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848.

Towards the end of the 1820s, David attended the Tuesday salon meetings of Madame de Lafayette, wife of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (1757-1834).

While General Lafayette stood upright like « a venerable oak », this salon, notes the sculptor,

« has a clear-cut physiognomy, » he writes. The men talk about serious matters, especially politics, and even the young men look serious: there’s something decided, energetic and courageous in their eyes and in their posture (…) All the ladies and also the demoiselles look calm and thoughtful; they look as if they’ve come to see or attend important deliberations, rather than to be seen. »

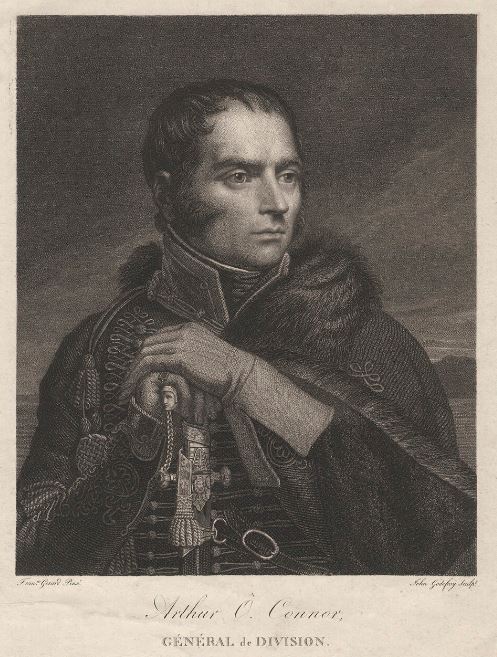

David met Lafayette’s comrade-in-arms, General Arthur O’Connor (1763-1852), a former Irish republican MP of the United Irishmen who had joined Lafayette’s volunteer General Staff in 1792.

Accused of stirring up trouble against the British Empire and in contact with General Lazare Hoche (1768-1797), O’Connor fled to France in 1796 and took part in the Irish Expedition. In 1807, O’Connor married the daughter of philosopher and mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet (1743-1794) and became a naturalized French citizen in 1818.

Lafayette and David d’Angers often got together with a small group of friends, a few « brothers » who were members of Masonic lodges: such as the chansonnier Pierre-Jean de Béranger, François Chateaubriand, Benjamin Constant, Alexandre Dumas (who corresponded with Edgar Allan Poe), Alphonse Lamartine, Henri Beyle dit Stendhal and the painters François Gérard and Horace Vernet.

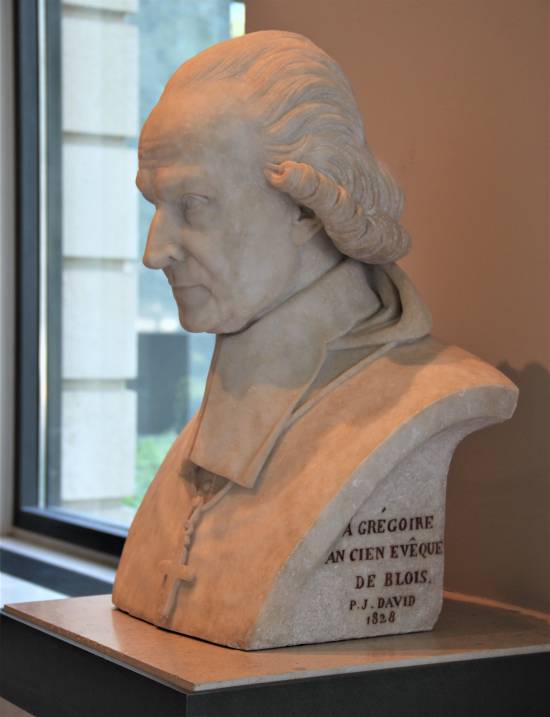

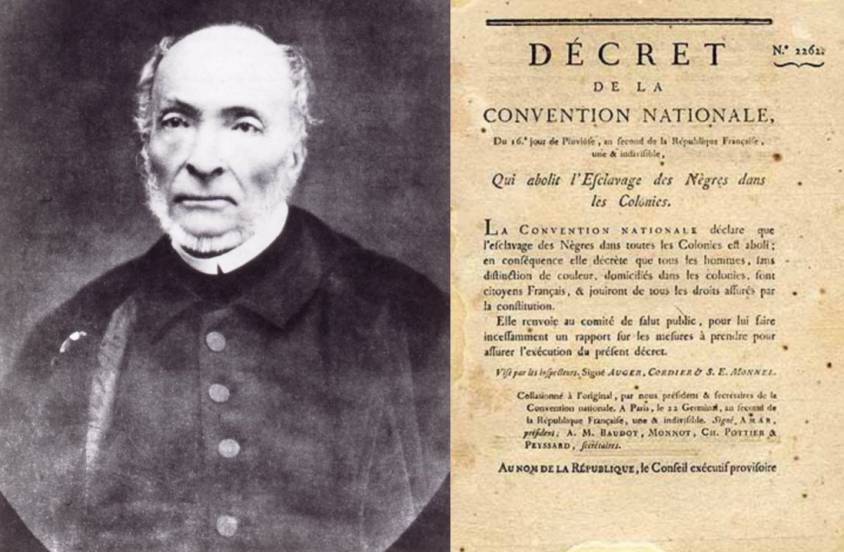

In these same circles, David also became acquainted with Henri (Abbé) Grégoire (1750-1831), and the issue of the abolition of slavery, which Grégoire had pushed through on February 4, 1794, was often raised. In their exchanges, Lafayette liked to recall the words of his youthful friend Nicolas de Condorcet:

« Slavery is a horrible barbarism, if we can only eat sugar at this price, we must know how to renounce a commodity stained with the blood of our brothers. »

For Abbé Gregoire, the problem went much deeper:

« As long as men are thirsty for blood, or rather, as long as most governments have no morals, as long as politics is the art of deceit, as long as people, unaware of their true interests, attach silly importance to the job of spadassin, and will allow themselves to be led blindly to the slaughter with sheep-like resignation, almost always to serve as a pedestal for vanity, almost never to avenge the rights of humanity, and to take a step towards happiness and virtue, the most flourishing nation will be the one that has the greatest facility for slitting the throats of others. »

(Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews)

Napoleon and slavery

The first abolition of slavery was, alas, short-lived. In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte, short of the money needed to finance his wars, reintroduced slavery, and nine days later excluded colored officers from the French army.

Finally, he outlawed marriages between « fiancés whose skin color is different ». David d’Angers remained very sensitive to this issue, having as a comrade a very young writer, Alexandre Dumas, whose father had been born a slave in Haiti.

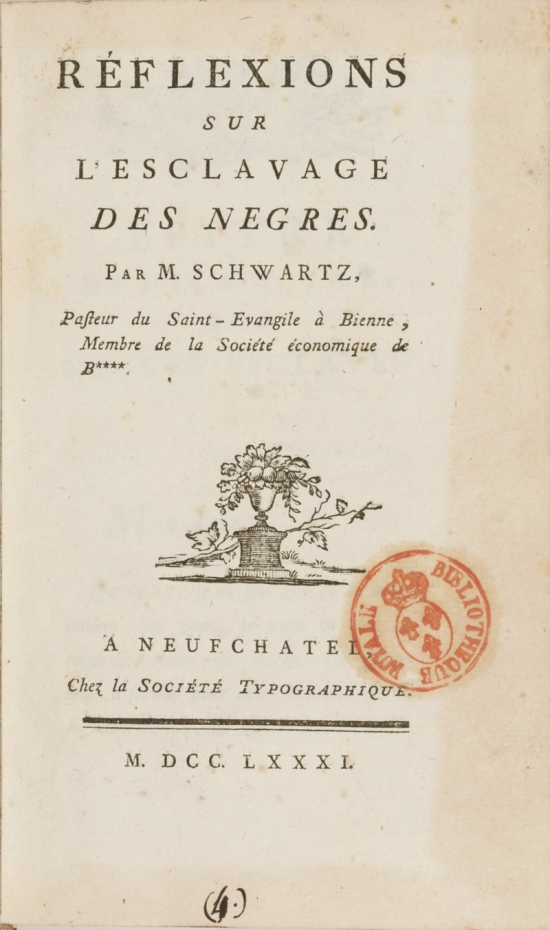

As early as 1781, under the pseudonym Schwarz (black in German), Condorcet had published a manifesto advocating the gradual disappearance of slavery over a period of 60 to 70 years, a view quickly shared by Lafayette. A fervent supporter of the abolitionist cause, Condorcet condemned slavery as a crime, but also denounced its economic uselessness: slave labor, with its low productivity, was an obstacle to the establishment of a market economy.

And even before the signing of the peace treaty between France and the United States, Lafayette wrote to his friend George Washington on February 3, 1783, proposing to join him in setting in motion a process of gradual emancipation of the slaves. He suggested a plan that would « frankly become beneficial to the black portion of mankind ».

The idea was to buy a small state in which to experiment with freeing slaves and putting them to work as farmers. Such an example, he explained, « could become a school and thus a general practice ». (NOTE 3)

Washington replied that he personally would have liked to support such a step, but that the American Congress (already) was totally hostile.

From the Society of Black Friends to the French Society for the Abolition of Slavery

In Paris, on February 19, 1788, Abbé Grégoire and Jacques Pierre Brissot (1754-1793) founded « La Société des amis des Noirs », whose rules were drawn up by Condorcet, and of which the Lafayette couple were also members.

The society’s aim was the equality of free whites and blacks in the colonies, the immediate prohibition of the black slave trade and the gradual abolition of slavery; on the one hand, to maintain the economy of the French colonies, and on the other, in the belief that before blacks could achieve freedom, they had to be prepared for it, and therefore educated.

After the virtual disappearance of the « Amis des Noirs », the offensive was renewed, with the founding in 1821 of the « Société de la Morale chrétienne », which in 1822 set up a « Comité pour l’abolition de la traite des Noirs », some of whose members went on to found the « Société française pour l’abolition de l’esclavage (SFAE) » in 1834.

Initially in favor of gradual abolition, the SFAE later favored immediate abolition. Prohibited from holding meetings, the SFAE decided to create abolitionist committees throughout the country to relay the desire to put an end to slavery, both locally and nationally.

Goethe and Schiller

In the summer of 1829, David d’Angers made his first trip to Germany and met Goethe (1749-1832), the poet and philosopher who had retired to Weimar. Several posing sessions enabled the sculptor to complete his portrait.

Writer and poet Victor Pavie (1808-1886), a friend of Victor Hugo and one of the founders of the « Cercles catholiques ouvriers » (Catholic Workers Circle), accompagnied him on the trip and recounts some of the pictoresques anecdotes of their travel in his « Goethe and David, memories of a voyage to Weimar » (1874).

In 1827, the French newspaper Globe published two letters recounting two visits to Goethe, in 1817 and 1825, by an anonymous « friend » (Victor Cousin), as well as a letter from Ampère on his return from the « Athens of Germany ». In these letters, the young scientist expressed his admiration, and gave numerous details that whetted the interest of his compatriots. During his stay in Weimar, Ampère added to his host’s knowledge of Romantic authors, particularly Mérimée, Vigny, Deschamps and Delphine Gay. Goethe already had a (positive) opinion of Victor Hugo, Lamartine and Casimir Delavigne, and of all they owed to Chateaubriand.

A subscriber to the Globe since its foundation in 1824, Goethe had at his disposal a marvellous instrument of French information. In any case, he had little left to learn about France when David and Pavie visited him in August 1829. On the strength of his unhappy experience with Walter Scott in London, David d’Angers had taken precautions this time, and had a number of letters of recommendation for the people of Weimar, as well as two letters of introduction to Goethe, signed by Abbé Grégoire and Victor Cousin. To show the illustrious writer what he could do, he had placed some of his finest medallions in a crate.

Once in Weimar, David d’Angers and Victor Pavie encountered great difficulties in their quest, especially as the recipients of the letters of recommendation were all absent. Stricken with despair and fearing failure, David blamed his young friend Victor Pavie:

« Yes, you jumped in with the optimism of a young man, without giving me time to think and get out of the way. It wasn’t as a coward or under the patronage of an adventurer, it was head-on and resolutely that we had to tackle the character. (…) You’re only as good as what you are, it’s a yes or no question. You know me, on my knees before genius, and imployable before power. Ah! court poets, great or small, everywhere the same!

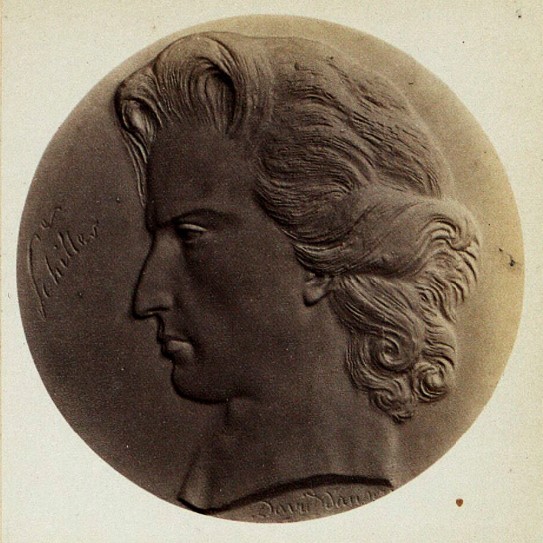

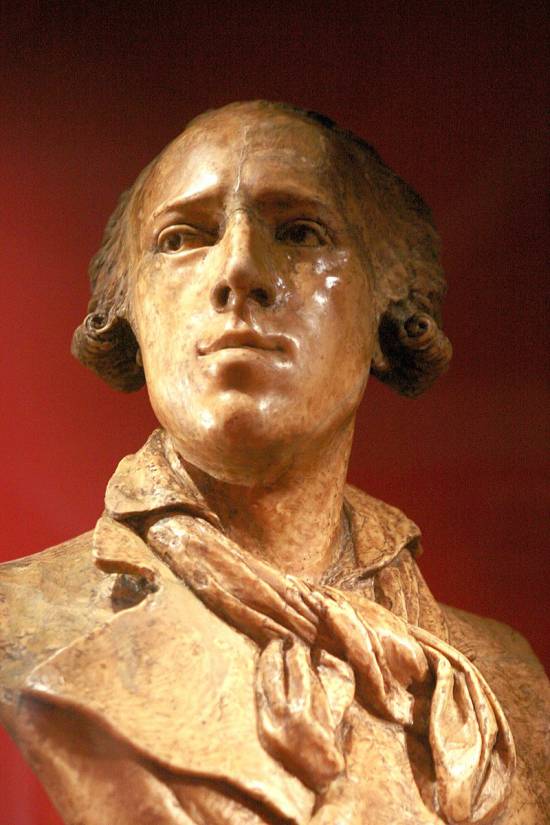

(…) And with a leap from the chair where he had insensitively let himself fall: Where’s Schiller? I’d like to kiss him! His grave, where I will strike, will not remain sealed for me; I will take him there, and bring him back glorious. What does it matter? Have I seen Corneille, have I seen Racine? The bust I’m planning for him will look all the better for it; the flash of his genius will gleam on his forehead. I’ll make him as I love and admire him, not with the pinched nose that Dannecker (image below) gave him, but with nostrils swollen with patriotism and freedom.

Victor Pavie’s account reveals the republican fervor animating the sculptor who, faithful to the ideals of Abbé Grégoire, was already thinking about the great anti-slavery sculpture he planned to create:

« At that moment, the half-open window of our bedroom, yielding to the evening breeze, opened wide. The sky was superb; the Milky Way unfurled with such brilliance that one could have counted the stars. He (David) remained silent for some time, dazzled; then, with that suddenness of impression that incessantly renewed the realm of feelings and ideas around him:

‘What a work, what a masterpiece! How poor we are compared to this!Would all your geniuses in one, writers, artists, poets, ever reach this incomparable poem whose tasks are splendors? Yet God knows your insatiable pretensions; we flay you in praise… And light! Remember this (and his presentiments in this regard were nothing less than a chimera), that such a one as received a marble bust from me as a token of my admiration, will one day literally lose the memory of it. – No, there is nothing more noble and great in humanity than that which suffers. I still have in my head, or rather in my heart, this protest of the human conscience against the most execrable iniquity of our times, the slave trade: after ten years of silence and suffering, it must burst forth with the voice of brass. You can see the group from here: the garroted slave, his eye on the sky, protector and avenger of the weak; next to him, lying broken, his wife, in whose bosom a frail creature is sucking blood instead of milk; at their feet, detached from the negro’s broken collar, the crucifix, the Man-God who died for his brothers, black or white. Yes, the monument will be made of bronze, and when the wind blows, you will hear the chain beating, and the rings ringing' ».

Finally, Goethe met the two Frenchmen, and David d’Angers succeeded in making his bust of the German poet. Victor Pavie:

« Goethe bowed politely to us, spoke the French language with ease from the start, and made us sit down with that calm, resigned air that astonished me, as if it were a simple thing to find oneself standing at eighty, face to face with a third generation, to which he had passed on through the second, like a living tradition.

(…) David carried with him, as the saying goes, a sample of his skills.He presented the old man with a few of his lively profiles, so morally expressive, so nervously and intimately executed, part of a great whole that is becoming more complete with our age, and which reserves for the centuries to come the monumental physiognomy of the 19th century. Goethe took them in his hand, considered them mute, with scrupulous attention, as if to extract some hidden harmony, and let out a muffled, equivocal exclamation that I later recognized as a mark of genuine satisfaction.Then, by a more intelligible and flattering transition, of which he was perhaps unaware, walking to his library, he charmingly showed us a rich collection of medals from the Middle Ages, rare and precious relics of an art that could be said to have been lost, and of which our great sculptor David has nowadays been able to recover and re-immerse the secret.

(…) The bust project did not have to languish for long: the very next day, one of the apartments in the poet’s immense house was transformed into a workshop, and a shapeless mound lay on the parquet floor, awaiting the first breath of existence. As soon as it slowly shifted into a human form, Goethe’s hitherto calm and impassive figure moved with it. Gradually, as if a secret, sympathetic alliance had developed between portrait and model, as the one moved towards life, the other blossomed into confidence and abandonment: we soon came to those artist’s confidences, that confluence of poetry, where the ideas of the poet and the sculptor come together in a common mold. He would come and go, prowling around this growing mass, (to use a trivial comparison) with the anxious solicitude of a landowner building a house. He asked us many questions about France, whose progress he was following with a youthful and active curiosity; and frolicking at leisure about modern literature, he reviewed Chateaubriand, Lamartine, Nodier, Alfred de Vigny, Victor Hugo, whose manner he had seriously pondered in Cromwell.

(…) David’s bust, writes Pavie, was as beautiful as Chateaubriand’s, Lamartine’s, Cooper’s, as any application of genius to genius, as the work of a chisel fit and powerful to reproduce one of those types created expressly by nature for the habitation of a great thought. Of all the likenesses attempted, with greater or lesser success, in all the ages of this long glory, from his youth of twenty to Rauch’s bust, the last and best understood of all, it is no prevention to say that David’s is the best, or, to put it even more bluntly, the only realization of that ideal likeness which is not the thing, but is more than the thing, nature taken within and turned inside out, the outward manifestation of a divine intelligence passed into human bark. And there are few occasions like this one, when colossal execution seems no more than a powerless indication of real effect. An immense forehead, on which rises, like clouds, a thick tuft of silver hair; a downward gaze, hollow and motionless, a look of Olympian Jupiter; a nose of broad proportion and antique style, in the line of the forehead ; then that singular mouth we were talking about earlier, with the lower lip a little forward, that mouth, all examination, questioning and finesse, completing the top with the bottom, genius with reason; with no other pedestal than its muscular neck, this head leans as if veiled, towards the earth:it’s the hour when the setting genius lowers his gaze to this world, which he still lights with a farewell ray. Such is David’s crude description of Goethe’s statue.- What a pity that in his bust of Schiller, so famous and so praised, the sculptor Dannecker prepared such a miserable counterpart!

When Goethe received his bust, he warmly thanked David for the exchange of letters, books and medallions… but made no mention of the bust ! For one simple reason: he didn’t recognize himself at all in the work, which he didn’t even keep at home… The German poet was depicted with an oversized forehead, to reflect his great intelligence. And his tousled hair symbolized the torments of his soul…

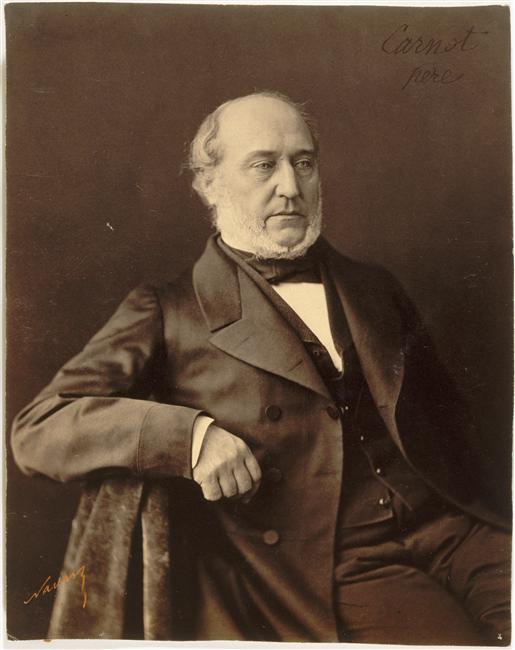

David d’Angers and Hippolyte Carnot

Among the founders of the SFAE (see earlier chapter on Abbé Grégoire) was Hippolyte Carnot (1801-1888), younger brother of Nicolas Sadi Carnot (1796-1832), pioneer of thermodynamics and son of « the organizer of victory », the military and scientific genius Lazare Carnot (1753-1823), whose work and struggle he recounted in his 1869 biography Mémoires sur Lazare Carnot 1753-1823 by his son Hippolyte.

In 1888, with the title Henri Grégoire, évêque (bishop) républicain, Hippolyte published the Mémoires of Grégoire the defender of all the oppressed of the time (negroes and Jews alike), a great friend of his father’s who had retained this friendship.

For the former bishop of Blois, « we must enlighten the ignorance that does not know and the poverty that does not have the means to know. »

Grégoire had been one of the Convention’s great « educators », and it was on his report that the Conservatoire des Arts-et-Métiers was founded on September 29, 1794, notably for the instruction of craftsmen. Grégoire also contributed to the creation of the Bureau des Longitudes on June 25, 1795 and the Institut de France on October 25, 1795.

Hippolyte Carnot and David d’Angers, who were friends, co-authored the Memoirs of Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (1755-1841), who acted as a sort of Minister of Information on the Comité de Salut Public, responsible for announcing the victories of the Republican armies to the Convention as soon as they arrived.

It was also Abbé Grégoire who, in 1826, commissioned David d’Angers, with the help of his friend Béranger, to bring some material and financial comfort to Rouget de Lisle (1860-1836), the legendary author of La Marseillaise, composed in Strasbourg when, in his old age, the composer was languishing in prison for debt.

Overcoming the sectarianism of their time, here are three fervent republicans full of compassion and gratitude for a musical genius who never wanted to renounce his royalist convictions, but whose patriotic creation would become the national anthem of the young French Republic.

Provisional Government

of the Second Republic

All these battles, initiatives and mobilizations culminated in 1848, when, for two months and 15 days (from February 24 to May 9), a handful of genuine republicans became part of the « provisional government » of the Second Republic.

In such a short space of time, so many good measures were taken or launched! Hippolyte Carnot was the Minister of Public Instruction, determined to create a high level of education for all, including women, following the models set by his father for Polytechnique and Grégoire for Arts et Métiers.

Article 13 of the 1848 Constitution « guarantees citizens (…) free primary education ».

On June 30, 1848, the Minister of Public Instruction, Lazare Hippolyte Carnot, submitted a bill to the Assembly that fully anticipated the Ferry laws, by providing for compulsory elementary education for both sexes, free and secular, while guaranteeing freedom of teaching. It also provided for three years’ free training at a teacher training college, in return for an obligation to teach for at least ten years, a system that was to remain in force for a long time. He proposed a clear improvement in their salaries. He also urged teachers « to teach a republican catechism ».

A member of the provisional government, the great astronomer and scientist François Arago (1886-1853) was Minister for the Colonies, having been appointed by Gaspard Monge to succeed him at the Ecole Polytechnique, where he taught projective geometry. His closest friend was none other than Alexander von Humboldt, friend of Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Friedrich Schiller.

He was another abolitionist activist who spent much of his adult life in Paris. Humboldt was a member of the Société d’Arcueil, formed around the chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet, where he also met, besides François Arago, Jean-Baptiste Biot and Louis-Joseph Gay-Lussac, with whom Humboldt became friends. They published several scientific articles together.

Humboldt and Gay-Lussac conducted joint experiments on the composition of the atmosphere, terrestrial magnetism and light diffraction, research that would later bear fruit for the great Louis Pasteur.

Napoleon, who initially wanted to expel Humboldt, eventually tolerated his presence. The Paris Geographical Society, founded in 1821, chose him as its president.

Humboldt, Arago, Schoelcher, David d’Angers and Hugo

Humboldt made no secret of his republican ideals. His Political Essay on the Island of Cuba (1825) was a bombshell. Too hostile to slavery practices, the work was banned from publication in Spain. London went so far as to refuse him access to its Empire.

Even more deplorably, John S. Trasher, who published an English-language version in 1856, removed the chapter devoted to slaves and the slave trade altogether! Humboldt protested vigorously against this politically motivated mutilation. Trasher was a slaveholder, and his redacted translation was intended to counter the arguments of North American abolitionists, who subsequently published the retracted chapter in the New York Herald and the US Courrier. Victor Schoelcher and the decree abolishing slavery in the French colonies.

In France, under Arago, the Under-Secretary of State for the Navy and the Colonies was Victor Schoelcher. He didn’t need much convincing to convince the astronomer that all the planets were aligned for him to act.

A Freemason, Schoelcher was a brother of David d’Angers’s lodge, « Les amis de la Vérité » (The Friends of Truth), also known as the Cercle social, in reality « a mixture of revolutionary political club, Masonic lodge and literary salon ».

On March 4, a commission was set up to resolve the problem of slavery in the French colonies. It was chaired by Victor de Broglie, president of the SFAE, to which five of the commission’s twelve members belonged. Thanks to the efforts of François Arago, Henri Wallon and above all Victor Schoelcher, its work led to the abolition of slavery on April 27.

Victor Hugo the abolitionist

Victor Hugo was one of the advocates of the abolition of slavery in France, but also of equality between what were still referred to as « the races » in the 19th century. « The white republic and the black republic are sisters, just as the black man and the white man are brothers », Hugo asserted as early as 1859. For him, as all men were creations of God, brotherhood was the order of the day.

When Maria Chapman, an anti-slavery campaigner, wrote to Hugo on April 27, 1851, asking him to support the abolitionist cause, Hugo replied: « Slavery in the United States! » he exclaimed on May 12, « is there any more monstrous misinterpretation? » How could a republic with such a fine constitution preserve such a barbaric practice?

Eight years later, on December 2, 1859, he wrote an open letter to the United States of America, published by the free newspapers of Europe, in defense of the abolitionist John Brown, condemned to death.

Starting from the fact that « there are slaves in the Southern states, which indignifies, like the most monstrous counter-sense, the logical and pure conscience of the Northern states », he recounts Brown’s struggle, his trial and his announced execution, and concludes: « there is something more frightening than Cain killing Abel, it is Washington killing Spartacus ».

A journalist from Port-au-Prince, Exilien Heurtelou, thanked him on February 4, 1860. Hugo replied on March 31:

« Hauteville-House, March 31, 1860.

You are, sir, a noble sample of this black humanity so long oppressed and misunderstood.

From one end of the earth to the other, the same flame is in man; and blacks like you prove it. Was there more than one Adam? Naturalists can debate the question, but what is certain is that there is only one God.

Since there is only one Father, we are brothers.

It is for this truth that John Brown died; it is for this truth that I fight. You thank me for this, and I can’t tell you how much your beautiful words touch me.

There are neither whites nor blacks on earth, there are spirits; you are one of them. Before God, all souls are white.

I love your country, your race, your freedom, your revolution, your republic. Your magnificent, gentle island pleases free souls at this hour; it has just set a great example; it has broken despotism. It will help us break slavery. »

Also in 1860, the American Abolitionist Society, mobilized behind Lincoln, published a collection of speeches. The booklet opens with three texts by Hugo, followed by those by Carnot, Humboldt and Lafayette.

On May 18, 1879, Hugo agreed to preside over a commemoration of the abolition of slavery in the presence of Victor Schoelcher, principal author of the 1848 emancipation decree, who hailed Hugo as « the powerful defender of all the underprivileged, all the weak, all the oppressed of this world » and declared:

« The cause of the Negroes whom we support, and towards whom the Christian nations have so much to reproach, must have had your sympathy; we are grateful to you for attesting to it by your presence in our midst. »

A start for the better

Another measure taken by the provisional government of this short-lived Second Republic was the abolition of the death penalty in the political sphere, and the abolition of corporal punishment on March 12, as well as imprisonment for debt on March 19.

In the political sphere, freedom of the press and freedom of assembly were proclaimed on March 4. On March 5, the government instituted universal male suffrage, replacing the censal suffrage in force since 1815. At a stroke, the electorate grew from 250,000 to 9 million. This democratic measure placed the rural world, home to three quarters of the population, at the heart of political life for many decades to come. This mass of new voters, lacking any real civic training, saw in him a protector, and voted en masse for Napoleon III in 1851, 1860 and 1870.

Victor Hugo

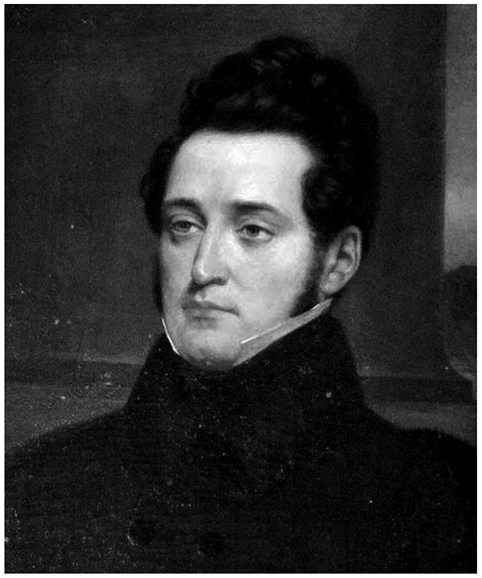

To return to David d’Angers, a lasting friendship united him with Victor Hugo (1802-1885). Recently married, Hugo and David would meet to draw. The poet and the sculptor enjoyed drawing together, making caricatures, painting landscapes or « architectures » that inspired them.

A shared ideal united them, and with the arrival of Napoleon III, both men went into political exile.

Out of friendship, David d’Angers made several busts of his friend. Hugo is shown wearing an elegant contemporary suit.

His broad forehead and slightly frowning eyebrows express the poet’s greatness, yet to come. Refraining from detailing the pupils, David lends this gaze an inward, pensive dimension that prompted Hugo to write: « my friend, you are sending me immortality. »

In 1842, David d’Angers produced another bust of Victor Hugo, crowned with laurel, where this time it was not Hugo the close friend who was evoked, but rather the genius and great man.

Finally, for Hugo’s funeral in 1885, the Republic of Haiti wished to show its gratitude to the poet by sending a delegation to represent it. Emmanuel-Edouard, a Haitian writer, presided over the delegation, and made the following statement at the Pantheon:

The Republic of Haiti has the right to speak on behalf of the black race; the black race, through me, thanks Victor Hugo for having loved and honored it so much, for having strengthened and comforted it.

The four bas-reliefs

of the Gutenberg statue

Once the reader has identified this « great arch » that runs through history, and the ideas and convictions that inspired David d’Angers, he will grasp the beautiful unity underlying the four bas-reliefs on the base of the statue commemorating Gutenberg in Strasbourg.

What stands out is the very optimistic idea that the human race, in all its great and magnificent diversity, is one and fraternal. Once freed from all forms of oppression (ignorance, slavery, etc.), they can live together in peace and harmony.

These bronze bas-reliefs were added in 1844. After bitter debate and contestation, they replaced the original 1840 painted plaster models affixed at the inauguration. They represent the benefits of printing in America, Africa, Asia and Europe. At the center of each relief is a printing press surrounded by characters identified by inscriptions, as well as schoolteachers, teachers and children.

To conclude, here’s an extract from the inauguration report describing the bas-reliefs. Without falling into wokism (for whom any idea of a « great man » is necessarily to be fought), let’s point out that it is written in the terms of the time and therefore open to discussion:

Plaster model for the base of the statue of Gutenberg, David d’Angers.

« Europe

is represented by a bas-relief featuring René Descartes in a meditative attitude, beneath Francis Bacon and Herman Boerhaave. On the left are William Shakespeare, Pierre Corneille, Molière and Racine. One row below, Voltaire, Buffon, Albrecht Dürer, John Milton and Cimarosa, Poussin, Calderone, Camoëns and Puget. On the right, Martin Luther, Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, Copernicus, Wolfgang Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Hegel, Richter, Klopstock. Rejected on the side are Linné and Ambroise Parée. Near the press, above the figure of Martin Luther, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Rousseau and Lessing. Below the tier, Volta, Galileo, Isaac Newton, James Watt, Denis Papin and Raphaël. A small group of children study, including one African and one Asian.«

Plaster model for the base of the statue of Gutenberg, David d’Angers.

« Asia.

A printing press is shown again, with William Jones and Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron offering books to Brahmins, who give them manuscripts in return. Near Jones, Sultan Mahmoud II is reading the Monitor in modern clothes, his old turban lies at his feet, and nearby a Turk is reading a book. One step below, a Chinese emperor surrounded by a Persian and a Chinese man is reading the Book of Confucius. A European instructs children, while a group of Indian women stand by an idol and the Indian philosopher Rammonhun-Roy.«

« Africa.

Leaning on a press, William Wilberforce hugs an African holding a book, while Europeans distribute books to other Africans and are busy teaching children. On the right, Thomas Clarkson can be seen breaking the shackles of a slave. Behind him, Abbé Grégoire helps a black man to his feet and holds his hand over his heart. A group of women raise their recovered children to the sky, which will now see only free men, while on the ground lie broken whips and irons. This is the end of slavery.«

« America.

The Act of Independence of the United States, fresh from the press, is in the hands of Benjamin Franklin. Next to him stand Washington and Lafayette, who holds the sword given to him by his adopted homeland to his chest. Jefferson and all the signatories of the Act of Independence are assembled. On the right, Bolivar shakes hands with an Indian. »

America

We can better understand the words spoken by Victor Hugo on November 29, 1884, shortly before his death, during his visit to the workshop of sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, where the poet was invited to admire the giant statue bearing the symbolic name « Liberty Enlightening the World », built with the help of Gustave Eiffel and ready to leave for the United States by ship. A gift from France to America, it will commemorate the active part played by Lafayette’s country in the Revolutionary War.

Initially, Hugo was most interested in American heroes and statesmen: William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, John Brown and Abraham Lincoln. Role models, according to Hugo, who enabled the people to progress. For the French politician who became a Republican in 1847, America was the example to follow. Even if he was very disappointed by the American position on the death penalty and slavery.

After 1830, the writer abandoned this somewhat idyllic vision of the New World and attacked the white « civilizers » who hunted down Indians:

« You think you civilize a world, when you inflame it with some foul fever [4], when you disturb its lakes, mirrors of a secret god, when you rape its virgin, the forest. When you drive out of the wood, out of the den, out of the shore, your naive and dark brother, the savage… And when throwing out this useless Adam, you populate the desert with a man more reptilian… Idolater of the dollar god, madman who palpitates, no longer for a sun, but for a nugget, who calls himself free and shows the appalled world the astonished slavery serving freedom!«

(NOTE 5)

Overcoming his fatigue, in front of the Statue of Liberty, Hugo improvised what he knew would be his last speech:

« This beautiful work tends towards what I have always loved, called: peace between America and France – France which is Europe – This pledge of peace will remain permanent. It was good that it was done!«

NOTES:

1. If the phrase appears in the Book of Genesis, it could also refer to Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) a novel by Victor Hugo, a great friend of the statue’s sculptor, David d’Angers. We know from a letter Hugo wrote in August 1832 that the poet brought David d’Angers the eighth edition of the book. The scene most directly embodied in the statue is the one in which the character of Frollo converses with two scholars (one being Louis XI in disguise) while pointing with one finger to a book and with the other to the cathedral, remarking: « Ceci tuera cela » (This will kill that), i.e. that one power (the printed press), democracy, will supplant the other (the Church), theocracy, a historical evolution Hugo thought ineluctable.

2. It was the encounter with Asia that brought countless technical know-how and scientific discoveries from the East to Europe, the best-known being the compass and gunpowder. Just as essential to printing as movable type was paper, the manufacture of which was perfected in China at the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (around the year 185). As for printing, the oldest printed book we have to date is the Diamond Sutra, a Chinese Buddhist scripture dating from 868. Finally, it was in the mid-11th century, under the Song dynasty, that Bi Sheng (990-1051) invented movable type. Engraved in porcelain, a viscous clay ceramic, hardened in fire and assembled in resin, they revolutionized printing. As documented by the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, it was the Korean Choe Yun-ui (1102-1162) who improved this technique in the 12th century by using metal (less fragile), a process later adopted by Gutenberg and his associates. The Anthology of Zen Teachings of Buddhist High Priests (1377), also known as the Jikji, was printed in Korea 78 years before the Gutenberg Bible, and is recognized as the world’s oldest book with movable metal type.

3. Etienne Taillemite, Lafayette and the abolition of slavery.

4. Victor Hugo undoubtedly wanted to rebound on the news that reached him from America. The Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic of 1862, which was brought from San Francisco to Victoria, devastated the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest coast, with a mortality rate of over 50% along the entire coast from Puget Sound to southeast Alaska. Some historians have described the epidemic as a deliberate genocide, as the colony of Vancouver Island and the colony of British Columbia could have prevented it, but chose not to, and in a way facilitated it.

5. Victor Hugo, La civilisation from Toute la lyre (1888 and 1893).

On Leonardo da Vinci’s « Vitruvian Man »

By Karel Vereycken

Leonardo da Vinci’s « Viruvian Man ». Since we’re commemorating this year (2019) Leonardo Da Vinci, who died 500 years ago, many silly things are presented by fake scholars trying to make a real living.

Since I was introduced into the canon of proportions of the human body during my training as a professional painter and engraver, I want offer you some hints on how to look at what is called Da Vinci’s « Vitruvian man », a drawing currently on exhibit at the Da Vinci show at the Louvre in Paris.

Hence, as Leonardo underlines himself in his notebooks, adopting Cusanus wordings, it is only with the « eyes of the mind » that art becomes visible, because the « eyes of the flesh » are intrensically blind to it.

Canons of proportions

Europe, and Classical Greece, as everybody should know, emerged largely by absorbing several major discoveries accomplished much earlier by other civilizations. Much of it came from Asia, but African and especially Egypt, were key.

The very practice of mummification, a process which takes at least 60 days of work, made Egypt the key area of anatomical research.

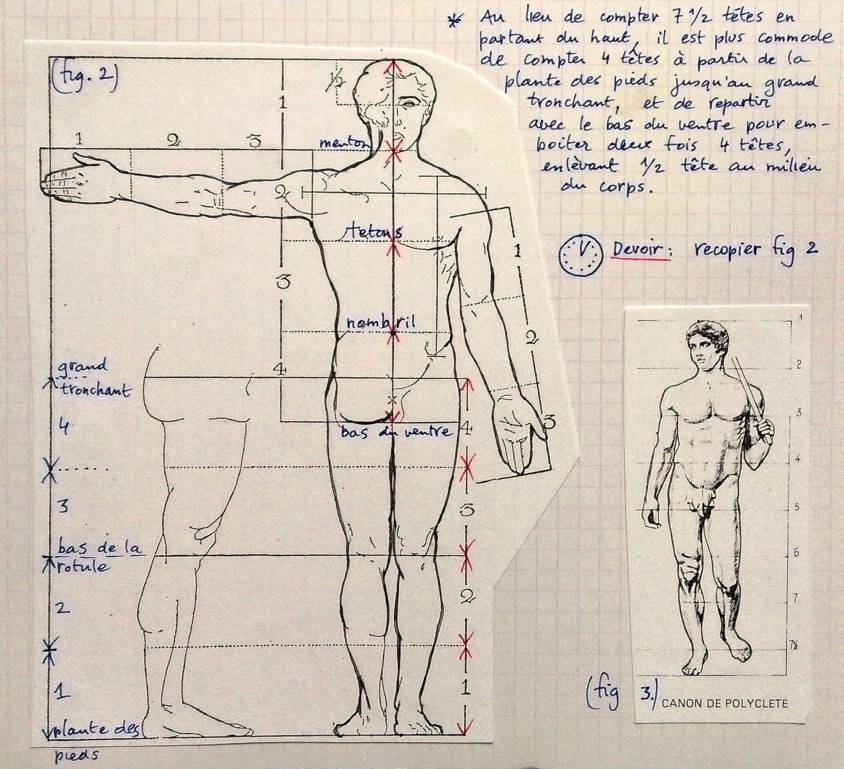

As demonstrated by early Egyptian sculpture, the exact size of the entire adult human body is 7,5 times the size of the head. The size of a newborn is only four heads, that of a seven year old, six heads and that of a 17 years old adolescent, 7 heads.

If one subdivides the overall 7.5 proportion, for an adult, from the top of the head till the lowest part of the torso, one measures four heads, one till the nipples, one till the belly button and a fourth one till the lowest part of the pubis. Going up from the sole till the middle of the pelvis, one measures 3.5 heads: 2 heads till the knee and 1.5 till the middle of the pelvis. That brings the total till 7.5 heads for the entire length of the adult human body and it is proportional in the sense that people with smaller heads also have small bodies.

Polikleitos versus Lysippus

In the Vth Century BC, the Greek sculptor Polikleitos’ spear bearer (The “Doryphoros”) of Naples National Archeological Museum applied this most beautiful canon of proportions, known as the “Polikleitos canon”.

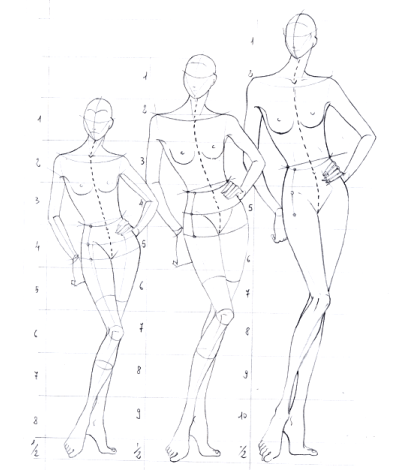

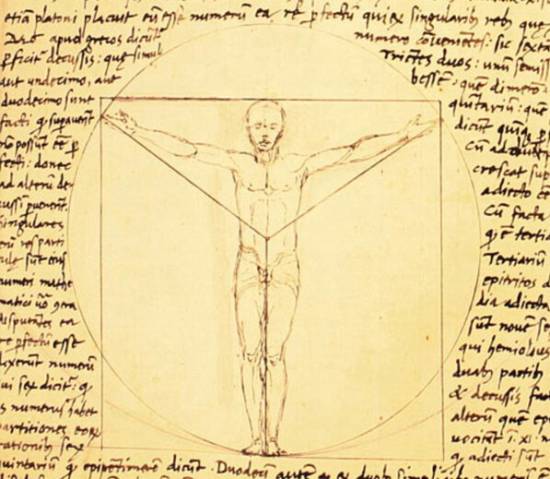

During the Renaissance, the nostalgics of the Roman Empire preferred another Greek canon, that of Greek sculptor Lysippus (4th Century BC), formalized by the Roman author, architect and civil engineer, Vitrivius (1st century BC).

Vitruvius only transcribed the prevalent taste of his epoch. Roman sculptors, in order to give an athletic and heroic look to the Emperors which they were portraying, adopting the canon of Lysippus, could reduce the head of their models to only an eight of the total length of the body. The trick was that by reducing the relative size of the head, the body looked more preeminent and powerful, something most emperors, who were often physical failures, appreciated and secured their popularity. Even extreme cases of 12 to 15 heads of body length appeared. In short, Public relations ruled at the detriment of science and truth.

Today’s comic strip drawers chose proportions according to purpose:

–For real life, 7.5 or “normal canon”

–For a movie star, 8 heads, with the “idealistic canon”;

–For a fashion magazine: 8.5 heads;

–For a comic book hero: 9 heads for the “heroic canon”

Vitruvian man

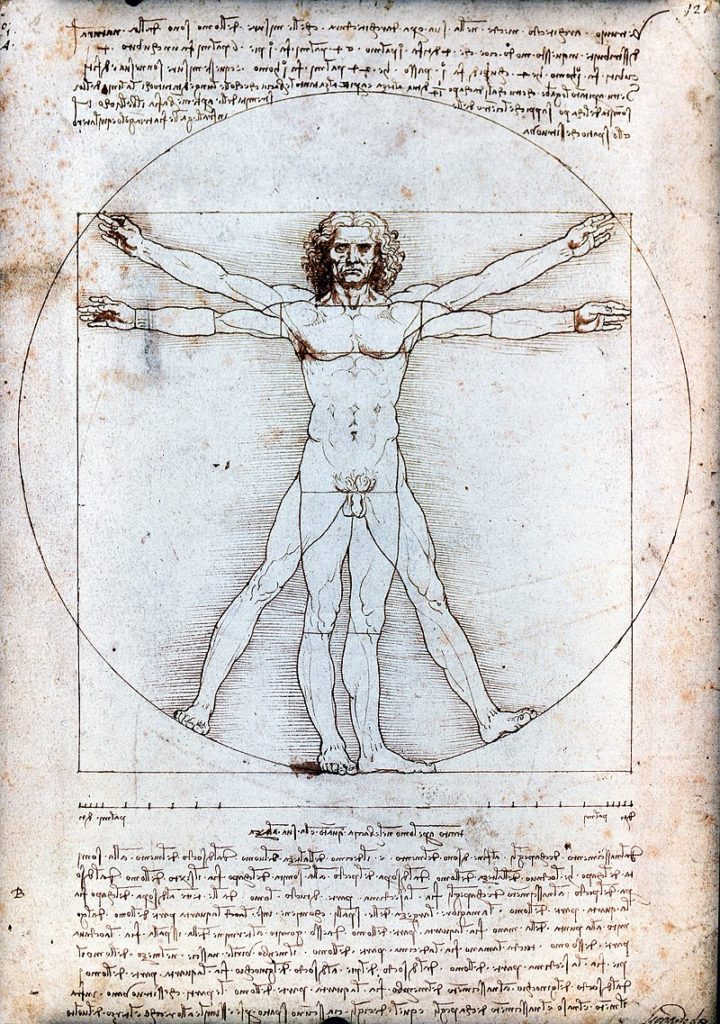

Text accompanying Leonardo DaVinci’s Vitruvian Man:

Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture that the measurements of the human body are distributed by Nature as follows that is that 4 fingers make 1 palm, and 4 palms make 1 foot, 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man’s height. And 4 cubits make one pace and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in his buildings. If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the centre of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle.

The length of a man’s outspread arms is equal to his height.

From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth of a man’s height; from the bottom of the chin to the top of his head is one eighth of his height; from the top of the breast to the top of his head will be one sixth of a man. From the top of the breast to the roots of the hair will be the seventh part of the whole man. From the nipples to the top of the head will be the fourth part of a man. The greatest width of the shoulders contains in itself the fourth part of the man. From the elbow to the tip of the hand will be the fifth part of a man; and from the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be the eighth part of the man. The whole hand will be the tenth part of the man; the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man. The foot is the seventh part of the man. From the sole of the foot to below the knee will be the fourth part of the man. From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be the fourth part of the man. The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the roots of the hair to the eyebrows is, in each case the same, and like the ear, a third of the face.

Of course, Da Vinci’s exploration of the Vitruvian man doesn’t mean he approves or disapproves the stated fakery in proportions.

Soul or muscle?

It should be known that in Italy, the pure Roman taste has become trendy again following the discovery in 1506 of the statue of the Laocoon on the site of Nero’s villa in Rome. From that moment, artist will feel obliged to increase the volume of the muscular masses in order to appear as working « in Antique style ».

Although Leonardo never openly criticized this trend, it is hard not to think of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, when the artist, seeking to raise the spirit to unequalled philosophical heights, advised painters: « do not give all the muscles of the figures an exaggerated volume » and « if you act differently, it is more a sort of representation of a sack of nuts that you will have achieved than to that of a human figure » (Codex Madrid II, 128r).

No doubt inspired by his friend, the architect Giacomo Andrea, in « The Vitruvian Man », Leonardo is above all interested by other harmonies: if a person extends his arms in a direction parallel to the ground, one obtains the same length as one’s entire height. This equality is inscribed by Leonardo in a square (symbol of the earthly realm). But if one stretches his arms and legs in a star shape, they are inscribed in a circle whose center is the navel. The location of the navel divides the body according to the golden ratio (in this example 5 heads out of a total of 8 heads, 5+3 being part of the Fibonnacci series: 1+2 = 3; 3+2 = 5; 5+3 = 8; 8+5 = 13; 13+8 = 21, etc.).

Leonardo clearly understood what the golden section really means: not a “magical” number in itself, but the reflexion of the dynamic of least action, the very principle uniting man (the square) with the creator and the universe (the circle).

So if you take a look, beware of what you see and especially what you don’t !

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on mars 13, 2022

Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio et l’art du commandement militaire

Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio et l’art du commandement militaire. Enquête et réflexions sur les événements clés et les réalisations artistiques qui ont fait la Renaissance. Par Karel Vereycken, Paris.

Prologue

S’il y a encore beaucoup à dire, à écrire et à apprendre sur les grands génies de la Renaissance européenne, il est temps aussi de s’intéresser à ceux que l’historien Georgio Vasari appela avec condescendance des « figures de transition ».

Comment mesurer l’apport de Pieter Bruegel l’Ancien sans connaître Pieter Coecke van Aelst ? Comment apprécier l’œuvre de Rembrandt sans connaître Pieter Lastman ? En quoi Raphaello Sanzio a-t-il innové par rapport à son maître Le Pérugin ?

En 2019, une exposition remarquable consacrée à Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-1488), à la National Gallery de Washington, a mis en lumière ses grandes réalisations, fulgurances étonnantes d’une beauté inouïe que son élève Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) a su théoriser et mettre à profit.

Le sfumato de Léonard ? Verrocchio en est le pionnier, notamment dans ses portraits de femmes, exécutés aux traits estompés combinant le crayon, la craie et la gouache.

Une découverte

En feuilletant le catalogue de cette exposition, ma joie fut grande en découvrant (et à ma connaissance, personne avant moi ne semble l’avoir remarqué) que l’image de l’ange énigmatique qui rencontre l’œil du spectateur dans le tableau de Léonard intitulé La Vierge aux rochers (1483-1486) (Louvre, Paris), à part sa posture plus posée, n’est grosso modo qu’une « citation visuelle » d’un haut-relief en terre cuite (Louvre, Paris) réalisé, nous dit-on, par « Verrocchio et un assistant ».

L’hypothèse qu’il s’agisse de Léonard en personne est plus que tentante, étant donné sa présence comme apprenti auprès du maître !

Bien d’autres ont fait leurs débuts dans l’atelier de Verrocchio, notamment Lorenzo de Credi, Sandro Botticelli, Piero Perugino (maître de Raphaël) et Domenico Ghirlandaio (maître de Michel-Ange).

S’inscrivant dans la tradition des grands chantiers lancés à Florence par le grand mécène de la Renaissance Côme de Medicis pour la réalisation des « portes du Baptistère » et l’achèvement de la coupole de Florence par Philippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), Verrocchio conçoit son atelier comme une véritable école « polytechnique ».

A Florence, pour les artistes, les commandes affluent. Afin de pouvoir répondre à toutes les demandes, Verrocchio, ayant lui-même reçu une formation d’orfèvre, forme ses élèves comme artisans-ingénieurs-artistes : dessin, anatomie, perspective, géologie, sculpture, travail des métaux, de la pierre et du bois, architecture, décoration intérieure, poésie, musique et enfin, peinture. Un niveau de liberté et une exigence de créativité malheureusement disparus depuis longtemps.

En peinture, Verrocchio aurait fait ses débuts chez le peintre Fra Filippo Lippi (1406-1469). Quant au métier de fondeur de bronze, il aurait été, comme Donatello, Masolino, Michelozzo, Uccello et Pollaiuolo, l’un des apprentis recrutés par Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455) dont l’atelier, à partir de 1401 et pendant plus de quarante ans, est chargé de concevoir et de réaliser les bas-reliefs en bronze de deux des immenses portes du Baptistère de Florence.

D’autres suggèrent que Verrocchio aurait été formé par Michelozzo, l’ancien compagnon de Ghiberti devenu par la suite l’associé en affaires de Donatello. Adolescent, ce dernier avait accompagné Brunelleschi lorsqu’il se rendait à Rome pour y étudier l’héritage de l’art grec et romain, et pas seulement au niveau architectural.

L’héritage humaniste de Ghiberti

En réalité, Verrocchio n’a fait que faire sienne l’approche de l’atelier « polytechnique » de Ghiberti, avec qui il avait appris le métier.

Excellent artisan qu’on accuse à tort d’être resté accroché au « style gothique », lui aussi est orfèvre, collectionneur d’art, musicien, lettré humaniste et historien.

Son génie, c’est d’avoir compris l’importance de la pluridisciplinarité pour les artistes. Selon lui « la sculpture et la peinture sont des sciences de plusieurs disciplines agrémentées de différents enseignements. »

Les dix disciplines qu’il juge important pour former les artistes sont la grammaire, la philosophie, l’histoire. Suivent ensuite la perspective, la géométrie, le dessin, l’astronomie, l’arithmétique, la médecine et l’anatomie.

On ne peut découvrir, pense Ghiberti, que lorsqu’on est parvenu à isoler l’objet de sa recherche de facteurs interférant, et on ne peut trouver qu’en se détachant d’un système dogmatique ;

Anticipant le type de biomimétisme qui va caractériser Léonard par la suite, Ghiberti affirme qu’il a cherché

Ghiberti, qui fréquente le cercle des humanistes animé par Ambrogio Traversari, a le souci de s’appuyer sur l’autorité des textes anciens, en particulier arabes :

Bien que volontairement ignoré et calomnié par Vasari, le livre des Commentaires de Ghiberti constitue un véritable manuel pour les artistes, écrit par un artiste. C’est d’ailleurs en lisant ce manuscrit que Léonard de Vinci se familiarise avec d’importantes contributions arabes à la science, en particulier l’œuvre remarquable d’Alhazen, dont le traité d’optique venait d’être traduit du latin en italien sous le titre De li Aspecti, œuvre longuement citée par Ghiberti dans son Commentario terzo. Saint Jean-Baptiste, bronze réalisé par Ghiberti, Orsanmichele, Florence.

Dans ce manuscrit, les apports de Ghiberti sont modestes. Cependant, pour les élèves de son élève Verrocchio, comme Léonard, qui ne maîtrisaient aucune langue étrangère, le livre de Ghiberti mettait à leur disposition en italien une série de citations originales de l’architecte romain Vitruve, de scientifiques et de polymathes arabes comme Alhazen, Avicenne, Averroès et de scientifiques européens ayant étudié l’optique arabe, tels que les franciscains d’Oxford Roger Bacon et John Pecham ou encore le moine polonais Witelo (Vitellion) à Padou.

Ce qui fait dire à l’historien A. Mark Smith que, par l’intermédiaire de Ghiberti, le Livre d’optique d’Alhazen

Enfin, en 1412, tout en coordonnant les travaux de la porte du Baptistère, Ghiberti est aussi, avec son Saint Jean-Baptiste, le premier sculpteur de la Renaissance à couler une statue en bronze d’une hauteur de 255 cm pour décorer Orsanmichele, la maison des Corporations à Florence.

La fonte « à la cire perdue »

Pour réaliser des bronzes d’une telle taille, vu le prix du métal, les artistes font appel à la technique dite de « fonte à la cire perdue ».

Elle consiste à confectionner d’abord un modèle en terre réfractaire (A), recouvert d’une épaisseur de cire correspondant à l’épaisseur de bronze recherchée (B). Ce modèle est ensuite recouvert d’une épaisse couche de plâtre qui, en se solidifiant, forme un moule extérieur. En pénétrant dans ce moule par des tiges prévues à cet effet (J), le bronze en fusion va se substituer à la cire. Enfin, une fois le métal solidifié, on brise le revêtement (K). Reste alors à affûter les détails et polir l’ensemble selon le choix de l’artiste (L).

Cette technique s’avérera par la suite fort utile pour fabriquer des canons et des cloches. Si elle semble avoir été parfaitement maîtrisée en Afrique, notamment à Ifé dès le XIIe siècle, en Europe, ce n’est qu’à la Renaissance, avec les commandes reçues par Ghiberti et Donatello, qu’elle sera entièrement réinventée.

En 1466, à la mort de Donatello, c’est Verrocchio qui devient à son tour le sculpteur en titre des Médicis pour lesquels il réalise une série d’œuvres, notamment, après Donatello, son propre David en bronze (musée national du Bargello, Florence).

Si, avec cette promotion, son ascendance sociale est certaine, Verrocchio se trouve devant le plus grand défi qu’un artiste de la Renaissance ait pu imaginer : comment égaler, voire dépasser Donatello, un artiste dont on n’a jamais assez loué le génie ?

L’art équestre

Le décor ainsi planté, abordons maintenant le sujet de l’art du commandement militaire en comparant quatre monuments équestres :

A) l’empereur romain Marc-Aurèle, sur la place du Capitole à Rome (175 après J.-C.) ;

B) la fresque de John Hawkwood par Paolo Uccello, dans l’église de Santa Maria del Fiore à Florence (1436) ;

C) Erasmo da Narni, dit « Gattamelata » (1446-1450), réalisé par Donatello à Padoue ;

D) Bartolomeo Colleoni par Andrea del Verrocchio à Venise (1480-1488).

Les statues équestres sont apparues en Grèce au milieu du VIe siècle avant J.-C. pour honorer les cavaliers victorieux d’une course. À partir de l’époque hellénistique, elles sont réservées aux plus hauts personnages de l’État, souverains, généraux victorieux et magistrats. À Rome, sur le forum, elles constituaient un honneur suprême, soumis à l’approbation du Sénat. Réalisées en bronze, ces statues équestres se dressent le plus souvent à l’endroit où les troupes ont combattu. Si chaque statue rappelle l’importance du commandement militaire et politique, la manière d’exercer cette responsabilité est bien différente.

A. Marc Aurèle à Rome