Étiquette : Da Vinci

Raphael 1520-2020: What Humanity can learn from « The School of Athens »

On the occasion of the five-hundredth anniversary of the death of the Italian painter Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), several exhibitions are honoring this artist, notably in Rome, Milan, Urbino, Belgrade, Washington, Pasadena, London, and Chantilly in France.

The master is honored, but what do we really know about the intention and meaning of his work?

Introduction

There is no doubt that in the collective mind of the West, Raphael, along with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, appears as one of the most brilliant artists and even as the best embodiment of the « Italian Renaissance”.

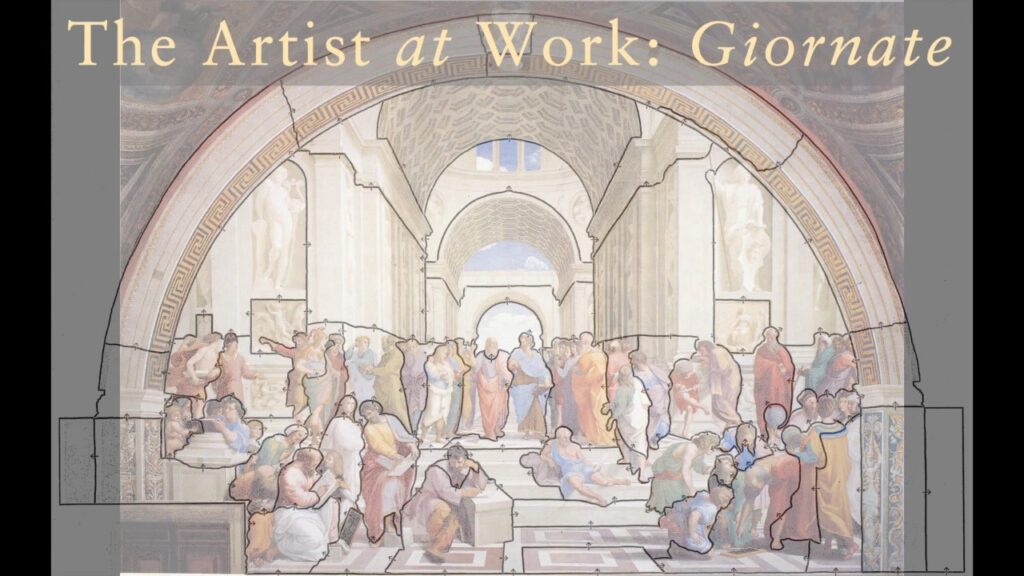

Although he died at the age of 37, Raphael was able to reveal his immense talent to the world, in particular by giving birth, between 1509 and 1511, to several monumental frescoes in the Vatican, the most famous of which, 7.7 meters long and 5 meters high, is known as The School of Athens.

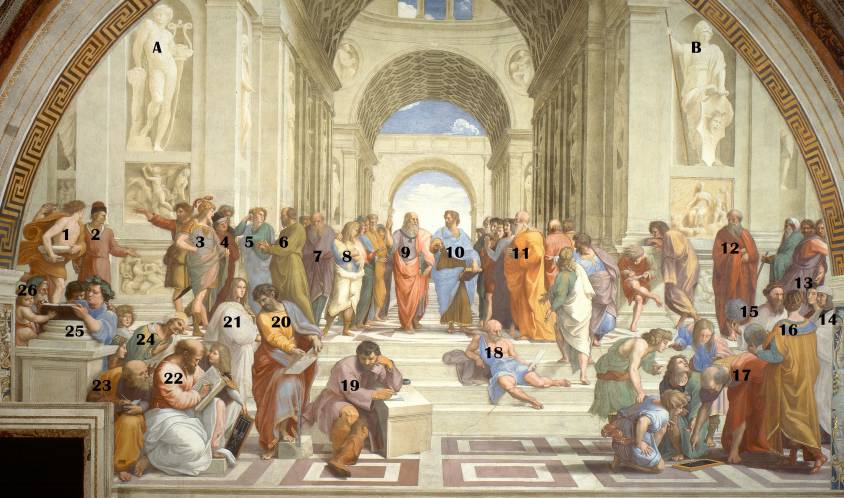

The viewer finds himself inside a building that brings together the thoughts of all mankind: united in a timeless space, fifty philosophers, mathematicians and astronomers of all ages meet to discuss their vision of man and nature.

The image of this fresco embodies so powerfully the « ideal » of a democratic republic, that in France, during the February 1848 revolution, the painting representing Louis Philippe (till then hanging behind the President of the National Assembly) was taken down and replaced by a representation of Raphael’s fresco, in the form of a tapestry from the Manufacture des Gobelins, produced between 1683 and 1688 at the request of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the founder of the French Academy of Sciences.

Then, in France, arrived the idea that Raphael, being « the Prince of painters », embodied « the ultimate artist ». Superior to Rubens or Titian, Raphael was thought to have achieved the subtle « synthesis » between the « divine grace » of a Leonardo da Vinci and the « silent strength » of a Michelangelo. What more can be said ? A true observation as long as one looks only at the purity of the « forms » and thus of the « style ». Adored or hated, Raphael was erected in France as a model to be imitated by every young talent attending our Academies of Fine Arts.

Hence, for five centuries, artists, historians and connoisseurs have not ceased to comment and often to confront each other, not on the intention or the meaning of the artist’s works, but on his style! In a way akin to some of our contemporaries who adore Star Wars and its special effects without paying attention to the ideology that, underhandedly, this TV series conveys…

For this brand of historians, « iconography », that branch of art history which is interested in the subjects represented, in the possible interpretations of the compositions or particular details, is only really useful to appreciate the « more primitive » paintings, that is to say that of the « Northern Schools »…

One knows well, especially in France, that once the « form » takes the appearance of perfection, it does not matter what the content is! This or that writer tells abject horrors, but « it is so well written! »

The good news is that in the last twenty years or so, a handful of leading historians and especially female art historians, have undertaken and published in depth new research.

I am thanking in particular of Marcia Hall (Temple University), Ingrid D. Rowland (University of Chicago), Reverend Timothy Verdon (Florence and Stanford), Jesuit historian John William O’Malley, and especially Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier.

The latter’s book Raphael’s Stanza della Signatura, Meaning and Invention (Cambridge University Press, 2002), which I was able to read (thanks to the pandemic lockdown), allowed me to adjust some of the leads and intuitions I had summarized in 2000 in, let’s be honest, a rather messy note.

If my work had consisted in trying to give some coherence to what is in the public domain, through their assiduous archival work in the Vatican and elsewhere, these historians, for whom neither Latin nor Greek have any secrets, have largely contributed to shed new light on the political, philosophical, cultural and religious context that contributed to the genesis of Raphael’s work.

Enriched by these readings, I have tried here, in a methodical way, to « make readable » what is rightly considered Raphael’s major work, The School of Athens.

Instead of identifying and commenting from the outset on the figures we see in the Stanza della Segnatura (« Room of the Segnatura” of the Vatican in Rome), I have chosen first to sketch a few backgrounds that serve as “eye-openers” to penetrate this work. For, in order to detect the painter’s intentions, actions and feelings, it is essential to penetrate the spirit of the epoch that engendered the artist’s: those days political and economic challenges, the cultural heritage of Rome and the Church, a close-up on the pope who commissioned the work, the philosophical convictions of the advisors who dictated the theme of the work, etc.

However, if all this seems too tedious for you dear reader, or if you are just eager to familiarize yourself with the work, nothing prevents you from going back and forth between the deciphering of the frescoes at the end of this article (Guided visit) and the contextualization that precedes them.

Cleaning our eyeglasses

To see the world as it is, let’s wipe our glasses and stop looking at the tint of our glasses. For as is often the case, what « prevents » the viewer from penetrating a work, from seeing its intention and meaning, is not what his eyes see as such, but the preconceived ideas that prevents him from looking at the outside world. Learning to see usually starts by challenging some of our preconceptions.

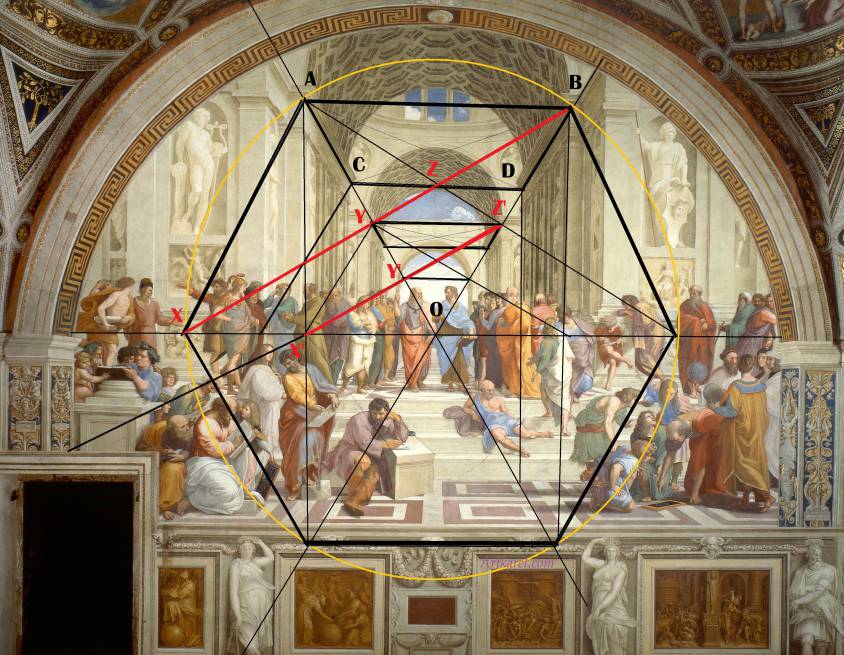

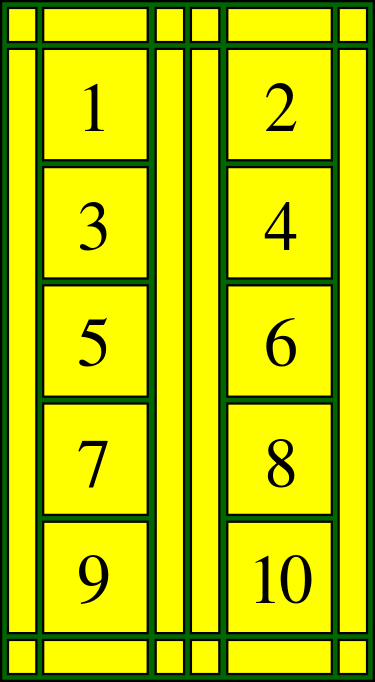

1. It’s not a easel painting! Since the 16th century, we Europeans have been thinking in terms of « easel paintings » (as opposed to mural). The artist paints on a support, a wooden panel or a canvas, which the client then hangs on the wall. However, The School of Athens, as such, is not a « painting » of this type, but simply, in the strict sense, a part or a « detail » of what we would call today, « an installation ». I explain myself. What constitutes the work here is the whole of the frescoes and decorations covering the ceiling, the floor and the four walls of the room! We will explain them to you. The viewer is, in a way, inside a cube that the artist has tried to make appear as a sphere. So, to « explain » the meaning of The School of Athens, in isolation from the rest and without demonstrating the thematic and symbolic interconnections with the iconography of the other walls, the ceiling and the floor, is not only an exercise in futility but utter incompetence.

2. Error of title! Neither at the time of its commission, nor at the time of its realization or in the words of Raphael, the fresco carried the name “School of Athens”! That name was given later. Everything indicates that the entire room covered with frescoes was to express a divine harmony uniting Philosophy (The School of Athens), Theology (on the opposite side), Poetry (on its right side) and Justice (on its left side). We will come back to that.

3. The theme is not the artist’s choice! The only person who met both Raphael and Pope Julius II during his lifetime was the physician Paolo Giovio (1483-1552) who arrived in Rome in 1512, a year before the death of Julius II. According to Giovio, it was the pontiff himself who, as early as 1506, that is, two years before Raphael’s arrival, conceived the contents of the « Signing Chamber ». This is logical, since it was the place where he installed his personal library, a collection of some 270 books, arranged on shelves below the frescoes and classified according to the themes of each wall decoration (Philosophy, Theology, Poetry and Justice). However, given the complexity of the themes, and given Julius II’s poor literary culture, historians agree that the intellectual authorship of the frescoes was attributed to the pope’s advisors and especially to the one who would have been able to synthesize them, his chief librarian, Thomaso Inghirami (1470-1516).

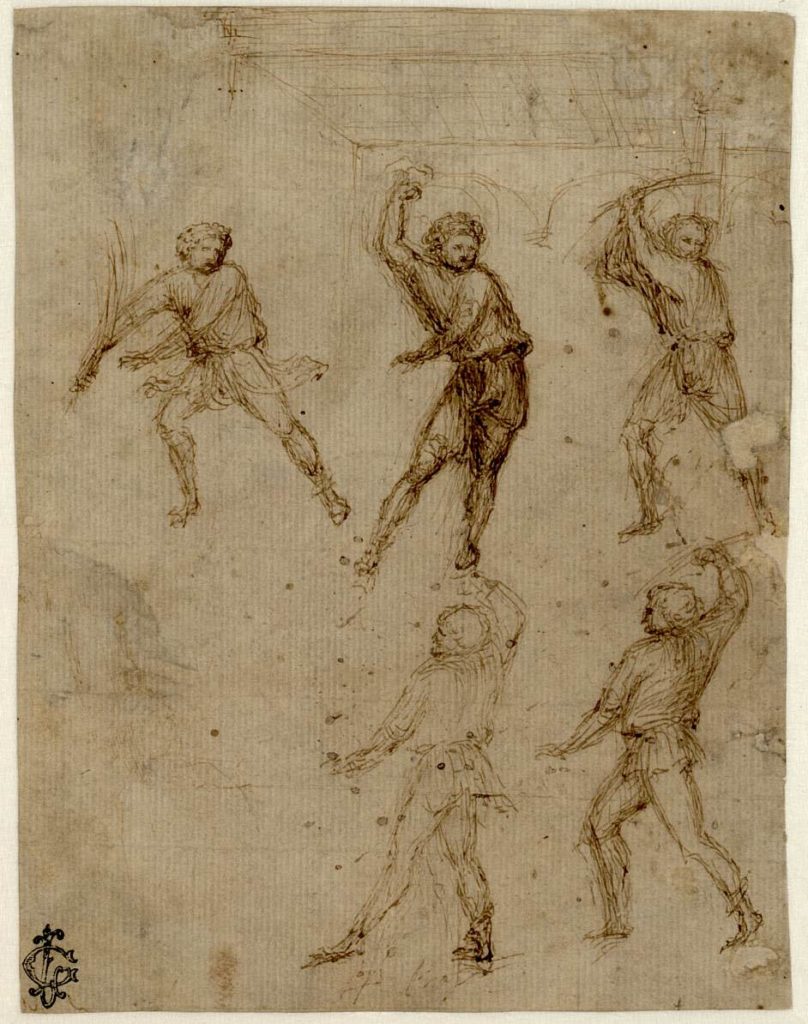

Raphael, who seems to have constantly modified his preparatory drawings according to the feedback and comments he received from the commissioners, was able to translate this theme and program into images with his vast talent. In short, if you like the images, congratulate Raphael; if you like or don’t like the content, talk to the « boss ».

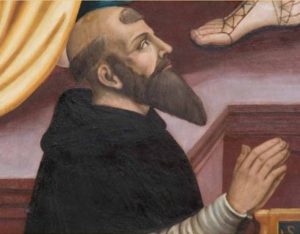

4. Painted by several people? What remains to be clarified is that, according to Vatican accounts, the entire decoration of the room was entrusted in mid-1508 to the talented fresco artist Giovanni Antonio Bazzi (1477-1549), six years older than Raphael and known as Il Sodoma. He appears to be the only person to have received any money for this work. Raphael does not appear in these accounts until 1513…

However, as the cycle of frescoes on the life of St. Benedict in the territorial abbey of Santa Maria in Monte Oliveto Maggiore testifies, Sodoma also had considerable talent, and above all, an incomparable know-how in fresco technique. Although he has never been honored, his style is so similar to Raphael’s that it is hard to mistake him.

It should also be noted that Sodoma, who came to Rome at the request of the pope’s banker Agostino Chigi (1466-1520), was asked to decorate the latter’s villa in 1508, which would have given Raphael free rein in the Vatican before joining him on the same site.

According to the french historian Bernard Levergeois, the sulphurous Pietro Aretino (1495-1556), a pornographic pamphleteer, before becoming the protégé and « cultural agent » of the banker Chigi in Rome, spent many years in Perugia.

There he took interest in the young pupils of Pietro Perugino (c. 1448-1523), Raphael’s master, and, says Levergeois, it was there that he

met the most prestigious painters of the day: Raphael, Sebastiano del Piombo, Julius Romano, Giovanni da Udine, Giovan Francesco Penni and Sodoma, all of whom took turns decorating the magnificent villa (the Farnesina) that Chigi had built in Rome. Some of them also worked on the no less famous Villa Madam (for pope Julius II), a grandiose project that was never completed.

As seen in the portrait painted by Titian, Aretino, nicknamed « the scourge of Princes », was a powerful, possessive and tyrannical character. A blackmailer, a flamboyant pansexual and well-informed about what was going on in the alcoves of the elites, he worked himself up, like FBI boss Edgar Hoover in the Kennedy era, as a king-maker, a power above power. Historians report that both Raphael and Michelangelo, before showing their works to the public, felt compelled to seek the advice of this pervert Aretino.

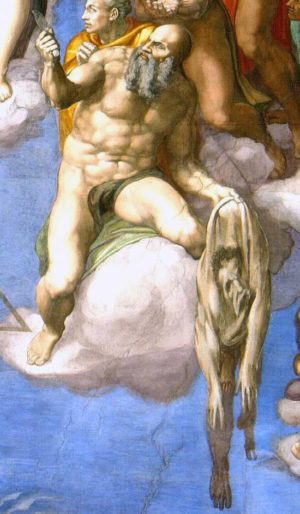

And in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo depicts St. Bartolomeo in the guise of the Aretino. The artist must have thought that the traditional attribute of the martyr flayed alive was a perfect fit for the one who was bullying him: he is wearing the remains of his own skin and holding in his hand the large knife that was used for the torture…

It is therefore tempting to think that it was Aretino, the favorite of the Pope’s banker, and not necessarily Renaissance architect Donato Bramante, as is commonly accepted, who may have played the role of intermediary in bringing both Sodoma and Raphael to Rome in order to revive the glory of his patron and the oligarchy that held the Eternal City in contempt.

To my knowledge, Raphael, neither in his own letters nor in the statements reported by his entourage, would have commented on the theme and intention of his work. Strange modesty. Did he consider himself a simple « decorative painter »?

Finally, if Sodoma‘s participation in the realization of the School of Athens remains to be clarified, his portrait does appear. He is in the foreground on the far right, standing side by side to a rather sad Raphael (both on the side of the Aristotelians). A double signature?

This makes the question arise: Can one continue to speak of the frescoes as painted « by Raphael »? Are they not rather the frescoes of the four men team composed of Julius II, Inghirami, Sodoma and Raphael?

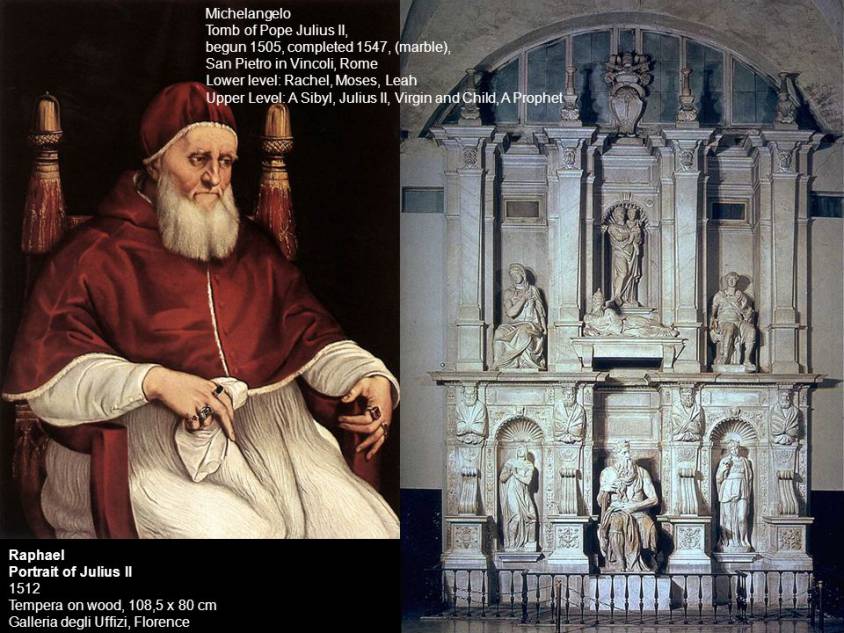

An unusual patron, « the warrior pope » Julius II

Before talking about these famous « impresarios of the Renaissance » and understanding their motivations, it is necessary to explore the character of future pope Julius II: Giuliano della Rovere (1443-1513). He was appointed bishop of Carpentras by Pope Sixtus IV, his uncle. He was also successively archbishop of Avignon and cardinal-bishop of Ostia.

On October 31, 1503, 37 of the 38 cardinals composing the Sacred College, make him the head of the Western Church, under the name of Julius II, until its death in 1513, a moment Giuliano had been waiting for 20 years.

Before him, others had made their way. In fact, in 1492, his personal enemy, the Spanish Rodrigo de Borgia (1431-1503), succeeded in getting himself elected as pope Alexander VI. True to the legendary corruption of the Borgia dynasty, he was one of the most corrupt popes in the history of the Church. Jealous and angry at his own failure, Giuliano accused the new pope of having bought a number of votes. Fearing for his life, he leaves for France to the court of King Charles VIII, whom he convinces to lead a military campaign in Italy, in order to depose Alexander VI and to recover the Kingdom of Naples… Accompanying the young French king in his Italian expedition, he enters Rome with him at the end of 1494 and prepares to launch a council to investigate the pope’s actions. But Alexander VI managed to circumvent the machinations of his enemy and preserved his pontificate until his death in 1503.

From the moment of his accession, Giuliano della Rovere confessed that he had chosen his name as pope, Julius II, not after Pope Julius I, but in reference to the bloodthirsty Roman dictator Julius Caesar. He asserts from the start his firm will to restore the political power of the popes in Italy. For him, Rome must once again become the capital of an Empire much larger than the Roman Empire of the past.

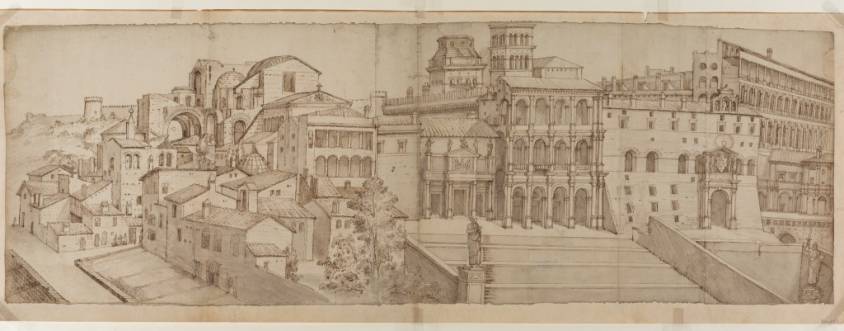

When Julius II took office, decadence and corruption had brought the Church to the brink. The territories that would later become Italy were a vast battlefield where Italian condottieri, French kings, German emperors and Spanish nobles came to fight. The ancient city of Rome was nothing more than a vast heap of ruins systematically plundered by rapacious entrepreneurs in the service of princes, bishops and popes, each one seeking to monopolize the smallest column or architrave likely to come and decorate their palace or church. Reportedly, out of the 50,000 inhabitants of the city, there were 10,000 prostitutes and courtesans…

Obviously, Julius II was the pope chosen by the oligarchy to restore a minimum of order in the house. For, particularly since 1492, the extension of Catholicism in the New World and then in the East, required a « rebirth », not of « Christian humanism », as during the Renaissance of the early 15th century, but of the authority of the Church.

For us today, the word « Renaissance » evokes the heyday of Italian culture. However, for the powerful oligarchs of Raphael’s time, it was a matter of resurrecting the splendor of Greco-Roman antiquity, embodied in the glory of the Roman « Republic », mistakenly idealized as a great and well-administered state, thanks to efficient laws, capable civil servants possessing a great culture, based on the assiduous study of Greek and Latin texts.

And it is well to this rebirth of the Roman authority that Julius II is going to dedicate himself. In first place by the sword. In less than three years (1503-1506), the rebellious César Borgia is reduced to impotence. He was the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI who, at the head of an army of mercenaries, waged war in the country and terrorized the Papal States,

In 1506, Julius II, quickly nicknamed « the warrior pope » at the head of his troops, took back Perugia and Bologna.

As the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (1467-1537), who was present in Italy and was an eyewitness to the sacking of Bologna by the papal troops, reproached him, Julius II preferred the helmet to the tiara. Questioned by Michelangelo in charge of immortalizing him with a bronze statue, to know if he did not wish to be represented with a book in his hand to underline his high degree of culture, Julius II answers:

Why a book? Rather, show me a sword in hand.

Originally from the region of Genoa (Liguria), Julius II undertook to chase the Venetians, whom he abhorred, out of Romagna, which they occupied. « I will reduce your Venice to the state of hamlet of fishermen from which it left, » had said one day the Ligurian pope to the ambassador Pisani, to which the proud patrician did not fail to retort:

And we, Holy Father, we will make of you a small village priest,

if you are not reasonable…

This language gives the measure of the bitterness to which one had arrived on both sides. In the bull of excommunication launched shortly afterwards (April 27, 1509) against the Venetians, these were accused of « uniting the habit of the wolf with the ferocity of the lion, and of flaying the skin by pulling out the hairs… ».

The League of Cambrai

Against the rapacious practices of Venice, on December 10, 1508, in Cambrai, Julius II officially rallies to the « League of Cambrai », a group of powers (including the French King Louis XII, the regent of the Netherlands Margaret of Austria, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and the German Emperor Maximilian I).

For Julius II, the happiness is total because Louis XII comes in person to expel the Venetians of the States of the Church. Better still, on May 14, 1509, after its defeat by the League of Cambrai at the battle of Agnadel, the Republic of Venice agonizes and finds itself at the mercy of an invasion. However, at that juncture, Julius II, fearing that the French would establish their influence on the country, made a spectacular turnaround. He organized, from one day to the next, the survival of Venice!

His treasurer general, the Sienese banker Agostino Chigi (a Sienese billionaire close to the Borgias, to whom he had lent colossal sums of money and later Raphael’s patron), set the conditions:

- In order to pay for the Swiss mercenaries capable of repelling the attackers of the Ligue of Cambrai, Chigi granted the Venetians a substantial loan.

- In exchange, the Serenissima agreed to give up its monopoly on the trade of alum that it imported from Constantinople. At the time, alum, an irreplaceable mineral used to fix fabric dyes, represented a real « strategic » issue.

- Once Venice stopped importing alum, the entire Mediterranean world was forced, from one day to the next, to obtain supplies, not from Venice, but from the Vatican, that is to say, from Chigi, who was in charge of exploiting the « alum of Rome » for the Papacy, located in the mines of the Tolfa mountains, northwest of Rome in the heart of the Papal States.

- Aware that its very survival was at stake, and for lack of an alternative, Venice grudgingly accepted the golden deal.

In his biography on Jules II, french historian Ivan Cloulas specifies:

Above all stands out Agostino Chigi, the banker from Siena, farmer of the pontifical mines of alum of Tolfa since the reign of Alexander VI. The favor that this character enjoyed with Julius II is surprising, since he was a banker who had long served Caesar Borgia. The pontiff, according to the tradition, conferred at the time of his accession the load of ‘depositary’ to one of his Genoese compatriots, Paolo Sauli, charged to carry out all the financial transactions of the Holy See in connection with the cardinal camerlingue Raffaelo Sansoni-Riario. But Chigi did not suffer disgrace, because he advanced Julian della Rovere considerable sums of money to buy electors [cardinal members of the Sacred College], and he made the exploitation and export of alum extracted from the pontifical mines a success. The experience and value of the Sienese made him a partner of the various bankers of the papacy, notably the Sauli and the Fugger, who gained new wealth as the fruitful trade in indulgences developed in Germany.

Hence, now in alliance with Venice, Julius II, in what appears to the naive as a spectacular « reversal of alliance », set up the « Holy League » to « expel from Italy the Barbarians » (Fuori i Barbari!). A coalition in which he made enter the Swiss, Venice, the kings Ferdinand of Aragon and Henri VIII of England, and finally, the emperor Maximilian. This league will then drive out the French out of Italy. Julius II said with irony:

If Venice had not existed,

it would have been necessary to invent it.

In response, Louis XII, the King of France, attempted to transpose the struggle into the spiritual realm. Thus, a national council, meeting in Orleans in 1510, he declared France exempt from the obedience of Julius II. A second council was convened in Italy itself, in Pisa, then in Milan (1512) trying to depose the pope. Julius II opposed to the King of France the Vth ecumenical council of the Lateran (1512) where he will welcome warmly those who abandoned that of Milan…

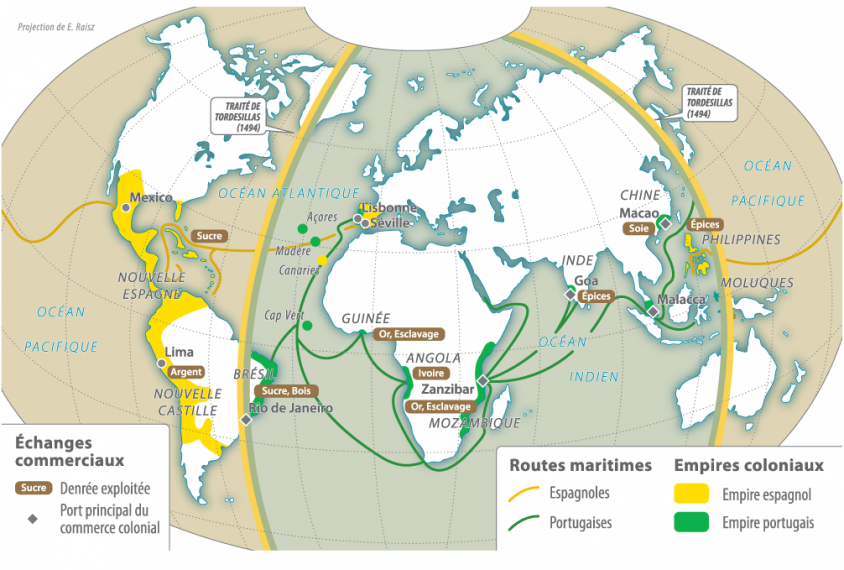

Maritime Empires

Julius II was determined to re-establish his authority both on land and on the oceans. A bit like in ancient Greece, Italy experienced a rather particular phenomenon, that of the emergence of « maritime republics ». If the « Republic of Venice » is famous, the maritime republics of Pisa, Ragusa (Dubrovnik on the Dalmatian coast), Amalfi (near Naples) and Genoa are less known.

In each case, operating from a port, a local oligarchy built a maritime empire and above all poisoned its competitors. However, maritime activity, by its very nature, implies taking risks over time. Hence the need for skillful, robust and forward-looking finance, offering insurance and purchase options on future assets and profits. It is therefore no coincidence that most financial empires developed in symbiosis with maritime empires, notably the Dutch and British, and with the West and East India Companies.

At the end of the 15th century, it was essentially Genoa and Venice that were fighting for control of the seas. On the one hand, Venice, historically the bridgehead of the Byzantine Empire and its capital Constantinople (Istanbul), was by far the largest city in the Mediterranean world in 1500 with 200,000 inhabitants. Since its heyday in the 13th century, the Serenissima has defended tooth and nail its status as a key intermediary on the Silk Road to the West. On the other hand, Genoa, which, after having established itself in the Levant thanks to the crusades, by taking control of Portugal, financed all the Portuguese colonial expeditions to West Africa from where it brought back gold and slaves.

Two maritime achievements will exacerbate this rivalry a little more:

- 1488. Although the works of the Persian scholar Al Biruni (11th century) and old maps, including that of the Venetion monk Fra Mauro, made it possible to foresee the bypassing of the African continent by the Atlantic Ocean to reach India, it was not until 1488 that Portuguese sailors passed the Cape of Good Hope. Thus, Genoa, without any intermediary, could directly load its ships in Asia and bring its goods back to Europe;

- 1492. Seeking to open a direct trade route to Asia without having to deal with the Venetians or the Portuguese (Genoese), Spain sent the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus west in 1492. More than a new route to Asia, Columbus discovered a new continent that would be the object of covetousness.

as signed on by Pope Alexander VI Borgia with the treaty of Tordesillas in 1494

Two years later, on June 7, 1494, the Portuguese and Spanish signed the Treaty of Tordesillas to divide the entire world between them. Basically, all of the New World for Spain, all of the old one (from the Azores to Macao) for Portugal. To delimit their empires, they drew an imaginary line, which Pope Alexander VI Borgia set in 1493 at 100 leagues west of the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands.

Later, the line was extended, at the request of the Portuguese, to 370 leagues. Any land discovered to the east of this line was to belong to Portugal; to the west, to Spain. At the same time, any other Western maritime power was denied access to the new continent. However, in 1500, to the horror of the Spaniards, it was a Portuguese who discovered Brazil. And given its geographical position, to the west of the famous line, this country fell under the control of the Portuguese Empire!

Julius II, a child of Liguria (region of Genoa, therefore linked to Portugal) and vomiting Alexander VI Borgia (Spanish), in 1506, takes great pleasure in confirming, by the bull Inter Cætera, the treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 allowing to fix the dioceses of the New World, obviously to the advantage of the Portuguese and therefore to his own.

The ultimate weapon, culture

On the « spiritual » and « cultural » level, if Julius II spent most of his time at war, posterity retains essentially the image of « one of the great popes of the Renaissance » as a great protector and patron of the arts.

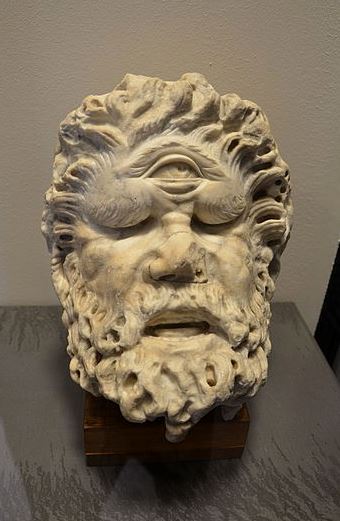

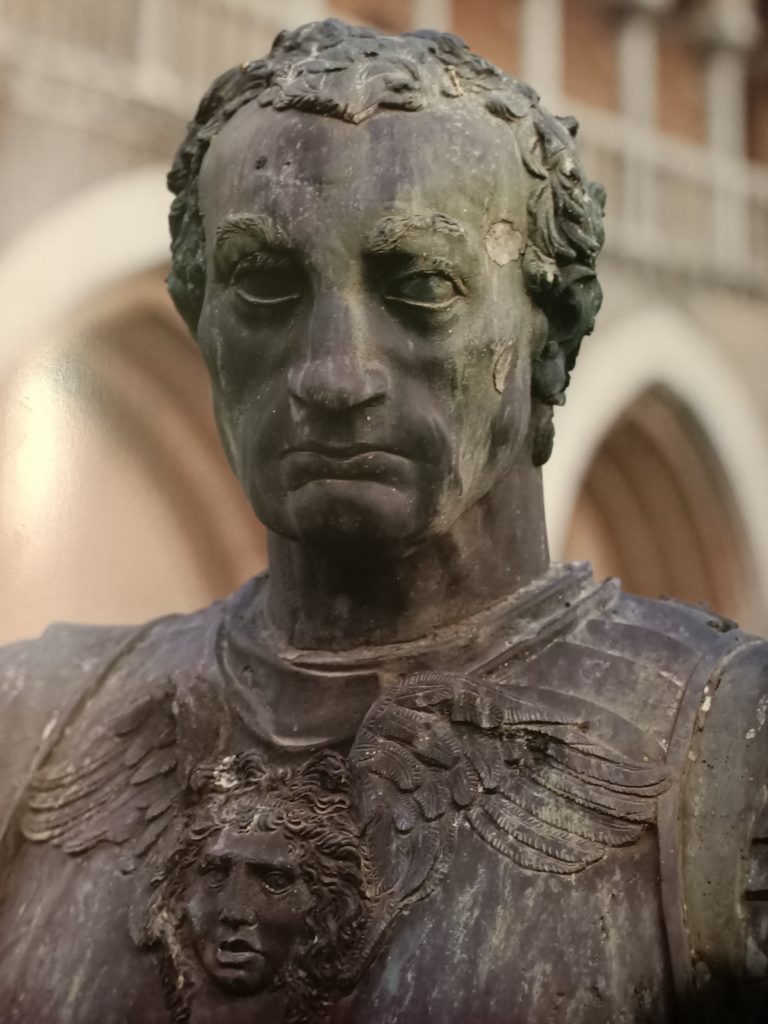

Indeed, to re-establish the prestige (the French word for soft power) and therefore the authority of Rome and its Empire, culture was considered a weapon as formidable as the sword. To begin with, Julius II opened new arteries in Rome, including the Via Giulia. He placed in the Belvedere courtyard the antiques he had acquired, in particular, the « Apollo of Belvedere » and the « Laocoon », discovered in 1506 in the ruins of Nero’s Imperial Palace.

In the same year, that is to say six years before the end of the military operations, Julius II also launched great projects, some of which were only partially or entirely completed after his death:

- The reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, a task entrusted to the architect and painter Donato Bramante (1444-1514) ;

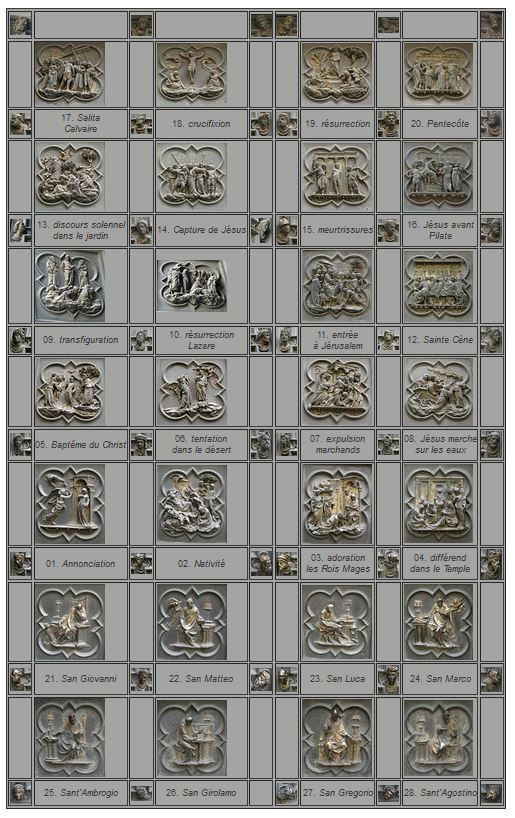

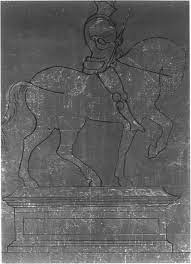

- The tomb of Julius II, which the sculptor Michelangelo was entrusted with in the apse of the new basilica and of which his famous statue of Moses, one of the 48 bronze statues and bas-reliefs originally planned, should have been part;

- The decoration of the vault of the Sistine Chapel built by Pope Sixtus IV, the uncle of Julius II, was also entrusted to Michelangelo. Julius II let himself be carried away by the creative spirit of the sculptor. Together, they worked on ever more grandiose projects for the decoration of the Chapel. The artist gave free rein to his imagination, in a different artistic genre that did not please the pope. Until October 31, 1512, Michelangelo painted more than 300 figures on the vault;

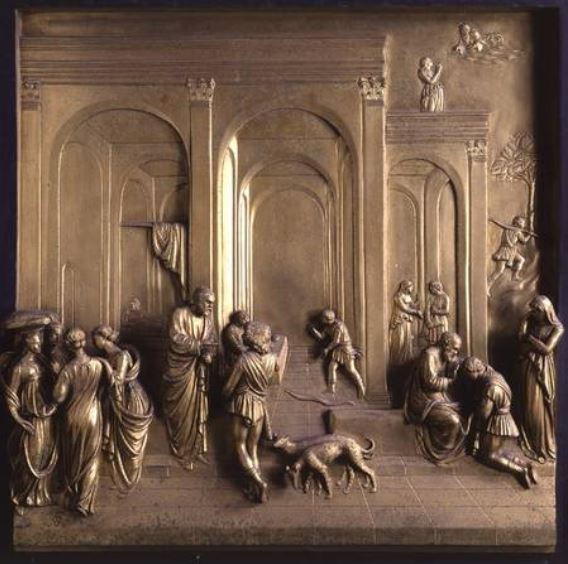

- The frescoes decorating the personal library of the pope will be entrusted to the painter Raphael, called to Rome in 1508, probably at the suggestion of Chigi, Aretino or Bramante. The Stanza was the place where the pope signed his briefs and bulls. This room later became the private library of the pontiff Julius II, then the room of the Tribunal of Apostolic Signatures of Grace and Justice and later, that of the Supreme instance of appeal and cassation. Before the arrival of Julius II, this room and « the room of Heliodorus », were covered with frescoes by Piero della Francesca (1417-1492), a painter protected by the great Renaissance genius cardinal philosopher Nicolaus of Cusa (1401-1464), immortalizing the great ecumenical council of Florence (1438). Decorations by Lucas Signorelli and Sodoma were added later. Following his election, Julius II, anxious to mark his presence in history, and to re-establish the authority of the oligarchy and the Church, had the frescoes of the Council of Florence covered with new ones. Convinced by his advisors, the pope agreed to entrust the direction of the work to Raphael. Officially, it is said that Raphael spared some of the frescoes on the ceiling, notably those executed by Sodoma, so as not to antagonize him entirely. But, as we have said, the content, the very elaborate theme and part of the iconography of the frescoes were decided upon as early as 1506, even before Raphael’s arrival in 1508;

- To modernize the city of Rome. Julius II, undoubtedly advised by the architect Bramante, singularly transformed the road system of Rome. In order for all the roads to converge towards St. Peter’s Basilica, he ordered the Via Giulia to be pierced on the left bank and the Lungara, the paths that meandered along the river on the right bank, to be transformed into a real street. His death interrupted the great works he had planned, in particular the construction of a monumental avenue leading to St. Peter’s and that of a new bridge to relieve the congestion of the bridge over St. Angelo, to which he had also facilitated access by widening the street leading to it. The extent of the work undertaken poses the problem of materials; although it was, in principle, forbidden to attack the ancient monuments, the reality was quite different. Ruinante, became the nickname of Bramante.

These major construction projects, patronage and military expenses drained the Holy See’s revenues. To remedy this, Julius II multiplied the sale of ecclesiastical benefits, dispensations and indulgences.

In the twelfth century, the Roman Catholic Church established the rules for the trade of « indulgences » (from the Latin indulgere, to grant) through papal decrees. They provided a framework for the total or partial remission before God of a sin, notably by promising, in exchange for a given amount of money, a reduction in the time spent in purgatory to the generous faithful after their death. In the course of time, this practice, essentially exploiting a form of religious superstition, turned into a business so lucrative that the Church could no longer do without it.

In northern Europe, particularly in Germany, the Fugger bankers of Augsburg were directly involved in organizing this trade. This practice was strongly denounced and fought against by the humanists, in particular by Erasmus, before Luther made it an essential part of the famous 95 theses that he posted, in 1517, on the doors of the church in Wittenberg.

In his book Erasmus and Italy, french historain Augustin Renaudet writes that Erasmus, after having met the highest authorities of the Vatican, was not fooled:

He was not long in understanding that apart from the Holy See, the services of the Curia and the Chancellery, apart from the cardinals, the innumerable prelates on mission and in charge, apart from a motley crowd of civil servants and scribes, who populated the administrative or financial offices and the courts, there was nothing in Rome. In all the cities he had known, in Brussels, in Paris, in London, in Milan, in Florence, and recently in Venice, an active economy, fed by industry, commerce, and finance, supported a strong urban bourgeoisie, or as in Venice, an aristocracy of shipowners. In Rome, all the economy, all the trade, all the finance, were in the hands of foreigners: Florentine or Genoese merchants, Florentine or Genoese bankers. These foreigners held in their dependence a people of small merchants, of small craftsmen who sold in the back room, of money changers and Jewish traffickers. Very little industry, the Roman population lived at the service of the Curia, the prelates and the convents. Erasmus marveled at the pride with which the descendants of the people-king pretended to maintain their ancient majesty.

The word of the Roman people was no longer an empty word; Erasmus was to write one day that, in the modern world, a Roman citizen counted less than a burgher of Basel.

Historians André Chastel and Robert Klein, in L’Humanisme, l’Europe de la Renaissance, share this observation:

Another trend, favorable to Caesar and Augustus, had emerged: Rome becoming again more and more the ‘imperial’ capital of all the powerful borrowed or sought to borrow a style from it.

This new style associates besides more and more arma and litterae, the sword and the book.

(…) Rich or poor, any sovereign of the Renaissance will occupy the artists and the scholars insofar as he needs prestige: the greatest patrons of the Renaissance were the ambitious and the warriors, Maximilian, Julius II, Henry VIII, François I, Charles V.

Raphael’s « impresarios »

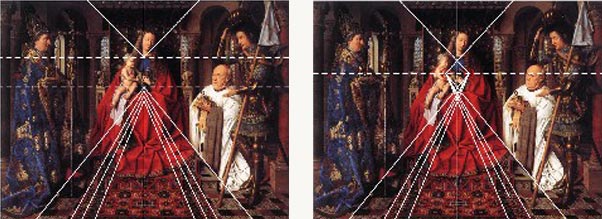

If, from a contemporary point of view, it seems close to unthinkable for an artist to be « dictated » the theme of his work, this was not the case at the time of the Renaissance and even less so in the Middle Ages. For example, although he was a high-level diplomat of the Duke of Burgundy Philip the Good, the Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck (, one of the first painters to sign his works with his name, was advised on theology by the Duke’s confessor, the erudite Dionysus the Cartusian (1401-1471), a close friend of Cardinal Nicolaus of Cusa. And no one will dare say that Van Eyck « did not paint » his masterpiece The Mystic Lamb.

Raphael’s position was more delicate. In his time, painters still had the status of craftsmen. Including Leonardo da Vinci, who was known for his superior intelligence, declared himself to be a « man without letters », that is to say, unable to read Latin or Greek. Raphael could read and write Italian, but was in the same condition. And when, towards the end of his short life, he was asked to work on architecture (St. Peter’s Basilica) and urban planning (Roman antiquities), he asked a friend to translate the Ten Books of the Roman architect Vitruvius into Italian. Now, any visitor to the « Chambers of the Signature » is immediately struck by the great harmony uniting several dozen philosophers, jurists, poets and theologians whose existence was virtually unknown to Raphael before his arrival in Rome in 1508.

Moreover, with the exception of The Marriage of the Virgin, painted in 1504 at the age of 21, based on the way his master Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci, known as Pietro Perugino (c. 1448-1523) had treated the same subject, Raphael had not yet had to meet the kind of challenge that the Stanza would pose to him.

As we have already said, the cartoons and other preparatory drawings, sometimes quite different from the final result, also suggest that, following the « commission, » discussions with one or more impresarios led the artist to modify, improve or change the iconography to arrive at the final result.

As for the theme, as we have already mentioned, the ideas and concepts seem to have emerged during a long period of maturation and were undoubtedly the result of multiple exchanges between Pope Julius II and several of his advisors, librarians, and « orators » of the papal court.

According to historian Ingrid D. Rowlands, the archival documents unquestionably indicate the decisive contribution of three very different personalities of the time:

- Battista Casali ;

- Giles of Viterbo;

- Tommaso « Fedra » Inghirami.

The thorough investigation of the historian Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier has established the predominant role of Inghirami. He was the only one in a position, and in a position, as the pope’s chief librarian, to set the program of the rooms. Raphael, will be his enthusiastic collaborator and will undoubtedly end up being « recruited » to the orientations and vision of his commissionners. This is evidenced by the fact that he demanded to be buried in the Roman Pantheon, considered the most Pythagorean, and believed to be the most neo-Platonic, temple of the Roman era.

Battista Casali

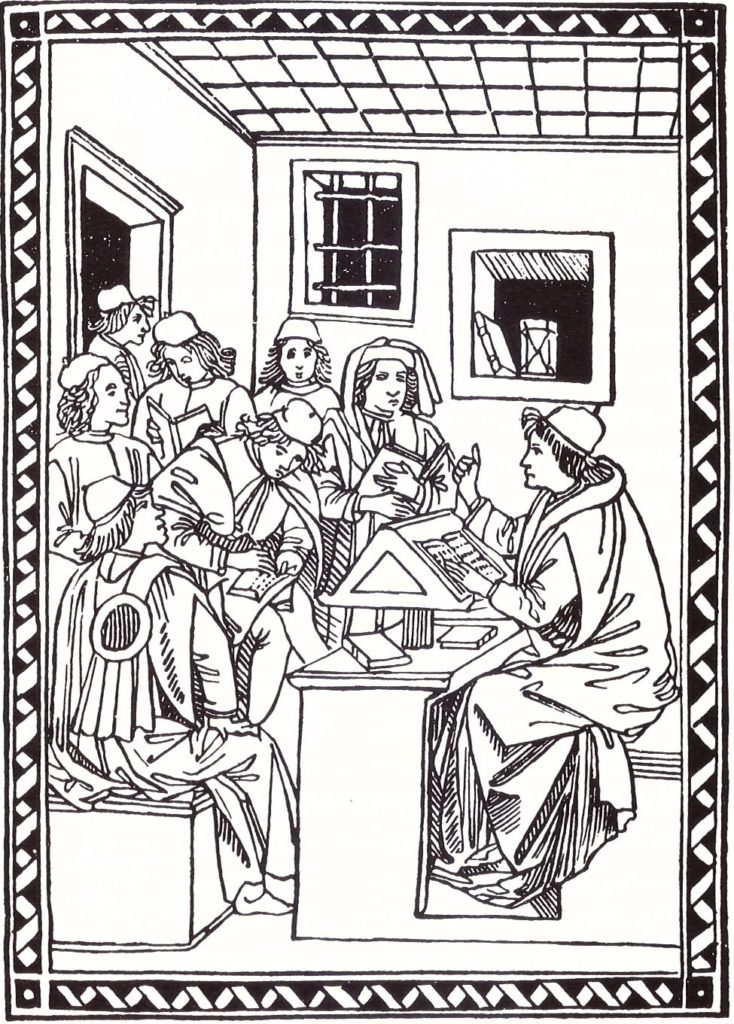

As documented by the Jesuit historian John William O’Malley, it was on January 1, 1508, the year of his appointment to St. John Lateran, a few months before Raphael’s arrival in Rome, that Battista Casali (1473-1525), a professor at the University of Rome, evoked the image of The School of Athens in an oration delivered in the Sistine Chapel in the presence of Julius II:

One day (… ) the beauty of Athens inspired a contest between the gods, where humanity, learning, religion, primacies, jurisprudence and law came into being before being distributed in every country, where the Athenaeum and so many other gymnasiums were founded, where so many princes of knowledge trained their youth and taught them virtue, fortitude, temperance and justice – all of this destroyed in the whirlwind of the Mohaematan war machine… ) However, just as [your illustrious uncle Pope] Sixtus IV [who ordered the construction of the Sistine Chapel], in a way, laid the foundations of education, you laid the cornice. Here is the Vatican library which he erected as if it had come from Athens itself, gathering the books he was able to save from the wreckage, and created in the image of the Academy. You, now, Julius II, supreme pontiff, have founded a new Athens when you invoke the downtrodden world of letters as if it were rising from the dead, and order it, surrounded by threats of suspended work, that Athens, its stadiums, its theaters and its Athenaeums, be restored.

Giles of Viterbo

Another major influence on the theme, Giles of Viterbo (1469-1532) of which we will say more below.

- An outstanding orator, he was called to Rome in 1497 by Pope Alexander VI Borgia ;

- In 1503, he became the Superior General of the Order of Hermits of Saint Augustine; with 8000 members, it was the most powerful order of its time;

- He is known for the boldness and seriousness of the speech he gave at the opening of the Fifth Lateran Council in 1512;

- He severely criticized the bellicose policy of Julius II and urged him to triumph by culture rather than by the sword;

- After the death of the latter, he became the preacher and theologian of Pope Leo X who appointed him cardinal in 1517.

Tommaso Inghirami

Finally, the prelate Tommaso Inghirami (1470-1516), who spoke both Latin and Greek, was also a formidable orator. The man owed his fortune to Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492).

Educated by the Neoplatonic philosopher Marsilio Ficino, Lorenzo the Magnificent was the patron of both Botticelli and Michelangelo who lived with him for three years.

Born in Volterra, Inghirami was also taken in by the Magnificent after the sacking of that city. He carefully supervised his studies and later sent him to Rome where Alexander VI Borgia welcomed him. Inghirami was a handsome and well-dressed man.

At 16, Inghirami earned the nickname « Phaedra » after brilliantly playing the role of the queen who commits suicide in a Seneca tragedy performed in a small circle at the residence of the influential Cardinal Raphael Riario, cousin of Julius II or nephew of Pope Sixtus IV and therefore cousin of Julius II. Thereafter, Phaedra, bon vivant and for whom the celestial and terrestrial pleasures were happily completed, gained in political and especially… physical weight.

- In 1475, he accompanied the nuncio of Pope Alexander VI to the court of Emperor Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire, who named him Count Palatine and poet laureate;

- On January 16, 1498, Inghirami delivered an oration in the Spanish Church of Rome in honor of the Infant Don Juan, the murdered son of the King of Spain. Inghirami, in the name of Alexander VI Borgia, fully endorsed the Spanish policy of the time: to extend Christianity as well as imperial looting into the New World, to drive the Moors out of Europe and to strengthen the colonial plunder of Africa. If Julius II hated Alexander VI, he will continue this policy;

- In 1508, Julius II nominates Inghirami to head the Library of the Vatican to be installed in the Stanza;

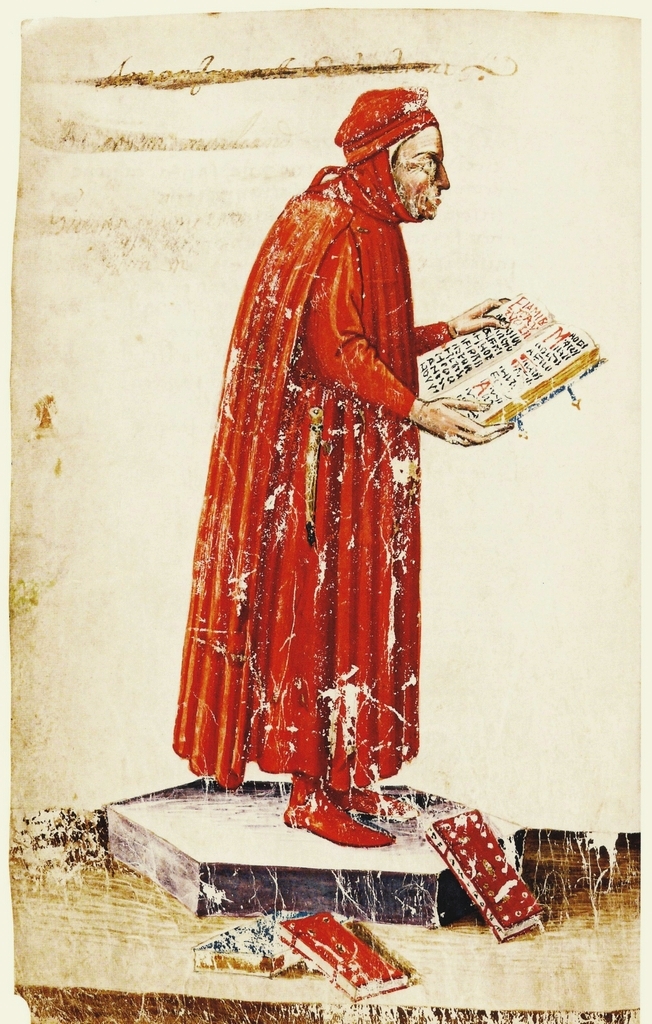

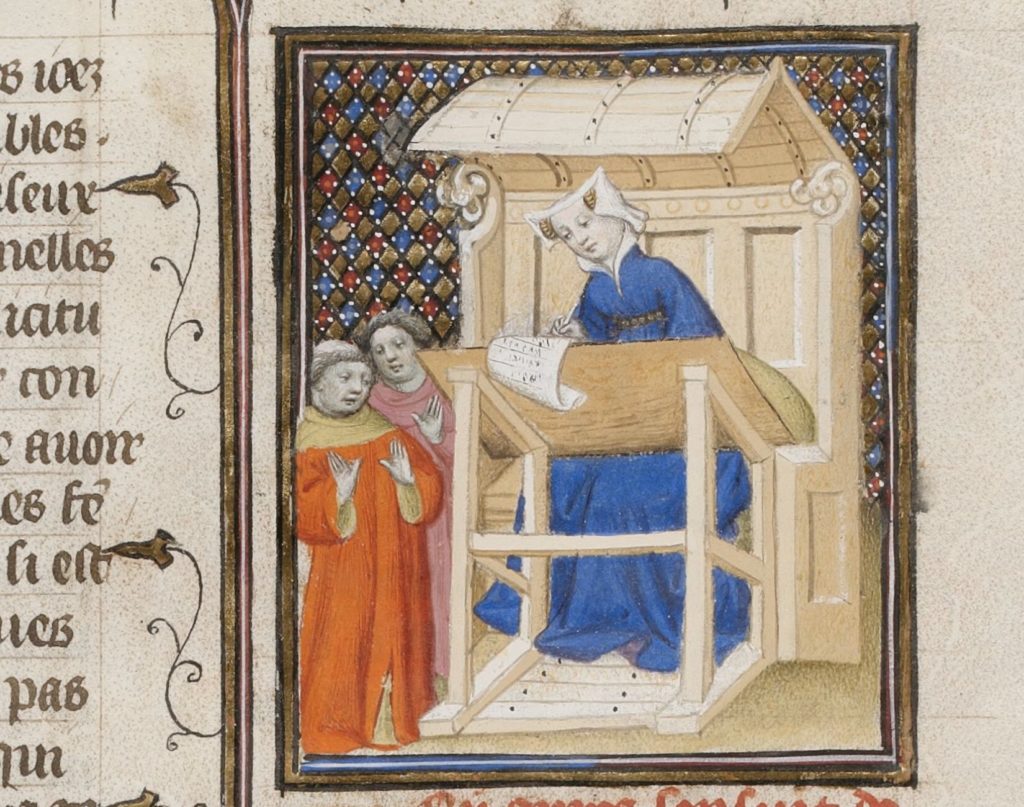

- In 1509, while he was heavily involved in the realization of the frescoes of the Stanza, Raphael made his portrait. Raphael shows us a man suffering from divergent strabismus who seems to turn his gaze towards the sky in order to signify where this « humanist » drew his inspiration from;

- In 1510, the Pope appointed him Bishop of Ragusa;

- Finally, in 1513, he became papal secretary and at the urgent request of the dying pope, Inghirami delivered his funeral oration: « Good God! What a mind this man had, what sense, what ability to manage and administer the Empire! What a supreme and unshakable strength! »

Inghirami soon served as secretary to the conclave electing Pope Leo X (John of Medici, second son of Lorenzo de Medici, also a great protector of neo-Platonists and « culture »), another pope whose portrait Raphael will paint.

In 1509, eager to reform the Catholic church on the basis of the study of the three languages (Latin-Greek-Hebrew) to settle the religious conflicts which were looming and announced the religious wars to come, Erasmus of Rotterdam meets Inghirami in Rome. The latter exposes to him the imposing cultural building sites which he directed. Erasmus does not say a word about it.

However, a long time after the death of Inghirami, Erasmus complained that the Vatican and the oligarchy recruited among the humanists. He notably fingerpointed the sect of “the Ciceronians”, omnipresent in the Roman Curia and of which Inghirami was one of the leaders.

Thus, in 1528, in a pamphlet titled The Ciceronians, Erasmus quoted Inghirami’s oration on Good Friday of 1509. He denounced the fact that the members of this sect, on the grounds of the elegance of the Latin language, only used Latin words that appeared as they were in the works of Cicero! As a result, all the new language of evangelical Christianity, enshrined in the Council of Florence, which Erasmus wished to promote, was either banned or « re-translated » into pagan terms and words of the Roman era! For example, in his sermon, Inghirami had presented Christ on the cross as a pagan god sacrificing himself heroically rather than as a redeemer.

Finally, shortly after Raphael’s death, Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto (1477-1547) wrote a treatise on philosophy in which Inghirami (meanwhile tragically deceased) defended rhetoric and denied the value of philosophy, his main argument being that everything written was already contained in the mystical and mythological texts of Orpheus and his followers…

Plato and Aristotle, the impossible synthesis

Now, in order to be able to « read » the theme deployed by Raphael in the « Chamber of the Signature, » let us examine this Florentine « neo-Platonism » that animated both Giles of Viterbo and Tommaso Inghirami.

The approach of these two orators consisted above all in putting their « neo-Platonism » and their imagination at the service of a cause: that of asserting with force that Julius II, the pontifex maximus at the head of a triumphant Church, embodied the ultimate outcome of a vast line of philosophers, theologians, poets and humanists. At the origin of a civilizational and theological « big bang » presumed to lead to the immeasurable lustre of the Catholic Church under Julius II, not only Plato and Aristotle themselves, but those who had preceded them including Apollo, Moses and especially Pythagoras.

From 1506 onwards, Giles de Viterbo, in an exercise that can be described as « beyond” impossible, wrote a text entitled Sententia ad mentem Platonis (« Sentences with the mind of Plato »). In it, he tried to combine into one ideology the Sentences of Peter Lombard (1096-1160), the scholastic text par excellence of the 13th century and the starting point for the commentaries of the Dominican Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) for his Summa Theologica, and the esoteric Florentine neo-Platonism of Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) * of whom Giles de Viterbe was a follower.

All this could only please a pope who, in order to establish his authority on earthly and spiritual matters, warmly welcomed this agreement between Faith and Reason defended by Thomas Aquinas who says that “the Truth being one”, reason’s only role is to confirm faith’s superiority.

The very idea to present the wedding of Aristotelian scholasticism (logic presented as « reason ») with Florentine neo-Platonism (Plotinus’ emanationism dressed as « faith ») as a source of poetry and justice as « The Signing Room » does, comes from this.

Let us recall that in the middle of the 13th century, two mendicant Orders, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, were contesting the drift of a Church that had become, above all, the simple manager of its earthly possessions. The one who would later be called St. Thomas Aquinas, opposed on this point (his competitor) St. Bonaventure (1221-1274), founding figure of the Franciscan Order.

For his part, Aquinas relies on Aristotle, whom Albert the Great (1200-1280), whose disciple he was in Cologne, had made known to him, to establish the primacy of « reason ». For the man who was nicknamed « the dumb ox », faith and human reason, each managing their own domain, had to move forward together, hand in hand while of course, the Church had the last word.

Several paintings (the great fresco of 1366 in the Spanish chapel of Santa Maria Novella in Florence; the painting by Filippino Lippi of 1488 in the Carafa chapel in Rome; or the painting by Benozzo Gozzoli (1421-1497), painted around 1470, in the Louvre in Paris), have immortalized the “Triumph of Thomas Aquinas”.

Gozzoli’s painting in the Louvre is of particular importance because several elements prefigure the iconography of the Signing Chamber, notably the three levels found in Theology (Trinity, Evangelists and religious leaders) as well as the couple Plato and Aristotle found in Philosophy.

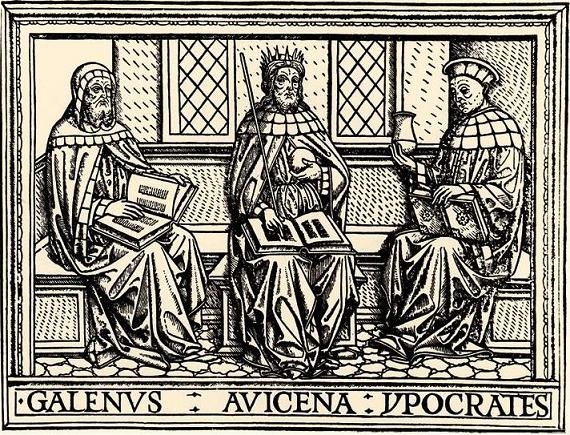

In Gozzoli’s painting, we see Aquinas, standing between Plato and Aristotle, throwing down before him the Arab philosopher Averroes (1126-1198) (Ibn-Rushd of Cordoba) expelled for having denied the immortality and the thought of the individual soul, in favor of a « Single Intellect » for all men that activates in us the intelligible ideas.

In the West, before the arrival of Greek delegations in Italy to attend the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438, if several works of Plato, including the Timaeus, were known to a handful of scholars, such as those of the School of Chartres or Italians as Leonardo Bruni in Florence, most of the West’s knowledge of Greek thought came down to the works of Aristotle.

For the Aristotelians, who became dominant in the Catholic Church with Aquinas, Plato had to be considered as incompatible with Christianity.

On the other hand, for the Platonists, including Augustine, Jerome and especially Nicholas of Cusa and Erasmus, who honored and adorned him that Erasmus called « Saint Socrates », Plato was to be venerated by Christians: he was monotheistic, believed in the immortality of the soul and venerated, in the form of the Pythagorean triad, the mystery of the Trinity.

In the 15th century, for lack of epistemological clarity and some confusion on the authorship of certain manuscripts, some humanists, in particular Nicolaus of Cusa‘s friend and close collaborator Cardinal John Bessarion (1403-1472), one of the key organizers of the reunification of the Eastern and Western Churches, presented Plato as the « equal » of Aristotle, the latter’s disciple, with the sole purpose of making Plato « as acceptable as possible » to the Catholic Church.

Hence Bessarion‘s now famous phrase « Colo et veneror Aristotelem, amo Platonem » (I cultivate and venerate Aristotle, I love Plato) which appears in his In Calumniatorem Platonis (republished in 1503), a rejoinder to the virulent charge against Plato elaborated by the Greek Georges Trébizond.

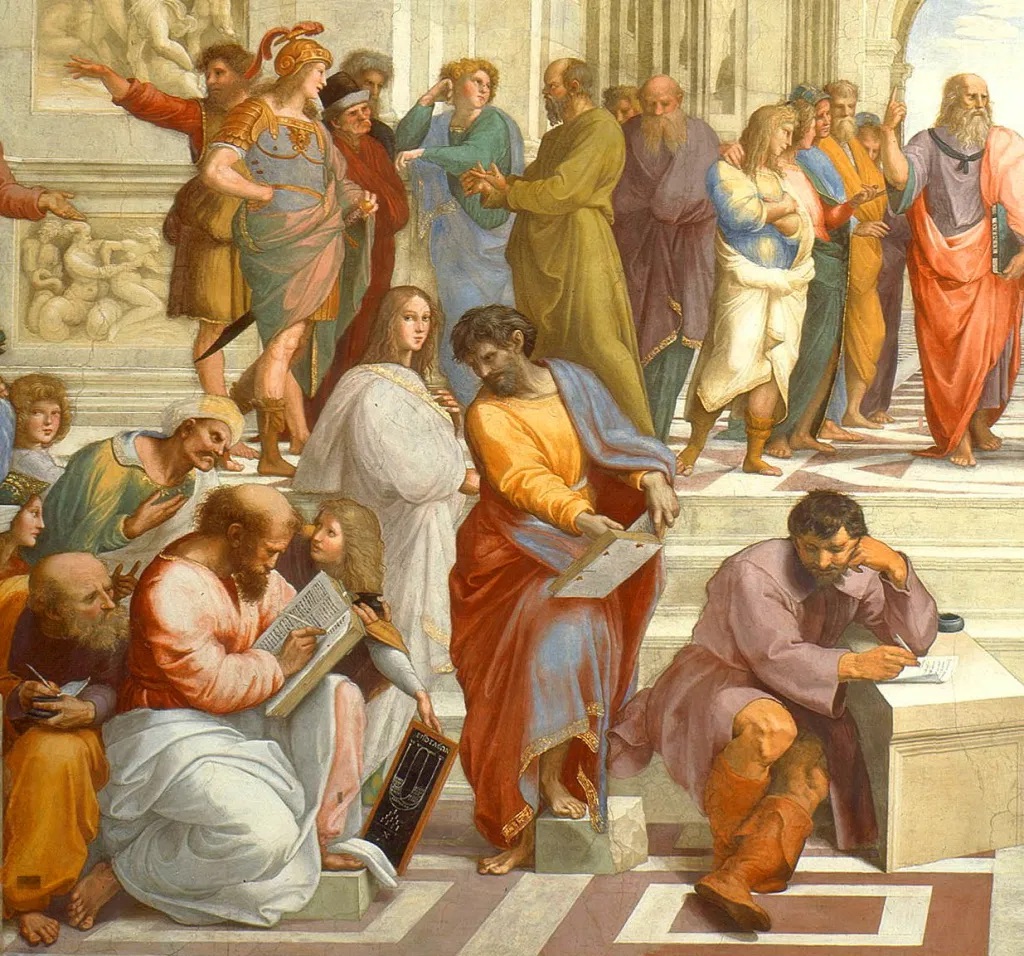

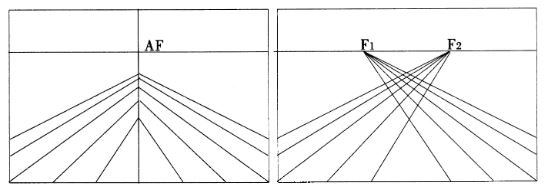

Thus, in the School of Athens painted by Raphael, Plato and Aristotle appear side by side, not confronting each other but complementing the other with their respective wisdom : the first holding his book the Timaeus (on the creation of the universe) in one hand, and with the other, pointing to the sky (To the One, to God), the second holding his Ethics (the science of the good in personal life) in one hand, and raising the other arm horizontally to indicate the earthly realm (Physics).

If the commissioners had wanted to underscore the opposition of both philosophers, Plato would have rather been portrayed with his Parmenides (On Ideas) and Aristotle with his Physics (On natural sciences). That is clearly not the case.

Giles de Viterbo in his Sententia ad mentem Platonis will mobilize extreme sophism to erase the irreconcilable and very real oppositions (see box below) between the Platonic thought and that of Aristotle.

Why Plato and Aristotle are not complementary

By Christine Bierre

The fundamental concepts that gave birth to our European civilization can be traced back to classical Greece, and through it, to Egypt and other even more ancient civilizations.

Among the Greek thinkers, Plato (-428/-347 B.C.) and Aristotle (-385/-323 B.C.) asked all the great questions that interest our humanity: who are we, what are our characteristics, how do we live, where are we situated in the universe, how can we know it?

The accounts that have come down to us from this distant period speak of the disagreements that led Aristotle to leave Plato’s Academy, of which he had been a disciple. History then bears witness to the violence of the oppositions between the disciples of the one and the other. During the Renaissance, the most reactionary Catholic currents, the Council of Trent in particular, were inspired by Aristotle, whereas Plato reigned supreme in the camp of humanism, in the hands of some of the greatest, such as Erasmus and Rabelais.

There were various attempts, however, to make them complementary, as discussed in this article by Karel Vereycken. If Plato represents the world of Ideas, Aristotle represents the world of matter. Impossible to build a world without both, we are told. It seems so obvious!

The Greek philosopher, Plato.

All this starts, however, from a false idea opposing these two characters. For Plato, we are told, reality is found in the existence of ideas, universal concepts which represent, in an abstract way, all the things which participate of this concept. For example, the general concept of man contains the concept of particular men such as Peter, Paul and Mary; similarly for good, which includes all good things whatever they are. For Aristotle, on the contrary, reality is located in matter, as such.

What is false in this reasoning is the concept that the Platonic Ideas are abstractions. The Platonic Ideas are, on the contrary, dynamic entities that generate and transform reality. In the myth of the cave in The Republic, Socrates says that at the origin of things is the sovereign Good. In The Phaedo, he explains that it is through « Ideas » that this sovereign Good has generated the world.

In the myth of the cave, Socrates uses an offspring of the idea of the good, the Sun, to help us understand what the sovereign Good is. The Good, he says, has generated the Sun, which is, in the visible world, in relation to sight and objects of sight, what the Good is in the intelligible world in relation to intelligence and intelligible objects. The prisoners in the cave saw only the shadows of reality, and then, on coming out, they saw, thanks to the Sun, the real objects, the firmament and the Sun. After this, they will come to the conclusion about the Sun, that it is he who produces the seasons and the years, that he governs everything in the visible world and that he is in some way the cause of all those things that he and his companions saw in the cave.

The Sun not only gives objects the ability to be seen, but is also the cause of their genesis and development. In the same way for the knowable objects, they hold from the Good the faculty to be known but, in addition, they owe him their existence and their essence. The idea of the Good is thus for Plato the dynamic cause of the things: material and immaterial and not dead universals.

Aristotle’s splintered « One »

For Aristotle, as for all the empiricist current which followed him, reality is situated at the level of the objects knowable by the senses. Nature sends us its signals that we decode with our mental faculties. Ideas are only abstractions of the sensible universe which constitutes reality. For him the universals have no real existence: man « in general », does not generate anything. It is only an abstraction of all the men in particular. The particular man is generated by the particular man; Peter is generated by Paul.

It is also said of Aristotle that he « exploded » Plato’s One. There are two ways of conceiving the One. One can think of it either as an absolute One (God or first cause), depending on whether one is a religious person or a philosopher, a purely intelligible principle but a dynamic cause that has generated all things; or one can think of it as the number « one » that determines each particular thing: the number one when we say: a man, a chair, an apple.

Aristotle‘s One simply becomes a particular unity, characteristic of all things that participate in unity. It is not the cause of what « is » but only the predicate of all the elements that are found in all the categories. The Being and the One, he will say, are the most universal of predicates. The One, he will say again, represents a definite nature in each kind but never the nature of the One will be the One in itself. And the Ideas are not the cause of change.

What is the point of all this?

Does this discussion make more sense than all the never-ending debates about the sexes of angels that gave scholasticism such a bad name in the Middle Ages? The One or the many, what does it matter in our daily lives?

This point is however essential. The fact of being able to go back to the intelligible causes of all that exists, puts the human species in a privileged situation in the universe. Unlike other species, it can not only understand the laws of the universe, but also be inspired by them, in order to improve human society. This is why, in history, it is the « Platonic » current that was at the origin of the great scientific, technological and cultural breakthroughs in astronomy, geometry, mechanics, architecture, but also the discovery of proportions that allow the expression of beauty in music, painting, poetry and dance.

As for Aristotle, it must be said that his conceptions of man and knowledge only led him to establish categories defining a dozen possible states of being. Aristotle was also the founder of formal logic, a system of thought that does not claim to know the truth, but only to define the rules of a correct reasoning. Logic is so little interested in the search for truth that one can consider that a judgment that is totally false in relation to reality can be said to be right if all the rules of « good reasoning » of logic have been used.

Suite

To begin with, Giles de Viterbo underlines that Aristotle is a « pupil » of Plato and that the « two princes of philosophy » could be reconciled. Very much imbued with the neo-Pythagorean spirit, and for whom Plato was only one of the greatest disciples of Pythagoras, the author argues that both philosophers agree that, contrary to the pagan pantheon, the « One » is the ultimate expression of the divine. Clearly, they were both monotheists and thus their convictions anticipated those of Christianity.

Giles of Viterbo:

Philosophy, which traces and examines all things, judges that all number and multiplicity are absent from God, as Plato and his pupil Aristotle say. Humanity has as its goal the understanding of divine things, as even Aristotle admits in his Ethics.

Thus, if it is necessary to pursue this goal, it is necessary to arrive at the understanding of God.

And he continues:

Now these princes of Philosophy [Plato and Aristotle] can be reconciled, and no matter how much they disagree about creation, the Ideas, or the goal of the Good, these points [of agreement] can be identified and demonstrated (…) [Then], they appear not to disagree with each other at all (…) These great princes can be reconciled if we postulate the double nature of things, one which is free from matter and the other which is within matter (…) Plato follows the first, Aristotle the second, and because of this, these two great leaders of philosophy hardly differ from each other. If you think that we are making this up, listen to them yourselves. For if we speak of humanity, after all the subject of our conversation, then Plato says the same thing, he says humanity is the soul, in the (First) Alcibiades; and in the Timaeus, he says that humanity has two natures, and we know one of these natures by means of the senses, and the other by means of reason. Also, in the same book, he teaches us that each part in us does not exist in isolation from the other, that each nature is concerned with the other nature. Aristotle, in the tenth book of his Ethics, calls humanity Understanding. So you can know that each philosopher (Plato and Aristotle) feels the same way, no matter how much it seems to you that they are not saying the same thing.

Pico della Mirandola the Neo-Platonist

Giles of Viterbo, like Tommaso Ingharimi, seems to have taken up the gauntlet thrown to them by John Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), the young disciple of Ficino.

A precocious scholar, a protégé of Lorenzo de’ Medici (like Inghirami), this man of omniscience was fearless. Thus, in 1485, at the age of 23, he announced his project to gather, at his own expense, in the eternal city and capital of Christianity, the greatest scholars of the world to debate the mysteries of theology, philosophy and foreign doctrines. The objective was to go back from scholasticism to Zoroaster, passing by the Arabs, the Kabbalah, Aristotle and Plato, to expose to the eyes of all, the concordance of wisdom. The affair failed. His initiative, which reserved an important place for magic, could only arouse distrust. For the Vatican, all this could only smell of sulfur, and the initiative was discarded at the time.

However, it will mark the minds of a generation. For his Oratio de hominis dignitate, his inaugural speech written in an elegant and almost Ciceronian style, intended for the presentation of his nine hundred theses, published together after his death, was a great success, especially among young scholars like… Inghirami.

Pico’s achievement, which was not well received by the authorities, was to give humanistic studies (studia humanitatis) a new purpose: to seek the concordance of doctrines and define the dignity of the human being. The aim was, by bringing out what unites them despite their differences, to discover their common ground and, by a coincidence of opposites, to have them meet in a unity that transcends them.

Pico della Mirandola:

That is why, not content with having added to the common doctrines a quantity of remarks on the primitive theology of Mercury Trismegistus, on the teachings of the Chaldeans and Pythagoras, on the most secret mysteries of the Jews, we have also proposed for discussion a certain number of discoveries and conceptions of our own in the physical and theological fields. First of all, we have argued that Plato and Aristotle agree: many have thought so before us, no one has proved it sufficiently. Among the Latins, Boethius had promised himself to do so, but there is no indication that he ever realized what was always his project. Among the Greeks, Simplicius had given himself the same program: heaven forbid that he should have lived up to his intentions! Augustine himself, in his work Against the Academicians, writes that many authors have conceived, with great finesse in argumentation, the project of establishing this same point, namely that the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle are one. Thus John the Grammarian [The Hellenist John Lascarus] affirms well that only those who do not hear the words of Plato believe him to be in disagreement with Aristotle, but it is to his successors that he left the care of the demonstration. We have also added various developments where the concordance between the opinions – reputedly discordant – of Scotus and Thomas on the one hand, of Averroes and Avicenna on the other hand, is affirmed. Secondly, our considerations on Aristotelian and Platonic philosophy have been enriched by seventy-two new physical and metaphysical propositions: by making them one’s own, if I am not mistaken (and I will soon be sure of this), one will be able to solve any problem of a natural or theological nature, according to a philosophical method which is quite different from the one taught orally in schools and which is in honor among the doctors of our time.

In a manuscript found unfinished at the time of his death in 1494 and entitled Concordia Platonis et Aristotelis, Pico della Mirandola explicitly mentions Plato’s Timaeus and Aristotle‘s Ethics, precisely the two books that appear as attributes of their authors in Raphael’s fresco.

Then, in his Heptaplus, a work he completed in 1489, Pico della Mirandola asserted that the writings of Moses and the Mosaic Law, according to him the foundation of all wisdom, were the basis of Greek civilization before becoming that of the Church of Rome. The Timaeus, the major work of Plato, says Pico, demonstrates that its author was an “attic Moses” (from Athens).

Cicero the Neo-platonist

For Inghirami, fascinated by the eloquence and the style of Cicero (-106/-43 BC) of whom he believed himself the reincarnation, the challenge launched by Pico della Mirandola to reconcile Apollo, Pythagoras, Plato and Aristotle, appeared almost as a divine test and the frescoes of Raphael decorating the Stanza will be above all his answer.

In addition, Cicero himself claimed to be a neo-Platonist. In the first volume of his work, the Academica, after condemning Socrates for continually asking questions without ever « laying the foundations of a system of thought », Cicero asserts, several centuries before Pico della Mirandola, that the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, in essence, « had the same principles »:

In the shadow of Plato’s genius, a fertile, varied, universal genius, a unique philosophy was established under the double banner of the academicians and the peripatetics, who, agreeing on things, differed only on the terms. For Plato, who had made Speusippus, son of his sister, the heir of his philosophy, also left two disciples of great talent and rare science, Xenocrates of Chalcedony and Aristotle of Stagire: those who followed Aristotle, were named peripatetics, because they discussed while walking in the Lyceum; whereas those who, according to the institution of Plato, held their assemblies and disserted in the Academy, the other gymnasium of Athens, received from this place the name of Academicians. But both of them, all penetrated by Plato’s fertile genius, formulated philosophy into a certain complete and finished system, and abandoned the universal doubt of Socrates, and his habit of discussing everything without affirming anything. There was then what Socrates entirely disapproved of, a philosophical science, with regular divisions and a whole methodical apparatus. This philosophy, as I have said, under a double name, was one; for between the doctrine of the peripatetic [Aristotle] and the ancient Academy [Plato] there was no difference. Aristotle prevailed, in my opinion, by the richness of his genius; but the one and the other had the same principles, and judged the goods and the evils in the same way.

Inghirami was also strengthened by the reading of countless Christian authors in this sense, such as the Frenchman, Bernard of Chartres (12th century), a Neoplatonist philosopher who played a fundamental role in the Chartres school, which he founded. He was appointed master (1112) and then became chancellor (1119) responsible for the teaching of the cathedral school.

You wonder the sculptures of Pythagoras and Aristotle appear side by side on the western portal of the cathedral?

Historian Etienne Gilson writes:

Bernard of Chartres was first of all influenced by Boethius, whose Platonism he adapts. He then set out to reconcile Plato’s thought with that of Aristotle, which made him the greatest Aristotelian and Platonic thinker of the 12th century. John of Salisbury affirmed, in the most formal terms, that Bernard of Chartres and his disciples did not believe that they were simply expounding Plato’s thought by explaining in this way the relation of ideas to things, but that they had the pretension of putting Aristotle in agreement with Plato. That the trouble they took was wasted, is what John of Salisbury clearly states. With a very British humor he notes that these philosophers arrived too late and that they worked uselessly to reconcile dead men who had been arguing all their lives.

Inghirami will have read St. Bonaventure (1217-1274), one of the founders of the Franciscan order, who pointed out that Plato and Aristotle each excelled in their own field:

And so it appears that among philosophers, Plato’s gift is to speak of wisdom, Aristotle‘s of science.

Or the Florentine Marsilio Ficino, this neo-Platonic philosopher of the XVth century whose « Platonic Academy » had put in saddle Pico della Mirandola. Ficino, had he not written in his Platonic Theology that

Plato treats natural things divinely while Aristotle treats even divine things naturally.

In the preface he wrote for The Fable of Orpheus, a play written by his disciple Poliziano (1454-1494), Ficino, referring to Saint Augustine, makes the mythical Hermes Trismegistus (Mercury) the first of the theologians: his teaching would have been transmitted successively to Orpheus, Aglaophemus, Pythagoras, Philolaos and finally Plato.

Thereafter, Ficino will place Zoroaster at the head of these prisci theologi, to finally attribute to Zoroaster and Mercury an identical role in the genesis of the ancient wisdom: Zoroaster teaches this one among the Persians at the same time as Trismegistus taught it among the Egyptians.

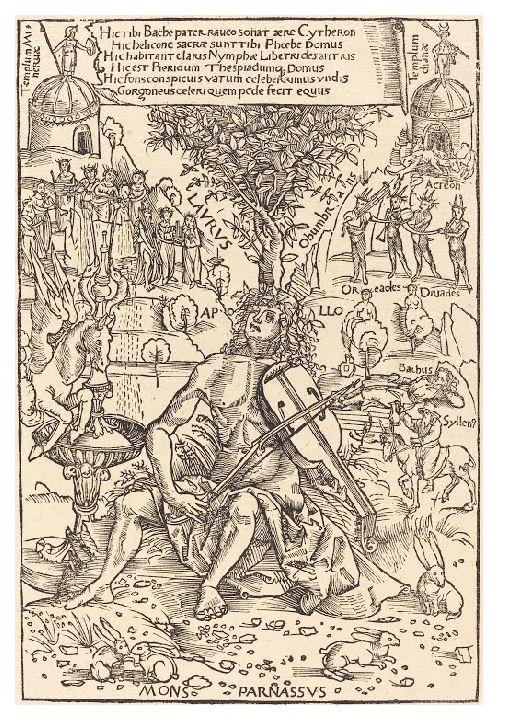

Preceding Plato, Pythagoras

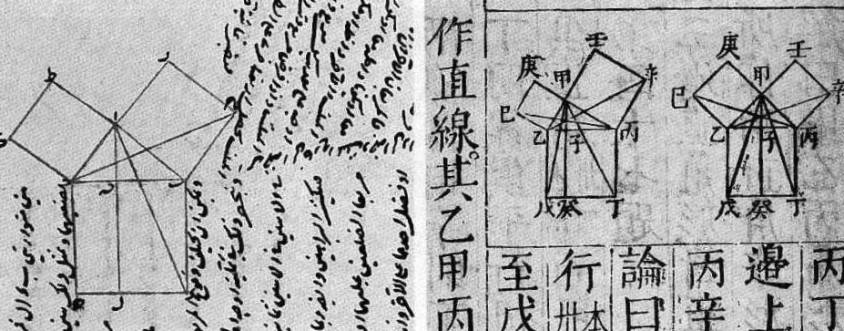

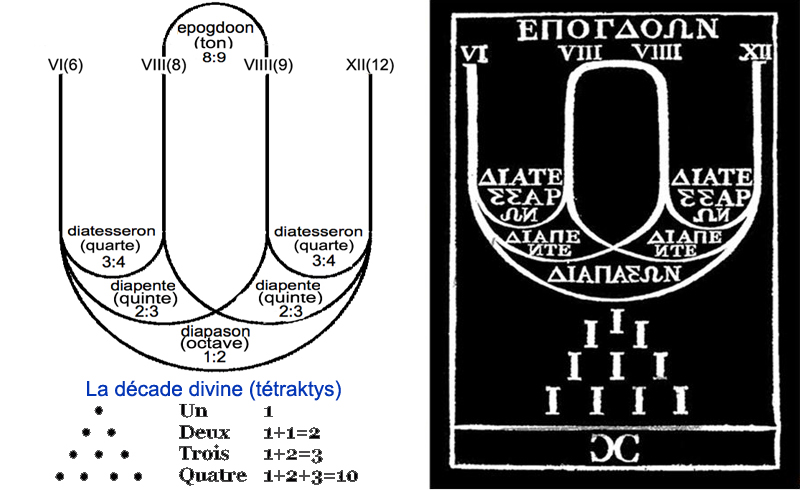

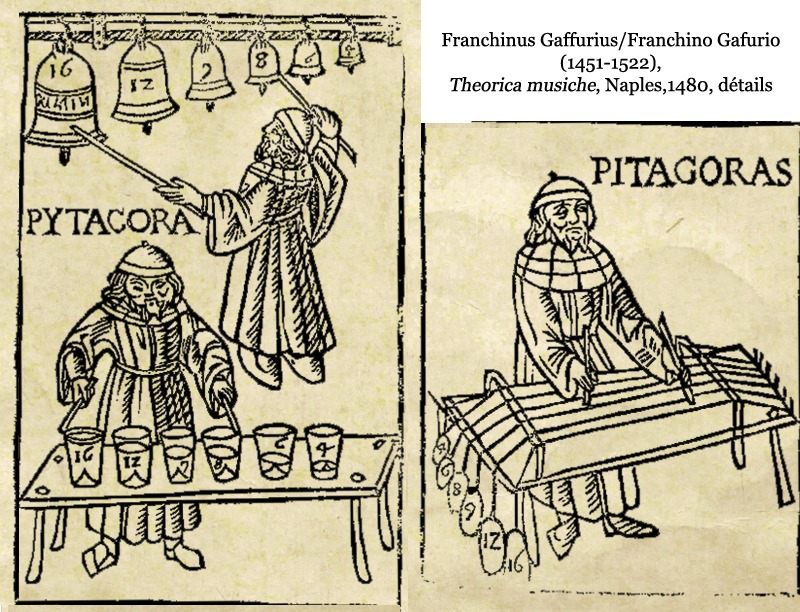

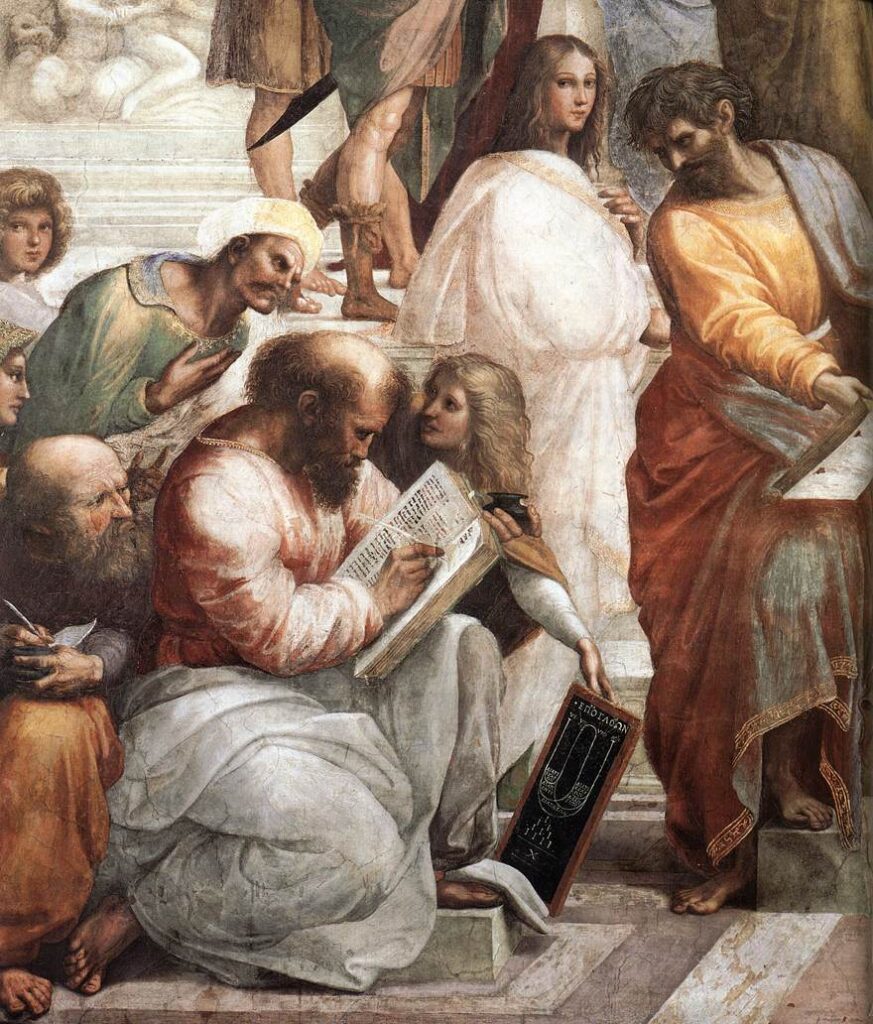

In Raphael’s School of Athens, the figure of Pythagoras of Samos (580-495 B.C.), surrounded by a group of admirers, takes a major place. He is clearly identifiable by a tablet on which the musical chords and the famous Tetraktys appear, which we will discuss here.

While historians have so far mainly explored the influence of the Platonic and Neo-Platonic currents on the Italian Renaissance, historian Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier, in her book Pythagoras and Renaissance Europe, has highlighted the extent to which the ideas of the great pre-Socratic thinker Pythagoras influenced the thought and art of the Renaissance.

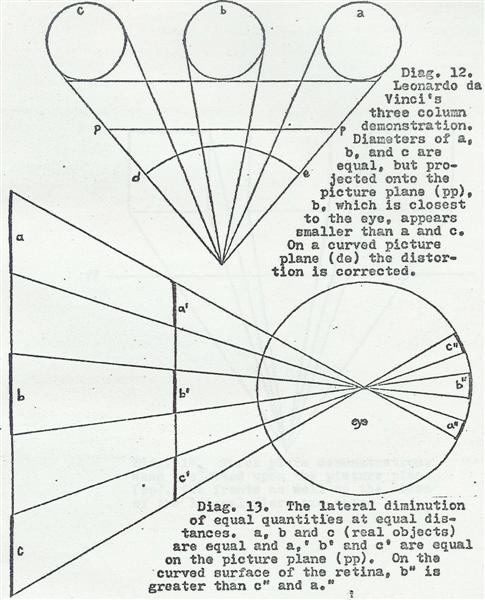

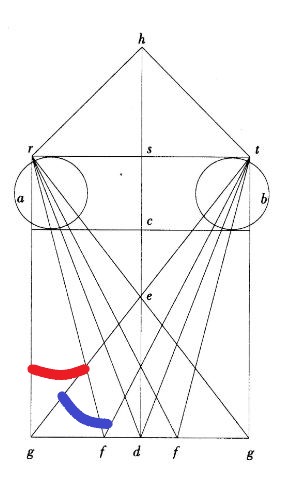

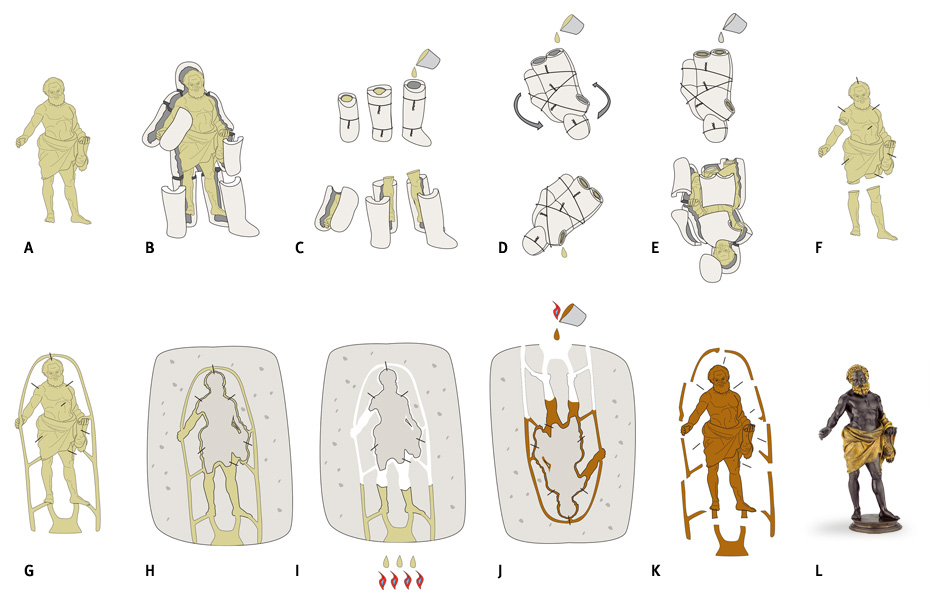

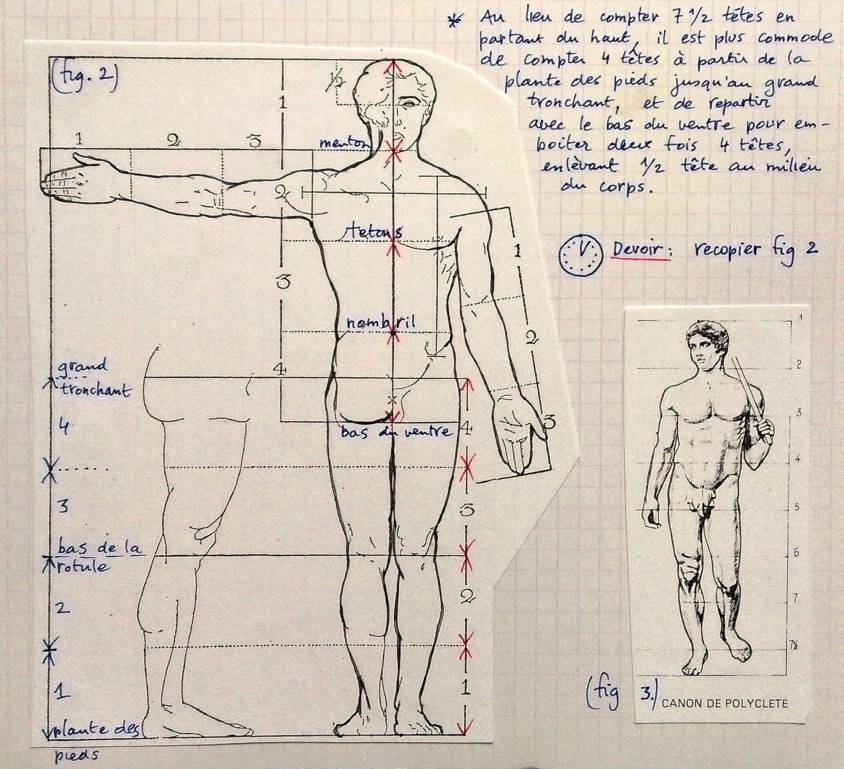

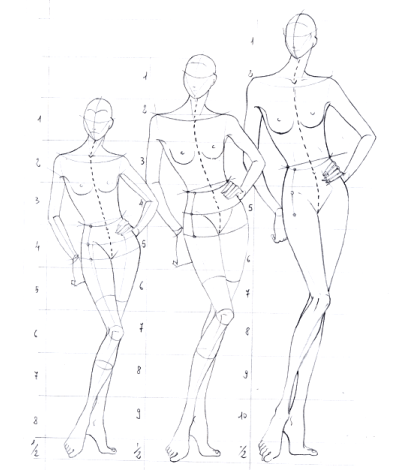

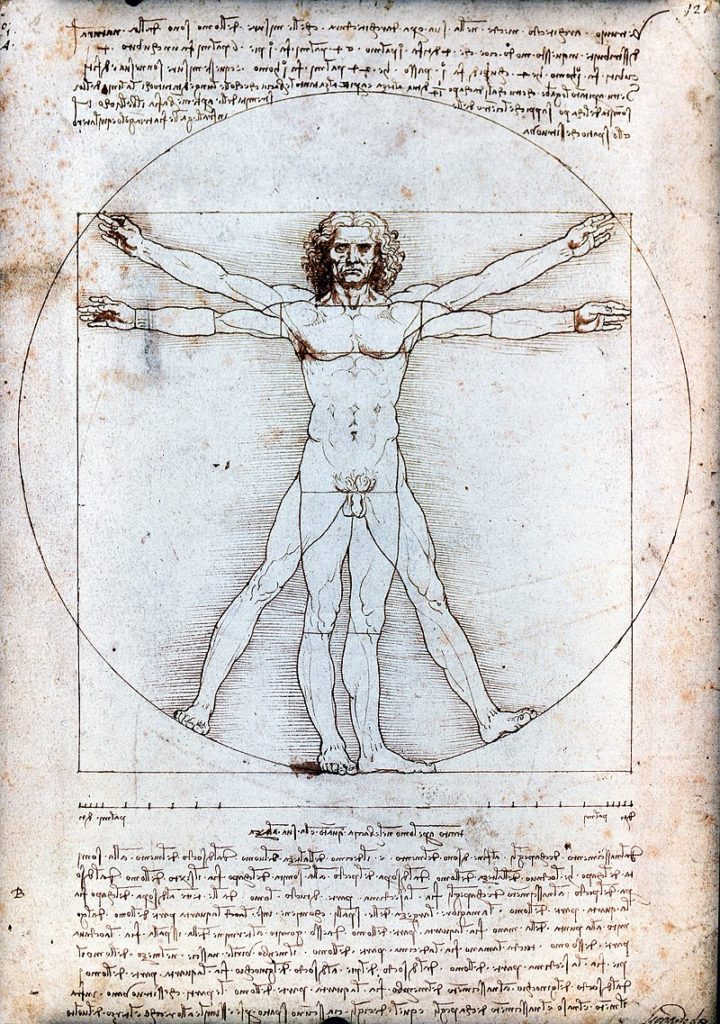

In art, Pythagoras inspired the Roman architect Vitruvius (90-15 BC), and later such theorists of the golden mean such as the Franciscan monk Luca Pacioli (1445-1517), whose treatise, De Divina Proportiona, illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, appeared in Venice in 1509.

However, if a theorem, probably from India, bears his name (attributed to Pythagoras by Vitruvius), little is known of his life. Just like Confucius, Socrates and Christ, if we are sure that he really existed, no writing from his hand has come down to us.

By necessity, Pythagoras

became a living legend, and even very active during the Renaissance, so much so that most people saw Plato as a mere « disciple » of the « divine Pythagoras ».

Born in the first half of the 6th century B.C. on the island of Samos in Asia Minor, Pythagoras was probably in contact with the school of geometer’s founded by Thales of Miletus (-625/-548 B.C.).

Around the age of 40, he left for Crotone in southern Italy to found a society of friends, both philosophical, political and religious, whose chapters were to multiply.

For Pythagoras, the issue is to build a bridge between man and the divine and on this basis to transform society and the city. When asked about his knowledge, Pythagoras, before Socrates and Cusa, asserted that he knew nothing, but that he sherished « the love of wisdom ». The word philo-sophy would have thus been born.

No Christian humanist, reading Saint Jerome (347-420), one of the Fathers of the Catholic Church, could escape the praise that the latter gives to Pythagoras.

In his polemic Apology against the Books of Rufinus, Jerome, in order to evoke an exemplary behavior, quotes what two disciples of Pythagoras would have said:

We must by all possible means avoid softness of the body, ignorance of the spirit, intemperance, civil dissensions, domestic dissensions and in general excess in all things.

And Jerome invokes the « Precepts of Pythagoras » :

Everything must be common among friends; a friend is another ourselves. We must consider two periods in life, the morning and the evening, that is, what we have done and what we must do. After God, we must seek the truth, which alone can bring men closer to the Creator.”

Secondly, Jerome believes that Pythagoras, in affirming the concept of the immortality of the soul, preceded Christianity:

Listen to what Pythagoras was the first to find in Greece, Jerome says: That souls are immortal, that they pass from one body into another, and, it is Virgil himself who tells us in the sixth book of the Aeneid: When they have made a revolution of a thousand years, God calls them in great numbers to the banks of the river Lethe, so that they may undoubtedly see again the heaven they no longer remember; it is then that they begin again to revive a new body, which first was Euphorbus, then Calide, then Hermoticus, then Perhius and finally Pythagoras ; and that after a certain time what has existed begins to be born again, that there is nothing new in the world, that philosophy is a collection of meditations on death, that every day it strives to free the soul from the chains that bind it to the body and to give it back its freedom. Plato communicates many other ideas in his writings, especially in the Phaedo and in the Timaeus.

The hidden geometry of numbers

For Pythagoras « the beginning is half of everything ». According to Theon of Smyrna (v. 70/v. 135), for the philosopher, « numbers are, so to speak, the principle, the source and the root of all things ».

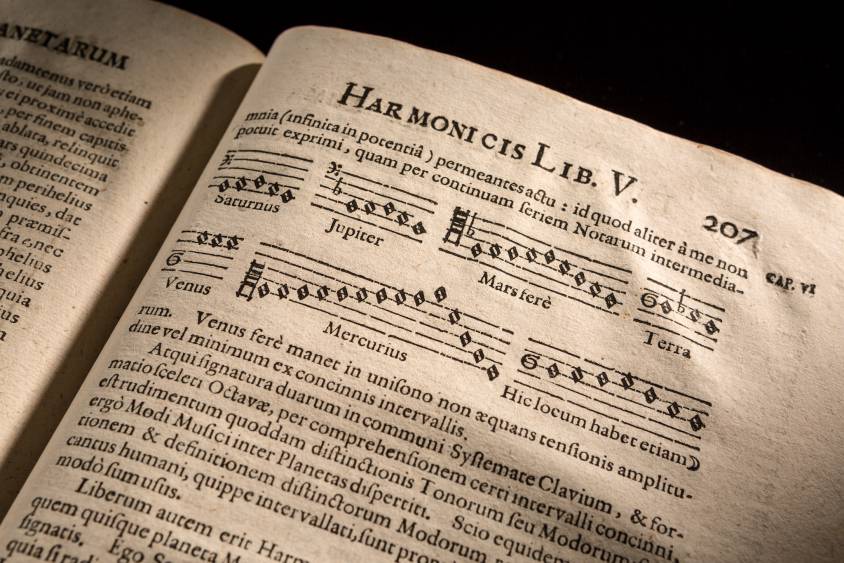

Aristotle, in his Metaphysics reports:

The Pythagoreans first applied themselves to mathematics… Finding that things [including musical sounds] model their nature mainly on the set of numbers and that numbers are the first principles of the whole of nature, the Pythagoreans concluded that the elements of numbers are also the elements of everything that exists, and they made the world a harmony and a number.

And as Cleinias of Tarantum (4th century BC), a Pythagorean friend of Plato, said:

When these things, therefore, are at rest, they give birth to mathematics and geometry, when they are in motion to the harmonica and astronomy.

The idea of the « monad », a dynamic unity participating in the One, perfected several centuries later by the philosopher and scientist Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) in his « Monadology« , comes to us from this period. Etymologically meaning « unity » (monas), it is the supreme unity (the One, God, the principle of numbers) which, while being at the same time the minimal unity, reflects in the microcosm the same dynamic activity that the One represents in the macrocosm.

Already, just the name of Apollo (a god considered as « the father » of Pythagoras) means, as Plato, Plutarch and other ancient authors point out: free of all multiplicity (Pollo = multiplicity; a-pollo = non-multiple).

Xenophanes of Colophones (born around 580 BC), asserts the existence of a unique God governing all things by the power of his intelligence. It is about a god not similar to the men, because eternal, incorporeal and spherical.

As much as this conception of a dynamic One has sometimes provoked an explosion of esoteric interpretations, it has stimulated the most creative minds and terrorized the formalists of thought.

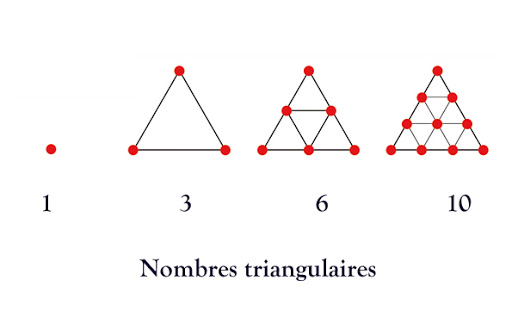

When speaking about simple things, arithmetic numbers, Pythagoras uses the terms of one, two, three, four, five, ten…, while to evoke ideal numbers and their power, he speaks about: monad, dyad, triad, tetrad, decad, etc. Thus, by conceiving numbers in a non-linear but figurative way, he offers an arithmetic applicable to astronomy, music and architecture. By arranging these numbers, like marbles, in a particular way, Pythagoras discovered the famous « geometry of numbers ». For example, in the case of triangular numbers, three points form a triangular surface. If we add three points below, we find the number 6, but it is still a triangle. And if we add four more points, we get the number 10, still a triangular number.

The Patriarch of Constantinople Photius (810-893) confirms that :

The Pythagoreans proclaimed that the complete number is ten.

The number ten, is a compound of the first four numbers that we count in their order. That is why they called Tetraktys the whole constituted by this number.

Besides the plane and triangular numbers (1, 3, 6, 10, etc.), Pythagoras explored the square numbers (1, 4, 9, 16, …), rectangular, cubic, pyramidal, star-shaped, etc. In doing so, Aristoxenus said, Pythagoras had « raised arithmetic above the needs of merchants ». This approach, that of seeing harmony above and within the multiple, has inspired many scientists throughout history. One thinks of Mendeleev for the elaboration of his table of elements or of Einstein.

The power of numbers was also well understood by the cardinal-philosopher Nicolaus of Cusa, who evokes Pythagoras in the first chapter of his treatise De Docta Ignorantia (1440), when he states that :

All those who search, judge the uncertain by comparing it to a certain presupposition by a system of proportions. All research is therefore comparative, and uses the means of proportion: if the object of research can be compared to the presupposition by a small proportional reduction, the judgment of apprehension is easy; but if we need many intermediaries, then difficulty and pain arise. This is well known in mathematics: the first propositions are easily brought back to the first principles which are very well known, whereas the following ones, because they need the intermediary of the first ones, have more difficulty. Therefore, all research consists of a comparative proportion, easy or difficult, and this is why the infinite, which escapes, as infinite, from all proportion, is unknown. Now, the proportion which expresses agreement in a thing on the one hand and otherness on the other hand, cannot be understood without the number. This is why the number encloses all that is susceptible of proportions. Therefore, it does not create a proportion in quantity only, but in everything that, in some way, by substance or by accident, can agree and differ. Therefore, Pythagoras strongly believed that everything was constituted and understood by the power of numbers. Now, the precision of combinations in material things and the exact adaptation of the known to the unknown are so far above human reason that Socrates considered that he knew nothing but his ignorance; at the same time as the very wise Solomon affirms that all things are difficult and that language cannot explain them.

The Geometry of numbers,

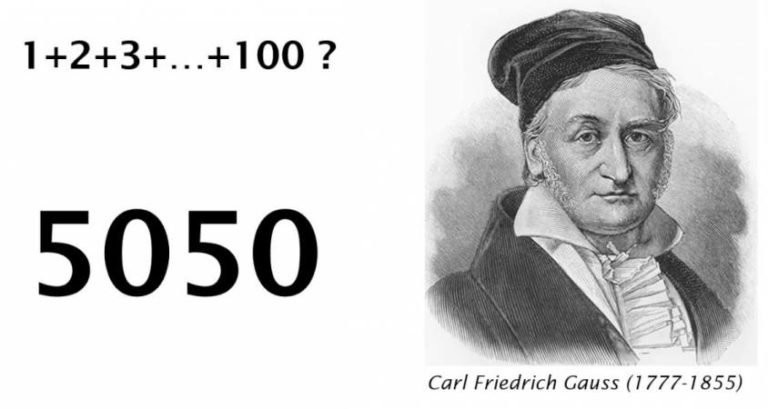

the secret of mental calculations

Here is a simple example.

One day, in Göttingen, the teacher of the young German mathematician Carl Gauss (1777-1855) asked his students to calculate the sum of all the numbers from one to one hundred. The students did so and began to add the numbers 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5, etc.

The young Gauss raises his hand and, following a mental calculation, announces the result of the operation: « 5050, Sir! »

The teacher, surprised, asks him how he arrived at the result so quickly. The young Gauss explains: to see if there is a geometry in the number 100, I added the first digit (1) with the last (100). This gives 101. Now, if I add the second digit (2) with the second to last one (99), it also makes 101. I concluded that within the number 100 there are fifty pairs of even and odd numbers whose sum is 101 each time. Thus, by multiplying 101 by the number of couples (50), I immediately arrive at 5050.

From Pythagoras to Plato

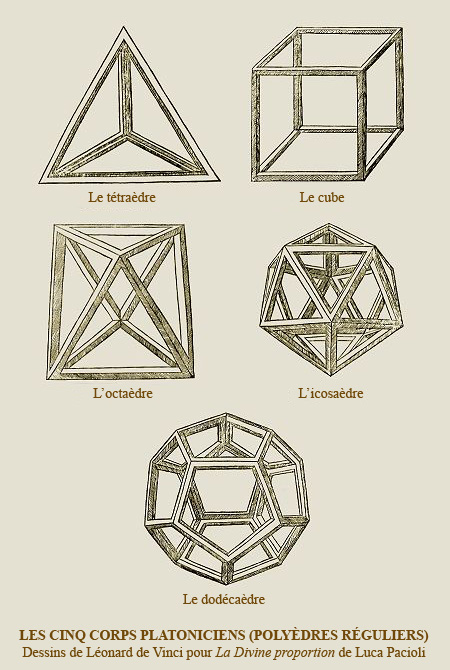

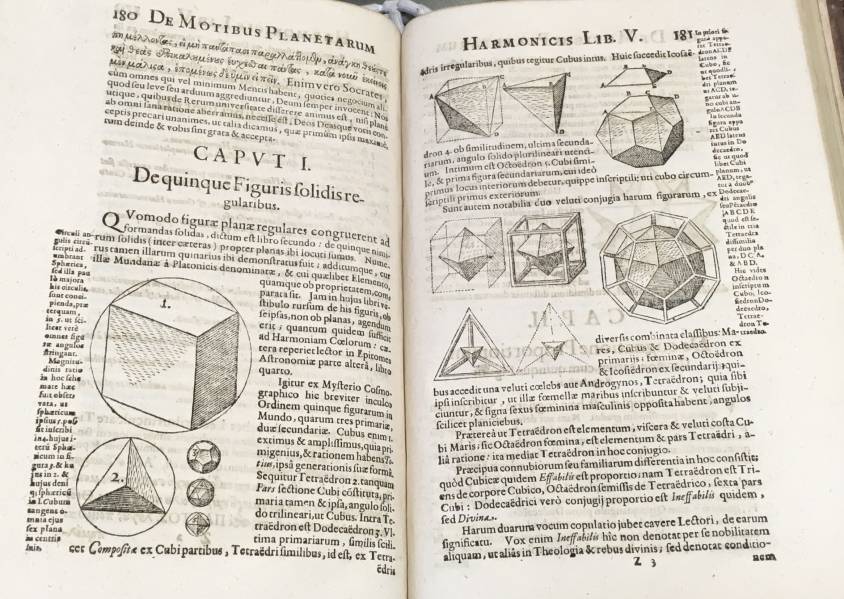

For Pythagoras, the most perfect surface is the circle and the ideal volume is the sphere since regular polyhedra can be inscribed. According to one of his disciples, the Italian Philolaus of Croton (-470/-390 BC), Pythagoras would have been the first to define the five regular polyhedrons:

- the cube,

- the tetrahedron (a pyramid with 4 triangular faces),

- the octahedron (composed of 8 triangles),

- the icosahedron (64 triangles) and

- the dodecahedron (composed of 12 pentagons).

Since Plato describes them in his work, the Timaeus, these regular polyhedra took the name of « Platonic solids ». Let’s recall that Plato went to Italy several times, notably to meet his close friend, the great Pythagorean scientist, astronomer, musical theorist and political leader, Archytas of Tarantum (-428/-387), considered today as « the father of robotics ».

A direct disciple of Philolaos, Archytas became the mathematics teacher of the brilliant Greek astronomer and physician Eudoxus of Cnidus (-408/-355).

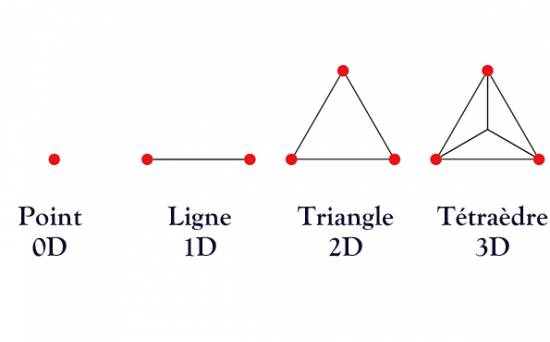

Starting with Archytas, the Pythagoreans associate the 1 to the point, the 2 to the line, the 3 to the surface (the two-dimensional geometrical figure: circle, triangle, square…), the 4 to the solid (the three-dimensional geometrical figure: tetrahedron, cube, sphere, etc.).

Let’s add that in the Timaeus, one of Plato’s last dialogues, after a brief exchange with Socrates, Critias and Hermocrates, the Pythagorean philosopher Timaeus of Locri (5th century BC) exposes a reflection on the origin and the nature of the physical world and of the human soul seen as the works of a demiurge while addressing the questions of scientific knowledge and the place of mathematics in the explanation of the world.

Cicero (Republic, I, X, 16) specifies that Timaeus of Locri was an intimate of Plato:

No doubt you have learned, Tuberon, that after the death of Socrates, Plato went first to Egypt to learn, then to Italy and Sicily, in order to learn all about the discoveries of Pythagoras.

There he lived for a long time in the intimacy of Archytas of Taranto and Timaeus of Locri, and had the chance to obtain the Commentaries of Philolaos.

The music of the spheres

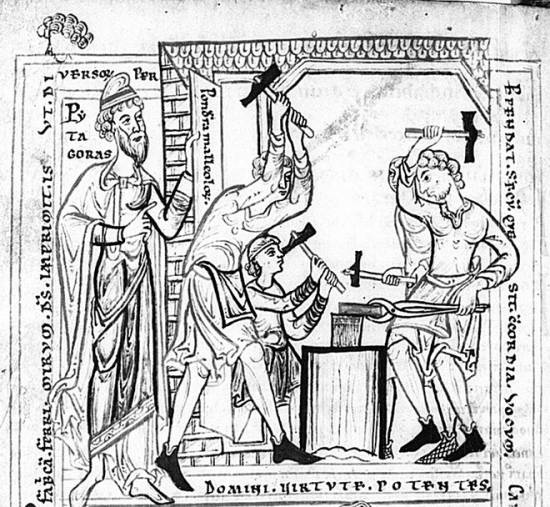

A magnificent bas-relief on the campanile of the Florence cathedral reflects what the early Italian humanists knew about Pythagoras.