Étiquette : Egypt

ARTKAREL AUDIO GUIDE: The Greek tradition behind the Fayum Mummy Portraits (Paris)

Karel Vereycken comments the Louvre’s Fayum Mummy Portraits.

Listen:

To the audio on this website

Read:

The ancient practice of debt cancellation

This article in RUSSIAN (pdf)

Cet article en FRANCAIS (en ligne)

While anyone with a modicum of rationality knows that a huge proportion of the world’s debts are absolutely unpayable, it’s a fact that today any debt cancellation, however odious or illegitimate, remains taboo.

By Karel Vereycken, December 2020.

Debt repayment is presented by heads of state and government, central banks, the IMF and the mainstream press as imperative, inevitable, indisputable, compulsory. Citizens have elected their governments, so they must resign themselves to paying the debt. For not to pay is more than violating a symbol: it is to exclude oneself from civilization, and to renounce in advance any new credit that is granted only to « good payers ». What counts is not the effectiveness of the act, but the expression of one’s « good faith », i.e. one’s willingness to submit to the strongest. The only possible discussion is how to modulate the distribution of the necessary sacrifices.

It seems that the ultra-liberal, monetarist model that has been surreptitiously imposed on us is that of the Roman Empire: zero debt for states and cities, and no debt forgiveness for citizens!

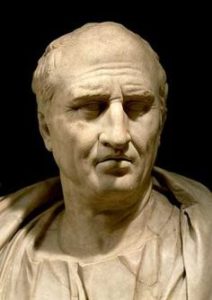

In his treatise on Duties (De officiis), written in 44-43, Cicero, who had just quelled a revolt by people demanding a debt remission, justifies the radical nature of his policy towards indebtedness:

« What does the establishment of new debt accounts [i.e., remission] mean, if not that you buy land with my money, that you have this land, and that I don’t have my money? That’s why we have to make sure there are no debts, which can harm the state. There are many ways of avoiding it, but if there are debts, not in such a way that the rich lose their property and the debtors acquire the property of others. Indeed, nothing maintains the State more strongly than good faith (fides), which cannot exist if there is no need to pay one’s debts. Never has anyone acted more forcefully to avoid paying their debts than under my Consulate. It was attempted by men of all kinds and ranks, with weapons in hand, and by setting up camps. But I resisted them in such a way that this entire evil was eliminated from the State. »

What has been carefully concealed is that another human practice has also existed: moratoria, partial and even generalized debt cancellations have taken place repeatedly throughout history and were carried out according to different contexts.

Often, proclamations of generalized debt cancellation were the initiative of self-preservation-minded rulers, aware that the only way to avoid complete social breakdown was to declare a « washing of the shelves » – those on which consumer debts were inscribed – cancelling them to start afresh.

The American anthropologist David Graeber, in Debt, the first 5000 years (2011), pointed out that the first word we have for « freedom » in any human language is Sumerian amargi, meaning freed from debt and, by extension, freedom in general, the literal meaning being « return to the mother » insofar as, once debts were cancelled, all debt slaves could return home.

Debt cancellations were sometimes the result of bitter social struggles, wars and crises. What is certain is that debt has never been a detail of history.

David Graeber sums it up:

« For millennia, the struggle between rich and poor has largely taken the form of conflicts between creditors and debtors – disputes over the justice or injustice of interest payments, peonage, amnesty, property seizure, restitution to the creditor, confiscation of sheep, seizure of vineyards and the sale of the debtor’s children as slaves. And over the last 5,000 years, with remarkable regularity, popular insurrections have begun in the same way: with the ritual destruction of debt registers – tablets, papyri, ledgers or other media specific to a particular time and place. (After which, the rebels generally attacked cadastres and tax registers.) »

And as the great ancient scholar Moses Finley was fond of saying,

« All revolutionary movements have had the same program: cancellation of debts and redistribution of land. »

Let us now examine some historical precedents for voluntary debt forgiveness.

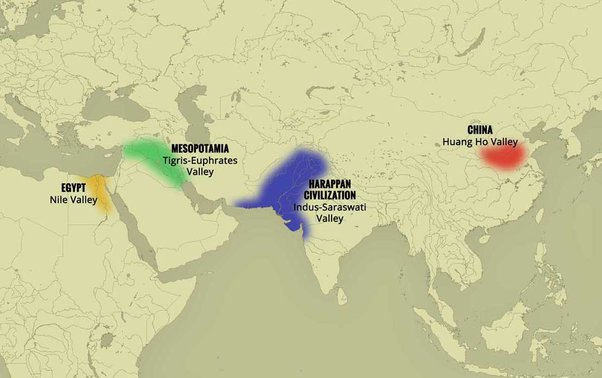

Debt cancellation in Mesopotamia

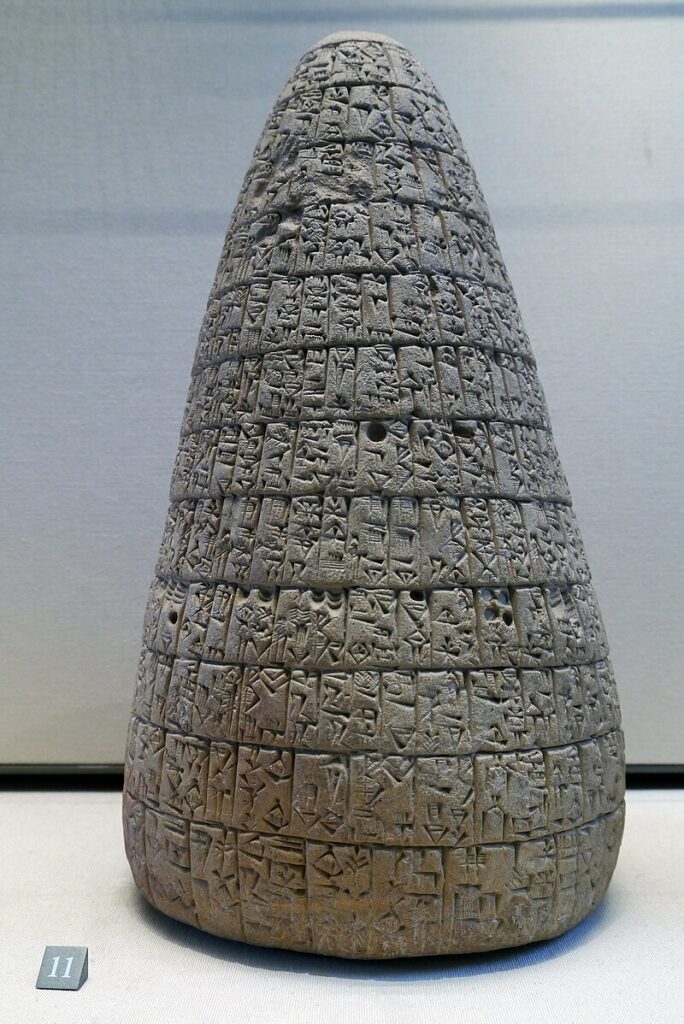

The earliest known debt cancellation was proclaimed in Mesopotemia by Entemena of Lagash c. 2400 BCE.

One of his successors, Urukagina, who was the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash, is known for his code of rules that includes debt cancelation.

Urukagina’s code is the first recorded example of government reform, seeking to achieve a higher level of freedom and equality by limiting the power of priesthood and a usurous land-owner oligarchy. Usury and seizure of property for debt payment were outlawed. « The widow and the orphan were no longer at the mercy of the powerful man ».

Similar measures were enacted by later Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian rulers of Mesopotamia, where they were known as « freedom decrees » (ama-gi in Sumerian).

This same theme exists in an ancient bilingual Hittite–Hurrian text entitled « The Song of Debt Release ».

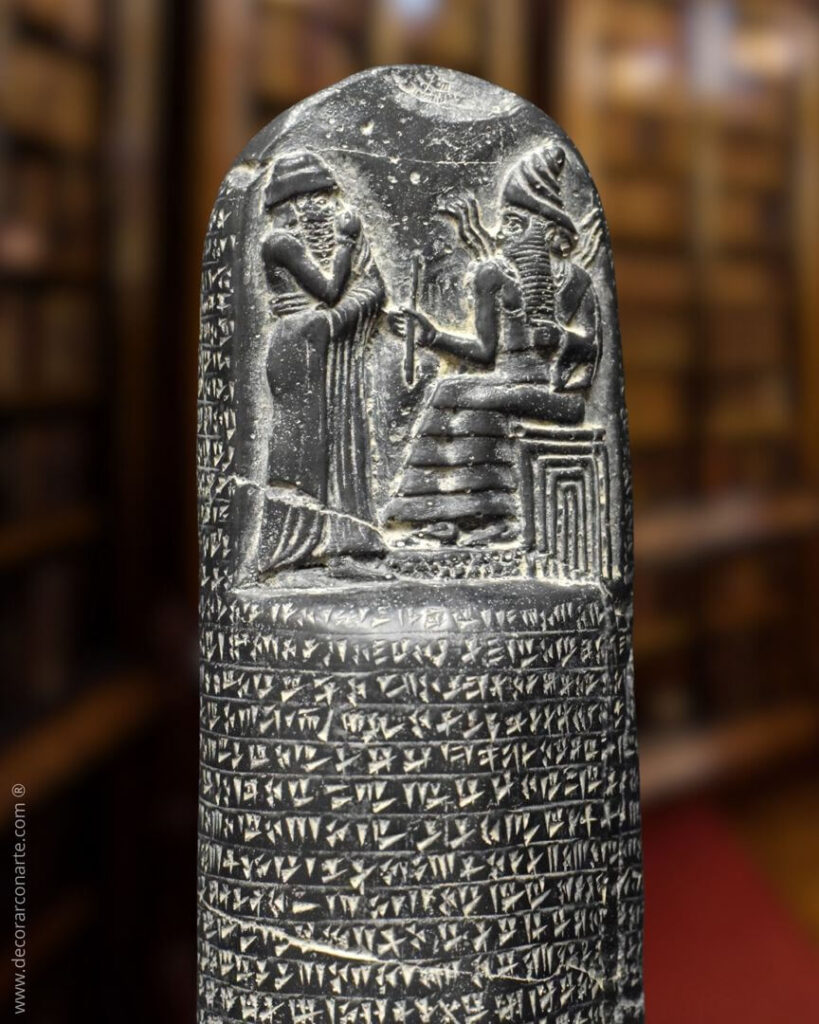

The reign of Hammurabi, King of Babylon (located in present-day Iraq), began in 1792 BC and lasted 42 years.

The inscriptions preserved on a 2-meter-high stele in the Louvre are known as the « Hammurabi Code ». It was placed in a public square in Babylon. If it is a long, very severe code of justice, prescribing the application of the law of retaliation (« an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth »), its epilogue nevertheless proclaims that « the powerful cannot oppress the weak, justice must protect the widow and the orphan (…) in order to render justice to the oppressed ».

Hammurabi, like the other rulers of the Mesopotamian city-states, repeatedly proclaimed a general cancellation of citizens’ debts to public authorities, their high officials and dignitaries.

Thanks to the deciphering of numerous documents written in cuneiform, historians have found indisputable evidence of four general debt cancellations during Hammurabi’s reign (at the beginning of his reign in 1792, in 1780, in 1771 and in 1762 BC).

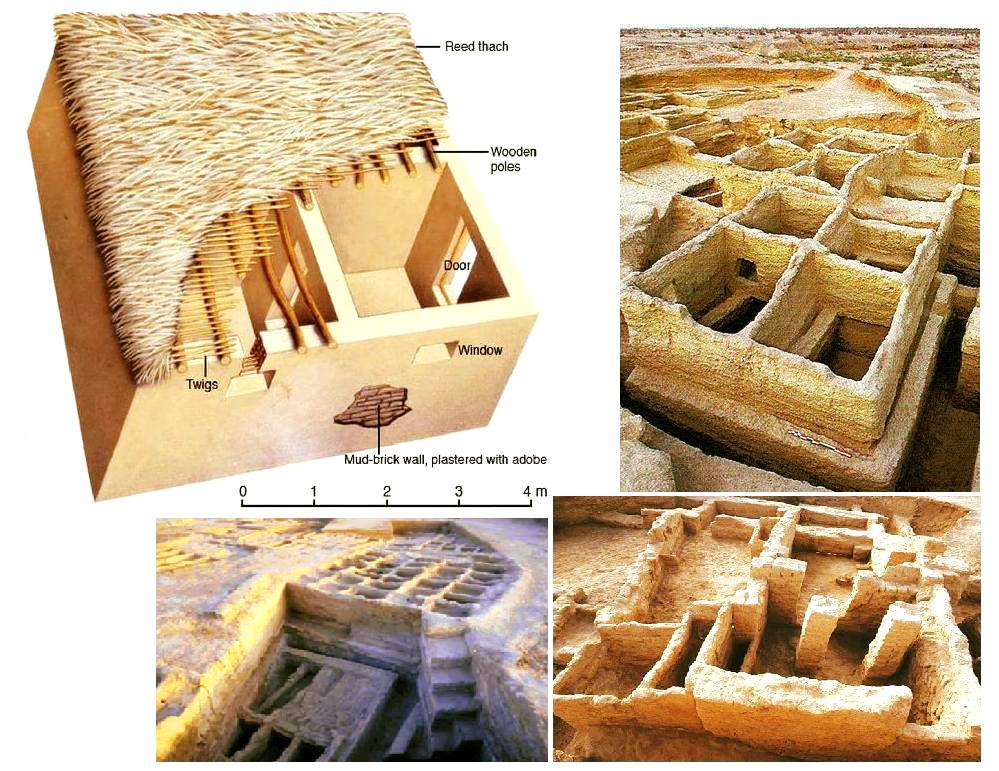

Babylonian society was predominantly agricultural. The temple and palace, and the scribes and craftsmen they employed, depended for their sustenance on a vast peasantry from whom land, tools and livestock were rented.

In exchange, each farmer had to offer part of his production as rent. However, when climatic hazards or epidemics made normal production impossible, producers went into debt.

The inability of peasants to repay debts could also lead to their enslavement (family members could also be enslaved for debt).

The Hammurabi Code obviously wanted to change this. Article 48 of the Code of Laws states:

« Whoever owes a loan, and a storm buries the grain, or the harvest fails, or the grain does not grow for lack of water, need not give any grain to the creditor that year, he wipes the tablet of the debt in the water and pays no interest for that year. »

This ideal of justice is notably supported by the terms kittum, « justice as the guarantor of public order », and « justice as the restoration of equity. » It was asserted in particular during the « edicts of grace » (designated by the term mîsharum), a general remission of public and private debts in the kingdom (including the release of people working for another person to repay a debt).

Thus, to preserve the social order, Hammurabi and the ruling power, acting in their own interests and in the interests of society’s future, periodically agreed to cancel all debts and restore the rights of peasants, in order to save the threatened old order in times of crisis, or as a kind of reset at the beginning of a sovereign’s reign.

Proclamations of general debt cancellation are not confined to the reign of Hammurabi; they began long before him and continued afterwards. There is evidence of debt cancellations as far back as 2400 BC, six centuries before Hammurabi’s reign, in the city of Lagash (Sumer); the most recent date back to 1400 BC in Nuzi.

In all, historians have accurately identified some thirty general debt cancellations in Mesopotamia between 2400 and 1400 BC.

These proclamations of debt cancellation were the occasion for great festivities, usually during the annual spring festival. Under the Hammurabi dynasty, the tradition of destroying the tablets on which debts were written was established.

In fact, the public authorities kept precise accounts of debts on tablets kept in the temple. Hammurabi died in 1749 BC after a 42-year reign. His successor, Samsuiluna, cancelled all debts to the state and decreed the destruction of all debt tablets except those relating to commercial debts.

When Ammisaduqa, the last ruler of the Hammurabi dynasty, acceded to the throne in 1646 BC, the general cancellation of debts he proclaimed was very detailed. The aim was clearly to prevent certain creditors from taking advantage of certain families. The annulment decree stipulates that official creditors and tax collectors who have expelled peasants must compensate them and return their property, on pain of execution.

After 1400 BC, no deeds of debt cancellation have been found, as the tradition has been lost. Land was taken over by large private landowners, and debt slavery returned.

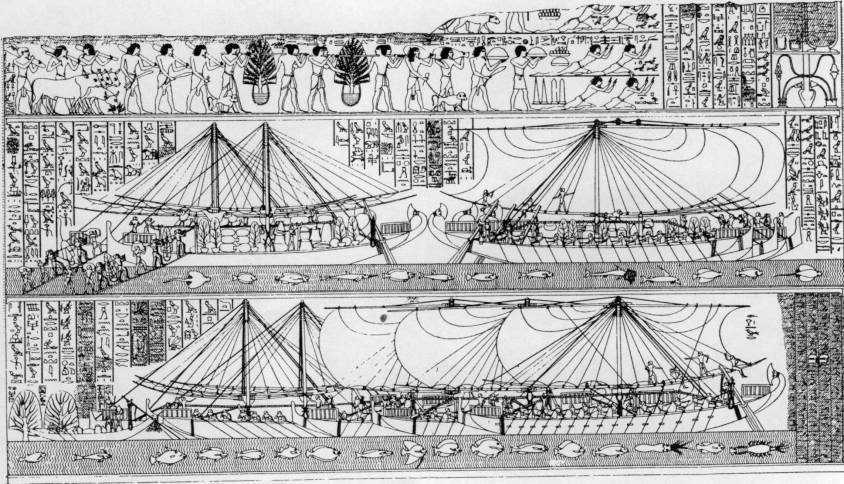

In Egypt

In Ancient Egypt interest-bearing debt did not exist for most of its history. When it started spreading in the Late Period, the rulers of Egypt regulated it and a number of debt remissions are known to have occurred during the Ptolemaic era, including the one whose proclamation was inscribed on the Rosetta Stone.

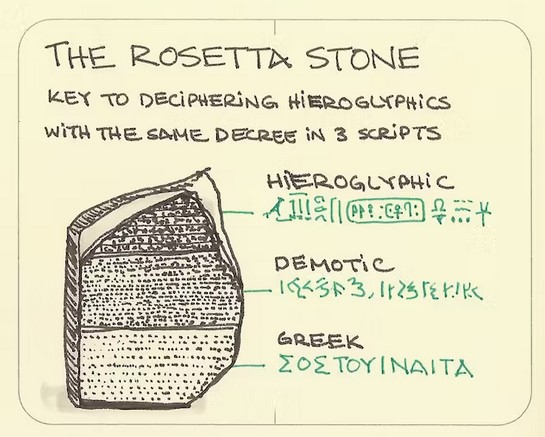

Now on display at the British Museum in London, the « Rosetta Stone » was discovered on July 15, 1799 at el-Rashid (Rosetta) by one of Napoleon’s soldiers during the Egyptian campaign. It contains the same text written in hieroglyphs, demotic (Egyptian cursive script) and Greek, giving Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) the key to the passage from one language to another.

This was a decree issued by Pharaoh Ptolemy V on March 27, 196 BC, announcing an amnesty for debtors and prisoners. The Greek Ptolemy dynasty that ruled Egypt institutionalized the regular cancellation of debts.

It was perpetuating known practices, since Greek texts mention that Pharaoh Bakenranef, who ruled Lower Egypt from c. 725 to 720 BC, had promulgated a decree abolishing debt slavery and condemning debt imprisonment.

TRANSCRIPTION OF THE PHARAOH’S DECREE

ON THE ROSETTA STONE:

Assembled the Chief Priests and Prophets there and those who enter the inner temple to worship the gods, and the Fanbearers and Sacred Scribes and all the other priests of the temples of the earth who have come to meet the king at Memphis, for the feast of the Assumption of PTOLEMEE, THE LIVING FOREVER, THE BELOVED OF PTAH, THE GOD EPIPHANES EUCHARISTOS, the successor of his father, All assembled in the temple of Memphis on this day when it was declared:

“that King PTOLEMEE, THE LIVING FOREVER, THE BELOVED OF PTAH, THE GOD EPIPHANES EUCHARISTOS, the son of King Ptolemy and Queen Arsinoe, the Philopator Gods, both benefactors of the temple and those who dwell therein, as well as their subjects, being a god from a god and the goddess loves Horus the son of Isis and Osiris who avenged his father Osiris by being favorably disposed towards the gods, delivered to the revenues of the temples silver and corn and undertook much expenditure for the prosperity of Egypt, and the maintenance of the temples, and was generous to all out of his own resources ;

“and exempted them from some of the revenues and taxes levied in Egypt and alleviated others so that his people and all others could be in prosperity during his reign ;

“and that he cleared the debts to the crown for many Egyptians and for the rest of the kingdom; ”

The existence of this decree therefore confirms that the practice had existed for many centuries.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (Ist Century BC) provides the following rationale for abolishing the debt bondage by Pharaoh Bakenranef:

« For it would be absurd… that a soldier, at the moment perhaps when he was setting forth to fight for his fatherland, should be haled to prison by his creditor for an unpaid loan, and that the greed of private citizens should in this way endanger the safety of all »

As one can see here, one of the very pragmatic reasons for debt cancellation was that the Pharaoh wanted to have a peasantry capable of producing enough food and, if need be, able to take part in military campaigns. For both of these reasons, it was important to ensure that peasants were not expelled from their lands under the thumb of creditors.

In another part of the region, the Assyrian emperors of the 1st millennium BC also adopted the tradition of debt cancellation.

In Greece: Solon of Athens

In Greece, the Athenian lawmaker Solon (c. 638 BC–558 BC), in order to rectify the widespread serfdom and slavery that had run rampant by the 6th century BCE, introduced a set of laws nown as the Seisachtheia introducing debt relief.

Before Solon, according to the account of the Constitution of the Athenians attributed to Aristotle, debtors unable to repay their creditors would surrender their land to them, then becoming hektemoroi, i.e. serfs who cultivated what used to be their own land and gave one sixth of produce to their creditors. However, should the debt exceed the perceived value of debtor’s total assets, then the debtor and his family would become the creditor’s slaves as well. The same would result if a man defaulted on a debt whose collateral was the debtor’s personal freedom. The fight for debt relief and the fight to abolish slavery were in practice identical.

Solon’s seisachtheia laws immediately cancelled all outstanding debts, retroactively emancipated all previously enslaved debtors, reinstated all confiscated serf property to the hektemoroi, and forbade the use of personal freedom as collateral in all future debts. The laws instituted a ceiling to maximum property size – regardless of the legality of its acquisition (i.e. by marriage), meant to prevent excessive accumulation of land by powerful families.

In the Torah and Old Testament

Social justice, particularly in the form of forgiving debts that shackle the poor to the rich, is a leitmotif in the history of Judaism. It was practiced in Jerusalem in the 5th century BC.

The writing of the Torah was completed at this time. Deuteronomy, 15 states:

The Year for Canceling Debts

15 At the end of every seven years you must cancel debts.

2 This is how it is to be done: Every creditor shall cancel any loan they have made to a fellow Israelite. They shall not require payment from anyone among their own people, because the Lord’s time for canceling debts has been proclaimed.

3 You may require payment from a foreigner, but you must cancel any debt your fellow Israelite owes you.

4 However, there need be no poor people among you, for in the land the Lord your God is giving you to possess as your inheritance, he will richly bless you,

5 if only you fully obey the Lord your God and are careful to follow all these commands I am giving you today.

6 For the Lord your God will bless you as he has promised, and you will lend to many nations but will borrow from none. You will rule over many nations but none will rule over you.

7 If anyone is poor among your fellow Israelites in any of the towns of the land the Lord your God is giving you, do not be hardhearted or tightfisted toward them.

8 Rather, be openhanded and freely lend them whatever they need.

9 Be careful not to harbor this wicked thought: “The seventh year, the year for canceling debts, is near,” so that you do not show ill will toward the needy among your fellow Israelites and give them nothing. They may then appeal to the Lord against you, and you will be found guilty of sin.

10 Give generously to them and do so without a grudging heart; then because of this the Lord your God will bless you in all your work and in everything you put your hand to.

11 There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore I command you to be openhanded toward your fellow Israelites who are poor and needy in your land.

Thus, the Israelites were obliged to free Hebrew slaves who had sold themselves to them for debt, and to offer them some of the produce of their small livestock, their fields and their wine presses, so that they would not return home empty-handed.

As the law is too rarely applied, Leviticus reaffirms it by modulating it:

The Year of Jubilee

8 “‘Count off seven sabbath years—seven times seven years—so that the seven sabbath years amount to a period of forty-nine years.

9 Then have the trumpet sounded everywhere on the tenth day of the seventh month; on the Day of Atonement sound the trumpet throughout your land.

10 Consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you; each of you is to return to your family property and to your own clan.

11 The fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you; do not sow and do not reap what grows of itself or harvest the untended vines.

12 For it is a jubilee and is to be holy for you; eat only what is taken directly from the fields.

13 “‘In this Year of Jubilee everyone is to return to their own property.

14 “‘If you sell land to any of your own people or buy land from them, do not take advantage of each other.

15 You are to buy from your own people on the basis of the number of years since the Jubilee. And they are to sell to you on the basis of the number of years left for harvesting crops.

16 When the years are many, you are to increase the price, and when the years are few, you are to decrease the price, because what is really being sold to you is the number of crops.

17 Do not take advantage of each other, but fear your God. I am the Lord your God.

Today, some will tell you that under these conditions, a year before the jubilee date, credit would necessarily be scarce and expensive, and that debt would thus find its limit!

This is a mistake, because to ensure that the law is followed, the codes describe in detail how purchases and sales of goods between private individuals must be carried out according to the number of years elapsed since the previous jubilee (i.e., the number of years remaining before the goods must be returned to their previous owner).

Another passage, this time from the prophet Jeremiah, vividly illustrates the scope of the law on the remission of debts.

Faced with the advance of enemy armies towards Jerusalem in 587 B.C., Jeremiah supports, in God’s name, the undertaking of King Zedekiah (then ruler of the Kingdom of Judea), who demands the immediate release of all those enslaved for debt from the powerful forces of his kingdom (Jer. 34:8-17).

Jeremiah forcefully recalls the ancient demand for the freeing of slaves… which the king, in fact, needs to patriotically reunite the social classes before the battle, and give himself sufficient troops free of all servile obligations!

A passage in the Book of (the prophet) Nehemiah (447 BC), the governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC), influenced by the ancient Mesopotamian tradition, also proclaims the cancellation of debts owed by indebted Jews to their rich compatriots.

The social situation Nehemiah discovered in Judea was appalling. To remedy the problem, Nehemiah placed the law of debt relief within a religious framework, the Covenant with Yahweh. From then on, it was God himself who commanded the forgiveness of debts and the liberation of slaves and their land, for the land belonged to God alone.

Nehemiah Helps the Poor

« Now the men and their wives raised a great outcry against their fellow Jews.

2 Some were saying, “We and our sons and daughters are numerous; in order for us to eat and stay alive, we must get grain.”

3 Others were saying, “We are mortgaging our fields, our vineyards and our homes to get grain during the famine.”

4 Still others were saying, “We have had to borrow money to pay the king’s tax on our fields and vineyards.

5 Although we are of the same flesh and blood as our fellow Jews and though our children are as good as theirs, yet we have to subject our sons and daughters to slavery. Some of our daughters have already been enslaved, but we are powerless, because our fields and our vineyards belong to others.”

6 When I heard their outcry and these charges, I was very angry.

7 I pondered them in my mind and then accused the nobles and officials. I told them, “You are charging your own people interest!” So I called together a large meeting to deal with them

8 and said: “As far as possible, we have bought back our fellow Jews who were sold to the Gentiles. Now you are selling your own people, only for them to be sold back to us!” They kept quiet, because they could find nothing to say.

9 So I continued, “What you are doing is not right. Shouldn’t you walk in the fear of our God to avoid the reproach of our Gentile enemies?

10 I and my brothers and my men are also lending the people money and grain. But let us stop charging interest!

11 Give back to them immediately their fields, vineyards, olive groves and houses, and also the money you are charging them—one percent of the money, grain, new wine and olive oil.”

12 “We will give it back,” they said. “And we will not demand anything more from them. We will do as you say.”

If we add to these passages the countless verses forbidding the lending of interest to fellow human beings and the taking of property as collateral, we get an idea of what the Israelites in the land of Canaan had put in place to try and maintain a certain social equilibrium.

Alas, in the first century AD, debt forgiveness and the freeing of slaves from debt were swept away from all Near Eastern cultures, including Judea.

The social situation there had deteriorated to such an extent that Rabbi Hillel was able to issue a decree requiring debtors to sign away their right to debt forgiveness.

In the Bible and New Testament

What happened to debt forgiveness in the New Testament?

While the Acts of the Apostles and the writings of the Fathers of the Church sometimes express a great docility, Jesus’ position on the forgiveness of debts, as reported repeatedly and most forcefully in Luke’s Gospel, chapter 4:16-21, appears to be marked by a revolutionary prophetic breath.

Luke places the passage at the beginning of Jesus’ public life. He makes it a key to everything that follows.

16 Jesus went to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, and on the Sabbath day he went into the synagogue, as was his custom. He stood up to read,

17 and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. Unrolling it, he found the place where it is written:

18 “The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

19 to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

20 Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him.

21 He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.”

Let’s not forget that the « year of the Lord’s favor (Jubilee Year) » to which he called, demanded at once rest for the land, forgiveness of debts and the liberation of slaves.

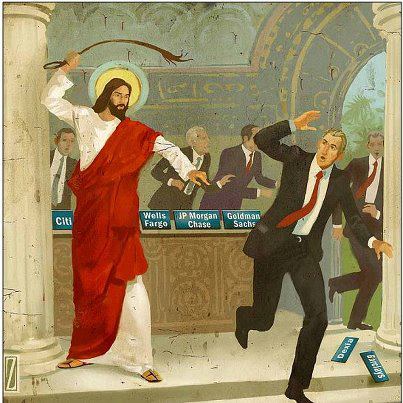

In the midst of the slave-owning Roman Empire, which fiercely rejected the concept of debt forgiveness, Jesus’ declaration could only be seen as a declaration of war on the ruling system.

Before he was arrested, Jesus made a highly symbolic material gesture: he forcefully overturned the tables of the money-changers in the Jerusalem temple. For the Jewish high priests and the Roman authorities, this was too much.

Peace of Westphalia of 1648

In 1648, after five years of negotiations, led by the French diplomat Abel Servien on the instructions of Cardinal Mazarin, the “Peace of Westphalia” was signed, putting an end to the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

Long before the UN Charter, 1648 made national sovereignty, mutual respect and the principle of non-interference the foundations of international law.

But there was more. As we have documented, the peace deal also included the cancelation of debts that had become the very reason for continuing the war.

Unpayable, unsustainable and illegitimate debts, interests, bonds, annuities and financial claims, explicitly identified as fueling a dynamic of perpetual war, were examined, sorted out and reorganized, most often through the cancellation of debts (articles 13 and 35, 37, 38 and 39), through moratoria or debt rescheduling according to specific timetables (article 69).

Article 40 concludes that debt cancellations will apply in most cases, “and yet the Sums of Money, which during the War have been exacted bona fide, and with a good intent, by way of Contributions, to prevent greater Evils by the Contributors, are not comprehended herein. » (Implying that these debts would have to be honored.)

Finally, looking to the future, for Commerce to be “reestablished”, the treaty abolished many tolls and customs established by “private” authorities for they were obstacles to the exchange of physical goods and know-how and hence to mutual development. (Art. 69 and 70).

TREATY OF WESTPHALIA (1648)

Art. 13:

“Reciprocally, the Elector of Bavaria renounces entirely for himself and his Heirs and Successors the Debt of Thirteen Millions, as also all his Pretensions in Upper Austria; and shall deliver to his Imperial Majesty immediately after the Publication of the Peace, all Acts and Arrests obtain’d for that end, in order to be made void and null.”

Art. 35:

“That the Annual Pension of the Lower Marquisate, payable to the Upper Marquisate, according to former Custom, shall by virtue of the present Treaty be entirely taken away and annihilated; and that for the future nothing shall be pretended or demanded on that account, either for the time past or to come.”

In the United States

It is poorly known that in the United States, on three separate occasions, governments have successfully repudiated public debts owed to private bankers?

First, in the 1830s, four States repudiated their debts – Mississippi, Arkansas, Florida and Michigan. The creditors were mainly British.

The Russian born Alexander Nahum Sack (1890-1955), a professor of Russian law specialized in international financial legislation, wrote in this regard: “One of the main reasons justifying these repudiations was the squandering of the sums borrowed: they were usually borrowed to establish banks or build railways; but the banks failed and the railway lines were never built. These questionable operations were often the result of agreements between crooked members of the government and dishonest creditors.” (Les effets des transformations des États sur leurs dettes publiques et autres obligations financières : traité juridique et financier, Recueil Sirey, Paris, 1927, p. 158).

Second, and more importantly, following the American Civil War (1861-1865), the US Federal government summoned the Confederate States to repudiate the debts they had contracted in order to carry on the war.

In an article titled « The Rebel Debt », the New York Times, on Nov. 9, 1865, wrote the following:

« The debts of the Confederate Government, contracted for the purposes of war, and for all other purposes, were swept away when the Confederacy fell. All its currency, bills, bonds, treasury notes, and « promises to pay » of every kind, became worthless to the holders, even though those holders had given for them real property or services of a positive value. After the fall of Richmond, hundred-dollar bills, based on the faith and credit of the Confederacy, were sold for a nickel cent a piece, and thousand-dollar notes were exchanged evenly for three-cent shinplasters. There is little if any talk in any part of the South about assuming any part of this debt. Its magnitude is appalling, and the States of the South did not become responsible for it in their individual capacity. On its face it was declared to be payable upon the establishment of the independence of the Southern Confederacy — thus linking its fortunes with that of the rebel government; and it was but logical that the Confederacy’s credit should cease to have a value when the Confederacy itself ceased to have an existence. »

The creditors had purchased securities issued by European bankers on behalf of the Confederate States, mainly in London and Paris. Among the creditors was the German Banque Erlanger of Paris and its London subsidiary. The risk was remunerated by an interest rate of 7% per annum, relatively high for the period.

The Civil War debt held by individual Confederate states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas) at the end of the war has been estimated at close to $67 million. Even larger, the debt of the Confederate States of America, which was reported to be $1.4 billion on October 1, 1864. And, if one adds in compensation for freed slaves (which was a rumored demand of Southerners), valued at $1.75 billion in 1860, the total bill the South might have presented to the North amounted to $3.2 billion.

And the The New York Times continued:

« But there has appeared in many of the States, and still appears in some of them, a strong party desirous of assuming the payment of the debts contracted by the various States individually, in aid of rebellion, and while members of the Confederacy.

« It is the repudiation of these which has been effected in Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, and, as appears by this morning’s telegrams, also in Georgia, at the suggestion of the President; and it is the failure to repudiate this debt by South Carolina, which has disappointed the intelligent supporters of the President’s policy of reconstruction. This debt has been the subject of earnest debate in the Georgia State Convention now in session at Milledgeville; and it was in reference to this debate that the President (Andrew Johnson, who became president after Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865) sent a dispatch to the Provisional Governor of Georgia, in which was pointedly and vigorously set forth the course that ought to be followed by the convention.

« He remarked: ‘The people of Georgia should not hesitate one single moment in repudiating every single dollar of debt created for the purpose of aiding the rebellion against the Government of the United States. It will not do to levy and collect taxes from a State and people that are loyal and in the Union to pay a debt that was created to aid in taking them out and subverting the Constitution of the United States. I do not believe the great mass of the people of the State of Georgia, when left uninfluenced, will ever submit to the payment of a debt which was the main cause of bringing on their past and present suffering, the result of the rebellion. Those who invested their capital in the creation of this debt must meet their fate, and take it as one of the inevitable results of the rebellion, though it may seem hard to them. It should at once be made known, at home and abroad, that no debt contracted for the purpose of dissolving the Union can or ever will be paid by taxes levied on the people for such purpose.’

« There was nothing in the Constitution preventing the United States from repudiating its own debt. Numerous individual states had done this in the past. In the 1840s, and within the memory of many, a number of states had defaulted on or totally repudiated their debts because of the stresses brought on by the panic of 1837. Now, twenty years later, after a civil war, why should not the United States follow their example and wipe the slate clean?«

In 1868, following the Civil War, Congress submitted to the states three amendments as part of its Reconstruction program to guarantee equal civil and legal rights to Black citizens.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, among its provisions, grants citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States,” thereby granting citizenship to formerly enslaved people.

And relevant for our discussion, section four of the 14th amendment stipulates that while the debt of the Union are considered legitimate and should be honored, those of the Confederacy are what one could call an « odious debt » and shouldn’t be paid.

“The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion [by the Union], shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.«

As a result, the bondholders of Confederate debt were never repaid due to the repudiation decreed by the Federal government and the application of Section 4 of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, since loans had served to finance the rebellion of the Southern States. It was the purpose of the loans, and above all the fact that they had been contracted by rebel forces, that was cited as justification. The reality was that imposing debt repayment would prevent any successful reconstruction policy, considered far more important.

Finally, a third wave of repudiations took place in the USA after 1877, when eight Southern States (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee) repudiated their debts on the grounds that the bonds issued during the period between the end of the American Civil War and 1877 had been used for illicit loans to corrupt politicians (including former slaves) who were supported by the Northern States. This repudiation was decided by (racist) government officials (often members of the Democrat party) who had returned to power in the South after the withdrawal of the federal troops who occupied the South until 1877.

During the Cold War

In the United States, Eisenhower was elected in November 1952.

His Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, otherwise an evil man, noted that, despite the Marshall Plan, Europe, still burdened by a mountain of debt dating from before the First World War and the Treaty of Versailles, was unable to regain momentum.

So much so that it is in danger of turning to the USSR!

Action was called for. In 1953, under the leadership of German banker Hermann Abs, a former Deutsche Bank executive, a major conference was organized in London.

It was decided to write off 66% of Germany’s 30 billion marks in debt.

It was wisely agreed that annual repayments of German debt should never exceed 5% of export earnings. Those wishing to have their debts repaid by Germany should instead buy its exports, enabling it to honor its debts.

In other words, nothing like the madness recently imposed on Greece to « save » the euro!

Although this was done in the name of geopolitical principles, i.e. « in favor of some » but « against others », once again, it was in the name of a better future, i.e. a Europe capable of being the showcase of capitalism in the face of Moscow, that we were able to shed the weight of the past.

The splendors of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin

The breathtaking beauty of the XIIth century bronze heads of Ife (Nigeria) challenge the colonial view that Africa was a virgin continent, populated by animals and a few primitive tribes which failed walking their first steps into « history ».

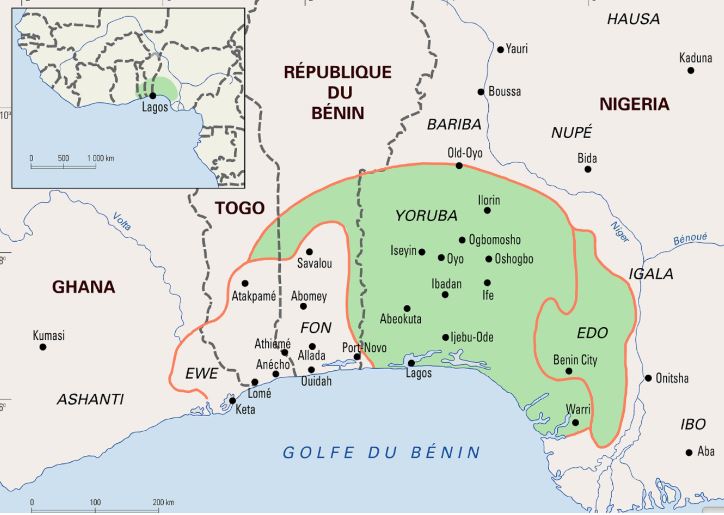

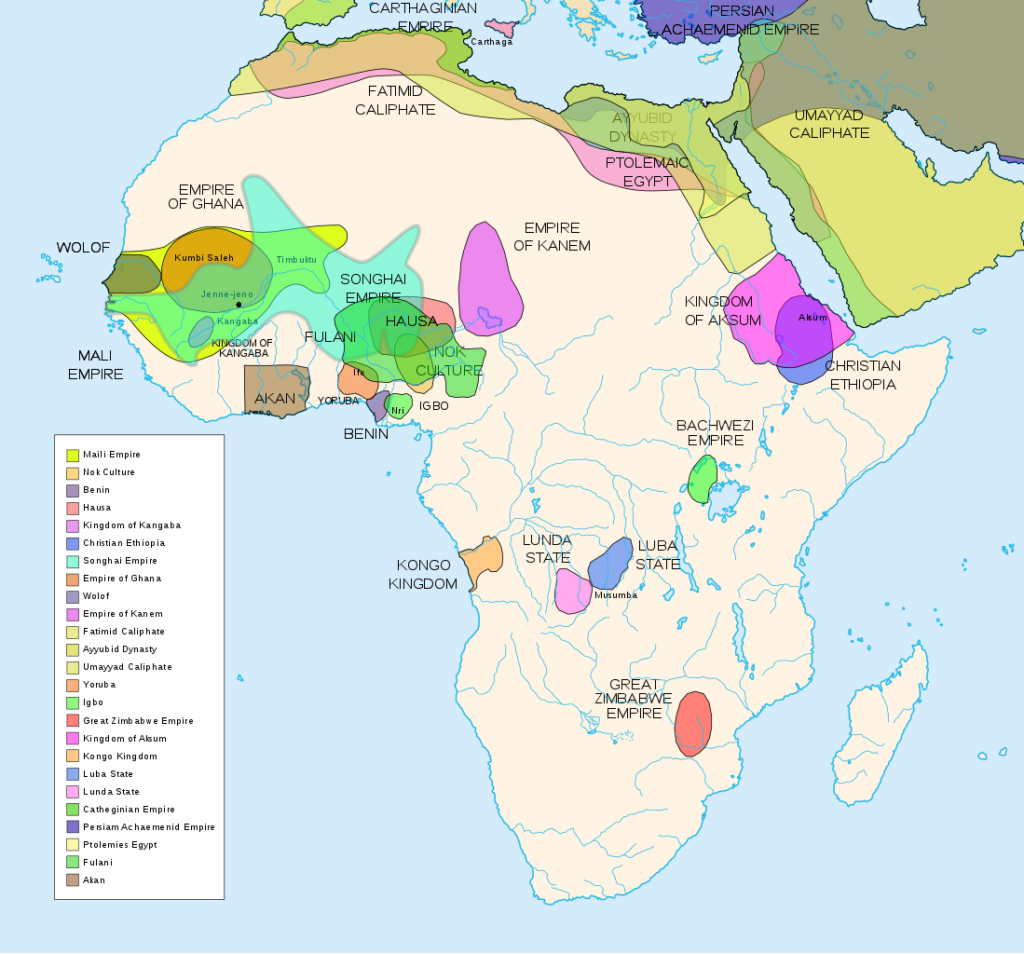

Today inhabited by a half million people, the city of Ife in southwest Nigeria, was formerly the religious center and former capital of the Yoruba people whose prosperity was essentially the fruit of their trade with the peoples of West Africa along the 4200 km long Niger River and beyond.

What some call today “Yorubu-land”, inhabited by some 55 million people, covered some 142,000 km2 comprising vast parts of countries such as today’s Nigeria (76%), Benin (18.9%) and Togo (6.5%).

Today, the Yoruba people live in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and, since the slave trade, in the United States. It is not surprising, therefore, that yoruba, also the name of one of the three major languages of Nigeria, is also spoken in parts of Benin and Togo, as well as in the West Indies and Latin America, including Cuba and other settlements populated by descendants of African slaves.

An extraordinary discovery

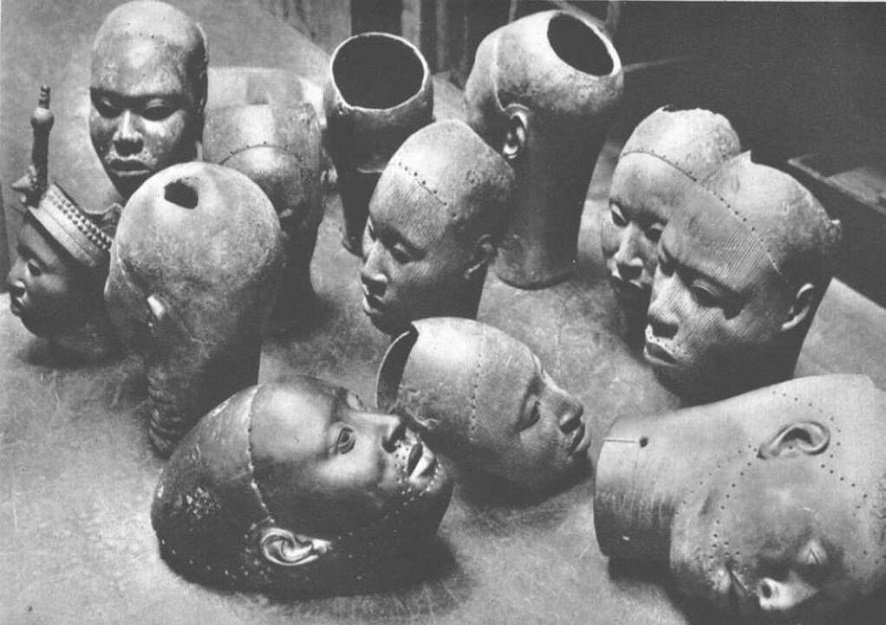

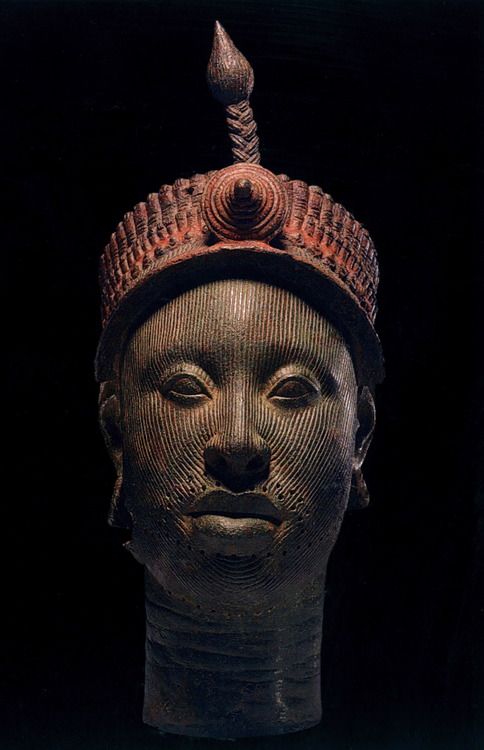

It was in January 1938, during excavation work for the construction of a house, that workers discovered an unusual treasure in the Wunmonije district of Ife. At a mere hundred meters distance away of the site of what once was the Royal Palace, they unearthed thirteen magnificent bronze heads dating from the XIIth century representing a king (an « Ooni« ), some women and courtiers. Others have since been unearthed.

Their faces, except for the lips, are covered with grooves. The hairstyle suggests a complex crown composed of several layers of tubular balls, topped by a crest with a rosette and an « egret ». The surface of this crown bears traces of red and black paint.

These large heads may have been used as effigies of the deceased in funeral ceremonies, which, among the Yoruba, sometimes took place a year after the rapid burial of the dead imposed by the tropical climate.

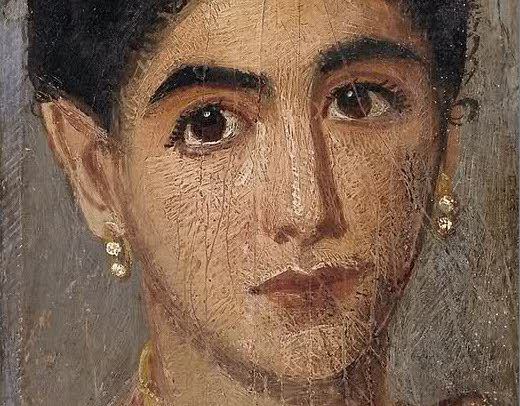

At the time of the discovery, the extremely naturalist rendering of the heads is considered anachronistic in the art of sub-Saharan Africa, and even more disturbing than the very “classical” i.e. realistic “mummy portraits” (Ist-IInd century) discovered as early as 1887 in the Faiyum depression of Egypt.

Yet a long tradition of figurative sculpture with similar characteristics as the bronze heads of Ife existed before, particularly among the Nok, a people of farmers who mastered iron metallurgy starting from 800 BC.

Hysteria

Since 1938, the « heads of Ife » have provoked reactions close to hysteria in Europe and the West in general.

On the one hand, the « modernists » and the « abstract » artists of the early XXth century, for whom the more abstract a sculpture is and the more distant it is from reality, the more it was considered as typically African. For those who were inspired by African « abstract » art to free themselves from what they considered as materialistic naturalism, the heads of Ife brutally challenged their self-deceiving “smart” narrative.

On the other hand, especially for the supporters of colonial imperialism, this art simply could not be. Frank Willett, at one point the head of the Nigerian Department of Antiquities and author of Ife, an African civilization (Editions Tallandier, 1967), reported that « Europeans visiting Ife frequently wonder how people living in houses of dried mud, with straw roofs, could have made such beautiful objects as the bronzes and terracotta in the museum ». Trying to answer that question, the publisher Sir Mortimer Wheeler replied: “The prejudice is alive and well that artistic creation and sensitivity cannot exist without domestic talent and sanitary comfort!”

The questions of the Europeans were numerous. How, in the XIIth century, could primitive peoples, who had never known an organized form of state, have made bronze heads of such refinement, using techniques that even Europe failed to master at that juncture? How could it have been possible, for tribes, subjected to superstition and irrational magic, could have observed the human anatomy so meticulously? How could savages have expressed such noble feelings towards both men and women? Faced with such an unbearable paradox, total denial was their only answer.

Hence, when the German archaeologist Leo Frobenius presented the bronze heads, western experts refused to believe in the existence of an African civilization capable of leaving artifacts of a quality they recognized as comparable to the best artistic achievements of ancient Rome or Greece. In a desperate attempt to explain what passed for an anomaly, Frobenius, without the slightest semblance of proof, came up with the theory that these heads had been cast by a Greek colony founded in the XIIIth century BC, and that the latter could be at the origin of the old legend of the lost civilization of Atlantis, a narrative immediately adopted in chorus by the mass media…

Bronze

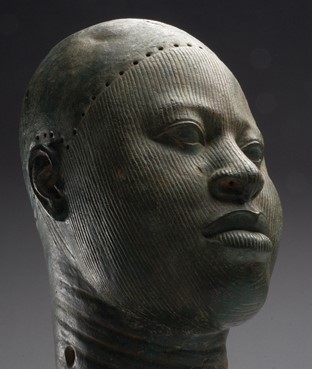

What first shocked Western experts was that these were not carved wood but sophisticated bronze heads (about 70 % copper, 16.5 % zinc and 11.3 % lead).

Given the extreme scarcity of copper ore in Nigeria, these objects demonstrate that the region had trade relations with distant countries. The ore is believed to have come from Central Europe, northwest Mauritania, the Byzantine Empire or, via the Niger River, from Timbuktu where the ore arrived by camel from southern Morocco.

If during the Neolithic period, copper, gold and silver nuggets were hammered cold or hot, it is only starting from the Bronze Age that man develops the science of real metallurgy. From ores, he was then able to extract metals thanks to a precise heat treatment, made possible by the experience of the ceramists of the time, great experts in the construction of high temperature ovens.

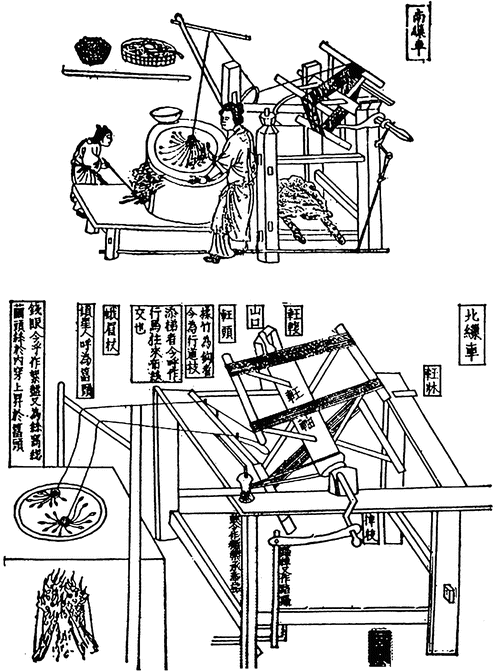

Copper only melts at 1083° Celsius, but by adding tin (which melts at 232°) and lead (which melts at 327°), it is possible to obtain bronze at 890° and brass at 900°. The terracotta is made at low temperature, around 600 to 800°. It should be underlined that in China, since the Shang Dynasty (1570-1045 BC), certain types of porcelain obtained much higher temperatures, between 1000 and 1300° Celsius, obtained thanks to the use of charcoal.

The oldest traces of ceramics in sub-Saharan Africa are thought to date back to more than 9000 BC, and perhaps earlier. Bu some fragmentary shards have been discovered in West Africa, in this case in Mali, and considered dating from 12000 BC. Ceramics also were produced further south, notably by the Nok culture in northern Nigeria at the beginning of the first millennium BC.

Lost-wax casting

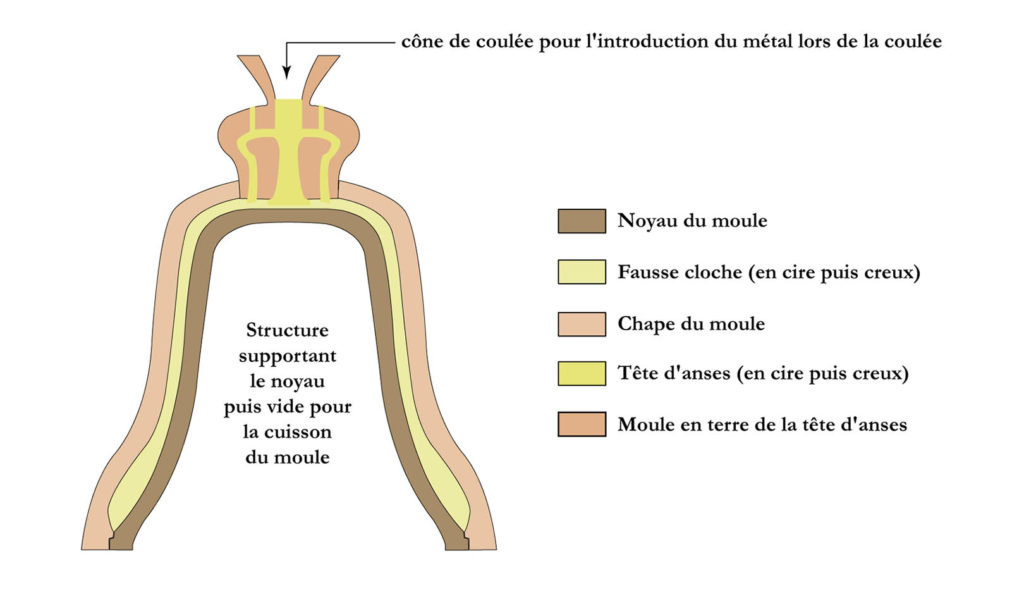

What also shocked the experts was that the technique used to make them was the quite sophisticated so-called « lost-wax casting » or “cire perdue” technique, a high precision molding process that is still used today to make church bells.

First, a model was made out of wax. This was covered with fine clay to form a mold, which was then heated so that the wax melted and ran away. Molten metal was poured into the clay mold which would be broken open to release the complete object.

Clearly, the foundries producing these artifacts required a highly skilled and well organized professional labor force.

The exceptional know-how and skills of the bronze founders of Ife was preceded by those of Igbo-Ukwu in eastern Nigeria where in 1939 a tomb filled with artifacts dating from the IXth century was discovered, revealing the existence of a powerful and refined kingdom mastering the famous lost-wax casting technique, but which so far could not be linked to any other culture in the region.

The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old wheel-shaped copper amulet found at Mehrgarh in today’s Pakistan. Although China, Greece and Rome mastered this technique, it was not until the Renaissance that it made its return to Europe.

Ife, an organized state

In reality, the art of Ife challenged the colonial theory that Africa was a virgin land, populated by animals and a few primitive tribes who had never taken their first steps in « history ».

Indeed, any evidence showing the existence of empires, kingdoms or great states on the African continent that allowed Africans to govern themselves peacefully for centuries could only de-legitimize the « civilizing mission » of colonialism.

However, according to oral traditions, Ife was founded in the 9th-10th centuries by Oduduwa, through the fusion of 13 villages into a single city becoming the hearth of Yoruba mythology, who considers Ife as the cradle of humanity and the center of the world.

Recognized as a minor god, Oduduwa became the first Ooni (King) and had an Aafin (palace) built. He ruled with the help of the isoro, former village chiefs who had recovered a religious title and were subject to royal political authority.

According to the same oral traditions, Oduduwa is said to have been an exiled Prince of a foreign people, who left his homeland and traveled south with his suite, settling among the Yoruba around the XIIth century. His religious faith, that he brought with him, was so important to him and his followers that it would have been the cause of their exodus in the first place.

Oduduwa’s land or country of origin remains a matter of debate. For some, he comes from Mecca, for others from Egypt, as the technical skills he brought with him are supposed to demonstrate.

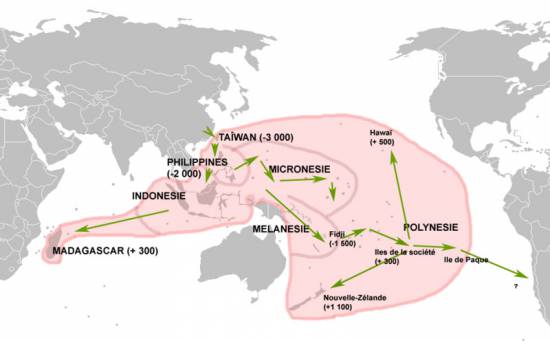

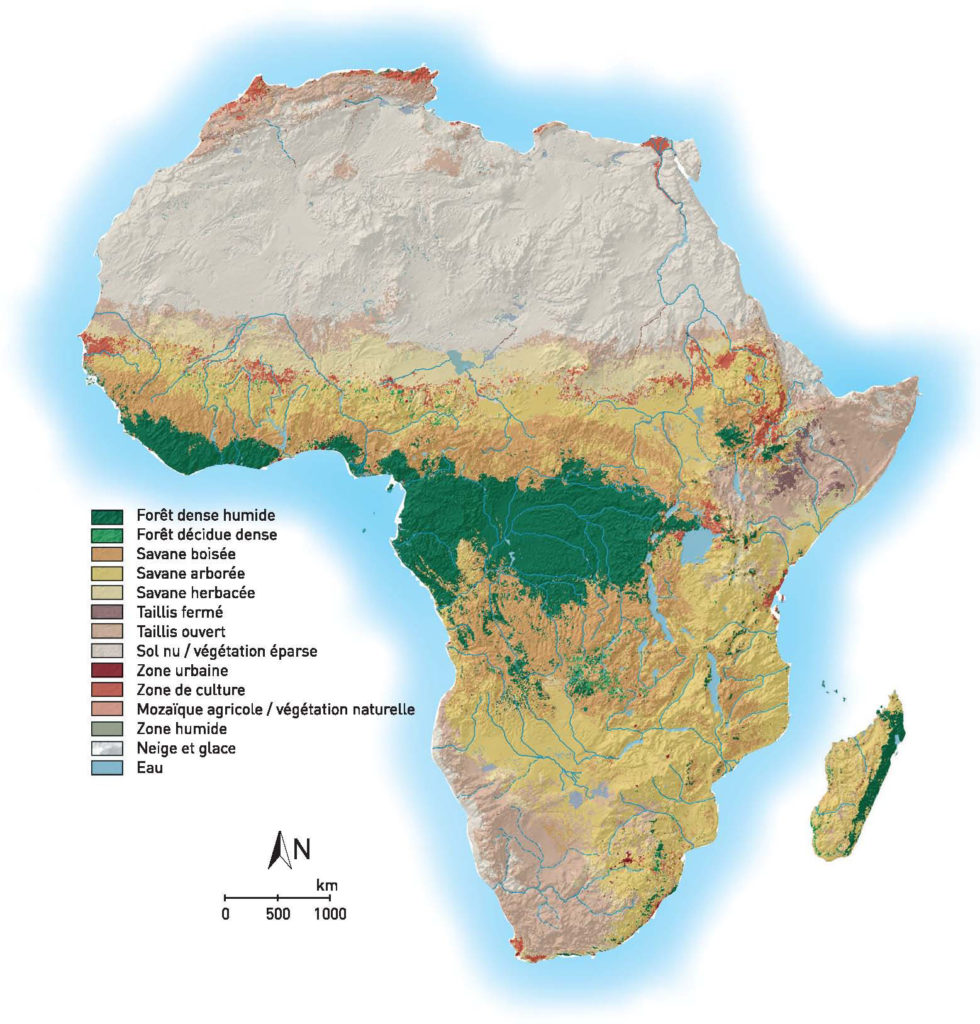

So far, most historians have looked to influences arriving by sea and waterways. However, it is a very plausible hypothesis that travel routs through the savanna, could have connected the Niger Delta with the Nile, like a sort of great transcontinental land-bridge, passing notably via Chad, a region where thousands of early cave paintings testify the vivacity of pictorial creativity.

As our good friend Kotto Essomé repeatedly underlined, African states often prospered along the climatic zones, following “horizontally” the latitudes. Colonial borders were deliberately drawn (laterally or “vertically”) to break the natural boundaries of pre-colonial African states.

Now, as this map clearly indicates, a horizontal “ribbon” of habitable urban areas, on the borderline between the herbaceous and wooded savanna, stretches over the entire continent from the Atlantic till the Southern Nile. Unsurprisingly, this particular climatic and geographical area might have been optimally suited for both hunting, agriculture and cattle raising.

From their part, the Edo people of Benin City believed that Oduduwa was in fact a prince of their extraction, who would have fled Benin during a fight over royal succession. This is why one of his descendants, Prince Oramiyan, would have been allowed to return and found the dynasty ruling the Kingdom of Benin. Prince Oramiyan was thus the first oba of Benin, successfully replacing the Ogiso monarchical system that had reigned until then.

Metallurgy

What deserves attention here is the fact that metallurgy occupies a central place in Ife. Oduduwa had a forge in his Royal palace (Ogun Laadin). Kings from different kingdoms installed their forges within the royal palace, showing the strong symbolic relationship between power and metallurgy.

Contrary to what happened on other continents, the Iron Age in Africa would have preceded the Copper Age in some regions. The oldest indications documenting the transformation of iron ore in Africa date back to the third millennium BC. They are the archaeological sites of Egaro in eastern Niger and Giza and Abydos in Egypt. While the site of Buhen in Egyptian Nubia (- 1991), after working iron, became a « copper factory », the sites of Oliga in Cameroon (-1300) and Nok in Nigeria (-925) testify clearly of a dynamic metallurgical activity.

As we have seen, bronze casting techniques demonstrate the existence of a very advanced technological know-how. Ife will also be a major center for glass production, especially glass beads. The waste material of this ancestral production, made up of parts of crucibles covered with molten glass, will be looked for in the XIXth century by the inhabitants of the region, although the origin of the glass beads was neglected.

Recent archaeological excavations have shown that the settlements of this area are very ancient. But as we have seen, it was only at the beginning of the 2nd millennium that developments in the field of metallurgy would have made it possible to improve agricultural tools and generate surplus food. Yam, cassava, maize and cotton are cultivated here, the latter giving birth to an important cloth weaving industry.

Hence, the city of Ife experienced a rapid demographic expansion thanks to this rise in agricultural productivity, itself the fruit of the mastery of an increased energy density allowing the transformation of « stones » (ores) into useful resources.

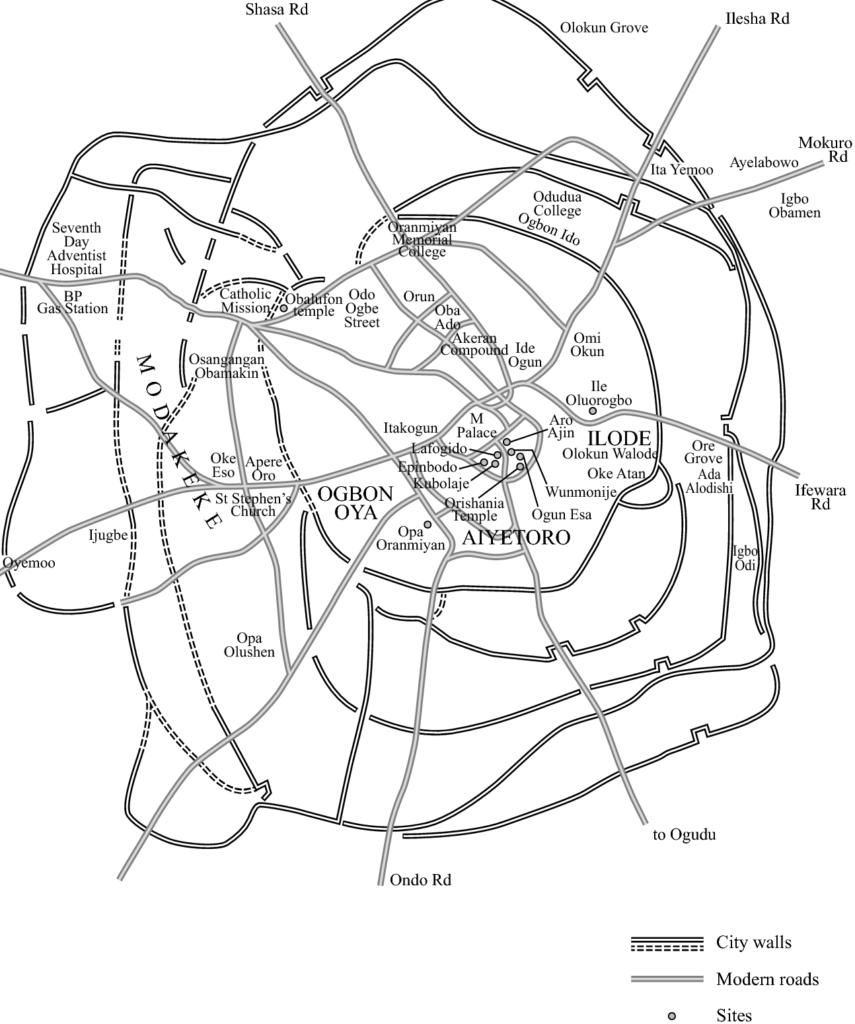

The medieval urbanization of Ife is today widely attested by the existence of numerous enclosures made of ditches and embankments, which seem to indicate the various spaces that have experienced a demographic concentration and the existence of a political body powerful enough to implement such great infrastructure programs.

Interesting, as a successful centralized state, Ife became increasingly a model for other states in the region and beyond. Several descendants and captains of Oduduwa founded their own kingdoms based on the same model and relying on the same legitimacy. The monarchical experience of Ife is exported with its cultural framework. The adé ilèkè, a crown of glass beads symbolizing royal power, is found in most monarchies in the region.

In total, depending on the sources, an estimated 7 to 20 kingdoms make up the Yoruba world in the first half of the second millennium AD.

- Oyo State in Nigeria was one of such powerful Yoruba city-states.

- Another example, the Kingdom of Ketou, currently in the southeast of Benin, is supposed to have been founded around the XIVth century by an alleged descendant of Oduduwa. He is said to have left Ife with his family and other members of his clan and moved westward, eventually settling in the city of Aro, northeast of the city of Ketou. Aro quickly became too small for the growing population, and the decision was made to settle in Ketou. King Ede therefore left Aro with 120 families and settled in this city.

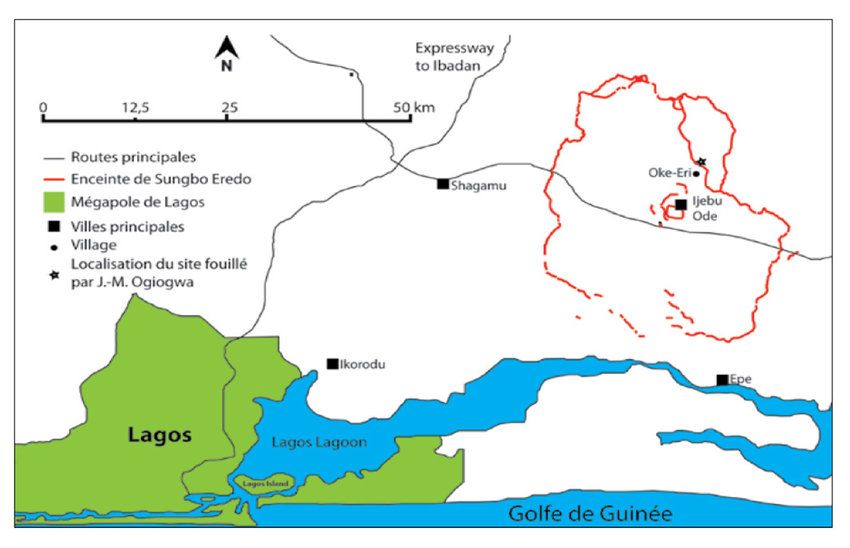

- Another demonstration of Yoruba building science is the Sungbo Eredo Wall, near the Nigerian capital Lagos, a system of walls and ditches built in the XIVth century and located southwest of the town of Ijebu Ode, in Ogun State, southwestern Nigeria. More than 160 km (100 miles) long, these fortifications, some as high as 20 meters (65 feet), consist of a smooth-walled ditch that forms an inner moat in relation to the walls that overhang it. The ditch forms an irregular ring (Map) around the lands of the ancient kingdom of Ijebu. This ring is about 40 km in the north-south direction and 35 km in the east-west direction, which is the equivalent of the Paris périphérique ! Invaded by vegetation, the construction today looks like a green tunnel.

From Ife to the Kingdom of Benin

In the XIVth century, Ife experienced a demographic collapse, characterized by the abandonment of certain enclosures and a strong advance of the forest into formerly residential areas. There was also a break in the transmission of know-how and artisan techniques.

This demographic collapse has been explained as the result of a Black Plague, according to some authors, who draw a parallel with the pandemic waves hitting Europe at the same period.

Part of the inhabitants of Ife were able to take refuge and bring their know-how in metallurgy to the Kingdom of Benin, which lasted for seven hundred years, from the XIIth century until its invasion by the British Empire at the end of the XIXth century. Benin was a coastal West African city-state dominated by the Edos, an ethnic group whose dynasty still survives today.

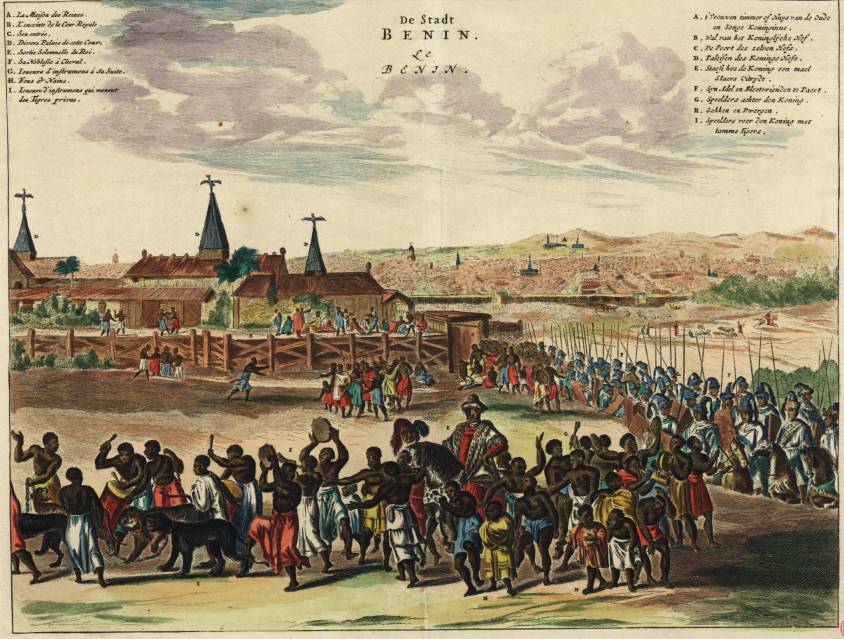

Its territory covers to present-day Benin, plus part of Togo and southwestern Nigeria, where today « Benin City », a historic port on the Benin River, is located. In the heart of the city, the royal residence with monumental proportions translated visually the importance given to political, spiritual and traditional power.

Benin City, a marvel

The social organization of the city impressed European visitors at the end of the XVth century. As a major regional economic trading pole, Benin was full of ivory, pepper and slaves. Benin offered the Europeans palm oil (the oil palm growing abundantly in the region). In exchange, they requested, and obtained guns, allowing the modernization of the Beninese armament.

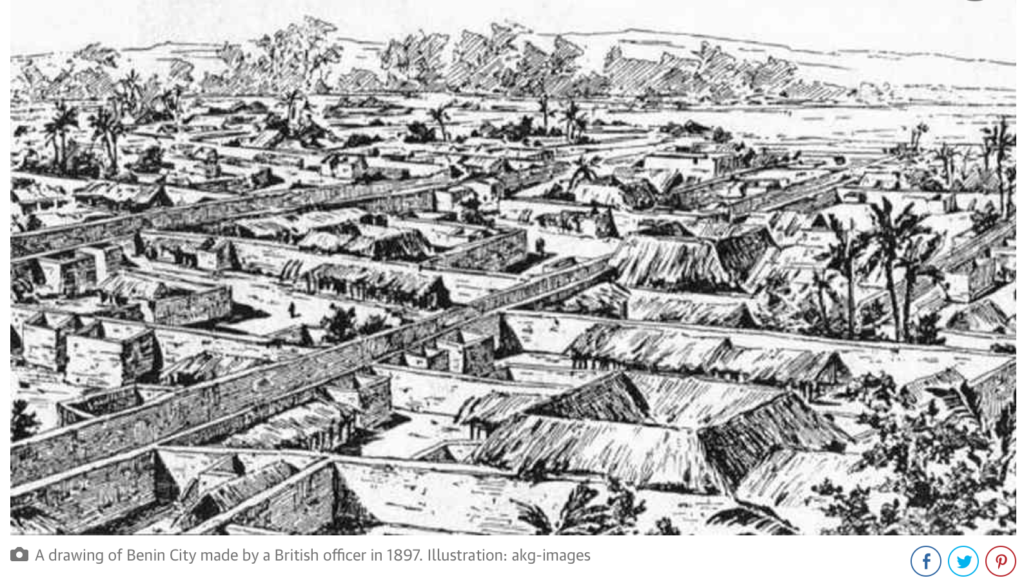

Located in a plain, Benin City is surrounded by massive walls to the south and deep ditches to the north. Beyond the city walls, many other walls have been erected that organize the entire region of the capital into some 500 separate boroughs.

In 2016, an article published by The Guardian recounted the lost splendor of the city. The paper reported:

“The Guinness Book of Records (1974 edition) described the walls of Benin City and its surrounding kingdom as the world’s largest earthworks carried out prior to the mechanical era. According to estimates by the New Scientist’s Fred Pearce, Benin City’s walls were at one point “four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops”.

Pearce writes that these walls “extended for some 16,000 km in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They covered 6,500 sq km and were all dug by the Edo people … They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet”.

Benin City was also one of the first cities to have a semblance of street lighting. Huge metal lamps, many feet high, were built and placed around the city, especially near the king’s palace. Fueled by palm oil, their burning wicks were lit at night to provide illumination for traffic to and from the palace.

When the Portuguese first “discovered” the city in 1485, they were stunned to find this vast kingdom made of hundreds of interlocked cities and villages in the middle of the African jungle.

In 1691, the Portuguese ship captain Lourenco Pinto observed:

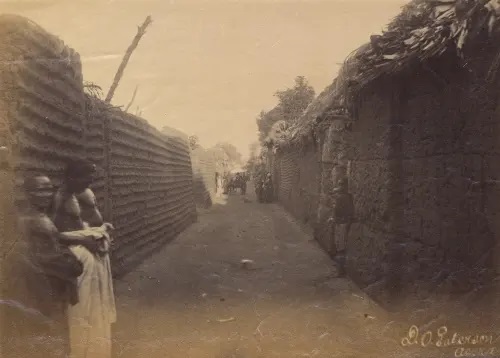

“Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

In contrast, London at the same time is described by Bruce Holsinger, professor of English at the University of Virginia, as being a city of “thievery, prostitution, murder, bribery and a thriving black market made the medieval city ripe for exploitation by those with a skill for the quick blade or picking a pocket”.

African fractals

Benin City’s planning and design was done according to careful rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition now known as fractal design. The mathematician Ron Eglash, author of African Fractals – which examines the patterns underpinning architecture, art and design in many parts of Africa – notes that the city and its surrounding villages were purposely laid out to form perfect fractals, with similar shapes repeated in the rooms of each house, and the house itself, and the clusters of houses in the village in mathematically predictable patterns.

As he puts it:

“When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganized and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.”

At the center of the city stood the king’s court, from which extended 30 very straight, broad streets, each about 120-ft wide. These main streets, which ran at right angles to each other, had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Many narrower side and intersecting streets extended off them. In the middle of the streets were turf on which animals fed.

“Houses are built alongside the streets in good order, the one close to the other,” writes the XVIIth-century Dutch visitor Olfert Dapper. “Adorned with gables and steps … they are usually broad with long galleries inside, especially so in the case of the houses of the nobility, and divided into many rooms which are separated by walls made of red clay, very well erected.”

Dapper adds that wealthy residents kept these walls “as shiny and smooth by washing and rubbing as any wall in Holland can be made with chalk, and they are like mirrors. The upper stores are made of the same sort of clay. Moreover, every house is provided with a well for the supply of fresh water”.

Family houses were divided into three sections: the central part was the husband’s quarters, looking towards the road; to the left the wives’ quarters (oderie), and to the right the young men’s quarters (yekogbe).

Daily street life in Benin City might have consisted of large crowds going though even larger streets, with people colorfully dressed – some in white, others in yellow, blue or green – and the city captains acting as judges to resolve lawsuits, moderating debates in the numerous galleries, and arbitrating petty conflicts in the markets.

The early foreign explorers’ descriptions of Benin City portrayed it as a place free of crime and hunger, with large streets and houses kept clean; a city filled with courteous, honest people, and run by a centralized and highly sophisticated bureaucracy.

The city was split into 11 divisions, each a smaller replication of the king’s court, comprising a sprawling series of compounds containing accommodation, workshops and public buildings – interconnected by innumerable doors and passageways, all richly decorated with the art that made Benin famous. The city was literally covered in it.

The exterior walls of the courts and compounds were decorated with horizontal ridge designs (agben) and clay carvings portraying animals, warriors and other symbols of power – the carvings would create contrasting patterns in the strong sunlight. Natural objects (pebbles or pieces of mica) were also pressed into the wet clay, while in the palaces, pillars were covered with bronze plaques illustrating the victories and deeds of former kings and nobles.

At the height of its greatness in the XIIth century – well before the start of the European Renaissance – the kings and nobles of Benin City patronized craftsmen and lavished them with gifts and wealth, in return for their depiction of the kings’ and dignitaries’ great exploits in intricate bronze sculptures.

“These works from Benin are equal to the very finest examples of European casting technique,” wrote Professor Felix von Luschan, formerly of the Berlin Ethnological Museum. Italian Renaissance artist “Benvenuto Celini could not have cast them better, nor could anyone else before or after him. Technically, these bronzes represent the very highest possible achievement.”

The fatal encounter with « civilization »

Following the Berlin Conference of 1885, where the British, Portuguese, Belgian, German, French, Italian and other European colonial powers shared Africa like a big chocolate cake that they intended to devour, in the name of the immutable laws of the freshly invented science of “geopolitics”, European invasions multiplied and gained in brutality.

Thus, following the king of Benin’s refusal to cede to the British the national monopoly on the production of palm oil and other products, Benin City was looted, burned and reduced to ashes during a British punitive expedition in 1897. The king (the oba) is arrested and forced into exile and thousands of beautiful « bronzes of Benin », though less realistic than those of Ife, are stolen, sold and partly lost.

They end up on the art market and in museums, including the British Museum (700 objects) and the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (500 pieces). The British government itself sells some of them « to cover the cost of the expedition« .

So, while some clearly entered history with their beautiful art, others exited civilization with their barbarian crimes.

Summary bibliography:

- Ifè, une civilisation africaine, Frank Willett, Jardin des Arts/Tallandier, Paris 1971;

- General History of Africa, Présence africaines/Edicef/Unesco, Paris 1987;

- Atlas historique de l’Afrique, Editions du Jaguar, Paris 1988;

- L’Afrique ancienne, de l’Acus au Zimbabwe, under the direction of François-Xavier Fauvelle, Belin/Humensis, Paris 2018.

On Leonardo da Vinci’s « Vitruvian Man »

By Karel Vereycken

Leonardo da Vinci’s « Viruvian Man ». Since we’re commemorating this year (2019) Leonardo Da Vinci, who died 500 years ago, many silly things are presented by fake scholars trying to make a real living.

Since I was introduced into the canon of proportions of the human body during my training as a professional painter and engraver, I want offer you some hints on how to look at what is called Da Vinci’s « Vitruvian man », a drawing currently on exhibit at the Da Vinci show at the Louvre in Paris.

Hence, as Leonardo underlines himself in his notebooks, adopting Cusanus wordings, it is only with the « eyes of the mind » that art becomes visible, because the « eyes of the flesh » are intrensically blind to it.

Canons of proportions

Europe, and Classical Greece, as everybody should know, emerged largely by absorbing several major discoveries accomplished much earlier by other civilizations. Much of it came from Asia, but African and especially Egypt, were key.

The very practice of mummification, a process which takes at least 60 days of work, made Egypt the key area of anatomical research.

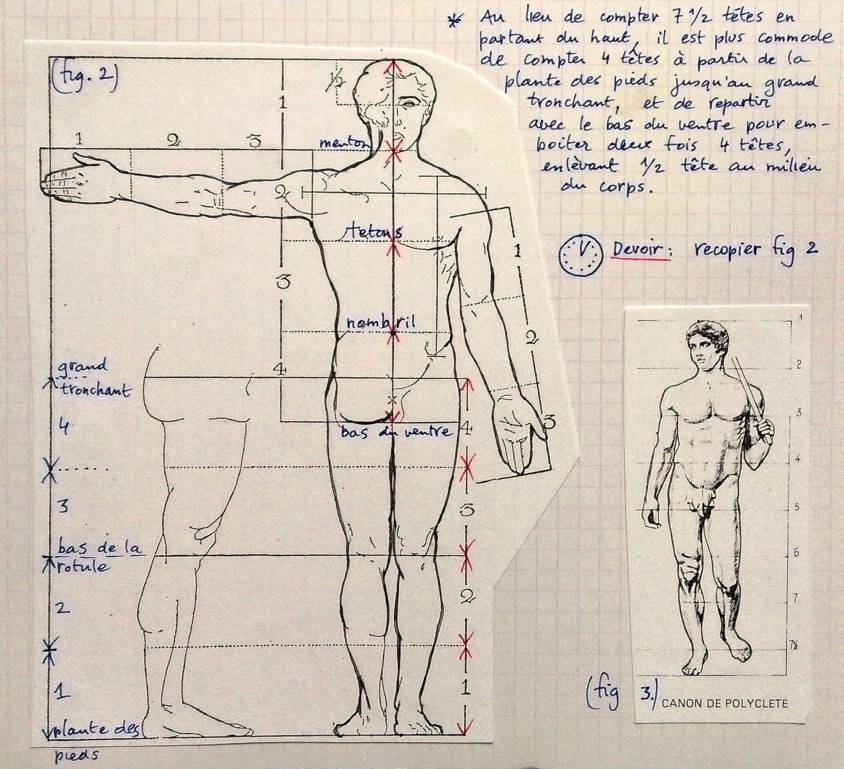

As demonstrated by early Egyptian sculpture, the exact size of the entire adult human body is 7,5 times the size of the head. The size of a newborn is only four heads, that of a seven year old, six heads and that of a 17 years old adolescent, 7 heads.

If one subdivides the overall 7.5 proportion, for an adult, from the top of the head till the lowest part of the torso, one measures four heads, one till the nipples, one till the belly button and a fourth one till the lowest part of the pubis. Going up from the sole till the middle of the pelvis, one measures 3.5 heads: 2 heads till the knee and 1.5 till the middle of the pelvis. That brings the total till 7.5 heads for the entire length of the adult human body and it is proportional in the sense that people with smaller heads also have small bodies.

Polikleitos versus Lysippus

In the Vth Century BC, the Greek sculptor Polikleitos’ spear bearer (The “Doryphoros”) of Naples National Archeological Museum applied this most beautiful canon of proportions, known as the “Polikleitos canon”.

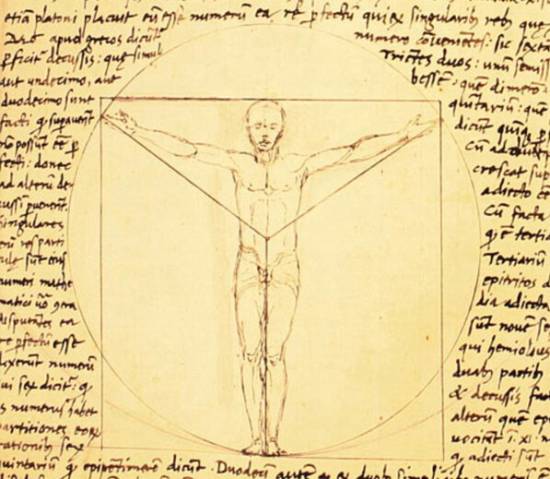

During the Renaissance, the nostalgics of the Roman Empire preferred another Greek canon, that of Greek sculptor Lysippus (4th Century BC), formalized by the Roman author, architect and civil engineer, Vitrivius (1st century BC).

Vitruvius only transcribed the prevalent taste of his epoch. Roman sculptors, in order to give an athletic and heroic look to the Emperors which they were portraying, adopting the canon of Lysippus, could reduce the head of their models to only an eight of the total length of the body. The trick was that by reducing the relative size of the head, the body looked more preeminent and powerful, something most emperors, who were often physical failures, appreciated and secured their popularity. Even extreme cases of 12 to 15 heads of body length appeared. In short, Public relations ruled at the detriment of science and truth.

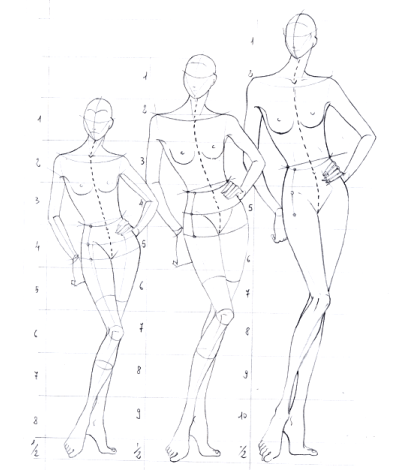

Today’s comic strip drawers chose proportions according to purpose:

–For real life, 7.5 or “normal canon”

–For a movie star, 8 heads, with the “idealistic canon”;

–For a fashion magazine: 8.5 heads;

–For a comic book hero: 9 heads for the “heroic canon”

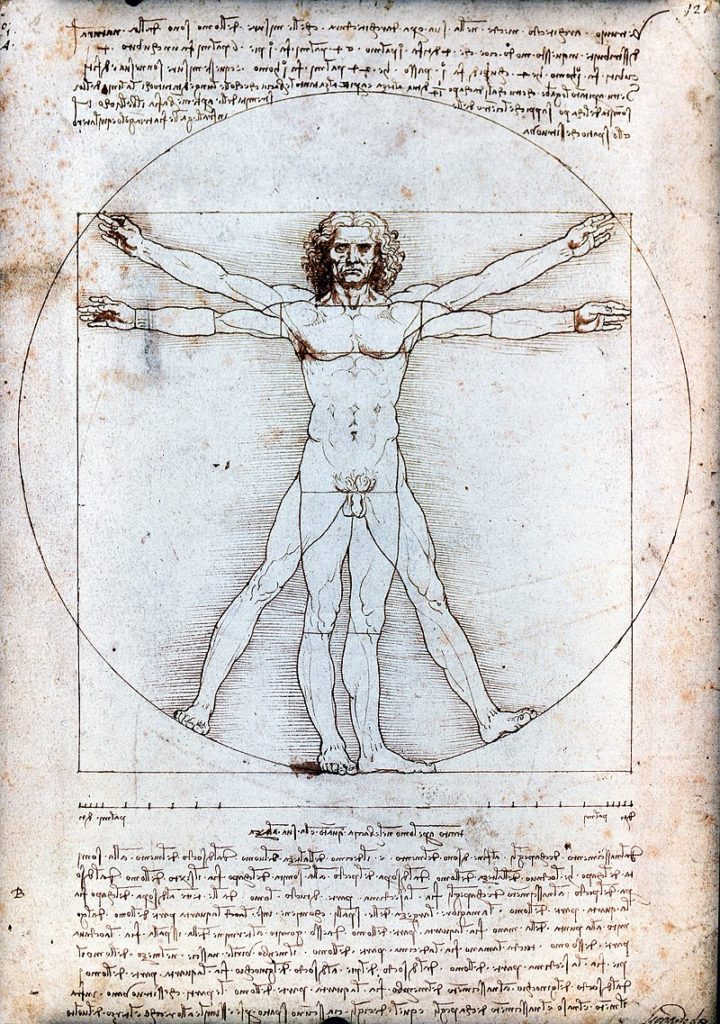

Vitruvian man

Text accompanying Leonardo DaVinci’s Vitruvian Man:

Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture that the measurements of the human body are distributed by Nature as follows that is that 4 fingers make 1 palm, and 4 palms make 1 foot, 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man’s height. And 4 cubits make one pace and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in his buildings. If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the centre of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle.

The length of a man’s outspread arms is equal to his height.

From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth of a man’s height; from the bottom of the chin to the top of his head is one eighth of his height; from the top of the breast to the top of his head will be one sixth of a man. From the top of the breast to the roots of the hair will be the seventh part of the whole man. From the nipples to the top of the head will be the fourth part of a man. The greatest width of the shoulders contains in itself the fourth part of the man. From the elbow to the tip of the hand will be the fifth part of a man; and from the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be the eighth part of the man. The whole hand will be the tenth part of the man; the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man. The foot is the seventh part of the man. From the sole of the foot to below the knee will be the fourth part of the man. From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be the fourth part of the man. The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the roots of the hair to the eyebrows is, in each case the same, and like the ear, a third of the face.

Of course, Da Vinci’s exploration of the Vitruvian man doesn’t mean he approves or disapproves the stated fakery in proportions.

Soul or muscle?

It should be known that in Italy, the pure Roman taste has become trendy again following the discovery in 1506 of the statue of the Laocoon on the site of Nero’s villa in Rome. From that moment, artist will feel obliged to increase the volume of the muscular masses in order to appear as working « in Antique style ».

Although Leonardo never openly criticized this trend, it is hard not to think of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, when the artist, seeking to raise the spirit to unequalled philosophical heights, advised painters: « do not give all the muscles of the figures an exaggerated volume » and « if you act differently, it is more a sort of representation of a sack of nuts that you will have achieved than to that of a human figure » (Codex Madrid II, 128r).

No doubt inspired by his friend, the architect Giacomo Andrea, in « The Vitruvian Man », Leonardo is above all interested by other harmonies: if a person extends his arms in a direction parallel to the ground, one obtains the same length as one’s entire height. This equality is inscribed by Leonardo in a square (symbol of the earthly realm). But if one stretches his arms and legs in a star shape, they are inscribed in a circle whose center is the navel. The location of the navel divides the body according to the golden ratio (in this example 5 heads out of a total of 8 heads, 5+3 being part of the Fibonnacci series: 1+2 = 3; 3+2 = 5; 5+3 = 8; 8+5 = 13; 13+8 = 21, etc.).

Leonardo clearly understood what the golden section really means: not a “magical” number in itself, but the reflexion of the dynamic of least action, the very principle uniting man (the square) with the creator and the universe (the circle).

So if you take a look, beware of what you see and especially what you don’t !