Étiquette : Bengal

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on septembre 26, 2023

The Maritime Silk Road, a history of 1001 Cooperations

Today, it’s fashionable to present maritime issues in the context of a moribund British geopolitical ideology that pits countries and peoples against each other. However, as this brief history of the Maritime Silk Road, drawn mainly from a document by the International Tourism Organization, demonstrates, the ocean has above all been a fantastic place for fertile encounters, cultural cross-fertilization and mutually beneficial cooperation.

The ancient Chinese invented many of the things we use today, including paper, matches, wheelbarrows, gunpowder, the noria (water elevator), sluice locks, the sundial, astronomy, porcelain, lacquer paint, the potter’s wheel, fireworks, paper money, the compass, the stern rudder, the tangram, the seismograph, dominoes, skipping rope, kites, the tea ceremony, the folding umbrella, ink, calligraphy, animal harnesses, card games, printing, the abacus, wallpaper, the crossbow, ice cream, and especially silk, which we’ll be talking about here.

The Origins of Silk

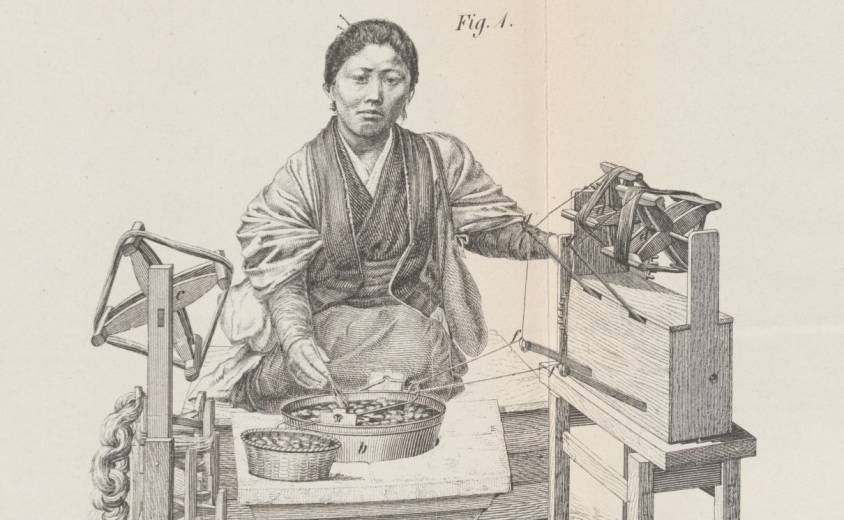

Before we talk about silk « routes », a few words about the origins of sericulture, i.e. the rearing of silkworms.

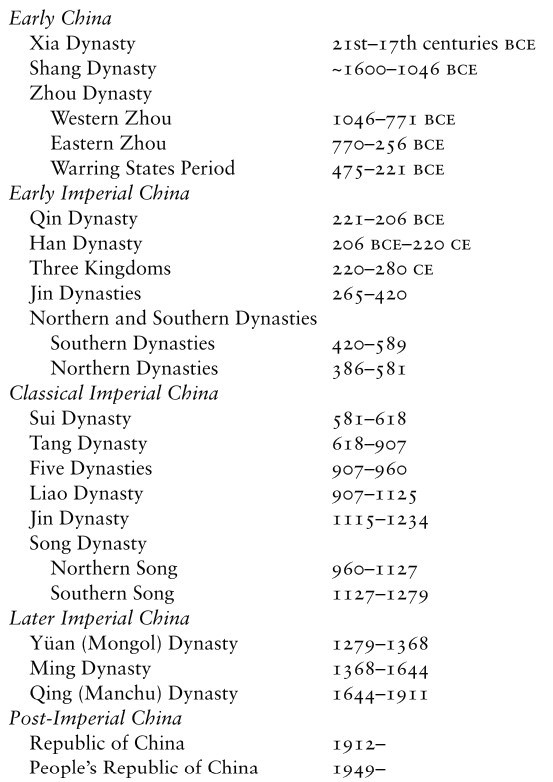

As recent archaeological discoveries confirm, silk production is an age-old skill. The presence of the mulberry tree for silkworm rearing was noted in China around the Yellow River by the Yangshao culture during the Middle Neolithic period in China, from 4500 to 3000 BC.

In general, we prefer to retain the legend that silk was discovered around 2500 BC, by the Chinese princess Si Ling-chi, when a cocoon accidentally fell into her tea bowl. When she tried to remove it, she discovered that the cocoon, softened by the hot water, had a delicate, soft and strong thread that could be unwound and assembled. Thus was born the idea of making cloth. The princess then decided to plant a number of white mulberry trees in her garden to raise silkworms.

The silkworms (or bombyx) and mulberry trees were divinely cared for by the princess (silkworms feed solely on the leaves of white mulberry trees).

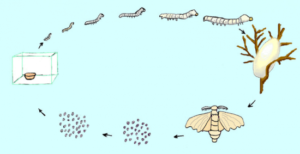

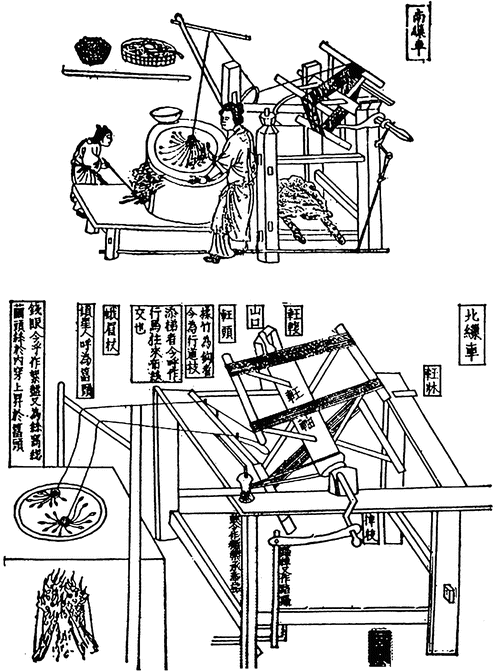

Silk production is a time-consuming process that requires careful monitoring. Silk moths lay around 500 eggs during their lives, which last from 4 to 6 days. After the eggs hatch, the baby worms feed on mulberry leaves in a controlled environment. They have a ferocious appetite and their weight can increase considerably. Once they’ve stored up enough energy, the worms secrete a white jelly from their silk glands and use it to build a cocoon around themselves. After eight or nine days, the worms are killed and the cocoons are immersed in boiling water to soften the protective filaments, which are wound onto a spool. These filaments can be 600 to 900 meters long. Several filaments are assembled to form a thread. The silk threads are then woven into a fabric or used for fine embroidery or brocade, a rich silk fabric embellished with brocaded designs in gold and silver thread.

The Early Silk Trade

Under threat of capital punishment, sericulture remained a well-kept secret, and China retained its monopoly on manufacturing for millennia.

It wasn’t until the Zhou dynasty (1112 BC) that a maritime Silk Road was established from China to Japan and Korea, as the government decided to send Chinese from the port in Bohai Bay (on the Shandong Peninsula) to train local inhabitants in sericulture and agriculture. The techniques of silkworm rearing, reeling and weaving were gradually introduced to Korea via the Yellow Sea.

When Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China (221 BC), many people from the states of Qi, Yan and Zhao fled to Korea, taking with them silkworms and their rearing techniques. This accelerated the development of silk spinning in Korea.

Korea played a central role in China’s international relations, particularly as an intellectual bridge between China and Japan. Its trade with China also enabled the spread of Buddhism and porcelain-making methods. Although initially reserved for the imperial court, silk spread throughout Asian culture, both geographically and socially. Silk quickly became the luxury fabric par excellence that the whole world craved.

During the Han dynasties (206 BC to 220), a dense network of trade routes exploded cultural and commercial exchanges across Central Asia, profoundly impacting civilizational dynamics. The Han dynasty continued to build the Great Wall, notably creating the commandery of Dunhuang (Gansu), a key post on the Silk Road. Over two centuries B.C., its trade extended to Greece and Rome, where silk was reserved for the elite.

In the IIIrd century, India, Japan and Persia (Iran) unlocked the secret of silk manufacture and became major producers.

Silk Reaches Europe

According to a story by Procopius, it was not until 552 AD that the Byzantine emperor Justinian obtained the first silkworm eggs. He had sent two Nestorian monks to Central Asia, and they were able to smuggle silkworm eggs to him hidden in rods of bamboo. While under the monks’ care, the eggs hatched, though they did not cocoon before arrival.

A church manufacture in the Byzantine Empire was thus able to make fabrics for the emperor. Later emerged the intention of developing a large silk industry in the Eastern Roman Empire, using techniques copied from the Persian Sassanids.

Another version claims that it was the Han emperor Wu (IInd century) who sent ambassadors, bearing gifts such as silk, to the West.

In the VIIth century, sericulture spread to Africa and Sicily, from where, under the impetus of Roger I of Sicily (c. 1034-1101) and his son Roger II (1093-1154), the silkworm and mulberry were introduced to the ancient Peloponnese.

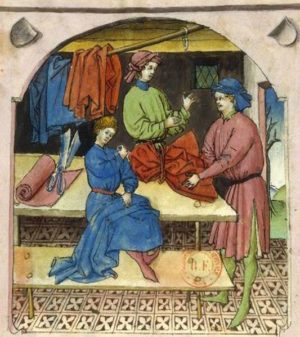

In the Xth century, Andalusia became the epicenter of silk manufacturing with Granada, Toledo and Seville. With the Arab conquest, sericulture spread to the rest of Spain, Italy (Venice, Florence and Milan) and France. The earliest French traces of sericulture date back to the 13th century, notably in the Gard (1234) and Paris (1290).

In the XVth century, faced with the ruinous import of Italian silk (raw or manufactured), Louis XI tried to set up silk factories, first in Tours on the Loire, then in Lyon, a city at the crossroads of north-south routes where Italian emigrants were already trading in silks.

In the XIXth century, silk production was industrialized in Japan, but in the XXth century, China regained its place as the world’s largest producer. Today, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Uzbekistan and Brazil all have large production capacities.

Cultural Melting Pot

As much as silk itself, the transportation of silk by sea dates back to time immemorial.

For the Chinese, there are two main routes: the East China Silk Road (to Korea and Japan) and the South China Silk Road (via the Strait of Malacca to India, the Persian Gulf, Africa and Europe).

In Vietnam, the Hanoi Museum holds a coin dating back to the year 152, bearing the effigy of the Roman emperor Antoninus the Pious. The coin was discovered in the remains of Oc Eo, a Vietnamese town south of the Mekong Delta, thought to have been the main port of the Funan Kingdom (Ist to IXth centuries).

This kingdom, which covered the territory of present-day Cambodia and the Mekong Delta administrative region of Vietnam, flourished from the 1st to the 9th century. The first mention of the Fou-nan kingdom appears in the report of a Chinese mission that visited the area in the 3rd century.

The Founamians were at the height of their power when Hinduism and Buddhism were introduced to Southeast Asia.

Then, from Egypt, Greek merchants reached the Bay of Bengal. Considerable quantities of pepper then reached Ostia, Rome’s port of entry. All the historical evidence shows that East-West trade was flourishing as early as the first millennium.

Persians and Arabs in India, China and Asia

On the western side, at the entrance to Kuwait Bay, 20 kilometers off the coast of Kuwait City, not far from the mouth of the shared estuary of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the Persian Gulf, the island of Failaka was one of the meeting places where Greece, Rome and China exchanged goods.

Under the Sassanid dynasty (226-651), the Persians developed their trade routes all the way to Southeast Asia, via India and Sri Lanka.

This trading infrastructure was later taken over by the Arabs when, in 762, they moved to Baghdad.

From the IXth century onwards, the city of Quilon (Kollam), the capital of Kerala in India, was home to colonies of Arab, Christian, Jewish and Chinese merchants.

On the western side, Persian and then Arab navigators played a central role in the birth of the maritime Silk Road. Following the Sassanid routes, the Arabs pushed their dhows, or traditional Arab sailing ships, from the Red Sea to the Chinese coast and as far as Malaysia and Indonesia.

These sailors brought with them a new religion, Islam, which spread throughout Southeast Asia. While the traditional pilgrimage (the hajj) to Mecca was initially only an aspiration for many Muslims, it became increasingly possible for them to make it.

During the monsoon season, when winds were favorable for sailing to India in the Indian Ocean, the twice-yearly trade missions were transformed into veritable international fairs, offering an opportunity to transport large quantities of goods by sea in conditions (apart from pirates and unpredictable weather) relatively less exposed to the dangers of overland transport.

The Maritime Silk Road under the Sui, Tang and Song Dynasties

It was under the Sui dynasty (581-618) that the Maritime Silk Road set out from Quanzhou, a coastal city in Fujian province in south-east China, on its first trade routes.

With its wealth of scenic spots and historic sites, Quanzhou has been proclaimed « the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road » by UNESCO.

It was at this time that the first printing methods appeared in China. Wooden blocks were used to print on textiles. In 593, the Sui emperor Wen-ti ordered the printing of Buddhist images and writings. One of the earliest printed texts is a Buddhist script dating from 868, found in a cave near Dunhuang, a stopover town on the Silk Road.

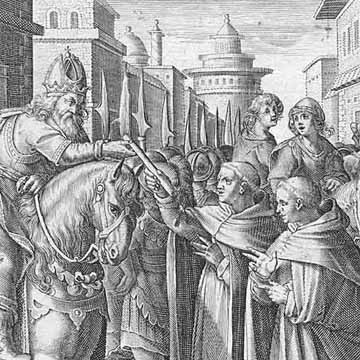

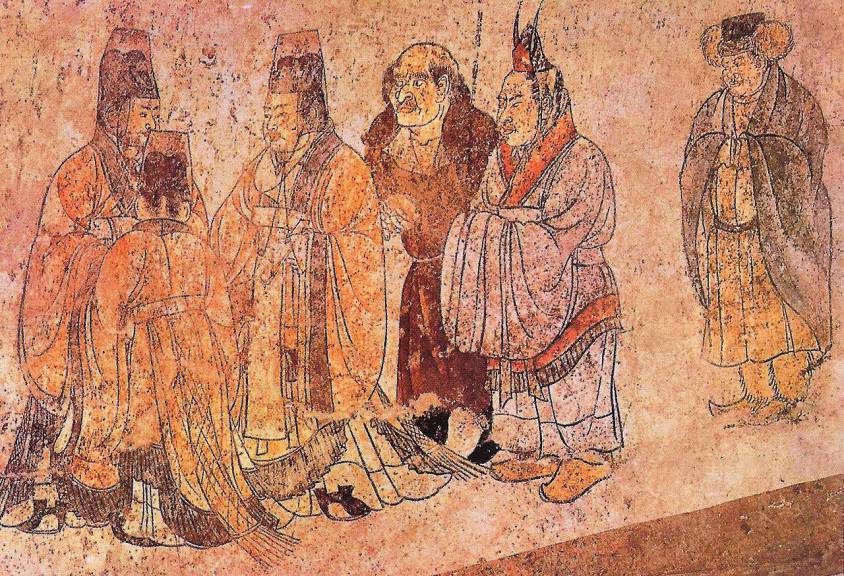

Under the Tang dynasty (618-907), the Kingdom’s military expansion brought security, trade and new ideas. The fact that the stability of Tang China coincided with that of Sassanid Persia enabled the land and sea Silk Roads to flourish. The great transformation of the maritime Silk Road began in the 7th century, when China opened up to international trade. The first Arab ambassador took up his post in 651.

The Tang Dynasty chose Chang’an (now Xi’an) as its capital. It adopted an open attitude towards different beliefs. Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian temples coexisted peacefully with mosques, synagogues and Nestorian Christian churches. As the terminus of the Silk Road, Chang’an’s western market is becoming the center of world trade. According to the Tang Authority Six register, over 300 nations and regions had trade relations with Chang’an.

Almost 10,000 foreign families from the west lived in the city, especially in the area around the western market. There were many foreign inns staffed by foreign maids chosen for their beauty. The most famous poet in Chinese history, Li Bai, often strolled among them. Foreign food, costumes and music were the fashion of Chang’an.

After the fall of the Tang dynasty, the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms (907-960), the arrival of the Song dynasty (960-1279) ushered in a new period of prosperity, characterized by increased centralization and economic and cultural renewal. The maritime silk route regained its momentum. In 1168, a synagogue was built in Kaifeng, capital of the Southern Song dynasty, to serve merchants on the Silk Road.

During the same period, as Islam expanded, trading posts sprang up all around the Indian Ocean and the rest of Southeast Asia.

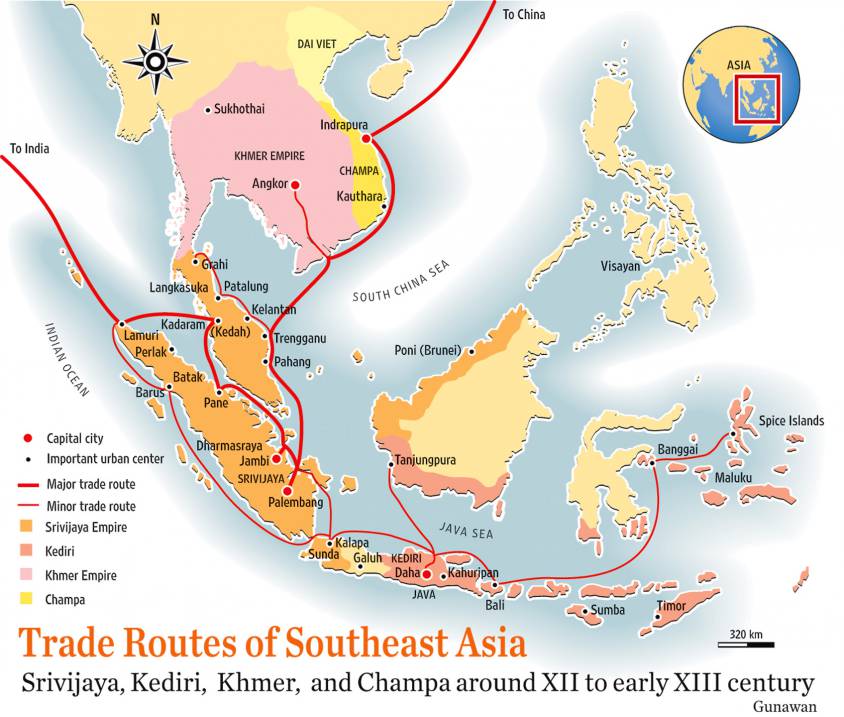

China encouraged its merchants to seize the opportunities offered by maritime traffic, in particular the sale of camphor, a highly sought-after medicinal plant. A veritable trade network developed in the East Indies under the auspices of the Kingdom of Sriwijaya, a city-state in southern Sumatra, Indonesia (see below), which for nearly six centuries served as a link between Chinese merchants on the one hand, and Indians and Malays on the other. A trade route truly emerged, deserving the name of the maritime « Silk Road ».

Increasing quantities of spices passed through India, the Red Sea and Alexandria in Egypt, before reaching the merchants of Genoa, Venice and other Western ports. From there, they moved on to the northern European markets of Lübeck (Germany), Riga (Lithuania) and Tallinn (Estonia), which from the 12th century onwards became important cities in the Hanseatic League.

In China, during the reign of the Song emperor Renzong (1022-1063), a great deal of money and energy was spent on bringing together knowledge and know-how. The economy was the first to benefit.

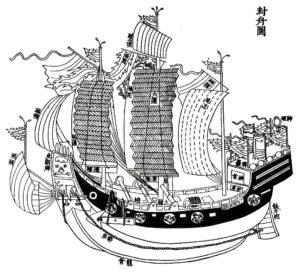

Drawing on the know-how of Arab and Indian sailors, Chinese ships became the most advanced in the world.

The Chinese, who had invented the compass (at least by 1119), quickly surpassed their competitors in cartography and the art of navigation, as the Chinese junk became the bulk carrier par excellence.

In his geographical treatise, Zhou Qufei, in 1178, reports:

« The big ships that cruise the South Sea are like houses. When they unfold their sails, they look like huge clouds. Their rudders are dozens of feet long. A single ship can house several hundred men. On board, there’s enough food to last a year.«

Archaeological digs confirm this reality, such as the wreck of a XIVth-century junk found off the coast of Korea, in which over 10,000 pieces of ceramic were discovered.

During this period, coastal trade gradually shifted from the hands of Arab traders to those of Chinese merchants. Trade expanded, notably with the inclusion of Korea and the integration of Japan, the Malabar coast of India, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea into existing trade networks.

China exported tea, silk, cotton, porcelain, lacquers, copper, dyes, books and paper. In return, it imported luxury goods and raw materials, including rare woods, precious metals, precious and semi-precious stones, spices and ivory.

Copper coins from the Song period have been discovered in Sri Lanka, and porcelain from this period has been found in East Africa, Egypt, Turkey, some Gulf states and Iran, as well as in India and Southeast Asia.

The Importance of Korea and the Kingdom of Silla

During the first millennium, culture and philosophy flourished on the Korean peninsula. A well-organized and well-protected trading network with China and Japan operated there.

On the Japanese island of Okino-shima, numerous historical traces bear witness to the intense exchanges between the Japanese archipelago, Korea and the Asian continent.

Excavations carried out in ancient tombs in Gyeongju, today a South Korean city of 264,000 inhabitants and capital of the ancient Kingdom of Silla (from 57 BC to 935), which controlled most of the peninsula from the VIIth to the IXth century, demonstrate the intensity of this kingdom’s exchanges with the rest of the world, via the Silk Road.

Indonesia, a Major Maritime Power at the Heart of the Maritime Silk Road

In Indonesia, Malaysia and southern Thailand, the Kingdom of Sriwijaya (VIIth to XIIIth centuries) played a major role as a maritime trading post, storing high-value goods from the region and beyond for later sale by sea. In particular, Sriwijaya controlled the Strait of Malacca, the essential sea passage between India and China.

At the height of its power in the XIth century, Sriwijaya’s network of ports and trading posts traded a vast array of products and commodities: rice, cotton, indigo and silver from Java, aloe (a succulent plant of African origin), vegetable resins, camphor, ivory and rhinoceros horns, tin and gold from Sumatra, rattan, redwoods and other rare woods, gems from Borneo, rare birds and exotic animals, iron, sandalwood and spices from East Indonesia, India and Southeast Asia, and porcelain, lacquer, brocade, textiles and silk from China.

With its capital at Palembang (population 1.7 million) on the Musi River in what is now the southern province of Sumatra, this Hindu-Buddhist-inspired kingdom, which flourished from the VIIIth to the XIIIth century, was the first major Indonesian kingdom and the country’s first maritime power.

By the VIIth century, it ruled a large part of Sumatra, the western part of Java and a significant part of the Malay Peninsula. It extended as far north as Thailand, where archaeological remains of Sriwijaya cities still exist.

Buddhism on the Maritime Silk Road

The museum in Palembang (today Indonesia) – a town where Chinese, Indian, Arab and Yemeni communities, each with their own particular institutions, have co-prospered for generations – tells a wonderful story of how the Maritime Silk Road generated exemplary mutual cultural enrichment.

Buddhism was closely tied to international or cross-boundary trade. Early inscriptions indicate it was common for seafarers to pray to the Buddha for a safe voyage.

The maritime routes were very challenging as they were often beset with cyclones and typhoons, and piracy was an ever-present danger.

As a consequence, merchant support for Buddhism along these travel routes helped to establish monastic life far beyond India. Monks and nuns also took passage on these trading ships, and the merchants sought good karma by helping them travel to spread the teachings of the Buddha.

Madagascar, Sanskrit and the Cinnamon Road

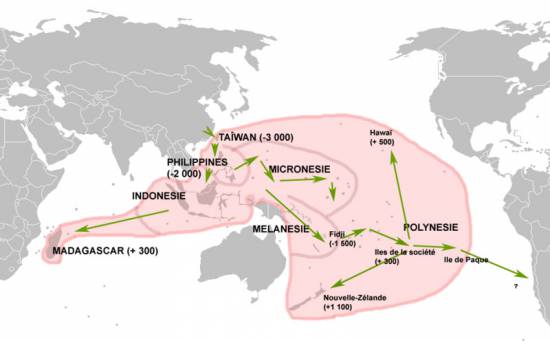

Map of the expansion of Austronesian languages.

Today, Madagascar is inhabited by Blacks and Asians. DNA tests have confirmed what has long been known: many of the island’s inhabitants are descended from Malay and Indonesian sailors who set foot on the island around the year 830, when the Sriwijaya Empire extended its maritime influence towards Africa.

Further evidence of this presence is the fact that the language spoken on the island borrows Sanskrit and Indonesian words.

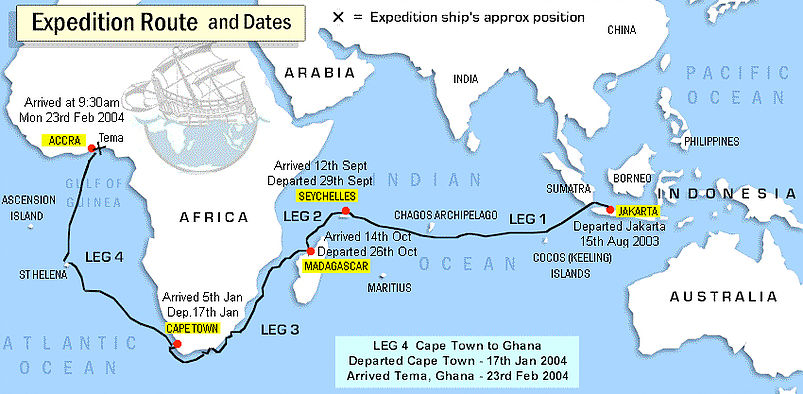

To demonstrate the feasibility of such sea voyages, in 2003 a team of researchers sailed from Indonesia to Ghana via Madagascar aboard the Borobudur, a reconstruction of one of the sailing ships featured in many of the 1,300 bas-reliefs decorating the 8th-century Buddhist temple of Borobudur on the island of Java in Indonesia.

Many believe that this vessel is a representation of those once used by Indonesian merchants to cross the ocean to Africa. Indonesian navigators usually used relatively small boats. To ensure balance, they fitted them with outriggers, both double (ngalawa) and single.

Their boats, whose hulls were carved from a single tree trunk, were called sanggara. Merchants from the Indonesian archipelago could reach as far east as Hawaii and New Zealand, a distance of over 7,000 km.

In any case, the researchers’ boat, equipped with an 18-meter-high mast, managed to cover the Jakarta – Maldives – Cape of Good Hope – Ghana route, a distance of 27,750 kilometers, or more than half the circumference of the Earth!

The expedition aimed to retrace a very specific route: the cinnamon route, which took Indonesian merchants all the way to Africa to sell spices, including cinnamon, a highly sought-after commodity at the time. Cinnamon was already highly prized in the Mediterranean basin long before the Christian era.

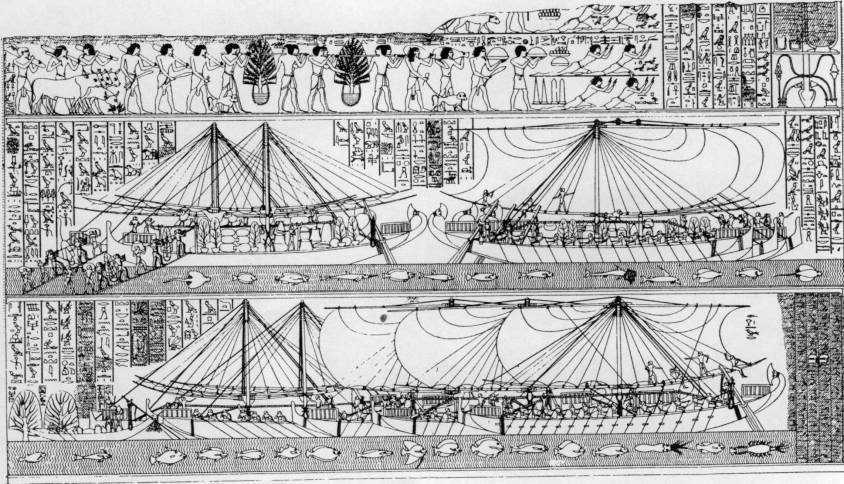

On the walls of the Egyptian temple at Deir el-Bahari (Luksor), a painting depicts a major naval expedition said to have been ordered by Queen Hatshepsut, who reigned from 1503 to 1482 BC. Around the painting, hieroglyphs explain that these ships carried various species of plants and fragrant essences destined for the cult. One of these was cinnamon. Rich in aroma, it was an important component of ritual ceremonies in the kingdoms of Egypt.

Cinnamon originally grew in Central Asia, the eastern Himalayas and northern Vietnam. The southern Chinese transplanted it from these regions to their own country and cultivated it under the name gui zhi.

From China, gui zhi spread throughout the Indonesian archipelago, finding a very fertile home there, particularly in the Moluccas. In fact, the international cinnamon trade was a monopoly held by Indonesian merchants. Indonesian cinnamon was prized for its excellent quality and highly competitive price.

The Indonesians sailed great distances, up to 8,000 km, across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar and northeast Africa. From Madagascar, products were transported to Rhapta, in a coastal region that later became known as Somalia. From there, Arab merchants shipped them north to the Red Sea.

The Strait of Malacca

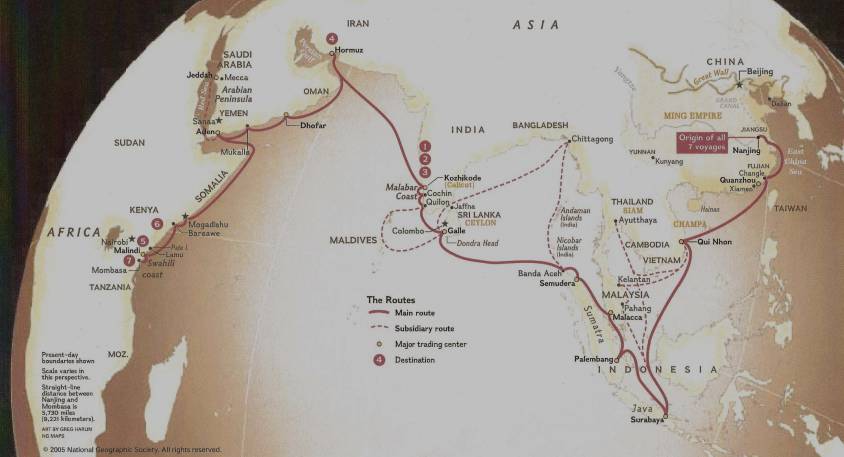

For China, the Strait of Malacca has always represented a major strategic interest. When the great Chinese admiral Zheng He led the first of his expeditions to India, the Near East and East Africa between 1405 and 1433, a Chinese pirate by the name of Chen Zuyi took control of Palembang.

Zheng He defeated Chen’s fleet and captured the survivors. As a result, the strait once again became a safe shipping route.

According to tradition, a prince of Sriwijaya, Parameswara, took refuge on the island of Temasek (present-day Singapore), but eventually settled on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula around 1400 and founded the city of Malacca, which would become the largest port in Southeast Asia, both successor to Sriwijaya and precursor to Singapore.

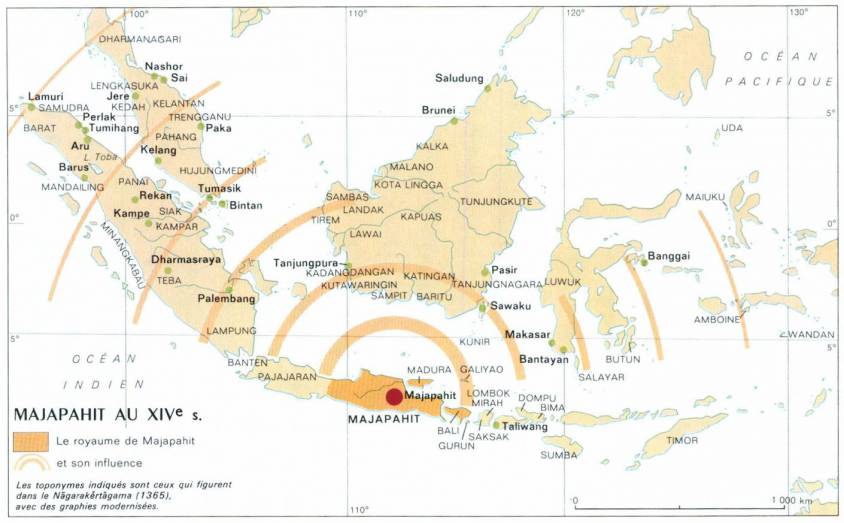

Following the decline of Sriwijaya, the Kingdom of Majapahit (1292-1527), founded at the end of the XIIIth century on the island of Java, came to dominate most of present-day Indonesia.

This was the period when Arab sailors began to settle in the region.

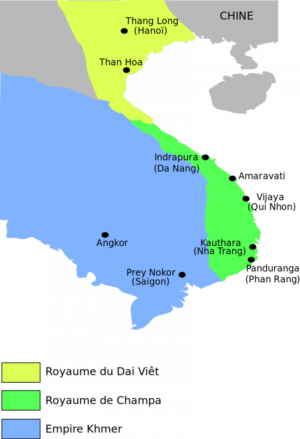

The Majapahit kingdom established relations with the Kingdom of Champa (192-1145; 1147-1190; 1220-1832) (South Vietnam), Cambodia, Siam (Thailand) and southern Myanmar.

The Majapahit kingdom also sent missions to China. As its rulers extended their power to other islands and sacked neighboring kingdoms, they sought above all to increase their share and control of the trade in goods passing through the archipelago.

The island of Singapore and the southernmost part of the Malay Peninsula was a key crossroads on the ancient maritime Silk Road.

Archaeological excavations in the Kallang estuary and along the Singapore River have uncovered thousands of shards of glass, natural and gold beads, ceramics and Chinese coins from the Northern Song period (960-1127).

The rise of the Mongol Empire in the middle of the XIIIth century led to an increase in seaborne trade and contributed to the vitality of the Maritime Silk Road.

Marco Polo, after a 17-year overland journey to China, returned by ship. After witnessing a shipwreck, he sailed from China to Sumatra in Indonesia, before setting foot on land again at Hormuz in Persia (Iran).

Under the Yuan and Ming Dynasties

Under the Song dynasty, large quantities of silk goods were exported to Japan. Under the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), the government set up the Shi Bo Si, a trade office, in a number of ports, including Ningbo, Canton, Shanghai, Ganpu, Wenzhou and Hangzhou, enabling silk exports to Japan.

During the Tang, Song and Yuan dynasties, and at the beginning of the Ming dynasty, each port set up an oceanic trading department to manage all foreign maritime trade.

Maritime travel was dependent on the seasonal winds: the summer monsoons blow from the south-west (May to September) and reverse direction in the winter (October to April). As a result, seafaring merchants developed sailing circuits that allowed them to use the monsoon winds to travel long distances, then return home when the wind patterns shifted.

Trade with southern India and the Persian Gulf flourished. Trade with East Africa also developed with the monsoon season, bringing ivory, gold and slaves. In India, guilds began to control Chinese trade on the Malabar coast and in Sri Lanka.

Trade relations became more formalized, while remaining highly competitive. Cochin and Kozhikode (Calicut), two major cities in the Indian state of Kerala, competed to dominate this trade.

Admiral Zheng He’s Maritime Explorations

Chinese maritime exploration reached its apogee in the early XVth century under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), which chose a Muslim court eunuch, Admiral Zheng He, to lead seven diplomatic naval expeditions.

Financed by Emperor Ming Yongle, these peaceful missions to Southeast Asia, East Africa, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea were intended above all to demonstrate the prestige and grandeur of China and its Emperor. The aim was also to recognize some thirty states and establish political and commercial relations with them.

In 1409, prior to one of these expeditions, the Chinese admiral Zheng He asked craftsmen to make a carved stone stele in Nanjing, the present-day capital of Jiangsu province (eastern China). The stele traveled with the flotilla and was left in Sri Lanka as a gift to a local Buddhist temple. Prayers to the deities in three languages – Chinese, Persian and Tamil – were engraved on the stele. It was found in 1911 in the town of Galle, in south-west Sri Lanka, and a replica is now in China.

Zheng’s armada was made up of armed bulk carriers, the most modest being larger than Columbus’ caravels. The largest were 100 meters long and 50 meters wide. According to Ming chronicles of the time, an expedition could comprise 62 ships, each carrying 500 people. Some carried military cavalry, others tanks of drinking water. Chinese shipbuilding was ahead of its time. The technique of hermetic bulkheads, imitating the internal structure of bamboo, offered incomparable safety. It became the standard for the Chinese fleet before being copied by the Europeans 250 years later. Compasses and celestial maps painted on silk were also used.

The synergy that may have existed between Arab, Indian and Chinese sailors, all men of the sea who fraternized in the face of ocean adversity, was impressive. For example, some historians believe that the name « Sindbad the Sailor », which appears in the Persian tale of a sailor’s adventures from the time of the Abbasid dynasty (VIIIth century) and was included in the Tales of the One Thousand and One Nights, derives from the word Sanbao, the honorary nickname given by the Chinese Emperor to Admiral Zheng He, literally meaning « The Three Jewels », i.e. the three indissociable capital virtues: essence, breath, and spirit.

Maritime museums in China (Hong Kong, Macau, Fuzhou, Tianjin and Nanjing), Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia showcase Admiral Zheng’s expeditions.

However, at least twelve other admirals carried out similar expeditions to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

In 1403, Admiral Ma Pi led an expedition to Indonesia and India. Wu Bin, Zhang Koqing and Hou Xian made others. After lightning caused a fire in the Forbidden City, a dispute broke out between the eunuch class, supporters of the expeditions, and the learned mandarins, who obtained the cessation of expeditions deemed too costly. The last voyage took place between 1430 and 1433, 64 years before the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived in 1497.

Japan, for its part, similarly restricted its contacts with the outside world during the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), although its trade with China was never suspended. It was only after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 that a Japan open to the world re-emerged.

Withdrawing into themselves, trade with both China and Japan fell into the hands of maritime trading posts such as Malacca in Malaysia or Hi An in Vietnam, two cities now recognized by Unesco as world heritage sites. H?i An was a major stopover port on the sea route linking Europe and Japan via India and China. In the shipwrecks found at Hi An, researchers have discovered ceramics awaiting their departure for Sinai in Egypt.

History of Chinese Ports

Over the years, the main ports on the Maritime Silk Road have changed. From the 330s onwards, Canton and Hepu were the two most important ports. However, Quanzhou replaced Canton from the end of the Song to the end of the Yuan dynasty. At that time, Quanzhou in Fujian province and Alexandria in Egypt were considered the world’s largest ports. Due to the policy of closure to the outside world imposed from 1435 and the influence of war, Quanzhou was gradually replaced by the ports of Yuegang, Zhangzhou and Fujian.

From the beginning of the IVth century, Canton was an important port on the Silk Road. Gradually, under the Tang and Song dynasties, it became not only the largest, but also the most renowned port of the Orient worldwide. During this period, the sea route linking Canton to the Persian Gulf via the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean was the longest in the world.

Although later supplanted by Quanzhou under the Yuan dynasty, Canton remained China’s second-largest commercial port. Compared with the others, it is considered to have been a consistently prosperous port over the 2,000-year history of the Maritime Silk Road.

The Tributary System of 1368

China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing, reigned from 1644 to 1912.

Since the arrival of the Ming dynasty, maritime trade with China proceded in two different ways:

- The Chinese « tributary system » ;

- The Canton system (1757-1842).

Born under the Ming in 1368, the « tributary system » reached its apogee under the Qing. It took the refined form of a mutually beneficial, inclusive hierarchy.

States adhering to it showed respect and gratitude by regularly presenting the Emperor with tribute made up of local products and performing certain ritual ceremonies, notably the « kowtow » (three genuflections and nine prostrations). They also demanded the Emperor’s investiture of their leaders and adopted the Chinese calendar. In addition to China, they included Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, the Ryükyü Islands, Laos, Myanmar and Malaysia.

Paradoxically, while occupying a central cultural status, the tributary system offered its vassals the status of sovereign entities, enabling them to exercise authority over a given geographical area.

The Emperor won their submission by showing virtuous concern for their welfare and promoting a doctrine of non-intervention and non-exploitation. Indeed, according to historians, in financial terms, China was never directly enriched by the tributary system. In general, all travel and subsistence expenses for tributary missions were covered by the Chinese government. In addition to the costs of running the system, the gifts offered by the Emperor were generally far more valuable than the tributes he received. Each tributary mission was entitled to be accompanied by a large number of merchants, and once the tribute had been presented to the Emperor, trade could begin.

It should be noted that when a country lost its status as a tributary state as a result of a disagreement, it would try at all costs, and sometimes violently, to be allowed to pay tribute again.

The Canton System of 1757

The second system concerned foreign, mainly European, powers wishing to trade with China. This involved the port of Guangzhou (then called Canton), the only port accessible to Westerners.

This meant that merchants, notably those of the British East India Company, could dock not in the port but off the coast of Canton, from October to March, during the trading season. It was in Macao, then a Portuguese possession, that the Chinese provided them with permission to do so. The Emperor’s representatives would then authorize Chinese merchants (hongs) to go on board to trade with foreign ships, while instructing them to collect customs duties before they left.

This way of trading expanded at the end of the XVIIIth century, particularly with the strong English demand for tea.

In fact, it was Chinese tea from Fujian that American « insurgents » threw into the sea during the famous « Boston Tea Party » in December 1773, one of the first events against the British Empire that sparked off the American Revolution.

Products from India, particularly cotton and opium, were exchanged by the East India Company for tea, porcelain and silk.

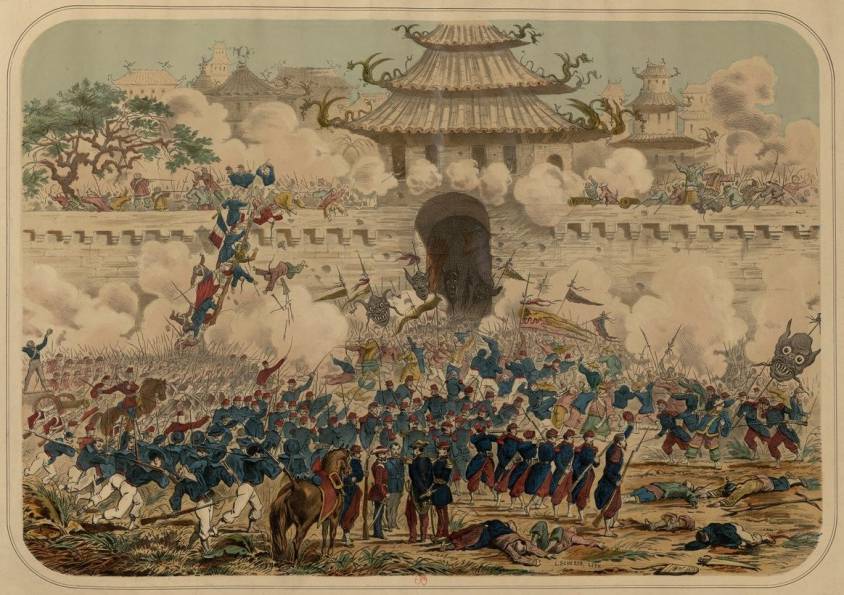

The customs duties collected by the Canton system were a major source of revenue for the Qing dynasty, even though it banned the purchase of opium from India. This restriction imposed by the Chinese Emperor in 1796 led to the outbreak of the Opium Wars, the first as early as 1839.

At the same time, rebellions broke out in the 1850-60s against the weakened Qing reign, coupled with further wars against hostile European powers.

In 1860, the former Summer Palace (Yuanming Park), with its collection of pavilions, temples, pagodas and libraries – the residence of the Qing dynasty emperors 15 kilometers northwest of Beijing’s Forbidden City – was ravaged by British and French troops during the Second Opium War.

This assault goes down in history as one of the worst acts of cultural vandalism of the XIXth century. The Palace was sacked a second time in 1900 by an eight-nation alliance against China.

Today, a statue of Victor Hugo and a text he wrote against Napoleon III and the destruction of French imperialism can be admired there, as a reminder that this was not the work of a nation, but of a government.

By the end of the First World War, China had 48 open ports where foreigners could trade according to their own jurisdictions.

The 20th century was an era of revolution and social change. The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 led to inward-looking attitudes.

It wasn’t until 1978 that Deng Xiaoping announced a policy of opening up to the outside world in order to modernize the country.

In the XXIst century, thanks to the One Belt (economic) One Road (maritime) Initiative launched by President Xi Jingping, China is re-emerging as a major world power offering mutually beneficial cooperation in the service of a better shared future for mankind.

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur The Maritime Silk Road, a history of 1001 Cooperations

Tags: Africa, Alandalus, artkarel, Bengal, Bonobudur, Brazil, Buddhism, Central Asia, China, compass, conflict, cooperation, dhow, Dynasties, Egypt, Gard, Ghana, Great Wall, gunpowder, Han, India, Indonesia, Islam, Italy, Japan, junk, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Korea, Koweit, Madgascar, Malaysia, maritime silk road, Modi, mulberry trees, navigation, noria, O, ocean, Ostia, paper money, printing, renaissance, Rome, Sanskrit, Sassanid, sea, sericulture, ship, Sicily, silk, silk road, silkworm, Singapore, Tang, Uzbekistan, Vereycken, Vietnam, Xi Jinping, Zheng He, Zou