Étiquette : Sanskrit

Le « miracle » du Gandhara : quand Bouddha s’est fait homme

C’est lors de mon voyage en Afghanistan, en novembre 2023, que j’ai réalisé à quel point j’ignorais tout de cette partie du monde. Si aujourd’hui l’islam prévaut en Afghanistan et au Pakistan, on oublie souvent qu’une région commune à ces deux pays, historiquement connue sous le nom de Gandhara, a joué, du Ier au IIIe siècle de notre ère, un rôle majeur dans l’épopée du bouddhisme, une spiritualité qui, en refusant toute idée de caste, va bousculer l’ordre du monde.

Carrefour obligé sur les Routes de la soie reliant l’Europe à l’Inde et à la Chine, c’est au Gandhara, qu’a eu lieu un véritable dialogue entre les cultures eurasiatiques, perses, turques, grecques, chinoises et indiennes.

Bouddha. C’est par le volontarisme de deux grands rois d’Asie centrale (Ashoka et Kanishka) que le bouddhisme, né au Népal, trouvera l’énergie et la détermination pour gagner les esprits et les cœurs du monde.

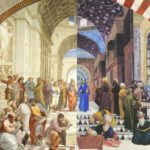

Enfin, c’est au Gandhara que l’art bouddhique, en rupture avec les consignes du maître, va s’approprier les plus belles formes de diverses cultures artistiques grecques, indiennes, perses et autres, pour présenter bouddha sous une forme humaine aux fidèles, un homme éclairé, plein de sagesse et animé de compassion.

En offrant fraîcheur, poésie et un sens du mouvement spectaculairement moderne, les premiers artistes bouddhistes du Gandhara nous invitent à identifier en nous-mêmes, un saut vers l’auto-perfectionnement. A ce titre, ils sont les précurseurs de l’humanisme classique et de bien des Renaissances.

N’est-il pas temps de reconnaître la juste place que mérite leur contribution à la civilisation universelle ?

Enfin, vu la situation actuelle du monde, je tiens à citer le Premier Ministre indien Nehru, qui, le 3 octobre 1960 s’adressait à l’Assemblée générale des Nations unies avec des paroles qui n’ont cessé de gagner en pertinence : « Dans un passé lointain, un grand fils de l’Inde, le Bouddha, a dit que la seule vraie victoire était celle où tous étaient également victorieux et où personne n’était vaincu. Dans le monde d’aujourd’hui, c’est la seule victoire concrète ; toute autre voie mène au désastre. »

- Introduction

- Bouddha, bio-express

- Les quatre vérités et l’octuple sentier

- Réincarnation

- Les Aryens et le védisme

- Les Brahmanes et le système des castes

- L’Inde avant le Bouddhisme

- Les grands conciles bouddhistes

- L’arrivée des Grecs

- L’Empire Maurya

- Le règne d’Ashoka le Grand

- Edits d’Ashoka

- Contenu des édits

- L’Empire Kouchan

- Le miracle de Gandhara

a) La poésie

b) La littérature

c) L’urbanisme

d) L’architecture, l’invention des stupa

e) Sculpture

–Aniconisme

–Fin de l’aniconisme

–Différence de forme, différence de contenu

1) Ecole greco-bouddhique de Gandhara

2) Ecole de Mathura

3) Ecole d’Andrah Pradesh

4) Ecole de la période Gupta. - Lorsque l’Asie rencontre la Grèce

a) Pièces de monnaies kouchanes

b) Reliquaire bimaran

c) Triade de Harra

d) Prendre la terre à témoin

e) Tous Bodhisattva - Le Bouddhisme aujourd’hui, l’exemple de Nehru

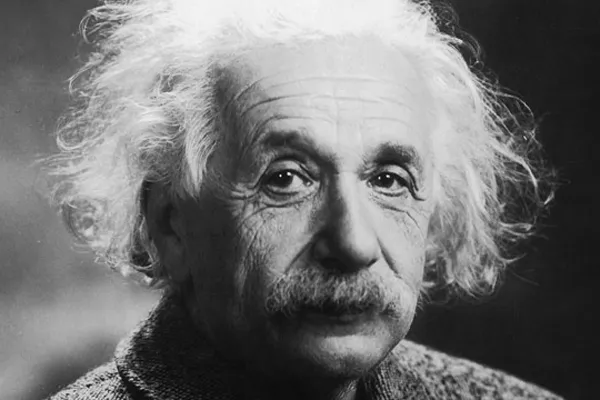

- Science et religion, Albert Einstein et Buddha.

Introduction

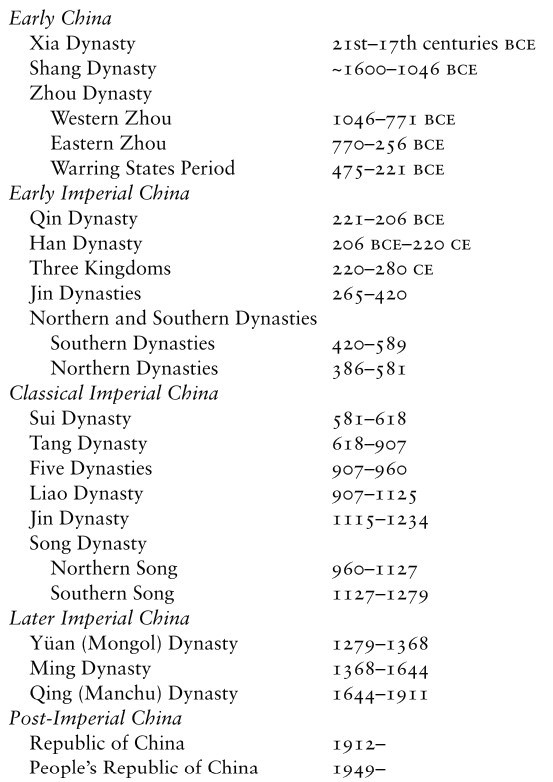

Les Ve et IVe siècles avant J.-C. furent une période d’effervescence intellectuelle mondiale. C’est l’époque des grands penseurs, tels que Socrate, Platon et Confucius, mais aussi Panini et Bouddha.

Dans le nord de l’Inde, c’est l’âge du Bouddha, après la mort duquel émerge une foi non théiste (Bouddha n’est qu’un homme…), qui se répand bien au-delà de sa région d’origine. Avec entre 500 millions et un milliard de croyants, le bouddhisme constitue aujourd’hui l’une des principales croyances religieuses et philosophiques du monde et sans doute une force potentielle redoutable pour la paix.

Bouddha, bio-express

« Le bouddha » (l’éveillé) est le nom donné à un homme appelé Siddhartha Gautama Shakyamuni (le muni ou sage du clan des Shakya). Il aurait atteint l’âge d’environ quatre-vingts an. Craignant l’idolâtrie, il refuse toute représentation de sa personne sous forme d’image.

Les traditions divergent sur les dates exactes de sa vie que la recherche moderne tend à situer de plus en plus tard : vers 623-543 av. J.-C. selon la tradition theravâda, vers 563-483 av. J.-C. selon la majorité des spécialistes du début du XXe siècle, tandis que d’autres le situent aujourd’hui entre 420 et 380 av. J.-C. (sa vie n’aurait pas dépassé les 40 ans).

Selon la tradition, Siddhartha Gautama est né à Lumbini (dans l’actuel Népal) en tant que prince de la famille royale de la ville de Kapilavastu, un petit royaume situé dans les contreforts de l’Himalaya, dans l’actuel Népal.

Un astrologue aurait mis en garde le père du garçon, le roi Suddhodana : lorsque l’enfant grandirait, il deviendrait soit un brillant souverain, soit un moine influent, en fonction de sa lecture du monde. Farouchement déterminé à en faire son successeur, le père de Siddhartha ne le laissa donc jamais voir le monde en dehors des murs du palais. Tout en lui offrant tous les plaisirs et distractions possibles, il en fait un prisonnier virtuel jusqu’à l’âge de 29 ans.

Lorsque le jeune homme s’échappe de sa cage dorée, il découvre l’existence de personnes affectées par leur grand âge, la maladie et la mort. Bouleversé par la souffrance des gens ordinaires qu’il rencontre, Siddhartha abandonne les plaisirs éphémères du palais pour rechercher un but plus élevé dans la vie. Il se soumet d’abord à un ascétisme draconien, qu’il abandonne six ans plus tard, estimant qu’il s’agissait d’un exercice futile.

Il s’assoit alors sous un grand figuier pour méditer et y fait l’expérience du nirvana (la bodhi : libération ou, en sanskrit, extinction). On le désigne désormais sous le nom de « Bouddha » (l’éveillé ou l’éclairé).

Les « quatre vérités » et « l’octuple sentier »

Avant d’en esquisser le développement politique, quelques mots sur la philosophie sous-jacente au bouddhisme.

A ses jeunes disciples, Bouddha enseigne la « Voie du milieu », entre les deux extrêmes de la mortification et de la satisfaction des désirs.

Et il énonce les Quatre nobles vérités :

- La noble vérité de la souffrance.

- La noble vérité de l’origine de la souffrance.

- La noble vérité de la cessation de la souffrance.

- La noble vérité de la voie menant à la cessation de la souffrance, celle du Noble Chemin octuple.

Ainsi que le feront Augustin et plus encore les Frères de la Vie commune dans le monde chrétien, le bouddhisme insiste sur le fait que notre attachement à l’existence terrestre implique la souffrance.

Chez les chrétiens, c’est ce qui conduirait au « péché », notion inexistante dans le bouddhisme, pour qui l’errance vient de l’ignorance du bon chemin.

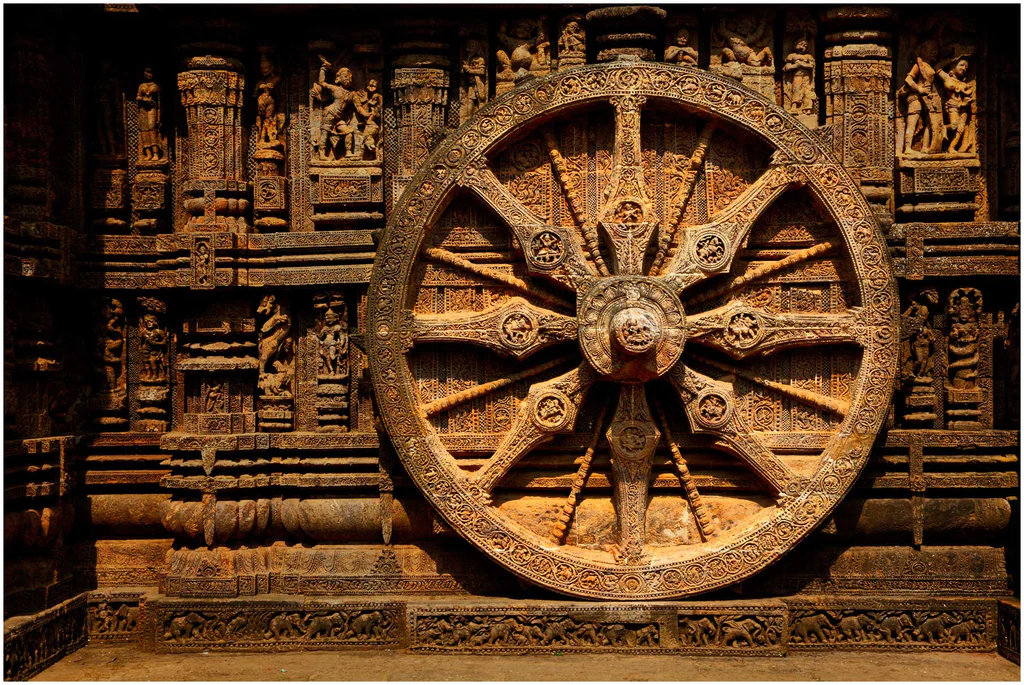

Pour Bouddha, il faut combattre, voire éteindre tout sens démesuré du moi (on dirait ego aujourd’hui). Il est possible de mettre fin à notre souffrance en transcendant ce fort sentiment de « moi », afin d’entrer dans une plus grande harmonie avec les choses en général. Les moyens d’y parvenir sont résumés dans le Noble Chemin octuple, parfois représenté par les huit rayons d’une Roue de la Loi (dharmachakra) que Bouddha mettra en marche, la Loi signifiant ici le dharma, un ensemble de préceptes moraux et philosophiques.

Ces huit points du Noble Chemin octuple sont :

- la vue juste

- la pensée juste

- la parole juste

- l’action juste

- les moyens d’existence justes

- l’effort juste

- la pleine conscience

- la concentration juste

– La vision juste est importante dès le départ, car sans cela, on ne peut pas voir la vérité des quatre nobles vérités.

– La pensée juste en découle naturellement. Le terme « juste » signifie ici « en accord avec les faits », c’est-à-dire avec la façon dont les choses sont (qui peut être différente de la façon dont je voudrais qu’elles soient).

– La pensée juste, la parole juste, l’action juste et les moyens d’existence justes impliquent une retenue morale – s’abstenir de mentir, de voler, de commettre des actes violents et gagner sa vie d’une manière qui ne soit pas préjudiciable aux autres. La retenue morale ne contribue pas seulement à l’harmonie sociale générale, elle nous aide aussi à contrôler et à diminuer le sentiment démesuré du « moi ». Comme un enfant gâté, le « moi » grandit et devient indiscipliné à mesure que nous le laissons agir à sa guise.

– Ensuite, l’effort juste est important parce que le « moi » prospère dans l’oisiveté et le mauvais effort ; certains des plus grands criminels sont les personnes les plus énergiques, donc l’effort doit être approprié à la diminution du « moi » (son ego, dirait-on aujourd’hui). Dans tous les cas, si nous ne sommes pas prêts à faire des efforts, nous ne pouvons pas espérer obtenir quoi que ce soit, ni dans le sens spirituel ni dans la vie. Les deux dernières étapes de la voie, la pleine conscience et la concentration ou absorption, représentent la première étape permettant de nous libérer de la souffrance.

Les ascètes qui avaient écouté le premier discours du Bouddha devinrent le noyau d’un sangha (communauté, mouvement) d’hommes (les femmes devaient entrer plus tard) qui suivaient la voie décrite par le Bouddha dans sa Quatrième noble vérité, celle précisant le Noble Chemin octuple.

Pour rendre le nirvana bouddhiste accessible au citoyen ordinaire, l’imagination bouddhiste a inventé le concept très intéressant de bodhisattva, mot dont le sens varie selon le contexte. Il peut aussi bien désigner l’état dans lequel se trouvait Bouddha lui-même avant son « éveil », qu’un homme ordinaire ayant pris la résolution de devenir un bouddha et ayant reçu d’un bouddha vivant la confirmation ou la prédiction qu’il en serait ainsi.

Dans le bouddhisme theravâda (l’école ancienne), seules quelques personnes choisies peuvent devenir des bodhisattvas, comme Maitreya, présenté comme le « Bouddha à venir ».

Mais dans le bouddhisme mahâyâna (Grand Véhicule), un bodhisattva désigne toute personne qui a généré la bodhicitta, un souhait spontané et un esprit compatissant visant à atteindre l’état de bouddha pour le bien de « tous les êtres sensibles », hommes aussi bien qu’animaux. Etant donné qu’une personne peut, dans une vie future, se réincarner dans un animal, le respect des animaux s’impose.

Réincarnation

Tout en voulant construire sa propre vision sur certains fondements de l’hindouisme, l’une des plus anciennes religions du monde, Siddhartha introduisit néanmoins des changements révolutionnaires aux implications politiques importantes.

Dans la plupart des croyances impliquant la réincarnation (hindouisme, jaïnisme, sikhisme), l’âme humaine est immortelle et ne se disperse pas après la disparition du corps physique. Après la mort, l’âme transmigre simplement (métempsychose) dans un nouveau-né ou un animal pour poursuivre son immortalité. La croyance en la renaissance de l’âme a été exprimée par les penseurs grecs anciens, à commencer par Pythagore, Socrate et Platon.

Le but du bouddhisme est d’apporter un bonheur durable et inconditionnel. Celui de l’hindouisme est de se libérer du cycle de naissance et de renaissance (samsara) pour atteindre, finalement, le moksha, qui en est la libération.

Le bouddhisme et l’hindouisme s’accordent sur le karma, le dharma, le moksha et la réincarnation. Mais ils diffèrent politiquement dans la mesure où le bouddhisme se concentre sur l’effort personnel de chacun et accorde par conséquent une moindre importance aux prêtres et aux rituels formels que l’hindouisme. Enfin, le bouddhisme ne reconnaît pas la notion de caste et prône donc une société plus égalitaire.

Alors que l’hindouisme soutient que l’on ne peut atteindre le nirvana que dans une vie ultérieure, le bouddhisme, plus volontariste et optimiste, soutient qu’une fois qu’on a réalisé que la vie est souffrance, on peut mettre un terme à cette souffrance dans sa vie présente.

Les bouddhistes décrivent leur renaissance comme une bougie vacillante qui vient en allumer une autre, plutôt que comme une âme immortelle ou un « moi » passant d’un corps à un autre, ainsi que le croient les hindous. Pour les bouddhistes, il s’agit d’une renaissance sans « soi », et ils considèrent la réalisation du non-soi ou du vide comme le nirvana (extinction), alors que pour les hindous, l’âme, une fois libérée du cycle des renaissances, ne s’éteint pas, mais s’unit à l’Être suprême et entre dans un éternel état de félicité divine.

Les Aryens et le védisme

L’une des grandes traditions ayant façonné l’hindouisme est la religion védique (védisme), qui s’est épanouie chez les peuples indo-aryens du nord-ouest du sous-continent indien (Pendjab et plaine occidentale du Gange) au cours de la période védique (1500-500 av. J.-C.).

Au cours de cette période, des peuples nomades venus du Caucase et se désignant eux-mêmes comme « Aryens » (« noble », « civilisé » et « honorable ») pénétrèrent en Inde par la frontière nord-ouest.

Le terme « aryen » a une très mauvaise connotation historique, en particulier depuis le XIXe siècle, lorsque plusieurs antisémites virulents, tels qu’Arthur de Gobineau, Richard Wagner et Houston Chamberlain, ont commencé à promouvoir le mythe d’une « race aryenne », soutenant l’idéologie suprémaciste blanche de l’aryanisme qui dépeint la race aryenne comme une « race des seigneurs », les non-aryens étant considérés non seulement comme génétiquement inférieurs (Untermensch, ou sous-homme) mais surtout comme une menace existentielle à exterminer.

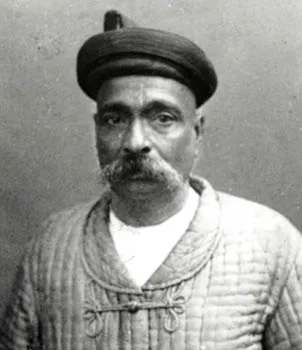

D’un point de vue purement scientifique, dans son livre The Arctic Home (1903), le patriote indien Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920), s’appuyant sur son analyse des observations astronomiques contenues dans les hymnes védiques, émet l’hypothèse selon laquelle le pôle Nord aurait été le lieu de vie originel des Aryens pendant la période préglaciaire, région qu’ils auraient quittée vers 8000 avant J.-C. à cause de changements climatiques, migrant vers les parties septentrionales de l’Europe et de l’Asie. Gandhi disait de Tilak, l’un des pères du mouvement de l’indépendance du pays, qu’il était « l’artisan de l’Inde moderne ».

Les Aryens arrivant du Nord étaient probablement moins barbares qu’on ne l’a suggéré jusqu’à présent. Grâce à leur supériorité militaire et culturelle, ils conquirent toute la plaine du Gange, avant d’étendre leur domination sur les plateaux du Deccan.

Cette conquête a laissé des traces jusqu’à nos jours, puisque les régions occupées par ces envahisseurs parlent des langues indo-européennes issues du sanskrit. (*1)

En réalité, la culture védique est profondément enracinée dans la culture eurasienne des steppes Sintashta (2200-1800 avant notre ère) du sud de l’Oural, dans la culture Andronovo d’Asie centrale (2000-900 avant notre ère), qui s’étend du sud de l’Oural au cours supérieur de l’Ienisseï en Sibérie centrale, et enfin dans la Civilisation de la vallée de l’Indus (Harappa) (4000-1500 avant notre ère).

Cette culture védique se fonde sur les fameux Védas (savoirs), quatre textes religieux consignant la liturgie des rituels et des sacrifices et les plus anciennes écritures de l’hindouisme. La partie la plus ancienne du Rig-Veda a été composée oralement dans le nord-ouest de l’Inde (Pendjab) entre 1500 et 1200 av. JC., c’est-à-dire peu après l’effondrement de la Civilisation de la vallée de l’Indus.

Le philologue, grammairien et érudit sanskrit Panini, qu’on croit être un contemporain de Bouddha, est connu pour son traité de grammaire sanskrite en forme de sutra, qui a suscité de nombreux commentaires de la part d’érudits d’autres religions indiennes, notamment bouddhistes.

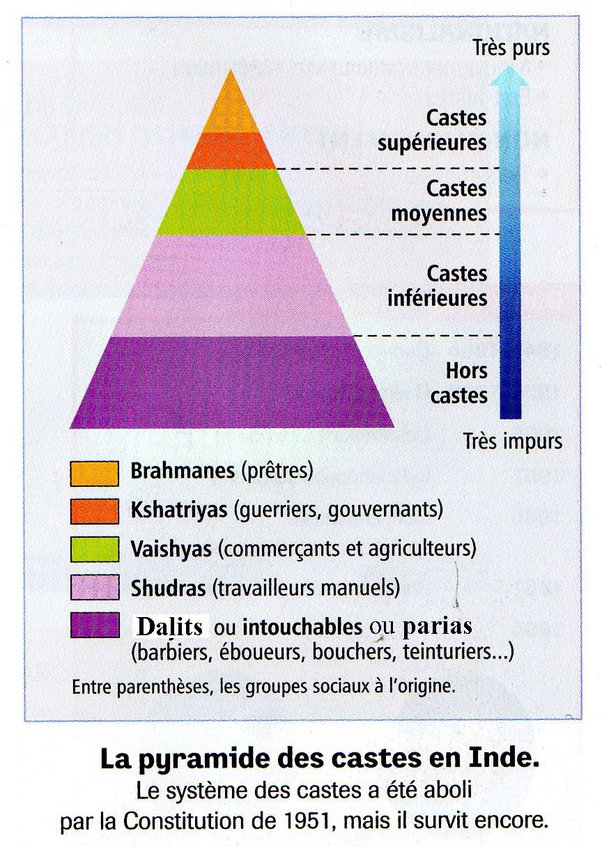

Les Brahmanes et le système des castes

Cependant, avec l’émergence de cette culture aryenne apparut ce que l’on appelle le « brahmanisme », c’est-à-dire la naissance d’une caste toute puissante de grands prêtres.

« De nombreuses études linguistiques et historiques font état de troubles socioculturels résultant de cette migration et de la pénétration de la culture brahmanique dans diverses régions, de l’ouest de l’Asie du Sud vers l’Inde du Nord, l’Inde du Sud et l’Asie du Sud-Est », constate aujourd’hui Gajendran Ayyathurai, un anthropologue indien de l’Université de Göttingen en Allemagne.

Le brahman, littéralement « supérieur », est un membre de la caste sacerdotale la plus élevée (à ne pas confondre avec les adorateurs du dieu hindou Brahma). Bien que le terme apparaisse dans les Védas, les chercheurs modernes tempèrent ce fait et soulignent qu’il « n’existe aucune preuve dans le Rig-Veda d’un système de castes élaboré, très subdivisé et très important ».

Mais avec l’émergence d’une classe dirigeante de brahmanes, devenus banquiers et propriétaires terriens, notamment sous la période Gupta (de 319 à 515 après J.-C.), un redoutable système de castes se met graduellement en place. La classe dirigeante féodale, ainsi que les prêtres, vivant des recettes des sacrifices, mettront l’accent sur des dieux locaux qu’ils intégreront progressivement au brahmanisme afin de séduire les masses. Même parmi les souverains, le choix des divinités indiquait des positions divergentes : une partie de la dynastie Gupta soutenait traditionnellement le dieu Vishnou, tandis qu’une autre soutenait le dieu Shiva.

Ce système déshumanisant des castes fut ensuite amplifié et utilisé à outrance par la Compagnie britannique des Indes orientales, une entreprise et une armée privée à la tête de l’Empire britannique, pour imposer son pouvoir aristocratique et colonial sur les Indes, une politique qui perdure encore aujourd’hui, surtout dans les esprits.

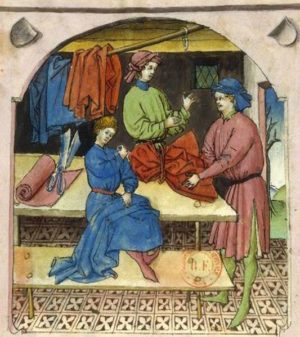

Le système hindou des castes s’articule autour de deux concepts clés permettant de catégoriser les membres de la société : le varṇa et la jati. Le varna (littéralement « couleur ») divise la société en une hiérarchie de quatre grandes classes sociales :

- Brahmanes (la classe sacerdotale)

- Kshatriyas (guerriers et dirigeants)

- Vaishyas (marchands)

- Shudras (travailleurs manuels)

En outre, la jati fait référence à plus de 3000 classifications hiérarchiques, à l’intérieur des quatre varnas, entre les groupes sociaux en fonction de la profession, du statut social, de l’ascendance commune et de la localité…

La justification de cette stratification sociale est intimement liée à la vision hindouiste du karma. Car la naissance de chacun est directement liée au karma, véritable bilan de sa vie précédente. Ainsi, la naissance dans le varna brahmanique est le résultat d’un bon karma…

« Ceux qui ont eu une bonne conduite ici auront rapidement une bonne naissance – naissance en tant que brahmane, kshatriya ou vaishya. Mais ceux dont la conduite ici a été mauvaise obtiendront rapidement une mauvaise naissance – naissance en tant que chien, porc ou chandala (bandit). »

(Chandogya Upanishad 5.10.7)

Selon cette théorie, le karma détermine la naissance de l’individu dans une classe, ce qui définit son statut social et religieux, qui fixe à son tour ses devoirs et obligations au regard de ce statut spécifique.

En 2021, une enquête a révélé que trois Indiens sur dix (30 %) s’identifient comme membres des quatre varnas et seulement 4,3 % des Indiens (60,5 millions) comme des brahmanes.

Certains d’entre eux sont prêtres, d’autres exercent des professions telles qu’éducateurs, législateurs, érudits, médecins, écrivains, poètes, propriétaires terriens et politiciens. Au fur et à mesure de l’évolution de ce système de castes, les brahmanes ont acquis une forte influence en Inde et ont exercé une discrimination à l’encontre des autres castes « inférieures ».

L’immense partie restante des Indiens (70 %), y compris parmi les hindous, déclare faire partie des dalits, encore appelés intouchables, des individus considérés, du point de vue du système des castes, comme hors castes et affectés à des fonctions ou métiers jugés impurs. Présents en Inde, mais également dans toute l’Asie du Sud, les dalits sont victimes de fortes discriminations. En Inde, une écrasante majorité de bouddhistes se déclarent dalits.

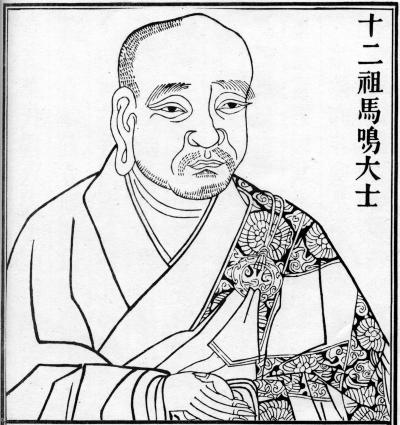

Dès le Ier siècle, le philosophe bouddhiste, dramaturge, poète, musicien et orateur indien Asvaghosa (v. 80 – v. 150 ap. J.-C.) a élevé la voix pour condamner ce système des castes, avec des arguments empruntés pour certains aux textes les plus vénérés des brahmanes eux-mêmes, et pour d’autres, fondés sur le principe de l’égalité naturelle entre tous les hommes.

Selon Asvaghosa,

« la qualité de brahmane n’est inhérente ni au principe qui vit en nous, ni au corps dans lequel réside ce principe, et elle ne résulte ni de la naissance, ni de la science, ni des pratiques religieuses, ni de l’observation des devoirs moraux, ni de la connaissance des Védas. Puisque cette qualité n’est ni inhérente ni acquise, elle n’existe pas, ou plutôt tous les hommes peuvent la posséder. »

Une allégorie bouddhiste rejette clairement et se moque de l’idée même du système de castes:

« De même que le sable ne devient pas de la nourriture simplement parce qu’un enfant le dit, lorsque de jeunes enfants jouant sur une route principale construisent des pâtés de sable et leur donnent des noms, en disant ‘Celui-ci est du lait, celui-ci de la viande et celui-ci du lait caillé’, il en va de même pour les quatre varnas, tels que vous, les brahmanes, les décrivez. »

L’Inde avant le bouddhisme

L’époque du Bouddha est celle de la deuxième urbanisation de l’Inde et d’une grande contestation sociale.

L’essor des shramaṇas, des philosophes ou moines errants ayant rejeté l’autorité des Védas et des brahmanes, était nouveau. Bouddha n’était pas le seul à explorer les moyens d’obtenir la libération (moksha) du cycle éternel des renaissances (saṃsara).

Le constat que les rituels védiques ne menaient pas à une libération éternelle conduisit à la recherche d’autres moyens. Le bouddhisme primitif, le yoga et des courants similaires de l’hindouisme, jaïnisme, ajivika, ajnana et chârvaka, étaient les shramanas les plus importants.

Malgré le succès obtenu en diffusant des idées et des concepts qui allaient bientôt être acceptés par toutes les religions de l’Inde, les écoles orthodoxes de philosophie hindoue (astika) s’opposaient aux écoles de pensée shramaṇiques et réfutèrent leurs doctrines en les qualifiant d’hétérodoxes (nastika), parce qu’elles refusaient d’accepter l’autorité épistémique des Védas.

Pendant plus de quarante ans, le Bouddha sillonna l’Inde à pied pour diffuser son dharma, un ensemble de préceptes et de lois sur le comportement de ses disciples. À sa mort, son corps fut incinéré, comme c’était la coutume en Inde, et ses cendres furent réparties dans plusieurs reliquaires, enterrés dans de grands monticules hémisphériques connus sous le nom de stupas. Alors déjà, sa religion était répandue dans tout le centre de l’Inde et dans de grandes villes indiennes comme Vaishali, Shravasti et Rajagriha.

Les grands conciles bouddhistes

Quatre grands conciles bouddhistes furent organisés, à l’instigation de différents rois qui cherchaient en réalité à briser l’omnipuissante caste des brahmanes.

Le premier eut lieu en 483 avant J.-C., juste après la mort du Bouddha, sous le patronage du roi Ajatasatru (492-460 av. J.-C.) du Royaume du Magadha, le plus grand des seize royaumes de l’Inde ancienne, afin de préserver les enseignements du Bouddha et de parvenir à un consensus sur la manière de les diffuser.

Le deuxième intervint en 383 avant J.-C., soit cent ans après la mort du Bouddha, sous le règne du roi Kalashoka. Des divergences d’interprétation s’installant sur des points de discipline au fur et à mesure que les adeptes s’éloignaient les uns des autres, un schisme menaçait de diviser ceux qui voulaient préserver l’esprit originel et ceux qui défendaient une interprétation plus large.

Le premier groupe, appelé Thera (signifiant « ancien » en pâli), est à l’origine du bouddhisme theravâda, engagé à préserver les enseignements du Bouddha dans l’esprit originel.

L’autre groupe était appelé Mahasanghika (Grande Communauté). Ils interprétaient les enseignements du Bouddha de manière plus libérale et nous ont donné le bouddhisme Mahâyâna.

Les participants au concile tentèrent d’aplanir leurs divergences, sans grande unité mais sans animosité non plus. L’une des principales difficultés venait du fait qu’avant d’être consignés dans des textes, les enseignements du Bouddha n’avaient été transmis qu’oralement pendant trois à quatre siècles. (*2)

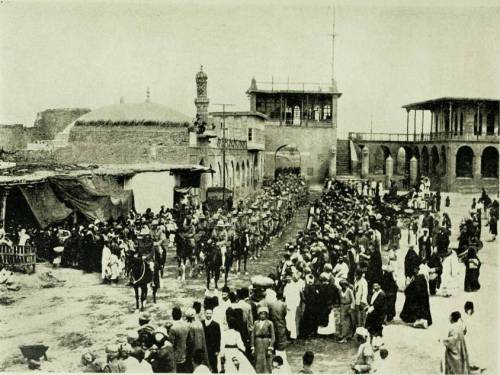

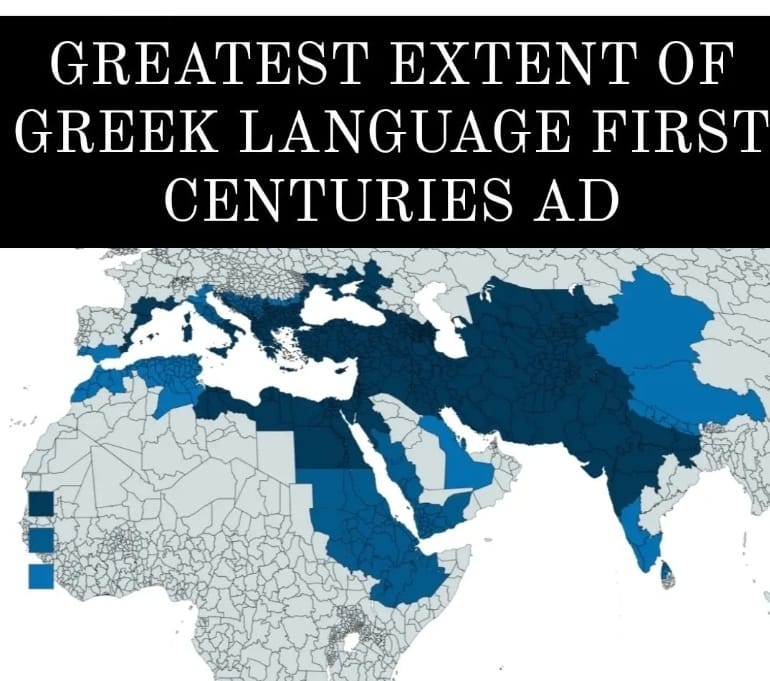

L’arrivée des Grecs

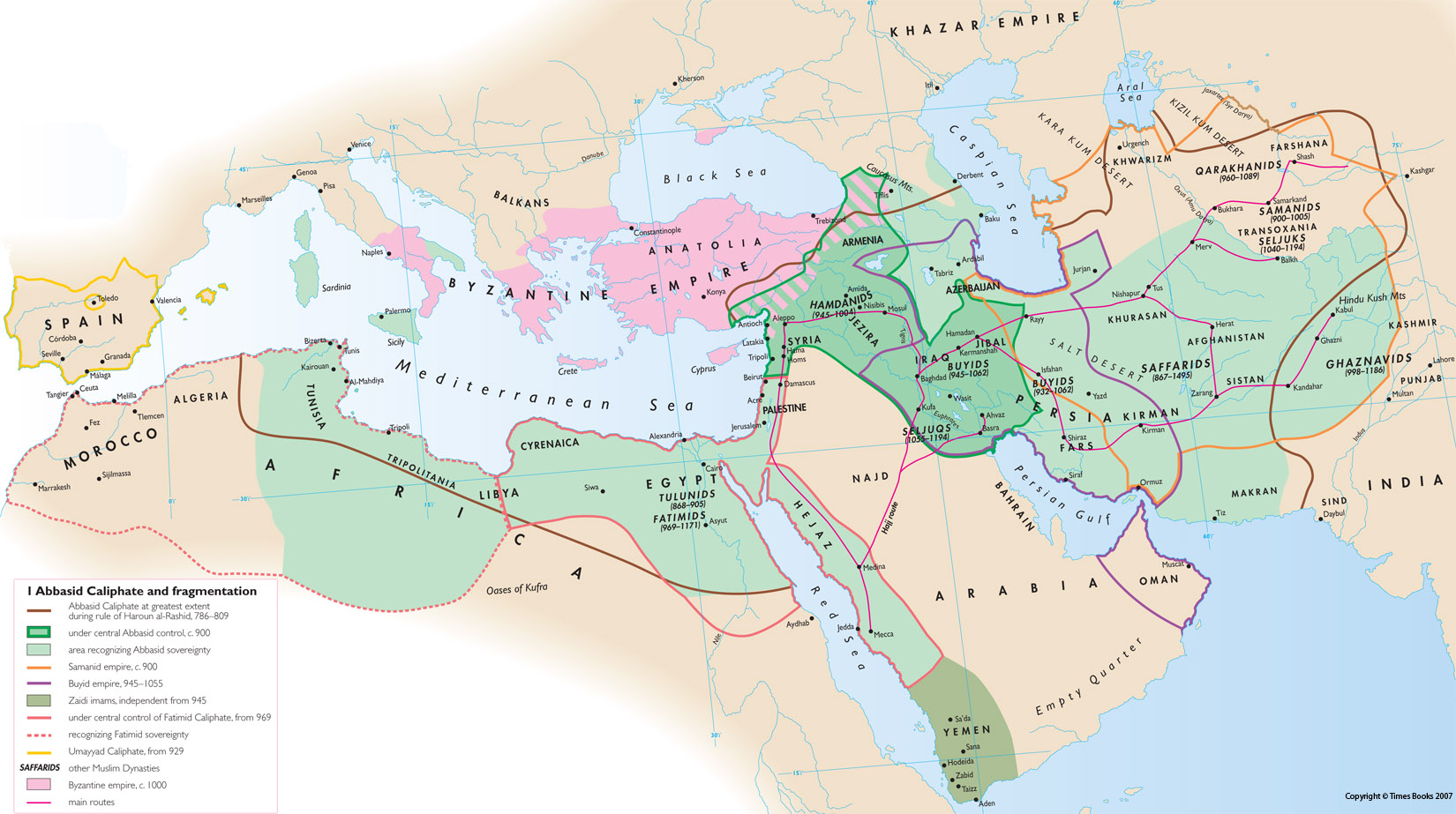

Ainsi que nous l’avons documenté par ailleurs, l’Asie centrale, et l’Afghanistan en particulier, furent le lieu de rencontre entre les civilisations perses, chinoises, grecques et indiennes.

C’est au Gandhara, région à cheval entre le Pakistan et l’Afghanistan, au cœur des Routes de la soie, que le bouddhisme prendra à deux reprises un envol majeur, donnant naissance à un art dit « gréco-bouddhiste », qui parviendra à faire la synthèse entre plusieurs cultures à travers des œuvres d’une beauté incomparable.

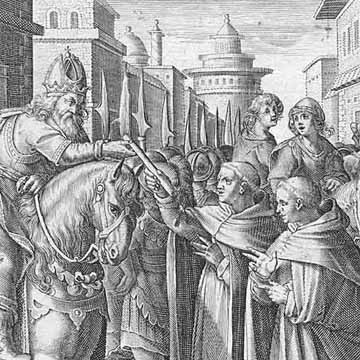

Les premiers Grecs commencèrent à s’installer dans la partie nord-ouest du sous-continent indien à l’époque de l’Empire perse achéménide. Après avoir conquis la région, le roi perse Darius le Grand (521 – 486 av. J.-C.) colonisa également une grande partie du monde grec, qui comprenait à l’époque toute la péninsule anatolienne occidentale.

Lorsque des villages grecs se rebellaient sous le joug perse, ils faisaient parfois l’objet d’un nettoyage ethnique et leurs populations étaient déportées à l’autre bout de l’empire.

C’est ainsi que de nombreuses communautés grecques virent le jour dans les régions indiennes les plus reculées de l’empire perse.

Au IVe siècle avant J.-C., Alexandre le Grand (356 – 323 av. J.-C.) vainquit et conquit l’empire perse. En 326 avant J.-C., cet empire comprenait la partie nord-ouest du sous-continent indien jusqu’à la rivière Beas (que les Grecs nommaient l’Hyphase). Alexandre établit des satrapies et fonde plusieurs colonies. Il se tourne vers le sud lorsque ses troupes, conscientes de l’immensité de l’Inde, refusent de pousser plus loin encore vers l’est.

Après sa mort, son empire se délite. De 180 av. J.-C. à environ l’an 10 de notre ère, plus de trente rois hellénistiques se succèdent, souvent en conflit entre eux. Cette époque est connue dans l’histoire sous le nom des « Royaumes indo-grecs ».

L’un d’eux a été fondé lorsque le roi gréco-bactrien Démétrius envahit l’Inde en 180 avant notre ère, créant ainsi une entité faisant sécession avec le puissant royaume gréco-bactrien, la Bactriane (comprenant notamment le nord de l’Afghanistan, une partie de l’Ouzbékistan, etc.).

Pendant les deux siècles de leur règne, ces rois indo-grecs intégrèrent dans une seule culture des langues et des symboles grecs et indiens, comme en témoignent leurs pièces de monnaie, et mêlèrent les anciennes pratiques religieuses grecques, hindoues et bouddhistes, comme le montrent les vestiges archéologiques de leurs villes et les signes de leur soutien au bouddhisme.

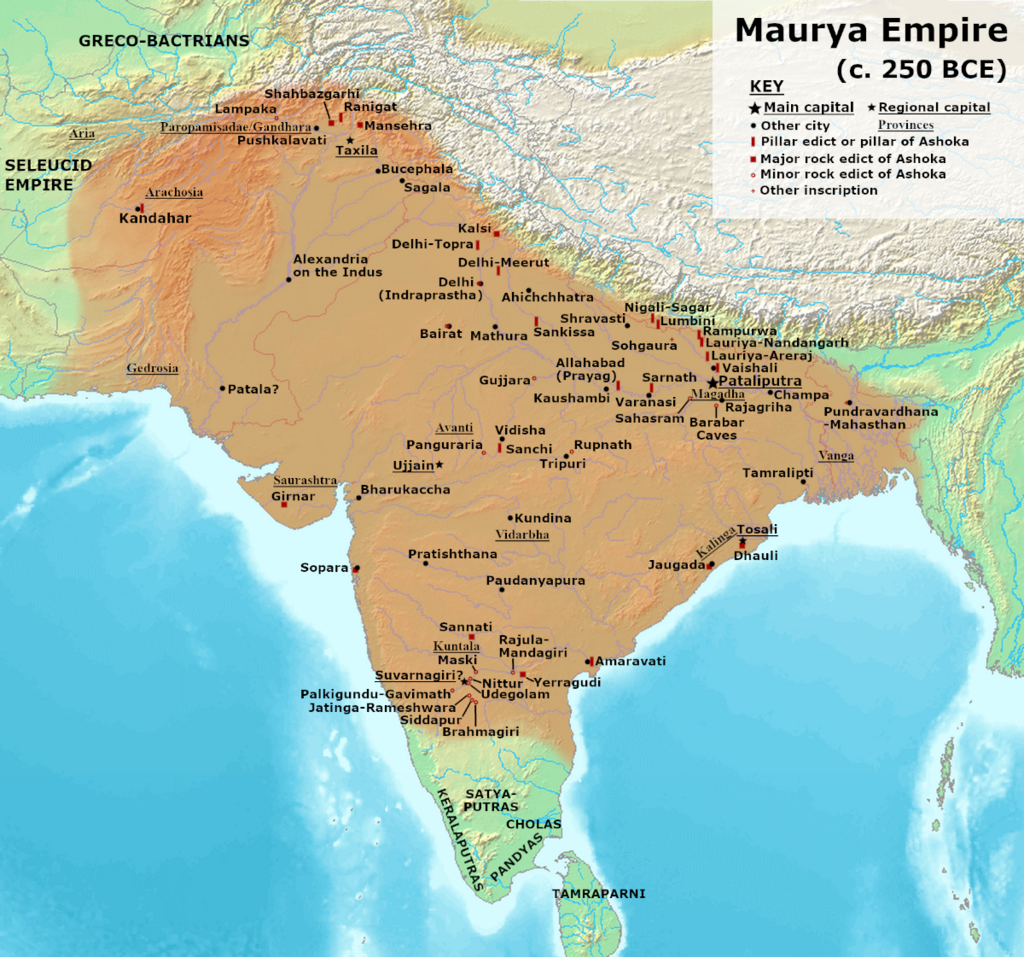

L’Empire Maurya

Vers 322 avant J.-C., les Grecs appelés Yona (Ioniens) ou Yavana dans les sources indiennes, participent, avec d’autres populations, au soulèvement de Chandragupta Maurya (né v. -340 et mort v. – 297), le fondateur de l’Empire maurya.

Le règne de Chandragupta ouvre une ère de prospérité économique, de réformes, d’expansion des infrastructures et de tolérance. De nombreuses religions ont ainsi prospéré dans son royaume et dans l’empire de ses descendants. Bouddhisme, jaïnisme et ajivika prennent de l’importance aux côtés des traditions védiques et brahmaniques, tout en respectant les religions minoritaires telles que le zoroastrisme et le panthéon grec.

Le règne d’Ashoka le Grand

(de 268 à 231 av. JC)

L’Empire Maurya atteint son apogée sous le règne du petit-fils de Chandragupta, Ashoka le Grand, de 268 à 231 av. J.-C. (parfois écrit Asoka).

Huit ans après sa prise de pouvoir, Ashoka mène une campagne militaire pour conquérir le Kalinga, un vaste royaume côtier du centre-est de l’Inde. Sa victoire lui permet de conquérir un territoire plus vaste que celui de tous ses prédécesseurs. Grâce aux conquêtes d’Ashoka, l’Empire Maurya devient une puissance centralisée couvrant une grande partie du sous-continent indien, s’étendant de l’actuel Afghanistan à l’ouest à l’actuel Bangladesh à l’est, avec sa capitale à Pataliputra (proche de l’actuelle Patna en Inde).

Alors que l’Empire Maurya avait existé dans un certain désordre jusqu’en 185 av. J.-C., Ashoka va transformer le royaume en recourant à une violence extrême qui caractérise le début de son règne. On parle de 100 000 à 300 000 morts, rien que lors de la conquête du Kalinga !

Mais le poids d’un tel carnage plonge le roi dans une grave crise personnelle. Ashoka est gravement choqué par la multitude de vies arrachées par ses armées. L’édit N° 13 d’Ashoka reflète le profond remords ressenti par le roi après avoir observé la destruction de Kalinga :

« Sa Majesté a éprouvé des remords à cause de la conquête de Kalinga car, lors de l’assujettissement d’un pays non conquis auparavant, il y a nécessairement des massacres, des morts et des captifs, et Sa Majesté en éprouve une profonde tristesse et un grand regret. »

Ashoka renonce alors aux démonstrations de force militaires et autres formes de violence, y compris la cruauté envers les animaux. Conquis par le bouddhisme, il se consacre alors à répandre sa vision du dharma, une conduite juste et morale. Il va encourager la diffusion du bouddhisme dans toute l’Inde. Selon l’archéologue et érudit français François Foucher, même si les cas de mauvais traitements envers les animaux ne disparurent pas du jour au lendemain, la croyance en la fraternité de tous les êtres vivants est plus florissante en Inde que partout ailleurs.

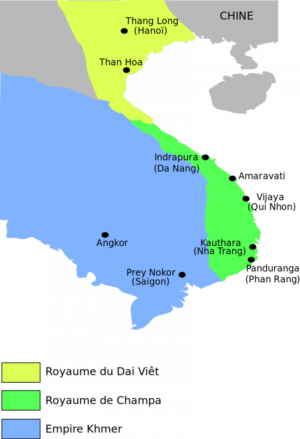

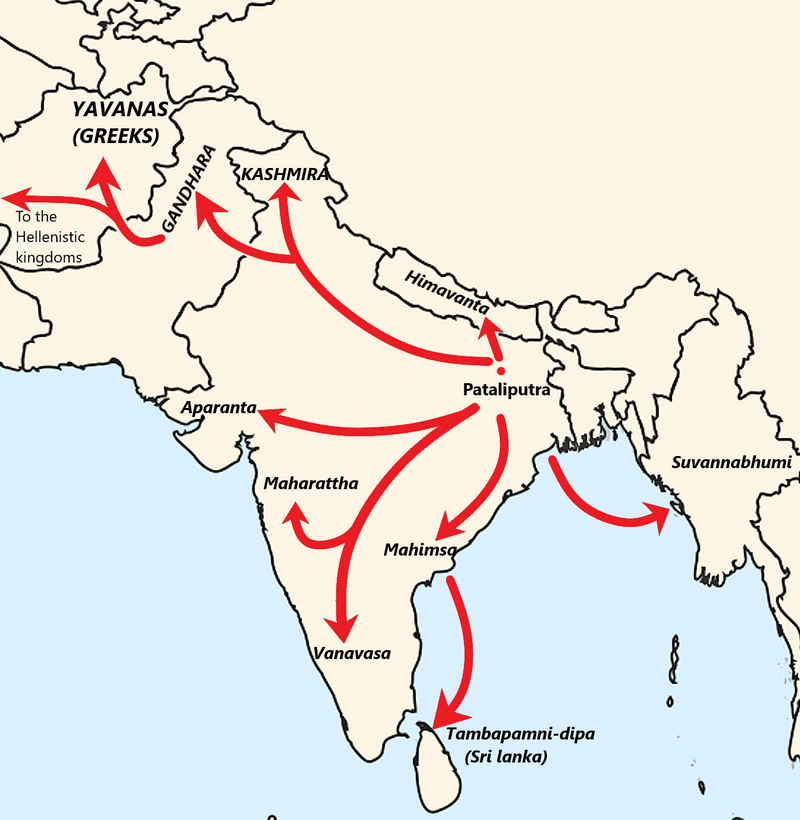

En 250 avant J.-C., Ashoka convoque le troisième concile bouddhique. Les sources theravâda mentionnent qu’en plus de régler les différends intérieurs, la principale fonction du concile était de planifier l’envoi de missionnaires bouddhistes dans différents pays afin d’y répandre la doctrine.

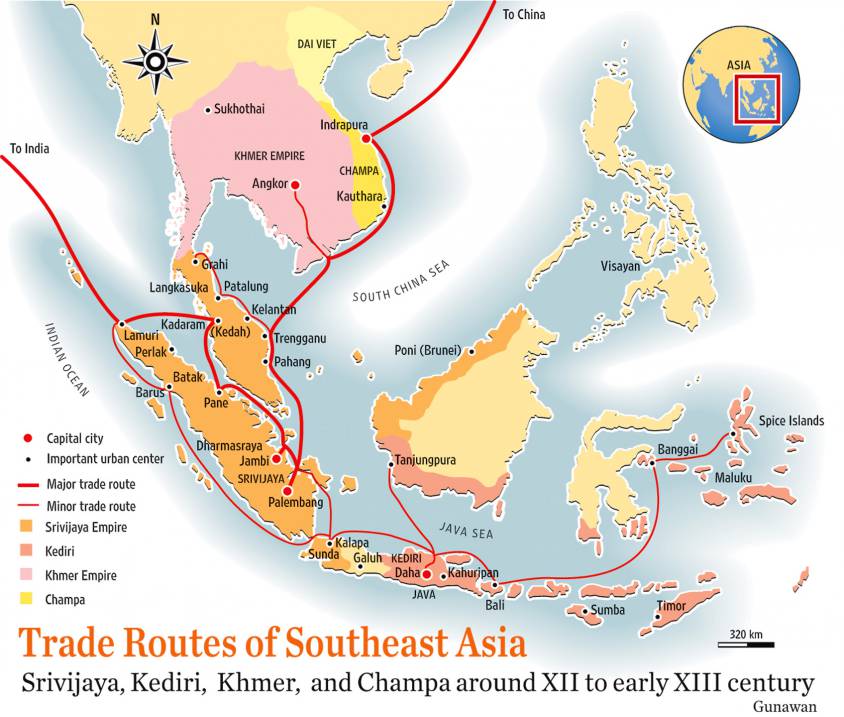

Ces missionnaires allèrent jusqu’aux royaumes hellénistiques de l’ouest, en commençant par la Bactriane voisine. Des missionnaires furent également envoyés en Inde du sud, au Sri Lanka et en Asie du Sud-Est (peut-être en Birmanie).

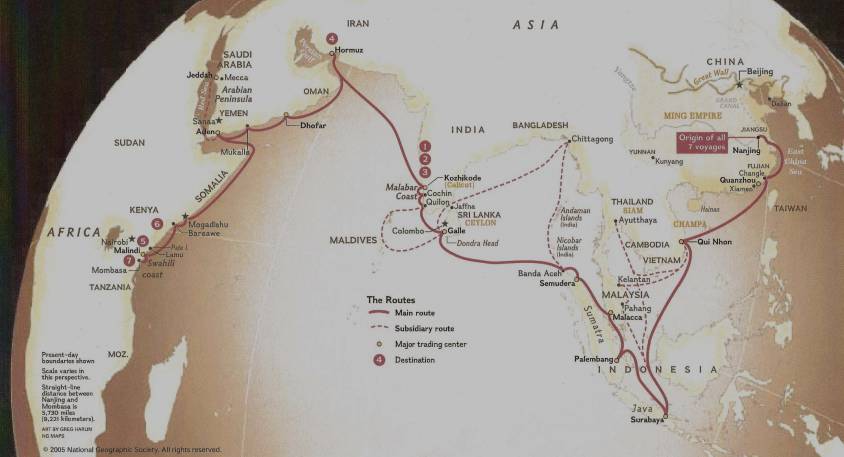

La forte implication de ces missions dans l’éclosion du bouddhisme en Asie à l’époque d’Ashoka est solidement étayée par des preuves archéologiques. Le bouddhisme ne s’est pas répandu par pur hasard, mais dans le cadre d’une opération politique créative, stimulante et bien planifiée, tout au long des Routes de la soie.

Le Mahavamsa ou Grande chronique (XII, 1er paragraphe), relatant l’histoire des rois cinghalais et tamouls de Ceylan (aujourd’hui Sri Lanka), donne la liste des missionnaires bouddhistes envoyés par le Concile et Ashoka :

- Le vieux Majjhantika prit la tête de la mission au Cachemire et au Gandhara (aujourd’hui le nord-ouest du Pakistan et l’Afghanistan) ;

- L’aîné Mahadeva dirigea la mission dans le sud-ouest de l’Inde (Mysore, Karnataka) ;

- Rakkhita, celle du sud-est de l’Inde (Tamil Nadu) ;

- Le vieux Yona (Ionien, Grec) Dharmaraksita partit vers Aparantaka (« frontière occidentale », comprenant le nord du Gujarat, le Kathiawar, le Kachch et le Sindh, toutes des parties de l’Inde à l’époque) ;

- L’aîné Mahadharmaraksita dirigea la mission de Maharattha (région péninsulaire occidentale de l’Inde) ;

- Maharakkhita (Maharaksita Thera) fut envoyé au pays des Yona (Ioniens), probablement la Bactriane et peut-être le royaume séleucide ;

- Majjhima Thera conduisit la mission dans la région d’Himavant (nord du Népal, contreforts de l’Himalaya) ;

- Sona Thera et Uttara Thera, celles de Suvannabhumi (quelque part en Asie du Sud-Est, peut-être au Myanmar ou en Thaïlande) ;

- Enfin, Mahinda, fils aîné d’Ashoka et donc le Prince de son royaume, accompagné de ses disciples Utthiya, Ittiya, Sambala et Bhaddasala, se rendit à Lankadipa (Sri Lanka).

Certaines de ces missions furent couronnées de succès, permettant d’implanter le bouddhisme en Afghanistan, au Gandhara et au Sri Lanka, par exemple.

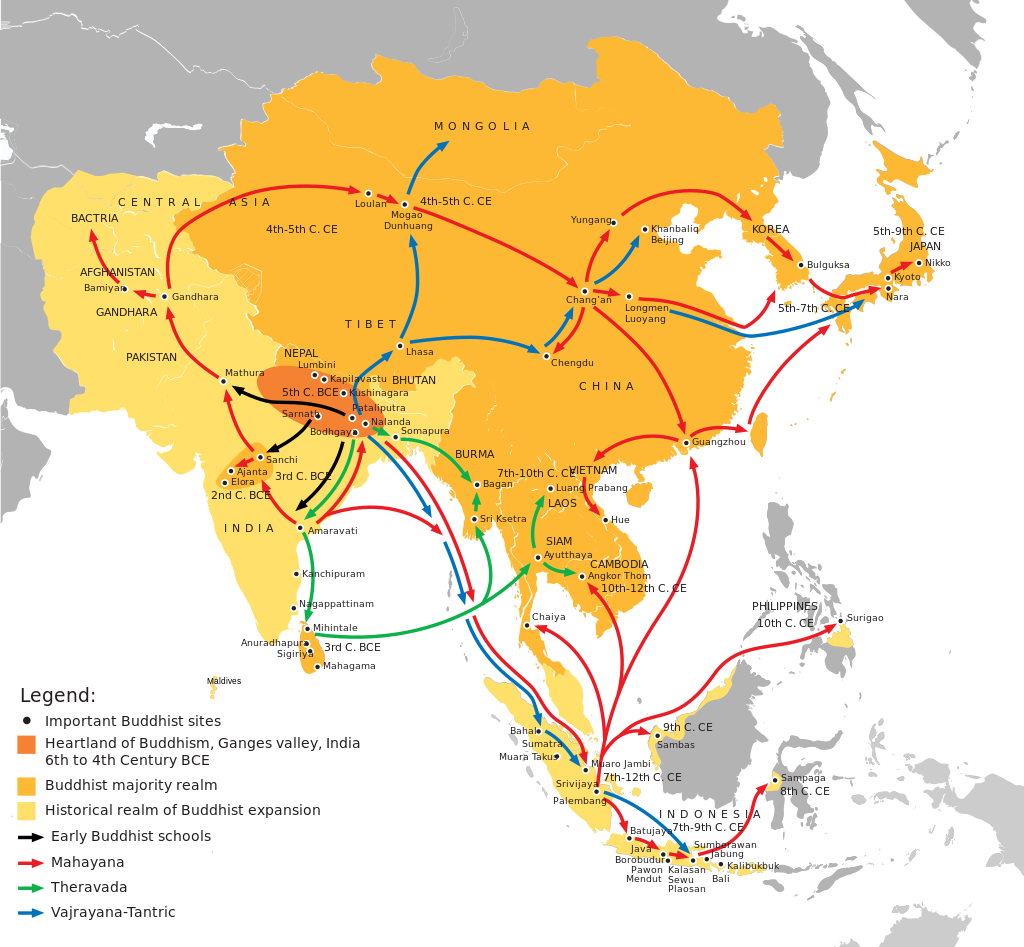

Le bouddhisme gandharien, le gréco-bouddhisme et le bouddhisme cinghalais ont puissamment inspiré le développement du bouddhisme dans le reste de l’Asie, notamment en Chine, et ceci pendant des générations.

Si les missions dans les royaumes hellénistiques méditerranéens semblent avoir été moins fructueuses, il est possible que des communautés bouddhistes se soient établies pendant une période limitée dans l’Alexandrie égyptienne, ce qui pourrait être à l’origine de la secte dite des Therapeutae, mentionnée dans certaines sources anciennes comme Philon d’Alexandrie (v. 20 av. J.-C. – 50 apr. J.-C.).

Le courant juif des Esséniens et les Thérapeutes d’Alexandrie seraient des communautés fondées sur le modèle du monachisme bouddhique. « C’est l’Inde qui serait, selon nous, au départ de ce vaste courant monastique qui brilla d’un vif éclat durant environ trois siècles dans le judaïsme même », affirme l’historien français André Dupont-Sommer, et cette influence aurait même contribué, selon lui, à l’émergence du christianisme.

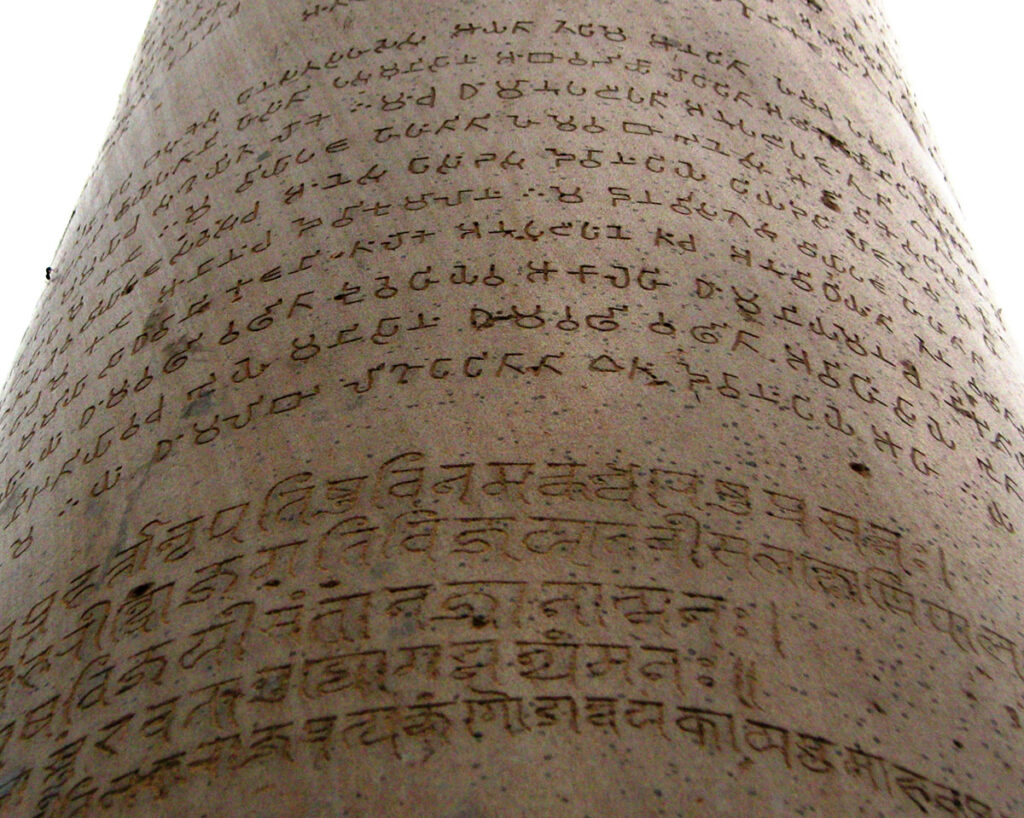

Edits d’Ashoka

Ashoka transmettait ses messages par le biais d’édits gravés sur des piliers et des rochers en divers lieux du royaume, proches des stupas, sur des lieux de pèlerinage et le long de routes commerciales très fréquentées.

Une trentaine d’entre eux ont été conservés. Ils sont souvent rédigés non pas en sanskrit, mais en grec (la langue du royaume gréco-bactrien voisin et des communautés grecques du royaume d’Ashoka), en araméen (langue officielle de l’ancien empire achéménide) ou en divers dialectes du prâkrit (une langue indo-aryenne moyenne), y compris le gândhârî ancien, langue parlée au Gandhara. (*3)

Ces édits utilisaient la langue pertinente pour la région. Par exemple, en Bactriane, ou les Grecs dominaient, on trouve près de l’actuelle Kandahar un édit rédigé uniquement en grec et en araméen.

Contenu des édits

Certains d’entre eux reflètent l’adhésion profonde d’Ashoka aux préceptes du bouddhisme et ses relations étroites avec le Sangha, l’ordre monastique bouddhiste. Il utilise également le terme spécifiquement bouddhiste de dharma pour désigner les qualités du cœur qui sous-tendent l’action morale.

Dans son édit mineur sur rocher N° 1, le roi se déclare « adepte laïc de l’enseignement du Bouddha depuis plus de deux ans et demi », mais avoue que jusqu’ici, il n’a « pas fait grand progrès ». « Depuis un peu plus d’un an, je me suis rapproché de l’Ordre », ajoute-t-il.

Dans l’édit mineur sur rocher N° 3 de Calcutta-Bairat, il affirme : « Tout ce qui a été dit par le Bouddha a été bien dit », décrivant les enseignements du Bouddha comme le véritable dharma.

Ashoka a reconnu les liens étroits entre l’individu, la société, le roi et l’État. Son dharma peut être compris comme la moralité, la bonté ou la vertu, et l’impératif de le poursuivre lui a donné le sens du devoir. Les inscriptions expliquent que le dharma intègre la maîtrise de soi, la pureté de la pensée, la libéralité, la gratitude, la dévotion ferme, la véracité, la protection de la parole et la modération dans les dépenses et les possessions.

Le dharma a également un aspect social. Il comprend l’obéissance aux parents, le respect des aînés, la courtoisie et la libéralité envers les adorateurs de Brahma, la courtoisie envers les esclaves et les serviteurs, et la libéralité envers les amis, les connaissances et les parents.

La non-violence, qui consiste à s’abstenir de blesser ou de tuer tout être vivant, était un aspect important du dharma d’Ashoka. Ne tuer aucun être vivant est décrit comme faisant partie du bien (Édit mineur sur rocher N° 11), de même que la douceur à leur égard (Édit mineur sur rocher N° 9). L’accent mis sur la non-violence s’accompagne de l’incitation à une attitude positive d’attention, de douceur et de compassion.

Ashoka adopte et préconise une politique fondée sur le respect et la tolérance des autres religions. L’un de ses édits préconise :

« Tous les hommes sont mes enfants. A mes enfants, je souhaite prospérité et bonheur dans ce monde et dans l’autre ; mes vœux sont les mêmes pour tous les hommes. »

Loin d’être sectaire, Ashoka, s’appuyant sur la conviction que toutes les religions partagent une essence commune et positive, encourage la tolérance et la compréhension des autres religions :

« Le bien-aimé des dieux, le roi Piyadassi (c’est-à-dire Ashoka), souhaite que toutes les sectes puissent habiter en tous lieux, car toutes recherchent la maîtrise de soi et la pureté de l’esprit. » (Édit majeur sur rocher N° 7)

Et il précise :

« Car quiconque loue sa propre secte ou blâme les autres sectes, –par pure dévotion à sa propre secte, dans le simple but de la glorifier, – en agissant ainsi, il porte au contraire gravement préjudice à sa propre secte. Mais la concorde est méritoire, (c’est-à-dire) que tous doivent écouter et obéir à la morale de l’autre. » (Édit majeur sur rocher N° 12)

Ashoka avait l’idée d’un empire politique et d’un empire moral, le second englobant le premier. Sa conception de sa circonscription s’étendait au-delà de ses sujets politiques pour inclure tous les êtres vivants, humains et animaux, vivant à l’intérieur comme à l’extérieur de son domaine politique. Ses inscriptions expriment sa conception paternelle de la royauté et décrivent ses mesures d’aide sociale, notamment la fourniture de traitements médicaux, la plantation d’herbes, d’arbres et de racines pour les hommes et les animaux, et le creusement de puits le long des routes (Edit majeur sur rocher N°2). Les efforts du roi pour propager son dharma ne se limitaient pas à son propre domaine politique, mais s’étendaient aux royaumes des autres souverains.

L’empereur est devenu un sage. Il dirige un gouvernement centralisé depuis Pataliputra, capitale de l’Empire Maurya. Son administration perçoit des impôts et il demande à ses inspecteurs de lui rendre des comptes. L’agriculture se développe grâce à des canaux d’irrigation. Il fait construire des routes de qualité pour relier les points stratégiques et les centres politiques, exigeant, des siècles avant notre grand Sully en France, qu’elles soient bordées d’arbres d’ombrage, de puits et d’auberges.

Si l’existence même d’Ashoka en tant que personnage historique a été quasiment oubliée, depuis le déchiffrement de sources écrites en brahmi au XIXe siècle, il est désormais considéré comme l’un des plus grands empereurs indiens. La roue bouddhiste d’Ashoka figure d’ailleurs sur le drapeau indien.

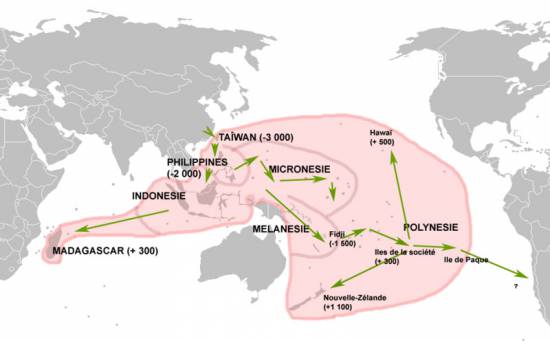

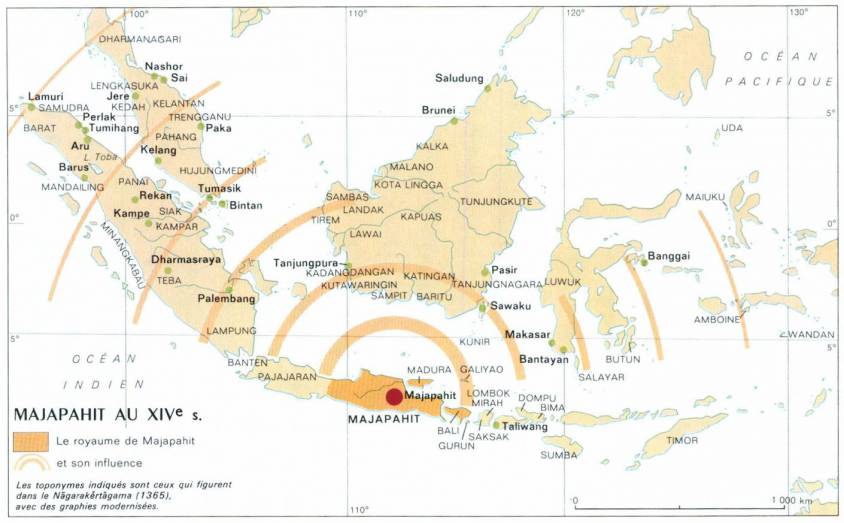

Comme nous l’avons déjà dit, Ashoka et ses descendants ont utilisé leur pouvoir pour construire des monastères et répandre l’influence bouddhiste en Afghanistan, dans de vastes régions de l’Asie centrale, au Sri Lanka et, au-delà, en Thaïlande, Birmanie, Indonésie, puis en Chine, en Corée et au Japon.

Des statues en bronze de son époque ont été déterrées dans les jungles d’Annam, de Bornéo et des Célèbes. La culture bouddhiste s’est implantée dans l’ensemble de l’Asie du Sud-Est, même si chaque région a su conserver une partie de sa personnalité et de son caractère propres.

L’Empire Kouchan

(du Ier siècle av. JC au IIIe siècle)

L’Empire Maurya, qui régnait sur la Bactriane et d’autres anciennes satrapies grecques, s’effondra en 185 avant J.-C., à peine cinq décennies après la mort d’Ashoka, accusé d’avoir trop dépensé pour les temples et les missions bouddhistes. Les mafias brahmaniques, qui avaient abhorré son règne, revinrent immédiatement au pouvoir.

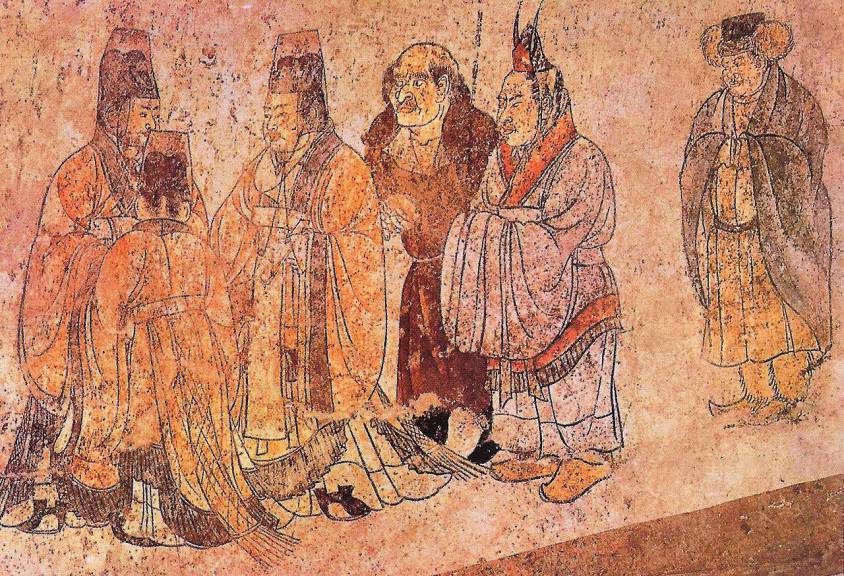

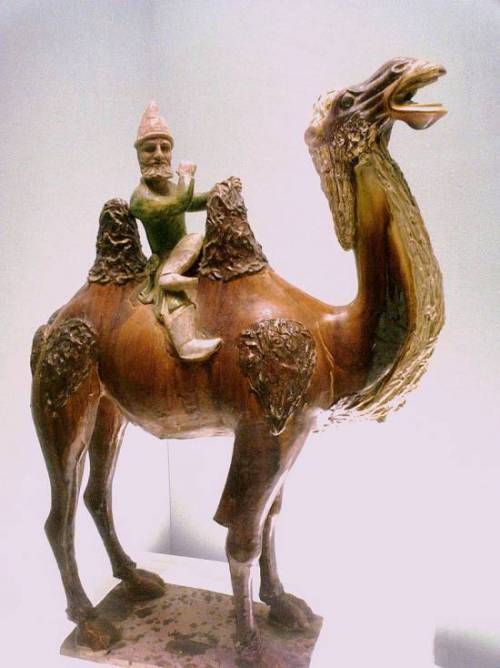

Mais la période est turbulente. Au premier siècle avant J.C., les Kouchans, l’une des cinq branches de la confédération nomade chinoise Yuezhi, émigrent du nord-ouest de la Chine (Xinjiang et Gansu) et s’emparent, après les nomades iraniens Saka, de l’ancienne Bactriane.

Ils forment l’Empire kouchan dans les territoires de la Bactriane. Cet empire s’étend assez vite à une grande partie de ce qui est aujourd’hui l’Ouzbékistan, l’Afghanistan, le Pakistan et le nord de l’Inde, au moins jusqu’à Saketa et Sarnath, près de la ville de Varanasi (Bénarès).

Le fondateur de la dynastie kouchane, Kujula Kadphisès, qui suit les idées culturelles et l’iconographie grecques après la tradition gréco-bactrienne, est un adepte de la secte shivaïte de l’hindouisme. Deux rois kouchans ultérieurs, Vima Kadphisès et Vasudeva II, furent également des mécènes de l’hindouisme et du bouddhisme. La patrie de leur empire se trouvait en Bactriane, où le grec était initialement la langue administrative, avant d’être remplacé par le bactrien écrit en caractères grecs jusqu’au VIIIe siècle, lorsque l’islam le remplace par l’arabe.

Les Kouchans devinrent également de grands mécènes du bouddhisme, en particulier l’empereur Kanishka le Grand (78-144 après J.-C.), qui joua un rôle important dans sa diffusion, via les Routes de la soie, vers l’Asie centrale et la Chine, inaugurant une période de paix relative de 200 ans, parfois décrite comme la « Pax Kouchana ».

Il semble également que dès ses débuts, le bouddhisme ait prospéré dans la classe des marchands, à qui la naissance interdisait l’accès aux ordres religieux de l’Inde et de l’Himalaya. La pensée et l’art bouddhistes se développèrent grâce aux routes commerciales entre l’Inde, l’Himalaya, l’Asie centrale, la Chine, la Perse, l’Asie du Sud-Est et l’Occident. Les voyageurs recherchaient la protection des images bouddhistes et faisaient des offrandes aux sanctuaires le long de la route, ramassant des objets et des sanctuaires portables pour leur usage personnel.

Le terme quatrième concile bouddhiste désigne deux évènements différents selon les écoles theravâda et mahâyâna.

1) La tradition theravâda : afin d’éviter que ne se perde l’enseignement du Bouddha, qui se serait jusqu’alors transmis oralement, cinq cents moines menés par le Vénérable Maharakkhita se réunirent à Tambapanni (Sri Lanka), sous le patronage du roi Vattagamani (r. 103 – 77 av. J.-C.) afin de coucher par écrit sur des feuilles de palme le Canon pâli. (*4)

Le travail, qui aurait duré trois ans, se serait déroulé dans la grotte Aloka lena, près de l’actuel Matale.

2) Selon la tradition mahâyâna, c’est 400 ans après l’extinction du Bouddha que cinq cents moines sarvastivadin se réunirent en 72 après J.-C. au Cachemire pour compiler et clarifier leurs doctrines sous la direction de Vasumitra et sous le patronage personnel de l’empereur Kanishka. Ils auraient ainsi produit le Mahavibhasa (Grande exégèse) en sanskrit.

Selon plusieurs sources, le moine bouddhiste indien Asvaghosa, considéré comme le premier dramaturge classique sanskrit et dont nous avons évoqué plus haut les attaques contre le système des castes, était le conseiller spirituel du roi Kanishka dans les dernières années de sa vie.

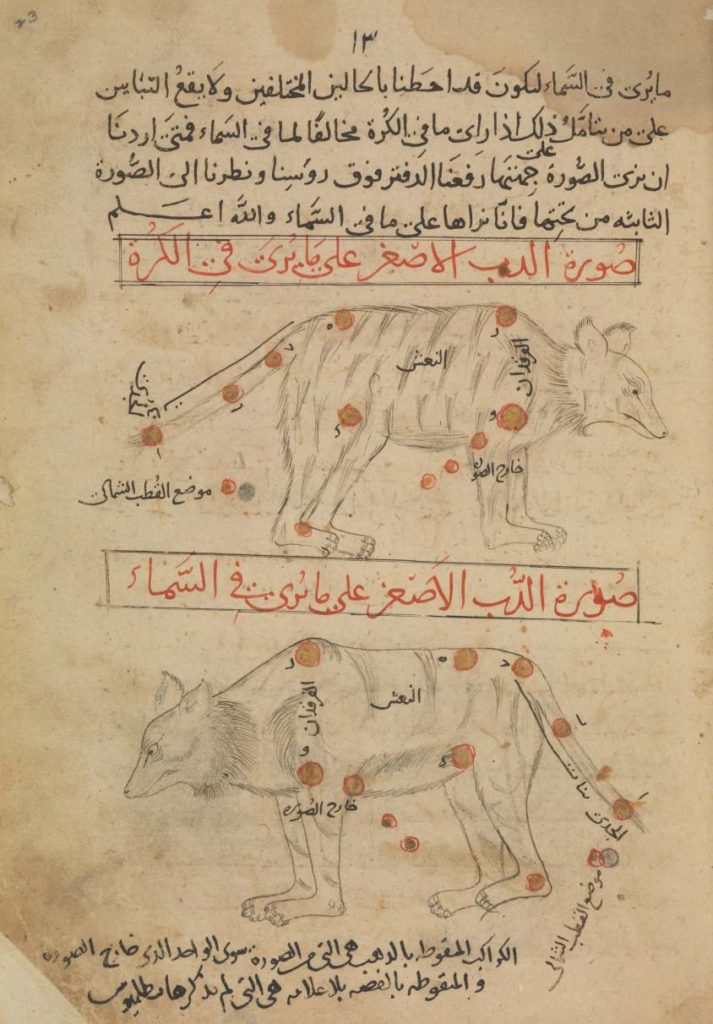

A noter que les plus anciens manuscrits bouddhiques découverts à ce jour, tels que les vingt-sept rouleaux d’écorce de bouleau acquis par la British Library en 1994 et datant du Ier siècle, ont été trouvés, non pas en Inde, mais enterrés dans les anciens monastères du Gandhara, la région centrale de l’empire maurya et kouchan, qui comprend les vallées de Peshawar et de Swat (Pakistan) et s’étend vers l’ouest jusqu’à la vallée de Kaboul en Afghanistan et vers le nord jusqu’à la chaîne du Karakoram

Ainsi, après le grand élan donné par le roi Ashoka le Grand, la culture du Gandhara connaîtra un second souffle sous le règne du roi kouchan Kanishka Ier.

Les villes de Begram, Taxila, Purushapura (aujourd’hui Peshawar) et Surkh Kotal atteignent alors des sommets de développement et de prospérité.

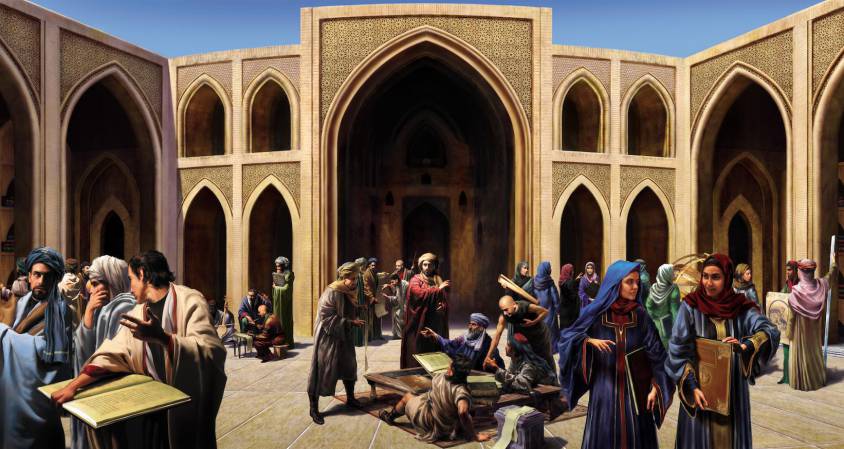

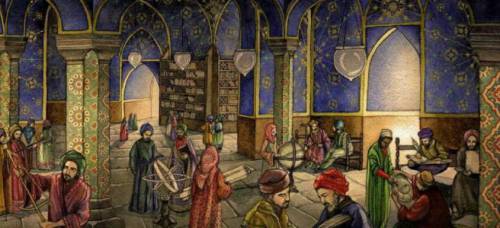

Le miracle de Gandhara

C’est peu dire que le Gandhara, surtout à l’époque kouchane, fut au cœur d’une véritable renaissance de la civilisation, avec une incroyable concentration de productions artistiques et une inventivité sans pareil. Si l’art bouddhiste était principalement centré sur les temples et les monastères, les objets de dévotion personnelle étaient très courants.

Grâce à l’art du Gandhara, le bouddhisme se mua en une grande force de beauté, d’harmonie et de paix, conquérant le monde.

Il favorisa alors une création artistique qui élève la pensée et la moralité en faisant appel à des paradoxes métaphoriques.

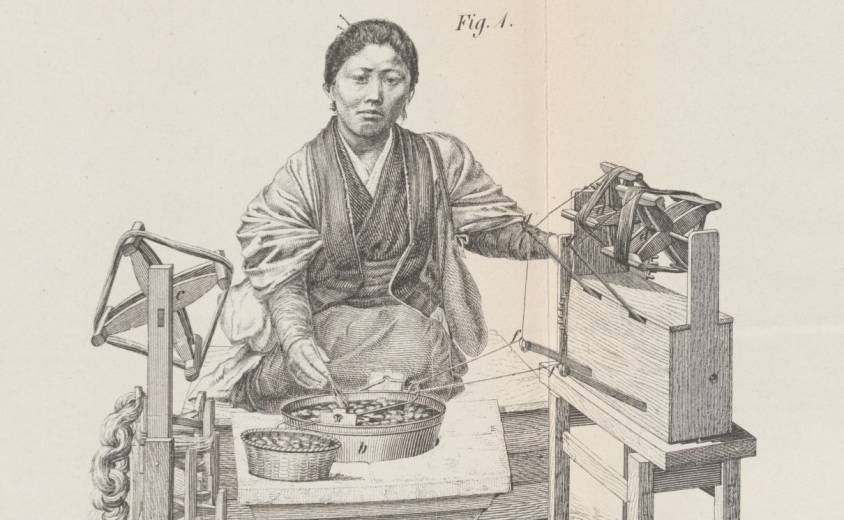

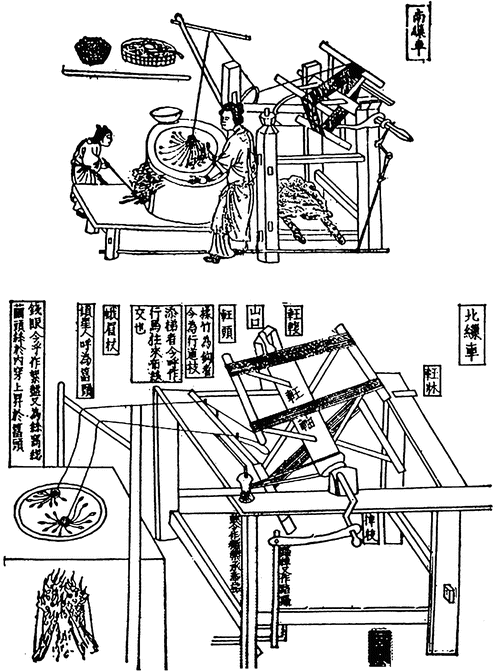

Les médiums et supports qui prévalent sont la peinture sur soie, les fresques, les livres illustrés et gravures, la broderie et autres arts du tissu, la sculpture (bois, métal, ivoire, pierre, jade) et l’architecture. Quelques exemples :

A. La poésie

Pour la plupart des Occidentaux, le bouddhisme est une émanation typique de la culture asiatique, généralement associée à l’Inde, au Tibet, au Népal, mais aussi à la Chine et à l’Indonésie.

Peu de gens savent que les plus anciens manuscrits bouddhistes connus à ce jour (Ier siècle de notre ère) ont été découverts, non pas en Asie, mais en Asie centrale, dans d’anciens monastères bouddhistes du Gandhara.

A l’origine, avant leur transcription en sanskrit (pendant longtemps la langue des élites), ils étaient écrits en gândhârî, une langue indo-aryenne du groupe prâkrit, transcrit avec l’alphabet kharosthi (une ancienne écriture indo-iranienne). Le gândhârî était la lingua franca de la pensée bouddhiste à ses débuts. Preuve en est, les manuscrits bouddhistes écrits en gândhârî qui ont voyagé jusqu’en Chine orientale pour se retrouver dans les inscriptions de Luoyang et d’Anyang.

Afin de préserver leurs écrits, les bouddhistes étaient à l’avant-garde de l’adoption des technologies chinoises liées à la fabrication de livres, notamment le papier et la xylographie. Cette technique d’impression consiste à reproduire le texte à imprimer sur une feuille de papier transparente qui est retournée et gravée sur une planche de bois tendre. L’encrage des parties saillantes permet ensuite des tirages multiples. C’est ce qui explique que le premier livre entièrement imprimé est le Sutra du diamant bouddhique (vers 868) réalisé par ce procédé

Le Khaggavisana Sutta, littéralement « la corne du rhinocéros », est une expression authentique de la poésie religieuse bouddhiste originale. Connu sous le nom de Sutra du rhinocéros, cette œuvre poétique fait partie du recueil pâli de textes courts Kuddhhaka Nikava, la cinquième partie du Sutta Pitaka, écrit au Ier siècle de notre ère.

Parce que la tradition accorde au rhinocéros asiatique une vie solitaire dans la forêt, l’animal n’aime pas les troupeaux, ce sutra (enseignement) porte le titre approprié d’essai « sur la valeur de la vie solitaire et errante ». L’allégorie du rhinocéros permet de communiquer aux dévots un sens aigu de la souveraineté individuelle que requièrent les engagements moraux prescrits par le Bouddha pour mettre fin à la souffrance en se déconnectant des plaisirs et des douleurs terrestres.

Extrait :

Refuser la violence à l’égard de tous les êtres,

ne jamais faire de mal à un seul d’entre eux,

aider avec compassion et un cœur aimant ;

erre seul comme un rhinocéros.

Celui qui tient compagnie nourrit l’affection

et de l’affection naît la souffrance.

Réalisant le danger qui découle de l’affection,

erre seul comme un rhinocéros.

En sympathisant avec les amis et les compagnons,

l’esprit se fixe sur eux et perd son chemin.

Percevoir ce danger, c’est la familiarité,

erre seul comme un rhinocéros.

Les préoccupations que l’on a pour ses fils et ses femmes

sont comme une pensée et un bambou enchevêtré.

Reste démêlé comme un jeune bambou,

erre seul comme un rhinocéros.

Comme un cerf qui erre librement dans la forêt,

va où il veut en broutant,

un homme sage, qui chérit sa liberté,

erre seul comme le rhinocéros.

Laissez derrière vous vos fils, vos femmes et votre argent,

tous vos biens, vos parents et vos amis.

Abandonnez tous vos désirs, quels qu’ils soient,

erre seul comme le rhinocéros. (…)

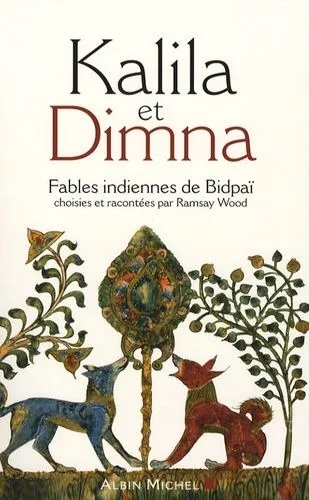

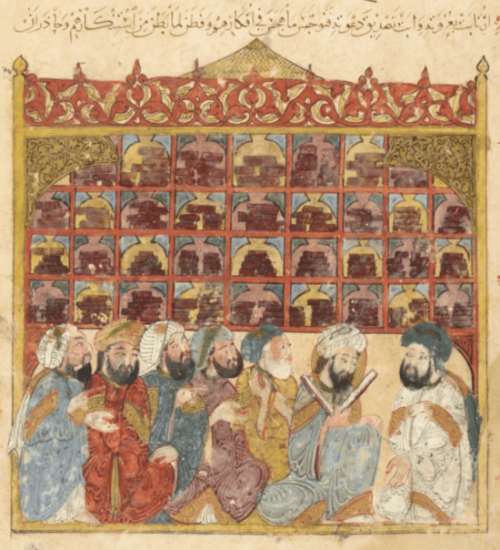

B. La littérature

Deux autres chefs-d’œuvre tirés du même recueil sont d’une part les célèbres Jataka (Récits des vies antérieures du Bouddha), et d’autre part, le Milindapanha (Les questions du roi Milinda).

Les Jataka, qui mettent en scène de nombreux animaux, montrent comment, avant la dernière incarnation humaine au cours de laquelle il atteignit le nirvana, le Bouddha lui-même s’était réincarné d’innombrables fois en animal (en diverses sortes de poissons, en crabe, coq, pivert, perdrix, francolin, caille, oie, pigeon, corbeau, zèbre, buffle, plusieurs fois en singe ou en éléphant, en antilope, cerf et cheval).

Et puisque c’est Bouddha qui est incarné dans cet animal, celui-ci a soudainement des propos d’une grande sagesse.

Mais en d’autres occasions, ce sont des personnages qui sont des animaux alors que notre Bodhisattva apparaît sous forme humaine. Ces contes sont souvent pimentés d’un humour piquant. On sait d’ailleurs qu’elles ont inspiré La Fontaine, qui a dû les entendre du docteur François Bernier, qui les avait lui-même apprises alors qu’il était médecin en Inde pendant huit ans.

Les questions du roi Milinda est un compte-rendu imagé, véritable dialogue platonicien entre le roi grec de Bactriane, Milinda (le Grec, Ménandre), qui régnait au Pendjab, et le sage bouddhiste Bhante Nagasena. Leur dialogue animé, dramatique et spirituel, éloquent et inspiré, explore les divers problèmes de la pensée et de la pratique bouddhistes du point de vue d’un intellectuel grec perspicace, à la fois perplexe et fasciné par la religion étrangement rationnelle qu’il découvre sur le sous-continent indien.

Par le biais de paradoxes, Nagasena amène le « rationaliste » grec à s’élever jusqu’à la dimension spirituelle, au-delà de la logique et de la simple rationalité. Car le nirvana, tout comme l’espace, n’a « pas de cause » formelle et, bien qu’il peut se produire, « ne peut pas être causé ». Mince, comment faire alors pour y aboutir ?

Et à l’un de ses disciples qui un jour lui posa la question de savoir si l’univers était fini ou infini, éternel ou non, si l’âme était distincte du corps, ce que devenait l’homme après la mort, le Bouddha répondit par une parabole :

« Supposons qu’un homme soit gravement atteint d’une flèche, que l’on l’amène chez un médecin, et que l’homme dise : “Je ne laisserai pas retirer cette flèche, avant de savoir qui m’a blessé, de quel caste il est, de quel village il est né, de quel arc il s’est servi, de quelle matière a été faite la flèche, de quelle direction elle a été tirée…” Alors cet homme mourrait certainement avant d’avoir les réponses. »

C. Urbanisme

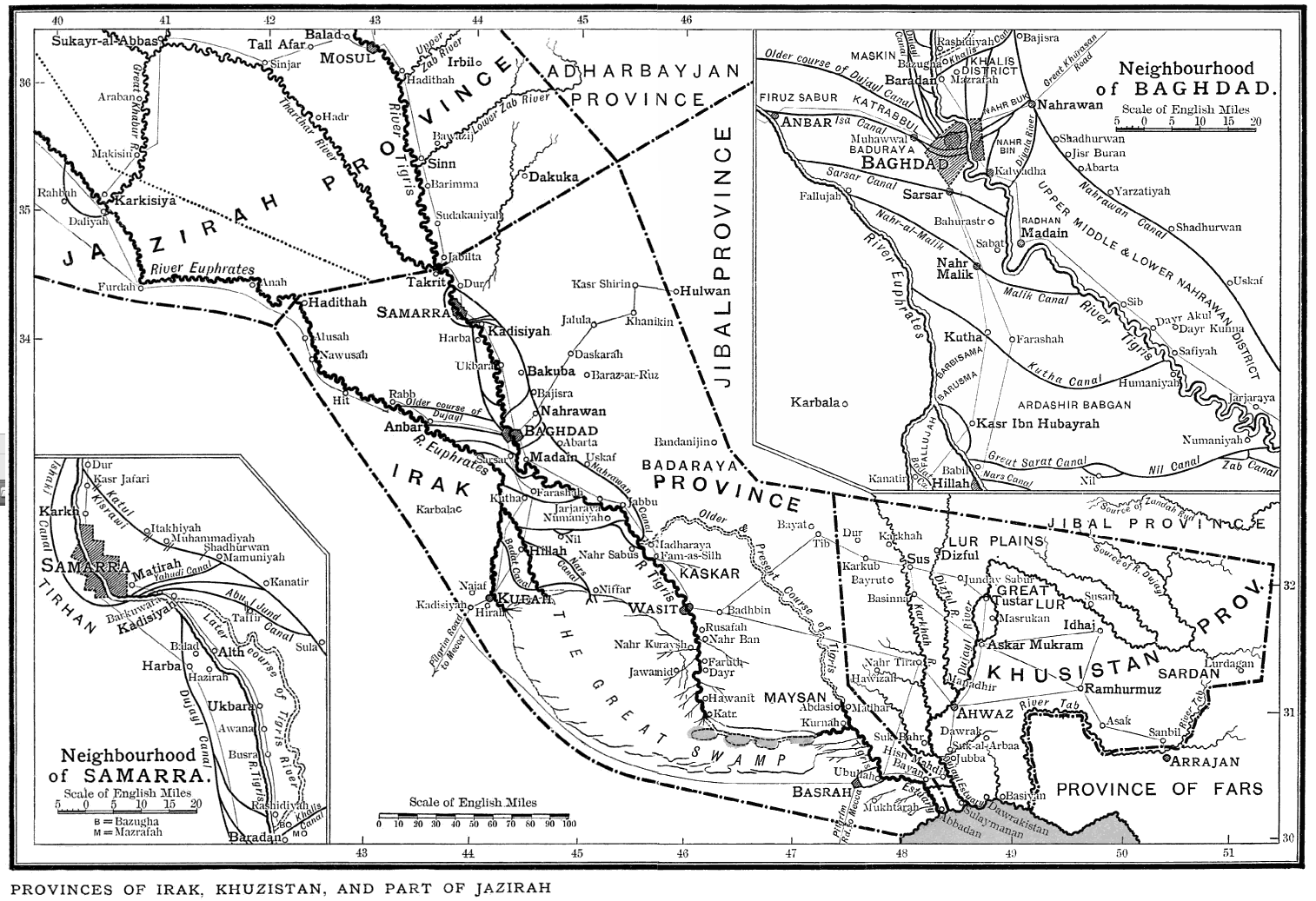

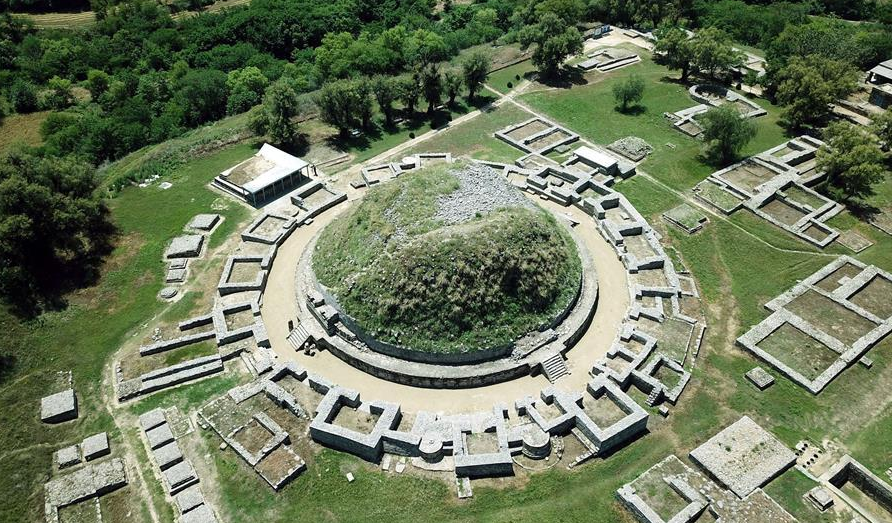

Taxila ou Takshashila (aujourd’hui au Pendjab), l’un des grands centres urbains et, pendant un certain temps, la capitale du Gandhara, fut fondée vers 1000 avant J.-C. sur les ruines d’une cité datant de la période Harappa et située sur la rive orientale de l’Indus, point de jonction entre le sous-continent indien et l’Asie centrale.

Certaines ruines de Taxila datent de l’époque de l’empire perse achéménide, suivi successivement par l’Empire Maurya, le royaume indo-grec, les Indo-Scythes et l’empire kouchan.

D’après certains témoignages, l’université de l’ancienne Taxila (des siècles avant l’université bouddhiste résidentielle de Nalanda fondée en 427 après J.-C.) peut être considérée comme l’un des premiers centres d’enseignement d’Asie du Sud. Dès 800 av. J.-C., la ville fonctionnait en grande partie comme une université, offrant des études supérieures. Avant d’y être admis, les étudiants devaient avoir terminé ailleurs leurs études primaires et secondaires. L’âge minimum requis était de seize ans. Non seulement les Indiens, mais aussi les étudiants de contrées voisines comme la Chine, la Grèce et l’Arabie affluaient dans cette ville d’apprentissage.

Vers 321 avant J.-C., c’est le grand philosophe, enseignant et économiste du Gandhara, Chanakya (375 à 283 av. J.-C.) qui aida le premier empereur maurya, Chandragupta, à accéder au pouvoir.

Sous la tutelle de Chanakya, Chandragupta avait reçu une éducation complète à Taxila, englobant les différents arts de l’époque, y compris l’art de la guerre, pendant sept à huit ans.

En 303 avant J.-C., Taxila tomba entre leurs mains et sous Ashoka le Grand, le petit-fils de Chandragupta, la ville devint un grand centre de l’enseignement et de l’art bouddhiste.

Chanakya, dont les écrits n’ont été redécouverts qu’au début du XXe siècle et qui fut le principal conseiller des deux empereurs Chandragupta et de son fils Bindusara, est considéré comme ayant joué un rôle majeur dans l’établissement de l’Empire Maurya.

Également connu sous les noms de Kauṭilya et Vishnugupta, Chanakya est l’auteur de l’Arthashastra, un traité politique sanskrit sur l’art de gouverner, la science politique, la politique économique et la stratégie militaire. L’Arthashastra aborde également la question d’une éthique collective assurant la cohésion de la société.

Il conseille au roi de lancer de grands projets de travaux publics dans les régions dévastées par la famine, les épidémies et autres catastrophes naturelles, ou par la guerre, tels que la création de voies d’irrigation et la construction de forts autour des principaux centres de production et villes stratégiques, et d’exonérer d’impôts les personnes touchées par ces catastrophes.

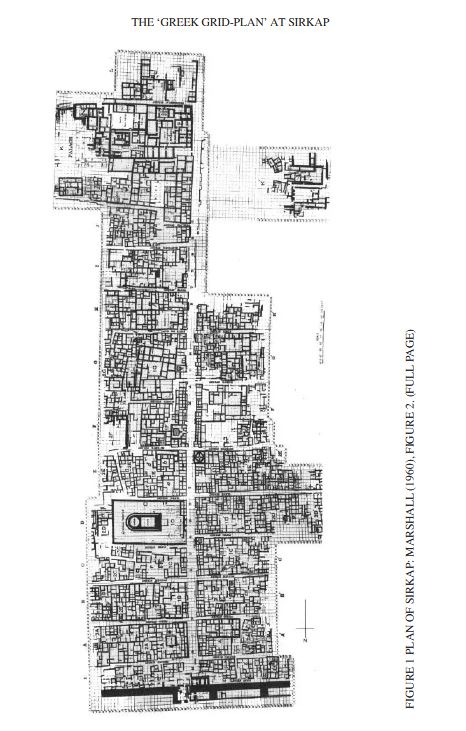

Au IIe siècle avant notre ère, Taxila fut annexée par le royaume indo-grec de Bactriane qui y érigea une nouvelle capitale nommée Sirkap, où des temples bouddhistes côtoyaient des temples hindous et grecs, signe de tolérance religieuse et de syncrétisme. Sirkap fut construite selon le plan quadrillé hippodamien (*5) caractéristique des villes grecques

Elle s’organise autour d’une avenue principale et de quinze rues perpendiculaires, couvrant une surface d’environ 1200 mètres sur 400, avec un mur d’enceinte de 5 à 7 mètres de large et de 4,8 kilomètres de long.

Après sa construction par les Grecs, la ville fut reconstruite lors des incursions des Indo-Scythes, puis par les Indo-Parthiens, après un tremblement de terre en l’an 30 de notre ère.

Certaines parties de la ville, notamment le stupa (reliquaire) bouddhiste de l’aigle bicéphale et le temple du dieu Soleil, furent construites par Gondophares, le premier roi du royaume indo-parthien. Enfin, des inscriptions datant de l’an 76 de notre ère démontrent que la ville était déjà passée sous la domination des Kouchans. Le souverain kouchan Kanishka érigera Sirsukh, à environ 1,5 km au nord-est de l’ancienne Taxila.

Des sutras bouddhistes de la région du Gandhara sont étudiés en Chine dès 147 de notre ère, lorsque le moine kouchan Lokakṣema (né en 147) commença à traduire en chinois certains des premiers sutras bouddhistes. Les plus anciennes de ces traductions montrent qu’elles ont été faites à partir de la langue

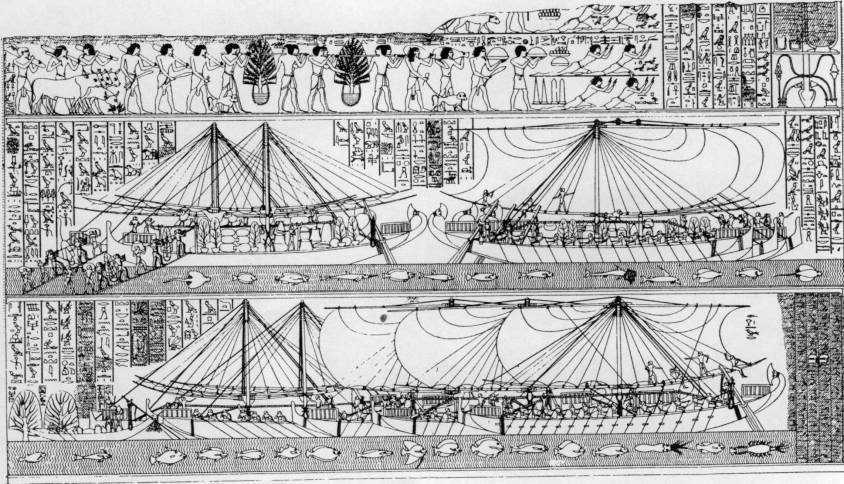

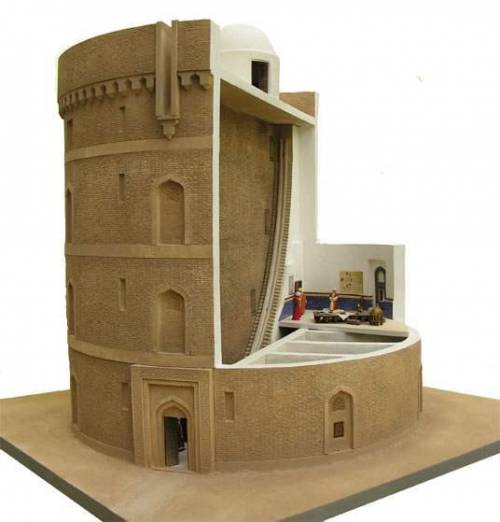

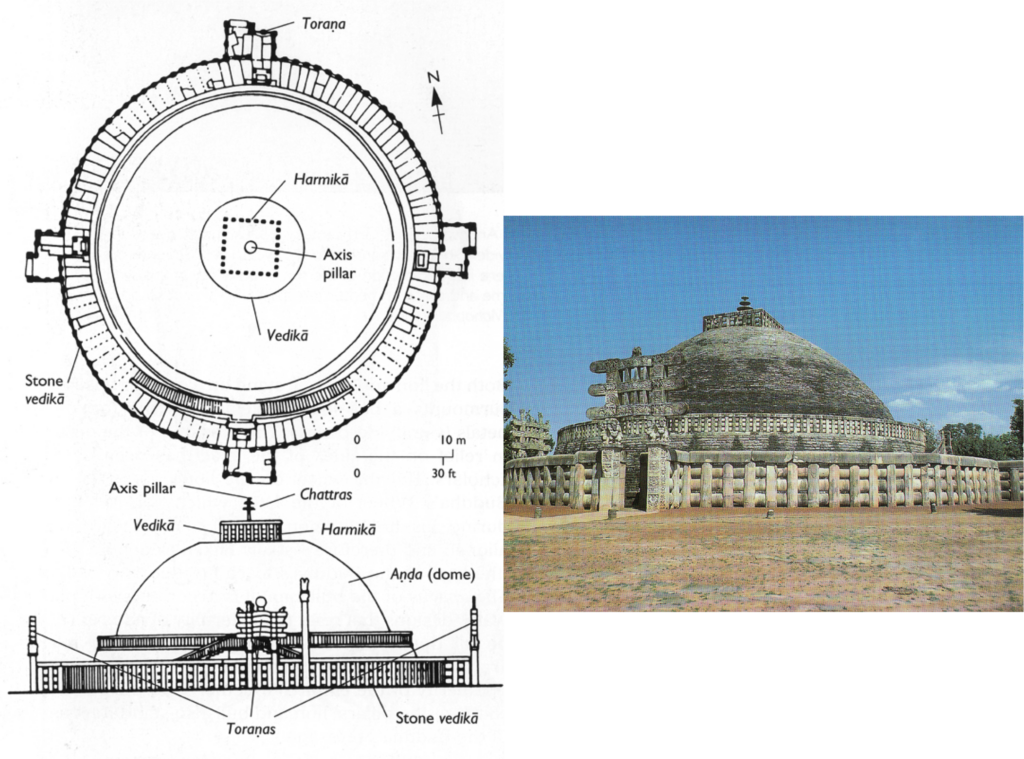

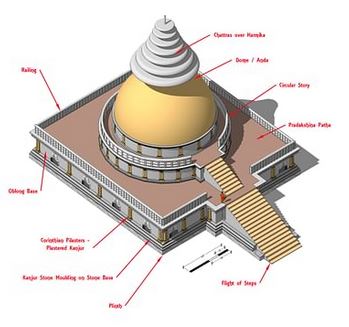

D. Architecture, l’invention des stupas

A l’origine, les édifices religieux sous forme de stupa (reliquaire) ont été érigés en Inde comme monuments commémoratifs associés à la conservation des reliques sacrées du Bouddha.

Construits en forme de dôme, ils sont entourés d’une balustrade qui sert de rampe pour la circumambulation rituelle. On accède à la zone sacrée par des portes situées aux quatre points cardinaux. Les stupas se situent souvent à proximité de sites funéraires préhistoriques beaucoup plus anciens, associés notamment à la Civilisation de la vallée de l’Indus.

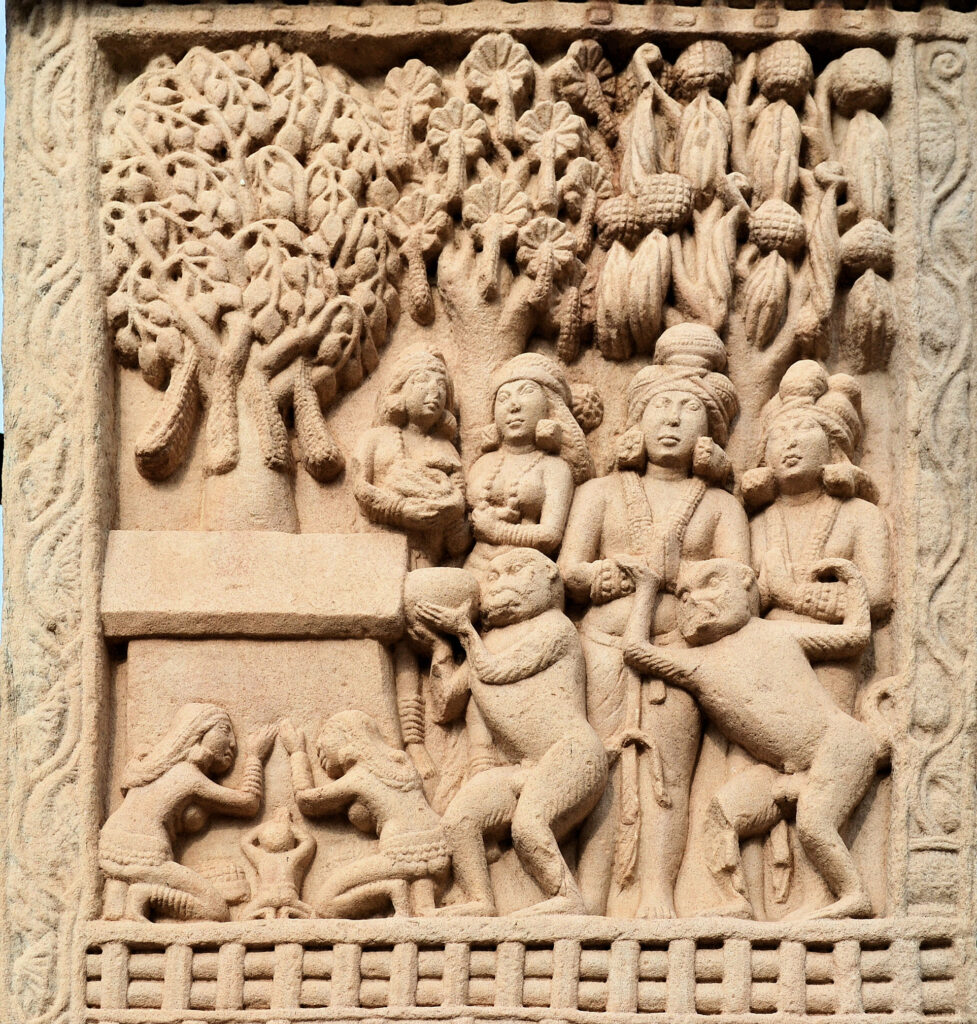

Des grilles et des portails en pierre, recouverts de sculptures, leur ont été ajoutés. Les thèmes favoris sont les événements de la vie historique du Bouddha, ainsi que de ses vies antérieures, au nombre de 550, décrites avec beaucoup d’ironie dans les Jatakas. (Voir B)

Les bas-reliefs des stupas sont comme des bandes dessinées qui nous racontent la vie quotidienne et religieuse du Gandhara : amphores, coupes à vin (kantaros), bacchanales, instruments de musique, vêtements grecs ou indiens, ornements, coiffures arrangées à la grecque, artisans, leurs outils, etc.

Sur un vase trouvé à l’intérieur d’un stupa, on trouve l’inscription d’un Grec, Théodore, gouverneur civil d’une province au Ier siècle avant J.-C., expliquant en alphabet kharosthi comment les reliques ont été déposées dans le stupa.

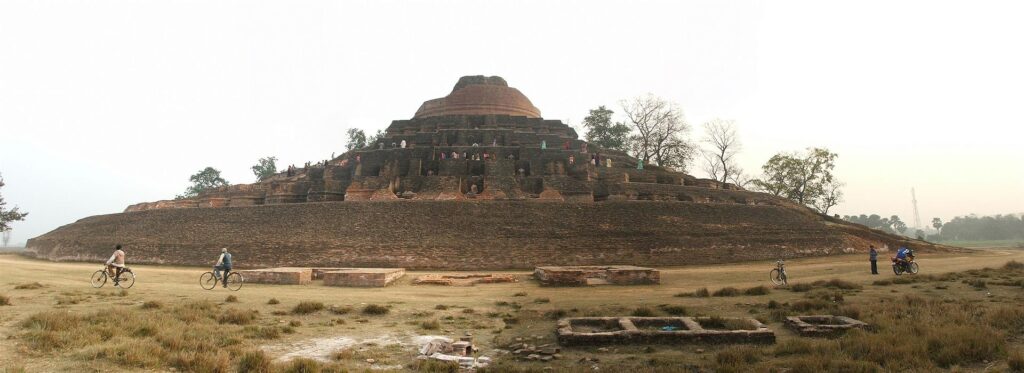

On pense que de nombreux stupas datent de l’époque d’Ashoka, comme celui de Sanchi (Inde centrale) ou de Kesariya (Inde de l’Est), où il a également érigé des piliers avec ses édits, et peut-être ceux de Bharhut (Inde centrale), Amaravati (sud-est de l’Inde) ou Dharmarajika (Taxila) dans le Gandhara (Pakistan).

Selon la tradition bouddhiste, l’empereur Ashoka aurait récupéré les reliques du Bouddha dans des stupas plus anciens et en aurait fait ériger 84 000 pour répartir l’ensemble de ces reliques sur tout le territoire indien.

Marchant dans les pas d’Ashoka, Kanishka ordonna la construction à Purushapura (Peshawar) du grand stupa de 400 pieds qui figure parmi les plus hauts édifices du monde antique.

Les archéologues qui en ont redécouvert la base en 1908-1909 ont estimé que ce stupa avait un diamètre de 87 mètres. Selon les rapports de pèlerins chinois tels que Xuanzang, il faisait environ 200 mètres de haut et était recouvert de pierres précieuses. Sous les Kouchans également, d’immenses statues du Bouddha furent érigées dans les monastères ou sculptées à flanc de colline.

E. Sculpture

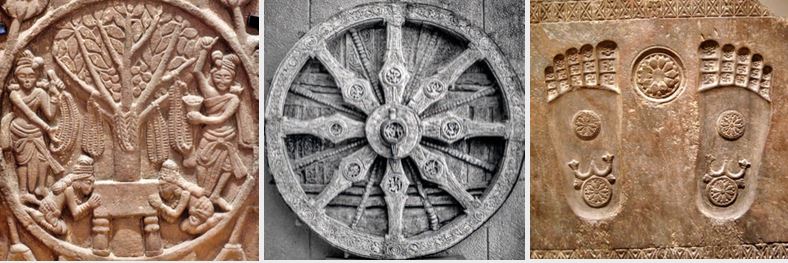

—PERIODE ANICONIQUE

Il est important de rappeler que dans les premiers temps, Bouddha n’était jamais représenté sous forme humaine.

Pendant plus de quatre siècles, sa présence est simplement suggérée par des éléments symboliques tel qu’une empreinte de pieds, une fleur de lotus (indiquant la pureté de sa naissance), une roue à huit rayons (symbolisant la dharma), un trône vide, un espace inoccupé sous un parasol, un cheval sans cavalier ou encore le figuier sous lequel il a atteint le nirvana.

–FIN DE L’ANICONISME

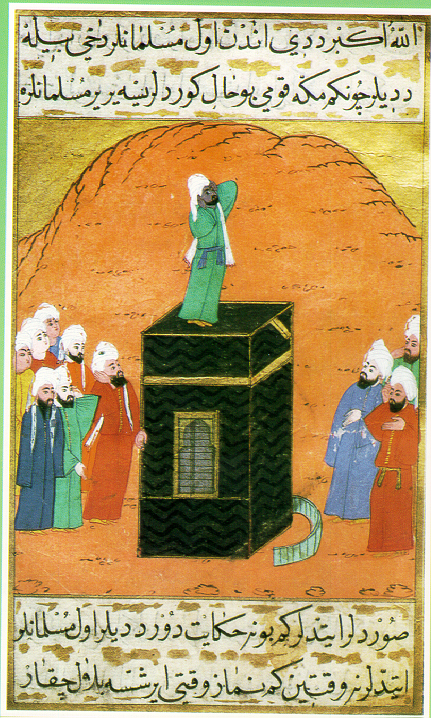

Ce qui a conduit les bouddhistes à renoncer aux représentations aniconiques reste un vaste mystère. Un tel développement est assez unique dans l’histoire des religions. Imaginons soudainement les musulmans promouvant des statues du prophète Mohammed !

Les explications avancées jusqu’ici nous laissent sur la faim.

Pour les uns, les bouddhistes auraient voulu séduire une clientèle grecque, mais aussi bien les populations grecques que le bouddhisme était au Gandhara bien avant la révolution iconographique en question.

Pour les autres, les pratiquants, en l’absence de Bouddha lui-même, auraient cherché désespérément un centre d’intérêt visuel, soit une statue, une peinture ou mêmes quelques cheveux… Ces représentations symboliques, on l’a vu, répondaient à cette demande.

« Le Jataka de Kalingabodhi (écrit majeur sur les vies multiples de Bouddha) relate la frustration des habitants de Sravasti, en découvrant un jour qu’ils n’ont personne à vénérer lorsqu’ils se rendent au Jetavana et trouvent le Bouddha ‘absent’, parti en voyage. Pour remédier à cette situation, à son retour, le Bouddha permet à [son disciple] Ananda de planter un figuier Bodhi devant le [monastère de] Jetavana (…) qui sert de centre de substitution pour les dévotions des gens, chaque fois que le Bouddha n’est pas en résidence », écrit John Strong, dans Reliques du Bouddha.

Bouddha, rapporte-t-on, aurait refusé qu’il soit représenté d’aucune façon, craignant de voir prospérer l’idolâtrie.

Avec le temps, le bouddhisme va évoluer. Au Gandhara, c’est le bouddhisme mahâyâna (Grand Véhicule) qui s’épanouit. Pour ce courant, l’objectif ne se limite plus à atteindre le nirvana à titre personnel mais de libérer toute l’humanité de la souffrance.

Si pour le bouddhisme theravâda, Siddhartha Gautama n’était qu’un homme éclairé donnant l’exemple, pour le bouddhisme mahâyâna, il s’agit indubitablement, avec Bouddha, d’une tentative (réussie) de personnifier le dharma (la force spirituelle omniprésente, le principe ultime et suprême de la vie) dans la conception du premier de tous les bouddhas. Une sorte de Jésus, un dieu devenu homme pour ainsi dire…

Comme plus tard Jésus dans le christianisme à partir du Ve siècle, Bouddha pouvait dès lors être représenté sous une forme humaine.

Certains bouddhas du Gandhara représentent également des états d’âme spécifiques, tels que la sagesse, la tendresse et la compassion.

Contrairement à de nombreux artistes chrétiens chez nous, qui, conformément à la doxa, ont représenté le Christ souffrant sur la Croix (événement fondamental de la foi chrétienne), les artistes du Gandhara présentent Bouddha comme un être totalement détaché de la douleur humaine, regardant avec compassion l’humanité tout entière.

Le but étant d’éliminer la souffrance chez tous les hommes, la compassion n’est pas une notion passive chez les bouddhistes. Ce n’est pas seulement de l’empathie, mais plutôt un altruisme empathique qui s’efforce activement de libérer les autres de la souffrance, un acte de bienveillance empreinte à la fois de sagesse et d’amour.

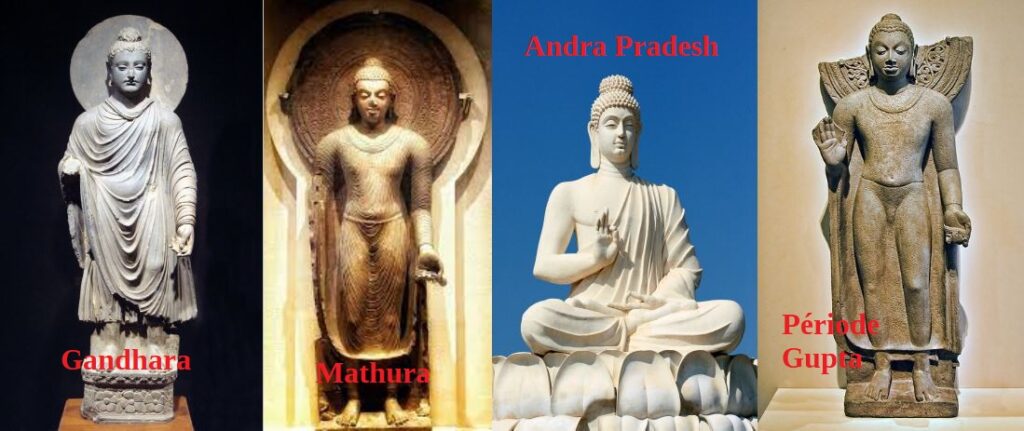

DIFFERENCES DE FORME, DIFFERENCE DE CONTENU

Avant de discuter de leurs différences, pour faire simple, distinguons ici, parmi tant d’autres, quatre types de représentations de bouddha:

- L’école dite « greco-bouddhique » de Gandhara produite dans la région qui va de Hadda (Afghanistan) à Taxila (Pundjab) en passant par Peshawar (Pakistan);

- L’école dite « indo-bouddhique » de Mathura;

- L’école d’Andra Pradesh, au sud de l’Inde;

- L’école de la période Gupta (3e au 5e siècle).

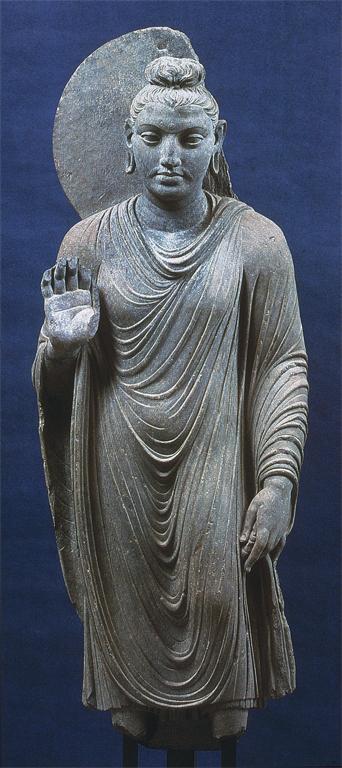

1. Greco-Bouddhique au Gandhara

Le terme « greco-bouddhique », renvoie à la thèse de l’archéologue Alfred Foucher (1865-1952) soutenue à la Sorbonne en 1905 sur l’art du Gandhara.

Comme l’écrivait André Malraux (1901-1976) dans les « Voix du silence », en 1951, l’art gréco-bouddhique est cette rencontre entre hellénisme et bouddhisme. Au lieu de dire que l’art venu de Grèce s’était métamorphosé en art bouddhique comme le disait Malraux, je pense plutot qu’au Gandhara, c’est l’art bouddhique qui s’est approprié le meilleur de l’esthétique indienne, grecque et des steppes.

Cependant, Foucher avait raison d’insister, contre ses amis anglais, qu’il s’agit bien d’une influence hellénique et non pas romaine. De leur coté, avec l’Inde s’émancipant de l’Empire britannique, les savants indiens ont tenté de valider la thèse d’une création autochtone de l’image de Buddha, opposant au style du Gandhara, que Foucher voulait gréco-bouddhique, le style de Mathura, dans la région de Delhi, lui aussi englobé dans l’empire des Kouchans, et vu par certains comme contemporain, même s’il est beaucoup moins prolixe que l’art du Gandhara.

L’art du Gandhara prit véritablement son essor à l’époque kouchane, et plus particulièrement sous le règne du roi Kanishka.

Des milliers d’images furent produites et répandues dans tous les coins de la région, depuis les bouddhas portatifs jusqu’aux statues monumentales des lieux de culte sacrés.

Au Gandhara, pour figurer Bouddha, on représente d’une façon très réaliste une belle personne, souvent un jeune homme, voire une femme. La charge spirituelle est telle que le genre n’est plus essentiel. On ne sait pas s’il s’agit de beaux portraits pris sur le vif, ou de purs fruits de l’imagination des artistes.

Bouddha y est souvent montré en posture méditative afin d’évoquer le moment où il atteint le nirvana.

Couronné d’une auréole, le visage grave ou souriant, les yeux mi-clos, il irradie la lumière. Plein de sérénité, il incarne le détachement, la concentration, la sagesse et la bienveillance.

Ses cheveux en chignon (l’ushnisha) au sommet du crâne indiquent qu’il est doué d’une connaissance supramondaine. Le point noire entre les deux yeux symbolise le troisième œil, celui de l’éveil.

Dans certaines sculptures, cette cavité contient une perle de cristal, symbole de lumière irradiante. Les lobes d’oreilles sont allongés et servent à accueillir les lourds bijoux que portait autrefois le jeune prince Siddhartha, durant sa jeunesse princière.

Le positionnement des mains, comme dans le reste de l’art indien, répond à des codes. Il peut s’agir de « l’abhayamudra », le geste qui rassure, la paume de la main tournée vers l’extérieur ; de la « varamudra », qui symbolise le don, la main pendante et ouverte avec le bras à demi plié, ou encore de la « vitarkamudra », qui symbolise l’argumentation, la main levée à hauteur de la poitrine, à demi fermée, paume en avant, l’index recourbé vers le pouce.

Au Gandhara, Bouddha est vêtu d’un manteau monastique qui lui couvre les deux épaules. L’étoffe n’est ni taillée, ni cousue, mais simplement drapée à la grecque autour du corps. Les plis à peine stylisés suivent les volumes naturels.

Le roi Kanitscha encouragea à la fois l’école d’art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhara (à Taxila, Peshawar et Hadda) et l’école indo-bouddhique (à Mathura, plus proche de l’Inde).

2. Ecole de Mathura

A Mathura, les artistes ont produit un Bouddha très différent. Son corps est dilaté par le souffle sacré (prana) et sa robe monastique est drapée à l’indienne de manière à laisser l’épaule droite dénudée.

On pense que les artistes, pour plaire à un public local, se sont inspirés des statues de yaksha, des esprits de la nature.

Dans les mythologies hindoue, jaïne et bouddhiste, le yakṣha a une double personnalité.

D’un côté, ce peut être une fée de nature inoffensive, associée aux forêts et aux montagnes ; mais il existe une version beaucoup plus sombre du yakṣa, qui est une sorte d’ogre, de fantôme ou de démon anthropophage qui harcèle et dévore les voyageurs.

3. Ecole d’Andrah Pradesh

Un troisième type de bouddha influent s’est développé dans l’Andhra Pradesh, au sud de l’Inde, où des représentations aux proportions imposantes, au visage grave, sans sourire, sont vêtues de robes qui laissent également apparaître l’épaule droite.

Ces sites méridionaux ont servi d’inspiration artistique à la terre bouddhiste du Sri Lanka, à la pointe sud de l’Inde, et les moines sri-lankais s’y rendaient régulièrement. Un certain nombre de statues de ce style se sont également répandues dans toute l’Asie du Sud-Est.

4. Ecole Gupta

La période Gupta, du IVe au VIe siècle de notre ère, dans le nord de l’Inde, souvent qualifiée d’âge d’or, est supposée avoir synthétisé les deux courants. En réalité, en cherchant une image idéale, elle a sombré dans le maniérisme. Les bouddhas gupta ont les cheveux disposés en petites boucles individuelles et leur tunique arbore un réseau de cordelettes suggérant les plis des draperies (comme à Mathura).

Avec leurs yeux baissés et leur aura spirituelle, les bouddhas gupta deviendront le modèle des futures générations d’artistes, que ce soit dans l’Inde post-Gupta et Pala ou au Népal, en Thaïlande et en Indonésie.

Des statues métalliques gupta du Bouddha, emportées par les pèlerins, ont également été disséminées le long de la Route de la soie jusqu’en Chine.

Mais les Bouddhas du Gandhara sont uniques et vraiment à part. Ce sont de véritables individualités échappant à toute codification et aux normes. Ils ont été fabriqués par des artistes habités d’une spiritualité élevée, explorant de nouvelles frontières de la beauté, du mouvement et de la liberté, et non produisant des objets pour satisfaire un marché émergent.

Aujourd’hui, Pakistanais, Indiens, Afghans et Européens aiment à se quereller. Tous prétendent avoir été les principaux parrains et auteurs du « miracle de Gandhara », mais peu se demandent comment il s’est produit.

Dès le Ier siècle avant J.-C., les artistes locaux délaissent les matériaux périssables avec lesquels ils travaillaient, comme la brique, le bois, le chaume et le bambou, pour adopter la pierre. Le nouveau matériau utilisé était principalement une pierre de schiste allant du gris clair au gris foncé (dans la vallée de la rivière Kaboul et la région de Peshawar). Les périodes ultérieures se caractérisent par l’utilisation du stuc et de l’argile (spécialité de Hadda).

Les techniques utilisées pour les sculptures et les pièces de monnaie du Gandhara sont très proches de celles de la Grèce. Ont-elles été créées par des sculpteurs grecs itinérants ou par des artistes locaux qu’ils ont formés ? Rien n’a été prouvé, mais est-ce vraiment important ?

Lorsque l’Asie rencontre la Grèce

Examinons maintenant des expressions artistiques attestant la belle rencontre entre la culture hellénique et les cultures indiennes et locales.

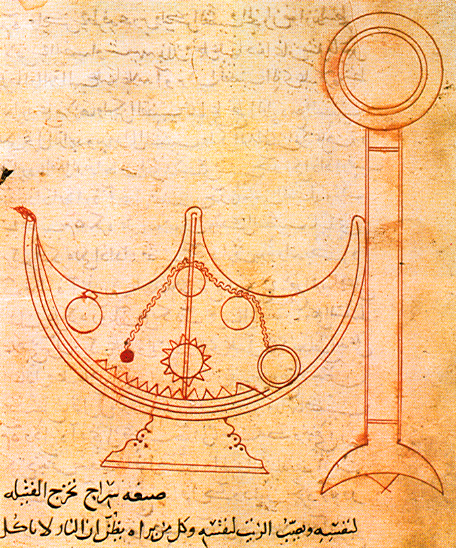

A. Pièces de monnaie kouchanes

Tout en soutenant toutes les religions qu’il jugeait dignes, Kanishka ne cachait pas sa préférence pour le bouddhisme.

Une pièce d’or datant de 120 après J.-C. montre le roi vêtu d’un lourd manteau kouchan et de longues bottes, des flammes sortant de ses épaules, un étendard dans la main gauche et faisant un sacrifice sur un autel, avec cette légende en caractères grecs : « Roi des rois, Kanishka le Kouchan. » Le revers de la même pièce représente un bouddha debout, en costume grec, faisant de la main droite le geste « ne craignez rien » (abhaya mudra) et tenant un pli de sa robe dans la main gauche. La légende en caractères grecs se lit désormais ΒΟΔΔΟ (Boddo), pour Bouddha.

B. Reliquaire bimaran

Un véritable thème classique du répertoire de tout artiste de l’époque consiste à montrer Bouddha entouré, accueilli et protégé des divinités d’autres croyances et de religions plus anciennes. La plus ancienne représentation de ce type connue à ce jour figure sur un reliquaire trouvé dans le stupa de Bimaran, au nord-ouest du Gandhara.

Sur cette petite urne en or, généralement datée de 50-60 après J.-C., figure, à l’intérieur de niches voûtées d’architecture gréco-romaine, une représentation hellénistique du Bouddha (coiffure, contrapposto, himation d’élite, etc.), entourée des divinités indiennes Brahma et Sakra.

Tout comme Ashoka, Kanishka, presque laïque, entendait régner, non pas contre mais avec, et surtout au-dessus de toutes les religions. Ainsi, à l’occasion, les divinités grecques, représentées sur les pièces de monnaie (Zeus, Apollon, Héraclès, Athéna, etc.), côtoient les divinités du védisme, du zoroastrisme et du bouddhisme.

Autre exemple, à Ellora, au centre de l’Inde, la grotte et le temple taillés dans le roc où se côtoient les représentants des trois religions (bouddhisme, hindouisme et jaïnisme).

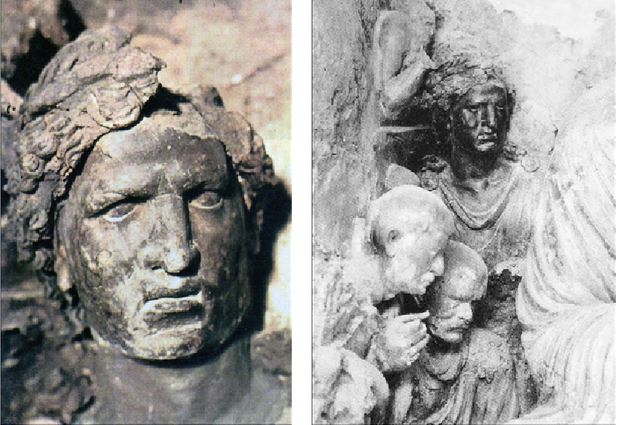

C. Triade de Hadda

Un autre exemple exquis de cet art gandharien est un groupe sculptural connu sous le nom de Triade de Hadda, excavé à Tapa Shotor, un grand monastère sarvastivadin près de Hadda en Afghanistan, datant du IIe siècle après J.-C.

Pour donner une idée de son activité, ce sont quelque 23 000 sculptures gréco-bouddhiques, en argile et en plâtre, qui ont été mises au jour rien qu’à Hadda, entre les années 1930 et 1970.

Le site, fortement endommagé lors des dernières guerres, possédait de belles statues, notamment un bouddha assis, vêtu d’une chlamyde grecque (manteau blanc), les cheveux bouclés, accompagné d’Héraclès et de Tyché (déesse grecque de la fortune et de la prospérité), vêtue d’un chiton (robe à la grecque) et tenant une corne d’abondance.

Seule adaptation aux traditions locales de l’iconographie grecque, Héraclès tient en main, non plus son habituelle massue, mais la foudre de Vajrapani (du sanskrit vajra, signifiant « foudre », et pani « en main »), l’une des trois premières divinités protectrices entourant le Bouddha.

C’est un bodhisattva. Il apparaît dès le IIe siècle dans l’iconographie mahāyāna comme doué d’une grande force et comme protecteur du Bouddha. Dans l’art gréco-bouddhique il ressemble à Héraclès ou Zeus, tenant en main une courte massue en forme de vajra, un foudre stylisé. On l’identifie au protecteur, « puissant comme un éléphant », qui aurait veillé sur Bouddha à sa naissance.

Une autre statue rappelle le portrait d’Alexandre le Grand.

De cet ensemble sculptural, il ne reste malheureusement que des photographies.

Selon l’archéologue afghan Zemaryalai Tarzi, le monastère de Tapa Shotor, avec ses sculptures en argile datées du IIe siècle de notre ère, représente le « chaînon manquant » entre l’art hellénistique de Bactriane et les sculptures en stuc plus tardives trouvées à Hadda, généralement datées du IIIe-IVe siècle de notre ère.

Traditionnellement, l’afflux d’artistes, maître de l’art hellénistique, a été attribué à la migration des populations grecques des villes gréco-bactriennes d’Aî-Khanoum et de Takht-I-Sangin (Nord de l’Afghanistan).

Tarzi suggère que les populations grecques se sont établies dans les plaines de Jalalabad, qui comprennent Hadda, autour de la ville hellénistique de Dionysopolis, et qu’elles sont à l’origine des créations bouddhistes de Tapa Shotor, au IIe siècle de notre ère.

Les colons grecs restés au Gandhara (les Yavanas) après le départ d’Alexandre, soit par choix, soit en tant que populations condamnées à l’exil par Athènes, ont grandement embelli les expressions artistiques de leur nouvelle spiritualité.

Offrant fraîcheur, poésie et un sens du mouvement spectaculairement moderne, les premiers artistes bouddhistes du Gandhara, saisissant des instants de « mouvement-changement » permettant à l’esprit humain d’appréhender un saut vers la perfection, sont une contribution inestimable à la culture de l’humanité tout entière. N’est-il pas temps de reconnaître ce magnifique travail ?

D. Prendre la terre à témoin

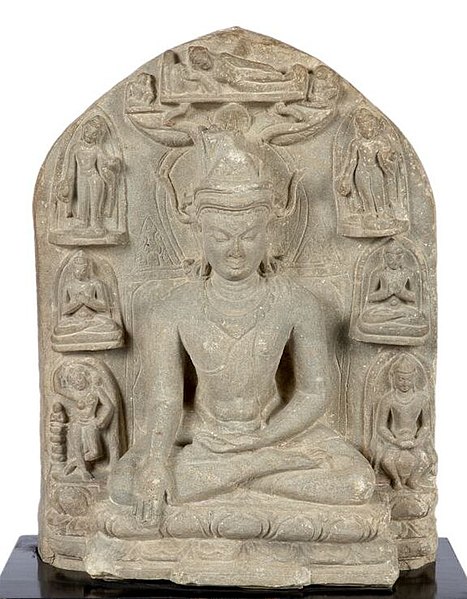

Parmi les autres types productions artistiques de Gandhara, ce magnifique bas-relief, aujourd’hui conservée au musée de Cleveland, illustre la lutte du Bouddha pour atteindre le nirvana.

Au centre de la composition se trouve l’arbre de la Bodhi, sous lequel le Bouddha atteignit l’illumination. Ce figuier sacré est vénéré depuis des temps ancestraux par les villageois locaux, car il passe pour être la résidence d’une divinité de la nature. L’autel lui-même est recouvert de kusha, herbe utilisée pour des offrandes sacrificielles.

Il y a environ 2500 ans, après être resté en méditation pendant 49 jours, assis sous cet arbre, le Bouddha est défié par des démons cauchemardesques qui remettent en cause l’authenticité de son illumination.

Leur chef Mara (littéralement, la mort), qui se tient à droite dans une posture arrogante, entouré de ses filles, fait tout pour empêcher Bouddha d’atteindre le nirvana (l’éveil).

Il le menace et encourage ses propres filles à le séduire. Innocemment, il lui demande s’il est sûr de pouvoir trouver quelqu’un pour témoigner qu’il a véritablement atteint le nirvana. En réponse à ce défi, le Bouddha touche alors la terre et la prend à témoin.

Selon la mythologie, la jeune déesse de la Terre surgit alors du sol et commença à essorer les eaux déferlant de ses cheveux pour noyer Mara. Sur la sculpture, on peut la voir, toute petite, au pied de l’autel, agenouillée devant Bouddha en signe de révérence. Elle a également pris forme humaine en sortant de terre. Les anciennes religions interviennent ici pour défendre et protéger la nouvelle, celle de Bouddha.

Semblant, eux aussi, regretter les anciens dieux et déesses de leur panthéon, les Indiens convertis au bouddhisme les ajoutent au-dessus de la tête de Bouddha ou à côté, comme, par exemple, le dieu védique Indra.

E. Tous bodhisattva ?

Enfin, pour conlure cette section sur la sculpture, deux mots sur le bodhisattva, figure très intéressante sortie de l’imaginaire bouddhiste pour rendre la spiritualité bouddhiste accessible au citoyen ordinaire.

Il peut s’agir soit d’une représentation de Bouddha en personnage princier orné de bijoux, avant son renoncement à la vie de palais, soit d’un humain ordinaire, déjà conscient qu’il est sur la voie de l’illumination et qu’il est devenu un outil au service du bien.

Animé d’altruisme et obéissant les disciplines destinées aux bodhisattvas, il doit aider par compassion d’abord les autres êtres sensibles à s’éveiller, y compris en retardant sa propre libération !

Les bodhisattvas se distinguent par de grandes qualités spirituelles telles que les « quatre demeures divines » que sont:

- l’amour bienveillant (maitri),

- la compassion (karuna),

- la joie empathique (mudita) et

- l’équanimité (upekṣa),

ainsi que les diverses perfections (paramitas), qui comprennent la prajnaparamita (« connaissance transcendante » ou « perfection de la sagesse ») et les moyens habiles (upaya).

Des bodhisattvas spirituellement avancés tels qu’Avalokiteshvara (ci-dessus), Maitreya et Manjushri, largement vénérés dans le monde bouddhiste mahâyâna, sont censés posséder un grand pouvoir, qu’ils utilisent pour aider tous les êtres vivants.

Pour certains courants bouddhistes, seul Maitreya mérite le titre de « Bouddha du futur ». Dans l’art on le représente à la fois comme un bouddha vêtu d’une robe monastique et comme un bodhisattva princier avant l’illumination.

Un magnifique bodhisattva de Gandhara peut être admiré au Dallas Museum of Art (ci-dessous).

Cette sculpture en terre cuite représente un « Bodhisattva pensant » de la région de Hadda en Afghanistan, une production typique du Gandhara.

Avec très peu d’éléments visuels, l’artiste réussit un travail gigantesque. Les piliers de sa large chaise sont des lions au regard un peu fou, représentation allégorique de ces passions qui nous font souffrir et qui sont maintenues sous un sage contrôle par l’effort hautement réflexif du Bodhisattva héroïque au centre de l’œuvre.

Le bouddhisme aujourd’hui, l’exemple de Nehru

Paradoxalement, le bouddhisme, en tant que religion, a presque cessé d’exister dans son propre berceau, l’Inde, depuis le XIIe siècle de notre ère.

Bel exemple de la lutte incessante des meilleurs esprits indiens pour l’émancipation, en 1956, près d’un demi-million « d’intouchables » se sont convertis au bouddhisme sous l’impulsion du dirigeant politique à la tête du comité chargé de rédiger la Constitution de l’Inde, le réformateur social B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956), et du Premier ministre indien et chef du Parti du Congrès Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), lui-même issu d’une famille de brahmanes.

En juin de la même année, le Courrier de l’UNESCO consacrait son édition à « 25 siècles d’art et de culture bouddhistes ».

En Inde, les deux hommes d’État ont orchestré une année de célébration en l’honneur de « 2500 ans de bouddhisme », non pas pour ressusciter une ancienne religion en soi, mais pour s’approprier le statut de berceau de cette vieille religion et renvoyer au monde une image de champion de la non-violence et du pacifisme.