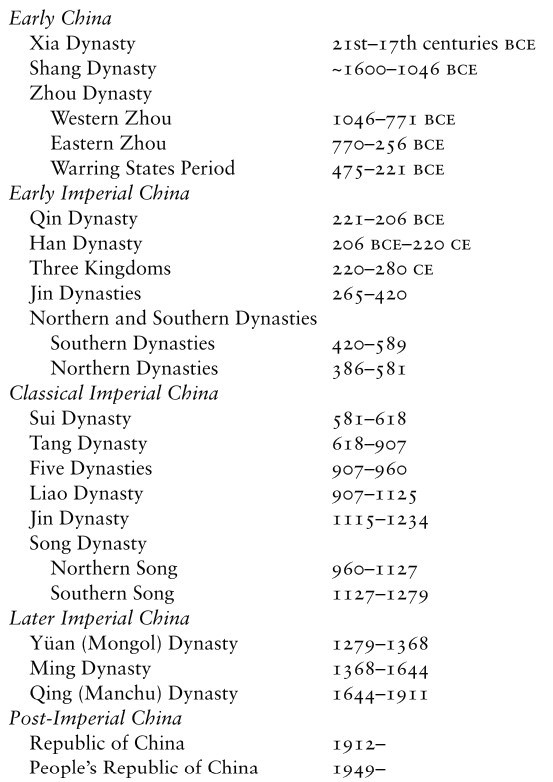

Étiquette : printing

The republican struggle of David d’Angers and the statue of Gutenberg in Strasbourg

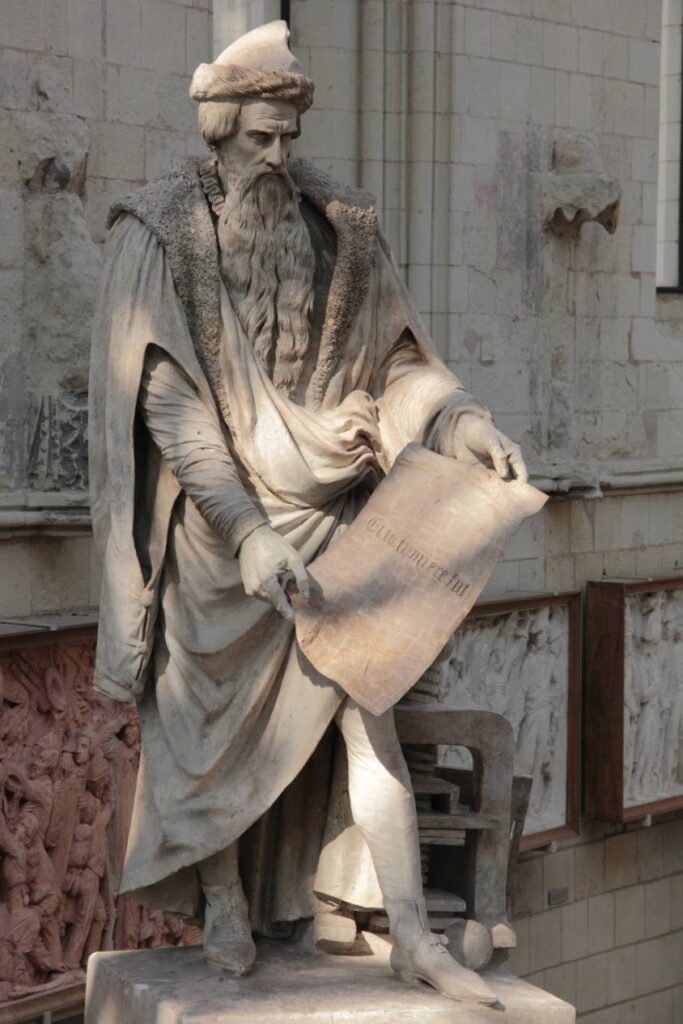

In the heart of downtown Strasbourg, a stone’s throw from the cathedral and with its back to the 1585 Chamber of Commerce, stands the beautiful bronze statue of the German printer Johannes Gutenberg, holding a barely-printed page from his Bible, which reads: « And there was light » (NOTE 1).

Evoking the emancipation of peoples thanks to the spread of knowledge through the development of printing, the statue, erected in 1840, came at a time when supporters of the Republic were up in arms against the press censorship imposed by Louis-Philippe under the July Monarchy.

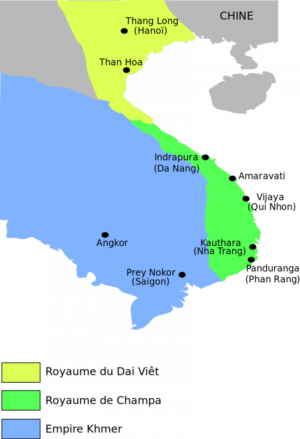

Strasbourg, Mainz and China

Born around 1400 in Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg, with money lent to him by the merchant and banker Johann Fust, carried out his first experiments with movable metal type in Strasbourg between 1434 and 1445, before perfecting his process in Mainz, notably by printing his famous 42-line Bible from 1452.

On his death (in Mainz) in 1468, Gutenberg bequeathed his process to humanity, enabling printing to take off in Europe. Chroniclers also mention the work of Laurens Janszoon Coster in Harlem, and the Italian printer Panfilo Castaldi, who is said to have brought Chinese know-how to Europe. It should be noted that the « civilized » world of the time refused to acknowledge that printing had originated in Asia with the famous « movable type » (made of porcelain and metal) developed several centuries earlier in China and Korea (NOTE 2).

In Europe, Mainz and Strasbourg vie for pride of place. On August 14, 1837, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the « invention » of printing, Mainz inaugurated its statue of Gutenberg, erected by sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsenalors, while in Strasbourg, a local committee had already commissioned sculptor David d’Angers to create a similar monument in 1835.

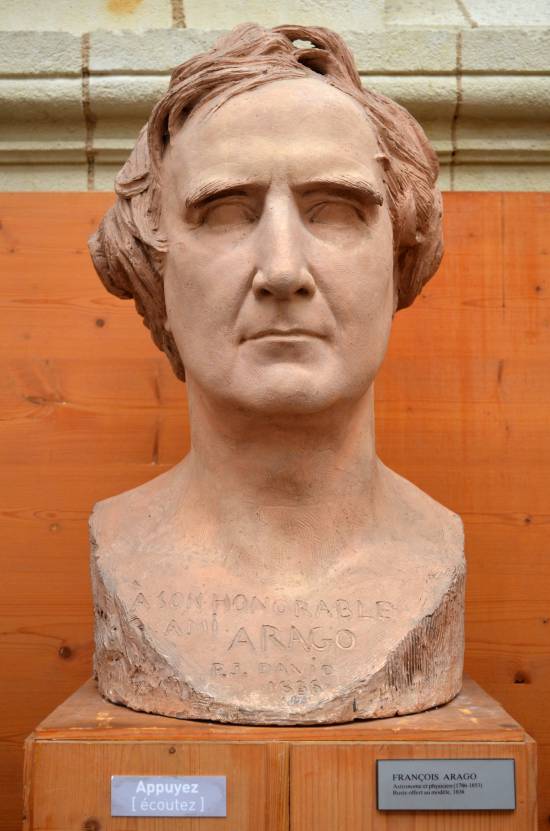

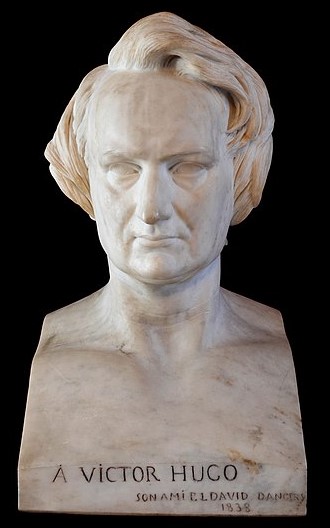

This little-known sculptor was both a great sculptor and close friend of Victor Hugo, and a fervent republican in personal contact with the finest humanist elite of his time in France, Germany and the United States. He was also a tireless campaigner for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery.

The sculptor’s life

French sculptor Pierre-Jean David, known as « David d’Angers » (1788-1856) was the son of master sculptor Pierre Louis David. Pierre-Jean was influenced by the republican spirit of his father, who trained him in sculpture from an early age. At the age of twelve, his father enrolled him in the drawing class at the École Centrale de Nantes. In Paris, he was commissioned to create the ornamentation for the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and the south facade of the Louvre Palace. Finally, he entered the Beaux-arts.

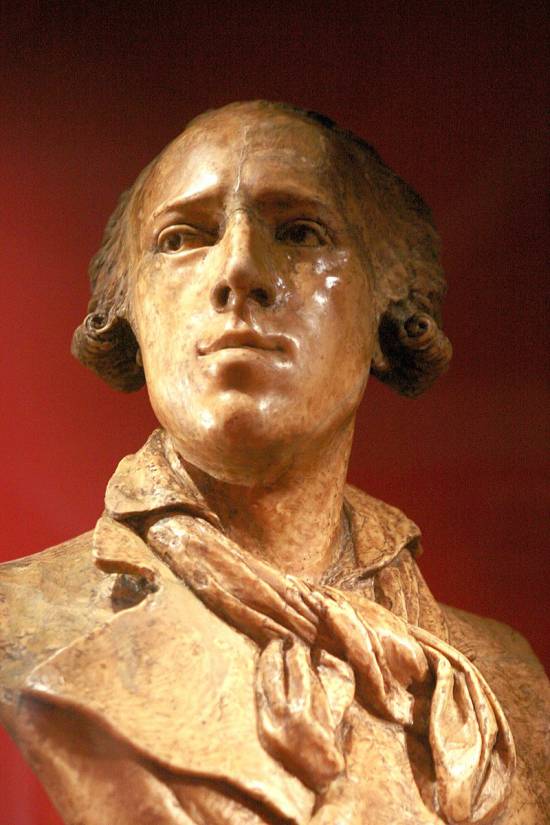

David d’Angers possessed a keen sense of interpretation of the human figure and an ability to penetrate the secrets of his models. He excelled in portraiture, whether in bust or medallion form. He is the author of at least sixty-eight statues and statuettes, some fifty bas-reliefs, a hundred busts and over five hundred medallions. Victor Hugo told his friend David: « This is the bronze coin by which you pay your toll to posterity. »

He traveled all over Europe, painting busts in Berlin, London, Dresden and Munich.

Around 1825, when he was commissioned to paint the funeral monument that the Nation was raising by public subscription in honor of General Foy, a tribune of the parliamentary opposition, he underwent an ideological and artistic transformation. He frequented the progressive intellectual circles of the « 1820 generation » and joined the international republican movement. He then turned his attention to the political and social problems of France and Europe. In later years, he remained faithful to his convictions, refusing, for example, the prestigious commission to design Napoleon’s tomb.

Artistic production

David’s art was thus influenced by a naturalism whose iconography and expression are in stark contrast to that of his academic colleagues and the dissident sculptors known as « romantics » at the time. For David, no mythological sensualism, obscure allegories or historical picturesqueness. On the contrary, sculpture, according to David, must generalize and transpose what the artist observes, so as to ensure the survival of ideas and destinies in a timeless posterity.

David adhered to this particular, limited conception of sculpture, adopting the Enlightenment view that the art of sculpture is « the lasting repository of the virtues of men », perpetuating the memory of the exploits of exceptional beings.

The somewhat austere image of « great men » prevailed, best known thanks to some 600 medallions depicting famous men and women from several countries, most of them contemporaries. Added to this are some one hundred busts, mostly of his friends, poets, writers, musicians, songwriters, scientists and politicians with whom he shared the republican ideal.

Among the most enlightened of his time were: Victor Hugo, Marquis de Lafayette, Wolfgang Goethe, Alfred de Vigny, Alphonse Lamartine, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Alfred de Musset, François Arago, Alexander von Humboldt, Honoré de Balzac, Lady Morgan, James Fenimore Cooper, Armand Carrel, François Chateaubriand, Ennius Quirinus Visconti and Niccolo Paganini.

To magnify his models and visually render the qualities of each one’s genius, David d’Angers invented a mode of idealization no longer based on antique-style classicism, but on a grammar of forms derived from a new science, the phrenology of Doctor Gall, who believed that the cranial « humps » of an individual reflected his intellectual aptitudes and passions. For the sculptor, it was a matter of transcending the model’s physiognomy, so that the greatness of the soul radiated from his forehead.

In 1826, he was elected member of the Institut de France and, the same year, professor at the Beaux-Arts. In 1828, David d’Angers was the victim of his first unsolved assassination attempt. Wounded in the head, he was confined to bed for three months. However, in 1830, still loyal to republican ideas, he took part in the revolutionary days and fought on the barricades.

In 1830, David d’Angers found himself ideally placed to carry out the most significant political sculpture commission of the July monarchy and perhaps of 19th century France: the new decoration of the pediment of the church of Sainte-Geneviève, which had been converted into the Pantheon in July.

As a historiographer, he wanted to depict the civilians and men of war who built Republican France. In 1837, the execution of the figures he had chosen and arranged in a sketch that was first approved, then suspended, was bound to lead to conflict with the high clergy and the government. On the left, we see Bichat, Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David, Cuvier, Lafayette, Manuel, Carnot, Berthollet, Laplace, Malesherbes, Mirabeau, Monge and Fénelon. While the government tried to have Lafayette’s effigy removed, which David d’Angers stubbornly refused, with the support of the liberal press, the pediment was unveiled without official ceremony in September 1837, without the presence of the artist, who had not been invited.

Entering politics

During the 1848 Revolution, he was appointed mayor of the 11th arrondissement of Paris, entered the National Constituent Assembly and then the National Legislative Assembly, where he voted with the Montagne (revolutionary left). He defended the existence of the Ecole des Beaux-arts and the Académie de France in Rome. He opposed the destruction of the Chapelle Expiatoire and the removal of two statues from the Arc de Triomphe (Resistance and Peace by sculptor Antoine Etex).

He also voted against the prosecution of Louis Blanc (1811-1882) (another republican statesman and intellectual condemned to exile), against the credits for Napoleon III’s Roman expedition, for the abolition of the death penalty, for the right to work, and for a general amnesty.

Exile

He was not re-elected deputy in 1849 and withdrew from political life. In 1851, with the advent of Napoleon III, David d’Angers was arrested and also sentenced to exile. He chose Belgium, then traveled to Greece (his old project). He wanted to revisit his Greek Maiden on the tomb of the Greek republican patriot Markos Botzaris (1788-1823), which he found mutilated and abandoned (he had it repatriated to France and restored).

Disappointed by Greece, he returned to France in 1852. With the help of his friend de Béranger, he was allowed to stay in Paris, where he resumed his work. In September 1855, he suffered a stroke which forced him to cease his activities. He died in January 1856.

Friendships with Lafayette, Abbé Grégoire and Pierre-Jean de Béranger

David d’Angers was a real link between 18th and 19th century republicans, and a living bridge between those of Europe and America.

Born in 1788, he had the good fortune to associate at an early age with some of the great revolutionary figures of the time, before becoming personally involved in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848.

Towards the end of the 1820s, David attended the Tuesday salon meetings of Madame de Lafayette, wife of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (1757-1834).

While General Lafayette stood upright like « a venerable oak », this salon, notes the sculptor,

« has a clear-cut physiognomy, » he writes. The men talk about serious matters, especially politics, and even the young men look serious: there’s something decided, energetic and courageous in their eyes and in their posture (…) All the ladies and also the demoiselles look calm and thoughtful; they look as if they’ve come to see or attend important deliberations, rather than to be seen. »

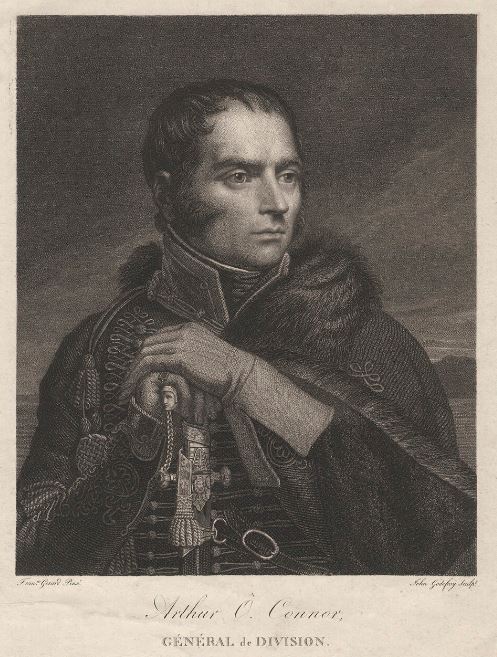

David met Lafayette’s comrade-in-arms, General Arthur O’Connor (1763-1852), a former Irish republican MP of the United Irishmen who had joined Lafayette’s volunteer General Staff in 1792.

Accused of stirring up trouble against the British Empire and in contact with General Lazare Hoche (1768-1797), O’Connor fled to France in 1796 and took part in the Irish Expedition. In 1807, O’Connor married the daughter of philosopher and mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet (1743-1794) and became a naturalized French citizen in 1818.

Lafayette and David d’Angers often got together with a small group of friends, a few « brothers » who were members of Masonic lodges: such as the chansonnier Pierre-Jean de Béranger, François Chateaubriand, Benjamin Constant, Alexandre Dumas (who corresponded with Edgar Allan Poe), Alphonse Lamartine, Henri Beyle dit Stendhal and the painters François Gérard and Horace Vernet.

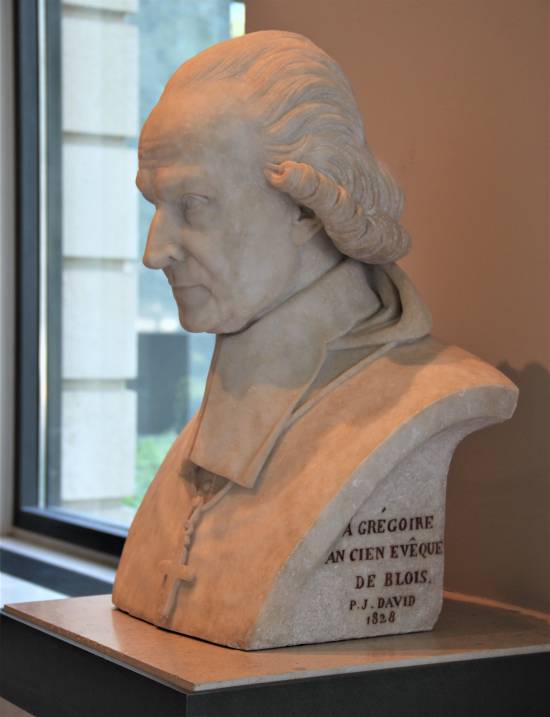

In these same circles, David also became acquainted with Henri (Abbé) Grégoire (1750-1831), and the issue of the abolition of slavery, which Grégoire had pushed through on February 4, 1794, was often raised. In their exchanges, Lafayette liked to recall the words of his youthful friend Nicolas de Condorcet:

« Slavery is a horrible barbarism, if we can only eat sugar at this price, we must know how to renounce a commodity stained with the blood of our brothers. »

For Abbé Gregoire, the problem went much deeper:

« As long as men are thirsty for blood, or rather, as long as most governments have no morals, as long as politics is the art of deceit, as long as people, unaware of their true interests, attach silly importance to the job of spadassin, and will allow themselves to be led blindly to the slaughter with sheep-like resignation, almost always to serve as a pedestal for vanity, almost never to avenge the rights of humanity, and to take a step towards happiness and virtue, the most flourishing nation will be the one that has the greatest facility for slitting the throats of others. »

(Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews)

Napoleon and slavery

The first abolition of slavery was, alas, short-lived. In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte, short of the money needed to finance his wars, reintroduced slavery, and nine days later excluded colored officers from the French army.

Finally, he outlawed marriages between « fiancés whose skin color is different ». David d’Angers remained very sensitive to this issue, having as a comrade a very young writer, Alexandre Dumas, whose father had been born a slave in Haiti.

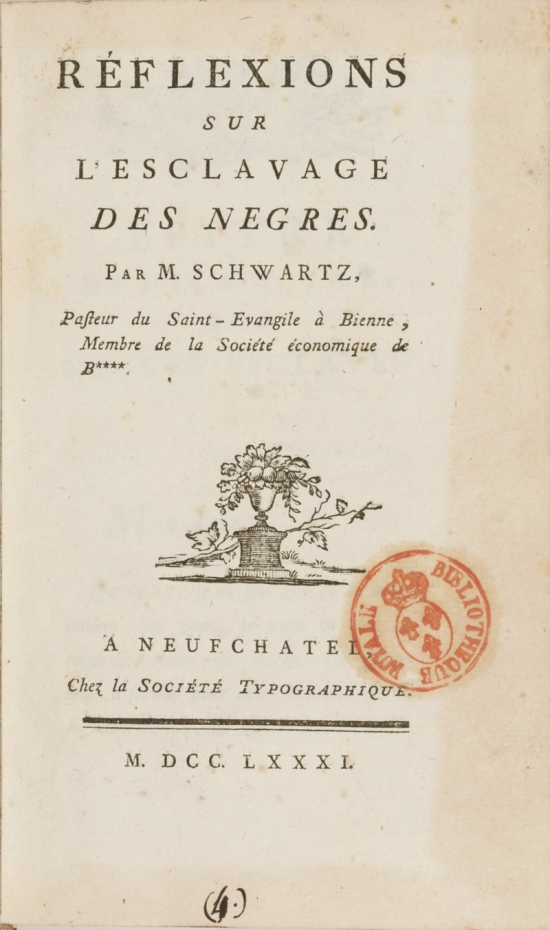

As early as 1781, under the pseudonym Schwarz (black in German), Condorcet had published a manifesto advocating the gradual disappearance of slavery over a period of 60 to 70 years, a view quickly shared by Lafayette. A fervent supporter of the abolitionist cause, Condorcet condemned slavery as a crime, but also denounced its economic uselessness: slave labor, with its low productivity, was an obstacle to the establishment of a market economy.

And even before the signing of the peace treaty between France and the United States, Lafayette wrote to his friend George Washington on February 3, 1783, proposing to join him in setting in motion a process of gradual emancipation of the slaves. He suggested a plan that would « frankly become beneficial to the black portion of mankind ».

The idea was to buy a small state in which to experiment with freeing slaves and putting them to work as farmers. Such an example, he explained, « could become a school and thus a general practice ». (NOTE 3)

Washington replied that he personally would have liked to support such a step, but that the American Congress (already) was totally hostile.

From the Society of Black Friends to the French Society for the Abolition of Slavery

In Paris, on February 19, 1788, Abbé Grégoire and Jacques Pierre Brissot (1754-1793) founded « La Société des amis des Noirs », whose rules were drawn up by Condorcet, and of which the Lafayette couple were also members.

The society’s aim was the equality of free whites and blacks in the colonies, the immediate prohibition of the black slave trade and the gradual abolition of slavery; on the one hand, to maintain the economy of the French colonies, and on the other, in the belief that before blacks could achieve freedom, they had to be prepared for it, and therefore educated.

After the virtual disappearance of the « Amis des Noirs », the offensive was renewed, with the founding in 1821 of the « Société de la Morale chrétienne », which in 1822 set up a « Comité pour l’abolition de la traite des Noirs », some of whose members went on to found the « Société française pour l’abolition de l’esclavage (SFAE) » in 1834.

Initially in favor of gradual abolition, the SFAE later favored immediate abolition. Prohibited from holding meetings, the SFAE decided to create abolitionist committees throughout the country to relay the desire to put an end to slavery, both locally and nationally.

Goethe and Schiller

In the summer of 1829, David d’Angers made his first trip to Germany and met Goethe (1749-1832), the poet and philosopher who had retired to Weimar. Several posing sessions enabled the sculptor to complete his portrait.

Writer and poet Victor Pavie (1808-1886), a friend of Victor Hugo and one of the founders of the « Cercles catholiques ouvriers » (Catholic Workers Circle), accompagnied him on the trip and recounts some of the pictoresques anecdotes of their travel in his « Goethe and David, memories of a voyage to Weimar » (1874).

In 1827, the French newspaper Globe published two letters recounting two visits to Goethe, in 1817 and 1825, by an anonymous « friend » (Victor Cousin), as well as a letter from Ampère on his return from the « Athens of Germany ». In these letters, the young scientist expressed his admiration, and gave numerous details that whetted the interest of his compatriots. During his stay in Weimar, Ampère added to his host’s knowledge of Romantic authors, particularly Mérimée, Vigny, Deschamps and Delphine Gay. Goethe already had a (positive) opinion of Victor Hugo, Lamartine and Casimir Delavigne, and of all they owed to Chateaubriand.

A subscriber to the Globe since its foundation in 1824, Goethe had at his disposal a marvellous instrument of French information. In any case, he had little left to learn about France when David and Pavie visited him in August 1829. On the strength of his unhappy experience with Walter Scott in London, David d’Angers had taken precautions this time, and had a number of letters of recommendation for the people of Weimar, as well as two letters of introduction to Goethe, signed by Abbé Grégoire and Victor Cousin. To show the illustrious writer what he could do, he had placed some of his finest medallions in a crate.

Once in Weimar, David d’Angers and Victor Pavie encountered great difficulties in their quest, especially as the recipients of the letters of recommendation were all absent. Stricken with despair and fearing failure, David blamed his young friend Victor Pavie:

« Yes, you jumped in with the optimism of a young man, without giving me time to think and get out of the way. It wasn’t as a coward or under the patronage of an adventurer, it was head-on and resolutely that we had to tackle the character. (…) You’re only as good as what you are, it’s a yes or no question. You know me, on my knees before genius, and imployable before power. Ah! court poets, great or small, everywhere the same!

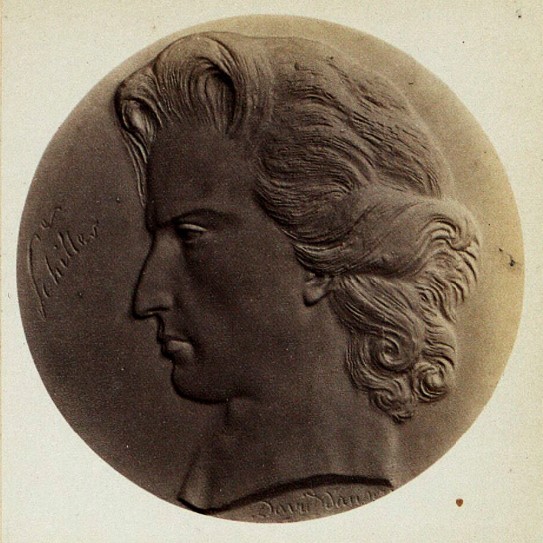

(…) And with a leap from the chair where he had insensitively let himself fall: Where’s Schiller? I’d like to kiss him! His grave, where I will strike, will not remain sealed for me; I will take him there, and bring him back glorious. What does it matter? Have I seen Corneille, have I seen Racine? The bust I’m planning for him will look all the better for it; the flash of his genius will gleam on his forehead. I’ll make him as I love and admire him, not with the pinched nose that Dannecker (image below) gave him, but with nostrils swollen with patriotism and freedom.

Victor Pavie’s account reveals the republican fervor animating the sculptor who, faithful to the ideals of Abbé Grégoire, was already thinking about the great anti-slavery sculpture he planned to create:

« At that moment, the half-open window of our bedroom, yielding to the evening breeze, opened wide. The sky was superb; the Milky Way unfurled with such brilliance that one could have counted the stars. He (David) remained silent for some time, dazzled; then, with that suddenness of impression that incessantly renewed the realm of feelings and ideas around him:

‘What a work, what a masterpiece! How poor we are compared to this!Would all your geniuses in one, writers, artists, poets, ever reach this incomparable poem whose tasks are splendors? Yet God knows your insatiable pretensions; we flay you in praise… And light! Remember this (and his presentiments in this regard were nothing less than a chimera), that such a one as received a marble bust from me as a token of my admiration, will one day literally lose the memory of it. – No, there is nothing more noble and great in humanity than that which suffers. I still have in my head, or rather in my heart, this protest of the human conscience against the most execrable iniquity of our times, the slave trade: after ten years of silence and suffering, it must burst forth with the voice of brass. You can see the group from here: the garroted slave, his eye on the sky, protector and avenger of the weak; next to him, lying broken, his wife, in whose bosom a frail creature is sucking blood instead of milk; at their feet, detached from the negro’s broken collar, the crucifix, the Man-God who died for his brothers, black or white. Yes, the monument will be made of bronze, and when the wind blows, you will hear the chain beating, and the rings ringing' ».

Finally, Goethe met the two Frenchmen, and David d’Angers succeeded in making his bust of the German poet. Victor Pavie:

« Goethe bowed politely to us, spoke the French language with ease from the start, and made us sit down with that calm, resigned air that astonished me, as if it were a simple thing to find oneself standing at eighty, face to face with a third generation, to which he had passed on through the second, like a living tradition.

(…) David carried with him, as the saying goes, a sample of his skills.He presented the old man with a few of his lively profiles, so morally expressive, so nervously and intimately executed, part of a great whole that is becoming more complete with our age, and which reserves for the centuries to come the monumental physiognomy of the 19th century. Goethe took them in his hand, considered them mute, with scrupulous attention, as if to extract some hidden harmony, and let out a muffled, equivocal exclamation that I later recognized as a mark of genuine satisfaction.Then, by a more intelligible and flattering transition, of which he was perhaps unaware, walking to his library, he charmingly showed us a rich collection of medals from the Middle Ages, rare and precious relics of an art that could be said to have been lost, and of which our great sculptor David has nowadays been able to recover and re-immerse the secret.

(…) The bust project did not have to languish for long: the very next day, one of the apartments in the poet’s immense house was transformed into a workshop, and a shapeless mound lay on the parquet floor, awaiting the first breath of existence. As soon as it slowly shifted into a human form, Goethe’s hitherto calm and impassive figure moved with it. Gradually, as if a secret, sympathetic alliance had developed between portrait and model, as the one moved towards life, the other blossomed into confidence and abandonment: we soon came to those artist’s confidences, that confluence of poetry, where the ideas of the poet and the sculptor come together in a common mold. He would come and go, prowling around this growing mass, (to use a trivial comparison) with the anxious solicitude of a landowner building a house. He asked us many questions about France, whose progress he was following with a youthful and active curiosity; and frolicking at leisure about modern literature, he reviewed Chateaubriand, Lamartine, Nodier, Alfred de Vigny, Victor Hugo, whose manner he had seriously pondered in Cromwell.

(…) David’s bust, writes Pavie, was as beautiful as Chateaubriand’s, Lamartine’s, Cooper’s, as any application of genius to genius, as the work of a chisel fit and powerful to reproduce one of those types created expressly by nature for the habitation of a great thought. Of all the likenesses attempted, with greater or lesser success, in all the ages of this long glory, from his youth of twenty to Rauch’s bust, the last and best understood of all, it is no prevention to say that David’s is the best, or, to put it even more bluntly, the only realization of that ideal likeness which is not the thing, but is more than the thing, nature taken within and turned inside out, the outward manifestation of a divine intelligence passed into human bark. And there are few occasions like this one, when colossal execution seems no more than a powerless indication of real effect. An immense forehead, on which rises, like clouds, a thick tuft of silver hair; a downward gaze, hollow and motionless, a look of Olympian Jupiter; a nose of broad proportion and antique style, in the line of the forehead ; then that singular mouth we were talking about earlier, with the lower lip a little forward, that mouth, all examination, questioning and finesse, completing the top with the bottom, genius with reason; with no other pedestal than its muscular neck, this head leans as if veiled, towards the earth:it’s the hour when the setting genius lowers his gaze to this world, which he still lights with a farewell ray. Such is David’s crude description of Goethe’s statue.- What a pity that in his bust of Schiller, so famous and so praised, the sculptor Dannecker prepared such a miserable counterpart!

When Goethe received his bust, he warmly thanked David for the exchange of letters, books and medallions… but made no mention of the bust ! For one simple reason: he didn’t recognize himself at all in the work, which he didn’t even keep at home… The German poet was depicted with an oversized forehead, to reflect his great intelligence. And his tousled hair symbolized the torments of his soul…

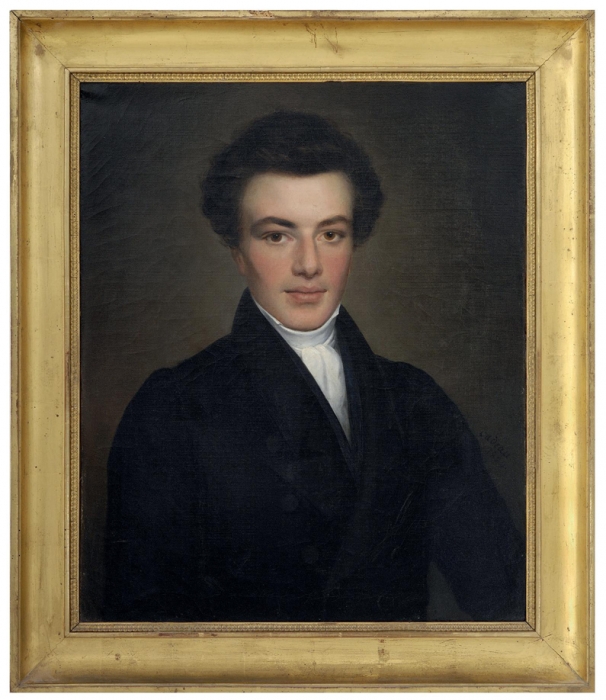

David d’Angers and Hippolyte Carnot

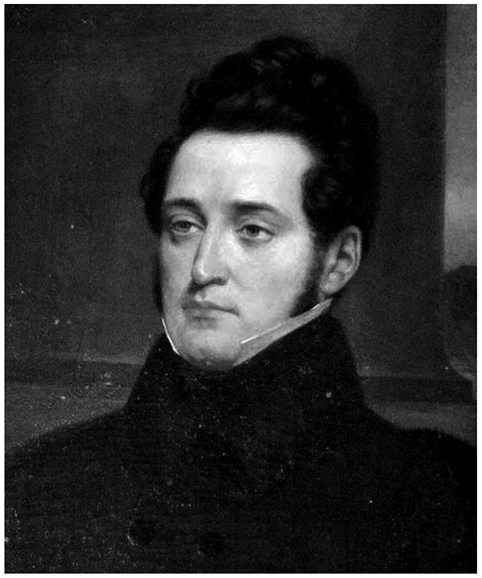

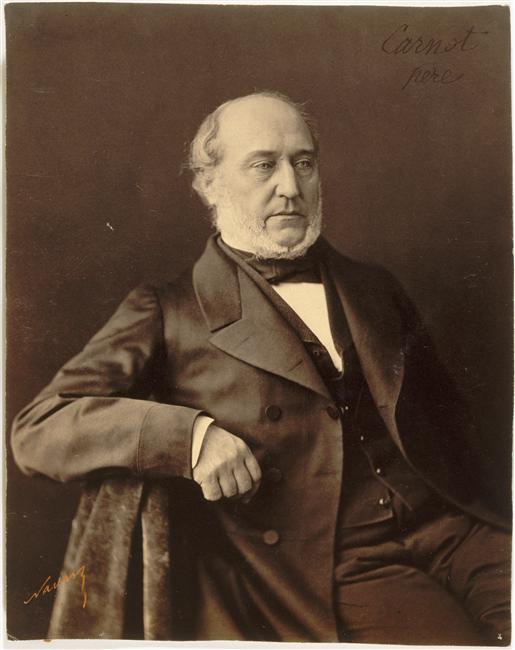

Among the founders of the SFAE (see earlier chapter on Abbé Grégoire) was Hippolyte Carnot (1801-1888), younger brother of Nicolas Sadi Carnot (1796-1832), pioneer of thermodynamics and son of « the organizer of victory », the military and scientific genius Lazare Carnot (1753-1823), whose work and struggle he recounted in his 1869 biography Mémoires sur Lazare Carnot 1753-1823 by his son Hippolyte.

In 1888, with the title Henri Grégoire, évêque (bishop) républicain, Hippolyte published the Mémoires of Grégoire the defender of all the oppressed of the time (negroes and Jews alike), a great friend of his father’s who had retained this friendship.

For the former bishop of Blois, « we must enlighten the ignorance that does not know and the poverty that does not have the means to know. »

Grégoire had been one of the Convention’s great « educators », and it was on his report that the Conservatoire des Arts-et-Métiers was founded on September 29, 1794, notably for the instruction of craftsmen. Grégoire also contributed to the creation of the Bureau des Longitudes on June 25, 1795 and the Institut de France on October 25, 1795.

Hippolyte Carnot and David d’Angers, who were friends, co-authored the Memoirs of Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (1755-1841), who acted as a sort of Minister of Information on the Comité de Salut Public, responsible for announcing the victories of the Republican armies to the Convention as soon as they arrived.

It was also Abbé Grégoire who, in 1826, commissioned David d’Angers, with the help of his friend Béranger, to bring some material and financial comfort to Rouget de Lisle (1860-1836), the legendary author of La Marseillaise, composed in Strasbourg when, in his old age, the composer was languishing in prison for debt.

Overcoming the sectarianism of their time, here are three fervent republicans full of compassion and gratitude for a musical genius who never wanted to renounce his royalist convictions, but whose patriotic creation would become the national anthem of the young French Republic.

Provisional Government

of the Second Republic

All these battles, initiatives and mobilizations culminated in 1848, when, for two months and 15 days (from February 24 to May 9), a handful of genuine republicans became part of the « provisional government » of the Second Republic.

In such a short space of time, so many good measures were taken or launched! Hippolyte Carnot was the Minister of Public Instruction, determined to create a high level of education for all, including women, following the models set by his father for Polytechnique and Grégoire for Arts et Métiers.

Article 13 of the 1848 Constitution « guarantees citizens (…) free primary education ».

On June 30, 1848, the Minister of Public Instruction, Lazare Hippolyte Carnot, submitted a bill to the Assembly that fully anticipated the Ferry laws, by providing for compulsory elementary education for both sexes, free and secular, while guaranteeing freedom of teaching. It also provided for three years’ free training at a teacher training college, in return for an obligation to teach for at least ten years, a system that was to remain in force for a long time. He proposed a clear improvement in their salaries. He also urged teachers « to teach a republican catechism ».

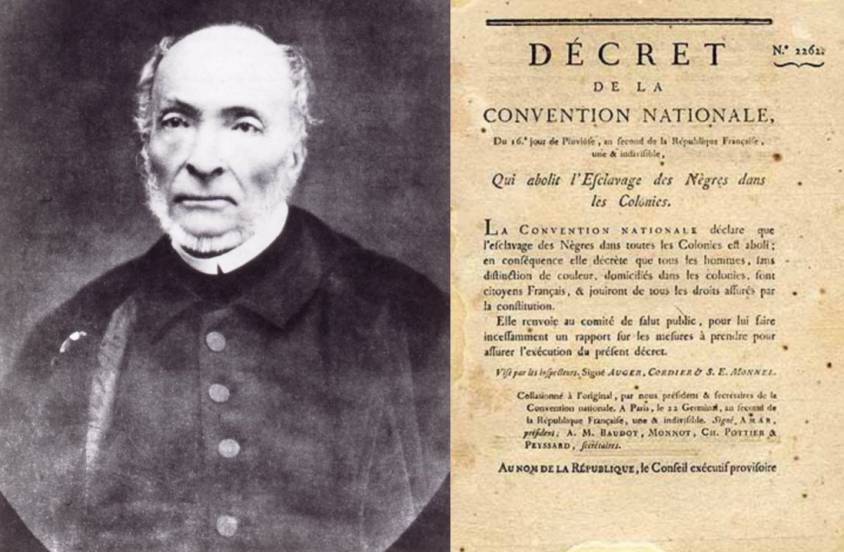

A member of the provisional government, the great astronomer and scientist François Arago (1886-1853) was Minister for the Colonies, having been appointed by Gaspard Monge to succeed him at the Ecole Polytechnique, where he taught projective geometry. His closest friend was none other than Alexander von Humboldt, friend of Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Friedrich Schiller.

He was another abolitionist activist who spent much of his adult life in Paris. Humboldt was a member of the Société d’Arcueil, formed around the chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet, where he also met, besides François Arago, Jean-Baptiste Biot and Louis-Joseph Gay-Lussac, with whom Humboldt became friends. They published several scientific articles together.

Humboldt and Gay-Lussac conducted joint experiments on the composition of the atmosphere, terrestrial magnetism and light diffraction, research that would later bear fruit for the great Louis Pasteur.

Napoleon, who initially wanted to expel Humboldt, eventually tolerated his presence. The Paris Geographical Society, founded in 1821, chose him as its president.

Humboldt, Arago, Schoelcher, David d’Angers and Hugo

Humboldt made no secret of his republican ideals. His Political Essay on the Island of Cuba (1825) was a bombshell. Too hostile to slavery practices, the work was banned from publication in Spain. London went so far as to refuse him access to its Empire.

Even more deplorably, John S. Trasher, who published an English-language version in 1856, removed the chapter devoted to slaves and the slave trade altogether! Humboldt protested vigorously against this politically motivated mutilation. Trasher was a slaveholder, and his redacted translation was intended to counter the arguments of North American abolitionists, who subsequently published the retracted chapter in the New York Herald and the US Courrier. Victor Schoelcher and the decree abolishing slavery in the French colonies.

In France, under Arago, the Under-Secretary of State for the Navy and the Colonies was Victor Schoelcher. He didn’t need much convincing to convince the astronomer that all the planets were aligned for him to act.

A Freemason, Schoelcher was a brother of David d’Angers’s lodge, « Les amis de la Vérité » (The Friends of Truth), also known as the Cercle social, in reality « a mixture of revolutionary political club, Masonic lodge and literary salon ».

On March 4, a commission was set up to resolve the problem of slavery in the French colonies. It was chaired by Victor de Broglie, president of the SFAE, to which five of the commission’s twelve members belonged. Thanks to the efforts of François Arago, Henri Wallon and above all Victor Schoelcher, its work led to the abolition of slavery on April 27.

Victor Hugo the abolitionist

Victor Hugo was one of the advocates of the abolition of slavery in France, but also of equality between what were still referred to as « the races » in the 19th century. « The white republic and the black republic are sisters, just as the black man and the white man are brothers », Hugo asserted as early as 1859. For him, as all men were creations of God, brotherhood was the order of the day.

When Maria Chapman, an anti-slavery campaigner, wrote to Hugo on April 27, 1851, asking him to support the abolitionist cause, Hugo replied: « Slavery in the United States! » he exclaimed on May 12, « is there any more monstrous misinterpretation? » How could a republic with such a fine constitution preserve such a barbaric practice?

Eight years later, on December 2, 1859, he wrote an open letter to the United States of America, published by the free newspapers of Europe, in defense of the abolitionist John Brown, condemned to death.

Starting from the fact that « there are slaves in the Southern states, which indignifies, like the most monstrous counter-sense, the logical and pure conscience of the Northern states », he recounts Brown’s struggle, his trial and his announced execution, and concludes: « there is something more frightening than Cain killing Abel, it is Washington killing Spartacus ».

A journalist from Port-au-Prince, Exilien Heurtelou, thanked him on February 4, 1860. Hugo replied on March 31:

« Hauteville-House, March 31, 1860.

You are, sir, a noble sample of this black humanity so long oppressed and misunderstood.

From one end of the earth to the other, the same flame is in man; and blacks like you prove it. Was there more than one Adam? Naturalists can debate the question, but what is certain is that there is only one God.

Since there is only one Father, we are brothers.

It is for this truth that John Brown died; it is for this truth that I fight. You thank me for this, and I can’t tell you how much your beautiful words touch me.

There are neither whites nor blacks on earth, there are spirits; you are one of them. Before God, all souls are white.

I love your country, your race, your freedom, your revolution, your republic. Your magnificent, gentle island pleases free souls at this hour; it has just set a great example; it has broken despotism. It will help us break slavery. »

Also in 1860, the American Abolitionist Society, mobilized behind Lincoln, published a collection of speeches. The booklet opens with three texts by Hugo, followed by those by Carnot, Humboldt and Lafayette.

On May 18, 1879, Hugo agreed to preside over a commemoration of the abolition of slavery in the presence of Victor Schoelcher, principal author of the 1848 emancipation decree, who hailed Hugo as « the powerful defender of all the underprivileged, all the weak, all the oppressed of this world » and declared:

« The cause of the Negroes whom we support, and towards whom the Christian nations have so much to reproach, must have had your sympathy; we are grateful to you for attesting to it by your presence in our midst. »

A start for the better

Another measure taken by the provisional government of this short-lived Second Republic was the abolition of the death penalty in the political sphere, and the abolition of corporal punishment on March 12, as well as imprisonment for debt on March 19.

In the political sphere, freedom of the press and freedom of assembly were proclaimed on March 4. On March 5, the government instituted universal male suffrage, replacing the censal suffrage in force since 1815. At a stroke, the electorate grew from 250,000 to 9 million. This democratic measure placed the rural world, home to three quarters of the population, at the heart of political life for many decades to come. This mass of new voters, lacking any real civic training, saw in him a protector, and voted en masse for Napoleon III in 1851, 1860 and 1870.

Victor Hugo

To return to David d’Angers, a lasting friendship united him with Victor Hugo (1802-1885). Recently married, Hugo and David would meet to draw. The poet and the sculptor enjoyed drawing together, making caricatures, painting landscapes or « architectures » that inspired them.

A shared ideal united them, and with the arrival of Napoleon III, both men went into political exile.

Out of friendship, David d’Angers made several busts of his friend. Hugo is shown wearing an elegant contemporary suit.

His broad forehead and slightly frowning eyebrows express the poet’s greatness, yet to come. Refraining from detailing the pupils, David lends this gaze an inward, pensive dimension that prompted Hugo to write: « my friend, you are sending me immortality. »

In 1842, David d’Angers produced another bust of Victor Hugo, crowned with laurel, where this time it was not Hugo the close friend who was evoked, but rather the genius and great man.

Finally, for Hugo’s funeral in 1885, the Republic of Haiti wished to show its gratitude to the poet by sending a delegation to represent it. Emmanuel-Edouard, a Haitian writer, presided over the delegation, and made the following statement at the Pantheon:

The Republic of Haiti has the right to speak on behalf of the black race; the black race, through me, thanks Victor Hugo for having loved and honored it so much, for having strengthened and comforted it.

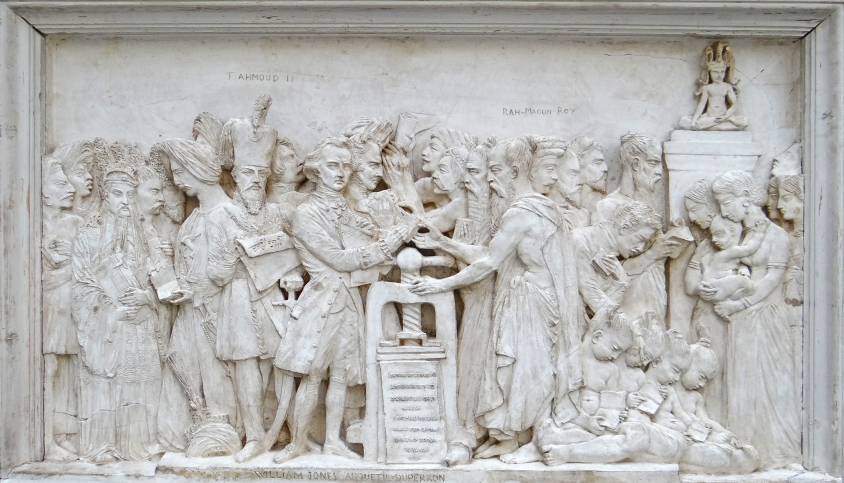

The four bas-reliefs

of the Gutenberg statue

Once the reader has identified this « great arch » that runs through history, and the ideas and convictions that inspired David d’Angers, he will grasp the beautiful unity underlying the four bas-reliefs on the base of the statue commemorating Gutenberg in Strasbourg.

What stands out is the very optimistic idea that the human race, in all its great and magnificent diversity, is one and fraternal. Once freed from all forms of oppression (ignorance, slavery, etc.), they can live together in peace and harmony.

These bronze bas-reliefs were added in 1844. After bitter debate and contestation, they replaced the original 1840 painted plaster models affixed at the inauguration. They represent the benefits of printing in America, Africa, Asia and Europe. At the center of each relief is a printing press surrounded by characters identified by inscriptions, as well as schoolteachers, teachers and children.

To conclude, here’s an extract from the inauguration report describing the bas-reliefs. Without falling into wokism (for whom any idea of a « great man » is necessarily to be fought), let’s point out that it is written in the terms of the time and therefore open to discussion:

Plaster model for the base of the statue of Gutenberg, David d’Angers.

« Europe

is represented by a bas-relief featuring René Descartes in a meditative attitude, beneath Francis Bacon and Herman Boerhaave. On the left are William Shakespeare, Pierre Corneille, Molière and Racine. One row below, Voltaire, Buffon, Albrecht Dürer, John Milton and Cimarosa, Poussin, Calderone, Camoëns and Puget. On the right, Martin Luther, Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, Copernicus, Wolfgang Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Hegel, Richter, Klopstock. Rejected on the side are Linné and Ambroise Parée. Near the press, above the figure of Martin Luther, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Rousseau and Lessing. Below the tier, Volta, Galileo, Isaac Newton, James Watt, Denis Papin and Raphaël. A small group of children study, including one African and one Asian.«

Plaster model for the base of the statue of Gutenberg, David d’Angers.

« Asia.

A printing press is shown again, with William Jones and Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron offering books to Brahmins, who give them manuscripts in return. Near Jones, Sultan Mahmoud II is reading the Monitor in modern clothes, his old turban lies at his feet, and nearby a Turk is reading a book. One step below, a Chinese emperor surrounded by a Persian and a Chinese man is reading the Book of Confucius. A European instructs children, while a group of Indian women stand by an idol and the Indian philosopher Rammonhun-Roy.«

« Africa.

Leaning on a press, William Wilberforce hugs an African holding a book, while Europeans distribute books to other Africans and are busy teaching children. On the right, Thomas Clarkson can be seen breaking the shackles of a slave. Behind him, Abbé Grégoire helps a black man to his feet and holds his hand over his heart. A group of women raise their recovered children to the sky, which will now see only free men, while on the ground lie broken whips and irons. This is the end of slavery.«

« America.

The Act of Independence of the United States, fresh from the press, is in the hands of Benjamin Franklin. Next to him stand Washington and Lafayette, who holds the sword given to him by his adopted homeland to his chest. Jefferson and all the signatories of the Act of Independence are assembled. On the right, Bolivar shakes hands with an Indian. »

America

We can better understand the words spoken by Victor Hugo on November 29, 1884, shortly before his death, during his visit to the workshop of sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, where the poet was invited to admire the giant statue bearing the symbolic name « Liberty Enlightening the World », built with the help of Gustave Eiffel and ready to leave for the United States by ship. A gift from France to America, it will commemorate the active part played by Lafayette’s country in the Revolutionary War.

Initially, Hugo was most interested in American heroes and statesmen: William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, John Brown and Abraham Lincoln. Role models, according to Hugo, who enabled the people to progress. For the French politician who became a Republican in 1847, America was the example to follow. Even if he was very disappointed by the American position on the death penalty and slavery.

After 1830, the writer abandoned this somewhat idyllic vision of the New World and attacked the white « civilizers » who hunted down Indians:

« You think you civilize a world, when you inflame it with some foul fever [4], when you disturb its lakes, mirrors of a secret god, when you rape its virgin, the forest. When you drive out of the wood, out of the den, out of the shore, your naive and dark brother, the savage… And when throwing out this useless Adam, you populate the desert with a man more reptilian… Idolater of the dollar god, madman who palpitates, no longer for a sun, but for a nugget, who calls himself free and shows the appalled world the astonished slavery serving freedom!«

(NOTE 5)

Overcoming his fatigue, in front of the Statue of Liberty, Hugo improvised what he knew would be his last speech:

« This beautiful work tends towards what I have always loved, called: peace between America and France – France which is Europe – This pledge of peace will remain permanent. It was good that it was done!«

NOTES:

1. If the phrase appears in the Book of Genesis, it could also refer to Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) a novel by Victor Hugo, a great friend of the statue’s sculptor, David d’Angers. We know from a letter Hugo wrote in August 1832 that the poet brought David d’Angers the eighth edition of the book. The scene most directly embodied in the statue is the one in which the character of Frollo converses with two scholars (one being Louis XI in disguise) while pointing with one finger to a book and with the other to the cathedral, remarking: « Ceci tuera cela » (This will kill that), i.e. that one power (the printed press), democracy, will supplant the other (the Church), theocracy, a historical evolution Hugo thought ineluctable.

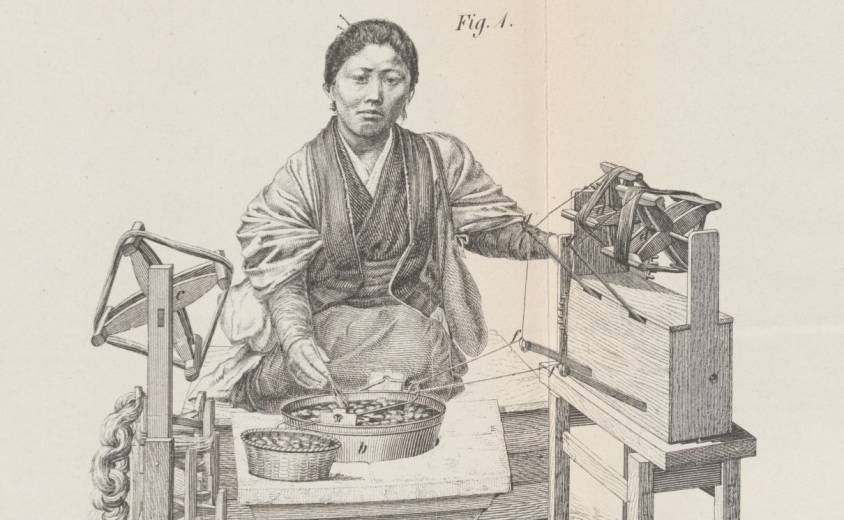

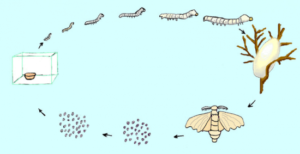

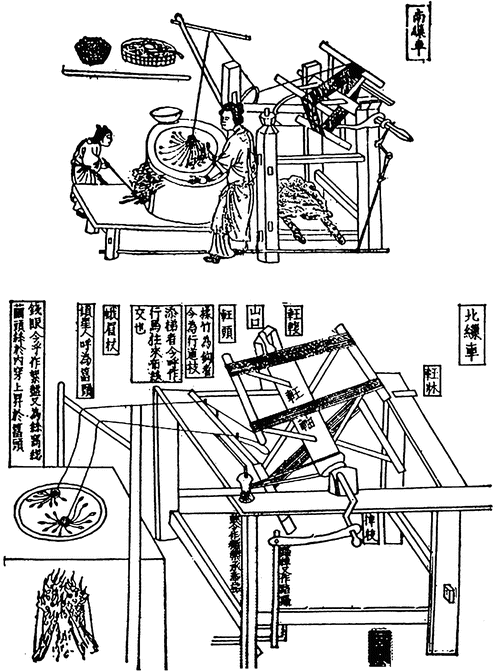

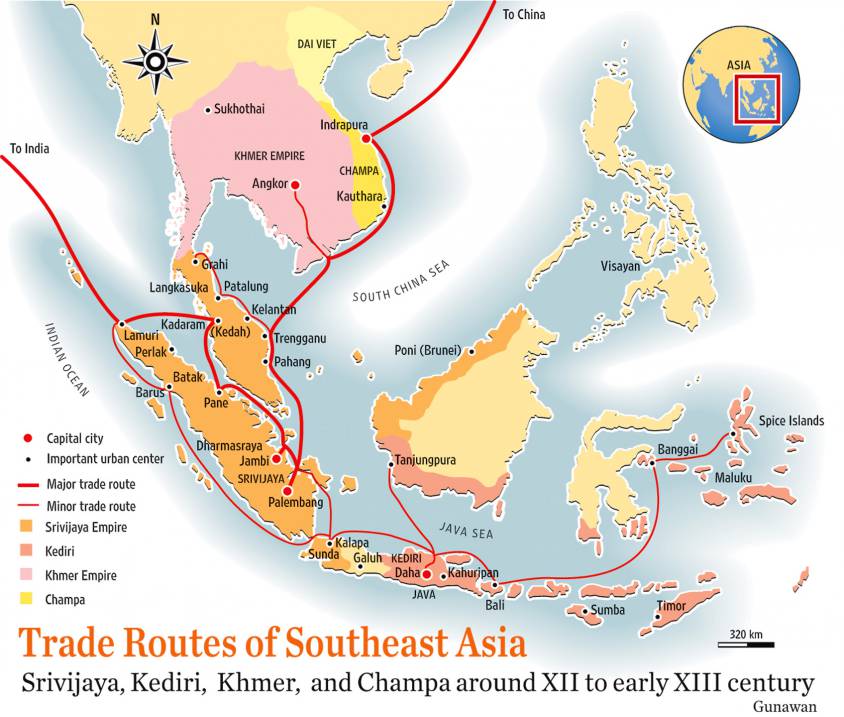

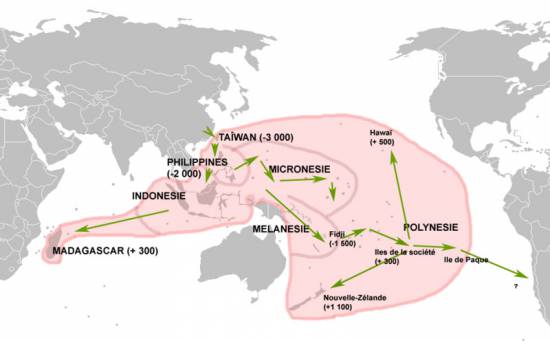

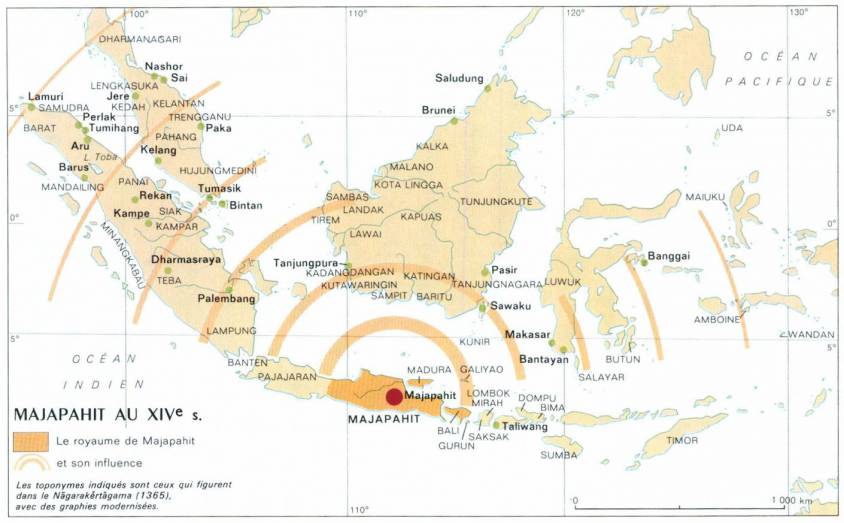

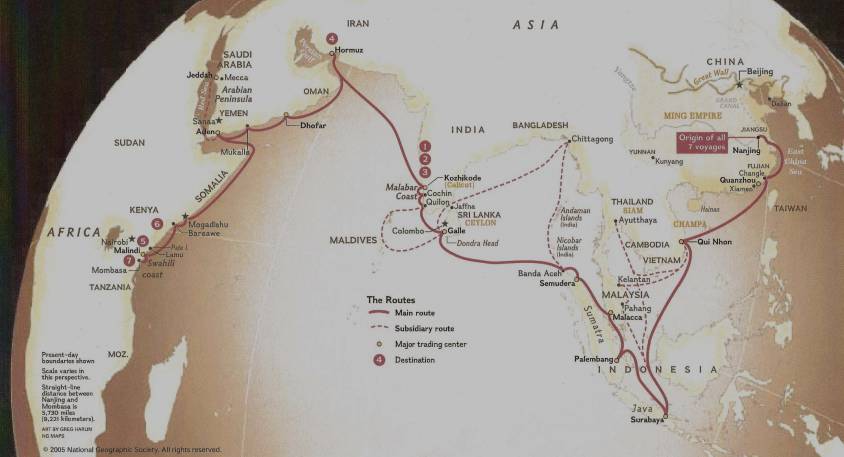

2. It was the encounter with Asia that brought countless technical know-how and scientific discoveries from the East to Europe, the best-known being the compass and gunpowder. Just as essential to printing as movable type was paper, the manufacture of which was perfected in China at the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (around the year 185). As for printing, the oldest printed book we have to date is the Diamond Sutra, a Chinese Buddhist scripture dating from 868. Finally, it was in the mid-11th century, under the Song dynasty, that Bi Sheng (990-1051) invented movable type. Engraved in porcelain, a viscous clay ceramic, hardened in fire and assembled in resin, they revolutionized printing. As documented by the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, it was the Korean Choe Yun-ui (1102-1162) who improved this technique in the 12th century by using metal (less fragile), a process later adopted by Gutenberg and his associates. The Anthology of Zen Teachings of Buddhist High Priests (1377), also known as the Jikji, was printed in Korea 78 years before the Gutenberg Bible, and is recognized as the world’s oldest book with movable metal type.

3. Etienne Taillemite, Lafayette and the abolition of slavery.

4. Victor Hugo undoubtedly wanted to rebound on the news that reached him from America. The Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic of 1862, which was brought from San Francisco to Victoria, devastated the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest coast, with a mortality rate of over 50% along the entire coast from Puget Sound to southeast Alaska. Some historians have described the epidemic as a deliberate genocide, as the colony of Vancouver Island and the colony of British Columbia could have prevented it, but chose not to, and in a way facilitated it.

5. Victor Hugo, La civilisation from Toute la lyre (1888 and 1893).

Bruegel, Petrarca and the « Triumph of Death »

By Karel Vereycken, april 2020.

The Triumph of Death? The simple fact that the heir to the throne of England, Prince Charles, and even the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, have tested positive to the terrifying coronavirus currently sweeping the planet, tells something to the public.

As some commentators pointed out (no irony) it “gave a face to the virus”. Until then, when an elderly person or a dedicated nurse died of the same, it “wasn’t real”.

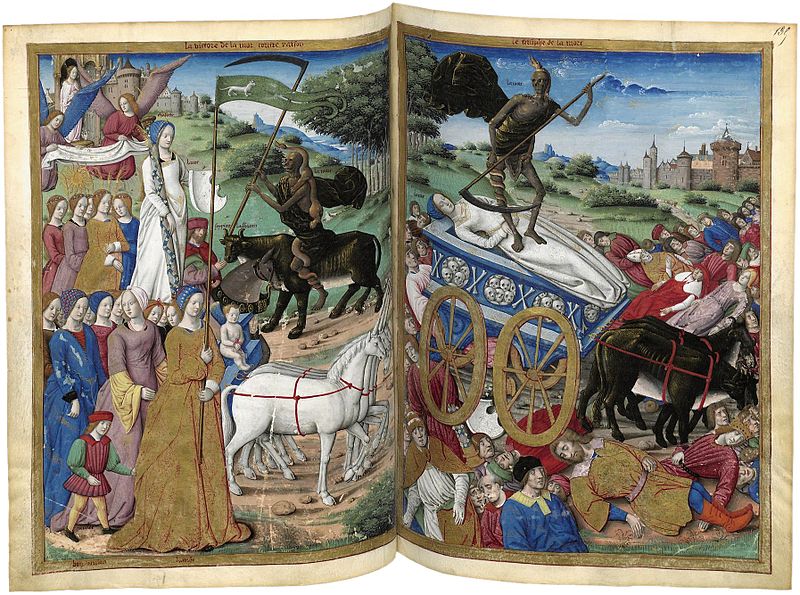

Realizing that these “higher-ups” are not part of the immortal Gods of Olympus but are mortals as all of us, brings to my mind “The Triumph of Death”, a large oil painting on panel (117 x 162 cm, Prado, Madrid), generally misunderstood, painted by the Flemish painter Peter Bruegel’s the elder (1525-1569), and thought to be executed between 1562 and his premature demise.

In order to discover, beyond the painting, the intention of the painter’s mind, it is always useful, before rushing into hazardous conclusions, to briefly describe what one sees.

What do we see in Bruegel’s « Triumph of Death« ? On the left, a skeleton, symbolizing death itself, holding a sand-glass in its hand, carries away a dead King. Next to him, another skeleton grabs the vast amounts of money no one can take with him into the grave. Death is driving a chariot. Below the charriot some people are crawling on their knees, hoping to remain unnoticed.

On the right, at the forefront, people are gambling and amusing themselves. A skeleton playing a musical instruments joins a prosperous young couple engaged in a musical dialogue and clearly unaware that Death is taking over the planet.

The message is simple and clear. No one can escape death, poor or rich, young or old, king or peasant, sick or healthy. When the hour comes, or at the end of all times, all mortals return to the creator since “physical” death triumphs over all of them.

Immortality

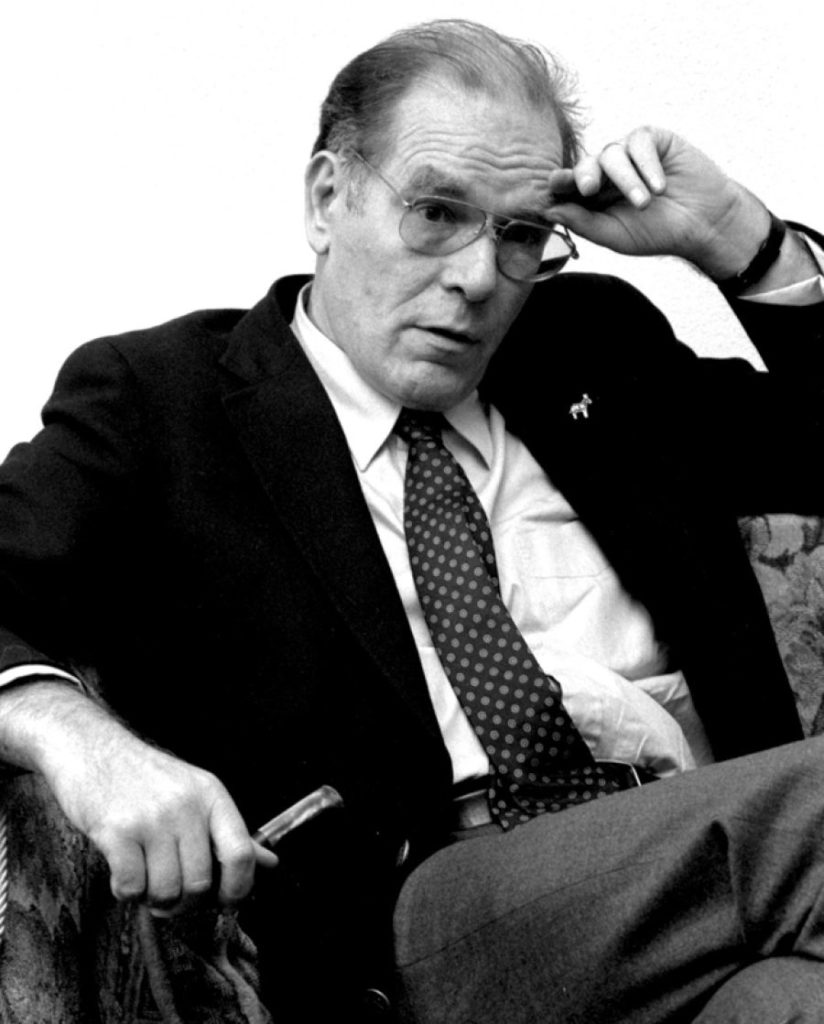

American thinker Lyndon LaRouche (1922-2019), in his speeches and writings, used to remind us, with his typical loving impatience: all human wisdom starts by a personal decision to acknowledge a fact proven without contest: we are all born and each of us, sooner or later, will die. So far, our bodies have all been proven mortal.

The duration of our mortal existence on the clock of the universe, he reminded, is less than a nanosecond.

Therefore, knowing this boundary condition of our mortal existence, we, each of us, have to make a personal sovereign decision: how will I spend the talent of my life ? Will I spend that talent chasing the earthly pleasures of the flesh, or dedicate my life to defending the truth, the beautiful and the good, to the great benefit of humanity as a whole, living in past, present and future ?

In 2011, in a discussion, LaRouche explained what he meant by saying that humanity has the potential to become an “immortal” species:

I live; as long as I live, I may generate ideas.

These conceptions give mankind a chance to move forward.

But then the time will come when I will die.

Now, two things happen: First of all, if these creative principles,

which have been developed by earlier generations,

are realized in the future, that means that mankind is an immortal species. We are not personally immortal;

but to the extent that we’re creative, we’re an immortal species.

And the ideas that we contribute to society

are permanent contributions to the human society.

We are therefore an immortal species,

based on mortal beings. And the key thing in life is to grasp that connection.

To say that we’re creative and die,

doesn’t tell us the story. If we, in our own lives, who are about to die,

can contribute something that is permanent, which will outlive our death, and be a benefit to mankind in future times, we have achieved the purpose of immortality.

And that is the crucial thing.

If people can actually face, with open minds, the fact that we’re each going to die—but look at it in the right way,

then we are impassioned to make the contributions,

to discover the principles, to do the work that is immortal.

Those discoveries of principle which are immortal, which pass on from one generation to the other. And thus, the dead live in the living;

because what the dead do, if they have done that in their lifetime, they are alive, not as in the flesh, but they’re alive in principle.

They’re part, an active part, of human society.

Christian humanism

LaRouche’s outlook, the “moral” obligation to live a “creative” existence on Earth in the image of the Creator, was deeply rooted in the philosophical outlook of both the Platonic and the Judeo-Christian tradition, whose happy marriage gave us the beautiful Christian humanism which, in the early XVth Century, ignited an unprecedented explosion, on a mass-scale and of unseen density of economic, scientific, artistic and cultural achievements, later qualified as a “Renaissance”.

In Plato’s Phaedon, Socrates develops the idea that our mortal body is a constant impediment to philosophers in their search for truth: “It fills us with wants, desires, fears, all sorts of illusions and much nonsense, so that, as it is said, in truth and in fact no thought of any kind ever comes to us from the body” (66c). To have pure knowledge, therefore, philosophers must escape from the influence of the body as much as is possible in this life. Philosophy (Literally “The love of wisdom”) itself is, in fact, a kind of “preparation for dying” (67e), a purification of the philosopher’s soul from its bodily attachment.

Also the Vulgate’s Latin rendering of Ecclesiastics 7:40 stresses: « in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin”. This passage finds expression in the christian ritual of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshippers’ heads with the words: “Remember Man that You are Dust and unto Dust You Shall Return.”

Is this a morbid ritual? No, it is a philosophy lesson. Christianity itself, as a religion, cherishes God’s own son made man, Jesus, for having renounced to his mortal life for the sake of mankind. It put Jesus’ death at the center. And in the XIVth century, Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), one of the leading intellectuals and founders of the Brothers of the Common Life, wrote that every Christian should shape his life in the “Imitation of Christ”. Both Nicolaus of Cusa (1401-1464) and Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) were powerfully influenced and trained by this intellectual current.

Concedo Nulli

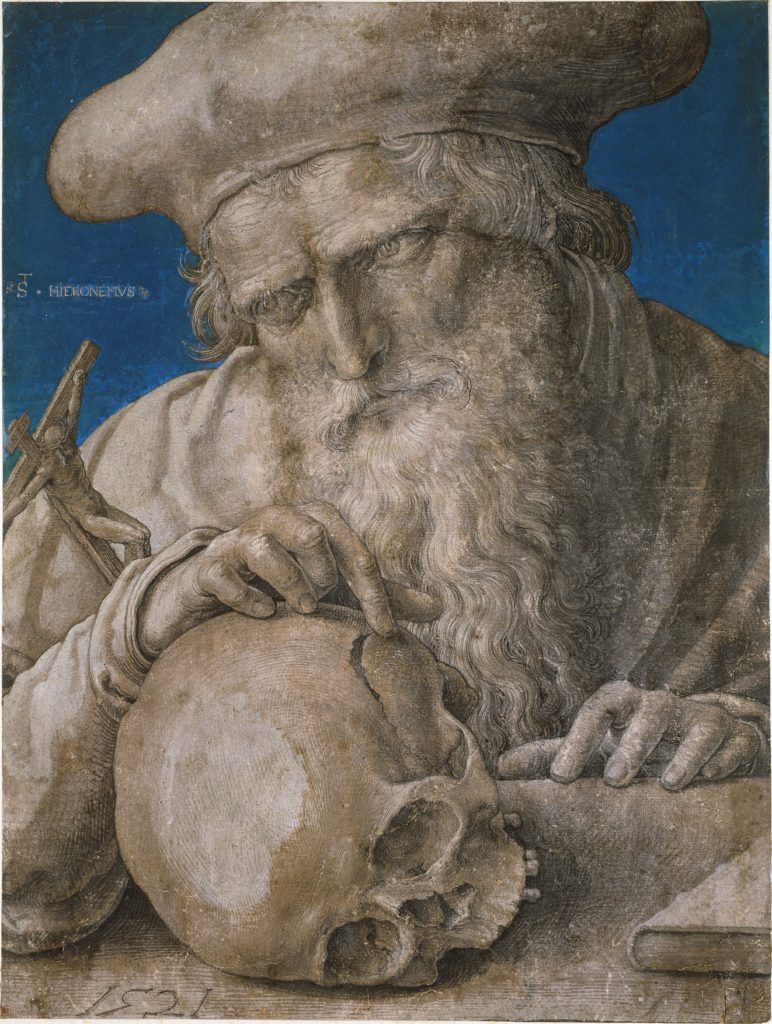

Erasmus’ personal armory was the juxtaposition of a skull and a sand-glass, referring to death and time as the boundary conditions of human existence.

In 1519, his friend, the Flemish painter and goldsmith Quentin Matsys (1466-1530) forged a bronze medal to the honor of the great humanist.

On one side of the medal there is an efigee of Erasmus and a Latin inscription informs us that this is “an image taken from life”. At the same time we are told in Greek, « his writings will make him better. known »

The reverse side of the medal shows solemn inscriptions surrounding an unusual image. At the top of a pillar that stands in rough, uneven ground, emerges the head of a young man with a stubbly chin and wild, flowing hair. Like Erasmus on the other side of the medal, he seems to have a faint smile upon his face. On either side of the head are the words “Concedo Nulli”– “I yield to no one.” On the pillar is inscribed Terminus, the name of a Roman god who presided over boundaries. Again bilingual quotations surround a profile. On the left, in Greek, is the instruction, « Keep in mind the end of a long life. » On the right, in Latin, is the stark reminder, « Death is the ultimate boundary of things. »

Adapting as his own motto “I yield to no one”, Erasmus took the great risk of using such a daring metaphor. Accused of intolerable arrogance by his sycophants, he underlined that “Concedo Nulli” had to be understood as death’s own statement, not his own. And who could argue with the assertion that death is the terminus that yields to no one?

Mozart, Brahms and Gandhi

Centuries later, the great humanist composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was the exact opposite of a morbid cynic. Revealing his inner mindset, Mozart once said that the secret of all genius, was love for humanity: “neither a lofty degree of intelligence nor imagination nor both together go to the making of genius. Love, love, love, that is the soul of genius”.

But on April 4, 1787, Mozart wrote to his father, Leopold, as he lay dying :

I need hardly tell you how greatly I am longing

to receive some reassuring news from yourself.

And I still expect it ; although I have now made a habit of being prepared in all affairs of life for the worst.

As death, when we come to consider it closely,

is the true goal of our existence,

I have formed during the last few years such close relations with this best and truest friend of mankind,

that his image is not only no longer terrifying to me,

but is indeed very soothing and consoling !

And I thank God for graciously granting me

the opportunity (you know what I mean)

of learning that death is the key

which unlocks the door to our true happiness.

I never lie down at night

without reflecting that –young as I am– I may not live to see another day.

Johannes Brahms 1865 German Requiem, quotes Peter 1:24-25 reminding us that

“For all flesh is as grass,

and all the glory of man as the flower of grass.

The grass withereth, and the flower thereof falleth away.

But the word of the Lord endureth for ever.”

Also Mahatma Gandhi, expressed, in his own way, somthing similar, about how one has to live simultaneously with mortality and immortality:

« Live as if you were to die tomorrow.

Learn as if you were to live forever. »

Memento Mori and Vanitas

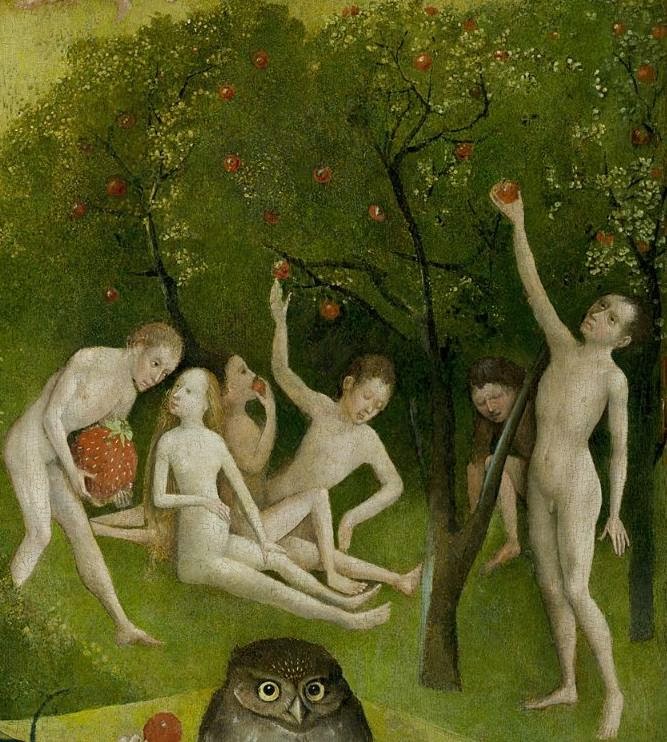

Just as Hieronymus Bosch’s (1450-1516) painting of the “Garden of Earthly Delights” (Prado, Madrid), where the great Dutch master uses the metaphor of naked humans incessantly chasing delicious fruits, calls on the viewer to become aware of his close-to-ridiculous, animal-like attachment to earthly pleasures and calls on his free will and his sens of humor to free himself, Bruegel’s “Triumph of Death” painting, on a first level, is fundamentally nothing else than a complex Memento Mori (Latin “remember that you must die”).

With this painting, Bruegel pays tribute to his intellectual godfather’s motto Concedo Nulli, that is, as Erasmus did in his writings, Bruegel paints the ineluctability of death, not by praising its horror, but with the aim of inspiring his fellow citizens to walk into immortality. In the same way Erasmus’ « In praise of folly » was in fact an inversion of his praise of reason, Brueghel’s « Triumph of Death » was conceived as a triumph of (immortal) life.

For the Catholic faith, the aim of a Memento Mori was to remind (and eventually terrorize) the believer that after death, he or she might end up in Purgatory or worse in Hell if they did not respect the Church and her rites. With the invention of oil painting in the early XVth century, panel paintings of this genre for private homes and small chapels were considered aesthetic objects crafted for the sake of religious and philosophical contemplation.

Hence, starting with the Renaissance, the Memento Mori painting became a much demanded artifact, re-branded in the following centuries as “Vanitas”, Latin for « emptiness » or « vanity ». Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, Vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies and hourglasses.

Iconography

A first source is of course, the famous designs and woodcuts executed by Erasmus intimate friend and illustrator of his “In Praise of Folly”, Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), for his satirical “Dance of Death” (1523), which –breaking with the way the “Dance macabre” was used before by the Flagellants and other madmen to desensitize the population in order to push them into a fatalistic retreat of the outer world– introduces the new philosophical dimension that Bruegel will develop.

The close-to-embarassing anamorphosic representation of a giant skull in Holbein’s work « The Ambassadors » (1533), demonstrates his profound understanding of the Memento Mori metaphor.

Erasmus’ friend Albrecht Dürer‘s engraving « Knight, Death and the Devil » (1513), or his « Saint Jerome in his study » (1514) (with skull and hourglass) are two other examples.

Bruegel and Italy

Ironically, Peter Bruegel the elder has always been presented as a painter of the Northern School who was completely closed to the “Italian” Renaissance.

The reality is that while rejected the transformation of the Renaissance into a form of mannerism in the XVIth century, he took most of his inspiration directly from two Italian Renaissance sources.

First, of course, the image of Death riding a horse, and even a group of persons such as the young couple engaged in their musical embrace, appear incontestably as taken from the Triumph of Deat”, a vast fresco from 1446 which decorated the walls of the Palazzo Sclafani in Palermo, Sicily. Bruegel’s trip to Southern Italy is a well documented fact.

The second source, which undoubtedly also inspired the painter of the fresco, is a series of allegorical poems known as “I Trionfi” (“The Triumphs”: Triomph of Love, of Chastity, of Death, of Fame, of Time and of Eternity), composed by the great Italian poet Francesco Petrarca, most likely following the “Black Death”, a pandemic outbreak which, starting with the 1345 banking crash, decimated a vast portion of the population of Europe.

Petrarca’s genius was precisely to offer to those terrified with the very idea of having to face their physical mortality, a philosophical answer to their anxiety.

As a result, his Trionfi became rapidly popular, not only in Italy but all over Europe. And for most painters, working on Petrarca’s themes became part of their common repertoire.

To conclude, here is an excerpt (English) of the poem, where Petrarca blasts the mad lust of Kings and Popes for wealth, pleasure and earthly power. In the face of death, he stresses, they are worthless. Petrarca’s wording fits to the detail the images used by Bruegel in his painting The Triumph of Death :

(…) afar we might perceive

Millions of dead heap’d on th’ adjacent plain;

No verse nor prose may comprehend the slain

Did on Death’s triumph wait, from India,

From Spain, and from Morocco, from Cathay,

And all the skirts of th’ earth they gather’d were;

Who had most happy lived, attended there:

Popes, Emperors, nor Kings, no ensigns wore

Of their past height, but naked show’d and poor.

Where be their riches, where their precious gems,

Their mitres, sceptres, robes, and diadems?

O miserable men, whose hopes arise

From worldly joys, yet be there few so wise

As in those trifling follies not to trust;

And if they be deceived, in end ’tis just:

Ah! more than blind, what gain you by your toil?

You must return once to your mother’s soil,

And after-times your names shall hardly know,

Nor any profit from your labour grow;

All those strange countries by your warlike stroke

Submitted to a tributary yoke;

The fuel erst of your ambitious fire,

What help they now? The vast and bad desire

Of wealth and power at a bloody rate

Is wicked,–better bread and water eat

With peace; a wooden dish doth seldom hold

A poison’d draught; glass is more safe than gold;

Whether Bruegel, who saw undoubtedly the fresco in Palermo during his trip in the 1550s, had read Petrarca’s poem remains an open question. It can be said that many of his direct friends were familiar with the Italian poet.

In Antwerp, the painter was a frequent guest of the Scola Caritatis, a humanist circle animated by one Hendrick Nicolaes, where Brueghel met poets, translaters, painters, engravers (Cock, Golzius) mapmakers (Mercator), cosmographers (Ortelius) and bookmakers such as the Antwerp printer Christophe Plantijn, who’se renowned printing shop would print Petrarca’s poetry.

Also in Antwerp, indicating how popular Petrarca’s poetry had become in the Low Countries and France, the franco-flemish Orlandus Lassus (1532-1594) published his first musical compositions, including his madrigals on each of the six Trionfi of Petrarca, among which the « Triumph of Death ».

Conclusion

All evil, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) hoped, can give birth to something good, far bigger and superior to the evil that provoked it. Therefore, we can hope that the current pandemic breakdown crisis will lead some of the leading decision-makers, with our help, to reflect on the sens and purpose of their lives. The worst would be to return to yesterday’s “normalcy” since that kind of “normal” is exactly what drove the planet currently to the verge of extinction.

At last, it should be stressed that in the same way Lyndon LaRouche, by his ruthless (Concedi Nulli) commitment to defend the sacred creative nature of every human individual, contributed to the enduring immortality of Plato, Petrarca, Erasmus and Bruegel, it is up to each of us to carry even further that battle.