Étiquette : Sicily

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on mars 25, 2024

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Antonello de Messina in the Image of Christ

Listen:

to the audio on this website:

Read:

- Les Frères de la vie commune et la Renaissance du nord (FR en ligne)

- Moderne Devotie en Broeders van het Gemene Leven, bakermat van het humanisme (NL online)

- Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life, the cradle of humanism in the North (EN online)

- Hugo van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne (FR en ligne);

Posted in ARTKAREL Louvre audio guide, Comprendre | Commentaires fermés sur LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Antonello de Messina in the Image of Christ

Tags: antonello, artkarel, chirst, column, dessin, Dutch, execution, hanging rope, Karel, Karel Vereycken, messina, Netherlands, peinture, renaissance, Sicily, tears

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on septembre 26, 2023

The Maritime Silk Road, a history of 1001 Cooperations

Today, it’s fashionable to present maritime issues in the context of a moribund British geopolitical ideology that pits countries and peoples against each other. However, as this brief history of the Maritime Silk Road, drawn mainly from a document by the International Tourism Organization, demonstrates, the ocean has above all been a fantastic place for fertile encounters, cultural cross-fertilization and mutually beneficial cooperation.

The ancient Chinese invented many of the things we use today, including paper, matches, wheelbarrows, gunpowder, the noria (water elevator), sluice locks, the sundial, astronomy, porcelain, lacquer paint, the potter’s wheel, fireworks, paper money, the compass, the stern rudder, the tangram, the seismograph, dominoes, skipping rope, kites, the tea ceremony, the folding umbrella, ink, calligraphy, animal harnesses, card games, printing, the abacus, wallpaper, the crossbow, ice cream, and especially silk, which we’ll be talking about here.

The Origins of Silk

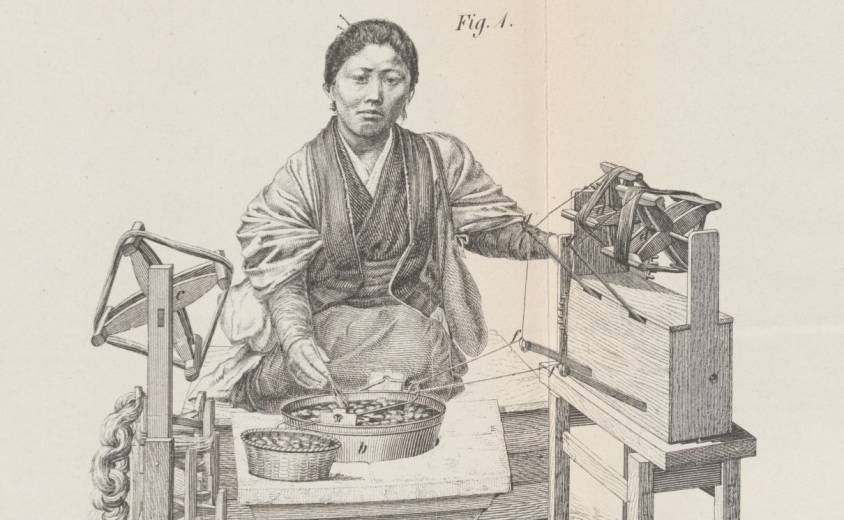

Before we talk about silk « routes », a few words about the origins of sericulture, i.e. the rearing of silkworms.

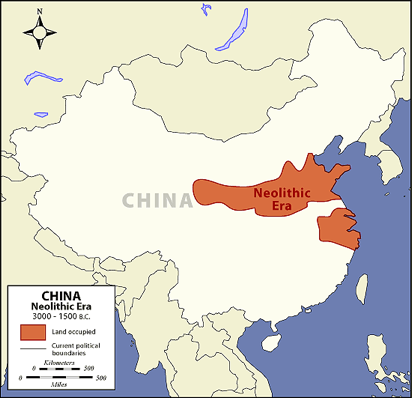

As recent archaeological discoveries confirm, silk production is an age-old skill. The presence of the mulberry tree for silkworm rearing was noted in China around the Yellow River by the Yangshao culture during the Middle Neolithic period in China, from 4500 to 3000 BC.

In general, we prefer to retain the legend that silk was discovered around 2500 BC, by the Chinese princess Si Ling-chi, when a cocoon accidentally fell into her tea bowl. When she tried to remove it, she discovered that the cocoon, softened by the hot water, had a delicate, soft and strong thread that could be unwound and assembled. Thus was born the idea of making cloth. The princess then decided to plant a number of white mulberry trees in her garden to raise silkworms.

The silkworms (or bombyx) and mulberry trees were divinely cared for by the princess (silkworms feed solely on the leaves of white mulberry trees).

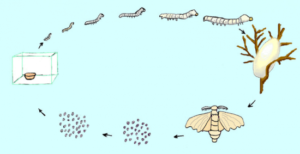

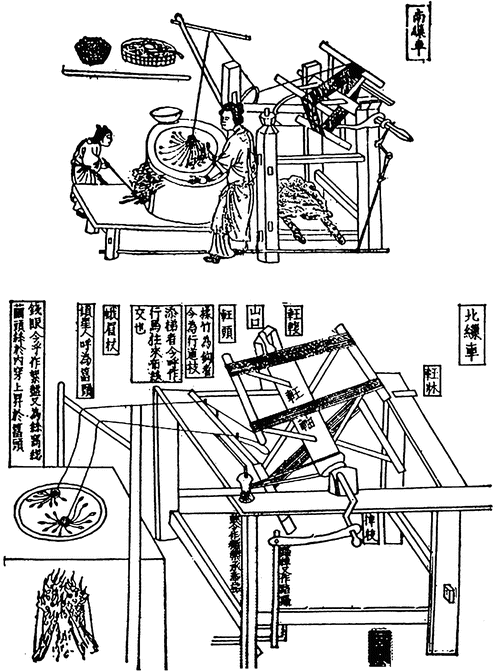

Silk production is a time-consuming process that requires careful monitoring. Silk moths lay around 500 eggs during their lives, which last from 4 to 6 days. After the eggs hatch, the baby worms feed on mulberry leaves in a controlled environment. They have a ferocious appetite and their weight can increase considerably. Once they’ve stored up enough energy, the worms secrete a white jelly from their silk glands and use it to build a cocoon around themselves. After eight or nine days, the worms are killed and the cocoons are immersed in boiling water to soften the protective filaments, which are wound onto a spool. These filaments can be 600 to 900 meters long. Several filaments are assembled to form a thread. The silk threads are then woven into a fabric or used for fine embroidery or brocade, a rich silk fabric embellished with brocaded designs in gold and silver thread.

The Early Silk Trade

Under threat of capital punishment, sericulture remained a well-kept secret, and China retained its monopoly on manufacturing for millennia.

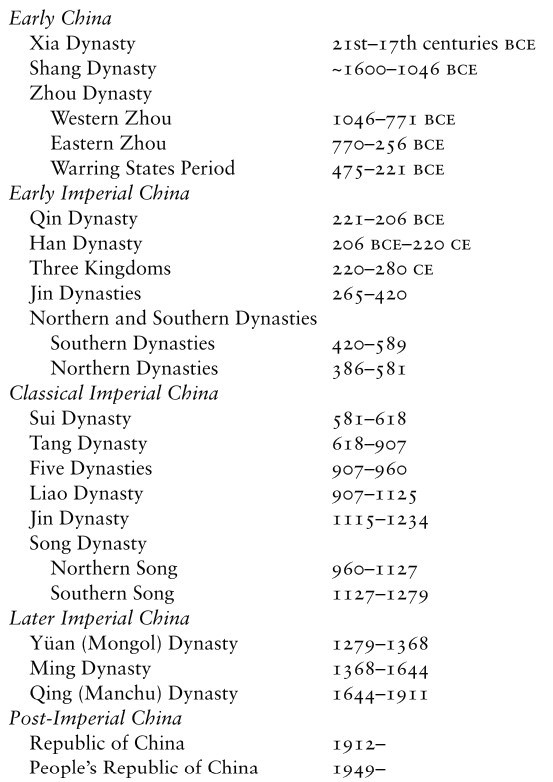

It wasn’t until the Zhou dynasty (1112 BC) that a maritime Silk Road was established from China to Japan and Korea, as the government decided to send Chinese from the port in Bohai Bay (on the Shandong Peninsula) to train local inhabitants in sericulture and agriculture. The techniques of silkworm rearing, reeling and weaving were gradually introduced to Korea via the Yellow Sea.

When Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China (221 BC), many people from the states of Qi, Yan and Zhao fled to Korea, taking with them silkworms and their rearing techniques. This accelerated the development of silk spinning in Korea.

Korea played a central role in China’s international relations, particularly as an intellectual bridge between China and Japan. Its trade with China also enabled the spread of Buddhism and porcelain-making methods. Although initially reserved for the imperial court, silk spread throughout Asian culture, both geographically and socially. Silk quickly became the luxury fabric par excellence that the whole world craved.

During the Han dynasties (206 BC to 220), a dense network of trade routes exploded cultural and commercial exchanges across Central Asia, profoundly impacting civilizational dynamics. The Han dynasty continued to build the Great Wall, notably creating the commandery of Dunhuang (Gansu), a key post on the Silk Road. Over two centuries B.C., its trade extended to Greece and Rome, where silk was reserved for the elite.

In the IIIrd century, India, Japan and Persia (Iran) unlocked the secret of silk manufacture and became major producers.

Silk Reaches Europe

According to a story by Procopius, it was not until 552 AD that the Byzantine emperor Justinian obtained the first silkworm eggs. He had sent two Nestorian monks to Central Asia, and they were able to smuggle silkworm eggs to him hidden in rods of bamboo. While under the monks’ care, the eggs hatched, though they did not cocoon before arrival.

A church manufacture in the Byzantine Empire was thus able to make fabrics for the emperor. Later emerged the intention of developing a large silk industry in the Eastern Roman Empire, using techniques copied from the Persian Sassanids.

Another version claims that it was the Han emperor Wu (IInd century) who sent ambassadors, bearing gifts such as silk, to the West.

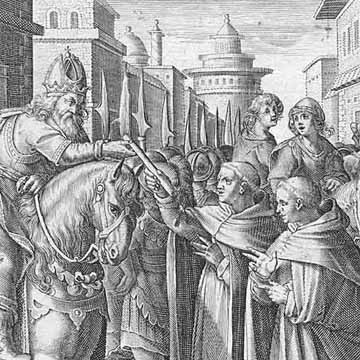

In the VIIth century, sericulture spread to Africa and Sicily, from where, under the impetus of Roger I of Sicily (c. 1034-1101) and his son Roger II (1093-1154), the silkworm and mulberry were introduced to the ancient Peloponnese.

In the Xth century, Andalusia became the epicenter of silk manufacturing with Granada, Toledo and Seville. With the Arab conquest, sericulture spread to the rest of Spain, Italy (Venice, Florence and Milan) and France. The earliest French traces of sericulture date back to the 13th century, notably in the Gard (1234) and Paris (1290).

In the XVth century, faced with the ruinous import of Italian silk (raw or manufactured), Louis XI tried to set up silk factories, first in Tours on the Loire, then in Lyon, a city at the crossroads of north-south routes where Italian emigrants were already trading in silks.

In the XIXth century, silk production was industrialized in Japan, but in the XXth century, China regained its place as the world’s largest producer. Today, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Uzbekistan and Brazil all have large production capacities.

Cultural Melting Pot

As much as silk itself, the transportation of silk by sea dates back to time immemorial.

For the Chinese, there are two main routes: the East China Silk Road (to Korea and Japan) and the South China Silk Road (via the Strait of Malacca to India, the Persian Gulf, Africa and Europe).

In Vietnam, the Hanoi Museum holds a coin dating back to the year 152, bearing the effigy of the Roman emperor Antoninus the Pious. The coin was discovered in the remains of Oc Eo, a Vietnamese town south of the Mekong Delta, thought to have been the main port of the Funan Kingdom (Ist to IXth centuries).

This kingdom, which covered the territory of present-day Cambodia and the Mekong Delta administrative region of Vietnam, flourished from the 1st to the 9th century. The first mention of the Fou-nan kingdom appears in the report of a Chinese mission that visited the area in the 3rd century.

The Founamians were at the height of their power when Hinduism and Buddhism were introduced to Southeast Asia.

Then, from Egypt, Greek merchants reached the Bay of Bengal. Considerable quantities of pepper then reached Ostia, Rome’s port of entry. All the historical evidence shows that East-West trade was flourishing as early as the first millennium.

Persians and Arabs in India, China and Asia

On the western side, at the entrance to Kuwait Bay, 20 kilometers off the coast of Kuwait City, not far from the mouth of the shared estuary of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the Persian Gulf, the island of Failaka was one of the meeting places where Greece, Rome and China exchanged goods.

Under the Sassanid dynasty (226-651), the Persians developed their trade routes all the way to Southeast Asia, via India and Sri Lanka.

This trading infrastructure was later taken over by the Arabs when, in 762, they moved to Baghdad.

From the IXth century onwards, the city of Quilon (Kollam), the capital of Kerala in India, was home to colonies of Arab, Christian, Jewish and Chinese merchants.

On the western side, Persian and then Arab navigators played a central role in the birth of the maritime Silk Road. Following the Sassanid routes, the Arabs pushed their dhows, or traditional Arab sailing ships, from the Red Sea to the Chinese coast and as far as Malaysia and Indonesia.

These sailors brought with them a new religion, Islam, which spread throughout Southeast Asia. While the traditional pilgrimage (the hajj) to Mecca was initially only an aspiration for many Muslims, it became increasingly possible for them to make it.

During the monsoon season, when winds were favorable for sailing to India in the Indian Ocean, the twice-yearly trade missions were transformed into veritable international fairs, offering an opportunity to transport large quantities of goods by sea in conditions (apart from pirates and unpredictable weather) relatively less exposed to the dangers of overland transport.

The Maritime Silk Road under the Sui, Tang and Song Dynasties

It was under the Sui dynasty (581-618) that the Maritime Silk Road set out from Quanzhou, a coastal city in Fujian province in south-east China, on its first trade routes.

With its wealth of scenic spots and historic sites, Quanzhou has been proclaimed « the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road » by UNESCO.

It was at this time that the first printing methods appeared in China. Wooden blocks were used to print on textiles. In 593, the Sui emperor Wen-ti ordered the printing of Buddhist images and writings. One of the earliest printed texts is a Buddhist script dating from 868, found in a cave near Dunhuang, a stopover town on the Silk Road.

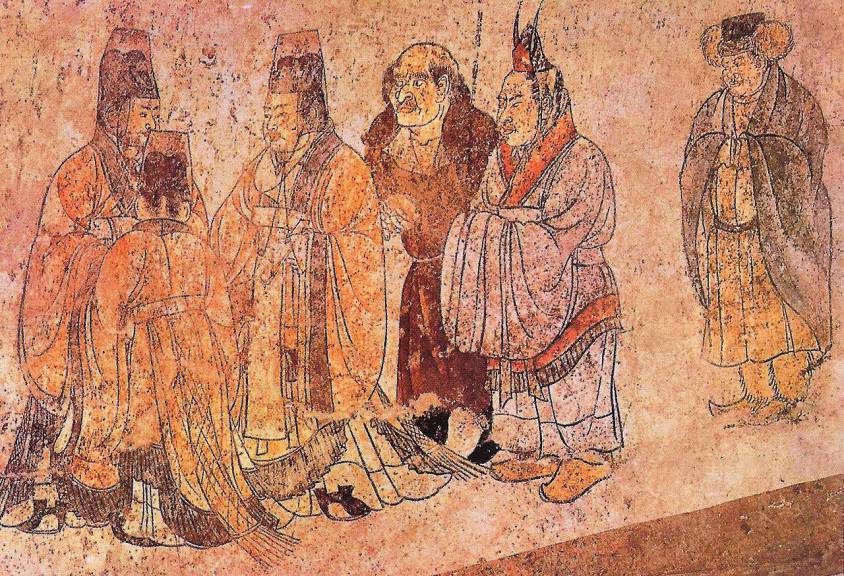

Under the Tang dynasty (618-907), the Kingdom’s military expansion brought security, trade and new ideas. The fact that the stability of Tang China coincided with that of Sassanid Persia enabled the land and sea Silk Roads to flourish. The great transformation of the maritime Silk Road began in the 7th century, when China opened up to international trade. The first Arab ambassador took up his post in 651.

The Tang Dynasty chose Chang’an (now Xi’an) as its capital. It adopted an open attitude towards different beliefs. Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian temples coexisted peacefully with mosques, synagogues and Nestorian Christian churches. As the terminus of the Silk Road, Chang’an’s western market is becoming the center of world trade. According to the Tang Authority Six register, over 300 nations and regions had trade relations with Chang’an.

Almost 10,000 foreign families from the west lived in the city, especially in the area around the western market. There were many foreign inns staffed by foreign maids chosen for their beauty. The most famous poet in Chinese history, Li Bai, often strolled among them. Foreign food, costumes and music were the fashion of Chang’an.

After the fall of the Tang dynasty, the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms (907-960), the arrival of the Song dynasty (960-1279) ushered in a new period of prosperity, characterized by increased centralization and economic and cultural renewal. The maritime silk route regained its momentum. In 1168, a synagogue was built in Kaifeng, capital of the Southern Song dynasty, to serve merchants on the Silk Road.

During the same period, as Islam expanded, trading posts sprang up all around the Indian Ocean and the rest of Southeast Asia.

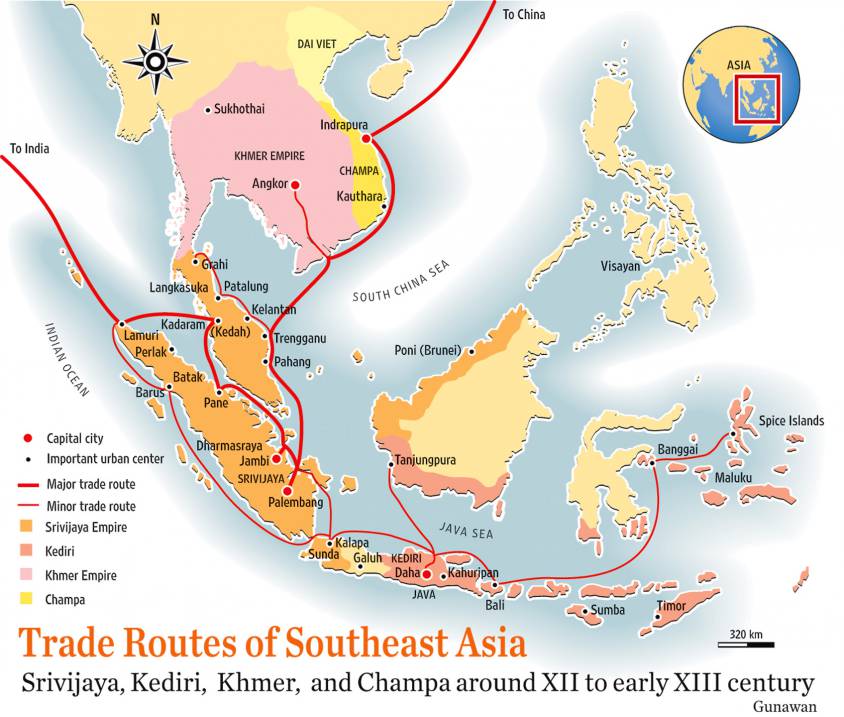

China encouraged its merchants to seize the opportunities offered by maritime traffic, in particular the sale of camphor, a highly sought-after medicinal plant. A veritable trade network developed in the East Indies under the auspices of the Kingdom of Sriwijaya, a city-state in southern Sumatra, Indonesia (see below), which for nearly six centuries served as a link between Chinese merchants on the one hand, and Indians and Malays on the other. A trade route truly emerged, deserving the name of the maritime « Silk Road ».

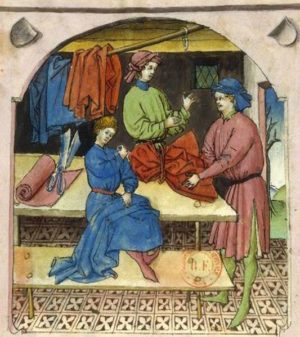

Increasing quantities of spices passed through India, the Red Sea and Alexandria in Egypt, before reaching the merchants of Genoa, Venice and other Western ports. From there, they moved on to the northern European markets of Lübeck (Germany), Riga (Lithuania) and Tallinn (Estonia), which from the 12th century onwards became important cities in the Hanseatic League.

In China, during the reign of the Song emperor Renzong (1022-1063), a great deal of money and energy was spent on bringing together knowledge and know-how. The economy was the first to benefit.

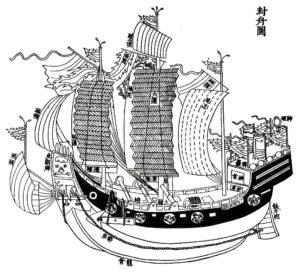

Drawing on the know-how of Arab and Indian sailors, Chinese ships became the most advanced in the world.

The Chinese, who had invented the compass (at least by 1119), quickly surpassed their competitors in cartography and the art of navigation, as the Chinese junk became the bulk carrier par excellence.

In his geographical treatise, Zhou Qufei, in 1178, reports:

« The big ships that cruise the South Sea are like houses. When they unfold their sails, they look like huge clouds. Their rudders are dozens of feet long. A single ship can house several hundred men. On board, there’s enough food to last a year.«

Archaeological digs confirm this reality, such as the wreck of a XIVth-century junk found off the coast of Korea, in which over 10,000 pieces of ceramic were discovered.

During this period, coastal trade gradually shifted from the hands of Arab traders to those of Chinese merchants. Trade expanded, notably with the inclusion of Korea and the integration of Japan, the Malabar coast of India, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea into existing trade networks.

China exported tea, silk, cotton, porcelain, lacquers, copper, dyes, books and paper. In return, it imported luxury goods and raw materials, including rare woods, precious metals, precious and semi-precious stones, spices and ivory.

Copper coins from the Song period have been discovered in Sri Lanka, and porcelain from this period has been found in East Africa, Egypt, Turkey, some Gulf states and Iran, as well as in India and Southeast Asia.

The Importance of Korea and the Kingdom of Silla

During the first millennium, culture and philosophy flourished on the Korean peninsula. A well-organized and well-protected trading network with China and Japan operated there.

On the Japanese island of Okino-shima, numerous historical traces bear witness to the intense exchanges between the Japanese archipelago, Korea and the Asian continent.

Excavations carried out in ancient tombs in Gyeongju, today a South Korean city of 264,000 inhabitants and capital of the ancient Kingdom of Silla (from 57 BC to 935), which controlled most of the peninsula from the VIIth to the IXth century, demonstrate the intensity of this kingdom’s exchanges with the rest of the world, via the Silk Road.

Indonesia, a Major Maritime Power at the Heart of the Maritime Silk Road

In Indonesia, Malaysia and southern Thailand, the Kingdom of Sriwijaya (VIIth to XIIIth centuries) played a major role as a maritime trading post, storing high-value goods from the region and beyond for later sale by sea. In particular, Sriwijaya controlled the Strait of Malacca, the essential sea passage between India and China.

At the height of its power in the XIth century, Sriwijaya’s network of ports and trading posts traded a vast array of products and commodities: rice, cotton, indigo and silver from Java, aloe (a succulent plant of African origin), vegetable resins, camphor, ivory and rhinoceros horns, tin and gold from Sumatra, rattan, redwoods and other rare woods, gems from Borneo, rare birds and exotic animals, iron, sandalwood and spices from East Indonesia, India and Southeast Asia, and porcelain, lacquer, brocade, textiles and silk from China.

With its capital at Palembang (population 1.7 million) on the Musi River in what is now the southern province of Sumatra, this Hindu-Buddhist-inspired kingdom, which flourished from the VIIIth to the XIIIth century, was the first major Indonesian kingdom and the country’s first maritime power.

By the VIIth century, it ruled a large part of Sumatra, the western part of Java and a significant part of the Malay Peninsula. It extended as far north as Thailand, where archaeological remains of Sriwijaya cities still exist.

Buddhism on the Maritime Silk Road

The museum in Palembang (today Indonesia) – a town where Chinese, Indian, Arab and Yemeni communities, each with their own particular institutions, have co-prospered for generations – tells a wonderful story of how the Maritime Silk Road generated exemplary mutual cultural enrichment.

Buddhism was closely tied to international or cross-boundary trade. Early inscriptions indicate it was common for seafarers to pray to the Buddha for a safe voyage.

The maritime routes were very challenging as they were often beset with cyclones and typhoons, and piracy was an ever-present danger.

As a consequence, merchant support for Buddhism along these travel routes helped to establish monastic life far beyond India. Monks and nuns also took passage on these trading ships, and the merchants sought good karma by helping them travel to spread the teachings of the Buddha.

Madagascar, Sanskrit and the Cinnamon Road

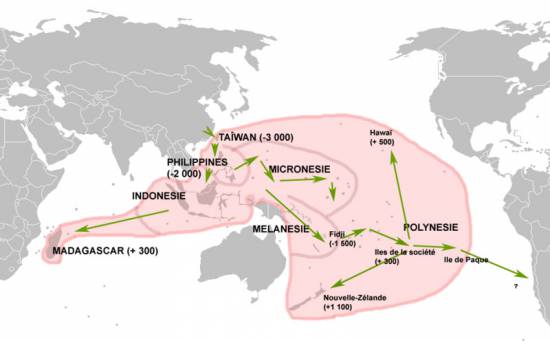

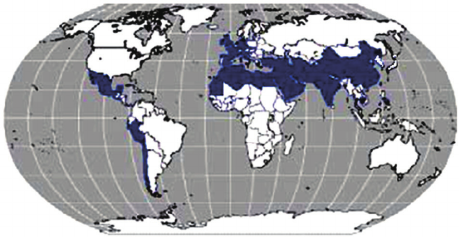

Map of the expansion of Austronesian languages.

Today, Madagascar is inhabited by Blacks and Asians. DNA tests have confirmed what has long been known: many of the island’s inhabitants are descended from Malay and Indonesian sailors who set foot on the island around the year 830, when the Sriwijaya Empire extended its maritime influence towards Africa.

Further evidence of this presence is the fact that the language spoken on the island borrows Sanskrit and Indonesian words.

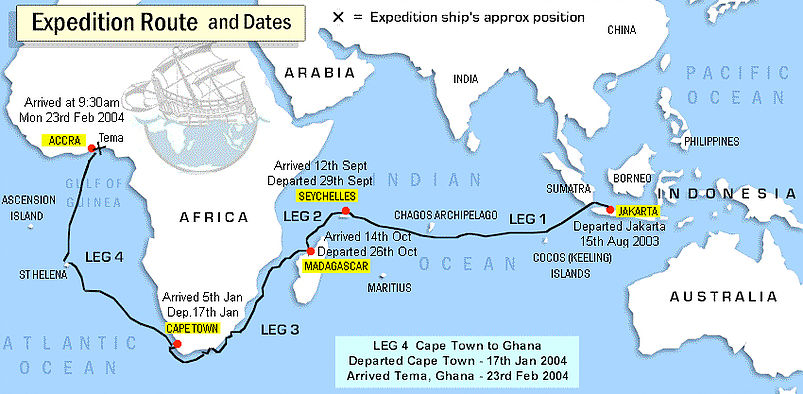

To demonstrate the feasibility of such sea voyages, in 2003 a team of researchers sailed from Indonesia to Ghana via Madagascar aboard the Borobudur, a reconstruction of one of the sailing ships featured in many of the 1,300 bas-reliefs decorating the 8th-century Buddhist temple of Borobudur on the island of Java in Indonesia.

Many believe that this vessel is a representation of those once used by Indonesian merchants to cross the ocean to Africa. Indonesian navigators usually used relatively small boats. To ensure balance, they fitted them with outriggers, both double (ngalawa) and single.

Their boats, whose hulls were carved from a single tree trunk, were called sanggara. Merchants from the Indonesian archipelago could reach as far east as Hawaii and New Zealand, a distance of over 7,000 km.

In any case, the researchers’ boat, equipped with an 18-meter-high mast, managed to cover the Jakarta – Maldives – Cape of Good Hope – Ghana route, a distance of 27,750 kilometers, or more than half the circumference of the Earth!

The expedition aimed to retrace a very specific route: the cinnamon route, which took Indonesian merchants all the way to Africa to sell spices, including cinnamon, a highly sought-after commodity at the time. Cinnamon was already highly prized in the Mediterranean basin long before the Christian era.

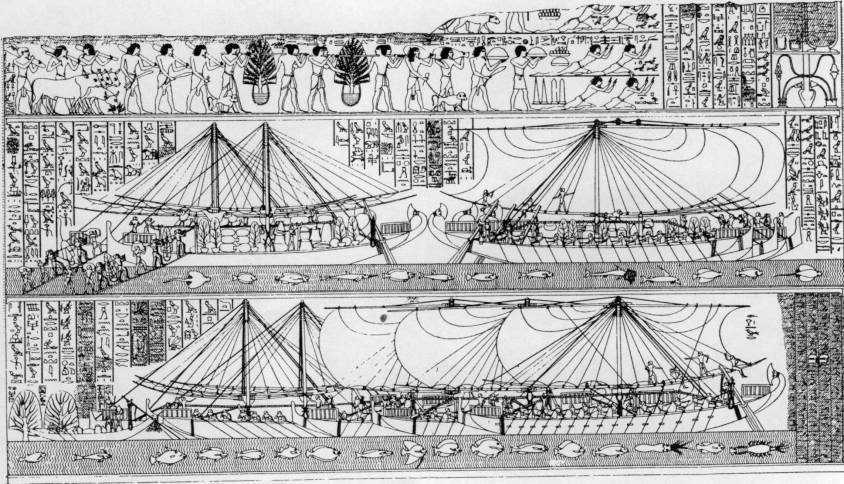

On the walls of the Egyptian temple at Deir el-Bahari (Luksor), a painting depicts a major naval expedition said to have been ordered by Queen Hatshepsut, who reigned from 1503 to 1482 BC. Around the painting, hieroglyphs explain that these ships carried various species of plants and fragrant essences destined for the cult. One of these was cinnamon. Rich in aroma, it was an important component of ritual ceremonies in the kingdoms of Egypt.

Cinnamon originally grew in Central Asia, the eastern Himalayas and northern Vietnam. The southern Chinese transplanted it from these regions to their own country and cultivated it under the name gui zhi.

From China, gui zhi spread throughout the Indonesian archipelago, finding a very fertile home there, particularly in the Moluccas. In fact, the international cinnamon trade was a monopoly held by Indonesian merchants. Indonesian cinnamon was prized for its excellent quality and highly competitive price.

The Indonesians sailed great distances, up to 8,000 km, across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar and northeast Africa. From Madagascar, products were transported to Rhapta, in a coastal region that later became known as Somalia. From there, Arab merchants shipped them north to the Red Sea.

The Strait of Malacca

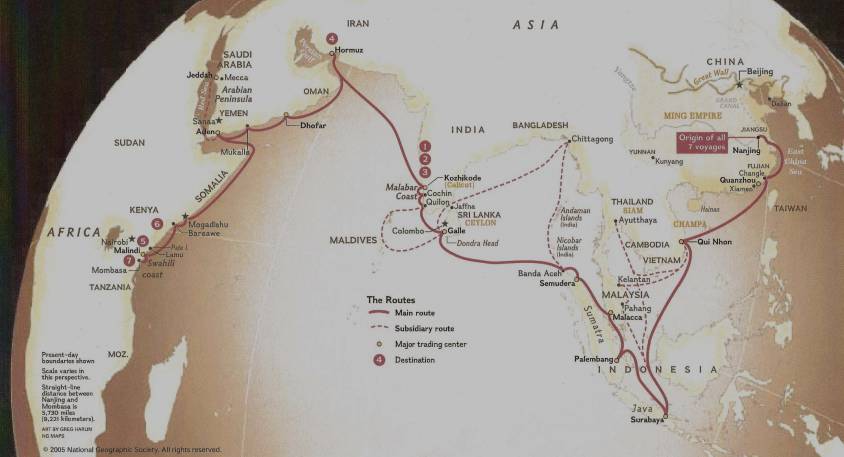

For China, the Strait of Malacca has always represented a major strategic interest. When the great Chinese admiral Zheng He led the first of his expeditions to India, the Near East and East Africa between 1405 and 1433, a Chinese pirate by the name of Chen Zuyi took control of Palembang.

Zheng He defeated Chen’s fleet and captured the survivors. As a result, the strait once again became a safe shipping route.

According to tradition, a prince of Sriwijaya, Parameswara, took refuge on the island of Temasek (present-day Singapore), but eventually settled on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula around 1400 and founded the city of Malacca, which would become the largest port in Southeast Asia, both successor to Sriwijaya and precursor to Singapore.

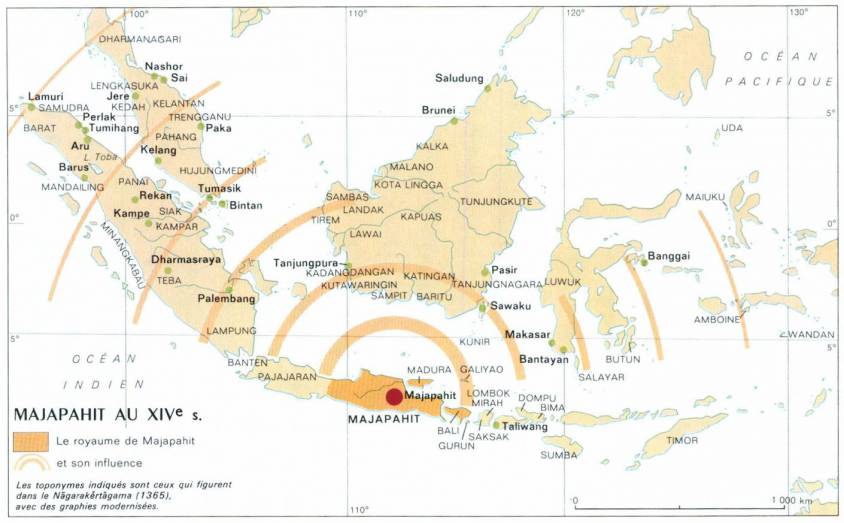

Following the decline of Sriwijaya, the Kingdom of Majapahit (1292-1527), founded at the end of the XIIIth century on the island of Java, came to dominate most of present-day Indonesia.

This was the period when Arab sailors began to settle in the region.

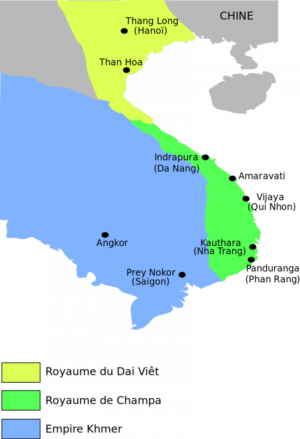

The Majapahit kingdom established relations with the Kingdom of Champa (192-1145; 1147-1190; 1220-1832) (South Vietnam), Cambodia, Siam (Thailand) and southern Myanmar.

The Majapahit kingdom also sent missions to China. As its rulers extended their power to other islands and sacked neighboring kingdoms, they sought above all to increase their share and control of the trade in goods passing through the archipelago.

The island of Singapore and the southernmost part of the Malay Peninsula was a key crossroads on the ancient maritime Silk Road.

Archaeological excavations in the Kallang estuary and along the Singapore River have uncovered thousands of shards of glass, natural and gold beads, ceramics and Chinese coins from the Northern Song period (960-1127).

The rise of the Mongol Empire in the middle of the XIIIth century led to an increase in seaborne trade and contributed to the vitality of the Maritime Silk Road.

Marco Polo, after a 17-year overland journey to China, returned by ship. After witnessing a shipwreck, he sailed from China to Sumatra in Indonesia, before setting foot on land again at Hormuz in Persia (Iran).

Under the Yuan and Ming Dynasties

Under the Song dynasty, large quantities of silk goods were exported to Japan. Under the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), the government set up the Shi Bo Si, a trade office, in a number of ports, including Ningbo, Canton, Shanghai, Ganpu, Wenzhou and Hangzhou, enabling silk exports to Japan.

During the Tang, Song and Yuan dynasties, and at the beginning of the Ming dynasty, each port set up an oceanic trading department to manage all foreign maritime trade.

Maritime travel was dependent on the seasonal winds: the summer monsoons blow from the south-west (May to September) and reverse direction in the winter (October to April). As a result, seafaring merchants developed sailing circuits that allowed them to use the monsoon winds to travel long distances, then return home when the wind patterns shifted.

Trade with southern India and the Persian Gulf flourished. Trade with East Africa also developed with the monsoon season, bringing ivory, gold and slaves. In India, guilds began to control Chinese trade on the Malabar coast and in Sri Lanka.

Trade relations became more formalized, while remaining highly competitive. Cochin and Kozhikode (Calicut), two major cities in the Indian state of Kerala, competed to dominate this trade.

Admiral Zheng He’s Maritime Explorations

Chinese maritime exploration reached its apogee in the early XVth century under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), which chose a Muslim court eunuch, Admiral Zheng He, to lead seven diplomatic naval expeditions.

Financed by Emperor Ming Yongle, these peaceful missions to Southeast Asia, East Africa, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea were intended above all to demonstrate the prestige and grandeur of China and its Emperor. The aim was also to recognize some thirty states and establish political and commercial relations with them.

In 1409, prior to one of these expeditions, the Chinese admiral Zheng He asked craftsmen to make a carved stone stele in Nanjing, the present-day capital of Jiangsu province (eastern China). The stele traveled with the flotilla and was left in Sri Lanka as a gift to a local Buddhist temple. Prayers to the deities in three languages – Chinese, Persian and Tamil – were engraved on the stele. It was found in 1911 in the town of Galle, in south-west Sri Lanka, and a replica is now in China.

Zheng’s armada was made up of armed bulk carriers, the most modest being larger than Columbus’ caravels. The largest were 100 meters long and 50 meters wide. According to Ming chronicles of the time, an expedition could comprise 62 ships, each carrying 500 people. Some carried military cavalry, others tanks of drinking water. Chinese shipbuilding was ahead of its time. The technique of hermetic bulkheads, imitating the internal structure of bamboo, offered incomparable safety. It became the standard for the Chinese fleet before being copied by the Europeans 250 years later. Compasses and celestial maps painted on silk were also used.

The synergy that may have existed between Arab, Indian and Chinese sailors, all men of the sea who fraternized in the face of ocean adversity, was impressive. For example, some historians believe that the name « Sindbad the Sailor », which appears in the Persian tale of a sailor’s adventures from the time of the Abbasid dynasty (VIIIth century) and was included in the Tales of the One Thousand and One Nights, derives from the word Sanbao, the honorary nickname given by the Chinese Emperor to Admiral Zheng He, literally meaning « The Three Jewels », i.e. the three indissociable capital virtues: essence, breath, and spirit.

Maritime museums in China (Hong Kong, Macau, Fuzhou, Tianjin and Nanjing), Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia showcase Admiral Zheng’s expeditions.

However, at least twelve other admirals carried out similar expeditions to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

In 1403, Admiral Ma Pi led an expedition to Indonesia and India. Wu Bin, Zhang Koqing and Hou Xian made others. After lightning caused a fire in the Forbidden City, a dispute broke out between the eunuch class, supporters of the expeditions, and the learned mandarins, who obtained the cessation of expeditions deemed too costly. The last voyage took place between 1430 and 1433, 64 years before the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived in 1497.

Japan, for its part, similarly restricted its contacts with the outside world during the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), although its trade with China was never suspended. It was only after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 that a Japan open to the world re-emerged.

Withdrawing into themselves, trade with both China and Japan fell into the hands of maritime trading posts such as Malacca in Malaysia or Hi An in Vietnam, two cities now recognized by Unesco as world heritage sites. H?i An was a major stopover port on the sea route linking Europe and Japan via India and China. In the shipwrecks found at Hi An, researchers have discovered ceramics awaiting their departure for Sinai in Egypt.

History of Chinese Ports

Over the years, the main ports on the Maritime Silk Road have changed. From the 330s onwards, Canton and Hepu were the two most important ports. However, Quanzhou replaced Canton from the end of the Song to the end of the Yuan dynasty. At that time, Quanzhou in Fujian province and Alexandria in Egypt were considered the world’s largest ports. Due to the policy of closure to the outside world imposed from 1435 and the influence of war, Quanzhou was gradually replaced by the ports of Yuegang, Zhangzhou and Fujian.

From the beginning of the IVth century, Canton was an important port on the Silk Road. Gradually, under the Tang and Song dynasties, it became not only the largest, but also the most renowned port of the Orient worldwide. During this period, the sea route linking Canton to the Persian Gulf via the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean was the longest in the world.

Although later supplanted by Quanzhou under the Yuan dynasty, Canton remained China’s second-largest commercial port. Compared with the others, it is considered to have been a consistently prosperous port over the 2,000-year history of the Maritime Silk Road.

The Tributary System of 1368

China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing, reigned from 1644 to 1912.

Since the arrival of the Ming dynasty, maritime trade with China proceded in two different ways:

- The Chinese « tributary system » ;

- The Canton system (1757-1842).

Born under the Ming in 1368, the « tributary system » reached its apogee under the Qing. It took the refined form of a mutually beneficial, inclusive hierarchy.

States adhering to it showed respect and gratitude by regularly presenting the Emperor with tribute made up of local products and performing certain ritual ceremonies, notably the « kowtow » (three genuflections and nine prostrations). They also demanded the Emperor’s investiture of their leaders and adopted the Chinese calendar. In addition to China, they included Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, the Ryükyü Islands, Laos, Myanmar and Malaysia.

Paradoxically, while occupying a central cultural status, the tributary system offered its vassals the status of sovereign entities, enabling them to exercise authority over a given geographical area.

The Emperor won their submission by showing virtuous concern for their welfare and promoting a doctrine of non-intervention and non-exploitation. Indeed, according to historians, in financial terms, China was never directly enriched by the tributary system. In general, all travel and subsistence expenses for tributary missions were covered by the Chinese government. In addition to the costs of running the system, the gifts offered by the Emperor were generally far more valuable than the tributes he received. Each tributary mission was entitled to be accompanied by a large number of merchants, and once the tribute had been presented to the Emperor, trade could begin.

It should be noted that when a country lost its status as a tributary state as a result of a disagreement, it would try at all costs, and sometimes violently, to be allowed to pay tribute again.

The Canton System of 1757

The second system concerned foreign, mainly European, powers wishing to trade with China. This involved the port of Guangzhou (then called Canton), the only port accessible to Westerners.

This meant that merchants, notably those of the British East India Company, could dock not in the port but off the coast of Canton, from October to March, during the trading season. It was in Macao, then a Portuguese possession, that the Chinese provided them with permission to do so. The Emperor’s representatives would then authorize Chinese merchants (hongs) to go on board to trade with foreign ships, while instructing them to collect customs duties before they left.

This way of trading expanded at the end of the XVIIIth century, particularly with the strong English demand for tea.

In fact, it was Chinese tea from Fujian that American « insurgents » threw into the sea during the famous « Boston Tea Party » in December 1773, one of the first events against the British Empire that sparked off the American Revolution.

Products from India, particularly cotton and opium, were exchanged by the East India Company for tea, porcelain and silk.

The customs duties collected by the Canton system were a major source of revenue for the Qing dynasty, even though it banned the purchase of opium from India. This restriction imposed by the Chinese Emperor in 1796 led to the outbreak of the Opium Wars, the first as early as 1839.

At the same time, rebellions broke out in the 1850-60s against the weakened Qing reign, coupled with further wars against hostile European powers.

In 1860, the former Summer Palace (Yuanming Park), with its collection of pavilions, temples, pagodas and libraries – the residence of the Qing dynasty emperors 15 kilometers northwest of Beijing’s Forbidden City – was ravaged by British and French troops during the Second Opium War.

This assault goes down in history as one of the worst acts of cultural vandalism of the XIXth century. The Palace was sacked a second time in 1900 by an eight-nation alliance against China.

Today, a statue of Victor Hugo and a text he wrote against Napoleon III and the destruction of French imperialism can be admired there, as a reminder that this was not the work of a nation, but of a government.

By the end of the First World War, China had 48 open ports where foreigners could trade according to their own jurisdictions.

The 20th century was an era of revolution and social change. The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 led to inward-looking attitudes.

It wasn’t until 1978 that Deng Xiaoping announced a policy of opening up to the outside world in order to modernize the country.

In the XXIst century, thanks to the One Belt (economic) One Road (maritime) Initiative launched by President Xi Jingping, China is re-emerging as a major world power offering mutually beneficial cooperation in the service of a better shared future for mankind.

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur The Maritime Silk Road, a history of 1001 Cooperations

Tags: Africa, Alandalus, artkarel, Bengal, Bonobudur, Brazil, Buddhism, Central Asia, China, compass, conflict, cooperation, dhow, Dynasties, Egypt, Gard, Ghana, Great Wall, gunpowder, Han, India, Indonesia, Islam, Italy, Japan, junk, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Korea, Koweit, Madgascar, Malaysia, maritime silk road, Modi, mulberry trees, navigation, noria, O, ocean, Ostia, paper money, printing, renaissance, Rome, Sanskrit, Sassanid, sea, sericulture, ship, Sicily, silk, silk road, silkworm, Singapore, Tang, Uzbekistan, Vereycken, Vietnam, Xi Jinping, Zheng He, Zou

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on juillet 26, 2021

Persian Qanâts and the Civilization of Hidden Waters

By Karel Vereycken, July 2021.

By Karel Vereycken, July 2021.

At a time when old diseases make their return and new ones emerge worldwide, the tragic vulnerability of much of humanity poses an immense challenge.

One wonders whether to laugh or cry when international authorities trumpet without further clarification that to stop the Covid-19 pandemic, “all you have to do” is “wash your hands with soap and water”!

They forget one small detail: 3 billion people do not have facilities to wash their hands at home and 1.4 billion have no access to either water or soap!

Yet, since the dawn of time, mankind has demonstrated its capacity to mobilize its creative genius to make water available in the most remote places.

Here is a short presentation of a marvel of such human genius, the “qanâts”, an underground water conveyance system dating from the Iron Age. Probably of Egyptian origin, it was deployed on a large scale in Persia from the beginning of the 1st millennium BC.

The qanât or underground aqueduct

Sometimes called “horizontal drilling”, the qanât is an underground aqueduct employed to draw water from a water table and convey it by simple gravitational effect to urban settlements and farmland. The word qanât is an old Semitic word, probably Accadian, derived from a root qanat (reed) from which come canna and canal.

This “drainage gallery”, cut into the rock or built by man, is certainly one of the earliest and most ingenious inventions for irrigation in arid and semi-arid regions. The technique offers a significant advantage: by conveying water through an underground conduit, contrary to open air canals, not a single drop of water is wasted by evaporation.

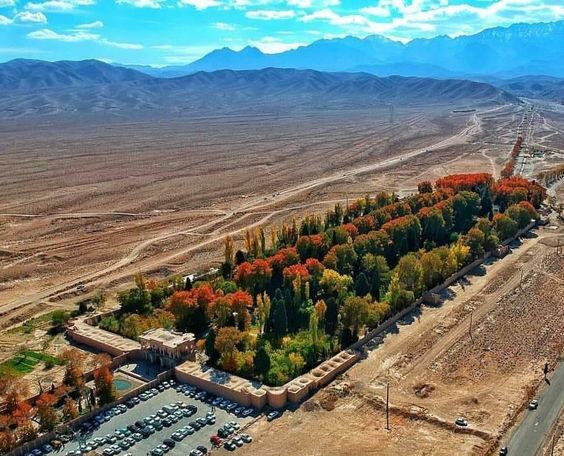

Oases’ are NOT natural phenomena. All known oases are man-made. It is the qanât technique that allows man, in a given geographic configuration, to create oases in the middle of the desert, when a water table is close enough to the ground level or at a site close to the bed of a river lost in the sands of the desert.

Copied and expanded by the Romans, the qanât technique was carried across the Atlantic to the New World by the Spaniards, where many such underground canals still function in Peru and Chile. In fact, there are even Persian qanâts in western Mexico.

While today this three thousand year old technique may not be appropriate everywhere to solve current water scarcity problems in arid and semi-arid regions, it has much to inspire us as a demonstration of human genius at its best, that is, capable of doing a lot with a little.

The oases of Egypt

Today, 95% of the Egyptian population prospers on only 5% of its territory, mainly around the Nile delta. Hence, from the earliest days of Egyptian civilization, irrigation and water storage techniques for the Nile floods were developed in order to conserve this silty, nutrient-rich water for use throughout the year.

The river water was diverted and transported by canals to the fields by gravity. Since water from the Nile did not reach the oases, the Egyptians used the gushing water from the springs, which came from the large aquifer reserves of the western desert, and conveyed it to the fields by irrigation canals.

One of the fruits of this attempt to “conquer the desert” was a sustained habitation of the Dakhleh oasis throughout the Pharaonic period, explicable not only by a commercial interest on the part of the Egyptian state, but also by the new agricultural perspectives it offered.

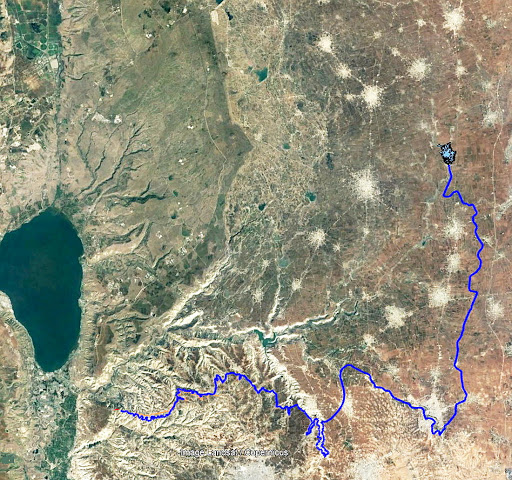

Roman aqueducts

Closer to us in time, the Qanât Fir’aun (The Watercourse of the Pharaoh) also known as the aqueduct of Gadara, a city today in Jordan. As far as we know, this 170 km long structure, depending on the geography, combines several bridge-aqueducts (of the same type as the Gard aqueduct in France) and 106 km of underground canals using the Persian qanât technique. It is not only the longest but also the most sophisticated aqueduct of antiquity, and the fruit of a years of hydraulic engineering.

In reality, the Romans, hiring persian water experts, did nothing more than terminate in the 2nd century an ancient project designed to supply water to the “Decapolis”, a collaborative group of ten cities founded by Greek and Macedonian settlers under the Seleucid king Antiochos III (223 – 187 BC), one of the successors of Alexander the Great.

These ten cities were located on the eastern border of the Roman Empire (now in Syria, Jordan and Israel), united by language, culture and political status, each with a degree of autonomy and self-rule. Its capital, Gadara, was home to more than 50,000 people and known for its cosmopolitan atmosphere, its own university attracting scholars, writers, artists, philosophers and poets. But this rich city lacked something existential : an abundance of water.

The Gadara qanat made the difference. “In the capital alone, there were thousands of fountains, watering holes and baths. Wealthy senators cooled themselves in private pools and decorated their gardens with cooling caves. The result was a record daily consumption of more than 500 liters of water per capita,” explains Matthias Schulz, author of a report on the aqueduct in Spiegel Online.

Persia

We all admire the roman aqueducts. But few of us are aware that the Romans only adapted the technique of the qanâts developed much earlier in Persia.

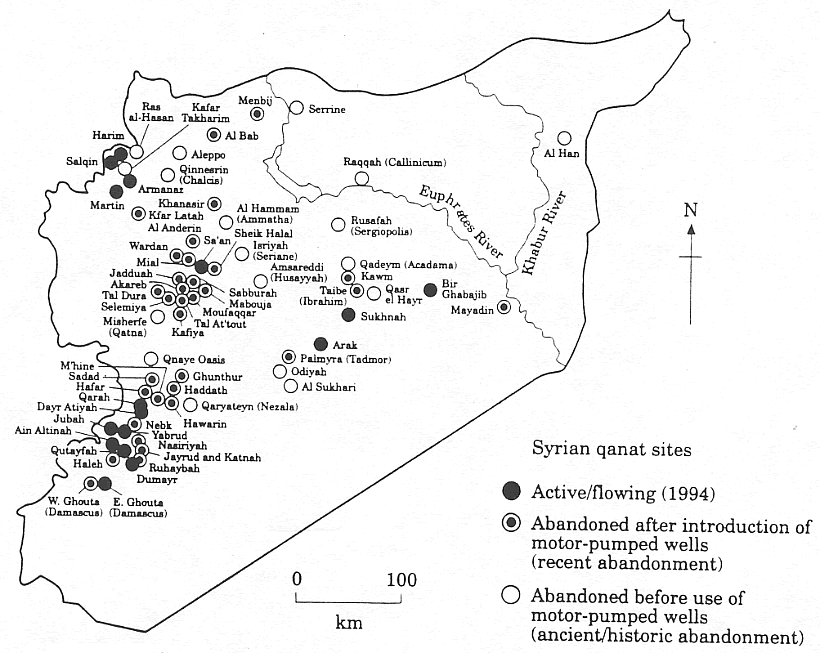

Indeed, it was under the Achaemenid Empire (around 559 – 330 BC.), that this technique spread slowly from Persia to the east and the west. Many qanâts can be found in North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Libya), in the South East Asia (Iran, Oman, Iraq) and further east, in Central Asia, from Afghanistan to China (Xinjiang), via India.

The development of these “draining galleries” is attested in different regions of the world under various names: qanât and kareez in Iran, Syria and Egypt, kariz, kehriz in Pakistan and Afghanistan, aflaj in Oman, galeria in Spain, kahn in Balochistan, kanerjing in China, foggara in North Africa, khettara in Morocco, ngruttati in Sicily, bottini of Siena, etc.

Historically, the majority of the populations of Iran and other arid regions of Asia or North Africa depended on the water provided by the qanâts; their construction lifted entire areas to a higher “economic platform”, made deserts habitable and opened new land for agriculture. The map of demographic expansion followed the trail of the development of this new higher platform.

In his article « Du rythme naturel au rythme humain : vie et mort d’une technique traditionnelle, le qanât » (From natural rhythm to human rhythm: the life and death of a traditional technique, the qanât), Pierre Lombard, a researcher at the French CNRS, points out that this is not an artisanal and marginal process:

“Until a few years ago, the importance of the ancestral technique of qanât was sometimes ignored in Central Asia, Iran, Syria, and even in the countries of the Arabian Peninsula. For example, the Public Authority for Water Resources of the Sultanate of Oman estimated in 1982 that all the qanâts still in operation conveyed more than 70 % of the total water used in that country and irrigated nearly 55% of the cereal lands. Oman was still one of the few states in the Middle East to maintain and sometimes even develop its qanât network; this situation, apart from its longevity, does not appear to be exceptional. If one turns to the edges of the Iranian Plateau, one can note with Wulff (1968) the obvious discrepancy between the relative aridity of this area (between 100 and 250 mm of annual precipitation) and its non-negligible agricultural production, and explain it by one of the densest networks of qanâts in the Middle East. It can also be recalled that until the construction of the Karaj dam in the early 1960s, the two million inhabitants of Tehran at that time consumed exclusively the water brought from the Elbourz foothills by several dozen regularly maintained qanâts. Finally, we can mention the case of some major oases in the Near and Middle East (Kharga in Egypt, Layla in Saudi Arabia, Al Ain in the United Arab Emirates, etc.) or in Central Asia (Turfan, in Chinese Turkestan) that owe their vast development, if not their very existence, to this remarkable technique.”

On the website ArchéOrient, the French archaeologist Rémy Boucharlat, Director of Research Emeritus at the CNRS, an Iran expert, explains:

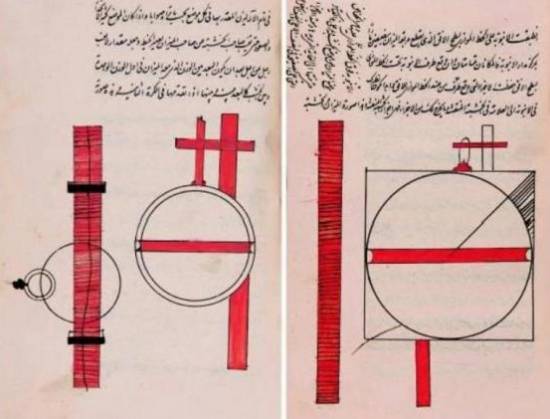

“Whatever the origin of the water, deep or not, the technique of construction of the gallery is the same. First, the issue is to identify the presence of water, either its going underground near a river, or the presence of a water table under a foothill, which requires the science and experience of specialists. A motherwell will be dug to reach the top of the water table, indicating at which depth the [horizontal] gallery should be drilled. It’s slope must be very small, less than 2‰, so that the flow of water is calm and regular, and conduct the water gradually to the surface area, according to a gradient much lower than the slope of the foothill.

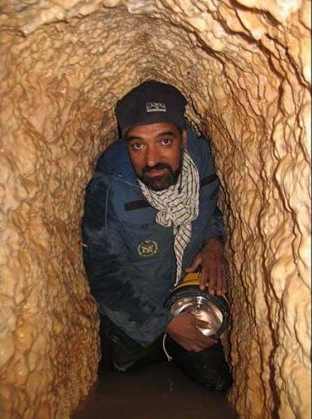

“The gallery is then dug, not starting from the mother well because it would be immediately flooded, but from downstream, from the point of arrival. The conduct is first dug in an open trench, then covered, and finally gradually sinks into the ground in a tunnel. For the evacuation of soil and ventilation during excavation, as well as to identify the direction of the gallery, shafts are dug from the surface at regular intervals, between 5 and 30 m depending on the nature of the land ».

In April 1973, Lyndon LaRouche’s friend, the French-Iranian professor and historian Aly Mazahéri (1914-1991), published his translation from Arab into French of “The Civilization of Hidden Waters”, a treatise on the exploitation of underground waters composed in the year 1017 by the Persian hydrologist Mohammed Al-Karaji, who lived in Baghdad. (Translated in English in 2011)

After an introduction and general considerations on geography, natural phenomena, the water cycle, the study of terrain and the instruments of the hydrologist, Al-Karaji gives a highly precise technical outline of the construction and maintenance of qanâts, as well as legal considerations respecting their management and maintenance.

In his introduction to Al-Karji’s treatise, Professor Mazaheri emphasizes the role of the Iranian city of Merv (now in Turkmenistan). This ancient city, he says, was part of

“the long series of oases extending at the foot of the northern slope of the Iranian plateau, from the Caspian to the first foothills of the Pamirs. There, between the geological extension of the Caspian towards the East, there is a strip of arable land, more or less wide, but very fertile. Now, to exploit it, a lot of ingenuity is needed: where, for example in Merv, a big river, such as the Marghab, coming from the glaciers of the central East-Iranian massif, crosses the chain, it is necessary to establish dams, above the strip of arable land, without which, the ‘river’, divided into several dozens of arms, rushes under the sands. Elsewhere, and it is almost all along the northern slope of the chain, one can create artificial oases, by bringing the water by underground aqueducts.” (p. 44)

“The construction of dams and underground aqueducts are among the most interesting legacies of their (the ancient Persians) irrigation techniques (…) Long before Islam, the Persian hydrologists had built thousands of aqueducts, allowing the creation of hundreds of villages, dozens of cities previously unknown. And very often, even where there was a river, because of the insufficiency of this one, the hydronomists had brought to light many aqueducts allowing the extension of the culture and the development of the city. Naishabur was such a city. Under the Sassanids, and later under the Caliphs, an important network of aqueducts had been created there, so that the inhabitants could afford the luxury of owning a ‘’bathing room’ in the basement, at the level of the aqueduct serving the house.”

Let us recall that most Persian scholars, including the famous mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, not suffering from today’s hyper-specialization that tends to curb creative thinking, excelled in mathematics, geometry, astronomy and medicine as well as in hydrology.

Mazaheri confirms that this “civilization of underground waters” spread well beyond the Iranian borders:

“Already, under the [Umayyad] Caliph Hisham (723-42), Persian hydronomists built aqueducts between Damascus and Mecca (…) Later, Mecca suffering from lack of water, Zubayda, the wife of Hâroun Al-Rachîd, sent Persian hydronomists there who endowed the city with a large underground aqueduct. And each time the latter was silted up, a new team left Persia to restore the network: such repairs took place periodically under Al-Muqtadir (908-32), under Al-Qa’im (1031-1075), under Al-Naçir (1180-1226) and, at the beginning of the fourteenth century, under the Mongol prince Emir Tchoban. We would say the same of Medina and the stages on the pilgrimage route, between Baghdad and Mecca, wherever it was possible to do so, hydronomic works were undertaken and ‘underground aqueducts’ were created.

“Hydronomy is a highly demanding skill. To practice it, it is not enough to have mathematical knowledge: decadal calculus, algebra, trigonometry, etc., it is necessary to spend long hours in the galleries at the risk of dying by flooding, landslide or lack of air. It is necessary to have an ancestral instinct of ‘dowser’.”

The annual rainfall in Iran is 273 mm, which is less than one third of the world’s average annual precipitation.

The temporal and spatial distribution of precipitation is not uniform; about 75% occurs in a small area, mainly on the southern coast of the Caspian Sea, while the rest of the country does not receive sufficient rainfall. On the temporal scale, only 25% of the precipitation occurs during the plant growing season.

7,7 x the circonférence of the Earth

Still in use today in Iran, qanâts currently supply about 7.6 billion m3 of water, close to 15% of the country’s total water needs.

Considering that the average length of each qanât is 6 km in most parts of the country, the total length of the 30,000 qanât systems (potentially exploitable today) is about 310,800 km, which is about 7.7 times the circumference of the Earth or 6/7th of the Earth-Moon distance!

This shows the enormous amount of work and energy applied to build the qanâts. In fact, while more than 38,000 qanâts were in operation in Iran till 1966, its number dropped to 20,000 in 1998 and is currently estimated at 18,000. According to the Iranian daily Tehran Times, historically, over 120,000 qanat sites are documented.

Moreover, while in 1965, 30-50% of Iran’s total water needs were met by qanats, this figure has dropped to 15% in recent decades.

According to the Face Iran website:

“The water flow of qanâts is estimated between 500 and 750 cubic meters per second. As land aridity tends to vary according to the abundance of rains in each region, this quantity of water is used as a more or less important supplement. This makes it possible to use good land that would otherwise be barren. The importance of the impact on the desert can be summarized in one figure: about 3 million hectares. In seven centuries of hard work, the Dutch conquered 1.5 million hectares from the marshes or the sea. In three millennia, the Iranians have conquered twice as much on the desert.

Indeed, to each new qanât corresponded a new village, new lands. From where a new human group absorbed the demographic surplus. Little by little the Iranian landscape was constituted. At the end of the qanat, is the house of the chief, often with one floor. It is surrounded by the villagers’ houses, animal shelters, gardens and market gardens.

The distribution of land and the days of irrigation of the plots were regulated by the chief of the villages. Thus, a qanat imposed a solidarity between the inhabitants.”

If each qanât is “invented” and supervised by a mirab (dowser-hydrologist and discoverer), the realization of a qanât is a collective task that requires several months or years, even for medium-sized qanâts, not to mention works of record dimensions (a 300 m deep mother-well, a 70 km long gallery classified in 2016 as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, in northeast Iran).

Each undertaking is carried out by a village or a group of villages. The absolute necessity of a collective investment in the infrastructure and its maintenance requires a higher notion of the common good, an indispensable complement to the notion of private property that rains and rivers do not take in account.

In the Maghreb, the management of water distributed by a khettara (the local name for qanâts) follows traditional distribution norms called “water rights”. Originally, the volume of water granted per user was proportional to the work contributed to build the khettara, translated into an irrigation time during which the beneficiary had access to the entire flow of the khettara for his fields. Even today, when the khettara has not dried up, this rule of the right to water persists and a share can be sold or bought. Because it is also necessary to take into account the surface area of the fields to be irrigated by each family.

The causes of the decline of the qanâts are numerous. Without endorsing the catastrophist theses of an anti-human ecology, it must be noted that in the face of the increasing urban population, the random construction of dams and the digging of deep wells equipped with electric pumps have disturbed and often depleted the aquifers and water tables.

A neoliberal ideology, falsely described as “modern”, also prefers the individualistic “manager” of a well to a collective management organized among neighbors and villages. A passive State authority has done the rest. In the absence of more thoughtful reflection on its future, the age-old system of qanâts is on the verge of extinction as a result.

In the meantime, the Iranian population has grown from 40 to over 82 million in 40 years. Instead of living off oil, the country is seeking to prosper through agriculture and industry. As a result, the need for water has increased substantially. To cope with rising demands, Iran is desalinating sea water at great cost. Its civilian nuclear program will be the key factor to provide water at a reasonable cost.

Beyond political and religious divisions, closer cooperation between all the countries in the region (Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Israel, Egypt, Jordan, etc.) with a perspective to improve, develop, manage and share water resources, will be beneficial to each and all.

Presented as an “Oasis Plan” and promoted for decades by the American thinker and economist Lyndon LaRouche, such a policy, translating word into action, is the only basis of a true peace policy.

Bibliography :

- Remy Boucharlat, The falaj or qanât, a polycentric and multi-period invention, ArcheOrient – Le Blog, September 2015 ;

- Pierre Lombard, Du rythme naturel au rythme humain : vie et mort d’une technique traditionnelle, le qanat, Persée, 1991 ;

- Aly Mazaheri, La civilisation des eaux cachées, un traité de l’exploitation des eaux souterraines composé en 1017 par l’hydrologue perse Mohammed Al-Karaji, Persée, 1973 ;

- Hassan Ahmadi, Arash Malekian, Aliakbar Nazari Samani, The Qanat: A Living History in Iran, January 2010;

- Evelyne Ferron, Egyptians, Persians and Romans: the interests and stakes of the development of Egyptian oasis environments.

NOTE:

[1] The ten cities forming the Decapolis were: 1) Damascus in Syria, much further north, sometimes considered an honorary member of the Decapolis; 2) Philadelphia (Amman in Jordan); 3) Rhaphana (Capitolias, Bayt Ras in Jordan); 4) Scythopolis (Baysan or Beit-Shean in Israel), which is said to be its capital; It is the only city west of the Jordan River; 5) Gadara (Umm Qeis in Jordan); 6) Hippos (Hippus or Sussita, in Israel); 7) Dion (Tell al-Ashari in Syria); 8) Pella (Tabaqat Fahil in Jordan); 9) Gerasa (Jerash in Jordan) and 10) Canatha (Qanawat in Syria)

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | No Comments »

Tags: Abbassid, Afghanistan, Al-Karaji, Al-Kwarizmi, Aly Mazahéri, Aqueduct, artkarel, canal, Chili, China, Damascus, Decapolis, Egypt, foggara, France, Gadara, galerias, Gard, Haroun Al-Rachid, hydrology, Iran, Iraq, irrigation, Israël, Jordan, Karel, Karel Vereycken, khettara, Libya, management, Merv, Mexico, mirab, Morocco, ngruttati, Oasis, Oman, Persia, Peru, Pierre Lombard, qanât, Rémy Boucharlat, renaissance, Romans, Sicily, Spain, Syria, Tehran, UNECO, Vereycken, village, water, World Heritage, Yazd