Étiquette : peinture

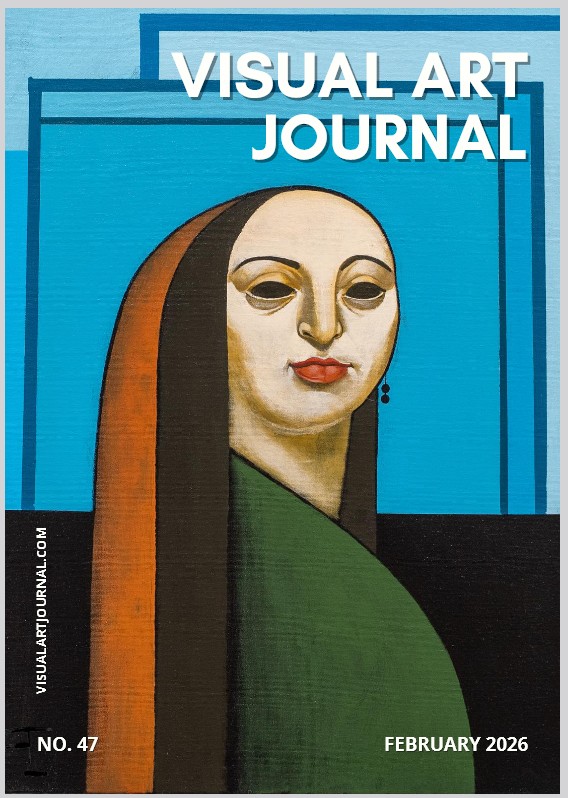

Karel Vereycken art featured in Visual Art Journal

The February 2026 issue #47 of Visual Art Magazine contains a two page feature with two works and a statement on the work of Franco-Belgian painter engraver and historian Karel Vereycken.

The entire magazine can be seen here:

https://visualartjournal.com/2026/02/01/issue-47-february-2026/

A print copy can be ordered here.

Website:

https://visualartjournal.com/

Instagram:

@visualartjournal

LinkedIn:

https://www.linkedin.com/company/visual-art-journal-official/

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, political commentator and pacifist

Five centuries after his birth, the publication of new research seems (finally) to do justice to the great Flemish painter « Pieter Bruegel the Jolly » , known as the Elder (1525-1569).

Until now, it was all too common to hear him described as « an unclassifiable figure. » In 2024, art historian Mónica Ann Walker Vadillo did not hesitate to write in the History section of the newspaper Le Monde that, since Bruegel painted peasant feasts and weddings, art critics « came to regard him as an unrefined man and disdainfully nicknamed him ‘Bruegel the Peasant,' » while expressing surprise that so many « academics, humanists, and wealthy businessmen—who appreciated his work and collected his paintings » associated with him.

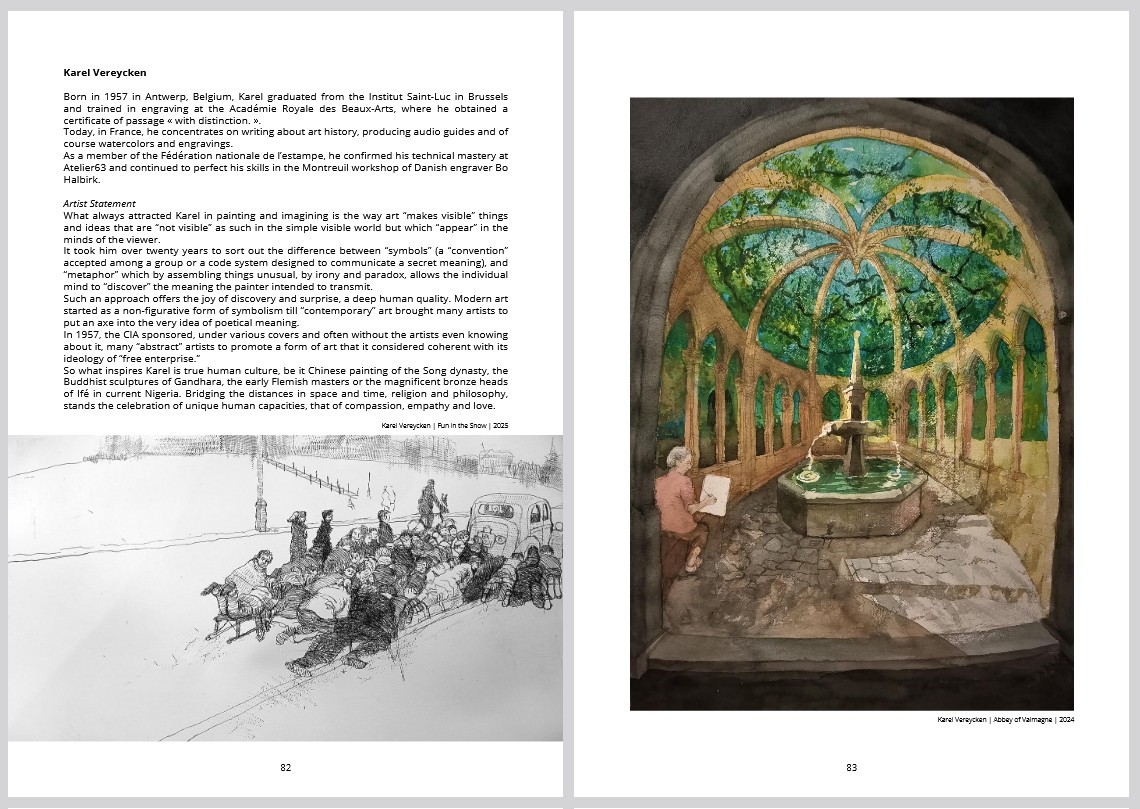

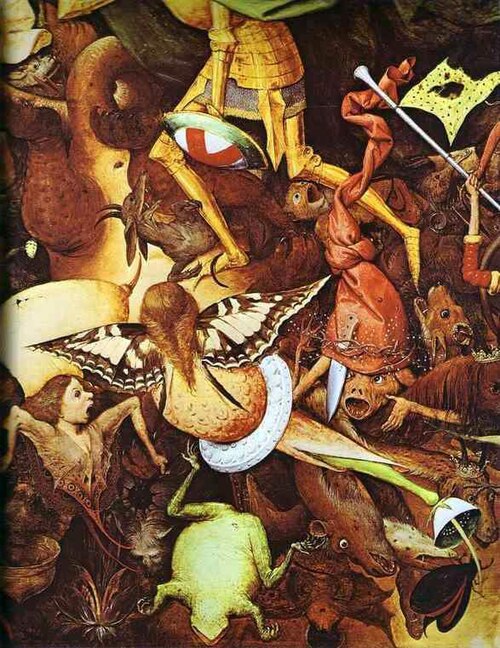

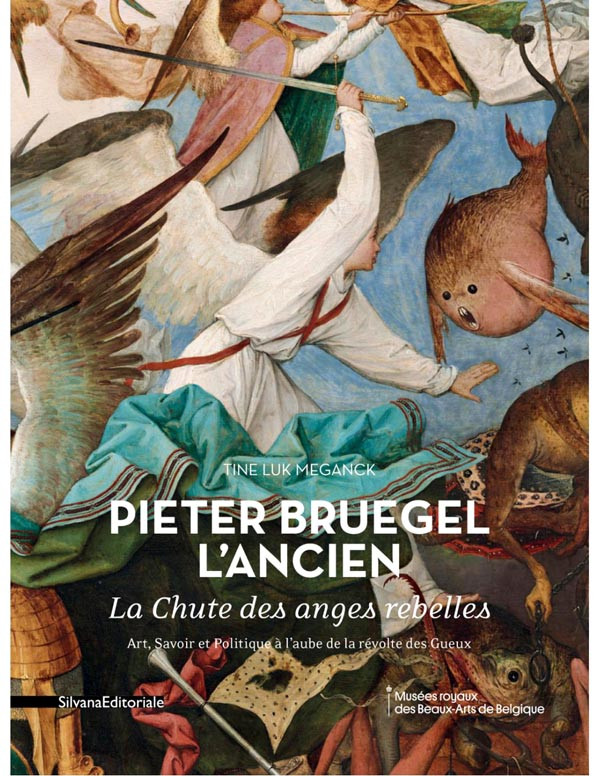

Fall of the Rebel Angels

In 2014, Tine Luk Meganck ‘s book, « Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Fall of the Rebel Angels. Art, knowledge and Politics on the Eve of the Dutch Revolt », especially with the last sentence of her title, had nevertheless reopened the debate on the political dimension of his work.

Meganck ventured a highly improbable hypothesis regarding the painting The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562, Brussels Museum): the jealous angels, whom God punishes for conspiring against him, are supposed to represent the alliance of nobles, the middle classes, and the common people, led by William the Silent against the rule of the Spanish Empire. Consequently, the commissioner of the work, according to the expert, was most likely the famous Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, one of the advisors to the regent Margaret of Parma and a fervent supporter of the persecution of heretics.

We have documented in an article why this interpretation seems unacceptable to us, as Cardinal Granvelle, a member of the « secret government, » was universally hated by the humanists of the time for his blind zeal in endorsing all the crimes of his masters.

Furthermore, no tangible proof exists that he commissioned any work from Bruegel. Certainly, he owned some, but apart from a « Flight into Egypt » (1563), a work devoid of any controversy, and a « View of the Bay of Naples, » a beautiful study inspired by drawings made during Bruegel’s trip to Italy, Granvelle was far from being « one of the greatest collectors » of Bruegel’s works, as is often repeated.

Landjuweel

That being said, the important contribution of Meganck’s book, let’s acknowledge it, was the recognition of the decisive influence of the Chambers of Rhetoric and the Antwerp Landjuweel of 1561, for understanding Bruegel’s visual language.

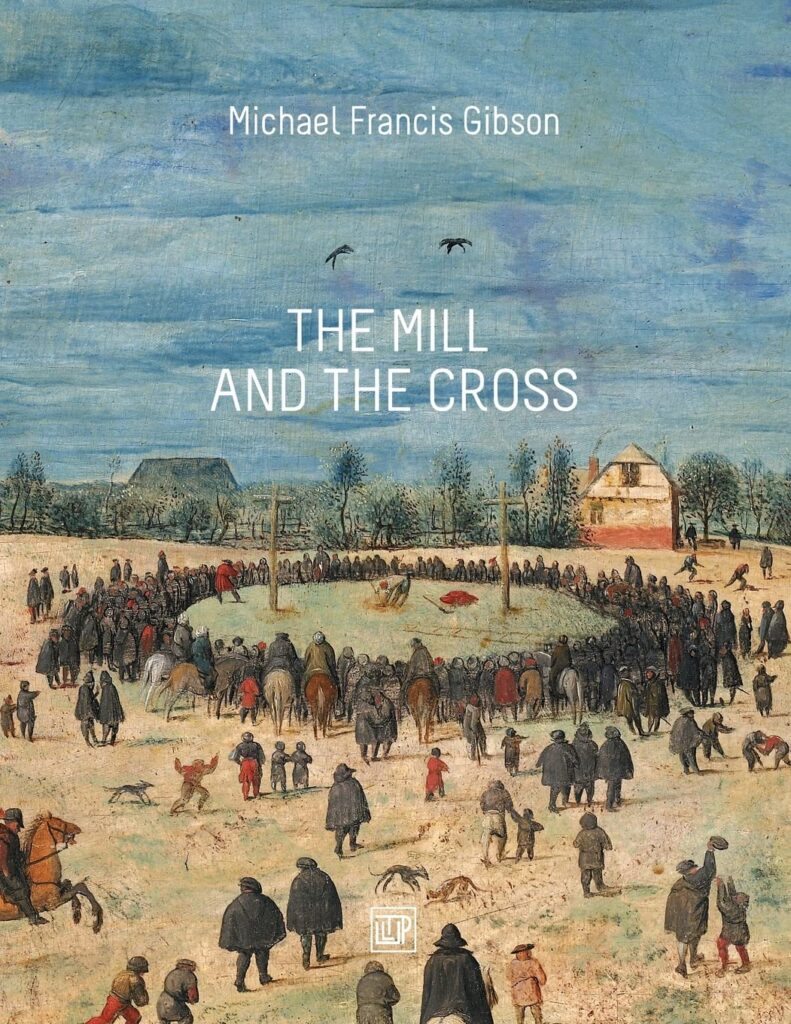

My friend, the late American art critic Michael Frances Gibson, had mentioned this possibility to me during an interview this author conducted with him.

He discusses this in his book The Carrying of the Cross (Editions Noêsis, Paris 1996), which was used in 2011 for the quite innovative film « Bruegel, the Mill and the Cross ».

In August 1561, Antwerp, where Bruegel resided, hosted an exceptional celebration, the Landjuweel, or national competition of the Chambers of Rhetoric.

In practice, the Antwerp Chamber « De Violieren« , in charge of organizing a festival that cost the city one hundred thousand crowns, operated as the literary division of the Guild of Saint Luke, the corporation that brought together painters, engravers, illustrators, architects, sculptors, cartographers, goldsmiths and printers.

It was there that people read in Flemish as well as in Latin or French, Plato, Homer, Petrarch, Erasmus and Rabelais, both during private gatherings and often, in public.

The first Bible in French? Printed in Antwerp in 1535 by the French humanist Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples (1450-1536), who published the first translations of the complete works of Nicholas of Cusa in Paris in 1514, three years before the publication, in the French capital, of the first edition of Erasmus‘s In Praise of Folly.

The Landjuweel of Antwerp stands historically as one of the most remarkable cultural renaissance events in European history. 2000 rhetoricians on horseback, from 10 cities, passed under 40 triumphal arches to the strident sounds of fifes, entering a city in full celebration. For a whole month, orators and poets, songwriters and actors competed without pausing for breath. Citizen’s were invited on every streetcorner to participate in polyphonic madrigals and chorusses. 5000 artists entertained close to a 100,000 viewers !

Bruegel had to follow them all the more since his dear friend Hans Frankaert (1520-1584), his friend and master Peeter Baltens (1527-1584), very well connected with the great local financiers who preferred commerce to war, as well as his first patron, the engraver Hieronymus Cock (1518-1570), were all involved in the organization of this event whose theme was peace and, two centuries before Kant and Schiller, this burning philosophical question: « What leads man most towards the arts? » This, then, was the bubbling cauldron of urban culture in which Bruegel was immersed from his beginnings.

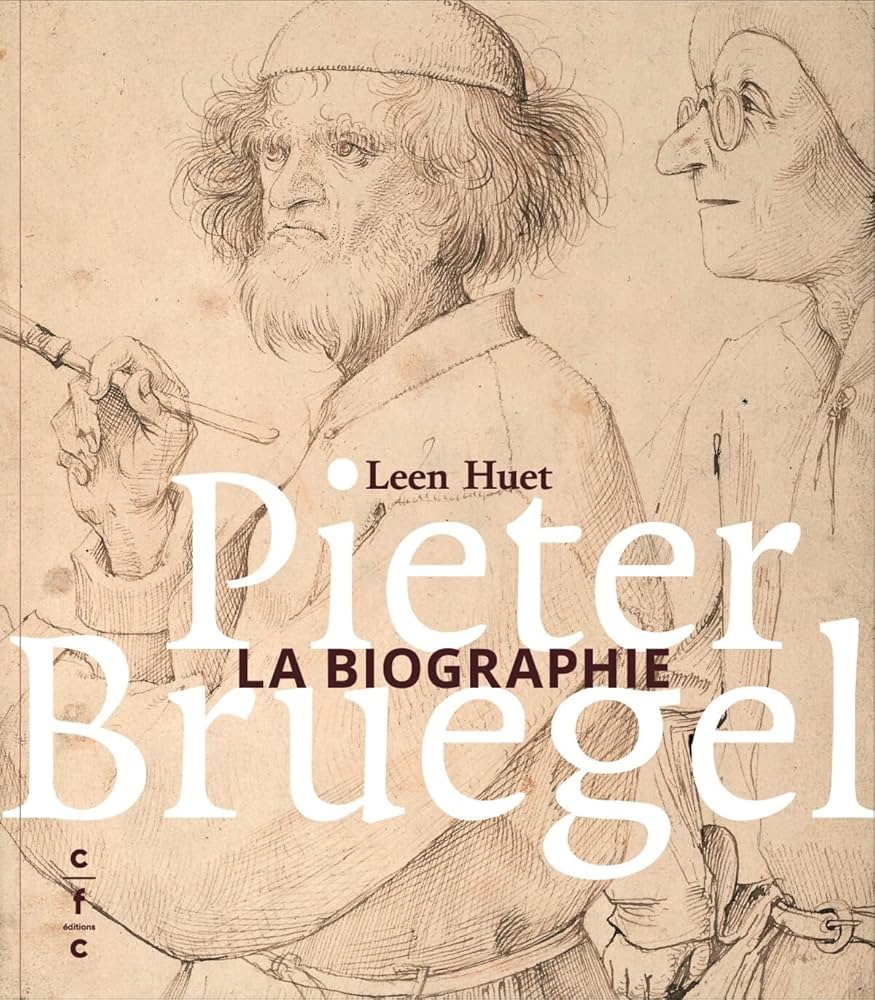

Moreover, as Belgian historian Leen Huet details in her sumptuous biography of the artist (first published in Dutch in 2016 by Polis, then in French by CFC in Brussels in 2021), when he crossed the Alps, Bruegel was probably accompanied by the painter Maarten de Vos (1532-1603) and the cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598), a close friend of Christophe Plantin, the head of the largest printing house in Antwerp, the team having thousands of addresses of collectors in connection with the printing house Les Quatre Vents of Jérôme Cock, in Antwerp.

The « Bruegel Code »

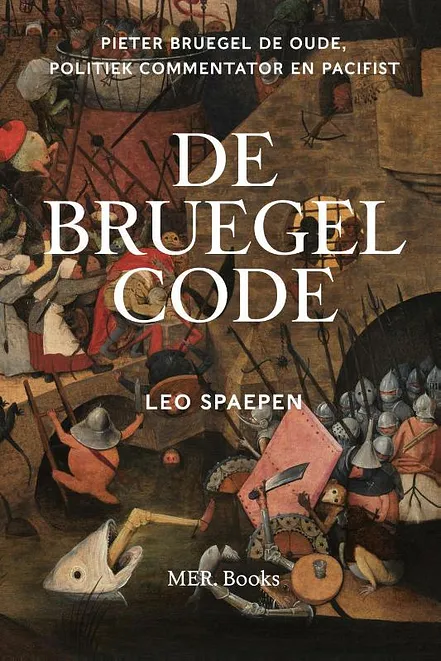

The image of Bruegel as a political commentator, deliberately obfuscating his message to thwart the regime’s Gestapo agents who were lying in wait for him, and embracing the Erasmian philosophy of the Landjuweel to defend peace and mutual understanding, is further developed by the classical historian Leo Spaepen, whose recent book, Pieter Bruegel de oude, politiek commentator en pacifist. De Bruegel Code (published in Dutch by MER Books, 2025), has stirred enthusiasm.

A good pedagogue, Spaepen establishes a kind of code for deciphering, or at least fruitfully approaching, Bruegel’s visual language. Escaping the Aristotelian confines, the aim is to immediately discard formal and symbolic representations in favor of what I would call a metaphorical approach.

Narrative A and B

Each painting contains a « narrative A » and a « narrative B. » The former typically reflects a concern shared by the humanist and Erasmian community regarding the socio-political events of the time, where corruption and violent Spanish repression brought the Hispano-Burgundian Netherlands to the brink of revolt. The « narrative B » often depicts a scene from the Bible or scripture.

As with any metaphor, the paradox arising from the analogy between narrative A and B brings forth, not on the canvas but in the viewer’s mind, a range of clues allowing them to grasp where the painter intends to lead them.

Spaepen, whose courage, rigor, and audacity deserve high praise, has sufficiently delved into the political and cultural history of Bruegel’s era to formulate compelling hypotheses that illuminate his major works. By testing this cognitive approach, painting by painting, the author generates not a scholarly compendium of facts or evidence, but an extremely interesting « gestalt » of the painter, whose true genius has often been denied recognition. It is therefore impossible, in a simple article like this, to reproduce the full richness of this approach.

« Mad Meg »

Let us nevertheless look at an emblematic work by Bruegel, known by its nickname, Dulle Griet (« Margot the Enraged » or « Mad Meg » ), a work painted in 1563, not to please a patron, but to provoke discussions with his relatives during meals at his home, as was the custom at the time.

The painting is striking in its contradictions. In the foreground, against a backdrop of burning cityscapes, a woman, mad with rage, sword in hand, carries a basket filled with jewels and precious metalwork. Behind her, a cohort of unarmed women bravely strives to subdue and repel an army of monsters and devils.

Finally, at the intersection of the painting’s diagonals, a strange creature appears, reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch ‘s Garden of Earthly Delights. A man carrying a large bubble on his back shakes his backside, from which silver coins fall, which some women hastily gather up.

As for narrative B, we find roughly the image that Bruegel had developed in a drawing used for a 1557 engraving representing one of the deadly sins, here rage ( Ira in Latin), again represented by a giant woman, with the subtitle: « Rage swells the lips and sours the character. It troubles the mind and blackens the blood. »

Spaepen also picks up on (p. 131) a great find by Leen Huet. The historian discovered that during the Landjuweel of Antwerp in 1561, the chamber of rhetoric of Mechelen had mentioned a « Griete die den roof haelt voor den helle » (a girl who goes to plunder hell), a figure perhaps taken from a play that is now lost.

Huet also mentions (p. 35) the Flemish proverb that says of an old harpy that she « could go and plunder hell and come back safe and sound. » At the same time, Huet notes (p. 48), the author Sartorius , in a collection of adages inspired by Erasmus, states a saying similar in spirit to the Dulle Griet sign:

« One woman alone makes a racket, two women cause much trouble, three women gather only to trade for an annual market, four women lead to strife, five women form an army, and against six women, Satan himself has no weapon to fight them. »

In reality, the status of urban women from the 15th century onwards in Flanders, with the beguinages, and especially in Brabant in the 16th century, was one of the most advanced in Europe1, probably explaining in part the concerns of some members of the male gender in the face of the growing power of women.

Granvelle

But Spaepen, a good observer, exonerates Bruegel from this kind of masculinist reaction by bringing back the reality of narrative A, the current political situation.

The painter, Spaepen believes, is denouncing here Cardinal Granvelle , zealous advisor to the regent Margaret of Parma, a woman torn between the general interest and submission to the tyranny of the Catholic Church, whose dogmas were instrumentalized by Madrid to plunder the country in order to repay the colossal debt of Charles V and Philip II to the Fugger bankers.

Personally, I thought for a moment that Bruegel had invented for the occasion an 8th deadly sin, « incitement to war » (Oorlogstokerij), but I am probably too much in the present.

In August 1561, disregarding Granvelle’s advice, Margaret had authorized the Guild of Saint Luke and the Violieren to organize the Antwerp Landjuweel to promote peace and mutual understanding. But immediately afterward, she yielded to pressure from Madrid by forbidding the publication of the proceedings of the Chambers of Rhetoric, which were accused of having united the entire country against the Emperor.

In 1563, the year Bruegel painted his Dulle Griet, the Council of Trent decided to curb polyphonic art by restoring the primacy of the sung text in music and prohibiting any ambiguity in a painting, linked to a role of propaganda, exactly as Granvelle wished.

In the painting « Mad Meg, » the strange creature in the center, draped in a red cloak, could very well be Cardinal Granvelle himself.

As Spaepen reminds us, Granvelle had just established a vast network of informants to hunt down heretics « even in the toilets. »

This targeted all those—Lutherans, Calvinists, Erasmians, or Anabaptists—who challenged the predatory grip of the regime. And yet, the money « shat out » by Granvelle is being recovered by women ready to plunder hell! Bruegel, not exactly kind to Mad Meg (Marguerite of Parma), could therefore be expressing his horror at this regent who has lost her mind, and especially at the idea that Flemish women, who had become so free and educated, could end up as informers for a totalitarian regime!

Familia Caritatis

Spaepen (p. 194) documents the strong influence exerted on Bruegel (who was not necessarily a member of the group) by the Familia Caritatis (Family of Charity), a philosophical and religious movement founded and led by Hendrik Niclaes (1502-1570), a prophetic and charismatic figure advocating peace and tolerance about whom little is known but who undoubtedly appeared to many, without reaching his wisdom and erudition, as a kind of successor to Erasmus.

Many humanists and a number of Bruegel’s acquaintances were in contact with this movement which, passing through England, would dissolve into the Quaker revolt against the Anglican Church.2

Plantin, considered the official printer of the Spanish regime, had the Familia Caritatis booklets (deemed heretical by the regime) printed (at night), with initial financial assistance for his printing press from Niclaes, himself a merchant. Niclaes’s major work, Terra Pacis, denounces the « Blind leading the Blind, » a theme also found in the work of Quinten Matsys‘s son (who fled the persecution), and later in Bruegel.

Niclaes draws upon Socrates and the philosophy of the Brethren of the Common Life , for whom selfless love (agape or caritas) should be the driving force of humankind. Another conviction he holds is that life is « a pilgrimage of the soul. »

As in the landscapes of Joachim Patinir, Homo Viator must constantly detach himself from earthly matters and move on. Through his free he must seek union with God by resisting earthly temptations. Inner peace—with oneself, with one’s conscience, and with the divine will—is the foundation of peace on Earth, an ideal that also clearly inspired the painter.

This is the true story, that of a great political commentator and resistance fighter of his time, a painter intellectually and spiritually committed to peace.

NOTES:

- See on this subject Myriam Greilsammer, L’envers du tableau : Mariage et maternité en Flandre médiévale , Armand Colin, 1990, as well as this author’s article on the Landjuweel. ↩︎

- These included the printers Christoffel Plantin and John Gailliart; the humanists Abraham Ortelius, Justus Lipsius, Andreas Masius, Goropius Becanus, and Benito Arias Montano; the poets Peeter Heyns, Jan van der Noot, Lucas d’Heere, Filips Galle, and Joris Hoefnagel; the theologian Hubert Duifhuis; the writer Dirck Volkertsz; Coornhert (right-hand man of William the Silent); the « familists » Daniel van Bombergen, Emanuel van Meteren, and Johan Radermacher; and the Antwerp merchants Marcus Perez and Ferdinando Ximines. ↩︎

The illusion of the Self

AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility

OPEN WEBPAGE TO LISTEN TO AUDIO: CLICK HERE

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

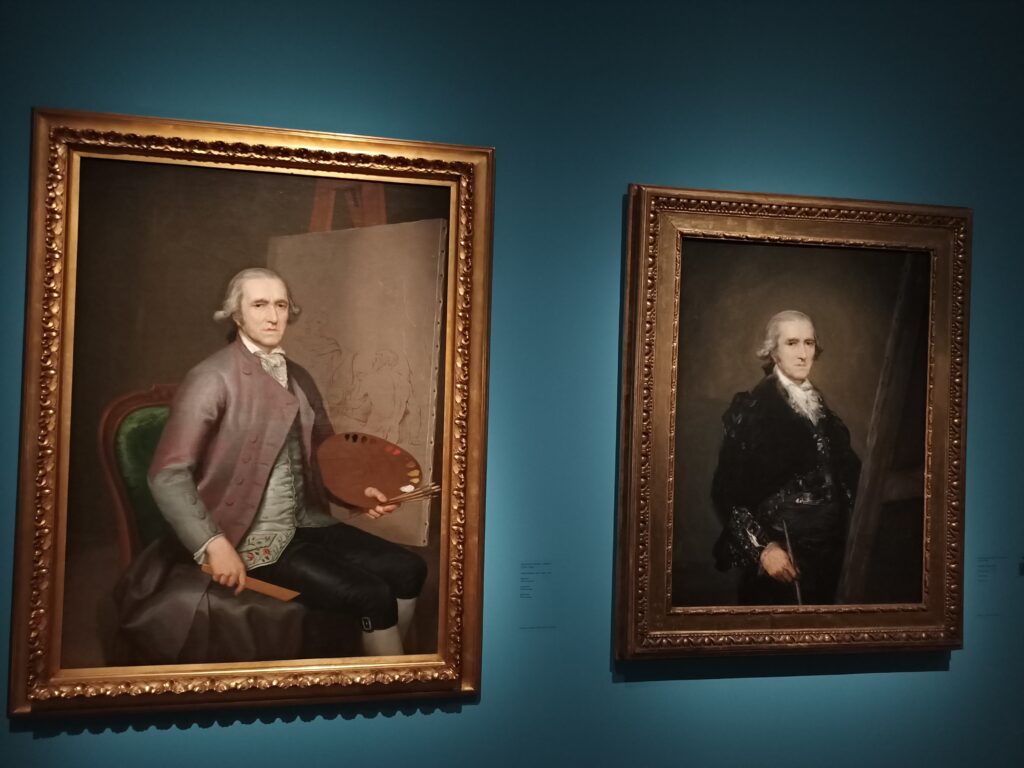

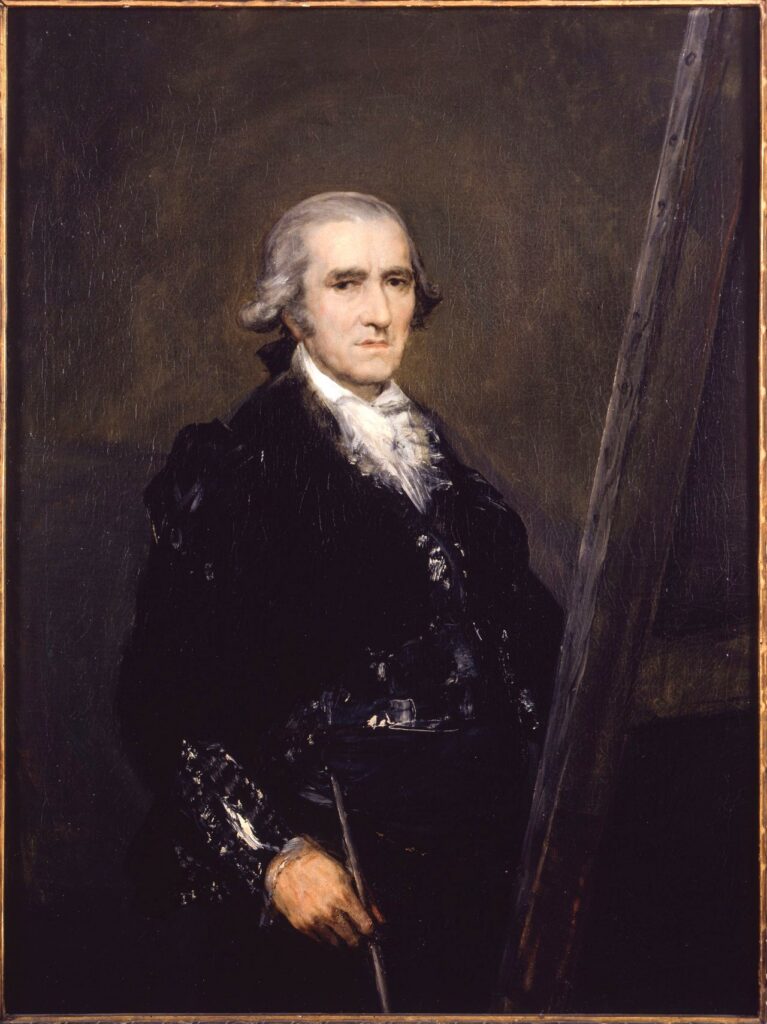

AUDIO: Goya’s portrait of Bayeu

For a complete and detailed study of Goya’s life and work, see my article online in EN, FR and ES.

AUDIO – Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

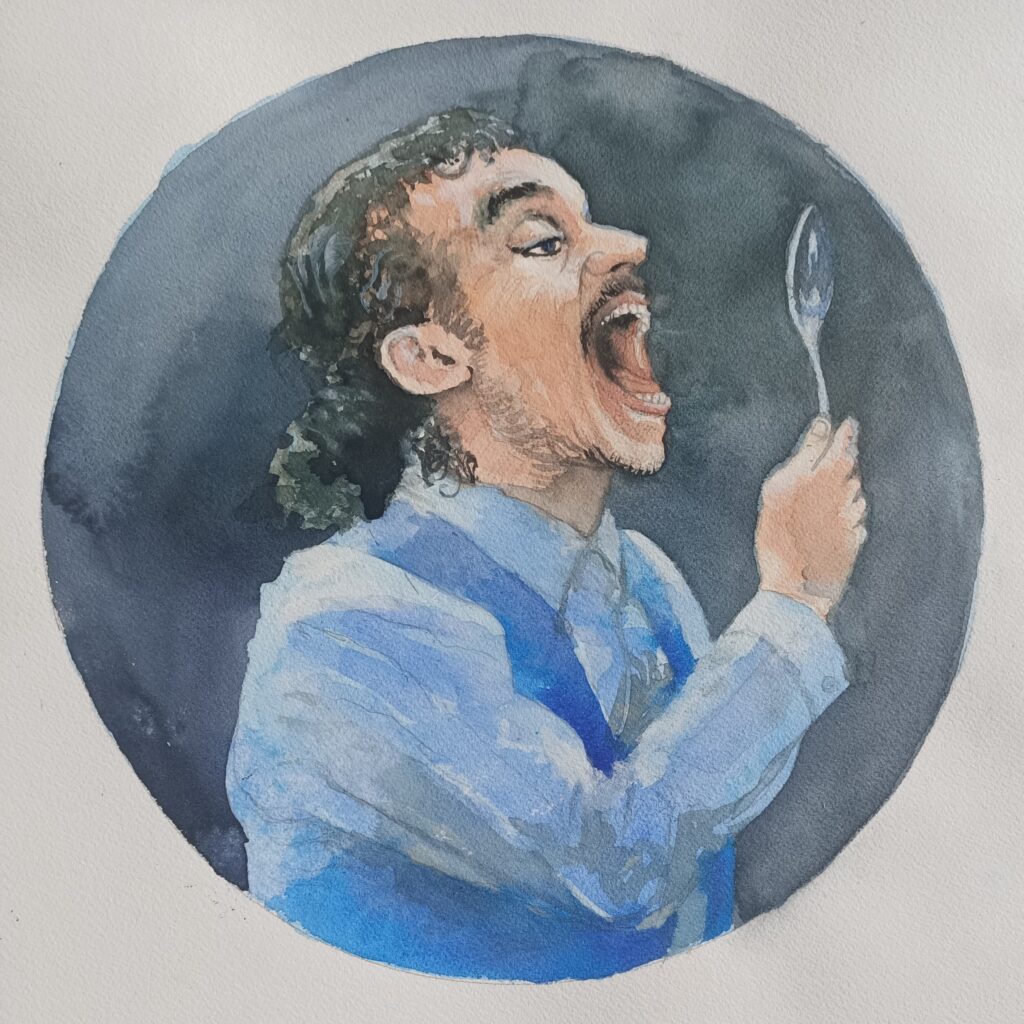

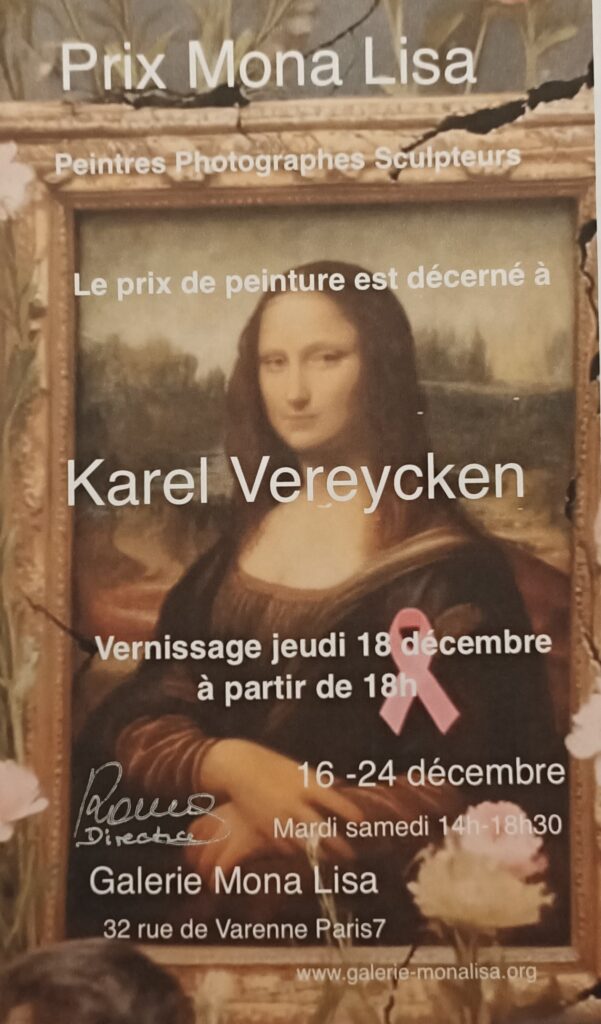

Karel Vereycken wins Paris « Mona Lisa Prize » for his art work

At the Dec. 18, 2025 opening reception (vernissage) of a collective exhibition at the Paris Galerie Mona Lisa, 32, rue de Varenne (Paris VII), Karel Vereycken was honored with the Mona Lisa Prize for painting. His work will be on show at the Galerie between Jan. 16 and Jan. 28, 2026 from Tuesday till Saturday between 2:30 and 6 pm.

Rembrandt, la science de « peindre l’invisible »

article in EN online on this website

article in RU at the bottom of this page

Intervention de Karel Vereycken, peintre-graveur, historien, vice-président de Solidarité & Progrès, lors de la conférence organisée par S&P et l’Institut Schiller à Paris, les 8 et 9 novembre 2025.

Je souhaite que cette présentation prenne la forme d’un atelier. C’est pourquoi je demande à ceux qui « savent déjà » ne pas répondre immédiatement à mes questions, mais de laisser la parole à ceux qui ne sont pas encore familiarisés avec ce domaine afin qu’ils puissent s’exprimer et formuler leurs hypothèses.

Dans l’art contemporain commercial, la seule science dont il est question consiste à renoncer à toute forme de rationalité et à laisser libre cours à une émotion quelconque qui s’empare de l’artiste, souvent plus dégradante qu’élévatrice. Cependant, dans les œuvres fondées sur des paradoxes métaphoriques, il existe une véritable « science de la composition », qui élève les idées et les émotions en mobilisant une combinaison de l’invention et de la maîtrise de la représentation.

Peu d’artistes nous ont permis de pénétrer dans les coulisses de leur processus créatif. L’un d’eux fut le grand poète américain Edgar Allan Poe qui, en 1846, dans sa Philosophie de la composition, expliqua la genèse de son célèbre poème Le Corbeau, composé un an auparavant.

L’humanité a la chance de pouvoir admirer « Cornelis Anslo et sa femme » de Rembrandt, une grande peinture à l’huile sur toile réalisée en 1641 et conservée à la Gemäldegalerie de Berlin. L’étude des dessins préparatoires et de leurs modifications au cours du processus de création nous permet de lever en partie le voile sur les étapes de ce processus et d’entrevoir le génie créatif de Rembrandt.

Anslo et les mennonites

Sur le tableau, on voit le prédicateur mennonite Cornelis Anslo assis à une table couverte de gros livres, s’adressant à une femme, très probablement son épouse.1

La composition est très asymétrique, ce qui était assez inhabituel pour l’époque. Le point de vue en contre-plongée, d’où l’on observe la table avec les livres, détermine en grande partie l’effet produit par le tableau. L’impression prévaut qu’Anslo, inspiré des saintes écritures, prononce un sermon du haut d’une chaire.

Le tableau est assez grand : 1,73 m de haut sur 2,07 m de large. L’homme au chapeau noir est Cornelis Claesz Anslo (1592-1646), un riche armateur et marchand de tissus. Il est né à Amsterdam, quatrième fils du marchand de tissus néerlandais d’origine norvégienne Claes Claeszoon Anslo. Anslo signifie « d’Oslo ». Certains prétendent qu’il porte un manteau de fourrure car le tableau a été réalisé en hiver, mais la fourrure ici n’est autre qu’un signe de richesse, de réussite et de statut social. Les frères d’Anslo étaient des figures majeures de la guilde des drapiers qui contrôlait l’industrie textile d’Amsterdam. Ils ont fait fortune en vendant des tapis comme celui-ci, posé sur la table.

Mais Cornelis était aussi un homme profondément religieux, pour qui la religion se traduisait par des actes et non par de simples paroles. Après son mariage, il fonda un hospice pour femmes âgées démunies. Instruit, il devint ensuite prédicateur à la Grote Spijker, l’église des Waterlanders, les mennonites d’Amsterdam.

Les mennonites étaient un groupe religieux néerlandais fondé à l’origine par Simon Menno (1496-1561), un prêtre qui quitta l’Église catholique pour créer sa propre branche au sein de la Réforme protestante. Certains Amish, aux États-Unis, descendent des mennonites néerlandais et flamands.

Il serait trop fastidieux de retracer leur histoire ici. En bref, ils se considéraient comme une communauté de chrétiens désireux de vivre à l’image de Dieu. Ils ne souhaitaient pas d’Église officielle. Ils se réunissaient simplement, lisaient la Bible et s’efforçaient de traduire son message en actes concrets. Par exemple, ils prenaient très au sérieux le passage des Écritures où Jésus nous invite à « aimer nos ennemis et à prier pour ceux qui nous persécutent ». De ce fait, les mennonites décidèrent de ne jamais faire la guerre à quiconque ni d’y prendre part. Ils n’étaient donc pas vraiment appréciés des autres confessions religieuses de l’époque, souvent engagées dans divers conflits armés. Contrairement à bon nombre de ses connaissances, Rembrandt n’a jamais été officiellement membre des mennonites. Il partageait néanmoins certains aspects de leur vision pacifique du monde.2

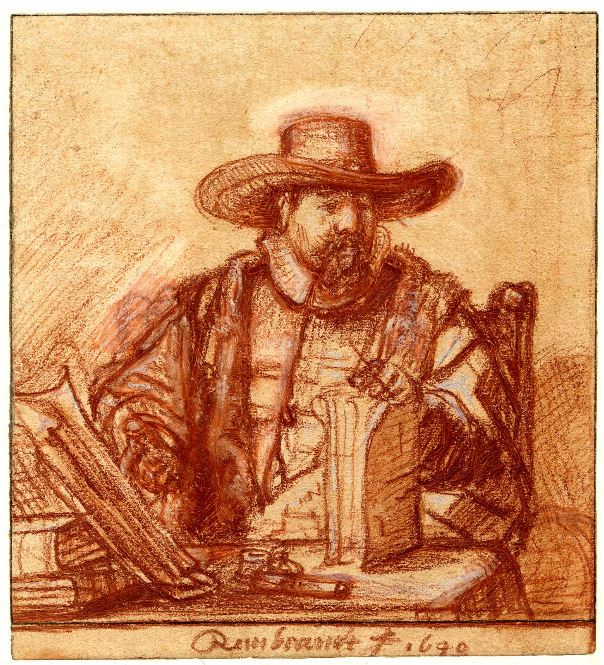

(Crédit: domaine public, British Museum.)

En 1640-1641, Anslo fit appel à Rembrandt pour son portrait. Le prédicateur demanda probablement au peintre de réaliser une esquisse afin de se faire une idée du résultat final. Le prédicateur apparaît sur le premier dessin à la sanguine conservé au British Museum.

QUESTION : Qu’y a-t-il de particulier dans ce dessin ?

PUBLIC : ….

KAREL : Alors qu’il était droitier, il tient sa plume de la main gauche, car le dessin est préparatoire à une gravure. Si l’on transfère l’image telle quelle sur une plaque de cuivre ou de zinc, puis qu’on l’imprime, on obtient une image en miroir. Ainsi, dans la gravure imprimée, Anslo apparaîtra avec une plume dans la main droite, puisque l’effet miroir inverse le sens de l’image. Il faut le prévoir dès le départ.

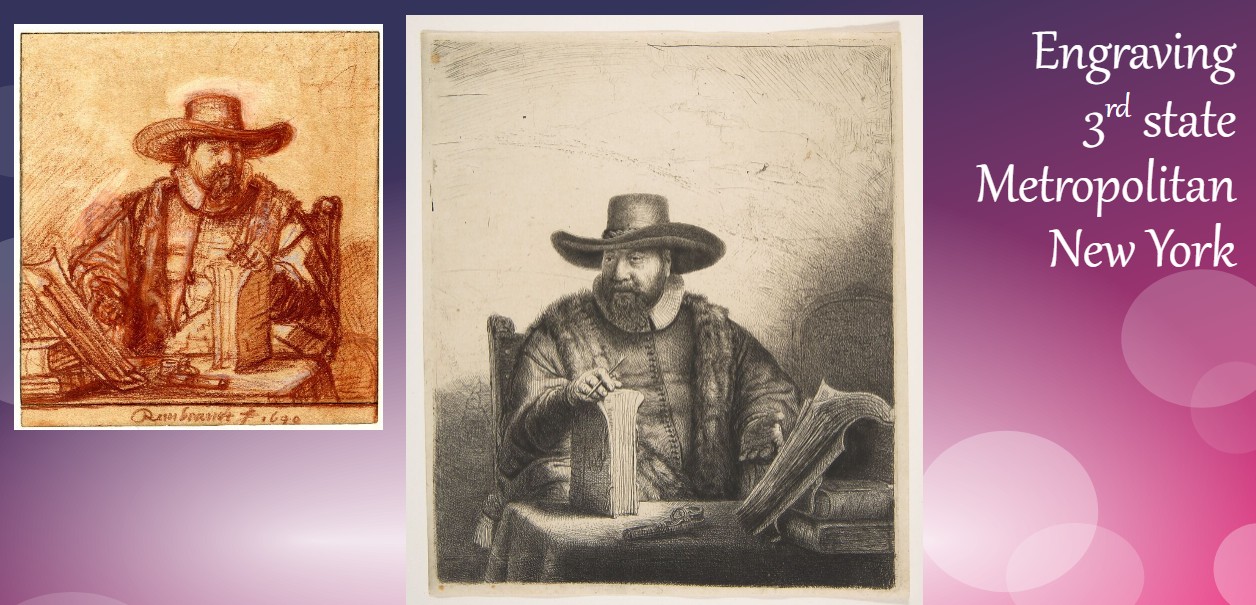

Nous avons ensuite la gravure de 1641, au Metropolitan Museum de New York.

QUESTION : Qu’est-ce qui différencie l’eau-forte du dessin ?

PUBLIC : ….

KAREL : Il a ajouté de l’espace vide. Pourquoi ?

PUBLIC : …

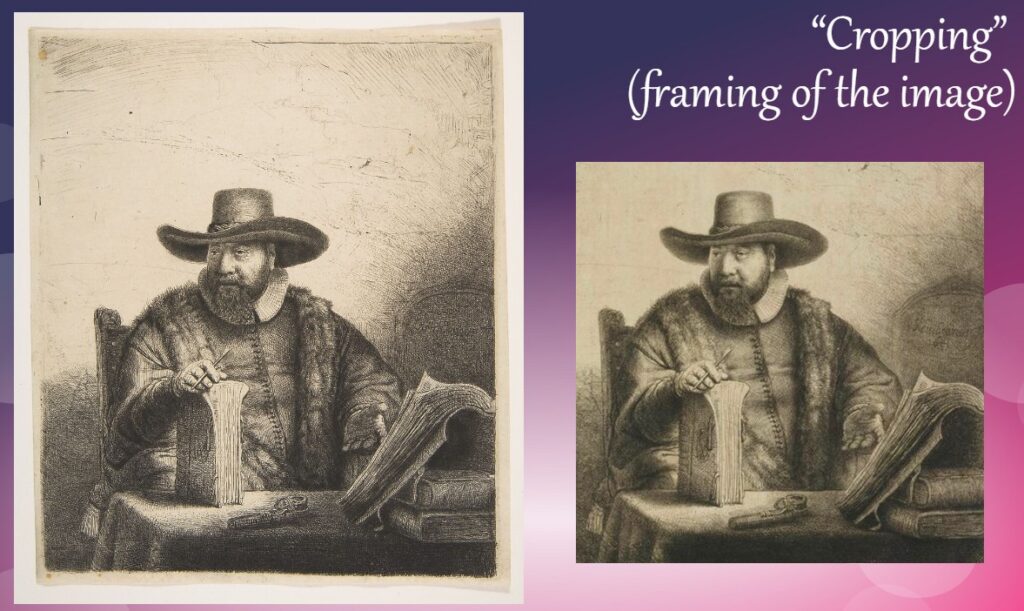

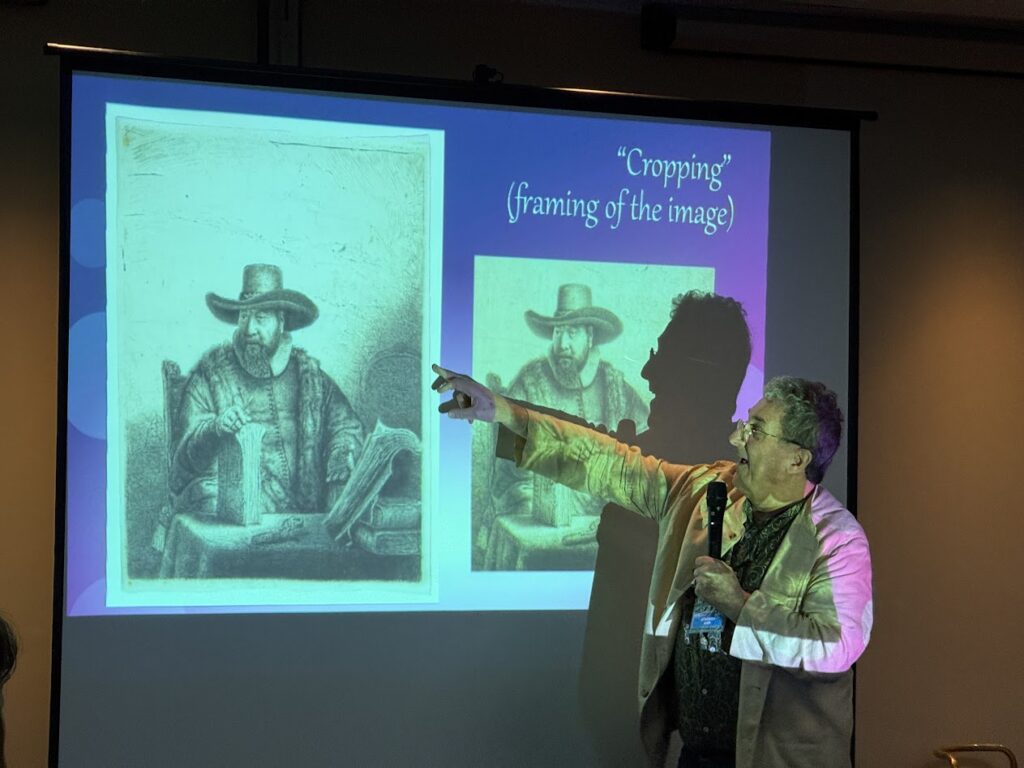

KAREL : Dans une bonne école d’art, on apprend à recadrer l’image.

à gauche, format intégral ; à droite, recadrée Metropolitan Museum, New York.

KAREL : Mais attendez une minute, cet espace supplémentaire est-il vraiment vide ?

PUBLIC : …

KAREL : En fait, il a ajouté deux choses :

- un clou dans le mur derrière lui (très esthétique !)

- un tableau posé au sol, l’image tournée vers le mur (également très esthétique).

Étrange ? Pas tant que ça, puisque la congrégation s’appelait De grote spijker (« Le grand clou », clou signifiant également le « grand magasin » ou la « grange » leur servant de temple).

Vondel et la poésie

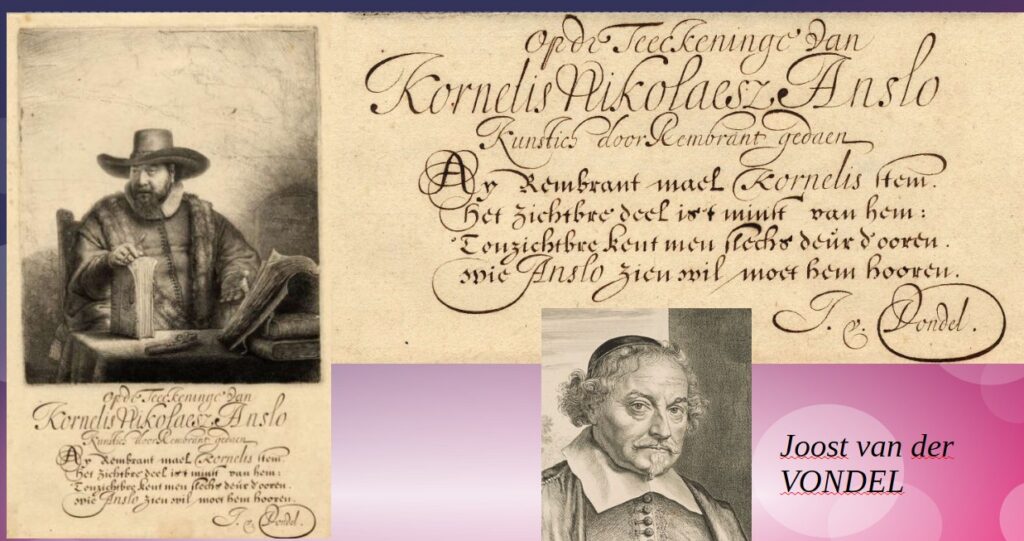

Pas vraiment. Pour trouver une réponse, il faut faire un petit détour. Ce que l’on sait peu, c’est qu’en dessous des tirages de la gravure apparaît souvent, ajouté à la main, un court poème de Joost van der Vondel, considéré comme le plus grand poète de langue néerlandaise :

On peut y lire en néerlandais/flamand :

“Op de Teekeninge van / Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo /

Kunstich door Rembrandt gedaen /

Ay Rembrandt mael Kornelis stem /

het zichtbare deel is’t minst van hem /

’t onzichtbare kent men slecht deur d’ooren /

wie Anslo zien wil, moet hem hooren. /

J. v. Vondel »

Traduction française :

« Ô Rembrandt, peins la voix de Cornelis.

La partie visible est la moindre de lui ;

l’invisible, nous ne le connaissons que par nos oreilles ;

celui qui veut voir Anslo doit l’entendre. »

J. v. Vondel

ou, la version rimée que m’a offerte mon amie russe:

« Rembrandt, ô peins, vibrant, la voix de Cornelis.

La part visible de lui n’est qu’une esquisse

Son invisible, c’est l’ouï qui nous le révèle;

Seul qui l’entend puisse voir Anslo tel quel.«

Jusqu’en 1641, Vondel fut le doyen des Waterlanders, le groupe mennonite d’Amsterdam dont Anslo était un prédicateur de premier plan.

Son poème mentionne un « tekening » (dessin) et, en effet, on peut déjà trouver le poème au verso de l’esquisse initiale. On peut penser qu’Anslo a montré, pour avis, l’esquisse préparatoire de Rembrandt à Vondel, le doyen de sa congrégation.

En réagissant par son poème, Vondel met en lumière trois points :

- Il affirme haut et fort la position officielle de la congrégation des mennonites, à savoir que la parole (et plus encore la voix, c’est-à-dire la parole prononcée) est supérieure à l’image pour évangéliser l’humanité. Transformer les autres par sa voix a plus de valeur que le simple apprentissage, et enfin, que pour connaître il faut enseigner.3

- Vondel fait subtilement comprendre que son propre art, la poésie, est supérieur à celui de Rembrandt, la peinture…

- Il dit que Rembrandt pourrait même faire mieux.

Il est clair que Rembrandt s’est senti interpellé par les remarques plutôt amicales du poète. La gravure pourrait constituer une première réponse du peintre, puisqu’elle souligne l’importance de la parole par cette idée du clou, symbolisant l’image décrochée et placée face contre le mur.

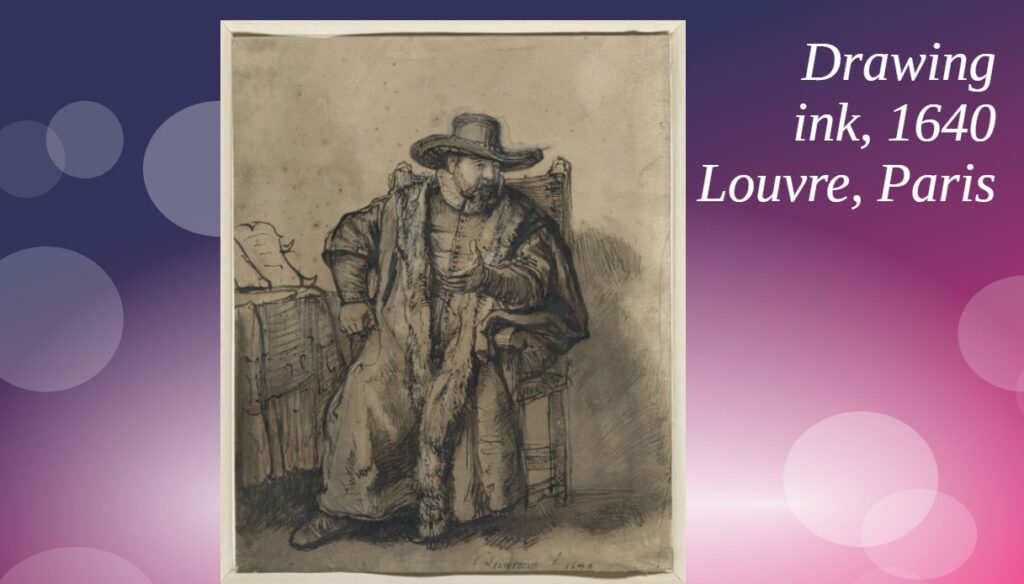

Mais pour préparer le grand tableau à l’huile, Rembrandt réalisa une nouvelle esquisse, aujourd’hui conservée au Louvre.

L’iconographie de la gravure était certainement comprise des mennonites, mais cela ne suffisait pas à toucher un public plus large au fil du temps. Il fallait donc inventer autre chose, visuellement parlant, pour présenter à un niveau supérieur le même argument et surmonter le défi de « peindre l’invisible ».

Déjà dans le dessin du Louvre, la main d’Anslo se déplace vers la gauche, ou plutôt sa tête vers la droite, donnant l’impression que le prédicateur se penche vers son interlocuteur. Dans ce deuxième dessin, si Anslo ne parle pas encore, bien qu’il soit « sur le point » de parler, il se trouve dans une position instable, disons de transition, entre deux mouvements, c’est-à-dire en « point de changement de mouvement » (mid-motion-change, comme l’a formulé Lyndon LaRouche).

La parole sera pleinement manifeste dans le tableau final : la bouche d’Anslo est ouverte et ses sourcils sont levés.

Mais au-delà du simple portrait d’Anslo, Rembrandt ajoute un élément totalement inédit : une personne qui écoute avec une attention extrême.

Ainsi, pour peindre la « voix » (le son), il peint un autre phénomène invisible, son contraire : le silence. Une voix qui résonne sans auditeur est aussi morte qu’un mot dans un livre.

Par là, Rembrandt surmonte le paradoxe de Vondel et affirme la supériorité de son art, la peinture, et le fait que, par l’image, les apparents opposés du son et du silence peuvent être dépassés et rendre visible la parole de Dieu, agissant à travers la voix d’Anslo et surtout l’écoute de sa femme.

Alors, la lumière céleste de Dieu pénètre dans la pièce et éteint la lumière terrestre des bougies pour faire place à la lumière céleste.

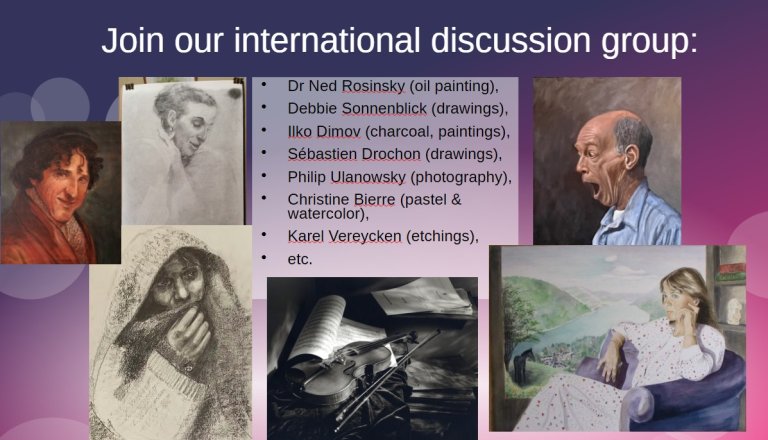

Pour conclure, si vous souhaitez poursuivre ce type de discussion, je vous invite à rejoindre le groupe de travail international sur l’art, parmi les artistes amateurs de notre mouvement. Ce groupe fut lancé par le Dr Ned Rosinsky. À ce jour, il comprend principalement son initiateur, Debbie Sonnenblick, Ilko Dimov, peut-être Sébastien Drochon, Philip Ulanowsky, Christine Bierre et moi-même. Vous pouvez voir quelques-unes de leurs œuvres ici. N’hésitez pas à me contacter à ce sujet.

Merci

BIOGRAPHIE SOMMAIRE :

- Corpus des peintures de Rembrandt, base de données

https://rembrandtdatabase.org/literature/corpus.html - Filippi, Elena, Weisheit zwischen Bild und Word in Fall Rembrandt, Coincidentia, groupe 2/1, 2011

- Haak, Bob, Rembrandt : sa vie, son œuvre et son époque, Thames & Hudson, 1969

- Kauffman, Ivan J., Voir la lumière, Essais sur les images religieuses de Rembrandt, Academia.edu, 2015

- Schama, Simon, Les yeux de Rembrandt, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999

- Schwartz, Gary, Rembrandt, Flammarion, Mercatorfonds, 2006

- Tümpel, Christian, Rembrandt, Albin Michel, Mercatorfonds, 1986

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt, bâtisseur de nation, Nouvelle Solidarité, 1985

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt et la lumière d’Agapè, Artkarel.com, 2001

- Wright, Christopher, Rembrandt, Citadelles et Mazenot, 2000.

- Les experts ont souvent divergé quant à l’identité de la femme. S’agit-il de sa mère, de son épouse ou d’une servante de l’hospice fondé par Anslo ? En 1767, Camelis van der Vliet, la gouvernante de l’hospice, rapporta un passage des archives indiquant qu’Anslo prêchait l’Évangile non seulement en public mais aussi « à sa femme et à ses enfants ; tout comme il est merveilleusement représenté dans le tableau susmentionné, parlant à sa femme de la Bible qui est ouverte devant lui, et que sa femme, représentée d’une manière inimitable et artistique, écoute avec une attention dévote ». A cela s’ajoute que la femme n’est pas vêtue comme une indigente pensionnaire d’un hospice, mais conformément à son statut d’épouse d’un riche marchand. Ce n’est que bien plus tard que le tableau, réalisé pour la demeure privée d’Anslo, deviendra propriété de l’hospice. ↩︎

- En 1686, le critique d’art italien Filippo Baldinucci déclara que « l’artiste professait à cette époque la religion des ménistes (mennonites) ». Des recherches récentes confirment que Rembrandt avait des liens étroits avec la communauté mennonite Waterlander d’Amsterdam, notamment par l’intermédiaire d’Hendrick Uylenburgh, un marchand d’art mennonite qui dirigeait un atelier d’artistes où Rembrandt travailla de 1631 à 1635. Rembrandt devint le peintre en chef de l’atelier et épousa en 1634 la cousine germaine de Van Uylenburgh, Saskia van Uylenburgh, qui n’était pas mennonite. ↩︎

- Le débat sur le rôle exact de la voix, de la parole et de l’image pour les prêcheurs, dégénéra en 1625 en une violente dispute entre les membres de la communauté des Waterlanders d’Amsterdam et d’ailleurs. Une faction affirmait que la parole écrite n’était qu’une voix « morte » et que seul importait la parole vivante, c’est-à-dire Jésus, qui était vivant en chacun en tant que « parole intérieure » des chrétiens. En publiant un pamphlet anonyme, Anslo a pu calmer le débat et réconcilier les croyants, évitant ainsi un schisme. ↩︎

Karel Vereycken’s work featured in giant World Art Collection book

Karel Vereycken’s artwork will be included in the « World Art Collection« , an incredible international project by Culturale Lab that brings together more than 5,000 artists from every corner of the globe, creating a monumental publication that celebrates creativity in all its forms.

This is to become the biggest art project book ever created, connecting artists, galleries, and art lovers worldwide. It will appear in the autumn of 2026.

Karel Vereycken selected for the book « 100 Artists of Europe »

Thrilled to announce that I’ve been selected to be featured in the forthcoming book « 100 Artists of Europe », to appear in 2026. Honored to be part of this initiative celebrating creativity across our continent. #100ArtistsOfEurope #EuropeanArt #CultureAndArt

Preview of publication

The Creative Principle in Painting

Discussion paper written (updated later but initially conceived in Belgium before 1980) by my beloved wife Christine (Ruth) BIERRE who was a precious source of many of my works, research and inspiration.

Abbaye de Vallemagne, 2025

AUDIO – Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Pearl Necklace

Karel Vereycken, on June 15, commenting Young Woman with a Pearl Necklace, a painting of Johannes Vermeer, at the Berlin Gemäldegalerie, Germany.

Listen:

this AUDIO

Read:

—Vermeer, Metsu, Ter Borch, Hals, l’éloge du quotidien. FR pdf (Nouvelle Solidarité)

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on décembre 30, 2025

AUDIO: Bruegel’s Mad Meg: we see her madness, but do we see ours ?

More information on Bruegel:

Posted in Audio comments, Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur AUDIO: Bruegel’s Mad Meg: we see her madness, but do we see ours ?

Tags: antwerpen, artkarel, audio, comment, dessin, Dulle Griet, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Maagdenhuis, Mayer van den Bergh, peinture