Étiquette : Antwerp

AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility

OPEN WEBPAGE TO LISTEN TO AUDIO: CLICK HERE

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

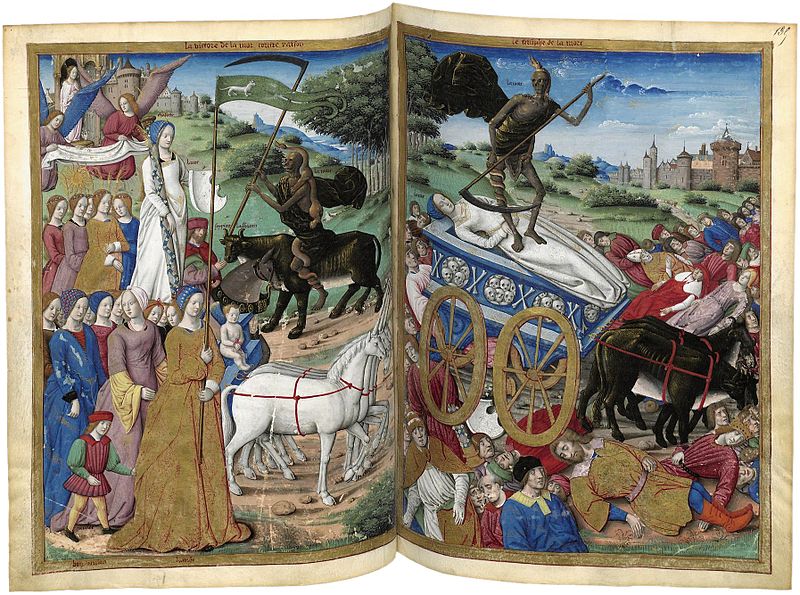

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

ARTKAREL AUDIO GUIDE — Bruegel’s Two Apes (Berlin)

Karel Vereycken, on June 15, analyzing and commenting Bruegel’s painting « The Two Apes » at Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, Germany.

Shakespeare’s lesson in Economics

Cet article en FR

by Karel Vereycken

As early as 1913, the very year that a handful of major Anglo-American banks set up the Federal Reserve to prevent that any form of national bank in the US fixes the rules for money and credit, Henry Farnam 1 , an economist at Yale University, noted that « if one examines the dramas of Shakespeare, one will notice that quite often in his plays the action turns entirely or partly on economic questions. »

The comedy The Merchant of Venice (circa 1596) is undoubtedly the most striking example. While the plot of the story is generally well known, the deeper meaning of this play, which can be read on different levels, is often overlooked. The sequence of events (the story itself) is one, what they reveal (the principles) is another.

The narrative

To help out his protégé Bassanio and enable him to engage with his beloved Portia, a Catholic Venetian merchant and shipowner named Antonio borrows money from a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Shylock hates Antonio, the very archetype of the hypocritical Christian, because the latter treats him with contempt. Antonio, on the other hand, hates Shylock because he is Jewish and because he is a usurer: he lends at interest.

Shakespeare makes us understand that the prosperity of Venice is based on the mutual hatred fueled by the oligarchs between Jews and Christians, according to the famous principle of « Divide and rule. » 2

Double-dealing

The Venetian oligarchy never lacked imagination in circumventing the standards it imposed on its adversaries.

Indeed, among both Jews and Christians, financial usury is condemned and even punished. Interest, which is simply defined as the remuneration of a creditor by his debtor for having lent him capital, is a very ancient concept that probably dates back to the Sumerians and is also found in other ancient civilizations such as the Egyptians or the Romans.

Now, let us recall here that Judaism, which is the first of the Abrahamic religions, clearly prohibits lending at interest. We encounter numerous passages that condemn interest in the Torah, such as the book of Exodus 22:25-27, Leviticus 25:36-37 and Deuteronomy 23:20-21.

However, this prohibition only applies to loans within the Jewish community. In Deuteronomy 23:20-21, it is stated that

« When you lend money, food, or anything else to a fellow countryman, you shall not charge him interest. You may charge interest when you lend to a foreigner, but you shall not lend at interest to your fellow countrymen. »

Initially, the same rule applied among Christians. It was not until the First Council of Nicaea (in 325) that lending at interest was prohibited. At the time, many churches were held by lineages of priests , just as nearby castles were controlled by lineages of lords, the two often being related. While its condemnation had been relatively mild in Christianity before then, interest became a serious sin and was heavily punished from the 1200s onwards.

The exploitation of Jews

Italy has been home to Jews since ancient times. They were dependent on popes, princes, or merchant republics. Rome, Sicily, and the Kingdom of Naples had large communities, and popes sometimes hired Jewish doctors. In the 13th century, some cities granted Jewish bankers, with papal license, a monopoly on pawnbroking.

Venice welcomed Jews but forbade them from practicing any profession other than lending for interest. Initially, the Jews publicly enriched themselves in Venice, drawing the ire of the rest of the population.

To « protect » the Jews, the Doge of Venice created the first ghetto (a Venetian word), offering, it must be said, the most unsanitary district of the lagoon to these Jews whom he detested while cherishing the financing they provided for Venetian colonial expeditions and the slave trade that « Catholic » Venice practiced without any qualms.

The Merchant of Venice

This is the essence of the Venetian system that Shakespeare unmasks in his comedy The Merchant of Venice . 3

So, when Antonio goes to ask Shylock for a loan of 3000 ducats for a period of three months, he first tells him:

« Shylock, I normally don’t lend or borrow money with interest, but in order to help my needy friend, I’ll break my custom. » 4

Shylock then replies:

« Sir Antonio, many times you have criticized me about my money and habit of charging interest in the Rialto. I have endured it all with patience and a shrug, because we Jews are known for our ability to endure. You say I believe in the wrong religion, call me a cut-throat dog, and spit on my Jewish clothing, all because I use my own money to make profit. And now it appears that you need my help. Okay, then!

You come to me and you say, « Shylock, I need money. » You tell me this! You who spat on my beard and kicked me as you’d kick a stray dog away from your threshold! You ask for money. What should I say to you? Shouldn’t I say, « Does a dog have money? Is it possible for a dog to lend you three thousand ducats? » Or should I get bend to my knees and with bated breath humbly whisper, « Fair sir, you spat on me last Wednesday; you spurned me then; another time you called me a dog—and for all this courtesy you’ve shown me, I will gladly lend you this much money? » 5

To which Antonio retorts:

« I am likely to call you such names again, spit on you again, and spurn you, too. If you decide to lend this money, don’t do it as if we are your friends. After all, when have friends ever charged each other interest? Lend me the money as your enemy and if I break my part of the agreement you can more happily punish me. » 6

Offended, Shylock replies:

« Why, look at your temper! I would be friends with you and have your affection, forget about how you have shamed me, lend you what you need and take no interest—but you won’t listen to me! I’m giving you a kind offer. » 7

Shylock, to escape from the mutual hatred, offers to lend him (according to the Jewish and Christian rule), as a friend, without interest.

But the « good » Catholic Antonio refuses to become friends with the Jew. He asserts that in business, one should not have friends , and demands that he lend to him as an enemy because it is easier to sanction in case of non-compliance with the contract.

As Churchill said, an empire has no friends, only interests. This principle would later be theorized by Nazi crown jurist Carl Schmidt to become the rule of today’s oligarchy: to exist, one needs an enemy, and if you lack one, hurry up to invent one!

The Venitian’s double game

As we can see, Shakespeare points out the hypocrisy of this Venetian system which bases its prosperity on a « win-win » policy, not between friends, but as a cynical game between concurring mafias.

Let us recall here that, although it was regularly at war with the Turks, Venice also created a ghetto for Turkish merchants and even a « Foundation », that is to say a functional trade representation in the city.

If a Venetian ambassador was reproached for this trade with the Ottomans which threatened the West, he would reply: « As merchants, we cannot live without them. »

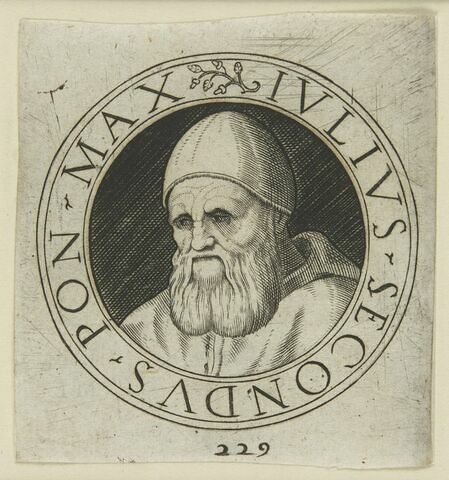

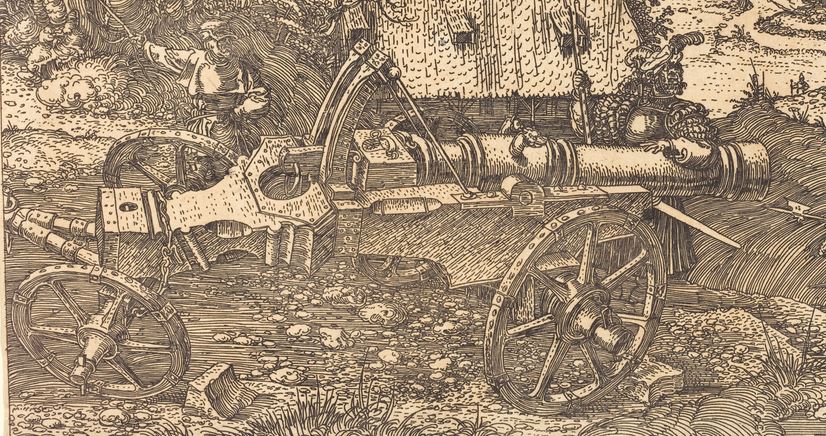

The Ottomans sold wheat, spices, raw silk, cotton, and ash (essential for glassmaking) to the Venetians, while Venice supplied them with finished products such as soap, paper, textiles, and… weapons. Although this was explicitly forbidden by the Pope, countries as France, England, the Low Countries, but especially Venice, Genoa, and Florence sold firearms and gunpowder to the Levant and the Turks. 8

Venice supplied the Turks with cannons and military engineers with its left hand, while renting ships at high prices to Christians who wanted to fight them with its right hand. Added to this was the rivalry with Genoa, which had allied itself with the Palaeologus dynasty but which the Ottomans defeated in favor of the Venetians.

In 1452, a year before the fall of Constantinople, the Hungarian engineer and founder Urban (or Orban), a specialist in large bombards, entered the service of the Ottomans. These cannons, he entrusted to the Sultan, were so powerful that they would bring down « the walls of Babylon. » We know what happened next in 1453.

When the Franks wanted to hire ships in Venice to go on crusade, they lacked money.

No problem: Venice finds the right arrangement. To pay for the ships’ rental, the Franks are invited to make a small detour along the route and begin the crusade by liberating Constantinople, which Venice wants to retake from the Ottomans. And it works! Venice increases its trading posts and military bases in Constantinople to expand its financial and commercial empire.

A Pound of Flesh

Faced with Antonio’s foolish and arrogant response, Shylock pushes his logic to the point of absurdity and, jokingly, suggests that if his debtor does not repay his debt on time, he would have the right to take a pound of flesh from him.

This can be seen as a literal and wacky interpretation of what was written on the « bonds » or « receipts of debt » of the time. Antonio, who is convinced that his ships will return to Venice in time to provide him with enough to repay Shylock, accepts the terms of the contract, almost laughing at their surreal nature.

This is where Shakespeare poses a fundamental question and offers us a beautiful lesson in economics, in the form of a tragic and paradoxical metaphor. In most ancient civilizations, failure to repay a debt could lead you to slavery, cost you your life, or send you to prison for the rest of your life. From monetary slavery, we thus moved on to physical slavery. 9

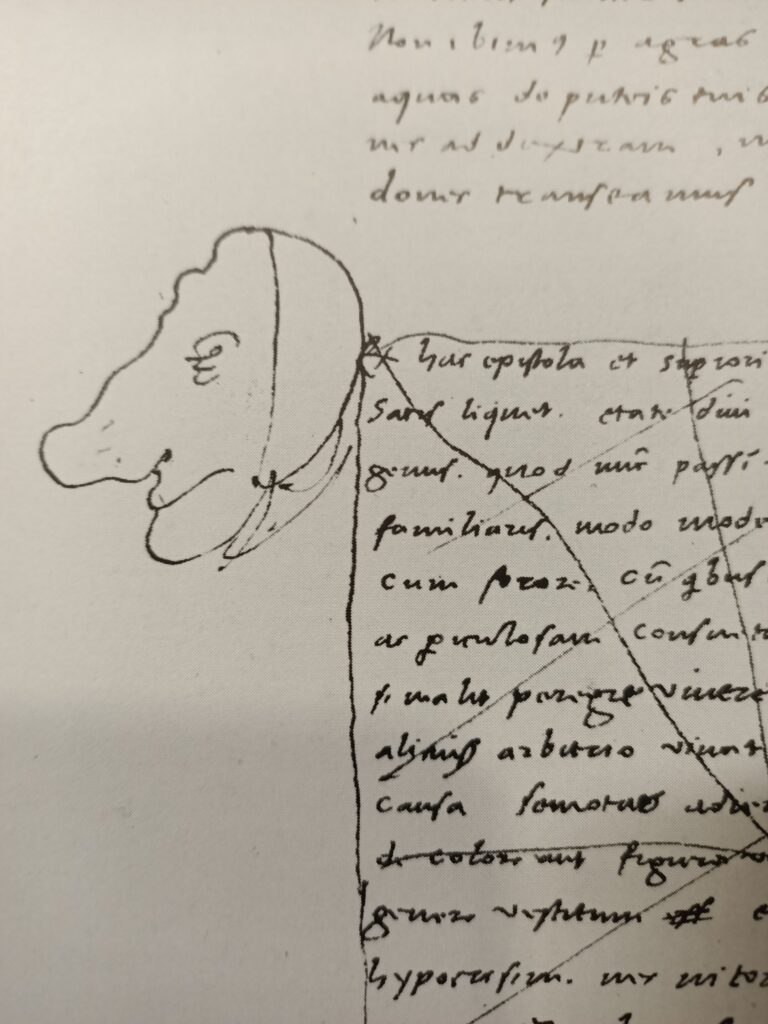

Later, for example, we find in the archives of the Antwerp courts the text of a trial in 1567 concerning an obligation between Coenraerd Schetz and Jan Spierinck:

« I, Jan Spierinck, confess and declare with my own hand that I owe the honorable Lord Coenraerdt Schetz the sum of four hundred Flemish pounds, and this on the basis of the equal sum that I have received from him to my satisfaction. I promise to pay in full the said Lord Coenraerdt Schetz or the bearer of this present, on the fourth day of the next month of August without any delay, by pledging myself and all my property now and in the future. In the year 1565, on the 11th of June. »

You read that right: « by pledging myself. » Taken literally, the debtor pledges his person as surety to his creditor. Let us also recall that in France, imprisonment for private debts was instituted by a royal ordinance of Philip the Fair in March 1303. Apart from two periods of abolition, from 1793 to 1797 and in 1848, the imprisonment of debtors persisted in France until its abolition in 1867.

During the Renaissance, the Christian humanism of Petrarch, Erasmus, Rabelais, and Thomas More combined Socrates’ notion of justice with that of love for others, and a new principle emerged: the life of each individual is sacred and has a value immeasurably greater than any financial debt.

It is a questioning of this principle that turns Shakespeare’s comedy into a drama. Little by little, the spectator learns that Antonio’s ships have all been swept away by storms and other misfortunes. He therefore does not have the necessary means to repay his debt in time.

The Merchant of Venice must therefore accept that Shylock takes a pound of flesh from him as stipulated in the debt title he signed… a financial claim duely validated by a notary and the laws of the Venetian Republic.

To save Antonio’s life, his friends then offer the lender double the initial sum borrowed, but Shylock, driven by a sense of revenge, will not listen, angry moreover at the fact that his daughter has left his house with a young Christian merchant, taking with her a tidy sum of ducats and family jewels.

Shylock viciously responds to the Doge’s request to show mercy, saying that he is asking for nothing more… than the application of the law. He also reminds the Venetians that they are in no position to give moral lessons, because in Venice one can « buy » people:

« What judgment shall I dread, doing no wrong? You have among you many a purchased slave, Which—like your asses and your dogs and mules— You use in abject and in slavish parts. Because you bought them. Shall I say to you, “Let them be free! Marry them to your heirs! Why sweat they under burdens? Let their beds Be made as soft as yours and let their palates Be seasoned with such viands”? You will answer, “The slaves are ours.” So do I answer you. The pound of flesh which I demand of him Is dearly bought. ‘Tis mine and I will have it. If you deny me, fie upon your law— There is no force in the decrees of Venice. 105 I stand for judgment. Answer, shall I have it? » 10

To this, the impotent Doge offers no counterargument. He himself must obey the laws of the city. The only thing he has the right to do is to allow a doctor of law who has examined the case to deliver his expert opinion.

Turnaround of the situation

Here Shakespeare introduces Portia, who, disguised as a law doctor and acting in the name of a higher principle, love for humanity and good, will succeed in turning the tide. 11

Having acknowledged the validity of Shylock’s claim, she turns the tables with the kind of audacity we lack today. Regarding the claim, she notes an important detail concerning the implementation of the sanction:

« Hold on a second. There’s something else. This agreement doesn’t give you any drop of blood. The literal words are « a pound of flesh. » So take what is yours, take your pound of flesh, but if in cutting it off you shed one drop of Christian blood, your lands and goods will be confiscated by the state of Venice by the city’s laws. » 12

This is another beautiful lesson Shakespeare teaches us. How many excellent laws are worthless simply because their authors didn’t bother to specify their implementation? Do you know the laws that allow you to defend yourself against the injustices the system inflicts on you? Because if the devil is in the details, the good Lord is sometimes not far away. It’s up to you to go and find him.

Shakespeare reminds us that economics is not limited to law and mathematics. Every economic choice remains a societal choice. In reality, only « political economy » should be taught in our universities and theaters.

Presenting the science of economics and finance as an « objective » reality and not as a reality of human choices is the best proof that we are subject to propaganda.

In conclusion, let us emphasize that unlike Christopher Marlowe‘s play, The Jew of Malta (circa 1589), the main actor in Shakespeare’s play is not the evil Jew Shylock (as claimed by anti-Semites who performed distorted versions of the play during the dark periods of our history), but rather the very Catholic merchant of Venice who, as we have seen, uses the Jews for his own interests. Let us recall that in the Jewish ghetto of Venice, the Jews were only allowed to deal with finance but nothing else…

Finally, in The Merchant of Venice , Shakespeare unmasks the workings of a mad and criminal finance which knows how to use formal interpretations of law (the appearance of justice) to satisfy its greed (true injustice).

NOTES:

- Henry Farnam, Shakespeare as an economist, p. 437, Yale Publishing Association, New Haven; ↩︎

- See Sinan Guven, The Conflict Between Interest and Abrahamic Religions , HEConomist, the student newspaper; ↩︎

- All the following quotes from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice are taken from the website Litcharts; ↩︎

- Act 1, Scene 3; ↩︎

- Act 1, Scene 3; ↩︎

- Act 1, Scene 3; ↩︎

- Act 1, Scene 3; ↩︎

- Salim Aydoz, Artillery Trade of the Ottoman Empire, Muslim Heritage website, Sept. 2006; ↩︎

- A case in point is the history of Haiti. See Invade Haiti, Wall Street urged, New York Times, 2022. ↩︎

- Act 4, Scene 1; ↩︎

- The principle of a « Promethean » woman intervening disguised as a man for the good of humanity will be, with the person of Leonore, at the center of Fidelio, Beethoven’s unique opera; ↩︎

- Act 4, Scene 1; ↩︎

The 1561 Landjuweel of Antwerp made Art a Weapon for Peace

Cet article, en FR

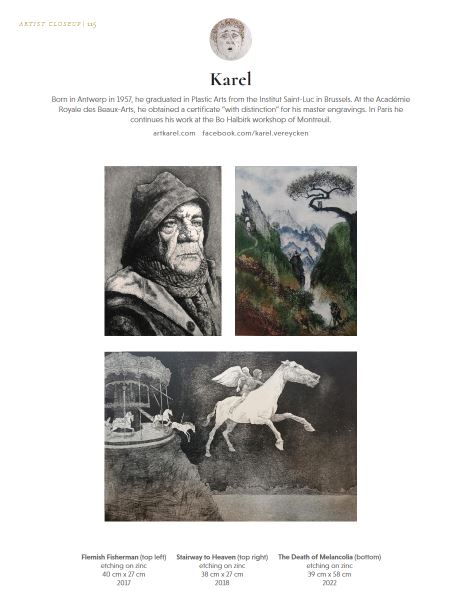

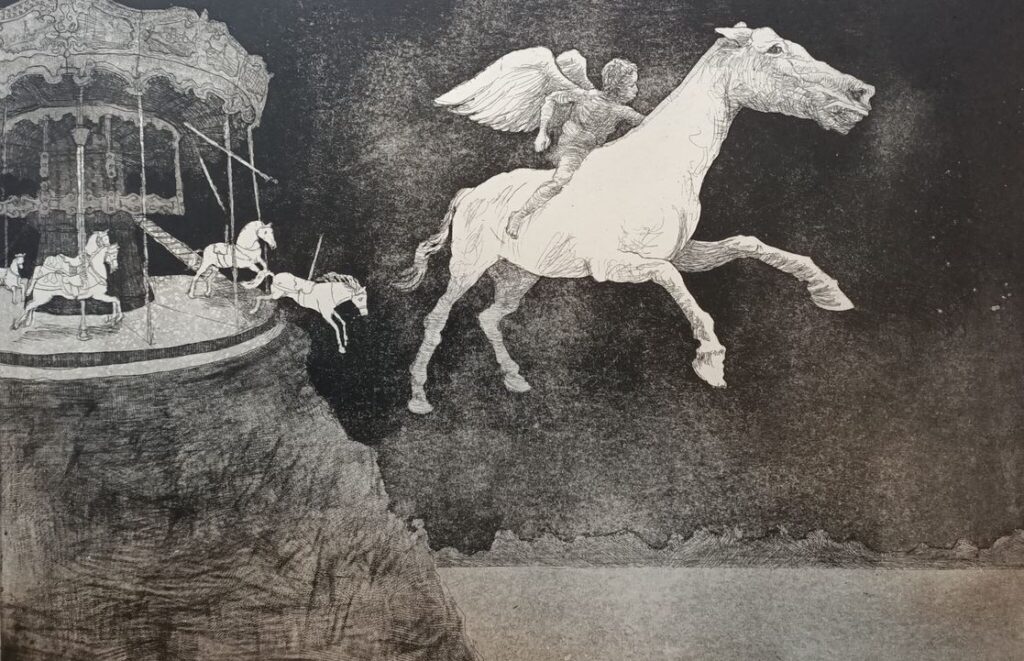

By Karel Vereycken, April 2025

Summary

- Introduction

- Early literacy (box)

- The Chambers of Rhetoric

- Rehabilitation

- Jousts, competitions and other festivals

- Landjuweel

- Political and economic context

- Ghent, 1539

- The influence of Erasmus

- De Violieren and the Guild of Saint Luke

- Antwerp, 1561

- Organization of the Landjuweel

- Philosophy

- A memorable day

- Peace and art, united for celebration

- Censorship, repression and revolt in the Burgundian Low Countries

Introduction

For foreigners it’s not always easy to accept that the countries of Northern Europe represented a peak of Renaissance culture in the XVIth century. However, those day’s Landjuweel (literally « jewel of the country ») poetry contests, mass-events with parades of allegorical floats, fireworks, drama, poetic recitations, farces, dances, refrains, songs and gastronomic feasts which thrilled the « Burgundian Low Countries » (a region including the present-day Netherlands, Belgium and northern France) should clearly become a source of inspiration for today.

Huge is my joy at discovering these treasures, but vast is my anger when I measure to what extent their true history was ignored and even hidden from all of us.

We focus here on the moral greatness of the zinne-spelen (allegorical drama’s) and intend to discuss the farces and the polyphonic musical contributions in some future writings.

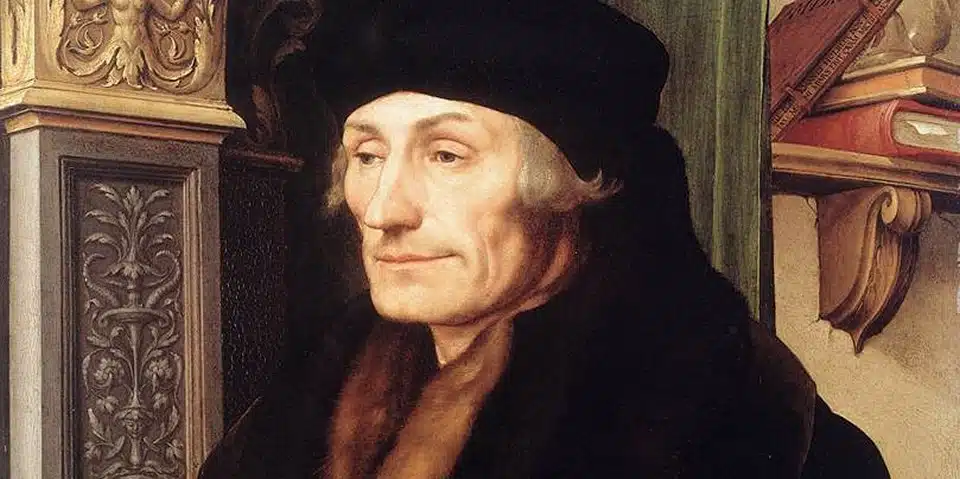

Of course, as it is well known, it is the victors who write history. Not that of humanity, but their own. The history of the « losers » falls by the wayside. Therefore, in the Low Countries, be it Belgium or the Netherlands, the official churches, be they Catholic, Lutheran or Calvinist, and ruling elites, chosen by Spain and the British, have carefully erased from the books the truth about the revolutionary role and impact of Erasmus. 1

As we document here, Erasmus succeded, through his noble spirit and delicious wit, to mobilize quite a large following, not only in educated layers of the European elites, but in a broad part of the rising middle-class working people, a social layer which might resemble today’s « Yellow Vests ».

For modern people, of course, the religious processions, parades of giants, and masked carnivals of Venice, Rio de Janeiro, or Dunkirk in France appear as sympathetic as mere folkloric manifestations on UNESCO’s list of the intangible cultural heritage of France and Belgium. Appealing, no doubt, but without any connection to « true culture »!

Qualifying these events and traditions as « folkloric » results mostly from a lack of knowledge and understanding of real history. Regarding both the intent and the content of some of these festivals, such as the « Landjuweel » of Ghent in 1539 and the one in Antwerp in 1561, with five thousand participants and many more spectators, placing art, poetry and music as the true source of durable peace and harmony among nations, states and peoples, in terms of refinement and beauty, it can be said that they rival, and I would even say surpass many supposedly « cultural » events of today.

Precociously high literacy rates

There’s a persistent idea that needs to be fought, i.e. the belief that before the XIXth century, the century of Hippolyte Carnot and Jules Ferry, the literacy rate barely exceeded 15%, whether in Renaissance Italy, France, or the Nordic countries. Cultural festivals for scholars could therefore be nothing other than events organized by a small elite with substantial means looking to indulge themselves…

Regarding the literacy rate, researchers believe the figures need to be revised. The absence of statistics does not necessarily mean the absence of schools. In fact, from the time of Charlemagne onward, most villages, towns, and villages in Europe had « small schools. » And with urbanization and the increase in trade, the learning of languages and arithmetic came to complement the learning of reading and writing.2

Let us take the case of the city Douai (Today’s northern France, but formerly the Low Countries), which Alain Derville mentions in his article The Literacy of the People at the End of the Middle Ages, published in 1984 in Revue du Nord 3:

« Around 1204-1208 there were at least 7 schoolmasters in Douai in the jurisdiction of Saint-Pierre, therefore not counting that of Saint-Amé, and the school fees were unknown (…) A fee of 18 deniers is cited in 1316-1318; it had risen in 1450 to 4 sous (of Flanders). At that date 5 masters and one mistress refused to pay it, saying, among other things, that many schoolchildren were poor, so much so that, sometimes, they were educated for free: a precious admission. In short, according to B. Delmaire, the case of Douai should rather be compared to that of Valenciennes: for this town, P. Pierrard found at least 20 masters in 1337, 49 masters and mistresses in 1388, 18 masters and 10 mistresses running 24 schools in 1497. In 1386, 516 children were in school, including 145 girls, in 1497, 791, including 161 girls.

In a town which, after the misfortunes of 1477-1493, must have had 10,000 inhabitants rather than 15,000, the children aged 7 to 10 must have been 12 to 1300, that is to say that, if the school lasted three years, the boys would have been educated at 100%, the girls at 25%, at least around 1500. (…) The interest of the laity was therefore very keen for the education of children, at least primary but also, as in Saint-Omer, secondary and even higher (foundations in the XIVth century of colleges and scholarships), and this from the beginning of the XIIIth, as [the Belgian historian Henri] Pirenne had clearly seen. We certainly did not wait until the XVIIth century to ‘invest in education’ « . 4

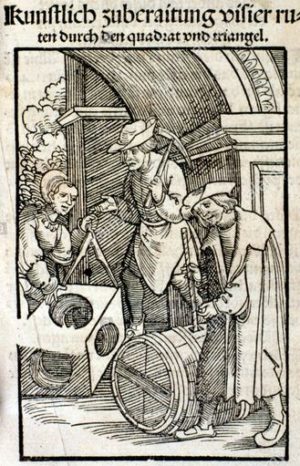

It was the same in Brabant and Flanders. As proof, a small conversation book, the Boec van de ambachten (Book of Trades), published in Bruges in 1347, with the help of which one could, with pedagogical examples, learn Dutch or French. 5

In 2013, an international team of researchers of the Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) documented that the advanced degree of literacy and educated workforce at the end of the XVth and XVIth Century has to be attributed to the influence of the Brothers of the Common Life. 6

In 1567, the Florentine merchant Francesco Guicciardini, in his very comprehensive description of the region, noted that « Here, in the Burgundian Low Countries, learned people have lived and still live, highly educated in all sciences and arts. The common people generally possess rudiments of grammar, the country people at least know how to read and write. Their knowledge of languages is astonishing. For there are people here who have never set foot anywhere but their own country and who know, in addition to their mother tongue, foreign languages, especially French, which is in common use. Many of them also speak German, English, Italian and other foreign languages. » 7

Another source reports that in Antwerp, a major crossroads of world trade, language schools were plentiful. If you want to learn French, he told his interlocutor, go to Antwerp, you’ll find what you need to learn the language there. 8

Another indication of Antwerp’s high cultural level is the account of Andreas Franciscanus, most likely secretary of a diplomatic mission from Venice, who wrote in 1497 that in Antwerp, where the cathedral has a carillon of 49 bells, « everyone is keen on music, and is so expert that even bells are played harmoniously and with such a full sound that they seem to sing (…) all the desired tunes. » 9

Desiderius Erasmus himself stated that “Nowhere else does one find a greater number of people of average education.” 10

In Antwerp, for every 200 workers, there was one teacher, compared with the proportion found in Lyon, an equally rich, busy and important city, where it was one teacher for every 4,000 workers… 11

WOMEN

Also, “Spanish visitors … noted the widespread literacy in the Low Countries. One of Prince Philip’s entourage, Vicente Alvarez, noted in his journal that ‘almost everyone’ knew how to read and write, even women …” 12

Niccolo Nettoli, an Italian passing through, is surprised that women in Antwerp enjoy a certain freedom unhampered by child marriage like young Italian women. Young women, single and living under the parental roof, could go out with young men. The parents approved, sent the couple out to eat during the day, drink, and dance « without any supervision, » and welcomed them back in the evening, thanking the lover for the honor they had done their family. In Antwerp, « Hugging is allowed for everyone, everywhere, and at all times, » the Italian worries. 13

A finding shared by Guicciardini, an Italian merchant living in Antwerp but still astonished:

« As for the women of this country, besides being beautiful, clean, and very pleasant, they are also very kind, courteous, and gracious in their actions: since they begin from their childhood to converse (according to the custom of the Country) freely with everyone, by this company they become bolder in practicing company, and quick to speak, and in all things; but with this great freedom and license, they strictly keep the duty of their honesty, going not only to the city for the housekeeping, and affairs of their houses; so also to the fields, with little retinue, without thereby incurring blame, nor giving occasion for suspicion. They are sober, and very active and careful, interfering not only in domestic affairs (of which the men here do not hesitate and do not worry much) and do everything that in other countries is common for slaves and servants. Thus they also go and buy and sell merchandise and goods; and if they put their hands and tongues to the affairs proper to men (…) » 14

The Chambers of Rhetoric

At the origin of these poetry festivals and competitions of the Landjuweel type, literary and drama societies called Kamers van rhetorike (Chambers of Rhetoric) which emerged from the end of the XIVth century in the northwest of France and in the former Low Countries, above all in the County of Flanders and the Duchy of Brabant.

While in the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries these chambers became literary clubs for a bourgeoisie enjoying exercises in eloquence and rhyme, in these early days rhetorical culture was not socially an elite culture, as most rhetoricians were tradespeople and did not belong to the ruling elite of their city.

Recent research has confirmed that the rhetorical chambers of Flanders and Brabant primarily recruited their members from the urban middle classes, more specifically from the circles of artisans (masons, joiners, carpenters, dyers, printers, painters, etc.), merchants, clerks, practitioners of intellectual professions, and merchants. 15

In 1530, among the 42 members of the Brussels Chamber of De Corenbloem, there were 32 craftsmen (butchers, brewers, millers, carpenters, tile layers, comb makers, fishermen, coachbuilders, stonemasons, etc. = 76.2%). 16

In the artistic professions, there was a glazier and two painters (7.1%), in commerce, a fruit seller, an innkeeper, a skipper and a rag seller (9.5%). The remaining members were a civil servant, a harp-player and an announcer.

For the period 1400-1650, records were found of 227 Dutch-speaking chambers of rhetoric in the Southern Low Countries and the Principality of Liège, meaning that virtually every town had at least one. In 1561, the Duchy of Brabant had about 40 recognized chambers of rhetoric, while the County of Flanders had 125. 17

Their organization was similar to that of the corporations: at the head of each chamber was the dean, usually a clergyman (the chambers retained a religious aspect). Since their creation, the chambers were of two kinds: the free (vrye), enjoying a communal grant, and the subject (onvrye or vrywillige), having no grant, but reporting to a supreme chamber (hoofdkamer). Among the rhetoricians were the founders (ouders), and the members (broeders or gezellen); at the head of all were an emperor, a prince, often a hereditary prince (opperprins or erfprins); then came an honorary president (hoofdman), a grand dean, a dean, an auditor (fiscael), a standard-bearer (vaendraeger or Alpherus), and a boy (knaep), who sometimes dabbled in poetry.

The most important of all were the « factors » or « factors », that is to say the poets who were in charge of the « factie » (composition), poems, plays, farces and the organization of festivities. Initially in the bosom of the ecclesiastics, the Chambers took their independence and established themselves, in practical terms, as a « Festival Committee », charged by the municipal authorities with brightening up with poetry and splendor the joyous entries and cultural events throughout the year.

Rehabilitation

Further research, primarily in the Netherlands, has led scholars to « rehabilitate » the Chambers of Rhetoric, now considered of having been institutions that played a major role in the development of vernacular Dutch during the period 1450-1620. 18

Admittedly, mostly composed as dialogues among allegorical figures, a legacy of the Middle Ages and the troubadour tradition, artistically speaking, with some exceptions, most of these plays never reached the level or quality of dramatic intensity or refinement of Shakespeare or Schiller.

But as we shall see, the desire and intent to emancipate the people through a form of literary and musical art that uplifts by its moral content and liberates through ironical « cathartic » laughter was clearly central to their admirable objectives.

Jeroen Vandommele suggests that experts should rethink their views:

« Until the end of the XXth century, the poetry and theater that emerged from these circles were mostly perceived negatively. Rhetoricians were seen as amateurs, low-level word artists, novice craftsmen who met weekly to entertain themselves with rhymes while drinking a lot of alcohol. They were seen as representatives of a second-rate literary and intellectual culture. Sixteenth-century humanism and the literary renaissance would have been manifested mainly in (neo)Latin texts and, as far as the vernacular is concerned, in texts written from the second half of the sixteenth century onwards, mainly outside the rhetorician circles. It is only in the last three decades that these qualifications and visions have been distanced from the literature and culture of the rhetoricians and an attempt has been made to give them meaning in relation to the urban context in which they emerged. » 19

The respected Dutch historian Herman Pleij, who has contributed to a better understanding of the phenomenon and gave a major boost to this approach by demonstrating, from the 1970s onwards, the potential of XVth- and XVIth-century literature to generate what he calls « late medieval urban culture, » a true expression of an autonomous civic and urban culture. 20

According to him, their works were intended to unleash a « civilizing offensive » that would encourage the urban elite and middle classes to develop intellectually and morally and to distinguish (and dissociate) themselves from their less civilized urban counterparts.

Jousts, competitions and other festivals

The Chambers cultivated the art of poetry by competing against each other in competitions that were among the major events they organized for themselves or for the public. Each chamber itself set the frequency of the competitions and the value of the prizes, often quite symbolic, that could be won. While for some chambers, four competitions per year were enough, for the Antwerp chamber, De Violieren, it was a weekly competition!

Very quickly, these activities gave rise to public festivities, celebrated successively in all the major cities. The Landjuweel skillfully combined several genres of theatrical and musical dramaturgy, which had previously been separate, into a single large city festival:

- The “Mystery Plays » and « Miracle Plays » (Mirakel-spelen, passie-spelen) street theater or large tableaux vivants, sometimes on floats (wagen-spelen). The Mystère de la Passion by Arnoul de Gréban, performed thousands of times throughout France, was a play of 34,000 verses requiring 394 actors reenacting the last five days of the life of Christ.

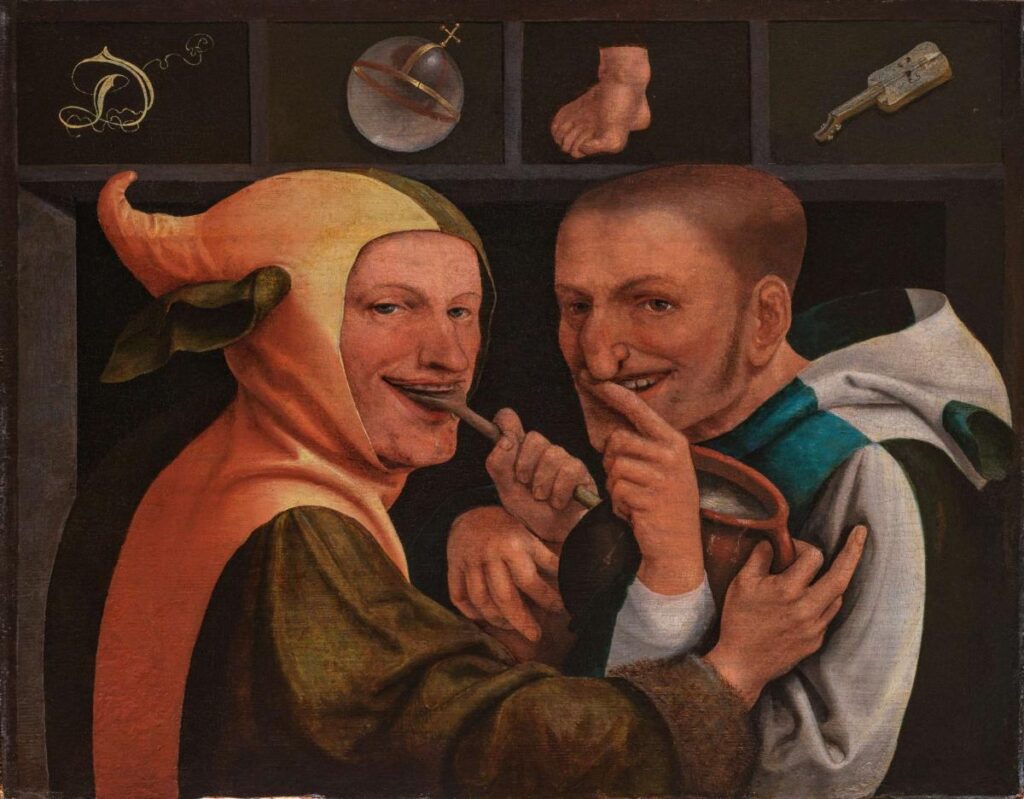

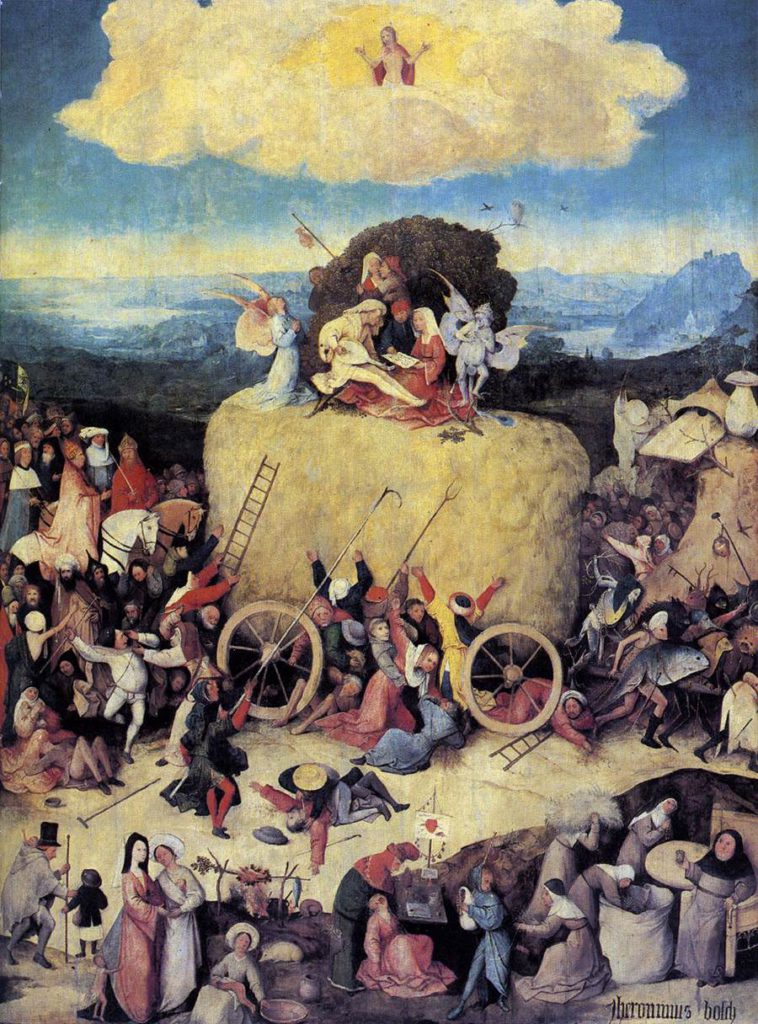

- The « Feast of Fools » or « Feast of the Innocents », masquerades and disguises organized by « joyous societies » in which the clergy had actively participated since the XIIth century. We were then witnessing a total reversal of society: the woman became the boy, the child the bishop, the teacher the student, … The pope was elected, the bishop of fools, the abbot of fools, old shoes were burned in censers, people danced in churches while mumbling Latin in such a way as to trigger many fits of laughter. People danced and sang, accompanied for this by musicians who played wind instruments (flute, trumpet or bagpipes) or string instruments (hurdy-gurdy, harp, lute). It was not uncommon to find serious confusion reigning within convents: nocturnal relations between the abbot of fools and the minor abbesses or even mock weddings between a bishop and a superior. For the Feast of Fools, the lower clergy disguised themselves, wore hideous masks and smeared themselves with soot. The costume and attributes of fools became established in the XVth century. Popes, councils and various authorities published texts aimed at suppressing the said festival from the XIIth century onwards.

- The Ommegang (literally « going around » the church and the city) were religious processions, organized by the church and the crossbowmen’s guilds in honor of the saints whose statues were carried on their shoulders. If in Brussels, the Ommegang became an opportunity for nobles to exhibit themselves in the city (as in 1549 to show their loyalty to the Spanish occupier), in Antwerp, two Ommegangs followed one another: the first, religious, at Pentecost, the second, on the feast of the Assumption, with a strong secular participation of the guilds, trades and chambers of rhetoric, each of them contributing a float to a procession in the streets of the city.

- Carnival, the new name given by the Church to the « Saturnalia, » the great eight-day Roman festivities in honor of Saturn, god of agriculture and time, during the winter solstice. This period of costumed celebrations and freedoms, particularly in Venice, which developed between the XIth and XIIIth centuries, was supervised by the Church, which considered it necessary to avoid popular revolts. It featured a reversal of roles and the election of a false king. Slaves were then free to speak and act as they wished and were served by their masters. The festivities were accompanied by large meals.

The Rhetoricians rightly believed that these genres complemented each other perfectly. The festivals therefore alternated, without losing the hierarchy of the depth of the meaning that one wanted to convey, both pieces with spiritual and religious content (mysteries, passions) and pieces with philosophical, didactic and moralizing content (zinne-spelen), without forgetting satire, farce and other humorous things (sotties, esbattements, etc.).

Historically, the stage where such events took place moved from the nave of churches, first to the forecourt of cathedrals and finally to the public space in the wider sense, first in the open air (in the Great Square, in the cemetery, on a chariot) before being forced by the authorities to occur exclusively in closed halls.

Among the competitions organized by the Chambers of Rhetoric, the oldest known was that of Brussels in 1394. The one in Oudenaarde, which took place in 1413, is better documented. These were followed by those of Furnes in 1419, Dunkirk in 1426, Bruges in 1427 and 1441, Mechelen in 1427 and Damme in 1431.

Landjuweel

The Landjuwelen were originally a cycle of seven competitions between communal militias practicing their skills in the use of weapons: the Schutterijen of the Duchy of Brabant. The highest luminaries of the country attended such shootings; they were even honored by sovereigns.

The idea was to organize a Landjuweel every three years. The winner of the first competition would organize the next competition and so on; the winners of the seventh Landjuweel would start a new cycle. The winner of the first tournament, having obtained a silver cup, would make two silver dishes for the winner of the second Landjuweel in a cycle, and the latter would in turn make three for the winner of the next competition, and so on until the seventh tournament in the cycle.

There was close cooperation between the knightly societies of the cities of Bruges and Lille in Flanders, as well as between Bruges and Brussels. Like Bruges, Lille organized an annual tournament, « L’Espinette. »

Every February, a delegation from Bruges came to Lille to compete in the tournament, just as the inhabitants of Lille participated in the annual competition of the White Bear in Bruges, which took place in May. This spectacle gave rise to festivities to which the poets of Bruges also contributed. They wrote the scenarios for the esbattements, recited praises, and reported on these activities in their chronicles.

There were no quarrels about differences of languages. Prizes were established to reward works in either French or Dutch, depending on the lingua franca of the city where the competition was held. But sometimes, at the same competition, a prize was awarded for works in both languages. This was notably the case in Ghent in 1439. Prizes were also awarded for the most beautiful entry.

Themes in the form of questions were suggested, which only authorized chambers could answer in verse. These questions were resolved by the « factors » and generally had a moral or political purpose. Thus, in 1431, in the midst of the wars between France and Flanders allied to Britain, the Chamber of Rhetoric of Arras, formerly a city named Atrecht in the Burgundian Low Countries, posed the question « Why is peace, so eagerly desired, so slow in coming »? Note that in 1435, the Peace of Arras, organized by the friends of Nicolas Cusanus, Jacques Coeur and Yolande d’Aragon, sealed the end of the Hundred Years’ War. 21

Political and economic context

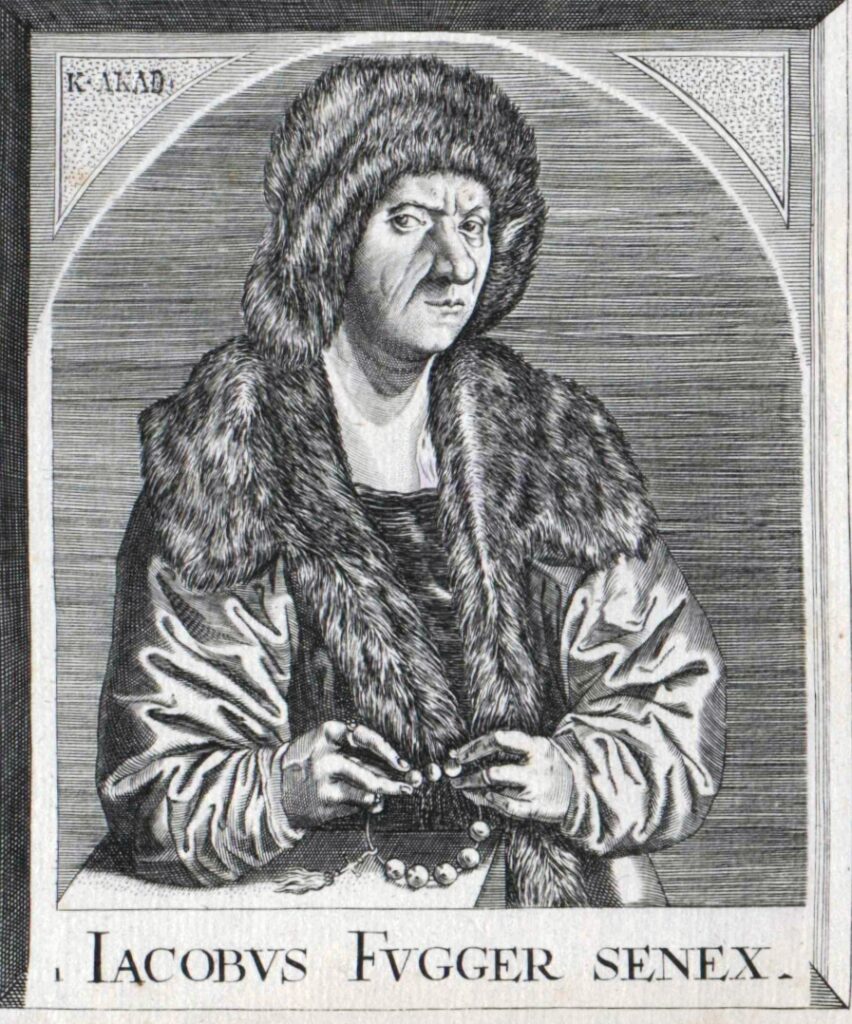

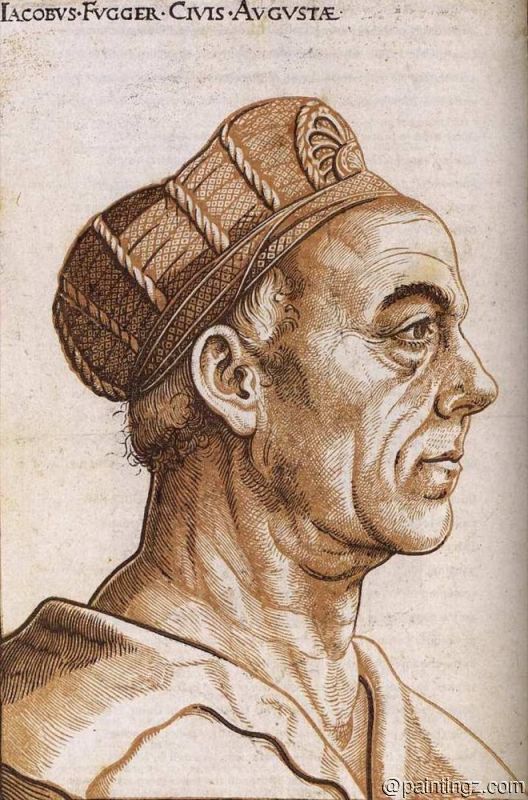

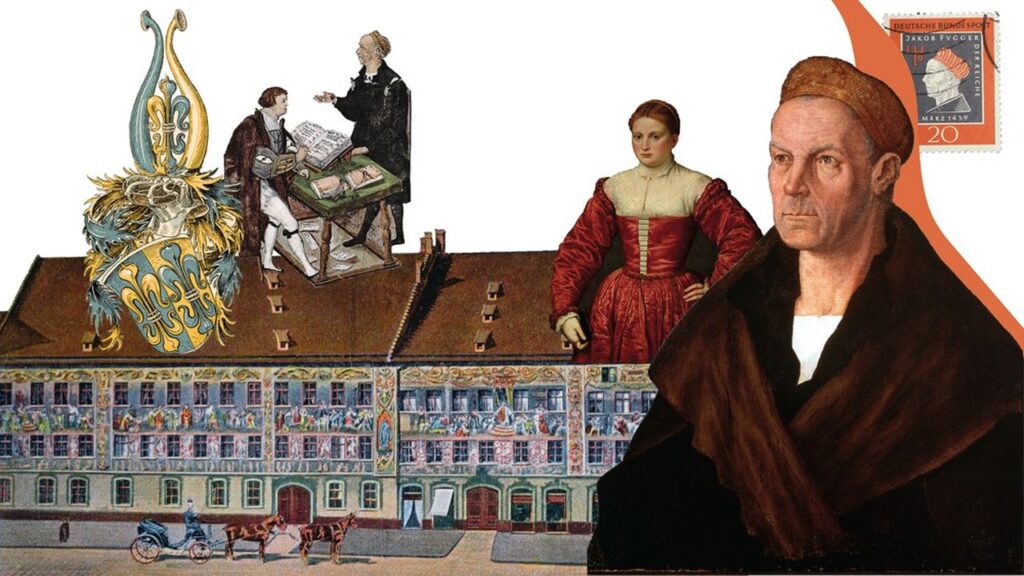

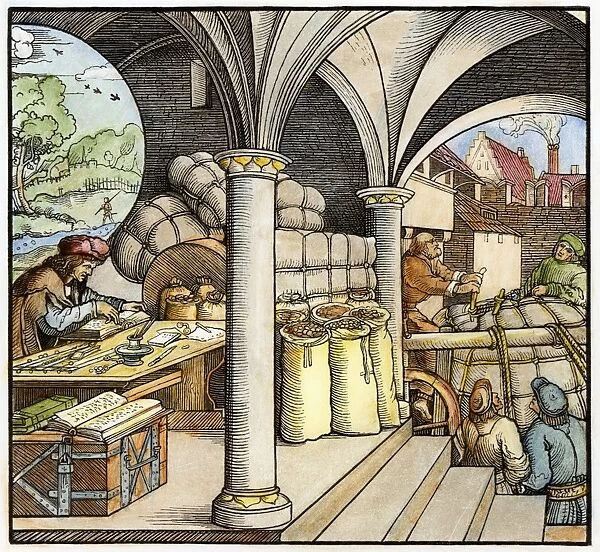

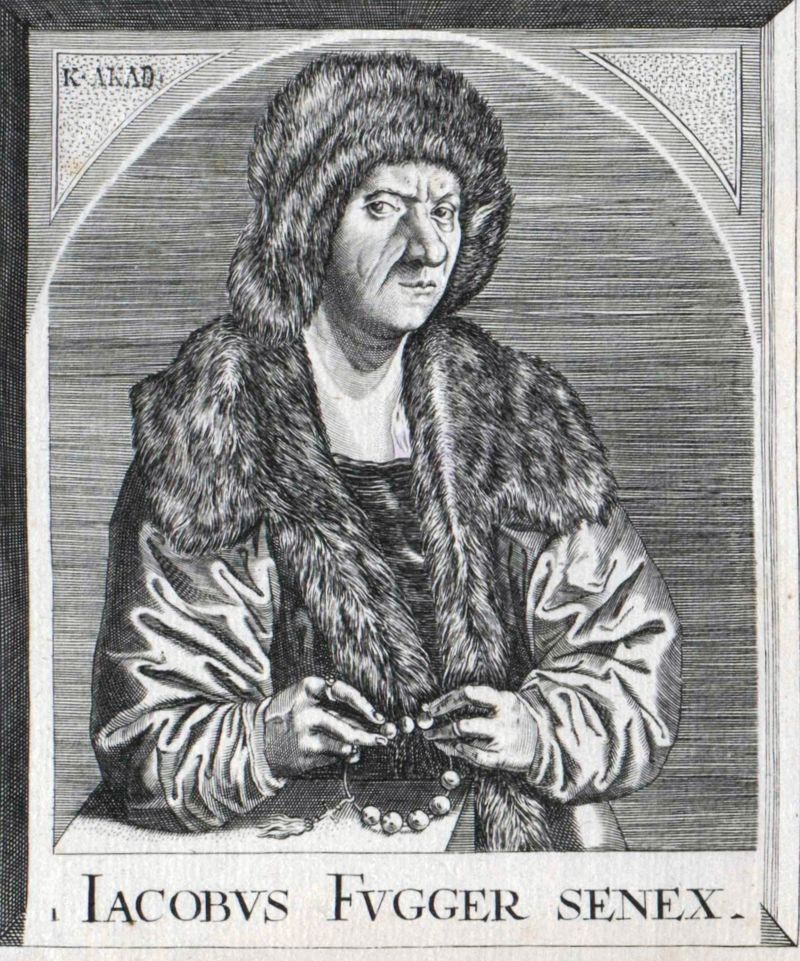

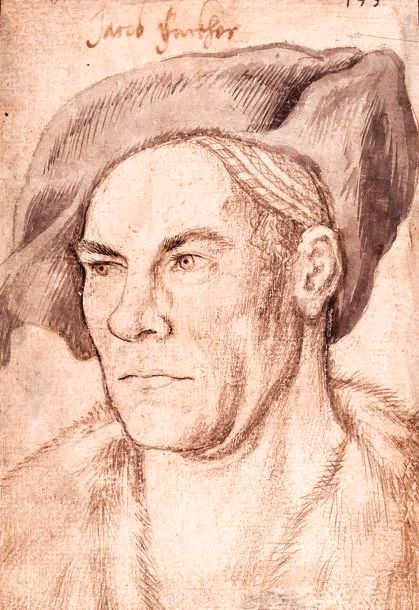

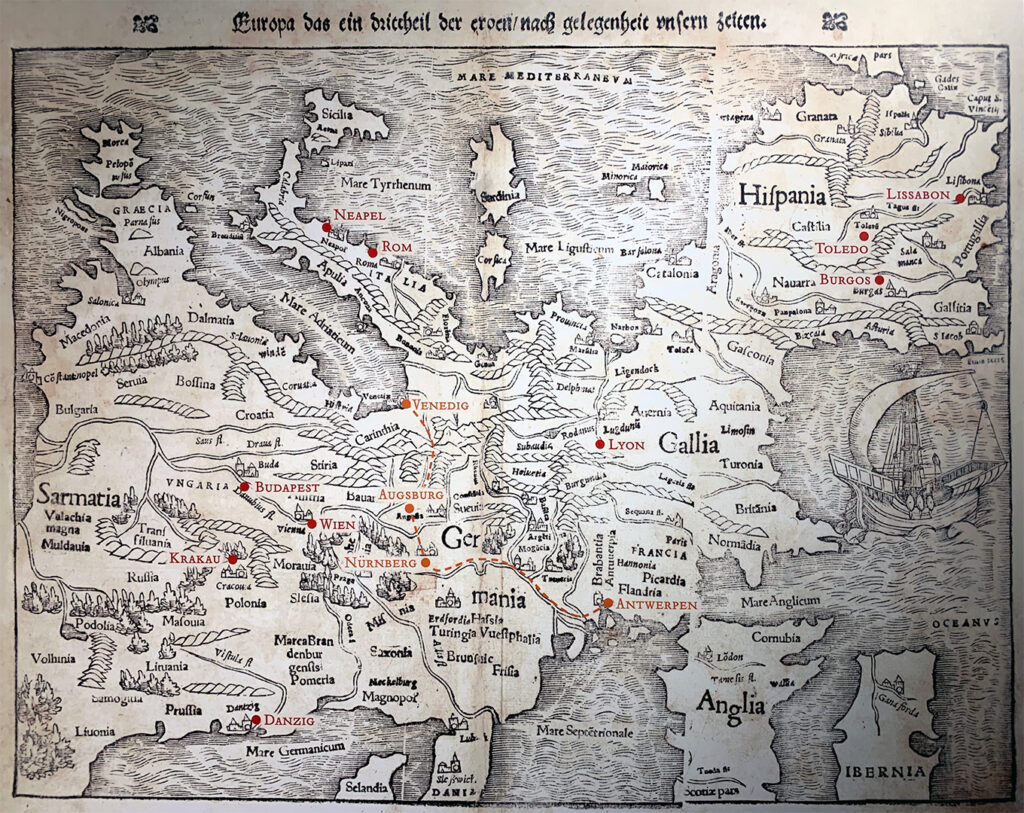

Through alliances and marriages, the Burgundian Low Countries fell under the control of the Habsburg family, who were completely at the mercy of the famous Augsburg bank, the evil Fuggers, known as the fathers of « financial fascism ». 22

Hence, when Maximilian I, of the Habsburg family and Holy Roman Emperor, died in 1519, he owed Jacob Fugger approximately 350,000 florins. To prevent default on this investment, Fugger assembled a cartel of bankers to gather all the necessary bribe money to enable Maximilian’s grandson, Charles V, to buy the vote and succeed him to the throne. Thus, Jacob Fugger, in direct liaison with Margaret of Austria, who joined the project because of her fears for peace in Europe, centrally gathered the money to bribe each Elector, taking advantage of the opportunity to dramatically strengthen his monopolistic positions, particularly over competitors such as the Welsers and the rapidly expanding port of Antwerp. 23

Charles V, in the 1520s, had to borrow at 18% and even 49% between 1553 and 1556. To maintain the enormous expenditures to oversee his vast Empire, Charles V had no choice but to pursue a predatory policy. He sold his mines to appease the bankers, gave them carte blanche to colonize the New World, and consented to the pillaging of the most prosperous region of his Empire, Flanders and Brabant, which were subject to taxes and tithes to pay for the « war economy. » 24

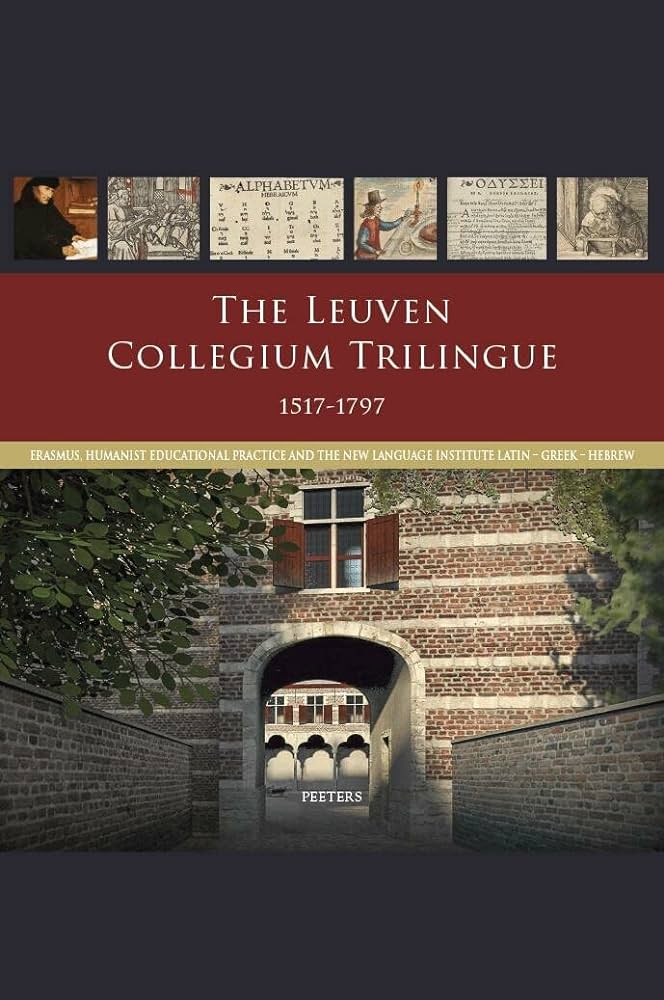

The rather spectacular rise of the Northern Renaissance, which gained access, thanks to the learning of Greek, Latin and Hebrew, notably thanks to the Three Language College founded by Erasmus in Louvain in 1515 25, to science and all the wealth of the classical period, was to collide head-on with the battering rams of feudal finance which had become an ogre.

Charles V ordered that a list of authors to be proscribed be drawn up in his states, thus foreshadowing the establishment of the Index a few years later. From 1520 to 1550, he promulgated thirteen repressive edicts against heresy, introducing a modern inquisition based on the Spanish model.

The application of these « placards » remained rather weak until the arrival of Philip II due to the lukewarm attitude of Queen Regent Mary of Hungary (1505-1558) and local elites towards them. Their application was entrusted to the urban and provincial judicial authorities, as well as to the Grand Council of Mechelen, with the supervision of a specific tribunal, established in 1522 in the Burgundian Low Countries based on the model of the Spanish Inquisition.

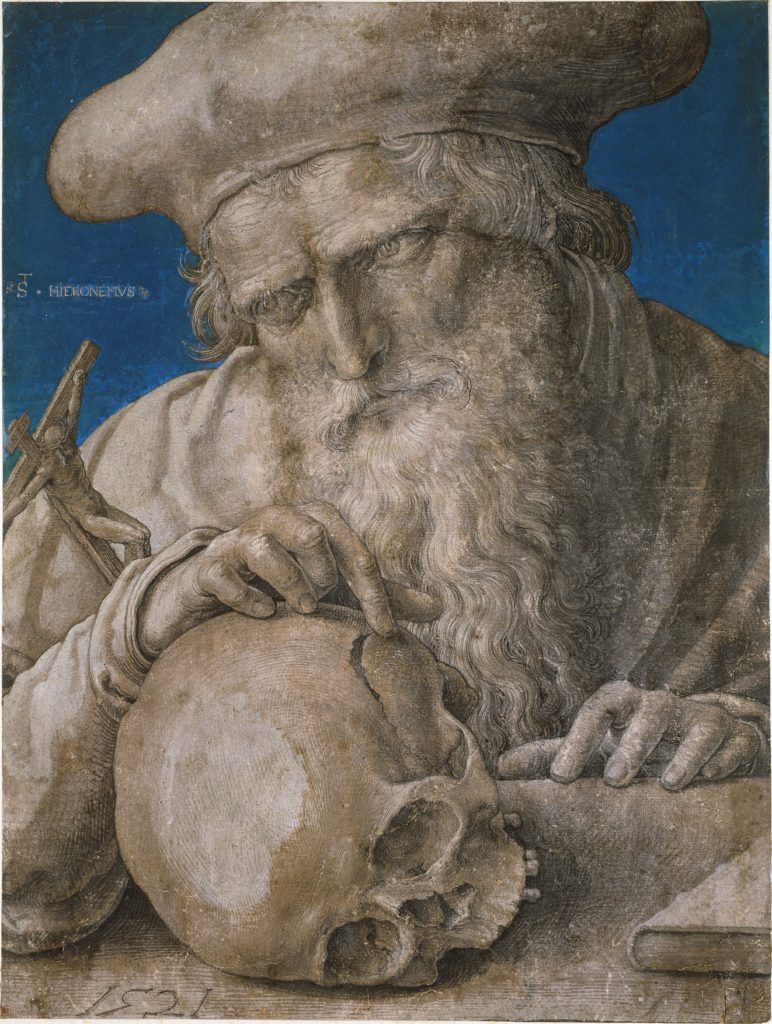

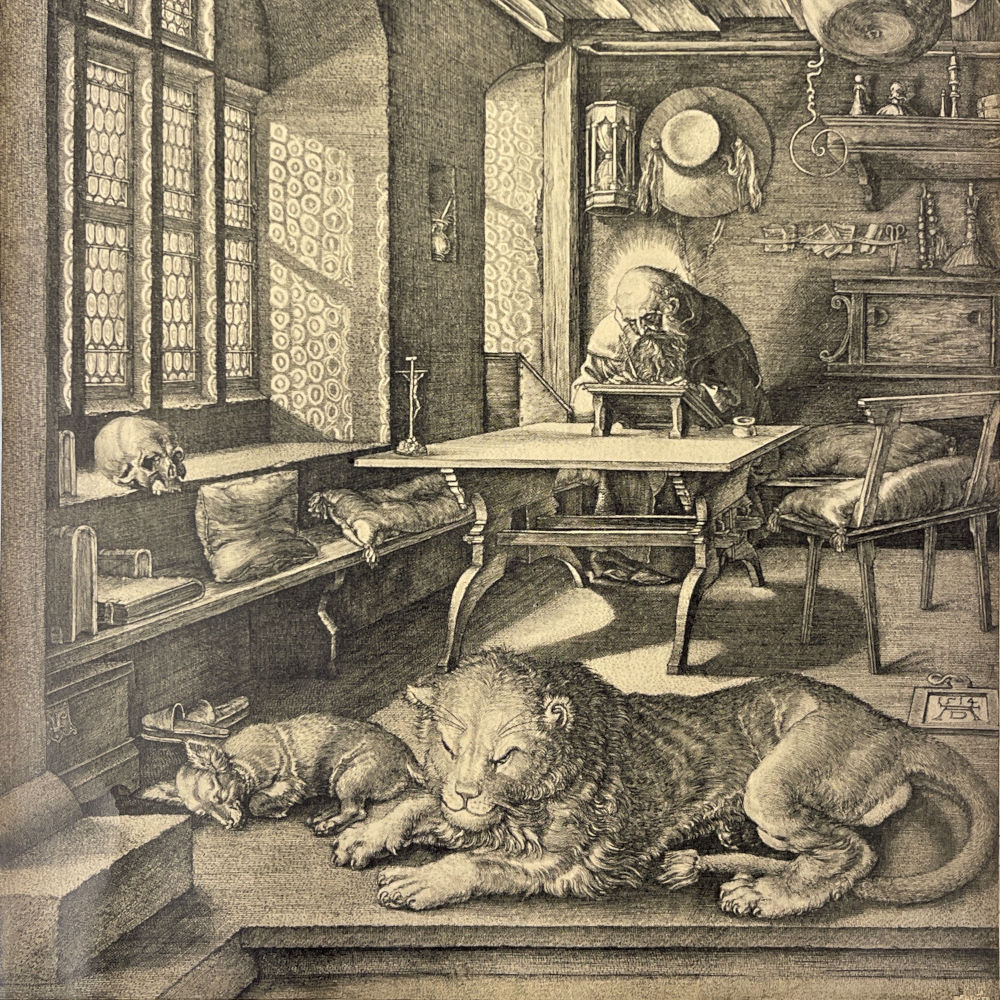

In 1540, the Jesuit order was founded, initially tasked with obtaining by word what could not be obtained by the sword. It quickly turned to the use of theater! From 1545 to 1563, the Council of Trent met to impose reforms and seek to eradicate Protestant heresy. Reading the Bible was now forbidden to ordinary mortals, as was discussing and illustrating it. Albrecht Dürer, the great German engraver and geometer based in Antwerp, packed his bags in 1521 to return to Nuremberg, and Erasmus went into exile in Basel the same year. The great Flemish cartographer Gerard Mercator, educated by the Erasmians and suspected of heresy, was imprisoned in 1544. Released from prison, he went into exile in Germany in 1552. Because of their religious beliefs, Jan and Cornelis, the two sons of Quinten Matsys 26, left Antwerp and went into exile in 1544.

Charles V abdicated in 1555 to leave his place to his son Philip II. The latter returned to Spain and entrusted the regency of the Burgundian Low Countries to his half-sister Margaret of Parma (1522-1586).

While the administration of the Burgundian Low Countries was officially carried out through the Council of State, composed of the stadholders and the high nobility, a secret council (the consulta) created by Philip II and composed of Charles de Berlaymont (1510-1578), Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (1517-1582) and Viglius van Aytta (1507-1577) was responsible for making the most important decisions, particularly concerning taxation, order, administration and religion, and thus transformed the Council of State into a simple consultative chamber.

Three disputes quickly arose: the presence of Spanish troops in the Seventeen Provinces, the establishment of new dioceses in the Burgundian Low Countries, and the fight against Protestantism. Spanish troops remaining from the Italian Wars, approximately 3,000 strong, were not paid and were pillaging the country. After much hesitation by Philip II, and under threat of the simultaneous resignation of Orange and Egmont, the troops finally left in January 1561.

The first victims of persecution in Europe were Antwerp’s Hendrik Vos and Jan Van Essen, two augustinian monks who had become friends of Luther, executed in Brussels on July 1, 1523. 27 The first Walloon victim was the Tournai theologian Jean Castellain, executed in Vic, Lorraine, on January 12, 1525. 28

Many victims were Catholic clergy who had converted to the Reformation, but also many women. From 1529, the persecutions took a dramatic turn following the adoption of the imperial placard generalizing the death penalty. 40% of executions for heresy in the West between 1523 and 1565 occurred in the Burgundian Low Countries. The 17 Provinces were one of the regions that suffered the highest rate of death sentences relative to its entire population. Approximately 1,500 people were executed, an intensity thirty times higher than in France. 29

They will only strengthen the opposition to the tyranny which will lead in 1576 William of Orange (known as « The Silent ») to take the lead in the revolt of the Burgundian Low Countries, ending 80 years later with the split between the north (the Netherlands, predominantly Protestant) and the south (Belgium, exclusively Catholic).

Ghent, 1539

In June 1539, the De Fonteine (The Fountain) Chamber of Ghent summoned the dramatic and literary societies of the country to a great landjuweel in honor of the Holy Trinity, for which Emperor Charles V granted permission and a month’s safe conduct to those wishing to participate.

An invitation charter was published on this subject. It posed, for the morality play, a question thus formulated: « What is the greatest consolation of the dying man? »

This subject clearly echoes one of Erasmus‘s popular writings, quickly translated into Dutch in the year of its publication in 1534, De preparatione ad Mortem. 30

Nineteen rhetorician societies responded to the call: these were chambers established in Antwerp, Oudenaarde, Axel, Bergues, Bruges, Brussels, Courtrai, Deinze, Enghien, Kaprijke, Leffinge, Lo (in the Furnes Trade), Menin, Messines, Neuve-Église, Nieuwpoort, Tielt, Tirlemont, and Ypres.

The chamber known as « De Violieren » from Antwerp won first prize. Pieter Huys de Bergues won second prize, consisting of three silver vases weighing seven marks on which the entrance to an academy was engraved. His poem comprises about five hundred verses in Dutch, and it features five allegorical figures under the names of Benevolence, Observance of the Laws, the Consoled Heart, Consolation, and the Contrite Heart. Each of them lists the goods in which man finds happiness at the hour of death. For De Violieren, the greatest consolation was « the resurrection of the body, » a purely Catholic dogma.

But that was without counting on the « off » part of the competition. Because the three other questions, to be answered in chorus, were:

- « Which animal in the world gains the most strength? »

- « Which nation in the world shows the most madness? »

- « Would I be relieved if I could talk to him? »

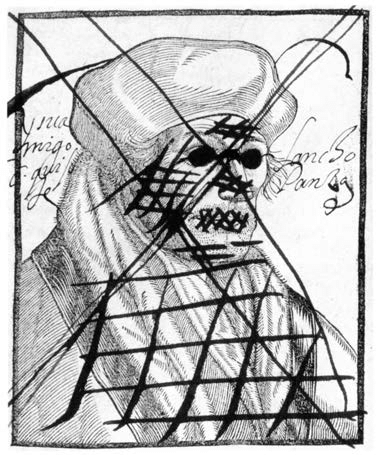

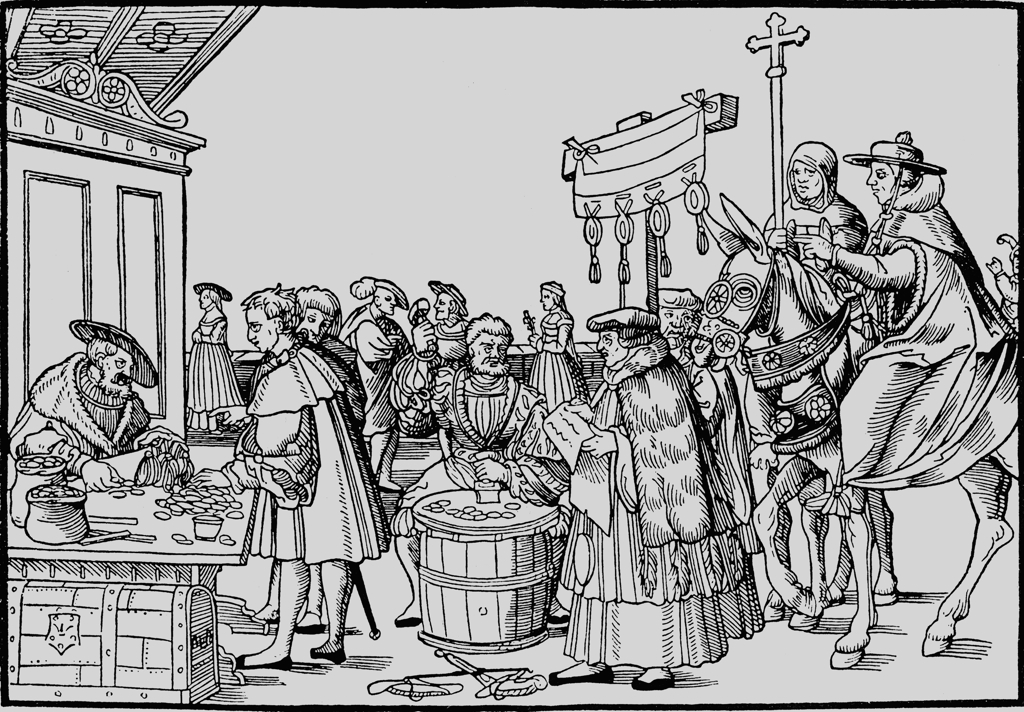

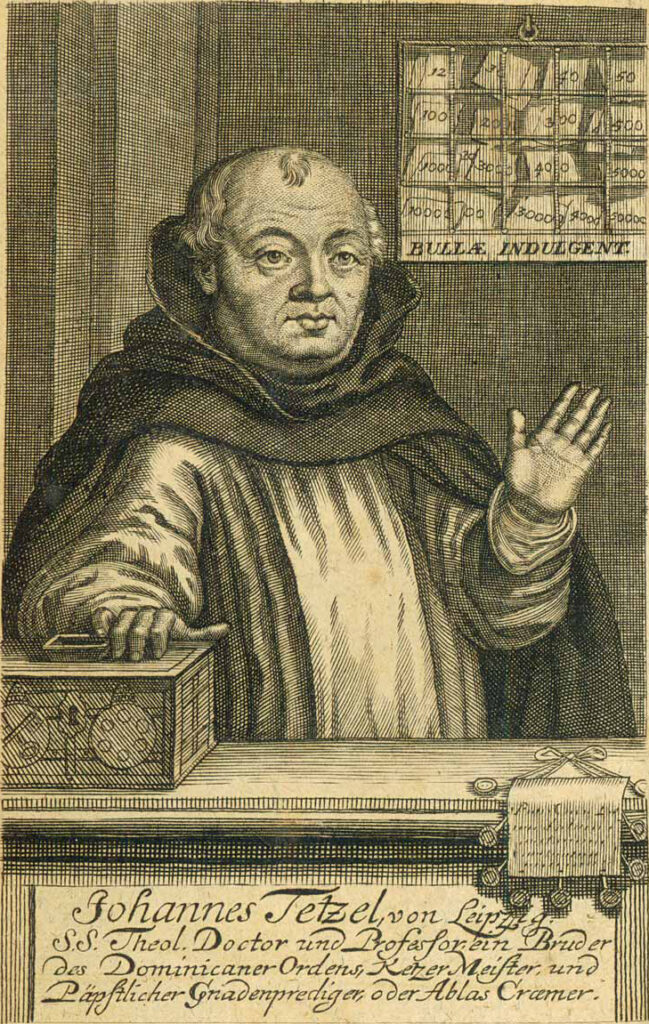

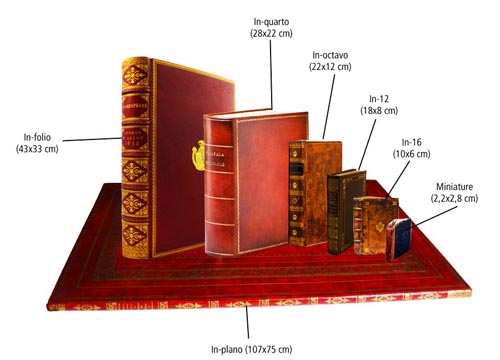

As a result, the majority of allegorical plays performed were bloody satires against the Pope, monks, indulgences, pilgrimages, Cardinal Granvelle, etc. The compositions of the Ghent laureates were published first in quarto format, then in duodecimo.

From the moment they appeared, these plays were banned, and it was not without reason that, later, this landjuweel was cited as the first to have stirred the literary country in favor of the Protestant Reformation. These works being far from favorable to the Spanish regime, the Duke of Alba ordered their suppression by the Index of 1571 and, later, the government of the Burgundian Low Countries even banned theatrical performances of the Chambers of Rhetoric.

The influence of Erasmus

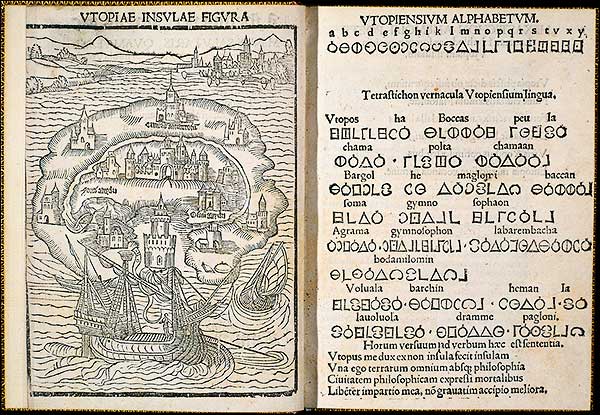

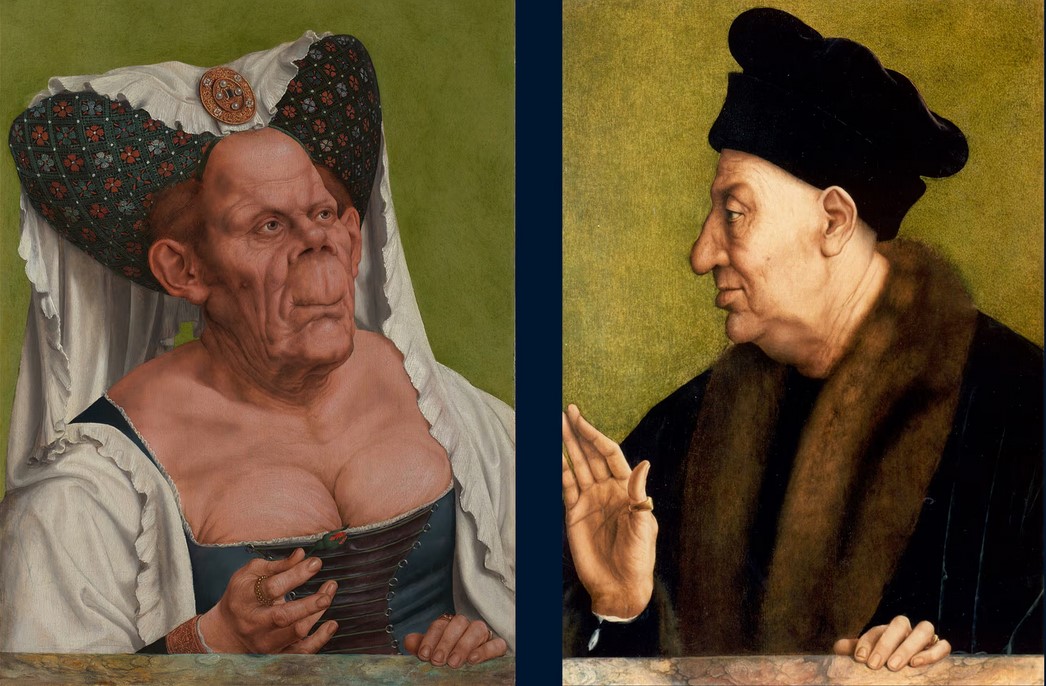

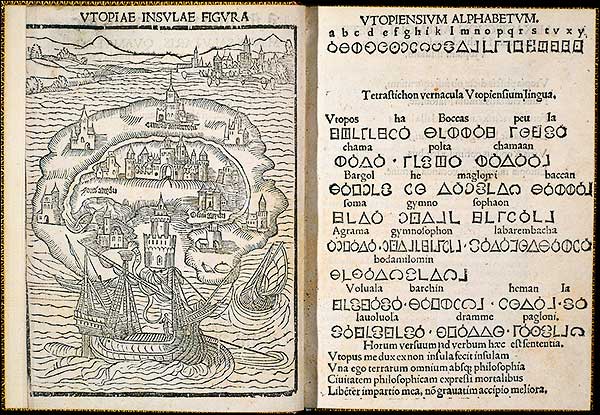

In Antwerp, Erasmus‘s influence was notable, and his presence was sought after. Well-known was his friendship to the city’s secretary Pieter Gilles 31, an Antwerp erudite humanist dearly appreciated by Thomas More 32 who integrated Gillis poems in his opus majus, Utopia. To please More, Pieter Gillis and Erasmus got their portraits done by Quinten Matsys33 to whom they offered their double portrait. Gillis house in Antwerp was also a regular meeting point for all the leading humanists of that time.

Between 1523 and 1584, 21 publishers published no fewer than 47 editions of the humanist’s works, and the rhetorician Cornelis Crul, before 1550, translated the Colloquies and other major works into Dutch.

Most rhetoricians mastered Latin and could therefore read Erasmus in the original. Some Latin schools, as documented in the case of Gouda for the year 152134, included selected writings for each grade in their curriculum. The humanist’s prestige spread throughout Europe.

Ferdinand Columbus (1488-1539), the very bibliophile son of Christopher Columbus, not only acquired a vast series of his works, but also traveled to Louvain in October 1520 to meet their author. 35

In a letter dated 1521, Hieronymus Aleander (1480-1542), the legate of Pope Leo X, warned of « elements having bad reputation » who were thriving in Antwerp. They presented themselves « as the defenders of good literature and were all from the school of our friend who became a great name [Erasmus]. » Aleander added that « He [Erasmus] has spoiled all of Flanders! » 36

De Violieren and the Guild of Saint Luke

Also in Antwerp, a Chamber of Rhetoric, De Violieren (The Gillyflowers), was officially created in 1480 within the Guild of Saint Luke, the artists’ guild dating back from 1382. 37

The rhetoricians’ motto was « Uyt ionsten versaemt » (United by affection. But « ionsten » is also close to « consten », the Flemish word for arts).

This symbiosis produced fruitful results. For most historians, De Violieren were, in a way, the literary branch of the Guild of Saint Luke.

The latter was composed of all trades related to the fine arts, including painters, sculptors, illuminators, engravers, and printers. Until 1664, the guild had its headquarters on the north side of Antwerp’s Grote Markt, in the Spaengien or Spanish House.

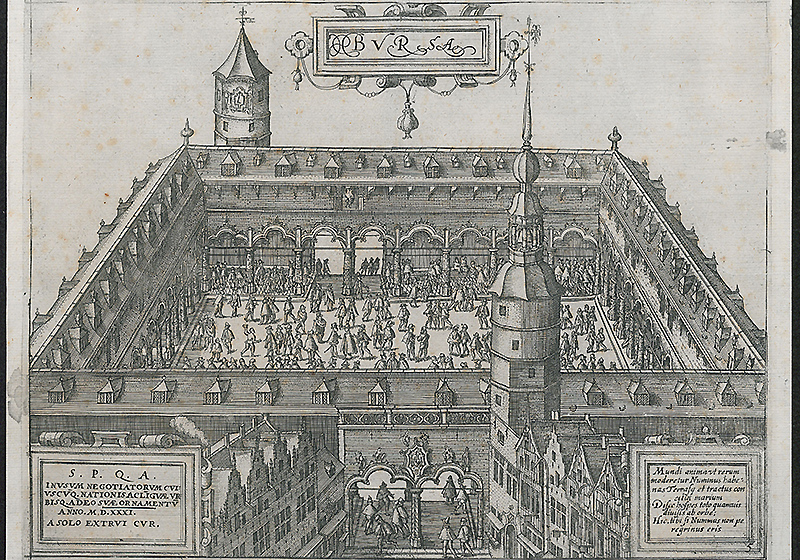

Between 1460 and 1560, to finance its activities, the Church rented out to artists the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwepand, a claustrum with galleries surrounding an open courtyard. In this building, art painters, sculptors, cabinetmakers and booksellers could rent a stand where they could display their wares for sale. It was the largest art fair in what was then Europe. After 1560, the market moved to the second floor of the new Handelsbeurs (Trade Exchange).

The Saint-Luke artist guild:

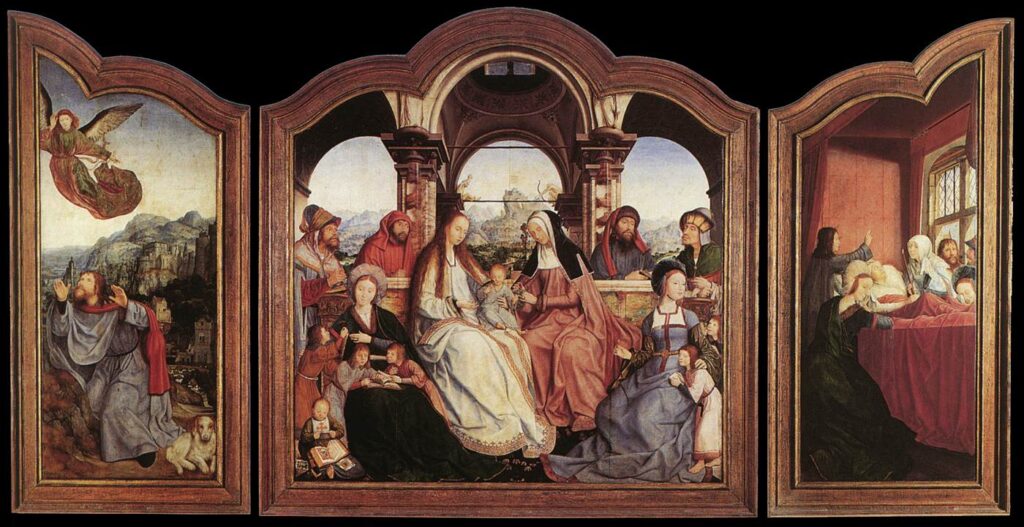

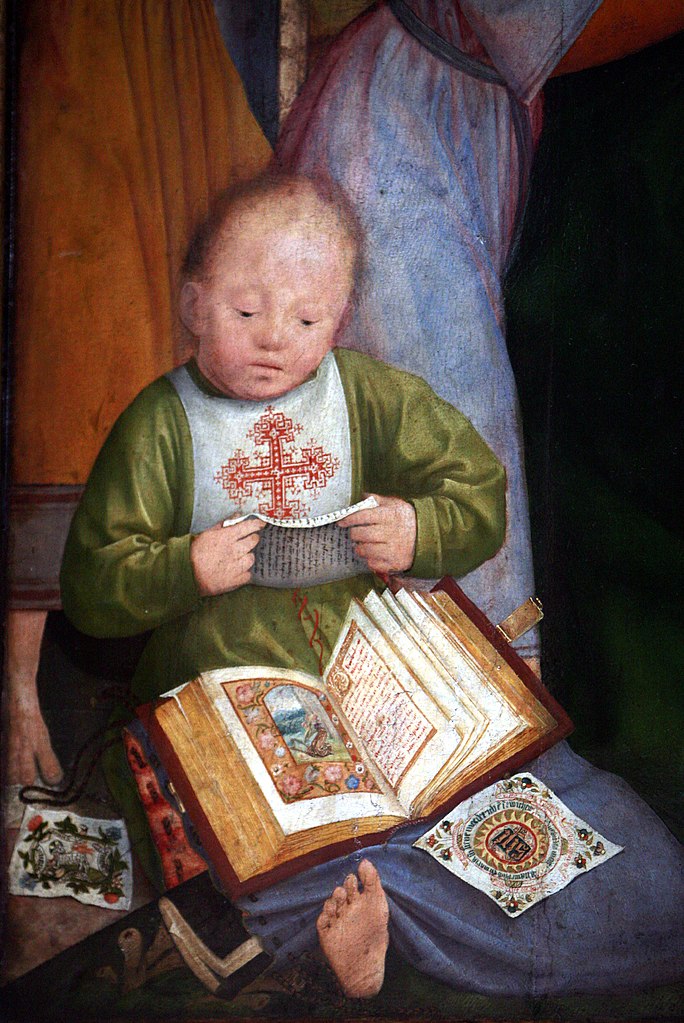

- In 1491, Erasmus’s friend, the painter Quinten Matsys 38, was listed as a master. One of his major commissions, the Triptych of the Lamentation of Christ, came from the carpenters’ guild. According to the Antwerp chief city archivist Van den Branden, Matsys himself was a member of De Violieren and wrote poems for their contests.

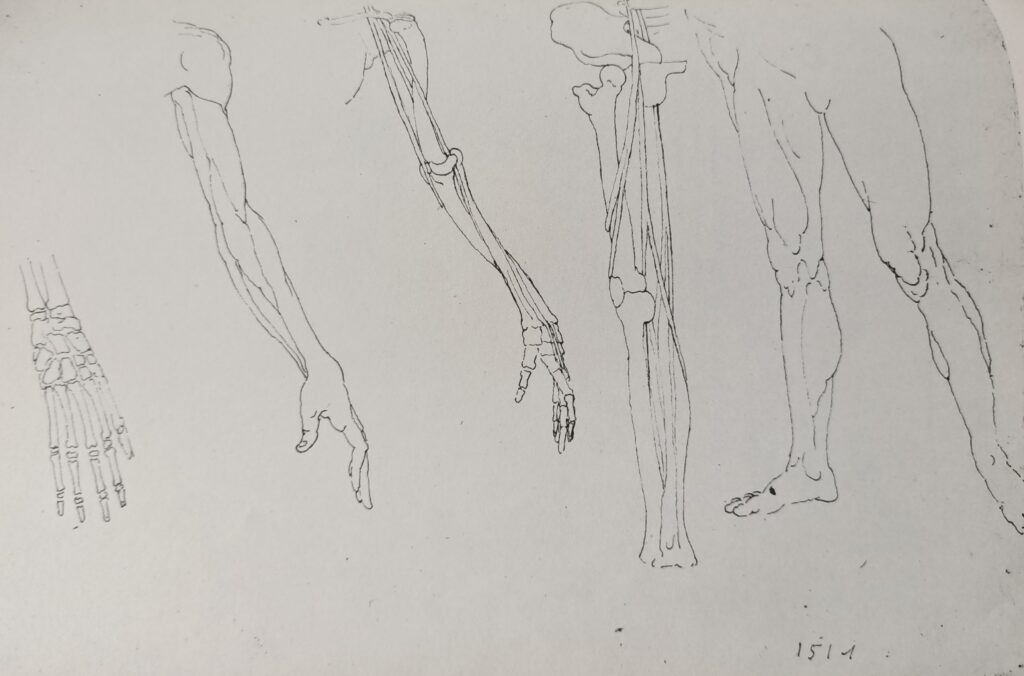

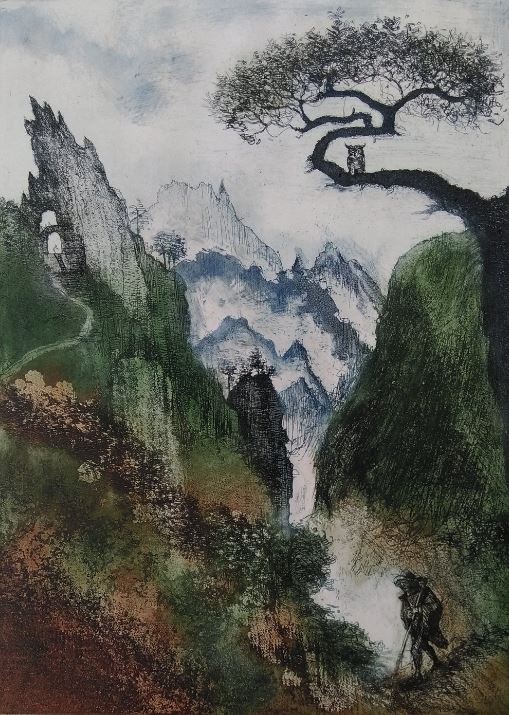

- In 1515, Matsys was joined in the Guild of Saint Luke by two other great artists equally inspired by the spirit of Erasmus, Joachim Patinir (1480-1524) and Gerard David (1460-1523).

- In 1519, the guild registers (The Liggeren 39) mention the registration of Jan Sanders van Hemessen (1500-1566), whose daughter Catharina (1528-1565) would become the first female painter in 1548 – and teacher of painting to men – to be admitted to the painters’ guild;

- In 1527, that of Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), Bruegel’s master;

- in 1531, those of Matsys’s two children, Jan and Cornelis;

- in 1540, that of Peter Baltens (1527-1584);

- in 1545, that of the engraver and printer Hieronymous Cock (1510-1570) whose workshop produced prints of Bruegel and Dutch revolutionary poet and translator Dirk Coornhert (1522-1590), close friend and collaborator of William the Silent (1533-1583);

- in 1550, that of the great printer Christophe Plantin (1520-1589);

- and in 1551, that of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569). 40

In short, several of the Low Countries towering cultural personalities, assisted or certainly could have asisted at the Antwerp 1561 Landjuweel: Jan Sanders van Hemissen and his daughter Catherina; Jan and Cornelis Matsys, sons of Quinten Matsys; Peter Baltens, Hieronymous Cock, Dirk Coornehert, William the Silent, Christophe Plantin and Pieter Breugel the Elder. 41

The daily exchanges between the rhetoricians and the most important artists of the day united in the Violieren had a beneficial influence on their activities and, after a few years, made them one of the most successful societies in Brabant.

In the most important competitions, De Violieren won laurels: first prize in 1493 in Brussels, in 1515 in Mechelen and in 1539 in Ghent, in a memorable fight in which 19 chambers from different regions of the country participated.

In August 1541, a competition was held in Diest, organized by the local Chamber De Lelie in which ten other chambers from Brabant participated. The grand prize was awarded to the Antwerp Chamber, De Violieren, for the presentation of an esbattement (farce).

Antwerp, 1561

As was customary, the Chamber that won the best prize was in turn to organize a Landjuweel. This was also the opinion of De Violieren, after his feat in Diest; however, the circumstances of the time meant that the subject was postponed. 20 years passed before anyone could think of organizing such an artistic competition.

Three leaders of De Violieren, with great courage, will fully commit to the initiative, risking their reputation, honor, life and heritage:

- Anthonis van Stralen (1521-1568) was the leader of De Violieren. As a member of the Antwerp city council, Van Stralen had been closely involved in obtaining the patent. His appointment as city leader, two months before the first attempt at rapprochement with the Council of Brabant, must have been a strategic move on the part of De Violieren. In May 1561, he was promoted to mayor of Antwerp, perhaps as a reward for his services. The success of the Landjuweel was largely due to the cooperation between the Antwerp magistrate and De Violieren’s board.

- Melchior Schetz (c. 1513-1583) was the Prince of De Violieren. He was Van Stralen’s brother-in-law and also an alderman.

He was one of the three children (Gaspard, Balthasar and Melchior) of the leading Antwerp merchant Erasmus Schetz (died in 1550), known as the « banker of Erasmus ». 42 With his three sons, he set up a major banking and merchant firm. 43 His friendship with Erasmus is symptomatic of the popularity Erasmus enjoyed in Antwerp. He provided him with his hospitable residence: the Huis van Aken, a palace where he had received Charles V himself. In a letter, he made him, among other things, this tempting proposition:

« My heart and the souls of so many people long for your presence among us. I have often wondered what enchantment it was that kept you there rather than among us. Peter Gillis [city secretary and their mutual friend] gave me a reason: we do not have Burgundy wine, which best suits your temperament, do not fear this, and if this is the only obstacle holding you back, do not hesitate to come back; we will see to it that you are supplied with wine, and not only Burgundy wine, but also Persian and Indian wine if you desire and need it . »

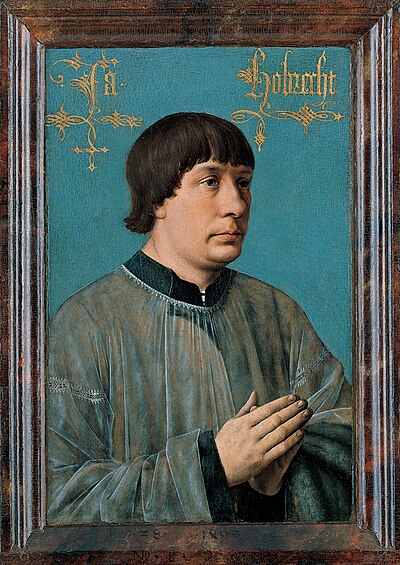

As Prince of De Violieren, his son Melchior represented the chamber most often publicly. He must also have been responsible for the financial organization of the Chamber. Schetz was one of the largest moneylenders in Antwerp. There is no doubt that the city financially facilitated the organization of the festival. - Willem van Haecht (1530-1585) : Born into a family of painters and engravers, he was a draughtsman and, presumably, also a bookseller by profession. His motto was Behaegt Gods wille (translated as « conform to the will of God »). Van Haecht was a friend of the Brussels humanist and author Johan Baptista Houwaert (1533-1599). He compares Houwaert to Cicero in the introductory eulogy to Houwaert’s The Lusthof der Maechden, written by him and published in 1582 or 1583. In his eulogy, Van Haecht states that every sensible man should recognize that Houwaert writes with eloquence and excellence. Van Haecht wrote lyrics for various songs, usually of Christian inspiration. This is the case for the lyrics of a five-part polyphonic song, Ghelijc den dach hem baert, diet al verclaert, probably composed by Hubert Waelrant (1517-1595) for the overture to the play De Violieren at the landjuweel of 1561. The poem was also printed on a loose leaf with musical notation. As early as 1552, Van Haecht was affiliated with De Violieren, whose members included Cornelis Floris de Vriendt (1514-1575), the main architect of the Renaissance-style Town Hall in Antwerp, as well as painters Frans Floris de Vriendt (c. 1519-1570) and Maerten de Vos (1532-1603). Van Haecht became the « factor » (title poet) of De Violieren in 1558.

Other people involved in the organization of the Landjuweel included printers such as Jan de Laet (1524-1566) and renowned artists such as Hieronymus Cock (c. 1510-1570) (founder of the In de Vier Winden printing house which published Bruegel’s engravings) and Jacob Grimmer (1510-1590).

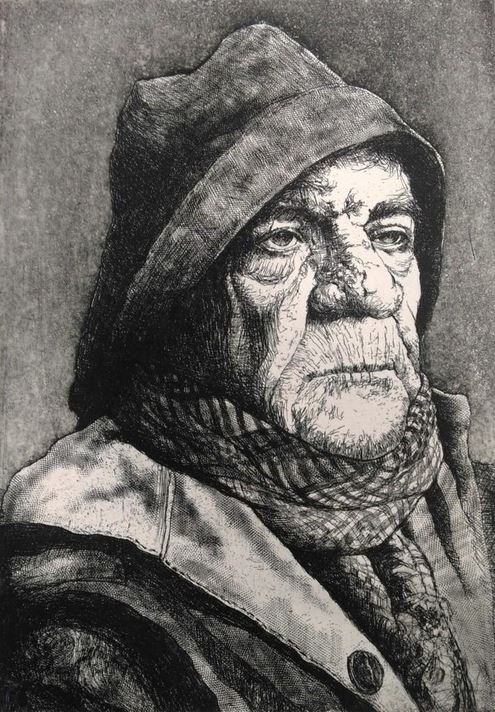

The other major figure was Peeter Baltens (1527-1584) 44 an Antwerp painter, rhetorician, engraver and publisher. Baltens was a member of the Guild of Saint Luke and De Violieren. Having partly trained Bruegel, Baltens’ role proved particularly important.

He formed close friendships (notably with the widows of both Hieronymus Cock (c. 1510-1570) and Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), the latter also being Bruegel’s stepmother) and collaborated with the greatest names in Antwerp of his time.

He associated with Antwerp patricians such as Jonker Jan van der Noot (1539-1595), the wealthy Schetz merchant family, and wealthy merchants such as Nicolaes Jonghelinck (1517-1570), merchant banker and Bruegel’s financial backer.

According to Lode Goukens,

« Baltens was instrumental to the lobbying of a group of powerbrokers belonging to the moderate party. A moderate party that valued peace, harmony and good business more than religion, extremism or state terror. A party that wanted to return to a status quo from before the troubles. »45

Herman Pleij notes that the Rhetoricians have as consignment to repolish the reputation of the Antwerp merchant by making the distinction between the honest ones and the sharks. 46

Research into the relationships between painters, poets (or rederijkers), and merchants has shown that these three groups developed a common cultural lifestyle in the XVIth century, in which the love of science and art occupied a central place.

To launch a rhetoric competition, permission had to be obtained from the country’s government, which was no longer easily done at that time. This was a consequence of the Ghent competition of 1539, when the ideas of new doctrines against the institutions of the Catholic religion were presented and defended without the slightest qualm.

However, De Violieren and the elected representatives of Antwerp (Van Stralen and Schetz) were fiercely determined to be able to organize their Landjuweel. The man who did the most to delay obtaining authorization was the hated Cardinal Perrenot de Granvelle (1517-1582), Archbishop of Mechelen and advisor to Margaret of Parma (1522-1586), following the abdication of the Emperor, her brother Charles V, the regent of the Burgundian Low Countries.

Organization of the Landjuweel

In February 1561, the delegates of the city of Antwerp approached Granvelle with a petition to the regent, in which they argued that De Violieren, compared to the other Chambers, were statutorily obliged to organize a competition.

Granvelle hoped to torpedo the initiative, but realizing that a brutal rejection would have inflamed the opposition, he sought various pretexts to postpone the event indefinitely. He politely made it clear to the delegates that he wished to postpone such an event for a while longer, using the pretext that, thanks to the peace agreement between France and the Habsburgs, the war had just been suspended, and that such festivals represented significant expenses, while the country could not or would not bear the costs. This did little to deter the people of Antwerp. They replied that the previous year, permission had been granted to the Chamber of Vilvoorde and that a postponement could not reasonably be imagined. Sensing that they would only renounce it with immense disgust, Granvelle reluctantly agreed to present their request to Marguerite, while asserting that the government had given itself the right to levy taxes on all those who came to the competition.

Fearing above all that the festival would become a sounding board for all those criticizing the Spanish occupation and the abuses of the Church, Granvelle also summoned them to inform the participating chambers that they would not intervene in their plays, their esbattements or their poems with a single word against religion, the clergy or the government, otherwise they would not only lose the prize they might have won, but would also be punished and deprived of their privileges and rights; and that the Chamber of Antwerp should ensure that the city was well guarded during the festivities and that no disturbances could arise.

Margaret of Parma, often at odds with Madrid, was less fearful and more open.

After consulting the report provided by the Council of Brabant, which was well aware that too much repression encouraged protest, she placed the apostille on March 22, 1561, inviting the Chancellor of the Duchy to provide Antwerp with the sealed letters required to organize the Landjuweel.

These letters were issued the same day in the name of the king and granted safe conduct from fourteen days before the start until fourteen days after the end of the Landjuweel to all those who wished to attend, with the exception of

« all murderers, thieves and other criminals, as well as declared enemies of the king, rebels and those banned from the Holy Roman Empire. »47

The Antwerp Chamber submitted 24 themes as potential topics for the Landjuweel competition (seen below). Among those, Margaret of Parma approved three topics among which the Chamber was free to pick one. 48

- Does experience or learning bring more wisdom? »

- « What most leads man towards the arts? »

- « Why does a rich and greedy man desire more wealth? »

Philosophy

To show how much our rhetoricians, under the direction of Van Straelen and Schertz, dealt with philosophical and political questions of all kinds, here are the whole of the twenty-four subjects which they had submitted 49:

- What made Rome triumph?

- What caused Rome to decline the most?

- Is it experience or knowledge that brings more wisdom?

- What can lead man most towards Art?

- What feeds art?

- Why is man so desirous of temporal things?

- What shortens the days of men?

- What lengthens the days of men?

- Why is average wealth the most happiness in the world?

- What is the greatest prosperity in this world ?

- What is the biggest setback in this world?

- How is it that all things are consumed every day?

- If a miserly man can be discouraged?

- Why does a rich miser desires even more wealth?

- Why does wealth not extinguish greed?

- Why is amusement followed by displeasure?

- Why does lust breed remorse?

- Why does lust bring its own punishment?

- How did the Romans achieve such a great prosperity?

- What sort of government kept the Romans prosperous ?

- What art is most necessary for a city?

- What can bring the world more rest [peace] ?

- What most drives people to worldly pride?

- What would be the best way to eradicate usery?

At first glance, one could say that by choosing the question « What can lead man most towards Art? »50, Van Stralen and Schetz choose the least « political » subject. This is to misunderstand Erasmus and Platonic thought for whom beauty and goodness form a unity and for whom any government that does not promote beauty, neglects it or worse still, despises it, condemns itself to failure! In practice, poets starting from this higher principle, ended blasting, without explicitly naming them, all the criminals and warmongereres of those days.

Moreover, Willem van Haecht, the « factor » (official poet) of De Violieren, in the play he composed especially for the Landjuweel of Antwerp in 1561, would say that what led Empires to their decline was, as it still is today, their lack of esteem for the Arts, including obviously Rhetoric.

So, it was on this theme that the 5000 participants (!) of the Landjuweel, and beyond a large part of the country, began to reflect, to compose songs, dramas, refrains, allegories, rebuses, pintings and farces and presented them to thousands of fellow citizens.

Amazingly, two centuries before (!) Friedrich Schiller, the German poet that earned the name of « poet of freedom » and who inspired many revolutions at the end of the XVIIIth century, a humanist elite enlightened by Erasmus in the Low Countries led a substantial part of the country to rise up to the conditions of a durable peace by emancipating itself from serfdom and ignorance through moral beauty! The Antwerp Landjuweel of 1561 was much more than a feast, it was a shift of paradigm and a real game changer. Hats off!

After receiving permission, the Chamber of Rhetoric and the City Council immediately set about giving the great literary festival as much pomp as possible. A rhymed invitation card was drawn up, stating the subject of the competition and the prizes to be won.

On April 23, this invitation card was presented by Mayor Nicolaas Rockox, in the presence of Melchior Schetz and Anthonis van Stralen, at the Antwerp City Hall to four sworn messengers, who were instructed to convey it to all the Chambers of Rhetoric in Brabant and to invite them to the Landjuweel as well. These messengers traveled at the city’s expense and first went to Leuven, the oldest city in Brabant. Everywhere, the news of a Landjuweel in Antwerp was greeted with extraordinary joy, and the messengers were very generously received.

While in most cities of Brabant the rhetoricians were busy composing and teaching plays and poems, making triumphal chariots and painting coats of arms, in Antwerp they were not inactive.

De Violieren had beautiful new clothes made for its members, at the suggestion of Melchior Schetz, for the welcoming ceremony offered to the participants.

An elegant theatre stage was erected on Antwerp’s Grote Markt (Great Square), designed by Cornelis Floris. Coincidentally, it was installed on the exact spot where the Inquisition had been beheading « heretics. » The audience watched the performances standing, with the exception of the jury and high-ranking officials, for whom benches were provided.

There was excitement and liveliness everywhere; every citizen wanted to do their part to welcome the foreign guests with all possible pomp and wealth. The city council, for its part, had taken the necessary measures.

All residents of the streets where the rhetoricians were to pass were ordered to clear the streets and remove any scaffolding or obstacles that might hinder their passage.

Everyone was eagerly awaiting August 3rd, the day when the formal entry would take place and the Landjuweel games would begin.

A memorable day

August 3, 1561, is indeed a memorable day in the history of Antwerp. The city was dressed in its festive attire; on the facades of houses, flags, pennants, and festoons; in public places, graceful arches in the opulent Renaissance style.

It’s no secret that the people of Antwerp like to make a lot of money. But they also like to spend it lavishly! In that marvelous XVIth century, they took pleasure in displaying a splendor on such occasions that, so to speak, surpasses our imagination.

Everywhere there was joy and life. Many strangers passed through the streets; all, foreigners and locals alike, agreed to maintain the best possible order amidst this agitation and commotion. 51

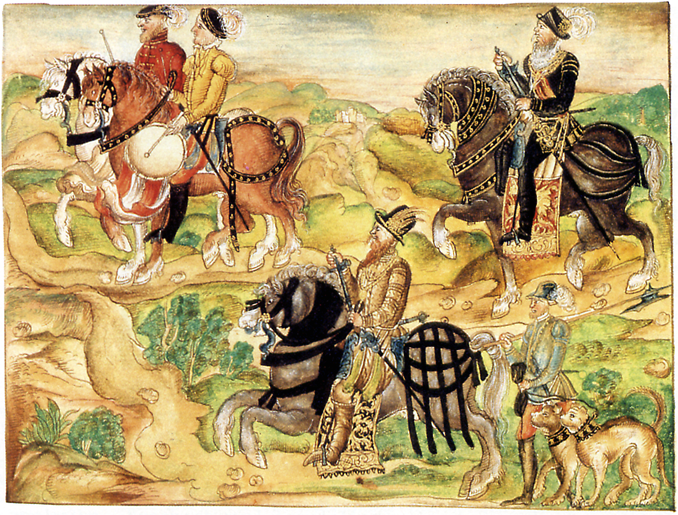

At 2:00 p.m., the « brothers » of De Violieren guild gathered to ride together to the Keizerspoort to meet the participating chambers. There were 65 of them, mounted on magnificently adorned horses, in their precious uniforms. These consisted of tabards of purple silk, striped with white satin or silver cloth, white doublets striped with red, white stockings and boots, and purple hats with red, white, and purple plumes.

At the Keizerspoort, the participating foreign chambers were solemnly received. There were 14 of them, and to the sound of bugles and the cheers of the crowd, they entered Antwerp, following the Huidevetterstraat, the Eiermarkt, and the Melkmarkt to the Grote Markt in front of the City Hall (at that time under construction).

The procession was grandiose and impressive; nothing like it had ever been seen before in these parts. Without the Guild brothers on the chariots, the coat-of-arms bearers, the squires, the footmen, the trumpeters, the drummers, and other musicians on foot, the number of mounted rhetoricians from all the towns amounted to 1,393, that of the chariots to 23, and that of the other chariots to 197. 52

After weeks of competition between the large and medium-sized towns during the Landjuweel, followed an additional week of « Hagespelen, » that is, the less lavish but less expensive competitions between the townships, villages, and municipalities. The formats were so varied that by the end of the month, not a single town, village, or municipality was without a prize.

And once back in their cities, all these cultural actors, actors, singers, poets, jokers, and comical fools, energized like never before by the encounter with an entire nation, reenacted at home the piece or play that had won them a prize. To the extent that each chamber that won a prize was obliged to organize a new competition, a true effect of cultural diffusion and contamination was infused into the country.

The joy and proudness was such that the Chamber of Vilvorde did a special performance for the opening of the newly built Brussels-Willebroek canal in octobre 1561. The project for a 28 km long canal, connecting Brussels to the Scheldt (and therefore to Antwerp and the Sea) had been discussed since 1415 but it was Mary of Hungary in 1550 who kickstarted its actual construction.

The splendid Landjuweel of Antwerp impressed the spectators, among them Richard Clough53, the representative of the English financier Thomas Gresham. The merchant did not hide his admiration and was full of praise for the festivities, drawing a comparison with the entry of Philip II and Charles V into Antwerp in 1549.

He could only note that the organization of the Landjuweel was larger and the spectacle more impressive:

« the arrival of King Philip II in Antwerp, with the cost of all the rhetoricians gathered in their robes, is not comparable to what the city of Brussels has done. (…) I wish to God that some of our great and noble men of England had seen this, (…) and it would make them think that there are others like us, and thus foresee the time to come; for those who can do this, can do more. »54

Peace and art, united for celebration

On Tuesday, August 5, two days after the grand reception of the participating chambers, the visiting rhetoricians, along with the rest of the spectators, were solemnly welcomed on the Grand Place in Antwerp.

De Violieren then offer a welcoming zinnespel (morality): Den Wellecomme (The Welcome), written by Willem van Haecht. At the heart of the play is the proclaimed peace of 1559, which made possible the organization of the Landjuweel, a national gathering symbolizing the renewed awakening of the Art of Rhetoric, for which peace was a necessary condition. The duchy had suffered greatly in the 1550s, but had slowly recovered after the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559). There was hope for better times. Literary reactions to the peace were therefore particularly optimistic. The dawn of a new golden age was on everyone’s mind.

The play features three flower nymphs—sisters—who together represent De Violieren. After years of war, the Chamber was given the opportunity to organize the Landjuweel. For this, the nymphs owe a great debt of gratitude to the people of Brabant. Despite the difficult times and growing divisions between the different social groups, the people remained united.

It is « Concordia, » the feeling of unity and solidarity, that now unites the defenders of the public good. Out of love for the art of rhetoric, everyone has come from far and wide to Antwerp to celebrate the Landjuweel together. According to the nymphs, it is high time that the character of Rethorica resumes her rightful place in society. Now that the war god Mars and the hated Discordia have been driven out, she alone can bring joy and peace to the country. Only the seed of rhetoric (« Rethorices saet ») can bear fruit of joy.

So the flowers set out in search of Rethorica. In other words: De Violieren primarily describes the Landjuweel as a festival of joy, organized by the Chambers of Rhetoric to strengthen the sense of community and bonds of friendship between the region’s cities.

Eventually, the nymphs find Rhetorica, asleep in the arms of a young girl (Antwerp), who has always protected her. While the goddesses of vengeance (« Erinniae ») ravaged the country for twenty years, rhetoric was always protected and cherished in Antwerp. Now it is time to awaken her from her long winter sleep.

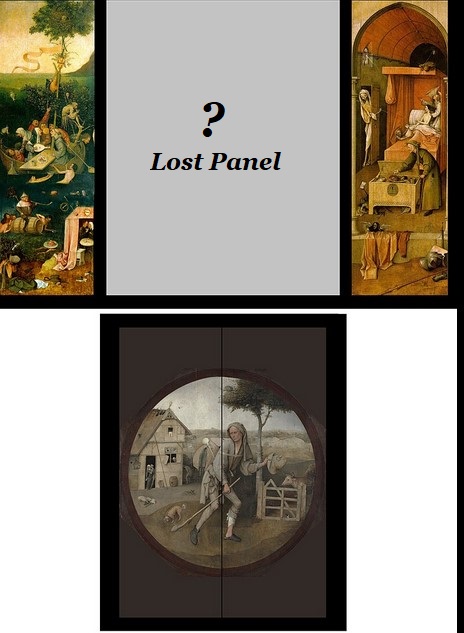

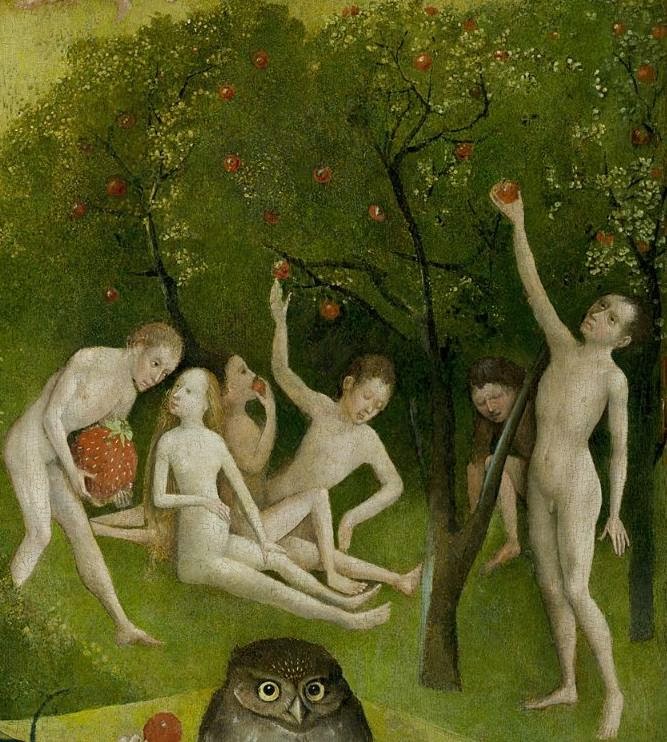

Once awakened, Rhetorica and the Landjuweel will mark the beginning of a period of prosperity and an awakening of the arts, for Antwerp and for the world, an allegorical theme developed by Frans Floris, the rhetorician and friend of Van Haecht, in his work The Awakening of the Arts (circa 1560).

This allegorical work commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, the most important peace agreement of the war-torn 16th century.

In a landscape ravaged by war, Philip II of Spain (it was hoped) assumes the role of Apollo, represented by the bearded figure in the center. The sun god awakens the liberal arts, represented by women endowed with attributes (sculptors’ cradles, poets’ feather, musicians’ scores, cartographers’ globes, etc.). With his left hand, Philip II shows four women warding off an abject Mars, the god of war, stripped of his sword and battle trophies. The scene symbolizes a new era of cultural prosperity made possible by peace.

The play Den Wellecomme not only exudes an atmosphere of joy and euphoria, but also launches a few barbs at the oppressors. The Chambers retained a bitter aftertaste. In the preceding years, several rhetoricians had been struck by fate. The previous factor, the highly praised Jan van den Berghe (died in 1559) , had died of old age. In addition, two prominent members had fallen victim to religious persecution. The printers Frans Fraet (1505-1558) and Willem Touwaert Cassererie (c. 1478-1558) were condemned and executed in 1558, despite the vigorous protests of their guild, for printing and being found in possession of forbidden books (Dutch Bibles).

Antwerp was the Northern European centre of heterodox publishing in the first half of the sixteenth century. From Antwerp the books were shipped all over Europe. Alastair Duke, who studied the methods of the Inquisition in this period, has suggested that of four thousand books published in Europe between 1500 and 1540, half were printed in Antwerp 55 almost half of those publications contained Protestant influences. 56

These persecutions increased the central government’s distrust of the rhetoricians. These were not easy times for them. The art of rhetoric « doesn’t have many friends, » as Van Haecht puts it. 57 Although the Landjuweel was designed to celebrate peace and not to express discontent, the horror of the past war years and the resulting divisions were clearly palpable.

The contest was to be held under the banner of friendship and solidarity – not without reason the motto of De Violieren. Referring to the miracle of Pentecost, the invitation card compares the Brabant rhetoricians to the apostles, who received the Holy Spirit by gathering together in unity, without disagreement or conflict. This motif was common among rhetoricians.

Already in the poems of Anthonis de Roovere (c. 1430-1482), the Ghent plays of 1539, and in Matthijs de Castelein ‘s Const van Rhetoriken (c. 1485-1550), the rhetorician’s inspiration were compared to the religious enthusiasm of the apostles at Pentecost. Rhetoricians saw their poetry as a gift from the Holy Spirit.

This is strongly reminiscent of the discourse Erasmus presents in his Querella pacis (The Complaint for Peace, 1517). In this famous pamphlet for peace, the miracle of Pentecost is also used to emphasize the importance of unity and love in society. Only the Christian religion, according to Erasmus, had the strength to defend itself against tyranny and war. The well-being of the whole society has always taken priority over any form of personal interest.

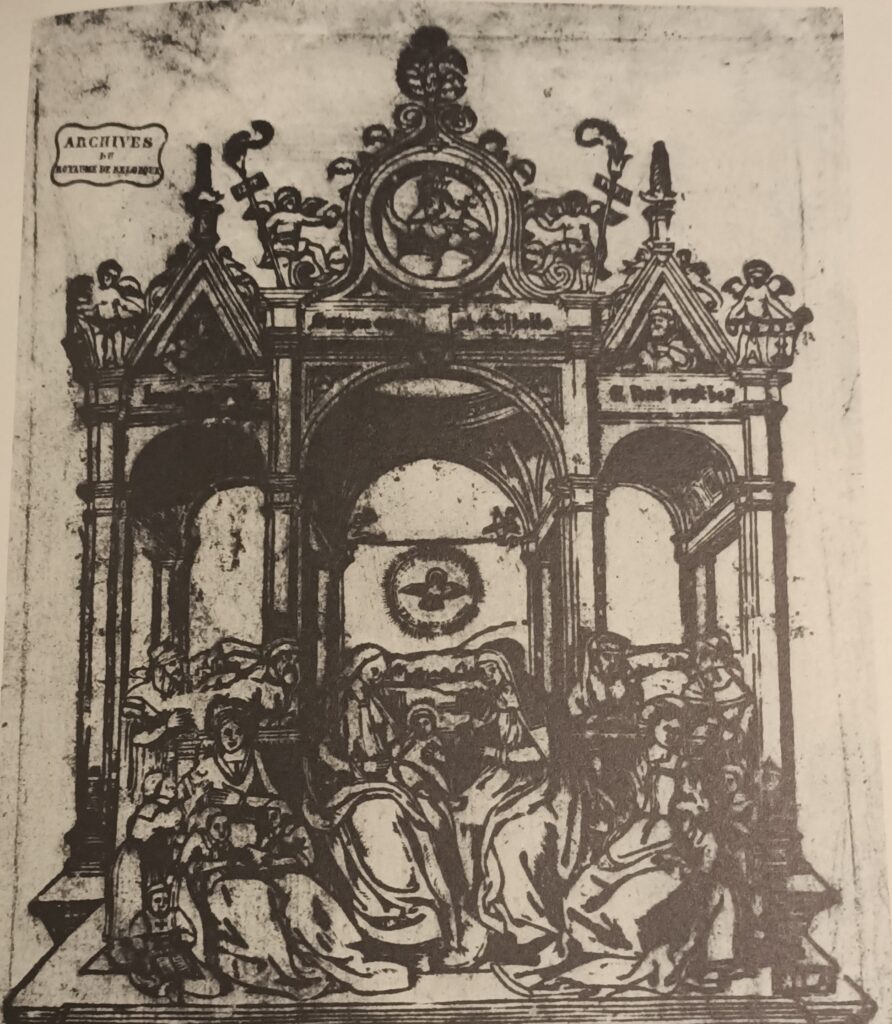

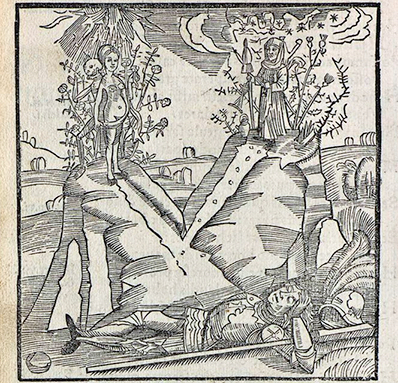

An « invitation card » was personnaly transmitted by messagers to all the chambers in Brabant, accompanied by a woodcut (probably also designed by Willem van Haecht). The print emphasizes the importance of rhetoric in achieving peace.

Rhetoric sits enthroned in the center, her attributes being a scroll and a lily, symbols respectively of the qualities of promoting knowledge and harmonizing the art of rhetoric. On either side of Rhetoric are Prudentia (left) and Inventio (right). Prudentia —Providence—is depicted holding a mirror (insight) and a serpent (prudence) in her hands. Inventio —Invention—has the attributes of a compass and a book. These two personifications refer to the qualities of careful design and erudition. Both personifications are intended to support Rhetoric. They stand on a raised step, on which grows the violet flower. Beneath the flower, the ox of the Guild of Saint Luke supports the coat of arms of the Antwerp painters’ guild. The personifications Pax, Charitas, and Ratio come to the left of the throne to pay homage to Rhetoric.