Étiquette : gold

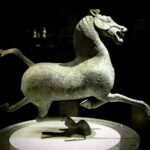

Horse-power, the Earthly Science behind China’s “Heavenly Horses”

Indicating the major role horses have played in the history of mankind, the fact that still today, when people talk about the engine of their cars, they use the term “horsepower” (hp) to indicate how much “work” the engine is capable of.

In a lecture on hydro-infrastructure in Kabul, Afghanistan, I recently used the domestication of the horse as an example of what one should understand when we talk about moving from a “lower” to a “higher infrastructure platform”.

The history of mankind completely changed with the domestication of the horse. Things considered “impossible” before the domestication of the horse became the “new normal”. How and when horses became domesticated has been disputed. Although horses appear in Paleolithic cave art as early as 36,000 BC (Chauvet cave, France), these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

Zoologists define « domestication » as human control over breeding, which can be detected in ancient skeletal samples by changes in the size and variability of ancient horse populations. Other researchers look at the broader evidence, including skeletal and dental evidence of working activity; weapons, art, and spiritual artifacts; and lifestyle patterns of human cultures. There is evidence that horses were kept as a source of meat and milk before they were trained as working animals.

In India, close to Bopal, the “Bhimbetka rock shelters”, which are the oldest known rock art of the country, figures dance and hunting scenes from the Stone Age as well as of warriors on horseback from a later time (10 000 BC).

Horses were a late addition to the barnyard. Dogs were domesticated 15,000 years ago; sheep, pigs and cattle, about 8,000 to 11,000 years ago. But clear evidence of horse domestication doesn’t appear in the archaeological record until about 5,500 years ago.

The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials. The earliest true chariots known are from around 2,000 BC, in burials of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in modern Russia in a cluster along the upper Tobol river, southeast of Magnitogorsk.

They contain spoke-wheeled chariots drawn by teams of two horses.

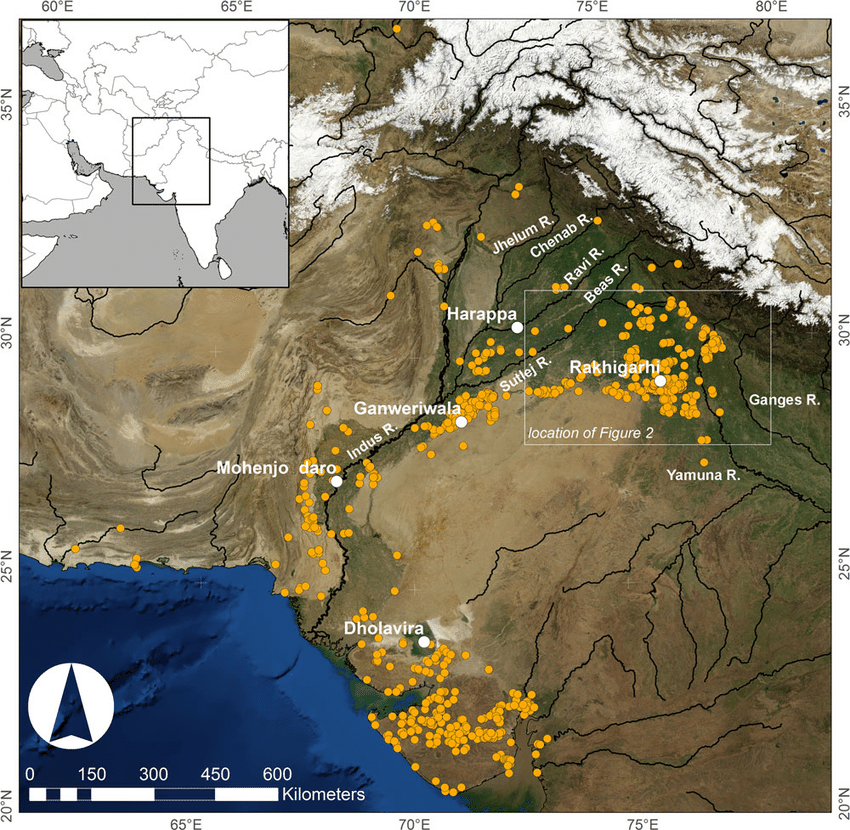

Kazakhstan and Ukraine

Up till recently, it was thought that the most common horse used today was a descendant of the horses domesticated by the Botai culture living in the steppes of the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan, around 3500 BC.

Recent genetic research points to the fact that the Botai horses were the forefathers of the Przewalski horse, a species that nearly disappeared.

Our common horse, the Equus ferus caballus, genetic research says, has been domesticated 4,200 years ago in Ukraine, in an area known as the Volga-Don, in the Pontic-Caspian steppe region of Western Eurasia, around 2,200 BC.

As these horses were domesticated, they were regularly interbred with wild horses.

Interesting in this respect, is the fact that according to the “Kurgan” or “steppe hypothesis”, most Indo-European languages spread from the same region throughout Europe and parts of Asia.

It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of what some call the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan, meaning tumulus or burial mound.

Tea Road, Horse Road or Silk Road?

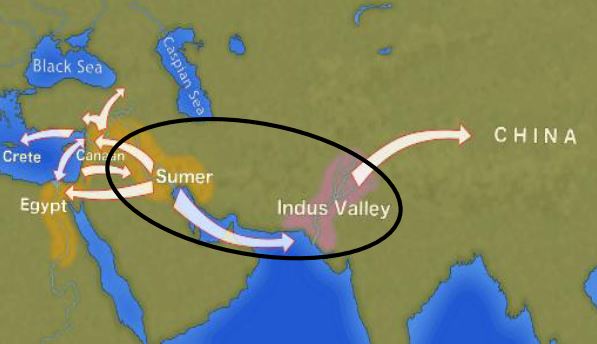

As a matter of fact, the main commodities traded on the “Silk Road” (a term only coined in 1877 by the German geographer Ferdinand Von Richthofen), were… horses, mules, camels, donkeys and onagers.

Silk and tea were of course traded, but appeared mainly as a means… to pay for horses. People “paid” with silk, gold, porcelain and tea, the animals they needed to secure the survival of their society!

What was known as the « Tea-Horse Road » (Southern Silk Road) extended from the city of Chengdu in Sichuan Province, China, south through Yunnan into India and the Indochina Peninsula, and extended westwards into Tibet. It was an important route for the tea trade throughout South China and Southeast Asia and contributed to the spread of religions like Taoism and Buddhism across the region.

Eurasian Steppe

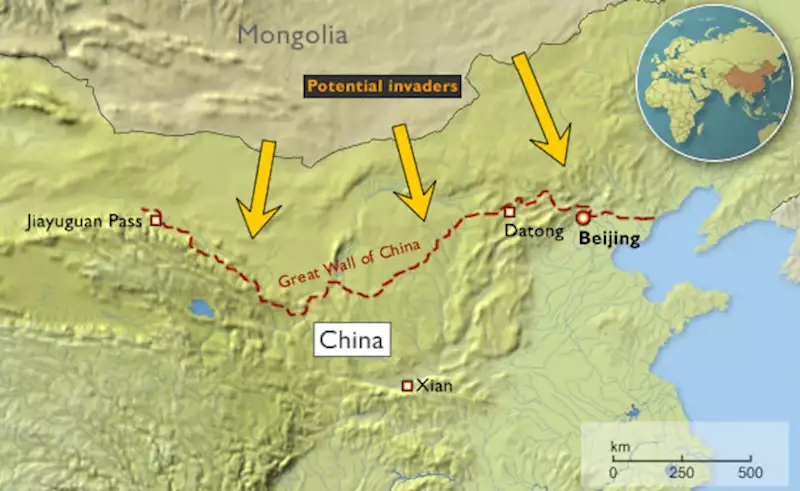

China, feeling itself under constant threat from the nomadic steppe people from the North, started building the first parts of its “Great Wall” as early as the VIIth Century BC, with selective stretches joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China and completed under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to become one of the most impressive feats in history.

The Eurasian nomads were groups of nomadic peoples living throughout the Eurasian Steppe. The generic title encompasses the varied ethnic groups who have at times inhabited the steppes of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, Russia, and Ukraine.

By the domestication of the horse around 2,200 BC (i.e. 4,200 years ago), they vastly increased the possibilities of nomadic life and subsequently their economy and culture emphasized horse breeding, horse riding, and nomadic pastoralism, usually engaging in trade with settled peoples around the steppe edges, be it in Europe, Asia or Central Asia.

Nomads, by definition, don’t create empires. It is thought they operated often as confederations. But it was them who developed the chariot, wagon, cavalry, and horseback archery and introduced innovations such as the bridle, bit, stirrup, and saddle and the very rapid rate at which innovations crossed the steppe-lands spread these widely, to be copied by settled peoples bordering the steppes.

During the Iron Age, Scythian (Persian) culture emerged among the Eurasian nomads, which was characterized by a distinct Scythian art.

China and the Horse

Throughout China’s long and storied past, no animal has impacted its history as greatly as the horse. Its significance was such that as early as the Shang dynasty (ca.1600-1100 BC), military might was measured by the number of the war chariots available to a particular kingdom.

The mounted cavalery, which emerged in the IIIrd century BC grew rapidly during the IInd century BC to meet the challenge of horse-riding peoples threatening China along the northern frontier.

Their large, powerful, horses were very new to China. As said before, traded for luxurious silk, they were the first major import to China from the “Silk Road.”

Chinese grave goods provide extraordinary amounts of information about how the ancient Chinese lived. Archaeological evidence shows that within a few years, the marvelous Arabian steeds had become immensely popular with military and aristocracy alike and upper-class tombs began to be filled with images of these great horses for use in the afterlife. But horses were hard to find in China.

Chinese diplomats and the Kingdom of Dayuan (Ferghana)

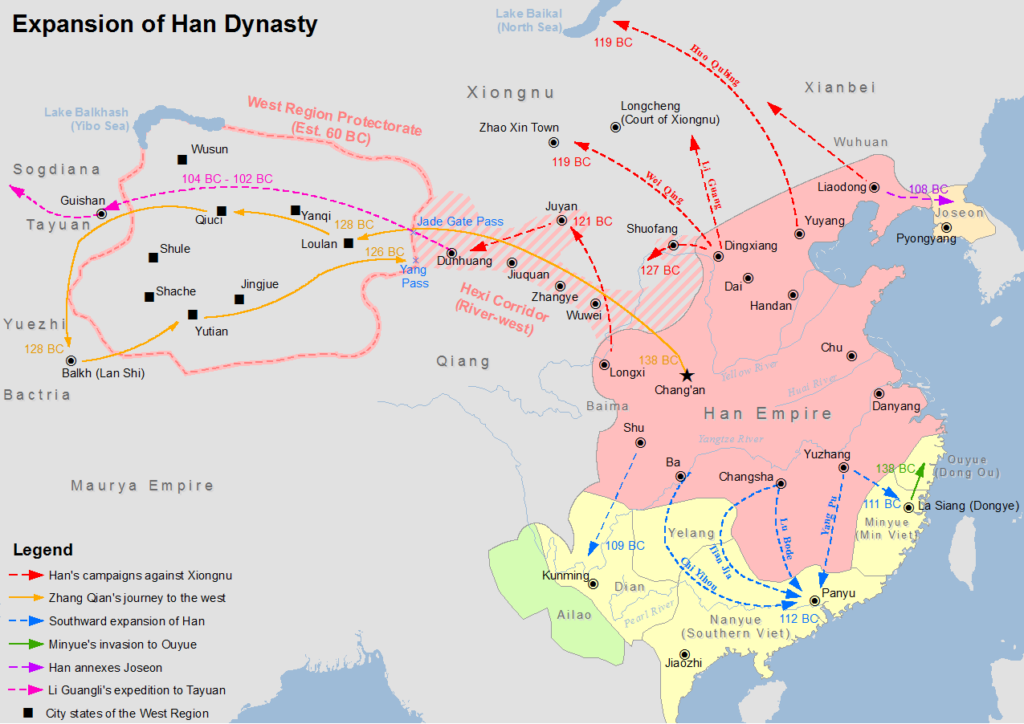

Something had to be done. In the late IInd Century BC, Zhang Qian, a Han dynasty diplomat and explorer, travels to Central Asia and discovers three sophisticated urban civilizations created by Greek settlers he named « Ionians ». The account of his visit to Bactria, including his recollection of his amazement at finding Chinese goods in the markets (acquired via India), as well as his travels to Parthia and Ferghana, are preserved in the works of the early Han historian Sima Qian.

Upon returning to China, his account prompts the Emperor to dispatch Chinese envoys across Central Asia to negotiate and encourage trade with China. Some historians say that this dicision gave « birth of the Silk Road.«

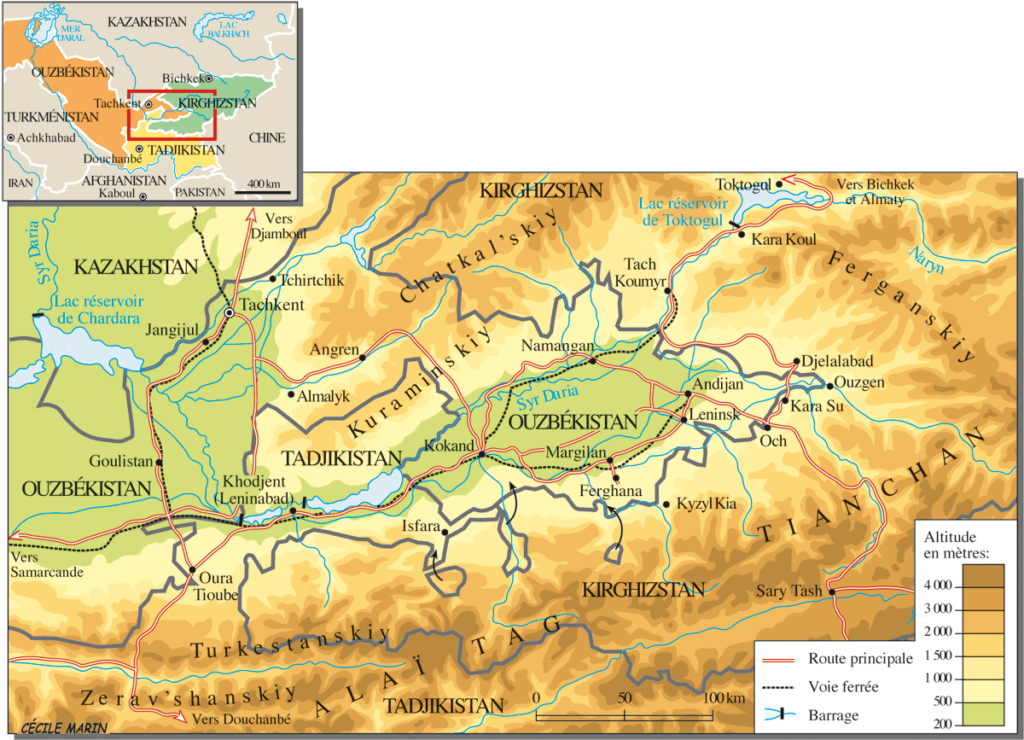

Besides Parthia and Bactria, where Chinese goods were being traded via Indian imports, Zhang Qian visited, in the fertile Ferghana valley (today essentially in Tajikistan), a State the Chinese called the “Kingdom of Dayuan” (“Da” meaning “great”, and “Yuan” being the transliteration of Sanskrit Yavana or Pali Yona, used throughout antiquity in Asia to designate « Ionians », i.e. Greek settlers).

The Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han describe the Dayuan as numbering several hundred thousand people living in 70 walled cities of varying size. They grew rice and wheat, and made wine from grapes. They had Caucasian features and “customs identical to those of Bactria” (the most Hellenistic state of the region since Alexander the Great) which is today’s northern Afghanistan.

The Chinese diplomat reported something of great strategic interest: unbelievable, fast and powerful horses raised by these Ionians in the Ferghana Valley!

Now, as said before, China felt under permanent threat by the nomadic people from the steppes and was in the process of building the “Great Wall”. China also was acutely aware that the nomadic steppe people derived their military superiority from something dramatically lacking at home: powerful horses !

Added to that, the fact that in terms of China’s scale of values, horses where nearly of the same mythological nature as dragons: they could fly and represented the divine, creative spirit of the universe itself, something essential for any Chinese emperor eager to acquire both military security for his Empire and for his personal immortality.

In short, having good horses became an issue of national security. So much, that in 100 BC, the Han dynasty started what is known as the “War of the Heavenly Horses” with Dayuan, when its ruler refused to provide high quality horses to China !

The War of the Heavenly Horses

The War of the Heavenly Horses was a military conflict fought in 104 BC and 102 BC between China and a part of the Saka-ruled (Scythian) Greco-Bactrian kingdom known to the Chinese as Dayuan, in the Ferghana Valley (between modern-day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan).

First, Emperor Wu decided to defeat the nomadic steppe Xiongnu, who had harassed the Han dynasty for decades.

As said earlier, in 139 BC, the emperor sent diplomat Zhang Qian to survey the west and forge a military alliance with the Yuezhi nomads against another group of nomads, the Xiongnu. On the way to Central Asia through the Gobi desert, Zhang was captured twice. On his return, he impressed the emperor with his description of the « Heavenly Horses » of Dayuan, that could greatly improve the quality of Han cavalry mounts when fighting the Xiongnu.

The Han court sent at least five or six, and perhaps as many as ten diplomatic groups annually to Central Asia during this period to get a hold on these “Heavenly Horses”.

A trade mission arrived in Dayuan with 1000 pieces of gold and a golden horse to purchase these precious animals.

Dayuan, who was one of the furthest western states to send envoys to the Han court at that point, had already been trading with the Han for quite some time and benefited greatly from it. Not only were they overflowed by eastern goods, they also learned from Han soldiers how to cast metal into coins and weapons. However unlike the other envoys to the Han court, the ones from Dayuan did not conform to the proper Han rituals and behaved with great arrogance and self-assurance, believing they were too far away to be in any danger of invasion.

Hence, in a stroke of folly and taken by pure arrogance, the Dayuan king not only refused the deal, but confiscated the payment in gold. The Han envoys cursed the men of Dayuan and smashed the golden horse they had brought. Enraged by this act of contempt, the nobles of Dayuan ordered Yucheng, which lay on their eastern borders, to attack and kill the envoys and seize their goods.

Upon receiving word of the trade mission’s demise, humiliated and enraged, the Han court sent an army led by General Li Guangli to subdue Dayuan, but their first incursion was poorly organized and under-supplied.

A second, larger and much better provisioned expedition was sent two years later and successfully laid siege to the Dayuan capital at Alexandria Eschate, and forced Dayuan to surrender unconditionally.

The Han expeditionary forces installed a pro-Han regime in Dayuan and left with 3,000 horses, although only 1,000 remained by the time they reached China in 101 BCE.

The Ferghana also agreed to send two Heavenly horses each year to the Emperor, and lucerne seed was brought back to China providing superior pasture for raising fine horses in China, to provide cavalry which could cope with the Xiongnu who threatened China.

The horses have since captured the popular imagination of China, leading to horse carvings, breeding grounds in Gansu, and up to 430,000 such horses in the cavalry during the Tang dynasty.

China and the agricultural revolution

After imposing its role in military strategy for the next centuries, horsepower, together with water management, became a crucial factor to raise the productivity of the world’s food production.

First, contrary to the Romans, who preferred to use “human cattle” (slaves) rather than animals (which they raised for race contests), the Chinese greatly contributed to the survival of mankind with two crucial innovations respecting a more efficient use of horse power.

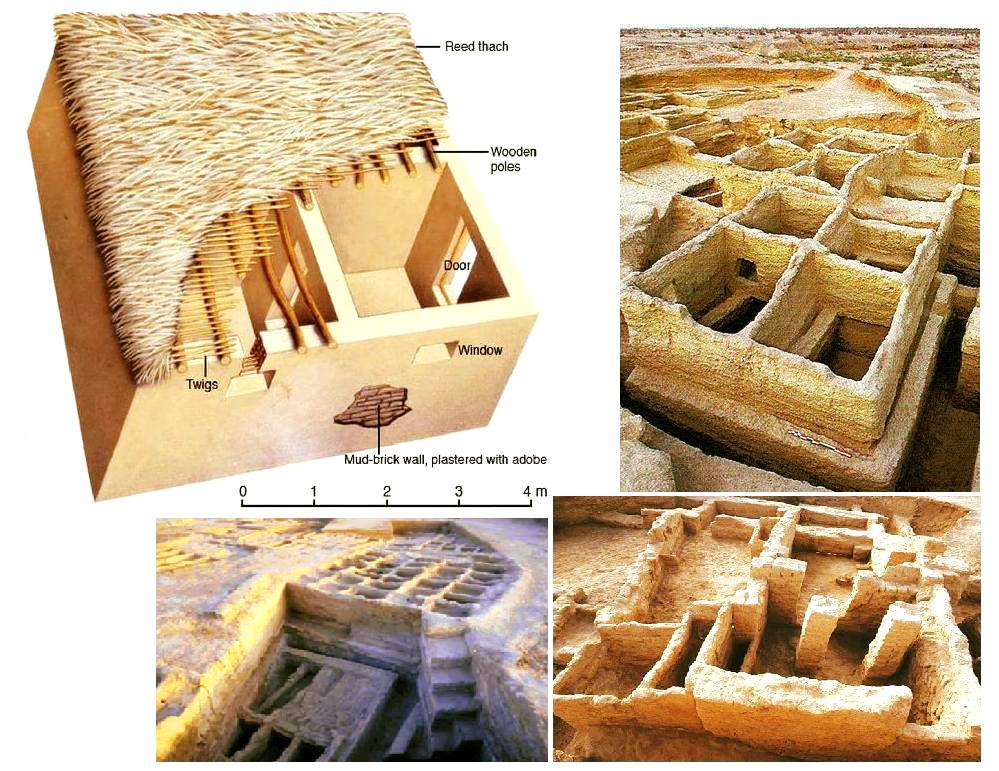

As can be seen in murals and paintings, through the ancient world, be it in Egypt or Greece, plows and carts were pulled using animal harnesses that had flat straps across the neck of the horse, with the load attached at the top of the collar, above the neck, in a manner similar to a yoke used for oxen.

In reality, this greatly limited a horse’s ability to exert itself as it was constantly choked at the neck. The harder the horse pulled, the harder it became to breathe.

Due to this physical limitation, oxen remained the preferred animal to do heavy work such as plowing. Yet oxen are hard to maneuver, are slow, and lack the quality of horses, whose power is equivalent but whose endurance is twice that of oxen.

China reportedly first invented the “breast strap” which was the first step in the right direction.

Then, in the Vth Century, China also invented what is called the “rigid horse collar”, designed as an oval that fits around the neck and shoulders of the horse.

It has the following advantages:

–First, it relieved the pressure of the horse’s windpipes. It left the airway of the horse free from constriction improving massively the animal’s energy through-put.

–Second, the traces could be attached to the sides of the collar. This allowed the horse to push forward with its more powerful hind-legs rather than pulling with the weaker front legs.

Now you can argue that this is anecdotal. It is NOT, because what appears as only a slight change had absolutely monumental consequences.

European Renaissance

In a strategic alliance and cooperation with the humanist Baghdad Abbasid caliphate, Charlemagne and his successors introduced the “rigid horse collar” in Europe.

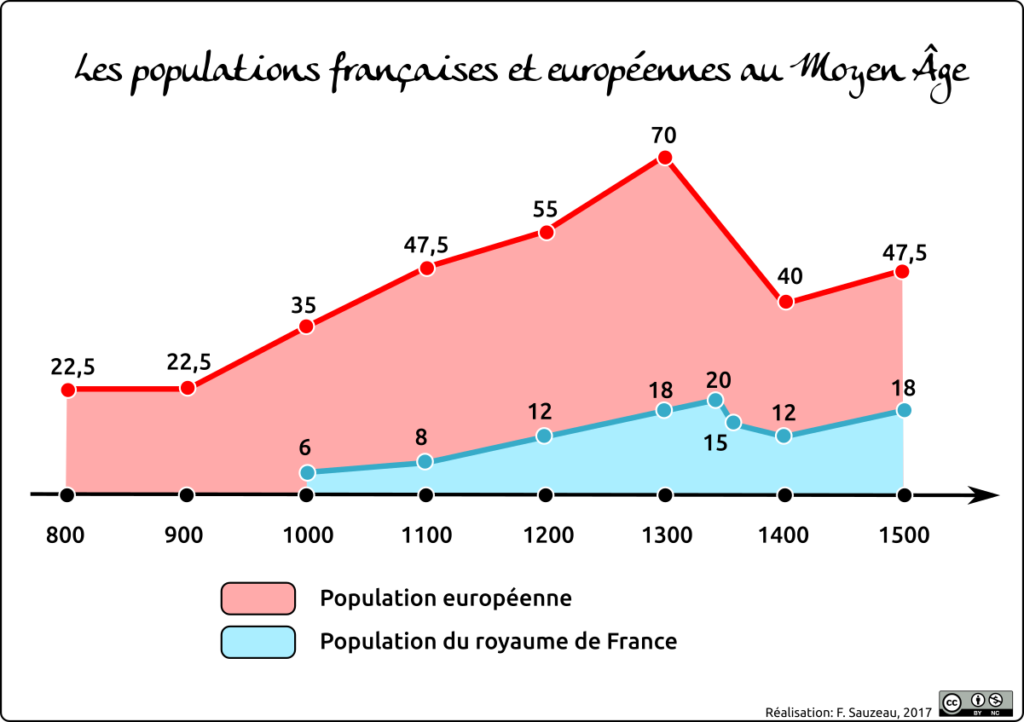

With that new, far more efficient tool, European farmers finally could take full advantage of a horse’s strength. The horse was able to pull another recent innovation, the heavy plow. This became particularly important in areas where the soil was hard and clay-like. This opened up new plots of lands to agriculture. The rigid horse collar, the heavy plow, and horseshoes helped usher in a period of increased agricultural production.

As a result, between 1000 CE and 1300 CE, it is estimated that in Europe, crop yields increased by threefold, allowing to feed a rising number of citizens in the urban cities appearing in the XVth century and kick starting the global “Golden” European Renaissance. Thank you, China!

Some numbers are nevertheless disturbing:

–it took humanity thousands of years to finally domesticate the horse (long after the cow), in 3200 BC.

–it took humanity another 3700 years to learn how to find out, in the Vth century AD, the most efficient way to use horse-power…

Shifting from a “lower” infrastructure platform to a “higher” infrastructure platform might take some time. Today’s new “higher” platforms are called “space data” and “fusion power.” Let’s not wait another century to find out how to use them correctly!

How Jacques Cœur put an end to the Hundred Years’ War

has much to inspire us today.

Without waiting for the end of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453), Jacques Cœur, an intelligent and energetic man of whom no portrait or treatise exists, decided to rebuild a ruined, occupied and tattered France.

Not only a merchant, but also a banker, land developer, shipowner, industrialist and master of mines in Forez, Jacques Coeur was a contemporary of Joan of Arc (1412-1431), who lived in 1429 in Coeur’s native city of Bourges.

First and foremost, he entered into collaboration with some of the humanist popes of the Renaissance, patrons of the scientific genius Nicolaus Cusanus and the painter Piero della Francesca. With Europe threatened with implosion and chaos, their priority was to put an end to interminable warfare and unify Christendom.

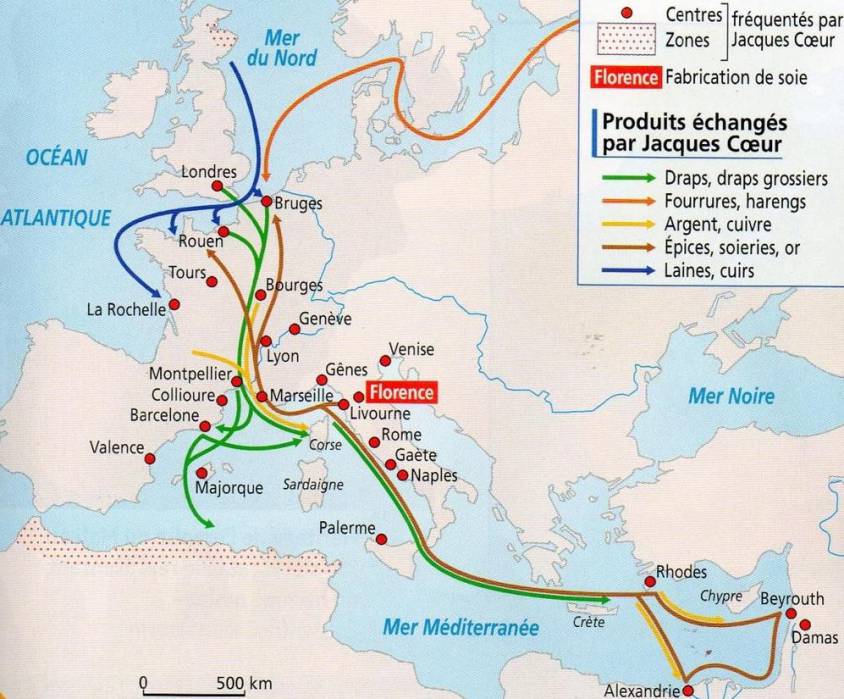

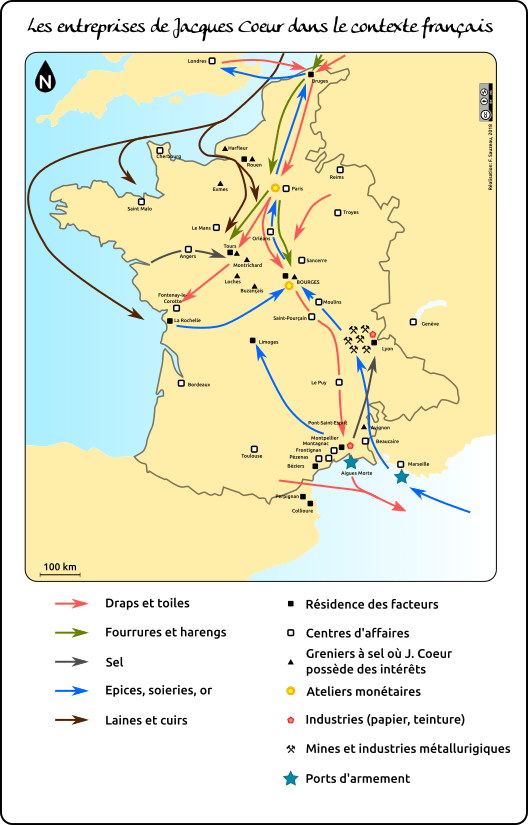

Secondly, following in the footsteps of Saint-Louis (King Louis IX), Cœur was one of the first to fully assume France’s role as a naval power. Finally, thanks to an intelligent foreign exchange policy and by taking advantage of the maritime and overland Silk Roads of his time, he encouraged international trade. In Bruges, Lyon and Geneva, he traded silk and spices for cloth and herring, while investing in sericulture, shipbuilding, mining and steelmaking.

Paving the way for the reign of Louis XI, and long before Jean Bodin, Barthélémy de Laffemas, Sully and Jean-Baptiste Colbert, his mercantilism heralded the political economy concepts later perfected by the German-American economist Friedrich List or the first American Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

We will concentrate here on his vision of man and economy, leaving aside important subjects such as the trial against him, his relationship with Agnès Sorel and Louis XI, to which many books have been dedicated.

Jacques Cœur (1400-1454) was born in Bourges, where his father, Pierre Cœur, was a merchant pelletier. Of modest income, originating from Saint-Pourçain, he married the widow of a butcher, which greatly improved his status, as the butchers’ guild was particularly powerful.

The Hundred Years’ War

The early XVth century was not a particularly happy time. The « Hundred Years’ War » pitted the Armagnacs against the Burgundians allied with England. As with the great systemic bankruptcy of the papal bankers in 1347, farmland was plundered or left fallow.

While urbanization had thrived thanks to a productive rural world, the latter was deserted by farmers, who joined the hungry hordes populating towns lacking water, hygiene and the means to support themselves. Epidemics and plagues became the order of the day; cutthroats, skinners, twirlers and other brigands spread terror and made real economic life impossible.

Jacques Cœur was fifteen years old when one of the French army’s most bitter defeats took place in France. The battle of Agincourt (1415) (Pas-de-Calais), where French chivalry was routed by outnumbered English soldiers, marked the end of the age of chivalry and the beginning of the supremacy of ranged weapons (bows, crossbows, early firearms, etc.) over melee (hand-to-hand combat). A large part of the aristocracy was decimated, and an essential part of the territory fell to the English. (see map)

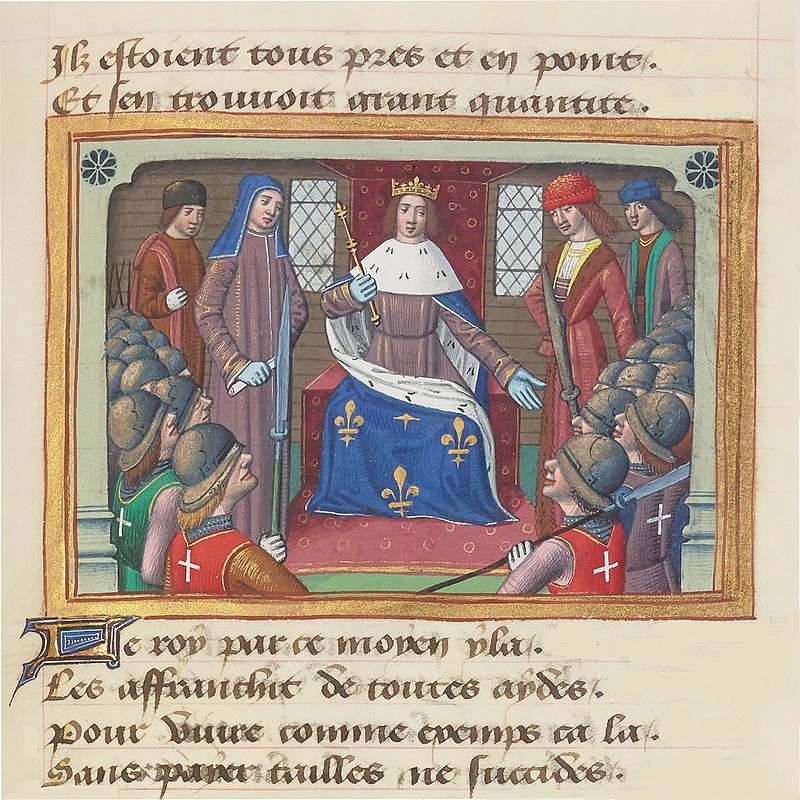

King Charles VII

In 1418, the Dauphin, the future Charles VII (1403-1461), as he is known thanks to a painting by the painter Jean Fouquet, escaped capture when Paris was taken by the Burgundians. He took refuge in Bourges, where he proclaimed himself regent of the kingdom of France, given the unavailability of his insane father (King Charles VI), who had remained in Paris and fallen to the power of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy.

The dauphin probably instigated the latter’s assassination on the Montereau bridge on September 10, 1419. By his ennemies, he was derisively nicknamed « the little King of Bourges ». The presence of the Court gave the city a boost as a center of trade and commerce.

Considered one of the most industrious and ingenious of men, Jacques Coeur married in 1420 Macée de Léodepart, daughter of a former valet to the Duke of Berry, who had become provost of Bourges.

As his mother-in-law was the daughter of a master of the mints, Jacques Coeur’s marriage in 1427 left him, along with two partners, in charge of one of the city’s twelve exchange offices. His position gave rise to much jealousy. After being accused of not respecting the quantity of precious metal contained in the coins he produced, he was arrested and sentenced in 1428, but soon benefited from a royal pardon.

Yolande d’Aragon

Although the Treaty of Troyes (1420) disinherited the dauphin from the kingdom of France in favor of a younger member of the House of Plantagenets, Charles VII nonetheless proclaimed himself King of France on his father’s death on October 21, 1422.

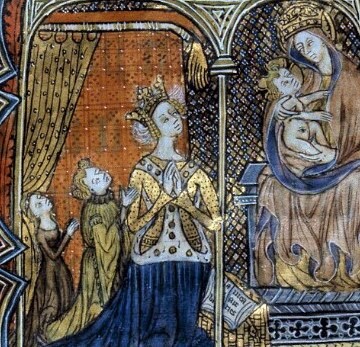

The de facto leader of the Armagnac party, retreating south of the Loire, saw his legitimacy and military situation considerably improved thanks to the intervention of Joan of Arc (1412-1431), operating under the benevolent protection of an exceptional world-historic person: the dauphin’s mother-in-law Yolande of Aragon (1384-1442), Duchess of Anjou, Queen of Sicily and Naples (Note 1).

Backed and guided by Yolande, Jeanne helped lift the siege of Orléans and had Charles VII crowned King of France in Reims in July 1429. In the mean time Yolande d’Aragon established contacts with the Burgundians in preparation for peace, and picked Jacques Coeur to be part of the Royal Court (Note 2).

The contemporary chronicler Jean Juvenal des Ursins (1433–44), Bishop of Beauvais described Yolande as « the prettiest woman in the kingdom. » Bourdigné, chronicler of the house of Anjou, says of her: « She who was said to be the wisest and most beautiful princess in Christendom. » Later, King Louis XI of France recalled that his grandmother had « a man’s heart in a woman’s body. »

A twentieth-century French author, Jehanne d’Orliac wrote one of the few works specifically on Yolande, and noted that the duchess remains unappreciated for her genius and influence in the reign of Charles VII. « She is mentioned in passing because she is the pivot of all important events for forty-two years in France », while « Joan [of Arc] was in the public eye only eleven months. »

Journey to the Levant

In 1430, Jacques Cœur, already renowned as a man « full of industry and high gear, subtle in understanding and high in comprehension; and all things, no matter how high, knowing how to lead by his work » (Note N° 3), with Barthélémy and Pierre Godard, two Bourges notables, set up,

« a company for all types of merchandise, especially for the King our lord, my lord the Dauphin and other lords, and for all other things for which they could provide proof ».

In 1431, Joan of Arc was handed over to the English by the Burgundians and burned alive at the stake in Rouen. One year later, in 1432, Jacques Cœur went to the Levant. A diplomat and humanist, Cœur went as an observer of customs as well as economic and political life.

His ship coasted from port to port, skirting the Italian coast as closely as possible, before rounding Sicily and arriving in Alexandria, Egypt. At the time, Alexandria was an imposing city of 70,000 inhabitants, bustling with thousands of Syrian, Cypriot, Genoese, Florentine and Venetian ships.

In Cairo, he discovered treasures arriving from China, Africa and India via the Red Sea. Around the Sultan’s Palace, Armenian, Georgian, Greek, Ethiopian and Nubian merchants offered precious stones, perfumes, silks and carpets. The banks of the Nile were planted with sugar cane and the warehouses full of sugar and spices.

Selling Silver at the Price of Gold

To understand Jacques Coeur’s financial strategy, a few words about bimetallism. At the time, unlike in China, paper money was not widely used. In the West, everything was paid for in metal coins, and above all in gold.

According to Herodotus, Croesus issued silver and pure gold coins in the 6th century BC. Under the Roman Empire, this practice continued. However, while gold was scarce in the West, silver-lead mines were flourishing.

Added to this, in the Middle Ages, Europe saw a considerable increase in the quantities of silver coinage in circulation, thanks to new mines discovered in Bohemia. The problem was that in France, national production was not sufficient to satisfy the needs of the domestic market. As a result, France was obliged to use its gold to buy what was lacking abroad, thus driving gold out of the country.

According to historians, during his trip to Egypt, Coeur observed that the women there dressed in the finest linens and wore shoes adorned with pearls or gold jewels. What’s more, they loved what was fashionable elsewhere, especially in Europe. Coeur was also aware of the existence of poorly exploited silver and copper mines in the Lyonnais region and elsewhere in France.

Historian George Bordonove, in his book Jacques Coeur, trésorier de Charles VII (Jacques Coeur, treasurer of Charles VII), reckons that Coeur was quick to note that the Egyptians « strangely preferred silver to gold, bartering silver for equal weight ». whereas in Europe, the exchange rate was 15 volumes of silver for one volume of gold !

In other words, he realized that the region « abounded in gold », and that the price of silver was very advantageous. The opportunity to enrich his country by obtaining a « golden » price for the silver and copper extracted from the French mines must have seemed obvious to him

What’s more, in China, only payments in silver were accepted. In other words, the Arab-Muslim world had gold, but lacked silver for its trade with the Far East, hence its huge interest in acquiring it from Europe…

Lebanon, Syria and Cyprus

Cœur then travels via Beirut to Damascus in Syria, at the time by far the biggest center of trade between East and West.

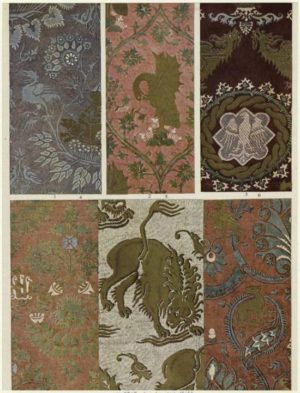

The city is renowned for its silk damasks, light gauze veils, jams and rose essences. Oriental fabrics were very popular for luxury garments.

Europe was supplied with silk and gold muslin from Mosul, damasks with woven motifs from Persia or Damascus, silks decorated with baldacchino figures, sheets with red or black backgrounds adorned with blue and gold birds from Antioch, and so on.

The « Silk Road » also brought Persian carpets and ceramics from Asia. The journey continues to another of the Silk Roads’ great maritime warehouses: Cyprus, an island whose copper had offered exceptional prosperity to the Minoan, Mycenaean and Phoenician civilizations.

The best of the West was bartered here for indigo, silk and spices.

Genoa and Venice

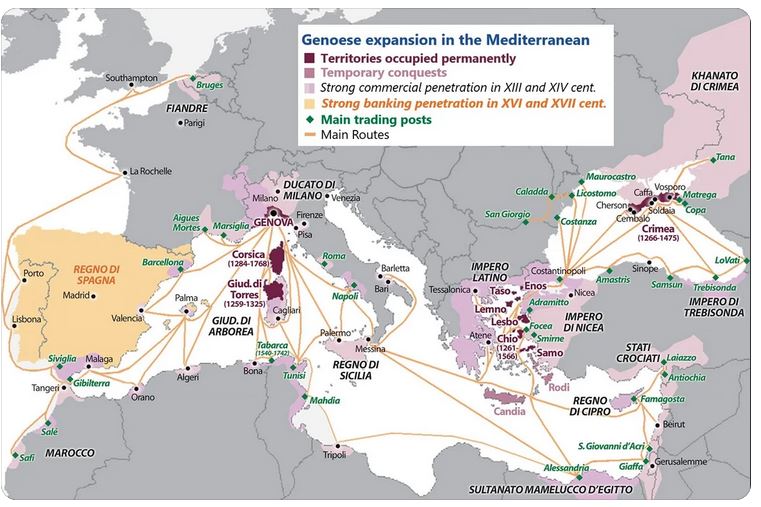

During his voyage, Coeur also discovered the maritime empires of Venice and Genoa, each enjoying the protection of a Vatican dependent on these financial powers.

The former, to justify their lucrative trade with the Muslims, claimed that « before being Christian », they were Venetians…

Like the British Empire, the Venetians promoted total free trade to subjugate their victims, while applying fierce dirigisme at home and prohibitive taxes to others. Any artist or person divulging Venetian know-how suffered terrible consequences.

Venice, outpost of the Byzantine Empire and supplier to the Court of Constantinople, a city of several million inhabitants, developed fabric dyeing, manufactured silks, velvets, glassware and leather goods, not to mention weapons. Its arsenal employs 16,000 workers.

Its rival, Genoa, with its highly skilled sailors and cutting-edge financial techniques, had colonized the Bosphorus and the Black Sea, from where treasures from Persia and Muscovy flowed. They also shamelessly engaged in the slave trade, a practice they would pass on to the Spanish and especially the Portuguese, who held a monopoly on trade with Africa.

Avoiding direct confrontation with such powers, Cœur kept a low profile. The difficulty was threefold: following the war, France was short of everything! It had no cash, no production, no weapons, no ships, no infrastructure!

So much so, in fact, that Europe’s main trade route had shifted eastwards. Instead of taking the route of the Rhône and Saône rivers, merchants passed through Geneva, and up the Rhine to Antwerp and Bruges. Another difficulty was soon added: a royal decree prohibited the export of precious metals! But what immense profits the Kingdom could draw from the operation.

The Oecumenial Councils

On his return from the Levant, France’s history accelerated. While preparing the economic reforms he wanted, Jacques Cœur also became involved in the major issues of the day. Through his brother Nicolas Cœur, the future bishop of Luçon, he played an important role in the process initiated by the humanists to unify the Western Church in the face of the Turkish threat.

Since 1378, there had been two popes, one in Rome and the other in Avignon. Several councils attempted to overcome the divisions. Nicolas Cœur attended them. First there was the Council of Constance (1414 to 1448), followed by the Council of Basel (1431), which, after a number of interruptions, was transferred to Florence (1439), establishing a doctrinal « union » between the Eastern and Western churches with a decree read out in Greek and Latin on July 6, 1439, in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, i.e. under the dome of Florence’s dome, built by Brunelleschi.

The central panel of the Ghent polyptych (1432), painted by the diplomatic painter Jan Van Eyck on the theme of the Lam Gods (the Lamb of God or Mystic Lamb), symbolizes the sacrifice of the Son of God for the redemption of mankind, and is capable of reuniting a church torn apart by internal differences. Hence the presence, on the right, of the three popes, here united before the Lamb. Van Eyck also painted portraits of Cardinal Niccolo Albergati, one of the instigators of the Council of Florence, and Chancellor Rolin, one of the architects of the Peace of Arras in 1435.

The Peace treaty of Arras

To achieve this, the humanists concentrated on France. First, they were to awaken Charles VII. After the victories won by Joan of Arc, wasn’t it time to win back the territories lost to the English?

However, Charles VII knew that peace with the English depended on reconciliation with the Burgundians. He therefore entered into negotiations with Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy.

The latter no longer expected anything from the English, and wished to devote himself to the development of his provinces. For him, peace with France was a necessity. He therefore agreed to treat with Charles VII, paving the way for the Arras Conference in 1435.

This was the first European peace conference. In addition to the Kingdom of France, whose delegation was led by the Duke of Bourbon, Marshal de La Fayette and Constable Arthur de Richemont, and Burgundy, led by the Duke of Burgundy himself and Chancellor Rolin, it brought together Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, Mediator Amédée VIII of Savoy, an English delegation, and representatives of the kings of Poland, Castile and Aragon.

Although the English left the talks before the end, thanks to the skill of the scholar Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, at that cardinal of Cyprus (and futur Pope Pius II) and spokesman for the Council of Basel, the signing of the Treaty of Arras in 1435 led to a peace agreement between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, the first step towards ending the Hundred Years’ War.

In the meantime, the Council of Basel, which had opened in 1431, dragged on but came to nothing, and on September 18, 1437, Pope Eugene IV, advised by cardinal philosopher Nicolaus Cusanus and arguing the need to hold a council of union with the Orthodox, transferred the Council from Basel to Ferrara and then Florence. Only the schismatic prelates remained in Basel. Furious, they « suspended » Eugene IV and named the Duke of Savoy, Amédée VIII, Felix V, as the new pope. This « anti-pope » won little political support. Germany remained neutral, and in France, Charles VII confined himself to implementing many of the reforms decreed in Basel by the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges on July 13, 1438.

King’s Treasurer and Great State Servant

In 1438, Cœur became Argentier de l’Hôtel du roi. L’Argenterie was not concerned with the kingdom’s finances. Rather, it was a sort of commissary responsible for meeting all the needs of the sovereign, his servants and the Court, for their daily lives, clothing, armament, armor, furs, fabrics, horses and so on.

Cœur was to supply the Court with everything that could neither be found nor manufactured at home, but which he could bring in from Alexandria, Damascus and Beirut, at the time major nodal points of the Silk Road by land and sea, where he set up his commercial agents, his « facteurs » (manufacturers).

Following this, in 1439, after having been appointed Master of the Mint of Bourges, Jacques Cœur became Master of the Mint in Paris, and finally, in 1439, the King’s moneyer. His role was to ensure the sovereign’s day-to-day expenses, which involved making advances to the Treasury and controlling the Court’s supply channels.

Then, in 1441, the King appointed him commissioner of the Languedoc States to levy taxes. Cœur often imposed taxes without ever undermining the productive reconstruction process. And in times of extreme difficulty, he would even lend money, at low, long-term rates, to those who had to pay it.

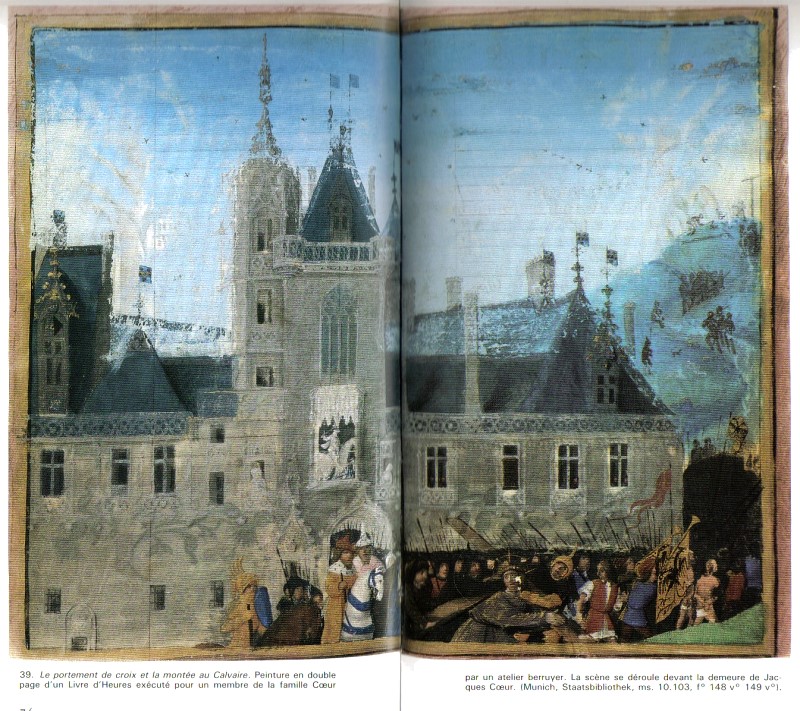

Ennobled, Coeur became the King’s strategic advisor in 1442. He acquired a plot of land in the center of Bourges to build his « grant’maison », currently the Palais Jacques Coeur. This magnificent edifice, with fireplaces in every room and an oven supplying the rest and bath room with hot water, has survived the centuries, although Coeur rarely had the occasion to live there.

Coeur is a true grand state servitor, with broad powers to collect taxes and negotiate political and economic agreements on behalf of the king. Having reached the top, Coeur is now in the ideal position to expand his long-cherished project.

Rule over Finance

On September 25, 1443, the Grande Ordonnance de Saumur, promulgated at Jacques Coeur’s instigation, put the state’s finances on a sounder footing.

As Claude Poulain recounts in his biography of Jacques Coeur:

« In 1444, after affirming the fundamental principle that the King alone had the right to levy taxes, but that his own finances should not be confused with those of the kingdom, a set of measures was enacted that affected the French at every level. »

These included: « Commoners owning noble fiefs were obliged to pay indemnities; nobles who had received seigneuries previously belonging to the royal domain would henceforth be obliged to share in the State’s expenses, on pain, once again, of seizure; finally, the kingdom’s financial services were organized, headed by a budget committee made up of high-ranking civil servants, ‘Messieurs des Finances’. »

In clear, the nobility was henceforth obliged to pay taxes for the Common Good of the Nation !

The King’s Council of 1444, headed by Dunois, was composed almost exclusively, not of noblement but of commoners (Jacques Coeur, Jean Bureau, Étienne Chevalier, Guillaume Cousinot, Jouvenel des Ursins, Guillaume d’Estouteville, Tancarville, Blainville, Beauvau and Marshal Machet). France recovered and enjoyed prosperity.

If France’s finances recovered, besides « taxing the rich », it was above all thanks to strategic investments in infrastructure, industry and trade. The revival of business activity enabled taxes to be brought in. In 1444, he set up the new Languedoc Parliament in conjunction with the Archbishop of Toulouse and, on behalf of the King, presided over the Estates General.

Master Plan

In reality, Jacques Cœur’s various operations, sometimes mistakenly considered to be motivated exclusively by his own personal greed, formed part of an overall plan that today we would describe as « connectivity » and at the service of the « physical economy ».

The aim was to equip the country and its territory, notably through a vast network of commercial agents operating both in France and abroad from the major trading cities of Europe (Geneva, Bruges, London, Antwerp, etc.), the Levant (Beirut and Damascus) and North Africa (Alexandria, Tunis, etc.), in order to promote win-win trade. ), to promote win-win trade, while reinvesting part of the profits in improving national productivity: mining, metallurgy, arms, shipbuilding, training, ports, roads, rivers, sericulture, textile spinning and dyeing, paper, etc.

Mining

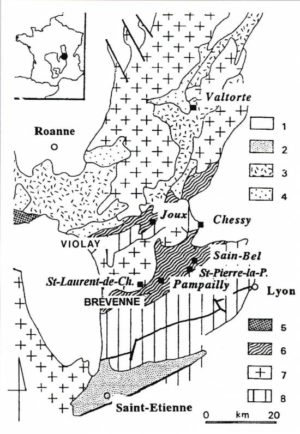

Of special interest were the silver mines of Pampailly, in Brussieu, south of l’Arbresle and Tarare, 25 kilometers west of Lyon, acquired and exploited as early as 1388 by Hugues Jossard, a Lyonnais jurist. They were very old, but their normal operation had been severely disrupted during the war. In addition, there were the Saint-Pierre-la-Palud and Joux mines, as well as the Chessy mine, whose copper was also used for weapons production.

Jacques Cœur made them operational. Near the mines, « martinets » – charcoal-fired blast furnaces – transformed the ore into ingots. Cœur brought in engineers and skilled workers from Germany, at the time a region far ahead of us in this field. However, without a pumping system, mining was no picnic.

Under Jacques Cœur’s management, the workers benefited from wages and comforts that were absolutely unique at the time. Each bunk had its own feather bed or wool mattress, a pillow, two pairs of linen sheets and blankets, a luxury that was more than unusual at the time. The dormitories were heated.

High quality food was provided to the laborers: bread containing four-fifths wheat and one-fifth rye, plenty of meat, eggs, cheese and fish, and desserts included exotic fruits such as figs and walnuts. A social service was organized: free hospitalization, care provided by a surgeon from Lyon who kept accident victims « en cure ». Every Sunday, a local priest came to celebrate a special mass for the miners. On the other hand, workers were subject to draconian discipline, governed by fifty-three articles of regulation that left nothing to chance.

The Ports of Montpellier and Marseille

On his return from the Levant in 1432, Jacques Coeur chose to make Montpellier the nerve center of his port and naval operations.

In principle, Christians were forbidden to trade with Infidels. However, thanks to a bull issued by Pope Urban V (1362-1370), Montpellier had obtained the right to send « absolved ships » to the East every year. Jacques Cœur obtained from the Pope that this right be extended to all his ships. Pope Eugene IV, by derogation of August 26, 1445, granted him this benefit, a permission renewed in 1448 by Pope Nicholas V.

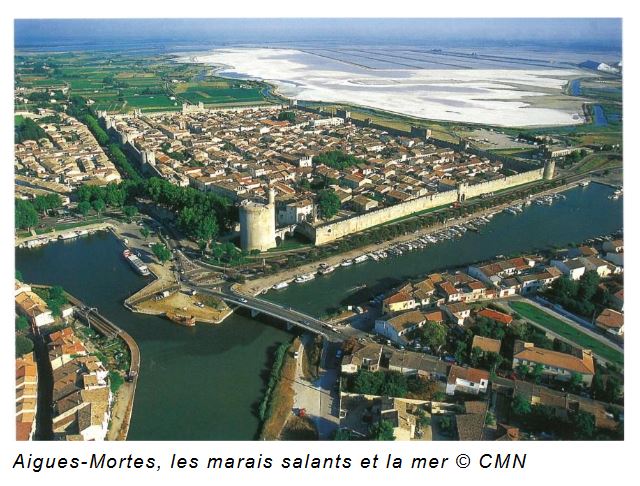

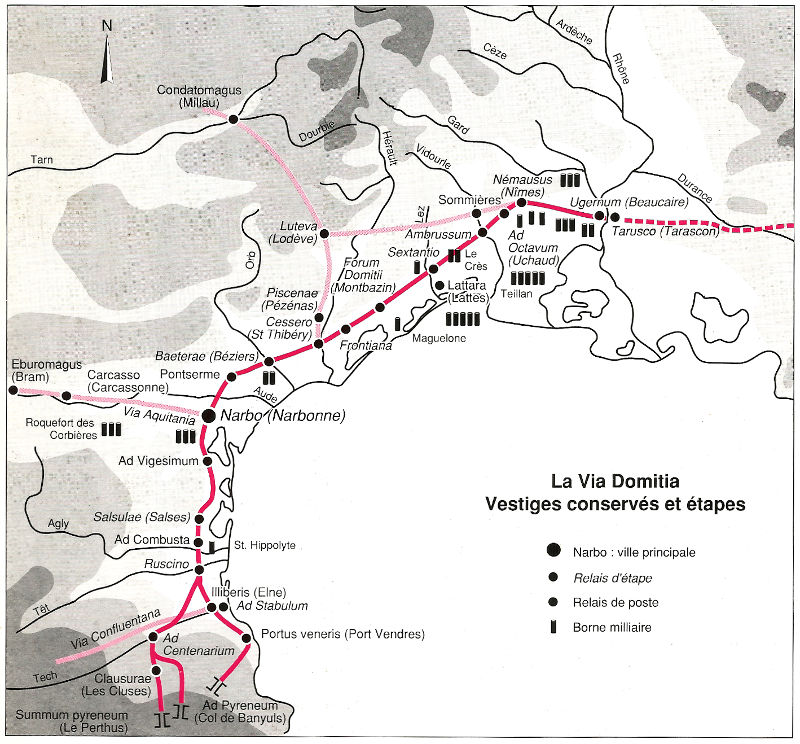

At the time, only Montpellier, in the middle of the east-west axis linking Catalonia to the Alps (the Roman Domitian Way) and whose outports were Lattes and Aigues-Mortes, had a hinterland with a network of roads that were more or less passable, an exceptional situation for the time.

In 1963, it was discovered that at the site of the village of Lattes (population 17,000), 4 km south of today’s Montpellier and on the River Lez, there had been an Etruscan port city called Lattara, considered by some to be the first port in Western Europe. The city was built in the last third of the VIth century BC. A city wall and stone and brick houses were built. Original objects and graffiti in Etruscan – the only ones known in France – have suggested that Etrurian brokers played a role in the creation and rapid urbanization of the settlement.

Trading with the Greeks and Romans, Lattara was a very active Gallic port until the 3rd century AD. Then maritime access changed, and the town fell into a state of numbness.

In the 13th century, under the impetus of the Guilhem family, lords of Montpellier, the port of Lattes was revitalized, only to regain its splendor when Jacques Cœur set up his warehouses there in the 15th century.

As for the port of Aigues-Mortes, built from top to bottom by Saint-Louis in the XIIIth century for the crusades, it was also one of the first in France. To connect the two, Saint-Louis dug the canal known as « Canal de la Radelle » (today’s Canal de Lunel), which ran from Aigues-Mortes across the Lake of Mauguio to the port of Lattes. Cœur restored this river-port complex to working order, notably by building Port Ariane in Lattes.

Over the following centuries, these disparate elements of canals and water infrastructure will become an efficient network built around the Canal du Rhône à Sète, a natural extension of the « bi-oceanic » Canal du Midi (between the Meditteranean and the Atlantic) begun by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (see map).

Coeur had the local authorities involved in his project, shaking Montpellier out of its age-old lethargy. At the time, the town had no market or covered sales buildings. Also lacking were moneychangers, shipowners and other cloth merchants.

In Montpellier, an entire district of merchants and warehouses was erected him, the Great Merchants Lodge, modeled on those in Perpignan, Barcelona and Valencia.

Numerous houses in Béziers, Vias and Pézenas also belonged to him, as did residences in Montpellier, including the Hôtel des Trésoriers de France, which, it is said, was topped by a tower so high that Jacques Cœur could watch his ships arrive at the nearby Port of Lattes.

And yet, as an old merchant and industrial city, Montpellier had long been home to Italians, Catalans, Muslims and Jews, who enjoyed a tolerance and understanding that was rare at the time. It’s easy to see why François Rabelais felt so at home here in the XVIth century.

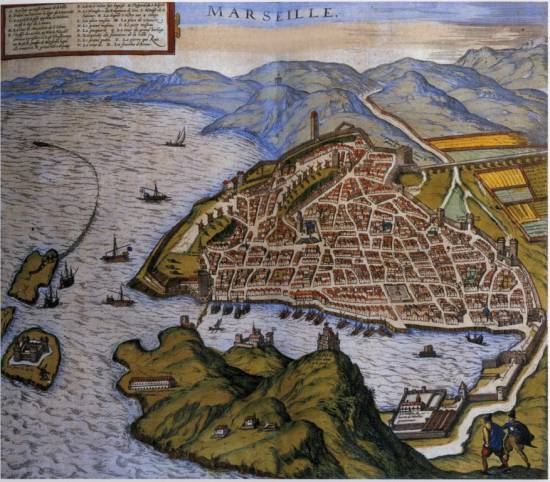

Port of Marseille

The hinterland was rich and industrious. It produced wine and olive oil, in other words, exportable goods. Its workshops produced leather, knives, weapons, enamels and, above all, drapery.

From 1448 onwards, faced with the limitations of the system and the constant silting-up of the port infrastructure, Coeur moved one of his agents, the navigator and diplomat Jean de Villages, his nephew by marriage, to the neighboring port of Marseille, at that time outside the Kingdom, to the home of King René d’Anjou, where port operations were easier, a deep harbor protected from the Mistral by hills and a port equipped with waterfront shops and storehouses. The boost that Jacques Coeur gave to Montpellier’s port Lattes, Jean de Villages, on Coeur’s behalf, immediately gave to Marseille.

Shipbuilding

Good ports mean ocean-going ships! Hence at that time, the best France could do was build a few river barges and fishing boats.

To equip himself with a fleet of ocean-going vessels, Cœur ordered a « galéasse » (an advanced model of the ancient three-masted « galley », designed primarily for boarding) from the Genoa arsenals.

The Genoese, who saw only immediate profit in the project, soon discovered that Coeur had had the shapes and dimensions of their ship copied by local carpenters in Aigues Mortes!

Furious, they landed at the shipyard and took it back, arguing that Languedoc merchants had no right to fit out ships and trade without the prior approval of the Doge of Venice!

Stained glass window of a ship (a caraque) in the Palais de Jacques Cœur in Bourges.

After complicated negotiations, but with the support of Charles VII, Coeur got his ship back. Cœur let the storm pass for a few years. Later, seven great ships would leave the Aigues-Mortes shipyard, including « La Madeleine » under the command of Jean de Villages, a great sailor and his loyal lieutenant.

Judging by the stained-glass window and bas-relief in the Palais de Coeur in Bourges, these were more like caraques, North Sea vessels with large square sails and much greater tonnage than galleasses. But that’s not all!

Having understood perfectly well that the quality of a ship depends on the quality of the wood with which it is built, Cœur, with the authorization of the Duke of Savoy, had his wood shipped from Seyssel. The logs were floated down the Rhône, then sent to Aigues-Mortes via the canal linking the town to the river.

The crews

One last problem remained to be solved: that of crews. Jacques Cœur’s solution was revolutionary: on January 22, 1443, he obtained permission from Charles VII to forcibly embark, in return for fair wages, the « idle vagabonds and caimans » who prowled the ports.

To understand just how beneficial such an institution was at the time, we need to remember that France was being laid to waste by bands of plunderers – the routiers, the écorcheurs, the retondeurs – thrown into the country by the Hundred Years’ War. As always, Coeur behaves not only according to his own personal interests, but according to the general interests of France.

Connecting France to the Silk Road

Now with financial clout, ports and ships at his disposal, Cœur organized win-win commercial exchanges and, in his own way, involved France in the land and Maritime Silk Road of the time. First and foremost, he organized « détente, understanding and cooperation » with the countries of the Levant.

After diplomatic incidents with the Venetians had led the Sultan of Egypt to confiscate their goods and close his country to their trade, Jacques Coeur, a gentleman but also in charge of a Kingdom that remained dependent on Genoa and Venice for their supplies of arms and strategic raw materials, had his agents on site mediating a happy end to the incident.

Seeing other potential conflicts that could disrupt his strategy, and possibly inspired by Admiral Zheng He‘s great Chinese diplomatic missions to Africa from 1405 onwards, he convinced the king to send an ambassador to Cairo in the person of Jean de Villages, his loyal lieutenant.

The latter handed over to the Sultan the various letters he had brought with him. Flattered, the Sultan handed him a reply to King Charles VII:

« Your ambassador, man of honor, gentleman, whom you name Jean de Villages, came to mine Porte Sainte, and presented me your letters with the present you mandated, and I received it, and what you wrote me that you want from me, I did.

« Thus I have made a peace with all the merchants for all my countries and ports of the navy, as your ambassador knew to ask of me… And I command all the lords of my lands, and especially the lord of Alexandria, that he make good company with all the merchants of your land, and on all the others having liberty in my country, and that they be given honor and pleasure; and when the consul of your country has come, he will be in favor of the other consuls well high…

« I send you, by the said ambassador, a present, namely fine balsam from our holy vine, a beautiful leopard and three bowls (cups) of Chinese porcelain, two large dishes of decorated porcelain, two porcelain bouquets, a hand-washer, a decorated porcelain pantry, a bowl of fine green ginger, a bowl of almond stones, a bowl of green pepper, almonds and fifty pounds of our fine bamouquet (fine balsam), a quintal of fine sugar. Dieu te mène à bon sauvement, Charles, Roy de France. »

To the Orient, Coeur exported furs, leathers and, above all, cloth of all kinds, notably Flanders cloth and Lyon canvas. His « factors » also offered Egyptian women dresses, coats, headdresses, ornaments and jewels from our workshops. Then came basketry from Montpellier, oil, wax, honey and flowers from Spain for the manufacture of perfumes.

From the Near East, he received animal-figured silks from Damascus (Syria), fabrics from Bukhara (Uzbekistan) and Baghdad (Iraq); velvet; wines from the islands; cane sugar; precious metals; alum; amber; coral; indigo; coral; indigo from Baghdad; madder from Egypt; shellac; perfumes made from the essence of the flowers he exported; spices – pepper, ginger, cloves, cinnamon, jams, nutmegs, etc. – and more.

From the Far East, by the Red Sea or by caravans from the Euphrates and Turkestan, came to him: gold from Sudan, cinnamon from Madagascar, ivory from Africa, silks from India, carpets from Persia, perfumes from Arabia – later evoked by Shakespeare in Macbeth – precious stones from India and Central Asia, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, pearls from Ceylon, porcelain and musk from China, ostrich feathers from the black Sudan.

Manufactures

As we saw in the case of mining, Coeur had no hesitation in attracting foreigners with valuable know-how to France to launch projects, implement innovative processes and, above all, train personnel. In Bourges, he teamed up with the Balsarin brothers and Gasparin de Très, gunsmiths originally from Milan. After convincing them to leave Italy, he set up workshops in Bourges, enabling them to train a skilled workforce. To this day, the Bourges region remains a major center of arms production.

In the early days of printing in Europe, Coeur bought a paper mill in Rochetaillée, on the Saône near Lyon.

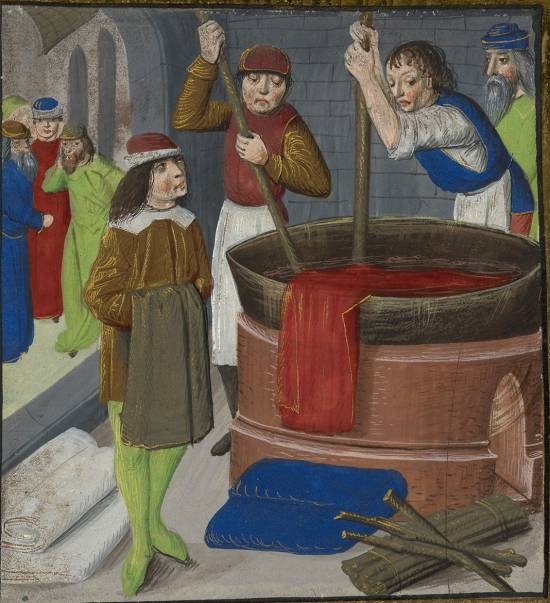

In Montpellier, he took an interest in the dyeing factories, once renowned for their cultivation of madder, a plant that had become acclimatized in the Languedoc region.

It’s easy to understand why Cœur had his agents buy indigo, kermes seeds and other coloring substances. The aim was to revive the manufacture of cloth, particularly scarlet cloth, which had previously been highly sought-after.

With this in mind, he built a fountain, the Font Putanelle, near the city walls, to serve the population and the dyers.

In Montpellier, he also teamed up with Florentine charterers based in the city, for maritime expeditions.

Through their intermediary, Coeur personally traveled to Florence in 1444, registering both his associate Guillaume de Varye and his own son Ravand as members of the « Arte della Seta » (silk production corporation), the prestigious Florentine guild whose members were the only ones authorized to produce silk in Florence.

Coeur engaged in joint ventures, as he often did in France, this time with Niccolo Bonnacorso and the Marini brothers (Zanubi and Guglielmo). The factory, in which he owned half the shares, manufactured, organized and controlled the production, spinning, weaving and dyeing of silk fabrics.

It is understood that Coeur was also co-owner of a gold cloth factory in Florence, and associated in certain businesses with the Medici, Bardi and Bucelli bankers and merchants. He was also associated with the Genevese and Bruges families.

Going International

Jacques Coeur organized a vast distribution network to sell his goods in France and throughout Europe. At a time when passable roads were extremely rare, this was no easy task. Most roads were little more than widened paths or poorly functioning tracks dating back to the Gauls.

Cœur, who had his own stables for land transport, renovated and expanded the network, abolished internal tolls on roads and rivers, and re-established the collection (abandoned during the Hundred Years’ War) of taxes (taille, fouage, gabelle) to replenish public finances.

Jacques Cœur’s network was essentially run from Bourges. From there, on the French level, we could speak of three major axes: the north-south being Bruges-Montpellier, the east-west being Lyon-Tours. Added to this was the old Roman road linking Spain (Barcelona) to the Alps (Briançon) via Languedoc.

From Bourges, for example, the Silverware, which served the Court, was transferred to Tours. This was only natural, since from 1444 onwards, Charles VII settled in a small castle near Tours, Plessis-les-Tours. So it was at the Argenterie de Tours that the exotic products the Court was so fond of were stocked. This did not prevent the goods from being shipped on to Bruges, Rouen or other towns in the kingdom.

Counters also existed in Orléans, Loches, Le Mans, Nevers, Issoudun and Saint-Pourçain, birthplace of the Coeur family, as well as in Fangeaux, Carcassonne, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Limoges, Thouars, Saumur, Angers and Paris.

Orléans and Bourges stocked salt from Guérande, the Vendée marshes and the Roche region. In Lyon, salt from the Camargue and Languedoc saltworks. River transport (on the Loire, Rhône, Saône and Seine rivers) doubled the number of road carts.

Jacques Coeur revived and promoted trade fairs. Lyon, with its rapid growth, geographic location and proximity to silver-lead and copper mines, was a particularly active trading post. Goods were shipped to Geneva, Germany and Flanders.

Montpellier received products from the Levant. However, trading posts were set up all along the coast, from Collioure (then in Catalonia) to Marseille (at the home of King René d’Anjou), and inland as far as Toulouse, and along the Rhône, in particular at Avignon and Beaucaire.

A trading post was set up in La Rochelle for the salt trade, certainly with a view to expanding maritime traffic. Jacques Cœur also had « factors » in Saint-Malo, Cherbourg and Harfleur. After the liberation of Normandy, these three centers grew in importance, and were joined by Exmes. In the north-east, Reims and Troyes are worth mentioning. They manufactured cloth and canvas. Abroad, Geneva was a first-rate trading post, as the city’s fairs and markets had already acquired an international character.

Coeur also had a branch in Bruges, bringing back spices and silks from the Levant, and shipping cloth and herring from there.

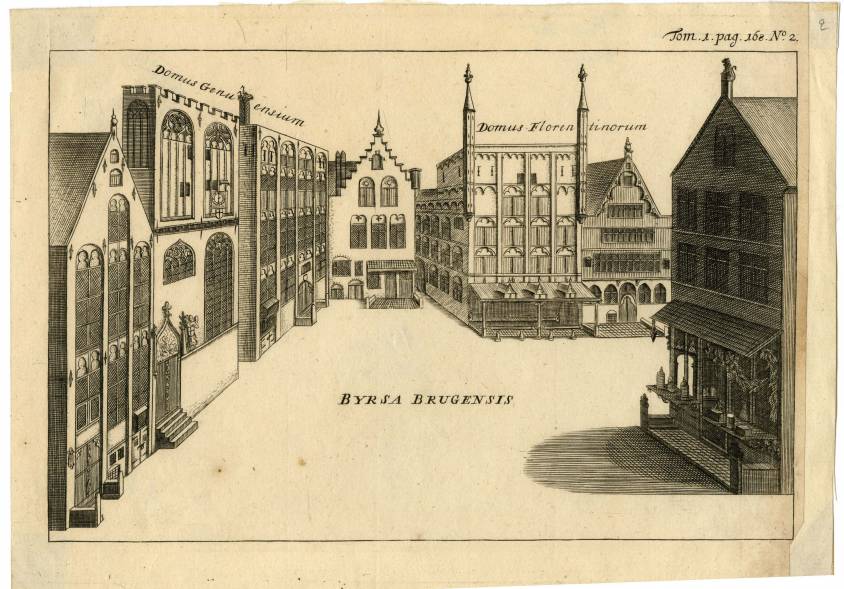

The fortunes of Bruges, like many other towns in Flanders, came from the cloth industry. The city flourished, and the power of its cloth merchants was considerable. In the 15th century, Bruges was one of the lungs of the Hanseatic League, which brought together the port cities of northern Europe.

It was in Bruges that business relations were handled, and loan and marine insurance contracts drawn up. After cloth, it was the luxury industries that ensured its prosperity, with tapestries. By land, it took less than three weeks to get from Bruges to Montpellier via Paris.

Between 1444 and 1449, during the Truce of Tours between France and the English, Jacques Coeur tried to build peace by forging trade links with England.

Coeur sent his representative Guillaume de Mazoran. His other trusted associate, Guillaume de Varye, began trading in sheets from London in February 1449. He also bought leather, cloth and wool in Scotland. Some went to La Rochelle, others to Bruges.

Internationally, Coeur continued to expand, with branches in Barcelona, Naples, Genoa (where a pro-French party was formed) and Florence.

At the time of his arrest in 1451, Jacques Coeur had at least 300 « factors » (associates, commercial agents, financial representatives and authorized agents), each responsible for his own trading post in his own region, but also running « factories » on the spot, promoting meetings and exchanges of know-how between all those involved in economic life. Several thousand people associated and cooperated with him in business.

The Military Reform that saved the Nation

Cœur used the profits from this lucrative business to serve his country. When in 1449, at the end of the truce, the English troops were left to their own devices, surviving by pillaging the areas they occupied, Agnès Sorel, the king’s mistress, Pierre de Brézé, the military leader, and Jacques Cœur, encouraged the king to launch a military offensive to finally liberate the whole country.

Coeur declared bluntly:

« Sire, under your shadow, I acknowledge that I have great proufis and honors, and mesme, in the land of the Infidels, for, for your honor, the souldan has given me safe-conduct to my galleys and factors… Sire, what I have, is yours. »

We’re no longer in 1435, when the king didn’t have a kopeck to face strategic challenges. Jacques Coeur, unlike other great lords, according to a contemporary account,

« spontaneously offered to lend the king a mass of gold, and provided him with a sum amounting, it is said, to around 100,000 gold ecus to use for this great and necessary purpose ».

Under the advice of Jacques Coeur and others, Charles VII was to carry out a decisive military reform.

On November 2, 1439, at the Estates General that had been meeting in Orleans since October of that year, Charles VII ordered a reform of the army following the Estates General’s complaint about the skinners and their actions.

As Charles V (the Wise) had tried to do before him, he set up a system of standing armies that would engage these flayers full-time against the English. The nobility got in the king’s way. In fact, they often used companies of skinners for their own interests, and refused to allow the king alone to be responsible for recruiting the army.

In February 1440, the king discovered that the nobles were plotting against him. Contemporaries named this revolt the Praguerie, in reference to the civil wars in Prague’s Hussite Bohemia.

Yolande d’Aragon passed away in November 1442, but Jacques Coeur would continue pressuring the King to go ahead with the required reforms.

Following the Truce of Tours in 1444, an ordinance was issued on May 26 announcing no general demobilization should occur; instead, the best of the larger units were reconstituted as “companies of the King’s ordinance » (Compagnies d’Ordonnance),” which were standing units of cavalry well selected and well equipped; they served as local guardians of peace at local expense. This consisted of some 10,000 men organized into 15 Ordonnance companies, entrusted to proven captains. These companies were subdivided into detachments of ten to thirty lances, which were assigned to garrisons to protect the towns’ inhabitants and patrol the countryside. In a territory similarly patrolled by the forerunners of our modern gendarmerie, robbery and plunder quickly ceased.

Although still a product of the nobility, this new military formation was the first standing army at the disposal of the King of France. Previously, when the king wished to wage war, he called upon his vassals according to the feudal custom of the ban. But his vassals were only obliged to serve him for forty days. If he wished to continue the war, the king had to recruit companies of mercenaries, a plague against which Machiavelli would later warn his readers. When the war ended, the mercenaries were dismissed. They then set about plundering the country. This is what happened at the start of the Hundred Years’ War, after the victories of Charles V and Du Guesclin.

Then, with the Ordinance of April 8, 1448, the Francs-Archers corps was created. The model for the royal « francs archiers » was probably taken from the militia of archers that the Dukes of Brittany had been raising, by parish, since 1425.

The Ordinance stipulated that each parish or group of fifty or eighty households had to arm, at its own expense, a man equipped with bow or crossbow, sword, dagger, jaque and salad, who had to train every Sunday in archery. In peacetime, he stays at home and receives no pay, but in wartime, he is mobilized and receives 4 francs a month. The Francs-Archers thus formed a military reserve unit with a truly national character.

As writes the Encyclopedia Brittanica:

« With the creation of the “free archers” (1448), a militia of foot soldiers, the new standing army was complete. Making use of a newly effective artillery, its companies firmly in the king’s control, supported by the people in money and spirit, France rid itself of brigands and Englishmen alike. »

At the same time, artillery grandmaster Gaspard Bureau and his brother Jean (Note N° 4) developed artillery, with bronze cannons capable of firing cast-iron cannonballs, lighter hand cannons, the ancestors of the rifle, and very long cannons or couleuvrines that could be dragged on wagons and taken to the battlefield.

As a result, when the time came to go on the offensive, the army went into battle. From all over the country, the Francs-Archers, made up of commoners trained in every region of France rather than nobles, began to converge on the north.

The war was on, and this time, « the gale changed sides ». The merciless French army, armed to the highest standards, pushed its opponents to the limit. This was particularly true at the Battle of Formigny near Bayeux, on April 15, 1450. It was a kind of Azincourt in reverse, with English losses amounting to 80% of the forces engaged, with 4,000 killed and 1,500 taken prisoner. At last, towns and strongholds returned to the Kingdom!

Helping a Humanist Pope

As mentioned above, the Council of Basel had ended in discord. On the one hand, with the support of Charles VII and Jacques Coeur, Eugene IV was elected Pope in Rome in 1431. On the other, in Basel, an assembly of prelates meeting in council sought to impose themselves as the sole legitimate authority to lead Christendom. In 1439, the Council declared Eugene IV deposed and appointed « his » own pope: the Duke of Savoy, Amédée VIII, who had abdicated and retired to a monastery. He became pope under the name of Felix V.

His election was based solely on the support of theologians and doctors of the universities, but without the support of a large number of prelates and cardinals.

In 1447, King Charles VII commissioned Jacques Coeur to intervene for Eugene IV’s return and Felix V’s renunciation. With a delegation, he went to Lausanne to meet Felix V. While the talks were going well, Eugene IV died. As Felix V saw no further obstacles to his pontificate, the Pontifical Council in Rome quickly proceeded to elect a new pope, the humanist scholar Nicholas V (Tommaso Parentucelli).

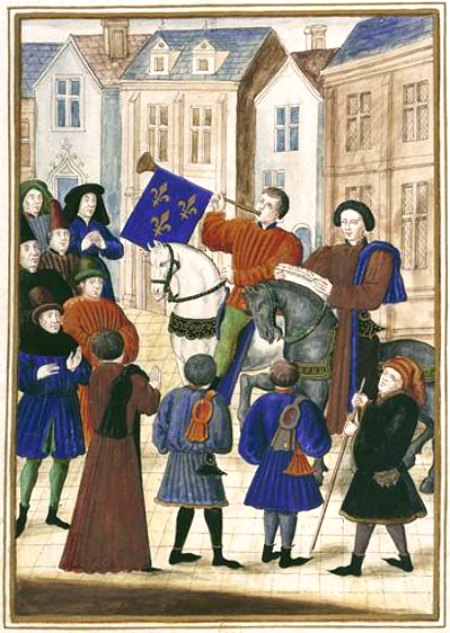

To make France’s case to him, Charles VII sent Jacques Coeur at the head of a large delegation. Before entering the Eternal City, the French formed a procession.

The parade was sumptuous: more than 300 horsemen, dressed in bright, shimmering colors, bearing weapons and glittering jewels, mounted on richly caparisoned horses, dazzled and impressed the whole of Rome, except for the English, who saw themselves doubled by the French to serve the Pope’s mission.

From the very first meeting, Nicholas V was charmed by Jacques Coeur. Slightly ill, Coeur was treated by the pope’s physician. Thanks to information obtained from the Pontiff, notably on the limits of concessions to be made, Coeur’s delegation subsequently obtained the withdrawal of Felix V, with whom Coeur remained on good terms.

Nicholas V, it should be remembered, was a happy exception. Nicknamed the « humanist pope », he knew Leonardo Bruni (Note N° 5), Niccolò Niccoli (Note N° 6) and Ambrogio Traversari (Note N° 7) in Florence, in the entourage of Cosimo de’ Medici.

With the latter and Eugenio IV, whose right-hand man he was, Nicholas V was one of the architects of the famous Council of Florence, which sealed a « doctrinal union » between the Western and Eastern Churches. (Note N° 8)

Elected pope, Nicholas V considerably increased the size of the Vatican Library. By the time of his death, the library contained over 16,000 volumes, more than any other princely library.

He welcomed the erudite humanist Lorenzo Valla to his court as apostolic notary. Under his patronage, the works of Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybius and Archimedes were reintroduced to Western Europe. One of his protégés, Enoch d’Ascoli, discovered a complete manuscript of Tacitus’ Opera minora in a German monastery.

In addition to these, he called to his court a whole series of scholars and humanists: the scholar and former chancellor of Florence Poggio Bracciolini, the Hellenist Gianozzo Manetti, the architect Leon Battista Alberti, the diplomat Pier Candido Decembrio, the Hellenist Giovanni Aurispa, the cardinal-philosopher Nicolas de Cues, founder of modern science, and Giovanni Aurispa, the first to translate Plato’s complete works from Greek into Latin.

Nicholas V also made gestures to his powerful neighbors: at the request of King Charles VII, Joan of Arc was rehabilitated.

Later, when he sought refuge in Rome, Jacques Coeur was received by Nicholas V as if he was a member of his family.

The Coup d’Etat against Jacques Coeur

Jacques Coeur’s adventurous life ended as if in a cloak-and-dagger novel. On July 31, 1451, Charles VII ordered his arrest and seized his possessions, from which he drew one hundred thousand ecus to wage war.

The result was one of the most scandalous trials in French history. The only reason for the trial was political. The hatred of the courtiers, especially the nobles, had built up. By making each of them a debtor, Coeur, believing he had made allies of them, made terrible enemies. By launching a number of national products, he undermined the financial empires of Genoa, Venice and Florence, which eternally sought to enrich themselves by exporting their products, notably silk, to France.

One of the most relentless, Otto Castellani, a Florentine merchant, treasurer of finances in Toulouse but based in Montpellier, and one of the accusers whom Charles VII appointed as commissioner to prosecute Jacques Coeur, practiced black magic and pierced a wax figure of the silversmith with needles!

Lastly, Charles VII undoubtedly feared collusion between Jacques Coeur and his own son, the Dauphin Louis, future Louis XI, who was stirring up intrigue after intrigue against him.

In 1447, following an altercation with Agnès Sorel, the Dauphin had been expelled from the Court by his father and would never see him again. Jacques Cœur lent money to the Dauphin, with whom he kept in touch through Charles Astars, who looked after the accounts of his mines.

« Trade with infidels », « Lèse majesté », « export of metals », and many other pretexts, the reasons put forward for Jacques Coeur’s trial and conviction are of little interest. They are no more than judicial window-dressing. The proceedings began with a denunciation that was almost immediately found to be slanderous.

A certain Jeanne de Mortagne accused Jacques Coeur of having poisoned Agnès Sorel, the king’s mistress and favorite, who died on February 9, 1450. This accusation was implausible and devoid of any serious foundation; for, having placed all her trust in Jacques Coeur, she had just appointed him as one of her three executors.

Coeur is imprisoned for a dozen equally questionable reasons. When he refused to admit what he was accused of, he was threatened with « the question » (torture). Confronted by the executioners, the accused, trembling with fear, claims that he « relies » on the words of the commissioners charged with breaking him.

His condemnation came on the same day as the fall of Constantinople, May 29, 1453. Only the intervention of Pope Nicholas V saved his life. With the help of his friends, he escaped from his prison in Poitiers, and took the route of the convents, including Beaucaire, to Marseille for Rome.

Pope Nicholas V welcomed him as a friend. The pontiff died and was succeeded by his successor. Jacques Cœur chartered a fleet in the name of his illustrious host, and set off to fight the infidels. Jacques Coeur, we are told, died on November 25, 1456 on the island of Chios, a Genoese possession, during a naval battle with the Turks.

The great King Louis XI, unloved son of Charles VII, as evidenced by his ordinances in favor of the productive economy, would continue the recovery of France begun by Jacques Coeur. Many of Coeur’s collaborators soon entered his service, including his son Geoffroy, who, as cupbearer, became Louis XI’s most trusted confidant.

Charles VII, by letters patent dated August 5, 1457, restored to Ravant and Geoffroy Coeur a small portion of their father’s property. It was only under Louis XI that Geoffroy obtained the rehabilitation of his father’s memory and more complete letters of restitution.

NOTES:

- During the five years between Joan of Arc’s first appearances and her departure for Chinon, several people attached to the Court stayed in Lorraine, including René d’Anjou, the youngest son of Yolande d’Aragon. While Charles VII remained undecided, his mother-in-law welcomed La Pucelle with maternal solicitude, opening doors for her and lobbying the king until he deigned to receive her. During the Poitiers trial, when Jeanne’s virginity had to be verified, she presided over the council of matrons in charge of the examination. She also provided financial support, helped her gather her equipment, provided safe stopping points on the road to Orléans, and gathered food and relief supplies for the besieged. To this end, she did not hesitate to open her purse wide, even going so far as to sell her jewelry and golden tableware. Yolande’s support was rewarded on April 30, 1429 with the liberation of Orléans, followed on July 17 by the King’s coronation in Reims. Although many of her contemporaries praised her simplicity, her closeness to her subjects and the warmth of her court, Yolande d’Aragon was a stateswoman. And whatever sympathy she may have felt for her protégée, she would not hesitate to abandon her to her sad fate when her warlike impulses no longer accorded with her own political objectives : to negociate a peaceful alliance with the Duchy of Burgundy. The Duchess knew how to be implacable, and like her comrades-in-arms, the Church and the King himself, she abandoned La Pucelle to the English, to Cauchon, to her trial and to the stake. For more: Gérard de Senneville, Yolande d’Aragon : La reine qui a gagné la guerre de Cent Ans, Editions Perrin)

- Georges Bordonove, Jacques Coeur, trésorier de Charles VII, p. 90, Editions Pygmalion, 1977).

- Description given by the great chronicler of the Dukes of Burgundy, Georges Chastellain (1405-1475), in Remontrances à la reine d’Angleterre.

- Jean Bureau was Charles VII’s grand master of artillery. On the occasion of his coronation in 1461, Louis XI knighted him and made him a member of the King’s Council. Louis XI stayed at Jean Bureau’s Porcherons house in northwest Paris after his solemn entry into the capital. Jean Bureau’s daughter Isabelle married Geoffroy Coeur, son of Jacques.

- Leonardo Bruni succeeded Coluccio Salutati as Chancellor of Florence, having joined his circle of scholars, which included Poggio Bracciolini and the erudite Niccolò Niccoli, to discuss the works of Petrarch and Boccaccio. Bruni was one of the first to study Greek literature, and contributed greatly to the study of Latin and ancient Greek, offering translations of Aristotle, Plutarch, Demosthenes, Plato and Aeschylus.

- Niccolò Niccoli built up one of the most famous libraries in Florence, and one of the most prestigious of the Italian Renaissance. He was assisted by Ambrogio Traversari in his work on Greek texts (a language he did not master). He bequeathed this library to the Florentine Republic on condition that it be made available to the public. Cosimo the Elder de’ Medici was entrusted with implementing this condition, and the library was entrusted to the Dominican convent of San Marco. Today, the library is part of the Laurentian Library.

- Prior General of the Camaldolese Order, Ambrogio Traversari was, along with Jean Bessarion, one of the authors of the decree of church union. According to the Urbino court historian Vespasiano de Bisticci, Traversari gathered in his convent at San Maria degli Angeli near Florence. There, Traversari brought together the heart of the humanist network: Nicolaus Cusanus; Niccolo Niccoli, who owned an immense library of Platonic manuscripts; Gianozzi Manetti, orator of the first Oration on the Dignity of Man; Aeneas Piccolomini, the future Pope Pius II; and Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, the physician-cartographer and future friend of Leonardo da Vinci, whom Piero della Francesca also frequented.

- Philosophically speaking, reminding the whole of Christendom of the primordial importance of the concept of the filioque, literally « and of the son », meaning that the Holy Spirit (divine love) came not only from the Father (infinite potential) but also from the Son (its realization, through his son Jesus, in whose living image every human being had been created), was a revolution. Man, the life of every man and woman, is precious because it is animated by a divine spark that makes it sacred. This high conception of each individual was reflected in the relationship between human beings and their relationship with nature, i.e., the physical economy.