Étiquette : war

Paris Schiller Institute stages Afghan civil society protest against UNESCO

Paris, Feb. 2024 – On Thursday February 22, between 10:00 am and 1:00 pm CET, members and supporters of the International Schiller Institute, founded and presided by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, gathered peacefully in front of one of the main buildings of the headquarters of UNESCO in Paris (1, rue Miollis, Paris 75015). An appeal (see below), endorsed by both Afghans and respected personalities of four continents, was presented to the Secretary General and other officials of UNESCO.

How it started

Following a highly successful conference in Kabul last November by the Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, a group of senior archaeologists of the Afghan Academy of Sciences (ASA), in discussion with the organizers and the invited experts of the Schiller Institute, suggested to launch a common appeal to UNESCO and Western governments to “lift the sanctions against cultural heritage cooperation.”

The Call

“We regret profoundly, says the call, that the Collective West, while weeping crocodile tears over destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, has imposed a selective ban of scientific cooperation on nations mistakenly considered as “opposed to its rules and values.” The complete freeze of all cooperation in the field of archaeology between France and both Syria and Afghanistan, is just one example of this tragedy.”

“The dramatic neglect of international cultural institutions and donors to Afghanistan, the lack of sufficient funds in the field of cultural heritage protection, and the political treatment of international cultural heritage institutions have seriously endangered Afghanistan,” underscores the petition.

Specifically, “UNESCO, which should raise its voice against any new form of ‘cultural and scientific apartheid,’ has repeatedly worsened the situation by politicizing issues beyond its prerogatives.”

To conclude, the signers call

“on the international community to immediately end this form of ‘collective punishment,’ which creates suffering and injustice, promotes ignorance, and endangers humanity’s capacity for mutual respect and understanding.”

Living Spirit of Afghanistan

To date, over 550 signatures have been collected, mainly from both Afghan male (370) and female (140) citizens, whose socio-professional profiles indicates they truly represent the « living spirit of the nation ».

Among the signatories: 62 university lecturers, 27 doctors, 25 teachers, 25 members of the Afghan Academy of Sciences, 23 merchants, 16 civil and women’s rights activists, 16 engineers, 10 directors and deans of private and public universities, 7 political analysts, 6 journalists, 5 prosecutors, several business leaders and dozens of qualified professionals from various sectors.

International support

On four continents (Europe, Asia, America, Africa), senior archaeologists, scientists, researchers, members of the Academy of Sciences, historians and musicians from over 20 countries have welcomed and signed this appeal.

Italian Professor Pino Arlacchi, a former member of the European Parliament and the former head of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) was the first to sign. Award-winning American filmmaker Oliver Stone, is a more recent signer.

In France, Syria, Italy, the UK and Russia, among the signers one finds senior researchers suffering the consequences of what some have identified as a « New Cultural Cold War. » Superseding the very different opinions they have on many questions, the signatories stand united on the core issue of this appeal: for science to progress, all players, beyond ideological, political and religious differences, and far from the geopolitical logic of ‘blocs’, must be able to exchange freely and cooperate, in particular to protect mankind’s historical and cultural heritage.

Testifying to the firm commitment of the Afghan authorities, the petition has also been endorsed by the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of Culture and Arts, and the Minister of Agriculture, as well as senior officials from the Ministries of Higher Education, Water and Energy, Mines, Finance, and others.

“The 46th session of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, to be held in New Delhi in July this year, offers UNESCO the opportunity to announce Afghanistan’s full return into world heritage cooperation, if we can have our voice heard,” says Karel Vereycken of the Paris Schiller Institute. “We certainly will not miss transmitting this appeal to HE Vishal V Sharma, India’s permanent representative to UNESCO, recently nominated to make the Delhi 46th session a success.”

For all information, interview requests in EN, FR and NL:

Karel Vereycken, Schiller Institute Paris

00 33 (0)6 19 26 69 38

Full text of the appeal

International Call to Lift Sanctions Against Cultural Heritage Cooperation

Following the international conference, organized by the Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center’s in Kabul in early November 2023, on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, a group of researchers launched the following petition:

We, the undersigned, researchers and experts in the domains of the history of civilizations, cultural heritage, archaeology, anthropology, sociology, and many other fields, and other enlightened citizens of the world, in Afghanistan, Syria, Russia, China, and many other countries, launch the following call.

1) We regret profoundly that the “Collective West”, while weeping crocodile tears over destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, has imposed a selective ban of scientific cooperation on nations mistakenly considered as “opposed to its rules and values.” The complete freeze of all cooperation in the field of archaeology between France and both Syria and Afghanistan, is just one example of this tragedy.

2) We request particular attention to the case of Afghanistan. Its neighboring countries, national and international institutions, and countries involved in international conventions for the protection of cultural and natural heritage are committed to cooperation in the field of guarding cultural heritage sites and artifacts and preventing their smuggling and destruction. Therefore, it is expected that in the current situation, they will fully play their role in the protection of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage in accordance with international laws and conventions. However, the dramatic neglect of international cultural institutions and donors to Afghanistan, the lack of sufficient funds in the field of cultural heritage protection, and the political treatment of international cultural heritage institutions have seriously endangered Afghanistan. Undoubtedly, the non-recognition of the Afghan government has dimmed the attention of cultural institutions. Considering the above, we expect these international institutions to renew their full support to protect both the tangible and the intangible cultural heritage of Afghanistan.

3) We regret that UNESCO, which should raise its voice against any new form of “cultural and scientific apartheid,” has repeatedly worsened the situation by politicizing issues beyond its prerogatives.

4) Therefore, we call on the international community to immediately end this form of “collective punishment,” which creates suffering and injustice, promotes ignorance, and endangers humanity’s capacity for mutual respect and understanding.

The progress of scientific knowledge, in a positive climate permitting all to share it, is by its very nature beneficial to each and to all and to the very foundation of a true peace.

SIGNERS:

A. FROM AFGHAN CIVIL SOCIETY:

– Hussain Burhani, Archaeologist, Numismatist, Afghanistan ;

– Ketab Khan Faizi, Archaeologist, Director of the Academy of Sciences at the International Centre for Kushan Studies in Kabul, Afghanistan;

– Stora Ishams Mayar, Archaeologist, member of the Academy of Sciences at the International Centre for Kushan Studies in Kabul, editor in chief of the journal of this mentioned center, Afghanistan;

– Mahmood Jan Drost, Senior Architect, head of protection of old cities of Afghanistan, Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, Afghanistan;

– Ghulam Haidar Kushkaky, Archaeologist, associate professor, Archaeology Investigation Center, Afghanistan ;

— Laieq Ahmadi, Archeologist, Former head, Archeology department of Bamiyan University, Afghanistan;

– Shawkatullah Abed, Chief of staff, Afghan Science Academy, Afghanistan;

– Sardar Ghulam Ali Balouch, Head of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan;

– Daud Azimi Shinwari, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Germany;

– Abdul Fatah Raufi, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Kabul, Afghanistan;

– Mirwais Popal, Dip, Master, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Germany;

B. FROM ABROAD:

(Russia, China, USA, Indonesia, France, Angola, Germany, Turkiye, Italy, UK, Mexico, Sweden, Iran, Belgium, Argentina, Czech Republic, Syria, Congo Brazzaville, Yemen, Venezuela, Pakistan, Spain, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo.)

– H.E. Mr Mohammad Homayoon Azizi, Afghanistan’s Ambassador to Paris, UNESCO and ICESCO, France;

— Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento, Researcher at the National Scientific Research Centre (CNRS), Archaeologist specializing in Central Asia; Former director of the Delegation of French Archaeologists in Afghanistan (DAFA) (2014-2018), France;

– Inès Safi, CNRS, Researcher in Theoretical Nanophysics, France;

– Pierre Leriche, Archeologist, Director of Research Emeritus at CNRS-AOROC, Scientific Director of the Urban Archaeology of the Hellenized Orient research program, France;

– Nadezhda A. Dubova, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Dr. in Biology, Prof. in History. Head of the Russian-Turkmen Margiana archaeological expedition, Russian Academy of Science (RAS), Russia;

— Alexandra Vanleene, Archaeologist, specialist in Gandhara Buddhist Art, Researcher, Independant Academic Advisor Harvard FAS CAMLab, France;

– Raffaele Biscione, retired, associate Researcher, Consiglio Nazionale delle Recerche (CNR); former first researcher of CNR, former director of the CNR archaeological mission in Eastern Iran (2009-2022), Italy;

— Sandra Jaeggi-Richoz, Professor, Historian and archaeologist of the Antiquity, France;

– Dr. Razia Sultanova, Professor, Cambridge University, UK;

– Dr. Houmam Saad, Archaeologist, Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums, Syria;

– Estelle Ottenwelter, Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Natural Sciences and Archaeometry, Post-Doc, Czech Republic;

– Didier Destremau, author, diplomat, former French Ambassador, President of the Franco-Syrian Friendship Association (AFS), France ;

– Wang Feng, Professor, South-West Asia Department of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), China;

– Dr. Engin Beksaç, Professor, Trakya University, Department of Art History, Turkiye;

– Bruno Drweski, Professor, National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO), France;

– Maurizio Abbate, National President of National Agency of Cultural Activities (ENAC), Italy;

– Patricia Lalonde, Former Member of the European Parliament, vice-president of Geopragma, author of several books on Afghanistan, France;

– Pino Arlacchi, Professor of sociology, Former Member of the European Parliament, former head of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Italy;

– Oliver Stone, Academy Award-winning Film director, Producer, and Screenwriter;

– Graham E. Fuller, Author, former Station chief for the CIA in Kabul until 1978, former Vice-Chair of the National Intelligence Council (1986), USA;

– Prof. H.C. Fouad Al Ghaffari, Advisor to Prime Minister of Yemen for BRICS Countries affairs, Yemen;

– Farhat Asif, President of Institute of Peace and Diplomatic Studies (IPDS), Pakistan;

— Dursun Yildiz, Director, Hydropolitics Association, Türkiye;

– Irène Neto, president, Fundacao Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto (FAAN), Angola;

– Luc Reychler, Professor international politics, University of Leuven, Belgium;

– Pierre-Emmanuel Dupont, Expert and Consultant in public International Law, Senior Lecturer at the Institut Catholique de Vendée, France;

— Irene Rodríguez, Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina;

– Dr. Ririn Tri Ratnasari, Professor, Head of Center for Halal Industry and Digitalization, Advisory Board at Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia;

– Dr. Clifford A. Kiracofe, Author, retired Professor of International Relations, USA;

– Bernard Bourdin, Dominican priest, Philosophy and Theology teacher, Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP), France;

– Dr. jur. Wolfgang Bittner, Author, Göttingen, Germany;

– Annie Lacroix-Riz, Professor Emeritus of Contemporary History, Université Paris-Cité, France;

– Mohammad Abdo Al-Ibrahim, Ph.D in Philology and Literature, University Lecturer and former editor in chief of the Syria Times, Syria;

– Jean Bricmont, Author, retired Physics Professor, Belgium;

– Syed Mohsin Abbas, Journalist, Broadcaster, Political Analyst and Political Justice activist, Pakistan;

– Eduardo D. Greaves PhD, Professor of Physics, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas, Venezuela;

– Dora Muanda, Scientific Director, Kinshasa Science and Technology Week, Democratic Republic of Congo;

– Dr. Christian Parenti, Professor of Political Economy, John Jay College CUNY, New York, USA;

– Diogène Senny, President of the Panafrican Ligue UMOJA, Congo Brazzaville;

– Waheed Seyed Hasan, Journalist based in Qatar, former Special correspondent of IRNA in New Delhi, former collaborator of Tehran Times, Iran;

– Alain Corvez, Colonel (retired), Consultant International Strategy consultant, France;

– Stefano Citati, Journalist, Italy;

– Gaston Pardo, Journalist, graduate of the National University of Mexico. Co-founder of the daily Liberacion, Mexico;

– Jan Oberg, PhD, Peace and Future Research, Art Photographer, Lund, Sweden.

– Julie Péréa, City Councilor for the town of Poussan (Hérault), delegate for gender equality and the fight against domestic violence, member of the Sète Agglopole Méditerranée gender equality committee, France;

– Helga Zepp-LaRouche, Founder and International President of the Schiller Institute, Germany;

– Abid Hussein, independent journalist, Pakistan;

– Anne Lettrée, Founder and President of the Garden of Titans, Cultural Relations Ambassador between France and China for the Greater Paris region, France;

– Karel Vereycken, Painter-engraver, amateur Art Historian, Schiller Institute, France;

– Carlo Levi Minzi, Pianist, Musician, Italy;

– Leena Malkki Brobjerg, Opera singer, Sweden;

– Georges Bériachvili, Pianist, Musicologist, France;

– Jacques Pauwels, Historian, Canada;

C. FROM AFGHAN AUTHORITIES

– Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, Deputy Foreign Minister, Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA);

– Mawlawi Muhibullah Wasiq, Head of Foreign Minister’s Office, IEA;

– Waliwullah Shahin, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Sayedull Afghani, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Hekmatullah Zaland, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Shafi Azam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Atiqullah Azizi, Deputy Minister of Culture and Art, Ministry of Information and Culture, IEA;

– Ghorzang Farhand, Ministry of Information and Culture, IEA;

– Ghulam Dastgir Khawari, Advisor of Ministry of Higher Education, IEA;

– Mawlawi Rahmat Kaka Zadah, Member of ministry of Interior Affairs, IEA;

– Mawlawi Arefullah, Member of Interior Affairs, IEA;

– Ataullah Omari, Acting Agriculture Minister, IEA;

– Mawlawi Hussain Ahmad, Head of office in Ministry of Agriculture, IEA:

– Musa Noorzai, Member of Ministry of Agriculture, IEA;

– Mawlawi Hussain Ahmad, Head of office, Ministry of Agriculture, IEA;

– Mawlawi Shar Aqa, Head of Kunar Agriculture Administration, IEA;

– Matiulah Mujadidi, Head of Communication of Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Zabiullah Noori, Executive Manager, Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Akbar Wazizi, Member of Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Nasrullah Ebrahimi, Auditor, Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Mir M. Haroon Noori, Representative, Ministry of Economy, IEA;

– Abdul Qahar Mahmodi, Ministry of Commerce, IEA;

– Dr. Ghulam Farooq Azam, Adviser, Ministry of Water & Energy (MoWE), IEA;

– Faisal Mahmoodi, Investment Facilitation Expert, Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, IEA;

– Rustam Hafiz Yar, Ministry of Transportation, IEA;

– Qudratullah Abu Hamza, Governor of Kunar, IEA;

– Mansor Faryabi, Member of Kabul Municipality, IEA;

– Mohammad Sediq Patman, Former Deputy Minister of Education for Academic Affairs, IEA;

COMPLEMENTARY LIST

A. FROM AFGHANS

- Jawad Nikzad, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Akram Azimi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Najibullah Totakhel, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Germany

- Ghulam Farooq Ansari, Professor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Imran Zakeria, Researcher at Regional Studies Center, Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan, Ibn Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Subhanullah Obaidi, Doctor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Germany ;

- Ali Shabeez, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Germany ;

- Mawlawi Wahid Ameen, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Shar M. Amir Zadah, Ibne-eSina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Rafiullah Halim, Professor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul Afghanistan ;

- Nazar Mohmmad Ragheb, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Faisal Mahmoodi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Basir, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Muneera Aman, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Shakoor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Waris Ebad, Employee of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Afghanistan ;

- Waisullah Sediqi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Hakim Aria, Employee of Ministry of Information and Culture, Afghanistan ;

- Nayebuddin Ekrami, Employee of Ministry of information and Culture, Afghanistan ;

- Latifa Azimi, Former Employee of Ministry of Education, Afghanistan ;

- Latifa Noori, Former Employee of Ministry of Education, Afghanistan ;

- Habibullah Haqani, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Shafiqullah Baburzai, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Abdullah Kamawal, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rashid Lodin, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Asef Nang, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Awal Khan Shekib, Member of Afghanistan Regional Studies Center, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Anwar Fayaz, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Farhad Ahmadi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Fayqa Lahza Faizi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hakim Haidar, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Rahimullah Harifal, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Sharifullah Dost, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Eshaq Momand, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Khalil Rahman Barekzal, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Haidar Kushkaki, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Nabi Hanifi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Marina Bahar, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Muhaidin Hashimi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Majid Nadim, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Elaha Maqsoodi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Khadim Ahmad Haqiqi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Shahidullah Safi, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Wahab Hamdard, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Burhanullah Niazi, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- M. Alam Eshaq Zai, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Hasan Farmand, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Zalmai Hewad Mal, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rahman Atash, Head of Afghanistan National Development Company (NDC), Afghanistan ;

- Obaidullah, Head of Public Library, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Abdul Maqdam, Head of Khawar construction company, Afghanistan ;

- Zaki Zarifi, Head of Zarifi company, Afghanistan ;

- Jamshid Faizi, Head of Faizi company, Afghanistan ;

- M. Yasin Farahman, Head of Agriculture Center, Afghanistan ;

- Mawlawi Nik M. Nikmal, Head of Planning in Technical Administration, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Wahid Rahimi, Member of Bashtani Bank, Afghanistan ;

- M. Daud Mangal, Head of Ariana Afghan Airlines, Afghanistan ;

- Mostafa Yari, entrepreneur, Afghanistan;

- Gharwal Roshan, Head of Kabul International Airfield, Afghanistan ;

- Eqbal Mirzad, Head of New Kabul City Project, Afghanistan ;

- Najibullah Sadiq, Vice-president of Afghan Chamber of Commerce and Indunstry (ACCI), Afghanistan;

- M. Yunis Mohmand, Vice-president of ACCI, Afghanistan;

- Khanjan Alikozai, Member of ACCI, Afghanistan;

- Mawlawi Abdul Rashid, Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Atiqullah Safi, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Jalil Safi, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Hujat Fazli, Head of Harakat, Afghanistan Investment Climate Facility Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mehrab Hamidi, Member of Economical Commission, Afghanistan;

- Hamid Pazhwak, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Awaz Ali Alizai, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- Shamshad Omar, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- Helai Fahang, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Alikozai, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Dunya Farooz, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Soman Khamoosh, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Drs. Shokoria Yousofi, Bachelor of Economy, Afghanistan;

- Sharifa Wardak, Specialist of Agriculture, Afghanistan;

- M. Asef Dawlat Shahi, Specialist of Chemistry, Afghanistan;

- Pashtana Hamami, Specialist of Statistics, Afghanistan;

- Asma Karimi, Master of Management, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Ahmad Zaki Afghanyar, Vice-President of Herat Health committee, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hashem Mudaber, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hekmatullah Arian, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Wahab Rahmani, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Karima Rahimyar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Sayeeda Basiri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Emran Sayeedi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Hadi Dawlatzai, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ghani Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Nafisa Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Ghani Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mohammad Younis Shouaib, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Halima Akbari, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Manizha Emaq, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Shafiq Shinwari, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Akbar Jan Foolad, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Haidar Omar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ehsanuddin Ehsan, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Wakil Matin, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Matalib, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Azizi Amer, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Nasr Sajar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Humayon Hemat, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Humaira Fayaq, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Sadruddin Tajik, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Baqi Ahmad Zai, Surgery Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Beqis Kohistani, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Nafisa Nasiri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Aziza Yousuf, Head of Malalai Hospital, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Yasamin Hashimi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Zuhal Najimi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Ahmad Salem Sedeqi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Fazel Raman, veterinary, Afghanistan;

- Khatera Anwary, Health, Afghanistan;

- Rajina Noori, Member of Afghanistan Journalists Union, Afghanistan ;

- Sajad Nikzad, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Suhaib Hasrat, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Shar Aqa Karimi, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Mohammad Suhrabi , Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Nasir Kuhzad, Journalist and Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Fazel Menallah, Political Analyst, Afghanistan;

- M. Wahid Benish, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Mahmood Jan Shafizada, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Fazel Rahman Orya, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Zarghon Shah Shinwari, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Ghafor Shinwari, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ahmad Yousufi, Dean, Kateb University, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Yayia Balaghat, Scientific Vice-President, Kateb University, Afghanistan ;

- Chaman Shah Etemadi, Head of Gharjistan University, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mesbah, Head of Salam University, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Pirzad Ahmad Fawad, Kabul University;

- Dr. Nasir Nawidi, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Zabiullah Fazli, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Ramish Adib, Vice of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- M. Taloot Muahid, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Ebrahim Ansari, School Manager, Afghanistan;

- Abas Ali Zimozai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Arshad Rahimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Fasihuddin Fasihi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Waisuddin Jawad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Murtaza Sharzoi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Matin Monis, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Wahid Benish, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Hussian Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Muhsin Reshad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Sadiq Baqori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Zahir Halimi, Univ. Lecturer , Afghanistan ;

- Rohla Qurbani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Murtaza Rezaee, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Rasoul Qarluq, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Najim Wahidi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Rashid Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rahman Matin, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Mujtaba Amin, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Amanullah Faqiri, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Abuzar Khpelwak Zazai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Belal Tayab, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Adel Hakimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Wasiqullah Ghyas, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Faridduin Atar, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Safiullah Jawhar, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Amir Jan Saqib, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Shekib Rahmani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Gulzar Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Taj Mohammad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Hekmatullah Mirzad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Haq Atid, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Fahim Momand, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Fawad Ehsas, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Naqibullah Sediqi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Maiwand Wahidi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- M. Nazir Hayati, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Najiba Rahmani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Abeda Baba Karkhil, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. M. Qayoum Karim, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Sayed Sharif Shabir, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Walid Howaida, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Zalmai Rahib, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Sadiq Baqori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mir Zafaruddin Ansari, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Atta Mohammad Alwak, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Zabiullah Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Hasan Fazaili, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- M. Jawad Jalili, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mukhtar Ali Nasto, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Namatullah Nabawi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ghulam Abas Noori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mustafa Anwari, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Fakhria Popal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Shiba Sharzai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Marya Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nilofar Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Munisa Hasan, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nazifa Azimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Sweeta Sharify, Lecturer; Afghanistan;

- Fayaz Gul, Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Zakia Ahmad Zai, Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nigani Barati, Education Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Azeeta Nazhand, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sughra, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Nadia Sharif, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Maryam Omari, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Masoud, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Zubair Ahmad, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Khalil Ahmad, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Khadija Omid, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Haida Rasouli, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Hemat Hamad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Wazir Safi, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Qasim, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Zamin Shah, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Qayas, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mehrabuddin, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Zahidullah Zahid, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Akmal Mahros, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sadia Mohammadi, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Mina Amiri, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- M. Sajad Nikzad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mursal Nikzad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Qadir Shahab, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- M. Hasan Sahi, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mirwais Haqmal, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Leeda Khurasai, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Karishma Hashimi, Instructor, Afghanistan;

- Majeed Shams, Architect, Afghanistan;

- Azimullah Esmati, Master of Civil Engineering, Afghanistan;

- Najibullah Hussaini, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Burhanuddin Nezami, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Hafiz Hafizi, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Bahir, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Wali Bayan, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Khaliq Najir, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Diana Niazi, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Imam Jan, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Khalil Ahmad Nadem, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Sayeed Aqa, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Edris Rasouli, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Raz Mohammad, Engineer of Mines, Afghanistan ;

- Nasrullah Rahimi, Technical Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Ehsanullah, Helmand, Construction Engineer, Netherlands;

- Ahmad Hamad, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Akmal Ahmadi, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Ershad Hurmati, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Akram Shafim, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Akbar Ehsan, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Raziullah, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Zaki Khorrami, IT Officer, Afghanistan ;

- Osman Nikzad, Graphic Designer, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Ayani, Carpet Weaver, Afghanistan ;

- Be be sima Hashimi, Tailor, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Masoumi, Tailor, Afghanistan ;

- Roya Mohammadi, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Nadia Sayes, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Nazdana Ebad, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Sima Ahmadi , Bachelor of Biology, Afghanistan;

- Sima Rasouli, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Khatera Nawabi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Haji Noor Agha Haqyar, Merchant, Afghanstan;

- Husna Anwari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Nargis Hashimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Shakira Barish, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Nasima Darwish, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Wajiha Haidari, Merchant of Jawzjan, Afghanistan ;

- Shagul, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Nik Rasoul, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Haji Farid Alikozai, Merchant, Afghanistan;

- Nigina Nawabi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Masouda Nazimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Najla Kohistani, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Kerisma Jawhari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Hasina Hashimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Husna Anwari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Maaz Baburzai, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Freshta Safari, Merchant, Afghanistan;

- Yalda Azimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Azim Jan Baba Karkhil, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Akhtar Mohammad, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- M. Haroon Ahmadzai, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Azizullah Faizi, Former head of Afghanistan Cricket Board, Afghanistan ;

- Wakil Akhar, Prosecutor, Afghanistan ;

- Akhtar M. Azimi, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Shabnam Noori, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Be be Abeda Wayar, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Madina Ahmad Zai, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Shakila Joya, Former Employee of Attorney General, Afghanistan;

- Sardar M. Akbar Bashash, Member, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Eng. Abdul Dayan Balouch, Spokesperson of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Shah Mahmood Lahoti, Member of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Khaliq Barekzai, Advisor, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Salahuddin Ayoubi Balouch, Advisor, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Faizuddin Lashkari Balouch, Member, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Ishaq Gilani, head of the National Solidarity Movement of Afghanistan, IEA;

- Haji Zalmai Latifi, Representative, Qizilbash tribes, Afghanistan ;

- Gul Nabi Ahmad Zai, Former Commander of Kabul Garrison, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Hussain Rezaee, Member, Habitat Organization, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Amani Adiba, Doctor of Liberal Arts in Architecture and Urban Planning, Afghanistan;

- Ismael Paienda, Afghan Peace Activist, France;

- Mohammad Belal Rahimi, Head of Peace institution, Afghanistan ;

- M. Mushtaq Hanafi, Head of Sayadan council, Afghanistan ;

- Sabira Waizi, Founder of T.W.P.S., Afghanistan ;

- Majabin Sharifi, Member of Women Network Organization, Afghanistan;

- Shekiba Saadat, Former head of women affairs, Afghanistan ;

- Atya Salik, Women rights activist, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Mahmoodi, Women rights activist, Afghanistan;

- Diana Rohin, Women rights activist , Afghanistan;

- Amena Hashimi, Head of Women Organization, Afghanistan;

- Fatanh Sharif, Former employee of Gender equality, Afghanistan;

- Sediq Mansour Ansari, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Sebghatullah Najibi, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Naemullah Nasiri, Civil Activist, Afghanistan;

- Reha Ramazani, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Lia Jawad, Civil Activist, Afghanistan;

- Arezo Khurasani, Social Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Beheshta Bairn, Social Activist, Afghanistan;

- Samsama Haidari, Social Activist, Afghanistan;

- Shabnam Nikzad, Humans Rights Activist, Afghanistan;

- Mliha Sadiqi, Head of Young Development Organization, Afghanistan;

- Mehria, Sharify, University Student;

- Shiba Azimi, Member of IPSO Organization, Afghanistan;

- Nadira Rashidi, Master of Management, Afghanistan;

- Sefatullah Atayee, Banking, Afghanistan;

- Khatira Yousufi, Employee of RTA, Afghanistan;

- Yalda Mirzad , Employee of Breshna Company, Afghanistan;

- Izzatullah Sherzad, Employee, Afghanistan;

- Erfanullah Salamzai , Afghanistan;

- Naser Abdul Rahim Khil, Afghanistan;

- Ghulam Rasoul Faizi, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mir Agha Hasan Khil, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Ghafor Muradi, Afghanistan;

- Gul M. Azhir, Afghanistan;

- Gul Ahmad Zahiryan, Afghanistan;

- Shamsul Rahman Shams, Afghanistan;

- Khaliq Stanekzai, Afghanistan;

- M. Daud Haidari, Afghanistan;

- Marhaba Subhani, Afghanistan;

- Maazullah Nasim, Afghanistan;

- Haji Mohammad Tayeb, Afghanistan;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Afghanistan ;

- Sweeta Sadiqi Hotak, Afghanistan ;

- Khatira Anwari, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Sharzad, Afghanistan ; Momen Shah Kakar, Afghanistan ;

- Shah Rukh Raufi, Afghanistan ;

- Hanifa Rasouli, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Qudsia Ebrahimi, Afghanistan ;

- Mahmood Haqiqat, Afghanistan ;

- Nasir Abdul Rahim Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Hamid Ahmadzai, Afghanistan ;

- Sardar Khan Sirat, Afghanistan ;

- Zurmatullah Ahmadi, Afghanistan ;

- Yasar Khogyani, Afghanistan ;

- Shar Sha Lodi, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Shah Omar, Afghanistan ;

- M. Azam Khan Ahmad Zai, Afghanistan;

- Nadia Farooq Sharzoi, Afghanistan;

- Shar Ali Tazari, Afghanistan ;

- Mayel Aqa Hakim, Afghanistan ;

- Khatira Hesar, Afghanistan ;

- Tamim Mehraban, Afghanistan ;

- Lina Noori, Afghanistan ;

- Khubaib Ghufran, Afghanistan ;

- M. Yasin Farahmand, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mir M. Ayoubi, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Namatullah Nabawi, Afghanistan ;

- Abozar Zazai, Afghanistan ;

- Atiqullah Rahimi, Afghanistan ;

- Fahim Ahmad Sultan, Afghanistan ;

- Humaira Farhangyar, Afghanistan ;

- Imam M. Wrimaj, Afghanistan ;

- Masoud Ashna, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Yahia Baiza, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Besmila, Afghanistan ;

- Ehsan Shorish, Germany;

- Irshad, Omer, Afghanistan;

- Musa Noorzai, Afghanistan;

- Lida Noori Nazhand, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Abdul Masood Panah, Afghanistan;

- Gholam Sachi Hassanzadah, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Sayed Ali Eqbal, Afghanistan;

- Hashmatullah Atmar, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Matin Safi, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Helmand, Afghanistan;

- Ehsanullah Helmand, Afghanistan;

- Izazatullah Sherzad, Afghanistan;

- Hafizullah Omarzai, Afghanistan;

- Hedayatullah Hilal, Afghanistan;

- Edris Ramez, student, Afghanistan;

- Amina Saadaty, Afghanistan;

- Muska Hamidi, Afghanistan;

- Raihana Ahmadi, Afghanistan;

- Zuhal Sherzad, Afghanistan;

- Meelad Ahmad, Afghanistan;

- Devah Kubra Falcone, Germany;

- Maryam Baburi, Germany;

- Suraya Paikan, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Fatah Ahmadzai, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mohammad Zalmai, Afghanistan ;

- Hashmatullah Parwarni, Afghanistan ;

- Asadullah, Afghanistan;

- Hedayat ullah Hillal, Afghanistan;

- Najibullah Zazai, Afghanistan;

- M. Yousuf Ahmadi, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Reshad Reka, Afghanistan;

- Sayed Ahmad Arghandiwal, Afghanistan;

- Nooria Noozai, Afghanistan;

- Eng. Fahim Osmani, Afghanistan;

- Wafiullah Maaraj, Afghanistan;

- Roya Shujaee, Afghanistan;

- Shakira Shujaee, Afghanistan ;

- Adina Ranjbar, Afghanistan;

- Ayesha Shafiq, Afghanistan;

- Hajira Mujadidi, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Zahir Shekib, Afghanistan;

- Zuhra Mohammad Zai, Afghanistan;

- Razia Ghaws, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Sabor Mubariz, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Khaliq Ferdows, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Shakoor Salangi, Afghanistan;

- Nasir Ahmad Basharyar, Afghanistan;

- Mohammad Mukhtar Sharifi, Afghanistan;

- Mukhtar Ahmad Haqtash, Afghanistan;

- Yousuf Amin Zazai, Afghanistan;

- Zakiri Sahib, Afghanistan;

- Mirwais Ghafori, Afghanistan;

- Nesar Rahmani, Afghanistan;

- Shar M. Amir Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Yasin Farahmand, Afghanistan;

- Faizul Haq Faizan, Afghanistan;

- Khaibar Sarwary, Afghanistan;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Afghanistan;

- Hamidullah Akhund Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Benish, Afghanistan;

- Hayatullah Fazel, Afghanistan;

- Faizullah Habibi, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Hamid Lyan, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Qayoum Qayoum Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Qazi Qudratullah Safi, Afghanistan;

- Noor Agha Haqyar, Afghanistan;

- Maryan Aiany, Afghanistan;

B. FROM ABROAD

- Odile Mojon, Schiller Institute, Paris, France ;

- Johanna Clerc, Choir Conductor, Schiller Institute Chorus, France ;

- Sébastien Perimony, Africa Department, Schiller Institute, France ;

- Christine Bierre, Journalist, Chief Editor of Nouvelle Solidarité, monthly, France ;

- Marcia Merry Baker, agriculture expert, EIR, Co-Editor, USA ;

- Bob Van Hee,Redwood County Minnesota Commissioner, USA ;

- Dr. Tarik Vardag, Doctor in Natural Sciences (RER), Business Owner, Germany;

- Richard Freeman, Department of Physical Economy, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Liliana Gorini, chairwoman of Movisol and singer, Italy;

- Ulrike Lillge,Editor Ibykus Magazine, Berlin, Germany ;

- Michelle Rasmussen, Vice President, Schiller Institute in Denmark, amateur musician;

- Feride Istogu Gillesberg, Vice President, Schiller Institute in Denmark;

- Jason Ross, Science Department, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Dennis Small, Director of the Economic Department, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Robert “Bob” Baker, Agriculture Commission, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Dr. Wolfgang Lillge, Medical Doctor, Editor, Fusion Magazine, Berlin, Germany ;

- Ulf Sandmark, Vice-Chairman of the Belt and Road Institute, Sweden ;

- Mary Jane Freeman, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Hussein Askary, South West Asia Coordinator, Schiller Institute, Sweden ;

- David Dobrodt, EIR News, USA ;

- Klaus Fimmen, 2nd Vice-Chairman of the Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität (Büso) party, Germany;

- Christophe Lamotte, Consulting Engineer, France ;

- Richard Burden, EIR production staff, USA ;

- Rolf Gerdes, Electronic Engineer, Germany;

- Marcella Skinner, USA ;

- Delaveau Mathieu, Farm Worker, France ;

- Shekeba Jentsch, StayIN, Board, Germany;

- Bernard Carail, retired Postal Worker, France ;

- Etienne Dreyfus, Social Activist, France ;

- Harrison Elfrink, Social Activist, USA ;

- Jason Seidmann,USA ;

Letter of the minister of Information and Culture

Since Western researchers, based on what happened in the past, wondered about the current Afghan government’s actual policy on the issue of preservation of cultural and historical heritage, the Ibn-e-Sina Research and Development Center questioned the relevant authorities in Kabul.

At the end of January 2024, the Minister of Arts and Culture, in an hand-signed letter, provided them (and the world) with the following response, which completely clarifies the matter.

Transcript below, bold as in the original.

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

Ministry of Information and Culture

Letter N° 220, Jan. 31, 2024

To the attention of Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, International experts and cultural organizations and to those it concerns:

The ministry of Information and culture of the Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) has, among others, the following tasks in its portfolio:

–To establish a suitable environment for the growth of genuine Afghan culture;

–To protect national identity, cultural diversity, and national unity;

–To preserve tangible and intangible cultural heritage;

–To support the development of creativities, initiatives and activities of various segments of the society in general and of the Afghan youth in particular;

–To support the freedom of speech;

–Development of tourism industry;

–Introduction and presentation of Afghan culture regionally and internationally, to transform Afghanistan into an important cultural hub and crossroads in the near future.

We would like to confirm that with preservation of tangible and intangible cultural heritage we mean all Afghan cultural heritage belonging to all periods of history, whether it belongs to Islamic or non/pre-Islamic periods of history.

This ministry expresses its concerns that due to insufficient means it is not able to preserve the Afghan cultural heritage sufficiently.

Therefore this ministry asks UNESCO and other international organizations, working on preservation of the world’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage, to support Afghanistan in preservation of its tangible and intangible cultural heritage, including the ones belonging to Islamic and non/pre-Islamic periods of its history. The cultural heritage of Afghanistan does deserve to be preserved without any political motivations.

Besides, this ministry also confirms it is ready for all kind of cooperation with all national and international organizations, working on preservation of world cultural heritage.

The ministry of Information and culture of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) supports and appreciates all efforts of the Ibn-e-Sina R&D centre and their international experts in appealing for urgent attention of national and international organizations and experts to resume their support and cooperation with Afghanistan to preserve its cultural heritage, an important part of world cultural and historical heritage.

Sincerely,

Mowlavi Atiqullah Azizi

Deputy Minister of Culture and Art

moicdocymentsliaison@gmail.com

Horse-power, the Earthly Science behind China’s “Heavenly Horses”

Indicating the major role horses have played in the history of mankind, the fact that still today, when people talk about the engine of their cars, they use the term “horsepower” (hp) to indicate how much “work” the engine is capable of.

In a lecture on hydro-infrastructure in Kabul, Afghanistan, I recently used the domestication of the horse as an example of what one should understand when we talk about moving from a “lower” to a “higher infrastructure platform”.

The history of mankind completely changed with the domestication of the horse. Things considered “impossible” before the domestication of the horse became the “new normal”. How and when horses became domesticated has been disputed. Although horses appear in Paleolithic cave art as early as 36,000 BC (Chauvet cave, France), these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

Zoologists define « domestication » as human control over breeding, which can be detected in ancient skeletal samples by changes in the size and variability of ancient horse populations. Other researchers look at the broader evidence, including skeletal and dental evidence of working activity; weapons, art, and spiritual artifacts; and lifestyle patterns of human cultures. There is evidence that horses were kept as a source of meat and milk before they were trained as working animals.

In India, close to Bopal, the “Bhimbetka rock shelters”, which are the oldest known rock art of the country, figures dance and hunting scenes from the Stone Age as well as of warriors on horseback from a later time (10 000 BC).

Horses were a late addition to the barnyard. Dogs were domesticated 15,000 years ago; sheep, pigs and cattle, about 8,000 to 11,000 years ago. But clear evidence of horse domestication doesn’t appear in the archaeological record until about 5,500 years ago.

The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials. The earliest true chariots known are from around 2,000 BC, in burials of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in modern Russia in a cluster along the upper Tobol river, southeast of Magnitogorsk.

They contain spoke-wheeled chariots drawn by teams of two horses.

Kazakhstan and Ukraine

Up till recently, it was thought that the most common horse used today was a descendant of the horses domesticated by the Botai culture living in the steppes of the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan, around 3500 BC.

Recent genetic research points to the fact that the Botai horses were the forefathers of the Przewalski horse, a species that nearly disappeared.

Our common horse, the Equus ferus caballus, genetic research says, has been domesticated 4,200 years ago in Ukraine, in an area known as the Volga-Don, in the Pontic-Caspian steppe region of Western Eurasia, around 2,200 BC.

As these horses were domesticated, they were regularly interbred with wild horses.

Interesting in this respect, is the fact that according to the “Kurgan” or “steppe hypothesis”, most Indo-European languages spread from the same region throughout Europe and parts of Asia.

It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of what some call the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan, meaning tumulus or burial mound.

Tea Road, Horse Road or Silk Road?

As a matter of fact, the main commodities traded on the “Silk Road” (a term only coined in 1877 by the German geographer Ferdinand Von Richthofen), were… horses, mules, camels, donkeys and onagers.

Silk and tea were of course traded, but appeared mainly as a means… to pay for horses. People “paid” with silk, gold, porcelain and tea, the animals they needed to secure the survival of their society!

What was known as the « Tea-Horse Road » (Southern Silk Road) extended from the city of Chengdu in Sichuan Province, China, south through Yunnan into India and the Indochina Peninsula, and extended westwards into Tibet. It was an important route for the tea trade throughout South China and Southeast Asia and contributed to the spread of religions like Taoism and Buddhism across the region.

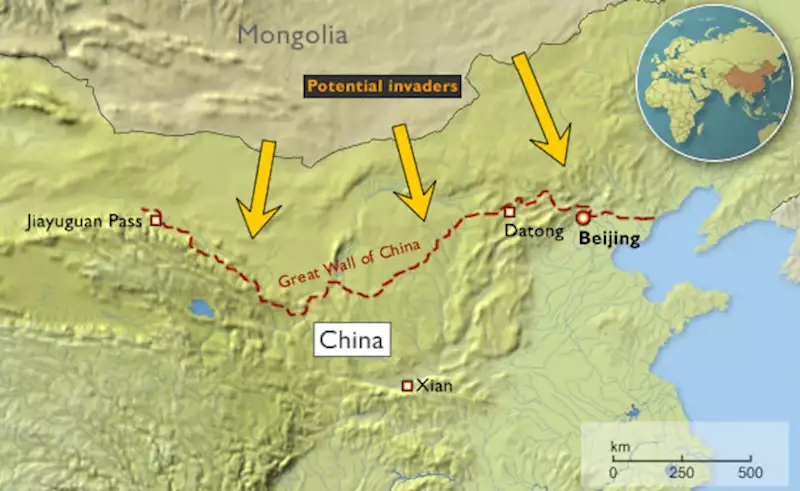

Eurasian Steppe

China, feeling itself under constant threat from the nomadic steppe people from the North, started building the first parts of its “Great Wall” as early as the VIIth Century BC, with selective stretches joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China and completed under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to become one of the most impressive feats in history.

The Eurasian nomads were groups of nomadic peoples living throughout the Eurasian Steppe. The generic title encompasses the varied ethnic groups who have at times inhabited the steppes of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, Russia, and Ukraine.

By the domestication of the horse around 2,200 BC (i.e. 4,200 years ago), they vastly increased the possibilities of nomadic life and subsequently their economy and culture emphasized horse breeding, horse riding, and nomadic pastoralism, usually engaging in trade with settled peoples around the steppe edges, be it in Europe, Asia or Central Asia.

Nomads, by definition, don’t create empires. It is thought they operated often as confederations. But it was them who developed the chariot, wagon, cavalry, and horseback archery and introduced innovations such as the bridle, bit, stirrup, and saddle and the very rapid rate at which innovations crossed the steppe-lands spread these widely, to be copied by settled peoples bordering the steppes.

During the Iron Age, Scythian (Persian) culture emerged among the Eurasian nomads, which was characterized by a distinct Scythian art.

China and the Horse

Throughout China’s long and storied past, no animal has impacted its history as greatly as the horse. Its significance was such that as early as the Shang dynasty (ca.1600-1100 BC), military might was measured by the number of the war chariots available to a particular kingdom.

The mounted cavalery, which emerged in the IIIrd century BC grew rapidly during the IInd century BC to meet the challenge of horse-riding peoples threatening China along the northern frontier.

Their large, powerful, horses were very new to China. As said before, traded for luxurious silk, they were the first major import to China from the “Silk Road.”

Chinese grave goods provide extraordinary amounts of information about how the ancient Chinese lived. Archaeological evidence shows that within a few years, the marvelous Arabian steeds had become immensely popular with military and aristocracy alike and upper-class tombs began to be filled with images of these great horses for use in the afterlife. But horses were hard to find in China.

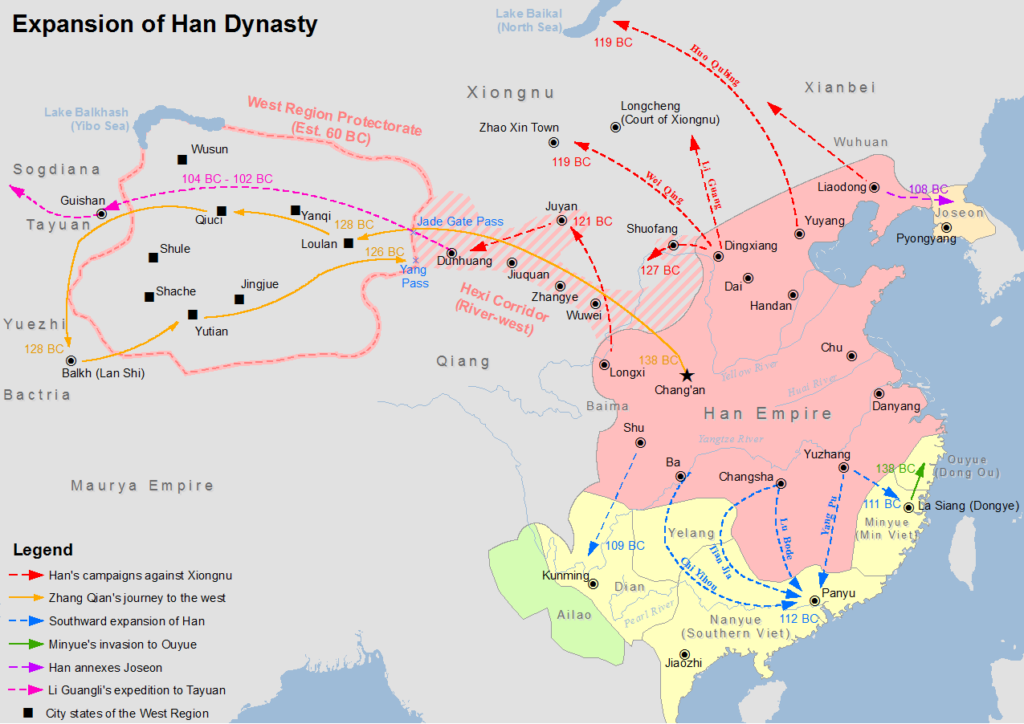

Chinese diplomats and the Kingdom of Dayuan (Ferghana)

Something had to be done. In the late IInd Century BC, Zhang Qian, a Han dynasty diplomat and explorer, travels to Central Asia and discovers three sophisticated urban civilizations created by Greek settlers he named « Ionians ». The account of his visit to Bactria, including his recollection of his amazement at finding Chinese goods in the markets (acquired via India), as well as his travels to Parthia and Ferghana, are preserved in the works of the early Han historian Sima Qian.

Upon returning to China, his account prompts the Emperor to dispatch Chinese envoys across Central Asia to negotiate and encourage trade with China. Some historians say that this dicision gave « birth of the Silk Road.«

Besides Parthia and Bactria, where Chinese goods were being traded via Indian imports, Zhang Qian visited, in the fertile Ferghana valley (today essentially in Tajikistan), a State the Chinese called the “Kingdom of Dayuan” (“Da” meaning “great”, and “Yuan” being the transliteration of Sanskrit Yavana or Pali Yona, used throughout antiquity in Asia to designate « Ionians », i.e. Greek settlers).

The Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han describe the Dayuan as numbering several hundred thousand people living in 70 walled cities of varying size. They grew rice and wheat, and made wine from grapes. They had Caucasian features and “customs identical to those of Bactria” (the most Hellenistic state of the region since Alexander the Great) which is today’s northern Afghanistan.

The Chinese diplomat reported something of great strategic interest: unbelievable, fast and powerful horses raised by these Ionians in the Ferghana Valley!

Now, as said before, China felt under permanent threat by the nomadic people from the steppes and was in the process of building the “Great Wall”. China also was acutely aware that the nomadic steppe people derived their military superiority from something dramatically lacking at home: powerful horses !

Added to that, the fact that in terms of China’s scale of values, horses where nearly of the same mythological nature as dragons: they could fly and represented the divine, creative spirit of the universe itself, something essential for any Chinese emperor eager to acquire both military security for his Empire and for his personal immortality.

In short, having good horses became an issue of national security. So much, that in 100 BC, the Han dynasty started what is known as the “War of the Heavenly Horses” with Dayuan, when its ruler refused to provide high quality horses to China !

The War of the Heavenly Horses

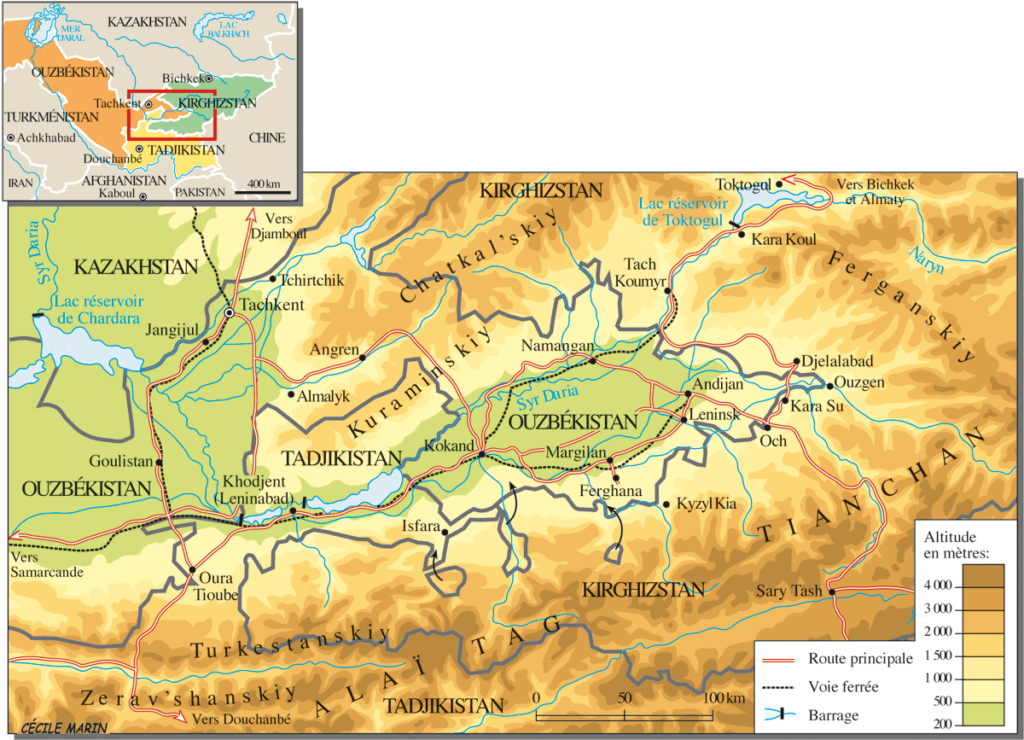

The War of the Heavenly Horses was a military conflict fought in 104 BC and 102 BC between China and a part of the Saka-ruled (Scythian) Greco-Bactrian kingdom known to the Chinese as Dayuan, in the Ferghana Valley (between modern-day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan).

First, Emperor Wu decided to defeat the nomadic steppe Xiongnu, who had harassed the Han dynasty for decades.

As said earlier, in 139 BC, the emperor sent diplomat Zhang Qian to survey the west and forge a military alliance with the Yuezhi nomads against another group of nomads, the Xiongnu. On the way to Central Asia through the Gobi desert, Zhang was captured twice. On his return, he impressed the emperor with his description of the « Heavenly Horses » of Dayuan, that could greatly improve the quality of Han cavalry mounts when fighting the Xiongnu.

The Han court sent at least five or six, and perhaps as many as ten diplomatic groups annually to Central Asia during this period to get a hold on these “Heavenly Horses”.

A trade mission arrived in Dayuan with 1000 pieces of gold and a golden horse to purchase these precious animals.

Dayuan, who was one of the furthest western states to send envoys to the Han court at that point, had already been trading with the Han for quite some time and benefited greatly from it. Not only were they overflowed by eastern goods, they also learned from Han soldiers how to cast metal into coins and weapons. However unlike the other envoys to the Han court, the ones from Dayuan did not conform to the proper Han rituals and behaved with great arrogance and self-assurance, believing they were too far away to be in any danger of invasion.

Hence, in a stroke of folly and taken by pure arrogance, the Dayuan king not only refused the deal, but confiscated the payment in gold. The Han envoys cursed the men of Dayuan and smashed the golden horse they had brought. Enraged by this act of contempt, the nobles of Dayuan ordered Yucheng, which lay on their eastern borders, to attack and kill the envoys and seize their goods.

Upon receiving word of the trade mission’s demise, humiliated and enraged, the Han court sent an army led by General Li Guangli to subdue Dayuan, but their first incursion was poorly organized and under-supplied.

A second, larger and much better provisioned expedition was sent two years later and successfully laid siege to the Dayuan capital at Alexandria Eschate, and forced Dayuan to surrender unconditionally.

The Han expeditionary forces installed a pro-Han regime in Dayuan and left with 3,000 horses, although only 1,000 remained by the time they reached China in 101 BCE.

The Ferghana also agreed to send two Heavenly horses each year to the Emperor, and lucerne seed was brought back to China providing superior pasture for raising fine horses in China, to provide cavalry which could cope with the Xiongnu who threatened China.

The horses have since captured the popular imagination of China, leading to horse carvings, breeding grounds in Gansu, and up to 430,000 such horses in the cavalry during the Tang dynasty.

China and the agricultural revolution

After imposing its role in military strategy for the next centuries, horsepower, together with water management, became a crucial factor to raise the productivity of the world’s food production.

First, contrary to the Romans, who preferred to use “human cattle” (slaves) rather than animals (which they raised for race contests), the Chinese greatly contributed to the survival of mankind with two crucial innovations respecting a more efficient use of horse power.

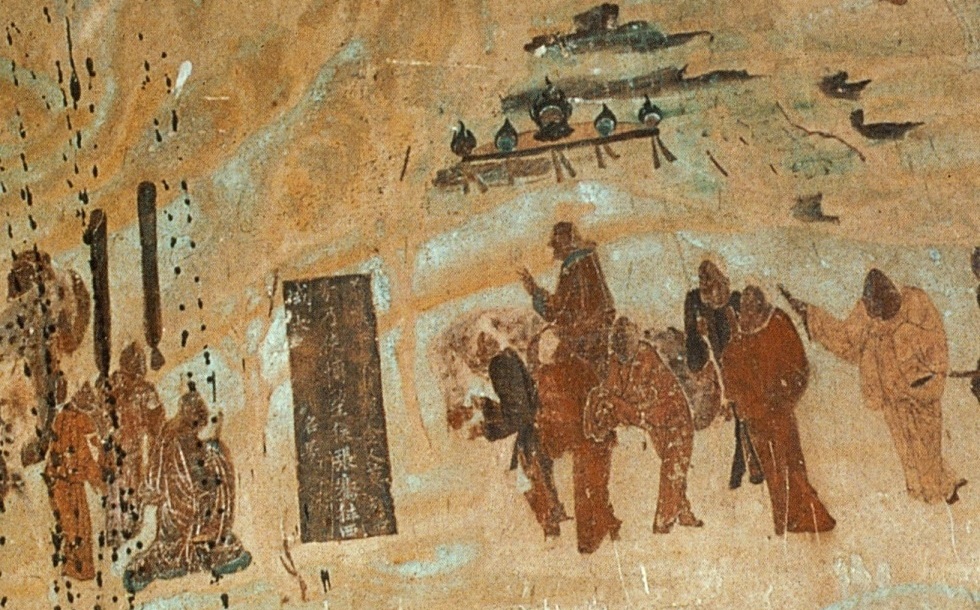

As can be seen in murals and paintings, through the ancient world, be it in Egypt or Greece, plows and carts were pulled using animal harnesses that had flat straps across the neck of the horse, with the load attached at the top of the collar, above the neck, in a manner similar to a yoke used for oxen.

In reality, this greatly limited a horse’s ability to exert itself as it was constantly choked at the neck. The harder the horse pulled, the harder it became to breathe.

Due to this physical limitation, oxen remained the preferred animal to do heavy work such as plowing. Yet oxen are hard to maneuver, are slow, and lack the quality of horses, whose power is equivalent but whose endurance is twice that of oxen.

China reportedly first invented the “breast strap” which was the first step in the right direction.

Then, in the Vth Century, China also invented what is called the “rigid horse collar”, designed as an oval that fits around the neck and shoulders of the horse.

It has the following advantages:

–First, it relieved the pressure of the horse’s windpipes. It left the airway of the horse free from constriction improving massively the animal’s energy through-put.

–Second, the traces could be attached to the sides of the collar. This allowed the horse to push forward with its more powerful hind-legs rather than pulling with the weaker front legs.

Now you can argue that this is anecdotal. It is NOT, because what appears as only a slight change had absolutely monumental consequences.

European Renaissance

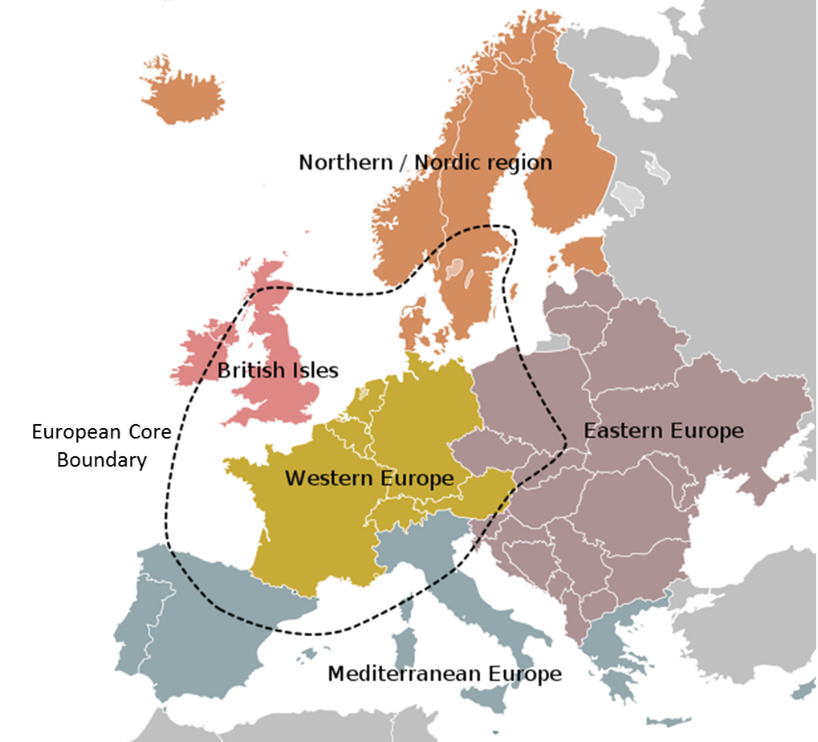

In a strategic alliance and cooperation with the humanist Baghdad Abbasid caliphate, Charlemagne and his successors introduced the “rigid horse collar” in Europe.

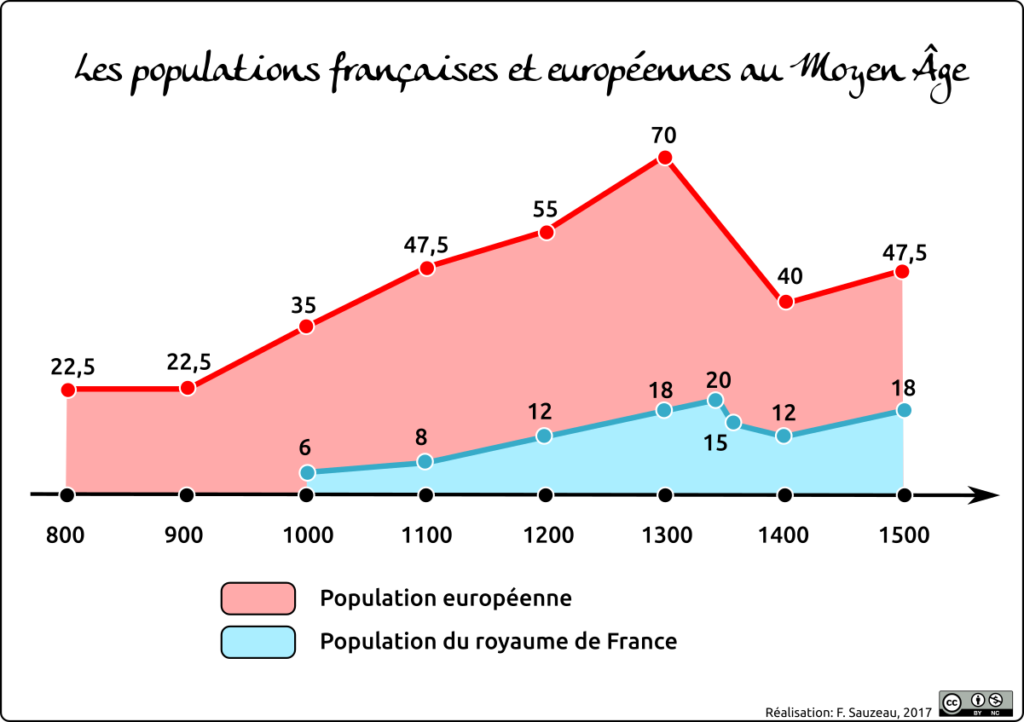

With that new, far more efficient tool, European farmers finally could take full advantage of a horse’s strength. The horse was able to pull another recent innovation, the heavy plow. This became particularly important in areas where the soil was hard and clay-like. This opened up new plots of lands to agriculture. The rigid horse collar, the heavy plow, and horseshoes helped usher in a period of increased agricultural production.

As a result, between 1000 CE and 1300 CE, it is estimated that in Europe, crop yields increased by threefold, allowing to feed a rising number of citizens in the urban cities appearing in the XVth century and kick starting the global “Golden” European Renaissance. Thank you, China!

Some numbers are nevertheless disturbing:

–it took humanity thousands of years to finally domesticate the horse (long after the cow), in 3200 BC.

–it took humanity another 3700 years to learn how to find out, in the Vth century AD, the most efficient way to use horse-power…

Shifting from a “lower” infrastructure platform to a “higher” infrastructure platform might take some time. Today’s new “higher” platforms are called “space data” and “fusion power.” Let’s not wait another century to find out how to use them correctly!

On the origins of Modern Art, the problem of Symbolism

“At the turn of this century, painting is in bad shape. And for those who love the fatherland of paintings, very soon there will only remain the closed spaces of museums, in the same way there remains parcs for the amateurs of nature, to cultivate the nostalgia of that what doesn’t exist any longer…”

Jean Clair, Harvard graduate, director of the Musée Picasso

and of the centenary of the Venice Biennale of Contemporary Art in 1995.

Karel Vereycken, April 1998

Something is fairly rotten in the kingdom of Art, and if today (1998), finally some kind of debate breaks out, it is, halas, for quite bad reasons. Since it is uniquely in the context of budget cuts imposed on Europe by the Maastricht treaty that some questions are raised to challenge public opinion on a question carefully avoided till now: can we go on indefinitely subsidizing “modern artistic creation”, or what pretends to be so, with the tax-payers money, without any demand and outside any criteria?

Abusively legitimated by its status as a victim of the totalitarian regimes of Hitler, Stalin and Mao, Modern Art’s value as an act of resistance to totalitarianism watered away with the collapse of these regimes.

While we oppose the current budgetary cuts, since it would finish off the sick patient, we nevertheless propose to examine truthfully the illness and the potential remedies to be administered.

In France, the slightest critique immediately provoked the traditional hysterical fits. Raising a question, formulating an interrogation or even simply expressing a doubt on the holiness of Modern Art continues to be considered tantamount to starting an Inquisition. Even well integrated critiques such as the « left » leaning author Jean Baudrillard, or the director of the Paris Picasso museum Jean Clair and even the modern painter Ben, immediately bombarded by acid counter-attacks from the french and international Art nomenclature, accusing them of being “reactionaries”, “obscurantist” and, to crown it all, of being “fascists”, “nazis” and even “anti-Semites”.

For seasoned observers these attacks remind the simplicity of Stalinist rhetoric: “Anybody discussing the revolution is a fascist”. Modernist musical composer Pierre Boulez even accused a journalist of being a “Vichy collaborator” because unconvinced of the utility of the computers of his musical research foundation IRCAM.

That spark of debate, if any, became rapidly poisoned by the possessive defense of the scarce budget allocations. Why all this noise? Jean Clair already exposed his views fourteen years ago in his book “Considérations sur l’Etat des Beaux-Arts, Critique de la Modernité” (1983) without provoking such a hullabaloo.

But in times of crisis, funds seem to provoke more passion than fundamentals. In any case, we welcome Clair’s courage. His ironical critique of the rampant snobbism of the tiny, incestuous world of contemporary Art makers is totally uncompromising. His defense of the necessary rebirth of the basic skills of drawing and pastel is on the mark.

Clair rightly makes a distinction between « Contemporary » art on one side and « Modern » art on the other side. Contemporary Art, broke with Modern Art from the point it became a systemic apology of “non-sense [absence of meaning] that was elected a system. » Reality, writes Clair, leads him to demand that we return to “meaning” (deliberately banned by « contempory » art) which was the very power of « Modern » Art.

To understand this difference, inspired by the insights and works of my friend, american art historian Michael Gibson, we shall document here that the birth of « Modern » art was nothing but a mutation from figaritive « Symbolism » to non-figurative (abstract) Symbolism, both accepting their role of expressing a symbolic meaning. « Contemporary art », profiting from the confusion of the idea of a « secret » meaning inherent in symbolic artistry, then sneaked in and tried to pretend that any sort of meaning should and could be eliminated from artistic expression.

QUESTION:

« So if I understood you correctly, you claim there exist criteria that are universal, enabling rational man to distinguish with reason between beauty and ugliness which would free art from the arbitrary caprices of taste?”

ANSWER:

« Uh, yes, and even if one cannot establish a catalogue filled with models and instructions enforceable till the end of all times, we firmly think there exists a way of looking at things, a mental attitude which we can prove to have been fruitful since the early cave paintings, as those of Chauvet in southern France dating from 50.000 years B.C., till today. »

To say it differently, there is no such thing as the aesthetics of form, but some kind of aesthetics of the soul.

Any attempt to frame aesthetics, as a set of formal rules of the visible forms is the shortest road to finish in a sterile academic dead end.

By analogy, we could say that such an attempt in the domain of language would make linguistics the science of poetry…

Leonardo da Vinci defined the mission of the painter as the one who has to « make visible the invisible ». So it is up to us to define the aesthetics of the invisible and how they manifest themselves in the visible realm.

How to represent the world

Let’s look at ways of representing phenomena by starting from what appears to be the « most simple ».

A. “Bounded objects” of an inorganic or organic nature: for example stones, a glass bottle, but also a flower or the body of an animal or a man. Their relative finiteness makes their representation easier. But to “make them alive”, one has to show their participation to something infinite: the infinite variations of the color or a stone, the numerous reflections of light shattered by the glass bottle, the relative infinite number of leaves of a tree, the huge number of successive gestures which dictate spirit and life to the bodies of living beings. As you can see now, these so-called “simple” phenomena oblige us to choose, beyond simple sense perception, perceptions that enable us to express the idea of the object rather than its mere form.

B. “Openly unbounded objects”: for example a wave of the ocean, a forest, the clouds in the sky, or the expression of the eyes of a human being. Even more than in A., the Chinese principle of the “li” has to be considered. Instead of imitating their exterior form, and since their sometimes turbulent shapes escape in any case from our limited sense-perceptions, the exterior form has to be regarded as the expression of the idea that was the generating principle and we have to concentrate on choosing elements in the visible realm that indicate that “higher reality”. That makes the difference between the portrait of a living being and the portrait of a wax model…

C. “Ideas free from an object”: for example Love, Justice, Fidelity, Laziness, Cold, etc. How can we build gangways to the visible capable of representing these “higher ideas”?

ANSWER:

- Instead of representing the idea, I can try to substitute it with the object of the idea (one of Plato’s favorite subjects). For example I can try to represent the idea of Love by representing a woman. However, she cannot be but the object or the subject of love (She is loved or loves), but she is not Love itself.

- Since I’m in trouble having a representation in the visible realm of an idea of a “superior” nature, I decide to designate it by symbol. For example, a little heart to symbolize Love. For a Martian visiting Earth in the context of interplanetary tourism, the little heart has no meaning. By logical deduction, he could arrive at the conclusion the heart indicates heart patients, or cardiologists or eventually the designed victims of an Aztec sacrificial cult. In order to understand what is involved, some earthling has to initiate him into the pre-convened meaning of the symbol to which the inhabitants of earth agreed to. If not, it might take some time before he understands the “secret” meaning of the symbol.

- That symbol can be a simple visible element but also a little story we call allegorical. Illustrating an allegory will always remain a simple didactical exercise far underneath the sublime mission of art.

- The notion of a parable, as those one finds in the Bible, brings us closer to the wanted solution by its metaphorical character (Meta-poros in Greek meaning: that which carries beyond). The isochronical presence of several paradoxes, provoking surprise and irony by the ambiguities of the painting shakes up the sense certainty of our empirical perceptions that darken so much our natural predisposition for beauty.

SYMBOL and METAPHOR, What’s the difference?

Symbol: designates a thing

Metaphor: carries beyond the thing

Symbol: its only value is expressed by itself

Metaphor: its only value is given to it by implicit analogy.

Symbol: its secret meaning can only be learnt by convention

Metaphor: its meaning can be discovered by sovereign cognition.

Rembrandt’s Saskia

Let us examine together Rembrandt’s painting “Saskia as Flora” (1641), where she offers a flower to the viewer. Is this a portrait of Rembrandt’s wife along with the portrait of a flower? Or is there a new concept involved that arises in our mind as a result of this juxtaposition that could be called Love or Fidelity (to you I offer my beauty, as I offer you this flower…) The putting into visual analogy of two quite different things make appear a third one, which is in fact the real subject.

The easiest example of a real metaphorical paradox can be seen at work in wordplay or a cartoon drawing. For example if I draw a young couple in love and replace the head of the young man with the head of a dog, a completely different meaning is given to the image. The viewer, intrigued by the love relationship is surprised by the possessive (or submissive) character suggested by the dog head. Variations of the type of dog and his expression will vary the very meaning of the image. Once again, it is by the use of an implicit analogy that an unexpected arrangement gives us the means to grapple an idea beyond the object represented.

The little light bulb that goes on in our heads when we solve a metaphorical paradox gives us a threefold happiness. First the joy to think, since our thought process is precisely based on that unique process. Second to live in harmony with our world, which being a creative process itself “condemns” us to be free. And finally the joy that derives from the sharing of that happiness of discovery with other human beings who get even more creative in turn. Hence, every scientific or artistic discovery becomes a ray of light enlightening the path for humanity to go. The glowing enders of yesterday give us the fire to illuminate tomorrow.

But to do so, one cannot represent in a formal way the solution found. One is obliged to recreate the context which obliges the viewer to walk the same road we did till the precise point where he discovers himself the poetical concept.

The science of enigmas of Leonardo da Vinci

Renaissance genius Leonardo da Vinci was a specialist of this kind of « organized » enigmas, conspiracies to have us think. Let’s have a look at his painting “Saint John the Baptist”, his last painting and somehow his last will resuming all the best science of his creative mind. The ambiguous character of the person has been often used as “proof” of Leonardo’s alleged homosexuality.

One can indeed ask the question if represented here we see a man or a woman? The strong muscles of the arms plead for male while the gracious face argues for female. Desperate, our mind asks if this is devil or angel? While one finger points to heaven, similar to Raphael’s Plato in the « School of Athens », the other hand rests on the heart, and in the same time a coquette smile meets intelligent eyes…

Of course, Saint-John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence served as the symbol of a humanist Platonic current that realized the fact that the « little lights » of classical Greece announced the coming of the « great light » of Christianity.

Scholastical Catholicism of those days pretended that anybody living before Christ could be nothing more than a pagan. So what about Saint John the Baptist? The compositional method here employed is not of a symbolical nature, but that of paradoxical metaphor, i.e. build by enigmas that guide us, if we accept the challenge, to reflect in a philosophical way about the nature of mankind: how is it possible we are finite in some parts and infinite in others? That we are mind, life and matter? Of divine and human nature?

That is in some words what we mean by the method of paradoxical metaphors, the only method which gives sense to the word « classic », since conceived in a universal way for all men in the time of all times.

The opposite approach is the symbolist one, officially named after an artistic current that swept over Europe at the end of the XIXth century.

Together with impressionism that capitulated to positivism, symbolism was the mother of Modern Art and its bastard son Contemporary Art.

The symbol, erected as a method of artistic expression, is characteristic of a society that is incapable of change. It celebrates the banishing of the movement of progress but masks that self-denial with the never-ending multiplication of images and objects, always equal to themselves. Symbolism is nothing but the transformation into an object of a strong emotion or a mystical thought. The increase of its effect through incantation, fetishism, repetition, etc., agitating the symbol for its magical value as such, evokes the same obsessive fixation as pornography. As the American thinker Lyndon LaRouche ironically underscored the point:

“the difference between Beethoven (method of metaphor) and Wagner (method of symbolism) is defined by the level at which emotions are provoked in the audience. In the case of Beethoven, the beauty evoked brings us to tears. In the case of Wagner, it is the chairs that get wet…”

From there on, as we will document in due course, the arising of “Modern Art” reveals itself to be nothing more than a mere linear transposition of “figurative” symbolism to “abstract” symbolism.

These terms are obviously empty shells, since all figuration is figurative, and all figuration is the expression of what could be called an “abstract” concept or idea, conscious or not.

So, contrary to Contemporary Art, whose aggressive meaning is that nothing has, can or has the right to have any meaning, Modern Art claims to possess a sense of meaning, but that meaning is mystical-symbolical and hermetic by nature. We are not saying that symbols should be banned from Art, but we cannot but underline that symbolistical though as a compositional method is incompatible with Art’s nature.

Real Art concentrates on communicating a unique human quality, the Sublime, that expresses freedom and not that of a man enslaved either to his sentiments neither to his principles.

Contemporary Art, as all large scale swindles, needs quite some rhetoric and literature to convince it’s public of its pure absolute relativity. It is said that each of us sees it differently; that we all possess our own criteria and that formulating any judgment is by itself already an act of a totalitarian fascist in germ. It is somehow like the thief who accuses his victim of cupidity and lack of brotherly love when the victim refuses to hand over his purse. But if one claims the right to create something without meaning, one equally revindicates the right to no critique, and therefore ends any form of real debate beyond « it gives me a kick » or « no kick ».

That Art, when it is sincere, by claiming it cannot be apprehended by human cognition, defines itself as egoistical and asocial. It cannot but harvest what it sows: indifference.

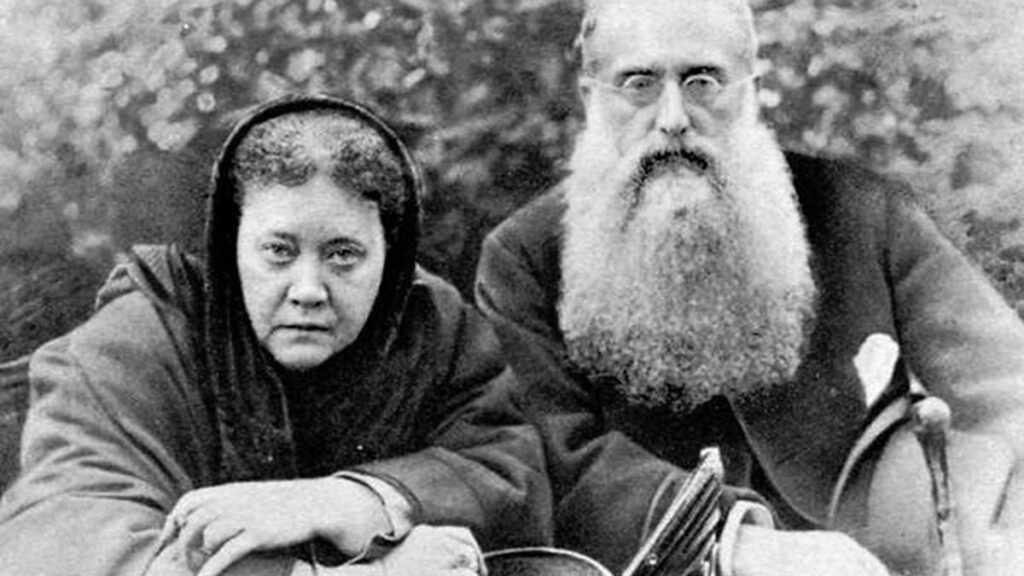

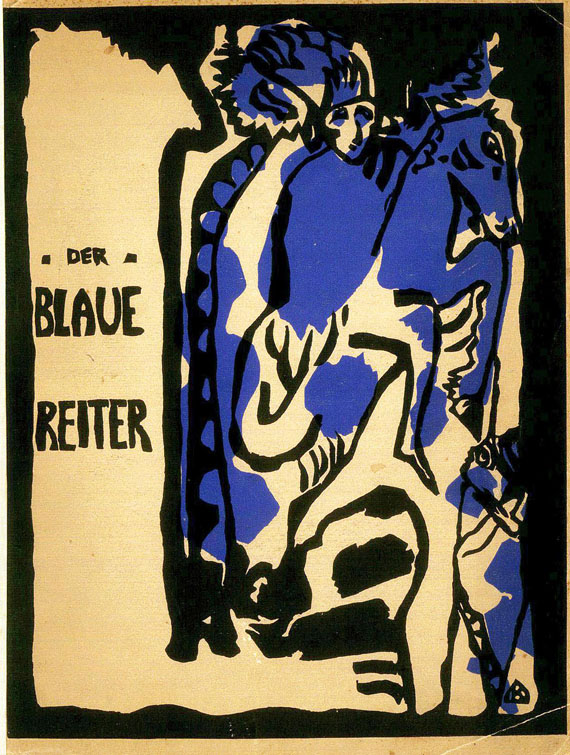

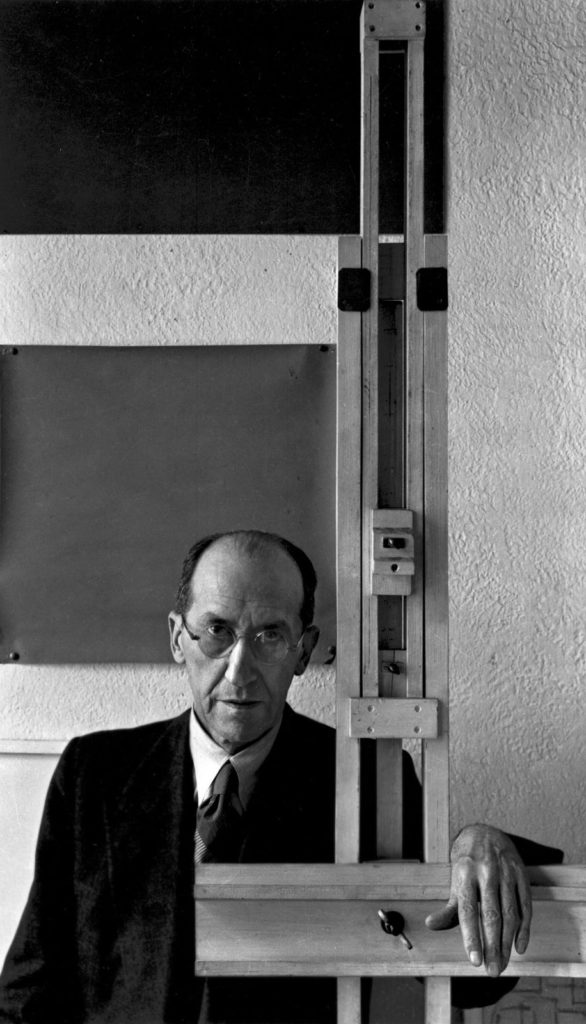

Before entering two personalities considered being the godfathers of Modern Art, Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), it is necessary to situate the historical context in which they operated. Then we will investigate a high level political operation: the Theosophical Society whose malefic theories exerted great influence on both godfathers of Modern Art.

Symbolism, the final stage of Romanticism