Étiquette : Jaurès

How James Ensor ripped off the mask off the oligarchy

By Karel Vereycken,

December 2022.

James Ensor was born on April 13, 1860 into a petty-bourgeois family in Ostend, Belgium. His father, James Frederic Ensor, a failed English engineer and anti-conformist, sank into alcoholism and heroin addiction.

His mother, Maria Catherina Haegheman, a Flemish-Belgian who did little to encourage his artistic vocation, ran a store selling souvenirs, shells, chinoiserie, glassware, stuffed animals and carnival masks – artifacts that were to populate the painter’s imagination.

A bubbly spirit, Ensor was passionate about politics, literature and poetry. Commenting on his birth at a banquet held in his honor, he once said:

« I was born in Ostend on a Friday, the day of Venus [goddess of peace]. Well, dear friends, as soon as I was born, Venus came to me smiling, and we looked into each other’s eyes for a long time. Ah! the beautiful green persian eyes, the long sandy hair. Venus was blonde and beautiful, all smeared with foam, smelling of the salty sea. I soon painted her, for she bit my brushes, ate my colors, coveted my painted shells, ran over my mother-of-pearl, forgot herself in my conch shells, salivated over my brushes ».

After an initial introduction to artistic techniques at the Ostend Academy, he moved to Brussels to live with his half-brother Théo Hannon, where he continued his studies at the Académie des Beaux Arts. In Théo’s company, he was introduced to the bourgeois circles of left-wing liberals that flourished on the outskirts of the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB).

With Ernest Rousseau, a professor at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), of which he was to become rector, Ensor discovered the stakes of the political struggle. Madame Rousseau was a microbiologist with a passion for insects, mushrooms and… art.

The Rousseaus held their salon on rue Vautier in Brussels, near Antoine Wiertz‘s studio and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. A privileged meeting place for artists, freethinkers and other influential minds.

Back in Ostend, Ensor set up his studio in the family home, where he produced his first masterpieces, portraits imbued with realism and landscapes inspired by Impressionism.

The Realm of Colors

« Life is but a palpitation« , exclaimed Ensor. His clouds are masses of gray, gold and azure above a line of roofs. His Lady at the Breakwater (1880) is caught in a glaze of gray and mother-of-pearl, at the end of the pier. Ensor is an orchestral conductor, using knives and brushes to spread paint in thin or thick layers, adding pasty accents here and there.

His genius takes full flight in his painting The Oyster Eater (1882). Although the picture seems to exude a certain tranquility, in reality he is painting a gigantic still life that seems to have swallowed his younger sister Mitche.

The artist initially called his work “In the Realm of Colors”, more abstract than La Mangeuse d’huîtres, since colors play the main role in the composition.

The mother-of-pearl of the shells, the bluish-white of the tablecloth, the reflections of the glasses and bottles – it’s all about variation, both in the elaboration and in the tonalities of color. Ensor retained the classical approach: he always used undercoats, whereas the Impressionists applied paint directly to the white canvas.

The pigments he uses are also very traditional: vermilion red, lead white, brown earth, cobalt blue, Prussian blue and synthetic ultramarine. The chrome yellow of La Mangeuse d’huîtres is an exception. The intensity of this pigment is much higher than that of the paler Naples yellow he had previously used.

The writer Emile Verhaeren, who later wrote the painter’s first monograph, contemplated La Mangeuse d’huîtres and exclaimed: « This is the first truly luminous canvas ».

Stunned, he wanted to highlight Ensor as the great innovator of Belgian art. But opinion was not unanimous. The critics were not kind: the colors were too garish and the work was painted in a sloppy manner. What’s more, it’s immoral to paint « a subject of second rank » (in monarchy, there are no citizens, only « subjects », a woman not being part of the aristocracy) in such dimensions – 207 cm by 150 cm.

In 1882, the Salon d’Anvers, which exhibited the best of contemporary art, rejected the work. Even his former Brussels colleagues at L’Essor rejected La Mangeuse d’huîtres a year later.

The XX group

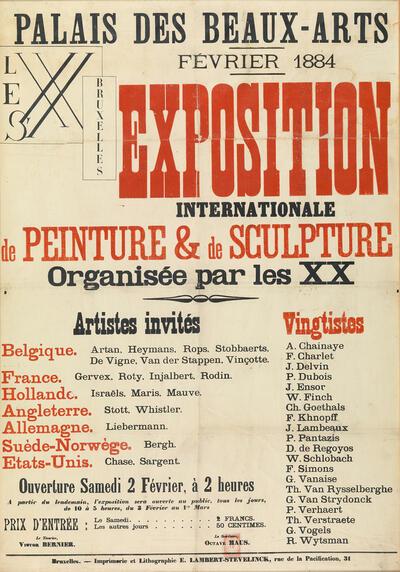

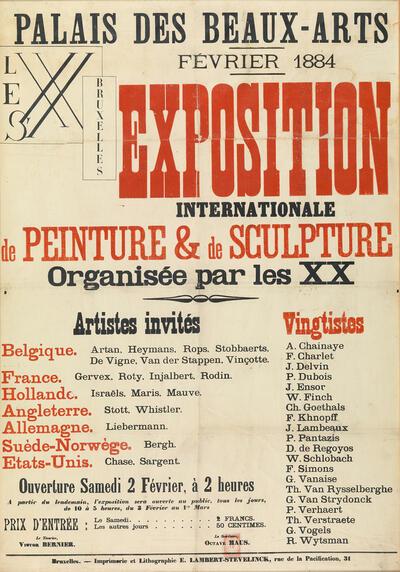

In Belgium, for example, the artistic revolution of 1884 began with a phrase uttered by a member of the official jury: « Let them exhibit at home! » he proclaimed, rejecting the canvases of two or three painters; and so they did, exhibiting at home, in « citizens’ salons », or creating their own cultural associations.

It was against this backdrop that Octave Maus and Ensor founded the « Groupe des XX », an avant-garde artistic circle in Brussels. Among the early « vingtists », in addition to Ensor, were Fernand Khnopff, Jef Lambeaux, Paul Signac, George Minne and Théo Van Rysselberghe, whose artists included Ferdinand Rops, Auguste Rodin, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, Gustave Caillebotte and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

It wasn’t until 1886, therefore, that Ensor was able to exhibit his innovative work La mangeuse d’huîtres for the first time at the Groupe des XX. But this was not the end of his ordeal. In 1907, the Liège municipal council decided not to buy the work for the city’s Musée des Beaux-Arts.

Fortunately, Ensor’s friend Emma Lambotte did not give up on the painter. She bought the painting and exhibited it in her salon citoyen.

Social and political commitment

The social unrest that coincided with his rise as a painter, and which culminated in tragedy with the deadly clashes between workers and civic guards in 1886, prompted him to find in the masses, as a collective actor, a powerful companion in misfortune. At the end of the 19th century, the Belgian capital was a bubbling cauldron of revolutionary, creative and innovative ideas. Karl Marx, Victor Hugo and many others found exile here, sometimes briefly. Symbolism, Impressionism, Pointillism and Art Nouveau all vied for glory.

While Marx was wrong on many points, he did understand that, at a time when finance derived its wealth from production, the modernization of the means of production bore the seeds of the transformation of social relations. Sooner or later, and at all levels, those who produce wealth will claim their rightful place in the decision-making process.

Ensor’s fight for freer art reflects and coincides with the epochal change taking place at the time.

Originating in Vienna, Austria, the banking crisis of May 1873 triggered a stock market crash that marked the beginning of a crisis known as the Great Depression, which lasted throughout the last quarter of the 19th century.

On September 18, 1873, Wall Street was panic-stricken and closed for 10 days. In Belgium, after a period marked by rapid industrialization, the Le Chapelier law, which had been in force since 1791, i.e. forty years before the birth of Belgium, and which prohibited the slightest form of workers’ organization, was repealed in 1867, but strikes were still a crime punishable by the State.

It was against this backdrop that a hundred delegates representing Belgian trade unions founded the Belgian Workers’ Party (POB) in 1885. Reformist and cautious, in 1894 they called not for the « dictatorship of the proletariat », but for a strong « socialization of the means of production ». That same year, the POB won 20% of the votes cast in the parliamentary elections and had 28 deputies. It participated in several governments until it was dissolved by the German invasion of May 1940.

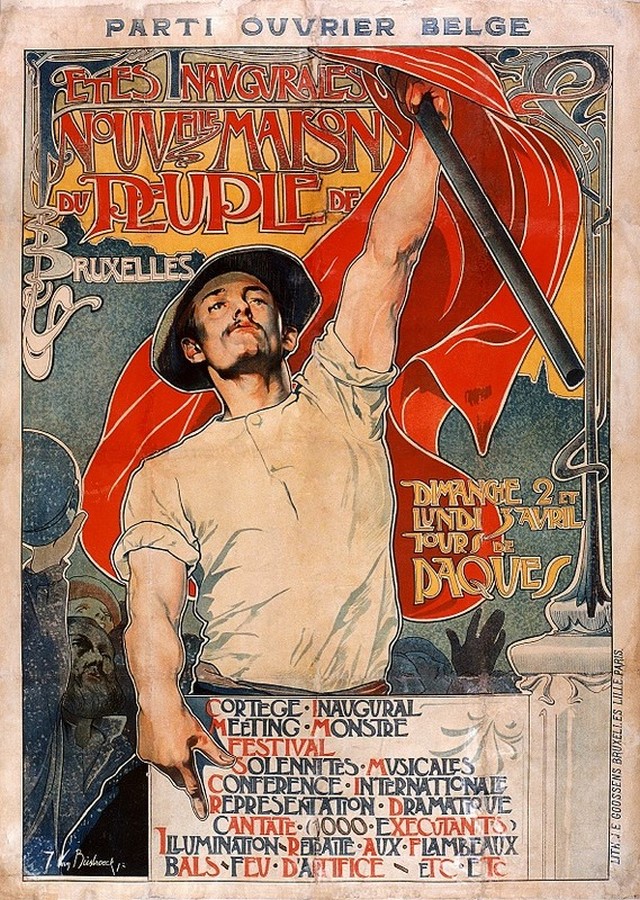

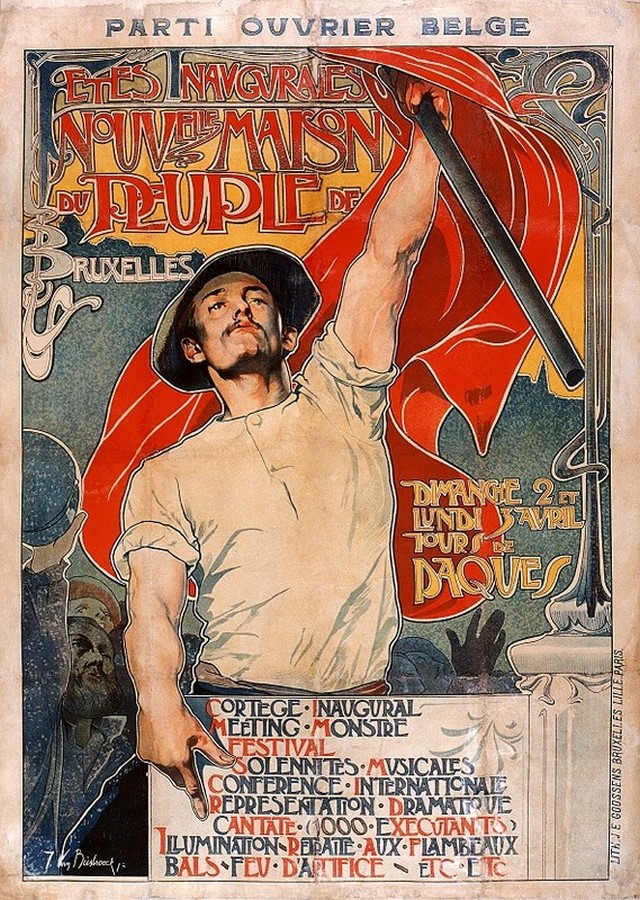

Victor Horta, Jean Jaurès and the Maison du Peuple in Brussels

The architect Victor Horta, a great innovator of Art Nouveau whose early houses symbolized a new art of living, was commissioned by the POB to build the magnificent « Maison du Peuple » in Brussels, a remarkable building made mainly of steel, housing a maximum of functionalities: offices, meeting room, stores, café, auditorium…

The building was inaugurated in 1899 in the presence of Jean Jaurès. In 1903, Lenin took part in the congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party.

Jean Jaurès gave his last speech on July 29, 1914, at the Cirque Royal in Brussels, during a major meeting of the Socialist International to save peace. Speaking of the threat of war, Jaurès said: « Attila is on the brink of the abyss, but his horse is still stumbling and hesitating ».

Opposing, as he did all his life, France’s submission to a subordinate role, he said:

« If we appeal to a secret treaty with Russia, we will appeal to a public treaty with Humanity ». And he ended his speech, the best of his life, with these prophetic words, written almost literally: « At the beginning of the war, everyone will be drawn in. But when the consequences and disasters unfold, the people will say to those responsible: ‘Go away and may God forgive you' ».

According to eyewitness accounts, Jaurès’ speech in Brussels aroused thousands of people from all classes of society. Two days later, on July 31, 1914, Jaurès was assassinated on his return to Paris, and the Maison du Peuple in Brussels was demolished in 1965 and replaced by a model of ugliness.

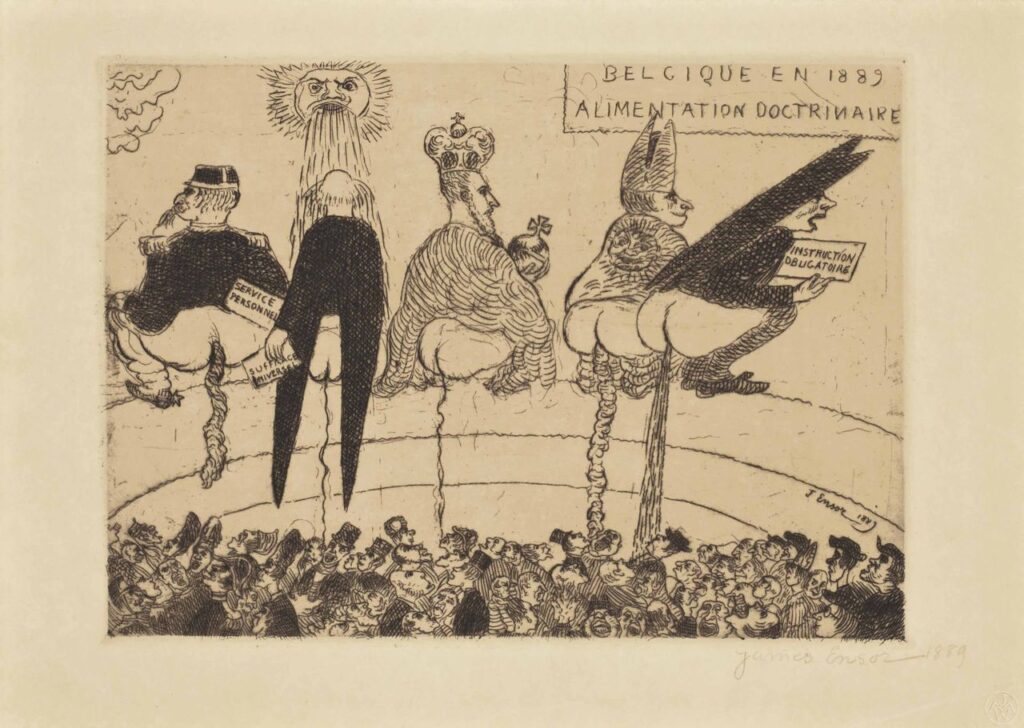

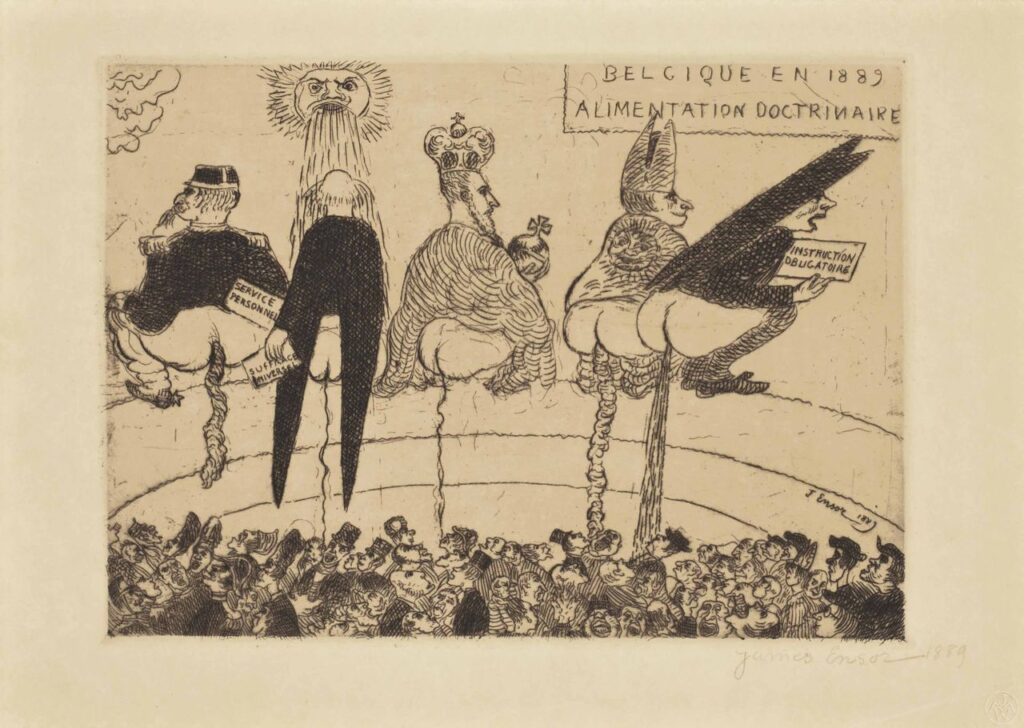

Doctrinary Food

Ensor’s art, especially his etchings, echoed this upheaval. His social and political criticism permeates his best work, none of which is perhaps as virulent as his etching Doctrinary Food (1889/1895) showing figures embodying the powers that be (the King of the Belgians, the clergy, etc.) literally defecating on the masses, a nasty habit that remains entrenched among our French « elites », if we review the treatment meted out, without the slightest discrimination, to our « yellow vests ».

In these engravings, Ensor presents the major demands of the POB: universal suffrage (passed in 1893, albeit imperfectly, at least for men), « personal » military service (i.e. for all, passed in 1913) and compulsory universal education (passed in 1914).

Revenge

Faced with injustice and incomprehension, Ensor can no longer suppress his righteous anger. For his own amusement – and, let’s face it, revenge – he set out to « get even » with those who ignored, despised and sabotaged him, above all the Belgian aristocracy, who clung to their privileges like mussels to rocks.

Deconstructing the straitjacket of academic rules, and drawing inspiration from Goya, Ensor forged a powerful language of metaphor and symbol. Between 1888 and 1892, Ensor began to deal with religious themes. Like Gauguin and Van Gogh, he identified with the persecuted Christ.

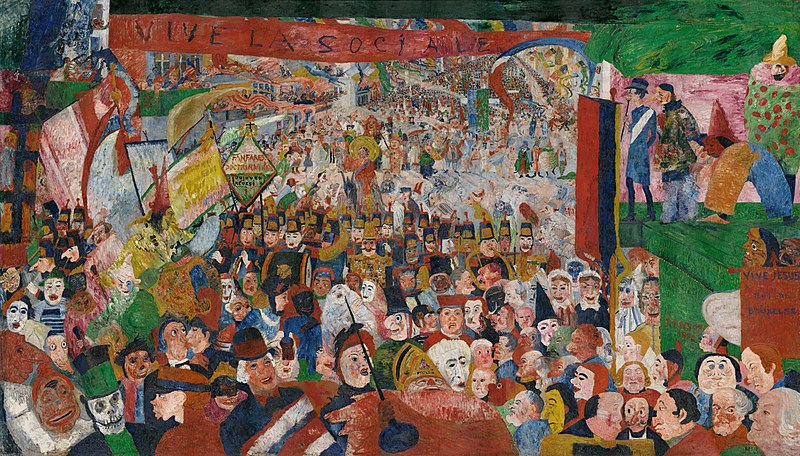

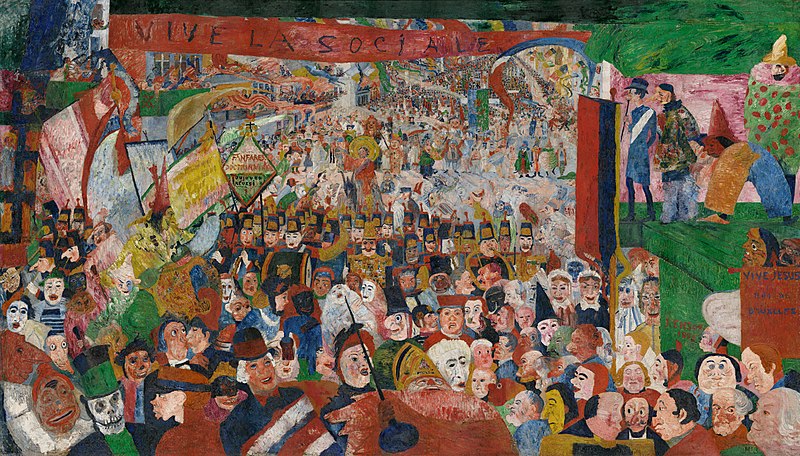

In 1889, at the age of 28, he painted L’Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, a vast satirical canvas that made his name. Even those closest to him, eager for recognition in order to exist, didn’t want it. The painting was rejected at the Salon des XX, where there was talk of excluding him from the Cercle, of which he was a founding member! Against Ensor’s wishes, the « vingtistes », racing towards success, split up four years later to re-create themselves under the name of La Libre Esthétique.

In this work, a large red banner reads « Vive la sociale », not « Vive le Christ ». Only a small panel on the side applauds Jesus, King of Brussels. But what on earth is the prophet, with the painter’s features and almost lost in the crowd, doing in Brussels? Has socialism replaced Christianity to such an extent that if Jesus were to return today, he would do so under the banner « For Ensor’s friends, he had lost his mind.

The Belgian lawyer and art critic Octave Maus, co-founder with Ensor of Les XX, famously summed up the reaction of contemporary art critics to Ensor’s « pictorial outburst »:

« Ensor is the leader of a clan. Ensor is in the limelight. Ensor summarizes and concentrates certain principles that are considered anarchist. In short, Ensor is a dangerous person who has initiated great changes (…) He is therefore marked for blows. All the harquebuses are aimed at him. It is on his head that the most aromatic containers of the so-called serious critics are poured ».

In 1894, he was invited to exhibit in Paris, but his work, more intellectual than aesthetic, aroused little interest. Desperate for success, Ensor persisted with his wild, saturated and violently variegated painting.

Skeletons and masks

Skulls, skeletons and masks burst into his work very early on. This is not the morbid imagination of a sick mind, as his slanderers claim. Radical? Insolent? Certainly; sarcastic, often; pessimistic? Never; anarchist? let’s rather say « yellow vest spirit », i.e. strongly contesting an established order that has lost all legitimacy and, absorbed in immense geopolitical maneuvers, is marching like a horde of sleepwalkers towards the « Great War » and the Second World War that’s coming behind!

Dead heads, symbols of truth

Poetically, Ensor resurrected the ultra-classical Renaissance metaphor of the « Vanities« , a very Christian theme that already appeared in « The Triumph of Death », the poem by Petrarch that inspired the Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Holbein’s series of woodcuts, « The Dance of Death ».

A skull juxtaposed with an hourglass were the basic elements for visualizing the ephemeral nature of human existence on earth. As humans, this metaphor reminds us, we constantly try not to think about it, but inevitably, we all end up dying, at least on a physical level. Our « vanity » is our constant desire to believe ourselves eternal.

Ensor did not hesitate to use symbols. To penetrate his work, you need to know how to read the meaning behind them. Visually, in the face of the triumph of lies and hypocrisy, Ensor, like a good Christian, sets up death as the only truth capable of giving meaning to our existence. Death triumphs over our physical existence.

Masks, symbols of lies

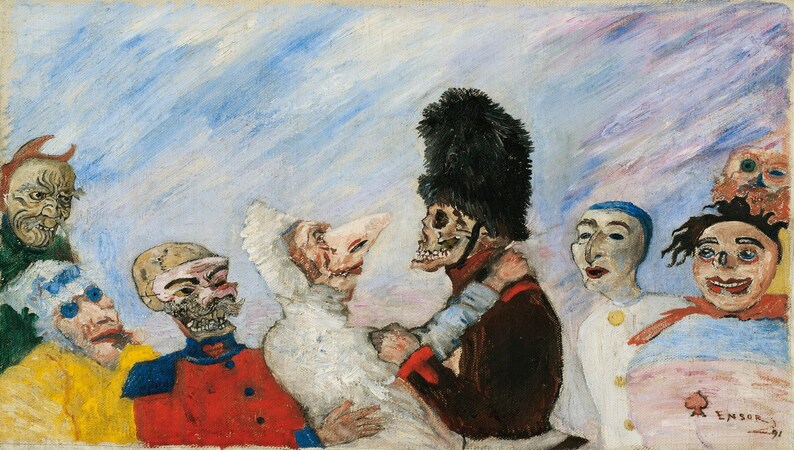

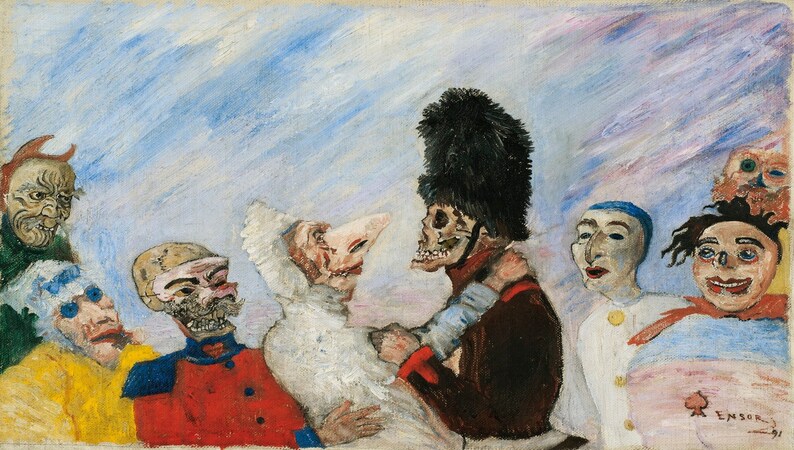

Gradually, as in Death and Masks (1897) (image at the top of this article), the artist dramatized this theme even further, pitting death against grotesque masks, symbols of human lies and hypocrisy.1

Often in his works, in a sublime reversal of roles, it is death who laughs and it is the masks who howl and weep, never the other way around.

It may sound grotesque and appalling, but in reality it’s only normal: truth laughs when it triumphs, and lies weep when they see their end coming! What’s more, when death returns to the living and shows the trembling flame of the candlestick, the latter howl, whereas the former has a big advantage: it’s already dead and therefore appears to live without fear!

No doubt thinking of the Brussels aristocracy who flocked to Ostend for a dip, Ensor wrote:

« Ah, you have to see the masks, under our great opal skies, and when, daubed in cruel colors, they evolve, miserable, their spines bent, pitiful under the rains, what a pitiful rout. Terrified characters, at once insolent and timid, snarling and yelping, voices in falsetto or like unleashed bugles ».

The same Ensor also castigated bad doctors pulling a huge tapeworm out of a patient’s belly, kings and priests whom he painted literally « shitting » on the people. He criticized the fishwives in the bars, the art critics who failed to see his genius and whom he painted in the form of skulls fighting over a kipper (a pun on « Art Ensor »).

The King’s Notebooks

In 1903, a scandal of unprecedented proportions shook Belgium, France and neighboring countries. Les Carnets du Roi (The King’s Notebooks), a work published anonymously in Paris and quickly banned in Brussels, portrayed a white-bearded autocrat: Leopold II, King of the Belgians, without naming him. Arrogant, pretentious and cunning, he was more concerned with enriching himself and collecting mistresses than ensuring the common good of his citizens and respect for the laws of a democratic state. The book, published by a Belgian publisher based in Paris, was the brainchild of a Belgian writer from the Liège region, Paul Gérardy (1870-1933), who happened to be a friend of Ensor.

The story of the Carnets du Roi is first and foremost that of a monarch who was not only mocked in writing and drawing throughout his reign, but also criticized extremely harshly for the methods used to govern his personal estate in the Congo. Divided into some thirty short chapters, the work is presented as a series of letters and advice from the aging king to his soon-to-be successor on the throne, his nephew Albert, who went on to become Ensor’s patron and, along with his friend Albert Einstein, whom he welcomed to Belgium, was deeply involved in preventing the outbreak of the Second World War.

In Les Carnets, a veritable satire, the monarch explains how hypocrisy, lies, treachery and double standards are necessary for the exercise of power: not to ensure the good of the « common people » or the stability of the monarchical state, but quite simply to shamelessly enrich himself.

The pages devoted to the exploitation of the people of the Congo and the « re-establishment of slavery » (sic) by a king who, via the explorer Stanley, was said to have been one of its eradicators, are ruthlessly lucid, and echo the most authoritative denunciations of the white-bearded monarch, to whom Gérardy lends these words:

« I took care to have it published that I was only concerned with civilizing the negroes, and as this nonsense was asserted with sincerity by a few convinced people, it was quickly believed and saved me some trouble ».

Meeting Albert Einstein

After 1900, the first exhibitions were devoted to him. Verhaeren wrote his first monograph. But, curiously, this success defused his strength as a painter. He contented himself with repeating his favorite themes or portraying himself, including as a skeleton. In 1903, he was awarded the Order of Leopold.

The whole world flocked to Ostend to see him. In early 1933, Ensor met Albert Einstein, who was visiting Belgium after fleeing Germany. Einstein, who resided for several months in Den Haan, not far from Ostend, was protected by the Belgian King, Albert I, with whom he coordinated his efforts to prevent another world war.

If it is claimed that Ensor and Einstein had little understanding of each other, the following quotation rather indicates the opposite.

Ensor, always lyrical, is quoted as saying:

« Let us all promptly praise the great Einstein and his relative orders, but let us condemn algebraism and its square roots, geometers and their cubic reasons. I say the world is round.… »

In 1929, King Albert I conferred the title of Baron on James Ensor. In 1934, listening to all that Franklin Roosevelt had to offer and seeing Belgium caught up in the turmoil of the 1929 crash, the King of the Belgians commissioned his Prime Minister De Broqueville to reorganize credit and the banking system along the lines of the Glass-Steagall Act model adopted in the United States in 1933.

On February 17, 1934, during a climb at Marche-les-Dames, Albert I died under conditions that have never been clarified. On March 6, De Broqueville made a speech to the Belgian Senate on the need to mourn the Treaty of Versailles and to reach an agreement with Germany on disarmament between the Allies of 1914-1918, failing which we would be heading for another war…

De Broqueville then energetically embarked on banking reform. On August 22, 1934, several Royal Decrees were promulgated, in particular Decree no. 2 of August 22, 1934, on the protection of savings and banking activities, imposing a split into separate companies, between deposit banks and business and market banks.

Pictorial bombs

From 1929 onwards, Ensor was dubbed the « Prince of Painters ». The artist had an unexpected reaction to this long-awaited recognition, which came too late for his liking: he gave up painting and devoted the last years of his life exclusively to contemporary music, before dying in 1949, covered in honors.

In 2016, a painting by Ensor from 1891, dubbed « Skeleton stopping masks », which had remained in the same family for almost a century and was unknown to historians, sold for 7.4 million euros, a world record for this artist. In the center, death (here a skull wearing the bearskin cap typical of the 1st Grenadier Regiment) is caught by the throat by strange masks that could represent the rulers of countries preparing for future conflicts.

Are the masks (the lie) about to strangle the truth (the skull and crossbones) without success? And so, over a hundred years later, Ensor’s pictorial bombs are still happily exploding in the heads of the narrow-minded, the floured bourgeois and the piss-poor, as he himself would have put it.

Notes:

- In 1819, another artist, the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, composed his political poem The Mask of Anarchy in reaction to the Peterloo massacre (18 dead, 700 wounded), when cavalry charged a peaceful demonstration of 60,000-80,000 people gathered to demand reform of parliamentary representation. In this call for liberty, he denounces an oligarchy that kills as it pleases (anarchy). Far from a call for anarchic counter-violence, it is perhaps the first modern declaration of the principle of non-violent resistance. ↩︎

Avec le peintre James Ensor, arrachons le masque à l’oligarchie !

James Ensor est né le 13 avril 1860 dans une famille de la petite-bourgeoisie d’Ostende en Belgique. Son père, James Frederic Ensor, un ingénieur raté anglais anti-conformiste, sombre dans l’alcoolisme et l’héroïne.

Sa mère, Maria Catherina Haegheman, belge flamande, qui n’encourage guère sa vocation artistique, tient un magasin de souvenirs, coquillages, chinoiseries, verroteries, animaux empaillés et masques de carnaval, des artefacts qui peupleront l’imagination du peintre.

Esprit pétillant, James se passionne pour la politique, la littérature et la poésie. Un jour, commentant sa naissance lors d’un banquet offert en son honneur, il dira :

« Je suis né à Ostende un vendredi, jour de Vénus [déesse de la Paix]. Eh bien ! chers amis, Vénus, dès l’aube de ma naissance, vint à moi souriante et nous nous regardâmes longuement dans les yeux. Ah ! les beaux yeux pers et verts, les longs cheveux couleur de sable. Vénus était blonde et belle, toute barbouillée d’écume, elle fleurait bon la mer salée. Bien vite je la peignis, car elle mordait mes pinceaux, bouffait mes couleurs, convoitait mes coquilles peintes, elle courait sur mes nacres, s’oubliait dans mes conques, salivait sur mes brosses.«

Après une première initiation aux techniques artistiques à l’Académie d’Ostende, il débarque à Bruxelles chez son demi-frère Théo Hannon pour y poursuivre ses études à l’Académie des Beaux Arts. En compagnie de Théo, il est introduit dans les cercles bourgeois de libéraux de gauche qui fleurissent en périphérie de l’Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB).

Chez Ernest Rousseau, professeur à l’Université libre de Bruxelles, dont il deviendra recteur, Ensor découvre les enjeux de la lutte politique. Madame Rousseau est microbiologiste, passionnée d’insectes, de champignons et… d’art. Les Rousseau tiennent salon, rue Vautier à Bruxelles, près de l’atelier d’Antoine Wiertz et de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique. Rendez-vous privilégié pour les artistes, les libres penseurs et autres esprits influents. Ensor y rencontre Félicien Rops et son beau-fils Eugène Demolder, mais aussi peut-être l’écrivain et critique d’art Joris-Karel Huysmans ainsi que l’anarchiste communard et géographe français Elisée Reclus.

De retour à Ostende, Ensor installe son atelier dans la maison familiale où il réalise ses premiers chefs-d’œuvre, portraits empreints de réalisme et paysages inspirés par l’impressionnisme.

Aux pays des couleurs

« La vie n’est qu’une palpitation ! », s’écrie Ensor. Ses nuages sont des masses grises, or et azur au-dessus d’une ligne de toits. Sa Dame au brise-lames (1880) est prise dans un glacis de gris et de nacre, au bout de la jetée.

Ensor est un chef d’orchestre se servant de couteaux et de pinceaux pour étaler la peinture en couches fines ou épaisses et ajouter par-ci par-là des accents pâteux.

Son génie prend tout son envol dans son tableau La Mangeuse d’huîtres (1882). Même si l’ensemble a l’air de dégager une certaine tranquillité, il peint en réalité une gigantesque nature morte qui semble avoir avalé sa sœur cadette Mitche.

L’artiste baptise d’abord le tableau Au pays des couleurs, plus abstrait que La Mangeuse d’huîtres, puisque ce sont bien les couleurs qui jouent le rôle principal dans la composition.

Nacres des coquillages, blanc bleuâtre de la nappe, reflets des verres et bouteilles, tout est dans la variation, tant dans l’élaboration que dans les tonalités de couleur. Ensor conserve l’approche classique : il utilise toujours des sous-couches tandis que les impressionnistes appliquent la peinture directement sur la toile blanche. Les pigments dont il se sert sont également très traditionnels : rouge vermillon, blanc de plomb, terre brune, bleu de cobalt, bleu de Prusse et outremer synthétique. Le jaune chrome de La Mangeuse d’huîtres fait exception. L’intensité de ce pigment est bien plus élevée que celle du jaune de Naples plus pâle qu’il utilisait auparavant. Mais ses couleurs, qu’il utilise souvent de manière pure au lieu de les mélanger, sont bien plus claires que celles des anciens.

L’écrivain Emile Verhaeren, qui écrira plus tard la première monographie du peintre, contemple La Mangeuse d’huîtres et s’exclame : « C’est la première toile réellement lumineuse ».

Epoustouflé, il souhaite mettre en avant Ensor comme le grand innovateur de l’art belge. Mais les avis ne sont pas unanimes. La critique n’est pas tendre : les couleurs sont trop criardes et l’œuvre est peinte de manière négligée.

De plus, il est immoral de peindre « un sujet de second rang » (En monarchie, il n’existe pas de citoyens, seulement des « sujets », une femme ne faisant pas partie de l’aristocratie) dans de telles dimensions – 207 cm sur 150 cm. Par la vue plongeante, librement appliquée, on a l’impression que tout dans le tableau va déborder de son cadre.

Le Salon d’Anvers, qui expose le meilleur de l’art actuel, refuse l’œuvre en 1882. Même les anciens compères bruxellois de L’Essor refusent La Mangeuse d’huîtres un an plus tard.

Le groupe des XX

C’est ainsi qu’en Belgique, la révolution artistique de 1884 démarrera par une phrase lancée par un membre du jury officiel : « Qu’ils exposent chez eux ! » avait-il clamé, refusant les toiles de deux ou trois peintres ; c’est donc ce qu’ils firent, en exposant chez eux, dans des « salons citoyens », ou en créant leur propres associations culturelles.

C’est dans ce contexte que Octave Maus et Ensor créeront à Bruxelles le « groupe des XX », cercle artistique d’avant-garde.

Parmi les « vingtistes » du début, outre Ensor, on trouve Fernand Khnopff, Jef Lambeaux, Paul Signac, George Minne et Théo Van Rysselberghe.

Parmi les artistes invités à venir exposer leurs œuvres à Bruxelles, de grands noms tels que Ferdinand Rops, Auguste Rodin, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, Gustave Caillebotte, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, etc.

C’est donc seulement en 1886 qu’Ensor peut exposer son œuvre novatrice La Mangeuse d’huîtres pour la première fois au groupe des XX.

Pour autant, ce n’est pas la fin de son calvaire. En 1907, le conseil communal de Liège décide de ne pas acheter l’œuvre pour le musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville.

Heureusement, Emma Lambotte, amie d’Ensor, ne laisse pas tomber le peintre. Elle achète le tableau et l’expose chez elle, dans son salon citoyen.

Engagement social et politique

Les troubles sociaux contemporains de son ascension en tant que peintre, qui virent à la tragédie lors des affrontements meurtriers de 1886 entre ouvriers et garde civique, l’incitent à trouver dans les masses en tant qu’acteur collectif un puissant compagnon d’infortune.

A la fin du XIXe siècle, la capitale belge, est une marmite bouillonnante d’idées révolutionnaires, créatrices et innovantes. Karl Marx, Victor Hugo et bien d’autres, y trouvent exil, parfois brièvement.

Le symbolisme, l’impressionnisme, le pointillisme et l’art nouveau s’y disputent leurs titres de gloire. Pour sa part, Ensor, il faut bien le reconnaître, puisant dans tous les courants, restera un inclassable s’élevant au-dessus des modes, des tendances du moment et des goûts éphémères, et de très loin.

Si Marx s’est trompé sur bien des points, il comprenait bien qu’à une époque où la finance tirait sa richesse de la production, la modernisation des moyens de production portait en germe la transformation des rapports sociaux. Tôt ou tard, et à tous les niveaux, ceux qui produisent la richesse clameront leur juste place dans le processus décisionnel.

Le combat d’Ensor pour un art plus libre reflète et coïncide avec le changement d’époque qui s’opère alors.

Partie de Vienne en Autriche, la crise bancaire de mai 1873 provoque un krach boursier qui marque le début d’une crise appelée la Grande Dépression, et qui court sur le dernier quart du XIXe siècle. Le 18 septembre 1873, Wall Street est pris de panique et ferme pendant 10 jours.

En Belgique, après une période marquée par une vertigineuse industrialisation, la loi Le Chapelier, une loi appliquée en 1791, soit quarante ans avant la naissance de la Belgique, qui interdisait la moindre forme d’organisation d’ouvriers, est abrogée en 1867, mais la grève est toujours un crime sanctionné par l’État.

C’est dans ce contexte qu’une centaine de délégués de représentants de syndicats belges fondèrent en 1885 le Parti ouvrier belge (POB). Réformistes et prudents, ils réclament en 1894, non pas la « dictature du prolétariat », mais une forte « socialisation des moyens de production ».

La même année, le POB obtient 20 % des suffrages exprimés aux élections législatives et compte 28 députés. Il participe à plusieurs gouvernements jusqu’à sa dissolution lors de l’invasion allemande en mai 1940.

Horta, Jaurès et la Maison du Peuple de Bruxelles

L’architecte Victor Horta, grand innovateur de l’Art Nouveau et dont les premières demeures symbolisent un nouvel art de vivre, sera chargé par le POB de construire la magnifique « Maison du Peuple » à Bruxelles, un bâtiment remarquable, fait principalement d’acier, abritant un maximum de fonctionnalités : bureaux, salle de réunion, magasins, café, salle de spectacle…

Le bâtiment fut inauguré en 1899 en présence de Jean Jaurès. En 1903, Lénine y participa au congrès du Parti ouvrier social-démocrate de Russie.

Jean Jaurès prononça d’ailleurs son dernier discours, le 29 juillet 1914, au Cirque Royal de Bruxelles, lors d’une grande réunion de l’Internationale socialiste pour sauver la paix.

En parlant des menaces de la guerre, Jaurès dit :

« Attila est au bord de l’abîme, mais son cheval trébuche et hésite encore ». S’opposant, comme il le fit toute sa vie, à ce que la France se soumît à un rôle subalterne, il dit textuellement : « Si l’on fait appel à un traité secret avec la Russie, nous en appellerons au traité public avec l’Humanité ».

Et il termina son discours, le meilleur de sa vie, par des paroles prophétiques dont voici le texte quasi littéral : « Au début de la guerre, tout le monde sera entraîné. Mais lorsque les conséquences et les désastres se développeront, les peuples diront aux responsables : ’Allez-vous en et que Dieu vous pardonne’ ».

Selon les témoins, à Bruxelles, le discours de Jaurès souleva l’auditoire, composé de milliers de personnes appartenant à toutes les classes de la société. Deux jours plus tard, le 31 juillet 1914, Jaurès, de retour à Paris, est assassiné.

Quant à la Maison du Peuple de Bruxelles, elle fut détruite en 1965 et remplacé par un remarquable chef-d’œuvre de la laideur.

Alimentation doctrinaire

L’art d’Ensor, surtout dans ses gravures, sera l’écho de ce grand chamboulement. Sa critique sociale et politique serpente à travers ses meilleures œuvres, dont aucune n’est peut-être aussi virulente que sa gravure Alimentation doctrinaire (1889/1895) montrant des figures incarnant les pouvoirs en place (Le roi des Belges, le clergé, etc.) littéralement déféquant sur les masses, une sale habitude qui reste bien enracinée chez nos « élites », si l’on revoit le traitement qu’on a infligé, sans la moindre discrimination, à nos « gilets jaunes ».

Ensor, dans ces gravures, présente les grandes revendications du POB : le suffrage universel (voté en 1893, de façon imparfaite, du moins pour les hommes), le service militaire « personnel » (c’est-à-dire pour tous, voté en 1913) et l’instruction universelle obligatoire (votée en 1914).

La revanche

Face à l’injustice et à l’incompréhension, Ensor ne peut plus réprimer sa juste colère. Pour s’amuser, et reconnaissons-le, se venger, il compte bien « se payer » ceux qui l’ignorent, le méprisent et le sabotent, avant tout cette aristocratie belge qui s’accroche à ses privilèges comme les moules aux roches.

Déconstruisant le carcan des règles académiques, s’inspirant de Goya, Ensor se forge alors un langage puissant de métaphores et de symboles.

Dans un premier temps, il veut renvoyer cette élite oligarchique belge, se prétendant hypocritement « catholique », aux fondements mêmes des principes humanistes qu’elle piétine.

Entre 1888 et 1892, Ensor a commencé à traiter des thèmes religieux. Comme le firent aussi Gauguin et Van Gogh, le peintre s’identifie au Christ persécuté.

En 1889, à 28 ans, il peint L’Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, une vaste toile satirique qui fit sa renommée. Même ses proches, désireux de à se faire reconnaître pour exister, n’en veulent pas. La toile est refusée au Salon des XX où il est question de l’exclure du Cercle dont il est pourtant l’un des membres fondateurs ! Contre le souhait d’Ensor, les « vingtistes », courant vers le succès, se séparent quatre ans après pour se recréer sous le nom de La Libre Esthétique.

Dans cette œuvre, une large banderole rouge renseigne « Vive la sociale » et non « Vive le Christ ». Seul un petit panneau sur le côté applaudit un Jésus, roi de Bruxelles. Mais que diable le prophète, qui a les traits du peintre et presque perdu dans la foule, vient-il faire à Bruxelles ? Le socialisme a-t-il remplacé le christianisme au point que si Jésus revenait aujourd’hui, il le ferait sous la banderole « Vive la sociale », référence à la « République sociale » dont les partisans mettaient en avant le droit au travail, le rôle de l’État dans la lutte contre les inégalités, le chômage et la maladie ?

Pour les amis d’Ensor, il avait perdu la raison. En effet, il fallait « être fou » pour prendre de face, aussi bien l’oligarchie dominante que le peuple dont il espérait obtenir respect et reconnaissance.

L’avocat et critique d’art belge Octave Maus, co-fondateur avec Ensor des XX, a résumé de manière célèbre la réaction des critiques d’art contemporains au « coup de gueule pictural » d’Ensor :

« Ensor est le chef d’un clan. Ensor est sous les feux de la rampe. Ensor résume et concentre certains principes qui sont considérés comme anarchistes. En bref, Ensor est une personne dangereuse qui a initié de grands changements (…) Il est par conséquent marqué pour les coups. C’est sur lui que sont dirigées toutes les arquebuses. C’est sur sa tête que sont déversés les récipients les plus aromatiques des soi-disant critiques sérieux.«

En 1894, invité à exposer à Paris, son œuvre, plus objet intellectif qu’esthétique, suscite peu d’intérêt. Désespéré de ne pas rencontrer le succès, Ensor, persistera avec une peinture survoltée, sauvage, saturée et violemment bariolée.

Squelettes et masques

Très tôt, des têtes de mort, des squelettes et des masques font irruption dans son œuvre. Il ne s’agit pas là de l’imagination morbide d’un esprit malade comme le prétendent ses calomniateurs.

Radical ? Insolent ? Certes ; sarcastique, souvent ; pessimiste ? Jamais ! ; anarchiste ? disons plutôt « esprit gilet jaune », c’est-à-dire fortement contestataire d’un ordre établi ayant perdu toute légitimité et, absorbé par d’immenses manœuvres géopolitiques, marchant comme une horde de somnambules vers la « Grande Guerre » et la Deuxième Guerre mondiale qui vient derrière !

Têtes de morts, symboles de la vérité

Poétiquement, Ensor va ressusciter la métaphore ultra-classique des « Vanités » de la Renaissance, thème en somme très chrétien qui figure déjà dans « Le Triomphe de la Mort », ce poème de Pétrarque qui inspira le peintre flamand Pieter Bruegel l’Ancien ou encore la série de gravures sur bois d’Holbein, « La danse macabre ».

Un crâne juxtaposé à un sablier étaient les éléments de base permettant de visualiser le caractère éphémère de l’existence humaine sur terre. En tant qu’humains, nous rappelle cette métaphore, nous essayons en permanence de ne pas y penser, mais fatalement, nous finissons tous par mourir, du moins sur le plan corporel.

Notre « vanité », c’est cette envie permanente de nous croire éternels.

Ensor, n’hésitait pas à faire appel aux symboles. Pour pénétrer son œuvre, il faut donc savoir lire le sens qu’ils « cachent ». Visuellement, face au triomphe du mensonge et de l’hypocrisie, Ensor, en bon chrétien, érige donc la mort en seule vérité capable de donner du sens à notre existence. C’est elle qui triomphe sur notre existence physique.

Les masques, symbole du mensonge.

Petit à petit, comme dans La Mort et les masques (1897) (image en tête d’article), l’artiste va dramatiser encore un peu plus cette thématique en opposant la mort à des masques grotesques, symbole du mensonge et de l’hypocrisie des hommes. 1

Souvent dans ses œuvres, dans une inversion sublime des rôles, c’est la mort qui rit et ce sont les masques qui hurlent et pleurent, jamais l’inverse.

On dira que c’est grotesque et effroyable, mais en réalité, ce n’est que normal : la vérité rit lorsqu’elle triomphe et le mensonge pleure lorsqu’il voit sa fin arriver ! A cela s’ajoute, que lorsque la mort revient parmi les vivants et montre la flamme tremblante du chandelier, ces derniers hurlent, alors que la première a un gros avantage : elle est déjà morte et donc apparaît vit sans crainte !

Pensant sans doute à cette aristocratie bruxelloise qui accourut à Ostende pour y faire trempette, Ensor écrit :

« Ah ! Il faut les voir les masques, sous nos grands ciels d’opale et quand barbouillés de couleurs cruelles, ils évoluent, misérables, l’échine ployée, piteux sous les pluies, quelle déroute lamentable. Personnages terrifiés, à la fois insolents et timides, grognant et glapissant, voix grêles de fausset ou de clairons déchaînés.«

Ce même Ensor fustigea également les mauvais médecins tirant un immense ver solitaire du ventre d’un patient, les rois et les prêtres qu’il peignit « chiant » littéralement sur le peuple. Il pourfend les poissardes des bars, les critiques d’art qui n’ont pas vu son génie et qu’il peint sous la forme de crânes se disputant un hareng saur (jeu de mot sur « Art Ensor »).

Les Carnets du Roi

En 1903, un scandale d’une ampleur inédite éclate et secoue la Belgique, la France, et les pays voisins. Les Carnets du Roi, un ouvrage publié anonymement à Paris, et rapidement interdit à Bruxelles, dresse le portrait d’un autocrate à barbe blanche.

Sans le nommer, on y voit aisément Léopold II, le roi des Belges. Arrogant, prétentieux et roublard, il se révèle plus soucieux de s’enrichir et de collectionner les maîtresses que de veiller au bien commun des citoyens et au respect des lois d’un état démocratique. L’ouvrage, publié par un éditeur belge installé à Paris, avait jailli sous la plume d’un écrivain belge de la région liégeoise, Paul Gérardy (1870-1933), par hasard, un ami d’Ensor.

L’histoire des Carnets du Roi est avant tout celle d’un monarque dont on ne manque pas de se gausser par l’écrit et le dessin durant tout son règne, mais dont on critique également de façon extrêmement virulente, les méthodes utilisées pour gouverner son domaine personnel du Congo.

Divisé en une trentaine de courts chapitres, l’ouvrage se présente comme une suite de lettres et de conseils que le roi vieillissant adresse à celui qui devrait bientôt lui succéder sur le trône, son neveu Albert, par la suite protecteur d’Ensor et très impliqué avec son ami Albert Einstein qu’il accueillit en Belgique, à prévenir l’avènement de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale.

Dans Les Carnets, véritable satire, le monarque explique combien l’hypocrisie, le mensonge, la trahison et le double langage sont nécessaires à l’exercice du pouvoir : non pas pour assurer le bien des « gens du peuple » ou la stabilité de l’État monarchique, mais tout simplement pour s’enrichir sans vergogne. Les pages consacrées à l’exploitation des populations du Congo et au « rétablissement de l’esclavage » (sic) par un roi qui passait, via l’explorateur Stanley, pour en avoir été l’un des éradicateurs, sont d’une impitoyable lucidité.

Elles rejoignent les dénonciations les plus autorisées du monarque à la barbe blanche, à qui Gérardy prête ces mots :

« J’ai eu soin de faire publier que je n’étais soucieux que de civiliser les nègres, et comme cette sottise était affirmée avec sincérité par quelques convaincus, on y a cru rapidement et cela m’évita quelques ennuis.«

Rencontre avec Albert Einstein

Après 1900, des premières expos lui sont consacrées. Verhaeren écrit sa première monographie. Mais, curieusement, ce succès a désamorcé sa force de peintre. Il se contente de répéter ses thèmes favoris ou de s’autoportraiturer, y compris en squelette. Il reçoit en 1903 l’Ordre de Léopold. Enfin reconnu !

Le monde entier défile à Ostende pour le voir. Au début de l’année 1933, Ensor y rencontre Albert Einstein, de passage en Belgique après avoir fui l’Allemagne. Einstein, qui a résidé pendant quelques mois à Den Haan, non loin d’Ostende, fut protégé par le roi des Belges, Albert Ier, avec qui il se coordonne pour tenter d’empêcher une nouvelle guerre mondiale.

Si l’on prétend qu’Ensor et Einstein ne se comprenaient guère, la citation suivante indique plutôt le contraire. Ensor, toujours lyrique, aurait dit :

« Louons tous promptement le grand Einstein et ses ordres relatifs, mais condamnons l’algébrisme et ses racines carrées, les géomètres et leurs raisons cubiques. Je dis que le monde est rond….«

En 1929, le roi Albert Ier accorde le titre de baron à James Ensor.

En 1934, à l’écoute de tout ce qu’apporte Franklin Roosevelt et voyant la Belgique prise dans le tumulte du krach de 1929, le roi des Belges missionne son Premier ministre De Broqueville pour réorganiser le crédit et le système bancaire à l’instar du modèle du Glass-Steagall Act adopté aux Etats-Unis en 1933.

Le 17 février 1934, lors d’une escalade à Marche-les-Dames, Albert I décède dans des conditions jamais élucidées. Le 6 mars, De Broqueville fait un discours au Sénat belge sur la nécessité de faire son deuil du Traité de Versailles et d’arriver à une entente des Alliés de 1914-1918 avec l’Allemagne sur le désarmement, faute de quoi on irait vers une nouvelle guerre…

De Broqueville entame ensuite avec énergie la réforme bancaire. Ainsi, le 22 août 1934 sont promulgués plusieurs Arrêtés Royaux notamment l’Arrêté n°2 du 22 août 1934, relatif à la protection de l’épargne et de l’activité bancaire, imposant une scission en sociétés distinctes, entre banques de dépôt et banques d’affaire et de marché.

Bombes picturales

A partir de 1929, Ensor est surnommé le « prince des peintres ». L’artiste a une réaction inattendue face à cette reconnaissance trop longtemps attendue et trop tard venue à son goût : il abandonne la peinture et consacre les dernières années de sa vie exclusivement à la musique contemporaine avant de mourir en 1949, couvert d’honneurs.

En 2016, une toile d’Ensor de 1891, surnommée « Squelette arrêtant masques », restée dans la même famille depuis près d’un siècle et inconnue des historiens, s’est vendu à 7,4 millions d’euros, record mondial pour cet artiste.

Au centre, la mort (ici un crâne coiffé du bonnet en peau d’ours typique du 1er régiment de grenadiers) prise à la gorge par d’étranges masques qui pourraient représenter les souverains de pays préparant les prochains conflits. Les masques (le mensonge) s’apprêtent à étrangler sans succès la vérité (la tête de mort) ? Ainsi, plus de cent ans plus tard, les bombes picturales d’Ensor explosent encore joyeusement à la tête des esprits étroits et frileux, des bourgeois enfarinés et des pisse-vinaigre, comme il l’aurait dit lui-même.

- En 1819, un autre artiste, le poète anglais Percy Bysshe Shelley avait composé son poème politique Le Masque de l’Anarchie en réaction au massacre de Peterloo (18 morts, 700 blessés) lorsque la cavalerie chargea une manifestation pacifique de 60 000 à 80 000 personnes rassemblées pour demander une réforme de la représentation parlementaire. Dans cet appel à la liberté, il dénonce une oligarchie tuant à sa guise (l’anarchie). Loin d’un appel à la contre-violence anarchique, il s’agit peut-être de la première déclaration moderne du principe de résistance non violente. ↩︎

On the origins of Modern Art, the problem of Symbolism

“At the turn of this century, painting is in bad shape. And for those who love the fatherland of paintings, very soon there will only remain the closed spaces of museums, in the same way there remains parcs for the amateurs of nature, to cultivate the nostalgia of that what doesn’t exist any longer…”

Jean Clair, Harvard graduate, director of the Musée Picasso

and of the centenary of the Venice Biennale of Contemporary Art in 1995.

Karel Vereycken, April 1998

Something is fairly rotten in the kingdom of Art, and if today (1998), finally some kind of debate breaks out, it is, halas, for quite bad reasons. Since it is uniquely in the context of budget cuts imposed on Europe by the Maastricht treaty that some questions are raised to challenge public opinion on a question carefully avoided till now: can we go on indefinitely subsidizing “modern artistic creation”, or what pretends to be so, with the tax-payers money, without any demand and outside any criteria?

Abusively legitimated by its status as a victim of the totalitarian regimes of Hitler, Stalin and Mao, Modern Art’s value as an act of resistance to totalitarianism watered away with the collapse of these regimes.

While we oppose the current budgetary cuts, since it would finish off the sick patient, we nevertheless propose to examine truthfully the illness and the potential remedies to be administered.

In France, the slightest critique immediately provoked the traditional hysterical fits. Raising a question, formulating an interrogation or even simply expressing a doubt on the holiness of Modern Art continues to be considered tantamount to starting an Inquisition. Even well integrated critiques such as the « left » leaning author Jean Baudrillard, or the director of the Paris Picasso museum Jean Clair and even the modern painter Ben, immediately bombarded by acid counter-attacks from the french and international Art nomenclature, accusing them of being “reactionaries”, “obscurantist” and, to crown it all, of being “fascists”, “nazis” and even “anti-Semites”.

For seasoned observers these attacks remind the simplicity of Stalinist rhetoric: “Anybody discussing the revolution is a fascist”. Modernist musical composer Pierre Boulez even accused a journalist of being a “Vichy collaborator” because unconvinced of the utility of the computers of his musical research foundation IRCAM.

That spark of debate, if any, became rapidly poisoned by the possessive defense of the scarce budget allocations. Why all this noise? Jean Clair already exposed his views fourteen years ago in his book “Considérations sur l’Etat des Beaux-Arts, Critique de la Modernité” (1983) without provoking such a hullabaloo.

But in times of crisis, funds seem to provoke more passion than fundamentals. In any case, we welcome Clair’s courage. His ironical critique of the rampant snobbism of the tiny, incestuous world of contemporary Art makers is totally uncompromising. His defense of the necessary rebirth of the basic skills of drawing and pastel is on the mark.

Clair rightly makes a distinction between « Contemporary » art on one side and « Modern » art on the other side. Contemporary Art, broke with Modern Art from the point it became a systemic apology of “non-sense [absence of meaning] that was elected a system. » Reality, writes Clair, leads him to demand that we return to “meaning” (deliberately banned by « contempory » art) which was the very power of « Modern » Art.

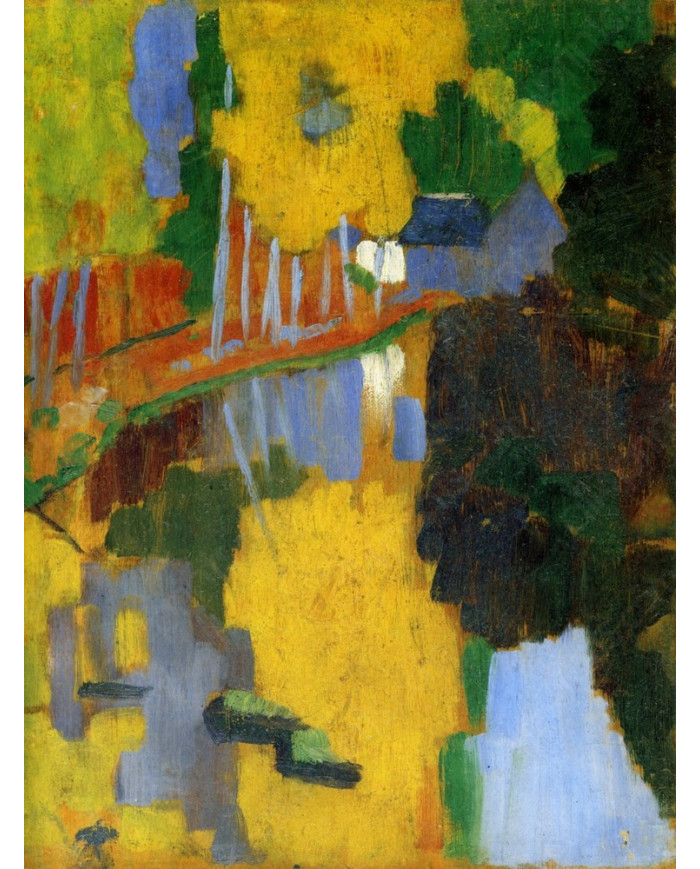

To understand this difference, inspired by the insights and works of my friend, american art historian Michael Gibson, we shall document here that the birth of « Modern » art was nothing but a mutation from figaritive « Symbolism » to non-figurative (abstract) Symbolism, both accepting their role of expressing a symbolic meaning. « Contemporary art », profiting from the confusion of the idea of a « secret » meaning inherent in symbolic artistry, then sneaked in and tried to pretend that any sort of meaning should and could be eliminated from artistic expression.

QUESTION:

« So if I understood you correctly, you claim there exist criteria that are universal, enabling rational man to distinguish with reason between beauty and ugliness which would free art from the arbitrary caprices of taste?”

ANSWER:

« Uh, yes, and even if one cannot establish a catalogue filled with models and instructions enforceable till the end of all times, we firmly think there exists a way of looking at things, a mental attitude which we can prove to have been fruitful since the early cave paintings, as those of Chauvet in southern France dating from 50.000 years B.C., till today. »

To say it differently, there is no such thing as the aesthetics of form, but some kind of aesthetics of the soul.

Any attempt to frame aesthetics, as a set of formal rules of the visible forms is the shortest road to finish in a sterile academic dead end.

By analogy, we could say that such an attempt in the domain of language would make linguistics the science of poetry…

Leonardo da Vinci defined the mission of the painter as the one who has to « make visible the invisible ». So it is up to us to define the aesthetics of the invisible and how they manifest themselves in the visible realm.

How to represent the world

Let’s look at ways of representing phenomena by starting from what appears to be the « most simple ».

A. “Bounded objects” of an inorganic or organic nature: for example stones, a glass bottle, but also a flower or the body of an animal or a man. Their relative finiteness makes their representation easier. But to “make them alive”, one has to show their participation to something infinite: the infinite variations of the color or a stone, the numerous reflections of light shattered by the glass bottle, the relative infinite number of leaves of a tree, the huge number of successive gestures which dictate spirit and life to the bodies of living beings. As you can see now, these so-called “simple” phenomena oblige us to choose, beyond simple sense perception, perceptions that enable us to express the idea of the object rather than its mere form.

B. “Openly unbounded objects”: for example a wave of the ocean, a forest, the clouds in the sky, or the expression of the eyes of a human being. Even more than in A., the Chinese principle of the “li” has to be considered. Instead of imitating their exterior form, and since their sometimes turbulent shapes escape in any case from our limited sense-perceptions, the exterior form has to be regarded as the expression of the idea that was the generating principle and we have to concentrate on choosing elements in the visible realm that indicate that “higher reality”. That makes the difference between the portrait of a living being and the portrait of a wax model…

C. “Ideas free from an object”: for example Love, Justice, Fidelity, Laziness, Cold, etc. How can we build gangways to the visible capable of representing these “higher ideas”?

ANSWER:

- Instead of representing the idea, I can try to substitute it with the object of the idea (one of Plato’s favorite subjects). For example I can try to represent the idea of Love by representing a woman. However, she cannot be but the object or the subject of love (She is loved or loves), but she is not Love itself.

- Since I’m in trouble having a representation in the visible realm of an idea of a “superior” nature, I decide to designate it by symbol. For example, a little heart to symbolize Love. For a Martian visiting Earth in the context of interplanetary tourism, the little heart has no meaning. By logical deduction, he could arrive at the conclusion the heart indicates heart patients, or cardiologists or eventually the designed victims of an Aztec sacrificial cult. In order to understand what is involved, some earthling has to initiate him into the pre-convened meaning of the symbol to which the inhabitants of earth agreed to. If not, it might take some time before he understands the “secret” meaning of the symbol.

- That symbol can be a simple visible element but also a little story we call allegorical. Illustrating an allegory will always remain a simple didactical exercise far underneath the sublime mission of art.

- The notion of a parable, as those one finds in the Bible, brings us closer to the wanted solution by its metaphorical character (Meta-poros in Greek meaning: that which carries beyond). The isochronical presence of several paradoxes, provoking surprise and irony by the ambiguities of the painting shakes up the sense certainty of our empirical perceptions that darken so much our natural predisposition for beauty.

SYMBOL and METAPHOR, What’s the difference?

Symbol: designates a thing

Metaphor: carries beyond the thing

Symbol: its only value is expressed by itself

Metaphor: its only value is given to it by implicit analogy.

Symbol: its secret meaning can only be learnt by convention

Metaphor: its meaning can be discovered by sovereign cognition.

Rembrandt’s Saskia

Let us examine together Rembrandt’s painting “Saskia as Flora” (1641), where she offers a flower to the viewer. Is this a portrait of Rembrandt’s wife along with the portrait of a flower? Or is there a new concept involved that arises in our mind as a result of this juxtaposition that could be called Love or Fidelity (to you I offer my beauty, as I offer you this flower…) The putting into visual analogy of two quite different things make appear a third one, which is in fact the real subject.

The easiest example of a real metaphorical paradox can be seen at work in wordplay or a cartoon drawing. For example if I draw a young couple in love and replace the head of the young man with the head of a dog, a completely different meaning is given to the image. The viewer, intrigued by the love relationship is surprised by the possessive (or submissive) character suggested by the dog head. Variations of the type of dog and his expression will vary the very meaning of the image. Once again, it is by the use of an implicit analogy that an unexpected arrangement gives us the means to grapple an idea beyond the object represented.

The little light bulb that goes on in our heads when we solve a metaphorical paradox gives us a threefold happiness. First the joy to think, since our thought process is precisely based on that unique process. Second to live in harmony with our world, which being a creative process itself “condemns” us to be free. And finally the joy that derives from the sharing of that happiness of discovery with other human beings who get even more creative in turn. Hence, every scientific or artistic discovery becomes a ray of light enlightening the path for humanity to go. The glowing enders of yesterday give us the fire to illuminate tomorrow.

But to do so, one cannot represent in a formal way the solution found. One is obliged to recreate the context which obliges the viewer to walk the same road we did till the precise point where he discovers himself the poetical concept.

The science of enigmas of Leonardo da Vinci

Renaissance genius Leonardo da Vinci was a specialist of this kind of « organized » enigmas, conspiracies to have us think. Let’s have a look at his painting “Saint John the Baptist”, his last painting and somehow his last will resuming all the best science of his creative mind. The ambiguous character of the person has been often used as “proof” of Leonardo’s alleged homosexuality.

One can indeed ask the question if represented here we see a man or a woman? The strong muscles of the arms plead for male while the gracious face argues for female. Desperate, our mind asks if this is devil or angel? While one finger points to heaven, similar to Raphael’s Plato in the « School of Athens », the other hand rests on the heart, and in the same time a coquette smile meets intelligent eyes…

Of course, Saint-John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence served as the symbol of a humanist Platonic current that realized the fact that the « little lights » of classical Greece announced the coming of the « great light » of Christianity.

Scholastical Catholicism of those days pretended that anybody living before Christ could be nothing more than a pagan. So what about Saint John the Baptist? The compositional method here employed is not of a symbolical nature, but that of paradoxical metaphor, i.e. build by enigmas that guide us, if we accept the challenge, to reflect in a philosophical way about the nature of mankind: how is it possible we are finite in some parts and infinite in others? That we are mind, life and matter? Of divine and human nature?

That is in some words what we mean by the method of paradoxical metaphors, the only method which gives sense to the word « classic », since conceived in a universal way for all men in the time of all times.

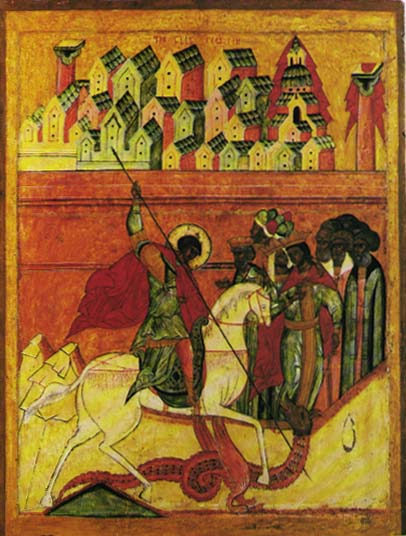

The opposite approach is the symbolist one, officially named after an artistic current that swept over Europe at the end of the XIXth century.

Together with impressionism that capitulated to positivism, symbolism was the mother of Modern Art and its bastard son Contemporary Art.

The symbol, erected as a method of artistic expression, is characteristic of a society that is incapable of change. It celebrates the banishing of the movement of progress but masks that self-denial with the never-ending multiplication of images and objects, always equal to themselves. Symbolism is nothing but the transformation into an object of a strong emotion or a mystical thought. The increase of its effect through incantation, fetishism, repetition, etc., agitating the symbol for its magical value as such, evokes the same obsessive fixation as pornography. As the American thinker Lyndon LaRouche ironically underscored the point:

“the difference between Beethoven (method of metaphor) and Wagner (method of symbolism) is defined by the level at which emotions are provoked in the audience. In the case of Beethoven, the beauty evoked brings us to tears. In the case of Wagner, it is the chairs that get wet…”

From there on, as we will document in due course, the arising of “Modern Art” reveals itself to be nothing more than a mere linear transposition of “figurative” symbolism to “abstract” symbolism.

These terms are obviously empty shells, since all figuration is figurative, and all figuration is the expression of what could be called an “abstract” concept or idea, conscious or not.

So, contrary to Contemporary Art, whose aggressive meaning is that nothing has, can or has the right to have any meaning, Modern Art claims to possess a sense of meaning, but that meaning is mystical-symbolical and hermetic by nature. We are not saying that symbols should be banned from Art, but we cannot but underline that symbolistical though as a compositional method is incompatible with Art’s nature.

Real Art concentrates on communicating a unique human quality, the Sublime, that expresses freedom and not that of a man enslaved either to his sentiments neither to his principles.

Contemporary Art, as all large scale swindles, needs quite some rhetoric and literature to convince it’s public of its pure absolute relativity. It is said that each of us sees it differently; that we all possess our own criteria and that formulating any judgment is by itself already an act of a totalitarian fascist in germ. It is somehow like the thief who accuses his victim of cupidity and lack of brotherly love when the victim refuses to hand over his purse. But if one claims the right to create something without meaning, one equally revindicates the right to no critique, and therefore ends any form of real debate beyond « it gives me a kick » or « no kick ».

That Art, when it is sincere, by claiming it cannot be apprehended by human cognition, defines itself as egoistical and asocial. It cannot but harvest what it sows: indifference.

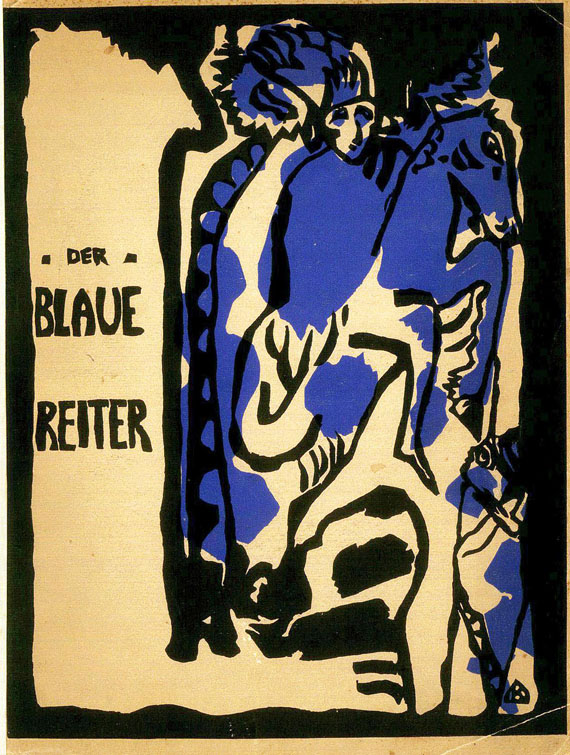

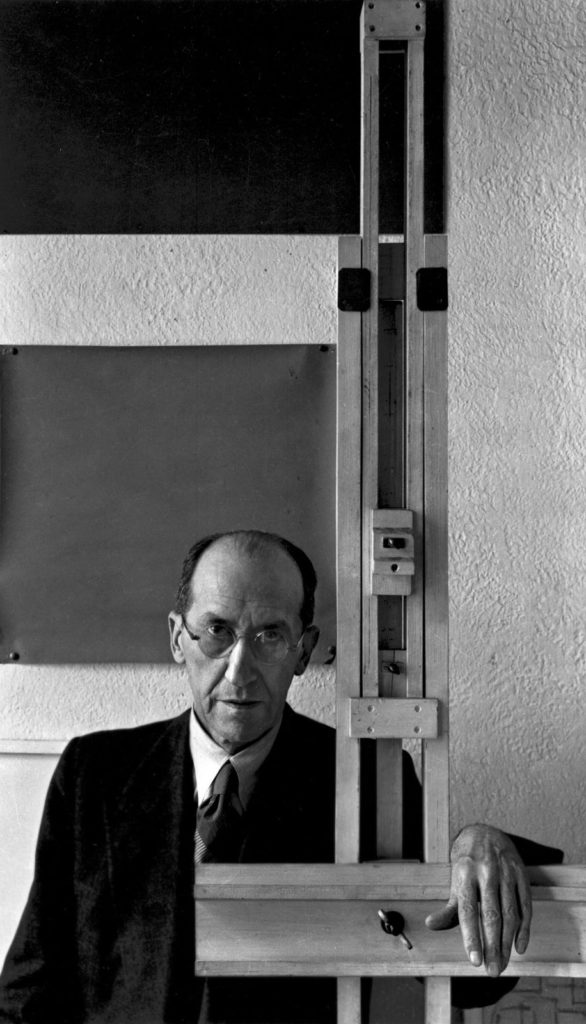

Before entering two personalities considered being the godfathers of Modern Art, Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), it is necessary to situate the historical context in which they operated. Then we will investigate a high level political operation: the Theosophical Society whose malefic theories exerted great influence on both godfathers of Modern Art.

Symbolism, the final stage of Romanticism

To crush the republican spirit that emerged at the end of the eighteenth century, which saw the American and French revolution, the European oligarchy deployed initially Napoleon Bonaparte.

Then, on the ruins of the Napoleonic wars, they promoted the iron corset of the Holy Alliance and the impotent ideology of regretting: the privilege of the suffering heart. Romanticism, often described as a “movement for the liberation of the me, as a reaction against the regularity of classicism and the rationality of the preceding centuries” became the official culture of the Restoration before being adopted by the Monarchy of July.

Even the talented French poet Baudelaire, prisoner of the zeitgeist stated shamelessly: “What is there more absurd than progress?” or, premonitory:

“Who says romanticism says Modern Art, i.e. intimacy, spirituality, color, aspiration towards the infinite”.

In a way this was the expression of a certain revolt against positivism, a “scientific” materialism which some tried to impose top down and for which the hearts of men were not mobilized.

We are light-years away from the “science for all” approach which radiated Gaspard Monge at the early Ecole Polytechnique, or Lazare Carnot’s “Ode to enthusiasm”. It was the same Holy alliance that forced Carnot into exile and outrooted Monge´s influence at the Ecole, crushing France’s scientific and industrial progress.

In 1871, Louis Pasteur, in a beautiful article “Why France did not find a superior man in the moment of peril” analyzed the dramatic events of those days.

But also Germany was living under a real cultural dictatorship. Prince Metternich, by the Carlsbad decrees forbade any representation of Friedrich Schiller‘s theatre plays. Also, the “sulfurous” poet Heinrich Heine, mocking the Salons of Mme de Stael and all the other nostalgics of the lost glory of the past, became the permanent target of the Holy Alliance’s police operations.

Francesco Goya, who strongly lambasted the massacres of Bonaparte’s Spanish expedition (1810-1814) in his series “The disasters of War”, characterized this particular historic moment in his engraving “The sleep of Reason generates monsters”.

The Great Upheaval

On the economic front, it was only after Abraham Lincoln defeated the British backed pro-slavery Confederacy and the then ensuing industrial buildup (1861-1876), that a little progress was tolerated in Europe.

The oligarchy had to solve the following paradox: How can we counterbalance the rising American power while in the same time prevent the emergence of Republics in Europe, inspired by the American System, on the ruins of the European empires?

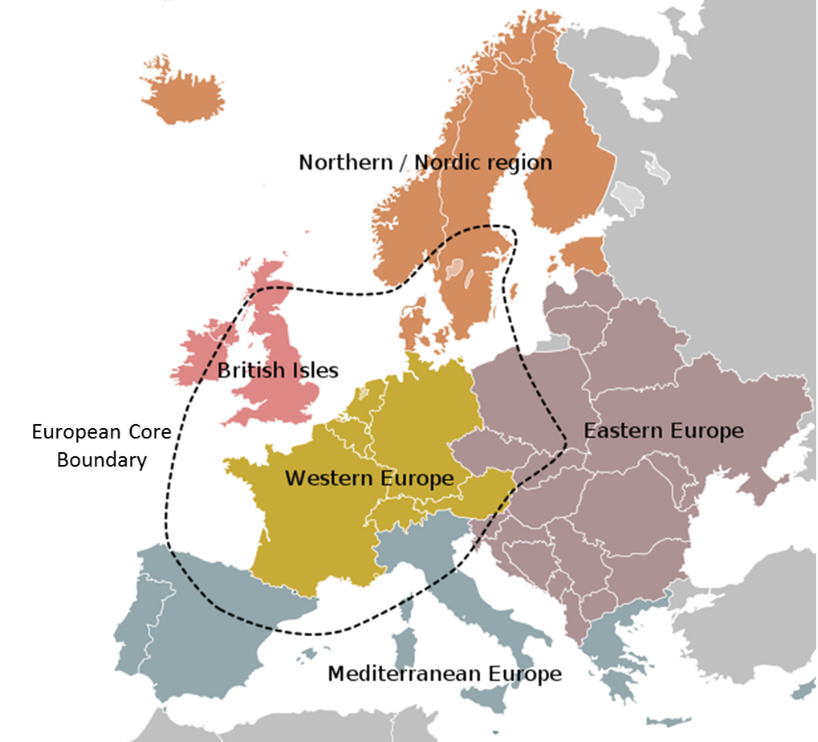

What some have called the « Great Upheaval » was nothing less than a profound transformation of daily life in Europe. It was precisely at that time that the Symbolist current got so dominant.

In the “industrial polygon of the Europe of steam” which connected Glasgow, Stockholm, Gdansk, Lodz, Trieste, Florence and Barcelona, it is estimated that of 7 persons from the country side, 1 stayed working the land, another went to the new world or the colonies, and the remaining 5 went working in the cities. The same estimate says that close to 60 million people left Europe. One can imagine the cultural choc for those who quit the magical world of pastoral backwardness.

In that sense, Symbolism was also a means for the oligarchy to deprive these incoming populations from the benefits of urban culture by keeping them in a state of irrationality.

The fear of political takeover by sovereign Nation-States dedicated to industrial and scientific progress was so great that the British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston (1784-1865), activated through his agent Guiseppe Mazzini (1805-1872), the “Young Europe” movement, uniting most revolutionary currents of those days. Under the auspices of the Foreign Office’s Arab Bureau, the east saw the sudden birth of a whole series of Arab countries, eventually localized on this or that oilfield.

The Theosophical Society

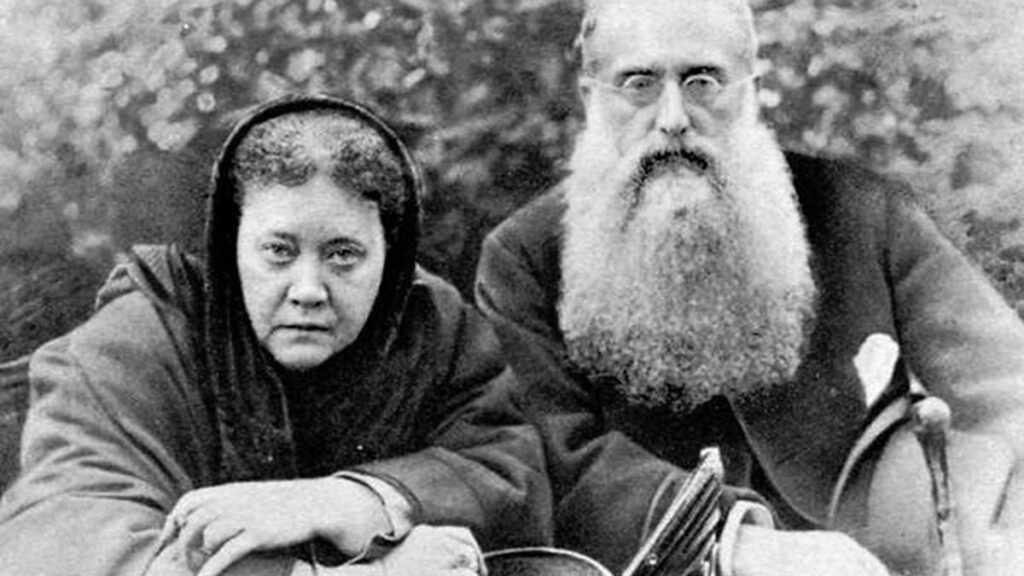

It is in that context that one has to situate the extraordinary offensive of the Theosophical Society (TS), one of these pseudo-religions rising out of the esoterical swamp of the second half of the nineteenth century. It is useful to zoom in on the life of Helena Petrowna Blavatsky (HPB) (1831-1891), the main front figure of the TS.

Granddaughter of the Prussian General Alexis von Rottenstern-Hahn, HPB was born in 1831 in Ukraine.

At the age of sixteen, her parents married her to an old General with the name of Nicéphore Blavatsky, vice-governor ofprovince of Erivan, which she quitted nearly immediately.

In 1848, she meets a Copt with the name of Paulos Metamon and as early as 1851 she turns up in London, where she meets the “spiritualists” and meets the “revolutionary” Mazzini. In 1856 she affiliates with the Young Europe’s Carbonarist association.

Then, she travels across different continents having become a toy in the hands of her British promoters which she refers to as her “Spiritual masters”, as she called one of her controlling agents “Master Morya”.

As soon as 1851 she travels to the US and Mexico, crossing Texas and Louisiana. After numerous trips in the Caucasus, Syria and Lebanon, we find her on November 3, 1867, riding a horse siding Garibaldi. Severely wounded at the battle of Mentana, she’s left for dead.

While recuperating in Paris, she meets a journalist with the name of Michal, and the founder of French spiritism, Allan Kardec. The former claim they discovered and developed HPB’s faculties as a medium. Deployed in that capacity to Cairo, and in the USA, she’s accused of being a fraudster. It is relevant to situate Edgar Allan Poe’s literary production as the effort of the pro American system faction to ridicule the British offensive in favor of esoteric irrationality.

Colonel Henry Steel Olcott

Around 1874, Blavatsky receives the order to enter into contact with a lawyer and insurance expert: Henry Steel Olcott.

Former officer of the Military Police, he became colonel during the civil war and shared his life in between Masonic lodges and spiritism. Active as a journalist, he was in charge of covering paranormal phenomena for the New York Sun and the New York Graphic.

Olcott got many inroads into the American esoterical scene of those days: John King, William Stainton Moses, Leadbeater, the Miracle Club of Philadelphia and a secret society called The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor whose members signed their writings with a swastika, symbol of the divinity of Tibet, the immense mountain plateau where supposedly the Aryan race found refuge at the time of the great deluge…

Then, on October 20, 1875 was founded in New York a “Society for Spiritualist investigations”. Its president was Olcott; the two vice-presidents were Felt and Pancoast, while Blavatsky figured as a mere secretary. Without willing to downplay her personal role, it looks she was brought in more for propagandistical reasons than in regard of her proper leadership qualities. As prominent members one can mention William Q. Judge and Charles Sotheran, both high dignitaries of Anglo-American masonry.

It is also remarkable that the Confederate General Albert Pike, Grand Master of the Scottish Rite of the Southern district based in Charleston, and one of the founders of the Ku Klux Klan met Blavatsky in those days, but seems to have dropped her, considering her to low level. Pike’s spiritual reputation is largely overdone and he has been accused of having extensively plagiarized the French occultist Elipha Levi.

Less than a month later, on November 17, 1875, the Society’s named was changed into “Theosophical Society”. Olcott and Blavatsky immediately started a great project to conquer the minds of India.

Officially, they pretended to establish “The Great Contact”, a bridge between the initiated of the East with those of the West and to fusion them together.

HPB gets without any difficulty the American nationality while Olcott obtains from the president of the United States, Rutherford Hayes, a handwritten clearance, a document requesting American diplomats all over the world to provide them their aid. Also, the US Secretary of State provided Olcott a diplomatic passport, something relatively rare for a non-career diplomat. When they reached ground in India, all this American help will give them the means to establish the “British Theosophical Society” (sic).

The British oligarchy seemed to have preferred Hinduism and its great toleration of the cast system where individuals’ desires for a better life are hoped for in the next one, as a preferential partner for the British oligarchy and its imperial class society.

The fundamental choice of the cultural matrix that defines the particular beliefs, transcending any particular form of regime, has always been the “secret weapon” guaranteeing the survival of the oligarchical system. In this way, it is not any longer necessary to police people’s minds on issues, since you control the underlying axioms shaping their thought process itself.

What the Theosophical Society claims today in regard to its role in the birth of a national consciousness of India is an ugly lie, and maybe without Theosophy India might have gained independence a century earlier!

While it is true that Gandhi, who encountered the TS in a vegetarian club in London, studied their works, he never really adopted their convictions. After having started the TS in India, Olcott, in the same geopolitical strategy, will explore Buddhism going through Asia and settle in Japan to wake up the “sleeping masses”.

Olcott composed a Buddhist catechism, created a multicolor Buddhist flag and a General Committee of Buddhist Affairs that functioned as a kind of Vatican for Buddhism. He also held an extraordinary conference in Japan’s military center, Hiroshima. There he distributes swastikas to the audience to which he predicts the coming of terrible wars will strike humanity and that Hiroshima will become one of the symbols for peace and fraternity in the world (sic)!

Swipe Christianity of the Earth!

Olcott and Blavatsky seemed to be quite effective in performing funny magical tricks. Some of them were described by one of their victims, Mme de Jelihowsky:

- Clear and direct answers, of telepathic nature.

- Formulas pronounced in Latin, by way of hits, for remedies which resulted always in healing.

- Divulgation in public of secrets concerning persons that were present but that hurted Blavatsky by their doubts.

- Change of the weight of furniture or persons at will.

- Letters written by unknown correspondents with a writing that was not hers. Often, when somebody asked a question she would say: go in your room, and in such or such a place you will find a letter answering your question.

- Appearance and disappearance of objects without a plausible explanation.

- Faculty to let music be heard at will, wherever and whenever desired.

When depressed, Blavatsky admitted she swindled her admirers.

In their magazine, “The Blue Lotus”, Olcott wrote on November 27, 1895, p. 418:

“Certain days, she was in such a state of mind that she denied the powers by which she had given us carefully controlled demonstrations and pretended to have deceived her public”.

Behind all this cheap mumbo-jumbo reserved for the naïve members of the TS, there was small initiated elite aware of their real geo-strategical imperialism of the mind.

“Our aim”, said Blavatsky, in line with British geopolitics, “is not to restore Hinduism, but to swipe Christianity of the Earth”.

After the cremation of Baron of Palm, a rich donator of the TS, the first one in the history of the United States against which over three thousand people demonstrated, and who’s only aim was to introduce Hinduism to the U.S. population, Olcott and HPB exposed confusedly their doctrine in 1878 in “Isis unveiled”, a 1300 pages book that she called “the work of her life”, available in a more popular version under the name of “The Secret Doctrine”.

From the standpoint of Theosophy (which some called Theosophistry), and in a pure remake of manicheanism, religious beliefs could be classified between male and female religions.

The latter gave preponderance to peace, tranquility, sensuality, fertility and adaptation to the environment, while the male religions gave extensive privilege to the spirit of conquest and undertaking, to proselytism and to the superiority of male virtues.

Of course, Abraham and Moses, founders of the great monotheistic religions in which man does not adapt but intervenes and even discovers his specific harmony by transforming nature and highering its order, were targeted as the animal to be hunted. It was indeed these religions that largely overruled the ancient cult of mother goddess Gaia that became the Isis cult.

Isis cult

ISIS

Isis is the most illustrious of the Egyptian goddesses, in charge of the home, marriage and fertility. Her power spread throughout the universe after she discovered the secret name of the supreme God, Ra.

She embodied the feminine principle, the magical source of all transformation, and was considered by all esotericists to be the Initiatrix, the one who held the secret of life, death and resurrection.

According to legend, she put back together her husband Osiris, whom the serpent Set had cut into fourteen pieces and scattered across Egypt. Only one piece was missing: the penis. Isis made one in silver. Her marriage to Osiris gave birth to Horus, who triumphed in the battle against the evil spirit, Set, but Isis asked him to spare her in order to maintain the cosmic battle between good and evil…

Often designated by the annealed cross, symbol of millions of years of future life, which is confused with the « Isis knot », symbol of immortality, Isis is also represented by the Ouroboros, or the snake that bites its own tail: sexual union with oneself, permanent self-fertilization, perpetual transformation from death to life.

To dominate the battlefield of the mind, a Machiavellian strategy was conceived:

1. Since the adoration of the mother goddess and the practice of female virtues nearly remained exclusively existent in India and Tibet, archaic Hinduism had to be revived. That is the reason why the Theosophists ran to India in order to prevent the nearby extinction of Hinduism. In France, Blavatsky’s main sponsor in that effort was the wealthy Duchesse de Pomar, a Spanish aristocrat descending from the Marquis of Northampton. For that aim, Orientalism and the practice of Yoga had to be encouraged and popularized.

2. Since the TS on its own was too tiny to weaken Christianity, Judaism and Islam, the TS combined its efforts with anti-progress Fabian Socialism. The just battle for republican secularism, founded on the mutual respect of religious freedom was distorted into a virulent denunciation of the Judeo-Christian philosophical outlook. The socialist inspiration of Jean Jaurès, while criticizing the inherent materialism of financial capitalism and Marxism passionately defended, in the name of a sense of transcendence, the right of entire growth and the pursuit of happiness for every human individual.

3. To fight “male supremacy”, it was decided by speech and action to defend anything that supposedly opposed it. Defend universal peace, to fight for the end of sexual discrimination, to make women free from their body, to make love become stronger than violence. For that reason, the TS always took a woman as its front figure. Annie Besant, an attractive Irish protestant and a member of the Fabian Society took the leadership of the TS after having directed the “Malthusian League” of England in 1877.

Such a project obviously didn’t rally much enthusiasm in those days, especially not in Catholic countries. The opposition was so strong that the TS adapted its outlook into some form of esoteric Christianity designed to penetrate the Christian strata. But for HPB, Judeo-Christian monotheism remained nothing else but a barbaric schism of Buddhism:

“What some called with despise paganism was the ancient wisdom full of divinity; and Judaism with its offshoots, Christianity and Islam took all their inspiration of their ethnic father…”

According to HPB, Jesus the Essenian was persecuted by the Jews because “the Essenian were converts, Buddhist missionaries that had come to Egypt, Greece and even Judea”

So, for her, Christianity had to be “de-judaizised” to make it again compatible with the female principle. The basic postulate behind all this was her fascination for the Aryan civilization whose symbol, the Swastika, of notorious nazi reputation, figures still today in the emblem of the ST.

THE SWASTIKA

A widespread symbol in all ancient civilizations (Asia, Central America, Mongolia, India, Northern Europe, Celts, Basques, Etruscans, etc.), it represents the vortex of creation.