Catégorie : Etudes historiques, politiques et scientifiques

Thanks to WEST’s new record, world’s nuclear fusion community moving forward

On Monday May 27, 2024, Karel Vereycken talked to physicist and nuclear fusion specialist Alain Bécoulet for Nouvelle Solidarité. He has been in charge of the ITER project’s engineering department since February 2020.

ITER is a large-scale scientific experiment intended to prove the viability of fusion as an energy source. ITER is currently under construction in the south of France. In an unprecedented international effort, seven partners—China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the United States—have pooled their financial and scientific resources to build the biggest fusion reactor in history.

Alain Bécoulet is a former research director at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), and in particular director of the IRFM, the Institut de recherche sur la fusion par confinement magnétique (Institute for Research on Fusion by Magnetic Confinement).

Karel Vereycken: Mr. Bécoulet, good morning, it’s great to have you on the phone.

Alain Bécoulet: Hello Mr. Vereycken, if I’ve understood correctly, you’re interested in what happened at WEST, in connection with the press releases that went out just about everywhere around May 15. (more below)

That’s right; I’ll give you my impressions and you can correct me. I understand that the Tore SUPRA Tokamak (in southern France)1, who with six minutes held a world record in duration till 2021, was a bit like your baby.

To tell the truth, I was director of the IRFM2, in charge of Tore SUPRA. If it can be considered “my baby”, it’s because under my governance it was radically modified and upgraded, and renamed “WEST”. Before me, it was Robert Aymar‘s baby3.

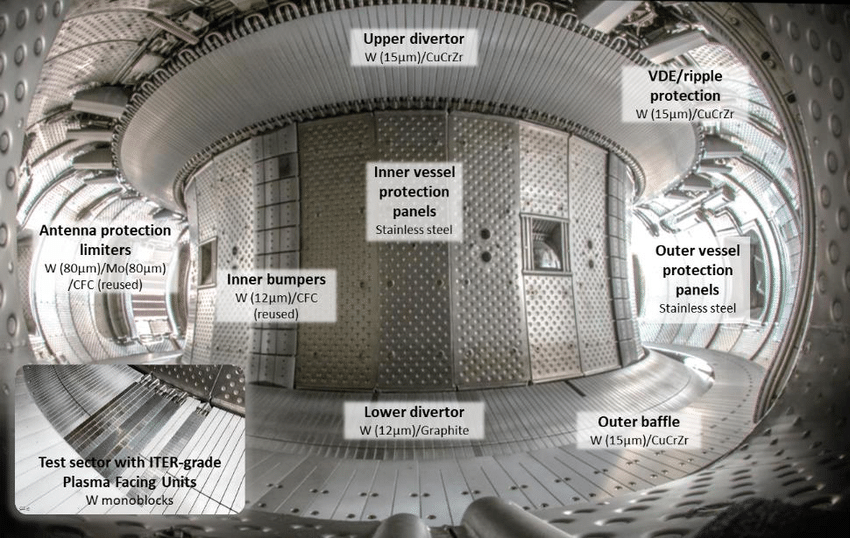

Right! But in WEST, it’s the W that does it all. And it’s a W for tungsten, a very heat resisting material that absorbs less than graphite and makes the machine more efficient?

Yes, it does. The major change we made with WEST, is that we went from a circular-limiter machine 4 to a “divertor” machine.5

On Tore SUPRA, the vertical plasma action was a circle resting on a graphite limiter and the plasma simply touched it.

For some years now, we’ve discovered that making a plasma in the shape of a D, or in the shape of a fish with an X point — called a “divertor” — produces much better results in terms of confining heat and impurities, particles, etc. So it was time for Tore SUPRA to go there.

At the same time, Tore SUPRA itself made it clear for us, that for ITER, it was not possible to continue with carbon – which was ITER’s original intention – and so ITER switched and was reconfigured to tungsten.

That’s when we took the opportunity to install a cooled tungsten divertor in Tore SUPRA. What’s more, Tore SUPRA’s mission has always been, even before ITER – we’ve been talking about it for a very long time now – the development and integration of technological solutions, and not so much performance-fusion.

If you put tritium in Tore SUPRA, you’re not going to get much in the way of power: it’s too small and not powerful enough in any ways to make fusion reactions of any note; but on the other hand, it’s perfectly relevant for all technological developments – it was on Tore SUPRA, it has to be recalled, that the first successful full-scale test of the superconducting coils now used in ITER took place!

I’m fully aware of that.

It was also Tore SUPRA that supplied all the rules for actively cooling all the components in front of the plasma, including diagnostics [i.e. measuring instruments], etc.; not forgetting solutions for continuous additional heating, in short a huge amount of technology.

So the idea, in the transition from Tore SUPRA to WEST, was to continue along the path of the “actively cooled tungsten divertor”.

I think the Koreans, too, with KSTAR, had already.…

There are several superconducting machines that have made equivalent advances –more successive than simultaneous– and that have inspired others; in this case, before talking about KSTAR, the machine that is closest to WEST, its little sister – you’re going to smile, but I didn’t call it WEST for nothing — is a machine that started up when Tore SUPRA was already operating, in Hefei, China, called EAST — with which we have cooperated enormously, both on coils and on plasma components, etc.

So the two laboratories have cooperated enormously; I chose the name WEST because we wanted to change the name of Tore SUPRA, to rejuvenate it and mark the fact that we were making this technology; so we called it WEST, a sort of sister machine to EAST, and the two machines really work together (EAST has now installed a tungsten divertor, etc.). ); even some of the modifications we made to WEST were made in cooperation, in partnership with the EAST machine, with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which supplied us with components, in particular the power supplies for the divertor coils, the new ICRH antennas, etc.; we had all this done by the Chinese.6

It’s extraordinary that this kind of cooperation can still take place in this world of conflict…

It really is! As for KSTAR, it’s quite a similar machine too, but I’d call it less pioneering. It’s only now arriving in this kind of world; it’s a long way behind –not that I’m blaming them, because since the teams are smaller, it’s more difficult– but that doesn’t stop us from cooperating a lot with KSTAR.

The only real difference with WEST lies in the coils, which are all inside a single cryostat (refrigeration system) – as with ITER, whereas in Tore SUPRA, when we built it, the coils were each in a separate cryostat.

To sum up: today, the large superconducting machines accompanying the ITER project are WEST, EAST, KSTAR and now the new JT60SA tokamak which has just gone into operation in Japan. It’s the size of the JET (at Culham in the UK) in superconductor, but doesn’t yet have a tungsten environment, and won’t for several years yet; so it’s not yet fully in a world as relevant, but it’s coming! And because it’s larger, it’ll probably outperform those EAST, WEST, etc. machines.

The press, and the official press release, reports a 15% gain in energy produced – which is still less than the energy spent on the reaction – and at the same time, they talk of a doubling of plasma density.

Please note: machines like WEST, EAST and KSTAR will never produce power fusion, for at least two good reasons:

- they’re too small;

- they’re not designed to hold tritium.

So there’s no fusion in these machines. Also, beware of energy gains and the like: these are gains in energy stored inside the machine, but not at all in energy supplied, in energy produced by fusion energy.

It’s not yet “break-even” (when the energy produced exceeds that of the reaction).

In fact, we improve confinement and increase confinement time. This improves the possibility of fusion, but we don’t enjoy fusion in these machines, which are too small and not powerful enough for that, particularly in terms of core plasma.

On the other hand, they are used because their edge plasma, i.e. the plasma inside the plasma interacting with structures such as tungsten, etc., is very similar to ITER’s. That’s why they’re so interesting, and as they can produce very long-lasting plasmas, the tests carried out in these machines are perfectly relevant to ITER.

So I’d like to come back to one of your questions, namely how this advances the promises of ITER. ITER is being built, and things are being manufactured, but ITER is a kind of big eater, constantly asking: “Can you continue the research?”

Obviously, we’re into things we’ve never tested, so anything we can test, anything that can debug things for us, is very welcome. So these machines, in particular WEST, EAST, etc., are helping us to consolidate our position, both in terms of design and in terms of manufacturing solutions –a divertor like the tungsten divertor currently cooled, it works!

And what WEST has just demonstrated– compared with the last time, when it achieved very high performance, particularly in terms of duration, with the Tore SUPRA configuration, on a carbon limiter, etc. — it did so in even more relevant conditions, thanks to a tungsten divertor.

The result of WEST was 364 seconds, or 6 minutes and 4 seconds, with an injected energy of 1.15 GJ, a stationary temperature of 50 million°C (4 keV) and an electron density twice that of the discharges obtained in the previous tokamak configuration, that of Tore SUPRA.

However, what’s really new and very important for ITER is that when these machines do this, it’s with components facing the plasma that are the same as ITER’s. We’ve taken great care to ensure that the WEST divertor has exactly the same technology as the ITER divertor. That’s how we test this technology, over timescales and with power flows arriving on these components that are highly relevant, as they are representative of the conditions in which they will live in ITER.

So ITER has become a globalized scientific experiment, decentralized and centralized at the same time.

ITER is the place where all the world’s fusion knowledge is being synthesized; but this process didn’t stop the day we signed the treaty, it’s being synthesized every day!

We continue to feed ITER with scientific and technical results. For example, if a machine says to us “wait a minute, you’ve done that, but we’ve found results that are different now that we’ve done more work”, we look at that very carefully, to find out whether or not there are any impacts. We’re in constant contact with all these people, to find out what’s coming out of the labs, experiments and simulations, and to find out whether or not there’s an impact on ITER, in which case we’re able to rectify the situation according to the scale of things

This sharing of cooperative data takes place in conditions of great trust?

It’s a scientific community that works like a scientific community, with no preconceptions, no ulterior motives, nothing at all.

A bit like the astronauts on the international space station?

Absolutely. We used to say “in the old days, it was taken for granted”, but now it’s true that it’s become almost surprising. If there’s a result in a Russian or Chinese machine, we have access to it and then we understand, we work, we discuss with them, it’s really very open.

That’s very promising.

We have to fight against the journalists who love to wonder whether there’s competition, whether someone has won or whatever…. That’s not what we’re about at all; we’re about cooperative scientific development. Everyone works in their own corner, of course, but for everyone! There’s no such thing as “I know, I know”, no, none of that exists in the world of fusion.

In the article I’m preparing, I’ll conclude by saying that the big problem with ITER is that there’s only one problem!

In a way, it’s almost true, it’s not the “big problem”, but it’s something that doesn’t encourage acceleration; competition encourages acceleration, we agree on that.

After all, the Chinese have 6 fusion reactors…

Be careful, they’re not “reactors”, beware of the vocabulary. They’re experiments, Tokamaks, plasma experiments, all much smaller. The biggest one I mentioned, in Japan, is ten times smaller than ITER!

Now there are start-ups and others, which we’re hosting here (at the CEA center in Cadarache, France) for three days; 50 start-ups are here, downstairs in the amphitheater, chatting with us; they’re all convinced they’re making reactors, but no! They’re just doing experiments, manips, experimental prototypes. Yes, even ITER isn’t a reactor. Mind you, the meaning of the word “reactor” is to produce electricity or energy, and we’re not there yet!

If someone tells you he is selling you a reactor, you can laugh in his face, because it’s not true, and it will remain so for a long time, unfortunately or fortunately, I don’t know. As far as the reactor phase is concerned, we’ve only just begun, with ITER, the transition to industry. That’s what we’re also doing these days, looking at how to transfer knowledge from laboratories – and ITER is THE world laboratory, in the true sense of the word, in the sense of a public research laboratory. How do we begin to transfer this to the industrialists who will have to build the reactors? But the time scale here isn’t next week!

Wouldn’t your real competitor be the National Ignition Facility (NIF)?7

Not even close! Because with the Americans, it’s in a way even worse, because they’re even less developed in their public research, it’s a long way from maturity. They once did a demonstration in a machine that wasn’t designed for it, and so on.

So if we wanted to go from the NIF to the reactor, we’d already have to make up all the ground we’ve accumulated since the state of magnetic fusion with the big JET experiments in 1997. So we’re almost 30 years away from reaching the levels of technological maturity, integration and overall maturity needed to move towards a reactor. And we, too, are still a long way from moving towards the reactor.

As far as competitors are concerned, to be honest, no one feels like a competitor today, and this is no joke: may the best man win! The problem is so complicated, and the stakes so high, that whoever comes up with the solution will have us all on our feet! There’s no such thing as competition.

We’re starting to see, with these new start-ups, people saying “yes, but we’re moving towards industrial solutions, etc., so we may develop patents that we obviously don’t want to reveal or sell”. Fair enough!

But hey, if they know how to make one of the “technological bricks” and it has a patent, good for them. But that’s not even going to stop us talking. A patent, once you’ve registered it, isn’t a secret, it’s simply something that belongs to you and that you can put on the public square; whoever uses it is just going to have to pay for it, that’s all. So it’s not a war or anything.

The problem is really extremely complicated, and we’re now entering the pre-industrial world of the thing, which is very exciting, isn’t it! I started my career as a theoretician 35 years ago, and I can tell you that we were really on the calculator and not even on the computer yet. Now we’re in: 1/ a complete demonstration of the feasibility of the whole system with ITER, which is in a way the end (the objective) of fundamental public research; 2/ the moment when we’ll say “here’s the great recipe, now it’s up to you to industrialize it, improve it, make it economically viable, etc.”. But ITER still has to show that we can do it, and I believe we can, even though we’re still building the machine and haven’t yet made plasma! But then again, on paper it’s always beautiful…

What do you see as the final hurdles? What more can the public authorities in the various countries do?

I’d encourage you to keep an eye on things until October-November, when the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) will issue a strategic document, prepared by all of us –and I’m one of its key authors. It’s a global strategy document on the development of fusion energy, i.e. the production of energy through fusion.

It’s a very interesting document which, in around twenty pages, covers all the regulatory, technological, scientific and industrial aspects – everything you could possibly dream of: it’s got it all!

And it gives a great deal of information on the challenges facing this community – which is in the process of moving from a purely public research community to a mixed public-private community, moving towards industry, etc. – and on what remains to be done by this community, in terms of nuclear regulations, industrialization, work on the overall efficiency of all sub-systems, and availability (a reactor can’t just run for three minutes every day, it has to work 24 hours a day for 40 years).

This strategic document, which will be issued by the International Agency, should enable all players – I’d almost say “outsiders”: investors, the press, politicians, etc. – to understand where the merger stands and what remains to be done. So it’s a fairly ambitious document, with such a lofty goal, but one that has been made simple and readable for once; we’ve put a lot of effort into it, and I think we’ve succeeded.

It’s really condensed: each paragraph covers 40 or 50 years of research (!), but I think it’s understandable; at the moment it’s being edited by the IAEA, and will be published in early autumn.

Ok, we’ll watch that.

And finally, here are my thoughts on what remains to be done for fusion:

- New technological building blocks. There are things that even ITER won’t be able to do, such as fully demonstrating the closure of the tritium cycle – how to make tritium, and how to really burn it in situ; we’re going to do a few demonstrations, but we don’t yet have the complete cycle, and we won’t have it just with ITER.

- Materials. Since magnetic fusion generates very energetic neutrons, and lots of them – a machine like ITER is designed to live for a certain time with a certain plasma rhythm, so it has no problem surviving these neutrons. But if we built the same ITER and ran it for 40 years, 24 hours a day, it wouldn’t last; its materials wouldn’t stand up to the shock. So we need other materials, and materials research and development.

- This brings us to maintenance: how can we learn to intervene in these kinds of objects without disturbing them too much, working with robotics and appropriate intelligence to understand these extremely complex systems? So we also need to model them; some elements are very difficult to manufacture, so we need to think about how to work on the design so that manufacturers have less difficulty in doing what they’re asked to do, etc.

- There are also nuclear regulations.

Is this new measuring device just demonstrated on WEST really a breakthrough?

The first to communicate this WEST result were the Americans, which surprised me, but hey, why not?

Yes, it surprised me too.

Because of an unfortunate sentence at the beginning of their article, we got the impression that WEST was a machine from the Princeton laboratory!

Yes, that’s right!

International Cooperation

I spoke to you about the collaboration with China; when I created WEST, we set up a collaborative, partnership-based process that is almost even more ambitious than ITER. We partnered some thirty laboratories around the world to help us build WEST. It thus became a kind of international machine, operated by the CEA without any problems, but an international machine, and we played the same role as ITER: we tried to do what we call supply in kind –I mentioned the Chinese, who gave us power supplies, heating antennas, etc., but there are many countries like that: the Indians have manufactured and supplied us with things, and in this case the Princeton laboratory has designed, manufactured and installed a diagnostic: what you call a measuring instrument is in fact an advance that we test on the machine, and the Americans, or the Princeton people now, can now say “there, we know how to do that, and the proof: we tested it there and there, etc.”. You can think of these major research instruments (like WEST, EAST, etc.), particularly in the field of fusion, as test benches for all kinds of things.

Do we have a machine that actually makes plasma? It’s a bit like CERN (Geneva based particle accellerator), where you’ve got a device that accelerates particles, and then you’ve got lots of people who come to watch, put particles together, make them collide like this, put them in this detector, make them do something, and exploit the science that goes with it.

A Tokamak is also a test bench somewhere, for testing components with plasma, diagnostics, heating systems and so on. So it lends itself well to partnership, because you’ve got a central unit, a central operator who’s going to do the bulk of the machine, who’s going to rectify the coils or the enclosures, etc.; and then afterwards, you can have a huge number of people who are going to come and contribute to a brick that we’re going to put into this machine.

And WEST works with China, with Korea, with many French laboratories –CNRS laboratories and universities that simply bring us diagnostics or simulations – with the United States, with India and with many other countries. And we have a steering committee; for this machine, it’s not just the CEA that decides on its experimental plan: once a year, people from all these labs get together to examine what we’ve done and what we want to do with this machine. Remember that these are always integrated contributions, mixing technology and physics.

It’s wonderful! Thank you for your answers, which have shown us the global, shared process towards a more peaceful world.

We’re trying… We believe in scientific diplomacy here. It’s not easy, it’s no easier than normal diplomacy, but scientific diplomacy does exist, it’s an aspect we believe in and demonstrate every day, we show that it exists and that it also contributes, effectively, to the planet’s progress, even if sometimes it’s more difficult… I’m used to comparing it to sports or artistic diplomacy; the Olympic Games shouldn’t turn as sour as it’s turning, it doesn’t make sense.

Thank you, congratulations, we’re proud of you and your teams, keep up the good work!

Thank you very much. See you soon.

- With a major radius of 2.25m (machine centre to plasma centre) and a minor radius of 0,70m, Tore Supra (before it was reconfigured as WEST) was one of the largest tokamaks in the world. Its main feature was the superconducting toroidal magnets which enabled generation of a permanent toroidal magnetic field. Tore Supra was also the only tokamak with plasma facing components actively cooled. Theses two features allow the study of plasma with long pulse duration. ↩︎

- Institut de recherche sur la fusion par confinement magnétique (Institute for Research on Fusion by Magnetic Confinement. ↩︎

- Robert Aymar was the Director General of CERN (2004–2008), serving a five-year term in that role. In 1977, Robert Aymar was appointed Head of the Tore Supra Project, to be constructed at Cadarache (France). In 1990, he was appointed Director of the Direction des Sciences de la Matière of the CEA, where he directed a wide range of basic research programmes, both experimental and theoretical. ↩︎

- The “Limiter” of the Tore SUPRA tokamak (made of graphite), was the element that extracted most of the energy contained in the plasma (in the shape of a flat circular ring located in the lower part of the donut shaped machine).

↩︎ - In WEST, the actively cooled 456-component divertor at the bottom of the vacuum vessel extracts the heat and ash produced by the fusion reaction, minimizes plasma contamination and protects the surrounding walls from thermal and neutron loads. ↩︎

- Most of this industrial production (i.e. 16,000 blocks of tungsten), was carried out by AT&M (China), with the support of the Chinese laboratory ASIPP as part of the joint CEA-China collaboration (SIFFER, SIno French Fusion Energy centeR). Already, in 2016, the Institute of Plasma Physics (ASIPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), had supplied ICRH (Ion Cyclotron Resonant Heating) antennas for Tore SUPRA. ↩︎

- In December 2022, an NIF experiment used 2.05 megajoules of laser energy to produce 3.15 megajoules of fusion energy.

↩︎

1953-1968: When « Water for Peace » was at the Center of US Politics

By Karel Vereycken, May 2024.

The current unprecedented bloody extermination of the Palestinians in Gaza reminds historians of some of the darkest pages of European history. Between 1940 and 1943, some 300,000 Jews confined in the Ghetto of Warsaw were killed by bullet or gas, combined with 92,000 victims of starvation and related diseases, the Ghetto’s Uprising, and the casualties of its final destruction.

Not in our name and never again! Only an immediate and durable cease-fire, concluded in the context of regional agreements for mutually beneficial reconstruction, can offer a perspective where peace becomes thinkable either in the form of two States, one State, or maybe even better, as a confederation. That might look ambitious and even Utopian.

This article looks at the ambitious proposals put on the table after the six days war of 1967, when major forces in the world stepped in and proposed, including by the smart use of civilian nuclear power, to increase the carrying capacity of the entire region. Nuclear desalination facilities and abundant energy from nuclear and hydropower, they thought, can provide the optimum conditions for both Israeli’s and Palestinian’s to have access to abundant fresh water for agriculture, industry and living.

The shock of the six year’s war

In June 1967, following border clashes over water resources and what appeared as a military mobilization of its Arab neighbors, Israel staged a sudden preemptive war against Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

- On June 5th, it destroyed more than 90 percent of Egypt’s air force on the tarmac. A similar air assault incapacitated the Syrian air force. Within three days the Israelis had achieved an overwhelming victory on the ground.

- On June 7, Israeli forces drove Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank. The UN Security Council called for a cease-fire on June 7 that was immediately accepted by Israel and Jordan. Egypt accepted the following day. Syria held out, however, and continued to shell villages in northern Israel.

- On June 9 Israel launched an assault on the fortified Golan Heights, capturing it from Syrian forces after a day of heavy fighting. Syria accepted the cease-fire on June 10. Israel’s decisive victory included the capture of the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, Old City of Jerusalem, and Golan Heights; the status of these territories subsequently became a major point of contention in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The Arab countries’ losses in the conflict were disastrous. Egypt’s casualties numbered more than 11,000, with 6,000 for Jordan and 1,000 for Syria, compared with only 700 for Israel. The conflict resulted in hundreds of thousands of refugees and brought more than one million Palestinians in the occupied territories under Israeli rule.

Months after the war, in November, the United Nations passed UN Resolution 242, which called for Israel’s withdrawal from the territories it had captured in the war in exchange for lasting peace.

For most western elites, including most Jewish elites all over the world, the 6 day war came both as a shock and a reminder that the two main causes of war had been left unsolved: refugees (that of Palestinians pushed out and Jews arriving) and water access for all.

The « Johnston Plan » for water sharing

In the early 50’s, at the request of the United Nations Refugee Works Administration (UNRWA), experts of the US Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), had designed an equitable water sharing program for the entire Jordan basin involving Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria.

Just as the orginal TVA, by building irrigation canals and dams, the program would have allowed the exansion of irrigated farmland and upshifting the economy and the living standards with energy from hydro-power.

In 1953, Eisenhower, pressured by his Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, sent Eric Johnston as his envoy to convince all the nations of the region to adopt the scheme known as the “Johnston plan.” To avoid countries willing to escape colonial exploitation joining the Communist or neutralist bloc, they argues, the US should offer development programs and keep them on the right side of history.

In Southwest Asia, a wonderful and well thought water sharing program was about to be adopted.

Unfortunately, Eisenhower, on March 28, 1956, approved the secret OMEGA Memorandum whose aim was to effect a reorientation of Nasser’s policies toward cooperation with the West while diminishing what were seen as his harmful attempts to influence other Middle East countries. Nasser, the first after Nepal, without informing his allies, had recognized Communist China on May 16. Pertaining to measures directed at Egypt, the provisions included a delay by the United States and Britain in concluding negotiations on financing the Aswan Dam.

As a result, John Foster Dulles, in cahoots with the British and the US southern cotton lobby1 , went ahead with suspending US financing of the Aswan dam (90%) which Nasser needed to irrigate farmland at home.

On Thursday July 19, 1956, Dulles asked the Egyptian Ambassador in Washington, Mr. Ahmed Hussein, to come to his office. When he arrived Mr. Dulles handed him a letter announcing the withdrawal of the United States offer to grant $56,000,000 towards financing the construction of the High Dam at Aswan.2

This decision unleashed a chain of events leading to the famous “Suez crisis” which Eisenhower fortunately brought to a halt once he realized it could end up in a nuclear conflict.

As a result, the most precious aspect of the “Johnston plan” for the ME, that of mutual trust building around the perspective of a shared, common future, was ruined after the Suez affair.

As a result, those that should have been partners of one single global plan to share the waters of the Jordan basin, went for it alone. Israel went ahead with its own National Water Carrier, tapping fresh water from the Sea of Galilee into a water conveyance systems bringing water from the northern border with Lebanon to the Negev desert deep South.

Jordan, with US financing, built the Eastern Ghor water conveyance system, now called “King Abdullah Canal”, to provide water for Jordan’s agriculture and capital while Syria constructed a dam on the Yarmuk, one of the tributaries of the Jordan river. 3

Nuclear desalination, the talk of the Day

Immediately after the six days war, however, the perspective of a massive investment in water and energy to solve the refugee and water crisis in the Middle East, became the talk of the day.

By these dramatic events, thanks to the men and women willing to answer them, the science, the technology and many of the plans elaborated between 1945 and 1967 to use nuclear power for peaceful aims came back on the table.

Key in this was leading US nuclear physicist Alvin Weinberg, who was the administrator of Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) during and after the Manhattan Project.

Weinberg was appointed in 1960 to the President’s Science Advisory Committee in the Eisenhower administration and later served on it in the Kennedy administration.

Weinberg inspired and organized his networks to propose projects for the peaceful use on civilian nuclear power. Weinberg’s career was brutally terminated when he was fired by Nixon in 1973 for pleading, just as Edward Teller did before his death, in favor of thorium fueled molten salt reactors (which don’t produce plutonium for nuclear bombs).

Water for Peace Conference of May 1967

Tragically and sadly, hardly three weeks before the Six day war, an international conference on “Water for Peace”, was held May 23-31, 1967, in Washington. President Lyndon Johnson (democrat) addressed the conference during the opening ceremonies, pledging that the United States would:

« continue work in every area which holds promise for the world’s water needs, » and would « share the fruits of this technology [nuclear desalination] with all of those who wish to share it with us. » 4

The Department of State Office of International Scientific and Technological Affairs considered the conference a « complete success, » and an internal report noted that,

« 94 countries were represented together with 24 international organizations; 635 official delegates, 61 participants from international organizations, and over 2,000 observers attended. » 5

One of the technical papers presented at the Water for Peace conference, entitled « Desalted Water for Agriculture » by Weinberg’s friend and colleague R. Philip Hammond, hypothesized that, with demonstrated methods of agriculture and « virtually demonstrated » methods of nuclear desalting, food could be grown with water costing 3 cents per day per person.

Alvin Weinberg was convinced, based on the work of his own institution, that these price estimates were « not unreasonable. »

After reading the paper in draft, Weinberg determined that more research was needed, and passed the paper on to Dr. J. George Harrar at the Rockefeller Foundation because of its « longstanding interest in the development of countries, such as Mexico, that suffer from a lack of water. »

Harrar, speaking about a recent discussion he had with Israeli President David Ben-Gurion, said:

« I understand that it is his hope and plan that atomic power for water desalination may become a reality in the Negev one day. »6

Weinberg reported that Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) Chairman Glenn T. Seaborg and AEC Commissioner James T. Ramey had “expressed interest in such agro-industrial complexes in several of their recent speeches. » 7(*5)

In a visionary speech, called “The Next Stage of Nuclear Energy,” Weinberg developed even more this idea of building “Food factories in the desert”:

“One can now visualize a new kind of desert agriculture, conducted in units so highly rationalized as to be designated « food factories » rather than farms. In these food factories, plants would be watered and fertilized at precisely the right time, and in precisely the right amounts. Fortunately fertile coastal deserts suitable for such food factories occur in many parts of the world.

The food factory would naturally be accompanied by other energy-intensive chemical processes, particularly those based on electrolytic hydrogen. I have already mentioned production of ammonia; one could imagine other processes such as reduction of iron ore by hydrogen, or electrolytic refining of bauxite to produce aluminium, or production of caustic and chlorine, and thence polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics.

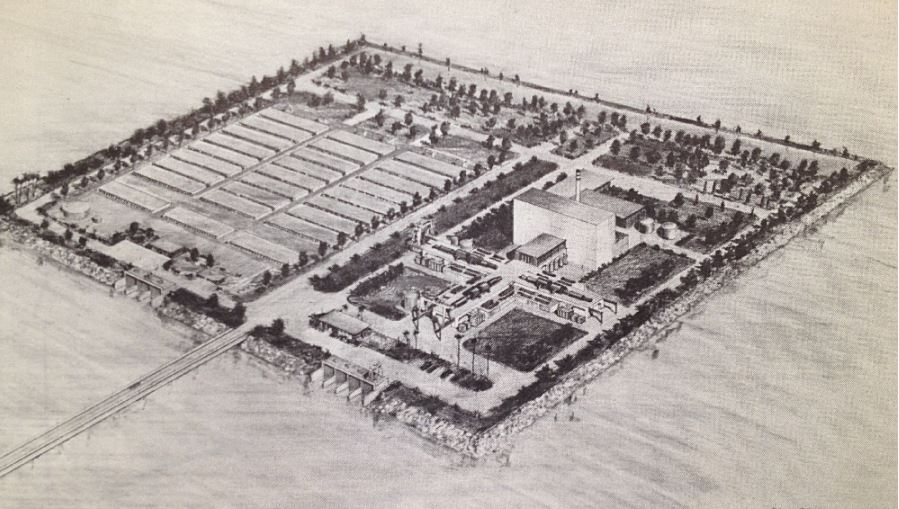

Altogether what one contemplates is the nuclear powered agro-industrial complex already alluded to by AEC Chairman Seaborg in his opening remarks. This summer we conducted at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory a study under the guidance of Professor E.A. Mason of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to examine in some detail just what such a nuclear powered agro-industrial complex might look like.

Even this near term complex, based on energy from light water reactors, seems surprisingly attractive. In this complex, a variety of crops would be grown on 140,000 acres of irrigated desert. Ammonia, phosphorus from phosphate rock, caustic, chlorine, and salt would be manufactured.

The total investment (including a 2000 Mwe reactor and a 500 million gallons a day desalting plant) comes to about $900 million. The annual value of products produced is $330 million, of which $100 million are agricultural products.

The profit on the venture is computed to be $136 million per year, or 15% of the capital investment. I believe that the nuclear powered agro-industrial complex may well become an impressively powerful instrument for development. But it is idle to speak of the agro-industrial complex unless the main ingredient — the cheap and reliable reactor — is available.” 8

On June 13, hardly days after the six day’s war, AEC chairman Seaborg wrote a letter to Johnson’s Secretary of State Dean Rusk:

“The recent developments in the Middle East prompt me to recall to your attention certain projects which have been under consideration for this region for some time in the past. I am referring to the two dual-purpose nuclear desalting projects, one proposed for installation in Israel and the other proposed for installation in the United Arab Republic (Egypt and Syria were one single state between 1958 and 1961), which were the subject of your memorandum to the President of May 21, 1966 … It occurs to us that the possible usefulness of these projects in the overall settlement of the Middle East dispute may be rather significant …

As you know, both Israel and the UAR have attached considerable importance to their respective projects. The proposed Israeli project, in particular, always had the advantage of providing Israel with a source of water not subject to interruption by neighboring states and not dependent on the allocation of the already inadequate water resources of the Jordan Valley.

Once again, it seems to me that the recent events may well intensify the problem of water allocation in the area rather than ease it. One or more desalting plants would both add significantly to the total volume of water available to the region …

It is interesting to note that at the recent Water for Peace Conference in Washington, UAR and Israeli representatives participated in a collateral meeting of nations interested in nuclear desalting and reaffirmed the strong interest of their governments in these projects.”

In the same letter, Seaborg underlined that US assistance for a nuclear desalination program,

“could possibly be used to secure Israeli agreement to place its entire nuclear program, including the Dimona project, under IAEA safeguards. It seems to me that the recent events probably increase rather than decrease the danger that one or more of the Middle Eastern countries will feel, however mistakenly, that its best interest in the future would be served by the acquisition of nuclear weapons.”

On June 23, 1967, Lewis Strauss, who was a founding member and, starting 1953, the head of the AEC till 1958, pressured his friend and protector Eisenhower to speak up for nuclear desalination for peace in the Middle East, by giving him the following memo called “A proposal for our Time”:

“Attention to the debates in the United Nations since the end of May must convince the observer that an end to the trouble in the Near East is not in sight. The introduction of a new and dramatic element will be required to establish a climate in which peace can begin to be negotiated. The resources of diplomacy appear exhausted, and the « lie direct » has been exchanged so often that men can hardly be expected to reach agreement by rational discussion in the atmosphere which has been created.

“The two fundamental problems in the Near East are (a) water, and (b) displaced populations. It is these issues which have exacerbated international relationships in that area over the years, and they are not to be resolved by political or military measures. By a simple, bold, and imaginative step, it is in our power to solve both problems … Two of the installations would be located at appropriate points on the Mediterranean coast of Israel and a smaller one at the northern end of the Gulf of Aqaba in either Jordan or Israel, as the most suitable terrain may dictate….

“Were the President of the United States to electrify the world by such a proposal, as President Eisenhower did in his Atoms-for-Peace speech to the United Nations in 1953, it would be hailed and welcomed by millions who now can see no way out of the morass in which the powers are presently floundering with its threat of triggering more widespread war. The proposal might well be the beginning of a new life in the lands of the oldest civilizations.

“The proposal, of course, does not settle the boundary disputes and other acute issues now confronting the belligerents, but their settlement would be immensely accelerated and facilitated by the pressure from all sides to get ahead with such a project where delay would be counted in human lives and misery. It could be announced that no affirmative steps would be taken until negotiations at least began. In the atmosphere that would immediately follow such a proposal, the leaders of the Near Eastern countries would be invited to come together on the basis of the proposals. They have a common forum in the International Atomic Energy Agency.”

“The introduction of fresh water from all three plants into the arid and semi-arid areas would have the effect of opening to settlement many hundred square miles which heretofore have never supported human life (other than on a nomadic basis), and the controversy over the division of the Jordan River would become de minimis.

“The work of building the great plants, laying the pipe lines, constructing reservoirs, power lines, irrigation ditches, etc., will absorb the unskilled labor of thousands of displaced persons. When the plants are in operation, the labor force could be settled in irrigated areas under conditions far superior to any life that they have ever experienced.

“Solely as a measure of magnitude, it might be noted that the completed project will represent substantially less than one year’s expenditure on the moon program. It will pay for itself and return income in perpetuity, retiring the borrowings incurred and rewarding the governments and individuals with vision enough to have subscribed to it initially.

“Cooperation of the Arab and Israeli governments will be necessary in order to agree upon a modus vivendi for allocating water and power, and it will be apparent that any government which simply declined to discuss or participate in such a cooperative arrangement would have to answer to its citizens sooner or later.” 9

Lewis Strauss

Lewis Strauss, started his career, not in nuclear science, but working as an investment banker at the Wall Street investment bank Kuhn, Loeb & Co. On March 5, 1923, he married Alice Hanauer, the daughter of Jerome J. Hanauer, who was one of the Kuhn Loeb partners.

But Strauss was also a philanthropist financing and leading several Jewish organizations. In 1933 he was a member of the executive committee of the American Jewish Committee. He was active in the Jewish Agricultural Society, for whom by 1941 he was honorary president. By 1938 he was also active in the Palestine Development Council, the Baron de Hirsch Fund, and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

However, he was not a Zionist and opposed the establishment of a Jewish state in Mandatory Palestine. He did not view Jews as belonging to a nation or a race; he considered himself an American of Jewish religion, and consequently he advocated for the rights of Jews to live as equal and integral citizens of the nations in which they resided.

Politically, Strauss got befriended and worked directly with President Herbert Hoover and felt irritated by FDR.

Edmond de Rothschild

One month after Strauss memo to Eisenhower, on July 18, US Ambassador Bruce reported the fact that French-Swiss banker Edmond Adolphe de Rothschild, in two letters to the London Times, had advocated for three nuclear desalting plants for Israel, Jordan, and the Gaza Strip to assist in the resettlement of more than 200,000 refugees.

This provoked comments and questions in the House of Commons, which generally approved the idea or at least further exploration of it.

British Prime Minister Wilson was convinced of the technical-economic feasibility of the plan, but the Foreign Office was concerned about the cost.

According to Embassy officials in London: “Apart from the obvious political difficulties, it was mainly a question of a very large amount of cheap money, which the UK did not have available.”

However, Edmond de Rothschild was apparently willing to put up 1 million pounds sterling of his own money. 10

Humanitarian and/or Business Plan?

Both Strauss and Rothschild shared the same idea, that of forming a corporation with a charter resembling that of COMSAT, a public, federally funded corporation created in 1962 intended to develop a commercial international satellite communication system. Although Comsat was government regulated, it was equally owned by some major communications corporations and independent investors.

The new corporation, wrote Strauss, should be created,

“with the Government subscribing to half of the stock, the balance to be offered for public subscription in the security markets of the world. The amount thus to be raised, say $200,000,000, would be used to begin construction of the first of three large nuclear plants for the dual purpose of producing kilowatts of electrical energy and desalting sea water, with emphasis on the latter purpose.”

“Private capital both in the United States and Great Britain would certainly respond to the challenge of such an enterprise on the initiative of the Government,” concluded Strauss.

Strauss and Eisenhower

Strauss was a staunch anti-communist and successfully lobbied Truman, who publicly announced the decision, as demanded by Strauss, to develop the hydrogen bomb on January 31, 1950. Less than three years later, the US detonated the world’s first H-bomb, only to have the Soviets follow suit 10 months later. Strauss’ determination to develop the hydrogen bomb was doggedly opposed by physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the chairman of the AEC’s general advisory committee who led the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Fearing the hydrogen bomb would only accelerate a dangerous Cold War arms race, Oppenheimer had argued for more openness about the size and capabilities of America’s nuclear arsenal, which Strauss thought would only benefit the Soviets.

After leaving the AEC in 1950, Strauss re-entered government when newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him as an atomic energy adviser in February 1953. Strauss, who had been a major donor to Eisenhower’s presidential campaign, wielded considerable power as all federal agencies were required to clear their atomic-related activities with him. Months later, Eisenhower asked Strauss to chair the AEC. Strauss agreed on one condition: that Oppenheimer no longer serve as a consultant to the commission…

Strauss’ plan for desalination became known as the “Strauss-Eisenhower plan” because Eisenhower, whose major speech Atoms for Peace at the UNGA in 1953 had been widely welcomed by the American public, published an article, largely inspired by the Strauss 1967 memo and edited by editor in chief of Reader’s Digest Ben Hibbs in that magazine’s June 1968 edition.

The full text of Eisenhower’s article was introduced as early on May 16 in the Congressional record (p. 13756), by Senator James G. Fulton.

Noteworthy, the fact that Robert F. Kennedy, who saved the world from nuclear extinction by using his back channels with Russian officials, was assassinated on June 8 of the same year.

In the overall inspiring article in his Reader’s Digest, former president Eisenhower, visibly convinced by Admiral Lewis Strauss and his banker’s friends such as Edmond de Rothschild who thought it was good business, wrote that:

“There is every reason to suppose that it could be a successful, self-sustaining business enterprise, whose revenues would derive from the sale of it products – water and electricity – to the users. Our government would make an initial investment in some of the corporation’s stock, and the rest would be sold to private investors in the security markets of the world. Additional money would be raised through the international marketing of convertible debentures. We are assured by international bankers that the financial world, under normal conditions, would welcome such an investment opportunity.”

However, Eisenhower made an extremely crucial point, that is very relevant for today:

”Most of the professional diplomats seem to think that we must have peace in the Middle East before the plan can be implemented. I contend that the reverse is true: the proposal itself is a way to peace.”

Unfortunately, in his Reader’s Digest article, the former president, or the editor, or by common decision of both, left out a key passage of Strauss earlier (June 1967) proposal, a passage implicitly proposing to make the Middle East desalting proposal the cornerstone for ending the Cold War!

Strauss, interestingly enough, had changed the axioms of his thinking, because the view he presented in 1967 (start some sort of peaceful cooperation with the USSR) was miles away from his views in 1950 (contain the Soviets at all cost). That said key passage reads as follows:

“Design and construction contracts would be let on bids in the several countries which have had experience in building large nuclear reactors, i.e., the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the USSR.”

Those days Political parties

While today’s US party platforms are utter lunacy, in 1968, when Nixon was running against Humphrey and Wallace, voters could choose between two parties favoring nuclear desalination!

The Democratic party platform:

“To maintain our leadership in the application of energy, we will push forward with research and development to assure a balanced program for the supply of energy for electric power, both public and private. This effort should go hand in hand with development of « breeder » reactors and large-scale nuclear desalting plants that can provide pure water economically from the sea for domestic use and agricultural and industrial development in arid regions, and with broadened medical and biological applications of atomic energy. In addition to the physical sciences, the social sciences will be encouraged and assisted to identify and deal with the problem areas of society.

“… Lasting peace in the Middle East depends upon agreed and secured frontiers, respect for the territorial integrity of all states, the guaranteed right of innocent passage through all international waterways, a humane resettlement of the Arab refugees, and the establishment of a non-provocative military balance. To achieve these objectives, we support negotiations among the concerned parties. We strongly support efforts to achieve an agreement among states in the area and those states supplying arms to limit the flow of military equipment to the Middle East. We support efforts to raise the living standards throughout the area, including desalinization and regional irrigation projects which cut across state frontiers.” 11

The Republican Party platform:

“We support efforts to increase our total fresh water supply by further research in weather modification, and in better methods of desalination of salt and brackish waters.”

And on the Middle East, it said:

“To replace the ancient rivalries of this region with new hope and opportunity, we vigorously support a well conceived plan of regional development, including the bold nuclear desalination and irrigation proposal of former President Eisenhower.” 12(*10)

Conclusion

In one way or another, Middle East Peace, based on the sharing of water and energy obtained by the most advanced technologies (in terms of energy density), were on the agenda those days, and sometimes even conceptualized as the cornerstone of a potential new international architecture of security and mutual development ending the geopolitics of the Cold War.

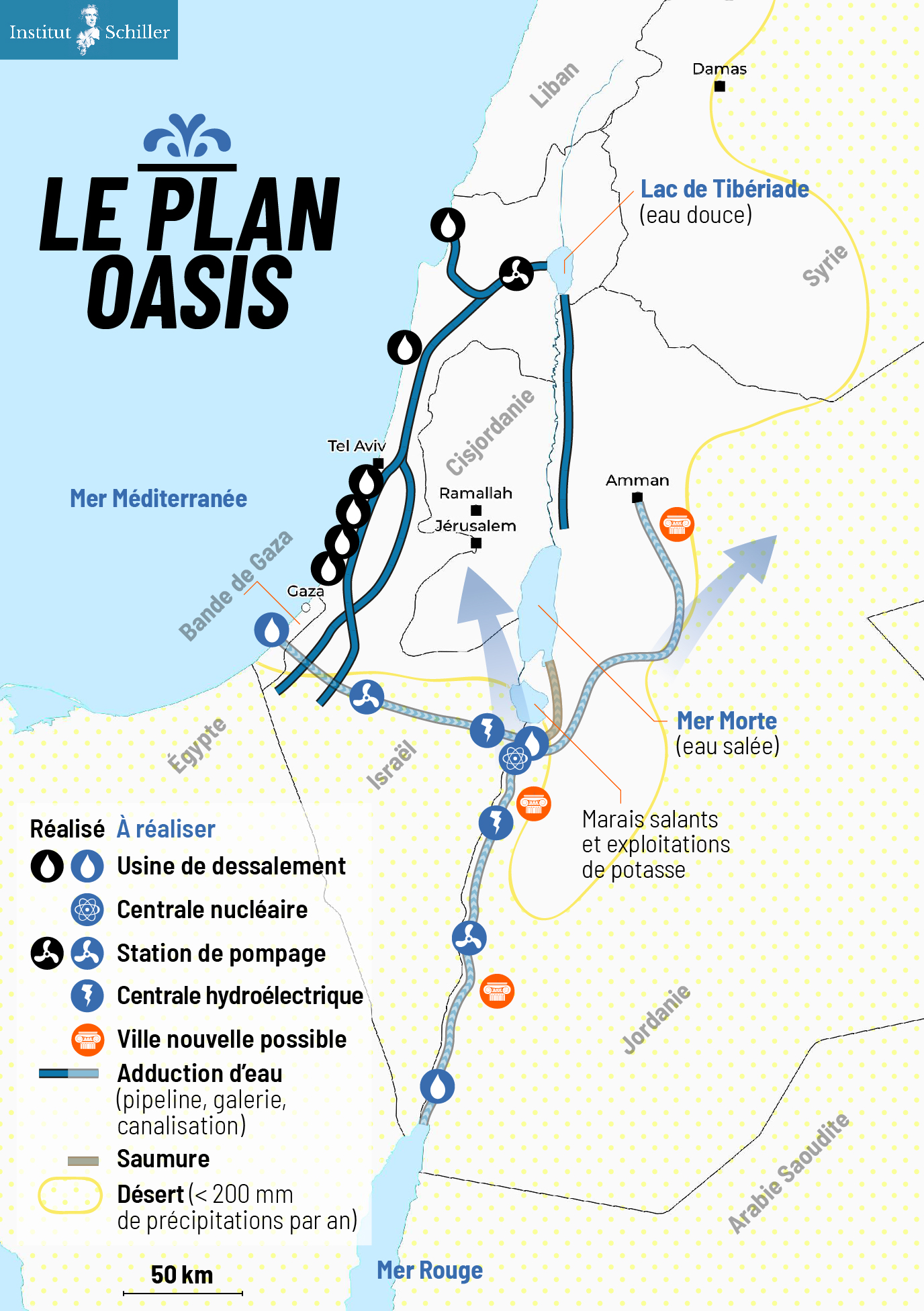

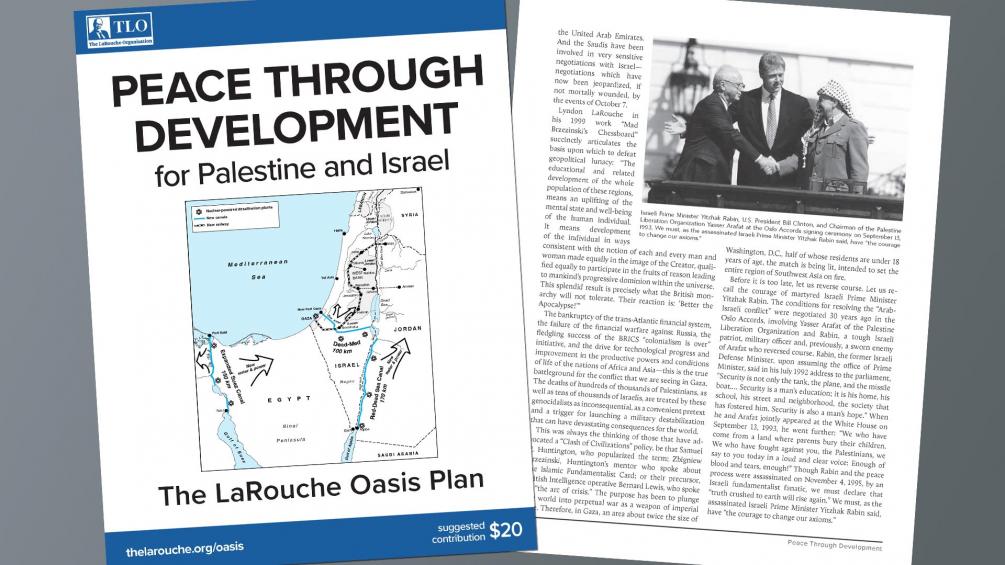

Lyndon LaRouche’s proposals in 1975 and his Oasis plan currently proposed and promoted by the international Schiller Institute want to do exactly that. 13

LaRouche’s « Blue Peace » Oasis plan, to be put on the table of diplomatic negotiations as the « spine » of a durable peace agreement », includes:

- Israel’s relinquishment of exclusive control over water resources in favor of a fair resource-sharing agreement between all the countries in the region;

- The reconstruction and economic development of the Gaza Strip, including the Yasser Arafat International Airport (inaugurated in 1998 and bulldozered by Israeli in 2002), a major seaport backed up by a hinterland equipped with industrial and agricultural infrastructure.

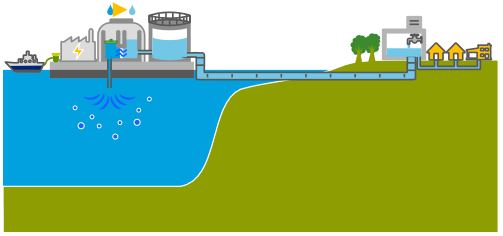

- A floating, underwater or off-shore desalination plant will be stationed in front of Gaza.

- The construction of a fast rail network reconnecting Palestine (including Gaza) and Israel to its neighbors;

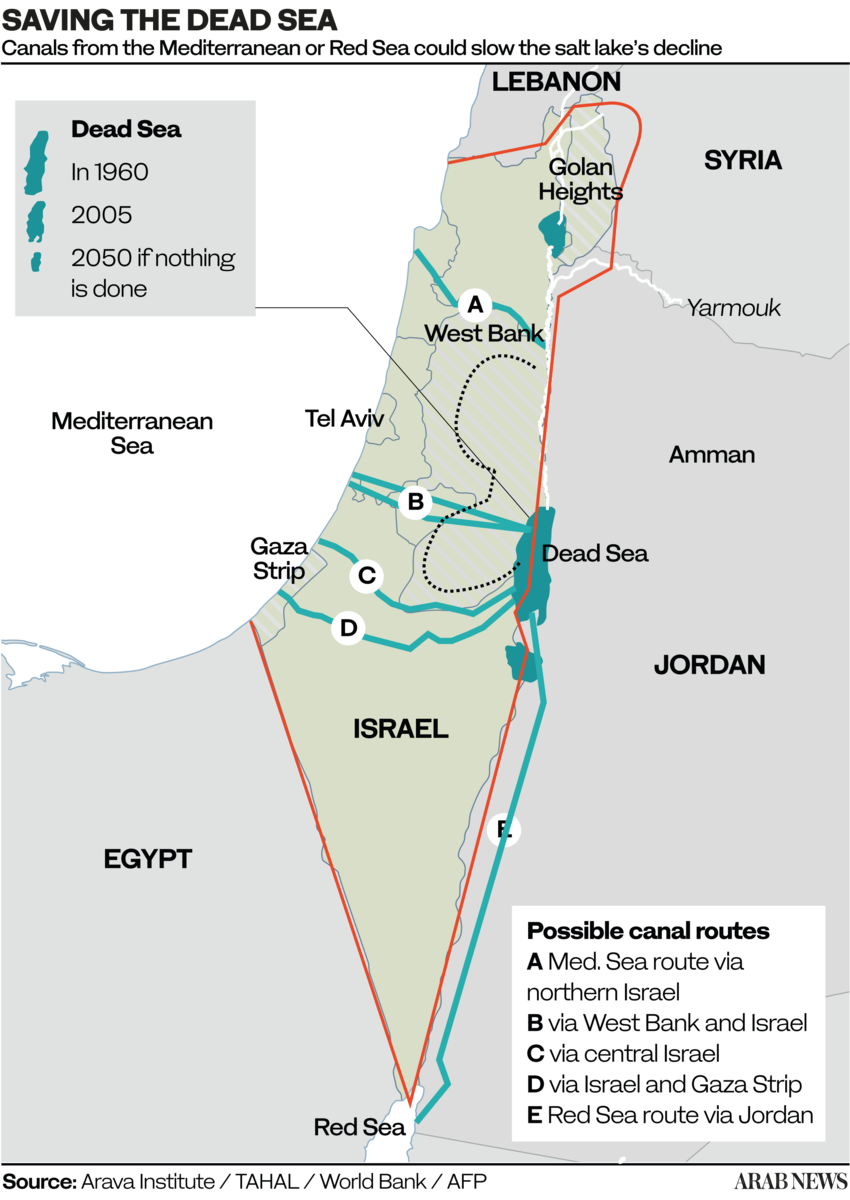

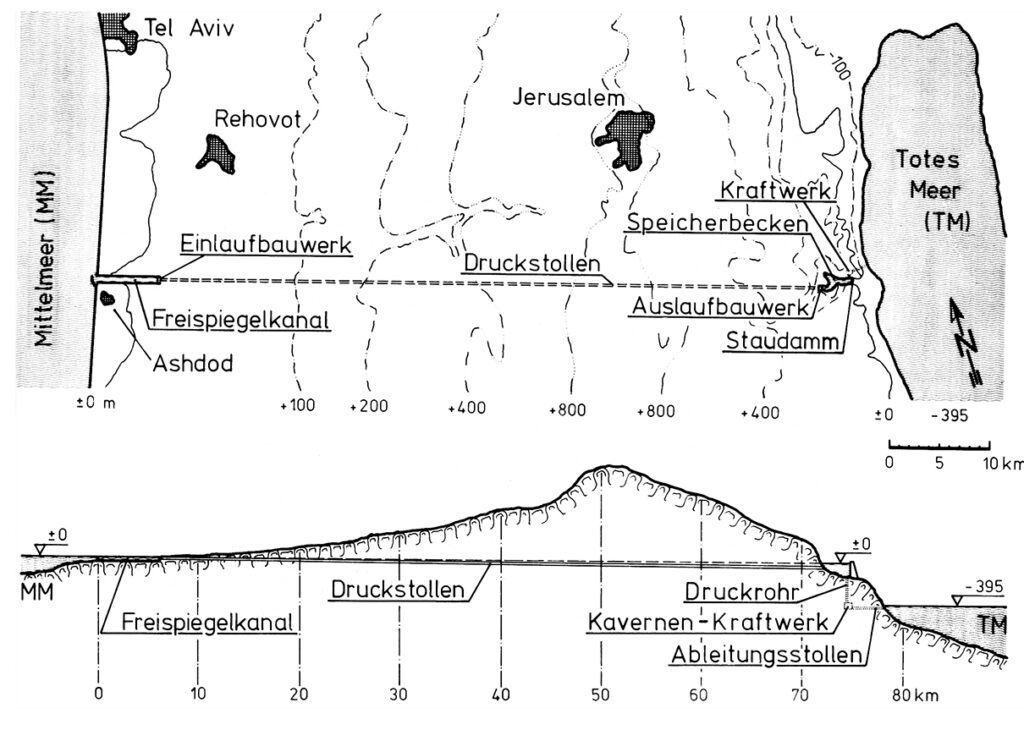

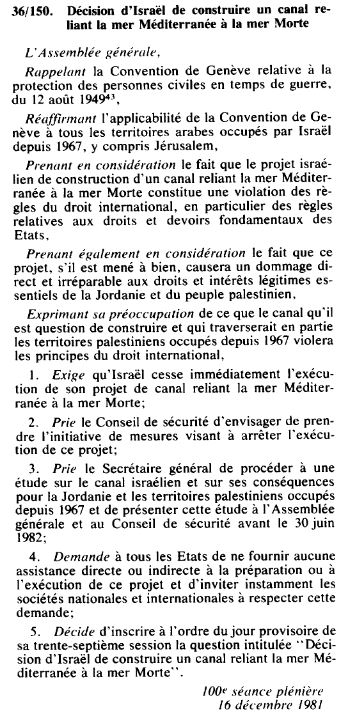

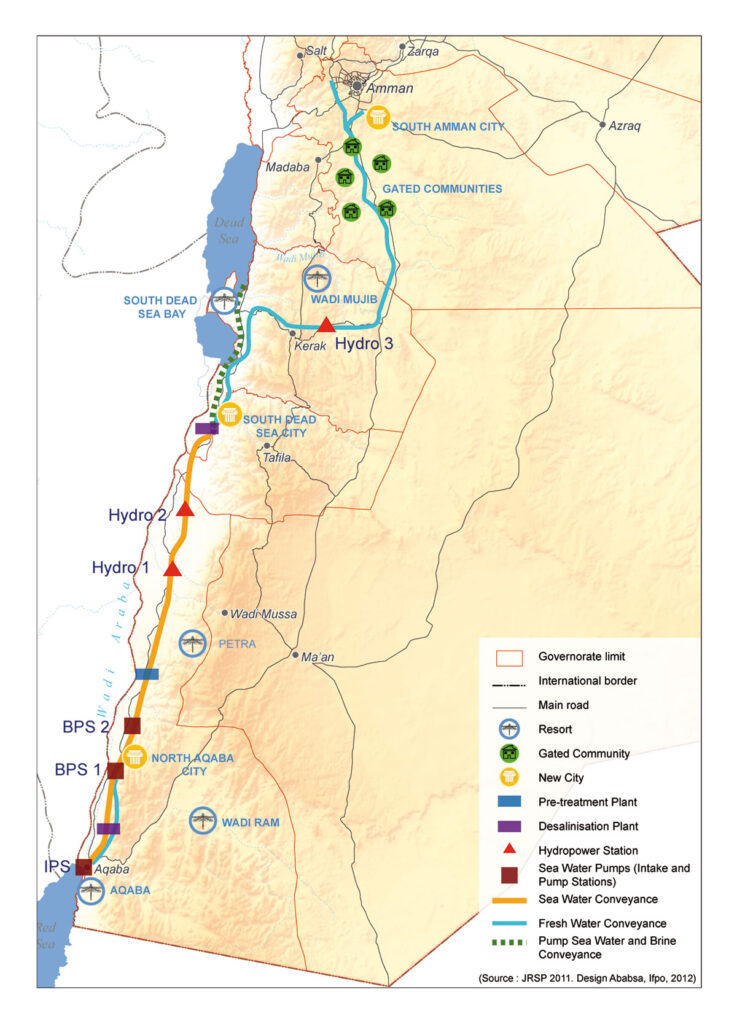

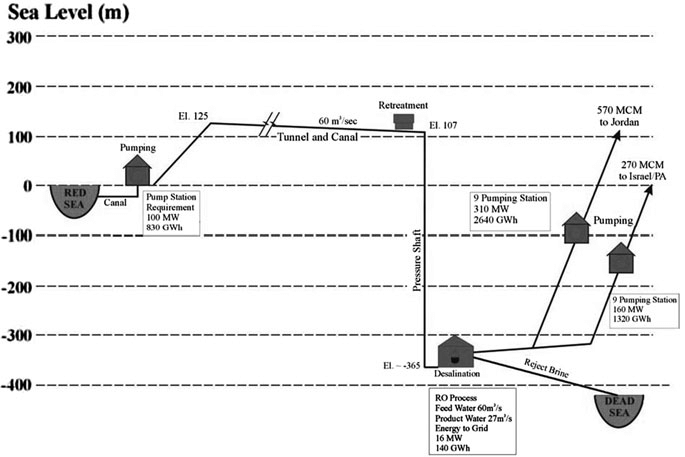

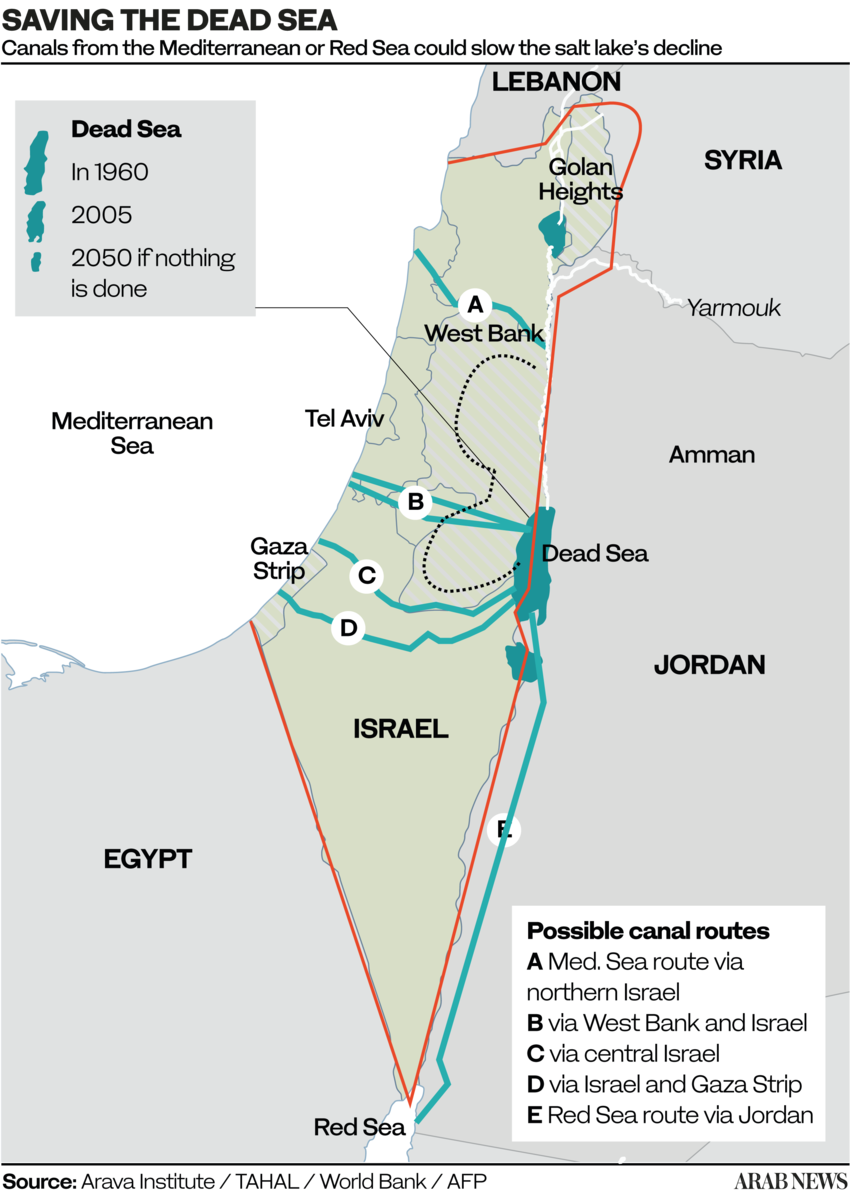

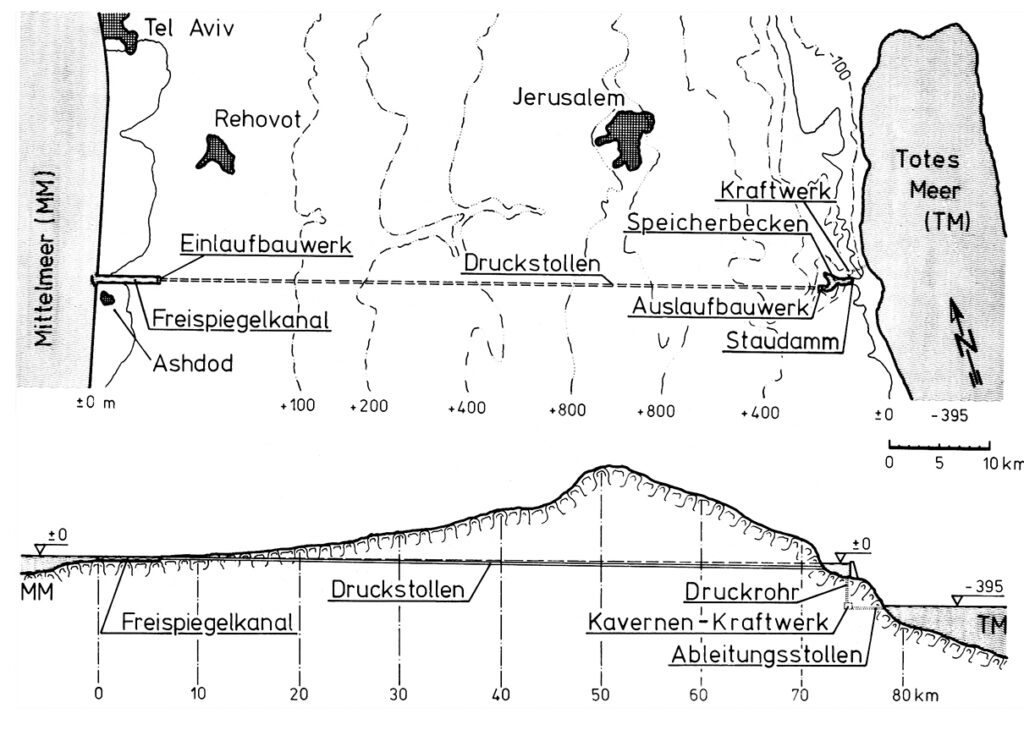

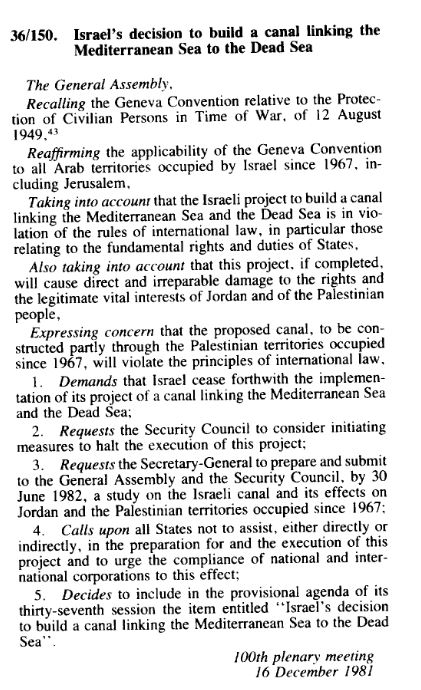

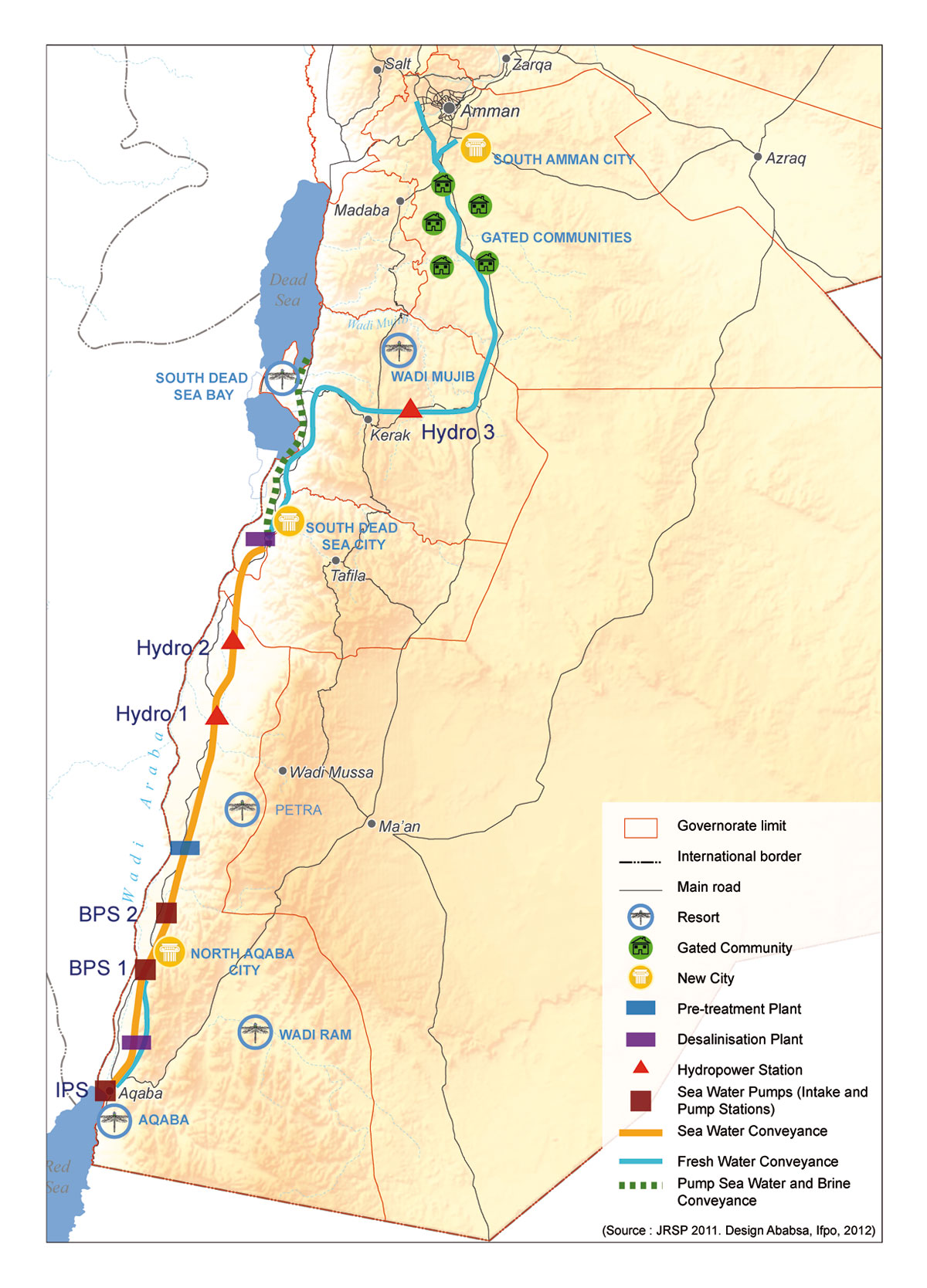

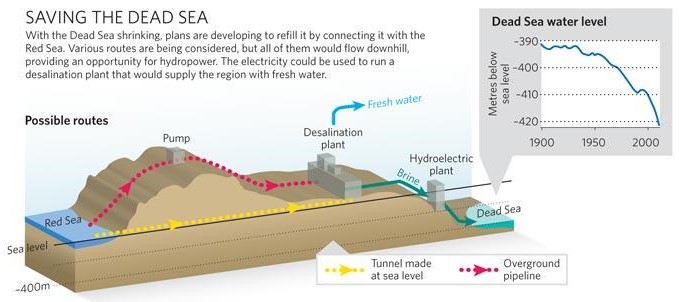

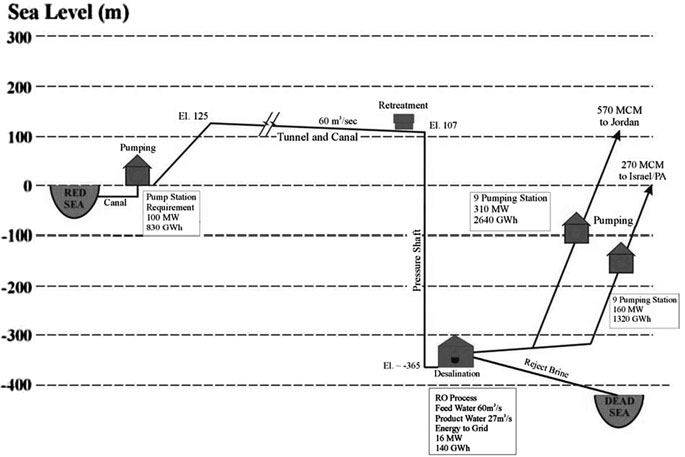

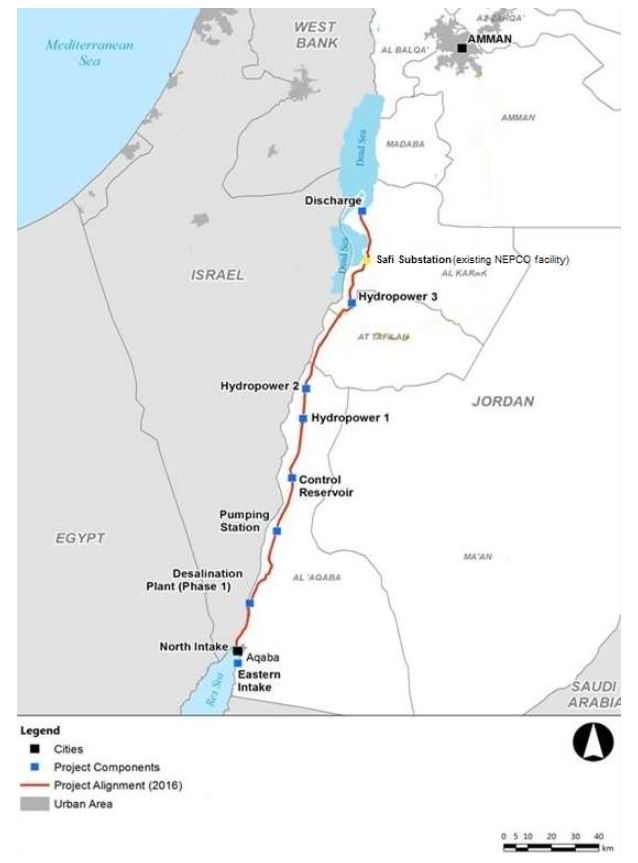

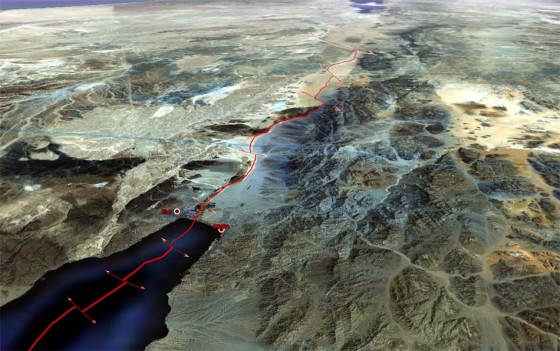

- The construction, for less than 20 billion US dollars of both the Red-Dead and the Med-Dead water conveyance system composed of tunnels, pipelines, water galeries, pumping stations, hydro-power units and nuclear powered desalination plants.

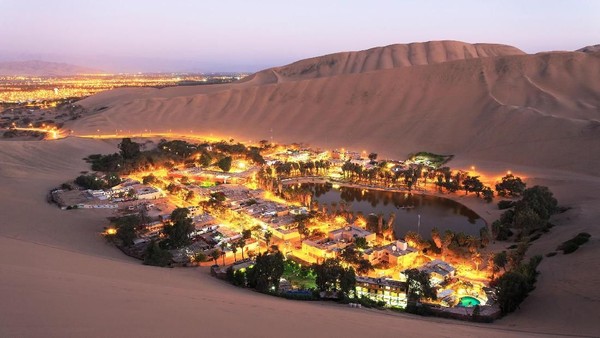

- Salted sea water, arriving at the Dead Sea, before desalination, will « fall » through a 400 meter deep shaft and generate hydro-electricity.

- Following desalination, the fresh water will go to Jordan, Palestine and Israel; the brine will refill and save the Dead Sea.

- The nuclear powered desalination plant will produce heat and electricity with « hybrid desalination » combining evaporation and Reverse Osmosis (RO) ;

- The industrial heat of the high temperature reactors (HTR) will also be tapped for industrial and agricultural purposes;

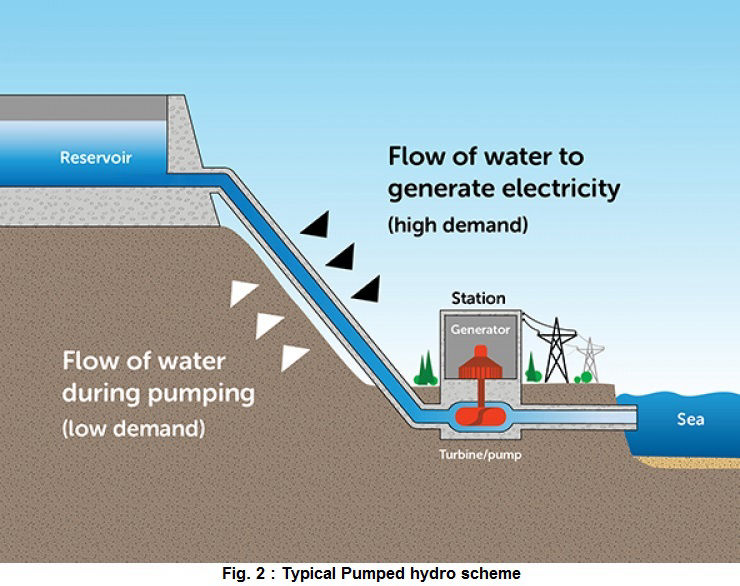

- The reservoirs of the water conveyance systems will also function as a Pumped Storage Power Plant (PSPP), essential for regulating the region’s power grids;

- Part of the seawater going through the Med-Dead Water conveyance system will be desalinated in Beersheba, the « capital of the Negev » whose population, with new fresh water supplies, can be doubled.

- New cities and « development corridors » will grow around the new water conveyance systems.

- Israel’s Dimona nuclear center and power plant (currently a military reactor and medical nuclear waste treatment center) can form the basis to create a civilian nuclear program and contribute to the construction of nuclear desalination plants. Jordan can contribute to the program with it vast reserves of thorium and uranium.

- US and Israeli plans to prepare the housing of 500,000/1 million people in the Negev exist but should be entirely reconfigured in terms of both scope and intent. They cannot be a mere extension of exclusively Jewish settlements, but should offer the opportunity to all Israeli citizens, in peaceful cooperation with the Bedouins who live there, the Palestinians and others, to roll back a common enemy: the desert.

- The policy of illegal settlements in the West Bank shall be halted. Settlers will be encouraged (through taxation, etc.) to relocate to the Negev, where they, in a shared effort with the Bedouins, Palestinians and others, can take up productive jobs and make the desert bloom (62% of Israeli territory).

PS: The Oasis Plan plan aims to bring peace to all through mutual development. It has nothing to do with Netanyahu’s Ben-Gurion canal project, a megalomaniac plan for a navigation canal connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean aimed to compete with the Suez Canal.

NOTES:

- The British Government was reported greatly concerned with the Russian arms offers; Prime Minister Eden regarded the offer to Egypt as the most “sinister” development in the East-West conflict since the Soviets took over Czechoslovakia. The British Government informed the United States in October 1955 it regarded a Russian undertaking to construct and finance the High Aswan Dam following the sale of Czech arms to Egypt would be a very serious blow to Western prestige and influence in the Middle East, providing the Russians with a means of exercising a dominating influence politically and economically in this area. ↩︎

- Myrl Kennedy Bailey, 1966 Thesis, « THE POLICIES OF- JOHN FOSTER DULLES RELATIVE TO THE SUEZ CRISIS OF 1956. »

↩︎ - Karel Vereycken, Israel-Palestine, Time to Make Water a Weapon for Peace, artkarel.com, March 2024. ↩︎

- Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, 1967, Book I, pages 555-558. ↩︎

- Department of State, SCI Files: Lot 69 D 217, The Department during the Administration of Lyndon B. Johnson, November 1963-January 1969, Vol. XI, Science and Technology. The proceedings of the conference were published as the “International Conference on Water for Peace,” May 23-31, 1967. ↩︎

- Letter from Harrar to Weinberg. ↩︎

- Letter from Weinberg to Bell. ↩︎

- https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/magazines/bulletin/bull9-6/09604701121.pdf ↩︎

- https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v34/d166 ↩︎

- Airgram A-222 from London, July 18; National Archives and Records Administration, RG 59, Records of the Department of State, Central Files, 1967-69, E 11-3 NEAR EAST. ↩︎

- https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/1968-democratic-party-platform ↩︎

- https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/republican-party-platform-1968 ↩︎

- See note 1. ↩︎

Israel-Palestine: Time to Make Water a Weapon for Peace

« If we solve all the problems in the Middle East,

but not the problem of sharing water, our region will explode.

Peace will not be possible »

(Yitzhak Rabin, former Israeli Prime Minister, 1992).

« You only make peace with your enemies. »

(Yitzhak Rabin.)

Contents:

Introduction

1. Geography of the Middle East

2. Rainfall and Water resources

3. Hydrography of the Jordan basin

A. Source

B. Tributaries

C. Lake of Tiberias

D. Yarmouk river

4. Water sources for Israel-Palestine

A. Surface water

B. Groundwater

C. Desalination

D. Reuse of Waste water

5. Water Infrastructure Projects

A. National Water Carrier (NWC)

B. Johnston Plan

C. Ghor Canal

D. Med – Dead Sea aqueduct

E. Red Sea – Dead Sea Water Conveyance

F. Turkish projects

G. Hidden defects and non-application of the Oslo agreements

H. Ben-Gurion Canal

I. Oasis Plan

J. Alvin Weinberg, Yitzhak Rabin and Lyndon LaRouche

Introduction

This article provides readers with the keys. To understand the history of the water wars that continue to ravage the Middle East, it is essential to understand the geological, hydrographical, geographical and political issues at stake. In the second part, we examine the various options for developing water resources as part of a strategy to overcome the crisis. We will deal with the gas issue, another subject of potential conflict or cooperation, in a later article.

1. Geography

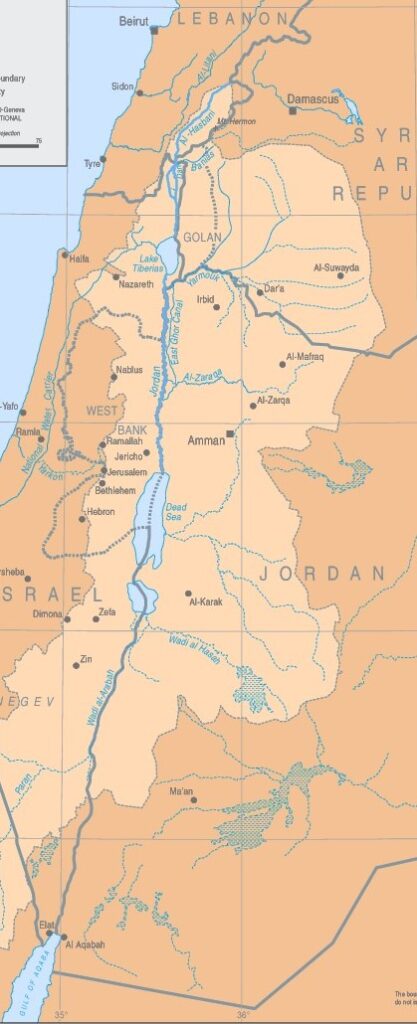

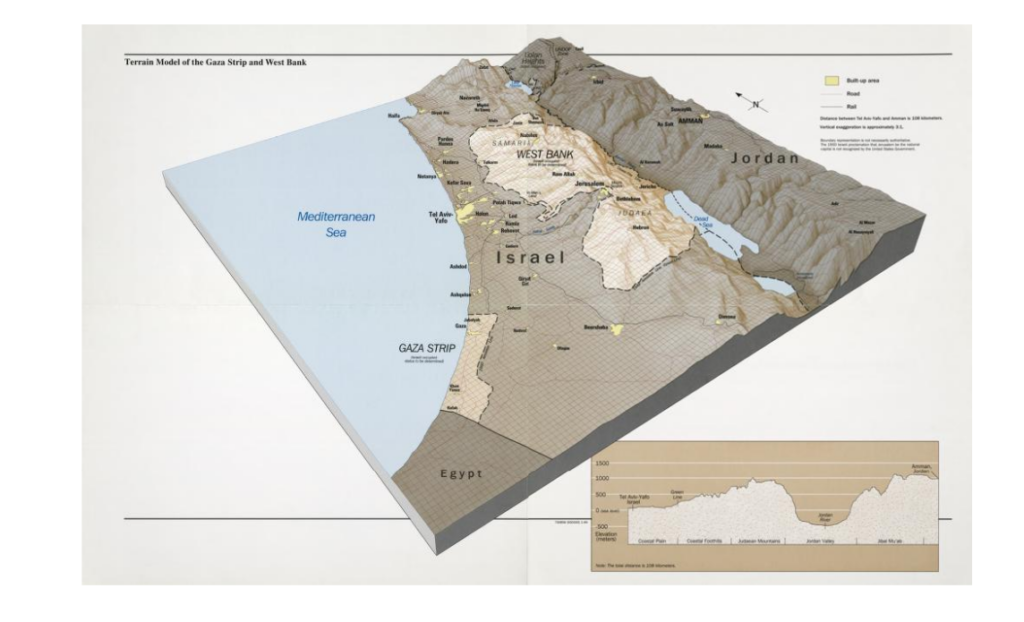

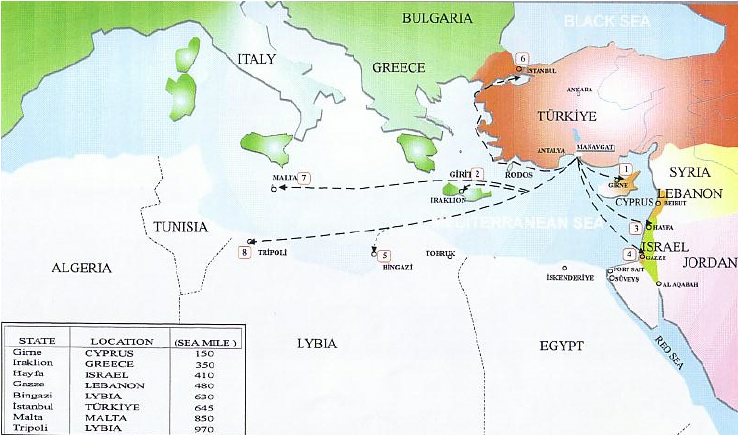

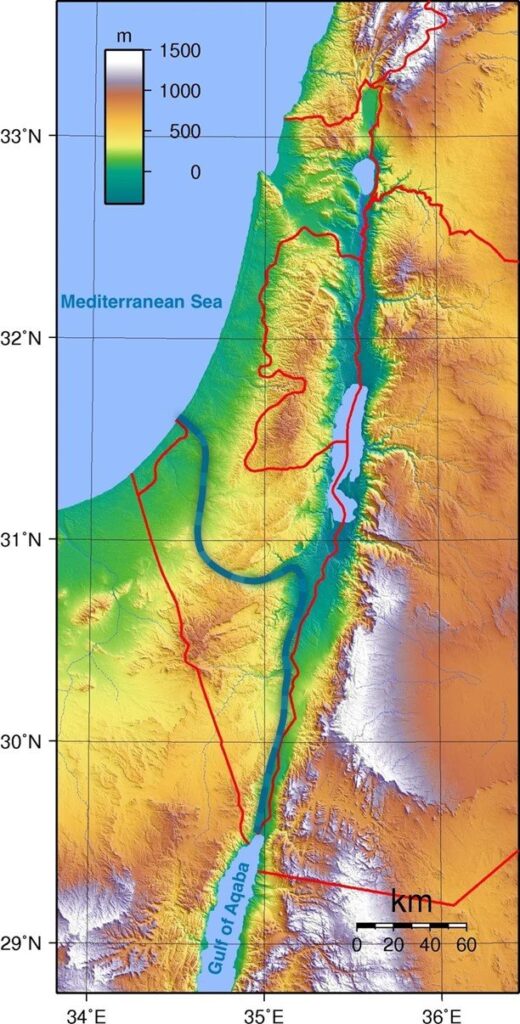

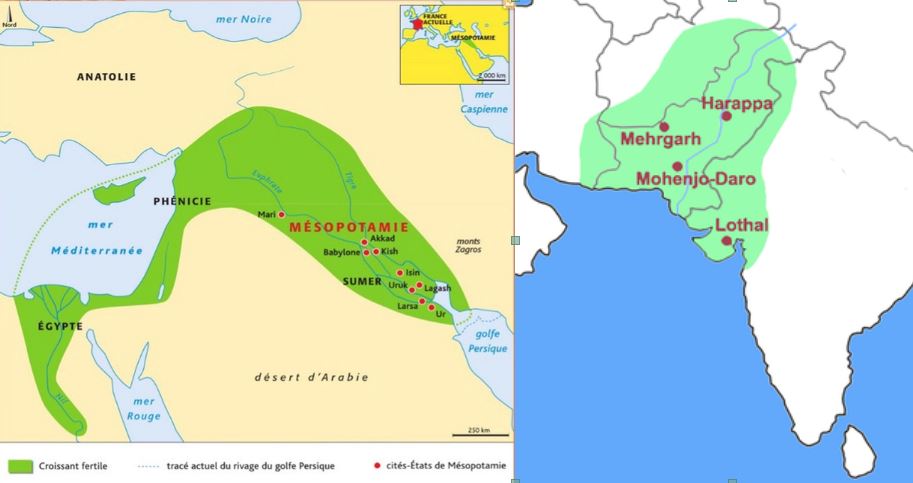

The Jordan River basin is shared by four countries: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel, plus the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza.

Situated in the hollow of a tectonic depression on the great fault that runs from Aqaba to Turkey, the Jordan Valley is one of the lowest-lying basins in the world, flowing into the Dead Sea at an altitude of 421 meters below sea level.

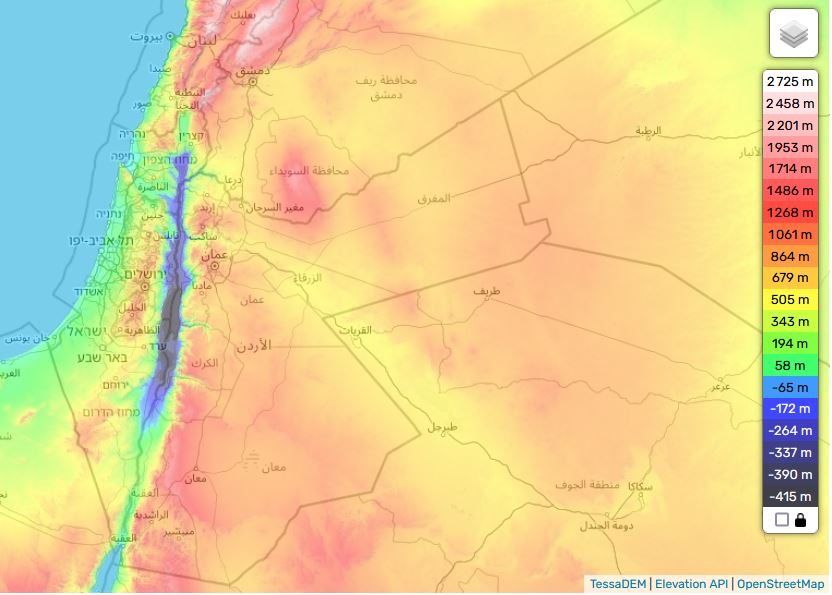

See interactive topographic map.

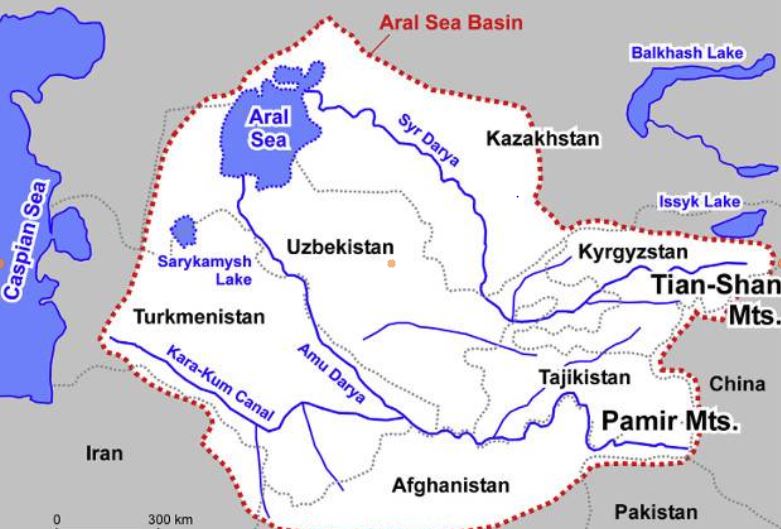

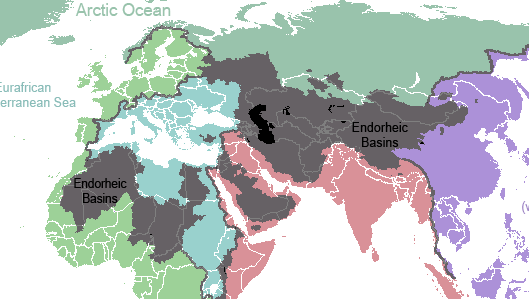

Added to this is the fact that this is an endorheic basin, i.e. a river that flows neither into the sea nor the ocean. As in the Aral Sea basin in Central Asia, this means that any water drawn or diverted upstream reduces the level of its ultimate receptacle, the Dead Sea (see below), and can even potentially make it disappear.

While remaining a fundamental artery for the entire region, the Jordan River has a number of drawbacks: its course is not navigable, its flow remains low and its waters, which are highly saline, are polluted.

As one of the key factors in the « Water, Energy, Food nexus » – three factors whose interdependence is such that we can’t deal with one without dealing with the other two – water resource management remains a key issue, and holds a primordial place for any future shared between Israel and its Arab neighbors. To grow food, one needs water. But to desalinate sea water, Israel spends 10 % of its electricity generated by consuming gas and oil.

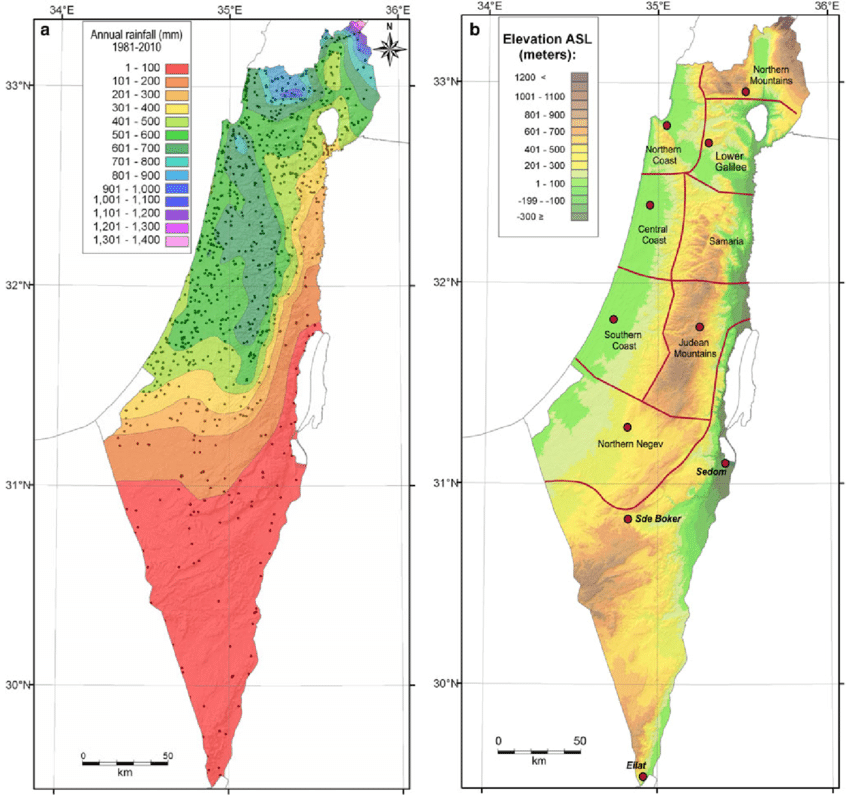

2. Rainfall and water resources

The Middle East forms a long, arid strip, only accidentally interrupted by areas of abundant rainfall (around 500-700 mm/year), such as the mountains of Lebanon, Palestine and Yemen.

Geographically, much of the Middle East lies south of the isohyet (imaginary line connecting points of equal rainfall) indicating 300 mm/year.

However, precipitation has only a limited effect due to its seasonality (October-February).

As a result, river flow and flooding are irregular throughout the year, as well as between years. The same applies to groundwater recharge.

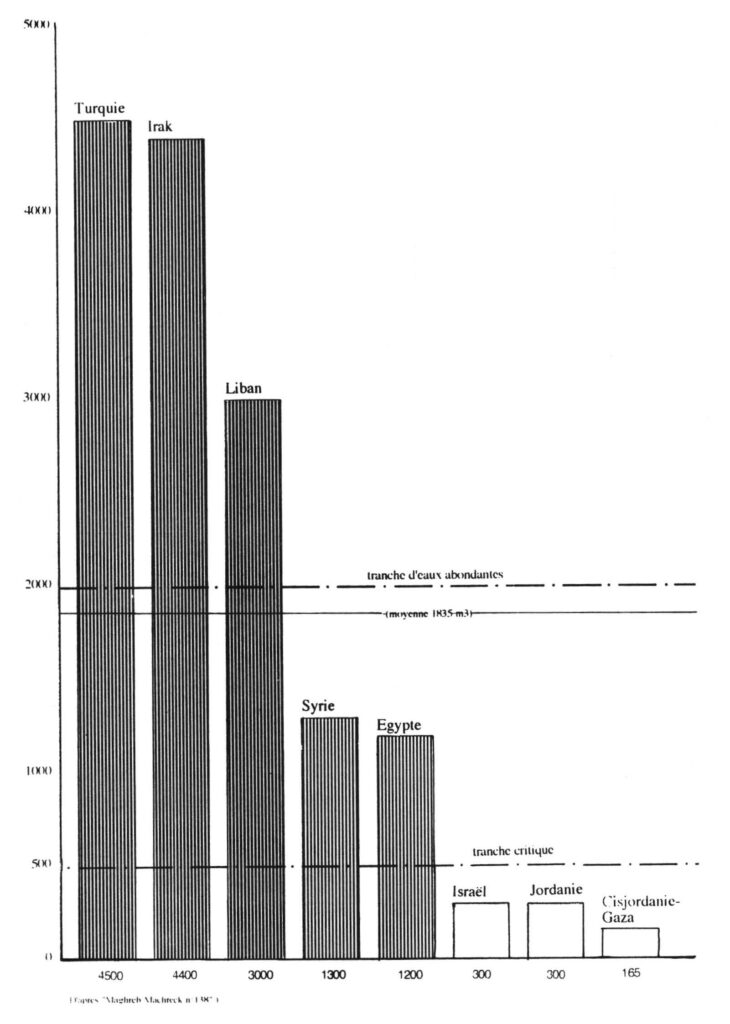

On a state-by-state basis, total water resources are very unevenly distributed in the region:

—Turkey and Iraq have over 4,000 cubic meters per person per year, and Lebanon around 3000 m³/person/year, which is above the regional average (1,800 m³/person/year).

—Syria and Egypt have around 1200 m³/person/year, one third lower.

On the other hand, some countries are below the critical 500 m³/year/capita bracket:

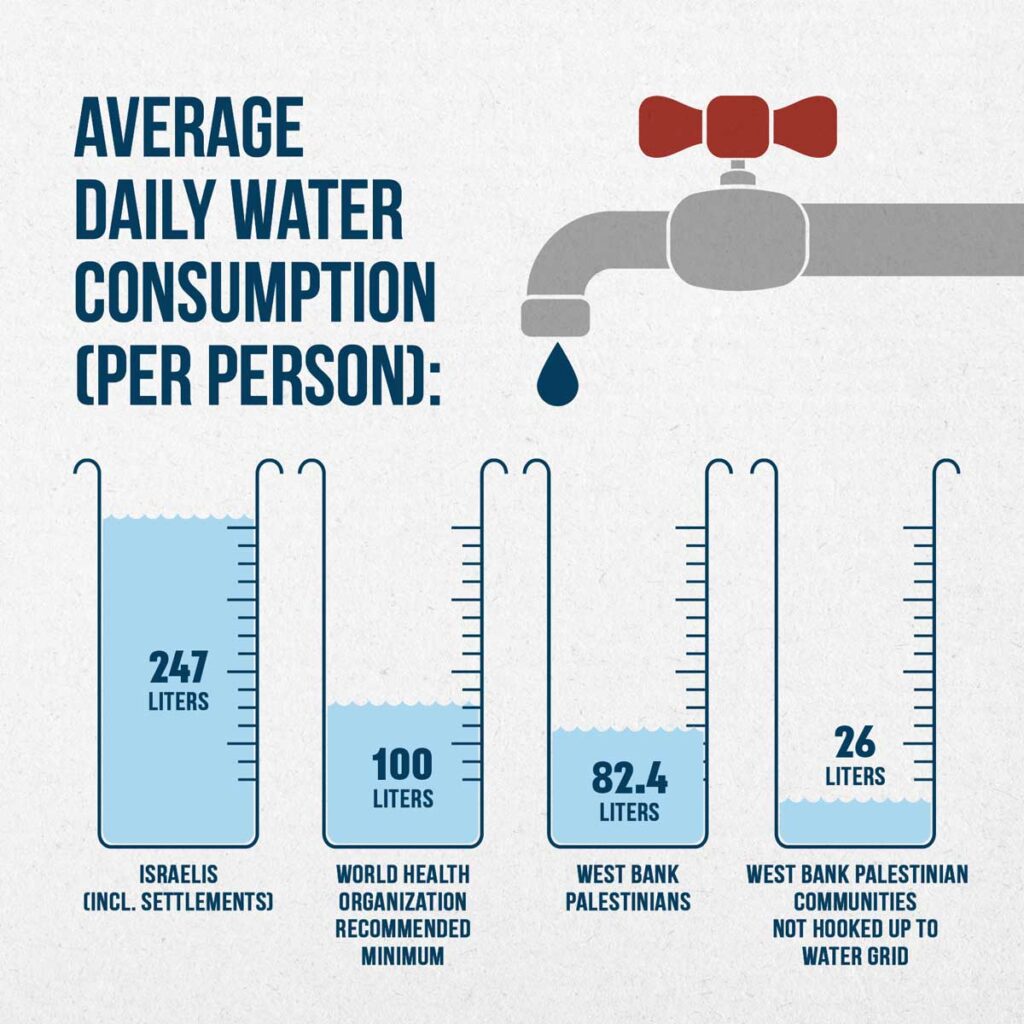

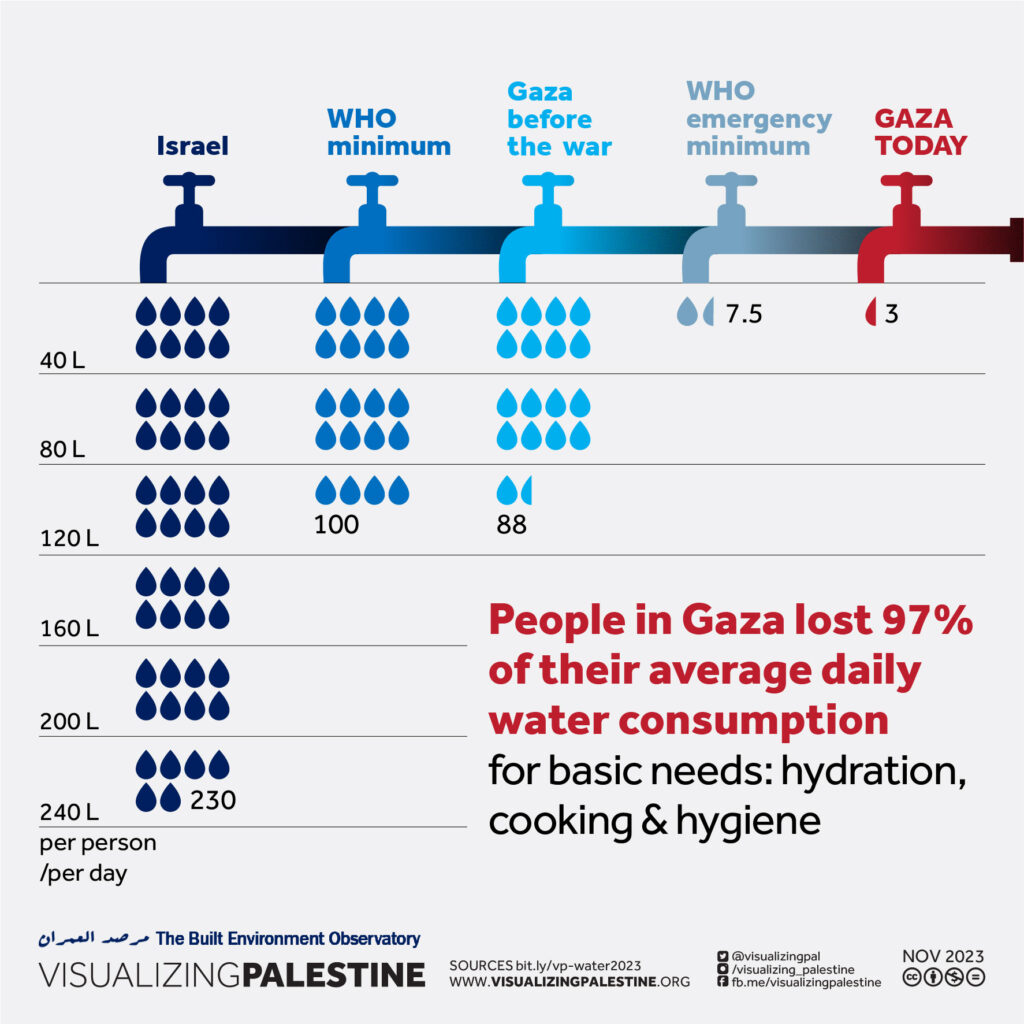

—Israel and Jordan have 300 m³/year/capita, and the Palestinian Territories (West Bank-Gaza) less than 200 m³/year/capita. They are in what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls a situation of « water stress ».

The Middle East enjoys plenty of water on a regional scale, but has many areas in chronic shortage, on a local scale.

3. Hydrography of the Jordan basin

A. Source

360 km long, the Jordan River rises from water flowing down the slopes of Jabal el-Sheikh (Mount Hermon) in southern Lebanon on the border with Syria.

B. Tributaries

Once over the Israeli border, three tributaries join the Jordan about 6 kilometers upstream from the former Lake Hula (now reclaimed):

1. The Hasbani, with a flow of 140 million cubic meters (MCM) per year, rises in Lebanon, a country it crosses over 21 kilometers. The upper reaches of the Hasbani vary greatly with the seasons, while the lower reaches are more regular.

2. The Banias, currently under Israeli control and 30 kilometers long, has an annual flow close to that of the Hasbani (140 MCM). It rises in Syria in the Golan Heights, and flows into Israel for around 12 kilometers before emptying into the Upper Jordan.

3. The Nahr Leddan (or Dan) forms in Israel when the waters of the Golan Heights come together. Although restricted, its course remains stable and its annual flow is greater than that of the other two tributaries of the Upper Jordan, exceeding 250 MCM per year.

C. Lake Tiberias or Kinneret (aka Sea of Galilee)

The Jordan then flows through 17 km of narrow gorges to reach Lake Tiberias, where the salinity is high, especially as the freshwater streams flowing into it have been diverted. Lake Tiberias, however, receives water from the many small streams running through the Golan Heights.

D. Yarmouk River

Next, the Jordan meets the Yarmouk River (bringing in water from Syria), then meanders for 320 km (109 km as the crow flies) to reach the Dead Sea. These 320 km are occupied by a humid plain (the humid zor), with subtropical vegetation, dominated on both sides (West Bank and Jordanian) by dry, gullied terraces.

4. Water sources for Israel

The Hebrew state has four main sources of water supply:

A. Surface Water

Israel benefits first and foremost from the freshwater reserves of Lake Tiberias in Galilee, in the north of the country. Crossed by the Jordan River, this small inland sea accounts for 25% of Israel’s water needs. The annexation of the Golan Heights and the occupation of southern Lebanon have made this source of water a sanctuary.

B. Groundwater

In addition to surface water (lakes and rivers), the country can rely on its coastal aquifers, from Haifa to Ashkelon.

Located between Israel and the occupied West Bank, the main aquifer, the Yarkon-Taninim mountain aquifer, has a capacity of 350 MCM per year. In the northeast and east of the West Bank are two other aquifers with capacities of 140 and 120 MCM per year respectively.

C. Seawater desalination

Five desalination plants built along the country’s coastline — in Ashkelon (2005), Palmachin (2007), Hadera (2010), Sorek (2013) and Ashdod (2015) — currently operate and two more are under construction. Collectively, these plants are projected to account for 85-90 per cent of Israel’s annual water consumption, marking a remarkable turnaround.

The Sorek desalination plant, located about 15 km south of Tel Aviv, became operational in October 2013 with a seawater treatment capacity of 624,000m³/day, which makes it world’s biggest seawater desalination plant. The desalination facility uses seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) process providing water to Israel’s National Water Carrier system (NWC, see below). A dozen more units of this type are considered for construction.

Israel, which has been facing severe droughts since 2013, even began pumping desalinated seawater from the Mediterranean into Lake Tiberias, a unique performance worldwide. While Israel faced water scarcity two decades ago, it now exports water to its neighbors (not too much to Palestine). Israel currently supplies Jordan with 100 MCM and fulfills 20 % of Jordan’s water needs.

From 100 liters of seawater, 52 liters of drinking water and 48 liters of brine (brackish water) can be obtained. Although highly efficient and useful, desalination technology has still to be perfected, as it currently discharges brine into the sea, disrupting the marine ecosystem. To reduce this pollution and transform it into solid waste, we need to increase treatment and therefore energy consumption.

D. Wastewater

The country prides itself on reusing between 80% and 90% of its wastewater for agriculture. Treated wastewater used for irrigation is known as effluent. Israel’s effluent utilization rate is one of the highest in the world. Reclamation is carried out by 87 large wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) that supply over 660 MCM per year. This represents around 50% of total water demand for agriculture and around 25% of the country’s total water demand. Israel aims to more than double the amount of effluent produced for the agricultural sector by 2050.

5. Water infrastructure projects

For Israel, acquiring water resources in a desert region, through technology, military conquest and/or diplomacy, was from the outset an imperative to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population and, in the eyes of the rest of the world, a demonstration of its sovereign power and its superiority.

This symbolism is particularly evident in the figure of the father of the Hebrew state, David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), whose aim was to make the Negev desert in the south of the country « blossom ».

In his book Southwards (1956), Ben Gourion described his ambition:

« It is absolutely vital for the State of Israel, both for economic and security reasons, to go south: we must direct the water and rain to there, send the young pioneers there […] as well as the bulk of our budget resources to development. »

A. National Water Carrier of Israel (NWC)

OBJECTIVE: provide fresh water for Israel’s agriculture and growing population.

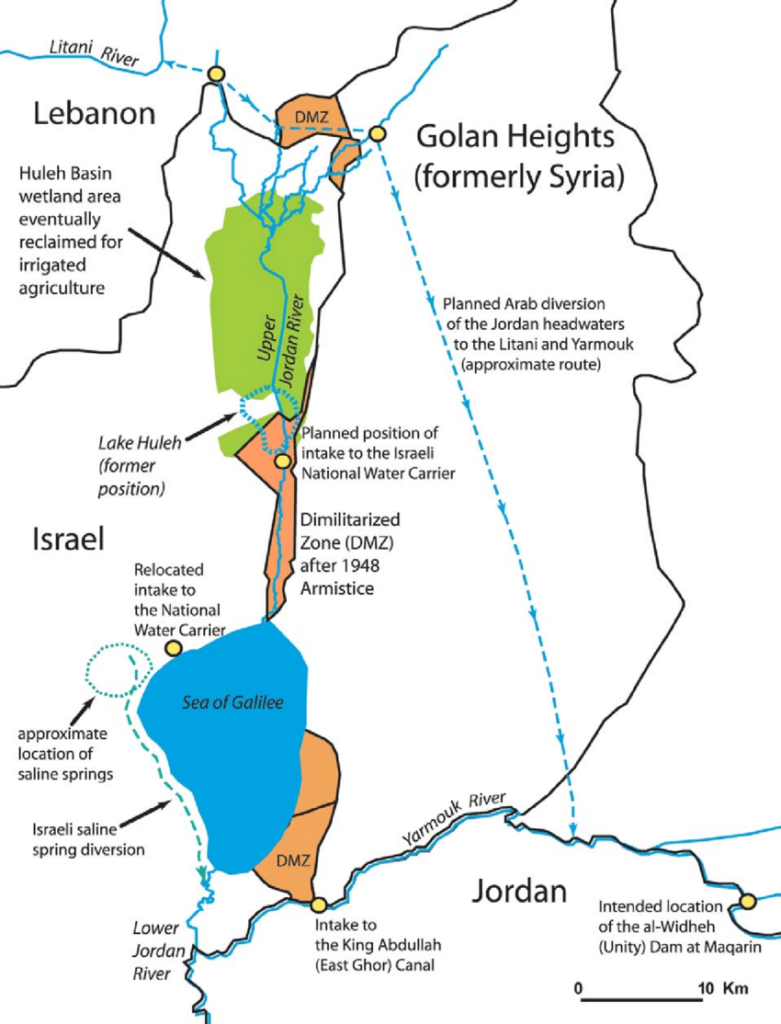

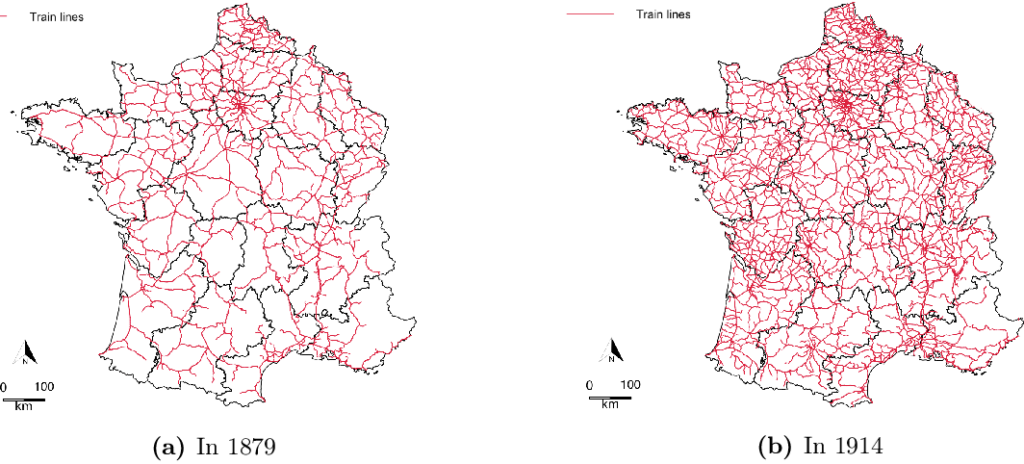

From 1959 to 1964, the Israelis built the National Water Carrier of Israel (NWC), the largest water project in Israel to date.

The first ideas appeared in Theodor Herzl‘s book Altneuland (1902), in which he spoke of using the springs of the Jordan for irrigation purposes and channeling seawater to generate electricity from the Mediterranean Sea near Haifa through the Beit She’an and Jordan valleys to a canal running parallel to the Jordan and Dead Sea.

In 1919, Chaïm Waizmann, leader of the World Zionist Organization, declared: « The whole economic future of Palestine depends on its water supply ».

However, he advocated incorporating the Litani Valley (in today’s southern Lebanon) into the Palestinian state.

The NWC project was conceived as early as 1937, although detailed planning began after the recognition of Israel in 1948. In practice, the natural flow of the Jordan River is prevented by the construction of a dam, built south of Lake Tiberias. From there, water is diverted to the NWC, a 130 km-long system combining giant pipes, open channels, tunnels, reservoirs and large-scale pumping stations. The aim is to transfer water from Lake Tiberias to the densely populated center and the arid south, including the Negev desert.

When it was inaugurated in 1964, 80% of its water was allocated to agriculture and 20% to drinking water. By 1990, the NWC supplied half of Israel’s drinking water. With the addition of water from seawater desalination plants, it now supplies Tel Aviv, a city of 3.5 million inhabitants, Jerusalem (1 million inhabitants) and (outside wartime) Gaza and the occupied territories of the West Bank.

Since 1948, the area of irrigated farmland has increased from 30,000 to 186,000 hectares. Thanks to micro-irrigation (drip irrigation, including subsurface irrigation), Israeli agricultural production increased by 26% between 1999 and 2009, although the number of farmers fell from 23,500 to 17,000.

The Water War

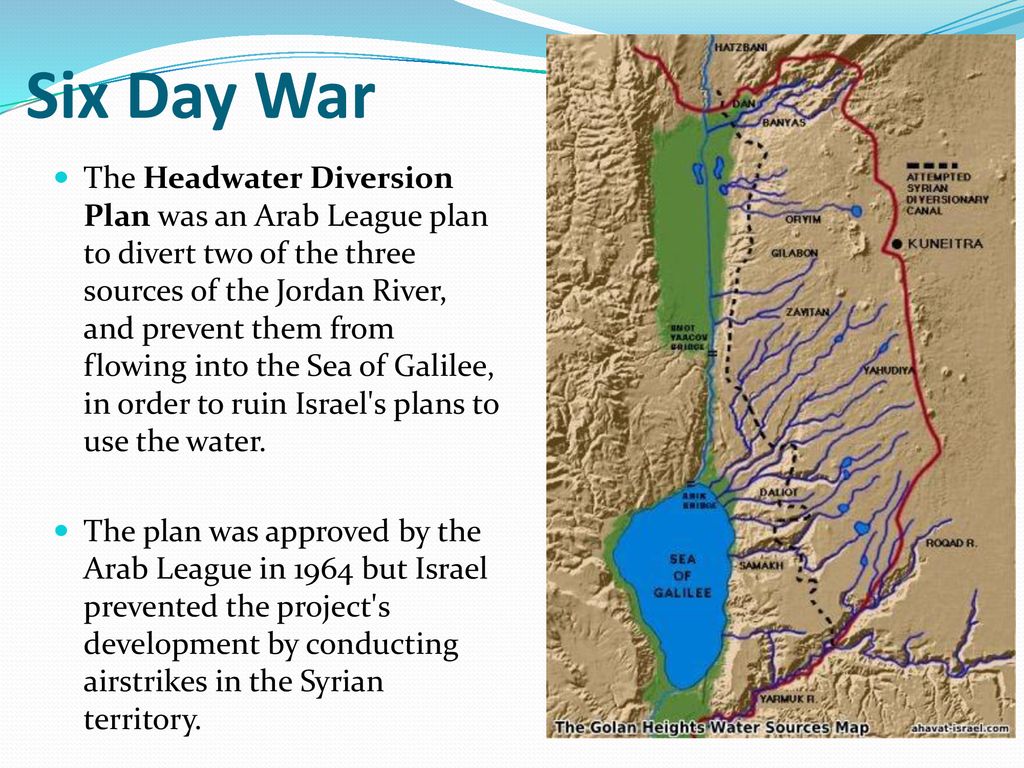

In launching its NWC, Israel went it alone, while for the rest of the world, it was clear that diverting the waters of the Jordan River would give rise to sharp tensions with neighboring countries, particularly with Jordan and Syria, not to mention the Palestinians who have been largely excluded from the project’s economic benefits.

As early as 1953, Israel began the unilateral draining of Lake Hula (or Huleh), north of Lake Tiberias, leading to skirmishes with Syria.

In 1959, Israel kickstarted the NWC. The project was initially interrupted by a halt in American funding, as the Americans did not want to see violence escalate in the context of the Cold War.

It should be noted that, following the Suez crisis of 1956, the Soviet Union established itself in Syria as the protecting power of Arab countries against the « Israeli threat ». As part of the deployment of its naval presence in the Mediterranean, it obtained facilities for its fleet at Latakia in Syria.

However, Israel managed to quietly resume and continue the work on the NWC. Filling the system by pumping of Lake Tiberias began in June 1964 in utmost secrecy. When the Arab countries learned of this, their anger was great. In November 1964, the Syrian army fired on Israeli patrols around the NWC pumping station, provoking Israeli counter-attacks. In January 1965, the NWC was the target of the first attack by the Fatah (organization fighting for the liberation of Palestine) led by Yasser Arafat.

The Arab states finally recognized that they would never be able to stop the project through direct military action.

They therefore adopted a plan, the Headwater Diversion Plan immediately implemented in 1965, to divert water upstream from the tributaries of the Jordan River into the Yarmouk River (in Syria). The project was technically complicated and costly, but if successful would have diverted 35% of the water Israel intended to withdraw from the upper Jordan…

Israel declared that it considered this deviation of the water as an infringement of its sovereign rights. Relations degenerated completely and border clashes followed, with Syrian forces firing on Israeli army farmers and patrols. In July 1966, the Israeli air force bombed a concentration of earth-moving equipment and shot down a Syrian MiG-21. The Arab states abandoned their counter plan, but the conflict continued along the Israel-Syria border, including an Israeli air attack on Syrian territory in April 1967.

For many analysts, this was a prelude to the Six-Day War in 1967, when Israel occupied the Golan Heights to protect its water supply. The Six-Day War profoundly altered the geopolitical situation in the basin, with Israel now occupying not only the Gaza Strip and Sinai, but also the West Bank and the Golan Heights.

As French researcher Hervé Amiot explains:

« Israel went from being a downstream country to an upstream one, enabling it to gain control of vast resources. Israel now controlled 20% of the northern bank of the Yarmouk and occupied the Golan Heights, controlling all the small rivers flowing into Lake Tiberias. What’s more, total occupation of the West Bank gives them control over the important water tables ».

In fact, as early as 1955, between a quarter and a third of the water came from the groundwater in the south-western part of the West Bank. Today, the West Bank aquifers supply Israel with 475 million m³ of water, i.e. 25-30% of the country’s water consumption (and 50% of its drinking water).

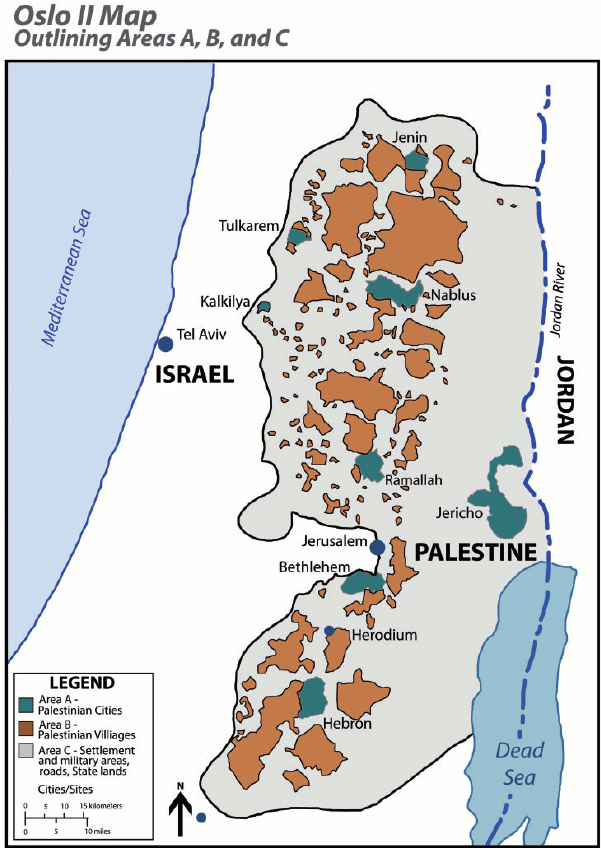

Two months after the seizure of the occupied territories, Israel issued “Military Decree 92”, transferring authority over all water resources in the occupied territories to the Israeli army and conferring « absolute power to control all water-related matters to the Water Resources Officer, appointed by the Israeli courts ». This decree revoked all drilling licenses issued by the Jordanian government and designated the Jordan region a military zone, thus depriving Palestinians of all access to water while granting Israel total control over water resources, including those used to support its settlement projects.

Today, returning the Golan to Syria and recognizing the sovereignty of the Palestinian Authority over the West Bank seems impossible for Israel, given the Hebrew state’s increasing dependence on the water resources of these occupied territories. The exploitation of these resources will therefore continue, despite Article 55 of the Regulations of the IVth Hague Convention, which stipulates that an occupying power does not become the owner of water resources and cannot exploit them for the needs of its civilians…

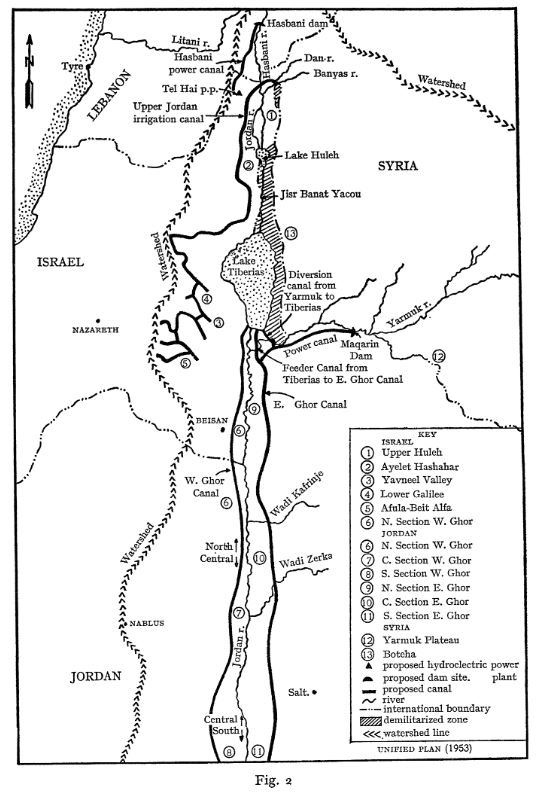

B. Johnston Plan

OBJECTIVE: In the context of the Cold War, counter Nasser’s growing influence in the region. Offer regional stability by building dams and canals allowing a just sharing of water resources and providing water and energy for both Israel and Arab states welcoming « unfortunate » Palestinian refugees.

One might think that the United States tried very early on to prevent the situation from degenerating in such a predictable way. They tried to take into account Israel’s legitimate interest in securing access to water, the absolute key to its survival and development, while at the same time offering neighboring countries (Jordan, Syria and Lebanon) sufficient resources to accommodate the millions of Palestinians exiled from their homes following the Nakba.

Faced with the risk of conflict, as early as 1953 – years before Israel launched its NWC plan – the American government proposed its mediation to resolve disputes over the Jordan basin. The result was the « Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan » (known as the « Johnston Plan »), named after Eric Allen Johnston, president of the United States Chamber of Commerce and US President Dwight Eisenhower‘s water envoy.

More concretely, “The Unified Development of the Water Resources of the Jordan Valley Region,” was prepared at the request of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees under the direction of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

On Oct. 13, 1953, Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, in a top secret letter instructed Johnston what his mission was all about and on Oct. 16, in a public statement Eisenhower explained:

« One of the major causes of disquiet in the Near East is the fact that some hundreds of thousands of Arab refugees are living without adequate means of support in the Arab states. The material wants of these people have been cared for through the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) … It has been evident from the start, however, that every effort must be made by the countries concerned, with the help of the international community, to find a means of giving these unfortunate people an opportunity to regain personal self-sufficiency.

« One of the major purposes of Mr. Johnston’s mission will be to undertake discussions with certain of the Arab states and Israel, looking to the mutual development of the water resources of the Jordan River Valley on a regional basis for the benefit of all the people of the area. …

« Such a regional approach holds a promise of extensive economic improvement in the countries concerned through the development of much needed irrigation and hydroelectric power and through the creation of an economic base on the land for a substantial proportion of the Arab refugees. It is my conviction that acceptance of a comprehensive plan for the development of the Jordan Valley would contribute greatly to stability in the Near East and to general economic progress of the region.«

This plan established the transboundary nature of the Jordan basin and proposed an equitable sharing of the resource, giving 52% of the water to Jordan, 31% to Israel, 10% to Syria and 3% to Lebanon.

The plan, just as the Tennessee Valley Authority during FDR’s New Deal, was essentially based on building dams for irrigation and hydropower. The water was there and correctly managed, sufficient for the needs of the population at that time. Its main features were:

- a dam on the Hasbani River to provide power and irrigate the Galilee area;

- dams on the Dan and Banias Rivers to irrigate Galilee;

- drainage of the Huleh swamps;

- a dam at Maqarin on the Yarmouk River for water storage (capacity of 175 million m³) and power generation;

- a small dam at Addassiyah on the Yarmouk to divert its water toward both the Lake Tiberias and south along the eastern Ghor;

- a small dam at the outlet of Lake Tiberias to increase its storage capacity;

- gravity-flow canals along the east and west sides of the Jordan valley to irrigate the area between the Yarmouk’s confluence with the Jordan and the Dead Sea;

- control works and canals to utilize perennial flows from the wadis that the canals cross.

See details of the Johnston plan in this comprehensive article.

The project was validated by the technical committees of Israel and the Arab League, and did not require Israel to abandon its ambition to green the Negev desert. Unfortunately, however, the presentation of the plan to the Knesset in July 1955 did not result in a vote.

The Arab Committee approved the plan in September 1955 and forwarded it to the Council of the Arab League for final approval. Tragically, this institution also chose not to ratify it on October 11, because of its opposition to an act implying an implicit act of recognition of Israel that would prevent the return of the Palestinian refugees to their home… The mistake here was to isolate the water issue from a broader agreement on peace and justice as the foundation of mutual development.