Étiquette : Xinjiang

Afghanistan: Qosh Tepa canal and prospects of Aral Sea basin water management

Presentation of Karel Vereycken at the second panel discussion of the « Water for Peace » seminar organized by the Schiller Institute on January 9, 2024 in Paris.

Let’s start with current events. In August 2021, faced with the Taliban takeover, the United States hastily withdrew from Afghanistan, one of the world’s poorest countries, whose population has doubled in 20 years to 39.5 million.

While the UN acknowledged that the country was facing « the worst humanitarian crisis » in the post-war era, overnight all international aid, which represented more than half of the Afghan budget, was suspended. At the same time, $9.5 billion of the country’s central bank assets, held in accounts at the US Federal Reserve and a number of European banks, were frozen.

Qosh Tepa canal

Despite these dramatic conditions, the Afghan government, via its state construction group, the National Development Company (NDC), committed $684 million to a major river infrastructure project, the Qosh Tepa Canal, which had been suspended since the Soviet invasion.

In less than a week, over 7,000 drivers flocked from the four corners of the country to work day and night on the first section of the canal, the first phase of which was completed in record time.

Politically, the canal project is a clear expression of the re-birth of an inclusive Afghanistan, as the region is mainly inhabited by Turkmen and Tajik populations, whereas the government is exclusively in the hands of the Pashtuns. The latter represent 57% rather than 37% of the country.

According to the FAO, 62.5% of the Abu Darya’s water comes from Tajikistan, 27.5% from Afghanistan (22 million m3), 6.3% from Uzbekistan, 1.9% from Kyrgyzstan and 1.9% from Turkmenistan.

The river irrigates 469,000 ha of farmland in Tajikistan, 2,000,000 ha in Turkmenistan and 2,321,000 ha in Uzbekistan.

So it’s only natural that Afghanistan should harness some of the river’s waters (10 million m³ out of a total of 61.5 to 80 million m³ per year) to irrigate its territory and boost its ailing agricultural production

By harnessing part of the waters of the Amu Daria river, the new 285 km-long canal will eventually irrigate 550,000 ha of arid land in ancient Bactria to the north, the « Land of a 1000 Cities » and« The Land of Oases » whose incomparable fertility was already praised by the 1st-century Greek historian Strabo.

In October 2023, the first 108 km section was impounded.

Agricultural production has been kick-started to consolidate the riverbanks, and 250,000 jobs are being created.

While opium poppy cultivation has been virtually eradicated in the Helmhand, the aim is to double the country’s wheat production and to become a grain net exporter.

Today, whatever one may think of the regime, the Afghans, who for 40 years have been self-destructing in proxy wars in the service of the Soviets and Americans, have decided to take their destiny into their own hands. Putting an end to the systemic corruption that has enriched an international oligarchy, they are determined to build their country and give their children a future, notably by making water available for irrigation, for health and for the inhabitants.

How did the world react?

On November 7, in The Guardian, Daanish Mustafa, a professor of « critical geography », explains that Pakistan must rid itself of the colonial spirit of water.

In his view, the floods that hit Pakistan in 2010 and 2022 demonstrate that « colonial » river and canal development is a recipe for disaster. It’s time, he concludes, to « decolonize » our imaginations on the subject of water by abandoning all our vanitous desires to manage water.

On November 9, the Khaama Press News agency reported:

« Tensions have risen between the de facto authorities of Afghanistan and Pakistan due to the ongoing deportation of Afghan migrants. Most recently, Pakistan has called for a halt to the Qush Tepa project. Abdul Haq Hamad, former head of media publications supervision, said in a televised debate that the Pakistani authorities had made it explicitly known at an official meeting with Taliban administration leaders that they must ‘stop operations on the Qush Tepa channel’.

« According to him, the Pakistani authorities are not satisfied with the completion of the Qosh Tepa Canal, as Afghanistan gains autonomy through this canal in managing its waters. »

Two days earlier, on November 7, Cédric Gras, Le Figaro‘s correspondent in Tashkent, published an article entitled:

« En Afghanistan, les Talibans creusent le canal de la discorde » (« In Afghanistan, the Taliban are digging the canal of discord »):

« The Afghanistan of the Taliban is in the process of digging a gigantic irrigation canal upstream from the Amou-Daria river. To the detriment of downstream countries and the Aral Sea, whose water supply and agricultural crops are threatened ».

Obviously, the aim is to create scare. But if the accusation is hasty, it touches on a fundamental issue that deserves explanation.

Endoreic basin

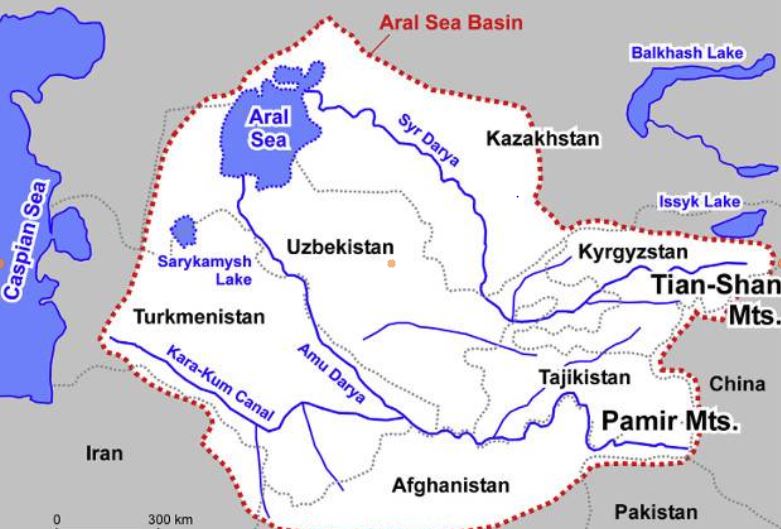

The Amu Daria, the 2539 km long river that the Greeks called the Oxus, and its brother, the 2212 km long Syr Daria, feed, or rather used to feed, the Aral Sea, which straddles the border between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. The water of both rivers were increasingly redirected by soviet experts to irrigate mainly cotton cultivation causing the Aral Sea to disappear.

I won’t go into detail here on the history of the ecological disaster that everyone has heard about but I am ready to answer your questions on that later;

The « Aral Sea Basin » essentially covers five Central Asian « stan » countries. To the North, these are Kazakhstan, followed by Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

In fact, Afghanistan, whose border with the latter three countries is formed by sections of the Amu Darya, is geologically and geographically part of the « Aral Sea Basin ».

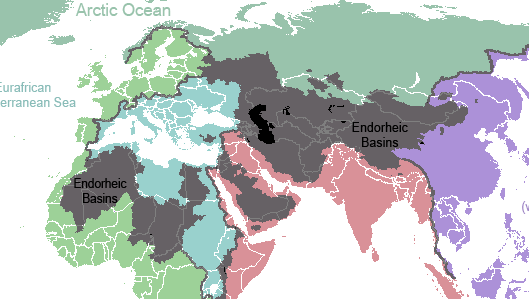

This is a so-called « endoreic basin ». (endo = inside; rhein = carried).

In Europe, we see falling rain and snowmelt flowing into rivers that discharge it into the sea. Not so in Central Asia. Rainwater, or water from melting snow, flows down mountain ranges. They eventually form rivers that either disappear under the sands, or form « inland seas » having no connection whatever to a larger sea and no outlet to the oceans. 18% of the world’s emerged surface is endoreic.

Among the best-known endoreic basins are the Dead Sea in Israel and Lake Chad in Africa.

In Asia, there are plenty of them. Just think of the Tarim Basin, the world’s largest endoreic river basin in Qinjiang, covering over 400,000 km². Then there’s the vast Caspian Sea, the Balkhach and Alakoll lakes in Kazakhstan, the Yssyk Kul in Kyrgyzstan and, as we’ve just said, the Aral Sea.

The very nature of an endoreic basin strongly reinforces the fear that water is a scarce limited source. That realty can either bolster the conviction that problems cannot but be solved true cooperation and discussion, or push countries to go to war one against the other. Democraphic growth, economic progress and climate/meteorogical chaos can worsen that perception and make water issues appear as a « time-bomb ».

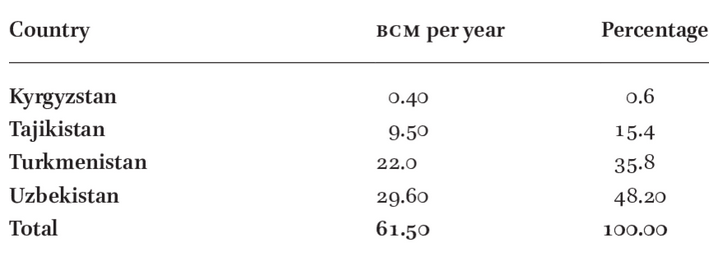

The early Soviet planners started with a strict quota system laid down in 1987 by Protocol 566 of the Scientific and Technical Council of the Soviet Ministry of Water Resources. The system fixed quotas for all countries, both in percentage and in BCM (Billions of Cubic Meters).

That simple quota system looks 100 % functional on paper. However, nations are not abstractions.

First, this system created quite rigid procedures and even would forbid some upstream countries to invest in their own agriculture since they had to deliver the water to their neighbors.

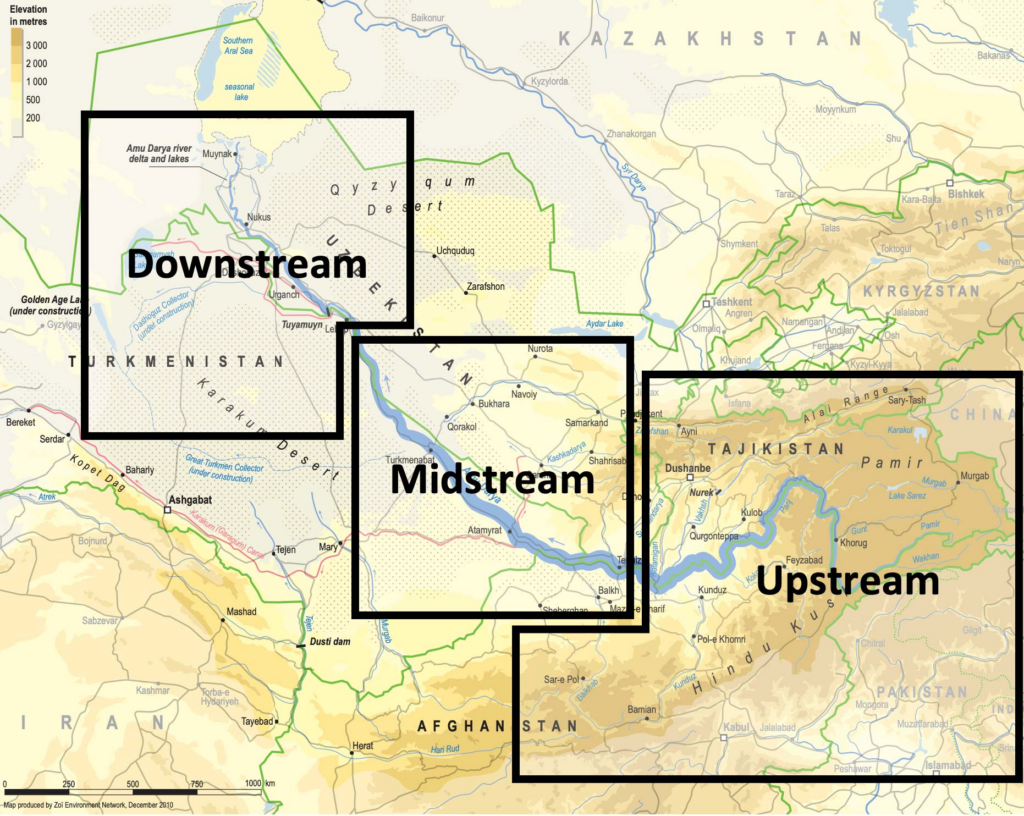

Second, conflict arose about dissymetric seasonal use of the water. The use of the water was completely different between « Upstream countries » such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and « Downstream countries » such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Upstream countries could accept releasing their water resources in autumn and winter since the release of the water provides them up to 90 % of their electricity via hydrodams.

Downstream countries however don’t need the water at that time but in spring and summer when their farmland needs to be irrigated.

However, in Central Asia, their seems to exist some sort of « geological justice » since downstream countries lacking water (Kazakhstan, Uzbekhistan and Turkmenistan) have vast hydrocarbon energy reserves such as coal, oil and gaz.

Therefore, not always stupid, Soviet planners, which realized that a simple quota system was insufficient to prevent conflict, created a compensation mechanism. Downstream nations, in exchange for water, would supply parts of their oil and gas to upstream nations to compensate the loss of potential energy that water represents.

However imperfect that mechanism, for want of a better one, it remained in place after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It can be said that by appealing to an external factor of a given problem, in this case to bring energy in the equation to solve the water problem, soviet planners conceived in a rudimentary form what became known as the « Water, Energy, Food Nexus ». One cannot deal with theses factors as separate factors. They have to be conceived as part of a single, dynamic Monad.

Today, we should avoid the geopolitical trap. If we consider the water resources to be shared between the states of Central Asia and Afghanistan to be « limited », or even « declining » due to meteorological phenomena such as El Nino, we might hastily and geopolitically conclude that, with the construction of the Qosh Tepa canal, which will tap water from the Amu Daria, the « water time bomb » cannot but explode.

Solutions

So we need to be creative. We don’t have all the solutions but some ideas about where to find them:

- In Central Asia, especially in Turkmenistan but also Uzbekistan, huge quantities of water from the Abu Daria water basin are wasted. In 2021, Chinese researchers, looking at Central Asia’s potential in terms of food production, estimated that with improvements in irrigation, better seeds and other « agricultural technology », 56 % of the water can be saved farming the same crops, meaning that today, about half of the water is simply wasted.

- The lack of investment into new water infrastructure and maintenance cannot but lead to the kind of disasters the world has seen in Libya or Pakistan where, predictably, systems collapsed for lack of mere maintenance;

- Uncontrolled and controlled flooding are very primitive and inefficient forms of irrigation and should be outphased and replaced by modern irrigation techniques;

- Therefore, a water emergency should be declared and a vast international effort should assist all the countries of the Abu Daria basin, including Afghanistan, to modernize and improve the efficiency of their water infrastructure, be it lakes, canals, rivers and irrigation systems.

- Such and effort can best organized within the framework of the « One Belt, One Road » initiative and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. BRICS countries such as China, Russia and India could help Afghanistan with data from their satellites and space programs.

- By improving the efficiency of water use, notably through targeted irrigation using « drip irrigation » as seen in the case of the Tarim basin in Xinjiang, it is possible to reduce the total amount of water used to obtain an even higher yield of agriculture production, while considerably increasing the availability of the water to be shared among neighbors. The know how and experience of African, South American, Israeli and Chinese agronomists, specialized in food production in arid countries, can play a key role.

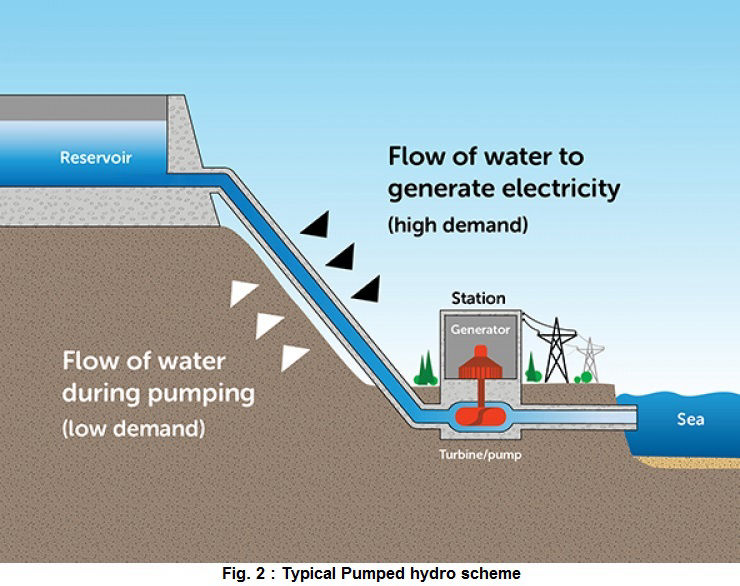

- In the near future, Pumped Hydro Energy Storage (PHES), which means storing water in high altitude reservoirs for a later use, can massively increase the independance and autonomy of countries such as Afghanistan and others. Having sufficient water at hand at any time means also having the water security required to operate mining activities and handle thermal and nuclear electricity production units. PHES infrastructure would be greatly efficient on both sides of the Abu Daria and jointly operated among friendly nations.

Over the past 1,200 years, nations bordering waterways have concluded 3,600 treaties on the sharing of river usufructs, whether for fishing, river transport or the sharing of water for domestic, agricultural and industrial uses.

Afghanistan’s Qosh Tepa canal project is a laudable and legitimate initiative. But it is true that by breaking the status quo, it obliges a new dialogue among nations allowing each and all of them to rise to a higher level, a willing to live together increasingly the opposite to the dominant paradigm in the Anglosphere and its european followers.

It’s up to all of us to make sure it works out fine.