Étiquette : Bactria

Afghanistan: Qosh Tepa canal and prospects of Aral Sea basin water management

Presentation of Karel Vereycken at the second panel discussion of the « Water for Peace » seminar organized by the Schiller Institute on January 9, 2024 in Paris.

Let’s start with current events. In August 2021, faced with the Taliban takeover, the United States hastily withdrew from Afghanistan, one of the world’s poorest countries, whose population has doubled in 20 years to 39.5 million.

While the UN acknowledged that the country was facing « the worst humanitarian crisis » in the post-war era, overnight all international aid, which represented more than half of the Afghan budget, was suspended. At the same time, $9.5 billion of the country’s central bank assets, held in accounts at the US Federal Reserve and a number of European banks, were frozen.

Qosh Tepa canal

Despite these dramatic conditions, the Afghan government, via its state construction group, the National Development Company (NDC), committed $684 million to a major river infrastructure project, the Qosh Tepa Canal, which had been suspended since the Soviet invasion.

In less than a week, over 7,000 drivers flocked from the four corners of the country to work day and night on the first section of the canal, the first phase of which was completed in record time.

Politically, the canal project is a clear expression of the re-birth of an inclusive Afghanistan, as the region is mainly inhabited by Turkmen and Tajik populations, whereas the government is exclusively in the hands of the Pashtuns. The latter represent 57% rather than 37% of the country.

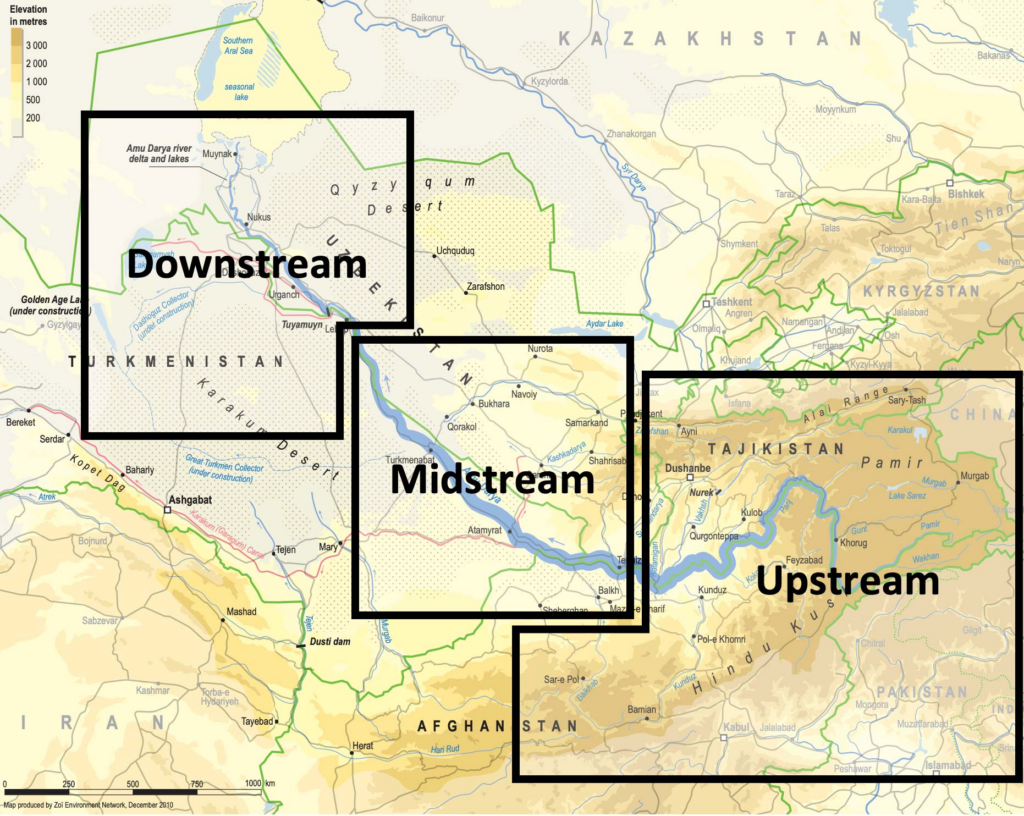

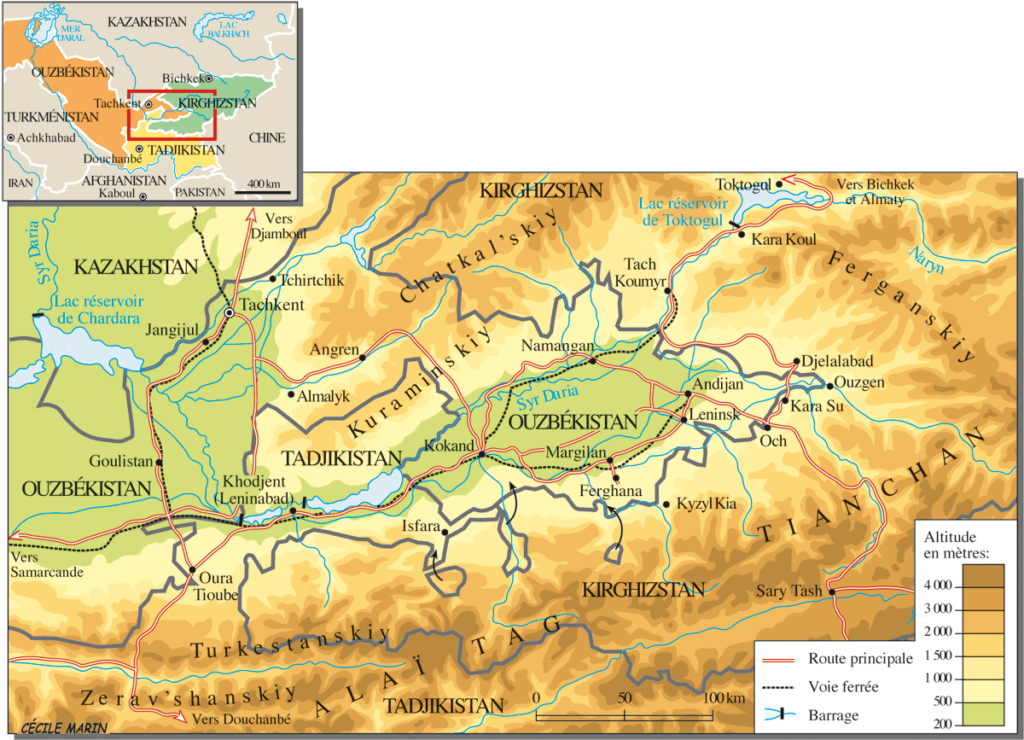

According to the FAO, 62.5% of the Abu Darya’s water comes from Tajikistan, 27.5% from Afghanistan (22 million m3), 6.3% from Uzbekistan, 1.9% from Kyrgyzstan and 1.9% from Turkmenistan.

The river irrigates 469,000 ha of farmland in Tajikistan, 2,000,000 ha in Turkmenistan and 2,321,000 ha in Uzbekistan.

So it’s only natural that Afghanistan should harness some of the river’s waters (10 million m³ out of a total of 61.5 to 80 million m³ per year) to irrigate its territory and boost its ailing agricultural production

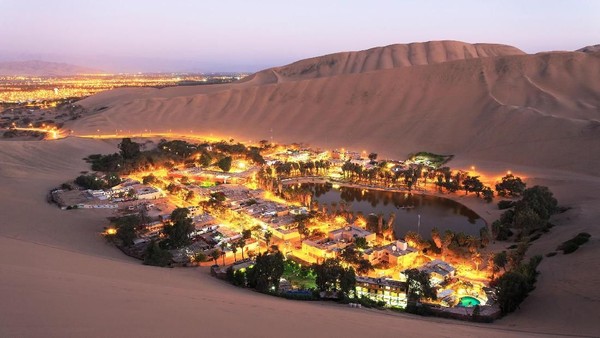

By harnessing part of the waters of the Amu Daria river, the new 285 km-long canal will eventually irrigate 550,000 ha of arid land in ancient Bactria to the north, the « Land of a 1000 Cities » and« The Land of Oases » whose incomparable fertility was already praised by the 1st-century Greek historian Strabo.

In October 2023, the first 108 km section was impounded.

Agricultural production has been kick-started to consolidate the riverbanks, and 250,000 jobs are being created.

While opium poppy cultivation has been virtually eradicated in the Helmhand, the aim is to double the country’s wheat production and to become a grain net exporter.

Today, whatever one may think of the regime, the Afghans, who for 40 years have been self-destructing in proxy wars in the service of the Soviets and Americans, have decided to take their destiny into their own hands. Putting an end to the systemic corruption that has enriched an international oligarchy, they are determined to build their country and give their children a future, notably by making water available for irrigation, for health and for the inhabitants.

How did the world react?

On November 7, in The Guardian, Daanish Mustafa, a professor of « critical geography », explains that Pakistan must rid itself of the colonial spirit of water.

In his view, the floods that hit Pakistan in 2010 and 2022 demonstrate that « colonial » river and canal development is a recipe for disaster. It’s time, he concludes, to « decolonize » our imaginations on the subject of water by abandoning all our vanitous desires to manage water.

On November 9, the Khaama Press News agency reported:

« Tensions have risen between the de facto authorities of Afghanistan and Pakistan due to the ongoing deportation of Afghan migrants. Most recently, Pakistan has called for a halt to the Qush Tepa project. Abdul Haq Hamad, former head of media publications supervision, said in a televised debate that the Pakistani authorities had made it explicitly known at an official meeting with Taliban administration leaders that they must ‘stop operations on the Qush Tepa channel’.

« According to him, the Pakistani authorities are not satisfied with the completion of the Qosh Tepa Canal, as Afghanistan gains autonomy through this canal in managing its waters. »

Two days earlier, on November 7, Cédric Gras, Le Figaro‘s correspondent in Tashkent, published an article entitled:

« En Afghanistan, les Talibans creusent le canal de la discorde » (« In Afghanistan, the Taliban are digging the canal of discord »):

« The Afghanistan of the Taliban is in the process of digging a gigantic irrigation canal upstream from the Amou-Daria river. To the detriment of downstream countries and the Aral Sea, whose water supply and agricultural crops are threatened ».

Obviously, the aim is to create scare. But if the accusation is hasty, it touches on a fundamental issue that deserves explanation.

Endoreic basin

The Amu Daria, the 2539 km long river that the Greeks called the Oxus, and its brother, the 2212 km long Syr Daria, feed, or rather used to feed, the Aral Sea, which straddles the border between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. The water of both rivers were increasingly redirected by soviet experts to irrigate mainly cotton cultivation causing the Aral Sea to disappear.

I won’t go into detail here on the history of the ecological disaster that everyone has heard about but I am ready to answer your questions on that later;

The « Aral Sea Basin » essentially covers five Central Asian « stan » countries. To the North, these are Kazakhstan, followed by Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

In fact, Afghanistan, whose border with the latter three countries is formed by sections of the Amu Darya, is geologically and geographically part of the « Aral Sea Basin ».

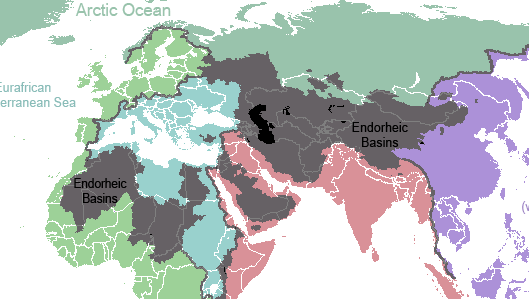

This is a so-called « endoreic basin ». (endo = inside; rhein = carried).

In Europe, we see falling rain and snowmelt flowing into rivers that discharge it into the sea. Not so in Central Asia. Rainwater, or water from melting snow, flows down mountain ranges. They eventually form rivers that either disappear under the sands, or form « inland seas » having no connection whatever to a larger sea and no outlet to the oceans. 18% of the world’s emerged surface is endoreic.

Among the best-known endoreic basins are the Dead Sea in Israel and Lake Chad in Africa.

In Asia, there are plenty of them. Just think of the Tarim Basin, the world’s largest endoreic river basin in Qinjiang, covering over 400,000 km². Then there’s the vast Caspian Sea, the Balkhach and Alakoll lakes in Kazakhstan, the Yssyk Kul in Kyrgyzstan and, as we’ve just said, the Aral Sea.

The very nature of an endoreic basin strongly reinforces the fear that water is a scarce limited source. That realty can either bolster the conviction that problems cannot but be solved true cooperation and discussion, or push countries to go to war one against the other. Democraphic growth, economic progress and climate/meteorogical chaos can worsen that perception and make water issues appear as a « time-bomb ».

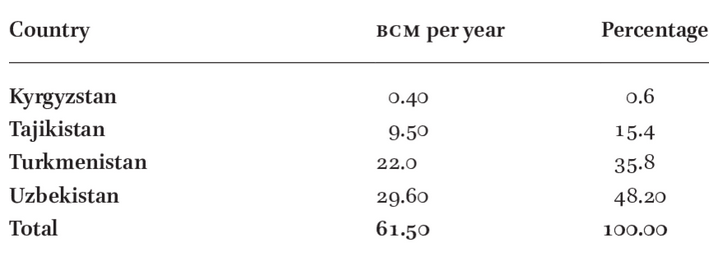

The early Soviet planners started with a strict quota system laid down in 1987 by Protocol 566 of the Scientific and Technical Council of the Soviet Ministry of Water Resources. The system fixed quotas for all countries, both in percentage and in BCM (Billions of Cubic Meters).

That simple quota system looks 100 % functional on paper. However, nations are not abstractions.

First, this system created quite rigid procedures and even would forbid some upstream countries to invest in their own agriculture since they had to deliver the water to their neighbors.

Second, conflict arose about dissymetric seasonal use of the water. The use of the water was completely different between « Upstream countries » such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and « Downstream countries » such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

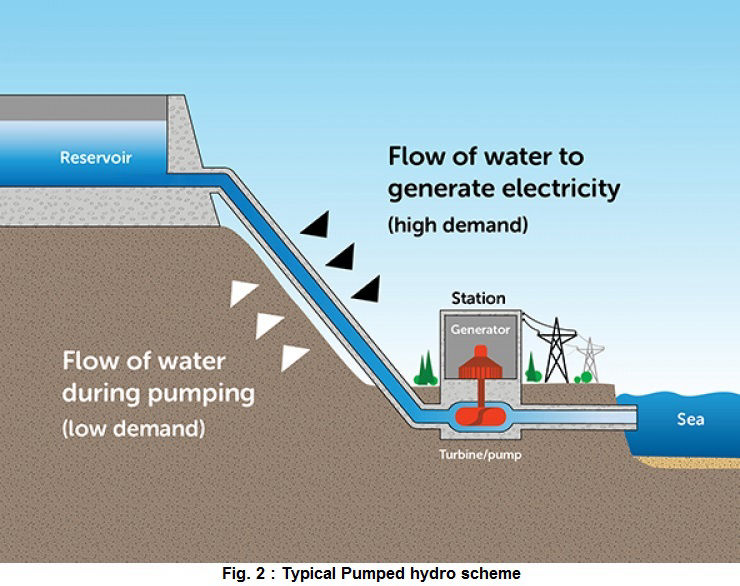

Upstream countries could accept releasing their water resources in autumn and winter since the release of the water provides them up to 90 % of their electricity via hydrodams.

Downstream countries however don’t need the water at that time but in spring and summer when their farmland needs to be irrigated.

However, in Central Asia, their seems to exist some sort of « geological justice » since downstream countries lacking water (Kazakhstan, Uzbekhistan and Turkmenistan) have vast hydrocarbon energy reserves such as coal, oil and gaz.

Therefore, not always stupid, Soviet planners, which realized that a simple quota system was insufficient to prevent conflict, created a compensation mechanism. Downstream nations, in exchange for water, would supply parts of their oil and gas to upstream nations to compensate the loss of potential energy that water represents.

However imperfect that mechanism, for want of a better one, it remained in place after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It can be said that by appealing to an external factor of a given problem, in this case to bring energy in the equation to solve the water problem, soviet planners conceived in a rudimentary form what became known as the « Water, Energy, Food Nexus ». One cannot deal with theses factors as separate factors. They have to be conceived as part of a single, dynamic Monad.

Today, we should avoid the geopolitical trap. If we consider the water resources to be shared between the states of Central Asia and Afghanistan to be « limited », or even « declining » due to meteorological phenomena such as El Nino, we might hastily and geopolitically conclude that, with the construction of the Qosh Tepa canal, which will tap water from the Amu Daria, the « water time bomb » cannot but explode.

Solutions

So we need to be creative. We don’t have all the solutions but some ideas about where to find them:

- In Central Asia, especially in Turkmenistan but also Uzbekistan, huge quantities of water from the Abu Daria water basin are wasted. In 2021, Chinese researchers, looking at Central Asia’s potential in terms of food production, estimated that with improvements in irrigation, better seeds and other « agricultural technology », 56 % of the water can be saved farming the same crops, meaning that today, about half of the water is simply wasted.

- The lack of investment into new water infrastructure and maintenance cannot but lead to the kind of disasters the world has seen in Libya or Pakistan where, predictably, systems collapsed for lack of mere maintenance;

- Uncontrolled and controlled flooding are very primitive and inefficient forms of irrigation and should be outphased and replaced by modern irrigation techniques;

- Therefore, a water emergency should be declared and a vast international effort should assist all the countries of the Abu Daria basin, including Afghanistan, to modernize and improve the efficiency of their water infrastructure, be it lakes, canals, rivers and irrigation systems.

- Such and effort can best organized within the framework of the « One Belt, One Road » initiative and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. BRICS countries such as China, Russia and India could help Afghanistan with data from their satellites and space programs.

- By improving the efficiency of water use, notably through targeted irrigation using « drip irrigation » as seen in the case of the Tarim basin in Xinjiang, it is possible to reduce the total amount of water used to obtain an even higher yield of agriculture production, while considerably increasing the availability of the water to be shared among neighbors. The know how and experience of African, South American, Israeli and Chinese agronomists, specialized in food production in arid countries, can play a key role.

- In the near future, Pumped Hydro Energy Storage (PHES), which means storing water in high altitude reservoirs for a later use, can massively increase the independance and autonomy of countries such as Afghanistan and others. Having sufficient water at hand at any time means also having the water security required to operate mining activities and handle thermal and nuclear electricity production units. PHES infrastructure would be greatly efficient on both sides of the Abu Daria and jointly operated among friendly nations.

Over the past 1,200 years, nations bordering waterways have concluded 3,600 treaties on the sharing of river usufructs, whether for fishing, river transport or the sharing of water for domestic, agricultural and industrial uses.

Afghanistan’s Qosh Tepa canal project is a laudable and legitimate initiative. But it is true that by breaking the status quo, it obliges a new dialogue among nations allowing each and all of them to rise to a higher level, a willing to live together increasingly the opposite to the dominant paradigm in the Anglosphere and its european followers.

It’s up to all of us to make sure it works out fine.

The science of Oases, from the Indus Valley to Persian qanats

Presentation of Karel Vereycken at the first panel discussion of the « Water for Peace » seminar organized by the Schiller Institute on January 9, 2024 in Paris.

While the dog was domesticated as early as 15,000 years BC, we associate the first human activities aimed at managing water with the Neolithic period, which began around 10,000 BC.

It is thought to be the moment at which mankind moved from a « tribal subsistence economy of hunter-gatherers » to agriculture and animal husbandry, giving rise to villages and cities, where pottery, weaving, metallurgy and the arts would start blooming.

Key to this, the domestication of animals. The goat was domesticated around 11,000 BC, the cow around 9,000 BC, the sheep around -8,000 BC, and finally the horse around 2,200 BC in the steppes of Ukraine.

The oldest archaeological sites showing agricultural activities and irrigation techniques were discovered in the Indus Valley and the « Fertile Crescent ».

The site of Mehrgarh, in the Indus Valley, now Pakistan Balochistan, discovered in 1974 by François and Cathérine Jarrige, two French archaeologists, demonstrates important agricultural practices from 7000 BC onward.

Cotton, wheat and barley were grown, and beer was brewed. Cattle, sheep and goats were raised. But Mehrgarh was much more than that.

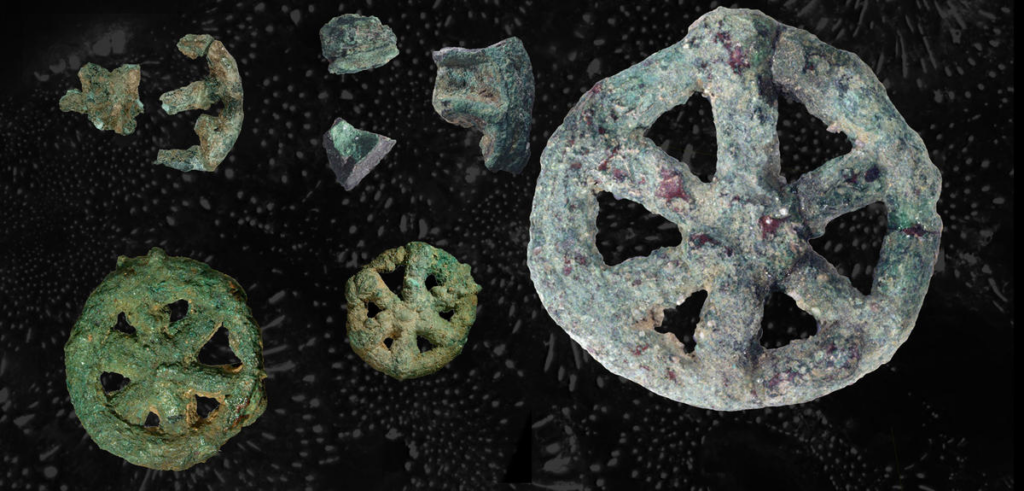

Contradicting the linear « developmental » schema, since we’re in the middle of the Neolithic, Mehrgarh is also home to the oldest pottery in South Asia and, above all, to the “Mehrgahr amulet”, the oldest bronze object casted with the « lost-wax » method.

The first seals made of terracotta or bone and decorated with geometric motifs were found here.

On the technological side, tiny bow drills were used, possibly for dental treatment, as evidenced by the pierced teeth of some skeletons found on site.

At the same time, or shortly afterwards, around 6000 B.C., Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, witnessed rapid urban development in terms of demographics, institutions, agriculture, techniques and trade.

A veritable « fertile crescent » emerged in the region stretching from Sumer to Egypt, passing through the whole of Mesopotamia and the Levant, i.e. Syria and the Jordan Valley.

Irrigation

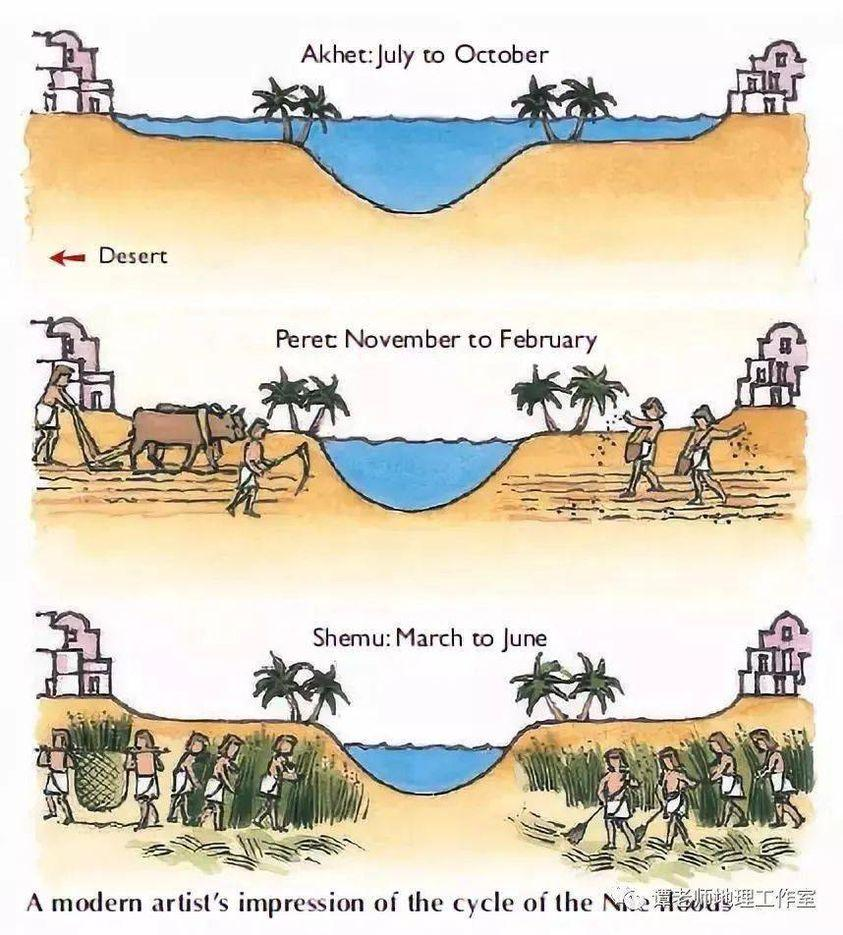

Whether in the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia or Egypt, the earliest irrigation techniques are nothing but retaining as much water as possible when Mother Nature has the sweet kindness to offer it to mankind.

Rainwater was collected in cisterns and, as much as possible, when snowmelt or monsoon rains swell the rivers, the objective was to amplify and steer seasonal « flooding » by canals and trenches carrying the water as far away as possible to areas to be cultivated, while at the same time protecting crops.

In Egypt, for example, where the Nile rises by around 8 meters, the water brings not only moisture but also silt to the soil near the river, providing crops with the nutrients they need to grow and thus maintain the soil’s fertility.

While the Egyptians complained about the harsh labor condition of their farmers, for the Greek historian Herodotus, this was the place in the world where work was least arduous. Of Egypt he says:

“Its soil is black and crumbly, made of silt and alluvium brought from Ethiopia by the river. Certainly, these people are today, of all the human race in Egypt as elsewhere, those who go to the least trouble to obtain their crops.

« They don’t bother to plough and weed. When the river has come of its own accord to water their fields and, its task done, has withdrawn, each man sows his land and lets the pigs loose: by trampling, the beasts sink the seeds into the earth, and the man has only to wait for the harvest.”

In Mehrgarh, where agriculture was born from 7000 BC, the work was indeed far more demanding.

However, the drainage system around the village and the rudimentary dams to control water-logging indicate that the inhabitants understood most of the basic principles involved. The cultivation of cotton, wheat and barley, as well as the domestication of animals, show that they were also familiar with canals and irrigation systems.

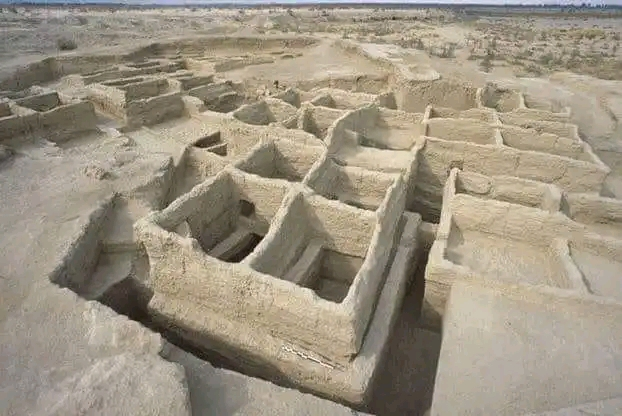

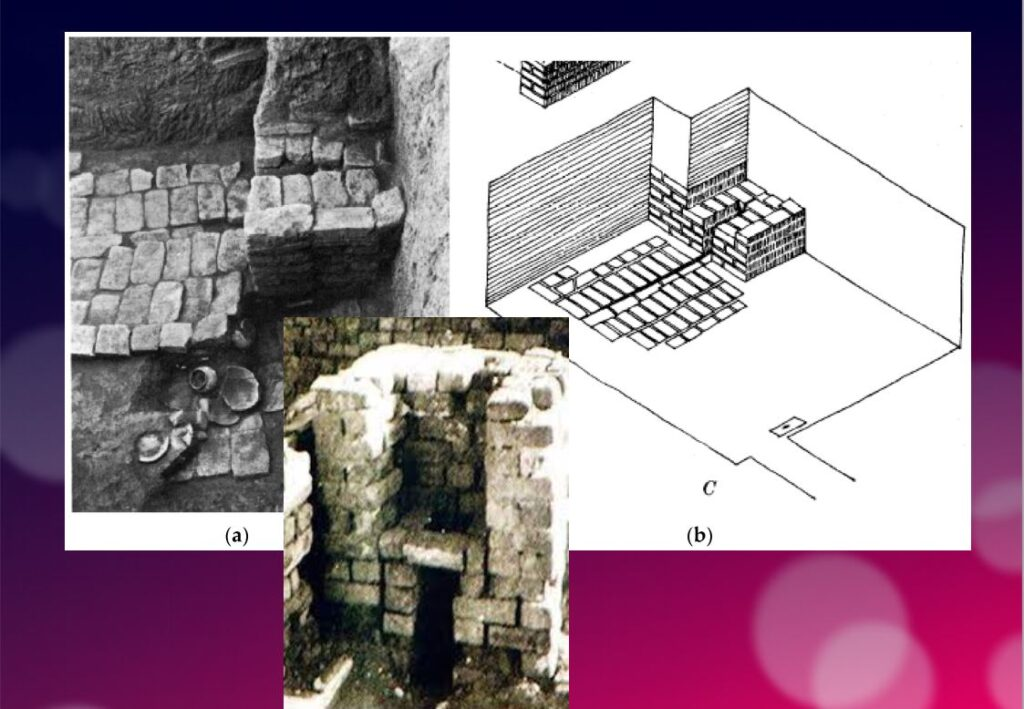

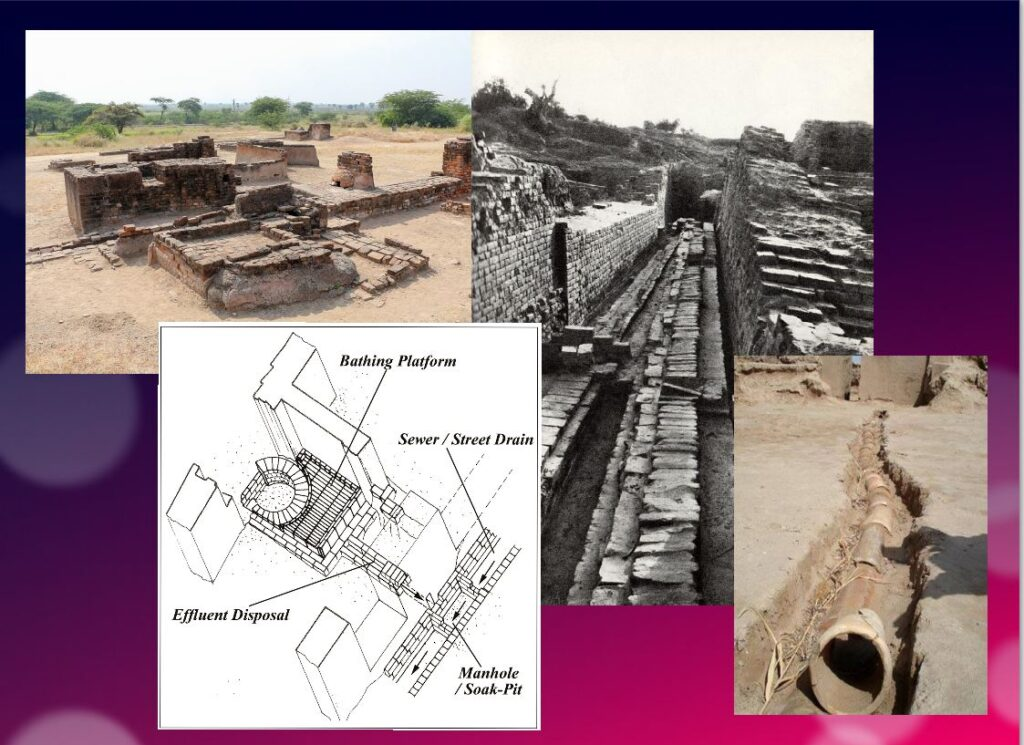

Constantly refined, this know-how enabled the civilization of the Indus Valley to create great cities that impress us by their modernity, notably Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, a city of 40,000 inhabitants with a public bath in its center, not a palace.

Pioneers of modern hygiene, these towns were equipped with small containers where residents could deposit their household waste.

Anticipating our « all-to-the-sewer » systems imagined in the early XVIth century by Leonardo da Vinci, for example in his plans for the new french capital of Romorantin, many towns had public water supplies as well as an ingenious sewage system.

In the port city of Lothal (now India), for example, many homes had private brick bathrooms and latrines. Wastewater was evacuated via a communal sewage system leading either to a canal in the port, or to a soaking pit outside the city walls, or to buried urns equipped with a hole for the evacuation of liquids, which were regularly emptied and cleaned.

Excavations at the Mohenjo Daro site reveal the existence of no fewer than 700 brick wells, houses equipped with bathrooms and individual and collective latrines.

Many of the city’s buildings had two floors or more. Water trickled down from cisterns installed on the roofs was channeled through closed clay pipes or open gutters that emptied into the covered sewers beneath the street.

This hydraulic and sanitary know-how was passed on to the civilization of Crete, the mother of Greece, before being implemented on a large scale by the Romans.

It was forgotten with the collapse of the Roman Empire, only to return during the Renaissance.

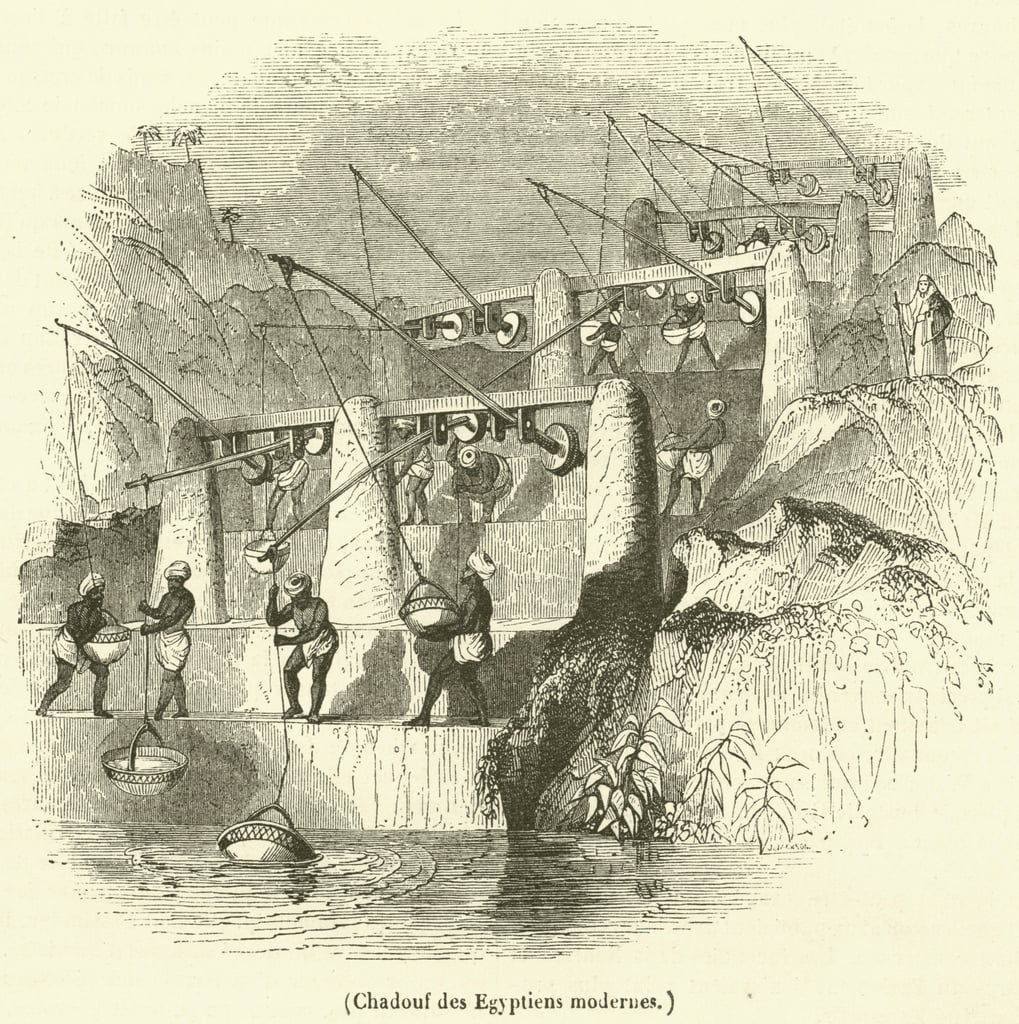

The first human contributions were aimed at maximizing water reservoirs and their gravity-flow capacity. To achieve this, it was necessary to transfer water from a lower level to higher ground and build « water towers ».

To this end, the Mesopotamian « chadouf » was widely used in Egypt, followed by the « Archimedean screw ».

Next came the « saquia » or « Persian wheel », a geared wheel driven by animal power, and finally the « noria », the best-known water-drawing machine, powered by the river itself.

Persian qanats

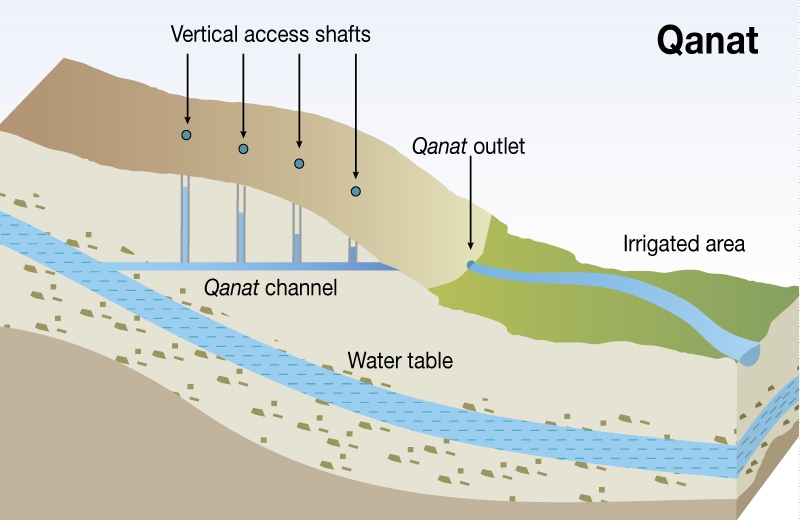

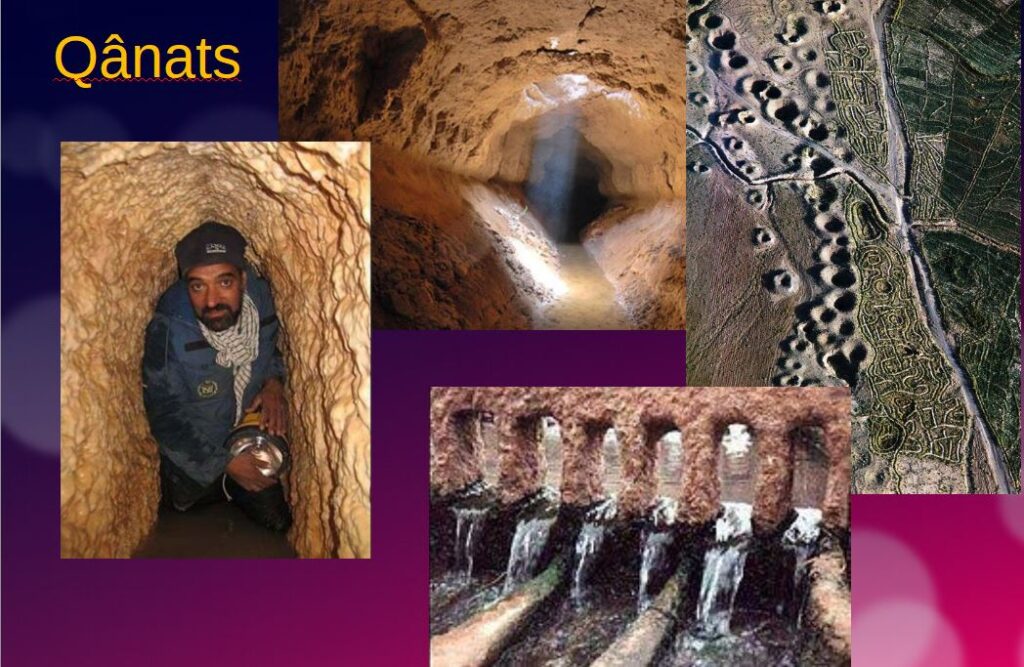

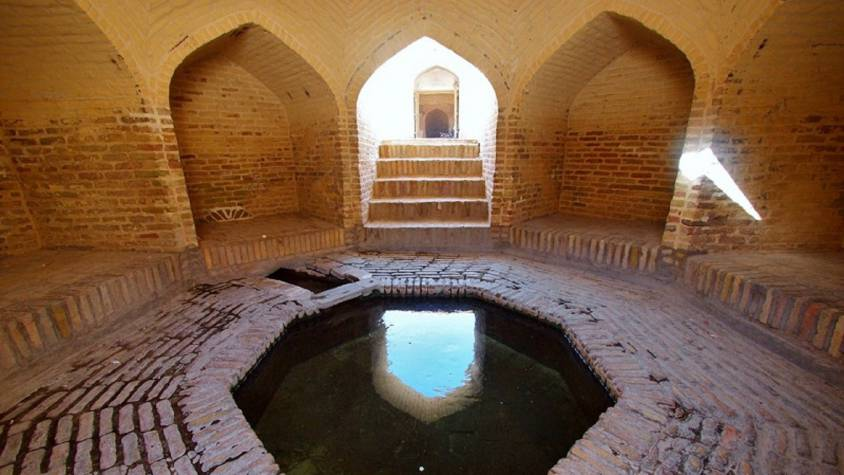

Before Alexander the Great, Persia’s Achaemenid Empire (6th century BC) developed the technique of underground qanats or underground aqueducts. This « draining gallery” cut into the rock or built by man, is one of the most ingenious inventions for irrigation in arid and semi-arid regions.

Whatever displeases our environmentalist friends, it’s not nature that magically produces « oases » in the desert.

It’s a scientific man who digs a drainage gallery from a water table close enough to the ground surface, or sometimes from an aquifer that flows into the desert.

On the website of ArchéOrient, archaeologist Rémy Boucharlat, Director of Emeritus Research at the French CNRS, an expert on Iran, explains:

« Whatever the origin of the water, deep or shallow, the gallery construction technique is the same. The first step is to identify the presence of the water, either its underflow near a river, or the presence of a deeper water table on a foothill, which requires the science and experience of specialists.

A motherwell reaches the upper part of this layer or water table, which indicates the depth at which the gallery should be dug. The slope of the gallery must be very shallow, less than 2‰, to ensure a calm and regular flow of water, and to gradually lead the water to the surface, at a gradient much lower than the slope of the piedmont.

The gallery is then excavated, not from the mother well, as it would be flooded immediately, but from downstream, from the arrival point. The pipe is first dug as an open trench, then covered, and finally gradually tunnelled into the ground.

Shafts are dug from the surface at regular intervals, between 5 and 30 m depending on the nature of the terrain, to evacuate soil and provide ventilation during excavation, and to mark the direction of the tunnel.”

Historically, the majority of the populations of Iran and other arid regions of Asia and North Africa depended on the water supplied by qanats; settlement areas thus corresponded to the places where their construction was possible.

The technique offers a significant advantage: as the water moves through an underground conduit, not a drop of water is lost through evaporation.

This technique spread throughout the world under various names: qanat and kareez in Iran, Syria and Egypt, kariz, kehriz in Pakistan and Afghanistan, aflaj in Oman, galeria in Spain, kahn in Balochistan, kanerjing in China, foggara in North Africa, khettara in Morocco, ngruttati in Sicily, bottini in Siena, etc.).

Improved by the Greeks and amplified by the Etruscans and the Romans, the qanats technique was carried by the Spaniards across the Atlantic to the New World, where numerous underground canals of this type still operate in Peru, Chile and western Mexico.

After Alexander the Great, Bactria, covering parts of today’s Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and the northern part of Afghanistan, was even known as the « Oasis civilization » or the “Land of a 1000 Golden Cities”.

Iran boasts it had the highest number of qanats in the world, with approximately 50,000 qanats covering a total length of 360,000 km, about 9 times the circumference of the Earth !

Thousands of them are still operational but increasingly destabilized by erratic well digging and demographic overconcentration.

Shared responsability

In 1017, the Baghdad-based hydrologist Mohammed Al-Karaji provided a detailed description of qanat construction and maintenance techniques, as well as legal considerations about the collective management of wells and pipes.

While each qanat is designed and supervised by a mirab (dowser-hydrologist and discoverer), building a qanat is a collective task that takes several months or years for a village or group of villages. The absolute necessity of collective investment in the infrastructure and its maintenance calls for a superior notion of the common good, an indispensable complement to the notion of private property that rains and rivers are not accustomed to respecting.

In North Africa, the management of water distributed by a khettara (the local name for qanâts) is governed by traditional distribution norms known as « water rights ».

Originally, the volume of water granted per user was proportional to the work involved in building the khettara, and translated into an irrigation period during which the beneficiary could use all the khettara’s flow for his or her fields. Even today, when the khettara has not dried up, this rule of water rights still applies, and a share can be bought or sold. The size of each family’s fields to be irrigated must also be taken into account

All of this demonstrates that good cooperation between man and nature can do miracles if man decides so.

Thank you for your attention and questions welcome!

Horse-power, the Earthly Science behind China’s “Heavenly Horses”

Indicating the major role horses have played in the history of mankind, the fact that still today, when people talk about the engine of their cars, they use the term “horsepower” (hp) to indicate how much “work” the engine is capable of.

In a lecture on hydro-infrastructure in Kabul, Afghanistan, I recently used the domestication of the horse as an example of what one should understand when we talk about moving from a “lower” to a “higher infrastructure platform”.

The history of mankind completely changed with the domestication of the horse. Things considered “impossible” before the domestication of the horse became the “new normal”. How and when horses became domesticated has been disputed. Although horses appear in Paleolithic cave art as early as 36,000 BC (Chauvet cave, France), these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

Zoologists define « domestication » as human control over breeding, which can be detected in ancient skeletal samples by changes in the size and variability of ancient horse populations. Other researchers look at the broader evidence, including skeletal and dental evidence of working activity; weapons, art, and spiritual artifacts; and lifestyle patterns of human cultures. There is evidence that horses were kept as a source of meat and milk before they were trained as working animals.

In India, close to Bopal, the “Bhimbetka rock shelters”, which are the oldest known rock art of the country, figures dance and hunting scenes from the Stone Age as well as of warriors on horseback from a later time (10 000 BC).

Horses were a late addition to the barnyard. Dogs were domesticated 15,000 years ago; sheep, pigs and cattle, about 8,000 to 11,000 years ago. But clear evidence of horse domestication doesn’t appear in the archaeological record until about 5,500 years ago.

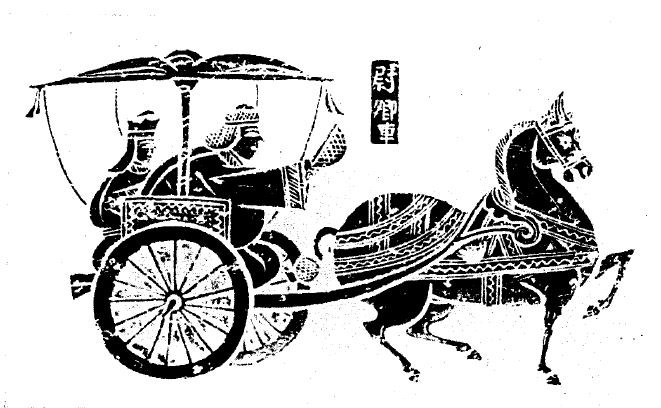

The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials. The earliest true chariots known are from around 2,000 BC, in burials of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in modern Russia in a cluster along the upper Tobol river, southeast of Magnitogorsk.

They contain spoke-wheeled chariots drawn by teams of two horses.

Kazakhstan and Ukraine

Up till recently, it was thought that the most common horse used today was a descendant of the horses domesticated by the Botai culture living in the steppes of the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan, around 3500 BC.

Recent genetic research points to the fact that the Botai horses were the forefathers of the Przewalski horse, a species that nearly disappeared.

Our common horse, the Equus ferus caballus, genetic research says, has been domesticated 4,200 years ago in Ukraine, in an area known as the Volga-Don, in the Pontic-Caspian steppe region of Western Eurasia, around 2,200 BC.

As these horses were domesticated, they were regularly interbred with wild horses.

Interesting in this respect, is the fact that according to the “Kurgan” or “steppe hypothesis”, most Indo-European languages spread from the same region throughout Europe and parts of Asia.

It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of what some call the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan, meaning tumulus or burial mound.

Tea Road, Horse Road or Silk Road?

As a matter of fact, the main commodities traded on the “Silk Road” (a term only coined in 1877 by the German geographer Ferdinand Von Richthofen), were… horses, mules, camels, donkeys and onagers.

Silk and tea were of course traded, but appeared mainly as a means… to pay for horses. People “paid” with silk, gold, porcelain and tea, the animals they needed to secure the survival of their society!

What was known as the « Tea-Horse Road » (Southern Silk Road) extended from the city of Chengdu in Sichuan Province, China, south through Yunnan into India and the Indochina Peninsula, and extended westwards into Tibet. It was an important route for the tea trade throughout South China and Southeast Asia and contributed to the spread of religions like Taoism and Buddhism across the region.

Eurasian Steppe

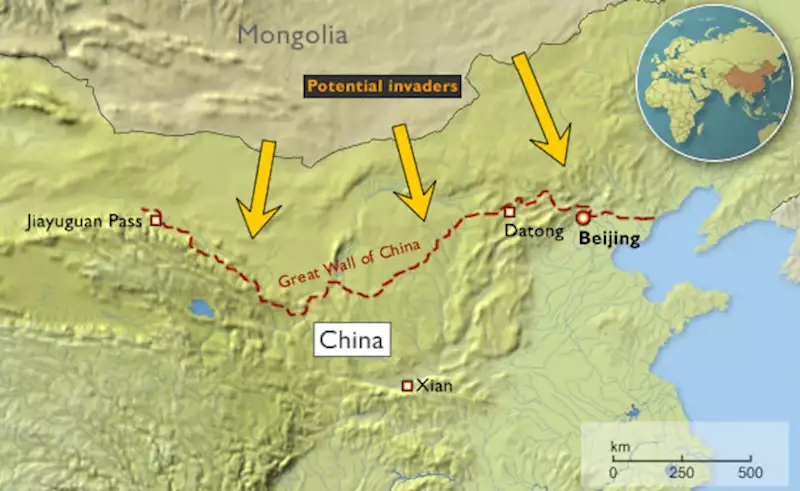

China, feeling itself under constant threat from the nomadic steppe people from the North, started building the first parts of its “Great Wall” as early as the VIIth Century BC, with selective stretches joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China and completed under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to become one of the most impressive feats in history.

The Eurasian nomads were groups of nomadic peoples living throughout the Eurasian Steppe. The generic title encompasses the varied ethnic groups who have at times inhabited the steppes of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, Russia, and Ukraine.

By the domestication of the horse around 2,200 BC (i.e. 4,200 years ago), they vastly increased the possibilities of nomadic life and subsequently their economy and culture emphasized horse breeding, horse riding, and nomadic pastoralism, usually engaging in trade with settled peoples around the steppe edges, be it in Europe, Asia or Central Asia.

Nomads, by definition, don’t create empires. It is thought they operated often as confederations. But it was them who developed the chariot, wagon, cavalry, and horseback archery and introduced innovations such as the bridle, bit, stirrup, and saddle and the very rapid rate at which innovations crossed the steppe-lands spread these widely, to be copied by settled peoples bordering the steppes.

During the Iron Age, Scythian (Persian) culture emerged among the Eurasian nomads, which was characterized by a distinct Scythian art.

China and the Horse

Throughout China’s long and storied past, no animal has impacted its history as greatly as the horse. Its significance was such that as early as the Shang dynasty (ca.1600-1100 BC), military might was measured by the number of the war chariots available to a particular kingdom.

The mounted cavalery, which emerged in the IIIrd century BC grew rapidly during the IInd century BC to meet the challenge of horse-riding peoples threatening China along the northern frontier.

Their large, powerful, horses were very new to China. As said before, traded for luxurious silk, they were the first major import to China from the “Silk Road.”

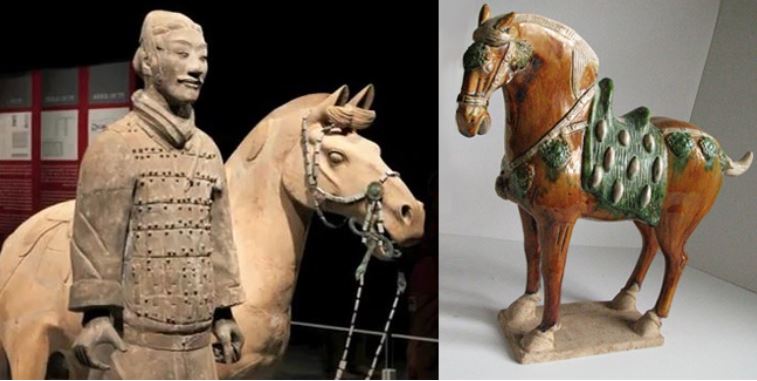

Chinese grave goods provide extraordinary amounts of information about how the ancient Chinese lived. Archaeological evidence shows that within a few years, the marvelous Arabian steeds had become immensely popular with military and aristocracy alike and upper-class tombs began to be filled with images of these great horses for use in the afterlife. But horses were hard to find in China.

Chinese diplomats and the Kingdom of Dayuan (Ferghana)

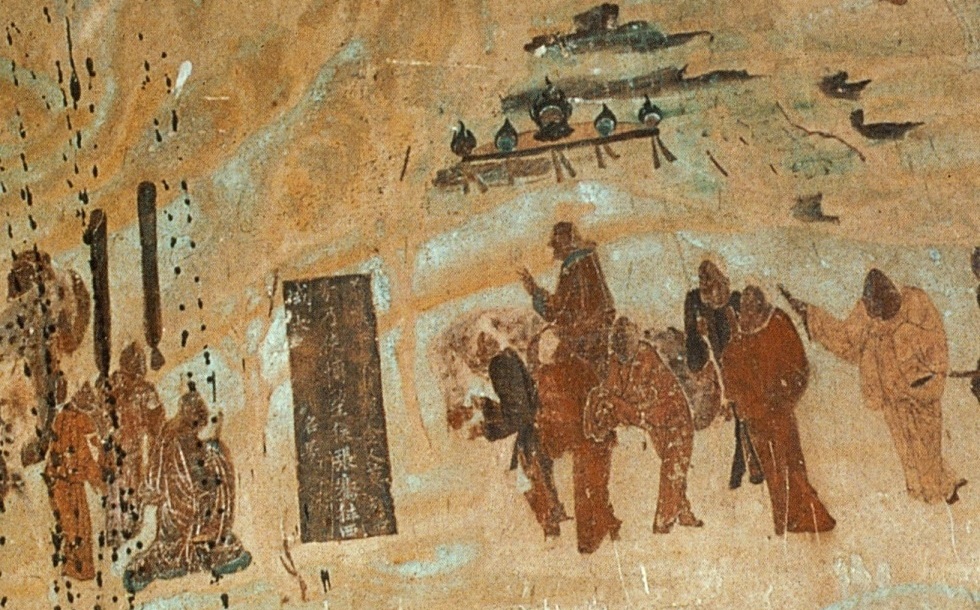

Something had to be done. In the late IInd Century BC, Zhang Qian, a Han dynasty diplomat and explorer, travels to Central Asia and discovers three sophisticated urban civilizations created by Greek settlers he named « Ionians ». The account of his visit to Bactria, including his recollection of his amazement at finding Chinese goods in the markets (acquired via India), as well as his travels to Parthia and Ferghana, are preserved in the works of the early Han historian Sima Qian.

Upon returning to China, his account prompts the Emperor to dispatch Chinese envoys across Central Asia to negotiate and encourage trade with China. Some historians say that this dicision gave « birth of the Silk Road.«

Besides Parthia and Bactria, where Chinese goods were being traded via Indian imports, Zhang Qian visited, in the fertile Ferghana valley (today essentially in Tajikistan), a State the Chinese called the “Kingdom of Dayuan” (“Da” meaning “great”, and “Yuan” being the transliteration of Sanskrit Yavana or Pali Yona, used throughout antiquity in Asia to designate « Ionians », i.e. Greek settlers).

The Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han describe the Dayuan as numbering several hundred thousand people living in 70 walled cities of varying size. They grew rice and wheat, and made wine from grapes. They had Caucasian features and “customs identical to those of Bactria” (the most Hellenistic state of the region since Alexander the Great) which is today’s northern Afghanistan.

The Chinese diplomat reported something of great strategic interest: unbelievable, fast and powerful horses raised by these Ionians in the Ferghana Valley!

Now, as said before, China felt under permanent threat by the nomadic people from the steppes and was in the process of building the “Great Wall”. China also was acutely aware that the nomadic steppe people derived their military superiority from something dramatically lacking at home: powerful horses !

Added to that, the fact that in terms of China’s scale of values, horses where nearly of the same mythological nature as dragons: they could fly and represented the divine, creative spirit of the universe itself, something essential for any Chinese emperor eager to acquire both military security for his Empire and for his personal immortality.

In short, having good horses became an issue of national security. So much, that in 100 BC, the Han dynasty started what is known as the “War of the Heavenly Horses” with Dayuan, when its ruler refused to provide high quality horses to China !

The War of the Heavenly Horses

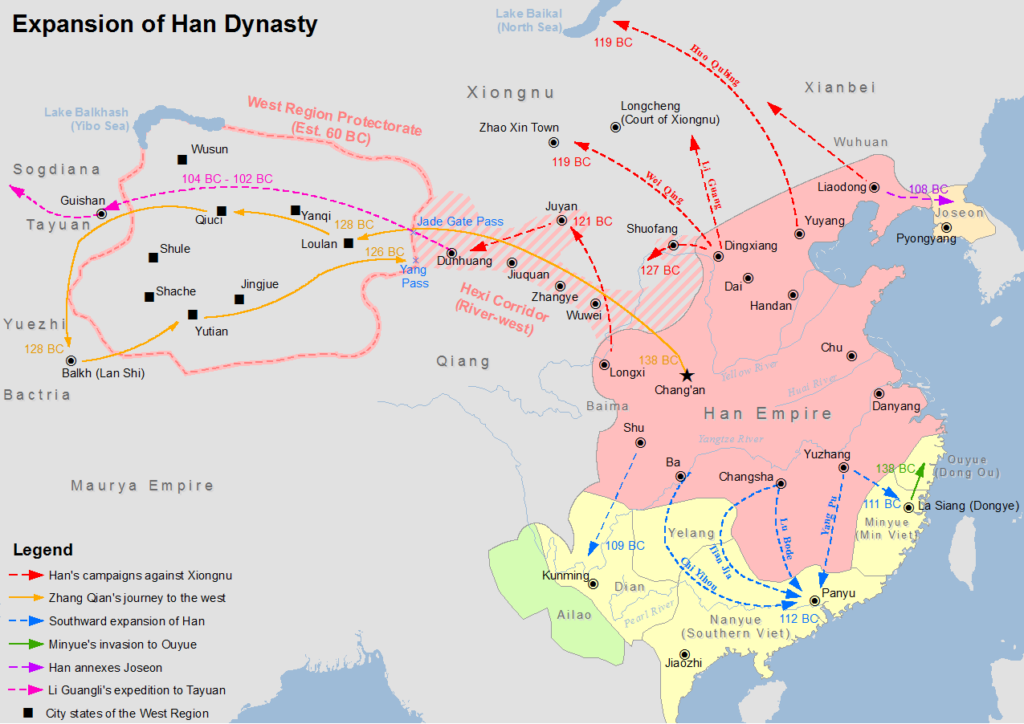

The War of the Heavenly Horses was a military conflict fought in 104 BC and 102 BC between China and a part of the Saka-ruled (Scythian) Greco-Bactrian kingdom known to the Chinese as Dayuan, in the Ferghana Valley (between modern-day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan).

First, Emperor Wu decided to defeat the nomadic steppe Xiongnu, who had harassed the Han dynasty for decades.

As said earlier, in 139 BC, the emperor sent diplomat Zhang Qian to survey the west and forge a military alliance with the Yuezhi nomads against another group of nomads, the Xiongnu. On the way to Central Asia through the Gobi desert, Zhang was captured twice. On his return, he impressed the emperor with his description of the « Heavenly Horses » of Dayuan, that could greatly improve the quality of Han cavalry mounts when fighting the Xiongnu.

The Han court sent at least five or six, and perhaps as many as ten diplomatic groups annually to Central Asia during this period to get a hold on these “Heavenly Horses”.

A trade mission arrived in Dayuan with 1000 pieces of gold and a golden horse to purchase these precious animals.

Dayuan, who was one of the furthest western states to send envoys to the Han court at that point, had already been trading with the Han for quite some time and benefited greatly from it. Not only were they overflowed by eastern goods, they also learned from Han soldiers how to cast metal into coins and weapons. However unlike the other envoys to the Han court, the ones from Dayuan did not conform to the proper Han rituals and behaved with great arrogance and self-assurance, believing they were too far away to be in any danger of invasion.

Hence, in a stroke of folly and taken by pure arrogance, the Dayuan king not only refused the deal, but confiscated the payment in gold. The Han envoys cursed the men of Dayuan and smashed the golden horse they had brought. Enraged by this act of contempt, the nobles of Dayuan ordered Yucheng, which lay on their eastern borders, to attack and kill the envoys and seize their goods.

Upon receiving word of the trade mission’s demise, humiliated and enraged, the Han court sent an army led by General Li Guangli to subdue Dayuan, but their first incursion was poorly organized and under-supplied.

A second, larger and much better provisioned expedition was sent two years later and successfully laid siege to the Dayuan capital at Alexandria Eschate, and forced Dayuan to surrender unconditionally.

The Han expeditionary forces installed a pro-Han regime in Dayuan and left with 3,000 horses, although only 1,000 remained by the time they reached China in 101 BCE.

The Ferghana also agreed to send two Heavenly horses each year to the Emperor, and lucerne seed was brought back to China providing superior pasture for raising fine horses in China, to provide cavalry which could cope with the Xiongnu who threatened China.

The horses have since captured the popular imagination of China, leading to horse carvings, breeding grounds in Gansu, and up to 430,000 such horses in the cavalry during the Tang dynasty.

China and the agricultural revolution

After imposing its role in military strategy for the next centuries, horsepower, together with water management, became a crucial factor to raise the productivity of the world’s food production.

First, contrary to the Romans, who preferred to use “human cattle” (slaves) rather than animals (which they raised for race contests), the Chinese greatly contributed to the survival of mankind with two crucial innovations respecting a more efficient use of horse power.

As can be seen in murals and paintings, through the ancient world, be it in Egypt or Greece, plows and carts were pulled using animal harnesses that had flat straps across the neck of the horse, with the load attached at the top of the collar, above the neck, in a manner similar to a yoke used for oxen.

In reality, this greatly limited a horse’s ability to exert itself as it was constantly choked at the neck. The harder the horse pulled, the harder it became to breathe.

Due to this physical limitation, oxen remained the preferred animal to do heavy work such as plowing. Yet oxen are hard to maneuver, are slow, and lack the quality of horses, whose power is equivalent but whose endurance is twice that of oxen.

China reportedly first invented the “breast strap” which was the first step in the right direction.

Then, in the Vth Century, China also invented what is called the “rigid horse collar”, designed as an oval that fits around the neck and shoulders of the horse.

It has the following advantages:

–First, it relieved the pressure of the horse’s windpipes. It left the airway of the horse free from constriction improving massively the animal’s energy through-put.

–Second, the traces could be attached to the sides of the collar. This allowed the horse to push forward with its more powerful hind-legs rather than pulling with the weaker front legs.

Now you can argue that this is anecdotal. It is NOT, because what appears as only a slight change had absolutely monumental consequences.

European Renaissance

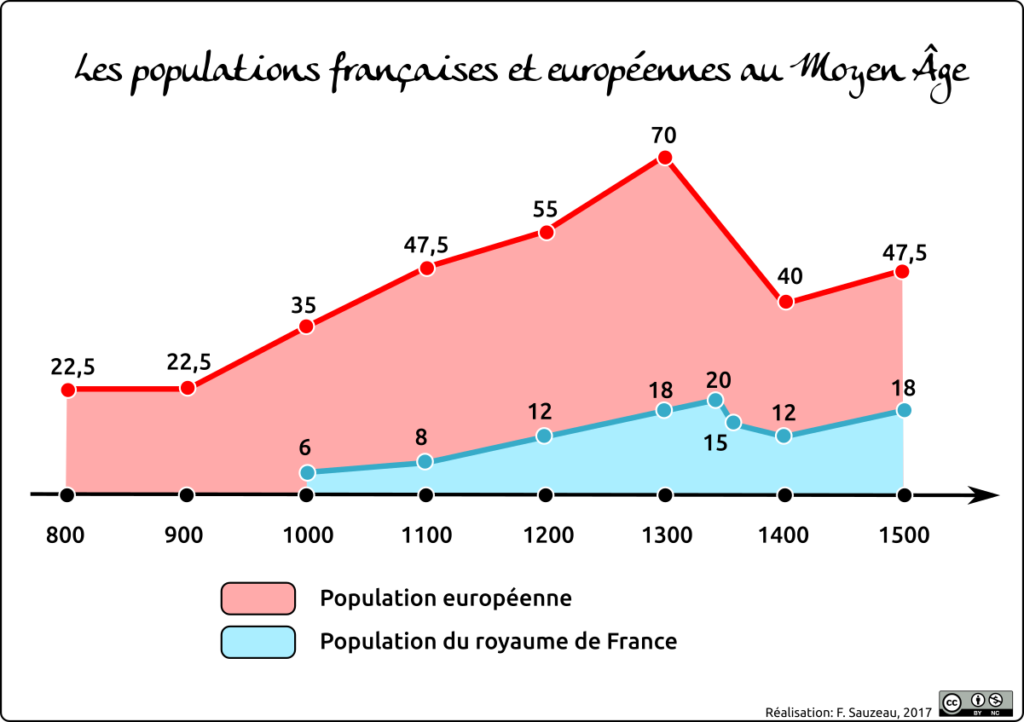

In a strategic alliance and cooperation with the humanist Baghdad Abbasid caliphate, Charlemagne and his successors introduced the “rigid horse collar” in Europe.

With that new, far more efficient tool, European farmers finally could take full advantage of a horse’s strength. The horse was able to pull another recent innovation, the heavy plow. This became particularly important in areas where the soil was hard and clay-like. This opened up new plots of lands to agriculture. The rigid horse collar, the heavy plow, and horseshoes helped usher in a period of increased agricultural production.

As a result, between 1000 CE and 1300 CE, it is estimated that in Europe, crop yields increased by threefold, allowing to feed a rising number of citizens in the urban cities appearing in the XVth century and kick starting the global “Golden” European Renaissance. Thank you, China!

Some numbers are nevertheless disturbing:

–it took humanity thousands of years to finally domesticate the horse (long after the cow), in 3200 BC.

–it took humanity another 3700 years to learn how to find out, in the Vth century AD, the most efficient way to use horse-power…

Shifting from a “lower” infrastructure platform to a “higher” infrastructure platform might take some time. Today’s new “higher” platforms are called “space data” and “fusion power.” Let’s not wait another century to find out how to use them correctly!