Étiquette : Karel

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 26, 2026

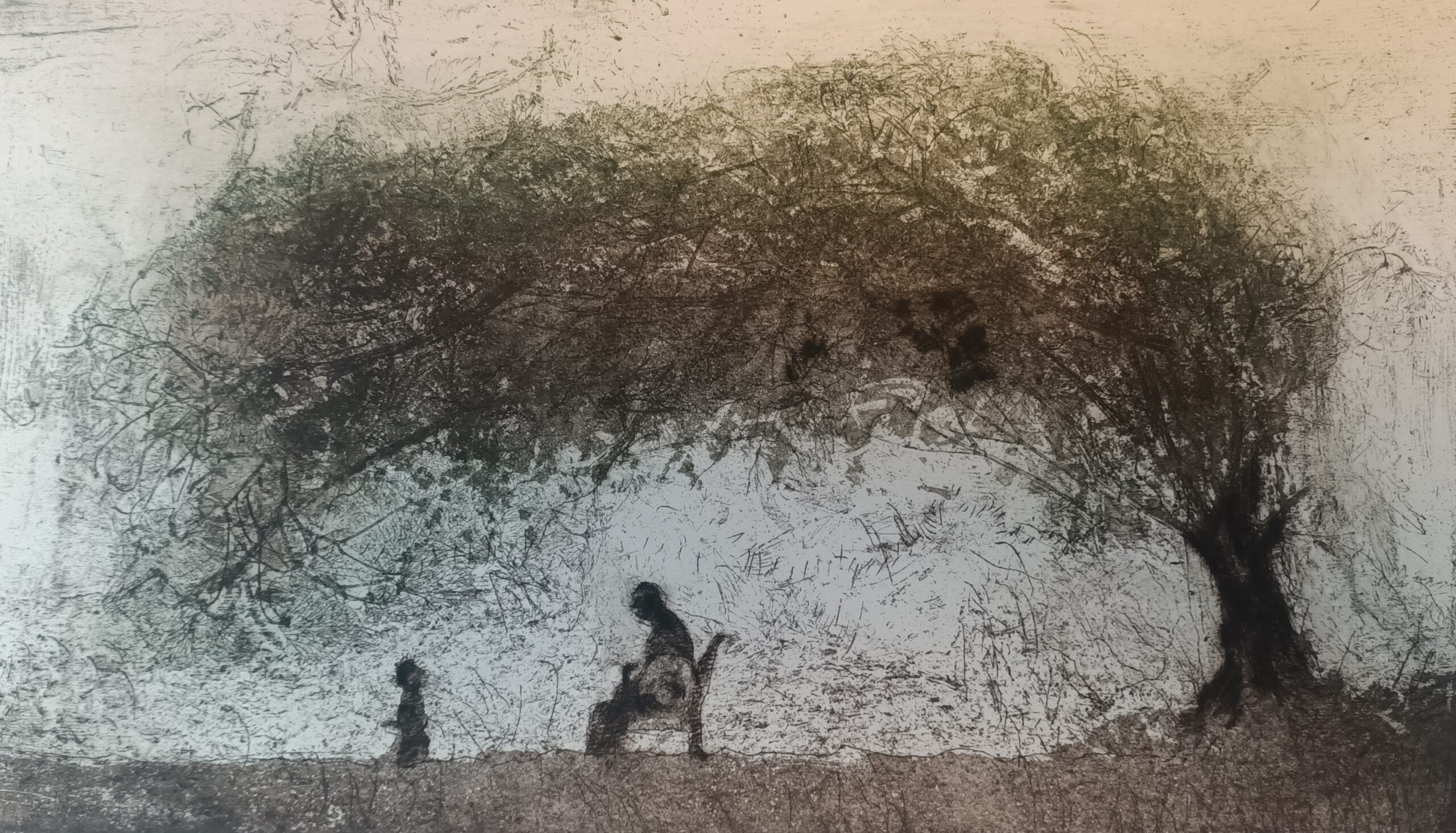

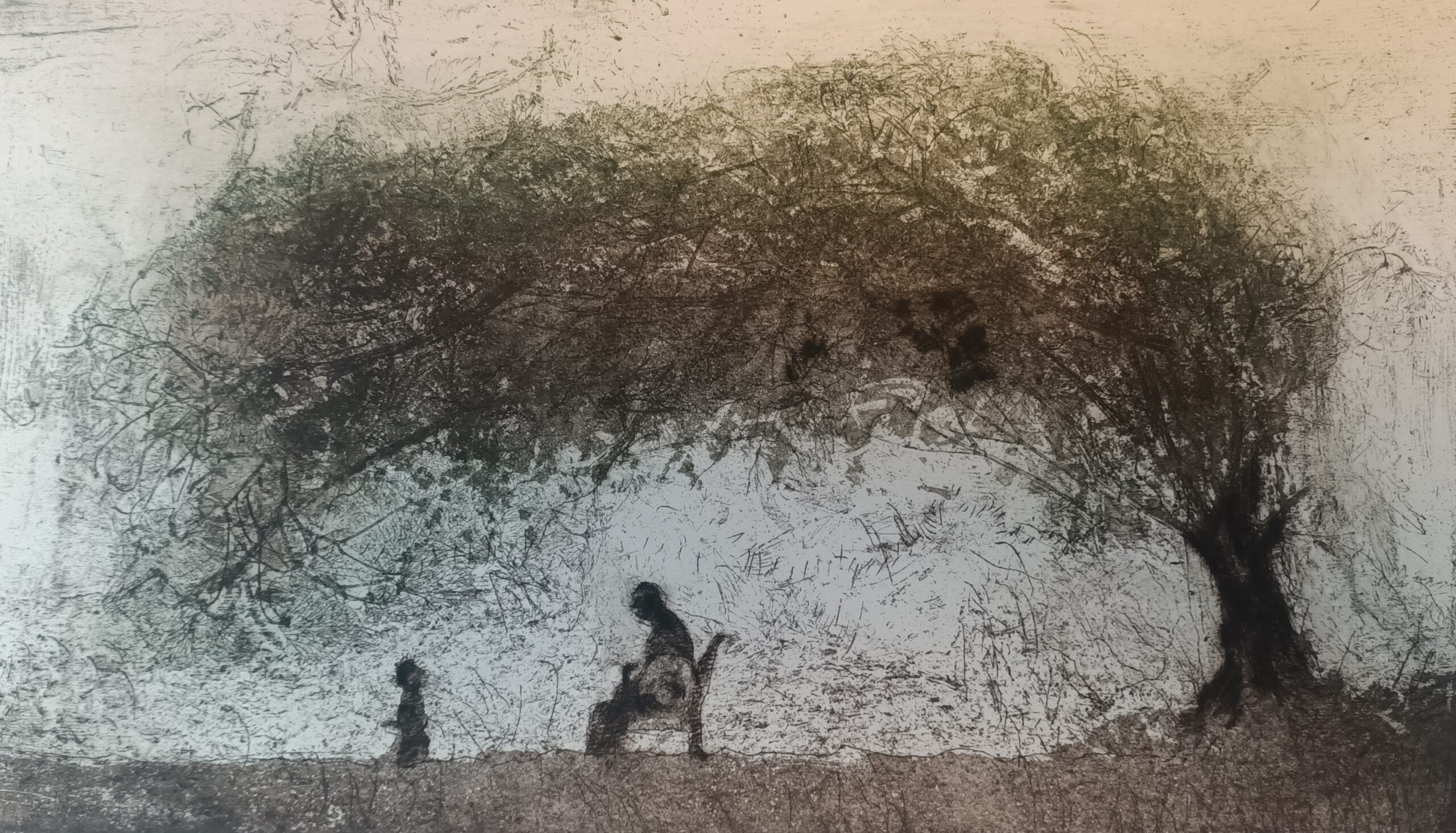

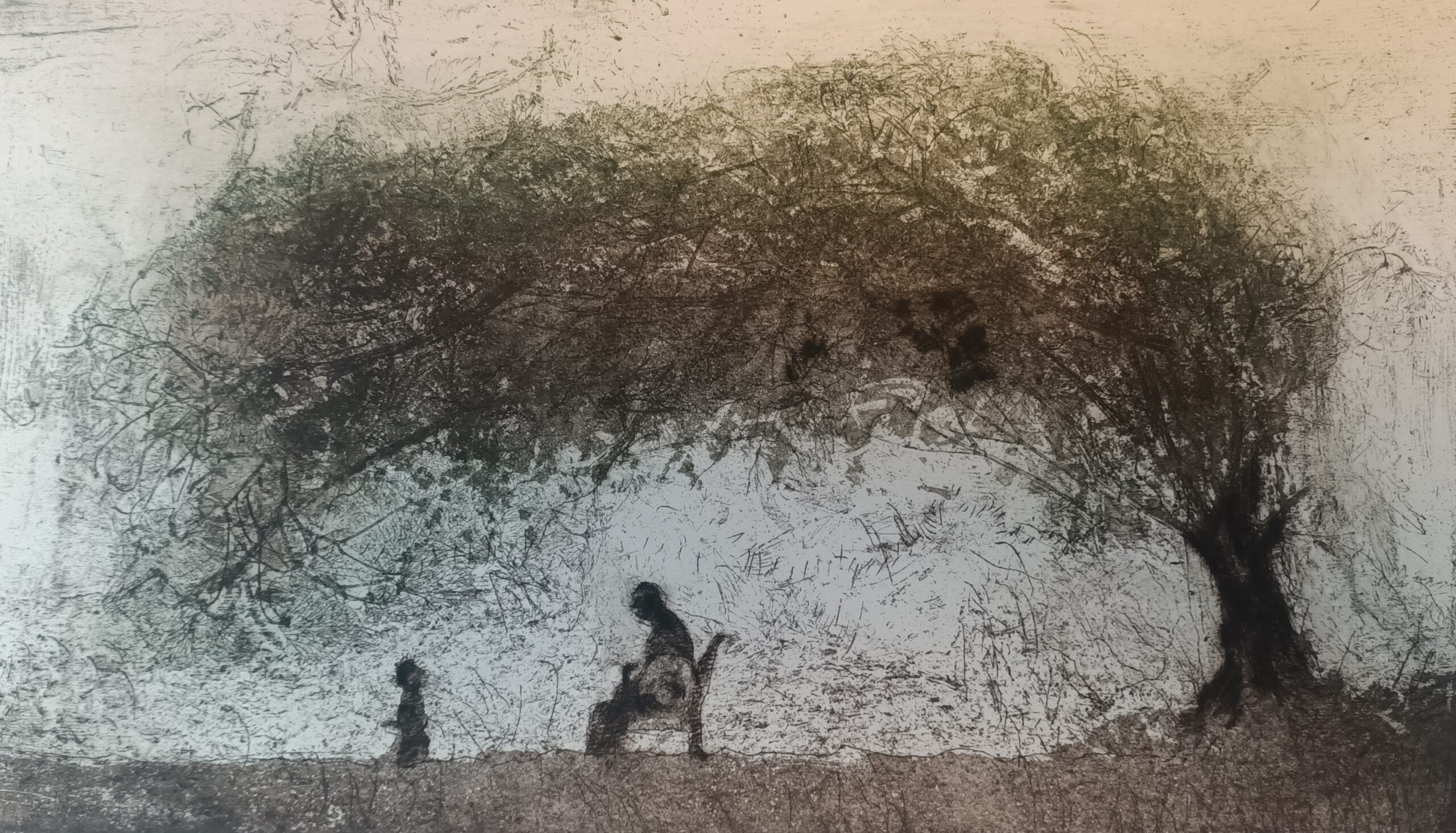

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, terre de sienne, bistre, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, terre de sienne, bistre, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

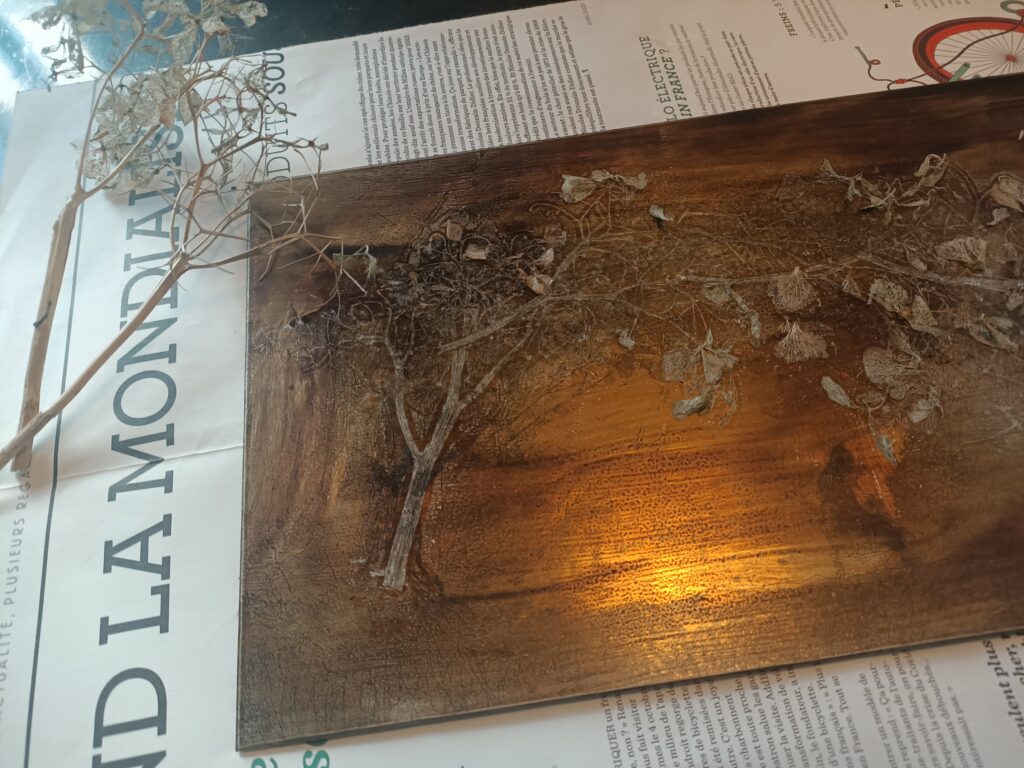

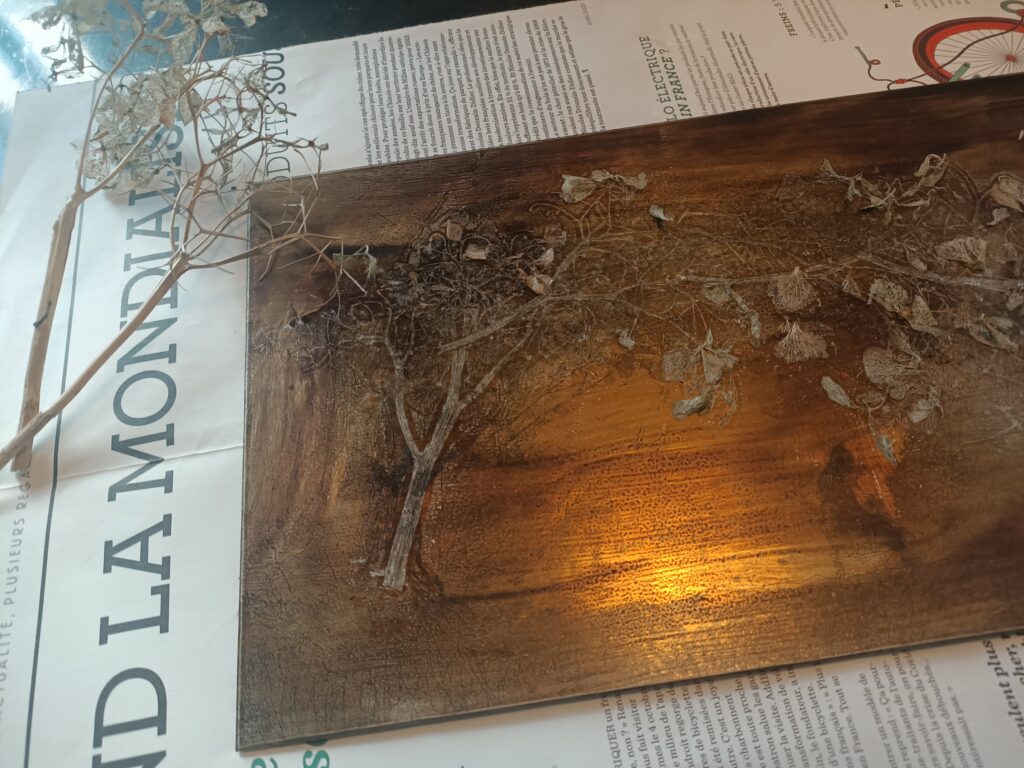

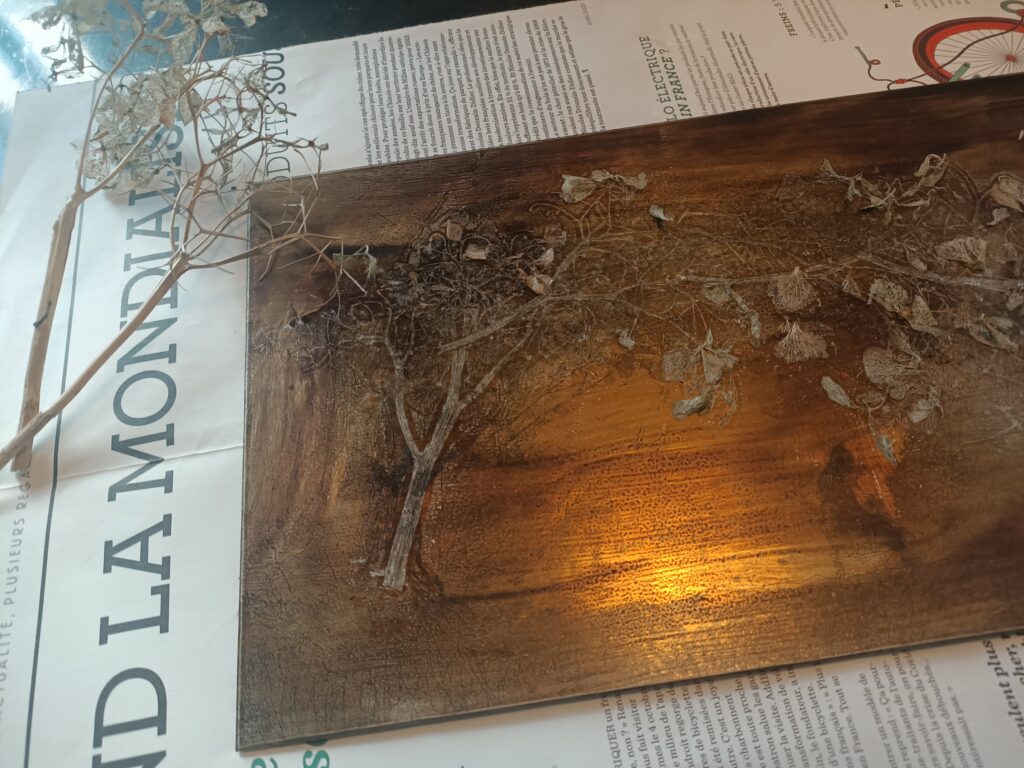

Préparation de vernis mou avant morsure avec branches sèchées de chrysanthèmes.

Préparation de vernis mou avant morsure avec branches sèchées de chrysanthèmes.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, terre de sienne brûlée, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, terre de sienne brûlée, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, bistre, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, bistre, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, vert de vessie, bistre, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, vert de vessie, bistre, 4e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, 3e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Karel Vereycken, L’Arbre de la vie, eau-forte sur zinc, vernis mou, 3e état, 40 x 23 cm, 2026.

Posted in Créer, Gravure, Toutes les oeuvres | Commentaires fermés sur L’arbre de la vie

Tags: artkarel, eau-forte, estampe, etching, gravure, intaglio, Karel, Karel Vereycken, L'arbre de la vie, Tree of Life, Vereycken, vernis mou, zinc

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Beethovens Meeresstille: Reise in eine Kultur des Entdeckens

Tags: artkarel, Beethoven, entdeckung, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Meeresstille, Musik, Reise, renaissance, Schubert, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Beethoven’s Meeresstille: voyage to a Culture of Discovery

Tags: artkarel, Beethoven, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Meeresstille Schubert, music, renaissance, Tranquility, Vereycken, water

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Dürer’s Fight Against Neo-Platonic Melancholy

Tags: acedia, Aristotle, artkarel, Ficino, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Melancholy, Mirandola, Pirckheimer, Plato, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 25, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Bookreview: Bruegel’s Mill and Way to Calvary

Tags: artkarel, Bruegel, cross, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Michael Gibson, mill, peinture, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Goya and the American Revolution

Tags: American Revolution, Amigos del Pais, artkarel, Benjamin Franklin, Cabarrus, Colbert, goya, Jovellanos, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Moratin, national bank, painting, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Rembrandt und das Gesicht Jesu

Tags: amsterdam, artkarel, Gesicht, gravure, Jesu, Jüden, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Rembrandt, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus

Tags: amsterdam, artkarel, dessin, Face of Jesus, Jesus, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Netherlands, Rembrandt, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur INTERVIEW — Michael Gibson: ‘For Bruegel, his world is vast’

Tags: artkarel, Bosch, Bruegel, Erasmus, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Landjuweel, painting, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Leonardo da Vinci, painter of movement

Tags: artkarel, Daniel Arrasse, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Leonardo, Movement, Painter of movement, renaissance, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Rembrandt’s Anslo, the science of « painting the invisible » (Russian)

Tags: Anslo, artkarel, Karel, Karel Vereycken, nail, Rembrandt, renaissance, Vereycken, voice, Vondel

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Matsys and Leonardo — The Age of Laughter and Creativity (Russian)

Tags: antwerpen, artkarel, Cranach, Dürer, Erasmus, humanism, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Landjuweel, Quinten Matsys, renaissance, Satire, Thomas More, Vereycken

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on février 24, 2026

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur The Egg without a Shadow of Piero della Francesca (Russian)

Tags: artkarel, cusanus, egg, Egg without a shadow, geometry, Karel, Karel Vereycken, perspective, Piero della Francesca, renaissance, Vereycken