Étiquette : Van der Weyden

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE : Van der Weyden and Cusanus

Listen:

To the audio on the website

Read :

- Rogier Van der Weyden, le maître de la compassion;

- The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance (EN online).

- Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life, the cradle of humanism in the North (EN online)

- Jan van Eyck, la beauté comme prégustation de la sagesse divine (FR en ligne) + EN on line.

- Jan Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics (EN online)

Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics?

What follows is an edited transcript of a lecture by Karel Vereycken on the subject of “Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting”.

It was delivered at the international colloquium “La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique” (The quest for the divine through geometrical space) at the Paris Sorbonne University on April 26-28, 2006, under the direction of Luc Bergmans, Department of Dutch Studies (Paris IV Sorbonne University).

Introduction

« Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting ». At first glance, this title may seem surprising. While the genius of fifteenth-century Flemish painters is universally attributed to their mastery of drying oil and their intricate sense of detail, their spatial geometry as such is usually identified as the very counter-example of the “right perspective”.

Disdained by Michelangelo and his faithful friend Vasari, the Flemish « primitives » would never have overcome the medieval, archaic and empirical model. For the classical “narritive”, still in force today, stipulates that only « Renaissance » perspective, obeying the canon of « linear », “mathematical” perspective, is the only « right », and the “scientific” one.

According to the same narrative, it was the research carried out around 1415-20 by the Duomo architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), superficially mentioned by Antonio Tuccio di Manetti some 60 years later, which supposedly enabled Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), proclaiming himself Brunelleschi’s intellectual heir, to invent « perspective ».

In 1435, in De Pictura, a book entirely devoid of graphic illustration, Alberti is said to have formulated the premises of a perspectivist canon capable of representing, or at least conforming to, our modern notions of Cartesian space-time (NOTE 1), a space-time characterized as « entirely rational, i.e. infinite, continuous and homogeneous », « in one word, a purely mathematical space [dixit Panofsky] » (NOTE 2)

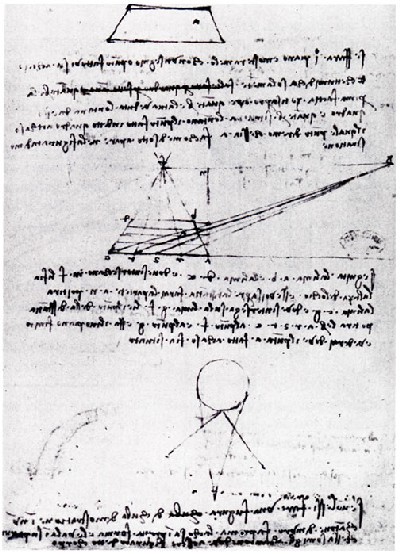

Long afterwards, in a drawing from the Codex Madrid, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) attempted to unravel the workings of this model.

But in the same manuscript, he rigorously demonstrated the inherent limitations of the Albertian Renaissance perspectivist canon.

The drawing on f°15, v° clearly shows that the simple projection of visual pyramid cross-sections on a plane paradoxically causes their size to increase the further they are from the point of vision, whereas reality would require exactly the opposite. (NOTE 3)

With this in mind, Leonardo began to question the mobility of the eye and the curvilinear nature of the retina. Refusing to immobilize the viewer on an exclusive point of vision (NOTE 4), Leonardo used curvilinear constructions to correct these lateral deformations. (NOTE 5) In France, Jean Fouquet and others worked along the same lines.

But Leonardo’s powerful arguments were ignored, and he was unable to prevent this rewriting of history.

Despite this official version of art history, it should be noted that at the time, Flemish painters were elevated to pinnacles by Italy’s greatest patrons and art connoisseurs, specifically for their ability to represent space.

Bartolomeo Fazio, around the middle of the 15th century, observed that the paintings of Jan van Eyck, an artist billed as the « principal painter of our time », showed « tiny figures of men, mountains, groves, villages and castles rendered with such skill that one would think them fifty thousand paces apart. » (NOTE 6)

Such was their reputation that some of the great names in Italian painting had no qualms about reproducing Flemish works identically. I’m thinking, for example, of the copy of Hans Memlinc‘s Christ Crowned with Thorns at the Genoa Museum, copied by Domenico Ghirlandajo (Philadelphia Museum).

But post-Michelangelo classicism deemed the non-conformity of Flemish spatial geometry with Descartes’ « extended substance » to be an unforgivable crime, and any deviation from, or insubordination to, the « Renaissance » perspectivist canon relegated them to the category of « primitives », i.e. « empiricists », clearly devoid of any scientific culture.

Today, ironically, it is almost exclusively those artists who explicitly renounce all forms of perspectivist construction in favor of pseudo-naïveté, who earn the label of modernity…

In any case, current prejudices mean that 15th-century Flemish painting is still accused of having ignored perspective.

It’s true, however, that at the end of the XIVth century, certain paintings by Melchior Broederlam (c. 1355-1411) and others by Robert Campin (1375-1444) (Master of Flémalle) show the viewer interiors where plates and cutlery on tables threaten to suddenly slide to the floor.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that whenever the artist « ignores » or disregards the linear perspective scheme, he seems to do so more by choice than by incapacity. To achieve a limpid composition, the painter prioritizes his didactic mission to the detriment of all other considerations.

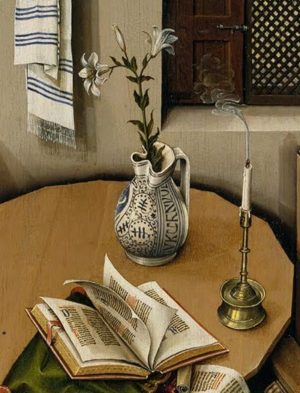

For example, in Campin’s Mérode Altarpiece, the exaggerated perspective of the table clearly shows that the vase is behind the candlestick and book.

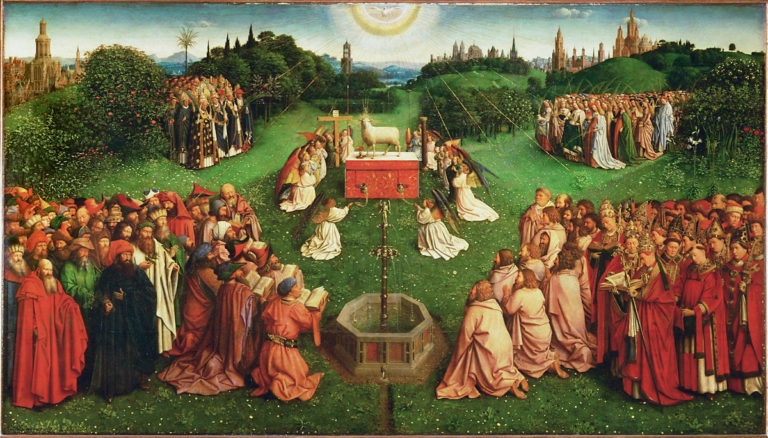

Jan van Eyck’s Lam Gods (Mystic Lamb) in Ghent is another example.

Never could so many figures, with so much detail and presence, be shown with a linear perspective where the figures in the foreground would hide those behind. (NOTE 7)

But the intention to approximate a credible sense of space and depth remains.

If this perspective seems flawed by its linear geometry, Campin imposes an extraordinary sense of space through his revolutionary treatment of shadows. As every painter knows, light is painted by painting shadow.

In Campin’s work, every object and figure is exposed to several sources of light, generating a darker central shadow as the fruit of crossed shadows.

Van Eyck influenced by Arab Optics?

Roger Bacon, statue in Oxord.

This new treatment of light-space has been largely ignored. However, there are several indications that this new conception was partly the result of the influence of « Arab » science, in particular its work on optics.

Translated into Latin and studied from the XIIth century onwards, their work was developed in particular by a network of Franciscans whose epicenter was in Oxford (Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) and whose influence spread to Chartres, Paris, Cologne and the rest of Europe.

It should be noted that Jan van Eyck (1395-1441), an emblematic figure of Flemish painting, was ambassador to Paris, Prague, Portugal and England.

I’ll briefly mention three elements that support this hypothesis of the influence of Arab science.

Curved mirrors

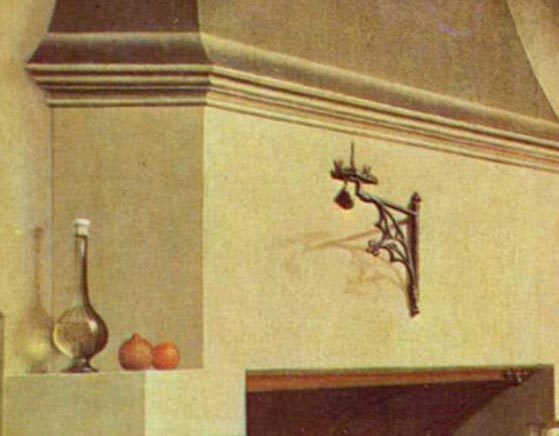

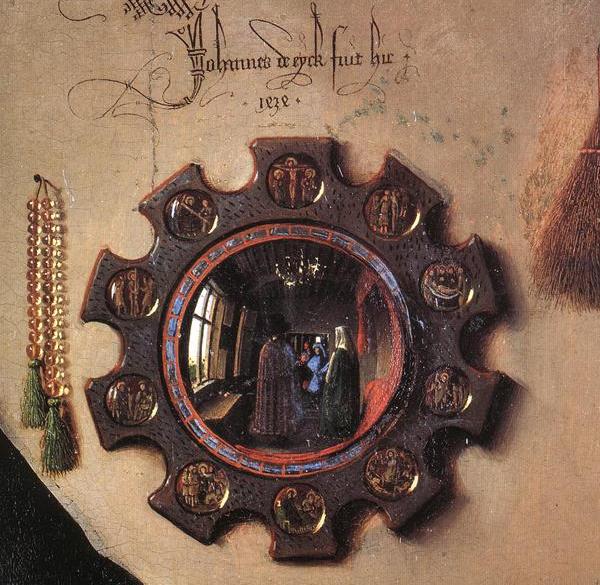

Robert Campin (master of Flémalle) in the Werl Triptych (1438) and Jan van Eyck in the Arnolfini portrait (1434), each feature convex mirrors of considerable size.

It is now certain that glaziers and mirror-makers were full members of the Saint Luc guild, the painters’ guild. (NOTE 8)

But it is relevant to know that Campin, now recognized as having run the workshop in Tournai where the painters Van der Weyden and Jacques Daret were trained, produced paintings for the Franciscans in this city. Heinrich Werl, who commissioned the altarpiece featuring the convex mirror, was an eminent Franciscan theologian who taught at the University of Cologne.

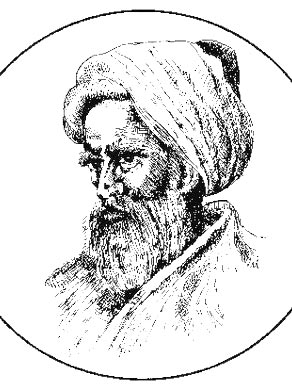

Artistic representation of Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen)

These convex and concave (or ardent) mirrors were much studied during the Arab renaissance of the IXth to XIth centuries, in particular by the Arab philosopher Al-Kindi (801-873) in Baghdad at the time of Charlemagne.

Arab scientists were not only in possession of the main body of Hellenic work on optics (Euclid‘s Optics, Ptolemy‘s Optics, the works of Heron of Alexandria, Anthemius of Tralles, etc.), but it was sometimes the rigorous refutation of this heritage that was to give science its wings.

After the decisive work of Ibn Sahl (Xth century), it was that of Ibn Al-Haytam (Latin name : Alhazen) (NOTE 9) on the nature of light, lenses and spherical mirrors that was to have a major influence. (NOTE 10)

As mentioned above, these studies were taken up by the Oxford Franciscans, starting with the English bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste (1168-1253).

In De Natura Locorum, for example, Grosseteste shows a diagram of the refraction of light in a spherical glass filled with water. And in his De Iride he marvels at this science which he connexts to perspective :

« This part of optics, so well understood, shows us how to make very distant things appear as if they were situated very near, and how we can make small things situated at a distance appear to the size we desire, so that it becomes possible for us to read the smallest letters from incredible distances, or to count sand, or grains, or any small object.«

Grosseteste’s pupil Roger Bacon (1212-1292) wrote De Speculis Comburentibus, a specific treatise on « Ardent Mirrors » which elaborates on Ibn Al-Haytam‘s work.

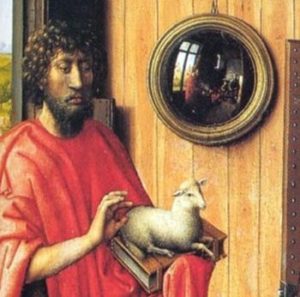

Flemish painters Campin, Van Eyck and Van der Weyden proudly display their knowledge of this new scientific and technological revolution metamorphosed into Christian symbolisms.

Their paintings feature not only curved mirrors but also glass bottles, which they use as a metaphor for the immaculate conception.

A Nativity hymn of that period says:

« As through glass the ray passed without breaking it, so of the Virgin Mother, Virgin she was and virgin she remained… » (NOTE 11)

The Treatment of Light

In his Discourse on Light, Ibn Al-Haytam develops his theory of light propagation in extremely poetic language, setting out requirements that remind us of the « Eyckian revolution ». Indeed, Flemish « realism » and perspective are the result of a new treatment of light and color.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« The light emitted by a luminous body by itself -substantial light- and the light emitted by an illuminated body -accidental light- propagate on the bodies surrounding them. Opaque bodies can be illuminated and then in turn emit light. »

This physical principle, theorized by Leonardo da Vinci, is omnipresent in Flemish painting. Just look at the images reflected in the helmet of St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele (NOTE 12).

In each curved surface of Saint George’s helmet, we can identify the reflection of the Virgin and even a window through which light enters the painting.

The shining shield on St. George’s back reflects the base of the adjacent column, and the painter’s portrait appears as a signature. Only a knowledge of the optics of curved surfaces can explain this rendering.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« Light can penetrate transparent bodies: water, air, crystal and their counterparts. »

And :

« Transparent bodies have, like opaque bodies, a ‘receiving power’ for light, but transparent bodies also have a ‘transmitting power’ for light.«

Isn’t the development of oil mediums and glazes by the Flemish an echo of this research? Alternating opaque and translucent layers on very smooth panels, the specificity of the oil medium alters the angle of light refraction.

In 1559, the painter-poet Lucas d’Heere referred to van Eyck‘s paintings as « mirrors, not painted scenes.«

Binocular perspective

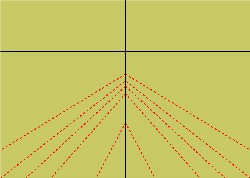

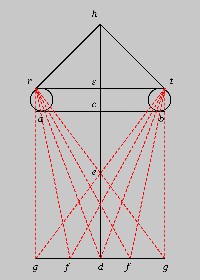

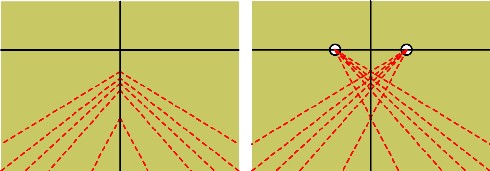

Before the advent of « right » central linear perspective, art historians sought a coherent explanation for its birth in the presence of several seemingly disparate vanishing points by theorizing a so-called central « fishbone » perspective.

In this model, a number of vanishing lines, instead of coinciding in a single central vanishing point on the horizon, either end up in a « vanishing region » (NOTE 13), or align with what some call a vertical « vanishing axis », forming a kind of « fishbone ».

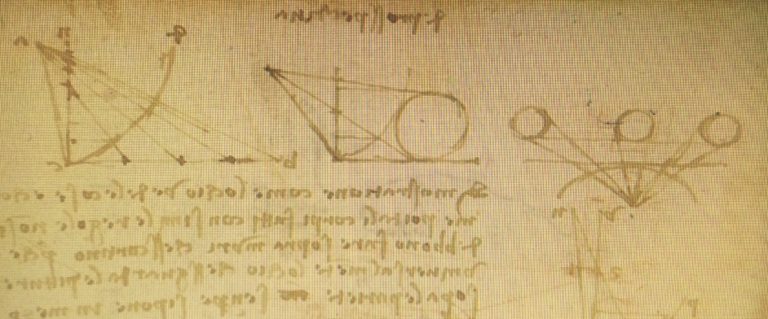

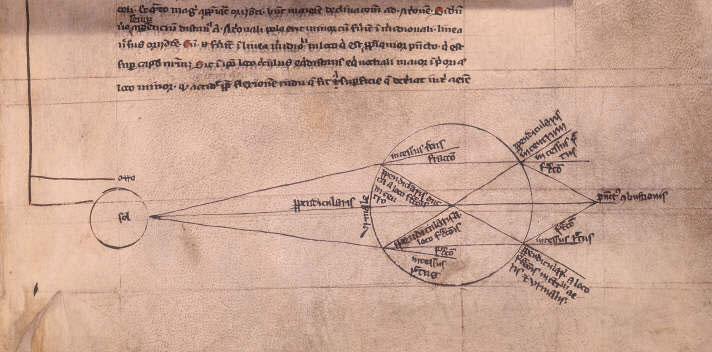

French Professor Dominique Raynaud, who worked for years on this issue, underscores that « all medieval treatises on perspective address the question of binocular vision », notably the Polish scholar Witelo (1230-1280) (NOTE 15) in his Perspectiva (I,27), an insight he also got from the works of Ibn Al-Haytam.

Witelo presents a figure to defend the idea that

« the two forms, which penetrate two homologous points of the surface of the two eyes, arrive at the same point of the concavity of the common nerve, and are superimposed at this point to become one » (Perspectiva, III, 37).

A similar line of reasoning can be found in Roger Bacon‘s Perspectiva Communis, written by John Pecham, Archbishop of Canterbury (1240-1290) for whom:

« the duality of the eyes must be reduced to unity »

So, as Professor Raynaud proposed, if we extend the famous vanishing lines (i.e., in our case, the « fish bones ») until they intersect, the « vanishing axis » problem disappears, as the vanishing lines meet. Interestingly, the result is a perspective with two vanishing points in the central region!

Suddenly, the diagrams drawn up to demonstrate the « empiricism » of the Flemish painters, if viewed from this point of view, reveal a legitimate construction probably based on optics as transmitted by Arab science and rediscovered by Franciscan networks and others.

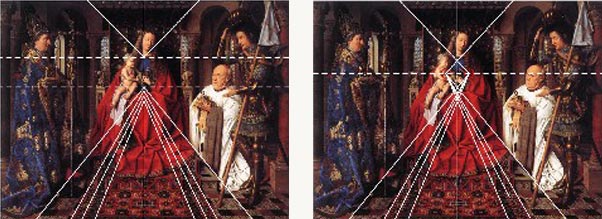

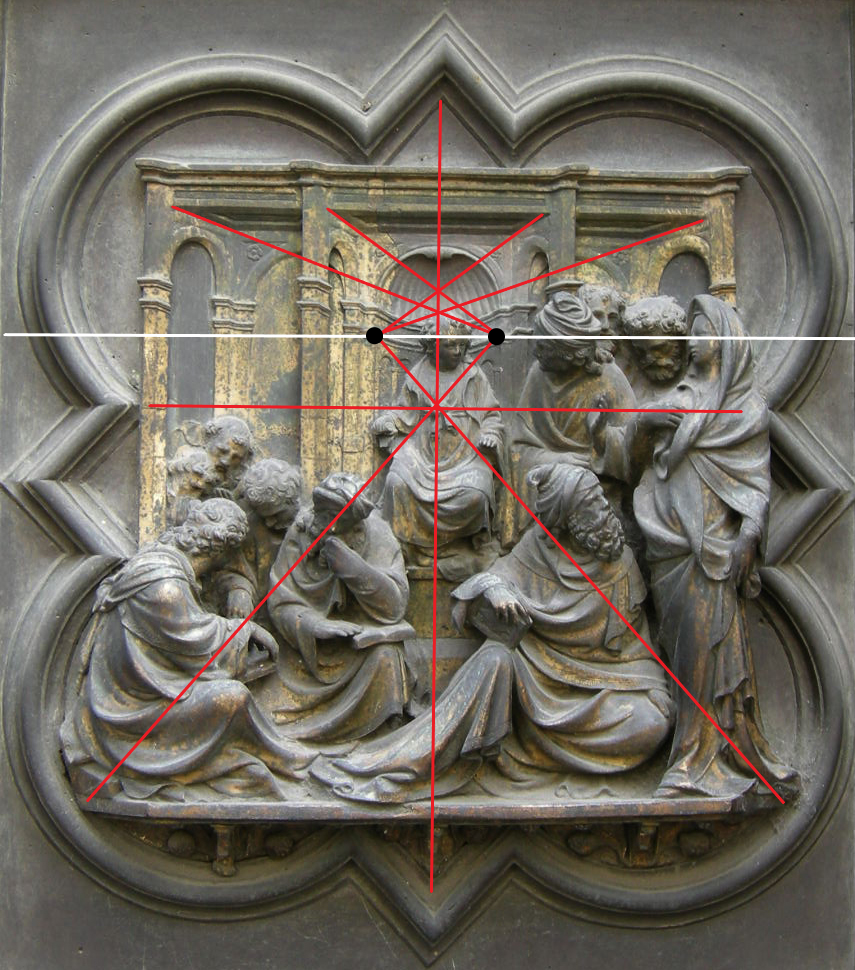

Two paintings by Jan van Eyck clearly demonstrate that he followed this approach: The Madonna with Canon van der Paele of 1436 and the Dresden Tryptic of 1437.

What seemed a clumsy, empirical approach in the form of a « fishbone » perspective (left) turns out to be a binocular perspective construction.

Was this type of perspective specifically Flemish?

A close examination of works by Ghiberti, Donatello and Paolo Uccello, generally dating from the first half of the XVth Century, reveals a mastery of the same principle.

Cusanus

But this whole demonstration is merely a look into the past through the eyes of modern scientific rationality. It would be a grave error not to take into account the immense influence of the Rhenish (Master Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso) and Flemish (Hadewijch of Antwerp, Jan van Ruusbroec, etc.) « mystics ».

This trend began to flourish again with the rediscovery of the Christianized neo-Platonism of Dionysius the Areopagite (Vth-VIth century), made accessible… by the new translations of the Franciscan Grosseteste in Oxford.

The spiritual vision of the Aeropagite, expressed in a powerful imagery language, is directly reminiscent of the metaphorical approach of the Flemish painters, for whom a certain type of light is simply the revelation of divine grace.

In On the Heavenly Hierarchy, Dionysius immediately presents light as a manifestation of divine goodness. It ennobles us and enables us to enlighten others:

« Let those who are illuminated be filled with divine clarity, and the eyes of their understanding trained to the work of chaste contemplation; finally, let those who are perfected, once their primitive imperfection has been abolished, share in the sanctifying science of the marvelous teachings that have already been manifested to them; similarly, let the purifier excel in the purity he communicates to others; let the illuminator, gifted with a greater penetration of spirit, equally fit to receive and transmit light, happily flooded with sacred splendor, pour it out in pressing streams on those who are worthy… » [Chap. III, 3]

Let’s think again of the St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele, which indeed pours forth the multiple images of the Virgin who enlightens him.

This theo-philosophical trend reached full maturity in the work of Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) (1401-1464) (NOTE 16), embodying the extremely fruitful encounter of this « negative theology » with Greek science, Socratic knowledge and Christian Humanism.

In contrast to both a science « without a hypothesis of God » and a metaphysics with an esoteric drift, an agapic love leads it to the education of the greatest number, to the defense of the weak and the humiliated.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, educating Erasmus of Rotterdam and inspiring Cusanus, are the best example of this.

But let’s sketch out some of Cusanus’ key ideas on painting.

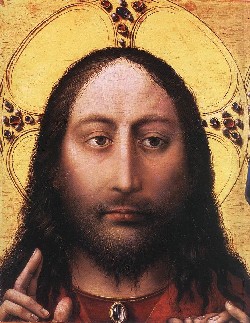

In De Icona (The Vision of God) (1453), which he sent to the Benedictine monks of the Tegernsee, Cusanus condenses his fundamental work On Learned Ignorance (1440), in which he develops the concept of the coincidence of opposites. His starting point was a self-portrait of his friend « Roger », the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden, which he sent together with his sermon to the monks.

This self-portrait, like the multiple faces of Christ painted in the XVth century, uses an « optical illusion » to create the effect of a gaze that fixes the viewer, regardless of his or her position in front of the altarpiece.

In De Icona, written as a sermon, Cusanus asks monks to stand in a semicircle around the painting and watch this gaze pursue them as they move along the segment of the curve. In fact, he elaborates a pedagogical paradox based on the fact that the Greek name for God, Theos, has its etymological origin in the verb theastai (to see, to look at).

As you can see, he says, God looks at you personally, and his gaze follows you everywhere. He is therefore one and many. And even when you turn away from him, his gaze falls on you. So, miraculously, although he looks at everyone at the same time, he nevertheless establishes a personal relationship with each one. If « seeing » for God is « loving », God’s point of vision is infinite, omniscient and omnipotent love.

A parallel can be drawn here with the spherical mirror at the center of Jan van Eyck’s painting The Arnolfini portrait, painted in 1434, nineteen years before this sermon.

Firstly, this circular mirror is surrounded by the ten stations of Christ’s Passion, juxtaposed by a rosary, an explicit reference to God.

Secondly, it reveals a view of the entire room, an image that completely escapes the linear perspective of the foreground. A view comparable to the allcompassing « Vision of God » developed by Cusanus.

Finally, we see two figures in the mirror, but not the image of the painter behind his easel. These are undoubtedly the two witnesses to the wedding. Instead of signing his painting with « Van Eyck invent. », the painter signed his painting above the mirror with « Van Eyck was here » (NOTE 17), identifying himself as a witness.

As Dionysius the Aeropagite asserted:

« [the celestial hierarchy] transforms its adepts into so many images of God: pure and splendid mirrors where the eternal and ineffable light can shine, and which, according to the desired order, reflect liberally on inferior things this borrowed brightness with which they shine. » [Chap. III, 2]

The Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381) evokes a very similar image in his Spiegel der eeuwigher salicheit (Mirror of eternal salvation) when he says:

« Ende Hi heeft ieghewelcs mensche ziele gescapen alse eenen levenden spieghel, daer Hi dat Beelde sijnre natueren in gedruct heeft. » (And he created each human soul as a living mirror, in which he imprinted the image of his nature).

And so, like a polished mirror, Van Eyck’s soul, illuminated and living in God’s truth, acts as an illuminating witness to this union. (NOTE 18)

So, although the Flemish painters of the XVth century clearly had a solid scientific foundation, they choose such or such perspective depending on the idea they wanted to convey.

In essence, their paintings remain objects of theo-philosophical speculation or as you like « intellectual prayer », capable of praising the goodness, beauty and magnificence of a Creator who created them in His own image. By the very nature of their approach, their interest lay above all in the geometry of a kind of « paradoxical space-light » capable, through enigma, of opening us up to a participatory transcendence, rather than simply seeking to « represent » a dead space existing outside metaphysical reality.

The only geometry worthy of interest was that which showed itself capable of articulating this non-linearity, a « divine » or « mystical » perspective capable of linking the infinite beauty of our commensurable microcosm with the immeasurable goodness of the macrocosm.

Thank you,

NOTES:

- Recently, Italian scholars have pointed to the role of Biagio Pelacani Da Parma (d. 1416), a professor at the University of Padua near Venice, in imposing such a perspective, which privileged only the « geometrical laws of the act of vision and the rules of mathematical calculation ».

- Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, p.41-42, Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris, 1975.

- Institut de France, Manuscrit E, 16 v° « the eye [h] perceives on the plane wall the images of distant objects greater than that of the nearer object. »

- Leonardo understands that Albertian perspective, like anamorphosis, condemns the viewer to a single, immobile point of vision.

- See, for example, the slight enlargement of the apostles at the ends of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in the Milan refectory.

- Baxandall, Bartholomaeus Facius on painting, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 27, (1964). Fazio is also enthusiastic about a world map (now lost) by Jan van Eyck, in which all the places and regions of the earth are depicted recognizably and at measurable distances.

- To escape this fate, Pieter Bruegel the Elder used a cavalier perspective, placing his horizon line high up.

- Lionel Simonot, Etude expérimentale et modélisation de la diffusion de la lumière dans une couche de peinture colorée et translucide. Application à l’effet visuel des glacis et des vernis, p.9 (PhD thesis, Nov. 2002).

- Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) wrote some 200 works on mathematics, astronomy, physics, medicine and philosophy. Born in Basra, after working on the development of the Nile in Egypt, he travelled to Spain. He is said to have carried out a series of highly detailed experiments on theoretical and experimental optics, including the camera obscura (darkroom), work that was later to feature in Leonardo da Vinci’s studies. Da Vinci may well have read the lengthy passages by Alhazen that appear in the Commentari of the Florentine sculptor Ghiberti. According to Gerbert d’Aurillac (the future Pope Sylvester II in 999), Bishop of Rheims, brought back from Spain the decimal system with its zero and an astrolabe, it was thanks to Gerard of Cremona (1114-c. 1187) that Europe gained access to Greek, Jewish and Arabic science. This scholar went to Toledo in 1175 to learn Arabic, and translated some 80 scientific works from Arabic into Latin, including Ptolemy’s Almagest, Apollonius’ Conics, several treatises by Aristotle, Avicenna‘s Canon, and the works of Ibn Al-Haytam, Al-Kindi, Thabit ibn Qurra and Al-Razi.

- In the Arab world, this research was taken up a century later by the Persian physicist Al-Farisi (1267-1319). He wrote an important commentary on Alhazen’s Treatise on Optics. Using a drop of water as a model, and based on Alhazen’s theory of double refraction in a sphere, he gave the first correct explanation of the rainbow. He even suggested the wave-like property of light, whereas Alhazen had studied light using solid balls in his reflection and refraction experiments. The question was now: does light propagate by undulation or by particle transport?

- Meiss, M., Light as form and symbol in some fifteenth century paintings, Art Bulletin, XVIII, 1936, p. 434.

- Note also the fact that the canon shows a pair of glasses…

- Brion-Guerry in Jean Pèlerin Viator, sa place dans l’histoire de la perspective, Belles Lettres, 1962, p. 94-96, states in obscure language that « the object of representation behaves most often in Van Eyck as a cubic volume seen from the front and from the inside. Perspectival foreshortening is achieved by constructing a rectangle whose sides form the base of four trapezoids. The orthogonals thus tend towards four distinct points of convergence, forming a ‘vanishing region' ».

- Dominique Raynaud, L’Hypothèse d’Oxford, essai sur les origines de la perpective, PUF, Paris 1998.

- Witelo was a friend of the Flemish Dominican scholar Willem van Moerbeke, a translator of Archimedes in contact with Saint Thomas Aquinas. Moerbeke was also in contact with the mathematician Jean Campanus and the Flemish neo-Platonic astronomer Hendrik Bate van Mechelen. Johannes Kepler‘s own work on human vision builds on that of Witelo.

- Cusanus was above all a man of science and theology. But he was also a political organizer. The painter Jan van Eyck fought for the same goals, as evidenced by the ecumenical theme of the Ghent polyptych. It shows the Mystic Lamb, symbolizing the sacrifice of the Son of God for the redemption of mankind, capable of reuniting a church torn apart by internal differences. Hence the presence of the three popes in the central panel, here united before the lamb. Van Eyck also painted a portrait of Cardinal Niccolo Albergati, one of the instigators of the great Ecumenical Council organized by Cusanus in Ferrara and then moved to Florence. If Cusanus called Van der Weyden « his friend Roger », it is also thought that Robert Campin may have met him, since he would have attended the Council of Basel, as did one of his commissioners, the Franciscan theologian Heinrich Werl.

- Jan Van Eyck was one of the first painters in the history of art to date and sign his paintings with his own name.

- Myriam Greilsammer’s book L’Envers du tableau, Mariage et Maternité en Flandre Médiévale (Editions Armand Colin, 1990) documents Arnolfini’s sexual escapades. Arnolfini was taken to court by one of his victims, a female servant. Van Eyck seems to have understood that the knightly Arnoult Fin, Lucchese financier and commercial representative of the House of Medici in Bruges, required the somewhat peculiar presence of the eye of the lord.

Hugo van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne

Le beau livre de l’historien néerlandais Bernhard Ridderbos, Schilderkunst in de Bourgondische Nederlanden (La peinture aux Pays-Bas bourguignon, Davidsfonds, Leuven 2015) est un régal pour les yeux et l’esprit.

Ridderbos, déjà irrité par l’habile campagne de propagande menée depuis des siècles par des banquiers italiens pour qui « la » Renaissance n’était qu’italienne et pour qui les fiammingo n’étaient que des « Primitifs », démarre son ouvrage en incendiant (non sans raison) une œuvre qui reste une référence, L’automne du Moyen Age (1919), de Johan Huizinga (1872-1945).

Pour cet historien néerlandais influant, recteur de l’Université de Leyden :

L’art de Van Eyck, dans sa capacité de figurer les choses saintes, a su atteindre un haut degré de détail et de naturalisme, marquant sans doute un point de départ sur le plan strict de l’histoire de l’art, mais signifiant en réalité une fin sur le plan historico-culturel. La tension extrême de l’imagination terrestre du divin fut atteint ici ; cependant, le contenu mystique de son imagination s’apprêtait à quitter ces images et à ne laisser les réjouissances qu’à la forme

Niant l’esprit clairement pré-renaissant des peintres flamands du début du XVe siècle, pour Huizinga, leur naturalisme n’était rien d’autre que « le déploiement ultime de l’esprit moyenâgeux tardif. »

Or, comme j’ai cherché à démontrer, en avril 2006, lors de mon exposé au Colloque international à la Sorbonne sur le thème de « La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique », Robert Campin, Jan van Eyck et d’autres peintres flamands, qu’on présente assez souvent comme récalcitrant à utiliser les modèles perspectivistes développés par l’italien Leon Battista Alberti et comme en témoigne la présence assez imposante de miroirs convexes dans leurs œuvres (Volets Werl, Epoux Arnolfini), se sont inspirés des travaux mathématiques et géométriques complexes du grand scientifique arabe Ibn Al-Haytam.

Mieux connu en Occident sous son nom latin Alhazen, ses travaux d’optique, notamment sur la lumière et les miroirs convexes, se retrouvent dans les carnets de Léonard de Vinci, lecteur assidu des Commentaires de Ghiberti. *

Libéré de cette chape de plomb de l’autocensure, Ridderbos approfondit l’iconographie, les contextes économiques, sociaux et culturels. Sans égarer le lecteur dans un marécage de détails et d’hypothèses stériles, il nous offre des éclairages très intéressants sur le comment et le pourquoi des créations artistiques de cette époque.

Ceux parmi vous qui n’ont jamais pris le temps de lire ni l’œuvre monumentale d’Erwin Panofsky, ni les imposantes monographies publiées en Belgique par le Fonds Mercator d’Anvers relatant in extenso la vie des grands peintres flamands tels que Robert Campin, Rogier Van der Weyden, Jan Van Eyck, Hans Memling, Thierry Bouts, Hugo Van der Goes et Gérard David, remercieront Ridderbos pour non seulement en avoir extrait la quintessence, mais pour les avoir mis en relation les unes avec les autres.

Les commanditaires

En premier lieu, il montre à quel point les artistes étaient soumis à des « carnets de charges » très stricts. Un tel monastère, une telle guilde, un tel seigneur passait commande. Ils fixaient la taille de l’œuvre, le sujet et les personnes à représenter. Plusieurs théologiens, spécialistes du thème à traiter, furent parfois nommés pour conseiller et accompagner le peintre dans sa représentation de sujets religieux. L’artiste exécuta d’abord, sur son panneau, un dessin. Et ce n’est qu’une fois validé par le commanditaire, souvent après de nombreuses modifications, qu’il appliqua les couleurs. Gérard David, par exemple, a du changer l’ensemble des portraits des échevins sur son œuvre, suite à l’élection d’une nouvelle équipe…

Rivalités

Ensuite, Ridderbos indique comment les rivalités des uns et des autres, princes, églises, mais aussi Cités-Etats, souvent en quête de prestige (le fameux « soft power » de nos jours), ont profité à la vie artistique flamande. Princes, ducs, rois et banquiers étrangers se disputaient les peintres flamands pour fanfaronner et se mettre en avant.

Pour monter en grade, un banquier des Médicis (Angelo Tani) commande un triptyque à Hans Memling, un Jugement dernier (1466-1473), largement inspiré de l’œuvre éponyme de Van Der Weyden pour l’Hospice de Beaune.

Lorsque son confrère (Tommaso Portinari, le fondé de pouvoir des Médicis à Bruges) l’apprend, il passe commande d’un autre triptyque, une Nativité (1475), bien plus grand et plus splendide encore chez Hugo Van der Goes. Ce « triptyque Portinari » sera dévoilé à Florence en 1483 et inspirera toute une série d’œuvres italiens, notamment celles du peintre italien Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Rogier Van der Weyden, après avoir travaillé pour la ville de Louvain, se voit offrir un bien meilleur salaire par la ville de Bruxelles, les deux villes cherchant à devenir la capitale de la région.

Lorsqu’il y peint pour l’Hôtel de Ville un grand retable sur la Justice (La Justice de Trajan et Herkenbald, ca. 1450), la ville de Louvain, pour ne pas être en reste, commandera plusieurs années après une œuvre semblable (La justice d’Otton III, 1473) à Thierry Bouts, provoquant à son tour une autre ville, celle de Bruges d’en commander un du même type (Le jugement de Cambyses, 1498) chez Gérard David, un disciple et proche de l’atelier de Van der Goes.

Ridderbos bien sûr ne se limite pas à tracer cette dynamique sociologique. Il analyse comment ces peintres vont dialoguer entre eux en reprenant à leur compte les apports techniques et iconographiques de leurs confrères. Tout en mobilisant le meilleur d’eux-mêmes, ils apportèrent des choses entièrement nouvelles. C’est un processus assez similaire à l’apport compositionnel d’un Ludwig van Beethoven montant lui-même « sur les épaules des géants » que furent avant lui Bach, Haydn et Mozart.

Van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne

Dans le chapitre VII, page 179, l’auteur fait un effort particulier pour mettre en valeur l’œuvre d’Hugo Van Der Goes, un peintre remarquable qu’on a rangé un peu vite dans l’ombre de Van Eyck, Van der Weyden et Memling.

Probablement né vers 1440 à Gand, Van der Goes est reçu maître de la guilde des peintres de cette ville en 1467 et en devient le doyen en 1474. Trois ans plus tard, il est à l’apogée de la reconnaissance professionnelle et de la réussite sociale.

C’est alors qu’il abandonne la vie bourgeoise pour s’associer au grand mouvement de réforme appelé la Dévotion moderne. Pour ce faire, Van Der Goes devient frère lai auprès des Soeurs et Frères de la Vie commune, plus précisément ceux de l’abbaye du Rouge-Cloître (Rooklooster) dans la Forêt de Soignes près de Bruxelles. Il y jouit de certains privilèges, comme d’être autorisé à continuer à peindre.

Deventer

La Dévotion moderne sera avant tout un mouvement éducateur. Elle fonda notamment à Deventer une école renommée ouverte aux pauvres et aux orphelins. Rudolf Agricola et son successeur Alexandre Hegius y enseignent le grec et le latin à toute une génération d’humanistes dont le plus connu s’appelle Erasme de Rotterdam.

Le fameux cardinal-philosophe, mathématicien et juriste allemand, Nicolas de Cues (1401-1464) tenait en haute estime les efforts des enseignants de Deventer. En 1469, cinq ans après sa mort, sans doute en accord avec ses derniers vœux, une partie de son héritage ira abonder (de 1470 à 1682) un fond dédié, la Bursa Cusana, permettant à une vingtaine d’élèves, dont la moitié originaire de la ville natale de Cues, d’y parfaire leur instruction.

Le piétisme de la Devotion moderne, centré sur l’intériorité, s’articule le mieux dans le petit livre de Thomas van Kempen (a Kempis) (1380-1471), L’imitation de Jésus Christ. Celui-ci souligne l’exemple à suivre de la passion du Christ tel que nous l’enseigne l’Évangile, message repris par Erasme.

Van Der Goes, animé à titre personnel par l’esprit de cette démarche, apparaît ainsi, sans l’avoir connu, avec le peintre anversois Quinten Matsys, comme « le plus erasmien » des peintres flamands. Et à ce titre, il sera capable de faire transparaître dans ses œuvres une tension dramatique plus aiguë, traduite par l’animation et l’expressivité des personnages.

Les bergers

On pense immédiatement aux magnifiques bergers du Triptyque Portinari. Cette œuvre est commanditée par un des banquiers les plus riches de l’époque et pourtant, ce ne sont pas les trois Rois mages qui se trouvent au premier plan, mais d’humbles bergers arrivés bien avant eux et les premiers à reconnaître l’enfant pour ce qu’il est.

Se démarquant nettement de la façon dont le peintre italien Andrea Mantegna les avait dépeint vingt ans plus tôt, c’est-à-dire comme des pauvres hères en haillons, hirsutes, sales et édentés, Van der Goes souligne leur dignité et met en avant leurs transformations.

D’ailleurs, les expressions des bergers incarneraient les trois étapes spirituelles définies par un autre inspirateur de la Devotion moderne, le mystique flamand Jan Van Ruysbroeck (1293-1381) : la vie active, la vie intérieure et la vie contemplative où l’Homme entre en communion spirituelle avec Dieu. **

Le chapeau de Nicodème

Autre exemple, son tableau La lamentation du Christ (après 1479) actuellement au Musée de Vienne. De prime abord rien de bien révolutionnaire dans cette représentation. On y voit la mère du Christ retenue par Jean lorsqu’elle s’effondre sur la dépouille mortelle de son fils.

C’est sur l’avant plan que deux figures méritent notre attention. S’appuyant sur les Geestelijke Opklimmingen (Des ascensions spirituelles) écrit par Gerard Zerbold de Zutphen (1367-1398), un auteur de la Dévotion moderne proche de Groote, Ridderbos identifie leur rôle dans cette œuvre.

A droite, d’abord, on voit Nicodème coiffé d’une capuche rouge. Selon l’Evangile selon Saint-Jean, Nicodème a été un des premiers pharisiens devenus secrètement disciples de Jésus. Ici, on le voit en pleine crise, pour ne pas dire agonie existentielle, portant un regard effrayé sur son riche chapeau posé par terre.

Or, lorsque l’on examine de plus près ce couvre-chef, on découvre qu’il est surmonté d’une couronne d’épines !

La métaphore est donc à l’image de la Dévotion moderne qui exigeait de chacun, non seulement de suivre fidèlement les rites, mais de « vivre à l’imitation du Christ », c’est-à-dire de s’élever à un tel niveau d’amour pour le Christ et l’humanité qu’on puisse offrir librement ses possessions, son patrimoine et même sa vie au vrai, au juste et au beau.

Enfin, pour compléter le tableau, à gauche, toujours au premier plan, la figure de Marie Madeleine, une autre disciple de Jésus qui le suit jusqu’à ses derniers jours.

Prostituée repentie, Marie Madeleine complète à merveille la métaphore en s’érigeant ici comme l’exemple même du travail d’introspection et d’auto-perfectionnement personnel qu’exigeaient les Sœurs et Frères de la Vie Commune.

Le message est fort : vous ne pouvez pas vous contenter d’adorer ou d’admirer le Christ ! Vous devez changer vos vies ! Un message qui n’a pas perdu de son actualité…

Notes:

* Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) écrivit quelques 200 ouvrages sur les mathématiques, l’astronomie, la physique, la médecine et la philosophie. Né à Bassora, et après avoir travaillé sur l’aménagement des cours du Nil en Égypte, il se serait rendu en Espagne. Il aurait mené une série d’expériences très précises sur l’optique théorique et expérimentale, y compris sur la camera obscura (chambre noire), travaux qu’on retrouve ultérieurement dans les études de Léonard de Vinci. Ce dernier a pu lire les longs passages d’Alhazen qui figurent dans les Commentari du sculpteur florentin Ghiberti. Après que l’évêque de Reims Gerbert d’Aurillac (le futur pape Sylvestre II en 999) ramena d’Espagne le système décimal avec son zéro et un astrolabe, c’est grâce à Gérard de Crémone (1114-vers 1187) que l’Europe va accéder à la science grecque, juive et arabe. Ce savant se rendra 1175 à Tolède pour y apprendre l’arabe et effectuera la traduction de quelques 80 ouvrages scientifiques de l’arabe en latin, notamment l’Almageste de Ptolémée, les Coniques d’Apollonius, plusieurs traités d’Aristote, le Canon d’Avicenne, les œuvres d’Ibn Al-Haytam, d’Al-Kindi, de Thabit ibn Qurra et d’Al-Razi. Dans le monde arabe, ces recherches furent reprises un siècle plus tard par le physicien persan Al-Farisi (1267-1319). Ce dernier a rédigé un important commentaire du Traité d’optique d’Alhazen. En prenant pour modèle une goutte d’eau et en s’appuyant sur la théorie d’Alhazen sur la double réfraction dans une sphère, il a donné la première explication correcte de l’arc-en-ciel. Il a même suggéré la propriété ondulatoire de la lumière, alors qu’Alhazen avait étudié la lumière à l’aide de balles solides dans ses expériences de réflexion et de réfraction. Désormais la question se posait ainsi : la lumière se propage-t-elle par ondulation ou par transport de particules ?

** Voir à ce propos : Nadeije Laneyrie-dagen, L’invention du corps : La représentation de l’homme du Moyen Âge à la fin du XIXe siècle, Paris 1997, 52. ; Delphine Rabier, Les trois degrés de la vision selon Ruysbroeck l’Admirable et les Bergers du triptyque Portinari de Hugo van der Goes, in Studies in Spirituality, 27, p. 163-179, 2017.