Étiquette : tempera

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE: Cimabue, Giotto, Fra Angelico; Wonders of the Italian Trecento

Listen

To the audio on this website.

Read:

- L’invention de la perspective FR pdf (Fusion) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- La révolution du grec ancien, Platon et la Renaissance (FR en ligne)

- The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance (EN online).

- Les Frères de la vie commune et la Renaissance du nord (FR en ligne)

- Moderne Devotie en Broeders van het Gemene Leven, bakermat van het humanisme (NL online)

- Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life, the cradle of humanism in the North (EN online)

Van Eyck : True Beauty, a foretaste of Divine Wisdom

Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441). How might we grasp the intention of this great Flemish painter, despite the five hundred years of distance separating us? Apart from looking at his work, here are three tracks that I’ve been able to uncover:

- The painter was undoubtedly initiated in the art of lectio divina, the multi-leveled interpretation of sacred texts;

- The influence of the French religious thinker Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141), an unknown but major figure who was an inspiration for the philosopher-cardinal Nicolas of Cusa;

- The advice given to the painter by theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), the confessor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, for whom the painter carried out diplomatic missions.

The writer would highly encourage all admirers of great art to get themselves a copy of the inspiring and scholarly work Landschap in Wereldbeeld, van Van Eyck tot Rembrandt (Landscape and Worldview, from Van Eyck to Rembrandt) by the Dutch art historian Boudewijn Bakker (published in 2004 at Thoth in Bossum, Netherlands, available in English). In a very rigorous and yet accessible work, Bakker offers us a series of important clues, which allow a XXIst century viewer to gain new insights into the often “hidden” meaning of Dutch and Flemish painting. For today’s viewers, what is often surprising in these works is the use of recurring references by the painters, their sponsors, religious officials and the general public of these countries.

Paradox

Before I read Bakker’s work, the paintings of northern Europe often appeared to me to be opposed to the prevailing philosophical and religious matrix of the fifteenth century, when in reality they were its very expression. Until now, I thought that, for the most part, the world view that prevailed at the end of the Middle-Ages was one rejecting the visible world as it was known through our senses. According to a scholastic misinterpretation of St. Augustine and Plato, the world was only deception and temptation, which one might have called the devil himself. Now, and herein lies the paradox in all its force, how can we reconcile the rejection of the visible world, particularly in sight of the work of the Flemish painter Van Eyck, who was able to show us human beings animated by kindness, glowing with beauty and surrounded by pristine nature?

I thought “How dare he show us so much beauty”, whereas in his day the doctrine of faith, which had been heralded as guardian of the temple, had kept reminding us that Man, in his glaring imperfection, was no God, and systematically warned us against the temptations of this world? Were the ironic but extremely moralizing pictures of Hieronymus Bosch and Joachim Patinier not intended to make us understand, albeit with violence, and yet with humor and great craft, that the origin of sin lay precisely in our excessive attachments to worldly things and the pleasures which were believed to be derived from them?

The Coincidence of Opposites

Without explicitly referring to the method of the great theologian-philosopher, Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa, the « coincidence of opposites » (coincidentia oppositorum), that is to say the paradoxes whose seemingly irreconcilable differences can be overcome from a higher conceptual level, Bakker demonstrates that the aforementioned paradox is also only one of appearance.

In order to make sense of this, Bakker first recalls that for the Augustinian current, for whom man was created in the living image of the creator (Imago Viva Dei), nature was neither more nor less than « theophany », that is to say, for those who were able to read it, it was the revelation of a divine intention.

For this current, God revealed himself to man, not by one, but by « two books, » the first of which was none other than « the book of nature, » read through our eyes; the second being the Bible, which was accessible through our eyes and ears. With this connection in mind, Bakker emphasizes two nearly forgotten yet first-rate Christian thinkers who had unfortunately fallen into obscurity following the hegemony of Aristotelianism, which had been ushered in by St. Thomas of Aquinas in tandem with the rise of nominalism and the counter-reformation. The first is the French abbot and theologian Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141), one of the medieval writers whose manuscripts were widely circulated at the time, and Denis the Carthusian (1402-1471), a Dutch friend and collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464) and also confessor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1396-1467).

The Lectio Divina of Nature

In respect to his interpretation of the paintings, Bakker did the work that any true art historian worthy of such a title should have necessarily done: he compared the paintings with, if they still existed, the writings of their times.

By using the writings of the time to inform his interpretation of the paintings, Bakker formulates a rigorous hypothesis around the idea that the masterpieces of Flemish painting, riddled with as many enigmas and mysteries as our beautiful cathedrals, are to be read « on several levels ». The said “four levels” was what the biblical exegesis of the day prescribed based on ancient tradition.

First, in Judaism, long before the arrival of Jesus, the study of the Torah appealed to the « doctrine of the four senses »:

- the literal meaning,

- the allegorical meaning,

- the allusive meaning, and

- the mystical meaning (possibly hidden, secret or kabalistic).

Then, Christians, especially Origen (185-254), then Ambrose of Milan in the fourth century, repeated this method with the Lectio Divina, that is to say, the exercise of spiritual reading aimed, by prayer, to penetrate a sacred text at its deepest level.

Finally, introduced in the fourth century by Ambrose, Augustine made Lectio Divina the basis of monastic prayer. It would then be taken over by Jerome, Venerable Bede, Scot Erigena, Hugue of Saint Victor, Richard of Saint Victor, Alain of Lille, Bonaventure and would impose itself upon Saint Thomas Aquinas and Bernard of Clairvaux.

Bakker takes care to specify these four levels of reading:

- The literal meaning is that which comes from the linguistic comprehension of the utterance. It tells the facts and « narrative » of a text while situating it in the context of its time;

- The allegorical meaning comes from Greek allos, meaning “other”, and agoreuein, to “say”. By stating one thing, Allegory also says another. Thus an allegory explains what a story symbolizes;

- The moral or tropological meaning (of the Latin tropos meaning « change »), offers us a lesson or advice. By understanding the figures, vices or virtues, passions or stages that the human mind must travel in its ascent to God, each person can draw on such wisdom for his own life;

- The anagogical meaning (adjective from the Greek anagogikos or elevation), is obtained by the interpretation of the Gospels, to give an idea of the last realities that will become visible at the end of time. In philosophy, for Leibniz, « anagogical induction » is something which can be traced back to a first cause.

These four meanings were formulated in the Middle Ages in a famous Latin couplet: littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria, moralis quid agas, quo tendas anagogia (the letters teach the facts, allegory what one must believe, morality is what one must do, anagogy what one should aspire to).

The reason I bring this issue of multi-level biblical exegesis is that Bakker says, from the standpoint of this worldview in the Middle Ages, this method of interpretation was thought to apply not only to the Bible, but to visible creation as well.

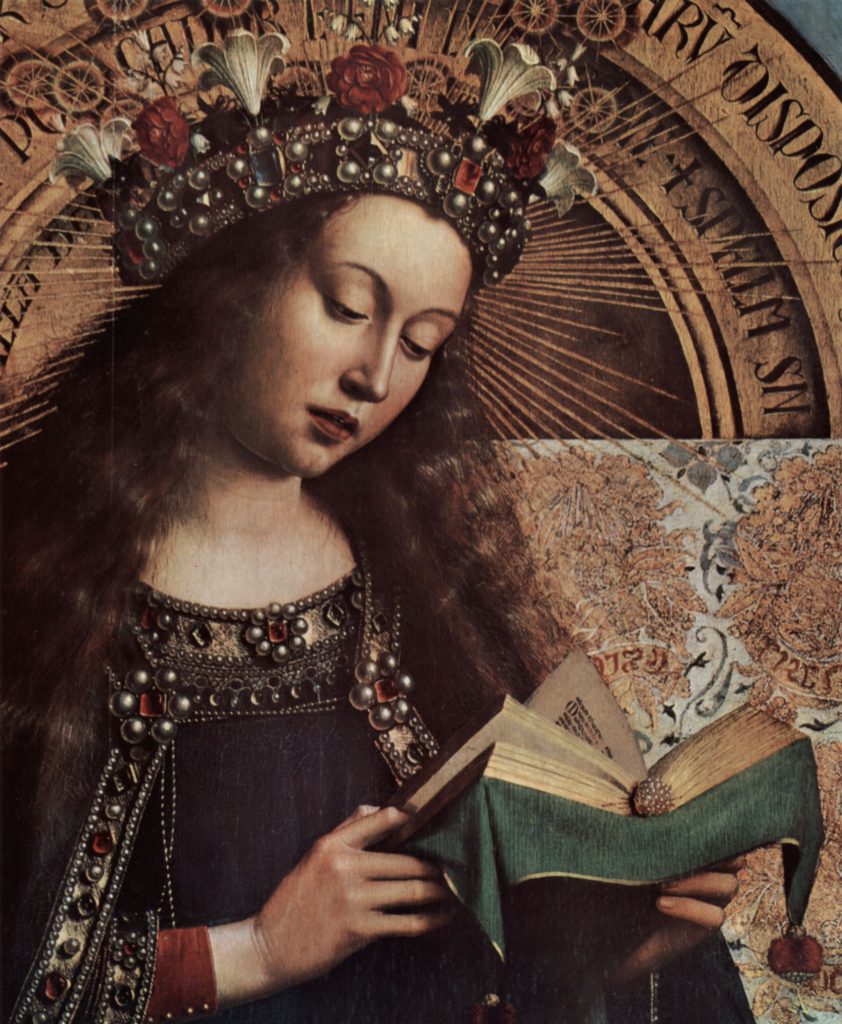

Close-up of the page of the book in front of which the Virgin in the Annunciation kneels, decorating the exterior shutters of the altarpiece of Ghent by Jan Van Eyck (1432). At the bottom of the page, one reads clearly (in red): « de visione dei », the title of the work of Nicolas de Cues of 1453.

But is this merely the instance of some kind of sentimental moment in which one is relishing in the beauty of creation for its own sake? Not at all ! Far from pantheism (a sin), it was a question of « reading », as Hugue of Saint Victor stated, « with the eyes of the mind », which « the eyes of the flesh » were not able to see, a concept that would be taken up again by Nicolas de Cusa in his work of 1543: On painting, or The Vision of God. The paradox can therefore be solved. For, in the allegory of the cavern evoked by Plato in The Republic, the man who is chained before a wall and only able to see shadows projected on the wall, was able to use his intelligence in order identify what the causes that made those shadows possible. Certainly, man cannot « know » God directly. However, by studying the effects of his action, he can come to discover his intention. It is therefore through Hugue of Saint Victor, that the Augustinian and Platonic current that inspired the Carolingian Renaissance resurfaced in Paris. In this current of thought, creation as a whole, from the anagogical point of view, was the shadow cast by a heavenly paradise and a direct reference to omnipotence, beauty and divine goodness. For Bakker:

All of these interpretations are easily illustrated by the works of Augustine, because they have inspired writers on nature throughout the Middle Ages. Augustine greatly loved the world as it appeared to us; he knew how to enjoy what he referred to as ‘the great and beautiful spaces of the city or the countryside, where the brilliance of its beauty immediately strikes the viewer. But such creation also contains innumerable ‘moral’ messages, allowing so many opportunities for a pious and acute observer to reflect on his soul and task on Earth. Time after time, Augustine emphasized this aspect when he spoke of natural phenomena. Each time, he would incite us to seek the invisible behind the visible, the eternal behind the temporal, etc. Thus the harmony that creation revealed was an indication of the peace that should rein among men. Each creature, taken separately, appeared as an example (negative or positive) which man could discern, were he willing. This applied particularly to the behavior of animals, for example. And in regards to the Earth as a whole, one should take heed and make sure to not overlook the hollows and chasms of a landscape, for they are its true wellsprings.

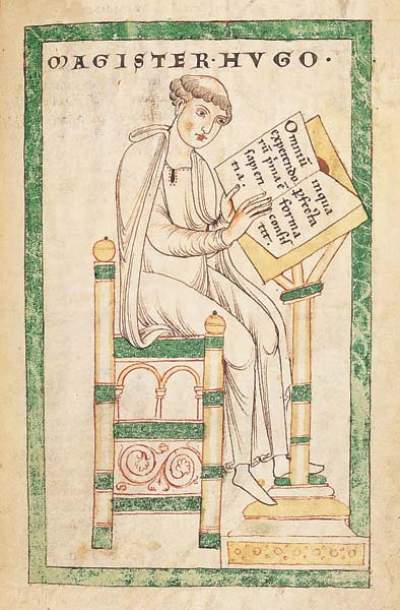

Hugue of Saint Victor

In France, it was with the advent of the XIIth century intellectual renaissance that centers of learning began to multiply (cathedral school, school of Abelard, school of Petit-Pont for Paris, Chartres, Laon etc…) and that an atmosphere of genuine knowledge turned France into a world-center for intellectual life. As well, numerous students originating from Germany, Italy, England, Scotland and Northern Europe all made their way to Paris in order to study first and foremost, dialectics and theology.

Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141) was of Saxon (or Flemish?) origin. Around 1127, he entered the house of the regular canons of Saint Victor shortly after the monastery’s founding on the outskirts of Paris.

The Victorins were distinguished from the beginning by the importance with which they regarded intellectual life. The canons of the abbey had a positive outlook on knowledge, hence the importance which they attached to their library.

The main teachers who influenced Hugue were: Raban Maur (himself a disciple of Charlemagne’s advisor, the Irishman Alcuin), Bede the Venerable, Yves de Chartres and Jean Scot Erigena and some others, perhaps Denys – The Areopagite himself of which he comments on The Celestial Hierarchy.

Propelled by an insatiable intellectual curiosity, Hugue advised his disciples to learn everything because, according to him, nothing is without use. He himself was the first to put the advice he gave to his disciples into practice. A notable part of his writings were devoted to the liberal arts, sciences, and philosophy, which he dealt with particularly in an introductory textbook on secular and sacred studies, still famous today, the Didascalicon.

His contemporaries considered him the greatest theologian of their time and gave him the glorious title of « New Augustine ». He influenced the Franciscans of Oxford (Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) whose influence on the painter Roger Campin has been well established, by whom Nicolas of Cusa was inspired.

In regards to the question of whether one should cherish or despise the world, Hugue of Saint Victor’s answer was that we must love the world, but with the condition that we never forget that we must love it with God always in sight, as a reflection of God, rather than something in and of itself.

In order for one to be able to reach such wisdom, man had to consider his existence as that of a pilgrim who was constantly breaking away from the place in which he resides, a very rich metaphor that would be found in the Flemish painters Bosch and Patinier. « The whole world is an exile for those who philosophize, » said Hugue.

Master Hugue posed the requirement of exceeding dilectio (jealous and possessive love of God) for condilectio (love welcoming and open to sharing). He advocated the idea of an agapic love turned towards others, and not centered on oneself, a love turned towards the neighbor, the love of God increased by the love of one’s neighbor. In a word: it was the idea of Christian charity and fraternal solidarity.

Hugues enumerated five spiritual exercises: reading, meditation, prayer, action and contemplation. The first granted understanding; the second provided a reflection; the third questioned, the fourth sought and the fifth found. These exercises were intended to allow one to reach the source of truth and charity, where the soul of man would be « transformed into a flame of love », resting in the hands of God in « a fullness of both knowledge and love.”

The subject which interests us here, is above all his optimistic vision of man and creation, which differed from the clichés that we have retained from medieval pessimism. For him, creation was a gift from God and the way to God was as much through reading the book of nature itself as it was from reading the Bible.

Thus, for Hugue of Saint Victor, the image that we perceive is nothing but revelation or the unveiling of God’s Divine Power, perceived

through the length, breadth, and depth of space, through the mountain ranges, the winding rivers, the rolling fields, the towering skies and the darkened chasms.

Thus, the painter who exceled in the representation of the physical universe, was only increasing his capacity to reveal the power of the creator!

The revelation of wisdom through Beauty. For Hugue, «the entirety of the sensible universe is one great book written by the hand of God” that is, created by a divine plan in which

every creature is a reflection of – not the product of human desire, but the fruit of divine providence’s will to manifest God’s great wisdom (…) Just as an illiterate looks at the lines of an open book without having knowledge of letters, a stupid and bestialized man ‘that does not understand the things that are of God’, sees in creatures only their external form, but has no understanding of their inner meaning.

To elevate oneself, Hugue proposed that the disciples of Saint Victor, all those who were able of « contemplating relentlessly, » to embrace « a spiritual vision » of the world. For his disciple, Richard of Saint Victor, the Bible and the great book of nature « share the same language and harmonize to reveal the wonders of a secret world. »

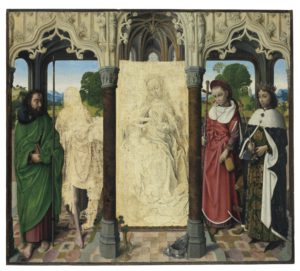

Denis the Carthusian,

the Key to Understanding Van Eyck

Two centuries after Hugue of Saint Victor, that same flame later animated the work of theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), a native of Belgian Limburg. Under the title The beauty of the world : ordo et varietas, Bakker devotes a whole chapter of his book to it. And you’ll soon understand why.

Two centuries after Hugue of Saint Victor, that same flame later animated the work of theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), a native of Belgian Limburg. Under the title The beauty of the world : ordo et varietas, Bakker devotes a whole chapter of his book to it. And you’ll soon understand why.

Before having joined the Carthusians of Roermond in the Netherlands, Denys was trained in the spirit of the Brothers of the Common Life at the Zwolle school in the Netherlands and then completed his studies at the University of Cologne.

With Jean Gerson (1363-1429) and Nicolas of Cusa (1402-1464), and despite an often much more wordy and sometimes confused style, Denis the Carthusian was counted as among the most well-read, most copied and most published authors of his day, once the printing press had replaced the laborious work of the copyist monks. Moreover, the first book published in Flanders, was none other than the Mirror of the Sinful Soul of Denis the Carthusian, printed in 1473 by Erasmus of Rotterdam’s friend, Dirk Martens.

At the Roermond Monastery in the Netherlands, Denis wrote 150 works including commentaries on the Bible and 900 sermons. After having read one, Pope Eugene IV, who had just ordered Brunelleschi to complete the cupola of the Santa Maria del Fiore Dome in Florence, exulted: « The Mother Church is delighted to have such a son! ».

As a scholar, theologian and advisor, Denys became very influential. « A number of gentlemen, clerics and bourgeois came to consult him in his cell in Roermond where he constantly resolved doubts, difficulties and cases of conscience. (…) He was in frequent contact with the House of Burgundy and serves as an adviser to Philip the Good « , confirms the Dutch historian Huizinga in his Autumn of the Middle Ages.

According to Bakker, having written a series of works on spiritual orientation, Denis performed the role of confessor and spiritual guide for the Christian sovereign Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and subsequently, that of his widow.

Together in Cologne, both attended the lecture of Flemish theologian Heymeric van de Velde (De Campo) who introduced them to the mystical theology of the Syrian Platonic monk known as Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite and to the work of Raymond Lulle and of Albert the Great as well. When, in 1432, Nicolas of Cusa declined an offer for the chair of Theology made to him by the University of Louvain, it was De Campo who accepted it at his request. Politically, from 1451 to 1452, Denis the Carthusian chose Nicolas of Cusa, then apostolic legate, to accompany him for several months during his tour of the Rhineland and Moselle to promote his approach to spiritual renewal, at the request of the pope.

Bakker notes that Denis had a predilection for music. He copied and illuminated scores with his hand and gave instructions on the best possible interpretation of the Psalms. His preference was for psalms praising God. And to praise the creator, Denis found images and words that would surface in the imagination of the painters of that time. However, for Denis, the beauty of God meant something deeper than mere visual appeal.

For you (Lord), ‘to be’ is ‘to be beautiful’.

Let us remember that in Christian philosophy sight was the most important of the five senses and the one which encapsulated all the others. In Denis’ Psalms, two notions prevailed. First, that of order and regularity. It was found in the celestial bodies that determined the cycles of days and years. But the Earth itself obeyed a divine order. And there Denis quoted the Book of Wisdom of Solomon (11,20) affirming: « You have ordained everything with measure, number and weight ». Then there was the idea of multiplicity and diversity. Regarding climatic phenomena, that is to say purely « physical » phenomena, Denis affirmed for example,

In the sky, lord, you generated multiple effects of pressure and air, such as clouds, winds, rains (…) and various phenomena: comets, luminous crowns, vortices, falling stars (…), frost and haze, hail, snow, the rainbow and the flying dragon.

For Denis, all this was not without a reason: it was to penetrate the divine being, his infinite greatness, his omnipotence and his love for man.

Make it so, my Lord, he writes, that in the effects of your universal laboriousness we perceive you, and that by the love with which it testifies, we inflame ourselves and waken to honor your greatness.

On God and Beauty, Denis wrote a great treatise on theological aesthetics under the title of De Venustate Mundi and Pulchritudine Dei (About the Attractiveness of the World and the Beauty of God).

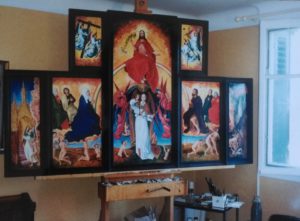

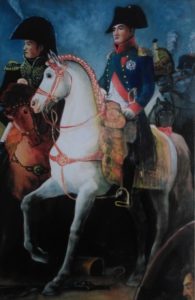

After having read what follows, the great polyptych painted by Jan Van Eyck, the altarpiece of Ghent known as The Mystic Lamb, comes to mind.

Knowing that this painter was in the service (painter and ambassador) of the same Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, of which Denis the Carthusian was the confessor and spiritual guide, one has good reason to believe that this text had impressed itself on the painter’s spirit at the time of this work’s creation.

Denis the Carthusian:

Just as every creature participates in the being of God and his goodness, so does the Creator also communicate to him something of his divine, eternal, uncreated beauty, whereby he is in part made like his Creator, participating in some measure in his beauty. In as much as a thing receives the essence of that being, so it receives the good and the beautiful of that being. There is therefore an uncreated beauty which is beautiful and beauty in its essence: God. The Other (as opposed to being) is the created beauty: the beautiful by participation. Just as every creature is thought of as being to the extent that it participates in the divine being and is assimilated with it by through a kind of imitation, so every creature is said to be beautiful in the degree to which it participates in this divine beauty and is brought in conformity with it. . Just as God has done all which is good since his nature is good, so he has done all things beautiful because he is essentially beautiful.

(…) The one and only son of God, true God himself, took our nature and became our brother. Through him, our nature has received a dignity of unspeakable majesty. God has also adorned the souls of the blessed who are in the heavenly homeland with his light and glory, and raised them to the beatific, immediate, clear and blessed vision of his all-pure Deity. By contemplating the uncreated and infinite beauty of the divine essence, they are made in his image in a supernatural and ineffable way. They are over-taken in this participation, this communion of goodness, this divine light and beauty, to the point of being entirely enthralled by him, configured to him, absorbed in him. They attain such beauty heights of beauty that the greatest splendors of world cannot even be compared with the smallest part of their beauty.

Back to Van Eyck

This last paragraph immediately evokes the upper panels of Jan Van Eyck’s polyptych in Gent. It’s hard to imagine the kind of effect that this painting would have had on believers: they saw not only Adam and Eve, raised on the same level as God, the Virgin and St. John the Baptist, but discovered there, at a time when less than one percent of the European population could read and write, the image of a beautiful young woman reading the Bible. Her name? Mary, mother of Jesus!

The lower part of the same work depicts another major event: the reunification, following the various ecumenical councils, of all Christians, whether they were from the East or West, divided by disagreements over the fundamental issue of the Christian faith: the sacrifice of the Son of God to free man from original sin. They are assembled in a chorus around all the most significant parts of the universe: the three popes, the philosophers, the poets (Virgil), the martyrs, the hermits, the prophets, the just judges, the Christian knights, the saints and the virgins.

Everything is presented in a landscape renewed by a true Christian “Spring”. Van Eyck did not hesitate to represent all the splendor of the microcosm with as much detail as possible, including a good fifty or so different plant species at the moment when all their most beautiful leaves and flowers are beheld by the world. It quite literally brings out the richness of creation in all its variety; allegorically, this represents the creator as the source of life; morally, it is the sacrifice of the son of God that will revive the Christian church; and finally, anagogically, it reminds us that we must strive towards becoming united with the creator, the source of all life, wisdom and good.

Once again, it is only in Denis the Carthusian, in the concluding passage of his Venestate Mundi and Pulchritudin Dei that one finds such passionate praise dedicated to the beauty of the visible world, including a reference to the famous « dark green meadows » so typical of Van Eyck:

Starting from the lowest level we have the elements of earth. In what immeasurable length and breadth are all extended; how wonderfully adorned is its surface with such innumerable species and various wonderful things. Look at the lilies and roses and other flowers of beautiful color as they emit their fragrant smells and healing herbs growing on the dark green meadows and in the shade of forests, the splendor of trees and lush fields, mountain heights, the freshness of trees, ponds, streams and rivers stretching to the sea in the distance! How beautiful He must be in and of himself, the One who created everything! Watch and admire the multitude of animals shining in their vast array of different colors! Our eye rejoices at the sigh of fish and birds and addresses our praise of the Creator. In what beauty and luster drape the large animals, the horse, the unicorn, the camel, the deer, the salmon and the pike, the phoenix, the peacock and the hawk. He is exalted, he who did all this!

With what we have just read in mind, the viewer can finally enjoy this beauty with confidence and without doubt, a beauty which is nothing but a foretaste of divine wisdom!

Bibliography:

- Boudewijn Bakker, Landschap en Wereldbeeld. Van Eyck tot Rembrandt, Thoth, 2004;·

- Patrice Sicard, Hugue of Saint Victor and his school, Brepols, 1991.·

- Denis the Carthusian, Towards the likeness, texts gathered and presented by Christophe Bagonneau, Word and Silence, 2003.·

- Karel Vereycken, Van Eyck, a Flemish painter in view of Arab optics, internet.

La Compagnie des ocres

Une adresse incontournable pour toutes celles et tous ceux qui fabriquent leurs propres couleurs:

La Compagnie des ocres

Sentier des Ocres

Roussillon (84220)

Tél.: 04 90 04 56 90

Courriel: contact@lacompagniedesocres.fr

Site internet:

www.lacompagniedesocres.fr

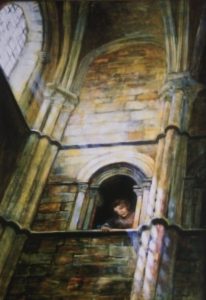

A la découverte d’un tableau

Jean-Luc, un jeune instituteur récemment titularisé, voulait faire découvrir la peinture à un petit groupe d’élèves. Il en choisit donc six parmi eux, qui étaient en âge de s’ouvrir à ce genre d’aventure, et les accompagna au musée du Louvre.

Lorsque l’instituteur parvint devant le tableau qu’il avait choisi d’expliquer aux enfants, les guides accrédités jetèrent un oeil noir sur ce groupe improvisé et y virent une concurrence déloyale.

L’un d’entre eux, une dame assez âgée munie de lunettes à montures étonnantes, les bouscula légèrement et déclama d’une voix nasillarde pour la douzième fois de la journée :

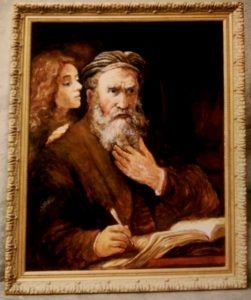

Domenico Ghirlandaio, né en 1449 et mort de la peste en 1494, à l’âge de 45 ans, fut l’un des peintres les plus importants de son époque. C’était le fils d’un orfèvre, Tommaso Corradi, surnommé Ghirlandaio parce qu’il fabriquait des parures en forme de guirlande très prisées des jeunes Florentines. A l’instar de Léonard de Vinci, Domenico fut formé par le peintre et sculpteur Andrea del Verrocchio ; il mit tout son talent au service des ordres religieux et des familles les plus riches du moment, les Medicis, les Malatestas. Le pape Sixte IV fit appel à lui pour la décoration de la chapelle Sixtine de Rome. Parmi les élèves de Ghirlandaio, l’un d’eux deviendra Michel-Ange, le plus grand sculpteur de tous les temps. De Ghirlandaio, voici le Portrait d’un vieillard et d’un jeune garçon réalisé vers 1485, peint sur bois avec une technique de tempera, astucieux mélange de jaune d’oeuf et d’huile.

Son allocution terminée, la guide se remit en route, suivie comme une mère poule par une quarantaine de touristes, dont certains avaient pris des photographies dans l’espoir de mieux comprendre… plus tard.

Jean-Luc, qui avait auparavant rêvé d’une carrière dans la bande dessinée, n’en revenait pas : vouloir tout voir sans rien comprendre lui semblait la meilleure façon de vous dégoûter pour toujours de l’art. Il avait, lui, une tout autre méthode : choisir une seule oeuvre, mais prendre le temps de l’approfondir.

Nous allons jouer aux devinettes, dit Jean-Luc à ses élèves. Moi, je prétends que le véritable nom de ce tableau n’est pas Portrait d’un vieillard et d’un jeune garçon. Ce n’est que le nom donné par le collectionneur qui a vendu le tableau. Alors, essayons de découvrir son véritable nom…

— Pourquoi a-t-il un nez grand et affreux qui semble tout gonflé par des piqûres de guêpes ? demanda Myriam en rougissant, sûre d’avoir dit ce qui lui passait par la tête, c’est-à-dire n’importe quoi.

— C’est vrai, tu as raison, il n’est pas très beau, mais bizarrement, le tableau, lui, est beau. Alors pourquoi ? interrogea Jean-Luc.

— L’enfant aussi est beau ; et en vieillissant, on attrapera tous des crevasses sur le pif ! remarqua malicieusement Pierre, l’éternel premier de la classe.

— Que voit-on d’autre sur ce tableau ? demanda le maître.

— Il y a une grosse montagne dans le fond, répondit Momo.

— Et un chemin qui y mène, ajouta Sarah.

— N’oublions pas le petit arbre tout près, qui lui aussi est jeune ! observa Pierre.

— Et tu n’as pas remarqué la petite église entourée de vieux arbres, sur la colline, note Myriam.

— Très bien, dit Jean-Luc, on avance dans la bonne direction. D’abord, on peut être laid à l’extérieur et posséder la beauté intérieure. Apprenez à ne pas juger vos camarades sur leur apparence. Notre enveloppe terrestre n’est pas si importante, parce qu’elle est de toute façon éphémère. Nous naissons tous et, dans le meilleur des cas, nous mourrons très vieux. Mais nul n’échappera à la mort.

— Mais ce n’est quand même pas le portrait de la mort, ce serait affreux ! s’exclama Florette.

— Le peintre a peut-être voulu dire que la vie est comme un chemin qui mène à la montagne. Ayant pris de la hauteur, on peut voir au-delà, revoir d’où le voyage a commencé. A cet instant, on peut réfléchir à ce qu’on a donné aux autres et à ceux qui survivront, proposa Jean-Luc…

— Mais c’est « l’amour » alors ! s’exclama Louise, pensant avoir trouvé le titre du tableau.

— Oui, concéda Jean-Luc, ces deux-là ont l’air de s’aimer, mais comment sont leurs visages ?

— Ils sont tristes, dit Sarah, comme s’ils allaient se séparer pour toujours. Peut-être que le vieux sait qu’il a une grave maladie et qu’il est au bout du voyage. C’est peut-être pour ça que son nez est si bizarre. En plus, il a le front tout fissuré !

— Les rayures qui apparaissent sur son front proviennent de la détérioration du tableau, expliqua Jean-Luc. La peinture à l’oeuf est un peu comme les illustrations des vieux manuscrits qui s’abîment quand ils sont exposés à la lumière et à l’air ambiant. Pour protéger les peintures, on eut plus tard l’idée de les vernir, puis d’utiliser le vernis lui-même comme moyen d’apposer les couleurs sur la surface à peindre.

Les Flamands furent parmi les premiers à pratiquer cette technique. Dès l’âge de huit ans, les apprentis-peintres apprenaient à broyer les couleurs et à encoller les panneaux de bois avec une colle à base de peau de lapin. Ces derniers étaient ensuite enduits d’une préparation composée de plâtre fin mêlé à une substance adhésive et de peinture blanche. Ils effectuaient ces tâches durant une douzaine d’années et leur maître leur confiait parfois la réalisation d’un dessin ou le détail d’un tableau.

Ainsi, le peintre Verrocchio demanda un jour à Léonard de Vinci, qui était alors son élève, de réaliser le détail d’un ange dans l’un de ses tableaux. Le résultat fut tellement beau que Verrocchio abandonna avec joie sa carrière de peintre pour celle de sculpteur, parce qu’il avait vu que son élève pouvait certainement le surpasser.

— Donc, si nous trouvons le titre du tableau, vous n’allez plus nous emmener dans les musées ? demanda Boris avec malice.

— Je crois qu’il est temps de rentrer, les enfants. Si nous voulons être à l’heure à la cantine, il faut partir maintenant, dit Jean-Luc en regardant sa montre.

— Mais le vrai nom du tableau ? demandèrent les enfants en choeur.

— Nous reviendrons, conclut Jean-Luc.

(fable écrite en 1994 par Karel Vereycken)

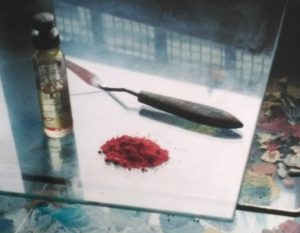

Peindre au tempera, à l’oeuf et à l’huile

(texte en préparation sur la peinture à l’oeuf et au tempera)

1. Le support idéal et pas cher: des dos d’armoires en chêne trouvés chez vous le jour des encombrants. Poncez bien avec un papier de verre.

2. Préparez en bain marie une colle « totin » (peau de lapin). Enduire les panneaux poncés de plusieurs couches de cette colle.

3. Après une bonne quinzaine de jours de séchage, enduire le panneau avec deux à huit couches de gesso pour obtenir une surface aussi lisse que du papier bristol, essentiel pour pouvoir y peindre des détails.

4. Appliquer sur l’ensemble du panneau une « impression » (couche préparatoire) de pigment sec (ici du jaune de mars) grâce à du jaune d’oeuf, un émulsifiant formidable. Attention: il est impératif de jeter la membrane du jaune d’œuf avant, Sinon pourrissement garantie et bonjour les odeurs.

5. Pour préparer la tempéra, mélangez un volume de jaune d’oeuf avec un volume d’huile de lin rectifié et deux volumes d’eau. Pour peindre les dernières couches, broyez vos couleurs directement avec d’huile de lin rectifiée. Clore aux glacis (secret maison).

Et la lumière fut !

Cette phrase est une traduction de la seconde partie de la locution latine Fiat lux et facta est lux présente au début de la Genèse (1:3).

Cette phrase est une traduction de la seconde partie de la locution latine Fiat lux et facta est lux présente au début de la Genèse (1:3).

Il s’agit de la première parole de Dieu dans le récit de la création du monde, traduisible en français par « Que la lumière soit, et la lumière fut ».

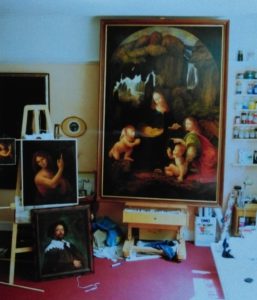

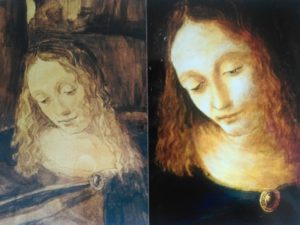

Can great techniques of oil painting be revived?

Uncorrected 1996 draft memorandum (12 pages) resuming my own experience reworking the old master techniques. Special thanks goes to my friend, the Belgian master of watercolor and schoolmate Leopold Geysen with whom I had the luck to discuss these issues in depth while working both of us in our own directions.