Étiquette : Nuremberg

Albrecht Dürer contre la Mélancolie néo-platonicienne

Fais en sorte par tous tes effortsQue Dieu te donne les huit sagesses.On appellera facilement homme sageCelui qui ne se laisse aveuglerNi par la richesse ni par la pauvreté.Celui qui cultive une grande sagesseSupporte également plaisir et tristesse.Est aussi un homme sageCelui qui supporte la honteComme la gloire.Celui qui se connaît soi-même et s’abstient du mal,Cet homme est sur le chemin de la sagesseQui en place de vengeancePrend son ennemi en pitié.Il s’éloigne par sa sagesse des flammes de l’enferCelui qui sait discerner la tentation du diable etSait y résister par la sagesse que Dieu lui octroi.Celui qui en toute circonstance garde son cœur purA choisi le couronnement de la sagesse.Et celui qui aime vraiment DieuEst un chrétien pur et pieux.Albrecht Dürer, 1509

Nuremberg, berceau de génies

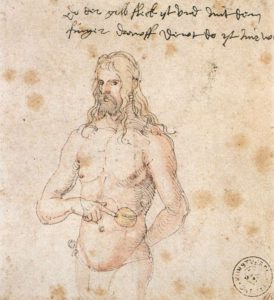

L’autoportrait (1484) d’Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) « fait devant un miroir », à l’âge de treize ans (Fig. 1) nous montre un enfant émerveillé. Son père, qui le guide dans cet effort, est un orfèvre d’origine Hongroise installé à Nuremberg et formé à la technique de dessin à la pointe d’argent « auprès des grands maîtres » flamands, spécialisés dans cette technique complexe.

Centre commercial, minier et sidérurgique qui fournissait la cour de Prague, Nuremberg, en 1500 est une ville riche de 50 000 âmes et attire, tel un aimant, tous les talents d’Allemagne et d’Europe. (Fig. 2) Grande ville de l’imprimerie naissante, Anton Koberger (v. 1445-1516) y fait tourner jusqu’à 24 presses à lui seul avec une centaine de compagnons. Friedrich Peypus, imprimeur des humanistes, y publie le grand platonicien Erasme de Rotterdam (1469-1536).

On produit des écrits ésotériques et des bibles, mais aussi tout ce que l’Italie peut fournir comme auteurs humanistes, avec les écrits scientifiques de Nicolas de Cuse (1401-1464) ou les lettres d’Enea Silvio Piccolomini (le pape anti-obscurantiste Pie II). Astronomes, géographes, mathématiciens, artisans, sculpteurs (Veit Stoss et Adam Kraft, entre autres), orfèvres, architectes et poètes y fleurissent. Le médecin Hartman Schedel (1440-1515) y rédige et imprime sa fameuse Chronique, illustrée de 1809 gravures. Martin Behaim (1459-1509), dont la maison familiale avoisine celle de Dürer, y fabrique les premiers globes terrestres.

Profitant de cet environnement intellectuel, culturel et scientifique exceptionnel, il va sans dire que Dürer, tout comme Rabelais, était un enfant de la « génération Erasme » [1]. Toute analyse de l’œuvre de Dürer nécessite donc une lecture d’Erasme, ce géant à l’origine du décloisonnement des esprits et des métiers ; son impulsion demeure incontournable pour circonscrire l’humanisme qui anime l’artiste. Cependant, c’est un autre géant, scientifique celui-ci, qui donne à Albrecht Dürer un atout supplémentaire.

De Bessarion à Dürer, en passant par Regiomontanus

Car en 1471, année de naissance de Dürer, le géographe, mathématicien et astronome Johannes Müller (1436-76), dit Regiomontanus (Fig. 3) , décide d’élire domicile à Nuremberg. Il est certain d’y trouver ce qu’il cherche : des érudits comme lui et des artisans hautement qualifiés, spécialisés dans la fabrication d’instruments scientifiques de précision, en particulier pour l’astronomie.

A la mort du mathématicien viennois Georg Peuerbach (1423-61), son mentor, Regiomontanus fait sienne la mission que ce dernier avait reçu du cardinal Jean Bessarion [2] (1403-1472) : re-traduire et publier l’abrégé de l’Almageste de l’astronome grec Claude Ptolémée (90-168), supposé donner une explication cohérente aux mouvements des planètes du système solaire. Ce travail, achevé en 1463 et imprimé pour la première fois en 1496 sous le titre Epitoma in Amagestum Ptolomei (avec des illustrations de Dürer) suscite de grandes controverses, reprises par des astronomes tels que Copernic, Galilée et Kepler.

Au service de Bessarion, Regiomontanus parcourt l’Italie de 1461 à 1467. Il fabrique un astrolabe, écrit sur la trigonométrie et la sphère armillaire. A l’université de Padoue il expose les idées d’al-Farghani et écrit une critique du Theorica Planetarum attribué à Gérard de Crémone.

A partir de ses propres observations, comme il le stipule dans une lettre à l’astronome Giovanni Bianchini, Regiomontanus constate que ni Ptolémée, ni aucune science astronomique connue à son époque ne réussissent à expliquer les phénomènes observés. C’est avec son appel pour une collaboration internationale capable d’y parvenir, que Regiomontanus apparaît comme l’homme qui fixa l’agenda pour une révolution théorique en astronomie, qu’accomplira ensuite Johannes Kepler.

De surcroît, dans ses bagages, Regiomontanus amène à Nuremberg une collection exceptionnelle de manuscrits. Il projette notamment d’y fonder sa propre imprimerie et de publier ses manuscrits, référencés dans un « prospectus » établi vers 1473. Cette collection rare et prestigieuse est alors sans pareil par sa teneur scientifique : on y trouve les œuvres d’Archimède (par Jacobus Cremonsis), quatre codex euclidiens (dont une version des Eléments ayant appartenu à Bessarion et traduite au début du XIIème siècle par Abelard de Bath), le De arte mensurandi (de Jean de Murs), De la Quadrature du Cercle de Nicolas de Cuse où encore le De speculis cimburrentibus (d’Alhazen) parmi beaucoup d’autres.

Poursuivant sa correspondance avec Paolo Toscanelli [3] (1397-1482), Regiomontanus et son élève Bernhardt Walther (1430-1504), élaborent et font imprimer à Nuremberg les fameuses éphémérides pour la période 1475-1506, qui, de pair avec la fameuse carte de Toscanelli, permettent à d’intrépides navigateurs, tel Christophe Colomb, d’élargir les horizons de l’humanité grâce à une nouvelle science : la navigation astronomique. [4]

Bien que très doué pour le dessin, le jeune Dürer est formé comme artisan et métallurgiste dans l’orfèvrerie de son père. En 1486, âgé de 15 ans, il entre dans l’atelier de Michael Wolgemut (1434-1519), un graveur qui illustre des publications de Regiomontanus.

Après le décès de ce dernier en 1476, c’est son disciple Walther qui hérite de sa riche bibliothèque et poursuit les recherches. En 1501 Walther achète la maison de Regiomontanus – qu’en 1509 Dürer acquiert à son tour, devenu membre du Grand Conseil de Nuremberg – et aménage le pignon sud en plate-forme d’observations astronomiques.

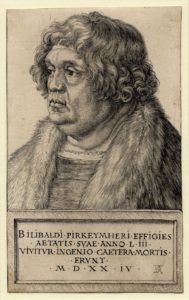

Cependant, Dürer, dépourvu d’une connaissance suffisante en latin et grec pour déchiffrer ces trésors, se voit obligé de passer des soirées entières avec le turbulent correspondant d’Erasme, le patricien Willibald Pirckheimer [5] (1470-1530) (Fig. 4) et d’autres humanistes de son entourage. Dans le cercle de Pirckheimer, l’artiste fait certainement connaissance avec le neveu du duc de Milan, Galeazzo de San Severino, un camarade d’université de Pirckheimer, réfugié à Nuremberg après 1499. Il faut savoir que c’est dans les écuries de Galeazzo que Léonard de Vinci étudie les proportions des chevaux, de plus, il est établi que plusieurs dessins anatomiques de Dürer sont des copies pures et simples de Léonard. En géométrie, on pense que Dürer a pu bénéficier du conseil et des explications d’un autre membre du cercle de Pirckheimer, le prêtre astronome et mathématicien Johannes Werner [6] (1468-1528), réputé pour aimer échanger et partager son savoir avec les artisans.

Comme on le découvre en explorant son environnement social immédiat : Dürer , ami d’un correspondant d’Erasme, est initié à la gravure par un proche collaborateur d’un grand scientifique, Regiomontanus et de plus, s’installe dans la maison qui abrite probablement la plus riche collection de manuscrits dont on peut rêver à l’époque, rassemblés par Bessarion et Nicolas de Cuse !

On peut bien dire qu’avant d’aller découvrir la Renaissance en Italie, le meilleur de la Renaissance du Quattrocento italien est venu à sa rencontre.

« Melencolia », ou Platon contre le néoplatonisme

Bien que Dürer tienne l’essentiel de sa réputation à des très nombreuse gravures à thème biblique sur bois et sur cuivre (Apocalypse, Petite Passion, Grande Passion, etc.), aujourd’hui on l’admire surtout pour ses études minutieuses de la nature (Le lièvre, La grande touffe d’herbe, etc.).

Nous avons choisi ici de traiter l’aspect plus énigmatique de son travail dans lequel il aborde un des défis majeurs de son époque et qui reste d’une brûlante actualité : comment donner aux penseurs, chercheurs et autres artistes, l’entière et saine maîtrise des processus créateurs de l’esprit humain, en évitant tout autant les procédés formels et stérilisants que les dérapages ésotériques et irrationnels, fuites confortables vers une douce folie ? Voyant sombrer son meilleur ami et tuteur Pirckheimer, exposé aux théories « néo-platoniciennes » très en vogue à l’époque, Dürer fait appel au « vrai » Platon pour élaborer en 1514, avec une grande ironie, sa gravure Melencolia I. La joie de découvrir cette œuvre nous livre d’emblée l’antidote au type de mélancolie qu’il dénonce.

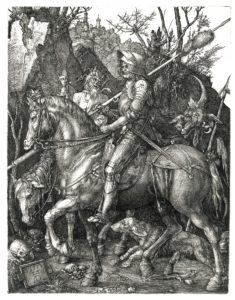

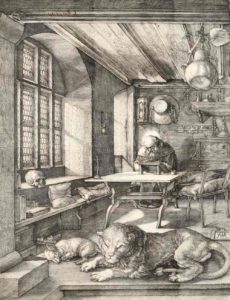

Trois gravures, connues sous le nom de Meisterstiche [chefs-d’œuvre gravés] nécessitent d’être juxtaposées pour mieux comprendre cette œuvre. Des témoignages d’époque rapportent que Dürer offre souvent plusieurs gravures de cette série.

Il s’agit du Chevalier, la mort et le diable (qui date de 1513), Saint Jérôme dans sa cellule ( 1514), et de Melencolia I (également de 1514). (Fig. 5, 6 et 7)

D’abord Le Chevalier, la mort et le diable pose d’une façon brutale le défi de l’existence humaine. Le chevalier passe son chemin sans se laisser impressionner par un diable presque ridicule et la mort qui lui présente un sablier. Crâne et os ne représentent pas tant la mort que le passage inexorable du temps assimilé tout naturellement à un memento mori (« Souviens-toi que tu dois mourir »), invitation à une vie de raison qui ne doit pas être gaspillée.

Ensuite, loin d’une vie contemplative et retirée du monde, Saint Jérôme dans sa cellule rayonne d’une activité débordante. Plus encore que le crâne et le sablier, c’est le potiron géant accroché au plafond qui nous interpelle. En raisons de ses nombreux pépins, il est symbole d’abondance et de fécondité, image métaphorique de nourriture d’immortalité. Un dicton chinois pose la question du sens de la vie : « Suis-je une calebasse qui doit rester pendue sans qu’on la mange ? »

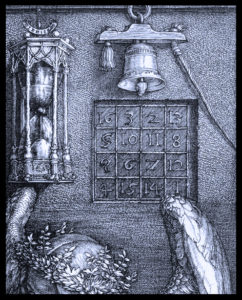

Enfin, l’énigmatique Melencolia I. On remarque dans une pénombre troublée par la chute d’une comète et d’un arc en ciel, une figure, qui bien qu’ailée, semble clouée au sol, assise au pied d’un monument érigé devant un plan d’eau, et une ville en arrière-plan. La créature porte une couronne de feuilles et une robe richement brodée. Elle exhibe une bourse bien remplie et un trousseau de clefs. Elle est entourée d’une collection d’objets et d’instruments ayant un rapport à la géométrie (un compas, une règle, une sphère, un polyèdre), au travail artisanal (un rabot, un gabarit pour moulures, un marteau, des clous, des tenailles, une scie, un creuset, une échelle, une balance, un sablier avec un cadran solaire), aux nombres (un carré magique), à la littérature (un encrier, un livre fermé) et à la musique (une cloche). On remarque aussi au centre un angelot ayant l’air bien inspiré, assis sur un tapis recouvrant partiellement une meule. Ce putto se concentre sur son activité d’écriture tandis qu’à terre repose un chien un peu misérable. Une chauve-souris, exhibant un écriteau avec le texte Melencolia I semble vouloir se jeter hors du tableau.

Pour comprendre cette œuvre, procédons par étapes.

La mélancolie, un virus aristotélicien

Point besoin d’avoir pénétré toutes les significations secrètes des objets et des attitudes pour constater le sens général de l’œuvre. La figure qui incarne la mélancolie semble ici peu satisfaite de sa propre inaction ; elle jette un regard jaloux sur le petit ange si travailleur et si heureux !

Les études de l’historien d’art Erwin Panofsky, reprenant ceux de Karl Giehlow de 1903, résument bien l’historique du thème : la mélancolie (du grec mélas signifiant le noir, et choler l’humeur), n’est qu’une forme aggravée de l’acedia [l’ennui]. L’acedia, cette apathie spirituelle décrite dès le quatrième siècle par le moine Evagrius Pontus comme la maladie des moines fut parfois appelée démon de midi. Le diable, sûr de lui, n’hésitait pas à opérer en plein jour, en particulier à midi, lorsque les moines, après une petite nuit et un long labeur matinal, manifestaient les premières signes de faiblesses…

Cette « torpeur de l’esprit qui ne peut entreprendre le bien » n’était pas une simple paresse au sens de fainéantise, et était considéré par les chrétiens comme un grave péché. [7] De nombreux chapiteaux de l’art roman font figurer le péché Désespoir sous forme d’un diable se suicidant, en opposition avec la vertu Espérance.

Si les chrétiens considéraient cette affection comme un grave péché, les médecins de l’antiquité n’y voyaient en général qu’une maladie. Ils considéraient la mélancolie comme l’une des quatre humeurs (sanguine, cholérique, mélancolique, lymphatique), tempéraments qui affectent tout les êtres humains. Mais si une d’entre elles domine trop, elle peut nous conduire au vice et même à la folie.

A la Renaissance, cette conception antique refait surface. Comme le souligne Erasme, ces humeurs ont certes des défauts, mais chez un homme « bien tempéré », elles laissent la place à d’autres qualités qui peuvent compenser les défauts de caractère : « Il arrive parfois que la nature, comme si elle faisait balance entre deux comptes, compense une maladie de l’âme par quelque sorte de qualité contraire : tel individu est sans doute plus porté à la volupté, mais nullement colérique, nullement jaloux ; un autre est d’une chasteté incorruptible, mais un peu bien hautain, plus porté à la colère, plus regardant à ses sous. » (Enchiridion f.46)

En art, la représentation moyenâgeuse de la mélancolie se construit donc à partir de celle de l’ennui (acedia), présentée parfois comme une fileuse ayant cessé de filer la quenouille (dérouler le fil de la vie). Par sa passivité, elle se rend vulnérable au diable. (Fig. 8)

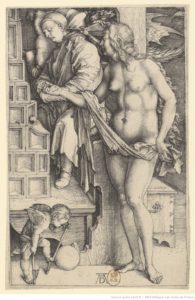

Dürer lui-même traite d’une façon semblable ce thème dans une gravure non datée, Le songe du Docteur. [8] (Fig. 9)

Une étude récente démontre d’une façon convaincante que le docteur endormi derrière son fourneau vers lequel le diable actionne un soufflet, n’est pas en proie à un rêve luxurieux. Il s’agit selon toute probabilité d’une polémique contre les alchimistes, qui, à force d’attendre devant leur athanor que le plomb se transforme en or, sont dans l’incapacité de répondre aux invitations de dame fortune.

Cependant, Melancolia I n’a rien à voir avec cette paresse dangereuse. Nous sommes ici devant quelque chose de radicalement différent : la figure ailée n’est pas dans un état de somnolence mais bien plutôt en état de super-éveil. Son visage sombre et son regard fixe expriment une quête intellectuelle, intense mais stérile. Elle a suspendu son travail, non par indolence, mais parce qu’il est devenu, à ses yeux, privé de sens. Comme le formule Panofsky : « Ce n’est pas le sommeil qui paralyse son énergie, c’est la pensée. »

Marsile Ficin à l’origine du romantisme ?

Cette interprétation « moderne » de la mélancolie arrive avec ce qu’on nomme abusivement les idées néo-platoniciennes. Il s’agit en réalité d’une attaque perverse contre l’essence de la pensée platonicienne menée par la personne, l’oeuvre et les disciples de Marsile Ficin (1433-1499), (Fig. 10) lui-même adepte des néo-platoniciens d’Alexandrie (Plotin, Porphyre…).

Comme Giehlow, Panofsky note, bien avant nous, que, cette personnalité dominante de l’académie néo-platonicienne de Florence a inversé le concept de Mélancolie. Que Dürer ait été confronté à ces idées nouvelles semble entièrement établit. Pirckheimer, encore étudiant à Pavie, envoie à son père une copie d’un écrit du Ficin. Notons aussi qu’Anton Koberger, le parrain de Dürer, imprime en 1497 à Nuremberg la correspondance de Ficin et que ses œuvres circulaient dans toute l’Allemagne. Il y a donc peu de doutes que son cercle en discute.

Observons d’abord que, dans sa Septième lettre, le Ficin reprend la belle métaphore de Platon où il conte que notre âme, après avoir contemplé les idées (justice, beauté, sagesse, harmonie) à l’état pur dans les cieux, se retrouve dégradée par les désirs des choses terrestres.

Pour y échapper, l’âme peut s’envoler grâce à deux ailes (deux vertus) : la justice qu’on obtient grâce à un comportement moral (actif) et la sagesse (contemplatif). On peut y voir Le Chevalier et Saint Jérôme. Le fait que Dürer représente sa Mélancolie avec des ailes trouve donc tout son sens. Quand l’âme voit une forme belle, elle « est enflammé par cette mémoire et, en secouant ses ailes, par degrés se purge du contact avec les corps et la saleté et devient possédée par la fureur divine ». (…)

Cependant, insiste le Ficin, « Platon nous dit que ce type d’amour naît de la maladie humaine et est remplie de troubles et d’angoisses, et qu’il se manifeste dans ces hommes dont l’esprit est tellement couvert de noirceur que ça n’a rien d’exalté, rien d’exceptionnel, rien d’au-delà de la faible image du petit corps. Il n’y a rien qui regarde les étoiles, parce que dans sa prison, les volets sont clos. »

Pour le Ficin, « l’âme immortelle de l’homme est en malheur constant dans le corps », ou elle « dort, rêve, délire et souffre », emplie d’une nostalgie infinie qui ne connaîtra nul repos avant qu’enfin elle ne « retourne d’où elle est venue ».

Ensuite, dans De Vita triplici (Les trois livres de la Vie, 1489), le Ficin reprend les idées de l’ennemi numéro un de Platon : Aristote. Ce dernier, dans son Problemata XXX, 1, définit le « mélancolique de nature » comme quelqu’un d’une sensibilité particulière que oscille tellement entre la paralysie et l’hyperactivité de ses pensées et ses émotions qu’il peut basculer dans la folie, le délire ou la faiblesse d’esprit, connu de nos jours comme le syndrome maniaco-dépressif ou encore les troubles bipolaires.

Pour Aristote, aucun doute : « tous les êtres véritablement hors du commun, que ce soit dans le domaine de la philosophie, de la conduite de l’Etat, de la poésie ou des arts, sont des mélancoliques -certains même au point qu’ils souffrent de troubles provoqués par la bile noire » puis déclare élégamment que, si le mélancolique réussit à marcher sur cette crête étroite séparant génie et folie, « le comportement de son anomalie devient admirable d’équilibre et de beauté ».

Le Ficin, lui-même proie d’une grave mélancolie s’efforce d’étoffer et d’amplifier cette affirmation. Après des arguments pseudo médicaux, il conclut que l’humeur noire « doibt estre autant cherchée et nourrie » que la blanche, car, si correctement exploitée, elle peut fournir une force formidable à l’âme : « Et tout ce qu’elle [l’âme mélancolique] recherche, aisément elle l’invente, le perçoit clairement, en juge sincèrement, et retient longtemps ce qu’elle a jugé. Adjoustez-y que comme cy dessus nous avons démonstré, que l’Ame par tel instrument qui convient en quelque sorte avecques le centre du monde, et (pour ainsi dire) qui recueille l’Ame comme en son centre, tend toujours au centre de toutes choses, et y pénètre au plus profond. En outre il convient avec Mercure et Saturne l’un desquels est le plus hault des Planètes qui élève l’homme de recherche aux plus hauts secrets. De là viennent les Filosophes singuliers, principalement quand l’ame est ainsi abstraite des mouvements externes et du propre corps, et que fort proche des divins, elle est faite instrument des choses divines. Donques estant remplie de divines influences et des oracles d’enhault, elle invente tousjours quelque chose de nouveau, et non usité, et prédit les choses futures. Ce qu’afferment non seulement Democrite et Platon : mais aussi Aristote au livre des Problèmes et Avicenne au livre des choses divines, et au livre de l’Ame le confessent. » (traduction française de Guy Le Fèvre de la Boderie, 1581).

Cette confusion permanente entre folie et génie apparaît une fois de plus dans De furore poetico (1482), la préface du Ficin pour sa traduction du dialogue de Platon Ion.

Dans ce dialogue, pour taquiner le rhapsode, Socrate affirme que « le poète est une chose légère, ailée et sacrée, qui ne peut composer avant d’être inspiré par un dieu, avant de perdre la raison, de se mettre hors d’elle-même. Tant qu’un homme reste en possession de son intellect, il est parfaitement incapable de faire œuvre poétique et de chanter des oracles ». Quand Socrate constate que le rhapsode Ion veut seulement être l’esclave des divinités [534d], et qu’il est avide de récompenses pécuniaires [535e], il le traite de Prothée [sophiste égyptien] [541e].

Pour Platon, l’inspiration divine doit conduire au perfectionnement de la raison souveraine et donc à la liberté. A contrario, dans Les Lois, VII, 790d, Platon évoque le « mal des Corybantes », ces prêtres mythiques qui honoraient la déesse-mère Cybèle par des danses frénétiques.

Mais dans sa préface, le Ficin, après avoir affirmé qu’une première forme de délire fait tomber l’homme « au dessous de l’apparence humaine et (…) en quelque sorte ramené à la bête », le florentin affirme, imitant en cela Plotin, qu’il existe une autre forme de délire, celui-ci divin (extase mystique).

Par ce stratagème, les néo-platoniciens de Florence reprirent à leur compte la doctrine aristotélicienne pour qui la furor melancolicus constitue le fondement scientifique de la conception platonicienne d’une furor divinus, la belle frénésie du poète ! Bien que le processus de créativité humaine, parfois qualifié d’agonie créatrice, implique de fortes tensions résultant de l’épuisement d’un niveau donné d’hypothèses, le plaisir de la découverte, que l’on éprouve par des sauts qualitatifs vers des géométries supérieures, renforce l’émotion fondamentale de joie et d’amour généreux envers l’humanité.

Voilà l’essence de l’identité d’un individu réellement adulte, ce que Platon appelle les « âmes d’or ». La nature de l’émotion fondamentale qui constitue son identité est agapique et non érotique.

Si ce processus dépasse la rationalité simple, il obéit néanmoins à une légitimité harmonieuse, diamétralement opposée à une crise existentialiste. Prétendre que la « souffrance » soit l’unique vivier de la créativité humaine est non seulement une escroquerie intellectuelle, mais une démarche visant à plonger le créateur dans un narcissisme infantile le rendant susceptible d’être manipulé.

Il apparaît ainsi que vouloir établir une équivalence automatique entre folie et créativité n’est qu’un instrument raffiné de l’oligarchie pour promouvoir une pensée irrationnelle, destructrice tant des arts que des sciences.

Ayant donc retrouvé son lustre grâce à ce mélange trompeur, la mélancolie, jusqu’à là tenue dans le mépris, s’auréola du sublime. (*9) Cette mélancolie sublime est l’essence même d’une grave maladie culturelle dont souffre encore le monde aujourd’hui : le romantisme. (*10)

Agrippa, Trithème et Zorzi

L’influence grandissante d’Erasme de Rotterdam et de Thomas More, disciples de Saint Socrate, engagés dans une réforme de la société civile et des pratiques religieuses, provoqua l’ire de l’oligarchie alors basée dans le centre du pouvoir financier et du renseignement : Venise.

Avant l’apparition de Luther, cette dernière fera tout pour promouvoir l’alchimie et l’occultisme pour confondre l’esprit des élites lettrés et érudits.

Ainsi, Johannes Reuchlin (1455-1522), passionné de Grec et d’hébreux, bascule dans l’ésotérisme cabalistique après sa rencontre avec le Ficin et Pic de la Mirandole. Erasme le défend quelque temps contre l’inquisition – car, obsédée, elle brûle tout les livres juifs – alors qu’à cette période où il marche dans les pas de Saint-Jérôme, il vise avec son projet de Collège Trilingue, avec les originaux grecs, latins et hébreux à offrir au monde une nouvelle traduction de l’évangile, espérant ainsi prévenir les guerres de religion.

Les réseaux érasmiens sont prompts à dénoncer ces déploiements alchimistes. Erasme, dans l’Eloge de la Folie écrit en 1511 : « Ceux qui par des pratiques nouvelles et mystérieuses essaient de changer la nature des éléments et en recherchent un cinquième, à savoir la quintessence, à travers la terre et les mers… Ils ont toujours à l’esprit quelques inventions merveilleuses qui les égarent et l’illusion leur est si chère qu’ils s’y perdent tout leurs biens et n’ont plus de quoi construire un dernier fourneau. » Il écrit également une préface pour De Re Metallica (publié en 1556) de Georg Agricola (1494-1555), pour stimuler les recherches scientifiques sur les processus géologiques, les fossiles, les minerais et leurs transformations utiles pour l’humanité.

D’autres de son entourage dénoncent l’alchimie, notamment Sébastien Brant (1458-1521) dans la « Nef des Fous » pour lequel Dürer grava des illustrations, ou encore Pierre Breughel l’aîné dans son dessin l’Al-ghemist([tout raté) de 1558. (Fig. 11)

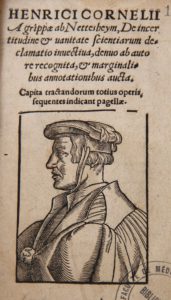

Au centre de l’offensive alchimiste on trouve Agrippa de Nettesheim (1486-1535) (Fig. 12). En 1510, il s’était rendu avec le jeune médecin suisse Paracelse (1493-1541) à Prague chez l’abbé bénédictin Trithème (1462-1516) (Fig. 13). Avec ce dernier, il fonde à Paris d’abord puis à Londres, une société internationale secrète, la « Communauté des Mages ».

Comme beaucoup d’autres « astrologues » et alchimistes de cette époque, Agrippa sert d’ambassadeur, d’espion et d’agent d’influence. Il travaille d’abord pour l’empereur Maximilien I, ensuite pour Charles V et pour la France. Dans ses fonctions d’ambassadeur de Maximilien I, on le retrouve à Londres où il est en contact avec le moine franciscain et ambassadeur de Venise, Francesco Giorgio (ou Zorzi). Pendant qu’en surface la hiérarchie Vaticane fait de Luther son ennemi officiel, les réseaux clandestins font tout pour promulguer en sous-main « l’hérésie » protestante anti-érasmienne, repoussoir confortable pour garder leur pouvoir « spirituel » devenu système terrestre. Convié à s’exprimer comme docteur de la loi sur le divorce de Henry VIII, Zorzi encourage vivement Henry VIII à rompre avec Rome, selon une stratégie forgée par les « jeunes » loups de Venise voulant faire de l’Angleterre la « Venise du Nord » idéalement située entre le nouveau et l’ancien monde.

Ce réseau, sous le masque de l’érudition, s’installe au plus près des élites humanistes. Agrippa lui-même tente de développer une correspondance avec Erasme et séjourne en Angleterre chez l’ami de celui-ci, John Colet (1469-1519), également en contact avec le Ficin et Pic de la Mirandole. Zorzi, maintient aussi des relations avec Guillaume Postel (1510-1581), le super espion ésotérique de François Ier.

Dans De Harmonia Mundi (1525), œuvre majeure de Zorzi dédiéee au pape Clement VII, on retrouve les thèmes hermétiques classiques des sept sphères, de l’angéologie et de l’influence des planètes, complétés par une approche kabbalistique. En réalité, il s’agit bien d’un retour au paganisme, présenté comme parfaitement compatible avec la doctrine chrétienne !

Cette offensive ésotérique ramène le sujet de la mélancolie au centre de l’actualité. Un premier écrit d’Agrippa : De l’incertitude et de la vanité de toutes sciences en arts aborde déjà le sujet. Initialement écrit pour faire semblant de nier les convictions kabbalistiques de son auteur et lui permettre d’échapper à l’Inquisition, De vanitate apparaît comme le livre d’homme déprimé ou suprêmement habile, écrivant que rien n’a de sens, tout est vain, même la métaphysique.

Comme Panofsky le note, Agrippa fait, dans le chapitre 60 (LX) de son livre De occulta philosophia (1510), l’éloge de la mélancolie d’Aristote, via Le Ficin. L’œuvre, qui lui apporta sa renommée d’occultiste, se construit avec des échantillons d’Hermès Trismégiste, de Picatrix, de Marsile Ficin, de Pic de la Mirandole et de Johannes Reuchlin. Il nous parle des vertus occultes de « l’âme du monde », c’est-à-dire des théories néoplatoniciennes de Plotin, caricaturalement reprises par le Ficin. L’occultiste anglais John Dee (1527-1609) et d’autres feront de De Occulta Philosophia d’Agrippa leur livre de chevet pour lancer la Rose-Croix (d’or) et la franc-maçonnerie naissante.

Mais alors ? Enfin tout s’explique !

Une lecture symboliste, et pourquoi pas alchimiste, de la gravure semble donc pouvoir « tout » expliquer !

Le carré magique (Fig. 14) dans la gravure de Dürer intègre la date de la gravure et de la mort de la mère de l’artiste, décédée quelques mois auparavant (le 17-5-1514 : 5 (mai) +15+14=34 ; 34 étant le chiffre qui englobe un carré magique de 4×4 cases, dont les sommes des chiffres additionnés en diagonale, à l’horizontale et à la verticale donnent chaque fois 34). Dürer n’est-il pas lui-même géomètre et grand architecte ?

A gauche, ne voit-on pas le creuset et les pincettes de l’alchimiste qui purifie la matière impure, métaphore du processus spirituel en cours chez le génie mélancolique ? Le visage noir de la Mélancolie ne fait-il pas penser à la nigredo, l’œuvre noir qui constitue la première phase de l’œuvre alchimique ? Les objets présents ne sont-ils pas les objets qui attendent le réveil du génie souffrant ?

L’échelle (à sept marches) n’est-elle pas une allégorie d’un parcours ascensionnel de l’âme à travers les sphères planétaires qu’on retrouve déjà dans la Genèse (XXVIII, 11) ? « Voici qu’était dressée sur terre une échelle dont le sommet touchait le ciel ; des anges de Dieu y montaient et y descendaient ». (Fig. 15)

Les deux ailes, ne sont elles pas les deux vertus que le Ficin a trouvé chez Platon ?

Et si l’on tient compte du fait que le nom du père de Dürer était Ajto (du hongrois signifiant « porte »), germanisé en Thür (pour devenir Dürer) et si on arrange les lettres du mot « Melencolia », on peut trouver « limen caelo » (*11), ou « porte vers le ciel », image que l’on retrouve sur le blason familiale de Dürer (Fig. 16)

Mais Dürer n’est-il pas lui-même aussi mélancolique que le Ficin ? Ses premiers autoportraits le montrent fortement affecté et triste, le visage soutenu par sa main. (Fig. 17).

Un autre dessin qu’il envoya à un médecin le montre pointant du doigt un endroit précis de son corps : la bile… (*12) (Fig. 18).

Melanchthon, dirigeant son école à Nuremberg mentionne lui aussi « la très excellente mélancolie de Dürer. »

Toutes les conditions « objectives » font apparaître un « faisceau de suspicions » donnant crédit à l’existence d’un artiste mélancolique.

Et puisque Dürer évoque lui-même « les idées platoniciennes » dès 1510, et puisque Trithème est de surcroît un ami de Pirckheimer, on pourrait être tenté de croire, comme malheureusement Erwin Panofsky et bien d’autres, que Melencolia I « est, dans un sens, un autoportrait spirituel de Dürer » ; celui d’un artiste adepte, disciple ou du moins fortement contaminé par l’air du temps pollué par Agrippa de Nettesheim et son réseau vénitien.

Car, comme nous l’avons vu, tout, ou presque tout, semble cohérent, à part le fait qu’on explique mal comment quelqu’un d’aussi croyant, d’aussi chrétien et surtout fortement attaché à l’émancipation du peuple, puisse nous offrir une œuvre aussi « occulte ».

C’est oublier un détail essentiel de la gravure : son auteur.

Platon contre les néo-platoniciens

Mais récemment, un historien d’art londonien, Patrick Doorly a jeté un pavé dans la mare Panofskyienne. En lisant l’un des premiers dialogues de Platon, Hippias Majeur, il constate de fortes similitudes entre les images employées par le philosophe et la gravure de Dürer. (*13)

Hippias d’Elis (vers 450 avant JC), l’un des pires sophistes de la place, est mis au pied du mur par Socrate qui l’interroge sur la véritable nature du beau. En réponse, le sophiste aligne alors une série de choses auxquelles la beauté peut être attribuée (une vierge [287e], l’or [289e], être riche [291d], être puissant [296a], un discours persuasif [304a], etc.), mais sans jamais vouloir accepter le niveau conceptuel posé par la question du beau en lui-même.

A un certain point Socrate, sans s’énerver, lui lance : « Car c’est ce qu’est le beau lui-même, cher homme, que je te demande, et je suis incapable de me faire mieux entendre que si tu étais assis devant moi comme une pierre, et même comme une meule sans oreille ni cervelle ! » [292d]

Voilà ce qui soudain donne un sens à cette meule sur laquelle est assis l’angelot ! Cette nouvelle piste d’une mélancolie personnifié par Hippias est peut-être encore plus convaincante parce qu’au lieu d’invalider les hypothèses antérieures sur certains détails, elles leur donne un nouveau sens, à un meilleur niveau.

Ici, la mélancolie semble bien être une pique ironique contre les disciples d’Agrippa (connu pour son chien noir nommé Monsieur) et leur croyance en l’angéologie.

Le fait que Dürer dénonce un état maladif se trouve confirmé par le fait que la couronne de feuilles, simulacre d’une couronne de lauriers qu’on offrait aux grands poètes, est ici formée par les feuilles de deux plantes aquatiques : la renoncule d’eau et le cresson de fontaine !

Ironie sur laquelle les tenants du symbolisme feront l’impasse, car souvent eux-mêmes fortement en panne d’humeur humoristique. En effet, la mélancolie étant souvent associée avec l’élément du feu, et de nature sèche, les médecins antiques conseillaient l’application de plantes aquatiques pour rééquilibrer le malade…

L’Hippias majeur et l’Hippias mineur font également état de la richesse matérielle du sophiste, ce qui expliquerai la belle robe vénitienne brodée (Hippias fabriquait ses vêtements), sa bourse bien remplie, symbole de richesse, et le trousseau de clefs, symbole de pouvoirs multiples. (*14)

Le polyèdre troublant et l’héritage de Piero della Francesca

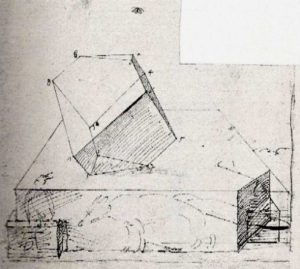

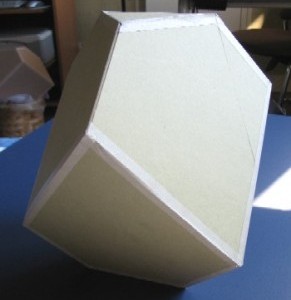

L’on peut dire que c’est l’hypothèse de l’Hippias Majeur qui donne son véritable sens (ironico-métaphorique et non mystico-symbolique) à cet étrange polyèdre situé au milieu de la composition ; qu’il en soit même le centre ressort clairement de l’étude préparatoire (Fig. 19).

Figure 19. Albrecht Dürer, étude préparatoire du polyèdre pour Melencolia I, carnet de croquis de Dresden, 1514

A première vue, on dirait un polyèdre formé de surfaces pentagonales irrégulières, sujet de conjectures sans fin. En 1509, le livre de Luca Pacioli, De Divina Proportione, établit que le pentagone n’est constructible qu’avec cette proportion (la proportion d’or). Le dodécaèdre, volume formé de 12 pentagones, se révèle comme le volume « limite » dans lequel les quatre autres solides réguliers peuvent s’inscrire, comme l’indique Platon dans le Timée.

Mais bizarrement, le volume que nous présente Dürer ne figure guère dans l’œuvre de Pacioli, et l’on se demande donc de quel type de polygone et donc de quel polyèdre il peut s’agir ?

Dürer semble avoir délibérément choisi de troubler nos sens, et donc nos certitudes, une tromperie dont Platon accuse les peintres dans La République [602d]. Egalement, dans l’Hippias mineur [sur la tromperie], il dit que « s’il existe un homme qui trompe à propos des figures géométriques, c’est bien celui-ci, le bon géomètre, car c’est lui qui en est capable » [367e].

Fig. 20: Un cube partiellement tronqué.

Figure 21. Un rhomboèdre partiellement tronqué

Si on tente de construire physiquement ce polyèdre, on a l’impression qu’il s’agit d’un volume « impossible », qui n’existe qu’à la limite d’un cube partiellement tronqué (Fig. 20) et d’un rhomboèdre partiellement tronqué (Fig. 21).

Déjà, en forçant le trait du raccourcissement perspectif d’un cube (*15) qui, vu d’un certain angle s’avère assez difficile à différentier d’un rhomboèdre (surtout quand il s’agit d’un rhomboèdre avec des losanges dont les angles aigus avoisinent les 80 degrés, c’est-à-dire proche des 90 degrés du carré), Dürer crée un entre-deux géométrique identifié en géométrie avec le point de vue instable ou non-générique. (*16)

Dürer sélectionne ici un angle de vision et une perspective très particulière (*17) où l’image des deux volumes « se frotte », tant ils se ressemblent ; à moins que ce frottement ne provienne directement du choix des caractéristiques des losanges du rhomboèdre.

Ce « frottement » trouve aussi son origine dans la similitude entre le carré partiellement tronqué, le losange partiellement tronqué et le pentagone. (Fig. 22)

Figure 22: Ce « frottement » trouve aussi son origine dans la similitude entre le carré partiellement tronqué, le losange partiellement tronqué et le pentagone.

Les deux premiers peuvent se présenter comme des coupes d’un cône de vision montrant l’image projetée d’un pentagone, incliné vers l’avant ou vers l’arrière (Fig. 23).

L’emploi de l’ambiguïté géométrique en perspective est l’apport original de Piero della Francesca dans l’art italien. (*18)

Pour Piero, ce type de paradoxe, qui pousse nos sens aux limites du visible, est incontournable pour une véritable œuvre d’art, car seul capable de communiquer des idées de l’ordre de l’incommensurable, c’est-à-dire du divin. Une géométrie simple, qui ne fait pas intervenir le domaine complexe, condamne l’homme à un enfermement dans un système mesurable, mais fini et donc « mort ».

Selon certains, anticipant l’élaboration du calcul infinitésimal, Dürer reprend ici l’idée platonicienne qu’en tronquant les angles et en les remplaçant par des facettes, on peut générer des corps de plus en plus complexes capable de fournir une bonne approximation pour les corps délimitées par des courbes quelconques, y compris le corps humain. Pacioli envisagea même de continuer ce procédé de troncature à l’infini.

Car, tout comme en science, le vrai message découle ici de la métaphysique. Dürer semble nous dire : beauté et vérité ne sont qu’une et même substance dans l’Un. Agrippa et ses adeptes, le sophiste Hippias, vivent dans un déni de réalité et se rendent donc inapte à comprendre ce que sont réellement la beauté et la réalité tout simplement.

Eventuellement, ceci explique pourquoi l’échelle se trouve derrière le monument et non devant : en se fixant sur la numérologie et les symboles, on se trompe d’angle d’approche !

La conclusion du dialogue de Platon pose une terrible exigence : « Et comment sauras-tu alors (…) quel discours est produit de belle manière ou non, et de même à propos de tout autre action, puisque tu ne connais pas le beau ? Et tant que tu seras dans cet état, crois-tu qu’il soit meilleur pour toi de vivre plutôt que de mourir ? » [304d].

Figure 23: Les coupes d’un cône de vision montrant l’image projetée d’un pentagone, incliné vers l’avant ou vers l’arrière

Ainsi Melencolia, prisonnière des sens, bien que perdu dans sa rêverie, ne peut mesurer que le visible, et à moins d’accepter de se transformer, n’accèdera jamais à l’invisible.

L’idée géniale de Dürer, consistant à faire coïncider dans une seule image une dame Fortuna ailée descendu de sa sphère, un ange personnifiant la Géométrie et l’Hippias de Platon afin d’attaquer la folie d’Agrippa et de son réseau, ne manque guère d’hubris (mot grec pour démesure) !

La comète fait apparaître, dans son éclat, un arc en ciel annonciateur d’une nouvelle alliance entre Dieu et l’homme, comme celle conclue après le déluge. Sa lumière est suffisante pour chasser hors du tableau la vespertilio, la chauve-souris à queue de lézard, symbole d’un être maléfique opérant la nuit, qui porte ici l’insigne « Melencolia I ».

Il existe beaucoup de spéculations sur le pourquoi du « I ». On oublie le petit signet qui sépare les deux, un espèce de « & ». Ainsi, le titre serait « la mélancolie et l’un », le Un étant le sujet philosophique principal des néo-platoniciens, mais également l’Un chrétien, Dieu, mesure de toute chose, « fons et origo numerorum ». Après tout, l’origine du mot religion vient du latin religare : relier l’homme (le multiple) au divin (Un).

Si la musique peut également soigner la mélancolie, c’est au spectateur de saisir la corde qui fera sonner la cloche…car comme le dit Socrate pour conclure l’Hippias Majeur : « il me semble que je comprends ce que peut signifier le proverbe qui dit que ‘les belles choses sont difficiles’ » [304e].

Notes:

- Erasme qui admire son ami Dürer lui demande à plusieurs reprises de lui faire son portrait. Il dit, avec raison, que « Dürer, (…) sait rendre en monochromie, c’est-à-dire en traits noirs [en gravure] – que ne sait il rendre ! Les ombres, la lumière, l’éclat, les reliefs, les creux, et… (la perspective). Mieux encore, il peint ce qu’il est impossible de peindre : le feu, le tonnerre, les éclairs, la foudre et même, comme on dit, les nuages sur le mur, tous les sentiments, enfin toute l’âme humaine reflétée dans la disposition du corps, et presque la parole elle-même. » La dernière gravure de la main de Dürer est un portrait d’Erasme, l’un des premiers aussi a recevoir une copie de son manuel de géométrie.

- Né en 1403 à Trébizonde (Turquie actuelle), au bord de la Mer Noire, Jean Bessarion est l’un des personnages clef pour le succès du grand Concile Œcuménique de Florence, en 1438, qu’il organise avec Traversari, Nicolas de Cuse et le pape Eugène IV.

- Paolo Toscanelli del Pozzo (1397-1482), un des plus grands esprits scientifiques de son temps, est simultanément l’ami de l’architecte du dôme de Florence, Brunelleschi, du peintre ingénieur Léonard de Vinci, et du cardinal philosophe Nicolas de Cuse.

- Karel Vereycken, « Percer les mystères du dôme de Florence », Fusion N°96, mai/juin 2003, p. 18-19.

- Pirckheimer, helléniste cultivé après sa formation à Padoue et Pavie, auteur de quelques 35 traductions d’écrivains classiques dont Cicéron, Lucien, Plutarque, Xénophon, ou Ptolémée. Militaire de haut rang et l’un des responsables politiques de la ville, il anime un cercle lettré de renommée internationale. Erasme y est invité à plusieurs reprises mais n’a jamais l’occasion de s’y rendre.

- Werner publie en 1522 un traité sur les sections coniques, suivi d’une discussion du problème de la duplication du cube et des onze solutions qu’ont pu y apporter les anciens, si l’on en croit Eutocius. Werner avait traduit le traité des Coniques d’Apollonius, dont une copie existait dans la bibliothèque de Regiomontanus. L’influence de Werner est avérée dans le manuel de géométrie de Dürer, le problème de la duplication du cube y étant évoqué dans le livre IV, 44-51a.

- Notamment par Saint Thomas d’Aquin (1224-1275), dans la Somme Théologique (Question 35).

- Claude Makowsky, dans son essai Albrecht Dürer, Le songe du Docteur et La Sorcière (Editions Jacqueline Chambon/Slatkine 2002).

- L’école d’Athènes de Raphaël nous montre un Héraclite avec ce qu’on croit être le visage de Michel-Ange avec une pose mélancolique. Michel-Ange utilise la pose après 1519 pour son Pensieroso du tombeau de Laurent de Medici ; Rodin l’utilisera pour son Penseur, un agrandissement de la figure assise devant sa Porte de l’enfer ; Goya nous met en garde contre la mélancolie dans Le sommeil de la raison engendre des monstres.

- Le néoplatonisme en esthétique fera prévaloir que toute beauté provenant de la grâce des formes visibles est forcément le reflet des vérités invisibles, respectables chacune dans son domaine. Cette doctrine sera popularisé par Pietro Bembo dans ses poèmes, les Asolani, et par Balthasar Castiglione dans son livre, Le Courtisan. Elle fera glisser l’art de la Belle Manière vers le Maniérisme. Le Romantisme, art officiel de la restauration monarchique imposé par le Congrès de Vienne en 1815, enfantera le Symbolisme qui accouchera dans les métastases de sa chute finale de deux autres rejetons : l’art moderne et l’art contemporain, imposé dans l’après-guerre à coup de dollars par l’opération du Congrès pour la Liberté de la Culture (CLC) dirigé par Alan Dulles à l’époque à la tête de la CIA. Une seule constante : on fera du culte du cœur souffrant et mélancolique l’essence même de l’artiste maudit. Gérard de Nerval parlait du « soleil noir de la mélancolie », tandis que Victor Hugo ironisait : « La mélancolie, c’est le bonheur d’être triste. »

- Hypothèse avancée par David R. Finkelstein, dans The relativity of Albrecht Dürer, April 24, 2005.

- On pense aujourd’hui que Dürer contracta une infection paludéenne dans des marécages lors d’un voyage aux Pays-Bas dans l’espoir d’y retrouver une baleine rejetée sur le littoral hollandais.

- Patrick Doorly, « Durers Melencolia I : Plato’s abandoned search for the beautiful », The Art Bulletin, June 2004. L’auteur se trompe lourdement. Il croit que Dürer, comme Socrate, qu’il voit dans Hippias (sic), renonce à l’idée qu’on puisse connaître le beau. En bref, il plaque la thèse moderniste d’Emmanuel Kant dans sa Critique de la Faculté de juger : le beau est indéfinissable, car entièrement relatif. Doorly prend des citations de Dürer hors contexte pour faire « coller » sa thèse.

- Dürer écrit sur un dessin préparatoire : bourse = richesse et clefs = pouvoir. Notons aussi le fait que le Ficin a écrit une lettre Quinque Platonicae Sapientiae Claves, [Les cinq clefs de la théologie platonicienne].

- Un des points de fuite du polyèdre semble coïncider avec le lieu d’arrivée de l’échelle : au ciel.

- Voir K. Vereycken, dans « Quand l’ambiguïté devient science géométrique en peinture », Fusion n°105, juin/juillet 2005, p. 42-43.

- Le traité de Jean Pèlerin Viator, De Artificiali Perspectiva, imprimé en 1505, avait introduit une perspective à deux points de fuite. Elle fait en sorte qu’un carré (quadrangle), vu en perspective se transforme nécessairement en losange. Gérard Desargues bâtira toute sa science géométrique sur cette démarche. La Présentation au temple de Dürer, reprend une salle à colonnades présente dans Viator, (fol.21, v.).

- Les sections du cône visuel donneront la science des anamorphoses, que Léonard de Vinci explore dans le Codex Atlanticus et qui sera poussée à son paroxysme par Holbein dans son tableau Les ambassadeurs (1533).

La Géométrie de Dürer :

« Mettre au grand jour et enseigner », le savoir utile aux ouvriers, « tenu secret par les érudits ».

A la fin de l’hiver 1506, Dürer revient de Venise décidé à élaborer un grand traité destiné à la formation de l’artiste et de l’artisan, véritable « nourriture pour peintres apprentis » [speisen der malerknaben]. Son but : rendre accessible au plus grand nombre les plus belles connaissances de l’humanité et dénoncer les oligarchies qui veulent confisquer le savoir.

De grands progrès restent à accomplir dans ce domaine. Si la plupart des artistes gardent jalousement leurs « secrets d’ateliers », beaucoup d’écrits restent aussi à l’état de simples manuscrits (Toscanelli, Léonard de Vinci) tandis que d’autres sont publié dépourvu de la moindre illustration, tel le fameux traité sur la perspective d’Alberti De Pictura (1432), ou le De Sculptura de Pomponio Gaurico, imprimé à Florence en 1504.

Le premier traité imprimé sur la perspective fut celui de l’ancien secrétaire de Louis XI, le chanoine Jean Pèlerin, dit Viator [1] (av.1445-1524), De Artificiali Perspectiva, publié à Toul en 1505, et en ce qui concerne la géométrie, il est établi que Dürer a pu puiser dans la Geometria Deutsch de Matthaüs Roritzer, imprimé en allemand en 1498.

Suite à une situation politique quasi-insurrectionnelle et la répression contre la réforme [2] , Dürer est obligé, comme Erasme, de quitter les Pays-Bas au début de l’été 1521. Il retourne alors à Nuremberg où il rassemble toutes ses recherches pour élaborer le grand traité qu’il souhaite terminer. Finalement, son travail ne débouchera que sur trois ouvrages, rédigés en allemand, dont un manuel de géométrie : l’Unterweysung der Messung [Instructions pour la mesure à la règle et au compas des lignes, plans et corps solides réunies par Albrecht Dürer et imprimées avec les figures correspondantes à l’usage de tous les amateurs d’art, en l’an 1525], un traité sur les fortifications (1527) et les fameux Quatre livres sur la proportion de l’homme, publié en 1528 par ses proches peu après sa mort.

L’origine de sa passion réside peut-être dans un évènement de sa vie. Le 20 avril 1500, un peintre vénitien Jacopo de Barbari (v.1445-1515), alors résident à Nuremberg, montra à Dürer « un homme et une femme qu’il avait fait d’après des proportions », tout en lui refusant la moindre indication sur la manière de procéder. Critiqué en Italie pour dessiner des figures maladroites [3], Dürer se penchera, comme Léonard de Vinci, sur Les dix livres d’Architecture, de l’architecte romain Vitruve (premier siècle av. JC) qui livre des indications à ce sujet.

Lors de son voyage en Italie, Dürer a très certainement rencontré le moine franciscain Luca Pacioli [4] (v.1445-1517) (Fig. A), professeur itinérant en mathématiques. C’est à l’époque le plus grand expert du mathématicien grec Euclide (325-265 av. J.C.), donton confondait alors le nom avec Euclide de Mégare (v. 450 – v.380 av.J.C.), un élèvede Platon. Pacioli, élève de Piero della Francesca (1420-1492)et collaborateur de Léonard de Vinci(1452-1519)àlacourdeMilan,estau fait desgrandesconquêtesscientifiques,mathématiqueset intellectuelles du Quattrocento italien. Dans son livre De Divina Proportione (1509), il démontre que la proportion d’or est un cas spécifique de la moyenne géométrique, divisant une droite en extrême et moyenne raison, comme l’indique Euclide dans les Eléments. En contact avec l’architecte Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) à Rome, Pacioli intègre les contributions de Piero dans son traité, dont la première copie est illustrée par Léonard de Vinci. A Milan, Pacioli assiste Léonard de Vinci dans la lecture des Elémentsd’Euclide et Dürer, comme d’autres à l’époque, envisage de le traduire en allemand.

Synthèse encyclopédique de recettes d’atelier, de traités italiens, français et allemands, enrichi par ses propres contributions originales, l’Unterweysung fait œuvre de pédagogie. Pour être accessible à tous, l’exposé est évolutif : partant de lignes droites et courbes, on développe les surfaces,les volumes et polyèdres, pour passer ensuite aux ombres et à la perspective.

-

Figure B: En bas au centre : Dürer , double projection d’une sélection elliptique d’un cône [Livre I, fig.34] ; En haut à gauche : Dürer, schéma d’une tête dans les Quatre Livres de la proportion de l’homme ; En haut, à droite : Piero della Francesca, schéma d’une tête dans De prospectiva pingendi.

Citons l’excellent travail de Jeanne Peiffer [5] quand elle dit : « Ceux qui ont étudié les Eléments d’Euclide n’y trouveront rien de neuf, croit-il bon d’avertir au début. Pourtant, c’est tout autre chose qu’une compilation de propositions euclidiennes qu’on trouve dans le corps de son ouvrage. Sa géométrie n’est pas démonstrative, mais constructive. Le but de Dürer est de construire des formes utiles aux artisans, par des procédés faciles à exercer à l’aide des instruments couramment utilisés, la règle et le compas notamment, et aisément répétables. Il n’y a aucun calcul d’aire ou de volume, si caractéristique des géométries pratiquées à l’époque. Dürer y obtient ses résultats les plus originaux, lorsqu’il applique des méthodes d’atelier à des objets mathématiques abstraits.

-

Figure C. L’Unterweysung der Messung, [Livre III, fig.10]

Ainsi, en appliquant la méthode de la double projection (Fig. B), familière aux maçons, tailleurs de pierre et architectes, aux sections coniques, il en obtient une construction très originale, dont Gaspard Monge codifiera la méthode, à la fin du XVIIIeme siècle, dans sa géométrie descriptive. Concevant, dans la partie consacrée à l’architecture, une colonne torse, Dürer en vient de considérer explicitement l’enveloppe des sphères de rayon constant en ayant leur centre sur une courbe. » [Livre III, fig.10] (Fig. C)

(…) « Ou encore, Dürer indique la construction originale d’une courbe inconnue par ailleurs [une conchoïde, ou courbe de coquillage] dite utile aux architectes et qui lui sert, d’après des dessins conservés à Dresde, à obtenir le galbe voulu des tours Renaissance. La loi de formation de cette courbe est explicitée : Un segment de longueur constante (c) se déplace avec l’une de ses extrémités le long d’un axe vertical, de telle sorte qu’un élément de longueur de la courbe qu’engendre sa seconde extrémité soit proportionnel à la distance parcourue sur l’axe vertical. » (Fig. D)

-

Figure D: La conchoïde (courbe de coquillage) de Dürer, avec Fig.151 du Livre des croquis de Dresden, (dans Annexe 4 de J. Peiffer).

L’exemple de la duplication du cube, et l’usage qui en est fait, sont particulièrement révélateurs de l’orientation pratique que Dürer veut donner à sa géométrie, mais aussi du style de travail du peintre. Il est conscient de l’ancienneté du problème, qui plonge ses racines dans la légende – puisque c’est à la demande d’Apollon et pour sauver la cité de la peste que les Athéniens sont dits avoir voulu doubler le volume de l’autel cubique. Il répète ce récit, en rendant hommage à Platon pour avoir su indiquer la bonne solution, puis écrit :

-

Figure E. L’Unterweysung der Messung, [Livre IV, fig.44]

« Comme ce savoir est très utile aux ouvriers, et comme par ailleurs il a été tenu caché et au grand secret par les érudits, je me propose de le mettre au grand jour et de l’enseigner. » En quoi ce savoir est-il utile ? Dürer l’indique : « On pourra faire fondre des bombardes et des cloches, les faire doubler de volume et les agrandir comme on veut, tout en conservant les justes proportions et leur poids. De même on pourra agrandir tonneaux, coffres, jauges, roues, chambres, tableaux, et tout ce que l’on veut. » Il donne trois solutions du problème, connues dans la littérature classique sous les noms de Sporus, Platon et Héron, et pour cette dernière, fait même une démonstration. » (Fig. E)

Notes

1. Jean Pèlerin aurait été en contact avec Alberti, Piero della Francesca et pourrait être le « maestro Giovanni Francese » évoqué par Léonard dans le Codex Atlanticus. Il était l’un des animateurs du Collège Vosgien, pépinière d’humanistes et de scientifiques à Saint Dié.

2. Suite aux placards de Charles V du 8 mai 1521, toute personne qui imprimait, illustrait ou même simplement lisait la bible, était considérée comme un « hérétique ».

3. Dürer écrira à Pirckheimer, le 7 février 1506 : « J’ai, parmi les Italiens, bon nombre de bons amis qui me mettent en garde de boire ou de manger avec les peintres d’ici. Beaucoup de ces peintres me sont hostiles ; ils copient mes œuvres dans les églises ou ailleurs, après quoi ils les dénigrent, arguant que, n’étant pas faites d’après l’antique, elles ne sauraient être bonnes. »

4. Bien que Dürer maîtrise déjà la perspective, il écrit dans sa lettre de Venise du 13 octobre 1506 à Pirckheimer : « Après quoi j’aimerais me rendre à Bologne pour apprendre l’art secret de la perspective que quelqu’un s’est proposé de m’enseigner. J’y resterai huit ou dix jours avant de repasser par Venise. »

5. Extrait de « La Géométrie de Dürer, un exercice pour la main et un entraînement pour l’œil », dans Alliage, numéro 23, 1995. Voir aussi Jeanne Peiffer, « Dürer géomètre », dans Albrecht Dürer, Géomètre, Editions du Seuil, Novembre 1995, Paris, et sa conférence en 2001à Lille « La géométrie d’Albrecht Dürer et ses lecteurs » devant la journée nationale de l’association des professeurs de mathématiques de l’enseignements public. Sa contribution, qui consistait à simplement reconnaître l’apport de Dürer à l’histoire des sciences, fut violemment critiqué par André Cauty, un professeur pinailleur de Bordeaux, scandalisé que l’on puisse voir en Dürer un précurseur de Gaspard Monge.

Figure F: Marsile Ficin (à gauche) avec ses disciples Cristoforo Landino, Angelo Poliziano et Demetrios Chalkondyles. Détail d’une fresque (1486-1490) de la chapelle Santa Maria Novella à Florence.

Le Ficin : un aristotélicien déguisé en platonicien !

Marsilio Ficino (1433-99) est médecin et fils du médecin de Côme de Médicis (1389-1464), un banquier, industriel, mécène et fondateur de la célèbre dynastie florentine. Lors du Concile de Florence en 1438, ce dernier, fut très impressionné par le discours de Georges Gémiste Pléthon (1355-1450) venu dans la suite de Jean Paléologue de Byzance.

Pléthon, violemment opposéàAristote est un acteur du Concile. Entre les sessions, il enthousiasme les florentinsen leur faisant découvrir Platon, mais aussi les néoplatoniciens d’Alexandrie [1]. Il n’est donc pas étonnant qu’il soit suspecté de dériver vers le paganisme parce qu’il évoque, face à un monde essentiellement centré sur le christianisme, l’existence d’autres croyances (judaïsme, zoroastrisme, islam, oracles chaldéennes, etc.), lesquelles ne sont pas forcément toutes bonnes à prendre.

En tout cas, Pléthon enthousiasme Côme de Médicis et le décide à faire traduire l’œuvre complète de Platon, alors peu ou partiellement connu en occident. Néanmoins, Côme semble avoir quelques doutes sur les aptitudes du traducteur qu’il sélectionne pour ce travail : le jeune Marsile Ficin. Car, quand ce dernier lui offre en 1456 sa première traduction Les institutions platoniciennes,il le prie de ne pas la publier et lui conseille d’apprendre d’abord le grec ! Mais, sentant venir sa fin, Côme finit, malgré tout, par lui confier la tâche. Pour cela, il lui accorde une rente annuelle et une villa à Careggi, à deux pas de Florence, où le Ficin organise une « académie platonicienne » avec quelques dizaines de disciples parmi lesquels Ange Politien (1454-94), Pic de la Mirandole (1463-1494)et Cristofore Landino(1424-1498).(Fig. F)

La nature anti-humaniste de l’entreprise apparaît clairement quand on sait qu’aucune réunion n’a lieu sans la présence de l’ambassadeur vénitien à Florence, le très influent oligarque Bernardo Bembo (1433-1519), futur historien officiel de la Sérénissime.

En 1462, avant de traduire Platon et à la demande de Côme, le Ficin porte ses efforts sur les Hymnes d’Orphée, les Dictons de Zoroastre et le Corpus Hermeticum d’Hermès Trismégiste [2]. l’Egyptien (entre 100 et 300 de notre ère), un manuscrit apporté par un moine venu de Macédoine.

Ce n’est qu’en 1469 que le Ficin complète ses traductions de Platon suite à une grave dépression, décrite par son biographe comme une « profonde mélancolie ». En 1470, reprenant le titre d’une œuvre de Proclus, il commence la rédaction de la Théologie Platonicienne ou de l’immortalité de l’âme.

Trois ans plus tard, bien que pénétré d’un néoplatonisme ésotérique, il se fait prêtre et écrit La religion chrétienne, tout en continuant une série de traductions de néoplatoniciens anti-chrétiens d’Alexandrie : Plotin (54 livres) (Fig. G) et Porphyre et avant de mourir, Jamblique.

Ainsi, l’académie néoplatonicienne florentine de Ficin est une opération delphique : défendre Platon pour mieux le détruire ; en faire l’éloge en des termes qui le discréditent. Et surtout, détruire son influence en opposant la religion à la science, alors même que Nicolas de Cuse et ses disciples humanistes réussissent le contraire. N’est-il pas remarquable que le nom de Nicolas de Cuse n’apparaisse pas une seule fois dans l’œuvre du Ficin, ni dans celle de Pic de la Mirandole, pourtant si confit d’omniscience. Le Ficin entretient des échanges épistolaires avec les élites de son époque. A Venise, c’est l’Académie Aldine, le cercle de l’imprimeur Alde Manuce qui en est l’extension. Selon son biographe Giovanni Corsi, le Ficin est également l’auteur principal de la thématique symboliste du peintre florentin Sandro Botticelli, mariage sensuel entre paganisme et christianisme. Son influence néfaste sur Raphaël, Michel-Ange et Titien est également établie.

Notes

1. Les néoplatoniciens d’Alexandrie furent également appelés « école d’Athènes », car ce courant opérait simultanément à Alexandrie en Egypte et à Athènes en Grèce. Plotin (205-270), né et formé en Egypte, en est le fondateur, essentiellement actif à Rome. On le tient responsable d’avoir réduit le Platonisme « à une religiosité qui chosifie les réalités spirituelles ». Défendant, à partir du Parménide de Platon, un Un qui n’est pas multiple, mais qui engendre la multiplicité, il est néanmoins le grand architecte d’une concorde entre Platon, Aristote et les stoïciens. Dans une démarche essentiellement intériorisante, Plotin se détache de tout engagement terrestre pour améliorer le sort de l’espèce humaine et se concentre sur une volonté individuelle de « pénétrer le système, voire le Principe ». Plotin pense que c’est en nous qu’il faut apprendre à découvrir le monde spirituel, car « c’est aux dieux de venir à moi, non à moi de monter vers eux ». A cette procession (de l’un à la matière) répond une ascension (conversion) vers le Un, qui opère par un travail de l’âme agissant sur l’âme. Cet « immanentisme » conduit Plotin à s’opposer aux rites religieux axés sur « l’extériorité », y compris à ceux des chrétiens.

Son disciple Porphyre de Tyr (234-v.310) va beaucoup plus loin. Imposant une lecture de plus en plus symboliste de Platon, il dénonce le christianisme, suivi en cela par Jamblique (250-330). Ce néoplatonisme est si délicieusement païen que l’empereur Julien l’Apostat tente de l’utiliser pour remplacer le christianisme.

A Athènes, l’école néo-platonicienne trouve un nouvel élan au cinquième siècle, grâce à Proclus (412-485), où l’académie néo-platonicienne est fermée par l’empereur Justinien en 529. Très étudié par Nicolas de Cuse, traducteur de Proclus, on peut envisager qu’une telle lecture « mélancolique » des néoplatoniciens ait pu servir de source d’inspiration pour Nietzsche (Zoroastre=Zarathoustra), Hannah Arendt, Heidegger et Léo Strauss.

2. Ficin, se référant à saint Augustin, fait d’Hermès Trismégiste le premier des théologiens : son enseignement aurait été transmis successivement à Orphée, à Aglaophème, à Pythagore, à Philolaos et enfin à Platon. Par la suite, Ficin place Zoroastre en tête de ces prisci theologi, [premiers théologiens] pour finalement lui attribuer, avec Mercure, un rôle identique dans la genèse de la sagesse antique : Zoroastre l’enseigne chez les Perses en même temps que Mercure l’enseigne chez les Égyptiens. Ficin souligne le caractère prophétique des écrits d’Hermès : il aurait prédit « la ruine de la religion antique, la naissance d’une nouvelle foi, l’avènement du Christ, le Jugement dernier, la Résurrection, la gloire des élus et le supplice des méchants ». La traduction d’Hermès Trismégiste par le Ficin, imprimée dès 1471, est le point de départ d’une véritable renaissance de l’hermétisme philosophique. Ainsi, c’est par une citation de l’Asclepius [un autre écrit de Trismégiste] que Pic de la Mirandole ouvre son Oratio de hominis dignitate [Oraison sur la dignité humaine] et qu’en 1488, une étonnante représentation du Trismégiste, attribuée à Giovanni di Stefano, est gravée dans le pavement même de la cathédrale de Sienne.