How James Ensor ripped off the mask off the oligarchy

By Karel Vereycken,

December 2022.

James Ensor was born on April 13, 1860 into a petty-bourgeois family in Ostend, Belgium. His father, James Frederic Ensor, a failed English engineer and anti-conformist, sank into alcoholism and heroin addiction.

His mother, Maria Catherina Haegheman, a Flemish-Belgian who did little to encourage his artistic vocation, ran a store selling souvenirs, shells, chinoiserie, glassware, stuffed animals and carnival masks – artifacts that were to populate the painter’s imagination.

A bubbly spirit, Ensor was passionate about politics, literature and poetry. Commenting on his birth at a banquet held in his honor, he once said:

« I was born in Ostend on a Friday, the day of Venus [goddess of peace]. Well, dear friends, as soon as I was born, Venus came to me smiling, and we looked into each other’s eyes for a long time. Ah! the beautiful green persian eyes, the long sandy hair. Venus was blonde and beautiful, all smeared with foam, smelling of the salty sea. I soon painted her, for she bit my brushes, ate my colors, coveted my painted shells, ran over my mother-of-pearl, forgot herself in my conch shells, salivated over my brushes ».

After an initial introduction to artistic techniques at the Ostend Academy, he moved to Brussels to live with his half-brother Théo Hannon, where he continued his studies at the Académie des Beaux Arts. In Théo’s company, he was introduced to the bourgeois circles of left-wing liberals that flourished on the outskirts of the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB).

With Ernest Rousseau, a professor at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), of which he was to become rector, Ensor discovered the stakes of the political struggle. Madame Rousseau was a microbiologist with a passion for insects, mushrooms and… art.

The Rousseaus held their salon on rue Vautier in Brussels, near Antoine Wiertz‘s studio and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. A privileged meeting place for artists, freethinkers and other influential minds.

Back in Ostend, Ensor set up his studio in the family home, where he produced his first masterpieces, portraits imbued with realism and landscapes inspired by Impressionism.

The Realm of Colors

« Life is but a palpitation« , exclaimed Ensor. His clouds are masses of gray, gold and azure above a line of roofs. His Lady at the Breakwater (1880) is caught in a glaze of gray and mother-of-pearl, at the end of the pier. Ensor is an orchestral conductor, using knives and brushes to spread paint in thin or thick layers, adding pasty accents here and there.

His genius takes full flight in his painting The Oyster Eater (1882). Although the picture seems to exude a certain tranquility, in reality he is painting a gigantic still life that seems to have swallowed his younger sister Mitche.

The artist initially called his work “In the Realm of Colors”, more abstract than La Mangeuse d’huîtres, since colors play the main role in the composition.

The mother-of-pearl of the shells, the bluish-white of the tablecloth, the reflections of the glasses and bottles – it’s all about variation, both in the elaboration and in the tonalities of color. Ensor retained the classical approach: he always used undercoats, whereas the Impressionists applied paint directly to the white canvas.

The pigments he uses are also very traditional: vermilion red, lead white, brown earth, cobalt blue, Prussian blue and synthetic ultramarine. The chrome yellow of La Mangeuse d’huîtres is an exception. The intensity of this pigment is much higher than that of the paler Naples yellow he had previously used.

The writer Emile Verhaeren, who later wrote the painter’s first monograph, contemplated La Mangeuse d’huîtres and exclaimed: « This is the first truly luminous canvas ».

Stunned, he wanted to highlight Ensor as the great innovator of Belgian art. But opinion was not unanimous. The critics were not kind: the colors were too garish and the work was painted in a sloppy manner. What’s more, it’s immoral to paint « a subject of second rank » (in monarchy, there are no citizens, only « subjects », a woman not being part of the aristocracy) in such dimensions – 207 cm by 150 cm.

In 1882, the Salon d’Anvers, which exhibited the best of contemporary art, rejected the work. Even his former Brussels colleagues at L’Essor rejected La Mangeuse d’huîtres a year later.

The XX group

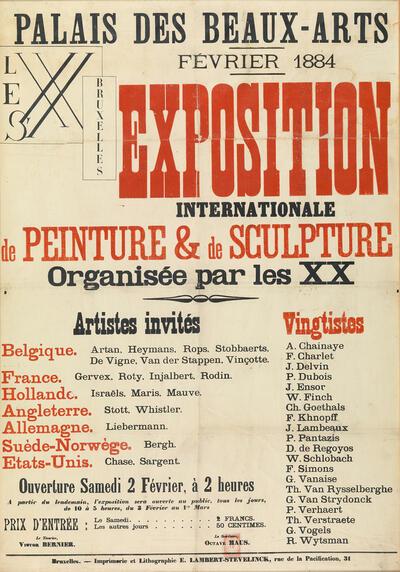

In Belgium, for example, the artistic revolution of 1884 began with a phrase uttered by a member of the official jury: « Let them exhibit at home! » he proclaimed, rejecting the canvases of two or three painters; and so they did, exhibiting at home, in « citizens’ salons », or creating their own cultural associations.

It was against this backdrop that Octave Maus and Ensor founded the « Groupe des XX », an avant-garde artistic circle in Brussels. Among the early « vingtists », in addition to Ensor, were Fernand Khnopff, Jef Lambeaux, Paul Signac, George Minne and Théo Van Rysselberghe, whose artists included Ferdinand Rops, Auguste Rodin, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, Gustave Caillebotte and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

It wasn’t until 1886, therefore, that Ensor was able to exhibit his innovative work La mangeuse d’huîtres for the first time at the Groupe des XX. But this was not the end of his ordeal. In 1907, the Liège municipal council decided not to buy the work for the city’s Musée des Beaux-Arts.

Fortunately, Ensor’s friend Emma Lambotte did not give up on the painter. She bought the painting and exhibited it in her salon citoyen.

Social and political commitment

The social unrest that coincided with his rise as a painter, and which culminated in tragedy with the deadly clashes between workers and civic guards in 1886, prompted him to find in the masses, as a collective actor, a powerful companion in misfortune. At the end of the 19th century, the Belgian capital was a bubbling cauldron of revolutionary, creative and innovative ideas. Karl Marx, Victor Hugo and many others found exile here, sometimes briefly. Symbolism, Impressionism, Pointillism and Art Nouveau all vied for glory.

While Marx was wrong on many points, he did understand that, at a time when finance derived its wealth from production, the modernization of the means of production bore the seeds of the transformation of social relations. Sooner or later, and at all levels, those who produce wealth will claim their rightful place in the decision-making process.

Ensor’s fight for freer art reflects and coincides with the epochal change taking place at the time.

Originating in Vienna, Austria, the banking crisis of May 1873 triggered a stock market crash that marked the beginning of a crisis known as the Great Depression, which lasted throughout the last quarter of the 19th century.

On September 18, 1873, Wall Street was panic-stricken and closed for 10 days. In Belgium, after a period marked by rapid industrialization, the Le Chapelier law, which had been in force since 1791, i.e. forty years before the birth of Belgium, and which prohibited the slightest form of workers’ organization, was repealed in 1867, but strikes were still a crime punishable by the State.

It was against this backdrop that a hundred delegates representing Belgian trade unions founded the Belgian Workers’ Party (POB) in 1885. Reformist and cautious, in 1894 they called not for the « dictatorship of the proletariat », but for a strong « socialization of the means of production ». That same year, the POB won 20% of the votes cast in the parliamentary elections and had 28 deputies. It participated in several governments until it was dissolved by the German invasion of May 1940.

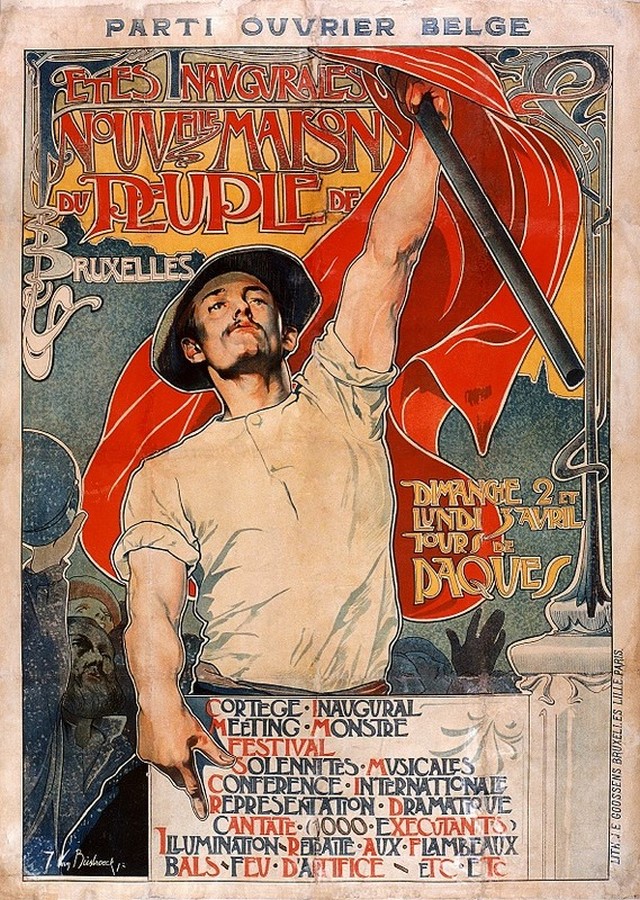

Victor Horta, Jean Jaurès and the Maison du Peuple in Brussels

The architect Victor Horta, a great innovator of Art Nouveau whose early houses symbolized a new art of living, was commissioned by the POB to build the magnificent « Maison du Peuple » in Brussels, a remarkable building made mainly of steel, housing a maximum of functionalities: offices, meeting room, stores, café, auditorium…

The building was inaugurated in 1899 in the presence of Jean Jaurès. In 1903, Lenin took part in the congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party.

Jean Jaurès gave his last speech on July 29, 1914, at the Cirque Royal in Brussels, during a major meeting of the Socialist International to save peace. Speaking of the threat of war, Jaurès said: « Attila is on the brink of the abyss, but his horse is still stumbling and hesitating ».

Opposing, as he did all his life, France’s submission to a subordinate role, he said:

« If we appeal to a secret treaty with Russia, we will appeal to a public treaty with Humanity ». And he ended his speech, the best of his life, with these prophetic words, written almost literally: « At the beginning of the war, everyone will be drawn in. But when the consequences and disasters unfold, the people will say to those responsible: ‘Go away and may God forgive you' ».

According to eyewitness accounts, Jaurès’ speech in Brussels aroused thousands of people from all classes of society. Two days later, on July 31, 1914, Jaurès was assassinated on his return to Paris, and the Maison du Peuple in Brussels was demolished in 1965 and replaced by a model of ugliness.

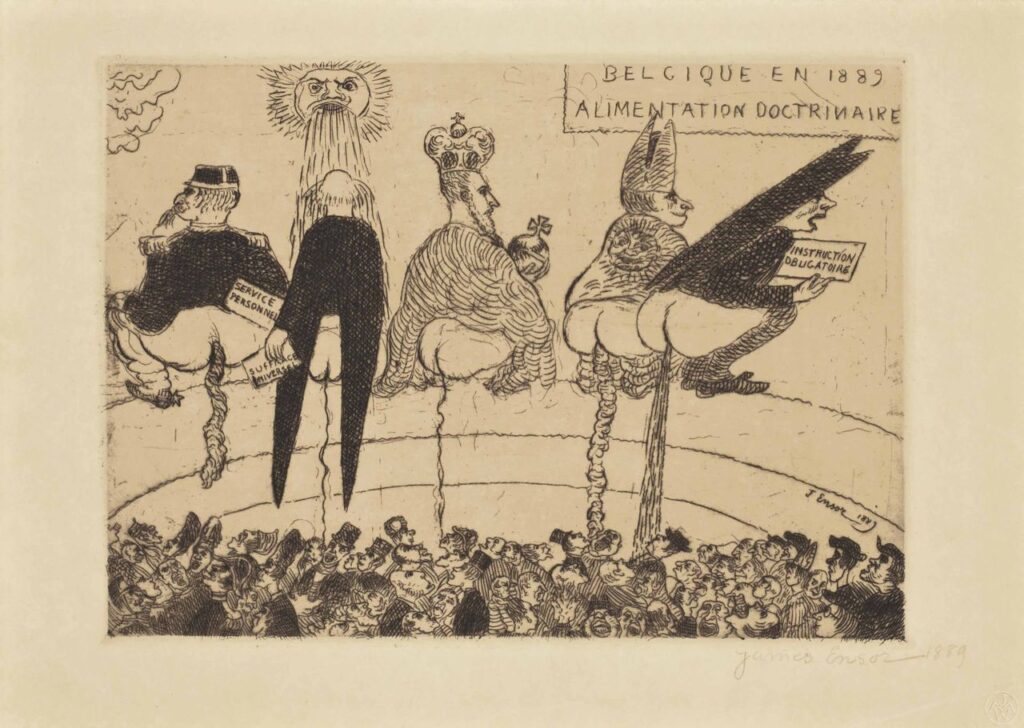

Doctrinary Food

Ensor’s art, especially his etchings, echoed this upheaval. His social and political criticism permeates his best work, none of which is perhaps as virulent as his etching Doctrinary Food (1889/1895) showing figures embodying the powers that be (the King of the Belgians, the clergy, etc.) literally defecating on the masses, a nasty habit that remains entrenched among our French « elites », if we review the treatment meted out, without the slightest discrimination, to our « yellow vests ».

In these engravings, Ensor presents the major demands of the POB: universal suffrage (passed in 1893, albeit imperfectly, at least for men), « personal » military service (i.e. for all, passed in 1913) and compulsory universal education (passed in 1914).

Revenge

Faced with injustice and incomprehension, Ensor can no longer suppress his righteous anger. For his own amusement – and, let’s face it, revenge – he set out to « get even » with those who ignored, despised and sabotaged him, above all the Belgian aristocracy, who clung to their privileges like mussels to rocks.

Deconstructing the straitjacket of academic rules, and drawing inspiration from Goya, Ensor forged a powerful language of metaphor and symbol. Between 1888 and 1892, Ensor began to deal with religious themes. Like Gauguin and Van Gogh, he identified with the persecuted Christ.

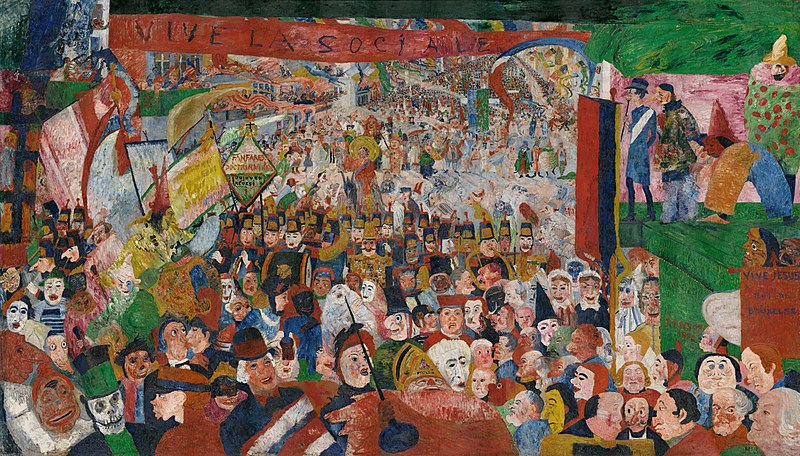

In 1889, at the age of 28, he painted L’Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, a vast satirical canvas that made his name. Even those closest to him, eager for recognition in order to exist, didn’t want it. The painting was rejected at the Salon des XX, where there was talk of excluding him from the Cercle, of which he was a founding member! Against Ensor’s wishes, the « vingtistes », racing towards success, split up four years later to re-create themselves under the name of La Libre Esthétique.

In this work, a large red banner reads « Vive la sociale », not « Vive le Christ ». Only a small panel on the side applauds Jesus, King of Brussels. But what on earth is the prophet, with the painter’s features and almost lost in the crowd, doing in Brussels? Has socialism replaced Christianity to such an extent that if Jesus were to return today, he would do so under the banner « For Ensor’s friends, he had lost his mind.

The Belgian lawyer and art critic Octave Maus, co-founder with Ensor of Les XX, famously summed up the reaction of contemporary art critics to Ensor’s « pictorial outburst »:

« Ensor is the leader of a clan. Ensor is in the limelight. Ensor summarizes and concentrates certain principles that are considered anarchist. In short, Ensor is a dangerous person who has initiated great changes (…) He is therefore marked for blows. All the harquebuses are aimed at him. It is on his head that the most aromatic containers of the so-called serious critics are poured ».

In 1894, he was invited to exhibit in Paris, but his work, more intellectual than aesthetic, aroused little interest. Desperate for success, Ensor persisted with his wild, saturated and violently variegated painting.

Skeletons and masks

Skulls, skeletons and masks burst into his work very early on. This is not the morbid imagination of a sick mind, as his slanderers claim. Radical? Insolent? Certainly; sarcastic, often; pessimistic? Never; anarchist? let’s rather say « yellow vest spirit », i.e. strongly contesting an established order that has lost all legitimacy and, absorbed in immense geopolitical maneuvers, is marching like a horde of sleepwalkers towards the « Great War » and the Second World War that’s coming behind!

Dead heads, symbols of truth

Poetically, Ensor resurrected the ultra-classical Renaissance metaphor of the « Vanities« , a very Christian theme that already appeared in « The Triumph of Death », the poem by Petrarch that inspired the Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Holbein’s series of woodcuts, « The Dance of Death ».

A skull juxtaposed with an hourglass were the basic elements for visualizing the ephemeral nature of human existence on earth. As humans, this metaphor reminds us, we constantly try not to think about it, but inevitably, we all end up dying, at least on a physical level. Our « vanity » is our constant desire to believe ourselves eternal.

Ensor did not hesitate to use symbols. To penetrate his work, you need to know how to read the meaning behind them. Visually, in the face of the triumph of lies and hypocrisy, Ensor, like a good Christian, sets up death as the only truth capable of giving meaning to our existence. Death triumphs over our physical existence.

Masks, symbols of lies

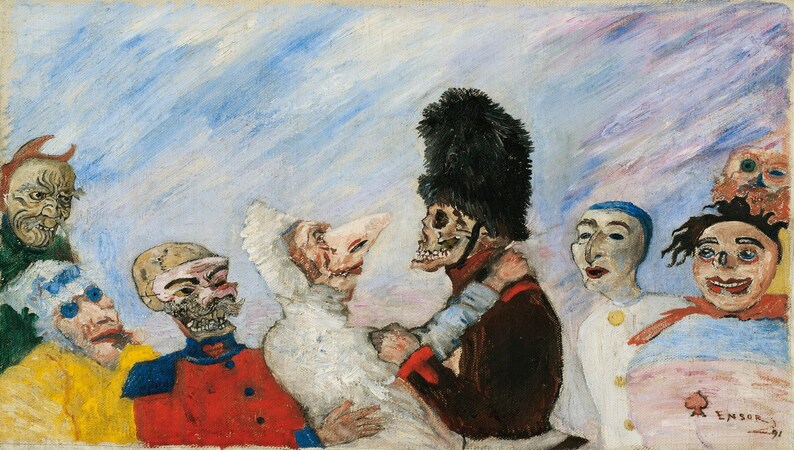

Gradually, as in Death and Masks (1897) (image at the top of this article), the artist dramatized this theme even further, pitting death against grotesque masks, symbols of human lies and hypocrisy.1

Often in his works, in a sublime reversal of roles, it is death who laughs and it is the masks who howl and weep, never the other way around.

It may sound grotesque and appalling, but in reality it’s only normal: truth laughs when it triumphs, and lies weep when they see their end coming! What’s more, when death returns to the living and shows the trembling flame of the candlestick, the latter howl, whereas the former has a big advantage: it’s already dead and therefore appears to live without fear!

No doubt thinking of the Brussels aristocracy who flocked to Ostend for a dip, Ensor wrote:

« Ah, you have to see the masks, under our great opal skies, and when, daubed in cruel colors, they evolve, miserable, their spines bent, pitiful under the rains, what a pitiful rout. Terrified characters, at once insolent and timid, snarling and yelping, voices in falsetto or like unleashed bugles ».

The same Ensor also castigated bad doctors pulling a huge tapeworm out of a patient’s belly, kings and priests whom he painted literally « shitting » on the people. He criticized the fishwives in the bars, the art critics who failed to see his genius and whom he painted in the form of skulls fighting over a kipper (a pun on « Art Ensor »).

The King’s Notebooks

In 1903, a scandal of unprecedented proportions shook Belgium, France and neighboring countries. Les Carnets du Roi (The King’s Notebooks), a work published anonymously in Paris and quickly banned in Brussels, portrayed a white-bearded autocrat: Leopold II, King of the Belgians, without naming him. Arrogant, pretentious and cunning, he was more concerned with enriching himself and collecting mistresses than ensuring the common good of his citizens and respect for the laws of a democratic state. The book, published by a Belgian publisher based in Paris, was the brainchild of a Belgian writer from the Liège region, Paul Gérardy (1870-1933), who happened to be a friend of Ensor.

The story of the Carnets du Roi is first and foremost that of a monarch who was not only mocked in writing and drawing throughout his reign, but also criticized extremely harshly for the methods used to govern his personal estate in the Congo. Divided into some thirty short chapters, the work is presented as a series of letters and advice from the aging king to his soon-to-be successor on the throne, his nephew Albert, who went on to become Ensor’s patron and, along with his friend Albert Einstein, whom he welcomed to Belgium, was deeply involved in preventing the outbreak of the Second World War.

In Les Carnets, a veritable satire, the monarch explains how hypocrisy, lies, treachery and double standards are necessary for the exercise of power: not to ensure the good of the « common people » or the stability of the monarchical state, but quite simply to shamelessly enrich himself.

The pages devoted to the exploitation of the people of the Congo and the « re-establishment of slavery » (sic) by a king who, via the explorer Stanley, was said to have been one of its eradicators, are ruthlessly lucid, and echo the most authoritative denunciations of the white-bearded monarch, to whom Gérardy lends these words:

« I took care to have it published that I was only concerned with civilizing the negroes, and as this nonsense was asserted with sincerity by a few convinced people, it was quickly believed and saved me some trouble ».

Meeting Albert Einstein

After 1900, the first exhibitions were devoted to him. Verhaeren wrote his first monograph. But, curiously, this success defused his strength as a painter. He contented himself with repeating his favorite themes or portraying himself, including as a skeleton. In 1903, he was awarded the Order of Leopold.

The whole world flocked to Ostend to see him. In early 1933, Ensor met Albert Einstein, who was visiting Belgium after fleeing Germany. Einstein, who resided for several months in Den Haan, not far from Ostend, was protected by the Belgian King, Albert I, with whom he coordinated his efforts to prevent another world war.

If it is claimed that Ensor and Einstein had little understanding of each other, the following quotation rather indicates the opposite.

Ensor, always lyrical, is quoted as saying:

« Let us all promptly praise the great Einstein and his relative orders, but let us condemn algebraism and its square roots, geometers and their cubic reasons. I say the world is round.… »

In 1929, King Albert I conferred the title of Baron on James Ensor. In 1934, listening to all that Franklin Roosevelt had to offer and seeing Belgium caught up in the turmoil of the 1929 crash, the King of the Belgians commissioned his Prime Minister De Broqueville to reorganize credit and the banking system along the lines of the Glass-Steagall Act model adopted in the United States in 1933.

On February 17, 1934, during a climb at Marche-les-Dames, Albert I died under conditions that have never been clarified. On March 6, De Broqueville made a speech to the Belgian Senate on the need to mourn the Treaty of Versailles and to reach an agreement with Germany on disarmament between the Allies of 1914-1918, failing which we would be heading for another war…

De Broqueville then energetically embarked on banking reform. On August 22, 1934, several Royal Decrees were promulgated, in particular Decree no. 2 of August 22, 1934, on the protection of savings and banking activities, imposing a split into separate companies, between deposit banks and business and market banks.

Pictorial bombs

From 1929 onwards, Ensor was dubbed the « Prince of Painters ». The artist had an unexpected reaction to this long-awaited recognition, which came too late for his liking: he gave up painting and devoted the last years of his life exclusively to contemporary music, before dying in 1949, covered in honors.

In 2016, a painting by Ensor from 1891, dubbed « Skeleton stopping masks », which had remained in the same family for almost a century and was unknown to historians, sold for 7.4 million euros, a world record for this artist. In the center, death (here a skull wearing the bearskin cap typical of the 1st Grenadier Regiment) is caught by the throat by strange masks that could represent the rulers of countries preparing for future conflicts.

Are the masks (the lie) about to strangle the truth (the skull and crossbones) without success? And so, over a hundred years later, Ensor’s pictorial bombs are still happily exploding in the heads of the narrow-minded, the floured bourgeois and the piss-poor, as he himself would have put it.

Notes:

- In 1819, another artist, the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, composed his political poem The Mask of Anarchy in reaction to the Peterloo massacre (18 dead, 700 wounded), when cavalry charged a peaceful demonstration of 60,000-80,000 people gathered to demand reform of parliamentary representation. In this call for liberty, he denounces an oligarchy that kills as it pleases (anarchy). Far from a call for anarchic counter-violence, it is perhaps the first modern declaration of the principle of non-violent resistance. ↩︎

Comments are Closed