Étiquette : Belgium

Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life: the cradle of humanism in the North

Presentation of Karel Vereycken, founder of Agora Erasmus, at a meeting with friends in the Netherlands on September 10, 2011.

The current financial system is bankrupt and will collapse in the coming days, weeks, months or years if nothing is done to end the paradigm of financial globalization, monetarism and free trade.

To exit this crisis implies organizing a break-up of the banks according to principles of the Glass-Steagall Act, an indispensable lever to recreate a true credit system in opposition to the current monetarist system. The objective is to guarantee real investments generating physical and human wealth, thanks to large infrastructure projects and highly qualified and well-paid jobs.

Can this be done? Yes, we can! However, the true challenge is neither economic, nor political, but cultural and educational: how to lay the foundations of a new Renaissance, how to effect a civilizational shift away from green and Malthusian pessimism towards a culture that sets itself the sacred mission of fully developing the creative powers of each individual, whether here, in Africa, or elsewhere.

Is there a historical precedent? Yes, and especially here, from where I am speaking to you this morning (Naarden, Netherlands) with a certain emotion. It probably overwhelms me because I have a rather well informed and precise sense of the role that several key individuals from the region where we are gathered this morning have played and how, in the fourteenth century, they made Deventer, Zwolle and Windesheim an intellectual hotbed and the cradle of the Renaissance of the North which inspired so many worldwide.

Let me summarize for you the history of this movement of lay clerics and teachers: the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, a movement that nurished our beloved Erasmus of Rotterdam, the humanist giant from whom we borrowed the name to create our political movement in Belgium.

As very often, it all begins with an individual decision of someone to overcome his shortcomings and give up those « little compromises » that end up making most of us slaves. In doing so, this individual quickly appears as a « natural » leader. Do you want to become a leader? Start by cleaning up your own mess before giving lessons to others!

Geert Groote, the founder

The spiritual father of the Brothers is Geert Groote, born in 1340 and son of a wealthy textile merchant in Deventer, which at that time, like Zwolle, Kampen and Roermond, were prosperous cities of the Hanseatic League.

In 1345, as a result of the international financial crash, the Black Death spread throughout Europe and arrived in the Netherlands around 1449-50. Between a third and a half of the population died and, according to some sources, Groote lost both parents. He abhorred the hypocrisy of the hordes of flagellants who invaded the streets and later advocated a less conspicuous, more interior spirituality.

Groote had talent for intellectual matters and was soon sent to study in Paris. In 1358, at the age of eighteen, he obtained the title of Master of Arts, even though the statutes of the University stipulated that the minimum age required was twenty-one.

He stayed eight years in Paris where he taught, while making a few excursions to Cologne and Prague. During this time, he assimilated all that could be known about philosophy, theology, medicine, canon law and astronomy. He also learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and was considered one of the greatest scholars of the time.

Around 1362 he became canon of Aachen Cathedral and in 1371 of that of Utrecht. At the age of 27, he was sent as a diplomat to Cologne and to the Court of Avignon to settle the dispute between the city of Deventer and the bishop of Utrecht with Pope Urban V. In principle, he could have met the Italian humanist Petrarch who was there at that time.

Full of knowledge and success, Groote got a big head. His best friends, conscious of his talents, kindly suggested him to detach himself from his obsession with « Earthly Paradise ». The first one was his friend Guillaume de Salvarvilla, the choirmaster of Notre-Dame of Paris. The second was Henri Eger of Kalkar (1328-1408) with whom Groote shared the benches of the Sorbonne.

In 1374, Groote got seriously ill. However, the priest of Deventer refused to administer the last sacraments to him as long as he refused to burn some of the books in his possession. Fearing for his life (after death), he decided to burn his collection of books on black magic. Finally, he felt better and healed. He also gave up living in comfort and lucre through fictitious jobs that allowed him to get rich without working too hard.

After this radical conversion, Groote decides to selfperfect. In his Conclusions and Resolutions he wrote:

« It is to the glory, honor and service of God that I propose to order my life and the salvation of my soul. (…) In the first place, not to desire any other benefit and not to put my hope and expectation from now on in any temporal profit. The more goods I have, the more I will probably want more. For according to the primitive Church, you cannot have several benefits. Of all the sciences of the Gentiles, the moral sciences are the least detestable: many of them are often useful and profitable both for oneself and for teaching others. The wisest, like Socrates and Plato, brought all philosophy back to ethics. And if they spoke of high things, they transmitted them (according to St. Augustine and my own experience) by moralizing them lightly and figuratively, so that morality always shines through in knowledge… ».

Groote then undertakes a spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen near Arnhem where he devotes himself to prayer and study.

However, after a three-year stay in isolation, the prior, his Parisian friend Eger of Kalkar, told him to go out and teach :

« Instead of remaining cloistered here, you will be able to do greater good by going out into the world to preach, an activity for which God has given you a great talent. »

Ruusbroec, the inspirer

Groote accepted the challenge. However, before taking action, he decided to make a last trip to Paris in 1378 to obtain the books he needed.

According to Pomerius, prior of Groenendael between 1431 and 1432, he undertook this trip with his friend from Zwolle, the teacher Joan Cele (around 1350-1417), the historical founder of the excellent Dutch public education system, the Latin School.

On their way to Paris, they visit Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), a Flemish “mystic” who lived in the Groenendael Priory on the edge of the Soignes Forest near Brussels.

Groote, still living in fear of God and the authorities, initially tries to make « more acceptable » some of the old sage’s writings while recognizing Ruusbroec as closer to the Lord than he is. In a letter to the community of Groenendael, he requested the prayer of the prior:

« I would like to recommend myself to the prayer of your provost and prior. For the time of eternity, I would like to be ‘the prior’s stepladder’, as long as my soul is united to him in love and respect.” (Note 1)

Back in Deventer, Groote concentrated on study and preaching. First he presented himself to the bishop to be ordained a deacon. In this function, he obtained the right to preach in the entire bishopric of Utrecht (basically the whole part of today’s Netherlands north of the great rivers, except for the area around Groningen).

First he preached in Deventer, then in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen and later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda and Delft. His success is so great that jealousy is felt in the church. Moreover, with the chaos caused by the great schism (1378 to 1417) installing two popes at the head of the church, the believers are looking for a new generation of leaders.

As early as 1374, Groote offered part of his parents’ house to accommodate a group of pious women. Endowed with a by-law, the first house of sisters was born in Deventer. He named them « Sisters of the Common Life », a concept developed in several works of Ruusbroec, notably in the final paragraph Of the Shining Stone (Van den blinckende Steen)

« The man who is sent from this height to the world below, is full of truth, and rich in all virtues. And he does not seek his own, but the honor of the one who sent him. And that is why he is upright and truthful in all things. And he has a rich and benevolent foundation grounded in the riches of God. And so he must always convey the spirit of God to those who need it; for the living fountain of the Holy Spirit is not a wealth that can be wasted. And he is a willing instrument of God with whom the Lord works as He wills, and how He wills. And it is not for sale, but leaves the honor to God. And for this reason he remains ready to do whatever God commands; and to do and tolerate with strength whatever God entrusts to him. And so he has a common life; for to him seeing [via contemplativa] and working [via activa] are equal, for in both things he is perfect.”

Radewijns, the organizer

Following one of his first sermons, Groote recruited Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Born in Utrecht, the latter received his training in Prague where, also at the early age of 18, he was awarded the title of Magister Artium.

Groote then sent him to the German city of Worms to be consecrated priest there. In 1380 Groote moved with about ten pupils to the house of Radewijns in Deventer; it would later be known as the « Sir Florens House” (Heer Florenshuis), the first house of the Brothers and above all its base of operation?

When Groote died of the plague in 1384, Radewijns decided to expand the movement which became the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Soon it will be branded the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion).

Books and beguinages

A number of parallels can be drawn with the phenomenon of the Beguines which flourished from the 13th century onward. (Note 2)

The first beguines were independent women, living alone (without a man or a rule), animated by a deep spirituality and daring to venture into the enormous adventure of a personal relationship with God. (Note 3)

Operating outside the official religious hierarchy, they didn’t beg but worked various jobs to earn their daily bread. The same goes for the Brothers of the Common Life, except that for them, books were at the center of all activities. Thus, apart from teaching, the copying and production of books represented a major source of income while allowing spreading the word to the many.

Lay Brothers and Sisters focused on education and their priests on preaching. Thanks to the scriptorium and printing houses, their literature and music will spread everywhere.

Windesheim

To protect the movement from unfair attacks and criticism, Radewijns founded a congregation of canons regular obeying the Augustinian rule.

In Windesheim, between Zwolle and Deventer, on land belonging to Berthold ten Hove, one of the members, a first cloister is erected. A second one, for women this time, is built in Diepenveen near Arnhem. The construction of Windesheim took several years and a group of brothers lived temporarily on the building site, in huts.

In 1399 Johannes van Kempen, who had stayed at Groote’s house in Deventer, became the first prior of the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and gave the movement new momentum. From Zwolle, Deventer and Windesheim, the new recruits spread all over the Netherlands and Northern Europe to found new branches of the movement.

In 1412, the congregation had 16 cloisters and their number reached 97 in 1500: 84 priories for men and 13 for women. To this must be added a large number of cloisters for canonesses which, although not formally associated with the Windesheim Congregation, were run by rectors trained by them.

Windesheim was not recognized by the Bishop of Utrecht until 1423 and in Belgium, Groenendael, associated with the Red Cloister and Korsendonc, wanted to be part of it as early as 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cusanus and Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was the brother of the famous Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). The latter, trained in Windesheim, animated the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and was one of the towering figures of the movement for seventy years. In addition to a biography he wrote of Groote and his account of the movement, his Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) became the most widely read work in history after the Bible.

Both Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) and Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), two of Erasmus’ tutors during his training in Deventer, were direct pupils of Thomas a Kempis. The Latin School of Deventer, of which Hegius was rector, was the first school in Northern Europe to teach the ancient Greek language to children.

While no formal prove exists, it is tempting to believe that Cusanus (1401-1464), who protected Agricola and, in his last will, via his Bursa Cusanus, offered a scholarship for the training of orphans and poor students of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, was also trained by this humanist network.

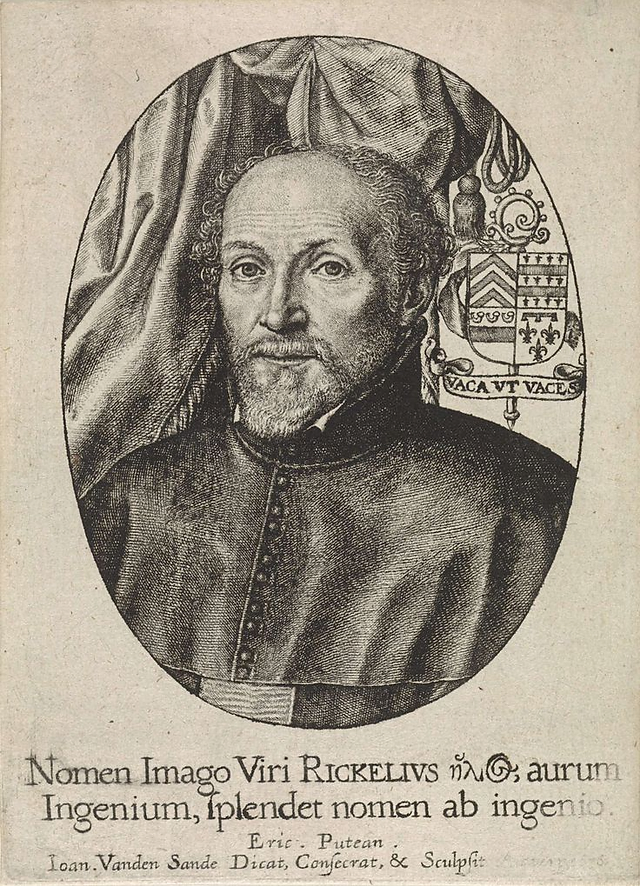

What is known is that when Cusanus came in 1451 to the Netherlands to put the affairs of the Church in order, he traveled with his friend Denis the Carthusian (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), a disciple of Ruusbroec, whom he commissioned to carry on this task.

A native of Limburg, trained at the famous Cele school in Zwolle, Dionysius the Carthusian also became the confessor of the Duke of Burgundy and is thought to be the “theological advisor” of the Duke’s ambassador and court painter, Jan Van Eyck. (Note 4)

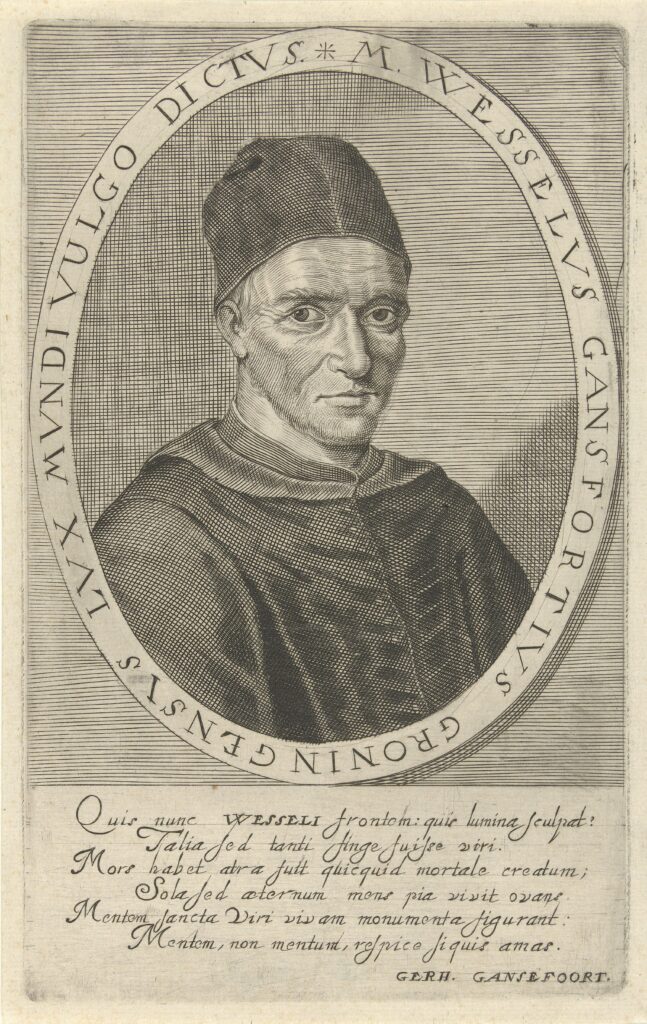

Gansfort

Wessel Gansfort (1419-1489), another exceptional figure of this movement was at the service of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion, the main collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) at the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1437. Gansfort, after attending the Brothers’ school in Groningen, was also trained by Joan Cele‘s Latin school in Zwolle.

The same goes for the first and only Dutch pope, Adrianus VI, who was trained in the same school before completing his training with Hegius in Deventer. This pope was very open to Erasmus’ reformist ideas… before arriving in Rome.

Hegius, in a letter to Gansfort, which he calls Lux Mundi (Light of the World), wrote:

« I send you, most honorable lord, the homilies of John Chrysostom. I hope that you will enjoy reading them, since the golden words have always been more pleasing to you than the pieces of this metal. As you know, I went to the library of Cusanus. There I found some books that I didn’t know existed (…) Farewell, and if I can do you a favor, let me know and consider it done.”

Rembrandt

A quick look on Rembrandt’s intellectual training indicates that he too was a late product of this educational epic. In 1609, Rembrandt, barely three years old, entered elementary school where, like other boys and girls of his generation, he learned to read, write and… draw.

The school opened at 6 in the morning, at 7 in the winter, and closes at 7 in the evening. Classes begin with prayer, reading and discussion of a passage from the Bible followed by the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt acquired an elegant writing style and much more than a rudimentary knowledge of the Gospels.

The Netherlands wanted to survive. Its leaders take advantage of the twelve-year truce (1608-1618) to fulfill their commitment to the public interest.

In doing so, the Netherlands at the beginning of the XVIIth century became the first country in the world where everyone had the chance to learn to read, write, calculate, sing and draw.

This universal educational system, no matter what its shortcomings, available to both rich and poor, boys and girls alike, stands as the secret behind the Dutch « Golden Century ». This high level of education also created those generations of active Dutch emigrants a century later in the American Revolution.

While others started secondary school at the age of twelve, Rembrandt entered the Leyden Latin School at the age of 7. There, the students, apart from rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn not only Greek and Latin, but also foreign languages such as English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, with no laws restricting young talents, Rembrandt enrolled in University. The subject he chose was not Theology, Law, Science or Medicine, but… Literature.

Did he want to add to his knowledge of Latin the mastery of Greek or Hebrew philology, or possibly Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Arabic/Latin dictionaries were already being published in Leiden at a time the city was becoming a major printing center in the world.

Thus, one realizes that the Netherlands and Belgium, first with Ruusbroec and Groote and later with Erasmus and Rembrandt, made an essential contribution in the not so distant past to the kind of humanism that can raise today humanity to its true dignity.

Hence, failing to extend our influence here, clearly seems to me something in the realm of the impossible.

Footnotes:

- Geert Groote, who discovered Ruusbroec’s work during his spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen, near Arnhem, has translated at least three of his works into Latin. He sent The Book of the Spiritual Tabernacle to the Cistercian Cloister of Altencamp and his friends in Amsterdam. The Spiritual Marriage of Ruusbroec being under attack, Groote personally defends it. Thus, thanks to his authority, Ruusbroec’s works are copied in number and carefully preserved. Ruusbroec’s teaching became popularized by the writings of the Modern Devotion and especially by the Imitation of Christ.

- At the beginning of the 13th century the Beguines were accused of heresy and persecuted, except… in the Burgundian Netherlands. In Flanders, they are cleared and obtain official status. In reality, they benefit from the protection of two important women: Jeanne and Margaret of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders. They organized the foundation of the Beguinages of Louvain (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerp (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ypres (1240), Lille (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Bruges (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Diest (1253), Mechelen (1258) and in 1271 it was Jan I, Count of Flanders, in person, who deposited the statutes of the great Beguinage of Brussels. In 1321, the Pope estimated the number of Beguines at 200,000.

- The platonic poetry of the Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (XIIIth Century) has a decisive influence on Jan van Ruusbroec.

- It is significant that the first book printed in Flanders in 1473, by Erasmus’ friend and printer Dirk Martens, is precisely a work of Denis the Carthusian.

Van Eyck : True Beauty, a foretaste of Divine Wisdom

Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441). How might we grasp the intention of this great Flemish painter, despite the five hundred years of distance separating us? Apart from looking at his work, here are three tracks that I’ve been able to uncover:

- The painter was undoubtedly initiated in the art of lectio divina, the multi-leveled interpretation of sacred texts;

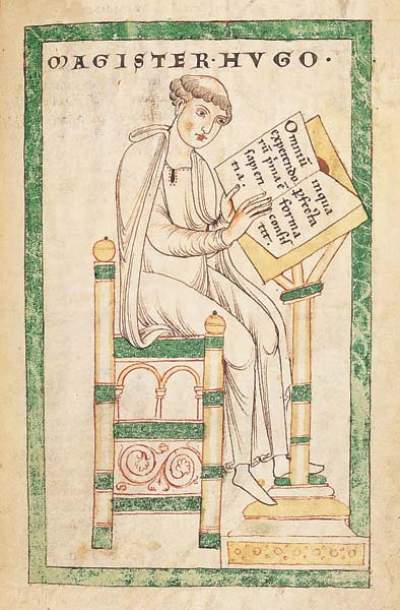

- The influence of the French religious thinker Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141), an unknown but major figure who was an inspiration for the philosopher-cardinal Nicolas of Cusa;

- The advice given to the painter by theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), the confessor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, for whom the painter carried out diplomatic missions.

The writer would highly encourage all admirers of great art to get themselves a copy of the inspiring and scholarly work Landschap in Wereldbeeld, van Van Eyck tot Rembrandt (Landscape and Worldview, from Van Eyck to Rembrandt) by the Dutch art historian Boudewijn Bakker (published in 2004 at Thoth in Bossum, Netherlands, available in English). In a very rigorous and yet accessible work, Bakker offers us a series of important clues, which allow a XXIst century viewer to gain new insights into the often “hidden” meaning of Dutch and Flemish painting. For today’s viewers, what is often surprising in these works is the use of recurring references by the painters, their sponsors, religious officials and the general public of these countries.

Paradox

Before I read Bakker’s work, the paintings of northern Europe often appeared to me to be opposed to the prevailing philosophical and religious matrix of the fifteenth century, when in reality they were its very expression. Until now, I thought that, for the most part, the world view that prevailed at the end of the Middle-Ages was one rejecting the visible world as it was known through our senses. According to a scholastic misinterpretation of St. Augustine and Plato, the world was only deception and temptation, which one might have called the devil himself. Now, and herein lies the paradox in all its force, how can we reconcile the rejection of the visible world, particularly in sight of the work of the Flemish painter Van Eyck, who was able to show us human beings animated by kindness, glowing with beauty and surrounded by pristine nature?

I thought “How dare he show us so much beauty”, whereas in his day the doctrine of faith, which had been heralded as guardian of the temple, had kept reminding us that Man, in his glaring imperfection, was no God, and systematically warned us against the temptations of this world? Were the ironic but extremely moralizing pictures of Hieronymus Bosch and Joachim Patinier not intended to make us understand, albeit with violence, and yet with humor and great craft, that the origin of sin lay precisely in our excessive attachments to worldly things and the pleasures which were believed to be derived from them?

The Coincidence of Opposites

Without explicitly referring to the method of the great theologian-philosopher, Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa, the « coincidence of opposites » (coincidentia oppositorum), that is to say the paradoxes whose seemingly irreconcilable differences can be overcome from a higher conceptual level, Bakker demonstrates that the aforementioned paradox is also only one of appearance.

In order to make sense of this, Bakker first recalls that for the Augustinian current, for whom man was created in the living image of the creator (Imago Viva Dei), nature was neither more nor less than « theophany », that is to say, for those who were able to read it, it was the revelation of a divine intention.

For this current, God revealed himself to man, not by one, but by « two books, » the first of which was none other than « the book of nature, » read through our eyes; the second being the Bible, which was accessible through our eyes and ears. With this connection in mind, Bakker emphasizes two nearly forgotten yet first-rate Christian thinkers who had unfortunately fallen into obscurity following the hegemony of Aristotelianism, which had been ushered in by St. Thomas of Aquinas in tandem with the rise of nominalism and the counter-reformation. The first is the French abbot and theologian Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141), one of the medieval writers whose manuscripts were widely circulated at the time, and Denis the Carthusian (1402-1471), a Dutch friend and collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464) and also confessor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1396-1467).

The Lectio Divina of Nature

In respect to his interpretation of the paintings, Bakker did the work that any true art historian worthy of such a title should have necessarily done: he compared the paintings with, if they still existed, the writings of their times.

By using the writings of the time to inform his interpretation of the paintings, Bakker formulates a rigorous hypothesis around the idea that the masterpieces of Flemish painting, riddled with as many enigmas and mysteries as our beautiful cathedrals, are to be read « on several levels ». The said “four levels” was what the biblical exegesis of the day prescribed based on ancient tradition.

First, in Judaism, long before the arrival of Jesus, the study of the Torah appealed to the « doctrine of the four senses »:

- the literal meaning,

- the allegorical meaning,

- the allusive meaning, and

- the mystical meaning (possibly hidden, secret or kabalistic).

Then, Christians, especially Origen (185-254), then Ambrose of Milan in the fourth century, repeated this method with the Lectio Divina, that is to say, the exercise of spiritual reading aimed, by prayer, to penetrate a sacred text at its deepest level.

Finally, introduced in the fourth century by Ambrose, Augustine made Lectio Divina the basis of monastic prayer. It would then be taken over by Jerome, Venerable Bede, Scot Erigena, Hugue of Saint Victor, Richard of Saint Victor, Alain of Lille, Bonaventure and would impose itself upon Saint Thomas Aquinas and Bernard of Clairvaux.

Bakker takes care to specify these four levels of reading:

- The literal meaning is that which comes from the linguistic comprehension of the utterance. It tells the facts and « narrative » of a text while situating it in the context of its time;

- The allegorical meaning comes from Greek allos, meaning “other”, and agoreuein, to “say”. By stating one thing, Allegory also says another. Thus an allegory explains what a story symbolizes;

- The moral or tropological meaning (of the Latin tropos meaning « change »), offers us a lesson or advice. By understanding the figures, vices or virtues, passions or stages that the human mind must travel in its ascent to God, each person can draw on such wisdom for his own life;

- The anagogical meaning (adjective from the Greek anagogikos or elevation), is obtained by the interpretation of the Gospels, to give an idea of the last realities that will become visible at the end of time. In philosophy, for Leibniz, « anagogical induction » is something which can be traced back to a first cause.

These four meanings were formulated in the Middle Ages in a famous Latin couplet: littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria, moralis quid agas, quo tendas anagogia (the letters teach the facts, allegory what one must believe, morality is what one must do, anagogy what one should aspire to).

The reason I bring this issue of multi-level biblical exegesis is that Bakker says, from the standpoint of this worldview in the Middle Ages, this method of interpretation was thought to apply not only to the Bible, but to visible creation as well.

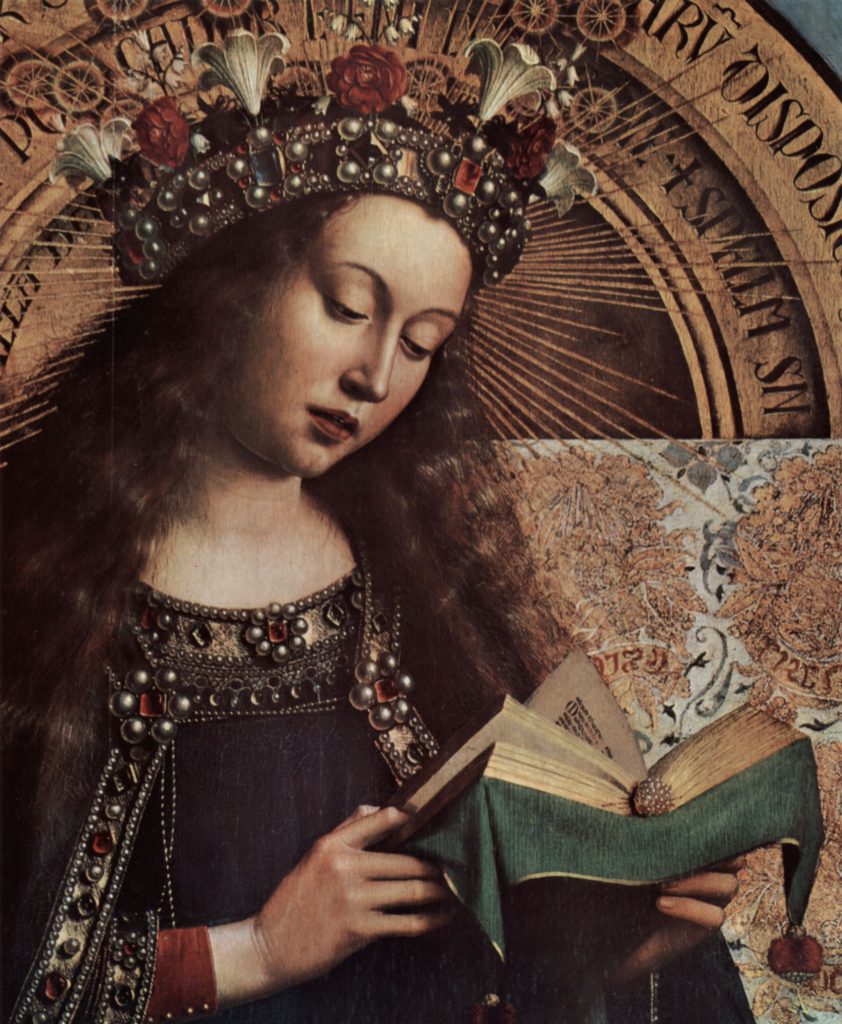

Close-up of the page of the book in front of which the Virgin in the Annunciation kneels, decorating the exterior shutters of the altarpiece of Ghent by Jan Van Eyck (1432). At the bottom of the page, one reads clearly (in red): « de visione dei », the title of the work of Nicolas de Cues of 1453.

But is this merely the instance of some kind of sentimental moment in which one is relishing in the beauty of creation for its own sake? Not at all ! Far from pantheism (a sin), it was a question of « reading », as Hugue of Saint Victor stated, « with the eyes of the mind », which « the eyes of the flesh » were not able to see, a concept that would be taken up again by Nicolas de Cusa in his work of 1543: On painting, or The Vision of God. The paradox can therefore be solved. For, in the allegory of the cavern evoked by Plato in The Republic, the man who is chained before a wall and only able to see shadows projected on the wall, was able to use his intelligence in order identify what the causes that made those shadows possible. Certainly, man cannot « know » God directly. However, by studying the effects of his action, he can come to discover his intention. It is therefore through Hugue of Saint Victor, that the Augustinian and Platonic current that inspired the Carolingian Renaissance resurfaced in Paris. In this current of thought, creation as a whole, from the anagogical point of view, was the shadow cast by a heavenly paradise and a direct reference to omnipotence, beauty and divine goodness. For Bakker:

All of these interpretations are easily illustrated by the works of Augustine, because they have inspired writers on nature throughout the Middle Ages. Augustine greatly loved the world as it appeared to us; he knew how to enjoy what he referred to as ‘the great and beautiful spaces of the city or the countryside, where the brilliance of its beauty immediately strikes the viewer. But such creation also contains innumerable ‘moral’ messages, allowing so many opportunities for a pious and acute observer to reflect on his soul and task on Earth. Time after time, Augustine emphasized this aspect when he spoke of natural phenomena. Each time, he would incite us to seek the invisible behind the visible, the eternal behind the temporal, etc. Thus the harmony that creation revealed was an indication of the peace that should rein among men. Each creature, taken separately, appeared as an example (negative or positive) which man could discern, were he willing. This applied particularly to the behavior of animals, for example. And in regards to the Earth as a whole, one should take heed and make sure to not overlook the hollows and chasms of a landscape, for they are its true wellsprings.

Hugue of Saint Victor

In France, it was with the advent of the XIIth century intellectual renaissance that centers of learning began to multiply (cathedral school, school of Abelard, school of Petit-Pont for Paris, Chartres, Laon etc…) and that an atmosphere of genuine knowledge turned France into a world-center for intellectual life. As well, numerous students originating from Germany, Italy, England, Scotland and Northern Europe all made their way to Paris in order to study first and foremost, dialectics and theology.

Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141) was of Saxon (or Flemish?) origin. Around 1127, he entered the house of the regular canons of Saint Victor shortly after the monastery’s founding on the outskirts of Paris.

The Victorins were distinguished from the beginning by the importance with which they regarded intellectual life. The canons of the abbey had a positive outlook on knowledge, hence the importance which they attached to their library.

The main teachers who influenced Hugue were: Raban Maur (himself a disciple of Charlemagne’s advisor, the Irishman Alcuin), Bede the Venerable, Yves de Chartres and Jean Scot Erigena and some others, perhaps Denys – The Areopagite himself of which he comments on The Celestial Hierarchy.

Propelled by an insatiable intellectual curiosity, Hugue advised his disciples to learn everything because, according to him, nothing is without use. He himself was the first to put the advice he gave to his disciples into practice. A notable part of his writings were devoted to the liberal arts, sciences, and philosophy, which he dealt with particularly in an introductory textbook on secular and sacred studies, still famous today, the Didascalicon.

His contemporaries considered him the greatest theologian of their time and gave him the glorious title of « New Augustine ». He influenced the Franciscans of Oxford (Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) whose influence on the painter Roger Campin has been well established, by whom Nicolas of Cusa was inspired.

In regards to the question of whether one should cherish or despise the world, Hugue of Saint Victor’s answer was that we must love the world, but with the condition that we never forget that we must love it with God always in sight, as a reflection of God, rather than something in and of itself.

In order for one to be able to reach such wisdom, man had to consider his existence as that of a pilgrim who was constantly breaking away from the place in which he resides, a very rich metaphor that would be found in the Flemish painters Bosch and Patinier. « The whole world is an exile for those who philosophize, » said Hugue.

Master Hugue posed the requirement of exceeding dilectio (jealous and possessive love of God) for condilectio (love welcoming and open to sharing). He advocated the idea of an agapic love turned towards others, and not centered on oneself, a love turned towards the neighbor, the love of God increased by the love of one’s neighbor. In a word: it was the idea of Christian charity and fraternal solidarity.

Hugues enumerated five spiritual exercises: reading, meditation, prayer, action and contemplation. The first granted understanding; the second provided a reflection; the third questioned, the fourth sought and the fifth found. These exercises were intended to allow one to reach the source of truth and charity, where the soul of man would be « transformed into a flame of love », resting in the hands of God in « a fullness of both knowledge and love.”

The subject which interests us here, is above all his optimistic vision of man and creation, which differed from the clichés that we have retained from medieval pessimism. For him, creation was a gift from God and the way to God was as much through reading the book of nature itself as it was from reading the Bible.

Thus, for Hugue of Saint Victor, the image that we perceive is nothing but revelation or the unveiling of God’s Divine Power, perceived

through the length, breadth, and depth of space, through the mountain ranges, the winding rivers, the rolling fields, the towering skies and the darkened chasms.

Thus, the painter who exceled in the representation of the physical universe, was only increasing his capacity to reveal the power of the creator!

The revelation of wisdom through Beauty. For Hugue, «the entirety of the sensible universe is one great book written by the hand of God” that is, created by a divine plan in which

every creature is a reflection of – not the product of human desire, but the fruit of divine providence’s will to manifest God’s great wisdom (…) Just as an illiterate looks at the lines of an open book without having knowledge of letters, a stupid and bestialized man ‘that does not understand the things that are of God’, sees in creatures only their external form, but has no understanding of their inner meaning.

To elevate oneself, Hugue proposed that the disciples of Saint Victor, all those who were able of « contemplating relentlessly, » to embrace « a spiritual vision » of the world. For his disciple, Richard of Saint Victor, the Bible and the great book of nature « share the same language and harmonize to reveal the wonders of a secret world. »

Denis the Carthusian,

the Key to Understanding Van Eyck

Two centuries after Hugue of Saint Victor, that same flame later animated the work of theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), a native of Belgian Limburg. Under the title The beauty of the world : ordo et varietas, Bakker devotes a whole chapter of his book to it. And you’ll soon understand why.

Two centuries after Hugue of Saint Victor, that same flame later animated the work of theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), a native of Belgian Limburg. Under the title The beauty of the world : ordo et varietas, Bakker devotes a whole chapter of his book to it. And you’ll soon understand why.

Before having joined the Carthusians of Roermond in the Netherlands, Denys was trained in the spirit of the Brothers of the Common Life at the Zwolle school in the Netherlands and then completed his studies at the University of Cologne.

With Jean Gerson (1363-1429) and Nicolas of Cusa (1402-1464), and despite an often much more wordy and sometimes confused style, Denis the Carthusian was counted as among the most well-read, most copied and most published authors of his day, once the printing press had replaced the laborious work of the copyist monks. Moreover, the first book published in Flanders, was none other than the Mirror of the Sinful Soul of Denis the Carthusian, printed in 1473 by Erasmus of Rotterdam’s friend, Dirk Martens.

At the Roermond Monastery in the Netherlands, Denis wrote 150 works including commentaries on the Bible and 900 sermons. After having read one, Pope Eugene IV, who had just ordered Brunelleschi to complete the cupola of the Santa Maria del Fiore Dome in Florence, exulted: « The Mother Church is delighted to have such a son! ».

As a scholar, theologian and advisor, Denys became very influential. « A number of gentlemen, clerics and bourgeois came to consult him in his cell in Roermond where he constantly resolved doubts, difficulties and cases of conscience. (…) He was in frequent contact with the House of Burgundy and serves as an adviser to Philip the Good « , confirms the Dutch historian Huizinga in his Autumn of the Middle Ages.

According to Bakker, having written a series of works on spiritual orientation, Denis performed the role of confessor and spiritual guide for the Christian sovereign Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and subsequently, that of his widow.

Together in Cologne, both attended the lecture of Flemish theologian Heymeric van de Velde (De Campo) who introduced them to the mystical theology of the Syrian Platonic monk known as Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite and to the work of Raymond Lulle and of Albert the Great as well. When, in 1432, Nicolas of Cusa declined an offer for the chair of Theology made to him by the University of Louvain, it was De Campo who accepted it at his request. Politically, from 1451 to 1452, Denis the Carthusian chose Nicolas of Cusa, then apostolic legate, to accompany him for several months during his tour of the Rhineland and Moselle to promote his approach to spiritual renewal, at the request of the pope.

Bakker notes that Denis had a predilection for music. He copied and illuminated scores with his hand and gave instructions on the best possible interpretation of the Psalms. His preference was for psalms praising God. And to praise the creator, Denis found images and words that would surface in the imagination of the painters of that time. However, for Denis, the beauty of God meant something deeper than mere visual appeal.

For you (Lord), ‘to be’ is ‘to be beautiful’.

Let us remember that in Christian philosophy sight was the most important of the five senses and the one which encapsulated all the others. In Denis’ Psalms, two notions prevailed. First, that of order and regularity. It was found in the celestial bodies that determined the cycles of days and years. But the Earth itself obeyed a divine order. And there Denis quoted the Book of Wisdom of Solomon (11,20) affirming: « You have ordained everything with measure, number and weight ». Then there was the idea of multiplicity and diversity. Regarding climatic phenomena, that is to say purely « physical » phenomena, Denis affirmed for example,

In the sky, lord, you generated multiple effects of pressure and air, such as clouds, winds, rains (…) and various phenomena: comets, luminous crowns, vortices, falling stars (…), frost and haze, hail, snow, the rainbow and the flying dragon.

For Denis, all this was not without a reason: it was to penetrate the divine being, his infinite greatness, his omnipotence and his love for man.

Make it so, my Lord, he writes, that in the effects of your universal laboriousness we perceive you, and that by the love with which it testifies, we inflame ourselves and waken to honor your greatness.

On God and Beauty, Denis wrote a great treatise on theological aesthetics under the title of De Venustate Mundi and Pulchritudine Dei (About the Attractiveness of the World and the Beauty of God).

After having read what follows, the great polyptych painted by Jan Van Eyck, the altarpiece of Ghent known as The Mystic Lamb, comes to mind.

Knowing that this painter was in the service (painter and ambassador) of the same Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, of which Denis the Carthusian was the confessor and spiritual guide, one has good reason to believe that this text had impressed itself on the painter’s spirit at the time of this work’s creation.

Denis the Carthusian:

Just as every creature participates in the being of God and his goodness, so does the Creator also communicate to him something of his divine, eternal, uncreated beauty, whereby he is in part made like his Creator, participating in some measure in his beauty. In as much as a thing receives the essence of that being, so it receives the good and the beautiful of that being. There is therefore an uncreated beauty which is beautiful and beauty in its essence: God. The Other (as opposed to being) is the created beauty: the beautiful by participation. Just as every creature is thought of as being to the extent that it participates in the divine being and is assimilated with it by through a kind of imitation, so every creature is said to be beautiful in the degree to which it participates in this divine beauty and is brought in conformity with it. . Just as God has done all which is good since his nature is good, so he has done all things beautiful because he is essentially beautiful.

(…) The one and only son of God, true God himself, took our nature and became our brother. Through him, our nature has received a dignity of unspeakable majesty. God has also adorned the souls of the blessed who are in the heavenly homeland with his light and glory, and raised them to the beatific, immediate, clear and blessed vision of his all-pure Deity. By contemplating the uncreated and infinite beauty of the divine essence, they are made in his image in a supernatural and ineffable way. They are over-taken in this participation, this communion of goodness, this divine light and beauty, to the point of being entirely enthralled by him, configured to him, absorbed in him. They attain such beauty heights of beauty that the greatest splendors of world cannot even be compared with the smallest part of their beauty.

Back to Van Eyck

This last paragraph immediately evokes the upper panels of Jan Van Eyck’s polyptych in Gent. It’s hard to imagine the kind of effect that this painting would have had on believers: they saw not only Adam and Eve, raised on the same level as God, the Virgin and St. John the Baptist, but discovered there, at a time when less than one percent of the European population could read and write, the image of a beautiful young woman reading the Bible. Her name? Mary, mother of Jesus!

The lower part of the same work depicts another major event: the reunification, following the various ecumenical councils, of all Christians, whether they were from the East or West, divided by disagreements over the fundamental issue of the Christian faith: the sacrifice of the Son of God to free man from original sin. They are assembled in a chorus around all the most significant parts of the universe: the three popes, the philosophers, the poets (Virgil), the martyrs, the hermits, the prophets, the just judges, the Christian knights, the saints and the virgins.

Everything is presented in a landscape renewed by a true Christian “Spring”. Van Eyck did not hesitate to represent all the splendor of the microcosm with as much detail as possible, including a good fifty or so different plant species at the moment when all their most beautiful leaves and flowers are beheld by the world. It quite literally brings out the richness of creation in all its variety; allegorically, this represents the creator as the source of life; morally, it is the sacrifice of the son of God that will revive the Christian church; and finally, anagogically, it reminds us that we must strive towards becoming united with the creator, the source of all life, wisdom and good.

Once again, it is only in Denis the Carthusian, in the concluding passage of his Venestate Mundi and Pulchritudin Dei that one finds such passionate praise dedicated to the beauty of the visible world, including a reference to the famous « dark green meadows » so typical of Van Eyck:

Starting from the lowest level we have the elements of earth. In what immeasurable length and breadth are all extended; how wonderfully adorned is its surface with such innumerable species and various wonderful things. Look at the lilies and roses and other flowers of beautiful color as they emit their fragrant smells and healing herbs growing on the dark green meadows and in the shade of forests, the splendor of trees and lush fields, mountain heights, the freshness of trees, ponds, streams and rivers stretching to the sea in the distance! How beautiful He must be in and of himself, the One who created everything! Watch and admire the multitude of animals shining in their vast array of different colors! Our eye rejoices at the sigh of fish and birds and addresses our praise of the Creator. In what beauty and luster drape the large animals, the horse, the unicorn, the camel, the deer, the salmon and the pike, the phoenix, the peacock and the hawk. He is exalted, he who did all this!

With what we have just read in mind, the viewer can finally enjoy this beauty with confidence and without doubt, a beauty which is nothing but a foretaste of divine wisdom!

Bibliography:

- Boudewijn Bakker, Landschap en Wereldbeeld. Van Eyck tot Rembrandt, Thoth, 2004;·

- Patrice Sicard, Hugue of Saint Victor and his school, Brepols, 1991.·

- Denis the Carthusian, Towards the likeness, texts gathered and presented by Christophe Bagonneau, Word and Silence, 2003.·

- Karel Vereycken, Van Eyck, a Flemish painter in view of Arab optics, internet.

Le peintre belge Léopold Geysen

Visitez le site de mon ami, le peintre belge Léopold Geysen

Aquarelles, peintures à l’huile, sculptures, etc.