Étiquette : histoire

La splendeur des Royaumes d’Ifè et du Bénin

Les têtes en bronze d’Ifè (Nigeria) mettent à mal la théorie coloniale pour qui l’Afrique n’était qu’un terrain vierge, peuplé d’animaux et de quelques peuplades primitives n’ayant jamais fait leurs premiers pas dans « l’histoire ».

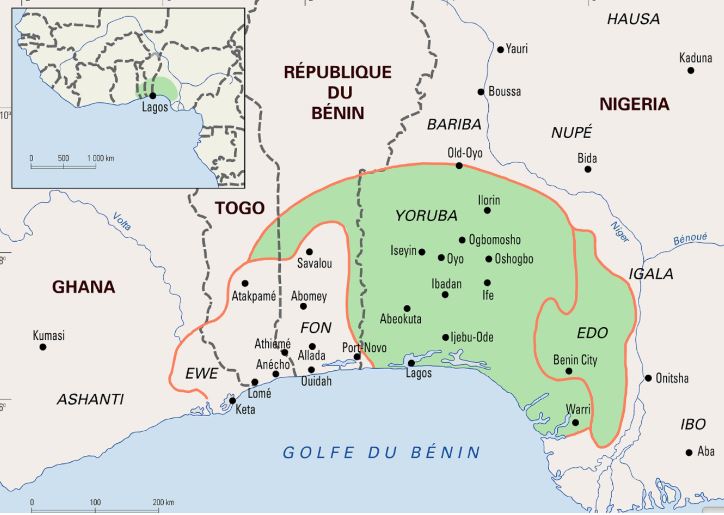

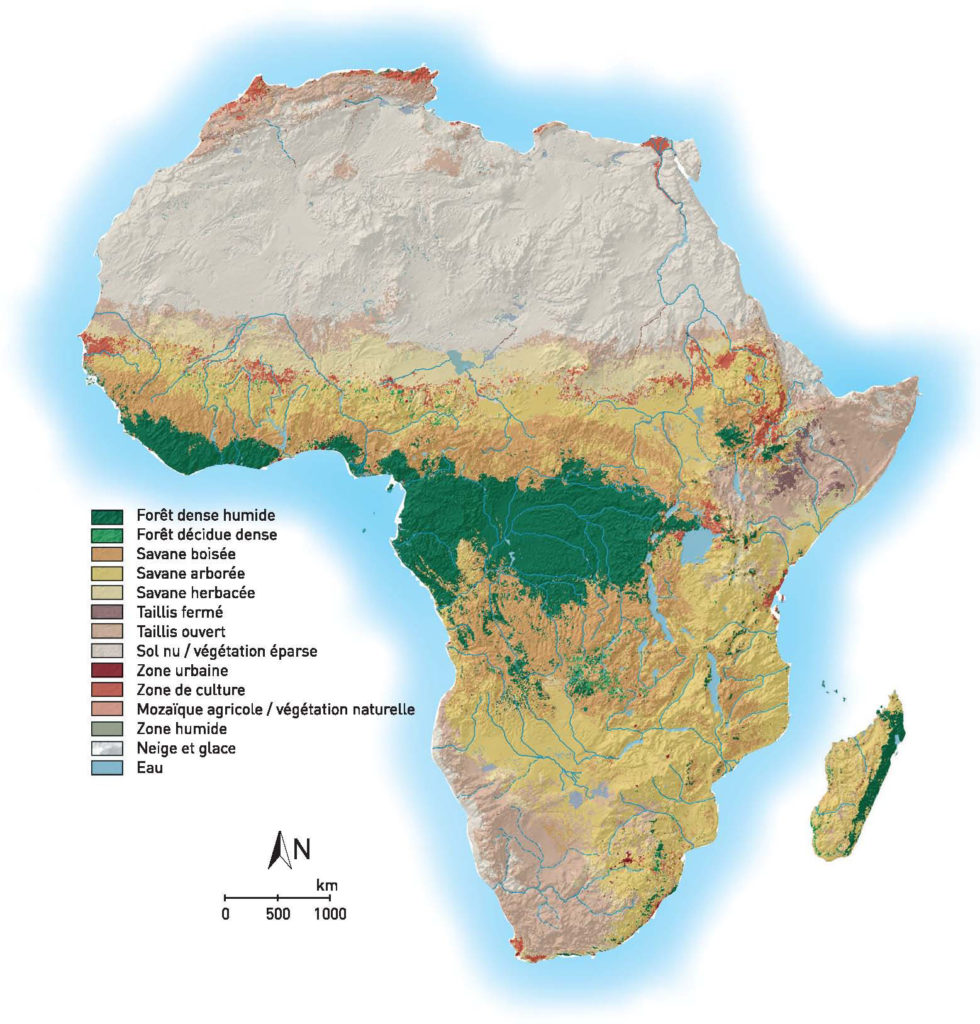

Aujourd’hui ville d’un demi-million d’habitants au sud-ouest du Nigeria, Ifè fut le centre religieux et l’ancienne capitale du peuple yoruba qui s’est développé pour l’essentiel grâce au commerce qu’il faisait sur le fleuve Niger, long de 4200 km, avec les peuples de l’Afrique de l’Ouest et au-delà.

Cet espace avant tout géoculturel de quelque 55 millions de personnes a prospéré dans une vaste ère géographique (Yoruba-land) d’environ 142 000 km², comprenant des régions entières de pays comme le Nigeria (76 %), le Bénin (18,9 %) et le Togo (6,5 %) actuels.

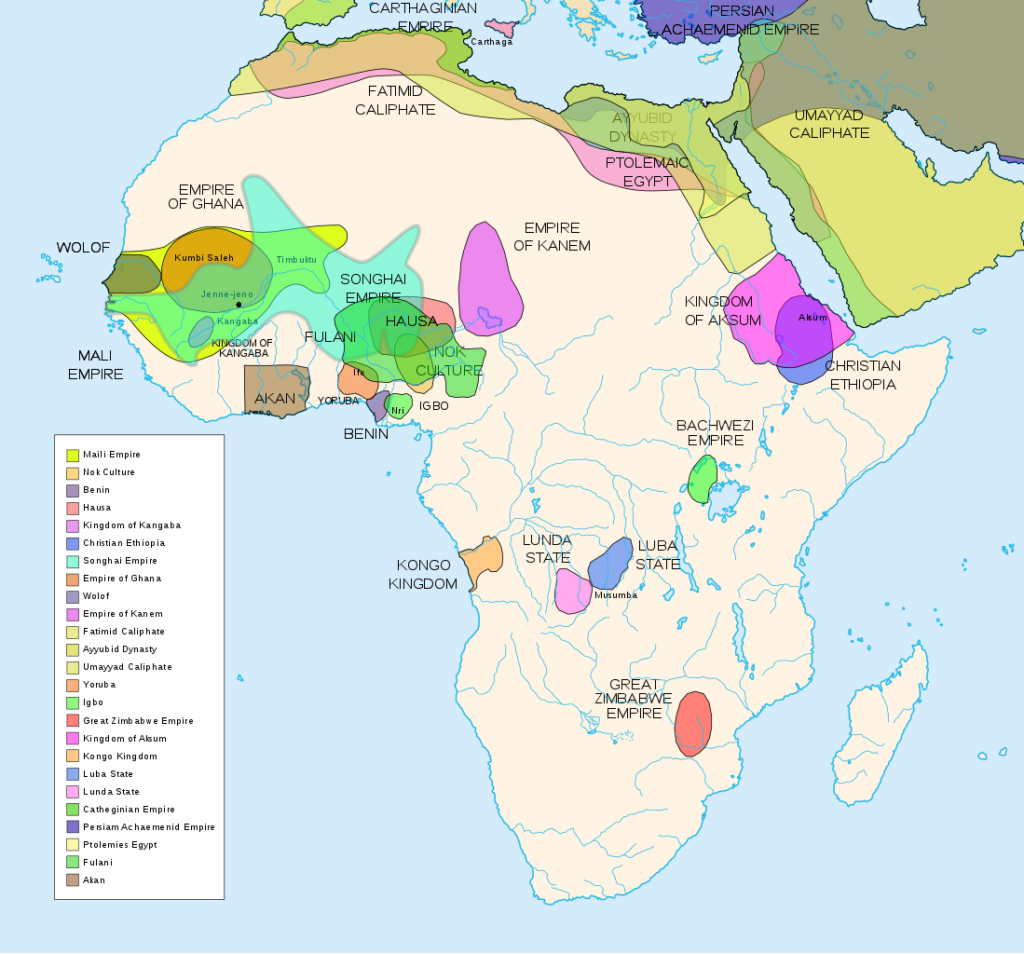

On trouve également des Yoruba au Ghana, au Burkina Faso, en Côte d’Ivoire et, depuis la traite négrière, aux Etats-Unis. Ce n’est donc pas surprenant que le yuroba, une langue à tons, soit l’une des trois grandes langues du Nigeria, également parlée dans certaines régions du Bénin et du Togo, ainsi qu’aux Antilles et en Amérique latine, notamment à Cuba par les descendants d’esclaves africains. Espace géo-culturel des yoruba autour d’Ifè et, à droite, celui du peuple edo au Royaume autour de Bénin City.

Un trésor hors du commun

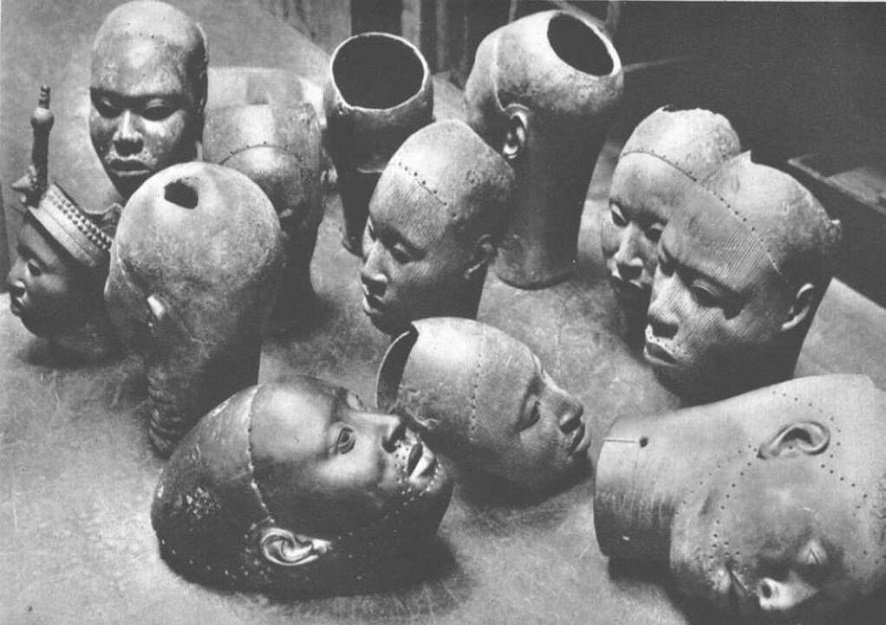

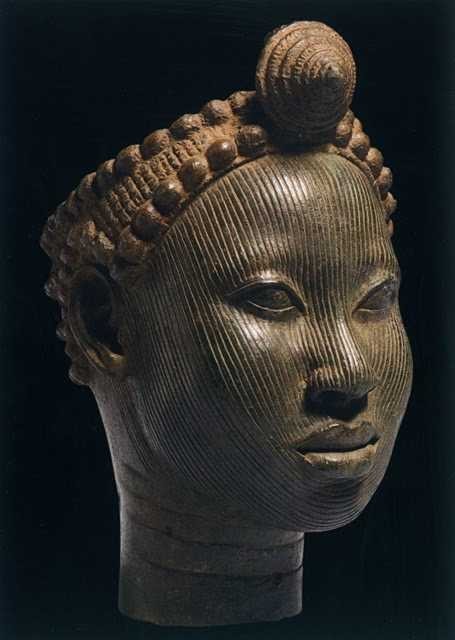

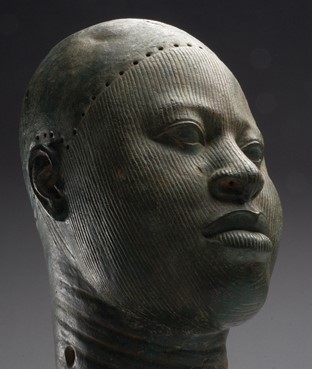

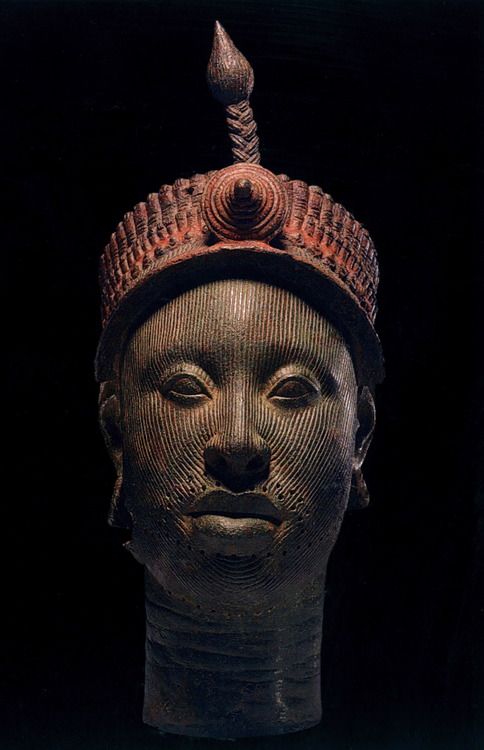

C’est en janvier 1938, lors de travaux de terrassement pour la construction d’une maison, que des ouvriers découvrent à Ifè, dans le quartier de Wunmonije, un trésor peu ordinaire. A une centaine de mètres du site du Palais Royal, ils déterrent treize magnifiques têtes en bronze datant du XIIe siècle représentant un roi (un « Ooni ») et des courtisans. D’autres ont été déterrées depuis.

Leurs visages, hormis les lèvres, sont couverts de striures. La coiffure fait penser à une couronne complexe composée de plusieurs couches de billes tubulaires, surmontée d’une crête avec une rosette et une « aigrette ».

La surface de cette couronne porte des traces de peinture rouge et noire. Ces grandes têtes ont pu servir d’effigies de défunts lors de cérémonies funéraires, qui, chez les Yoruba, ont parfois lieu un an après l’enterrement rapide des morts qu’impose le climat tropical.

Le rendu très ressemblant et naturaliste des têtes est alors considéré comme anachronique dans l’art de l’Afrique subsaharienne, et encore plus troublant que celui des portraits de momie, très réalistes, du Fayoum égyptien (I-IIe siècle)..

Pourtant, une longue tradition de sculpture figurative présentant des caractéristiques semblables existait avant la création de ces sculptures de métal, en particulier chez les Nok, un peuple de cultivateurs maîtrisant le fer à partir de 800 ans avant notre ère.

Hystérie

Depuis 1938, les « têtes d’Ifè » ont provoqué des réactions proches de l’hystérie en Europe et en Occident.

D’un côté, les « modernistes » et les « abstraits » du début du XXe siècle, pour qui plus une sculpture est abstraite et s’éloigne de la réalité, plus elle est considérée comme typiquement africaine.

Pour ceux qui s’inspiraient de « l’abstrait » africain pour se libérer du naturalisme matérialiste, les têtes d’Ifè venaient donc brutalement bousculer leurs théories savamment construites.

De l’autre, surtout pour les partisans de l’impérialisme colonial, cet art ne pouvait tout simplement pas exister.

A Frank Willett, le responsable du Département nigérian des Antiquités et auteur d’Ifè, une civilisation africaine (Editions Tallandier, 1967), qui rapportait que « les Européens en visite à Ifè se demandent fréquemment comment des gens vivant dans des maisons de boue séchée, aux toits de paille, ont pu fabriquer d’aussi beaux objets que les bronzes et terres cuites au musée », l’éditeur Sir Mortimer Wheeler répondit :

Le préjugé a la vie dure, qui veut que la création et la sensibilité artistiques ne puissent exister sans les talents domestiques et le confort sanitaire !

Les interrogations des Européens étaient nombreuses. Comment, au XIIe siècle, des peuples primitifs, n’ayant jamais connu de forme d’État organisé, auraient-ils pu fabriquer des têtes en bronze d’un tel raffinement, faisant appel à des techniques que même l’Europe ne maîtrisait pas à cette époque ? Comment des tribus, vivant dans la superstition et la magie la plus irrationnelle, auraient-elles pu observer avec tant de minutie l’anatomie humaine ? Comment des sauvages auraient-ils pu exprimer des sentiments aussi nobles, aussi bien envers des hommes que des femmes ?

Devant un paradoxe aussi insoutenable, le déni fut la règle.

Ainsi, lorsque l’archéologue allemand Leo Frobenius présenta le premier ce type de tête, les experts refusèrent de croire à l’existence d’une civilisation africaine capable de laisser des artefacts d’une qualité qu’ils reconnaissaient comparable aux meilleures réalisations artistiques de la Rome ou de la Grèce antiques. Pour tenter d’expliquer ce qui passait pour une anomalie, Frobenius avança alors, sans le moindre début de preuve, la théorie que ces têtes auraient été moulées par une colonie grecque fondée au XIIIe siècle av. J.-C., et que cette dernière pouvait être à l’origine de la vieille légende de la civilisation perdue de l’Atlantide, un récit repris en chœur par la presse populaire…

Bronze

Ce qui choqua en premier lieu les experts occidentaux, c’est qu’il s’agissait de têtes en bronze, en réalité en laiton au plomb (environ 70 % de cuivre, 16,5 % de zinc et 11,3 % de plomb).

Etant donné la rareté de ce minerai au Nigeria, ces objets démontrent que la région entretenait des relations commerciales avec des pays lointains. On pense qu’il provenait de l’Europe centrale, du nord-ouest de la Mauritanie, de l’Empire byzantin ou, via le fleuve Niger, de Tombouctou, où le minerai arrivait, à dos de dromadaire, du sud du Maroc.

Si durant la période du Néolithique, des pépites de cuivre, d’or et d’argent sont martelés à froid ou à chaud, ce n’est qu’à partir de l’Age du bronze que l’homme découvre la métallurgie. A partir de minerais, il est alors capable d’extraire des métaux grâce à un traitement thermique précis, rendu possible par l’expérience des céramistes de l’époque, grands experts dans la maîtrise de la chaleur et des fours de cuisson.

Or, le cuivre ne fond qu’à 1083° Celsius, mais en y ajoutant de l’étain (qui fond à 232°) et du plomb (qui fond à 327°), on peut obtenir du bronze à 890° et du laiton à 900°. La terre cuite se fait, elle, à basse température, aux alentours de 600 à 800°.

Cependant, en Chine, dès la dynastie des Shang (1570 – 1045 av. JC), certaines porcelaines exigent des températures beaucoup plus élevées, entre 1000 et 1300°.

Les plus anciennes traces de céramique en Afrique subsaharienne semblent dater de plus de 9000 av. J.-C., voire plus encore, quelques tessons fragmentaires, datés de 12 000 av. J.-C. ayant été découverts en Afrique de l’Ouest, en l’occurrence au Mali.

La céramique se manifeste également plus au sud, notamment avec la culture Nok dans le nord du Nigeria au début du Premier millénaire av. JC.

Cire perdue

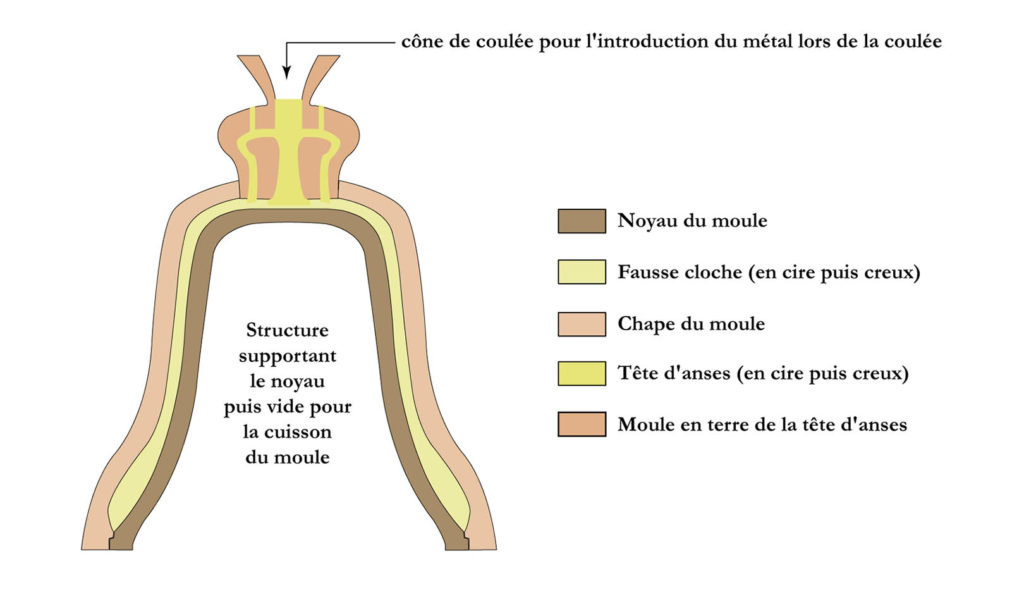

Ensuite, ce qui choqua tout autant les experts, c’est que la technique mise en œuvre pour leur réalisation était la technique dite « à cire perdue », un procédé de moulage de précision qu’on utilise encore de nos jours pour la fabrication des cloches d’églises. Le moule se compose de trois parties distinctes et superposées : le noyau, la cloche ou la statue (en cire) et la « carapace » ou chape. Par différentes astuces, le bronze en fusion qu’on laisse pénétrer va se substituer au modèle en cire. Lors de la coulée, différents conduits doivent permettre d’évacuer aussi bien la fumée qu’une partie de la cire lorsqu’elle fond.

En clair, il faut des artisans très qualifiés pour exercer le métier de fondeur de bronze professionnel.

Le savoir-faire exceptionnel des fondeurs d’Ifè fut précédé de peu par ceux d’Igbo-Ukwu au Nigeria oriental où l’on découvrit en 1939 un tombeau plein d’objets d’art datant du IXe siècle révélant l’existence d’un royaume puissant et raffiné maîtrisant la fameuse technique à la cire perdue, mais qui ne peut être rattachée à aucune autre culture de la région.

Historiquement, l’amulette de Mehrgarh au Pakistan, âgée de 6000 ans, est le premier objet connu façonné à la cire perdue. Si la Chine, la Grèce et Rome maîtrisent cette technique, il faut attendre la Renaissance pour qu’elle fasse son retour en Europe.

Ifè, un Etat organisé

Cartes des différents royaumes et empires africains avant la colonisation. Terre cuite en provenance du site d’Ita Yemoo, Ifè, Nigeria (XIIe au XIVe siècle).

En réalité, l’art d’Ifè mettait à mal la théorie coloniale pour qui l’Afrique n’était qu’un terrain vierge, peuplé d’animaux et de quelques peuplades primitives n’ayant jamais fait leurs premiers pas dans « l’histoire ».

En effet, toute preuve démontrant sur le continent africain l’existence d’empires, de royaumes ou de grands Etats ayant permis aux Africains de s’autogouverner de façon pacifique pendant des siècles, ne pouvait que délégitimer la « mission civilisatrice » du colonialisme.

Or, selon la tradition orale, Ifè fut fondée aux IXe-Xe siècles par Oduduwa, par le regroupement de 13 villages en une cité qui sera la ville centrale de la mythologie yoruba, pour qui elle est le berceau de l’humanité et le centre du monde.

Reconnu comme un dieu mineur, Oduduwa devint ainsi le premier Ooni (Roi) et se fit construire un Aafin (palais). Il gouverna à l’aide des isoro, anciens chefs de village ayant récupéré un titre religieux et assujettis à l’autorité politique royale.

Toujours selon les traditions orales, Oduduwa serait un prince exilé d’un peuple étranger, ayant quitté sa patrie avec une suite et voyagé en direction du sud, s’installant parmi les Yoruba vers le XIIe siècle. Sa foi, qu’il aura apportée, était si importante pour ses disciples et lui qu’elle aurait été la cause de leur exode en premier lieu.

La terre ou le pays d’origine d’Oduduwa sont sujet à débat. Pour les uns, il vient de La Mecque, pour les autres, d’Egypte, comme les savoir-faire qu’il apporta sont supposés le démontrer.

Il est vrai qu’on s’est avant tout intéressé aux routes conduisant vers la mer et les fleuves, il ne fait pas de doute que la savane, au cours des siècles précédents, a pu relier le delta du Niger au Nil, telle une sorte de grande route transcontinentale, passant notamment par le Tchad où des milliers de peintures pariétales témoignent d’un sens artistique créateur.

Le peuple Edo de Bénin City croit, quant à lui, qu’Oduduwa était en fait un prince de chez eux. Il aurait quitté le Bénin à cause d’une lutte pour la succession royale. C’est pourquoi l’un de ses descendants, le prince Oramiyan, fut par la suite autorisé à revenir, et fonda la dynastie qui régna sur le Royaume du Bénin. Le prince Oramiyan fut donc le premier oba du Benin, remplaçant ainsi avec succès le système monarchique Ogiso qui régnait jusque-là.

Métallurgie

Ce qui mérite l’attention, c’est que la métallurgie occupe une place centrale à Ifè. Oduduwa possédait une forge dans son palais (Ogun Laadin). Les rois des différents royaumes installaient leurs forges dans l’enceinte du palais royal, montrant ainsi le rapport symbolique fort entre pouvoir et métallurgie.

Les plus anciennes traces documentant la transformation du minerai de fer en Afrique remontent au IIIe millénaire av. JC. Il s’agit des sites archéologiques d’Egaro au Niger oriental et de Gizeh et Abydos en Egypte.

Tandis que le site de Buhen en Nubie égyptienne (- 1991), après avoir travaillé le fer, deviendra une « usine à cuivre », les sites d’Oliga au Cameroun (-1300) et de Nok au Nigeria (-925) témoignent d’une activité métallurgique dynamique.

Contrairement à ce qui s’est passé sur d’autres continents, l’Age de fer en Afrique aurait précédé dans certaines régions celui du cuivre. Comme nous l’avons vu, les techniques de production du laiton montrent un savoir-faire technologique très avancé. Ifè sera également un centre majeur de production verrière, en particulier de perles de verre. Les déchets de cette production ancestrale, constitués de parties de creusets recouverts de verre fondu, seront recherchés au XIXe siècle par les habitants de la région, bien que l’origine en soit à l’époque oubliée.

Des fouilles archéologiques récentes ont démontré que le peuplement de cette aire est très ancien. Mais comme nous l’avons vu, ce n’est qu’au début du IIe millénaire que des évolutions dans le domaine de la métallurgie auraient permis d’améliorer les outils agricoles et de générer des excédents de nourriture. On y cultive l’igname, le manioc, le maïs et le coton, qui est aussi à la source d’une importante industrie de tissage de vêtements.

La ville connaîtra ainsi une expansion démographique rapide grâce à cet essor de la productivité agricole, dû à la maîtrise d’une densité énergétique accrue permettant de transformer des « pierres » en ressources utiles.

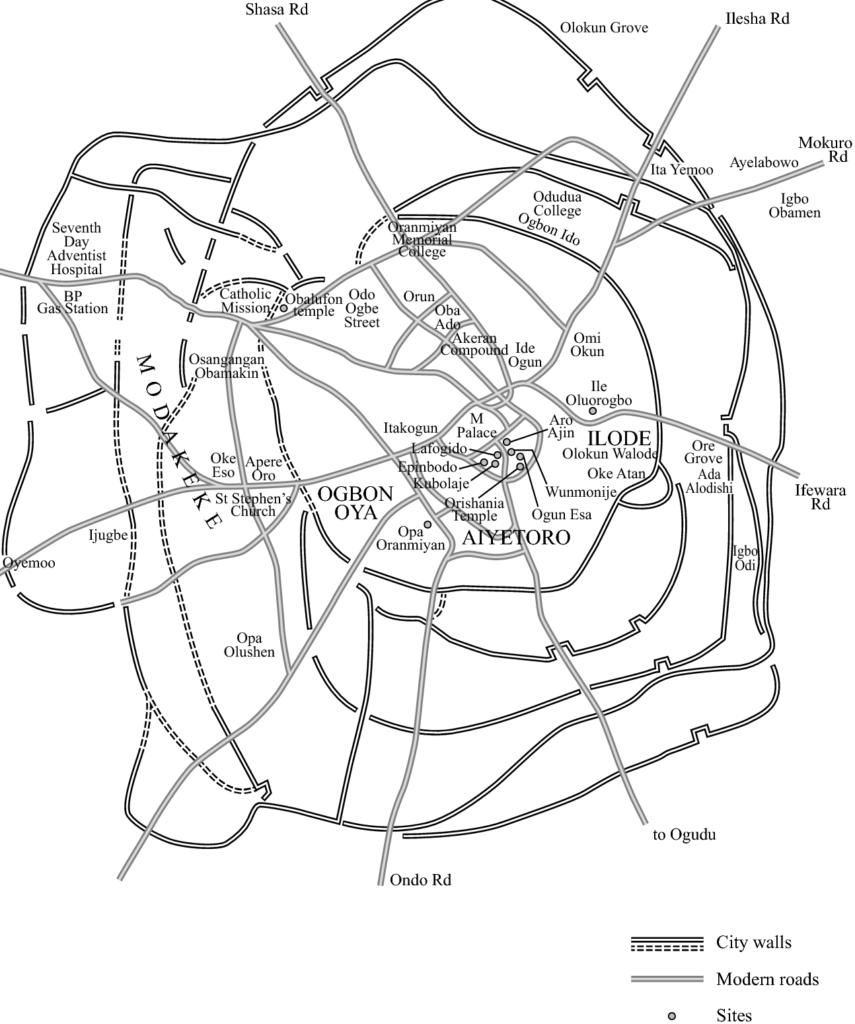

L’urbanisation médiévale d’Ifè est aujourd’hui largement attestée par l’existence de nombreuses enceintes faites de fossés et de talus, qui semblent indiquer les différents espaces ayant connu une concentration démographique et une entité politique suffisamment puissante pour mettre en œuvre de tels travaux.

Ainsi, en tant qu’Etat centralisé, Ifè s’érige très tôt en modèle pour d’autres Etats dans la région et au-delà. Plusieurs descendants et capitaines d’Oduduwa ont fondé d’autres royaumes sur le même modèle et s’appuyant sur la même légitimité. L’expérience monarchique d’Ifè s’exporte avec son cadre culturel. L’adé ilèkè, une couronne de perles de verre symbolisant le pouvoir royal, se retrouve dans la plupart des monarchies de la région.

En tout, de 7 à 20 royaumes selon les sources composent le monde yoruba dans la première moitié du deuxième millénaire de notre ère.

- L’État d’Oyo au Nigeria fut l’une des plus puissantes cités-États yoruba.

- Autre exemple, le Royaume de Kétou, actuellement au sud-est du Bénin, aurait été fondé vers le XIVe siècle par un prétendu descendant d’Oduduwa. Il aurait quitté Ifè avec sa famille et d’autres membres de son clan, pour se diriger vers l’ouest, avant de s’installer finalement dans la cité d’Aro, au nord-est de la ville de Kétou. Rapidement, Aro devint trop petit pour la population grandissante du clan, et la décision fut prise de s’installer à Kétou. Le roi Ede quitta donc Aro avec 120 familles et s’installa dans cette ville.

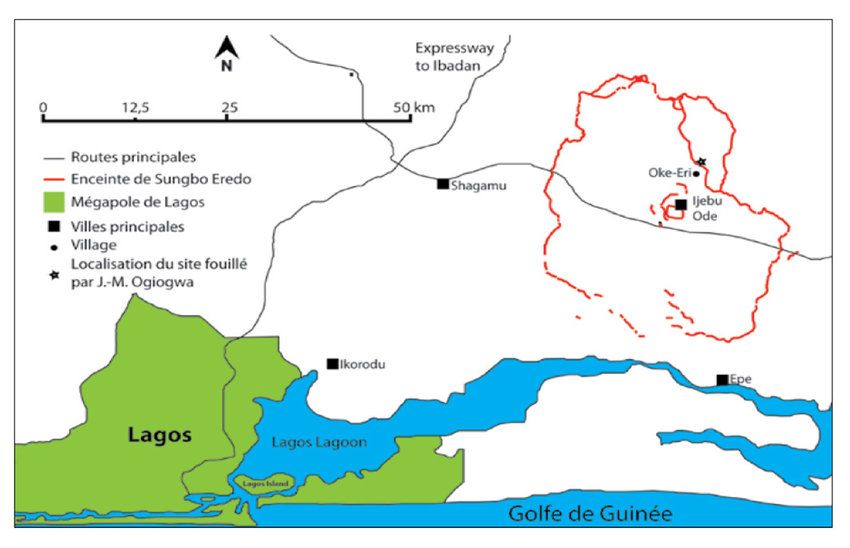

- Autre démonstration des bâtisseurs yoruba, près de la capitale nigeriane Lagos, l’enceinte de Sungbo Eredo, un système de murailles et de fossés construit au XIVe siècle e situé au sud-ouest de la ville d’Ijebu Ode, dans l’État d’Ogun, au sud-ouest du Nigeria. Sur plus de 160 km de long, ces fortifications, parfois hautes de 20 mètres, consistent en un fossé aux parois lisses, formant une douve intérieure par rapport aux murs qui le surplombent. Le fossé forme un anneau irrégulier autour des terres de l’ancien royaume d’Ijebu. Cet anneau fait environ 40 km dans le sens nord-sud et 35 km dans le sens est-ouest, c’est-à-dire l’équivalent du boulevard périphérique parisien ! Envahi par la végétation, l’édifice ressemble aujourd’hui à un tunnel verdoyant.

D’Ifè au Royaume du Bénin

Au XIVe siècle, Ifè connaît un effondrement démographique, caractérisé par l’abandon de certaines enceintes et une forte avancée de la forêt dans des zones anciennement occupées. On constate également une rupture dans les savoir-faire et les techniques artisanales. Cet effondrement démographique pourrait s’expliquer par une épidémie de peste noire, selon certains auteurs, qui font un parallèle avec les grandes épidémies constatées en Europe sur des périodes proches.

Une partie des habitants a pu se réfugier et apporter son savoir-faire en métallurgie au Royaume du Bénin, qui dura du XIIe siècle jusqu’à son invasion par l’Empire britannique à la fin du XIXe siècle. Il s’agit d’un Etat d’Afrique de l’Ouest côtière dominé par les Edos, une ethnie dont la dynastie survit encore aujourd’hui. Son territoire correspond au Bénin actuel, plus une partie du Togo et le sud-ouest de l’actuel Nigeria, où se trouve d’ailleurs aujourd’hui « Bénin City », un port historique sur le fleuve Bénin. Au cœur de la cité, la résidence royale aux proportions monumentales traduit dans l’espace l’importance accordée au pouvoir politique, spirituel et traditionnel.

Bénin City, une merveille

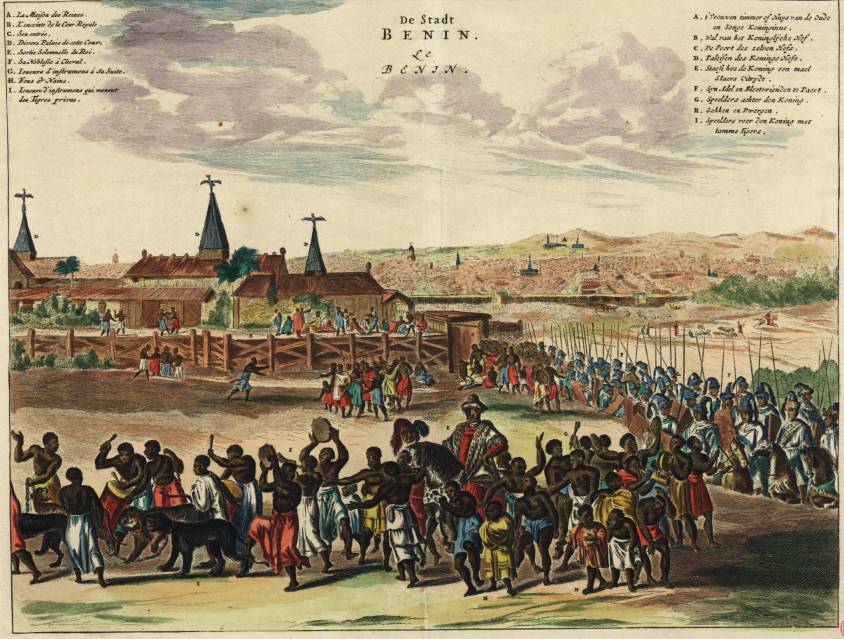

L’organisation sociale de la ville impressionne les visiteurs européens à la fin du XVe siècle. Important pôle économique régional, on y trouve de l’ivoire, du poivre et des esclaves. Les Européens y échangent de l’huile de palme (le palmier à huile poussant abondamment dans la région) contre des fusils, permettant la modernisation de l’armement béninois.

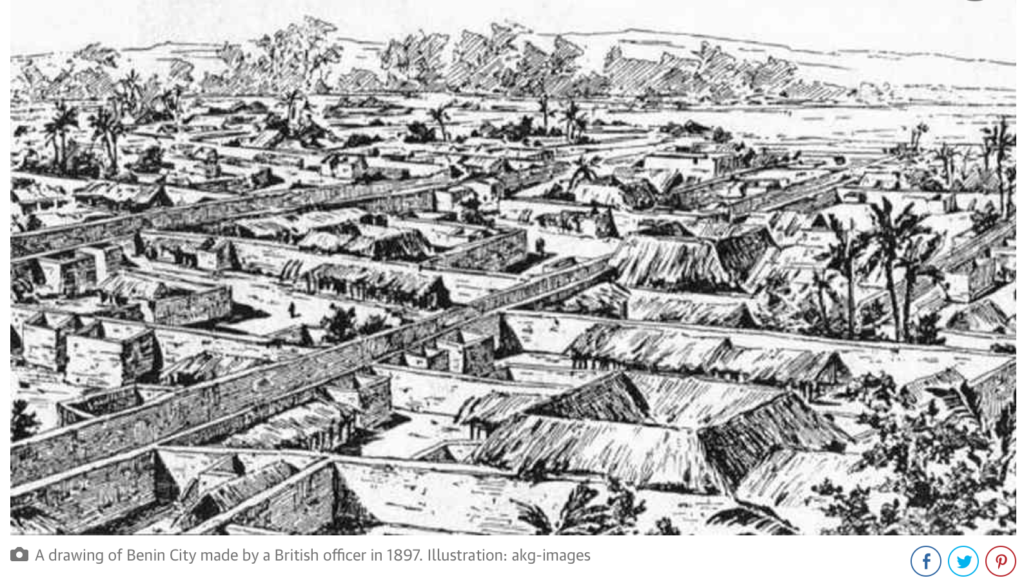

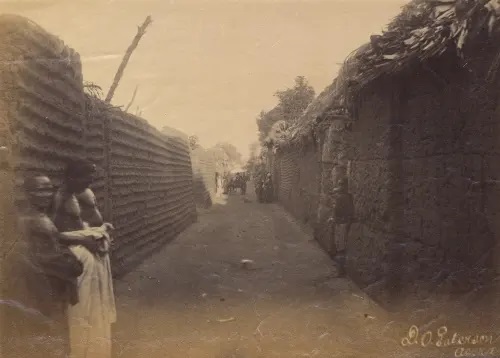

Située dans une plaine, Bénin City est entourée de murs massifs au sud et de profonds fossés au nord. Au-delà des murs de la ville, de nombreuses autres murailles ont été érigées qui séparent les environs de la capitale en quelque 500 villages distincts.

En 2016, un article du Guardian retraçait la splendeur de la ville. Le journal rapporte que le livre des records Guinness de 1974 décrit les murs de Bénin City comme les plus grands travaux de terrassement au monde réalisés avant l’ère mécanique. Selon les estimations de Fred Pearce, du New Scientist, les murs de Bénin City étaient à un moment donné « quatre fois plus longs que la Grande Muraille de Chine et employaient cent fois plus de matériaux que la Grande Pyramide de Khéops ».

Pearce précise que ces murs « s’étendaient sur quelque 16 000 km en tout, dans une mosaïque de plus de 500 limites de colonies interconnectées. Ils couvraient 6500 km2 et ont tous été creusés par le peuple Edo… On estime qu’il a fallu 150 millions d’heures pour les construire et qu’ils constituent peut-être le plus grand phénomène archéologique de la planète ».

Bénin City fut également l’une des premières villes à s’équiper d’un semblant d’éclairage public. D’énormes lampes métalliques, hautes de plusieurs mètres, se dressaient autour de la ville, en particulier près du palais du roi. Alimentées par de l’huile de palme, leurs mèches brûlaient pendant la nuit pour éclairer la circulation à destination et en provenance du palais.

Lorsque les Portugais découvrirent la ville pour la première fois en 1485, ils furent stupéfaits de trouver ce vaste royaume, fait de centaines de villes et de villages imbriqués les uns dans les autres au milieu de la jungle africaine. Ils l’appelèrent la « Grande ville du Bénin », à une époque où il n’y avait aucun autre endroit en Afrique que les Européens reconnaissent comme une ville. Ils la classèrent comme l’une des villes les plus belles et les mieux aménagées du monde. Bénin City en 1686.

En 1691, le capitaine de navire portugais Lourenco Pinto constatait :

Le Grand Bénin, où réside le roi, est plus grand que Lisbonne ; toutes les rues sont droites et à perte de vue. Les maisons sont grandes, en particulier celle du roi, qui est richement décorée et possède de belles colonnes. La ville est riche et industrieuse. Elle est si bien gouvernée que le vol est inconnu et les gens vivent dans une telle sécurité qu’ils n’ont pas de portes pour leurs maisons.

En revanche, à la même époque, Londres est décrite par Bruce Holsinger, professeur d’anglais à l’université de Virginie, comme une ville

de vol, prostitution, meurtre, corruption et marché noir florissant, ce qui a rendu la ville médiévale mûre pour l’exploitation par ceux qui savent manier la lame rapide ou faire les poches.

Les fractales africaines

La planification et la conception de Bénin City ont été faites selon des règles précises de symétrie, de proportionnalité et de répétition, aujourd’hui connues sous le nom de « fractales ».

Le mathématicien Ron Eglash, auteur de African Fractals (qui traite des motifs sous-tendant l’architecture, l’art et le design dans de nombreuses régions d’Afrique), note que la ville et les villages environnants ont été délibérément aménagés pour former des fractales parfaites, avec des formes similaires répétées dans les pièces de chaque maison, la maison elle-même et les groupes de maisons du village selon des motifs mathématiquement prévisibles.

Lorsque les Européens arrivèrent en Afrique, précise-t-il, ils considéraient l’architecture comme très désorganisée et donc primitive. Il ne leur est jamais venu à l’esprit que les Africains pouvaient utiliser une forme de mathématiques qu’eux-mêmes n’avaient pas encore découverte.

Au centre de la ville se trouvait le Palais royal, entouré d’une trentaine de rues droites et larges chacune d’environ 120 pieds. Ces rues principales, perpendiculaires les unes par rapport aux autres, étaient dotées d’un drainage souterrain constitué d’un impluvium, avec une sortie pour évacuer les eaux d’orage. De nombreuses rues plus étroites et se croisant s’étendaient à l’extérieur. Au milieu des rues, il y avait du gazon que les animaux pouvaient paître.

Les maisons sont construites le long des rues en bon ordre, l’une à côté de l’autre, écrit Olfert Dapper, visiteur hollandais du XVIIe siècle. Elles sont généralement larges, avec de longues galeries à l’intérieur, surtout dans le cas des maisons de la noblesse, et divisées en de nombreuses pièces qui sont séparées par des murs en argile rouge, très bien érigés.

Dapper ajoute que les riches résidents ont gardé ces murs

aussi brillants et lisses en les lavant et en les frottant que n’importe quel mur en Hollande fait avec de la craie, et ils sont comme des miroirs. Les étages supérieurs sont faits de la même sorte d’argile. De plus, chaque maison est équipée d’un puits pour l’approvisionnement en eau douce.

Les maisons familiales sont divisées en trois parties : la partie centrale est le quartier du mari, qui donne sur la route ; à gauche le quartier des femmes (oderie), et à droite le quartier des jeunes hommes (yekogbe).

La vie quotidienne à Bénin City voyait peut-être se déplacer dans des rues encore plus grandes, des foules constituées de gens vêtus de couleurs vives, certains en blanc, d’autres en jaune, bleu ou vert, les capitaines de la ville jouant le rôle de juges dans les procès, modérant les débats dans les nombreuses galeries et arbitrant les petits conflits sur les marchés.

Les premiers explorateurs étrangers décrivent Benin City comme un lieu exempt de criminalité et de faim, avec de grandes rues et des maisons propres, une ville remplie de gens courtois et honnêtes, et gérée par une bureaucratie centralisée et très sophistiquée. Bénin : plaque en laiton (bronze) montrant l’entrée du Palais royal où d’autres plaques décorent les piliers.

La ville est divisée en 11 arrondissements, chacune étant une réplique en plus petit de la cour du roi, comprenant une série tentaculaire de complexes incluant des logements, des ateliers et des bâtiments publics – reliés entre eux par d’innombrables portes et passages, tous richement décorés avec l’art qui a rendu le Bénin célèbre. La ville en était littéralement recouverte.

Les murs extérieurs des cours et les faîtes des enceintes sont décorés de motifs horizontaux (agben) et de sculptures en argile représentant des animaux, des guerriers et d’autres symboles de pouvoir.

Les sculptures sont conçues pour créer des motifs contrastés sous le fort soleil. Des objets naturels (galets ou morceaux de silicium) sont également pressés dans l’argile humide, tandis que dans les palais, les piliers sont recouverts de plaques de bronze illustrant les victoires et les exploits des anciens rois et nobles.

À l’apogée de sa grandeur, au XIIe siècle (bien avant le début de la Renaissance européenne), les rois et les nobles de Bénin City ont accordé leur mécénat aux artisans et les ont comblés de cadeaux et de richesses, en échange de la représentation des grands exploits des rois et des dignitaires dans des sculptures en bronze complexes.

Ces œuvres du Bénin sont à la hauteur des plus beaux exemples de la technique de fonte européenne », écrit Felix von Luschan, ancien professeur au Musée d’ethnologie de Berlin. « [Le sculpteur et fondeur italien] Benvenuto Celini n’aurait pas pu mieux les couler, ni personne d’autre avant ou après lui. Techniquement, ces bronzes représentent la plus haute réalisation possible.

La rencontre avec « la civilisation »

Suite à la conférence de Berlin de 1885 où Britanniques, Français, Allemands et autres puissances européennes se partagent, au nom des lois immuables de la géopolitique germano-britannique, l’Afrique comme un gros gâteau qu’il entendent dévorer, les invasions européennes se multiplient et gagnent en brutalité.

Ainsi, suite au refus du roi de céder aux Britanniques son monopole sur la production de l’huile de palme et d’autres productions, lors d’une expédition punitive en 1897, Bénin City est pillée, incendiée et réduite en cendres par les Britanniques. Le roi (l’oba) est chassé et plusieurs milliers de « bronzes du Bénin », certes moins réalistes que ceux d’Ifè, sont dispersés et en partie perdus.

Ils finissent par se retrouver sur le marché de l’art et aboutissent dans des musées, notamment au British Museum (700 objets) et au Musée d’ethnologie de Berlin (500 pièces). Le gouvernement britannique lui-même en vend une partie « pour couvrir les frais de l’expédition ». Comme quoi les uns entrent dans l’histoire avec leur art, les autres avec leurs crimes. Expédition punitive de 1897. Une fois le palais royal brûlé, les pilleurs britanniques alignent les pièces en cuivre et en laiton qu’ils ramèneront en Europe.

Bibliographie sommaire :

- Ifè, une civilisation africaine, Frank Willett, Jardin des Arts/Tallandier, Paris 1971 ;

- Histoire générale de l’Afrique, Présence africaines/Edicef/Unesco, Paris 1987 ;

- Atlas historique de l’Afrique, Editions du Jaguar, Paris 1988 ;

- L’Afrique ancienne, de l’Acus au Zimbabwe, sous la direction de François-Xavier Fauvelle, Belin/Humensis, Paris 2018.

Van Eyck : True Beauty, a foretaste of Divine Wisdom

Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441). How might we grasp the intention of this great Flemish painter, despite the five hundred years of distance separating us? Apart from looking at his work, here are three tracks that I’ve been able to uncover:

- The painter was undoubtedly initiated in the art of lectio divina, the multi-leveled interpretation of sacred texts;

- The influence of the French religious thinker Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141), an unknown but major figure who was an inspiration for the philosopher-cardinal Nicolas of Cusa;

- The advice given to the painter by theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), the confessor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, for whom the painter carried out diplomatic missions.

The writer would highly encourage all admirers of great art to get themselves a copy of the inspiring and scholarly work Landschap in Wereldbeeld, van Van Eyck tot Rembrandt (Landscape and Worldview, from Van Eyck to Rembrandt) by the Dutch art historian Boudewijn Bakker (published in 2004 at Thoth in Bossum, Netherlands, available in English). In a very rigorous and yet accessible work, Bakker offers us a series of important clues, which allow a XXIst century viewer to gain new insights into the often “hidden” meaning of Dutch and Flemish painting. For today’s viewers, what is often surprising in these works is the use of recurring references by the painters, their sponsors, religious officials and the general public of these countries.

Paradox

Before I read Bakker’s work, the paintings of northern Europe often appeared to me to be opposed to the prevailing philosophical and religious matrix of the fifteenth century, when in reality they were its very expression. Until now, I thought that, for the most part, the world view that prevailed at the end of the Middle-Ages was one rejecting the visible world as it was known through our senses. According to a scholastic misinterpretation of St. Augustine and Plato, the world was only deception and temptation, which one might have called the devil himself. Now, and herein lies the paradox in all its force, how can we reconcile the rejection of the visible world, particularly in sight of the work of the Flemish painter Van Eyck, who was able to show us human beings animated by kindness, glowing with beauty and surrounded by pristine nature?

I thought “How dare he show us so much beauty”, whereas in his day the doctrine of faith, which had been heralded as guardian of the temple, had kept reminding us that Man, in his glaring imperfection, was no God, and systematically warned us against the temptations of this world? Were the ironic but extremely moralizing pictures of Hieronymus Bosch and Joachim Patinier not intended to make us understand, albeit with violence, and yet with humor and great craft, that the origin of sin lay precisely in our excessive attachments to worldly things and the pleasures which were believed to be derived from them?

The Coincidence of Opposites

Without explicitly referring to the method of the great theologian-philosopher, Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa, the « coincidence of opposites » (coincidentia oppositorum), that is to say the paradoxes whose seemingly irreconcilable differences can be overcome from a higher conceptual level, Bakker demonstrates that the aforementioned paradox is also only one of appearance.

In order to make sense of this, Bakker first recalls that for the Augustinian current, for whom man was created in the living image of the creator (Imago Viva Dei), nature was neither more nor less than « theophany », that is to say, for those who were able to read it, it was the revelation of a divine intention.

For this current, God revealed himself to man, not by one, but by « two books, » the first of which was none other than « the book of nature, » read through our eyes; the second being the Bible, which was accessible through our eyes and ears. With this connection in mind, Bakker emphasizes two nearly forgotten yet first-rate Christian thinkers who had unfortunately fallen into obscurity following the hegemony of Aristotelianism, which had been ushered in by St. Thomas of Aquinas in tandem with the rise of nominalism and the counter-reformation. The first is the French abbot and theologian Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141), one of the medieval writers whose manuscripts were widely circulated at the time, and Denis the Carthusian (1402-1471), a Dutch friend and collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464) and also confessor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1396-1467).

The Lectio Divina of Nature

In respect to his interpretation of the paintings, Bakker did the work that any true art historian worthy of such a title should have necessarily done: he compared the paintings with, if they still existed, the writings of their times.

By using the writings of the time to inform his interpretation of the paintings, Bakker formulates a rigorous hypothesis around the idea that the masterpieces of Flemish painting, riddled with as many enigmas and mysteries as our beautiful cathedrals, are to be read « on several levels ». The said “four levels” was what the biblical exegesis of the day prescribed based on ancient tradition.

First, in Judaism, long before the arrival of Jesus, the study of the Torah appealed to the « doctrine of the four senses »:

- the literal meaning,

- the allegorical meaning,

- the allusive meaning, and

- the mystical meaning (possibly hidden, secret or kabalistic).

Then, Christians, especially Origen (185-254), then Ambrose of Milan in the fourth century, repeated this method with the Lectio Divina, that is to say, the exercise of spiritual reading aimed, by prayer, to penetrate a sacred text at its deepest level.

Finally, introduced in the fourth century by Ambrose, Augustine made Lectio Divina the basis of monastic prayer. It would then be taken over by Jerome, Venerable Bede, Scot Erigena, Hugue of Saint Victor, Richard of Saint Victor, Alain of Lille, Bonaventure and would impose itself upon Saint Thomas Aquinas and Bernard of Clairvaux.

Bakker takes care to specify these four levels of reading:

- The literal meaning is that which comes from the linguistic comprehension of the utterance. It tells the facts and « narrative » of a text while situating it in the context of its time;

- The allegorical meaning comes from Greek allos, meaning “other”, and agoreuein, to “say”. By stating one thing, Allegory also says another. Thus an allegory explains what a story symbolizes;

- The moral or tropological meaning (of the Latin tropos meaning « change »), offers us a lesson or advice. By understanding the figures, vices or virtues, passions or stages that the human mind must travel in its ascent to God, each person can draw on such wisdom for his own life;

- The anagogical meaning (adjective from the Greek anagogikos or elevation), is obtained by the interpretation of the Gospels, to give an idea of the last realities that will become visible at the end of time. In philosophy, for Leibniz, « anagogical induction » is something which can be traced back to a first cause.

These four meanings were formulated in the Middle Ages in a famous Latin couplet: littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria, moralis quid agas, quo tendas anagogia (the letters teach the facts, allegory what one must believe, morality is what one must do, anagogy what one should aspire to).

The reason I bring this issue of multi-level biblical exegesis is that Bakker says, from the standpoint of this worldview in the Middle Ages, this method of interpretation was thought to apply not only to the Bible, but to visible creation as well.

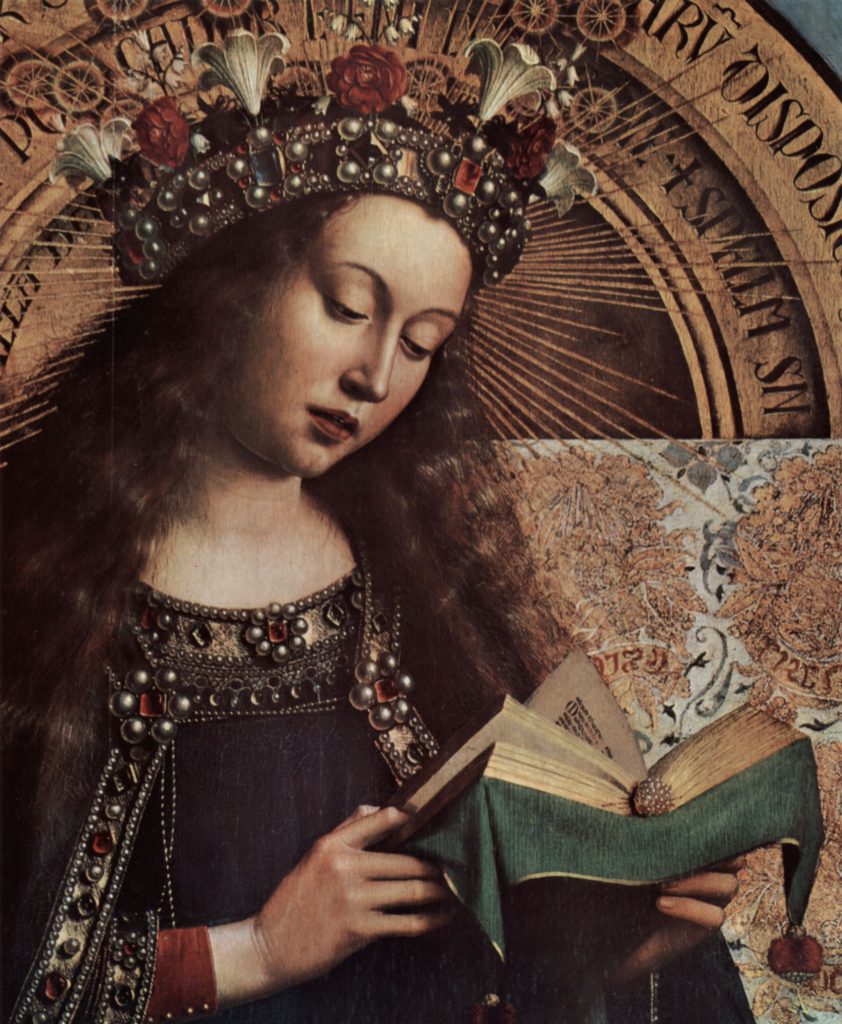

Close-up of the page of the book in front of which the Virgin in the Annunciation kneels, decorating the exterior shutters of the altarpiece of Ghent by Jan Van Eyck (1432). At the bottom of the page, one reads clearly (in red): « de visione dei », the title of the work of Nicolas de Cues of 1453.

But is this merely the instance of some kind of sentimental moment in which one is relishing in the beauty of creation for its own sake? Not at all ! Far from pantheism (a sin), it was a question of « reading », as Hugue of Saint Victor stated, « with the eyes of the mind », which « the eyes of the flesh » were not able to see, a concept that would be taken up again by Nicolas de Cusa in his work of 1543: On painting, or The Vision of God. The paradox can therefore be solved. For, in the allegory of the cavern evoked by Plato in The Republic, the man who is chained before a wall and only able to see shadows projected on the wall, was able to use his intelligence in order identify what the causes that made those shadows possible. Certainly, man cannot « know » God directly. However, by studying the effects of his action, he can come to discover his intention. It is therefore through Hugue of Saint Victor, that the Augustinian and Platonic current that inspired the Carolingian Renaissance resurfaced in Paris. In this current of thought, creation as a whole, from the anagogical point of view, was the shadow cast by a heavenly paradise and a direct reference to omnipotence, beauty and divine goodness. For Bakker:

All of these interpretations are easily illustrated by the works of Augustine, because they have inspired writers on nature throughout the Middle Ages. Augustine greatly loved the world as it appeared to us; he knew how to enjoy what he referred to as ‘the great and beautiful spaces of the city or the countryside, where the brilliance of its beauty immediately strikes the viewer. But such creation also contains innumerable ‘moral’ messages, allowing so many opportunities for a pious and acute observer to reflect on his soul and task on Earth. Time after time, Augustine emphasized this aspect when he spoke of natural phenomena. Each time, he would incite us to seek the invisible behind the visible, the eternal behind the temporal, etc. Thus the harmony that creation revealed was an indication of the peace that should rein among men. Each creature, taken separately, appeared as an example (negative or positive) which man could discern, were he willing. This applied particularly to the behavior of animals, for example. And in regards to the Earth as a whole, one should take heed and make sure to not overlook the hollows and chasms of a landscape, for they are its true wellsprings.

Hugue of Saint Victor

In France, it was with the advent of the XIIth century intellectual renaissance that centers of learning began to multiply (cathedral school, school of Abelard, school of Petit-Pont for Paris, Chartres, Laon etc…) and that an atmosphere of genuine knowledge turned France into a world-center for intellectual life. As well, numerous students originating from Germany, Italy, England, Scotland and Northern Europe all made their way to Paris in order to study first and foremost, dialectics and theology.

Hugue of Saint Victor (1096-1141) was of Saxon (or Flemish?) origin. Around 1127, he entered the house of the regular canons of Saint Victor shortly after the monastery’s founding on the outskirts of Paris.

The Victorins were distinguished from the beginning by the importance with which they regarded intellectual life. The canons of the abbey had a positive outlook on knowledge, hence the importance which they attached to their library.

The main teachers who influenced Hugue were: Raban Maur (himself a disciple of Charlemagne’s advisor, the Irishman Alcuin), Bede the Venerable, Yves de Chartres and Jean Scot Erigena and some others, perhaps Denys – The Areopagite himself of which he comments on The Celestial Hierarchy.

Propelled by an insatiable intellectual curiosity, Hugue advised his disciples to learn everything because, according to him, nothing is without use. He himself was the first to put the advice he gave to his disciples into practice. A notable part of his writings were devoted to the liberal arts, sciences, and philosophy, which he dealt with particularly in an introductory textbook on secular and sacred studies, still famous today, the Didascalicon.

His contemporaries considered him the greatest theologian of their time and gave him the glorious title of « New Augustine ». He influenced the Franciscans of Oxford (Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) whose influence on the painter Roger Campin has been well established, by whom Nicolas of Cusa was inspired.

In regards to the question of whether one should cherish or despise the world, Hugue of Saint Victor’s answer was that we must love the world, but with the condition that we never forget that we must love it with God always in sight, as a reflection of God, rather than something in and of itself.

In order for one to be able to reach such wisdom, man had to consider his existence as that of a pilgrim who was constantly breaking away from the place in which he resides, a very rich metaphor that would be found in the Flemish painters Bosch and Patinier. « The whole world is an exile for those who philosophize, » said Hugue.

Master Hugue posed the requirement of exceeding dilectio (jealous and possessive love of God) for condilectio (love welcoming and open to sharing). He advocated the idea of an agapic love turned towards others, and not centered on oneself, a love turned towards the neighbor, the love of God increased by the love of one’s neighbor. In a word: it was the idea of Christian charity and fraternal solidarity.

Hugues enumerated five spiritual exercises: reading, meditation, prayer, action and contemplation. The first granted understanding; the second provided a reflection; the third questioned, the fourth sought and the fifth found. These exercises were intended to allow one to reach the source of truth and charity, where the soul of man would be « transformed into a flame of love », resting in the hands of God in « a fullness of both knowledge and love.”

The subject which interests us here, is above all his optimistic vision of man and creation, which differed from the clichés that we have retained from medieval pessimism. For him, creation was a gift from God and the way to God was as much through reading the book of nature itself as it was from reading the Bible.

Thus, for Hugue of Saint Victor, the image that we perceive is nothing but revelation or the unveiling of God’s Divine Power, perceived

through the length, breadth, and depth of space, through the mountain ranges, the winding rivers, the rolling fields, the towering skies and the darkened chasms.

Thus, the painter who exceled in the representation of the physical universe, was only increasing his capacity to reveal the power of the creator!

The revelation of wisdom through Beauty. For Hugue, «the entirety of the sensible universe is one great book written by the hand of God” that is, created by a divine plan in which

every creature is a reflection of – not the product of human desire, but the fruit of divine providence’s will to manifest God’s great wisdom (…) Just as an illiterate looks at the lines of an open book without having knowledge of letters, a stupid and bestialized man ‘that does not understand the things that are of God’, sees in creatures only their external form, but has no understanding of their inner meaning.

To elevate oneself, Hugue proposed that the disciples of Saint Victor, all those who were able of « contemplating relentlessly, » to embrace « a spiritual vision » of the world. For his disciple, Richard of Saint Victor, the Bible and the great book of nature « share the same language and harmonize to reveal the wonders of a secret world. »

Denis the Carthusian,

the Key to Understanding Van Eyck

Two centuries after Hugue of Saint Victor, that same flame later animated the work of theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), a native of Belgian Limburg. Under the title The beauty of the world : ordo et varietas, Bakker devotes a whole chapter of his book to it. And you’ll soon understand why.

Two centuries after Hugue of Saint Victor, that same flame later animated the work of theologian Denis the Carthusian (1401-1471), a native of Belgian Limburg. Under the title The beauty of the world : ordo et varietas, Bakker devotes a whole chapter of his book to it. And you’ll soon understand why.

Before having joined the Carthusians of Roermond in the Netherlands, Denys was trained in the spirit of the Brothers of the Common Life at the Zwolle school in the Netherlands and then completed his studies at the University of Cologne.

With Jean Gerson (1363-1429) and Nicolas of Cusa (1402-1464), and despite an often much more wordy and sometimes confused style, Denis the Carthusian was counted as among the most well-read, most copied and most published authors of his day, once the printing press had replaced the laborious work of the copyist monks. Moreover, the first book published in Flanders, was none other than the Mirror of the Sinful Soul of Denis the Carthusian, printed in 1473 by Erasmus of Rotterdam’s friend, Dirk Martens.

At the Roermond Monastery in the Netherlands, Denis wrote 150 works including commentaries on the Bible and 900 sermons. After having read one, Pope Eugene IV, who had just ordered Brunelleschi to complete the cupola of the Santa Maria del Fiore Dome in Florence, exulted: « The Mother Church is delighted to have such a son! ».

As a scholar, theologian and advisor, Denys became very influential. « A number of gentlemen, clerics and bourgeois came to consult him in his cell in Roermond where he constantly resolved doubts, difficulties and cases of conscience. (…) He was in frequent contact with the House of Burgundy and serves as an adviser to Philip the Good « , confirms the Dutch historian Huizinga in his Autumn of the Middle Ages.

According to Bakker, having written a series of works on spiritual orientation, Denis performed the role of confessor and spiritual guide for the Christian sovereign Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and subsequently, that of his widow.

Together in Cologne, both attended the lecture of Flemish theologian Heymeric van de Velde (De Campo) who introduced them to the mystical theology of the Syrian Platonic monk known as Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite and to the work of Raymond Lulle and of Albert the Great as well. When, in 1432, Nicolas of Cusa declined an offer for the chair of Theology made to him by the University of Louvain, it was De Campo who accepted it at his request. Politically, from 1451 to 1452, Denis the Carthusian chose Nicolas of Cusa, then apostolic legate, to accompany him for several months during his tour of the Rhineland and Moselle to promote his approach to spiritual renewal, at the request of the pope.

Bakker notes that Denis had a predilection for music. He copied and illuminated scores with his hand and gave instructions on the best possible interpretation of the Psalms. His preference was for psalms praising God. And to praise the creator, Denis found images and words that would surface in the imagination of the painters of that time. However, for Denis, the beauty of God meant something deeper than mere visual appeal.

For you (Lord), ‘to be’ is ‘to be beautiful’.

Let us remember that in Christian philosophy sight was the most important of the five senses and the one which encapsulated all the others. In Denis’ Psalms, two notions prevailed. First, that of order and regularity. It was found in the celestial bodies that determined the cycles of days and years. But the Earth itself obeyed a divine order. And there Denis quoted the Book of Wisdom of Solomon (11,20) affirming: « You have ordained everything with measure, number and weight ». Then there was the idea of multiplicity and diversity. Regarding climatic phenomena, that is to say purely « physical » phenomena, Denis affirmed for example,

In the sky, lord, you generated multiple effects of pressure and air, such as clouds, winds, rains (…) and various phenomena: comets, luminous crowns, vortices, falling stars (…), frost and haze, hail, snow, the rainbow and the flying dragon.

For Denis, all this was not without a reason: it was to penetrate the divine being, his infinite greatness, his omnipotence and his love for man.

Make it so, my Lord, he writes, that in the effects of your universal laboriousness we perceive you, and that by the love with which it testifies, we inflame ourselves and waken to honor your greatness.

On God and Beauty, Denis wrote a great treatise on theological aesthetics under the title of De Venustate Mundi and Pulchritudine Dei (About the Attractiveness of the World and the Beauty of God).

After having read what follows, the great polyptych painted by Jan Van Eyck, the altarpiece of Ghent known as The Mystic Lamb, comes to mind.

Knowing that this painter was in the service (painter and ambassador) of the same Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, of which Denis the Carthusian was the confessor and spiritual guide, one has good reason to believe that this text had impressed itself on the painter’s spirit at the time of this work’s creation.

Denis the Carthusian:

Just as every creature participates in the being of God and his goodness, so does the Creator also communicate to him something of his divine, eternal, uncreated beauty, whereby he is in part made like his Creator, participating in some measure in his beauty. In as much as a thing receives the essence of that being, so it receives the good and the beautiful of that being. There is therefore an uncreated beauty which is beautiful and beauty in its essence: God. The Other (as opposed to being) is the created beauty: the beautiful by participation. Just as every creature is thought of as being to the extent that it participates in the divine being and is assimilated with it by through a kind of imitation, so every creature is said to be beautiful in the degree to which it participates in this divine beauty and is brought in conformity with it. . Just as God has done all which is good since his nature is good, so he has done all things beautiful because he is essentially beautiful.

(…) The one and only son of God, true God himself, took our nature and became our brother. Through him, our nature has received a dignity of unspeakable majesty. God has also adorned the souls of the blessed who are in the heavenly homeland with his light and glory, and raised them to the beatific, immediate, clear and blessed vision of his all-pure Deity. By contemplating the uncreated and infinite beauty of the divine essence, they are made in his image in a supernatural and ineffable way. They are over-taken in this participation, this communion of goodness, this divine light and beauty, to the point of being entirely enthralled by him, configured to him, absorbed in him. They attain such beauty heights of beauty that the greatest splendors of world cannot even be compared with the smallest part of their beauty.

Back to Van Eyck

This last paragraph immediately evokes the upper panels of Jan Van Eyck’s polyptych in Gent. It’s hard to imagine the kind of effect that this painting would have had on believers: they saw not only Adam and Eve, raised on the same level as God, the Virgin and St. John the Baptist, but discovered there, at a time when less than one percent of the European population could read and write, the image of a beautiful young woman reading the Bible. Her name? Mary, mother of Jesus!

The lower part of the same work depicts another major event: the reunification, following the various ecumenical councils, of all Christians, whether they were from the East or West, divided by disagreements over the fundamental issue of the Christian faith: the sacrifice of the Son of God to free man from original sin. They are assembled in a chorus around all the most significant parts of the universe: the three popes, the philosophers, the poets (Virgil), the martyrs, the hermits, the prophets, the just judges, the Christian knights, the saints and the virgins.

Everything is presented in a landscape renewed by a true Christian “Spring”. Van Eyck did not hesitate to represent all the splendor of the microcosm with as much detail as possible, including a good fifty or so different plant species at the moment when all their most beautiful leaves and flowers are beheld by the world. It quite literally brings out the richness of creation in all its variety; allegorically, this represents the creator as the source of life; morally, it is the sacrifice of the son of God that will revive the Christian church; and finally, anagogically, it reminds us that we must strive towards becoming united with the creator, the source of all life, wisdom and good.

Once again, it is only in Denis the Carthusian, in the concluding passage of his Venestate Mundi and Pulchritudin Dei that one finds such passionate praise dedicated to the beauty of the visible world, including a reference to the famous « dark green meadows » so typical of Van Eyck:

Starting from the lowest level we have the elements of earth. In what immeasurable length and breadth are all extended; how wonderfully adorned is its surface with such innumerable species and various wonderful things. Look at the lilies and roses and other flowers of beautiful color as they emit their fragrant smells and healing herbs growing on the dark green meadows and in the shade of forests, the splendor of trees and lush fields, mountain heights, the freshness of trees, ponds, streams and rivers stretching to the sea in the distance! How beautiful He must be in and of himself, the One who created everything! Watch and admire the multitude of animals shining in their vast array of different colors! Our eye rejoices at the sigh of fish and birds and addresses our praise of the Creator. In what beauty and luster drape the large animals, the horse, the unicorn, the camel, the deer, the salmon and the pike, the phoenix, the peacock and the hawk. He is exalted, he who did all this!

With what we have just read in mind, the viewer can finally enjoy this beauty with confidence and without doubt, a beauty which is nothing but a foretaste of divine wisdom!

Bibliography:

- Boudewijn Bakker, Landschap en Wereldbeeld. Van Eyck tot Rembrandt, Thoth, 2004;·

- Patrice Sicard, Hugue of Saint Victor and his school, Brepols, 1991.·

- Denis the Carthusian, Towards the likeness, texts gathered and presented by Christophe Bagonneau, Word and Silence, 2003.·

- Karel Vereycken, Van Eyck, a Flemish painter in view of Arab optics, internet.