Étiquette : coton

La splendeur des Royaumes d’Ifè et du Bénin

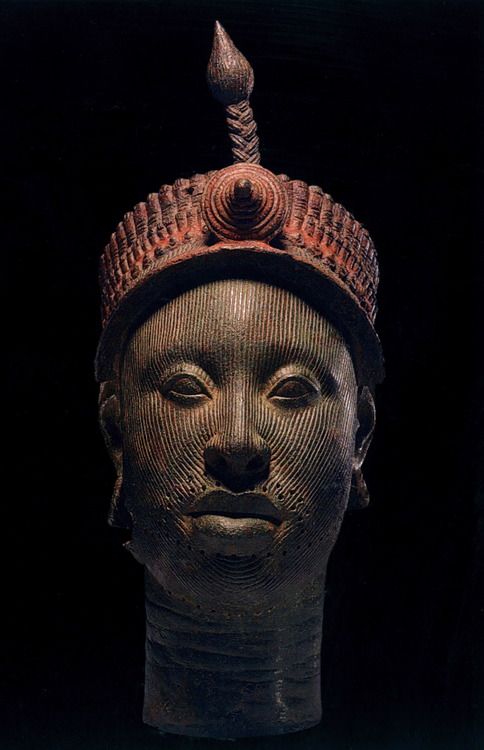

Les têtes en bronze d’Ifè (Nigeria) mettent à mal la théorie coloniale pour qui l’Afrique n’était qu’un terrain vierge, peuplé d’animaux et de quelques peuplades primitives n’ayant jamais fait leurs premiers pas dans « l’histoire ».

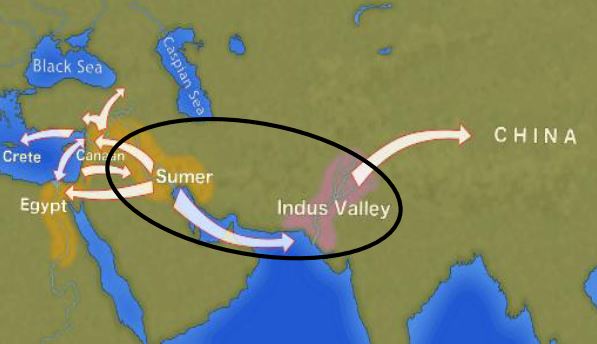

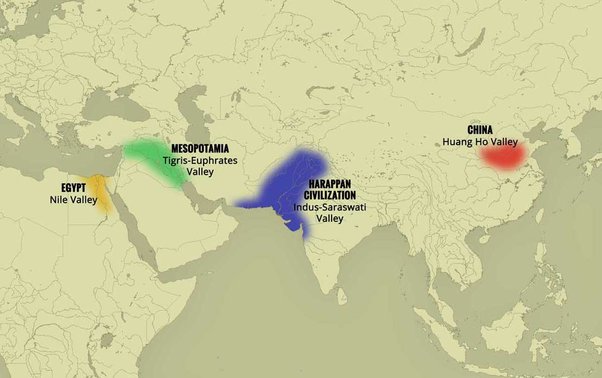

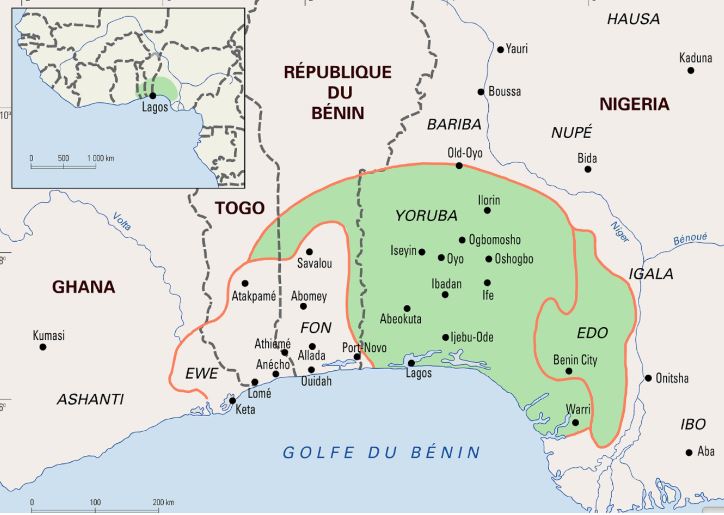

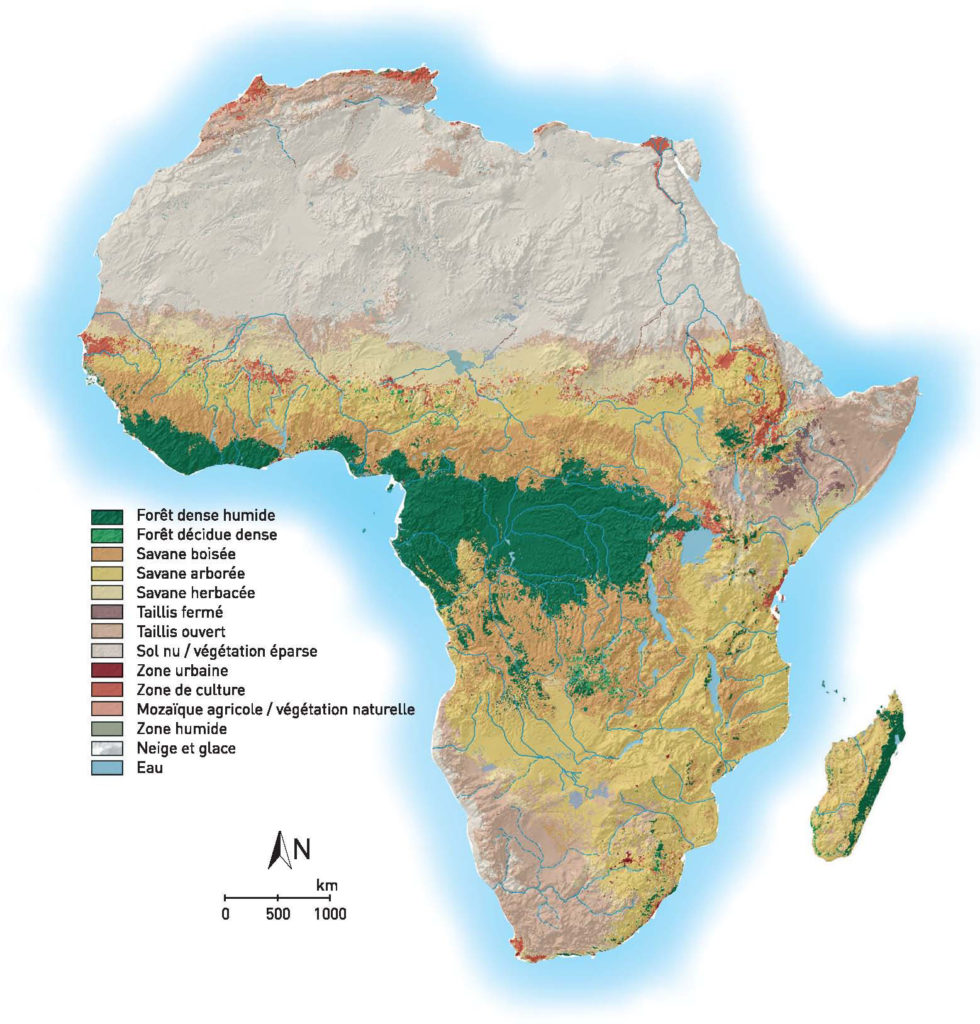

Aujourd’hui ville d’un demi-million d’habitants au sud-ouest du Nigeria, Ifè fut le centre religieux et l’ancienne capitale du peuple yoruba qui s’est développé pour l’essentiel grâce au commerce qu’il faisait sur le fleuve Niger, long de 4200 km, avec les peuples de l’Afrique de l’Ouest et au-delà.

Cet espace avant tout géoculturel de quelque 55 millions de personnes a prospéré dans une vaste ère géographique (Yoruba-land) d’environ 142 000 km², comprenant des régions entières de pays comme le Nigeria (76 %), le Bénin (18,9 %) et le Togo (6,5 %) actuels.

On trouve également des Yoruba au Ghana, au Burkina Faso, en Côte d’Ivoire et, depuis la traite négrière, aux Etats-Unis. Ce n’est donc pas surprenant que le yuroba, une langue à tons, soit l’une des trois grandes langues du Nigeria, également parlée dans certaines régions du Bénin et du Togo, ainsi qu’aux Antilles et en Amérique latine, notamment à Cuba par les descendants d’esclaves africains. Espace géo-culturel des yoruba autour d’Ifè et, à droite, celui du peuple edo au Royaume autour de Bénin City.

Un trésor hors du commun

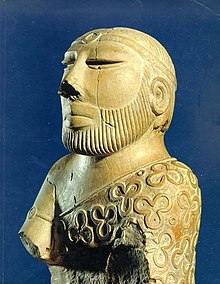

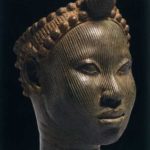

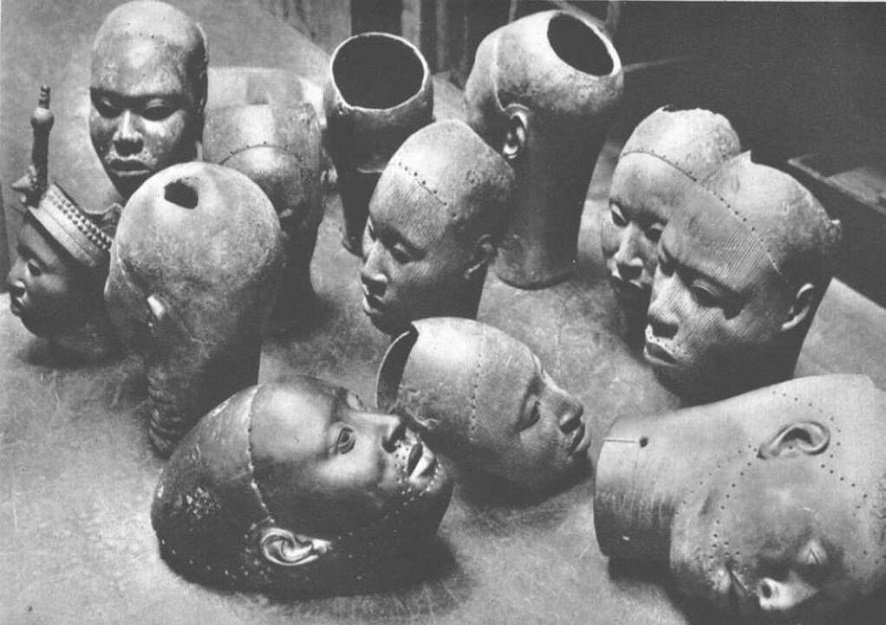

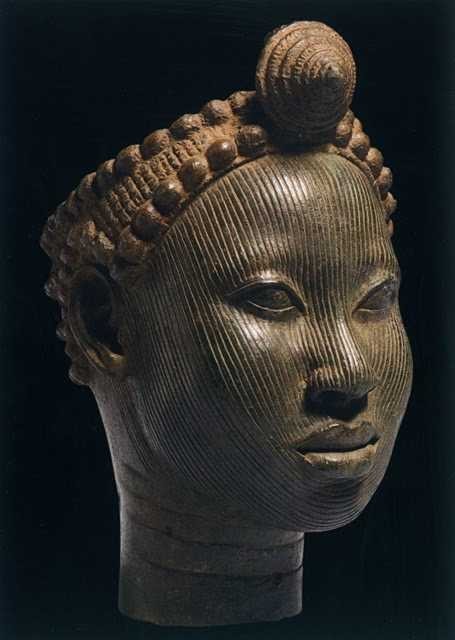

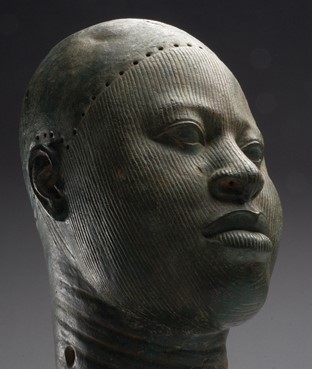

C’est en janvier 1938, lors de travaux de terrassement pour la construction d’une maison, que des ouvriers découvrent à Ifè, dans le quartier de Wunmonije, un trésor peu ordinaire. A une centaine de mètres du site du Palais Royal, ils déterrent treize magnifiques têtes en bronze datant du XIIe siècle représentant un roi (un « Ooni ») et des courtisans. D’autres ont été déterrées depuis.

Leurs visages, hormis les lèvres, sont couverts de striures. La coiffure fait penser à une couronne complexe composée de plusieurs couches de billes tubulaires, surmontée d’une crête avec une rosette et une « aigrette ».

La surface de cette couronne porte des traces de peinture rouge et noire. Ces grandes têtes ont pu servir d’effigies de défunts lors de cérémonies funéraires, qui, chez les Yoruba, ont parfois lieu un an après l’enterrement rapide des morts qu’impose le climat tropical.

Le rendu très ressemblant et naturaliste des têtes est alors considéré comme anachronique dans l’art de l’Afrique subsaharienne, et encore plus troublant que celui des portraits de momie, très réalistes, du Fayoum égyptien (I-IIe siècle)..

Pourtant, une longue tradition de sculpture figurative présentant des caractéristiques semblables existait avant la création de ces sculptures de métal, en particulier chez les Nok, un peuple de cultivateurs maîtrisant le fer à partir de 800 ans avant notre ère.

Hystérie

Depuis 1938, les « têtes d’Ifè » ont provoqué des réactions proches de l’hystérie en Europe et en Occident.

D’un côté, les « modernistes » et les « abstraits » du début du XXe siècle, pour qui plus une sculpture est abstraite et s’éloigne de la réalité, plus elle est considérée comme typiquement africaine.

Pour ceux qui s’inspiraient de « l’abstrait » africain pour se libérer du naturalisme matérialiste, les têtes d’Ifè venaient donc brutalement bousculer leurs théories savamment construites.

De l’autre, surtout pour les partisans de l’impérialisme colonial, cet art ne pouvait tout simplement pas exister.

A Frank Willett, le responsable du Département nigérian des Antiquités et auteur d’Ifè, une civilisation africaine (Editions Tallandier, 1967), qui rapportait que « les Européens en visite à Ifè se demandent fréquemment comment des gens vivant dans des maisons de boue séchée, aux toits de paille, ont pu fabriquer d’aussi beaux objets que les bronzes et terres cuites au musée », l’éditeur Sir Mortimer Wheeler répondit :

Le préjugé a la vie dure, qui veut que la création et la sensibilité artistiques ne puissent exister sans les talents domestiques et le confort sanitaire !

Les interrogations des Européens étaient nombreuses. Comment, au XIIe siècle, des peuples primitifs, n’ayant jamais connu de forme d’État organisé, auraient-ils pu fabriquer des têtes en bronze d’un tel raffinement, faisant appel à des techniques que même l’Europe ne maîtrisait pas à cette époque ? Comment des tribus, vivant dans la superstition et la magie la plus irrationnelle, auraient-elles pu observer avec tant de minutie l’anatomie humaine ? Comment des sauvages auraient-ils pu exprimer des sentiments aussi nobles, aussi bien envers des hommes que des femmes ?

Devant un paradoxe aussi insoutenable, le déni fut la règle.

Ainsi, lorsque l’archéologue allemand Leo Frobenius présenta le premier ce type de tête, les experts refusèrent de croire à l’existence d’une civilisation africaine capable de laisser des artefacts d’une qualité qu’ils reconnaissaient comparable aux meilleures réalisations artistiques de la Rome ou de la Grèce antiques. Pour tenter d’expliquer ce qui passait pour une anomalie, Frobenius avança alors, sans le moindre début de preuve, la théorie que ces têtes auraient été moulées par une colonie grecque fondée au XIIIe siècle av. J.-C., et que cette dernière pouvait être à l’origine de la vieille légende de la civilisation perdue de l’Atlantide, un récit repris en chœur par la presse populaire…

Bronze

Ce qui choqua en premier lieu les experts occidentaux, c’est qu’il s’agissait de têtes en bronze, en réalité en laiton au plomb (environ 70 % de cuivre, 16,5 % de zinc et 11,3 % de plomb).

Etant donné la rareté de ce minerai au Nigeria, ces objets démontrent que la région entretenait des relations commerciales avec des pays lointains. On pense qu’il provenait de l’Europe centrale, du nord-ouest de la Mauritanie, de l’Empire byzantin ou, via le fleuve Niger, de Tombouctou, où le minerai arrivait, à dos de dromadaire, du sud du Maroc.

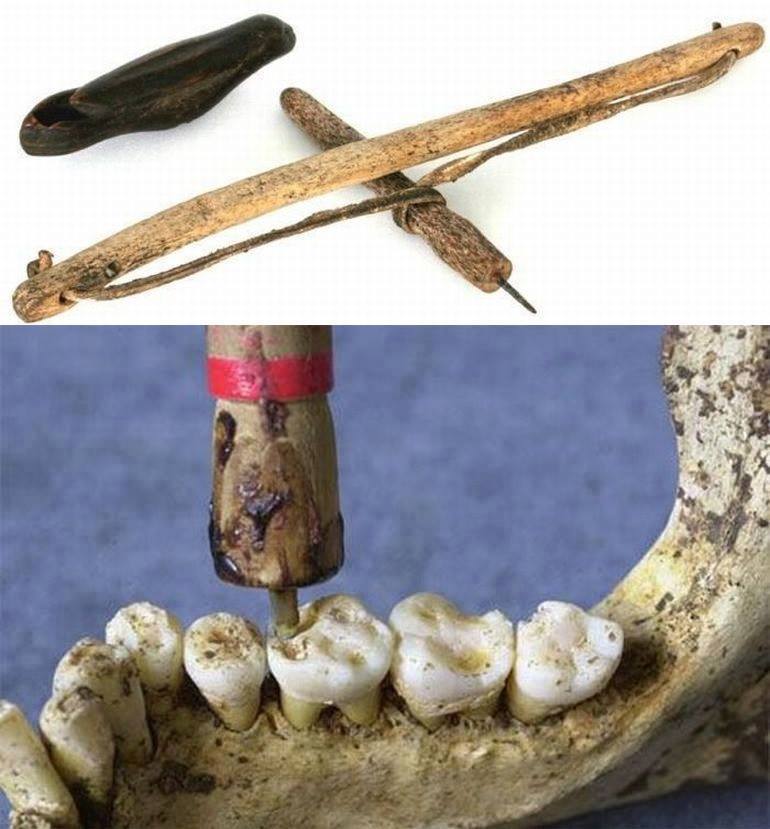

Si durant la période du Néolithique, des pépites de cuivre, d’or et d’argent sont martelés à froid ou à chaud, ce n’est qu’à partir de l’Age du bronze que l’homme découvre la métallurgie. A partir de minerais, il est alors capable d’extraire des métaux grâce à un traitement thermique précis, rendu possible par l’expérience des céramistes de l’époque, grands experts dans la maîtrise de la chaleur et des fours de cuisson.

Or, le cuivre ne fond qu’à 1083° Celsius, mais en y ajoutant de l’étain (qui fond à 232°) et du plomb (qui fond à 327°), on peut obtenir du bronze à 890° et du laiton à 900°. La terre cuite se fait, elle, à basse température, aux alentours de 600 à 800°.

Cependant, en Chine, dès la dynastie des Shang (1570 – 1045 av. JC), certaines porcelaines exigent des températures beaucoup plus élevées, entre 1000 et 1300°.

Les plus anciennes traces de céramique en Afrique subsaharienne semblent dater de plus de 9000 av. J.-C., voire plus encore, quelques tessons fragmentaires, datés de 12 000 av. J.-C. ayant été découverts en Afrique de l’Ouest, en l’occurrence au Mali.

La céramique se manifeste également plus au sud, notamment avec la culture Nok dans le nord du Nigeria au début du Premier millénaire av. JC.

Cire perdue

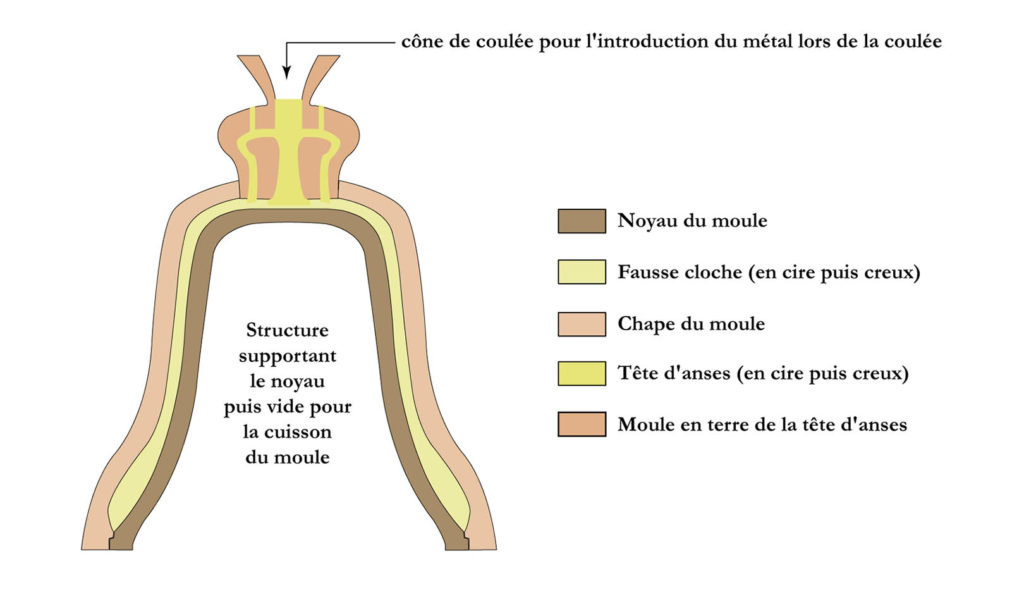

Ensuite, ce qui choqua tout autant les experts, c’est que la technique mise en œuvre pour leur réalisation était la technique dite « à cire perdue », un procédé de moulage de précision qu’on utilise encore de nos jours pour la fabrication des cloches d’églises. Le moule se compose de trois parties distinctes et superposées : le noyau, la cloche ou la statue (en cire) et la « carapace » ou chape. Par différentes astuces, le bronze en fusion qu’on laisse pénétrer va se substituer au modèle en cire. Lors de la coulée, différents conduits doivent permettre d’évacuer aussi bien la fumée qu’une partie de la cire lorsqu’elle fond.

En clair, il faut des artisans très qualifiés pour exercer le métier de fondeur de bronze professionnel.

Le savoir-faire exceptionnel des fondeurs d’Ifè fut précédé de peu par ceux d’Igbo-Ukwu au Nigeria oriental où l’on découvrit en 1939 un tombeau plein d’objets d’art datant du IXe siècle révélant l’existence d’un royaume puissant et raffiné maîtrisant la fameuse technique à la cire perdue, mais qui ne peut être rattachée à aucune autre culture de la région.

Historiquement, l’amulette de Mehrgarh au Pakistan, âgée de 6000 ans, est le premier objet connu façonné à la cire perdue. Si la Chine, la Grèce et Rome maîtrisent cette technique, il faut attendre la Renaissance pour qu’elle fasse son retour en Europe.

Ifè, un Etat organisé

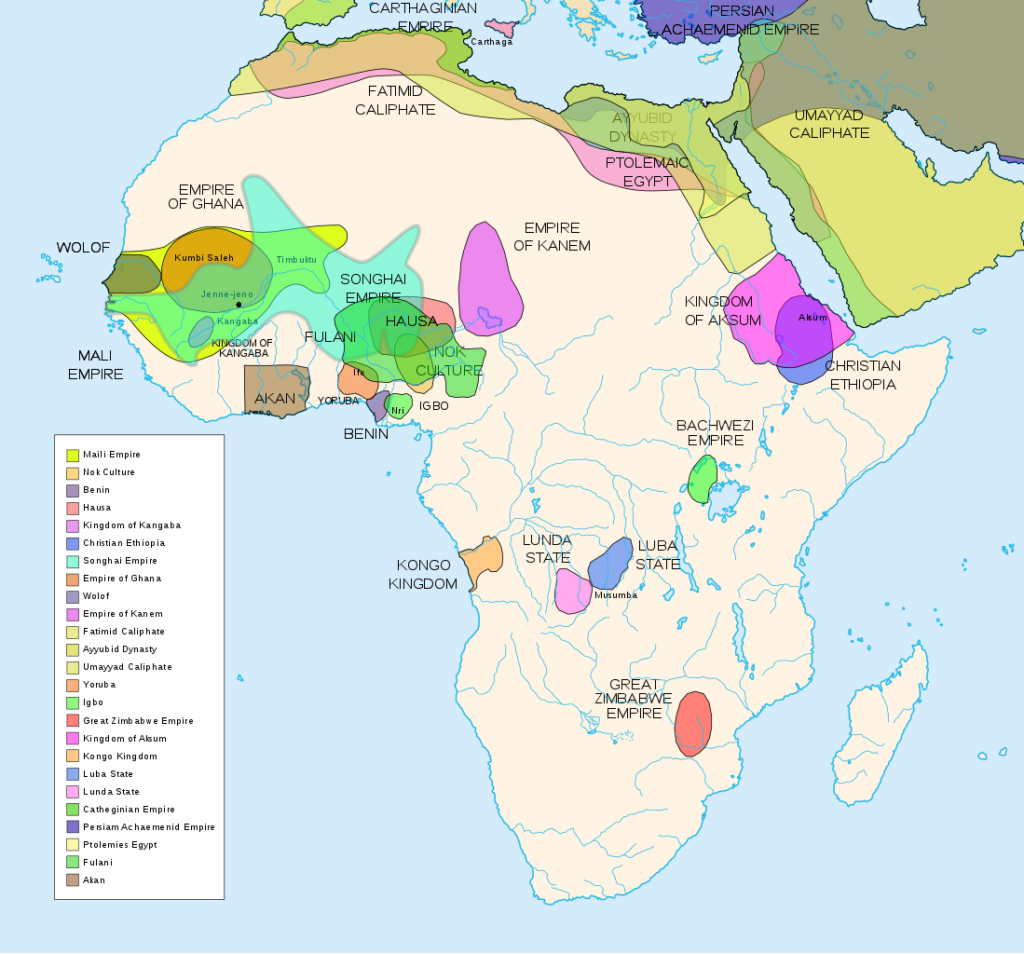

Cartes des différents royaumes et empires africains avant la colonisation. Terre cuite en provenance du site d’Ita Yemoo, Ifè, Nigeria (XIIe au XIVe siècle).

En réalité, l’art d’Ifè mettait à mal la théorie coloniale pour qui l’Afrique n’était qu’un terrain vierge, peuplé d’animaux et de quelques peuplades primitives n’ayant jamais fait leurs premiers pas dans « l’histoire ».

En effet, toute preuve démontrant sur le continent africain l’existence d’empires, de royaumes ou de grands Etats ayant permis aux Africains de s’autogouverner de façon pacifique pendant des siècles, ne pouvait que délégitimer la « mission civilisatrice » du colonialisme.

Or, selon la tradition orale, Ifè fut fondée aux IXe-Xe siècles par Oduduwa, par le regroupement de 13 villages en une cité qui sera la ville centrale de la mythologie yoruba, pour qui elle est le berceau de l’humanité et le centre du monde.

Reconnu comme un dieu mineur, Oduduwa devint ainsi le premier Ooni (Roi) et se fit construire un Aafin (palais). Il gouverna à l’aide des isoro, anciens chefs de village ayant récupéré un titre religieux et assujettis à l’autorité politique royale.

Toujours selon les traditions orales, Oduduwa serait un prince exilé d’un peuple étranger, ayant quitté sa patrie avec une suite et voyagé en direction du sud, s’installant parmi les Yoruba vers le XIIe siècle. Sa foi, qu’il aura apportée, était si importante pour ses disciples et lui qu’elle aurait été la cause de leur exode en premier lieu.

La terre ou le pays d’origine d’Oduduwa sont sujet à débat. Pour les uns, il vient de La Mecque, pour les autres, d’Egypte, comme les savoir-faire qu’il apporta sont supposés le démontrer.

Il est vrai qu’on s’est avant tout intéressé aux routes conduisant vers la mer et les fleuves, il ne fait pas de doute que la savane, au cours des siècles précédents, a pu relier le delta du Niger au Nil, telle une sorte de grande route transcontinentale, passant notamment par le Tchad où des milliers de peintures pariétales témoignent d’un sens artistique créateur.

Le peuple Edo de Bénin City croit, quant à lui, qu’Oduduwa était en fait un prince de chez eux. Il aurait quitté le Bénin à cause d’une lutte pour la succession royale. C’est pourquoi l’un de ses descendants, le prince Oramiyan, fut par la suite autorisé à revenir, et fonda la dynastie qui régna sur le Royaume du Bénin. Le prince Oramiyan fut donc le premier oba du Benin, remplaçant ainsi avec succès le système monarchique Ogiso qui régnait jusque-là.

Métallurgie

Ce qui mérite l’attention, c’est que la métallurgie occupe une place centrale à Ifè. Oduduwa possédait une forge dans son palais (Ogun Laadin). Les rois des différents royaumes installaient leurs forges dans l’enceinte du palais royal, montrant ainsi le rapport symbolique fort entre pouvoir et métallurgie.

Les plus anciennes traces documentant la transformation du minerai de fer en Afrique remontent au IIIe millénaire av. JC. Il s’agit des sites archéologiques d’Egaro au Niger oriental et de Gizeh et Abydos en Egypte.

Tandis que le site de Buhen en Nubie égyptienne (- 1991), après avoir travaillé le fer, deviendra une « usine à cuivre », les sites d’Oliga au Cameroun (-1300) et de Nok au Nigeria (-925) témoignent d’une activité métallurgique dynamique.

Contrairement à ce qui s’est passé sur d’autres continents, l’Age de fer en Afrique aurait précédé dans certaines régions celui du cuivre. Comme nous l’avons vu, les techniques de production du laiton montrent un savoir-faire technologique très avancé. Ifè sera également un centre majeur de production verrière, en particulier de perles de verre. Les déchets de cette production ancestrale, constitués de parties de creusets recouverts de verre fondu, seront recherchés au XIXe siècle par les habitants de la région, bien que l’origine en soit à l’époque oubliée.

Des fouilles archéologiques récentes ont démontré que le peuplement de cette aire est très ancien. Mais comme nous l’avons vu, ce n’est qu’au début du IIe millénaire que des évolutions dans le domaine de la métallurgie auraient permis d’améliorer les outils agricoles et de générer des excédents de nourriture. On y cultive l’igname, le manioc, le maïs et le coton, qui est aussi à la source d’une importante industrie de tissage de vêtements.

La ville connaîtra ainsi une expansion démographique rapide grâce à cet essor de la productivité agricole, dû à la maîtrise d’une densité énergétique accrue permettant de transformer des « pierres » en ressources utiles.

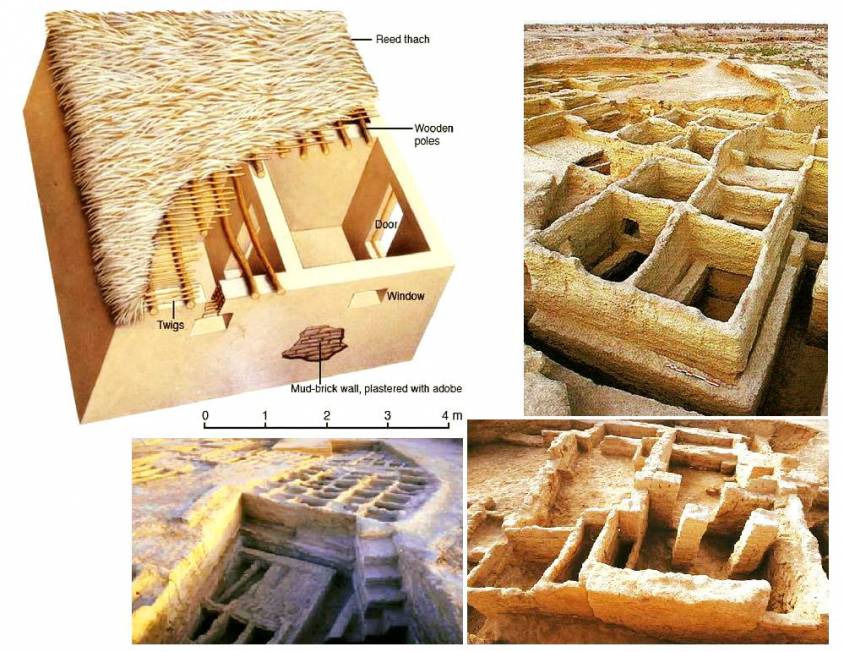

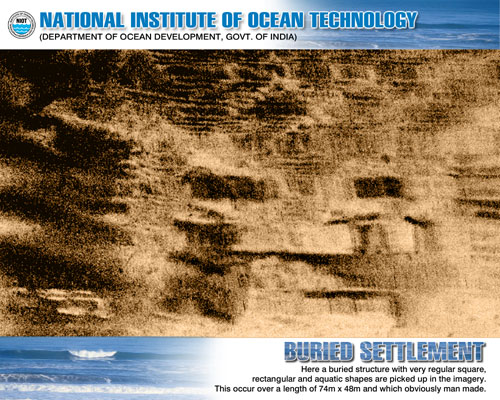

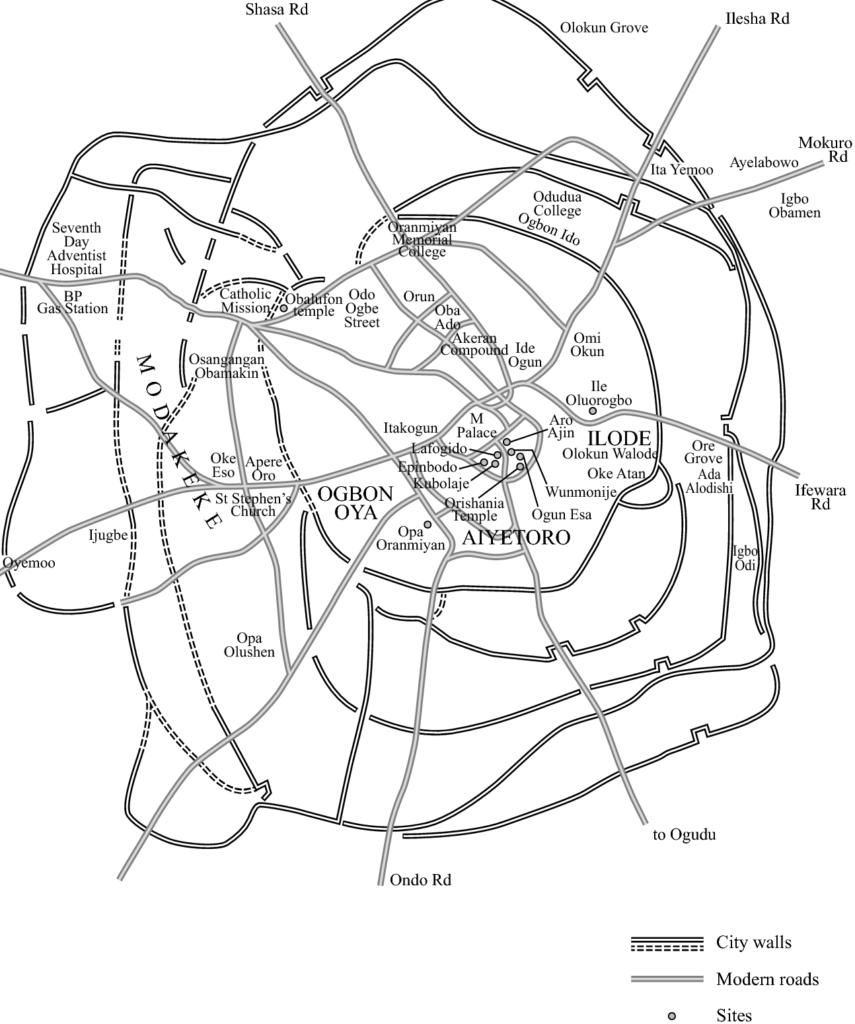

L’urbanisation médiévale d’Ifè est aujourd’hui largement attestée par l’existence de nombreuses enceintes faites de fossés et de talus, qui semblent indiquer les différents espaces ayant connu une concentration démographique et une entité politique suffisamment puissante pour mettre en œuvre de tels travaux.

Ainsi, en tant qu’Etat centralisé, Ifè s’érige très tôt en modèle pour d’autres Etats dans la région et au-delà. Plusieurs descendants et capitaines d’Oduduwa ont fondé d’autres royaumes sur le même modèle et s’appuyant sur la même légitimité. L’expérience monarchique d’Ifè s’exporte avec son cadre culturel. L’adé ilèkè, une couronne de perles de verre symbolisant le pouvoir royal, se retrouve dans la plupart des monarchies de la région.

En tout, de 7 à 20 royaumes selon les sources composent le monde yoruba dans la première moitié du deuxième millénaire de notre ère.

- L’État d’Oyo au Nigeria fut l’une des plus puissantes cités-États yoruba.

- Autre exemple, le Royaume de Kétou, actuellement au sud-est du Bénin, aurait été fondé vers le XIVe siècle par un prétendu descendant d’Oduduwa. Il aurait quitté Ifè avec sa famille et d’autres membres de son clan, pour se diriger vers l’ouest, avant de s’installer finalement dans la cité d’Aro, au nord-est de la ville de Kétou. Rapidement, Aro devint trop petit pour la population grandissante du clan, et la décision fut prise de s’installer à Kétou. Le roi Ede quitta donc Aro avec 120 familles et s’installa dans cette ville.

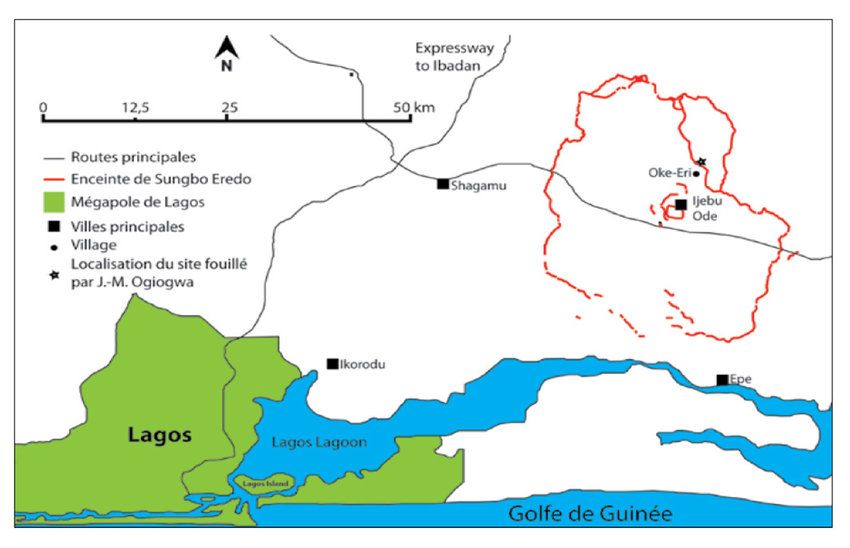

- Autre démonstration des bâtisseurs yoruba, près de la capitale nigeriane Lagos, l’enceinte de Sungbo Eredo, un système de murailles et de fossés construit au XIVe siècle e situé au sud-ouest de la ville d’Ijebu Ode, dans l’État d’Ogun, au sud-ouest du Nigeria. Sur plus de 160 km de long, ces fortifications, parfois hautes de 20 mètres, consistent en un fossé aux parois lisses, formant une douve intérieure par rapport aux murs qui le surplombent. Le fossé forme un anneau irrégulier autour des terres de l’ancien royaume d’Ijebu. Cet anneau fait environ 40 km dans le sens nord-sud et 35 km dans le sens est-ouest, c’est-à-dire l’équivalent du boulevard périphérique parisien ! Envahi par la végétation, l’édifice ressemble aujourd’hui à un tunnel verdoyant.

D’Ifè au Royaume du Bénin

Au XIVe siècle, Ifè connaît un effondrement démographique, caractérisé par l’abandon de certaines enceintes et une forte avancée de la forêt dans des zones anciennement occupées. On constate également une rupture dans les savoir-faire et les techniques artisanales. Cet effondrement démographique pourrait s’expliquer par une épidémie de peste noire, selon certains auteurs, qui font un parallèle avec les grandes épidémies constatées en Europe sur des périodes proches.

Une partie des habitants a pu se réfugier et apporter son savoir-faire en métallurgie au Royaume du Bénin, qui dura du XIIe siècle jusqu’à son invasion par l’Empire britannique à la fin du XIXe siècle. Il s’agit d’un Etat d’Afrique de l’Ouest côtière dominé par les Edos, une ethnie dont la dynastie survit encore aujourd’hui. Son territoire correspond au Bénin actuel, plus une partie du Togo et le sud-ouest de l’actuel Nigeria, où se trouve d’ailleurs aujourd’hui « Bénin City », un port historique sur le fleuve Bénin. Au cœur de la cité, la résidence royale aux proportions monumentales traduit dans l’espace l’importance accordée au pouvoir politique, spirituel et traditionnel.

Bénin City, une merveille

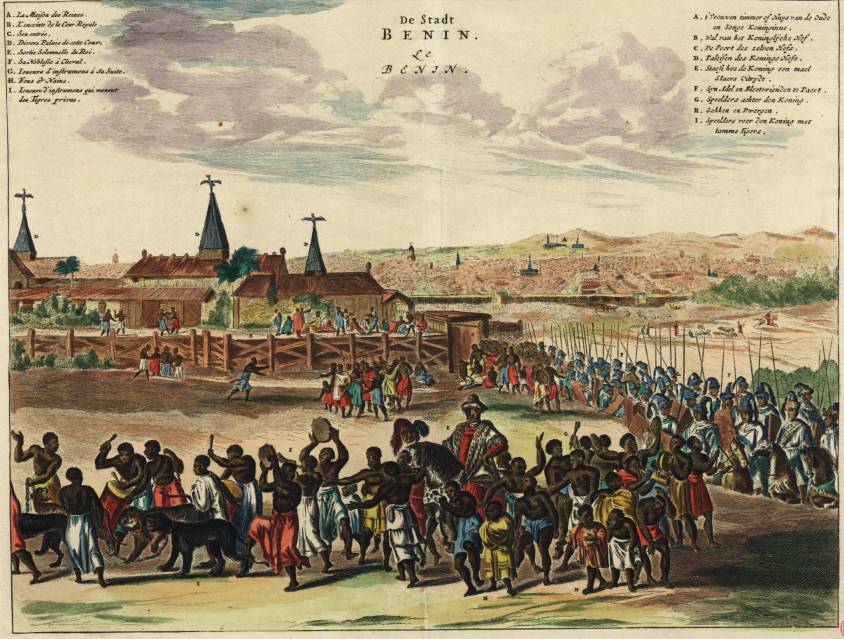

L’organisation sociale de la ville impressionne les visiteurs européens à la fin du XVe siècle. Important pôle économique régional, on y trouve de l’ivoire, du poivre et des esclaves. Les Européens y échangent de l’huile de palme (le palmier à huile poussant abondamment dans la région) contre des fusils, permettant la modernisation de l’armement béninois.

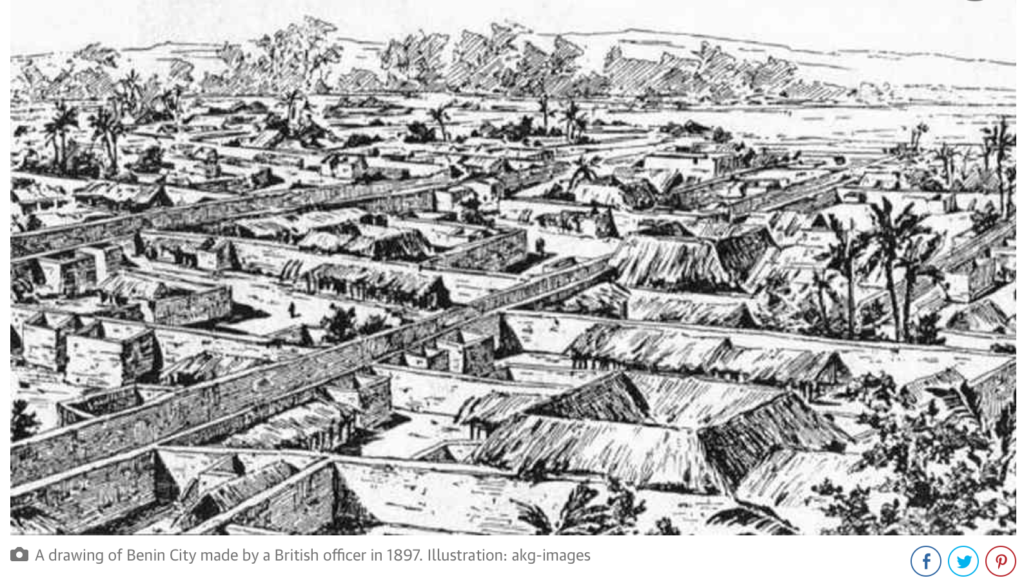

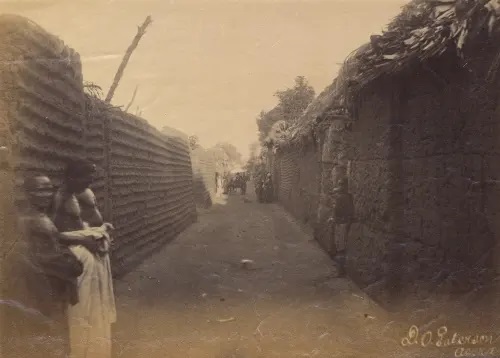

Située dans une plaine, Bénin City est entourée de murs massifs au sud et de profonds fossés au nord. Au-delà des murs de la ville, de nombreuses autres murailles ont été érigées qui séparent les environs de la capitale en quelque 500 villages distincts.

En 2016, un article du Guardian retraçait la splendeur de la ville. Le journal rapporte que le livre des records Guinness de 1974 décrit les murs de Bénin City comme les plus grands travaux de terrassement au monde réalisés avant l’ère mécanique. Selon les estimations de Fred Pearce, du New Scientist, les murs de Bénin City étaient à un moment donné « quatre fois plus longs que la Grande Muraille de Chine et employaient cent fois plus de matériaux que la Grande Pyramide de Khéops ».

Pearce précise que ces murs « s’étendaient sur quelque 16 000 km en tout, dans une mosaïque de plus de 500 limites de colonies interconnectées. Ils couvraient 6500 km2 et ont tous été creusés par le peuple Edo… On estime qu’il a fallu 150 millions d’heures pour les construire et qu’ils constituent peut-être le plus grand phénomène archéologique de la planète ».

Bénin City fut également l’une des premières villes à s’équiper d’un semblant d’éclairage public. D’énormes lampes métalliques, hautes de plusieurs mètres, se dressaient autour de la ville, en particulier près du palais du roi. Alimentées par de l’huile de palme, leurs mèches brûlaient pendant la nuit pour éclairer la circulation à destination et en provenance du palais.

Lorsque les Portugais découvrirent la ville pour la première fois en 1485, ils furent stupéfaits de trouver ce vaste royaume, fait de centaines de villes et de villages imbriqués les uns dans les autres au milieu de la jungle africaine. Ils l’appelèrent la « Grande ville du Bénin », à une époque où il n’y avait aucun autre endroit en Afrique que les Européens reconnaissent comme une ville. Ils la classèrent comme l’une des villes les plus belles et les mieux aménagées du monde. Bénin City en 1686.

En 1691, le capitaine de navire portugais Lourenco Pinto constatait :

Le Grand Bénin, où réside le roi, est plus grand que Lisbonne ; toutes les rues sont droites et à perte de vue. Les maisons sont grandes, en particulier celle du roi, qui est richement décorée et possède de belles colonnes. La ville est riche et industrieuse. Elle est si bien gouvernée que le vol est inconnu et les gens vivent dans une telle sécurité qu’ils n’ont pas de portes pour leurs maisons.

En revanche, à la même époque, Londres est décrite par Bruce Holsinger, professeur d’anglais à l’université de Virginie, comme une ville

de vol, prostitution, meurtre, corruption et marché noir florissant, ce qui a rendu la ville médiévale mûre pour l’exploitation par ceux qui savent manier la lame rapide ou faire les poches.

Les fractales africaines

La planification et la conception de Bénin City ont été faites selon des règles précises de symétrie, de proportionnalité et de répétition, aujourd’hui connues sous le nom de « fractales ».

Le mathématicien Ron Eglash, auteur de African Fractals (qui traite des motifs sous-tendant l’architecture, l’art et le design dans de nombreuses régions d’Afrique), note que la ville et les villages environnants ont été délibérément aménagés pour former des fractales parfaites, avec des formes similaires répétées dans les pièces de chaque maison, la maison elle-même et les groupes de maisons du village selon des motifs mathématiquement prévisibles.

Lorsque les Européens arrivèrent en Afrique, précise-t-il, ils considéraient l’architecture comme très désorganisée et donc primitive. Il ne leur est jamais venu à l’esprit que les Africains pouvaient utiliser une forme de mathématiques qu’eux-mêmes n’avaient pas encore découverte.

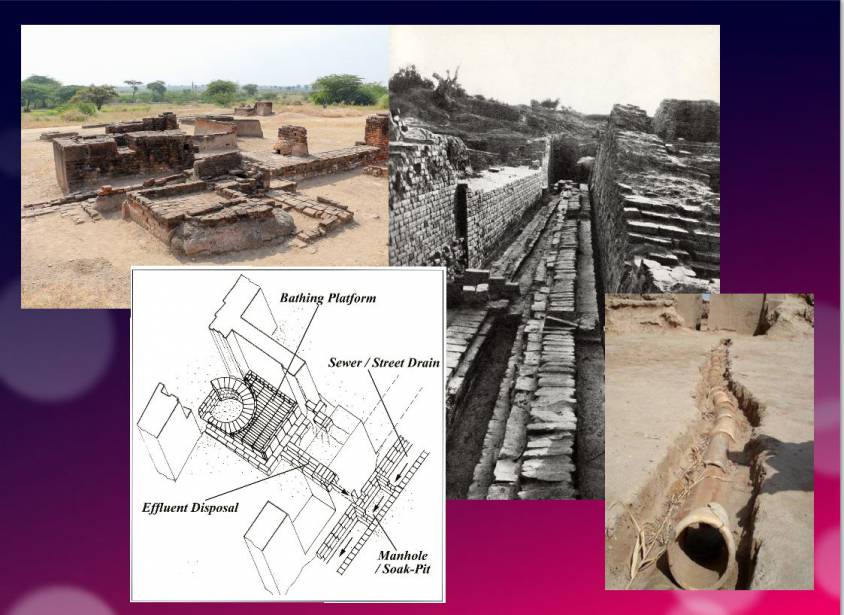

Au centre de la ville se trouvait le Palais royal, entouré d’une trentaine de rues droites et larges chacune d’environ 120 pieds. Ces rues principales, perpendiculaires les unes par rapport aux autres, étaient dotées d’un drainage souterrain constitué d’un impluvium, avec une sortie pour évacuer les eaux d’orage. De nombreuses rues plus étroites et se croisant s’étendaient à l’extérieur. Au milieu des rues, il y avait du gazon que les animaux pouvaient paître.

Les maisons sont construites le long des rues en bon ordre, l’une à côté de l’autre, écrit Olfert Dapper, visiteur hollandais du XVIIe siècle. Elles sont généralement larges, avec de longues galeries à l’intérieur, surtout dans le cas des maisons de la noblesse, et divisées en de nombreuses pièces qui sont séparées par des murs en argile rouge, très bien érigés.

Dapper ajoute que les riches résidents ont gardé ces murs

aussi brillants et lisses en les lavant et en les frottant que n’importe quel mur en Hollande fait avec de la craie, et ils sont comme des miroirs. Les étages supérieurs sont faits de la même sorte d’argile. De plus, chaque maison est équipée d’un puits pour l’approvisionnement en eau douce.

Les maisons familiales sont divisées en trois parties : la partie centrale est le quartier du mari, qui donne sur la route ; à gauche le quartier des femmes (oderie), et à droite le quartier des jeunes hommes (yekogbe).

La vie quotidienne à Bénin City voyait peut-être se déplacer dans des rues encore plus grandes, des foules constituées de gens vêtus de couleurs vives, certains en blanc, d’autres en jaune, bleu ou vert, les capitaines de la ville jouant le rôle de juges dans les procès, modérant les débats dans les nombreuses galeries et arbitrant les petits conflits sur les marchés.

Les premiers explorateurs étrangers décrivent Benin City comme un lieu exempt de criminalité et de faim, avec de grandes rues et des maisons propres, une ville remplie de gens courtois et honnêtes, et gérée par une bureaucratie centralisée et très sophistiquée. Bénin : plaque en laiton (bronze) montrant l’entrée du Palais royal où d’autres plaques décorent les piliers.

La ville est divisée en 11 arrondissements, chacune étant une réplique en plus petit de la cour du roi, comprenant une série tentaculaire de complexes incluant des logements, des ateliers et des bâtiments publics – reliés entre eux par d’innombrables portes et passages, tous richement décorés avec l’art qui a rendu le Bénin célèbre. La ville en était littéralement recouverte.

Les murs extérieurs des cours et les faîtes des enceintes sont décorés de motifs horizontaux (agben) et de sculptures en argile représentant des animaux, des guerriers et d’autres symboles de pouvoir.

Les sculptures sont conçues pour créer des motifs contrastés sous le fort soleil. Des objets naturels (galets ou morceaux de silicium) sont également pressés dans l’argile humide, tandis que dans les palais, les piliers sont recouverts de plaques de bronze illustrant les victoires et les exploits des anciens rois et nobles.

À l’apogée de sa grandeur, au XIIe siècle (bien avant le début de la Renaissance européenne), les rois et les nobles de Bénin City ont accordé leur mécénat aux artisans et les ont comblés de cadeaux et de richesses, en échange de la représentation des grands exploits des rois et des dignitaires dans des sculptures en bronze complexes.

Ces œuvres du Bénin sont à la hauteur des plus beaux exemples de la technique de fonte européenne », écrit Felix von Luschan, ancien professeur au Musée d’ethnologie de Berlin. « [Le sculpteur et fondeur italien] Benvenuto Celini n’aurait pas pu mieux les couler, ni personne d’autre avant ou après lui. Techniquement, ces bronzes représentent la plus haute réalisation possible.

La rencontre avec « la civilisation »

Suite à la conférence de Berlin de 1885 où Britanniques, Français, Allemands et autres puissances européennes se partagent, au nom des lois immuables de la géopolitique germano-britannique, l’Afrique comme un gros gâteau qu’il entendent dévorer, les invasions européennes se multiplient et gagnent en brutalité.

Ainsi, suite au refus du roi de céder aux Britanniques son monopole sur la production de l’huile de palme et d’autres productions, lors d’une expédition punitive en 1897, Bénin City est pillée, incendiée et réduite en cendres par les Britanniques. Le roi (l’oba) est chassé et plusieurs milliers de « bronzes du Bénin », certes moins réalistes que ceux d’Ifè, sont dispersés et en partie perdus.

Ils finissent par se retrouver sur le marché de l’art et aboutissent dans des musées, notamment au British Museum (700 objets) et au Musée d’ethnologie de Berlin (500 pièces). Le gouvernement britannique lui-même en vend une partie « pour couvrir les frais de l’expédition ». Comme quoi les uns entrent dans l’histoire avec leur art, les autres avec leurs crimes. Expédition punitive de 1897. Une fois le palais royal brûlé, les pilleurs britanniques alignent les pièces en cuivre et en laiton qu’ils ramèneront en Europe.

Bibliographie sommaire :

- Ifè, une civilisation africaine, Frank Willett, Jardin des Arts/Tallandier, Paris 1971 ;

- Histoire générale de l’Afrique, Présence africaines/Edicef/Unesco, Paris 1987 ;

- Atlas historique de l’Afrique, Editions du Jaguar, Paris 1988 ;

- L’Afrique ancienne, de l’Acus au Zimbabwe, sous la direction de François-Xavier Fauvelle, Belin/Humensis, Paris 2018.