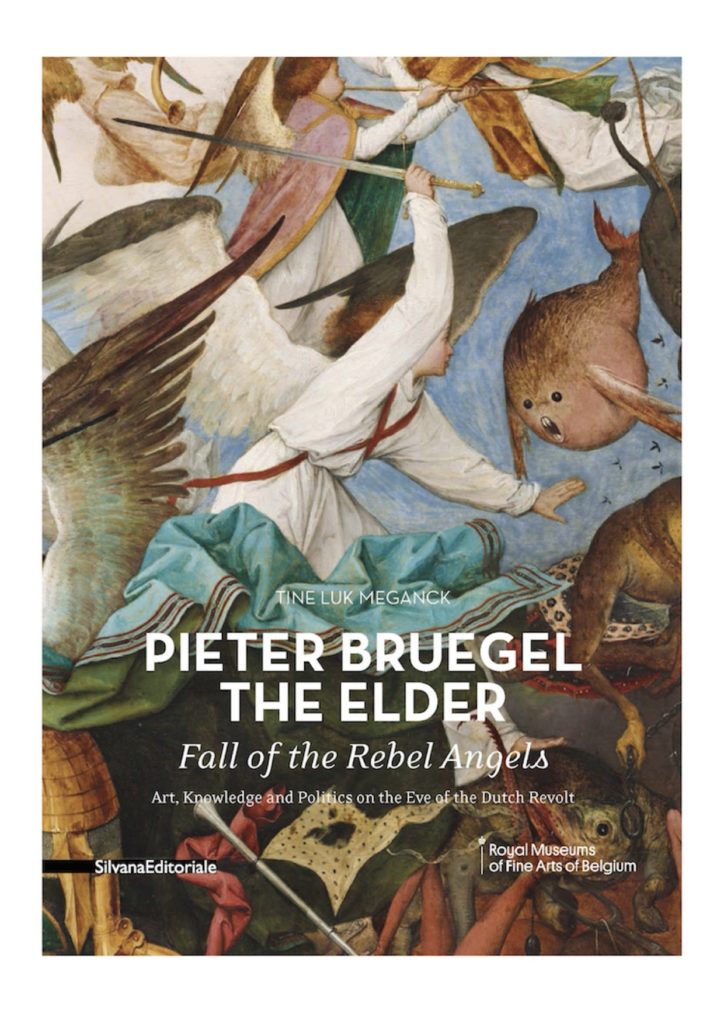

A propos du livre de Tine Luk Meganck, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Fall of the rebel angels, Art, Politics and Knowledge at the eve of the Dutch Revolt, (Pierre Bruegel l’Ancien, La chute des anges rebelles, art, savoirs et politique à la veille de la révolte des Pays-Bas) (2014, Editions Silvana Editoriale, Collection des Cahiers des Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique).

Ayant pu régulièrement admirer ce tableau à ce qui s’appelait encore le Musée royal d’Art ancien lors de ma formation à l’Institut Saint-Luc de Bruxelles, la Chute des anges rebelles de Pieter Bruegel l’Ancien méritait bien qu’on lui consacre un jour une recherche approfondie.

Ayant pu régulièrement admirer ce tableau à ce qui s’appelait encore le Musée royal d’Art ancien lors de ma formation à l’Institut Saint-Luc de Bruxelles, la Chute des anges rebelles de Pieter Bruegel l’Ancien méritait bien qu’on lui consacre un jour une recherche approfondie.

C’est désormais chose faite avec l’étude de Tine Luk Meganck, docteur en histoire de l’art diplômée par l’Université de Princeton et chercheure attachée au Musée de Bruxelles, dont les recherches furent publiées en anglais en 2014 dans la Collection des Cahiers des Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique.

Si ce livre, qu’il faut saluer, en rappelant aussi bien le milieu culturel que la situation politique exerçant une influence sur la démarche du peintre, permet de mieux « lire » l’œuvre paradoxale du peintre flamand, l’étude, en évitant certains détails précieux tout en faisant des gros plans sur d’autres, nous laisse sur notre faim quant à l’essentiel.

Pire, à force d’étoffer ce qui ne reste que des simples hypothèses, Mme Meganck a bien du mal à résister à la tentation de vouloir nous faire partager d’office des conclusions qui n’ont pas lieu d’être mais qui lui permettraient de conforter une hypothèse déjà ancienne disant que le cardinal Granvelle, figure plus qu’ambigu du pouvoir impérial espagnol, aurait pu être un des commanditaires de Bruegel. Avant de répondre à cette question, revenons au tableau.

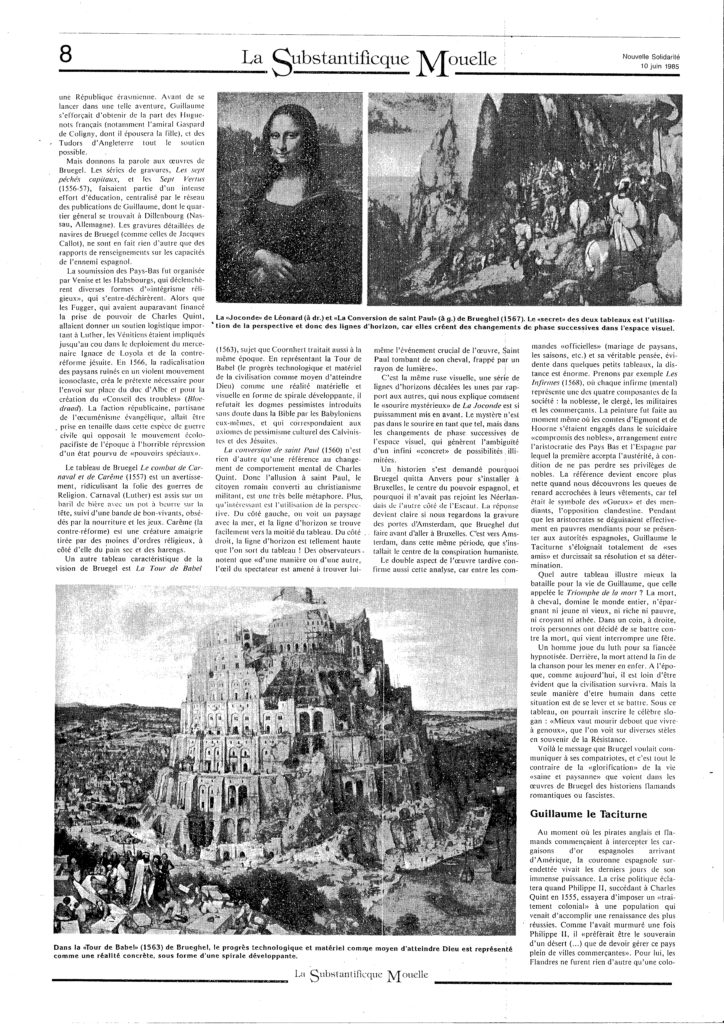

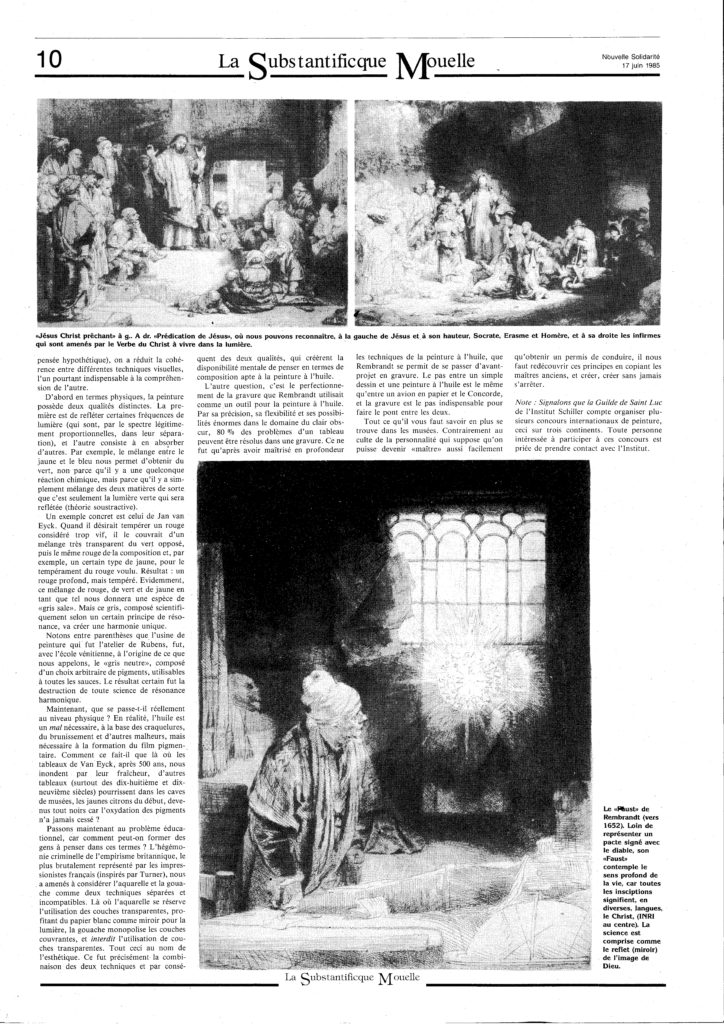

La Chute des anges rebelles, vaste tableau (117 x 162) peint sur bois de chêne par Pieter Bruegel l’Ancien en 1562, reprend une vieille thématique chrétienne qui cherche à répondre aux interrogations des croyants :

Si Dieu était le créateur de tout ce qui existe, a-t-il également créé le mal ?

La chute des anges rebelles, miniature d’un maître anonyme, Livre des bonnes mœurs de Jacques Legrand, Bourgogne, XVe siècle. (Crédit : BNF)

Bien avant la Théodicée du philosophe allemand Leibniz (1646-1716) qui répond en profondeur à cette question, Augustin d’Hippone (354-430), en rompant avec le manichéisme pour qui l’histoire n’était qu’une lutte incessante entre le « bien » et le « mal », souligne que le mal n’a aucune légitimité et n’est que simple « absence » du bien. En clair, si l’homme fait le choix de faire le bien, le mal, sans vecteur de propagation, est obligé de battre en retrait.

Une autre allégorie fut ajoutée pour expliquer l’origine du mal, celle de l’ange déchu. Le poète anglais John Milton (1608-1674), dans son célèbre Paradis perdu (1667) ainsi que le poète néerlandais Joost Van den Vondel (1587-1679), dans son Lucifer (1654) brodent sur ce thème. Lorsque Dieu créa l’homme à son image, avancent-ils, les anges qui l’entouraient, succombaient à la jalousie. Le Seigneur les chargea d’observer le comportement des hommes qu’il avait créé à son image. Constatant la beauté et l’harmonie de l’existence humaine, les anges furent pris de panique : avec des humains si près et tant aimés de Dieu, qu’allons-nous devenir ?

L’évêque Irénée de Lyon (130-202), affirma que l’ange

à cause de la jalousie et de l’envie qu’il éprouvait à l’égard de l’homme pour les nombreux dons que Dieu lui avait accordés, fit de l’homme un pécheur en le persuadant de désobéir au commandement de Dieu, provoqua sa ruine.

Découvrant la déchéance de certains anges, Dieu ordonna leur expulsion.

Plusieurs prophètes annoncent, après une guerre féroce, le triomphe de l’archange Michel et de sa milice céleste d’anges sur Lucifer, prince des lumières. Ce n’est plus une lutte éternelle mais la victoire du bien et de Dieu sur le mal annonçant le Royaume de Dieu dans l’univers.

D’après le livre de l’Apocalypse de l’apôtre Jean (chapitre 12, verset 7-9),

Il y eut guerre dans le ciel : Michel et ses anges sont allés à la guerre avec le dragon. Et le dragon et ses anges. Et il a réussi, ni était un endroit pour eux dans le ciel. Et le grand dragon fut précipité, le serpent ancien, appelé le diable et Satan, qui trompe le monde entier, a été jeté à la terre, et ses anges furent précipités avec lui.

Depuis Origène (185-253), la chute de l’ange provient du péché d’orgueil. Reprenant le Livre d’Isaïe (versets 12 à 14), Origène affirme :

Comment Lucifer est-il tombé du ciel, lui qui se levait le matin ? Il s’est brisé et abattu sur la terre, lui qui s’en prenait à toutes les nations. Mais toi, tu as dit dans ton esprit : Je monterai au ciel, sur les étoiles du ciel je poserai mon trône, je siégerai sur le mont élevé au-dessus des monts élevés qui sont vers l’Aquilon. Je monterai au-dessus des nuées, je serai semblable au Très Haut. Or maintenant tu as plongé dans la région d’en bas et dans les fondements de la terre.

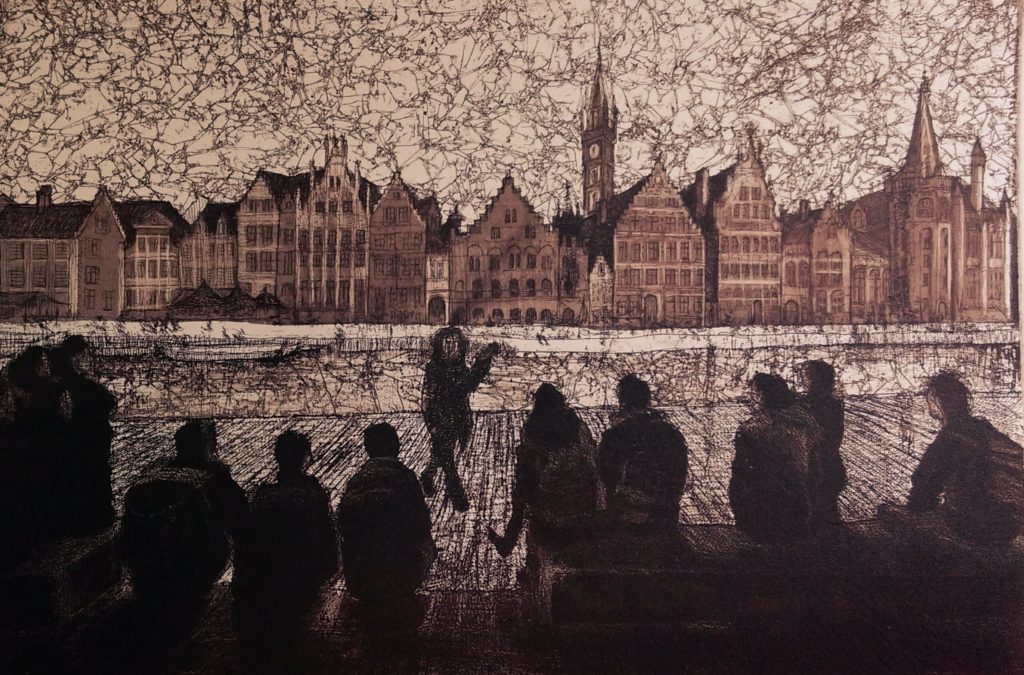

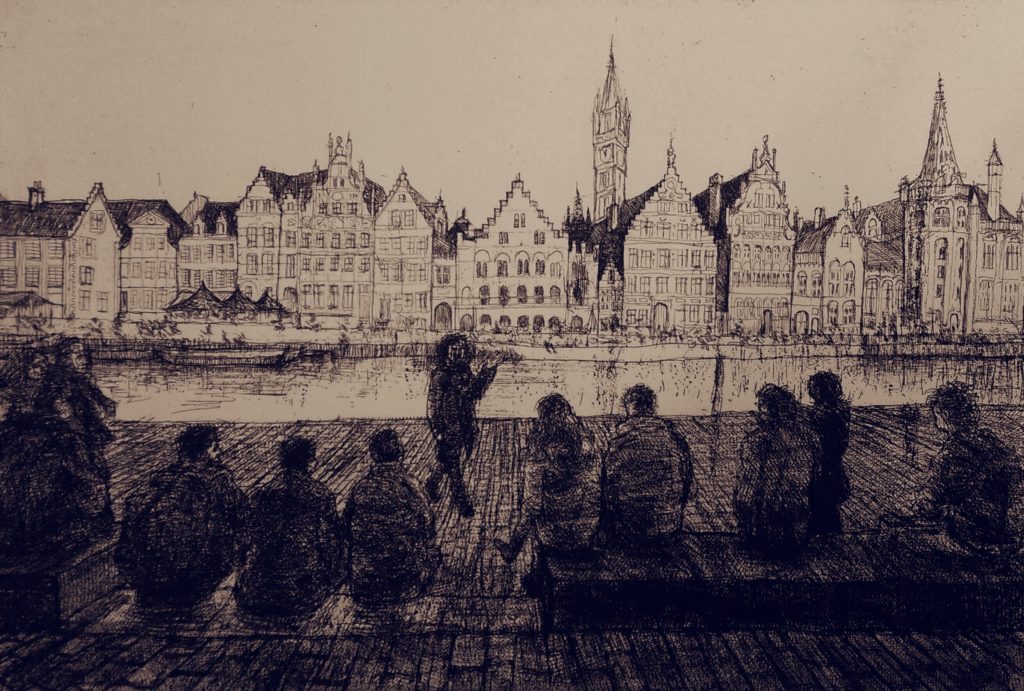

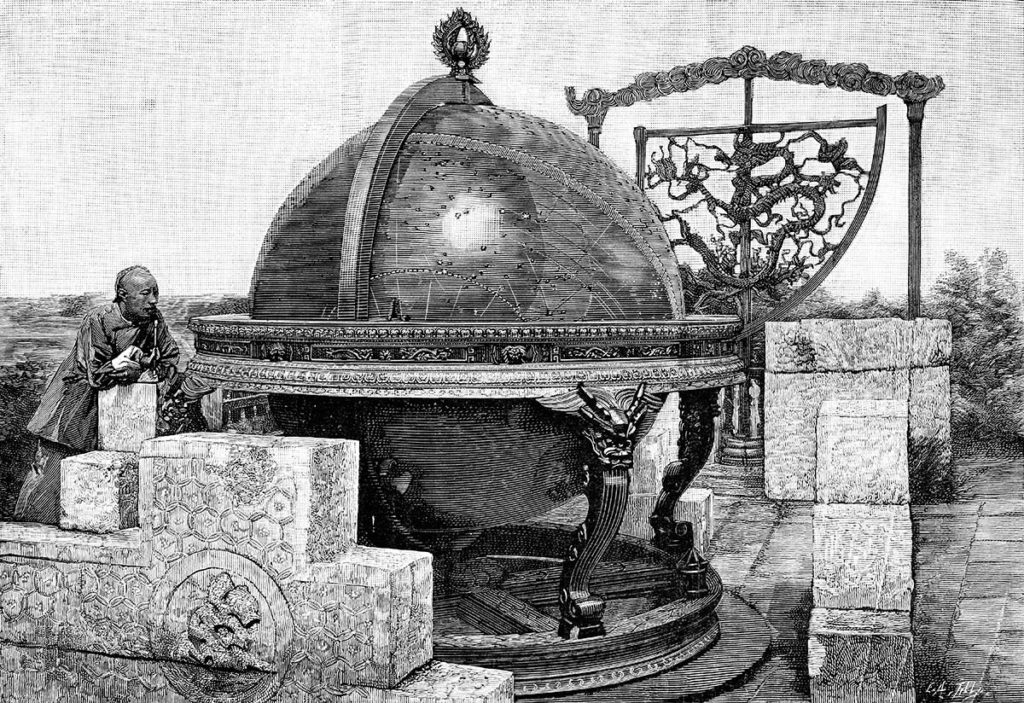

Aux Quatre Vents

-

Bruegel va y ajouter son imagination et la philosophie érasmienne qu’il a rencontré en travaillant à Anvers dans l’atelier Aux Quatre Vents du graveur Jérôme Cock, fils de Jan Wellens Cock, un disciple de Jérôme Bosch.

Dans cet atelier, il a pu croiser le graveur néerlandais Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert (1522-1590), formé par le jeune secrétaire d’Erasme, Quirin Talesius (1505-1575), lui-même traducteur d’Erasme en néerlandais et futur secrétaire d’Etat du prince d’Orange, Guillaume le Taciturne (1533-1585) le grand dirigeant humaniste qui souleva les Pays-Bas contre l’Empire espagnol.

Coornhert s’occupe de graver l’œuvre du peintre Maarten van Heemskerk et de Frans Floris, lui aussi l’auteur en 1554 (donc huit ans avant Bruegel) d’un tableau sur le thème de la Chute des anges rebelles. En 1560, lorsque Coornhert devient éditeur, son élève s’appelle Philippe Galle qui grava plusieurs dessins de Bruegel pour l’éditeur Jérôme Cock.

Pour l’atelier de Cock, Bruegel élabora deux séries de gravures : les « Sept péchés capitaux » et les « Sept vertus ».

Comme le note Mme Meganck, Bruegel, renouant avec une vieille tradition qui date du moyen-âge, place à coté de chaque péché un animal symbolisant le coté bestial de la chose : à coté de la rage, un ours ; à coté de la paresse, un âne ; à coté de l’orgueil, un paon ; à coté de l’avarice, un crapaud ; à coté de la gourmandise, un sanglier ; à coté de la jalousie, une dinde et enfin, à coté de la luxure, un coq.

Déjà, dans sa gravure la Fortitude qui fait partie des Sept vertus et qui anticipe d’une certaine façon la Chute des anges rebelles, Bruegel montre une armée d’hommes tabassant un ours (la rage), tuant le sanglier (la gourmandise), égorgeant le paon (l’orgueil), frappant le crapaud (l’avarice), etc. Sous la gravure on peut lire en latin :

Vaincre ses impulsions, pour retenir sa rage ainsi que d’autres vices et émotions, voila ce qui est la vraie fortitude (force).

Or, chez Bruegel, les anges rebelles, dans leur chute, ne se transforment pas en démons à cornes mais en oiseaux plumés, en crapauds, en singes et autres cochons sauvages —qui font tous plus rire que trembler— ratiboisés par des anges restés fidèles et annonçant, à coup de buisines, leur triomphe.

Et lorsque Mme Meganck affirme sans hésitation qu’un des cochons avec un bonnet rouge est une référence au peintre et diplomate humaniste flamand Jan Van Eyck, pour la raison toute simple qu’il était connu pour avoir porté un turban rouge, je ne sais plus s’il faut rire ou pleurer…

Il n’existe d’ailleurs aucune preuve formelle permettant de conclure que le portrait d’un homme avec un turban rouge, peint sans doute par Van Eyck en 1433 est un autoportrait.

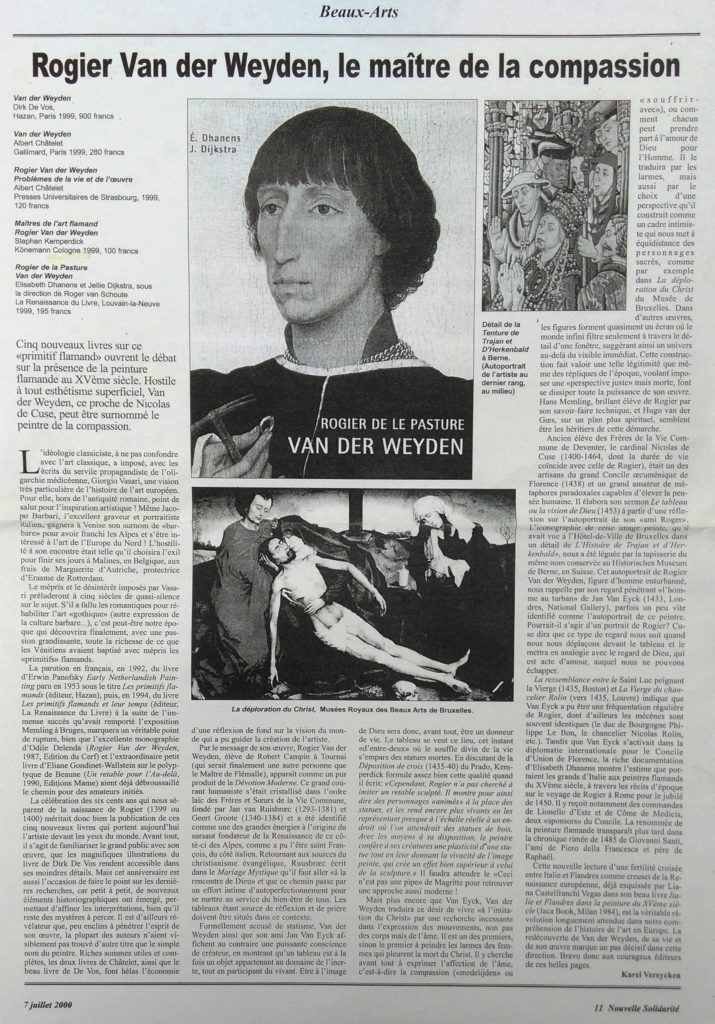

En tout cas, pour le courant humaniste augustinien que nous évoquions, le mal n’est pas systématiquement quelque chose d’extérieur à l’homme mais également une chose à surmonter par chaque homme en lui-même en faisant le choix du bien. Rappelons que déjà, dans le polyptyque du Jugement dernier de Roger Van Der Weyden à l’Hospice de Beaune, ce n’est nullement le diable qui tire l’homme en enfer, mais d’autres hommes et femmes !

Ce qui est incontestable, c’est que lorsque Bruegel peint La chute des anges rebelles, il vise directement l’orgueil de ceux qui « se prennent pour Dieu » ou se croient même au-dessus de lui.

Reste alors à savoir à qui il s’adresse ? Pense-t-il comme le cardinal Granvelle aux Luthériens contestant l’autorité de l’Eglise de Rome ? Ou pense-t-il aux Catholiques espagnols dont l’absolutisme répressif et orgueilleux en défense de leur pouvoir terrestre, allait totalement à l’encontre de la vraie « philosophie du Christ » telle qu’elle fut défendue par Guillaume le Taciturne, lecteur d’Erasme et de Rabelais ?

C’est là, où notre analyse diffère radicalement de celle de Mme Meganck.

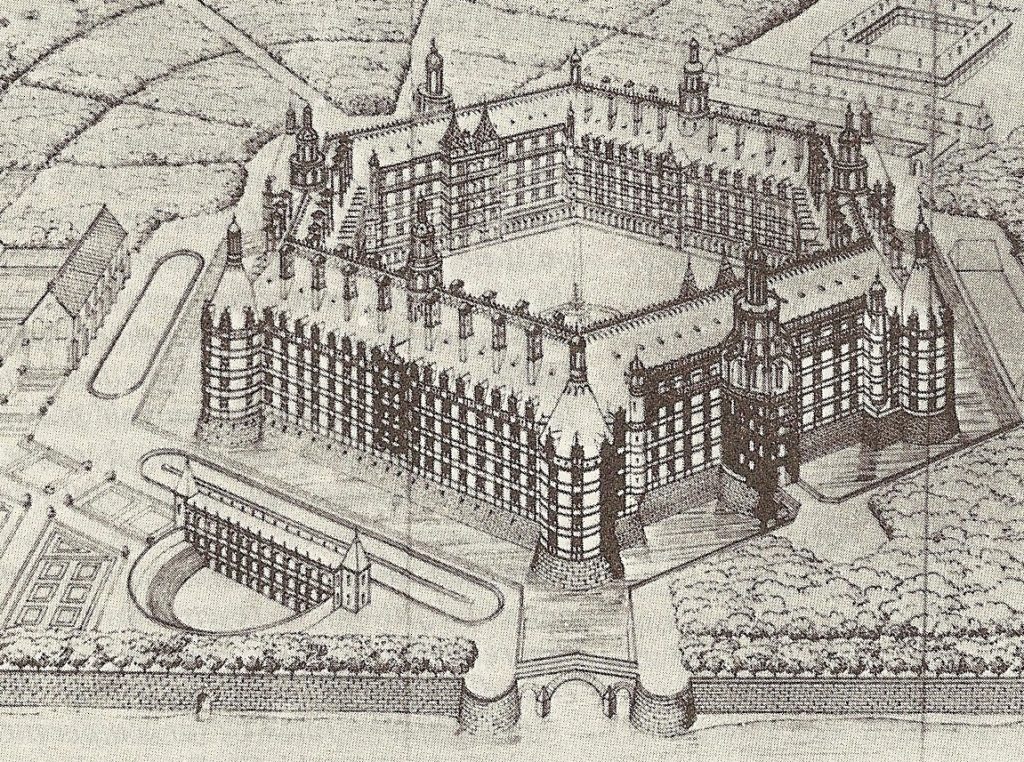

En 1562, en effet, Bruegel s’installe à Bruxelles où il se marie l’année suivante avec Mayken Coeck, fille de son maître Pieter Coecke van Aelst. La Cour de Bruxelles avec celle de Madrid, est alors l’endroit où se joue aussi bien le destin des Flandres que celui des Habsbourg.

Or, à cette époque, l’Empire espagnol qui règne sur les Pays-Bas bourguignons, en dépit des arrivages d’or du Nouveau monde, subira les conséquences dramatiques de quatre faillites d’État : 1557, 1560, 1575 et 1596. Or, comme aujourd’hui, pour faire perdurer la valeur de plus en plus fictive de certains titres financiers, il faut, y compris par la force de l’épée, extorquer la richesse physique des populations qui sont sommées à régler la facture.

Ainsi, comme l’a fort bien analysé feu l’historien d’art Michael Gibson, lorsque Bruegel peint Le dénombrement de Bethléem (1566, année où commence le mouvement iconoclaste), il peint l’occupant espagnol collectant la dîme et lorsqu’il peint Le massacre des innocents (1565), pour figurer les troupes romaines, il peint les sinistres tuniques rouges (les Rhoode Rox) de la gendarmerie impériale de Philippe II qu’on retrouve également dans Le portement de croix (1564). Et lorsqu’il peint la Tour de Babel (1563), où défile le Pape à un des étages supérieurs, il dénonce l’orgueil d’un pouvoir terrestre s’estimant, péché suprême, au-dessus de celui de son Seigneur.

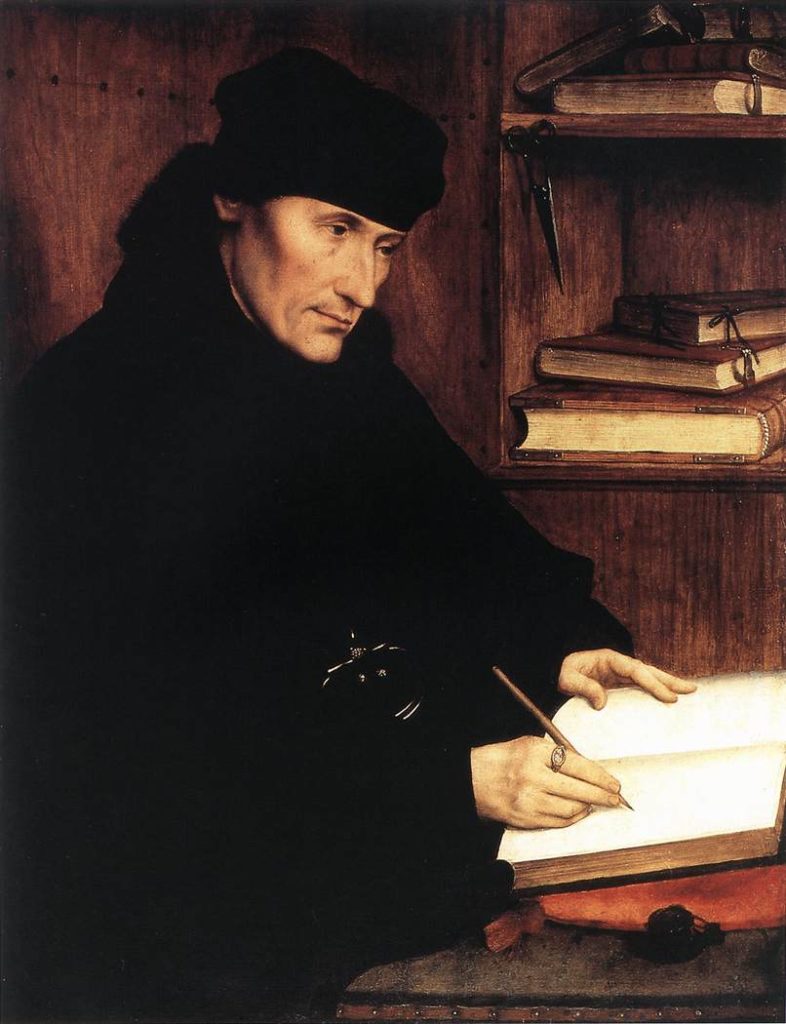

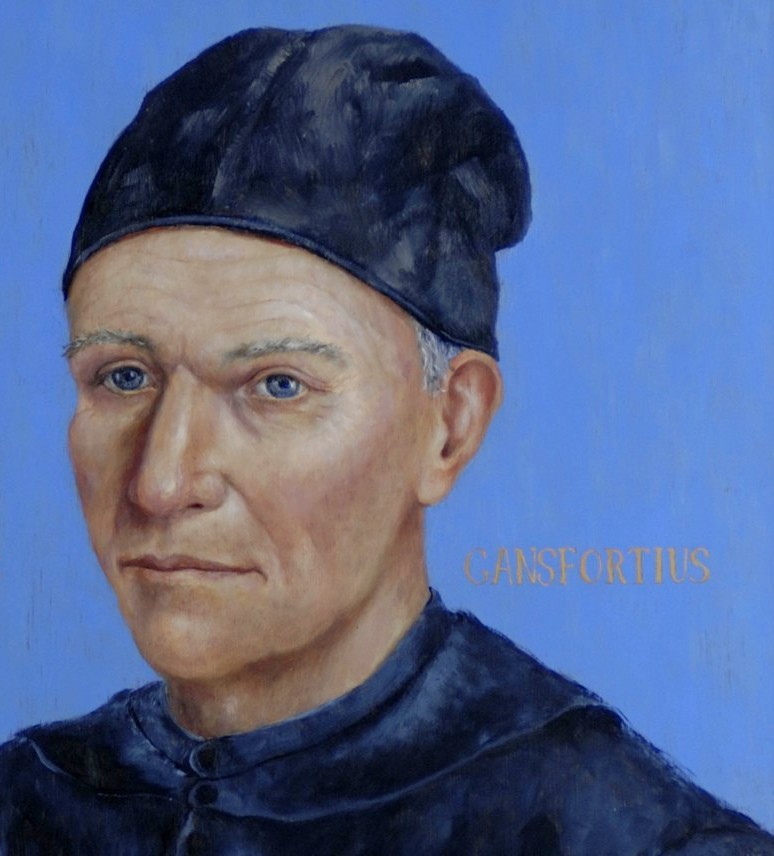

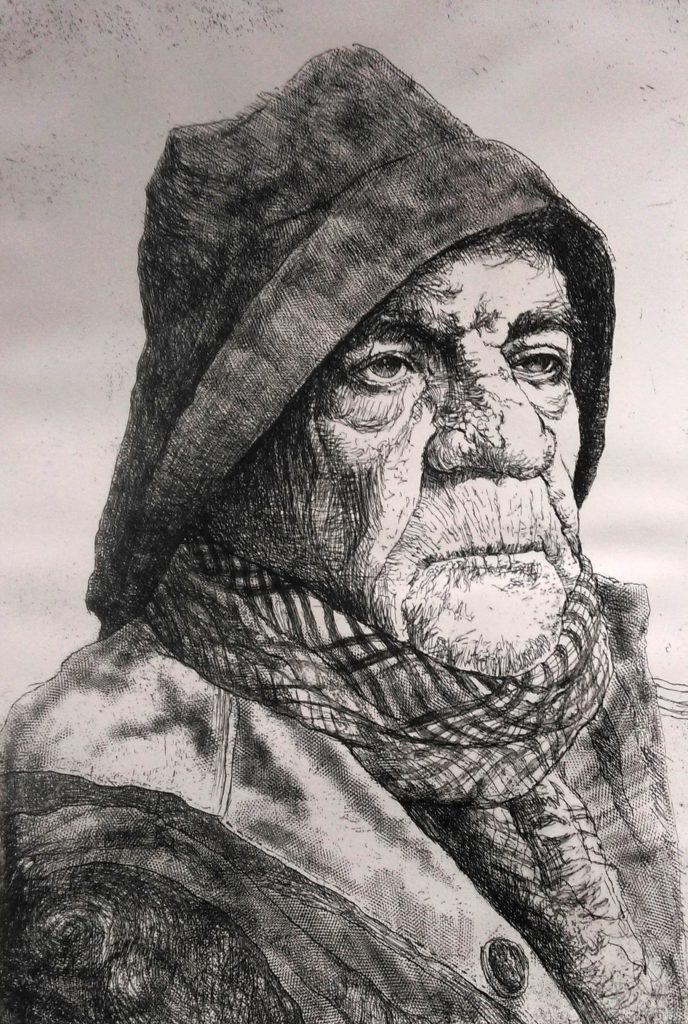

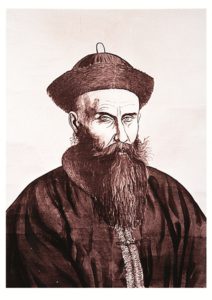

Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle

En tant que fils d’un notable influent, Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (1517-1586), sans être d’origine aristocratique, a eu une carrière fulgurante.

Dès l’âge de 21 ans il est appelé à se mettre au service des Habsbourg en tant qu’évêque d’Arras. Après le décès de son père, il devient le garde des Seaux et le secrétaire d’État de l’Empereur Charles Quint.

A Bruxelles il fait ériger un palais grandiose style Renaissance et il se fait peindre son portrait par le Titien.

Il est à la manœuvre pour marier Philippe II avec Marie Tudor et œuvre comme diplomate, notamment lors du traité de Cateau-Cambrésis (1559). Granvelle sera le conseiller principal de Philippe II dans les années précédent la révolte des Pays-Bas.

Réticent à titre personnel devant la répression, sa loyauté quasi-religieuse au Roi l’amena à appliquer sans état d’âme les mesures les plus extrêmes de l’Inquisition et de Philippe II.

Lorsque ce dernier rentre à Madrid, Granvelle, en contact permanent avec le Roi, imposa sa politique à la jeune Margarite de Parme, la régente.

La Consulta, un cabinet secret de seulement trois personnes assure sa tutelle : Charles de Berlaymont, un administrateur dévoué, Wigle van Aytta (Viglius), un ex-érasmien ayant perdu tout courage pour s’imposer face à un Granvelle omnipuissant. Lorsque la ville d’Anvers devient une poudrière luthérienne, Granvelle fait multiplier les diocèses et se fait nommer en 1561 cardinal-archevêque de Malines obtenant ainsi une voix au Conseil d’État.

La révolte des nobles

En mai 1561, constatant leur mise à l’écart dans l’exercice du pouvoir, dix membres de l’Ordre de la Toison d’or, c’est-à-dire des membres de la noblesse, notamment le comte Lamoral d’Egmont, Philippe de Montmorency comte de Hornes et huit autres seigneurs se réunissent alors chez le Prince Guillaume d’Orange (le « Taciturne »), pour former une « Ligue contre Granvelle » exigeant son départ et celui des troupes espagnoles. Sous la pression, le roi finit par retirer les troupes en 1561 et renvoi Granvelle en Franche-Comté en 1564. Trop peu et trop tard pour aplanir les tensions entre la noblesse et Madrid. Egmont tente alors de plaider la cause à Madrid mais revient avec des promesses assez vagues.

-

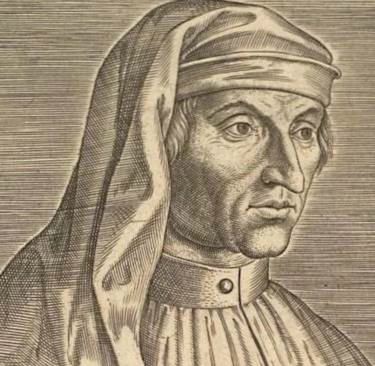

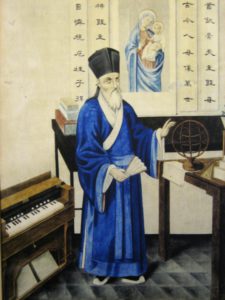

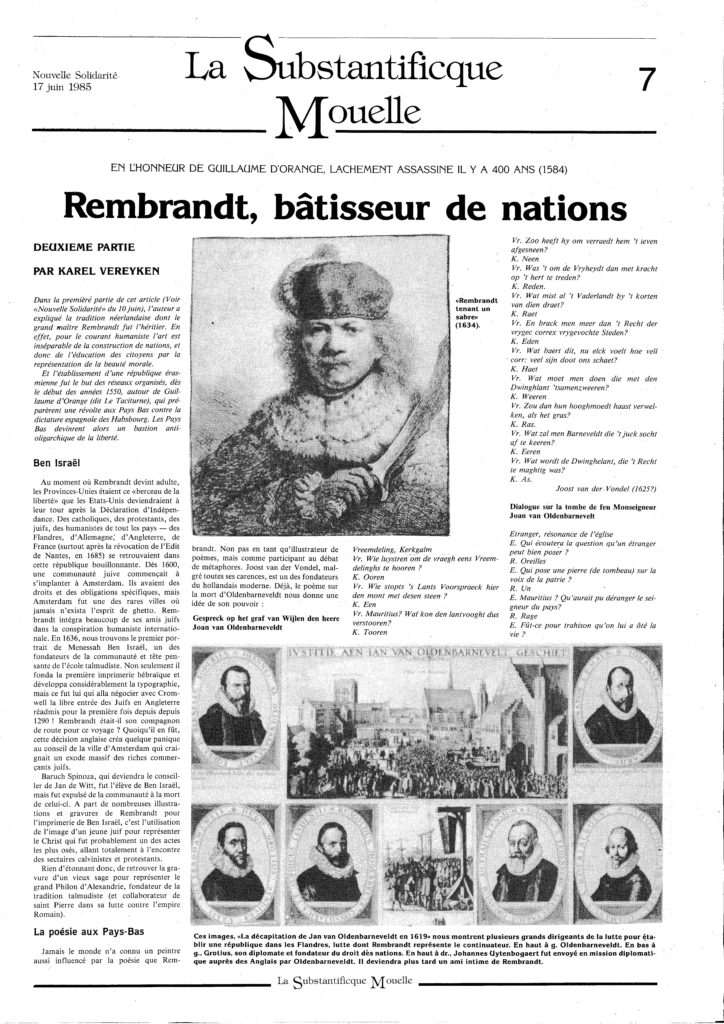

Guillaume d’Orange, dit le Taciturne, lecteur d’Erasme et fondateur de la République des Pays-Bas.

Reprenant à son compte la thèse qui prétend que l’origine de la révolte des Pays-Bas fut un conflit entre d’un coté la noblesse « de robe », du type du cardinal Granvelle et de l’autre, la « noblesse d’épée » comme Guillaume d’Orange, Mme Meganck affirme que

la raison pour la détérioration des relations entre Granvelle et Orange n’était pas tellement un conflit idéologique mais un conflit pour des positions de pouvoir.

Or rien n’est plus faux et méprisant pour ce dirigeant hors du commun. Il serait fastidieux ici de résumer en quelques lignes la biographie très documentée d’Yves Cazaux, Guillaume le Taciturne (Fond Mercator, Albin Michel, Anvers 1973). Le prince d’Orange, tout comme Erasme dès 1517, estimait que si le Vatican persistait à faire de Luther son ennemi principal, les guerres de religions risquaient de ravager l’Europe pendant un siècle et de diviser gravement la chrétienté. Ancien conseiller des Finances, Guillaume savait aussi que la présence des troupes espagnoles, que Granvelle cherchait à renforcer, ne pouvait qu’accélérer le pillage des populations et donc accélérer la désunion.

Dans un moment relativement unique, aux Pays-Bas, aussi bien la noblesse que le peuple voyait leur liberté religieuse, économique et culturelle menacé. Alors que pour Granvelle la défense de son pouvoir personnel et sa richesse coïncidait avec la défense de l’absolutisme espagnol, Guillaume d’Orange défendait, essentiellement en engageant sa fortune personnelle, l’idéal de l’unité et du bien commun.

Notons que l’acte de la Haye (dit « acte d’abjuration ») de 1581, qui formalise l’indépendance des Pays-Bas, souligne que « le prince est là pour ses sujets, sans lesquels il n’est point prince ».

Le même texte utilise le terme néerlandais « verlatinghe » (abandon). Car pour les fondateurs de la République néerlandaise, c’était Philippe II d’Espagne, par ses exactions et en violation de l’intérêt général, qui a abandonné les Dix-sept Provinces, non pas le contraire.

Parlant de Granvelle, grand ami du sanguinaire duc d’Albe chargé de mettre de l’ordre dans le pays après Granvelle, Yves Cazaux estime que

ce prélat ambitieux, distingué, humaniste et jouisseur n’était sans doute pas le plus assoiffé de sang et il a pu écrire avec une certaine vraisemblance qu’il avait tempéré la répression autant qu’il avait pu. On trouve aussi dans ses papiers, sa doctrine et son programme politique pour les Pays-Bas : il avait conseillé au Roi d’incorporer tous les pays ‘en un seule royaume et s’en faire couronner roi absolu’. Au roi absolu de Granvelle, le prince d’Orange opposait la Généralité dans la liberté et la conception érasmienne de la souveraineté nationale. A la croisade de toute la catholicité, vœu de Granvelle et des Guise, le prince opposait la tolérance et la liberté religieuse. Les deux hommes étaient faits pour s’affronter en combat mortel, sans peut-être avoir perdu toute estime pour l’autre.

Chambres de Rhétorique

-

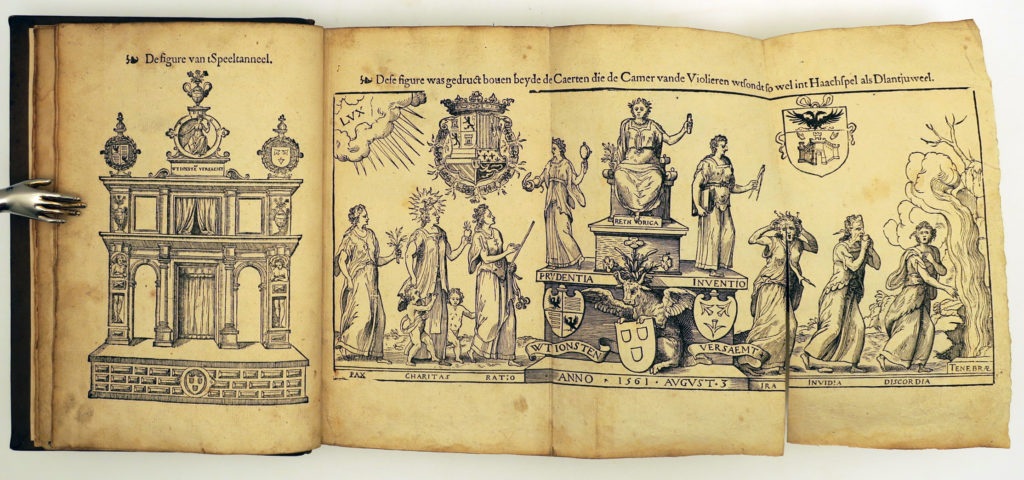

En 1561, lors du Landjuweel d’Anvers (concours public en plein air de poésie, de chansons, de théâtre et de farces), une pièce de théâtre mettait en scène comment —éclairées par la lumière—, la paix, la charité et la raison, avec l’aide de la prudence, de la rhétorique et de l’inventivité, chassaient la rage, la jalousie et la discorde.

Apport nouveau et important de Mme Meganck, l’influence des Chambres de Rhétorique et le Landjuweel d’Anvers de 1561 sur Bruegel, une piste dont me parla déjà Michael Gibson et qu’il développa dans son livre Le portement de croix (Éditions Noêsis, Paris 1996) qui servira par la suite à la réalisation du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix ».

Montrant à quel point la population voyait venir l’orage, en 1562, lorsqu’une Chambre de Rhétorique posa la question : « Qu’est-ce qui permettrait le maintien de la paix ? », les réponses qui prévalaient étaient « la sagesse », « l’obéissance », « la crainte de Dieu » et « l’unité ». Détail intéressant évoqué par Mme Meganck, 4 des 70 réponses évoquaient la chute de Lucifer et les anges rebelles, tellement le thème était populaire.

Un rhétoricien de la Chambre du Saint Esprit de Geraardsbergen ajouta par ailleurs que

La sagesse est également un bien en politique, car la sagesse n’est ni l’orgueil ni le rejet, mais l’amour tendre qui amène les bergers à diriger la communauté, pas avec des préjugés mais avec un cœur joyeux, sans penser à eux-mêmes ou être assoiffé de pouvoir, mais en cherchant le bien-être du peuple, comme un père le fait pour ses enfants : voilà les bon dirigeants pour la communauté laïque.

Alors que ces expressions culturelles étaient une soupape de sécurité inestimable permettant d’éviter l’explosion de la cocotte-minute sociétale, dès la moindre critique des ecclésiastiques, la répression frappait.

Après qu’une Chambre de rhétorique avait ironisé en 1560 sur le clergé et le saint Esprit, et après une enquête approfondie à propos de ces « pièces scandaleuses » menée par Granvelle en personne, un placard ordonna qu’à partir de là, toutes les chansons et poèmes, avant d’être chantés ou récités, nécessitaient une autorisation préalable par les autorités religieuses et temporelles.

Commanditaire ?

Lorsque Mme Meganck écrit (p. 155) que « L’hypothèse que Granvelle aurait commandité la Chute des anges, ou que Bruegel aurait adressé son invention spécifiquement à lui, permettrait de jeter une nouvelle lumière sur le cœur de son iconographie », je peux souscrire à la deuxième partie de son énoncé.

Cependant, lorsqu’elle poursuit « Dans le contexte de la révolte de la noblesse locale des Pays-Bas contre Granvelle, l’intention du tableau semble extrêmement pertinent : ceux qui se rebellent contre l’ordre établi finiront en ruine », on ne la suit plus. Car rien n’est plus juste, de contester une autorité illégitime (mais parfois légale), au nom d’une autorité supérieure fondée sur le bien, le vrai et le beau, comme l’a fait le général De Gaulle contre l’occupation Nazie et un régime collaborationniste qui le condamna à mort ! Si l’on appliquait ce raisonnement à la France de 1940, De Gaulle aurait été Lucifer !

Pour sa défense, Mme Meganck, qui récuse « la propagande de la révolte néerlandaise » pour qui Granvelle aurait été « un monstre assoiffé de sang », rapporte que ce dernier, un collectionneur passionné de tableaux et de curiosités de toutes sortes, artificielles et naturelles, et disposant d’un nain à son service, s’intéressait aussi bien à l’œuvre de Jérôme Bosch qu’à celle de Bruegel. Philippe II aurait même retardé son redéploiement à Besançon tellement il approvisionnait la cour de Madrid avec toutes sortes d’objets extravagants.

Mme Meganck rappelle que l’inventaire de la collection de Granvelle, une collection enrichie après sa mort par sa famille, comprenait en 1607 La fuite en Égypte, une œuvre de Bruegel l’Ancien datée de 1563. En 1575, plusieurs années après la mort de Bruegel, l’évêque de Tournai Maximilien Morillon, son confident, signale à Granvelle que les prix des tableaux du peintre ont nettement augmenté.

Mme Meganck, se contredisant, nous dit qu’il est regrettable qu’aucune preuve formelle n’existe pour affirmer que Granvelle aurait commandité une œuvre auprès de Bruegel tout en disant, page 146 :

Granvelle est un des rares amateurs d’art connu qui a probablement possédé des peintures de Bruegel durant la vie de l’artiste.

Collectionneur érudit

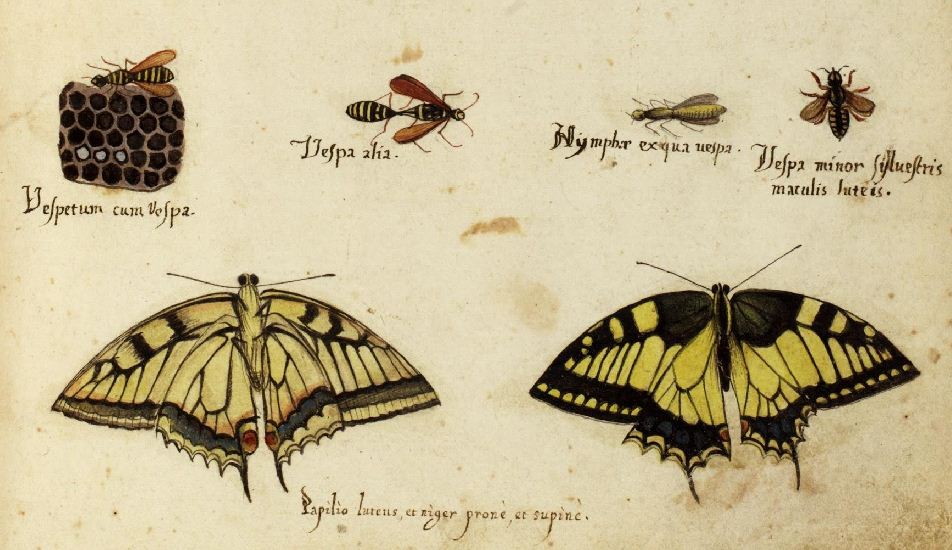

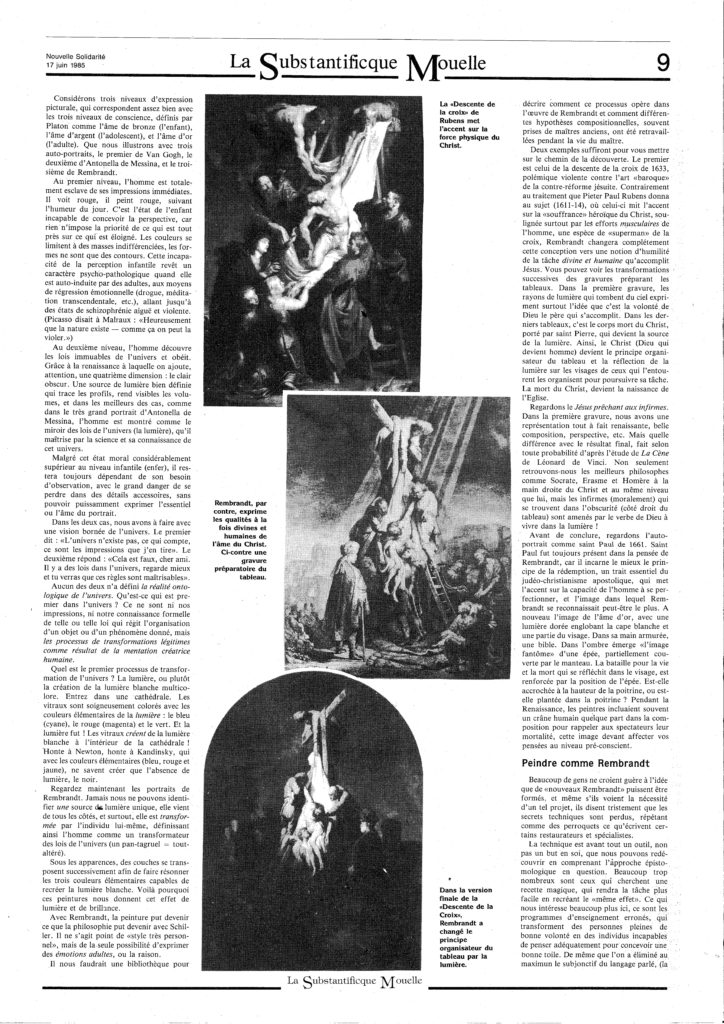

Le livre de Mme Meganck constate également que le tableau de Bruegel grenouille (c’est le cas de le dire) de références à des objets exotiques qui commençaient à faire la fierté des collectionneurs érudits tel que Granvelle : papillons, oiseaux et poissons exotiques, cadrans solaires et instruments de musique, pièces d’armures, casques et calices.

Le livre de Mme Meganck constate également que le tableau de Bruegel grenouille (c’est le cas de le dire) de références à des objets exotiques qui commençaient à faire la fierté des collectionneurs érudits tel que Granvelle : papillons, oiseaux et poissons exotiques, cadrans solaires et instruments de musique, pièces d’armures, casques et calices.

Par exemple, Mme Meganck épingle dans son livre un beau papillon qui aurait pu faire partie de ce genre de collections et qu’on le retrouve au centre de La chute des anges rebelles.

Notez que ce type de papillon figure également dans la Vanité (1540) de Jan Sanders Van Hemessen comme métaphore du caractère éphémère de l’existence humaine, une thématique qui ne pouvait qu’intéresser l’érasmien qu’était Bruegel. Bruegel aurait-il voulu séduire Granvelle en étalant de tels objets exotiques ? tente l’auteure.

Tout au contraire, notre Bruegel, Pierre le drôle, semble bien avoir cherché à montrer comment des individus comme Granvelle, des possédants possédés par leurs possessions, finiraient bien par emporter leurs riches collections luxueuses dans leur chute.

Un dernier détail, un des rares qui semble bizarrement avoir échappé à l’auteure, conforte plutôt notre hypothèse tout en mettant à mal la sienne : en bas au milieu du tableau quelques unes des sept têtes couronnées de couronnes du dragon de l’Apocalypse (Note 1) symbolisent de façon métaphorique le pouvoir absolutiste si cher à Granvelle. Le commanditaire serait donc plutôt à chercher du côté de Guillaume le Taciturne.

Soulignons que c’est lorsqu’en juin 1580 Philippe II signe un édit promettant à quiconque tuerait Guillaume d’Orange, l’anoblissement et 25 000 écus, que Balthazar Gérard, un franche-comtois fanatisé (Note 2), se rend à Delft aux Pays-Bas et l’abat de trois balles de pistolet.

Pour conclure, précisons également que Mme Meganck n’a pas trouvé l’endroit propice dans son texte pour rapporter l’affirmation de Karel Van Mander, auteur du Schilderboeck de 1604, que peu avant sa mort et au moment où chaque famille bruxelloise se voit contrainte par l’occupant d’accueillir chez elle des soldats espagnols sans solde, Bruegel ordonna à sa femme de brûler ses lettres et œuvres sur papier par crainte des ennuis qu’elles pourraient lui procurer à elle et ses enfants.

Pour conclure, précisons également que Mme Meganck n’a pas trouvé l’endroit propice dans son texte pour rapporter l’affirmation de Karel Van Mander, auteur du Schilderboeck de 1604, que peu avant sa mort et au moment où chaque famille bruxelloise se voit contrainte par l’occupant d’accueillir chez elle des soldats espagnols sans solde, Bruegel ordonna à sa femme de brûler ses lettres et œuvres sur papier par crainte des ennuis qu’elles pourraient lui procurer à elle et ses enfants.

La bonne nouvelle, c’est que la Chute des anges rebelles, certes un livre ouvert pour ceux qui voudront bien le lire, gardera encore pour un certain temps ses mystères.