Le système financier actuel est en faillite et sombrera dans les jours, semaines ou mois à venir si rien n’est fait pour en finir avec le paradigme formé par la mondialisation financière, le monétarisme et le libre-échange.

Sortir « par le haut » de cette crise implique d’offrir sans tarder une retraite anticipée au président Barack Obama et une scission des banques (principe du Glass-Steagall Act), levier indispensable pour recréer un véritable système de crédit en opposition avec le système monétariste. Il s’agit de garantir de vrais investissements engendrant des richesses physiques et humaines, grâce à de grands projets et des emplois hautement qualifiés et bien rémunérés.

Peut-on le faire ? Oui, on le peut ! Cependant, le gigantesque défi à relever n’est ni économique, ni politique, mais culturel et éducationnel : comment jeter les fondations d’une nouvelle Renaissance, comment effectuer un tournant civilisationnel qui nous éloigne du pessimisme vert et malthusien vers une culture qui se fixe comme mission sacrée de développer pleinement les pouvoirs créateurs de chaque individu, qu’il soit ici, en Afrique, ou ailleurs.

Existe-t-il un précédent historique ? Oui, et surtout ici, d’où je vous parle ce matin (Naarden, aux Pays-Bas, nda) avec une certaine émotion. Elle m’envahit sans doute parce que j’ai un sens relativement précis du rôle qu’ont pu jouer plusieurs personnages de cette région où nous sommes réunis ce matin et comment, au XIVe siècle, ils ont fait de Deventer, Zwolle et Windesheim un « accélérateur de neurones » en quelque sorte, pour la toute la culture européenne et mondiale.

Permettez-moi de vous résumer l’histoire de ce mouvement de clercs laïcs et enseignants : les Frères et sœurs de la Vie Commune, un mouvement qui a enfanté notre Erasme de Rotterdam chéri, ce génie humaniste dont nous avons emprunté le nom pour créer le mouvement politique larouchiste en Belgique.

Comme très souvent, tout commence avec un individu décidant, autant qu’humainement possible, de mettre fin à ses manquements et renonçant à ces « petits compromis » qui finissent par rendre esclave la plupart d’entre nous. Ce faisant, cet individu apparaît rapidement comme un dirigeant « naturel ». Vous voulez devenir un leader ? Commencez par faire le ménage dans vos propres affaires avant de donner des leçons aux autres !

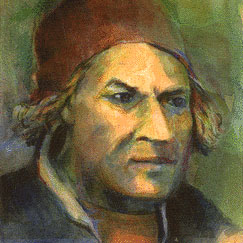

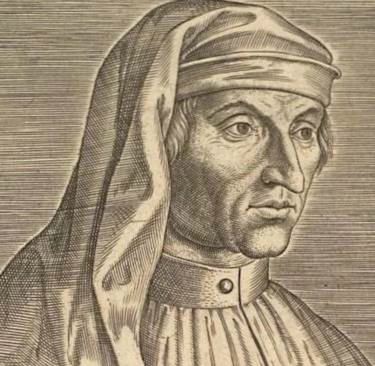

Geert Groote, le fondateur

- Le père spirituel des Frères est Geert Groote, né en 1340 et fils d’un riche marchand de textile à Deventer, qui à cette époque, tout comme Zwolle, Kampen et Roermond, sont des villes prospères de la Ligue hanséatique.

En 1345, suite au krach financier international, la peste noire se répand à travers toute l’Europe et arrive aux Pays-Bas vers 1349-50. Entre un tiers et la moitié de la population y laisse la vie et, d’après certaines sources, Groote perd ses deux parents. Il abhorre l’hypocrisie des hordes de flagellants qui envahissent les rues et prônera par la suite une spiritualité moins voyante, plus intérieure.

Groote a du talent pour les choses intellectuelles et on l’envoi rapidement étudier à Paris. En 1358, à dix-huit ans, il obtient le titre de Maître ès arts, alors que les statuts de l’Université stipulent que l’âge minimum requis est de vingt et un ans. Il reste huit ans à Paris où il enseigne, tout en faisant quelques excursions à Cologne et Prague. Pendant ce temps-là, il assimile tout ce qu’on peut savoir de la philosophie, de la théologie, de la médecine, du droit canonique et de l’astronomie. Il apprend également le latin, le grec et l’hébreu et il est considéré comme l’un des plus grands érudits de l’époque.

Vers 1362, il devient chanoine de la cathédrale d’Aix-la-Chapelle et en 1371 d’Utrecht. A 27 ans il est envoyé comme diplomate à Cologne et à la Cour d’Avignon afin de régler avec le pape Urbain V le différent qui oppose la ville de Deventer à l’évêque d’Utrecht. Qu’il ait rencontré à l’occasion l’humaniste italien Pétrarque qui s’y trouvait n’est pas impossible.

Plein de connaissance et de succès, Groote a la grosse tête. Ses meilleurs amis, conscients de ses talents lui suggèrent gentiment de se détacher de l’obsession du « paradis terrestre ». Le premier est Guillaume de Salvarvilla, le maître de cœur de Notre-Dame de Paris. Le deuxième est Henri Eger de Kalkar (1328-1408) avec qui il a partagé les bancs de la Sorbonne.

En 1374, Groote tombe gravement malade. Pourtant, le prêtre de Deventer refuse de lui administrer les derniers sacrements tant qu’il refuse de brûler certains des livres en sa possession. Craignant pour sa vie, il se résout alors à brûler sa collection de livres sur la magie noire. Enfin, il se sent mieux et guérit. Il renonce également à vivre dans le confort et le lucre grâce à des emplois fictifs qui lui permettaient de s’enrichir sans trop travailler.

Après cette conversion radicale, il prend de bonnes résolutions. Dans ses Conclusions et résolutions il écrit :

C’est à la gloire, à l’honneur et au service de Dieu que je me propose d’ordonner ma vie, ainsi qu’au salut de mon âme. (…) En premier lieu, ne désirer aucun autre bénéfice et ne mettre désormais mon espoir et mon attente dans un quelconque profit temporel. Plus j’aurai des biens, plus j’en voudrai sans doute davantage. Car selon l’Eglise primitive, tu ne peux avoir plusieurs bénéfices. (…) Parmi toutes les sciences des gentils [païens], les sciences morales sont les moins détestables : plusieurs d’entre elles sont souvent utiles et profitables tant pour soi-même que pour enseigner les autres. Les plus sages, comme Socrate et Platon, ramenaient toute la philosophie à l’éthique. Et s’ils ont parlé de choses élevées, ils les ont transmises (selon saint Augustin et ma propre expérience) en les moralisant avec légèreté et de façon figurée, afin que la morale transparaisse toujours dans la connaissance…

Groote entreprend ensuite une retraite spirituelle chez les Chartreux de Monnikshuizen près d’Arnhem où il se consacre à la prière et à l’étude. Après un séjour de trois ans, le prieur, son ami parisien Eger de Kalkar lui dit : « Au lieu de rester cloîtré ici, tu pourras faire un plus grand bien en allant prêcher dans le monde, une activité pour laquelle Dieu t’a donné un grand talent ».

Jan van Ruusbroec, l’inspirateur

Groote relève le défi. Cependant, avant de passer à l’action, il décide d’effectuer en 1378 un dernier voyage à Paris pour se procurer les livres dont il aura besoin.

D’après Pomerius, il entreprend ce déplacement avec son ami de Zwolle, l’instituteur Joan Cele (vers 1350-1417), fondateur historique de l’excellent système d’enseignement public néerlandais, les Latijnse School (Ecoles de latin).

Sur le chemin de Paris, ils rendent visite à Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), un mystique flamand installé au prieuré de Groenendael en bordure de la Forêt de Soignes près de Bruxelles.

Groote, vivant encore dans la crainte de Dieu et des autorités, essaye initialement de rendre « plus présentable » certains écrits du vieux sage tout en reconnaissant Ruusbroec plus proche que lui du Seigneur.

Dans une lettre à la communauté de Groenendael, il sollicite ainsi la prière du prieur : « Je tiens à me recommander à la prière de votre prévôt et prieur. Pour le temps de l’éternité, je voudrais être « l’escabeau du prieur », tant que mon âme lui est unie dans l’amour et le respect. » (Note 1)

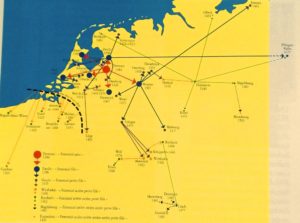

De retour à Deventer, Groote se concentre sur l’étude et la prédication. D’abord il se présente à l’évêque pour être ordonné diacre. Dans cette fonction, il obtient le droit de prêcher dans tout l’évêché d’Utrecht (en gros, toute la partie des Pays-Bas d’aujourd’hui située au nord des grands fleuves, à l’exception des environs de Groningen). D’abord il prêche à Deventer, ensuite à Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen et plus tard à Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda et Delft.

Son succès est si éclatant qu’au sein de l’église la jalousie se fait ressentir. Par ailleurs, avec le chaos provoqué par le grand schisme (1378 à 1417) installant deux papes à la tête de l’Eglise, les croyants cherchent de nouvelles voies.

Dès 1374, Groote offre une partie de la maison de ses parents pour y accueillir un groupe de femmes pieuses. Dotée d’un règlement, la première maison de sœurs est née à Deventer. Il les nomme « Sœurs de la Vie Commune », un concept développé dans plusieurs œuvres de Ruusbroec, notamment dans le paragraphe final De la pierre brillante :

L’homme qui est envoyé de cette hauteur vers le monde ci-bas, est plein de vérité, et riche de toutes les vertus. Et il ne cherche pas le sien, mais l’honneur de celui qui l’a envoyé. Et c’est pourquoi il est droit et véridique dans toute chose. Et il possède un fond riche et bienveillant fondé dans la richesse de Dieu. Et ainsi il doit toujours transmettre l’esprit de Dieu à ceux qui en ont besoin ; car la fontaine vivante du Saint-Esprit n’est pas une richesse qu’on peut gâcher. Et il est un instrument volontaire de Dieu avec lequel le Seigneur travaille comme Il veut, et comment Il veut. Et il ne s’en vente nullement mais laisse l’honneur à Dieu. Et pour cela il reste prêt à tout faire que Dieu ordonne ; et de faire et de tolérer avec force tout ce que Dieu lui confie. Et ainsi il a une vie commune ; car pour lui, voir [contempler] et travailler lui sont égales, car dans les deux choses il est parfait .

Florens Radewijns, l’organisateur

Suite à l’un de ses premiers prêches, Groote recrute Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Natif d’Utrecht, ce dernier a reçu sa formation à Prague où, lui aussi à l’âge précoce de 18 ans, reçoit le titre de Magister Artium.

Groote l’envoi ensuite à Worms pour y être consacré prêtre. En 1380 Groote s’installe avec une dizaine d’élèves dans la maison de Radewijns à Deventer ; elle sera ultérieurement connue comme le « Heer Florenshuis », première maison des Frères et surtout sa base d’opérations.

Quand il décède à son tour de la peste en 1384, Radewijns décide d’étendre le mouvement qui devient les Frères et Sœurs de la Vie Commune. Rapidement, ils se nommeront la Devotio Moderna (Dévotion moderne).

Livres et béguinages

On peut établir un certain nombre de parallèles avec la mouvance des Béguines qui prospère à partir du XIIIe siècle. (Note 2)

Les premières béguines sont des femmes indépendantes, vivant seules (sans homme ni règle), animées d’une spiritualité profonde et osant se risquer à l’aventure énorme d’un rapport personnel avec Dieu. (Note 3)

Sans lien spécial avec la hiérarchie religieuse, elle ne mendient pas mais travaillent pour gagner leur pain quotidien. Idem pour les Frères de la Vie Commune, sauf que pour eux, les livres sont au centre de toutes leurs activités.

Sans lien spécial avec la hiérarchie religieuse, elle ne mendient pas mais travaillent pour gagner leur pain quotidien. Idem pour les Frères de la Vie Commune, sauf que pour eux, les livres sont au centre de toutes leurs activités.

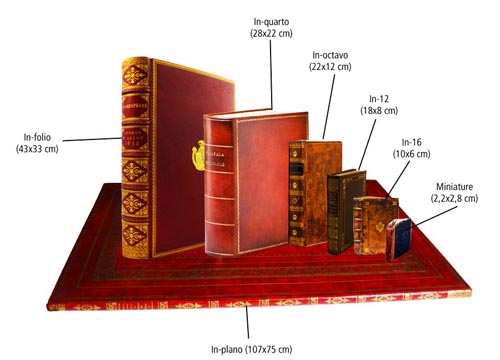

Ainsi, à part l’enseignement, la copie et la production de livres représentent une source majeure de revenus tout en permettant de répandre la bonne parole au plus grand nombre. Les Frères et Sœurs laïcs se concentrent sur l’éducation et leurs prêtres sur la prédication. Grâce au scriptorium et aux imprimeries, leur littérature et leur musique se répandront partout.

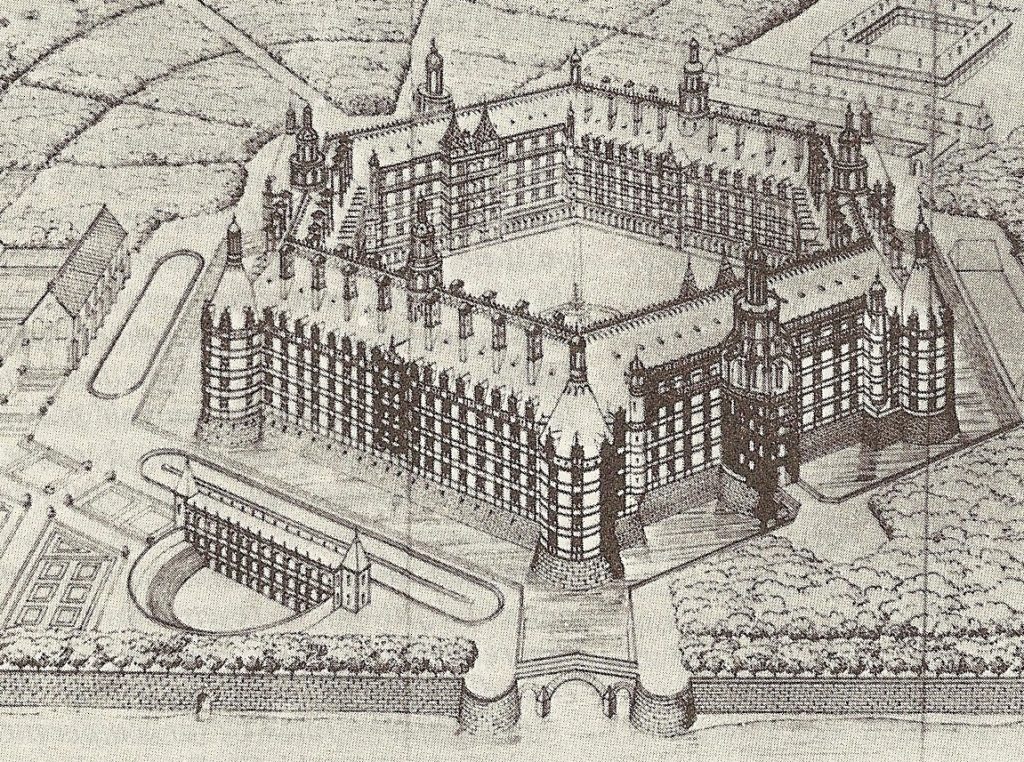

Congrégation de Windesheim

Pour mettre le mouvement à l’abri d’attaques et de critiques injustes, Radewijns fonde une congrégation de chanoines réguliers obéissant à la règle augustinienne. A Windesheim, entre Zwolle et Deventer, sur un terrain appartenant à Berthold ten Hove, un des membres, un premier cloître est érigé. Un deuxième, pour femmes cette fois, voit le jour à Diepenveen près d’Arnhem. La construction de Windesheim prend plusieurs années et un groupe de frères vit temporairement sur le chantier, dans des huttes.

Quand en 1399 Johannes van Kempen, qui a habité chez Groote à Deventer, devient le premier prieur du cloître du Mont Saint-Agnès près de Zwolle, le mouvement prend un nouvel élan. A partir de Zwolle, Deventer et Windesheim, les nouvelles recrues se répandent sur tous les Pays-Bas et l’Europe du nord pour y fonder de nouvelles antennes du mouvement.

En 1412, la congrégation possède 16 cloîtres et leur nombre atteint 97 en 1500 : 84 prieurés pour hommes et 13 pour femmes. A cela il faut ajouter un grand nombre de cloîtres pour chanoinesses qui, bien que n’étant pas formellement associé à la Congrégation de Windesheim, sont dirigés par des recteurs formés par elle. Windesheim n’est reconnue par l’évêque d’Utrecht qu’en 1423 et Groenendael, associé avec le Rouge Cloître et Korsendonc, désire en faire partie dès 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cues et Erasme

Johannes van Kempen n’est autre que le frère du très renommé Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). Ce dernier, formé à Windesheim, anime le cloître du Mont Saint-Agnès près de Zwolle et est une des grandes figures du mouvement pendant soixante-dix ans.

A sa biographie de Groote et son récit du mouvement s’ajoute surtout l’Imitatione Christi (L’imitation du Christ), œuvre la plus lue de l’histoire après la Bible.

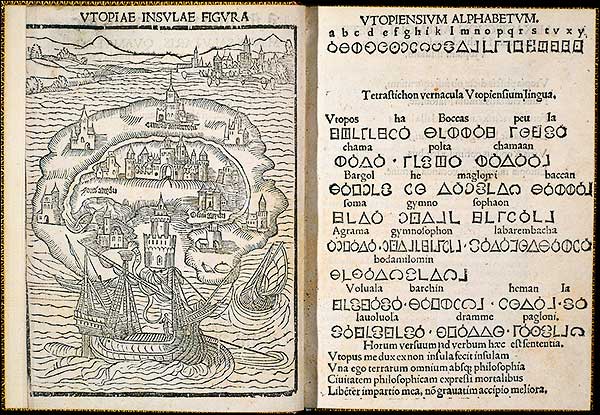

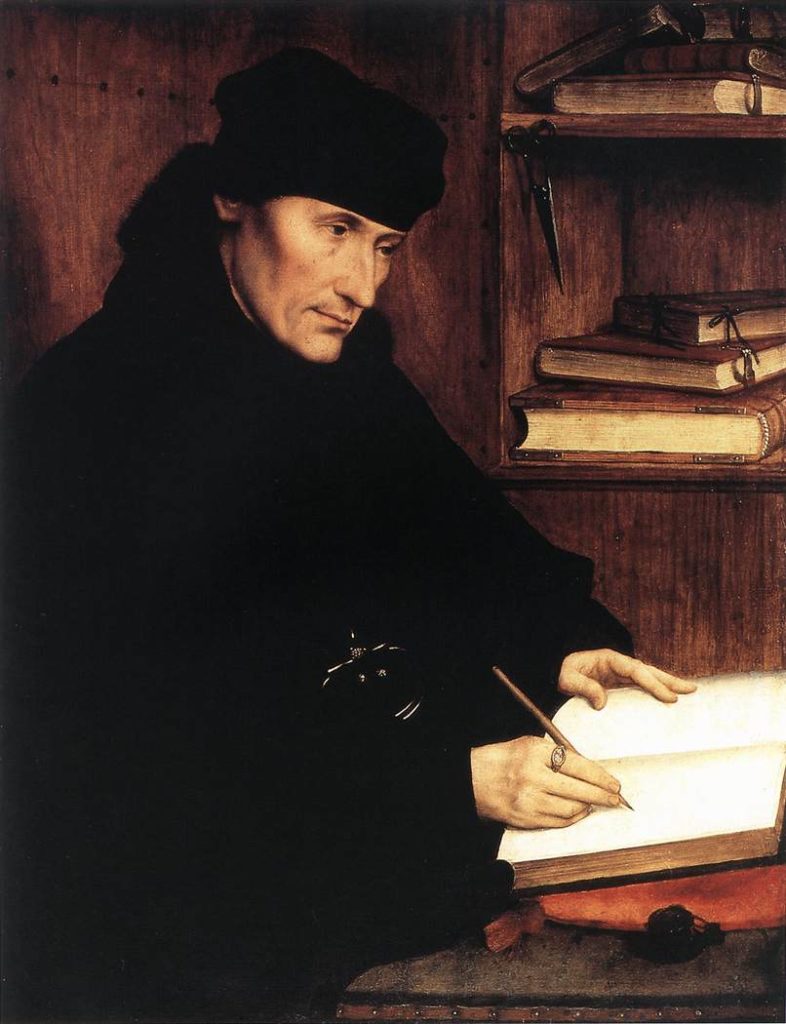

Tant Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) qu’Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), deux des précepteurs d’Erasme lors de sa formation à Deventer, sont des élèves directs de Thomas a Kempis. L’Ecole Latine de Deventer dont Hegius fut recteur est la première école d’Europe du nord à enseigner le Grec ancien aux enfants.

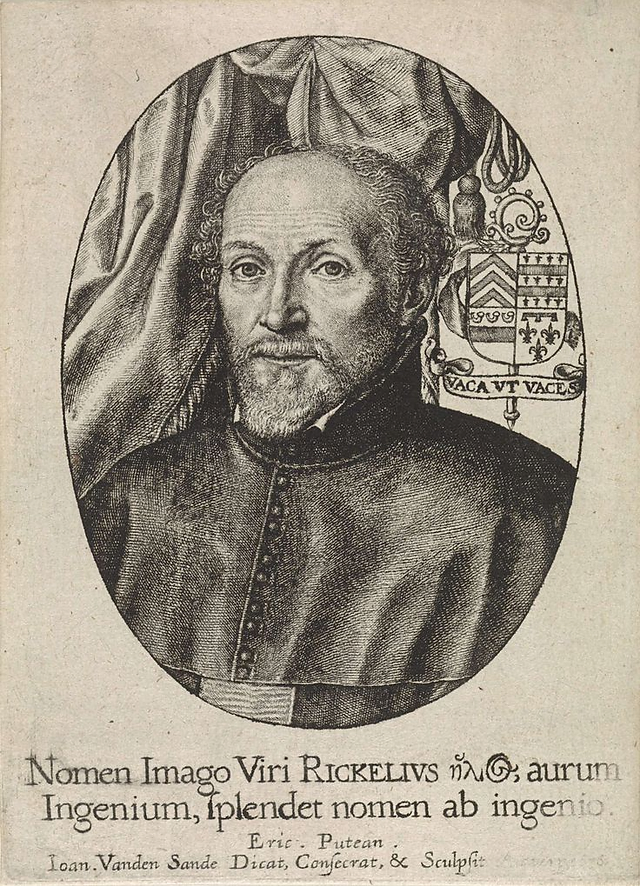

Certains pensent que ce tableau de Petrus Christus représente l’ami de Nicolas de Cues, Denis le Chartreux. La mouche sur le bord du cadre est ici symbole de la nature éphémère de l’existence humaine.

On pense généralement que Nicolas de Cues (1401-1464), qui protégeait Agricola et qui, par sa Bursa Cusanus offrait une bourse pour la formation d’orphelins et d’étudiants pauvres, a également été formé par les Frères de la Vie Commune.

Quand le cusain est envoyé en 1451 aux Pays-Bas pour mettre de l’ordre dans les affaires de l’Eglise, il voyage avec Denis le Chartreux (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), un disciple de Ruusbroec qu’il charge de mener cette tâche à bien. Natif du Limbourg, il fut lui aussi formé par la fameuse école de Joan Cele à Zwolle. [4]

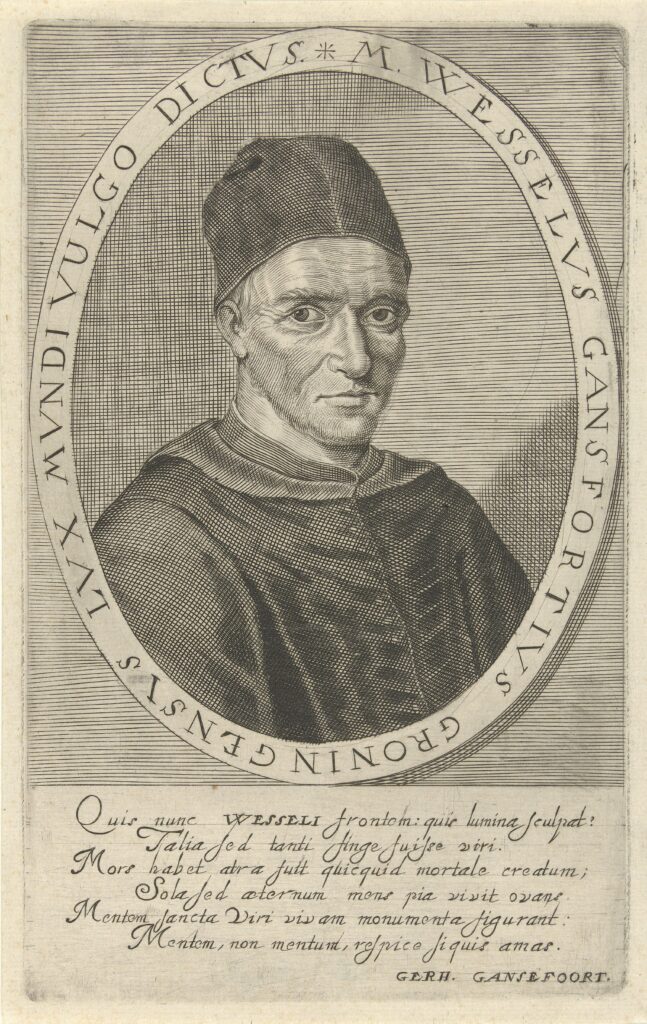

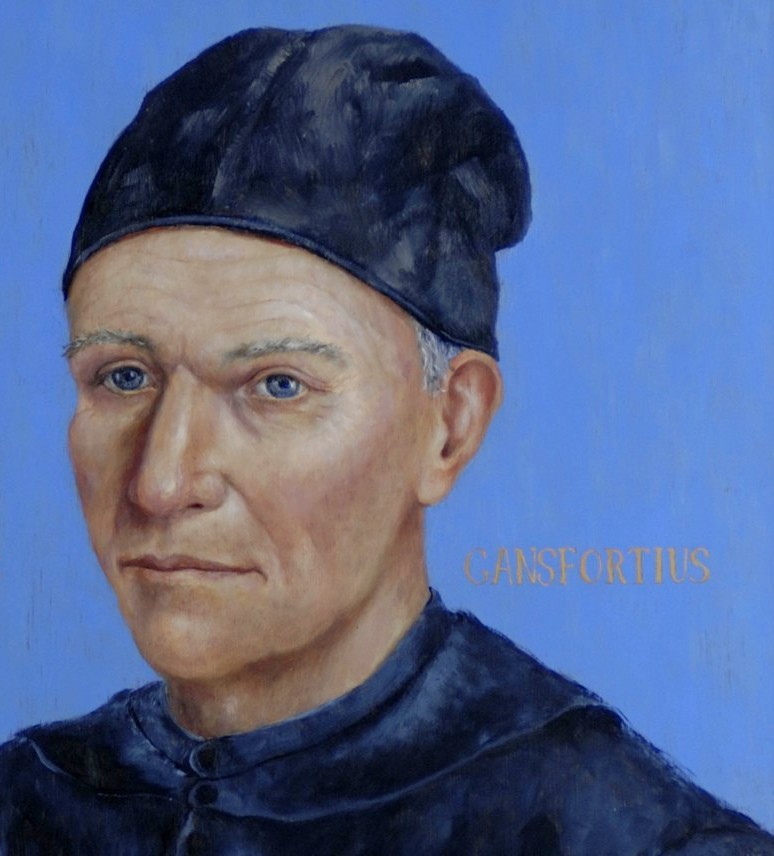

Wessel Gansfoort

Wessel Gansfoort (1419-1489), autre figure exceptionnelle de cette mouvance est au service du cardinal grec Bessarion, le principal collaborateur de Nicolas de Cues lors du Concile de Ferrare-Florence de 1437.

Gansfoort, après avoir suivi l’école des Frères à Groningen, est lui aussi formé par l’école Latine de Joan Cele à Zwolle.

Idem pour le premier et unique pape néerlandais, Adrianus VI, formé dans la même école avant de parfaire une formation avec Hegius à Deventer.

Ce pape se montra très ouvert aux idées réformatrices d’Erasme… avant d’arriver à Rome.

Hegius, dans une lettre envoyé à Gansfoort qu’il qualifie de Lux Mundi (lumière du monde), écrit :

Je vous envoie, très honorable seigneur, les homélies de Jean Crysostome. J’espère que leur lecture vous plaira, puisque que les paroles d’or vous ont toujours été plus agréable que les pièces de ce métal. Comme vous le savez, je suis allé dans la bibliothèque du cusain. Là, j’ai trouvé des livres dont j’ignorais totalement l’existence (…) Adieu, et si je peux vous rendre un service, faites-le moi savoir et considérez la chose faite.

Rembrandt van Rijn

-

Un regard sur la formation de Rembrandt indique que lui aussi fut un produit tardif de cette épopée éducatrice. En 1609, Rembrandt, trois ans à peine, entre à l’école élémentaire, où, comme les autres garçons et filles de sa génération, il apprend à lire, à écrire et… à dessiner.

L’école ouvre à six heures du matin, à sept heures en hiver, pour fermer à sept heures du soir. Les cours commencent avec la prière, la lecture et la discussion d’un passage de la Bible suivi du chant de psaumes. Ici Rembrandt acquiert une écriture élégante et bien plus qu’une connaissance rudimentaire des Évangiles.

Les Pays-Bas veulent survivre. Ses dirigeants profitent de la trêve de douze ans pour accomplir leur engagement envers l’Intérêt général. Ce faisant, les Pays-Bas du début du dix-septième siècle sont peut-être le premier pays au monde où chacun a la chance de pouvoir apprendre à lire, écrire, calculer, chanter et dessiner. Ce système éducationnel universel, peu importe ses défauts, à la disposition des riches comme des pauvres, des garçons que des filles, est le secret à l’origine du « Siècle d’or » Hollandais. Ce haut niveau d’instruction créa aussi ces générations d’émigrés hollandais actifs un siècle plus tard dans la révolution américaine.

Tandis que d’autres entamaient l’école secondaire à douze ans, Rembrandt entre à l’Ecole Latine de Leyden à sept ans.

Là, les élèves, hormis la rhétorique, la logique et la calligraphie, n’apprennent pas seulement le grec et le latin, mais aussi des langues étrangères, comme l’anglais, le français, l’espagnol ou le portugais. Ensuite, en 1620, à quatorze ans, aucune loi ne faisant obstacle aux jeunes talents, Rembrandt s’inscrit à l’université.

Son choix n’est pas la théologie, le droit, la science ou la médecine, mais… la littérature.

Voulait-il ajouter à sa connaissance du latin la maîtrise de la philologie grecque ou hébraïque, ou éventuellement le chaldéen, le copte ou l’arabe ?

Après tout, on publiait déjà à Leyden des dictionnaires Arabe/Latin à une époque où la ville devient un centre majeur de l’imprimerie dans le monde.

Ainsi, on se rend compte que les Pays-Bas et la Belgique, avec Ruusbroec et Groote d’abord puis avec Erasme et Rembrandt ensuite, ont fourni dans un passé pas si lointain, une contribution essentielle au type d’humanisme qui peut élever l’humanité à sa véritable dignité.

Échouer à étendre ici notre mouvement me semble donc du domaine de l’impossible.