Étiquette : Peter Gillis

Erasmus’ dream: the Leuven Three Language College

In autumn 2017, a major exhibit organized at the University library of Leuven and later in Arlon, also in Belgium, attracted many people. Showing many historical documents, the primary intent of the event was to honor the activities of the famous Three Language College (Collegium Trilingue), founded in 1517 by the efforts of the Christian Humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (1467-1536) and his allies. Though modest in size and scope, Erasmus’ initiative stands out as one of the cradles of European civilization, as you will discover here.

Revolutionary political figures, such as William the Silent (1533-1584), organizer of the Revolt of the Netherlands against the Habsburg tyranny, humanist poets and writers such as Thomas More, François Rabelais, Miguel Cervantes and William Shakespeare, all of them, recognized their intellectual debt to the great Erasmus of Rotterdam, his exemplary fight, his humor and his great pedagogical project.

For the occasion, the Leuven publishing house Peeters has taken through its presses several nice catalogues and essays, published in Flemish, French as well as English, bringing together the contributions of many specialists under the wise (and passionate) guidance of Pr Jan Papy, a professor of Latin literature of the Renaissance at the Leuven University, with the assistance of a “three language team” of Latinists which took a fresh look at close to all the relevant and inclusively some new documents scattered over various archives.

“The Leuven Collegium Trilingue: an appealing story of courageous vision and an unseen international success. Thanks to the legacy of Hieronymus Busleyden, counselor at the Great Council in Mechelen, Erasmus launched the foundation of a new college where international experts would teach Latin, Greek and Hebrew for free, and where bursaries would live together with their professors”, reads the back cover of one of the books.

For the researchers, the issue was not necessarily to track down every detail of this institution but rather to answer the key question: “What was the ‘magical recipe’ which attracted rapidly to Leuven between three and six hundred students from all over Europe?”

Erasmus’ initiative was unprecedented. Having an institution, teaching publicly Latin and, on top, for free, Greek and Hebrew, two languages considered “heretic” by the Vatican, was already tantamount to starting a revolution.

Was it that entirely new? Not really. As early as the beginning of the XIVth century, for the Italian humanists in contact with Greek erudites in exile in Venice, the rigorous study of Greek, Hebraic and Latin sources as well as the Fathers and the New Testament, was the method chosen by the humanists to free mankind from the Aristotelian worldview suffocating Christianity and returning to the ideals, beauty and spirit of the “Primitive Church”.

For Erasmus, as for his inspirer, the Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla (1403-1457), the « Philosophy of Christ » (agapic love), has to come first and opens the road to end the internal divisions of Christianity and to uproot the evil practices of greed (indulgences, simony) and religious superstition (cult of relics) infecting the Church from the top to the bottom, and especially the mendicant orders.

To succeed, Erasmus sets out to clarify the meaning of the Holy Writings by comparing the originals written in Greek, Hebrew and Latin, often polluted following a thousand years of clumsy translations, incompetent copying and scholastic commentaries.

Brothers of the Common Life

My own research allows me to recall that Erasmus was a true disciple of the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life of Deventer in the Netherlands, a hotbed of humanism in Northern Europe. The towering figures that founded this lay teaching order are Geert Groote (1340-1384), Florent Radewijns (1350-1400) and Wessel Gansfort (1420-1489), all three said to be fluent in precisely these three languages.

The religious faith of this current, also known as the “Modern Devotion”, centered on interiority, as beautifully expressed in the little book of Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), the Imitation of Christ. This most read book after the Bible, underlines the importance for the believer to conform one owns life to that of Christ who gave his life for mankind.

Rudolph Agricola

Hence, in 1475, Erasmus father, fluent in Greek and influenced by famous Italian humanists, sends his son to the chapter of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, at that time under the direction of Alexander Hegius (1433-1499), himself a pupil of the famous Rudolph Agricola (1442-1485) which Erasmus had the chance to listen to and which he calls a “divine intellect”.

Follower of the cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464), enthusiastic advocate of the Italian Renaissance and the Good Letters, Agricola would tease his students by saying:

“Be cautious in respect to all that you learned so far. Reject everything! Start from the standpoint you will have to un-learn everything, except that what is based on your sovereign authority, or on the basis of decrees by superior authors, you have been capable of re-appropriating yourself”.

Erasmus, with the foundation of the Collegium Trilingue will carry this ambition at a level unreached before. To do so, Erasmus and his friend apply a new pedagogy. Hence, instead of learning by heart medieval commentaries, pupils are called to formulate their proper judgment and take inspiration of the great thinkers of the Classical period, especially “Saint Socrates”. Latin, a language that degenerated during the Roman Empire, will be purified from barbarisms.

With this approach, for pupils, reading a major text in its original language is only the start. An explorative work is required: one has to know the history and the motivations of the author, his epoch, the history of the laws of his country, its geography, cosmography, all considered to be indispensable instruments to put each text in its specific literary and historical context and allowing reading, beyond the words, the intention of their author.

This “modern” approach (questioning, critical study of sources, etc.) of the Collegium Trilingue, after having demonstrated its efficiency by clarifying the message of the Gospel, will rapidly travel over Europe and reach many other domains of knowledge, notably scientific issues! By uplifting young talents, out of the small and sleepy world of scholastic certitudes, this institution rapidly grew into a hotbed for creative minds.

For the ignorant reader who often considers Erasmus as some kind of comical writer praising madness which lost it after an endless theological dispute with Martin Luther, such a statement might come as a surprise.

Scientific Renaissance

While Belgium’s contributions to science, under Emperor Charles Vth, are broadly recognized and respected, few are those understanding the connection uniting Erasmus with a mathematician as Gemma Frisius and his pupil and friend Gerard Mercator, an anatomist such as Andreas Vesalius or a botanist such as Rembert Dodonaeus.

Hence, as already thoroughly documented in 2011 by Professor Jan Papy in a remarkable article, the scientific renaissance which bloomed in the Netherlands and Belgium in the early XVIth century, could not have taken place if it were for the “linguistic revolution” provoked by the Collegium Trilingue.

Because, beyond the mastery of their vernacular languages (French and Dutch), hundreds of youth, by studying Greek, Latin and Hebrew, suddenly got access to all the scientific treasures of Greek Philosophy and the best authors in those newly discovered languages.

At last, they could read Plato in the text, but also Anaxagoras, Heraclites, Thales of Millet, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Pythagoras, Eratosthenes, Archimedes, Galen, Vitruvius, Pliny the elder, Euclid and Ptolemy whose work they will master and eventually correct.

As the books published by Peeters account in great detail, during the first century of its existence, the Collegium Trilingue had a rough time confronting political uproar and religious strife. Heavy critique came especially form the “traditionalists”, a handful of theologians for which the Greeks were nothing but schismatics and the Jews the assassins of Christ and esoterics.

The opposition was such that Erasmus himself never could teach at the Collegium and, while keeping in close contact, decided to settle in Basel, Switzerland, in 1521.

Despite all of this, the Erasmian revolution conquered Europe overnight and a major part of the humanists of that period were trained or influenced by this institution. From abroad, hundreds of pupils arrived to follow classes given by professors of international reputation.

27 European universities integrated pupils of the Collegium in their teaching staff: among them stood Jena, Wittenberg, Cologne, Douai, Bologna, Avignon, Franeker, Ingolstadt, Marburg, etc.

Teachers at the Collegium were secured a decent income so that they weren’t obliged to give private lectures to secure a living and could offer public classes for free. As was the common practice of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, a system of bursa allowed talented though poor students, including many orphans, to have access to higher learning. “Something not necessarily unusual those days, says Pr Jan Papy, and done for the sake of the soul of the founder (of the Collegium, reference to Busleyden)”.

While visiting Leuven and contemplating the worn-out steps of the spiral staircase (wentelsteen), one of the last remains of the building that had a hard time resisting the assaults of time and ignorance, one can easily imagine those young minds jumping down the stairs with enthusiasm going from the dormitory to the classroom. Looking at the old shopping list of the school’s kitchen one can conclude the food was excellent with lots of meat, poultry but also vegetables and fruits, and sometimes wine from Beaune in Burgundy, especially when Erasmus came for a visit! While over the years, of course, the quality of the learning transmitted, would vary in accordance with the excellence of its teachers, the Collegium Trilingue, whose activity would last till the French revolution, gave its imprint in history by giving birth to what some have called the “Little Renaissance” of the first half of the XVIth century.

In France, the Sorbonne University reacted with fear and in 1523, the study of Greek was outlawed in France.

François Rabelais, at that time a monk in Vendée, saw his books confiscated by the prior of his monastery and deserts his order. Later, as a doctor, he translated the medical writings of the Greek scientist Galen from Greek into French. Rabelais’s letter to Erasmus shows the highest possible respect and intellectual debt to Erasmus.

In 1530, Marguerite de Navarre, sister of King Francis, and reader and admirer of Erasmus, at war with the Sorbonne, convinced her brother to allow Guillaume Budé, a friend of Erasmus, to create the “Collège des Lecteurs Royaux” (ancestor of the Collège de France) on the model of the Collegium Trilingue. And to protect its teachers, many coming directly from Leuven, they got the title of “advisors” of the King. The Collège taught Latin, Hebrew and Greek, and rapidly added Arab, Syriac, medicine, botany and philosophy to its curriculum.

Dirk Martens

Also celebrated for the occasion, Dirk Martens (1446-1534), rightly considered as one of the first humanists to introduce printing in the Southern Netherlands.

Born in Aalst in a respected family, the young Dirk got his training at the local convent of the Hermits of Saint William. Eager to know the world and to study, Dirk went abroad. In Venice, at that time a cosmopolite center harboring many Greek erudite in exile, Dirk made his first steps into the art of printing at the workshop of Gerardus de Lisa, a Flemish musician who set up a small printing shop in Treviso, close to Venice.

Back in Aalst, together with his partner John of Westphalia, Martens printed in 1473 the first book in the country with a movable type printing press, a treatise of Dionysius the Carthusian (1401-1471), a friend and collaborator of cardinal-philosopher Nicolas of Cusa, as well as the spiritual advisor of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy and thought to be the occasional « theological » advisor of the latter’s court painter, Jan Van Eyck.

If the oldest printed book known to us is a Chinese Buddhist writing dating from 868, the first movable printing types, made first out of wood and then out of hardened porcelain and metal, came from China and Korea in 1234.

The history of two lovers, a poem written by Aeneas Piccolomini before he became the humanist Pope Pius II, was another early production of Marten’s print shop in Aalst.

Proud to have introduced this new technique allowing a vast increase in the spreading of good and virtuous ideas, Martens wrote in one of the prefaces: “This book was printed by me, Dirk Martens of Aalst, the one who offered the Flemish people all the know-how of Venice”.

After some years in Spain, Martens returned to Aalst and started producing breviaries, psalm books and other liturgical texts. While technically elaborate, the business never reached significant commercial success.

Martens then moved to Antwerp, at that time one of the main ports and cross-roads of trade and culture. Several other Flemish humanists born in Aalst played eminent roles in that city and animate its intellectual and cultural life. Among these:

—Cornelis De Schrijver (1482-1558), the secretary of the City of Aalst, better known under his latin name Scribonius and later as Cornelius Grapheus. Writer, translator, poet, musician and friend of Erasmus, he was accused of heresy and hardly escaped from being burned at the stake.

—Pieter Gillis (1486-1533), known as Petrus Aegidius. Pupil of Martens, he worked as a corrector in his company before becoming Antwerp’s chief town clerk. Friend of Erasmus and Thomas More, he appears with Erasmus in the double portrait painted by another friend of both, Quinten Metsys (1466-1530).

—Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), editor, painter and scenographer. After a trip to Italy, he set up a workshop in Antwerp. Pieter will produce patrons for tapestries, translated with the help of his wife the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius into Dutch and trained the young Flemish painter Bruegel the Elder who will marry his daughter.

Invention of pocket books

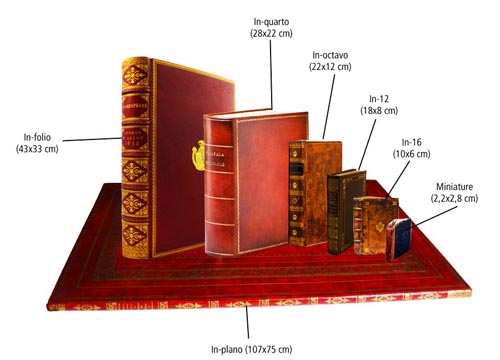

In Antwerp, Martens became part of this milieu and his workshop became a meeting place for painters, musicians, scientists, poets and writers. With the Collegium Trilingue, Martens opens a second shop, this time in Leuven to work with Erasmus. In order to provide adequate books to the Collegium, Martens proudly became, in the footsteps of the Venetian Printer Aldo Manuce, one of the first printers to concentrate on in-octavo 8° (22 x 12 cm), i.e. “pocket” size books affordable by all and which students could take home !

For the specialists of the Erasmus house of Anderlecht, close to Brussels,

“Martens innovated in nearly all domains. As well as in terms of printing types as lay-out. He was the first to introduce Italics, Greek and Hebrew letter types. He also generalized the use of ‘New Roman’ letter type so familiar today. During the first thirty years of the XVIth century, he also operated the revolution in lay-out (chapters and paragraphs) that gave birth to the modern book as we know it today. All this progress, he achieved in close cooperation with Erasmus”.

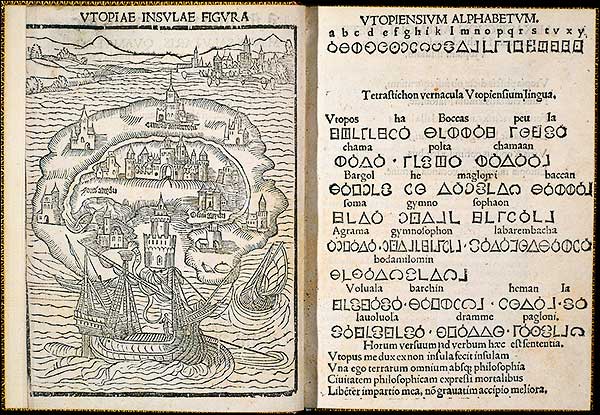

Thomas More’s Utopia

In 1516, it was Dirk Martens who printed the first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia. Among the hundreds of editions he printed mostly alone, 61 books and writings of Erasmus, notably In Praise of Folly. He also produced More’s edition of the roman satirist Lucian and Columbus’ account of the discovery of the new world. In 1423, Martens printed the complete works of Homer, quite a challenge!

In 1520, a papal bull of Leo X condemned the errors of Martin Luther and ordered the confiscation of his writings to be burned in public in front of the clergy and the people.

For Erasmus, burning books didn’t automatically erased their their content from the minds of the people. “One starts by burning books, one finishes by burning people” Erasmus warned years before Heinrich Heine said that “There, were one burns books, one ends up burning people”.

Printers and friends of Erasmus, especially in France, died on the stake opening the doors for the religious wars that will ravage Europe for the century to come.

What Erasmus feared above all, is that with the Vatican’s brutal war against Luther, it is the entire cultural renaissance and the learning of languages that got threatened with extinction.

In July 1521, confronted with the book burning, the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer, who made his living with bible illustrations, left Antwerp with his wife to return to his native Nuremberg.

Thirty years later, in 1552, the great cartographer Gerardus Mercator, a brilliant pupil of the Collegium Trilingue, for having called into question the views of Aristotle, went into exile and settled in Duisbourg, Germany.

In 1521, at the request of his friends who feared for his life, Erasmus left Leuven for Basel and settled in the workshop of another humanist, the Swiss printer Johann Froben.

In 1530, with a foreword of Erasmus, Froben published Georgius Agricola’s inventory of mining techniques, De Re Metallica, a key book that vastly contributed to the industrial revolution of Saxen, Switzerland, Germany and the whole of Europe.

Conclusion

If certain Catholic historians try to downplay the hostility of their Church towards Erasmus, the fact remains that between 1559 and 1900, the full works of Erasmus were on the “Index Vaticanus” and therefore “forbidden readings” for Catholics.

If Thomas More, whom Erasmus considered as his twin brother, was canonized by Pius XI in 1935 and recognized as the patron saint of the political leaders, Erasmus himself was never rehabilitated.

Interrogated by this author in a letter, the Pope Francis returned a polite but evasive answer.

Let’s rebuild the Collegium Trilingue !

With the exception of the staircase, only a few stones remain of the historical building housing the Collegium Trilingue. In 1909, the University of Louvain planned to buy up and rebuild the site but the First World War changed priorities. Before becoming social housing, part of the building was used as a factory. As a result, today, there is no overwhelming charm. However, seeing the historical value of the site, we cannot but fully support a full reconstruction plan of the building and its immediate environment.

It would make the historical center of Leuven so much nicer, so much more attractive and very much more loyal to its own history. On top, such a reconstruction wouldn’t cost much and might interest private investors. The images in 3 dimensions produced for the Leuven exhibit show a nice Flemish Renaissance building, much in the style of the marvels constructed by architect Rombout II Keldermans.

Every period has the right to honestly “re-write” its own history, without falsifications, according to its own vision of the future.

It has to be noted here that the world famous “Rubenshuis” in Antwerp, is not at all the original building, but a scrupulous reconstruction of the late 1930s.