Étiquette : Paris

Paris Schiller Institute stages Afghan civil society protest against UNESCO

Paris, Feb. 2024 – On Thursday February 22, between 10:00 am and 1:00 pm CET, members and supporters of the International Schiller Institute, founded and presided by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, gathered peacefully in front of one of the main buildings of the headquarters of UNESCO in Paris (1, rue Miollis, Paris 75015). An appeal (see below), endorsed by both Afghans and respected personalities of four continents, was presented to the Secretary General and other officials of UNESCO.

How it started

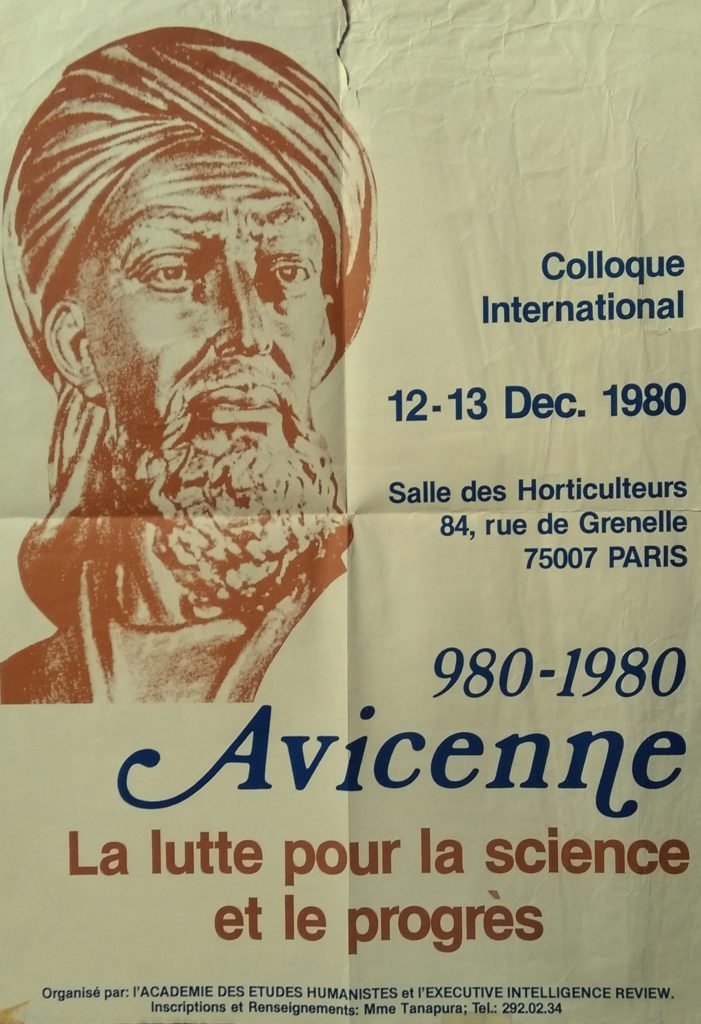

Following a highly successful conference in Kabul last November by the Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, a group of senior archaeologists of the Afghan Academy of Sciences (ASA), in discussion with the organizers and the invited experts of the Schiller Institute, suggested to launch a common appeal to UNESCO and Western governments to “lift the sanctions against cultural heritage cooperation.”

The Call

“We regret profoundly, says the call, that the Collective West, while weeping crocodile tears over destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, has imposed a selective ban of scientific cooperation on nations mistakenly considered as “opposed to its rules and values.” The complete freeze of all cooperation in the field of archaeology between France and both Syria and Afghanistan, is just one example of this tragedy.”

“The dramatic neglect of international cultural institutions and donors to Afghanistan, the lack of sufficient funds in the field of cultural heritage protection, and the political treatment of international cultural heritage institutions have seriously endangered Afghanistan,” underscores the petition.

Specifically, “UNESCO, which should raise its voice against any new form of ‘cultural and scientific apartheid,’ has repeatedly worsened the situation by politicizing issues beyond its prerogatives.”

To conclude, the signers call

“on the international community to immediately end this form of ‘collective punishment,’ which creates suffering and injustice, promotes ignorance, and endangers humanity’s capacity for mutual respect and understanding.”

Living Spirit of Afghanistan

To date, over 550 signatures have been collected, mainly from both Afghan male (370) and female (140) citizens, whose socio-professional profiles indicates they truly represent the « living spirit of the nation ».

Among the signatories: 62 university lecturers, 27 doctors, 25 teachers, 25 members of the Afghan Academy of Sciences, 23 merchants, 16 civil and women’s rights activists, 16 engineers, 10 directors and deans of private and public universities, 7 political analysts, 6 journalists, 5 prosecutors, several business leaders and dozens of qualified professionals from various sectors.

International support

On four continents (Europe, Asia, America, Africa), senior archaeologists, scientists, researchers, members of the Academy of Sciences, historians and musicians from over 20 countries have welcomed and signed this appeal.

Italian Professor Pino Arlacchi, a former member of the European Parliament and the former head of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) was the first to sign. Award-winning American filmmaker Oliver Stone, is a more recent signer.

In France, Syria, Italy, the UK and Russia, among the signers one finds senior researchers suffering the consequences of what some have identified as a « New Cultural Cold War. » Superseding the very different opinions they have on many questions, the signatories stand united on the core issue of this appeal: for science to progress, all players, beyond ideological, political and religious differences, and far from the geopolitical logic of ‘blocs’, must be able to exchange freely and cooperate, in particular to protect mankind’s historical and cultural heritage.

Testifying to the firm commitment of the Afghan authorities, the petition has also been endorsed by the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of Culture and Arts, and the Minister of Agriculture, as well as senior officials from the Ministries of Higher Education, Water and Energy, Mines, Finance, and others.

“The 46th session of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, to be held in New Delhi in July this year, offers UNESCO the opportunity to announce Afghanistan’s full return into world heritage cooperation, if we can have our voice heard,” says Karel Vereycken of the Paris Schiller Institute. “We certainly will not miss transmitting this appeal to HE Vishal V Sharma, India’s permanent representative to UNESCO, recently nominated to make the Delhi 46th session a success.”

For all information, interview requests in EN, FR and NL:

Karel Vereycken, Schiller Institute Paris

00 33 (0)6 19 26 69 38

Full text of the appeal

International Call to Lift Sanctions Against Cultural Heritage Cooperation

Following the international conference, organized by the Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center’s in Kabul in early November 2023, on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, a group of researchers launched the following petition:

We, the undersigned, researchers and experts in the domains of the history of civilizations, cultural heritage, archaeology, anthropology, sociology, and many other fields, and other enlightened citizens of the world, in Afghanistan, Syria, Russia, China, and many other countries, launch the following call.

1) We regret profoundly that the “Collective West”, while weeping crocodile tears over destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, has imposed a selective ban of scientific cooperation on nations mistakenly considered as “opposed to its rules and values.” The complete freeze of all cooperation in the field of archaeology between France and both Syria and Afghanistan, is just one example of this tragedy.

2) We request particular attention to the case of Afghanistan. Its neighboring countries, national and international institutions, and countries involved in international conventions for the protection of cultural and natural heritage are committed to cooperation in the field of guarding cultural heritage sites and artifacts and preventing their smuggling and destruction. Therefore, it is expected that in the current situation, they will fully play their role in the protection of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage in accordance with international laws and conventions. However, the dramatic neglect of international cultural institutions and donors to Afghanistan, the lack of sufficient funds in the field of cultural heritage protection, and the political treatment of international cultural heritage institutions have seriously endangered Afghanistan. Undoubtedly, the non-recognition of the Afghan government has dimmed the attention of cultural institutions. Considering the above, we expect these international institutions to renew their full support to protect both the tangible and the intangible cultural heritage of Afghanistan.

3) We regret that UNESCO, which should raise its voice against any new form of “cultural and scientific apartheid,” has repeatedly worsened the situation by politicizing issues beyond its prerogatives.

4) Therefore, we call on the international community to immediately end this form of “collective punishment,” which creates suffering and injustice, promotes ignorance, and endangers humanity’s capacity for mutual respect and understanding.

The progress of scientific knowledge, in a positive climate permitting all to share it, is by its very nature beneficial to each and to all and to the very foundation of a true peace.

SIGNERS:

A. FROM AFGHAN CIVIL SOCIETY:

– Hussain Burhani, Archaeologist, Numismatist, Afghanistan ;

– Ketab Khan Faizi, Archaeologist, Director of the Academy of Sciences at the International Centre for Kushan Studies in Kabul, Afghanistan;

– Stora Ishams Mayar, Archaeologist, member of the Academy of Sciences at the International Centre for Kushan Studies in Kabul, editor in chief of the journal of this mentioned center, Afghanistan;

– Mahmood Jan Drost, Senior Architect, head of protection of old cities of Afghanistan, Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, Afghanistan;

– Ghulam Haidar Kushkaky, Archaeologist, associate professor, Archaeology Investigation Center, Afghanistan ;

— Laieq Ahmadi, Archeologist, Former head, Archeology department of Bamiyan University, Afghanistan;

– Shawkatullah Abed, Chief of staff, Afghan Science Academy, Afghanistan;

– Sardar Ghulam Ali Balouch, Head of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan;

– Daud Azimi Shinwari, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Germany;

– Abdul Fatah Raufi, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Kabul, Afghanistan;

– Mirwais Popal, Dip, Master, Ibn-e-Sina Research & Development Center, Germany;

B. FROM ABROAD:

(Russia, China, USA, Indonesia, France, Angola, Germany, Turkiye, Italy, UK, Mexico, Sweden, Iran, Belgium, Argentina, Czech Republic, Syria, Congo Brazzaville, Yemen, Venezuela, Pakistan, Spain, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo.)

– H.E. Mr Mohammad Homayoon Azizi, Afghanistan’s Ambassador to Paris, UNESCO and ICESCO, France;

— Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento, Researcher at the National Scientific Research Centre (CNRS), Archaeologist specializing in Central Asia; Former director of the Delegation of French Archaeologists in Afghanistan (DAFA) (2014-2018), France;

– Inès Safi, CNRS, Researcher in Theoretical Nanophysics, France;

– Pierre Leriche, Archeologist, Director of Research Emeritus at CNRS-AOROC, Scientific Director of the Urban Archaeology of the Hellenized Orient research program, France;

– Nadezhda A. Dubova, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Dr. in Biology, Prof. in History. Head of the Russian-Turkmen Margiana archaeological expedition, Russian Academy of Science (RAS), Russia;

— Alexandra Vanleene, Archaeologist, specialist in Gandhara Buddhist Art, Researcher, Independant Academic Advisor Harvard FAS CAMLab, France;

– Raffaele Biscione, retired, associate Researcher, Consiglio Nazionale delle Recerche (CNR); former first researcher of CNR, former director of the CNR archaeological mission in Eastern Iran (2009-2022), Italy;

— Sandra Jaeggi-Richoz, Professor, Historian and archaeologist of the Antiquity, France;

– Dr. Razia Sultanova, Professor, Cambridge University, UK;

– Dr. Houmam Saad, Archaeologist, Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums, Syria;

– Estelle Ottenwelter, Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Natural Sciences and Archaeometry, Post-Doc, Czech Republic;

– Didier Destremau, author, diplomat, former French Ambassador, President of the Franco-Syrian Friendship Association (AFS), France ;

– Wang Feng, Professor, South-West Asia Department of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), China;

– Dr. Engin Beksaç, Professor, Trakya University, Department of Art History, Turkiye;

– Bruno Drweski, Professor, National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO), France;

– Maurizio Abbate, National President of National Agency of Cultural Activities (ENAC), Italy;

– Patricia Lalonde, Former Member of the European Parliament, vice-president of Geopragma, author of several books on Afghanistan, France;

– Pino Arlacchi, Professor of sociology, Former Member of the European Parliament, former head of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Italy;

– Oliver Stone, Academy Award-winning Film director, Producer, and Screenwriter;

– Graham E. Fuller, Author, former Station chief for the CIA in Kabul until 1978, former Vice-Chair of the National Intelligence Council (1986), USA;

– Prof. H.C. Fouad Al Ghaffari, Advisor to Prime Minister of Yemen for BRICS Countries affairs, Yemen;

– Farhat Asif, President of Institute of Peace and Diplomatic Studies (IPDS), Pakistan;

— Dursun Yildiz, Director, Hydropolitics Association, Türkiye;

– Irène Neto, president, Fundacao Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto (FAAN), Angola;

– Luc Reychler, Professor international politics, University of Leuven, Belgium;

– Pierre-Emmanuel Dupont, Expert and Consultant in public International Law, Senior Lecturer at the Institut Catholique de Vendée, France;

— Irene Rodríguez, Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina;

– Dr. Ririn Tri Ratnasari, Professor, Head of Center for Halal Industry and Digitalization, Advisory Board at Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia;

– Dr. Clifford A. Kiracofe, Author, retired Professor of International Relations, USA;

– Bernard Bourdin, Dominican priest, Philosophy and Theology teacher, Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP), France;

– Dr. jur. Wolfgang Bittner, Author, Göttingen, Germany;

– Annie Lacroix-Riz, Professor Emeritus of Contemporary History, Université Paris-Cité, France;

– Mohammad Abdo Al-Ibrahim, Ph.D in Philology and Literature, University Lecturer and former editor in chief of the Syria Times, Syria;

– Jean Bricmont, Author, retired Physics Professor, Belgium;

– Syed Mohsin Abbas, Journalist, Broadcaster, Political Analyst and Political Justice activist, Pakistan;

– Eduardo D. Greaves PhD, Professor of Physics, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas, Venezuela;

– Dora Muanda, Scientific Director, Kinshasa Science and Technology Week, Democratic Republic of Congo;

– Dr. Christian Parenti, Professor of Political Economy, John Jay College CUNY, New York, USA;

– Diogène Senny, President of the Panafrican Ligue UMOJA, Congo Brazzaville;

– Waheed Seyed Hasan, Journalist based in Qatar, former Special correspondent of IRNA in New Delhi, former collaborator of Tehran Times, Iran;

– Alain Corvez, Colonel (retired), Consultant International Strategy consultant, France;

– Stefano Citati, Journalist, Italy;

– Gaston Pardo, Journalist, graduate of the National University of Mexico. Co-founder of the daily Liberacion, Mexico;

– Jan Oberg, PhD, Peace and Future Research, Art Photographer, Lund, Sweden.

– Julie Péréa, City Councilor for the town of Poussan (Hérault), delegate for gender equality and the fight against domestic violence, member of the Sète Agglopole Méditerranée gender equality committee, France;

– Helga Zepp-LaRouche, Founder and International President of the Schiller Institute, Germany;

– Abid Hussein, independent journalist, Pakistan;

– Anne Lettrée, Founder and President of the Garden of Titans, Cultural Relations Ambassador between France and China for the Greater Paris region, France;

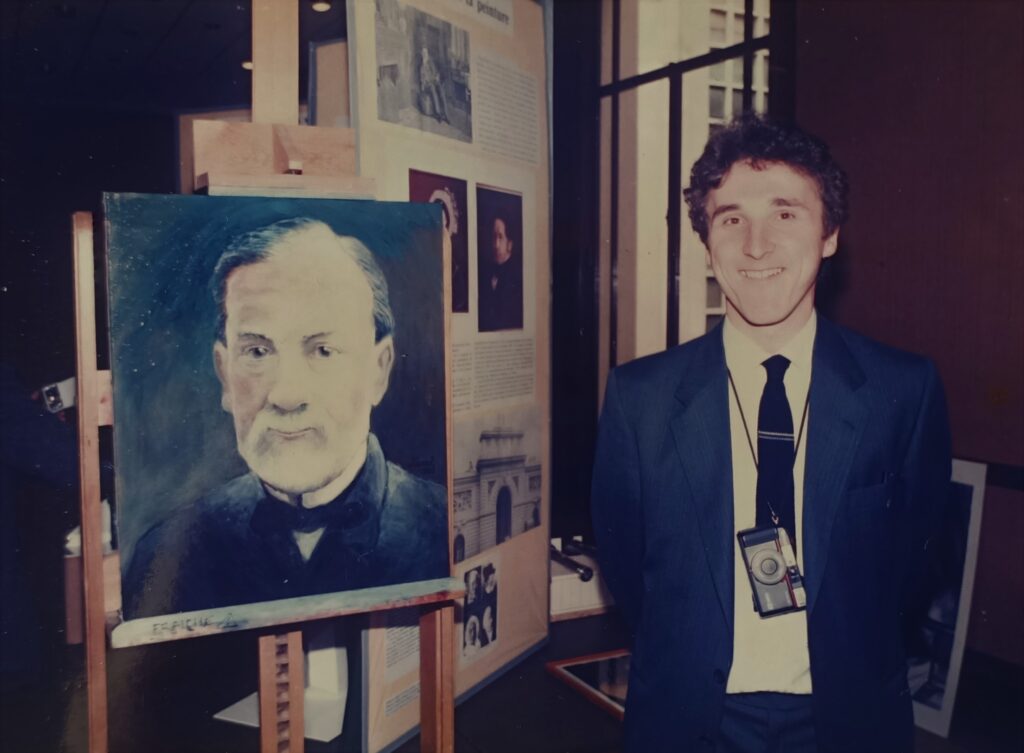

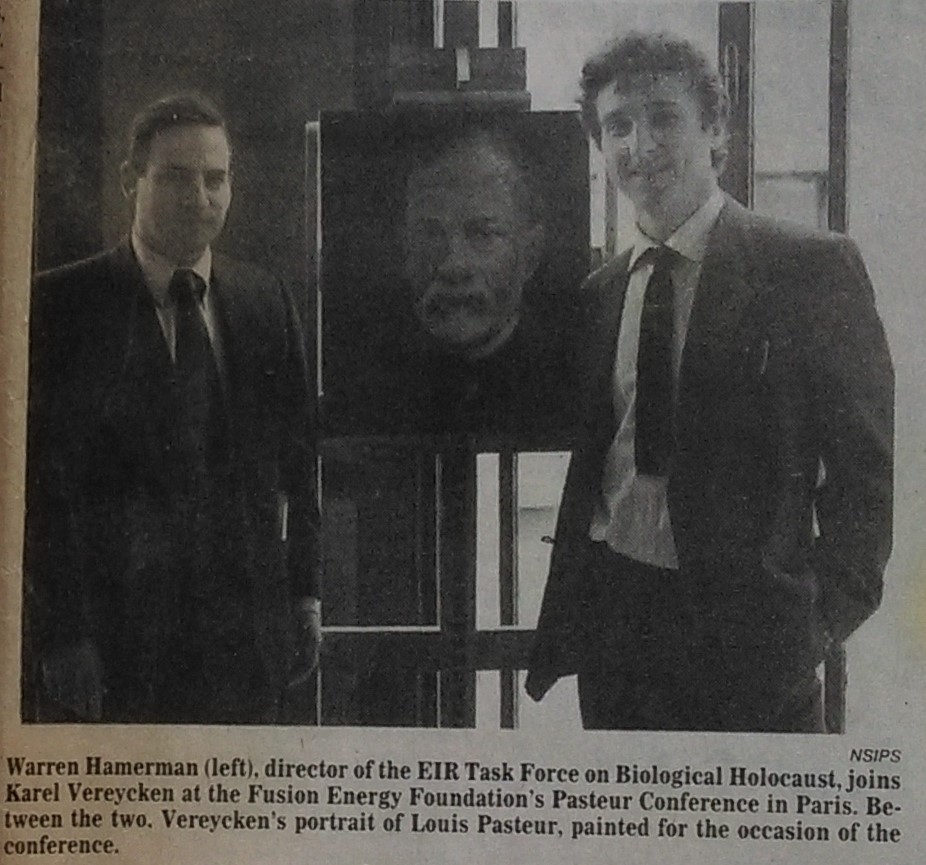

– Karel Vereycken, Painter-engraver, amateur Art Historian, Schiller Institute, France;

– Carlo Levi Minzi, Pianist, Musician, Italy;

– Leena Malkki Brobjerg, Opera singer, Sweden;

– Georges Bériachvili, Pianist, Musicologist, France;

– Jacques Pauwels, Historian, Canada;

C. FROM AFGHAN AUTHORITIES

– Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, Deputy Foreign Minister, Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA);

– Mawlawi Muhibullah Wasiq, Head of Foreign Minister’s Office, IEA;

– Waliwullah Shahin, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Sayedull Afghani, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Hekmatullah Zaland, Member of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Shafi Azam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IEA;

– Atiqullah Azizi, Deputy Minister of Culture and Art, Ministry of Information and Culture, IEA;

– Ghorzang Farhand, Ministry of Information and Culture, IEA;

– Ghulam Dastgir Khawari, Advisor of Ministry of Higher Education, IEA;

– Mawlawi Rahmat Kaka Zadah, Member of ministry of Interior Affairs, IEA;

– Mawlawi Arefullah, Member of Interior Affairs, IEA;

– Ataullah Omari, Acting Agriculture Minister, IEA;

– Mawlawi Hussain Ahmad, Head of office in Ministry of Agriculture, IEA:

– Musa Noorzai, Member of Ministry of Agriculture, IEA;

– Mawlawi Hussain Ahmad, Head of office, Ministry of Agriculture, IEA;

– Mawlawi Shar Aqa, Head of Kunar Agriculture Administration, IEA;

– Matiulah Mujadidi, Head of Communication of Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Zabiullah Noori, Executive Manager, Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Akbar Wazizi, Member of Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Nasrullah Ebrahimi, Auditor, Ministry of Finance, IEA;

– Mir M. Haroon Noori, Representative, Ministry of Economy, IEA;

– Abdul Qahar Mahmodi, Ministry of Commerce, IEA;

– Dr. Ghulam Farooq Azam, Adviser, Ministry of Water & Energy (MoWE), IEA;

– Faisal Mahmoodi, Investment Facilitation Expert, Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, IEA;

– Rustam Hafiz Yar, Ministry of Transportation, IEA;

– Qudratullah Abu Hamza, Governor of Kunar, IEA;

– Mansor Faryabi, Member of Kabul Municipality, IEA;

– Mohammad Sediq Patman, Former Deputy Minister of Education for Academic Affairs, IEA;

COMPLEMENTARY LIST

A. FROM AFGHANS

- Jawad Nikzad, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Akram Azimi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Najibullah Totakhel, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Germany

- Ghulam Farooq Ansari, Professor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Imran Zakeria, Researcher at Regional Studies Center, Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan, Ibn Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Subhanullah Obaidi, Doctor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Germany ;

- Ali Shabeez, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Germany ;

- Mawlawi Wahid Ameen, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Shar M. Amir Zadah, Ibne-eSina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Rafiullah Halim, Professor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul Afghanistan ;

- Nazar Mohmmad Ragheb, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Faisal Mahmoodi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Basir, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Muneera Aman, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Shakoor, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Waris Ebad, Employee of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Afghanistan ;

- Waisullah Sediqi, Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Hakim Aria, Employee of Ministry of Information and Culture, Afghanistan ;

- Nayebuddin Ekrami, Employee of Ministry of information and Culture, Afghanistan ;

- Latifa Azimi, Former Employee of Ministry of Education, Afghanistan ;

- Latifa Noori, Former Employee of Ministry of Education, Afghanistan ;

- Habibullah Haqani, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Shafiqullah Baburzai, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Abdullah Kamawal, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rashid Lodin, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Asef Nang, Cultural Heritage, Afghanistan ;

- Awal Khan Shekib, Member of Afghanistan Regional Studies Center, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Anwar Fayaz, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Farhad Ahmadi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Fayqa Lahza Faizi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hakim Haidar, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Rahimullah Harifal, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Sharifullah Dost, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Eshaq Momand, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Khalil Rahman Barekzal, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Haidar Kushkaki, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Nabi Hanifi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Marina Bahar, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Muhaidin Hashimi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Majid Nadim, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Elaha Maqsoodi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Khadim Ahmad Haqiqi, Lecturer, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Shahidullah Safi, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Wahab Hamdard, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Burhanullah Niazi, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- M. Alam Eshaq Zai, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Hasan Farmand, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Zalmai Hewad Mal, Member, Afghanistan Science Academy, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rahman Atash, Head of Afghanistan National Development Company (NDC), Afghanistan ;

- Obaidullah, Head of Public Library, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Abdul Maqdam, Head of Khawar construction company, Afghanistan ;

- Zaki Zarifi, Head of Zarifi company, Afghanistan ;

- Jamshid Faizi, Head of Faizi company, Afghanistan ;

- M. Yasin Farahman, Head of Agriculture Center, Afghanistan ;

- Mawlawi Nik M. Nikmal, Head of Planning in Technical Administration, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Wahid Rahimi, Member of Bashtani Bank, Afghanistan ;

- M. Daud Mangal, Head of Ariana Afghan Airlines, Afghanistan ;

- Mostafa Yari, entrepreneur, Afghanistan;

- Gharwal Roshan, Head of Kabul International Airfield, Afghanistan ;

- Eqbal Mirzad, Head of New Kabul City Project, Afghanistan ;

- Najibullah Sadiq, Vice-president of Afghan Chamber of Commerce and Indunstry (ACCI), Afghanistan;

- M. Yunis Mohmand, Vice-president of ACCI, Afghanistan;

- Khanjan Alikozai, Member of ACCI, Afghanistan;

- Mawlawi Abdul Rashid, Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Atiqullah Safi, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Jalil Safi, Employee of Kabul Municipality, Afghanistan ;

- Hujat Fazli, Head of Harakat, Afghanistan Investment Climate Facility Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mehrab Hamidi, Member of Economical Commission, Afghanistan;

- Hamid Pazhwak, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Awaz Ali Alizai, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- Shamshad Omar, Economist, Afghanistan ;

- Helai Fahang, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Alikozai, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Dunya Farooz, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Soman Khamoosh, Economy Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Drs. Shokoria Yousofi, Bachelor of Economy, Afghanistan;

- Sharifa Wardak, Specialist of Agriculture, Afghanistan;

- M. Asef Dawlat Shahi, Specialist of Chemistry, Afghanistan;

- Pashtana Hamami, Specialist of Statistics, Afghanistan;

- Asma Karimi, Master of Management, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Ahmad Zaki Afghanyar, Vice-President of Herat Health committee, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hashem Mudaber, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Hekmatullah Arian, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Wahab Rahmani, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Karima Rahimyar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Sayeeda Basiri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Emran Sayeedi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Hadi Dawlatzai, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ghani Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Nafisa Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Ghani Naseri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mohammad Younis Shouaib, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Halima Akbari, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Manizha Emaq, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Shafiq Shinwari, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Akbar Jan Foolad, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Haidar Omar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ehsanuddin Ehsan, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Wakil Matin, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Matalib, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Azizi Amer, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Nasr Sajar, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Humayon Hemat, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Humaira Fayaq, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Sadruddin Tajik, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Abdul Baqi Ahmad Zai, Surgery Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Beqis Kohistani, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Nafisa Nasiri, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Aziza Yousuf, Head of Malalai Hospital, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Yasamin Hashimi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Zuhal Najimi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Ahmad Salem Sedeqi, Medical Doctor, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Fazel Raman, veterinary, Afghanistan;

- Khatera Anwary, Health, Afghanistan;

- Rajina Noori, Member of Afghanistan Journalists Union, Afghanistan ;

- Sajad Nikzad, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Suhaib Hasrat, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Shar Aqa Karimi, Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Mohammad Suhrabi , Journalist, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Nasir Kuhzad, Journalist and Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Fazel Menallah, Political Analyst, Afghanistan;

- M. Wahid Benish, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Mahmood Jan Shafizada, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Fazel Rahman Orya, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Zarghon Shah Shinwari, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Ghafor Shinwari, Political Analyst, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Ahmad Yousufi, Dean, Kateb University, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Yayia Balaghat, Scientific Vice-President, Kateb University, Afghanistan ;

- Chaman Shah Etemadi, Head of Gharjistan University, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mesbah, Head of Salam University, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Pirzad Ahmad Fawad, Kabul University;

- Dr. Nasir Nawidi, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Zabiullah Fazli, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Ramish Adib, Vice of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- M. Taloot Muahid, Dean of a Private University, Afghanistan;

- Ebrahim Ansari, School Manager, Afghanistan;

- Abas Ali Zimozai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Arshad Rahimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Fasihuddin Fasihi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Waisuddin Jawad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Murtaza Sharzoi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Matin Monis, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Wahid Benish, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Hussian Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Muhsin Reshad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Sadiq Baqori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Zahir Halimi, Univ. Lecturer , Afghanistan ;

- Rohla Qurbani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Murtaza Rezaee, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Rasoul Qarluq, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Najim Wahidi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Rashid Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Rahman Matin, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Mujtaba Amin, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Amanullah Faqiri, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Abuzar Khpelwak Zazai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Belal Tayab, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Adel Hakimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Wasiqullah Ghyas, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Faridduin Atar, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Safiullah Jawhar, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Amir Jan Saqib, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Shekib Rahmani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Gulzar Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- Taj Mohammad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Hekmatullah Mirzad, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Haq Atid, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan ;

- M. Fahim Momand, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Fawad Ehsas, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Naqibullah Sediqi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Maiwand Wahidi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- M. Nazir Hayati, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Najiba Rahmani, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Abeda Baba Karkhil, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. M. Qayoum Karim, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Sayed Sharif Shabir, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Walid Howaida, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Zalmai Rahib, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Sadiq Baqori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mir Zafaruddin Ansari, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Atta Mohammad Alwak, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Zabiullah Iqbal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Hasan Fazaili, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- M. Jawad Jalili, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mukhtar Ali Nasto, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Namatullah Nabawi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Ghulam Abas Noori, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Mustafa Anwari, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Fakhria Popal, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Shiba Sharzai, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Marya Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nilofar Hashimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Munisa Hasan, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nazifa Azimi, Univ. Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Sweeta Sharify, Lecturer; Afghanistan;

- Fayaz Gul, Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Zakia Ahmad Zai, Lecturer, Afghanistan;

- Nigani Barati, Education Specialist, Afghanistan ;

- Azeeta Nazhand, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sughra, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Nadia Sharif, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Maryam Omari, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Masoud, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Zubair Ahmad, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Khalil Ahmad, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Khadija Omid, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Haida Rasouli, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Hemat Hamad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Wazir Safi, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mohammad Qasim, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Zamin Shah, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Qayas, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mehrabuddin, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Zahidullah Zahid, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Akmal Mahros, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Sadia Mohammadi, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- Mina Amiri, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- M. Sajad Nikzad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mursal Nikzad, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Qadir Shahab, Teacher, Afghanistan;

- M. Hasan Sahi, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Mirwais Haqmal, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Leeda Khurasai, Teacher, Afghanistan ;

- Karishma Hashimi, Instructor, Afghanistan;

- Majeed Shams, Architect, Afghanistan;

- Azimullah Esmati, Master of Civil Engineering, Afghanistan;

- Najibullah Hussaini, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Burhanuddin Nezami, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Hafiz Hafizi, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Bahir, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Wali Bayan, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Khaliq Najir, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Diana Niazi, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Imam Jan, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Khalil Ahmad Nadem, Engineer, Afghanistan;

- Sayeed Aqa, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Edris Rasouli, Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Raz Mohammad, Engineer of Mines, Afghanistan ;

- Nasrullah Rahimi, Technical Engineer, Afghanistan ;

- Ehsanullah, Helmand, Construction Engineer, Netherlands;

- Ahmad Hamad, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Akmal Ahmadi, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Ershad Hurmati, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Akram Shafim, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- M. Akbar Ehsan, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Raziullah, Technologist, Afghanistan ;

- Zaki Khorrami, IT Officer, Afghanistan ;

- Osman Nikzad, Graphic Designer, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Ayani, Carpet Weaver, Afghanistan ;

- Be be sima Hashimi, Tailor, Afghanistan ;

- Maryam Masoumi, Tailor, Afghanistan ;

- Roya Mohammadi, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Nadia Sayes, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Nazdana Ebad, Craftsman, Afghanistan ;

- Sima Ahmadi , Bachelor of Biology, Afghanistan;

- Sima Rasouli, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Khatera Nawabi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Haji Noor Agha Haqyar, Merchant, Afghanstan;

- Husna Anwari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Nargis Hashimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Shakira Barish, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Nasima Darwish, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Wajiha Haidari, Merchant of Jawzjan, Afghanistan ;

- Shagul, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Nik Rasoul, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Haji Farid Alikozai, Merchant, Afghanistan;

- Nigina Nawabi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Masouda Nazimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Najla Kohistani, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Kerisma Jawhari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Hasina Hashimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Husna Anwari, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Maaz Baburzai, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Freshta Safari, Merchant, Afghanistan;

- Yalda Azimi, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Azim Jan Baba Karkhil, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Akhtar Mohammad, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- M. Haroon Ahmadzai, Merchant, Afghanistan ;

- Azizullah Faizi, Former head of Afghanistan Cricket Board, Afghanistan ;

- Wakil Akhar, Prosecutor, Afghanistan ;

- Akhtar M. Azimi, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Shabnam Noori, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Be be Abeda Wayar, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Madina Ahmad Zai, Prosecutor, Afghanistan;

- Shakila Joya, Former Employee of Attorney General, Afghanistan;

- Sardar M. Akbar Bashash, Member, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Eng. Abdul Dayan Balouch, Spokesperson of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Shah Mahmood Lahoti, Member of Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Khaliq Barekzai, Advisor, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Salahuddin Ayoubi Balouch, Advisor, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Faizuddin Lashkari Balouch, Member, Afghanistan Balochs Union, Afghanistan ;

- Sayed Ishaq Gilani, head of the National Solidarity Movement of Afghanistan, IEA;

- Haji Zalmai Latifi, Representative, Qizilbash tribes, Afghanistan ;

- Gul Nabi Ahmad Zai, Former Commander of Kabul Garrison, Afghanistan ;

- Ghulam Hussain Rezaee, Member, Habitat Organization, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Amani Adiba, Doctor of Liberal Arts in Architecture and Urban Planning, Afghanistan;

- Ismael Paienda, Afghan Peace Activist, France;

- Mohammad Belal Rahimi, Head of Peace institution, Afghanistan ;

- M. Mushtaq Hanafi, Head of Sayadan council, Afghanistan ;

- Sabira Waizi, Founder of T.W.P.S., Afghanistan ;

- Majabin Sharifi, Member of Women Network Organization, Afghanistan;

- Shekiba Saadat, Former head of women affairs, Afghanistan ;

- Atya Salik, Women rights activist, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Mahmoodi, Women rights activist, Afghanistan;

- Diana Rohin, Women rights activist , Afghanistan;

- Amena Hashimi, Head of Women Organization, Afghanistan;

- Fatanh Sharif, Former employee of Gender equality, Afghanistan;

- Sediq Mansour Ansari, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Sebghatullah Najibi, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Naemullah Nasiri, Civil Activist, Afghanistan;

- Reha Ramazani, Civil Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Lia Jawad, Civil Activist, Afghanistan;

- Arezo Khurasani, Social Activist, Afghanistan ;

- Beheshta Bairn, Social Activist, Afghanistan;

- Samsama Haidari, Social Activist, Afghanistan;

- Shabnam Nikzad, Humans Rights Activist, Afghanistan;

- Mliha Sadiqi, Head of Young Development Organization, Afghanistan;

- Mehria, Sharify, University Student;

- Shiba Azimi, Member of IPSO Organization, Afghanistan;

- Nadira Rashidi, Master of Management, Afghanistan;

- Sefatullah Atayee, Banking, Afghanistan;

- Khatira Yousufi, Employee of RTA, Afghanistan;

- Yalda Mirzad , Employee of Breshna Company, Afghanistan;

- Izzatullah Sherzad, Employee, Afghanistan;

- Erfanullah Salamzai , Afghanistan;

- Naser Abdul Rahim Khil, Afghanistan;

- Ghulam Rasoul Faizi, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Mir Agha Hasan Khil, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Ghafor Muradi, Afghanistan;

- Gul M. Azhir, Afghanistan;

- Gul Ahmad Zahiryan, Afghanistan;

- Shamsul Rahman Shams, Afghanistan;

- Khaliq Stanekzai, Afghanistan;

- M. Daud Haidari, Afghanistan;

- Marhaba Subhani, Afghanistan;

- Maazullah Nasim, Afghanistan;

- Haji Mohammad Tayeb, Afghanistan;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Afghanistan ;

- Sweeta Sadiqi Hotak, Afghanistan ;

- Khatira Anwari, Afghanistan ;

- Fatima Sharzad, Afghanistan ; Momen Shah Kakar, Afghanistan ;

- Shah Rukh Raufi, Afghanistan ;

- Hanifa Rasouli, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Qudsia Ebrahimi, Afghanistan ;

- Mahmood Haqiqat, Afghanistan ;

- Nasir Abdul Rahim Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Hamid Ahmadzai, Afghanistan ;

- Sardar Khan Sirat, Afghanistan ;

- Zurmatullah Ahmadi, Afghanistan ;

- Yasar Khogyani, Afghanistan ;

- Shar Sha Lodi, Afghanistan ;

- Ahmad Shah Omar, Afghanistan ;

- M. Azam Khan Ahmad Zai, Afghanistan;

- Nadia Farooq Sharzoi, Afghanistan;

- Shar Ali Tazari, Afghanistan ;

- Mayel Aqa Hakim, Afghanistan ;

- Khatira Hesar, Afghanistan ;

- Tamim Mehraban, Afghanistan ;

- Lina Noori, Afghanistan ;

- Khubaib Ghufran, Afghanistan ;

- M. Yasin Farahmand, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mir M. Ayoubi, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Namatullah Nabawi, Afghanistan ;

- Abozar Zazai, Afghanistan ;

- Atiqullah Rahimi, Afghanistan ;

- Fahim Ahmad Sultan, Afghanistan ;

- Humaira Farhangyar, Afghanistan ;

- Imam M. Wrimaj, Afghanistan ;

- Masoud Ashna, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Yahia Baiza, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Besmila, Afghanistan ;

- Ehsan Shorish, Germany;

- Irshad, Omer, Afghanistan;

- Musa Noorzai, Afghanistan;

- Lida Noori Nazhand, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Abdul Masood Panah, Afghanistan;

- Gholam Sachi Hassanzadah, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Sayed Ali Eqbal, Afghanistan;

- Hashmatullah Atmar, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Matin Safi, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Helmand, Afghanistan;

- Ehsanullah Helmand, Afghanistan;

- Izazatullah Sherzad, Afghanistan;

- Hafizullah Omarzai, Afghanistan;

- Hedayatullah Hilal, Afghanistan;

- Edris Ramez, student, Afghanistan;

- Amina Saadaty, Afghanistan;

- Muska Hamidi, Afghanistan;

- Raihana Ahmadi, Afghanistan;

- Zuhal Sherzad, Afghanistan;

- Meelad Ahmad, Afghanistan;

- Devah Kubra Falcone, Germany;

- Maryam Baburi, Germany;

- Suraya Paikan, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Fatah Ahmadzai, Afghanistan ;

- Dr. Mohammad Zalmai, Afghanistan ;

- Hashmatullah Parwarni, Afghanistan ;

- Asadullah, Afghanistan;

- Hedayat ullah Hillal, Afghanistan;

- Najibullah Zazai, Afghanistan;

- M. Yousuf Ahmadi, Afghanistan;

- Ahmad Reshad Reka, Afghanistan;

- Sayed Ahmad Arghandiwal, Afghanistan;

- Nooria Noozai, Afghanistan;

- Eng. Fahim Osmani, Afghanistan;

- Wafiullah Maaraj, Afghanistan;

- Roya Shujaee, Afghanistan;

- Shakira Shujaee, Afghanistan ;

- Adina Ranjbar, Afghanistan;

- Ayesha Shafiq, Afghanistan;

- Hajira Mujadidi, Afghanistan ;

- Abdul Zahir Shekib, Afghanistan;

- Zuhra Mohammad Zai, Afghanistan;

- Razia Ghaws, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Sabor Mubariz, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Khaliq Ferdows, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Shakoor Salangi, Afghanistan;

- Nasir Ahmad Basharyar, Afghanistan;

- Mohammad Mukhtar Sharifi, Afghanistan;

- Mukhtar Ahmad Haqtash, Afghanistan;

- Yousuf Amin Zazai, Afghanistan;

- Zakiri Sahib, Afghanistan;

- Mirwais Ghafori, Afghanistan;

- Nesar Rahmani, Afghanistan;

- Shar M. Amir Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Yasin Farahmand, Afghanistan;

- Faizul Haq Faizan, Afghanistan;

- Khaibar Sarwary, Afghanistan;

- Ali Sina Masoumi, Afghanistan;

- Hamidullah Akhund Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Dr. Benish, Afghanistan;

- Hayatullah Fazel, Afghanistan;

- Faizullah Habibi, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Hamid Lyan, Afghanistan;

- Abdul Qayoum Qayoum Zadah, Afghanistan;

- Qazi Qudratullah Safi, Afghanistan;

- Noor Agha Haqyar, Afghanistan;

- Maryan Aiany, Afghanistan;

B. FROM ABROAD

- Odile Mojon, Schiller Institute, Paris, France ;

- Johanna Clerc, Choir Conductor, Schiller Institute Chorus, France ;

- Sébastien Perimony, Africa Department, Schiller Institute, France ;

- Christine Bierre, Journalist, Chief Editor of Nouvelle Solidarité, monthly, France ;

- Marcia Merry Baker, agriculture expert, EIR, Co-Editor, USA ;

- Bob Van Hee,Redwood County Minnesota Commissioner, USA ;

- Dr. Tarik Vardag, Doctor in Natural Sciences (RER), Business Owner, Germany;

- Richard Freeman, Department of Physical Economy, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Liliana Gorini, chairwoman of Movisol and singer, Italy;

- Ulrike Lillge,Editor Ibykus Magazine, Berlin, Germany ;

- Michelle Rasmussen, Vice President, Schiller Institute in Denmark, amateur musician;

- Feride Istogu Gillesberg, Vice President, Schiller Institute in Denmark;

- Jason Ross, Science Department, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Dennis Small, Director of the Economic Department, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Robert “Bob” Baker, Agriculture Commission, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Dr. Wolfgang Lillge, Medical Doctor, Editor, Fusion Magazine, Berlin, Germany ;

- Ulf Sandmark, Vice-Chairman of the Belt and Road Institute, Sweden ;

- Mary Jane Freeman, Schiller Institute, USA ;

- Hussein Askary, South West Asia Coordinator, Schiller Institute, Sweden ;

- David Dobrodt, EIR News, USA ;

- Klaus Fimmen, 2nd Vice-Chairman of the Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität (Büso) party, Germany;

- Christophe Lamotte, Consulting Engineer, France ;

- Richard Burden, EIR production staff, USA ;

- Rolf Gerdes, Electronic Engineer, Germany;

- Marcella Skinner, USA ;

- Delaveau Mathieu, Farm Worker, France ;

- Shekeba Jentsch, StayIN, Board, Germany;

- Bernard Carail, retired Postal Worker, France ;

- Etienne Dreyfus, Social Activist, France ;

- Harrison Elfrink, Social Activist, USA ;

- Jason Seidmann,USA ;

Letter of the minister of Information and Culture

Since Western researchers, based on what happened in the past, wondered about the current Afghan government’s actual policy on the issue of preservation of cultural and historical heritage, the Ibn-e-Sina Research and Development Center questioned the relevant authorities in Kabul.

At the end of January 2024, the Minister of Arts and Culture, in an hand-signed letter, provided them (and the world) with the following response, which completely clarifies the matter.

Transcript below, bold as in the original.

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

Ministry of Information and Culture

Letter N° 220, Jan. 31, 2024

To the attention of Ibn-e-Sina R&D Centre, International experts and cultural organizations and to those it concerns:

The ministry of Information and culture of the Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) has, among others, the following tasks in its portfolio:

–To establish a suitable environment for the growth of genuine Afghan culture;

–To protect national identity, cultural diversity, and national unity;

–To preserve tangible and intangible cultural heritage;

–To support the development of creativities, initiatives and activities of various segments of the society in general and of the Afghan youth in particular;

–To support the freedom of speech;

–Development of tourism industry;

–Introduction and presentation of Afghan culture regionally and internationally, to transform Afghanistan into an important cultural hub and crossroads in the near future.

We would like to confirm that with preservation of tangible and intangible cultural heritage we mean all Afghan cultural heritage belonging to all periods of history, whether it belongs to Islamic or non/pre-Islamic periods of history.

This ministry expresses its concerns that due to insufficient means it is not able to preserve the Afghan cultural heritage sufficiently.

Therefore this ministry asks UNESCO and other international organizations, working on preservation of the world’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage, to support Afghanistan in preservation of its tangible and intangible cultural heritage, including the ones belonging to Islamic and non/pre-Islamic periods of its history. The cultural heritage of Afghanistan does deserve to be preserved without any political motivations.

Besides, this ministry also confirms it is ready for all kind of cooperation with all national and international organizations, working on preservation of world cultural heritage.

The ministry of Information and culture of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) supports and appreciates all efforts of the Ibn-e-Sina R&D centre and their international experts in appealing for urgent attention of national and international organizations and experts to resume their support and cooperation with Afghanistan to preserve its cultural heritage, an important part of world cultural and historical heritage.

Sincerely,

Mowlavi Atiqullah Azizi

Deputy Minister of Culture and Art

moicdocymentsliaison@gmail.com

Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life: the cradle of humanism in the North

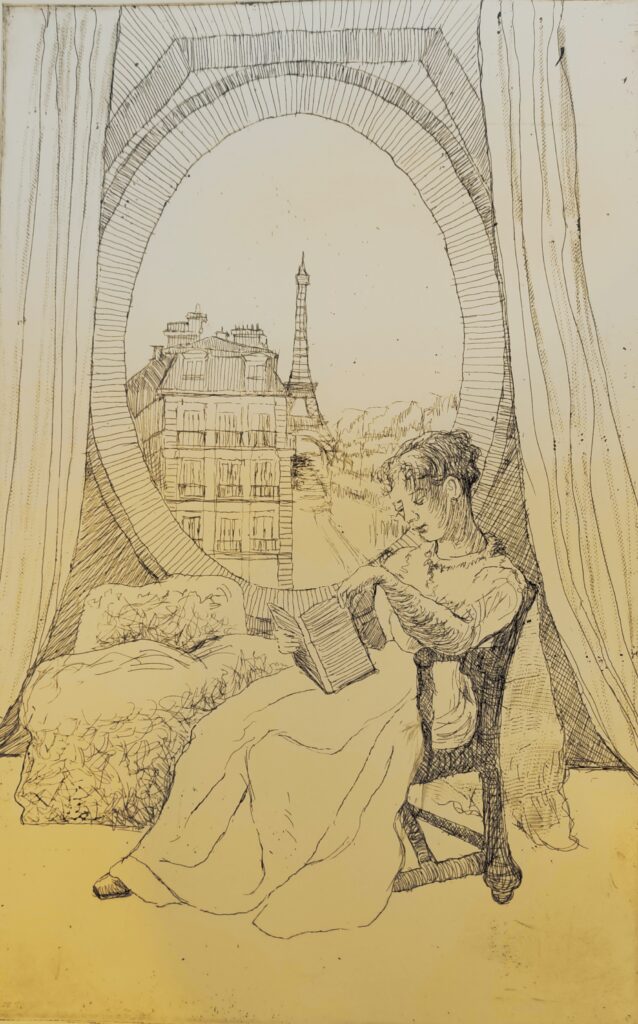

Presentation of Karel Vereycken, founder of Agora Erasmus, at a meeting with friends in the Netherlands on September 10, 2011.

The current financial system is bankrupt and will collapse in the coming days, weeks, months or years if nothing is done to end the paradigm of financial globalization, monetarism and free trade.

To exit this crisis implies organizing a break-up of the banks according to principles of the Glass-Steagall Act, an indispensable lever to recreate a true credit system in opposition to the current monetarist system. The objective is to guarantee real investments generating physical and human wealth, thanks to large infrastructure projects and highly qualified and well-paid jobs.

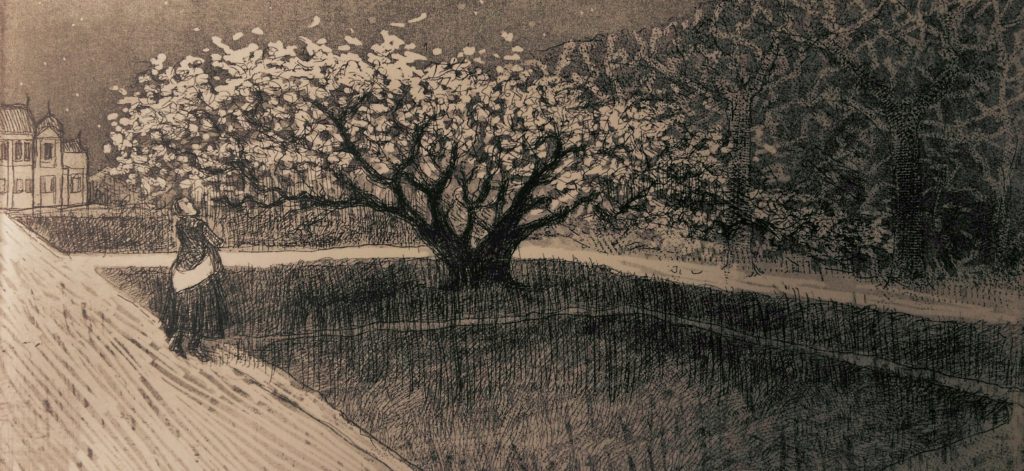

Can this be done? Yes, we can! However, the true challenge is neither economic, nor political, but cultural and educational: how to lay the foundations of a new Renaissance, how to effect a civilizational shift away from green and Malthusian pessimism towards a culture that sets itself the sacred mission of fully developing the creative powers of each individual, whether here, in Africa, or elsewhere.

Is there a historical precedent? Yes, and especially here, from where I am speaking to you this morning (Naarden, Netherlands) with a certain emotion. It probably overwhelms me because I have a rather well informed and precise sense of the role that several key individuals from the region where we are gathered this morning have played and how, in the fourteenth century, they made Deventer, Zwolle and Windesheim an intellectual hotbed and the cradle of the Renaissance of the North which inspired so many worldwide.

Let me summarize for you the history of this movement of lay clerics and teachers: the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, a movement that nurished our beloved Erasmus of Rotterdam, the humanist giant from whom we borrowed the name to create our political movement in Belgium.

As very often, it all begins with an individual decision of someone to overcome his shortcomings and give up those « little compromises » that end up making most of us slaves. In doing so, this individual quickly appears as a « natural » leader. Do you want to become a leader? Start by cleaning up your own mess before giving lessons to others!

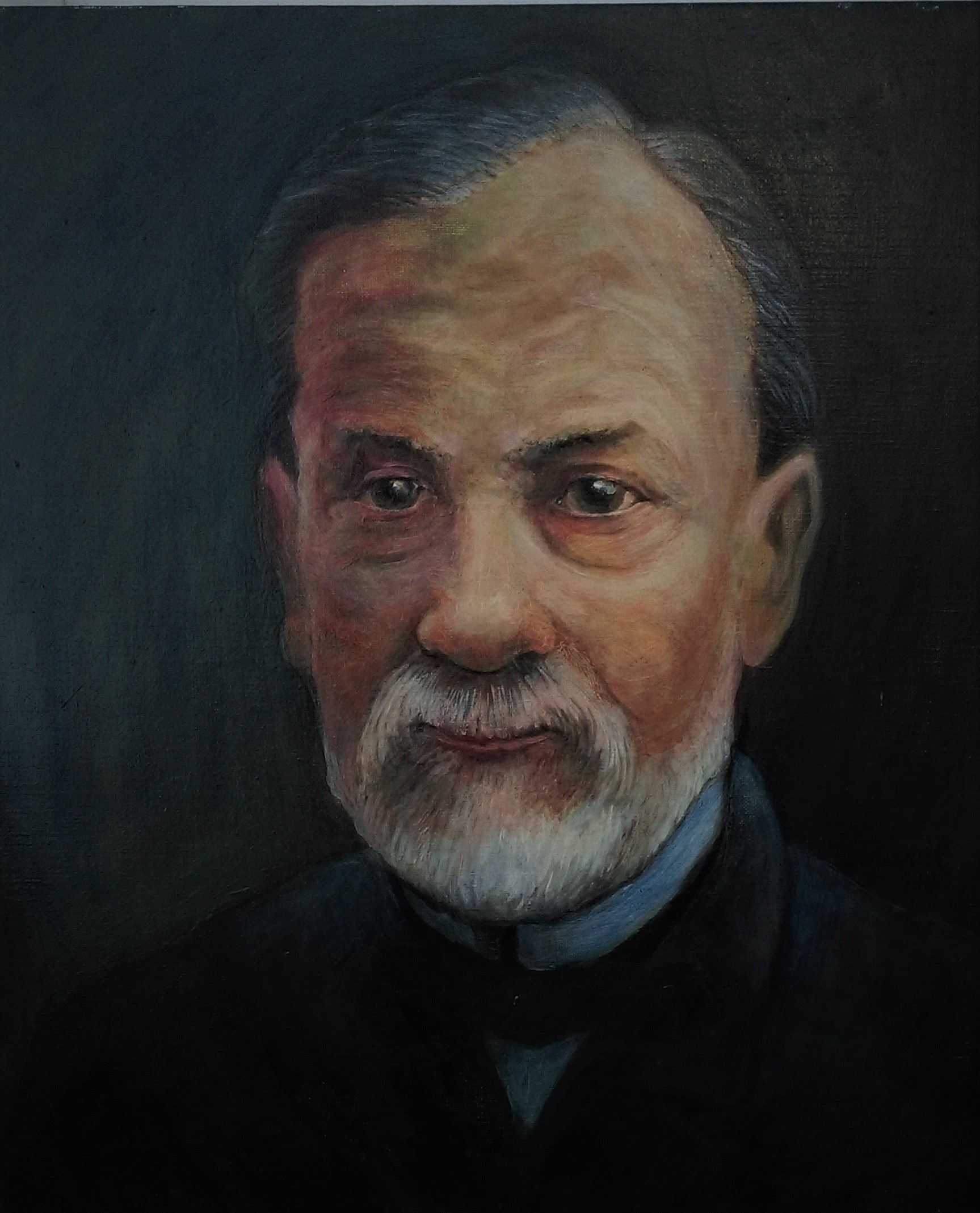

Geert Groote, the founder

The spiritual father of the Brothers is Geert Groote, born in 1340 and son of a wealthy textile merchant in Deventer, which at that time, like Zwolle, Kampen and Roermond, were prosperous cities of the Hanseatic League.

In 1345, as a result of the international financial crash, the Black Death spread throughout Europe and arrived in the Netherlands around 1449-50. Between a third and a half of the population died and, according to some sources, Groote lost both parents. He abhorred the hypocrisy of the hordes of flagellants who invaded the streets and later advocated a less conspicuous, more interior spirituality.

Groote had talent for intellectual matters and was soon sent to study in Paris. In 1358, at the age of eighteen, he obtained the title of Master of Arts, even though the statutes of the University stipulated that the minimum age required was twenty-one.

He stayed eight years in Paris where he taught, while making a few excursions to Cologne and Prague. During this time, he assimilated all that could be known about philosophy, theology, medicine, canon law and astronomy. He also learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and was considered one of the greatest scholars of the time.

Around 1362 he became canon of Aachen Cathedral and in 1371 of that of Utrecht. At the age of 27, he was sent as a diplomat to Cologne and to the Court of Avignon to settle the dispute between the city of Deventer and the bishop of Utrecht with Pope Urban V. In principle, he could have met the Italian humanist Petrarch who was there at that time.

Full of knowledge and success, Groote got a big head. His best friends, conscious of his talents, kindly suggested him to detach himself from his obsession with « Earthly Paradise ». The first one was his friend Guillaume de Salvarvilla, the choirmaster of Notre-Dame of Paris. The second was Henri Eger of Kalkar (1328-1408) with whom Groote shared the benches of the Sorbonne.

In 1374, Groote got seriously ill. However, the priest of Deventer refused to administer the last sacraments to him as long as he refused to burn some of the books in his possession. Fearing for his life (after death), he decided to burn his collection of books on black magic. Finally, he felt better and healed. He also gave up living in comfort and lucre through fictitious jobs that allowed him to get rich without working too hard.

After this radical conversion, Groote decides to selfperfect. In his Conclusions and Resolutions he wrote:

« It is to the glory, honor and service of God that I propose to order my life and the salvation of my soul. (…) In the first place, not to desire any other benefit and not to put my hope and expectation from now on in any temporal profit. The more goods I have, the more I will probably want more. For according to the primitive Church, you cannot have several benefits. Of all the sciences of the Gentiles, the moral sciences are the least detestable: many of them are often useful and profitable both for oneself and for teaching others. The wisest, like Socrates and Plato, brought all philosophy back to ethics. And if they spoke of high things, they transmitted them (according to St. Augustine and my own experience) by moralizing them lightly and figuratively, so that morality always shines through in knowledge… ».

Groote then undertakes a spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen near Arnhem where he devotes himself to prayer and study.

However, after a three-year stay in isolation, the prior, his Parisian friend Eger of Kalkar, told him to go out and teach :

« Instead of remaining cloistered here, you will be able to do greater good by going out into the world to preach, an activity for which God has given you a great talent. »

Ruusbroec, the inspirer

Groote accepted the challenge. However, before taking action, he decided to make a last trip to Paris in 1378 to obtain the books he needed.

According to Pomerius, prior of Groenendael between 1431 and 1432, he undertook this trip with his friend from Zwolle, the teacher Joan Cele (around 1350-1417), the historical founder of the excellent Dutch public education system, the Latin School.

On their way to Paris, they visit Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), a Flemish “mystic” who lived in the Groenendael Priory on the edge of the Soignes Forest near Brussels.

Groote, still living in fear of God and the authorities, initially tries to make « more acceptable » some of the old sage’s writings while recognizing Ruusbroec as closer to the Lord than he is. In a letter to the community of Groenendael, he requested the prayer of the prior:

« I would like to recommend myself to the prayer of your provost and prior. For the time of eternity, I would like to be ‘the prior’s stepladder’, as long as my soul is united to him in love and respect.” (Note 1)

Back in Deventer, Groote concentrated on study and preaching. First he presented himself to the bishop to be ordained a deacon. In this function, he obtained the right to preach in the entire bishopric of Utrecht (basically the whole part of today’s Netherlands north of the great rivers, except for the area around Groningen).

First he preached in Deventer, then in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen and later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda and Delft. His success is so great that jealousy is felt in the church. Moreover, with the chaos caused by the great schism (1378 to 1417) installing two popes at the head of the church, the believers are looking for a new generation of leaders.

As early as 1374, Groote offered part of his parents’ house to accommodate a group of pious women. Endowed with a by-law, the first house of sisters was born in Deventer. He named them « Sisters of the Common Life », a concept developed in several works of Ruusbroec, notably in the final paragraph Of the Shining Stone (Van den blinckende Steen)

« The man who is sent from this height to the world below, is full of truth, and rich in all virtues. And he does not seek his own, but the honor of the one who sent him. And that is why he is upright and truthful in all things. And he has a rich and benevolent foundation grounded in the riches of God. And so he must always convey the spirit of God to those who need it; for the living fountain of the Holy Spirit is not a wealth that can be wasted. And he is a willing instrument of God with whom the Lord works as He wills, and how He wills. And it is not for sale, but leaves the honor to God. And for this reason he remains ready to do whatever God commands; and to do and tolerate with strength whatever God entrusts to him. And so he has a common life; for to him seeing [via contemplativa] and working [via activa] are equal, for in both things he is perfect.”

Radewijns, the organizer

Following one of his first sermons, Groote recruited Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Born in Utrecht, the latter received his training in Prague where, also at the early age of 18, he was awarded the title of Magister Artium.

Groote then sent him to the German city of Worms to be consecrated priest there. In 1380 Groote moved with about ten pupils to the house of Radewijns in Deventer; it would later be known as the « Sir Florens House” (Heer Florenshuis), the first house of the Brothers and above all its base of operation?

When Groote died of the plague in 1384, Radewijns decided to expand the movement which became the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Soon it will be branded the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion).

Books and beguinages

A number of parallels can be drawn with the phenomenon of the Beguines which flourished from the 13th century onward. (Note 2)

The first beguines were independent women, living alone (without a man or a rule), animated by a deep spirituality and daring to venture into the enormous adventure of a personal relationship with God. (Note 3)

Operating outside the official religious hierarchy, they didn’t beg but worked various jobs to earn their daily bread. The same goes for the Brothers of the Common Life, except that for them, books were at the center of all activities. Thus, apart from teaching, the copying and production of books represented a major source of income while allowing spreading the word to the many.

Lay Brothers and Sisters focused on education and their priests on preaching. Thanks to the scriptorium and printing houses, their literature and music will spread everywhere.

Windesheim

To protect the movement from unfair attacks and criticism, Radewijns founded a congregation of canons regular obeying the Augustinian rule.

In Windesheim, between Zwolle and Deventer, on land belonging to Berthold ten Hove, one of the members, a first cloister is erected. A second one, for women this time, is built in Diepenveen near Arnhem. The construction of Windesheim took several years and a group of brothers lived temporarily on the building site, in huts.

In 1399 Johannes van Kempen, who had stayed at Groote’s house in Deventer, became the first prior of the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and gave the movement new momentum. From Zwolle, Deventer and Windesheim, the new recruits spread all over the Netherlands and Northern Europe to found new branches of the movement.

In 1412, the congregation had 16 cloisters and their number reached 97 in 1500: 84 priories for men and 13 for women. To this must be added a large number of cloisters for canonesses which, although not formally associated with the Windesheim Congregation, were run by rectors trained by them.

Windesheim was not recognized by the Bishop of Utrecht until 1423 and in Belgium, Groenendael, associated with the Red Cloister and Korsendonc, wanted to be part of it as early as 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cusanus and Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was the brother of the famous Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). The latter, trained in Windesheim, animated the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and was one of the towering figures of the movement for seventy years. In addition to a biography he wrote of Groote and his account of the movement, his Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) became the most widely read work in history after the Bible.

Both Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) and Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), two of Erasmus’ tutors during his training in Deventer, were direct pupils of Thomas a Kempis. The Latin School of Deventer, of which Hegius was rector, was the first school in Northern Europe to teach the ancient Greek language to children.

While no formal prove exists, it is tempting to believe that Cusanus (1401-1464), who protected Agricola and, in his last will, via his Bursa Cusanus, offered a scholarship for the training of orphans and poor students of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, was also trained by this humanist network.

What is known is that when Cusanus came in 1451 to the Netherlands to put the affairs of the Church in order, he traveled with his friend Denis the Carthusian (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), a disciple of Ruusbroec, whom he commissioned to carry on this task.

A native of Limburg, trained at the famous Cele school in Zwolle, Dionysius the Carthusian also became the confessor of the Duke of Burgundy and is thought to be the “theological advisor” of the Duke’s ambassador and court painter, Jan Van Eyck. (Note 4)

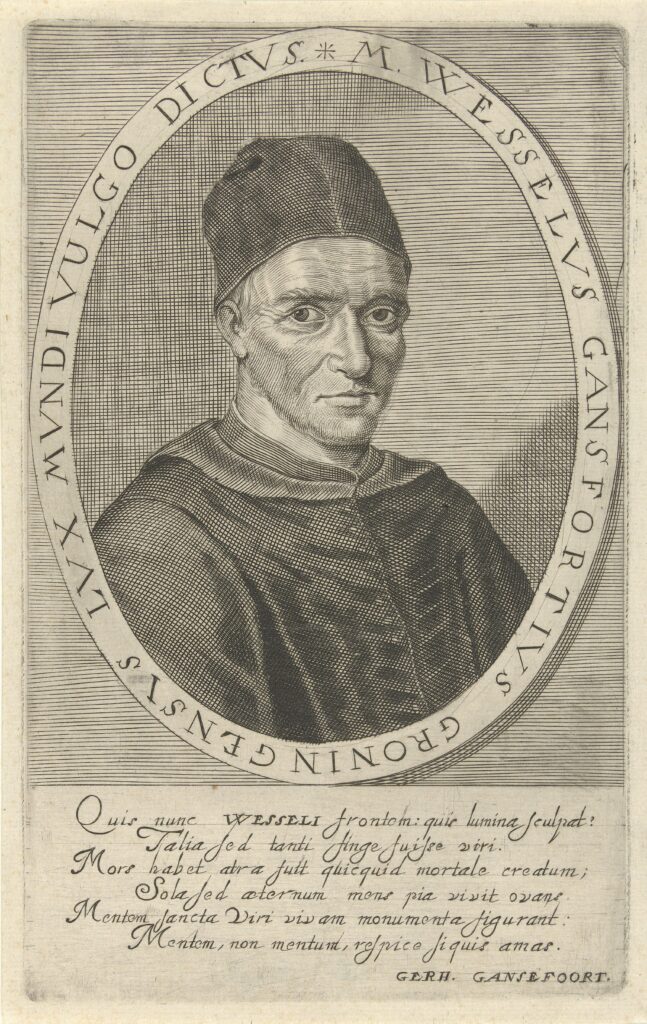

Gansfort

Wessel Gansfort (1419-1489), another exceptional figure of this movement was at the service of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion, the main collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) at the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1437. Gansfort, after attending the Brothers’ school in Groningen, was also trained by Joan Cele‘s Latin school in Zwolle.

The same goes for the first and only Dutch pope, Adrianus VI, who was trained in the same school before completing his training with Hegius in Deventer. This pope was very open to Erasmus’ reformist ideas… before arriving in Rome.

Hegius, in a letter to Gansfort, which he calls Lux Mundi (Light of the World), wrote:

« I send you, most honorable lord, the homilies of John Chrysostom. I hope that you will enjoy reading them, since the golden words have always been more pleasing to you than the pieces of this metal. As you know, I went to the library of Cusanus. There I found some books that I didn’t know existed (…) Farewell, and if I can do you a favor, let me know and consider it done.”

Rembrandt

A quick look on Rembrandt’s intellectual training indicates that he too was a late product of this educational epic. In 1609, Rembrandt, barely three years old, entered elementary school where, like other boys and girls of his generation, he learned to read, write and… draw.

The school opened at 6 in the morning, at 7 in the winter, and closes at 7 in the evening. Classes begin with prayer, reading and discussion of a passage from the Bible followed by the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt acquired an elegant writing style and much more than a rudimentary knowledge of the Gospels.

The Netherlands wanted to survive. Its leaders take advantage of the twelve-year truce (1608-1618) to fulfill their commitment to the public interest.

In doing so, the Netherlands at the beginning of the XVIIth century became the first country in the world where everyone had the chance to learn to read, write, calculate, sing and draw.

This universal educational system, no matter what its shortcomings, available to both rich and poor, boys and girls alike, stands as the secret behind the Dutch « Golden Century ». This high level of education also created those generations of active Dutch emigrants a century later in the American Revolution.

While others started secondary school at the age of twelve, Rembrandt entered the Leyden Latin School at the age of 7. There, the students, apart from rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn not only Greek and Latin, but also foreign languages such as English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, with no laws restricting young talents, Rembrandt enrolled in University. The subject he chose was not Theology, Law, Science or Medicine, but… Literature.

Did he want to add to his knowledge of Latin the mastery of Greek or Hebrew philology, or possibly Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Arabic/Latin dictionaries were already being published in Leiden at a time the city was becoming a major printing center in the world.

Thus, one realizes that the Netherlands and Belgium, first with Ruusbroec and Groote and later with Erasmus and Rembrandt, made an essential contribution in the not so distant past to the kind of humanism that can raise today humanity to its true dignity.

Hence, failing to extend our influence here, clearly seems to me something in the realm of the impossible.

Footnotes:

- Geert Groote, who discovered Ruusbroec’s work during his spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen, near Arnhem, has translated at least three of his works into Latin. He sent The Book of the Spiritual Tabernacle to the Cistercian Cloister of Altencamp and his friends in Amsterdam. The Spiritual Marriage of Ruusbroec being under attack, Groote personally defends it. Thus, thanks to his authority, Ruusbroec’s works are copied in number and carefully preserved. Ruusbroec’s teaching became popularized by the writings of the Modern Devotion and especially by the Imitation of Christ.

- At the beginning of the 13th century the Beguines were accused of heresy and persecuted, except… in the Burgundian Netherlands. In Flanders, they are cleared and obtain official status. In reality, they benefit from the protection of two important women: Jeanne and Margaret of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders. They organized the foundation of the Beguinages of Louvain (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerp (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ypres (1240), Lille (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Bruges (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Diest (1253), Mechelen (1258) and in 1271 it was Jan I, Count of Flanders, in person, who deposited the statutes of the great Beguinage of Brussels. In 1321, the Pope estimated the number of Beguines at 200,000.

- The platonic poetry of the Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (XIIIth Century) has a decisive influence on Jan van Ruusbroec.

- It is significant that the first book printed in Flanders in 1473, by Erasmus’ friend and printer Dirk Martens, is precisely a work of Denis the Carthusian.

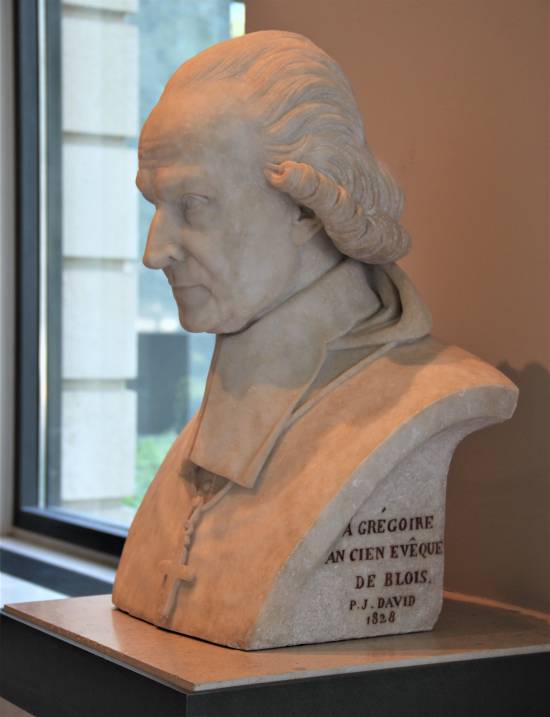

The republican struggle of David d’Angers and the statue of Gutenberg in Strasbourg

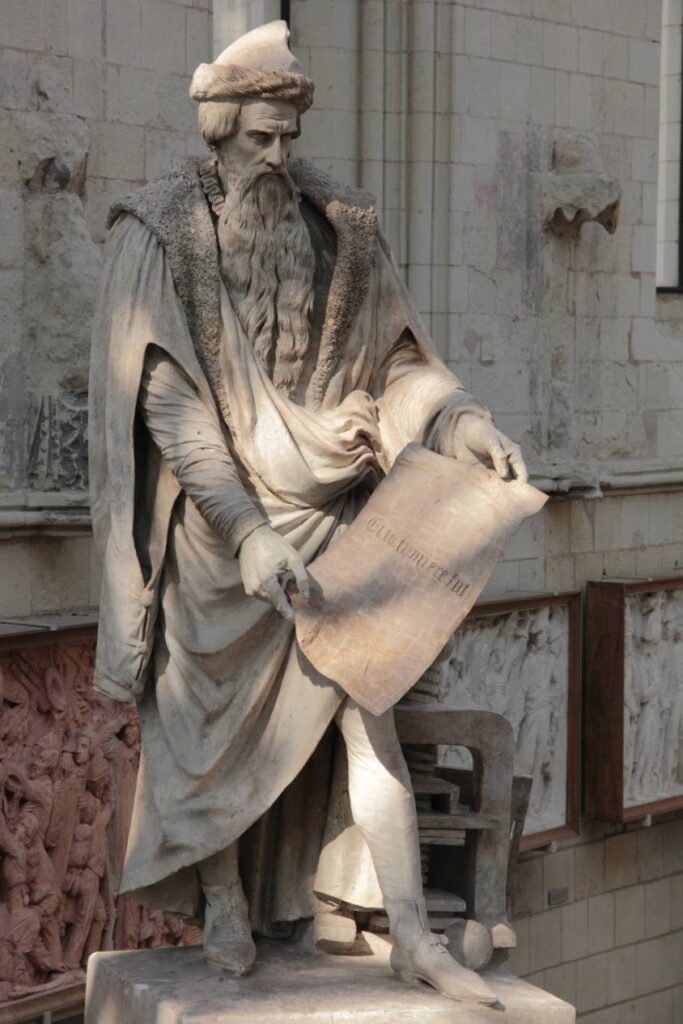

In the heart of downtown Strasbourg, a stone’s throw from the cathedral and with its back to the 1585 Chamber of Commerce, stands the beautiful bronze statue of the German printer Johannes Gutenberg, holding a barely-printed page from his Bible, which reads: « And there was light » (NOTE 1).

Evoking the emancipation of peoples thanks to the spread of knowledge through the development of printing, the statue, erected in 1840, came at a time when supporters of the Republic were up in arms against the press censorship imposed by Louis-Philippe under the July Monarchy.

Strasbourg, Mainz and China

Born around 1400 in Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg, with money lent to him by the merchant and banker Johann Fust, carried out his first experiments with movable metal type in Strasbourg between 1434 and 1445, before perfecting his process in Mainz, notably by printing his famous 42-line Bible from 1452.

On his death (in Mainz) in 1468, Gutenberg bequeathed his process to humanity, enabling printing to take off in Europe. Chroniclers also mention the work of Laurens Janszoon Coster in Harlem, and the Italian printer Panfilo Castaldi, who is said to have brought Chinese know-how to Europe. It should be noted that the « civilized » world of the time refused to acknowledge that printing had originated in Asia with the famous « movable type » (made of porcelain and metal) developed several centuries earlier in China and Korea (NOTE 2).

In Europe, Mainz and Strasbourg vie for pride of place. On August 14, 1837, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the « invention » of printing, Mainz inaugurated its statue of Gutenberg, erected by sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsenalors, while in Strasbourg, a local committee had already commissioned sculptor David d’Angers to create a similar monument in 1835.

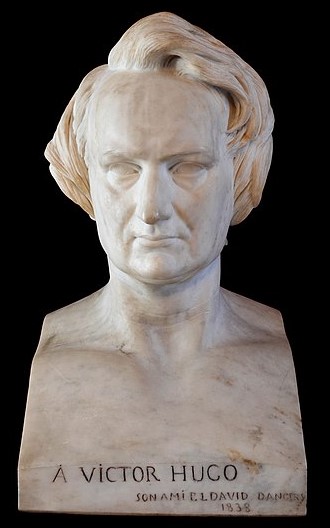

This little-known sculptor was both a great sculptor and close friend of Victor Hugo, and a fervent republican in personal contact with the finest humanist elite of his time in France, Germany and the United States. He was also a tireless campaigner for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery.

The sculptor’s life

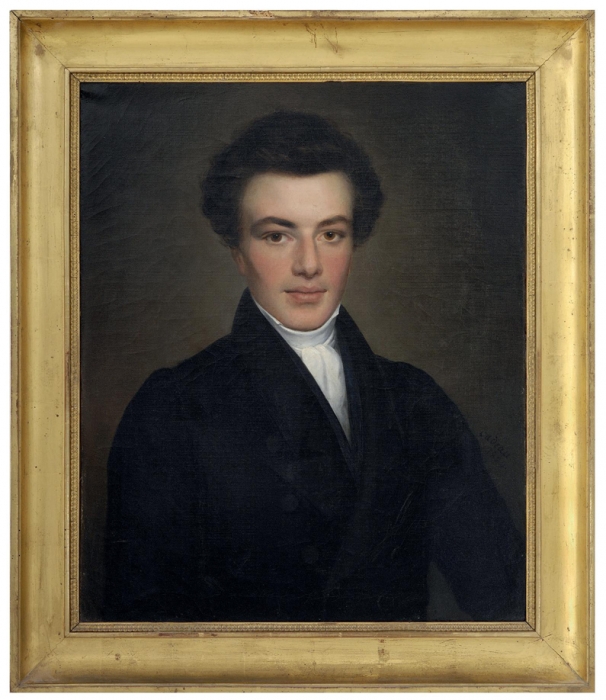

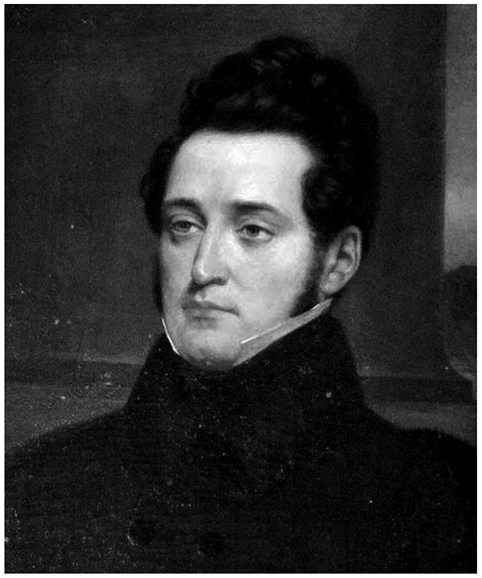

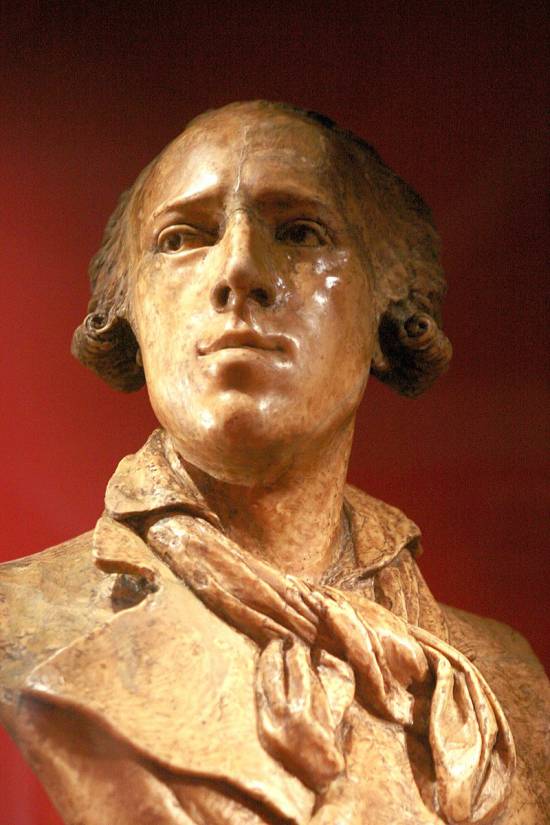

French sculptor Pierre-Jean David, known as « David d’Angers » (1788-1856) was the son of master sculptor Pierre Louis David. Pierre-Jean was influenced by the republican spirit of his father, who trained him in sculpture from an early age. At the age of twelve, his father enrolled him in the drawing class at the École Centrale de Nantes. In Paris, he was commissioned to create the ornamentation for the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and the south facade of the Louvre Palace. Finally, he entered the Beaux-arts.

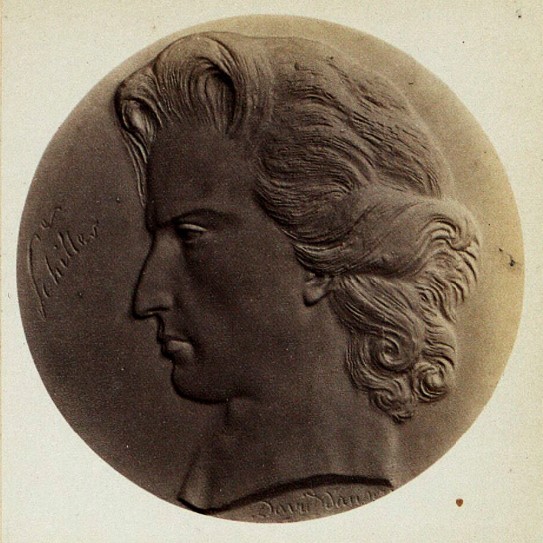

David d’Angers possessed a keen sense of interpretation of the human figure and an ability to penetrate the secrets of his models. He excelled in portraiture, whether in bust or medallion form. He is the author of at least sixty-eight statues and statuettes, some fifty bas-reliefs, a hundred busts and over five hundred medallions. Victor Hugo told his friend David: « This is the bronze coin by which you pay your toll to posterity. »

He traveled all over Europe, painting busts in Berlin, London, Dresden and Munich.

Around 1825, when he was commissioned to paint the funeral monument that the Nation was raising by public subscription in honor of General Foy, a tribune of the parliamentary opposition, he underwent an ideological and artistic transformation. He frequented the progressive intellectual circles of the « 1820 generation » and joined the international republican movement. He then turned his attention to the political and social problems of France and Europe. In later years, he remained faithful to his convictions, refusing, for example, the prestigious commission to design Napoleon’s tomb.

Artistic production

David’s art was thus influenced by a naturalism whose iconography and expression are in stark contrast to that of his academic colleagues and the dissident sculptors known as « romantics » at the time. For David, no mythological sensualism, obscure allegories or historical picturesqueness. On the contrary, sculpture, according to David, must generalize and transpose what the artist observes, so as to ensure the survival of ideas and destinies in a timeless posterity.

David adhered to this particular, limited conception of sculpture, adopting the Enlightenment view that the art of sculpture is « the lasting repository of the virtues of men », perpetuating the memory of the exploits of exceptional beings.

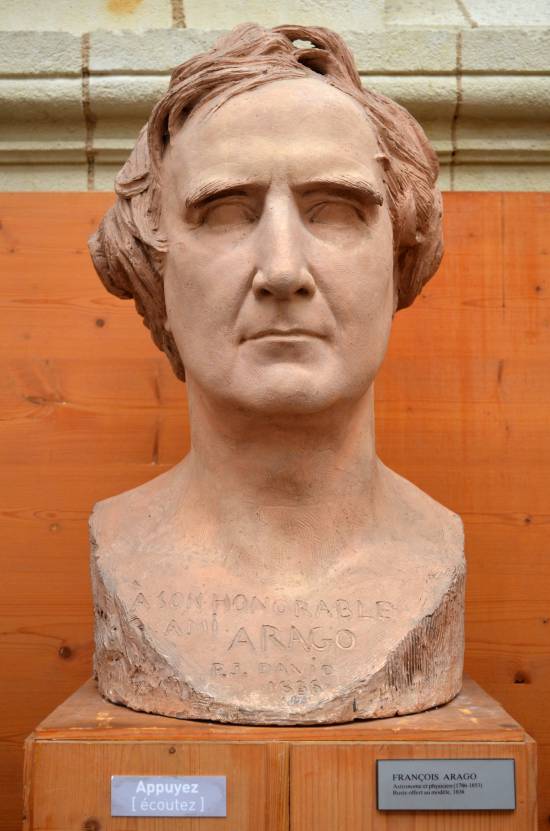

The somewhat austere image of « great men » prevailed, best known thanks to some 600 medallions depicting famous men and women from several countries, most of them contemporaries. Added to this are some one hundred busts, mostly of his friends, poets, writers, musicians, songwriters, scientists and politicians with whom he shared the republican ideal.

Among the most enlightened of his time were: Victor Hugo, Marquis de Lafayette, Wolfgang Goethe, Alfred de Vigny, Alphonse Lamartine, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Alfred de Musset, François Arago, Alexander von Humboldt, Honoré de Balzac, Lady Morgan, James Fenimore Cooper, Armand Carrel, François Chateaubriand, Ennius Quirinus Visconti and Niccolo Paganini.

To magnify his models and visually render the qualities of each one’s genius, David d’Angers invented a mode of idealization no longer based on antique-style classicism, but on a grammar of forms derived from a new science, the phrenology of Doctor Gall, who believed that the cranial « humps » of an individual reflected his intellectual aptitudes and passions. For the sculptor, it was a matter of transcending the model’s physiognomy, so that the greatness of the soul radiated from his forehead.

In 1826, he was elected member of the Institut de France and, the same year, professor at the Beaux-Arts. In 1828, David d’Angers was the victim of his first unsolved assassination attempt. Wounded in the head, he was confined to bed for three months. However, in 1830, still loyal to republican ideas, he took part in the revolutionary days and fought on the barricades.

In 1830, David d’Angers found himself ideally placed to carry out the most significant political sculpture commission of the July monarchy and perhaps of 19th century France: the new decoration of the pediment of the church of Sainte-Geneviève, which had been converted into the Pantheon in July.

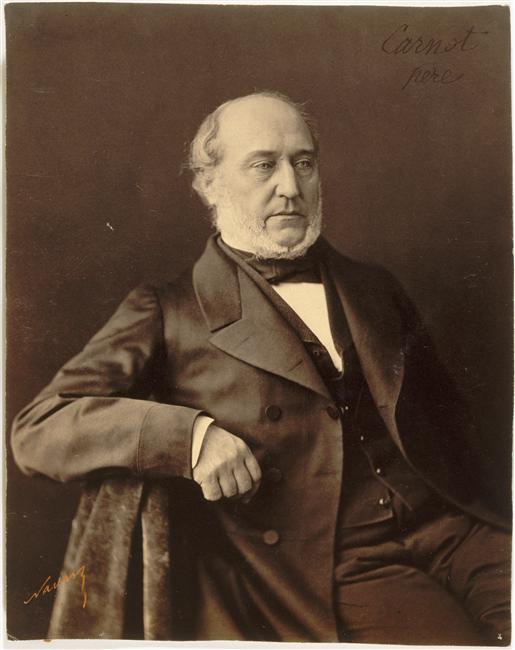

As a historiographer, he wanted to depict the civilians and men of war who built Republican France. In 1837, the execution of the figures he had chosen and arranged in a sketch that was first approved, then suspended, was bound to lead to conflict with the high clergy and the government. On the left, we see Bichat, Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David, Cuvier, Lafayette, Manuel, Carnot, Berthollet, Laplace, Malesherbes, Mirabeau, Monge and Fénelon. While the government tried to have Lafayette’s effigy removed, which David d’Angers stubbornly refused, with the support of the liberal press, the pediment was unveiled without official ceremony in September 1837, without the presence of the artist, who had not been invited.

Entering politics

During the 1848 Revolution, he was appointed mayor of the 11th arrondissement of Paris, entered the National Constituent Assembly and then the National Legislative Assembly, where he voted with the Montagne (revolutionary left). He defended the existence of the Ecole des Beaux-arts and the Académie de France in Rome. He opposed the destruction of the Chapelle Expiatoire and the removal of two statues from the Arc de Triomphe (Resistance and Peace by sculptor Antoine Etex).

He also voted against the prosecution of Louis Blanc (1811-1882) (another republican statesman and intellectual condemned to exile), against the credits for Napoleon III’s Roman expedition, for the abolition of the death penalty, for the right to work, and for a general amnesty.

Exile

He was not re-elected deputy in 1849 and withdrew from political life. In 1851, with the advent of Napoleon III, David d’Angers was arrested and also sentenced to exile. He chose Belgium, then traveled to Greece (his old project). He wanted to revisit his Greek Maiden on the tomb of the Greek republican patriot Markos Botzaris (1788-1823), which he found mutilated and abandoned (he had it repatriated to France and restored).

Disappointed by Greece, he returned to France in 1852. With the help of his friend de Béranger, he was allowed to stay in Paris, where he resumed his work. In September 1855, he suffered a stroke which forced him to cease his activities. He died in January 1856.

Friendships with Lafayette, Abbé Grégoire and Pierre-Jean de Béranger

David d’Angers was a real link between 18th and 19th century republicans, and a living bridge between those of Europe and America.

Born in 1788, he had the good fortune to associate at an early age with some of the great revolutionary figures of the time, before becoming personally involved in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848.

Towards the end of the 1820s, David attended the Tuesday salon meetings of Madame de Lafayette, wife of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (1757-1834).

While General Lafayette stood upright like « a venerable oak », this salon, notes the sculptor,

« has a clear-cut physiognomy, » he writes. The men talk about serious matters, especially politics, and even the young men look serious: there’s something decided, energetic and courageous in their eyes and in their posture (…) All the ladies and also the demoiselles look calm and thoughtful; they look as if they’ve come to see or attend important deliberations, rather than to be seen. »

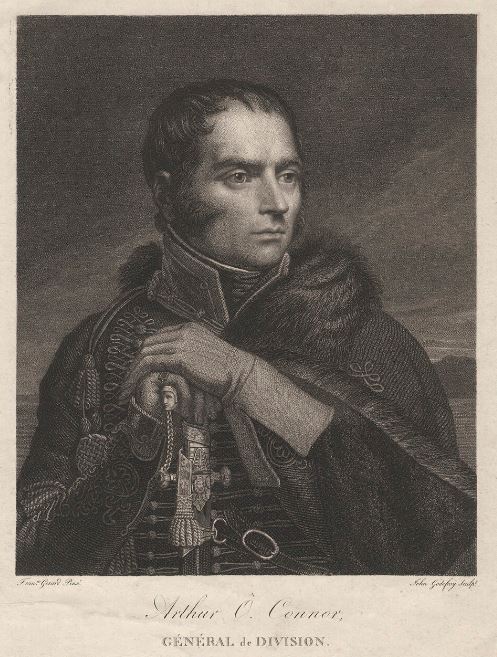

David met Lafayette’s comrade-in-arms, General Arthur O’Connor (1763-1852), a former Irish republican MP of the United Irishmen who had joined Lafayette’s volunteer General Staff in 1792.

Accused of stirring up trouble against the British Empire and in contact with General Lazare Hoche (1768-1797), O’Connor fled to France in 1796 and took part in the Irish Expedition. In 1807, O’Connor married the daughter of philosopher and mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet (1743-1794) and became a naturalized French citizen in 1818.

Lafayette and David d’Angers often got together with a small group of friends, a few « brothers » who were members of Masonic lodges: such as the chansonnier Pierre-Jean de Béranger, François Chateaubriand, Benjamin Constant, Alexandre Dumas (who corresponded with Edgar Allan Poe), Alphonse Lamartine, Henri Beyle dit Stendhal and the painters François Gérard and Horace Vernet.

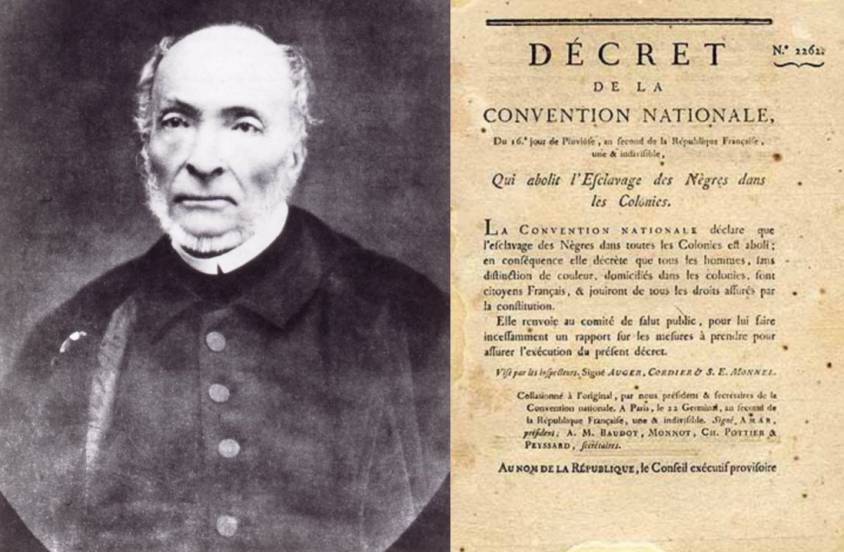

In these same circles, David also became acquainted with Henri (Abbé) Grégoire (1750-1831), and the issue of the abolition of slavery, which Grégoire had pushed through on February 4, 1794, was often raised. In their exchanges, Lafayette liked to recall the words of his youthful friend Nicolas de Condorcet:

« Slavery is a horrible barbarism, if we can only eat sugar at this price, we must know how to renounce a commodity stained with the blood of our brothers. »

For Abbé Gregoire, the problem went much deeper:

« As long as men are thirsty for blood, or rather, as long as most governments have no morals, as long as politics is the art of deceit, as long as people, unaware of their true interests, attach silly importance to the job of spadassin, and will allow themselves to be led blindly to the slaughter with sheep-like resignation, almost always to serve as a pedestal for vanity, almost never to avenge the rights of humanity, and to take a step towards happiness and virtue, the most flourishing nation will be the one that has the greatest facility for slitting the throats of others. »

(Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews)

Napoleon and slavery

The first abolition of slavery was, alas, short-lived. In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte, short of the money needed to finance his wars, reintroduced slavery, and nine days later excluded colored officers from the French army.

Finally, he outlawed marriages between « fiancés whose skin color is different ». David d’Angers remained very sensitive to this issue, having as a comrade a very young writer, Alexandre Dumas, whose father had been born a slave in Haiti.

As early as 1781, under the pseudonym Schwarz (black in German), Condorcet had published a manifesto advocating the gradual disappearance of slavery over a period of 60 to 70 years, a view quickly shared by Lafayette. A fervent supporter of the abolitionist cause, Condorcet condemned slavery as a crime, but also denounced its economic uselessness: slave labor, with its low productivity, was an obstacle to the establishment of a market economy.

And even before the signing of the peace treaty between France and the United States, Lafayette wrote to his friend George Washington on February 3, 1783, proposing to join him in setting in motion a process of gradual emancipation of the slaves. He suggested a plan that would « frankly become beneficial to the black portion of mankind ».

The idea was to buy a small state in which to experiment with freeing slaves and putting them to work as farmers. Such an example, he explained, « could become a school and thus a general practice ». (NOTE 3)

Washington replied that he personally would have liked to support such a step, but that the American Congress (already) was totally hostile.

From the Society of Black Friends to the French Society for the Abolition of Slavery

In Paris, on February 19, 1788, Abbé Grégoire and Jacques Pierre Brissot (1754-1793) founded « La Société des amis des Noirs », whose rules were drawn up by Condorcet, and of which the Lafayette couple were also members.