Étiquette : Brugge

Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life: the cradle of humanism in the North

Presentation of Karel Vereycken, founder of Agora Erasmus, at a meeting with friends in the Netherlands on September 10, 2011.

The current financial system is bankrupt and will collapse in the coming days, weeks, months or years if nothing is done to end the paradigm of financial globalization, monetarism and free trade.

To exit this crisis implies organizing a break-up of the banks according to principles of the Glass-Steagall Act, an indispensable lever to recreate a true credit system in opposition to the current monetarist system. The objective is to guarantee real investments generating physical and human wealth, thanks to large infrastructure projects and highly qualified and well-paid jobs.

Can this be done? Yes, we can! However, the true challenge is neither economic, nor political, but cultural and educational: how to lay the foundations of a new Renaissance, how to effect a civilizational shift away from green and Malthusian pessimism towards a culture that sets itself the sacred mission of fully developing the creative powers of each individual, whether here, in Africa, or elsewhere.

Is there a historical precedent? Yes, and especially here, from where I am speaking to you this morning (Naarden, Netherlands) with a certain emotion. It probably overwhelms me because I have a rather well informed and precise sense of the role that several key individuals from the region where we are gathered this morning have played and how, in the fourteenth century, they made Deventer, Zwolle and Windesheim an intellectual hotbed and the cradle of the Renaissance of the North which inspired so many worldwide.

Let me summarize for you the history of this movement of lay clerics and teachers: the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, a movement that nurished our beloved Erasmus of Rotterdam, the humanist giant from whom we borrowed the name to create our political movement in Belgium.

As very often, it all begins with an individual decision of someone to overcome his shortcomings and give up those « little compromises » that end up making most of us slaves. In doing so, this individual quickly appears as a « natural » leader. Do you want to become a leader? Start by cleaning up your own mess before giving lessons to others!

Geert Groote, the founder

The spiritual father of the Brothers is Geert Groote, born in 1340 and son of a wealthy textile merchant in Deventer, which at that time, like Zwolle, Kampen and Roermond, were prosperous cities of the Hanseatic League.

In 1345, as a result of the international financial crash, the Black Death spread throughout Europe and arrived in the Netherlands around 1449-50. Between a third and a half of the population died and, according to some sources, Groote lost both parents. He abhorred the hypocrisy of the hordes of flagellants who invaded the streets and later advocated a less conspicuous, more interior spirituality.

Groote had talent for intellectual matters and was soon sent to study in Paris. In 1358, at the age of eighteen, he obtained the title of Master of Arts, even though the statutes of the University stipulated that the minimum age required was twenty-one.

He stayed eight years in Paris where he taught, while making a few excursions to Cologne and Prague. During this time, he assimilated all that could be known about philosophy, theology, medicine, canon law and astronomy. He also learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and was considered one of the greatest scholars of the time.

Around 1362 he became canon of Aachen Cathedral and in 1371 of that of Utrecht. At the age of 27, he was sent as a diplomat to Cologne and to the Court of Avignon to settle the dispute between the city of Deventer and the bishop of Utrecht with Pope Urban V. In principle, he could have met the Italian humanist Petrarch who was there at that time.

Full of knowledge and success, Groote got a big head. His best friends, conscious of his talents, kindly suggested him to detach himself from his obsession with « Earthly Paradise ». The first one was his friend Guillaume de Salvarvilla, the choirmaster of Notre-Dame of Paris. The second was Henri Eger of Kalkar (1328-1408) with whom Groote shared the benches of the Sorbonne.

In 1374, Groote got seriously ill. However, the priest of Deventer refused to administer the last sacraments to him as long as he refused to burn some of the books in his possession. Fearing for his life (after death), he decided to burn his collection of books on black magic. Finally, he felt better and healed. He also gave up living in comfort and lucre through fictitious jobs that allowed him to get rich without working too hard.

After this radical conversion, Groote decides to selfperfect. In his Conclusions and Resolutions he wrote:

« It is to the glory, honor and service of God that I propose to order my life and the salvation of my soul. (…) In the first place, not to desire any other benefit and not to put my hope and expectation from now on in any temporal profit. The more goods I have, the more I will probably want more. For according to the primitive Church, you cannot have several benefits. Of all the sciences of the Gentiles, the moral sciences are the least detestable: many of them are often useful and profitable both for oneself and for teaching others. The wisest, like Socrates and Plato, brought all philosophy back to ethics. And if they spoke of high things, they transmitted them (according to St. Augustine and my own experience) by moralizing them lightly and figuratively, so that morality always shines through in knowledge… ».

Groote then undertakes a spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen near Arnhem where he devotes himself to prayer and study.

However, after a three-year stay in isolation, the prior, his Parisian friend Eger of Kalkar, told him to go out and teach :

« Instead of remaining cloistered here, you will be able to do greater good by going out into the world to preach, an activity for which God has given you a great talent. »

Ruusbroec, the inspirer

Groote accepted the challenge. However, before taking action, he decided to make a last trip to Paris in 1378 to obtain the books he needed.

According to Pomerius, prior of Groenendael between 1431 and 1432, he undertook this trip with his friend from Zwolle, the teacher Joan Cele (around 1350-1417), the historical founder of the excellent Dutch public education system, the Latin School.

On their way to Paris, they visit Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), a Flemish “mystic” who lived in the Groenendael Priory on the edge of the Soignes Forest near Brussels.

Groote, still living in fear of God and the authorities, initially tries to make « more acceptable » some of the old sage’s writings while recognizing Ruusbroec as closer to the Lord than he is. In a letter to the community of Groenendael, he requested the prayer of the prior:

« I would like to recommend myself to the prayer of your provost and prior. For the time of eternity, I would like to be ‘the prior’s stepladder’, as long as my soul is united to him in love and respect.” (Note 1)

Back in Deventer, Groote concentrated on study and preaching. First he presented himself to the bishop to be ordained a deacon. In this function, he obtained the right to preach in the entire bishopric of Utrecht (basically the whole part of today’s Netherlands north of the great rivers, except for the area around Groningen).

First he preached in Deventer, then in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen and later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda and Delft. His success is so great that jealousy is felt in the church. Moreover, with the chaos caused by the great schism (1378 to 1417) installing two popes at the head of the church, the believers are looking for a new generation of leaders.

As early as 1374, Groote offered part of his parents’ house to accommodate a group of pious women. Endowed with a by-law, the first house of sisters was born in Deventer. He named them « Sisters of the Common Life », a concept developed in several works of Ruusbroec, notably in the final paragraph Of the Shining Stone (Van den blinckende Steen)

« The man who is sent from this height to the world below, is full of truth, and rich in all virtues. And he does not seek his own, but the honor of the one who sent him. And that is why he is upright and truthful in all things. And he has a rich and benevolent foundation grounded in the riches of God. And so he must always convey the spirit of God to those who need it; for the living fountain of the Holy Spirit is not a wealth that can be wasted. And he is a willing instrument of God with whom the Lord works as He wills, and how He wills. And it is not for sale, but leaves the honor to God. And for this reason he remains ready to do whatever God commands; and to do and tolerate with strength whatever God entrusts to him. And so he has a common life; for to him seeing [via contemplativa] and working [via activa] are equal, for in both things he is perfect.”

Radewijns, the organizer

Following one of his first sermons, Groote recruited Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Born in Utrecht, the latter received his training in Prague where, also at the early age of 18, he was awarded the title of Magister Artium.

Groote then sent him to the German city of Worms to be consecrated priest there. In 1380 Groote moved with about ten pupils to the house of Radewijns in Deventer; it would later be known as the « Sir Florens House” (Heer Florenshuis), the first house of the Brothers and above all its base of operation?

When Groote died of the plague in 1384, Radewijns decided to expand the movement which became the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Soon it will be branded the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion).

Books and beguinages

A number of parallels can be drawn with the phenomenon of the Beguines which flourished from the 13th century onward. (Note 2)

The first beguines were independent women, living alone (without a man or a rule), animated by a deep spirituality and daring to venture into the enormous adventure of a personal relationship with God. (Note 3)

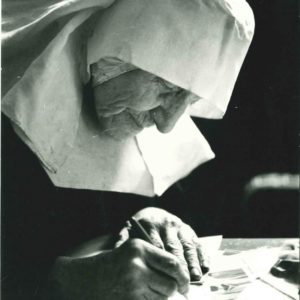

Operating outside the official religious hierarchy, they didn’t beg but worked various jobs to earn their daily bread. The same goes for the Brothers of the Common Life, except that for them, books were at the center of all activities. Thus, apart from teaching, the copying and production of books represented a major source of income while allowing spreading the word to the many.

Lay Brothers and Sisters focused on education and their priests on preaching. Thanks to the scriptorium and printing houses, their literature and music will spread everywhere.

Windesheim

To protect the movement from unfair attacks and criticism, Radewijns founded a congregation of canons regular obeying the Augustinian rule.

In Windesheim, between Zwolle and Deventer, on land belonging to Berthold ten Hove, one of the members, a first cloister is erected. A second one, for women this time, is built in Diepenveen near Arnhem. The construction of Windesheim took several years and a group of brothers lived temporarily on the building site, in huts.

In 1399 Johannes van Kempen, who had stayed at Groote’s house in Deventer, became the first prior of the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and gave the movement new momentum. From Zwolle, Deventer and Windesheim, the new recruits spread all over the Netherlands and Northern Europe to found new branches of the movement.

In 1412, the congregation had 16 cloisters and their number reached 97 in 1500: 84 priories for men and 13 for women. To this must be added a large number of cloisters for canonesses which, although not formally associated with the Windesheim Congregation, were run by rectors trained by them.

Windesheim was not recognized by the Bishop of Utrecht until 1423 and in Belgium, Groenendael, associated with the Red Cloister and Korsendonc, wanted to be part of it as early as 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cusanus and Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was the brother of the famous Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). The latter, trained in Windesheim, animated the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and was one of the towering figures of the movement for seventy years. In addition to a biography he wrote of Groote and his account of the movement, his Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) became the most widely read work in history after the Bible.

Both Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) and Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), two of Erasmus’ tutors during his training in Deventer, were direct pupils of Thomas a Kempis. The Latin School of Deventer, of which Hegius was rector, was the first school in Northern Europe to teach the ancient Greek language to children.

While no formal prove exists, it is tempting to believe that Cusanus (1401-1464), who protected Agricola and, in his last will, via his Bursa Cusanus, offered a scholarship for the training of orphans and poor students of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, was also trained by this humanist network.

What is known is that when Cusanus came in 1451 to the Netherlands to put the affairs of the Church in order, he traveled with his friend Denis the Carthusian (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), a disciple of Ruusbroec, whom he commissioned to carry on this task.

A native of Limburg, trained at the famous Cele school in Zwolle, Dionysius the Carthusian also became the confessor of the Duke of Burgundy and is thought to be the “theological advisor” of the Duke’s ambassador and court painter, Jan Van Eyck. (Note 4)

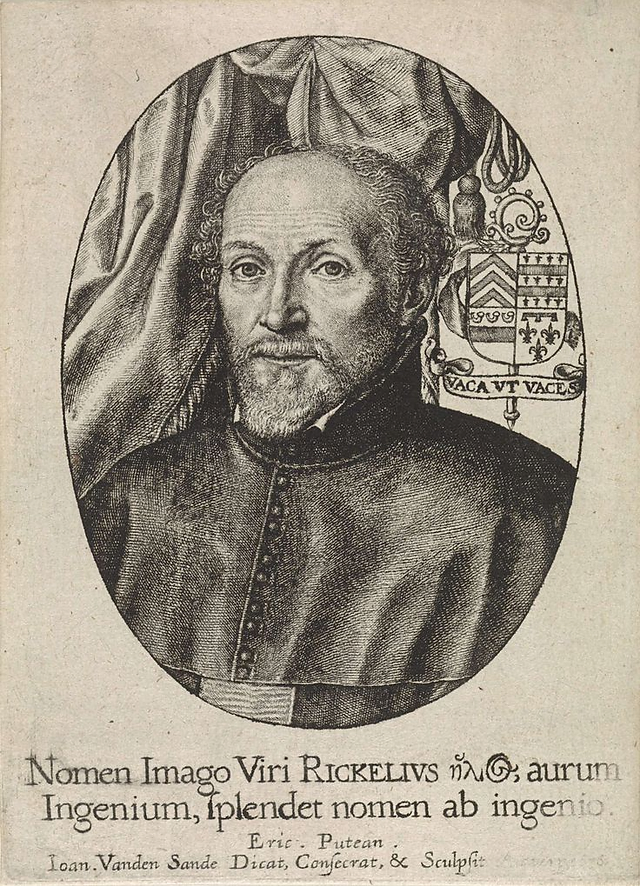

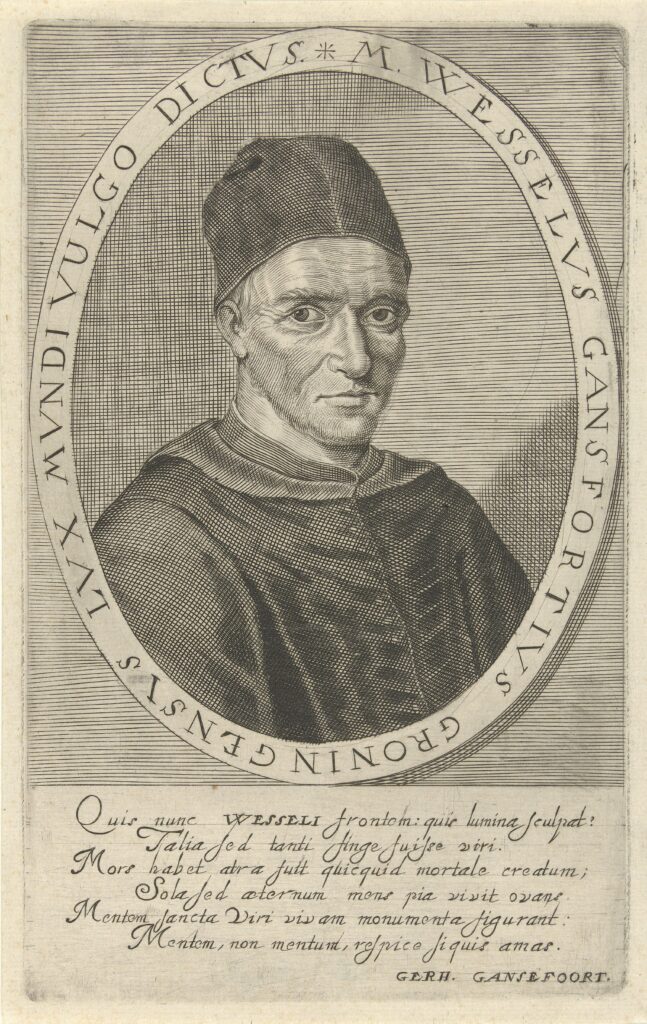

Gansfort

Wessel Gansfort (1419-1489), another exceptional figure of this movement was at the service of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion, the main collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) at the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1437. Gansfort, after attending the Brothers’ school in Groningen, was also trained by Joan Cele‘s Latin school in Zwolle.

The same goes for the first and only Dutch pope, Adrianus VI, who was trained in the same school before completing his training with Hegius in Deventer. This pope was very open to Erasmus’ reformist ideas… before arriving in Rome.

Hegius, in a letter to Gansfort, which he calls Lux Mundi (Light of the World), wrote:

« I send you, most honorable lord, the homilies of John Chrysostom. I hope that you will enjoy reading them, since the golden words have always been more pleasing to you than the pieces of this metal. As you know, I went to the library of Cusanus. There I found some books that I didn’t know existed (…) Farewell, and if I can do you a favor, let me know and consider it done.”

Rembrandt

A quick look on Rembrandt’s intellectual training indicates that he too was a late product of this educational epic. In 1609, Rembrandt, barely three years old, entered elementary school where, like other boys and girls of his generation, he learned to read, write and… draw.

The school opened at 6 in the morning, at 7 in the winter, and closes at 7 in the evening. Classes begin with prayer, reading and discussion of a passage from the Bible followed by the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt acquired an elegant writing style and much more than a rudimentary knowledge of the Gospels.

The Netherlands wanted to survive. Its leaders take advantage of the twelve-year truce (1608-1618) to fulfill their commitment to the public interest.

In doing so, the Netherlands at the beginning of the XVIIth century became the first country in the world where everyone had the chance to learn to read, write, calculate, sing and draw.

This universal educational system, no matter what its shortcomings, available to both rich and poor, boys and girls alike, stands as the secret behind the Dutch « Golden Century ». This high level of education also created those generations of active Dutch emigrants a century later in the American Revolution.

While others started secondary school at the age of twelve, Rembrandt entered the Leyden Latin School at the age of 7. There, the students, apart from rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn not only Greek and Latin, but also foreign languages such as English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, with no laws restricting young talents, Rembrandt enrolled in University. The subject he chose was not Theology, Law, Science or Medicine, but… Literature.

Did he want to add to his knowledge of Latin the mastery of Greek or Hebrew philology, or possibly Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Arabic/Latin dictionaries were already being published in Leiden at a time the city was becoming a major printing center in the world.

Thus, one realizes that the Netherlands and Belgium, first with Ruusbroec and Groote and later with Erasmus and Rembrandt, made an essential contribution in the not so distant past to the kind of humanism that can raise today humanity to its true dignity.

Hence, failing to extend our influence here, clearly seems to me something in the realm of the impossible.

Footnotes:

- Geert Groote, who discovered Ruusbroec’s work during his spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen, near Arnhem, has translated at least three of his works into Latin. He sent The Book of the Spiritual Tabernacle to the Cistercian Cloister of Altencamp and his friends in Amsterdam. The Spiritual Marriage of Ruusbroec being under attack, Groote personally defends it. Thus, thanks to his authority, Ruusbroec’s works are copied in number and carefully preserved. Ruusbroec’s teaching became popularized by the writings of the Modern Devotion and especially by the Imitation of Christ.

- At the beginning of the 13th century the Beguines were accused of heresy and persecuted, except… in the Burgundian Netherlands. In Flanders, they are cleared and obtain official status. In reality, they benefit from the protection of two important women: Jeanne and Margaret of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders. They organized the foundation of the Beguinages of Louvain (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerp (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ypres (1240), Lille (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Bruges (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Diest (1253), Mechelen (1258) and in 1271 it was Jan I, Count of Flanders, in person, who deposited the statutes of the great Beguinage of Brussels. In 1321, the Pope estimated the number of Beguines at 200,000.

- The platonic poetry of the Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (XIIIth Century) has a decisive influence on Jan van Ruusbroec.

- It is significant that the first book printed in Flanders in 1473, by Erasmus’ friend and printer Dirk Martens, is precisely a work of Denis the Carthusian.

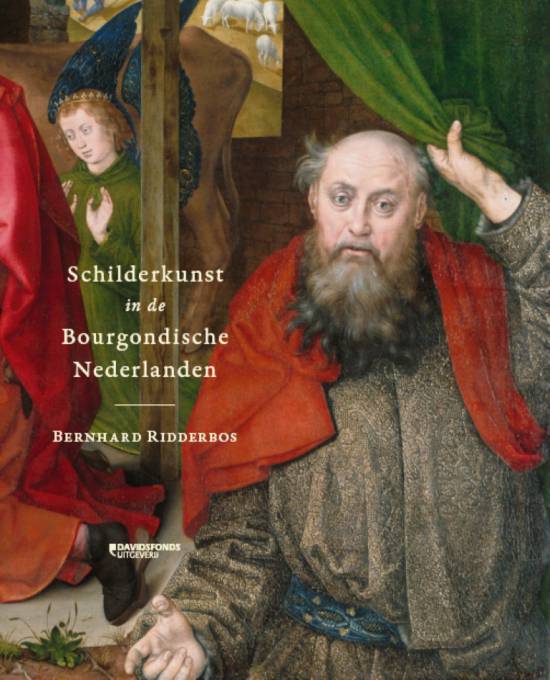

Hugo van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne

Le beau livre de l’historien néerlandais Bernhard Ridderbos, Schilderkunst in de Bourgondische Nederlanden (La peinture aux Pays-Bas bourguignon, Davidsfonds, Leuven 2015) est un régal pour les yeux et l’esprit.

Ridderbos, déjà irrité par l’habile campagne de propagande menée depuis des siècles par des banquiers italiens pour qui « la » Renaissance n’était qu’italienne et pour qui les fiammingo n’étaient que des « Primitifs », démarre son ouvrage en incendiant (non sans raison) une œuvre qui reste une référence, L’automne du Moyen Age (1919), de Johan Huizinga (1872-1945).

Pour cet historien néerlandais influant, recteur de l’Université de Leyden :

L’art de Van Eyck, dans sa capacité de figurer les choses saintes, a su atteindre un haut degré de détail et de naturalisme, marquant sans doute un point de départ sur le plan strict de l’histoire de l’art, mais signifiant en réalité une fin sur le plan historico-culturel. La tension extrême de l’imagination terrestre du divin fut atteint ici ; cependant, le contenu mystique de son imagination s’apprêtait à quitter ces images et à ne laisser les réjouissances qu’à la forme

Niant l’esprit clairement pré-renaissant des peintres flamands du début du XVe siècle, pour Huizinga, leur naturalisme n’était rien d’autre que « le déploiement ultime de l’esprit moyenâgeux tardif. »

Or, comme j’ai cherché à démontrer, en avril 2006, lors de mon exposé au Colloque international à la Sorbonne sur le thème de « La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique », Robert Campin, Jan van Eyck et d’autres peintres flamands, qu’on présente assez souvent comme récalcitrant à utiliser les modèles perspectivistes développés par l’italien Leon Battista Alberti et comme en témoigne la présence assez imposante de miroirs convexes dans leurs œuvres (Volets Werl, Epoux Arnolfini), se sont inspirés des travaux mathématiques et géométriques complexes du grand scientifique arabe Ibn Al-Haytam.

Mieux connu en Occident sous son nom latin Alhazen, ses travaux d’optique, notamment sur la lumière et les miroirs convexes, se retrouvent dans les carnets de Léonard de Vinci, lecteur assidu des Commentaires de Ghiberti. *

Libéré de cette chape de plomb de l’autocensure, Ridderbos approfondit l’iconographie, les contextes économiques, sociaux et culturels. Sans égarer le lecteur dans un marécage de détails et d’hypothèses stériles, il nous offre des éclairages très intéressants sur le comment et le pourquoi des créations artistiques de cette époque.

Ceux parmi vous qui n’ont jamais pris le temps de lire ni l’œuvre monumentale d’Erwin Panofsky, ni les imposantes monographies publiées en Belgique par le Fonds Mercator d’Anvers relatant in extenso la vie des grands peintres flamands tels que Robert Campin, Rogier Van der Weyden, Jan Van Eyck, Hans Memling, Thierry Bouts, Hugo Van der Goes et Gérard David, remercieront Ridderbos pour non seulement en avoir extrait la quintessence, mais pour les avoir mis en relation les unes avec les autres.

Les commanditaires

En premier lieu, il montre à quel point les artistes étaient soumis à des « carnets de charges » très stricts. Un tel monastère, une telle guilde, un tel seigneur passait commande. Ils fixaient la taille de l’œuvre, le sujet et les personnes à représenter. Plusieurs théologiens, spécialistes du thème à traiter, furent parfois nommés pour conseiller et accompagner le peintre dans sa représentation de sujets religieux. L’artiste exécuta d’abord, sur son panneau, un dessin. Et ce n’est qu’une fois validé par le commanditaire, souvent après de nombreuses modifications, qu’il appliqua les couleurs. Gérard David, par exemple, a du changer l’ensemble des portraits des échevins sur son œuvre, suite à l’élection d’une nouvelle équipe…

Rivalités

Ensuite, Ridderbos indique comment les rivalités des uns et des autres, princes, églises, mais aussi Cités-Etats, souvent en quête de prestige (le fameux « soft power » de nos jours), ont profité à la vie artistique flamande. Princes, ducs, rois et banquiers étrangers se disputaient les peintres flamands pour fanfaronner et se mettre en avant.

Pour monter en grade, un banquier des Médicis (Angelo Tani) commande un triptyque à Hans Memling, un Jugement dernier (1466-1473), largement inspiré de l’œuvre éponyme de Van Der Weyden pour l’Hospice de Beaune.

Lorsque son confrère (Tommaso Portinari, le fondé de pouvoir des Médicis à Bruges) l’apprend, il passe commande d’un autre triptyque, une Nativité (1475), bien plus grand et plus splendide encore chez Hugo Van der Goes. Ce « triptyque Portinari » sera dévoilé à Florence en 1483 et inspirera toute une série d’œuvres italiens, notamment celles du peintre italien Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Rogier Van der Weyden, après avoir travaillé pour la ville de Louvain, se voit offrir un bien meilleur salaire par la ville de Bruxelles, les deux villes cherchant à devenir la capitale de la région.

Lorsqu’il y peint pour l’Hôtel de Ville un grand retable sur la Justice (La Justice de Trajan et Herkenbald, ca. 1450), la ville de Louvain, pour ne pas être en reste, commandera plusieurs années après une œuvre semblable (La justice d’Otton III, 1473) à Thierry Bouts, provoquant à son tour une autre ville, celle de Bruges d’en commander un du même type (Le jugement de Cambyses, 1498) chez Gérard David, un disciple et proche de l’atelier de Van der Goes.

Ridderbos bien sûr ne se limite pas à tracer cette dynamique sociologique. Il analyse comment ces peintres vont dialoguer entre eux en reprenant à leur compte les apports techniques et iconographiques de leurs confrères. Tout en mobilisant le meilleur d’eux-mêmes, ils apportèrent des choses entièrement nouvelles. C’est un processus assez similaire à l’apport compositionnel d’un Ludwig van Beethoven montant lui-même « sur les épaules des géants » que furent avant lui Bach, Haydn et Mozart.

Van der Goes et la Dévotion moderne

Dans le chapitre VII, page 179, l’auteur fait un effort particulier pour mettre en valeur l’œuvre d’Hugo Van Der Goes, un peintre remarquable qu’on a rangé un peu vite dans l’ombre de Van Eyck, Van der Weyden et Memling.

Probablement né vers 1440 à Gand, Van der Goes est reçu maître de la guilde des peintres de cette ville en 1467 et en devient le doyen en 1474. Trois ans plus tard, il est à l’apogée de la reconnaissance professionnelle et de la réussite sociale.

C’est alors qu’il abandonne la vie bourgeoise pour s’associer au grand mouvement de réforme appelé la Dévotion moderne. Pour ce faire, Van Der Goes devient frère lai auprès des Soeurs et Frères de la Vie commune, plus précisément ceux de l’abbaye du Rouge-Cloître (Rooklooster) dans la Forêt de Soignes près de Bruxelles. Il y jouit de certains privilèges, comme d’être autorisé à continuer à peindre.

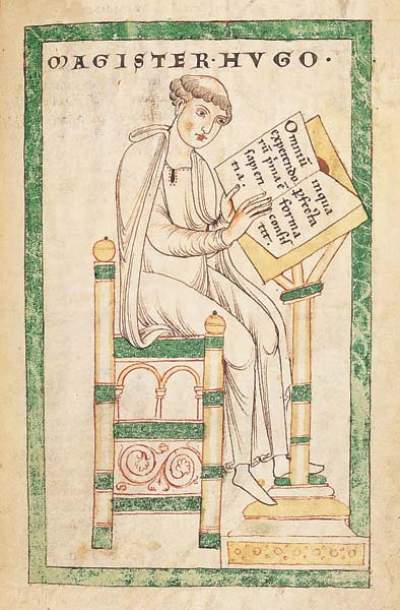

Deventer

La Dévotion moderne sera avant tout un mouvement éducateur. Elle fonda notamment à Deventer une école renommée ouverte aux pauvres et aux orphelins. Rudolf Agricola et son successeur Alexandre Hegius y enseignent le grec et le latin à toute une génération d’humanistes dont le plus connu s’appelle Erasme de Rotterdam.

Le fameux cardinal-philosophe, mathématicien et juriste allemand, Nicolas de Cues (1401-1464) tenait en haute estime les efforts des enseignants de Deventer. En 1469, cinq ans après sa mort, sans doute en accord avec ses derniers vœux, une partie de son héritage ira abonder (de 1470 à 1682) un fond dédié, la Bursa Cusana, permettant à une vingtaine d’élèves, dont la moitié originaire de la ville natale de Cues, d’y parfaire leur instruction.

Le piétisme de la Devotion moderne, centré sur l’intériorité, s’articule le mieux dans le petit livre de Thomas van Kempen (a Kempis) (1380-1471), L’imitation de Jésus Christ. Celui-ci souligne l’exemple à suivre de la passion du Christ tel que nous l’enseigne l’Évangile, message repris par Erasme.

Van Der Goes, animé à titre personnel par l’esprit de cette démarche, apparaît ainsi, sans l’avoir connu, avec le peintre anversois Quinten Matsys, comme « le plus erasmien » des peintres flamands. Et à ce titre, il sera capable de faire transparaître dans ses œuvres une tension dramatique plus aiguë, traduite par l’animation et l’expressivité des personnages.

Les bergers

On pense immédiatement aux magnifiques bergers du Triptyque Portinari. Cette œuvre est commanditée par un des banquiers les plus riches de l’époque et pourtant, ce ne sont pas les trois Rois mages qui se trouvent au premier plan, mais d’humbles bergers arrivés bien avant eux et les premiers à reconnaître l’enfant pour ce qu’il est.

Se démarquant nettement de la façon dont le peintre italien Andrea Mantegna les avait dépeint vingt ans plus tôt, c’est-à-dire comme des pauvres hères en haillons, hirsutes, sales et édentés, Van der Goes souligne leur dignité et met en avant leurs transformations.

D’ailleurs, les expressions des bergers incarneraient les trois étapes spirituelles définies par un autre inspirateur de la Devotion moderne, le mystique flamand Jan Van Ruysbroeck (1293-1381) : la vie active, la vie intérieure et la vie contemplative où l’Homme entre en communion spirituelle avec Dieu. **

Le chapeau de Nicodème

Autre exemple, son tableau La lamentation du Christ (après 1479) actuellement au Musée de Vienne. De prime abord rien de bien révolutionnaire dans cette représentation. On y voit la mère du Christ retenue par Jean lorsqu’elle s’effondre sur la dépouille mortelle de son fils.

C’est sur l’avant plan que deux figures méritent notre attention. S’appuyant sur les Geestelijke Opklimmingen (Des ascensions spirituelles) écrit par Gerard Zerbold de Zutphen (1367-1398), un auteur de la Dévotion moderne proche de Groote, Ridderbos identifie leur rôle dans cette œuvre.

A droite, d’abord, on voit Nicodème coiffé d’une capuche rouge. Selon l’Evangile selon Saint-Jean, Nicodème a été un des premiers pharisiens devenus secrètement disciples de Jésus. Ici, on le voit en pleine crise, pour ne pas dire agonie existentielle, portant un regard effrayé sur son riche chapeau posé par terre.

Or, lorsque l’on examine de plus près ce couvre-chef, on découvre qu’il est surmonté d’une couronne d’épines !

La métaphore est donc à l’image de la Dévotion moderne qui exigeait de chacun, non seulement de suivre fidèlement les rites, mais de « vivre à l’imitation du Christ », c’est-à-dire de s’élever à un tel niveau d’amour pour le Christ et l’humanité qu’on puisse offrir librement ses possessions, son patrimoine et même sa vie au vrai, au juste et au beau.

Enfin, pour compléter le tableau, à gauche, toujours au premier plan, la figure de Marie Madeleine, une autre disciple de Jésus qui le suit jusqu’à ses derniers jours.

Prostituée repentie, Marie Madeleine complète à merveille la métaphore en s’érigeant ici comme l’exemple même du travail d’introspection et d’auto-perfectionnement personnel qu’exigeaient les Sœurs et Frères de la Vie Commune.

Le message est fort : vous ne pouvez pas vous contenter d’adorer ou d’admirer le Christ ! Vous devez changer vos vies ! Un message qui n’a pas perdu de son actualité…

Notes:

* Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) écrivit quelques 200 ouvrages sur les mathématiques, l’astronomie, la physique, la médecine et la philosophie. Né à Bassora, et après avoir travaillé sur l’aménagement des cours du Nil en Égypte, il se serait rendu en Espagne. Il aurait mené une série d’expériences très précises sur l’optique théorique et expérimentale, y compris sur la camera obscura (chambre noire), travaux qu’on retrouve ultérieurement dans les études de Léonard de Vinci. Ce dernier a pu lire les longs passages d’Alhazen qui figurent dans les Commentari du sculpteur florentin Ghiberti. Après que l’évêque de Reims Gerbert d’Aurillac (le futur pape Sylvestre II en 999) ramena d’Espagne le système décimal avec son zéro et un astrolabe, c’est grâce à Gérard de Crémone (1114-vers 1187) que l’Europe va accéder à la science grecque, juive et arabe. Ce savant se rendra 1175 à Tolède pour y apprendre l’arabe et effectuera la traduction de quelques 80 ouvrages scientifiques de l’arabe en latin, notamment l’Almageste de Ptolémée, les Coniques d’Apollonius, plusieurs traités d’Aristote, le Canon d’Avicenne, les œuvres d’Ibn Al-Haytam, d’Al-Kindi, de Thabit ibn Qurra et d’Al-Razi. Dans le monde arabe, ces recherches furent reprises un siècle plus tard par le physicien persan Al-Farisi (1267-1319). Ce dernier a rédigé un important commentaire du Traité d’optique d’Alhazen. En prenant pour modèle une goutte d’eau et en s’appuyant sur la théorie d’Alhazen sur la double réfraction dans une sphère, il a donné la première explication correcte de l’arc-en-ciel. Il a même suggéré la propriété ondulatoire de la lumière, alors qu’Alhazen avait étudié la lumière à l’aide de balles solides dans ses expériences de réflexion et de réfraction. Désormais la question se posait ainsi : la lumière se propage-t-elle par ondulation ou par transport de particules ?

** Voir à ce propos : Nadeije Laneyrie-dagen, L’invention du corps : La représentation de l’homme du Moyen Âge à la fin du XIXe siècle, Paris 1997, 52. ; Delphine Rabier, Les trois degrés de la vision selon Ruysbroeck l’Admirable et les Bergers du triptyque Portinari de Hugo van der Goes, in Studies in Spirituality, 27, p. 163-179, 2017.