Étiquette : cusanus

LOUVRE AUDIO GUIDE : Van der Weyden and Cusanus

Listen:

To the audio on the website

Read :

- Rogier Van der Weyden, le maître de la compassion;

- The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance (EN online).

- Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life, the cradle of humanism in the North (EN online)

- Jan van Eyck, la beauté comme prégustation de la sagesse divine (FR en ligne) + EN on line.

- Jan Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics (EN online)

Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics?

What follows is an edited transcript of a lecture by Karel Vereycken on the subject of “Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting”.

It was delivered at the international colloquium “La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique” (The quest for the divine through geometrical space) at the Paris Sorbonne University on April 26-28, 2006, under the direction of Luc Bergmans, Department of Dutch Studies (Paris IV Sorbonne University).

Introduction

« Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting ». At first glance, this title may seem surprising. While the genius of fifteenth-century Flemish painters is universally attributed to their mastery of drying oil and their intricate sense of detail, their spatial geometry as such is usually identified as the very counter-example of the “right perspective”.

Disdained by Michelangelo and his faithful friend Vasari, the Flemish « primitives » would never have overcome the medieval, archaic and empirical model. For the classical “narritive”, still in force today, stipulates that only « Renaissance » perspective, obeying the canon of « linear », “mathematical” perspective, is the only « right », and the “scientific” one.

According to the same narrative, it was the research carried out around 1415-20 by the Duomo architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), superficially mentioned by Antonio Tuccio di Manetti some 60 years later, which supposedly enabled Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), proclaiming himself Brunelleschi’s intellectual heir, to invent « perspective ».

In 1435, in De Pictura, a book entirely devoid of graphic illustration, Alberti is said to have formulated the premises of a perspectivist canon capable of representing, or at least conforming to, our modern notions of Cartesian space-time (NOTE 1), a space-time characterized as « entirely rational, i.e. infinite, continuous and homogeneous », « in one word, a purely mathematical space [dixit Panofsky] » (NOTE 2)

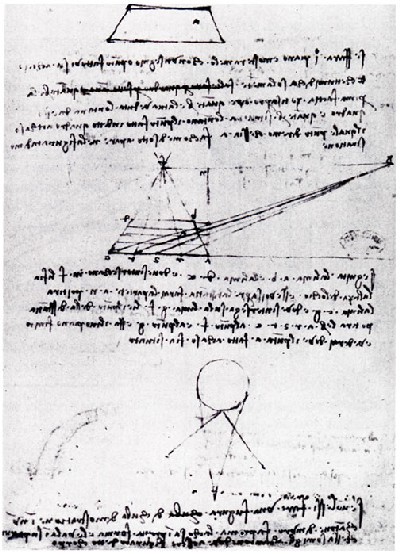

Long afterwards, in a drawing from the Codex Madrid, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) attempted to unravel the workings of this model.

But in the same manuscript, he rigorously demonstrated the inherent limitations of the Albertian Renaissance perspectivist canon.

The drawing on f°15, v° clearly shows that the simple projection of visual pyramid cross-sections on a plane paradoxically causes their size to increase the further they are from the point of vision, whereas reality would require exactly the opposite. (NOTE 3)

With this in mind, Leonardo began to question the mobility of the eye and the curvilinear nature of the retina. Refusing to immobilize the viewer on an exclusive point of vision (NOTE 4), Leonardo used curvilinear constructions to correct these lateral deformations. (NOTE 5) In France, Jean Fouquet and others worked along the same lines.

But Leonardo’s powerful arguments were ignored, and he was unable to prevent this rewriting of history.

Despite this official version of art history, it should be noted that at the time, Flemish painters were elevated to pinnacles by Italy’s greatest patrons and art connoisseurs, specifically for their ability to represent space.

Bartolomeo Fazio, around the middle of the 15th century, observed that the paintings of Jan van Eyck, an artist billed as the « principal painter of our time », showed « tiny figures of men, mountains, groves, villages and castles rendered with such skill that one would think them fifty thousand paces apart. » (NOTE 6)

Such was their reputation that some of the great names in Italian painting had no qualms about reproducing Flemish works identically. I’m thinking, for example, of the copy of Hans Memlinc‘s Christ Crowned with Thorns at the Genoa Museum, copied by Domenico Ghirlandajo (Philadelphia Museum).

But post-Michelangelo classicism deemed the non-conformity of Flemish spatial geometry with Descartes’ « extended substance » to be an unforgivable crime, and any deviation from, or insubordination to, the « Renaissance » perspectivist canon relegated them to the category of « primitives », i.e. « empiricists », clearly devoid of any scientific culture.

Today, ironically, it is almost exclusively those artists who explicitly renounce all forms of perspectivist construction in favor of pseudo-naïveté, who earn the label of modernity…

In any case, current prejudices mean that 15th-century Flemish painting is still accused of having ignored perspective.

It’s true, however, that at the end of the XIVth century, certain paintings by Melchior Broederlam (c. 1355-1411) and others by Robert Campin (1375-1444) (Master of Flémalle) show the viewer interiors where plates and cutlery on tables threaten to suddenly slide to the floor.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that whenever the artist « ignores » or disregards the linear perspective scheme, he seems to do so more by choice than by incapacity. To achieve a limpid composition, the painter prioritizes his didactic mission to the detriment of all other considerations.

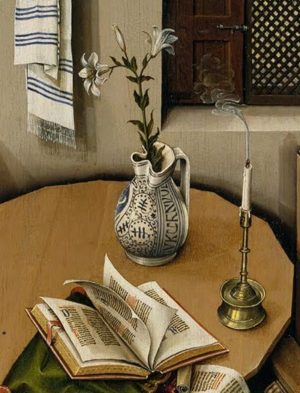

For example, in Campin’s Mérode Altarpiece, the exaggerated perspective of the table clearly shows that the vase is behind the candlestick and book.

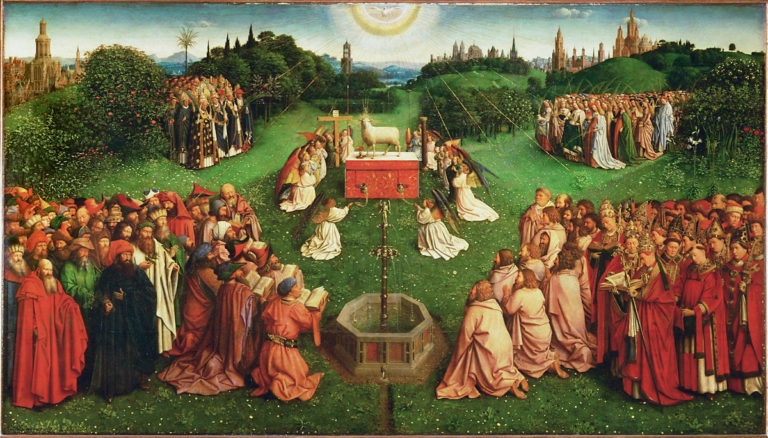

Jan van Eyck’s Lam Gods (Mystic Lamb) in Ghent is another example.

Never could so many figures, with so much detail and presence, be shown with a linear perspective where the figures in the foreground would hide those behind. (NOTE 7)

But the intention to approximate a credible sense of space and depth remains.

If this perspective seems flawed by its linear geometry, Campin imposes an extraordinary sense of space through his revolutionary treatment of shadows. As every painter knows, light is painted by painting shadow.

In Campin’s work, every object and figure is exposed to several sources of light, generating a darker central shadow as the fruit of crossed shadows.

Van Eyck influenced by Arab Optics?

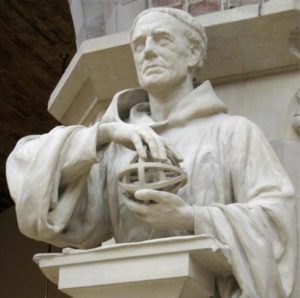

Roger Bacon, statue in Oxord.

This new treatment of light-space has been largely ignored. However, there are several indications that this new conception was partly the result of the influence of « Arab » science, in particular its work on optics.

Translated into Latin and studied from the XIIth century onwards, their work was developed in particular by a network of Franciscans whose epicenter was in Oxford (Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) and whose influence spread to Chartres, Paris, Cologne and the rest of Europe.

It should be noted that Jan van Eyck (1395-1441), an emblematic figure of Flemish painting, was ambassador to Paris, Prague, Portugal and England.

I’ll briefly mention three elements that support this hypothesis of the influence of Arab science.

Curved mirrors

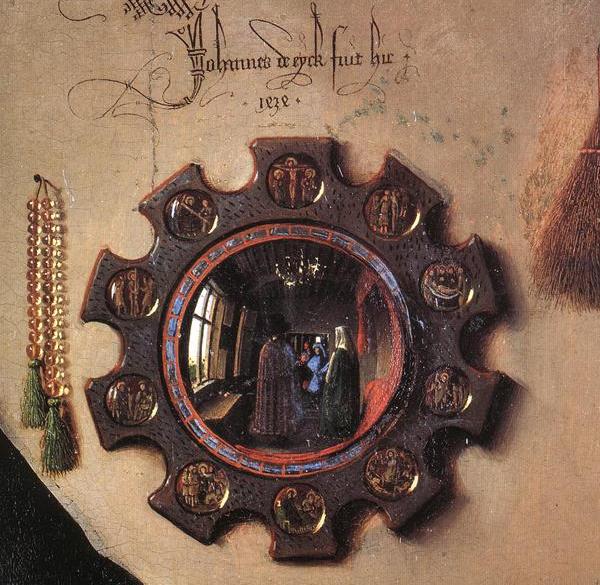

Robert Campin (master of Flémalle) in the Werl Triptych (1438) and Jan van Eyck in the Arnolfini portrait (1434), each feature convex mirrors of considerable size.

It is now certain that glaziers and mirror-makers were full members of the Saint Luc guild, the painters’ guild. (NOTE 8)

But it is relevant to know that Campin, now recognized as having run the workshop in Tournai where the painters Van der Weyden and Jacques Daret were trained, produced paintings for the Franciscans in this city. Heinrich Werl, who commissioned the altarpiece featuring the convex mirror, was an eminent Franciscan theologian who taught at the University of Cologne.

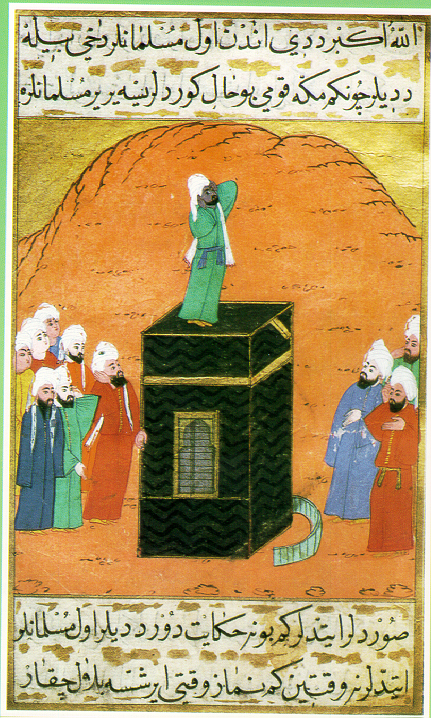

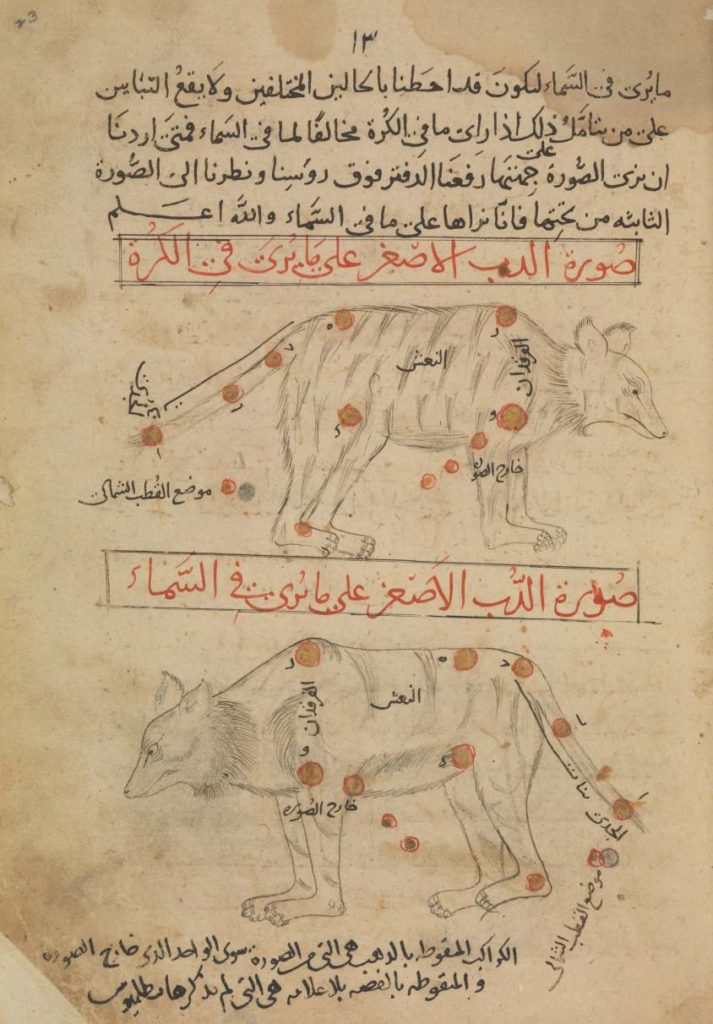

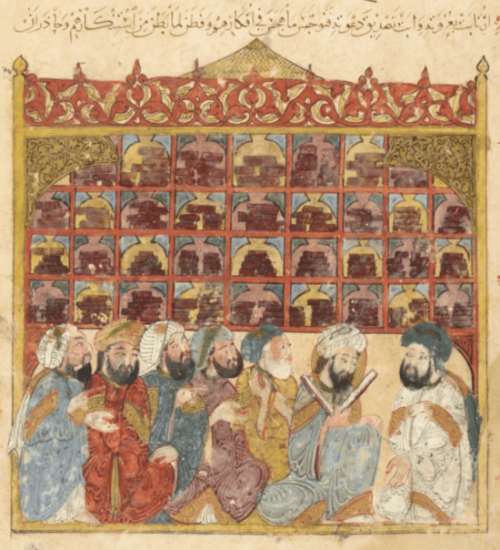

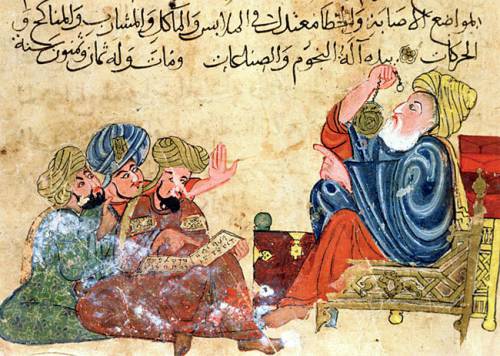

Artistic representation of Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen)

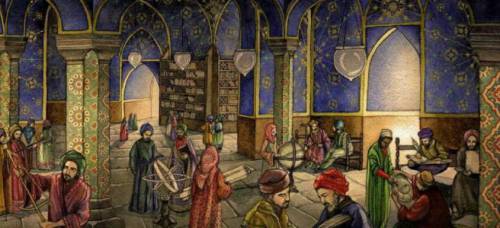

These convex and concave (or ardent) mirrors were much studied during the Arab renaissance of the IXth to XIth centuries, in particular by the Arab philosopher Al-Kindi (801-873) in Baghdad at the time of Charlemagne.

Arab scientists were not only in possession of the main body of Hellenic work on optics (Euclid‘s Optics, Ptolemy‘s Optics, the works of Heron of Alexandria, Anthemius of Tralles, etc.), but it was sometimes the rigorous refutation of this heritage that was to give science its wings.

After the decisive work of Ibn Sahl (Xth century), it was that of Ibn Al-Haytam (Latin name : Alhazen) (NOTE 9) on the nature of light, lenses and spherical mirrors that was to have a major influence. (NOTE 10)

As mentioned above, these studies were taken up by the Oxford Franciscans, starting with the English bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste (1168-1253).

In De Natura Locorum, for example, Grosseteste shows a diagram of the refraction of light in a spherical glass filled with water. And in his De Iride he marvels at this science which he connexts to perspective :

« This part of optics, so well understood, shows us how to make very distant things appear as if they were situated very near, and how we can make small things situated at a distance appear to the size we desire, so that it becomes possible for us to read the smallest letters from incredible distances, or to count sand, or grains, or any small object.«

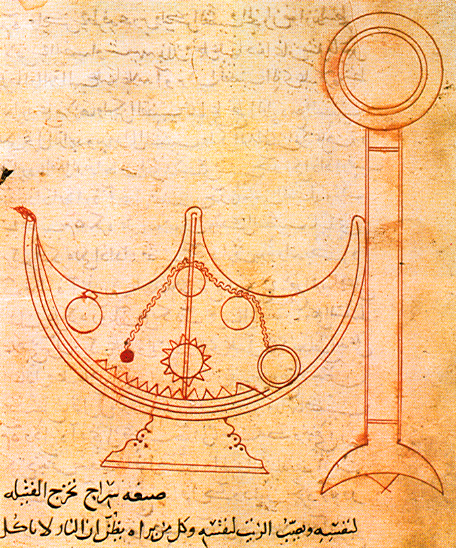

Grosseteste’s pupil Roger Bacon (1212-1292) wrote De Speculis Comburentibus, a specific treatise on « Ardent Mirrors » which elaborates on Ibn Al-Haytam‘s work.

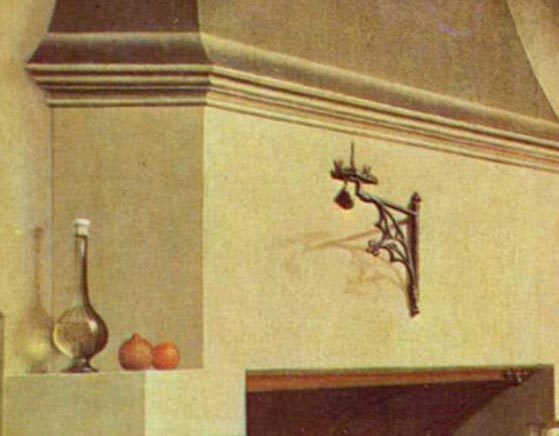

Flemish painters Campin, Van Eyck and Van der Weyden proudly display their knowledge of this new scientific and technological revolution metamorphosed into Christian symbolisms.

Their paintings feature not only curved mirrors but also glass bottles, which they use as a metaphor for the immaculate conception.

A Nativity hymn of that period says:

« As through glass the ray passed without breaking it, so of the Virgin Mother, Virgin she was and virgin she remained… » (NOTE 11)

The Treatment of Light

In his Discourse on Light, Ibn Al-Haytam develops his theory of light propagation in extremely poetic language, setting out requirements that remind us of the « Eyckian revolution ». Indeed, Flemish « realism » and perspective are the result of a new treatment of light and color.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« The light emitted by a luminous body by itself -substantial light- and the light emitted by an illuminated body -accidental light- propagate on the bodies surrounding them. Opaque bodies can be illuminated and then in turn emit light. »

This physical principle, theorized by Leonardo da Vinci, is omnipresent in Flemish painting. Just look at the images reflected in the helmet of St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele (NOTE 12).

In each curved surface of Saint George’s helmet, we can identify the reflection of the Virgin and even a window through which light enters the painting.

The shining shield on St. George’s back reflects the base of the adjacent column, and the painter’s portrait appears as a signature. Only a knowledge of the optics of curved surfaces can explain this rendering.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« Light can penetrate transparent bodies: water, air, crystal and their counterparts. »

And :

« Transparent bodies have, like opaque bodies, a ‘receiving power’ for light, but transparent bodies also have a ‘transmitting power’ for light.«

Isn’t the development of oil mediums and glazes by the Flemish an echo of this research? Alternating opaque and translucent layers on very smooth panels, the specificity of the oil medium alters the angle of light refraction.

In 1559, the painter-poet Lucas d’Heere referred to van Eyck‘s paintings as « mirrors, not painted scenes.«

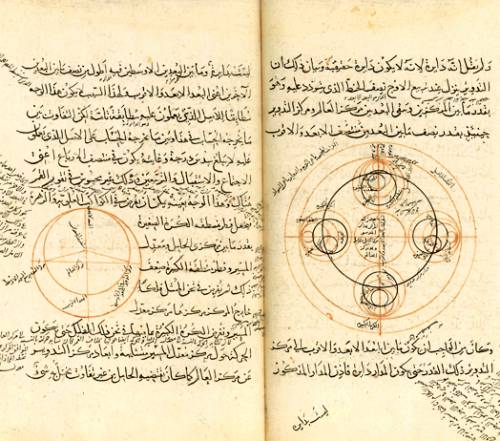

Binocular perspective

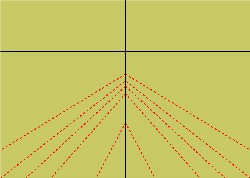

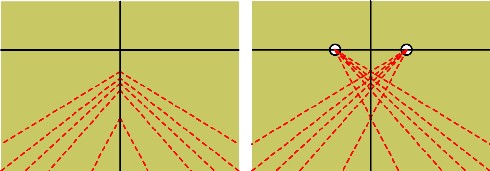

Before the advent of « right » central linear perspective, art historians sought a coherent explanation for its birth in the presence of several seemingly disparate vanishing points by theorizing a so-called central « fishbone » perspective.

In this model, a number of vanishing lines, instead of coinciding in a single central vanishing point on the horizon, either end up in a « vanishing region » (NOTE 13), or align with what some call a vertical « vanishing axis », forming a kind of « fishbone ».

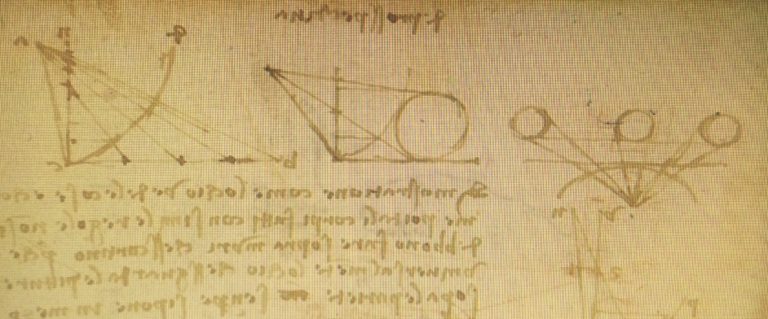

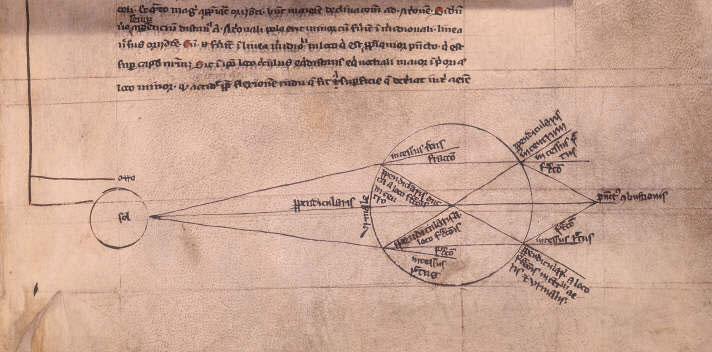

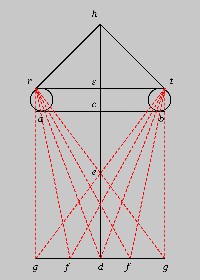

French Professor Dominique Raynaud, who worked for years on this issue, underscores that « all medieval treatises on perspective address the question of binocular vision », notably the Polish scholar Witelo (1230-1280) (NOTE 15) in his Perspectiva (I,27), an insight he also got from the works of Ibn Al-Haytam.

Witelo presents a figure to defend the idea that

« the two forms, which penetrate two homologous points of the surface of the two eyes, arrive at the same point of the concavity of the common nerve, and are superimposed at this point to become one » (Perspectiva, III, 37).

A similar line of reasoning can be found in Roger Bacon‘s Perspectiva Communis, written by John Pecham, Archbishop of Canterbury (1240-1290) for whom:

« the duality of the eyes must be reduced to unity »

So, as Professor Raynaud proposed, if we extend the famous vanishing lines (i.e., in our case, the « fish bones ») until they intersect, the « vanishing axis » problem disappears, as the vanishing lines meet. Interestingly, the result is a perspective with two vanishing points in the central region!

Suddenly, the diagrams drawn up to demonstrate the « empiricism » of the Flemish painters, if viewed from this point of view, reveal a legitimate construction probably based on optics as transmitted by Arab science and rediscovered by Franciscan networks and others.

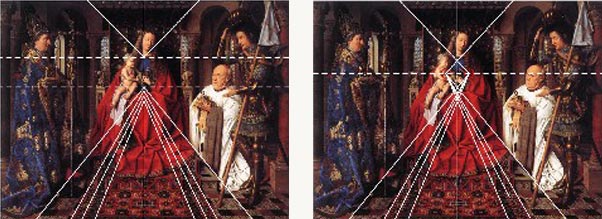

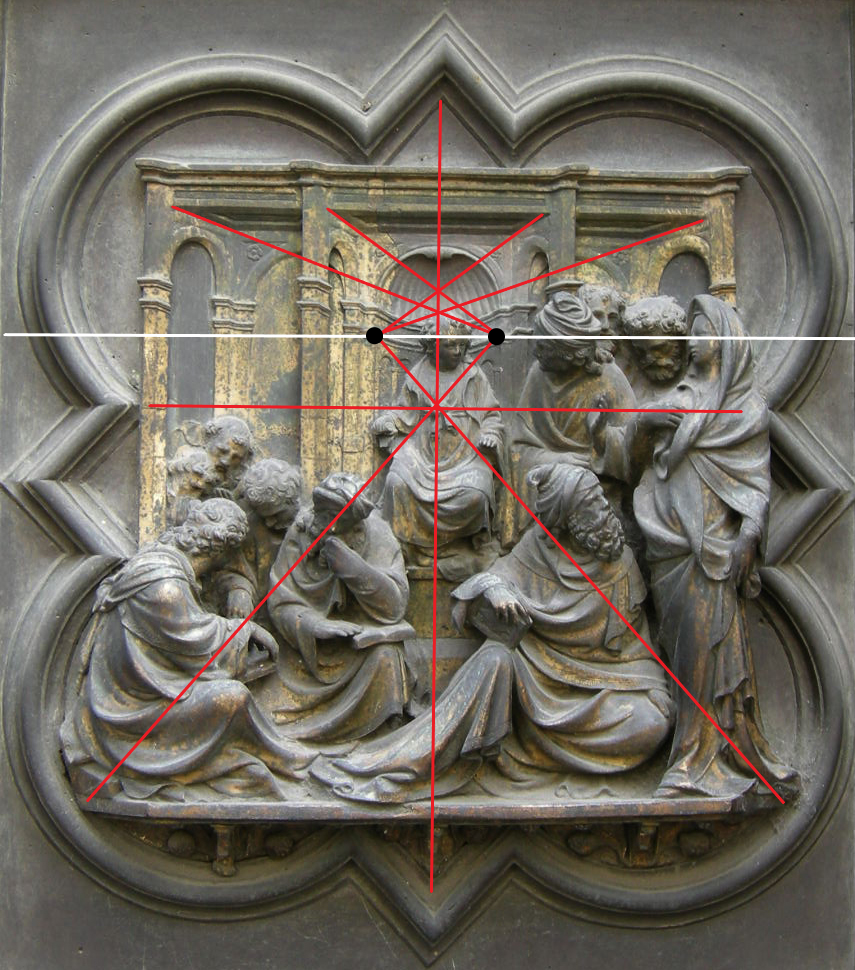

Two paintings by Jan van Eyck clearly demonstrate that he followed this approach: The Madonna with Canon van der Paele of 1436 and the Dresden Tryptic of 1437.

What seemed a clumsy, empirical approach in the form of a « fishbone » perspective (left) turns out to be a binocular perspective construction.

Was this type of perspective specifically Flemish?

A close examination of works by Ghiberti, Donatello and Paolo Uccello, generally dating from the first half of the XVth Century, reveals a mastery of the same principle.

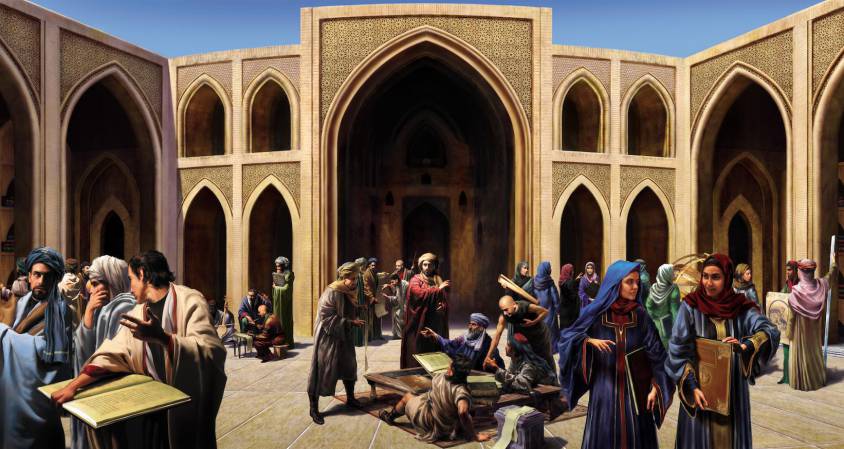

Cusanus

But this whole demonstration is merely a look into the past through the eyes of modern scientific rationality. It would be a grave error not to take into account the immense influence of the Rhenish (Master Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso) and Flemish (Hadewijch of Antwerp, Jan van Ruusbroec, etc.) « mystics ».

This trend began to flourish again with the rediscovery of the Christianized neo-Platonism of Dionysius the Areopagite (Vth-VIth century), made accessible… by the new translations of the Franciscan Grosseteste in Oxford.

The spiritual vision of the Aeropagite, expressed in a powerful imagery language, is directly reminiscent of the metaphorical approach of the Flemish painters, for whom a certain type of light is simply the revelation of divine grace.

In On the Heavenly Hierarchy, Dionysius immediately presents light as a manifestation of divine goodness. It ennobles us and enables us to enlighten others:

« Let those who are illuminated be filled with divine clarity, and the eyes of their understanding trained to the work of chaste contemplation; finally, let those who are perfected, once their primitive imperfection has been abolished, share in the sanctifying science of the marvelous teachings that have already been manifested to them; similarly, let the purifier excel in the purity he communicates to others; let the illuminator, gifted with a greater penetration of spirit, equally fit to receive and transmit light, happily flooded with sacred splendor, pour it out in pressing streams on those who are worthy… » [Chap. III, 3]

Let’s think again of the St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele, which indeed pours forth the multiple images of the Virgin who enlightens him.

This theo-philosophical trend reached full maturity in the work of Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) (1401-1464) (NOTE 16), embodying the extremely fruitful encounter of this « negative theology » with Greek science, Socratic knowledge and Christian Humanism.

In contrast to both a science « without a hypothesis of God » and a metaphysics with an esoteric drift, an agapic love leads it to the education of the greatest number, to the defense of the weak and the humiliated.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, educating Erasmus of Rotterdam and inspiring Cusanus, are the best example of this.

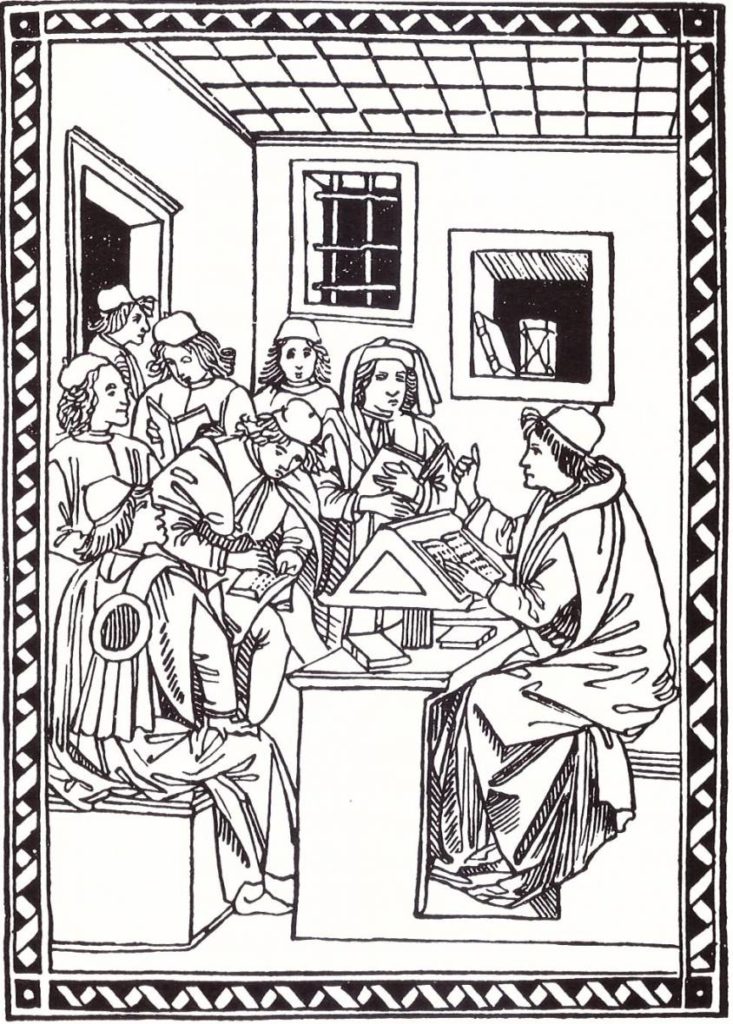

But let’s sketch out some of Cusanus’ key ideas on painting.

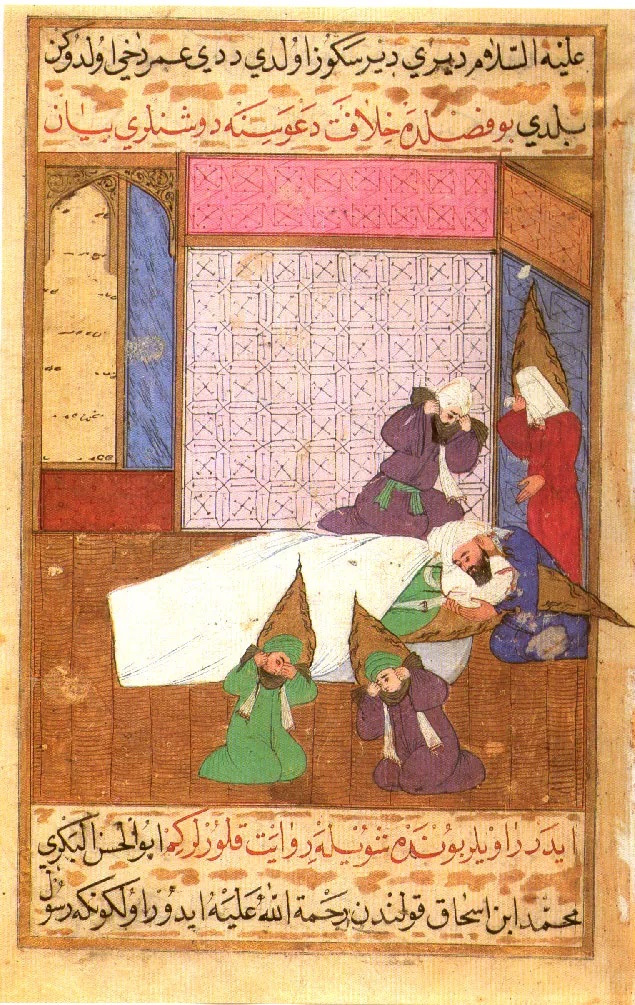

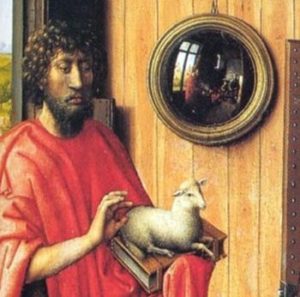

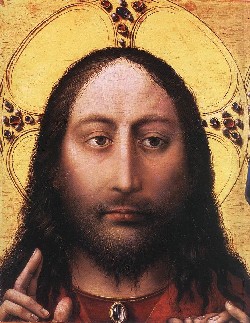

In De Icona (The Vision of God) (1453), which he sent to the Benedictine monks of the Tegernsee, Cusanus condenses his fundamental work On Learned Ignorance (1440), in which he develops the concept of the coincidence of opposites. His starting point was a self-portrait of his friend « Roger », the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden, which he sent together with his sermon to the monks.

This self-portrait, like the multiple faces of Christ painted in the XVth century, uses an « optical illusion » to create the effect of a gaze that fixes the viewer, regardless of his or her position in front of the altarpiece.

In De Icona, written as a sermon, Cusanus asks monks to stand in a semicircle around the painting and watch this gaze pursue them as they move along the segment of the curve. In fact, he elaborates a pedagogical paradox based on the fact that the Greek name for God, Theos, has its etymological origin in the verb theastai (to see, to look at).

As you can see, he says, God looks at you personally, and his gaze follows you everywhere. He is therefore one and many. And even when you turn away from him, his gaze falls on you. So, miraculously, although he looks at everyone at the same time, he nevertheless establishes a personal relationship with each one. If « seeing » for God is « loving », God’s point of vision is infinite, omniscient and omnipotent love.

A parallel can be drawn here with the spherical mirror at the center of Jan van Eyck’s painting The Arnolfini portrait, painted in 1434, nineteen years before this sermon.

Firstly, this circular mirror is surrounded by the ten stations of Christ’s Passion, juxtaposed by a rosary, an explicit reference to God.

Secondly, it reveals a view of the entire room, an image that completely escapes the linear perspective of the foreground. A view comparable to the allcompassing « Vision of God » developed by Cusanus.

Finally, we see two figures in the mirror, but not the image of the painter behind his easel. These are undoubtedly the two witnesses to the wedding. Instead of signing his painting with « Van Eyck invent. », the painter signed his painting above the mirror with « Van Eyck was here » (NOTE 17), identifying himself as a witness.

As Dionysius the Aeropagite asserted:

« [the celestial hierarchy] transforms its adepts into so many images of God: pure and splendid mirrors where the eternal and ineffable light can shine, and which, according to the desired order, reflect liberally on inferior things this borrowed brightness with which they shine. » [Chap. III, 2]

The Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381) evokes a very similar image in his Spiegel der eeuwigher salicheit (Mirror of eternal salvation) when he says:

« Ende Hi heeft ieghewelcs mensche ziele gescapen alse eenen levenden spieghel, daer Hi dat Beelde sijnre natueren in gedruct heeft. » (And he created each human soul as a living mirror, in which he imprinted the image of his nature).

And so, like a polished mirror, Van Eyck’s soul, illuminated and living in God’s truth, acts as an illuminating witness to this union. (NOTE 18)

So, although the Flemish painters of the XVth century clearly had a solid scientific foundation, they choose such or such perspective depending on the idea they wanted to convey.

In essence, their paintings remain objects of theo-philosophical speculation or as you like « intellectual prayer », capable of praising the goodness, beauty and magnificence of a Creator who created them in His own image. By the very nature of their approach, their interest lay above all in the geometry of a kind of « paradoxical space-light » capable, through enigma, of opening us up to a participatory transcendence, rather than simply seeking to « represent » a dead space existing outside metaphysical reality.

The only geometry worthy of interest was that which showed itself capable of articulating this non-linearity, a « divine » or « mystical » perspective capable of linking the infinite beauty of our commensurable microcosm with the immeasurable goodness of the macrocosm.

Thank you,

NOTES:

- Recently, Italian scholars have pointed to the role of Biagio Pelacani Da Parma (d. 1416), a professor at the University of Padua near Venice, in imposing such a perspective, which privileged only the « geometrical laws of the act of vision and the rules of mathematical calculation ».

- Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, p.41-42, Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris, 1975.

- Institut de France, Manuscrit E, 16 v° « the eye [h] perceives on the plane wall the images of distant objects greater than that of the nearer object. »

- Leonardo understands that Albertian perspective, like anamorphosis, condemns the viewer to a single, immobile point of vision.

- See, for example, the slight enlargement of the apostles at the ends of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in the Milan refectory.

- Baxandall, Bartholomaeus Facius on painting, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 27, (1964). Fazio is also enthusiastic about a world map (now lost) by Jan van Eyck, in which all the places and regions of the earth are depicted recognizably and at measurable distances.

- To escape this fate, Pieter Bruegel the Elder used a cavalier perspective, placing his horizon line high up.

- Lionel Simonot, Etude expérimentale et modélisation de la diffusion de la lumière dans une couche de peinture colorée et translucide. Application à l’effet visuel des glacis et des vernis, p.9 (PhD thesis, Nov. 2002).

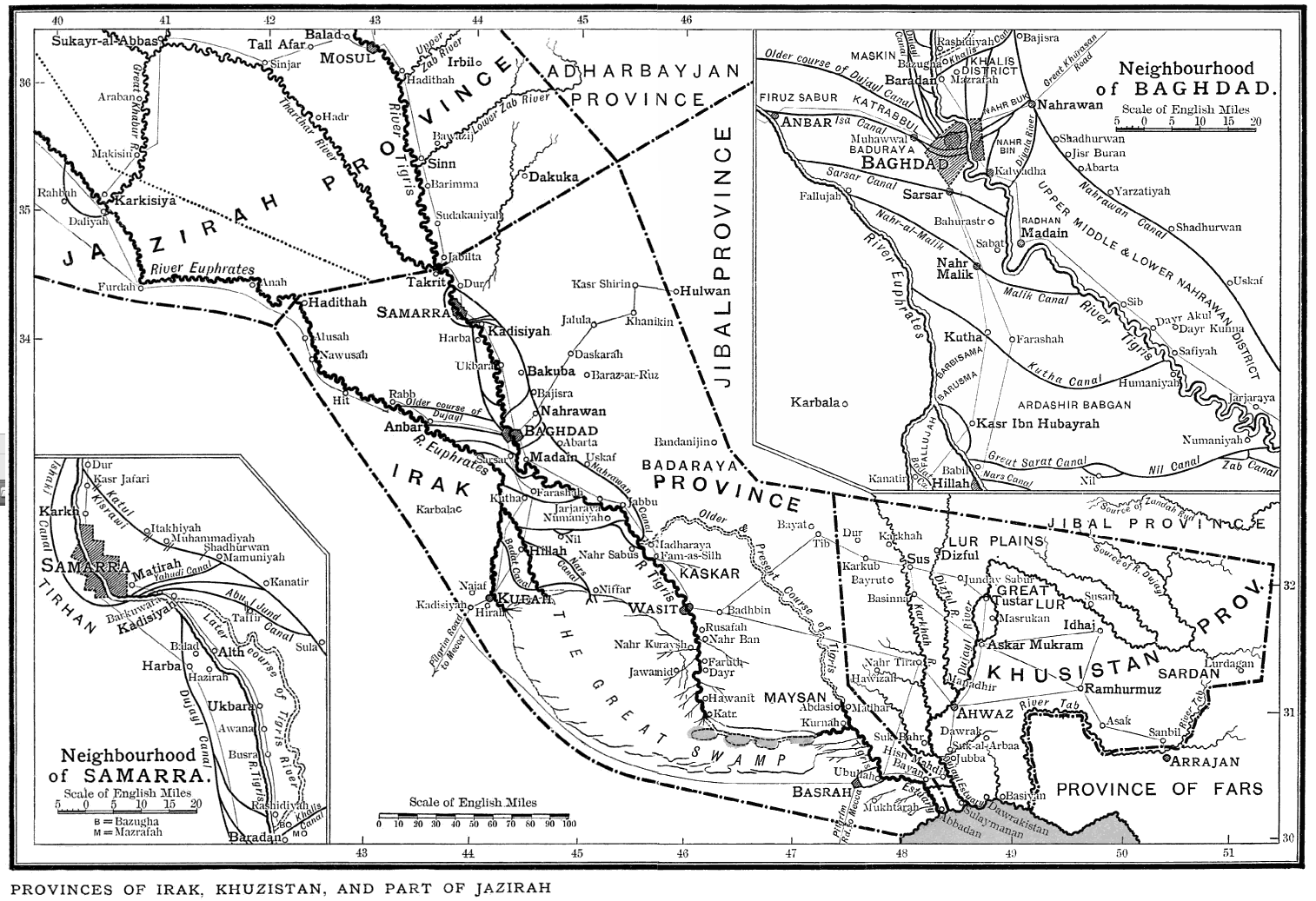

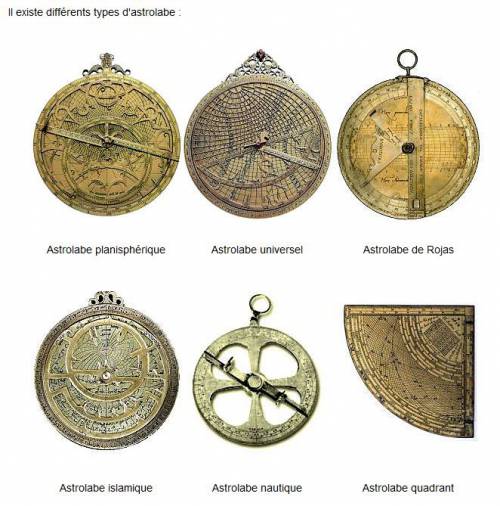

- Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) wrote some 200 works on mathematics, astronomy, physics, medicine and philosophy. Born in Basra, after working on the development of the Nile in Egypt, he travelled to Spain. He is said to have carried out a series of highly detailed experiments on theoretical and experimental optics, including the camera obscura (darkroom), work that was later to feature in Leonardo da Vinci’s studies. Da Vinci may well have read the lengthy passages by Alhazen that appear in the Commentari of the Florentine sculptor Ghiberti. According to Gerbert d’Aurillac (the future Pope Sylvester II in 999), Bishop of Rheims, brought back from Spain the decimal system with its zero and an astrolabe, it was thanks to Gerard of Cremona (1114-c. 1187) that Europe gained access to Greek, Jewish and Arabic science. This scholar went to Toledo in 1175 to learn Arabic, and translated some 80 scientific works from Arabic into Latin, including Ptolemy’s Almagest, Apollonius’ Conics, several treatises by Aristotle, Avicenna‘s Canon, and the works of Ibn Al-Haytam, Al-Kindi, Thabit ibn Qurra and Al-Razi.

- In the Arab world, this research was taken up a century later by the Persian physicist Al-Farisi (1267-1319). He wrote an important commentary on Alhazen’s Treatise on Optics. Using a drop of water as a model, and based on Alhazen’s theory of double refraction in a sphere, he gave the first correct explanation of the rainbow. He even suggested the wave-like property of light, whereas Alhazen had studied light using solid balls in his reflection and refraction experiments. The question was now: does light propagate by undulation or by particle transport?

- Meiss, M., Light as form and symbol in some fifteenth century paintings, Art Bulletin, XVIII, 1936, p. 434.

- Note also the fact that the canon shows a pair of glasses…

- Brion-Guerry in Jean Pèlerin Viator, sa place dans l’histoire de la perspective, Belles Lettres, 1962, p. 94-96, states in obscure language that « the object of representation behaves most often in Van Eyck as a cubic volume seen from the front and from the inside. Perspectival foreshortening is achieved by constructing a rectangle whose sides form the base of four trapezoids. The orthogonals thus tend towards four distinct points of convergence, forming a ‘vanishing region' ».

- Dominique Raynaud, L’Hypothèse d’Oxford, essai sur les origines de la perpective, PUF, Paris 1998.

- Witelo was a friend of the Flemish Dominican scholar Willem van Moerbeke, a translator of Archimedes in contact with Saint Thomas Aquinas. Moerbeke was also in contact with the mathematician Jean Campanus and the Flemish neo-Platonic astronomer Hendrik Bate van Mechelen. Johannes Kepler‘s own work on human vision builds on that of Witelo.

- Cusanus was above all a man of science and theology. But he was also a political organizer. The painter Jan van Eyck fought for the same goals, as evidenced by the ecumenical theme of the Ghent polyptych. It shows the Mystic Lamb, symbolizing the sacrifice of the Son of God for the redemption of mankind, capable of reuniting a church torn apart by internal differences. Hence the presence of the three popes in the central panel, here united before the lamb. Van Eyck also painted a portrait of Cardinal Niccolo Albergati, one of the instigators of the great Ecumenical Council organized by Cusanus in Ferrara and then moved to Florence. If Cusanus called Van der Weyden « his friend Roger », it is also thought that Robert Campin may have met him, since he would have attended the Council of Basel, as did one of his commissioners, the Franciscan theologian Heinrich Werl.

- Jan Van Eyck was one of the first painters in the history of art to date and sign his paintings with his own name.

- Myriam Greilsammer’s book L’Envers du tableau, Mariage et Maternité en Flandre Médiévale (Editions Armand Colin, 1990) documents Arnolfini’s sexual escapades. Arnolfini was taken to court by one of his victims, a female servant. Van Eyck seems to have understood that the knightly Arnoult Fin, Lucchese financier and commercial representative of the House of Medici in Bruges, required the somewhat peculiar presence of the eye of the lord.

Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life: the cradle of humanism in the North

Presentation of Karel Vereycken, founder of Agora Erasmus, at a meeting with friends in the Netherlands on September 10, 2011.

The current financial system is bankrupt and will collapse in the coming days, weeks, months or years if nothing is done to end the paradigm of financial globalization, monetarism and free trade.

To exit this crisis implies organizing a break-up of the banks according to principles of the Glass-Steagall Act, an indispensable lever to recreate a true credit system in opposition to the current monetarist system. The objective is to guarantee real investments generating physical and human wealth, thanks to large infrastructure projects and highly qualified and well-paid jobs.

Can this be done? Yes, we can! However, the true challenge is neither economic, nor political, but cultural and educational: how to lay the foundations of a new Renaissance, how to effect a civilizational shift away from green and Malthusian pessimism towards a culture that sets itself the sacred mission of fully developing the creative powers of each individual, whether here, in Africa, or elsewhere.

Is there a historical precedent? Yes, and especially here, from where I am speaking to you this morning (Naarden, Netherlands) with a certain emotion. It probably overwhelms me because I have a rather well informed and precise sense of the role that several key individuals from the region where we are gathered this morning have played and how, in the fourteenth century, they made Deventer, Zwolle and Windesheim an intellectual hotbed and the cradle of the Renaissance of the North which inspired so many worldwide.

Let me summarize for you the history of this movement of lay clerics and teachers: the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, a movement that nurished our beloved Erasmus of Rotterdam, the humanist giant from whom we borrowed the name to create our political movement in Belgium.

As very often, it all begins with an individual decision of someone to overcome his shortcomings and give up those « little compromises » that end up making most of us slaves. In doing so, this individual quickly appears as a « natural » leader. Do you want to become a leader? Start by cleaning up your own mess before giving lessons to others!

Geert Groote, the founder

The spiritual father of the Brothers is Geert Groote, born in 1340 and son of a wealthy textile merchant in Deventer, which at that time, like Zwolle, Kampen and Roermond, were prosperous cities of the Hanseatic League.

In 1345, as a result of the international financial crash, the Black Death spread throughout Europe and arrived in the Netherlands around 1449-50. Between a third and a half of the population died and, according to some sources, Groote lost both parents. He abhorred the hypocrisy of the hordes of flagellants who invaded the streets and later advocated a less conspicuous, more interior spirituality.

Groote had talent for intellectual matters and was soon sent to study in Paris. In 1358, at the age of eighteen, he obtained the title of Master of Arts, even though the statutes of the University stipulated that the minimum age required was twenty-one.

He stayed eight years in Paris where he taught, while making a few excursions to Cologne and Prague. During this time, he assimilated all that could be known about philosophy, theology, medicine, canon law and astronomy. He also learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and was considered one of the greatest scholars of the time.

Around 1362 he became canon of Aachen Cathedral and in 1371 of that of Utrecht. At the age of 27, he was sent as a diplomat to Cologne and to the Court of Avignon to settle the dispute between the city of Deventer and the bishop of Utrecht with Pope Urban V. In principle, he could have met the Italian humanist Petrarch who was there at that time.

Full of knowledge and success, Groote got a big head. His best friends, conscious of his talents, kindly suggested him to detach himself from his obsession with « Earthly Paradise ». The first one was his friend Guillaume de Salvarvilla, the choirmaster of Notre-Dame of Paris. The second was Henri Eger of Kalkar (1328-1408) with whom Groote shared the benches of the Sorbonne.

In 1374, Groote got seriously ill. However, the priest of Deventer refused to administer the last sacraments to him as long as he refused to burn some of the books in his possession. Fearing for his life (after death), he decided to burn his collection of books on black magic. Finally, he felt better and healed. He also gave up living in comfort and lucre through fictitious jobs that allowed him to get rich without working too hard.

After this radical conversion, Groote decides to selfperfect. In his Conclusions and Resolutions he wrote:

« It is to the glory, honor and service of God that I propose to order my life and the salvation of my soul. (…) In the first place, not to desire any other benefit and not to put my hope and expectation from now on in any temporal profit. The more goods I have, the more I will probably want more. For according to the primitive Church, you cannot have several benefits. Of all the sciences of the Gentiles, the moral sciences are the least detestable: many of them are often useful and profitable both for oneself and for teaching others. The wisest, like Socrates and Plato, brought all philosophy back to ethics. And if they spoke of high things, they transmitted them (according to St. Augustine and my own experience) by moralizing them lightly and figuratively, so that morality always shines through in knowledge… ».

Groote then undertakes a spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen near Arnhem where he devotes himself to prayer and study.

However, after a three-year stay in isolation, the prior, his Parisian friend Eger of Kalkar, told him to go out and teach :

« Instead of remaining cloistered here, you will be able to do greater good by going out into the world to preach, an activity for which God has given you a great talent. »

Ruusbroec, the inspirer

Groote accepted the challenge. However, before taking action, he decided to make a last trip to Paris in 1378 to obtain the books he needed.

According to Pomerius, prior of Groenendael between 1431 and 1432, he undertook this trip with his friend from Zwolle, the teacher Joan Cele (around 1350-1417), the historical founder of the excellent Dutch public education system, the Latin School.

On their way to Paris, they visit Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), a Flemish “mystic” who lived in the Groenendael Priory on the edge of the Soignes Forest near Brussels.

Groote, still living in fear of God and the authorities, initially tries to make « more acceptable » some of the old sage’s writings while recognizing Ruusbroec as closer to the Lord than he is. In a letter to the community of Groenendael, he requested the prayer of the prior:

« I would like to recommend myself to the prayer of your provost and prior. For the time of eternity, I would like to be ‘the prior’s stepladder’, as long as my soul is united to him in love and respect.” (Note 1)

Back in Deventer, Groote concentrated on study and preaching. First he presented himself to the bishop to be ordained a deacon. In this function, he obtained the right to preach in the entire bishopric of Utrecht (basically the whole part of today’s Netherlands north of the great rivers, except for the area around Groningen).

First he preached in Deventer, then in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen and later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda and Delft. His success is so great that jealousy is felt in the church. Moreover, with the chaos caused by the great schism (1378 to 1417) installing two popes at the head of the church, the believers are looking for a new generation of leaders.

As early as 1374, Groote offered part of his parents’ house to accommodate a group of pious women. Endowed with a by-law, the first house of sisters was born in Deventer. He named them « Sisters of the Common Life », a concept developed in several works of Ruusbroec, notably in the final paragraph Of the Shining Stone (Van den blinckende Steen)

« The man who is sent from this height to the world below, is full of truth, and rich in all virtues. And he does not seek his own, but the honor of the one who sent him. And that is why he is upright and truthful in all things. And he has a rich and benevolent foundation grounded in the riches of God. And so he must always convey the spirit of God to those who need it; for the living fountain of the Holy Spirit is not a wealth that can be wasted. And he is a willing instrument of God with whom the Lord works as He wills, and how He wills. And it is not for sale, but leaves the honor to God. And for this reason he remains ready to do whatever God commands; and to do and tolerate with strength whatever God entrusts to him. And so he has a common life; for to him seeing [via contemplativa] and working [via activa] are equal, for in both things he is perfect.”

Radewijns, the organizer

Following one of his first sermons, Groote recruited Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Born in Utrecht, the latter received his training in Prague where, also at the early age of 18, he was awarded the title of Magister Artium.

Groote then sent him to the German city of Worms to be consecrated priest there. In 1380 Groote moved with about ten pupils to the house of Radewijns in Deventer; it would later be known as the « Sir Florens House” (Heer Florenshuis), the first house of the Brothers and above all its base of operation?

When Groote died of the plague in 1384, Radewijns decided to expand the movement which became the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Soon it will be branded the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion).

Books and beguinages

A number of parallels can be drawn with the phenomenon of the Beguines which flourished from the 13th century onward. (Note 2)

The first beguines were independent women, living alone (without a man or a rule), animated by a deep spirituality and daring to venture into the enormous adventure of a personal relationship with God. (Note 3)

Operating outside the official religious hierarchy, they didn’t beg but worked various jobs to earn their daily bread. The same goes for the Brothers of the Common Life, except that for them, books were at the center of all activities. Thus, apart from teaching, the copying and production of books represented a major source of income while allowing spreading the word to the many.

Lay Brothers and Sisters focused on education and their priests on preaching. Thanks to the scriptorium and printing houses, their literature and music will spread everywhere.

Windesheim

To protect the movement from unfair attacks and criticism, Radewijns founded a congregation of canons regular obeying the Augustinian rule.

In Windesheim, between Zwolle and Deventer, on land belonging to Berthold ten Hove, one of the members, a first cloister is erected. A second one, for women this time, is built in Diepenveen near Arnhem. The construction of Windesheim took several years and a group of brothers lived temporarily on the building site, in huts.

In 1399 Johannes van Kempen, who had stayed at Groote’s house in Deventer, became the first prior of the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and gave the movement new momentum. From Zwolle, Deventer and Windesheim, the new recruits spread all over the Netherlands and Northern Europe to found new branches of the movement.

In 1412, the congregation had 16 cloisters and their number reached 97 in 1500: 84 priories for men and 13 for women. To this must be added a large number of cloisters for canonesses which, although not formally associated with the Windesheim Congregation, were run by rectors trained by them.

Windesheim was not recognized by the Bishop of Utrecht until 1423 and in Belgium, Groenendael, associated with the Red Cloister and Korsendonc, wanted to be part of it as early as 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cusanus and Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was the brother of the famous Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). The latter, trained in Windesheim, animated the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and was one of the towering figures of the movement for seventy years. In addition to a biography he wrote of Groote and his account of the movement, his Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) became the most widely read work in history after the Bible.

Both Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) and Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), two of Erasmus’ tutors during his training in Deventer, were direct pupils of Thomas a Kempis. The Latin School of Deventer, of which Hegius was rector, was the first school in Northern Europe to teach the ancient Greek language to children.

While no formal prove exists, it is tempting to believe that Cusanus (1401-1464), who protected Agricola and, in his last will, via his Bursa Cusanus, offered a scholarship for the training of orphans and poor students of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, was also trained by this humanist network.

What is known is that when Cusanus came in 1451 to the Netherlands to put the affairs of the Church in order, he traveled with his friend Denis the Carthusian (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), a disciple of Ruusbroec, whom he commissioned to carry on this task.

A native of Limburg, trained at the famous Cele school in Zwolle, Dionysius the Carthusian also became the confessor of the Duke of Burgundy and is thought to be the “theological advisor” of the Duke’s ambassador and court painter, Jan Van Eyck. (Note 4)

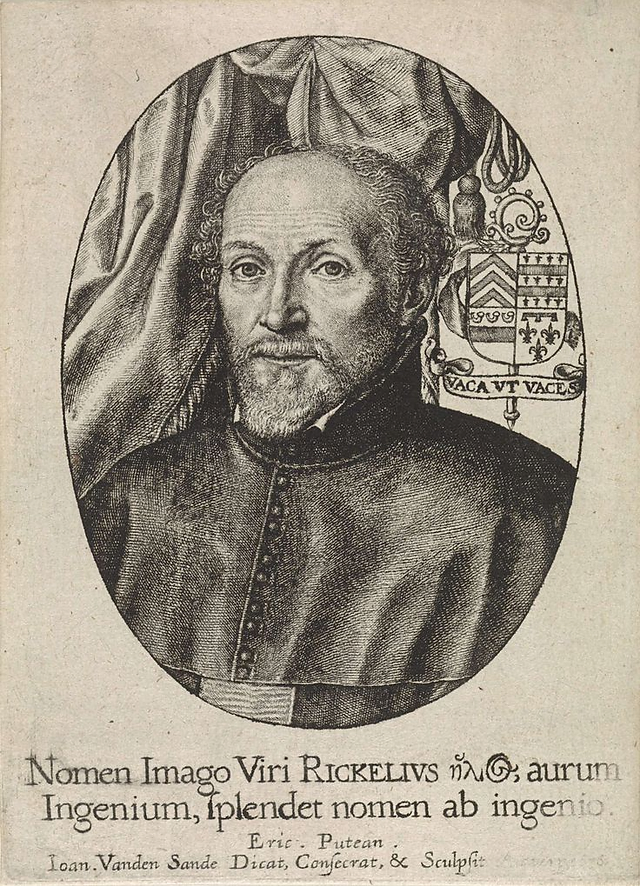

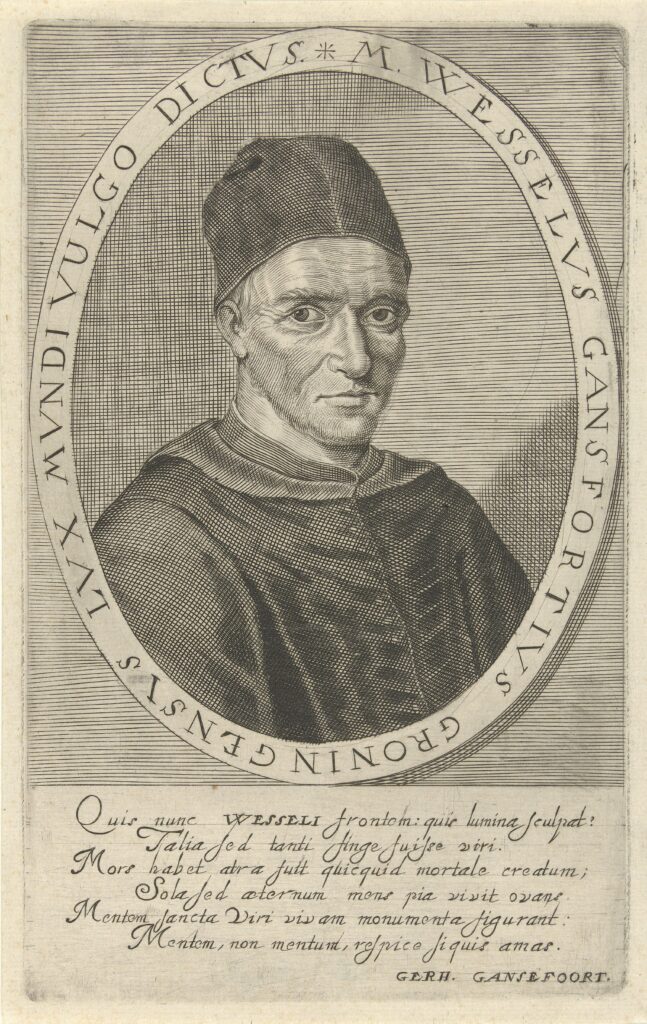

Gansfort

Wessel Gansfort (1419-1489), another exceptional figure of this movement was at the service of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion, the main collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) at the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1437. Gansfort, after attending the Brothers’ school in Groningen, was also trained by Joan Cele‘s Latin school in Zwolle.

The same goes for the first and only Dutch pope, Adrianus VI, who was trained in the same school before completing his training with Hegius in Deventer. This pope was very open to Erasmus’ reformist ideas… before arriving in Rome.

Hegius, in a letter to Gansfort, which he calls Lux Mundi (Light of the World), wrote:

« I send you, most honorable lord, the homilies of John Chrysostom. I hope that you will enjoy reading them, since the golden words have always been more pleasing to you than the pieces of this metal. As you know, I went to the library of Cusanus. There I found some books that I didn’t know existed (…) Farewell, and if I can do you a favor, let me know and consider it done.”

Rembrandt

A quick look on Rembrandt’s intellectual training indicates that he too was a late product of this educational epic. In 1609, Rembrandt, barely three years old, entered elementary school where, like other boys and girls of his generation, he learned to read, write and… draw.

The school opened at 6 in the morning, at 7 in the winter, and closes at 7 in the evening. Classes begin with prayer, reading and discussion of a passage from the Bible followed by the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt acquired an elegant writing style and much more than a rudimentary knowledge of the Gospels.

The Netherlands wanted to survive. Its leaders take advantage of the twelve-year truce (1608-1618) to fulfill their commitment to the public interest.

In doing so, the Netherlands at the beginning of the XVIIth century became the first country in the world where everyone had the chance to learn to read, write, calculate, sing and draw.

This universal educational system, no matter what its shortcomings, available to both rich and poor, boys and girls alike, stands as the secret behind the Dutch « Golden Century ». This high level of education also created those generations of active Dutch emigrants a century later in the American Revolution.

While others started secondary school at the age of twelve, Rembrandt entered the Leyden Latin School at the age of 7. There, the students, apart from rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn not only Greek and Latin, but also foreign languages such as English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, with no laws restricting young talents, Rembrandt enrolled in University. The subject he chose was not Theology, Law, Science or Medicine, but… Literature.

Did he want to add to his knowledge of Latin the mastery of Greek or Hebrew philology, or possibly Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Arabic/Latin dictionaries were already being published in Leiden at a time the city was becoming a major printing center in the world.

Thus, one realizes that the Netherlands and Belgium, first with Ruusbroec and Groote and later with Erasmus and Rembrandt, made an essential contribution in the not so distant past to the kind of humanism that can raise today humanity to its true dignity.

Hence, failing to extend our influence here, clearly seems to me something in the realm of the impossible.

Footnotes:

- Geert Groote, who discovered Ruusbroec’s work during his spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen, near Arnhem, has translated at least three of his works into Latin. He sent The Book of the Spiritual Tabernacle to the Cistercian Cloister of Altencamp and his friends in Amsterdam. The Spiritual Marriage of Ruusbroec being under attack, Groote personally defends it. Thus, thanks to his authority, Ruusbroec’s works are copied in number and carefully preserved. Ruusbroec’s teaching became popularized by the writings of the Modern Devotion and especially by the Imitation of Christ.

- At the beginning of the 13th century the Beguines were accused of heresy and persecuted, except… in the Burgundian Netherlands. In Flanders, they are cleared and obtain official status. In reality, they benefit from the protection of two important women: Jeanne and Margaret of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders. They organized the foundation of the Beguinages of Louvain (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerp (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ypres (1240), Lille (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Bruges (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Diest (1253), Mechelen (1258) and in 1271 it was Jan I, Count of Flanders, in person, who deposited the statutes of the great Beguinage of Brussels. In 1321, the Pope estimated the number of Beguines at 200,000.

- The platonic poetry of the Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (XIIIth Century) has a decisive influence on Jan van Ruusbroec.

- It is significant that the first book printed in Flanders in 1473, by Erasmus’ friend and printer Dirk Martens, is precisely a work of Denis the Carthusian.

Moderne Devotie en Broeders van het Gemene Leven, bakermat van het humanisme

Ce même texte en français

Op 10 september 2011, gaf Karel Vereycken van het Schiller Institute, de volgende presentatie voor een kleine groep vrienden van de LaRouche Studiegroep Nederland.

Het huidige globale financiële systeem is failliet en zal in elkaar zakken over de komende dagen, weken en maanden, als er niets gedaan wordt om het rotte economische paradigma van vrijhandel, globalisatie en monetarisme te verdelgen.

De weg uit de crisis betekent onmiddellijk brugpensioen voor Obama et de splitsing van banken (Glass-Steagall Act) als hefboom om terug een echt krediet systeem op te bouwen, in tegenstelling tot een geldsysteem. Het gaat erom echte investeringen te bemiddelen in de schepping van fysieke en menselijke rijkdom via grootschalige infrastructuur projecten en de creatie van hooggekwalificeerde en welbetaalde banen.

Kan dat gedaan worden? Ja, dat kan, maar de grootste uitdaging is niet de politieke uitdaging. De echte uitdaging die ons toekomt, is het leggen van de grondvesten van een nieuwe renaissance, een fundamentele wending, weg van het groene en malthusiaanse pessimisme, naar een cultuur die er naar streeft de creatieve vermogens van elke persoon, hier, in Afrika en elders, volledig te doen opbloeien.

Was dat ooit gedaan in verleden? Ja, en vooral vanwaar ik hier spreek, beroerd door een grote emotie. Misschien omdat ik het privilege heb een zeker inzicht te bezitten over de rol van enkele leidende figuren die in de XIVde eeuw Zwolle tot “neuronenversneller” van de Europese cultuur hebben gemaakt.

Vergun me het plezier om hier in het kort de geschiedenis te schetsen van een beweging van lekenbroeders en onderwijzers, de Broeders en Zusters van het Gemene Leven, die in feite de peetvaders zijn van onze geliefde Erasmus van Rotterdam.

Zoals heel dikwijls, begint alles met een persoon die beslist een einde te maken aan zijn eigen tekortkomingen, en daarom oprijst als een natuurlijke leider. Je wilt een leidinggevende persoon worden? Begin met je eigen boel op te kuisen vooraleer je gaat preken bij anderen!

Geert Groote, de stichter

De geestelijke vader van de Broeders is Geert Groote, geboren in 1340 als zoon van een rijke textielhandelaar van Deventer, in die tijd, zoals Zwolle, Kampen en Roermond, een rijke handelsstad van de Hanze liga.

In 1345, na de internationale financiële krach, woekert de pest over heel Europa en bereikt onze gewesten in 1449-50. Meer dan 50 % van de bevolking verliest het leven en Groote, volgens sommige bronnen, verliest beide ouders.

Groote walgde voor de schijnheiligheid van de hordes van flagellanten die door de straten trekken. In plaats van openlijke zelfkastijding meent hij dat innerlijke boetedoening belangrijker is.

Groote heeft aanleg voor studeren en wordt snel naar Parijs gestuurd. Als hij 18 is, geeft men hem de titel van Magister Artium normaal alleen maar toereikbaar aan studenten ouder dan 20. Hij blijft acht jaar in Parijs maar maakt waarschijnlijk enkele uitstapjes naar Keulen en Praag.

Gedurende die periode assimileert hij alles wat men weten moest en kon op het gebied van Wijsbegeerte, Theologie, Geneeskunst, Kerkelijk Recht en Astronomie. Volgens sommigen leert hij Grieks, Latijns en Hebreeuws en beschouwd als een van de meest erudiete personen van zijn tijd.

Vervolgens krijgt hij een prebende van de kapittels van Aken (1368) en Utrecht (1371-1374). Op zevenentwintigjarige leeftijd wordt hij als diplomaat naar Keulen en naar het hof in Avignon in Frankrijk gestuurd om met paus Urbanus V een verschil te regelen tussen Deventer en de bisschop van Utrecht.

Groote’s hoofd, vol met kennis en successen, wordt groter en groter. Zijn beste vrienden, bewust van zijn talenten, zeggen hem vriendelijk op te passen en zich los te werken van de obsessie van het aardse paradijs. De eerste is Guillaume de Salvarvilla, de koormeester van Notre Dame in Parijs. De andere is Heinrich Eger von Kalkar (1328-1408) met wie hij studeerde in Parijs en die nu de nieuwe prior was van het Kartuizerklooster van Monnikshuizen bij Arnhem.

In 1372 is Groote doodziek, maar de priester van Deventer weigert hem, zolang hij niet afstand doet van zijn boeken over zwarte kunst, de laatste sacramenten toe te dienen. Vrezend voor zijn leven, verbrandt Groote koortsig al deze boeken op de markplaats van Deventer. Nu voelt hij zich stukken beter en begint te genezen. Hij beslist ook afscheid te nemen van het luxe leventje met erebanen waar hij weinig voor hoefde te doen en die hem veel geld opleverde.

Na deze bekering neemt Groote keiharde resoluties. In zijn Besluiten en voornemens schrijft hij:

Mijn leven wil ik ordenen op de eer en verheerlijking en de dienst van God en op het heil van mijn ziel. Geen enkel tijdelijk goed: noch zingenot, noch eer, noch tijdelijke goederen, noch wetenschap zal ik stellen boven het heil van mijn ziel… Mijn eerste voornemen is niet langer mijn hoop te vestigen in, of in de toekomst naar het verlangen van aardse winst; want hoe meer ik zal bezitten des te hebzuchtiger ik zal worden; en in tweede instantie, volgens de regels van de primitieve kerk, kan men niet tegelijkertijd winst halen uit meerdere voordelen [zowel uit het wereldlijke als het geestelijke]… Onder de wetenschappen van de heidenen, dient hun morele filosofie het minst vermeden te worden – want ze is dikwijls van groot nut en voordelig voor eigen studie en om anderen te beleren. Dat is zo omdat de wijste onder hen, zoals Socrates en Plato, alle filosofie doortrokken tot morele beschouwingen, en wanneer zij diepe onderwerpen aanspraken deden zij dat op figuurlijke en lichte wijze, met een klemtoon op hun moreel aspect…

Hij trekt zich terug bij de Kartuizers in Monnikshuizen. Maar na drie jaar zegt zijn voormalige schoolkameraad en vriend, de prior Eger van Kalkar aan Groote: “U kunt veel meer goeds doen door in de wereld te gaan preken, waarvoor God U groot talent heeft gegeven, dan hier te blijven in het klooster”.

Vooraleer aan de slag te gaan, doet Groote in 1378 een laatste reis naar Parijs om daar de boeken te kopen die hij nodig heeft. Volgens Pomerius maakte Groote die reis met zijn vriend van Zwolle, de toen al vermaarde schoolmeester Joan Cele (circa 1350-1417).

Jan van Ruusbroec, bron van inspiratie

Onderweg bezoeken ze Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), de Vlaamse mystieker en prior van Groenendaal, een kluis aan de rand van het Zoniënwoud bij Brussel. Groote trachtte eerst diens originele geschriften “te verbeteren” maar schreef later in een brief: “Voor tijd en eeuwigheid zou ik ‘des priors voetschabel’ willen zijn, zo sterk is mijn ziel in liefde en eerbied met hem verenigd”. (Nota 1)

Terug in Deventer, spits Groote zich toe op studeren en preken. Eerst meld hij zich in 1379 bij zijn bisschop om tot diaken te worden gewijd. Als diaken krijgt hij het recht te prediken in heel het bisdom Utrecht (ruwweg het huidige Nederland boven de grote rivieren, met uitzondering van de Groningse Ommelanden).

Grote gaat al predikend rond door de Nederlanden en verzamelt vele volgelingen om zich heen. Zijn roem spreidt zich snel over de Lage landen en van overal komt men naar hem luisteren. Hij preekt eerst in Deventer, dan in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen en later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda, Delft en verder. Zijn succes was zo groot dat er binnen de kerk wel wat jaloersheid ontstond. Anderzijds is het ook begrijpelijk dat de wanorde binnen de westerse kerk, namelijk grote schisma tussen 1378 en 1417, Groote’s inspanningen bewerkstelligden.

Al vanaf 1374, schenkt hij het huis van zijn ouders aan een groep arme vrouwen die er samen willen gaan wonen en voorziet hen van een reglement: het eerste zusterhuis van de ???? is in Deventer geboren. Hij noemt hen de Zusters van het Gemene Leven, een concept ontwikkeld door Ruusbroec in verschillende van zijn werken zoals in de slotparagraaf van Vanden Blinckenden Steen:

Die mensche die ute deser hoocheit van Gode neder-ghesent wert inde werelt, hi es volder waerheit, ende rijcke van allen doechden. Ende hi en soeket sijns niet, maer Des-gheens eere diene ghesonden heeft. Ende daer-omme es hi gherecht ende warechtich in alle dinghen. Ende hi heeft eenen rijcken melden [milden] gront, die ghefondeert es inde rijcheit Gods. Ende daeromme moet hi altoes vloeyen in alle die-ghene die sijns behoeven; want die levende fonteyne des Heilich Gheests die es sine rijcheit diemen niet versceppen en mach. Ende hi es een levende willich instrument Gods daar Gode mede werct wt Hi wilt ende hoe Hi wilt; ende des en dreecht hi hem nit ane, maar hi gheeft Gode die eere. Ende daarom blijft hi willich ende ghereet alles te doene dat God ghebiedt; ende sterc ende ghenendich alt te dogene ende te verdraghene dat God op hem gestaedt. Ende hier-omme heeft hi een ghemeyn leven; want hem es scouwen [contemplatie] ende werken even ghereet, ende in beiden is hi volcomen.

Florens Radewijns, de doener

Gedurende een van zijn eerste preken, rekruteert Groote Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Geboren in Utrecht, studeerde deze in Praag waar ook hij Magister Artium werd op achttienjarige leeftijd. Groote stuurt hem eerst naar Worms om daar tot priester gewijd te worden.

In 1380 neemt Groote zelf met een groepje van tien leerlingen zijn intrek in het huis van Radewijns in Deventer. Dit huis zou later als ‘Heer Florenshuis’ of ‘Rijke Fratershuis’ bekend komen te staan: het eerste broederhuis. Het werd de uitvalsbasis van veel van Geert Groote’s activiteiten.

Wanneer Groote sterft in 1384 van de pest beslist Radewijns, de beweging die Groote uit te bouwen tot de Broeders en Zusters van het Gemene leven.

Al snel noemen ze zich de Devotio Moderna (Moderne Devotie).

Boeken en begijnhoven

Een aantal sterke overeenkomsten bestaan er met de Begijnen die in het begin van de XIIIde eeuw ontstonden. (Nota 2)

De eerste begijnen waren onafhankelijke, alleenwonende, geestelijk diepbewogen vrouwen (zonder man noch regel) die in de wereld het geweldige avontuur aandurfden van een persoonlijke verhouding met God. (Nota 3)

Ze verlangden geen geloften, geen klooster en geen speciale band met de hiërarchie. Ze leefden niet van aalmoezen maar werkten zelf voor hun dagelijkse kost.

Nog meer dan voor de Begijnen staan boeken centraal in alle activiteiten van de Broeders en Zusters van het Gemene Leven.

Het overschrijven en maken van boeken is een voorname bron van inkomsten die tegelijkertijd het goede woord aan de grote massa kan brengen.

De Broeder- en Zusterhuizen spitsen zich toe op onderwijs en hun priesters of preken. Dankzij hun scriptorium en drukkerijen zal hun geestelijke literatuur en ook hun muziek zich ver verspreiden.

Congregatie van Windesheim

Om de beweging tegen ongerechte kritiek te beschermen, richt Radewijns een klooster op van reguliere kanunniken die de regel volgen van Augustinus. In Windesheim, tussen Zwolle en Deventer, op een stukje land van Berthold ten Hove, een van hun leden, wordt een klooster opgebouwd. Een tweede klooster, ditmaal voor vrouwen, komt er in Diepenveen bij Arnhem. De bouw van Windesheim nam meerdere jaren tijd in beslag en verschillende broeders leefden daar tijdelijk in hutten op de werf.

Toen in 1399 Johannes van Kempen, die ook bij Groote had gewoond in Deventer, de eerste prior werd van het klooster Agnietenberg bij Zwolle, kreeg de beweging een nieuw elan. Van Zwolle, Deventer en Windesheim, zwermde de nieuwe leden uit over de lage landen en de rest van noord-Europa om overal nieuwe godshuizen te vestigen.

In 1412 kende de congregatie 16 kloosters en hun aantal rees tot 97 in 1500: 84 mannen- en 13 vrouwenpriorijen. Bovendien bestonden er talrijke kloosters van kanunnikessen, die niet formeel tot het kapittel van Windesheim behoorden, maar die een Windesheimer als rector hadden. Groenendaal en vele andere kloosters maakten vanaf 1394 deel uit van de Congregatie van Windesheim, slechts erkend door de bisschop van Utrecht in 1423.

A Kempis, Cusanus en Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was natuurlijk de broer van de wereldberoemde Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471) die, na lange jaren leiding van de Broeders van het Gemene Leven, op 92 jarige leeftijd stierf in het klooster Agnietenberg van Zwolle. Behalve een relaas over het leven van Groote en de opkomst van de beweging schreef hij de Imitatione Christi (In navolging Christus), na de Bijbel, het meest gelezen boek ter wereld.

Zowel Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) als Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), twee markante professors van Erasmus van Rotterdam en onvergelijkbare meesters van het Latijn, het Grieks en het Hebreeuws, werden in Deventer door de Broeders opgeleid en in Zwolle door Thomas a Kempis.

Ook Nicolaus Cusanus (1401-1464), die Agricola beschermde en na zijn dood, via een Bursa Cusana geld gaf om wezen en arme studenten op te leiden, werd mogelijkerwijs door de Broeders opgeleid. Wanneer Cusanus in 1451 naar de Nederlanden reist om daar de scheefgegroeide situaties recht te trekken, bezoekt hij de streek met Dionysius de Karthuizer (van Rykel) (1402-1471), een volgeling van Ruusbroec aan wie hij de opdracht geeft deze taak af te ronden. Geboren in Limburg, volgde ook Dionysius de Karthuizer school in Zwolle. (Nota 4)

Wessel Ganzevoort

Een andere uitzonderlijke figuur was Wessel Ganzevoort (1419-1489) die samenwerkte met de Griekse kardinaal Bessarion, zelf een intieme medewerker van Cusanus voor het Oecumenische concilie van Ferrare-Firenze.

Gansfoort werd opgeleid in de door de Broeders geleide Sint Maartensschool van Groningen alvorens verder te studeren aan de Latijnse School van Groote’s vriend Joan Cele in Zwolle. Ook de eerste Nederlandse paus, Adrianus VI, werd opgeleid aan de Zwolse Latijnse school alvorens te studeren onder Hegius in Deventer. Vooraleer hij naar Rome ging, stond deze paus open voor de ideeën van Erasmus.

In een brief verzonden van Deventer schrijft Hegius aan Ganzevoort, wie hij de Lux Mundi (het licht der wereld) noemt:

Ik stuur U, zeer eerwaarde heer, de Homiliën van Johannes Crysostomus. Ik hoop dat hun lectuur U mag behagen. Gezien gouden woorden U altijd meer plezier deden dan gouden geldstukken. Ik ben, zoals u weet, in Cusanus’s bibliotheek geweest. Daar vond ik veel boeken die me helemaal onbekend waren… (…) Vaarwel, en als U wilt dat ik voor U iets doe, geef me een teken en beschouw de zaak als gedaan.

Rembrandt van Ryn

Een blik op de vorming van Rembrandt bewijst dat ook hij een later product was van al deze inspanningen. In 1609 gaat Rembrandt, amper drie jaar oud, naar de basisschool waar jongens en meisjes leren lezen, schrijven en rekenen.

In de zomer beginnen de lessen om zes uur ’s morgens en om zeven in de winter. De lessen worden beëindigd om zeven uur ’s avonds. De lessen beginnen met bidden, het bespreken van passages uit de Bijbel en het zingen van psalmen. Het is daar dat Rembrandt een elegant handschrift ontwikkelt en meer dan een basisbegrip krijgt over godsdienst.

Gedurende die jaren trachten de Nederlanden te overleven. Het twaalfjarige bestand wordt gebruikt om het algemene goed to ontwikkelen en Nederland wordt één van de eerste landen waar iedereen de kans krijgt om te leren lezen, schrijven en rekenen.

Deze universele educatie voor zowel rijk als arm, zij het met enige tekortkomingen, was het geheim van de “Gouden Eeuw” en de belezenheid van Nederlandse immigranten in Amerika zal een eeuw later ook een voorname rol spelen gedurende de Amerikaanse revolutie.

Hoewel de meeste kinderen het secundair onderwijs aanpakten op twaalfjarige leeftijd, begon Rembrandt zijn opleiding op de Latijnse School van Leiden op zevenjarige leeftijd!

Daar leerde men, buiten retorica, logica en kalligrafie, niet alleen Grieks en Latijns maar ook Engels, Frans, Spaans of Portugees. In 1620, wanneer Rembrandt veertien jaar oud is, schrijft hij in als student aan de universiteit gezien toen geen wet jonge talenten kon weerhouden.

Als vak kiest hij niet Theologie, Rechten, Wetenschap of Geneeskunst, maar… Literatuur. Wilde Rembrandt Griekse en Hebreeuwse filologie en misschien Koptisch of Arabisch aan zijn brede cultuur toevoegen?

Men beseft dus, dat de Nederlanden, België inbegrepen, met Ruusbroec en Groote en later met Erasmus en Rembrandt, in een niet zo ver verleden, een bakermat was voor het soort humanisme dat de mensheid tot de grootste mogelijkheden kan verheffen. Hier falen om onze beweging uit te breiden is dus onmogelijk.

VOETNOTEN:

1. Geert Groote vertaalde in het Latijn op zijn minst drie van Ruusbroec’s werken die hij waarschijnlijk in Monnikshuizen voor het eerst had ontdekt. Hij stuurde het boek over het Tabernakel naar de cisterciënzers van Altencamp en naar zijn vrienden in Amsterdam. Toen de Brulocht werd aangevallen, nam hij persoonlijk de verdediging op van Ruusbroec. Dankzij het gezag van Groote werden de werken van Ruusbroec overvloedig gekopieerd en zorgvuldig bewaard. Ruusbroec’s leer werd gevulgariseerd in de geschriften van de Moderne Devotie en vooral in de Navolging van Christus.

2. In het begin van de XIIIde eeuw werden de begijnen beschuldigd van ketterij en vervolgd, behalve in de Bourgondische Nederlanden. In Vlaanderen werden ze vrijgesproken en kregen ze een officieel statuut. In feite genoten zij de bescherming van twee belangrijke vrouwen: Johanna en Margareta van Constantinopel, gravinnen van Vlaanderen. Zij organiseerden de stichting van de begijnhoven van Leuven (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerpen (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ieper (1240), Rijsel (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Brugge (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Bergen (1248), Anderlecht (1252), Breda (1252), Diest (1253), Lier (1258), Tongeren (1257), Mechelen (1258), Haarlem (1262) en in 1271 deponeerde Jan I, graaf van Vlaanderen, persoonlijk de statuten van het Groot Begijnhof van Brussel. In 1321 schatte de Paus het aantal begijnen op 200.000.

3. Het poëtisch Platonisme van de Antwerpse begijn Hadewijch heeft een onmiskenbare invloed gehad op Jan van Ruusbroec.

4. Het eerste boek gedrukt in Vlaanderen door Erasmus’ vriend Dirk Martens, was Dionysius’ werk Een spiegel van de bekering van de zondaars in 1473.

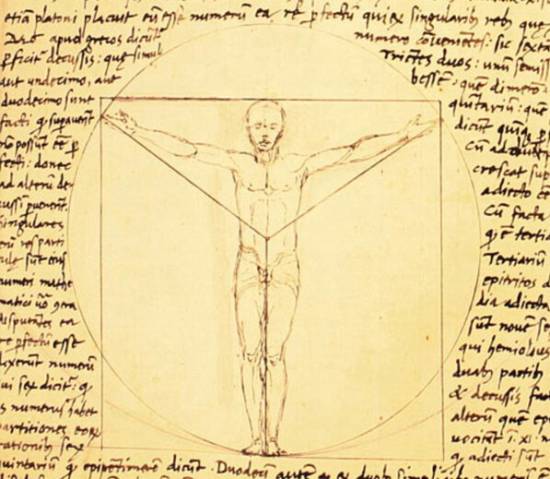

On Leonardo da Vinci’s « Vitruvian Man »

By Karel Vereycken

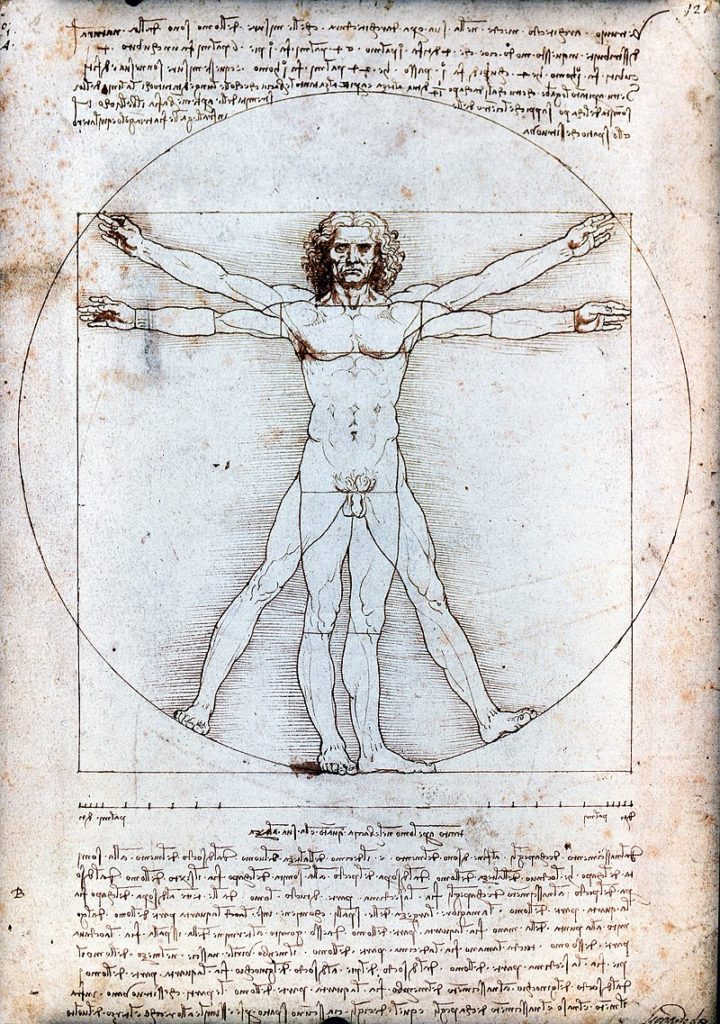

Leonardo da Vinci’s « Viruvian Man ». Since we’re commemorating this year (2019) Leonardo Da Vinci, who died 500 years ago, many silly things are presented by fake scholars trying to make a real living.

Since I was introduced into the canon of proportions of the human body during my training as a professional painter and engraver, I want offer you some hints on how to look at what is called Da Vinci’s « Vitruvian man », a drawing currently on exhibit at the Da Vinci show at the Louvre in Paris.

Hence, as Leonardo underlines himself in his notebooks, adopting Cusanus wordings, it is only with the « eyes of the mind » that art becomes visible, because the « eyes of the flesh » are intrensically blind to it.

Canons of proportions

Europe, and Classical Greece, as everybody should know, emerged largely by absorbing several major discoveries accomplished much earlier by other civilizations. Much of it came from Asia, but African and especially Egypt, were key.

The very practice of mummification, a process which takes at least 60 days of work, made Egypt the key area of anatomical research.

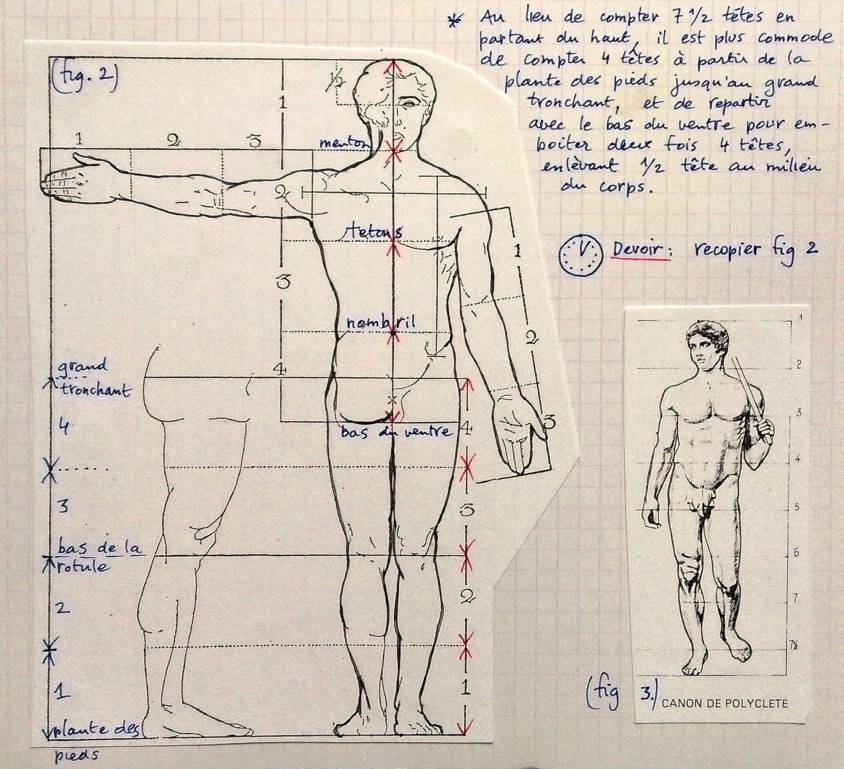

As demonstrated by early Egyptian sculpture, the exact size of the entire adult human body is 7,5 times the size of the head. The size of a newborn is only four heads, that of a seven year old, six heads and that of a 17 years old adolescent, 7 heads.

If one subdivides the overall 7.5 proportion, for an adult, from the top of the head till the lowest part of the torso, one measures four heads, one till the nipples, one till the belly button and a fourth one till the lowest part of the pubis. Going up from the sole till the middle of the pelvis, one measures 3.5 heads: 2 heads till the knee and 1.5 till the middle of the pelvis. That brings the total till 7.5 heads for the entire length of the adult human body and it is proportional in the sense that people with smaller heads also have small bodies.

Polikleitos versus Lysippus

In the Vth Century BC, the Greek sculptor Polikleitos’ spear bearer (The “Doryphoros”) of Naples National Archeological Museum applied this most beautiful canon of proportions, known as the “Polikleitos canon”.

During the Renaissance, the nostalgics of the Roman Empire preferred another Greek canon, that of Greek sculptor Lysippus (4th Century BC), formalized by the Roman author, architect and civil engineer, Vitrivius (1st century BC).

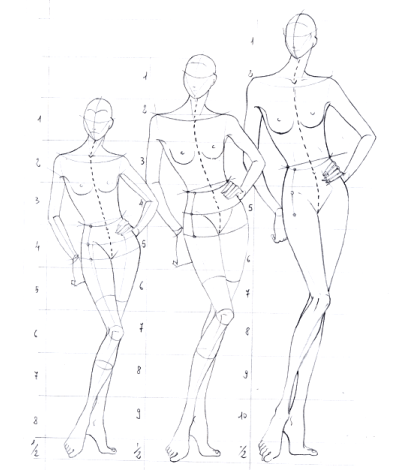

Vitruvius only transcribed the prevalent taste of his epoch. Roman sculptors, in order to give an athletic and heroic look to the Emperors which they were portraying, adopting the canon of Lysippus, could reduce the head of their models to only an eight of the total length of the body. The trick was that by reducing the relative size of the head, the body looked more preeminent and powerful, something most emperors, who were often physical failures, appreciated and secured their popularity. Even extreme cases of 12 to 15 heads of body length appeared. In short, Public relations ruled at the detriment of science and truth.

Today’s comic strip drawers chose proportions according to purpose:

–For real life, 7.5 or “normal canon”

–For a movie star, 8 heads, with the “idealistic canon”;

–For a fashion magazine: 8.5 heads;

–For a comic book hero: 9 heads for the “heroic canon”

Vitruvian man

Text accompanying Leonardo DaVinci’s Vitruvian Man:

Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture that the measurements of the human body are distributed by Nature as follows that is that 4 fingers make 1 palm, and 4 palms make 1 foot, 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man’s height. And 4 cubits make one pace and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in his buildings. If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the centre of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle.

The length of a man’s outspread arms is equal to his height.

From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth of a man’s height; from the bottom of the chin to the top of his head is one eighth of his height; from the top of the breast to the top of his head will be one sixth of a man. From the top of the breast to the roots of the hair will be the seventh part of the whole man. From the nipples to the top of the head will be the fourth part of a man. The greatest width of the shoulders contains in itself the fourth part of the man. From the elbow to the tip of the hand will be the fifth part of a man; and from the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be the eighth part of the man. The whole hand will be the tenth part of the man; the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man. The foot is the seventh part of the man. From the sole of the foot to below the knee will be the fourth part of the man. From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be the fourth part of the man. The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the roots of the hair to the eyebrows is, in each case the same, and like the ear, a third of the face.

Of course, Da Vinci’s exploration of the Vitruvian man doesn’t mean he approves or disapproves the stated fakery in proportions.

Soul or muscle?

It should be known that in Italy, the pure Roman taste has become trendy again following the discovery in 1506 of the statue of the Laocoon on the site of Nero’s villa in Rome. From that moment, artist will feel obliged to increase the volume of the muscular masses in order to appear as working « in Antique style ».

Although Leonardo never openly criticized this trend, it is hard not to think of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, when the artist, seeking to raise the spirit to unequalled philosophical heights, advised painters: « do not give all the muscles of the figures an exaggerated volume » and « if you act differently, it is more a sort of representation of a sack of nuts that you will have achieved than to that of a human figure » (Codex Madrid II, 128r).

No doubt inspired by his friend, the architect Giacomo Andrea, in « The Vitruvian Man », Leonardo is above all interested by other harmonies: if a person extends his arms in a direction parallel to the ground, one obtains the same length as one’s entire height. This equality is inscribed by Leonardo in a square (symbol of the earthly realm). But if one stretches his arms and legs in a star shape, they are inscribed in a circle whose center is the navel. The location of the navel divides the body according to the golden ratio (in this example 5 heads out of a total of 8 heads, 5+3 being part of the Fibonnacci series: 1+2 = 3; 3+2 = 5; 5+3 = 8; 8+5 = 13; 13+8 = 21, etc.).

Leonardo clearly understood what the golden section really means: not a “magical” number in itself, but the reflexion of the dynamic of least action, the very principle uniting man (the square) with the creator and the universe (the circle).

So if you take a look, beware of what you see and especially what you don’t !