Étiquette : Piccolomini

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on mars 5, 2021

La révolution du grec ancien, Platon et la Renaissance

les élèves ont bien du mal à se concentrer.

Par Karel Vereycken,

peintre-graveur, zoographe, passionné d’histoire.

cet article en PDF

Des amis m’ont interrogé sur les conditions ayant conduit à la découverte de la philosophie grecque, en particulier les idées de Platon, et le rôle qu’a pu jouer la découverte du grec ancien pendant la Renaissance européenne.

On entend parfois dire que c’est à l’occasion des grands conciles œcuméniques de Ferrare et de Florence (1439) qu’en apportant avec lui les manuscrits grecs de Byzance, le cardinal Nicolas de Cues (Cusanus), avec ses amis Pléthon et Bessarion, aurait permis à l’Europe occidentale d’accéder aux trésors de la philosophie grecque, notamment en redécouvrant Platon dont les œuvres étaient perdues depuis des siècles.

C’est l’introduction par Nicolas de Cues de la vision positive de l’homme qui aurait suscité en partie la Renaissance. Comme preuve, le fait qu’après le Concile de Florence, les Médicis auraient été les premiers à financer la traduction de l’œuvre complète de Platon, une percée qui aurait permis à la Renaissance de devenir ce qu’elle est devenue.

Si tout ceci n’est pas entièrement faux, permettez-moi d’y apporter quelques précisions.

La Renaissance fut-elle le fruit du Concile de Florence ?

Pas vraiment. C’est le programme de renouveau des études grecques et hébraïques, lancé par Coluccio Salutati (1332-1406), futur chancelier de Florence, qui marqua le début du processus.

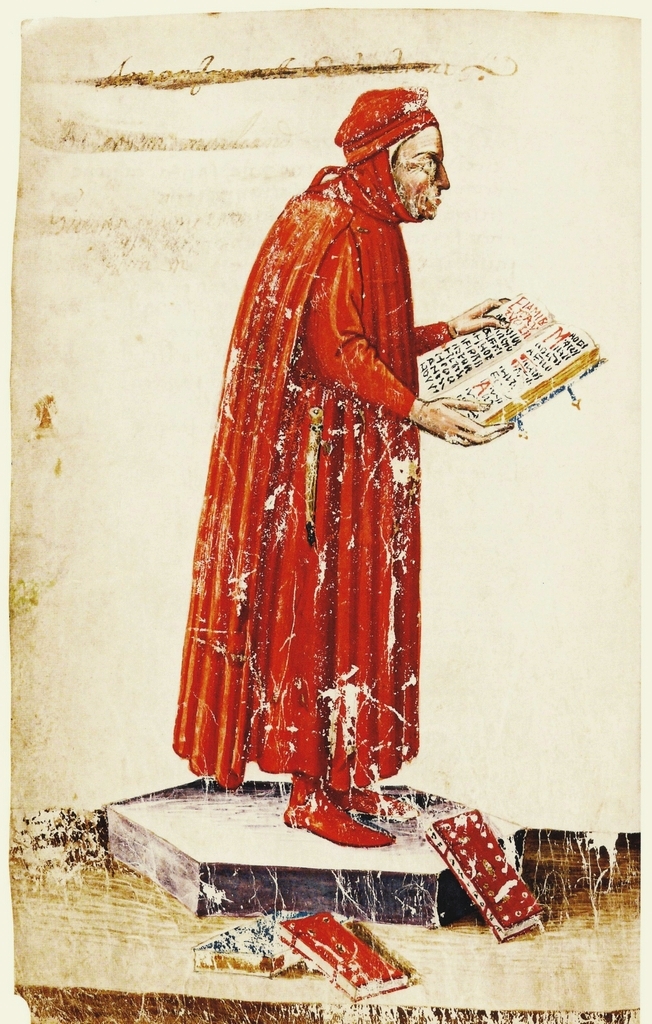

L’idée lui vient de Pétrarque et de Boccace. Avec Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), c’est sans doute le poète italien Pétrarque (1304-1374) qui incarne le mieux l’idéal qui animait les humanistes de la Renaissance.

Toute sa vie, il tenta de « retrouver le très riche enseignement des auteurs classiques dans toutes les disciplines et, à partir de cette somme de connaissances le plus souvent dispersées et oubliées, de relancer et de poursuivre la recherche que ces auteurs avaient engagée ». *

Après avoir suivi ses parents à Avignon, Pétrarque fit ses études à Carpentras où il apprit la grammaire, puis à Montpellier, la rhétorique, et enfin à Bologne, où il passa sept ans à l’école de jurisconsultes.

Cependant, au lieu d’étudier le droit qui ouvrait sur une belle carrière, Pétrarque, en secret, lira tous les classiques alors connus, notamment Cicéron et Virgile, malgré le fait que son père ait brûlé ses livres à l’occasion.

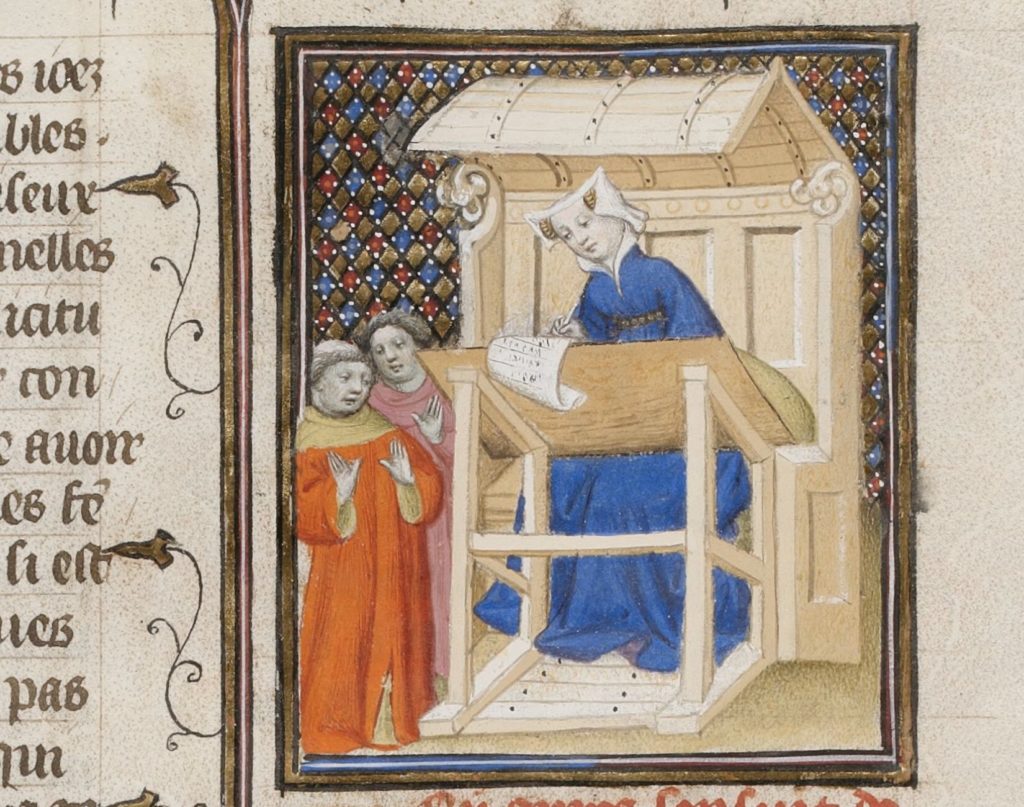

Barlaam de Seminara

traverse une rivière. Haguenau, 1469. Encre et lavis sur papier.

Sous le pontificat de Benoît XII, Pétrarque tenta d’acquérir les rudiments de la langue grecque grâce à un savant moine de l’ordre de Saint-Basile, Barlaam de Seminara (1290-1348), dit Barlaam le Calabrais, venu en 1339 à Avignon en tant qu’ambassadeur d’Andronic III Paléologue afin de tenter, en vain, de mettre un terme au schisme entre les Églises orthodoxe et catholique.

Philosophe, théologien et mathématicien, Barlaam, tout en ayant une connaissance limitée du grec et du latin, fut un des premiers à souhaiter que l’étude de la langue et de la philosophie grecques renaisse en Europe.

Dans son Traité sur sa propre ignorance et celle de beaucoup d’autres (1367), Pétrarque se déclara fier de ses manuscrits grecs – et de sa bibliothèque en général – et évoqua avec admiration Barlaam :

J’ai chez moi seize œuvres de Platon. Je ne sais pas si mes amis en ont jamais entendu nommer les titres […]. Et ce n’est là qu’une petite partie de l’œuvre de Platon, car j’en ai vu, de mes yeux, un grand nombre, en particulier chez le calabrais Barlaam, modèle moderne de sagesse grecque qui commença à m’enseigner le grec alors que j’ignorais encore le latin et qui l’aurait peut-être fait avec succès si la mort ne me l’eût ravi et n’eût fait obstacle à mes honnêtes projets, comme de coutume.

En 1350, c’est-à-dire deux ans après le décès de Barlaam, Pétrarque rencontra Boccace (1313-1375). Ce dernier, comme Pétrarque, se prit d’un vif amour pour le grec. Dans sa jeunesse, à Naples, il avait lui aussi rencontré Barlaam et appris quelques mots de grec, recopiant avec une émouvante maladresse des alphabets, des vers, y joignant la traduction latine et des indications de prononciation.

traducteur d’Euripide, d’Aristote et d’Homère.

Pour se remettre au grec, Boccace fit alors venir de Thessalonique un disciple de Barlaam, Léonce Pilate (mort en 1366), un personnage austère, laid et de fort mauvais caractère. Mais ce Calabrais lui expliqua l’Iliade et l’Odyssée d’Homère et lui traduisit seize dialogues de Platon. Comment se fâcher avec lui ?

Boccace le garda trois ans dans sa maison et fit créer pour lui, chose totalement nouvelle, une chaire de grec à Florence. Mais Pilate ne maîtrisait pas vraiment cette langue. Bien que se faisant passer pour un Grec de souche, l’homme n’avait qu’une maigre connaissance du grec ancien et ses traductions ne dépassèrent jamais le niveau du mot-à-mot. Quant aux leçons qu’il donna à Pétrarque, elles étaient si brutales qu’il l’en dégoûta pour toujours.

Ce qui ne l’empêchera pas, sur les instances de Boccace, de traduire l’Iliade et l’Odyssée d’Homère en latin à partir d’un manuscrit grec envoyé à Pétrarque par Nicolaos Sigeros, l’ambassadeur de Byzance à Avignon.

L’histoire étant ce qu’elle est, c’est grâce à cette traduction très imparfaite que l’Europe redécouvrit une des grandes œuvres fondatrices de sa culture !

Et sur ce terreau fragile s’élèvera une flamme qui va révolutionner le monde.

Ne fut-ce pas moi, écrit Boccace dans sa Généalogie des Dieux, qui eus la gloire et l’honneur de me servir le premier de vers grecs parmi les Toscans ? Ne fut-ce pas moi qui amenai par mes prières, Pilate à s’établir à Florence et qui l’y logeait ? J’ai fait venir à mes frais des exemplaires d’Homère et d’autres auteurs grecs alors qu’il n’en existait pas en Toscane. Je fus le premier des Italiens à qui fut expliqué, en particulier, Homère, et je le fis ensuite expliquer en public.

La chasse aux manuscrits

Ce qui importe, c’est qu’au cours de ces rencontres, Pétrarque créa un réseau culturel couvrant toute l’Europe, qui se prolongea jusqu’en Orient.

Il demanda alors à ses relations et amis, qui partageait son idéal humaniste, de l’aider à retrouver dans leur pays ou leur province, les textes latins des anciens que pouvaient posséder les bibliothèques des abbayes, des particuliers ou des villes. Au cours de ses propres voyages il retrouva plusieurs textes majeurs tombés dans l’oubli.

C’est à Liège (Belgique) qu’il découvrit le Pro Archia et à Vérone, Ad Atticum, Ad Quintum et Ad Brutum, tous de Cicéron. Lors d’un séjour à Paris, il mit la main sur les poèmes élégiaques de Properce, puis, en 1350, sur une œuvre du Quintilien. Dans un souci constant de restituer le texte le plus authentique, il soumet ces manuscrits à un minutieux travail philologique et leur apporte des corrections par rapprochements avec d’autres manuscrits. C’est ainsi qu’il recomposa la première et la quatrième décade de l’Histoire Romaine de Tite-Live à partir de fragments et qu’il restaura certains textes de Virgile.

Ces manuscrits, qu’il conserva dans sa propre bibliothèque, en sortirent par la suite sous forme de copies et devinrent ainsi accessibles au plus grand nombre. Tout en reconnaissant que « la vraie foie » manquait aux païens, Pétrarque estimait que lorsqu’on parle vertu, le vieux et le nouveau monde ne firent pas en lutte.

Le « Circolo di Santo Spirito »

A partir des années 1360, Boccace réunira un premier groupe d’humanistes connu sous le nom de « Circolo di Santo Spirito » (Cercle du Saint Esprit), emprunté au couvent augustinien florentin datant du XIIIe siècle.

Forme embryonnaire d’une université, son Studium Generale (reconnu en 1284) était alors au cœur d’un vaste centre intellectuel comprenant des écoles, des hospices et des réfectoires pour les indigents.

Avant son décès en 1375, Boccace, qui avait récupéré une partie de la bibliothèque de Pétrarque, léguera au couvent l’ensemble de cette précieuse collection de livres et manuscrits anciens.**

Ensuite, dans les années 1380 et au début des années 1390, un deuxième cercle d’humanistes s’y réunit quotidiennement dans la cellule du moine augustinien Luigi Marsili (1342-1394). Ce dernier, qui avait étudié la philosophie et la théologie aux universités de Paris et de Padoue, où il était déjà entré en contact avec Pétrarque en 1370, se lia rapidement d’amitié avec Boccace.

En fréquentant à partir de 1375 le Cercle du Saint Esprit, le futur chancelier de Florence Coluccio Salutati (1332-1406) s’éprit à son tour d’un amour infini pour les études grecques.

En invitant à Florence le savant grec Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415) pour y enseigner le grec ancien, c’est Salutati qui donnera l’impulsion décisive conduisant à la fin du schisme entre l’Orient et l’Occident et donc à l’unification des Églises, consacrée lors du Concile de Florence de 1439.

Un siècle avant Salutati, le philosophe et scientifique anglais Roger Bacon (1214-1294), un moine franciscain résidant à Oxford, auteur d’une de l’une des premières grammaires grecques, appela déjà de ses vœux une telle « révolution linguistique ».

Comme le précise Dean P. Lockwood dans son article Roger Bacon’s Vision of the Study of Greek (1919) :

« De toute évidence, le grec ancien était la clé de voûte du grand entrepôt des connaissances antiques, l’hébreu et l’arabe étant les deux autres. En outre, nous ne devons pas oublier qu’à l’époque de Bacon, la supériorité des anciens était un fait incontestable. Le monde moderne a surpassé les Grecs et les Romains dans d’innombrables domaines ; les penseurs médiévaux se rapprochaient encore du standard hellénique.« Trois choses étaient claires pour Roger Bacon : la nécessité de maîtriser la langue grecque, l’ignorance qu’on avait de cette langue à son époque et aussi, l’occasion réelle de pouvoir l’acquérir. On peut dire la même chose de l’hébreu, mais Bacon faisait passer, à juste titre, le grec en premier. Le programme de Bacon était simple :

1. Rechercher les Grecs byzantins natifs résidant en Europe, de préférence des grammairiens. Ils sont très peu nombreux, bien sûr, mais on peut les trouver dans les monastères grecs du sud de l’Italie.

2. A partir de ceux-ci et de toute autre source disponible, retrouver des livres en grec ancien. Si l’on réalisait ce programme, Bacon prophétisa avec confiance que les résultats ne se feraient pas attendre ».

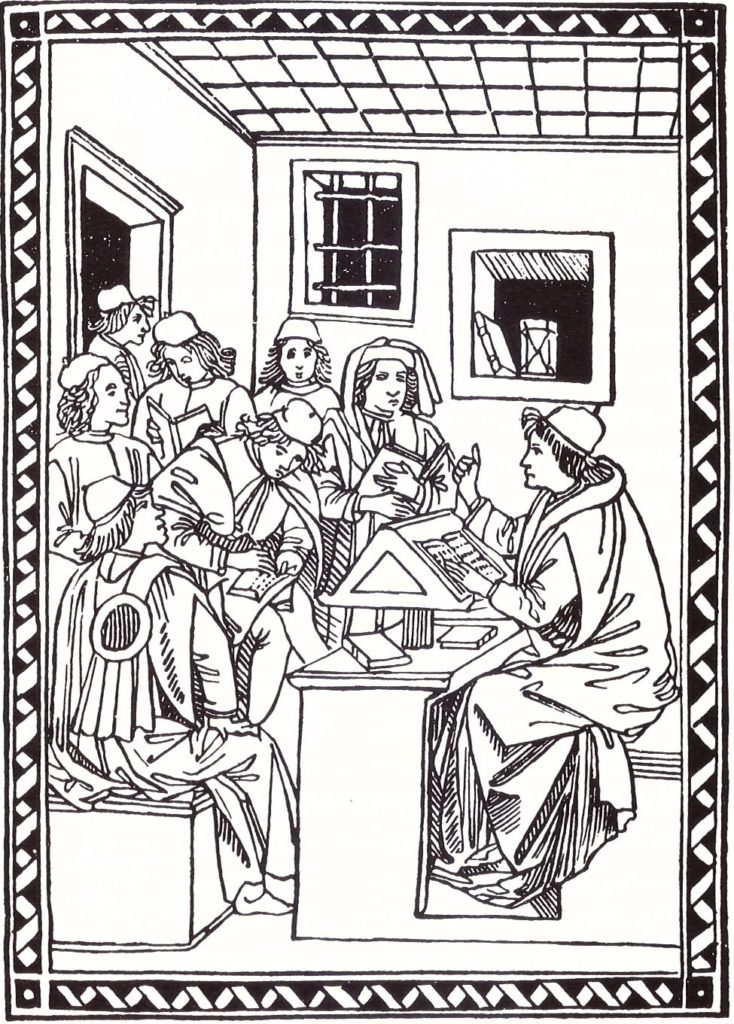

Leonardo Bruni

Manuel Chrysoloras arriva à Florence à l’hiver 1397, un événement qui apparaîtra comme une nouvelle grande opportunité selon l’un de ses élèves les plus célèbres, le savant humaniste Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444). Celui-ci occupera le poste de chancelier de Florence lors du Concile qu s’y déroula. Bruni disait qu’il y avait beaucoup de professeurs de droit, mais que personne n’avait étudié le grec ancien en Italie du Nord depuis 700 ans.

En faisant venir Chrysoloras à Florence, Salutati permit à un groupe de jeunes, dont Bruni et Vergerio, la lecture d’Aristote et de Platon en grec original.

bas-relief de Luca della Robbia.

Jusque-là, en Europe, les chrétiens connaissaient les noms de Pythagore, Socrate et Platon par leurs lectures des pères de l’Eglise : Origène, Saint-Jérôme et Saint Augustin. Ce dernier, dans sa Cité de Dieu, n’hésite pas à affirmer que les « platoniciens », c’est-à-dire Platon et ceux qui ont assimilé son enseignement (Plato et qui eum bene intellexerunt), étaient supérieurs à tous les autres philosophes païens.

Comme nous l’avons démontré ailleurs, notamment dans notre étude sur Raphaël et l’École d’Athènes, c’est en grande partie la démarche philosophique optimiste et prométhéenne de Platon, pour qui la connaissance provient avant tout de la capacité d’hypothèse et non pas du simple témoignage des sens, comme le prétend Aristote, qui fournit la sève permettant à l’arbre de la Renaissance d’offrir à l’humanité tant de fruits merveilleux.

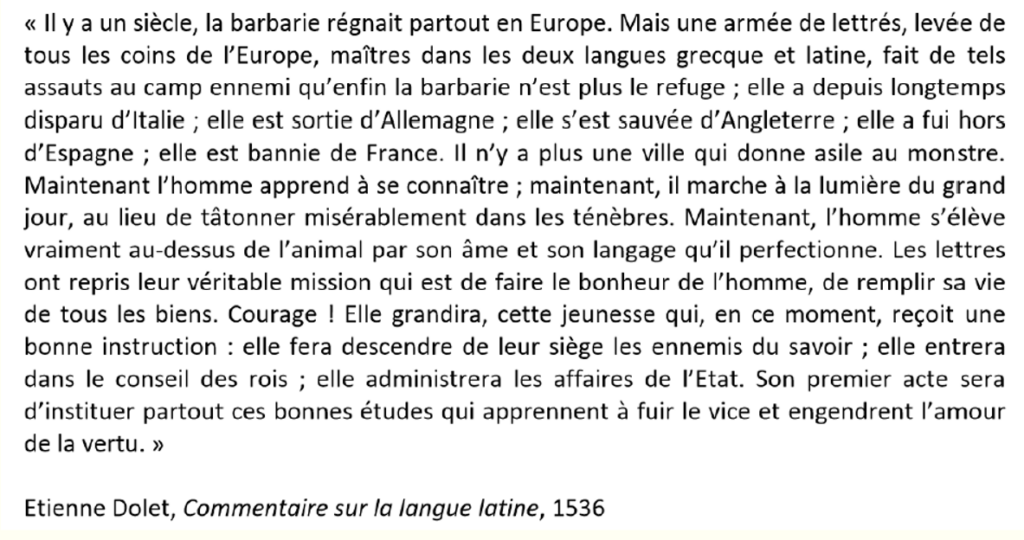

Le témoignage suivant, de l’imprimeur français Etienne Dolet, mort sur le bûcher à Paris en 1546, révèle bien que pour les humanistes, il s’agissait d’un projet civilisationnel décidé à faire reculer la barbarie en élevant l’homme « au-dessus de l’animal par son âme ».

Le cercle d’Ambrogio Traversari

L’élève le plus célèbre de Chrysoloras fut Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439) qui devint général de l’ordre des Camaldules. Aujourd’hui honoré comme un saint par son ordre, Traversari fut l’un des premiers à conceptualiser le type « d’humanisme chrétien » que promouvront le Cusain et plus tard Erasme de Rotterdam (qui forgea le concept de « Saint-Socrate » en unissant Platon aux Saintes Ecritures et aux Pères de l’Eglise), ainsi que celui qui se considérait comme son disciple, le bouillonnant François Rabelais.

Traversari, l’un des principaux organisateurs du Concile de Florence, fut également le protecteur personnel du grand peintre de la Renaissance Piero della Francesca et l’architecte du Dôme Filippo Brunelleschi.

Selon Vespasiano de Bisticci, l’historien de la cour d’Urbino, Traversari animait des séances de travail hebdomadaires sur Platon et la philosophie grecque au couvent florentin Sainte-Marie-des-Anges avec la fine fleur de l’humanisme européen dans le domaine des lettres, de la théologie, de la science, de la politique, de l’aménagement des villes et des territoires, de l’éducation et des beaux-arts. Parmi eux :

- Le cardinal-philosophe allemand Nicolas de Cues ;

- Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, le célèbre médecin et cartographe, lui aussi ami et protecteur de Piero della Francesca et de Léonard de Vinci ;

- L’érudit collectionneur de manuscrits Niccolò Niccoli, conseiller de Côme l’ancien, héritier de l’empire industriel et financier des Médicis. Considéré à l’époque comme l’homme le plus riche d’Occident, il fut l’un des mécènes du sculpteur Donatello ;

- Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, le futur pape humaniste Pie II ;

- Le secrétaire apostolique du pape Innocent VII puis de ses trois successeurs, Leonardo Bruni, élève de Chrysoloras. Il succèdera à Coluccio Salutati à la chancellerie de Florence (1410-1411 et 1427-1444).

- L’homme d’Etat italien Carlo Marsuppini, passionné de l’Antiquité grecque et successeur de Bruni, à sa mort en 1444, au poste de chancelier de la République de Florence.

- Le philosophe, antiquaire et écrivain Poggio Bracciolini. Après avoir conseillé pas moins de neuf papes (!), il est nommé chancelier de la République de Florence suite à la mort de Marsuppini en 1453 ;

- L’homme politique et ambassadeur Gianozzi Manetti. Amoureux du grec ancien et de l’hébreu, son cercle comprend Francesco Filelfo, Palla Strozzi et Lorenzo Valla. Valla ;

Manuel Chrysoloras à Florence

dessin de Paolo Uccello.

Chrysoloras ne resta que quelques années à Florence, de 1397 à 1400. Tout comme à Bologne, Venise et Rome, il y enseigna les rudiments du grec ancien. Parmi les nombreux jeunes qui profiteront de ses cours, plusieurs de ses élèves comptèrent parmi les figures les plus marquantes du renouveau des études grecques dans l’Italie de la Renaissance.

Outre Leonardo Bruni et Ambrogio Traversari, on compte parmi eux Guarino da Verona et le banquier florentin Palla Strozzi (1372-1462), par la suite l’ami et protecteur du sculpteur et traducteur Lorenzo Ghiberti). A noter, le fait que Strozzi prit à sa charge une partie du traitement de Chrysoloras et fit venir de Constantinople et de Grèce les livres nécessaires à l’enseignement nouveau.

Chrysoloras se rendit à Rome à l’invitation de Bruni, à l’époque secrétaire du pape Grégoire XII. En 1408, le savant grec fut envoyé à Paris par l’empereur Manuel II Paléologue (1350-1425) pour une importante mission. En 1413, choisi pour y représenter l’Église d’Orient, il se rendit également en Allemagne pour une ambassade auprès de l’empereur Sigismond, dont l’objet est de décider du lieu du Concile sur l’union des églises, qui se tiendra à Constance en 1415.

Chrysoloras a traduit en latin les œuvres d’Homère et La République de Platon. Son Erotemata (Questions-réponses), qui fut la première grammaire grecque de base employée en Europe occidentale, circula d’abord sous forme de manuscrit avant d’être publiée en 1484.

Réimprimée à de multiples reprises, elle connut un succès considérable non seulement auprès de ses élèves à Florence, mais également auprès des humanistes les plus éminents de l’époque, dont Thomas Linacre à Oxford et Erasme lorsqu’il résida à Cambridge. Son texte devint le manuel de base des élèves du fameux « Collège Trilingue » créé en 1515 par Erasme à Louvain en Belgique.

Traversari rencontra Chrysoloras à l’occasion des deux séjours qu’il fit à Florence pendant l’été 1413, puis en janvier-février 1414, et le vieux lettré byzantin fut impressionné par la culture bilingue du jeune moine. Il lui adressera une longue lettre philosophique en grec sur le thème de l’amitié. Ambrogio lui-même exprima dans ses lettres la plus grande considération pour Chrysoloras et son émotion pour la bienveillance qu’il lui avait témoigna.

Notons également que le riche érudit humaniste Niccolò Niccoli, grand collectionneur de livres, ouvrit sa bibliothèque à Traversari et le mit en relation avec les cercles érudits de Florence (notamment Leonardo Bruni, et aussi Côme de Médicis dont il était le conseiller), de Rome et de Venise.

En 1423, le pape Martin V envoie deux lettres, l’une au prieur du couvent Sainte-Marie-des-Anges, le Père Matteo, l’autre à Traversari lui-même, exprimant son soutien au grand développement des études patristiques dans cet établissement, et tout particulièrement au travail de traduction des Pères grecs mené par Traversari.

Le pape avait en vue les négociations qu’il allait mener avec l’Église grecque : début 1423, son légat Antoine de Massa rapporta de Constantinople plusieurs manuscrits grecs qu’il confia à Traversari pour traduction : notamment l’Adversus Græcos de Manuel Calécas, et pour les classiques les Vies et doctrines des philosophes illustres de Diogène Laërce, qui ne sera longtemps diffusé que dans la traduction latine de Traversari.

C’est suite à ce travail que Traversari manifesta son intérêt à voir résolu le schisme entre les Eglises latine et grecque. Fin 1423, Niccolò Niccoli procura à Traversari un vieux volume contenant tout le corpus des anciens canons ecclésiastiques. Le savant moine exprima dans sa correspondance avec l’humaniste son enthousiasme de pouvoir se plonger dans la vie de l’Église chrétienne antique alors unie. Sur sa lancée il traduira en grec une longue lettre du pape Grégoire le Grand aux prélats d’Orient.

Bessarion et Pléthon furent-ils les premiers à introduire l’ensemble de l’œuvre de Platon en Europe ?

Pas vraiment. Si Jean Bessarion (1403-1472) apporta effectivement en 1437 sa propre collection des « œuvres complètes de Platon » à Florence, elles avaient déjà été introduites plus tôt en Italie, notamment en 1423 par le Sicilien Giovanni Aurispa (1376-1459), le précepteur de Lorenzo Valla (un autre collaborateur du Cusain, avec lequel il dénonça la fraude de la « Donation de Constantin » et dont les travaux influenceront fortement Erasme).

En 1421, Aurispa, travaillant avec Traversari, fut envoyé par le pape Martin V afin de servir de traducteur au marquis Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, en mission diplomatique auprès de l’empereur byzantin Manuel II Paléologue. Sur place, Aurispa gagna la faveur du fils et successeur de l’empereur, Jean VIII Paléologue (1392-1448), qui fit de lui son secrétaire. Deux ans plus tard, Aurispa accompagnera l’empereur byzantin dans une mission à la cour d’Europe.

fresque de Benozzo Gozzoli.

Le 15 décembre 1423, 16 ans avant le Concile de Florence de 1439, Aurispa arriva à Venise avec la plus grande et la plus belle collection de textes grecs à pénétrer en Occident ; donc avant ceux apportés par Bessarion.

En réponse à une lettre de Traversari, il précisa avoir ramené 238 manuscrits. Ceux-ci contenaient toutes les œuvres de Platon, dont la plupart jusqu’alors n’étaient connues que très partiellement ou pas du tout en Occident, à quelques exceptions près. Par exemple, en Sicile, dès 1160, Henri Aristippe de Calabre (1105-1162) avait traduit en latin le Phèdre et le Ménon, deux dialogues de Platon.

Le virus du néo-platonisme

Les authentiques platoniciens (tels que Pétrarque, Traversari, Nicolas de Cues ou Erasme), s’opposèrent avec force aux « néo-platoniciens » (tels que Plotin, Proclus, Jamblique, le Ficin et autres Pic de la Mirandole) dont l’influence suscitera ce que l’on peut et doit appeler une « contre-Renaissance ».

Quelques siècles plus tard, le philosophe humaniste Leibniz mettra lui aussi fortement en garde contre les « néo-platoniciens » et exigera que l’on étudie Platon dans ses écrits originaux plutôt qu’à travers ses commentateurs, aussi brillants soient-ils :

« Non ex Plotino aut Marsilio Ficino, qui mira semper et mystica affectantes diceren tanti uiri doctrinam corrupere. » Il faut étudier Platon, dit-il, « mais non pas Plotin ou le Ficin, qui, en s’efforçant toujours de parler merveilleusement et mystiquement, corrompent la doctrine d’un si grand homme. »

Examinons maintenant, dans ce contexte, la figure de Pléthon, qui estimait que Platon et Aristote pouvaient jouer chacun leur propre rôle.

fresque de Benozzo Gozzoli.

George Gemistos « Pléthon » (1355-1452), fut un disciple du neo-platonicien radical Michael Psellos (1018-1080).

Vers 1410, Gemistos ouvrit son académie « néo-platonicienne » à Mistra (près du site de l’ancienne Sparte) et ajouta « Pléthon » à son nom pour ressembler à Platon. A part Platon, il admirait aussi Pythagore et les « Oracles chaldéens », qu’il attribua à Zoroastre.

Alors que la plupart des écrits de Pléthon, soupçonné d’hérésie, furent brûlés, une partie de son œuvre finira entre les mains de son ancien élève, le cardinal Jean Bessarion. Ce dernier, avant de mourir, légua sa vaste collection de manuscrits et de livres à la bibliothèque Saint-Marc de Venise (ville où résidaient plus de 4000 Grecs). Parmi ces livres et manuscrits se trouvait le Résumé des Doctrines de Zoroastre et de Platon. Ce texte, un mélange de croyances polythéistes et d’éléments néo-platoniciens, était un résumé que Pléthon avait écrit en partant de l’œuvre de Platon, Les Lois.

Jean Bessarion, ce véritable humaniste qui participa au Concile de Ferrare (1437) et de Florence (1439), en tant que représentant des Grecs et a signa le décret de l’Union, il s’en tint au principe :

« J’honore et respecte Aristote, j’aime Platon » (colo et veneror Aristotelem, amo Platonem).

Pour lui, la pensée platonicienne ne serait acceptable pour le monde latin (Occident) que lorsqu’elle obtiendrait le même droit que la pensée aristotélicienne en apparaissant comme une interprétation irénique de l’aristotélisme, sans être en contradiction avec le christianisme.

Les Médicis financèrent-ils un programme intensif pour traduire les œuvres de Platon ?

En 1397, le banquier et industriel Giovannni « di Bicci » de’ Medici (1360-1429) fonda la Banque des Médicis. Giovanni possédait deux manufactures de laine à Florence et fut membre de deux guildes : l’Arte della Lana et l’Arte del Cambio. En 1402, il fut l’un des juges du jury qui sélectionna le projet du sculpteur Lorenzo Ghiberti pour les magnifiques bas-reliefs en bronze des portes du Baptistère de Florence.

En 1418, Giovanni di Bicci, souhaitant doter les Medicis de leur propre église familiale, confia à Filippo Brunelleschi, futur réalisateur du Duomo, la fameuse coupole de la cathédrale de Santa Maria del Fioro, le Duomo, le soin de transformer radicalement l’église basilique de San Lorenzo et chargea Donatello de réaliser les sculptures.

Politiquement, la puissante famille des Médicis, actifs dans la finance et l’industrie textile, n’accéda au pouvoir qu’en 1434, trois ans avant le Concile de Florence alors que la Renaissance battait déjà son plein.

Certes, le fils et héritier de Giovanni di Bicci, Cosimo (Côme) di Medici (1389-1464), connu comme l’homme le plus riche de son siècle, fut si enthousiasmé par les paroles de Pléthon qu’il acquit une bibliothèque complète de manuscrits grecs. Il lui acheta également un ensemble de 24 dialogues de Platon, ainsi qu’un exemplaire du Corpus Hermeticum d’Hermès Trismégiste l’Égyptien (entre 100 et 300 après JC.), trouvé en Macédoine par un moine italien, Leonardo de Pistoia.

Cosimo songea à faire traduire du grec ancien au latin la totalité des œuvres de Platon. Cependant, comme nous l’avons déjà dit, Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444), chancelier de la république florentine de 1427 à 1444, avait déjà traduit bien avant une grande partie des œuvres de Platon du grec ancien vers le latin.

Cosimo choisit comme traducteur Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), le fils de son médecin personnel, âgé seulement de cinq ans au moment du Concile de Florence en 1439. Ayant de sérieux doutes sur les capacités du Ficin lorsque ce dernier lui offre en 1456 sa première traduction, Les institutions platoniques, Cosimo lui demanda de ne pas publier cet ouvrage et d’apprendre d’abord la langue grecque… que le Ficin apprit auprès du savant byzantin Jean Argyropoulos (1395 -1487), un élève aristotélicien de Bessarion.

Avancé en âge et gagné par la corruption, Cosimo lui donna finalement le poste. Il lui alloue une bourse annuelle, les manuscrits nécessaires et une villa à Careggi, un quartier de Florence, où le Ficin fonda son « Académie platonicienne » avec une poignée d’adeptes, parmi lesquels Angelo Poliziano (1454-94), Jean Pic de la Mirandole (1463-1494) et Cristoforo Landino (1424-1498).

L’Académie du Ficin, reprenant (comme il le dit lui-même) l’ancienne tradition néo-platonicienne de Plotin et de Porphyre organisait chaque année, le 7 novembre, un banquet cérémonial « négligé depuis mille deux cents ans ». Cette date correspondait, selon lui, à la fois à l’anniversaire de Platon et de sa mort.

Après le dîner, les participants lisaient le Symposium de Platon, puis chacun d’entre eux commentait l’un des discours de l’œuvre. Il s’agissait de démonstrations sans véritable dialogue et dépourvus de l’essence de toute vraie dialectique socratique : l’ironie.

En outre, il est à noter que la plupart des réunions de l’Académie du Ficin avaient lieu en présence de l’ambassadeur de Venise à Florence, en particulier le puissant oligarque Bernardo Bembo (1433-1519), père du cardinal « poète » Pietro Bembo, plus tard conseiller spécial du pape guerrier, le génois Jules II.

C’est cette alliance formée par la famille des Médicis, de plus en plus dégénérée, des Vénitiens et des néo-platoniciens qui permit de consolider une emprise oligarchique sur l’Église catholique romaine.

Les Médicis eurent peu de considération pour Léonard de Vinci dont ils jugeaient trop lente l’exécution de ses œuvres et ses fresques défaillantes techniquement. Déçu de n’obtenir aucune commande de la part du pape, Léonard se rendit en France où le roi François Ier l’attendait.

Giorgio Vasari, peintre médiocre, fut l’homme orchestre des Médicis. Dans sa Vies des peintres, il répandit le mythe que la Renaissance fut le bébé quasi-exclusif des ses employeurs.

Soulignons également qu’avant de traduire les œuvres de Platon, et à la demande expresse de Cosimo, le Ficin traduira d’abord (en 1462) les Hymnes orphiques, les Dictons de Zoroastre et le Corpus Hermeticum d’Hermès Trismégiste.

Ce n’est qu’en 1469 (trente ans après le Concile de Florence) que le Ficin achèvera ses traductions de Platon après une dépression nerveuse en 1468, décrite par ses contemporains comme une crise de « profonde mélancolie ».

En 1470, sous le titre plagié de Proclus, le Ficin écrivit sa Théologie platonicienne de l’immortalité des âmes. Bien que complètement gagné au néo-platonisme ésotérique, il devint prêtre en 1473 et écrira son Livre de la religion chrétienne sans renoncer à sa vision païenne néo-platonicienne, puisqu’il entreprit alors toute une nouvelle série de traductions des néo-platoniciens d’Alexandrie : les cinquante-quatre livres des Ennéades de Plotin ainsi que les œuvres de Porphyre et de Proclus.

Le Ficin, dans ses « Cinq questions concernant l’esprit », s’attaqua explicitement à la conception prométhéenne de l’homme :

Rien n’est plus déraisonnable que l’homme qui, par la raison, est le plus parfait de tous les animaux, non, de toutes les choses du ciel, le plus parfait, dis-je, par rapport à cette perfection formelle qui nous est donnée dès le commencement, que l’homme, également par la raison, devrait être le moins parfait de tous par rapport à cette perfection finale pour laquelle la première perfection est donnée. Cela semble être celui du plus malheureux Prométhée. Instruit par la sagesse divine de Pallas, il a pris possession du feu céleste, c’est-à-dire de la raison. C’est à cause de cette possession, sur le plus haut sommet de la montagne, c’est-à-dire à la place la plus élevée de la contemplation, qu’il est à juste titre jugé le plus misérable de tous, car il est rendu misérable par le rongement continuel du plus vorace des vautours, c’est-à-dire par le tourment de l’enquête…

(…) Que disent les philosophes de ces choses ? Certainement que les Mages, disciples de Zoroastre et d’Ostanès, affirment quelque chose de similaire. Ils disent que, à cause d’une certaine vieille maladie de l’esprit humain, tout ce qui est très malsain et difficile nous arrive…

L’Académie néo-platonicienne florentine, soutenue par le flamboyant Lorenzo de Médicis (1449-1492) dit « Laurent le Magnifique », ne fut jamais à l’origine d’une quelconque Renaissance. Bien au contraire, elle servira d’opération « delphique » : défendre Platon pour mieux le détruire ; le louer en des termes tels qu’il en devienne discrédité.

Et surtout détruire l’influence de Platon en opposant la religion à la science, à un moment où Nicolas de Cues et ses partisans réussirent à fertiliser l’une avec la semence de l’autre. N’est-il pas étrange que le nom du Cusain n’apparaisse pas une seule fois dans les œuvres du Ficin ou de Pic de la Mirandole, si érudits ?

Infecté par ce néo-platonisme ésotérique, Thomaso Inghirami (1470-1516), le bibliothécaire en chef du pape Jules II, n’accomplira rien d’autre que cela en dictant au peintre Raphaël le contenu des Stanze (chambres) au Vatican quelques décennies plus tard.

La « mélancolie » néo-platonicienne, que l’ami d’Erasme, le peintre-graveur Albrecht Dürer, prendra comme thème de sa célèbre gravure, deviendra la matrice philosophique des romantiques, des symbolistes et de l’école dite moderne.

Quant à la révolution que susciteront les études grecques dans les sciences, j’ai eu l’occasion d’expliquer la question dans mon texte « 1512-2012 : De la cosmographie aux cosmonautes, Gérard Mercator et Gemma Frisius ».

Humanistes et traducteurs

Pour conclure, voici une courte liste de traducteurs (il en manque certainement) et des langues étrangères qu’ils maîtrisaient.

Remercions-les pour tout ce qu’ils nous ont apporté. Sans eux, l’homme n’aurait certainement pas pu poser le pied sur la Lune !

- Cicéron, 106-43 av. JC. : italien, latin et grec ;

- Philon d’Alexandrie, vers 20 av. JC- 45 apr. JC : hébreu, grec ;

- Origène, v. 185-v. 253 après JC. : grec, latin ;

- Saint Jérôme (de Stridon), 342-420 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Boèce, 477-524 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Bède le Vénérable, 672-735 : anglais, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Charlemagne, 742-814, parlait couramment le latin et connaissait le grec, l’hébreu, le syriaque et l’esclavon (l’ancien serbo-croate) ;

- Jean Scot Erigène, 800-876 : irlandais, grec, arabe et hébreu ;

- Hunayn ibn Ishaq, 809-873 : arabe, syriaque, persan et grec ;

- Thabit ibn Qurra, 826-901 : syriaque, arabe et grec ;

- Al-Fârâbi, 872-950 : farsi, sogdien et grec ;

- Al-Biruni, 973-1048, chorasmien, farsi, arabe, syriaque, sanskrit, hindi, hébreu et grec ;

- Héloïse, 1092-1141 : français, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Hugues de Saint Victor, 1096-1141 : français, latin, grec ;

- Constantin l’Africain, XIe siècle. : arabe, latin, grec et italien ;

- Jean Sarrazin, XIIe siècle : latin et grec ;

- Henri Aristippe, 1105-1162 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Gérard de Crémone, 1114-1187 : Italien, latin et arabe ;

- Robert Grosseteste, 1168-1253 : anglais, latin et grec;

- Michael Scot, 1175-1232 : écossais, latin, grec, hébreu et arabe;

- Moïse de Bergame, XIIe siècle : italien, latin et grec ;

- Burgundio de Pise, XIIe siècle : italien, latin et grec ;

- Jacques de Venise, mort après 1147 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Roger Bacon, 1214-1294 : anglais, latin, grec, hébreu, arabe et chaldéen ;

- Guillaume de Moerbeke, 1215-1286 : flamand, latin et grec ;

- Raymond Lulle, 1232-1315 : catalan, latin et arabe ;

- Dante Alighieri, 1265-1321 : italien et latin

- Léonce Pilate, (?-1366) : italien, latin et grec ;

- Francesco Pétrarque, 1304-1374 : Italien, latin et notions de grec ;

- Giovanni Boccaccio (Bocace), 1313-1375 : italien, latin et notions de grec ;

- Coluccio Salutati, 1331-1406 : italien et latin ;

- Geert Groote, 1340-1384 : néerlandais, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Florens Radewijns, 1350-1400 : néerlandais et latin ;

- Manuel Chrysoloras, 1355-1415 : grec, latin et italien ;

- Jacopo d’Angelo, 1360-1410, italien, latin, grec ;

- Georgius Gemistus Pléthon, 1360-1452 : grec ;

- Pier Paolo Vergerio (l’Ancien), 1370-1445 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Leonardo Bruni, 1370-1441 : italien, latin, grec, hébreu et arabe ;

- Guarino Guarini (de Vérone), 1370-1460 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Palla di Onorio Strozzi, 1372-1462 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Giovanni Aurispa, 1376-1459 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Vittorino da Feltre, 1378-1446 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Poggio Bracciolini, 1380-1459 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Ambrogio Traversari, 1386-1439 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Gianozzo Manetti, 1396-1459 : italien, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Jean Argyropoulos, 1395-1487 : grec, italien et latin ;

- Georges de Trébizonde, 1396-1472 : grec, latin et italien ;

- Tommaso Parentucelli (pape Nicolas V), 1397-1494 : italien et latin ;

- Francesco Filelfo, 1398-1481 : Italien, latin et grec ;

- Carlo Marsuppini, 1399-1453 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Théodore de Gaza, 1400-1478 : grec et latin ;

- Jean Bessarion, 1403-1472 : grec, latin et italien ;

- Lorenzo Valla, 1407-1457 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Nicolas de Cues, 1401-1464 : allemand, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- John Wessel Gansfoort, 1419-1489 : néerlandais, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Georg von Peuerbach, 1423-1461 : allemand, latin et grec ;

- Démétrios Chalcondyle, 1423-1511 : grec et latin ;

- Marcilio Ficino, 1433-1499 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Constantin Lascaris, 1434-1501 : grec, latin, italien ;

- Regiomontanus, 1436-1476 : allemand, latin et grec ;

- Alexander Hegius, 1440-1498 : néerlandais, latin et grec ;

- Rudolf Agricola, 1444-1485 : néerlandais, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Janus Lascaris, 1445-1535 : grec et latin ;

- William Grocyn, 1446-1519, anglais, latin et grec ;

- Angelo Poliziano, 1454-1494 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Johannes Reuchlin, 1455-1522 : allemand, latin, grec et hébreu ;

- Thomas Linacre, 1460-1524 : anglais, latin et grec ;

- Erasme de Rotterdam, 1467-1536 : néerlandais, français, latin et grec ;

- Guillaume Budé, 1467-1540 : français, latin et grec ;

- William Latimer, 1467-1545 : anglais, latin et grec ;

- Willibald Pirckhimer, 1470-1530 : allemand, latin et grec ;

- Marcus Musurus, 1470-1517, italien, latin et grec ;

- Thomas More, 1478-1535 : anglais, latin et grec ;

- Pietro Bembo, 1470-1547 : italien, latin et grec ;

- Jérôme Aléandre, 1480-1542, italien, latin et grec;

- François Rabelais, 1483-1553 : français, latin et grec ;

- Germain de Brie, 1490-1538 : français, latin et grec;

- Juan Luis Vivès, 1492-1540 : espagnol, latin, grec et hébreu.

* * * * *

NOTES :

*A. Artus et M. Maynègre, La Fontaine de Pétrarque, n° spécial consacré au 700e anniversaire de la naissance de François Pétrarque, Avignon, 2004.

**Dans son testament du 28 août 1374, Boccace avait prédisposé qu’à sa mort (advenue le 21 décembre 1375), une partie de sa riche bibliothèque (l’essentiel des textes latins et grecs, à l’exclusion donc des œuvres en langue vernaculaire) aille en héritage au frère augustin Martino da Signa et que celui-ci, à sa propre mort (survenue en 1387), la lègue intégralement à son institution d’appartenance, le couvent de Santo Spirito à Florence.

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur La révolution du grec ancien, Platon et la Renaissance

Tags: arabe, Argyropoulos, Aristote, artkarel, Aurispa, Barlaam, Bembo, Bessarion, Boccace, Bologne, Bracciolini, Brunelleschi, Bruni, Chrysoloras, cicéron, Collège Trilingue, Côme, Concile de Ferrare, Concile de Florence, cusanus, Dante, Dieu, Donatello, Dürer, Erasme, Ficin, Filelfo, Florence, Frisius, Ghiberti, grec ancien, Guarino, hébreu, Homère, humanisme, Iliade, Italie, Jamblique, Jules II, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Laërce, Landino, latin, Léonard, Léonce Pilate, Linacre, Luigi Marsili, Manetti, Marsuppini, Martin V, Médicis, Mercator, néo-platonicien, Niccoli, Nicolas de Cues, Odyssée, Origène, Padoue, Paléologue, Pétrarque, Pic della Mirandole, Piccolomini, Piero della Francesca, Platon, platoniciens, Pléthon, Plotin, Poliziano, Porphyre, Proclus, Prométhée, Properce, Pythagore, Quintilien, renaissance, Roger Bacon, Romains, Saint Augustin, Saint-Jérôme, Salutati, Santo Spirito, Sigismond, Strozzi, Tite-Live, Toscane, toscanelli, Traversari, Trismégiste, Valla, Vasari, Vatican, Vereycken, Vergerio, Virgile

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on janvier 2, 2021

The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance

By Karel Vereycken

Some friends asked me to elaborate on the following:

It is sometimes said that the introduction of Plato in the context of the Councils of Ferrara and Florence (1439) “triggered the explosion of the Italian Renaissance”.

And of the great humanist, the German Cardinal-philosopher Cusanus, it is said that he “brought to Florence Bessarion and Plethon, who were both Greek scholars of Plato and brought the entire works of Plato which had been lost in Europe for centuries”.

At the same time, goes the narrative, “the Medicis financed a crash program to translate the works of Plato. This excitement made the Italian Renaissance what it became”.

While Plato’s ideas and the renewal of greek studies did play a major role in triggering the European Renaissance, the preceding affirmations, as we shall document here, require some refinement.

Was the Italian Renaissance “triggered” by the Council of Florence?

Not really. It was rather –40 years earlier–, the “Greek language revival project” project of Coluccio Salutati (1332-1406), who would become the chancellor of Florence and invite the Greek scholar Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415) to his city, that “triggered” a revival of Greek and Hebrew studies, which in return lead to the unification of the churches at the Council of Florence (1439).

The idea had regained interest from Petrarch and Boccaccio, which Salutati admired. Along with Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), it is undoubtedly the Italian poet Petrarch (1304-1374) who best embodies the ideals guiding the humanists of the Renaissance.

All his life, it is said, Petrarch tried to

« rediscover the very rich teaching of classical authors in all disciplines and, starting from this sum of knowledge, most often scattered and forgotten, to revive and pursue the research that these authors had begun. »

After following his parents to Avignon, Petrarch studied in Carpentras where he learned grammar, then in Montpellier, rhetoric, and finally in Bologna, where he spent seven years at the school of jurisconsults.

However, instead of studying law, which in those days paved the way to a brilliant career, Petrarch secretly read all the classics hitherto known, including Cicero and Virgil, despite the fact that his father occasionally burned his books.

Petrarch and Barlaam of Samara

Under the pontificate of Benedict XII, Petrarch tried to learn Greek language with the help of a learned monk of the Order of St. Basil, Barlaam of Seminara (1290-1348), known as Barlaam the Calabrian, who came to Avignon in 1339 as ambassador of Andronic III Paleologus in an unsuccessful attempt to put an end to the schism between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches.

A philosopher, theologian and mathematician, Barlaam, while having limited knowledge of Greek and Latin, was one of the first to wish that the study of the Greek language and philosophy be reborn in Europe.

In his Treatise On my own ignorance and that of many others (1367), Petrarch declared himself proud of his Greek manuscripts – and of his library in general – and expressed his deep admiration for Barlaam:

« I have at home sixteen works of Plato. I don’t know if my friends have ever heard the titles […]. And this is only a small part of Plato’s work, for I have seen, with my own eyes, a large number of them, especially in possession of the Calabrian Barlaam, a modern model of Greek wisdom who began to teach me Greek while I was still ignorant of Latin, and who might have done so successfully if death had not taken him away from me and hindered my honest plans, as usual.«

In 1350, two years after Barlaam’s death, Petrarch met the son of a banker, Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). The latter, like Petrarch, fell in love with the Greek culture and language. In his youth, in Naples, he too had met Barlaam and learned a few words of Greek, meticulously copying alphabets and verses, adding the Latin translation and pronunciation indications.

Boccaccio and Leontius Pilatus

To increase his mastery of Greek, Boccaccio then called from Thessaloniki a disciple of Barlaam, Leontius Pilatus (died in 1366), an austere, ugly and very bad-tempered character. But this Calabrian lectured him on Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and translated sixteen of Plato’s dialogues. How could one get angry with him?

Boccaccio offered him shelter and food for three years in his home and had a chair of Greek created for him in Florence, the first time ever!

Unfortunately, Pilatus did not really master this language. Although posing as a native Greek, the man had poor knowledge of ancient Greek and his translations never got beyond the level of word-for-word. As for the lessons he gave Petrarch, they were so brutal that he disgusted him forever.

This did not prevent Pilatus, at the insistence of Boccaccio, from translating Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey into Latin from a Greek manuscript sent to Petrarch by Nicolaos Sigeros, the Byzantine ambassador to Avignon.

Hence, history being what it is, it was thanks to this highly imperfect translation that Europe rediscovered one of the great founding works of its culture!

And on this fragile ground will rise a flame that will revolutionize the world.

« Was it not I, » writes Boccaccio in his Genealogy of the Gods, « who had the glory and honor of employing the first Greek verses among the Tuscans? Was it not I who, through my prayers, led Pilatus to settle in Florence and who housed him there? I brought at my own expense copies of Homer and other Greek authors when none existed in Tuscany. I was the first of the Italians to whom Homer, in particular, was explained, and then I had him explained in public.«

The hunt for manuscripts

What is important is that during these encounters Petrarch created a cultural network covering the whole of Europe, a network reaching into the East.

He then asked his relations and friends, who shared his humanist ideals, to help him find in their respective country or province, the Latin texts of the ancients that the libraries of abbeys, individuals or cities might possess. In the course of his own travels, he found several major texts that had fallen into oblivion.

It is in Liege (Belgium) that he discovered the Pro Archia and in Verona, Ad Atticum, Ad Quintum and Ad Brutum, all by Cicero. During a stay in Paris, he got his hands on the elegiac poems of Propertius, then, in 1350, on a work by Quintilian. In a constant concern to restore the most authentic text, he subjected these manuscripts to meticulous philological work and made corrections by comparing them with other manuscripts. This is how he reconstructed the first and fourth decades of the Roman History of Titus Livius from fragments and restored some of Virgil’s texts.

These manuscripts, which he kept in his own library, later came out in the form of copies and thus became accessible to the greatest number of people. While acknowledging that the pagans lacked the « true faith, » Petrarch believed that when one speaks of virtue, the old and new worlds are not at war.

The « Circolo di Santo Spirito »

From the 1360s onwards, Boccaccio gathered a first group of humanists known as the « Circolo di Santo Spirito » (Circle of the Holy Spirit), whose name was borrowed from the 13th century Florentine Augustinian convent.

An embryonic form of a university, its Studium Generale (1284) was then at the heart of a vast intellectual center including schools, hospices and refectories for the needy.

Before his death in 1375, Boccaccio, who had recovered part of Petrarch’s library, bequeathed to the convent his entire collection of precious ancient books and manuscripts.

Then, in the 1380s and early 1390s, a second circle of humanists met daily in the cell of the Augustinian monk Luigi Marsili (1342-1394). The latter, who had studied philosophy and theology at the universities of Paris and Padua, where he already established contact with Petrarch in 1370, became friends with Boccaccio. Hence, by attending the Cercle Santo Spirito from 1375 onwards, Coluccio Salutati in turn fell in love with Greek studies.

By inviting the Greek scholar Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415) to Florence to teach Ancient Greek, it was Salutati who gave the decisive impulse leading to the end of the schism between East and West and thus to the unification of the Churches, consecrated at the Council of Florence in 1439.

Roger Bacon

A century before Salutati, the English philosopher and scientist Roger Bacon (1214-1294), a Franciscan monk residing in Oxford, author of one of the first Greek grammars, already called for such a « linguistic revolution ».

As wrote Dean P. Lockwood in Roger Bacon’s Vision of the Study of Greek (1919):

« Obviously, Greek was the master-key to the great storehouse of ancient knowledge, Hebrew and Arabic to lesser chambers. Furthermore, we must not forget that in Bacon’s day the superiority of the ancients was an indisputable fact. The modern world has outstripped the Greek and the Romans in countless ways; the medieval thinkers were still climbing toward the Hellenic standard.

« Three things were clear to Roger Bacon: the need of Greek, the contemporary ignorance of Greek, and the feasibility of acquiring Greek. The same may be said of Hebrew, but Bacon rightly put Greek first. Bacon’s program was simple:

« 1. Seek out the native Byzantine Greeks resident in Europe, preferably grammarians. The latter were very few, of course, but might be found in the Greek monasteries of Southern Italy.

« 2. From these and from any other available sources let Greek books be sought. If this program were to be carried out, Bacon confidently prophetized that results would not be long in forthcoming.«

Leonardo Bruni

Manuel Chrysoloras, arrived in winter 1397, an event remembered by one of his most famous pupils, the humanist scholar Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444) and later chancellor of Florence at the time of the Council of Florence, as a great new opportunity: there were many teachers of law, but no one had studied Greek in northern Italy for 700 years.

Thanks to Chrysoloras, Bruni and Pier Paolo Vergerio the Elder were able to read Aristotle and especially Plato in the original Greek version.

Until then, in Europe, Christians knew the names of Pythagoras, Socrates and Plato by their reading of the church fathers Origen, St. Jerome and St. Augustine.

The latter, in his City of God, did not hesitate to affirm that the « Platonists », that is Plato and those who assimilated his teaching (Plato et qui eum bene intellexerunt), were superior to all other pagan philosophers.

As we have demonstrated elsewhere, in particular in our study on Raphael and the School of Athens, it is to a large extent Plato’s optimistic and Promethean philosophical approach, for whom knowledge comes above all from the capacity for hypothesis and not from the mere testimony of the senses as Aristotle claims, that clearly provided the sap that allowed the Renaissance tree to offer humanity so many wonderful fruits.

Traversari’s humanist circle

The most famous pupil of Chrysoloras was Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439), who became general of the Camaldolese order. Today honored as a saint by his order, Traversari was one of the first to conceptualize the type of “Christian Humanism” that would be promoted by Nicolaus of Cusa (Cusanus) and later Erasmus of Rotterdam (who framed the concept of “Saint-Socrates”) and the latter’s admirer Rabelais, uniting Plato with the Holy Scriptures, and the fathers of the Church.

Traversari, a key organizer of the Council of Florence, was also the personal protector of the great Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca and of the architect of the Dome Filippo Brunelleschi.

According to Vespasiano de Bisticci, the court historian of the Court of Urbino, Traversari had weekly working sessions on Plato and Greek philosophy at the Santa Maria degli Angeli convent with the crème de la crème of European humanism in the fields of literature, theology, science, politics, architecture, infrastructure, urban planning, education and the fine arts. Among those :

- The German cardinal-philosopher Nicholas of Cusa (Cusanus);

- Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, the great physician and cartographer, also friend and protector of Piero della Francesca and Leonardo da Vinci.

- The erudite manuscript collector Niccolò Niccoli, adviser to Cosimo the Elder, heir to the Medici’s industrial and financial empire. Considered at the time to be the richest man in the West, Cosimo was one of the patrons of the sculptor Donatello;

- Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, the future humanist pope Pius II;

- Leonardo Bruni, the apostolic secretary of Pope Innocent VII and his three successors. He succeeded Coluccio Salutati at the chancellery of Florence (1410-1411 and 1427-1444).

- The Italian statesman Carlo Marsuppini, passionate about Greek Antiquity, and successor of Bruni as Chancellor of the Republic of Florence after the latter’s death in 1444.

- The philosopher, antiquarian and writer Poggio Bracciolini. After having advised no less than nine popes (!), he was appointed Chancellor of the Republic of Florence following the death of Marsuppini in 1453;

- The politician and ambassador Gianozzi Manetti. In love with ancient Greek and Hebrew, his circle includes the éducator Francesco Filelfo, the banker Palla Strozzi and the founder of the Vatican library Lorenzo Valla ;

Chrysoloras in Florence

Chrysoloras remained only a few years in Florence, from 1397 to 1400, teaching Greek, starting with the rudiments. He moved on to teach in Bologna and later in Venice and Rome. Though he taught widely, a handful of his chosen students remained a close-knit group, among the first humanists of the Renaissance. As said before, among his pupils one could count some of the foremost figures of the revival of Greek studies in Renaissance Italy.

Aside from Bruni and Ambrogio Traversari, they included Guarino da Verona and the Florentine banker Palla Strozzi (1372-1462), later the friend and protector of the sculptor and translator Lorenzo Ghiberti. It is worth noting that Strozzi paid part of Chrysoloras’ salary and had the books necessary for the new teaching brought from Constantinople and Greece.

Chrysoloras went to Rome on the invitation of Bruni, who was then secretary to Pope Gregory XII. In 1408, he was sent to Paris on an important mission from the emperor Manuel II Palaeologus (1350-1425). In 1413, he went to Germany on an embassy to the emperor Sigismund, the object of which was to decide on the site for the church council that assembled at Constance in 1415. Chrysoloras was on his way there, having been chosen to represent the Greek Church, when he died that year.

Chrysoloras translated the works of Homer and Plato’s Republic from Greek into Latin. His Erotemata (Questions-answers), which was the first basic Greek grammar in use in Western Europe, circulated initially as a manuscript before being published in 1484.

Widely reprinted, it enjoyed considerable success not only among his pupils in Florence, but also among later leading humanists, being immediately studied by Thomas Linacre at Oxford and by Erasmus when he resided at Cambridge. It’s text became the basic manual used by pupils of the Three Language College set up by Erasmus in Leuven (Belgium) in 1515.

Traversari meets Chrysoloras during his two stays in Florence in the summer of 1413 and in January-February 1414, and the old Byzantine scholar is impressed by the bilingual culture of the young monk; he sends him a long philosophical letter in Greek on the theme of friendship. Ambrogio himself expresses in his letters the highest consideration for Chrysoloras, and emotion for the benevolence he showed him.

It should also be noted that the rich humanist scholar Niccolò Niccoli, a great collector of books, opened his library to Traversari and put him in constant contact with the scholarly circles of Florence (notably Leonardo Bruni, and also Cosimo de Medici, of whom he was advisor), but also of Rome and Venice.

In 1423, Pope Martin V sent two letters, one to the prior of the Convent of Santa Maria degli Angeli, Father Matteo, and the other to Traversari himself, expressing his support for the great development of patristic studies in this establishment, and especially for the work of translation of the Greek Fathers carried out by Traversari.

The Pope had in mind the negotiations he was conducting at the time with the Greek Church: at the beginning of 1423, his legate Antonio de Massa returned from Constantinople and brought back with him several Greek manuscripts which were to be entrusted to Traversari for translation: notably the Adversus Græcos by Manuel Calécas, and for the classics the Lives and Doctrines of the Illustrious Philosophers by Diogenes Laërtius, a text which circulated for a long time only in Traversari’s Latin translation.

It was following these undertakings that Traversari expressed his great interest in seeing the schism between the Latin and Greek Churches resolved. At the end of 1423, Niccolò Niccoli provides Traversari with an old volume containing the entire corpus of the ancient ecclesiastical canons, and the learned monk expresses in his correspondence with the humanist his enthusiasm for being able to immerse himself in the life of the then united ancient Christian Church, and in the process, he translates into Greek a long letter from Pope Gregory the Great to the prelates of the East.

Arrival of Plato’s mind

Were Bessarion and Plethon the first to bring the entire works of Plato to Europe?

Not really. While John Bessarion did indeed bring his own collection of the “complete works of Plato” in 1437 to Florence, they had already been brought to Italy earlier, most notably in 1423 by the Sicilian Giovanni Aurispa (1376-1459), who was the teacher of Lorenzo Valla (another collaborator with whom Cusanus exposed the fraud of the “Donation of Constantine” and a major source of inspiration of Erasmus).

In 1421 Aurispa was sent by Pope Martin V to act as the translator for the Marquis Gianfrancesco Gonzaga on a diplomatic mission to the Byzantine emperor, Manuel II Palaiologos.

After their arrival, he gained the favor of the emperor’s son and successor, John VIII Paleologus (1392-1448), who took him on as his own secretary. Two years later, he accompanied his Byzantine employer on a mission to the courts of Europe.

On 15 December 1423, 16 years prior to the Council of Florence of 1439, Aurispa arrived in Venice with the largest and finest collection of Greek texts to reach the west prior to those brought by Bessarion. In reply to a letter from Traversari, he says that he brought back 238 manuscripts.

These contained all of Plato’s works, most of them hitherto unknown in the West.

Plato’s works so far were only known very partially. In Sicily, Henry Aristippus of Calabria (1105-1162) had translated into Latin Plato’s Phaedo and Meno dialogues as early as 1160.

Evil neo-Platonist

Platonists (such as Petrarch, Traversari, Cusanus or Erasmus), have nothing to do and even violently opposed “Neo-platonist” (such as Plotinus, Proclus, Iamblicus, Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola) whose influence would create what could and should be called a “counter-Renaissance”.

Already Leibniz strongly warned against the “neo-Platonists” and demanded Plato be studied in his original writings rather than through his commentators, however brilliant they might be:

“non ex Plotino aut Marsilio Ficino, qui mira semper et mystica affectantes diceren tanti uiri doctrinam corrupere.”

[In English: Plato should be studied, but “Not from Plotinus nor Marsilio Ficino, who, by always striving to speak wonderfully and mystically, corrupt the doctrine of so great a man. »]

George Gemisthos « Plethon »

Now, let us enter Plethon, who thought Plato and Aristotle could each one play their own role. George Gemistos « Plethon » (1355-1452), was a follower of the radical “neo-Platonist” Michael Psellos (1018-1080). Around 1410 Gemistos created a “neo-Platonic” academy in Mistra (near the site of ancient Sparta) and added “Plethon” to his name to make it resemble to « Plato ». He was also an admirer of Pythagoras, Plato, and the “Chaldean Oracles”, which he ascribed to Zoroaster.

Gemistos came for the first time to Florence when he was fifteen years old and became an authority in Mistra. So at the time of the Council, the Emperor, John VIII Paleologus, knew they were going to face some of the finest minds in the Roman Church on their own soil; he therefore wanted the best minds available in support of the Byzantine cause to accompany him. Consequently, the Emperor appointed George Gemistos as part of the delegation. Despite the fact that he was a secular philosopher — a rare creature at this time in the West — Gemistos was renowned both for his wisdom and his moral rectitude. Among the clerical lights in the delegation were John Bessarion, Metropolitan of Nicaea, and Mark Eugenikos, Metropolitan of Ephesus. Both had been students of Gemistos in their youth. Another non-clerical member of the delegation was George Scholarios: both a future adversary of Gemistos and a future Patriarch of Constantinople as Gennadios II. Initially, Gemistos was opposed to the unity of the western and eastern churches.

Not assisting at every theological debate during the Council of Florence of 1439, he went in town to give lectures to intellectuals and nobles on the essence of Plato and Neo-platonic philosophy. Plethon also brought with him the text of the “Chaldean Oracles” attributed to Zoroaster.

While most of Plethon’s writing were burned, since he was suspected of heresy, a large number of Plethon’s autograph manuscripts ended up in the hands of his former student Cardinal Bessarion. On Bessarion’s death, he willed his personal library to the library of San Marco in Venice (where over 4000 Greeks resided). Among these books and manuscripts was Plethon’s Summary of the Doctrines of Zoroaster and Plato. This Summary was a summary of the Book of Laws, which Plethon wrote inspired by Plato’s laws. The Summary is a mixture of polytheistic beliefs with neo-Platonist elements.

While John Bessarion (1403-1472), a real humanist, took part in the Council in Ferrara (1437) and Florence (1439), and as the representative of the Greek, signed the decree of the Florentine Union, he held nevertheless to the principle: “I honor and respect Aristotle, I love Plato” (colo et veneror Aristotelem, amo Platonem). For him Platonic thought would have the right of citizenship equal to Aristotelian thought in the Latin world only when it appeared in an irenic interpretation to Aristotelianism and as not in contradiction with Christianity, since only such an interpretation of Platonism could succeed at that time.

Cosimo di Medici and Ficino

Did the Medicis finance a crash program to translate the works of Plato?

In 1397, Giovannni « di Bicci » de’ Medici (1360-1429) set up the Medici Bank. Giovanni owned two wool factories in Florence and was a member of two guilds: the Arte della Lana and the Arte del Cambio.

In 1402, he was one of the judges on the jury that selected Lorenzo Ghiberti’s design for the bronzes for the doors of the Baptistery of Florence.

In 1418, Giovanni di Bicci, wishing to endow his family with their own church, entrusted Filippo Brunelleschi, future architect of the famous dome of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fioro, the Duomo, with the task of radically transforming the basilica church of San Lorenzo and ordered Donatello to execute the sculptures.

Politically, the Medici family did not come to power until 1434, three years before the Council of Florence and at a time when the Renaissance was already in full swing.

Admittedly, Giovanni’s son and inheritor of his financial empire, Cosimo di Medici (1389-1464), known as the richest man of his epoch, became so inspired by Plethon that he acquired a complete library of Greek manuscripts. He bought a copy of the Platonic Corpus (24 dialogues) from Plethon, and a copy of the Corpus Hermeticum of Hermes Trismegistus, acquired in Macedonia by an Italian monk, Lionardo of Pistoia. Cosimo also decided to initiate a project to translate from the Greek into Latin, the totality of Plato’s works.

However, as said before, Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444), who after having been papal secretary became chancellor of the Florentine republic from 1427 till 1444, had already translated close to all of Plato’s works from Greek into Latin.

It should be underlined that the translator chosen by Cosimo was Marsilio Ficino (1433-99), the son of his personal physician and only five years old at the time of the Council of Florence in 1439. Cosimo had some severe doubts concerning Ficino’s capacities as translator. When the latter offers in 1456 his first translation, The Platonic Institutions, Cosimo asks him kindly not to publish this work and to learn first the Greek language… which Ficino learns then from Byzantine scholar John Argyropoulos (1415-1487), an Aristotelian pupil of Bessarion who rejected the Council of Florence’s epistemological revolution.

But seeing his age advancing and despite his unfortunate descent into corruption, Cosimo finally gave him the post. He allocates him an annual stipend, the required manuscripts and a villa at Careggi, close to Florence, where Ficino would set up his “Platonic Academy” with a handful of followers, among which Angelo Poliziano (1454-94), Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) and Cristoforo Landino (1424-1498).

Ficino’s “Academy”, taking up the ancient neo-platonic tradition of Plotinus and Porphyry (as Ficino states himself) would organize each year a ceremonial banquet “neglected since one thousand two hundred years” on November 7, thought to be simultaneously the birthday of Plato and the day of his death.

After the dinner, the attendants would read Plato’s Symposium and then each of them would comment on one of the speeches. The comments are demonstrations, without any real dialogue and void of the essence of real platonic thinking: irony. On top of that it is remarkable that most gatherings of Ficino’s academy were attended by the ambassador of Venice in Florence, notably the powerful oligarch Bernardo Bembo (1433-1519), father of “poet” cardinal Pietro Bembo, later special advisor to the evil Genovese “Warrior Pope” Julius II.

It was this alliance of the increasingly more degenerated Medici family, the Venetian Empire’s maritime slave trade and the anti-Platonic neo-Platonists that gained dominant influence over the Curia of the Roman Catholic Church. The Medici’s clearly disliked Da Vinci (who never got an order from the Vatican and subsequently left Italy), and through their propaganda man Vasari made the world belief that the Renaissance was exclusively their baby.

But before translating Plato, and at the specific demand of Cosimo, Ficino translated first (in 1462) the Orphic Hymns, the Sayings of Zoroaster, and the Corpus Hermeticum of Hermes Trismegistus the Egyptian (between 100 and 300 after BC).

It will be only in 1469 that Ficino will finish his translations of Plato after a nervous breakdown in 1468, described by his contemporaries as a crisis of “profound melancholy”.

In 1470, and with a title plagiarized from Proclus, Ficino wrote his “Platonic Theology or on the immortality of the Soul.” While completely taken in by esoteric neo-Platonism, he became a priest in 1473 and wrote “The Christian Religion” without changing his neo-platonic pagan outlook, producing an entire new series of translations of the neo-Platonists of Alexandria: he translated the fifty-four books of Plotinus “Enneads”, Porphyry and Proclus.

Ficino, in his “Five Questions Concerning the Mind” explicitly attacks the Promethean conception of man:

« Nothing indeed can be imagined more unreasonable than that man, who through reason is the most perfect of all animals, nay, of all things underheaven, most perfect, I say, with regard to that formal perfection that is bestowed upon us from the beginning, that man, also through reason, should be the least perfect of all with regard to that final perfection for the sake of which the first perfection is given. This seems to be that of the most unfortunate Prometheus. Instructed by the divine wisdom of Pallas, he gained possession of the heavenly fire, that is, reason. Because of this very possession, on the highest peak of the mountain, that is, at the very height of contemplation, he is rightly judged most miserable of all, for he is made wretched by the continual gnawing of the most ravenous of vultures, that is, by the torment of inquiry…” (…) “What do the philosophers say to these things? Certainly, the Magi, followers of Zoroaster and Hostanes, assert something similar. They say that, because of a certain old disease of the human mind, everything that is very unhealthy and difficult befalls us…«

The Florentine Neo-Platonic Academy, backed by the libido-driven Lorenzo de Medici (1449-1492) “The Magnificent”, will serve as a “Delphic” operation: defend Plato to better destroy him; praise him in such terms that he becomes discredited. And especially destroying Plato’s influence by opposing religion to science, at a point where Cusanus and his followers are succeeding to do exactly the opposite. Isn’t it bizarre that Cusa’s name doesn’t appear a single time in the works of Ficino or Pico della Mirandola, so overfed with all-encompassing knowledge?

Lorenzo did protect artists such as Sandro Botticelli, whose Birth of Venus exemplifies Lorenzo’s neo-platonic symbolism.

Infected with this evil neo-Platonism, Thomaso Inghirami (1470-1516), the chief librarian of pope Julius II, will accomplish nothing but this when dictating to the painter Raphaël the content of the Stanza in the Vatican some decades later.

Neo-platonic “melancholy”, which Albrecht Dürer went after in his famous engraving, will become the matrix for the romantics, the destructive virus affecting the symbolists and the so-called modern school. As for the revolution that Greek studies will bring about in the sciences, I refer you to our article on this website: 1512-2012: From Cosmography to Cosmonauts, Gerard Mercator and Gemma Frisius.

To conclude, here is a short list of translators, and I certainly forgot some of them, and their mastery of foreign languages. Even if some of them can’t be called « humanists », let’s thank them for everything they allowed us to discover. I’m profoundly convinced that without them, man would certainly not have set foot on the Moon!

- Marcus Tullius Cicero 106-43 BC: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Philo of Alexandria 20 BC – 40 AD: hebrew, Greek;

- Origen of Alexandria 184 – 253: Greek and Latin;

- Jerome of Stridon 342-420: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Boethius 477-524: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Bede the Venerable 672-735: English, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Charlemagne 742-814, spoke Latin and understood Greek, Hebrew and Slavonic;

- John Scotus Eriugena 800-876: Irish, Greek, Arab and Hebrew;

- Ḥunayn ibn Isḥaq 809-873: Arabic, Syriac, Persian and Greek;

- Thābit ibn Qurra 826-901: Syriac, Arabic and Greek;

- Al-Fârâbi 872-950: Farsi, Sogdian and Greek;

- Al–Biruni, 973-1048: Chorasmian, Farsi, Frabic, Syriac, Sanskrit, Hindi, Hebrew and Greek ;

- Adelard of Bath 1080-1152: English, Latin and Arabic;

- Héloïse 1092-1141: French, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Hugh of Saint Victor 1096-1141: French, Latin, Greek;

- Constantine the African XIth Cent: Arabic, Latin, Greek and Italian;

- John Sarrazin XIIth Cent: Latin and Greek;

- Henricus Aristippus 1105-1162: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Gerard of Cremona 1114-1187: Italian, Latin and Arabic;

- Robert Grosseteste 1168-1253: English, Latin and Greek;

- Michael Scot 1175-1232: Scottish, Latin, Greek, Arab and Hebrew;

- Moses of Bergamo (XIIth Century): Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Burgundio of Pisa (XIIth Century): Italian, Latin and Greek;

- James of Venice (second half IIth Century, dies after 1147): Italian, Latin and Greek ;

- Roger Bacon 1214-1294: English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic and Chaldean ;

- William of Moerbeke 1215-1286: Dutch, Latin and Greek;

- Raymond Lull 1232-1315: Catalan, Latin and Arabic;

- Arnaldus de Villa Nova 1240-1311: Catalan, Latin, Greek and Arabic;

- Dante Alighieri 1265-1321: Italian and Latin;

- Francesco Petrarch 1304-1375: Italian and Latin;

- Giovanni Boccaccio 1313-1375: Italian and Latin;

- Coluccio Salutati 1331-1406: Italian and Latin;

- Geert Groote 1340-1384: Dutch, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Florens Radewijns 1350-1400: Dutch and Latin;

- Manuel Chrysoloras 1355-1415: Greek, Latin and Italian;

- Georgius Gemistus « Pletho » 1360-1452: Greek;

- Jacopo d’Angelo 1360-1410, Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Pier Paolo Vergerio (the Elder) 1370-1445: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Leonardo Bruni 1370-1441: Italian, Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Arabic;

- Guarino Guarini 1370-1460: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Palla di Onofrio Strozzi 1372-1462: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Giovanni Aurispa 1376-1459: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Vittorino da Feltre 1378-1446: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Poggio Bracciolini 1380-1459: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Ambrogio Traversari 1386-1439: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Gianozzo Manetti 1396-1459: Italian, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Georges of Trebizond 1396-1472: Greek, Latin and Italian;

- Tommaso Perentucelli (Pope Nicolas V) 1397-1494: Italian and Latin;

- Francesco Filelfo 1398-1481: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Carlo Marsuppini 1399-1453: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Theodorus Gaza 1400-1478: Greek and Latin;

- John Bessarion 1403-1472: Greek, Latin and Italian;

- Lorenzo Valla 1407-1457: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Nicolas of Cusa 1401-1464: German and Latin;

- John Wessel Gansfoort 1419-1489: Dutch, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Georg von Peuerbach 1423-1461: German, Latin and Greek;

- Demetrios Chalkokondyles 1423-1511: Greek and Latin;

- Marcilio Ficino 1433-1499: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Constantine Lascaris 1434-1501: Greek, Latin and Italian;

- Regiomontanus 1436-1476: German, Latin and Greek;

- Alexander Hegius 1440-1498: Dutch, Latin and Greek;

- Rudolf Agricola 1444-1485: Dutch, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Janus Lascaris 1445-1535: Greek and Latin;

- William Grocyn 1446-1519,: English, Latin and Greek;

- Poliziano 1454-1494: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Johannes Reuchlin 1455-1522: German, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

- Thomas Linacre 1460-1524: English, Latin and Greek;

- Erasmus of Rotterdam 1467-1536: Dutch, Latin and Greek;

- William Latimer 1467-1545 : English, Latin and Greek;

- Guillaume Budé 1467-1540: French, Latin and Greek;

- Marcus Musurus 1470-1517: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Willibald Pirckheimer 1470-1530: German, Latin and Greek;

- Pietro Bembo 1470-1547: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Thomas More 1478-1535: English, Latin and Greek;

- Girolamo Aleandro, 1480-1542: Italian, Latin and Greek;

- Germain de Brie 1490-1538: French, Latin and Greek;

- Juan Luis Vivès 1492-1540: Spanish, Latin, Greek and Hebrew;

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance

Tags: Aristippus, Aristotle, artkarel, Augustine, Aurispa, Barlaam, Bessarion, Boccaccio, Bologna, Bracciolini, Brunelleschi, Bruni, Chrysoloras, Cicero, Classical Greek, Cosimo, Cusa, Da Vinci, Dante, Donatello, Dürer, Erasmus, Ficino, Filelfo, Florence, greek, hebrew, Ingirami, Julius II, Karel, Karel Vereycken, language, latin, Leontius Pilatus, Linacre, Manetti, Marsuppini, Medicis, Mirandola, neo-platonists, Origen, Padua, Petrach, Piccolomini, Piero della Francesca, Plato, Plethon, Plotinus, Porphyry, Proclus, Raphael, Rome, Salutati, Santo Spirito, School of Athens, Socrates, Strozzi, toscanelli, Traversari, Valla, Vasari, Vereycken, Virgil