Étiquette : persian wheel

The science of Oases, from the Indus Valley to Persian qanats

Presentation of Karel Vereycken at the first panel discussion of the « Water for Peace » seminar organized by the Schiller Institute on January 9, 2024 in Paris.

While the dog was domesticated as early as 15,000 years BC, we associate the first human activities aimed at managing water with the Neolithic period, which began around 10,000 BC.

It is thought to be the moment at which mankind moved from a « tribal subsistence economy of hunter-gatherers » to agriculture and animal husbandry, giving rise to villages and cities, where pottery, weaving, metallurgy and the arts would start blooming.

Key to this, the domestication of animals. The goat was domesticated around 11,000 BC, the cow around 9,000 BC, the sheep around -8,000 BC, and finally the horse around 2,200 BC in the steppes of Ukraine.

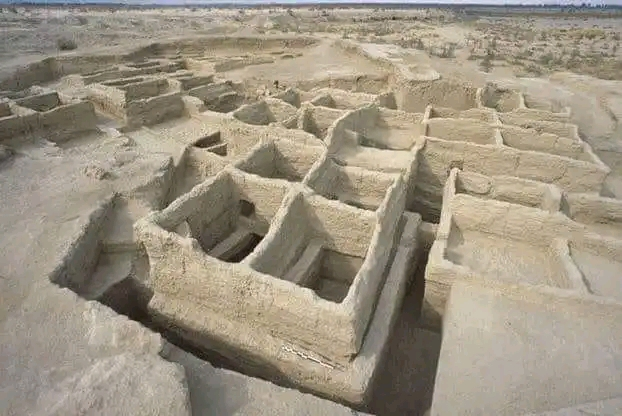

The oldest archaeological sites showing agricultural activities and irrigation techniques were discovered in the Indus Valley and the « Fertile Crescent ».

The site of Mehrgarh, in the Indus Valley, now Pakistan Balochistan, discovered in 1974 by François and Cathérine Jarrige, two French archaeologists, demonstrates important agricultural practices from 7000 BC onward.

Cotton, wheat and barley were grown, and beer was brewed. Cattle, sheep and goats were raised. But Mehrgarh was much more than that.

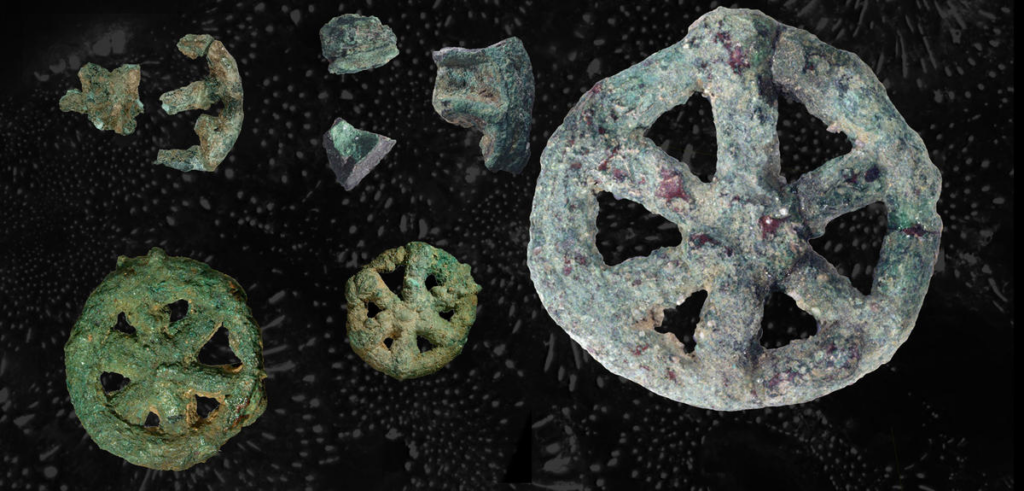

Contradicting the linear « developmental » schema, since we’re in the middle of the Neolithic, Mehrgarh is also home to the oldest pottery in South Asia and, above all, to the “Mehrgahr amulet”, the oldest bronze object casted with the « lost-wax » method.

The first seals made of terracotta or bone and decorated with geometric motifs were found here.

On the technological side, tiny bow drills were used, possibly for dental treatment, as evidenced by the pierced teeth of some skeletons found on site.

At the same time, or shortly afterwards, around 6000 B.C., Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, witnessed rapid urban development in terms of demographics, institutions, agriculture, techniques and trade.

A veritable « fertile crescent » emerged in the region stretching from Sumer to Egypt, passing through the whole of Mesopotamia and the Levant, i.e. Syria and the Jordan Valley.

Irrigation

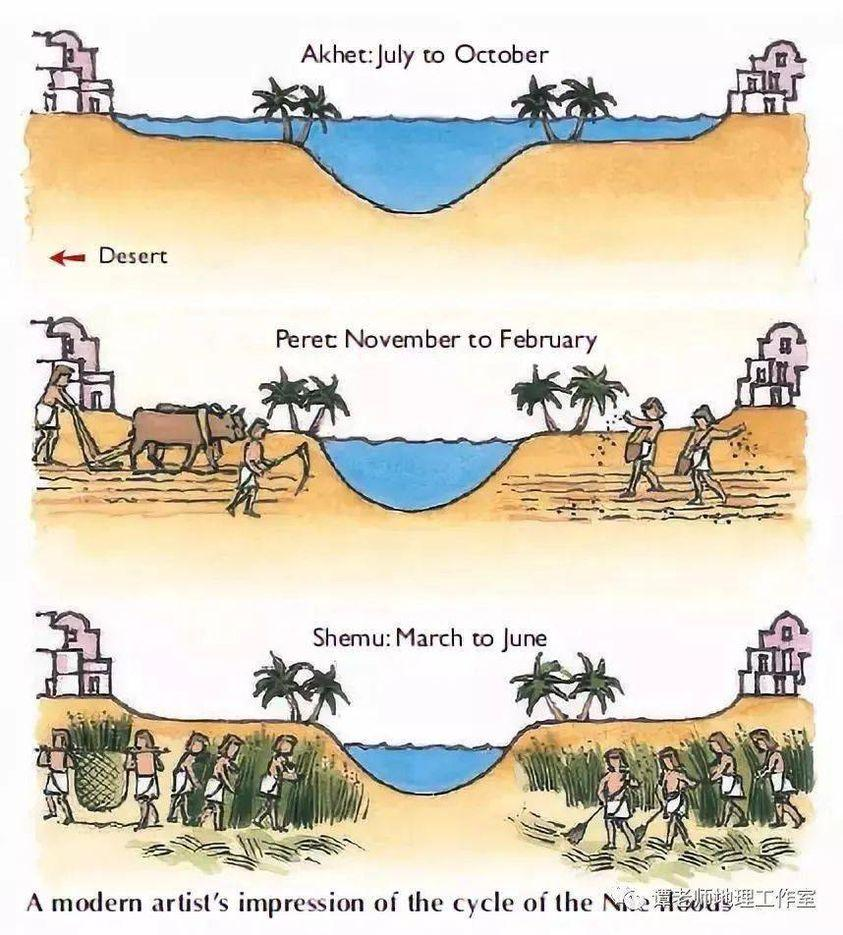

Whether in the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia or Egypt, the earliest irrigation techniques are nothing but retaining as much water as possible when Mother Nature has the sweet kindness to offer it to mankind.

Rainwater was collected in cisterns and, as much as possible, when snowmelt or monsoon rains swell the rivers, the objective was to amplify and steer seasonal « flooding » by canals and trenches carrying the water as far away as possible to areas to be cultivated, while at the same time protecting crops.

In Egypt, for example, where the Nile rises by around 8 meters, the water brings not only moisture but also silt to the soil near the river, providing crops with the nutrients they need to grow and thus maintain the soil’s fertility.

While the Egyptians complained about the harsh labor condition of their farmers, for the Greek historian Herodotus, this was the place in the world where work was least arduous. Of Egypt he says:

“Its soil is black and crumbly, made of silt and alluvium brought from Ethiopia by the river. Certainly, these people are today, of all the human race in Egypt as elsewhere, those who go to the least trouble to obtain their crops.

« They don’t bother to plough and weed. When the river has come of its own accord to water their fields and, its task done, has withdrawn, each man sows his land and lets the pigs loose: by trampling, the beasts sink the seeds into the earth, and the man has only to wait for the harvest.”

In Mehrgarh, where agriculture was born from 7000 BC, the work was indeed far more demanding.

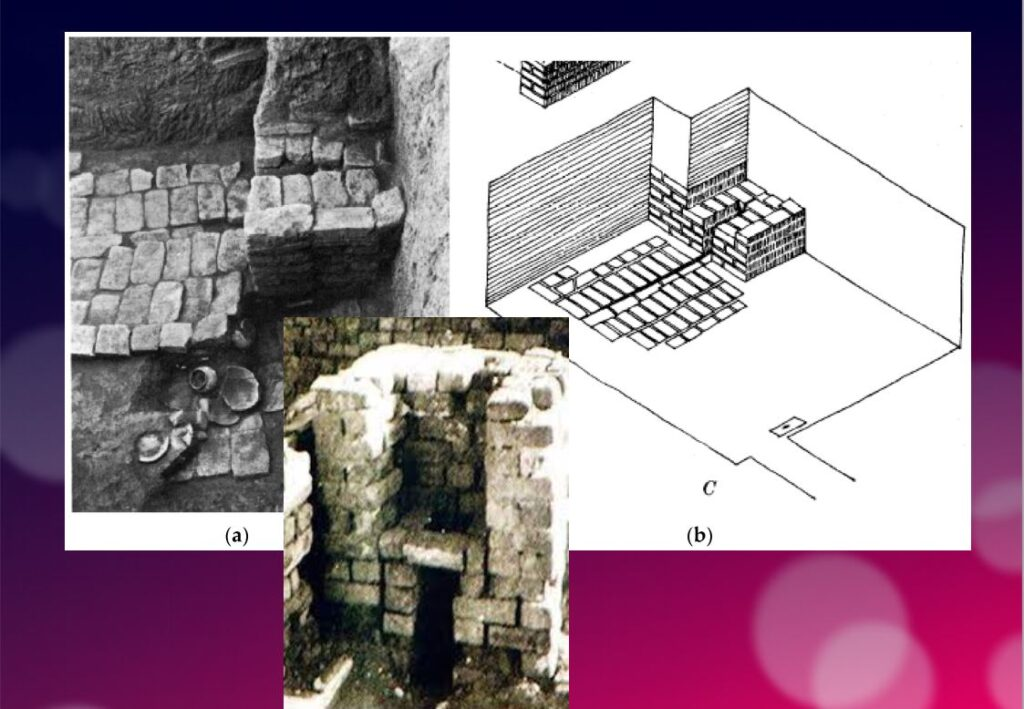

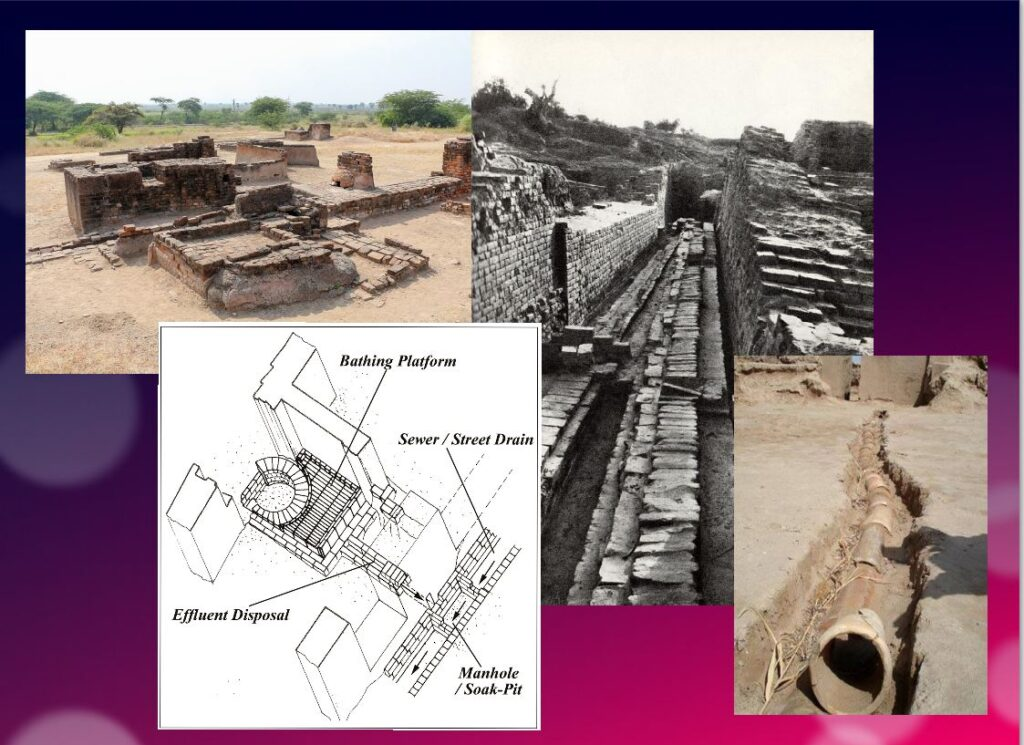

However, the drainage system around the village and the rudimentary dams to control water-logging indicate that the inhabitants understood most of the basic principles involved. The cultivation of cotton, wheat and barley, as well as the domestication of animals, show that they were also familiar with canals and irrigation systems.

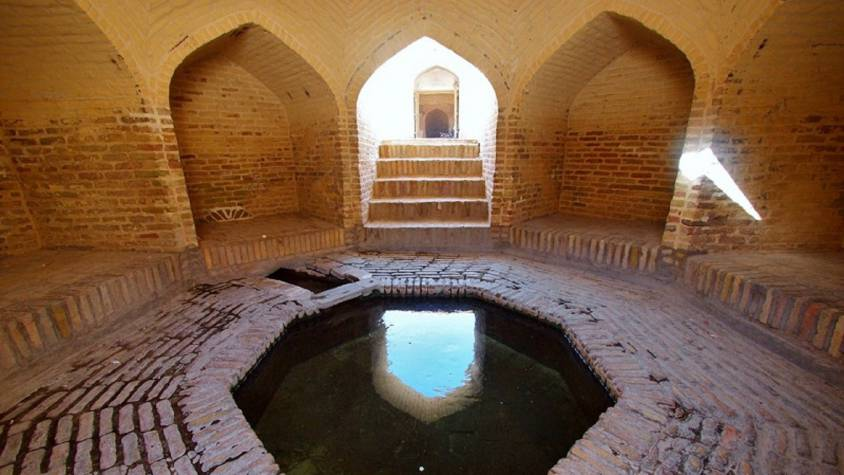

Constantly refined, this know-how enabled the civilization of the Indus Valley to create great cities that impress us by their modernity, notably Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, a city of 40,000 inhabitants with a public bath in its center, not a palace.

Pioneers of modern hygiene, these towns were equipped with small containers where residents could deposit their household waste.

Anticipating our « all-to-the-sewer » systems imagined in the early XVIth century by Leonardo da Vinci, for example in his plans for the new french capital of Romorantin, many towns had public water supplies as well as an ingenious sewage system.

In the port city of Lothal (now India), for example, many homes had private brick bathrooms and latrines. Wastewater was evacuated via a communal sewage system leading either to a canal in the port, or to a soaking pit outside the city walls, or to buried urns equipped with a hole for the evacuation of liquids, which were regularly emptied and cleaned.

Excavations at the Mohenjo Daro site reveal the existence of no fewer than 700 brick wells, houses equipped with bathrooms and individual and collective latrines.

Many of the city’s buildings had two floors or more. Water trickled down from cisterns installed on the roofs was channeled through closed clay pipes or open gutters that emptied into the covered sewers beneath the street.

This hydraulic and sanitary know-how was passed on to the civilization of Crete, the mother of Greece, before being implemented on a large scale by the Romans.

It was forgotten with the collapse of the Roman Empire, only to return during the Renaissance.

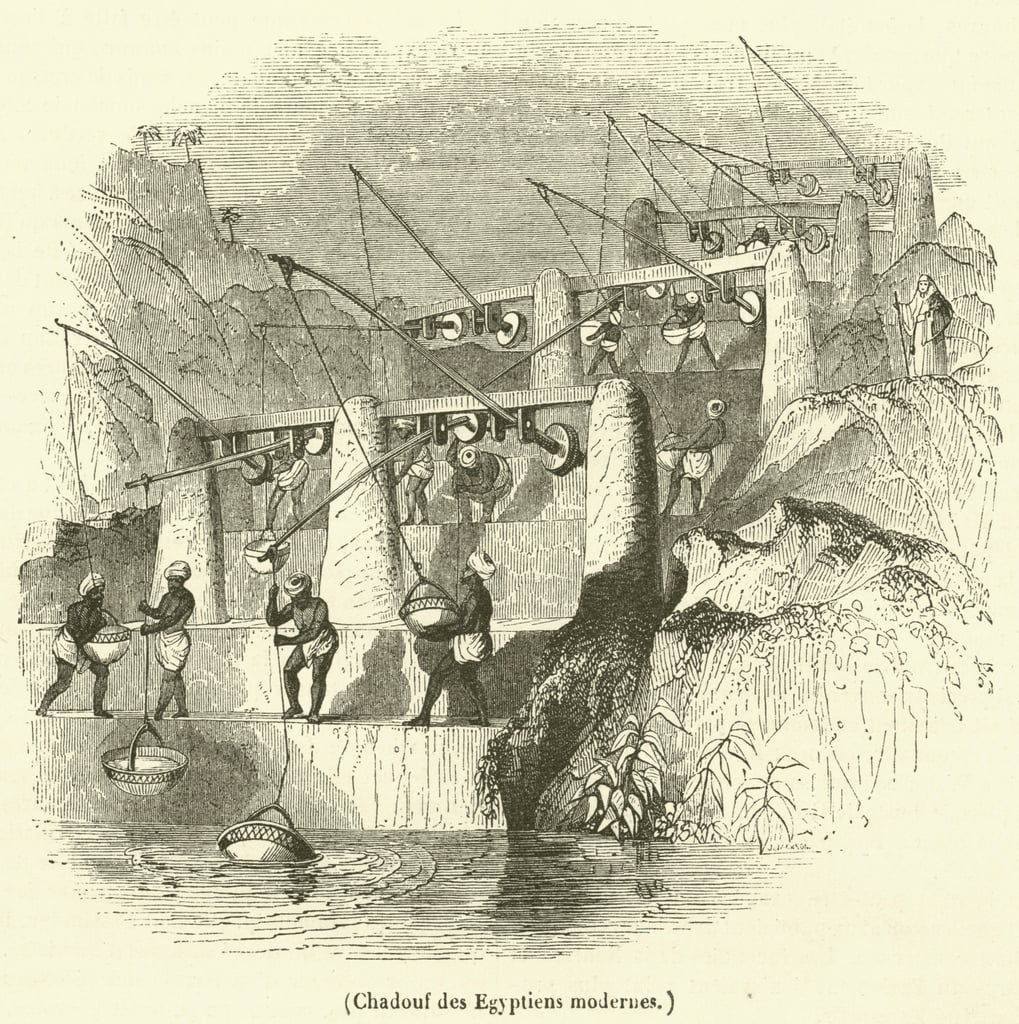

The first human contributions were aimed at maximizing water reservoirs and their gravity-flow capacity. To achieve this, it was necessary to transfer water from a lower level to higher ground and build « water towers ».

To this end, the Mesopotamian « chadouf » was widely used in Egypt, followed by the « Archimedean screw ».

Next came the « saquia » or « Persian wheel », a geared wheel driven by animal power, and finally the « noria », the best-known water-drawing machine, powered by the river itself.

Persian qanats

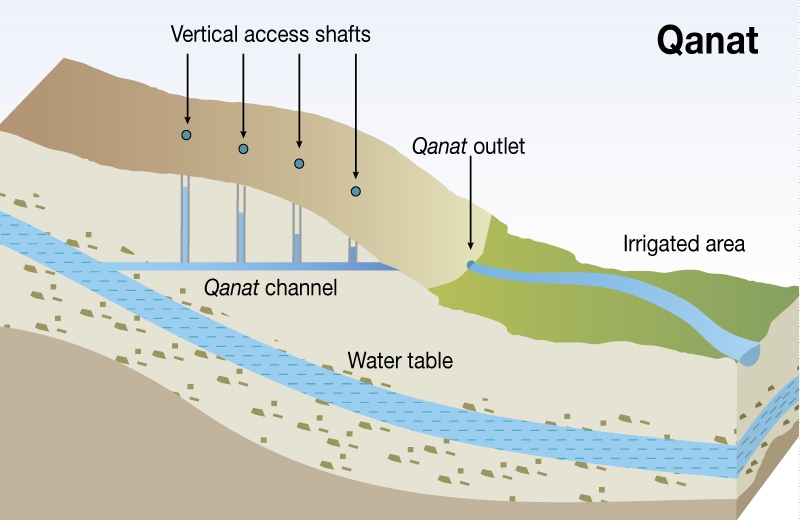

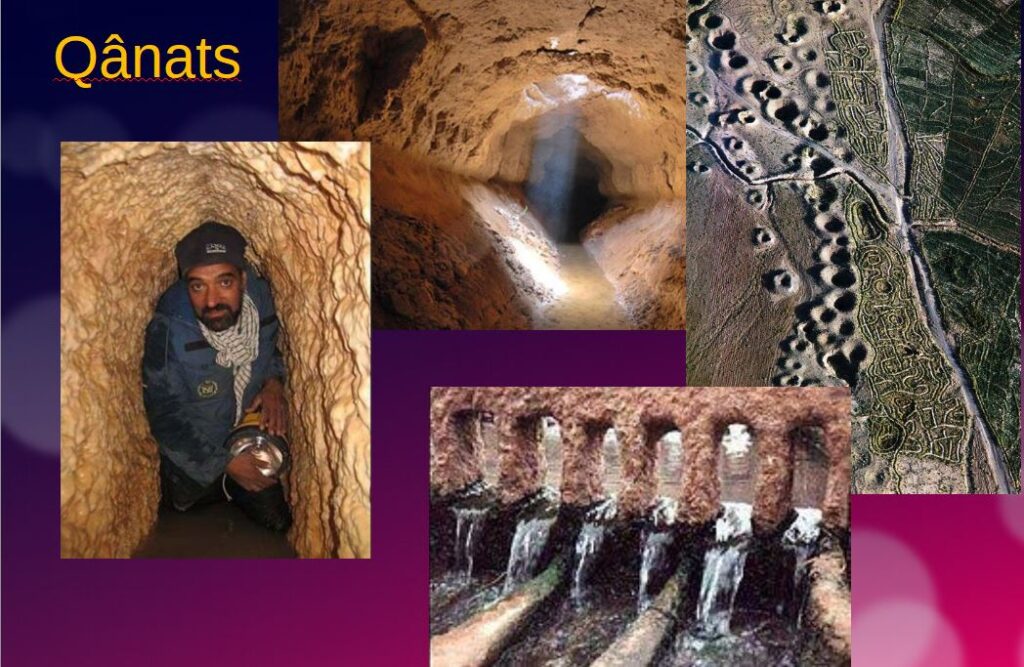

Before Alexander the Great, Persia’s Achaemenid Empire (6th century BC) developed the technique of underground qanats or underground aqueducts. This « draining gallery” cut into the rock or built by man, is one of the most ingenious inventions for irrigation in arid and semi-arid regions.

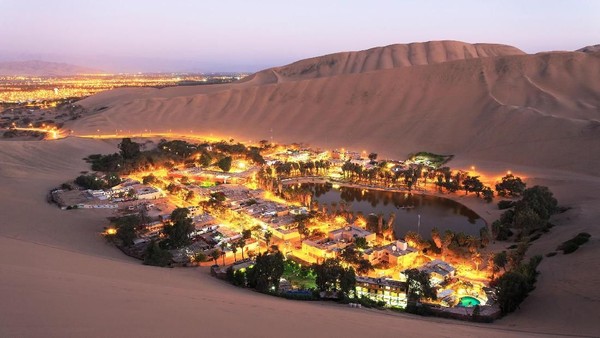

Whatever displeases our environmentalist friends, it’s not nature that magically produces « oases » in the desert.

It’s a scientific man who digs a drainage gallery from a water table close enough to the ground surface, or sometimes from an aquifer that flows into the desert.

On the website of ArchéOrient, archaeologist Rémy Boucharlat, Director of Emeritus Research at the French CNRS, an expert on Iran, explains:

« Whatever the origin of the water, deep or shallow, the gallery construction technique is the same. The first step is to identify the presence of the water, either its underflow near a river, or the presence of a deeper water table on a foothill, which requires the science and experience of specialists.

A motherwell reaches the upper part of this layer or water table, which indicates the depth at which the gallery should be dug. The slope of the gallery must be very shallow, less than 2‰, to ensure a calm and regular flow of water, and to gradually lead the water to the surface, at a gradient much lower than the slope of the piedmont.

The gallery is then excavated, not from the mother well, as it would be flooded immediately, but from downstream, from the arrival point. The pipe is first dug as an open trench, then covered, and finally gradually tunnelled into the ground.

Shafts are dug from the surface at regular intervals, between 5 and 30 m depending on the nature of the terrain, to evacuate soil and provide ventilation during excavation, and to mark the direction of the tunnel.”

Historically, the majority of the populations of Iran and other arid regions of Asia and North Africa depended on the water supplied by qanats; settlement areas thus corresponded to the places where their construction was possible.

The technique offers a significant advantage: as the water moves through an underground conduit, not a drop of water is lost through evaporation.

This technique spread throughout the world under various names: qanat and kareez in Iran, Syria and Egypt, kariz, kehriz in Pakistan and Afghanistan, aflaj in Oman, galeria in Spain, kahn in Balochistan, kanerjing in China, foggara in North Africa, khettara in Morocco, ngruttati in Sicily, bottini in Siena, etc.).

Improved by the Greeks and amplified by the Etruscans and the Romans, the qanats technique was carried by the Spaniards across the Atlantic to the New World, where numerous underground canals of this type still operate in Peru, Chile and western Mexico.

After Alexander the Great, Bactria, covering parts of today’s Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and the northern part of Afghanistan, was even known as the « Oasis civilization » or the “Land of a 1000 Golden Cities”.

Iran boasts it had the highest number of qanats in the world, with approximately 50,000 qanats covering a total length of 360,000 km, about 9 times the circumference of the Earth !

Thousands of them are still operational but increasingly destabilized by erratic well digging and demographic overconcentration.

Shared responsability

In 1017, the Baghdad-based hydrologist Mohammed Al-Karaji provided a detailed description of qanat construction and maintenance techniques, as well as legal considerations about the collective management of wells and pipes.

While each qanat is designed and supervised by a mirab (dowser-hydrologist and discoverer), building a qanat is a collective task that takes several months or years for a village or group of villages. The absolute necessity of collective investment in the infrastructure and its maintenance calls for a superior notion of the common good, an indispensable complement to the notion of private property that rains and rivers are not accustomed to respecting.

In North Africa, the management of water distributed by a khettara (the local name for qanâts) is governed by traditional distribution norms known as « water rights ».

Originally, the volume of water granted per user was proportional to the work involved in building the khettara, and translated into an irrigation period during which the beneficiary could use all the khettara’s flow for his or her fields. Even today, when the khettara has not dried up, this rule of water rights still applies, and a share can be bought or sold. The size of each family’s fields to be irrigated must also be taken into account

All of this demonstrates that good cooperation between man and nature can do miracles if man decides so.

Thank you for your attention and questions welcome!