Étiquette : Christian

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on décembre 8, 2023

Joachim Patinir and the invention of landscape painting

In November 2008, a symposium was held at the Centre d’études supérieures sur la Renaissance in Tours on the theme of « Contemplation in Flemish painting (14th-16th centuries) ».

Here is a transcript of the contribution by Karel Vereycken on Joachim Patinir, a little-known Belgian painter who is essential to the history of art.

It is generally believed that the « modern » concept of landscape in Flemish painting only emerged with the work of Joachim Patinir (1485-1524), a Dinant-born painter working in Antwerp in the early 16th century.

For Viennese art historian Ludwig von Baldass (1887-1963), writing at the beginning of the 20th century, Patinir‘s work, presented as clearly ahead of its time, would herald landscape as überschauweltlandschaft, translatable as « panoramic landscape of the world », a truly cosmic and totalizing representation of the visible universe.

What characterizes Patinir‘s work, say the proponents of this analysis, is the sheer scale of the landscapes it presents for the viewer to contemplate.

This breadth has a dual character: the space depicted is immense (due to a panoramic viewpoint situated high up, almost « celestial »), while at the same time it encompasses, without concern for geographical verisimilitude, the greatest possible number of different phenomena and representative specimens, typical of what the earth can offer as curiosities, sometimes even imaginary, dreamlike, unreal, fantastic motifs: fields, woods, anthropomorphic mountains, villages and cities, deserts and forests, rainbows and storms, swamps and rivers, rivers and volcanoes.

For example, the « Bayart Rock », which borders the Meuse not far from Patinir‘s native town of Dinant.

In addition to this panoramic perspective, Patinir uses aerial perspective – theorized at the time by Leonardo da Vinci – by dividing the space into three color planes: brown-ochre for the first plane, green for the middle plane and blue for the distant plane.

However, the painter preserves the visibility of the totality of details with a meticulousness, minutiae and preciousness worthy of the Flemish masters of the XVth century, who, by tending towards a quantitative infinity (consisting in showing everything), sought to approach a qualitative infinity (allowing us to see everything).

For their part, the authors of the weltlandschaft thesis, after showering with praise, do not hesitate to strongly relativize his contribution, saying:

« For landscape painting to become anything other than a virtuoso but compulsive accumulation of motifs, and more precisely, the quasi-documentary capture of an infinitesimal fragment of contingent reality, we have to wait for the XVIIth century and the full maturity of Dutch painting… ».

And it’s here that the trap of this approach, which consists in making us believe that the advent of landscape as an autonomous genre, its so-called « secularization », is simply the result of emancipation from a medieval and religious mental matrix, considered necessarily retrograde, for which landscape was reduced to a pure emanation or incarnation of divine power, is clearly identified.

Patinir, the first, would thus have demonstrated a purely « modern » aesthetic conception, and these « realistic » landscapes would mark the transition from a religious – and therefore obscurantist – cultural paradigm to a modern one, i.e. one devoid of meaning… which he would later be criticized for.

This is how the romantic and fantastic minds of the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries viewed the artists of the XVth and XVIth centuries.

Von Baldass was undoubtedly influenced by the writings of Goethe, who, no doubt in a moment of enthusiasm for Greek paganism, analyzed the increasingly diminished role of religious figures in XVIth-century Flemish paintings and deduced that it was no longer the religious subject that was the subject, but the landscape.

Just as Rubens would have used the pretext of painting Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise to be able to paint nudes, Patinir would simply have seized the pretext of a biblical passage to be able to indulge his true passion, landscape…

A little detour via Hieronymus Bosch

A fresh look at Patinir’s work clearly demonstrates the error of this analysis.

To arrive at a more accurate reading, I suggest a detour to Hieronymus Bosch, whose spirit was very much alive among Erasmus‘ circle of friends in Antwerp (Gérard David, Quentin Massys, Jan Wellens Cock, Albrecht Dürer, etc.), of which Patinir was a member.

Bosch, contrary to the clichés still in vogue today, is above all a pious and moralizing spirit. If he shows vice, it’s not so much to praise it as to make us aware of just how much it attracts us. Faithful to the Augustinian traditions of Devotio Moderna, promoted by the Brothers of the Common Life (a spiritual renewal movement to which he was close), Bosch believes that man’s attachment to earthly things leads him to sin. This is the central theme of all his work, the spirit of which can only be penetrated by reading The Imitation of Christ, written, in all probability, by the founding soul of the Devotio Moderna, Geert Groote (1340-1384), or his disciple, Thomas à Kempis (1379-1471), to whom this work is generally attributed.

In this work, the most widely read in human history after the Bible, we read:

« Vanity of vanities, all is vanity, except loving God and serving Him alone.

Sovereign wisdom is to strive for the kingdom of heaven by despising the world.

—Vanity, then, to hoard perishable riches and hope in them.

—Vanity to aspire to honors and to rise to the highest.

—Vanity, to follow the desires of the flesh and seek that for which one must soon be rigorously punished.

—Vanity, to wish for a long life and not care about living well.

—Vanity, to think only of the present life and not to foresee what will follow it.

—Vanity, to cling to what passes so quickly and not hasten towards the joy that never ends.

Remember often the words of the wise man: the eye is not satisfied with what it sees, nor the ear with what it hears.

Apply yourselves, therefore, to detaching your heart from the love of visible things, to bring it entirely to the invisible ones, for those who follow the lure of their senses defile their souls and lose the grace of God. »

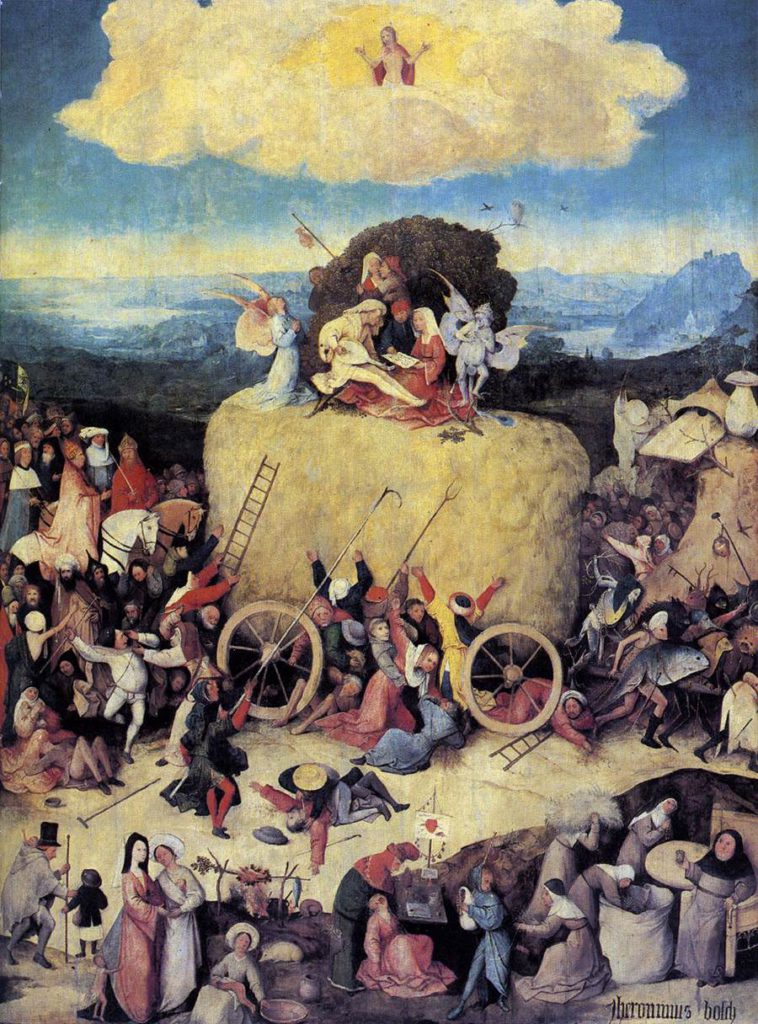

Bosch treats this subject with great compassion and humor in his painting The Hay Wagon (Prado Museum, Madrid).

The allegory of straw already exists in the Old Testament. Isaiah 40:6 :

« All flesh is grass,

and all its brightness like the flower of the field;

The grass withers, the flower withers,

when the breath of Yahweh passes over it.

« Yes, the people are grass.

The grass withers, the flower withers,

but the word of our God

is fulfilled forever.«

It was echoed in the New Testament by the apostle Peter (1:24):

« For all flesh is like grass,

and all its glory like the flower of grass.

The grass withers,

and the flower falls. »

Johannes Brahms uses this passage in the second movement of his German Requiem.

Bosch‘s triptych depicts a hay wagon, an allegory of the vanity of earthly riches, pulled by strange creatures on their way to hell.

The Duke of Burgundy, the Emperor of Germany and even the Pope himself (this is the time of Julius II…) follow close behind, while a dozen or so characters fight to the death for a blade of straw. It’s a bit like the huge speculative securities bubble that is leading our era into a great depression…

It’s easy to imagine the bankers who sabotaged the G20 summit to perpetuate their system, which is so profitable in the very short term. But this corruption doesn’t just affect the big boys. In the foreground of the picture, an abbot has entire sacks of hay filled, a false dentist and also gypsies cheat people for a bit of straw.

The peddler and the Homo Viator

The closed triptych sums up the same topos in the form of a peddler (not the prodigal son). This peddler, eternal homo viator, is an allegory of Man who fights to stay on the right path and insists on staying on it.

In another version of the same subject painted by Bosch (Museum Boijmans Beuningen, Rotterdam), the peddler advances op een slof en een schoen (on a slipper and a shoe), i.e. he chooses precariousness, leaving the visible world of sin (we see a brothel and drunkards) and abandoning his material possessions.

With his staff (symbol of faith), he fends off the infernal dogs (symbol of temptation), who try to hold him back.

Once again, these are not manifestations of Bosch‘s exuberant imagination, but of a metaphorical language common at the time. We find this representation in the margin of the famous Luttrell Psalter, a XIVth-century English psalter.

This theme of homo viator, the man who detaches himself from earthly goods, is also recurrent in the art and literature of this period, particularly since the Dutch translation of Pèlerinage de la vie et de l’âme humaine (pilgrimage of life and the human soul), written in 1358 by the Norman Cistercian monk Guillaume de Degulleville (1295-after 1358).

A miniature from this work shows a soul on its way, dressed as a peddler.

Nevertheless, while in the XIVth century this spiritual requirement may have dictated a sometimes excessive rigorism, the liberating laughter of nascent humanism (Brant, Erasmus, Rabelais, etc.) would bring happier, freer colors to Flemish Brabant culture (Bosch, Matsys, Bruegel), albeit later stifled by the dictates of the Council of Trent.

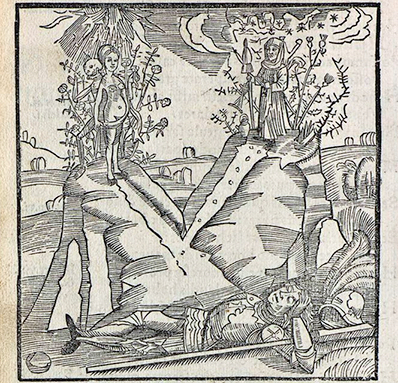

Man’s foolish attachment to earthly goods became a laughing matter. Published in Basel in 1494, Sébastien Brant’s Ship of Fools, a veritable inventory of all the follies that can lead man to his doom, left its mark on an entire generation, which rediscovered creativity and optimism thanks to the liberating laughter of Erasmus and his disciple, the Christian humanist François Rabelais.

In any case, for Bosch, Patinir and the Devotio Moderna, contemplation was the very opposite of pessimism and scholastic passivity. For them, laughter is the ideal antidote to despair, acedia (weariness) and melancholy.

Contemplation thus took on a new dimension. Each member of the faithful is encouraged to live out his or her Christian commitment, through personal experience and individual imitation of Christ. They must stop blaming themselves on the great figures of the Bible and Sacred History.

Man can no longer rely on the intercession of the Virgin Mary, the apostles and the saints. While following their examples, he must give personal content to the ideal of the Christian life. Driven to action, each individual, fully aware of his or her sinful nature, is constantly led to choose good over evil. These are just a few of the cultural backgrounds that enable us to approach Patinir’s landscapes in a different way.

Charon crossing the Styx

Patinir’s painting Charon Crossing the Styx (Prado Museum, Madrid), which combines ancient and Christian traditions, will serve here as our « Rosetta stone ». Inspired by the sixth book of the Aeneid, in which the Roman writer Virgil describes the catabasis, or descent into hell, or Dante‘s Inferno (3, line 78) taken from Virgil, Patinir places a boat at the center of the work.

The tall figure standing in this boat is Charon, the Ferryman of the Underworld, usually portrayed as a gloomy, sinister old man. His task is to ferry the souls of the deceased across the River Styx.

In payment, Charon takes a coin placed in the mouths of the corpses. The passenger in the boat is thus a human soul.

Although the scene takes place after the person’s physical death, the soul – and this may come as a surprise – is tormented by the choice between Heaven and Hell.

Since the Council of Trent, it has been considered that a bad life irrevocably sends man to Hell from the moment of his death. But Christian faith continues, even today, to distinguish the Last Judgment from what is known as the « particular judgment ».

According to this concept, which is sometimes disputed within denominations, at the moment of death, although our final fate is fixed (Hebrews 9:27), all the consequences of this particular Judgment will not be drawn until the general Judgment, which will take place when Christ returns at the end of time.

So, the « particular judgment » that is supposed to immediately follow our death, concerns our last act of freedom, prepared by all that our life has been. Helping us to contemplate this ultimate moment therefore seems to be the primary aim of Patinir‘s painting, with other metaphors thrown in for good measure.

However, a closer look at the lower part of the painting reveals a contradiction that is absent from Virgil’s poem. While Hell is on the right (Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the gateway to Hell, can be seen), the gateway seems easily accessible, with splendid trees dotting the lawns.

To the left is Paradise. An angel tries to attract the attention of the soul in the boat, but it seems much more attracted by a seemingly welcoming Hell.

What’s more, the dimly-lit path to paradise seems perilous, with rocks, swamps and other dangerous obstacles. Once again, it’s our senses that may lead us to make a literally hellish choice.

The subject of the painting is clearly that of the bivium, the binary choice at the crossroads that offers the pilgrim viewer the choice between the path of vice and that of salvation.

This theme was widespread at the time. We find it again in Sébastien Brant‘s Ship of Fools, in the form of Hercules at the crossroads. In this illustration, on the left, at the top of a hill, a naked woman represents vice and idleness. Behind her, death smiles down on us.

On the right, planted at the top of a higher hill, at the end of a rocky path, awaits virtue symbolized by work. Let’s also remember that the Gospel (Matthew 7:13-14) clearly evokes the choice we will face:

« Enter by the narrow gate.

For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction,

and there are many who enter by it.

But the gate is narrow and the way to life is narrow,

and there are few who find it ».

Landscape as an object of contemplation

The art historian Reindert Leonard Falkenburg, in his 1985 doctoral thesis, was the first to note that Patinir takes pleasure in transposing this metaphorical language to the whole of his landscape.

Although the image of impassable rocks as a metaphor for the virtue achieved by choosing the difficult path is nothing new, Patinir exploits this idea with unprecedented virtuosity.

We thus discover that the theme of man courageously turning away from the temptation of a world that traps our sensorium, is the underlying theo-philosophical theme of almost all Patinir’s landscapes. In this way, his work finds its raison d’être as an object of contemplation, where man measures himself against the infinite.Let’s return to our Landscape with Saint Jerome by Patinir (National Gallery, London).

Here we discover the « narrow gate » leading to a difficult path that takes us to the first plateau. This is not the highest mountain. The highest, like the Tower of Babylon, is a symbol of pride.

Next, let’s look at Resting on the Road to Egypt (Prado Museum, Madrid). At the side of the road, Mary is seated, and in front of her, on the ground, are the peddler’s staff and his typical basket.

In conclusion, we could say that, driven by his spiritual and humanist fervor, by painting increasingly impassable rocks – reflecting the immense virtue of those who decide to climb them – Patinir elaborates not « realistic » landscapes, but « spiritual landscapes », dictated by the immense need to tell the spiritual journey of the soul.

Hence, far from being mere aesthetic objects, his spiritual landscapes serve contemplation.

Like a half-ironic mirror image, they enable those who wish to do so to prepare for the choices their soul will face during, and after, life’s pilgrimage.

Bibliography:

- R.L. Falkenburg, Joachim Patinir, Het landschap als beeld van de levenspelgrimage, Nijmegen, 1985;

- Maurice Pons and André Barret, Patinir ou l’harmonie du monde, Robert Laffont, 1980;

- Eric de Bruyn, De vergeten beeldentaal van Jheronimus Bosch, Adr. Heinen, s’Hertogenbosch, 2001;

- Dirk Bax, Hieronymus Bosch, his picture-writing deciphered, A. A. Balkema, Capetown, 1979;

- Georgette Epinay-Burgard, Gérard Groote, fondateur de la Dévotion Moderne, Brepols, 1998.

- Karel Vereycken, Devotio Moderna, cradle of Humanism in the North, Artkarel.com, 2011;

- Karel Vereycken, With Hieronymus Bosch on the track of the Sublime, Schiller Institute, 2007.

- Karel Vereycken, How Erasmus Folly saved our Civilization, Schiller Institute, 2004.

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur Joachim Patinir and the invention of landscape painting

Tags: Antwerp, artkarel, Barret, Bax, bible, bivium, Bosch, brabant, Brahms, Brant, Brothers of the Common Life, Bruegel, Burgundy, Charon, Christ, Christian, commitment, contemplation, Council of Trent, crossroads, Dante, Degulleville, Devotio Moderna, Egypt, Epinay-Burgard, Erasme, Eric de Bruyn, Falkenburg, Germany, Groote, Hercules, Hieronymus, Homo Viator, invention of landscape, irony, Julius II, Karel, Karel Vereycken, landscape, Lutrell Psalter, Matsys, Netherlands, Patinir, peddler, peinture, Pons, Pope, prodigal son, Rabelais, realism, renaissance, Requiem, Sacred History, Ship of Fools, Soul, spirituality, Styx, Vereycken, Virgil, Wellens Cock

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on décembre 4, 2023

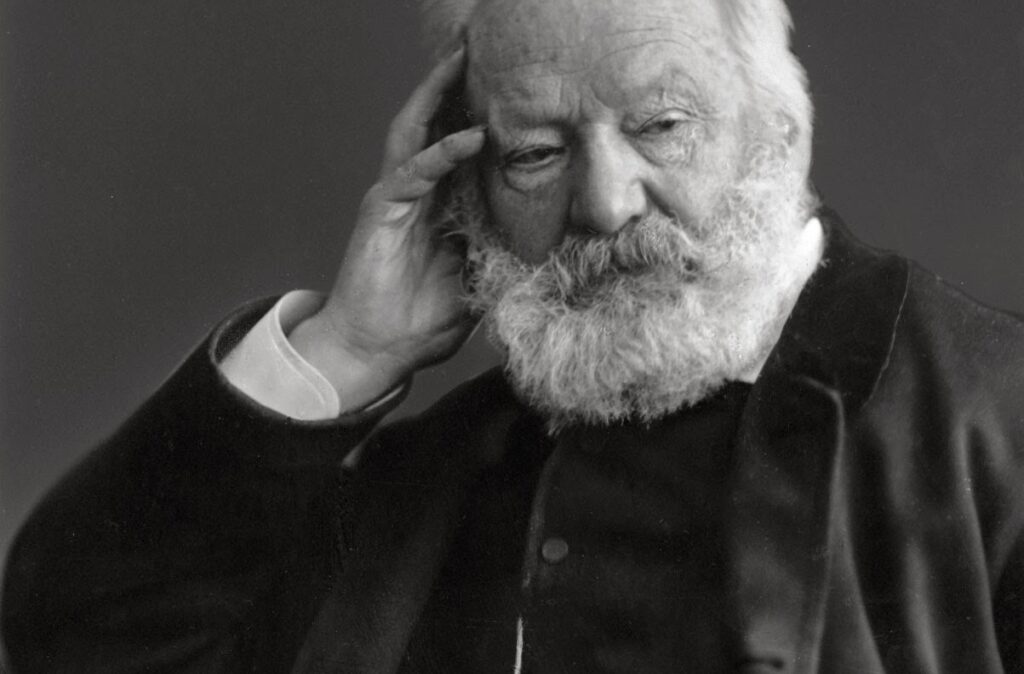

Victor Hugo and the awakening of the colossus

As Christophe Hardy notes in an article on the website L’Eléphant (April 2014), from which I drew heavily, the author of Les Misérables rightly passes for a man who, in his writings and commitments, « defended the cause of the people. »

Steeped in a worldview of Christian humanism and love for the other, the french state sman, critic, author and poet Victor Hugo (1802-1885) felt challenged by the people and the misery in which they found themselves, without falling for a purely idealized or romantic vision. And when he sees the people rise, Hugo takes the measure of their colossal power, be it for good or for evil.

In his poem To the People (Les Châtiments, Book VI), he uses the powerful metaphor of the Ocean to characterize this often unpredictable force. In evoking it, Hugo addresses the people:

« It resembles you; it is terrible and peaceful (…)

Its wave, where one hears like shocks of armors,

Fills the dark night with monstrous murmurs,

And one feels that this wave, like you, human abyss,

Having roared tonight, will devour tomorrow. »

During the first half of his life, Hugo witnessed several popular uprisings. The years 1830 are particularly agitated. Riots and strikes broke out in the big cities, in Paris, Lyon, Marseille, provoked by the harshness of life that was aggravated by the crisis in agricultural production. Generally speaking, the rigor of working conditions was the result of absurd market mechanisms: faced with the collapse of industrial prices (1817-1851), entrepreneurs decided purely and simply to reduce wages!

Pauperization exploded and the workers rebelled against this dramatic decrease in their income. In Paris, Hugo had before his eyes the spectacle of a laboring mass, coming from the provinces to crowd into the center of the capital, uprooted, living in insalubrity and precariousness, exposed to epidemics (cholera in 1832), quick to riot (February and September 1831, June 1832, April 1834).

However, the workers, who represented only a small minority in a largely agricultural and peasant country, struggled to assert their demands, especially for shorter working days. Not yet structured, their fragmentation prevented them from acquiring a true consciousness of class solidarity. This battered mass, regularly agitated by brutal shocks, frightened the notables and the owners, who saw it as a dangerous class threatening their privileges.

Love stronger than pity

Hugo is very early aware that the misery of the people is the main “social question”. This sensitivity to the fate of the poorest is not that of the hypocritical lady-do-rightly, it is the bottom of his soul. And when, elected deputy, he evokes it in the Assembly, the conservatives of which he thought he was close until 1849, started to yell.

« All my thoughts, Hugo said, I could summarize them in one sentence: vigorous hatred of anarchy, tender and deep love of the people! »

The misery of the working classes, the poet knew and had reported on it: misery of the prison (visit to the Conciergerie, in Choses vues, September 1846), misery of working-class life (visit to the cellars of Lille in February 1851, speech not delivered that will inspire the poem of the Châtiments « Joyful life »). He is convinced that it can be eradicated.

Contradicting the conservatives, the working classes are not, in his eyes, « dangerous classes ». They are even in danger, and the fact that they are in danger threatens the stability of the whole society:

« I denounce to you the misery, which is the scourge of one class and a danger for all! I denounce to you the misery which is not only the suffering of the individual, which is the ruin of the society. »

(Speech of July 9, 1849.)

If he abandons his convictions as a young Royalist to become a passionate Republican of progress, Hugo fears chaos and needless bloodshed. Although he did not live through 1793 and the Terror, he is obsessed with the memory of the bloody days of the French Revolution, when the guillotine was in full swing.

Reporting on the insurrection, in 1832, more than the violence as such, he denounced the extremists who, for personal calculations and not to fight against injustice, excite the masses to revolt and announce for the end of the month « four beautiful permanent guillotines on the four main squares of Paris”.

Hugo considers this strategy as a political dead end (« Don’t ask for rights as long as the people ask for heads »), while understanding its legitimacy:

« It is of the essence of the revolutionary riot, which should not be confused with other kinds of riots, to be almost always wrong in form and right in substance. »

With irony, he points out to the powerful that « the most excellent symbol of the people is the pavement. You walk on it until it falls on your head. » (Things Seen, 1830 to 1885.)

Like the German poet Friedrich Schiller, Hugo believes that the role of the artist and the poet is to elevate the debate. Art, like the polar star shining in the night for sailors lost on the ocean, is essential to guide the people to safety.

Magnanimous

Politically, in order to lay the foundations of a peaceful and harmonious future destiny, he affirms that compassion and forgiveness must prevail over hatred and vengeance.

« He who murdered on the highways who, better directed,

would have been the most excellent servant of the city.

This head of the common man,

cultivate it, clear it, water it, fertilize it,

enlighten it, moralize it, use it;

you will not need to cut it off.”

(Claude Gueux, novel, 1834.)

Lucid, the poet declares that « to open a school is to close a prison, » for « when the people are intelligent, only then will the people be sovereign. »

This is the treatment applied to Jean Valjean, the main hero of Les Misérables: the poor thief, an escaped convict, will eventually become the great soul that his host of one evening, Monsignor Myriel, had been able to detect in him while the rest of society proved unable to identify it … Hugo will spend his life to de-demonize « the beggars » (les gueux), that is to say the people.

In 1812, in his song Les gueux, the popular chansonnier Pierre-Jean de Béranger*, whom he admired, intoned:

« Let us sing the praise of the beggars.

How many beggars are good men!

It is necessary that finally the spirit

avenges the honest man who has nothing.”

In one of his greatest speeches (in July 1851, on the reform of the Constitution), Hugo claimed for the people (and for all) the right to material life (assured work, organized assistance, abolition of the death penalty) and the right to intellectual life (compulsory and free education, freedom of conscience, freedom of expression, freedom of the press).

In short, in embryo, the vision of a Jaurès and a De Gaulle that we will find in « Les Jours heureux » (The Happy Days), the program of the National Council of the Resistance (CNR), and the antithesis of the financial globalization that is inflicted on us today.

A whistleblower

In 1527, in a letter to his friend Thomas More, the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam warned the powerful: if the Church of Rome does not adopt the measures of progressive and peaceful reform that he, Erasmus, proposes, they will be guilty of having provoked a century of violence.

In Les années funestes (1852), knowing the power of the colossus, Victor Hugo also warned the oligarchy. A warning that keeps its topicality:

« You have not taken heed of the people that we are.

With us, in the great days, the children are men,

The men are heroes, the old men are giants.

Oh, how stupid and gaping you will be,

The day when you will see, laughable escogriffs,

This great people of France escape from your claws!

The day when you will see fortune, dignities,

Powers, places, honors, beautiful pledges well counted,

All the heaps of your fierce pride,

Fall at the first step that the colossus will make!

Confounded, furious, vainly clinging

To the wavering debris of your collapse,

You will still try to shout, to proscribe,

To insult, and History will burst out laughing. »

NOTE:

*Christine Bierre: « Pierre-Jean de Béranger : la chanson, une arme républicaine » in Nouvelle Solidarité N°07/2022.

Posted in Comprendre, Etudes historiques, politiques et scientifiques | Commentaires fermés sur Victor Hugo and the awakening of the colossus

Tags: agricultural, artist, artkarel, Béranger, Châtiments, cholera, Choses Vues, Christian, colosse, colossus, dangerous, De Gaulle, Erasmus, fragmentation, goya, gueux, guillotine, humanism, insalubrity, Jaurès, Karel, Karel Vereycken, labor, livelihood, Love, metaphor, Misérables, misery, National Council of the Resistance, ocean, pity, poet, poverty, power, prison, renaissance, revolution, riot, schiller, uprising, Valjean, Vereycken, Victor Hugo, wages, working-class