Étiquette : Quentin Matsys

Bruegel, Petrarca and the « Triumph of Death »

By Karel Vereycken, april 2020.

The Triumph of Death? The simple fact that the heir to the throne of England, Prince Charles, and even the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, have tested positive to the terrifying coronavirus currently sweeping the planet, tells something to the public.

As some commentators pointed out (no irony) it “gave a face to the virus”. Until then, when an elderly person or a dedicated nurse died of the same, it “wasn’t real”.

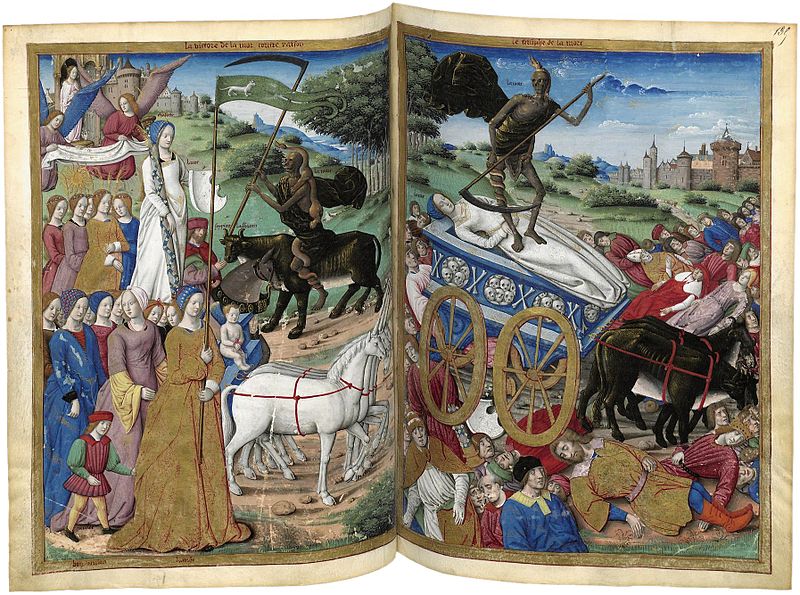

Realizing that these “higher-ups” are not part of the immortal Gods of Olympus but are mortals as all of us, brings to my mind “The Triumph of Death”, a large oil painting on panel (117 x 162 cm, Prado, Madrid), generally misunderstood, painted by the Flemish painter Peter Bruegel’s the elder (1525-1569), and thought to be executed between 1562 and his premature demise.

In order to discover, beyond the painting, the intention of the painter’s mind, it is always useful, before rushing into hazardous conclusions, to briefly describe what one sees.

What do we see in Bruegel’s « Triumph of Death« ? On the left, a skeleton, symbolizing death itself, holding a sand-glass in its hand, carries away a dead King. Next to him, another skeleton grabs the vast amounts of money no one can take with him into the grave. Death is driving a chariot. Below the charriot some people are crawling on their knees, hoping to remain unnoticed.

On the right, at the forefront, people are gambling and amusing themselves. A skeleton playing a musical instruments joins a prosperous young couple engaged in a musical dialogue and clearly unaware that Death is taking over the planet.

The message is simple and clear. No one can escape death, poor or rich, young or old, king or peasant, sick or healthy. When the hour comes, or at the end of all times, all mortals return to the creator since “physical” death triumphs over all of them.

Immortality

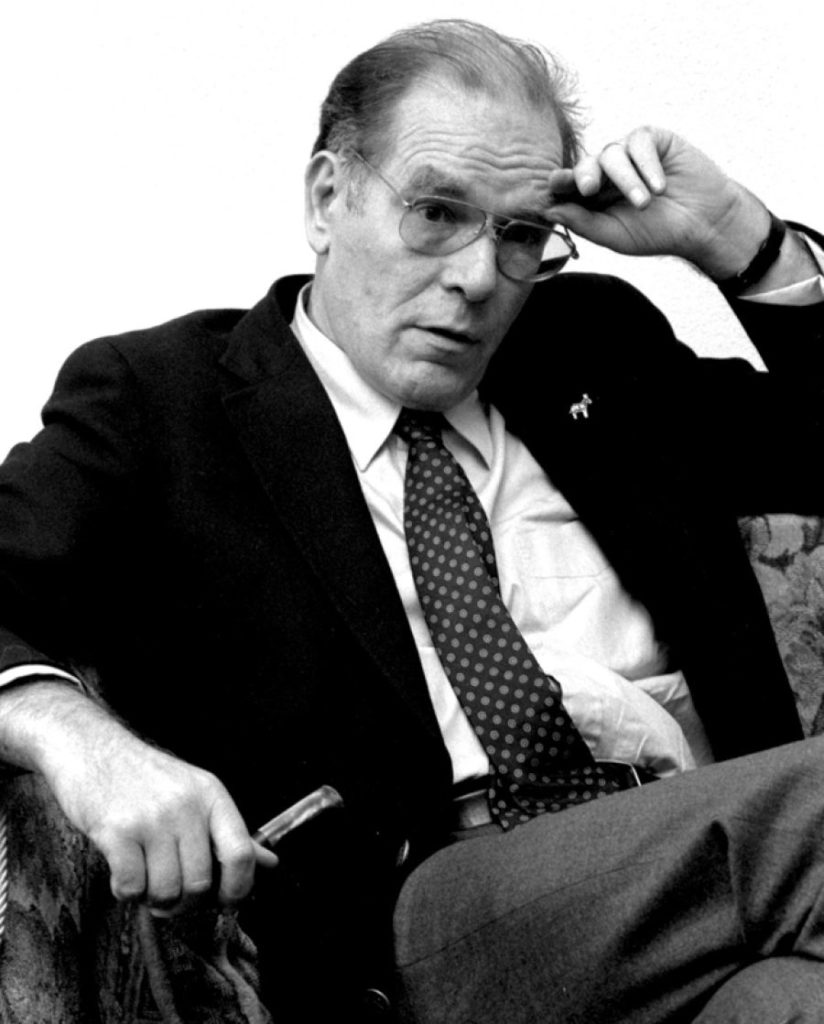

American thinker Lyndon LaRouche (1922-2019), in his speeches and writings, used to remind us, with his typical loving impatience: all human wisdom starts by a personal decision to acknowledge a fact proven without contest: we are all born and each of us, sooner or later, will die. So far, our bodies have all been proven mortal.

The duration of our mortal existence on the clock of the universe, he reminded, is less than a nanosecond.

Therefore, knowing this boundary condition of our mortal existence, we, each of us, have to make a personal sovereign decision: how will I spend the talent of my life ? Will I spend that talent chasing the earthly pleasures of the flesh, or dedicate my life to defending the truth, the beautiful and the good, to the great benefit of humanity as a whole, living in past, present and future ?

In 2011, in a discussion, LaRouche explained what he meant by saying that humanity has the potential to become an “immortal” species:

I live; as long as I live, I may generate ideas.

These conceptions give mankind a chance to move forward.

But then the time will come when I will die.

Now, two things happen: First of all, if these creative principles,

which have been developed by earlier generations,

are realized in the future, that means that mankind is an immortal species. We are not personally immortal;

but to the extent that we’re creative, we’re an immortal species.

And the ideas that we contribute to society

are permanent contributions to the human society.

We are therefore an immortal species,

based on mortal beings. And the key thing in life is to grasp that connection.

To say that we’re creative and die,

doesn’t tell us the story. If we, in our own lives, who are about to die,

can contribute something that is permanent, which will outlive our death, and be a benefit to mankind in future times, we have achieved the purpose of immortality.

And that is the crucial thing.

If people can actually face, with open minds, the fact that we’re each going to die—but look at it in the right way,

then we are impassioned to make the contributions,

to discover the principles, to do the work that is immortal.

Those discoveries of principle which are immortal, which pass on from one generation to the other. And thus, the dead live in the living;

because what the dead do, if they have done that in their lifetime, they are alive, not as in the flesh, but they’re alive in principle.

They’re part, an active part, of human society.

Christian humanism

LaRouche’s outlook, the “moral” obligation to live a “creative” existence on Earth in the image of the Creator, was deeply rooted in the philosophical outlook of both the Platonic and the Judeo-Christian tradition, whose happy marriage gave us the beautiful Christian humanism which, in the early XVth Century, ignited an unprecedented explosion, on a mass-scale and of unseen density of economic, scientific, artistic and cultural achievements, later qualified as a “Renaissance”.

In Plato’s Phaedon, Socrates develops the idea that our mortal body is a constant impediment to philosophers in their search for truth: “It fills us with wants, desires, fears, all sorts of illusions and much nonsense, so that, as it is said, in truth and in fact no thought of any kind ever comes to us from the body” (66c). To have pure knowledge, therefore, philosophers must escape from the influence of the body as much as is possible in this life. Philosophy (Literally “The love of wisdom”) itself is, in fact, a kind of “preparation for dying” (67e), a purification of the philosopher’s soul from its bodily attachment.

Also the Vulgate’s Latin rendering of Ecclesiastics 7:40 stresses: « in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin”. This passage finds expression in the christian ritual of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshippers’ heads with the words: “Remember Man that You are Dust and unto Dust You Shall Return.”

Is this a morbid ritual? No, it is a philosophy lesson. Christianity itself, as a religion, cherishes God’s own son made man, Jesus, for having renounced to his mortal life for the sake of mankind. It put Jesus’ death at the center. And in the XIVth century, Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471), one of the leading intellectuals and founders of the Brothers of the Common Life, wrote that every Christian should shape his life in the “Imitation of Christ”. Both Nicolaus of Cusa (1401-1464) and Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) were powerfully influenced and trained by this intellectual current.

Concedo Nulli

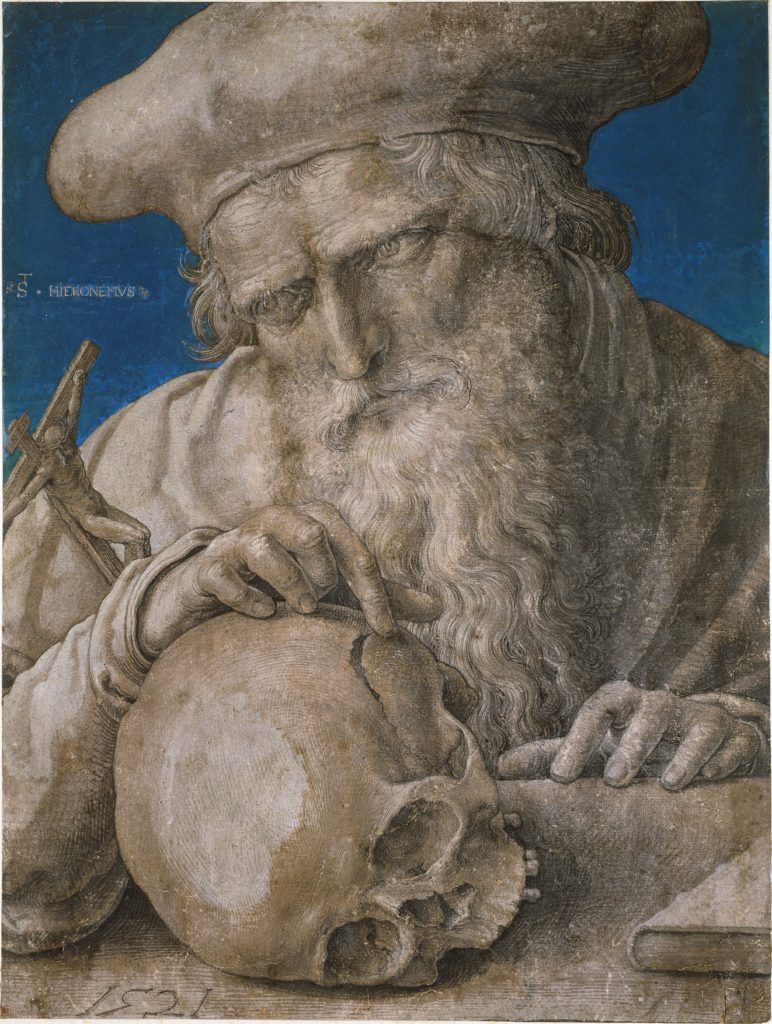

Erasmus’ personal armory was the juxtaposition of a skull and a sand-glass, referring to death and time as the boundary conditions of human existence.

In 1519, his friend, the Flemish painter and goldsmith Quentin Matsys (1466-1530) forged a bronze medal to the honor of the great humanist.

On one side of the medal there is an efigee of Erasmus and a Latin inscription informs us that this is “an image taken from life”. At the same time we are told in Greek, « his writings will make him better. known »

The reverse side of the medal shows solemn inscriptions surrounding an unusual image. At the top of a pillar that stands in rough, uneven ground, emerges the head of a young man with a stubbly chin and wild, flowing hair. Like Erasmus on the other side of the medal, he seems to have a faint smile upon his face. On either side of the head are the words “Concedo Nulli”– “I yield to no one.” On the pillar is inscribed Terminus, the name of a Roman god who presided over boundaries. Again bilingual quotations surround a profile. On the left, in Greek, is the instruction, « Keep in mind the end of a long life. » On the right, in Latin, is the stark reminder, « Death is the ultimate boundary of things. »

Adapting as his own motto “I yield to no one”, Erasmus took the great risk of using such a daring metaphor. Accused of intolerable arrogance by his sycophants, he underlined that “Concedo Nulli” had to be understood as death’s own statement, not his own. And who could argue with the assertion that death is the terminus that yields to no one?

Mozart, Brahms and Gandhi

Centuries later, the great humanist composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was the exact opposite of a morbid cynic. Revealing his inner mindset, Mozart once said that the secret of all genius, was love for humanity: “neither a lofty degree of intelligence nor imagination nor both together go to the making of genius. Love, love, love, that is the soul of genius”.

But on April 4, 1787, Mozart wrote to his father, Leopold, as he lay dying :

I need hardly tell you how greatly I am longing

to receive some reassuring news from yourself.

And I still expect it ; although I have now made a habit of being prepared in all affairs of life for the worst.

As death, when we come to consider it closely,

is the true goal of our existence,

I have formed during the last few years such close relations with this best and truest friend of mankind,

that his image is not only no longer terrifying to me,

but is indeed very soothing and consoling !

And I thank God for graciously granting me

the opportunity (you know what I mean)

of learning that death is the key

which unlocks the door to our true happiness.

I never lie down at night

without reflecting that –young as I am– I may not live to see another day.

Johannes Brahms 1865 German Requiem, quotes Peter 1:24-25 reminding us that

“For all flesh is as grass,

and all the glory of man as the flower of grass.

The grass withereth, and the flower thereof falleth away.

But the word of the Lord endureth for ever.”

Also Mahatma Gandhi, expressed, in his own way, somthing similar, about how one has to live simultaneously with mortality and immortality:

« Live as if you were to die tomorrow.

Learn as if you were to live forever. »

Memento Mori and Vanitas

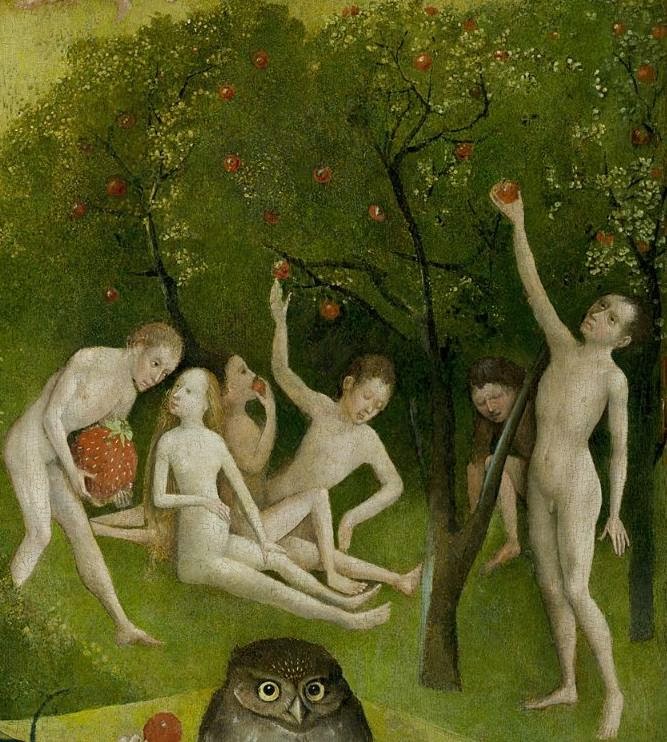

Just as Hieronymus Bosch’s (1450-1516) painting of the “Garden of Earthly Delights” (Prado, Madrid), where the great Dutch master uses the metaphor of naked humans incessantly chasing delicious fruits, calls on the viewer to become aware of his close-to-ridiculous, animal-like attachment to earthly pleasures and calls on his free will and his sens of humor to free himself, Bruegel’s “Triumph of Death” painting, on a first level, is fundamentally nothing else than a complex Memento Mori (Latin “remember that you must die”).

With this painting, Bruegel pays tribute to his intellectual godfather’s motto Concedo Nulli, that is, as Erasmus did in his writings, Bruegel paints the ineluctability of death, not by praising its horror, but with the aim of inspiring his fellow citizens to walk into immortality. In the same way Erasmus’ « In praise of folly » was in fact an inversion of his praise of reason, Brueghel’s « Triumph of Death » was conceived as a triumph of (immortal) life.

For the Catholic faith, the aim of a Memento Mori was to remind (and eventually terrorize) the believer that after death, he or she might end up in Purgatory or worse in Hell if they did not respect the Church and her rites. With the invention of oil painting in the early XVth century, panel paintings of this genre for private homes and small chapels were considered aesthetic objects crafted for the sake of religious and philosophical contemplation.

Hence, starting with the Renaissance, the Memento Mori painting became a much demanded artifact, re-branded in the following centuries as “Vanitas”, Latin for « emptiness » or « vanity ». Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, Vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies and hourglasses.

Iconography

A first source is of course, the famous designs and woodcuts executed by Erasmus intimate friend and illustrator of his “In Praise of Folly”, Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), for his satirical “Dance of Death” (1523), which –breaking with the way the “Dance macabre” was used before by the Flagellants and other madmen to desensitize the population in order to push them into a fatalistic retreat of the outer world– introduces the new philosophical dimension that Bruegel will develop.

The close-to-embarassing anamorphosic representation of a giant skull in Holbein’s work « The Ambassadors » (1533), demonstrates his profound understanding of the Memento Mori metaphor.

Erasmus’ friend Albrecht Dürer‘s engraving « Knight, Death and the Devil » (1513), or his « Saint Jerome in his study » (1514) (with skull and hourglass) are two other examples.

Bruegel and Italy

Ironically, Peter Bruegel the elder has always been presented as a painter of the Northern School who was completely closed to the “Italian” Renaissance.

The reality is that while rejected the transformation of the Renaissance into a form of mannerism in the XVIth century, he took most of his inspiration directly from two Italian Renaissance sources.

First, of course, the image of Death riding a horse, and even a group of persons such as the young couple engaged in their musical embrace, appear incontestably as taken from the Triumph of Deat”, a vast fresco from 1446 which decorated the walls of the Palazzo Sclafani in Palermo, Sicily. Bruegel’s trip to Southern Italy is a well documented fact.

The second source, which undoubtedly also inspired the painter of the fresco, is a series of allegorical poems known as “I Trionfi” (“The Triumphs”: Triomph of Love, of Chastity, of Death, of Fame, of Time and of Eternity), composed by the great Italian poet Francesco Petrarca, most likely following the “Black Death”, a pandemic outbreak which, starting with the 1345 banking crash, decimated a vast portion of the population of Europe.

Petrarca’s genius was precisely to offer to those terrified with the very idea of having to face their physical mortality, a philosophical answer to their anxiety.

As a result, his Trionfi became rapidly popular, not only in Italy but all over Europe. And for most painters, working on Petrarca’s themes became part of their common repertoire.

To conclude, here is an excerpt (English) of the poem, where Petrarca blasts the mad lust of Kings and Popes for wealth, pleasure and earthly power. In the face of death, he stresses, they are worthless. Petrarca’s wording fits to the detail the images used by Bruegel in his painting The Triumph of Death :

(…) afar we might perceive

Millions of dead heap’d on th’ adjacent plain;

No verse nor prose may comprehend the slain

Did on Death’s triumph wait, from India,

From Spain, and from Morocco, from Cathay,

And all the skirts of th’ earth they gather’d were;

Who had most happy lived, attended there:

Popes, Emperors, nor Kings, no ensigns wore

Of their past height, but naked show’d and poor.

Where be their riches, where their precious gems,

Their mitres, sceptres, robes, and diadems?

O miserable men, whose hopes arise

From worldly joys, yet be there few so wise

As in those trifling follies not to trust;

And if they be deceived, in end ’tis just:

Ah! more than blind, what gain you by your toil?

You must return once to your mother’s soil,

And after-times your names shall hardly know,

Nor any profit from your labour grow;

All those strange countries by your warlike stroke

Submitted to a tributary yoke;

The fuel erst of your ambitious fire,

What help they now? The vast and bad desire

Of wealth and power at a bloody rate

Is wicked,–better bread and water eat

With peace; a wooden dish doth seldom hold

A poison’d draught; glass is more safe than gold;

Whether Bruegel, who saw undoubtedly the fresco in Palermo during his trip in the 1550s, had read Petrarca’s poem remains an open question. It can be said that many of his direct friends were familiar with the Italian poet.

In Antwerp, the painter was a frequent guest of the Scola Caritatis, a humanist circle animated by one Hendrick Nicolaes, where Brueghel met poets, translaters, painters, engravers (Cock, Golzius) mapmakers (Mercator), cosmographers (Ortelius) and bookmakers such as the Antwerp printer Christophe Plantijn, who’se renowned printing shop would print Petrarca’s poetry.

Also in Antwerp, indicating how popular Petrarca’s poetry had become in the Low Countries and France, the franco-flemish Orlandus Lassus (1532-1594) published his first musical compositions, including his madrigals on each of the six Trionfi of Petrarca, among which the « Triumph of Death ».

Conclusion

All evil, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) hoped, can give birth to something good, far bigger and superior to the evil that provoked it. Therefore, we can hope that the current pandemic breakdown crisis will lead some of the leading decision-makers, with our help, to reflect on the sens and purpose of their lives. The worst would be to return to yesterday’s “normalcy” since that kind of “normal” is exactly what drove the planet currently to the verge of extinction.

At last, it should be stressed that in the same way Lyndon LaRouche, by his ruthless (Concedi Nulli) commitment to defend the sacred creative nature of every human individual, contributed to the enduring immortality of Plato, Petrarca, Erasmus and Bruegel, it is up to each of us to carry even further that battle.