Étiquette : Bacon

Avicenna and Ghiberti’s role in the invention of perspective during the Renaissance

By Karel Vereycken, Paris, France.

Same article in FR, même article en FR.

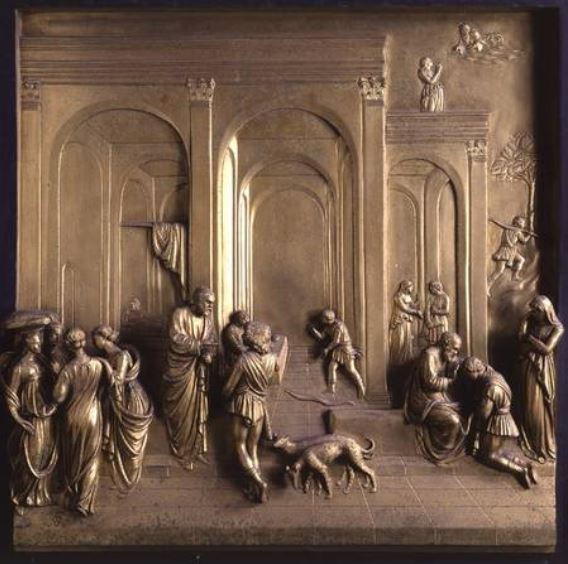

No visitor to Florence can miss the gilded bronze reliefs decorating the Porta del Paradiso (Gates of Paradise), the main gate of the Baptistery of Florence right in front of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore surmounted by Filippo Brunelleschi’s splendid cupola.

In this article, Karel Vereycken sheds new light on the contribution of Arab science and Ghiberti’s crucial role in giving birth to the Renaissance.

Historical context

The Baptistery, erected on what most Florentines thought to be the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the Roman God of Mars, is one of the oldest buildings in the city, constructed between 1059 and 1128 in the Florentine Romanesque style. The Italian poet Dante Alighieri and many other notable Renaissance figures, including members of the Medici family, were baptized in this baptistery.

During the Renaissance, in Florence, corporations and guilds competed for the leading role in design and construction of great projects with illustrious artistic creations.

While the Arte dei Lana (corporation of wool producers) financed the Works (Opera) of the Duomo and the construction of its cupola, the Arte dei Mercantoni di Calimala (the guild of merchants dealing in buying foreign cloth for finishing and export), took care of the Baptistery and financed the embellishment of its doors.

The Gates of Paradise

The Baptistry, an octagonal building, has four entrances (East, West, North and South) of which only three (South, North and East) have sets of artistically important bronze doors with relief sculptures. Three dates are key : 1329, 1401 and 1424.

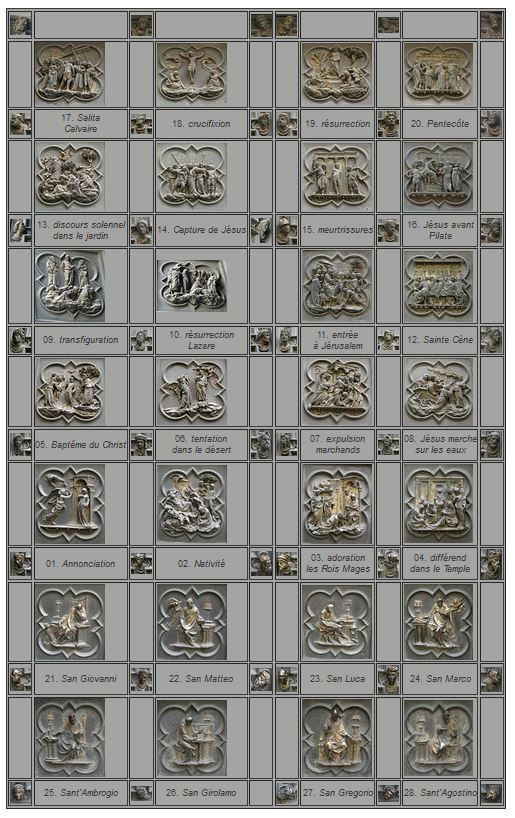

- In 1329, the Calimala Guild, on Giotto‘s recommendation, ordered Andrea Pisano (1290-1348) to decorate a first set of doors (initialy installed as the East doors, i.e. seen when one leaves the Cathedral, but today South). These consist of 28 quatrefoil (clover-shaped) panels, with the 20 top panels depicting scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist (the patron of the edifice). The 8 lower panels depict the eight virtues of hope, faith, charity, humility, fortitude, temperance, justice, and prudence, praised by Plato in his Republic and represented during the XVIth century by the Flemish humanist painter and reader of Petrarch, Peter Brueghel the Elder. Construction took 8 years, from 1330 till 1338.

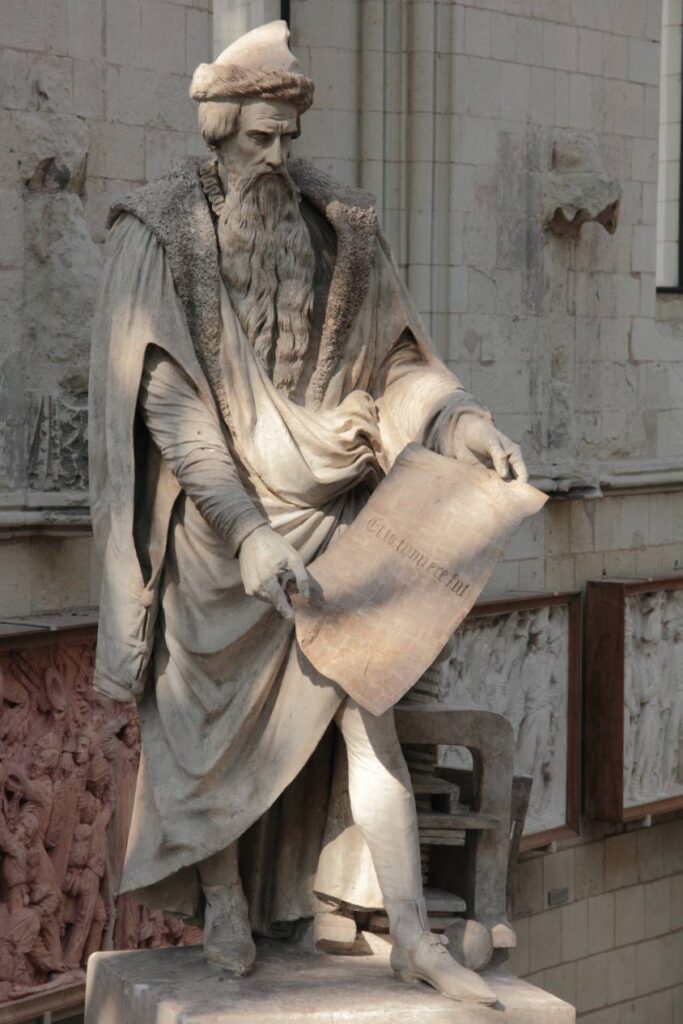

- In 1401, after having narrowly won the competition with Brunelleschi, the 23 year old and inexperienced young goldsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455), is commissioned by the Calima Guild to decorate the doors which are today the North Gate. Ghiberti cast the bronze high reliefs using a method known as lost-wax casting, a technique that he had to reinvent entirely since it was lost since the fall of the Roman Empire. One of the reasons Ghiberti won the contest, was that his technique was so advanced that it required 20 % less (7 kg per panel) bronze than that of his competitors, bronze being a dense material far more costly than marble. His technique, applied to the entire decoration of the North Gate, as compared to his competitors, would save some estimated 100 kg of bronze. And since in 1401, with the plague regularly hitting Florence, economic conditions were poor, even the wealthy Calimala took into account the total costs of the program.

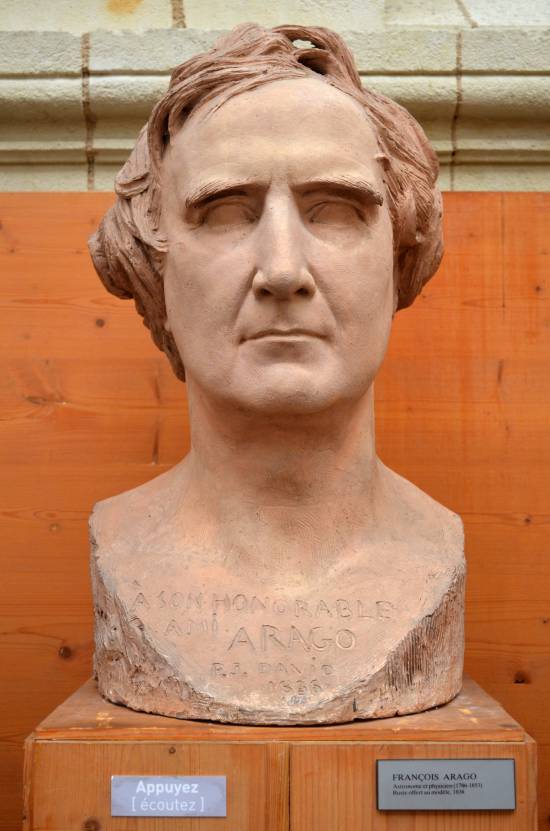

The bronze doors are comprised of 28 panels, with 20 panels depicting the life of Christ from the New Testament. The 8 lower panels show the four Evangelists and the Church Fathers Saint Ambrose, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory, and Saint Augustine. The construction took 24 years.

- In 1424, Ghiberti, at age 46, was given—unusually, with no competition—the task of also creating the East Gate. Only in 1452 did Ghiberti, then seventy-four years old, install the last bronze panels, since construction lasted this time 27 years! According to Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) later judged them « so beautiful they would grace the entrance to Paradise ».

Over two generations, a bevy of well paid assistants and pupils were trained by Ghiberti, including exceptional artists, such as Luca della Robbia, Donatello, Michelozzo, Benozzo Gozzoli, Bernardo Cennini, Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Verrocchio and Ghiberti’s sons, Vittore and Tommaso. And over time, the seventeen-foot-tall, three-ton bronze doors became an icon of the Renaissance, one of the most famous works of art in the world.

In 1880, the French sculptor Auguste Rodin was inspired by it for his own Gates of Hell on which he worked for 38 year

Revolution

Of utmost interest for our discussion here is the dramatic shift in conception and design of the bronze relief sculptures that occurred between the North and the East Gates, because it reflects how bot the artist as well as his patrons used the occasion to share with the broader public their newest ideas, inventions and exciting discoveries.

The themes of the North Gate of 1401 were inspired by scenes from the New Testament, except for the panel made by Ghiberti, « The Sacrifice of Isaac », which had won him the selection competition the same year. To complete the ensemble, it was therefore only logical that the East Gate of 1424 would take up the themes of the Old Testament.

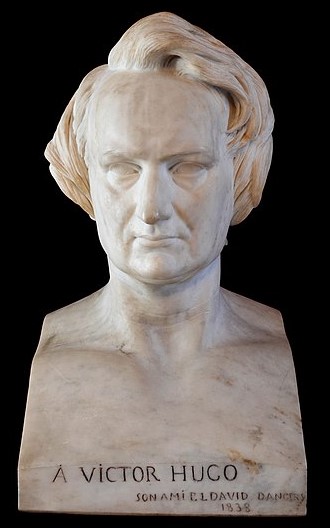

Originally, it was the scholar and former chancellor of Florence Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444) who planned an iconography quite similar to the two previous doors. But, after heated discussions, his proposal was rejected for something radically new. Instead of realizing 28 panels, it was decided, for aesthetic reasons, to reduce the number of panels to only 10 much larger square reliefs, between borders containing statuettes in niches and medallions with busts.

Hence, since each of the 10 chapters of the Old Testament contains several events, the total number of scenes illustrated, within the 10 panels has risen to 37 and all appear in perspective :

- Adam and Eve (The Creation of Man)

- Cain and Abel (Jalousie is the origin of Sin)

- Noah (God’s punishment)

- Abraham and Isaac (God is just)

- Jacob and Esau

- Joseph

- Moses

- Joshua

- David (Good commandor)

- Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

The general theme is that of salvation based on Latin and Greek patristic tradition. Very shocking for the time, Ghiberti places in the center of the first panel the creation of Eve, that of Adam appearing at the bottom left.

After the first three panels, focusing on the theme of sin, Ghiberti began to highlight more clearly the role of God the Savior and the foreshadowing of Christ’s coming. Subsequent panels are easier to understand. One example is the panel with Isaac, Jacob and Esau where the figures are merged with the surrounding landscape so that the eye is led toward the main scene represented in the top right.

Many of the sources for these scenes were written in ancient Greek, and since knowledge of Greek at that time was not so common, it appears that Ghiberti’s “theological advisor” was Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439), with whom he had many exchanges.

Traversari was a close friend of Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464), a protector of Piero della Francesca (1412-1492) and a key organizer of the Ecumenical Council of Florence of 1438-1439, which attempted to put an end to the schism separating the Church of the East from that of the West.

Perspective

The bronze reliefs, known for their vivid illusion of deep space in relief, are one of the revolutionary events that epitomize the Renaissance. In the foreground are figures in high relief, which gradually become less protruding thereby exploiting the full illusionistic potential of the stiacciato technique later brought to its high point by Donatello. Using this form of “inbetweenness”, they integrate in one single image, what appears both as a painting, a low relief as well as a high relief. Or maybe one has to look at it another way: these are flat images traveling gradually from a surface into the full three dimensions of life, just as Ghiberti, in one of the first self-portraits of art history, reaches his head out of a bronze medal to look down on the viewers. The artist desired much more than perspective, he wanted breathing space!

This new approach will influence Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1517). As art historian Daniel Arasse points out :

(…) It was in connection with the practice of Florentine bas-relief, that of Ghiberti at the Gate of Paradise (…) that Leonardo invented his way of painting. As Manuscript G (folio 23b) would much later state, ‘the field on which an object is painted is a capital thing in painting. (…) The painter’s aim is to make his figures appear to stand out from the field’ – and not, one might add, to base his art on the alleged transparency of that same field. It is by the science of shadow and light that the painter can obtain an effect of emergence from the field, an effect of relief, and not by that of the linear perspective.

Donatello

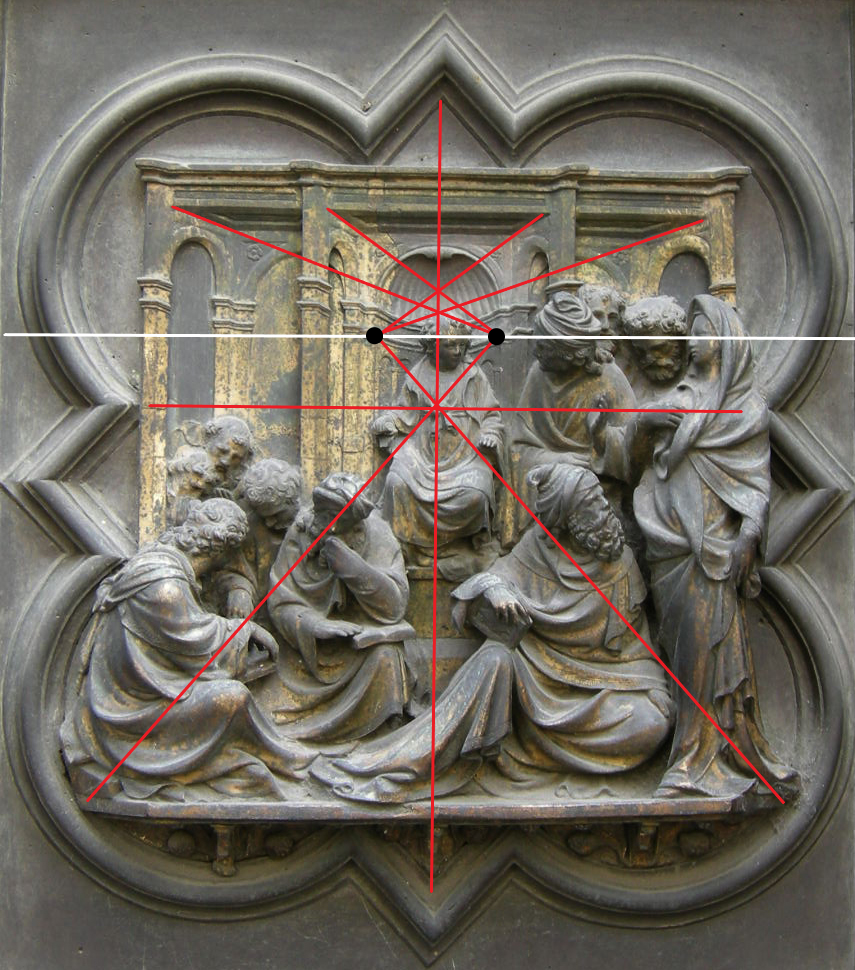

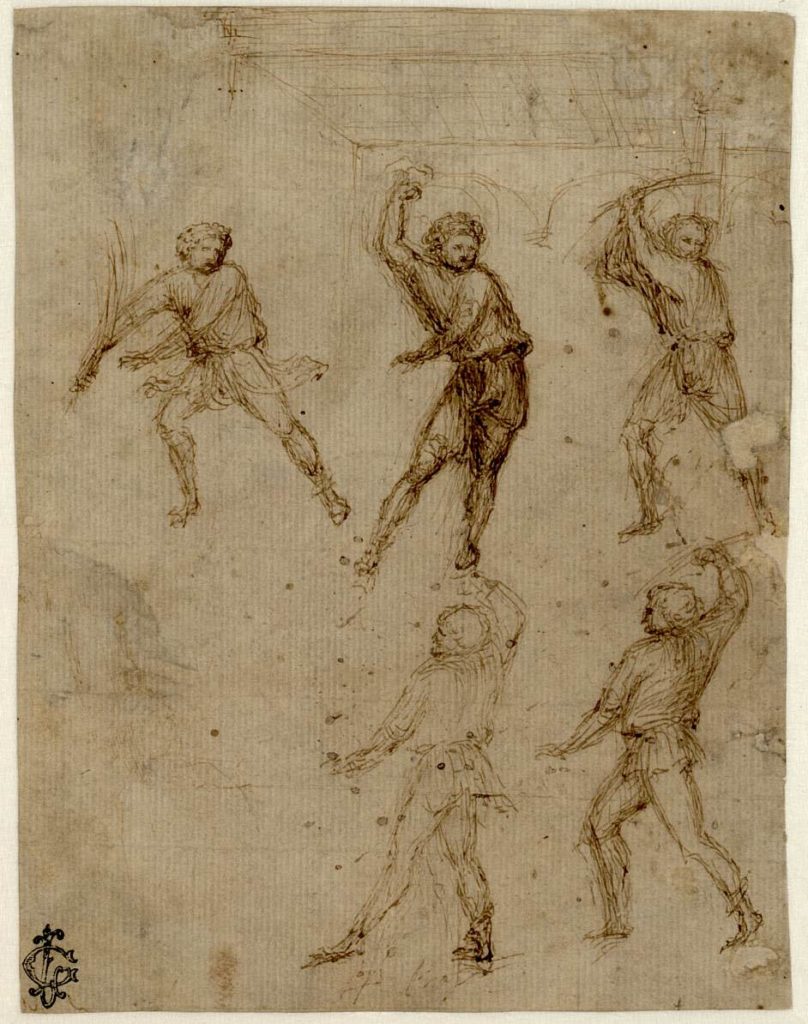

At the beginning of the 15th century, several theoretical approaches existed and eventuall contradicted each other. Around 1423-1427, the talentful sculptor Donatello, a young collaborator of Ghiberti, created his Herod’s Banquet, a bas-relief in the stiacciato technique for the baptismal font of the Siena Baptistery.

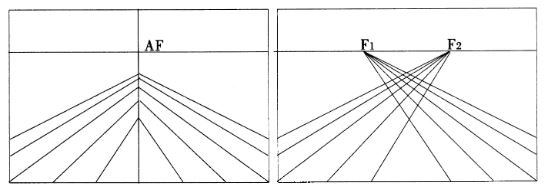

In this work, the sculptor deploys a harmonious perspective with a single central vanishing point. Around the same time, in Florence, the painter Massacchio (1401-1428) used a similar construction in his fresco The Trinity.

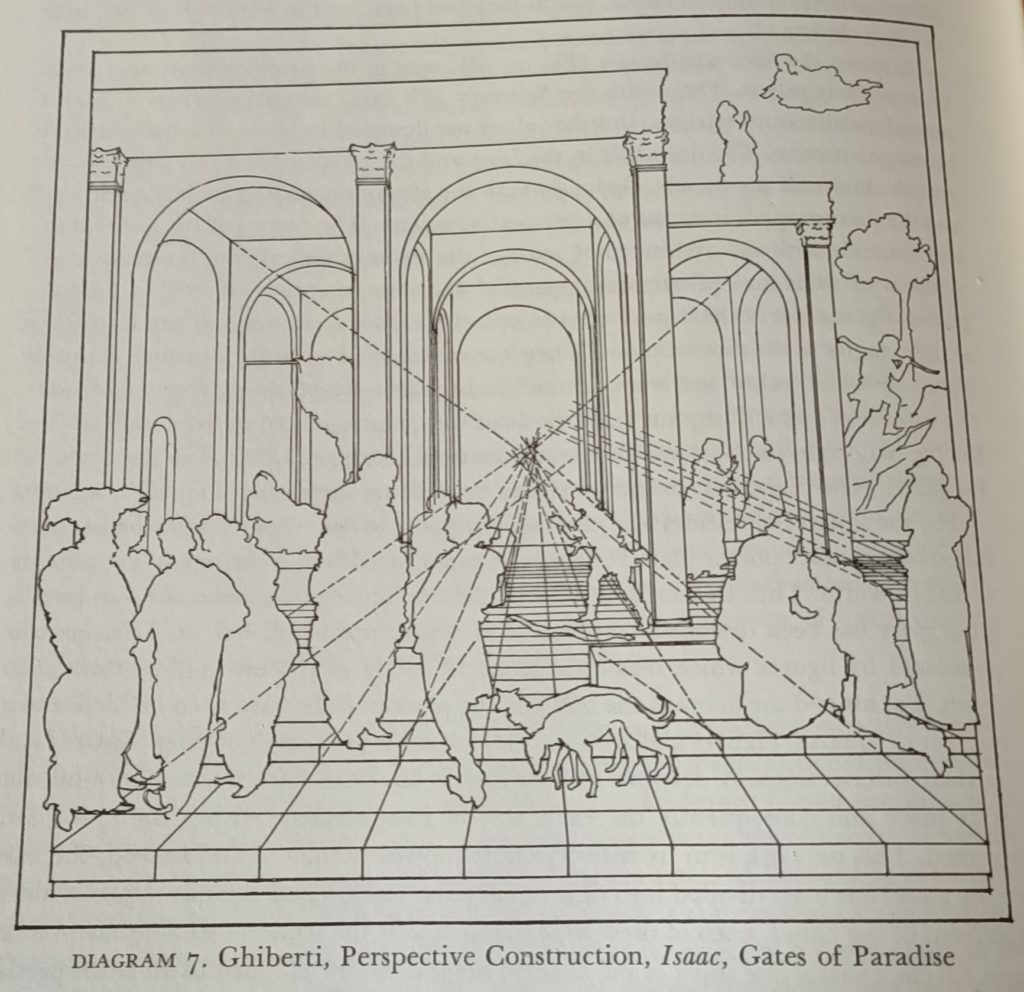

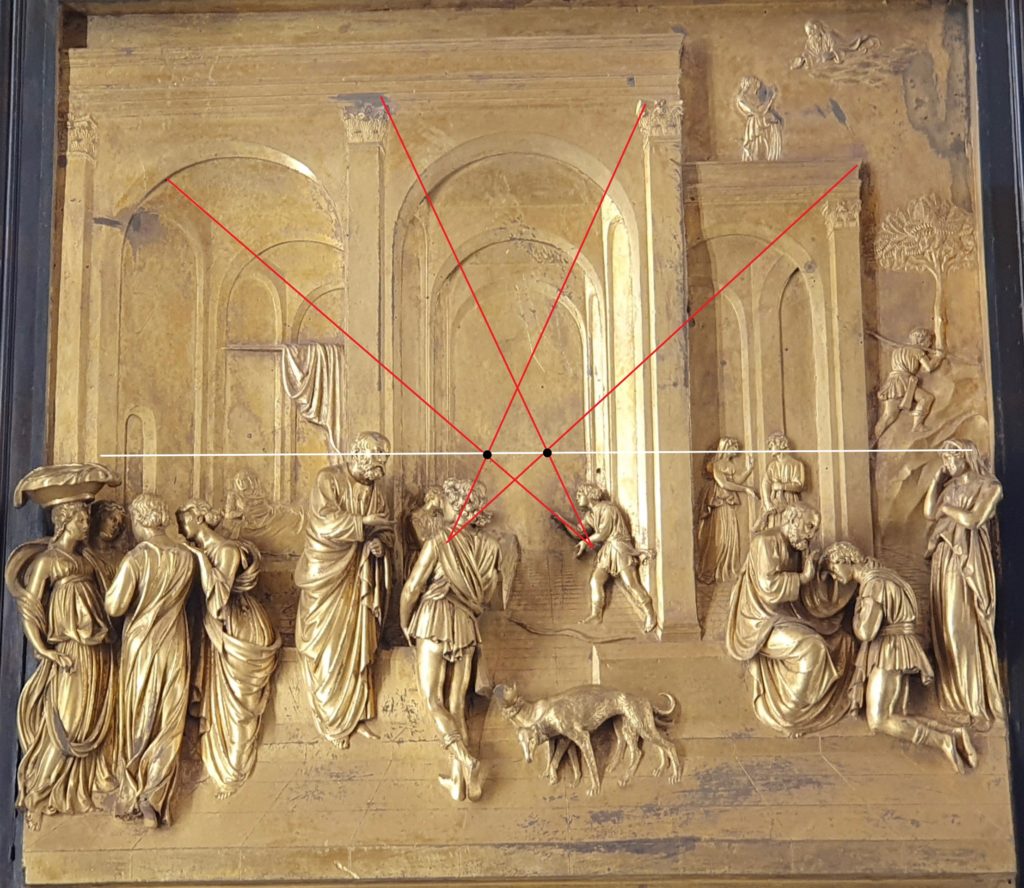

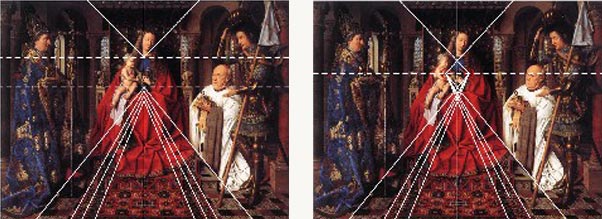

As we will see, Ghiberti, starting from the anatomy of the eye, opposed such an abstract approach in his works as well as in his writings and explored, as early as 1401, other geometrical models, called « binocular ». (see below).

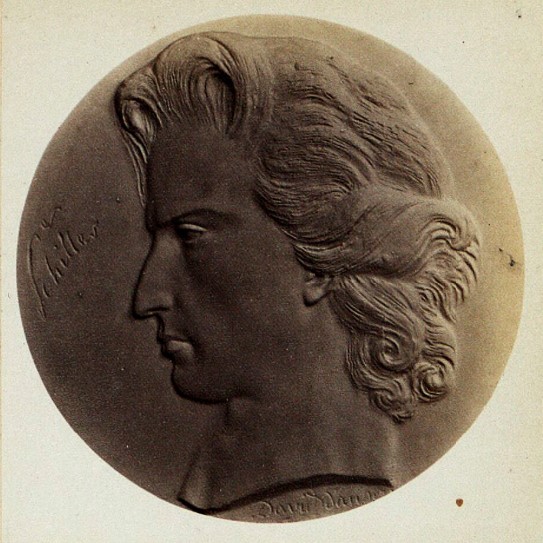

Christ among the Doctors, Ghiberti, before 1424.

Christ among the Doctors, Ghiberti, before 1424.

Then, as far as our knowledge reaches, in 1407, Brunelleschi had conducted several experiments on this question, most likely based on the ideas presented by another friend of Cusa, the Italian astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (1397-1482), in the latter’s now lost treaty Della Prospettiva. What we do know is that Brunelleschi sought above all to demonstrate that all perspective is an optical illusion.

Finally, it was in 1435, that the humanist architect Leon Baptista Alberti (1406-1472), in his treatise Della Pictura, attempted, on the basis of Donatello’s approach, to theorize single vanishing point perspective as a representation of a harmonious and unified three-dimensional space on a flat surface. Noteworthy but frustrating for us today is the fact that Alberti’s treatise doesn’t contain any illustrations.

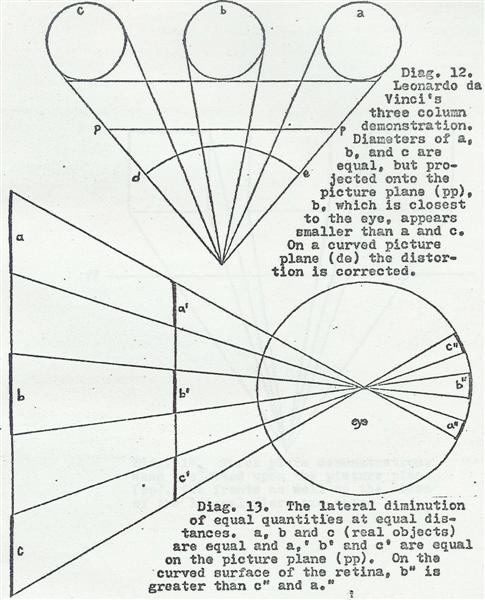

However, Leonardo, who read and studied Ghiberti’s writings on, would use the latter’s arguments to indicate the limits and even demonstrate the dysfunctionality of Alberti’s “perfect” perspective construction especially when one goes beyond a 30 degres angle.

In the Codex Madrid, II, 15 v. da Vinci realizes that « as such, the perspective offered by a rectilinear wall is false unless it is corrected (…) ».

Perspectiva artificialis versus perspectiva naturalis

Alberti’s “perspectiva artificialis” is nothing but an abstraction, necessary and useful to represent a rational organization of space. Without this abstraction, it is fairly impossible to define with mathematical precision the relationships between the appearance of objects and the receding of their various proportions on a flat screen: width, height and depth.

From the moment that a given image on a flat screen was thought about as the intersection of a plane cutting a cone or pyramid, a method emerged for what was mistakenly considered as an “objective” representation of “real” three dimensional space, though it is nothing but an “anamorphosis”, i.e. a tromp-l’oeil or visual illusion.

What has to be underscored, is that this construction does away with the physical reality of human existence since it is based on an abstract construct pretending:

- that man is a single eyed cyclops;

- that vision emanates from one single point, the apex of the visual pyramid;

- that the eye is immobile;

- that the image is projected on a flat screen rather than on a curved retina.

Slanders and gossip

The crucial role of Ghiberti, an artist which “Ghiberti expert” Richard Krautheimer mistakenly presents as a follower of Alberti’s perspectiva artificialis, has been either ignored or downplayed.

Ghiberti’s unique manuscript, the three volumes of the Commentarii, which include his autobiography and which established him as the first modern historian of the fine arts, is not even fully translated into English or French and was only published in Italian in 1998.

Today, because of his attention to minute detail and figures « sculpted » with wavy and elegant lines, as well as the variety of plants and animals depicted, Ghiberti is generally presented as “Gothic-minded”, and therefore “not really” a Renaissance artist!

Giorgio Vasari, often acting as the paid PR man of the Medici clan, slanders Ghiberti by saying he wrote « a work in the vernacular in which he treated many different topics but arranged them in such a fashion that little can be gained from reading it. »

Admittedly, tension among humanists, was not uncommon. Self-educated craftsmen, such as Ghiberti and Brunelleschi on the one side, and heirs of wealthy wool merchants, such as Niccoli on the other side, came from entirely different worlds. For example, according to a story told by Guarino Veronese in 1413, Niccoli greeted Filippo Brunelleschi haughtily: « O philosopher without books, » to which Filippo replied with his legendary irony: « O books without philosopher ».

For sure, the Commentarii, are not written according to the rhetorical rules of those days. Written at the end of Ghiberti’s life, they may have simply been dictated to a poorly trained clerk who made dozens of spelling errors.

The humanists

The Commentarii does reveal a highly educated author and a thinker having profound knowledge of many classical Greek and Arab thinkers. Ghiberti was not just some brilliant handcraft artisan but a typical “Renaissance man”.

In dialogue with Bruni, Traversari and the “manuscript hunter” Niccolo Niccoli, Ghiberti, who couldn’t read Greek but definitely knew Latin, was clearly familiar with the rediscovery of Greek and Arab science, a task undertaken by Boccaccio’s and Salutati’s “San Spirito Circle” whose guests (including Bruni, Traversari, Cusa, Niccoli, Cosimo di Medici, etc.) later would convene every week at the Santa Maria degli Angeli convent. Ghiberti exchanges moreover with Giovanni Aurispa, a collaborator of Traversari who brought back from Byzantium, years before Bessarion, the whole of Plato’s works to the West.

Amy R. Bloch, in her well researched study Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, Humanism, History, and Artistic Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance (2016), writes that « Traverari and Niccoli can be tied directly to the origins of the project for the Gates and were clearly interested in sculptural commissions being planned for the Baptistery. On June 21, 1424, after the Calima requested from Bruni his program for the doors, Traversari wrote to Niccoli acknowledging, in only general terms, Niccoli’s ideas for the stories to be included and mentioning, without evident disapproval, that the guild had instead turned to Bruni for advice. »

Palla Strozzi

Ghiberti’s patron, sometimes advisor, and close associate was Palla Strozzi (1372-1462), who, besides being the the richest man in Florence with a gross taxable assets of 162,925 florins in 1427, including 54 farms, 30 houses, a banking firm with a capital of 45,000 florins, and communal bonds, was also a politician, a writer, a philosopher and a philologist whose library contained close to 370 volumes in 1462.

Just as Traversari and Bruni, Strozzi learned Latin and studied Greek under the direction of the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras, invited to Florence by Salutati.

Ghiberti’s close relationship with Strozzi, writes Bloch, « gave him access to his manuscripts and, as importantly, to Strozzi’s knowledge of them. »

But there was more. « The relationship between Ghiberti and Palla Strozzi was so close that, when Palla went to Venice in 1424 as one of two Florentine ambassadors charged with negociating an alliance with the Venetians, Ghiberti accompanied him in his retinue. »

Strozzi was known as a real humanist, always looking to preserve peace while strongly opposing oligarchical rule, both in Florence as in Venice.

In fact it was Palla Strozzi, not Cosimo de’ Medici, who first set in motion plans for the first public library in Florence, and he intended for the sacristy of Santa Trinita to serve as its entryway. While Palla’s library was never realized due to the dramatic political conflict knows as the Albizzi Coup that led to his exile in 1434, Cosimo who got a free hand to rule over Florence, would make the library project his own.

A bold statement

Ghiberti begins the Commentarii with a bold and daring statement for a Christian man in a Christian world, about how the art of antiquity came to be lost:

The Christian faith was victorious in the time of Emperor Constantine and Pope Sylvester. Idolatry was persecuted to such an extent that all the statues and pictures of such nobility, antiquity an perfection were destroyed and broken in to pieces. And with the statues and pictures, the theoretical writings, the commentaries, the drawing and the rules for teaching such eminent and noble arts were destroyed.

Ghiberti understood the importance of multidisciplinarity for artists. According to him, “sculpture and painting are sciences of several disciplines nourished by different teachings”.

In book I of his Commentarii, Ghiberti gives a list of the 10 liberal arts that the sculptor and the painter should master : philosophy, history, grammar, arithmic, astronomy, geometry, perspective, theory of drawing, anatomy and medecine and underlines that the necessity for an artist to assist at anatomical dissections.

As Amy Bloch underscores, while working on the Gates, in the intense process of visualizing the stories of God’s formation of the world and its living inhabitants, Ghiberti’s engagement « stimulated in him an interest in exploring all types of creativity — not only that of God, but also that of nature and of humans — and led him to present in the opening panel of the Gates of Paradise (The creation of Adam and Eve) a grand vision of the emergence of divine, natural, and artistic creation. »

The inclusion of details evoking God’s craftmanship, says Bloch, « recalls similes that liken God, as the maker of the world, to an architect, or, in his role as creator of Adam, to a sculptor or painter. Teh comparison, which ultimately derives from the architect-demiurge who creates the world in Plato’s Timaeus, appears commonly in medieval Jewish and Christian exegesis. »

Philo of Alexandria wrote that man was modeled « as by a potter » and Ambrose metaphorically called God a « craftsman (artifex) and a painter (pictor) ». Consequently, if man is « the image of God » as says Augustine and the model of the « homo faber – man producer of things », then, according to Salutati, « human affairs have a similarity to divine ones ».

The power of vision and the composition of the Eye

Concerning vision, Ghiberti writes:

I, O most excellent reader, did not have to obey to money, but gave myself to the study of art, which since my childhood I have always pursued with great zeal and devotion. In order to master the basic principles I have sought to investigate the way nature functions in art; and in order that I might be able to approach her, how images come to the eye, how the power of vision functions, how visual [images] come, and in what way the theory of sculpture and painting should be established.

Now, any serious scholar, having worked through Leonardo’s Notebooks, who then reads Ghiberti’s I Commentarii, immediately realizes that most of Da Vinci’s writings were basically comments and contributions about things said or answers to issues raised by Ghiberti, especially respecting the nature of light and optics in general. Leonardo’s creative mindset was a direct outgrowth of Ghiberti’s challenging world outlook.

In Commentario 3, 6, which deals with optics, vision and perspective, Ghiberti, opposing those for whom vision can only be explained by a purely mathematical abstraction, writes that “In order that no doubt remains in the things that follow, it is necessary to consider the composition of the eye, because without this one cannot know anything about the way of seeing.” He then says, that those who write about perspective don’t take into account “the eye’s composition”, under the pretext that many authors would disagree.

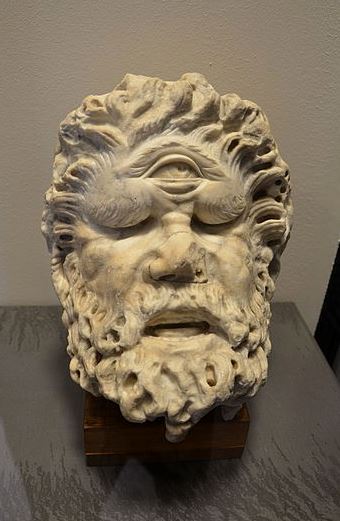

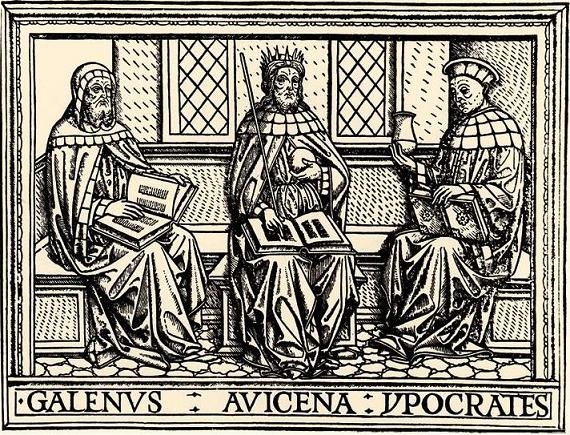

Ghiberti regrets that despite the fact that many “natural philosophers” such as Thales, Democritus, Anaxagoras and Xenophanes have examined the subject along with others devoted to human health such as “Hippocrates, Galen and Avicenna”, there is still so much confusion.

Indeed, he says, “speaking about this matter is obscure and not understood, if one does not have recourse to the laws of nature, because more fully and more copiously they demonstrate this matter.”

Avicenna, Alhazen and Constantine

Therefore, says Ghiberti:

it is necessary to affirm some things that are not included in the perspective model, because it is very difficult to ascertain these things but I will try to clarify them. In order not to deal superficially with the principles that underlie all of this, I will deal with the composition of the eye according to the writings of three authors, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), in his books, Alhazen (Ibn al Haytham) in his first volume on perspective (Optics), and Constantine (the Latin name of the Arab scholar and physician Qusta ibn Luqa) in his ‘First book on the Eye’; for these authors suffice and deal with much certainty in these subjects that are of interest to us.

This is quite a statement! Here we have “the” leading, founding figure of the Italian and European Renaissance with its great contribution of perspective, saying that to get any idea about how vision functions, one has to study three Arab scientists: Ibn Sina, Ibn al Haytham and Qusta ibn Luqa ! Cultural Eurocentrism might be one reason why Ghiberti’s writings were kept in the dark.

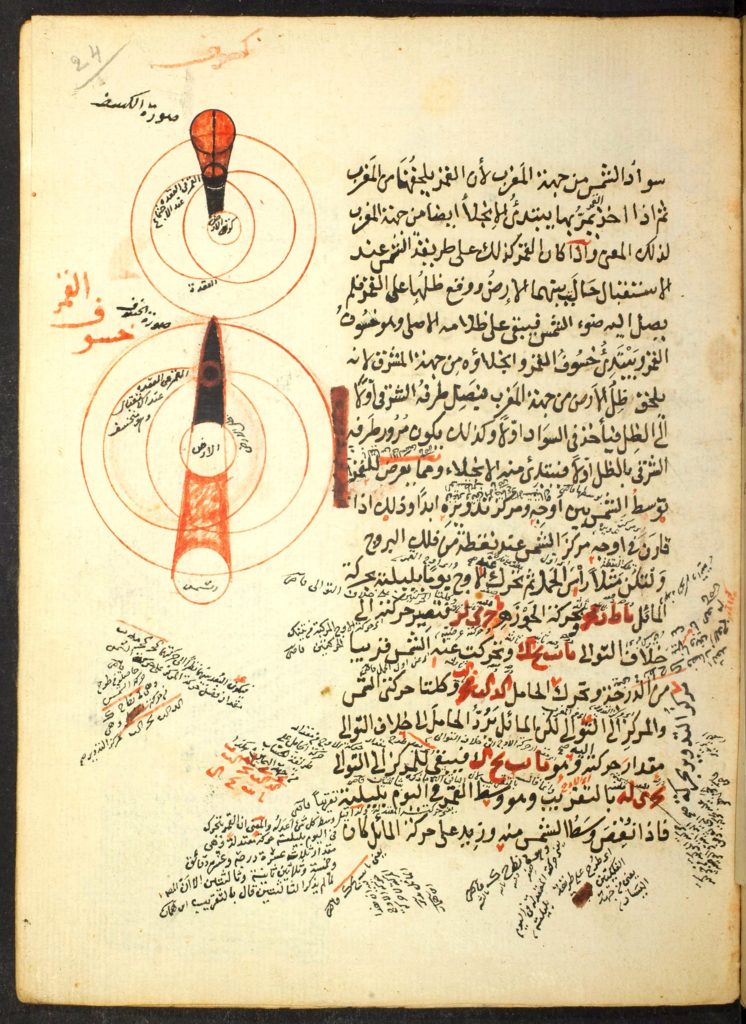

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) made important contributions to opthalmology and improved upon earlier conceptions of the processes involved in vision and visual perception in his Treatise on Optics (1021), which is known in Europe as the Opticae Thesaurus. Following his work on the camera oscura (darkroom) he was also the first to imagine that the retina (a curved surface), and not the pupil (a point) could be involved in the process of image formation.

Avicenna, in the Canon of Medicine (ca. 1025), describes sight and uses the word retina (from the Latin word rete meaning network) to designate the organ of vision.

Later, in his Colliget (medical encyclopedia), Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126-1198) was the first to attribute to the retina the properties of a photoreceptor.

Avicenna’s writings on anatomy and medical science were translated and circulating in Europe since the XIIIth century, Alhazen’s treatise on optics, which Ghiberti quotes extensively, had just been translated into Italian under the title De li Aspecti.

It is now recognized that Andrea del Verrocchio, whose best known pupil was Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1517) was himself one of Ghiberti’s pupils. Unlike Ghiberti, who mastered Latin, neither Verrocchio nor Leonardo mastered a foreign language.

What is known is that while studying Ghiberti’s Commentarii, Leonardo had access in Italian to a series of original quotations from the Roman architect Vitruvius and from Arab scientists such as Avicenna, Alhazen, Averroes and from those European scientists who studied Arab optics, notably the Oxford Fransciscans Roger Bacon (1214-1294), John Pecham (1230-1292) and the Polish monk working in Padua, Erazmus Ciolek Witelo (1230-1275), known by his Latin name Vitellion.

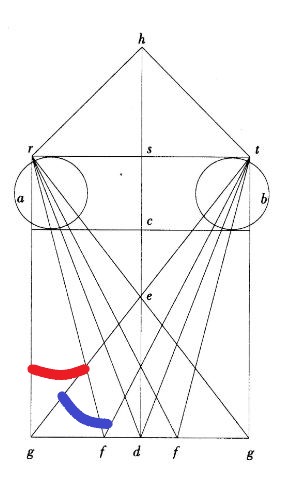

As stressed by Professor Dominque Raynaud, Vitellion introduces the principle of binocular vision for geometric considerations.

He gives a figure where we see the two eyes (a, b) receiving the images of points located at equal distance from the hd axis.

He explains that the images received by the eyes are different, since, taken from the same side, the angle grf (in red) is larger than the angle gtf (in blue). It is necessary that these two images are united at a certain point in one image (Diagram).

Where does this junction occur? Witelo says: « The two forms, which penetrate in two homologous points of the surface of the two eyes, arrive at the same point of the concavity of the common nerve, and are superimposed in this point to become one ».

The fusion of the images is thus a product of the internal mental and nervous activity.

The great astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) will use Alhazen’s and Witelo’s discoveries to develop his own contribution to optics and perspective. “Although up to now the [visual] image has been [understood as] a construct of reason,” Kepler observes in the fifth chapter of his Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena (1604), “henceforth the representations of objects should be considered as paintings that are actually projected on paper or some other screen.” Kepler was the first to observe that our retina captures an image in an inverted form before our brain turns it right side up.

Out of this Ghiberti, Uccello and also the Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck, in contact with the Italians, will construct as an alternative to one cyclopic single eye perspective revolutionary forms of “binocular” perspective while Leonardo and Louis XI’ court painter Jean Fouquet will attempt to develop curvilinear and spherical space representations.

In China, eventually influenced by Arab optical science breakthrough’s, forms of non-linear perspective, that integrate the mobility of the eye, will also make their appearance during the Song Dynasty.

Light

Ghiberti will add another dimension to perspective: light. One major contribution of Alhazen was his affirmation, in his Book of Optics, that opaque objects struck with light become luminous bodies themselves and can radiate secondary light, a theory that Leonardo will exploit in his paintings, including in his portraits.

Already Ghiberti, in the way he treats the subject of Isaac, Jacob and Esau (Figure), gives us an astonishing demonstration of how one can exploit that physical principle theorized by Alhazen. The light reflected by the bronze panel, will strongly differ according to the angle of incidence of the arriving rays of light. Arriving either from the left of from the right side, in both cases, the Ghiberti’s bronze relief has been modeled in such a way that it magnificently strengthens the overall depth effect !

While the experts, especially the neo-Kantians such as Erwin Panofsky or Hans Belting, say that these artists were “primitives” because applying the “wrong” perspective model, they can’t grasp the fact that they were in reality exploring a far “higher domain” than the mere pure mathematical abstraction promoted by the Newton-Galileo cult that became the modern priesthood ruling over “science”.

Much more about all of this can and should be said. Today, the best way to pay off the European debt to “Arab” scientific contributions, is to reward not just the Arab world but all future generations with a better future by opening to them the “Gates of Paradise”.

See all of Ghiberti’s works at the WEB GALLERY OF ART

Short Biography

- Arasse, Daniel, Léonard de Vinci, Hazan, 2011;

- Avery, Charles, La sculpture florentine de la Renaissance, Livre de poche, 1996, Paris;

- Belting, Hans, Florence & Baghdad, Renaissance art and Arab science, Harvard University Press, 2011;

- Bloch, Amy R., Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise; Humanism, History and Artistic Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance, Cambridge University Press, 2016, New York;

- Borso, Franco et Stefano, Uccello, Hazan, Paris, 2004 ;

- Butterfield, Andrew, Verrocchio, Sculptor and painter of Renaissance Florence, National Gallery, Princeton University Press, 2020 ;

- Butterfield, Andrew, Art and Innovation in Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, High Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2007;

- Kepler, Johannes, Paralipomènes à Vitellion, 1604, Vrin, 1980, Paris;

- Krautheimer, Richard and Trude, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1990;

- Martens, Maximiliaan, La révolution optique de Jan van Eyck, dans Van Eyck, Une révolution optique, Hannibal – MSK Gent, 2020.

- Pope-Hennessy, John, Donatello, Abbeville Press, 1993 ;

- Radke, Gary M., Lorenzo Ghiberti: Master Collaborator; The Gates of Paradise, Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Renaissance Masterpiece, High Museum of Atlanta and Yale University Press, 2007;

- Rashed, Roshi, Geometric Optics, in History of Arab Sciences, edited by Roshdi Rashed, Vol. 2, Mathematics and physics, Seuil, Paris, 1997.

- Raynaud, Dominique, L’hypothèse d’Oxford, essai sur les origines de la perspective, PUF, 1998, Paris.

- Raynaud, Dominique, Ibn al-Haytham on binocular vision: a precursor of physiological optics, Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2003, 13, pp. 79-99.

- Raynaud, Dominique, Perspective curviligne et vision binoculaire. Sciences et techniques en perspective, Université de Nantes, Equipe de recherche: Sciences, Techniques, et Sociétés, 1998, 2 (1), pp.3-23.;

- Vereycken, Karel, interview with People’s Daily: Leonardo Da Vinci’s « Mona Lisa » resonates with time and space with traditional Chinese painting, 2019.

- Vereycken, Karel, Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio and the art of military command, 2022.

- Vereycken, Karel, The Invention of Perspective, Fidelio, 1998.

- Vereycken, Karel, Van Eyck, un peintre flamand dans l’optique arabe, 1998.

- Vereycken, Karel, Mutazilism and Arab astronomy, two bright stars in our firmament, 2021.

- Walker, Paul Robert, The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance, How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti changed the World, HarperCollins, 2002.

Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio and the art of military command

Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio and the art of military command. An inquiry into the key events and artistic achievements that created the Renaissance. By Karel Vereycken, Paris.

Prologue

If there is still a lot to say, write and learn about the great geniuses of the European Renaissance, it is also time to take an interest in those whom the historian Georgio Vasari condescendingly called « transitional figures ».

How can one measure the contributions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder without knowing Pieter Coecke van Aelst? How can we value Rembrandt’s work without knowing Pieter Lastman? How did Raphaelo Sanzio innovate in relation to his master Perugino?

In 2019, an exceptional exhibition on Andrea Del Verrocchio (1435-1488), at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., highlighted his great achievements, truly inspiring outbursts of great beauty that his pupil Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) would theorize and put to his greatest advantage.

The sfumato of Leonardo ? Verrochio is the pioneer, especially in the blurred features of portraits of women made with mixed techniques (pencil, chalk and gouache).

The joy of discovery

Leafing through the catalog of this exhibition, my joy got immense when I discovered (and to my knowledgne nobody else seems to have made this observation before me) that the enigmatic angel the viewer’s eye meets in Leonardo’s painting titled The Virgin on the Rocks (1483-1486) (Louvre, Paris), besides the movement of the body, is grosso modo a visual “quote” of the image of a terra cotta high relief (Louvre, Paris) attributed to Verrochio and “one of his assistants”, possibly even Leonardo himself, since the latter was training with the master as early as age seventeen ! The finesse of its execution and drapery also reminds us of the only known statue of Da Vinci, The Virgin with the laughing Child.

Many others made their beginnings in Verrocchio’s workshop, notably Lorenzo de Credi, Sandro Botticelli, Piero Perugino (Raphael’s teacher) and Domenico Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s teacher).

Coming out of the tradition of the great building sites launched in Florence by the great patron of the Renaissance, Cosimo de Medici for the realization of the doors of the Baptistery and the completion of the dome of Florence by Philippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), Verrocchio conceived his studio as a true “polytechnic” school.

In Florence, for the artists, the orders flowed in. In order to be able to respond to all requests, Verrocchio, initially trained as a goldsmith, trained his students as craftsman-engineer-artists: drawing, calculation, interior decoration, sculpture, geology, anatomy, metal and woodworking, perspective, architecture, poetry, music and painting. A level of freedom and a demand for creativity that has unfortunately long since disappeared.

The Ghiberti legacy

In painting, Verrocchio is said to have begun with the painter Fra Filippo Lippi (1406-1469). As for the bronze casting trade, he would have been, like Donatello, Masolino, Michelozzo, Uccello and Pollaiuolo, one of the apprentices recruited by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455) whose workshop, starting from 1401, over forty years, will be in charge of casting the bronze bas-reliefs of two of the huge doors of the Baptistery of Florence.

Others suggest that Verrocchio was most likely trained by Michelozzo, the former companion of Ghiberti who said up shop with Donatello. As a teenager, Donatello had accompanied Brunelleschi on their joint expeditions to Rome to investigate the legacy of Greek and Roman art, and not only the architectural legacy.

In reality, Verrocchio only perpetuated and developed the model of Ghiberti’s « polytechnic » studio, where he learned the art. An excellent craftsman, Ghiberti was also goldsmith, art collector, musician and humanist scolar and historian.

His genius is to have understood the importance of multidisciplinarity for artists. According to him « sculpture and painting are sciences of several disciplines nourished by different teachings ».

The ten disciplines that he considered important to train artists are grammar, philosophy, history, followed by perspective, geometry, drawing, astronomy, arithmetic, medicine and anatomy.

You can discover, says Ghiberti, only when you managed to isolate the object of your research from interfering factors, and you can discover by detaching oneself from a dogmatic system;

as the nature of things want it, the sciences hidden under artifices are not constituted so that the men with narrow chests can judge them.

Anticipating the type of biomimicry that will characterize Leonardo thereafter, Ghiberti affirms that he sought:

to discover how nature functioned and how he could approach it to know how the objects come to the eye, how the sight functions and in which way one has to practice sculpture and painting.

Ghiberti, who was familiar with some of the leading members of the circle of humanists led by Salutati and Traversari, based his own reflexions on optics on the authority of ancient texts, especially Arabic. He wrote:

But in order not to repeat in a superficial and superfluous way the principles that found all opinions, I will treat the composition of the eye particularly according to the opinions of three authors, namely Avicenna [Ibn Sina], in his books, Alhazen [Ibn al Haytam], in the first book of his perspective, and Constantine [Qusta ibn Luqa] in the first book on the eye; for these authors are sufficient and treat with more certainty the things that interest us.

Deliberately ignored (but copied) by Vasari, Ghiberti’s Commentaries are a real manuel for artists, written by an artist. Most interestingly, it is by reading Ghiberti’s Commentaries that Leonardo da Vinci became familiar with important Arab contributions to science, in particular the outstanding work of Ibn al Haytam (Alhazen) whose treatise on optics had just been translated from Latin into Italian under the title De li Aspecti, and is quoted at length by Ghiberti in his Commentario Terzio. Author A. Mark Smith suggests that, through Ghiberti, Alhazen’s Book of Optics

may well have played a central role in the development of artificial perspective in early Renaissance Italian painting.

Ghiberti’s comments are not extensive. However, for the pupils of his pupil Verrocchio, such as Leonardo, who didn’t command any foreign language, Ghiberti’s book did make available in italian a series of original quotes from the roman architect Vitruvius, arab scientists such as Alhazen), Avicenna, Averroes and those european scientists having studied arab optics, notably the Oxford fransciscans Roger Bacon, John Pecham and the Polish monk working in Padua, Witelo.

Finally, in 1412, Ghiberti, while busy coordinating all the works on the Gates of the Baptistry, was also the first Renaissance sculptor to cast a life-size statue in bronze, his Saint John the Baptist, to decorate Orsanmichele, the house of the Corporations in Florence.

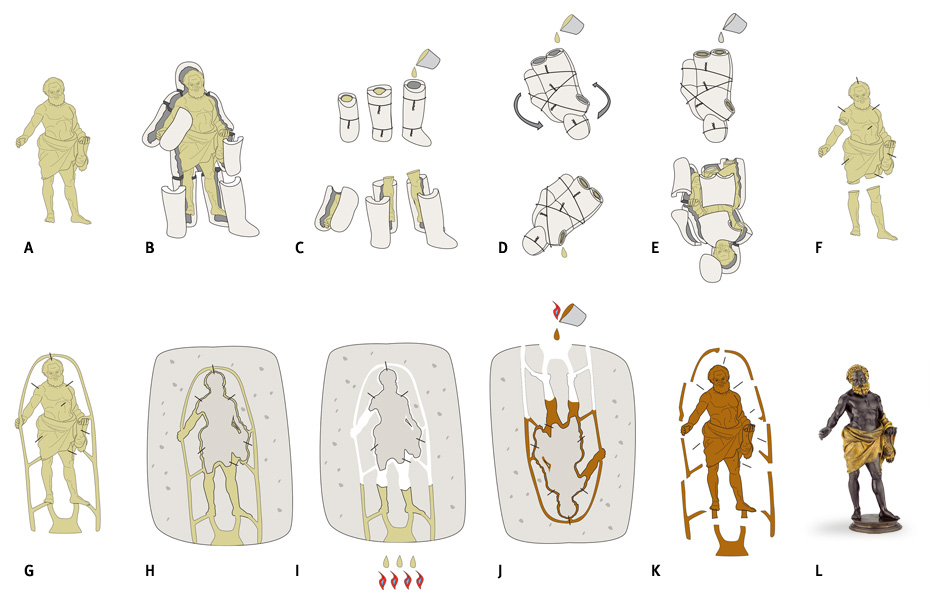

Lost wax casting

However, in order to cast bronzes of such a size, the artists, considering the price of metal, would use the technique known as “lost wax casting”.

This technique consists of first making a model in refractory clay (A), covered with a thickness of wax corresponding to the thickness of the bronze thought necessary.

The model is then covered with a thick layer of wet plaster (B) which, as it solidifies, forms an outer mold. Finally, the very hot molten bronze, pored into the mold it penetrates by rods (J) provided for this purpose, will replace the wax.

Finally, once the metal has solidified, the coating is broken. The details of the bronze (K) are then adjusted and polished (L) according to the artist’s choice.

This technique would become crucial for the manufacture of bells and cannons. While it was commonly used in Ifé in Africa in the 12th century for statuary, in Europe it was only during the Renaissance, with the orders received by Ghiberti and Donatello, that it was entirely reinvented.

In 1466, after the death of Donatello, it was Verrocchio’s turn to become the Medici’s sculptor in title for whom he produced a whole series of works, notably, after Donatello, his own David in bronze (Bargello National Museum, Florence).

If with this promotion his social ascendancy is certain, Verrocchio found himself facing the greatest challenge that any artist of the Renaissance could have imagined: how to equal or even surpass Donatello, an artist whose genius has never been praised enough?

Equestrian art

This being said, let us now approach the subject of the art of military command by comparing four equestrian monuments:

- Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius on the Capitoline square in Rome (175 AD) ;

- Paolo Uccello’s fresco of John Hawkwood in the church of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (1436);

- Erasmo da Narni, known as “Gattamelata” (1446-1450), casted by Donatello in Padua.

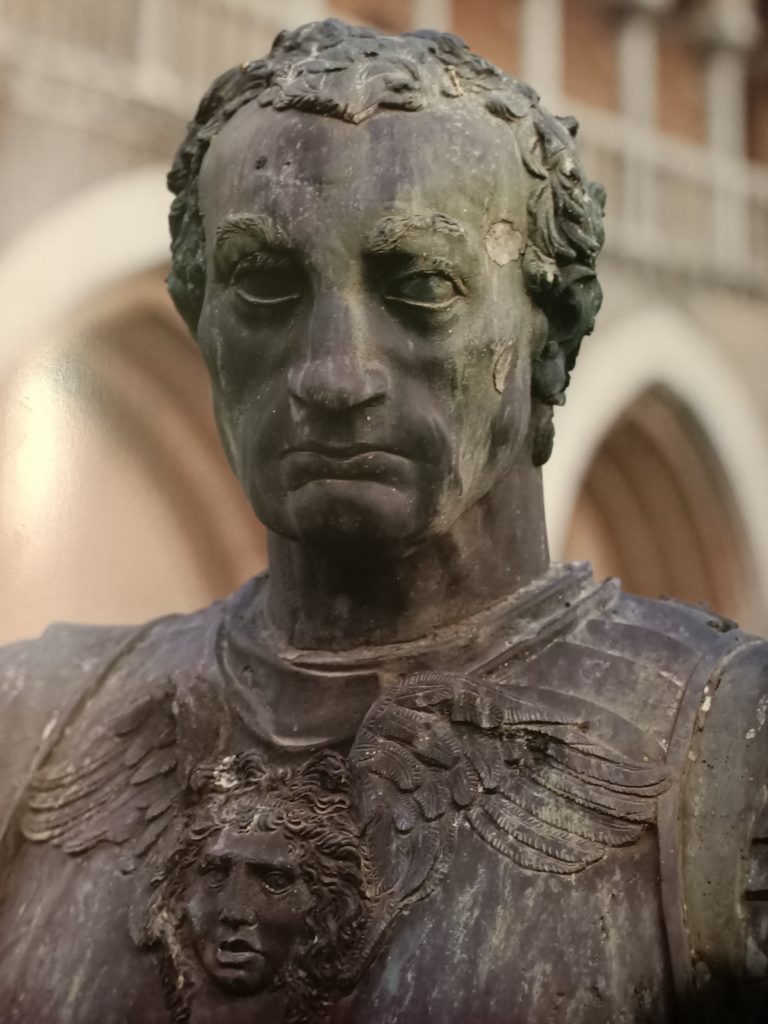

- Bartolomeo Colleoni by Andrea del Verrocchio in Venice (1480-1488).

Equestrian statues appeared in Greece in the middle of the 6th century B.C. to honor the victorious riders in a race. From the Hellenistic period onward, they were reserved for the highest state figures, sovereigns, victorious generals and magistrates. In Rome, on the forum, they constituted a supreme honor, subject to the approval of the Senate. Apart from being bronze equestrian statues, each one is placed in a place where their troops fought.

While each statue is a reminder of the importance of military and political command, the way in which this responsibility is exercised is quite different.

Marcus Aurelius in Rome

Marcus Aurelius was born in Rome in 121 A.D., into a noble family of Spanish origin. He was the nephew of the emperor Hadrian. After the death of Marcus Aurelius’ father, Hadrian entrusted him to his successor Antonin. The latter adopts and gives him an excellent education. He was initiated early in philosophy by his master Diognetus.

Interested in the stoics, he adopted for a while their lifestyle, sleeping on the ground, wearing a rough tunic, before he was dissuaded by his mother.

He went to Athens in 175 A.D. and became a promotor of philosophy. He helps financially the philosophers and the rhetoricians by granting them a fixed salary. Concerned with pluralism, he supported the Platonic Academy, the Lyceum of Aristotle, the Garden of Epicurus and the Stoic Portico.

On the other hand, during his reign, persecutions against Christians were numerous. He saw them as troublemakers – since they refused to recognize the Roman gods, and as fanatics.

Erected in 175 A.D., the statue was entirely gilded. Its location in antiquity is unknown, but in the Middle Ages it stood in front of the Basilica of St. John Lateran, founded by Constantine, and the Lateran Palace, then the papal residence.

In 1538, Pope Paul III had the monument of Marcus Aurelius transferred to the Capitol, the seat of the city’s government. Michelangelo restored the statue and redesigned the square around it, one of the fanciest in Rome. It is undoubtedly the most famous equestrian statue, and above all the only one dating back to ancient Rome that has survived, the others having been melted down into coins or weapons…

If the statue survived, it is thanks to a misunderstanding: it was thought that it represented Constantine, the first Roman emperor to have converted to Christianity at the beginning of the 4th century, and it was out of the question to destroy the image of a Christian ruler.

Neither the date nor the circumstances of the commission are known.

But the presence of a defeated enemy under the right foreleg of the horse (attested by medieval testimonies and since lost), the emperor’s gesture and the shape of the saddle cloth, unusual in the Roman world, make us to belief that the statue commemorated Marcus Aurelius’ victories, perhaps on the occasion of his triumph in Rome in 176, or even after his death. Indeed, his reign (161-180) was marked by incessant wars to counter the incursions of Germanic or Eastern peoples on the borders of an Empire that was now threatened and on the defensive.

The horse, while not that large, but looking powerful, has been sculpted with great care and represented with realism. Its nostrils are strongly dilated, its lips pulled by the bit reveal its teeth and tongue.

One leg raised, he has just been stopped by his rider, who holds the reins with his left hand. Like him, the horse turns his head slightly to the right, a sign that the statue was made to be seen from that side. Part of his harness is preserved, but the reins have disappeared.

The size of the athletic rider nevertheless dominates that of a powerful horse that he rides without stirrups (accessories unknown to the Romans). He is dressed in a short tunic belted at the waist and a ceremonial cloak stapled on the right shoulder. It is a civil and not a military garment, adapted to a peaceful context. He is wearing leather shoes held together by intertwined straps.

The statue is striking for its size (424 cm high) and for the majesty it exudes. Without armor or weapons, eyes wide open and without emotion, the emperor raises his right arm. His authority derives above all from the function he embodies: he is the Emperor who protects his Empire and his people by punishing their enemies without mercy.

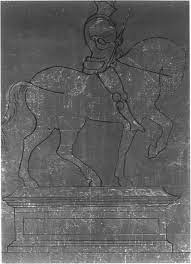

The fresco by Paolo Uccello

In 1436, at the request of Cosimo de’ Medici, the young Paolo Uccello was commissioned to paint a fresco depicting John Hawkwood (1323-1394), the son of an English tanner who had become a warlord during the Hundred Years’ War in France and whose name would be Italicized into Giovanno Acuto.

Serving the highest bidder, especially rival Italian cities, Hawkwood’s company of mercenaries was no slouch.

In Florence, although it may seem paradoxical, it was the humanist chancellor Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406) who put Hawkwood at the head of a regular army in the service of the Signoria.

This approach is not unlike that of Louis XI in France, who, in order to control the skinners and other cutthroats who were ravaging the nation, did not hesitate to discipline them by incorporating them into a standing army, the new royal army.

The humanists of the Renaissance, notably Leonardo Bruni (1370-1440) in his De Militia (1420), became aware of the curse of using mercenaries in conflicts and of the fact that only standing army, i.e. a permanent army formed of professionals and even better by citizens and maintained by a state or a city could guarantee a lasting peace.

Although Hawkwood faithfully protected the city for 18 years, his ugly “professionalism” as a mercenary was not unanimously accepted, to the point of inspiring the proverb “Inglese italianato è un diavolo Incarnato” (« An Italianized Englishman is a devil incarnate »).

Petrarch denounced him, Boccaccio tried in vain to mount a diplomatic offensive against him, St. Catherine of Sienna begged him to leave Italy, Chaucer met him and, no doubt, used him as a model for The Knight’s Tale (The Canterbury Tales).

All this will not prevent Cosimo, a member of the humanist conspiracy and a great patron of the arts, returning from exile, from wanting to honor him. But in the absence of the bronze equestrian statue (which had been promised to him…), Florence, will only offer him a fresco in the nave of Santa Maria del Fiore, that is to say under right under the cupola of the Duomo.

From the very beginning, Paolo Uccello’s fresco seems to have stirred quite a controversy. A preparatory drawing in the collections of Florence’s Uffizi Museum indicates the commander, more armed, taller, and, with his horse in a more military position. Uccello had originally depicted Hawkwood as « more threatening », with his baton raised and horse « at the ready ».

A recent ultraviolet study confirms the fact that the painter had originally depicted the condottiere armed from head to toe. In the final version, he wears a sleeveless jacket, the giornea, and a coat; only his legs and feet are protected by a piece of armor. The final version presents a less imposing rider, less warlike, more human and more individualized

In the dispute, it was not Uccello who was considered faulty, but his sponsors. Moreover, the painter was quickly given the task of redoing the fresco in a way deemed “more appropriate”.

Unfortunately, there is no record of the debates that must have raged among the officials of the church fabric (Opera Del Domo). What is certain is the fact that in the final version, visible today, the condottiere has been transformed from a warlord running a gang of mercenaries, into the image of philosopher-king whose only weapon is his commanding staff. At the bottom of the fresco, we can read in Latin: “Giovanno Acuto, British knight, who was in his time held as a very prudent general and very expert in military affairs.”

The position of the horse and the perspective of the sarcophagus have been changed from a simple profile to a di sotto in su view.

If this perspective is somewhat surrealistic and the pose of the horse, raising both legs on the same side, simply impossible, it remains a fact that Uccello’s fresco will set “the standards” of the ideal and impassive image of virtue and command that must embody the hero of the Renaissance: his goal is no longer to “win” a war (the objective of the mercenary), but to preserve the peace by preventing it (the objective of a philosopher-king or simply a wise head of state).

Paradigm shift

As such, one might say that Uccello’s fresco announces the “paradigm shift” marking the end of the age of perpetual feudal wars, to that of the Renaissance, that is to say to that of a necessary concord between sovereign nation-states whose security is indivisible, the security of one being the guarantee of the security of the other, a paradigm even more rigorously defined in 1648 at the Peace of Westphalia, when it made the agapic notion of the “advantage of the other” the basis of its success.

One historian suggests that the recommissioning of Uccello’s fresco was part of the « refurbishing » of the cathedral associated with its rededication as Santa Maria del Fiore by the humanist Pope Eugene IV in March 1436, determined to convince the Eastern and Western Churches to peacefully overcome their divisions and réunite as was attempted at the Council of Florence of 1437-1438 and for which the Duomo was central.

Interesting is the fact that Uccello’s fresco appeared at around the same time that Yolande d’Aragon and Jacques Coeur, who had his Italian connections, persuaded the French king Charles VII to put an end to the Hundred Years’ War by setting up a permanent, standing army.

In 1445, an ordinance was passed to discipline and rationalize the army in the form of cavalry units grouped into Compagnies d’Ordonnances, the first permanent army at the disposal, not of warlords or aristocrats, but of the King of France.

Donatello’s “Gattamelata” (1447-1453)

It was only some years later, in Padua, between 1447 and 1453, that Donatello would work on the statue of Erasmo da Narni (1370-1443), a Renaissance condottiere, i.e. the leader of a professional army in the service of the Republic of Venice, which at the time ruled the city of Padua. An important detail is that Erasmo was nicknamed “il Gattamelata”.

In French, « faire la chattemite » means to affect a false air of sweetness to deceive or seduce… Others explain that his nickname of “honeyed cat” comes from the fact that his mother was called Melania Gattelli or that he wore a crest (a helmet) in the shape of a honey-colored cat in battle…

The man was of humble origin, the son of a baker, born in Umbria around 1370. He learned to handle weapons from Ceccolo Broglio, lord of Assisi, and then, when he was in his thirties, from the captains of Braccio da Montone, who was known for recruiting the best fighters.

In 1427, Erasmo, who had the confidence of Cosimo de’ Medici, signed a seven-year contract with the humanist Pope Martin V, who wished to strengthen an army corps loyal to his cause with the aim of bringing to heel the lords of Emilia, Romagna and Umbria who were rebellious against papal authority.

He bought a huge suit of armor to reinforce his high stature. He was not an impetuous fighter, but a master of siege warfare, which forced him to take slow, thoughtful and progressive action. He spied on his prey for a long time before trapping it.

In 1432, he captured the fortress of Villafranca near Imola by cunning alone and without fighting. The following year he did the same to capture the fortified town of Castelfranco, thus sparing his soldiers and his treasure.

Those who were unable to grasp his tactics, accused him of being a coward for “running away” from the front-line, not realizing, that on a given moment, this was part of the tactics of his winning strategy.

He was a prudent captain, with a very well-mannered troop, and he was careful to maintain good relations with the magistrates of the towns that employed him. He obtained the rank of captain-general of the army of the Republic of Venice during the fourth war against the Duke of Milan in 1438 and died in Padua in 1443. Following his death, the Venetian Republic gave him full honors and Giacoma della Leonessa, his widow, commissioned a sculpture in honor of her late husband for 1650 ducats.

The statue, which represents the life-size condottiere, in antique-style armor and bareheaded, holding his commanding staff in his raised right hand, on his horse, was made by the lost-wax method. As early as 1447, Donatello made the models for the casting of the horse and the condottiere. The work progresses at full speed and the work is completed in 1453 and placed on its pedestal in the cemetery that adjoins the Basilica of Padua.

Brilliant for his cunning and guile, Gattamelata was a thoughtful and effective fighter in action, the type of leader recommended by Machiavelli in The Prince, and which appears in the sixteenth century by François Rabelais in his account of the “Picrocholine wars”.

Not the brute power of weapons, but the cunning and the intelligence will be the major qualities that Donatello will make appear powerfully in his work.

Contrary to Marcus Aurelius, it is not his social status that gives the commander his authority, but his intelligence and his creativity in the government of the city and the art of war. Donatello had an eye for detail. Looking at the horse, we see that it is a massive animal but far from static. It has a slow and determined gait, without any hesitation.

But that’s not all. A rigorous analysis shows that the proportions of the horse are of a “higher order” than those of the condottiere. Did Donatello make a mistake and make Erasmo too small and the horse too large? No, the sculptor made this choice to emphasize the value of Gattamelata who, thanks to his skills, is able to tame even wild and gigantic animals. In addition, the horse’s eyes show him as wild and untameable. Looking at him, one could say that it is impossible to ride him, but Gattamelata manages it with ease and without effort.

Because if you look at the reins in the hands of the protagonist, you will notice that he holds them in complete tranquility. This is another detail that highlights Erasmus’ powerful cunning and ingenuity.

Next, did you notice that one of the horse’s legs rests on a sphere? If this sphere (which could also be a cannonball, since Erasmus was a warrior) serves to give stability to Donatello’s composition as a whole, it also indicates how this animal of gigantic strength (symbolizing here warlike violence), once tamed and well used, allows the globe (the earthly kingdom) to be kept in balance.

Having told you about the horse, it is time to know more about the condottiere.

He has a proud and determined expression. The baton of command, which he holds in his hand, delicately touches the horse’s mane. The baton is not just a symbolic object; he may have received it in 1438 from the Republic of Venice.

Unlike Uccello’s fresco, Gattamelata is not dressed as a contemporary prince of commander, but as a figure beyond time embodying both the past, the present and the future. To capture this, Donatello, who takes care of every detail, has taken an ancient model and modernized it with incredible results. The details of the protagonist’s armor include purely classical motifs such as the head of Medusa, taken from Marcus Aurelius, in Greek mythology one of the three gorgons whose eyes had the power to petrify any mortal who crossed her gaze.

Although the helmet of Gattamelata would have allowed to identify him at eyesight, Donatello has discarded this option. With a helmet on his head, he would have been the symbol of a bloodthirsty warrior, rather than a cunning man. Even better, the absence of a helmet allows the artist to show us a fearless commander whose fixed gaze shows his determination. With the figure slightly bowed and legs extended, the sword in its scabbard placed at an angle, Donatello gives the illusion of an “imbalance” that reinforces in the viewer’s mind the idea that the horse is advancing with full strength.

Art historian John Pope-Hennessy is emphatic:

The fundamental differences between the Gattamelata and Marcus Aurelius are obvious. The (roman) emperor sits passively on his horse, legs dangling. In the fifteenth century, on the other hand, the art of riding implies the use of spurs. The impression of authority that emanates from the monument designed by Donatello comes from the total domination of the condottiere over his horse. (…) The soles of the feet are exactly parallel to the surface of the pedestal, as are the large six-pointed spurs, stretched to the middle of the animal’s flank.

As a result, Gattamelata is not a remake of the “classical Greek or Roman sculpture” of a hero with a sculpted physique, but a kind of new man who succeeds through reason. The fact that the statue has such a high pedestal also has its reason. Placed at such a height, the Gattamelata does not “share” our own space. It is in another dimension, eternal and out of time.

Verrocchio’s Colleoni

Some thirty years later, between 1480 and 1488, Andrea del Verrocchio, after a contest, was selected to make a large bronze equestrian statue of another Italian condottiere named Bartolomeo Colleoni (1400-1475).

A ruthless mercenary, working for a patron one day and his rival the next day, he served from 1454 the Republic of Venice with the title of general-in-chief (capitano generale). He died in 1475 leaving a will in which he bequeathed part of his fortune to Venice in exchange for the commitment to erect a bronze statue to his honor in St. Mark’s Square.

The Venetian Senate agreed to erect an equestrian monument to his memory, while charging the costs to the widow of the deceased…

In addition, the Senate refused to erect it in St. Mark’s Square, which was, along with St. Mark’s Basilica, at the heart of the city’s life. The Senate therefore decided to interpret the conditions set by Colleoni in his last will and testament without contradicting them, choosing to erect his statue in 1479, not in St. Mark’s Square, but in an area further from the city center in front of the Scuola San Marco, on the campo dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Although Verrocchio had started working on the project since 1482, it remained unfinished at his death in 1488. And it is, not as Verrocchio wished, his heir Lorenzo di Credi who will cast the statue, but the Venetian Alessandro Leopardi (who lost the contest to Verrocchio), who will not hesitate to sign it!

If the horse is in conformity with the typology of the magnificent horses composing the quadriga overseeing the Basilica of Saint Mark of Venice (Greek statuary of the IVth century BC brought back by the crusaders from Constantinople to Venice in 1204) and of the horse of Marcus Aurelius, its musculature is more nervously underlined and traced. Objectively, this statue is ideally more proportionate. There is also more fine detail, a result of new pre-sculpture techniques, making the work captivating and realistic to look at.

The sculpture overflows its pedestal. According to André Suarès quoted in The Majesty of Centaurs:

Colleone on horseback walks in the air, he will not fall. He cannot fall. He leads his earth with him. His base follows him […] He has all the strength and all the calm. Marcus Aurelius, in Rome, is too peaceful. He does not speak and does not command. Colleone is the order of the force, on horseback. The force is right, the man is accomplished. He goes a magnificent amble. His strong beast, with the fine head, is a battle horse; he does not run, but neither slow nor hasty, this nervous step ignores the fatigue. The condottiere is one with the glorious animal: he is the hero in arms.

His baton of command is even metamorphosed into a bludgeon! But since it is not Verrocchio who finished this work, let us not blame the latter for the warlike fury that emanates from this statue.

Venice, a vicious slave-trading financial and maritime Empire fronting as a “Republic”, clearly took its revenge here on the beautiful conception developed during the Renaissance of a philosopher-king defending the nation-state.

On the aesthetic level, this mercenary smells like an animal. As a good observer, Leonardo warned us: when an artist represents a man entirely imprisoned by a single emotion (joy, rage, sadness, etc.), he ends up painting something that takes us away from the truly human soul. This is what we see in this equestrian statue.

If, on the contrary, the artist shows several emotions running through the figure represented, the human aspect will be emphasized. This is the case, as we have seen, with Donatello’s Gattamelata, uniting cunning, determination and prudence to overcome fear the face of threat.

Leonardo’s own, gigantic project to erect a gigantic bronze horse, on which he worked for years and developed new bronze casting techniques, unfortunately was never build, seen the hectic circumstances.

Finally, beyond all the interpretations, let us admire the admirable know-how of these artists. In terms of craft and skill, it generally took an entire life to become able to realize such great works, not even mentioning the patience and boundless passion required.

Up to us to bring it back to life !

Bibliography:

- Verrocchio, Sculptor and Painter of Renaissance Florence, Andrew Butterfield, National Gallery, Princeton University Press, 2020;

- Donatello, John Pope-Hennessy, Abbeville Press, 1993;

- Uccello, Franco and Stefano Borsi, Hazan, 2004;

- Les Commentaires de Lorenzo Ghiberti dans la culture florentine du Quattrocento, Pascal Dubourg-Glatigny, Histoire de l’Art, N° 23, 1993, Varia, pp. 15-26;

- Monumento Equestre al Gattamelata di Donatello: la Statua del Guerriero Astuto, blog de Dario Mastromattei, mars 2020;

- La sculpture florentine de la Renaissance, Charles Avery, Livre de poche, 1996 ;

- La sculpture de la Renaissance au XXe siècle, Taschen, 1999;

- Ateliers de la Renaissance, Zodiaque-Desclée de Brouwer, 1998;

- Rabelais et l’art de la guerre, Christine Bierre, 2007.

- The Greek language project, Plato and the Renaissance, Karel Vereycken, jan. 2021.